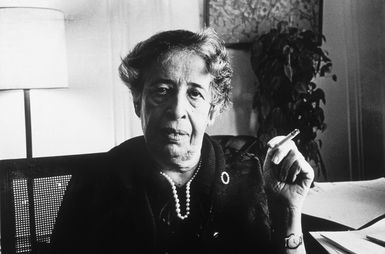

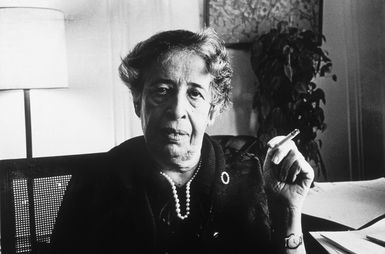

ハンナ・アーレント

池田光穂

★ハンナ・アーレント(Hannah Arendt)の英 語ウィキペディアからの翻訳を紹介する。彼女の年譜や参照文献については「ハンナ・アーレント (年譜)」 を参照してください。

| Hannah Arendt

(/ˈɛərənt, ˈɑːr-/,[9][10] US also /əˈrɛnt/,[11] German: [ˌhana ˈaːʁənt]

ⓘ;[12] born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a

German-American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most

influential political theorists of the 20th century.[5][13][14] Her works cover a broad range of topics, but she is best known for those dealing with the nature of power and evil, as well as politics, direct democracy, authority, and totalitarianism. She is also remembered for the controversy surrounding the trial of Adolf Eichmann, her attempt to explain how ordinary people become actors in totalitarian systems, which was considered by some an apologia, and for the phrase "the banality of evil." She is commemorated by institutions and journals devoted to her thinking, the Hannah Arendt Prize for political thinking, and on stamps, street names, and schools, amongst other things. Hannah Arendt was born to a Jewish family in Linden (now a district of Hanover, Germany) in 1906. When she was three, her family moved to the East Prussian capital of Königsberg for her father's health care. Paul Arendt had contracted syphilis in his youth, but was thought to be in remission when Arendt was born. He died when she was seven. Arendt was raised in a politically progressive, secular family, her mother being an ardent Social Democrat. After completing secondary education in Berlin, Arendt studied at the University of Marburg under Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a four-year affair.[15] She obtained her doctorate in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg in 1929. Her dissertation was entitled Love and Saint Augustine and her supervisor was the existentialist philosopher Karl Jaspers. Hannah Arendt married Günther Stern in 1929, but soon began to encounter increasing antisemitism in 1930s Nazi Germany. In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler came to power, Arendt was arrested and briefly imprisoned by the Gestapo for performing illegal research into antisemitism. On release, she fled Germany, living in Czechoslovakia and Switzerland before settling in Paris. There she worked for Youth Aliyah, assisting young Jews to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine. She was stripped of her German citizenship in 1937. Divorcing Stern that year, she then married Heinrich Blücher in 1940. When Germany invaded France that year she was detained by the French as an alien. She escaped and made her way to the United States in 1941 via Portugal. She settled in New York, which remained her principal residence for the rest of her life. She became a writer and editor and worked for the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, becoming an American citizen in 1950. With the publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, her reputation as a thinker and writer was established and a series of works followed. These included the books The Human Condition in 1958, as well as Eichmann in Jerusalem and On Revolution in 1963. She taught at many American universities, while declining tenure-track appointments. She died suddenly of a heart attack in 1975, at the age of 69, leaving her last work, The Life of the Mind, unfinished. |

ハンナ・アーレント(/ˈɛər-/, [9][10]

米国でも/əˈɛ, [11] ドイツ語: [ˈɛ] ˈ, [12] 本名:ヨハンナ・アーレント、1906年10月14日 -

1975年12月4日)は、ドイツ系アメリカ人の歴史家、哲学者。20世紀において最も影響力のある政治理論家の一人である[5][13][14]。 彼女の著作は幅広いテーマを扱っているが、権力と悪の本質、政治、直接民主制、権威、全体主義を扱ったものが最もよく知られている。また、アドルフ・アイ ヒマン裁判をめぐる論争や、一般人がいかにして全体主義体制の行為者となるかを説明しようとした彼女の試み(一部では弁明とみなされた)、"the banality of evil"(悪の凡庸性)という言葉も記憶に新しい。ハンナ・アーレントは、彼女の思想に特化した機関や雑誌、政治思想のためのハンナ・アーレント賞、切 手、通りの名前、学校などで記念されている。 ハンナ・アーレントは1906年、リンデン(現ドイツ・ハノーファー地区)のユダヤ人家庭に生まれた。彼女が3歳のとき、父親の健康管理のために一家は東 プロイセンの首都ケーニヒスベルクに引っ越した。パウル・アーレントは若い頃に梅毒にかかったが、アーレントが生まれたときには寛解していたと考えられて いた。彼は彼女が7歳の時に亡くなった。アーレントは政治的に進歩的で世俗的な家庭に育ち、母親は熱心な社会民主党員だった。1929年にハイデルベルク 大学で哲学博士号を取得。学位論文のタイトルは『愛と聖アウグスティヌス』で、指導教官は実存主義の哲学者カール・ヤスパースであった。 ハンナ・アーレントは1929年にギュンター・シュテルンと結婚したが、やがて1930年代のナチス・ドイツで反ユダヤ主義が強まることになる。アドル フ・ヒトラーが政権を握った1933年、アーレントは反ユダヤ主義に関する違法な研究を行ったとしてゲシュタポに逮捕され、短期間投獄された。釈放後、彼 女はドイツを逃れ、チェコスロバキアとスイスに住んだ後、パリに定住した。そこでユース・アリヤのために働き、若いユダヤ人のイギリス委任統治領パレスチ ナへの移住を支援した。1937年にドイツ国籍を剥奪される。同年シュテルンと離婚し、1940年にハインリッヒ・ブリュッヒャーと結婚。同年ドイツがフ ランスに侵攻すると、彼女は外国人としてフランス軍に拘束された。1941年、ポルトガルを経由して米国に渡る。ニューヨークに居を構え、その後の生涯を ニューヨークで過ごした。作家、編集者となり、ユダヤ文化復興のために働き、1950年にアメリカ国籍を取得。1951年に『全体主義の起源』を出版し、 思想家・作家としての名声を確立。1958年の『人間の条件』、1963年の『エルサレムのアイヒマン』、『革命について』などである。テニュアトラック の任命を辞退しながらも、アメリカの多くの大学で教鞭をとった。1975年、心臓発作のため69歳で急逝。遺作『The Life of the Mind』は未完のままであった。 |

| Early life and education

(1906–1929) Family Parents Photo of Hannah's mother, Martha Cohn, in 1899 Paul Arendt c. 1900 Photo of Hannah's father, Paul Arendt, in 1900 Martha Cohn c. 1899 Hannah Arendt was born as Johanna Arendt[16][17] in 1906, in the Wilhelmine period. Her Jewish family in Germany were comfortable, educated and secular in Linden, Prussia (now a part of Hanover). They were merchants of Russian extraction from Königsberg.[a] Her grandparents were members of the Reform Jewish community. Her paternal grandfather, Max Arendt [de], was a prominent businessman, local politician,[18] and leader of the Königsberg Jewish community, a member of the Central Organization for German Citizens of Jewish Faith (Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens). Like other members of the Centralverein he primarily saw himself as German, disapproving of Zionist activities including Kurt Blumenfeld, a frequent visitor and later one of Hannah's mentors. Of Max Arendt's children, Paul Arendt was an engineer and Henriette Arendt a policewoman and social worker.[19][20] Hannah was the only child of Paul and Martha Arendt (née Cohn), who were married on 11 April 1902. She was named after her paternal grandmother.[21][22] The Cohns had originally come to Königsberg from nearby Russian territory (now Lithuania) in 1852, as refugees from antisemitism, and made their living as tea importers, J. N. Cohn & Company being the largest business in the city. The Arendts reached Germany from Russia a century earlier.[23][24] Hannah's extended family contained many more women, who shared the loss of husbands and children. Hannah's parents were more educated and politically more to the left than her grandparents. The young couple were Social Democrats,[16] rather than the German Democrats that most of their contemporaries supported. Paul Arendt was educated at the Albertina (University of Königsberg). Though he worked as an engineer, he prided himself on his love of Classics, with a large library that Hannah immersed herself in. Martha Cohn, a musician, had studied for three years in Paris.[20] In the first four years of their marriage, the Arendts lived in Berlin, and were supporters of the socialist journal Socialist Monthly Bulletins (Sozialistische Monatshefte).[b][25] At the time of Hannah's birth, Paul Arendt was employed by an electrical engineering firm in Linden, and they lived in a frame house on the market square (Marktplatz).[26] They moved back to Königsberg in 1909 because of Paul's deteriorating health.[7][27] He suffered from chronic syphilis and was institutionalized in the Königsberg psychiatric hospital in 1911. For years afterward, Hannah had to have annual WR tests for congenital syphilis.[28] He died on 30 October 1913, when Hannah was seven, leaving her mother to raise her.[21][29] They lived at Hannah's grandfather's house at Tiergartenstraße 6, a leafy residential street adjacent to the Königsberg Tiergarten, in the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Hufen.[30] Although Hannah's parents were non-religious, they were happy to allow Max Arendt to take Hannah to the Reform synagogue. She also received religious instruction from the rabbi, Hermann Vogelstein, who would come to her school for that purpose.[c] Her family moved in circles that included many intellectuals and professionals. It was a social circle of high standards and ideals. As she recalled it:[31] My early intellectual formation occurred in an atmosphere where nobody paid much attention to moral questions; we were brought up under the assumption: Das Moralische versteht sich von selbst, moral conduct is a matter of course. This time was a particularly favorable period for the Jewish community in Königsberg, an important center of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment).[32][33] Arendt's family was thoroughly assimilated ("Germanized")[34] and she later remembered: "With us from Germany, the word 'assimilation' received a 'deep' philosophical meaning. You can hardly realize how serious we were about it."[35] Despite these conditions, the Jewish population lacked full citizenship rights, and although antisemitism was not overt, it was not absent.[36] Arendt came to define her Jewish identity negatively after encountering overt antisemitism as an adult.[35] She came to greatly identify with Rahel Varnhagen, the Prussian socialite[29] who desperately wanted to assimilate into German culture, only to be rejected because she was born Jewish.[35] Arendt later said of Varnhagen that she was "my very closest woman friend, unfortunately dead a hundred years now."[35][d] In the last two years of the First World War, Hannah's mother organized social democratic discussion groups and became a follower of Rosa Luxemburg as socialist uprisings broke out across Germany.[25][38] Luxemburg's writings would later influence Hannah's political thinking. In 1920, Martha Cohn married Martin Beerwald, an ironmonger and widower of four years, and they moved to his home, two blocks away, at Busoldstrasse 6,[39][40] providing Hannah with improved social and financial security. Hannah was 14 at the time and acquired two older stepsisters, Clara and Eva.[39] Education Early education Schools Photo of Hufen-Oberlyzeum, Hannah's first school Hufen-Oberlyzeum c. 1923 Photo of Hannah's secondary school, the Queen Louise School for girls Königin-Luise-Schule in Königsberg c. 1914 Hannah Arendt's mother, who considered herself progressive, brought her daughter up on strict Goethean lines. Among other things this involved the reading of Goethe's complete works, summed up as Was aber ist deine Pflicht? Die Forderung des Tages (And just what is your duty? The demands of the day).[e] Goethe, was then considered the essential mentor of Bildung (education), the conscious formation of mind, body and spirit. The key elements were considered to be self-discipline, constructive channeling of passion, renunciation and responsibility for others. Hannah's developmental progress (Entwicklung) was carefully documented by her mother in a book, she called Unser Kind (Our Child), measuring her against the benchmark of what was then considered normale Entwicklung ("normal development").[41] Arendt attended kindergarten from 1910 where her precocity impressed her teachers and enrolled in the Szittnich School, Königsberg (Hufen-Oberlyzeum), on Bahnstraße in August 1913,[42] but her studies there were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, forcing the family to temporarily flee to Berlin on 23 August 1914, in the face of the advancing Russian army.[43] There they stayed with her mother's younger sister, Margarethe Fürst, and her three children, while Hannah attended a girl's Lyzeum school in Berlin-Charlottenburg. After ten weeks, when Königsberg appeared to be no longer threatened, the Arendts were able to return,[43] where they spent the remaining war years at her grandfather's house. Arendt's precocity continued, learning ancient Greek as a child,[44] writing poetry in her teenage years,[45] and starting both a Graecae (reading group for studying classical literature) and philosophy club at her school. She was fiercely independent in her schooling and a voracious reader,[f] absorbing French and German literature and poetry (committing large amounts to heart) and philosophy. By the age of 14, she had read Kierkegaard, Jaspers' Psychologie der Weltanschauungen and Kant's Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason). Kant, whose home town was also Königsberg, was an important influence on her thinking, and it was Kant who had written about Königsberg that "such a town is the right place for gaining knowledge concerning men and the world even without travelling".[47][48] Arendt attended the Königin-Luise-Schule for her secondary education, a girls' Gymnasium on Landhofmeisterstraße.[49] Most of her friends, while at school, were gifted children of Jewish professional families, generally older than she and went on to university education. Among them was Ernst Grumach, who introduced her to his girlfriend, Anne Mendelssohn,[g] who would become a lifelong friend. When Anne moved away, Ernst became Arendt's first romantic relationship.[h] |

