サドとともにいるカント

JACQUES LACAN: KANT WITH SADE, Translated

by James B. Swenson Jr.

☆ 「サドの作品が倒錯のカタログという点においてフロイトを先取りしているというのは、文学者たちの間で延々と繰り返される愚かな言葉である。 これに対し、私たちはサドの寝室(閨房:セックスをする場所)は、古代哲学の学派が名前に用いた場所、すなわちアカデミア、リュケイオン、ストアと同等であると主張する。ここでも、そ こでも、科学への道は倫理の立場を正すことによって準備される。この点において、確かに、100年にわたって深みのある趣味を乗り越えて進むべき道が開拓 される。その理由を説明するには、さらに60を数える必要がある。 フロイトが快楽原則を明言する際に、それが伝統的な倫理における快楽原則と区別される機能を心配する必要もなく、2000年にわたる議論の余地のない偏見 の残響として受け取られる危険性もなく、生物を善に導くという宿命的な魅力を思い起こし、善意のさまざまな神話に刻まれた心理学を引用する必要さえなかっ たことを考えると、これは19世紀を通じて「悪の幸福」というテーマが暗示的に台頭したことによるものだとしか考えられない。 ここでサドは、転覆の第一歩である。カントは転覆の転換点であり、その冷酷さについて面白く思えるかもしれないが、そのようなものとして、我々の知る限り では決して注目されてはいない。 『閨房哲学』は『実践理性批判』から8年後に発表された。もし前者が後者と一致することが明らかになった後、後者が前者を完成させることを示せば、我 々は『実践理性批判』の真理が明らかになったと言うだろう。 そのため、後者が頂点に達する命題は、進歩、神聖さ、さらには愛さえも抑圧する不死の弁明、法律から生じる可能性のある満足をもたらすものすべて、法律が 言及する対象が理解できる意志から求められる保証、カントがそれらに制限した効用の機能の支えさえも失うことで、その仕事をダイヤモンドのような破壊へと 戻す。これが、学問的敬虔さによって事前に警告を受けていない読者がそこから受ける信じられないほどの高揚感を説明するものである。これについて説明でき ることは何もないが、この効果を損なうことはない。」——ジャック・ラカン「サドとともにいるカント」

・ 欲求(d)は快楽に服従したものとして出発する(邦訳:268)

・ 快楽は意志の共犯者(268)

・ 空想は欲求に固有の快楽をうみだす(268)

・ 欲求は主体ではない(268)

・ 快楽は空想のなかに捕らえられる(774/269)

《サ

ドの空想》

p.774

p.774

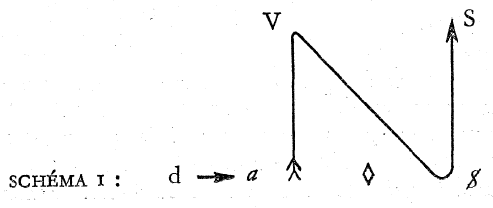

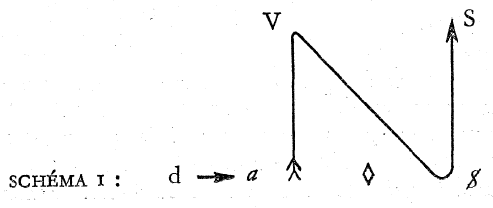

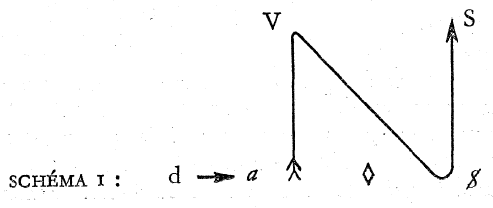

・ 欲求は対象a に向かう。そこから出発して対象a =空想の対象(=ジュリエット一味)はV(意志)を与える。$(カント的な実践理性の主体=唯一者であるジュスティヌ)の経由して、病理的(サド的な?) な主体(S)につくりかえる。

・

「この意志の場所において出会うのは、まさしくカントの意志であるけれども、それは、享楽の道具でしかないという代価を払ってはじめてこれが疎外の構成さ

れた主体であるという説明なしには、享楽の意志であると言うことはできない」(445/270)

[=空想、それ自体]

[=空想、それ自体]

・◇ (錐)は《の欲求》と読まれる。$◇a「幻想、たいていは「根源的幻想」を表すマ テーム(=ファンタスムのマテーム)ないし公式。 「対象との関係における主体」と読むことができ、このような関係は菱形(錐)が持っているあらゆる意味によって定義される。対象a を、主体を〈他者〉と出会わせる享楽のトラウマ的経験と理解すれば、この幻想の公式は次のことを示唆している。すなわち、主体はそのような危険な欲望と ちょうどいい距離を維持しようとして、誘引と反発のバランスを繊細に取るということである」(ブルース・フィンクによる説明)

《サ

ドの生の論理》(778/274)

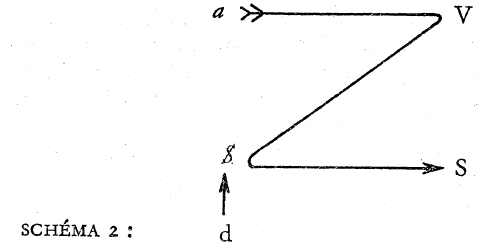

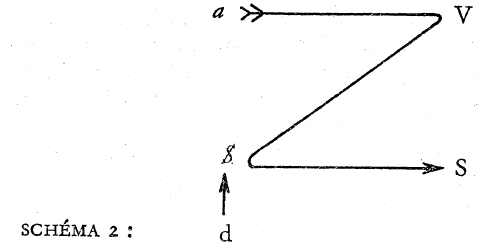

・ 享楽の権利の委託(274)

・ 享楽の意志(V)は、モンルイユ議長夫人により冷酷におこなわれる。

・ 主体に対する道徳的拘束には、異議がとなえられない

・ 主体については、その分裂が唯一の身体のなかに結合されるのを要求していないことがわかる。

・ 第一総督ボナパルトのみが、この分裂を、行政的に認められた疎外の結果により確固としたものとされる。

・S は、サドに対する忠実な姿をとる

・ $は、主体として、ことが極限までいたったとき、その消滅によって、その名を記入する。(779/275)

・

☆ 本文(英訳『エクリ』からの重訳)

| 765 | Que

l' œuvre de Sade anticipe Freud, fût-ce au regard du catalogue des

perversions, est une sottise, qui se redit dans les lettres,

de quoi la faute, comme toujours, revient aux spécialistes. Par contre nous tenons que le boudoir sadien s'égale à ces lieux dont les écoles de la philosophie antique prirent leur nom : Académie, Lycée, Stoa. Ici comme là, on prépare la science en rectifiant la position de l'éthique. En cela, oui, un déblaiement s'opère qui doit cheminer cent ans dans les profondeurs du goût pour que la voie de Freud soit praticable. Comptez-en soixante de plus pour qu'on dise pourquoi tout ça. Si Freud a pu énoncer son principe du plaisir sans avoir même à se soucier de marquer ce qui le distingue de sa fonction dans l'éthique traditionnelle, sans plus risquer qu'il fût entendu, en écho au préjugé incontesté de deux millénaires, pour rappeler l'attrait préordonnant la créature à son bien avec la psychologie qui s'inscrit dans divers mythes de bienveillance, nous ne pouvons qu'en rendre hommage à la montée insinuante à travers le xrxe siècle du thème du << bonheur dans le mal >>. Ici Sade est le pas inaugural d'une subversion, dont, si piquant que cela semble au regard de la froideur de l'homme, Kant est le point tournant, et jamais repéré, que nous sachions, comme tel. La Philosophie dans le boudoir vient huit ans après la Critique de la raison pratique. Si, après avoir vu qu'elle s'y accorde, nous démontrons qu'elle la complète, nous dirons qu'elle donne la vérité de la Critique. +++++++++++++++ ■■■■■■■■■ +++++++++++++++ The notion that Sade's work anticipated Freud's—if nothing else, as a catalogue of the perversions—is a stupidity repeated in works of literary criticism, the blame for which goes, as usual, to the specialists. I, on the contrary, maintain that the Sadean bedroom is of the same stature as those places from which the schools of ancient philosophy borrowed their names: Academy, Lyceum, and Stoa. Here as there, one paves the way for science by rectifying one's ethical position. In this respect, Sade did indeed begin the groundwork that was to progress for a hundred years in the depths of taste in order for Freud's path to be passable. Add to that another sixty years before one could say why. If Freud was able to enunciate his pleasure principle without even having to worry about indicating what distinguishes it from the function of pleasure in traditional ethics—without risking that it be understood, by echoing a bias uncontested for two thousand years, as reminiscent of the attractive notion that a creature is preordained for its good and of the psychology inscribed in different myths of benevolence—we can only credit this to the insinuating rise in the nineteenth century of the theme of "delight in evil" \bonheur dans le mal\ Sade represents here the first step of a subversion of which Kant, as piquant as this may seem in light of the coldness of the man himself, represents the turning point—something that has never been pointed out as such, to the best of my knowledge. Philosophy in the Bedroom came eight years after the Critique of Practical Reason. If, after showing that the former is consistent with the latter, I can demonstrate that the former completes the latter, I shall be able to claim that it yields the truth of the Critique. |

サドの作品がフロイトの作品を先取りしているというのは、たとえ倒錯の

目録という点だけであったとしても、文献の中で繰り返されているナンセンスなことであり、その責任はいつものように専門家にある。 その一方で、サディアンの寝室は、古代の哲学の学派がその名を冠した場所、すなわちアカデミー、リセウム、ストアと同列のものであると我々は信じている。 ここでも、そこと同様に、科学は倫理の立場を正すことによって準備される。そう、フロイトの道が実践可能であるためには、嗜好の深みへと100年を旅しな ければならないのだ。その理由を語るには、あと60年はかかるだろう。 もしフロイトが、伝統的な倫理学における快楽原則の機能と何が異なるかを示す心配をする必要さえなく、また、二千年にわたる議論の余地のない偏見を響かせ ながら、善意に関するさまざまな神話に刻まれているような心理で、善に対する被造物のあらかじめ定められた魅力を思い起こさせるようなことを聞かれる危険 を冒すことなく、快楽原則を発表できたとしたら、私たちは、二十世紀を通じて「悪における幸福」というテーマが仄めかされながら台頭してきたことに敬意を 表するしかない。 ここでサドは転覆の第一歩を踏み出したが、その転機となったのはカントであり、カントの冷淡さからは辛辣に見えるかもしれないが、私たちが知る限りでは、 そのような転機が見出されることはなかった。 『寝室の哲学』は、『実践理性批判』の8年後の作品である。もしこの本が『実践理性批判』に合致していることを確認した上で、この本が『実践理性批判』を 完成させていることを示せば、この本は『実践理性批判』の真理を明らかにしたことになる。 +++++++++++++++ ■■■■■■■■■ +++++++++++++++ サドの作品がフロイトを予見していたという見解——少なくとも倒錯のリストとして——は、文学批評の著作で繰り返し述べられている愚かな主張であり、その責任は、いつものように専門家たちに帰すべきだ。 それどころか、私は、サドの寝室は、古代哲学の学派が名前を借りた場所、すなわちアカデミー、リセウム、ストアと同じような地位にあると主張する。ここで もそこでも、倫理的立場を正すことで科学の道を開く。この点で、サドは確かに、フロイトの道が通れるようになるために、味覚の深部で百年間進展する土台を 築いた。さらに六十年間を経て、その理由を説明できるようになった。 フロイトは、伝統的な倫理における快の機能との違いを指摘することさえ気にせずに、快の原則を明確に表現することができた。2000 年間にわたって議論の余地のない偏見を反映して、生物は自分の幸福のためにあらかじめ運命づけられているという魅力的な概念や、さまざまな慈悲の伝説に刻 み込まれた心理学を彷彿とさせるという誤解を受ける危険もなかった。——それを説明できるのは、19 世紀に「悪の喜び」\bonheur dans le mal\ サドはここで、この転覆の第一歩を表している。カントは、彼自身の冷酷さから考えると皮肉なことに、この転覆の転換点である。私の知る限り、このことはこれまで指摘されたことがない。 『寝室の哲学』は『実践理性批判』から8年後に発表された。前者(『寝室の哲学』)が後者(『実践理性批判』)と一致することを示した上で、前者(『寝室 の哲学』)が後者(『実践理性批判』)を完成させることを証明できれば、前者(『寝室の哲学』)が後者(『実践理性批判』)の真実を導き出すと主張できる だろう。 |

