カント『実践理性批判』解説

Critique of Practical

Reason,

Kritik der praktischen Vernunft

☆ 『実践理性批判(KpV)』(じっせんりせいひはん、ドイツ語: Kritik der praktischen Vernunft)は、イマヌエル・カントが1788年に発表した3つの批 評のうちの2番目である。カントの最初の批評である『純粋理性批判』に続くもの で、彼の道徳哲学を扱っている。カントはすでに道徳哲学の重要な著作である『道 徳の形而上学の基礎づけ(GMS)』(1785年;『人倫の形而上 学の基礎づ け』Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten)を発表していたが、この『実践理性批 判』は、より広い範囲をカバーし、彼の倫理観を批判哲学の体系という大きな枠組みの中に位置づけることを意図していた。第2批判すなわち『実践理性批判』 は、その後の倫理学・道徳哲学の発展に決定的な影響を及ぼし、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテの『科学の教義』に始まり、20世紀には非本質論的道徳哲学 の主要な参照点となった(→「カント『実践理性批判』ノート」)。

★ つまり、イマヌエル・カントの道徳哲学を理解するためには、『実践理性批判 (KpV)』と『道 徳の形而上学の基礎づけ(GMS)』の2冊が重要な著作になる。とくに、後者は比較的薄くてわかりやすいので、まず『道 徳の形而上学の基礎づけ(GMS)』から着手されることをおすすめする。(実践理性批判が出版された1788年から9年後にカントは道徳に関する 大きな著作『道徳形而上学』を1797年に出版する)

☆

カントにおいて、経験的なものはすべて「病的」である。この経験的なものなかに日常的な「正常」な行動も含まれる。しかし、それは経験的であるがゆえに

「病的」なものである。ただし、病的なものの反対概念は正常ではなく、自由である(ここから快楽もまた病的なものである)(ジュパンチッチ

2003:21-24)。

| Moral thought Main article: Kantian ethics Kant developed his ethics, or moral philosophy, in three works: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and Metaphysics of Morals (1797). With regard to morality, Kant argued that the source of the good lies not in anything outside the human subject, either in nature or given by God, but rather is only the good will itself. A good will is one that acts from duty in accordance with the universal moral law that the autonomous human being freely gives itself. This law obliges one to treat humanity—understood as rational agency, and represented through oneself as well as others—as an end in itself rather than (merely) as means to other ends the individual might hold. Kant is known for his theory that all moral obligation is grounded in what he calls the "categorical imperative", which is derived from the concept of duty. He argues that the moral law is a principle of reason itself, not based on contingent facts about the world, such as what would make us happy; to act on the moral law has no other motive than "worthiness to be happy".[124] |

道徳思想 主な記事 カント倫理学(→カ ント主義倫理) カントは3つの著作で倫理学(道徳哲学)を展開した: 道徳形而上学の基礎づけ』(1785年)、『実践理性批判』(1788年)、『道徳形而上学』(1797年)である。道徳に関してカントは、善の源泉は人 間主体の外部にあるもの、自然の中や神から与えられたものにはなく、むしろ善い意志そのものにしかないと主張した。善い意志とは、自律した人間が自らに自 由に与える普遍的な道徳法則に従って義務から行動するものである。この法則は、人間性-理性的主体性として理解され、自分自身だけでなく他者を通して表現 される-を、(単に)個人が保持するかもしれない他の目的のための手段としてではなく、それ自体の目的として扱うことを義務づけている。 カントは、すべての道徳的義務は義務概念から派生した「定言命法」と呼ばれるものに根ざしているという理論で知られている(→「義務論=デオントロジー」)。彼は、道徳律は理性そのものの原理であり、何が私たちを幸福にす るかといった世界に関する偶発的な事実に基づくものではないと主張する。 |

| The idea of freedom In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant distinguishes between the transcendental idea of freedom, which as a psychological concept is "mainly empirical" and refers to "whether a faculty of beginning a series of successive things or states from itself is to be assumed",[125] and the practical concept of freedom as the independence of our will from the "coercion" or "necessitation through sensuous impulses". Kant finds it a source of difficulty that the practical idea of freedom is founded on the transcendental idea of freedom,[126] but for the sake of practical interests uses the practical meaning, taking "no account of ... its transcendental meaning", which he feels was properly "disposed of" in the Third Antinomy, and as an element in the question of the freedom of the will is for philosophy "a real stumbling block" that has embarrassed speculative reason.[125] Kant calls practical "everything that is possible through freedom"; he calls the pure practical laws that are never given through sensuous conditions, but are held analogously with the universal law of causality, moral laws. Reason can give us only the "pragmatic laws of free action through the senses", but pure practical laws given by reason a priori[125] dictate "what is to be done".[127] Kant's categories of freedom function primarily as conditions for the possibility for actions (i) to be free, (ii) to be understood as free, and (iii) to be morally evaluated. For Kant, although actions as theoretical objects are constituted by means of the theoretical categories, actions as practical objects (objects of practical use of reason, and which can be good or bad) are constituted by means of the categories of freedom. Only in this way can actions, as phenomena, be a consequence of freedom, and be understood and evaluated as such.[128] |

自由の概念 『純粋理性批判』においてカントは、心理学的概念として「主として経験的」であり、「そ れ自体から一連の連続的な事物や状態を開始する能力が想定されるかどうか」に言及する自由の超越論的概念[125]と、「感覚的衝動による強制」や「必然 性」からの意志の独立としての自由の実践的概念とを区別している。カントは自由の実践的観念が自由の超越論的観念の上に基礎づけられていることを困難の原 因であると考えるが[126]、実践的な利益のために実践的な意味を用い、「...その超越論的な意味を考慮に入れない」のであり、その超越論的な意味は 第三アンチノミーにおいて適切に「処分された」ものであり、意志の自由の問題の要素として哲学にとって思弁的理性を困惑させた「真のつまずき」であると感 じている[125]。 カントは実践的なものを「自由によって可能なすべてのもの」と呼び、感覚的な条件によって与えられることはないが、普遍的な因果律と類似して保持される純 粋な実践的法則を道徳的法則と呼ぶ。理性は「感覚を通じた自由な行為のプラグマティックな法則」しか与えることができないが、ア・プリオリ[125]に理 性によって与えられる純粋実践法則は「何をなすべきか」を指示する[127]。 カントの自由の範疇は主として、(i)行為が自由であり、(ii)自由であると理解され、(iii)道徳的に評価される可能性の条件として機能している。 カントにとって、理論的対象としての行為は理論的カテゴリーによって構成されるが、実践的対象(理性の実践的使用の対象であり、善であることも悪であるこ ともありうるもの)としての行為は自由のカテゴリーによって構成される。このようにしてのみ、現象としての行為は自由の結果であり、そのように理解され評 価されうるのである[128]。 |

| The categorical imperative In his Groundwork, Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative: "Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you at the same time can will that it become a universal law." Kant makes a distinction between categorical and hypothetical imperatives. A hypothetical imperative is one that we must obey to satisfy contingent desires. A categorical imperative binds us regardless of our desires: for example, everyone has a duty to not lie, regardless of circumstances, even though it is sometimes in our narrowly selfish interest to do so. These imperatives are morally binding because they are based on reason, rather than contingent facts about an agent.[129] Unlike hypothetical imperatives, which bind us insofar as we are part of a group or society which we owe duties to, we cannot opt out of the categorical imperative, because we cannot opt out of being rational agents. We owe a duty to rationality by virtue of being rational agents; therefore, rational moral principles apply to all rational agents at all times.[130] Stated in other terms, with all forms of instrumental rationality excluded from morality, "the moral law itself, Kant holds, can only be the form of lawfulness itself, because nothing else is left once all content has been rejected".[131] Kant provides three formulations for the categorical imperative. He claims that these are necessarily equivalent, as all being expressions of the pure universality of the moral law as such.[132] Many scholars, however, are not convinced.[133] |

定言命法 イマヌエル・カントは『下地』の中で、定言命法を紹介した。「その格律に従ってのみ行動し、それによって同時にそれが普遍的な法則となるように意志するこ とができる」。 カントは定言命法と仮言命法を区別している。仮言的命令とは、偶発的な欲望を満たすために従わなければならない命令である。定言命法は、私たちの欲望に関 係なく私たちを拘束するものである。例えば、私たちの狭い利己的な利益のために嘘をつくことがあるとしても、状況に関係なく、誰にでも嘘をつかない義務が ある。これらの命令文が道徳的に拘束力を持つのは、それが行為者に関する偶発的な事実ではなく、理性に基づいているからである[129]。私たちが義務を 負う集団や社会の一員である限りにおいて私たちを拘束する定言命法とは異なり、私たちは合理的な行為者であることを選ぶことができないため、定言命法から 逃れることはできない。したがって、理性的な道徳原理は、すべての理性的な主体に対して常に適用される[130]。別の言い方をすれば、道具的な理性のあ らゆる形態が道徳から排除されることで、「道徳律それ自体が合法性の形態そのものとなりうるだけであり、すべての内容が拒絶されれば、それ以外のものは何 も残らないからである」とカントは主張している[131]。 カントは、定言命法について 3 つの定式化を提示している。彼は、これらはすべて道徳律そのものの純粋な普遍性を表現しているものであり、必然的に同等であると主張している[132]。 しかし、多くの学者はこの主張に納得していない[133]。 |

| The formulas are as follows: Formula of Universal Law: "Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you at the same time can will that it become a universal law";[134] alternatively, Formula of the Law of Nature: "So act, as if the maxim of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature."[134] Formula of Humanity as End in Itself: "So act that you use humanity, as much in your own person as in the person of every other, always at the same time as an end and never merely as a means".[135] Formula of Autonomy: "the idea of the will of every rational being as a will giving universal law",[136] or "Not to choose otherwise than so that the maxims of one's choice are at the same time comprehended with it in the same volition as universal law";[137] alternatively, Formula of the Realm of Ends: "Act in accordance with maxims of a universally legislative member for a merely possible realm of ends."[138][139] Kant defines maxim as a "subjective principle of volition", which is distinguished from an "objective principle or 'practical law.'" While "the latter is valid for every rational being and is a 'principle according to which they ought to act[,]' a maxim 'contains the practical rule which reason determines in accordance with the conditions of the subject (often their ignorance or inclinations) and is thus the principle according to which the subject does act.'"[140] Maxims fail to qualify as practical laws if they produce a contradiction in conception or a contradiction in the will when universalized. A contradiction in conception happens when, if a maxim were to be universalized, it ceases to make sense, because the "maxim would necessarily destroy itself as soon as it was made a universal law".[141] For example, if the maxim 'It is permissible to break promises' was universalized, no one would trust any promises made, so the idea of a promise would become meaningless; the maxim would be self-contradictory because, when it is universalized, promises cease to be meaningful. The maxim is not moral because it is logically impossible to universalize—that is, we could not conceive of a world where this maxim was universalized.[142] A maxim can also be immoral if it creates a contradiction in the will when universalized. This does not mean a logical contradiction, but that universalizing the maxim leads to a state of affairs that no rational being would desire. |

公式は以下の通りである: 普遍的法則の公式 ★普遍的法則の公式:「その格言に従ってのみ行動し、それによって同時にそれが普遍的法則となるように意志することができる」[134]、 ★自然の法則の公式: 「あなたの行動の極意が、あなたの意志によって普遍的な自然の法則となるかのように、行動しなさい」[134]。 ★それ自体が目的としての人間性の公式: "だから、人間性を、自分自身においても、他のあらゆる人の人間性においても、常に同時に目的として、決して単に手段として用いることのないように行動し なさい"[135]。 ★自律の公式: 「すべての理性的存在の意志が普遍的な法則を与える意志であるという考え方」[136]、あるいは「自分の選択の極意が同時に普遍的な法則として同じ意志 の中にそれとともに包含されるようにすること以外の選択をしないこと」[137]、 目的の領域の公式:「単に可能な目的の領域のために普遍的に立法されたメンバーの格言に従って行動する」[138][139]。 カントはマキシムを「意志の主観的原理」と定義しており、これは「客観的原理または『実践的法則』」とは区別される。後者がすべての理性的存在にとって有 効であり、「それに従って行動すべき原理」であるのに対して、マキシムは「理性が主体の条件(しばしばその無知や傾向)に従って決定する実践的規則を含 み、したがって主体がそれに従って行動する原理である」[140]。 マクシム(格律)は、それが普遍化されたときに観念における矛盾や意志における矛盾を生じさせる場合には、実践法則としての資格を有しない。例えば、「約 束を破る ことは許される」という格言が普遍化された場合、誰も約束を信用しなくなるので、約束という観念が意味をなさなくなる。つまり、この格言が普遍化されるよ うな世界を考えることはできないのである[142]。格言はまた、それが普遍化されたときに意志の中に矛盾を生じさせる場合にも不道徳となりうる。これは 論理的な矛盾を意味するのではなく、その格言を普遍化することで、理性的な存在であれば誰も望まないような状態をもたらすことを意味する。 |

| "The Doctrine of Virtue" As Kant explains in the 1785 Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (and as its title directly indicates) that text is "nothing more than the search for and establishment of the supreme principle of morality".[143] His promised Metaphysics of Morals, however, was much delayed and did not appear until its two parts, "The Doctrine of Right" and "The Doctrine of Virtue", were published separately in 1797 and 1798.[144] The first deals with political philosophy, the second with ethics. "The Doctrine of Virtue" provides "a very different account of ordinary moral reasoning" than the one suggested by the Groundwork.[145] It is concerned with duties of virtue or "ends that are at the same time duties".[146] It is here, in the domain of ethics, that the greatest innovation by The Metaphysics of Morals is to be found. According to Kant's account, "ordinary moral reasoning is fundamentally teleological—it is reasoning about what ends we are constrained by morality to pursue, and the priorities among these ends we are required to observe".[147] More specifically, There are two sorts of ends that it is our duty to have: our own perfection and the happiness of others (MS 6:385). "Perfection" includes both our natural perfection (the development of our talents, skills, and capacities of understanding) and moral perfection (our virtuous disposition) (MS 6:387). A person's "happiness" is the greatest rational whole of the ends the person set for the sake of her own satisfaction (MS 6:387–388).[148] Kant's elaboration of this teleological doctrine offers up a moral theory very different from the one typically attributed to him on the basis of his foundational works alone. |

