無意識

the

unconscious

☆ 精神分析学やその他の心理学理論では、無意識(または潜在意識)とは、内省できない精神の一部分である。これらのプロセスは意識的な認識の表面下に存在し ているが、意識的な思考プロセスや行動に影響を及ぼすと考えられている。経験的な証拠によると、無意識の現象には、抑圧された感情や欲望、記憶、自動的な スキル、サブリミナル知覚、自動的な反応などが含まれる。この言葉は、18世紀のドイツのロマン派哲学者フリードリヒ・シェリングによって造語され、後に詩人・随筆家のサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジによって英語に導入された。 心理学や一般文化における無意識の概念の登場は、主にオーストリアの神経学者・精神分析学者ジークムント・フロイトの研究によるものであった。 精神分析理論では、無意識は抑圧のメカニズムの影響を受けた考えや衝動から構成される。幼少期の不安を引き起こす衝動は意識から排除されるが、存在し続 け、常に意識の方向へと圧力をかける。しかし、無意識の内容は、夢や神経症症状、失言や冗談など、偽装や歪曲された形で表現されることで、意識にのみ知覚 される。精神分析医は、抑圧されたものの本質を理解するために、こうした意識的な表れを解釈しようとする。 無意識は、夢や自動思考(明確な原因なく現れる思考)、忘れられた記憶(後になって意識に再び現れる可能性がある記憶)、暗黙知(よく学んだことで、何も 考えずにできてしまうこと)の源と見なすことができる。半意識に関連する現象には、覚醒、潜在的記憶、サブリミナルメッセージ、トランス、入眠時幻覚、催 眠などがある。睡眠、夢遊病、夢、せん妄、昏睡は、無意識のプロセスが存在することを示唆する場合があるが、これらのプロセスは、無意識そのものではな く、その症状として見なされる。 一部の批評家は、無意識の存在自体を疑っている。

★「無意識は主体をもつ」——ジャック・ラカン(ジュランヴィル 1991)

| In psychoanalysis

and other psychological theories, the unconscious mind (or the

unconscious) is the part of the psyche that is not available to

introspection.[1] Although these processes exist beneath the surface of

conscious awareness, they are thought to exert an effect on conscious

thought processes and behavior.[2] Empirical evidence suggests that

unconscious phenomena include repressed feelings and desires, memories,

automatic skills, subliminal perceptions, and automatic reactions. The

term was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher

Friedrich Schelling and later introduced into English by the poet and

essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[3][4] The emergence of the concept of the unconscious in psychology and general culture was mainly due to the work of Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. In psychoanalytic theory, the unconscious mind consists of ideas and drives that have been subject to the mechanism of repression: anxiety-producing impulses in childhood are barred from consciousness, but do not cease to exist, and exert a constant pressure in the direction of consciousness. However, the content of the unconscious is only knowable to consciousness through its representation in a disguised or distorted form, by way of dreams and neurotic symptoms, as well as in slips of the tongue and jokes. The psychoanalyst seeks to interpret these conscious manifestations in order to understand the nature of the repressed. The unconscious mind can be seen as the source of dreams and automatic thoughts (those that appear without any apparent cause), the repository of forgotten memories (that may still be accessible to consciousness at some later time), and the locus of implicit knowledge (the things that we have learned so well that we do them without thinking). Phenomena related to semi-consciousness include awakening, implicit memory, subliminal messages, trances, hypnagogia and hypnosis. While sleep, sleepwalking, dreaming, delirium and comas may signal the presence of unconscious processes, these processes are seen as symptoms rather than the unconscious mind itself. Some critics have doubted the existence of the unconscious altogether.[5][6][7][8] |

精神分析学やその他の心理学理論では、無意識(または潜在意識)とは、

内省できない精神の一部分である[1]。これらのプロセスは意識的な認識の表面下に存在しているが、意識的な思考プロセスや行動に影響を及ぼすと考えられ

ている[2]。経験的な証拠によると、無意識の現象には、抑圧された感情や欲望、記憶、自動的なスキル、サブリミナル知覚、自動的な反応などが含まれる。

この言葉は、18世紀のドイツのロマン派哲学者フリードリヒ・シェリングによって造語され、後に詩人・随筆家のサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジによっ

て英語に導入された[3][4]。 心理学や一般文化における無意識の概念の登場は、主にオーストリアの神経学者・精神分析学者ジークムント・フロイトの研究によるものであった。精神分析理 論では、無意識は抑圧のメカニズムの影響を受けた考えや衝動から構成される。幼少期の不安を引き起こす衝動は意識から排除されるが、存在し続け、常に意識 の方向へと圧力をかける。しかし、無意識の内容は、夢や神経症症状、失言や冗談など、偽装や歪曲された形で表現されることで、意識にのみ知覚される。精神 分析医は、抑圧されたものの本質を理解するために、こうした意識的な表れを解釈しようとする。 無意識は、夢や自動思考(明確な原因なく現れる思考)、忘れられた記憶(後になって意識に再び現れる可能性がある記憶)、暗黙知(よく学んだことで、何も 考えずにできてしまうこと)の源と見なすことができる。半意識に関連する現象には、覚醒、潜在的記憶、サブリミナルメッセージ、トランス、入眠時幻覚、催 眠などがある。睡眠、夢遊病、夢、せん妄、昏睡は、無意識のプロセスが存在することを示唆する場合があるが、これらのプロセスは、無意識そのものではな く、その症状として見なされる。 一部の批評家は、無意識の存在自体を疑っている[5][6][7][8]。 |

| Historical overview German The term "unconscious" (German: unbewusst) was coined by the 18th-century German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling (in his System of Transcendental Idealism, ch. 6, § 3) and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge (in his Biographia Literaria).[9][10] Some rare earlier instances of the term "unconsciousness" (Unbewußtseyn) can be found in the work of the 18th-century German physician and philosopher Ernst Platner.[11][12] Vedas Influences on thinking that originate from outside an individual's consciousness were reflected in the ancient ideas of temptation, divine inspiration, and the predominant role of the gods in affecting motives and actions. The idea of internalised unconscious processes in the mind was present in antiquity, and has been explored across a wide variety of cultures. Unconscious aspects of mentality were referred to between 2,500 and 600 BC in the Hindu texts known as the Vedas, found today in Ayurvedic medicine.[13][14][15] Paracelsus Paracelsus is credited as the first to make mention of an unconscious aspect of cognition in his work Von den Krankheiten (translates as "About illnesses", 1567), and his clinical methodology created a cogent system that is regarded by some as the beginning of modern scientific psychology.[16] Shakespeare William Shakespeare explored the role of the unconscious[17] in many of his plays, without naming it as such.[18][19][20] Philosophy Western philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer,[21][22] Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, Carl Gustav Carus, Søren Aabye Kierkegaard, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche[23] and Thomas Carlyle[24] used the word unconscious.[25] In 1880 at the Sorbonne, Edmond Colsenet defended a philosophy thesis (PhD) on the unconscious.[26] Elie Rabier and Alfred Fouillee performed syntheses of the unconscious "at a time when Freud was not interested in the concept".[27] |