| 766 |

As a result, the postulates with

which the Critique concludes—the alibi of

immortality in the name of which it suppresses progress, holiness, and

even

love (everything satisfying that could come from the law), and its need

for a

will to which the object that the law concerns is intelligible—losing

even the

lifeless support of the function of utility to which Kant confined

them, reduce

the work to its subversive core. This explains the incredible

exaltation that

anyone not prepared by academic piety feels upon reading it—a reaction

that

will not be spoiled by my having explained it. One might say that the shift involved in the notion that it feels good to do evil [qu on soit bien dans le mal]—or, if you will, that the eternal feminine does not elevate us—was made on the basis of a philological remark: namely, that the idea that had been accepted up until then, which is that it feels good to do good [quon est bien dans le bien], is based on a homonymy not found in German: Manfilhlt sich wohl im Guten. This is how Kant introduces us to his Critique of Practical Reason. The pleasure principle is the law of feeling good [bien], which is wohl in German and might be rendered as "well-being" [bien-etre]. In practice, this principle would submit the subject to the same phenomenal sequence that determines his objects. The objection that Kant raises against this is, in accordance with his rigorous style, intrinsic. No phenomenon can lay claim to a constant relationship to pleasure. No law of feeling good can thus be enunciated that would define the subject who puts it into practice as "will." The quest to feel good would thus be a dead end were it not reborn in the form of das Gute, the good that is the object of the moral law. Experience tells us that we make ourselves hear commandments inside of ourselves, the imperative nature of which is presented as categorical, in other words, unconditional. Note that this good [bien] is assumed to be the Good [Bien] only if it presents itself, as I just said, in spite of all objects that would place conditions upon it—that is, only if it opposes any and every uncertain good that these objects might bring one according to some theoretical equivalence, such that it impresses us as superior owing to its universal value. Thus the weight of the Good appears only by excluding everything the subject may suffer from due to his interest in an object, whether drive or feeling—what Kant designates, for that reason, as "pathological." |

そ

の結果、『批判』が結論付ける公理——進歩、聖性、さらには愛(法から生じ得るあらゆる満足)を抑制する「不滅の免罪符」の名の下に、法が関わる対象が理

解可能な意志への必要性——は、カントがそれらを限定した「有用性の機能」という無機質な支えさえ失い、作品をその破壊的な核心に還元する。これが、学問

的な敬虔さで準備されていない者がこれを読む際に感じる驚くべき高揚感を説明する。この反応は、私がそれを説明したことで損なわれることはない。 悪を行うことは良いことだ [qu on soit bien dans le mal]、あるいは、永遠の女らしさは私たちを高揚させるものではない、という概念の変化は、言語学的見解、すなわち、それまで受け入れられていた「善を 行うことは良いことだ [quon est bien dans le bien]」という概念は、ドイツ語には見られない同音異義語に基づいている、という見解に基づいて生じたものと言えるだろう。Manfilhlt sich wohl im Guten。カントは、このように『実践的理性の批判』を紹介している。 快楽原則(Lustprinzip) は、ドイツ語で「wohl」である「良い」という感覚の法則であり、「幸福」と訳すこともできる。実際には、この原則は、対象を決定する同じ現象の連鎖に 主体を従わせる。カントがこれに対して提起する反論は、彼の厳格なスタイルに従って、本質的なものだ。いかなる現象も、快楽との一定の関係性を主張するこ とはできない。したがって、それを実践する主体を「意志」と定義する、快の法則を明言することはできない。 したがって、気分が良いことを追求することは、道徳律の対象である「善(das Gute)」という形で生まれ変わらなければ、行き詰まりになってしまう。経験から、私たちは自分の中で、その命令的な性質が定言的、つまり無条件である ように表現される命令を聞くことがわかっている。 この「善」(bien)が「善」(Bien)として仮定されるのは、先ほど述べたように、あらゆる条件を課す対象にもかかわらず現れる場合のみだ。つま り、これらの対象が理論的な等価性に基づいてもたらすあらゆる不確実な善に反対し、その普遍的価値により私たちに優越感を抱かせる場合のみだ。したがっ て、善の重みは、対象に対する興味(衝動や感情)によって主体が被るあらゆる苦悩を排除することによってのみ現れる。カントは、この苦悩を「病的な」もの と指定している。 |

| 767 |

We would thus find anew here the

Sovereign Good of the Greeks by

induction from this effect, if Kant, as is his wont, did not specify

once more

that this Good does not act as a counterweight but rather, so to speak,

as an

anti-weight—that is, as subtracting weight from the pride

[amour-propre]

(Selbstsucht) the subject experiences as contentment (arrogantia) in

his pleasures,

insofar as a look at this Good renders these pleasures less

respectable.2

This is both precisely what the text says and quite suggestive. Let us consider the paradox that it is at the very moment at which the subject no longer has any object before him that he encounters a law that has no other phenomenon than something that is already signifying; the latter is obtained from a voice in conscience, which, articulating in the form of a maxim in conscience, proposes the order of a purely practical reason or will there. For this maxim to constitute a law, it is necessary and sufficient that, being put to the test of such reason, the maxim may be considered universal as far as logic is concerned. This does not mean—let us recall what "logic" entails— that it forces itself on everyone, but rather that it is valid in every case or, better stated, that it is not valid in any case if it is not valid in every case. But this test, which must be based on pure, though practical, reason, can only be passed by maxims of the type that allows for analytic deduction. This type is illustrated by the faithfulness required in returning a deposit:3 we can get some shut-eye after making a deposit knowing that the depositary must remain blind to any condition that would oppose this faithfulness. In other words, there is no deposit without a depositary worthy of his task. One can sense the need for a more synthetic foundation, even in such an obvious case. At the risk of some irreverence, let me, in turn, illustrate the flaw in it with a maxim by Father Ubu that I have modified slightly: "Long live Poland, for if there were no Poland, there would be no Poles." |

し

たがって、カントがいつものように、この善は対抗物としてではなく、むしろ、いわば反重量として、つまり、主体が快楽において経験する自己愛(amour

-propre)から満足(arrogantia)を差し引くものとして作用する、と再び特定しなければ、私たちはこの効果から、ギリシャ人の至高の善を

再び発見することになるだろう。(Selbstsucht)から差し引くものとして作用する、と再び明言しなかったならば、この効果から、ギリシャ人の至

高の善を導き出すことができるだろう。 主体がもはや自分の前にいかなる対象も持たないまさにその瞬間に、すでに意味を持つもの以外の現象を持たない法則に出会うというパラドックスを考えてみよ う。この法則は、良心の声から得られるものであり、良心の中で格律の形で表現され、純粋に実践的な理性または意志の秩序をそこで提案している。 この格律が法則を構成するためには、そのような理性の試練にさらされたときに、その格律が論理的に普遍的であるとみなされることが必要かつ十分である。こ れは、「論理」が意味することを思い起こせば、それがすべての人に強制されるという意味ではなく、むしろ、あらゆる場合に有効である、より正確に言えば、 あらゆる場合に有効でない場合は、いかなる場合にも有効ではないという意味だ。 しかし、純粋ではあるが実践的な理由に基づくこの試練に合格できるのは、分析的推論が可能なタイプの格律だけだ。 このタイプは、預け物を返す際に求められる誠実さによって説明できる。預け主は、預け主がこの誠実さに反する条件を知ることがないことを知っているので、 預け物を預けた後、安心して眠ることができる。つまり、その任務にふさわしい預け主がいなければ、預け物はないということだ。このような明白なケースで も、より総合的な基礎の必要性を感じます。不遜な発言になるかもしれませんが、その欠陥を、私が少し変更したウブ神父の格律で説明させてください。「ポー ランド万歳、ポーランドがなければポーランド人は存在しないからだ」。 |

| 768 |

Let no one, out of some slowness

of wit or emotivity, doubt my attachment

to a freedom without which the people mourn. But while the analytic

explanation of it here is irrefutable, its indefectibility is tempered

by the

observation that the Poles have always been known for their remarkable

resistance to the eclipses of Poland, and even to the lamentation that

ensued.

We encounter anew here what led Kant to express his regret that no

intuition

offers up a phenomenal object in the experience of the moral law. I agree that this object slips away throughout the Critique. But it can be surmised in the trace left by the implacable suite Kant provides to demonstrate its slipping away, from which the work derives an eroticism that is no doubt innocent, but perceptible, the well-foundedness of which I shall show through the nature of the said object. This is why I will ask those of my readers who are still virgins with respect to the Critique, never having read it, to stop reading my text here and to return to it after perusing Kant's. Let them see if it does, indeed, have the effect I say it does. In any case, I promise them the pleasure that is brought by the feat itself. The other readers will follow me now into Philosophy in the Bedroom, at least into the reading thereof. It proves to be a pamphlet, but a dramatic one, in which the stage lighting allows the dialogue and the action to be taken to the very limits of what is imaginable. The lights go dark for a moment to make room for a diatribe—a sort of pamphlet within the pamphlet—entitled "Yet Another Effort, Frenchmen, If You Would Become Republicans." What is enunciated in it is ordinarily understood, if not appreciated, as a mystification. One need not be alerted to the fact that a dream within a dream points to a closer relationship to the real to see an indication of the same kind in the text's deriding of the historical situation. It is blatant and one would do well to look twice at the text. The crux of the diatribe is, let us say, found in the maxim that proposes a rule for jouissance, which is odd in that it defers to Kant's mode in being laid down as a universal rule. Let us enunciate the maxim:..... |

知

性の鈍さや感情の激しさから、私が人民が嘆き悲しむ自由への愛着を疑う者があってはならない。しかし、その分析的説明はここで反駁の余地のないものである

が、その完全性は、ポーランド人はポーランドの没落、さらにはその後に続いた嘆き悲しみにさえも、常に驚くべき抵抗力を持って対応してきたという事実に

よって和らげられている。ここでもまた、カントが道徳法の経験において現象的な対象を提示する直観が存在しないことを後悔した理由に直面する。 私は、この対象が『批判』全体で逃げていくことに同意する。しかし、カントがその逃げていくことを示すために提供する不可避的な一連の論証の跡から、その 存在を推察することができる。この作品はその跡から、疑いなく無垢だが感知可能なエロティシズムを導き出しており、その正当性は、当該の対象の性質を通じ て示すつもりだ。 これが、批判について未読の読者に対し、ここで私のテキストを読むのをやめ、カントの著作を読んだ後に戻ってくるよう求める理由だ。彼らが、確かに私が言うような効果があるかどうかを確認してほしい。いずれにせよ、その業そのものがもたらす喜びを約束する。 他の読者は、私と共に「寝室の哲学」へと進もう。少なくともその読解へと。 それは小冊子だが、劇的なもので、舞台照明が対話と行動を想像の限界まで押し上げる。一瞬、照明が暗転し、小冊子の中の小冊子ともいえる「フランス人よ、もしあなたがたが共和主義者になりたいのなら、また別の努力を」と題された演説が挿入される。 その中で述べられていることは、通常、理解はされても評価はされない、神秘化として受け取られる。夢の中の夢が現実とのより深い関係を示唆していることに 気づかなくても、テキストが歴史的状況を嘲笑している点に同じような暗示を見出すことはできる。それは明白であり、テキストを二度読み返す価値がある。 この痛烈な批判の要点は、快楽の規則を提唱する格律にあるといえるだろう。この格律は、カントの様式に従って普遍的な規則として定めている点で奇妙だ。その格律を引用しよう。 |

| 769 |

"I have the right to enjoy your

body," anyone can say to me, "and I will

exercise this right without any limit to the capriciousness of the

exactions

I may wish to satiate with your body." Such is the rule to which everyone 's will would be submitted, assuming a society were to forcibly implement the rule. To any reasonable being, both the maxim and the consent assumed to be given it are at best an instance of black humor. But aside from the fact that if the deductions in the Critique prepared us for anything, it is for distinguishing the rational from the sort of reasonable that is no more than resorting in a confused fashion to the pathological, we now know that humor betrays the very function of the "superego" in comedy. A fact that—to bring this psychoanalytic agency to life by instantiating it and to wrest it from the renewed obscurantism of our contemporaries' use of it— can also spice up [relever] the Kantian test of the universal rule with the grain of salt it is missing. Are we not thus incited to take more seriously what is presented to us as not entirely serious? As you may well suspect, I will not ask if it is necessary or sufficient that a society sanction a right to jouissance, by permitting everyone to lay claim to it, for its maxim to thus be legitimated by the imperative of moral law. No de facto legality can decide if this maxim can assume the rank of a universal rule, since this rank may also possibly oppose it to all de facto legalities. This is not a question that can be settled simply by imagining it, and the extension of the right that the maxim invokes to everyone is not what is at issue here. At best one could demonstrate here the mere possibility of generalizability, which is not universaUzability; the latter considers things as they are grounded and not as they happen to work out. I cannot pass up the opportunity to point out the exorbitant nature of the role people grant to the moment of reciprocity in structures, especially subjective ones, that are intrinsically incompatible with reciprocity. Reciprocity—a relation that is reversible since it is established along a simple line that unites two subjects who, due to their "reciprocal" position, consider this relation to be equivalent—is difficult to situate as the logical time of any sort of breakthrough [franchissement] on the subject's part in his relation to the signifier, and far less still as a step in any sort of development, whether or not it can be considered psychical (in which it is always so con- 770 venient to blame the child when providing veneers with a pedagogical intent). |