「徳の教義」 カントが1785年の『道徳形而上学の基礎づけ』で説明しているように(そ してそのタイトルが直接示しているように)、そのテキストは「道徳の最高原理を探求 し、確立することにほかならない」[143]。しかし、彼の約束した『道徳形而上学』は大幅に遅れ、その2つの部分、『権利の教義』と『徳の教義』が 1797年と1798年に別々に出版されるまで現れなかった[144]。 『徳の教義』は、『根拠』によって示唆されたものとは「通常の道徳的推論 のまったく異なる説明」を提供する[145]。それは徳の義務、あるいは「同時に義 務である目的」[146]に関するものである。カントの説明によれば、「通常の道徳的推論は基本的に目的論的なものであり、私たちが道徳によってどのよう な目的を追求するよう拘束されているか、そしてこれらの目的のうちで私たちが守るべき優先順位について推論するものである」[147]、 私たちの義務である目的には、私たち自身の完全性と他者の幸福という2 種類がある(MS 6:385)。「完全性」には、私たちの自然的完全性(才能、技能、理解能力の発達)と道徳的完全性(高潔な気質)の両方が含まれる(MS 6:387)。人の「幸福」とは、その人が自己満足のために設定した目的の最大の合理的全体である(MS 6:387-388)[148]。 カントがこの目的論的教義を推敲することで、彼の基礎となる著作だけに 基づいて一般的にカントに帰せられるものとはまったく異なる道徳理論が提示される。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Kant |

カント入門 |

★︎実践理性の二律背反▶︎人倫の形而上学の基礎づ

け▶︎︎道

徳の形而上学の基礎づけ(GMS)▶︎純粋理性批判▶︎︎カントの定言命法▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

★GMSは、自然的意識からスタートする。KpVは、実践理性の能力を分 析を試みる限りで『純粋理性批判KrV(Kritik der reinen Vernunft)』に似ている。

★

章立て

|

序文 序論 実践理性批判の理念について 第1部 純粋実践理性の原理論 純粋実践理性の分析論 純粋実践理性の原則について 純粋実践理性の対象の概念について 純粋実践理性の動機について 純粋実践理性の弁証論 純粋実践理性一般の弁証論について 最高善の概念を規定するさいの純粋理性

の弁証論について 第2部 純粋実践理性の方法論 通常の倫理的理性認識から哲学的な倫理 的理性認識への移行 大衆的な倫理哲学から倫理の形而上学へ の移行 倫理の形而上学から純粋実践理性の批判 への移行 |

***

| Kritik der praktischen Vernunft (KpV) ist der Titel des zweiten Hauptwerks Immanuel Kants; es wird auch als „zweite Kritik“ (nach der Kritik der reinen Vernunft und vor der Kritik der Urteilskraft) bezeichnet und erschien erstmals 1788 in Riga. Die KpV enthält Kants Theorie der Moralbegründung und gilt bis heute als eines der wichtigsten Werke der Praktischen Philosophie überhaupt. | 『実践理性批判』(Critique of Practical Reason、CpR)は、イマヌエル・カントの2番目の主要著作のタイトルであり、「第二批判」(『純粋理性批判』の後、『判断力批判』の前)としても 知られ、1788年にリガで初めて出版された。批判』にはカントの道徳的理性論が収められており、現在でも実践哲学の最も重要な著作のひとつとみなされて いる。 |

| Wie die drei Jahre zuvor erschienene Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten (GMS) ist die KpV eine Grundlegungsschrift, die also keine Auseinandersetzung mit der praktischen Anwendung der Grundsätze der Moral zum Gegenstand hat, sondern auf die Frage antwortet, wie das sittliche Handeln durch die praktische Vernunft bestimmt werden kann. In der KpV geht es vor allem darum, das grundlegende Prinzip der Moral, ihre Aufgaben und Grenzen festzusetzen. Dies ist der Kategorische Imperativ (KI), den Kant in der KpV wie folgt formuliert: | その3年前に出版された『Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten(人倫/道徳の形而上学の基礎 づけ)』 (GMS)と同様、『KpV』は道徳原理の実践的適用を扱わない基礎的著作であるが、道徳的行動が実践理性によってどのように決定されうるかという疑問に 答えるものである。KpVは、道徳の基本原理、その課題と限界を確立することに主眼を置いている。これが定言命法(CIP)であり、カントは『KpV』で 次のように定式化している: |

| „Handle so, daß die Maxime deines Willens jederzeit zugleich als Prinzip einer allgemeinen Gesetzgebung gelten könne.“[1] | 「あ なたの意志の最大公約数が、常に一般的な立法の原理として同時に有効であるように行動しなさい」[1]。 |

| Damit lehnt Kant die seinerzeit traditionellen Weisen der Moralbegründung im moralischen Gefühl, im Willen Gottes oder in der Suche nach dem höchsten Gut als Glück ab. Für ihn liegt die einzige Möglichkeit, das oberste Prinzip der Moral zu bestimmen, in der reinen praktischen Vernunft. Die Vernunft ist einerseits auf das Erkenntnisvermögen gerichtet (‚Was kann ich wissen?‘). Das ist Thema der Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Zum anderen ist in ganz anderer Stoßrichtung das menschliche Handeln (‚Was soll ich tun?‘) Inhalt vernünftiger Überlegungen. Dies ist Gegenstand der KpV. Sein und Sollen sind bei Kant zwei nicht voneinander abhängige Aspekte der einen Vernunft. Für die menschliche Praxis ist die Freiheit als Grundlage autonomer Entscheidungen notwendig und evident, während sie in der theoretischen Vernunft nur als möglich erwiesen werden kann. Ein Handeln ohne Freiheit kann nicht gedacht werden. Dabei erkennen wir die Freiheit nur durch das Bewusstsein des Sittengesetzes. | このようにカントは、道徳を道徳感情や神の意志や幸福としての最高善の 探求に根拠づける伝統的な方法を否定している。彼にとって、道徳の最高原理を決定す る唯一の方法は、純粋な実践理性にある。一方では、理性は知識の能力(「私は何を知りうるか[‚Was kann ich wissen?‘]」)に向けられている。これが 『純粋理性批判』の主題である。 他方、人間の行動(「私は何をすべきか[‚Was soll ich tun?‘]」) は、まったく別の方向における理性的考察の内容である。これが『実践理性批判(KpV)』の主題である。カントにとって、「存在する こと」と「なすべきこと」は、一つの理性の非独立的な二つの側面である。人間の実践にとって、自由は自律的決定の基礎として必要であり明白であるが、理論 的理性においては、それは可能であることを示すことができるだけである。自由のない行動は考えられない。私たちは道徳法則を意識することによってのみ、自 由を認識する。 |

| Kant zeigt, dass man das Sittengesetz nicht durch Erfahrung erkennen, sondern nur als ein allgemeines Gesetz der Form nach bestimmen kann. Diese Form, der KI, ist dann auf die subjektiven Handlungsregeln, die Maximen, anzuwenden und das Prüfkriterium ist, ob die jeweilige Maxime dem Grundprinzip der Verallgemeinerbarkeit standhält. Ob eine Maxime moralisch akzeptabel oder sogar geboten ist, kann nach Kant bereits der „gemeine Menschenverstand“ (also jedermann) erkennen. Hierzu bedarf es keiner besonderen Theorie. Der Mensch kann nur moralisch handeln, weil er selbstbestimmt (autonom) ist und weil die Vernunft ein unabweisbares Faktum ist. Maßstab für die Beurteilung einer Maxime sind die Begriffe Gut und Böse als Kategorien der Freiheit, d. h. als sittliche und nicht als empirische Begriffe. Wie nun eine mögliche Handlung sittlich einzustufen ist, dazu bedarf es der praktischen Urteilskraft. Mit deren Hilfe wird das sittliche Wollen als gut oder böse bestimmt. Gründe und Motive (Triebfedern) für moralisches Handeln sieht Kant in einer besonderen Einsicht der praktischen Vernunft, die in der Achtung für das Sittengesetz resultiert. | カントは、道徳法則は経験を通じて認識することは不可能であり、形の一 般法則としてのみ決定できることを示す。そして、この形式であるCIは、主観的な行 動規則である最大公約数に適用され、それぞれの最大公約数が一般化可能性の基本原則に耐えられるかどうかがテスト基準となる。カントによれば、「常識」 (すなわち、誰でも)は、ある極意が道徳的に受け入れられるかどうか、あるいは必要であるかどうかさえ、すでに認識することができる。これには特別な理論 は必要ない。人が道徳的に行動できるのは、人が自己決定的(自律的)であり、理性が反論の余地のない事実であるからにほかならない。格言の判断基準は、自 由の範疇としての善と悪の概念、すなわち道徳的な概念であり、経験的な概念ではない。可能な行為を道徳的にどのように分類するかは、実践的な判断を必要と する。その助けを借りて、道徳的意志は善か悪か決定される。カントは、道徳的行動の理由と動機(原動力)を実践理性の特別な洞察に見る。 |

| In der Dialektik der reinen

praktischen Vernunft wird die Frage ‚Was

darf ich hoffen?‘ zum Gegenstand der Betrachtung. Hier entwickelt Kant

seine Gedanken zur Bestimmung des höchsten Guts. Es ist die Frage nach

dem Unbedingten im praktischen Sinn. In der KrV hatte Kant gezeigt,

dass man die unbedingten Ideen von Freiheit, Gott und Unsterblichkeit

der Seele zwar nicht beweisen, wohl aber als regulative Ideen für

möglich halten kann. Für die praktische Vernunft sind diese Ideen aus

Sicht von Kant denknotwendig und können deshalb als Postulate der

reinen praktischen Vernunft als wirklich angesehen werden. Im sehr

kurzen zweiten Teil der KpV, der Methodenlehre, entwirft Kant ein

knappes Konzept der moralischen Erziehung, mit dem junge Menschen dazu

angeregt werden sollen, ihre Urteilskraft mit Blick auf moralische

Fragen auszubilden. Kants Auffassungen zur praktischen Moralphilosophie

finden sich in der Metaphysik der Sitten sowie in seinen Vorlesungen

zur Moralphilosophie.[2] |

『純粋実践理性の弁証法』では、「何を望むか[‚Was darf ich hoffen?‘]」という問いが考察の対象となる。ここでカントは最高善の決定についての考えを展開する。実践的な意 味での無 条 件の問題である。『実践理性批判(KpV)』においてカントは、自由、神、魂の不滅という無条件の観念は証明することはできないが、調整的観念としては可 能であると考えられ ることを示した。カントの見解では、これらの観念は実践理性にとって必要であり、それゆえ純粋実践理性の真の定立とみなすことができる。『実践理性批判 (KpV)』の非常に短 い第二部である『方法序説』において、カントは道徳教育の簡単な概念を概説している。実践的な道徳哲学に関するカントの見解は、『道徳の形而上学』や『道 徳哲学講義』[2]に見出すことができる。 |

| Der Philosoph Lewis White Beck hat beobachtet, dass Kants Kritik der praktischen Vernunft von modernen Gelehrten manchmal vernachlässigt und in ihren Köpfen sogar durch Kants Grundlagen der Metaphysik der Moral verdrängt wurde. Er argumentiert weiter, dass der Student von Kants Werken leicht ein vollständiges Verständnis von Kants Moralphilosophie erlangen kann, indem er Kants Analyse der Konzepte Freiheit und praktische Vernunft durchgeht, wie sie in seiner "zweiten Kritik" dargelegt werden. Beck behauptet, dass Kants „zweite Kritik“ dazu dient, jeden dieser unterschiedlichen Stränge zu einem einheitlichen Muster für eine umfassende Theorie moralischer Autorität im Allgemeinen zu verweben.[3][4][5] | 哲学者のルイス・ホワイト・ベックは、カントの『実践理性批判』が現代 の学者たちの間で軽視され、カントの『道徳形而上学の基礎づ け』に取って代わられることさえあると指摘している。彼はさらに、カントの著作を学ぶ者は、「第二批判」で示された自由と実践理性の概念についてのカント の分析を経ることによって、カントの道徳哲学の完全な理解を容易に得ることができると主張する。ベックは、カントの「第二批判」は、道徳的権威の包括的な 理論一般を統一的なパターンにするために、それぞれの異なる筋を織り込む役割を果たしていると主張している[3][4][5]。 |

***

| Inhaltsverzeichnis |

目次 |

| 1 Gliederung

des Werks 2 Zielsetzung des Werks 3 Handlungstheorie 4 Analytik 4.1 Grundsätze

der praktischen Vernunft

5 Wichtigste Ausgaben4.1.1

Kategorischer Imperativ

4.2 Begriffe der reinen praktischen Vernunft4.1.2 Faktum der Vernunft 4.1.3 Autonomie und Heteronomie 4.1.4 Traditionelle Grundsätze der Moral 4.2.1 Das Gute

und das Böse

4.3 Triebfedern der reinen praktischen Vernunft4.2.2 Kategorien der praktischen Vernunft 4.2.3 Typik der reinen praktischen Urteilskraft 4.4 Kritische Beleuchtung 6 Literatur 7 Siehe auch 8 Weblinks |

1 作品構成 2 作品の目的 3 行動論 4 分析 4.1 実践理性の原理

5 最も重要な版4.1.1 定言命法

4.2 純粋実践理性の概念4.1.2 理性の事実 4.1.3 自律と他律 4.1.4 伝統的道徳原理 4.2.1 善と悪

4.3 純粋実践理性の原動力4.2.2 実践理性のカテゴリー 4.2.3 純粋実践的判断の種類 4.4 批判的照明 6 文献 7 関連項目 8 ウェブリンク |

| Gliederung des Werks Der Aufbau des Werks ist an die Struktur, die Kant bereits in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft verwendet hatte, angelehnt. Nach einer Vorrede und einer Einleitung gibt es zwei Hauptteile. Die „Elementarlehre der reinen praktischen Vernunft“ und die „Methodenlehre der reinen praktischen Vernunft“. In der Elementarlehre unterscheidet Kant wiederum die Analytik und die Dialektik der reinen praktischen Vernunft. In der Analytik entwickelt Kant seine theoretische Position. Dabei skizziert er zunächst die Grundsätze, dann analysiert er Begriffe und schließlich befasst er sich mit den nicht-empirischen „Triebfedern“ der Moral. Die Dialektik ist dann die „Darstellung und Auflösung des Scheins in Urteilen der praktischen Vernunft“.[6] Der zweite Teil, die Methodenlehre, umfasst nur 12 der 163 Seiten, die das Werk in der Akademie-Ausgabe ausmacht. Hier skizziert Kant eine Theorie der moralischen Erziehung. Am Ende der KpV steht der „Beschluss“ mit dem berühmten Zitat: „Zwei Dinge erfüllen das Gemüt mit immer neuer und zunehmender Bewunderung und Ehrfurcht, je öfter und anhaltender sich das Nachdenken damit beschäftigt: Der bestirnte Himmel über mir, und das moralische Gesetz in mir. Beide darf ich nicht als in Dunkelheiten verhüllt, oder im Überschwenglichen, außer meinem Gesichtskreise, suchen und bloß vermuten; ich sehe sie vor mir und verknüpfe sie unmittelbar mit dem Bewußtsein meiner Existenz.“ – KpV 161/162[7] |