生い立ちと教育(1906-1929) 家族 両親 1899年、ハンナの母マーサ・コーンの写真 1900年頃のポール・アレント 1900年、ハンナの父ポール・アレント。 1899年頃のマーサ・コーン ハンナ・アーレントは1906年、ヴィルヘルミーネ時代にヨハンナ・アーレント[16][17]として生まれた。ドイツにいた彼女のユダヤ人家族は、プロ イセンのリンデン(現在はハノーファーの一部)で快適な生活を送り、教育を受け、世俗的であった。祖父母は改革派ユダヤ人コミュニティのメンバーだった。 父方の祖父マックス・アーレントは著名な実業家であり、地元の政治家であり[18]、ケーニヒスベルクのユダヤ人コミュニティの指導者であり、ユダヤ教ド イツ市民中央組織(Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens)のメンバーであった。中央連盟の他のメンバーと同様、彼は自らをドイツ人とみなし、頻繁に訪れていたクルト・ブルーメンフェルトをはじ めとするシオニストの活動には否定的で、のちにハンナの師匠のひとりとなる。マックス・アーレントの子供のうち、パウル・アーレントはエンジニア、ヘンリ エッテ・アーレントは警察官兼ソーシャルワーカーであった[19][20]。 ハンナは、1902年4月11日に結婚したパウルとマーサ・アレント(旧姓コーン)の一人っ子。コーン家は1852年に反ユダヤ主義からの難民として近隣 のロシア領(現在のリトアニア)からケーニヒスベルクに移住し、紅茶の輸入業者として生計を立てていた。ハンナの大家族には、夫や子供を失ったことを分か ち合う多くの女性がいた。ハンナの両親は祖父母よりも教養があり、政治的には左寄りだった。若い夫婦は社会民主党員であり[16]、むしろ同時代の人々の 多くが支持していたドイツ民主党員であった。パウル・アーレントはアルベルティーナ(ケーニヒスベルク大学)で教育を受けた。彼はエンジニアとして働いて いたが、古典が好きで、ハンナが没頭した大きな図書館が自慢だった。音楽家のマーサ・コーンは、パリで3年間勉強したことがあった[20]。 結婚して最初の4年間、アーレント夫妻はベルリンに住み、社会主義雑誌『社会主義月報』(Sozialistische Monatshefte)の支持者であった[b][25]。ハンナが生まれたとき、パウル・アーレントはリンデンの電気技術会社に勤めており、二人はマル クト広場(Marktplatz)のフレームハウスに住んでいた。 [26] パウルの健康状態が悪化したため、1909年にケーニヒスベルクに戻った[7][27]。ハンナの両親は無宗教であったが、マックス・アーレントがハンナ を改革派のシナゴーグに連れて行くことを喜んで許可した。ハンナの家族は、多くの知識人や専門家を含むサークルの中で生活していた。高水準で理想的な社交 界だった。彼女は次のように回想している[31]。 私の初期の知的形成は、誰も道徳的な問題にあまり関心を払わないような雰囲気の中で行われた: 道徳的な行いは当然のことである。 この時期は、ハスカラ(ユダヤ啓蒙主義)の重要な中心地であったケーニヒスベルクのユダヤ人社会にとって、特に好ましい時期であった[32][33]。 アーレントの家族は徹底的に同化(「ドイツ化」)され[34]、彼女は後にこう回想している: ドイツ出身の私たちにとって、"同化 "という言葉は "深い "哲学的な意味を持っていました。このような状況にもかかわらず、ユダヤ人は完全な市民権を持たず、反ユダヤ主義はあからさまではなかったが、ないわけで はなかった[36]。 [彼女はプロイセンの社交界で活躍したラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲン[29]に強く共感するようになり、彼女はドイツ文化への同化を切実に望んでいたが、ユダ ヤ人として生まれたという理由だけで拒絶された[35]。 第一次世界大戦の最後の2年間、ハンナの母は社会民主主義的な討論会を組織し、ドイツ全土で社会主義的な反乱が勃発する中、ローザ・ルクセンブルクの信奉 者となる。1920年、マーサ・コーンは4年前に結婚した鉄工所の男やもめのマルティン・ビアヴァルトと結婚し、2ブロック離れたブゾルドシュトラーセ6 番地の彼の家に引っ越した[39][40]。ハンナは当時14歳で、クララとエヴァという2人の姉を得た[39]。 教育 早期教育 学校 ハンナの最初の学校、フーフェン・オーバーライツァウムの写真 1923年頃のフーフェン・オーバーライツァウム ハンナの中等学校、クイーン・ルイーズ女学校の写真 ケーニヒスベルクのケーニヒン・ルイゼ女学校 1914年頃 ハンナ・アーレントの母親は、自らを進歩的な人間だと考えていたが、娘を厳格なゲーテ主義に基づいて育てた。特にゲーテの全集を読ませた。ゲーテは当時、 心・体・精神の意識的な形成であるビルドゥング(教育)の本質的な指導者とみなされていた。重要な要素は、自己鍛錬、情熱の建設的な注ぎ方、放棄、他者へ の責任であると考えられていた。ハンナの発達は、母親によって『私たちの子ども』という本の中で注意深く記録され、当時、正常な発達と考えられていた基準 に照らし合わせて測定された[41]。 アーレントは1910年から幼稚園に通い、その早熟さが教師に感銘を与え、1913年8月にバーン通りにあるケーニヒスベルク(フーフェン・オーバーライ ツァウム)のシットニヒ学校に入学する[42]。 [ハンナはベルリン・シャルロッテンブルクにあるリツェウム女学校に通った。10週間後、ケーニヒスベルクの脅威がなくなると、アーレント一家は祖父の家 に戻ることができた[43]。幼い頃から古代ギリシャ語を学び[44]、10代の頃には詩を書き[45]、学校ではグラエカ(古典文学を学ぶ読書会)と哲 学クラブを立ち上げた。彼女は学校教育において独立心が強く、読書家であり[f]、フランスやドイツの文学や詩(大量に暗記した)、哲学を吸収した。14 歳までにキルケゴール、ヤスパースの『世界観の心理学』、カントの『純粋理性批判』を読んだ。ケーニヒスベルクを故郷とするカントは彼女の思考に重要な影 響を与え、ケーニヒスベルクについて「このような町は、旅行しなくても人間と世界に関する知識を得るのに適した場所である」と書いたのもカントであった [47][48]。 アーレントは中等教育のためにケーニッヒ・ルイゼ・シューレ(ランドホフマイスター通りにある女子ギムナジウム)に通った[49]。在学中、彼女の友人の ほとんどはユダヤ人の職業家系の英才教育を受けていた。その中にエルンスト・グルマッハがおり、彼のガールフレンドであったアンネ・メンデルスゾーン [g]を紹介され、生涯の友人となる。アンネが引っ越すと、エルンストはアーレントにとって初めての恋愛関係になった[h]。 |

