ジャック・ラカン

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan,

1901-1981

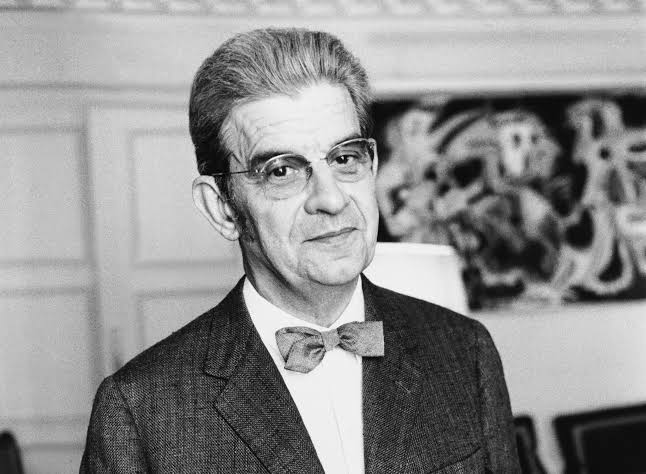

☆ ジャッ ク・マリー・エミール・ラカン(1901年4月13日 - 1981年9月9日)は、フランスの精神分析家、精神科医。フロイト以来の最も論争的な精神分析家」と評され、ラカンは1953年から1981年ま で毎年パリでセミナーを開き、後に『Écrits』という本にまとめられた論文を発表した。ラカンの研究は、ポスト構造主義、批評理論、フェミニズム理 論、映画理論などの大陸哲学や文化理論、さらには精神分析の実践そのものに大きな影響を与えた。 ラカンは、フロイトの思想の哲学的な側面を強調し、言語学や人類学の構造主義から派生した概念を自身の著作の展開に適用し、述語論理学や位相幾何学の公式 を用いることによって、フロイトの概念をさらに増大させることになる。このような新たな方向性を打ち出し、臨床実践に物議を醸すような革新を導入したこと で、ラカンとその支持者たちは国際精神分析協会から除名されることになった。その結果、ラカンは、心理学の一般的な傾向や社会規範への適応と結託し た組織的な精神分析に対抗して、「フロイトへの回帰」であると宣言した自身の仕事を推進し発展させるために、新たな精神分析機関を設立することになった。

| Jacques Marie Émile

Lacan (UK: /læˈkɒ̃/,[3] US: /ləˈkɑːn/,[4][5] French: [ʒak

maʁi emil

lakɑ̃]; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst

and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst

since Freud",[6] Lacan gave yearly seminars in Paris, from 1953 to

1981, and published papers that were later collected in the book

Écrits. His work made a significant impact on continental philosophy

and cultural theory in areas such as post-structuralism, critical

theory, feminist theory and film theory, as well as on the practice of

psychoanalysis itself. Lacan took up and discussed the whole range of Freudian concepts, emphasizing the philosophical dimension of Freud's thought and applying concepts derived from structuralism in linguistics and anthropology to its development in his own work, which he would further augment by employing formulae from predicate logic and topology. Taking this new direction, and introducing controversial innovations in clinical practice, led to expulsion for Lacan and his followers from the International Psychoanalytic Association.[7] In consequence, Lacan went on to establish new psychoanalytic institutions to promote and develop his work, which he declared to be a "return to Freud", in opposition to prevalent trends in psychology and institutional psychoanalysis collusive of adaptation to social norms. |

ジャック・マリー・エミール・ラカン(1901年4月13日 -

1981年9月9日)は、フランスの精神分析家、精神科医。フロイト以来の最も論争的な精神分析家」と評され[6]、ラカンは1953年から1981年ま

で毎年パリでセミナーを開き、後に『Écrits』という本にまとめられた論文を発表した。ラカンの研究は、ポスト構造主義、批評理論、フェミニズム理

論、映画理論などの大陸哲学や文化理論、さらには精神分析の実践そのものに大きな影響を与えた。 ラカンは、フロイトの思想の哲学的な側面を強調し、言語学や人類学の構造主義から派生した概念を自身の著作の展開に適用し、述語論理学や位相幾何学の公式 を用いることによって、フロイトの概念をさらに増大させることになる。このような新たな方向性を打ち出し、臨床実践に物議を醸すような革新を導入したこと で、ラカンとその支持者たちは国際精神分析協会から除名されることになった[7]。その結果、ラカンは、心理学の一般的な傾向や社会規範への適応と結託し た組織的な精神分析に対抗して、「フロイトへの回帰」であると宣言した自身の仕事を推進し発展させるために、新たな精神分析機関を設立することになった。 |

| Biography Early life Lacan was born in Paris, the eldest of Émilie and Alfred Lacan's three children. His father was a successful soap and oils salesman. His mother was ardently Catholic – his younger brother entered a monastery in 1929. Lacan attended the Collège Stanislas between 1907 and 1918. An interest in philosophy led him to a preoccupation with the work of Spinoza, one outcome of which was his abandonment of religious faith for atheism. There were tensions in the family around this issue, and he regretted not persuading his brother to take a different path, but by 1924 his parents had moved to Boulogne and he was living in rooms in Montmartre.[8]: 104 During the early 1920s, Lacan actively engaged with the Parisian literary and artistic avant-garde. Having met James Joyce, he was present at the Parisian bookshop where the first readings of passages from Ulysses in French and English took place, shortly before it was published in 1922.[9] He also had meetings with Charles Maurras, whom he admired as a literary stylist, and he occasionally attended meetings of Action Française (of which Maurras was a leading ideologue),[8]: 104 of which he would later be highly critical. In 1920, after being rejected for military service on the grounds that he was too thin, Lacan entered medical school. Between 1927 and 1931, after completing his studies at the faculty of medicine of the University of Paris, he specialised in psychiatry under the direction of Henri Claude at the Sainte-Anne Hospital, the major psychiatric hospital serving central Paris, at the Infirmary for the Insane of the Police Prefecture under Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault and also at the Hospital Henri-Rousselle.[10]: 211 |

略歴(バイオグラフィー) 生い立ち ラカンはエミリーとアルフレッド・ラカンの3人兄弟の長男としてパリに生まれる。父親は石鹸と油のセールスマンとして成功した。母親は熱心なカトリック信 者で、弟は1929年に修道院に入った。1907年から1918年までコレージュ・スタニスラスで学ぶ。哲学に興味を持ち、スピノザの著作に夢中になる。 この問題をめぐって家族には緊張が走り、弟に別の道を歩むよう説得できなかったことを悔やんだが、1924年までに両親はブローニュに移り住み、彼はモン マルトルの部屋に住んでいた[8]: 104 1920年代初頭、ラカンはパリの文学や芸術の前衛芸術と積極的に関わった。1922年に『ユリシーズ』が出版される直前には、ジェイムズ・ジョイスと出 会い、『ユリシーズ』の一節をフランス語と英語で初めて朗読したパリの書店に立ち会った[9]。また、文筆家として敬愛するシャルル・モーラスとも会合を 持ち、アクション・フランセーズ(モーラスは主要な思想家であった)の会合にも時折出席した[8]: 104の会合に出席することもあった[8]。 1920年、痩せすぎを理由に兵役を拒否されたラカンは医学部に入学。1927年から1931年にかけて、パリ大学医学部で学んだ後、アンリ・クロードの 指導の下、パリ中心部の主要な精神病院であるサント=アンヌ病院、ガエタン・ガティアン・ド・クレランボーのもと警察県精神異常者診療所、アンリ=ルーセ ル病院で精神医学を専門とした[10]: 211。 |

| 1930s Lacan was involved with the Parisian surrealist movement of the 1930s, associating with André Breton, Georges Bataille, Salvador Dalí, and Pablo Picasso.[11] For a time, he served as Picasso's personal therapist. He attended the mouvement Psyché that Maryse Choisy founded and published in the Surrealist journal Minotaure. "[Lacan's] interest in surrealism predated his interest in psychoanalysis," former Lacanian analyst and biographer Dylan Evans explains, speculating that "perhaps Lacan never really abandoned his early surrealist sympathies, its neo-Romantic view of madness as 'convulsive beauty', its celebration of irrationality."[12] Translator and historian David Macey writes that "the importance of surrealism can hardly be over-stated... to the young Lacan... [who] also shared the surrealists' taste for scandal and provocation, and viewed provocation as an important element in psycho-analysis itself".[13] In 1931, after a second year at the Sainte-Anne Hospital, Lacan was awarded his Diplôme de médecin légiste (a medical examiner's qualification) and became a licensed forensic psychiatrist. The following year he was awarded his Diplôme d'État de docteur en médecine [fr] (roughly equivalent to an M.D. degree) for his thesis "On Paranoiac Psychosis in its Relations to the Personality" ("De la Psychose paranoïaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité".[14][10]: 21 [a] Its publication had little immediate impact on French psychoanalysis but it did meet with acclaim amongst Lacan's circle of surrealist writers and artists. In their only recorded instance of direct communication, Lacan sent a copy of his thesis to Sigmund Freud who acknowledged its receipt with a postcard.[10]: 212 Lacan's thesis was based on observations of several patients with a primary focus on one female patient whom he called Aimée. Its exhaustive reconstruction of her family history and social relations, on which he based his analysis of her paranoid state of mind, demonstrated his dissatisfaction with traditional psychiatry and the growing influence of Freud on his ideas.[15] Also in 1932, Lacan published a translation of Freud's 1922 text, "Über einige neurotische Mechanismen bei Eifersucht, Paranoia und Homosexualität" ("Some Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia and Homosexuality") as "De quelques mécanismes névrotiques dans la jalousie, la paranoïa et l'homosexualité" in the Revue française de psychanalyse [fr]. In Autumn 1932, Lacan began his training analysis with Rudolph Loewenstein, which was to last until 1938.[16] In 1934 Lacan became a candidate member of the Société psychanalytique de Paris (SPP). He began his private psychoanalytic practice in 1936 whilst still seeing patients at the Sainte-Anne Hospital,[8]: 129 and the same year presented his first analytic report at the Congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) in Marienbad on the "Mirror Phase". The congress chairman, Ernest Jones, terminated the lecture before its conclusion, since he was unwilling to extend Lacan's stated presentation time. Insulted, Lacan left the congress to witness the Berlin Olympic Games. No copy of the original lecture remains, Lacan having decided not to hand in his text for publication in the conference proceedings.[17] Lacan's attendance at Kojève's lectures on Hegel, given between 1933 and 1939, and which focused on the Phenomenology and the master-slave dialectic in particular, was formative for his subsequent work,[10]: 96–98 initially in his formulation of his theory of the mirror phase, for which he was also indebted to the experimental work on child development of Henri Wallon.[8]: 143 It was Wallon who commissioned from Lacan the last major text of his pre-war period, a contribution to the 1938 Encyclopédie française entitled "La Famille" (reprinted in 1984 as "Les Complexes familiaux dans la formation de l'individu", Paris: Navarin). 1938 was also the year of Lacan's accession to full membership (membre titulaire) of the SPP, notwithstanding considerable opposition from many of its senior members who were unimpressed by his recasting of Freudian theory in philosophical terms.[8]: 122 Lacan married Marie-Louise Blondin in January 1934 and in January 1937 they had the first of their three children, a daughter named Caroline. A son, Thibaut, was born in August 1939 and a daughter, Sybille, in November 1940.[8]: 129 |

1930s ラカンは1930年代のパリのシュルレアリスム運動に参加し、アンドレ・ブルトン、ジョルジュ・バタイユ、サルバドール・ダリ、パブロ・ピカソらと交際し た[11]。マリーズ・ショワジーが創設したムーヴメント・サイケに参加し、シュルレアリスムの雑誌『ミノタウール』に掲載された。ラカンのシュルレアリ スムへの関心は、彼の精神分析への関心よりも先にあった」と元ラカンの分析家で伝記作家のディラン・エヴァンスは説明し、「おそらくラカンは初期のシュル レアリスムへの共感、『痙攣する美』としての狂気に対する新ロマン主義的な見方、非合理性の賛美を決して捨てなかったのだろう」と推測する[12]。[彼 は)シュルレアリストたちのスキャンダルと挑発の趣味を共有し、挑発を心理分析そのものの重要な要素とみなしていた」[13]。 1931年、サント・アンヌ病院で2年目を過ごした後、ラカンはDiplôme de médecin légiste(監察医資格)を授与され、法医学精神科医の資格を得る。翌年、彼は論文「人格との関係におけるパラノイアック精神病について」("De la Psychose paranoïaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité")で医学博士号(Diplôme d'État de docteur en médecine [fr])を授与される。ラカンはジークムント・フロイトに論文のコピーを送り、ジークムント・フロイトは葉書でその受領を認めた。 ラカンの論文は、彼がエメと呼ぶ一人の女性患者を中心に、数人の患者の観察に基づいていた。彼女の家族歴と社会関係を徹底的に再構築し、それに基づいて彼 女の妄想的な精神状態を分析したことで、伝統的な精神医学に対する彼の不満と、フロイトの影響が彼の思想に大きくなっていることが示された[15]。 [15] また1932年、ラカンはフロイトの1922年の文章 "Über einige neurotische Mechanismen bei Eifersucht, Paranoia und Homosexualität"(「嫉妬、パラノイア、同性愛におけるいくつかの神経症的メカニズム」)の翻訳を "De quelques mécanismes névrotiques dans la jalousie, la paranoïa et l'homosexualité"(「嫉妬、パラノイア、同性愛におけるいくつかの神経症的メカニズム」)としてRevue française de psychanalyse [fr]に発表した。1932年秋、ラカンはルドルフ・ローヴェンシュタイン(Rudolph Loewenstein)のもとで1938年まで続く分析実習を開始する[16]。 1934年、ラカンはパリ精神分析協会(SPP)の会員候補となる。1936年、サント・アンヌ病院で患者を診察する傍ら、個人的に精神分析の仕事を始め る[8]: 129。同年、マリエンバードで開催された国際精神分析協会(IPA)の大会で、「鏡像段階」に関する最初の分析報告を行った。大会議長の アーネスト・ジョーンズは、ラカンの発表時間の延長を望まなかったため、講演を途中で打ち切った。侮辱されたラカンは、ベルリン・オリンピックを見るため に大会を去った。ラカンは会議録に掲載するためのテキストを提出しないことを決めたため、オリジナルの講演のコピーは残っていない[17]。 1933年から1939年にかけて行われたコジェーヴのヘーゲルに関する講義に出席したラカンは、特に現象学と主従弁証法に焦点を当てたものであったが、 この講義は彼のその後の仕事にとって形成的なものであった[10]: 96-98: 143 ラカンの戦前期最後の主要なテキストである1938年の『百科全書』への寄稿文「家族」(1984年に『個体形成における家族的複合体』として再版、パ リ)をラカンに依頼したのはワロンであった: ナヴァラン)。1938年はラカンがSPPの正会員(membre titulaire)になった年でもあったが、彼のフロイト理論を哲学的な用語で再構成することに感銘を受けなかった多くの上級会員からの反対にもかかわ らずであった[8]: 122 ラカンは1934年1月にマリー=ルイーズ・ブロンダンと結婚し、1937年1月には3人の子供のうち最初の子供である娘カロリーヌをもうけた。1939 年8月には息子のティボーが、1940年11月には娘のシビルが生まれた[8]: 129 |

