快楽原則

Pleasure principle

☆ フロイトの精神分析学では、快楽原則(ドイツ語:Lustprinzip)とは、生物学的および心理学的欲求を満たすために快楽を求め、苦痛を避ける本能的な欲求である。具体的には、快楽原則はイドの原動力である(→『快楽原則の彼岸, 1920』)。

| In Freudian psychoanalysis, the pleasure principle (German: Lustprinzip)[1]

is the instinctive seeking of pleasure and avoiding of pain to satisfy

biological and psychological needs.[2] Specifically, the pleasure

principle is the animating force behind the id.[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleasure_principle_(psychology) |

フロイトの精神分析学では、快楽原則(ドイツ語:Lustprinzip)[1]とは、生物学的および心理学的欲求を満たすために快楽を求め、苦痛を避ける本能的な欲求である[2]。具体的には、快楽原則はイドの原動力である[3]。 |

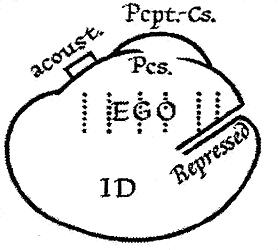

| Id (one of Psychic apparatus) Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of bodily needs and wants, emotional impulses and desires, especially aggression and the sexual drive.[9] The id acts according to the pleasure principle—the psychic force oriented to immediate gratification of impulse and desire.[10] Freud described the id as "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". Understanding of the id is limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and it can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: it is concerned only with satisfaction of drives in accordance with the pleasure principle.[11] It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time."[12] The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."[13] Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle.[14][15] The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the principle of reality into account. Freud describes the id as "the great reservoir of libido",[16] the energy of desire, usually conceived as sexual in nature, the life instincts that are constantly seeking a renewal of life. He later also postulated a death drive, which seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state."[17] For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms"[18] through aggression. Since the id includes all instinctual impulses, the destructive instinct, as well as eros or the life instincts, is considered to be part of the id.[19]  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Id,_ego_and_superego#Id |

イド(精神の装置の一つ) フロイトは、イドを身体の欲求や欲求、感情的な衝動や欲望、特に攻撃性や性的衝動の無意識的な源として考えた[9]。イドは快楽原則に従って行動する。快楽原則とは、衝動や欲求を即座に満たすことを指向する精神的な力のことである[10]。 フロイトはイドを「私たちのパーソナリティの暗く、手の届かない部分」と表現した。イドの理解は、夢や神経症症状の分析に限られており、自我との対比とい う観点でしか説明できない。 組織や集団的意志を持たず、快楽原則に従って衝動の満足のみに関わっている[11]。 理性や通常の意識生活の前提を無視しており、「相反する衝動が互いに打ち消し合うことなく、共存している。イドには否定と対比できるものは何もな い。...イドには時間の概念に相当するものは何もない。」[12] イドには「価値判断がない。善悪も道徳もない。...本能的なカタルシスを求める衝動、それが私たちの考えるイドのすべてである。」[13] 発達段階では、イドは自我に先立つ。イドは、誕生時に備わっている基本的な本能的衝動から成り、肉体的組織に内在し、快楽原則のみによって支配されている [14][15]。精神装置は未分化のイドとして始まり、その一部が構造化された「自我」へと発達する。自我とは、現実の原則を考慮に入れた自己概念であ る。 フロイトはイドを「リビドーの巨大な貯蔵庫」[16]、つまり欲望のエネルギー、通常は性的な性質を持つと考えられ、生命の更新を常に求める生命本能と表 現している。彼は後に「有機的生命を無機的な状態に戻す」[17]ことを求める死の衝動も提唱した。フロイトにとって、「死の衝動は、おそらく一部だけで あろうが、外の世界や他の生物に対する破壊本能として、攻撃性を通して表現されると思われる」[18]。イドには本能的な衝動がすべて含まれているため、 破壊的な本能だけでなく、エロスや生命本能もイドの一部であると考えられている[19]。 |

| Precursors Epicurus in the ancient world, and later Jeremy Bentham, laid stress upon the role of pleasure in directing human life, the latter stating: "Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure".[4] Freud's most immediate predecessor and guide however was Gustav Theodor Fechner and his psychophysics.[5] |

