カント主義倫理

Kantian ethics

☆ カントの倫理とは、ドイツの哲学者イマニュエル・カントが展開した義務論的倫理理論を指し、「私は、自らの格言が普遍的な法則となることを意志することも できるような方法でしか行動すべきではない」という考えに基づいている(→定言命法)。また、「世界において、あるいは世界を超えたところにおいて、制限なく善であると 見なされるものは、善意以外にはまったく存在しえない」という考え方とも関連している。この理論は啓蒙主義的合理主義の文脈で発展した。この理論では、行 動が道徳的であるためには、義務感によって動機づけられ、その行動の原則が普遍的かつ客観的な法則として合理的に意志されるものでなければならないとされ ている。 カントの道徳律理論の中心となるのは、絶対命令である。カントは絶対命令をさまざまな形で定式化した。普遍化可能性の原理は、ある行為が許容されるために は、矛盾が生じることなく、その行為をすべての人に適用できるものでなければならないと要求する。カントの定式化による人間性、すなわち絶対命令の第二の 定式化は、人間はそれ自体として、他者を単に目的達成のための手段として扱うのではなく、常にそれ自体として扱うことが求められると述べる。自律性の定式 化では、理性的な存在者は自らの意志によって道徳律に縛られると結論づけている。一方、カントの「目的の王国」の概念では、人々はあたかも自らの行動の原 則が仮想の王国のための法を制定しているかのように行動することが求められる。 カントの道徳思想が与えた多大な影響は、その影響を受けた人々や批判の広がり、そして現実世界におけるその応用例の多さからも明らかである。

☆定言命法とは「あなたの意志の格律が常に同時に普遍的な立法の原理として妥当しうるように行為せよ」というものである。イマヌエル・カントの定言命法とは『人倫の形而上学の 基礎づけ』 (Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten, 1785) において示され、1781年『純粋理性批判』Kant, Immanuel: Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Riga: J. F. Hartknoch 1781, 856 Seiten, Erstdruck.に、理論的に修正されたもの。『人倫の形而上学の基礎づけ』(じんりんのけいじじょうがくのきそづけ、独: Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten)は、1785年に出版されたイマヌエル・カントの倫理学・形而上学に関する著作。3年後の1788年に出版される『実践理性批判』と共に実践哲 学を扱っている。実践理性批判、人倫の形而上学と並びカント倫理学の主要著書の一つである。『道徳形而上学の基礎づけ』や『道徳形而上学原論』とも訳され てきた。

★アドルノによると、カント的倫理は、次の3つの命題があるという:1)意思の自由[自然神学]、2)魂の不死[宇宙論]、4)神の存在[存在論](アドルノ 2006:121)。 さて、ここからカント流の道徳哲学を導くには次ようなレトリックが用いられる。まず、これらは、理性の関心、「私は何を知ることができるか?」 「私は何をしなければならないか?」「私は何を望むか?」に関わる。この3つの命題が、私たちの知識にとって、不要でもあるのに、理性がこの3つの命題を 推奨するのであれば、この命題は「本来実践的なもののみに関係するものでしかありえない」(純粋理性批判 A799/B827)。道徳法則は「所与」であり「事実」であるということを導くために「定言命法」が動員される。

| Kantian

ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory developed by German

philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that "I ought

never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim

should become a universal law." It is also associated with the idea

that "it is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or

indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation

except a good will." The theory was developed in the context of

Enlightenment rationalism. It states that an action can only be moral

if it is motivated by a sense of duty, and its maxim may be rationally

willed a universal, objective law. Central to Kant's theory of the moral law is the categorical imperative. Kant formulated the categorical imperative in various ways. His principle of universalizability requires that, for an action to be permissible, it must be possible to apply it to all people without a contradiction occurring. Kant's formulation of humanity, the second formulation of the categorical imperative, states that as an end in itself, humans are required never to treat others merely as a means to an end, but always as ends in themselves. The formulation of autonomy concludes that rational agents are bound to the moral law by their own will, while Kant's concept of the Kingdom of Ends requires that people act as if the principles of their actions establish a law for a hypothetical kingdom. The tremendous influence of Kant's moral thought is evident both in the breadth of appropriations and criticisms it has inspired and in the many real world contexts in which it has found application. |

カントの倫理とは、ドイツの哲学者イマニュエル・カントが展開した義務

論的倫理理論を指し、「私は、自らの格言が普遍的な法則となることを意志することもできるような方法でしか行動すべきではない」という考えに基づいてい

る。また、「世界において、あるいは世界を超えたところにおいて、制限なく善であると見なされるものは、善意以外にはまったく存在しえない」という考え方

とも関連している。この理論は啓蒙主義的合理主義の文脈で発展した。この理論では、行動が道徳的であるためには、義務感によって動機づけられ、その行動の

原則が普遍的かつ客観的な法則として合理的に意志されるものでなければならないとされている。 カントの道徳律理論の中心となるのは、絶対命令である。カントは絶対命令をさまざまな形で定式化した。普遍化可能性の原理は、ある行為が許容されるために は、矛盾が生じることなく、その行為をすべての人に適用できるものでなければならないと要求する。カントの定式化による人間性、すなわち絶対命令の第二の 定式化は、人間はそれ自体として、他者を単に目的達成のための手段として扱うのではなく、常にそれ自体として扱うことが求められると述べる。自律性の定式 化では、理性的な存在者は自らの意志によって道徳律に縛られると結論づけている。一方、カントの「目的の王国」の概念では、人々はあたかも自らの行動の原 則が仮想の王国のための法を制定しているかのように行動することが求められる。 カントの道徳思想が与えた多大な影響は、その影響を受けた人々や批判の広がり、そして現実世界におけるその応用例の多さからも明らかである。 |

| Outline Although all of Kant's works develop his ethical theory, it is most clearly defined in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, the Critique of Practical Reason, and the Metaphysics of Morals. Additionally, while the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals is important for understanding Kant's ethics, one gets an incomplete understanding of his moral thought if one only reads the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals and the Critique of Practical Reason, or is not at least aware that his other ethical writings discuss other important details about Kant's moral philosophy as a whole since "one is all the more misled if he is not aware that they form only part of the picture."[1] As part of the Enlightenment tradition, Kant based his ethical theory on the belief that reason should be used to determine how people ought to act.[2] He did not attempt to prescribe specific action, but instructed that reason should be used to determine how to behave.[3] Good will and duty In his combined works, Kant construed as a basis for the ethical law by the concept of duty.[4] Kant began his ethical theory by arguing that the only virtue that can be an unqualified good is a good will. No other virtue, or thing in the broadest sense of the term, has this status because every other virtue, every other thing, can be used to achieve immoral ends. For example, the virtue of loyalty is not good if one is loyal to an evil person. The good will is singularly unique in that it is always good and maintains its moral value regardless of whether or not it achieves its moral intentions.[5] Kant regarded the good will as a single moral principle that freely chooses to use the other virtues for genuinely moral ends.[6] For Kant, a good will has a broader conception than a will that acts from duty. A will that acts from duty alone is distinguishable as a will that overcomes hindrances in order to keep the moral law. A dutiful will is thus a special case of a good will that becomes visible in adverse conditions. Kant argues that only such acts performed with regard to duty have moral worth. This is not to say that acts performed merely in accordance with duty are worthless (these still merit approval and encouragement), but that distinctively moral esteem is given to acts that are performed out of duty, or from duty, alone.[7] Kant's conception of duty does not entail that people perform their duties grudgingly. Although duty often constrains people and prompts them to act against their inclinations, it still comes from an agent's volition: they desire to keep the moral law from respect of the moral law. Thus, when an agent performs an action from duty it is because their moral incentives are chosen over and above any opposing inclinations. Kant wished to move beyond the conception of morality as externally imposed duties, and present an ethics of autonomy, when rational agents freely recognize the claims reason makes upon them.[8] Perfect and imperfect duties Applying the categorical imperative, duties arise because failure to fulfill them would either result in a contradiction in conception or in a contradiction in the will. The former are classified as perfect duties, the latter as imperfect. A perfect duty always holds true. Kant eventually argues that there is in fact only one perfect duty—the categorical imperative. An imperfect duty allows flexibility—beneficence is an imperfect duty because we are not obliged to be completely beneficent at all times, but may choose the times and places in which we are.[9] Kant believed that perfect duties are more important than imperfect duties: if a conflict between duties arises, the perfect duty must be followed.[10] Categorical imperative Main article: Categorical imperative The foundation of Kant's ethics is the categorical imperative, for which he provides four formulations.[11][12] Kant made a distinction between categorical and hypothetical imperatives. A hypothetical imperative is one that we must obey if we want to satisfy our desires: 'go to the doctor' is a hypothetical imperative because we are only obliged to obey it if we want to get well. A categorical imperative binds us regardless of our desires: everyone has a duty to not lie, regardless of circumstances and even if it is in our interest to do so. These imperatives are morally binding because they are based on reason, rather than contingent facts about an agent.[13] Unlike hypothetical imperatives, which bind us insofar as we are part of a group or society which we owe duties to, we cannot opt out of the categorical imperative because we cannot opt out of being rational agents. The categorical imperative makes our duty to the moral law a requirement of reason which holds for us as rational agents; therefore, rational moral principles apply to all rational agents at all times.[14] Universalizability Main article: Universalizability Kant's first formulation of the categorical imperative is that of universalizability:[15] Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law. — Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785)[16] Kant defines maxim as a "subjective principle of volition," which is distinguished from an "objective principle or 'practical law.'" While "the latter is valid for every rational being and is a 'principle according to which they ought to act[,]' a maxim 'contains the practical rule which reason determines in accordance with the conditions of the subject (often their ignorance or inclinations) and is thus the principle according to which the subject does act.'"[17] A maxim may be a practical law, yet regardless of whether or not that is so, it is always the principle that the person themself acts from. Maxims lapse into mere subjectivity, and thus become unable to qualify as practical laws, if they produce a contradiction in conception or a contradiction in the will when universalized. A contradiction in conception happens when, if a maxim were to be universalized, it ceases to make coherent sense because the "maxim would necessarily destroy itself as soon as it was made a universal law."[18] For example, if maxims equivalent to 'I will break a promise when doing so secures my advantage' were universalized, no one would trust any promises, so the idea of a promise would become meaningless; the maxim would be self-contradictory because, when universalized, promises cease to be meaningful. The maxim is not moral because it is logically impossible to universalize—we could not conceive of a world where this maxim was universalized.[19] A maxim can also be immoral if it creates a contradiction in the will when universalized. This does not mean it is logically impossible to universalize, but that doing so leads to a state of affairs that no rational being would desire. Kant believed that morality is the objective law of reason: just as objective physical laws necessitate physical actions (e.g., apples fall down because of gravity), objective rational laws necessitate rational actions. He thus believed that a perfectly rational being must also be perfectly moral, because a perfectly rational being subjectively finds it necessary to do what is rationally necessary. Because humans are not perfectly rational (they partly act by instinct), Kant believed that humans must conform their subjective will with objective rational laws, which he called conformity obligation.[20] Kant argued that the objective law of reason is a priori, existing externally from rational being. Just as physical laws exist prior to physical beings, rational laws (morality) exist prior to rational beings. Therefore, according to Kant, rational morality is universal and cannot change depending on circumstance.[21] Some have postulated a similarity between the first formulation of the categorical imperative and the Golden Rule.[22][23] Kant himself criticized the Golden Rule as neither purely formal nor necessarily universally binding.[24] His criticism can be seen in a footnote stating: Let it not be thought that the trite quod tibi non vis fieri etc. [what you do not want others to do to you, etc.] can serve as norm of principle here. For it is, though with various limitations, only derived from the latter. It can be no universal law because it contains the ground neither of duties to oneself nor of duties of love to others (for many a man would gladly agree that others should not benefit him if only he might be excused from showing them beneficence), and finally it does not contain the ground of duties owed to others; for a criminal would argue on this ground against the judge punishing him, and so forth[25] Humanity as an end in itself Main article: Means to an end Kant's second formulation of the categorical imperative is to treat humanity as an end in itself: So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means. — Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785)[26] Kant argued that rational beings can never be treated merely as means to ends; they must always also be treated as ends in themselves, requiring that their own reasoned motives must be equally respected. This derives from Kant's claim that the sense of duty, the rational respect for law, motivates morality: it demands that we respect the rationality of all beings. A rational being cannot rationally consent to be used merely as a means to an end, so they must always be treated as an end.[27] Kant justified this by arguing that moral obligation is a rational necessity: that which is rationally willed is morally right. Because all rational agents rationally will themselves to be an end and never merely a means, it is morally obligatory that they are treated as such.[28] This does not mean that we can never treat a human as a means to an end, but that when we do, we also treat them as an end in themselves.[27] Formula of autonomy Kant's formula of autonomy expresses the idea that an agent is obliged to follow the categorical imperative because of their rational will, rather than any outside influence. Kant believed that any moral law motivated by the desire to fulfill some other interest would deny the categorical imperative, leading him to argue that the moral law must only arise from a rational will.[29] This principle requires people to recognize the right of others to act autonomously and means that, as moral laws must be universalizable, what is required of one person is required of all.[30][31][32] Kingdom of Ends Main article: Kingdom of Ends Another formulation of Kant's categorical imperative is the Kingdom of Ends: A rational being belongs as a member to the kingdom of ends when he gives universal laws in it but is also himself subject to these laws. He belongs to it as sovereign when, as lawgiving, he is not subject to the will of any other. A rational being must always regard himself as lawgiving in a kingdom of ends possible through freedom of the will, whether as a member or as sovereign. — Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785)[33] This formulation requires that actions be considered as if their maxim is to provide a law for a hypothetical Kingdom of Ends. Accordingly, people have an obligation to act upon principles that a community of rational agents would accept as laws.[14] In such a community, each individual would only accept maxims that can govern every member of the community without treating any member merely as a means to an end.[34] Although the Kingdom of Ends is an ideal—the actions of other people and events of nature ensure that actions with good intentions sometimes result in harm—we are still required to act categorically, as legislators of this ideal kingdom.[35] The Metaphysics of Morals As Kant explains in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (and as its title directly indicates), that short 1785 text is "nothing more than the search for and establishment of the supreme principle of morality."[36] Kant further states, just because moral laws are to hold for every rational being as such, to derive them from the universal concept of a rational being as such, and in this way to set forth completely the whole of morals, [a metaphysics of morals] needs anthropology for its application to human beings.[37][38] His promised Metaphysics of Morals, however, was much delayed and did not appear until its two parts, The Doctrine of Right and The Doctrine of Virtue, were published separately in 1797 and 1798.[39] In the twelve years between the Groundwork and The Doctrine of Right, Kant decided that the metaphysics of morals and its application should, after all, be integrated (though still as distinct from practical anthropology).[40] The distinction between its groundwork (or foundation) and the metaphysics of morals itself, however, continues to apply. Moreover, the account provided in the latter Metaphysics of Morals provides "a very different account of ordinary moral reasoning" than the one suggested by the Groundwork.[41] The Doctrine of Right deals with juridical duties, which are "concerned only with protecting the external freedom of individuals" and indifferent to incentives. (Although we do have a moral duty "to limit ourselves to actions that are right, that duty is not part of [right] itself.")[41] Its basic political idea is that "each person’s entitlement to be his or her own master is only consistent with the entitlements of others if public legal institutions are in place."[42] The Doctrine of Virtue is concerned with duties of virtue or "ends that are at the same time duties."[43] It is here, in the domain of ethics, that The Metaphysics of Morals's greatest innovation is to be found. According to Kant's account, "ordinary moral reasoning is fundamentally teleological—it is reasoning about what ends we are constrained by morality to pursue, and the priorities among these ends we are required to observe."[44] More specifically, There are two sorts of ends that it is our duty to have: our own perfection and the happiness of others (MS 6:385). "Perfection" includes both our natural perfection (the development of our talents, skills, and capacities of understanding) and moral perfection (our virtuous disposition) (MS 6:387). A person’s "happiness" is the greatest rational whole of the ends the person set for the sake of her own satisfaction (MS 6:387–8).[45] Kant's elaboration of this teleological doctrine offers up a very different moral theory than the one typically attributed to him on the basis of his foundational works alone. |

