マルキ・ド・サド

Marques de

Sade, 1740-1814

Depiction of the Marquis de Sade by H. Biberstein in L'Œuvre

du marquis de Sade, Guillaume Apollinaire (Edit.), Bibliothèque des

Curieux, Paris, 1912

マルキ・ド・サド

Marques de

Sade, 1740-1814

Depiction of the Marquis de Sade by H. Biberstein in L'Œuvre

du marquis de Sade, Guillaume Apollinaire (Edit.), Bibliothèque des

Curieux, Paris, 1912

マルキ・ド・サド(Marquis de Sade, 1740-1814)は啓蒙の時代初期に現れた「早すぎ た自由思想」の思想家である(→「マルキ・ド・サドと啓蒙」)。そして、時代 を超えても、それを嫌う人たちには、時代を超えた極悪人である。しかし、サドそのものは、現代では単純で粗暴な 大悪人ではない。サドが、近代啓蒙の幕開けの時期に、人びとの想像力がもつ可能性を極限まで押し広げたということを、文章による創作活動を通しておこなっ たことが、嫌われているのである。これは奇矯な結末である。澁澤龍彦(1928-1987)は「サド復活」のなかでこういう。:「ちょうど開幕したばかり の19世紀が、前世紀の遺産を受け継ぐことを好まず、サドという一作家に具現された前世紀の抵当権を消去することを何よりも早急に欲したかのごとくであっ た」(澁澤 1989:171)。

私はかって次のように書いたことがある。

「倫理学の反省が18世紀の終わり要請された。すな わち、18世紀の80年代に、カントの先験主義、ベンサムの功利主義的合理性の考量、そして(功利主義とは逆行する)マルキ・ド・サドの哲学というヴァ リエーションとともに、モラルの反省理論たるべき倫理学は登場したのである(ルーマン1992:11)。ところが、「先験主義的倫理学におけると同様、功 利主義的倫理学においても、問題となったのはモラルの判断の合理 性もしくは(特殊ドイツ的状況において)理性的基礎づけであった。‥‥。いづれにせよ、生活様式の決定と目的選択とに対し距離をとる契機が 組み込まれた。」(ルーマン1992:16-7)」(→「心霊治療においてモラルを問うこと」「啓蒙の弁証法」「啓蒙と暴力」)

ここでのルーマンの文献は、1992 『パラダイム・ロスト』土方昭訳,国文社.である

●クローゼットの中のカント主義者と してのマルキ・ ド・サド

「性別化された時間とは、フロイトが死の欲動として指し示したものの時間である。つ まり、生と死を超えて永続する反復強迫という忌まわしい不死性である。この忌まわしい不死性の論理を最初に 形式化したのは、クローゼット内のカント主義者、マルキ・ド・サドである。そして、この形式化にともなうパ ラドクスは、サドの作品において、性的快楽を探し求める実践が脱性別化されるということ、より正確には脱官 能化されるということである。サドは、あらゆる障害を退け回り道を避けて、可能なかぎりもっとも直接的なや り方で快楽を追求しようとするので、その結果目にすることになるのは、われわれが本物のエロティシズムから 連想する焦らしと悶えを欠いた、完全に機械的で冷淡なセクシュアリティとなる。この意味で、サド的主体はほ ぼ間違いなく、ポストヒューマンのセクシュアリティの最初の形式をわれわれに突きつけている。こうした理由 からのみ、「不死の」循環的時間の湾曲は熟考に値する」——ジジェク『性と頓挫する絶対』中山徹・鈴木英明訳、p.229 、青土社、2021年

★サドと現代思想

| Appraisal and

criticism Numerous writers and artists, especially those concerned with sexuality, have been both repelled and fascinated by Sade. An article in The Independent, a British online newspaper, gives contrasting views: the French novelist Pierre Guyotat said, "Sade is, in a way, our Shakespeare. He has the same sense of tragedy, the same sweeping grandeur" while public intellectual Michel Onfray said, "it is intellectually bizarre to make Sade a hero... Even according to his most hero-worshipping biographers, this man was a sexual delinquent".[11] |

評価と批評 数多くの作家や芸術家、特にセクシュアリティに関わる人々が、サドに反発し、また魅了されてきた。イギリスのオンライン新聞「インディペンデント」の記事 では、フランスの小説家ピエール・ギュイヨタが「サドはある意味、我々のシェイクスピアだ」と述べている。一方、知識人のミシェル・オンフレイは、「サド を英雄にするのは知的好奇心をそそる」と述べている。彼の最も英雄を崇拝する伝記作家たちによれば、この男は性的不良であった」と述べている[11]。 |

| The contemporary rival

pornographer Rétif de la Bretonne published an Anti-Justine in 1798. |

同時代のライバルであるポルノ作家レティフ・ド・ラ・ブルトンヌは、

1798年に『アンチ・ジュスティーヌ』を出版している。 |

| Geoffrey Gorer, an English

anthropologist and author (1905–1985), wrote one of the earliest books

on Sade, entitled The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade in

1935. He pointed out that Sade was in complete opposition to

contemporary philosophers for both his "complete and continual denial

of the right to property" and for viewing the struggle in late 18th

century French society as being not between "the Crown, the

bourgeoisie, the aristocracy or the clergy, or sectional interests of

any of these against one another", but rather all of these "more or

less united against the proletariat." By holding these views, he cut

himself off entirely from the revolutionary thinkers of his time to

join those of the mid-nineteenth century. Thus, Gorer argued, "he can

with some justice be called the first reasoned socialist."[33] |

イギリスの人類学者で作家のジェフリー・ゴラー(1905-1985)

は、1935年に『サド侯爵の革命思想』というサドに関する最も早い本の一つを書い

た。彼は、サドが同時代の哲学者と完全に対立していたのは、「財産権を完全かつ継続的に否定」していたことと、18世紀末のフランス社会における闘争を

「王室、ブルジョアジー、貴族、聖職者、あるいはこれらのうちのどれかが互いに対立する部門利益」ではなく、「プロレタリアートに対して多かれ少なかれ団

結」していると考えていたためであると指摘している。このような見解を持つことによって、彼は同時代の革命的思想家たちとは完全に縁を切り、19世紀半ば

の思想家たちの仲間入りをしたのである。したがってゴーラーは、「彼はある正義をもって最初の理性的な社会主義者と呼ぶことができる」と論じていた

[33]。 |

| Simone de Beauvoir (in her essay

Must we burn Sade?, published in Les Temps modernes, December 1951 and

January 1952) and other writers have attempted to locate traces of a

radical philosophy of freedom in Sade's writings, preceding modern

existentialism by some 150 years. He has also been seen as a precursor

of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis in his focus on sexuality as a motive

force. The surrealists admired him as one of their forerunners, and

Guillaume Apollinaire famously called him "the freest spirit that has

yet existed".[34] |

シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール(『レ・タン・モダン』1951年12月

号、1952年1月号に掲載された論文「サドを焼くべきか」)などは、現代の実存主

義より150年も前に、サドの著作の中にラディカルな自由哲学の痕跡を見出そうと試みている。また、性欲を原動力とするジークムント・フロイトの精神分析

学の先駆けであるとも言われている。シュルレアリスムは彼を彼らの先駆者の一人として賞賛し、ギョーム・アポリネールは彼を「未だかつて存在した最も自由

な精神」と呼んだのは有名である[34]。 |

| Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947

book Sade Mon Prochain ("Sade My Neighbour"), analyzes Sade's

philosophy as a precursor of nihilism, negating Christian values and

the materialism of the Enlightenment. |

ピエール・クロソウスキーは、1947年の著書『隣人サド』で、サドの

哲学を、キリスト教の価値観と啓蒙主義の唯物論を否定するニヒリズムの先駆けとして 分析している。 |

| One of the essays in Max

Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) is

titled "Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality" and interprets the

ruthless and calculating behavior of Juliette as the embodiment of the

philosophy of Enlightenment. |

マックス・ホルクハイマーとテオドール・アドルノの『啓蒙の弁証法』

(1947年)のエッセイの一つに「ジュリエット、あるいは啓蒙と道徳」というタイト

ルがあり、ジュリエットの冷酷で計算高い行動を啓蒙哲学の体現と解釈している。 |

| Similarly, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan posited in his 1963 essay Kant avec Sade that Sade's ethics was the complementary completion of the categorical imperative originally formulated by Immanuel Kant. | 同様に、精神分析医のジャック・ラカンは、1963年の論文『Kant avec Sade(カントとサド)』で、サドの倫理はもともとイマニュエ

ル・カントが定式化した定言命法を補完的に完成したものであると仮定している。 |

| In contrast, G. T. Roche argued

that Sade, contrary to what some have claimed, did indeed express or

discuss specific philosophical views in his work. He concludes most

were views current in the Enlightenment period (some of them responding

to others', such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau's). Yet others he finds to

also be prescient of later philosophers, for instance Friedrich

Nietzche, in certain ways. Roche criticizes and discusses some of these

views in detail.[35] He criticizes Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer's

view that Sade was a quintessential Enlightenment thinker whose ideas

had been born out negatively later in their work Dialectic of

Enlightenment.[36] Additionally, he criticizes the idea Sade showed

morality cannot have a rational basis, and acting morally is no more

justified than being immoral.[37] |

これに対して、G. T.

ロッシュは、一部の主張とは異なり、サドが作品の中で特定の哲学的見解を表明し、論じていたことを指摘した。そして、そのほとんどが啓蒙主義時代の見解で

あり(中にはジャン・ジャック・ルソーのような他者の見解に反応したものもある)、また、後世の哲学者の先見性を示すものもあると結論づけた。また、後世

の哲学者、たとえばフリードリヒ・ニーチェの先見性を見出すものもある。ロシュはこれらの見解のいくつかを詳細に批判し、議論している[35]。

彼はサドが典型的な啓蒙思想家であり、その思想は後に彼らの著作『啓蒙の弁証法』で否定的に生まれたというテオドール・アドルノとマックス・ホルクハイ

マーの見解を批判する[36]。

さらに彼はサドによって道徳は合理的根拠を持ち得ず、道徳的に振る舞うのは不道徳であるよりも正当でないとする考え方を批判している[37]。 |

| In his 1988 Political Theory and

Modernity, William E. Connolly analyzes Sade's Philosophy in the

Bedroom as an argument against earlier political philosophers, notably

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes, and their attempts to

reconcile nature, reason, and virtue as bases of ordered society. |

ウィリアム・E・コノリーは1988年の『政治理論と近代』において、

サドの『寝室の哲学(閨房哲学)』を、それ以前の政治哲学者、特にジャン=ジャック・ルソーやト

マス・ホッブズが秩序ある社会の基盤として自然、理性、美徳を調和させようとしていたことに対する議論として分析している。 |

| Similarly, Camille Paglia[38] argued that Sade can be best understood as a satirist, responding "point by point" to Rousseau's claims that society inhibits and corrupts mankind's innate goodness: Paglia notes that Sade wrote in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when Rousseauist Jacobins instituted the bloody Reign of Terror and Rousseau's predictions were brutally disproved. "Simply follow nature, Rousseau declares. Sade, laughing grimly, agrees."[39] | 同様に、カミーユ・パリア [38]は、サドは、社会が人間の生来の善を阻害し堕落させるというルソーの主張に対して「一点一点」応答する風刺作家として理解するのが最善であると論 じている。パグリアは、サドが書いたのはフランス革命の直後で、ルソー派のジャコバン派が血生臭いテロルの支配を行い、ルソーの予言が残酷に反故にされた 時期であると指摘する。ルソーは「ただ自然に従え」と宣言した。サドは不気味に笑いながら同意している」[39]。 |

| In The Sadeian Woman: And the

Ideology of Pornography (1979), Angela Carter provides a feminist

reading of Sade, seeing him as a "moral pornographer" who creates

spaces for women. |

サド的な女:And the Ideology of

Pornography (1979)