先駆者 古代のエピクロス、そして後にジェレミー・ベンサムは、人間の生活を導く上で快楽が果たす役割を強調した。ベンサムは「自然は人類を、苦痛と快楽という2人の主君に支配させた」と述べている[4]。 しかし、フロイトの最も直接的な先駆者であり、指針となったのはグスタフ・テオドール・フェヒナーと彼の心理物理学であった[5]。 |

| Freudian developments Freud used the idea that the mind seeks pleasure and avoids pain in his Project for a Scientific Psychology of 1895,[6] as well as in the theoretical portion of The Interpretation of Dreams of 1900, where he termed it the 'unpleasure principle'.[7] In the Two Principles of Mental Functioning of 1911, contrasting it with the reality principle, Freud spoke for the first time of "the pleasure-unpleasure principle, or more shortly the pleasure principle".[7][8] In 1923, linking the pleasure principle to the libido he described it as the watchman over life; and in Civilization and Its Discontents of 1930 he still considered that "what decides the purpose of life is simply the programme of the pleasure principle".[9] While on occasion Freud wrote of the near omnipotence of the pleasure principle in mental life,[10] elsewhere he referred more cautiously to the mind's strong (but not always fulfilled) tendency towards the pleasure principle.[11] |

フロイトの理論の発展 フロイトは、1895年の『精神科学のための心理学プロジェクト』[6]や、1900年の『夢判断』の理論部分で、心は快楽を求め、苦痛を避けるという概念を用いた。 1911年の『精神機能の2つの原理』[1]では、現実の原理と対比させながら、フロイトは初めて「快楽と苦痛の原理、あるいはより簡潔に快楽の原理」に ついて述べた[7][8]。 1911年の『精神機能の2つの原理』では、現実原理と対比させながら、フロイトは初めて「快楽不快原理、あるいはより簡潔に快楽原理」について述べた [7][8]。1923年には快楽原理とリビドーを結びつけ、快楽原理を生命の監視者であると表現した。また、1930年の『文明とその不満足』では、 930年、彼は「人生の目的を決定するのは、単に快楽原則のプログラムである」とまだ考えていた[9]。 フロイトは、精神生活における快楽原則のほぼ全能について時折書いていたが[10]、他の場所では、快楽原則に対する心の強い(しかし常に満たされるわけではない)傾向についてより慎重に言及していた[11]。 |

| Two principles Freud contrasted the pleasure principle with the counterpart concept of the reality principle, which describes the capacity to defer gratification of a desire when circumstantial reality disallows its immediate gratification. In infancy and early childhood, the id rules behavior by obeying only the pleasure principle. People at that age only seek immediate gratification, aiming to satisfy cravings such as hunger and thirst, and at later ages the id seeks out sex.[12] Maturity is learning to endure the pain of deferred gratification. Freud argued that "an ego thus educated has become 'reasonable'; it no longer lets itself be governed by the pleasure principle, but obeys the reality principle, which also, at bottom, seeks to obtain pleasure, but pleasure which is assured through taking account of reality, even though it is pleasure postponed and diminished".[12] The beyond In his book Beyond the Pleasure Principle, published in 1921, Freud considered the possibility of "the operation of tendencies beyond the pleasure principle, that is, of tendencies more primitive than it and independent of it".[13] By examining the role of repetition compulsion in potentially over-riding the pleasure principle,[14] Freud ultimately developed his opposition between Libido, the life instinct, and the death drive. |

