フロイト的ナルシシズムの理解

Freudian Narcissim

フロイト的ナルシシズムの理解

Freudian Narcissim

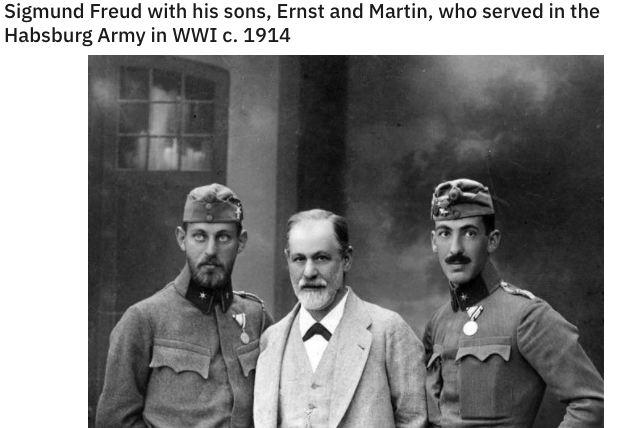

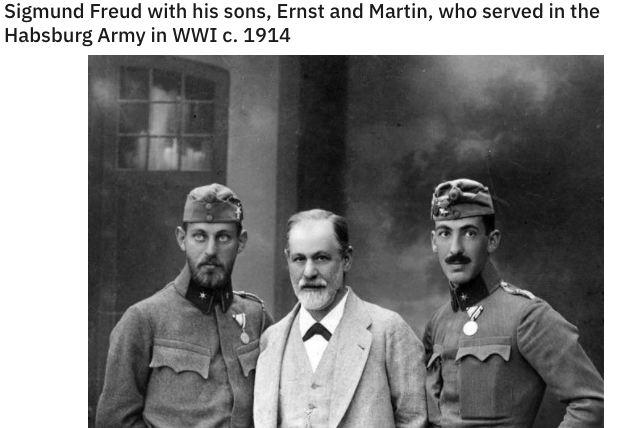

「ナルシシズム入門」Zur Einführung des Narzißmusは、ジークムント・フロイト(Sigmund Freud, 1856-1939)の1914年(58歳時)に発表された著作である。

ナルシシズムの定義に始まり、今日でいうところの統 合失調症(スキゾフレニー)——フロイトが好んで使った用語はパラフレニー——患者に見られるリビドー理論を検証するために、ナルシシズムを様態を観察を 通して検証する理論的考察という体裁をとる。3部構成で、冒頭の第1部は、リビドー 概念の検証で、自我リビドーと性の欲動リビドー(あるいは対象リビ ドー)が検証されるが、袂を分かったカール・ユングの解釈が批判される。第2部は、ナルシシズムを、1)器質的疾患、2)ヒポコンデリー、3)男性女性の両 性の愛情生活の観察から考察しようとするものである。特に3番目の男女のナルシシズムの違いを説明するのに、冒頭でザドガーが、同性愛者に ナルシシズム傾 向があるという指摘に着目して、男性と女性の欲動の対象化パターン(ナルシシズム型と依存型の2類型がある)の非対称性について言及している(留意点:同 性愛嗜好は現在ではノーマライズされているので病理で説明する必要はもはやないが、男性と女性の振る舞い=パフォーマンスという点を考慮して同性愛の欲動 をリビドー概念で説明すれば現在でも通用する主張がある)。第3部ではアドラーのコ ンプレックス概念からヒントを得ながらも距離をとりつつ、自我概念、昇 華、検閲などの心的機能概念が検討される。リビドーと自我のダイナミックスはナルシシズムの表出形態にさまざまな影響を与えることをフロイ トは比較的自由 奔放に記述している。最後は7つほどの自我論の命題が列挙されて、唐突に終えられて いる印象は避けがたい。

1914(フロイト58歳) ユングは国際精神分析学会を脱退。「ナルシシズム入門」Zur Einführung des Narzißmus.

| 邦訳 |

paragraph |

JAPOn-Narcissism-Sigmund-Freud.pdf

with password |

英訳 https://bit.ly/2ZcPhaw |

| 109 |

1 |

Section I ・リビドー理論を考えるための第1の流れ:学説の誕生 ・ナルシシズムのP・ネッケ(1899)の定義:「ある人間が自分の肉体をあたかも対象のように取り扱う、つまり性的な快楽をいだいてこれを眺め、さす り、愛撫して、ついてには完全な満足にいたる行為」 ・フロイトの見立て→ナルシシズム研究はパヴァージョンのこと、パヴァージョン研究に役立つ可能性 ※ナルシスのようにと書いたのは1898年のハヴェロック・エリス |

The term

narcissism is derived from clinical description and was chosen by Paul

Näcke in 1899 to 1

denote the attitude of a person who treats his own body in the same way

in which the body of a

sexual object is ordinarily treated—who looks at it, that is to say,

strokes it and fondles it till he

obtains complete satisfaction through these activities. Developed to

this degree, narcissism has the

significance of a perversion that has absorbed the whole of the

subject's sexual life, and it will

consequently exhibit the characteristics which we expect to meet within

the study of all perversions. ++ 1. In a footnote added by Freud in 1920 to his Three Essays (1905d, Standard Ed., 7, 218n.) he said that he was wrong in stating in the present paper that the term ‘narcissism’ was introduced by Näcke and that he should have attributed it to Havelock Ellis. Ellis himself, however, subsequently (1927)wrote a short paper in which he corrected Freud's correction and argued that the priority should, in fact, be divided between himself and Näcke, explaining that the term ‘narcissus- like’ had been used by him in 1898 as a description of a psychological attitude, and that Näcke in 1899 had introduced the term ‘Narcismus’ to describe a sexual perversion. The German word used by Freud is ‘Narzissmus’. In his paper on Schreber (1911c), near the beginning of Section III, he defends this form of the word on the ground of euphony against the possibly more correct ‘Narzissismus’. |

| 2 |

・サドガーは、ナルシシズムは同性愛者に

傾向がみられる ・ナルシシズム=リビドーの保管(an allocation of the libido )——リビドーの存在する場所の概念の示唆 ・リビドー概念から、ナルシシズムはパヴァージョンは、生物の自己保存本能を補完する(the libidinal complement to the egoism of the instinct of self-preservation, a measure of which may justifiably be attributed to every living creature)。 Otto Rank, 1884-1939 |

Psycho-analytic

observers were subsequently struck by the fact that individual features

of the

narcissistic attitude are found in many people who suffer from other

disorders—for instance, as

Sadger has pointed out, in homosexuals—and, finally, it seemed probable

that an allocation of the

libido such as deserved to be described as narcissism might be

present

far more extensively, and that

it might claim a place in the regular course of human sexual

development. Difficulties in 2

psycho-analytic work upon neurotics led to the same supposition, for it

seemed as though this kind

of narcissistic attitude in them constituted one of the limits to their

susceptibility to influence.

Narcissism in this sense would not be a perversion, but the libidinal

complement to the egoism of

the instinct of self-preservation, a measure of which may justifiably

be attributed to every living

creature. ++ 2.Otto Rank (1911c). |

|

| 110 |

3 |

・リビドー理論を考えるための第2の流

れ:スキゾフレニーとリビドー理論 ・第一次的で正常なナルシシズム概念の研究は、(今日でいうところのブロイラーの)統合失調症の理解におけるリビドー概念の適用からうまれた。 ・フロイトの用語は「パラフレニア」が相当するが、その特徴は、1)誇大妄想、と、2)外界の人物や事物の関心の離反。 ・ヒステリーや強迫神経症も、現実から遊離しているが、エロティックな関係は失われていない。 ・ユングはそれを「リビドーの内向」というのが、この場合にのみ言及すべきで、パラフレニーに拡張してはならぬ。 |

A pressing motive

for occupying ourselves with the conception of a primary and normal

narcissism

arose when the attempt was made to subsume what we know of dementia

praecox (Kraepelin) or

schizophrenia (Bleuler) under the hypothesis of the libido theory.

Patients of this kind, whom I have

proposed to term paraphrenics, display two fundamental characteristics:

megalomania and diversion 3

of their interest from the external world—from people and things. In

consequence of the latter

change, they become inaccessible to the influence of psychoanalysis and

cannot be cured by our

efforts. But the paraphrenic's turning away from the external world

needs to be more precisely

characterized. A patient suffering from hysteria or obsessional

neurosis has also, as far as his illness

extends, given up his relation to reality. But analysis shows that he

has by no means broken off his

erotic relations to people and things. He still retains them in

phantasy; i.e. he has, on the one hand,

substituted for real objects imaginary ones from his memory, or has

mixed the latter with the

former; and on the other hand, he has renounced the initiation of motor

activities for the attainment

of his aims in connection with those objects. Only to this condition of

the libido may we legitimately

apply the term ‘introversion’ of the libido which is used by Jung

indiscriminately. It is otherwise 4

with the paraphrenic. He seems really to have withdrawn his libido from

people and things in the

external world, without replacing them by others in phantasy. When he

does so replace them, the

process seems to be a secondary one and to be part of an attempt at

recovery, designed to lead the

libido back to objects.5 +++ 3 For a discussion of Freud's use of this term, see a long Editor's footnote near the end of Section III of the Schreber analysis (1911c). 4 Cf. a footnote in ‘The Dynamics of Transference’ (1912b). 5 In connection with this see my discussion of the ‘end of the world’ in [Section III of] the analysis of Senatspräsident Schreber [1911c]; also Abraham, 1908. |

| 4 |

・誇大妄想はリビドーの犠牲による ・一次的なナルシシズム、二次的なナルシシズム |

The question arises: What happens to the libido which has been withdrawn from external objects in schizophrenia? The megalomania characteristic of these states points the way. This megalomania has no doubt come into being at the expense of object-libido. The libido that has been withdrawn from the external world has been directed to the ego and thus gives rise to an attitude which may be called narcissism. But the megalomania itself is no new creation; on the contrary, it is, as we know, a magnification and plainer manifestation of a condition which had already existed previously. This leads us to look upon the narcissism which arises through the drawing in of object-cathexes as asecondary one, superimposed upon a primary narcissism that is obscured by a number of different influences. | |

| 111 |

5 |

・この論文はスキゾフレニーの問題の解明

を目的とはしない ※「自伝的に記述されたパノイア(妄想性痴呆)の一症例に関する精神分析的考察」著作集9) ※「自我の発達」の「リビドーの発達」のテーマは、早発性痴呆=スキゾフレニー分析にふさわしいとフロイトは考えていた。 |