歴史的概観 ドイツ語 無意識」(ドイツ語:unbewusst)という用語は、18世紀のドイツのロマン主義哲学者フリードリヒ・シェリング(『超越論的観念論』第6章第3 節)によって造語され、後に詩人・随筆家のサミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジ(『文学伝』)によって英語に導入された[9][10]。「無意識」 (Unbewußtseyn)という用語の初期の事例は、18世紀のドイツの医師兼哲学者エルンスト・プラットナーの作品に見られる[11][12]。 ヴェーダ 個人の意識の外から生じる思考への影響は、誘惑、神の啓示、動機や行動に影響を与える神々の支配的な役割という古代の思想に反映されていた。心の中で無意 識のプロセスが内面化されるという考えは古代から存在しており、さまざまな文化で研究されてきた。精神の無意識的側面は、紀元前2500年から600年の 間に、ヴェーダとして知られるヒンドゥー教の経典で言及されており、今日ではアーユルヴェーダ医学でも見受けられる[13][14][15]。 パラケルスス パラケルススは、著書『病気について』(1567年)の中で、認知の無意識的側面について初めて言及した人物として知られている。また、彼の臨床方法論は説得力のある体系を生み出した。これは、現代科学心理学の始まりであると見なされている。 シェイクスピア ウィリアム・シェイクスピアは、多くの戯曲の中で無意識の役割を探求したが、それを明示することはなかった。 哲学 アーサー・ショーペンハウアー、バルク・スピノザ、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテ、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘル ム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、カール・ロベルト・エドゥアルト・フォン・ハルトマン、カール・グスタフ・カルス 、セーレン・アビア・キルケゴール、フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ニーチェ[23]、トーマス・カーライル[24]が「無意識」という言葉を使用していた [25]。 1880年、ソルボンヌ大学でエドモン・コルセネが「無意識」に関する哲学論文(博士論文)を擁護した[26]。エリー・ラビエとアルフレッド・フイユは、「フロイトがその概念に興味を示していなかった時期」に無意識の総合的な研究を行った[27]。 |