「私はあなたの身体を楽しむ権利がある」と、誰でも私に言うことができる。「そして、私は、あなたの身体で満たしたいと思う気まぐれな要求に、何の制限も受けずにこの権利を行使する」。 このようなルールが、社会が強制的に実施すると仮定した場合、すべての人の意志が従わなければならないルールとなる。 合理的な人間なら、この格律も、それに同意することが当然であるとする考えも、せいぜいブラックユーモアと受け止めるだろう。 しかし、『(実践理性)批判』の推論が私たちに何か準備を してくれたとすれば、それは、合理的なものと、病的なものに混乱して頼るだけの「合理的」なものを区別することだ。そして、ユーモアはコメディにおける 「超自我」の機能を裏切るものであることが、今ではわかっている。この事実——この精神分析的代理を具体化して生命を吹き込み、現代人の使用における新た な暗黒主義から引き剥がすために——は、カントの普遍的規則のテストに欠けていた塩の粒を加えることで、それをより刺激的にする可能性がある。 そうして、私たちは、完全に真剣ではないと提示されるものを、より真剣に受け止めるよう促されるのではないだろうか?ご想像のとおり、私は、社会が、すべ ての人が快楽の権利を主張することを認め、その格律を道徳律の義務によって正当化することが、その格律の正当性にとって必要かつ十分であるかどうかを問う つもりはない。 この格律が普遍的な規則としての地位を獲得できるかどうかは、事実上の合法性によって決定することはできない。なぜなら、この地位は、事実上の合法性すべ てと対立する可能性があるからだ。これは、想像するだけで解決できる問題ではなく、格律がすべての人に適用される権利の拡張が問題となっているわけではな い。 せいぜい、ここでは、普遍化の可能性を単に指摘することしかできない。普遍化とは、物事が偶然にうまくいくというのではなく、その根拠に基づいて物事を考えることだ。 私は、相互関係と本質的に相容れない構造、特に主観的な構造において、人々が相互関係に与える役割の過大な性質について指摘しておかなければならないと思う。 相互関係、つまり、2 つの主体が「相互」の位置にあるためにこの関係を同等のものとみなす、単純な線に沿って確立される可逆的な関係は、主体が記号との関係において何らかの突 破(franchissement)を果たす論理的な瞬間として位置付けることは困難だ。、それが心理的であるかどうか(その場合は、教育的な意図を持っ て子供たちを非難するのが常に都合が良い)にかかわらず、あらゆる種類の展開の一歩として位置付けることはさらに困難だ。 |

| 770 |

Be that as it may, we can

already credit our maxim with serving as a paradigm

for a statement that as such excludes reciprocity (reciprocity and not

"my turn next time"). Any judgment regarding the odious social order that would enthrone our maxim is, thus, of no import here, for the question is whether to grant or refuse to grant this maxim the characteristic of a rule acceptable as universal in moral philosophy—moral philosophy being recognized, since Kant's time, as involving the unconditional practice of reason. We must obviously acknowledge this characteristic in the maxim for the simple reason that its sole proclamation (its kerygma) has the virtue of instating both the radical rejection of the pathological (that is, of every preoccupation with goods, passion, or even compassion—in other words, the rejection by which Kant cleared the field of moral law) and the form of this law, which is also its only substance, insofar as the will becomes bound to the law only by eliminating from its practice every reason that is not based on the maxim itself. Of course, these two imperatives—between which moral life can be stretched, even if it snaps our very life—are imposed on us, according to the Sadean paradox, as if upon the Other, and not upon ourselves. But this only differs from Kant's view at first blush, for the moral imperative latently does no less, since its commandment requisitions us as Other. We perceive quite nakedly here what the aforementioned parody of the obvious universality of the depositary's duty was designed to introduce us to—namely, that the bipolarity upon which the moral law is founded is nothing but the split [refente] in the subject brought about by any and every intervention of the signifier: the split between the enunciating subject [sujet de I'enonciation] and the subject of the statement [sujet de I'enonce], The moral law has no other principle. Yet it must be blatant, for otherwise it lends itself to the mystification we sense in the gag* "Long live Poland!" In coming out of the Other's mouth, Sade's maxim is more honest than Kant's appeal to the voice within, since it unmasks the split in the subject that is usually covered up. The enunciating subject stands out here as clearly as in "Long live Poland," where the only thing that sticks out is what its manifestation amusingly evokes. |

とはいえ、この格律は、その性質上、互恵性(「次は私の番」ではなく、互恵性)を排除する発言のパラダイムとして、すでにその役割を果たしているといえるでしょう。 したがって、この格律を君臨させるような忌まわしい社会秩序に関する判断は、ここでは重要ではない。なぜなら、問題は、この格律に、道徳哲学において普遍 的に受け入れられる規則としての特徴を認めるか、認めないかということだからだ。道徳哲学は、カントの時代から、無条件の理性の実践を含むものと認識され ている。 この格律には、その宣言(ケリグマ)だけが、病的なもの(つまり、財、情熱、あるいは同情といったあらゆる関心事、言い換えれば、カントが道徳律の分野か ら排除したものを排除すること)の徹底的な拒絶と、この格律の形式(この格律の唯一の substance である)の両方を確立する長所がある、という単純な理由から、この特徴を明らかに認めなければならない。カントが道徳律の分野から排除した拒絶)と、この 律法の形式(これはその唯一の実体でもある)を確立する効力を持っているからだ。もちろん、道徳的な生活は、たとえそれが私たちの生命そのものを断ち切る としても、この 2 つの命令の間に引き伸ばされるものであり、サドのパラドックスによれば、それは私たち自身ではなく、他者に対して課せられたもののように私たちに課せられ ている。 しかし、これは一見カントの見解と異なるだけだ。なぜなら、道徳的命令は、その命令が私たちを他者として要求する以上、潜在的には同じことをしているからだ。 ここで、前述の保管者の義務の明白な普遍性をパロディ化したものが、私たちに紹介しようとしたものがはっきりとわかる。つまり、道徳律の基盤となる二極性 は、記号が介入するたびに生じる、主体における分裂(refente)に他ならないということだ。発話主体(sujet de I『enonciation)と発言主体(sujet de I』enonce)の分裂だ。 道徳律には他の原理はない。しかし、それは明白でなければならない。そうでなければ、「ポーランド万歳!」というギャグ*に感じられるような神秘化に陥っ てしまうからだ。他者の口から発せられたサドの格律は、通常隠されている主体の分裂を明らかにするため、カントの内なる声への訴えよりも正直だ。 発話主体は、「ポーランド万歳!」の場合と同じように、その表現が面白く連想させるものだけが際立つように、ここでははっきりと際立っている。 |

| 771 |

To confirm this view, one need

but consider the doctrine with which Sade

himself establishes the reign of his principle: the doctrine of human

rights.

He cannot use the notion that no man can be the property, or in any way

the

prerogative, of another man as a pretext for suspending everyone's

right to

enjoy him, each in his own way.4 The constraint he endures here is not

so

much one of violence as of principle, the problem for the person who

makes

it into a sentence not being so much to make another man consent to it

as to

pronounce it in his place. Thus the discourse of the right to jouissance clearly posits the Other qua free—the Other's freedom—as its enunciating subject, in a way that does not differ from the Tu es which is evoked out of the lethal depths [fonds tuant] of every imperative. But this discourse is no less determinant for the subject of the statement, giving rise to him with each addressing of its equivocal content: since jouissance, shamelessly avowed in its very purpose, becomes one pole in a couple, the other pole being in the hole that jouissance already drills in the Other's locus in order to erect the cross of Sadean experience in it. Leaving off my discussion of its mainspring here, let me recall instead that pain, which projects its promise of ignominy here, merely intersects the express mention of it made by Kant among the connotations of moral experience. What pain is worth in Sadean experience will be seen better by approaching it via what might be disconcerting in the artifice the Stoics used with regard to it: scorn. Imagine a revival of Epictetus in Sadean experience: "You see, you broke it," he says, pointing to his leg. To reduce jouissance to the misery of an effect in which one's quest stumbles—doesn't this transform it into disgust? This shows that jouissance is that by which Sadean experience is modified. For it only proposes to monopolize a will after having already traversed it in order to instate itself at the inmost core of the subject whom it provokes beyond that by offending his sense of modesty [pudeur]. |

こ

の見解を確認するためには、サド自身が自らの原理の支配を確立するために採用した教義、すなわち人権の教義を検討すれば十分だ。彼は、人間は他の人間の所

有物でも、その特権でもあり得ないという概念を、各人がそれぞれ自分のやり方で彼を楽しむ権利を停止する口実として用いることはできない。4

彼がここで受けている制約は、暴力というよりもむしろ原則によるものであり、それを文にした人格者が抱える問題は、他の人間にそれを同意させることではな

く、その代わりにそれを口にするということにある。 したがって、ジョイサンスの権利に関する言説は、その発話主体として、他者を自由な存在、すなわち他者の自由を明確に前提としている。これは、あらゆる命令の致命的な深層(fonds tuant)から呼び起こされる「Tu es」と何ら変わらない。 しかし、この言説は、その曖昧な内容に言及するたびに、その発言の主体にとっても決定的な意味を持つ。なぜなら、その目的そのものを恥知らずに公言する 「享楽」は、一対の両極のうちの一極となり、もう一極は、サドの経験の十字架をその場所に立て上げるために、享楽がすでに他者の位置に掘った穴にあるから だ。 その原動力についての議論はここまでにし、代わりに、ここでの恥辱の約束を投影する痛みは、カントが道徳的経験の連想の一つとして言及した痛みの言及と単 に交差しているに過ぎないことを思い出そう。サド的経験における痛みの価値は、ストア派が痛みに対して用いた人工物における不快な点、すなわち軽蔑を通じ て近づくことでより明確になるだろう。 サドの経験におけるエピクテトスの復活を想像してみよう。「見ろ、お前が壊した」と彼は自分の足指さして言う。快楽を、探求が躓く効果の悲惨さに還元する——これはそれを嫌悪に変えるのではないのか? これは、ジョイアスがサドの体験を変えるものであることを示している。なぜなら、ジョイアスは、その対象者の謙虚さ(pudeur)を傷つけることで、そ の対象者を挑発し、その最深部に定着するために、まずその意志を横切り、それを独占することを提案しているだけだからだ。 |

| 772 |

For modesty is an amboceptor

with respect to the circumstances of being: between the two, the one's

immodesty by itself violating the other's modesty.