で、アンジェラ・カーターはサドを女性のための空間を作り出す「道徳的ポルノ製作者」として捉え、フェミニスト的な読解を提供している。 |

| Similarly, Susan Sontag defended both Sade and Georges Bataille's Histoire de l'œil (Story of the Eye) in her essay "The Pornographic Imagination" (1967) on the basis their works were transgressive texts, and argued that neither should be censored. | 同様に、スーザ

ン・ソンタグはそのエッセイ『ポルノグラフィーの想像力』(1967年)のなかで、サドとジョルジュ・バタイユの『目の物語』を、その作品がトランスグ

レッシブなテキストであるとして擁護し、どちらも検閲されるべきではないと論じている。 |

| By contrast, Andrea Dworkin saw Sade as the exemplary woman-hating pornographer, supporting her theory that pornography inevitably leads to violence against women. One chapter of her book Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1979) is devoted to an analysis of Sade. Susie Bright claims that Dworkin's first novel Ice and Fire, which is rife with violence and abuse, can be seen as a modern retelling of Sade's Juliette.[40] | 対照的に、アンドレア・ドウォーキンは、サドを女性嫌悪のポルノグ ラファーの典型とみなし、ポルノは必然的に女性に対する暴力につながるという自説を支持した。彼女の著書『ポルノグラフィー』(1979年)の一章は、 「男が女を憑依させる。Men Possessing Women (1979)の一章は、サドの分析に費やされている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marquis_de_Sade |

★伝記的素描

Portrait of Donatien Alphonse François de Sade by Charles Amédée Philippe van Loo.[1] The drawing dates to 1760, when Sade was 19 years old, and is the only known authentic portrait of him.[2] +++++++++++++++++++ Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (French: [dɔnasjɛ̃ alfɔ̃z fʁɑ̃swa maʁki də sad]; 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814), was a French nobleman, revolutionary politician, philosopher and writer famous for his literary depictions of a libertine sexuality. His works include novels, short stories, plays, dialogues, and political tracts. In his lifetime some of these were published under his own name while others, which Sade denied having written, appeared anonymously. Sade is best known for his erotic works, which combined philosophical discourse with pornography, depicting sexual fantasies with an emphasis on violence, suffering, anal sex (which he calls sodomy), child rape, crime, and blasphemy against Christianity. Many of the characters in his works are teenagers or adolescents. His work is a depiction of extreme absolute freedom, unrestrained by morality, religion, or law. The words sadism and sadist are derived in reference to the works of fiction he wrote which portrayed numerous acts of sexual cruelty. While Sade mentally explored a wide range of sexual deviations, his known behavior includes "only the beating of a housemaid and an orgy with several prostitutes—behavior significantly departing from the clinical definition of sadism".[6][7] In 1774, Sade also forcibly held five young women and one man hostage in his chateau while forcing them to commit various sexual acts for six weeks.[8] Sade was a proponent of free public brothels paid for by the state: In order both to prevent crimes in society that are motivated by lust and to reduce the desire to oppress others using one’s own power, Sade recommended public brothels where people can satisfy their wishes to command and be obeyed.[9] Despite having no legal charge brought against him,[6] Sade was incarcerated in various prisons and an insane asylum for about 32 years of his life (or, after 1777, solely due to Lettres de cachet and involuntary commitment): seven years in the Château de Vincennes, five years in the Bastille, a month in the Conciergerie, two years in a fortress, a year in Madelonnettes Convent, three years in Bicêtre Asylum, a year in Sainte-Pélagie Prison, and 12 years in the Charenton Asylum. During the French Revolution, he was an elected delegate to the National Convention. Many of his works were written in prison. There continues to be a fascination with Sade among scholars and in popular culture. Prolific French intellectuals such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault published studies of him.[10] In contrast, the French hedonist philosopher Michel Onfray has attacked this interest in Sade, writing that "It is intellectually bizarre to make Sade a hero."[11] There have also been numerous film adaptations of his work, including Pasolini's Salò, an adaptation of Sade's controversial book The 120 Days of Sodom, as well as many of the films of Spanish director Jesús Franco.[12] |

シャルル・アメデ・フィリップ・ファン・ルーによるドナティアン・アルフォンス・フランソワ・ド・サドの肖像画。このデッサンは1760年、サドが19歳 の時のもので、唯一知られている本物の肖像画である。 +++++++++++++++++++ ドナティアン アルフォンス フランソワ、マルキ・ド・サド(フランス語: [dɔnasjɛ̃ z f̃ swa maʁ də sad]; 1740年6月2日から1814年12月2日)はフランスの貴族、革命政治家、哲学者、文学者で、自由な性描写をしたことで有名であった。小説、短編小 説、戯曲、対話集、政治的論説などがある。生前は実名で出版されたものもあれば、サドが書いたと否定しているものもあり、匿名で出版された。 サドは、哲学的言説とポルノグラフィーを組み合わせたエロティックな作品で最もよく知られており、暴力、苦痛、アナルセックス(彼はソドミーと呼んでい る)、児童レイプ、犯罪、キリスト教に対する冒涜に重点を置いて性的ファンタジーを描いている。作品の登場人物の多くはティーンエイジャーや青年である。 彼の作品は、道徳、宗教、法律にとらわれない、極端な絶対的自由を描いている。サディズムやサディストという言葉は、彼が書いた数々の性的残虐行為を描い たフィクション作品にちなんでつけられたものである。サドは精神的には様々な性的逸脱を探求していたが、彼の行動として知られているのは「女中への殴打と 複数の娼婦との乱交のみで、臨床的なサディズムの定義からは大きく逸脱した行動」[6][7]。 また1774年にサドは若い女性5人と男性1人を自分のシャトーで無理やり人質にし、6週間にわたって様々な性的行為を強要していた[8]。サドは国家に よる無料の公的売春宿を推進する立場であった。欲望に起因する社会的犯罪を防ぐため、また自分の力を使って他人を抑圧したいという欲求を減らすために、サ ドは人々が命令したり従ったりしたいという欲求を満たすことのできる公共の売春宿を推奨した[9]。 法的な告発がなかったにもかかわらず、サドは生涯約32年間(あるいは1777年以降はレトル・ド・カシェと強制収容のみによる)様々な刑務所や精神病院 に収監された[6]。ヴァンセンヌ城に7年、バスティーユに5年、コンシェルジュリーに1ヶ月、要塞に2年、マドロネット修道院に1年、ビセートル精神病 院に3年、サント・ペラジー監獄に1年、シャラントン精神病院に12年であった。フランス革命時には国民公会の代議員に選出された。彼の作品の多くは、獄 中で書かれたものである。 サドの魅力は、学者や大衆文化の中に今もなお残っている。ロラン・バルト、ジャック・デリダ、ミシェル・フーコーなどのフランスの著名な知識人はサドに関 する研究を発表した[10]。 これに対し、フランスの快楽主義哲学者ミシェル・オンフレーは「サドを英雄とするのは知的に奇妙である」と書いて、サドへの関心を攻撃している[11]。 "11]また、サドの問題作『ソドムの120日』を映画化したパゾリーニ監督の『サロ』や、スペイン人監督ヘスス・フランコの作品の多くなど、彼の作品の 映画化も数多く行われている[12]。 |

Sade was born on 2 June 1740, in the Hôtel de Condé, Paris, to Jean Baptiste François Joseph, Count de Sade and Marie Eléonore de Maillé de Carman, distant cousin and lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Condé. His parents' only surviving child,[13] Sade and his family were soon abandoned by his father. He was raised by servants who indulged "his every whim", which led to his becoming "known as a rebellious and spoiled child with an ever-growing temper." After an incident in which he severely beat Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé, six-year-old Sade was sent to live under instruction of his uncle, the Abbé de Sade, who "introduced him to debauchery". Shortly thereafter, his mother—already distant and cold to her son—abandoned him, joining a convent.[14]  Later in his childhood, ten-year-old Sade was sent to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris,[14] a Jesuit college, for four years.[13] While at the school, he was tutored by Abbé Jacques-François Amblet, a priest.[15] Later in life, at one of Sade's trials the Abbé testified, saying that Sade had a "passionate temperament which made him eager in the pursuit of pleasure" but had a "good heart."[15] At the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, he was subjected to "severe corporal punishment," including "flagellation," and he "spent the rest of his adult life obsessed with the violent act."[14] At age 14, Sade began attending an elite military academy.[13] After twenty months of training, on 14 December 1755, at age 15, Sade was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant, becoming a soldier.[15] After thirteen months as a sub-lieutenant, he was commissioned to the rank of cornet in the Brigade de S. André of the Comte de Provence's Carbine Regiment.[15] He eventually became Colonel of a Dragoon regiment and fought in the Seven Years' War. In 1763, on returning from war, he courted a rich magistrate's daughter, but her father rejected his suitorship and instead arranged a marriage with his elder daughter, Renée-Pélagie de Montreuil; that marriage produced two sons and a daughter.[16] In 1766, he had a private theatre built in his castle, the Château de Lacoste, in Provence. In January 1767, his father died. |

サドは1740年6月2日、パリのオテル・ド・コンデで、サド伯爵ジャ ン・バティスト・フランソワ・ジョセフと、コンデ公妃の遠縁にあたるマリー・エレオノア・ド・マイレ・ド・カーマンの間に生まれる。両親の間に生まれた唯 一の子供であったが[13]、サドとその家族はすぐに父に捨てられることになった。サドは使用人に育てられ、「気まぐれの激しい、反抗的で甘やかされた子 供」として知られるようになった[13]。コンデ公ルイ・ジョセフをひどく殴った事件の後、6歳のサドは叔父のサド修道院長のもとで暮らすことになり、彼 は「放蕩を始めた」という。その後まもなく、すでに息子に対してよそよそしく冷たい態度をとっていた母親は、サドを捨てて修道院に入った[14]。  その後、10歳のサドはパリのイエズス会の大学であるリセ・ルイ・ル・グランに4年間送られた[14]。在学中、彼は司祭であるジャック=フランソワ・ア ンベールに指導を受けた[13]。 [後年、サドの裁判でアベは、サドには「快楽の追求に熱心な情熱的な気質」があったが「善良な心」を持っていたと証言している[15]。 リセ・ルイ・ル・グランでは、「旗振り」などの「厳しい体罰」を受け、「暴力行為に取り付かれて残りの成人期を過ごす」ことになった[14]。 14歳の時、サドはエリート軍事学校に通い始めた[13]。 20ヶ月の訓練の後、1755年12月14日、15歳になったサドは少尉に任じられ、軍人となった[15]。 少尉として13ヶ月後、プロヴァンス伯爵のカービン連隊のサントレ旅団でコルネットに任命され、最終的にはドラグーン連隊大佐になって七年戦争に参戦した [15]。1763年、戦争から戻ると、金持ちの奉行所の娘に求婚したが、彼女の父親に断られ、代わりに長女のルネ=ペラジー・ド・モントルイユと結婚さ せた。1766年、プロヴァンスの城、シャトー・ド・ラコステに私設劇場を建設させた[16]。1767年1月、父親が死去。 |

| Title and heirs The men of the Sade family alternated between using the marquis and comte (count) titles. His grandfather, Gaspard François de Sade, was the first to use marquis;[17] occasionally, he was the Marquis de Sade, but is identified in documents as the Marquis de Mazan. The Sade family were noblesse d'épée, claiming at the time the oldest, Frankish-descended nobility, so assuming a noble title without a King's grant was customarily de rigueur. Alternating title usage indicates that titular hierarchy (below duc et pair) was notional; theoretically, the marquis title was granted to noblemen owning several countships, but its use by men of dubious lineage caused its disrepute. At Court, precedence was by seniority and royal favor, not title. There is father-and-son correspondence, wherein father addresses son as marquis.[citation needed] For many years, Sade's descendants regarded his life and work as a scandal to be suppressed. This did not change until the mid-20th century, when the Comte Xavier de Sade reclaimed the marquis title, long fallen into disuse,[18] and took an interest in his ancestor's writings. At that time, the "divine marquis" of legend was so unmentionable in his own family that Xavier de Sade learned of him only in the late 1940s when approached by a journalist.[18] He subsequently discovered a store of Sade's papers in the family château at Condé-en-Brie, and worked with scholars for decades to enable their publication.[2] His youngest son, the Marquis Thibault de Sade, has continued the collaboration. The family have also claimed a trademark on the name.[19] The family sold the Château de Condé in 1983.[20] As well as the manuscripts they retain, others are held in universities and libraries. Many, however, were lost in the 18th and 19th centuries. A substantial number were destroyed after Sade's death at the instigation of his son, Donatien-Claude-Armand.[21] |

