フロイトの生涯

Biography of Sigmund Freud

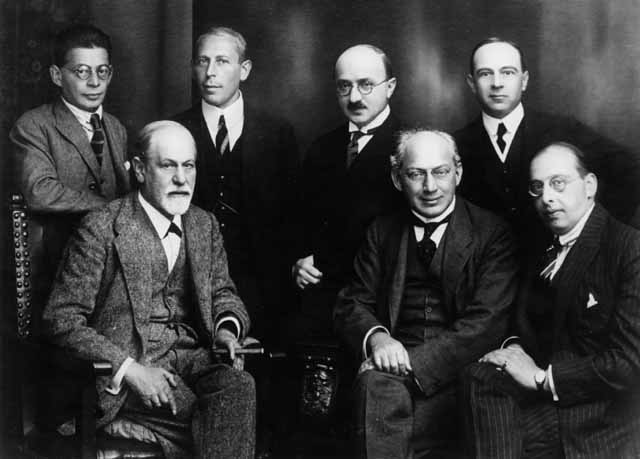

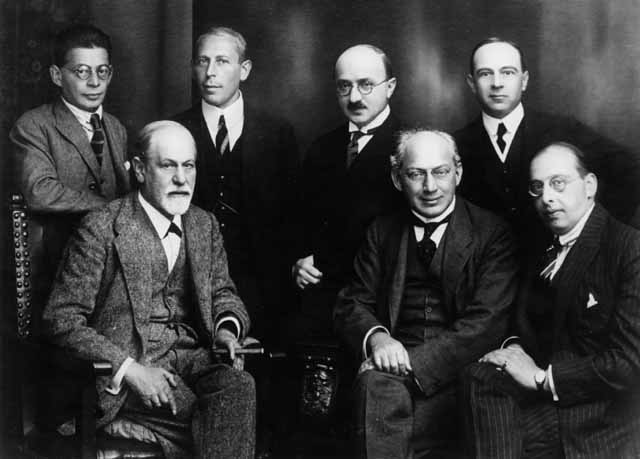

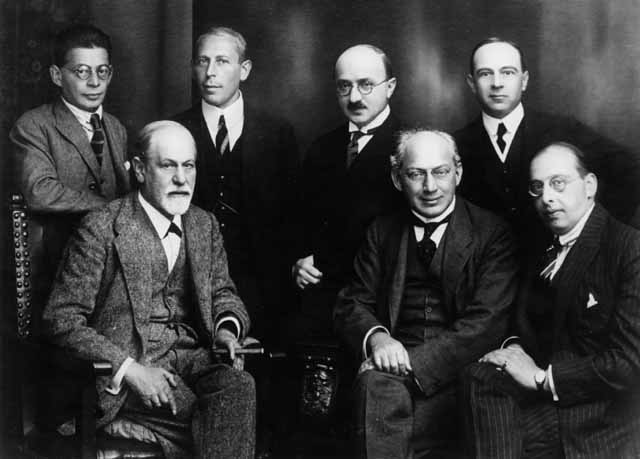

The

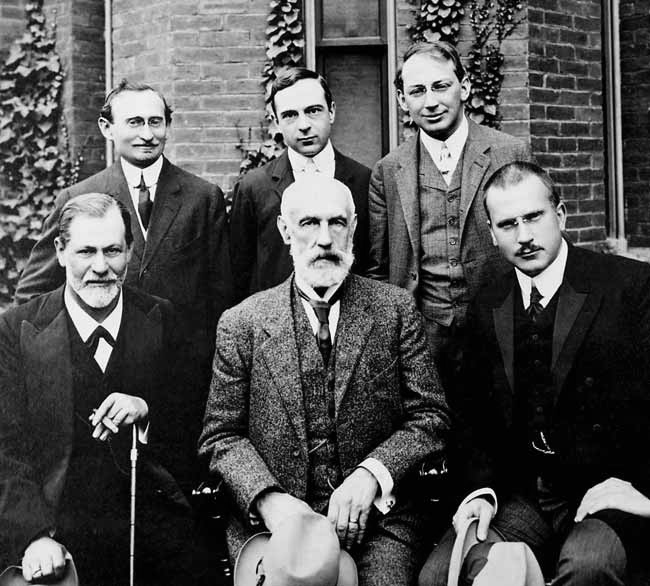

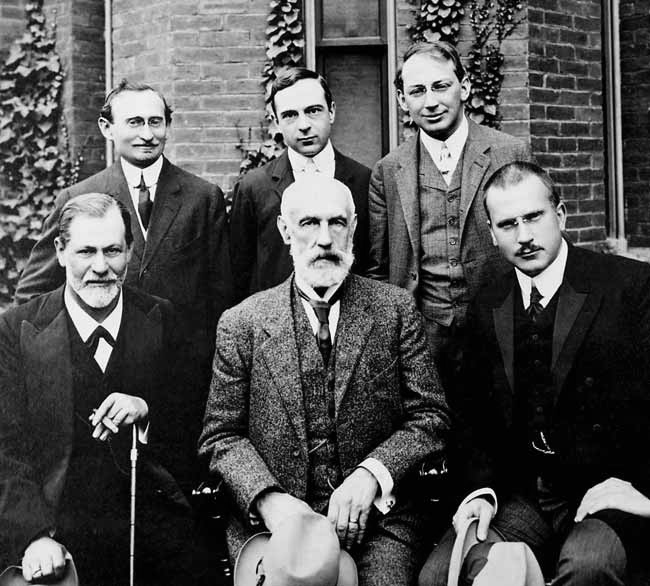

Committee in 1922 (from left to right): Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud[66歳],

Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, and Hanns

Sachs

☆ フロイトの人生とその業績(サマリー)(→小此木啓吾『フロイト思想のキーワード』)

ジークムント・フロイト(/frɔɪ FROYD、ドイツ語: [ˈzi-]、シギスムント・シュロモ・フロイト(Sigismund Schlomo Freud、1856年5月6日 - 1939年9月23日;83歳)はオーストリアの神経学者であり、患者と精神分析医との対話を通じて、精神内の葛藤に由来すると見なされる病理を評価し治療する臨 床方法である精神分析と、そこから導き出される独特の精神論および人間作用論の創始者である。

フロイトはオーストリア帝国のモラヴィア地方の町フライベルクでガリシア系ユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれた。1881年、ウィーン大学で医学博士の資格を 取得。1885年にハビリタチオンを修了すると、神経病理学の教官に任命され、1902年には提携教授となった。1886年、フロイトはウィーンで臨 床を開始した。1938年3月のドイツによるオーストリア併合(アンシュルス)後、フロイトはナチスの迫害から逃れるためにオーストリアを離れた。1939年、亡命先のイ ギリスで死去。

(1)精神分析の創始者であるフロイトは、自由連想の使用などの治療技法を開発し、転移を発見し、分析過程における転移の中心的役割を確立した。

(2)フロイトは、セ クシュアリティを幼児的な形態も含めて再定義し、精神分析理論の中心的な考え方としてエディプス・コンプレックスを定式化した。願望充足としての夢の分析 は、症状の形成と抑圧の基礎にあるメカニズムを臨床的に分析するためのモデルを提供した。

(3)これに基づいてフロイトは無意識の理論を精緻化し、イド、自我、 超自我からなる精神構造のモデルを発展させた(→「フロイト主義者の理論」「フロイトの理論とその後の遺産」)。

(4)フロイトは、リビドー(精神過程や精神構造が投資され、エロティックな愛着を生み出す性的エネルギー)と、 死の衝動(強迫的反復、憎悪、攻撃性、神経症的罪悪感の源)の存在を仮定した。

(5)その後のフロイトは、宗教と文化について幅広い解釈と批判を展開した。

診断や臨床の実践としては全体的に衰退しているものの、精神分析は心理学、精神医学、心理療法、そして人文科学全体において影響力を持ち続けている。それ ゆえ精神分析は、その治療効果、科学的地位、フェミニズムの大義を前進させるか妨げるかに関して、広範かつ非常に論争的な議論を生み続けている。それにも かかわらず、フロイトの作品は現代の西洋思想や大衆文化に浸透している。W・H・オーデンが1940年に発表したフロイトへの詩的賛辞は、フロイトが「私 たちがさまざまな人生を営むための/意見全体の風土」を作り上げたと表現している。(→「ジークムント・フロイト」より)

★その後のフロイト

︎▶文化にひそむ不安▶︎フロイトの理論とその後の遺産▶︎︎幻想の未来▶フロイトとユーモア︎▶フロイト的ナルシシズムの理解︎︎▶シニョール・シニョレッリの思い出︎▶︎︎フロイトの夢判断▶ゲザ・ローハイム︎▶︎︎自我とエスの関係▶超自我の道徳性について︎▶︎︎ミンスキー先生と感情▶︎︎小此木啓吾『フロイト思想のキーワード』▶︎フロイトの年譜▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

Early life and education Freud's birthplace, a rented room in a locksmith's house, Freiberg, Austrian Empire (Příbor, Czech Republic)  Freud (aged 16) and his mother, Amalia, in 1872 Sigmund Freud was born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg,[12][13] in the Austrian Empire (in Czech Příbor, now Czech Republic), the first of eight children.[14] Both of his parents were from Galicia. His father, Jakob Freud, a wool merchant, had two sons, Emanuel and Philipp, by his first marriage. Jakob's family were Hasidic Jews and, although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study. He and Freud's mother, Amalia Nathansohn, who was 20 years younger and his third wife, were married by Rabbi Isaac Noah Mannheimer on 29 July 1855.[15] They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith's house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born.[16] He was born with a caul, which his mother saw as a positive omen for the boy's future.[17] In 1859, the Freud family left Freiberg. Freud's half-brothers immigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the "inseparable" playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel's son, John.[18] Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud's sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born: Rosa (b. 1860), Marie (b. 1861), Adolfine (b. 1862), Paula (b. 1864), Alexander (b. 1866). In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved to be an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors. He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.[19] Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17. He had planned to study law, but joined the medical faculty at the university, where his studies included philosophy under Franz Brentano, physiology under Ernst Brücke, and zoology under Darwinist professor Carl Claus.[20] In 1876, Freud spent four weeks at Claus's zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an inconclusive search for their male reproductive organs.[21] In 1877, Freud moved to Ernst Brücke's physiology laboratory where he spent six years comparing the brains of humans with those of other vertebrates such as frogs, lampreys as well as also invertebrates, for example crayfish. His research work on the biology of nervous tissue proved seminal for the subsequent discovery of the neuron in the 1890s.[22] Freud's research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year's compulsory military service. The lengthy downtimes enabled him to complete a commission to translate four essays from John Stuart Mill's collected works.[23] He graduated with an MD in March 1881.[24] |

