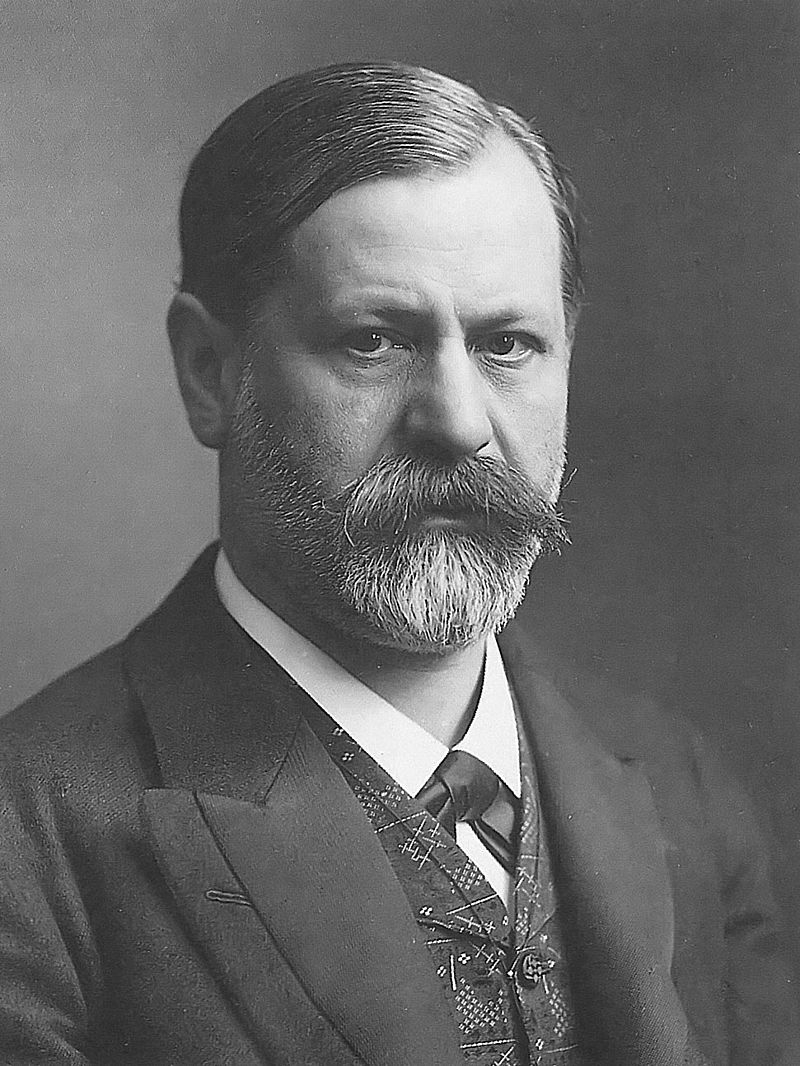

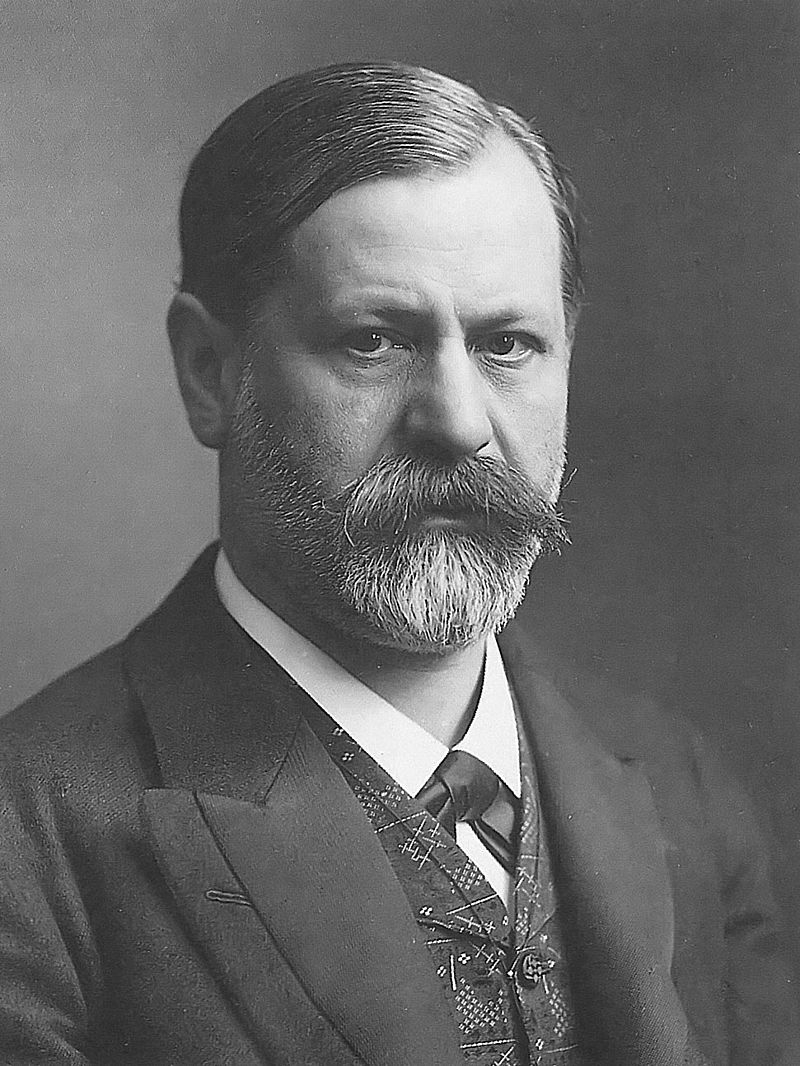

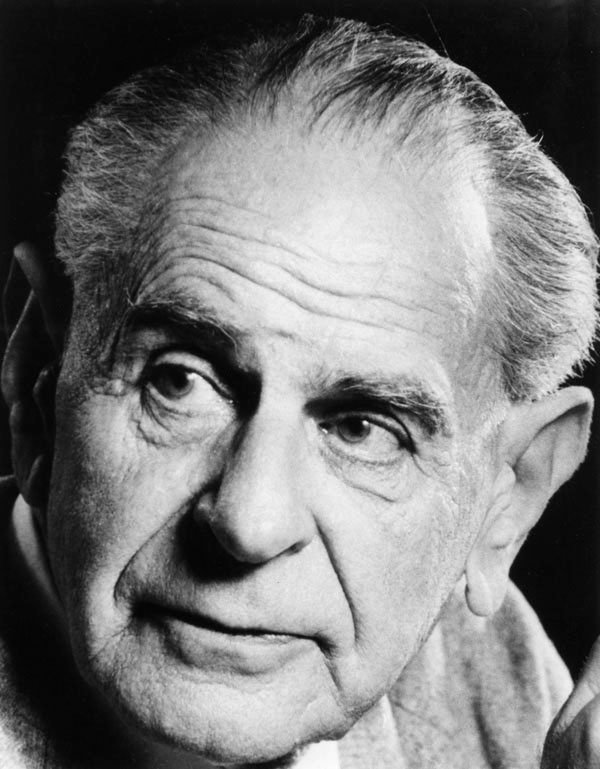

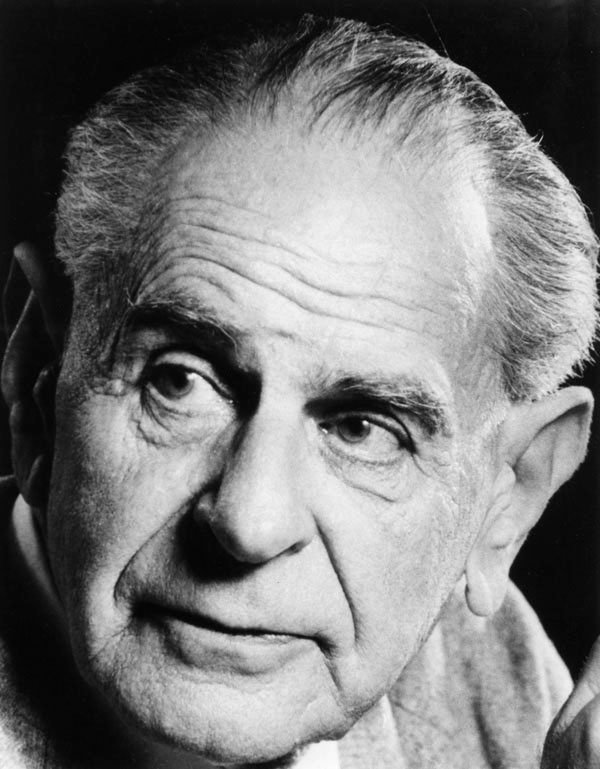

ジークムント・フロイト

ジークムント・フロイト

このページは、ジークム ント・フロイト(Sigmund Freud, 1856-1939)におけるさまざまな理論図式を理解するために、まず「フロイトの生涯」 を理解するためのページです。

ジークムント・フロイト(/frɔɪ FROYD、ドイツ語:

[ˈzi-]、シギスムント・シュロモ・フロイト(Sigismund Schlomo Freud、1856年5月6日 -

1939年9月23日)はオーストリアの神経学者であり、患者と精神分析医との対話を通じて、精神内の葛藤に由来すると見なされる病理を評価し治療する臨

床方法である精神分析と、そこから導き出される独特の精神論および人間作用論の創始者である。

フロイトはオーストリア帝国のモラヴィア地方の町フライベルクでガリシア系ユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれた。1881年、ウィーン大学で医学博士の資格を

取得。1885年にハビリタチオン(Habilitation)

を修了すると、神経病理学の教官に任命され、1902年には提携教授となった。1886年、フロイトはウィーンで臨

床を開始した。1938年3月のドイツによるオーストリア併合後、フロイトはナチスの迫害から逃れるためにオーストリアを離れた。1939年、亡命先のイ

ギリスで死去。

精神分析の創始者であるフロイトは、自由連想の使用などの治療技法を開発し、転移を発見し、分析過程における転移の中心的役割を確立した。フロイトは、セ

クシュアリティを幼児的な形態も含めて再定義し、精神分析理論の中心的な考え方としてエディプス・コンプレックスを定式化した。願望充足としての夢の分析

は、症状の形成と抑圧の基礎にあるメカニズムを臨床的に分析するためのモデルを提供した。これに基づいてフロイトは無意識の理論を精緻化し、イド、自我、

超自我からなる精神構造のモデルを発展させた。フロイトは、リビドー(精神過程や精神構造が投資され、エロティックな愛着を生み出す性的エネルギー)と、

死の衝動(強迫的反復、憎悪、攻撃性、神経症的罪悪感の源)の存在を仮定した。その後のフロイトは、宗教と文化について幅広い解釈と批判を展開した(→「フロイトの理論とその後の遺産」)。

診断や臨床の実践としては全体的に衰退しているものの、精神分析は心理学、精神医学、心理療法、そして人文科学全体において影響力を持ち続けている。それ

ゆえ精神分析は、その治療効果、科学的地位、フェミニズムの大義を前進させるか妨げるかに関して、広範かつ非常に論争的な議論を生み続けている。それにも

かかわらず、フロイトの作品は現代の西洋思想や大衆文化に浸透している。W・H・オーデンが1940年に発表したフロイトへの詩的賛辞は、フロイトが「私

たちがさまざまな人生を営むための/意見全体の風土」を作り上げたと表現している。

| ●伝記的事実:(→「フロイトの生涯」) |

●出典:Sigmund Freud

wiki in English.

|

●伝記的事実:(→「フロイトの生涯」)

1856_Age_01 出生。記載はウィキペディ ア「ジークムント・フロイト」などによる(文章は今後適宜変える予定です)。

オーストリア帝国・モラヴィア辺境伯国のフライベル ク(Freiberg, チェコ・プシーボルでアシュケナージであった毛織物商人ヤーコプ・フロイト(Jacob Freud)の45歳時の息子として生まれる。母親もブロディ出身のアシュケナージであるアマーリア・ナータンゾーン(1835年 – 1930年)で、ユダヤ法学者レブ・ナータン・ハレーヴィの子孫と伝えられている。同母妹にアンナ、ローザ、ミッチー、アドルフィーネ、パウラがおり、同 母弟にアレクサンダーがいる。このほか、父の前妻にも2人の子がいる。モラヴィアの伝説の王Sigismundとユダヤの賢人王ソロモンにちなんで命名さ れた。そのため、生まれた時の名はジギスムント・シュローモ・フロイト (Sigismund Schlomo Freud、ヘブライ語: זיגיסמונד שלמה פרויד) だが、21歳の時にSigmundと改めた。

1873_Age_17 ウィーン大学に入学、2年 間物理などを学 び、医学部のエルンスト・ブリュッケの生理学研究所に入りカエルやヤツメウナギなど両生類・魚類の脊髄神経細胞を研究し、その論文は、ウィーン科学協会で ブリュッケ教授が発表した

1881_Age_25 ウィーン大学卒業

1882_Age_26 将来のの妻マルタ・ベルナ イスと出逢う。 彼は知的好奇心が旺盛であり、古典やイギリス哲学を愛し、シェークスピアを愛読した。また非常に筆まめで、友人や婚約者、後には弟子たちとも、親しく手紙 を交わした。

1884-1886

フロイトはコカイン研究に情熱 を傾けていた。その結果、目・鼻などの粘膜に対する局所麻酔剤としての使用を着想し、友人の眼科医らとともに眼科領域でコカインを使用した手術に成功し た。その後、コカインを臨床研究に使用し始める。しかし1886年になると世界各地からコカインの常習性と中毒性が報告され、危険物質との認識が広まっ た。そのため、不当治療の唱導者として医学界からは追放されなかったものの、不審の目で見られるようになってしまった

1885_Age_29

選考を経て留学奨学金が与えられたためパリへと行 き、ヒステリーの研究で有名だった神経学者ジャン=マルタン・シャルコー(Jean-Martin Charcot, 1825-1893)のもとで催眠によるヒステリー症状の治療法を学んだ。神経症は器質的疾患ではなく機能的疾患であるとシャルコーは説き、フロイトは ウィーン医学会での古い認識を乗り越えることとなった。このころの彼の治療観は、のちの精神分析による根治よりも、むしろ一時的に症状を取り除くことに向 かっていた。この治療観が、のちの除反応(独: Abreaktion)という方法論や、催眠暗示の方法から人間の意識にはまだ知られていない強力な作用、無意識があるのではという発想につながってい く。

1886_Age_30

パリから帰国して1886年に「男性のヒステリーに ついて」という論文を医師会で発表したのだが、大きな反発を受けた。当時のウィーンでは新しい動向として自由主義、科学的合理主義が現れ始 めていたのだ が、古くからの伝統と因習が根強く残っていた。そのため女性の病気とされていたヒステリーが、男性にも起こりうるという事実を容認できなかったのである。 この論文には解剖学教授マイネルトも真向から反対し、厳格な自然科学の訓練を施したのに、シャルコーはフロイトを誘惑して逸脱させた、と怒りを顕にした。