称号と相続人 サド家の男子は侯爵とコント(伯爵)の称号を交互に使っていた。祖父のガスパール・フランソワ・ド・サドは初めて侯爵を名乗った[17]。時折、サド侯爵 であったが、文献上ではマザン侯爵とされている。サド家は当時最も古いフランク人の血を引く貴族であり、王の許しを得ずに貴族の称号を得ることが慣習的に 行われていた。侯爵の称号は、理論的には複数の伯爵位を所有する貴族に与えられるが、血筋の怪しい者が使用したため、評判が悪くなった。宮廷での優先順位 は、称号ではなく、年功序列と王室の恩恵によるものであった。父親が息子に侯爵と呼びかける親子文通がある[要出典]。 サドの子孫は長い間、彼の人生と仕事をスキャンダルとして封印していた。20世紀半ば、グザヴィエ・ド・サド伯爵が、長い間使われていなかった侯爵の称号 を取り戻し[18]、祖先の著作に関心を持つようになるまで、この状況は変わらなかった。当時、伝説の「神の侯爵」は一族内で言及されることがなく、グザ ヴィエ・ド・サドは1940年代後半にジャーナリストから話を持ちかけられて初めて彼のことを知った[18]。 その後、コンデ・アン・ブリー城にあるサド家の蔵書を発見し、その出版のために学者と数十年にわたって協力し合った。 末子のチボー・ド・サド侯もこの協力関係を継続している[2]。1983年、一族はコンデ城を売却した[20]。しかし、その多くは18世紀と19世紀に 失われた。サドの死後、息子のドナティアン=クロード=アルマンの扇動により、かなりの数が破壊された[21]。 |

| Scandals and imprisonment Sade lived a scandalous libertine existence and repeatedly procured young prostitutes as well as employees of both sexes in his castle in Lacoste. He was also accused of blasphemy, which was considered a serious offense. His behavior also included an affair with his wife's sister, Anne-Prospère, who had come to live at the castle.[2] Beginning in 1763, Sade lived mainly in or near Paris. Four months following his marriage on 17 May 1763, Sade was charged with outrage to public morals, blasphemy and profanation of the image of Christ.[22] On 18 October 1763, Sade procured the services of a local prostitute named Jeanne Testard for sodomy, which was refused. He then locked her in his apartment room, before asking whether she believed in God. When she stated that she did, Sade proceeded to shout various obscenities and impieties concerning Jesus and the Virgin Mary, stating there was no god. Sade then masturbated into a church chalice, proceeding to stomp on an ivory crucifix while masturbating with another as he exclaimed blasphemies,[23][2] before ordering her to beat him with a cane whip and an iron whip which had been heated by fire. During the twelve-hour ordeal, Sade forced Testard to stomp on a crucifix while repeating, "Bastard, I don't give a fuck about you!" under threat of a scabbard as he recited various blasphemous poems throughout the night. Following the incident, Testard then reported Sade to authorities, who arrested him on 29 October 1763, holding him for fifteen days in the prison of Vincennes.[24] After several contrite letters in which Sade expressed remorse and begged to see a priest, the King ordered his release on 13 November.[21] In September 1764, Sade returned to Paris, gradually developing a bad reputation which prompted the chief police inspector to advise to local madams that their prostitutes not accompany him to his countryside residence. Because of his sexual infamy, he was put under surveillance by the police, who made detailed reports of his activities over the course of the following years, writing in October 1767, "We will soon be hearing again of the horrors of the Comte de Sade."[25] On 3 April 1768, Easter Sunday, Sade had encountered a 36-year-old German widow named Rose Keller at the Place des Victoires; upon reassuring her that he required house service which included cleaning his bedroom, they rode in his carriage to Sade's country residence in Arcueil, where she was subsequently locked and held captive. Sade proceeded to bind Keller before proceeding to flagellate her with a whip over the course of two days.[26][22][2] Although court documents suggest Sade may have made incisions on Keller's back, buttocks, and thighs before pouring hot wax into the wounds,[23][21][26] Keller failed to produce evidence of her claims to authorities two days after the incident took place.[27] On the day of her escape, Sade applied ointment to Keller as she cried and unbound her, ordering Keller to clean the bloodstains from her gown as he briefly departed. Through a window, Keller then fled before informing nearby locals and authorities, prompting Sade's arrest in June.[22] He was briefly incarcerated in the then-prison Château de Saumur, and exiled to his château at Lacoste in 1768[21] as Keller was immediately bribed to drop charges.[2][26] On 27 June 1772, Sade procured four prostitutes with the aid of his manservant, Latour. During the ordeal, Sade whipped the prostitutes and requested they do the same. He then opted to engage in anal intercourse with the prostitutes, two of whom had refused, before engaging in mutual sodomy with his manservant. After the orgy, Sade offered them chocolates laced with an aphrodisiac in the hopes that the chocolate would allow him to fulfill his sexual fantasies with them.[24][21] When the young women—suspicious of the chocolate's contents—grew pale and sick, they alerted authorities of the sodomy and perceived attempted poisoning and an investigation was opened.[26] The two men were sentenced to death in absentia and charged with sodomy, attempted poisoning, and outrage to the country's morals.[22][n 1] They fled to Italy, Sade taking his wife's sister—whom he had been in love with from the time she was 13—with him. With the help of Sade's mother-in-law, Sade and Latour were caught and imprisoned at the Fortress of Miolans in French Savoy in late 1772, but escaped four months later.[2]  Sade later hid at Lacoste where he rejoined his wife, who became an accomplice in his subsequent endeavors. In the winter of 1774, Sade began to partake in orgies at his home in his wife's presence in which he enacted a series of theatrical sexual performances with five young females and a young manservant[29][2] aged between 14 and 16 years old.[21] By January 1775, the servants' parents began making complaints that Sade had abducted and seduced their children. When one of the female servants fled to his uncle's residence, Sade promptly urged him to hold her prisoner before making further efforts to suppress the scandal. Authorities learned of his sexual debauchery, however, and Sade was forced to flee to Italy once again following accusations of kidnapping and rape.[21] It was during this time he wrote Voyage d'Italie. In 1776, he returned to Lacoste, again hired several women, most of whom soon fled. In 1777, the father of one of these employees went to Lacoste to claim his daughter, and attempted to shoot the Marquis at point-blank range, but the gun misfired. Later that year, Sade was tricked into going to Paris to visit his supposedly ill mother, who in fact had recently died. He was arrested and imprisoned in the Château de Vincennes. He successfully appealed his death sentence in 1778 but remained imprisoned under the lettre de cachet. He escaped but was soon recaptured. He resumed writing and met fellow prisoner Comte de Mirabeau, who also wrote erotic works. Despite this common interest, the two came to dislike each other intensely.[30] In 1784, Vincennes was closed, and Sade was transferred to the Bastille. The following year, he wrote the manuscript for his magnum opus Les 120 Journées de Sodome (The 120 Days of Sodom), which he wrote in minuscule handwriting on a continuous roll of paper he rolled tightly and placed in his cell wall to hide. He was unable to finish the work; on 4 July 1789, he was transferred "naked as a worm" to the insane asylum at Charenton near Paris, two days after he reportedly incited unrest outside the prison by shouting to the crowds gathered there, "They are killing the prisoners here!" Sade was unable to retrieve the manuscript before being removed from the prison. The storming of the Bastille, a major event of the French Revolution, occurred ten days after Sade left, on 14 July. To his despair, he believed that the manuscript was destroyed in the storming of the Bastille, though it was actually saved by a man named Arnoux de Saint-Maximin two days before the Bastille was attacked. It is not known why Saint-Maximin chose to bring the manuscript to safety, nor indeed is anything else about him known.[2] In 1790, Sade was released from Charenton after the new National Constituent Assembly abolished the instrument of lettre de cachet. His wife obtained a divorce soon afterwards. |