生い立ちと教育(→フロイトの年譜) フロイトの生家、鍵屋の間借り、オーストリア帝国フライベルク(チェコ共和国プジボル市)  1872年、フロイト(16歳)と母アマリア ジークムント・フロイトは、オーストリア帝国のモラヴィア人の町フライベルク[12][13]で、アシュケナージ系ユダヤ人の両親のもとに8人兄弟の長男 として生まれた[14]。父は羊毛商のヤコブ・フロイトで、最初の結婚でエマニュエルとフィリップの2人の息子をもうけた。ヤコブの家族はハシディック・ ユダヤ人であり、ヤコブ自身はその伝統から離れていたが、彼は律法の研究で知られるようになった。1855年7月29日、フロイトの母で20歳年下のアマ リア・ナタンソンと3番目の妻として、ラビのイサク・ノア・マンハイマーによって結婚させられた[15]。経済的に苦しく、シュローセルガッセ117番地 の鍵屋の一室を借りて暮らしていた時、息子のシグムントが生まれた[16]。 1859年、フロイト一家はフライベルクを離れる。フロイトの異母兄弟はイギリスのマンチェスターに移住し、幼少期の「切っても切れない」遊び相手であっ たエマニュエルの息子ジョンと別れた[18]。ヤコブ・フロイトは、妻と2人の子供(フロイトの妹アンナは1858年に生まれ、1857年生まれの弟ユリ ウスは幼少期に亡くなっていた)を連れて、まずライプツィヒに、そして1860年にはウィーンに移住し、4人の姉妹と1人の弟が生まれた: ローザ(1860年生まれ)、マリー(1861年生まれ)、アドルフィーネ(1862年生まれ)、パウラ(1864年生まれ)、アレクサンダー(1866 年生まれ)である。1865年、9歳のフロイトは、有名な高等学校であるレオポルトシュテッター国民体育学校に入学した。彼は優秀な生徒であることが証明 され、1873年にマトゥーラを優秀な成績で卒業した。文学が好きで、ドイツ語、フランス語、イタリア語、スペイン語、英語、ヘブライ語、ラテン語、ギリ シャ語に堪能だった[19]。 フロイトは17歳でウィーン大学に入学した。フランツ・ブレンターノの下で哲学を、エルンスト・ブリュッケの下で生理学を、ダーウィン主義者のカール・ク ラウス教授の下で動物学を学んだ[20]。1876年、フロイトはトリエステにあるクラウスの動物学研究所で4週間を過ごし、雄の生殖器を探すために何百 匹ものウナギを解剖した。 [21] 1877年、フロイトはエルンスト・ブリュッケの生理学研究所に移り、そこで6年間、カエルやヤツメウナギなどの脊椎動物やザリガニなどの無脊椎動物と人 間の脳を比較した。神経組織の生物学に関する彼の研究成果は、その後の1890年代の神経細胞の発見にとって決定的なものとなった。その長い休養期間のお かげで、彼はジョン・スチュアート・ミルの著作集から4つのエッセイを翻訳する仕事を完成させることができた[23]。1881年3月、彼は医学博士号を 取得して卒業した[24]。 |

| Early career and marriage In 1882 Freud began his medical career at Vienna General Hospital. His research work in cerebral anatomy led to the publication in 1884 of an influential paper on the palliative effects of cocaine, and his work on aphasia would form the basis of his first book On Aphasia: A Critical Study, published in 1891.[25] Over a three-year period, Freud worked in various departments of the hospital. His time spent in Theodor Meynert's psychiatric clinic and as a locum in a local asylum led to an increased interest in clinical work. His substantial body of published research led to his appointment as a university lecturer or docent in neuropathology in 1885, a non-salaried post but one which entitled him to give lectures at the University of Vienna.[26] In 1886 Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in "nervous disorders". The same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg. Freud was, as an atheist, dismayed at the requirement in Austria for a Jewish religious ceremony and briefly considered, before dismissing, the prospect of joining the Protestant 'Confession' to avoid one.[27] A civil ceremony for Bernays and Freud took place on 13 September and a religious ceremony took place the following day, with Freud having been hastily tutored in the Hebrew prayers.[28] The Freuds had six children: Mathilde (b. 1887), Jean-Martin (b. 1889), Oliver (b. 1891), Ernst (b. 1892), Sophie (b. 1893), and Anna (b. 1895). From 1891 until they left Vienna in 1938, Freud and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19, near Innere Stadt. On 8 December 1897 Freud was initiated into the German Jewish cultural association B'nai B'rith, to which he remained linked for all his life. Freud gave a speech on the interpretation of dreams, which had an enthusiastic reception. It anticipated the book of the same name, which was published for the first time two years later.[29][30][31][32]  Freud's home at Berggasse 19, Vienna In 1896, Minna Bernays, Martha Freud's sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé. The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumours, started by Carl Jung, of an affair. The discovery of a Swiss hotel guest-book entry for 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst travelling with his sister-in-law, has been presented as evidence of the affair.[33] Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker.[34] He believed smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it. Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually developing buccal cancer.[35] Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, "the one great habit."[36] Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection. Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874). Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept.[37] Freud owned and made use of Charles Darwin's major evolutionary writings and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann's The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). Other texts of importance to Freud were by Fechner and Herbart,[38] with the latter's Psychology as Science arguably considered to be of underrated significance in this respect.[39] Freud also drew on the work of Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main contemporary theorists of the concepts of the unconscious and empathy.[40] Though Freud was reluctant to associate his psychoanalytic insights with prior philosophical theories, attention has been drawn to analogies between his work and that of both Schopenhauer[41] and Nietzsche. In 1908, Freud said that he occasionally read Nietzsche, and was strongly fascinated by his writings, but did not study him, because he found Nietzsche's "intuitive insights" resembled too much his own work at the time, and also because he was overwhelmed by the "wealth of ideas" he encountered when he read Nietzsche. Freud sometimes would deny the influence of Nietzsche's ideas. One historian quotes Peter L. Rudnytsky, who says that based on Freud's correspondence with his adolescent friend Eduard Silberstein, Freud read Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy and probably the first two of the Untimely Meditations when he was seventeen.[42][43] In 1900, the year of Nietzsche's death, Freud bought his collected works; he told his friend, Fliess, that he hoped to find in Nietzsche's works "the words for much that remains mute in me." Later, he said he had not yet opened them.[44] Freud came to treat Nietzsche's writings "as texts to be resisted far more than to be studied." His interest in philosophy declined after he decided on a career in neurology.[45] Freud read William Shakespeare in English; his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare's plays.[46] Freud's Jewish origins and his allegiance to his secular Jewish identity were of significant influence in the formation of his intellectual and moral outlook, especially concerning his intellectual non-conformism, as he pointed out in his Autobiographical Study.[47] They would also have a substantial effect on the content of psychoanalytic ideas, particularly in respect of their common concerns with depth interpretation and "the bounding of desire by law".[48] |

初期のキャリアと結婚 1882年、フロイトはウィーン総合病院で医学者としてのキャリアをスタートさせた。彼の大脳解剖学の研究は、1884年にコカインの緩和効果に関する影 響力のある論文を発表することにつながり、失語症に関する彼の研究は、1891年に出版された彼の最初の著書『On Aphasia: A Critical Study』の基礎となる。テオドール・マイナートの精神科クリニックや、地元の精神病院での臨時雇いとして過ごした時間は、臨床的な仕事への関心を高め ることにつながった。1885年に神経病理学の大学講師に任命され、無給ではあったがウィーン大学で講義をする権利を得た[26]。 1886年、フロイトは病院のポストを辞し、「神経障害」を専門とする個人開業医となった。同年、彼はハンブルクのラビ長アイザック・バーネイズの孫娘で あるマーサ・バーネイズと結婚した。フロイトは無神論者であったため、オーストリアではユダヤ教の宗教的儀式が必要であることに落胆し、それを避けるため にプロテスタントの「告解式」に参加することを一時考えたが、断念した[27]。9月13日にバーネイズとフロイトのための市民的儀式が行われ、翌日に宗 教的儀式が行われた: マチルド(1887年生まれ)、ジャン=マルタン(1889年生まれ)、オリヴァー(1891年生まれ)、エルンスト(1892年生まれ)、ソフィー (1893年生まれ)、アンナ(1895年生まれ)である。1891年から1938年にウィーンを離れるまで、フロイトとその家族は、インネレ・シュタッ ト近くのベルクガッセ19番地のアパートに住んでいた。 1897年12月8日、フロイトはドイツのユダヤ人文化団体B'nai B'rithに入会し、終生この団体と結びついた。フロイトは夢の解釈に関するスピーチを行い、熱狂的な歓迎を受けた。それは、2年後に初めて出版された 同名の本を先取りするものであった[29][30][31][32]。  ウィーンのベルクガッセ19番地にあるフロイトの自宅 1896年、マーサ・フロイトの妹であるミンナ・バーネイズは、婚約者の死後、フロイト家の永久メンバーとなった。彼女がフロイトと親密な関係を築いたこ とから、カール・ユングが不倫関係にあるという噂を流した。1898年8月13日のスイスのホテルの宿泊記が発見され、義理の姉と旅行していたフロイトが 署名していたことが、不倫の証拠として提出された[33]。 フロイトは24歳の時にタバコを吸い始め、最初はタバコを吸っていたが、葉巻を吸うようになった[34]。同僚のヴィルヘルム・フリースからの健康上の警 告にもかかわらず、彼は喫煙者であり続け、最終的には頬癌を発症した[35]。1897年にフロイトはフリースに、タバコを含む依存症は「一つの偉大な習 慣」であるマスターベーションの代用品であると示唆した[36]。 フロイトは、知覚と内観の理論で知られる哲学の家庭教師ブレンターノを非常に尊敬していた。ブレンターノは『経験的立場からの心理学』(1874年)の中 で、無意識の存在の可能性について論じている。ブレンターノは無意識の存在を否定していたが、彼の無意識に関する議論は、おそらくフロイトに無意識の概念 を紹介する助けとなった。フロイトにとって重要な他のテキストはフェヒナーとヘルバルトによるものであり[38]、後者の『科学としての心理学』はこの点 において過小評価された重要性を持つと考えられる[39]。 フロイトは自身の精神分析的洞察を先行する哲学的理論と関連づけることに消極的であったが、彼の仕事とショーペンハウアー[41]やニーチェの仕事との類 似性に注目が集まっている。1908年、フロイトは時折ニーチェを読み、彼の著作に強く魅了されたが、ニーチェの「直観的な洞察」が当時の彼自身の仕事と あまりにも似ていると感じたため、またニーチェを読んだときに出会った「豊かな思想」に圧倒されたため、彼を研究しなかったと述べている。フロイトはニー チェの思想の影響を否定することもあった。ある歴史家はピーター・L・ルドニツキー(Peter L. Rudnytsky)の言葉を引用し、フロイトが思春期の友人エドゥアルド・シルベルシュタイン(Eduard Silberstein)と交わした書簡から、フロイトは17歳の時にニーチェの『悲劇の誕生』とおそらく『不時の瞑想』の最初の2冊を読んだと述べてい る[42][43]。 ニーチェが亡くなった1900年、フロイトはニーチェの著作集を購入し、友人のフリース(Fliess)に、ニーチェの著作の中に「私の中に無言のまま 残っている多くのもののための言葉」を見出したいと語った。その後、フロイトはニーチェの著作を 「研究するよりもはるかに抵抗すべきテキスト 」として扱うようになった。神経学の道に進むことを決めた後、彼の哲学への関心は低下した[45]。 フロイトはウィリアム・シェイクスピアを英語で読んでいた。彼の人間心理に対する理解は、部分的にはシェイクスピアの戯曲に由来していたかもしれない[46]。 フロイトのユダヤ人としての出自と世俗的なユダヤ人としてのアイデンティティへの忠誠は、『自伝的研究』の中で彼が指摘しているように、彼の知的・道徳的 な展望の形成、特に彼の知的不適合主義に関して重要な影響を及ぼしていた[47]。 それらはまた、特に深層解釈と「法則による欲望の束縛」という共通の関心事に関して、精神分析思想の内容にも大きな影響を及ぼすことになる[48]。 |