| Higher education (1922–1929) Almae matres University of Berlin Berlin University University of Marburg Marburg University University of Freiburg Freiburg University University of Heidelberg Heidelberg University Photo of Hannah in 1924 Hannah, 1924 Berlin (1922–1924) Arendt was expelled from the Luise-Schule in 1922, at the age of 15, for leading a boycott of a teacher who insulted her. Her mother sent her to Berlin to Social Democrat family friends. She lived in a student residence and audited courses at the University of Berlin (1922–1923), including classics and Christian theology under Romano Guardini. She successfully sat the entrance examination (Abitur) for the University of Marburg, where Ernst Grumach had studied under Martin Heidegger (appointed as a professor in 1922). Her mother had engaged a private tutor, and her aunt Frieda Arendt, a teacher, also helped, while Frieda's husband Ernst Aron provided financial tuition assistance.[52] Marburg (1924–1926) In Berlin, Guardini had introduced her to Kierkegaard, and she resolved to make theology her major field.[48] At Marburg (1924–1926) she studied classical languages, German literature, Protestant theology with Rudolf Bultmann and philosophy with Nicolai Hartmann and Heidegger.[53] She arrived in the fall in the middle of an intellectual revolution led by the young Heidegger, of whom she was in awe, describing him as "the hidden king [who] reigned in the realm of thinking".[54][55] Heidegger had broken away from the intellectual movement started by Edmund Husserl, whose assistant he had been at University of Freiburg before coming to Marburg.[56] This was a period when Heidegger was preparing his lectures on Kant, which he would develop in the second part of his Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) in 1927 and Kant und das Problem der Metaphysik (1929). In his classes, he and his students struggled with the meaning of "Being" as they studied Aristotle's and Plato's Sophist concept of truth, to which Heidegger opposed the pre-Socratic term ἀλήθεια.[56] Many years later Arendt would describe these classes, how people came to Marburg to hear him, and how, above all he imparted the idea of Denken ("thinking") as activity, which she qualified as "passionate thinking".[57] Arendt was restless, finding her studies neither emotionally or intellectually satisfying. She was ready for passion, finishing her poem Trost (Consolation, 1923) with the lines:[58] Die Stunden verrinnen, Die Tage vergehen, Es bleibt ein Gewinnen Das bloße Bestehen. (The hours run down. The days pass on. One achievement remains: merely being alive.) Her encounter with Heidegger represented a dramatic departure from the past. He was handsome, a genius, romantic, and taught that thinking and "aliveness" were but one.[59] The 17-year-old Arendt then began a long romantic relationship with the 35-year-old Heidegger,[60] who was married with two young sons.[i][56] Arendt later faced criticism for this because of Heidegger's support for the Nazi Party after his election as rector at Freiburg University in 1933. Nevertheless, he remained one of the most profound influences on her thinking,[61] and he would later relate that she had been the inspiration for his work on passionate thinking in those days. They agreed to keep the details of the relationship a secret although preserving their letters.[62] The relationship was unknown until Elisabeth Young-Bruehl's biography of Arendt appeared in 1982. At the time of publishing, Arendt and Heidegger were deceased but Heidegger's wife, Elfride, was still alive. The affair was not well known until 1995, when Elzbieta Ettinger gained access to the sealed correspondence[63] and published a controversial account that was used by Arendt's detractors to cast doubt on her integrity. That account,[j] which caused a scandal, was subsequently refuted.[65][66][64] At Marburg, Arendt lived at Lutherstraße 4.[67] Among her friends was Hans Jonas, her only Jewish classmate. Another fellow student of Heidegger's was Jonas' friend, the Jewish philosopher Günther Siegmund Stern, who would later become her first husband.[68] Stern had completed his doctoral dissertation with Edmund Husserl at Freiburg, and was now working on his Habilitation thesis with Heidegger, but Arendt, involved with Heidegger, took little notice of him at the time.[69] Die Schatten (1925) In the summer of 1925, while home at Königsberg, Arendt composed her sole autobiographical piece, Die Schatten (The Shadows), a "description of herself"[70][71] addressed to Heidegger.[k][73] In this essay, full of anguish and Heideggerian language, she reveals her insecurities relating to her femininity and Jewishness, writing abstractly in the third person.[l] She describes a state of "Fremdheit" (alienation), on the one hand an abrupt loss of youth and innocence, on the other an "Absonderlichkeit" (strangeness), the finding of the remarkable in the banal.[74] In her detailing of the pain of her childhood and longing for protection she shows her vulnerabilities and how her love for Heidegger had released her and once again filled her world with color and mystery. She refers to her relationship with Heidegger as "Eine starre Hingegebenheit an ein Einziges" ("an unbending devotion to a unique man").[35][75][76] This period of intense introspection was also one of the most productive of her poetic output,[77] such as In sich versunken (Lost in Self-Contemplation).[78] |

高等教育(1922-1929) 出身大学 ベルリン大学 ベルリン大学 マールブルク大学 マールブルク大学 フライブルク大学 フライブルク大学 ハイデルベルク大学 ハイデルベルク大学 1924年のハンナ 1924年のハンナ ベルリン(1922-1924) アーレントは1922年、15歳のとき、自分を侮辱した教師のボイコットを指導したため、ルイーゼシューレを追放された。母親は彼女をベルリンに送り、社 会民主党の家族の友人たちのところに預けた。学生寮に住み、ベルリン大学でロマーノ・グアルディーニの古典学とキリスト教神学を聴講した (1922~1923年)。エルンスト・グルマッハがマルティン・ハイデガー(1922年に教授に就任)に師事していたマールブルク大学の入学試験(アビ トゥア)に合格。母親が家庭教師を雇い、教師であった叔母のフリーダ・アーレントも援助し、フリーダの夫エルンスト・アロンが学費を援助した[52]。 マールブルク(1924-1926) ベルリンでは、グアルディーニからキルケゴールを紹介され、彼女は神学を専攻分野とすることを決意した[48]。マールブルク(1924-1926年)で は、古典語、ドイツ文学、プロテスタント神学をルドルフ・ブルトマンに、哲学をニコライ・ハルトマンとハイデガーに師事した[53]。彼女は、若きハイデ ガーが率いる知的革命の真っ只中の秋に到着し、ハイデガーに対して畏敬の念を抱き、彼を「思考の領域に君臨する(隠れた)王」と評した[54][55]。 ハイデガーは、マールブルクに来る前にフライブルク大学で助手をしていたエドムント・フッサールによって始められた知的運動から脱却していた[56]。こ の時期は、ハイデガーが1927年に『存在と時間(Sein und Zeit)』の第2部、1929年に『カントと形而上学の問題(Kant und das Problem der Metaphysik)』で展開することになるカントについての講義を準備していた時期であった。ハイデガーはソクラテス以前の用語ἀλήθεια に反対していた[56]。何年も経ってから、アーレントはこのような授業について、また彼の話を聞くためにマールブルクを訪れる人々の様子について、そし て何よりもハイデガーが活動としての「考えること」(Denken)の考え方をどのように伝えたかについて述べている。 アーレントは落ち着きがなく、自分の研究は感情的にも知的にも満足のいくものではなかった。彼女は情熱を求める準備ができており、詩『Trost』(慰 め、1923年)を次のような台詞で締めくくっている[58]。 Die Stunden verrinnen、 日々は過ぎ去り この詩の中で彼女は Das bloße Bestehen. (時は過ぎゆく。 日々は過ぎてゆく。 一つの達成が残る: ただ生きていること。) ハイデガーとの出会いは、過去からの劇的な出発だった。17歳のアーレントはその後、35歳のハイデガーと長い恋愛関係を始めるが[60]、ハイデガーは 結婚しており、2人の幼い息子をもうけていた[i][56]。とはいえ、ハイデガーは彼女の思考に最も深い影響を与えた人物の一人であることに変わりはな く[61]、ハイデガーは後に、当時の情熱的な思考に関する研究のインスピレーションは彼女が与えてくれたのだと語っている。1982年にエリザベート・ ヤング=ブリューエルによるアーレントの伝記が出版されるまで、その関係は知られていなかった。出版当時、アーレントとハイデガーは亡くなっていたが、ハ イデガーの妻エルフリデはまだ生きていた。1995年にエルツビエタ・エッティンガーが封印された書簡[63]にアクセスし、物議を醸すような記述を発表 するまで、この不倫関係はあまり知られていなかった。スキャンダルを引き起こしたその記述[j]はその後反論されている[65][66][64]。 マールブルクでは、アーレントはルター通り4番地に住んでいた[67]。シュテルンはフライブルクでエドムント・フッサールの博士論文を完成させ、現在は ハイデガーのハビリテーション論文に取り組んでいたが、ハイデガーに関与していたアーレントは当時彼のことをほとんど気にかけていなかった[69]。 ディ・シャッテン』(1925年) 1925年の夏、ケーニヒスベルクに滞在していたアーレントは、ハイデガーに宛てた「自分自身の記述」[70][71]である唯一の自伝的作品『影』 (Die Schatten)を執筆している[k][73]。苦悩とハイデガー的な言葉に満ちたこのエッセイにおいて、彼女は三人称で抽象的に書きながら、女性性と ユダヤ人であることに関連する不安を露わにしている。 [一方では若さと無邪気さの突然の喪失であり、他方では平凡なものの中に驚くべきものを見出す「アブソンデルリヒカイト」(奇妙さ)である。幼少期の苦痛 と保護への憧れを詳述する中で、彼女は自分の弱さと、ハイデガーへの愛がいかに彼女を解放し、再び彼女の世界を色彩と神秘で満たしたかを示している。彼女 はハイデガーとの関係を「Eine starre Hingegebenheit an ein Einziges」(「唯一無二の男への屈しない献身」)と呼んでいる[35][75][76]。この激しい内省の時期は、『In sich versunken(自己観照の喪失)』など、彼女の詩作[77]において最も生産的な作品のひとつでもあった[78]。 |

| Freiburg and Heidelberg

(1926–1929) After a year at Marburg, Arendt spent a semester at Freiburg, attending the lectures of Husserl.[5] In 1926 she moved to the University of Heidelberg, completing her dissertation in 1929 under Karl Jaspers.[38] Jaspers, a friend of Heidegger, was the other leading figure of the then new and revolutionary Existenzphilosophie.[44] Her thesis was entitled Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin: Versuch einer philosophischen Interpretation (On the concept of love in the thought of Saint Augustine: Attempt at a philosophical interpretation).[79] She remained a lifelong friend of Jaspers and his wife, Gertrud Mayer, developing a deep intellectual relationship with him.[80] At Heidelberg, her circle of friends included Hans Jonas, who had also moved from Marburg to study Augustine, working on his Augustin und das paulinische Freiheitsproblem. Ein philosophischer Beitrag zur Genesis der christlich-abendländischen Freiheitsidee (1930),[m] and also a group of three young philosophers: Karl Frankenstein, Erich Neumann and Erwin Loewenson.[81] Other friends and students of Jaspers were the linguists Benno von Wiese and Hugo Friedrich (seen with Hannah, below), with whom she attended lectures by Friedrich Gundolf at Jaspers' suggestion and who kindled in her an interest in German Romanticism. She also became reacquainted, at a lecture, with Kurt Blumenfeld, who introduced her to Jewish politics. At Heidelberg, she lived in the old town (Altstadt) near the castle, at Schlossberg 16. The house was demolished in the 1960s, but the one remaining wall bears a plaque commemorating her time there (see image below).[82] On completing her dissertation, Arendt turned to her Habilitationsschrift, initially on German Romanticism,[83] and thereafter an academic teaching career. However 1929 was also the year of the Depression and the end of the golden years (Goldene Zwanziger) of the Weimar Republic, which was to become increasingly unstable over its remaining four years. Arendt, as a Jew, had little if any chance of obtaining an academic appointment in Germany.[84] Nevertheless, she completed most of the work before she was forced to leave Germany.[85] |

