自我とエスの関係

Ich und Es

「G ・グロデック氏……はわれわれが 自我と呼ぶものは、生においては基本的に受動的にふるまうものであり、未知の統御でき ない力によって「生かされている」(同氏の表現)と繰り返し強調している。この洞察を考慮にいれて、知覚システムから発生し、当初は前意識的 (vbw)であるものを〈自我〉と名づけ、無意識的(ubw)なものとしてふるまうものを 〈エス〉と名づけることを提案する」(フロイト 1996:220)。

フロイトの原注「原注(5) G ・グロデック『エ スの書』国際精神分析出版、1923年。; 原注(6)グロデック氏自身がニーチェの例に従っているのは確実である。ニーチェは、われわれのあ りかたにおいて非人称的なもの、いわば自然必然的なものを〈エス〉という文法的な表現で呼ぶのをつ ねとしていた」(フロイト 1996:220)。

※訳者、中山元の訳注:「フロイトは原注で、グロ デック氏がニーチェに依拠していることを指摘している。フロイトとグロデ ツタの往復書簡によると、フロイトはそれまでの自我論における意識/前意識/無意識の局所論では満 足できず、それらを包括するような自我と、これと対立する〈抑圧されたもの〉という対立関係に考察 の重点を移そうとしていて、グロデックの「エス」という概念に出会ったという」(フロイト 1996:221)。