スキャンダルと投獄 サドはスキャンダラスな放蕩生活を送り、ラコスト城で若い娼婦や男女の従業員を何度も調達していた。また、神への冒涜という重大な罪にも問われた。また、 城に住むようになった妻の妹、アンヌ=プロスペールとの不倫もあった[2]。 1763年から、サドは主にパリやその近郊で生活した。1763年5月17日の結婚から4ヶ月後、サドは風紀紊乱、冒涜、キリスト像の冒涜の罪で起訴され た[22] 1763年10月18日、サドは地元のジャンヌ・テスタールという娼婦に性交を申し込んだが、拒否された。そして、彼女を自分のアパートの部屋に閉じ込 め、彼女が神を信じるかどうかを尋ねた。彼女が信じていると答えると、サドはイエスと聖母マリアに関する様々な卑猥な言葉を叫び続け、神は存在しないと述 べた。その後、サドは教会の聖杯で自慰をし、象牙の十字架を踏みつけながら、別のもので自慰をし、神を冒涜するような言葉を発し、鞭と火で熱した鉄の鞭で 叩くように命じた[23][2]。12時間の試練の間、サドはテスタールに鞘で脅しながら「クソ野郎、お前のことなど知ったことか!」と繰り返しながら十 字架を踏みつけさせ、彼が一晩中様々な冒涜的な詩を朗読するように仕向けたという。この事件の後、テスタールはサドを当局に報告し、当局は1763年10 月29日に彼を逮捕、ヴァンセンヌの刑務所に15日間拘束した[24]。サドが反省を表明し、司祭に会わせてほしいと願う数通の手紙の後、王は11月13 日に彼の釈放を命じた[21]。 1764年9月、サドはパリに戻ったが、次第に評判が悪くなり、警視総監は地元のマダムたちに、娼婦たちを彼の田舎の住居に同行させないように忠告するよ うになった。その性的悪評のため、彼は警察の監視下に置かれ、警察はその後の彼の活動を詳細に報告し、1767年10月には「我々はすぐにサド伯爵の恐怖 を再び聞くことになるだろう」と書いている[25]。 1768年4月3日、復活祭の日、サドはヴィクトワール広場でローズ・ケラーという36歳のドイツ人未亡人に出会い、寝室の掃除などの家事を頼まれ、彼の 馬車でアルカイユのサドの田舎家まで行き、そこで彼女は監禁された。サドはケラーを拘束した後、2日間にわたり鞭で鞭打ちを続けた[26][22] [2]。裁判資料では、サドはケラーの背中、尻、太ももに切り込みを入れ、傷口に熱いロウを流し込んでいた可能性を示唆しているが、事件が起きた2日後に ケラーは当局に対して彼女の主張を証明するものを提示しなかった[23][21][26]。 [27] 脱獄の日、サドは泣きながらケラーに軟膏を塗り、拘束を解き、ケラーにガウンの血痕をきれいにするよう命じ、短時間で立ち去りました。ケラーは窓から逃げ 出し、近くの住民や当局に知らせたため、サドは6月に逮捕された[22]。彼は当時の刑務所であるソミュール城に一時収監され、1768年にラコステの自 分の城に流された[21]が、ケラーはすぐに賄賂を渡して告訴を取り下げさせた[2][26]。 1772年6月27日、サドは下男のラトゥールの助けを借りて4人の娼婦を調達した。その際、サドは娼婦たちを鞭打ち、彼女たちにも同じようにするよう要 求した。そして、娼婦たちのうち2人は拒否したが、彼は肛門性交を選択し、その後下男と相互性交を行った。乱交の後、サドは媚薬入りのチョコレートを差し 出し、そのチョコレートで自分の性的な幻想を実現させることを期待した[24][21]。チョコレートの中身を疑った若い女性たちが青ざめ、気分が悪くな ると、彼らは淫行と中毒未遂を警察に知らせ、捜査が開始された[26]。 [26] 2人は欠席裁判で死刑判決を受け、ソドミー、毒殺未遂、風紀紊乱の罪に問われた[22][n 1] 彼らはイタリアに逃げ、サドは13歳の時から恋していた妻の妹を連れて行った。サドの義母の助けにより、サドとラトゥールは1772年末にフランス領サ ヴォワのミオランス要塞に捕らえられ投獄されたが、4ヶ月後に脱走した[2]。  その後、サドはラコステに身を隠し、妻と再会するが、妻はその後の活動の共犯者となった。1774年の冬、サドは妻のいる自宅で乱交を始め、5人の若い女 性と14歳から16歳の若い下男[29][2]と一連の芝居じみた性的パフォーマンスを行った[21]。1775年1月には、使用人の両親がサドが子供を 誘拐し誘惑したと苦情を言い始めるようになる。使用人の一人が叔父の屋敷に逃げ込むと、サドはすぐに彼女を監禁するように促し、スキャンダルを抑える努力 をした。しかし、サドの放蕩ぶりは当局に知られ、誘拐と強姦の告発を受けて再びイタリアに逃亡せざるを得なかった[21]。1776年、彼はラコステに戻 り、再び数人の女性を雇ったが、そのほとんどはすぐに逃げ出してしまった。1777年、これらの従業員の一人の父親が娘を引き取りにラコステに行き、至近 距離から侯爵を撃とうとしたが、銃は誤射された。 その年の暮れ、サドは病気のはずの母を見舞うためにパリに向かったが、実は母が亡くなったばかりだった。彼は逮捕され、ヴァンセンヌ城に幽閉された。 1778年、彼は死刑判決を不服として控訴したが、レトル・ド・カシェの下に幽閉されたままだった。しかし、すぐに捕らえられた。そこで、同じ囚人のミラ ボー伯爵と出会い、ミラボー伯爵もまたエロティックな作品を書いていた。この共通の興味にもかかわらず、二人は激しく憎み合うようになった[30]。 1784年、ヴァンセンヌは閉鎖され、サドはバスティーユに移送された。翌年、彼は大作『ソドムの120日』の原稿を書いた。この原稿は、極小の字で連続 したロール紙に書き、固く丸めて独房の壁に挟んで隠しておいた。1789年7月4日、彼は「虫のように裸で」パリ近郊のシャラントンの精神病院に移され た。その2日後、彼は刑務所の外に集まった群衆に向かって「彼らはここで囚人を殺している!」と叫び、不安をあおったことが伝えられている。サドは牢屋か ら出される前に原稿を取り返すことができなかった。フランス革命の大事件であるバスティーユ襲撃は、サドが出て行ってから10日後の7月14日に起きてい る。しかし、バスティーユ襲撃の2日前、アルヌー・ド・サンマクシマンという人物に救われたのである。1790年、新国立議会がレトル・ド・カシェを廃止 したため、サドはシャラントンを釈放される。彼の妻はその後すぐに離婚をした。 |

| Return to freedom, delegate to

the National Convention, and imprisonment During Sade's time of freedom, beginning in 1790, he published several of his books anonymously. He met Marie-Constance Quesnet, a former actress with a six-year-old son, who had been abandoned by her husband. Constance and Sade stayed together for the rest of his life. He initially adapted well to the new political order after the revolution, supported the Republic,[31] called himself "Citizen Sade", and managed to obtain several official positions despite his aristocratic background. Because of the damage done to his estate in Lacoste, which was sacked in 1789 by an angry mob, he moved to Paris. In 1790, he was elected to the National Convention, where he represented the far left. He was a member of the Piques section, notorious for its radical views. He wrote several political pamphlets, in which he called for the implementation of direct vote. However, there is much evidence suggesting that he suffered abuse from his fellow revolutionaries due to his aristocratic background. Matters were not helped by his son's May 1792 desertion from the military, where he had been serving as a second lieutenant and the aide-de-camp to an important colonel, the Marquis de Toulengeon. Sade was forced to disavow his son's desertion in order to save himself. Later that year, his name was added—whether by error or wilful malice—to the list of émigrés of the Bouches-du-Rhône department.[32] While claiming he was opposed to the Reign of Terror in 1793, he wrote an admiring eulogy for Jean-Paul Marat.[18] At this stage, he was becoming publicly critical of Maximilien Robespierre and, on 5 December, he was removed from his posts, accused of moderatism, and imprisoned for almost a year. He was released in 1794 after the end of the Reign of Terror. In 1796, now completely destitute, he had to sell his ruined castle in Lacoste. |

自由への復帰、国民会議代表、そして投獄 1790年から自由を得たサドは、いくつかの著書を匿名で出版した。そして、夫に捨てられ、6歳の息子を持つ元女優のマリー=コンスタンス・ケスネと知り 合う。コンスタンスとサドは生涯を共にした。 革命後の新しい政治体制に当初はうまく適応し、共和国を支持し、「市民サド」を名乗り[31]、貴族出身でありながらいくつかの公職に就くことができた。 ラコステの領地が1789年に怒った暴徒によって略奪されたため、パリに移住した。1790年、国民公会議員に選出され、極左の代表として活躍した。彼 は、過激な意見で悪名高いピケ派のメンバーであった。彼はいくつかの政治小冊子を書き、その中で直接投票の実施を訴えた。しかし、貴族出身であったため に、革命家たちから虐待を受けていたことを示唆する証拠が多く残っている。1792年5月、トゥーランゴン侯爵の側近として少尉を務めていた彼の息子が脱 走したことは、事態を悪化させた。サドは自分の身を守るため、息子の脱走を否定せざるを得なかった。その年の暮れには、誤認か故意か、ブーシュ=デュ= ローヌ県の移住者リストに彼の名前が加えられた[32]。 この頃、マクシミリアン・ロベスピエールを公に批判するようになり、12月5日、穏健主義者として罷免され、1年近く投獄される。テラーの支配が終わり、 1794年に釈放された。 1796年、すっかり貧しくなった彼は、ラコステの廃墟となった城を売らざるを得なかった。 |

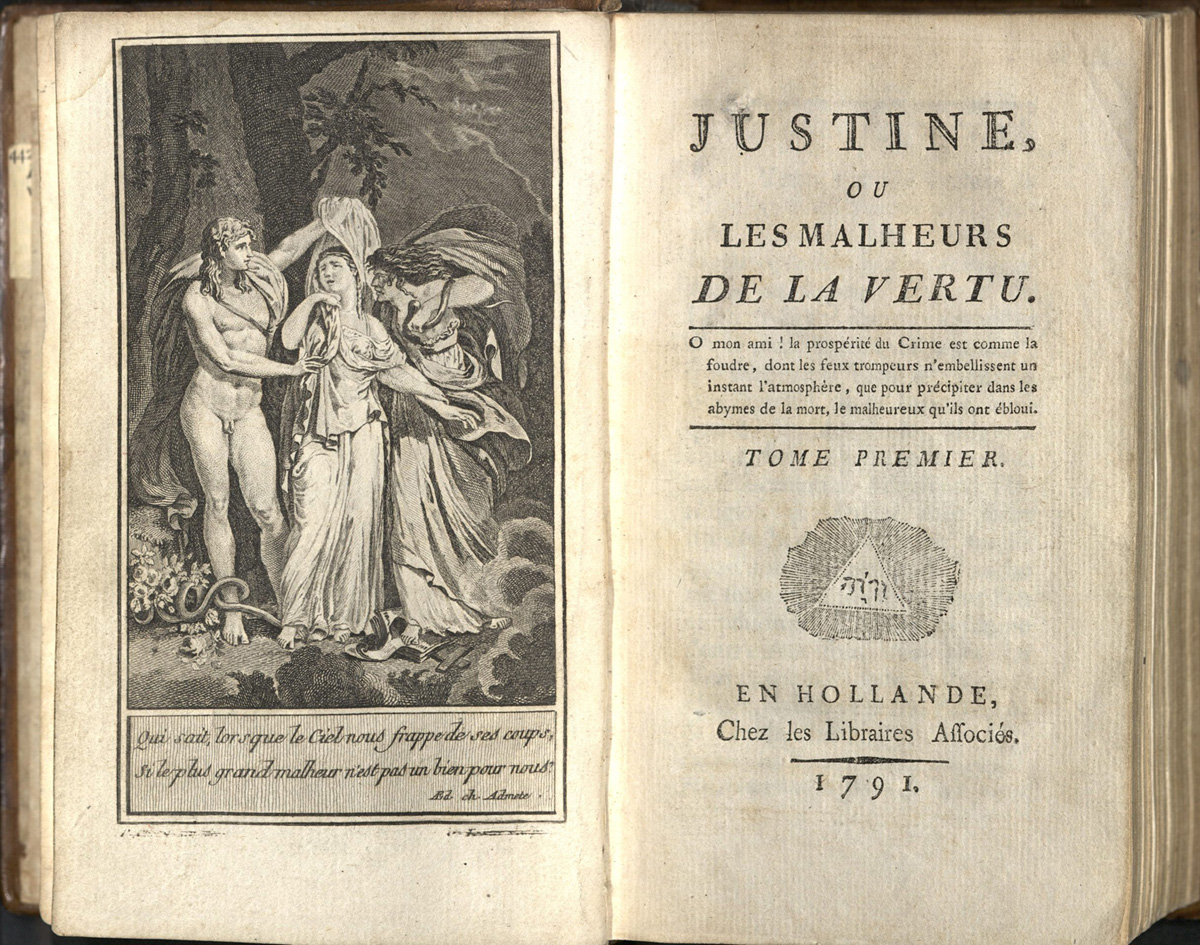

Imprisonment for his writings

and death The first page of Sade's Justine, one of the works for which he was imprisoned +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the anonymous author of Justine and Juliette,[2] expressing outrage after he had been sent a copy of the latter novel by Sade.[22] Sade was arrested at his publisher's office and imprisoned without trial; first in the Sainte-Pélagie Prison and, following allegations that he had tried to seduce young fellow prisoners there, in the harsh Bicêtre Asylum. After intervention by his family, he was declared insane in 1803 and transferred once more to the Charenton Asylum. His ex-wife and children had agreed to pay his pension there. Constance, pretending to be his relative, was allowed to live with him at Charenton. The director of the institution, Abbé de Coulmier, allowed and encouraged him to stage several of his plays, with the inmates as actors, to be viewed by the Parisian public.[2] Coulmier's novel approaches to psychotherapy attracted much opposition. In 1809, new police orders put Sade into solitary confinement and deprived him of pens and paper. In 1813, the government ordered Coulmier to suspend all theatrical performances. Sade began a sexual relationship with 14-year-old Madeleine LeClerc, daughter of an employee at Charenton. This lasted some four years, until his death in 1814. He had left instructions in his will forbidding that his body be opened for any reason whatsoever, and that it remain untouched for 48 hours in the chamber in which he died, and then placed in a coffin and buried on his property located in Malmaison near Épernon. These instructions were not followed; he was buried at Charenton. His skull was later removed from the grave for phrenological examination.[2] His son had all his remaining unpublished manuscripts burned, including the immense multi-volume work Les Journées de Florbelle. |