1886年(30歳)、ウィーンへ帰り、シャルコー

から学んだ催眠によるヒステリーの治療法を一般開業医として実践に移した。治療経験を重ねるうちに、治療技法にさまざまな改良を加え、最終的にたどりつい

たのが自由連想法であった。これを毎日施すことによって患者はすべてを思い出

すことができるとフロイトは考え、この治療法を精神分析(独:

Psychoanalyse)と名づけた。

1887-1904

1887年(31歳)から1904年(48歳)の 17年間にわたって、親友である耳鼻科医ヴィルヘルム・フリース(Wilhelm Fließ, 1858-1928)と交わされた文通は、フロイトにとって自己の構造や精神分析学の基礎を見い出していったプロセスであり、ちょうど後世に精神分析を志 す者たちが精神分析医になるために行う訓練分析にあたる自己省察を、フリースを相手に突き詰めていった。『フリースへの書簡集』1887-1904年 (With Robert Fliess: "The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess", Belknap Press, 1986)

1889_Age_33

(39歳)フロイトは、ヒステリーの原因は幼少期に

受けた性的虐待の結果であるという病因論ならびに精神病理を発表した。今日で言う心的外傷やPTSDの概念に通じるものである[注

1]。これに基づいて彼は、ヒステリー患者が無意識に封印した内容を、身体症状として表出するのではなく、回想し言語化して表出することができれば、症状

は消失する(除反応、独:

Abreaktion)という治療法にたどりついた。この治療法はお話し療法と呼ばれた。今日の精神医学におけるナラティブセラピーの原型と考えることも

できる。自然科学者として、彼の目指す精神分析はあくまでも「科学」であった。彼の理論の背景には、ヘルムホルツに代表される機械論的な生理学、唯物論的

な科学観があった。脳神経の働きと心の動きがすべて解明されれば、人間の無意識の存在はおろか、その働きについてもすべて実証的に説明できると彼は信じて

いた。しかし、彼は脳神経に考察を限っていたわけでもなかった。当時の脳細胞の研究は一段落ついており[要出典]、かわって心理学や、当時の流行病であり

謎でもあったヒステリーの解明が新たな挑戦課題となっていた。彼はその挑戦とともに、ヒステリーの解明の鍵であった「性」という領域に、乗り出していった

のだった[注

2]。彼はギムナジウム時代に受けた啓蒙的な教育からして、終生無神論者であり、宗教もしくは宗教的なものに対して峻厳な拒否を示しつづけ、そのため後年

にアドラー、ユングをはじめ多くの仲間や弟子たちと袂を分かつことにもなった。

1895_Age_39 『ヒステリー研究』

(Studien

über Hysterie) ヨーゼフ・ブロイアーとの共著

1896_Age_40

父ヤーコプが82歳で生涯を終えた。この出来事に強 い衝撃を受け、以前からの不安症が悪化して友人ヴィルヘルム・フリースへの依存を高めた。フリースが分析者となり、1年間の幼児体験を回想する自己分析と 夢分析から、自己の無意識内に母に対する性愛と父に対する敵意と罪悪感を見出した。この体験について『喪とメランコリー』や『「狼男」の分析』などに表 し、のちに『トーテムとタブー』や『幻想の未来』に代表される、精神分析理論の核であるエディプス・コンプレックスへと昇華することとなる。 自己・夢分析 を始めて1年ほど経った1897年の4月頃、自身の見た夢の分析を通し、フリースへの怒りと敵意を自覚し始める。父親の死について自己の中であらかた整理 がつき、フリースに頼る必要が無くなってきたのである。次第にフリースの説くバイオリズムという占星術風の理論、神経症の発症・消失は生命周期によって左 右する、というものが荒唐無稽に見え始め、厳しい批判が向くこととなる。

1900_Age_44

1900年に出版された『夢判断(Die Traumdeutung)』は600部印刷されたのだが、完売には8年ほどかかり、1905年の『性に関する三つの論文』は各方面から悪評を浴びせられ るなど、ウィーンでの理解者は皆無に等しかった。このような孤立の中で支えとなったのは、身近に集まった弟子や、フェレンツィ、ユング、ビンスワンガー、 その他ロンドンやアメリカなどの国際的な支持であった。

1900年の夏には(4年前には精神的に依存してい たヴィルヘルム・フリースと)お互いに批判、非難し合う。

1901_Age_45 『日常の精神病理学』

(Zur

Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens)

1902_Age_46

その後ウィーンでもカハーネやライトレル が興味を示し始め、シュテーケルとアドラーを招待した1902年の秋に「心理学水曜会」という集会が開かれるようになる。1902年の晩夏には完全に (ヴィルヘルム・フリースと)決別し た。やがて彼の関心は心的外傷から無意識そのものへと移り、精神分析は無意識に関する科学として方向付けられた。そして父親への依存を振り切ったフロイト は、自我・エス・超自我からなる構造論と神経症論を確立させた。自身がユダヤ人であったためか、弟子もそのほとんどがユダヤ人であった。

また当時、ユダヤ 人は大学で教職を持ち、研究者となることが困難であったので、フロイトも市井の開業医として生計を立てつつ研究に勤しんだ[注 3]。彼は臨床経験と自己分析を通じて洞察を深めていった。『夢判断』を含む多くの著作はこの期間に書かれていった。フロイトは日中の大部分を患者の治療 と思索にあて、決まった時間に家族で食事をとり、夜は論文の編纂にいそしんだ。夏休みは家族とともに旅行を楽しんだという。

1905_Age_49 『性理論に関する三つの

エッセイ』

(Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie)。『ジョークと無意識との関連』(Der Witz und seine

Beziehung zum Unbewußten)

1908_Age_52 「心理学水曜会」が 「ウィーン精神分析協 会」に改称。1908年にスタンリー・ホールの招待を受け渡米することになる。『性格と肛門愛』(Charakter und Analerotik)。

1909_Age_53 『神経症者の家族小説』 (Der Familienroman der Neurotiker)

ユング、フェレンツィと共にクラーク大学創立20周 年式典に出席、講演後に大学長から博士号を授与された。滞在中に米国の心理学者ウィリアム・ジェームズと出会う。2人が道を歩いていた時にジェームズは狭 心症発作を起こした。彼は鞄をフロイトに預け、後で追いつくから先に行っていてくれと言った。この彼の態度にフロイトは感銘を受け、自分に死が近づいて来 ても彼のように恐れず毅然とした態度をとりたいと願った。ハーバード大学に行った際にはJ.パットナムという終生の友を得た。その後ウィーンから来た3人 は観光でナイアガラの滝を見物、9月21日にニューヨークを発ち、10月2日に帰国した。しかしながらフロイトのアメリカに対する偏見は変わることは無 かった。帰国してから数年間、自分の体調不良はアメリカに行ったせいだ、筆跡まで悪くなったと語っていた。この偏見の理由は、アメリカ的な自由気ままの雰 囲気がヨーロッパの学問の尊厳を侵すように感じられたこと、英語が不自由であったことが主な原因であった。他にも食事が合わなかったことや虫垂炎の再発と 頻尿に悩まされていたのもあったが、フロイトを尊敬する国になり、後に多数の弟子たちの安住の地となった。

1910_Age_54 「国際精神分析学会」創立 時、フロイトは ユングを初代会長に就任させ、個人的にもしばらく蜜月状態ともいうべき時期が続いたが、無意識の範囲など学問的な見解の違いから両者はしだいに距離を置く ようになる。

1911_Age_55 アドラー「ウィーン精神分 析協会」離脱。

1912_Age_56 シュテーケル「ウィーン精 神分析協会」離 脱。

1913_Age_57 ミュンヘンにおける第4回 の国際精神分析 大会で以前からの(フロイトとユングの)不和が決定的となり決裂してしまう。『トーテムと タブー』(Totem und Tabu)

1914_Age_58 ユングは国際精神分析学会 を脱退。「ナル シシズム入門」Zur Einführung des Narzißmus.

1915_Age_59 『欲動とその運命』 (Triebe und Triebschicksale)。『抑圧』(Die Verdrängung)。『戦争と死に関する時評』(Zeitgemässes über Krieg und Tod)

1917_Age_61 『精神分析入門』

(Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die

Psychoanalyse)。『欲動転換、特に肛門愛の欲動転換について』(Über Triebumsetzungen,

insbesondere der Analerotik)

1918_Age_62

第1次世界大戦は終結したのだが、数年の間ウィーン の市民は困窮に苦しんでいた。薄いスープのみの食事に加えて、冬は暖房が使えないなど酷な生活にあえいでいた。フロイトは寒さと飢えにもかかわらず患者の 治療と草稿を書き、手紙を返信し続けていた。インフレのために老後の蓄えは使い果たされてしまったのだが、E.ジョーンズがイギリスから患者を回し、彼の もとに集まった若い研究者たちの支援によって困窮を支えられていた。

1919_Age_63 『子供が叩かれる』(,

Ein

Kind wird geschlagen‘)

1920_Age_64 『快楽原則の彼岸 / 快原理の彼岸』(Jenseits des Lustprinzips)

親しくしていた弟子フォン・フロイントが亡くなり、

その数日後にも娘ゾフィーが亡くなった。大戦に続くこの不幸が「死の欲動(デストルドー)[2]」の着想として重くのしかかり、患者の精神分析の結果と合

わせて同年に『快感原則の彼岸』として形を成した。1921年になると動悸や頻脈に苦しむようになり、暗い死の思いにとらわれるようになった。その中で、

またしても身内がこの世を去ってしまう。1922年に姪がベロナールを服用して死亡し、翌1923年6月には娘ゾフィーの息子である孫ハイネルレが粟粒結

核で5歳に満たぬまま死んだ。フロイトは同年2月に喫煙が原因とみられる白板症(ロイコプラキア)を発症しており、後に33回も行う手術の1回目を受け

た。孫ハイネルレも扁桃腺の手術を受けており、両者は術後に初めて会ったのだが、この時ハイネルレは「僕はもうパンの皮がたべられるようになったけど、お

じいちゃんはいかが?[3]」と聞いた。すでに粟粒結核に罹っていた。孫の死後、この時にだけしか知られていない涙を流し、友人たちには、自分の中の何か

をこれを限りに殺してしまった、自分の人生を楽しむことができない、と語った。

1921_Age_65 集団心理学と自我の分析 = Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse.

1923_Age_67

『幼児の性器体制』(Die infantile

Genitalorganisation)。『リビドー理論』(Libidotheorie, Handwörterbuch der

Sexualwissenschaft)。『自我とエス』(Das Ich

und das Es)

フロイトを支えていたオットー・ランクが離反した。 大戦後からランクは躁うつ的な精神不調に陥り、仕事も独善的なやり方をするようになったため、たびたび協会メンバーと衝突を繰り返していた。理論的にも 『出産のトラウマ』の刊行で完全に決別してしまった。大戦後からの精神的、肉体的苦痛にみちた日々を過ごす中で、1923年に精神分析における体系的な論 文、『自我とエス』を発表した。心の構造と、自我・エス・超自我の力動的関連などを解明し、自我を主体にして人格全体を考察する自我心理学の基礎を築い た。悲劇に苛まれるフロイトの慰めが、娘アンナが心理学の道に進んだ事とシュニッツラー、シュテファン・ツヴァイク、アルノルト・ツヴァイクら友人達との 交流であった。そして1923年から作家ロマン・ロランとの文通が始まった。

「私の生涯の大部分を人類の幻想を破壊することに費

やしてきました」ロマン・ロラン宛 1923年3月4日付

1924_Age_68 市議会で名誉市民に相当す る市民権を与え ることが決定。『マゾヒズムの経済論的問題』(Das ökonomische Problem des Masochismus)。『エディプス・コンプレックスの崩壊』(Der Untergang des Ödipuskomplexes)。

1925_Age_69 『解剖学的な性差の心的な

帰結』

(Einige psychische Folgen des anatomischen

Geschlechtsunterschieds)。『否定』(Die Verneinung)

1926_Age_70 『制止、症状、不安』 (Hemmung, Symptom und Angst)。『素人分析の問題』(Die Frage der Laienanalyse)。

70歳の誕生日を祝って国内外から祝電や手紙が送ら れ、中でもヘブライ大学と物理学者アインシュタインから送られたものがフロイトを喜ばせた。アインシュタインとは、人には他者を攻撃しなければならない理 由があるのではないか、という質問について文通で議論を交わした。弟子たちからは3万マルクが送られ、そのうち5分の4を国際精神分析出版所に、残りを精 神分析診療所に寄付した。そして当日の演説では精神分析運動から退くことを表明するとともに、「われわれは外見上の成功にあざむかれて、自分を見失っては ならぬ[4]」という趣旨の演説をした。同年に不安自我の防衛機能に関する包括的研究の『制止、症状、不安』を発表し、その後は理論の構築を小休止して精 神分析の応用研究を始める。

1927_Age_71 『幻想の未来Die Zukunft einer Illusion』。『フェティシズム』(Fetischismus)

1928_Age_72 『ドストエフスキーと父親 殺し (Dostojewski und die Vatertötung)』

1930_Age_74 『文明への不満』(Das Unbehagen in der Kultur)

9月、母アマーリアが95歳で生涯を閉じた。父ヤー コプの時とは違う自分の反応について、「それは自由、解放の感情であって、その理由は、彼女が生きているかぎり、私は死ぬことを許されなかったが、今は私 も死んでいいのです。どういうわけか、人生の価値が心の奥深い層で著しく変化してしまいました[4]」と、意味深長に述べた。同年に早期の母子関係に関す るメラニー・クラインの研究に言及し、ロマン・ロランが『幻想の未来』発表後に手紙で指摘した「大洋感情」をめぐった論文『文化への不満』を発表した。

1931_Age_75 『女性の性愛について』 (Über die weibliche Sexualität)。『リビドー的類型について』(Über die libidinöse Typen)

ウィーン医師協会がフロイトを名誉会員に指名し、故 郷フライベルクの市議会が生家に銅版の銘をはりつけて、その名誉を記念した。また同年に開催された第六回国際精神療法医学大会では、議長クレッチマーが 75回の誕生日に敬愛の情のあふれる演説を行った。翌年には作家トーマス・マンが訪れて、互いに親しい間がらとなった

1932_Age_76 ナチスによるユダヤ人迫害

は激しくなる。

1933_Age_77 『心的な人格の解明』 (Neue Folge der Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse)

喜びと引き換えるように25年間もの付き合いがあっ たフェレンツィ・シャーンドルが死亡する。「フェレンツィとともに古い時代は去ってゆく。そして私が死ねば、新しいものがはじまるだろう。今は、運命、諦 め、それだけしかない[5]」と、精神的喪失の大きさを語った。フロイトの友人達は国外に亡命していった。出版していた本は禁書に指定されて焼き捨てられ たのだが、これに対して当人は、「なんという進歩でしょう。中世ならば、彼らは私を焼いたことでしょうに[6]」と、微笑んでいた。ユダヤ人である弟子た ちも亡命し始め、弟子がヨーロッパにはアーネスト・ジョーンズ1人となった。ドイツでは精神分析が一掃され、ナチス支配下の精神療法学会の会員は『我が闘 争』の研究を要求されたため、これに反発したクレッチマーが辞職。後任の会長はユングとなり、精神分析の用語(エディプス・コンプレックスなど)さえも規 制された。