| 1940s The SPP was disbanded due to Nazi Germany's occupation of France in 1940. Lacan was called up for military service which he undertook in periods of duty at the Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris, whilst at the same time continuing his private psychoanalytic practice. In 1942 he moved into apartments at 5 rue de Lille, which he would occupy until his death. During the war he did not publish any work, turning instead to a study of Chinese for which he obtained a degree from the École spéciale des langues orientales.[8]: 147 [18] In a relationship they formed before the war, Sylvia Bataille (née Maklès), the estranged wife of his friend Georges Bataille, became Lacan's mistress and, in 1953, his second wife. During the war their relationship was complicated by the threat of deportation for Sylvia, who was Jewish, since this required her to live in the unoccupied territories. Lacan intervened personally with the authorities to obtain papers detailing her family origins, which he destroyed. In 1941 they had a child, Judith. She kept the name Bataille because Lacan wished to delay the announcement of his planned separation and divorce until after the war.[8]: 147 After the war, the SPP recommenced their meetings. In 1945 Lacan visited England for a five-week study trip, where he met the British analysts Ernest Jones, Wilfred Bion and John Rickman. Bion's analytic work with groups influenced Lacan, contributing to his own subsequent emphasis on study groups as a structure within which to advance theoretical work in psychoanalysis. He published a report of his visit as 'La Psychiatrique anglaise et la guerre' (Evolution psychiatrique 1, 1947, pp. 293–318). In 1949, Lacan presented a new paper on the mirror stage, 'The Mirror-Stage, as Formative of the I, as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience', to the sixteenth IPA congress in Zurich. The same year he set out in the Doctrine de la Commission de l'Enseignement, produced for the Training Commission of the SPP, the protocols for the training of candidates.[10]: 220–221 |

1940s 1940年、ナチス・ドイツのフランス占領によりSPPは解散。ラカンは兵役に召集され、パリのヴァル・ド・グラース軍事病院に勤務する傍ら、個人的な精 神分析活動を続けた。1942年、リール通り5番地のアパートに移り、死ぬまでそこに住み続けた。戦時中は著作を発表せず、中国語の研究に没頭し、東洋言 語高等研究院で学位を取得した[8]: 147 [18] 戦前に結ばれた関係では、友人ジョルジュ・バタイユの別居中の妻シルヴィア・バタイユ(旧姓マクレス)がラカンの愛人となり、1953年には2番目の妻と なった。戦時中、二人の関係は、ユダヤ人であったシルヴィアが非占領地域に住まなければならないため、国外追放の危機にさらされ、複雑なものとなった。ラ カンは個人的に当局に働きかけ、彼女の家族の出自を詳細に記した書類を手に入れたが、それは破棄された。1941年、二人はジュディスという子供をもうけ た。彼女はバタイユという名前を名乗っていたが、それはラカンが予定していた別居と離婚の発表を戦後まで遅らせたかったからである[8]: 147 戦後、SPPは会合を再開。1945年、ラカンは5週間の研修旅行でイギリスを訪れ、そこでイギリスの分析家アーネスト・ジョーンズ、ウィルフレッド・ビ オン、ジョン・リックマンに出会う。ビオンのグループによる分析作業はラカンに影響を与え、精神分析における理論的作業を進めるための構造として研究グ ループを重視するようになった。彼は訪問の報告を「La Psychiatrique anglaise et la guerre」(精神医学の進化1、1947年、293-318頁)として出版した。 1949年、ラカンはチューリヒで開催された第16回IPA大会で、鏡像段階に関する新しい論文「精神分析的経験において明らかにされた、私の形成として の鏡像段階」を発表した。同年、彼はSPPの訓練委員会のために作成された『教育委員会の教義』の中で、候補者の訓練のためのプロトコルを示した [10]: 220-221 |

| 1950s With the purchase in 1951 of a country mansion at Guitrancourt, Lacan established a base for weekend retreats for work, leisure—including extravagant social occasions—and for the accommodation of his vast library. His art collection included Courbet's L'Origine du monde, which he had concealed in his study by a removable wooden screen on which an abstract representation of the Courbet by the artist André Masson was portrayed.[8]: 294 In 1951, Lacan started to hold a private weekly seminar in Paris in which he inaugurated what he described as "a return to Freud," whose doctrines were to be re-articulated through a reading of Saussure's linguistics and Levi-Strauss's structuralist anthropology. Becoming public in 1953, Lacan's 27-year-long seminar was highly influential in Parisian cultural life, as well as in psychoanalytic theory and clinical practice.[8]: 299 In January 1953 Lacan was elected president of the SPP. When, at a meeting the following June, a formal motion was passed against him criticising his abandonment of the standard analytic training session for the variable-length session, he immediately resigned his presidency. He and a number of colleagues then resigned from the SPP to form the Société Française de Psychanalyse (SFP).[10]: 227 One consequence of this was to eventually deprive the new group of membership of the International Psychoanalytical Association. Encouraged by the reception of "the return to Freud" and of his report "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis," Lacan began to re-read Freud's works in relation to contemporary philosophy, linguistics, ethnology, biology, and topology. From 1953 to 1964 at the Sainte-Anne Hospital, he held his Seminars and presented case histories of patients. During this period he wrote the texts that are found in the collection Écrits, which was first published in 1966. In his seventh seminar "The Ethics of Psychoanalysis" (1959–60), which according to Lewis A. Kirshner "arguably represents the most far-reaching attempt to derive a comprehensive ethical position from psychoanalysis,"[19] Lacan defined the ethical foundations of psychoanalysis and presented his "ethics for our time"—one that would, in the words of Freud, prove to be equal to the tragedy of modern man and to the "discontent of civilization." At the roots of the ethics is desire: the only promise of analysis is austere, it is the entrance-into-the-I (in French a play on words between l'entrée en je and l'entrée en jeu). "I must come to the place where the id was," where the analysand discovers, in its absolute nakedness, the truth of his desire. The end of psychoanalysis entails "the purification of desire." He defended three assertions: that psychoanalysis must have a scientific status; that Freudian ideas have radically changed the concepts of subject, of knowledge, and of desire; and that the analytic field is the only place from which it is possible to question the insufficiencies of science and philosophy.[20] |

1950s 1951年、ギトランコールの田舎の邸宅を購入したラカンは、仕事、レジャー(贅沢な社交の場を含む)、膨大な蔵書のために週末を過ごすための拠点を確立 した。彼の美術コレクションにはクールベの『現代の起源』が含まれ、彼は書斎に取り外し可能な木製スクリーンを設置し、そこに画家アンドレ・マッソンによ るクールベの抽象的な表現を隠していた[8]: 294。 1951年、ラカンはパリで毎週開かれる個人的なセミナーを始め、そこで彼は「フロイトへの回帰」と表現し、その教義をソシュールの言語学とレヴィ=スト ロースの構造主義人類学の読解を通して再解釈することになる。1953年に公開されたラカンの27年にわたるセミナーは、パリの文化生活や精神分析理論、 臨床実践に大きな影響を与えた[8]: 299。 1953年1月、ラカンはSPPの会長に選出された。翌年6月の会合で、ラカンが標準的な分析訓練セッションを放棄し、可変長セッションを採用したことを 批判する正式な動議が提出されると、ラカンは即座に会長職を辞任した。その後、彼と多くの同僚たちはSPPを脱退し、フランス精神分析協会(SFP)を結 成した。 フロイトへの回帰」と彼の報告書「精神分析における音声と言語の機能と領域」の反響に後押しされ、ラカンはフロイトの著作を現代の哲学、言語学、民族学、 生物学、位相幾何学との関連で読み直し始めた。1953年から1964年まで、サント・アンヌ病院でセミナーを開き、患者の症例を発表した。この間に、 1966年に出版された『Écrits』に収められている文章を執筆した。ルイス・A・カーシュナーによれば、「間違いなく、精神分析から包括的な倫理的 立場を導き出そうとする最も遠大な試みである」[19]。ラカンは第7回セミナー『精神分析の倫理』(1959-60年)で、精神分析の倫理的基盤を定義 し、「現代のための倫理」を提示した。この倫理の根底にあるのは欲望である。分析の唯一の約束は厳格であり、それは「私」への入口(フランス語で l'entrée en jeとl'entrée en jeuの語呂合わせ)である。「私はイドのあった場所に来なければならない」。そこで分析者は、自分の欲望の真実を、その絶対的な裸の状態で発見するので ある。精神分析の終わりは「欲望の浄化」を意味する。精神分析は科学的な地位を持たなければならないこと、フロイトの思想は主体、知識、欲望の概念を根本 的に変えてしまったこと、そして分析領域は科学や哲学の不十分さを問うことができる唯一の場所であることである[20]。 |

| 1960s Starting in 1962, a complex negotiation took place to determine the status of the SFP within the IPA. Lacan's practice (with its controversial indeterminate-length sessions) and his critical stance towards psychoanalytic orthodoxy led, in August 1963, to the IPA setting the condition that registration of the SFP was dependent upon the removal of Lacan from the list of SFP analysts.[21] With the SFP's decision to honour this request in November 1963, Lacan had effectively been stripped of the right to conduct training analyses and thus was constrained to form his own institution in order to accommodate the many candidates who desired to continue their analyses with him. This he did, on 21 June 1964, in the "Founding Act"[22] of what became known as the École Freudienne de Paris (EFP), taking "many representatives of the third generation with him: among them were Maud and Octave Mannoni, Serge Leclaire ... and Jean Clavreul".[23]: 293 With the support of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Louis Althusser, Lacan was appointed lecturer at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. He started with a seminar on The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis in January 1964 in the Dussane room at the École Normale Supérieure. Lacan began to set forth his own approach to psychoanalysis to an audience of colleagues that had joined him from the SFP. His lectures also attracted many of the École Normale's students. He divided the École Freudienne de Paris into three sections: the section of pure psychoanalysis (training and elaboration of the theory, where members who have been analyzed but have not become analysts can participate); the section for applied psychoanalysis (therapeutic and clinical, physicians who either have not started or have not yet completed analysis are welcome); and the section for taking inventory of the Freudian field (concerning the critique of psychoanalytic literature and the analysis of the theoretical relations with related or affiliated sciences).[24] In 1967 he invented the procedure of the Pass, which was added to the statutes after being voted in by the members of the EFP the following year. 1966 saw the publication of Lacan's collected writings, the Écrits, compiled with an index of concepts by Jacques-Alain Miller. Printed by the prestigious publishing house Éditions du Seuil, the Écrits did much to establish Lacan's reputation to a wider public. The success of the publication led to a subsequent two-volume edition in 1969. By the 1960s, Lacan was associated, at least in the public mind, with the far left in France.[25] In May 1968, Lacan voiced his sympathy for the student protests and as a corollary his followers set up a Department of Psychology at the University of Vincennes (Paris VIII). However, Lacan's unequivocal comments in 1971 on revolutionary ideals in politics draw a sharp line between the actions of some of his followers and his own style of "revolt."[26] In 1969, Lacan moved his public seminars to the Faculté de Droit (Panthéon), where he continued to deliver his expositions of analytic theory and practice until the dissolution of his school in 1980. |

1960s 1962年から、IPAにおけるSFPの地位を決定するために複雑な交渉が行われた。1963年8月、IPAはSFPの登録は、SFPの分析者リストから ラカンを削除することに依存しているという条件を設定した[21]。1963年11月にSFPがこの要求を尊重することを決定したことで、ラカンは事実 上、トレーニング分析を行う権利を剥奪され、その結果、彼と分析を続けることを望む多くの候補者を受け入れるために、彼自身の機関を設立することを余儀な くされた。1964年6月21日、ラカンは「第三世代の多くの代表者たち:モードとオクターヴ・マンノーニ、セルジュ・ルクレール......そしてジャ ン・クラヴルール」[23]: 293を連れて、パリ・フロイト学院(EFP)として知られるようになる「創立法」[22]を行った。 クロード・レヴィ=ストロースとルイ・アルチュセールの支援により、ラカンは高等師範学校の講師に任命された。彼は1964年1月、高等師範学校のデュサ ンの部屋で『精神分析の四つの基本概念』についてのセミナーを始めた。ラカンは、SFPから参加した同僚の聴衆を前に、精神分析への独自のアプローチを示 し始めた。ラカンの講義は、ノルマル高等師範学校の学生の多くも魅了した。彼はパリ・エコール・フロイデンを3つのセクションに分けた:純粋精神分析のセ クション(理論の訓練と精緻化、分析を受けたが分析者にはなっていないメンバーも参加可能)、応用精神分析のセクション(治療と臨床、分析を始めていない 医師やまだ分析を終えていない医師も歓迎)、そしてフロイトの分野の棚卸しのセクション(精神分析文献の批評と関連または関連する諸科学との理論的関係の 分析に関する)。 [24]1967年、彼は合格の手続きを考案し、翌年EFPのメンバーによって投票された後、規約に追加された。 1966年、ジャック=アラン・ミラーが概念索引を編纂したラカンの著作集『Écrits』が出版された。権威ある出版社Éditions du Seuilによって印刷された『Écrits』は、ラカンの名声を広く一般に知らしめるのに大いに貢献した。この出版物の成功により、1969年には2巻 からなる版が出版された。 1960年代には、ラカンは少なくとも世間一般ではフランスの極左と結びつけられていた。1968年5月、ラカンは学生デモへの同情を表明し、付随して彼 の支持者たちはヴァンセンヌ大学(パリ第8大学)に心理学科を設立した。しかし、1971年にラカンが政治における革命的理想について明確にコメントした ことは、彼の信奉者たちの行動と彼自身の「反乱」のスタイルとの間に鋭い一線を引くものであった[26]。 1969年、ラカンは公開セミナーをFaculté de Droit (Panthéon)に移し、1980年に彼の学校が解散するまで、分析理論と実践の解説を続けた。 |

| 1970s Throughout the final decade of his life, Lacan continued his widely followed seminars. During this period, he developed his concepts of masculine and feminine jouissance and placed an increased emphasis on the concept of "the Real" as a point of impossible contradiction in the "symbolic order". Lacan continued to draw widely on various disciplines, working closely on classical Chinese literature with François Cheng[27][28] and on the life and work of James Joyce with Jacques Aubert.[29] The growing success of the Écrits, which was translated (in abridged form) into German and English, led to invitations to lecture in Italy, Japan and the United States. He gave lectures in 1975 at Yale, Columbia and MIT.[30] Last years Lacan's failing health made it difficult for him to meet the demands of the year-long Seminars he had been delivering since the fifties, but his teaching continued into the first year of the eighties. After dissolving his School, the EFP, in January 1980,[31] Lacan travelled to Caracas to found the Freudian Field Institute on 12 July.[32] The Overture to the Caracas Encounter was to be Lacan's final public address. His last texts from the spring of 1981 are brief institutional documents pertaining to the newly formed Freudian Field Institute. Lacan died on 9 September 1981.[33] |