フライブルクとハイデルベルク(1926-1929年) ハイデッガーの友人であったヤスパースは、当時新しく革命的であった実存哲学のもう一人の中心的人物であった[44]: ハイデルベルクでは、同じくアウグスティヌスを研究するためにマールブルクから移ってきたハンス・ヨナス(Hans Jonas)らと『アウグスティヌスとパウリンの自由問題(Augustin und das paulinische Freiheitsproblem. Ein philosophischer Beitrag zur Genesis der christlich-abendländischen Freiheitsidee, 1930)[m]、また3人の若い哲学者のグループもいた: ヤスパースの友人であり弟子であったのは、言語学者のベンノ・フォン・ヴィーゼとフーゴ・フリードリッヒ(下の写真はハンナと)であり、ヤスパースの勧め でフリードリッヒ・グンドルフの講義に参加した。また、ある講演会でクルト・ブルーメンフェルトと再会し、ユダヤ人政治にも興味を持つようになる。ハイデ ルベルクでは、城に近い旧市街(アルトシュタット)のシュロスベルク16番地に住んだ。その家は1960年代に取り壊されたが、残された一枚の壁には、彼 女がそこに住んでいたことを記念するプレートが掲げられている(下の画像参照)[82]。 学位論文を完成させたアーレントは、当初はドイツ・ロマン主義に関する論文に取り組み[83]、その後は教職に就いた。しかし、1929年は大恐慌の年で もあり、ワイマール共和国の黄金時代(Goldene Zwanziger)が終わりを告げ、残り4年間でますます不安定になっていく。ユダヤ人であるアーレントは、ドイツで学問的な地位を得るチャンスはほと んどなかった[84]。にもかかわらず、彼女はドイツを離れることを余儀なくされる前に著作のほとんどを完成させた[85]。 |

| Career Germany (1929–1933) Berlin-Potsdam (1929) Photo of Günther Stern with Hannah Arendt in 1929 Günther Stern and Hannah Arendt in 1929 In 1929, Arendt met Günther Stern again, this time in Berlin at a New Year's masked ball,[86] and began a relationship with him.[n][38][68] Within a month she had moved in with him in a one-room studio, shared with a dancing school in Berlin-Halensee. Then they moved to Merkurstraße 3, Nowawes,[87] in Potsdam[88] and were married there on 26 September.[o][90] They had much in common and the marriage was welcomed by both sets of parents.[69] In the summer, Hannah Arendt successfully applied to the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft for a grant to support her Habilitation, which was supported by Heidegger and Jaspers among others, and in the meantime, with Günther's help was working on revisions to get her dissertation published.[91] Wanderjahre (1929–1931) After Arendt and Stern were married, they began two years of what Christian Dries refers to as the Wanderjahre (years of wandering) with the ultimately fruitless aim of having Stern accepted for an academic appointment.[92] They lived for a while in Drewitz,[93] a southern neighborhood of Potsdam, before moving to Heidelberg, where they lived with the Jaspers. After Heidelberg, where Stern completed the first draft of his Habilitation thesis, the two then moved to Frankfurt where Stern hoped to finish his writing. There, Arendt participated in the university's intellectual life, attending lectures by Karl Mannheim and Paul Tillich, among others.[94] The couple collaborated intellectually, writing an article together[95] on Rilke's Duino Elegies (1923)[96] and both reviewing Mannheim's Ideologie und Utopie (1929).[97] The latter was Arendt's sole contribution in sociology.[68][69][98] In both her treatment of Mannheim and Rilke, Arendt found love to be a transcendent principle "Because there is no true transcendence in this ordered world, one also cannot exceed the world, but only succeed to higher ranks".[p] In Rilke she saw a latter day secular Augustine, describing the Elegies as the letzten literarischen Form religiösen Dokumentes (ultimate form of religious document). Later, she would discover the limitations of transcendent love in explaining the historical events that pushed her into political action.[99] Another theme from Rilke that she would develop was the despair of not being heard. Reflecting on Rilke's opening lines, which she placed as an epigram at the beginning of their essay Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen? (Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders?) Arendt and Stern begin by stating:[100] The paradoxical, ambiguous, and desperate situation from which standpoint the Duino Elegies may alone be understood has two characteristics: the absence of an echo and the knowledge of futility. The conscious renunciation of the demand to be heard, the despair at not being able to be heard, and finally the need to speak even without an answer–these are the real reasons for the darkness, asperity, and tension of the style in which poetry indicates its own possibilities and its will to form[q] Arendt also published an article on Augustine (354–430) in the Frankfurter Zeitung[101] to mark the 1500th anniversary of his death. She saw this article as forming a bridge between her treatment of Augustine in her dissertation and her subsequent work on Romanticism.[102][103] When it became evident Stern would not succeed in obtaining an appointment,[r] the Sterns returned to Berlin in 1931.[29] Return to Berlin (1931–1933) In Berlin, where the couple initially lived in the predominantly Jewish area of Bayerisches Viertel (Bavarian Quarter or "Jewish Switzerland") in Schöneberg,[105][106] Stern obtained a position as a staff-writer for the cultural supplement of the Berliner Börsen-Courier, edited by Herbert Ihering, with the help of Bertold Brecht. There he started writing using the pen name Günther Anders, i.e. "Günther Other".[s][68] Arendt assisted Günther with his work, but the shadow of Heidegger hung over their relationship. While Günther was working on his Habilitationsschrift, Arendt had abandoned the original subject of German Romanticism for her thesis in 1930, and turned instead to Rahel Varnhagen and the question of assimilation.[83][108] Anne Mendelssohn had accidentally acquired a copy of Varnhagen's correspondence and excitedly introduced her to Arendt, donating her collection to her. A little later, Arendt's own work on Romanticism led her to a study of Jewish salons and eventually to those of Varnhagen. In Rahel, she found qualities she felt reflected her own, particularly those of sensibility and vulnerability.[109] Rahel, like Hannah, found her destiny in her Jewishness. Hannah Arendt would come to call Rahel Varnhagen's discovery of living with her destiny as being a "conscious pariah".[110] This was a personal trait that Arendt had recognized in herself, although she did not embrace the term until later.[111] Back in Berlin, Arendt found herself becoming more involved in politics and started studying political theory, and reading Marx and Trotsky, while developing contacts at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik.[112] Despite the political leanings of her mother and husband she never saw herself as a political leftist, justifying her activism as being through her Jewishness.[113] Her increasing interest in Jewish politics and her examination of assimilation in her study of Varnhagen led her to publish her first article on Judaism, Aufklärung und Judenfrage ("The Enlightenment and the Jewish Question", 1932).[114][115] Blumenfeld had introduced her to the "Jewish question", which would be his lifelong concern.[116] Meanwhile, her views on German Romanticism were evolving. She wrote a review of Hans Weil's Die Entstehung des deutschen Bildungsprinzips (The Origin of German Educational Principle, 1930),[117] which dealt with the emergence of Bildungselite (educational elite) in the time of Rahel Varnhagen.[118] At the same time she began to be occupied by Max Weber's description of the status of Jewish people within a state as Pariavolk (pariah people) in his Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (1922),[119][120] while borrowing Bernard Lazare's term paria conscient (conscious pariah)[121] with which she identified.[t][122][123][124] In both these articles she advanced the views of Johann Herder.[115] Another interest of hers at the time was the status of women, resulting in her 1932 review[125] of Alice Rühle-Gerstel's book Das Frauenproblem in der Gegenwart. Eine psychologische Bilanz (Contemporary Women's Issues: A psychological balance sheet).[126] Although not a supporter of the women's movement, the review was sympathetic. At least in terms of the status of women at that time, she was skeptical of the movement's ability to achieve political change.[127] She was also critical of the movement, because it was a women's movement, rather than contributing with men to a political movement, and abstract rather than striving for concrete goals. In this manner she echoed Rosa Luxemburg. Like Luxemburg, she would later criticize Jewish movements for the same reason. Arendt consistently prioritized political over social questions.[128] By 1932, faced with a deteriorating political situation, Arendt was deeply troubled by reports that Heidegger was speaking at National Socialist meetings. She wrote, asking him to deny that he was attracted to National Socialism. Heidegger replied that he did not seek to deny the rumors (which were true), and merely assured her that his feelings for her were unchanged.[35] As a Jew in Nazi Germany, Arendt was prevented from making a living and discriminated against and confided to Anne Mendelssohn that emigration was probably inevitable. Jaspers had tried to persuade her to consider herself as a German first, a position she distanced herself from, pointing out that she was a Jew and that "Für mich ist Deutschland die Muttersprache, die Philosophie und die Dichtung" (For me, Germany is the mother tongue, philosophy and poetry), rather than her identity. This position puzzled Jaspers, replying "It is strange to me that as a Jew you want to be different from the Germans".[129] By 1933, life for the Jewish population in Germany was becoming precarious. Adolf Hitler became Reichskanzler (Chancellor) in January, and the Reichstag was burned down (Reichstagsbrand) the following month. This led to the suspension of civil liberties, with attacks on the left, and, in particular, members of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (German Communist Party: KPD). Stern, who had communist associations, fled to Paris, but Arendt stayed on to become an activist. Knowing her time was limited, she used the apartment at Opitzstraße 6 in Berlin-Steglitz that she had occupied with Stern since 1932 as an underground railway way-station for fugitives. Her rescue operation there is now recognized with a plaque on the wall.[130][131] Plaque on the wall at Hannah's apartment building on Opitzstraße, commemorating her Memorial at Opitzstraße 6 Photo of exterior of Prussian State Library in 1939 Prussian State Library 1939 Arendt had already positioned herself as a critic of the rising Nazi Party in 1932 by publishing "Adam-Müller-Renaissance?"[132] a critique of the appropriation of the life of Adam Müller to support right wing ideology. The beginnings of anti-Jewish laws and boycott came in the spring of 1933. Confronted with systemic antisemitism, Arendt adopted the motiv "If one is attacked as a Jew one must defend oneself as a Jew. Not as a German, not as a world citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man."[44][133] This was Arendt's introduction of the concept of Jew as Pariah that would occupy her for the rest of her life in her Jewish writings.[134] She took a public position by publishing part of her largely completed biography of Rahel Varnhagen as "Originale Assimilation: Ein Nachwort zu Rahel Varnhagen 100 Todestag" ("Original Assimilation: An Epilogue to the One Hundredth Anniversary of Rahel Varnhagen's Death") in the Kölnische Zeitung on 7 March 1933 and a little later also in Jüdische Rundschau.[u][84] In the article she argues that the age of assimilation that began with Varnhagen's generation had come to an end with an official state policy of antisemitism. She opened with the declaration:[136] Today in Germany it seems Jewish assimilation must declare its bankruptcy. The general social antisemitism and its official legitimation affects in the first instance assimilated Jews, who can no longer protect themselves through baptism or by emphasizing their differences from Eastern Judaism.[v] As a Jew, Arendt was anxious to inform the world of what was happening to her people in 1930–1933.[44] She surrounded herself with Zionist activists, including Kurt Blumenfeld, Martin Buber and Salman Schocken, and started to research antisemitism. Arendt had access to the Prussian State Library for her work on Varnhagen. Blumenfeld's Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland (Zionist Federation of Germany) persuaded her to use this access to obtain evidence of the extent of antisemitism, for a planned speech to the Zionist Congress in Prague. This research was illegal at the time.[138] Her actions led to her being denounced by a librarian for anti-state propaganda, resulting in the arrest of both Arendt and her mother by the Gestapo. They served eight days in prison but her notebooks were in code and could not be deciphered, and she was released by a young, sympathetic arresting officer to await trial.[29][53][139] |