Let me insist that

I am not proposing here to explain or penetrate further into the

problem of schizophrenia, but that I am merely putting together what

has already been said elsewhere, in order 6 to justify the introduction

of the concept of narcissism. ++ 6 See, in particular, the works referred to in the last footnote. On p. 86 below, Freud in fact penetrates further into the problem. |

| 6 |

・リビドー理論を考えるための第3の流

れ:児童や原始人の精神生活の観察 ・「自我にふりあてられた根源的なリビドーの割当」 ・リビドーの格納(原生動物の偽足の比喩) ・自我リビドーと対象リビドーのあいだの対立(→トレードオフ) ・つまり、一方が余計に使われれば、他方がそれだけ減る ・対象リビドーに使う最高段階は恋着である ・心的エネルギーは、ナルシシズムの場合は共存している ・性的エネルギー=リビドーを自我本能のエネルギーから区別するおとは、対象への割当をまってはじめて可能となる。 |

This extension of the libido theory—in my opinion, a legitimate one— receives reinforcement from a third quarter, namely, from our observations and views on the mental life of children and primitive peoples. In the latter we find characteristics which, if they occurred singly, might be put down to megalomania: an over-estimation of the power of their wishes and mental acts, the ‘omnipotence of thoughts’, a belief in the thaumaturgic force of words, and a technique for dealing with the external world—‘magic’—which appears to be a logical application of these grandiose premisses. In the 7 children of to-day, whose development is much more obscure to us, we expect to find an exactly analogous attitude towards the external world. Thus we form the idea of there being an original 8 libidinal cathexis of the ego, from which some is later given off to objects, but which fundamentally persists and is related to the object-cathexes much as the body of an amoeba is related to the pseudopodia which it puts out. In our research, taking, as they did, neurotic symptoms for their 9 starting-point, this part of the allocation of libido necessarily remained hidden from us at the outset. All that we noticed were the emanations of this libido—the object-cathexes, which can be sent out and drawn back again. We also see, broadly speaking, an antithesis between ego-libido and object-libido. The more of the one is employed, the more the other becomes depleted. The highest 10 phase of development of which object-libido is capable is seen in the state of being in love, when the subject seems to give up his own personality in favour of an object-cathexis; while we have the opposite condition in the paranoic's phantasy (or self-perception) of the ‘end of the world’. Finally, 11 as regards the differentiation of psychical energies, we are led to the conclusion that to begin with, during the state of narcissism, they exist together and that our analysis is too coarse to distinguish between them; not until there is object-cathexis is it possible to discriminate a sexual energy—the libido—from an energy of the ego-instincts.12 | |

| 112 |

7 |

英訳ではパラグラフで改行されていて、ま

た論理的に適切である。 ・審問1)ナルシシズムは、リビドーの初期状態として記述する自体愛とどんな関係にあるか? ・審問2)もしリビドーの第一次割当が自我に与えられていたら、性的リビドー(sexual libido)を性的でない自我欲動(ego- instincts) のエネルギーとどのように区別することは、なんのために役立つか? 第1の審問には)自我に比べうるような統一は最初から個人にはない ・ナルシシズム形成には、自体愛になにかほかの心的作用がつけ加わる必要がある。 |

Before going any

further I must touch on two questions which lead us to the heart of the

difficulties

of our subject. In the first place, what

is the relation of the

narcissism of which we are now speaking

to auto-erotism, which we have described as an early state of the

libido? Secondly, if we grant the 13

ego a primary cathexis of libido, why

is there any necessity for

further distinguishing a sexual libido

from a non-sexual energy of the ego- instincts? Would not the

postulation of a single kind of

psychical energy save us all the difficulties of differentiating an

energy of the ego-instincts from

ego-libido, and ego-libido from object-libido?14 As regards the first question, I may point out that we are bound to suppose that a unity comparable to the ego cannot exist in the individual from the start; the ego has to be developed. The auto-erotic instincts, however, are there from the very first; so there must be something added to auto-erotism—a new psychical action—in order to bring about narcissism. |

| 8 |

第2の審問に答えるには、困難さ(=不快

さ)が生じる。——自我リビドーやじ自我欲動エネルギーなどの思弁的議論の前に、しっかりとした、経験のうえに築かれた学問が必要。 ・その議論の基礎は、観察である。 ・観察こそが最上部にある。 |

To be asked to

give a definite answer to the second question must occasion perceptible

uneasiness in

every psycho-analyst. One dislikes the thought of abandoning

observation for barren theoretical

controversy, but nevertheless one must not shirk an attempt at

clarification. It is true that notions

such as that of an ego-libido, an energy of the ego-instincts, and so

on, are neither particularly easy

to grasp, nor sufficiently rich in content; a speculative theory of the

relations in question would

begin by seeking to obtain a sharply defined concept as its basis. But

I am of the opinion that that is just the difference between a

speculative theory and a science erected on empirical interpretation.

The latter will not envy speculation its privilege of having a smooth,

logically unassailable

foundation, but will gladly content itself with nebulous, scarcely

imaginable basic concepts, which it

hopes to apprehend more clearly in the course of its development, or

which it is even prepared to

replace by others. For these ideas are not the foundation of science,

upon which everything rests:

that foundation is observation alone.

They are not the bottom but the

top of the whole structure,

and they can be replaced and discarded without damaging it. The same

thing is happening in our day

in the science of physics, the basic notions of which as regards

matter, centres of force, attraction,

etc., are scarcely less debatable than the corresponding notions in

psycho-analysis.15 |

|

| 113 |

9 |

・自我リビドー(

‘ego-libido’ )、対象リビドー(‘object-libido’):The value of the

concepts ‘ego-libido’ and ‘object-libido’ lies in the fact that they

are derived from

the study of the intimate characteristics of neurotic and psychotic

processes. |

The value of the

concepts ‘ego-libido’ and ‘object-libido’ lies in the fact that they

are derived from

the study of the intimate characteristics of neurotic and psychotic

processes. A differentiation of

libido into a kind which is proper to the ego and one which is attached

to objects is an unavoidable

corollary to an original hypothesis which distinguished between sexual

instincts and ego-instincts. At

any rate, analysis of the pure transference neuroses (hysteria and

obsessional neurosis) compelled me

to make this distinction and I only know that all attempts to account

for these phenomena by other

means have been completely unsuccessful. |

| 10 |

・we may

be permitted, or rather, it is incumbent upon us, to start off by

working out some hypothesis to its

logical conclusion until it either breaks down or is confirmed. 1)飢餓と愛いの区別 2)生物学的な考察 ・個人は現実的には二重の存在:ひとつは自己目的的、他方は鎖の一部 ・個人は遺伝形質の付属物、そのために自分の力を快楽に捧げている。 ・人間は不滅の実体を担う死すべき者 ・性の欲動と自我欲動を区別することが、その二重性の機能を明らかにする 3)有機体である担い手を基盤にせよ ・性愛は化学的なプロセス |

In the total

absence of any theory of the instincts which would help us to find our

bearings, we may

be permitted, or rather, it is incumbent upon us, to start off by

working out some hypothesis to its

logical conclusion until it either breaks down or is confirmed. There

are various points in favor of

the hypothesis of there having been from the first a separation between

sexual instincts and others,

ego-instincts, besides the serviceability of such a hypothesis in the

analysis of the transference

neuroses. I admit that this latter consideration alone would not be

unambiguous, for it might be a

question of an indifferent psychical energy which only becomes libido

through the act of 16

cathecting an object. But, in the first place, the distinction made in

this concept corresponds to the common, popular distinction between

hunger and love. In the second place, there are biological

considerations in its favor. The individual does actually carry on a

twofold existence: one to serve his

own purposes and the other as a link in a chain, which he serves

against his will, or at least

involuntarily. The individual himself regards sexuality as one of his

own ends; whereas from another

point of view he is an appendage to his germplasm, at whose disposal he

puts his energies in return

for a bonus of pleasure. He is the mortal vehicle of a (possibly)

immortal substance—like the

inheritor of an entailed property, who is only the temporary holder of

an estate which survives him.