1936_Age_80

迫害と癌の進行が激しさを増すなかで、ジュール・ロ マン、H・G・ウェルズ、ヴァージニア・ウルフら総勢191名の作家、芸術家からの署名を集めた挨拶状が80歳の誕生日にトーマス・マンによって送られ、 9月には4人の子供たちから金婚式のお祝いを受けた。

1938_Age_82

3月11日、アドルフ・ヒトラー率いるナチス・ドイ ツがオーストリアに侵攻した。フロイト宅にもゲシュタポが2度にわたって侵入し、娘アンナが拉致された。夜には無事に帰ってきたものの、拷問されて強制収 容所に送られるのでは、と不安になり、1日中立て続けに葉巻を吸ってはうろうろと部屋を歩き回った。ユダヤ人を学会から追放した時、ユングは自身が会長を 務める『国際心理療法医学会』の会員としてドイツ国内のユダヤ人医師を受入れ身分を保証すること、学会の機関紙にユダヤ人の論文を自由に掲載することの2 点を決定し、フロイトに打診した。だが、フロイトは「敵の恩義に与ることは出来ない」と言って援助を拒否し、この為ユダヤ人の医師たちは仕事を失い、強制 収容所のガス室に送られた[注 4]。ロンドンへの亡命を説得するためにジョーンズが危険を冒してウィーンに入るも、故郷を去ることは兵士が持ち場を逃げ出す事と同じだ、としてなかなか 同意しなかった。最後はジョーンズの熱意に動かされ、愛するウィーンを去る決心をした。出国手続きで3ヶ月かかったのだが、その間にブロイアーの長男の妻 の助けに応じて、アメリカ大使ブリットに働きかけて亡命を助けるなど、ここに彼の温かい人柄の一端を忍ばせている。それでも残して来ざるをえなかった4人 の妹たちは数年後に収容所で焼き殺されてしまった。6月4日にウィーンを発ち、パリを経由して6月6日にロンドンに到着すると熱狂的な歓迎を受けた。フロ イトは亡命先の家に落ち着くと、ハイル・ヒトラーと叫びたいくらいだ、と冗談を言えるほどに回復した。やがてウェルズやマリノフスキー、サルバドール・ダ リらが次々に訪問した。フロイトは亡命先でも毎日4人の患者の分析治療をし、ユダヤ人はなぜ迫害されるかを改めて問い直した『モーセと一神教』を発表し た。その他にも未完に終わった『精神分析概説』や『防衛過程における自我分裂』を執筆するなど、学問活動を続けた。この頃には癌の進行により、手術不能の 状態となった。癌性潰瘍によって眼窩と頬が瘦せ細り、手術による傷口からは異臭が漂っていた。それにも関わらず鎮痛剤の使用を嫌い、シュテファン・ツヴァ イクが使用を勧めるも、はっきりと考えられないのなら苦痛の中で考えた方がましだ、と彼に訴えた。8月に入ると食事も困難となり、9月には敗血症を合併し て意識も不明瞭となった。

1939_Age_83 『モーゼと一神教』 (Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion)

9月21日、末期ガンに冒されたフロイトは10年来

の主治医を呼び、「シュール君、はじめて君に診てもらった時の話をおぼえているだろうね。いよいよもう駄目と決まった時には、君は手をかしてくれると約束

してくれたね。いまではもう苦痛だけで、なんの光明もない[7]」と言い、翌朝に過量のモルヒネが投与されて、23日夜にロンドンで83歳4か月の生涯を

終えた。遺体は火葬された後、骨はマリー・ボナパルト(Marie

Bonaparte, 1882-1962)から送られたギリシャの壺に収められ、現在グリーン・ガーデン墓地に妻マルタと共に眠っている。

1940 『精神分析概説』(Abriß der Psychoanalyse)。『メドゥーサの首』(Medusenhaupt)[1922]

1983 『系統発生的幻想 - 転移神経症概観』の手稿が発見される。

●フロイトの理論枠組とその後のフロイトの遺産(→今後は「フロイト派の理論」で展開します。現在はミラーですが、将来は消えるかも?!)

★出典:Sigmund Freud

wiki in English.

| Early work Freud began his study of medicine at the University of Vienna in 1873.[128] He took almost nine years to complete his studies, due to his interest in neurophysiological research, specifically investigation of the sexual anatomy of eels and the physiology of the fish nervous system, and because of his interest in studying philosophy with Franz Brentano. He entered private practice in neurology for financial reasons, receiving his M.D. degree in 1881 at the age of 25.[129] Amongst his principal concerns in the 1880s was the anatomy of the brain, specifically the medulla oblongata. He intervened in the important debates about aphasia with his monograph of 1891, Zur Auffassung der Aphasien, in which he coined the term agnosia and counselled against a too locationist view of the explanation of neurological deficits. Like his contemporary Eugen Bleuler, he emphasized brain function rather than brain structure. Freud was also an early researcher in the field of cerebral palsy, which was then known as "cerebral paralysis". He published several medical papers on the topic and showed that the disease existed long before other researchers of the period began to notice and study it. He also suggested that William John Little, the man who first identified cerebral palsy, was wrong about lack of oxygen during birth being a cause. Instead, he suggested that complications in birth were only a symptom. The origin of Freud's early work with psychoanalysis can be linked to Josef Breuer. Freud credited Breuer with opening the way to the discovery of the psychoanalytical method by his treatment of the case of Anna O. In November 1880, Breuer was called in to treat a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman (Bertha Pappenheim) for a persistent cough and hallucinations that he diagnosed as hysterical. He found that while nursing her dying father, she had developed some transitory symptoms, including visual disorders and paralysis and contractures of limbs, which he also diagnosed as hysterical. Breuer began to see his patient almost every day as the symptoms increased and became more persistent, and observed that she entered states of absence. He found that when, with his encouragement, she told fantasy stories in her evening states of absence her condition improved, and most of her symptoms had disappeared by April 1881. Following the death of her father in that month her condition deteriorated again. Breuer recorded that some of the symptoms eventually remitted spontaneously and that full recovery was achieved by inducing her to recall events that had precipitated the occurrence of a specific symptom.[130] In the years immediately following Breuer's treatment, Anna O. spent three short periods in sanatoria with the diagnosis "hysteria" with "somatic symptoms",[131] and some authors have challenged Breuer's published account of a cure.[132][133][134] Richard Skues rejects this interpretation, which he sees as stemming from both Freudian and anti-psychoanalytical revisionism — revisionism that regards both Breuer's narrative of the case as unreliable and his treatment of Anna O. as a failure.[135] |

初期の研究 フロイトは1873年にウィーン大学で医学の勉強を始めたが[128]、神経生理学的研究、特にウナギの性解剖学と魚類の神経系の生理学の研究に興味を持 ち、またフランツ・ブレンターノとともに哲学を学ぶことに関心があったため、学業を終えるまでにほぼ9年を要した。経済的な理由から神経学の個人開業医と なり、1881年に25歳で医学博士号を取得した[129]。1880年代の主な関心事のひとつは脳の解剖学で、特に延髄についてであった。彼は1891 年の単行本Zur Auffassung der Aphasienで失語症に関する重要な論争に介入し、その中で失語症という用語を作り、神経学的欠損の説明のあまりに位置主義的な見方に対して忠告し た。同時代のオイゲン・ブルーラーのように、彼は脳の構造よりもむしろ脳の機能を強調した。 フロイトはまた、当時「脳性麻痺」として知られていた脳性麻痺の分野の初期の研究者でもあった。彼はこのテーマでいくつかの医学論文を発表し、当時の他の 研究者たちがこの病気に気づき研究を始めるずっと前から、この病気が存在していたことを示した。彼はまた、脳性麻痺を最初に特定したウィリアム・ジョン・ リトルが、出産時の酸素不足が原因であるというのは間違いであると示唆した。その代わり、出産時の合併症は症状に過ぎないと示唆した。 フロイトの初期の精神分析の原点は、ヨゼフ・ブロイヤーにある。1880年11月、ブロイヤーは、ヒステリーと診断された咳と幻覚が続く21歳の聡明な女 性(ベルタ・パッペンハイム)の治療に呼ばれた。瀕死の父親を看病している間に、彼女は視覚障害、手足の麻痺や拘縮などの一過性の症状を発症していたこと がわかり、これもヒステリーと診断した。ブロイヤーは、症状が強くなり、持続するようになると、ほとんど毎日患者を診察するようになり、彼女が不在の状態 に入るのを観察した。彼の励ましによって、彼女が夜の不在の状態で空想の物語を語るようになると、病状は改善し、1881年4月までに症状のほとんどが消 失した。その月に父親が亡くなり、彼女の病状は再び悪化した。症状の一部はやがて自然に寛解し、特定の症状が起こるきっかけとなった出来事を思い出させる ことで完全に回復したと、ブロイヤーは記録している。ブロイヤーの治療直後の数年間、アンナ・Oは「身体症状」を伴う「ヒステリー」と診断され、療養所で 3回の短期間過ごした。] リチャード・スクエスはこの解釈を否定している。彼は、この解釈はフロイトと反精神分析的修正主義の両方から生じていると見ている。修正主義とは、この症 例に関するブロイアーの叙述を信頼できないと見なし、アンナ・Oの治療を失敗だったと見なすものである。 |

| Seduction theory Main article: Freud's seduction theory In the early 1890s, Freud used a form of treatment based on the one that Breuer had described to him, modified by what he called his "pressure technique" and his newly developed analytic technique of interpretation and reconstruction. According to Freud's later accounts of this period, as a result of his use of this procedure, most of his patients in the mid-1890s reported early childhood sexual abuse. He believed these accounts, which he used as the basis for his seduction theory, but then he came to believe that they were fantasies. He explained these at first as having the function of "fending off" memories of infantile masturbation, but in later years he wrote that they represented Oedipal fantasies, stemming from innate drives that are sexual and destructive in nature.[136] Another version of events focuses on Freud's proposing that unconscious memories of infantile sexual abuse were at the root of the psychoneuroses in letters to Fliess in October 1895, before he reported that he had actually discovered such abuse among his patients.[137] In the first half of 1896, Freud published three papers, which led to his seduction theory, stating that he had uncovered, in all of his current patients, deeply repressed memories of sexual abuse in early childhood.[138] In these papers, Freud recorded that his patients were not consciously aware of these memories, and must therefore be present as unconscious memories if they were to result in hysterical symptoms or obsessional neurosis. The patients were subjected to considerable pressure to "reproduce" infantile sexual abuse "scenes" that Freud was convinced had been repressed into the unconscious.[139] Patients were generally unconvinced that their experiences of Freud's clinical procedure indicated actual sexual abuse. He reported that even after a supposed "reproduction" of sexual scenes the patients assured him emphatically of their disbelief.[140] As well as his pressure technique, Freud's clinical procedures involved analytic inference and the symbolic interpretation of symptoms to trace back to memories of infantile sexual abuse.[141] His claim of one hundred percent confirmation of his theory only served to reinforce previously expressed reservations from his colleagues about the validity of findings obtained through his suggestive techniques.[142] Freud subsequently showed inconsistency as to whether his seduction theory was still compatible with his later findings.[143] In an addendum to The Aetiology of Hysteria he stated: "All this is true [the sexual abuse of children], but it must be remembered that at the time I wrote it I had not yet freed myself from my overvaluation of reality and my low valuation of phantasy".[144] Some years later Freud explicitly rejected the claim of his colleague Ferenczi that his patients' reports of sexual molestation were actual memories instead of fantasies, and he tried to dissuade Ferenczi from making his views public.[143] Karin Ahbel-Rappe concludes in her study "'I no longer believe': did Freud abandon the seduction theory?": "Freud marked out and started down a trail of investigation into the nature of the experience of infantile incest and its impact on the human psyche, and then abandoned this direction for the most part."[145] |

誘惑理論 主な記事 フロイトの誘惑理論 1890年代初頭、フロイトは、ブロイヤーが彼に説明した治療法に基づき、彼が「プレッシャー・テクニック」と呼ぶものと、新たに開発した解釈と再構成の 分析技法によって修正した治療法を用いた。この時期に関するフロイトの後年の記述によると、この治療法を用いた結果、1890年代半ばの患者のほとんど が、幼少期の性的虐待を訴えていたという。彼はこれらの報告を信じ、それを誘惑理論の基礎としたが、やがてそれが空想であると考えるようになった。彼は最 初、これらを幼児期の自慰の記憶を「かわす」機能があると説明していたが、後年には、性的で破壊的な性質をもつ生得的な衝動に由来するエディプスの幻想を 表していると書いている[136]。 もう一つの出来事のバージョンは、フロイトが1895年10月にフリースに宛てた手紙の中で、幼児期の性的虐待の無意識の記憶が精神神経症の根底にあると 提唱したことに焦点を当てている。 [1896 年前半、フロイトは、彼の誘惑理論につながる3つの論文を発表し、現在の患者のすべてにおいて、幼児期の性的虐待の深く抑圧された記憶を発見したと述べた [138]。これらの論文の中で、フロイトは、彼の患者がこれらの記憶を意識的に認識しておらず、したがって、ヒステリー症状や強迫神経症の原因となるの であれば、無意識の記憶として存在しなければならないと記録した。患者は、フロイトが無意識に抑圧されていると確信した幼児期の性的虐待の「場面」を「再 現」するようにかなりの圧力をかけられていた。彼は、性的な場面の「再現」とされるものの後でさえ、患者は自分たちの不信を力強く断言したと報告している [140]。 彼の圧迫技法と同様に、フロイトの臨床手順には、分析的推論と幼児期の性的虐待の記憶にさかのぼるための症状の象徴的解釈が含まれていた[141]。 彼の理論の100パーセントの確証という主張は、彼の同僚たちから、彼の暗示的技法によって得られた所見の妥当性について以前から表明されていた保留を補 強することになっただけであった[142]。 その後、フロイトは、彼の誘惑理論が後の所見と依然として両立するかどうかに関して矛盾を示していた[143]。 ヒステリーの病因』の補遺において、彼はこう述べている: 「このことはすべて真実である(子どもへの性的虐待)が、これを書いた当時、私はまだ現実の過大評価と幻想の低評価から解放されていなかったことを忘れて はならない」。 [144] 数年後、フロイトは、性的虐待に関する患者の報告が空想ではなく実際の記憶であるという同僚のフェレンツィの主張を明確に否定し、フェレンツィが自分の見 解を公にするのを思いとどまらせようとした[143]。 カリン・アーベル=ラッペは、その研究「『私はもはや信じない』:フロイトは誘惑理論を放棄したのか」の中で次のように結論付けている: 「フロイトは、幼児期の近親相姦の経験の性質とそれが人間の精神に与える影響についての調査の跡を示し、それを始めたが、その後、この方向性をほとんど放 棄した」[145]。 |

| Cocaine As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. He believed that cocaine was a cure for many mental and physical problems, and in his 1884 paper "On Coca" he extolled its virtues. Between 1883 and 1887 he wrote several articles recommending medical applications, including its use as an antidepressant. He narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering its anesthetic properties of which he was aware but had mentioned only in passing.[146] (Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud's in Vienna, received that distinction in 1884 after reporting to a medical society the ways cocaine could be used in delicate eye surgery.) Freud also recommended cocaine as a cure for morphine addiction.[147] He had introduced cocaine to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, who had become addicted to morphine taken to relieve years of excruciating nerve pain resulting from an infection acquired after injuring himself while performing an autopsy. His claim that Fleischl-Marxow was cured of his addiction was premature, though he never acknowledged that he had been at fault. Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of "cocaine psychosis", and soon returned to using morphine, dying a few years later still suffering from intolerable pain.[148] The application as an anaesthetic turned out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, and as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world, Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished.[149] After the "Cocaine Episode"[150] Freud ceased to publicly recommend the use of the drug, but continued to take it himself occasionally for depression, migraine and nasal inflammation during the early 1890s, before discontinuing its use in 1896.[151] |