A connection that could justify, were such justification necessary,

what I said

before regarding the subject's assertion in the Other's place. Let us question this jouissance, which is precarious because it depends on an echo that it sets off in the Other, only to abolish it little by little by attaching the intolerable to it. In the end, doesn't it seem to us to be thrilled only by itself, like another horrible freedom? Thus we will see appear the third term that, according to Kant, is lacking in moral experience—namely, the object that Kant, in order to guarantee it to the will in the implementation of the Law, is constrained to relegate to the unthinkability of the thing in itself. But is this not the very object we find in Sadean experience, which is no longer inaccessible and is instead revealed as the being-in-the-world, the Dasein^ of the tormenting agent? Yet it retains the opacity of that which is transcendent. For this object is strangely separated from the subject. Let us observe that the herald of the maxim need be no more here than a point of broadcast. It could be a voice on the radio recalling the right promoted by the supplemental effort the French would have consented to make in response to Sade's appeal, the maxim having become an organic Law of their regenerated Republic. Such voice-related phenomena, especially those found in psychosis, truly have this object-like appearance. And in its early days, psychoanalysis was not very far from relating the voice of conscience to psychosis. Here we see why Kant views this object as evading every determination of transcendental aesthetics, even though it does not fail to appear in a certain bulge in the phenomenal veil, being not without hearth or home, time in intuition, modality situated in the unreal [irreel], or effect in reality. It is not simply that Kant's phenomenology is lacking here, but that the voice—even if insane—forces [upon us] the idea of the subject, and that the object of the law must not suggest malignancy on the part of the real God. Christianity has assuredly taught men to pay little attention to God's jouissance, and this is how Kant makes palatable his voluntarism of Law-for- Law's-sake, which is something that exaggerates, one might say, the ataraxia of the Stoics. One might be tempted to think that Kant feels pressured here by what he hears too close by, not from Sade but from some nearby mystic, in the sigh that muffles what he glimpses beyond, having seen that his God is faceless: Grimmigkeit? Sade says: supremely-evil-being. |

なぜなら、謙虚さは存在の状況に対する受容者であり、その2つの間では、一方の不謙虚さが他方の謙虚さを侵害するからだ。このような関連性は、もしそのような正当化が必要であれば、私が先ほど述べた、他者の立場で主体が主張することについて正当化することができるだろう。 この享楽を疑問視しよう。それは、他者の中に引き起こす反響に依存しているため不安定であり、やがて耐え難いものをそれに結びつけることで少しずつ消滅させていくからだ。結局、それは自分自身によってのみ興奮しているように見え、別の恐ろしい自由のように思えないか? このようにして、カントが道徳的経験に欠如していると指摘した第三の項が現れる。すなわち、カントが、法の実施において意志にそれを保証するために、物自 体のもつ不可思性に追いやらざるを得なかった対象だ。しかし、これはまさに、サドの経験に見られる対象そのものではないだろうか。それはもはや到達不可能 なものではなく、むしろ、苦悩を与える行為者の世界における存在、ダーザイン(現存在)として明らかにされている。 しかし、それは超越的なものの不透明さを保持している。なぜなら、この対象は主体から奇妙に分離されているからだ。格律の伝達者は、ここでは放送の発信点 にすぎないことに注目しよう。それは、サドの呼びかけに応じてフランス人が合意した追加的な努力によって促進された権利を想起させるラジオの声であるかも しれない。その格律は、再生した共和国の有機的な法律となったのだ。 このような声に関連する現象、特に精神病に見られるものは、まさにこの対象のような外観を持っている。そして、その初期の頃、精神分析は良心の声と精神病を関連付けることにそれほど遠くなかった。 ここで、カントがこの対象を超越的審美学のあらゆる決定から逃れるものと見なす理由がわかる。それは、現象のヴェールの一つの膨らみとして現れるにもかか わらず、暖炉や家、直観における時間、非現実(irreel)に位置するモダリティ、現実における効果など、存在の根拠を欠いていないからだ。ここでは、 カントの現象学が欠けているというだけでなく、その声は、たとえ狂気であっても、主体の概念を私たちに強いるものであり、法の目的は、現実の神の悪意を暗 示してはならないということだ。 キリスト教は確かに人間に神の享楽に注意を払わないように教えた。これが、カントが「法のための法」の意志主義を飲み込ませる方法であり、これは、ストア 派の無動の平静を過剰に強調するものと言えるかもしれない。カントはここで、サドではなく、近くにいる神秘家から聞こえてくる声に圧迫されているように思 える。彼が垣間見たものを覆い隠すため息の中に、彼の神が顔を持たないことを知ったからである:グリムミヒェイト?サドは言う:至高の悪の存在。 |

| 773 |

But humph! Schwarmereien, black

swarms—I chase you away in order to

return to the function of presence in the Sadean fantasy. This fantasy has a structure that we will see again further on; in it the object is but one of the terms in which the quest it figures can die out [s'eteindre]. When jouissance petrifies in the object, it becomes the black fetish, in which can be recognized the form that was verily and truly offered up at a certain time and place, and still is in our own time, so that one can adore the god therein. This is what becomes of the executioner in sadism when, in the most extreme case, his presence is reduced to being no more than the instrument. But the fact that the executioner's jouissance becomes fixated there does not spare his jouissance the humility of an act in which he cannot help but become a being of flesh and, to the very marrow, a slave to pleasure. This duplication neither reflects nor reciprocates (why wouldn't it "mutualize"?) the duplication that took place in the Other owing to the subject's two alterities. Desire—which is the henchman of the subject's split—would no doubt be willing to call itself "will to jouissance." But this appellation would not make desire any more worthy of the will it invokes in the Other, in tempting that will [to go right] to the extreme of its division from its pathos; for when it does so, desire departs [part] beaten down, doomed to impotence. For desire disappears [part] under pleasure's sway, pleasure's law being such as to make it always fall short of its aim: the homeostasis of the living being, always too quickly reestablished at the lowest threshold of tension at which he scrapes by, the ever early fall of the wing, with which desire is able to sign the reproduction of its form—a wing which here must nevertheless rise to the function of representing the link between sex and death. Let us lay that wing to rest behind its Eleusinian veil. Pleasure, a rival of the will in Kant's system that provides a stimulus, is thus in Sade's work no more than a flagging [defaillant] accomplice. At the moment of climax [jouissance], it would simply be out of the picture if fantasy did not intervene to sustain it with the very discord to which it succumbs. |

しかし、ふふっ!シュヴァルメリー、黒い群れたちよ、私はあなたたちを追い払って、サドの幻想における存在の機能に戻ろう。 この幻想は、後で再び見る構造を持っている。そこでは、対象は、それが表す探求が消滅する(s'eteindre)ことができる用語のひとつにすぎない。 jouissance が対象の中で石化すると、それは黒いフェティシズムとなり、ある時ある場所で真に、そして実際に捧げられた形が認識され、それは今でも私たちの時代にも存 在し、その中に神を崇拝することができる。 これは、サディズムにおいて、最も極端な場合、その存在が単なる道具に還元された死刑執行人がどうなるかを表している。 しかし、死刑執行人のジョイサンスがそこに固定化されるという事実によって、彼のジョイサンスは、彼が肉体の存在となり、その骨髄まで快楽の奴隷となることを避けられないという、その行為の謙虚さから逃れることはできない。 この二重化は、主体の 2 つの他者性によって他者において生じた二重化を反映も相互化もしていない(なぜ「相互化」しないのか?)。 主体の分裂の走狗である欲望は、間違いなく自らを「快楽への意志」と呼ぶことを望んでいるだろう。しかし、この呼称は、その欲望が他者に呼び起こす意志の 価値を高めるものではない。なぜなら、その意志をそのパトスからの分裂の極限まで誘惑するからである。そうすることで、欲望は打ちのめされ、無力化に運命 づけられて去っていくからだ。 なぜなら、欲望は快楽の支配下で(一部)消滅するからだ。快楽の法則は、その目的を常に達成できないようにしている。それは、生き物の恒常性であり、生き 物がかろうじて生き残る最低の緊張の限界で常にあまりにも早く回復してしまうものであり、欲望がその形の再現を象徴する翼の早すぎる落下である。しかし、 ここでは、その翼は、性と死のつながりを表現する機能に昇華しなければならない。その翼をエレウシスのベールに覆って休ませよう。 カントの体系において意志のライバルであり刺激を与える快楽は、サドの作品では衰弱した共犯者に過ぎない。クライマックス(jouissance)の瞬間、幻想が介入して、それが屈服する不協和音そのものでそれを支えていなければ、快楽は単に画面から消えてしまうだろう。 |

| 774 |

Stated differently, fantasy

provides the pleasure that is characteristic of

desire. Let us recall that desire is not the subject, for it cannot be

indicated

anywhere in a signifier of any demand whatsoever, for it cannot be

articulated

in the signifier even though it is articulated there. Taking pleasure in fantasy is easy to grasp here. Physiology shows that pain has a longer cycle than pleasure in every respect, since a stimulation provokes pain at the point at which pleasure stops. However prolonged one assumes it to be, pain, like pleasure, nevertheless comes to an end—when the subject passes out. Such is the vital datum that fantasy takes advantage of in order to fixate— in the sensory aspect of Sadean experience—the desire that appears in its agent. Fantasy is defined by the most general form it receives in an algebra I have constructed for this purpose—namely, the formula ($0a) in which the lozenge () is to be read as "desire for," being read right to left in the same way, introducing an identity that is based on an absolute non-reciprocity. (This relation is coextensive with the subject's formations.) Be that as it may, this form turns out to be particularly easy to animate in the present case. Indeed, it relates the pleasure that has been replaced by an instrument (object a in the formula) here to the kind of sustained division of the subject that experience orders.v This only occurs when its apparent agent freezes with the rigidity of an object, in view of having his division as a subject entirely reflected in the Other.v From the vantage point of the unconscious, a quadripartite structure can always be required in the construction of a subjective ordering. My didactic schemas take this into account.v Let us modulate the Sadean fantasy with a new schema of this kind:....  |

別の言い方をすれば、幻想は欲望に特徴的な快楽をもたらす。欲望は、いかなる要求のシニフィアンにもどこにも表わすことができないため、主体ではないことを思い出そう。欲望は、たとえシニフィアンで表現されたとしても、そのシニフィアンでは表現できないからだ。 幻想から快楽を得ることは、ここで容易に理解できる。 生理学によれば、刺激は快楽が途絶えた時点で痛みを誘発するため、あらゆる点で痛みは快楽よりも周期が長い。しかし、その持続時間がどれほど長くても、痛 みは快楽と同様に、主体が意識を失うことで終焉を迎える。これは、ファンタジーが、サドの体験の感覚的側面において、その主体に現れる欲望を固定するため に利用する重要なデータだ。 ファンタジーは、私がこの目的のために構築した代数において、それが最も一般的な形で定義される。すなわち、菱形()は「~への欲望」と読み、右から左に 同じように読み、絶対的な非相互性に基づく同一性を導入する定式($0a)である。(この関係は、主体の形成と同一範囲である。 いずれにせよ、この形式は、今回のケースでは特に表現しやすいことがわかる。実際、この形式は、ここでは道具(定式における対象 a)に置き換えられた快楽を、経験によって秩序づけられる主体の持続的な分裂と関連付けている。v これは、その表層的な主体が、主体としての分裂が他者に完全に反映されることで、対象としての硬直性に凍りつく場合にのみ生じる。v 無意識の観点からは、主観的な秩序の構築には、常に 4 分割の構造が必要とされる。私の教育的な模式図はこれを考慮している。サドの幻想を、このような新しい模式図で変調してみよう:....  |

| 775 |

The lower line accounts for the

order of fantasy insofar as it props up the Utopia of desire. The curvy line depicts the chain that allows for a calculus of the subject. It is oriented, and its orientation constitutes here an order in which the appearance of object a in the place of the cause is explained by the universality of its relationship to the category of causality; forcing its way into Kant's transcendental deduction, this universality would base a new Critique of Reason on the linchpin [ckeville] of impurity. Next there is the V which, occupying the place of honor here, seems to impose the will [volonte] that dominates the whole business, but its shape also evokes the union [reunion] of what it divides by holding it together with a vel—namely, by offering up to choice what will create the $ of practical reason from S, the brute subject of pleasure (the "pathological" subject). Thus it is clearly Kant's will that is encountered in the place of this will that can only be said to be a will to jouissance if we explain that it is the subject reconstituted through alienation at the cost of being nothing but the instrument of jouissance. Thus Kant, being interrogated "with Sade"—that is, Sade serving here, in our thinking as in his sadism, as an instrument— avows what is obvious in the question "What does he want?" which henceforth arises for everyone. Let us now make use of this graph in its succinct form to find our way around in the forest of the fantasy that Sade develops according to a systematic plan in his work. We will see that there is a statics of the fantasy, whereby the point of aphanisis, assumed to lie in $, must in one's imagination be indefinitely pushed back. This explains the hardly believable survival that Sade grants to the victims of the abuse and tribulations he inflicts in his fable. The moment of their death seems to be motivated there merely by the need to replace them in a combinatory, which alone requires their multiplicity. Whether unique (Justine) or multiple, the victim is characterized by the monotony of the subject's relation to the signifier, in which, if we rely on our graph, she consists. The troupe of tormentors (see Juliette), being object a in the fantasy and situating themselves in the real, can have more variety. The requirement that the victims' faces always be of incomparable (and, moreover, unalterable, as I just said) beauty is another matter, which we cannot account for with a few banal and quickly fabricated postulates about sex appeal. Rather, we should see here the grimace of what I have shown regarding the function of beauty in tragedy: the ultimate barrier that forbids access to a fundamental horror. Consider Sophocles' Antigone and the moment when the words XXXXXXXXXXXX ring out.5 |