The separation of the sexual instincts from the ego-instincts would

simply reflect this twofold

function of the individual. Thirdly, we must recollect that all our

provisional ideas in psychology 17

will presumably someday be based on an organic substructure. This makes

it probable that it is

special substances and chemical processes which perform the operations

of sexuality and provide for

the extension of individual life into that of the species. We are

taking this probability into account in

replacing the special chemical substances by special psychical forces. |

|

| 114 |

11 |

・自我欲動と、性の欲動を区別するのが

「リビドー理論」 ・リビドー理論は、生物学による ・性的エネルギー=リビドー ・リビドーと心的エネルギーの根源的同一性 ・自我欲動と性欲動のこのあたりの言い回しは、まわりくどく、わかりにくい ※【欲動には2種類あり】《自我欲動》と《性的欲動》をわける。これ は「飢餓」と「性的欲望」の二分に相当し、そのフラストレーションも性格が異なることを示す。→「性欲論3編」1905年に遡れる。 |

I try in general

to keep psychology clear from everything that is different in nature

from it, even

biological lines of thought. For that very reason, I should like at

this point expressly to admit that

the hypothesis of separate ego-instincts and sexual instincts (that is

to say, the libido theory) rests

scarcely at all upon a psychological basis, but derives its principal

support from biology. But I shall

be consistent enough [with my general rule] to drop this hypothesis if

psycho-analytic work should

itself produce some other, more serviceable hypothesis about the

instincts. So far, this has not

happened. It may turn out that, most basically and on the longest view,

sexual energy—libido—is

only the product of a differentiation in the energy at work generally

in the mind. But such an

assertion has no relevance. It relates to matters which are so remote

from the problems of our

observation, and of which we have so little cognizance, that it is as

idle to dispute it as to affirm it;

this primal identity may well have as little to do with our analytic

interests as the primal kinship of all

the races of mankind has to do with the proof of kinship required in

order to establish a legal right

of inheritance. All these speculations take us nowhere. Since we cannot

wait for another science to

present us with the final conclusions on the theory of the instincts,

it is far more to the purpose that we should try to see what light may

be thrown upon this basic problem of biology by a synthesis of

the psychological phenomena. Let us face the possibility of error; but

do not let us be deterred from

pursuing the logical implications of the hypothesis we first adopted of

an antithesis between 18

ego-instincts and sexual instincts (a hypothesis to which we were

forcibly led by analysis of the

transference neuroses), and from seeing whether it turns out to be

without contradictions and

fruitful, and whether it can be applied to other disorders as well,

such as schizophrenia. |

| 115 |

12 |

・ユング批判、スキゾフレニーにはリビ

ドー理論が役立たないというユングの主張は、筋違いである。 ・シュレーバー分析の困難さに直面して、リビドー概念を拡張する必要がある。 ・ユングに対するルサンチマンがつづく。 ・ユングを批判するフィレンツィを支持することで、フロイトはユングを批判。 ・ユングの引用などなど ・スイス学派の業績、1)健常者にもコンプレックスは存在する、2)神経症患者の空想の所産が民族神話と類似する。 ・総じて、フロイトはリビドー理論の可能性を擁護する。 ※自我の発達と、リビドーの発達→自我リビドー=ナルシシズムリビドーというアイディア。これは『精神分析入門』26講を参照。 |

It would, of

course, be a different matter if it were proved that the libido theory

has already come to

grief in the attempt to explain the latter disease. This has been

asserted by C. G. Jung (1912) and it is

on that account that I have been obliged to enter upon this last

discussion, which I would gladly

have been spared. I should have preferred to follow to its end the

course embarked upon in the

analysis of the Schreber case without any discussion of its premises.

But Jung's assertion is, to say the

least of it, premature. The grounds he gives for it are scanty. In the

first place, he appeals to an

admission of my own that I myself have been obliged, owing to the

difficulties of the Schreber

analysis, to extend the concept of libido (that is, to give up its

sexual content) and to identify libido

with psychical interest in general. Ferenczi (1913b), in an exhaustive

criticism of Jung's work, has

already said all that is necessary in correction of this erroneous

interpretation. I can only corroborate

his criticism and repeat that I have never made any such retractation

of the libido theory. Another

argument of Jung's, namely, that we cannot suppose that the withdrawal

of the libido is in itself

enough to bring about the loss of the normal function of reality, is no

argument but a dictum. It 19

begs the question’, and saves discussion; for whether and how this is

possible was precisely the point

that should have been under investigation. In his next major work, Jung

(1913 [339-40]) just misses

the solution I had long since indicated: ‘At the same time’, he writes,

‘there is this to be further taken

into consideration (a point to which, incidentally, Freud refers in his

work on the Schreber case

[1911c])—that the introversion of the libido sexualis leads to a

cathexis of the “ego”, and that it may

possibly be this that produces the result of a loss of reality. It is

indeed a tempting possibility to

explain the psychology of the loss of reality in this fashion.’ But

Jung does not enter much further into a discussion of this possibility.

A few lines later he dismisses it with the remark that this 20

determinant ‘would result in the psychology of an ascetic anchorite,

not in a dementia praecox’. How

little this inapt analogy can help us to decide the question may be

learnt from the consideration that

an anchorite of this kind, who ‘tries to eradicate every trace of

sexual interest’ (but only in the

popular sense of the word ‘sexual’), does not even necessarily display

any pathogenic allocation of

the libido. He may have diverted his sexual interest from human beings

entirely, and yet may have

sublimated it into a heightened interest in the divine, in nature, or

in the animal kingdom, without

his libido having undergone an introversion on to his phantasies or a

return to his ego. This analogy

would seem to rule out in advance the possibility of differentiating

between interest emanating from

erotic sources and from others. Let us remember, further, that the

researches of the Swiss school,

however valuable, have elucidated only two features in the picture of

dementia praecox—the

presence in it of complexes known to us both in healthy and neurotic

subjects, and the similarity of

the phantasies that occur in it to popular myths—but that they have not

been able to throw any

further light on the mechanism of the disease. We may repudiate Jung's

assertion, then, that the

libido theory has come to grief in the attempt to explain dementia

praecox, and that it is therefore

disposed of for the other neuroses as well. |

| 116 |

13 |

Section II ・ナルシシズムを研究への困難のひとつは、パラフレニア(→スキゾフレニー)の分析にある。 ・ナルシシズムの理解に近く方法;1)器質的疾患、2)ヒポコンデリー、3)両性間の愛情生活の観察(→パラグラフ22) |

Section II Certain special difficulties seem to me to lie in the way of a direct study of narcissism. Our chief means of access to it will probably remain the analysis of the paraphrenias. Just as the transference neuroses have enabled us to trace the libidinal instinctual impulses, so dementia praecox and paranoia will give us an insight into the psychology of the ego. Once more, in order to arrive at an understanding of what seems so simple in normal phenomena, we shall have to turn to the field of pathology with its distortions and exaggerations. At the same time, other means of approach remain open to us, by which we may obtain a better knowledge of narcissism. These I shall now discuss in the following order: the study of organic disease, of hypochondria and of the erotic life of the sexes. |

| 117 |

14 |

(英訳では13-14パラグラフは一緒)

In estimating the influence of organic disease...... 1)器質的疾患 |

In estimating the influence of organic disease upon the distribution of libido, I follow a suggestion made to me orally by Sándor Ferenczi. It is universally known, and we take it as a matter of course, that a person who is tormented by organic pain and discomfort gives up his interest in the things of the external world, in so far as they do not concern his suffering. Closer observation teaches us that he also withdraws libidinal interest from his love-objects: so long as he suffers, he ceases to love. The commonplace nature of this fact is no reason why we should be deterred from translating it into terms of the libido theory. We should then say: the sick man withdraws his libidinal cathexes back upon his own ego, and sends them out again when he recovers. ‘Concentrated is his soul’, says Wilhelm Busch of the poet suffering from toothache, ‘in his molar's narrow hole.’ Here libido and 21 ego-interest share the same fate and are once more indistinguishable from each other. The familiar egoism of the sick person covers both. We find it so natural because we are certain that in the same situation we should behave in just the same way. The way in which a lover's feelings, however strong, are banished by bodily ailments, and suddenly replaced by complete indifference, is a theme that has been exploited by comic writers to an appropriate extent |

| 15 |

The condition of

sleep, too, resembles illness in implying a narcissistic withdrawal of

the positions of

the libido on to the subject's own self, or, more precisely, on to the

single wish to sleep. The egoism

of dreams fits very well into this context. [Cf. below, p. 223.] In

both states, we have, if nothing else,

examples of changes in the distribution of libido that are consequent

upon an alteration of the ego. |

||

| 16 |

邦訳の最後の疑問文(But what

could these changes be?)は、英訳では17パラグラフの冒頭にある 2)ヒポコンデリー ・ヒポコンデリー患者は、関心とリビドーを外界の対象からひっこめ、両者を自分が気を取られている器官に集中する |

