フロイト『モーセと一神教』

フロイト『モーセと一神教』

フロイト『モーセと一神教』

フロイト『モーセと一神教』

Sigmund Freud's Moses and Monotheism, 1939

☆ジークムント・フロイトは オーストリアの神経科医で、精神分析の創始者である。精神分析とは、患 者と精神分析医との対話を通して精神病理学を治療する臨床手法である。彼は病気の末期まで、患者を診察し続けた。また、1938年にドイツ 語で、翌年には英語で出版された『モーセと一神教』と、死後に出版された未完の『精神分析概論』の執筆にも取り組んだ。『 モーセと一神教』(1937年)は、モーセは(ユダヤ人ではなく逆に)ユダヤ人によって殺されたエジプトの部族の父なる家族であり、彼ら(=ユダヤ人)は 一神教のユダヤ教を確立するのに資する反応形成に よって心理的に父殺しに対処したと提唱している。同様に、彼はローマ・カトリックの聖体拝領の儀式を、聖なる父の殺害と貪食の文化的証拠である と述べている。

★『モーゼと一神教』はジークムント・フロイトの研究書である。1939年、82歳で没する

年にロンドン亡命中に出版された彼の遺作である(→「宗教にかんするジークムント・フロイトの見解」)。

| Der

Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion

ist eine Studie von Sigmund Freud. Es ist seine letzte Schrift, die er

in seinem Todesjahr 1939 im Alter von 82 Jahren in seinem Londoner Exil

herausgegeben hat. |

『モーゼと一神教』はジークムント・フロイトの研究書である。1939

年、82歳で没する年にロンドン亡命中に出版された彼の遺作である。 |

| Einleitung Freud leitet seine Schrift mit einem Bekenntnis ein: „Einem Volkstum den Mann abzusprechen, den es als den größten unter seinen Söhnen rühmt, ist nichts, was man gern oder leichthin unternehmen wird, zumal wenn man selbst diesem Volke angehört. Aber man wird sich durch kein Beispiel bewegen lassen, die Wahrheit zugunsten vermeintlicher nationaler Interessen zurückzusetzen, und man darf ja auch von der Klärung eines Sachverhalts einen Gewinn für unsere Einsicht erwarten.“ Freud stützt sich in seinen weiteren Ausführungen auf die damals neuesten Erkenntnisse der Historiker bzw. Ägyptologen James H. Breasted, Eduard Meyer und Ernst Sellin, indem er den Religionsstifter Moses nicht einen Juden, sondern einen Ägypter nennt, und entwickelt die Aufsehen erregende Theorie, dass Moses, der während der Regentschaft des Reform-Pharao Echnaton (Amenhotep, Ikhnaton) gelebt haben soll, den semitischen Stämmen, die seit Jahrhunderten als Sklaven in Ägypten arbeiteten, die neue Aton-Religion „beigebracht“ habe.  Echnaton mit Familie in Anbetung von Aton Dass Moses ein Ägypter gewesen sein soll, leitete Freud u. a. aus den beschriebenen Sprachproblemen Moses ab, der sich zuweilen seines Bruders Aaron bediente, wenn er zu den Israeliten sprechen wollte. Nach dem Bericht der Bibel Ex 2,1-10 EU werden Moses Eltern als dem Stamm Levi (Ex 2,1) angehörig bezeichnet. Die Adoption durch die Tochter des Pharao und der scheinbare Widerspruch der völkischen Zugehörigkeit (Ägypter / Hebräer) wird von Sigmund Freud nach dem Konzept des Familienromans ausgelegt.[1] |

序論 フロイトは、ある告白で自分の著作を紹介している: 「ある国民が、その息子の中で最も偉大であると賞賛している人物を否定することは、特にその国民に属している者にとっては、喜んで軽々しく引き受けること ではない。しかし、どのような例によっても、想定される国益を優先して真実を脇に置くことに心を動かされることはないだろう。 さらにフロイトは、歴史家でありエジプト学者であるジェイムズ・H・ブレスト、エドゥアルド・マイの最新の研究成果を紹介している。Breasted, Eduard Meyer and Ernst Sellinの最新の知見を引き、宗教の創始者モーセをユダヤ人ではなくエジプト人と呼び、改革派のファラオ、アクエンアテン(アメンホテプ、イクナト ン)の治世に生きたとされるモーセが、何世紀にもわたってエジプトで奴隷として働いていたセム系民族に新しいアトンの宗教を「教えた」というセンセーショ ナルな説を展開している。  家族とともにアトンを礼拝するアクエンアテン フロイトは、モーセがイスラエルの民と話すときに弟のアロンを使うことがあったというモーセの言葉の問題から、モーセがエジプト人であったことを推測し た。 出エジプト記2:1-10 EUの聖書の記述によれば、モーセの両親はレビ族に属するとされている(出エジプト記2:1)。ファラオの娘による養子縁組と、民族的所属(エジプト人/ ヘブライ人)の明らかな矛盾は、ジークムント・フロイトによって家族小説の概念に従って解釈されている[1]。 |

| Echnaton als Begründer des

Monotheismus Freud nimmt weiter detailliert an, dass bis zur Herrschaft Echnatons (um 1350 v. Chr.) Ägypten von einer einflussreichen, konservativen Priesterschaft dominiert wurde, die dem Amun-Kult der Vielgötterei und dem Jenseitsglauben (prächtige Grabstätten, Grabbeigaben, Totenkult, Mumifizierung) anhing. Echnaton erkannte, dass alles Leben von der „Energie“ der Sonne (Sonnenstrahlen, Sonnenlicht) abhängig war, und soll aus dieser Erkenntnis gemeinsam mit seiner Gemahlin Nofretete die erste monotheistische Religion entwickelt haben, die erstmals Moral, aber kein Jenseits kannte. Im neuen Kult gab es nur noch den Sonnengott Aton, dargestellt durch eine Sonnenscheibe. |

一神教の創始者としてのアケナテン(イクナートン) フロイトはさらに、アケナテンの治世(紀元前1350年頃)までのエジプトは、多神教のアメン崇拝と死後の世界への信仰(壮大な墓、墓用品、死神崇拝、ミ イラ化)を信奉する有力で保守的な神官団によって支配されていたと詳述する。アケナテンは、すべての生命が太陽の「エネルギー」(太陽光線、日光)に依存 していることを認識し、妻のネフェルティティとともにこの認識から最初の一神教を発展させたと言われている。この新しい教団には、太陽の円盤で表された太 陽神アテンしかいなかった。 |

| Der Vatermord an Moses Ähnlich wie Breasted nimmt Freud an, nach dem Tod Echnatons habe das alte Priester-System wieder die Macht gewonnen, die Aton-Ketzerei abgeschafft und alle Symbole und Bauwerke, die daran erinnerten, vernichtet. Moses, ein Anhänger, Gouverneur oder Priester des Echnaton, habe die neue Religion so sehr verinnerlicht, dass er sie als große Idee den hebräischen Stämmen, dem „auserwählten Volke“, nahegebracht habe und später mit ihnen aus Ägypten geflohen sei. Auf der Halbinsel Sinai ließen sie sich nieder und vermischten sich dort mit anderen hebräischen Stämmen, den Midianitern. Diese beteten den strengen Vulkangott JHWH (Jahwe) an. Offensichtlich, so spekuliert Freud, kam es dann zu einer Art „Religionskrieg“, bei dem Moses ermordet wurde. Seine engen Vertrauten, die Leviten, hätten jedoch die Aton-Lehre lebendig gehalten, und so habe sich im Lauf von Generationen „das schlechte Gewissen über den Vatermord“ zu einer Art Trauma und einer Moses-Verehrung gewandelt, die in den jüdischen Schriften – die Jahrhunderte später entstanden – ihren mystifizierten Ausdruck gefunden hätten. Vor allem in der Zeit des babylonischen Exils der jüdischen Stämme hätten die Propheten „die alten Moses-Zeiten“ glorifiziert und den Glauben an den Messias (Erlöser/Befreier) wachgehalten. Freud schreibt dazu: „Es scheint, dass ein wachsendes Schuldbewusstsein sich des jüdischen Volkes, vielleicht der ganzen damaligen Kulturwelt bemächtigt hatte, als Vorläufer der Wiederkehr des verdrängten Inhalts. Bis dann einer aus dem jüdischen Volk in der Justifizierung eines politisch-religiösen Agitators den Anlass fand, mit dem eine neue, die christliche Religion sich vom Judentum ablöste. Paulus, ein römischer Jude aus Tarsus, griff dieses Schuldbewusstsein auf und führte es richtig auf seine urgeschichtliche Quelle zurück. Er nannte sie die ,Erbsünde‘, es war ein Verbrechen gegen Gott, das nur durch den Tod gesühnt werden konnte. Mit der ,Erbsünde‘ war der Tod in die Welt gekommen. Aber es wurde nicht an die Mordtat erinnert, sondern anstatt dessen ihre Sühnung phantasiert, und darum konnte diese Phantasie als Erlösungsbotschaft begrüßt werden. Ein ,Sohn Gottes‘ hatte sich als Unschuldiger töten lassen und damit die Schuld aller auf sich genommen. Es musste ein Sohn sein, denn es war ja ein Mord am Vater gewesen. Wahrscheinlich hatten Traditionen aus orientalischen und griechischen Mysterien auf den Ausbau der Erlösungsphantasie Einfluss genommen.“ |