概要 カントのすべての著作は彼の倫理理論を発展させているが、それは『実践理性批判』、『道徳形而上学の基礎』、『道徳哲学』において最も明確に定義されてい る。さらに、『実践理性批判』はカントの倫理を理解する上で重要であるが、『実践理性批判』と『実践理性批判』だけを読んだ場合、カントの道徳思想を不完 全にしか理解できない 少なくとも、カントの他の倫理に関する著作が、カントの道徳哲学全体について、他の重要な詳細を論じていることを認識していない場合、「それらが全体像の 一部にすぎないことを認識していない場合、人はさらに大きな誤解を招くことになる」[1] 啓蒙主義の伝統の一部として、カントは、人々が行動すべき方法を決定するには理性を用いるべきであるという信念に基づいて倫理理論を構築した。[2] カントは特定の行動を規定しようとはしなかったが、行動の決定には理性を用いるべきであると説いた。[3] 善意と義務 カントは、その著作のなかで、義務という概念を倫理法の基礎として解釈している。[4] カントは、無条件に善であることのできる唯一の美徳は善意であると主張することから、倫理理論を展開した。他の美徳や、その最も広い意味での事物は、すべ て不道徳な目的を達成するために利用できるため、この地位にあるものは他にない。例えば、悪人に忠誠を誓うのであれば、忠誠という美徳は善ではない。善き 意志は、常に善であり、その道徳的意図を達成するかどうかに関わらず、その道徳的価値を維持するという点において、他に類を見ない。カントは、善き意志 を、他の美徳を純粋に道徳的な目的のために自由に選択する唯一の道徳的原則であるとみなした。 カントにとって、善意とは義務から行動する意志よりも広い概念である。義務のみに基づいて行動する意志は、道徳律を維持するために障害を克服する意志とし て区別される。従って、義務的な意志は、逆境において顕著となる善意の特別なケースである。カントは、義務を考慮して行われる行為のみに道徳的価値があ る、と主張している。これは、義務に従って行われる行為が価値のないものである、という意味ではない(それらも依然として承認と奨励に値する)。しかし、 義務から、あるいは義務のみに基づいて行われる行為には、際立った道徳的評価が与えられる、ということである。 カントの義務観は、人々が義務を嫌々果たすことを意味するものではない。義務はしばしば人を束縛し、その傾向に反する行動を促すが、それでもそれは行為者 の意志から生じるものである。すなわち、道徳律を尊重したいという願いからである。したがって、行為者が義務から行動を起こすのは、道徳的な動機が、あら ゆる反対の傾向を上回って選択されるからである。カントは、道徳を外から課せられた義務としてではなく、理性的な主体が理性の要求を自由に認識する自律性 の倫理として提示することを望んでいた。[8] 完全な義務と不完全な義務 定言的命法を適用すると、義務は、それを果たさないと、概念上の矛盾または意志上の矛盾が生じるために生じる。前者は完全な義務、後者は不完全な義務とし て分類される。完全な義務は常に真実である。カントは最終的に、完全な義務は実際にはただ一つ、すなわち「定言的命法」だけであると主張する。不完全な義 務は柔軟性を許容する。すなわち、私たちは常に完全に慈悲深い存在であることを義務付けられているわけではなく、その時と場合を選ぶことができるため、慈 悲深さは不完全な義務である。[9] カントは不完全な義務よりも完全な義務の方が重要であると考えた。義務の間に矛盾が生じた場合、完全な義務に従わなければならない。[10] 定言命法 詳細は「定言命法」を参照 カントの倫理学の基礎は定言命法であり、彼はそのために4つの定式化を提供している。[11][12] カントは、定言命法と仮言命法を区別した。仮言的命令とは、私たちが望むことを実現したいのであれば従わなければならない命令である。「医者に診てもら う」ことは、仮言的命令である。なぜなら、私たちが健康になりたいと望む場合にのみ従う義務があるからだ。 カテゴリー的命令は、私たちの望みに関わらず私たちを拘束する。つまり、状況に関わらず、また、嘘をつくことが私たちにとって得策である場合でも、誰もが 嘘をついてはならない義務を負っている。これらの命令は、道徳的に拘束力を持つ。なぜなら、それは行為者に関する偶発的な事実ではなく、理性に基づいてい るからである。[13] 仮言的命令とは異なり、義務を負う集団や社会の一員である限りにおいて私たちを拘束するのに対し、私たちは理性的な行為者であることを放棄することはでき ないため、絶対命令から離脱することはできない。カテゴリー的命法は、道徳律に対する私たちの義務を、理性的存在者としての私たちに適用される理性の要件 とする。したがって、理性的な道徳的原則は、すべての理性的存在者に常に適用される。[14] 普遍化可能性 詳細は「普遍化可能性」を参照 カントによる「定言的命法」の最初の定式化は、普遍化可能性である。 同時にそれが普遍法となることを望むことのできるその格言に従ってのみ行動せよ。 —『実践理性批判』(1785年)[16] カントは格言を「主観的な意志の原理」と定義し、それを「客観的な原理または『実践法則』」と区別している。「後者はあらゆる理性的存在に対して妥当し、 『彼らがそうあるべきであるという原理』である。一方、格言は『主題(しばしばその無知や傾向)の条件に従って理性が決定する実践的な規則を含み、 。格言は実践法であるかもしれないが、そうであるかどうかに関わらず、その人物自身が従って行動する原則であることに変わりはない。 格言が普遍化された際に観念上の矛盾や意志上の矛盾を生み出す場合、格言は単なる主観性に陥り、実用的な法としての条件を満たさなくなる。観念上の矛盾 は、格言が普遍化された際に首尾一貫した意味をなさなくなる場合に起こる。なぜなら、「格言は普遍的な法とされた途端に、必然的に自己を破壊する」からで ある。[18] 例えば、「 そうすることで自分の利益が確保できるなら、約束を破る」という格言が普遍化された場合、誰も約束を信用しなくなるため、約束という概念は意味をなさなく なる。普遍化された場合、約束は意味をなさなくなるため、この格言は自己矛盾をはらむことになる。この格言は普遍化することが論理的に不可能であるため、 道徳的ではない。この格言が普遍化された世界を想像することはできない。 格言が普遍化された際に意志の矛盾を生み出す場合、その格言は不道徳である可能性もある。これは、普遍化が論理的に不可能であることを意味するのではなく、普遍化が理性的な存在であれば誰も望まないような状態を引き起こすことを意味する。 カントは、道徳とは理性の客観的な法則であると考えた。客観的な物理法則が物理的な作用を必然とするように(例えば、りんごは重力によって落ちる)、客観 的な理性の法則は理性的な作用を必然とする。したがって、カントは、完全に理性的な存在は完全に道徳的でなければならないと考えた。なぜなら、完全に理性 的な存在は主観的に、理性的に必要なことを行う必要があると考えるからだ。人間は完全な理性の持ち主ではない(本能に従って行動することもある)ため、カ ントは、人間は主観的な意志を客観的な合理的な法則に適合させなければならないと考え、これを「適合義務」と呼んだ。[20] カントは、理性の客観的な法則は先験的であり、理性的な存在の外側に存在すると主張した。物理法則が物理的な存在に先立って存在するように、理性的な法則 (道徳)は理性的な存在に先立って存在する。したがって、カントによれば、理性的な道徳は普遍的であり、状況によって変わることはない。[21] カテゴリー的命題の最初の定式化と黄金律との類似性を主張する者もいる。[22][23] カント自身は、黄金律は純粋に形式的でもなければ、必ずしも普遍的に適用できるものでもないと批判している。[24] 彼の批判は、脚注に次のように記載されている。 ありふれた「クオド・ティビ・ノン・ヴィ・フィエリ(自分がされて嫌なことは他人にもするな)」などが、ここで原則の規範となり得るなどとは考えないでほ しい。なぜなら、それは様々な制限があるとはいえ、後者から派生したものに過ぎないからだ。なぜなら、それは自己に対する義務の根拠も、他者に対する愛の 義務の根拠も含まないからである(多くの人間は、他者から恩恵を受けないですむのであれば、他者に対して恩恵を示すことを喜んで拒否するだろう)。そし て、最終的には、他者に対する義務の根拠も含まれていない。犯罪者は、自分を罰する裁判官に対して、この根拠に基づいて反論するだろう。 人間性それ自体を目的とする 詳細は「目的のための手段」を参照 カントの第二の定言命法の定式化は、人間性それ自体を目的として扱うことである。 人間性を使うように行動せよ。それは、自分自身であれ、他の誰かであれ、常に同時に目的としてであり、決して単なる手段としてではない。 —『人倫の形而上学の基礎づけ』(1785年)[26] カントは、理性的存在は決して手段としてのみ扱われるべきではないと主張した。彼らは常に、それ自体が目的であるものとして扱われなければならない。その ためには、彼ら自身の理性的な動機も同様に尊重されなければならない。これは、義務感、すなわち法に対する理性的な敬意が道徳心を動機づけるというカント の主張に由来する。それは、あらゆる存在の理性を尊重することを要求する。理性的な存在は、単に目的を達成するための手段として利用されることに理性的に 同意することはできない。したがって、常に目的として扱われなければならない。[27] カントは、道徳的義務は理性的必然性であると主張することで、これを正当化した。すなわち、理性的に意図されたものは道徳的に正しい。すべての理性的な存 在者は、理性的に自らを目的としようとし、決して単なる手段とはしないため、そのような存在者として扱われることは道徳的に義務である。[28] これは、人間を手段として扱うことが決してできないという意味ではなく、人間を手段として扱う場合には、同時にそれらをそれ自体が目的であるものとして扱 うべきであるという意味である。[27] 自律性の公式 カントの自律性の公式は、行為者は外的要因ではなく、理性的な意志によって、カテゴリー的命法に従う義務があるという考え方を表現している。カントは、他 の利益を満たしたいという欲望によって動機づけられた道徳律は、絶対命令を否定するものであると考え、道徳律は理性の意志から生じるものでなければならな いと主張した。この原則は、人々が他者の自律的に行動する権利を認めることを要求し、道徳律は普遍化されなければならないため、ある人に対して要求される ことはすべての人に対して要求されることを意味する。 目的の王国 詳細は「目的の王国」を参照 カントの定言命法の別の定式化は、目的の王国である。 理性的存在者は、普遍法則を定めると同時にそれらの法則に従う存在者として、目的の王国の構成員となる。また、法を定める存在者として、いかなる他者の意志にも従属しない存在者として、目的の王国の主権者となる。 理性的存在者は、自由意志によって可能となる目的王国において、構成員としてであれ、主権者としてであれ、常に自らを法制定者としてみなさなければならない。 —『人倫の形而上学の基礎づけ』(1785年)[33] この定式化では、行動はあたかもその行動の究極の目的が仮想的な「目的の王国」のための法を定めることであるかのように考えられなければならない。した がって、人々は、理性的な行為者たちの共同体が法として受け入れるであろう原則に従って行動する義務がある。[14] そのような共同体では、各個人は、共同体内のすべての構成員を単に目的を達成するための手段として扱うことなく、共同体内のすべての構成員を統治できるよ うな原則のみを受け入れるだろう。。[34] 理想郷は理想ではあるが、他人の行動や自然現象によって、善意で行った行動が時に害をもたらすことが確実である。それでも、私たちはこの理想郷の立法者と して、断固とした行動を取ることが求められる。[35] 道徳の形而上学 カントが『道徳の形而上学の基礎』(そのタイトルが直接示すように)で説明しているように、この1785年の短い著作は「道徳の最高の原則の探究と確立に他ならない」[36]。カントはさらに次のように述べている。 道徳法則はあらゆる理性的存在に対してそのまま妥当するものであるため、それを理性的存在の普遍的概念から導き出し、この方法で道徳の全体を完全に提示するには、[道徳の形而上学]は人間への適用に人類学を必要とする。[37][38] しかし、彼が約束した『道徳形而上学』は大幅に遅れ、その2部作である『法論』と『徳論』が1797年と1798年に別々に出版されるまで、刊行されるこ とはなかった。[39] 『基礎』と『 カントは、『実践理性批判』の12年後、道徳の形而上学とその応用は、やはり統合されるべきであると判断した(ただし、依然として実践的人間学とは区別さ れる)。[40] しかし、その基礎(または土台)と道徳の形而上学との区別自体は、引き続き適用される。さらに、『後期道徳形而上学』で提示された説明は、『基盤』で示唆 されたものとは「まったく異なる通常の道徳的推論の説明」である。 『法理論』は法的な義務を扱っており、それは「個人の外的自由の保護のみに関係する」ものであり、インセンティブには無関心である。(ただし、私たちは 「正しい行動に自らを限定する」という道徳的義務を負っているが、その義務は「正義」の一部ではない。)[41] その基本的な政治思想は、「各人が自身の主人となる権利は、公共の法的制度が整備されている場合にのみ、他者の権利と一致する」というものである。 [42] 『徳の理論』は、徳の義務、すなわち「義務であると同時に目的であるもの」について論じている。[43] 『実践理性批判』の最大の革新性は、倫理の領域に見られる。カントの説明によると、「通常の道徳的推論は基本的に目的論的である。すなわち、道徳によって 追求することが求められる目的について、また、それらの目的の優先順位について推論することである」[44]。より具体的には、 私たちが持つべき義務である目的には、2つの種類がある。すなわち、私自身の完成と他者の幸福である(MS 6:385)。「完成」には、生まれながらの完成(才能、技能、理解力の育成)と道徳的な完成(徳の高い性向)の両方が含まれる(MS 6:387)。ある人の「幸福」とは、その人が自身の満足のために定めた目的の最も大きな合理的な全体である(MS 6:387-8)[45]。 カントによるこの目的論的教義の精緻な説明は、彼の基礎的な著作のみに基づいて一般的に彼に帰属されているものとは非常に異なる道徳理論を提示している。 |