| Relationship with Fliess See also: Metapsychology § Freud and the als ob problem During the formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin-based ear, nose, and throat specialist whom he had first met in 1887. Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality. Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudoscientific. He shared Freud's views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality – masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms – in the etiology of what was then called the "actual neuroses," primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.[49] They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess's speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own ideas. His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his Project for a Scientific Psychology, was developed as a metapsychology with Fliess as interlocutor.[50] However, Freud's efforts to build a bridge between neurology and psychology were eventually abandoned after they had reached an impasse, as his letters to Fliess reveal,[51] though some ideas of the Project were to be taken up again in the concluding chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams.[52] Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat "nasal reflex neurosis",[53] and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him. According to Freud, her history of symptoms included severe leg pains with consequent restricted mobility, as well as stomach and menstrual pains. These pains were, according to Fliess's theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked, was curable by removal of part of the middle turbinate.[54][55] Fliess's surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding; he had left a half-metre of gauze in Eckstein's nasal cavity whose subsequent removal left her permanently disfigured. At first, though aware of Fliess's culpability and regarding the remedial surgery in horror, Freud could bring himself only to intimate delicately in his correspondence with Fliess the nature of his disastrous role, and in subsequent letters maintained a tactful silence on the matter or else returned to the face-saving topic of Eckstein's hysteria. Freud ultimately, in light of Eckstein's history of adolescent self-cutting and irregular nasal (and menstrual) bleeding, concluded that Fliess was "completely without blame", as Eckstein's post-operative haemorrhages were hysterical "wish-bleedings" linked to "an old wish to be loved in her illness" and triggered as a means of "rearousing [Freud's] affection". Eckstein nonetheless continued her analysis with Freud. She was restored to full mobility and went on to practice psychoanalysis herself.[56][57][54] Freud, who had called Fliess "the Kepler of biology", later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his "specifically Jewish mysticism" lay behind his loyalty to his Jewish friend and his consequent overestimation of both his theoretical and clinical work. Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud's unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work. After Fliess failed to respond to Freud's offer of collaboration over the publication of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1906, their relationship came to an end.[58] |

フリースとの関係 も参照のこと: メタ心理学§フロイトとアルス・オブ問題 1887年に初めて出会ったベルリンの耳鼻咽喉科医である友人ヴィルヘルム・フリエスの知的・精神的支えを、フロイトは重要視し、頼りにするようになっ た。二人とも、性についての急進的な新理論を発展させるという野心を持っていたため、自分たちは一般的な臨床や理論の主流から孤立していると考えていた。 フリースは、人間のバイオリズムと鼻生殖器のつながりに関する非常に風変わりな理論を展開したが、これは今日では疑似科学的とみなされている。彼は、当時 「現実の神経症」と呼ばれていたもの、主に神経衰弱や身体的に現れる不安症状の病因における、マスターベーション、性交中断、コンドームの使用といったセ クシュアリティのある側面の重要性に関するフロイトの見解に共感していた[49]。二人は広範な文通を続け、その中でフロイトは、幼児期のセクシュアリ ティや両性愛に関するフリエスの思索を参考にして、彼自身の考えを推敲・修正した。しかし、神経学と心理学の架け橋となるためのフロイトの努力は、『夢の 解釈』の最終章で再び取り上げられることになったものの、フリースへの手紙から明らかなように、行き詰まった末に結局放棄された[51]。 フロイトは「鼻反射神経症」を治療するためにフリースに繰り返し鼻と副鼻腔の手術を受けさせ[53]、その後彼の患者であるエマ・エクスタインを紹介し た。フロイトによれば、彼女の症状の病歴には、激しい脚の痛みとそれに伴う運動制限、胃痛や月経痛が含まれていた。これらの痛みは、フリエスの理論によれ ば、習慣的な自慰行為によって引き起こされたものであり、鼻の組織と性器は連動していたため、中耳甲介の一部を切除することで治癒可能であった[54] [55]。フリエスの手術は悲惨な結果となり、大量の鼻出血が再発した。当初、フロイトは、フリースに非があることを自覚し、恐怖のあまりその治療手術に 臨んだが、フリースとの手紙の中で、自分の悲惨な役割の本質を繊細に伝えることしかできなかった。その後の手紙の中では、この件に関しては機転を利かせて 沈黙を守り、あるいはエックシュタインのヒステリーの話題に戻って、面目を保った。フロイトは最終的に、エックシュタインの思春期の自切と不正鼻出血(お よび月経出血)の履歴を考慮し、エックシュタインの術後出血は「病気の中で愛されたいという昔からの願い」と結びついたヒステリックな「願望出血」であ り、「(フロイトの)愛情を再沸騰させる」手段として引き起こされたものであるとして、フリエスには「まったく非がない」と結論づけた。それでもエクスタ インはフロイトのもとで分析を続けた。彼女は完全な運動能力を回復し、自ら精神分析を実践するようになった[56][57][54]。 フリースを「生物学のケプラー」と呼んでいたフロイトは、後に、彼のユダヤ人の友人に対する忠誠心と、その結果としての彼の理論的・臨床的仕事に対する過 大評価の背景には、ホモエロティックな愛着と、彼の「特にユダヤ的な神秘主義」の残滓の組み合わせがあると結論づけた。二人の友情は険悪な結末を迎え、フ リースはフロイトが自分の性的周期性に関する一般理論を支持しようとしないことに腹を立て、自分の著作の盗作を共謀したと非難した。1906年に『性愛理 論に関する3つの試論』の出版をめぐるフロイトの協力の申し出にフリースが応じなかった後、2人の関係は終焉を迎えた[58]。 |

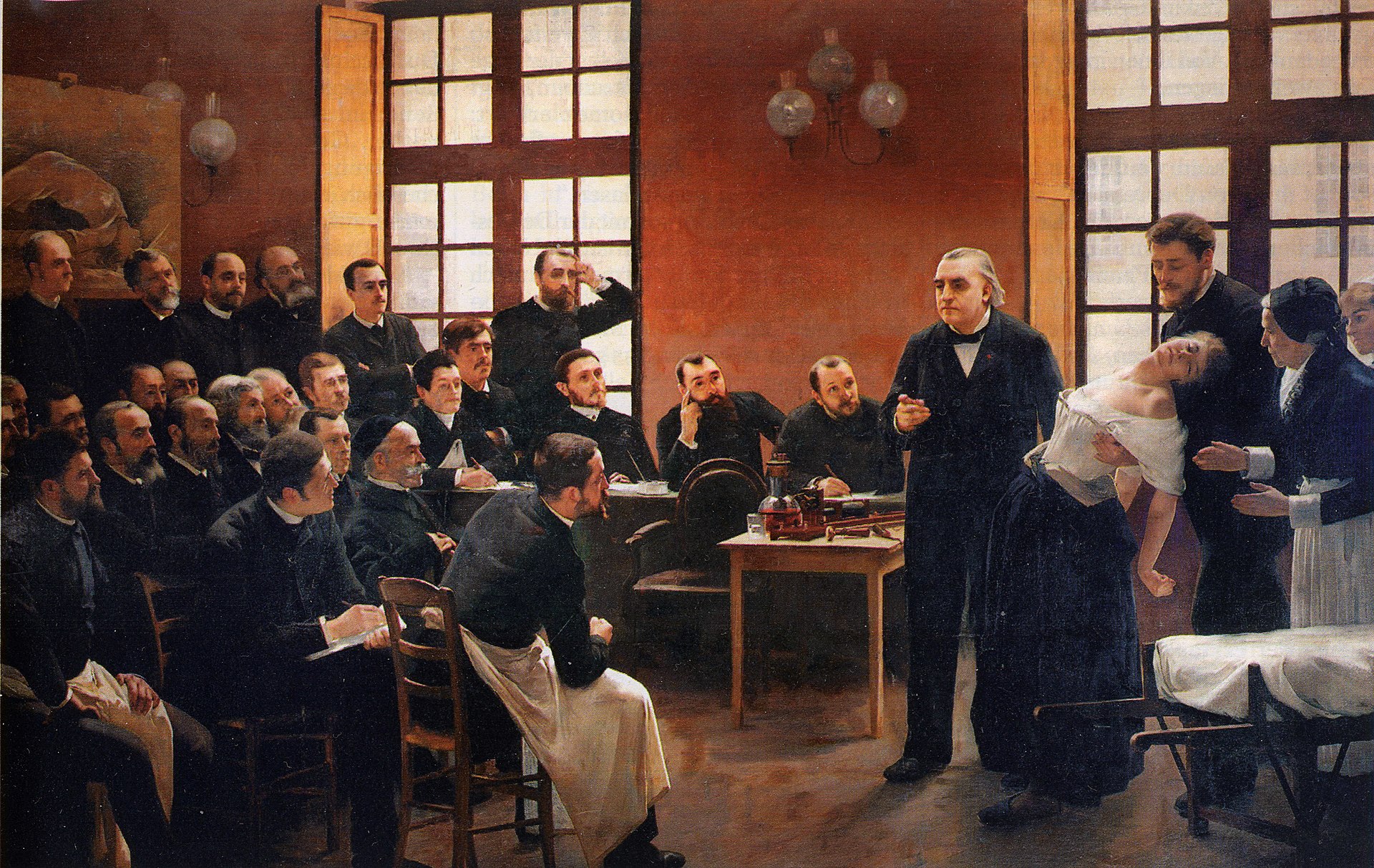

Development of psychoanalysis André Brouillet's A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887) depicting a Charcot demonstration. Freud had a lithograph of this painting placed over the couch in his consulting rooms.[59] In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a three-month fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was conducting scientific research into hypnosis. He was later to recall the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.[60] Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience. Once he had set up in private practice in Vienna in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work. He adopted the approach of his friend and collaborator, Josef Breuer, in a type of hypnosis that was different from the French methods he had studied, in that it did not use suggestion. The treatment of one particular patient of Breuer's proved to be transformative for Freud's clinical practice. Described as Anna O., she was invited to talk about her symptoms while under hypnosis (she would coin the phrase "talking cure"). Her symptoms became reduced in severity as she retrieved memories of traumatic incidents associated with their onset. The inconsistent results of Freud's early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having concluded that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition, about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them. He called this procedure "free association". In conjunction with this, Freud found that patients' dreams could be fruitfully analyzed to reveal the complex structuring of unconscious material and to demonstrate the psychic action of repression which, he had concluded, underlay symptom formation. By 1896 he was using the term "psychoanalysis" to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.[61]  Ornate staircase, a landing with an interior door and window, staircase continuing up Approach to Freud's consulting rooms at Berggasse 19 Freud's development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a "neurasthenia" which he linked to the death of his father in 1896[62] and which prompted a "self-analysis" of his own dreams and memories of childhood. His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother's affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses. Based on his early clinical work, Freud postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud's seduction theory.[63] In the light of his self-analysis, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and that in either case, they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.[64] This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud's subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus complex.[65] Freud described the evolution of his clinical method and set out his theory of the psychogenetic origins of hysteria, demonstrated in several case histories, in Studies on Hysteria published in 1895 (co-authored with Josef Breuer). In 1899, he published The Interpretation of Dreams in which, following a critical review of existing theory, Freud gives detailed interpretations of his own and his patients' dreams in terms of wish-fulfillments made subject to the repression and censorship of the "dream-work". He then sets out the theoretical model of mental structure (the unconscious, pre-conscious and conscious) on which this account is based. An abridged version, On Dreams, was published in 1901. In works that would win him a more general readership, Freud applied his theories outside the clinical setting in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905).[66] In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its "polymorphous perverse" forms and the functioning of the "drives", to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity.[67] The same year he published Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.[68] Known as the 'Dora' case study, for Freud it was illustrative of hysteria as a symptom and contributed to his understanding of the importance of transference as a clinical phenomena. In other of his early case studies Freud set out to describe the symptomatology of obsessional neurosis in the case of the Rat man, and phobia in the case of Little Hans.[69] Transference is the process by which patients displace onto their analyst feelings and ideas which derive from previous figures in their lives. Transference was first seen as a regrettable phenomenon that interfered with the recovery of repressed memories and disturbed patients' objectivity, but by 1912, Freud had come to see it as an essential part of the therapeutic process.[70] |