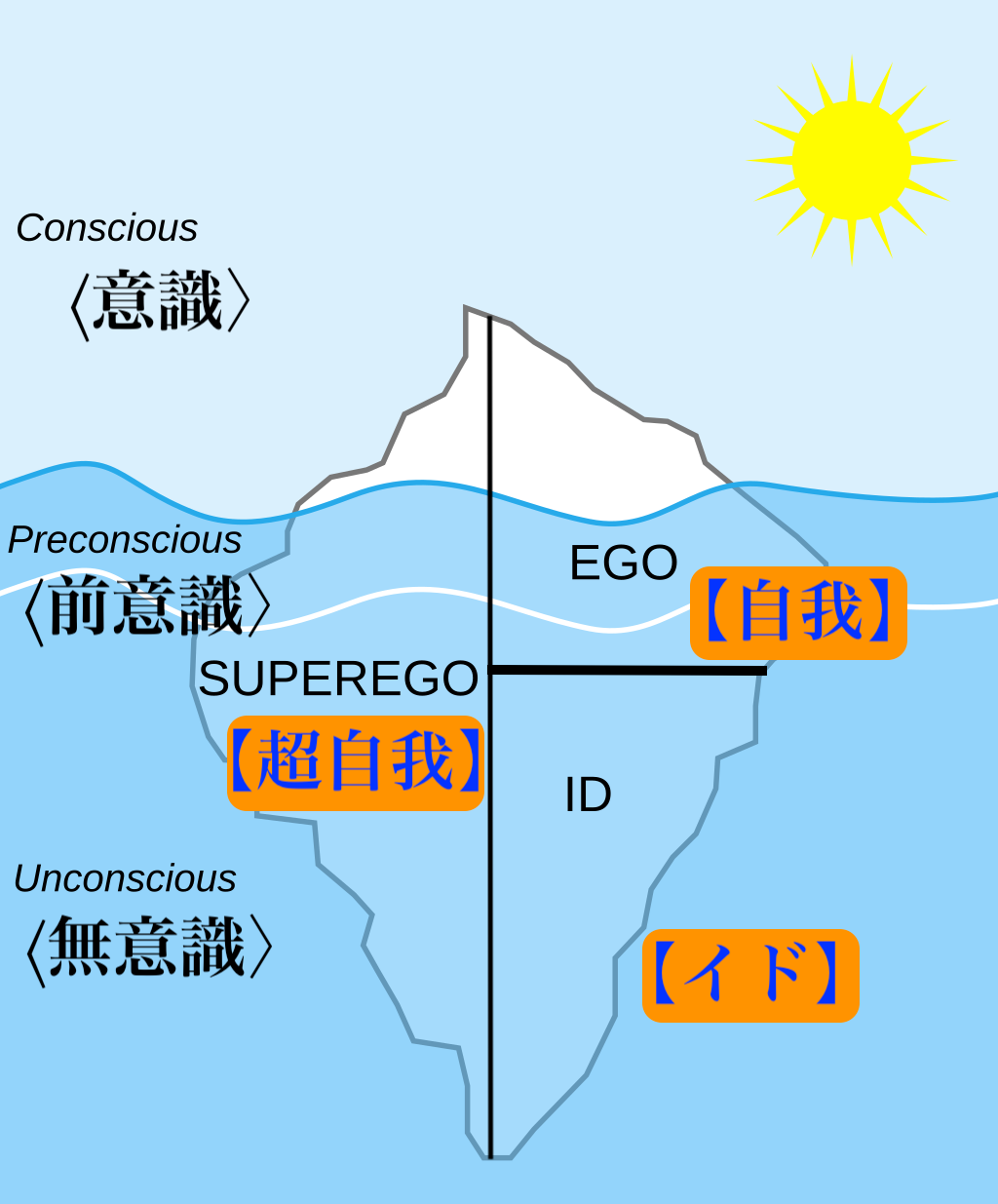

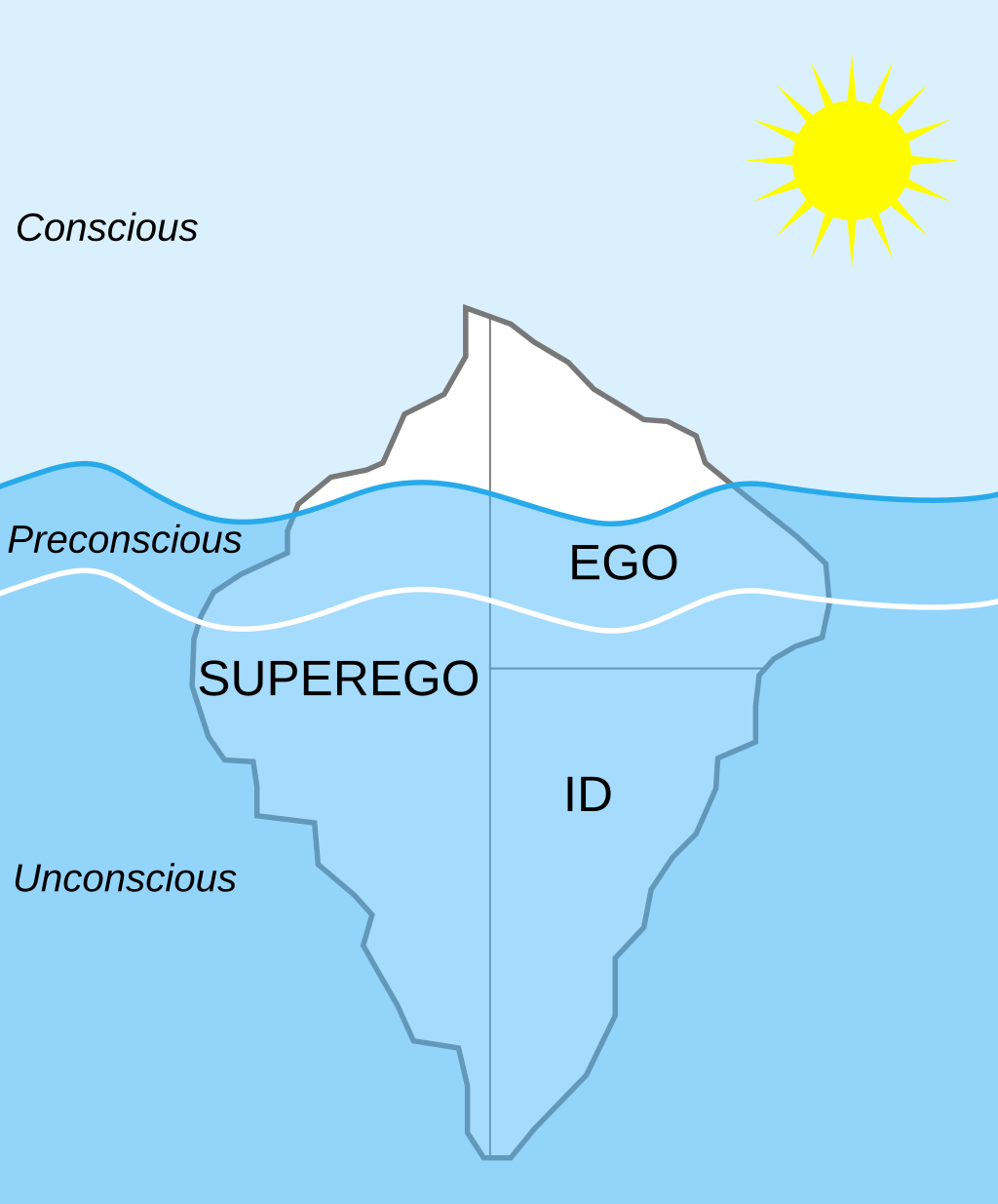

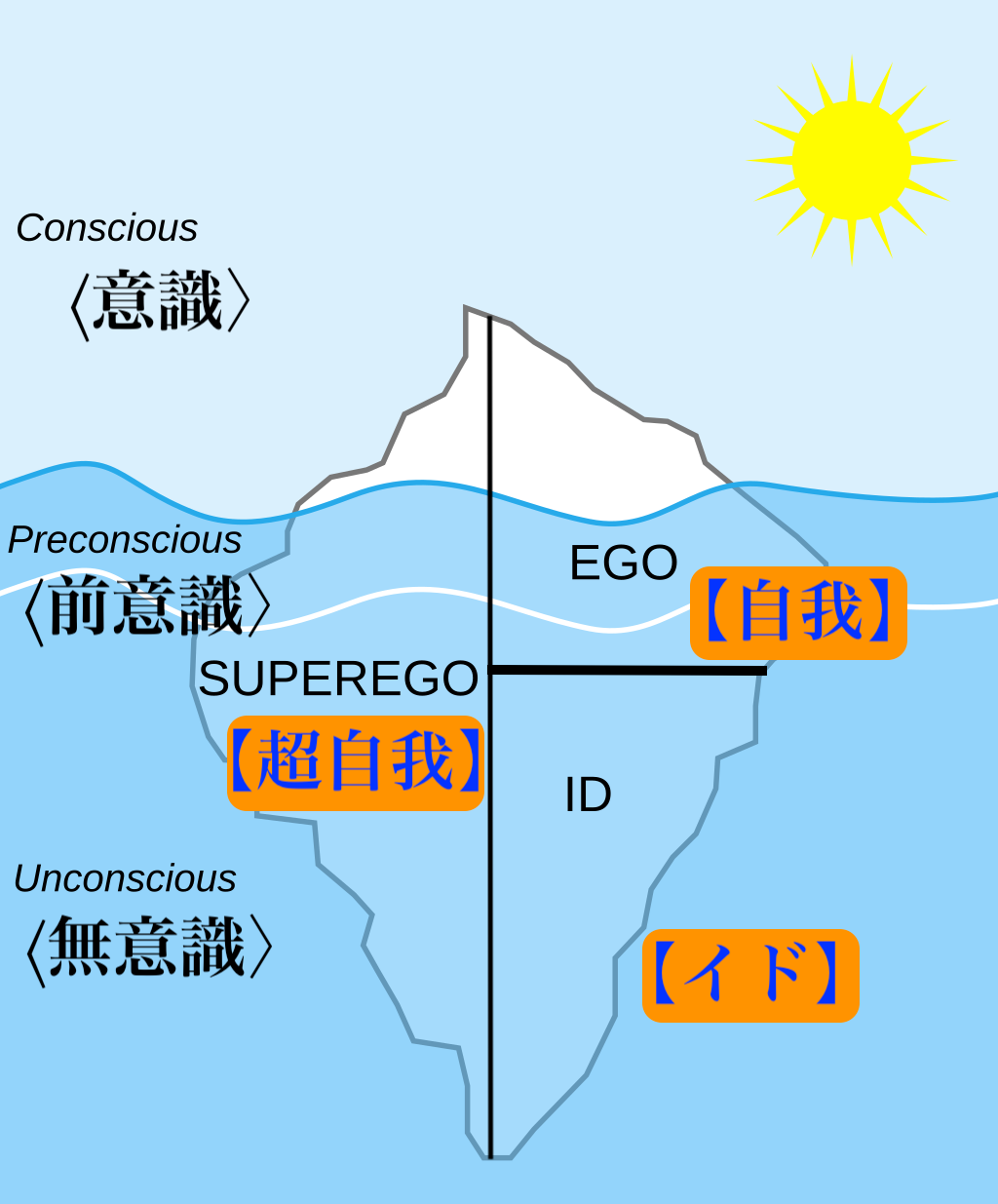

| Psychology Nineteenth century According to historian of psychology Mark Altschule, "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance."[28] In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in his monumental treatise on psychology (The Principles of Psychology), examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious.'"[29] German psychologists, Gustav Fechner and Wilhelm Wundt, had begun to use the term in their experimental psychology, in the context of manifold, jumbled sense data that the mind organizes at an unconscious level before revealing it as a cogent totality in conscious form."[30] Eduard von Hartmann published a book dedicated to the topic, Philosophy of the Unconscious, in 1869. Freud  The iceberg metaphor proposed by G. T. Fechner is often used to provide a visual representation of Freud's theory that most of the human mind operates unconsciously.[31] Sigmund Freud and his followers developed an account of the unconscious mind. He worked with the unconscious mind to develop an explanation for mental illness.[32] It plays an important role in psychoanalysis. Freud divided the mind into the conscious mind (or the ego) and the unconscious mind. The latter was then further divided into the id (or instincts and drive) and the superego (or conscience). In this theory, the unconscious refers to the mental processes of which individuals are unaware.[33] Freud proposed a vertical and hierarchical architecture of human consciousness: the conscious mind, the preconscious, and the unconscious mind—each lying beneath the other. He believed that significant psychic events take place "below the surface" in the unconscious mind.[34] Contents of the unconscious mind go through the preconscious mind before coming to conscious awareness.[35] He interpreted such events as having both symbolic and actual significance. In psychoanalytic terms, the unconscious does not include all that is not conscious, but rather that which is actively repressed from conscious thought. In the psychoanalytic view, unconscious mental processes can only be recognized through analysis of their effects in consciousness. Unconscious thoughts are not directly accessible to ordinary introspection, but they are capable of partially evading the censorship mechanism of repression in a disguised form, manifesting, for example, as dream elements or neurotic symptoms. Such symptoms are supposed to be capable of being "interpreted" during psychoanalysis, with the help of methods such as free association, dream analysis, and analysis of verbal slips and other unintentional manifestations in conscious life. Jung Main articles: Carl Jung and Collective unconscious Carl Gustav Jung agreed with Freud that the unconscious is a determinant of personality, but he proposed that the unconscious be divided into two layers: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious is a reservoir of material that was once conscious but has been forgotten or suppressed, much like Freud's notion. The collective unconscious, however, is the deepest level of the psyche, containing the accumulation of inherited psychic structures and archetypal experiences. Archetypes are not memories but energy centers or psychological functions that are apparent in the culture's use of symbols. The collective unconscious is therefore said to be inherited and contain material of an entire species rather than of an individual.[36] The collective unconscious is, according to Jung, "[the] whole spiritual heritage of mankind's evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual".[37] In addition to the structure of the unconscious, Jung differed from Freud in that he did not believe that sexuality was at the base of all unconscious thoughts.[38] |