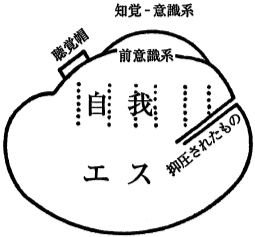

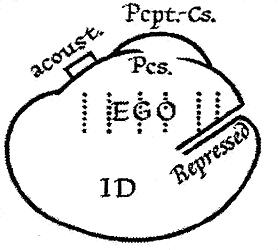

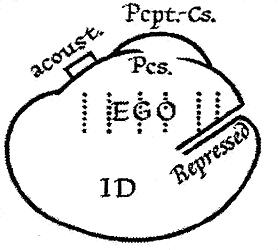

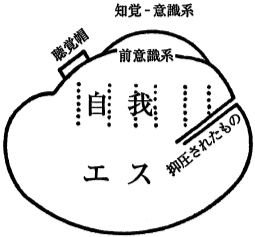

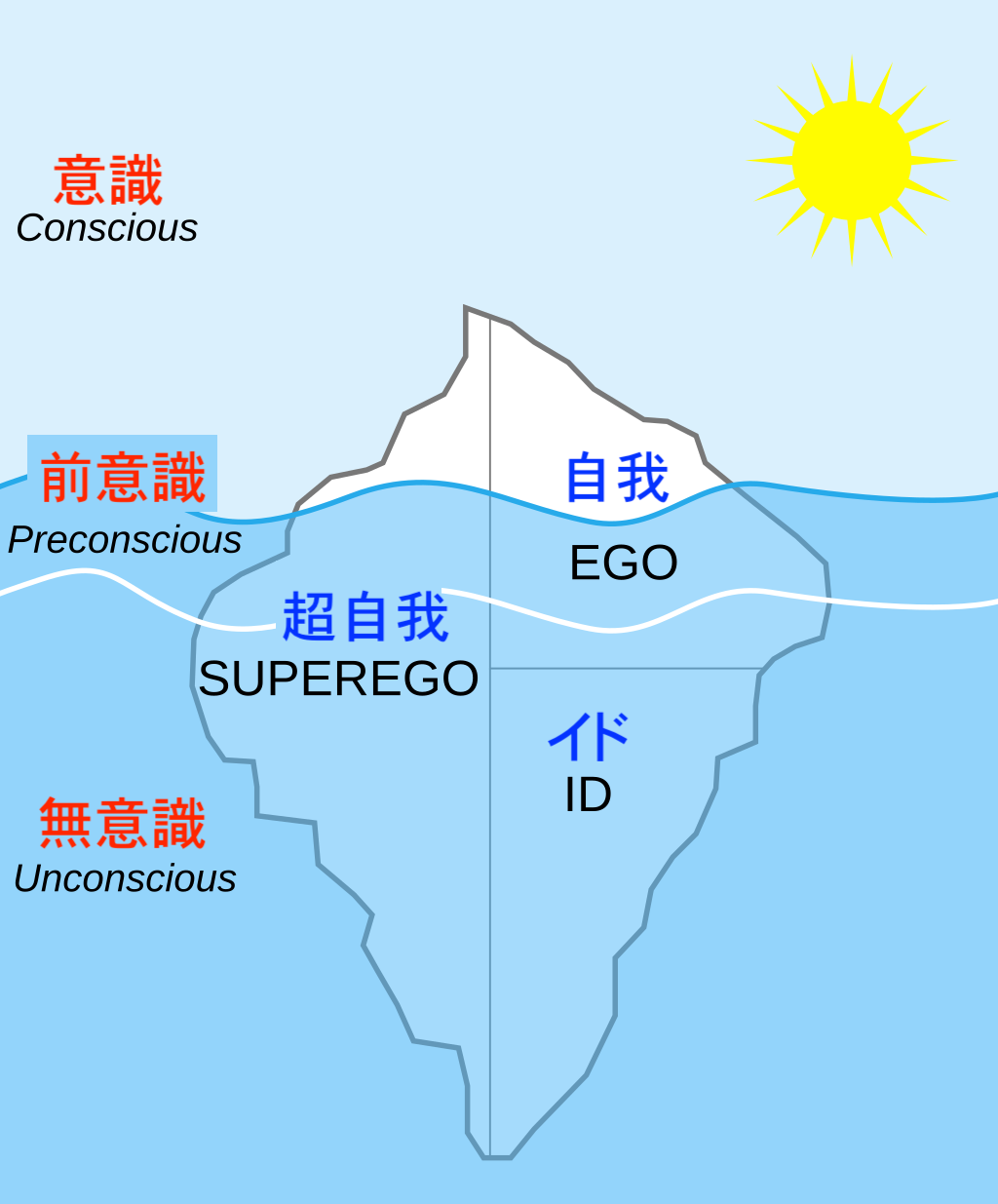

「このような名称を使うことで、記述と理解の面でど のような効用があるかは、いずれ明 らかになろう。われわれにとっては個人とは、一つの心的なエス、未知で無意識的なもの である。自我はその表面にのっているのであり、自我からその核として知覚(W) シス テムが形成される。これは図解すると次のようになる。 自我はエスの全体を覆うものではなく、肺が卵の上 にのっているように、知覚(W)システムが自我の 上にのっている範囲に限って、自我はエスを覆ってい るのである。自我とエスの聞に明瞭な境界はなく、自 我は下の方でエスと合流している。/ しかし抑圧されたものもエスと合流するのであり、 その一部を構成するにすぎない。抑圧されたものは、 抑圧抵抗によって自我と明瞭に区別されるのであり、 抑圧されたものはエスを通じて自我と連絡することができる」(フロイト 1996:221)。

「自我は「聴覚帽」を

かぶっているが、脳の解剖学的な経験から、この帽子は片側だけにあることが示されている」(フロイト 1996:222)。

「フロイト理論を単純に言えばこうだ。無意識あるいは『エス』というものがあり、そこには無 意識の欲望が息づいている。その場所は、 欲望にとって安全な場所であるがしかし、もしそこに収まりきれぬ場合、欲望は、われわれを戸惑わせ、葛藤や矛盾を生じさせ、問題をおこしてしまう。意識は 精神(=心:引用者)の一部分であり、そこはわれわれがアクセスすることのできる部分だ。たとえば、イマージュや感情や想念などを、自分のうちに見つける ことは簡単だ。乱暴に言えば、これを、フロイトは『自我』と呼んだのだ。フロイトは、自我を、無意識と世界との間で折衝する、外皮や外壁であると考えた」 フィリップ・ヒル『ラカン』新宮一成・村田智子訳、筑摩書房、26ページ、2007年

| Id (Es) Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of bodily needs and wants, emotional impulses and desires, especially aggression and the sexual drive.[9] The id acts according to the pleasure principle—the psychic force oriented to immediate gratification of impulse and desire.[10] Freud described the id as "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". Understanding of the id is limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and it can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: it is concerned only with satisfaction of drives in accordance with the pleasure principle.[11] It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time."[12] The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."[13] Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle.[14][15] The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the principle of reality into account. Freud describes the id as "the great reservoir of libido",[16] the energy of desire, usually conceived as sexual in nature, the life instincts that are constantly seeking a renewal of life. He later also postulated a death drive, which seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state."[17] For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms"[18] through aggression. Since the id includes all instinctual impulses, the destructive instinct, as well as eros or the life instincts, is considered to be part of the id.[19] |