| Influences on Kantian ethics Biographer of Kant, Manfred Kuhn, suggested that the values Kant's parents held, of "hard work, honesty, cleanliness, and independence", set him an example and influenced him more than their pietism did. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Michael Rohlf suggests that Kant was influenced by his teacher, Martin Knutzen, himself influenced by the work of Christian Wolff and John Locke, and who introduced Kant to the work of English physicist Isaac Newton.[46] Eric Entrican Wilson and Lara Denis emphasize David Hume's influence on Kant's ethics. Both of them try to reconcile freedom with a commitment to causal determinism and believe that morality’s foundation is independent of religion.[47] Louis Pojman has suggested four strong influences on Kant's ethics: 1. Lutheran Pietism, to which Kant's parents subscribed, emphasised honesty and moral living over doctrinal belief, more concerned with feeling than rationality. Kant believed that rationality is required, but that it should be concerned with morality and good will. Kant's description of moral progress as the turning of inclinations towards the fulfilment of duty has been described as a version of the Lutheran doctrine of sanctification.[48] 2. Political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Social Contract influenced Kant's view on the fundamental worth of human beings. Pojman also cites contemporary ethical debates as influential to the development of Kant's ethics. Kant favoured rationalism over empiricism, which meant he viewed morality as a form of knowledge, rather than something based on human desire. 3. Natural law, the belief that the moral law is determined by nature.[49] 4. Intuitionism, the belief that humans have intuitive awareness of objective moral truths.[49] |

カントの倫理観に与えた影響 カントの伝記作家マンフレッド・クーンは、カントの両親が持つ「勤勉、誠実、清潔、自立」という価値観が、敬虔主義よりもカントに大きな影響を与えたと示 唆している。スタンフォード哲学百科事典では、マイケル・ロルフがカントは師であるマルティン・クヌッツェンから影響を受け、クヌッツェン自身はクリス ティアン・ヴォルフとジョン・ロックの研究から影響を受け、クヌッツェンはカントにイギリスの物理学者アイザック・ニュートンの研究を紹介したと示唆して いる。[46] エリック・エントリカン・ウィルソンとララ・デニスは、カントの倫理観にデイヴィッド・ヒュームが与えた影響を強調している。両者とも自由と因果決定論へ の献身を調和させようとし、道徳の基礎は宗教とは独立していると信じている。 ルイ・ポジュマンはカントの倫理に強い影響を与えた4つの要因を挙げている。 1. カントの両親が信仰していたルター派の敬虔主義は、教義上の信仰よりも正直さや道徳的な生き方を重視し、理性よりも感情を重視していた。カントは、理性は 必要であるが、それは道徳性や善意に関わるべきであると考えていた。カントが道徳的進歩を、義務の遂行に向かう傾向の転換として説明したことは、ルター派 の聖化の教義の一形態であると説明されている。 2. 政治哲学者ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの『社会契約論』は、人間の根本的な価値に関するカントの見解に影響を与えた。ポイマンは、カントの倫理観の発展に影 響を与えたものとして、同時代の倫理論争も挙げている。カントは経験論よりも合理論を好み、道徳を人間の欲望に基づくものではなく、知識の一形態として捉 えていた。 3. 自然法、すなわち道徳法則は自然によって決定されるという考え方。[49] 4. 直観主義、人間は客観的な道徳的真理を直観的に認識しているという信念。[49] |