モーセの父殺 ブレストと同様、フロイトは、アクエンアテンの死後、古い祭司制度が権力を取り戻し、異端のアトンを廃止し、それを思い起こさせるシンボルや建物をすべて 破壊したと仮定している。アクエンアテンの従者、総督、あるいは祭司であったモーセは、この新しい宗教を内面化し、「選ばれし民」であるヘブライ人部族に 偉大な思想として紹介し、後に彼らとともにエジプトを脱出した。彼らはシナイ半島に定住し、他のヘブライ部族であるミディアン人と混血した。彼らは厳格な 火山神YHWH(ヤハウェ)を崇拝していた。どうやらこれが一種の「宗教戦争」を引き起こし、モーセは殺害されたようだとフロイトは推測している。しか し、彼の側近であったレビ人は、アトンの教義を守り続けた。そのため、何世代にもわたって、「父を殺したことに対する罪の意識」は、一種のトラウマとな り、モーセへの崇拝となった。特にユダヤ諸部族がバビロンに追放された間、預言者たちは「昔のモーゼの時代」を美化し、メシア(救済者/解放者)への信仰 を守り続けた。フロイトはこう書いている: 「抑圧された内容が戻ってくる前触れとして、罪悪感の意識がユダヤ人を、おそらくは当時の文化世界全体を支配していたようだ。ユダヤ人の一人が、政治的・ 宗教的扇動家としての正当性をもって、ユダヤ教から脱却する新しい宗教、キリスト教の契機を見出すまでは。タルソス出身のローマ系ユダヤ人であるパウロ は、この罪の意識を取り上げ、先史時代の源まで正しく遡った。パウロはこれを「原罪」と呼んだ。原罪は神に対する罪であり、死によってのみ償うことができ る。死は「原罪」とともにこの世に生まれた。しかし、殺人という行為は記憶されることはなく、代わりにその贖罪が空想され、それゆえこの空想は贖罪のメッ セージとして歓迎された。神の子」が無実の人間として殺されることを許し、すべての罪を一身に背負ったのだ。父親が殺されたのだから、息子でなければなら なかったのだ。東洋やギリシャの秘儀の伝統が、贖罪の幻想の発展に影響を与えたのだろう」。 |

| Von Moses zu Christus Freud vermutet weiter, „dass die Reue um den Mord an Moses den Antrieb zur Wunschphantasie des Messias gab, der wiederkommen und seinem Volk die Erlösung und die versprochene ‚Weltherrschaft‘ bringen soll. Wenn Moses dieser erste Messias war, dann ist Christus sein Ersatzmann und Nachfolger geworden.“ In seiner Zusammenfassung über die Entstehung des Monotheismus schreibt Freud, es gebe bei der Masse der Menschen ein starkes Bedürfnis nach einer Autorität, die man bewundern kann, der man sich beugt, von der man beherrscht, eventuell sogar misshandelt wird. Dies sei die Sehnsucht nach dem Vater, die jedem von seiner Kindheit her innewohne. |

モーゼからキリストへ フロイトはさらに、「モーセが殺されたことに対する後悔の念が、メシアが復活して救済と約束された 「世界征服 」を自分の民にもたらすという願望的な幻想を生んだ」と推測している。モーセがこの最初のメシアであったとすれば、キリストはその身代わりであり、後継者 であった」。 フロイトは、一神教の出現に関する彼の要約の中で、大衆の間には、賞賛し、頭を下げ、支配され、場合によっては虐待さえも受けることのできる権威に対する 強いニーズがあると書いている。これは、子供の頃から誰にでも備わっている父親への憧れである。 |

| Kritik am Gottesglauben und

Erklärung des Antisemitismus Freud resümiert seine Ausführungen mit einer grundsätzlichen Kritik an den Gottesglauben: „Wie beneidenswert erscheinen uns – den Armen im Glauben – jene Forscher, die von der Existenz eines höheren Wesens überzeugt sind! Für diesen großen Geist hat die Welt kein Problem, weil er selbst alle ihre Einrichtungen geschaffen hat. Wir verstehen, dass der Primitive einen Gott braucht als Weltschöpfer, Stammesoberhaupt, persönlichen Fürsorger. Dieser Gott hat seine Stelle hinter den verstorbenen Vätern, von denen die Tradition noch etwas zu sagen weiß. Der Mensch späterer Zeiten, unserer Zeit, benimmt sich in der gleichen Weise. Auch er bleibt infantil und schutzbedürftig – selbst als Erwachsener.“ Freud sieht im jüdischen Monotheismus gegenüber den Bildreligionen einen „Fortschritt in der Geistigkeit“. Im Bilderverbot (in den Zehn Geboten) stecke der entscheidende rationalistische Impuls. Der Monotheismus fundiere mit seinem Bilderverbot, der Verwerfung des magisch wirkenden Zeremoniells und der Betonung der ethischen Forderung des Gesetzes eine „existentielle Weltfremdheit“ und damit „allmähliche Entstrickung des Menschen aus den Zwängen der Idolatrie“ (der Anbetung von Götzenbildern), die seinen Geist gefangen halten. Im Antisemitismus kann Freud dann eine Reaktionsbildung gegen den Geist sehen, einen Antiintellektualismus. Er sieht den Antisemitismus als Aufbegehren gegen die Triebverzicht verlangende monotheistische Religion: „Unter einer dünnen Tünche von Christentum sind sie geblieben, was ihre Ahnen waren, die einem barbarischen Polytheismus huldigten. Sie haben ihren Groll gegen die neue, ihnen aufgedrängte Religion nicht überwunden, aber sie haben ihn auf die Quelle verschoben, von der das Christentum zu ihnen kam. (…) Ihr Judenhass ist im Grunde Christenhass.“ |

神への信仰批判と反ユダヤ主義の説明 フロイトは、神への信仰に対する根本的な批判で発言をまとめている: 「高次の存在の存在を確信している研究者、つまり信仰心の乏しい研究者たちは、われわれから見ればなんと羨ましく見えることだろう!この偉大な精神にとっ て、世界には何の問題もないのだ。原始人には、世界の創造主、部族の長、個人的な世話人としての神が必要なのだ。この神は、亡くなった父祖たちの後ろに位 置し、その父祖たちについては伝統が今なお語り継いでいる。後世の人間も、現代の人間も、同じように振る舞っている。彼もまた幼児的であり、保護を必要と している。 フロイトは、ユダヤ教の一神教を、イメージ宗教に比べて「霊性の進歩」であると見なしている。十戒における)像の禁止には、決定的な合理主義的衝動が含ま れている。像の禁止、呪術的儀式の拒絶、律法の倫理的要求の強調によって、一神教は「世界からの実存的疎外」を確立し、その結果、人間の精神を虜にする 「偶像崇拝の束縛から徐々に解き放たれる」のである。フロイトは反ユダヤ主義を、精神に対する反動、つまり反知性主義としてとらえることができる。彼は反 ユダヤ主義を、本能の放棄を要求する一神教への反抗と見ている: 「キリスト教という薄皮の下で、彼らは野蛮な多神教に敬意を表した祖先のままである。彼らは、自分たちに押し付けられた新しい宗教に対する憤りを克服して いないが、その憤りをキリスト教が自分たちにやって来た源に転嫁している。(彼らのユダヤ人に対する憎しみは、基本的にはキリスト教徒に対する憎しみなの である」。 |