コカイン 医学研究者であったフロイトは、早くからコカインを愛用し、鎮痛薬としてだけでなく興奮薬としても推奨していた。彼はコカインが多くの精神的・肉体的問題 の治療薬であると信じ、1884年の論文『コカについて』ではその美徳を讃えた。1883年から1887年にかけて、彼は抗うつ剤としての使用など、医療 への応用を勧める論文をいくつか書いた。フロイトは、コカインに麻酔作用があることは知っていたが、それについて少し触れただけであったため、科学的な優 先権を得ることを惜しくも逃した[146](ウィーンでフロイトの同僚であったカール・コラーは、1884年に、コカインが繊細な目の手術に使用できるこ とを医学会に報告し、その栄誉を得た)。フロイトはまた、モルヒネ中毒の治療薬としてコカインを推奨していた[147]。彼は、解剖中に怪我をした後に感 染症にかかり、長年にわたる耐え難い神経痛を和らげるために服用したモルヒネ中毒になっていた友人エルンスト・フォン・フライシュル=マルクスハウにコカ インを紹介していた。フライシュル=マルクスハウの中毒が治ったという彼の主張は時期尚早であったが、彼は決して自分に非があったとは認めなかった。フラ イシュル=マルクスオは急性「コカイン精神病」を発症し、すぐにモルヒネの使用に戻り、数年後に耐え難い痛みに苦しみながら死亡した[148]。 麻酔薬としての使用は、コカインの数少ない安全な使用法の一つであることが判明し、中毒や過剰摂取の報告が世界各地から寄せられ始めたため、フロイトの医 学的評判はいくらか低下した[149]。 コカイン・エピソード」[150]の後、フロイトは公に薬物の使用を推奨することをやめたが、1896年に使用を中止するまでの間、1890年代初期にう つ病、偏頭痛、鼻炎のために時折自ら服用を続けた[151]。 |

| The unconscious Main article: Unconscious mind The concept of the unconscious was central to Freud's account of the mind. Freud believed that while poets and thinkers had long known of the existence of the unconscious, he had ensured that it received scientific recognition in the field of psychology.[152] Freud states explicitly that his concept of the unconscious as he first formulated it was based on the theory of repression. He postulated a cycle in which ideas are repressed, but remain in the mind, removed from consciousness yet operative, then reappear in consciousness under certain circumstances. The postulate was based upon the investigation of cases of hysteria, which revealed instances of behaviour in patients that could not be explained without reference to ideas or thoughts of which they had no awareness and which analysis revealed were linked to the (real or imagined) repressed sexual scenarios of childhood. In his later re-formulations of the concept of repression in his 1915 paper 'Repression' (Standard Edition XIV) Freud introduced the distinction in the unconscious between primary repression linked to the universal taboo on incest ('innately present originally') and repression ('after expulsion') that was a product of an individual's life history ('acquired in the course of the ego's development') in which something that was at one point conscious is rejected or eliminated from consciousness.[152] In his account of the development and modification of his theory of unconscious mental processes he sets out in his 1915 paper 'The Unconscious' (Standard Edition XIV), Freud identifies the three perspectives he employs: the dynamic, the economic and the topographical. The dynamic perspective concerns firstly the constitution of the unconscious by repression and secondly the process of "censorship" which maintains unwanted, anxiety-inducing thoughts as such. Here Freud is drawing on observations from his earliest clinical work in the treatment of hysteria. In the economic perspective the focus is on the trajectories of the repressed contents ("the vicissitudes of sexual impulses") as they undergo complex transformations in the process of both symptom formation and normal unconscious thought such as dreams and slips of the tongue. These were topics Freud explored in detail in The Interpretation of Dreams and The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. Whereas both these former perspectives focus on the unconscious as it is about to enter consciousness, the topographical perspective represents a shift in which the systemic properties of the unconscious, its characteristic processes, and modes of operation such as Condensation and Displacement, are placed in the foreground. This "first topography" presents a model of psychic structure comprising three systems: The System Ucs – the unconscious: "primary process" mentation governed by the pleasure principle characterised by "exemption from mutual contradiction, ... mobility of cathexes, timelessness, and replacement of external by psychical reality." ('The Unconscious' (1915) Standard Edition XIV). The System Pcs – the preconscious in which the unconscious thing-presentations of the primary process are bound by the secondary processes of language (word presentations), a prerequisite for their becoming available to consciousness. The System Cns – conscious thought governed by the reality principle. In his later work, notably in The Ego and the Id (1923), a second topography is introduced comprising id, ego and super-ego, which is superimposed on the first without replacing it.[153] In this later formulation of the concept of the unconscious the id[154] comprises a reservoir of instincts or drives, a portion of them being hereditary or innate, a portion repressed or acquired. As such, from the economic perspective, the id is the prime source of psychical energy and from the dynamic perspective it conflicts with the ego[155] and the super-ego[156] which, genetically speaking, are diversifications of the id. |

無意識 主な記事 無意識 無意識の概念はフロイトの心の説明の中心であった。フロイトは、詩人や思想家が無意識の存在を長い間知っていた一方で、彼はそれが心理学の分野で科学的な 認知を受けるようにしたと考えていた[152]。 フロイトは、彼が最初に定式化した無意識の概念は抑圧の理論に基づいていたと明言している。彼は、観念が抑圧され、しかし心の中に残り、意識から取り除か れ、しかし作動し、ある状況下で再び意識の中に現れるというサイクルを仮定した。この仮説は、ヒステリーの症例を調査した結果、患者には自覚がなく、分析 によって明らかになった幼少期に抑圧された(現実の、あるいは想像上の)性的な場面に関連する考えや思考を参照しなければ説明できないような行動があるこ とを明らかにしたことに基づいている。1915年の論文「抑圧」(標準版XIV)における抑圧の概念の後の再定式化において、フロイトは無意識において、 近親相姦に対する普遍的なタブーと結びついた一次的抑圧(「生得的にもともと存在している」)と、個人の生活史の産物(「自我の発達の過程で獲得され た」)である抑圧(「追放された後」)との区別を導入した。 1915年の論文「無意識」(Standard Edition XIV)の中で彼が示した無意識的な精神プロセスの理論の発展と修正に関する彼の説明の中で、フロイトは彼が採用した3つの視点、すなわち動的視点、経済 的視点、および地形的視点を識別している。 動的な視点は、第一に抑圧による無意識の構成、第二に不要で不安を誘発する思考をそのようなものとして維持する「検閲」のプロセスに関するものである。こ こでフロイトは、ヒステリーの治療における初期の臨床作業から得た観察に基づいている。 経済的な観点では、抑圧された内容(「性的衝動の変動」)が、症状形成の過程と、夢や舌の滑りのような通常の無意識的思考の過程の両方で複雑な変容を遂げ る際の軌跡に焦点が当てられている。これらはフロイトが『夢の解釈』と『日常生活の精神病理学』の中で詳細に探求したテーマである。 これらの前者の視点がいずれも、意識に入り込もうとしている無意識に焦点を当てているのに対し、トポグラフィ的視点は、無意識の体系的特性、その特徴的な プロセス、そして「凝縮」や「変位」のような作動様式が前景に置かれる転換を表している。 この「最初のトポグラフィー」は、3つのシステムからなる精神構造のモデルを提示する: システムUcs-無意識:「相互矛盾からの免除、......カテキスの可動性、無時間性、精神的現実による外部の置き換え」によって特徴づけられる快楽 原則によって支配される「第一のプロセス」精神化。(無意識』(1915年)標準版XIV)。 システムPcs - 前意識で、一次過程の無意識の事物提示が、意識に利用可能になるための前提条件である言語の二次過程(言葉の提示)によって束縛される。 システムCns - 現実原理によって支配される意識的思考。 この後の無意識の概念の定式化では、イド[154]は本能や衝動の貯蔵庫を構成しており、その一部は遺伝的あるいは生得的であり、一部は抑圧されているか 後天的に獲得されたものである。このように、経済的な観点からすると、イドは精神的エネルギーの主要な源であり、動的な観点からすると、遺伝的に言えばイ ドの多様化である自我[155]や超自我[156]と対立する。 |

| Dreams Main article: The Interpretation of Dreams Freud believed the function of dreams is to preserve sleep by representing as fulfilled wishes that which would otherwise awaken the dreamer.[157] In Freud's theory dreams are instigated by the daily occurrences and thoughts of everyday life. In what Freud called the "dream-work", these "secondary process" thoughts ("word presentations"), governed by the rules of language and the reality principle, become subject to the "primary process" of unconscious thought ("thing presentations") governed by the pleasure principle, wish gratification and the repressed sexual scenarios of childhood. Because of the disturbing nature of the latter and other repressed thoughts and desires which may have become linked to them, the dream-work operates a censorship function, disguising by distortion, displacement, and condensation the repressed thoughts to preserve sleep.[158] In the clinical setting, Freud encouraged free association to the dream's manifest content, as recounted in the dream narrative, to facilitate interpretative work on its latent content – the repressed thoughts and fantasies – and also on the underlying mechanisms and structures operative in the dream-work. As Freud developed his theoretical work on dreams he went beyond his theory of dreams as wish-fulfillments to arrive at an emphasis on dreams as "nothing other than a particular form of thinking. ... It is the dream-work that creates that form, and it alone is the essence of dreaming".[159] |

夢 主な記事 夢の解釈 フロイトは、夢の機能は、そうでなければ夢想家を目覚めさせるであろうことを満たされた願いとして表すことによって、睡眠を維持することであると信じてい た[157]。 フロイトの理論では夢は日常生活の日常の出来事や思考によって扇動される。フロイトが「夢作業」と呼んだものにおいて、言語の規則と現実原理によって支配 されるこれらの「二次過程」の思考(「言葉の提示」)は、快楽原理、願望充足、幼少期の抑圧された性的なシナリオによって支配される無意識の思考(「事物 の提示」)の「一次過程」の対象となる。後者や他の抑圧された思考や欲望は不穏な性質を持つため、夢作業は検閲機能を作動させ、睡眠を維持するために抑圧 された思考を歪曲、変位、凝縮によって偽装する[158]。 臨床の場においてフロイトは、夢の物語で語られるような夢の顕在的な内容に対する自由な連想を奨励し、その潜在的な内容-抑圧された思考や空想-に関する 解釈作業を促進し、また夢作品において作用する根本的なメカニズムや構造に関する解釈作業を促進した。フロイトは夢についての理論的研究を進めるうちに、 願望充足としての夢という彼の理論を越えて、「思考の特殊な形態にほかならない」としての夢に重点を置くようになった。... その形式を作り出すのは夢作業であり、それだけが夢見の本質である」[159]。 |

| Psychosexual development Main article: Psychosexual development Freud's theory of psychosexual development proposes that following on from the initial polymorphous perversity of infantile sexuality, the sexual "drives" pass through the distinct developmental phases of the oral, the anal, and the phallic. Though these phases then give way to a latency stage of reduced sexual interest and activity (from the age of five to puberty, approximately), they leave, to a greater or lesser extent, a "perverse" and bisexual residue which persists during the formation of adult genital sexuality. Freud argued that neurosis and perversion could be explained in terms of fixation or regression to these phases whereas adult character and cultural creativity could achieve a sublimation of their perverse residue.[160] After Freud's later development of the theory of the Oedipus complex this normative developmental trajectory becomes formulated in terms of the child's renunciation of incestuous desires under the fantasised threat of (or fantasised fact of, in the case of the girl) castration.[161] The "dissolution" of the Oedipus complex is then achieved when the child's rivalrous identification with the parental figure is transformed into the pacifying identifications of the Ego ideal which assume both similarity and difference and acknowledge the separateness and autonomy of the other.[162] Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and turned to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material arguing that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.[163] |

精神発達 主な記事 性の心理的発達 フロイトの精神性発達理論では、幼児期の性的衝動が最初の多形的な変態性(=倒錯)を経て、性的「衝動」は口唇、肛門、男根という明確な発達段階を通過す ると提唱している。これらの段階は、その後、性的関心や性的活動が減少する潜伏期(およそ5歳から思春期まで)に移行するものの、多かれ少なかれ、「変態 的」でバイセクシュアルな残滓を残し、それが成人の性器性欲の形成期に持続する。フロイトは、神経症と倒錯はこれらの段階への固定化または退行という観点 から説明することができるのに対して、成人の性格と文化的創造性はその倒錯的残滓の昇華を達成することができると主張した[160]。 フロイトが後にエディプス・コンプレックスの理論を発展させた後、この規範的な発達の軌跡は、空想された去勢の脅威(あるいは少女の場合は空想された事 実)のもとで子どもが近親相姦的な欲望を放棄するという観点から定式化されるようになる。 [そしてエディプス・コンプレックスの「解消」は、子どもの親像に対する対抗的な同一化が、類似性と差異性の両方を想定し、他者の分離性と自律性を認める 自我の理想のなだめるような同一化へと変容するときに達成される[162]。 フロイトは自分のモデルが普遍的に有効であることを証明することを望み、トーテミズムが部族的なエディプスの葛藤の儀式化された制定を反映していると主張 して、比較の材料として古代の神話や現代の民族誌に目を向けた[163]。 |