著作のための投獄と死 サドが投獄された作品のひとつ、『ジュスティーヌ』の最初のページ。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 1801年、ナポレオン・ボナパルトは『ジュスティーヌとジュリエット』の作者の逮捕を命じ、サドから後者の小説を送られたことに憤慨した[2]。 家族の介入により、1803年に精神異常と判断され、再びシャラントンの精神病院に移された。前妻と子供たちは、そこで彼の年金を支払うことに同意してい たのだ。コンスタンスは親族のふりをして、シャラントンで彼と一緒に暮らすことを許された。施設長であるクルミエ修道院長は、パリの大衆に見てもらうため に、収容者を俳優として彼の劇をいくつか上演することを許可し、奨励した[2]。クルミエの精神療法の新しいアプローチは多くの反対を集めた。1809 年、警察の新しい命令により、サドは独房に入れられ、ペンと紙を奪われた。1813年、政府はクーリエにすべての演劇の上演を中止するよう命じた。 サドは、シャラントンの従業員の娘で14歳のマドレーヌ・ルクレールと性的関係を持つようになった。これは1814年に亡くなるまで4年ほど続いた。 彼は遺言で、いかなる理由があっても自分の遺体を開けてはならないこと、自分が死んだ部屋で48時間そのままにしておき、その後棺に入れてエペルノン近郊 のマルメゾンにある自分の所有地に埋葬することを遺していたのだ。この指示は守られず、彼はシャラントンに埋葬された。彼の息子は、膨大な量の著作『フ ローベルの旅』を含む、残された未発表の原稿をすべて焼却した[2]。 |

Depiction of the Marquis de Sade by H. Biberstein in L'Œuvre du marquis de Sade, Guillaume Apollinaire (Edit.), Bibliothèque des Curieux, Paris, 1912 |

H.ビベルシュタインによるサド侯爵の描写(L'Œuvre du marquis de Sade, Guillaume Apollinaire (Ed.), Bibliothèque des Curieux, Paris, 1912年所収 |

| Influence Sexual sadism disorder, a mental condition named after Sade, has been defined as experiencing sexual arousal in response to extreme pain, suffering or humiliation done non-consensually to others (as described by Sade in his novels).[41] Other terms have been used to describe the condition, which may overlap with other sexual preferences that also involve inflicting pain. It is distinct from situations where consenting individuals use mild or simulated pain or humiliation for sexual excitement.[42] Various influential cultural figures have expressed a great interest in Sade's work, including the French philosopher Michel Foucault,[43] the American film maker John Waters[44] and the Spanish filmmaker Jesús Franco. The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne is also said to have been highly influenced by Sade.[45] Nikos Nikolaidis' 1979 film The Wretches Are Still Singing was shot in a surreal way with a predilection for the aesthetics of the Marquis de Sade; Sade is said to have influenced Romantic and Decadent authors such as Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Flaubert, and Rachilde; and to have influenced a growing popularity of nihilism in Western thought.[46] The philosopher of egoist anarchism, Max Stirner, is also speculated to have been influenced by Sade's work.[47] Serial killer Ian Brady, who with Myra Hindley carried out torture and murder of children known as the Moors murders in England during the 1960s, was fascinated by Sade, and the suggestion was made at their trial and appeals[48] that the tortures of the children (the screams and pleadings of whom they tape-recorded) were influenced by Sade's ideas and fantasies. According to Donald Thomas, who has written a biography on Sade, Brady and Hindley had read very little of Sade's actual work; the only book of his they possessed was an anthology of excerpts that included none of his most extreme writings.[49] In the two suitcases found by the police that contained books that belonged to Brady was The Life and Ideas of the Marquis de Sade.[50] Hindley herself claimed that Brady would send her to obtain books by Sade, and that after reading them he became sexually aroused and beat her.[51] In Philosophy in the Bedroom Sade proposed the use of induced abortion for social reasons and population control, marking the first time the subject had been discussed in public. It has been suggested that Sade's writing influenced the subsequent medical and social acceptance of abortion in Western society.[52 |

影響 サドにちなんで名付けられた精神疾患である性的サディズム障害は、(サドが小説の中で記述したように)他者に同意なく行われる極度の苦痛、苦しみ、屈辱に 反応して性的興奮を経験することと定義されている。 [41] この状態を記述するのに他の用語が使われており、痛みを与えることも含む他の性的嗜好と重なる可能性もある。それは、同意した個人が性的興奮のために軽度 または模擬的な苦痛や屈辱を用いる状況とは区別される[42]。 フランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコー[43]、アメリカの映画監督ジョン・ウォーターズ[44]、スペインの映画監督ヘスス・フランコなど、影響力のある 様々な文化人がサドの作品に大きな興味を示している。詩人のアルジャーノン・チャールズ・スウィンバーンもサドに強い影響を受けたと言われている [45]。ニコス・ニコライディス監督の1979年の映画『哀れな者たちはまだ歌っている』は、サド侯爵の美学に傾倒したシュールな手法で撮影されてお り、シャルル・ボードレア、ギュスターヴ・フローベット、ラチルドなどのロマン派・デカダン作家にも影響を与えていると言われ、西洋思想におけるニヒリズ ムがますます人気を集めることに影響を与えたとされている[46]。 [エゴイズムの哲学者であるマックス・シュティルナーもサドの作品から影響を受けたと推測されている[47]。 1960年代にイギリスでムーア人殺人事件として知られる子供たちの拷問と殺人をマイラ・ヒンドレーとともに行った連続殺人犯イアン・ブレディはサドに魅 了され、彼らの裁判と控訴審では、子供たちへの拷問(彼らが録音した叫び声と嘆願)はサドの思想と幻想に影響されているという指摘がなされた[48]。サ ドの伝記を書いたドナルド・トーマスによれば、ブレイディとヒンドレーはサドの実際の作品をほとんど読んでおらず、彼らが持っていた唯一の彼の本は、彼の 最も過激な著作を含まない抜粋のアンソロジーであった[49]。 [49] 警察が見つけたブレイディの本が入っていた2つのスーツケースの中には『サド侯爵の生涯と思想』があった[50] ヒンドリー自身は、ブレイディがサドの本を入手するために彼女を送り、それを読んだ後に性的興奮を覚えて彼女を殴ったと主張している[51]。 サドは『閨房哲学(=寝室の哲学)』の中で、社会的理由と人口抑制のために人工妊娠中絶を使うことを提案し、このテーマが初めて公の場で議論されることに なった。サドの著作は、その後の西洋社会における中絶の医学的・社会的受容に影響を与えたと言われている[52]。 |

| Cultural depictions There have been many and varied references to the Marquis de Sade in popular culture, including fictional works and biographies. The eponym of the psychological and subcultural term sadism, his name is used variously to evoke sexual violence, licentiousness, and freedom of speech.[10] In modern culture his works are simultaneously viewed as masterful analyses of how power and economics work, and as erotica.[53] It could be argued that Sade's sexually explicit works were a medium for the articulation but also for the exposure of the corrupt and hypocritical values of the elite in his society, and that it was primarily this inconvenient and embarrassing satire that led to his long-term detention. With this view, he becomes a symbol of the artist's struggle with the censor and that of the moral philosopher with the constraints of conventional morality. Sade's use of pornographic devices to create provocative works that subvert the prevailing moral values of his time inspired many other artists in a variety of media. The cruelties depicted in his works gave rise to the concept of sadism. Sade's works have to this day been kept alive by certain artists and intellectuals because they themselves espouse a philosophy of extreme individualism.[54] But Sade's life was lived in flat contradiction and breach of Kant's injunction to treat others as ends in themselves and never merely as means to an agent's own ends. In the late 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in Sade; leading French intellectuals like Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault[55] to publish studies of the philosopher, and interest in Sade among scholars and artists continued.[10] In the realm of visual arts, many surrealist artists had an interest in the "Divine Marquis." Sade was celebrated in surrealist periodicals, and feted by figures such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Heine; Man Ray admired Sade because he and other surrealists viewed him as an ideal of freedom.[54] The first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) announced that "Sade is surrealist in sadism", and extracts of the original draft of Justine were published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.[56] In literature, Sade is referenced in several stories by horror and science fiction writer (and author of Psycho) Robert Bloch, while Polish science fiction author Stanisław Lem wrote an essay analyzing the game theory arguments appearing in Sade's Justine.[57] The writer Georges Bataille applied Sade's methods of writing about sexual transgression to shock and provoke readers.[54] Sade's life and works have been the subject of numerous fictional plays, films, pornographic or erotic drawings, etchings, and more. These include Peter Weiss's play Marat/Sade, a fantasia extrapolating from the fact that Sade directed plays performed by his fellow inmates at the Charenton asylum.[58] Yukio Mishima, Barry Yzereef, and Doug Wright also wrote plays about Sade; Weiss's and Wright's plays have been made into films. His work is referenced on film at least as early as Luis Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (1930), the final segment of which provides a coda to 120 Days of Sodom, with the four debauched noblemen emerging from their mountain retreat. In 1969, American International Films released a German-made production called de Sade, with Keir Dullea in the title role. Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), updating Sade's novel to the brief Salò Republic; in 1989, Henri Xhonneux and Roland Topor made Marquis, which was partially based on the memoirs of de Sade;[59] Benoît Jacquot's Sade and Philip Kaufman's Quills (from the play of the same name by Doug Wright) both hit cinemas in 2000. Quills, inspired by Sade's imprisonment and battles with the censorship in his society,[54] portrays him (Geoffrey Rush) as a literary freedom fighter who is a martyr to the cause of free expression.[60] Sade is a 2000 French film directed by Benoît Jacquot starring Daniel Auteuil as the Marquis de Sade, which was adapted by Jacques Fieschi and Bernard Minoret from the novel La terreur dans le boudoir by Serge Bramly. Often Sade himself has been depicted in American popular culture less as a revolutionary or even as a libertine and more akin to a sadistic, tyrannical villain. For example, in the final episode of the television series Friday the 13th: The Series, Micki, the female protagonist, travels back in time and ends up being imprisoned and tortured by Sade. Similarly, in the horror film Waxwork, Sade is among the film's wax villains to come alive. While not personally depicted, Sade's writings feature prominently in the novel Too Like the Lightning, first book in the Terra Ignota sequence written by Ada Palmer. Palmer's depiction of 25th-century Earth relies heavily on the philosophies and prominent figureheads of the Enlightenment, such as Voltaire and Denis Diderot in addition to Sade, and in the book the narrator Mycroft, after showing his fictional "reader" a sex scene formulated off of Sade's own, takes this imaginary reader's indignation as an opportunity to delve into Sade's ideas. Additionally, one of the central locations in the novel, a brothel advertising itself as a "bubble of the 18th century", features an inscription over the proprietor's door dedicating the establishment as a temple to Sade, an homage to Voltaire's "Le Temple du goût, par M. de Voltaire." Marquis de Sade was also portrayed in the video game Assassin's Creed Unity, as an occasional ally to the protagonist Arno.[61] |