心理学 19世紀 心理学者マーク・アルトシューレによると、「無意識の思考を、現実であるだけでなく最も重要であると認識していなかった19世紀の心理学者や精神科医を見 つけるのは難しい、あるいは不可能である」[28]。1890年、精神分析がまだ知られていなかった当時、 ウィリアム・ジェームズは、心理学に関する記念碑的な論文(『心理学原理』)の中で、ショーペンハウアー、フォン・ハルトマン、ジャネット、ビネらが「無 意識」や「潜在意識」という用語をどのように使用していたかを検証した。この用語を、心が無意識レベルで整理した、多種多様な感覚データが混在する状況と いう文脈で、実験心理学において使い始めたのである。意識的な形で説得力のある全体像としてそれを明らかにする前に。[30] エドゥアルト・フォン・ハルトマンは、このテーマに捧げた著書『無意識の哲学』を1869年に出版した。 フロイト  G. T. フェヒナーが提唱した氷山に例えた比喩は、人間の心の大部分が無意識に作用するというフロイトの理論を視覚的に表現するためにしばしば用いられる[31]。 ジークムント・フロイトと彼の信奉者たちは、無意識の心の説明を開発した。彼は、精神疾患の説明を開発するために無意識の心に働きかけた[32]。それは精神分析において重要な役割を果たしている。 フロイトは心を、意識(または自我)と無意識に分けた。後者はさらに、イド(本能や衝動)と超自我(良心)に分けられる。この理論では、無意識とは個人が 自覚していない精神過程を指す[33]。フロイトは、人間の意識を縦の階層構造として提案した。すなわち、意識、前意識、無意識であり、それぞれが他の下 位に位置する。彼は、重要な心理的出来事は無意識の「表面下」で起こると信じていた[34]。無意識の内容が意識に認識される前に、前意識を通過する [35]。彼はそのような出来事を象徴的かつ実際的な意味を持つと解釈した。 精神分析の用語では、無意識とは意識されていないすべてのことを指すのではなく、意識的な思考から積極的に抑圧されているものを指す。精神分析学の見解で は、無意識の精神過程は、意識におけるその影響の分析を通じてのみ認識できる。無意識の思考は、通常の内省では直接的にアクセスできないが、抑圧の検閲メ カニズムを偽装した形で部分的に回避し、例えば夢の内容や神経症の症状として現れる可能性がある。このような症状は、自由連想、夢分析、言語の誤用や意識 下の無意識的な行動の分析などの手法を用いて、精神分析において「解釈」できるとされている。 ユング 主な項目:カール・グスタフ・ユングと集合的無意識 カール・グスタフ・ユングは、無意識が人格を決定づけるものであるというフロイトの考えに同意したが、無意識を2つの層、すなわち個人的無意識と集合的無 意識に分けている。個人的無意識とは、かつては意識されていたが、忘れられたり抑圧されたりした材料の貯蔵庫であり、フロイトの概念とよく似ている。しか し、集合的無意識は精神の最も深いレベルにあり、遺伝的に受け継がれた心理構造と原型的な経験の蓄積を含んでいる。原型とは記憶ではなく、文化における象 徴の使用に現れるエネルギーセンターや心理機能である。集合的無意識は、したがって、個人ではなく種全体の記憶を継承し、その材料を含んでいると言われて いる[36]。集合的無意識は、ユングによれば、「人類の進化の精神的遺産全体であり、あらゆる個人の脳構造に新たに生まれる」ものである[37]。 無意識の構造に加えて、ユングは、無意識の思考の根底に性的なものが存在すると信じていなかった点でフロイトと異なっていた[38]。 |

| Dreams Freud The purpose of dreams, according to Freud, is to fulfill repressed wishes while simultaneously allowing the dreamer to remain asleep. The dream is a disguised fulfillment of the wish because the unconscious desire in its raw form would disturb the sleeper and can only avoid censorship by associating itself with elements that are not subject to repression. Thus Freud distinguished between the manifest content and latent content of the dream. The manifest content consists of the plot and elements of a dream as they appear to consciousness, particularly upon waking, as the dream is recalled.[39] The latent content refers to the hidden or disguised meaning of the events and elements of the dream. It represents the unconscious psychic realities of the dreamer's current issues and childhood conflicts, the nature of which the analyst is seeking to understand through interpretation of the manifest content.[40][41] In Freud's theory, dreams are instigated by the events and thoughts of everyday life. In what he called the "dream-work", these events and thoughts, governed by the rules of language and the reality principle, become subject to the "primary process" of unconscious thought, which is governed by the pleasure principle, wish gratification and the repressed sexual scenarios of childhood. The dream-work involves a process of disguising these unconscious desires in order to preserve sleep. This process occurs primarily by means of what Freud called condensation and displacement.[42] Condensation is the focusing of the energy of several ideas into one, and displacement is the surrender of one idea's energy to another more trivial representative. The manifest content is thus thought to be a highly significant simplification of the latent content, capable of being deciphered in the analytic process, potentially allowing conscious insight into unconscious mental activity. Neurobiological theory of dreams Allan Hobson and colleagues developed what they called the activation-synthesis hypothesis which proposes that dreams are simply the side effects of the neural activity in the brain that produces beta brain waves during REM sleep that are associated with wakefulness. According to this hypothesis, neurons fire periodically during sleep in the lower brain levels and thus send random signals to the cortex. The cortex then synthesizes a dream in reaction to these signals in order to try to make sense of why the brain is sending them. However, the hypothesis does not state that dreams are meaningless, it just downplays the role that emotional factors play in determining dreams.[41] |