精神分析の発展 シャルコーのデモンストレーションを描いたアンドレ・ブリュイエの『サルペトリエールでの臨床レッスン』(1887年)。フロイトはこの絵のリトグラフを診察室のソファの上に置かせた[59]。 1885年10月、フロイトは、催眠術の科学的研究を行っていた有名な神経学者ジャン=マルタン・シャルコーのもとで学ぶため、3ヶ月間の研究員としてパ リに赴いた。シャルコーは、ヒステリーや催眠に対する感受性の研究を専門としており、聴衆の前で舞台の上で患者を相手に催眠のデモンストレーションを頻繁 に行った。 1886年にウィーンで個人開業すると、フロイトは臨床で催眠を使い始めた。彼は、友人であり共同研究者であったヨーゼフ・ブロイヤーのアプローチを採用 した。この催眠術は、彼が研究していたフランスの方法とは異なり、暗示を用いないタイプであった。ブロイアーのある患者の治療は、フロイトの臨床に大きな 変革をもたらした。アンナ・Oと呼ばれた彼女は、催眠中に自分の症状について話すように誘われた(彼女は「トーキング・キュア」という言葉を生み出すこと になる)。彼女の症状は、その発症に関連したトラウマ的出来事の記憶を呼び起こすにつれて、重症度が軽減していった。 フロイトの初期の臨床研究の一貫性のない結果から、彼は最終的に催眠術を放棄することになった。彼はこの方法を「自由連想」と呼んだ。これと関連して、フ ロイトは患者の夢を分析することで、無意識の物質の複雑な構造を明らかにし、症状形成の根底にあると結論づけた抑圧の心理作用を実証することができること を発見した。1896年までに、彼は「精神分析」という言葉を、彼の新しい臨床方法とそれに基づく理論を指すのに使うようになった[61]。  装飾された階段、室内ドアと窓のある踊り場、階段は上へと続く ベルクガッセ19番地にあるフロイトの診察室へのアプローチ フロイトがこれらの新しい理論を発展させたのは、彼が1896年の父の死[62]に関連する「神経衰弱」、心臓の不整脈、不穏な夢、憂鬱な時期を経験し、 彼自身の夢や幼少期の記憶の「自己分析」を促した時期のことであった。父親に対する敵意や母親の愛情に対する対抗的な嫉妬の感情を探求したことで、彼は神 経症の起源に関する理論を根本的に見直すことになった。 フロイトは初期の臨床研究に基づき、幼児期の性的虐待の無意識の記憶が精神神経症(ヒステリーや強迫神経症)の必要な前提条件であると仮定し、この定式化 は現在ではフロイトの誘惑理論として知られている。 [フロイトは、自己分析に照らして、すべての神経症は幼児期の性的虐待の影響にまで遡ることができるという理論を放棄し、幼児期の性的なシナリオは依然と して原因となる機能を持っているが、それが現実のものであるか想像のものであるかは問題ではなく、いずれの場合においても、抑圧された記憶として作用する ときにのみ病原性となると主張した[64]。 すべての神経症がどのように発生するかについての一般的な説明としての幼児期の性的トラウマの理論から、自律的な幼児期のセクシュアリティを前提とする理論へのこの移行は、フロイトがその後エディプス・コンプレックスの理論を定式化するための基礎となった[65]。 フロイトは、1895年に出版された『ヒステリー研究』(ヨーゼフ・ブロイヤーとの共著)の中で、彼の臨床方法の発展について述べ、いくつかの症例史の中 で実証されたヒステリーの心因的起源についての彼の理論を示した。1899年、彼は『夢の解釈』を出版し、既存の理論を批判的に検討した後、フロイトは 「夢作業」の抑圧と検閲の対象となった願望充足の観点から、彼自身と彼の患者の夢の詳細な解釈を行った。そして、この説明の基礎となる精神構造の理論モデ ル(無意識、前意識、意識)を示している。1901年に要約版『夢について』が出版された。より一般的な読者層を獲得することになる著作において、フロイ トは『日常生活の精神病理学』(1901年)と『ジョークと無意識との関係』(1905年)において、臨床の場以外で彼の理論を適用した[66]。 1905年に出版された『セクシュアリティの理論に関する3つのエッセイ』において、フロイトは幼児期のセクシュアリティに関する彼の理論を精緻化し、そ の「変態的な多形」の形態と、性的アイデンティティの形成においてそれが生じる「衝動」の機能について述べている。 [67] 同年、フロイトは『ヒステリーの症例分析の断片』を発表し、これはフロイトの症例研究の中でも最も有名で論争の的となった[68]。フロイトは初期の他の 事例研究において、ネズミ男の事例では強迫神経症の症状を、リトル・ハンスの事例では恐怖症の症状を説明することに着手した[69]。 転移とは、患者が自分の人生における以前の人物に由来する感情や観念を分析者の上に置き換えるプロセスである。転移は最初、抑圧された記憶の回復を妨げ、 患者の客観性を乱す残念な現象とみなされていたが、1912年までにフロイトはそれを治療過程の本質的な部分とみなすようになった[70]。 |