作品の構造 作品の構成は、カントがすでに『純粋理性批判』で用いていた構成に基づいている。序文と序論の後、2つの主要なセクションがある。純粋実践理性の初歩理 論」と「純粋実践理性の方法論」である。初等理論』では、カントは純粋実践理性の分析的なものと弁証法的なものを区別している。カントは『分析論』におい て理論的立場を展開する。まず原理を概説し、次に概念を分析し、最後に道徳の非経験的な「原動力」を扱う。そして弁証法とは「実践理性の判断における外観 の表象と解消」である[6]。 第二部、方法序説は、アカデミー版では163ページ中12ページしかない。ここでカントは道徳教育の理論を概説している。KpVの最後には、有名な引用を 含む「決意」がある: 「二つの物自体が、思考をそれらに集中させればさせるほど、常に新しい、増大する感嘆と畏敬の念で心を満たす: 私の頭上に広がる星空と、私の内なる道徳律である。私はこの二つを、私の視野の輪の向こうの、曖昧さや溢れ出るものの中にベールに包まれたものとして探し 求め、単に推測してはならない。 - KpV 161/162[7] を参照。 |

| Zielsetzung des Werks Der Titel Kritik der praktischen Vernunft klingt ähnlich dem der Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Die Stoßrichtung ist jedoch unterschiedlich. In der KrV wollte Kant zeigen, welche Grenzen der reinen Vernunft als Vermögen der Erkenntnis aufgegeben sind. Es gibt keine Erkenntnis ohne empirische Anschauungen. In der KpV hingegen richtet sich die Kritik gegen Ansprüche der empirisch-praktischen Vernunft, denen er Grenzen setzen will. Das Sittengesetz ist ein Produkt der reinen Vernunft und nicht empirischer Erfahrung, so dass es nicht zu kritisieren ist.[8] In der Vorrede und in der Einleitung spricht Kant eine Reihe von Absichten an, die er mit der KpV verfolgt. Er möchte darlegen, dass die reine Vernunft praktisch werden kann.[9] dass die Ideen von Freiheit, Gott und Unsterblichkeit, die in der spekulativen Kritik nur als Möglichkeit aufgezeigt werden konnten, in der praktischen Vernunft als Realität angenommen werden können.[10] dass die Prinzipien der reinen praktischen Vernunft in Einklang mit der Kritik der reinen Vernunft stehen.[11] dass die empirisch bedingte Vernunft nicht das Sittengesetz als solches erfassen kann, weil die Bedingung von Allgemeinheit und Notwendigkeit nicht erfüllt ist.[12] Kant geht es in seiner Ethik nicht darum, eine neue Moral zu erfinden, sondern das im allgemeinen Verständnis immer schon vorhandene Bewusstsein der Sittlichkeit philosophisch zu analysieren und präzise zu formulieren. So formuliert er im Anhang zu Der Streit der Fakultäten: „Ich habe aus der Kritik der reinen Vernunft gelernt, daß Philosophie nicht etwa eine Wissenschaft der Vorstellungen, Begriffe und Ideen, oder eine Wissenschaft aller Wissenschaft, oder sonst etwas Ähnliches sei; sondern eine Wissenschaft des Menschen, seines Vorstellens, Denkens und Handelns; sie soll den Menschen nach allen seinen Bestandteilen darstellen, wie er ist und sein soll, d. h. sowohl nach seinen Naturbestimmungen, als auch nach seinem Moralitäts- und Freiheitsverhältnis.“[13] |

作品の目的 『実践理性批判』というタイトルは、『純粋理性批判』と似ているように聞こえる。しかし、その趣旨は異なる。カントは『純粋理性批判』において、認識能力 としての純粋理性の限界を示したかった。経験的見解なしには知識は存在しない。一方、KpVでは、経験的実践的理性の主張に対する批判であり、その限界を 示したいのである。道徳律は純粋理性の産物であり、経験的経験の産物ではないから、それを批判することはできない[8]。 序文と序論において、カントはKpVで追求するいくつかの意図を述べている。彼は次のことを示したいと考えている。 純粋理性は実践的になりうる[9]。 思弁的批評においては可能性としてしか示されなかった自由、神、不死の観念が、実践的理性においては現実として受容されうることを示す[10]。 純粋実践理性の原理は純粋理性批判と矛盾しない[11]。 経験的に条件づけられた理性は、一般性と必然性の条件が満たされないために、道徳法則をそのようなものとして把握することができないこと[12]。 カントの倫理学は新しい道徳を発明することではなく、一般的な理解の中に常に存在していた道徳の意識を哲学的に分析し、正確に定式化することに関心があ る。こうして彼は『諸能力の論争』の付録でこう述べている: 私は『純粋理性批判』から、哲学とは概念、観念、観念の科学、あるいはすべての科学の科学、あるいはそれに類するものではなく、人間の科学、人間の観念、 思考、行動の科学であることを学んだ。 |

| Handlungstheorie In Kants Werken findet sich keine eigene Abhandlung oder geschlossene Ausführung zur Handlungstheorie.[14] Für das Verständnis der Ausführungen Kants zum moralischen Handeln in der Kritik der praktischen Vernunft ist jedoch ein Einblick in seine Konzeption des Handelns hilfreich.[15] In seiner empirischen Natur ist der Mensch nach Kant den Kausalgesetzen der Natur unterworfen. Zugleich hat der Mensch das Vermögen der praktischen Vernunft, das ein Vermögen der Selbstbestimmung beinhaltet (KrV B 562).[16] Kants Handlungstheorie beruht damit auf zwei Aspekten und integriert einerseits die Vorstellungen des Rationalismus der Wolff’schen Schule, für die die Erkenntnis des Guten das Motiv zum moralischen Handeln ist, und andererseits die empirischen Thesen der britischen Moral-Sense-Theoretiker (Hutcheson, Hume), die der Vernunft absprechen, moralisches Handeln motivieren zu können, so dass moralisches Handeln allein auf Gefühlen beruht.[17] Durch Sachverhalte wird der Mensch affiziert. Diese äußeren Wirkungen lösen nach Kant beim Menschen Gefühle der Lust oder der Unlust aus. Aus diesen Gefühlen entstehen Begehrungen (Vgl. MS VI, 211–214). Diese Begehrungen nennt Kant auch Neigungen oder, bei nachhaltigerer, auf vernünftigen Überlegungen gestützter Einstellung, Interessen (GMS 413). Aufgrund dieser Interessen hat der Mensch ein Bedürfnis zu handeln. Dabei setzt er sich mit Hilfe der praktischen Vernunft (Ratschläge der Klugheit) Zwecke zur Beförderung seiner eigenen Glückseligkeit.[18] Dies ist ein natürliches Streben des Menschen, bei dem der innere Sinn mit Annehmlichkeit affiziert wird. (Anmerkung auf [19]) Durch sein Begehrungsvermögen ist der Mensch in der Lage, eine Vorstellung von der Wirkung einer möglichen Handlung zu entwickeln. (KrV B 576 und Immanuel Kant: AA V, 9[20]) Dabei setzt er die Nötigung sinnlicher Antriebe (KrV B 830) nach Regeln der Klugheit (KrV B 828) um. Der Mensch handelt nach Kant grundsätzlich nach Maximen, d. h. subjektiven Handlungsregeln. Diese sind subjektive Prinzipien des Wollens (GMS 400 Anm.), die sich aus den Neigungen und Interessen des Handelnden ergeben.[21] Der Mensch kann sich nach Kant frei entscheiden, ob er die vorgestellte Handlung in eine konkrete Handlung überführen will. Entscheidet er sich für die Ausführung der Handlung, wird der Mensch durch seine Willensbestimmung zur intelligiblen Ursache eines neuen Sachverhalts (Kausalität aus Freiheit, KrV B 566). Er ist damit schlechthin erster Anfang einer Reihe von Erscheinungen (KrV B 478). Diese Fähigkeit, eine Handlung gemäß der eigenen Entscheidung auszuführen, nennt Kant freie Willkür des eigentlichen Subjekts. (KrV B 562/B 574, vgl. auch MS VI, 226–227). Der physische Handlungsvollzug wird durch die Willensmeinung, die in der jeweiligen Maxime zum Ausdruck kommt, zur Existenz gebracht. +++++++++++++++++++++ Die reine Vernunft hat die Eigenschaft, dass sie sich sowohl theoretisch als auch praktisch vollständig von den empirischen Erfahrungen distanzieren kann. Kant spricht dann von der intelligiblen Welt. (z. B. KrV B 475) Reine praktische Vernunft ist das Vermögen, nach Vorstellungen von Gesetzen zu handeln. Der Mensch besitzt damit nicht nur die negative Freiheit von empirischen Einflüssen (Willkürfreiheit), sondern auch die positive Freiheit, sich ein unbedingtes Gesetz zu denken, das die reine praktische Vernunft sich selbst vorschreibt. (Autonomie, GMS IV, 412). Dies ist das Sittengesetz, dessen Handlungsregel Kant als Kategorischen Imperativ formuliert. Es ist das Grundgesetz der reinen praktischen Vernunft.[22] Mit Hilfe der reinen praktischen Urteilskraft kann der Mensch beurteilen, ob eine beabsichtigte Handlung und deren Maxime moralisch gut oder böse ist. Es gibt für Kant keine Handlung, ohne dass der Mensch sich zu seiner Handlungsabsicht, seinem Zweck, eine Maxime gebildet hat (Rel 6. 23–24).[23] Die reine praktische Vernunft gebietet nun, dem sich selbst aus Autonomie gegebenen Gesetz zu folgen und gute Handlungen auszuführen sowie schlechte Handlungen zu unterlassen. Hier bestimmt die Vernunft durch die bloße Form der praktischen Regel den Willen.Anm.[24] Dieses uneingeschränkte Gebot der reinen Vernunft ist aber für den Menschen nicht bindend, da er nicht nur Vernunftwesen, sondern zugleich auch Sinnenwesen ist, das sich entsprechend seinem Vermögen der freien Willkür entscheiden kann, auch anders als moralisch zu handeln. Der Mensch handelt dann nicht autonom, sondern der von äußeren Umständen fremdbestimmte Wille dient nur der vernünftigen Befolgung pathologischer (heteronomer) Gesetze.[25] Aus Gründen ergibt sich noch keine Motivation. Hierfür bedarf es einer Triebfeder, worunter der „subjektive Bestimmungsgrund des Willens eines Wesens verstanden wird, dessen Vernunft nicht schon vermöge seiner Natur dem objectiven Gesetz notwendig gemäß ist.“ ([26]) Das Sollen aus der reinen Vernunft heraus ist eine Art von (innerer) Notwendigkeit und eine Verknüpfung mit Gründen. (KrV B 575). Da das Moralgesetz uneingeschränkt gültig ist, stehen aus Gründen alle menschlichen Handlungen unter der Verbindlichkeit des Gesetzes. (MS 214) Damit wird der Kategorische Imperativ zum Gesetz der Pflicht.[27] Ein unmittelbares Motiv, so zu handeln, ergibt sich aber erst aus Einsicht in die Richtigkeit des Sittengesetzes, also aus Achtung für das Gesetz, die ein vernunftgewirktes Gefühl ist. Wer aus Achtung für das Gesetz handelt (moralisch motiviert ist), handelt nicht nur gemäß seiner Pflicht, sondern aus Pflicht[28]. „Das Wesentliche alles sittlichen Werts der Handlungen kommt darauf an, daß das moralische Gesetz den Willen unmittelbar bestimmt.“[29] Die Handlungstheorie Kants wird gelegentlich als „kausal“ bezeichnet.[30] Da Kant aber jeder Handlung einen Wert beimisst, d. h. jede Handlung einen normativen Inhalt hat, der als solcher kausal nicht erklärt werden kann, stellt sich die Frage, ob man die Handlungstheorie nicht eher als teleologisch, d. h. als an Zwecken orientiert, beschreiben muss.[31] |