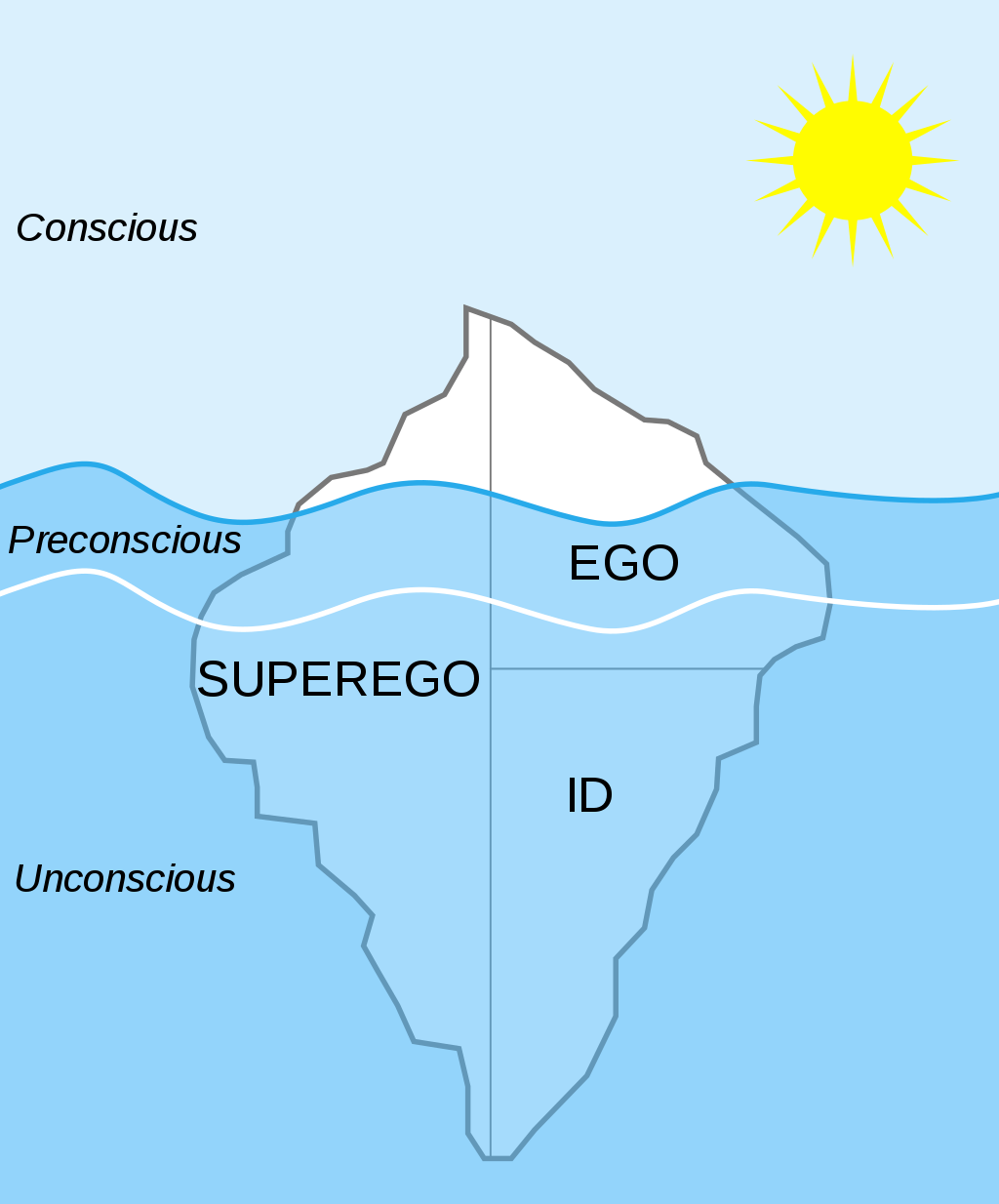

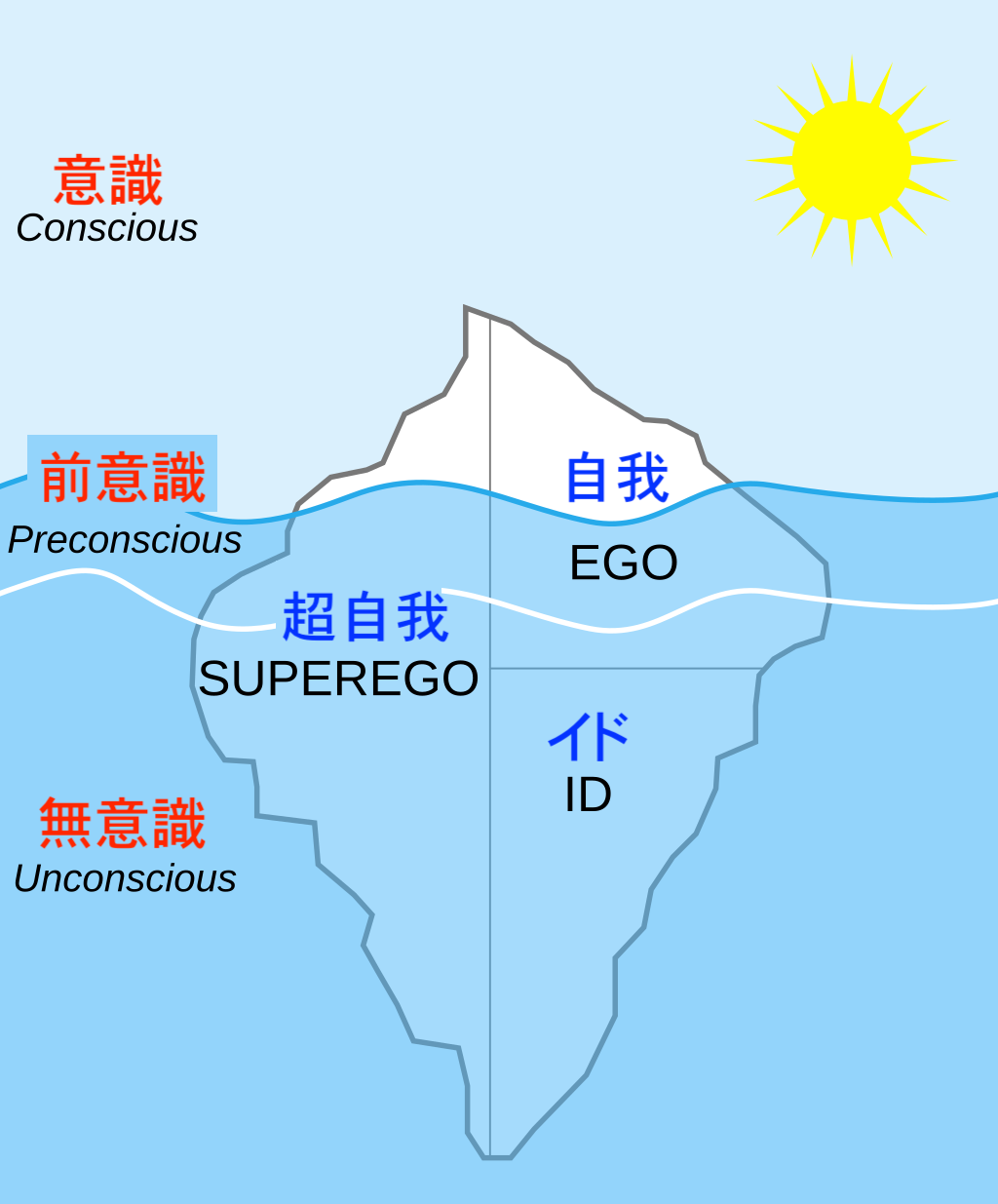

| Id, ego, and super-ego Main article: Id, ego and super-ego  The iceberg metaphor is often used to explain the psyche's parts in relation to one another. Freud proposed that the human psyche could be divided into three parts: Id, ego, and super-ego. Freud discussed this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923), in which he developed it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (i.e., conscious, unconscious and preconscious). The id is the unconscious portion of the psyche that operates on the "pleasure principle" and is the source of basic impulses and drives; it seeks immediate pleasure and gratification.[164] Freud acknowledged that his use of the term Id (das Es, "the It") derives from the writings of Georg Groddeck.[154][165] The super-ego is the moral component of the psyche.[156] The rational ego attempts to exact a balance between the impractical hedonism of the id and the equally impractical moralism of the super-ego;[155] it is the part of the psyche that is usually reflected most directly in a person's actions. When overburdened or threatened by its tasks, it may employ defence mechanisms including denial, repression, undoing, rationalization, and displacement. This concept is usually represented by the "Iceberg Model".[166] This model represents the roles the id, ego, and super-ego play in relation to conscious and unconscious thought. Freud compared the relationship between the ego and the id to that between a charioteer and his horses: the horses provide the energy and drive, while the charioteer provides direction.[164] |

イド、自我、超自我 主な記事 イド、自我、超自我  氷山の比喩は、精神の各部分を互いに関連して説明するためによく使われる。 フロイトは、人間の精神は3つの部分に分けられると提唱した: イド、自我、超自我である。フロイトはこのモデルについて、1920年のエッセイ『快楽原則を超えて』で論じ、『自我とイド』(1923年)で、それまで のトポグラフィ・スケーマ(すなわち、意識、無意識、前意識)に代わるものとして発展させた。イドは「快楽原則」で作動する精神の無意識の部分であり、基 本的な衝動と衝動の源である。 超自我は精神の道徳的な構成要素である[156]。理性的な自我はイドの非現実的な快楽主義と超自我の同じく非現実的な道徳主義の間でバランスを取ろうと する[155]。その任務によって過度の負担を強いられたり脅かされたりすると、否認、抑圧、取り消し、合理化、変位などの防衛機制を用いることがある。 この概念は通常「氷山モデル」[166]によって表される。このモデルは、意識的思考と無意識的思考との関係においてイド、自我、超自我が果たす役割を表 している。 フロイトは自我とイドの関係を戦車乗りとその馬の関係に例えた:馬はエネルギーと原動力を提供し、戦車乗りは指示を与える。 |

| Life and death drives Main articles: Libido, Death drive, and Repetition compulsion Freud believed that the human psyche is subject to two conflicting drives: the life drive or libido and the death drive. The life drive was also termed "Eros" and the death drive "Thanatos", although Freud did not use the latter term; "Thanatos" was introduced in this context by Paul Federn.[167][168] Freud hypothesized that libido is a form of mental energy with which processes, structures, and object-representations are invested.[169] In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud inferred the existence of a death drive. Its premise was a regulatory principle that has been described as "the principle of psychic inertia", "the Nirvana principle",[170] and "the conservatism of instinct". Its background was Freud's earlier Project for a Scientific Psychology, where he had defined the principle governing the mental apparatus as its tendency to divest itself of quantity or to reduce tension to zero. Freud had been obliged to abandon that definition, since it proved adequate only to the most rudimentary kinds of mental functioning, and replaced the idea that the apparatus tends toward a level of zero tension with the idea that it tends toward a minimum level of tension.[171] Freud in effect readopted the original definition in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, this time applying it to a different principle. He asserted that on certain occasions the mind acts as though it could eliminate tension, or in effect to reduce itself to a state of extinction; his key evidence for this was the existence of the compulsion to repeat. Examples of such repetition included the dream life of traumatic neurotics and children's play. In the phenomenon of repetition, Freud saw a psychic trend to work over earlier impressions, to master them and derive pleasure from them, a trend that was before the pleasure principle but not opposed to it. In addition to that trend, there was also a principle at work that was opposed to, and thus "beyond" the pleasure principle. If repetition is a necessary element in the binding of energy or adaptation, when carried to inordinate lengths it becomes a means of abandoning adaptations and reinstating earlier or less evolved psychic positions. By combining this idea with the hypothesis that all repetition is a form of discharge, Freud concluded that the compulsion to repeat is an effort to restore a state that is both historically primitive and marked by the total draining of energy: death.[171] Such an explanation has been described by some scholars as "metaphysical biology".[172] |

生と死のドライブ(衝動) 主な記事 リビドー、死の衝動、反復強迫 フロイトは、人間の精神は2つの相反する衝動に支配されていると考えた。生命衝動は「エロス」とも呼ばれ、死の衝動は「タナトス」とも呼ばれたが、フロイ トは後者の言葉を使わなかった。 快楽原則を超えて』(1920年)において、フロイトは死の衝動の存在を推論した。その前提は、「精神的慣性の原理」、「涅槃の原理」[170]、「本能 の保守性」と表現される調節原理であった。その背景には、フロイトの以前の『科学的心理学のためのプロジェクト』があり、そこでは、精神装置を支配する原 理を、精神装置自身が量的なものから解放される傾向、あるいは緊張をゼロにする傾向として定義していた。フロイトは、その定義が最も初歩的な種類の精神機 能に対してのみ適切であることが判明したため、その定義を放棄せざるを得なくなり、装置が張力ゼロのレベルに向かう傾向があるという考えを、張力の最小レ ベルに向かう傾向があるという考えに置き換えた[171]。 フロイトは『快楽原則の彼方へ』において、事実上、元の定義を再度採用し、今度はそれを別の原理に適用した。彼は、ある特定の場面において、心は緊張をな くすことができるかのように、あるいは事実上、それ自体を消滅状態にまで低下させることができるかのように行動すると主張し、これに対する彼の重要な証拠 は反復の強迫の存在であった。このような繰り返しの例としては、トラウマを持つ神経症患者の夢の生活や子供の遊びなどがあった。フロイトは繰り返しという 現象に、以前の印象を克服し、それをマスターし、そこから快感を得ようとする心理的傾向を見た。その傾向に加えて、快楽原則に対立する、つまり快楽原則を 「超える」原理も働いていた。繰り返しがエネルギーや適応を束ねるために必要な要素であるとすれば、それが過度に長引けば、適応を放棄し、以前の、あるい はあまり進化していない精神的立場を復活させる手段となる。この考えを、すべての反復は放電の一形態であるという仮説と組み合わせることによって、フロイ トは、反復への強迫は、歴史的に原始的であり、かつエネルギーの完全な消耗によって特徴づけられる状態、すなわち死を回復しようとする努力であると結論づ けた[171]。このような説明は、一部の学者によって「形而上学的生物学」と表現されている[172]。 |

| Melancholia In his 1917 essay "Mourning and Melancholia", Freud distinguished mourning, painful but an inevitable part of life, and "melancholia", his term for pathological refusal of a mourner to "decathect" from the lost one. Freud claimed that, in normal mourning, the ego was responsible for narcissistically detaching the libido from the lost one as a means of self-preservation, but that in "melancholia", prior ambivalence towards the lost one prevents this from occurring. Suicide, Freud hypothesized, could result in extreme cases, when unconscious feelings of conflict became directed against the mourner's own ego.[173][174] |

メランコリア 1917年のエッセイ『喪とメランコリア』において、フロイトは、苦痛を伴うが人生の必然的な一部である「喪」と、喪に服した者が失われた者から「離脱」 することを病的に拒否することを指す「メランコリア」を区別した。フロイトは、正常な喪服の場合、自我は自己保存の手段として、失われたものからリビドー を自己愛的に切り離す責任があるが、「メランコリア」の場合、失われたものに対する事前の両価性がそれを妨げると主張した。フロイトは、無意識的な葛藤の 感情が喪主自身の自我に向けられるようになる極端な場合には、自殺に至る可能性があるという仮説を立てた[173][174]。 |

| Femininity and female sexuality Freud's account of femininity is grounded in his theory of psychic development as it traces the uneven transition from the earliest stages of infantile and childhood sexuality, characterised by polymorphous perversity and a bisexual disposition, through to the fantasy scenarios and rivalrous identifications of the Oedipus complex and on to the greater or lesser extent these are modified in adult sexuality. There are different trajectories for the boy and the girl which arise as effects of the castration complex. Anatomical difference, the possession of a penis, induces castration anxiety for the boy whereas the girl experiences a sense of deprivation. In the boy's case the castration complex concludes the Oedipal phase whereas for the girl it precipitates it.[175] The constraint of the erotic feelings and fantasies of the girl and her turning away from the mother to the father is an uneven and precarious process entailing "waves of repression". The normal outcome is, according to Freud, the vagina becoming "the new leading zone" of sexual sensitivity, displacing the previously dominant clitoris, the phallic properties of which made it indistinguishable in the child's early sexual life from the penis. This leaves a legacy of penis envy and emotional ambivalence for the girl which was "intimately related to the essence of femininity" and leads to "the greater proneness of women to neurosis and especially hysteria."[176] In his last paper on the topic Freud likewise concludes that "the development of femininity remains exposed to disturbance by the residual phenomena of the early masculine period... Some portion of what we men call the 'enigma of women' may perhaps be derived from this expression of bisexuality in women's lives."[177] Initiating what became the first debate within psychoanalysis on femininity, Karen Horney of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute set out to challenge Freud's account of femininity. Rejecting Freud's theories of the feminine castration complex and penis envy, Horney argued for a primary femininity and penis envy as a defensive formation rather than arising from the fact, or "injury", of biological asymmetry as Freud held. Horney had the influential support of Melanie Klein and Ernest Jones who coined the term "phallocentrism" in his critique of Freud's position.[178] In defending Freud against this critique, feminist scholar Jacqueline Rose has argued that it presupposes a more normative account of female sexual development than that given by Freud. She finds that Freud moved from a description of the little girl stuck with her 'inferiority' or 'injury' in the face of the anatomy of the little boy to an account in his later work which explicitly describes the process of becoming 'feminine' as an 'injury' or 'catastrophe' for the complexity of her earlier psychic and sexual life.[179] Throughout his deliberations on what he described as the "dark continent" of female sexuality and the "riddle" of femininity, Freud was careful to emphasise the "average validity" and provisional nature of his findings.[177] He did, however, in response to his critics, maintain a steadfast objection "to all of you ... to the extent that you do not distinguish more clearly between what is psychic and what is biological..."[180] |