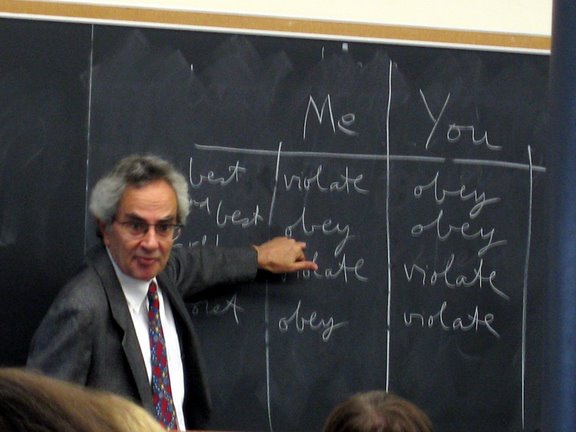

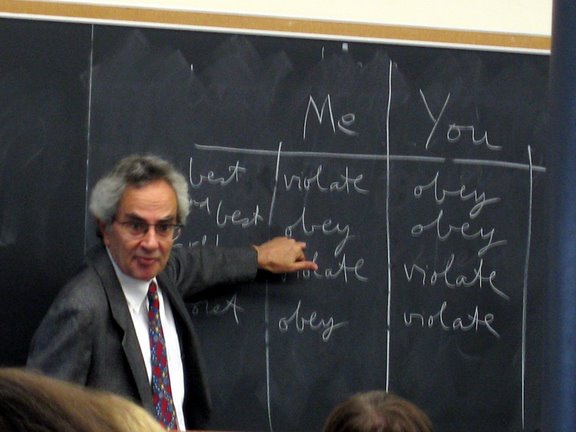

| Influenced by Kantian ethics Jürgen Habermas  Photograph of Jürgen Habermas, whose theory of discourse ethics was influenced by Kantian ethics German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has proposed a theory of discourse ethics that he claims is a descendant of Kantian ethics.[50] He proposes that action should be based on communication between those involved, in which their interests and intentions are discussed so they can be understood by all. Rejecting any form of coercion or manipulation, Habermas believes that agreement between the parties is crucial for a moral decision to be reached.[51] Like Kantian ethics, discourse ethics is a cognitive ethical theory, in that it supposes that truth and falsity can be attributed to ethical propositions. It also formulates a rule by which ethical actions can be determined and proposes that ethical actions should be universalizable, in a similar way to Kant's ethics.[52] Habermas argues that his ethical theory is an improvement on Kant's,[52] and rejects the dualistic framework of Kant's ethics. Kant distinguished between the phenomena world, which can be sensed and experienced by humans, and the noumena, or spiritual world, which is inaccessible to humans. This dichotomy was necessary for Kant because it could explain the autonomy of a human agent: although a human is bound in the phenomenal world, their actions are free in the intelligible world. For Habermas, morality arises from discourse, which is made necessary by their rationality and needs, rather than their freedom.[53] John Rawls The social contract theory of political philosopher John Rawls, developed in his work A Theory of Justice, was influenced by Kant's ethics.[54] Rawls argued that a just society would be fair. To achieve this fairness, he proposed a hypothetical moment prior to the existence of a society, at which the society is ordered: this is the original position. This should take place from behind a veil of ignorance, where no one knows what their own position in society will be, preventing people from being biased by their own interests and ensuring a fair result.[55] Rawls' theory of justice rests on the belief that individuals are free, equal, and moral; he regarded all human beings as possessing some degree of reasonableness and rationality, which he saw as the constituents of morality and entitling their possessors to equal justice. Rawls dismissed much of Kant's dualisms, arguing that the structure of Kantian ethics, once reformulated, is clearer without them—he described this as one of the goals of A Theory of Justice.[56] Thomas Nagel  Nagel in 2008, teaching ethics Thomas Nagel has been highly influential in the related fields of moral and political philosophy. Supervised by John Rawls, Nagel has been a long-standing proponent of a Kantian and rationalist approach to moral philosophy. His distinctive ideas were first presented in the short monograph The Possibility of Altruism, published in 1970. That book seeks by reflection on the nature of practical reasoning to uncover the formal principles that underlie reason in practice and the related general beliefs about the self that are necessary for those principles to be truly applicable to us. Nagel defends motivated desire theory about the motivation of moral action. According to motivated desire theory, when a person is motivated to moral action it is indeed true that such actions are motivated—like all intentional actions—by a belief and a desire. But it is important to get the justificatory relations right: when a person accepts a moral judgment he or she is necessarily motivated to act. But it is the reason that does the justificatory work of justifying both the action and the desire. Nagel contrasts this view with a rival view which believes that a moral agent can only accept that he or she has a reason to act if the desire to carry out the action has an independent justification. An account based on presupposing sympathy would be of this kind.[57] There is a very close parallel between prudential reasoning in one's own interests and moral reasons to act to further the interests of another person. When one reasons prudentially, for example about the future reasons that one will have, one allows the reason in the future to justify one's current action without reference to the strength of one's current desires. If a hurricane were to destroy someone's car next year at that point he will want his insurance company to pay him to replace it: that future reason gives him a reason, now, to take out insurance. The strength of the reason ought not to be hostage to the strength of one's current desires. The denial of this view of prudence, Nagel argues, means that one does not really believe that one is one and the same person through time. One is dissolving oneself into distinct person-stages.[58] Lewis White Beck Within the framework of his extensive editorial commentaries on the works of Kant, Lewis White Beck strove to illustrate the manner in which Kantian ethics might prove relevant to several of the moral dilemmas which confronted mankind in the mid 20th century. In his Six Secular Philosophers (1966) Beck argued than a modern secular philosophy which accommodates religious thoughts and values can be successfully formulated through an appeal to mankind's freedom of thought. With this in mind, he illustrated the central role which Kantian ethics might assume within such a formulation. He specifically identifies two "families" of philosophers whose works might be considered relevant to the evolution of such a modern secular philosophy.[59][60][61][62] In one such family, Beck calls our attention to philosophers who utilized an appeal to mankind's scientific and philosophical endeavors in order to impose various limits upon the scope, validity and content of religious beliefs. Beck included the works of Baruch Spinoza, David Hume and Immanuel Kant within this family. In Beck's view, Kantian ethics paved the way toward a more comprehensive modern secular philosophical paradigm in several ways. By specifically rejecting Spinoza's appeal to a strict monism, Kant parted ways with Spinoza's reliance upon a deity to assume a central role in modern ethical theory. Beck argued further that Kant's ethical theories are in agreement with Hume's assertion that scientific interpretations of nature cannot by themselves serve to confirm religious belief. Yet, as Beck quickly reminds his readers, Kant also distanced himself from Hume by insisting that mankind is not consequently left entirely adrift without a moral compass. According to Beck's reading, Kant clearly asserts that mankind should regard moral law "as if" it were a divine command which unites people "as if" they were in common allegiance to such a "supposed" deity.[63] This is accomplished through Kant's appeal to a different rational basis for religious thoughts and values which can be found in mankind's moral consciousness.[59][60][61][62] Contemporary Kantian ethicists Onora O'Neill Philosopher Onora O'Neill, who studied under John Rawls at Harvard University, is a contemporary Kantian ethicist who supports a Kantian approach to issues of social justice. O'Neill argues that a successful Kantian account of social justice must not rely on any unwarranted idealizations or assumption. She notes that philosophers have previously charged Kant with idealizing humans as autonomous beings, without any social context or life goals, though maintains that Kant's ethics can be read without such an idealization.[64] O'Neill prefers Kant's conception of reason as practical and available to be used by humans, rather than as principles attached to every human being. Conceiving of reason as a tool to make decisions with means that the only thing able to restrain the principles we adopt is that they could be adopted by all. If we cannot will that everyone adopts a certain principle, then we cannot give them reasons to adopt it. To use reason, and to reason with other people, we must reject those principles that cannot be universally adopted. In this way, O'Neill reached Kant's formulation of universalisability without adopting an idealistic view of human autonomy.[65] This model of universalisability does not require that we adopt all universalisable principles, but merely prohibits us from adopting those that are not.[66] From this model of Kantian ethics, O'Neill begins to develop a theory of justice. She argues that the rejection of certain principles, such as deception and coercion, provides a starting point for basic conceptions of justice, which she argues are more determinate for human beings that the more abstract principles of equality or liberty. Nevertheless, she concedes that these principles may seem to be excessively demanding: there are many actions and institutions that do rely on non-universalisable principles, such as injury.[67] Marcia Baron In his paper "The Schizophrenia of Modern Ethical Theories", philosopher Michael Stocker challenges Kantian ethics (and all modern ethical theories) by arguing that actions from duty lack certain moral value. He gives the example of Smith, who visits his friend in hospital out of duty, rather than because of the friendship; he argues that this visit seems morally lacking because it is motivated by the wrong thing.[68] Marcia Baron has attempted to defend Kantian ethics on this point. After presenting a number of reasons that we might find acting out of duty objectionable, she argues that these problems only arise when people misconstrue what their duty is. Acting out of duty is not intrinsically wrong, but immoral consequences can occur when people misunderstand what they are duty-bound to do. Duty need not be seen as cold and impersonal: one may have a duty to cultivate their character or improve their personal relationships.[69] Baron further argues that duty should be construed as a secondary motive—that is, a motive that regulates and sets conditions on what may be done, rather than prompt specific actions. She argues that, seen this way, duty neither reveals a deficiency in one's natural inclinations to act, nor undermines the motives and feelings that are essential to friendship. For Baron, being governed by duty does not mean that duty is always the primary motivation to act; rather, it entails that considerations of duty are always action-guiding. A responsible moral agent should take an interest in moral questions, such as questions of character. These should guide moral agents to act from duty.[70] Christine Korsgaard In her 1981 doctoral dissertation The Standpoint of Practical Reason, philosopher Christine Korsgaard argues that there are four basic types of interpretation of the formula of universal law:[71] 1. The Theoretical Contradiction Interpretation: there is a logical or physical impossibility in universalizing the maxim. 2. The Terrible Consequences Interpretation: universalizing the maxim would cause terrible consequences. 3. The Teleological Contradiction Interpretation: the universalized maxim could not be willed as a teleological law of nature. 4. The Practical Contradiction Interpretation: were the maxim to be universalized, the agent would be unable to achieve the purpose in their maxim. Korsgaard argues that the Practical Contradiction Interpretation is the correct interpretation. She further argues that there are two ways a maxim may violate the formula of universal law: 1. The first contradiction test: A maxim fails the first contradiction test if it cannot even be universalized without a contradiction. 2. The second contradiction test: A maxim fails the second contradiction test if it can be universalized, but it cannot be willed without a contradiction. |