行動理論 カントの著作には、行動理論に関する独自の論考や完結した説明は見当たらない[14]。しかし、実践的理性批判におけるカントの道徳的行動に関する説明を 理解するには、カントの行動概念について理解することが役立つ[15]。 カントによれば、人間はその経験的性質上、自然の因果法則に支配されている。同時に、人間は実践的理性を有しており、その中には自己決定の能力が含まれて いる(『純粋理性批判』B 562)。[16] したがって、カントの行動理論は 2 つの側面に基づいており、一方では、善の認識が道徳的行動の動機となるというヴォルフ学派の合理主義の考え方を、 善の認識が道徳的行動の動機であるとする考え方を統合し、他方では、道徳的行動の動機付けは理性には不可能であり、道徳的行動は感情のみに根ざしていると 主張する、英国の道徳感覚理論者(ハッチェソン、ヒューム)の経験的主張を統合している[17]。 人間は事実によって影響を受ける。カントによれば、これらの外的影響は、人間に快または不快の感情を引き起こす。これらの感情から欲望が生まれる(MS VI、211-214 参照)。カントは、この欲望を「傾向」とも呼び、より持続的で合理的な考察に基づく態度については「利益」と呼んでいる(GMS 413)。この利益に基づいて、人間は行動する欲求を持つ。その際、人間は実践的理性(賢明な助言)の助けを借りて、自分の幸福を促進するための目的を設 定する。[18] これは、内面の感覚が快で影響を受ける、人間の自然な欲求である。([19] の注釈)人間は、欲望能力によって、可能な行動の結果について想像力を働かせることができる(KrV B 576 およびイマヌエル・カント:AA V、9[20])。その際、人間は、知恵の規則(KrV B 828)に従って、感覚的衝動(KrV B 830)を強制する。カントによれば、人間は基本的に格律、すなわち主観的な行動規則に従って行動する。これらは、行動者の傾向や興味から生じる主観的な 意志の原則(GMS 400 注)である。[21] カントによれば、人間は、想像した行動を具体的な行動に移すかどうかを自由に決定することができる。その行動を実行することを決定した場合、人間は、その 意志決定によって、新しい事実の知的な原因となる(自由による因果関係、KrV B 566)。したがって、人間は、一連の現象の最初の始まりそのものである(KrV B 478)。自分の決定に従って行動を実行するこの能力を、カントは「真の主体の自由意志」と呼んでいる(KrV B 562/B 574、MS VI、226-227 も参照)。物理的な行動の実行は、それぞれの格律に表現される意志の意思によって実現される。 +++++++++++++++++++++ 純粋な理性には、理論的にも実践的にも、経験的経験から完全に距離を置くことができるという特性がある。カントはこれを「知的な世界」と呼んでいる。 (例:KrV B 475) 純粋実践的理性とは、法則の概念に従って行動する能力だ。人間は、経験的影響から解放される(恣意の自由)だけでなく、純粋実践的理性が自らに課す無条件 の法則を思考する積極的な自由も持っている。(自律性、GMS IV、412)。これが、カントが定言命法として定式化した行動の規則である道徳律である。これは、純粋実践的理性の基本法則である[22]。純粋実践的 判断力の助けを借りて、人間は、意図した行動とその格律が道徳的に善か悪かを判断することができる。カントにとって、人間が自分の行動意図、目的について 格律を形成しない限り、行動は存在しない(Rel 6. 23–24)。[23] 純粋実践的理性は、自律性から自らに課した法則に従い、善い行動を行い、悪い行動は控えるよう命じる。ここでは、理性は、実践的規則の純粋な形式によって 意志を決定する。注[24] しかし、この純粋な理性の無制限の命令は、人間には拘束力がない。なぜなら、人間は理性を持つ存在であると同時に、自由意志の能力に応じて、道徳的ではな い行動も選択できる感覚的な存在でもあるからだ。その場合、人間は自律的に行動しているのではなく、外部の状況によって決定された意志が、病的な(他律的 な)法則を合理的に従うためにのみ機能している[25]。 理由だけではまだ動機にはならない。そのためには、その「存在の意志の主観的な決定要因、すなわち、その存在の理性そのものが、その性質によって客観的な 法則に必然的に従うものではない」という原動力が必要だ。([26])純粋な理性から生じる「すべきこと」は、一種の(内的な)必然性であり、理由と結び ついている(KrV B 575)。道徳律は制限なく有効であるため、理由により、すべての人間の行為は道徳律の拘束力の下にある。(MS 214) これにより、定言命法は義務の法則となる。[27] しかし、そのように行動する直接的な動機は、道徳律の正当性を理解すること、つまり、理性によって生じる感情である道徳律の尊重から初めて生じる。法に対 する敬意から行動する者(道徳的に動機付けられている者)は、義務に従って行動するだけでなく、義務から行動する[28]。「行為の道徳的価値の本質は、 道徳法が意志を直接決定する点にある」[29]。 カントの行為理論は、時折「因果的」と表現されることがある[30]。しかし、カントはあらゆる行為に価値を付与している、つまり、あらゆる行為には規範 的な内容があり、それ自体は因果的に説明できないと主張しているため、この行為理論はむしろ「目的論的」、つまり目的に向けたものと表現すべきではないか という疑問が生じる[31]。 |

| Analytik Grundsätze der praktischen Vernunft Kategorischer Imperativ Das erste Hauptstück der Analytik dient der Herleitung des Kategorischen Imperativs und hat insoweit seine Entsprechung zum zweiten Teil der GMS. Der Plural in der Überschrift weist darauf hin, dass es Kant nicht nur um die Aufstellung seines eigenen obersten Grundsatzes der Moralphilosophie geht, sondern auch um die Zurückweisung der verschiedenen Grundsätze der bisherigen Moralphilosophien. Kant bezeichnet zunächst praktische Grundsätze als Regeln, die subjektiv oder objektiv sein können. Subjektive Regeln nennt er Maximen, objektive Regeln praktische Gesetze.[32] Objektiv bedeutet, dass die Regel nicht nur für das Subjekt, sondern für jedermann gültig ist.[33] Objektive Grundsätze sind universell geltende Handlungsregeln.[34] Solche praktischen Gesetze sind Imperative, die kategorisch gelten und frei von Zufälligkeit sind. Hiervon zu unterscheiden sind hypothetische Imperative, die als Zweck-Mittel-Relation nur Vorschriften der Geschicklichkeit oder Regeln der Klugheit sind, bloß für ein Subjekt gelten und keine allgemeinen Gesetze sind. Hypothetische Imperative sind objektiv gültig, aber nur subjektiv praktisch, weil der Zweck an ein Subjekt gebunden ist.[35] Grundsätze sind fundamentale praktische Sätze, die eine allgemeine Willensbestimmung enthalten und verschiedene praktische Regeln unter sich haben.[36] Ist der Satz auf eine Materie gerichtet, d. h. einen Gegenstand, dessen Wirklichkeit begehrt wird, so ist die Regel, unter der dieser Gegenstand erreicht werden soll, stets empirisch. Die Handlungsregel, der der Mensch folgt, beruht auf einer Maxime, die nur für ihn als Subjekt gültig ist. Das Streben nach einer Sache oder einem Sachverhalt entstammt den Sinnen und ist mit dem Gefühl der Lust oder Unlust verbunden. Kant nennt die Vorstellung, Ursache von der Wirklichkeit eines Gegenstandes (einer Tatsache) sein zu können, das BegehrungsvermögenFN[37]. Sofern das Begehrungsvermögen auf Vorstellungen der Lust beruht, nennt er es das untere Begehrungsvermögen. Das obere Begehrungsvermögen ist hingegen ein rationales Wollen, das allein durch die praktische Vernunft geleitet wird und keine Rücksicht auf sinnliche Strebungen nimmt. Es ist die Fähigkeit eines Wollens, das nicht von Neigungen abhängt. Kant ist der Auffassung, dass das Prinzip des Sittengesetzes (handle moralisch, d.i. gut und nicht böse[38]) nur aus dem oberen Begehrungsvermögen vermittelst der reinen praktischen Vernunft abgeleitet werden kann. Die in seiner Zeit klassischen Positionen des Strebens nach Glückseligkeit (Eudämonismus / Hedonismus) und der Selbstliebe (Egoismus) sind für Kant in der Natur des Menschen angelegt und jeder hat ein Recht darauf, danach zu streben. Doch beide Positionen sind von der Perspektive des Einzelnen abhängig und deshalb nicht geeignet, als oberstes Moralprinzip zu dienen. Sie sind kontingent und können deshalb die Forderung nach Allgemeingültigkeit und Notwendigkeit des Sittengesetzes nicht gewährleisten. Nachdem Kant festgestellt hat, dass das Sittengesetz formal sein muss, um nicht empirischen Zufälligkeiten zu unterliegen, diskutiert er den Zusammenhang von Sittengesetz und Freiheit.[39] Beide Begriffe sind a priori und vor aller Erfahrung.[40] Wenn das Sittengesetz rein formal ist und keinen empirischen Einflüssen unterliegt, dann muss das Wollen der reinen praktischen Vernunft auf einer Freiheit beruhen, die sowohl negativ als auch positiv von keinen empirischen Faktoren bestimmt wird. Diese absolute Freiheit ist mit der transzendentalen Freiheit in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft identisch.[41] Andererseits hat es die praktische Vernunft mit dem Bewusstsein des Sittengesetzes zu tun, das für ein endliches Vernunftwesen wie den Menschen unabweisbar ist. Aus dem Bewusstsein des Sittengesetzes folgt das Bewusstsein der Freiheit. In einer Fußnote verweist Kant bereits in der Einleitung auf die wechselseitige Bedingtheit von Freiheit und Sittengesetz hin: „Damit man hier nicht Inconsequenzen anzutreffen wähne, wenn ich jetzt die Freiheit die Bedingung des moralischen Gesetzes nenne und in der Abhandlung nachher behaupte, daß das moralische Gesetz die Bedingung sei, unter der wir uns allererst der Freiheit bewußt werden können, so will ich nur erinnern, daß die Freiheit allerdings die ratio essendi des moralischen Gesetzes, das moralische Gesetz aber die ratio cognoscendi der Freiheit sei. Denn wäre nicht das moralische Gesetz in unserer Vernunft eher deutlich gedacht, so würden wir uns niemals berechtigt halten, so etwas, als Freiheit ist (ob diese gleich sich nicht widerspricht), anzunehmen. Wäre aber keine Freiheit, so würde das moralische Gesetz in uns gar nicht anzutreffen sein.“ – Immanuel Kant: AA V, 4[42], vgl. [43] sowie GMS 447 Ich weiß, dass ich auch anders hätte handeln können. Freiheit ist in der KpV nicht nur möglich, sondern auch real, d. h. für die praktische Vernunft objektiv gegeben. Freiheit ist eine Gegebenheit der Erfahrung aufgrund des Sittengesetzes.[44] Henry Allison nennt dieses Wechselverhältnis die „Reprocity Thesis“.[45] Für Henri Lauener wäre diese Beziehung ein Zirkel, wenn Freiheit und Sittengesetz nicht durch die These vom Faktum der Vernunft (s.u.) vermittelt wären.[46] Der Mensch verfügt über praktische Vernunft, die seinen Willen bestimmt. Da er aber als endliches Wesen nicht nur über ein oberes Begehrungsvermögen verfügt, sondern auch ein unteres Begehrungsvermögen hat, das durch seine Lust (Triebe, Neigungen, Interessen, Annehmlichkeiten) beeinflusst wird, braucht er ein Prinzip für das richtige Handeln, das ihm ermöglicht, seine Pflicht zu erkennen. Dieses ist der Kategorische Imperativ (KI) als „Grundgesetz der reinen praktischen Vernunft“: „Handle so, daß die Maxime deines Willens jederzeit zugleich als Prinzip einer allgemeinen Gesetzgebung gelten könne.“ – Immanuel Kant: AA V, 30[47] Der KI ist ein rein formales aus der reinen Vernunft abgeleitetes Prinzip, das keinen empirischen Einflüssen unterliegt. Die Materie wird erst durch die inhaltliche Formulierung einer Maxime in den KI eingebracht. Dennoch hat der KI mit der Forderung nach der Universalisierung der Maxime ein inhaltliches Element, insofern hier die Anerkennung der gleichen Ansprüche aller vernünftigen Wesen beinhaltet ist. Kant formuliert den KI in der KpV nur in seiner Grundformel. Auf die Varianten, die in der GMS ausführlich behandelt werden (Naturgesetzformel, Menschenrechtsformel, Autonomieformel, Reich der Zwecke – Formel), geht Kant in der KpV nicht ein. Offensichtlich setzt er diese Varianten in der KpV als bekannt voraus. Insofern ergänzen sich beide Schriften ähnlich wie bei der Analyse hypothetischer Imperative, die in der GMS ebenfalls wesentlich ausführlicher ausfällt. Mit der Aufstellung des KI hat Kant zwei seiner in der Einleitung formulierten Ziele erreicht, nämlich dass reine Vernunft praktisch werden kann und dass sein Freiheitsbegriff in der KpV mit dem Begriff der transzendentalen Freiheit in der KrV übereinstimmt. Kant fasst sein Ergebnis zusammen: Das aufgestellte unbedingte Gesetz ist ein kategorisch praktischer Satz a priori. Gesetzgebend ist die reine praktische Vernunft. Das Gesetz ist eine objektive Regel, die bloß den Willen in Ansehung der Form seiner Maximen bestimmt, nicht aber die Materie selbst, die in der subjektiven Maxime enthalten ist. |