文化的描写 サド侯爵は、フィクションや伝記など、大衆文化において様々な形で言及されてきた。サディズムという心理学・サブカルチャー用語の代名詞である彼の名前 は、性的暴力、放縦、言論の自由を喚起するために様々に使われている[10]。現代文化において彼の作品は、権力と経済がいかに機能するかを見事に分析し たと同時にエロティックなものとして捉えられている[53]。 サドの性的に露骨な作品は、彼の社会におけるエリートの腐敗した偽善的な価値観を表現するための媒体であると同時に暴露するための媒体であり、主にこの不 都合で恥ずかしい風刺が彼の長期拘留につながったと主張することができる[53]。このような見解から、彼は芸術家の検閲官との闘い、道徳哲学者の従来の 道徳の制約との闘いの象徴となるのである。サドはポルノグラフィーの装置を使い、当時の一般的な道徳観を覆すような挑発的な作品を作り、様々なメディアで 多くの芸術家を刺激しました。彼の作品に描かれた残酷さは、サディズムという概念を生み出しました。しかし、サドの人生は、他者をそれ自体の目的として扱 い、決して代理人自身の目的のための手段としては扱わないというカントの命題に平然と矛盾し、違反して生きていた[54]。 20世紀後半には、ロラン・バルト、ジャック・ラカン、ジャック・デリダ、ミシェル・フーコー[55]などのフランスの代表的な知識人がサドに関する研究 を発表し、学者や芸術家の間でサドへの関心が続いた[10]。 視覚芸術の領域では、多くのシュールレアリストの芸術家が「神の侯爵」に関心を抱いていた。サドはシュルレアリスムの定期刊行物で賞賛され、ギョーム・ア ポリネール、ポール・エリュアール、モーリス・ハイネなどの人物によって祭り上げられた。マン・レイは、彼と他のシュルレアリスムが彼を自由の理想として 見ていたのでサドを賞賛した[54]。 シュルレアリスムの最初の宣言(1924)は、「サドとはサディズムにおける超現実主義者」だと公表し、『ジュスティン』の原案からの抜きがLe Surréalisme au service de la révolutionに出版されていた[56]。 [文学では、サドはホラーやSF作家(『サイコ』の作者)であるロベルト・ブロックのいくつかの物語で言及されており、ポーランドのSF作家スタニスワ フ・レムはサドの『ジュスティーヌ』に現れるゲーム理論の議論を分析したエッセイを書いている[57]。作家ジョルジュ・バタイユは読者にショックを与え 刺激するために性的侵害について書くサドの手法を適用した[54]。 サドの人生と作品は、数多くのフィクションの劇、映画、ポルノやエロチックな絵、銅版画などの題材になっている。三島由紀夫、バリー・イゼリフ、ダグ・ラ イトもサドを題材にした戯曲を書いており、イゼリフとライトの戯曲は映画化されている。彼の作品は、少なくともルイス・ブニュエルの『L'Âge d'Or』(1930年)の時点で映画化されており、その最終セグメントは『ソドムの120日』のコーダとなり、放蕩三昧の4人の貴族が山荘から姿を現す シーンとなっている。1969年、アメリカン・インターナショナル・フィルムズは、キール・ダレアがタイトルロールを演じたドイツ製の『ド・サド』という 作品を公開した。ピエル・パオロ・パソリーニは『サロ、あるいはソドムの120日』(1975年)を撮影し、サドの小説を短いサロ共和国に更新した。 1989年には、アンリ・ショニューとローラン・トポールがド・サドの回想録に一部基づいた『マルキ』を作った[59] ブノワ・ジャコーの『サド』とフィリップ・カウフマンの『クイール』は(ダグ・ライトの同名の劇から)2000年に映画館で公開されている。サドの投獄と 社会における検閲との戦いに触発された『Quills』は、彼(Geoffrey Rush)を表現の自由のために殉じた文学の自由の闘士として描いています[60] 。サド』はブノワ・ジャコー監督の2000年のフランス映画で、サド侯爵役のダニエル・オートゥイルが出演し、ジャック・フィエスキとベルナルド・ミノレ がセルジュ・ブラムリの小説『La terreur dans le boudoir』を脚色した。 サド自身は、革命家とか自由主義者というよりも、サディスティックで専制的な悪役として描かれることが多い。例えば、テレビシリーズ『13日の金曜日』の 最終回では、主人公の女性ミッキーがタイムスリップして、サドに投獄され拷問を受けることになる。同様に、ホラー映画『Waxwork』では、サドはこの 映画の中で生き返る蝋人形の悪役の一人である。 個人的には描かれていないが、エイダ・パーマーが書いたテラ・イグノタの最初の本である小説「Too Like the Lightning」には、サドの著作が大きく取り上げられている。パーマーが描く25世紀の地球は、サドのほか、ヴォルテールやドゥニ・ディドロといっ た啓蒙主義の哲学や著名な人物に大きく依存しており、本書では語り手のマイクロフトが、架空の「読者」にサド自身のセックスシーンを模して見せた後、その 架空の読者の怒りをきっかけにサドの思想について掘り下げていくことになります。また、小説の中心的な舞台のひとつである「18世紀の泡」のような売春宿 の扉には、ヴォルテールの「Le Temple du goût, par M. de Voltaire」へのオマージュとして、この店をサドの神殿として奉る碑文が掲げられている。 マルキ・ド・サドはビデオゲーム『アサシン クリード ユニティ』でも、主人公アルノの味方として時折描かれた[61]。 |

| Writing Literary criticism The Marquis de Sade viewed Gothic fiction as a genre that relied heavily on magic and phantasmagoria. In his literary criticism Sade sought to prevent his fiction from being labeled "Gothic" by emphasizing Gothic's supernatural aspects as the fundamental difference from themes in his own work. But while he sought this separation he believed the Gothic played a necessary role in society and discussed its roots and its uses. He wrote that the Gothic novel was a perfectly natural, predictable consequence of the revolutionary sentiments in Europe. He theorized that the adversity of the period had rightfully caused Gothic writers to "look to hell for help in composing their alluring novels." Sade held the work of writers Matthew Lewis and Ann Radcliffe high above other Gothic authors, praising the brilliant imagination of Radcliffe and pointing to Lewis' The Monk as without question the genre's best achievement. Sade nevertheless believed that the genre was at odds with itself, arguing that the supernatural elements within Gothic fiction created an inescapable dilemma for both its author and its readers. He argued that an author in this genre was forced to choose between elaborate explanations of the supernatural or no explanation at all and that in either case the reader was unavoidably rendered incredulous. Despite his celebration of The Monk, Sade believed that there was not a single Gothic novel that had been able to overcome these problems, and that a Gothic novel that did would be universally regarded for its excellence in fiction.[62] Many assume that Sade's criticism of the Gothic novel is a reflection of his frustration with sweeping interpretations of works like Justine. Within his objections to the lack of verisimilitude in the Gothic may have been an attempt to present his own work as the better representation of the whole nature of man. Since Sade professed that the ultimate goal of an author should be to deliver an accurate portrayal of man, it is believed that Sade's attempts to separate himself from the Gothic novel highlights this conviction. For Sade, his work was best suited for the accomplishment of this goal in part because he was not chained down by the supernatural silliness that dominated late 18th-century fiction.[63] Moreover, it is believed that Sade praised The Monk (which displays Ambrosio's sacrifice of his humanity to his unrelenting sexual appetite) as the best Gothic novel chiefly because its themes were the closest to those within his own work.[64] |

執筆活動 文芸批評 サド侯爵は、ゴシック小説を魔術や幻想に大きく依存するジャンルとして捉えていた。サドは文学評論の中で、ゴシック小説が「ゴシック」のレッテルを貼られ ないように、ゴシックの超自然的な側面を強調し、自分の作品のテーマとは根本的に異なるものであることを示そうとしました。しかし、その一方で、彼はゴ シックが社会的に必要な役割を果たすと考え、その根源と使われ方について論じた。彼は、ゴシック小説はヨーロッパにおける革命的な感情がもたらした至極当 然の結果であり、予測可能なものであると書いた。彼は、この時代の逆境が、ゴシック小説家たちに「魅力的な小説を書くために地獄に助けを求める」ことを当 然のこととして引き起こしたと理論づけています。サドはマシュー・ルイスやアン・ラドクリフの作品を他のゴシック作家よりも高く評価し、ラドクリフの輝か しい想像力を賞賛し、ルイスの『修道士』をこのジャンルにおける最高の業績として疑いもなく挙げている。しかし、サドはこのジャンルが自分自身と対立して いると考え、ゴシック小説の中の超自然的な要素が作者と読者の双方に逃れられないジレンマを生み出していると主張した。このジャンルの作家は、超自然現象 について精緻な説明をするか、まったく説明をしないかの選択を迫られ、いずれの場合も読者は不可避的に信じられなくなる、と主張した。僧侶』を賞賛してい たにもかかわらず、サドはこれらの問題を克服できたゴシック小説は一つもなく、克服できたゴシック小説はその優れたフィクションとして普遍的に評価される だろうと考えていた[62]。 サドのゴシック小説批判は、『ジュスティーヌ』のような作品の拡大解釈に対する不満の反映であるとする見方が多い。ゴシック小説の真実性の欠如に対する彼 の反論の中には、人間の本質をよりよく表現するものとして自らの作品を提示しようとする姿勢があったのかもしれない。サドは、作家の究極の目標は人間を正 確に描写することであると公言していたので、サドがゴシック小説から自らを切り離そうとしたのは、この信念を強調するものであったと思われる。また、サド がゴシック小説の中で最も優れていると評価したのは、アンブロジオが性欲のために人間性を犠牲にする『修道士』のテーマが、自身の作品に最も近いからだと 考えられている[63]。 |

| Libertine novels Sade's fiction has been classified under different genres, including pornography, Gothic, and baroque. Sade's most famous books are often classified not as Gothic but as libertine novels, and include the novels Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue; Juliette; The 120 Days of Sodom; and Philosophy in the Bedroom. These works challenge traditional perceptions of sexuality, religion, law, age, and gender. His fictional portrayals of sexual violence and sadism stunned even those contemporaries of Sade who were quite familiar with the dark themes of the Gothic novel during its popularity in the late 18th century. Suffering is the primary rule, as in these novels one must often decide between sympathizing with the torturer or the victim. While these works focus on the dark side of human nature, the magic and phantasmagoria that dominates the Gothic is noticeably absent and is the primary reason these works are not considered to fit the genre.[65] Through the unreleased passions of his libertines, Sade wished to shake the world at its core. With 120 Days, for example, Sade wished to present "the most impure tale that has ever been written since the world exists."[66] Despite his literary attempts at evil, his characters and stories often fell into repetition of sexual acts and philosophical justifications. Simone de Beauvoir and Georges Bataille have argued that the repetitive form of his libertine novels, though hindering the artfulness of his prose, ultimately strengthened his individualist arguments.[67][68] The repetitive and obsessive nature of the account of Justine's abuse and frustration in her strivings to be a good Christian living a virtuous and pure life may on a superficial reading seem tediously excessive. Paradoxically, however, Sade checks the reader's instinct to treat them as laughable cheap pornography and obscenity by knowingly and artfully interweaving the tale of her trials with extended reflections on individual and social morality. |