| Freuds Aussagen zur Entstehung

seiner Schrift Freud war lange Zeit sehr unzufrieden über den aktuellen Zustand seiner Studie. In seinem Briefwechsel mit Arnold Zweig geht er an mehreren Stellen darauf ein. Er erwähnt den neuen Text erstmals am 30. September 1934: „Ich habe nämlich in einer Zeit relativer Ferien aus Ratlosigkeit, was mit dem Überschuß an Muße anzufangen, selbst etwas geschrieben, und das nahm mich gegen ursprüngliche Absicht so in Anspruch, daß alles andere unterblieb. Nun freuen Sie sich nicht, denn ich wette, Sie werden es nicht zum Lesen bekommen. Aber lassen Sie sich erklären, wie das zugeht […]“ „Angesichts der neuen Verfolgungen“ [der Juden durch die Nazis in Deutschland] „fragt man sich wieder, wie der Jude geworden ist und warum er sich diesen unsterblichen Haß zugezogen hat. Ich hatte bald die Formel heraus. Moses hat den Juden geschaffen, und meine Arbeit bekam den Titel: Der Mann Moses, ein historischer Roman […]“ „Das Zeug gliedert sich in drei Abschnitte, der erste romanhaft interessant, der zweite mühselig und langwierig, der dritte gehalt- und anspruchsvoll. An dem dritten scheiterte das Unternehmen, denn er brachte eine Theorie der Religion, nichts Neues zwar für mich nach >Totem und Tabu<, aber doch eher etwas Neues und Fundamentales für Fremde.“[2] Dann geht Freud darauf ein, warum er diesen Text zu diesem Zeitpunkt nicht veröffentlichen will. In der „katholischen Strenggläubigkeit“ des damaligen Österreich fürchtet er, dass durch diesen ‚Angriff’ auf die christliche Religion die Ausübung der Psychoanalyse in Wien verboten werden würde und die Psychoanalytiker alle erwerbslos wären. „Und dahinter steht, daß mir meine Arbeit weder so sehr gesichert scheint noch so sehr gut gefällt. Es ist also nicht der richtige Anlaß zu einem Martyrium. Schluß vorläufig!“[3] Zweig machte Freud daraufhin den Vorschlag, den Text als kleinen Privatdruck und nur für ‚Eingeweihte’ in Jerusalem erscheinen zu lassen, worauf sich Freud nicht einlässt. Am 16. Dezember 1934 schrieb Freud: „Mit dem Moses lassen Sie mich in Ruhe. Daß dieser wahrscheinlich letzte Versuch, etwas zu schaffen, gescheitert ist, deprimiert mich genug. Nicht daß ich davon losgekommen wäre. Der Mann, und was ich aus ihm machen wollte, verfolgt mich unablässig. Aber es geht nicht, die äußeren Gefahren und die inneren Bedenken erlauben keinen anderen Ausgang des Versuchs.“[4] Am 13. Februar 1935 schrieb er an Arnold Zweig, der damals in Haifa lebte: „Meinem eigenen Moses ist nicht zu helfen. Wenn Sie einmal wieder nach Wien kommen, dürfen Sie gerne dies zur Ruhe gelegte Manuskript lesen, um mein Urteil zu bestätigen.“[5] Zweig informiert Freud von Israel aus über einige Bücher, die ihm beim Moses-Thema möglicherweise weiterhelfen würden. Daraufhin schrieb Freud am 14. März 1935: „Dies die Enttäuschung. Bestärkt wurde mein Urteil über die Schwäche meiner historischen Konstruktion, die mich von der Veröffentlichung der Arbeit mit Recht abgehalten hat. Der Rest ist wirklich Schweigen.“[6] Dann kommt Freud eine unerwartete archäologische Entdeckung zu Hilfe. Er schrieb am 2. Mai 1935 an Zweig: „In einem Bericht über Tell el-Amarna, das noch nicht halb ausgegraben ist, habe ich eine Bemerkung über einen Prinzen Thotmes gelesen, von dem sonst nichts bekannt ist. Wäre ich ein Pfund-Millionär, so würde ich die Fortsetzung der Ausgrabungen finanzieren. Dieser Thotmes könnte mein Moses sein, und ich dürfte mich rühmen, daß ich ihn erraten habe.“[7] Nach Freuds Umzug nach London 1938 ändert sich der Ton seiner Stellungnahmen zu seinem Moses-Buch. Er muss nunmehr keine Rücksichten auf Wiener Verhältnisse nehmen und blickt der Veröffentlichung seines letzten Buches entspannter entgegen. Von London aus schrieb er am 28. Juni 1938 an Zweig: „Ich schreibe hier mit Lust am dritten Teil des Moses. Eben vor einer halben Stunde hat mir die Post einen Brief eines jungen jüdischen Amerikaners gebracht, in dem ich gebeten werde, den armen unglücklichen Volksgenossen nicht den einzigen Trost zu rauben, der ihnen im Elend geblieben ist. Der Brief war nett und wohlmeinend, aber welche Überschätzung! Soll man wirklich glauben, daß meine trockene Abhandlung auch nur einem durch Heredität und Erziehung Gläubigen, selbst wenn sie ihn erreicht, den Glauben stören wird?“[8] |

執筆の発端に関するフロイトの発言 フロイトは長い間、自分の研究の現状に大きな不満を持っていた。アーノルド・ツヴァイクとの往復書簡の中で、彼は何箇所かでこのことに言及している。 1934年9月30日、彼は初めてこの新しい文章に言及した。「比較的休暇の多い時期、余った余暇をどうしたらいいか困惑して、私は自分で何かを書いた。 今さら喜んでも仕方がない。きっと読む気にはならないだろうから。しかし、どうしてこのようなことが起こるのか説明しよう[......]」。 「ドイツにおけるナチスによるユダヤ人への)新たな迫害を前にして、ユダヤ人はどうなってしまったのか、なぜこのような永遠の憎悪を抱くようになったの か、あらためて不思議に思う。私はすぐにこう考えた。モーゼがユダヤ人を創り、私の作品に歴史小説『モーゼの男』というタイトルが与えられた。 「この作品は3つのセクションに分かれており、1つ目は小説として面白く、2つ目は退屈で長く、3つ目は実質的で厳しいものであった。それは『トーテム』 と『タブー』の後の私にとっては目新しいものではなく、むしろ見知らぬ人々にとっては新しく根本的なものであった」[2]。 フロイトは次に、なぜこの文章をこの時期に発表したくないのかについて説明する。当時のオーストリアの「カトリック正統主義」において、彼はこのキリスト 教への「攻撃」によって、ウィーンで精神分析の実践が禁止され、精神分析医が全員失業することを恐れた。 「そしてこの背景には、私の仕事がそれほど安全とも思えず、それほど喜ばしいものでもないという事実がある。だから、これは殉教のための適切な機会ではな い。今はもう十分だ!」[3]。 ツヴァイクはフロイトに、この文章をエルサレムで「内部関係者」だけのために小さな私家版として出版することを提案したが、フロイトは同意しなかった。 1934年12月16日、フロイトはこう書いた。何かを創り出そうというこのおそらく最後の試みが失敗したという事実は、私を十分に落ち込ませた。そこか ら逃げたわけではない。モーゼという男、そして私がモーゼを作りたかったものが、絶えず私を悩ませている。しかし、それはうまくいかない。外的な危険と内 的な不安が、この試みに他の結果を許さないのだ」[4]。 1935年2月13日、彼は当時ハイファに住んでいたアーノルド・ツヴァイクに手紙を書いた。もしあなたがまたウィーンに来ることがあれば、私の判断を確 かめるために、安置されているこの原稿を読むことを歓迎します」[5]。 ツヴァイクは、イスラエルからフロイトに、モーセというテーマについて彼を助けるかもしれないいくつかの本について知らせた。それに対して、フロイトは 1935年3月14日にこう書いている。私の歴史的構築の弱さについての私の判断が裏付けられた。あとは本当に沈黙だ」[6]。 そんなフロイトに、思いがけない考古学的発見がもたらされた。1935年5月2日、彼はツヴァイクにこう書いた。「まだ半分も発掘されていないテル・エ ル・アマルナに関する報告書の中で、それ以外何も知られていないトトメス王子に関する記述を読んだ。もし私が大金持ちだったら、発掘を続ける資金を提供す るだろう。このトットメスは私のモーゼかもしれず、私は彼を推理したと自慢したい」[7]。 1938年にフロイトがロンドンに移ってからは、モーゼの本に関するコメントのトーンが変わった。彼はもはやウィーンの事情を考慮する必要がなくなり、最 後の本の出版についてよりリラックスしていた。1938年6月28日、彼はロンドンからツヴァイクにこう書いている。30分前、郵便がユダヤ系アメリカ人 の若者から手紙を運んできた。哀れな不幸な人々から、その悲惨さの中で残された唯一の慰めを奪わないでほしいというものだった。その手紙は親切で善意によ るものだったが、なんという過大評価だろう!私の乾いた論説が、たとえ彼に届いたとしても、遺伝と教育によって一人の信者の信仰さえも乱すと、本当に信じ られるだろうか」[8]。 |