下側の線は、欲望のユートピアを支える限りにおいて、幻想の秩序を表している。 曲線は、主体の計算を可能にする連鎖を表している。この曲線は方向性を持っており、その方向性は、原因の場所に現れる対象 a が、因果関係のカテゴリーとの普遍的な関係によって説明されるという秩序を構成している。この普遍性は、カントの超越的演繹に割り込み、不純という要 (linchpin)に基づいて、新たな「理性批判」の基盤となるだろう。 次に、ここでは名誉の座を占める V がある。これは、全体を支配する意志(volonte)を課すように見えるが、その形は、ヴェールでそれを結びつけることで、それが分割するものを結合 (reunion)させることも連想させる。つまり、快楽の野生の主体(S、つまり「病的な」主体)から、実践的理性の $ を作り出すものを選択に委ねることを意味する。 したがって、この意志の代わりに現れるのは、明らかにカントの意志であり、それは、快楽の道具にすぎないという代償を払って疎外によって再構成された主体 である、と説明しなければ、快楽の意志とは呼べないものだ。このように、サドと共に問われるカント——つまり、サドが、私たちの思考においても、彼のサ ディズムにおいても、道具として機能している——は、「彼は何を望んでいるのか?」という、これからは誰もが抱くことになる質問の明らかな答えを明言して いる。 このグラフを簡潔な形で活用して、サドが作品において体系的な計画に従って展開する幻想の森林をナビゲートしよう。 私たちは、幻想の静学が存在することを知るだろう。すなわち、$に置かれると仮定されるアファニシスの点が、想像の中で無限に後退させられる必要があるの だ。これが、サドが彼の寓話で加える虐待と苦難の被害者に与える、信じがたい生存を説明する。彼らの死の瞬間は、彼らの多さを要求する組み合わせに彼らを 置き換える必要性によってのみ動機付けられているように見える。犠牲者は、それが単一(ジュスティーン)であれ、複数であれ、主体と記号との関係の単調さ によって特徴づけられる。この関係において、私たちのグラフを信頼すれば、犠牲者は構成されている。拷問者たち(ジュリエットを参照)は、幻想の中で対象 a であり、現実の中に位置しているため、より多様性を持つことができる。 被害者の顔が常に比較不能(しかも、先ほど述べたように変更不能な)美しさであるという要件は別の問題で、性的な魅力に関する単純で急ごしらえの仮定で説 明できない。むしろ、これは私が悲劇における美の機能について示したものの歪んだ表情と見なすべきだ:根本的な恐怖へのアクセスを禁じる最終的な障壁。ソ フォクレスの『アンティゴネー』と、XXXXXXXXXXXX という台詞が鳴り響く瞬間を考えてみてください。 |

| 776 |

This excursus would be of no

value here did it not introduce what one

might call the discordance between the two deaths, introduced by the

existence of the condemnation. The between-two-deaths of the shy of

[I'en-defd]

is essential to show us that it is no other than the one by which the

beyond

[I'au-deld] is sustained. This can be clearly seen in the paradox constituted in Sade's work by his position regarding hell. The idea of hell, refuted a hundred times by him and cursed as religious tyranny's way of constraining people, curiously returns to explain the gestures of one of his heroes who is, nevertheless, among the most taken with libertine subversion in its reasonable form: the hideous Saint-Fond.6 The practices, whose final agony he imposes on his victims, are based on his belief that he can render their torment eternal in the hereafter [I'au-deld]. He highlights the authenticity of this behavior by concealing it from his accomplices and the authenticity of this credence by the difficulty he has explaining himself. Thus we hear him, a few pages later, try to make his behavior and credence sound plausible in his discourse with the myth of an attraction tending to gather together the "particles of evil." This incoherence in Sade's work, overlooked by sadists (they, too, are a bit hagiographic), could be explained by noting in his writings the formally expressed term "the second death." The assurance he expects from it against the awful routine of nature (which crime, as he tells us elsewhere, serves to disrupt) would require that it go to an extreme in which the vanishing [evanouissement] of the subject is redoubled. He symbolizes this in his wish that the very decomposed elements of our body be destroyed so that they can never again be assembled. |

こ

の余談は、非難の存在によって導入された、2つの死の間の不調和と呼ばれるものを紹介しなければ、ここでは何の価値も持たないだろう。[I『en-

defd] の恥ずかしがり屋の「2つの死の間」は、それがまさに [I』au-deld]

の彼方を支えているものであることを示すために不可欠である。 これは、サドの作品における地獄に関する彼の立場によって構成されるパラドックスにはっきりと見られる。彼によって百回も反駁され、人民を拘束する宗教的 専制の手段として呪われた地獄の概念は、奇妙なことに、その合理的な形態で自由奔放な破壊行為に最も熱中している彼の英雄の一人、醜悪なサン・フォン (Saint-Fond)の行動を説明するために再び登場する。6 彼が被害者に課す最終的な苦痛の行為は、彼らが来世[I'au-deld]で永遠の苦痛を受けると信じることに基づいている。彼は、この行為を共犯者から 隠すことでその真実性を強調し、説明の困難さを通じてこの信仰の真実性を示している。数ページ後、彼は「悪の粒子」を結びつける傾向のある吸引力の神話を 用いて、自分の行動と信仰を説得力のあるものとして説明しようとしている。 サドの作品におけるこの不整合は、サディストたち(彼らもまた、やや聖人伝的である)によって見落とされているが、彼の著作に形式的に表現されている「第 二の死」という用語に注目することで説明できるかもしれない。自然界の恐ろしい日常(サドは別の場所で、犯罪はそれを破壊する役割を果たす、と述べてい る)に対して彼がそこから期待する確信は、主体の消滅(evanouissement)が倍増するほどの極端な形をとらなければならないだろう。彼は、私 たちの体の非常に分解した要素が、二度と組み立てられないように破壊されることを望むことで、これを象徴している。 |

| 777 |

The fact that Freud nevertheless

recognizes the dynamism of this wish7 in

certain of his clinical cases, and that he very clearly, perhaps too

clearly,

reduces its function to something analogous to the pleasure principle

by relating it to a "death drive" (demand [demande] for death)—this

will not be

accepted by those who have been unable to learn from the technique they

owe Freud, or from his teachings, that language has effects that are

not simply

utilitarian or, at the very most, for purposes of display. Freud is

[only] of

use to them at conventions. In the eyes of such puppets, the millions of men for whom the pain of existence is the original reason for the practices of salvation that they base on their faith in Buddha, are undoubtedly underdeveloped; or, rather, they think like Buloz, the director of La Revue des Deux Mondes, who told Renan8 straight out when he turned down his article on Buddhism (this according to Burnouf) at some point during the eighteen-fifties, that it is "impossible that there are people that dumb." If they believe that they have better ears than other psychiatrists, have they somehow escaped hearing such pain in a pure state model the song of certain patients referred to as melancholic? Have they not heard one of those dreams by which the dreamer remains overwhelmed, having, in the felt condition of an inexhaustible rebirth, plumbed the depths of the pain of existence? Or, in order to put hell's torments back in their place, torments which could never be imagined beyond what men traditionally inflict in this world, shall we implore them to think of our everyday life as having to be eternal? We must hope for nothing, not even hopelessness, to combat such stupidity, which is, in the end, sociological; I am mentioning it here only so that people on the outside will not expect too much, concerning Sade, from the circles of those who have a surer experience of forms of sadism. Especially regarding a certain equivocal notion that has been gaining ground about the relation of reversion that supposedly unites sadism with a certain idea of masochism—it is difficult for those outside such circles to imagine the muddle this notion creates. We would do better to learn from it the lesson contained in a fine little tale told about the exploitation of one man by another, which is the definition of capitalism, as we know. And socialism, then? It is the opposite. Unintended humor—this is the tone with which a certain circulation of psychoanalysis occurs. It fascinates people because it goes, moreover, unnoticed. |

フ

ロイトが、それでもなお、彼の臨床例の一部においてこの願望7のダイナミズムを認めていること、そして、それを「死の欲動」に関連付けることで、その機能

を快楽原則に類似したものに、おそらくは過度に明確に還元していることは、

(死の要求[demande])と関連付けることで、その機能を快楽原則に類似したものと非常に明確に、おそらくは過剰に単純化している点——これは、フ

ロイトから学んだ技術や彼の教義から、言語が単なる実用的な目的や、最も良い場合でも見せびらかすための目的を超えた効果を持つことを理解できなかった人

々には受け入れられないだろう。フロイトは彼らにとって、単なる形式的な存在に過ぎない。 そのような操り人形たちの目には、存在の苦痛が救済の実践の根本的な理由である数百万の人々は、疑いなく未発達だ。むしろ、1850年代のある時点で、レ ナン8 の仏教に関する論文を拒否した際(これはブルヌフによる)、ラ・レヴュー・デ・ドゥ・モンド誌の編集長ブルーズが「それほど愚かな人民がいるはずがない」 と率直に述べたように、ブルーズのような考えを持っている。 もし彼らが他の精神科医よりも優れた耳を持っていると信じるなら、彼らは、憂鬱症と診断された患者の歌に表れるような、純粋な形態の痛みを聴き逃したのだろうか? 彼らは、夢見る者が、尽きることのない再生の感覚に襲われ、存在の痛みの深淵を覗き込んだような夢の一つを聞いたことがないのだろうか? あるいは、地獄の苦痛をその適切な位置に戻すために、人間が伝統的にこの世界で加える苦痛を超えたものを想像できない苦痛を、私たちの日常が永遠に続くものだと考えるよう彼らに懇願すべきだろうか? このような愚かさは、結局のところ社会学的なものなので、絶望さえも期待すべきではない。私は、サドについて、サディズムの形態についてより確実な経験を持つ人々のサークルについて、部外者が過大な期待を抱かないように、ここでこのことを述べているだけだ。 特に、サディズムとある種のサディズムの考え方を結びつける逆転の関係について、ある曖昧な概念が定着しつつあるが、その概念が引き起こす混乱は、その サークルに属さない者にとっては想像し難いものだ。その代わりに、ある人間による別の人間の搾取について語られた、素晴らしい短編小説に込められた教訓を 学んだほうがよいだろう。その小説は、私たちが知っている資本主義の定義そのものである。では、社会主義とは?それはその反対だ。 意図しないユーモア――これは、ある種の精神分析の流通に見られるトーンだ。さらに、それは気づかれることがないため、人々を魅了する。 |

| 778 |

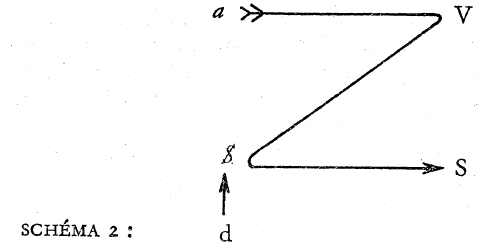

But there are doctrinaires who

strive for tidier appearances. One acts the

part of a do-good existentialist, another, more soberly, that of a

ready-made*

personalist. This results in the claim that the sadist "denies the

Other's existence."