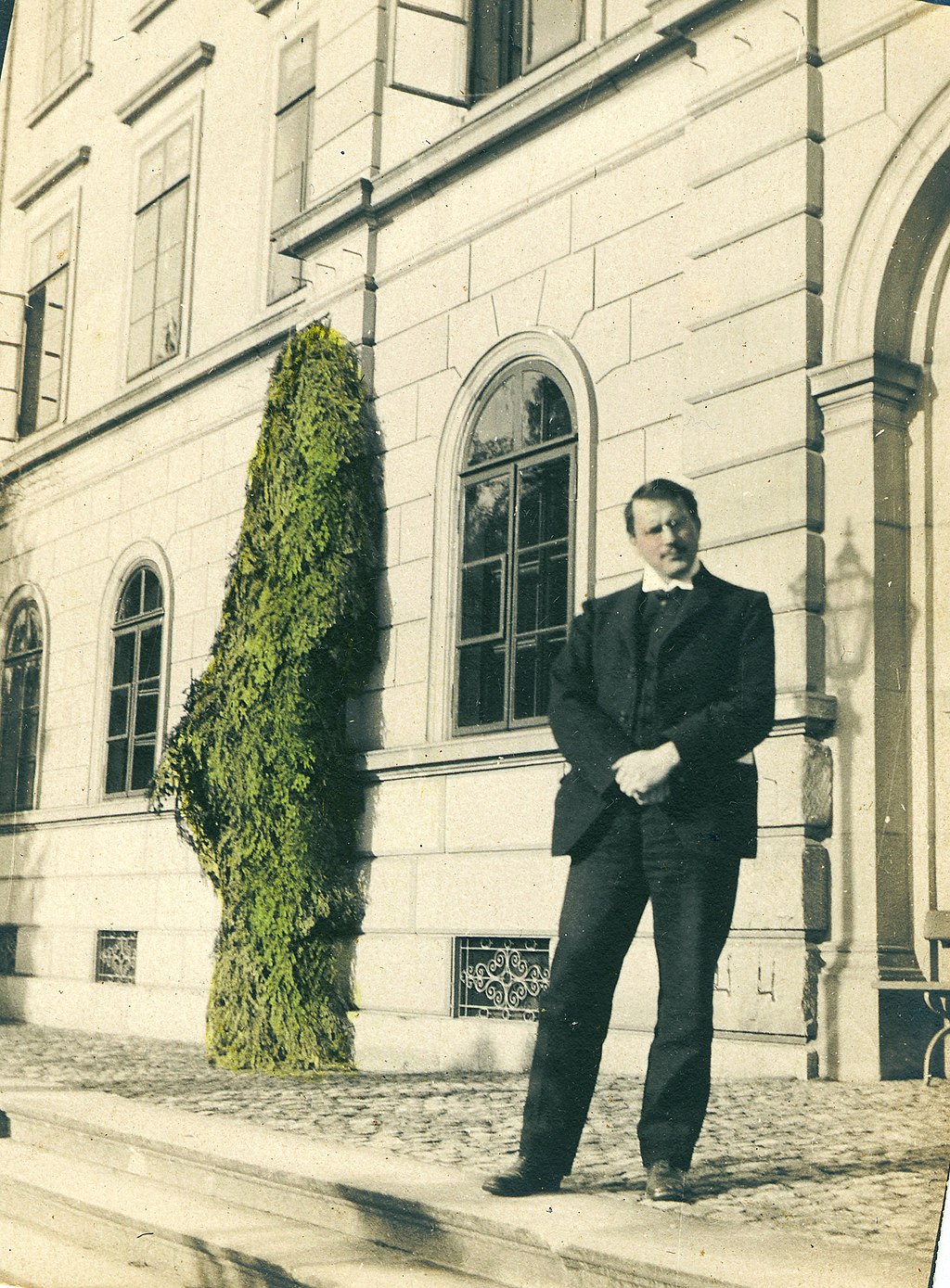

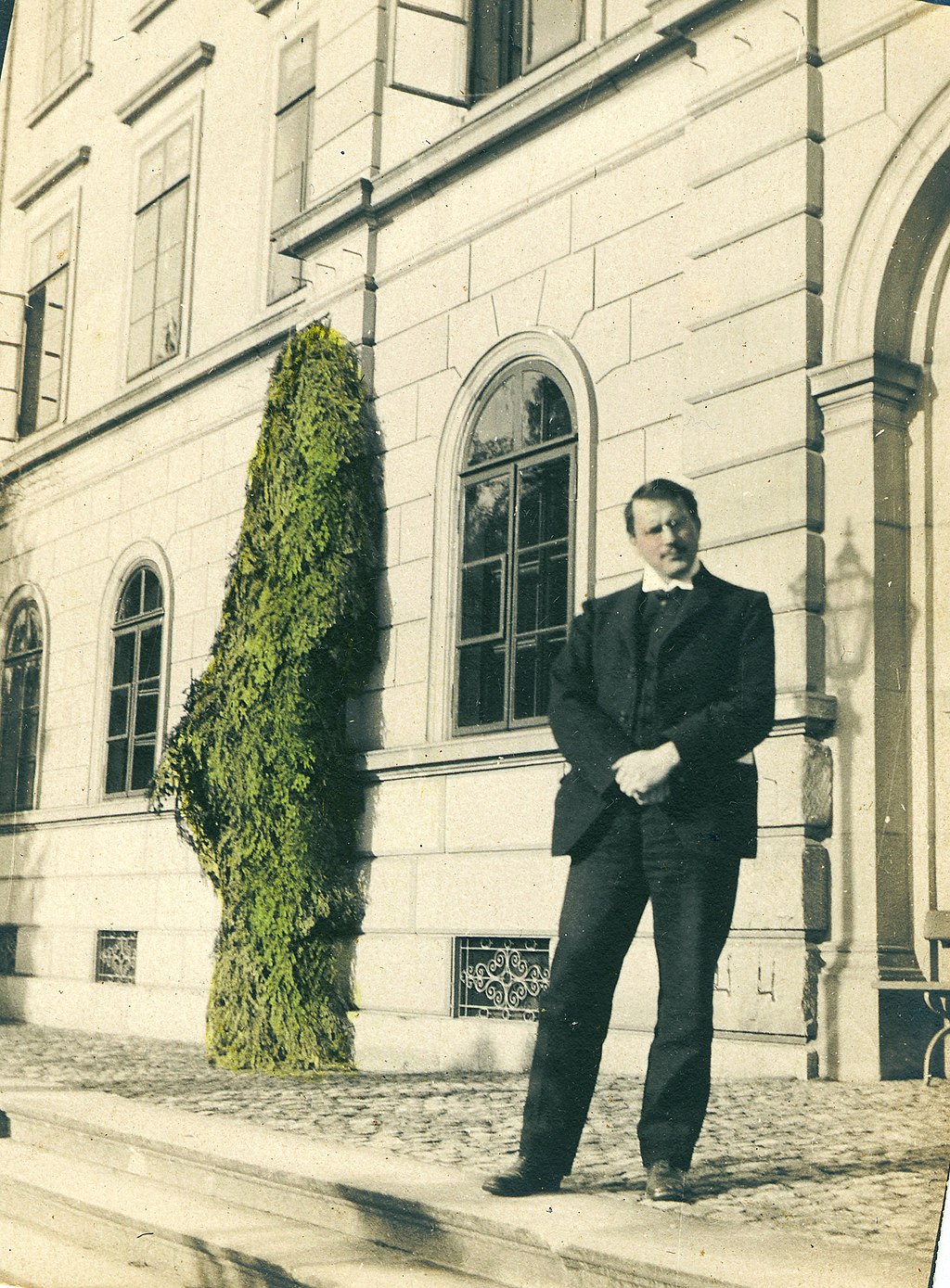

Early followers At Clark University, 1909. Front row: Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung; back row: Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi In 1902, Freud, at last, realised his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor. The title "professor extraordinarius"[71] was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of "professor ordinarius" in 1920).[72] Despite support from the university, his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was secured only with the intervention of an influential ex-patient, Baroness Marie Ferstel, who (supposedly) had to bribe the minister of education with a valuable painting.[73] Freud continued with the regular series of lectures on his work which, since the mid-1880s as a docent of Vienna University, he had been delivering to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the university's psychiatric clinic.[74] From the autumn of 1902, a number of Viennese physicians who had expressed interest in Freud's work were invited to meet at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology.[75] This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft) and it marked the beginnings of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.[76] Freud founded this discussion group at the suggestion of the physician Wilhelm Stekel. Stekel had studied medicine; his conversion to psychoanalysis is variously attributed to his successful treatment by Freud for a sexual problem or as a result of his reading The Interpretation of Dreams, to which he subsequently gave a positive review in the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt.[77] The other three original members whom Freud invited to attend, Alfred Adler, Max Kahane, and Rudolf Reitler, were also physicians[78] and all five were Jewish by birth.[79] Both Kahane and Reitler were childhood friends of Freud who had gone to university with him and kept abreast of Freud's developing ideas by attending his Saturday evening lectures.[80] In 1901, Kahane, who first introduced Stekel to Freud's work,[74] had opened an out-patient psychotherapy institute of which he was the director in Vienna.[75] In the same year, his medical textbook, Outline of Internal Medicine for Students and Practicing Physicians, was published. In it, he provided an outline of Freud's psychoanalytic method.[74] Kahane broke with Freud and left the Wednesday Psychological Society in 1907 for unknown reasons and in 1923 committed suicide.[81] Reitler was the director of an establishment providing thermal cures in Dorotheergasse which had been founded in 1901.[75] He died prematurely in 1917. Adler, regarded as the most formidable intellect among the early Freud circle, was a socialist who in 1898 had written a health manual for the tailoring trade. He was particularly interested in the potential social impact of psychiatry.[82] Max Graf, a Viennese musicologist and father of "Little Hans", who had first encountered Freud in 1900 and joined the Wednesday group soon after its initial inception,[83] described the ritual and atmosphere of the early meetings of the society: The gatherings followed a definite ritual. First one of the members would present a paper. Then, black coffee and cakes were served; cigars and cigarettes were on the table and were consumed in great quantities. After a social quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin. The last and decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself. There was the atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet who made the heretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial.[82]  Carl Jung in 1910 By 1906, the group had grown to sixteen members, including Otto Rank, who was employed as the group's paid secretary.[82] In the same year, Freud began a correspondence with Carl Gustav Jung who was by then already an academically acclaimed researcher into word-association and the Galvanic Skin Response, and a lecturer at Zurich University, although still only an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zürich.[84][85] In March 1907, Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, also a Swiss psychiatrist, travelled to Vienna to visit Freud and attend the discussion group. Thereafter, they established a small psychoanalytic group in Zürich. In 1908, reflecting its growing institutional status, the Wednesday group was reconstituted as the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society[86] with Freud as president, a position he relinquished in 1910 in favor of Adler in the hope of neutralizing his increasingly critical standpoint.[87] The first woman member, Margarete Hilferding, joined the Society in 1910[88] and the following year she was joined by Tatiana Rosenthal and Sabina Spielrein who were both Russian psychiatrists and graduates of the Zürich University medical school. Before the completion of her studies, Spielrein had been a patient of Jung at the Burghölzli and the clinical and personal details of their relationship became the subject of an extensive correspondence between Freud and Jung. Both women would go on to make important contributions to the work of the Russian Psychoanalytic Society founded in 1910.[89] Freud's early followers met together formally for the first time at the Hotel Bristol, Salzburg on 27 April 1908. This meeting, which was retrospectively deemed to be the first International Psychoanalytic Congress,[90] was convened at the suggestion of Ernest Jones, then a London-based neurologist who had discovered Freud's writings and begun applying psychoanalytic methods in his clinical work. Jones had met Jung at a conference the previous year and they met up again in Zürich to organize the Congress. There were, as Jones records, "forty-two present, half of whom were or became practising analysts."[91] In addition to Jones and the Viennese and Zürich contingents accompanying Freud and Jung, also present and notable for their subsequent importance in the psychoanalytic movement were Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon from Berlin, Sándor Ferenczi from Budapest and the New York-based Abraham Brill. Important decisions were taken at the Congress to advance the impact of Freud's work. A journal, the Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologische Forschungen, was launched in 1909 under the editorship of Jung. This was followed in 1910 by the monthly Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse edited by Adler and Stekel, in 1911 by Imago, a journal devoted to the application of psychoanalysis to the field of cultural and literary studies edited by Rank and in 1913 by the Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse, also edited by Rank.[92] Plans for an international association of psychoanalysts were put in place and these were implemented at the Nuremberg Congress of 1910 where Jung was elected, with Freud's support, as its first president. Freud turned to Brill and Jones to further his ambition to spread the psychoanalytic cause in the English-speaking world. Both were invited to Vienna following the Salzburg Congress and a division of labour was agreed with Brill given the translation rights for Freud's works, and Jones, who was to take up a post at the University of Toronto later in the year, tasked with establishing a platform for Freudian ideas in North American academic and medical life.[93] Jones's advocacy prepared the way for Freud's visit to the United States, accompanied by Jung and Ferenczi, in September 1909 at the invitation of Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, where he gave five lectures on psychoanalysis.[94] The event, at which Freud was awarded an Honorary Doctorate, marked the first public recognition of Freud's work and attracted widespread media interest. Freud's audience included the distinguished neurologist and psychiatrist James Jackson Putnam, Professor of Diseases of the Nervous System at Harvard, who invited Freud to his country retreat where they held extensive discussions over a period of four days. Putnam's subsequent public endorsement of Freud's work represented a significant breakthrough for the psychoanalytic cause in the United States.[94] When Putnam and Jones organised the founding of the American Psychoanalytic Association in May 1911 they were elected president and secretary respectively. Brill founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society the same year. His English translations of Freud's work began to appear from 1909. |