カント主義倫理の影響を受けた ユルゲン・ハーバーマス  ユルゲン・ハーバーマスの写真。彼の討議倫理学の理論は、カント主義倫理の影響を受けている ドイツの哲学者ユルゲン・ハーバーマスは、カント主義倫理の末裔であると主張する討議倫理学の理論を提唱している。[50] 彼は、行動は関係者間のコミュニケーションに基づいて行われるべきであり、そのコミュニケーションにおいて、関係者の利害や意図が議論され、全員が理解で きるようにすべきであると提唱している。強制や操作を一切排除するハーバーマスは、当事者間の合意が道徳的な決定に不可欠であると考える。[51] ディスクール倫理は、カント倫理と同様に、認識論的な倫理理論であり、倫理的命題に真偽を帰属させることができると仮定している。また、倫理的行動を決定 するルールを定式化し、カントの倫理と同様に、倫理的行動は普遍化できるべきであると提案している。[52] ハーバーマスは、自身の倫理理論はカントの理論を改良したものであると主張し、[52] カントの倫理学の二元論的枠組みを否定している。 カントは、人間が知覚し経験できる現象世界と、人間には到達できないヌーメナ(精神世界)を区別した。この二分法はカントにとって必要であった。なぜな ら、それは人間の主体の自律性を説明できるからである。人間は現象界に束縛されているが、彼らの行動は悟性界においては自由である。ハバーマスにとって、 道徳は、人間の自由よりもむしろ彼らの理性とニーズによって必要とされる、言説から生じるものである。[53] ジョン・ロールズ 政治哲学者ジョン・ロールズの社会契約論は、著書『正義論』で展開されており、カントの倫理学の影響を受けている。[54] ロールズは、公正な社会は公平であると主張した。この公平性を達成するために、ロールズは社会が存在する前の仮想的な瞬間を提案した。この瞬間において、 社会は秩序づけられる。これが「原初状態」である。これは「無知のベール」の背後で行われるべきであり、そこでは誰も自分が社会でどのような立場になるか を知らないため、人々が自身の利益によって偏った判断を下すことを防ぎ、公平な結果を確保できる。[55] ローウェルズの正義論は、個人は自由で平等であり、道徳的であるという信念に基づいている。彼は、すべての人間はある程度の良識と理性を備えていると考 え、それらを道徳の構成要素と見なし、それらを持つ者に平等な正義を与える権利があると主張した。ロールズはカントの二元論の多くを退け、カント倫理学の 構造は一度再定式化すれば、それらを排除してもより明確になる、と主張した。彼はこれを『正義論』の目標の一つであると述べた。[56] トマス・ネーゲル  2008年、倫理学を教えるネーゲル トマス・ネーゲルは道徳哲学および政治哲学の関連分野において、多大な影響力をもっている。ジョン・ロールズの指導の下、ネーゲルは道徳哲学に対するカン ト主義的かつ合理主義的なアプローチの提唱者として長年活動してきた。彼の独特な考え方は、1970年に出版された短い論文『利他主義の可能性』で初めて 提示された。この本では、実践的な推論の本質を考察することで、実践的な推論の根底にある形式的な原則と、その原則が真に私たちに適用されるために必要な 自己に関する一般的な信念を明らかにしようとしている。 ネーゲルは、道徳的行動の動機に関する動機づけられた欲求理論を擁護している。動機づけられた欲求理論によると、人が道徳的行動を起こす動機づけがある場 合、そのような行動は、意図的な行動すべてと同様に、信念と欲求によって動機づけられていることは確かに真実である。しかし、正当化の関係を正しく理解す ることが重要である。人が道徳的判断を受け入れる場合、必然的に行動を起こす動機づけがある。しかし、行動と欲求の両方を正当化する正当化の役割を果たす のは理性である。ネーゲルは、この見解を、道徳的な行為者は、行動を起こす理由があると認めることができるのは、その行動を起こしたいという欲求が独立し た正当性を持つ場合のみであると考える対立する見解と対比している。共感を前提とする説明は、この種のものとなるだろう。 自分の利益のための慎重な推論と、他者の利益を促進するための行動の道徳的理由の間には、非常に近い類似点がある。たとえば将来の理由について慎重に判断 する場合、人は現在の欲求の強弱に関係なく、将来の理由によって現在の行動を正当化することを認める。もしハリケーンが来年の今頃誰かの車を破壊してし まったら、その人は保険会社に保険金を支払って車を買い替えてもらいたいと思うだろう。その将来の理由が、今、保険に加入する理由となる。その理由の強さ は、現在の欲望の強さに左右されるべきではない。この思慮分別に関する見解を否定することは、人は時間を通じて同一人物であるとは本当に信じていないこと を意味すると、ネーゲルは主張する。人は、明確な人格の段階に自己を溶解させているのだ。[58] ルイス・ホワイト・ベック カントの著作に関する広範な論評の枠組みの中で、ルイス・ホワイト・ベックは、カントの倫理が20世紀半ばに人類が直面したいくつかの道徳的ジレンマに関 連している可能性を説明しようと試みた。著書『6人の世俗的哲学者』(1966年)の中で、ベックは、宗教的な思想や価値観を受け入れる現代の世俗哲学 は、人間の思考の自由を訴えることでうまく定式化できると主張した。この考えに基づき、彼はカントの倫理がそのような理論において中心的な役割を担う可能 性を示した。彼は特に、そのような近代的世俗哲学の進化に関連すると考えられる2つの「哲学者の系統」を特定している。[59][60][61][62] そのうちの一つのグループについて、ベックは、宗教的信念の範囲、妥当性、内容に様々な制限を課すために、人類の科学的・哲学的努力に訴えることを利用し た哲学者たちに注目している。ベックは、このグループにバルーフ・スピノザ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、イマヌエル・カントの著作を含めている。ベックの見 解では、カントの倫理は、いくつかの点でより包括的な近代の世俗的哲学パラダイムへの道筋をつけた。スピノザの厳格な一元論への訴えを明確に否定すること で、カントはスピノザが神を拠り所とし、近代の倫理理論の中心的な役割を担うことを拒絶した。ベックはさらに、カントの倫理理論は、自然の科学的解釈はそ れ自体では宗教的信念を裏付けることはできないというヒュームの主張と一致していると論じた。しかし、ベックはすぐに読者に思い出させるように、カント は、人間は道徳的な指針なしに完全に放浪することにはならないと主張することで、ヒュームから距離を置いている。ベックの解釈によると、カントは、道徳律 を神の命令であるかのように考え、人々を「神への共通の忠誠心」で結びつけるべきだと明確に主張している。[63] これは、宗教的な思考や価値観の異なる合理的な基盤を、人類の道徳意識に見出すというカントの主張によって達成される。[59][60][61][62] 現代のカント主義倫理学者 オノラ・オニール 哲学者オノラ・オニールは、ハーバード大学でジョン・ロールズに師事した。社会正義の問題に対するカント主義的アプローチを支持する現代のカント主義倫理 学者である。オニールは、社会正義に関するカント主義の説明が成功するためには、いかなる不当な理想化や仮定にも依拠してはならないと主張する。彼女は、 哲学者たちはこれまでカントが人間を社会的文脈や人生の目標を持たない自律的存在として理想化していると非難してきたが、カントの倫理はそうした理想化を 抜きにして読むことができると主張している。[64] オニールは、理性を人間に備わる原理としてではなく、人間が利用できる実践的なものとしてカントが捉えていたことを好んでいる。理性を意思決定の手段とし て捉えることで、採用した原則が万人に受け入れられる可能性があるという唯一の制約を考慮に入れることができる。もし、万人が特定の原則を採用することを 望まない場合、その原則を採用する理由を与えることはできない。理性を用い、他の人々と議論するためには、万人に受け入れられない原則を拒否しなければな らない。このようにして、オニールは人間の自律性に関する観念論的な見解を採用することなく、カントの普遍化可能性の定式に到達した。[65] この普遍化可能性のモデルは、普遍化可能な原則をすべて採用することを要求するものではなく、普遍化不可能な原則を採用することを禁じるだけである。 [66] カントの倫理のこのモデルから、オニールは正義の理論を展開し始める。彼女は、欺瞞や強制といった特定の原則を拒絶することが、正義の基本概念の起点とな ることを論証している。彼女は、平等や自由といったより抽象的な原則よりも、人間にとってより決定的なものであると論じている。しかし、彼女は、これらの 原則が過度に要求の厳しいものであるように見えることを認めている。傷害行為など、普遍化不可能な原則に依存する行動や制度は数多く存在する。 マーシャ・バロン 哲学者のマイケル・シュトッカーは論文「近代倫理理論の分裂」で、義務から生じる行動にはある種の道徳的価値が欠けていると主張し、カントの倫理(および すべての近代倫理理論)に異議を唱えている。彼は、友情からではなく義務感から病院の友人を訪れるスミスの例を挙げ、この訪問は動機が間違っているため、 道徳的に欠けているように見えると論じている。 マーシャ・バロンは、この点についてカントの倫理を擁護しようとしている。義務から行動することは好ましくないかもしれないといういくつかの理由を提示し た後、彼女は、これらの問題は、人々が自分の義務が何であるかを誤解した場合にのみ生じる、と主張している。義務から行動することは本質的に間違っている わけではないが、人々が自分が義務を負っていることを誤解した場合、不道徳な結果が生じることがある。義務は、冷淡で非人間的なものと見なされる必要はな い。人格を磨いたり、人間関係を改善したりする義務もあるかもしれない。[69] バロンはさらに、義務は二次的な動機として解釈されるべきであると主張している。つまり、特定の行動を促すのではなく、何をすべきかを規制し、条件を設定 する動機である。彼女は、このように考えれば、義務は行動を起こそうとする自然な傾向の欠如を示すものではなく、友情に不可欠な動機や感情を損なうもので もないと主張している。バロンにとって、義務によって行動が左右されるということは、義務が常に第一の動機となって行動を起こすということではない。むし ろ、義務を考慮することは常に行動の指針となるということである。責任ある道徳的行為者は、人格の問題など道徳的な問題に関心を持つべきである。これらは 道徳的行為者を義務から行動するように導くべきである。[70] クリスティン・コルサガード 1981年の博士論文『実践理性の立場』において、哲学者クリスティン・コルサガードは、普遍的法則の公式の解釈には4つの基本的なタイプがある、と論じている。[71] 1. 理論的矛盾解釈:格言を普遍化することは論理的または物理的に不可能である。 2. 恐ろしい結果解釈:格言を普遍化すると、恐ろしい結果を招く。 3. 目的論的矛盾解釈:普遍化された格言は、目的論的自然法として意図されることはありえない。 4. 実践的矛盾解釈:格言が普遍化された場合、行為者はその格言の目的を達成することができない。 コルスガードは、実践的矛盾解釈が正しい解釈であると主張している。さらに、格言が普遍的法則の公式に違反する可能性は2通りあると主張している。 1. 第一の矛盾テスト:矛盾なく普遍化できない場合、格言は第一の矛盾テストに不合格となる。 2. 第二の矛盾テスト:普遍化は可能だが、矛盾なく意志決定できない場合、格言は第二の矛盾テストに不合格となる。 |