Which is precisely, one must admit, what has just come out in my

analysis. To pursue my analysis, is it not the case, rather, that the sadist discharges the pain of existence into [rejette dans] the Other, but without seeing that he himself thereby turns into an "eternal object," if Whitehead is willing to let us have this term back. But why wouldn't it belong to both of us? Isn't this—redemption and immortal soul—the status of the Christian? Let us not proceed too quickly, so as not to go too far either. Let us note, instead, that Sade is not duped by his fantasy, insofar as the rigor of his thinking is integrated into the logic of his life. Let me give my readers an assignment here. The fact that Sade delegates a right to jouissance to everyone in his Republic is not translated in my graph by any symmetrical reversal [reversion] along an axis or around some central point, but only by a 90-degree rotation of the graph, as follows:.....  V, the will to jouissance, leaves no further doubt as to its nature, because it appears in the moral force implacably exercised by the President of Montreuil [Sade's mother-in-law] on the subject; it can be seen that the subject's division does not have to be pinned together [reunie] in a single body. (Let us note that it is only the First Consul who seals this division with its effect of administratively confirmed alienation.) |

し

かし、より整然とした外観を追求する教条主義者もいる。一人は善行を装った実存主義者を演じ、もう一人はより冷静に、既成の個人主義者を演じる。その結

果、サディストは「他者の存在を否定する」という主張が生まれる。これはまさに、私の分析で明らかになったことだと認めざるを得ない。 私の分析を続けるなら、むしろサディストは存在の苦痛を他者へ放り込む([rejette dans])が、そのことで自身も「永遠の対象」へと変貌することを自覚していないのではないか。ホワイトヘッドがこの用語の使用を許してくれるなら、そう言えるだろう。 しかし、なぜそれは私たち両方に属さないのか?贖罪と不滅の魂は、キリスト教徒の地位ではないのか?あまり急いで進まないようにしよう。行き過ぎないように。 代わりに、サドは幻想に欺かれていないことを指摘しておこう。彼の思考の厳格さは、彼の生活の論理に統合されているからだ。 読者に課題を出そう。 サドが共和国において享楽の権利をすべての人に委譲しているという事実は、私のグラフでは、軸に沿った対称的な反転[逆転]や中心点周りの回転によって表現されていない。代わりに、グラフを90度回転させることで表現されている。具体的には、以下の通りだ:.....  V、快楽への意志は、その性質についてもはや疑いの余地を残さない。なぜなら、それはモンテルイの社長(サドの義母)が対象に対して容赦なく行使する道徳的力の中に現れているからだ。対象者の分裂は、単一の身体の中で「再統合」される必要がないことがわかる。 (この分裂を行政的に確認された疎外の効果で封印するのは、第一執政だけであることに注意しよう。) |

| 779 |

This division here pins together

[re'unit] as S the brute subject incarnating

the heroism characteristic of the pathological in the form of

faithfulness to

Sade manifested by those who at first tolerated his excesses—his wife,

his

sister-in-law, and why not his manservant too?9—and others who have

been

effaced from his history.

For Sade, $ (barred S), we finally see that, as a subject, it is

through his

disappearance that he makes his mark, things having come to their term.

Incredibly, Sade disappears without anything—even less than for

Shakespeare—

of his image remaining to us, after he gave orders in his will to have

a thicket efface the very last trace on stone of a name that sealed his

fate.

Mr| (jptivai,10 "not to be born"—Sade's curse is less holy than

Oedipus',

and does not carry him toward the Gods, but is immortalized in his

work,

whose unsinkable buoyancy Jules Janin backhandedly shows us, saluting

it

behind the books that hide it, if we are to believe him, in every

worthy

library, like the writings of St. John Chrysostom or Pascal's Pensees.

But Sade's work is annoying, according to you—yes, like thieves at a

fair—your honor and member of the Academie Franchise; but his work

always suffices to bother you, one of you by the other, both one and

the

other, and one in the other.11

A fantasy is, in effect, quite bothersome, since we do not know where

to

situate it due to the fact that it just sits there, complete in its

nature as a fantasy, whose only reality is as [de] discourse and which

expects nothing of your

powers, asking you, rather, to square accounts with your own desires. The reader should now reverentially approach those exemplary figures who, in the Sadean boudoir, assemble and disassemble in a carnival-act-like rite: "Change of positions." It is a ceremonial pause, a sacred scansion. |

こ

の区分は、S

を、サドの過剰を当初容認していた者たち(彼の妻、義姉、そしておそらくは彼の使用人9)や、彼の歴史から抹殺された者たちによって体現される、病的なも

のの特徴である英雄主義を体現する野蛮な主体として結びつける(再統合する)。Sade、つまり $(S

にバーが付いた記号)については、主体として、物事がその終焉を迎えたときに、その失踪によってその存在を印象づけることが、ついに明らかになった。信じ

られないことに、Sade

は、シェイクスピアよりもさらに、私たちに自分のイメージをまったく残すことなく、自分の運命を決定づけた石に刻まれた自分の名前を、遺言で茂みに覆い隠

して消去するよう指示して、この世を去った。ミスター| (jptivai,10

「生まれざるべき」—サドの呪いはオイディプスのものより神聖ではなく、神々へと導くものではなく、彼の作品に不滅の形で刻まれる。その沈まない浮力につ

いて、ジュール・ジャニンは皮肉を交えて示し、もし彼を信じるなら、あらゆる価値ある図書館に隠された本の後ろから、聖ヨハネ・クリソストムやパスカルの

『パンセ』のように、その作品を称賛している。しかし、サドの作品はあなたにとって煩わしいものだ——そう、市井の盗賊のように——あなたのような名誉あ

るフランスのアカデミー会員にとって。しかし、彼の作品は常にあなたを煩わすのに十分だ。あなたの一人が他の一人を、両方とも互いに、そして一方が他方の

中に。11

幻想は、実際、非常に厄介なものだ。なぜなら、それはただそこに存在し、幻想としての本質を完全に備えているため、どこに位置付けるべきか分からないから

だ。その唯一の現実は[de]言説であり、あなたの力に何も求めず、むしろあなた自身の欲望と清算するよう求めている。 読者は今、サドの寝室で、カーニバルの儀式のような「ポジションの変更」を繰り返す、模範的な人物たちに敬虔に近づくべきだ。 それは儀式的な休止、神聖なリズムだ。 |

| 780 |

Let us salute here the objects

of the law, of which you will know nothing

unless you know how to find your way around in the desires those

objects

cause. It is good to be charitable But to whom? That is the question. A certain Monsieur Verdoux answered this question every day by putting women in an oven until he himself got the electric chair. He thought that his family wanted to live in greater comfort. More enlightened, the Buddha offered himself up to be devoured by those who did not know the way. Despite this eminent patronage, which might well be based solely on a misunderstanding (it is not clear that a tigress enjoys eating Buddha), Verdoux's abnegation stemmed from an error that deserves to be dealt with severely, since a little lesson from the Critique, which does not cost much, would have helped him avoid it. No one doubts but that the practice of Reason would have been both more economical and more legal, even if his family would have had to go hungry now and then. "But what's with all these metaphors," you will say, "and why . . . ?" The molecules that are monstrous insofar as they assemble here for an obscene jouissance, awaken us to the existence of other more ordinary jouissances encountered in life, whose ambiguities I have just mentioned. They are suddenly more respectable than these latter, appearing purer in their valences. Desires . . . here are the only things that bind them, and they are exalted in making it clear that desire is the Other's desire. If you have read my work up to this point, you know that, more accurately stated, desire is propped up by a fantasy, at least one foot [pied] of which is in the Other, and precisely the one that counts, even and above all if it happens to limp. The object, as I have shown in Freudian experience—the object of desire, where we see it in its nakedness—is but the slag of a fantasy in which the subject does not come to after blacking out [syncope]. It is a case of necrophilia. The object generally vacillates in a manner that is complementary to the subject's vacillation]. This is what makes it as ungraspable as is the object of the Law according to Kant. But here we suspect that a rapprochement is necessary: Doesn't the moral law represent desire in the case in which it is no longer the subject, but rather the object that is missing [fait defaut]? |

ここで、この法律の対象について考えてみよう。その対象が引き起こす欲望をうまくコントロールする方法を知らなければ、その対象について何も理解することはできないだろう。 慈善心を持つことは良いことだ しかし、誰に対して?それが問題だ。 あるヴェルドゥー氏は、この質問に毎日答え、女性をオーブンに入れて、最終的には電気椅子で死刑になった。彼は、自分の家族がより快適な生活を送ってほし いと願っていたのだ。より賢明な仏陀は、道を知らない者たちに自らを食わせた。この高貴な庇護は、単なる誤解に基づいている可能性もある(虎が仏陀を食べ ることを楽しむかどうかは不明だ)。しかし、ヴェルドゥの自己犠牲は、厳しく非難されるべき誤りから生じたものだ。なぜなら、『批判』からの小さな教訓 が、彼にそれを避ける手助けをしたはずだからだ。誰も疑わないだろうが、理性の実践は、彼の家族が時折飢えを耐えなければならないとしても、より経済的で 法的な方法だっただろう。 「しかし、なぜこのような隠喩を使うのか、そしてなぜ...?」とあなたは言うだろう。ここで卑猥な快楽のために集結している、怪物のような分子は、私が 先ほど述べたような、人生で遭遇するよりありふれた快楽の存在に私たちを気づかせる。それらは、その価値においてより純粋に見え、突然、後者よりも尊敬に 値するものとなる。 欲望……ここにあるのは、それらを結びつける唯一の要素であり、欲望が他者の欲望であることを明確にすることで高揚されるものだ。 私の著作をここまで読んだ人なら、より正確に言えば、欲望は幻想によって支えられており、その幻想の少なくとも片足は他者の中にあり、まさにその足が重要であり、たとえそれが跛行していても、それ以上に重要であることを知っているだろう。 フロイトの経験で私が示したように、欲望の対象、つまりその裸の姿で私たちに見られる対象は、主体が失神(失神)後に目覚めることのない幻想の残骸にすぎない。これは死体愛好症の場合だ。 対象は通常、主体の揺らぎと相補的な形で揺らぎを見せる。 これが、カントの「法」の対象と同じように、それを把握できないものにしている。しかし、ここでは、接近が必要ではないかと疑われる。道徳律は、もはや主体ではなく、対象が欠落している(fait defaut)場合に、欲望を表しているのではないだろうか? |

| 781 |

Doesn't the subject—alone

remaining present, in the form of the voice

within, speaking nonsensically most of the time—seem to be adequately

signified

by the bar with which the signifier $ bastardizes him, that signifier

being released from the fantasy ($§a) from which it derive, in the two

senses

of the term [derive meaning both derives and drifts]? Although this symbol returns the commandment from within at which Kant marvels to its rightful place, it opens our eyes to the encounter which, from Law to desire, goes further than the slipping away of their object, for both the Law and desire. It is the encounter in which the ambiguity of the word "freedom" plays a part; the moralist, by grabbing freedom for himself, always strikes me as more impudent still than imprudent. But let us listen to Kant himself illustrate it once more: Suppose someone alleges that his lustful inclination is quite irresistible to him when he encounters the favored object and the opportunity. [Ask him] whether, if in front of the house where he finds this opportunity a gallows were erected on which he would be strung up immediately after gratifying his lust, he would not then conquer his inclination. One does not have to guess long what he would reply. But ask him whether, if his prince demanded, on the threat of the same prompt penalty of death,12 that he give false testimony against an honest man whom the prince would like to ruin under specious pretenses, he might consider it possible to overcome his love of life, however great it may be. He will perhaps not venture to assure us whether or not he would overcome that love, but he must concede without hesitation that doing so would be possible for him. He judges, therefore, that he can do something because he is conscious that he ought to do it, and he cognizes freedom within himself— the freedom with which otherwise, without the moral law, he would have remained unacquainted.13 The first response that is presumed to be given here by a subject, about whom we are first told that a great deal transpires by means of words, gives me the impression that we are not being given the letter [of what he said] when that is the crux of the matter. For the fact is that, in order to express it, Kant prefers to rely on someone whose sense of shame we would, in any case, risk offending, for in no case would he stoop so low: namely, the ideal bourgeois to whom Kant elsewhere declares that he takes his hat off, no doubt in order to counter Fontenelle, the overly gallant centenarian.14 |