Hypochondria, like organic disease, manifests itself in distressing and painful bodily sensations, and it has the same effect as organic disease on the distribution of libido. The hypochondriac withdraws both interest and libido—the latter specially markedly—from the objects of the external world and concentrates both of them upon the organ that is engaging his attention. A difference between hypochondria and organic disease now becomes evident: in the latter, the distressing sensations are based upon demonstrable [organic] changes; in the former, this is not so. But it would be entirely in keeping with our general conception of the processes of neurosis if we decided to say that hypochondria must be right: organic changes must be supposed to be present in it, too. | |

| 118 |

17 |

・ヒポコンデリーは第三の神経症 |

But what could

these changes be? We will let ourselves be guided at this point by our

experience,

which shows that bodily sensations of an unpleasurable nature,

comparable to those of

hypochondria, occur in the other neuroses as well. I have said before

that I am inclined to class

hypochondria with neurasthenia and anxiety-neurosis as a third ‘actual’

neurosis. It would probably

not be going too far to suppose that in the case of the other neuroses

a small amount of

hypochondria was regularly formed at the same time as well. We have the

best example of this, I

think, in anxiety neurosis with its superstructure of hysteria. Now the

familiar prototype of an organ

that is painfully tender, that is in some way changed and that is yet

not diseased in the ordinary

sense, is the genital organ in its states of excitation. In that

condition, it becomes congested with

blood, swollen and humectant, and is the seat of a multiplicity of

sensations. Let us now, taking any

part of the body, describe its activity of sending sexually exciting

stimuli to the mind as its

‘erotogenicity’, and let us further reflect that the considerations on

which our theory of sexuality was

based have long accustomed us to the notion that certain other parts of

the body—the ‘erotogenic’

zones—may act as substitutes for the genitals and behave analogously to

them. We have then only one more step to take. We can decide to regard

erotogenicity as a general characteristic of all organs

and may then speak of an increase or decrease of it in a particular

part of the body. For every such

change in the erotogenicity of the organs, there might then be a

parallel change of libidinal cathexis

in the ego. Such factors would constitute what we believe to underlie

hypochondria and what may

have the same effect upon the distribution of libido as is produced by

a material illness of the

organs. |

| 18 |

・ヒポコンデリー論のまとめの部分 |

We see that, if we

follow up this line of thought, we come up against the problem not only

of

hypochondria but of the other ‘actual’ neuroses— neurasthenia and

anxiety neurosis. Let us,

therefore, stop at this point. It is not within the scope of a purely

psychological inquiry to penetrate

so far behind the frontiers of physiological research. I will merely

mention that from this point of

view we may suspect that the relation of hypochondria to paraphrenia is

similar to that of the other

‘actual’ neuroses to hysteria and obsessional neurosis: we may suspect,

that is, that it is dependent on

ego- libido just as the others are on object-libido, and that

hypochondriacal anxiety is the

counterpart, as coming from ego-libido to neurotic anxiety. Further,

since we are already familiar

with the idea that the mechanism of falling ill and of the formation of

symptoms in the transference

neuroses— the path from introversion to of ego-libido as well and may

bring this idea into relation

with the phenomena of hypochondria and paraphrenia. |

|

| 119 |

19 |

・自我におけるリビドーの鬱積 Krankheit ist wohl der letzte Grund Des ganzen Schöpferdrangs gewesen; Erschaffend konnte ich genesen, Erschaffend wurde ich gesund. 病いこそは創造のあらゆる 衝動の究極の根拠なり 創作しつつ我は治癒され 創作しつつ我は健康になる (ハインリッヒ・ハイネ) |

At this point, our

curiosity will, of course, raise the question why this damming-up of

libido in the

ego should have to be experienced as unpleasurable. I shall content

myself with the answer that

unpleasure is always the expression of a higher degree of tension, and

that therefore what is

happening is that a quantity in the field of material events is being

transformed here as elsewhere

into the psychical quality of unpleasure. Nevertheless, it may be that

what is decisive for the

generation of unpleasure is not the absolute magnitude of the material

event, but rather some

particular function of that absolute magnitude. Here we may even

venture to touch on the question 23

of what makes it necessary at all for our mental life to pass beyond

the limits of narcissism and to attach the libido to objects. The

answer which would follow from our line of thought would once 24

more be that this necessity arises when the cathexis of the ego with

libido exceeds a certain amount.

A strong egoism is a protection against falling ill, but in the last

resort we must begin to love in order

not to fall ill, and we are bound to fall ill if, in consequence of

frustration, we are unable to love.

This follows somewhat on the lines of Heine's picture of the

psychogenesis of the Creation: Krankheit ist wohl der letzte Grund Des ganzen Schöpferdrangs gewesen; Erschaffend konnte ich genesen, Erschaffend wurde ich gesund.25 |

| 20 |

・心的装置のなかには、ある能力があり、

それがないと苦痛を感じたり、病原的な作用が発動する ・内向性リビドーの鬱積 |

We have recognized

our mental apparatus as being first and foremost a device designed for

mastering excitations which would otherwise be felt as distressing or

would have pathogenic effects.

Working them over in the mind helps remarkably towards an internal

draining away of excitations

which are incapable of direct discharge outwards, or for which such a

regression—is to be linked to

a damming-up of object-libido, we may come to closer quarters with the

idea of a damming-up 26

discharge is for the moment undesirable. In the first instance,

however, it is a matter of indifference

whether this internal process of working-over is carried out upon real

or imaginary objects. The

difference does not appear till later—if the turning of the libido on

to unreal objects (introversion)

has led to its being dammed up. In paraphrenics, megalomania allows of

a similar internal

working-over of libido which has returned to the ego; perhaps it is

only when the megalomania fails

that the damming-up of libido in the ego becomes pathogenic and starts

the process of recovery

which gives us the impression of being a disease. |

|

| 120 |

21 |

パラフレニアまとめ |

I shall try here

to penetrate a little further into the mechanism of paraphrenia and

shall bring

together those views which already seem to me to deserve consideration.

The difference between paraphrenic affections and the transference

neuroses appears to me to lie in the circumstance that, in

the former, the libido that is liberated by frustration does not remain

attached to objects in phantasy,

but withdraws on to the ego. Megalomania would accordingly correspond

to the psychical mastering

of this latter amount of libido, and would thus be the counterpart of

the introversion on to

phantasies that are found in the transference neuroses; a failure of

this psychical function gives rise

to the hypochondria of paraphrenia and this is homologous to the

anxiety of the transference

neuroses. We know that this anxiety can be resolved by further

psychical working-over, i.e. by

conversion, reaction-formation or the construction of protections

(phobias). The corresponding

process in paraphrenics is an attempt at restoration, to which the

striking manifestations of the

disease are due. Since paraphrenia frequently, if not usually, brings

about only a partial detachment of

the libido from objects, we can distinguish three groups of phenomena

in the clinical picture: 1. those representing what remains of a normal state or of neurosis (residual phenomena); 2. those representing the morbid process (detachment of libido from its objects and, further, megalomania, hypochondria, affective disturbance and every kind of regression); 3. those representing restoration, in which the libido is once more attached to objects, after the manner of a hysteria (in dementia praecox or paraphrenia proper), or of an obsessional neurosis (in paranoia). This fresh libidinal cathexis differs from the primary one in that it starts from another level and under other conditions.27 The difference between the transference neuroses brought about in the case of this fresh kind of libidinal cathexis and the corresponding formations where the ego is normal should be able to afford us the deepest insight into the structure of our mental apparatus. |

| 22 |

3)両性間の愛情生活の観察 ・依存型 ・性目標倒錯者、同性愛者=リビドー発達の障害をこうむった人物は、ナルシシズムに陥る |

A third way in

which we may approach the study of narcissism is by observing the

erotic life of

human beings, with its many kinds of differentiation in man and woman.

Just as object-libido at first

concealed ego-libido from our observation, so too in connection with

the object-choice of infants

(and of growing children) what we first noticed was that they derived

their sexual objects from their experiences of satisfaction. The first

auto-erotic sexual satisfactions are experienced in connection

with vital functions which serve the purpose of self-preservation. The

sexual instincts are at the

outset attached to the satisfaction of the ego-instincts; only later do

they become independent of

these, and even then we have an indication of that original attachment

in the fact that the persons

who are concerned with a child's feeding, care, and protection become

his earliest sexual objects:

that is to say, in the first instance his mother or a substitute for

her. Side by side, however, with this

type and source of object-choice, which may be called the ‘anaclitic’

or ‘attachment’ type,28

psycho-analytic research has revealed a second type, which we were not

prepared for finding. We

have discovered, especially clearly in people whose libidinal

development has suffered some

disturbance, such as perverts and homosexuals, that in their later

choice of love-objects they have

taken as a model, not their mother but their own selves. They are

plainly seeking themselves as a

love-object, and are exhibiting a type of object-choice which must be

termed ‘narcissistic’. In this

observation, we have the strongest of the reasons which have led us to

adopt the hypothesis of

narcissism. |

|

| 121 |

23 |

・我々の根源的な性対象:1)自分自身、

2)世話をしてくれる女性 ・すべての人間は一次的ナルシシズムをもつ |

We have, however,

not concluded that human beings are divided into two sharply

differentiated

groups, according as their object-choice conforms to the anaclitic or

to the narcissistic type; we

assume rather that both kinds of object-choice are open to each

individual, though he may show a

preference for one or the other. We say that a human being has

originally two sexual

objects—himself and the woman who nurses him— and in doing so we are

postulating a primary narcissism in everyone, which may in some cases

manifest itself in a dominating fashion in his

object- choice. |

| 24 |

・依存型にのっとった完全な対象愛=男性

の特色 ・対象愛、性的過大評価(=過備給)=これは小児の根源的ナルシシズムに由来=性対象へのナルシシズムの転移 ・女性は、思春期に性器が発達するので、根源的ナルシシズムにみえるが、性的過大評価をともなる正規の対象愛 ・女性は、男性に愛される同じ強さで自分自身を愛している。 ・彼女は愛することを求めるのではなく、愛されることを求めるのだ。そして、そのような男性を求める。 |