| Rezeption Freuds 'historischer Roman' vermochte lange Zeit wenig zu überzeugen. In der neueren, wesentlich von der Studie von Yerushalmi und Derridas Auseinandersetzung mit ihr angestoßenen Diskussion werden Freuds Verdienste um das Verständnis von Tradition und kulturellem Gedächtnis gewürdigt. Bernstein hat die Moses-Studie als die Antwort auf eine Frage gedeutet, die sich Freud 1930 in seinem Vorwort zu der hebräischen Ausgabe von Totem und Tabu selbst gestellt hatte: "Fragte man ihn [den Autor von Totem und Tabu, also Freud selbst] Was ist an dir noch jüdisch, wenn du all diese Gemeinsamkeiten mit deinen Volksgenossen aufgegeben hast? so würde er antworten: Noch sehr viel, wahrscheinlich die Hauptsache. Aber dieses Wesentliche könnte er gegenwärtig nicht in klare Worte fassen. Es wird sicherlich später einmal wissenschaftlicher Einsicht zugänglich sein."[9] Freuds Werk motivierte Jan Assmann zu seinem Werk Moses der Ägypter, das den Grundstein zu einer Debatte über die Zusammenhänge von Monotheismus und Gewalt legte. Der Politikwissenschaftler Paul Roazen hält "Freuds Beharren auf eine bestimmte historische Rekonstruktion" dafür verantwortlich, dass sein letztes Werk in seiner enormen Bedeutung für das politische Denken und die Methodologie der Geschichtsschreibung nicht ausreichend gewürdigt werde. Roazen schreibt hierzu: "Die Möglichkeiten, die Psychoanalyse derart auf die Geschichte anzuwenden, werden bei jedem größeren Versuch, die Geschichte eines Volkes zu verstehen, erkennbar; indem wir die Vergangenheit verstehen, indem wir uns die verschiedenen Kräfte bewusst machen, deren Bedeutung vernachlässigt wurde, kann Geschichte überwunden, die Vergangenheit gemeistert, Wiederholung vermieden werden."[10] |

レセプション 長い間、フロイトの「歴史小説」はあまり説得力のあるものではなかった。最近の議論では、主にイェルシャルミの研究とそれに関するデリダの議論に端を発 し、伝統と文化的記憶の理解に対するフロイトの貢献が認められている。バーンスタインは、モーゼの研究を、フロイトが1930年に『トーテムとタブー』の ヘブライ語版への序文で自らに問いかけた質問に対する答えと解釈している: おそらく、それが主なものだろう。しかし、現時点では、この本質を明確な言葉にすることはできないだろう。それは後に必ず科学的洞察にアクセスできるよう になるだろう」[9]。 フロイトの研究は、ヤン・アスマンに『エジプト人のモーゼ』を書かせ、一神教と暴力のつながりに関する議論の基礎を築いた。 政治学者のポール・ロアゼンは、「フロイトが特定の歴史的再構成に固執した」ことが、彼の遺作が政治思想や歴史学の方法論にとって非常に重要であるにもか かわらず、十分に認識されていない原因であると考えている。このように精神分析を歴史に応用することの可能性は、ある民族の歴史を理解しようとするあらゆ る主要な試みにおいて明らかになる。過去を理解することによって、その重要性が無視されてきた様々な力に気づくことによって、歴史は克服され、過去は習得 され、繰り返しは回避される」[10]。 |

| Ausgaben Erstausgabe: Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion. Drei Abhandlungen. De Lange, Amsterdam 1939. Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-26300-X. Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion. Hrsg. Assmann, Jan. Reclam, ISBN 978-3-15-018721-0. |

エディション 初版:モーセという男と一神教。3つの論考。De Lange, Amsterdam 1939. The man Moses and the monotheistic religion, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main, 1999, ISBN 3-596-26300-X. モーセという人間と一神教, Fiscfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-26300X. Assmann, Jan Reclam 編, ISBN 978-3-15-018721-0. |

| Sekundärliteratur Jan Assmann: Moses der Ägypter: Entzifferung einer Gedächtnisspur. Fischer, Frankfurt 2004. Jan Assmann: Freuds Konstruktion des Judentums. In: Zs. Psyche, Februar 2002. Richard J. Bernstein: Freud und das Vermächtnis des Moses. Philo, Wien 2003. Jacques Derrida: Dem Archiv verschrieben. Eine Freudsche Impression. Brinkmann und Bose, Berlin 1997. Ilse Grubrich-Simitis: Freuds Moses-Studie als Tagtraum. Ein biographischer Essay. Fischer, Frankfurt 1994. Wolfgang Hegener: Wege aus der vaterlosen Psychoanalyse. Vier Abhandlungen über Freuds „Mann Moses“. Edition diskord, Tübingen 2001. Eveline List (Hrsg.): Der Mann Moses und die Stimme des Intellekts. Geschichte, Gesetz und Denken in Sigmund Freuds historischem Roman. Studienverlag, Innsbruck-Wien-Bozen 2007. Franz Maciejewski: Der Moses des Sigmund Freud. Ein unheimlicher Bruder. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-45374-4. Peter Schäfer: Der Triumph der reinen Geistigkeit. Sigmund Freuds "Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion". Philo, Wien 2003. Thomas Schmidinger: Moses, der Antisemitismus und die Wiederkehr des Verdrängten. In: Transversal. Zeitschrift für jüdische Studien. 13. Jg., H. 2, Studienverlag, Graz 2012 ISSN 1607-629X S. 101–130. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi: Freuds Moses. Endliches und unendliches Judentum. Wagenbach, Berlin 1992. |

二次文献 Jan Assmann: Moses der Ägypter: Entzifferung einer Gedächtnisspur. Fischer, Frankfurt 2004. Jan Assmann: Freud's construction of Judaism. Zs. Psyche, February 2002. リチャード・J・バーンスタイン:フロイトとモーセの遺産。Philo, Vienna 2003. ジャック・デリダ:アーカイブに捧げる。フロイト的印象。Brinkmann and Bose, Berlin 1997. Ilse Grubrich-Simitis: 白昼夢としてのフロイトのモーゼ研究。伝記的エッセイ。Fischer, Frankfurt 1994. ヴォルフガング・ヘゲナー:父親のいない精神分析からの脱出。フロイトの「人間モーゼ」に関する4つのエッセイ。Edition diskord, Tübingen 2001. エヴリーネ・リスト編:『モーセの男』と知性の声。ジークムント・フロイトの歴史小説における歴史、法、思想。Studienverlag, Innsbruck-Vienna-Bolzano 2007. フランツ・マチェイェフスキ:ジークムント・フロイトのモーゼ。不気味な兄弟。Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-45374-4. ペーター・シェーファー:純粋霊性の勝利。ジークムント・フロイトの『モーゼという人間と一神教』。Philo, Vienna 2003. Thomas Schmidinger: モーゼ、反ユダヤ主義、抑圧されたものの回帰。In: Transversal. ユダヤ研究ジャーナル。13. vol. 2, Studienverlag, Graz 2012 ISSN 1607-629X pp. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi: Freud's Moses. Finite and infinite Judaism. Wagenbach, Berlin 1992. |

| Der

Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion |

モーセと一神教(ドイツ語テキスト) |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Der_Mann_Moses_und_die_monotheistische_Religion |

****

| On Sigmund Freud Sigmund Freud (/frɔɪd/ FROYD;[3] German: [ˈziːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt]; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst....In the Freuds' new home, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, North London, Freud's Vienna consulting room was recreated in faithful detail. He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness. He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and in English the following year[112] and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis which was published posthumously.... Moses and Monotheism (1937) proposes that Moses was the tribal pater familias, killed by the Jews, who psychologically coped with the patricide with a reaction formation conducive to their establishing monotheist Judaism;[180] analogously, he described the Roman Catholic rite of Holy Communion as cultural evidence of the killing and devouring of the sacred father.[112][181]... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund_Freud |