夢 フロイト フロイトによると、夢の目的は、抑圧された願望を叶えながら、同時に夢見る者を眠ったままにしておくことである。夢は願望を偽装して叶えるものである。な ぜなら、生のままの無意識の欲望は眠っている人を妨げるため、抑圧の対象とならない要素と関連付けることでのみ検閲を回避できるからである。したがって、 フロイトは夢の顕在的内容と潜在的内容を区別した。顕在的内容とは、夢が想起される際に、特に目覚めたときに意識に現れる夢のプロットや要素のことである [39]。潜在的内容とは、夢の中の出来事や要素の隠された、または偽装された意味を指す。それは夢を見る人の現在の問題や幼少期の葛藤といった無意識の 心理的現実を表しており、分析者は顕在内容の解釈を通じてその本質を理解しようとする[40][41]。フロイトの理論では、夢は日常生活における出来事 や思考によって引き起こされる。彼が「夢の仕事」と呼んだものにおいて、これらの出来事や思考は、言語のルールと現実の原則によって支配され、快楽原則、 願望充足、そして抑圧された幼少期の性的シナリオによって支配される無意識思考の「一次過程」の対象となる。夢の仕事は、睡眠を維持するためにこれらの無 意識の欲望を偽装するプロセスを含む。このプロセスは、主にフロイトが凝縮と置き換えと呼んだ方法で行われる[42]。凝縮とは、複数のアイデアのエネル ギーを1つに集中させること、置き換えとは、あるアイデアのエネルギーを、より些細な別の表現に委ねることを意味する。顕在的内容は、潜在的内容を非常に 簡略化したものであり、分析プロセスで解読できる可能性があり、無意識の精神活動を意識的に洞察できる可能性があると考えられている。 夢の神経生物学的理論 アラン・ホブソンと彼の同僚たちは、彼らが「活性化合成仮説」と呼ぶ理論を展開した。この仮説によると、夢はレム睡眠中にβ脳波を発生させる脳の神経活動 の副産物であり、覚醒状態と関連している。この仮説によると、睡眠中に下位脳レベルでニューロンが周期的に発火し、大脳皮質にランダムな信号を送信する。 大脳皮質は、脳がこれらの信号を発している理由を理解しようと試みるため、これらの信号に反応して夢を合成する。しかし、この仮説は夢が無意味であると述 べているわけではなく、夢を決定づける感情的要因の役割を過小評価しているだけである[41]。 |

| Contemporary cognitive psychology Research There is an extensive body of research in contemporary cognitive psychology devoted to mental activity that is not mediated by conscious awareness. Most of this research on unconscious processes has been done in the academic tradition of the information processing paradigm. The cognitive tradition of research into unconscious processes does not rely on the clinical observations and theoretical bases of the psychoanalytic tradition; instead it is mostly data driven. Cognitive research reveals that individuals automatically register and acquire more information than they are consciously aware of or can consciously remember and report.[43] Much research has focused on the differences between conscious and unconscious perception. There is evidence that whether something is consciously perceived depends both on the incoming stimulus (bottom up strength)[44] and on top-down mechanisms like attention.[45] Recent research indicates that some unconsciously perceived information can become consciously accessible if there is cumulative evidence.[46] Similarly, content that would normally be conscious can become unconscious through inattention (e.g. in the attentional blink) or through distracting stimuli like visual masking. Unconscious processing of information about frequency An extensive line of research conducted by Hasher and Zacks[47] has demonstrated that individuals register information about the frequency of events automatically (outside conscious awareness and without engaging conscious information processing resources). Moreover, perceivers do this unintentionally, truly "automatically", regardless of the instructions they receive, and regardless of the information processing goals they have. The ability to unconsciously and relatively accurately tally the frequency of events appears to have little or no relation to the individual's age,[48] education, intelligence, or personality. Thus it may represent one of the fundamental building blocks of human orientation in the environment and possibly the acquisition of procedural knowledge and experience, in general. |

現代認知心理学 研究 現代認知心理学では、意識的な認識を介さない精神活動に関する広範な研究が行われている。無意識のプロセスに関するこれらの研究のほとんどは、情報処理パ ラダイムの学術的伝統に基づいて行われている。無意識のプロセスに関する認知研究の伝統は、精神分析の伝統の臨床観察や理論的基盤に依存しておらず、その ほとんどがデータ駆動型である。認知研究によると、個人は、意識的に認識している、あるいは意識的に記憶し報告できる以上の情報を自動的に認識し、獲得し ていることが明らかになっている[43]。 多くの研究は、意識的知覚と無意識的知覚の違いに焦点を当てている。ある事象が意識的に知覚されるかどうかは、入ってくる刺激(ボトムアップ効果) [44]と、注意などのトップダウン効果の両方に依存するという証拠がある[45]。最近の研究では、無意識的に知覚された情報であっても、それが累積的 に蓄積されれば、意識的にアクセス可能になる場合があることが示されている[46]。同様に、通常であれば意識されるはずのコンテンツであっても、不注意 (注意の瞬きなど)や視覚的マスキングのような注意をそらす刺激によって無意識になる可能性がある。 頻度の情報に関する無意識の処理 ハッシャーとザックスによる広範な研究[47]は、個人が自動的に(意識的な認識や意識的な情報処理リソースを使用せずに)事象の頻度に関する情報を認識 することを実証している。さらに、知覚者は、受け取る指示や情報処理目標に関係なく、意図せずに、まさに「自動的に」これを行う。無意識のうちに、比較的 正確に事象の発生頻度を把握する能力は、個人の年齢、教育、知能、性格とはほとんど、あるいはまったく関係がないようである[48]。したがって、これ は、環境における人間の方向感覚や、一般的に手続き的知識と経験の獲得の基礎となる要素の一つである可能性がある。 |

| Criticism of the Freudian concept The notion that the unconscious mind exists at all has been disputed.[49][50][51][52] Franz Brentano rejected the concept of the unconscious in his 1874 book Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, although his rejection followed largely from his definitions of consciousness and unconsciousness.[53] Jean-Paul Sartre offers a critique of Freud's theory of the unconscious in Being and Nothingness, based on the claim that consciousness is essentially self-conscious. Sartre also argues that Freud's theory of repression is internally flawed. Philosopher Thomas Baldwin argues that Sartre's argument is based on a misunderstanding of Freud.[54] Erich Fromm contends that "The term 'the unconscious' is actually a mystification (even though one might use it for reasons of convenience, as I am guilty of doing in these pages). There is no such thing as the unconscious; there are only experiences of which we are aware, and others of which we are not aware, that is, of which we are unconscious. If I hate a man because I am afraid of him, and if I am aware of my hate but not of my fear, we may say that my hate is conscious and that my fear is unconscious; still my fear does not lie in that mysterious place: 'the' unconscious."[55] John Searle has offered a critique of the Freudian unconscious. He argues that the Freudian cases of shallow, consciously held mental states would be best characterized as 'repressed consciousness,' while the idea of more deeply unconscious mental states is more problematic. He contends that the very notion of a collection of "thoughts" that exist in a privileged region of the mind such that they are in principle never accessible to conscious awareness, is incoherent. This is not to imply that there are not "nonconscious" processes that form the basis of much of conscious life. Rather, Searle simply claims that to posit the existence of something that is like a "thought" in every way except for the fact that no one can ever be aware of it (can never, indeed, "think" it) is an incoherent concept. To speak of "something" as a "thought" either implies that it is being thought by a thinker or that it could be thought by a thinker. Processes that are not causally related to the phenomenon called thinking are more appropriately called the nonconscious processes of the brain.[56] Other critics of the Freudian unconscious include David Stannard,[57] Richard Webster,[58] Ethan Watters,[59] Richard Ofshe,[59] and Eric Thomas Weber.[60] Some scientific researchers proposed the existence of unconscious mechanisms that are very different from the Freudian ones. They speak of a "cognitive unconscious" (John Kihlstrom),[61][62] an "adaptive unconscious" (Timothy Wilson),[63] or a "dumb unconscious" (Loftus and Klinger),[64] which executes automatic processes but lacks the complex mechanisms of repression and symbolic return of the repressed, and the "deep unconscious system" of Robert Langs. In modern cognitive psychology, many researchers have sought to strip the notion of the unconscious from its Freudian heritage, and alternative terms such as "implicit" or "automatic" have been used. These traditions emphasize the degree to which cognitive processing happens outside the scope of cognitive awareness, and show that things we are unaware of can nonetheless influence other cognitive processes as well as behavior.[65][66][67][68][69] Active research traditions related to the unconscious include implicit memory (for example, priming), and Pawel Lewicki's nonconscious acquisition of knowledge. |