A comparison of

the male and female sexes then shows that there are fundamental

differences

between them in respect of their type of object- choice, although these

differences are of course not

universal. Complete object-love of the attachment type is, properly

speaking, characteristic of the

male. It displays the marked sexual overvaluation which is doubtless

derived from the child's original

narcissism and thus corresponds to a transference of that narcissism to

the sexual object. This sexual

overvaluation is the origin of the peculiar state of being in love, a

state suggestive of a neurotic

compulsion, which is thus traceable to an impoverishment of the ego as

regards libido in favor of

the love-object. A different course is followed in the type of female

most frequently met with, 29

which is probably the purest and truest one. With the onset of puberty

the maturing of the female

sexual organs, which up till then have been in a condition of latency,

seems to bring about an

intensification of the original narcissism, and this is unfavorable to

the development of a true objectchoice with its accompanying sexual

overvaluation. Women, especially if they grow up with good

looks, develop a certain self-contentment which compensates them for

the social restrictions that are

imposed upon them in their choice of object. Strictly speaking, it is

only themselves that such

women love with an intensity comparable to that of the man's love for

them. Nor does their need lie

in the direction of loving, but of being loved; and the man who

fulfills this condition is the one who

finds favor with them. The importance of this type of woman for the

erotic life of mankind is to be

rated very high. Such women have the greatest fascination for men, not

only for aesthetic reasons

since as a rule, they are the most beautiful but also because of a

combination of interesting

psychological factors. For it seems very evident that another person's

narcissism has a great

attraction for those who have renounced part of their own narcissism

and are in search of

object-love. The charm of a child lies to a great extent in his

narcissism, his self-contentment, and

inaccessibility, just as does the charm of certain animals which seem

not to concern themselves

about us, such as cats and the large beasts of prey. Indeed, even great

criminals and humorists, as

they are represented in literature, compel our interest by the

narcissistic consistency with which they manage to keep away from their

ego anything that would diminish it. It is as if we envied them for

maintaining a blissful state of mind—an unassailable libidinal position

which we ourselves have since

abandoned. The great charm of narcissistic women has, however, its

reverse side; a large part of the

lover's dissatisfaction, of his doubts of the woman's love, of his

complaints of her enigmatic nature,

has its root in this incongruity between the types of object-choice. |

|

| 122 |

25 |

・女性をまったく侮辱しているわけではな

い。 ・男性的な類型にしたがって恋愛する女性もいる。 |

Perhaps it is not

out of place here to give an assurance that this description of the

feminine form of

erotic life is not due to any tendentious desire on my part to

depreciate women. Apart from the fact

that tendentiousness is quite alien to me, I know that these different

lines of development

correspond to the differentiation of functions in a highly complicated

biological whole; further, I am

ready to admit that there are quite a number of women who love

according to the masculine type

and who also develop the sexual overvaluation proper to that type. |

| 26 |

・ナルシシズム的な女性にも完全な対象愛

に導く方途がある ・対象愛(子供をもつこと?) ・(このあたりのフロイトのジェンダーステレオタイプは、非常に退屈) |

Even for

narcissistic women, whose attitude towards men remains cool, there is a

road that leads to

complete object-love. In the child which they bear, a part of their own

body confronts them like an

extraneous object, to which, starting out from their narcissism, they

can then give complete

object-love. There are other women, again, who do not have to wait for

a child in order to take the

step in development from (secondary) narcissism to object-love. Before

puberty they feel masculine

and develop some way along masculine lines; after this trend has been

cut short on their reaching

female maturity, they still retain the capacity of longing for a

masculine ideal—an ideal which is, in

fact, a survival of the boyish nature that they themselves once

possessed. |

|

| 123 |

27 |

まとめ ・人が愛するのは、 1)ナルシズム型では、 A) 現在の自分 B) 過去の自分 C) そうたりたい自分 D) 自分自身の一部であった人物 2)依存型では、 E) 養育してくれる女性 F) 保護してくれる男性 |

What I have so far

said by way of indication may be concluded by a short summary of the

paths

leading to the choice of an object. A person may love:— 1. According to the narcissistic type: a. what he himself is (i.e. himself), b. what he himself was, c. what he himself would like to be, d. someone who was once part of himself.30 2. According to the anaclitic (attachment) type: a. the woman who feeds him, b. the man who protects him, c. and the succession of substitutes who take their place. The inclusion of case (1 c) of the first type cannot be justified until a later stage of this discussion. |

| 28 |

・男性の同性愛、ナルシシズム的対象選択

がもつ意義は、評価されるべし |

The significance

of narcissistic object-choice for homosexuality in men must be

considered in another connection.31 |

|

| 29 |

・小児の一次的ナルシシズム ・自己のナルシシズムの復活 ・ナルシシズム的痕跡 |

The primary

narcissism of children which we have assumed and which forms one of the

postulates

of our theories of the libido, is less easy to grasp by direct

observation than to confirm by inference

from elsewhere. If we look at the attitude of affectionate parents

towards their children, we have to

recognize that it is a revival and reproduction of their own

narcissism, which they have long since

abandoned. The trustworthy pointer constituted by overvaluation, which

we have already recognized

as a narcissistic stigma in the case of object-choice, dominates, as we

all know, their emotional

attitude. Thus they are under a compulsion to ascribe every perfection

to the child—which sober

observation would find no occasion to do—and to conceal and forget all

his shortcomings.

(Incidentally, the denial of sexuality in children is connected with

this.) Moreover, they are inclined to

suspend in the child's favour the operation of all the cultural

acquisitions which their own narcissism

has been forced to respect, and to renew on his behalf the claims to

privileges which were long ago

given up by themselves. The child shall have a better time than his

parents; he shall not be subject to

the necessities which they have recognized as paramount in life.

Illness, death, renunciation of

enjoyment, restrictions on his own will, shall not touch him; the laws

of nature and of society shall

be abrogated in his favour; he shall once more really be the centre and

core of creation—‘His Majesty the Baby’, as we once fancied ourselves.

The child shall fulfil those wishful dreams of the 32

parents which they never carried out—the boy shall become a great man

and a hero in his father's

place, and the girl shall marry a prince as a tardy compensation for

her mother. At the most touchy

point in the narcissistic system, the immortality of the ego, which is

so hard-pressed by reality,

security is achieved by taking refuge in the child. Parental love,

which is so moving and at bottom so

childish, is nothing but the parents' narcissism born again, which,

transformed into object-love,

unmistakably reveals its former nature. |

|

| 124 |

30 |

Section III ・小児の根源的ナルシシズム ・去勢コンプレックス(男児のペニス不安、女児のペニス羨望) ・男性的抗議(A・アドラー) |

Section III The disturbances to which a child's original narcissism is exposed, the reactions with which he seeks to protect himself from them and the paths into which he is forced in doing so—these are themes which I propose to leave on one side, as an important field of work which still awaits exploration. The most significant portion of it, however, can be singled out in the shape of the ‘castration complex’ (in boys, anxiety about the penis— in girls, envy for the penis) and treated in connection with the effect of early deterrence from sexual activity. Psycho-analytic research ordinarily enables us to trace the vicissitudes undergone by the libidinal instincts when these, isolated from the ego-instincts, are placed in opposition to them; but in the particular field of the castration complex, it allows us to infer the existence of an epoch and a psychical situation in which the two groups of instincts, still operating in unison and inseparably mingled, make their appearance as narcissistic interests. It is from this context that Adler [1910]has derived his concept of the ‘masculine protest’, which he has elevated almost to the position of the sole motive force in the formation of character and neurosis alike and which he bases not on a narcissistic, and therefore still a libidinal, trend, but on a social valuation. Psycho-analytic research has from the very beginning recognized the existence and importance of the ‘masculine protest’, but it has regarded it, in opposition to Adler, as narcissistic in nature and derived from the castration complex. The ‘masculine protest’ is concerned in the formation of character, into the genesis of which it enters along with many other factors, but it is completely unsuited for explaining the problems of the neuroses, with regard to which Adler takes account of nothing but the manner in which they serve the ego-instincts. I find it quite impossible to place the genesis of neurosis upon the narrow basis of the castration complex, however powerfully it may come to the fore in men among their resistances to the cure of a neurosis. Incidentally, I know of cases of neurosis in which the ‘masculine protest’, or, as we regard it, the castration complex, plays no pathogenic part, and even fails to appear at all.33 |

| 125 |

31 |

・正常成人=1)誇大妄想の抑制、2)小

児的ナルシシズムの姿が暈されている |

Observation of

normal adults shows that their former megalomania has been damped down

and

that the psychical characteristics from which we inferred their

infantile narcissism have been effaced.

What has become of their ego-libido? Are we to suppose that the whole

amount of it has passed

into object-cathexes? Such a possibility is plainly contrary to the

whole trend of our argument; but

we may find a hint at another answer to the question in the psychology

of repression. |

| 32 |

・リビドー的欲動活動が、個人ならびに文

化的、倫理的諸観念を衝突すると、病的抑圧を被る ・抑圧は自我から発する。抑圧は、自我の自尊から発する |

We have learnt

that libidinal instinctual impulses undergo the vicissitude of

pathogenic repression if

they come into conflict with the subject's cultural and ethical ideas.

By this we never mean that the

individual in question has a merely intellectual knowledge of the

existence of such ideas; we always

mean that he recognizes them as a standard for himself and submits to

the claims they make on him.

Repression, we have said, proceeds from the ego; we might say with

greater precision that it

proceeds from the self-respect of the ego. The same impressions,

experiences, impulses and desires

that one man indulges or at least works over consciously will be

rejected with the utmost indignation

by another, or even stifled before they enter consciousness. The

difference between the two, which 34

contains the conditioning factor of repression, can easily be expressed

in terms which enable it to be

explained by the libido theory. We can say that the one man has set up

an ideal in himself by which

he measures his actual ego, while the other has formed no such ideal.