経歴 ドイツ(1929-1933) ベルリン-ポツダム(1929年) ギュンター・シュテルンとハンナ・アーレントの写真(1929年 1929年のギュンター・シュテルンとハンナ・アーレント 1929年、アーレントはベルリンの新年の仮面舞踏会でギュンター・シュテルンと再会し[86]、交際を始める。その後、二人はポツダムのノヴァウェス通 り3番地[87]に引っ越し[88]、9月26日にそこで結婚した[o][90]。二人は多くの共通点を持ち、結婚は双方の両親に歓迎された[69]。夏 には、ハンナ・アーレントはハイデガーやヤスパースらも支援するドイツ学術協会(Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft)に彼女のハビリテーションを支援するための助成金を申請することに成功し、その間にギュンターの助けを借りて論文を出版するた めの修正作業を行っていた[91]。 放浪時代(1929年-1931年) アーレントとシュテルンは結婚後、クリスチャン・ドリースが「放浪の年」と呼ぶ2年間の生活を始める。ハイデルベルクでシュテルンがハビリテーション論文 の初稿を書き上げた後、二人はフランクフルトに移り、そこでシュテルンは執筆を終えることを望んだ。そこでアーレントは大学の知的生活に参加し、カール・ マンハイムやパウル・ティリッヒなどの講義に出席していた[94]。 夫婦は知的共同作業を行い、リルケの『ドゥイノ・エレジーズ』(1923年)に関する論文[95]を共に執筆し[96]、マンハイムの『イデオロギーと ユートピア』(1929年)を共に書評していた[97]。 [この秩序ある世界には真の超越は存在しないので、人はまた世界を超えることはできず、より高いランクに成功するのみである」[p] 。後に彼女は、自分を政治活動へと駆り立てた歴史的な出来事を説明する上で、超越的な愛の限界を発見することになる。リルケの冒頭の一節を振り返り、彼女 はそれをエピグラムとしてエッセイの冒頭に置いた。 Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen? (もし私が叫んだら、天使たちの中で誰が私の声を聞いてくれるだろうか?) アーレントとシュテルンはまずこう述べている[100]。 逆説的で、曖昧で、絶望的な状況は、『ドゥイーノ哀歌』の立場からのみ理解されうるが、そこには二つの特徴がある。聴かれたいという要求の意識的な放棄、 聴かれないことへの絶望、そして最後には答えがなくとも語る必要性-これらが、詩が自らの可能性と形成への意志を示す文体の暗さ、険しさ、緊張の真の理由 である[q]。 アーレントはまた、アウグスティヌス(354-430)の没後1500年を記念して、アウグスティヌスに関する論文をフランクフルター・ツァイトゥング誌 に発表した[101]。彼女はこの論文を、学位論文におけるアウグスティヌスの扱いとその後のロマン主義に関する研究との架け橋になると考えていた [102][103]。シュテルンが任命を得ることに成功しないことが明らかになると[r]、シュテルン夫妻は1931年にベルリンに戻る[29]。 ベルリンへの帰還(1931-1933) シュテルン夫妻は当初、シェーネベルクのバイエリッシュ・ヴィアテル(バイエルン人街または「ユダヤ人のスイス」)というユダヤ人の多い地域に住んでいた が[105][106]、シュテルンはベルトルド・ブレヒトの協力を得て、ヘルベルト・イヘリングが編集する『ベルリナー・ベルセン・クーリエ』紙の文化 欄のスタッフ・ライターの職を得る。そこで彼はギュンター・アンダース、すなわち「ギュンター・アザー」というペンネームを使って執筆を始めた[s] [68]。アーレントはギュンターの仕事を手伝ったが、ハイデガーの影が2人の関係につきまとっていた。ギュンターが Habilitationsschriftを執筆している間、アーレントは1930年の卒論のためにドイツ・ロマン主義という当初の主題を放棄し、代わり にラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲンと同化の問題に目を向けていた[83][108]。 アンネ・メンデルスゾーンは偶然ヴァーンハーゲンの書簡のコピーを手に入れ、興奮しながら彼女をアーレントに紹介し、彼女のコレクションを寄贈した。それ からしばらくして、アーレントはロマン主義に関する自身の研究をきっかけに、ユダヤ人サロンの研究を始め、最終的にはヴァルナーゲンのサロンにたどり着 く。ラヘルは、ハンナと同様、ユダヤ人であることに運命を見出した。ハンナ・アーレントはラヘル・ヴァルンハーゲンが自分の運命とともに生きることを発見 したことを「意識的亡者」と呼ぶようになる[110]。 ベルリンに戻ると、アーレントは政治により深く関わるようになり、政治理論を学び、マルクスとトロツキーを読み始める。 [113]ユダヤ人政治への関心の高まりとヴァルンハーゲンの研究における同化の考察から、彼女はユダヤ教に関する最初の論文『Aufklärung und Judenfrage』(「啓蒙思想とユダヤ人問題」、1932年)を発表する。彼女はハンス・ヴァイルの『ドイツ教育原理の起源』(Die Entstehung des deutschen Bildungsprinzips、1930年)の書評を書き、ラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲンの時代における教育エリート(Bildungselite)の出 現を扱った[117]。 [118]同時に彼女は、マックス・ヴェーバーが『Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft』(1922年)において国家内におけるユダヤ人の地位をパリアヴォルク(偏狭な人々)と表現したことに心を奪われ始め [119][120]、同時にベルナール・ラザールのパリア・コンシャント(意識的偏狭者)という用語を借用した[121]。 [これらの論文の両方で彼女はヨハン・ヘルダー(Johann Herder)の見解を支持していた[115]。当時の彼女のもう一つの関心は女性の地位であり、その結果、1932年にアリス・リューレ=ゲルステル (Alice Rühle-Gerstel)の著書『Das Frauenproblem in der Gegenwart. この書評は女性運動の支持者ではなかったが、共感的なものであった[126]。少なくとも当時の女性の地位という点では、彼女はこの運動が政治的変化を達 成する能力に対して懐疑的であった[127]。彼女はまた、この運動が男性とともに政治運動に貢献するのではなく女性の運動であり、具体的な目標に邁進す るのではなく抽象的であったことから、この運動に対して批判的であった。この点で、彼女はローザ・ルクセンブルクと同じであった。ルクセンブルクと同じよ うに、彼女は後に同じ理由でユダヤ人運動を批判することになる。アーレントは一貫して社会的な問題よりも政治的な問題を優先していた[128]。 1932年までに、政治状況の悪化に直面したアーレントは、ハイデガーが国家社会主義者の集会で演説しているという報道に深く悩まされていた。彼女はハイ デガーに、自分が国家社会主義に惹かれていることを否定するよう求めた。ナチス・ドイツのユダヤ人として、アーレントは生計を立てることを妨げられ、差別 され、アンネ・メンデルスゾーンに移住は避けられないだろうと打ち明けた。ヤスパースは彼女を説得し、まず自分をドイツ人だと考えるよう促したが、彼女は 自分がユダヤ人であること、そして自分のアイデンティティよりもむしろ「私にとってドイツは母語であり、哲学であり、詩である」(Für mich ist Deutschland die Muttersprache, die Philosophie und die Dichtung)と指摘し、この立場から距離を置いた。このような立場にヤスパースは困惑し、「ユダヤ人としてあなたがドイツ人とは違う存在でありたい というのは、私には奇妙なことです」と答えた[129]。 1933年になると、ドイツにおけるユダヤ人の生活は不安定になっていた。アドルフ・ヒトラーは1月に帝国首相に就任し、翌月には帝国議会が焼き払われ た。これによって市民的自由が停止され、左派、とりわけドイツ共産党(KPD)党員への攻撃が始まった。共産主義に傾倒していたシュテルンはパリに逃れた が、アーレントはそのまま活動家になった。時間が限られていることを知っていた彼女は、1932年からシュテルンと住んでいたベルリン・シュテグリッツの オピッツ通り6番地のアパートを、逃亡者のための地下鉄道の中継所として利用した。そこでの彼女の救出作戦は、現在、壁に掲げられたプレートで認識されて いる[130][131]。 オピッツ通りにあるハンナのアパートの壁にある彼女を記念するプレート オピッツ通り6番地の記念碑 1939年のプロイセン国立図書館外観写真 プロイセン国立図書館 1939年 アーレントは1932年、右翼イデオロギーを支持するためにアダム・ミュラーの生涯が流用されたことを批判する『アダム=ミュラー=ルネッサンス』 [132]を出版し、台頭するナチ党を批判する立場をすでに確立していた。反ユダヤ法とボイコットの始まりは1933年の春だった。組織的な反ユダヤ主義 に直面したアーレントは、「もしユダヤ人として攻撃されたら、ユダヤ人として自分を守らなければならない。ドイツ人としてではなく、世界市民としてでもな く、人間の権利の支持者としてでもない: Ein Nachwort zu Rahel Varnhagen 100 Todestag"(「原初の同化: この記事の中で彼女は、ヴァーンハーゲンの世代から始まった同化の時代は、国家の公式な反ユダヤ主義政策によって終焉を迎えたと主張している[u] [84]。彼女は冒頭で次のように宣言した[136]。 今日ドイツでは、ユダヤ人の同化は破産を宣言しなければならないようだ。一般的な社会的反ユダヤ主義とその公的な正当化は、まず第一に同化したユダヤ人に 影響を及ぼし、彼らはもはや洗礼を受けたり、東方ユダヤ教との違いを強調したりすることによって自らを守ることはできない[v]。 ユダヤ人であったアーレントは、1930年から1933年にかけて自分たちの民族に何が起きていたのかを世界に知らせたいと願っていた。アーレントは、 ヴァルンハーゲンに関する研究のためにプロイセン国立図書館を利用した。ブルーメンフェルトのドイツ・シオニスト連盟(Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland)は、プラハで開かれるシオニスト会議での演説のために、反ユダヤ主義の程度を示す証拠を入手するために、このアクセス権を利用す るよう彼女を説得した。この研究は当時違法であった[138]。彼女の行動は、図書館員から反国家的プロパガンダであると糾弾され、その結果、アーレント と母親はゲシュタポに逮捕された。二人は8日間服役したが、彼女のノートは暗号で解読できず、若い同情的な逮捕将校によって釈放され、裁判を待つことに なった[29][53][139]。 |