分析学 実践理性の原理 定言命法 アナリティクスの最初の主要部分は、定言命法を導き出すためのものであり、この点でGMSの第2部分に相当する。タイトルの複数形は、カントが自らの道徳 哲学の最高原理を確立するだけでなく、それまでの道徳哲学の諸原理を否定することにも関心を抱いていることを示している。 カントはまず、実践原理を主観的または客観的な規則として説明する。彼は主観的な規則を格言と呼び、客観的な規則を実践法則と呼ぶ[32]。客観的とは、 その規則が主体のみならず万人に対して有効であることを意味する[33]。これは仮説的命令とは区別されるべきものであり、仮説的命令は巧みさの規則や目 的と手段の関係としての慎重さの規則にすぎず、一人の主体にのみ適用され、一般的な法則ではない。仮言的命令は客観的には有効であるが、目的が主体に拘束 されているため、主観的には実践的であるにすぎない[35]。 原理とは、意志の一般的な決定を含む基本的な実践的命題であり、その中にはさまざまな実践的規則がある[36]。命題がある事柄、すなわちその現実が望ま れる対象に向けられているのであれば、この対象が達成されるべき規則はつねに経験的なものである。人間が従う行動の規則は、主体としての彼にのみ有効な格 言に基づいている。ある事物や状態を求める努力は感覚に由来し、快・不快の感情と結びついている。カントは、ある対象(事実)の実在の原因となりうるとい う考えを欲望の能力と呼んでいるFN[37]。欲望の能力が快の観念に基づいている限りにおいて、カントはそれを欲望の下位の能力と呼ぶ。他方、欲望の上 位の能力は、実践的理性のみによって導かれ、感覚的欲求を考慮に入れない理性的な意志である。それは、傾倒に依存しない意志の能力である。 カントは、道徳律の原理(道徳的に行動すること、すなわち善であって悪ではないこと[38])は、純粋な実践理性によってのみ、欲望という上位の能力から 導き出すことができるという意見である。カントにとって、幸福への努力(eudaemonism / hedonism)と自己愛(egoism)という古典的な立場は人間の本性に内在するものであり、誰もがそのために努力する権利がある。しかし、どちら の立場も個人の視点に依存するものであり、最高の道徳原理として機能するには適していない。それらは偶発的なものであり、それゆえ道徳律の普遍的妥当性と 必然性の要求を保証することはできない。 カントは、道徳律が経験的偶発性に左右されないためには形式的でなければならないことを立証した後、道徳律と自由との関係について論じている[39]。ど ちらの概念もアプリオリであり、すべての経験に先立つものである[40]。道徳律が純粋に形式的であり、経験的な影響を受けないのであれば、純粋な実践理 性の意志は、否定的にも肯定的にも、いかなる経験的要因によっても決定されない自由に基づいていなければならない。この絶対的自由は、『純粋理性批判』に おける超越論的自由と同一である[41]。他方、実践的理性は、人間のような有限の理性的存在にとって反論の余地のない道徳法則の認識と関係している。道 徳法則の認識から、自由の認識が生まれる。序章の脚注で、カントは自由と道徳律の相互条件性に言及している: 「私が今、自由を道徳律の条件と呼び、その後、道徳律が、私たちがまず自由を意識することができる条件であると論考の中で主張することが、ここで矛盾して いると思われないように、私はただ、自由は確かに道徳律の比率essendiであるが、道徳律は自由の比率cognoscendiであることを思い出させ るだけである。というのも、もし道徳律がわれわれの理性においてむしろ明確に認識されるものでなかったとしたら、われわれは、そのようなものを自由である と仮定することが(たとえそれ自体に矛盾がないとしても)正当化されるとは決して考えないであろうからである。しかし、もし自由がなければ、道徳律はわれ われの中にはまったく見いだされないであろう。」 - イマヌエル・カント:AA V, 4[42], [43], GMS 447参照 私は、もっと違う行動ができたはずだと知っている。KpVでは、自由は可能であるだけでなく、現実のもの、すなわち実践的理由のために客観的に与えられた ものでもある。ヘンリー・アリソンはこの相互関係を「互酬性のテーゼ」と呼んでいる[45]。アンリ・ローネルにとって、自由と道徳律が理性の事実のテー ゼ(下記参照)によって媒介されなければ、この関係は循環的なものとなる[46]。 人間は実践的理性を持っており、それが彼の意志を決定する。しかし、有限の存在である人間は、欲望という上位の能力だけでなく、欲望(衝動、傾向、興味、 快楽)に影響される下位の能力も持っているため、自分の義務を認識することを可能にする正しい行動のための原理が必要である。これが「純粋実践理性の基本 法則」としての定言命法(CI)である: 「あなたの意志の最大公約数が、一般的な立法の原理として常に有効であるように行動しなさい」。 - イマヌエル・カント:AA V, 30[47]. CIは純粋な理性に由来する純粋に形式的な原理であり、経験的な影響を一切受けない。物質がCIに導入されるのは、格言の実体的定式化を通じてのみであ る。とはいえ、格言の普遍化の要求によって、すべての理性的存在の平等な主張の承認がここに含まれる限り、CIは実体的な要素を持つ。カントは『KpV』 において、CIをその基本式においてのみ定式化している。カントは、GMSで詳細に扱われている変形(自然法公式、人権公式、自治公式、目的の王国公式) をKpVでは扱っていない。彼は明らかに、これらの変種がKpVで知られていることを前提としている。この点で、2つの著作は、GMSではより詳細な仮言 的命令に関する分析と同様に、互いに補完し合っている。 KIを確立することによって、カントは序論で定式化した目標のうち2つを達成した。すなわち、純粋理性が実践的になりうるということと、KpVにおける自 由の概念がKrVにおける超越論的自由の概念に対応するということである。カントはその結果を要約する: 確立された無条件の法則は、先験的に範疇的に実践的な命題である。 純粋な実践的理性は法の制定者である。 法則は客観的な規則であり、その極意の形式に関して意志を決定するだけであって、主観的な極意に含まれる事柄そのものを決定するわけではない。 |

| Faktum der Vernunft Anders als in der GMS (GMS III) bemüht sich Kant in der KpV nicht um eine weitere Begründung des Freiheitsbegriffs, sondern formuliert: „Man kann das Bewußtsein dieses Grundgesetzes ein Faktum der Vernunft nennen, weil man es nicht aus vorhergehenden Datis der Vernunft, z.B. dem Bewußtsein der Freiheit (denn dieses ist uns nicht vorher gegeben), herausvernünfteln kann, sondern weil es sich für sich selbst uns aufdrängt als ein synthetischer Satz a priori, der auf keiner, weder reinen noch empirischen Anschauung gegründet ist, […] Doch man muß, um dieses Gesetz als gegeben anzusehen, wohl bemerken: daß es kein empirisches, sondern das einzige Faktum der reinen Vernunft sei, die sich dadurch als ursprünglich gesetzgebend (sic volio, sic iubeo [so will ich, so befehle ich]) ankündigt.“ – Immanuel Kant: AA V, 31[48] Diese Aussage Kants ist in der Rezeption umstritten[49] Es gibt Autoren, die in der These vom Faktum der Vernunft ein Scheitern der Begründungsversuche Kants für seine Moralphilosophie sehen.[50] Einige Autoren sehen darin eine rein intuitionistische Antwort auf die Frage, warum man moralisch handeln soll.[51] Dieter Henrich spricht von dem Faktum als einer „sittlichen Einsicht“ und spricht dieser „Tatsache“ ein ontologisches Sein zu.[52] Lewis White Beck hat darauf hingewiesen, dass es für die Interpretation wichtig ist, ob im Begriff „Faktum der Vernunft“ das Sittengesetz als ein Faktum für die Vernunft (Gentivus objectivus) bezeichnet wird, oder ob das Faktum die Vernunft selbst ist (Genetivus subjectivus), die sich reflektierend als existent versteht. Im ersten Fall wäre der Intuitionismus-Vorwurf berechtigt und das Faktum eine eher zufällige Basis der kantischen Ethik, die nicht jeder erkennen muss. Für die zweite Interpretation spricht die Aussage Kants: „Denn, wenn sie, als reine Vernunft, wirklich praktisch ist, so beweiset sie ihre und ihrer Begriffe Realität durch die Tat, und alles Vernünfteln wider die Möglichkeit, es zu sein, ist vergeblich.“[53][54] Der Begriff des Faktums kann nach Marcus Willaschek bei Kant einerseits Tatsache bedeuten, andererseits auch Tat als Handlung.[55] Willaschek beschreibt das Faktum als eine Leistung der Vernunft, die ein Handlungsmotiv ist.[56] Klaus Steigleder warnt davor, dem Begriff des Faktums nur die Bedeutung einer Tat der Vernunft zu geben, es also allein mit moralischen Handlungen gleichzusetzen. Vielmehr gehört zum Faktum der Vernunft die Einsicht, dass es neben dem natürlichen Streben ein Gebot gibt, das unabhängig von Wünschen unbedingt verpflichtet. Das unbedingte Sollen ist eine Tatsache, die in der reinen praktischen Vernunft begründet ist.[57] Bettina Stangneth verweist darauf, dass das Faktum der Vernunft für Kant als etwas Gegebenes der Philosophie vorgängig ist.[58] Das Faktum ist „an die Hand gegeben“[59], es besteht „vor allem Vernünfteln über seine Möglichkeit“[60]. Es ist unbestreitbar[61], nicht empirisch[62], unleugbar[63], gründet auf keiner Anschauung[64], drängt sich uns auf[65], ist apodiktisch gewiss[66], liegt im Urteil des gemeinen Verstandes[67]. Die Wirkung des Faktums der Vernunft besteht in einem intellektuellen Zwang[68]. Der Mensch fühlt sich durch etwas genötigt, das nicht auf empirischen Prinzipien beruht[69]. Andreas Trampota erinnert daran, dass Kant bereits in der Kritik der reinen Vernunft darauf verwiesen hat, dass empirische Begriffe aufgrund der Realität ihres Gegenstandes eine Bedeutung haben, für die keine Deduktion (diskursive Begründung) erforderlich ist. (KrV B 116)[70] Analog führt Kant in der KpV aus, dass das Faktum der Vernunft nicht begründet werden kann. „Also kann die objective Realität des moralischen Gesetzes durch keine Deduction, durch alle Anstrengung der theoretischen, speculativen oder empirisch unterstützten Vernunft, bewiesen und also, wenn man auch auf die apodiktische Gewißheit Verzicht thun wollte, durch Erfahrung bestätigt und so a posteriori bewiesen werden, und steht dennoch für sich selbst.“[71]. Die praktische Vernunft ist ein nicht zu begründendes Grundvermögen des Menschen und damit ebenso real und unableitbar wie empirische Fakten. „Man kann dieses Faktum nicht begründen, sondern lediglich gegen Reduktionsversuche verteidigen, indem man seine unvermeidliche und irreduzible phänomenale Faktizität im vorphilosophischen Moralbewusstsein ,von jedermann' so deutlich wie möglich herausarbeitet.“[72] Für Otfried Höffe ist das Theoriestück vom Faktum der Vernunft ein Instrument zur Abwehr des Skeptizismus. Die Moralität ist eine Wirklichkeit, die wir immer schon anerkennen. Es ist die „moralische Selbsterfahrung des reinen praktischen Vernunftwesens.“[73] Höffe weist auch darauf hin, dass mit dem Faktum der Vernunft kein Fehlschluss von einem Sein auf ein Sollen (Humes Gesetz) vorliegt, weil Kant klar zwischen theoretischer und praktischer Vernunft trennt und das Sittengesetz aus der reinen praktischen Vernunft ohne jede empirische Basis ableitet.[74] Die auf das praktische Handeln ausgerichtete Vernunft enthält von vornherein den ihr immanenten Anspruch des Sollens, macht aber keine Aussage über Seiendes, weil der Kategorische Imperativ rein formal gewonnen wurde. |

理性の事実 『GMS』(GMS III)とは異なり、『KpV』ではカントは自由の概念をさらに正当化しようとはせず、代わりに定式化している: 「この基本法則の自覚を理性の事実と呼ぶことができる。しかし、この法則を与えられたものとみなすためには、次のことに注意しなければならない: それは経験的なものではなく、純粋理性の唯一の事実であり、それによって自らを元来法則を与えるもの(sic volio, sic iubeo [so I will, so I command])であると告げるのである。 」 - イマヌエル・カント:AA V, 31[48]. 理性の事実というテーゼに、道徳哲学を正当化しようとしたカントの試みの失敗を見る著者もいる[50]。 [52] ルイス・ホワイト・ベックは、「理性の事実」という用語において、道徳法則が理性にとっての事実(Gentivus objectivus)として記述されるのか、それともその事実が理性そのもの(Genetivus subjectivus)であり、理性は自らを反省的に存在すると理解するのかが解釈にとって重要であると指摘している。前者の場合、直観主義という非難 は正当化され、事実はカント倫理のむしろ偶然的な基礎となり、誰もが認識する必要はないだろう。もし純粋理性としての理性が本当に実践的であるならば、そ れは行為を通じてその実在性とその概念の実在性を証明するのであり、そうである可能性に反対するすべての推論は無駄だからである」[53][54]。 マルクス・ウィラシェックによれば、カントにおける事実の概念は、事実と行為としての事実の両方を意味することができる[55]。むしろ、理性の事実に は、自然的な努力に加えて、欲望に関係なく無条件に義務づけられる戒律が存在するという認識が含まれる。無条件の「べき」は、純粋な実践理性に立脚した事 実である[57]。 ベッティーナ・スタングネスは、カントにとって理性という事実は与えられたものとして哲学に先立つものであると指摘している[58]。事実は「手に与えら れた」ものであり[59]、「その可能性に関するあらゆる推論に先立って」存在する[60]。それは議論の余地のないもの[61]であり、経験的なもので はなく[62]、否定できないもの[63]であり、いかなる見解にも基づくものではなく[64]、われわれに自らを課すものであり[65]、アポディク ティヴに確かなものであり[66]、常識の判断の中にあるものである[67]。理性という事実の効果は知的強制力[68]にある。人間は経験的原則に基づ かないものによって強制されると感じる[69]。 アンドレアス・トランポタは、カントがすでに『純粋理性批判』において、経験的概念はその対象の実在性に起因する意味を持っており、そのために演繹(弁証 法的正当化)は必要ないと指摘していたことを想起する。(KrV B 116)[70] 同様に、カントは『KpV』において、理性の事実は正当化できないと述べている。「したがって、道徳法則の客観的実在性は、理論的、思弁的、経験的に支持 された理性のいかなる努力によっても、いかなる演繹によっても証明されることはなく、したがって、たとえアポディクティヴな確実性を放棄したくても、それ は経験によって確認され、したがって事後的に証明されることができ、しかもそれ自体として成り立つ」[71]。実践的理性は人間の基本的な能力であり、正 当化することはできず、したがって経験的事実と同様に現実的であり、証明することは不可能である。この事実を正当化することはできないが、「すべての人 」の哲学以前の道徳意識において、その不可避で還元不可能な現象的事実性を可能な限り明確に強調することによってのみ、縮小の試みからこの事実を擁護する ことができる」[72]。 オトフリート・ヘッフェにとって、理性の事実の理論は懐疑論から身を守るための道具である。道徳とは、私たちがすでに認識している現実である。それは「純 粋実践理性の道徳的自己認識」である[73]。ヘッフェはまた、カントが理論的理性と実践的理性を明確に区別し、経験的根拠なしに純粋実践理性から道徳法 則を導き出しているため、理性の事実があれば、存在からべきへの誤った結論(ヒュームの法則)は存在しないと指摘している。 [定言命法は純粋に形式的に得られたものであるからである。 |