For the ego the formation of

an ideal would be the conditioning factor of repression.35 |

|

| 33 |

・理想自我(Idealich) ・自己愛 ・自我理想 |

This ideal ego is

now the target of the self-love which was enjoyed in childhood by the

actual ego.

The subject's narcissism makes its appearance displaced on to this new

ideal ego, which, like the

infantile ego, finds itself possessed of every perfection that is of

value. As always where the libido is

concerned, man has here again shown himself incapable of giving up a

satisfaction he had once

enjoyed. He is not willing to forgo the narcissistic perfection of his

childhood; and when, as he

grows up, he is disturbed by the admonitions of others and by the

awakening of his own critical udgement, so that he can no longer retain

that perfection, he seeks to recover it in the new form of

an ego ideal. What he projects before him as his ideal is the

substitute for the lost narcissism of his

childhood in which he was his own ideal.36 |

|

| 126 |

34 |

・sublimationは「昇華」 ・理想形成と昇華のあいだの探求 |

We are naturally

led to examine the relation between this forming of an ideal and

sublimation.

Sublimation is a process that concerns object-libido and consists in

the instinct's directing itself

towards an aim other than, and remote from, that of sexual

satisfaction; in this process the accent

falls upon deflection from sexuality. Idealization is a process that

concerns the object; by it that

object, without any alteration in its nature, is aggrandized and

exalted in the subject's mind.

Idealization is possible in the sphere of ego-libido as well as in that

of object-libido. For example, the

sexual overvaluation of an object is an idealization of it. In so far

as sublimation describes something

that has to do with the instinct and idealization something to do with

the object, the two concepts

are to be distinguished from each other.37 |

| 35 |

・「自我理想の形成はしばしば、理解が欠

けているために欲動の

昇華ととり違えられる。高い自我理想の尊敬と引換えにナルシ

シズムをえた者は、それゆえに、リビドー的欲動の昇華に成功

したものである必要はない。自我理想はとのような昇華を要求

はするが、これを強要することはできない。昇華はあくまでも

一つの特殊な過程なのであって、その開始は理想に刺激されて

行なわれるのかもしれないが、その成就はこのような刺激とは

あくまでもまったく無関係なのである」126) |

The formation of

an ego ideal is often confused with the sublimation of instinct, to the

detriment of

our understanding of the facts. A man who has exchanged his narcissism

for homage to a high ego

ideal has not necessarily on that account succeeded in sublimating his

libidinal instincts. It is true

that the ego ideal demands such sublimation, but it cannot enforce it;

sublimation remains a special

process which may be prompted by the ideal but the execution of which

is entirely independent of

any such prompting. It is precisely in neurotics that we find the

highest differences of potential

between the development of their ego ideal and the amount of

sublimation of their primitive

libidinal instincts; and in general it is far harder to convince an

idealist of the inexpedient location of

his libido than a plain man whose pretensions have remained more

moderate. Further, the formation

of an ego ideal and sublimation are quite differently related to the

causation of neurosis. As we have

learnt, the formation of an ideal heightens the demands of the ego and

is the most powerful factor favouring repression; sublimation is a way

out, a way by which those demands can be met without

involving repression.38 |

|

| 127 |

36 |

・特殊な心的法廷 ・良心はこの法的にかかわる |

It would not

surprise us if we were to find a special psychical agency which

performs the task of

seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured and

which, with this end in view,

constantly watches the actual ego and measures it by that ideal. If

such an agency does exist, we 39

cannot possibly come upon it as a discovery—we can only recognize it;

for we may reflect that what

we call our ‘conscience’ has the required characteristics. Recognition

of this agency enables us to

understand the so-called ‘delusions of being noticed’ or more

correctly, of being watched, which 40

are such striking symptoms in the paranoid diseases and which may also

occur as an isolated form of

illness, or intercalated in a transference neurosis. Patients of this

sort complain that all their thoughts

are known and their actions watched and supervised; they are informed

of the functioning of this

agency by voices which characteristically speak to them in the third

person (‘Now she's thinking of

that again, ‘now he's going out’). This complaint is justified; it

describes the truth. A power of this

kind, watching, discovering and criticizing all our intentions, does

really exist. Indeed, it exists in

every one of us in normal life. |

| 37 |

・良心=番人 |

Delusions of being

watched present this power in a regressive form, thus revealing its

genesis and

the reason why the patient is in revolt against it. For what prompted

the subject to form an ego

ideal, on whose behalf his conscience acts as watchman, arose from the

critical influence of his

parents (conveyed to him by the medium of the voice), to whom were

added, as time went on, those

who trained and taught him and the innumerable and indefinable host of

all the other people in his

environment —his fellow-men—and public opinion. |

|

| 38 |

英訳は2つのパラグラフにわけられてい

る。 ・本質的同性愛的なリビドーは大量のナルシシズム的自我理想の形成に引き入れられた ・良心(つづき) ・検閲機構に対する反抗 |

In this way large

amounts of libido of an essentially homosexual kind are drawn into the

formation

of the narcissistic ego ideal and find outlet and satisfaction in

maintaining it. The institution of

conscience was at bottom an embodiment, first of parental criticism,

and subsequently of that of

society—a process which is repeated in what takes place when a tendency

towards repression

develops out of a prohibition or obstacle that came in the first

instance from without. The voices, as

well as the undefined multitude, are brought into the foreground again

by the disease, and so the

evolution of conscience is reproduced regressively. But the revolt against this ‘censoring agency’ arises out of the subject's desire (in accordance with the fundamental character of his illness) to liberate himself from all these influences, beginning with the parental one, and out of his withdrawal of homosexual libido from them. His conscience then confronts him in a regressive form as a hostile influence from without. |

|

| 128 |

39 |

・「パラノイア患者の訴えはまた、自己観

察のうえにきずかれた

良心の自己批判が結局はこの自己観察と一致するものであるこ

とをしめしている。良心の機能をひきうけていた同じ一つの心

的活動がつまり内界探求の役目をも果たしていたのであって、

この内界探求は哲学に対してその思考活動の材料を提供するの

である。このことは偏執病の特徴である思弁的体系形成への発

動力と無関係ではないであろう」128) |

The complaints

made by paranoics also show that at bottom the self- criticism of

conscience

coincides with the self-observation on which it is based. Thus the

activity of the mind which has

taken over the function of conscience has also placed itself at the

service of internal research, which

furnishes philosophy with the material for its intellectual operations.

This may have some bearing on

the characteristic tendency of paranoics to construct speculative

systems.41 +++ 41) I should like to add to this, merely by way of suggestion, that the developing and strengthening of this observing agency might contain within it the subsequent genesis of (subjective) memory and the time-factor, the latter of which has no application to unconscious processes. |

| 40 |

・機能的現象 |

It will certainly

be of importance to us if evidence of the activity of this critically

observing

agency—which becomes heightened into conscience and philosophic

introspection—can be found

in other fields as well. I will mention here what Herbert Silberer has

called the ‘functional

phenomenon’, one of the few indisputably valuable additions to the

theory of dreams. Silberer, as we

know, has shown that in states between sleeping and waking we can

directly observe the translation

of thoughts into visual images, but that in these circumstances we

frequently have a representation,

not of a thought-content, but of the actual state (willingness,

fatigue, etc.) of the person who is

struggling against sleep. Similarly, he has shown that the conclusions

of some dreams or some divisions in their content merely signify the

dreamer's own perception of his sleeping and waking.

Silberer has thus demonstrated the part played by observation—in the

sense of the paranoic's

delusions of being watched— in the formation of dreams. This part is

not a constant one. Probably

the reason why I overlooked it is because it does not play any great

part in my own dreams; in

persons who are gifted philosophically and accustomed to introspection

it may become very evident.

42 |

|

| 41 |

・夢の形成 ・夢の検閲者 |

We may here recall

that we have found that the formation of dreams takes place under the

dominance of a censorship which compels distortion of the

dream-thoughts. We did not, however,

picture this censorship as a special power, but chose the term to

designate one side of the repressive

trends that govern the ego, namely the side which is turned towards the

dream-thoughts. If we enter

further into the structure of the ego, we may recognize in the ego

ideal and in the dynamic

utterances of conscience the dream-censor as well. If this censor is to

some extent on the alert 43

even during sleep, we can understand how it is that its suggested

activity of self-observation and selfcriticism—with such thoughts as,

‘now he is too sleepy to think’, ‘now he is waking up’—makes a

contribution to the content of the dream.44 +++ 44) 4 I cannot here determine whether the differentiation of the censoring agency from the rest of the ego is capable of forming the basis of the philosophic distinction between consciousness and self-consciousness. |

|

| 129 |

42 |

英訳は、42と43は同じパラグラフ ・自我感情 |

At this point we

may attempt some discussion of the self-regarding attitude in normal

people and in

neurotics. |

| 43 |

・自我感情は自我誇大 |

s. In the first

place self-regard appears to us to be an expression of the size of the

ego; what

the various elements are which go to determine that size is irrelevant.

Everything a person possesses

or achieves, every remnant of the primitive feeling of omnipotence

which his experience has

confirmed, helps to increase his self-regard. |

|

| 44 |

・ナルシシズム的リビドー |

Applying our

distinction between sexual and ego-instincts, we must recognize that

self-regard has a

specially intimate dependence on narcissistic libido. Here we are

supported by two fundamental

facts: that in paraphrenics self-regard is increased, while in the

transference neuroses it is diminished;

and that in love-relations not being loved lowers the self- regarding

feelings, while being loved raises

them. As we have indicated, the aim and the satisfaction in a

narcissistic object-choice is to be loved.