ほとんどの場合、無意味なことを口にする、内なる声という形で唯一存在し続ける主体は、その意味を、それを表す記号「$」によって十分に表現されているように見えないか?この記号は、その由来である幻想($§a)から、2つの意味(由来と漂流)で解放されている。 この記号は、カントが驚嘆した命令をその正当な位置に戻す一方で、法から欲望への移行において、その対象の消失を超えた出会いに私たちの目を覚まさせる。法と欲望の両方にとって。 この出会いは、「自由」という言葉の曖昧さが役割を果たす。道徳家は、自由を自分用に奪い取ることで、私にとって、不注意よりもさらに無礼な存在に映る。 しかし、カント自身に再び説明させてみよう。 ある人が、好む対象と機会に出会ったとき、自分の欲望の傾向は自分にはまったく抗いがたいと主張するとしよう。[彼に] もし、その機会を見つけた家の前に、欲望を満たした直後に絞首刑に処される絞首台が建てられていた場合、彼はその傾向に打ち勝つことができないかどうか尋 ねてみよう。彼がどう答えるかは、長く考える必要はない。しかし、もし彼の君主が、同じ即時の死刑を脅しに、彼が正直な男を偽証して破滅させたいと要求し た場合、彼は、その愛がどれだけ大きかろうと、それを克服できると考えるかどうか尋ねてみろ。彼は、その愛を克服できるかどうかを断言する勇気はないかも しれないが、そうすることが可能であることは躊躇なく認めるだろう。彼は、自分がすべきだと自覚しているからこそ、何かをすることができると判断し、自分 自身の中に自由を認識している——道徳法がなければ、彼はその自由を知らなかっただろう。13 ここでは、言葉によって多くのことが明らかになると最初に述べられている主体が、ここで与えると思われる最初の反応は、肝心な部分について(その言葉の) 文字通りの意味が伝えられていないという印象を与える。なぜなら、それを表現するために、カントは、いずれにせよ私たちの恥の感覚を傷つけるリスクを冒す 人物に依拠することを好むからだ。なぜなら、彼は決してそのような低俗な行為に及ばないからだ。すなわち、カントがフォンテネルという過剰に礼儀正しい百 歳老人に対抗するために、おそらくは帽子を脱ぐと宣言した理想的なブルジョアである。14 |

| 782 |

We will excuse the hoodlum,

then, from having to testify under oath. But it

is possible that a partisan of passion, who would be blind enough to

combine

it with questions of honor, would make trouble for Kant by forcing him

to recognize

that no occasion precipitates certain people more surely toward their

goal than one that involves defiance of or even contempt for the

gallows. For the gallows is not the Law, nor can the gallows be wheeled in by the Law here. Only the police have the necessary trucks, and while the police can be the State, as Hegel says, the Law is something else, as we have known since Antigone. Kant, besides, does not contradict this with his apologue. The gallows is brought in merely so that he can attach to it, along with the subject, his love of life. Now, this is what the desire in the maxim Et non propter vitam vivendi perdere cansas can become in a moral being, rising, precisely because he is moral, to the rank of a categorical imperative, assuming he has his back to the wall [aupieddu mur]—which is precisely where he is forced here. Desire, what is called desire, suffices to make life meaningless if it turns someone into a coward. And when law is truly present, desire does not stand up, but that is because law and repressed desire are one and the same thing—which is precisely what Freud discovered. We are ahead at halftime, professor. Let us chalk up our success to the infantry, the key to the game, as we know. For we have not brought in either our knight—which would have been easy, since it would be Sade, whom we believe to be qualified enough here—our bishop, our rook (human rights, freedom of thought, your body is your property), or our queen, an appropriate figure with which to designate the daring deeds of courtly love. This would have involved moving too many people for a less certain result. |

そ

れでは、この暴漢は宣誓の下で証言する義務を免除しよう。しかし、情熱に駆られた党派者が、それを名誉の問題と結びつけて盲目的に行動し、カントに、ある

特定の者たちにとって、絞首台への挑戦、あるいは絞首台への軽蔑ほど、その目標の達成を確実に早めるものはないことを認めさせるような問題を引き起こす可

能性もある。 なぜなら、絞首台は法ではないし、法によってここに持ち込まれるものでもないからだ。必要なトラックを持っているのは警察だけであり、ヘーゲルが言うように、警察は国家であるかもしれないが、アンティゴネー以来、法とは別のものだということは、私たちも知っている。 さらに、カントは、この寓話でこれに矛盾しているわけではない。絞首台は、彼が主体とともに、自分の生命への愛を結びつけるために持ち込まれたに過ぎない。 さて、これは、格律「Et non propter vitam vivendi perdere cansas」における欲望が、道徳的な存在において、まさに彼が道徳的であるからこそ、背水の陣(aupieddu mur)に立たされた状況において、定言命法(categorical imperative)の地位にまで昇華する姿である。 欲望、いわゆる欲望は、人を臆病者に変えるなら、人生を無意味にするのに十分だ。そして、法が真に存在する場合、欲望は立ち向かわない。しかし、それは法 と抑圧された欲望が同一のものだからだ——これがまさにフロイトが発見した点だ。私たちはハーフタイムでリードしている、教授。 私たちの成功は、ゲームのカギを握る歩兵たちに帰そう。なぜなら、私たちは、騎士(これは簡単だっただろう。この役割には、この場にはふさわしいサドがふ さわしいと思う)も、ビショップ(人権、思想の自由、自分の体は自分の所有物である)も、ルーク(自分の体は自分の所有物である)も、そして、宮廷の愛の 大胆な行為を表すのにふさわしい女王も、まだ登場させていないからだ。 これは、あまり確実ではない結果のために、あまりにも多くの人々を動かし過ぎることになるからだ。 |

| 783 |

For if I claim that for a few

bantering remarks, Sade risked—knowing full

well what he was doing (consider what he did with his "outings,"

whether

licit or illicit)—imprisonment in the Bastille for a third of his

lifetime (it was

rather well-aimed banter, no doubt, but all the more demonstrative with

respect to its recompense), I'll have Pinel and his Pinelopies taking

aim at me.

Moral madness, the latter opine. In any case, a fine affair it is! I am

reminded

to show respect for Pinel, to whom we owe one of the noblest steps of

humanity. "Thirteen years in Charenton for Sade were, however, part of

this

step," [I retort]. "But he should not have been sent there," [I am

told].

"That's the whole point," [I continue]. It was Pinel's step that led

him there.

His place, and all thinkers agree on this point, was elsewhere. But

there you

have it: those who think clearly [quipensent Hen] think that his place

was outside,

and the right-thinking [les bien-pensants], starting with

Royer-Collard,

who demanded it at the time, wanted him condemned to hard-labor, if not

to

the scaffold. This is precisely why Pinel was an important moment in

the history

of thought. Willy-nilly, he supported the destruction, on the right and

the left, by thought of freedoms that the Revolution had just

promulgated in

the very name of thought. For if w« consider human rights from the vantage point of philosophy, we see what, in any case, everyone now knows about their truth. They boil down to the freedom to desire in vain. A lot of good that does us [Belle jambe]\ But it gives us an opportunity to recognize in it the impulsive \de prime-saut] freedom we saw earlier, and to confirm that it is clearly the freedom to die. But it also gives us the opportunity to be frowned upon by those who find it low in nutritional value. They are plentiful in our time. We see here the renewed conflict between needs and desires in which, as if by chance, it is the Law that empties the shell [qui vide l'ecaille]. To counter Kant's apologue, courtly love offers us a no less tempting path, but it requires us to be erudite. To be erudite by one's position is to bring on the attack of the erudites, and in this field that is tantamount to the entrance of the clowns. Kant could very easily make us lose our serious demeanor here already since he hasn't the slightest sense of comedy (this is proved by what he says about it when he discusses it). But someone who has no sense of comedy whatsoever is Sade, as has been pointed out. This topic could perhaps be fatal to him, but a preface is not designed to do the author a disservice.15 |

な

ぜなら、もし私が、サドが、自分が何をしているかを十分に承知の上で(彼の「外出」が合法か違法かに関わらず)、いくつかの軽口のために、人生の3分の1

をバスティーユ監獄で過ごすリスクを冒したと言うなら(それは確かに的を射た軽口だったかもしれないが、その報いに関してはより示唆に富むものだった)、

ピネルと彼のピネロピーたちが私を非難するだろう。後者は「道徳的狂気」と主張するだろう。いずれにせよ、素晴らしい話だ!ピネルへの敬意を示すべきだと

気づかされる。私たちは彼に人類の最も高貴な一歩を欠くことはできないからだ。「しかし、サドがシャルドンで13年間過ごしたことは、この一歩の一部だっ

た」[私は反論する]。「しかし、彼はそこに送られるべきではなかった」[私は言われる]。「それがまさにポイントだ」[私は続ける]。彼をそこに導いた

のはピネルの一歩だった。彼の居場所は、すべての思想家が一致するところだが、他の場所にあった。しかし、それが現実だ:明確に考える者たち[ヘンが皮肉

る]は、彼の居場所は外にあると考えていた。一方、正しい考えを持つ者たち[レ・ビアン・パンサン]は、ロワール=コラーールをはじめ、当時彼を重労働

刑、あるいは絞首台に送るよう要求した。これがまさに、ピネルが思想史における重要な瞬間であった理由だ。彼は、革命が思想の名の下に公布した自由を、右

も左も、思想によって破壊することを、意に反して支持した。 なぜなら、人権を哲学の観点から考察すると、その真実について、今では誰もが知っていることがわかるからだ。人権とは、結局のところ、無駄に欲望する自由である。 それなら、私たちに何の役にも立たない[Belle jambe]\ しかし、それによって、私たちは、先ほど見た衝動的な「de prime-saut」の自由を認識し、それが明らかに「死ぬ自由」であることを確認する機会を得られる。 しかし、それはまた、それを栄養価が低いと考える人々から非難される機会も与えてくれる。そのような人々は現代に多く存在する。ここには、偶然にも法が殻を空にする[qui vide l'ecaille]ことで、必要と欲望の新たな対立が表れている。 カントの寓話に対抗して、宮廷愛は私たちに同じように魅力的な道を提示するが、それは学識を要する。地位によって学識を持つことは、学識者たちの攻撃を招くことであり、この分野ではそれは道化師の登場に等しい。 カントはここで私たちを真剣な態度から簡単に失わせることができる。なぜなら、彼はコメディの感覚を全く持っていないからだ(彼がそれについて議論する際に述べたことがそれを証明している)。 しかし、コメディの感覚を全く持たない人物はサドだ、と指摘されている。このテーマは彼にとって致命的なものかもしれないが、序文は作者に不利益を与えるために存在するものではない。15 |

| 784 |

Let us thus turn to the second

stage of Kant's apologue. It no more proves his

point than the first stage did. For assuming that Kant's helot here has

the slightest

presence of mind, he will ask Kant if perchance it would be his duty to

bear

true witness were this the means by which the tyrant could satisfy his

desire. Should he say that the innocent man is a Jew, for example, if he truly is one, before a tribunal (we have seen such situations) that considers this a punishable offense? Or that he is an atheist, when it is quite possible that he himself has a better grasp on the import of the accusation than a consistory that simply wants to establish a file? And in the case of some deviation from "the party line," will he plead that this deviation is not guilty at a time and a place where the name of the game is autocritique? Why wouldn't he? After all, is an innocent man ever completely spotless? Will he say what he knows? We could make the maxim that one must counter a tyrant's desire into a duty, if a tyrant is someone who appropriates the power to enslave the Other's desire. Thus with regard to the two examples (and the precarious mediation between them) that Kant uses as a lever to show that the Law weighs in the scales not only pleasure but also pain, happiness and even the burden of abject poverty, not to mention the love of life—in short, everything pathological— it turns out that desire can have not only the same success but can obtain it more legitimately. But if the credence we lent the Critique due to the alacrity of its argumentation owed something to our desire to know where it was heading, can't the ambiguity of this success turn the movement back toward a revising of the concessions we unwittingly made? For example, the disgrace that rather quickly befell all objects that were proposed as goods [Hens] because they were incapable of achieving a harmony of wills: simply because they introduce competition. Such was the case of Milan, about which both Charles V and Francois I knew what it cost them for each to see the same good in it. For that is clearly to misrecognize the status of the object of desire. I can introduce its status here only by reminding you what I teach about desire, which must be formulated as the Other's desire [desir de VAutre] since it is originally desire for what the Other desires [desir de son desir]. This is what makes the harmony of desires conceivable, but not devoid of danger. For when desires line up in a chain that resembles the procession of Breughel's blind men, each one, no doubt, has his hand in the hand of the one in front of him, but no one knows where they are all going. |