2つの原則 フロイトは快楽原則と、状況的現実が即時の満足を禁じている場合に欲求の満足を先延ばしにする能力を説明する現実原則という対極の概念を比較した。乳児期 および幼児期には、イドは快楽原則に従うことによって行動を支配する。この年齢の人々は、空腹や渇きといった欲求を満たすことを目指し、ただただ即時の快 楽を求めるだけであり、年齢を重ねると、イドはセックスを求めるようになる[12]。 成熟とは、快楽を先延ばしにする苦痛に耐えることを学ぶことである。フロイトは、「こうして教育された自我は『合理的』になる。もはや快楽原則に支配され ることはなく、現実原則に従う。現実原則も、根底では快楽を得ようとするが、それは現実を考慮することで得られる快楽であり、先延ばしされ、減少した快楽 である」と主張した[12]。 その先 1921年に出版された著書『快楽原則の彼方』で、フロイトは 1921年に出版された『快楽原則の彼方』の中で、フロイトは「快楽原則を超えた傾向、つまり快楽原則よりも原始的で、快楽原則から独立した傾向」の可能 性について考察した[13]。快楽原則を覆す可能性のある反復強迫の役割を検証することで[14]、フロイトは最終的に、生命本能であるリビドーと死の衝 動の対立を明らかにした。 |

| Hedonism Id, ego and super-ego Ignacio Matte Blanco Jouissance Pierre Janet Reality principle Self-control Utilitarianism |

快楽主義 自我、超自我 イグナシオ・マッテ・ブランコ 快楽 ピエール・ジャネ 現実原則 自制 功利主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleasure_principle_(psychology) |

|

| Das Lustprinzip

ist ein zentrales Konzept der klassischen psychoanalytischen Theorie

von Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), weil grundlegend für viele seiner

weiteren theoretischen Vorstellungen. So ist nach Freuds Auffassung die

topologische Struktur des Es Voraussetzung für das Streben nach

sofortiger und ungehinderter Befriedigung elementarer Triebe bzw.

innerer Bedürfnisse. Das Erleben von Lust ist nach dem Konstanzprinzip

identisch mit dem Abbau von Triebspannung. Der komplementäre psychische

Wirkmechanismus zum Lustprinzip ist das sogenannte Realitätsprinzip.

Dieses erfordert Anpassung an die Außenwelt und ihre Gegensätze. Das

notwendige Gleichgewicht zwischen Lust- und Realitätsprinzip wird durch

Verdrängung unlustbesetzter Vorstellungen aufrechterhalten. Entgegen einem weit verbreiteten Irrtum bezieht Freud das Lustprinzip in seinen späteren Werken nicht mehr ausschließlich auf das sexuelle Lustempfinden, sondern kommt zu dem Ergebnis, dass es für jede Art von Bedürfnissen oder Mängeln maßgeblich ist, die ein Lebewesen ausgleichen muss, um sich und seine Art zu erhalten. |

快

楽原則は、ジークムント・フロイト(1856年~1939年)の古典的な精神分析理論の中心的な概念であり、彼のその後の多くの理論的構想の基盤となって

いる。フロイトの考えによれば、イドのトポロジカルな構造は、基本的な本能や内的な欲求の即時かつ妨げられない満足を求める欲求の前提条件である。快楽の

経験は、恒常性の原理に従って、本能の緊張の解消と同一である。快楽原則と相補的な心理的メカニズムは、いわゆる現実原則だ。これは、外界とその対極への

適応を必要とする。快楽原則と現実原則の必要なバランスは、不快な想像を排除することによって維持されている。 広く流布している誤解に反して、フロイトは後の著作において、快楽原則を性的快楽のみに限定して解釈することはなく、生物が自身とその種を維持するために補う必要のあるあらゆる種類の欲求や欠乏に決定的な役割を果たすという結論に達している。 |