フロイトの概念に対する批判 無意識の概念は、存在するか否かについて議論されてきた[49][50][51][52]。 フランツ・ブレナノは、1874年に出版した著書『経験主義的心理学』の中で無意識の概念を否定した。しかし、彼の拒絶は主に彼の意識と無意識の定義に由来していた[53]。 ジャン=ポール・サルトルは『存在と無』の中で、意識は本質的に自己意識であるという主張に基づいて、フロイトの無意識の理論を批判している。サルトルは また、フロイトの抑圧理論は内部的に欠陥があると主張している。哲学者トーマス・ボールドウィンは、サルトルの主張はフロイトに対する誤解に基づいている と主張している[54]。 エリック・フロムは、「無意識」という言葉は実際には神秘化である(たとえ便宜上の理由で使うとしても、私がこの本の中で使っているように)。無意識など というものは存在しない。あるのは、私たちが自覚している経験と、自覚していない経験、つまり無意識である経験だけだ。ある人を恐れているために嫌ってい る場合、その嫌っている気持ちに気づいているが、恐れている気持ちには気づいていないのであれば、その嫌っている気持ちは意識的なものであり、恐れている 気持ちは無意識的なものであると言えるだろう。それでもなお、その恐れている気持ちは「無意識」という神秘的な場所にあるわけではない。 ジョン・サールはフロイトの無意識について批判を展開している。彼は、フロイトの言う浅い、意識的に抱く精神状態は「抑圧された意識」として最もよく特徴 づけられるが、より深い無意識の精神状態という考えはより問題が多いと主張している。彼は、心の特権的な領域に存在し、原則として意識的な認識には決して アクセスできない「思考」の集合という概念そのものが矛盾していると主張している。これは、意識的な生活の基盤となる「無意識」のプロセスが存在しないと いうことを意味しているわけではない。むしろ、サールは、誰もがそれを意識すること(実際にそれを「考える」こと)ができないという事実を除いて、あらゆ る点で「思考」のようなものの存在を前提とすることは、矛盾した概念であると主張しているだけである。「何か」を「思考」と呼ぶということは、それが思考 者によって思考されているか、あるいは思考者によって思考されうることを意味する。思考と呼ばれる現象と因果関係のないプロセスは、脳の無意識プロセスと 呼ぶのがより適切である[56]。 フロイトの無意識を批判する他の学者には、デビッド・スタナード[57]、リチャード・ウェブスター[58]、イーサン・ワターズ[59]、リチャード・オフシェ[59]、エリック・トーマス・ウェーバー[60]がいる。 一部の科学的研究者は、フロイトのものと大きく異なる無意識のメカニズムの存在を提唱している。彼らは「認知的無意識」(ジョン・キルストロム)[61] [62]、「適応的無意識」(ティモシー・ウィルソン)[63]、「無言の無意識」(ロフタスとクリンガー)[64]、すなわち自動的なプロセスを実行す るが、抑圧や抑圧されたものの象徴的回帰といった複雑なメカニズムを欠いているもの、あるいはロバート・ラングスの「深層無意識システム」について語って いる。 現代の認知心理学では、多くの研究者が無意識の概念をフロイトの遺産から切り離そうとしており、「暗黙的」や「自動的」といった別の用語が使用されてい る。これらの伝統は、認知処理が認知的認識の範囲外で行われる度合いを強調しており、私たちが気づいていないことが、他の認知プロセスや行動にも影響を与 える可能性があることを示している[65][66][67][68][69]。無意識に関連する活発な研究分野には、潜在的記憶(例えばプライミング)や パウエル・レウィツキによる無意識的な知識の獲得などがある。 |

| Adaptive unconscious Consciousness Introspection illusion Philosophy of mind Preconscious Subconscious Unconscious cognition Unconscious communication Unconscious spirit Dreams in analytical psychology |

適応的無意識 意識 内省的錯覚 心の哲学 前意識 潜在意識 無意識の認知 無意識のコミュニケーション 無意識の精神 分析心理学における夢 |

| Adaptive unconscious The adaptive unconscious, first coined by social psychologist Daniel Wegner in 2002,[1] is described as a set of mental processes that is able to affect judgement and decision-making, but is out of reach of the conscious mind. It is thought to be adaptive as it helps to keep the organism alive.[2] Architecturally, the adaptive unconscious is said to be unreachable because it is buried in an unknown part of the brain. This type of thinking evolved earlier than the conscious mind, enabling the mind to transform information and think in ways that enhance an organism's survival. It can be described as a quick sizing up of the world which interprets information and decides how to act very quickly and outside the conscious view. The adaptive unconscious is active in everyday activities such as learning new material, detecting patterns, and filtering information. It is also characterized by being unconscious, unintentional, uncontrollable, and efficient without requiring cognitive tools. Lacking the need for cognitive tools does not make the adaptive unconscious any less useful than the conscious mind as the adaptive unconscious allows for processes like memory formation, physical balancing, language, learning, and some emotional and personalities processes that includes judgement, decision making, impression formation, evaluations, and goal pursuing. Despite being useful, the series of processes of the adaptive unconscious will not always result in accurate or correct decisions by the organism. The adaptive unconscious is affected by things like emotional reaction, estimations, and experience and is thus inclined to stereotyping and schema which can lead to inaccuracy in decision making. The adaptive conscious does however help decision making to eliminate cognitive biases such as prejudice because of its lack of cognitive tools. |

適応的無意識 適応的無意識は、2002年に社会心理学者ダニエル・ウェグナーが提唱した概念である[1]。判断や意思決定に影響を与えるが、意識の及ばない一連の精神 過程として説明されている。適応的無意識は、生物の生存維持に役立つため、適応的であると考えられている[2]。構造的には、適応的無意識は脳の未知の部 分に埋もれているため、到達不可能であると言われている。この思考法は意識よりも早く進化しており、生物の生存力を高めるような情報の変換や思考を可能に する。これは、情報を解釈し、意識の外側で非常に素早く行動を決定する、世界を素早く把握する能力と表現できる。適応的無意識は、新しい教材の学習、パ ターンの検出、情報のフィルタリングなど、日常的な活動において活発に機能している。また、無意識的、意図的でない、制御不能、認知ツールを必要とせず効 率的であることも特徴である。認知ツールを必要としないからといって、適応的無意識が意識的思考よりも有用でないわけではない。適応的無意識は、記憶形 成、身体バランス、言語、学習、判断、意思決定、印象形成、評価、目標追求などの感情や人格形成プロセスを含むプロセスを可能にするためである。適応的無 意識の一連のプロセスは有用であるにもかかわらず、生物の意思決定が常に正確で正しいものになるとは限らない。適応的無意識は感情的な反応、評価、経験な どの影響を受けるため、ステレオタイプやスキーマに陥りやすく、意思決定の正確性を損なう可能性がある。しかし、適応的意識は認知ツールを持たないため、 偏見などの認知バイアスを排除し、意思決定に役立つ。 |