| Autonomie und Heteronomie Im Anschluss an die Formulierung des KI stellt Kant fest: „Die Autonomie des Willens ist das alleinige Princip aller moralischen Gesetze und der ihnen gemäßen Pflichten: […] Also drückt das moralische Gesetz nichts anders aus, als die Autonomie der reinen praktischen Vernunft, d. i. der Freiheit, und diese ist selbst die formale Bedingung aller Maximen, unter der sie allein mit dem obersten praktischen Gesetze zusammenstimmen können.“[75] Für Kant sind ein freier Wille, ein moralischer Wille und reine praktische Vernunft einerlei[76] (vgl. GMS 447). Freiheit im negativen Sinn ist die Freiheit von materiellen Einflüssen. Freiheit im positiven Sinn ist die Freiheit, sich selbst Gesetze zu geben (Autonomie = Selbstgesetzgebung).[77] Der Begriff der Autonomie ist bei Kant mehrschichtig.[78] Zum einen wird damit das Vermögen bezeichnet, sich allein aus der Vernunft heraus unabhängig von empirischen Einflüssen selbst, wenn auch nur formale, Gesetze zu geben. Die Gesetzgebung der reinen praktischen Vernunft fordert von dem endlichen, nicht allein vernünftigen Menschen einer allgemeinen und á priori erkannten Regel zu folgen. Sie legt dem Menschen eine Verbindlichkeit auf. Das Selbst kennzeichnet Kant als „übersinnliche Natur“ der Menschen, als eine „Existenz nach Gesetzen, die von aller empirischen Bedingung unabhängig sind.“[79]. Autonomie ist damit bei Kant Bedingung der Möglichkeit von Moral.[80] Ohne Autonomie wäre praktisches Handeln nach dem moralischen Gesetz nicht möglich. Autonomie in diesem Sinne ist die Freiheit, nach einem selbst bestimmten Willen zu handeln. Dies ist reine Autonomie im Sinne der Selbstgesetzgebung durch reine praktische Vernunft. Der Gegenbegriff zur Autonomie ist für Kant die Heteronomie (Fremdbestimmung). Das sind Handlungsgründe (nicht Ursachen), die ihren Ursprung in sinnlich, empirischen Quellen haben. Der Mensch handelt mit heteronomen Motiven zwar frei im praktischen Sinn, folgt aber nicht dem selbst gegebenen (autonomen) Gesetz der reinen praktischen Vernunft. Dies ist praktische Autonomie im Sinne einer freien Willkür, mit der der endliche Mensch seine Handlungen auch aus nicht moralischen Gründen wählen kann, aber nicht muss. Autonomie ist hier die Fähigkeit nach Klugheit zu entscheiden (hypothetischer Imperativ = Handlungsrationalität). Man kann hier von „natürlicher“ im Gegensatz zur „moralischer“ Autonomie sprechen.[81] +++++++++++++++++ Kants Konzept der Autonomie ist umstritten. Zum einen wird in der Literatur häufig behauptet, Kant reduziere die freien Handlungen auf moralisch gute Handlungen, weil heteronome Handlungen für Kant von Naturgesetzen abhängig seien.[82] Dabei wird übersehen, dass Autonomie für Kant eine Handlungsmöglichkeit darstellt.[83] Der Mensch nach Kant ist frei, auch heteronomen Gründen zu folgen. Das Sittengesetz ist nur unter der Perspektive der reinen praktischen Vernunft notwendig, nicht aber im praktischen Leben. Handelt der Mensch aber aus heteronomen Gründen, läuft er Gefahr, die unbedingte Verbindlichkeit aus dem selbst (autonom) gegebenen Gesetz der reinen praktischen Vernunft zu verletzen. Er handelt dann bestenfalls gemäß seiner Pflicht und nicht aus Pflicht (s.u.) In der Diskussion ist der Einwand von Gerold Prauss bekannt, für den Kant alles nicht-moralische Handeln durch die Einstufung als heteronom auf einen Naturprozess reduziert. Entsprechend ist die kantische Unterscheidung des Handelns aus Pflicht und aus Neigung für Prauss problematisch, da ein Handeln aus Neigung kein autonomes Handeln sei.[84] Dem steht entgegen, dass für Kant auch Handeln gemäß der Pflicht und böses Handeln autonom im Sinne praktischer Autonomie sein kann. Auch „wenn die Vernunft lediglich „Dienerin der Neigungen“ ist“, kann sie eine kausale Rolle im Handeln spielen.[85] Rüdiger Bittner trägt vor, dass es bei Kant aufgrund der Mehrdeutigkeit des Begriffs der Autonomie als Gesetz der praktischen Vernunft und Autonomie als Gebot der reinen praktischen Vernunft (Kategorischer Imperativ) zu einer nicht bemerkten Verwechselung kommt.[86] Fremde Gesetze sind für Bittner bloße Fakten, die in Rechnung zu stellen sind. Hieraus schließt er „Autonomie kommt hier dem Handelnden überhaupt zu, sie gehört zum Begriff des Handelns. Entsprechend kommt Heteronomie nicht anderen Handlungen, sondern gar keinen zu. „Heteronomie“ bezeichnet nicht eine Gefahr, sondern eine Täuschung“.[87] Klaus Steigleder merkt hierzu an, dass Bittner „Handlungsfähigkeit von vornherein als „Autonomie“ anspricht.“[88] Bittner ignoriert hiermit die Unterscheidung Kants zwischen praktischer Vernunft als Instrument rationaler Entscheidungen und reiner praktischer Vernunft, durch die der Mensch sich ein unbedingtes Gesetz gibt, an das er sich selbstbezüglich auch gebunden hält, wenn er moralisch handeln will. +++++++++++++++++ In der Absolutsetzung der Autonomie sieht Giovanni B. Sala eine Vergottung des Menschen als ethischem Wesen, die er durch Äußerungen Kants im Opus postumum bestätigt sieht: „Gott ist keine außer mir befindliche Substanz, sondern bloß ein moralisches Verhältnis in mir.“ (AA XXI, S. 149)[89] Hans Krämer spricht von einem „Ersatzgott“ und verweist auf das von Kant in der Ethik verwendete „Begriffsfeld von Heiligkeit, Ehrfurcht, Gehorsam, Demut“ mit theologischem Ursprung.[90] Krämer bezweifelt auch das á priori des Sittengesetzes: „Daß ein Bedingtes, Partikulares aus sich eine unbedingte Forderung hervorbringt und auf sich selbst bezieht, ist nicht einsichtig zu machen. Eine unbedingte Forderung kann sinnvollerweise nur von einem an sich Unbedingtem ausgehen. Der endliche Wille kann aus sich heraus eine solche exzessive Leistung schwerlich erbringen, ohne daß die Gefahr einer Münchhausen-Situation heraufbeschworen wird. Die Rede vom unbedingten Selbstbefehl und Selbstgehorsam ist also keine sinnvolle Rede.“[91] |

自律性と他律性 CIに続いて、カントはこう述べている: 「意志の自律性は、すべての道徳法則とそれに対応する義務の唯一の原理である: [したがって、道徳律は純粋な実践理性の自律性、すなわち自由以外の何ものをも表現しておらず、このこと自体がすべての格言の形式的条件であり、この条件 下においてのみ、最高の実践法則と一致することができる」[75]。カントにとって、自由意志、道徳的意志、純粋な実践理性は一体である[76](GMS 447参照)。否定的な意味での自由とは、物質的影響からの自由である。肯定的な意味での自由とは、自分に法則を与える自由(自律=自己規定)である [77]。 カントの自律性の概念は多層的であり[78]、一方では、たとえ形式的なものであっても、経験的な影響から独立して、理性のみに基づいて自分自身に法を与 える能力を指している。純粋な実践理性の立法は、一般的かつ先験的に認識された規則に従うことを、理性的な人間だけでなく有限の人間に要求する。それは人 間に義務を課すものである。カントは自己を人間の「超感覚的本性」として、「あらゆる経験的条件から独立した法則に従った存在」として特徴づけている [79]。 したがって、自律性はカントにとっての道徳の可能性の条件である[80]。自律性がなければ、道徳法則に従った実践的行動は不可能である。この意味での自 律性とは、自己決定された意志に従って行動する自由である。これは純粋な実践的理性による自己規定という意味での純粋な自律性である。 カントにとって、自律性の反対はヘテロノミー(他律)である。これは、感覚的、経験的源泉に起源をもつ行動の理由(原因ではない)である。人はヘテロノ ミーな動機で実践的な意味で自由に行動するが、純粋実践理性という自らに与えられた(自律的な)法則には従わない。これは自由意志の意味での実践的自律性 であり、有限の人間は非道徳的な理由で行動を選択することができるが、その必要はない。ここでの自律性とは、賢く決定する能力である(仮定的命令=行動の 合理性)。ここでは「道徳的」自律性とは対照的に「自然的」自律性について語ることができる[81]。 +++++++++++++++++ カントの自律性の概念は議論の的となっている。一方では、文献では、カントは自由な行為を道徳的に良い行為に還元しているとよく主張されている。なぜな ら、カントにとって、他律的な行為は自然法則に依存しているからだ[82]。しかし、カントにとって自律性は行為の可能性を表している[83]ことを見落 としている。カントによると、人間は他律的な理由に従う自由も持っている。道徳法は、純粋実践的理性という観点からのみ必要であり、実践的な生活において は必要ではない。しかし、人間が他律的な理由に基づいて行動すると、純粋実践的理性によって自ら(自律的に)与えた法則の絶対的な拘束力を侵害する危険が ある。その場合、人間はせいぜい義務に従って行動しているだけで、義務から行動しているわけではない(下記参照)。この議論では、カントは、道徳的でない 行動をすべて他律的と分類することで、それを自然過程に還元している、というゲロルト・プラウスの反論が知られている。したがって、プラウスにとって、カ ントの義務による行動と傾向による行動の区別は問題となる。なぜなら、傾向による行動は自律的な行動ではないからだ[84]。これに対抗する意見として は、カントにとって、義務に従った行動や悪行も、実践的自律性の意味での自律的な行動である可能性があることが挙げられる。また、「理性が単に「傾向の 僕」である」場合でも、行動において因果的な役割を果たすことができる[85]。リュディガー・ビットナーは、実践的理性の法則としての自律と、純粋実践 的理性の命令としての自律(定言命法)という概念の多義性により、カントでは気づかない混同が生じている、と主張している。[86] ビットナーにとって、他者の法律は、考慮すべき単なる事実だ。このことから、彼は「ここでは、自律性は行為者自身に属し、行為の概念に属するものだ。した がって、他律性は他の行為ではなく、いかなる行為にも属さない。他律性とは、危険ではなく、欺瞞を指す」と結論付けている。[87] Klaus Steigleder は、この点について、ビットナーは「行為能力を最初から「自律性」として扱っている」と指摘している。[88] ビットナーはここで、合理的な決定の手段としての実践的理性と、人間が道徳的に行動したい場合に自らに課し、自らも遵守する無条件の法則を与える純粋実践 的理性の区別を無視している。 -+++++++++++++++ ジョヴァンニ・B・サラは、自律性の絶対化において、人間を倫理的存在として神格化する傾向を見出し、カントの『遺著』における発言によってそれを確認し ている。「神は私以外の存在ではなく、私の中にある道徳的関係にすぎない」。(AA XXI、149 ページ)[89] ハンス・クレーマーは「代用神」について述べ、カントが倫理学で使用した「神聖、畏敬、服従、謙遜」という神学的な起源を持つ概念分野を指摘している。 [90] クレーマーは、道徳律の先験性も疑っている。「条件付き、個別的なものが、それ自体から無条件の要求を生み出し、それ自体に関連付けることは理解できな い。無条件の要求は、本質的に無条件のものからしか生じ得ない。有限の意志は、ミュンヒハウゼン症候群のような状況を引き起こさない限り、それ自体からそ のような過剰な行為を行うことは困難だ。したがって、無条件の自己命令や自己服従という議論は意味を成さない。」[91] |

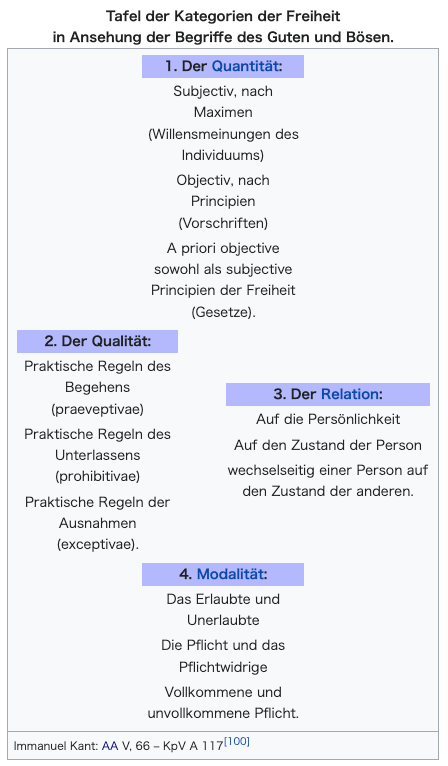

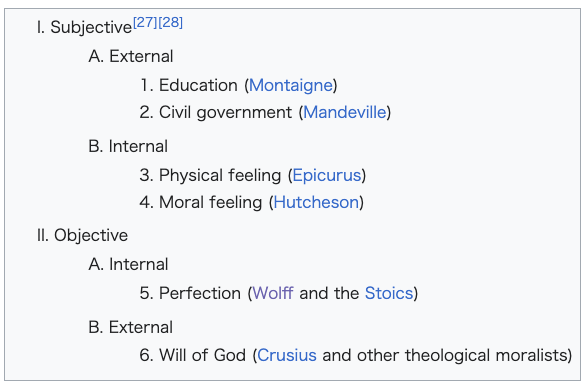

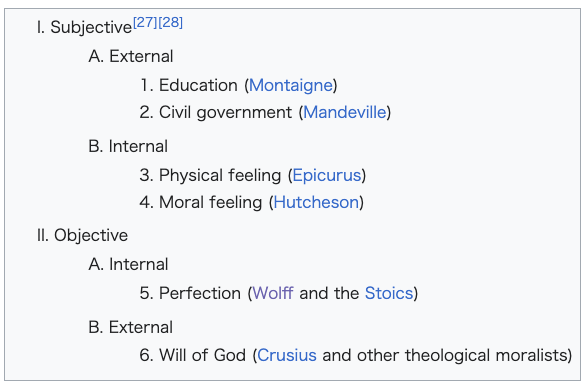

| Traditionelle Grundsätze der

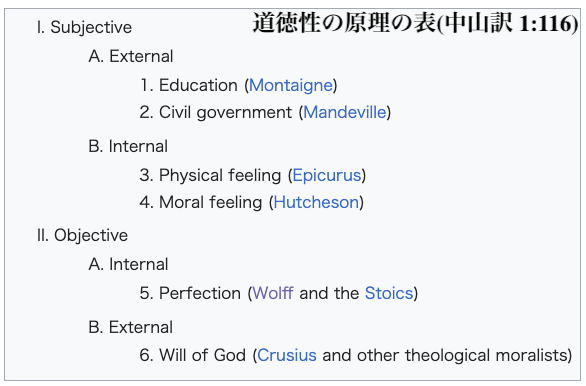

Moral Um seine auf der Autonomie gründende Ethik zu untermauern, grenzt sich Kant von den traditionellen Moralkonzepten ab, die er alle als der eigenen Glückseligkeit verpflichtet betrachtet. Dabei geht er eher kursorisch ohne philologische Genauigkeit auf diese Konzepte ein. Ihm geht es vorrangig um das Prinzip der Heteronomie, das er in allen Alternativen sieht. Kant listet tabellarisch folgende Konzepte als materiale Bestimmungsgründe der Moral auf, wobei er eher willkürlich jeweils einen typischen Vertreter der entsprechenden Richtung nennt:[92] |