| Exile: France (1933–1941) Paris (1933–1940) Portrait of Rahel Varnhagen in 1800 Rahel Varnhagen c. 1800 On release, realizing the danger she was now in, Arendt and her mother fled Germany[29] following the established escape route over the Ore Mountains by night into Czechoslovakia and on to Prague and then by train to Geneva. In Geneva, she made a conscious decision to commit herself to "the Jewish cause". She obtained work with a friend of her mother's at the League of Nations' Jewish Agency for Palestine, distributing visas and writing speeches.[140] From Geneva the Arendts traveled to Paris in the autumn, where she was reunited with Stern, joining a stream of refugees.[141] While Arendt had left Germany without papers, her mother had travel documents and returned to Königsberg and her husband.[140] In Paris, she befriended Stern's cousin, the Marxist literary critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin and also the Jewish French philosopher Raymond Aron.[141] Arendt was now an émigrée, an exile, stateless, without papers, and had turned her back on the Germany and Germans of the Nazizeit.[44] Her legal status was precarious and she was coping with a foreign language and culture, all of which took its toll on her mentally and physically.[142] In 1934 she started working for the Zionist-funded outreach program Agriculture et Artisanat,[143] giving lectures, and organizing clothing, documents, medications and education for Jewish youth seeking to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine, mainly as agricultural workers. Initially she was employed as a secretary, and then office manager. To improve her skills she studied French, Hebrew and Yiddish. In this way she was able to support herself and her husband.[144] When the organization closed in 1935, her work for Blumenfeld and the Zionists in Germany brought her into contact with the wealthy philanthropist Baroness Germaine Alice de Rothschild (born Halphen, 1884–1975),[145] wife of Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild, becoming her assistant. In this position she oversaw the baroness' contributions to Jewish charities through the Paris Consistoire, although she had little time for the family as a whole.[140][w] Later in 1935, Arendt joined Youth Aliyah (Youth immigration),[x] an organization similar to Agriculture et Artisanat that was founded in Berlin on the day Hitler seized power. It was affiliated with Hadassah,[147][148] which later saved many from the Holocaust,[149][150][29] and there Arendt eventually became Secretary-General (1935–1939).[17][141] Her work with Youth Aliyah also involved finding food, clothing, social workers and lawyers, but above all, fund raising.[53] She made her first visit to British Mandate of Palestine in 1935, accompanying one of these groups and meeting with her cousin Ernst Fürst there.[y][142] With the Nazi annexation of Austria and invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, Paris was flooded with refugees, and she became the special agent for the rescue of the children from those countries.[17] In 1938, Arendt completed her biography of Rahel Varnhagen,[37][152][153] although this was not published until 1957.[29][154] In April 1939, following the devastating Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, Martha Beerwald realized her daughter would not return and made the decision to leave her husband and join Arendt in Paris. One stepdaughter had died and the other had moved to England, Martin Beerwald would not leave and she no longer had any close ties to Königsberg.[155] Heinrich Blücher In 1936, Arendt met the self-educated Berlin poet and Marxist philosopher Heinrich Blücher in Paris.[29][156] Blücher had been a Spartacist and then a founding member of the KPD, but had been expelled due to his work in the Versöhnler (Conciliator faction).[116][157][158] Although Arendt had rejoined Stern in 1933, their marriage existed in name only, with their having separated in Berlin.[z] She fulfilled her social obligations and used the name Hannah Stern, but the relationship effectively ended when Stern, perhaps recognizing the danger better than she, emigrated to America with his parents in 1936.[142] In 1937, Arendt was stripped of her German citizenship and she and Stern divorced. She had begun seeing more of Blücher, and eventually they began living together. It was Blücher's long political activism that began to move Arendt's thinking towards political action.[116] Arendt and Blücher married on 16 January 1940, shortly after their divorces were finalized.[159] Internment and escape (1940–1941) Memorial plaque at Camp Gurs to al who were detained there Memorial at Camp Gurs On 5 May 1940, in anticipation of the German invasion of France and the Low Countries that month, the military governor of Paris issued a proclamation ordering all "enemy aliens" between 17 and 55 who had come from Germany (predominantly Jews) to report separately for internment. The women were gathered together in the Vélodrome d'Hiver on 15 May, so Hannah Arendt's mother, being over 55, was allowed to stay in Paris. Arendt described the process of making refugees as "the new type of human being created by contemporary history ... put into concentration camps by their foes and into internment camps by their friends".[159][160] The men, including Blücher, were sent to Camp Vernet in southern France, close to the Spanish border. Arendt and the other women were sent to Camp Gurs, to the west of Gurs, a week later. The camp had earlier been set up to accommodate refugees from Spain. On 22 June, France capitulated and signed the Compiègne armistice, dividing the country. Gurs was in the southern Vichy controlled section. Arendt describes how, "in the resulting chaos we succeeded in getting hold of liberation papers with which we were able to leave the camp",[161] which she did with about 200 of the 7,000 women held there, about four weeks later.[162] There was no Résistance then, but she managed to walk and hitchhike north to Montauban,[aa] near Toulouse where she knew she would find help.[160][163] Montauban had become an unofficial capital for former detainees,[ab] and Arendt's friend Lotta Sempell Klembort was staying there. Blücher's camp had been evacuated in the wake of the German advance, and he managed to escape from a forced march, making his way to Montauban, where the two of them led a fugitive life. Soon they were joined by Anne Mendelssohn and Arendt's mother. Escape from France was extremely difficult without official papers; their friend Walter Benjamin had taken his own life after being apprehended trying to escape to Spain. One of the best known illegal routes operated out of Marseilles, where Varian Fry, an American journalist, worked to raise funds, forge papers and bribe officials with Hiram Bingham, the American vice-consul there. Fry and Bingham secured exit papers and American visas for thousands, and with help from Günther Stern, Arendt, her husband, and her mother managed to secure the requisite permits to travel by train in January 1941 through Spain to Lisbon, Portugal, where they rented a flat at Rua da Sociedade Farmacêutica, 6b.[ac][167] They eventually secured passage to New York in May on the Companhia Colonial de Navegação's S/S Guiné II.[168] A few months later, Fry's operations were shut down and the borders sealed.[169][170] |