45 |

|

| 45 |

・自我感情は愛情生活へのナルシシズム的

な関与と関連がある |

Applying our

distinction between sexual and ego-instincts, we must recognize that

self-regard has a

specially intimate dependence on narcissistic libido. Here we are

supported by two fundamental

facts: that in paraphrenics self-regard is increased, while in the

transference neuroses it is diminished;

and that in love-relations not being loved lowers the self- regarding

feelings, while being loved raises

them. As we have indicated, the aim and the satisfaction in a

narcissistic object-choice is to be loved.

45 |

|

| 46 |

・自我の貧困化 |

The realization of

impotence, of one's own inability to love, in consequence of mental or

physical

disorder, has an exceedingly lowering effect upon self-regard. Here, in

my judgement, we must look

for one of the sources of the feelings of inferiority which are

experienced by patients suffering from

the transference neuroses and which they are so ready to report. The

main source of these feelings

is, however, the impoverishment of the ego, due to the extraordinarily

large libidinal cathexes which

have been withdrawn from it—due, that is to say, to the injury

sustained by the ego through sexual

trends which are no longer subject to control. |

|

| 130 |

47 |

・アドラーの仕事の論評 ・「A・アドラーが、自己の器官の劣等性を知覚することは、能 力のある精神生活に刺激的な作用をおよぼし、過剰代償的な仕 方でいっそう多くの仕事を達成させる、と主張しているのは正 しい。しかし、もしもすべての立派な仕事を、アドラーになら って、本来的な器官の劣等性というこの条件に帰そうとするな らば、それはまったくの行き過ぎであろう。すべての画家が眼 病にかかっていたわけではないし、すべての雄弁家が生来ども りであったわけではない。またすぐれた素質をもつ器官によっ てあげられた優秀な業績もたくさんにある。神経症の病因とし ては器官の劣等性や萎縮はとるに足らない役割しか演じてはい ないのであって、それはちょうど、現実の知覚素材が夢の形成 に対して果たしている役割に似ている。神経症患者はこうした ことを、役に立つ他のあらゆる契機と同様に口実として利用す るのである。ある女性の神経症患者が、自分は不美人で、醜く て、魅力がないから、誰にも愛されず、そのために病気になら ざるをえなかったのだといって訴えるのを、もしも信用してや るならば、今度はみたところ十人並以上に魅力的であり、また 求愛もされているのに、神経症や性の拒否にとりつかれている 神経症患者がでできて、いっそうよい教訓をあたえてくれるだ ろう」130) |

Adler [1907] is

right in maintaining that when a person with an active mental life

recognizes an

inferiority in one of his organs, it acts as a spur and calls out a

higher level of performance in him

through overcompensation. But it would be altogether an exaggeration

if, following Adler's example,

we sought to attribute every successful achievement to this factor of

an original inferiority of an

organ. Not all artists are handicapped with bad eyesight, nor were all

orators originally stammerers.

And there are plenty of instances of excellent achievements springing

from superior organic

endowment. In the aetiology of neuroses organic inferiority and

imperfect development play an

insignificant part—much the same as that played by currently active

perceptual material in the formation of dreams. Neuroses make use of

such inferiorities as a pretext, just as they do of every

other suitable factor. We may be tempted to believe a neurotic woman

patient when she tells us that

it was inevitable she should fall ill, since she is ugly, deformed or

lacking in charm, so that no one

could love her; but the very next neurotic will teach us better—for she

persists in her neurosis and in

her aversion to sexuality, although she seems more desirable, and is

more desired, than the average

woman. The majority of hysterical women are among the attractive and

even beautiful

representatives of their sex, while, on the other hand, the frequency

of ugliness, organic defects and

infirmities in the lower classes of society does not increase the

incidence of neurotic illness among

them. |

| 48 |

・対象リビドーと自我リビドー |

The relations of

self-regard to erotism—that is, to libidinal object- cathexes—may be

expressed

concisely in the following way. Two cases must be distinguished,

according to whether the erotic

cathexes are ego- syntonic, or, on the contrary, have suffered

repression. In the former case (where

the use made of the libido is ego-syntonic), love is assessed like any

other activity of the ego. Loving

in itself, in so far as it involves longing and deprivation, lowers

self-regard; whereas being loved,

having one's love returned, and possessing the loved object, raises it

once more. When libido is

repressed, the erotic cathexis is felt as a severe depletion of the

ego, the satisfaction of love is

impossible, and the re-enrichment of the ego can be effected only by a

withdrawal of libido from its

objects. The return of the object-libido to the ego and its

transformation into narcissism represents,

as it were, a happy love once more; and, on the other hand, it is also

true that a real happy love 46

corresponds to the primal condition in which object-libido and ego-

libido cannot be distinguished.

The importance and extensiveness of the topic must be my justification

for adding a few more

remarks which are somewhat loosely strung together. |

|

| 49 |

邦訳のこのパラグラフ部分は、英訳では

48の末尾に挿入されている。 |

The importance and extensiveness of the topic must be my justification for adding a few more remarks which are somewhat loosely strung together. | |

| 50 |

a) |

The development of the ego consists in a departure from primary narcissism and gives rise to a vigorous attempt to recover that state. This departure is brought about by means of the displacement of libido on to an ego ideal imposed from without; and satisfaction is brought about from fulfilling this ideal. | |

| 131 |

51 |

b) |

At the same time

the ego has sent out the libidinal object-cathexes. It becomes

impoverished in

favour of these cathexes, just as it does in favour of the ego ideal,

and it enriches itself once more

from its satisfactions in respect of the object, just as it does by

fulfilling its ideal. |

| 52 |

c) |

One part of

self-regard is primary—the residue of infantile narcissism; another

part arises out of the

omnipotence which is corroborated by experience (the fulfilment of the

ego ideal), whilst a third

part proceeds from the satisfaction of object-libido. |

|

| 53 |

d) |

The ego ideal has

imposed severe conditions upon the satisfaction of libido through

objects; for it

causes some of them to be rejected by means of its censor, as being

incompatible. Where no such

ideal has been formed, the sexual trend in question makes its

appearance unchanged in the

personality in the form of a perversion. To be their own ideal once

more, in regard to sexual no less

than other trends, as they were in childhood—this is what people strive

to attain as their happiness. |

|

| 54 |

e) |

Being in love

consists in a flowing-over of ego-libido on to the object. It has the

power to remove

repressions and reinstate perversions. It exalts the sexual object into

a sexual ideal. Since, with the

object type (or attachment type), being in love occurs in virtue of the

fulfilment of infantile

conditions for loving, we may say that whatever fulfils that condition

is idealized. |

|

| 55 |

邦訳は1つのパラグラフであるが、英訳は

2つにパラグラフわけられている。つまり、(それどころか、彼は……=Indeed, he cannot believe in any other

mechanism of cure)の部分から後半のパラグラフに分割される。 f) |

The sexual ideal

may enter into an interesting auxiliary relation to the ego ideal. It

may be used for

substitutive satisfaction where narcissistic satisfaction encounters

real hindrances. In that case a

person will love in conformity with the narcissistic type of

object-choice, will love what he once was

and no longer is, or else what possesses the excellences which he never

had at all (cf. (c) [p. 90]). The

formula parallel to the one there stated runs thus: what possesses the

excellence which the ego lacks

for making it an ideal, is loved. This expedient is of special

importance for the neurotic, who, on

account of his excessive object-cathexes, is impoverished in his ego

and is incapable of fulfilling his

ego ideal. He then seeks a way back to narcissism from his prodigal

expenditure of libido upon

objects, by choosing a sexual ideal after the narcissistic type which

possesses the excellences to

which he cannot attain. This is the cure by love, which he generally

prefers to cure by analysis. Indeed, he cannot believe in any other mechanism of cure; he usually brings expectations of this sort with him to the treatment and directs them towards the person of the physician. The patient's incapacity for love, resulting from his extensive repressions, naturally stands in the way of a therapeutic plan of this kind. An unintended result is often met with when, by means of the treatment, he has been partially freed from his repressions: he withdraws from further treatment in order to choose a love-object, leaving his cure to be continued by a life with someone he loves. We might be satisfied with this result, if it did not bring with it all the dangers of a crippling dependence upon his helper in need. |

|

| 132 |

56 |

g) ・「自我理想からは群衆心理学を理解するための重要な道が通じ ている。この理想は個人的な部分のほかに社会的な部分ももっ ており、それはまた家族や、階級や、国民の共通の理想で る。それはナルシシズム的リビドーのほかにひとりの人間の同 性愛的リビドーを大量に拘束しているのであるが、これはこの 道を通って自我に回帰してきたものなのである。こういう理想 が実現されないために不満が生じると、それは同性愛的なリビドー を解放し、これが罪責の意識(社会的不安)に変化する。 罪責の意識は元来は両親の罰に対する不安の念であったし、よ り正確にいうならば、両親の愛を失うととに対する不安であっ た。両親にかわって、のちに同胞という不特定多数者が現われ てきたのである。自我が傷つけられることや、自我理想の領域 で満足が拒まれることがしばしばパラノイアの原因になるとい うことが、こうしていっそうわかりやすくなるし、また自我理 想のなかで理想形成と昇華とが同時に行なわれることや、パラ フレニア的な疾患において、昇華の萎縮や理想の一時的な作り かえが行なわれるということも、いっそうわかりやすくなるの である」132) |