フロイトさんのこと 彼はオーストリアの神経科医で、精神分析の創始者である。精神分析の創 始者とは、患者と精神分析医との対話を通して精神病理学を治療する臨床手法の創始者である。彼は病気の末期まで、そこで患者を診察し続けた。また、 1938年にドイツ語で、翌年には英語で出版された『モーセと一神教』[112]と、死後に出版された未完の『精神分析概論』の執筆にも取り組んだ。 モーセと一神教』(1937年)は、モーセはユダヤ人によって殺された部族の父なる家族であり、彼らは一神教のユダヤ教を確立するのに資する反応形成に よって心理的に父殺しに対処したと提唱している[180]。同様に、彼はローマ・カトリックの聖体拝領の儀式を、聖なる父の殺害と貪食の文化的証拠である と述べている。 |

| Moses

and Monotheism Moses and Monotheism (German: Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion, lit. 'The man Moses and the monotheist religion') is a 1939 book about the origins of monotheism written by Sigmund Freud,[1] the founder of psychoanalysis. It is Freud's final original work and it was completed in the summer of 1939 when Freud was, effectively speaking, already "writing from his death-bed."[2][3] It appeared in English translation the same year. Moses and Monotheism shocked many of its readers because of Freud's suggestion that Moses was actually born into an Egyptian household, rather than being born as a Hebrew slave and merely raised in the Egyptian royal household as a ward (as recounted in the Book of Exodus).[4][5] Freud proposed that Moses had been a priest of Akhenaten who fled Egypt after the pharaoh's death and perpetuated monotheism through a different religion,[6] and that he was murdered by his followers, who then via reaction formation revered him and became irrevocably committed to the monotheistic idea he represented.[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_and_Monotheism |

『モー

セと一神教』 『モー セと一神教』(ドイツ語: Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion、英語: Moses and Monotheism)は、精神分析の創始者ジークムント・フロイト[1]が一神教の起源について書いた1939年の著書である。 ドイツ語:Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion)は、精神分析の創始者ジークムント・フロイト[1]が一神教の起源について書いた1939年の著書である。フロイトの最後の原著であ り、1939年の夏に完成した。事実上、フロイトはすでに「死の床から書いていた」[2][3]。 モーセと一神教』は、モーセはヘブライ人の奴隷として生まれ、(『出エジプト記』に記されているように)エジプト王家の被後見人として育てられただけでな く、実際にはエジプトの家庭に生まれたというフロイトの示唆から、多くの読者に衝撃を与えた。 [4][5]フロイトは、モーセはアクエンアテンの祭司であり、ファラオの死後にエジプトを逃れ、別の宗教を通して一神教を永続させた[6]。 |

| Synopsys The book consists of three essays and is an extension of Freud's work on psychoanalytic theory as a means of generating hypotheses about historical events, in combination with his obsessive fascination with Egyptological scholarship and antiquities.[5][6] Freud hypothesizes that Moses was not Hebrew, but actually born into Ancient Egyptian nobility and was probably a follower of Akhenaten, "the world's earliest recorded monotheist."[7] The biblical story of Moses is reinterpreted by Freud in light of new findings at Tel-El-Amarna. Archaeological evidence of the Amarna Heresy, Akhenaten's monotheistic Aten cult, had only been discovered in 1887 and the interpretation of that evidence was still in an early phase.[8] Freud's monograph on the subject, for all the controversy that it ultimately provoked, was one the first popular accounts of these findings.[5] In Freud's retelling of the events, Moses led only his close followers into freedom (during an unstable period in Egyptian history after Akhenaten's death ca. 1350 BCE), that they subsequently killed the Egyptian Moses in rebellion, and still later joined with another monotheistic tribe in Midian who worshipped a volcano god called Yahweh.[1][9] Freud supposed that the monotheistic solar god of the Egyptian Moses was fused with Yahweh (the Midianite volcano god), and that the deeds of Moses were ascribed to a Midianite priest who also came to be called Moses.[10] Moses, in other words, is a composite figure, from whose biography the uprising and murder of the original Egyptian Amarna-cult priest has been excised.[1] Freud explains that centuries after the murder of the Egyptian Moses, the rebels regretted their action, thus forming the concept of the Messiah as a hope for the return of Moses as the Saviour of the Israelites. Freud claimed that repressed (or censored) collective guilt stemming from the murder of Moses was passed down through the generations; leading the Jews to neurotic expressions of legalistically religious sentiment to disperse or cope with their inheritance of trauma and guilt. In many respects, the book reiterates the theogony that Freud first argued in Totem and Taboo,[11] as Freud acknowledges in the text of Moses & Monotheism on several occasions. For example, he writes: “[This] conviction I acquired when I wrote my book on Totem and Taboo (1912), and it has only become stronger since. From then on, I have never doubted that religious phenomena are to be understood only on the model of the neurotic symptoms of the individual, which are so familiar to us, as a return of long forgotten important happenings in the primeval history of the human family, that they owe their obsessive character to that very origin and therefore derive their effect on mankind from the historical truth that they contain."[1]" |

あらすじ(シノプス) この本は 3 つのエッセイで構成されており、歴史的出来事に関する仮説を生み出す手段として、精神分析理論に関するフロイトの研究を、エジプト学や古代遺物に対する彼 の強迫的な興味と組み合わせたものである。 フロイトは、モーゼはヘブライ人ではなく、実際には古代エジプトの貴族の家に生まれ、おそらく「世界で最も古い記録に残る一神教の信者」であるアメンヘテ プ3世の信者だったのではないかと仮説を立てている。モーゼの聖書の物語は、テル・エル・アマルナで新たに発見された事実に基づいて、フロイトによって再 解釈された。アマルナ異端、アケナテンの一神教アテン教の考古学的証拠は、1887年に発見されたばかりで、その証拠の解釈はまだ初期段階にあった。フロ イトがこのテーマについて書いた単行本は、最終的に多くの論争を巻き起こしたが、これらの発見に関する最初の一般向け解説の1つであった。フロイトが再構 成した物語によると、モーゼは(紀元前1350年頃、アメンヘテプ3世の死後、エジプトの歴史上不安定な時代)彼の側近だけを自由へと導いたが、その後、 彼らはエジプトのモーゼを反逆罪で殺害し、さらに後になって、ヤハウェと呼ばれる火山神を崇拝するミディアンの一神教の部族に加わった。 フロイトは、エジプトのモーゼの太陽神一神教がヤハウェ(ミディアンの火山神)と融合し、モーゼの偉業はモーゼとも呼ばれるようになったミディアンの司祭 に帰せられたと推測した。つまり、モーゼは合成された人物であり、その伝記から、エジプトのアマルナ教司祭の反乱と殺害の記述が削除されたのである。フロ イトは、エジプトのモーゼが殺害されてから何世紀も経った後、反乱軍が自分たちの行為を後悔し、イスラエル民族の救世主としてモーゼが戻ってくることを期 待する救世主という概念が生まれたと説明している。フロイトは、モーゼ殺害に端を発する抑圧された(あるいは検閲された)集団的罪悪感が世代を超えて受け 継がれ、ユダヤ人が法的に宗教的な感情を神経質に表現することで、トラウマや罪悪感を受け継いだことを払拭したり、対処したりしていると主張した。 多くの点において、この本は『トーテムとタブー』で初めて主張された神話生成説を繰り返し述べている。 例えば、彼は次のように書いている。「この確信は、『トーテムとタブー』(1912年)を執筆したときに得たものであり、それ以来さらに強くなっている。 それ以来、私は宗教的現象を理解するには、私たちにとって馴染み深い個人の神経症的症状のモデルに当てはめるしかない、と疑ったことは一度もない。それ は、人類家族の太古の歴史において、長い間忘れ去られていた重要な出来事が蘇ったものとして理解すべきであり、その強迫的な性格はまさにその起源に由来 し、それゆえ、それらが内包する歴史的事実から人類への影響が生じるのである。。 +++++++++ 日本語のシノプシス:ヨセフ・ハイーム・イェルシャ ルミ(Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, 1932-2009)による(小森謙一郎訳) |