伝統的な道徳原理 自律性に基づく倫理を支えるために、カントは伝統的な道徳概念から距離を置く。彼はこれらの概念を、言語学的な正確さを欠いた、かなりざっくりとしたもの として扱っている。彼は主に、あらゆる選択肢に見られるヘテロノミーの原則に関心を寄せている。 カントは道徳の物質的決定要因として以下の概念を表形式で列挙しており、それによってそれぞれの場合において対応する方向の典型的な代表者をかなり恣意的 に挙げている:[92]。 |

| I. subjektive A. äußere 1. der Erziehung (Montaigne – ein gebildeter und wohlerzogener Mensch zu sein)[93] 2. der bürgerlichen Verfassung (Mandeville – Bürger eines wohlgeordneten Gemeinwesens zu sein) B. innere 3. des physischen Gefühls (Epikur – Wohlstand und physisches Wohlergehen zu erlangen) 4. des moralischen Gefühls (Hutcheson – in Sympathie und Wohlwollen mit anderen harmonisch verbunden zu sein) II. objektive A. innere 5. der Vollkommenheit (Wolff und die Stoiker – die innere Vollkommenheit eines vernunftgemäßen Lebens zu erreichen) B. äußere 6. des Wille Gottes (Crusius und andere theologische Moralisten – dem Willen Gottes gemäß zu leben)  |

I. 主観的 A. 外的なもの 1.教育(モンテーニュ-教養のある品行方正な人間になること)[93]。 2.市民憲法(マンデヴィル-秩序ある共同体の市民であること) B. 内面 3.身体的感情(エピクロス-繁栄と身体的幸福を達成すること) 4.道徳的感情(ハッチェソン-共感と博愛において他者と調和的に団結すること) II. 目的 A. 内面的なもの 5.完全性(ヴォルフとストア派-理性的な生活の内的完全性を達成すること) B. 外的なもの 6.神の意志(クルシウスとその他の神学的道徳主義者-神の意志に従って生きること)  |

| Es fehlen Klassiker der

Moralphilosophie wie Platon, Aristoteles oder aus der mittelalterlichen

Philosophie etwa Thomas von Aquin sowie wichtige britische Sensualisten

wie David Hume und Adam Smith. Es wäre spannend zu sehen, wie Kant

diese in sein Schema aufgenommen hätte. Aber eine Vollständigkeit und

philologische Exaktheit der Beispiele scheint Kant nicht interessiert

zu haben, auch wenn er das Schema als vollständig betrachtet. Selbst der gemeine Menschenverstand ist nach Kant in der Lage, das Grundprinzip der Moral zu erkennen und sich mit seiner Urteilskraft für das moralisch richtige Handeln zu entscheiden. Wer aber um der eigenen Glückseligkeit willen jemand anderen täuscht, weiß sehr genau, dass das gegen das Sittengesetz verstößt. Das Gleiche gilt für den möglicherweise unentdeckten Betrug. Kant erweitert sein Argument auch auf das Streben nach allgemeiner, überindividueller Glückseligkeit.[94] Denn weil jeder die Glückseligkeit anders bestimmt und dafür Erfahrung notwendig ist, kann es für dieses Prinzip kein einheitliches Urteil geben. Man kann hier ein Argument gegen den erst nach Kant aufkommenden Utilitarismus sehen. Kant wendet sich auch gegen das Prinzip der empirischen Rationalität als Grundlage der Moral. Selbst große Klugheit und langfristiges Denken machen das Erkennen des richtigen moralischen Handelns schwierig,[95] während die Einsicht in die moralische Pflicht dagegen einfach ist. Niemand wird dafür bestraft, wenn er seiner Glückseligkeit Abbruch tut. Übertritt man aber das Sittengesetz, so hat man auch das Gefühl für eine angemessene, gerechte Strafe. Wer tugendhaft handelt und sich daran erfreut, der hat bereits ein Gefühl für das moralisch richtige Verhalten. Bei den klassischen Tugendlehren gibt es aber erst das Richtige und dann das Gute. Also sind auch Tugenden allein nicht Ursprung der Moral.[96] Dies ist ein Argument auch gegen die Neo-Aristoteliker der Gegenwart. Ähnliches gilt für das moralische Gefühl. Woher soll das kommen, was man fühlt, wenn nicht aus der Vernunft. Ein nur subjektives Gefühl (Mitleid, Sympathie, Wohlgesonnenheit) kann keine objektive Gültigkeit haben. Das Argument wendet sich gegen die Theorie der ethischen Gefühle, die Kant vor seiner kritischen Philosophie vertreten hatte. Hier spricht sich Kant gegen die ontologische Existenz von Werten aus. Damit würde Kant auch den modernen ethischen Intuitionismus ablehnen. Dabei ist es für ihn durchaus hilfreich und sinnvoll, in der Auseinandersetzung mit moralischen Fragen in der Praxis einen moralischen Sinn zu entwickeln. Vollkommenheit und Gott sind abstrakte Ideen, die nur durch Vernunft gebildet werden können. Vollkommenheit im praktischen Sinne beruht aber auf dem Gedanken, nur auf Talent und Geschicklichkeit zu setzen. Von Gott vorgegebene Prinzipien müssen ebenfalls einen materialen Gehalt haben. Sie sind daher nur empirisch zu erfassen und taugen so nicht für die Allgemeingültigkeit und Notwendigkeit, die Kant allein in der formalen Formel des Sittengesetzes sieht. “Sie [die Moral] bedarf also zum Behuf ihrer selbst (sowohl objektiv, was das Wollen, als subjektiv, was das Können betrifft) keineswegs der Religion, sondern vermöge der reinen praktischen Vernunft ist sie sich selbst genug” (Rel 6:3, siehe auch KpV 5:158). Unter dem externen Gebot Gottes wäre der Mensch nicht autonom und könnte so nicht frei dem selbstgegebenen Gesetz folgen. |

プラトンやアリストテレス、トマス・アクィナスといった中世哲学の道徳

哲学の古典や、デイヴィッド・ヒュームやアダム・スミスといったイギリスの重要な感覚主義者が欠けている。カントがこれらをどのように自分のスキームに組

み込んだのか、興味深いところである。しかし、カントは、たとえこの図式が完全なものであると考えていたとしても、例の完全性や文献学的正確さには関心が

なかったようである。 カントによれば、常識でさえ道徳の基本原理を認識し、その判断力を使って道徳的に正しい行為を決定することができる。しかし、自分の幸福のために他人を欺 く者は、それが道徳律に違反していることをよく知っている。発見されないかもしれない詐欺についても同様である。カントはまた、彼の議論を一般的な、超個 人的な幸福の追求にまで拡張している[94]。なぜなら、幸福の判断は人によって異なり、そのためには経験が必要であるため、この原理に対する統一的な判 断はありえないからである。これは、カント以降に初めて登場した功利主義に対する反論として見ることができる。カントはまた、道徳の基礎としての経験的合 理性の原理にも反対している。偉大な思慮深さや長期的な思考をもってしても、正しい道徳的行為を認識することは困難である[95]。自分の幸福を害しても 誰も罰せられない。しかし、道徳律に背いた場合、人は適切で公正な罰の感覚も持つ。徳のある行動をし、それを享受する人は、すでに道徳的に正しい行動につ いての感覚を持っている。しかし、古典的な徳の教義では、まず正しいことがあり、次に善がある。したがって、徳だけでは道徳の起源にはならない。同じこと が道徳的感情にも当てはまる。人が感じるものは、理性からでなければどこから来るのだろうか。単なる主観的な感情(思いやり、同情、博愛)は客観的な妥当 性を持ち得ない。この議論は、カントが批判哲学以前に唱えていた倫理的感情論に対して向けられている。ここでカントは、価値の存在論的存在に反対してい る。こうしてカントは、現代の倫理的直観主義をも否定することになる。同時に、彼が道徳的な問題を実践的に扱う際に、道徳的感覚を養うことはかなり有益で あり、意味のあることである。完全性と神は、理性によってのみ形成される抽象的な観念である。しかし、実践的な意味での完璧さは、才能や技術だけに頼る考 えに基づいている。神から与えられた原理もまた、物質的な内容を持たなければならない。したがって、それらは経験的にしか把握することができず、したがっ てカントが道徳律の形式的定式にのみ見出す普遍性や必然性には適さない。「それゆえ、(道徳は)それ自体のために宗教を必要とするのではなく(意志という 客観的な意味でも、能力という主観的な意味でも)、純粋な実践的理性によってそれ自体で十分なのである」(Rel 6:3、KpV 5:158も参照)。神の外的な戒めのもとでは、人間は自律することができず、したがって、自らに与えられた掟に自由に従うことができない。 |

| Begriffe der reinen praktischen

Vernunft Im zweiten Hauptstück der Analytik befasst Kant sich insbesondere mit der Frage, auf welche Weise moralische Urteile zu fassen sind (principium dijudicationis). Hierzu untersucht er die Bedeutung der Begriffe gut und böse in Hinblick auf die reine praktische Vernunft. Es folgt eine kurze Skizze der Kategorien der praktischen Vernunft, durch die das Feld der Überlegungen zu praktischen Urteilen umrissen wird. Schließlich befasst er sich mit der Bedeutung der Urteilskraft für moralische Urteile. Das Gute und das Böse Die praktische Vernunft befasst sich mit der Vorstellung einer möglichen Wirkung einer autonomen Handlung. Dabei muss zunächst beurteilt werden, ob die vorgestellte Handlung auch verwirklicht werden kann. In einer weiteren Überlegung folgt dann die Beurteilung, ob die vorgestellte Handlung dem Sittengesetz entspricht. Was moralisch gut ist, wird durch das Urteil der reinen praktischen Vernunft bestimmt und nicht durch eine externe Quelle oder empirische Empfindungen.[97] Kant unterscheidet das Begriffspaar Gut und Böse von dem Angenehmen und Unangenehmen. Letztere beruhen auf Gefühlen der Lust oder Unlust, die ihre Quelle in empirischen Erfahrungen haben. Hierfür hat Kant auch die Begriffe Wohl und Übel (manchmal auch Weh). Gegenstand der praktischen Vernunft ist auch das Verhältnis von Mittel und Zweck.[98] In diesem Sinne wäre das Gute nur das Nützliche. Die Begriffe Gut und Böse reserviert Kant für die moralischen Urteile der reinen praktischen Vernunft, die allgemeingültig sind, während Wohl und Übel möglicherweise generell gelten, aber nicht allgemeingültig, weil sie subjektiv bestimmt sind. Gut und Böse beziehen sich immer auf Absichten, Handlungen und Personen, nicht aber auf Sachen und Sachverhalte, die als solche moralisch neutral sind. Ein körperlicher Schmerz ist ein Übel, aber nicht böse. Eine Lüge in dieser Hinsicht ist böse und nur unter Umständen ein Übel. Weil der Mensch ein bedürftiges Wesen ist, gehört es zu den Aufgaben der Vernunft, nach seiner Glückseligkeit zu streben. Der Mensch ist aber nicht nur ein tierisches Wesen, sondern in der Lage, jenseits seines sinnlichen Begehrungsvermögens mit einer reinen, sinnlich nicht interessierten Vernunft zwischen gut und böse zu unterscheiden.[99] |

純粋実践理性の概念 分析篇の第二部では、カントは特に、道徳的判断はどのようになされるべきか(principium dijudicationis)という問題を扱う。この目的のために、彼は純粋実践理性に関する善と悪の概念の意味を検討する。続いて、実践的判断に関す る考察の場の概略を示す実践理性のカテゴリーについて簡単に概説する。最後に、道徳的判断における判断力の意義について述べる。 善と悪 実践的理性は、自律的な行為によって起こりうる効果について考える。まず、想像された行為が実現可能かどうかが評価されなければならない。さらに考察を進 めると、想像された行為が道徳法則に対応しているかどうかが判断される。何が道徳的に善であるかは、純粋な実践理性の判断によって決定されるのであって、 外的な情報源や経験的な感情によって決定されるのではない[97]。 カントは善と悪の概念的な対を快と不快から区別している。後者は経験的経験に源泉を持つ快・不快の感情に基づいている。このために、カントは善と悪(時に は災いでもある)の概念も持っている。実践理性の主題は、手段と目的との関係でもある[98]。この意味で、善とは有用なものでしかない。カントは善悪の 概念を、普遍的に妥当する純粋実践理性の道徳的判断のために留保しているが、善悪は一般的に適用されるかもしれないが、主観的に決定されるので普遍的に妥 当するものではない。 善と悪は常に、意図、行為、人について言及するが、物事や状況については言及しない。肉体的苦痛は悪であるが、悪ではない。この点で嘘は悪であり、特定の 状況下でのみ悪となる。人間は困窮した存在であるから、彼の幸福のために努力することは理性の仕事の一つである。しかし、人間は単なる動物的存在ではな く、感覚に関心のない純粋な理性によって、感覚的な欲望能力を超えて善悪を区別することができる。 |