初期のフォロワーたち 1909年、クラーク大学にて。前列: フロイト、G.スタンレー・ホール、カール・ユング、後列: 後列:アブラハム・ブリル、アーネスト・ジョーンズ、サンドル・フェレンツィ 1902年、フロイトはついに、大学教授になるという長年の野望を実現した。フロイトにとって「特任教授」[71]という称号は、給与や教務を伴わないポ ストであるにもかかわらず、名誉と認知を与える重要なものであった(彼は1920年に「特任教授」という上級の地位を与えられる)[72]。大学からの支 援にもかかわらず、彼の任命は政治当局によって何年も阻止されており、影響力のある元患者のマリー・フェルステル男爵夫人の介入によってのみ、その地位を 得ることができた。 フロイトは、1880年代半ばからウィーン大学の教官として、毎週土曜日の夕方、大学の精神科クリニックのレクチャーホールで小さな聴衆に向けて行ってい た、彼の仕事に関する定期的な講義シリーズを続けた[74]。 [このグループは、水曜心理学会(Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft)と呼ばれ、世界的な精神分析運動の始まりとなった[76]。 フロイトは、医師ヴィルヘルム・シュテッケルの提案でこの討論会を設立した。シュテッケルは医学を学んでいたが、彼が精神分析に転向したのは、性的な問題 に対するフロイトの治療が成功したためであるとか、ウィーンの日刊紙『ノイエス・ウィーナー・タグブラット』で好意的な批評をした『夢の解釈』を読んだ結 果であるとか、様々な説がある[77]。 [79] カハネとライトラーはともにフロイトの幼なじみであり、フロイトとともに大学に進学し、土曜日の夜の講義に出席することでフロイトの発展途上の思想を把握 していた[80] 。1901年、ステッケルにフロイトの仕事を最初に紹介したカハネは[74]、ウィーンで外来患者向けの心理療法研究所を開設し、その所長を務めていた [75] 。カハネはフロイトと決別し、1907年に原因不明の理由で水曜心理学会を脱退し、1923年に自殺した[81]。ライトラーは、1901年に設立された ドロテエルガッセの温熱療法を提供する施設の所長であった[75]。アドラーは、初期のフロイト・サークルの中で最も手ごわい知性とみなされていたが、 1898年に仕立物業のための健康マニュアルを書いた社会主義者であった。彼は特に精神医学の潜在的な社会的影響に関心を持っていた[82]。 ウィーンの音楽学者であり、「小さなハンス」の父親であったマックス・グラフは、1900年にフロイトと初めて出会い、水曜グループの発足後すぐに参加した[83]: 集会は明確な儀式に従っていた。まずメンバーの一人が論文を発表する。それからブラックコーヒーとケーキが出され、葉巻と煙草がテーブルに置かれ、大量に 消費された。社交的な時間が25分ほど過ぎると、討論が始まった。最後に決定的な言葉を発するのは、いつもフロイト自身だった。その部屋には、ある宗教が 設立されようとしている雰囲気があった。フロイト自身がその新しい預言者であり、これまで一般的であった心理学的調査の方法を表面的なものに見せかけたの である[82]。  1910年のカール・ユング 同年、フロイトはカール・グスタフ・ユングとの文通を開始した。ユングはその頃すでに言葉連想とガルバニック皮膚反応の研究者として学術的に高く評価され ており、チューリッヒ大学で講師を務めていたが、まだチューリッヒのブルクホルツリ精神病院でオイゲン・ブルーラーの助手をしていただけであった。 [84] [85] 1907年3月、ユングは、同じくスイスの精神科医であったルートヴィヒ・ビンスワンガーとともに、フロイトを訪ね、討論会に出席するためにウィーンを訪 れた。その後、彼らはチューリッヒに小さな精神分析グループを設立した。1908年、その組織的地位の高まりを反映して、水曜日のグループは、フロイトを 会長とするウィーン精神分析協会として再構成された[86]。 最初の女性会員であるマルガレーテ・ヒルファーディングは1910年に協会に入会し[88]、翌年にはロシア人精神科医でチューリッヒ大学医学部を卒業し たタチアナ・ローゼンタールとサビーナ・シュピールラインが入会した。スピールラインは、彼女の研究が完了する前に、ブルクヘルツリでユングの患者であ り、二人の関係の臨床的および個人的な詳細は、フロイトとユングの間の広範な書簡の主題となった。二人の女性は、1910年に設立されたロシア精神分析協 会の活動に重要な貢献をすることになる[89]。 フロイトの初期の支持者たちは、1908年4月27日にザルツブルクのホテル・ブリストルで初めて正式に集まった。この会議は、振り返ってみると最初の国 際精神分析会議とみなされ[90]、当時ロンドンを拠点としていた神経科医で、フロイトの著作を発見し、臨床に精神分析的手法を適用し始めていたアーネス ト・ジョーンズの提案によって開催された。ジョーンズは前年の学会でユングに会っており、大会を組織するためにチューリッヒで再会した。ジョーンズが記録 しているように、「42人が出席し、そのうちの半数が実践的な分析者であったか、あるいは分析者となった」[91]。ジョーンズと、フロイトとユングに随 行したウィーンおよびチューリッヒの参加者に加えて、ベルリンのカール・アブラハムとマックス・アイティングン、ブダペストのサンドル・フェレンツィ、そ してニューヨークを拠点とするアブラハム・ブリルが出席し、その後の精神分析運動において重要な役割を果たした。 大会では、フロイトの著作の影響力を高めるための重要な決定がなされた。1909年、ユングが編集長を務める雑誌『精神分析・精神病理学研究』 (Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathische Forschungen)が創刊された。1910年にはアドラーとステーケルが編集する月刊誌『精神分析』(Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse)、1911年にはランクが編集する文化・文学研究分野への精神分析の応用に特化した雑誌『イマーゴ』(Imago)、 1913年には同じくランクが編集する『精神分析国際誌』(Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse)が続いた[92]。精神分析家の国際的な協会の計画が立てられ、これらは1910年のニュルンベルク大会で実行に移され、ユ ングはフロイトの支持を得て初代会長に選出された。 フロイトは、英語圏に精神分析の大義を広めるという野望を実現するために、ブリルとジョーンズに注目した。ザルツブルグ大会の後、両者はウィーンに招か れ、フロイトの著作の翻訳権をブリルに与え、その年の暮れにトロント大学に赴任する予定であったジョーンズは、北米の学術界と医学界にフロイトの思想の基 盤を確立する任務を負うという役割分担が合意された [93] 。 [ジョーンズの提唱は、1909年9月にマサチューセッツ州ウスターにあるクラーク大学の学長スタンレー・ホールの招きで、ユングとフェレンツィを伴って フロイトがアメリカを訪問し、精神分析に関する5つの講義を行うための道を準備した[94]。 フロイトに名誉博士号が授与されたこのイベントは、フロイトの研究が初めて公に認められたことを意味し、広くメディアの関心を集めた。フロイトの聴衆の中 には、著名な神経学者で精神科医のジェームズ・ジャクソン・パットナム(ハーバード大学神経系疾患教授)も含まれており、パットナムはフロイトを彼の田舎 の隠れ家に招き、4日間にわたって広範な議論を行った。1911年5月にパトナムとジョーンズがアメリカ精神分析協会の設立を組織したとき、彼らはそれぞ れ会長と幹事に選ばれた。ブリルは同じ年にニューヨーク精神分析協会を設立した。1909年からフロイトの著作の英訳が出版され始めた。 |

| Resignations from the IPA Some of Freud's followers subsequently withdrew from the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) and founded their own schools. From 1909, Adler's views on topics such as neurosis began to differ markedly from those held by Freud. As Adler's position appeared increasingly incompatible with Freudianism, a series of confrontations between their respective viewpoints took place at the meetings of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in January and February 1911. In February 1911, Adler, then the president of the society, resigned his position. At this time, Stekel also resigned from his position as vice president of the society. Adler finally left the Freudian group altogether in June 1911 to form his own organization with nine other members who had also resigned from the group.[95] This new formation was initially called Society for Free Psychoanalysis but it was soon renamed the Society for Individual Psychology. In the period after World War I, Adler became increasingly associated with a psychological position he devised called individual psychology.[96]  The Committee in 1922 (from left to right): Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, and Hanns Sachs In 1912, Jung published Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious) making it clear that his views were taking a direction quite different from those of Freud. To distinguish his system from psychoanalysis, Jung called it analytical psychology.[97] Anticipating the final breakdown of the relationship between Freud and Jung, Ernest Jones initiated the formation of a Secret Committee of loyalists charged with safeguarding the theoretical coherence and institutional legacy of the psychoanalytic movement. Formed in the autumn of 1912, the Committee comprised Freud, Jones, Abraham, Ferenczi, Rank, and Hanns Sachs. Max Eitingon joined the Committee in 1919. Each member pledged himself not to make any public departure from the fundamental tenets of psychoanalytic theory before he had discussed his views with the others. After this development, Jung recognised that his position was untenable and resigned as editor of the Jahrbuch and then as president of the IPA in April 1914. The Zürich branch of the IPA withdrew from membership the following July.[98] Later the same year, Freud published a paper entitled "The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement", the German original being first published in the Jahrbuch, giving his view on the birth and evolution of the psychoanalytic movement and the withdrawal of Adler and Jung from it. The final defection from Freud's inner circle occurred following the publication in 1924 of Rank's The Trauma of Birth which other members of the Committee read as, in effect, abandoning the Oedipus Complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytic theory. Abraham and Jones became increasingly forceful critics of Rank and though he and Freud were reluctant to end their close and long-standing relationship the break finally came in 1926 when Rank resigned from his official posts in the IPA and left Vienna for Paris. His place on the committee was taken by Anna Freud.[99] Rank eventually settled in the United States where his revisions of Freudian theory were to influence a new generation of therapists uncomfortable with the orthodoxies of the IPA. |

IPAからの退会 フロイトの信奉者の中には、その後、国際精神分析協会(IPA)から脱退し、独自の学派を設立した者もいた。 1909年以降、神経症などに関するアドラーの見解は、フロイトが抱いていたものとは著しく異なるようになった。アドラーの立場がフロイト主義とますます 相容れないと思われるようになると、1911年1月と2月にウィーンで開かれた精神分析学会で、両者の見解の対立が相次いだ。1911年2月、当時会長で あったアドラーはその職を辞した。この時、ステッケルも副会長の職を辞した。1911年6月、アドラーはついにフロイト派から完全に離脱し、同じくフロイ ト派から離脱した9人のメンバーとともに独自の組織を結成した。第一次世界大戦後の時期には、アドラーは個人心理学と呼ばれる彼が考案した心理学的立場と の結びつきを強めていった[96]。  1922年の委員会(左から右へ): オットー・ランク、ジークムント・フロイト、カール・アブラハム、マックス・アイティンゴン、サンドル・フェレンツィ、アーネスト・ジョーンズ、ハンス・サックス。 1912年、ユングは『無意識の心理学(Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido)』(1916年に英語版として出版)を発表し、フロイトとはまったく異なる方向性を明らかにした。フロイトとユングの関係が最終的に破綻す ることを予期していたアーネスト・ジョーンズは、精神分析運動の理論的一貫性と制度的遺産を守ることを任務とする忠誠者たちによる秘密委員会の結成に着手 した。1912年秋に結成されたこの委員会は、フロイト、ジョーンズ、アブラハム、フェレンツィ、ランク、ハンス・ザックスで構成されていた。マックス・ アイティンゴンは1919年に委員会に加わった。各メンバーは、自分の意見を他のメンバーと話し合う前に、精神分析理論の基本的な考え方から公の場で逸脱 しないことを誓った。このような展開の後、ユングは自分の立場が成り立たなくなったことを認識し、1914年4月にJahrbuch誌の編集長を、そして IPAの会長を辞任した。IPAのチューリッヒ支部は翌年7月に脱退した[98]。 同年末、フロイトは「精神分析運動の歴史」と題する論文を発表し、ドイツ語の原文はジャーブッフ誌に初めて掲載され、精神分析運動の誕生と発展、アドラーとユングの脱退についての見解を述べた。 フロイトの側近からの最終的な離反は、1924年に出版されたランクの『誕生のトラウマ』(The Trauma of Birth)の後に起こったが、委員会の他のメンバーは、これを事実上、精神分析理論の中心的信条としてのエディプス・コンプレックスを放棄したものと読 んだ。エイブラハムとジョーンズは次第にランクを強く批判するようになり、彼とフロイトは長年にわたる親密な関係を終わらせたがらなかったが、1926 年、ランクがIPAの公式ポストを辞任し、ウィーンからパリに向かった時、ついに断絶が訪れた。最終的にランクはアメリカに定住し、そこでフロイト理論の 改訂を行い、IPAの正統主義に違和感を持つ新しい世代のセラピストに影響を与えることになる。 |