1970s 晩年の10年間、ラカンは広く支持されるセミナーを続けた。この時期、ラカンは男性的・女性的ジュイサンスの概念を発展させ、「象徴秩序」における不可能 な矛盾点としての「実在」の概念をより重視した。ラカンはさまざまな学問分野を幅広く利用し続け、フランソワ・チェン[27][28]と中国古典文学につ いて、ジャック・オベール[29]とジェイムズ・ジョイスの生涯と作品について緊密に研究した。1975年にはイェール大学、コロンビア大学、マサチュー セッツ工科大学で講義を行った[30]。 晩年 ラカンの健康状態が悪化したため、50年代から行っていた1年がかりのセミナーの要求に応えることが難しくなったが、80年代の最初の年まで彼の指導は続 いた。1980年1月に彼の学校であるEFPを解散した後[31]、ラカンは7月12日にフロイト分野研究所を設立するためにカラカスに向かった [32]。 カラカスの出会いへの序曲』はラカンの最後の公的な演説となった。1981年春からのラカンの最後のテキストは、新しく設立されたフロイト野研究所に関す る簡単な組織的文書である。 ラカンは1981年9月9日に死去した[33]。 |

| Major concepts Return to Freud Lacan's "return to Freud" emphasizes a renewed attention to the original texts of Freud, and included a radical critique of ego psychology, whereas "Lacan's quarrel with Object Relations psychoanalysis"[34]: 25 was a more muted affair. Here he attempted "to restore to the notion of the Object Relation... the capital of experience that legitimately belongs to it",[35] building upon what he termed "the hesitant, but controlled work of Melanie Klein... Through her we know the function of the imaginary primordial enclosure formed by the imago of the mother's body",[36] as well as upon "the notion of the transitional object, introduced by D. W. Winnicott... a key-point for the explanation of the genesis of fetishism".[37] Nevertheless, "Lacan systematically questioned those psychoanalytic developments from the 1930s to the 1970s, which were increasingly and almost exclusively focused on the child's early relations with the mother... the pre-Oedipal or Kleinian mother";[38] and Lacan's rereading of Freud—"characteristically, Lacan insists that his return to Freud supplies the only valid model"[39]—formed a basic conceptual starting-point in that oppositional strategy. Lacan thought that Freud's ideas of "slips of the tongue", jokes, and the interpretation of dreams all emphasized the agency of language in subjects' own constitution of themselves. In "The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason Since Freud," he proposes that "the psychoanalytic experience discovers in the unconscious the whole structure of language". The unconscious is not a primitive or archetypal part of the mind separate from the conscious, linguistic ego, he explained, but rather a formation as complex and structurally sophisticated as consciousness itself. Lacan is associated with the idea that "the unconscious is structured like a language", but the first time this sentence occurs in his work,[40] he clarifies that he means that both the unconscious and language are structured, not that they share a single structure; and that the structure of language is such that the subject cannot necessarily be equated with the speaker. This results in the self being denied any point of reference to which to be "restored" following trauma or a crisis of identity. André Green objected that "when you read Freud, it is obvious that this proposition doesn't work for a minute. Freud very clearly opposes the unconscious (which he says is constituted by thing-presentations and nothing else) to the pre-conscious. What is related to language can only belong to the pre-conscious".[34]: 5n Freud certainly contrasted "the presentation of the word and the presentation of the thing... the unconscious presentation is the presentation of the thing alone"[41] in his metapsychology. Dylan Evans, however, in his Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, "... takes issue with those who, like André Green, question the linguistic aspect of the unconscious, emphasizing Lacan's distinction between das Ding and die Sache in Freud's account of thing-presentation".[34]: 8n Green's criticism of Lacan also included accusations of intellectual dishonesty, he said, "[He] cheated everybody... the return to Freud was an excuse, it just meant going to Lacan."[42] |

主要概念 フロイトへの回帰 ラカンの「フロイトへの回帰」は、フロイトの原典への新たな関心を強調し、自我心理学に対する急進的な批判を含んでいたが、「ラカンの対象関係論精神分析 との論争」[34]:25はより穏やかなものであった。ここで彼は「対象関係という概念に......それに正当に属する経験の資本を回復させる」 [35]ことを試み、彼が「メラニー・クラインの......躊躇しつつも制御された仕事」と呼ぶものを土台とした。彼女を通して、われわれは母親の身体 のイマーゴによって形成される想像上の原初的な囲いの機能を知る」[36]。また「D・W・ウィニコットによって導入された移行的対象という概念... フェティシズムの発生を説明するためのキーポイント」[37]にも基づいている。 [37]にもかかわらず、「ラカンは、1930年代から1970年代にかけての、子どもの母親との初期の関係...エディプス以前の、あるいはクライン的 な母親...にますます、そしてほとんど独占的に焦点を当てていた精神分析の展開に体系的に疑問を呈していた」[38]のであり、ラカンのフロイトの再読 -「特徴的なことに、ラカンは、フロイトへの回帰が唯一の有効なモデルを提供すると主張している」[39]-は、その対立戦略の基本的な概念的出発点を形 成していた。 ラカンは、フロイトの「舌の滑り」、ジョーク、夢の解釈といった考え方はすべて、主体自身の自己構成における言語の主体性を強調するものだと考えていた。 彼は『無意識における文字のインスタンス、あるいはフロイト以後の理性』の中で、「精神分析的経験は無意識の中に言語の構造全体を発見する」と提唱してい る。無意識とは、意識的で言語的な自我から切り離された、心の原始的あるいは原型的な部分ではなく、むしろ意識そのものと同じくらい複雑で構造的に洗練さ れた形成物である、と彼は説明した。ラカンは「無意識は言語のように構造化されている」という考えと結びついているが、彼の著作の中でこの文章が初めて登 場したとき[40]、彼は、無意識と言語の両方が構造化されているという意味であって、それらが単一の構造を共有しているという意味ではないこと、言語の 構造は、主体が必ずしも話し手と同一視できないようなものであることを明らかにしている。その結果、トラウマやアイデンティティの危機の後では、自己を 「回復」させる参照点が否定されることになる。 アンドレ・グリーンは、「フロイトを読めば、この命題がちょっとやそっとでは通用しないことは明らかだ」と異議を唱えた。フロイトは、無意識(フロイトに よれば、無意識は事物表象によって構成され、それ以外の何ものでもない)と前意識とをはっきりと対立させている。言語に関係するものは前意識にしか属しえ ない」[34]: 5n フロイトは確かに彼の形而上学において「言葉の提示と事物の提示...無意識の提示は事物だけの提示である」[41]と対比していた。しかしディラン・エ ヴァンスは『ラカン精神分析事典』の中で、「...アンドレ・グリーンのように、無意識の言語的側面に疑問を投げかけ、フロイトの事物提示の説明における das Dingとdie Sacheの間のラカンの区別を強調する人々に異議を唱えている」[34]: 8n グリーンのラカン批判には知的不誠実さの非難も含まれており、彼は「(彼は)皆をだました...フロイトへの回帰は言い訳であり、それはただラカンに行く ことを意味していた」と述べている[42]。 |

| Mirror stage Main article: Mirror stage Lacan's first official contribution to psychoanalysis was the mirror stage, which he described as "formative of the function of the 'I' as revealed in psychoanalytic experience." By the early 1950s, he came to regard the mirror stage as more than a moment in the life of the infant; instead, it formed part of the permanent structure of subjectivity. In the "imaginary order", the subject's own image permanently catches and captivates the subject. Lacan explains that "the mirror stage is a phenomenon to which I assign a twofold value. In the first place, it has historical value as it marks a decisive turning-point in the mental development of the child. In the second place, it typifies an essential libidinal relationship with the body-image".[43] As this concept developed further, the stress fell less on its historical value and more on its structural value.[44] In his fourth seminar, "La relation d'objet", Lacan states that "the mirror stage is far from a mere phenomenon which occurs in the development of the child. It illustrates the conflictual nature of the dual relationship. " The mirror stage describes the formation of the ego via the process of objectification, the ego being the result of a conflict between one's perceived visual appearance and one's emotional experience. This identification is what Lacan called "alienation". At six months, the baby still lacks physical co-ordination. The child is able to recognize itself in a mirror prior to the attainment of control over their bodily movements. The child sees its image as a whole and the synthesis of this image produces a sense of contrast with the lack of co-ordination of the body, which is perceived as a fragmented body. The child experiences this contrast initially as a rivalry with its image, because the wholeness of the image threatens the child with fragmentation—thus the mirror stage gives rise to an aggressive tension between the subject and the image. To resolve this aggressive tension, the child identifies with the image: this primary identification with the counterpart forms the ego.[44] Lacan understood this moment of identification as a moment of jubilation, since it leads to an imaginary sense of mastery; yet when the child compares its own precarious sense of mastery with the omnipotence of the mother, a depressive reaction may accompany the jubilation.[45] Lacan calls the specular image "orthopaedic", since it leads the child to anticipate the overcoming of its "real specific prematurity of birth". The vision of the body as integrated and contained, in opposition to the child's actual experience of motor incapacity and the sense of his or her body as fragmented, induces a movement from "insufficiency to anticipation".[46] In other words, the mirror image initiates and then aids, like a crutch, the process of the formation of an integrated sense of self. In the mirror stage a "misunderstanding" (méconnaissance) constitutes the ego—the "me" (moi) becomes alienated from itself through the introduction of an imaginary dimension to the subject. The mirror stage also has a significant symbolic dimension, due to the presence of the figure of the adult who carries the infant. Having jubilantly assumed the image as their own, the child turns their head towards this adult, who represents the big other, as if to call on the adult to ratify this image.[47] |

ミラーステージ(鏡像段階) 主な記事 鏡像段階 ラカンの精神分析への最初の公式な貢献は鏡像段階であり、彼はこれを「精神分析的経験において明らかにされる『私』の機能の形成的なもの」と説明した。 1950年代初頭までに、彼は鏡像段階を幼児の人生の一時期以上のものとみなすようになった。想像の秩序」においては、主体自身のイメージが主体を永続的 にとらえ、魅了する。ラカンは「鏡の段階は、私が二重の価値を与える現象である」と説明する。第一に、子どもの精神発達における決定的な転換点を示すもの として、歴史的価値がある。第二に、それは身体イメージとの本質的なリビドー的関係を象徴している」[43]。 この概念がさらに発展するにつれて、その歴史的価値よりもその構造的価値の方が強調されるようになった[44]。ラカンは彼の第4のセミナーである "La relation d'objet "の中で、「鏡の段階は子どもの発達の中で起こる単なる現象からはかけ離れている。それは二重関係の葛藤的性質を示している。" 鏡の段階は、対象化の過程を経た自我の形成について述べており、自我とは、知覚された視覚的外見と感情的経験との間の葛藤の結果である。この同一化は、ラ カンが「疎外」と呼んだものである。生後6ヶ月の赤ちゃんは、まだ身体的な協調性に欠けている。身体の動きをコントロールできるようになる前に、子供は鏡 の中の自分を認識することができる。子どもは自分のイメージを全体として見ており、このイメージの統合によって、断片的な身体として知覚される身体の協調 性の欠如との対比の感覚が生まれる。なぜなら、イメージの全体性が子どもを断片化で脅かすからである。このように鏡の段階は、主体とイメージの間に攻撃的 な緊張を生じさせる。この攻撃的な緊張を解決するために、子どもはイメージと同一化する。この第一次的な相手との同一化は自我を形成する[44]。ラカン はこの同一化の瞬間を、想像上の支配者意識につながるので、歓喜の瞬間として理解した。 ラカンは鏡像のことを「整形外科的」と呼ぶが、それは「誕生という現実的な未熟さ」の克服を予期するように子どもを導くからである。統合され、内包された 身体としての身体像は、運動能力の欠如という子どもの実際の経験や、断片化された身体としての感覚と対立し、「不全から予期へ」の動きを誘発する [46]。言い換えれば、鏡像が、統合された自己の感覚の形成のプロセスを、松葉杖のように開始し、そして援助する。 鏡の段階では「誤解」(méconnaissance)が自我を構成し、「私」(moi)は主体に想像的な次元を導入することによって、それ自体から疎外 される。鏡の段階はまた、幼児を抱く大人の姿の存在によって、重要な象徴的側面を持っている。歓喜してそのイメージを自分のものとして引き受けた子ども は、このイメージを批准するように大人に呼びかけるかのように、大きな他者を象徴するこの大人の方に顔を向ける[47]。 |