| Criticisms of Kantian ethics Friedrich Schiller While Friedrich Schiller appreciated Kant for basing the source of morality on a person's reason rather than on God, he also criticized Kant for not going far enough in the conception of autonomy, as the internal constraint of reason would also take away a person's autonomy by going against their sensuous self. Schiller introduced the concept of the "beautiful soul," in which the rational and non-rational elements within a person are in such harmony that a person can be led entirely by his sensibility and inclinations. "Grace" is the expression in appearance of this harmony. However, given that humans are not naturally virtuous, it is in exercising control over the inclinations and impulses through moral strength that a person displays "dignity." Schiller's main implied criticism of Kant is that the latter only saw dignity while grace is ignored.[72] Kant responded to Schiller in a footnote that appears in Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason. While he admits that the concept of duty can only be associated with dignity, gracefulness is also allowed by the virtuous individual as he attempts to meet the demands of the moral life courageously and joyously.[73] G. W. F. Hegel  Portrait of G. W. F. Hegel German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel presented two main criticisms of Kantian ethics. He first argued that Kantian ethics provides no specific information about what people should do because Kant's moral law is solely a principle of non-contradiction.[3] He argued that Kant's ethics lack any content and so cannot constitute a supreme principle of morality. To illustrate this point, Hegel and his followers have presented a number of cases in which the Formula of Universal Law either provides no meaningful answer or gives an obviously wrong answer. Hegel used Kant's example of being trusted with another man's money to argue that Kant's Formula of Universal Law cannot determine whether a social system of property is a morally good thing, because either answer can entail contradictions. He also used the example of helping the poor: if everyone helped the poor, there would be no poor left to help, so beneficence would be impossible if universalized, making it immoral according to Kant's model.[74] Hegel's second criticism was that Kant's ethics forces humans into an internal conflict between reason and desire. Because it does not address the tension between self-interest and morality, Kant's ethics cannot give individuals any reason to be moral.[75] Arthur Schopenhauer German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer criticised Kant's belief that ethics should concern what ought to be done, insisting that the scope of ethics should be to attempt to explain and interpret what actually happens. Whereas Kant presented an idealized version of what ought to be done in a perfect world, Schopenhauer argued that ethics should instead be practical and arrive at conclusions that could work in the real world, capable of being presented as a solution to the world's problems.[76] Schopenhauer drew a parallel with aesthetics, arguing that in both cases prescriptive rules are not the most important part of the discipline. Because he believed that virtue cannot be taught—a person is either virtuous or is not—he cast the proper place of morality as restraining and guiding people's behavior, rather than presenting unattainable universal laws.[77] Friedrich Nietzsche Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche criticised all contemporary moral systems, with a special focus on Christian and Kantian ethics. He argued that all modern ethical systems share two problematic characteristics: first, they make a metaphysical claim about the nature of humanity, which must be accepted for the system to have any normative force; and second, the system benefits the interests of certain people, often over those of others. Although Nietzsche's primary objection is not that metaphysical claims about humanity are untenable (he also objected to ethical theories that do not make such claims), his two main targets—Kantianism and Christianity—do make metaphysical claims, which therefore feature prominently in Nietzsche's criticism.[78] Nietzsche rejected fundamental components of Kant's ethics, particularly his argument that morality, God, and immorality, can be shown through reason. Nietzsche cast suspicion on the use of moral intuition, which Kant used as the foundation of his morality, arguing that it has no normative force in ethics. He further attempted to undermine key concepts in Kant's moral psychology, such as the will and pure reason. Like Kant, Nietzsche developed a concept of autonomy; however, he rejected Kant's idea that valuing our own autonomy requires us to respect the autonomy of others.[79] A naturalist reading of Nietzsche's moral psychology stands contrary to Kant's conception of reason and desire. Under the Kantian model, reason is a fundamentally different motive to desire because it has the capacity to stand back from a situation and make an independent decision. Nietzsche conceives of the self as a social structure of all our different drives and motivations; thus, when it seems that our intellect has made a decision against our drives, it is actually just an alternative drive taking dominance over another. This is in direct contrast with Kant's view of the intellect as opposed to instinct; instead, it is just another instinct. There is thus no self-capable of standing back and making a decision; the decision the self-makes is simply determined by the strongest drive.[80] Kantian commentators have argued that Nietzsche's practical philosophy requires the existence of a self capable of standing back in the Kantian sense. For an individual to create values of their own, which is a key idea in Nietzsche's philosophy, they must be able to conceive of themselves as a unified agent. Even if the agent is influenced by their drives, he must regard them as his own, which undermines Nietzsche's conception of autonomy.[81] Nietzsche criticizes Kant even in his autobiography Ecce Homo: "Leibniz and Kant - these two great breaks upon the intellectual honesty of Europe!"[82] Nietzsche argues that virtues should be personally crafted to serve our own needs and protect ourselves. He warns against adopting virtues based solely on abstract notions of "virtue" itself, as advocated by Kant, as they can be harmful to our lives, in his quote: A virtue must be our invention; it must spring out of our personal need and defence. In every other case it is a source of danger. That which does not belong to our life menaces it; a virtue which has its roots in mere respect for the concept of “virtue,” as Kant would have it, is pernicious.[83] John Stuart Mill The Utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill criticizes Kant for not realizing that moral laws are justified by a moral intuition based on utilitarian principles (that the greatest good for the greatest number ought to be sought). Mill argued that Kant's ethics could not explain why certain actions are wrong without appealing to utilitarianism.[84] As basis for morality, Mill believed that his principle of utility has a stronger intuitive grounding than Kant's reliance on reason, and can better explain why certain actions are right or wrong.[85] Virtue ethics Virtue ethics is a form of ethical theory which emphasizes the character of an agent, rather than specific acts; many of its proponents have criticised Kant's deontological approach to ethics. Elizabeth Anscombe criticised modern ethical theories, including Kantian ethics, for their obsession with law and obligation.[86] As well as arguing that theories which rely on a universal moral law are too rigid, Anscombe suggested that, because a moral law implies a moral lawgiver, they are irrelevant in modern secular society.[87] In his work After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre criticises Kant's formulation of universalisability, arguing that various trivial and immoral maxims can pass the test, such as "Keep all your promises throughout your entire life except one." He further challenges Kant's formulation of humanity as an end in itself by arguing that Kant provided no reason to treat others as means: the maxim "Let everyone except me be treated as a means," though seemingly immoral, can be universalized.[88] Bernard Williams argues that, by abstracting persons from character, Kant misrepresents persons and morality and Philippa Foot identified Kant as one of a select group of philosophers responsible for the neglect of virtue by analytic philosophy.[89] Roman Catholic priest Servais Pinckaers regarded Christian ethics as closer to the virtue ethics of Aristotle than Kant's ethics. He presented virtue ethics as freedom for excellence, which regards freedom as acting in accordance with nature to develop one's virtues.[90] Autonomy A number of philosophers (including Elizabeth Anscombe, Jean Bethke Elshtain, Servais Pinckaers, Iris Murdoch, and Kevin Knight)[91] have all suggested that the Kantian conception of ethics rooted in autonomy is contradictory in its dual contention that humans are co-legislators of morality and that morality is a priori. They argue that if something is universally a priori (i.e., existing unchangingly prior to experience), then it cannot also be in part dependent upon humans, who have not always existed. On the other hand, if humans truly do legislate morality, then they are not bound by it objectively, because they are always free to change it. This objection seems to rest on a misunderstanding of Kant's views since Kant argued that morality is dependent upon the concept of a rational will (and the related concept of a categorical imperative: an imperative which any rational being must necessarily will for itself).[92] It is not based on contingent features of any being's will, nor upon human wills in particular, so there is no sense in which Kant makes ethics "dependent" upon anything which has not always existed. Furthermore, the sense in which our wills are subject to the law is precisely that if our wills are rational, we must will in a lawlike fashion; that is, we must will according to moral judgments we apply to all rational beings, including ourselves.[93] This is more easily understood by parsing the term "autonomy" into its Greek roots: auto (self) + nomos (rule or law). That is, an autonomous will, according to Kant, is not merely one which follows its own will, but whose will is lawful-that is, conforming to the principle of universalizability, which Kant also identifies with reason. Ironically, in another passage, willing according to immutable reason is precisely the kind of capacity Elshtain ascribes to God as the basis of his moral authority, and she commands this over an inferior voluntarist version of divine command theory, which would make both morality and God's will contingent.[94] As O'Neill argues, Kant's theory is a version of the first rather than the second view of autonomy, so neither God nor any human authority, including contingent human institutions, play any unique authoritative role in his moral theory. Kant and Elshtain, that is, both agree God has no choice but to conform his will to the immutable facts of reason, including moral truths; humans do have such a choice, but otherwise their relationship to morality is the same as that of God's: they can recognize moral facts, but do not determine their content through contingent acts of will. |

カント的倫理への批判 フリードリヒ・シラー フリードリヒ・シラーは、カントが道徳の源泉を神ではなく人間の理性に求めたことを評価する一方で、理性の内的制約が感覚的な自己に反することで人間の自 律性をも奪うことになるとして、カントの自律性の概念が十分ではないと批判した。シラーは「美しい魂」という概念を導入し、その概念では、理性と非理性の 要素が調和し、人が感性や傾向に完全に導かれることを可能にする。「優雅さ」は、この調和の外見上の表現である。しかし、人間は生まれつき善良ではないた め、道徳的な強さによって傾向や衝動を制御することによって、人は「威厳」を示すのである。シラーがカントに対して暗に示した主な批判は、カントが尊厳の みに目を向け、優雅さを無視しているというものである。 カントは『理性の枠内での宗教』の脚注でシラーに反論している。義務の概念は尊厳と結びつくのみであることを認めながらも、高潔な人物は、勇気と喜びをもって道徳的な生活の要求に応えようとする際に、優雅さも許容する。 G. W. F. ヘーゲル  G. W. F. ヘーゲルの肖像 ドイツの哲学者G. W. F. ヘーゲルは、カントの倫理に対して主に2つの批判を行った。まず、カントの倫理は、カントの道徳律が単に非矛盾律の原理であるため、人々は何をすべきかに ついて具体的な情報を提供していないと主張した。[3] ヘーゲルは、カントの倫理は内容に欠けているため、道徳の最高原則を構成することはできないと主張した。この点を説明するために、ヘーゲルとその追随者た ちは、普遍的法則の公式が意味のある答えを提示しない、あるいは明らかに誤った答えを提示する、という事例を数多く提示している。ヘーゲルは、カントの例 である「他人の金銭を信頼して預かる」という状況を引用し、カントの普遍的法則の公式では、財産の社会システムが道徳的に良いものであるかどうかを判断で きないと論じた。なぜなら、どちらの答えも矛盾をはらむ可能性があるからだ。また、貧者を助けるという例も挙げた。もし誰もが貧者を助けるならば、助ける べき貧者はいなくなってしまうため、普遍化すれば博愛は不可能となり、カントのモデルによればそれは不道徳となる。[74] ヘーゲルの第二の批判は、カントの倫理は人間を理性と欲望の間の内的な葛藤に追い込むというものであった。自己利益と道徳の間の緊張関係を扱っていないた め、カントの倫理は個人が道徳的である理由を与えることができない。[75] アルトゥル・ショーペンハウアー ドイツの哲学者アルトゥル・ショーペンハウアーは、倫理とは「なされるべきこと」を扱うべきであるというカントの信念を批判し、倫理の対象は実際に起こる ことを説明し解釈しようと試みることであると主張した。カントが完全な世界における理想的な「あるべき姿」を提示したのに対し、ショーペンハウアーは倫理 はむしろ現実的であるべきであり、現実世界で機能する結論に達し、世界の諸問題に対する解決策として提示できるものでなければならないと主張した。 [76] ショーペンハウアーは美学との類似点を指摘し、いずれの場合も規範的な規則がその分野で最も重要な部分ではないと論じた。美徳は教えることができない(人 は美徳を備えているか、備えていないかのどちらかである)と信じていたため、彼は、達成不可能な普遍的法則を提示するよりも、むしろ人々の行動を抑制し導 くことこそが道徳の適切な役割であると主張した。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェ 哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、キリスト教とカント主義の倫理に特に焦点を当てて、当時のあらゆる道徳体系を批判した。彼は、すべての近代的な倫理体系 には2つの問題のある特徴がある、と主張した。第1に、その体系が規範的な力を発揮するためには、人間の本質に関する形而上学的主張を受け入れなければな らないこと。第2に、その体系は特定の人の利益に役立つものであり、しばしば他の人々の利益を犠牲にするものであること。ニーチェの主な異議は、人間性に 関する形而上学的主張が受け入れられないというものではないが(彼はそのような主張をしない倫理理論にも異議を唱えていた)、彼の主な標的であるカント主 義とキリスト教は形而上学的主張を行っているため、ニーチェの批判のなかで目立った特徴となっている。[78] ニーチェはカントの倫理の基本的要素、特に道徳、神、不道徳が理性によって示されるという主張を否定した。ニーチェはカントが道徳の基礎として用いた道徳 的直観に疑いを投げかけ、それは倫理には規範的な力を持たないと論じた。さらに、カントの道徳心理学における主要概念、例えば「意志」や「純粋理性」など を弱体化させようとした。カントと同様に、ニーチェも自律性の概念を展開したが、カントの「自己の自律性を尊重することは他者の自律性を尊重することを必 要とする」という考えを否定した。[79] ニーチェの道徳心理学を自然主義的に解釈することは、カントの理性と欲望の概念とは対立するものである。カントのモデルでは、理性は状況から距離を置き、 独立した判断を下す能力を持つため、欲望とは根本的に異なる動機である。ニーチェは自己を、私たちのさまざまな衝動や動機からなる社会的な構造体と捉えて いる。そのため、私たちの知性が衝動に反する決定を下したように思える場合でも、実際には単に別の衝動が優勢になっているだけである。これは、カントの知 性は本能とは対立するものであるという見解とは正反対であり、むしろそれは単なる別の本能である。したがって、一歩引いた立場から決定を下すことのできる 自己は存在せず、自己が下す決定は、最も強い衝動によって単純に決定されるのである。[80] カント主義の論者たちは、ニーチェの実用哲学はカント主義的な意味での一歩引いた立場から決定を下すことのできる自己の存在を必要とする、と主張してい る。ニーチェの哲学の主要な考え方である、個人が独自の価値観を創造するためには、自己を統一された主体として捉えることが必要である。たとえその主体が 衝動に影響されていたとしても、それを自己の衝動として認識しなければならず、それはニーチェの自律性の概念を損なうことになる。[81] ニーチェは自伝『 Ecce Homo 』の中でカントを批判している。「ライプニッツとカント、この2人はヨーロッパの知的誠実さを大きく損なった!」[82] ニーチェは、美徳は個人のニーズに応え、自己を守るために個人的に作り出すべきだと主張している。カントが唱えたように、「美徳」という抽象的な概念のみ に基づいて美徳を採用することは、人生に有害であると警告している。 美徳は、私たち自身が発明しなければならない。それは、私たちの個人的な必要性と防御から生じなければならない。それ以外の場合は、危険の元となる。私た ちの生活に属さないものは、それを脅かす。カントが主張するように、「美徳」という概念に対する単なる敬意に根ざした美徳は有害である。 ジョン・スチュアート・ミル 功利主義哲学者ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは、道徳法則は功利主義の原則(最大多数の最大幸福を追求すべきである)に基づく道徳的直観によって正当化され ることを理解していないとして、カントを批判した。ミルは、カントの倫理では功利主義に訴えなければ、ある行動がなぜ間違っているのかを説明できないと主 張した。[84] 道徳の根拠として、ミルは、カントの理性への依存よりも自身の功利主義の原則の方が直観的な根拠が強く、ある行動が正しいか間違っているかをよりよく説明 できると信じていた。[85] 徳倫理学 徳倫理学は、特定の行為よりも行為者の人格を重視する倫理理論の一形態である。多くの支持者たちは、カントの義務論的アプローチを批判している。エリザベ ス・アンスコムは、カントの倫理学を含む近代の倫理理論を、法と義務に執着しているとして批判した。[86] 普遍的な道徳律に依拠する理論は硬直的すぎると主張するだけでなく、アンスコムは、道徳律には道徳律制定者が存在することを暗示しているため、現代の世俗 社会では無関係であると示唆した。[87] アラスデア・マッキンタイアは著書『善のその後』で、カントの普遍化可能性の定式化を批判し、例えば「生涯において、1つを除いてはすべての約束を守る」 といった、些細で不道徳な格言もそのテストに合格しうることを論証している。さらに、カントが他者を手段として扱う理由を提示していないことを論拠に、カ ントの「私以外のすべての人を手段として扱え」という格言は、一見不道徳であるように見えるが、普遍化できると主張し、カントの人間性それ自体としての目 的という定式化に異議を唱えている。[88] バーナード・ウィリアムズは、カントが人格を性格から抽象化することで、人格と道徳を誤って表現していると論じ、フィリッパ・フットは、カントを分析哲学 による徳の軽視に責任のある少数の哲学者の一人であると指摘している。[89] ローマ・カトリックの司祭セルヴェ・ピンカエースは、カントの倫理よりもむしろアリストテレスの徳の倫理に近いものとしてキリスト教の倫理を捉えていた。彼は、徳の倫理を卓越性の自由として提示し、自由とは、自分の徳を育むために自然に従って行動することであるとした。 自律 多くの哲学者(エリザベス・アンコム、ジーン・ベトケ・エルスチーン、セルヴェ・ピンカエース、アイリス・マードック、ケビン・ナイトなど)は、カントの 倫理観は自律性に根ざしているが、人間が道徳の共同立法者であるという主張と、道徳は先験的であるという主張という、二つの主張が矛盾していると指摘して いる。彼らは、もし普遍的に先験的(すなわち、経験に先立って不変に存在する)なものが存在するとすれば、それは常に存在してきたわけではない人間に部分 的に依存しているものでもありえないと主張する。一方、もし人間が本当に道徳を立法しているとすれば、人間はそれを客観的に拘束されるものではない。なぜ なら、人間はいつでもそれを変更できる自由を持っているからだ。 この反論は、カントの考えを誤解しているように思われる。なぜなら、カントは道徳が理性的意志の概念(および、それに関連するカテゴリー的命令の概念:あ らゆる理性的存在が必然的に自ら望まなければならない命令)に依存していると主張しているからである。[92] それは、いかなる存在の意志の偶発的な特徴にも基づいていないし、特に人間の意志にも基づいていない。したがって、カントが倫理を「依存」させるものが、 常に存在してきたものでないという意味はない。さらに、私たちの意志が法則に従うという意味は、まさに私たちの意志が理性的であるならば、私たちは法則に 従うように意志しなければならないということである。つまり、私たち自身を含め、すべての理性的な存在に適用される道徳的判断に従って意志しなければなら ないということである。 このことは、「自律性」という用語をギリシャ語の語源に分解することでより容易に理解できる。すなわち、カントによれば、自律的な意志とは、単に自身の意 志に従うものではなく、その意志が合法的なものであることを意味する。つまり、普遍化可能性の原則に適合するものであり、カントはこれを理性とも同一視し ている。皮肉なことに、別の箇所では、不変の理性に従う意志こそが、エルシュタインが神の道徳的権威の根拠として帰する能力そのものである。そして、彼女 は、道徳性と神の意志の両方を偶発的なものとする、劣った意志決定論に基づく神の命令説よりも、この考え方を優先している。神の意志を偶発的なものとす る。[94] オニールが主張するように、カントの理論は自律性の第2の観点ではなく、第1の観点のバージョンであるため、神も偶発的な人間の制度を含むいかなる人間の 権威も、彼の道徳理論において独自の権威的な役割を果たすことはない。カントとエルシュタインは、つまり、両者とも神には選択の余地はなく、道徳的真理を 含む理性の不変の事実に対して自らの意志を適合させるしかないという点で一致している。人間にはそのような選択の余地があるが、それ以外では、彼らの道徳 性に対する関係は神のそれと同じである。すなわち、彼らは道徳的事実を認識することはできるが、偶発的な意志の行為によってその内容を決定することはでき ない。 |