| Entwicklung der Theorie Wirklichkeit Aufgrund der Primärvorgänge ist eine Tendenz zur Abkehr von der Realität erkennbar. Sie ist in ontogenetischer und entwicklungsgeschichtlicher Hinsicht konkretisierbar. Durch Verdrängung zieht sich psychische Tätigkeit zurück von Vorstellungen und Akten, welche Unlust erregen können.[1] Die Libido Die Herkunft aller Formen der Lust, die auf der biologischen Ebene erkennbar werden, sah Freud in einer universalen, triebenergetischen Lebenskraft, die er Libido nannte, vergleichbar mit „Lebenskraft“ bzw. „élan vital“ im Sinn Henri Bergsons. An sich monistisch, äußere sich diese nicht empirisch messbare Energie ab dem Moment ihrer Verwirklichung dualistisch, d. h. nimmt nach Freud geist-körperliche oder zeit-räumliche Formen und Verhaltensweisen an, also zugleich den Aspekt der Psyche und Physis. Beide sind erst wieder im „Es“ harmonisch vereinigt. Vor allem ist dies der Fall in dem Moment, da das Gleichgewicht zwischen den sich mit Unlust meldenden Grundbedürfnissen und der (lustvollen) Befriedigung des ihnen innewohnenden Begehrens hergestellt worden ist. Die in den früheren Werken Freuds vertretene Hypothese eines nur in der Sexualität wirkenden Lustprinzips war begründet in Patientinnen, die an der sog. Hysterie litten und deren Träume – wie mittels ihrer Freien Assoziationen deutlich wurde – häufig zu ihren unbewussten genitalen Bedürfnissen verwiesen. Kindliche Lust Aus Beobachtungen von Kleinkindern schloss Freud bald auf ein von Geburt an bestehendes Luststreben. Dies erschien ihm jedoch als so vielgestaltig und unspezifisch, dass er es nicht als Vorläufer ausschließlich sexueller Lust bezeichnen wollte. Stattdessen prägte er zur Benennung des kindlichen Lustverhaltens den aus heutiger Sicht irreführend anmutenden Begriff der „polymorphen Perversionen“ – eine Maßnahme, die Freud ergriff, um von seinen zeitgenössischen Fachkollegen überhaupt annähernd verstanden zu werden, da in dieser Zeit Kindern die körperliche Lustbetätigung von der Religion wie der Wissenschaft konsequent abgesprochen wurde. Kindheit war als „asexuell“ definiert, also unschuldiger Engelszustand im Sinne der kirchlichen Lehre. Die so genannten polymorph-perversen[Anm 1] kindlichen Regungen äußern sich nach Freud nicht nur in der Befriedigung über die Geschlechtsorgane (Onanie bereits in der Wiege, 'Doktorspiele'), sondern ganz allgemein in jeder Form des Lustgewinns durch Körperkontakt (Haut an Haut zu mehreren, allein an Gegenständen sich reiben, Saugen, Nuckeln mit und ohne Nahrungsaufnahme, Ausscheidung, Nasebohren usw.). Schon Ansätze von Lustfeindlichkeit durch einschränkende moralische Erziehung führen Freuds Theorie zufolge zu einer Einschränkung der natürlichen Antriebe und zu Neurosen. |