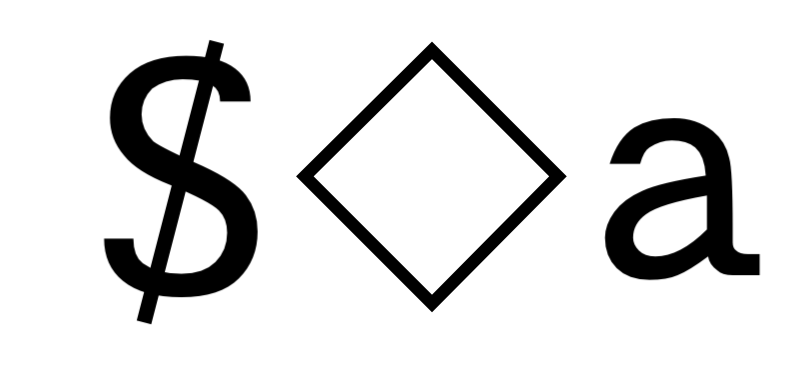

| Other While Freud uses the term "other", referring to der Andere (the other person) and das Andere (otherness), Lacan (influenced by the seminar of Alexandre Kojève) theorizes alterity in a manner more closely resembling Hegel's philosophy. Lacan often used an algebraic symbology for his concepts: the big other (l'Autre) is designated A, and the little other (l'autre) is designated a.[48] He asserts that an awareness of this distinction is fundamental to analytic practice: "the analyst must be imbued with the difference between A and a, so he can situate himself in the place of Other, and not the other".[44]: 135 Dylan Evans explains that: The little other is the other who is not really other, but a reflection and projection of the ego. Evans adds that for this reason the symbol a can represent both the little other and the ego in the schema L.[49] It is simultaneously the counterpart and the specular image. The little other is thus entirely inscribed in the imaginary order. The big other designates radical alterity, an other-ness which transcends the illusory otherness of the imaginary because it cannot be assimilated through identification. Lacan equates this radical alterity with language and the law, and hence the big other is inscribed in the order of the symbolic. Indeed, the big other is the symbolic insofar as it is particularized for each subject. The other is thus both another subject, in its radical alterity and unassimilable uniqueness, and also the symbolic order which mediates the relationship with that other subject."[50] For Lacan "the Other must first of all be considered a locus in which speech is constituted," so that the other as another subject is secondary to the other as symbolic order.[51] We can speak of the other as a subject in a secondary sense only when a subject occupies this position and thereby embodies the other for another subject.[52] In arguing that speech originates in neither the ego nor in the subject but rather in the other, Lacan stresses that speech and language are beyond the subject's conscious control. They come from another place, outside of consciousness—"the unconscious is the discourse of the Other".[53] When conceiving the other as a place, Lacan refers to Freud's concept of psychical locality, in which the unconscious is described as "the other scene". "It is the mother who first occupies the position of the big Other for the child", Dylan Evans explains, "it is she who receives the child's primitive cries and retroactively sanctions them as a particular message".[44] The castration complex is formed when the child discovers that this other is not complete because there is a "lack (manque)" in the other. This means that there is always a signifier missing from the trove of signifiers constituted by the other. Lacan illustrates this incomplete other graphically by striking a bar through the symbol A; hence another name for the castrated, incomplete other is the "barred other".[54] |

他者(大文字の他者:Other) フロイトが「他者」という用語を使い、der Andere(他者)やdas Andere(他者性)に言及しているのに対して、ラカンは(アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのセミナーの影響を受け)ヘーゲル哲学により近い方法で分身を理 論化している。 大文字の他者(l'Autre)はAと命名され、小文字の他者(l'autre)はaと命名される: 「分析者はAとaの違いに染まらなければならず、そうすれば他者ではなく他者の場所に自らを位置づけることができる」[44]: 135 ディラン・エヴァンスは次のように説明している: 小文字の他者とは、本当の他者ではなく、自我の反映であり投影である他者である。このため、記号aはスキーマLにおいて、小文字の他者と自我の両方を表す ことができる[49]。このように、小文字の他者は完全に想像上の秩序に刻み込まれている。 大文字の他者は急進的な分身、つまり同一化によって同化することができないために、想像上の幻想的な他者性を超越する他者性を指定する。ラカンはこの急進 的な変質を言語や法と同一視しており、それゆえ大文字の他者は象徴の秩序に刻み込まれている。実際、大文字の他者は、それがそれぞれの主体にとって特殊化 されている限りにおいて象徴的である。したがって他者とは、その根本的な変質性と同化不可能な独自性において、別の主体であると同時に、その別の主体との 関係を媒介する象徴的秩序でもある」[50]。 ラカンにとって「他者はまず第一に、発話が構成される場所と見なされなければならない」ので、別の主体としての他者は象徴秩序としての他者にとって二次的 なものである[51]。 ある主体がこの位置を占め、それによって別の主体にとっての他者を体現するときにのみ、二次的な意味での主体としての他者を語ることができる[52]。 発話は自我でも主体でもなく、むしろ他者に由来すると主張する中で、ラカンは発話と言語は主体の意識的な制御を超えたところにあると強調している。無意識 は他者の言説である」[53]。他者を場所として考えるとき、ラカンはフロイトの精神的局所性の概念を参照し、そこでは無意識が「もうひとつの場面」とし て記述されている。 「子どもの原始的な叫びを受け取り、それを特定のメッセージとして遡及的に承認するのは母親である」とディラン・エヴァンスは説明する。つまり、他者に よって構成されるシニフィエの宝庫から常にシニフィエが欠落しているということである。ラカンはこの不完全な他者を、記号Aを貫く棒を打つことによって図 式的に示している。それゆえ去勢された不完全な他者に対する別の名前は「棒を打たれた他者」である[54]。 |

| Phallus Feminist thinkers have both utilised and criticised Lacan's concepts of castration and the phallus. Feminists such as Avital Ronell, Jane Gallop,[55] and Elizabeth Grosz,[56] have interpreted Lacan's work as opening up new possibilities for feminist theory. Some feminists have argued that Lacan's phallocentric analysis provides a useful means of understanding gender biases and imposed roles, while others, most notably Luce Irigaray, accuse Lacan of maintaining the sexist tradition in psychoanalysis.[57] For Irigaray, the phallus does not define a single axis of gender by its presence or absence; instead, gender has two positive poles. Like Irigaray, French philosopher Jacques Derrida, in criticizing Lacan's concept of castration, discusses the phallus in a chiasmus with the hymen, as both one and other.[58][59] |

ファルス(男根であるがファルスと読む) フェミニストの思想家たちはラカンの去勢とファルスの概念を利用し、また批判してきた。アヴィタル・ローネル、ジェーン・ギャロップ[55]、エリザベ ス・グロシュ[56]といったフェミニストたちは、ラカンの仕事をフェミニズム理論に新たな可能性を開くものとして解釈してきた。 一部のフェミニストはラカンのファルス中心主義的な分析がジェンダーの偏見や押し付けられた役割を理解する有用な手段を提供すると主張しているが、一方で 他の者、特にルーチェ・イリガライは精神分析における性差別的な伝統をラカンが維持していると非難している[57]。 イリガライにとってファルスはその有無によってジェンダーの単一の軸を定義するものではなく、その代わりにジェンダーには2つの肯定的な極がある。イリガ ライと同様に、フランスの哲学者ジャック・デリダはラカンの去勢の概念を批判する中で、ファルスを♀とのキアスムスにおいて、一方であり他方でもあるもの として論じている[58][59]。 |

| Three orders (plus one) Lacan considered psychic functions to occur within a universal matrix. The Real, Imaginary and Symbolic are properties of this matrix, which make up part of every psychic function. This is not analogous to Freud's concept of id, ego and superego since in Freud's model certain functions take place within components of the psyche while Lacan thought that all three orders were part of every function. Lacan refined the concept of the orders over decades, resulting in inconsistencies in his writings. He eventually added a fourth component, the sinthome.[60]: 77 |

3つの秩序(プラス1) ラカンは、心的機能は普遍的なマトリックスの中で起こると考えた。現実(Real)、想像(Imaginary)、象徴(Symbolic)はこのマト リックスの特性であり、あらゆる精神機能の一部を構成している。これはフロイトのイド、自我、超自我の概念とは似て非なるもので、フロイトのモデルでは特 定の機能が精神の構成要素の中で起こるのに対し、ラカンは3つの秩序すべてがすべての機能の一部であると考えたからである。ラカンは数十年にわたって秩序 の概念を洗練させたが、その結果、彼の著作には矛盾が生じた。彼は最終的に第四の構成要素である罪家を追加した。 |

| The Imaginary (psychoanalysis) The Imaginary is the field of images and imagination. The main illusions of this order are synthesis, autonomy, duality, and resemblance. Lacan thought that the relationship created within the mirror stage between the ego and the reflected image means that the ego and the Imaginary order itself are places of radical alienation: "alienation is constitutive of the Imaginary order".[61] This relationship is also narcissistic. In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan argues that the Symbolic order structures the visual field of the Imaginary, which means that it involves a linguistic dimension. If the signifier is the foundation of the symbolic, the signified and signification are part of the Imaginary order. Language has symbolic and Imaginary connotations—in its Imaginary aspect, language is the "wall of language" that inverts and distorts the discourse of the Other. The Imaginary, however, is rooted in the subject's relationship with his or her own body (the image of the body). In Fetishism: the Symbolic, the Imaginary and the Real, Lacan argues that in the sexual plane the Imaginary appears as sexual display and courtship love. Insofar as identification with the analyst is the objective of analysis, Lacan accused major psychoanalytic schools of reducing the practice of psychoanalysis to the Imaginary order.[62] Instead, Lacan proposes the use of the symbolic to dislodge the disabling fixations of the Imaginary—the analyst transforms the images into words. "The use of the Symbolic", he argued, "is the only way for the analytic process to cross the plane of identification."[63] |

イマジナリー=想像界(精神分析) イマジナリーとはイメージと想像力の分野である。この秩序の主な幻想は、統合、自律性、二元性、類似性である。ラカンは、自我と映し出されたイメージの間 に鏡の段階で生まれる関係は、自我とイマジナリー秩序そのものが根本的な疎外の場であることを意味すると考えた: 「疎外はイマジナリー秩序を構成するものである」[61]。 『精神分析の4つの基本概念』の中でラカンは、象徴秩序がイマジナリーの視覚的場を構造化しており、それは言語的次元を含んでいることを意味していると論じ ている。シニフィエが象徴の基礎であるならば、シニフィエとシニフィケーションはイマジナリー秩序の一部である。言語には象徴的な意味合いとイマジナリー な意味合いがあり、イマジナリーな側面では、言語は他者の言説を反転させ、歪曲させる「言語の壁」である。しかし、イマジナリーは、主体が自らの身体(の イメージ)との関係に根ざしている。ラカンは『フェティシズム:象徴、イマジナリー、リアル』の中で、性的な平面においてイマジナリーは性的なディスプレ イや求愛として現れると論じている。 分析者との同一化が分析の目的である限り、ラカンは主要な精神分析学派が精神分析の実践をイマジナリー秩序に還元していると非難している。「象徴の使用」 は「分析過程が同一化の平面を越える唯一の方法である」と彼は主張した[63]。 |

| The Symbolic In his Seminar IV, "La relation d'objet", Lacan argues that the concepts of "Law" and "Structure" are unthinkable without language—thus the Symbolic is a linguistic dimension. This order is not equivalent to language, however, since language involves the Imaginary and the Real as well. The dimension proper to language in the Symbolic is that of the signifier—that is, a dimension in which elements have no positive existence, but which are constituted by virtue of their mutual differences. The Symbolic is also the field of radical alterity—that is, the Other; the unconscious is the discourse of this Other. It is the realm of the Law that regulates desire in the Oedipus complex. The Symbolic is the domain of culture as opposed to the Imaginary order of nature. As important elements in the Symbolic, the concepts of death and lack (manque) connive to make of the pleasure principle the regulator of the distance from the Thing (in German, "das Ding an sich") and the death drive that goes "beyond the pleasure principle by means of repetition"—"the death drive is only a mask of the Symbolic order".[48] By working in the Symbolic order, the analyst is able to produce changes in the subjective position of the person undergoing psychoanalysis. These changes will produce imaginary effects because the Imaginary is structured by the Symbolic.[44] |

象徴界(シンボリック) ラカンはセミナーIV「オブジェの関係」の中で、「法則」と「構造」という概念は言語なしには考えられないと主張する。しかし、この秩序は言語と等価では ない。言語にはイマジナリーやリアルも含まれるからだ。シンボリックにおける言語にふさわしい次元とは、シニフィアン(記号)の次元であり、つまり、要素 が積極的な存在を持たず、相互の差異によって構成される次元である。 無意識はこの他者の言説である。それはエディプス・コンプレックスにおける欲望を規制する法の領域である。象徴とは、自然の想像的秩序とは対照的な文化の 領域である。象徴的秩序における重要な要素として、死と欠落(manque)の概念は、快楽原理を事物からの距離(ドイツ語では「das Ding an sich」)の調整装置とし、「反復によって快楽原理を超える」死の衝動--「死の衝動は象徴的秩序の仮面にすぎない」--となるように企図する [48]。 象徴秩序に働きかけることによって、分析者は精神分析を受けている人の主観的立場に変化をもたらすことができる。イマジナリーは象徴によって構造化されて いるため、こうした変化はイマジナリーな効果を生み出すことになる[44]。 |

| The Real Lacan's concept of the Real dates back to 1936 and his doctoral thesis on psychosis. It was a term that was popular at the time, particularly with Émile Meyerson, who referred to it as "an ontological absolute, a true being-in-itself".[44]: 162 Lacan returned to the theme of the Real in 1953 and continued to develop it until his death. The Real, for Lacan, is not synonymous with reality. Not only opposed to the Imaginary, the Real is also exterior to the Symbolic. Unlike the latter, which is constituted in terms of oppositions (i.e. presence/absence), "there is no absence in the Real".[48] Whereas the Symbolic opposition "presence/absence" implies the possibility that something may be missing from the Symbolic, "the Real is always in its place".[63] If the Symbolic is a set of differentiated elements (signifiers), the Real in itself is undifferentiated—it bears no fissure. The Symbolic introduces "a cut in the real" in the process of signification: "it is the world of words that creates the world of things—things originally confused in the 'here and now' of the all in the process of coming into being".[64] The Real is that which is outside language and that resists symbolization absolutely. In Seminar XI Lacan defines the Real as "the impossible" because it is impossible to imagine, impossible to integrate into the Symbolic, and impossible to attain. It is this resistance to symbolization that lends the Real its traumatic quality. Finally, the Real is the object of anxiety, insofar as it lacks any possible mediation and is "the essential object which is not an object any longer, but this something faced with which all words cease and all categories fail, the object of anxiety par excellence."[48] |