| Early psychoanalytic movement After the founding of the IPA in 1910, an international network of psychoanalytical societies, training institutes, and clinics became well established and a regular schedule of biannual Congresses commenced after the end of World War I to coordinate their activities and as a forum for presenting papers on clinical and theoretical topics.[100] Abraham and Eitingon founded the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society in 1910 and then the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute and the Poliklinik in 1920. The Poliklinik's innovations of free treatment, and child analysis, and the Berlin Institute's standardisation of psychoanalytic training had a major influence on the wider psychoanalytic movement. In 1927, Ernst Simmel founded the Schloss Tegel Sanatorium on the outskirts of Berlin, the first such establishment to provide psychoanalytic treatment in an institutional framework. Freud organised a fund to help finance its activities and his architect son, Ernst, was commissioned to refurbish the building. It was forced to close in 1931 for economic reasons.[101] The 1910 Moscow Psychoanalytic Society became the Russian Psychoanalytic Society and Institute in 1922. Freud's Russian followers were the first to benefit from translations of his work, the 1904 Russian translation of The Interpretation of Dreams appearing nine years before Brill's English edition. The Russian Institute was unique in receiving state support for its activities, including publication of translations of Freud's works.[102] Support was abruptly annulled in 1924, when Joseph Stalin came to power, after which psychoanalysis was denounced on ideological grounds.[103] After helping found the American Psychoanalytic Association in 1911, Ernest Jones returned to Britain from Canada in 1913 and founded the London Psychoanalytic Society. In 1919, he dissolved this organisation and, with its core membership purged of Jungian adherents, founded the British Psychoanalytical Society, serving as its president until 1944. The Institute of Psychoanalysis was established in 1924 and the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis was established in 1926, both under Jones's directorship.[104] The Vienna Ambulatorium (Clinic) was established in 1922 and the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1924 under the directorship of Helene Deutsch.[105] Ferenczi founded the Budapest Psychoanalytic Institute in 1913 and a clinic in 1929. Psychoanalytic societies and institutes were established in Switzerland (1919), France (1926), Italy (1932), the Netherlands (1933), Norway (1933), and in Palestine (Jerusalem, 1933) by Eitingon, who had fled Berlin after Adolf Hitler came to power.[106] The New York Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1931. The 1922 Berlin Congress was the last Freud attended.[107] By this time his speech had become seriously impaired by the prosthetic device he needed as a result of a series of operations on his cancerous jaw. He kept abreast of developments through regular correspondence with his principal followers and via the circular letters and meetings of the Secret Committee which he continued to attend. The Committee continued to function until 1927 by which time institutional developments within the IPA, such as the establishment of the International Training Commission, had addressed concerns about the transmission of psychoanalytic theory and practice. There remained, however, significant differences over the issue of lay analysis – i.e. the acceptance of non-medically qualified candidates for psychoanalytic training. Freud set out his case in favour in 1926 in his The Question of Lay Analysis. He was resolutely opposed by the American societies who expressed concerns over professional standards and the risk of litigation (though child analysts were made exempt). These concerns were also shared by some of his European colleagues. Eventually, an agreement was reached allowing societies autonomy in setting criteria for candidature.[108] In 1930, Freud received the Goethe Prize in recognition of his contributions to psychology and German literary culture.[109] |

初期の精神分析運動 1910年にIPAが設立された後、精神分析学会、トレーニング機関、クリニックの国際的なネットワークが確立され、第一次世界大戦の終結後、それらの活 動を調整するために、また臨床的および理論的なトピックに関する論文を発表する場として、年2回の定期的な大会が開始された[100]。 アブラハムとアイティングンは1910年にベルリン精神分析協会を設立し、1920年にはベルリン精神分析研究所とポリクリニクを設立した。ポリクリニク の自由診療や児童分析の革新、ベルリン研究所の精神分析トレーニングの標準化は、より広い精神分析運動に大きな影響を与えた。1927年、エルンスト・ジ ンメルがベルリン郊外にシュロス・テーゲル療養所を設立した。このような施設は、制度的な枠組みで精神分析治療を提供した最初の施設である。フロイトはそ の活動資金を援助するための基金を組織し、建築家の息子エルンストが建物の改修を依頼された。1931年に経済的な理由から閉鎖を余儀なくされた [101]。 1910年のモスクワ精神分析協会は、1922年にロシア精神分析協会と研究所となった。フロイトのロシア人信奉者たちは、フロイトの著作の翻訳の恩恵を 最初に受けた。1904年の『夢の解釈』のロシア語訳は、ブリルによる英語版より9年早く出版された。ロシア研究所は、フロイトの著作の翻訳出版を含むそ の活動に対して国家からの支援を受けていた点でユニークであった[102]。支援は、1924年にヨシフ・スターリンが政権を握ると突然取り消され、その 後、精神分析はイデオロギー的な理由で非難された[103]。 1911年にアメリカ精神分析協会の設立に貢献したアーネスト・ジョーンズは、1913年にカナダからイギリスに戻り、ロンドン精神分析協会を設立した。 1919年、彼はこの組織を解散し、ユング派の信奉者を一掃したコアメンバーで英国精神分析協会を設立し、1944年まで会長を務めた。精神分析研究所は 1924年に設立され、ロンドン精神分析クリニックは1926年に設立された。 ウィーン精神分析研究所は1924年にヘレーネ・ドイッチの監督の下で設立された。フェレンツィは1913年にブダペスト精神分析研究所を設立し、1929年にクリニックを設立した[105]。 精神分析協会や研究所は、スイス(1919年)、フランス(1926年)、イタリア(1932年)、オランダ(1933年)、ノルウェー(1933年)、そしてパレスチナ(エルサレム、1933年)に設立された。 1922年のベルリン大会がフロイトが出席した最後の大会となった[107]。この頃までに、フロイトは、がんを患った顎の一連の手術の結果必要となった 義肢によって、発話に深刻な障害を抱えるようになっていた。彼は、主要な信奉者たちとの定期的な手紙のやり取りや、彼が出席し続けた秘密委員会の回覧や会 議を通じて、動向を把握していた。 この委員会は1927年まで機能し続け、その頃には国際研修委員会の設立など、IPA内の制度的な整備が進み、精神分析の理論と実践の継承に関する懸念に 対処していた。しかし、一般人による分析の問題、すなわち医療資格を持たない精神分析研修生の受け入れについては、大きな相違が残っていた。フロイトは 1926年、『素人分析の問題』(The Question of Lay Analysis)の中で、賛成の立場を示した。しかしフロイトは、専門的水準や訴訟リスクに対する懸念を表明したアメリカの学会から、断固として反対さ れた(ただし、児童分析家は免除された)。このような懸念は、ヨーロッパの同僚たちにも共有されていた。最終的には、学会が立候補の基準を設定する際の自 主性を認めることで合意に達した[108]。 1930年、フロイトは心理学とドイツ文学文化への貢献が認められ、ゲーテ賞を受賞した[109]。 |

| Patients Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories. Some patients known by pseudonyms were Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945); Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser); Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss);[110] Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich); Fräulein Lucy R.; Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973); Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer); Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild);[111] and Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff). Other famous patients included Prince Pedro Augusto of Brazil; H.D.; Emma Eckstein; Gustav Mahler, with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation; Princess Marie Bonaparte; Edith Banfield Jackson;[112] and Albert Hirst.[113] |

患者たち フロイトはケースヒストリーに偽名を用いた。仮名で知られる患者には、ケシリー・M(アンナ・フォン・リーベン)、ドーラ(イーダ・バウアー、1882- 1945)、フラウ・エミー・フォン・N(ファニー・モーザー)、エリザベート・フォン・R(イローナ・ヴァイス)、カタリーナ(アウレリア・クロニッ チ)、ルーシー・R(ルーシー・R)、リトル・ハンス(ヘルベルト・グラフ、1903-1973)、ネズミ男(エルンスト・ランツァー)、エノス・フィン ギ(ジョシュア・ワイルド)、狼男(セルゲイ・パンケジェフ)などがいる[111]。その他の有名な患者には、ブラジルのペドロ・アウグスト王子、 H.D.、エマ・エクスタイン、グスタフ・マーラー(フロイトは一度だけ長期間のカウンセリングを行った)、マリー・ボナパルト王女、エディス・バン フィールド・ジャクソン[112]、アルバート・ハーストなどがいた[113]。 |

| Cancer In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. He initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed. Freud consulted the dermatologist Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but minimizing the growth's importance. Freud later saw Felix Deutsch, who identified it to Freud using the euphemism "a bad leukoplakia" instead of the technical diagnosis epithelioma. Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised. Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a rhinologist whose competence he had previously questioned. Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic's outpatient department. Freud bled during and after the operation and may narrowly have escaped death. At a subsequent visit Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required but did not tell Freud he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might commit suicide.[114] |

癌 1923年2月、フロイトは自分の口元に白板症(多量の喫煙に伴う良性の増殖)を発見した。彼は当初このことを秘密にしていたが、1923年4月、アーネ スト・ジョーンズに報告し、腫瘍が取り除かれたことを伝えた。フロイトは皮膚科医のマクシミリアン・シュタイナーに相談し、禁煙を勧められたが、その増殖 の重要性は最小限にとどめられた。その後、フロイトはフェリックス・ドイッチュの診察を受け、専門的な診断である上皮腫の代わりに「悪い白板症」という婉 曲的な表現を使ってフロイトにこの病変を認めた。ドイッチュはフロイトに禁煙と切除を勧めた。フロイトは、以前からその能力に疑問を持っていた鼻科医マー カス・ハイエックに治療を受けた。ハジェックはクリニックの外来で不必要な美容整形手術を行った。フロイトは手術中も手術後も出血し、危うく死を免れたか もしれなかった。その後の診察で、ドイチュはさらなる手術が必要であることを察したが、フロイトが自殺することを心配したため、フロイトに癌であることを 告げなかった[114]。 |

| Escape from Nazism In January 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those they burned. Freud remarked to Ernest Jones: "What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books."[115] Freud underestimated the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938 and the outbreaks of violent antisemitism that ensued.[116] Jones, the then president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), flew into Vienna on 15 March determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain. This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave.[116] Jones left for London the following week with a list provided by Freud of the party of émigrés for whom immigration permits would be required. Back in London, Jones used his personal acquaintance with the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, to expedite the granting of permits. There were seventeen in all, and work permits were provided where relevant. Jones also used his influence in scientific circles, persuading the president of the Royal Society, Sir William Bragg, to write to the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, requesting to good effect that diplomatic pressure be applied in Berlin and Vienna on Freud's behalf. Freud also had support from American diplomats, notably his ex-patient and American ambassador to France, William Bullitt. Bullitt alerted U.S. President Roosevelt to the increased dangers facing the Freuds, resulting in the American consul-general in Vienna, John Cooper Wiley, arranging regular monitoring of Berggasse 19. He also intervened by phone during the Gestapo interrogation of Anna Freud.[117] The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938. Freud's grandson, Ernst Halberstadt, and Freud's son Martin's wife and children left for Paris in April. Freud's sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud's daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.[118] By the end of the month, arrangements for Freud's own departure for London had become stalled, mired in a legally tortuous and financially extortionate process of negotiation with the Nazi authorities. Under regulations imposed on the Jewish population by the Nazis, a Kommissar was appointed to manage Freud's assets and those of the IPA. Freud was allocated to Dr Anton Sauerwald, who had studied chemistry at Vienna University under Professor Josef Herzig, an old friend of Freud's. Sauerwald read Freud's books to further learn about him and became sympathetic. Though required to disclose details of all Freud's bank accounts to his superiors and to arrange the destruction of the historic library of books housed at the IPA, Sauerwald did neither. Instead, he removed evidence of Freud's foreign bank accounts to his own safe-keeping and arranged the storage of the IPA library in the Austrian National Library, where it remained until the end of the war.[119]  Freud's last home, now dedicated to his life and work as the Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, north London  Close up of his commemorative Blue plaque (commissioned by English Heritage) at his Hampstead home Though Sauerwald's intervention lessened the financial burden of the Reich Flight Tax on Freud's declared assets, other substantial charges were levied concerning the debts of the IPA and the valuable collection of antiquities Freud possessed. Unable to access his own accounts, Freud turned to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the most eminent and wealthy of his French followers, who had travelled to Vienna to offer her support, and it was she who made the necessary funds available.[120] This allowed Sauerwald to sign the necessary exit visas for Freud, his wife Martha, and daughter Anna. They left Vienna on the Orient Express on 4 June, accompanied by their housekeeper and a doctor, arriving in Paris the following day, where they stayed as guests of Marie Bonaparte, before travelling overnight to London, arriving at London Victoria station on 6 June. Among those soon to call on Freud in London to pay their respects were Salvador Dalí, Stefan Zweig, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, and H. G. Wells. Representatives of the Royal Society called with the Society's Charter for Freud, who had been elected a Foreign Member in 1936, to sign himself into membership. Marie Bonaparte arrived near the end of June to discuss the fate of Freud's four elderly sisters in Vienna. Her subsequent attempts to get them exit visas failed; they all were murdered in Nazi concentration camps.[121] In early 1939, Sauerwald arrived in London in mysterious circumstances, where he met Freud's brother Alexander.[122] He was tried and imprisoned in 1945 by an Austrian court for his activities as a Nazi Party official. Responding to a plea from his wife, Anna Freud wrote to confirm that Sauerwald "used his office as our appointed commissar in such a manner as to protect my father". Her intervention helped secure his release in 1947.[123] The Freud's new family home was established in Hampstead at 20 Maresfield Gardens in September 1938. Freud's architect son, Ernst, designed modifications of the building including the installation of an electric lift. The study and library areas were arranged to create the atmosphere and visual impression of Freud's Vienna consulting rooms.[124] He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness. He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and in English the following year[125] and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis, which was published posthumously. |