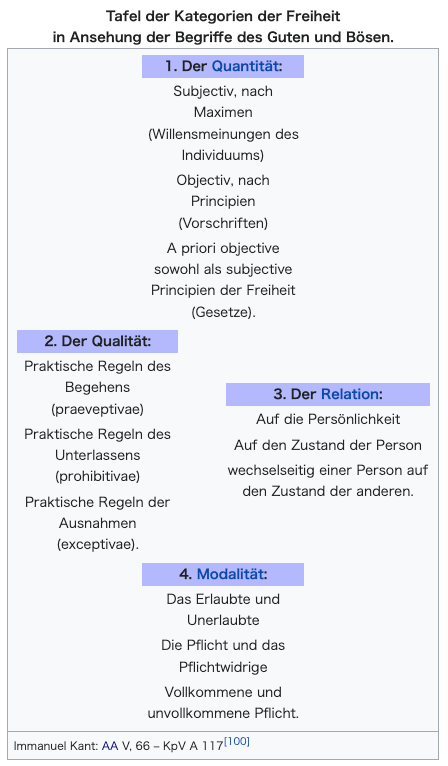

| Tafel der Kategorien der Freiheit in Ansehung der Begriffe des Guten und Bösen. 1. Der Quantität: Subjectiv, nach Maximen (Willensmeinungen des Individuums) Objectiv, nach Principien (Vorschriften) A priori objective sowohl als subjective Principien der Freiheit (Gesetze). 2. Der Qualität: Praktische Regeln des Begehens (praeveptivae) Praktische Regeln des Unterlassens (prohibitivae) Praktische Regeln der Ausnahmen (exceptivae). 3. Der Relation: Auf die Persönlichkeit Auf den Zustand der Person wechselseitig einer Person auf den Zustand der anderen. 4. Modalität: Das Erlaubte und Unerlaubte Die Pflicht und das Pflichtwidrige Vollkommene und unvollkommene Pflicht. Immanuel Kant: AA V, 66 – KpV A 117[100]  |

自由のカテゴリーの表 善と悪の概念に関する。 1.量: 主観的、最大公約数(個人の意志的意見)による。 客観的、原理(規則)による。 先験的な客観的原理と主観的自由の原理(法則)。 2.質: 実践的行動規則 (プレーヴェプティヴァー) 不作為の実践的規則 (禁止事項) 例外に関する実践的規則 (exceptivae)である。 3. 関係 人格との関係 人格の状態に対して 相互的に、一方の人格と他方の人格の状態へ。 4. モダリティ 許可されたものと許可されていないもの 義務と義務に反するもの 完全な義務と不完全な義務 イマヌエル・カント:AA V, 66 - KpV A 117[100].  |

| Kategorien der praktischen

Vernunft Ausgehend vom KI als oberstem Grundsatz der reinen praktischen Vernunft und der ebenfalls rein rationalen Unterscheidung von gut und böse entwickelt Kant eine Tafel der Kategorien der Freiheit, deren Begriffe die reinen Formen von Handlungsabsichten beschreiben. Kant belässt es bei einer sehr knappen Erläuterung, „weil sie für sich verständig genug ist.“[101] Entgegen Kants Erwartungen gibt es eine Vielzahl divergierender Interpretationen.[102] Die folgende Darstellung folgt im Wesentlichen Jochen Bojanowski, der sich weitgehend an Kants Text hält.[103] Im Aufbau und den Oberbegriffen folgt die Tafel den analogen Tafeln in der Transzendentalen Ästhetik der KrV. Anders als in der KrV, wo die Kategorien auf die Naturerkenntnis von Gegenständen der Anschauung gerichtet sind, betrachtet Kant mit den Kategorien der Freiheit die Willensbestimmung, die dem Handeln zugrunde liegt. Gegenstand der praktischen Vernunft ist nur die Handlungsabsicht und deren Entstehung im Bewusstsein, nicht aber die Ausführung der Handlung in der empirischen Welt. Selbstverständlich kann eine Handlung auch im Nachhinein moralisch bewertet werden. Dabei kommt es aber immer noch auf den Willen an und nicht auf das, was tatsächlich passiert ist. Jede Vorstellung einer Handlung ist bestimmt durch die in der Kategorientafel unterschiedenen formalen Elemente Quantität, Qualität, Relation und Modalität. Die Kategorien selbst haben keinen moralischen Wert. |

実践的理性のカテゴリー 純粋実践理性の最高原理としてのKIと、同様に純粋に理性的な善悪の区別から出発して、カントは、その用語が行為意図の純粋な形態を記述する自由のカテゴ リーの表を展開する。カントの期待に反して、多くの解釈が分かれている[102]。以下の説明は、基本的にカントのテキストにほぼ忠実なヨッヘン・ボヤノ フスキに従っている[103]。カテゴリーが観照の対象の性質の認識に向けられているKrVとは異なり、カントは自由のカテゴリーを用いて、行為の根底に ある意志の決定を考察する。実践理性の対象は、行為の意図と意識におけるその出現だけであり、経験的世界における行為の実行ではない。もちろん、行為は後 から振り返って道徳的に評価することもできる。しかし、それはやはり意図に依存するのであって、実際に何が起こったかには依存しない。 行為に関するあらゆる観念は、カテゴリー表で区別される量、質、関係、様態の形式的要素によって決定される。カテゴリー自体には道徳的価値はない。 |

| Quantität Jede Handlung des Menschen erfolgt nach Kant auf der Grundlage einer Maxime. Wie diese Maxime zu bewerten ist, ob sie gut oder böse ist, entscheidet sich aufgrund der Beurteilung der Handlungsabsicht. Maximen gelten zunächst nur für das einzelne Subjekt. Wenn Maximen für mehrere Menschen einer Gemeinschaft gültig sind, handelt es sich um Vorschriften, die ihrerseits wieder gut oder böse sein können. Von Vorschriften spricht Kant z. B. bei den Regeln, die ein Arzt zur Behandlung eines Patienten befolgt (Immanuel Kant: AA V, 19[104], GMS 415). Gesetze spricht Kant im Plural an. Damit ist also nicht das allgemeine Gesetz der Sittlichkeit, der KI, gemeint, sondern Maximen, die nach der Prüfung durch die Urteilskraft die Eignung haben, nicht nur subjektiv relevant zu sein, sondern auch geeignet sind, ein allgemeines Gesetz zu werden. Analog zu den Kategorien der Natur folgen auch die Kategorien der Freiheit den Urteilsformen einzeln, besonders und allgemein. |

量 カントによれば、人間の行動はすべて格律に基づいている。この格律をどのように評価するか、それが善であるか悪であるかは、行動しようとする意図の判断に 基づいて決定される。当初、格律は個々の主体にのみ適用される。格律が共同体の複数の人々に有効であれば、それは規則となり、善にも悪にもなりうる。カン トは、たとえば医者が患者を治療するときに従う規則について述べている(Immanuel Kant: AA V, 19[104], GMS 415)。カントは法律を複数形で呼んでいる。これは道徳の一般法則であるAIを指しているのではなく、判断力によって吟味された結果、主観的に妥当であ るだけでなく、一般法則となるにふさわしい格律を指しているのである。自然の範疇と同様に、自由の範疇もまた、個々に、特に、一般的に、判断の形式に従 う。 |

| Qualität Begehen bedeutet, eine positive Handlungsabsicht zu haben. Mit dieser Kategorie wird alles menschliche Tun erfasst, wobei zu bewerten ist, ob die Maxime der Handlung ein Modus des Guten oder des Bösen ist. Zu dem Begehen zählen auch Unterlassungen, soweit sie eine Entscheidung gegen ein Begehen sind, wie etwa eine nicht ausgesprochene Entschuldigung oder eine unterlassene Hilfeleistung. Zur Kategorie der Unterlassung zählen solche möglichen Handlungsabsichten, die überhaupt nicht angestrebt werden, wie etwa die, eine Ausbildung zum Krankenpfleger zu machen oder Briefmarken zu sammeln. Auch fehlende Handlungsabsichten als Negation des Begehens unterliegen der Frage, ob sie moralisch gut oder böse sind. Als Beispiel kann hier die Maxime dienen, dass ich nicht ins Wasser springe, um einem Ertrinkenden zu helfen. Diese Maxime kann sowohl klug als auch moralisch gut sein, wenn ich nicht schwimmen kann und das Holen von Hilfe die bessere Lösung ist. Maximen der Ausnahme sind noch anders gelagert. Damit sind keine Konflikte bei den Handlungsabsichten (Dilemmata) angesprochen. Diese müssen nach Kant durch die Urteilskraft gelöst werden. Ausnahmen bezeichnen Handlungsabsichten, die von einer Maxime des Begehens oder des Unterlassens abweichen. Eine derartige Maxime wäre, dass ich jeden Tag eine Stunde spazieren gehe, außer ich muss einen Kranken pflegen. Ausnahmen sind auch juridische Pflichten, die einen Vorrang vor den Tugendpflichten haben. |

質 コミットするということは、行動するという積極的な意図を持つということである。この範疇には人間のあらゆる行為が含まれ、その行為の格律が善であるか悪 であるかが評価されなければならない。コミットすることには、謝罪しない、援助を提供しないなど、コミットしないことを決定する限りにおいて、不作為も含 まれる。不作為の範疇には、看護師になるための訓練や切手の収集など、まったく追求されない可能性のある行動意図も含まれる。コミットすることの否定とし ての行動意図の不在は、道徳的に善か悪かという問題の対象にもなる。溺れている人を助けるために水に飛び込むべきでないという格律がその例である。もし私 が泳げず、助けを求める方が良い解決策であれば、この格律は賢明であると同時に道徳的に善である。例外の格律は異なる。これは行動意図の葛藤(ジレンマ) には対処しない。カントによれば、これらは判断力によって解決されなければならない。例外とは、「する・しない」の格律から逸脱した行動意図を指す。その ような格律のひとつは、病人の世話をしなければならない場合を除き、毎日1時間散歩に行くというものである。例外はまた、徳の高い義務よりも優先される法 的義務でもある。 |

| Relation Bei der Kategoriengruppe der Relation ist wichtig zu verstehen, was Kant mit den Begriffen Persönlichkeit und Person meint. Unter Persönlichkeit versteht Kant das intelligible Bewusstsein eines Menschen. Bin ich risikofreudig oder konfliktscheu. Bin ich extrovertiert oder habe ich schon ein ausgeprägtes moralisches Bewusstsein. Von diesen inneren Einstellungen sind meine Handlungsabsichten abhängig. Die Handlungsabsichten in Hinblick auf den äußeren Zustand einer Person sind abhängig von Gegebenheiten der sozialen Situation, aber auch von körperlichen Möglichkeiten oder der Bildung und Erfahrungen eines Menschen. Je nachdem kann es zu unterschiedlichen Handlungsabsichten kommen. Handlungsabsichten können auch davon abhängen, wie die wechselseitige Beziehung zwischen Personen ausfällt. Je nachdem kann die gewählte Maxime einer vorgestellten Handlung unterschiedlich ausfallen. |

関係 関係というカテゴリー群では、カントが人格と人という用語で何を意味しているかを理解することが重要である。カントは人格を人の知的意識として理解してい る。私は危険を冒すタイプなのか、それとも争いを避けるタイプなのか。私は外向的なのか、それともすでに顕著な道徳意識を持っているのか。私の行動意図 は、これらの内的態度によって決まる。人の外的状態に関する行動意図は、社会的状況の状況に依存するだけでなく、その人の身体的能力や教育や経験にも依存 する。そのため、行動意図が異なることもある。また、人と人との相互関係がどのようになるかによっても、行動の意図が左右されることがある。これによっ て、想像した行動の格律が異なるものになる。 |

| Modalität Mit den Kategorien der Quantität, der Qualität und der Relation kann man die Struktur einer Handlungsabsicht vollständig beschreiben. Die Kategorie der Modalität gibt nun an, welchen Charakter die Handlungsabsicht in Hinblick auf ihre Moralität hat. Die Kategorie des Erlaubten oder Unerlaubten stellt die Frage nach der sittlichen Möglichkeit einer Handlung. Nicht erlaubt sind nach Kant Handlungen, die in sich widersprüchlich sind. Dazu gehören etwa falsche Versprechen. Wenn die Maxime eines falschen Versprechens akzeptabel wäre, würde so einem Versprechen niemand mehr vertrauen. Die zweite Kategorie der Modalität wirft die Frage auf, ob eine Handlungsabsicht der Pflicht entspricht oder ob sie pflichtwidrig ist. Kant sagt hier nicht aus Pflicht, d. h. es ist noch nicht geklärt, ob die vorgestellte Handlung auch moralisch motiviert ist. Unter diese Kategorie dürften damit auch Handlungsabsichten fallen, die nur pflichtgemäß sind. Diesen Handlungsabsichten würde dann noch die moralische Motivation fehlen. Sie hätten aus sittlicher Perspektive nur Legalität, aber noch keine Moralität. Die Kategorie der vollkommenen und unvollkommenen Pflichten klassifiziert Handlungsabsichten in jedem Fall als moralisch. Vollkommene Pflichten sind in jedem Fall geboten. Bei unvollkommenen Pflichten liegt es im Urteil des Handelnden, in welchem Umfang er seiner Pflicht nachkommen muss. Ein Beispiel hierfür ist etwa das Maß der Spenden zur Unterstützung Bedürftiger. |

モダリティ(様相) 量、質、関係のカテゴリーを使って、行為意図の構造を完全に説明することができる。モダリティの範疇は、行動意図の道徳性に関する性格を示す。何が許され るか、許されないかという範疇は、行為の道徳的可能性の問題を提起する。カントによれば、本質的に矛盾する行為は許されない。これには例えば、偽りの約束 が含まれる。もし偽りの約束の格律が許されるなら、誰もそのような約束を信用しないだろう。モダリティの第二のカテゴリーは、行為意図が義務に従っている のか、それとも義務に反しているのかという問題を提起する。ここで、カントは義務に反するとは言っていない。つまり、想像される行為が道徳的動機に基づく ものであるかどうかは、まだ明らかにされていないのである。したがって、この範疇には、義務にのみ従った行動意図も含まれるはずである。このような行動意 図には道徳的動機がない。道徳的観点からは、合法性はあっても道徳性はまだないのである。完全な義務と不完全な義務の範疇は、あらゆる場合において行動意 図を道徳的なものとして分類する。完全義務はあらゆる場合に求められる。不完全な義務の場合、どこまで義務を果たさなければならないかは、行動する人の判 断に委ねられる。例えば、困窮者を支援するための寄付の範囲である。 |

| Typik der reinen praktischen