亡命 フランス(1933-1941) パリ(1933-1940) 1800年のラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲンの肖像 1800年頃のラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲン 釈放されたアーレントは、母親とともにドイツを脱出し[29]、夜間にオーレ山脈を越えてチェコスロバキアに入り、プラハから列車でジュネーヴに向かっ た。ジュネーヴで彼女は「ユダヤ人の大義」に身を捧げることを意識的に決意した。母親の友人と国際連盟のパレスチナ・ユダヤ人機関で働き、ビザを配布した り、演説を書いたりした[140]。 ジュネーヴから秋にパリに向かったアーレントは、そこでシュテルンと再会し、難民の流れに加わる。アーレントが書類を持たずにドイツを離れたのに対し、母 親は旅行書類を持っており、ケーニヒスベルクとその夫のもとに戻った[140]。 パリでは、シュテルンのいとこであるマルクス主義の文芸批評家で哲学者のヴァルター・ベンヤミンや、ユダヤ系フランス人の哲学者レイモン・アロンと親しく なった[141]。 彼女の法的地位は不安定であり、異国の言語と文化に対処していた。 [1934年、彼女はシオニストが資金を提供するアウトリーチプログラムAgriculture et Artisanatで働き始め[143]、講義を行い、主に農業労働者としてイギリス委任統治領パレスチナへの移住を目指すユダヤ人の若者のために衣服、 書類、薬、教育を組織した。当初は秘書として雇われ、その後事務長になった。スキルアップのため、フランス語、ヘブライ語、イディッシュ語を勉強した。 1935年に組織が閉鎖されると、ブルーメンフェルドとドイツのシオニストのために働いていた彼女は、裕福な慈善家のジェルメーヌ・アリス・ド・ロスチャ イルド男爵夫人(ハルフェン生まれ、1884-1975)と接触するようになり[145]、エドゥアール・アルフォンス・ジェームス・ド・ロスチャイルド の妻となり、彼女のアシスタントになった。この地位で、彼女はパリ・コンシストワールを通じて男爵夫人のユダヤ人慈善事業への寄付を監督していたが、一族 全体と関わる時間はほとんどなかった[140][w]。 その後、1935年にアーレントは、ヒトラーが政権を掌握した日にベルリンで設立された「農業と職人」に似た組織である「ユース・アリヤー(青年移民)」 [x]に参加する。それは後に多くの人々をホロコーストから救ったハダッサと提携しており[147][148]、アーレントはそこで最終的に事務局長とな る(1935-1939年)[17][141]。ユース・アリヤでの彼女の活動は、食料、衣料、ソーシャルワーカー、弁護士を見つけることでもあったが、 何よりも資金調達であった[53]。 [1938年にナチスがオーストリアを併合し、チェコスロバキアに侵攻すると、パリは難民で溢れかえり、彼女はこれらの国々からの子どもたちの救出のため の特別代理人となった[17]。1938年、アーレントはラヘル・ヴァーンハーゲンの伝記を完成させたが[37][152][153]、これが出版された のは1957年のことであった。 [1939年4月、1938年11月の壊滅的な水晶の夜のポグロムの後、マルタ・ビアヴァルトは娘が戻ってこないことを悟り、夫と別れてパリでアーレント と合流する決断をする。継娘の一人は亡くなり、もう一人はイギリスに移住していたが、マルティン・ビアヴァルトは去ろうとせず、彼女はもはやケーニヒスベ ルクとの密接なつながりはなかった[155]。 ハインリヒ・ブリュッヒャー 1936年、アーレントはベルリンの独学詩人でマルクス主義哲学者のハインリッヒ・ブリュッヒャーとパリで出会う[29][156]。ブリュッヒャーはス パルタシストであり、その後KPDの創設メンバーであったが、Versöhnler(調停者派)での活動のために追放されていた[116][157] [158]。 [1937年、アーレントはドイツ国籍を剥奪され、スターンとは離婚。彼女はブリュッヒャーと付き合うようになり、やがて二人は一緒に暮らし始めた。アー レントとブリュッヒャーは離婚が成立した直後の1940年1月16日に結婚した[159]。 抑留と逃亡(1940-1941年) 収容所グルスに設置された、収容された人々への慰霊碑 グルス収容所の慰霊碑 1940年5月5日、同月にドイツがフランスと低地諸国に侵攻することを予期して、パリの軍総督は、ドイツから来た17歳から55歳までの「敵性外国人」 (主にユダヤ人)に、収容のために別々に出頭するよう命じる布告を出した。女性たちは5月15日にヴェロドローム・ディヴェールに集められ、ハンナ・アー レントの母親は55歳以上であったため、パリに留まることが許された。アーレントは難民化のプロセスを「現代の歴史が生み出した新しいタイプの人 間......敵によって強制収容所に入れられ、友によって収容所に入れられた」と表現した[159][160]。ブリュッヒャーを含む男性たちは、スペ イン国境に近い南フランスのヴェルネ収容所に送られた。アーレントと他の女性たちは一週間後、グルス西方のグルス収容所に送られた。このキャンプはスペイ ンからの難民を収容するために設置されたものだった。6月22日、フランスは降伏し、コンピエーニュ休戦協定に調印して国内を分割した。グルスは南部ヴィ シーの支配下にあった。その結果生じた混乱の中で、私たちは解放の書類を手に入れることに成功し、それによって収容所を出ることができた」とアーレントは 描写しており[161]、彼女は収容されていた7,000人の女性のうち約200人とともに、約4週間後にその書類を手に入れた[162]。当時レジスタ ンスは存在しなかったが、彼女はなんとか歩いてヒッチハイクで北上し、トゥールーズ近郊のモントーバン[aa]まで行き、そこで助けを見つけることができ ると知っていた[160][163]。 モントーバンは元拘禁者のための非公式な首都となっており[ab]、アーレントの友人ロッタ・センペル・クレンボートはそこに滞在していた。ブリュッ ヒャーの収容所はドイツ軍の進撃に伴って退去させられ、彼は強制行進から逃れてモントーバンにたどり着き、そこで二人は逃亡生活を送った。間もなく、アン ネ・メンデルスゾーンとアーレントの母親が加わった。彼らの友人ヴァルター・ベンヤミンは、スペインに逃れようとして逮捕され、自ら命を絶った。最も有名 な非合法ルートのひとつはマルセイユからで、アメリカ人ジャーナリストのヴァリアン・フライは、同地のアメリカ人副領事ハイラム・ビンガムとともに、資金 調達、書類の偽造、役人への賄賂の供与に努めた。 フライとビンガムは数千人分の出国書類とアメリカのビザを確保し、ギュンター・シュテルンの助けを借りて、アーレントとその夫、そして母親は1941年1 月にスペインを経由してポルトガルのリスボンまで列車で旅行するために必要な許可を得ることに成功し、そこで彼らはRua da Sociedade Farmacêutica, 6bにアパートを借りた。 [ac][167]彼らは最終的に5月にコンパニア・コロニアル・デ・ナヴェガサォンのS/SギネII号でニューヨークへの航路を確保した[168]。 |

| New York (1941–1975) World War II (1941–1945) Upon arriving in New York City on 22 May 1941 with very little, Hannah's family received assistance from the Zionist Organization of America and the local German immigrant population, including Paul Tillich and neighbors from Königsberg. They rented rooms at 317 West 95th Street and Martha Arendt joined them there in June. There was an urgent need to acquire English, and it was decided that Hannah Arendt should spend two months with an American family in Winchester, Massachusetts, through Self-Help for Refugees, in July.[171] She found the experience difficult but formulated her early appraisal of American life, Der Grundwiderspruch des Landes ist politische Freiheit bei gesellschaftlicher Knechtschaft (The fundamental contradiction of the country is political freedom coupled with social slavery).[ad][172] On returning to New York, Arendt was anxious to resume writing and became active in the German-Jewish community, publishing her first article, "From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today" (in translation from her German) in July 1941.[ae][174] While she was working on this article, she was looking for employment and in November 1941 was hired by the New York German-language Jewish newspaper Aufbau and from 1941 to 1945, she wrote a political column for it, covering antisemitism, refugees and the need for a Jewish army. She also contributed to the Menorah Journal, a Jewish-American magazine,[175] and other German émigré publications.[29] Arendt and Blücher were residents at 370 Riverside Drive in New York City. Arendt's first full-time salaried job came in 1944, when she became the director of research and executive director for the newly emerging Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, a project of the Conference on Jewish Relations.[af] She was recruited "because of her great interest in the Commission's activities, her previous experience as an administrator, and her connections with Germany". There she compiled lists of Jewish cultural assets in Germany and Nazi occupied Europe, to aid in their recovery after the war.[178] Together with her husband, she lived at 370 Riverside Drive in New York City and at Kingston, New York, where Blücher taught at nearby Bard College for many years.[29][179] Post-war (1945–1975) Photo of Hannah and Heinrich Blücher in New York in 1950 Hannah Arendt with Heinrich Blücher, New York 1950 In July 1946, Arendt left her position at the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction to become an editor at Schocken Books, which later published some of her works.[29][180] In 1948, she became engaged with the campaign of Judah Magnes for a solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[116] She famously opposed the establishment of a Jewish nation state in Palestine and initially also opposed the establishment of a binational Arab-Jewish state. Instead, she advocated for the inclusion of Palestine into a multi-ethnic federation. Only in 1948 in an effort to forestall partition did she support a binational one-state solution.[181] She returned to the Commission in August 1949. In her capacity as executive secretary, she traveled to Europe, where she worked in Germany, Britain and France (December 1949 to March 1950) to negotiate the return of archival material from German institutions, an experience she found frustrating, but provided regular field reports.[182] In January 1952, she became secretary to the Board, although the work of the organization was winding down[ag] and she was simultaneously pursuing her own intellectual activities; she retained this position until her death.[ah][178][183][184] Arendt's work on cultural restitution provided further material for her study of totalitarianism.[185] In the 1950s Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951),[186] The Human Condition (1958)[187] followed by On Revolution (1963).[29][188] Arendt began corresponding with the American author Mary McCarthy, six years her junior, in 1950 and they soon became lifelong friends.[189][190] In 1950, Arendt also became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[191] The same year, she started seeing Martin Heidegger again, and had what the American writer Adam Kirsch called a "quasi-romance", lasting for two years, with the man who had previously been her mentor, teacher, and lover.[35] During this time, Arendt defended him against critics who noted his enthusiastic membership in the Nazi Party. She portrayed Heidegger as a naïve man swept up by forces beyond his control, and pointed out that Heidegger's philosophy had nothing to do with National Socialism.[35] She suspected that loyal followers of Horkheimer and Adorno in Frankfurt were plotting against Heidegger. For Adorno she had a real aversion: "Half a Jew and one of the most repugnant men I know".[192][80] According to Arendt, the Frankfurt School was willing, and quite capable of doing so, to destroy Heidegger: "For years they have branded anti-Semitism on anyone in Germany who opposes them, or have threatened to raise such an accusation".[192][80] In 1961 she traveled to Jerusalem to report on Eichmann's trial for The New Yorker. This report strongly influenced her popular recognition, and raised much controversy (see below). Her work was recognized by many awards, including the Danish Sonning Prize in 1975 for Contributions to European Civilization.[44][193] A few years later she spoke in New York City on the legitimacy of violence as a political act: "Generally speaking, violence always rises out of impotence. It is the hope of those who have no power to find a substitute for it and this hope, I think, is in vain. Violence can destroy power, but it can never replace it."[194] Teaching Photo of Hannah Arendt lecturing in Germany, 1955 Hannah Arendt lecturing in Germany, 1955 Arendt taught at many institutions of higher learning from 1951 onwards, but, preserving her independence, consistently refused tenure-track positions. She was a visiting scholar at the University of Notre Dame, University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University (where she was the first woman to be appointed a full professor in 1959) and Northwestern University. She also taught at the University of Chicago from 1963 to 1967, where she was a member of the Committee on Social Thought, [179][195] Yale University, where she was a fellow and the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University (1961–62, 1962–63). From 1967 she was a professor at the New School for Social research in Manhattan, New York City.[29][196] She was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1962[197] and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1964.[198] In 1974, Arendt was instrumental in the creation of Structured Liberal Education (SLE) at Stanford University. She wrote a letter to the president of Stanford to persuade the university to enact Stanford history professor Mark Mancall's vision of a residentially-based humanities program.[179] At the time of her death, she was University Professor of Political Philosophy at The New School.[179] Relationships See also: § Correspondence Portrait of Hannah Arendt with Mary McCarthy Arendt with Mary McCarthy In addition to her affair with Heidegger, and her two marriages, Arendt had close friendships. Since her death, her correspondence with many of them has been published, revealing much information about her thinking. To her friends she was both loyal and generous, dedicating several of her works to them.[199] Freundschaft (friendship) she described as being one of "tätigen Modi des Lebendigseins" (the active modes of being alive),[200] and, to her, friendship was central both to her life and to the concept of politics.[199][201] Hans Jonas described her as having a "genius for friendship", and, in her own words, "der Eros der Freundschaft" (love of friendship).[199][202] Her philosophy-based friendships were male and European, while her later American friendships were more diverse, literary, and political. Although she became an American citizen in 1950, her cultural roots remained European, and her language remained her German "Muttersprache" (mother tongue).[203] She surrounded herself with German-speaking émigrés, sometimes referred to as "The Tribe". To her, wirkliche Menschen (real people) were "pariahs", not in the sense of outcasts, but in the sense of outsiders, unassimilated, with the virtue of "social nonconformism ... the sine qua non of intellectual achievement", a sentiment she shared with Jaspers.[204] Arendt always had a beste Freundin (best friend [female]). In her teens she had formed a lifelong relationship with her Jugendfreundin, Anne Mendelssohn Weil ("Ännchen"). After her emigration to America, Hilde Fränkel, Paul Tillich's secretary and mistress, filled that role until the latter's death in 1950. After the war, Arendt was able to return to Germany and renew her relationship with Weil, who made several visits to New York, especially after Blücher's death in 1970. Their last meeting was in Tegna, Switzerland in 1975, shortly before Arendt's death.[205] With Fränkel's death, Mary McCarthy became Arendt's closest friend and confidante.[51][206][207] |