リベルタン小説 サドの小説は、ポルノ、ゴシック、バロックなど、さまざまなジャンルに分類されている。サドの最も有名な作品は、ゴシックではなくリバティーン小説に分類 されることが多く、「ジュスティーヌ、あるいは美徳の不幸」「ジュリエット」「ソドムの120日」「ベッドルームの哲学」などがあります。これらの作品 は、性、宗教、法律、年齢、性別に関する伝統的な認識を覆すものである。サドは、18世紀後半に流行したゴシック小説の暗いテーマに慣れ親しんでいた同時 代の作家たちをも唖然とさせるような性的暴力とサディズムをフィクションで描いている。これらの小説では、拷問する側とされる側のどちらに共感するかを決 めなければならないことが多く、苦しみが第一義的なルールとなっている。これらの作品は人間の暗黒面に焦点を当てているが、ゴシックに支配的な魔法やファ ンタズマゴリアは顕著に欠如しており、これらの作品がこのジャンルに適合しないと見なされる主な理由となっている[65]。 解放されない自由民の情熱を通して、サドは世界をその核心から揺るがすことを望んだ。例えば、『120日』でサドは「世界が存在して以来、これまで書かれ た中で最も不純な物語」を提示しようとした[66]。悪に対する彼の文学的試みにもかかわらず、彼のキャラクターや物語はしばしば性的行為や哲学的正当化 の反復に陥っていた。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールとジョルジュ・バタイユは、彼の放蕩小説の反復形式は、彼の散文の芸術性を妨げるものの、最終的には彼 の個人主義的な主張を強化することになると論じている[67][68] ジュスティーヌの虐待と高潔で純粋な人生を送る良いキリスト教徒になろうとする挫折についての説明の反復と執着の性質は、表層の読解では退屈なほど過剰に 見えるかもしれない。しかし、逆説的に言えば、サドは、彼女の試練の物語を、個人と社会の道徳についての幅広い考察と故意に、芸術的に織り交ぜることに よって、それらを笑い飛ばすような安っぽいポルノや猥褻物として扱おうとする読者の本能を牽制しているのである。 |

| Short fiction In The Crimes of Love, subtitled "Heroic and Tragic Tales", Sade combines romance and horror, employing several Gothic tropes for dramatic purposes. There is blood, banditti, corpses, and of course insatiable lust. Compared to works like Justine, here Sade is relatively tame, as overt eroticism and torture is subtracted for a more psychological approach. It is the impact of sadism instead of acts of sadism itself that emerge in this work, unlike the aggressive and rapacious approach in his libertine works.[64] The modern volume entitled Gothic Tales collects a variety of other short works of fiction intended to be included in Sade's Contes et Fabliaux d'un Troubadour Provencal du XVIII Siecle. An example is "Eugénie de Franval", a tale of incest and retribution. In its portrayal of conventional moralities it is something of a departure from the erotic cruelties and moral ironies that dominate his libertine works. It opens with a domesticated approach: To enlighten mankind and improve its morals is the only lesson which we offer in this story. In reading it, may the world discover how great is the peril which follows the footsteps of those who will stop at nothing to satisfy their desires. Descriptions in Justine seem to anticipate Radcliffe's scenery in The Mysteries of Udolpho and the vaults in The Italian, but, unlike these stories, there is no escape for Sade's virtuous heroine, Justine. Unlike the milder Gothic fiction of Radcliffe, Sade's protagonist is brutalized throughout and dies tragically. To have a character like Justine, who is stripped without ceremony and bound to a wheel for fondling and thrashing, would be unthinkable in the domestic Gothic fiction written for the bourgeoisie. Sade even contrives a kind of affection between Justine and her tormentors, suggesting shades of masochism in his heroine.[69] |

短編小説 英雄と悲劇の物語」と題された『愛の罪』では、サドはロマンスとホラーを組み合わせ、ドラマチックな目的のためにゴシックのトロフィーをいくつか用いてい る。血、盗賊、死体、そしてもちろん、飽くことのない欲望。ジュスティーヌ』などの作品と比べると、この『サド』は比較的おとなしく、あからさまなエロ ティシズムや拷問は排除され、より心理的なアプローチで描かれている。この作品では、サディズムの行為そのものではなく、サディズムの影響が現れており、 自由主義的な作品における攻撃的で強欲なアプローチとは異なっている[64]。『ゴシック物語』と題する現代の一冊には、サドの『18世紀のプロヴァンス 人遊侠物語』に収録しようとした他の様々な短編小説が集められている。 例えば、近親相姦と報復の物語である「ウジェニー・ド・フランヴァル」はその一例である。この作品は、彼の自由主義的な作品に見られるエロティックな残酷 さや道徳的な皮肉とは一線を画しており、従来の道徳観が描かれている。この作品は、家庭的なアプローチで始まる。 人類を啓発し、そのモラルを向上させることが、この物語で提供する唯一の教訓である。この物語を読んで、欲望を満たすためには手段を選ばない人々の足跡を たどる危険がいかに大きいか、世界が知ることができますように。 『ジャスティーヌ』の描写は、ラドクリフの『ウドルーフォの謎』の風景や『イタリア』の金庫を先取りしているようだが、これらの物語とは異なり、サドの高 潔なヒロイン、ジャスティーヌには逃げ場がないのである。ラドクリフのような穏やかなゴシック小説とは異なり、サドの主人公は終始残虐に扱われ、悲劇的な 死を遂げる。ジュスティーヌのように、何の儀式もなく裸にされ、車輪に縛りつけられ、撫で回されるキャラクターは、ブルジョワジーのために書かれた家庭的 なゴシック小説では考えられないことだろう。サドはジュスティーヌと彼女の苛めっ子の間に一種の愛情を作り出し、彼のヒロインのマゾヒズムの影を示唆さえ している[69]。 |

| Marquis

de Sade bibliography BDSM Fetish fashion Leopold von Sacher-Masoch Sexual fetishism Jesús Franco directed films based on the Marquis de Sade's works |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marquis_de_Sade |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Works cited Bongie, Laurence Louis (1998). Sade: A Biographical Essay. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06420-4. Camus, Albert (1953). The Rebel. Translated by Bower, Anthony. London: Hamish Hamilton. Carter, Angela (1978). The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-75893-5. Crocker, Lester G. (1963). Nature and Culture: Ethical Thought in the French Enlightenment. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. Dworkin, Andrea (1981). Pornography: Men Possessing Women. London: The Women's Press. ISBN 0-7043-3876-9. Gorer, Geoffrey (1964). The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade (3rd ed.). London: Panther Books. Gray, Francine du Plessix (1998). At Home with the Marquis de Sade: a life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80007-1. Gray, John (2018). Seven Types of Atheism. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Lever, Maurice (1993). Marquis de Sade, a biography. Translated by Goldhammer, Arthur. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-246-13666-9. Love, Brenda (2002). The Encyclopedia of Unusual Sex Practices. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11535-1. Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the impossible: a history of Anarchism. Oakland: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-60486-064-1. Paglia, Camille (1990). Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-679-73579-8. Phillips, John (2005). How to Read Sade. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-32822-8. Queenan, Joe (2004). Malcontents. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-1697-4. Sade, Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de (1965). Seaver, Richard; Wainhouse, Austryn (eds.). The Complete Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom and other writings. Grove Press. Sade, Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de (2000). Seaver, Richard (ed.). Letters from Prison. London: Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-807-1. Schaeffer, Neal (2000). The Marquis de Sade: a Life. New York City: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-67400-392-7. Shattuck, Roger (1996). Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14602-7. |

引用文献 ボンジー、ローレンス・ルイ(1998)。『サド:伝記的エッセイ』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-06420-4。 カミュ、アルベール (1953)。反逆者。バウアー、アンソニー訳。ロンドン:ハミルトン。 カーター、アンジェラ (1978)。サディストの女性とポルノのイデオロギー。ニューヨーク:パンテオン・ブックス。ISBN 0-394-75893-5。 クロッカー、レスター G. (1963)。『自然と文化:フランス啓蒙思想の倫理観』。ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンス・プレス。 ドワークイン、アンドレア (1981)。『ポルノグラフィー:女性を所有する男性たち』。ロンドン:ウィメンズ・プレス。ISBN 0-7043-3876-9。 ゴア、ジェフリー (1964)。サド侯爵の革命的な思想 (第 3 版)。ロンドン:パンサー・ブックス。 グレイ、フランシーヌ・デュ・プレシス (1998)。サド侯爵の家庭生活:その生涯。ニューヨーク:サイモン&シュスター。ISBN 0-684-80007-1。 グレイ、ジョン (2018)。『7 種類の無神論』。ニューヨーク:ファラー・ストラウス・ギル。 レバー、モーリス (1993)。『サド侯爵、伝記』。ゴールドハンマー、アーサー訳。ロンドン:ハーパー・コリンズ。ISBN 0-246-13666-9。 ラブ、ブレンダ (2002)。『珍しいセックスの百科事典』。ロンドン:アバカス。ISBN 978-0-349-11535-1。 マーシャル、ピーター (2008)。『不可能を要求する:アナキズムの歴史』。オークランド:PM プレス。ISBN 978-1-60486-064-1。 パリア、カミール(1990)。『セクシャル・ペルソナ:ネフェルティティからエミリー・ディキンソンまでの芸術と退廃』。ニューヨーク:ヴィンテージ。 ISBN 0-679-73579-8。 フィリップス、ジョン(2005)。『サドを読む方法』。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン・アンド・カンパニー。ISBN 0-393-32822-8。 クイーンアン、ジョー(2004)。『不満者たち』。フィラデルフィア:ランニング・プレス。ISBN 978-0-7624-1697-4。 サド、ドナティエン・アルフォンス・フランソワ、マルキ・ド(1965)。シーバー、リチャード;ウェインハウス、オースティン(編)。『完全版 ジュスティーヌ、寝室の哲学、その他の著作』。グローブ・プレス。 サド、ドナティエン・アルフォンス・フランソワ、侯爵(2000)。シーバー、リチャード(編)。『刑務所からの手紙』。ロンドン:ハーヴィル・プレス。 ISBN 1-86046-807-1。 シェイファー、ニール(2000)。『侯爵ド・サド:その生涯』。ニューヨーク:Knopf Doubleday。ISBN 978-0-67400-392-7。 シャタック、ロジャー (1996)。禁断の知識:プロメテウスからポルノグラフィーまで。ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス。ISBN 0-312-14602-7。 |

| Marquis de Sade: his life and

works. (1899) by Iwan Bloch Sade Mon Prochain. (1947) by Pierre Klossowski Lautréamont and Sade. (1949) by Maurice Blanchot The Marquis de Sade, a biography. (1961) by Gilbert Lely Philosopher of Evil: The Life and Works of the Marquis de Sade. (1962) by Walter Drummond Sade, Fourier, Loyola. (1971) by Roland Barthes De Sade: A Critical Biography. (1978) by Ronald Hayman The Marquis de Sade: the man, his works, and his critics: an annotated bibliography. (1986) by Colette Verger Michael Sade, his ethics and rhetoric. (1989) collection of essays, edited by Colette Verger Michael The philosophy of the Marquis de Sade. (1995) by Timo Airaksinen Sade contre l'Être suprême. (1996) by Philippe Sollers A Fall from Grace (1998) by Chris Barron An Erotic Beyond: Sade. (1998) by Octavio Paz Sade: A Sudden Abyss. (2001) by Annie Le Brun Sade: from materialism to pornography. (2002) by Caroline Warman Marquis de Sade: the genius of passion. (2003) by Ronald Hayman Pour Sade. (2006) by Norbert Sclippa Outsider Biographies; Savage, de Sade, Wainewright, Ned Kelly, Billy the Kid, Rimbaud and Genet: Base Crime and High Art in Biography and Bio-Fiction, 1744–2000 (2014) by Ian H. Magedera Sade's Sensibilities. (2014) edited by Kate Parker and Norbert Sclippa (A collection of essays reflecting on Sade's influence on his bicentennial anniversary.) |