| Summary Further information: Sigmund Freud's views on religion, Origins of Judaism, The Exodus, and Yahwism The book consists of three essays and is an extension of Freud's work on psychoanalytic theory as a means of generating hypotheses about historical events, in combination with his obsessive fascination with Egyptological scholarship, archaeology, and antiquities.[7][8] Freud hypothesizes that Moses was not Hebrew, but actually born into Ancient Egyptian nobility and was probably a follower of Akhenaten, "the world's earliest recorded monotheist."[9] The biblical account of Moses is reinterpreted by Freud in light of new findings at Tel-El-Amarna. Archaeological evidence of the Amarna Heresy, Akhenaten's monotheistic worship of the Ancient Egyptian solar god Aten, had only been discovered in 1887 and the interpretation of that evidence was still in an early phase.[10] Freud's monograph on the subject, for all the controversy that it ultimately provoked, was one of the first popular accounts of these findings.[7] In Freud's retelling of the events, Moses led only his close followers into freedom (during an unstable period in Ancient Egyptian history after Akhenaten's death ca. 1350 BCE), that they subsequently killed the Egyptian Moses in rebellion, and still later joined with another monotheistic tribe in Midian who worshipped a volcano god called Yahweh.[4][11] Freud supposed that the monotheistic solar god Aten of the Egyptian Moses was fused with Yahweh, the Midianite volcano god, and that the deeds of Moses were ascribed to a Midianite priest who also came to be called Moses.[12] Moses, in other words, is a composite figure, from whose biography the uprising and murder of the original Egyptian Amarna-cult priest has been excised.[4] Freud explains that centuries after the murder of the Egyptian Moses, the rebels regretted their action, thus forming the concept of the Messiah as a hope for the return of Moses as the Saviour of the Israelites. Freud claimed that repressed (or censored) collective guilt stemming from the murder of Moses was passed down through the generations; leading the Jews to neurotic expressions of legalistically religious sentiment to disperse or cope with their inheritance of trauma and guilt. In many respects, the book reiterates the theogony that Freud first argued in Totem and Taboo,[13] as Freud acknowledges in the text of Moses & Monotheism on several occasions. For example, he writes: "[This] conviction I acquired when I wrote my book on Totem and Taboo (1912), and it has only become stronger since. From then on, I have never doubted that religious phenomena are to be understood only on the model of the neurotic symptoms of the individual, which are so familiar to us, as a return of long forgotten important happenings in the primeval history of the human family, that they owe their obsessive character to that very origin and therefore derive their effect on mankind from the historical truth that they contain."[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_and_Monotheism |

概要(サマリー) さらに詳しい情報 ジークムント・フロイトの宗教観、ユダヤ教の起源、出エジプト記、ヤハウィズム フロイトは、モーセはヘブライ人ではなく、実際には古代エジプトの貴族の生まれであり、おそらく「世界で最も早く記録された一神教徒」であるアクエンアテ ンの従者であったという仮説を立てた[7][8]。 聖書のモーセに関する記述は、テル=エル=アマルナでの新たな発見を踏まえてフロイトによって再解釈された。古代エジプトの太陽神アテンに対するアクエン アテンの一神教崇拝であるアマルナ異端の考古学的証拠は、1887年に発見されたばかりであり、その解釈はまだ初期段階にあった[10]。 フロイトの再話では、モーセは(紀元前1350年頃のアクエンアテンの死後の古代エジプト史における不安定な時期に)彼の親しい従者たちだけを自由へと導 き、彼らはその後反乱を起こしてエジプトのモーセを殺し、さらにその後、ヤハウェと呼ばれる火山の神を崇拝するミディアンの別の一神教の部族と合流した。 [4][11]フロイトは、エジプトのモーセの一神教的な太陽神アテンが、ミディアンの火山神ヤハウェと融合し、モーセの行いが、同じくモーセと呼ばれる ようになったミディアンの祭司に帰属すると仮定した[12]。言い換えれば、モーセは複合的な人物であり、その伝記からは、オリジナルのエジプトのアマル ナ教祭司の反乱と殺害は除外されている[4]。 フロイトは、エジプトのモーセが殺害された数世紀後、反乱者たちは自分たちの行為を後悔し、その結果、イスラエル人の救世主としてのモーセの復活を願うメ シアの概念が形成されたと説明している。フロイトは、モーセ殺害に由来する抑圧された(あるいは検閲された)集団的罪悪感が世代を超えて受け継がれ、ユダ ヤ人がトラウマと罪悪感の継承を分散させたり対処したりするために、律法主義的な宗教的感情を神経症的に表現するようになったと主張した。フロイトが 『モーセと一神教』の本文中で何度か認めているように、多くの点で、本書はフロイトが『トーテムとタブー』[13]で最初に主張した神義論を繰り返してい る。例えば、彼はこう書いている: この確信は)『トーテムとタブー』(1912年)を書いたときに得たものであり、それ以来ますます強くなっている。それ以来、私は宗教的現象は個人の神経 症的症状をモデルとしてのみ理解されるべきであり、それは人類一族の原始の歴史において長い間忘れられていた重要な出来事の再来として、私たちにとって非 常に馴染み深いものであり、その強迫的な性格はまさにその起源に負っており、それゆえ、それが含む歴史的真実から人類に影響を与えるのだと信じて疑わな い」[4]。 |

| Reception According to the historian of religion Kimberly B. Stratton, in Moses and Monotheism Freud "posits a primal act of murder as the origin of religion, and specifically ties the memory (and repression) of it to the exodus story and birth of biblical monotheism".[1] The mythologist Joseph Campbell wrote that Freud's suggestion that Moses was an Egyptian "delivered a shock to many of his admirers". According to Campbell, Freud's proposal was widely attacked, "both with learning and without." Campbell himself refrained from passing judgment on Freud's views about Moses, although he considered Freud's willingness to publish his work despite its potential offensiveness "noble".[14] The philosopher Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen and the psychologist Sonu Shamdasani argued that in Moses and Monotheism Freud applied to history "the same method of interpretation that he used in the privacy of his office to 'reconstruct' his patients' forgotten and repressed memories."[15] The Anglican theologian Rowan Williams stated that Freud's accounts of the origins of Judaism are "painfully absurd", and that Freud's explanations are not scientific but rather "imaginative frameworks".[16] Biblical scholar Richard Elliot Friedman wrote that it "is remarkably insightful and of enormous instructive value even if Freud was mistaken on individual points — as he was perfectly willing to acknowledge."[17] Biblical archaeologist William Foxwell Albright dismissed Freud's book by stating that it "is totally devoid of serious historical method and deals with historical data even more cavalierly than with the data of instrospective and experimental psychology".[18] More recently, Israeli archaeologist Aren Maier was also critical toward Freud's work and called his analysis "simplistic and largely incorrect", while Egyptologist Brian Murray Fagan stated that it "had no basis in historical fact".[19] Egyptologist Donald Bruce Redford wrote in 2015: Before much of the archaeological evidence from Thebes and from Tell el-Amarna became available, wishful thinking sometimes turned Akhenaten into a humane teacher of the true God, a mentor of Moses, a christlike figure, a philosopher before his time. But these imaginary creatures are now fading away as the historical reality gradually emerges. There is little or no evidence to support the notion that Akhenaten was a progenitor of the full-blown monotheism that we find in the Bible.[20] Joseph and His Brothers, novel by Thomas Mann The Egyptian, novel by Mika Waltari https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_and_Monotheism |