| Applications Medical ethics Kant believed that the shared ability of humans to reason should be the basis of morality, and that it is the ability to reason that makes humans morally significant. He, therefore, believed that all humans should have the right to common dignity and respect.[95] Margaret L. Eaton argues that, according to Kant's ethics, a medical professional must be happy for their own practices to be used by and on anyone, even if they were the patient themselves. For example, a researcher who wished to perform tests on patients without their knowledge must be happy for all researchers to do so.[96] She also argues that Kant's requirement of autonomy would mean that a patient must be able to make a fully informed decision about treatment, making it immoral to perform tests on unknowing patients. Medical research should be motivated out of respect for the patient, so they must be informed of all facts, even if this would be likely to dissuade the patient.[97] Jeremy Sugarman has argued that Kant's formulation of autonomy requires that patients are never used merely for the benefit of society, but are always treated as rational people with their own goals.[98] Aaron E. Hinkley notes that a Kantian account of autonomy requires respect for choices that are arrived at rationally, not for choices which are arrived at by idiosyncratic or non-rational means. He argues that there may be some difference between what a purely rational agent would choose and what a patient actually chooses, the difference being the result of non-rational idiosyncrasies. Although a Kantian physician ought not to lie to or coerce a patient, Hinkley suggests that some form of paternalism—such as through withholding information which may prompt a non-rational response—could be acceptable.[99] Abortion In How Kantian Ethics Should Treat Pregnancy and Abortion, Susan Feldman argues that abortion should be defended according to Kantian ethics. She proposes that a woman should be treated as a dignified autonomous person, with control over their body, as Kant suggested. She believes that the free choice of women would be paramount in Kantian ethics, requiring abortion to be the mother's decision.[100] Dean Harris has noted that, if Kantian ethics is to be used in the discussion of abortion, it must be decided whether a fetus is an autonomous person.[101] Kantian ethicist Carl Cohen argues that the potential to be rational or participation in a generally rational species is the relevant distinction between humans and inanimate objects or irrational animals. Cohen believes that even when humans are not rational because of age (such as babies or fetuses) or mental disability, agents are still morally obligated to treat them as an ends in themselves, equivalent to a rational adult such as a mother seeking an abortion.[102] Sexual ethics Kant viewed humans as being subject to the animalistic desires of self-preservation, species-preservation, and the preservation of enjoyment. He argued that humans have a duty to avoid maxims that harm or degrade themselves, including suicide, sexual degradation, and drunkenness.[103] This led Kant to regard sexual intercourse as degrading because it reduces humans to an object of pleasure. He admitted sex only within marriage, which he regarded as "a merely animal union." He believed that masturbation is worse than suicide, reducing a person's status to below that of an animal; he argued that rape should be punished with castration and that bestiality requires expulsion from society.[104] Commercial sex Feminist philosopher Catharine MacKinnon has argued that many contemporary practices would be deemed immoral by Kant's standards because they dehumanize women. Sexual harassment, prostitution, and pornography, she argues, objectify women and do not meet Kant's standard of human autonomy. Commercial sex has been criticised for turning both parties into objects (and thus using them as a means to an end); mutual consent is problematic because in consenting, people choose to objectify themselves. Alan Soble has noted that more liberal Kantian ethicists believe that, depending on other contextual factors, the consent of women can vindicate their participation in pornography and prostitution.[105] Animal ethics Because Kant viewed rationality as the basis for being a moral patient—one due moral consideration—he believed that animals have no moral rights. Animals, according to Kant, are not rational, thus one cannot behave immorally towards them.[106] Although he did not believe we have any duties towards animals, Kant did believe being cruel to them was wrong because our behaviour might influence our attitudes toward human beings: if we become accustomed to harming animals, then we are more likely to see harming humans as acceptable.[107] Ethicist Tom Regan rejected Kant's assessment of the moral worth of animals on three main points: First, he rejected Kant's claim that animals are not self-conscious. He then challenged Kant's claim that animals have no intrinsic moral worth because they cannot make a moral judgment. Regan argued that, if a being's moral worth is determined by its ability to make a moral judgment, then we must regard humans who are incapable of moral thought as being equally undue moral consideration. Regan finally argued that Kant's assertion that animals exist merely as a means to an end is unsupported; the fact that animals have a life that can go well or badly suggests that, like humans, they have their own ends.[108] Christine Korsgaard has reinterpreted Kantian theory to argue that animal rights are implied by his moral principles.[109] Lying Kant believed that the categorical imperative provides us with the maxim that we ought not to lie in any circumstances, even if we are trying to bring about good consequences, such as lying to a murderer to prevent them from finding their intended victim. Kant argued that, because we cannot fully know what the consequences of any action will be, the result might be unexpectedly harmful. Therefore, we ought to act to avoid the known wrong—lying—rather than to avoid a potential wrong. If there are harmful consequences, we are blameless because we acted according to our duty.[110] Julia Driver argues that this might not be a problem if we choose to formulate our maxims differently: the maxim 'I will lie to save an innocent life' can be universalized. However, this new maxim may still treat the murderer as a means to an end, which we have a duty to avoid doing. Thus we may still be required to tell the truth to the murderer in Kant's example.[111] |