女性性と女性の性 フロイトの女性性に関する説明は、彼の精神発達論に基づくものであり、多形性倒錯や両性具有的気質によって特徴づけられる幼児期や児童期の性愛の初期段階 から、エディプス・コンプレックスの空想的シナリオや対抗的同一化、そしてそれらが成人期の性愛において大なり小なり修正されるまでの不均等な移行をたど るものである。少年と少女には、去勢コンプレックスの影響として生じる異なる軌跡がある。解剖学的な違い、つまりペニスの所有が、少年に去勢不安を引き起 こすのに対し、少女は剥奪感を経験する。男の子の場合、去勢コンプレックスはエディプス期を終結させるが、女の子の場合はエディプス期を促進させる [175]。 少女のエロティックな感情や空想が束縛され、母から父へと向かうのは、「抑圧の波」を伴う不均等で不安定な過程である。フロイトによれば、正常な結果は、 膣が性的感受性の「新しい主役」になり、それまで支配的だったクリトリスに取って代わることである。このことは、「女性性の本質に密接に関係する」ペニス への羨望と感情的なアンビバレンスの遺産を少女に残し、「神経症、特にヒステリーに対する女性のより大きな傾向」[176]につながる。われわれ男性が "女性の謎 "と呼ぶもののある部分は、おそらく女性の生活における両性具有のこの表現に由来しているかもしれない」[177]。 ベルリン精神分析研究所のカレン・ホーニーは、精神分析における女性性に関する最初の議論を開始し、フロイトの女性性に関する説明に異議を唱えようとし た。フロイトの女性的去勢コンプレックスとペニス羨望に関する理論を否定したホーニーは、フロイトが主張したような生物学的非対称性という事実(あるいは 「傷害」)から生じるのではなく、防衛的形成としての第一次的女性性とペニス羨望を主張した。ホーニーは、メラニー・クラインやアーネスト・ジョーンズの 影響力のある支持を得ており、彼はフロイトの立場を批判する際に「男根中心主義」という言葉を作った[178]。 この批判からフロイトを擁護するために、フェミニスト学者のジャクリーン・ローズは、フロイトが与えたものよりも規範的な女性の性的発達の説明を前提とし ていると主張している。彼女は、フロイトが、小さな男の子の解剖学的構造を前にして、その「劣等性」や「傷害」から抜け出せない少女についての記述から、 彼の後期の著作において、「女性的」になる過程を、彼女のそれまでの精神生活や性生活の複雑さに対する「傷害」や「破局」として明確に記述する記述へと移 行したことを発見している[179]。 女性のセクシュアリティの「暗黒大陸」や女性性の「謎」と表現したものについての考察を通して、フロイトは自分の発見が「平均的な妥当性」と暫定的な性質 であることを強調するように注意していた[177]。 しかしながら、彼は批評家たちに対して、「あなた方すべてに対して......あなた方が精神的なものと生物学的なものとの間をより明確に区別しない限り において......」[180]不動の異議を維持していた。 |

| Phallic monism Phallic monism is a term introduced by Chasseguet-Smirgel[1] to refer to the theory that in both sexes the male organ—i.e. the question of possessing the penis or not—was the key to psychosexual development.[2] The theory was upheld by Sigmund Freud. His critics maintain it was a result of an unconscious adherence to an infantile sexual theory.[3] Freud Freud identified as the central theme of the phallic stage a state of mind in which "maleness exists, but not femaleness. The antithesis here is between having a male genital and being castrated".[4] He believed that the mind-set was shared both by little boys and little girls[5]—a viewpoint shared by the orthodox strand of his following, as epitomised for example in the work of Otto Fenichel.[6] Freud considered such phallic monism to be at the core of neurosis to the very end of his career.[7] Critics Trenchant early criticism of Freud's monism was made by Karen Horney, who suggested that the psychoanalytic view had itself become fixated at the level of the small boy aggrandising himself at his sister's expense.[8] Ernest Jones too was quick to maintain that woman was not, as Freud seemed to suggest, "un homme manqué...struggling to console herself with secondary substitutes alien to her true nature".[9] Jacques Lacan reformulated Freud's phallic monism through his theory of the phallus as signifier;[10] but Kleinians, post-Kleinians, and those influenced by second-wave feminism have all articulated a more positive view of femininity, articulating the belief in phallic monism as a survival into adulthood of a (male) infantile sexual theory.[11] Phallic monism has also been linked to sexual fetishism, fueled by an over-aggressive super-ego.[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phallic_monism |

男根一元論 男根一元論とはシャスゲ=スミルゲル[1]によって提唱された用語で、 両性において男性器、すなわちペニスを所有するか否かが心理性発達の鍵であるという理論を指す[2]。 この理論はジークムント・フロイトによって支持された。彼の批評家は、それは幼児的な性理論に無意識に固執した結果であると主張している[3]。 フロイト フロイトは男根期の中心的なテーマとして、「男性性は存在するが、女性性は存在しない」心の状態を挙げた。ここでのアンチテーゼは、男性器を持つことと去 勢されることの間にある」[4]。彼は、この心境は幼い少年と幼い少女の両方に共有されていると考えていた[5]。 フロイトはそのような男根一元論が神経症の核心であると彼のキャリアの最後まで考えていた[7]。 批評家 フロイトの一元論に対する初期の痛烈な批判はカレン・ホーニーによってなされ、彼は精神分析的な見方自体が、妹を犠牲にして自分を誇示する小さな男の子の レベルで固定化されてしまったと示唆した[8]。 ジャック・ラカンはシニフィアンとしての男根の理論を通してフロイトの男根一元論を再定義した[10]が、クライン派、ポスト・クライン派、そして第二波 フェミニズムの影響を受けた人々は皆、女性性に対してより肯定的な見方を明確にしており、男根一元論への信念を(男性の)幼児的な性理論の成人期への生き 残りとして明確にしている[11]。 男根一元論はまた、過剰に攻撃的な超自我に煽られた性的フェティシズムとも関連している[12]。 |

| Religion Main article: Freud and religion Freud regarded the monotheistic God as an illusion based upon the infantile emotional need for a powerful, supernatural pater familias. He maintained that religion – once necessary to restrain man's violent nature in the early stages of civilization – in modern times, can be set aside in favor of reason and science.[181] "Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices" (1907) notes the likeness between faith (religious belief) and neurotic obsession.[182] Totem and Taboo (1913) proposes that society and religion begin with the patricide and eating of the powerful paternal figure, who then becomes a revered collective memory.[183] These arguments were further developed in The Future of an Illusion (1927) in which Freud argues that the function of religious belief is psychological consolation. He argues that the belief in a supernatural protector serves as a buffer against man's "fear of nature", just as the belief in an afterlife serves as a buffer against man's fear of death. The core idea of the work is that religious belief can be explained through its function in society, not through its relation to the truth. In the first part of Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), he considers the "oceanic feeling" of wholeness, limitlessness, and eternity (brought to his attention by his friend Romain Rolland), as a possible source for religious feelings. He notes that he has no experience of this feeling himself, and suggests that it is a regression into the state of consciousness that precedes the ego's differentiation of itself from the world of objects and others.[184] Moses and Monotheism (1937) proposes that Moses was the tribal pater familias, killed by the Jews, who psychologically coped with the patricide with a reaction formation conducive to their establishing monotheistic Judaism;[185][186] analogously, he described the Roman Catholic rite of Holy Communion as cultural evidence of the killing and devouring of the sacred father.[121][187] Moreover, he perceived religion, with its suppression of violence, as mediator of the societal and personal, the public and the private, conflicts between Eros and Thanatos, the forces of life and death.[188] Later works indicate Freud's pessimism about the future of civilization, which he noted in the 1931 edition of Civilization and its Discontents.[189] Humphrey Skelton described Freud's worldview as one of "stoical humanism".[190] The Humanist Heritage project summed his contributions to understanding of religion by saying: Freud's ideas on the origins of the religious impulse, and the comforting illusion religion provided, were a significant contribution to a tradition of scientific humanist thought, in which research and reason were the means of uncovering truth. They also served to highlight the powerful resonance of childhood influences on adult lives, not least in the realm of religion.[190] In a footnote of his 1909 work, Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy, Freud theorized that the universal fear of castration was provoked in the uncircumcised when they perceived circumcision and that this was "the deepest unconscious root of antisemitism".[191] |

宗教 主な記事 フロイトと宗教 フロイトは一神教の神を、強力で超自然的な父なる家族に対する幼児的な感情的欲求に基づく幻想とみなした。彼は、かつて文明の初期において人間の暴力性を 抑制するために必要であった宗教は、現代においては理性と科学を優先するために脇に置かれることができると主張した[181] 「強迫行為と宗教的実践」(1907年)は、信仰(宗教的信念)と神経症的強迫観念との類似性を指摘している。 [182] 『トーテムとタブー』(Totem and Taboo、1913年)は、社会と宗教は強力な父性的人物の尊属殺人と食事から始まり、その父性的人物は崇敬される集団的記憶となると提唱している。超 自然的な庇護者に対する信仰は、死後の世界に対する信仰が人間の死に対する恐怖に対する緩衝材として機能するように、人間の「自然に対する恐怖」に対する 緩衝材として機能すると彼は主張する。この作品の核となる考え方は、宗教的信仰は、真理との関係ではなく、社会におけるその機能を通して説明できるという ものである。文明とその不満』(1930年)の第1部では、宗教的感情の源となりうるものとして、全体性、無限性、永遠性といった「大洋的感覚」(友人の ロマン・ロランによってもたらされた)を考察している。彼自身はこの感覚を経験したことがないとし、それは自我が物や他者の世界から自我を分化させる前の 意識状態への回帰であると示唆している。 [184] 『モーゼと一神教』(1937年)は、モーゼはユダヤ人によって殺された部族の父なる家族であり、彼らは一神教的なユダヤ教を確立することに資する反応形 成によって心理的に父殺しに対処したと提唱している[185][186]。同様に、彼はローマ・カトリックの聖体拝領の儀式を、神聖な父を殺し、むさぼり 食うことの文化的な証拠であると述べている[121][187]。 さらに彼は、暴力を抑制する宗教を、社会的なものと個人的なもの、公的なものと私的なもの、エロスとタナトス、生と死の力の間の葛藤を媒介するものとして 認識していた。 [188]後の著作は、フロイトが文明の未来について悲観的であったことを示しており、彼は1931年版の『文明とその不満』においてそれを指摘している [189]。 ハンフリー・スケルトンはフロイトの世界観を「ストイックなヒューマニズム」のひとつと評している[190]: 宗教的衝動の起源と、宗教がもたらす安らぎの幻想に関するフロイトの考えは、研究と理性が真理を解明する手段である科学的ヒューマニズム思想の伝統に大き く貢献した。それらはまた、少なくとも宗教の領域においてはそうであったが、幼少期に受けた影響が大人の人生に与える強力な影響力を強調する役割を果たし た[190]。 1909年の著作である『5歳の少年の恐怖症の分析』の脚注において、フロイトは、割礼を知覚したときに、去勢に対する普遍的な恐怖が割礼を受けていない 人々に引き起こされ、これが「反ユダヤ主義の最も深い無意識の根源」であると理論化している[191]。 |

| Freud's

legacy Freud's legacy, though a highly contested area of controversy, has been assessed as "one of the strongest influences on twentieth-century thought, its impact comparable only to that of Darwinism and Marxism,"[192] with its range of influence permeating "all the fields of culture ... so far as to change our way of life and concept of man."[193] |

フ

ロイトの遺産 フ ロイトの遺産は、非常に論争が多い分野ではあるが、「20世紀の思想に最も強い影響を与えたもののひとつであり、その影響はダーウィニズムとマルクス主義 に匹敵する」[192]と評価されており、その影響範囲は「文化のあらゆる分野......私たちの生き方や人間の概念を変えるほど」浸透している [193]。 |