ニューヨーク(1941-1975) 第二次世界大戦(1941-1945) 1941年5月22日、わずかな資金でニューヨークに到着したハンナ一家は、アメリカのシオニスト組織や、パウル・ティリッヒやケーニヒスベルク出身の隣 人を含む地元のドイツ系移民から援助を受けた。彼らは西95丁目317番地に部屋を借り、6月にはマルタ・アーレントもそこに加わった。英語の習得が急務 であったため、ハンナ・アーレントは7月にSelf-Help for Refugeesを通じてマサチューセッツ州ウィンチェスターのアメリカ人家族のもとで2ヶ月間過ごすことが決定された[171]。 ニューヨークに戻ると、アーレントは執筆活動を再開することを望み、ドイツ系ユダヤ人コミュニティで活動するようになり、1941年7月に最初の論文「ド レフュス事件から今日のフランスへ」(ドイツ語からの翻訳)を発表した[ae][174]。この論文に取り組んでいる間、彼女は就職活動をしており、 1941年11月にニューヨークのドイツ語版ユダヤ人新聞『アウフバウ』に雇われ、1941年から1945年まで、反ユダヤ主義、難民、ユダヤ人軍隊の必 要性を取り上げた政治コラムを執筆した。また、ユダヤ系アメリカ人の雑誌『メノラ・ジャーナル』[175]やその他のドイツ系移民の出版物にも寄稿してい た[29]。 アーレントとブリュッヒャーはニューヨークのリバーサイド・ドライブ370番地に住んでいた。 アーレントが初めてフルタイムのサラリーマンとなったのは1944年のことで、ユダヤ関係者会議のプロジェクトであった新興のヨーロッパ・ユダヤ文化復興 委員会の調査部長兼事務局長となった[af]。そこで彼女はドイツとナチス占領下のヨーロッパにあるユダヤ人文化財のリストを作成し、戦後の復興を支援し た[178]。夫とともにニューヨークのリバーサイド・ドライブ370番地とニューヨークのキングストンに住み、ブリュッヒャーは近くのバード・カレッジ で長年教鞭をとった[29][179]。 戦後(1945-1975) 1950年、ニューヨークでのハンナとハインリヒ・ブリュッヒャーの写真 ハンナ・アーレントとハインリッヒ・ブリュッヒャー、ニューヨーク、1950年 1946年7月、アーレントはヨーロッパ・ユダヤ文化復興委員会の職を辞し、ショッケン・ブックスの編集者となる。その代わりに、彼女はパレスチナを多民 族連邦に含めることを提唱した。1948年になって初めて、分割を阻止するために、二国間の一国家による解決を支持した[181]。1949年8月に委員 会に復帰。1949年12月から1950年3月まで、ドイツ、イギリス、フランスでドイツの機関からのアーカイブ資料の返還交渉に携わった。 [182]1952年1月、彼女は理事会の秘書となったが、理事会の仕事は終わりつつあり[ag]、同時に彼女は自身の知的活動を追求していた。 1950年代にアーレントは『全体主義の起源』(1951年)[186]、『人間の条件』(1958年)[187]、そして『革命について』(1963 年)を執筆している[29][188]。 アーレントは1950年に6歳年下のアメリカ人作家メアリー・マッカーシーと文通を始め、すぐに生涯の友人となった[189][190]。 [同じ年、彼女はマルティン・ハイデガーと再び付き合い始め、アメリカの作家アダム・カーシュが「擬似恋愛」と呼ぶような関係を、それまで彼女の師であ り、教師であり、恋人であった彼と2年間続けた[35]。この間、アーレントは彼のナチ党への熱心な入党を指摘する批評家たちからハイデガーを擁護した。 彼女はハイデガーを、自分の力ではどうすることもできない力に振り回されたナイーブな人間として描き、ハイデガーの哲学は国家社会主義とは何の関係もない と指摘した。彼女はアドルノに嫌悪感を抱いていた: 「アーレントによれば、フランクフルト学派はハイデガーを破壊することを望んでおり、またそうすることが可能であった: 「彼らは何年もの間、ドイツで自分たちに反対する者に反ユダヤ主義の烙印を押したり、そのような非難をすると脅したりしてきた」[192][80]。 1961年、彼女は『ニューヨーカー』誌のためにアイヒマンの裁判を取材するためにエルサレムを訪れた。この報道は彼女の知名度に大きな影響を与え、多く の論争を巻き起こした(下記参照)。1975年には「ヨーロッパ文明への貢献」でデンマークのソニング賞を受賞するなど、多くの賞を受賞している[44] [193]。 数年後、彼女はニューヨークで政治的行為としての暴力の正当性について語った: 「一般的に言って、暴力は常に無力感から生まれる。一般的に言って、暴力は常に無力感から生まれるものです。暴力は、権力を持たない人々が権力に代わるも のを見出そうとする希望であり、この希望は無駄なものだと思います。暴力は権力を破壊することはできるが、権力に取って代わることは決してできない」 [194]。 講義 ドイツで講義するハンナ・アーレントの写真(1955年 ドイツで講義するハンナ・アーレント(1955年 アーレントは1951年以降、多くの高等教育機関で教鞭をとったが、独立性を保つため、一貫して終身雇用の職を拒否していた。ノートルダム大学、カリフォ ルニア大学バークレー校、プリンストン大学(1959年に女性初の正教授に就任)、ノースウェスタン大学で客員研究員を務めた。また、1963年から 1967年までシカゴ大学で教鞭をとり、社会思想委員会のメンバーであった。[179][195] イェール大学ではフェローを務め、ウェズリアン大学高等研究センター(1961-62年、1962-63年)でも教鞭をとった。1967年からはニュー ヨークのマンハッタンにあるニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチの教授を務めていた[29][196]。 1974年、アーレントはスタンフォード大学の構造化された教養教育(Structured Liberal Education, SLE)の創設に尽力。彼女はスタンフォード大学の学長に手紙を書き、スタンフォード大学の歴史学教授であるマーク・マンコールの構想である居住型の人文 学プログラムを実現するよう大学を説得した[179]。 人間関係 以下も参照: § 往復書簡 メアリー・マッカーシーとハンナ・アーレントの肖像 メアリー・マッカーシーとアーレント ハイデガーとの関係や2度の結婚に加え、アーレントには親しい友人関係があった。彼女の死後、多くの友人との往復書簡が出版され、彼女の考え方に関する多 くの情報が明らかになった。彼女は友人に対して忠実であり、また寛大であり、いくつかの著作を彼らに捧げている[199]。友情 (Freundschaft)は「tätigen Modi des Lebendigseins」(生きていることの能動的な様式)のひとつであると彼女は述べており[200]、彼女にとって友情は彼女の人生にとっても政 治という概念にとっても中心的なものであった。 彼女の哲学に基づく交友関係は男性的でヨーロッパ的なものであったが、その後のアメリカでの交友関係はより多様で文学的、政治的なものであった。1950 年にアメリカ国籍を取得したが、彼女の文化的ルーツはヨーロッパのままであり、彼女の言語はドイツ語の「母国語」のままであった[203]。彼女にとって wirkliche Menschen(現実の人々)は「亡者」であり、のけ者という意味ではなく、「社会的不適合......知的達成のシン・クア・ノン」という美徳を持 つ、同化されていないアウトサイダーという意味であり、ヤスパースと共通の感情であった[204]。 アーレントには常に親友がいた。10代の頃、彼女はユーゲントフロインディンであるアンネ・メンデルスゾーン・ヴァイルと生涯を共にする。彼女がアメリカ に移住した後は、パウル・ティリッヒの秘書兼愛人であったヒルデ・フレンケルが、1950年にティリッヒが亡くなるまでその役割を果たした。戦後、アーレ ントはドイツに戻り、ヴァイルとの関係を新たにすることができた。ヴァイルは、特に1970年にブリュッヒャーが亡くなった後、何度かニューヨークを訪れ ている。フレンケルの死後、メアリー・マッカーシーはアーレントの最も親しい友人であり親友となった[51][206][207]。 |