マルキ・ド・サド:その生涯と作品(1899年) イワン・ブロッホ著 Sade Mon Prochain(1947年) ピエール・クロソフスキー著 ラトゥールモンとサド(1949年) モーリス・ブランショ著 マルキ・ド・サド、伝記(1961年) ギルバート・リー著 悪の哲学者:マルキ・ド・サドの生涯と作品。(1962)ウォルター・ドラモンド サド、フーリエ、ロヨラ。(1971)ロラン・バルト ド・サド:批判的伝記。(1978)ロナルド・ヘイマン マルキ・ド・サド:その人物、作品、批評家たち:注釈付き書誌目録。(1986)コレット・ヴェルジェ・マイケル サド、その倫理と修辞学。(1989)エッセイ集、コレット・ヴェルジェ・マイケル編 マルキ・ド・サドの哲学。(1995)ティモ・アイラキネン サド対至高の存在。(1996)フィリップ・ソラーズ 『堕落』(1998年)クリス・バロン 『エロティックの彼方:サド』(1998年)オクタヴィオ・パス 『サド:突然の深淵』(2001年)アニー・ル・ブラン 『サド:唯物論からポルノグラフィーへ』(2002年)キャロライン・ウォーマン 『マルキ・ド・サド:情熱の天才』。(2003)ロナルド・ヘイマン著 サドのために。(2006)ノーバート・スクリッパ著 アウトサイダーの伝記:サヴェージ、サド、ウェインライト、ネッド・ケリー、ビリー・ザ・キッド、ランボー、ジェネット:伝記とバイオフィクションにおけ る低俗な犯罪と高貴な芸術、1744-2000(2014)イアン・H・マゲデラ著 サドの感性。(2014)ケイト・パーカーとノーバート・スクリッパ編(サドの没後200周年を記念して、サドの影響について考察したエッセイ集。) |

Illustration of a Dutch

printing of the book Juliette by the Marquis de Sade, c. 1800

●サド年譜

1740 6月2日パリにて生まれる

1750 コレージュ・ルイ・ル・グランに入学

1754 ドイツと七年戦争勃発。従軍し、近衛少尉 から騎兵大尉に昇進。

1763

父親が縁談をまとめる。モントルイユの20歳になる 娘ルネ。しかし、サドは、16歳の妹ルイズと恋に陥る。オペラ座の舞踊家マドモアゼル・リヴィエールから誘われるが袖にする。同年ルネと結婚。結婚直後か ら放蕩、一度警察に逮捕、収監される。

1763-1764 パリへの入城の禁止された

1765 高級娼婦ボオヴォアザンを情婦にして同衾 する。この頃には、警察からは監視対象になる。

1767 父親死す。この年、長男が生まれる。

1768 ケレル事件=アルクイユ事件(ゴーラ 1981:26)。

パン屋の未亡人36歳のロオル・ケレルを居城に連れ ていき、拷問をし監禁、性的虐待を加える。彼女は逃亡し、警察は捜査を開始する。ケレルの主張とサド側の主張が食い違うが、サドは事件をもみ消そうとして さらに炎上する。起訴され、ケレルには支払いがなされ、サドはルイ15世への嘆願が認められて釈放される。

1770-1772 大人しく過ごす。

1772 6月有毒ボンボン事件(ゴーラ 1981:32)。

これはマルセイユに乱行にでかけ、召使いが娼婦や女 性たちに与えたボンボンに毒が入っていたという疑惑である。その後有罪確定。「毒殺未遂と肛門性交の罪」で死刑判決。

1774 ルイ15世崩御によりサド収監の封印が失 効する。

1776 高等法院、サド裁判審理。

1778 サド裁判の判決。シャトー・ド・ヴァンセ ンヌ(Château de Vincennes)に収監(ゴーラ 1981:42)。

1784 2月バスティーユ牢獄に移動(ゴーラ 1981:46)。

1785 10月22日に、バスチーユ牢獄内にて 『ソドム百二十日あるいは淫蕩学校( Les Cent Vingt Journées de Sodome ou l’École du libertinage)』の清書を始める。

1787 『美徳の不幸』 (Les

Infortunes de la Vertu)のちの『ジュスティーヌあるいは美徳の不幸』 (Justine ou les Malheurs

de la Vertu) 、さらに『新ジュスティーヌ』 (Nouvelle Justine)

| Justine ou les

Malheurs de la Vertu, 1787 |

l'Histoire de Juliette ou les Prospérités du vice, 1797-1808 |

| 修道院を出たジュスティーヌは、宗教的美

徳や礼節に忠実であろうとするばかりに、幾度も貶められたり辱められたりした挙げ句、ついには窃盗や殺人の罪を着せられるに至る。本作は、彼女が嘗めた辛

酸の数々を通じて、「美徳を守ろうとする者には不幸が降り掛かり、悪徳に身を任せる者には繁栄が訪れる」というサドの哲学的主題が描かれている。また、サ

ドは彼女が関わった面々に無神論を語らせたり、「人間は万物の霊長である」との考えを否定する主張をさせたりしている。こうした台詞の数々からは、サドの

思想の近代性を見ることができる。次々と罠に落ちては虐待され続けるジュスティームの流転は、思い切ってテンポの速い描写によっており、全身タイツ姿で強

制重労働に酷使されるなど、の描写も見られる(出典:「美徳の不幸」)。 |

修道院で敬虔な女性として育てられた主人

公のジュリエットは、13歳のときに、道徳や宗教やらの善の概念は無意味だと言うある女性にそそのかされ、以来悪徳と繁栄の生涯を歩むこととなる。作品の

全編を通して、神や道徳、悔恨や愛といった概念に対する攻撃的な思索が繰り広げられている。

彼女は自身の快楽を追求するために、家族や友人といった親しい人間までもをありとあらゆる方法で殺す(出典:「ジュリエット物語」) |

1789 7月2日、バスティーユ襲撃。その後、 シャラントン精神病院。

1790 憲法議会は、封印状により逮捕されていた すべての囚人の解放を命じる。そのためサドも釈放。

1793 12月5日から1年間投獄

1795 『閨房哲学』(けいぼうてつがく: La Philosophie dans le boudoir)

「15歳の少女ウージェニーと、姉弟で交合するサ

ン・タンジュ夫人、放蕩生活者のドルマンセとの情欲を賛美する対話を軸に展開され、無神論、不倫、近親相姦の肯定などが書かれている。小説の形式が取られ

ているが、登場人物が台詞で自らの思想を長文で論理的に解説する部分に紙面が割かれている。

本書には5枚の挿絵が挿入されており、同一作者であると見られているが、一説には『シル・ブラース物語』や『デカメロン』の挿絵画家であるクロード・ボル

ネの作であると言われている(出典「閨房哲学」)」

1797-1808 『ジュリエット物語あるいは悪

徳の栄え』(仏: l'Histoire de Juliette ou les Prospérités du vice)

1801 ナポレオン・ボナパルトは、匿名で出版さ れていた『美徳の不幸』と『ジュリエット物語あるいは悪徳の栄え』を書いた人物を投獄するよう命じる。

1803 シャラントン精神病院(〜1814年)

1806 1月30日遺言状が認められる(死後開

封)

1808 ナポレオンに釈放を嘆願。

1814 12月2日74歳の生涯を終える。

●ジェフリー・ゴーラ『マルキ・ド・ サドの生涯と思想』(荒地出版社、1981年)

文献資料として、ジェフリー・ゴーラ『マルキ・ド・ サドの生涯と思想』(荒地出版社、1981年)を取り上げよう。その章立ては以下のごとくである。

| 序文 | |

| 予備的判断 | |

| 1.生涯:1740-1814年 | |

| 2.文学作品 | |

| 3.哲学 | |

| 4.神と自然 | |

| 5.政治1:診断 | |

| 6.政治2:解決策提案 | |

| 7.性・快楽および恋愛 | |

| 8.サディズムとアルゴラグニア s(苦痛淫楽症) |

|

| 9.20年後 |

●澁澤龍彦『サド復活:自由と反抗思想の先駆者』 (現代芸術論叢書)弘文堂、1959年/日本文芸社, 1989年

| 1 |

暗黒のユーモアあるいは文学的テロル |

|

| 2 |

暴力と表現あるいは自由の塔 |

|

| 3 |

権力意思と悪あるいは倫理の夜 |

|

| 4 |

薔薇の帝国あるいはユートピア |

|

| 5 |

母性憎悪あるいは思想の牢獄 |

|

| 6 |

サド復活:デッサン・ビオグラフィック |

|

| 7 |

文明否定から新しき神話へ:詩とフロイ

ディズム |

|

| 8 |

非合理の表現:映画と悪 |

●啓蒙の 弁証法:Dialektik der Aufklarung: Philosophische Fragmente(ウィキペディア日本語による)

| 概略 |

『啓蒙の弁証法』(Dialektik

der Aufklarung: Philosophische Fragmente)とはホルクハイマーとアドルノによって著された近代批判の

研究である。ホルクハイマーとアドルノは、反ユダヤ主義のドイツを逃れてアメリカに亡命し、第2次世界大戦中に本書を執筆を開始し、1947年にアムステ

ルダムで出版した。 |

・マックス・ホルクハイマー(Max Horkheimer,

1895-1973) ・テオドール・ルートヴィヒ・アドルノ=ヴィーゼングルント(Theodor Ludwig Adorno-Wiesengrund, 1903-0969) |

| 啓蒙の本質 |

ホルクハイマーとアドルノは、人間が啓蒙

化されたにも関わらず、ナチスのような新しい野蛮へなぜ向かうのかを批判理論によって考察しようとした。その考察を開始するために、啓蒙の本質について規

定するものである。 |

|

| 啓蒙の弁証法 |

啓蒙は、人間の理性を使って、あらゆる現実を概念化することを意味する。そこで

は、人間の思考も画一化されることになり、数学的な形式が社会のあらゆる局面で徹底

化される。したがって、理性は、人間を非合理性から解放する役割とは裏腹に、暴力的な画一化をもたらすことになる。ホルクハイマーとアドル

ノは、このような事態を「啓蒙の弁証法」と呼んでいる。 |

・啓蒙の思考の画一化だが、プラグマティ

ズム思考にみられるように、人間の思考の多様性とその尊重にはどう考えるのか? |

| オデュッセウスとジュリエット物語あるい

は悪徳の栄え |

この事態はいくつかの側面から説明するこ

とができ、その考察にあたりオデュッセウスとジュリエット物語あるいは悪徳の栄えが言及される。人間は、外部の自然を支配するために、内面の自然を抑制することで、主体性を抹殺した。

また、論理形式的な理性によって、達成すべき内容ある価値は、転倒してしまう。

さらに、芸術においても、美は、規格化された情報の商品として、大衆に供給される。

ホルクハイマーとアドルノは、反ユダヤ主義の原理に啓蒙があったと考

えており、啓蒙的な支配によってもたらされた抑制や画一化の不満が、ユダヤ人へと向けられたと位置づける |

・この啓蒙時代の芸術=商品化の論理は、

アドルノに特有なものか? ・全体主義=なんでもありのハンナ・アーレントの見解とは異にする。 |

| 啓蒙における理性と感性の融和(反省の機能) |

啓蒙の精神は、自らの本質が支配にあると自覚することで、反省的な理性を可能にするものでもあ

る。この反省によって、啓蒙における理性と感性の融和が、可能となり

うると考えられる。 |

あまりにも能天気な発想かな? |

リンク

文献

Do not copy and paste, but you might [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

☆

☆

☆