| Psychotherapy Though not the first methodology in the practice of individual verbal psychotherapy,[194] Freud's psychoanalytic system came to dominate the field from early in the twentieth century, forming the basis for many later variants. While these systems have adopted different theories and techniques, all have followed Freud by attempting to achieve psychic and behavioral change through having patients talk about their difficulties.[3] Psychoanalysis is not as influential as it once was in Europe and the United States, though in some parts of the world, notably Latin America, its influence in the later 20th century expanded substantially. Psychoanalysis also remains influential within many contemporary schools of psychotherapy and has led to innovative therapeutic work in schools and with families and groups.[195] There is a substantial body of research which demonstrates the efficacy of the clinical methods of psychoanalysis[196] and of related psychodynamic therapies in treating a wide range of psychological disorders.[197] The neo-Freudians, a group including Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm, rejected Freud's theory of instinctual drive, emphasized interpersonal relations and self-assertiveness, and made modifications to therapeutic practice that reflected these theoretical shifts. Adler originated the approach, although his influence was indirect due to his inability to systematically formulate his ideas. The neo-Freudian analysis places more emphasis on the patient's relationship with the analyst and less on the exploration of the unconscious.[198] Carl Jung believed that the collective unconscious, which reflects the cosmic order and the history of the human species, is the most important part of the mind. It contains archetypes, which are manifested in symbols that appear in dreams, disturbed states of mind, and various products of culture. Jungians are less interested in infantile development and psychological conflict between wishes and the forces that frustrate them than in integration between different parts of the person. The object of Jungian therapy was to mend such splits. Jung focused in particular on problems of middle and later life. His objective was to allow people to experience the split-off aspects of themselves, such as the anima (a man's suppressed female self), the animus (a woman's suppressed male self), or the shadow (an inferior self-image), and thereby attain wisdom.[198] Jacques Lacan approached psychoanalysis through linguistics and literature. Lacan believed that most of Freud's essential work had been done before 1905 and concerned the interpretation of dreams, neurotic symptoms, and slips, which had been based on a revolutionary way of understanding language and its relation to experience and subjectivity, and that ego psychology and object relations theory were based upon misreadings of Freud's work. For Lacan, the determinative dimension of human experience is neither the self (as in ego psychology) nor relations with others (as in object relations theory), but language. Lacan saw desire as more important than need and considered it necessarily ungratifiable.[199] Wilhelm Reich developed ideas that Freud had developed at the beginning of his psychoanalytic investigation but then superseded but never finally discarded. These were the concept of the Actualneurosis and a theory of anxiety based upon the idea of dammed-up libido. In Freud's original view, what really happened to a person (the "actual") determined the resulting neurotic disposition. Freud applied that idea both to infants and to adults. In the former case, seductions were sought as the causes of later neuroses and in the latter incomplete sexual release. Unlike Freud, Reich retained the idea that actual experience, especially sexual experience, was of key significance. By the 1920s, Reich had "taken Freud's original ideas about sexual release to the point of specifying the orgasm as the criteria of healthy function." Reich was also "developing his ideas about character into a form that would later take shape, first as "muscular armour", and eventually as a transducer of universal biological energy, the "orgone"."[198] Fritz Perls, who helped to develop Gestalt therapy, was influenced by Reich, Jung, and Freud. The key idea of gestalt therapy is that Freud overlooked the structure of awareness, "an active process that moves toward the construction of organized meaningful wholes ... between an organism and its environment." These wholes, called gestalts, are "patterns involving all the layers of organismic function – thought, feeling, and activity." Neurosis is seen as splitting in the formation of gestalts, and anxiety as the organism sensing "the struggle towards its creative unification." Gestalt therapy attempts to cure patients by placing them in contact with "immediate organismic needs." Perls rejected the verbal approach of classical psychoanalysis; talking in gestalt therapy serves the purpose of self-expression rather than gaining self-knowledge. Gestalt therapy usually takes place in groups, and in concentrated "workshops" rather than being spread out over a long period of time; it has been extended into new forms of communal living.[198] Arthur Janov's primal therapy, which has been influential post-Freudian psychotherapy, resembles psychoanalytic therapy in its emphasis on early childhood experience but has also differences with it. While Janov's theory is akin to Freud's early idea of Actualneurosis, he does not have a dynamic psychology but a nature psychology like that of Reich or Perls, in which need is primary while wish is derivative and dispensable when need is met. Despite its surface similarity to Freud's ideas, Janov's theory lacks a strictly psychological account of the unconscious and belief in infantile sexuality. While for Freud there was a hierarchy of dangerous situations, for Janov the key event in the child's life is an awareness that the parents do not love it.[198] Janov writes in The Primal Scream (1970) that primal therapy has in some ways returned to Freud's early ideas and techniques.[200] Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, co-authors of The Courage to Heal (1988), are described as "champions of survivorship" by Frederick Crews, who considers Freud the key influence upon them, although in his view they are indebted not to classic psychoanalysis but to "the pre-psychoanalytic Freud ... who supposedly took pity on his hysterical patients, found that they were all harboring memories of early abuse ... and cured them by unknotting their repression." Crews sees Freud as having anticipated the recovered memory movement by emphasizing "mechanical cause-and-effect relations between symptomatology and the premature stimulation of one body zone or another", and with pioneering its "technique of thematically matching a patient's symptom with a sexually symmetrical 'memory.'" Crews believes that Freud's confidence in accurate recall of early memories anticipates the theories of recovered memory therapists such as Lenore Terr, which in his view have led to people being wrongfully imprisoned or involved in litigation.[201] |

心理療法 個人的な言葉による心理療法の実践における最初の方法論ではないが[194]、フロイトの精神分析システムは20世紀初頭からこの分野を支配するようにな り、後の多くの変種の基礎を形成した。これらのシステムは、異なる理論や技法を採用しているが、すべて患者が自分の困難について話すことを通して精神的、 行動的変化を達成しようとするフロイトに追随している[3]。精神分析は、ヨーロッパやアメリカではかつてほどの影響力はないが、世界のいくつかの地域、 特にラテンアメリカでは、20世紀後半にその影響力が大幅に拡大した。精神分析はまた、現代の心理療法の多くの流派の中でも影響力を持ち続けており、学校 や家族・集団での革新的な治療活動につながっている[195]。精神分析の臨床方法[196]や関連する精神力動的療法が広範な心理障害を治療する上で有 効であることを実証する研究が数多く存在する[197]。 アルフレッド・アドラー、オットー・ランク、カレン・ホーニー、ハリー・スタック・サリバン、エーリッヒ・フロムを含むグループである新フロイト派は、フ ロイトの本能的衝動理論を否定し、対人関係と自己主張を強調し、これらの理論的転換を反映した治療実践に修正を加えた。アドラーはこのアプローチを創始し たが、彼の考えを体系的に定式化することができなかったため、その影響は間接的なものであった。ネオ・フロイト派の分析は、患者と分析者との関係に重きを 置き、無意識の探求にはあまり重きを置いていない[198]。 カール・ユングは、宇宙的秩序と人類種の歴史を反映する集合的無意識が心の最も重要な部分であると考えていた。その中には原型が含まれており、それは夢や 心の乱れた状態、文化の様々な産物の中に現れる象徴の中に現れている。ユング派は、人間のさまざまな部分間の統合よりも、幼児期の発達や、願望とそれを挫 く力との間の心理的葛藤にあまり関心がない。ユングのセラピーの目的は、そのような分裂を修復することであった。ユングは特に中年以降の人生の問題に焦点 を当てた。彼の目的は、アニマ(男性の抑圧された女性の自己)、アニムス(女性の抑圧された男性の自己)、あるいはシャドー(劣った自己イメージ)といっ た、分裂した自分の側面を人々が経験することを可能にし、それによって知恵を獲得することであった[198]。 ジャック・ラカンは言語学と文学を通して精神分析にアプローチした。ラカンは、フロイトの本質的な仕事のほとんどは1905年以前になされたものであり、 夢、神経症状、滑落の解釈に関するものであり、それは言語と経験と主観性との関係を理解する革命的な方法に基づいており、自我心理学と対象関係論はフロイ トの仕事の誤読に基づいていると考えていた。ラカンにとって、人間の経験の決定的な次元は、(自我心理学のような)自己でも(対象関係論のような)他者と の関係でもなく、言語であった。ラカンは欲求を必要性よりも重要視し、それは必然的に感謝できないものであると考えた[199]。 ヴィルヘルム・ライヒは、フロイトが精神分析の研究の初期に発展させたが、その後取って代わられたものの、最終的に破棄されることはなかった考え方を発展 させた。これらはアクチュアルノイローゼの概念と、堰き止められたリビドーの考えに基づく不安の理論であった。フロイトの当初の見解では、ある人に実際に 起こったこと(「実際」)が、結果として生じる神経症的気質を決定した。フロイトはこの考えを幼児と成人の両方に適用した。前者では、誘惑が後の神経症の 原因として求められ、後者では不完全な性的解放が求められた。フロイトとは異なり、ライヒは実際の経験、特に性的経験が重要な意味を持つという考えを保持 した。1920年代までに、ライヒは「性的解放に関するフロイトの独創的な考えを、健全な機能の基準としてオーガズムを特定するところまで発展させた」。 ライヒはまた、「性格に関する彼の考えを、最初は「筋肉の鎧」として、最終的には普遍的な生物学的エネルギーの変換器である「オルゴン」として、後に形に なるものへと発展させていた」[198]。 ゲシュタルト療法の発展に貢献したフリッツ・パールズは、ライヒ、ユング、フロイトの影響を受けていた。ゲシュタルト療法の重要な考え方は、フロイトが意 識の構造を見落としていたことであり、「生物とその環境との間に......組織化された意味のある全体が構築される方向に向かう能動的なプロセス」であ る。ゲシュタルトと呼ばれるこれらの全体は、"思考、感情、活動といった生物学的機能のすべての層を含むパターン "である。神経症はゲシュタルトの形成における分裂であり、不安は有機体が "その創造的統一に向けた闘争 "を感知することであると考えられている。ゲシュタルト療法は、患者を "直接的な生物学的ニーズ "と接触させることによって治癒を試みる。パールズは、古典的な精神分析の言葉によるアプローチを否定した。ゲシュタルト療法における会話は、自己認識を 得ることよりも、むしろ自己表現を目的としている。ゲシュタルト療法は通常、集団の中で行われ、長期間にわたって行われるのではなく、集中的な「ワーク ショップ」の中で行われる。 フロイト以後の心理療法に影響を与えたアーサー・ヤノフの原始療法は、幼児期の経験に重点を置いている点で精神分析療法に似ているが、それとは異なる点も ある。ジャノフの理論は、フロイトの初期のアクチュアル・ノイローゼの考え方に似ているが、動的心理学ではなく、ライヒやパールズのような自然心理学であ る。フロイトの考えと表面的には似ているが、ヤノフの理論には、無意識や幼児性愛に対する信念について、厳密に心理学的な説明が欠けている。フロイトに とっては危険な状況の階層があったのに対して、ヤノフにとっては、子どもの人生における重要な出来事は、親が自分を愛していないという自覚である [198]。ヤノフは『原始の叫び』(1970年)の中で、原始療法はある意味でフロイトの初期の考えや技法に戻ってきたと書いている[200]。 癒す勇気』(1988年)の共著者であるエレン・バスとローラ・デイヴィスは、フレデリック・クルーズによって「サバイバーシップの擁護者」と評され、彼 はフロイトが彼らに重要な影響を与えたと考えているが、彼の見解では、彼らは古典的な精神分析ではなく、「精神分析以前のフロイト......彼はヒステ リー患者を憐れみ、彼らがみな初期の虐待の記憶を抱えていることを発見し......彼らの抑圧の結び目を解くことによって彼らを治療した」とされてい る。クルーズは、フロイトが「症状と身体部位の早すぎる刺激との間の機械的な因果関係」を強調し、「患者の症状と性的に対称的な "記憶 "とを主題的に一致させる技法」を開拓したことで、回復記憶運動を先取りしたと見ている。クルーズは、初期の記憶の正確な想起に対するフロイトの自信は、 レノア・テールのような回復記憶療法家の理論を先取りしたものであり、それが不当に投獄されたり、訴訟に巻き込まれたりする原因になっていると考えている [201]。 |

| Science Research projects designed to test Freud's theories empirically have led to a vast literature on the topic.[202] American psychologists began to attempt to study repression in the experimental laboratory around 1930. In 1934, when the psychologist Saul Rosenzweig sent Freud reprints of his attempts to study repression, Freud responded with a dismissive letter stating that "the wealth of reliable observations" on which psychoanalytic assertions were based made them "independent of experimental verification."[203] Seymour Fisher and Roger P. Greenberg concluded in 1977 that some of Freud's concepts were supported by empirical evidence. Their analysis of research literature supported Freud's concepts of oral and anal personality constellations, his account of the role of Oedipal factors in certain aspects of male personality functioning, his formulations about the relatively greater concern about the loss of love in women's as compared to men's personality economy, and his views about the instigating effects of homosexual anxieties on the formation of paranoid delusions. They also found limited and equivocal support for Freud's theories about the development of homosexuality. They found that several of Freud's other theories, including his portrayal of dreams as primarily containers of secret, unconscious wishes, as well as some of his views about the psychodynamics of women, were either not supported or contradicted by research. Reviewing the issues again in 1996, they concluded that much experimental data relevant to Freud's work exists, and supports some of his major ideas and theories.[204] Other viewpoints include those of psychologist and science historian Malcolm Macmillan, who concludes in Freud Evaluated (1991) that "Freud's method is not capable of yielding objective data about mental processes".[205] Morris Eagle states that it has been "demonstrated quite conclusively that because of the epistemologically contaminated status of clinical data derived from the clinical situation, such data have questionable probative value in the testing of psychoanalytic hypotheses".[206] Richard Webster, in Why Freud Was Wrong (1995), described psychoanalysis as perhaps the most complex and successful pseudoscience in history.[207] Crews believes that psychoanalysis has no scientific or therapeutic merit.[208] University of Chicago research associate Kurt Jacobsen takes these critics to task for their own supposedly dogmatic and historically naive views both about psychoanalysis and the nature of science.[209] I.B. Cohen regards Freud's Interpretation of Dreams as a revolutionary work of science, the last such work to be published in book form.[210] In contrast Allan Hobson believes that Freud, by rhetorically discrediting 19th century investigators of dreams such as Alfred Maury and the Marquis de Hervey de Saint-Denis at a time when study of the physiology of the brain was only beginning, interrupted the development of scientific dream theory for half a century.[211] The dream researcher G. William Domhoff has disputed claims of Freudian dream theory being validated.[212]  Karl Popper argued that Freud's psychoanalytic theories were unfalsifiable. The philosopher Karl Popper, who argued that all proper scientific theories must be potentially falsifiable, claimed that Freud's Psychoanalytic Theories were presented in unfalsifiable form, meaning that no experiment could ever disprove them.[213] The philosopher Adolf Grünbaum argues in The Foundations of Psychoanalysis (1984) that Popper was mistaken and that many of Freud's theories are empirically testable, a position with which others such as Eysenck agree.[214][215] The philosopher Roger Scruton, writing in Sexual Desire (1986), also rejected Popper's arguments, pointing to the theory of repression as an example of a Freudian theory that does have testable consequences. Scruton nevertheless concluded that psychoanalysis is not genuinely scientific, because it involves an unacceptable dependence on metaphor.[216] The philosopher Donald Levy agrees with Grünbaum that Freud's theories are falsifiable but disputes Grünbaum's contention that therapeutic success is only the empirical basis on which they stand or fall, arguing that a much wider range of empirical evidence can be adduced if clinical case material is taken into consideration.[217] In a study of psychoanalysis in the United States, Nathan Hale reported on the "decline of psychoanalysis in psychiatry" during the years 1965–1985.[218] The continuation of this trend was noted by Alan Stone: "As academic psychology becomes more 'scientific' and psychiatry more biological, psychoanalysis is being brushed aside."[219] Paul Stepansky, while noting that psychoanalysis remains influential in the humanities, records the "vanishingly small number of psychiatric residents who choose to pursue psychoanalytic training" and the "nonanalytic backgrounds of psychiatric chairpersons at major universities" among the evidence he cites for his conclusion that "Such historical trends attest to the marginalisation of psychoanalysis within American psychiatry."[220] Nonetheless, Freud was ranked as the third most cited psychologist of the 20th century, according to a Review of General Psychology survey of American psychologists and psychology texts, published in 2002.[221] It is also claimed that in moving beyond the "orthodoxy of the not so distant past ... new ideas and new research has led to an intense reawakening of interest in psychoanalysis from neighbouring disciplines ranging from the humanities to neuroscience and including the non-analytic therapies".[222] Research in the emerging field of neuropsychoanalysis, founded by neuroscientist and psychoanalyst Mark Solms,[223] has proved controversial with some psychoanalysts criticising the very concept itself.[224] Solms and his colleagues have argued for neuro-scientific findings being "broadly consistent" with Freudian theories pointing out brain structures relating to Freudian concepts such as libido, drives, the unconscious, and repression.[225][226] Neuroscientists who have endorsed Freud's work include David Eagleman who believes that Freud "transformed psychiatry" by providing "the first exploration of the way in which hidden states of the brain participate in driving thought and behavior"[227] and Nobel laureate Eric Kandel who argues that "psychoanalysis still represents the most coherent and intellectually satisfying view of the mind."[228] |