リアル(現実界) ラカンの現実界の概念は1936年、精神病に関する博士論文にまで遡る。それは当時流行していた用語であり、特にエミール・メイヤソンはそれを「存在論 的な絶対的存在、自己のなかの真の存在」と呼んでいた[44]: 162 ラカンは1953年に現実界のテーマに戻り、亡くなるまでそれを発展させ続けた。ラカンにとっての「実在」は現実と同義ではない。想像界と対立する だけでなく、現実界はシンボリックの外部でもある。シンボリックの「存在/不在」という対立が、シンボリックから何かが欠落している可能性を示唆している のに対して、「現実界は常にその場所にある」[63]。記号は記号化の過程において「現実における切れ目」を導入する: それは、ものの世界を創造する言葉の世界であり、それは元来、すべてのものが誕生する過程の「今、ここ」で混同されていたものである」[64]。実在と は、言語の外側にあり、象徴化に絶対的に抵抗するものである。ラカンは『セミナーXI』において、現実界を「不可能なもの」と定義しているが、それは想像 することが不可能であり、象徴に統合することが不可能であり、到達することが不可能だからである。この象徴化への抵抗こそが、現実界にトラウマ的な質を与 えているのである。最後に、現実界は、それがいかなる可能な媒介をも欠いており、「もはや対象ではない本質的な対象であるが、すべての言葉が停止し、すべ てのカテゴリーが失敗するこの何かに直面している、卓越した不安の対象」である限りにおいて、不安の対象である[48]。 |

| Sinthome The term "sinthome" (French: [sɛ̃tom]) was introduced by Jacques Lacan in his seminar Le sinthome (1975–76). According to Lacan, sinthome is the Latin way (1495 Rabelais, IV,63[65]) of spelling the Greek origin of the French word symptôme, meaning symptom. The seminar is a continuing elaboration of his topology, extending the previous seminar's focus (RSI) on the Borromean Knot and an exploration of the writings of James Joyce. Lacan redefines the psychoanalytic symptom in terms of his topology of the subject. In "Psychoanalysis and its Teachings" (Écrits) Lacan views the symptom as inscribed in a writing process, not as ciphered message which was the traditional notion. In his seminar "L'angoisse" (1962–63) he states that the symptom does not call for interpretation: in itself it is not a call to the Other but a pure jouissance addressed to no-one. This is a shift from the linguistic definition of the symptom—as a signifier—to his assertion that "the symptom can only be defined as the way in which each subject enjoys (jouit) the unconscious in so far as the unconscious determines the subject". He goes from conceiving the symptom as a message which can be deciphered by reference to the unconscious structured like a language to seeing it as the trace of the particular modality of the subject's jouissance. |

サントーム(→このページで後述) 「サントーム」(仏: [sɛ̃tom])という用語は、ジャック・ラカンが自身のセミナーLe sinthome(1975-76)で紹介した。ラカンによれば、sinthomeとは、症状を意味するフランス語のsymptômeのギリシャ語源をラ テン語風に綴ったもの(1495 Rabelais, IV,63[65])。このセミナーは、前回のセミナー(RSI)で焦点を当てた「ボロミアンの結び目」とジェイムズ・ジョイスの著作の探求を発展させ、 彼のトポロジーを引き続き精緻化したものである。ラカンは精神分析的症状を、彼の主題のトポロジーという観点から再定義する。 精神分析とその教え」(Écrits)において、ラカンは、従来の概念であった暗号化されたメッセージとしてではなく、書くプロセスに刻まれたものとして 症状を捉えている。ラカンはセミナー『L'angoisse』(1962-63年)の中で、症状は解釈を求めるものではないと述べている。これは、記号と しての徴候の言語的定義から、「無意識が主体を決定する限りにおいて、各主体が無意識を享受(jouit)する方法としてのみ、徴候を定義することができ る」という彼の主張への転換である。彼は症状を、言語のように構造化された無意識を参照することで解読可能なメッセージと考えることから、それを、主体の ジュワッサンスの特殊な様式の痕跡とみなすようになる。 |

| Desire Lacan's concept of desire is related to Hegel's Begierde, a term that implies a continuous force, and therefore somehow differs from Freud's concept of Wunsch.[67] Lacan's desire refers always to unconscious desire because it is unconscious desire that forms the central concern of psychoanalysis. The aim of psychoanalysis is to lead the analysand to recognize his/her desire and by doing so to uncover the truth about his/her desire. However this is possible only if desire is articulated in speech:[68] "It is only once it is formulated, named in the presence of the other, that desire appears in the full sense of the term."[69] And again in The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: "what is important is to teach the subject to name, to articulate, to bring desire into existence. The subject should come to recognize and to name her/his desire. But it isn't a question of recognizing something that could be entirely given. In naming it, the subject creates, brings forth, a new presence in the world."[70] The truth about desire is somehow present in discourse, although discourse is never able to articulate the entire truth about desire; whenever discourse attempts to articulate desire, there is always a leftover or surplus.[71] Lacan distinguishes desire from need and from demand. Need is a biological instinct where the subject depends on the Other to satisfy its own needs: in order to get the Other's help, "need" must be articulated in "demand". But the presence of the Other not only ensures the satisfaction of the "need", it also represents the Other's love. Consequently, "demand" acquires a double function: on the one hand, it articulates "need", and on the other, acts as a "demand for love". Even after the "need" articulated in demand is satisfied, the "demand for love" remains unsatisfied since the Other cannot provide the unconditional love that the subject seeks. "Desire is neither the appetite for satisfaction, nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second."[72] Desire is a surplus, a leftover, produced by the articulation of need in demand: "desire begins to take shape in the margin in which demand becomes separated from need".[72] Unlike need, which can be satisfied, desire can never be satisfied: it is constant in its pressure and eternal. The attainment of desire does not consist in being fulfilled but in its reproduction as such. As Slavoj Žižek puts it, "desire's raison d'être is not to realize its goal, to find full satisfaction, but to reproduce itself as desire".[73] Lacan also distinguishes between desire and the drives: desire is one and drives are many. The drives are the partial manifestations of a single force called desire.[74] Lacan's concept of "objet petit a" is the object of desire, although this object is not that towards which desire tends, but rather the cause of desire. Desire is not a relation to an object but a relation to a lack (manque). ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis Lacan argues that "man's desire is the desire of the Other." This entails the following: 1. Desire is the desire of the Other's desire, meaning that desire is the object of another's desire and that desire is also desire for recognition. Here Lacan follows Alexandre Kojève, who follows Hegel: for Kojève the subject must risk his own life if he wants to achieve the desired prestige.[75] This desire to be the object of another's desire is best exemplified in the Oedipus complex, when the subject desires to be the phallus of the mother. 2. In "The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious",[76] Lacan contends that the subject desires from the point of view of another whereby the object of someone's desire is an object desired by another one: what makes the object desirable is that it is precisely desired by someone else. Again Lacan follows Kojève. who follows Hegel. This aspect of desire is present in hysteria, for the hysteric is someone who converts another's desire into his/her own (see Sigmund Freud's "Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria" in SE VII, where Dora desires Frau K because she identifies with Herr K). What matters then in the analysis of a hysteric is not to find out the object of her desire but to discover the subject with whom she identifies. 3. Désir de l'Autre, which is translated as "desire for the Other" (though it could also be "desire of the Other"). The fundamental desire is the incestuous desire for the mother, the primordial Other.[77] 4. Desire is "the desire for something else", since it is impossible to desire what one already has. The object of desire is continually deferred, which is why desire is a metonymy.[78] 5. Desire appears in the field of the Other—that is, in the unconscious. Last but not least for Lacan, the first person who occupies the place of the Other is the mother and at first the child is at her mercy. Only when the father articulates desire with the Law by castrating the mother is the subject liberated from desire for the mother.[79] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan |

欲望(ラカン派) ラ カンの欲望の概念は、ヘーゲルの Begierde(欲望)と関連しており、これは継続的な力を示唆する用語であるため、フロイトの Wunsch(願望)の概念とはある程度異なる[67]。ラカンの欲望は常に無意識の欲望を指す。なぜなら、精神分析の中心的な関心事は無意識の欲望であ るからだ。 精神分析の目的は、被分析者が自身の欲望を認識し、そうすることで自身の欲望の真実を明らかにすることである。しかし、これは欲望が言語化されて初めて可 能となる:[68]「欲望が言葉として表現され、他者の前で名付けられて初めて、欲望は言葉の完全な意味において現れる」[69]。そして『フロイトの理 論における自我と精神分析の技術』でも再び述べている。「重要なのは、対象者に名前を付け、言語化し、欲望を存在させることを教えることである。対象者は 自分の欲望を認識し、名前付けるようになるべきである。しかし、それは完全に与えられる可能性のあるものを認識する問題ではない。それを名付けることで、 主体は世界に新たな存在を生み出し、引き起こすのである。」[70]欲望の真実は、言説の中に何らかの形で存在している。しかし、言説は欲望の真実のすべ てを明確に表現することはできない。欲望を表現しようとするたびに、常に何かが残ったり余ったりするのだ。[71] ラカンは、欲望と必要、そして要求を区別している。「必要」とは、主体が自らの必要を満たすために他者に依存する生物学的本能である。他者の助けを得るた めには、「必要」は「要求」として表明されなければならない。しかし、他者の存在は「必要」を満たすだけでなく、他者の愛をも象徴する。その結果、「要 求」は二重の機能を持つことになる。一方では「必要」を表明し、他方では「愛の要求」として機能する。需要として表明された「欲求」が満たされた後も、 「愛の要求」は満たされないままである。なぜなら、他者は主体が求める無条件の愛を提供できないからだ。「欲望とは、満足を求める食欲でも、愛の要求でも ない。前者を後者から差し引いた差である」[72]。欲望とは、需要として表明された「欲求」から生じる余剰、残余である。「欲望は、需要がニーズから切 り離された余白の中で形を成すようになる」[72]。満たされる可能性のあるニーズとは異なり、欲望は決して満たされることはない。それは絶え間なく圧力 をかけ続け、永遠に続く。欲望の達成とは、満たされることではなく、欲望そのものの再生産にある。スラヴォイ・ジジェクは、「欲望の存在理由は、目標を達 成することや完全な満足を得ることではなく、欲望として自らを再生産することにある」と述べる[73]。 ラカンもまた、欲望と衝動を区別している。欲望は一つであり、衝動は多数ある。衝動とは、欲望と呼ばれる一つの力の部分的な現れである[74]。ラカンの 「オブジェ・プティ・ア」の概念は、欲望の対象である。ただし、この対象は欲望が向かう対象ではなく、欲望の原因である。欲望とは、対象との関係ではな く、欠如(マンク)との関係である。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『精神分析の四つの基本概念』の中でラカンは、「人間の欲望とは他者の欲望である」と主張している。 1.欲望とは他者の欲望の欲望であり、欲望とは他者の欲望の対象であ り、欲望とはまた承認を求める欲望でもある。ここでラカンは、ヘーゲルに続くアレクサンドル・コジェーヴの考えに従っている。コジェーヴによれば、主体が 望みの名声を得ようとするなら、自らの命を危険にさらさなければならない[75]。他者の欲望の対象となることを望むこの欲望は、主体が母親のファルスと なることを望むエディプス・コンプレックスに最もよく表れている。 2. 「フロイトの無意識における主体の転覆と欲望の弁証法」[76]において、ラカンは、ある人の欲望の対象が別の誰かによって欲望される対象であることか ら、主体は別の誰かの視点から欲望すると主張している。つまり、ある対象が欲望の対象となるのは、まさに他の誰かによって欲望されるからなのだ。ここでも ラカンは、ヘーゲルに従うアレクサンドル・コジェーヴに従っている。この欲望の側面はヒステリーにも見られる。ヒステリー患者は他人の欲望を自分の欲望に 変換する人物だからである(ジークムント・フロイト『精神分析におけるヒステリー症例分析の断片』SE VII を参照。ドーラがフラウ・ケーに憧れるのは、ケー夫人と自分を同一視しているからである)。したがって、ヒステリー患者の分析において重要なのは、彼女の 欲望の対象を突き止めることではなく、彼女が同一視する主体を発見することである。 3. Désir de l'Autre(他者への欲望)は、「他者への欲望」(あるいは「他者の欲望」)とも訳される。根源的な欲望とは、母親に対する近親相姦的な欲望であり、原初的な他者に対する欲望である[77]。 4.欲望とは「何か他のものへの欲望」である。なぜなら、すでに持っているものを望むことは不可能だからである。欲望の対象は絶えず先延ばしされるため、欲望は換喩である[78]。 5. 欲望は他者の領域、つまり無意識に現れる。 ラカンにとって最も重要なのは、他者の位置を占める最初の存在は母親であり、最初は子どもが母親のなすがままになるということである。父親が母親を去勢することで欲望を法と結びつけるとき初めて、主体は母親への欲望から解放される[79]。 |

| Drive Lacan maintains Freud's distinction between drive (Trieb) and instinct (Instinkt). Drives differ from biological needs because they can never be satisfied and do not aim at an object but rather circle perpetually around it. He argues that the purpose of the drive (Triebziel) is not to reach a goal but to follow its aim, meaning "the way itself" instead of "the final destination"—that is, to circle around the object. The purpose of the drive is to return to its circular path and the true source of jouissance is the repetitive movement of this closed circuit.[79] Lacan posits drives as both cultural and symbolic constructs: to him, "the drive is not a given, something archaic, primordial".[79] He incorporates the four elements of drives as defined by Freud (pressure, end, object and source) to his theory of the drive's circuit: the drive originates in the erogenous zone, circles round the object, and returns to the erogenous zone. Three grammatical voices structure this circuit: 1. the active voice (to see) 2. the reflexive voice (to see oneself) 3. the passive voice (to be seen) The active and reflexive voices are autoerotic—they lack a subject. It is only when the drive completes its circuit with the passive voice that a new subject appears, implying that, prior to that instance, there was no subject.[79] Despite being the "passive" voice, the drive is essentially active: "to make oneself be seen" rather than "to be seen". The circuit of the drive is the only way for the subject to transgress the pleasure principle. To Freud sexuality is composed of partial drives (i.e. the oral or the anal drives) each specified by a different erotogenic zone. At first these partial drives function independently (i.e. the polymorphous perversity of children), it is only in puberty that they become organized under the aegis of the genital organs.[80] Lacan accepts the partial nature of drives, but (1) he rejects the notion that partial drives can ever attain any complete organization—the primacy of the genital zone, if achieved, is always precarious; and (2) he argues that drives are partial in that they represent sexuality only partially and not in the sense that they are a part of the whole. Drives do not represent the reproductive function of sexuality but only the dimension of jouissance.[79] Lacan identifies four partial drives: the oral drive (the erogenous zones are the lips (the partial object the breast—the verb is "to suck"), the anal drive (the anus and the faeces, "to shit"), the scopic drive (the eyes and the gaze, "to see") and the invocatory drive (the ears and the voice, "to hear"). The first two drives relate to demand and the last two to desire. The notion of dualism is maintained throughout Freud's various reformulations of the drive-theory. From the initial opposition between sexual drives and ego-drives (self-preservation) to the final opposition between the life drives (Lebenstriebe) and the death drives (Todestriebe).[81] Lacan retains Freud's dualism, but in terms of an opposition between the symbolic and the imaginary and not referred to different kinds of drives. For Lacan all drives are sexual drives, and every drive is a death drive (pulsion de mort) since every drive is excessive, repetitive and destructive.[82] The drives are closely related to desire, since both originate in the field of the subject.[79] But they are not to be confused: drives are the partial aspects in which desire is realized—desire is one and undivided, whereas the drives are its partial manifestations. A drive is a demand that is not caught up in the dialectical mediation of desire; drive is a "mechanical" insistence that is not ensnared in demand's dialectical mediation.[83] |