| Overview The adaptive unconscious is defined as different from conscious processing in a number of ways. It is faster, effortless, more focused on the present, and less flexible.[3] It is thought to be adaptive as it helps to keep us alive.[2] Processing information without us even realising then feeding any we do need to know to our conscious brain. In other theories of the mind, the unconscious is limited to "low-level" activities, such as carrying out goals which have been decided consciously. In contrast, the adaptive unconscious is now thought to also be involved in "high-level" cognition such as goal-setting. The theory of the adaptive unconscious was influenced by some of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung's views on the unconscious mind. According to Freud, the unconscious mind stored a lot of mental content which needs to be repressed; however, the term adaptive unconscious reflects the idea that much of what the unconscious does is actually beneficial to the organism, in closer accordance with Jung's thought. For example, its various processes have been streamlined through evolution to quickly evaluate and respond to patterns in an organism's environment.[4] |

概要 適応的無意識は、意識的な処理とはさまざまな点で異なるものと定義されている。より速く、より労力を要さず、現在に焦点を当て、柔軟性に欠ける[3]。適 応的であるとされるのは、それが私たちを生かしておくのに役立つからだと考えられている[2]。私たちが気づかないうちに情報を処理し、必要な情報を意識 的な脳に送り込む。 心の他の理論では、無意識は、意識的に決定された目標を実行するなど、「低次」の活動に限定されている。これに対し、適応的無意識は、目標設定などの「高次」認知にも関与していると考えられている。 適応的無意識の理論は、ジークムント・フロイトとカール・ユングの無意識心に関する見解の影響を受けている。フロイトによると、無意識は抑圧されるべき多 くの精神的内容を蓄えているが、適応的無意識という用語は、無意識の行うことの多くは実際には生物にとって有益であるという、ユングの考え方に近い考え方 を反映している。例えば、そのさまざまなプロセスは、生物の環境におけるパターンを素早く評価し、それに対応するために、進化の過程で合理化されてきた [4]。 |

| Intuition Malcolm Gladwell described intuition, not as an emotional reaction, but a very quick thinking.[5] He said that if an individual realized that a truck is about to hit him, there would be no time to think through all of his options and, to survive, he must rely on this kind of decision-making apparatus, which is capable of making very quick judgments based on little information.[6] Gladwell also cited another example in the case of a kouros acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. A team of scientists vouched for its authenticity but some historians, such as Thomas Hoving, instantly knew otherwise - that they felt an "intuitive repulsion" for the piece, which was eventually proved as fake.[7] Intuition comes from tapping into the adaptive unconscious. The adaptive unconscious is that liminal zone between dreams and reality, what might be called a reciprocal of experiences, memories, and dreams. Working within the adaptive unconscious involves browsing through a series of sense impressions and making comparisons regarding a situation and using past experiences to dissolve sensory boundaries which then results in intuition. There is also a study that cited intuition as a result of the way our brain stores, processes and uses the information of our subconscious.[8] It becomes useful when reasoning and rationality provide no rapid answer.[8] |

直感 マルコム・グラッドウェルは、直感を感情的な反応ではなく、非常に素早い思考であると表現している[5]。彼は、トラックに轢かれそうになったときに、す べての選択肢について考える時間はないため、生き延びるためには 生き残るためには、わずかな情報に基づいて非常に迅速な判断を下すことのできる、このような意思決定のメカニズムに頼らざるを得ないのだ[6]。グラッド ウェルは、ロサンゼルスにあるゲティ美術館が購入したクーロスの例も挙げている。科学者チームが本物であると保証したが、トーマス・ホーヴィングなどの歴 史家たちは、直感的に偽物だと感じた。 直感は、適応無意識に働きかけることによって得られる。適応無意識とは、夢と現実の狭間にある領域であり、経験、記憶、夢の相互関係とも呼べるものであ る。適応無意識の中で作業を行うには、一連の感覚的印象を閲覧し、状況について比較を行い、過去の経験を利用して感覚的な境界線を解消し、直観に至る。ま た、脳が潜在意識の情報を保存、処理、利用する方法の結果として直観を引用する研究もある[8]。推論や合理性が迅速な答えを提供しない場合に役立つ [8]。 |

| The introspection illusion Main article: Introspection illusion The debate over the existence of introspection began in the late 19th century with experiments involving placing people in different stimuli contexts and them thinking about their thoughts and feelings after. Similar experiments have continued since, all relying on asking the participant to think about how they feel and their thoughts. These research efforts have however been hampered by the fact it is currently impossible to know if they are actually accessing their unconscious as they do this, or if the information is just coming from their conscious mind.[2] This fundamental flaw makes experiments in this area less reliable in creating the debate over introspection. More recent research suggests that many of our preferences, attitudes, and ideas come from the adaptive unconscious. However, subjects themselves do not realize this, and they are "unaware of their own unawareness".[9] People wrongly think they have direct insight into the origins of their mental states. A subject is likely to give explanations for their behavior (i.e. their preferences, attitudes, and ideas), but the subject tends to be inaccurate in this "insight." The false explanations of their own behavior is what psychologists call the introspection illusion. In some experiments, subjects provide explanations that are fabricated, distorted, or misinterpreted memories, but not lies – a phenomenon called confabulation. This suggests that introspection is instead an indirect, unreliable process of inference.[10] It has been argued that this "introspection illusion" underlies a number of perceived differences between the self and other people, because people trust these unreliable introspections when forming attitudes about themselves but not about others.[11][12][13] However, this theory of the limits of introspection has been highly controversial, and it has been difficult to test unambiguously how much information individuals get from introspection.[14] The difficulties in understanding the introspective method resulted in a lack of theoretical development of the mind and more into behaviourism. The difficulties of finding a method that worked (i.e. not self-reporting by the patient) mean there was a halt in this area of research until the cognitive revolution. Due to this the need to understand the unconscious mind increased. Psychologists started to focus on the limits of the conscious mind and more stimuli and learning paradigm focused experiments for the unconscious mind.[2] This helps understand the limitations of introspection or the lack of as some would argue. |