ナチズムからの脱出 1933年1月、ナチ党がドイツを掌握し、フロイトの著書が焚書された。フロイトはアーネスト・ジョーンズにこう言った: 「なんて進歩しているんだ。中世なら、彼らは私を燃やしていただろう。フロイトはナチスの脅威の高まりを過小評価し、1938年3月13日のアンシュルス とそれに続く激しい反ユダヤ主義の勃発の後でも、ウィーンに留まる決意を固めていた[116]。当時国際精神分析協会(IPA)の会長であったジョーンズ は、3月15日にウィーンに飛び、フロイトに考えを改めさせ、イギリスに亡命することを決意させた。この見通しと、ゲシュタポによるアンナ・フロイトの逮 捕と尋問の衝撃によって、フロイトはついに、英国を去るときが来たと確信した[116]。ジョーンズは翌週、フロイトから提供された、移民許可証が必要と なる移民団のリストを持ってロンドンに向かった。ロンドンに戻ったジョーンズは、内務大臣サミュエル・ホア卿との個人的な知己を利用して、許可証の発行を 早めた。全部で17の許可証が発行され、関連する場合には労働許可証も発行された。ジョーンズは科学界にも影響力を行使し、王立協会会長のサー・ウィリア ム・ブラッグを説得して、外務大臣ハリファックス卿に手紙を書かせ、フロイトのためにベルリンとウィーンで外交的圧力をかけるよう要請した。フロイトはま た、アメリカの外交官、特に彼の元患者で駐仏アメリカ大使のウィリアム・ブリットからも支援を受けていた。ウイリアム・ブリットは、ルーズベルト米大統領 にフロイト一家が直面する危険の増大を警告し、その結果、在ウィーン米国総領事ジョン・クーパー・ワイリーは、ベルクガッセ19番地の定期的な監視を手配 した。彼はまた、ゲシュタポによるアンナ・フロイトの尋問の際に電話で介入した[117]。 ウィーンからの出発は1938年4月から5月にかけて段階的に始まった。フロイトの孫、エルンスト・ハルバーシュタットとフロイトの息子マルティンの妻と 子供たちは4月にパリに向かった。フロイトの義理の妹であるミンナ・バーネイズは5月5日に、マルティン・フロイトは翌週に、そしてフロイトの娘マチルド とその夫であるロベルト・ホリッチャーは5月24日にロンドンに向けて出発した[118]。 その月の終わりには、フロイト自身のロンドンへの出発の手配は行き詰まり、ナチス当局との交渉は、法的にも紆余曲折し、金銭的にも恐喝的なプロセスに陥っ ていた。ナチスがユダヤ人に課した規制により、フロイトとIPAの資産を管理する公使が任命された。フロイトは、ウィーン大学でフロイトの旧友ヨーゼフ・ ヘルツィヒ教授の下で化学を学んでいたアントン・ザウアーヴァルト博士に割り当てられた。ザウアーヴァルトは、フロイトについてさらに学ぶためにフロイト の本を読み、彼に共感するようになった。フロイトのすべての銀行口座の詳細を上司に開示し、IPAに収蔵されていた歴史的な蔵書の破棄を手配するよう求め られたが、ザウアーヴァルトはそれをしなかった。その代わりに、彼はフロイトの外国の銀行口座の証拠を自分の安全な場所に移し、IPAの蔵書をオーストリ ア国立図書館に保管するよう手配し、終戦までそこに保管された[119]。  フロイトの終の棲家、現在はフロイト博物館として彼の人生と仕事に捧げられている。  ハムステッドにあるフロイトの自宅の記念の青いプレート(イングリッシュ・ヘリテージによる依頼)のクローズアップ。 ザウアーヴァルトの介入により、フロイトの申告資産に対する帝国飛行税による経済的負担は軽減されたものの、IPAの負債やフロイトが所有していた貴重な 古美術品のコレクションに関しては、他にも多額の請求がなされた。このため、ザウアーヴァルトは、フロイト、妻マーサ、娘アンナのために必要な出国ビザに 署名することができた[120]。彼らは家政婦と医師を伴って6月4日にオリエント急行でウィーンを出発し、翌日パリに到着してマリー・ボナパルトの客と して滞在した。 間もなく、サルバドール・ダリ、ステファン・ツヴァイク、レナード・ウルフとヴァージニア・ウルフ、H・G・ウェルズらがロンドンでフロイトに敬意を表し た。王立協会の代表は、1936年に外国人会員に選出されたフロイトのために、同協会の会員証を持って訪れ、会員になるための署名を求めた。マリー・ボナパルトは、ウィーンにいるフロイトの4人の老姉妹の運命について話し合うために、6月末近くに到着した。その後、彼女は彼女たちに出国ビザを取得させよう と試みたが失敗に終わり、彼女たち全員がナチスの強制収容所で殺害された[121]。 1939年初頭、ザウアーヴァルトは謎めいた状況でロンドンに到着し、そこでフロイトの兄アレクサンダーと出会う。アンナ・フロイトは、彼の妻からの嘆願 に応え、ザウアーヴァルトが「父を守るために、私たちの任命した委員としての地位を利用した」ことを確認するために手紙を書いた。彼女の介入によって、 1947年に彼は釈放された[123]。 1938年9月、フロイト一家の新しい家がハムステッドのマレスフィールド・ガーデンズ20番地に建てられた。フロイトの建築家である息子のエルンスト は、電動エレベーターの設置を含む建物の改造を設計した。書斎と図書室は、フロイトのウィーンの診察室の雰囲気と視覚的な印象を作り出すように配置され た。また、1938年にドイツ語で出版され、翌年には英語で出版された『モーセと一神教』[125]や、死後に出版された未完の『精神分析概論』の執筆に も取り組んだ。 |

Death Freud's ashes in the "Freud Corner" at Golders Green Crematorium, London By mid-September 1939, Freud's cancer of the jaw was causing him increasingly severe pain and had been declared inoperable. The last book he read, Balzac's La Peau de chagrin, prompted reflections on his own increasing frailty, and a few days later he turned to his doctor, friend, and fellow refugee, Max Schur, reminding him that they had previously discussed the terminal stages of his illness: "Schur, you remember our 'contract' not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense." When Schur replied that he had not forgotten, Freud said, "I thank you," and then, "Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it's right, then make an end of it." Anna Freud wanted to postpone her father's death, but Schur convinced her it was pointless to keep him alive; on 21 and 22 September, he administered doses of morphine that resulted in Freud's death at around 3 am on 23 September 1939.[126][127] However, discrepancies in the accounts Schur gave of his role in Freud's final hours led to inconsistencies between Freud's main biographers. A revised account proposes that Schur was absent from Freud's deathbed when a third and final dose of morphine was administered by Dr. Josephine Stross, a colleague of Anna Freud, leading to Freud's death at around midnight on 23 September 1939.[128] Three days after his death, Freud's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium, with Harrods acting as funeral directors, on the instructions of his son, Ernst.[129] Funeral orations were given by Ernest Jones and the Austrian author Stefan Zweig. Freud's ashes were later placed in a corner of the crematorium's Ernest George Columbarium on a plinth designed by his son, Ernst,[130] in a sealed[129] ancient Greek bell krater painted with Dionysian scenes that Freud had received as a gift from Marie Bonaparte, and which he had kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After his wife, Martha, died in 1951, her ashes were also placed in the urn.[131] |

死 ゴールダーズ・グリーン火葬場の「フロイト・コーナー」に安置されたフロイトの遺灰(ロンドン) 1939年9月中旬までに、フロイトの顎の癌はますます激しい痛みを引き起こし、手術不可能と宣告された。数日後、彼は主治医であり、友人であり、難民仲 間であったマックス・シュアーに向かい、以前病気の末期について話し合ったことを思い出した: シュール、その時が来ても私を見捨てないという私たちの 「契約 」を覚えているだろう。今となっては拷問以外の何物でもなく、何の意味もない」。シュールが忘れていないと答えると、フロイトは「ありがとう」と言い、 「アンナとよく話し合って、彼女が正しいと思うなら、終わりにしてくれ」と言った。アンナ・フロイトは父の死を延期することを望んだが、シューアは父を生 かしておくことは無意味だと彼女を説得した。9月21日と22日、彼はモルヒネを投与し、その結果、フロイトは1939年9月23日の午前3時頃に死亡し た[126][127]。しかし、フロイトの最期の時間における彼の役割についてシューアが語った内容に食い違いがあったため、フロイトの主な伝記作家の 間で矛盾が生じた。改訂された説明では、アンナ・フロイトの同僚であったジョセフィン・シュトロス博士によって3回目の最後のモルヒネ投与が行われたと き、シュアはフロイトの死の床におらず、1939年9月23日の真夜中頃にフロイトは死亡したとされている[128]。 死後3日後、フロイトの遺体は、息子のエルンストの指示により、ハロッズが葬儀屋を務めるゴルダーズ・グリーン火葬場で火葬された[129]。葬儀の辞 は、アーネスト・ジョーンズとオーストリアの作家シュテファン・ツヴァイクによって行われた。その後、フロイトの遺灰は、火葬場のアーネスト・ジョージ霊 廟の一角に息子のエルンストがデザインした台座の上に置かれ[130]、フロイトがマリー・ボナパルトからの贈り物として受け取り、長年ウィーンの書斎に 保管していたディオニュソスの場面が描かれた封印された[129]古代ギリシャの鐘のクラテルの中に納められた。1951年に妻マーサが亡くなった後、彼 女の遺灰もこの骨壷に納められた[131]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund_Freud |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