イド フロイトは、イドを身体的な欲求や欲求、感情的な衝動や欲望、特に攻撃性や性的衝動の無意識的な源として考えた[9]。イドは快楽原則に従って行動する。 快楽原則とは、衝動や欲求を即座に満たそうとする心理的な力のことである[10]。 フロイトはイドを「私たちのパーソナリティの暗く、手の届かない部分」と表現した。イドを理解することは、夢や神経症の症状を分析することに限られてお り、自我との対比という観点でしか説明できない。それは組織も集団的な意志もなく、快楽原則に従って衝動を満たすことのみに関心を向けている[11]。理 性や通常の意識生活における前提を無視しており、「相反する衝動は互いに打ち消し合うことなく、共存している。 . .イドには否定と比較できるものは何もない。...イドには時間の概念に相当するものは何もない」[12]。イドは「価値判断を知らない。善悪も道徳もな い。...本能的なカタルシスを求めること、それが私たちの考えるイドのすべてである」[13]。 発達段階では、イドは自我よりも先行する。イドは、誕生時に備わっている基本的な本能的衝動から成り、肉体的組織に内在し、快楽原則のみによって支配され ている[14][15]。精神装置は未分化のイドとして始まり、その一部が構造化された「自我」へと発達する。自我とは、現実の原則を考慮に入れた自己概 念である。 フロイトはイドを「リビドーの巨大な貯蔵庫」[16]、つまり欲望のエネルギー、通常は性的な性質を持つと考えられ、生命の更新を常に求める生命本能と表 現している。彼は後に「有機的生命を無機的な状態に戻す」[17]ことを求める死の衝動も提唱した。フロイトにとって、「死の衝動は、おそらく一部だけで あろうが、外の世界や他の生物に対する破壊本能として、攻撃性を通して表現されると思われる」[18]。イドには本能的な衝動がすべて含まれているため、 破壊的な本能だけでなく、エロスや生命本能もイドの一部であると考えられている[19]。 |

| Ego The ego acts according to the reality principle. Since the id's drives are frequently incompatible with social reality, the ego attempts to direct its energy and satisfy its demands in accordance with the imperatives of that reality.[20] According to Freud the ego, in its role as mediator between the id and reality, is often "obliged to cloak the (unconscious) commands of the id with its own preconscious rationalizations, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."[21] Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean the sense of self, but later expanded it to include psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego is the organizing principle upon which thoughts and interpretations of the world are based.[22] According to Freud, "the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions... it is like a tug of war... with the difference that in the tug of war the teams fight against one another in equality, while the ego is against the much stronger 'id'."[23] In fact, the ego is required to serve "three severe masters...the external world, the superego and the id."[21] It seeks to find a balance between the primitive drives of the id, the limitations imposed by reality, and the strictures of the superego. It is concerned with self-preservation: it strives to keep the id's desires within limits, adapted to reality and submissive to the superego. Thus "driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality" the ego struggles to bring about harmony among the competing forces. Consequently, it can easily be subject to "realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the superego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id."[24] The ego may wish to serve the id, trying to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts, while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the superego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority. To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms reduce the tension and anxiety by disguising or transforming the impulses that are perceived as threatening.[25] Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. His daughter Anna Freud identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatization, splitting, and substitution. "The ego is not sharply separated from the id; its lower portion merges into it.... But the repressed merges into the id as well, and is merely a part of it. The repressed is only cut off sharply from the ego by the resistances of repression; it can communicate with the ego through the id." (Sigmund Freud, 1923)  In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted as being half in the conscious, a quarter in the preconscious, and the other quarter in the unconscious. |