理論の展開 現実 一次過程により、現実からの離脱傾向が見られる。これは、個体発生および進化史の観点から具体化することができる。抑圧により、精神活動は不快感を引き起こす可能性のある想像や行為から後退する[1]。 リビドー フロイトは、生物学的レベルで認識できるあらゆる快楽の源を、普遍的な衝動エネルギーである「リビドー」に見た。これは、アンリ・ベルクソンの「生命力」や「エラン・ヴィタール」に匹敵するものだ。 本質的には一元論的であるこのエネルギーは、実現の瞬間から、経験的に測定できない二元的な形で表現される。つまり、フロイトによれば、このエネルギー は、精神と身体、あるいは時間と空間という形や行動を取り、精神と肉体という側面を同時に持つ。この2つは、「イド」において初めて調和して統合される。 これは、不快感をもたらす基本的欲求と、その欲求に内在する(快楽的な)満足とのバランスが取れた瞬間に特に顕著だ。 フロイトの初期の著作で提唱された、快楽原則は性だけに作用するという仮説は、いわゆるヒステリーに苦しむ女性患者たちに基づいていました。彼女たちの自由連想から、その夢はしばしば無意識の性的な欲求に関連していることが明らかになったからです。 幼児の快楽 幼児の観察から、フロイトはすぐに、誕生から存在する快楽追求の傾向を結論付けた。しかし、これは非常に多様で非特異的であることから、彼はそれを純粋に 性的快楽の前兆とは見なしたくなかった。その代わりに、彼は幼児の快楽行動を表す用語として、今日の観点からは誤解を招きやすい「多形性倒錯」という用語 を考案した。これは、当時、子供たちの肉体的快楽行為は宗教も科学も断固として否定していたため、同時代の同業者たちに少しでも理解してもらうためにフロ イトが取った措置だった。子供時代は「無性」と定義され、教会の教義における無垢な天使のような状態とされていた。 フロイトによると、いわゆる多形性倒錯[注 1] である子供の衝動は、性器による満足(揺りかごでの自慰行為、 「お医者さんごっこ」など)だけでなく、身体接触によるあらゆる形の快楽(複数の人と肌と肌を接触させる、物体に体をこすりつける、吸う、乳を吸う(食物 の摂取の有無は問わない)、排泄、鼻をほじるなど)にも現れる。フロイトの理論によれば、制限的な道徳教育による快楽嫌悪の傾向は、自然な衝動の抑制と神 経症につながる。 |

| Das Lustprinzip Freud entdeckte das Lustprinzip anhand der Traumanalyse, aus deren Befunden er den Hauptteil seiner Erkenntnisse gewann. Das Anstreben von Lust und vernunftgelenktes Meiden von Unlust verkörpern die zwei elementarsten Aspekte des Lustprinzips. Das Lustprinzip wirkt sowohl in dem Bedürfnis nach Nahrungsaufnahme zur unmittelbaren Lebenserhaltung wie auch in der sexuellen Lustbefriedigung zur arterhaltenden Vermehrung, ferner im geistigen Streben nach Lust (Wissensdurst), im Sozialen und in den anderen naturgemäßen Bedürfnissen. Ein unbefriedigtes Grundbedürfnis ist reines Begehren. Es erzeugt wesensmäßig energetische Spannungen, die entweder auf eher körperlicher oder auf eher geistiger Ebene spürbar werden; je nachdem, welches Bedürfnis es war, das unbefriedigt blieb. In Frage kommen z. B. Einsamkeitsspannungen infolge sozialer Frustrationen, oder Unsicherheit infolge eines Sachverhaltes, der (geistig) nicht geklärt wurde; ebenso "Hunger" als vielleicht reinste Form des immer auf Triebenergie reduzierbaren Verlangens. Jeder der Antriebe verlangt auf seine je eigene Weise nach Befriedigung (Lustgewinn bis zur Stillung des Bedürfnisses). Es wird dabei nach dem Prinzip der Triebökonomie verfahren, d. h. die Energie investiert zunächst etwas von sich selbst, um die Erzeugung von Unlustgefühlen wie z. B. Hunger zu bewirken. Erst deren innere Wahrnehmung veranlasst den Organismus – d. h. sein "Ich" – nach den zu ihrer Stillung geeigneten Objekten zu suchen, wobei als Mehrwert der Investition Lust gewonnen wird. Das ICH/Bewusstsein hat dabei die Aufgabe, nach Klarheit in sich und nach äußeren Lebensquellen zu suchen: So sind Menschen also fähig, im wechselseitig fruchtbaren Austausch die sozialen Spannungen abzubauen, die sich aus einer vorherigen Frustration ergaben, oder auch sich um Nahrung zu kümmern, bei der sich die Lust über deren Einverleibung einstellt. |