受容 宗教史家のキンバリー・B・ストラットンによれば、『モーゼと一神教』の中でフロイトは「宗教の起源として原始的な殺人行為を仮定し、その記憶(と抑圧) を特に出エジプトの物語と聖書の一神教の誕生に結びつけている」[1]。神話学者のジョセフ・キャンベルは、モーゼがエジプト人であったというフロイトの 提案は「彼の崇拝者の多くに衝撃を与えた」と書いている。キャンベルによれば、フロイトの提案は「学問のあるなしにかかわらず」広く攻撃されたという。 キャンベル自身は、モーセに関するフロイトの見解について判断を下すことを控えたが、彼は、その潜在的な不快感にもかかわらず、フロイトが自分の著作を出 版しようとしたことを「高貴」だと考えていた[14]。 哲学者のミケル・ボルヒ=ヤコブセンと心理学者のソヌ・シャムダサニは、『モーセと一神教』においてフロイトは、「患者の忘れられた抑圧された記憶を『再 構築』するために、自分のオフィスのプライバシーで用いたのと同じ解釈の方法」を歴史に適用したと主張した[15]。 聖書学者であるリチャード・エリオット・フリードマンは、「たとえフロイトが個々の点で間違いを犯していたとしても、彼が完全に認めることを厭わなかった ように、この本は驚くほど洞察に富んでおり、非常に有益な価値がある」と書いている[17]。 聖書考古学者のウィリアム・フォックスウェル・オルブライトは、フロイトの著書について「まともな歴史的手法がまったくなく、歴史的データを内省的・実験 的な心理学のデータ以上に軽率に扱っている」と断じた[18]。 最近では、イスラエルの考古学者アレン・マイヤーもフロイトの著作に批判的で、彼の分析を「単純化されており、大部分が間違っている」とし、エジプト学者 のブライアン・マーレー・フェイガンは「歴史的事実に根拠がない」と述べた[19]: テーベとテル・エル・アマルナの考古学的証拠の多くが入手可能になる前は、希望的観測によってアケナテンは真の神の人道的な教師、モーゼの指導者、キリス トのような人物、時代以前の哲学者に仕立て上げられることがあった。しかし、こうした想像上の生き物は、歴史的現実が徐々に明らかになるにつれて、今や消 え去りつつある。アクエンアテンが聖書に見られるような本格的な一神教の始祖であったという考えを裏付ける証拠はほとんどない[20]。 |

Monotheism is the belief that one god is the only deity.[1][2][3][4][5] A distinction may be made between exclusive monotheism, in which the one God is a singular existence, and both inclusive and pluriform monotheism, in which multiple gods or godly forms are recognized, but each are postulated as extensions of the same God.[2] Monotheism is distinguished from henotheism, a religious system in which the believer worships one god without denying that others may worship different gods with equal validity, and monolatrism, the recognition of the existence of many gods but with the consistent worship of only one deity.[6] The term monolatry was perhaps first used by Julius Wellhausen.[7] The prophets of ancient Israel were the first to teach Monotheism[dubious – discuss], establishing it as a foundational tenet of the Jewish religious tradition, which endures as one of its most profound and enduring legacies.[8][9] Monotheism characterizes the traditions of Zoroastrianism,[10] Bábism, the Baháʼí Faith, Christianity,[11] Deism, Druzism,[12] Eckankar, Sikhism, Manichaeism, Islam, Judaism, Samaritanism, Mandaeism, Rastafari, Seicho-no-Ie, Tenrikyo, Yazidism, and Atenism. Elements of monotheistic thought are found in early religions such as ancient Chinese religion, Tengrism, and Yahwism.[2][13][14] |

一神教とは? 一神教とは、唯一神を唯一の神と信じる信仰である[1][2][3][4][5]。一神教には、唯一神が唯一の存在である排他的一神教と、複数の神や神格 が認められる包括的一神教と多神教があり、それぞれは同じ神の延長として想定されている[2]。 一神教は、信者が崇拝する神が唯一であるという宗教体系であるヘノテイスムと区別される。他の神々を崇拝することも同様に正当であると否定することなく、 1人の神のみを崇拝する宗教体系であるヘノテイスム(Henotheism)や、多くの神々の存在を認めるが、常に1人の神のみを崇拝する一神教 (Monolatry)と区別される[6]。 一神教を最初に説いたのは、おそらくユリウス・ヴェッルハウゼン(Julius Wellhausen)である[7]。古代イスラエルの預言者たちは、一神教を初めて説き[疑わしい – 議論する]、ユダヤ教の宗教的伝統の根本的な教義として確立した。これは、最も深遠で永続的なものの1つとして今もなお受け継がれている。遺産である。 [8][9] 一神教は、ゾロアスター教、[10]バビ教、バハイ教、キリスト教、[11]自然神教、ドルーズ派、[12]エックナンカル、シーク教、マニ教、イスラム 教、ユダヤ教、サマリア教、マンダ教、ラスタファリ、生長の家、天理教、ヤジディ教、アテニズムなどの伝統の特徴である。一神教の思想の要素は、古代中国 の宗教、テングリズム、ヤハウィズムなどの初期の宗教に見られる[2][13][14]。 |

| Julius

Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) Julius Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist. In the course of his career, his research interest moved from Old Testament research through Islamic studies to New Testament scholarship. Wellhausen contributed to the composition history of the Pentateuch/Torah and studied the formative period of Islam. For the former, he is credited as one of the originators of the documentary hypothesis.[1][2][3] Biography Wellhausen was born at Hamelin in the Kingdom of Hanover. The son of a Protestant pastor,[4] he later studied theology at the University of Göttingen under Georg Heinrich August Ewald and became Privatdozent for Old Testament history there in 1870. In 1872, he was appointed professor ordinarius of theology at the University of Greifswald. However, he resigned from the faculty in 1882 for reasons of conscience, stating in his letter of resignation: I became a theologian because the scientific treatment of the Bible interested me; only gradually did I come to understand that a professor of theology also has the practical task of preparing the students for service in the Protestant Church, and that I am not adequate to this practical task, but that instead despite all caution on my own part I make my hearers unfit for their office. Since then my theological professorship has been weighing heavily on my conscience.[5][6] He became professor extraordinarius of oriental languages in the faculty of philology at Halle, was elected professor ordinarius at Marburg in 1885 and was transferred to Göttingen in 1892, where he stayed until his death. Among theologians and biblical scholars, he is best known for his book, Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (Prolegomena to the History of Israel); his work in Arabic studies (specifically, the magisterial work entitled The Arab Kingdom and its Fall) remains celebrated, as well.[7] After a detailed synthesis of existing views on the origins of the first five books of the Bible, Wellhausen aimed at placing the development of these books into a historical and social context.[8][9] The resulting argument, called the documentary hypothesis, became the dominant model for many biblical scholars and remained so for most of the 20th century. According to Alan Levenson, Wellhausen considered theological anti-Judaism, as well as antisemitism, to be normative.[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Wellhausen |

ユリウス・ヴェーハウゼン(Julius

Wellhausen、1844年5月17日 - 1918年1月7日) ユリウス・ヴェーハウゼン(Julius Wellhausen、1844年5月17日 - 1918年1月7日)は、ドイツの聖書学者、東洋学者である。 彼の研究関心は、旧約聖書研究からイスラム研究、そして新約聖書学へと移っていった。 ヴェーハウゼンは、五書/トーラーの成立史に貢献し、イスラム教の形成期を研究した。前者については、彼は「文書説」の創始者の一人として評価されている [1][2][3]。 経歴 ウェルハウゼンは、ハノーファー王国のハーメルンで生まれた。プロテスタントの牧師の息子[4]であった彼は、後にゲオルク・ハインリヒ・アウグスト・エ ヴァルトの下でゲッティンゲン大学で神学を学び、1870年に旧約聖書史の講師となった。1872年、グライフスヴァルト大学で神学部の正教授に任命され た。しかし、良心の呵責から1882年に辞職し、辞表にこう記した。 私は聖書の科学的解釈に興味を抱き神学者になったが、神学教授にはプロテスタント教会で奉仕する学生を育成するという実践的な任務もあることを徐々に理解 するようになった。そして、私はこの実践的な任務には適しておらず、むしろ私が細心の注意を払っても、私の講義を聴く学生がその職務にふさわしくない人間 にしてしまうことに気づいた。それ以来、神学教授としての職責は私の良心に重くのしかかっている[5][6]。 彼はハレの文献学部の東洋言語の臨時教授となり、1885年にマールブルクで正教授に選出された。1892年にはゲッティンゲンに転任し、亡くなるまでそ こに留まった。 神学者や聖書学者の中では、彼の著書『イスラエル史序説』(Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels)で最もよく知られている。また、アラビア研究(特に『アラブ王国とその滅亡』という権威ある著作)でも高い評価を得ている。聖書の最初の 5つの書の起源に関する既存の考え方を詳細に統合した後、ウェルハウゼンはこれらの書の発展を歴史的および社会的文脈に位置づけることを目指した[8] [9]。その結果として生まれた議論は「文書説」と呼ばれ、多くの聖書学者にとって支配的なモデルとなり、20世紀の大半にわたってその地位を維持した。 アラン・レベンソンによると、ウェルハウゼンは神学的反ユダヤ主義を、反ユダヤ主義と同様に規範的であると考えていた[10]。 |

| Prolegomena zur Geschichte

Israels and documentary hypothesis Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels and Documentary hypothesis Wellhausen was famous for his critical investigations into Old Testament history and the composition of the Hexateuch. He is perhaps best known for his Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (1883, first published in 1878 as Geschichte Israels) in which he advanced a definitive formulation of the documentary hypothesis. It argues that the Torah had its origins in a redaction of four originally-independent texts dating from several centuries after the time of Moses, their traditional author. Wellhausen's hypothesis remained the dominant model for Pentateuchal studies until the last quarter of the 20th century, when it began to be advanced by other biblical scholars who saw more and more hands at work in the Torah and ascribed them to periods even later than Wellhausen had proposed. The emergence of conflicting answers which, by statistics, display certain similarities is better known empirically as 'spurious results'. Regarding his sources, Wellhausen described Wilhelm de Wette as "the epoch-making opener of the historical criticism of the Pentateuch." In 1806, De Wette provided an early, coherent mapping of the Old Testament writings of the J, E, D, and P, authors. He was so far ahead of his time, however, that he was soon cast out of his university post. Young Julius Wellhausen largely continued the work of de Wette, and transformed those studies into historical monuments. |