内省錯覚 メイン記事:内省錯覚 内省の存在をめぐる議論は、19世紀後半に、参加者にさまざまな刺激的な状況を与え、その後に自分の思考や感情について考えさせる実験から始まった。それ 以来、同様の実験が続けられており、いずれも参加者に自分の感情や思考について考えさせるという方法に頼っている。しかし、これらの研究は、被験者が無意 識にアクセスしているのか、それとも意識的な思考から得た情報なのかを判断することが現状では不可能であるという事実によって妨げられてきた[2]。この 根本的な欠陥により、この分野の実験は、内省に関する議論を生み出す上で信頼性が低いものとなっている。 より最近の研究では、私たちの好み、態度、考え方の多くは、適応的な無意識から来ていることが示唆されている。しかし被験者自身はそれに気づいておらず、 「自分自身の無自覚」に気づいていない[9]。人々は、自分の精神状態の起源を直接洞察していると思い込んでいる。被験者は自分の行動(つまり、自分の好 み、態度、考え)を説明する傾向があるが、この「洞察」は不正確であることが多い。自分の行動に対する誤った説明は、心理学者が内省幻想と呼ぶものであ る。 ある実験では、被験者は作り話や歪曲、誤った解釈による記憶を根拠に説明を行うが、嘘はつかない。この現象は虚偽記憶と呼ばれる。このことから、内省は間 接的で信頼性の低い推論プロセスであることが示唆される[10]。この「内省による錯覚」が、自己と他者との認識の違いの根底にあると主張されている。な ぜなら、人々は自分自身について態度を形成する際には、他者については形成しないが、この信頼性の低い内省を信頼しているからである[11][1 2][13] しかし、内省能力の限界に関するこの理論は大きな論争を巻き起こしており、個人が内省から得る情報の量を明確に検証することは困難であった[14]。内省 的手法を理解することが困難であったため、心の理論的発展は停滞し、行動主義に傾倒するようになった。有効な方法(すなわち、被験者による自己報告ではな い方法)を見つけることが難しかったため、認知革命が起こるまで、この分野の研究は中断されていた。そのため、無意識を理解する必要性が高まった。心理学 者は、意識の限界と、無意識を対象としたより多くの刺激と学習パラダイムに焦点を当てた実験に注目し始めた[2]。これにより、内省には限界がある、ある いは限界がないという議論に対する理解が深まる。 |

| Implicit-explicit relationships The theory of introspection is highly controversial. This is due to research showing inconsistencies between our introspective reports and factors affecting our stimuli. This issue lead to a new way to study introspective access by using the adaptive unconsciousness. This is done by looking at the implicit-explicit relationship, specifically the differences between the two. Explicit processes involve cognitive resources and are done with awareness. On the other hand, implicit processes require at least one of the following, lack of intention, lack of management, reduced awareness of where the responses came from and finally high efficiency of processing. This shows the differences that occur between the two processes and the contention around the differences as they cannot be pinned down to one specific thing.[15] These differences between implicit and explicit factors is argued to be able to be used as evidence for introspection existence.[16] If implicit processes become weaker than explicit processes then it can result in larger differences between the two. This results in consequences for future information processing and the well-being of the person. However, if this occurs in the right conditions it can allow for implicit processing output to enter the conscious mind. This leads to a small self-insight into the adaptive unconscious allowing us to understand it more.[17] Arguably, this argument of the independence of introspection existence based on the implicit-explicit relationship may actually be more conditional than originally thought. This view coincides with the idea that access to our unconsciousness is dependent on the competition between processes and their surrounding contexts. These contexts provide the association our stimuli have with certain aspects of society. For example, if you found pleasure in running, when running your cognitive processes either implicit or explicit would tell your unconscious you are feeling joy without you realising this was occurring. This could then be translated into the conscious mind.[17] |

暗黙的-明示的関係 内省理論は、非常に議論を呼ぶものである。これは、内省的報告と刺激に影響を与える要因との間に矛盾があるとする研究によるものである。この問題は、適応 的無意識を用いて内省的アクセスを研究する新たな方法につながった。これは、暗黙的-明示的関係、特に両者の違いに注目することで行われる。明示的プロセ スは認知資源を必要とし、意識的に行われる。一方、暗黙的なプロセスには、少なくとも以下の1つが必要とされる。意図の欠如、管理能力の欠如、反応の源に 対する認識の低下、そして最後に処理効率の高さである。これは、2つのプロセス間に生じる違いと、その違いをめぐる論争を示している。これらの違いは、1 つの特定の要因に特定できないためである[15]。暗黙的要因と明示的要因の違いを内省的存在の証拠として用いることができると主張されている[16]。 暗黙的プロセスが明示的プロセスよりも弱くなると、2つのプロセスの違いが大きくなる可能性がある。その結果、今後の情報処理や個人の幸福に影響を及ぼす ことになる。しかし、これが適切な条件下で発生した場合、潜在的な処理出力が意識的な思考に入り込む可能性がある。これは、適応的な無意識への小さな自己 洞察につながり、無意識をより理解できるようになる[17]。 おそらく、潜在的・顕在的関係に基づく内省的存在の独立性に関するこの議論は、当初考えられていたよりも実際には条件付きである可能性がある。この見解 は、無意識へのアクセスがプロセスとその周囲のコンテキスト間の競争に依存するという考えと一致している。これらのコンテキストは、刺激が社会の特定の側 面と結びつくことを提供する。例えば、ランニングに喜びを見出した場合、ランニングをしているときに認知プロセスが暗黙的または明示的であるかは関係な く、無意識に喜びを感じていることを認識することなく、それが起こっていることを無意識に伝える。そして、それが意識に翻訳される可能性がある[17]。 |

| Adaptive unconscious versus conscious thinking Many used to think most of our behaviours, thoughts, feelings all came from our conscious brain. However, as our understanding has grown it is obvious our adaptive unconscious does much more than we originally thought. Once we thought the creation of goals and self-reflection occurred consciously but now we realise its all in our unconscious. Our unconscious and conscious minds do have to work together though for us to continue efficiently functioning. We need to understand the dual system our brain uses between our adaptive unconscious and our conscious mind more. Analysing information, attitudes and feelings in the unconscious mind first which then contributes and creates our conscious versions of this.[2] The debate is no longer whether the adaptive unconscious exists but more which is more important in our everyday decision making? The adaptive unconscious or the conscious mind. Some would say it is becoming more and more apparent that our unconscious seems to be much more important than we originally thought especially compared to our conscious brain. The low-level processing we used to think our adaptive unconscious did we now realise may actually be the job of our conscious mind.[18] Our adaptive unconscious may actually be the power house in our brain making the important decisions and holding the important information. It does this all without us even realising. |

適応的無意識と意識的思考 かつては、私たちの行動、思考、感情のほとんどは意識的な脳から生み出されると考えられていた。しかし、私たちの理解が進んだ今、適応的無意識が当初考え られていたよりもはるかに多くの役割を果たしていることが明らかになっている。かつては、目標の設定や自己反省は意識的に行われると考えられていたが、今 ではそのすべてが無意識下で行われていることが分かっている。しかし、私たちが効率的に機能し続けるためには、無意識と意識が連携する必要がある。適応無 意識と意識の2つのシステムについて、脳がどのように機能するのか、もっと理解する必要がある。無意識の心の情報、態度、感情をまず分析し、それが意識的 なものの形成に寄与し、生み出すのである[2]。適応無意識の存在が議論されることはもはやないが、日常的な意思決定において、適応無意識と意識のどちら がより重要なのかが議論されている。適応無意識か、それとも意識か。無意識は、私たちがもともと考えていたよりもはるかに重要であることが、特に意識的な 脳と比較すると、ますます明らかになっているという人もいるだろう。私たちが適応無意識だと考えていた低レベルの処理は、実は意識的な心の仕事であること に、今になって気づいた人もいるかもしれない[18]。適応無意識は、重要な意思決定を行い、重要な情報を保持する、脳内の動力源である可能性がある。私 たちはそれに気づかないまま、無意識がすべてを行っているのだ。 |

| Cognitive module Ego depletion Unconscious mind Subconscious Neuroscience of free will Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking Intuition |

認知モジュール エゴの枯渇 無意識 潜在意識 自由意志の神経科学 『まばたき:考えない思考の力』 直感 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_unconscious |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