快楽原則 フロイトは、夢分析から快楽原則を発見し、その分析結果から彼の知見の大部分を得た。快楽の追求と、理性によって導かれる不快の回避は、快楽原則の最も基 本的な2つの側面を体現している。快楽原則は、生命維持のための食物摂取の欲求、種族保存のための性的快楽の満足、さらに知的な快楽の追求(知識欲)、社 会的な欲求、その他の自然的な欲求にも作用している。 満たされない基本的な欲求は、純粋な欲望である。それは本質的にエネルギー的な緊張を生み出し、その緊張は、満たされなかった欲求の種類に応じて、より肉 体的なレベルまたはより精神的なレベルで感じられる。例えば、社会的欲求不満による孤独の緊張、あるいは(精神的に)解決されていない事実による不安、そ しておそらくは本能的エネルギーに還元できる最も純粋な形の欲求である「空腹」などが考えられる。それぞれの衝動は、その満足(欲求の満足から欲求の解消 まで)を、それぞれ独自の方法で求める。 その過程では、衝動経済学の原則、すなわち、エネルギーはまず、飢えなどの不快な感情を引き起こすために、それ自体のエネルギーの一部を投資する。その内 的な知覚によって初めて、有機体、すなわち「自我」は、その満足に適した対象を探し求め、その投資の付加価値として快楽を得る。 その際、「自我」/意識は、自己の明確さと外部の生命源を探す役割を担っている。このように、人間は、相互に有益な交流を通じて、以前の欲求不満から生じた社会的緊張を緩和したり、摂取によって快感が得られる食物を求めたりすることができる。 |

| Strukturmodell der Psyche Interpassivität Hedonismus |

精神の構造モデル 相互受動性 快楽主義 |

| Sigmund

Freud: Jenseits des Lustprinzips. Internationaler Psychoanalytischer

Verlag, Leipzig, Wien und Zürich 1920 (Erstdruck), 2. überarbeitete

Auflage 1921, 3. überarb. Auflage 1923 Marie-Ann Lenner: Benjamin Barber: Psychologische Dimensionen der Demokratietheorie. GRIN Verlag, Norderstedt 2011, S. 3 ff. (online) |

ジークムント・フロイト:『快楽原則の彼方』。国際精神分析出版社、ライプツィヒ、ウィーン、チューリヒ、1920年(初版)、1921年改訂第2版、1923年改訂第3版 マリー・アン・レンナー:ベンジャミン・バーバー:民主主義理論の心理学的次元。GRIN Verlag、ノルダーシュテット、2011年、3ページ以降(オンライン) |

| Einzelnachweise Sigmund Freud: Formulierungen über die zwei Prinzipien des psychischen Geschehens. [1911] In: Gesammelte Werke, Band VIII, „Werke aus den Jahren 1909-1913“, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt / M 1999, ISBN 3-596-50300-0; S. 231 zu Stw. „Lustprinzip“. |

参考文献 ジークムント・フロイト:精神現象の2つの原理に関する考察。[1911] 『全集』第8巻「1909年から1913年の著作」 Fischer Taschenbuch、フランクフルト / M 1999、ISBN 3-596-50300-0; 231ページ、「快楽原則」の項。 |

| Anmerkungen Um 1900 nannte man alle Arten der Lust, die nicht direkt und ausschließlich nur im Dienste der Fortpflanzung stehen - wie der „homoerotische“ Lustaustausch - eine 'perverse' Entartung. So galt es etwa als unschickliche Obszönität, den Appetit auf eine bestimmte Speise mit "Lust auf .." zu benennen. Der Begriff 'Perversionen' wurde von Freud nie wörtlich verstanden (lat.: perversum = verdreht, unnatürlich, abartig. Griech.: poly- = viel und morphos = Gestalt). |

注釈 1900年頃、生殖に直接かつ排他的に関わるものではないあらゆる種類の欲望(例えば「同性愛的な」欲望の交換など)は、「倒錯」という「異常」とみなさ れていました。例えば、特定の食べ物に対する食欲を「...への欲望」と表現することは、下品で卑猥な表現とされていました。「倒錯」という用語は、フロ イトによって文字通り(ラテン語:perversum=歪んだ、不自然な、異常な。ギリシャ語:poly-=多くの、morphos=形)に理解されたこ とはなかった。 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lustprinzip |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