The ego ideal opens up an

important avenue for the understanding of group psychology. In addition

to its individual side, this ideal has a social side; it is also the

common ideal of a family, a class or a

nation. It binds not only a person's narcissistic libido, but also a

considerable amount of his

homosexual libido, which is in this way turned back into the ego. The

want of satisfaction which 47

arises from the non-fulfilment of this ideal liberates homosexual

libido, and this is transformed into

a sense of guilt (social anxiety). Originally this sense of guilt was a

fear of punishment by the parents,

or, more correctly, the fear of losing their love; later the parents

are replaced by an indefinite number

of fellow-men. The frequent causation of paranoia by an injury to the

ego, by a frustration of

satisfaction within the sphere of the ego ideal, is thus made more

intelligible, as is the convergence

of ideal-formation and sublimation in the ego ideal, as well as the

involution of sublimations and the

possible transformation of ideals in paraphrenic disorders. |

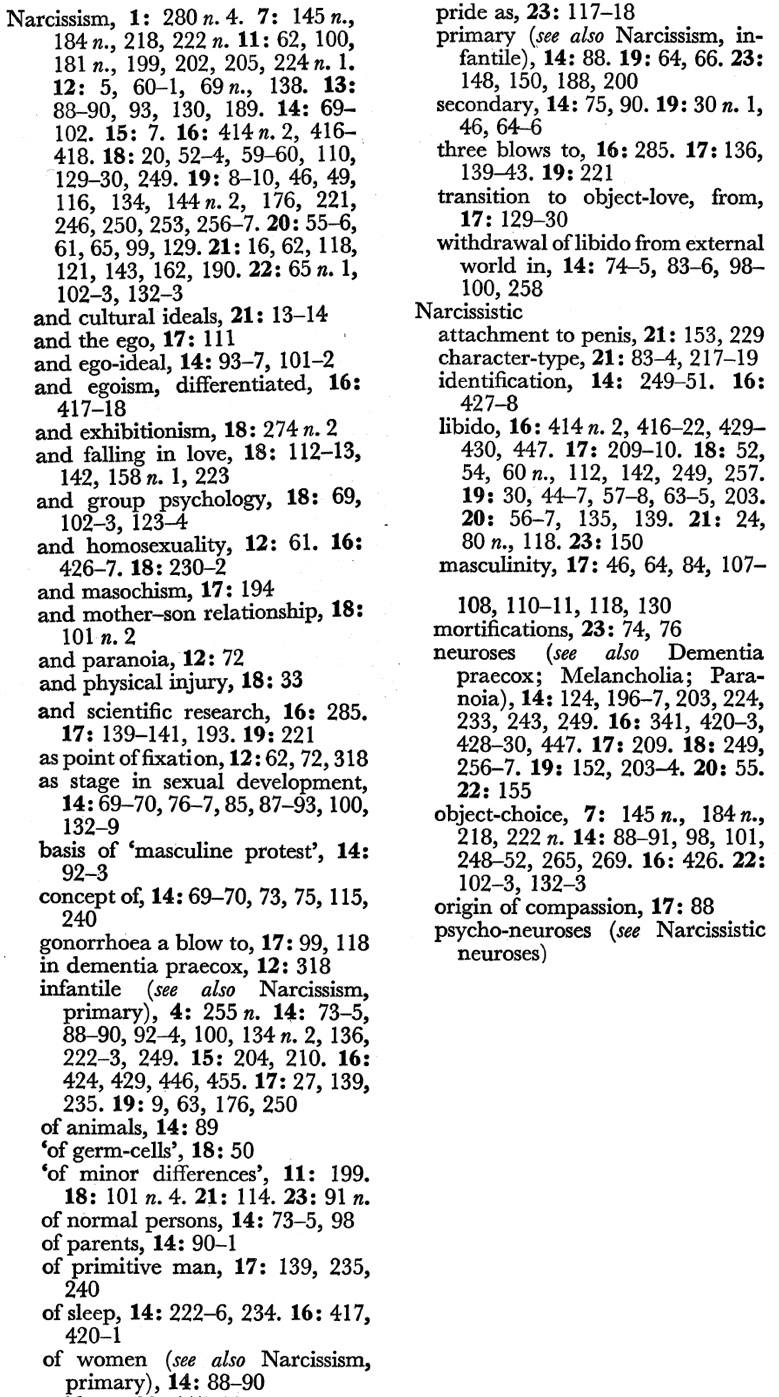

| 英語版フロイト全集の、ナルシシズム関連項目 Narcissism, 1: 280n.4. 7: 145n., 184 n., 218, 222 n. 11: 62, 100, 181 n., 199, 202, 205, 224 n. 1. 12: 5, 60-1, 69 n., 138. 13: 88-90, 93, 130, 189. 14: 69- 102. 15: 7. 16: 414 n. 2, 416- 418. 18: 20, 52-4, 59-60, 110, 129-30, 249. 19: 8-10, 46, 49, 116, 134, 144 n. 2, 176, 221, 246, 250, 253, 256-7. 20: 55-6, 61, 65, 99, 129. 21: 16, 62, 118, 121, 143, 162, 190. 22: 65 n. 1, 102-3, 132-3 and cultural ideals, 21: 13-14 and the ego, 17: 111 and ego-ideal, 14: 93-7, 101-2 and egoism, differentiated, 16: 417-18 and exhibitionism, 18: 274 n. 2 and falling in love, 18: 112-13, 142, 158 n. 1, 223 and group psychology, 18: 69, 102-3, 123-4 and homosexuality, 12: 61. 16: 426-7. 18: 230-2 and masochism, 17: 194 and mother-son relationship, 18: 101 n. 2 and paranoia, 12: 72 and physical injury, 18: 33 and scientific research, 16: 285. 17: 139-141, 193. 19: 221 as point of fixation, 12: 62, 72,318 as stage in sexual development, 14: 69-70, 76-7, 85, 87-93, 100, 132-9 basis of 'masculine protest' 14: 92-3 ' concept of, 14: 69-70, 73, 75, 115 240 ' gonorrhoea a blow to, 17: 99, 118 in dementia praecox, 12: 318 infantile (see also Narcissism primary), 4: 255 n. 14: 73-5; 88-90, 92-4, 100, 134 n. 2, 136, 222-3, 249. 15: 204, 210. 16: 424, 429, 446, 455. 17: 27, 139, 235. 19: 9, 63,176,250 of animals, 14: 89 'of germ-cells', 18: 50 'of minor differences', 11: 199. 18: 101 n. 4. 21: 114. 23: 91 n. of normal persons, 14: 73-5, 98 of parents, 14: 90-1 of primitive man, 17: 139 235 240 ' ' of sleep, 14: 222-6, 234. 16: 417 420-1 ' of women (see also Narcissism primary), 14: 88-90 ' pride as, 23: 117-18 primary (see also Narcissism, infantile), 14: 88. 19: 64, 66. 23: 148, 150, 188, 200 secondary, 14: 75, 90. 19: 30 n. 1 46, 64-6 ' three blows to, 16: 285. 17: 136, 139-43. 19: 221 transition to object-love, from 17: 129-30 ' withdrawal oflibido from external world in, 14: 74-5, 83-6 98- 100, 258 ' Narcissistic attachment to penis, 21: 153, 229 character-type, 21: 83-4, 217-19 identification, 14: 249-51. 16: 427-8 libido, 16: 414 n. 2, 416-22, 429- 430, 447. 17: 209-10. 18: 52, 54, 60 n., 112, 142, 249, 257. 19: 30, 44-7, 57-8, 63-5, 203. 20: 56-7, 135, 139. 21: 24, 80 n., 118. 23: 150 masculinity, 17: 46, 64, 84, 107-108, 110-11, 118, 130 mortifications, 23: 74, 76 neuroses (see also Dementia praecox; Melancholia; Paranoia), 14: 124, 196-7, 203, 224, 233, 243, 249. 16: 341, 420-3, 428-30, 447. 17: 209. 18: 249, 256-7. 19: 152, 203-4. 20: 55. 22: 155 object-choice, 7: 145 n., 184 n., 218, 222 n. 14: 88-91, 98, 101, 248-52, 265, 269. 16: 426. 22: 102-3, 132-3 origin of compassion, 17: 88 psycho-neuroses (see Narcissistic neuroses) |

|

1856 出生。記載はウィキペディア「ジークムント・フロイト」などによる(文章は今後適宜変える予定です)。

オーストリア帝国・モラヴィア辺境伯国のフライベル ク(Freiberg, チェコ・プシーボルでアシュケナージであった毛織物商人ヤーコプ・フロイト(Jacob Freud)の45歳時の息子として生まれる。母親もブロディ出身のアシュケナージであるアマーリア・ナータンゾーン(1835年 – 1930年)で、ユダヤ法学者レブ・ナータン・ハレーヴィの子孫と伝えられている。同母妹にアンナ、ローザ、ミッチー、アドルフィーネ、パウラがおり、同 母弟にアレクサンダーがいる。このほか、父の前妻にも2人の子がいる。モラヴィアの伝説の王Sigismundとユダヤの賢人王ソロモンにちなんで命名さ れた。そのため、生まれた時の名はジギスムント・シュローモ・フロイト (Sigismund Schlomo Freud、ヘブライ語: זיגיסמונד שלמה פרויד) だが、21歳の時にSigmundと改めた。

1873 ウィーン大学に入学、2年間物理などを学 び、医学部のエルンスト・ブリュッケの生理学研究所に入りカエルやヤツメウナギなど両生類・魚類の脊髄神経細胞を研究し、その論文は、ウィーン科学協会で ブリュッケ教授が発表した

1881 ウィーン大学卒業