応用 医療倫理 カントは、人間が共有する推論能力が道徳の基礎となるべきであり、人間を道徳的に有意義なものとしているのは推論能力であると考えた。したがって、すべて の人間は共通の尊厳と敬意を受ける権利を持つべきであると信じていた。[95] マーガレット・L・イートンは、カントの倫理観によれば、医療従事者は、たとえ自分が患者であったとしても、自分の診療が誰かに利用されたり、誰かに施さ れたりすることを喜ばなければならないと主張している。例えば、患者に知られないように検査を行いたいと考える研究者は、すべての研究者がそうすることを 喜ばなければならない。[96] また、カントの自律性の要件は、患者が治療について十分な情報を得た上で決定を下せるようにすべきであることを意味し、患者に知らせずに検査を行うことは 非道徳的であると彼女は主張している。医療研究は患者への敬意から動機付けられるべきであり、たとえ患者が研究への参加を拒む可能性が高くても、患者には すべての事実を知らせる必要がある。 ジェレミー・シュガーマンは、カントの自律性の定義では、患者は社会の利益のために利用されるべきではなく、常に自身の目標を持つ理性的な人間として扱わ れるべきであると主張している。[98] アーロン・E・ヒンクリーは、カントの自律性の定義では、合理的手段によって到達された選択は尊重されるべきであるが、特異的または非合理的な手段によっ て到達された選択は尊重されるべきではないと指摘している。彼は、純粋に理性的な主体が選択するものと患者が実際に選択するものとの間には、非理性的な特 異性による違いがあるかもしれないと論じている。カント主義の医師は患者に対して嘘をついたり強制したりすべきではないが、非理性的な反応を促す可能性の ある情報を隠すなど、ある種の温情主義は容認できるとヒンクリーは示唆している。 中絶 『カント主義的倫理が妊娠と中絶にどう対処すべきか』において、スーザン・フェルドマンは、カント主義的倫理に従って中絶を擁護すべきだと主張している。 彼女は、カントが示唆したように、女性は尊厳のある自律した存在として扱われるべきであり、自分の身体をコントロールできるべきだと提案している。彼女 は、カント主義的倫理においては女性の自由な選択が最も重要であり、中絶は母親の決断でなければならないと考えている。 ディーン・ハリスは、カント倫理を中絶の議論に用いるのであれば、胎児が自律した存在であるかどうかを決定しなければならないと指摘している。カント倫理 学者のカール・コーエンは、理性的になる可能性、または一般的に理性的な種への参加が、人間と無生物または非理性的な動物との間の関連する区別であると主 張している。コーエンは、人間が年齢(例えば、乳児や胎児)や精神障害により理性的でない場合でも、代理人は、中絶を求める母親のような理性的な成人と同 様に、それらをそれ自体の目的として扱う道徳的義務があると信じている。 性的倫理 カントは人間は自己保存、種保存、快楽の維持といった動物的な欲求に従う存在であるとみなした。彼は、人間には自殺、性的堕落、酩酊など、自らを傷つけた り堕落させるような格言を避ける義務があると主張した。[103] これに基づき、カントは性交渉は人間を快楽の対象に貶めるものであるとして、それを堕落的なものとみなした。彼は結婚内でのみセックスを認めており、結婚 を「単なる動物の結合」とみなしていた。彼は自慰行為は自殺よりも悪く、人の地位を動物以下に貶めるものだと考えていた。また、レイプは去勢刑に処すべき であり、獣姦は社会からの追放を必要とする、と主張した。 商業的性行為 フェミニスト哲学者のキャサリン・マッキノンは、多くの現代の慣習は女性を人間扱いしないため、カントの基準では不道徳とみなされるだろうと主張してい る。彼女は、セクハラ、売春、ポルノグラフィーは女性を客体化し、カントの人間の自律性の基準を満たしていないと主張している。商業的性行為は両当事者を 客体化し(したがって、目的達成のための手段として利用している)、相互の合意は問題である。なぜなら、合意することで、人は自らを客体化することを選択 しているからである。アラン・ソーベルは、よりリベラルなカント主義の倫理学者たちは、他の文脈的要因によっては、女性の同意があればポルノや売春への参 加を正当化できると信じていると指摘している。[105] 動物倫理 カントは、道徳的な患者であること、つまり正当な道徳的配慮の基礎として理性を捉えていたため、動物には道徳的な権利はないと考えていた。カントによれ ば、動物は理性的ではないため、動物に対して非道な行動を取ることはできない。[106] カントは、動物に対して私たちが何らかの義務を負っているとは考えていなかったが、動物に対して残酷な態度を取ることは間違っていると考えていた。なぜな ら、私たちの行動は人間に対する態度に影響を与える可能性があるからだ。動物に危害を加えることに慣れてしまうと、人間に危害を加えることも容認できると 考えるようになる可能性が高くなる。[107] 倫理学者トム・リーガンは、カントの動物の道徳的価値に関する評価を主に3つの点で否定した。まず、彼はカントの主張である「動物は自意識を持たない」と いう主張を否定した。次に、動物は道徳的判断を下すことができないため、本質的な道徳的価値を持たないというカントの主張に異議を唱えた。リーガンは、も しある存在の道徳的価値が道徳的判断を行う能力によって決定されるのであれば、道徳的思考が不可能な人間も同様に不当な道徳的配慮の対象であると見なさな ければならないと主張した。リーガンは最後に、動物は単に人間の目的を達成するための手段として存在しているというカントの主張は裏付けられていないと主 張した。動物には良いことも悪いことも起こり得る生活があるという事実は、人間と同様に動物にも独自の目的があることを示唆している。 クリスティン・コルサガードはカントの理論を再解釈し、動物の権利は彼の道徳的原則によって暗示されていると主張している。 嘘をつくこと カントは、殺人犯に嘘をついて被害者を見つけられないようにするなど、良い結果をもたらそうとしている場合でも、いかなる状況でも嘘をついてはならないと いう格言を、カテゴリー命令(定言命法)が私たちに与えていると信じていた。 カントは、どのような行動の結果がもたらされるかを完全に知ることはできないため、結果が思いがけず有害なものになる可能性があると論じた。 したがって、潜在的な悪を避けるよりも、既知の悪である嘘をつくことを避けるように行動すべきである。有害な結果が生じたとしても、私たちは義務に従って 行動したのだから非難されることはない。[110] ジュリア・ドライバーは、私たちが別の格言を定めることを選択すれば、これは問題にならないかもしれないと主張している。「私は無実の命を救うために嘘を つく」という格言は普遍化できる。しかし、この新しい格言は、私たちが避けるべき義務を負う殺人者を依然として手段として扱っている可能性がある。した がって、カントの例における殺人者には、やはり真実を告げる必要があるかもしれない。[111] |

| Bibliography Anscombe, G. E. M. (1958). "Modern Moral Philosophy". Philosophy. 33 (124): 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0031819100037943. ISSN 0031-8191. JSTOR 3749051. S2CID 197875941. Athanassoulis, Nafsika (7 July 2010). "Virtue Ethics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 11 September 2013. Atwell, John (1986). Ends and principles in Kant's moral thought. Springer. ISBN 978-90-247-3167-1. Axinn, Sidney; Kneller, Jane (1998). Autonomy and Community: Readings in Contemporary Kantian Social Philosophy. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3743-8. Baron, Marcia (1999). Kantian Ethics Almost Without Apology. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8604-3. Benn, Piers (1998). Ethics. UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-453-4. Blackburn, Simon (2008). "Morality". Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (Second edition revised ed.). Brinton, Crane (1967). "Enlightenment". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 2. Macmillan. Brooks, Thom (2012). Hegel's Philosophy of Right. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-8813-5. Brooks, Thom; Freyenhagen, Fabian (2005). The Legacy of John Rawls. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-7843-6. Cohen, Carl (1986). "The Case For the Use of Animals in Biomedical Research". New England Journal of Medicine. 315 (14): 865–69. doi:10.1056/NEJM198610023151405. PMID 3748104. S2CID 20009545. Beenfeldt, Christian (2007). Collin, Finn (ed.). "Ungrounded Semantics: Searle's Chinese Room Thought Experiment, the Failure of Meta and Subsystemic Understanding, and Some Thoughts about Thought-Experiments". Danish Yearbook of Philosophy. 42. Museum Tusculanum Press: 75–96. doi:10.1163/24689300_0420104. ISSN 0070-2749. Denis, Lara (April 1999). "Kant on the Wrongness of "Unnatural" Sex". History of Philosophy Quarterly. 16 (2). University of Illinois Press: 225–248. Driver, Julia (2007). Ethics: The Fundamentals. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1154-6. Eaton, Margaret (2004). Ethics and the Business of Bioscience. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4250-4. Ellis, Ralph D. (1998). Just Results: Ethical Foundations for Policy Analysis. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-667-8. Elshtain, Jean Bethke (2008). Sovereignty: God, State, and Self. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03759-9. Engelhardt, Hugo Tristram (2011). Bioethics Critically Reconsidered: Having Second Thoughts. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-2244-6. Freeman, Samuel (2019). "Original Position". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 March 2020. Guyer, Paul (2011). "Chapter 8: Kantian Perfectionism". In Jost, Lawrence; Wuerth, Julian (eds.). Perfecting Virtue: New Essays on Kantian Ethics and Virtue Ethics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49435-9. Hare, John (2011). "Kant, The Passions, And The Structure Of Moral Motivation". Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers. 28 (1): 54–70. doi:10.5840/faithphil201128116. Harris, Dean (2011). Ethics in Health Services and Policy: A Global Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-53106-8. Hill, Thomas (2009). The Blackwell Guide to Kant's Ethics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-2581-9. Hirst, E. W. (1934). "The Categorical Imperative and the Golden Rule". Philosophy. 9 (35): 328–335. doi:10.1017/S0031819100029442. ISSN 0031-8191. JSTOR 3746418. S2CID 170983087. Janaway, Christopher (2002). Schopenhauer: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280259-3. Janaway, Christopher; Robertson, Simon (2012). Nietzsche, Naturalism, and Normativity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958367-6. Johnson, Robert (2008). "Kant's Moral Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 11 September 2013. Kant, Immanuel (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals – via Wikisource. Kant, Immanuel (1788). Critique of Practical Reason – via Wikisource. Kant, Immanuel (1991). The Moral Law: Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. Translated by Paton, Herbert James. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-07843-6. Knight, Kevin (2009). "Catholic Encyclopedia: Categorical Imperative". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 June 2012. Korsgaard, Christine (1996). Creating the Kingdom of Ends. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52149-962-0. Korsgaard, Christine (2004). "Fellow Creatures: Kantian Ethics and Our Duties to Animals". The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Retrieved 7 March 2020. Korsgaard, Christine M. (2015). "A Kantian Case for Animal Rights". In Višak, Tatjana; Garner, Robert (eds.). The Ethics of Killing Animals. pp. 154–174. Leiter, Briain (2004). "Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 July 2013. Liu, JeeLoo (May 2012). "Moral Reason, Moral Sentiments and the Realization of Altruism: A Motivational Theory of Altruism" (PDF). Asian Philosophy. 22 (2): 93–119. doi:10.1080/09552367.2012.692534. S2CID 11457496. Louden, Robert B. (2011). Kant's Human Being:Essays on His Theory of Human Nature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991110-3. MacIntyre, Alasdair (2013). After Virtue. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-62356-525-1. Manninon, Gerard (2003). Schopenhauer, religion and morality: the humble path to ethics. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0823-3. Miller, Dale (2013). John Stuart Mill. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-7359-2. Murdoch, Iris (1970). The Sovereignty of the Good. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-415-25399-4. O'Neill, Onora (2000). Bounds of Justice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44744-7. Palmer, Donald (2005). Looking At Philosophy: The Unbearable Heaviness of Philosophy Made Lighter (Fourth ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-803826-6. Payrow Shabani, Omid (2003). Democracy, power and legitimacy: the critical theory of Jürgen Habermas. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8761-4. Pietrzykowski, Tomasz (2015). "Kant, Korsgaard and the Moral Status of Animals". Archihwum Filozofii Prawa I Filozofi Społecznej. 2 (11): 106–119. Retrieved 29 July 2018. Pinckaers, Servais (2003). Morality: The Catholic View. St. Augustine's Press. ISBN 978-1-58731-515-2. Pojman, Louis (2008). Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-50235-7. Pyka, Marek (2005). "Thomas Nagel on Mind, Morality, and Political Theory". American Journal of Theology & Philosophy. 26 (1/2): 85–95. ISSN 0194-3448. JSTOR 27944340. Rachels, James (1999). The Elements of Moral Philosophy (Third ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-116754-4. Regan, Tom (2004). The case for animal rights. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52024-386-6. Richardson, Henry (18 November 2005). "John Rawls (1921–2002)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 29 March 2012. Rohlf, Michael (20 May 2010). "Immanuel Kant". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2 April 2012. Singer, Peter (1983). Hegel: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-160441-6. Soble, Alan (2006). Sex from Plato to Paglia: A Philosophical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33424-5. Stern, Robert (2012). Understanding Moral Obligation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Stocker, Michael (12 August 1976). "The Schizophrenia of Modern Ethical Theories". The Journal of Philosophy. 73 (14). Journal of Philosophy: 453–466. doi:10.2307/2025782. JSTOR 2025782. S2CID 169644076. Sugarman, Jeremy (2010). Methods in Medical Ethics. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-701-6. Sullivan, Roger (1989). Immanuel Kant's Moral Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36908-4. Walker, Paul; Walker, Ally (2018). "The Golden Rule Revisited". Philosophy Now. Wilson, Eric Entrican; Denis, Lara (2018). "Kant and Hume on Morality". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Wood, Allen (2008). Kantian Ethics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67114-9. Wood, Allen (1999). Kant's Ethical Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64836-3. Wood, Allen W. (2006). "Kant's Practical Philosophy". In Karl Ameriks (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to German Idealism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–75. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521651786.004. ISBN 978-0-8014-8604-3. |