衝動 ラカンはフロイトの「衝動(Trieb)」と「本能(Instinkt)」の区別を維持している。衝動が生物学的欲求と異なるのは、決して満たされること がなく、対象を目指すのではなく、むしろその周囲を永遠に回り続けるからである。彼は、衝動(Triebziel)の目的はゴールに到達することではな く、その目的をたどることであり、それは「最終目的地」ではなく「道そのもの」を意味する、つまり対象の周囲を周回することであると主張する。ラカンはド ライブを文化的かつ象徴的な構築物として仮定している。彼にとって「ドライブは所与のものではなく、古風で根源的なもの」[79]であり、フロイトによっ て定義されたドライブの4つの要素(圧力、終末、対象、源)をドライブの回路の理論に組み込んでいる。この回路を構成するのは3つの文法的声部である: 1. 能動態(見る) 2. 反射音声(自分を見る) 3. 受動態(見られる) 能 動態と再帰動態は自己愛的であり、主語を持たない。その回路が完結して初めて、新しい主体が現れる。それ以前は主体が存在しなかったことを意味する。 [79]「受動的」な声であるにもかかわらず、その衝動は本質的に能動的である。「見られる」のではなく、「自らを見させる」。その回路は、主体が快楽原 則を逸脱する唯一の手段である。 フロイトにとってセクシュアリティとは、それぞれが異なるエロトジェニック・ゾーンによって規定される部分的な衝動(すなわち口腔衝動や肛門衝動)から構 成される。これらの部分的な衝動は、最初は独立して機能し(すなわち、子どもの多形性倒錯)、思春期になって初めて、生殖器の庇護のもとに組織化される。 [80] ラカンは衝動の部分的な性質を認めるが、(1)部分的な衝動が完全な組織に到達しうるという概念を否定する-生殖器領域の優位性は、達成されたとしても、 常に不安定なものである。ドライヴはセクシュアリティの生殖機能を表象しているのではなく、ジュイサンスの次元のみを表象しているのである[79]。 ラカンは4つの部分的なドライヴを識別している:オーラル・ドライヴ(エロジナスゾーンは唇(部分的な対象は乳房-動詞は「吸う」)、アナル・ドライヴ (肛門と糞便、「糞をする」)、スコピック・ドライヴ(目と視線、「見る」)、インボカトリー・ドライヴ(耳と声、「聞く」)。最初の2つの衝動は需要に 関係し、最後の2つは欲望に関係する。 この二元論の概念は、フロイトの様々な欲求理論の再定義を通して維持されている。性的衝動と自我の衝動(自己保存)の間の最初の対立から、生の衝動 (Lebenstriebe)と死の衝動(Todestriebe)の間の最終的な対立に至るまで[81]。ラカンはフロイトの二元論を保持しているが、 象徴と想像の間の対立という観点からであり、異なる種類の衝動に言及してはいない。ラカンにとってすべての衝動は性的衝動であり、すべての衝動は過剰で反 復的で破壊的であるため、すべての衝動は死の衝動(pulsion de mort)である[82]。 欲望は欲望が実現される部分的な側面であり、欲望は一つであり分裂していないが、欲望はその部分的な現れである。衝動とは欲望の弁証法的媒介に巻き込まれ ない要求であり、衝動とは要求の弁証法的媒介に巻き込まれない「機械的な」主張である[83]。 |