自我 自我は現実の原則に従って行動する。イドの衝動は社会的現実と相容れない場合が多いため、自我はそのエネルギーを現実の要請に従って方向付け、要求を満た そうとする[20]。フロイトによると、自我はイドと現実の仲介役として、イドの(無意識の)命令を自身の前意識的な合理化で覆い隠し、 イドと現実の葛藤を隠蔽し、イドが頑固で融通の利かない状態にある場合でも、現実を認識していると主張する」[21]。 もともとフロイトは自我を自己意識という意味で使用していたが、後に判断力、寛容さ、現実の検証、コントロール、計画、防衛、情報の統合、知的機能、記憶 などの心理的機能を含むように拡大した。自我は、思考や世界に対する解釈の基盤となる組織化原理である[22]。 フロイトによると、「自我とは、外部の世界からの直接的な影響によって変化したイドの一部である。...自我は、情熱を内包するイドとは対照的に、理性や 常識と呼ばれるものを表す。それは綱引きのようなもので、綱引きでは両チームが対等に戦うが、自我ははるかに強力な「イド」と戦うという違いがある。 23] 実際、自我は「3人の厳しい主人...外界、超自我、イド」に仕えることが求められる[21]。自我は、イドの原始的な衝動、現実が課す制限、超自我の制 約のバランスを取ろうとする。自我は自己保存に関心を向け、イドの欲望を現実に適合し、超自我に従順な範囲内に抑えるよう努める。 このように「イドに駆り立てられ、超自我に束縛され、現実から反発される」自我は、対立する力間の調和をもたらすために奮闘する。その結果、自我は「現実 世界に対する現実的不安、超自我に対する道徳的不安、そしてイドにおける情念の強さに対する神経症的不安」[24]に簡単に陥ってしまう。自我はイドに従 いたいと思い、現実を尊重しているふりをしながら、葛藤を最小限に抑えるために現実の細かい点を無視しようとするかもしれない。しかし、超自我は常に自我 の動きを監視しており、罪悪感や不安、劣等感といった感情で自我を罰する。 これを克服するために、自我は防衛機制を用いる。防衛機制とは、脅威と認識される衝動を偽装したり変換したりすることで、緊張や不安を軽減するものである [25]。フロイトが特定した防衛機制には、否認、転嫁、知性化、空想、補償、投影、合理化、反動形成、退行、抑圧、昇華がある。彼の娘であるアナ・フロ イトは、元に戻す、抑制、解離、理想化、同一視、内面化、逆転、身体化、分裂、代替などの概念を明らかにした。 「自我はイドと明確に区別されているわけではなく、その下層部はイドと融合している。しかし、抑圧されたものはイドにも融合しており、その一部でしかな い。抑圧されたものは、抑圧の抵抗によって自我から鋭く切り離されているだけであり、自我とイドを通じてコミュニケーションをとることができる」(ジーク ムント・フロイト、1923年)  「心の構造と表象モデル」の図では、自我は意識の半分、前意識の4分の1、無意識の4分の1を占めるものと描かれている。 |

| Superego The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly as absorbed from parents, but also other authority figures, and the general cultural ethos.[10] Freud developed his concept of the superego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the "special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our 'conscience'."[26] For him the superego can be described as "a successful instance of identification with the parental agency", and as development proceeds it also absorbs the influence of those who have "stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models". Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.[27] The superego aims for perfection.[25] It is the part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency, commonly called "conscience", that criticizes and prohibits the expression of drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. Thus the superego works in contradiction to the id. It is an internalized mechanism that operates to confine the ego to socially acceptable behaviour, whereas the id merely seeks instant self-gratification.[28] The superego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex.[29] In the case of the little boy, it forms during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex, through a process of identification with the father figure, following the failure to retain possession of the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration. Freud described the superego and its relationship to the father figure and Oedipus complex thus: The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.[30] In The Ego and the Id, Freud presents "the general character of harshness and cruelty exhibited by the [ego] ideal — its dictatorial Thou shalt". The earlier in the child's development, the greater the estimate of parental power. . . . nor must it be forgotten that a child has a different estimate of his parents at different periods of his life. At the time at which the Oedipus complex gives place to the super-ego they are something quite magnificent; but later, they lose much of this. Identifications then come about with these later parents as well, and indeed they regularly make important contributions to the formation of character; but in that case they only affect the ego, they no longer influence the super-ego, which has been determined by the earliest parental images. — New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 64. Thus when the child is in rivalry with the parental imago[31] it feels the dictatorial Thou shalt—the manifest power that the imago represents—on four levels: (i) the auto-erotic, (ii) the narcissistic, (iii) the anal, and (iv) the phallic.[32] Those different levels of mental development, and their relations to parental imagos, correspond to specific id forms of aggression and affection.[33] The concept of superego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore, for Freud, "their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men...they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility."[34] However, Freud went on to modify his position to the effect "that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their human identity, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics, otherwise known as human characteristics."[35] |