『イスラエル史序説』と「文書説」 ウェルハウゼンは、旧約聖書の歴史と「六書」の構成に関する批判的な調査で有名であった。彼はおそらく、『イスラエル史序説』(1883年、1878年に 『Geschichte Israels』として初版)で最もよく知られている。この本の中で、彼は「文書説」の決定的な定式化を提示した。この仮説は、モーセの時代から数世紀後 に書かれた、もともと独立した4つのテキストを編集したものがトーラー(律法)の起源であると主張している。 ウェルハウゼンの仮説は、20世紀最後の四半期まで、五書研究における支配的なモデルであり続けた。その後、トーラーにはさらに多くの手が加えられてお り、ウェルハウゼンが提案したよりもさらに後の時代にまでさかのぼると考える他の聖書学者たちによって、この仮説が支持されるようになった。統計的に見る と、ある種の類似性が見られる相反する答えの出現は、経験的に「偽りの結果」としてよりよく知られている。 ウェルハウゼンは、自身の情報源について、ヴィルヘルム・デ・ヴェッテを「五書の歴史的批評の画期的な先駆者」と評した。1806年、デ・ヴェッテは、 J、E、D、Pの著者による旧約聖書の記述の初期の一貫したマッピングを提供した。しかし、彼は時代を先取りしすぎたため、すぐに大学を追放されてしまっ た。若きユリウス・ヴェーレンハウゼンは、デ・ヴェッテの仕事をほぼ引き継ぎ、それらの研究を歴史的な業績へと変貌させた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_and_Monotheism |

●日本語のシノプシス:ヨセフ・ハイーム・イェルシャ ルミ(Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, 1932-2009)による(小森謙一郎訳)

「一神教はユダヤ起源ではなく、エジプトで見出され

た。アメンホテプ四世は、ここから太陽の力——あるい

はアトン——をもっぱら崇拝対象とする国家宗教を確立し、これにちなんでみずからイクナートンと改名し

た。フロイトによれば、アトン教の特徴は唯一神への排他的信仰にあり、そこでは擬人観や呪術や魔法は

否され、死後の生も完全に否定されていた。しかしながら、イクナートンの死後、彼の偉大なる異端信仰は

急速に取り消され、エジプト人はかつての神々へと戻っていった。モーセはへブライ人

ではなくエジプト人

の神官か貴族であり、熱心な一神教徒だった。彼はアトン教が消滅しないように、当時エジプトにあって

害されていたセム系の部族の先頭に立ち、彼らを奴隷の身分から解放して新たな民族を創始した。そして、

さらに精神化され非偶像化された一神宗教を与え、また彼らを〔自分の民族として〕区別するため、割礼という

エジプトの慣習を導入した。だが、かつての奴隷から成る粗野な群衆は、新たな信仰が要求する厳しさに耐

えられなかった。そのため暴動が起こり、モーセは殺され、殺害の記憶は抑圧された。イスラエル人はミデ

イアンにいたセム系の近縁部族と妥協的な同盟関係を結び、ヤハウェと呼ばれた凶暴な火山神が今や彼らの

民族神となった。その結果、モーセの神はヤハウエに統合され、彼の事業も同じくモーセと呼ばれたミデイ

アンの祭司に帰せられた。しかしながら、真なる信仰とその創設者についての埋もれた伝承は、何世紀もの

あいだに再び自己を主張するのに十分な力を蓄え、ついに勝利を得るに至った。それ以後、ヤハウエにはモーセ

の神の普遍的で精神的な性質が賦与されたものの、他方モーセ殺害の記憶はユダヤ人のあいだでは抑圧

されたままであり、キリスト教の台頭とともに偽装された形でのみ再浮上する」(Pp.5-6)

For all undergraduate students!!!, you do not copy & paste but [re]think my message. Remind Wittgenstein's phrase, "I should not like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking. But, if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own," - Ludwig Wittgenstein

●《ミッドナイ・スカイ拾遺》——ネタバレ注意で す!!!

山に囲まれた=「山寨」観測所から通信するところが ファンタジー、言葉の話せない少女は、交信相手の少女時代で、昔の交際相手の科学者の実の娘、西洋の没落ならぬ、西洋のアイデンティティ喪失の愛惜の気持 ちがにじみ出ている。透析をする主人公が最後、マイクの向こうで事切れるのも、クルーニーの美学というか、子供騙しのロマンだな。

ものいわぬ副主人公の少女は、冒頭に最初の観測所コ

ミュニティから疎開する時に、はぐれた「実際の」子供ということになっている。そして、はじめて映像の中で姿を表すのは、本人の身体ではなく、主人公が失

念したと勘違いする朝食のシリアル(=幻ではなく実際の生きた少女である徴)なのである。

→ウィキペディアからの引用「「山寨(shānzhài)」 とは、元々は中国語で文字通り「山に囲まれた塞」を意味する言葉である。『水滸伝』においては、山賊のすみかであった山寨を好漢らが梁山泊と名付けて拠点 としたことで知られる。そこから転じて「模倣、ニセモノ、ゲリラ」などを指す、どちらかと言えば否定的な言葉であった。しかし、近年では、「反主流の文化 の代表」という肯定的な意味でも使われるようになった言葉」。

山寨文化:「山

寨文化,源自於中文「山寨」一詞,泛指对知名或权威事物的仿冒,多含有贬义。常见于但不只限於电子产品领域,尤其是繼成衣、球鞋、手机、後,近來

陸續延伸到智能家電與所有3C产品領域,甚至汽機車等高度複雜的工業產品。」

モーセとイクナートンの天使 写真は、 Courtesy of Philippe Antonello/Netflix

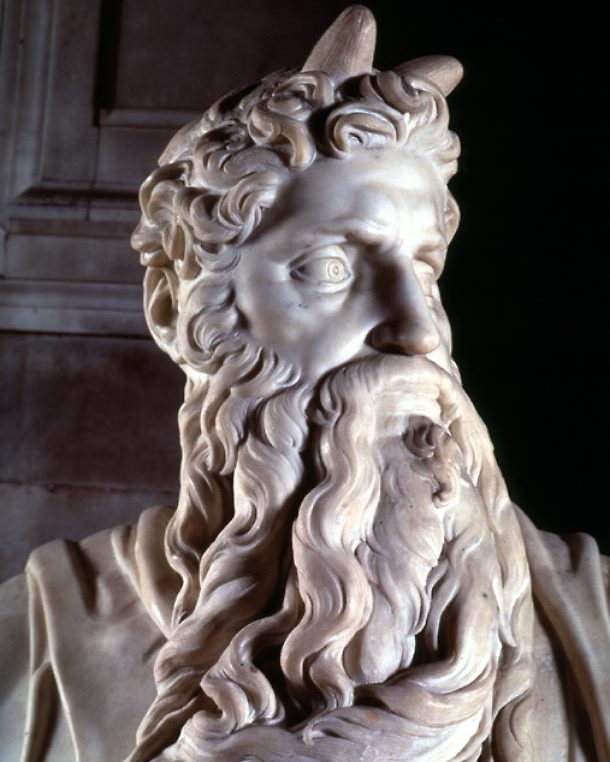

●大魔神としてのモーセ/モーセとしての大魔神

リンク

文献

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099