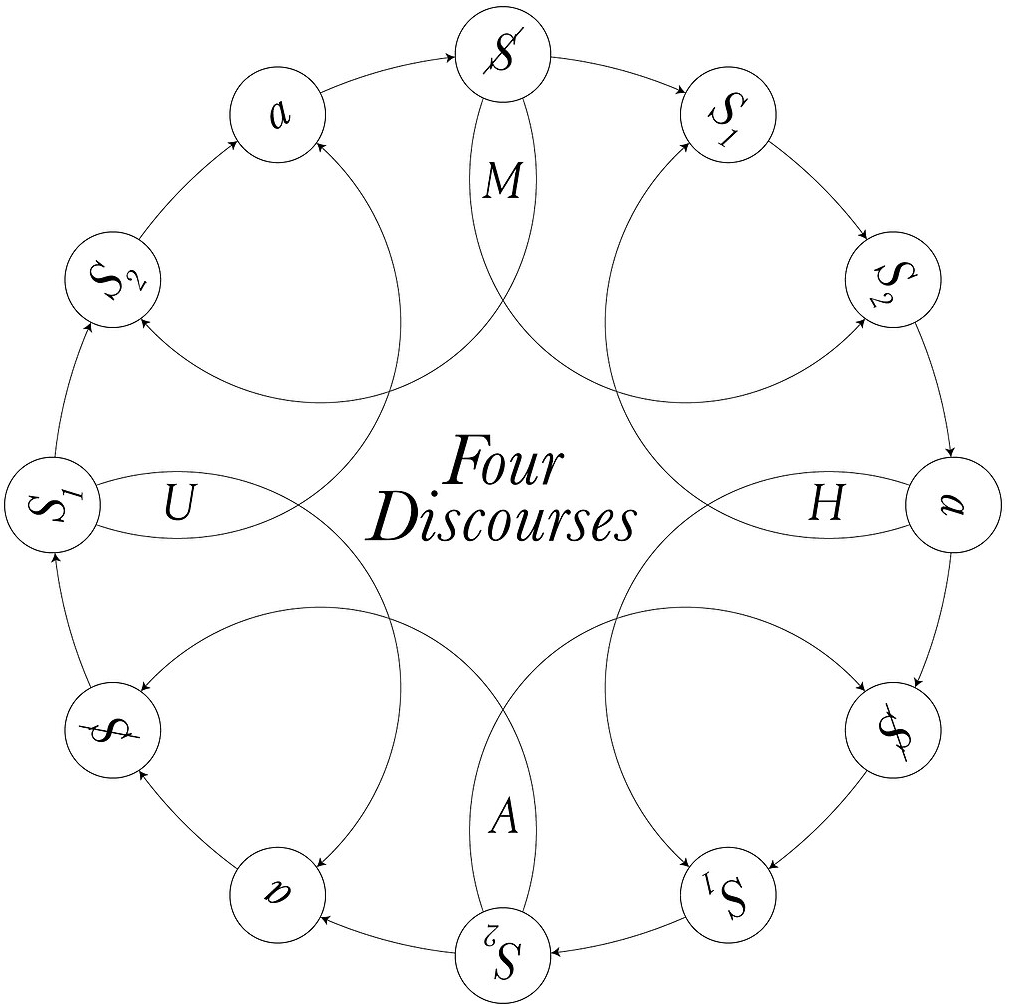

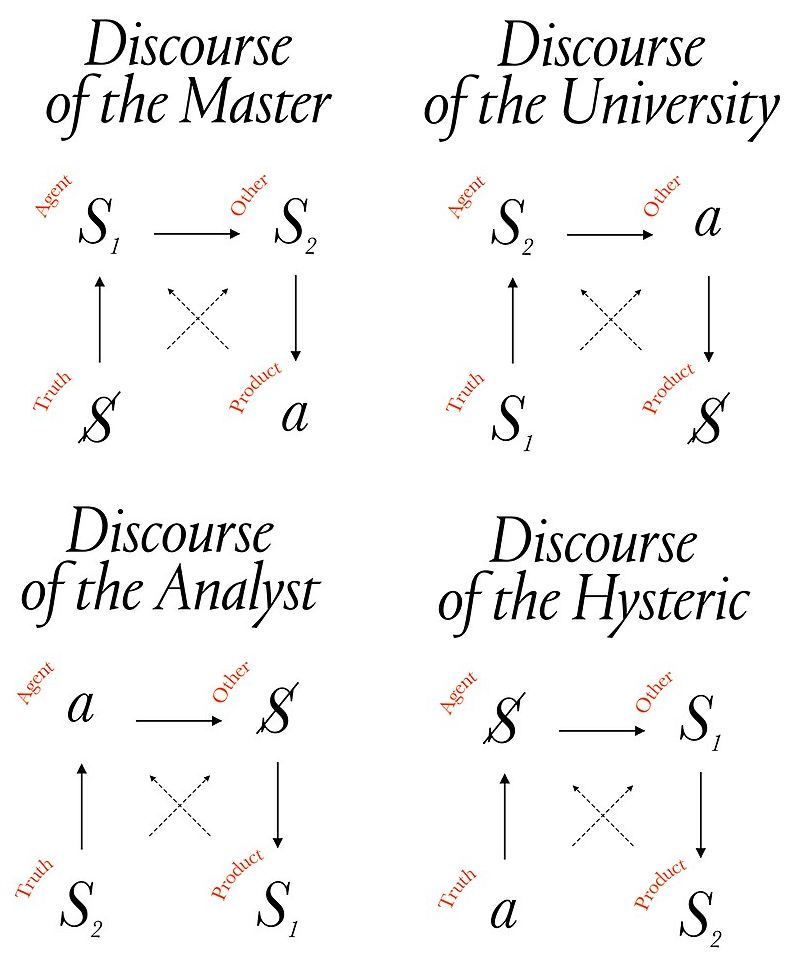

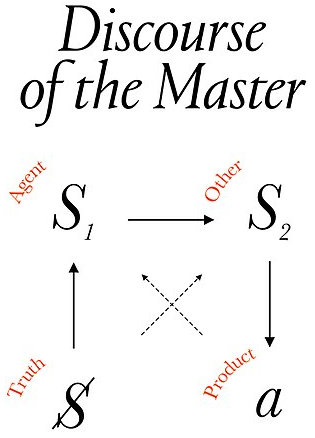

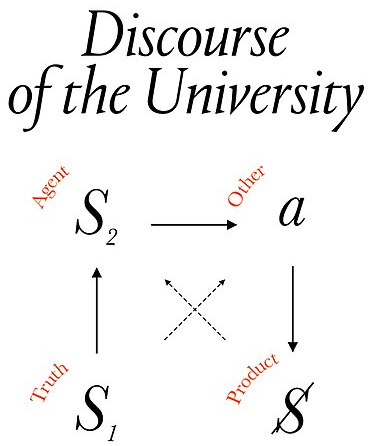

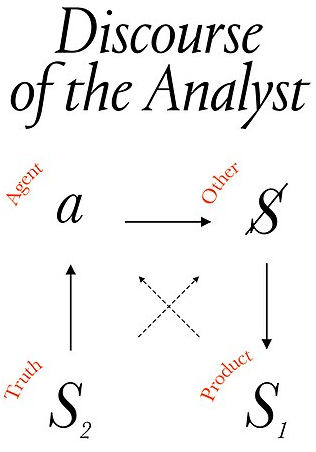

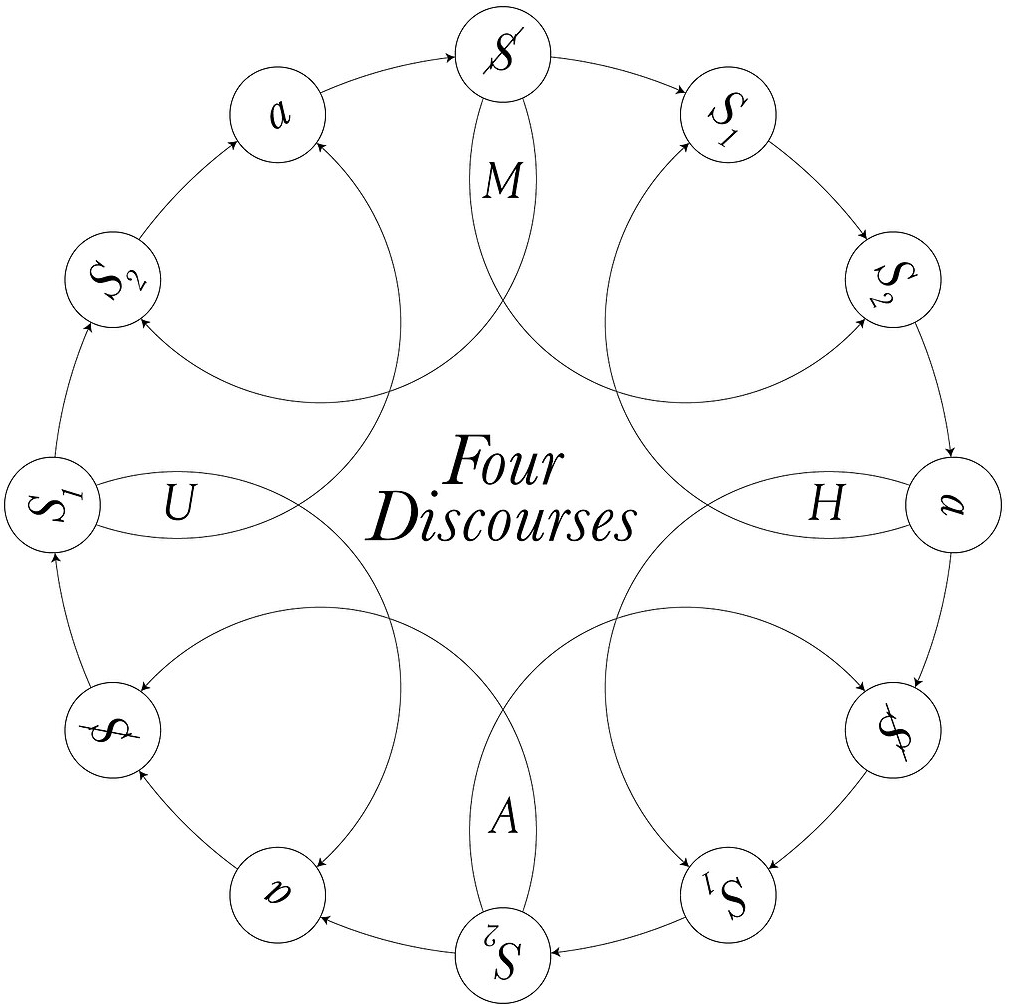

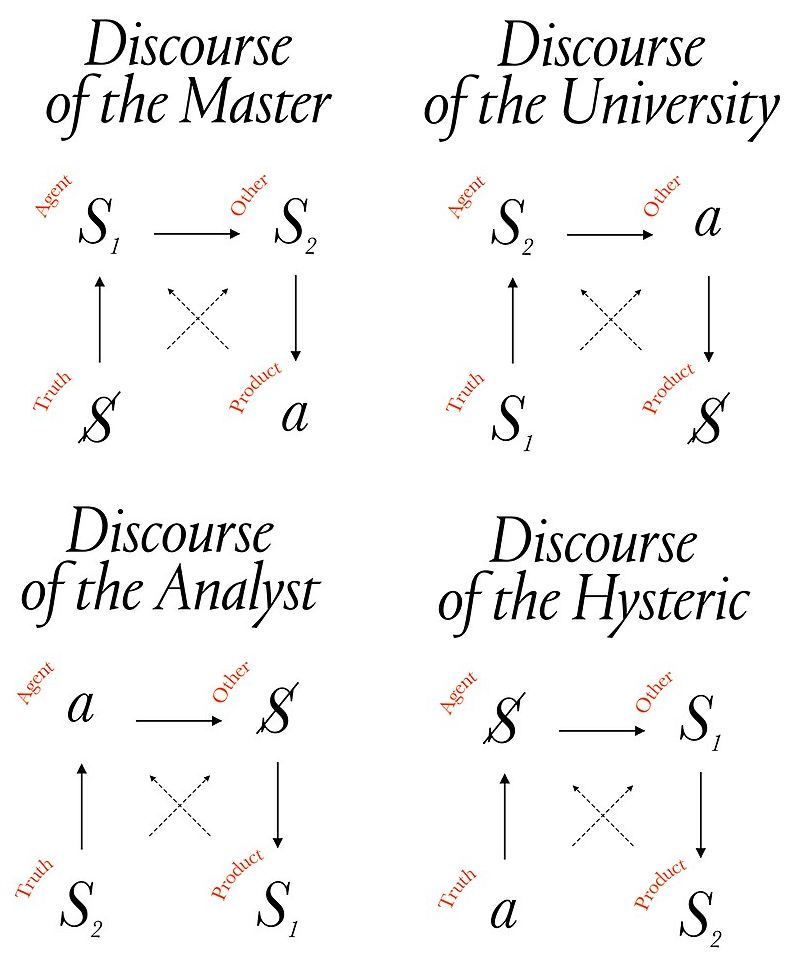

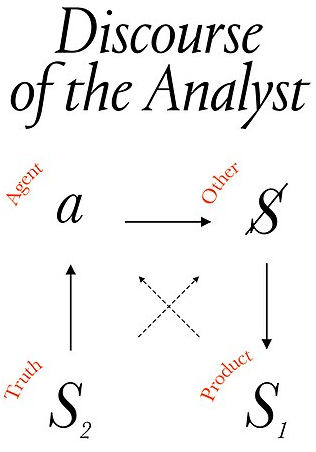

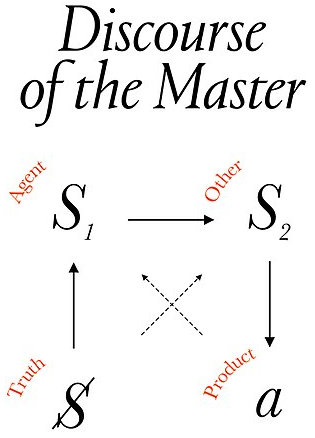

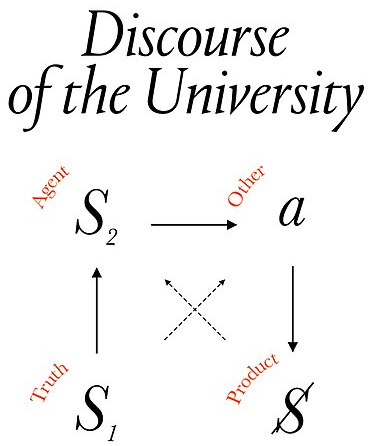

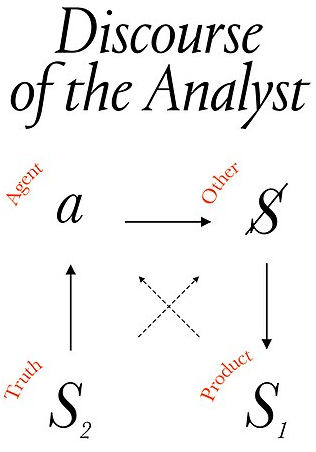

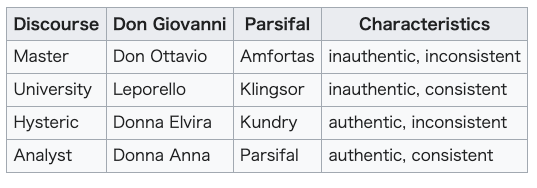

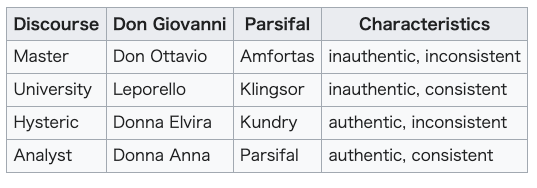

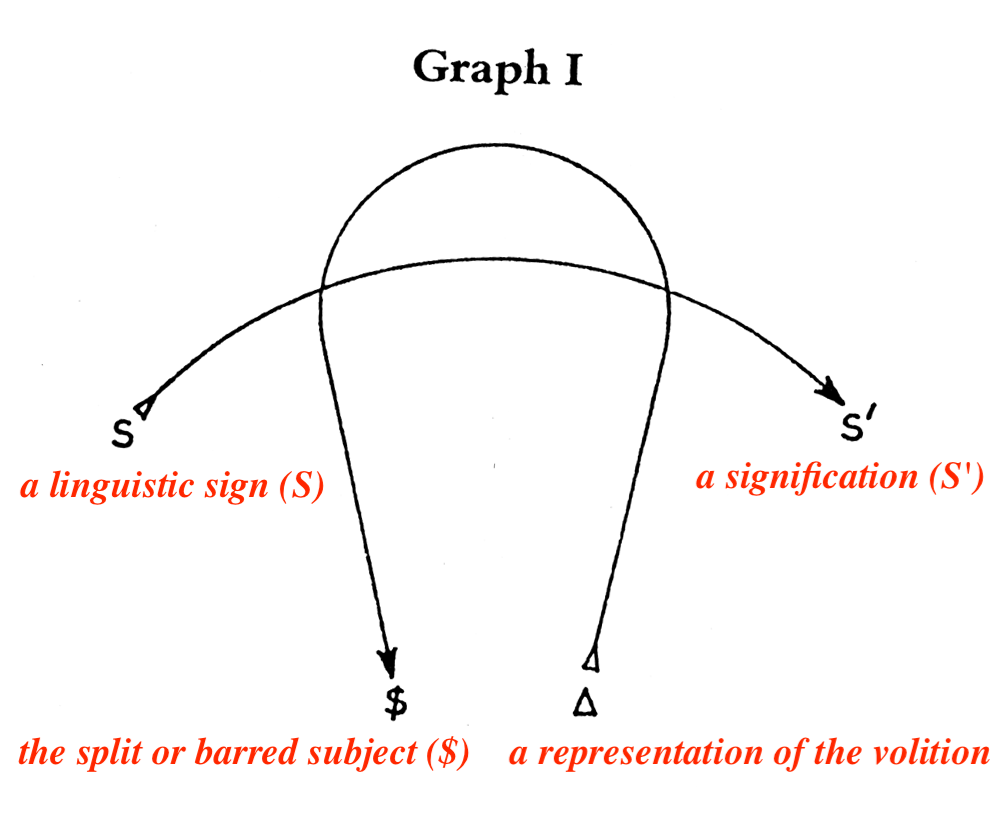

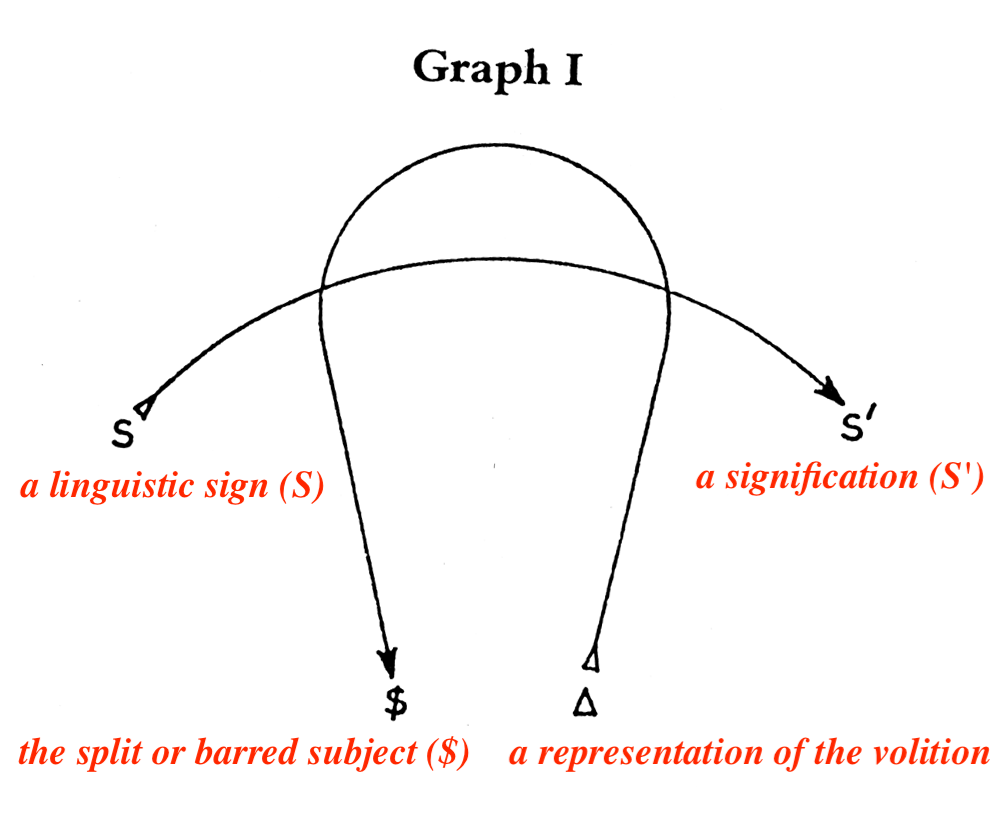

| Foreclosure (psychoanalysis) The Four discourses The graph of desire Lack (manque) The "Lamella"(→The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis) Matheme Name of the Father Objet petit a Sinthome |

差し押さえ(精神分析)[Foreclosure (psychoanalysis)] 四つの談話[The Four discourses] 欲望のグラフ[The graph of desire] 欠如(マンク)[Lack (manque)] 「ラメラ」[The "Lamella"(→The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis)] マテーム[Matheme] 父の名前[Name of the Father] 小さなa (小文字の他者)の対象[Objet petit a] シンソーム(→サントーム)[Sinthome] |

| Lacan on error and knowledge Building on Freud's The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Lacan long argued that "every unsuccessful act is a successful, not to say 'well-turned', discourse", highlighting as well "sudden transformations of errors into truths, which seemed to be due to nothing more than perseverance".[84] In a late seminar, he generalised more fully the psychoanalytic discovery of "truth—arising from misunderstanding", so as to maintain that "the subject is naturally erring... discourse structures alone give him his moorings and reference points, signs identify and orient him; if he neglects, forgets, or loses them, he is condemned to err anew".[85] Because of "the alienation to which speaking beings are subjected due to their being in language",[86] to survive "one must let oneself be taken in by signs and become the dupe of a discourse... [of] fictions organized in to a discourse".[87] For Lacan, with "masculine knowledge irredeemably an erring",[88] the individual "must thus allow himself to be fooled by these signs to have a chance of getting his bearings amidst them; he must place and maintain himself in the wake of a discourse... become the dupe of a discourse... les non-dupes errent".[87] Lacan comes close here to one of the points where "very occasionally he sounds like Thomas Kuhn (whom he never mentions)",[89] with Lacan's "discourse" resembling Kuhn's "paradigm" seen as "the entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community".[90] |

エラーと知識についてのラカン フロイトの『日常生活の精神病理学』に基づいて、ラカンは長い間、「すべての失敗した行為は、『うまく転回した』とは言わないまでも、成功した言説であ る」と主張し、「忍耐以外の何ものでもないように思われる、誤りから真理への突然の転化」を強調した [84] 。 [84]後期のセミナーにおいて、彼は「誤解から生じる真理」という精神分析学的発見をより完全に一般化し、「主体は自然に誤りを犯すものであ る......言説の構造だけが、彼に宙づりと参照点を与え、標識が彼を識別し、方向づけるのであり、もし彼がそれを無視したり、忘れたり、失ったりすれ ば、彼は新たに誤りを犯すことになる」と主張した[85]。 言語を話す存在が言語の中にいるために受ける疎外」[86]のために、生き延びるためには「記号に取り込まれ、言説の......カモにならなければなら ない」。[ラカンにとって、「男性的な知識は救いようのないほど誤り」[87]であり、個人は「それゆえ、記号の中で自分の方向性を見定める機会を得るた めには、記号に惑わされることを許さなければならない。 ラカンの「言説」はクーンの「パラダイム」に似ており、「ある共同体の 成員によって共有される信念、価値観、技法などの全構成」[90]と見なされている[89]。 |

| Clinical contributions Variable-length session The "variable-length psychoanalytic session" was one of Lacan's crucial clinical innovations,[91] and a key element in his conflicts with the IPA, to whom his "innovation of reducing the fifty-minute analytic hour to a Delphic seven or eight minutes (or sometimes even to a single oracular parole murmured in the waiting-room)"[92] was unacceptable. Lacan's variable-length sessions lasted anywhere from a few minutes (or even, if deemed appropriate by the analyst, a few seconds) to several hours.[citation needed] This practice replaced the classical Freudian "fifty minute hour". With respect to what he called "the cutting up of the 'timing'", Lacan asked the question: "Why make an intervention impossible at this point, which is consequently privileged in this way?"[93] By allowing the analyst's intervention on timing, the variable-length session removed the patient's—or, technically, "the analysand's"—former certainty as to the length of time that they would be on the couch.[94]: 18 When Lacan adopted the practice, "the psychoanalytic establishment were scandalized"[94]: 17 [95]—and, given that "between 1979 and 1980 he saw an average of ten patients an hour", it is perhaps not hard to see why: "psychoanalysis reduced to zero",[23]: 397 if no less lucrative. At the time of his original innovation, Lacan described the issue as concerning "the systematic use of shorter sessions in certain analyses, and in particular in training analyses";[96] and in practice it was certainly a shortening of the session around the so-called "critical moment"[97] which took place, so that critics wrote that 'everyone is well aware what is meant by the deceptive phrase "variable length"... sessions systematically reduced to just a few minutes'.[98] Irrespective of the theoretical merits of breaking up patients' expectations, it was clear that "the Lacanian analyst never wants to 'shake up' the routine by keeping them for more rather than less time".[99] Lacan's shorter sessions enabled him to take many more clients than therapists using orthodox Freudian methods, and this growth continued as Lacan's students and followers adopted the same practice.[100] Accepting the importance of "the critical moment when insight arises",[101] object relations theory would nonetheless quietly suggest that "if the analyst does not provide the patient with space in which nothing needs to happen there is no space in which something can happen".[102] Julia Kristeva, if in very different language, would concur that "Lacan, alert to the scandal of the timeless intrinsic to the analytic experience, was mistaken in wanting to ritualize it as a technique of scansion (short sessions)".[103] |