超自我 超自我は、主に親から、またその他の権威者から吸収した文化的なルールの内面化、および一般的な文化的倫理観を反映している[10]。フロイトは、自我の 理想と「自我の理想からナルシシズム的な満足が得られるように見張る特別な心理的機関...私たちが『良心』と呼ぶもの」[26]を以前組み合わせたこと から、超自我の概念を発展させた。自我の理想が確実に満たされるように...私たちが「良心」と呼ぶもの」[26]。彼にとって、超自我は「親の代理と一 体化した成功例」と表現でき、発達が進むにつれ、「親の代わりを務める人々(教育者、教師、理想的なモデルとして選ばれた人々)」の影響も吸収する。 したがって、子どもの超自我は、実際には両親ではなく両親の超自我をモデルとして構築される。その内容も同じであり、伝統や世代から世代へと受け継がれて きた価値判断のすべてを表すものとなる[2 7] 超自我は完璧を目指している[25]。それは人格構造の一部であり、主に、しかし完全に無意識というわけではない。個人の自我の理想、精神的な目標、そし て一般的に「良心」と呼ばれる精神的な代理機関を含み、衝動、空想、感情、行動の表現を批判し、禁止する。したがって、超自我はイドと相反する働きをす る。それは、自我を社会的に許容される行動に制限するために機能する内面化されたメカニズムである。一方、イドはただ即時の自己満足を求めるだけである [28]。 超自我と自我は、2つの重要な要因の産物である。すなわち、子どもの無力感とエディプスコンプレックスである[29]。 [29] 男の子の場合、去勢への恐怖から母親を愛の的として手放せなかった結果、父親像との同一化プロセスを経てエディプスコンプレックスが解消される過程で形成 される。フロイトは、超自我と父権的象徴およびエディプス・コンプレックスの関係について、次のように述べている。 超自我は父親の性格を保持しており、エディプスコンプレックスがより強力で、より急速に抑圧(権威、宗教的教え、学校教育、読書の影響による)に屈服する ほど、後に超自我が自我を支配する度合いが厳しくなる。 自我が自我を支配する度合いが、後に強くなる。それは良心の形をとるか、あるいは無意識の罪悪感の形をとるだろう[30]。 『自我とエス』の中でフロイトは、「(自我の)理想が示す厳格さと残酷さという一般的な特徴、すなわち独裁的な汝の義務」について述べている。子どもの発 育の初期段階では、親の権力に対する評価はより大きくなる。. . . また、子どもが生涯のさまざまな時期において、両親に対する評価が異なることも忘れてはならない。エディプスコンプレックスが超自我に取って代わる時期に は、両親は素晴らしい存在である。しかし、その後、子どもはその多くを失う。その後、これらの後期の親に対しても同一化が生じ、実際、人格形成に重要な影 響を及ぼすことはよくある。しかし、この場合、自我にのみ影響を与え、最も初期の親のイメージによって決定された超自我にはもはや影響を与えない。 —『精神分析入門講義』第64ページ したがって、子どもが親イマゴ[31]と対立しているとき、イマゴが象徴する明白な力である独裁的な「汝、汝の義務」を4つのレベルで感じる。(i) 自己愛、(ii) ナルシシズム、(iii) 肛門愛、(iv) ファリスティック[32]。これらの異なる精神発達レベルと、それらが親イマゴスとの関係は、特定のイドの攻撃性と愛情の形態に対応している[33]。 超自我とエディプスコンプレックスの概念は、その性差別的であると批判されている。すでに去勢されたと考えられている女性は、父親と同一化しないため、フ ロイトにとって「彼女たちの超自我は、男性に対して我々が要求するほど、決して容赦なく、非人間的、感情的な起源から独立していることはない...彼女た ちは、しばしば、愛情や敵意の感情によって判断が左右されることが多い」[34]。愛情や敵意といった感情によって判断が左右されることが多い」 [34]。しかし、フロイトはその後、自分の見解を修正し、「大多数の男性も、男性的な理想からは程遠い存在であり、人間としてのアイデンティティを持つ 人間は、人間的な特性として知られる男性的および女性的な特性を兼ね備えている」[35]と述べた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Id,_ego_and_superego |

|

|

エス(Es)は、左の図では、イド(id)に相当する領域である。 |

+++

●ジジェクによると、フロイトは、自我を自分の家の主人であることすら気づいていない(ジ

ジェク 2008:16)

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