科学 フロイトの理論を実証的に検証するために計画された研究プロジェクトは、このテーマに関する膨大な文献をもたらした[202]。アメリカの心理学者は、 1930年頃に実験室で抑圧を研究する試みを始めた。1934年、心理学者ソール・ローゼンツヴァイクがフロイトに抑圧を研究する試みの印刷物を送ったと き、フロイトは、精神分析的主張が基づいている「信頼できる観察の豊かさ」がそれらを「実験的検証から独立したもの」にしているとする却下的な書簡で返信 した[203]。彼らの研究文献の分析は、口唇と肛門の性格コンステレーションに関するフロイトの概念、男性の性格機能のある側面におけるエディプス的要 因の役割に関する彼の説明、男性の性格経済と比較して女性の性格経済における愛の喪失に関する比較的大きな懸念に関する彼の定式化、妄想の形成における同 性愛的不安の誘発効果に関する彼の見解を支持していた。彼らはまた、同性愛の発達に関するフロイトの理論に対する限定的であいまいな支持を発見した。フロ イトの他の理論(夢を主に秘密の無意識の願望の容器として描写したことや、女性の精神力学に関する見解のいくつかを含む)のいくつかは、研究によって支持 されていないか、あるいは矛盾していることがわかった。1996年に再びこの問題を見直すと、彼らはフロイトの仕事に関連する多くの実験データが存在し、 彼の主要なアイデアや理論のいくつかを支持していると結論づけた[204]。 他の視点としては、心理学者であり科学史家でもあるマルコム・マクミランの見解があり、彼は『フロイトの評価』(1991年)の中で「フロイトの方法は、 精神的プロセスに関する客観的なデータをもたらすことができない」と結論づけている[205]。 モリス・イーグルは、「臨床的状況から得られた臨床データの認識論的に汚染された状態のために、そのようなデータは精神分析的仮説の検証において疑わしい 証明的価値を有する」ことがかなり決定的に実証されていると述べている[206]。 [206] リチャード・ウェブスターは、『フロイトはなぜ間違っていたのか』(1995年)の中で、精神分析はおそらく歴史上最も複雑で成功した疑似科学であると述 べている[207] クルーズは、精神分析は科学的にも治療的にもメリットがないと考えている[208] 。 I.B.コーエンは、フロイトの『夢の解釈』を科学の革命的作品であり、そのような作品が書籍として出版された最後の作品であるとみなしている。 [210] 対照的に、アラン・ホブソンは、脳の生理学の研究が始まったばかりの時期に、アルフレッド・モーリーやヘルヴェイ・ド・サン・ドニ侯爵のような19世紀の 夢の研究者を美辞麗句で信用しないことによって、フロイトは半世紀にわたって科学的な夢理論の発展を中断させたと考えている[211]。 夢の研究者であるG.ウィリアム・ドムホフは、フロイトの夢理論が検証されたという主張に異議を唱えている[212]。  カール・ポパーはフロイトの精神分析理論は反証不可能であると主張した。 哲学者のカール・ポパーは、すべての適切な科学的理論は潜在的に反証可能でなければならないと主張し、フロイトの精神分析理論は反証不可能な形で提示され ており、いかなる実験も反証することはできないと主張した。 [213] 哲学者のアドルフ・グリュンバウムは『精神分析の基礎』(1984年)の中で、ポパーは間違っており、フロイトの理論の多くは経験的に検証可能であると主 張しており、アイゼンクのような他の人々もこの立場に同意している[214][215] 哲学者のロジャー・スクルートンも『性の欲望』(1986年)の中で、検証可能な結果を持つフロイトの理論の例として抑圧の理論を指摘し、ポパーの議論を 否定している。哲学者のドナルド・レヴィは、フロイトの理論が反証可能であるという点ではグリュンバウムに同意しているが、治療的成功がその理論が成り立 つか否かの唯一の経験的根拠であるというグリュンバウムの主張には異議を唱えており、臨床例の資料を考慮に入れれば、より広範な経験的証拠を提示すること ができると論じている[217]。 ネイサン・ヘイルは、アメリカにおける精神分析に関する研究の中で、1965年から1985年の間における「精神医学における精神分析の衰退」について報 告している[218]。この傾向が続いていることは、アラン・ストーンによって指摘されている: 学術的な心理学がより「科学的」になり、精神医学がより生物学的になるにつれて、精神分析は脇に追いやられつつある」[219]。 ポール・ステパンスキーは、精神分析が人文科学において影響力を持ち続けていることを指摘しながらも、「精神分析的訓練を受けることを選択する精神科研修 医の数が驚くほど少ない」ことや、「主要大学の精神科主任教授の経歴が非分析的である」ことを、「このような歴史的な傾向は、アメリカの精神医学において 精神分析が疎外されていることを証明している」という結論の根拠として挙げている。 それにもかかわらず、フロイトは、2002年に発表されたアメリカの心理学者と心理学のテキストを対象とした「Review of General Psychology」の調査によれば、20世紀で最も引用された心理学者の第3位にランクされている[221]。 また、「それほど遠くない過去の正統性......新しいアイデアと新しい研究」を超えていくことで、人文科学から神経科学まで、また非分析療法を含む近 隣の学問領域から、精神分析に対する強い関心が再び呼び起こされていると主張されている[222]。 神経科学者であり精神分析家でもあるマーク・ソルムズによって創設された神経精神分析という新興分野の研究は[223]、その概念自体を批判する精神分析 家もおり、論争を巻き起こしている[224]。ソルムズと彼の同僚は、神経科学的知見がフロイトの理論と「大まかに一致」していると主張し、リビドー、衝 動、無意識、抑圧といったフロイトの概念に関連する脳の構造を指摘している。 [225][226]フロイトの研究を支持する神経科学者には、フロイトが「思考や行動の原動力に脳の隠された状態がどのように関与しているかを初めて探 求した」[227]ことで、「精神医学を変革した」と考えるデイヴィッド・イーグルマンや、「精神分析は今もなお、最も首尾一貫した、知的に満足のいく心 の見方を示している」と主張するノーベル賞受賞者のエリック・カンデルがいる[228]。 |

| Philosophy See also: Freudo-Marxism  Herbert Marcuse saw similarities between psychoanalysis and Marxism. Psychoanalysis has been interpreted as both radical and conservative. By the 1940s, it had come to be seen as conservative by the European and American intellectual community. Critics outside the psychoanalytic movement, whether on the political left or right, saw Freud as a conservative. Fromm had argued that several aspects of psychoanalytic theory served the interests of political reaction in his The Fear of Freedom (1942), an assessment confirmed by sympathetic writers on the right. In Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), Philip Rieff portrayed Freud as a man who urged men to make the best of an inevitably unhappy fate, and admirable for that reason. In the 1950s, Herbert Marcuse challenged the then prevailing interpretation of Freud as a conservative in Eros and Civilization (1955), as did Lionel Trilling in Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture and Norman O. Brown in Life Against Death (1959).[229] Eros and Civilization helped make the idea that Freud and Karl Marx were addressing similar questions from different perspectives credible to the left. Marcuse criticized neo-Freudian revisionism for discarding seemingly pessimistic theories such as the death instinct, arguing that they could be turned in a utopian direction. Freud's theories also influenced the Frankfurt School and critical theory as a whole.[230] Freud has been compared to Marx by Reich, who saw Freud's importance for psychiatry as parallel to that of Marx for economics,[231] and by Paul Robinson, who sees Freud as a revolutionary whose contributions to twentieth-century thought are comparable in importance to Marx's contributions to the nineteenth-century thought.[232] Fromm calls Freud, Marx, and Einstein the "architects of the modern age", but rejects the idea that Marx and Freud were equally significant, arguing that Marx was both far more historically important and a finer thinker. Fromm nevertheless credits Freud with permanently changing the way human nature is understood.[233] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari write in Anti-Oedipus (1972) that psychoanalysis resembles the Russian Revolution in that it became corrupted almost from the beginning. They believe this began with Freud's development of the theory of the Oedipus complex, which they see as idealist.[234] Jean-Paul Sartre critiques Freud's theory of the unconscious in Being and Nothingness (1943), claiming that consciousness is essentially self-conscious. Sartre also attempts to adapt some of Freud's ideas to his own account of human life, and thereby develop an "existential psychoanalysis" in which causal categories are replaced by teleological categories.[235] Maurice Merleau-Ponty considers Freud to be one of the anticipators of phenomenology,[236] while Theodor W. Adorno considers Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, to be Freud's philosophical opposite, writing that Husserl's polemic against psychologism could have been directed against psychoanalysis.[237] Paul Ricœur sees Freud as one of the three "masters of suspicion", alongside Marx and Nietzsche,[238] for their unmasking 'the lies and illusions of consciousness'.[239] Ricœur and Jürgen Habermas have helped create a "hermeneutic version of Freud", one which "claimed him as the most significant progenitor of the shift from an objectifying, empiricist understanding of the human realm to one stressing subjectivity and interpretation."[240] Louis Althusser drew on Freud's concept of overdetermination for his reinterpretation of Marx's Capital.[241] Jean-François Lyotard developed a theory of the unconscious that reverses Freud's account of the dream-work: for Lyotard, the unconscious is a force whose intensity is manifest via disfiguration rather than condensation.[242] Jacques Derrida finds Freud to be both a late figure in the history of western metaphysics and, with Nietzsche and Heidegger, a precursor of his own brand of radicalism.[243] Several scholars see Freud as parallel to Plato, writing that they hold nearly the same theory of dreams and have similar theories of the tripartite structure of the human soul or personality, even if the hierarchy between the parts of the soul is almost reversed.[244][245] Ernest Gellner argues that Freud's theories are an inversion of Plato's. Whereas Plato saw a hierarchy inherent in the nature of reality and relied upon it to validate norms, Freud was a naturalist who could not follow such an approach. Both men's theories drew a parallel between the structure of the human mind and that of society, but while Plato wanted to strengthen the super-ego, which corresponded to the aristocracy, Freud wanted to strengthen the ego, which corresponded to the middle class.[246] Paul Vitz compares Freudian psychoanalysis to Thomism, noting St. Thomas's belief in the existence of an "unconscious consciousness" and his "frequent use of the word and concept 'libido' – sometimes in a more specific sense than Freud, but always in a manner in agreement with the Freudian use." Vitz suggests that Freud may have been unaware his theory of the unconscious was reminiscent of Aquinas.[33] |

哲学 こちらもご覧ください: フロイト=マルクス主義  ヘルベルト・マルクーゼは、精神分析とマルクス主義の間に類似点を見出した。 精神分析は急進的とも保守的とも解釈されてきた。1940年代までには、欧米の知識人社会からは保守的と見なされるようになっていた。精神分析運動以外の 批評家たちは、政治的な左派であれ右派であれ、フロイトを保守的と見ていた。フロムは『自由の恐怖』(1942年)の中で、精神分析理論のいくつかの側面 が政治的反動の利益に資するものであると主張していたが、この評価は右派の共感的な作家たちによっても支持されていた。フロイト モラリストの心』(1959年)の中で、フィリップ・リーフはフロイトを、必然的に不幸になる運命の中で最善を尽くすよう促し、そのために称賛される人間 として描いた。1950年代には、ハーバート・マルクーゼが『エロスと文明』(1955年)の中で、当時一般的であったフロイトを保守派とする解釈に異議 を唱え、ライオネル・トリリングが『フロイトとわれわれの文化の危機』(1959年)の中で、ノーマン・O・ブラウンが『死に対する生』(1959年)の 中で述べている。マルクーゼは、新フロイト修正主義が死の本能のような一見悲観的な理論を捨てていることを批判し、それらはユートピア的な方向に転じるこ とができると主張した。フロイトの理論はフランクフルト学派や批評理論全体にも影響を与えた[230]。 精神医学におけるフロイトの重要性を経済学におけるマルクスの重要性と並列に捉えるライヒや[231]、20世紀思想への貢献が19世紀思想へのマルクス の貢献に匹敵する重要性を持つ革命家としてフロイトを捉えるポール・ロビンソンによって、フロイトはマルクスと比較されてきた[232]。 [フロムは、フロイト、マルクス、アインシュタインを「近代の建築家」と呼んでいるが、マルクスとフロイトが同じくらい重要であったという考えは否定して おり、マルクスの方が歴史的にはるかに重要であり、より優れた思想家であったと主張している。ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリは『アンチ・オイ ディプス』(1972年)の中で、精神分析がほとんど最初から腐敗してしまったという点で、ロシア革命に似ていると書いている。これはフロイトがエディプ ス・コンプレックスの理論を発展させたことから始まったと彼らは考えている。 ジャン=ポール・サルトルは『存在と無』(1943年)の中でフロイトの無意識の理論を批判し、意識は本質的に自己意識的であると主張している。サルトル はまた、フロイトのアイデアのいくつかを彼自身の人間生活の説明に適応させようと試みており、それによって因果的カテゴリーが目的論的カテゴリーに置き換 えられる「実存的精神分析」を発展させている[235]。アドルノは現象学の創始者であるエドムント・フッサールをフロイトの哲学的対立者であると考えて おり、フッサールの心理主義に対する極論は精神分析に対して向けられたものであったかもしれないと書いている[237]。 ポール・リクールはフロイトを「意識の嘘と幻想」の仮面を剥いだことでマルクスとニーチェと並ぶ3人の「疑惑の巨匠」の1人と見なしている[238]。 [239]リクールとユルゲン・ハーバーマスは「解釈学的なフロイトのバージョン」を作り上げることに貢献しており、それは「人間領域に対する客観的で経 験主義的な理解から主観性と解釈を強調するものへのシフトの最も重要な始祖としてフロイトを主張している」[240]。 [241]ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールはフロイトの夢作業に関する説明を逆転させる無意識の理論を展開した。 何人かの学者はフロイトをプラトンとパラレルであると見ており、彼らは夢についてほぼ同じ理論を持っており、魂の部分間の階層がほぼ逆転しているとして も、人間の魂や人格の三部構造について似たような理論を持っていると書いている[244][245] アーネスト・ゲルナーはフロイトの理論はプラトンの理論の逆転であると論じている。プラトンが現実の本質に内在するヒエラルキーを見て、規範を正当化する ためにそれに依存していたのに対して、フロイトはそのようなアプローチに従うことができない自然主義者であった。しかし、プラトンが貴族階級に相当する超 自我を強化しようとしたのに対し、フロイトは中産階級に相当する自我を強化しようとした。 [246] ポール・ヴィッツはフロイトの精神分析をトミズムと比較し、聖トマスが「無意識の意識」の存在を信じていたこと、そして「『リビドー』という言葉や概念を 頻繁に用いていた-時にはフロイトよりも具体的な意味で用いていたこともあったが、常にフロイトの用法と一致する形で用いていた」ことを指摘している。 ヴィッツは、フロイトは自分の無意識の理論がアクィナスを想起させるものであることに気づいていなかったかもしれないと示唆している[33]。 |