で

は、カントの寓話の第二段階に移ろう。この段階も、第一段階と同様に、カントの主張を証明するものではない。なぜなら、カントのヘロットが少しでも理性を

保っているなら、彼はカントに、もしこれが暴君が欲望を満たす手段であるなら、真実を証言する義務があるかどうかを尋ねるだろう。 例えば、彼が本当にユダヤ人である場合、裁判所で(私たちはそのような状況を見たことがある)これが罰則対象の罪とみなされる場合、彼は「その人はユダヤ 人だ」と証言すべきか?あるいは、彼が自分自身でその告発の真意を、単にファイルを作成したいだけの教会裁判所よりもよく理解している可能性が高い場合、 彼は「彼は無神論者だ」と証言すべきか?「党の路線」からの逸脱の場合、彼は「自己批判」が求められる時と場所で、その逸脱は無罪だと主張するだろうか? なぜそうしないのか?畢竟、無実の者は完全に汚れのない存在なのか?彼は知っていることを言うだろうか? 暴君とは、他者の欲望を奴隷化する権力を手中に収める人物であるならば、暴君の欲望に対抗することは義務である、という格律を立てることができるだろう。 カントが、法が天秤に pleasure だけでなく pain、happiness、さらには abject poverty の重荷、さらには life の愛——要するに、すべて病理的なもの——を乗せることを示すために用いた二つの例(およびその間の不安定な仲介)に関して、欲望は同じ成功を収めるだけ でなく、より正当にそれを得る可能性があることが判明する。 しかし、批判の論理の迅速さゆえに批判に与えた信頼が、私たちの「それがどこへ向かっているのかを知りたい」という欲望に依存していたとすれば、この成功の曖昧さが、私たちが無意識に与えた譲歩の見直しへと動きを逆転させる可能性はないだろうか? 例えば、善として提案されたすべての対象は、意志の調和を実現することができないという理由だけで、すぐに不名誉な扱いを受けるようになった。それは、単 に競争をもたらすという理由だけだった。ミラノの場合もそうだった。カール5世とフランソワ1世は、それぞれミラノに同じ善を見出そうとして、その代償を 支払ったことをよく知っていた。 それは、欲望の対象の地位を明らかに誤解しているからだ。 その地位をここで紹介するには、私が欲望について教えていることを思い出していただくしかない。欲望は、もともと他者が望むもの(desir de son desir)に対する欲望(desir de VAutre)として定式化されなければならない。これにより、欲望の調和は考えられるようになるが、危険がなくなるわけではない。なぜなら、欲望がブ リューゲルの盲人の行列のような連鎖を形成すると、それぞれは確かに前の人と手を繋いでいるが、全員がどこへ向かっているのか誰も知らないからだ。 |

| 785 |

Now, in retracing their steps,

they all clearly experience a universal rule,

but this is because they do not know any more about it. Would the solution in keeping with practical reason be that they go around in circles? Even when lacking, the gaze is clearly the object that presents each desire with its universal rule, by materializing its cause, in binding to it the subject's division "between center and absence." Let us therefore confine ourselves to saying that a practice like psychoanalysis, which takes desire as the subject's truth, cannot misrecognize what follows without demonstrating what it represses. In psychoanalysis, displeasure is understood to provide a pretext for repressing desire, displeasure arising, as it does, along the pathway of desire 's satisfaction; but displeasure is also understood to provide the form this very satisfaction takes in the return of the repressed. Similarly, pleasure redoubles its aversion when it recognizes the law, by supporting the desire to comply with it that constitutes defense. If happiness means that the subject finds uninterrupted pleasure in his life, as the Critique of Practical Reason defines it quite classically,16 it is clear that happiness is denied to whomever does not renounce the pathway of desire. This renunciation can be willed, but at the cost of man's truth, which is quite clear from the disapproval of those who upheld the common ideal that the Epicureans, and even the Stoics, met with. Their ataraxia deposed their wisdom. We fail to realize that they degraded desire; and not only do we not consider the Law to be commensurably exalted by diem, but it is precisely because of this degrading of desire that, whether we know it or not, we sense that they cast down the Law. Sade, the former aristocrat, takes up Saint-Just right where one should. The proposition that happiness has become a political factor is incorrect. It has always been a political factor and will bring back the scepter and the censer that make do with it very well. Rather, it is the freedom to desire that is a new factor, not because it has inspired a revolution—people have always fought and died for a desire—but because this revolution wants its struggle to be for the freedom of desire. |

さて、彼らの足跡をたどると、彼らは皆、明らかに普遍的な規則を体験している。しかし、それは彼らがそれについてそれ以上知らないからである。 実践的理性による解決は、彼らが堂々巡りをするということだろうか? たとえ欠けていたとしても、視線は、その原因を具体化し、主体の「中心と欠如」という分裂を結びつけることで、各欲望に普遍的な規則を提示する対象であることは明らかだ。 したがって、欲望を主体の真実とする精神分析のような実践は、抑圧しているものを明らかにしなければ、その結果を誤って認識することはできない、とだけ述べておこう。 精神分析では、嫌悪は、欲望の満足の過程において生じる、欲望を抑圧する口実となるものと理解されている。しかし、嫌悪は、抑圧されたものが戻ってくる際に、その満足が取る形も与えていると理解されている。 同様に、快は、その法則を認識すると、その法則に従うという防衛を構成する欲望を支え、その嫌悪を倍増させる。 幸福とは、実践的理性批判が古典的に定義しているように、主体が人生において途切れることのない快楽を見出すことを意味するならば、欲望の道を放棄しない 者には幸福は否定されることは明らかだ。この放棄は意志によって行うことができるが、その代償として人間の真実が犠牲になる。これは、エピクロス派、さら にはストア派が抱いていた共通の理想を支持した者たちが受けた非難から明らかだ。彼らのアタラクシアは彼らの知恵を奪った。私たちは、彼らが欲望を貶めた ことに気づいていない。そして、私たちは、ディエムによって法が相応に高揚されているとは考えていないだけでなく、欲望を貶めたからこそ、それを知ってい るかどうかに関わらず、彼らが法を貶めたと感じているのだ。 元貴族のサドは、まさにその点でサン・ジュストの考えを引き継いでいる。幸福が政治的要因となったという主張は間違っている。幸福は常に政治的要因であ り、幸福と相性の良い王笏と香炉を復活させるだろう。むしろ、新しい要因は欲望の自由だ。それは、欲望が革命を引き起こしたからではなく、人々は常に欲望 のために戦い、死んできたからだ。しかし、この革命は、欲望の自由のために闘うことを望んでいるからだ。 |

| 786 |

Consequently, the revolution

also wants the law to be free, so free that it

must be a widow, the Widow par excellence, the one that sends your head

to

the basket if it so much as balks regarding the matter at hand. Had

Saint-

Just's head remained full of the fantasies in Organt, Thermidor might

have

been a triumph for him. Were the right to jouissance recognized, it would consign the domination of the pleasure principle to an obsolete era. In enunciating this right, Sade imperceptibly displaces for each of us the ancient axis of ethics, which is but the egoism of happiness. One cannot say that every reference to it is eliminated in Kant's work, given the very familiarity with which it accompanies him, and still more given the offshoots of it seen in the exigencies that make him argue both for some retribution in the hereafter and progress in this world. Should another happiness be glimpsed whose name I first uttered, the status of desire would change, demanding a reexamination of it. But it is here that something must be gauged. How far does Sade lead us in the experience of this jouissance, or simply of its truth? For the human pyramids he describes, which are fabulous insofar as they demonstrate the cascading nature of jouissance, these water buffets of desire built so that jouissance makes the Villa d'Este Gardens sparkle with a baroque voluptuousness—the higher they try to make jouissance spurt up into the heavens, the more insistently the question "What is it that is flowing here?" demands to be answered. Unpredictable quanta by which the love/hate atom glistens in the vicinity of the Thing from which man emerges through a cry, what is experienced, beyond certain limits, has nothing to do with what desire is propped up by in fantasy, which is in fact constituted on the basis of these limits. We know that Sade went beyond these limits in real life. Otherwise, he probably would not have given us this blueprint of his fantasy in his work. Perhaps I will surprise people when I call into question what his work also tries to convey of this real experience. Confining our attention to the bedroom, for a rather lively glimpse of a girl's feelings about her mother, the fact remains that wickedness \mechancete\ so suitably situated by Sade in its transcendence, does not teach us much that is new here about her changes of heart. |

し

たがって、革命は法も自由であることを求めている。その自由は、法が未亡人、すなわち未亡人そのものであり、その問題に関して少しでも躊躇すれば、あなた

の首を籠に送るようなものでなければならない。サン・ジュストの頭がオルガントの幻想で満たされたままだったなら、テルミドールは彼にとって勝利となった

かもしれない。 快楽の権利が認められれば、快楽原則の支配は時代遅れのものとなるだろう。この権利を明言することで、サドは私たち一人一人から、幸福の利己主義に他ならない古代の倫理の軸を、気づかれないようにずらしている。 カントの著作から、この概念が完全に排除されているとは言い難い。なぜなら、この概念はカントの著作に頻繁に登場し、さらに、来世での報復と現世での進歩の両方を主張するカントの主張の根底にあるものだからだ。 もし、私が初めて口にした名前の幸福がもう一つ見出されたなら、欲望の地位は変わり、その再検討が求められるだろう。 しかし、ここで測らなければならないことがある。サドは、この快楽、あるいは単にその真実の経験において、私たちをどこまで導いているのか? 彼が描く人間のピラミッドは、ジョイサンスの連鎖的な性質を示す点で幻想的だ。欲望の水の噴水のように築かれたこれらの構造物は、ジョイサンスがヴィラ・ デステの庭園をバロック的な官能で輝かせるように設計されている——ジョイサンスを天へと噴き上げようとすればするほど、「ここには何流れているのか?」 という問いが執拗に迫ってくる。 人間が叫び声を通じて現れる「もの」の近辺で、愛と憎しみの原子がきらめく不規則な量——ある限界を超えたところで経験されるものは、欲望が幻想の中で支えられているものとは何の関係もない。その幻想は、実はこれらの限界に基づいて構成されているからだ。 サドが現実の生活の中でこの限界を超えたことは、よく知られている。 そうでなければ、彼は自分の作品の中で、この幻想の青写真を私たちに見せなかっただろう。 彼の作品がこの現実の体験について何を伝えようとしているのか、私が疑問を投げかけると、人々は驚くだろう。 寝室に注意を限定し、少女の母親に対する感情の活き活きとした一瞥を得るとしても、サドが超越性の中に適切に位置付けた「悪」は、彼女の心の変化について、ここに新しいことを多く教えてはくれない。 |

| 787 |

A work that wishes to be bad

[mechant] cannot allow itself to be a bad piece

of work, and one has to admit that Philosophy in the Bedroom leaves

itself

open to this ironic remark by a whole strain of good works found in it.

It's a little too preachy. Of course, it is a treatise on the education of girls17 and it is subject, as such, to the laws of a genre. Despite its merit of bringing to light the "anal sadism" that obsessively permeated this subject for the two preceding centuries, it remains a treatise on education. The victim is bored to death by the preaching and the teacher is full of himself. The historical or, better, erudite information here is dreary and makes us miss someone like La Mothe-le-Vayer. The physiology contained in it is made up of wet nurses' notions, and as for what might pass for sex education, one has the impression that one is reading a modern medical treatise on the subject, which says it all. More coherence in his scandal would help him see, in the usual impotence of educational intentions, the very impotence against which fantasy here fights—whence arises the obstacle to every valid account of the effects of education, since what brought about the results cannot be admitted to in discussing the intention. This remark [trait] would have been priceless, due to the praiseworthy effects of sadistic impotence. The fact that Sade failed to make it gives us pause for thought. His failure here is confirmed by another that is no less remarkable: The work never presents us with a successful seduction in which his fantasy would nevertheless find its crowning glory—that is, a seduction in which the victim, even if she were at her last gasp, would consent to her tormentor's intention, or even join his side in the fervor of her consent. This demonstrates from another vantage point that desire is the flip side of the law. In the Sadean fantasy, we see how they support each other. For Sade, one is always on the same side, the good or the bad; no wrongdoing can change that. It is thus the triumph of virtue: This paradox merely comes down to the derision characteristic of edifying books, the kind Justine aims at too much not to have adopted it. |