臨床への貢献 可変長のセッション 可変長の精神分析セッション」はラカンの決定的な臨床的革新のひとつであり[91]、「50分の分析時間をデルフィックな7、8分に短縮する(あるいは時 には待合室でつぶやかれるオラクル的なパロールひとつにさえ短縮する)という革新」[92]が受け入れられなかったIPAとの対立における重要な要素で あった。ラカンの可変長セッションは、数分(あるいは分析者が適切と判断すれば数秒)から数時間まで続いた[citation needed]。この実践は、古典的なフロイトの「50分1時間」に取って代わった。 彼が「『タイミング』の切断」と呼んだものに関して、ラカンは質問した: 「なぜこの時点で介入を不可能にするのか、それは結果的にこのように特権化されているからである」[93]。タイミングに関する分析者の介入を認めること によって、可変長のセッションは、患者、厳密に言えば「分析者」の、ソファに座っている時間の長さに関する以前の確信を取り除いたのである[94]: 18 ラカンがこの実践を採用したとき、「精神分析の権威はスキャンダラスになった」[94]: 17 [95]-そして、「1979年から1980年にかけて、彼は1時間に平均10人の患者を診察していた」ことを考えれば、その理由がわからないでもないだ ろう: 「精神分析はゼロになった」[23]: 397。 ラカンは当初の革新の時点で、この問題を「特定の分析、特に訓練分析において、より短いセッションを組織的に用いること」に関するものであると説明してお り[96]、実際には、いわゆる「臨界の瞬間」[97]の前後でセッションが短縮されることは確かに行われていた。患者の期待を打ち砕くことの理論的な利 点とは関係なく、「ラカンの分析家は、患者をより短い時間ではなく、より長い時間拘束することによって、日常を『揺るがす』ことを決して望んでいない」こ とは明らかであった[99]。 ラカンの短いセッションは、オーソドックスなフロイトの方法を用いるセラピストよりも多くのクライアントを受け持つことを可能にし、ラカンの弟子や追随者 が同じ実践を採用するにつれて、この成長は続いた[100]。 洞察が生じる決定的瞬間」の重要性を受け入れつつも[101]、対象関係論はそれにもかかわらず、「もし分析者が何も起こる必要のない空間を患者に提供し なければ、何かが起こりうる空間は存在しない」[102]と静かに示唆することになる。 ジュリア・クリステヴァは、まったく異なる言葉ではあるが、「ラカンは分析的経験に内在する時間を超越したスキャンダルに注意を払っていたが、それを拡大 解釈(短いセッション)の技法として儀式化しようとしたのは間違いであった」と同意している[103]。 |

| Writings and writing style According to Jean-Michel Rabaté, Lacan in the mid-1950s classed the seminars as commentaries on Freud rather than presentations of his own doctrine (like the writings), while Lacan by 1971 placed the most value on his teaching and "the interactive space of his seminar" (in contrast to Sigmund Freud). Rabaté also argued that from 1964 onward, the seminars include original ideas. However, Rabaté also wrote that the seminars are "more problematic" because of the importance of the interactive performances, and because they were partly edited and rewritten.[104] Most of Lacan's psychoanalytic writings from the 1940s through to the early 1960s were compiled with an index of concepts by Jacques-Alain Miller in the 1966 collection, titled simply Écrits. Published in French by Éditions du Seuil, they were later issued as a two-volume set (1970/1) with a new "Preface". A selection of the writings (chosen by Lacan himself) were translated by Alan Sheridan and published by Tavistock Press in 1977. The full 35-text volume appeared for the first time in English in Bruce Fink's translation published by Norton & Co. (2006). The Écrits were included on the list of 100 most influential books of the 20th century compiled and polled by the broadsheet Le Monde. Lacan's writings from the late sixties and seventies (thus subsequent to the 1966 collection) were collected posthumously, along with some early texts from the nineteen thirties, in the Éditions du Seuil volume Autres écrits (2001). Although most of the texts in Écrits and Autres écrits are closely related to Lacan's lectures or lessons from his Seminar, more often than not the style is denser than Lacan's oral delivery, and a clear distinction between the writings and the transcriptions of the oral teaching is evident to the reader. An often neglected aspect of Lacan's oral and writing style is his influence from his colleague and personal friend Henry Corbin, who introduced Lacan to the thought of Ibn Arabi.[105][106][107] Both Lacan and Ibn Arabi share nearly identical ideas and writing styles according to the researcher Abdesselem Rechak.[108] Jacques-Alain Miller is the sole editor of Lacan's seminars, which contain the majority of his life's work. "There has been considerable controversy over the accuracy or otherwise of the transcription and editing", as well as over "Miller's refusal to allow any critical or annotated edition to be published".[109] Despite Lacan's status as a major figure in the history of psychoanalysis, some of his seminars remain unpublished. Since 1984, Miller has been regularly conducting a series of lectures, "L'orientation lacanienne." Miller's teachings have been published in the US by the journal Lacanian Ink. Lacan's writing is notoriously difficult, due in part to the repeated Hegelian/Kojèvean allusions, wide theoretical divergences from other psychoanalytic and philosophical theory, and an obscure prose style. For some, "the impenetrability of Lacan's prose... [is] too often regarded as profundity precisely because it cannot be understood".[110] Arguably at least, "the imitation of his style by other 'Lacanian' commentators" has resulted in "an obscurantist antisystematic tradition in Lacanian literature".[111] Although Lacan is a major influence on psychoanalysis in France and parts of Latin America, in the English-speaking world his influence on clinical psychology has been far less and his ideas are best known in the arts and humanities. However, there are Lacanian psychoanalytic societies in both North America and the United Kingdom that carry on his work.[44] One example of Lacan's work being practiced in the United States is found in the works of Annie G. Rogers (A Shining Affliction; The Unsayable: The Hidden Language of Trauma), which credit Lacanian theory for many therapeutic insights in successfully treating sexually abused young women.[112] Lacan's work has also reached Quebec, where The Interdisciplinary Freudian Group for Research and Clinical and Cultural Interventions (GIFRIC) claims that it has used a modified form of Lacanian psychoanalysis in successfully treating psychosis in many of its patients, a task once thought to be unsuited for psychoanalysis, even by psychoanalysts themselves.[113] |

著作と文体 ジャン=ミシェル・ラバテによれば、1950年代半ばのラカンは、セミナーを(著作のような)自らの教義の発表ではなく、フロイトの解説に分類していた。 一方、1971年までのラカンは、(ジークムント・フロイトとは対照的に)自らの教えと「セミナーの対話的空間」に最も価値を置いていた。ラバテはまた、 1964年以降のセミナーには独創的なアイデアが含まれていると主張した。しかしながら、ラバテはまた、セミナーは対話的なパフォーマンスが重要であり、 部分的に編集され書き換えられているため、「より問題が多い」とも書いている[104]。 1940年代から1960年代初頭までのラカンの精神分析的著作の大半は、ジャック=アラン・ミラーによって概念の索引とともに1966年に編纂され、 『Écrits』と題された。1966年、ジャック=アラン・ミラーによって、概念の索引とともに「Écrits」と題された全集が編纂され、後に Éditions du Seuilから2巻セットとして出版された(1970/1年)。ラカン自身によって選ばれた)著作の一部はアラン・シェリダンによって翻訳され、1977 年にタヴィストック出版社から出版された。2006年、ノートン社から出版されたブルース・フィンクの翻訳により、全35巻が初めて英語で出版された。 Écrits』は、大衆紙『ル・モンド』が編集・投票した「20世紀で最も影響力のある100冊」のリストに含まれている。 ラカンの60年代後半から70年代にかけての著作(したがって、1966年の著作集より後)は、1930年代の初期のテキストとともに、死後に Éditions du SeuilのAutres écrits(2001年)に収録された。 Écrits』と『Autres écrits』に収められているテクストのほとんどは、ラカンの講義や『ゼミナール』の授業と密接に関連しているが、その文体はラカンの口話よりも濃密で あることが多く、著作と口話の書き写しとの明確な区別が読者には明らかである。 ラカンの口話と文体においてしばしば軽視される側面は、ラカンにイブン・アラビの思想を紹介した同僚であり個人的な友人でもあるヘンリー・コービンからの 影響である[105][106][107]。研究者アブデセレム・レチャックによれば、ラカンとイブン・アラビはともにほぼ同じ思想と文体を共有している [108]。 ジャック=アラン・ミラーはラカンのセミナーの唯一の編集者であり、そこには彼のライフワークの大半が含まれている。「ラカンは精神分析史における重要人 物であるにもかかわらず、いくつかのセミナーは未発表のままである。1984年以来、ミラーは定期的に講義シリーズ "L'orientation lacanienne "を行っている。ミラーの教えはラカニアン・インク誌によって米国で出版されている。 ラカンの文章は、ヘーゲル/コジェーヴ的な引用が繰り返されること、他の精神分析理論や哲学理論との理論的乖離が大きいこと、不明瞭な散文スタイルである ことなどから、難解であることで有名である。ラカンの散文の不可解さは...」と言う人もいる。[少なくとも、「他の『ラカン的』論者たちによる彼の文体 の模倣」は「ラカン文学における不明瞭主義的な反体系的伝統」をもたらした[111]。 ラカンはフランスやラテンアメリカの一部では精神分析に大きな影響を及ぼしているが、英語圏では臨床心理学への影響ははるかに小さく、彼の思想は芸術や人 文科学で最もよく知られている。しかし、北米とイギリスには彼の仕事を継承するラカン派の精神分析学会が存在する[44]。 ラカンの研究がアメリカで実践されている一例としては、アニー・G・ロジャースの著作(A Shining Affliction; The Unsayable: The Hidden Language of Trauma)があり、性的虐待を受けた若い女性の治療に成功した多くの治療的洞察についてラカンの理論を評価している。 [ラカンの研究はケベック州にも及んでおり、学際的フロイト研究グループ(The Interdisciplinary Freudian Group for Research and Clinical and Cultural Interventions:GIFRIC)は、精神分析家自身によってさえも、かつては精神分析には不向きであると考えられていた精神病の治療に、ラカ ンの精神分析を修正した形で使用し、多くの患者の治療に成功していると主張している[113]。 |

| Legacy and criticism In his introduction to the 1994 Penguin edition of Lacan's The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, translator and historian David Macey describes Lacan as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud".[6] His ideas had a significant impact on post-structuralism, critical theory, 20th-century French philosophy, film theory, and clinical psychoanalysis.[114] In 2003, Rabaté described "The Freudian Thing" (1956) as one of his "most important and programmatic essays".[104] In Fashionable Nonsense (1997), Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont criticize Lacan's use of terms from mathematical fields such as topology, accusing him of "superficial erudition" and of abusing scientific concepts that he does not understand, accusing him of producing statements that are not even wrong.[115]: 21 However, they note that they do not want to enter into the debate over the purely psychoanalytic part of Lacan's work.[115]: 17 Other critics have dismissed Lacan's work wholesale. François Roustang [fr] called it an "incoherent system of pseudo-scientific gibberish", and quoted linguist Noam Chomsky's opinion that Lacan was an "amusing and perfectly self-conscious charlatan".[116] The former Lacanian analyst Dylan Evans (who published a dictionary of Lacanian terms in 1996) eventually dismissed Lacanianism as lacking a sound scientific basis and as harming rather than helping patients, and has criticized Lacan's followers for treating his writings as "holy writ".[117] Richard Webster has decried what he sees as Lacan's obscurity, arrogance, and the resultant "Cult of Lacan".[118] Others have been more forceful still, describing him as "The Shrink from Hell"[119][120] and listing the many associates—from lovers and family to colleagues, patients, and editors—left damaged in his wake. Roger Scruton included Lacan in his book Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left, and named him as the only 'fool' included in the book—his other targets merely being misguided or frauds.[121] His type of charismatic authority has been linked to the many conflicts among his followers and in the analytic schools he was involved with.[122] His intellectual style has also come in for much criticism. Eclectic in his use of sources,[123] Lacan has been seen as concealing his own thought behind the apparent explication of that of others.[23]: 46 Thus his "return to Freud" was called by Malcolm Bowie "a complete pattern of dissenting assent to the ideas of Freud . . . Lacan's argument is conducted on Freud's behalf and, at the same time, against him".[124] Bowie has also suggested that Lacan suffered from both a love of system and a deep-seated opposition to all forms of system.[125] Many feminist thinkers have criticised Lacan's thought. Philosopher and psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray accuses Lacan of perpetuating phallocentric mastery in philosophical and psychoanalytic discourse.[126] Others have echoed this accusation, seeing Lacan as trapped in the very phallocentric mastery his language ostensibly sought to undermine.[127] The result—Castoriadis would maintain—was to make all thought depend upon himself, and thus to stifle the capacity for independent thought among all those around him.[23]: 386 Their difficulties were only reinforced by what Didier Anzieu described as a kind of teasing lure in Lacan's discourse; "fundamental truths to be revealed . . . but always at some further point".[128] This was perhaps an aspect of the sadistic narcissism that feminists especially accused Lacan of.[129] Claims surrounding misogynistic tendencies were further fueled when his wife Sylvia Lacan referred to her late husband as a "domestic tyrant" during a series of interviews conducted by anthropologist Jamer Hunt.[130] In a 2012 interview with Veterans Unplugged, Noam Chomsky said: "quite frankly I thought he was a total charlatan. He was just posturing for the television cameras in the way many Paris intellectuals do. Why this is influential, I haven't the slightest idea. I don't see anything there that should be influential."[131] |