涙なしのジャック・ラカン

Easygoing

Lacan and/or Reading Lacan without tear

https://www.boredpanda.com/creative-ad-advertising-photo-arthur-mebius/

by Arthur Mebius

☆ここでは、涙なしのジャック・ ラカンへ(Jacques Lacan, 1901-1981)の入門を考える。ここで利用される資料は、すべてインターネットから仕入れたもので、このページの制作者のオリジナリティはゼロであ る。そのために、このページの内容保証は一切ない。

★ラカン理論のアーキテクチャー:ラカン読解入門 / ジョエル・ドール [著] ; 小出浩之訳, 東京 : 岩波書店 , 1989.8

土台:1 フロイトへの回帰

| I. 言語学と無意識の形成物 |

2. 夢の作業における圧縮と置き換え |

|

| 3. 構造という概念 |

||

| 4. 構造言語学の要素 |

||

| 5. 記号の価値とラカンのクッションの綴じ目 |

||

| 6. 隠喩-換喩とシニフィアンの優越 |

||

| 7. 隠喩過程としての圧縮 |

||

| 8. 置き換えと、換喩の過程としての夢作業 |

||

| 9. 隠喩-換喩的過程としての機知 |

||

| 10. 隠喩過程としての症状 |

||

| II. 主体性の構造的交叉点としての父の隠喩 | 11. ファルスの優越 |

|

| 12. 鏡像段階とエディプス |

||

| 13. 父の隠喩ー父の名、欲望の換喩 |

||

| 14. 父の名の排除——精神病過程への接近 |

||

| 15. シニフィアンの秩序による主体の分裂と無意識の降誕 |

||

| 16. 主体の分割:ランガージュへの疎外 |

||

| 17. 無意識の主体-言表行為の主体、言表内容の主体 |

||

| 18. 自我への主体の疎外、シェーマL-主体の排除 |

||

| 19. 意識の弁証法と欲望の弁証法 |

||

| III. 欲望、ランガージュ、無意識 |

20. 欲求、欲望、要求 |

|

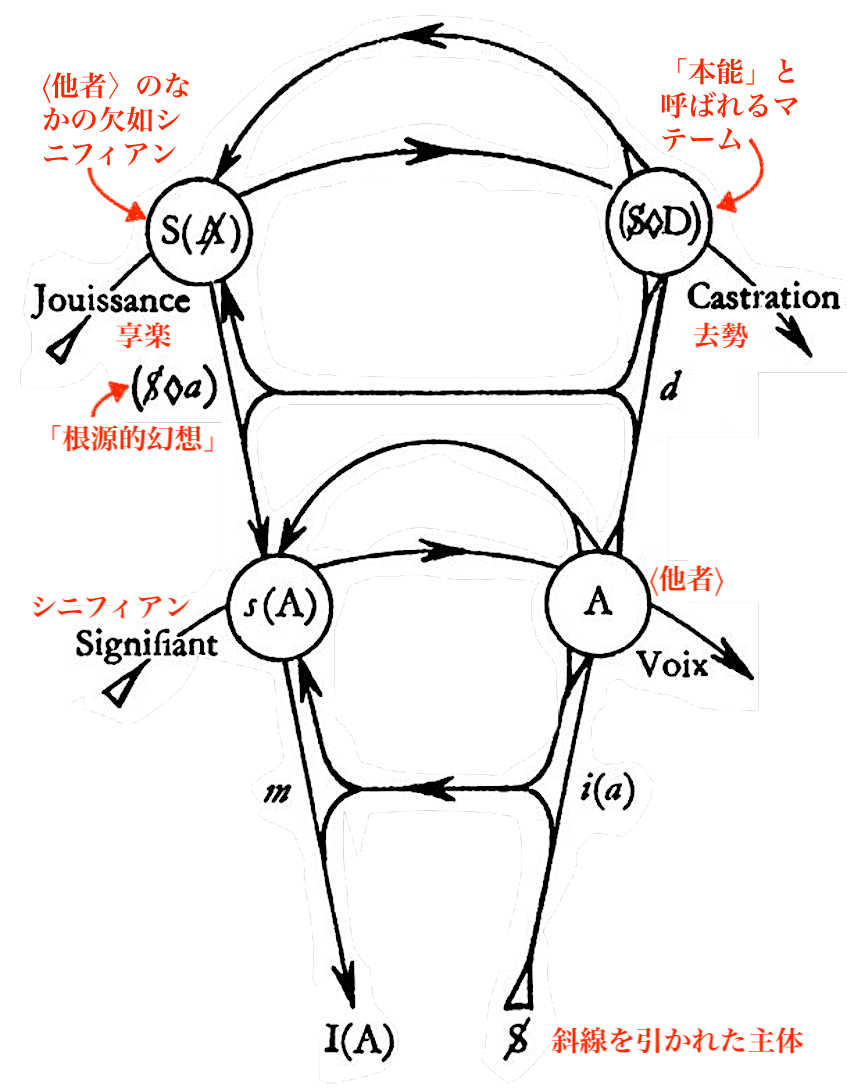

| 21. 欲望のグラフ1:クッションの綴じ目からパロールの挽臼へ |

||

| 22. コミュニケーションの定式と他者(A)のディスクールとしての無意識 |

||

| 23. 欲望のグラフ2:機知というシニフィアンの技法における意味の創造と、ランガージュにおける無意識の撹乱 |

||

| 24. 欲望のグラフ3:欲望とシニフィアンとの結合 |

||

| 25. グラフの生成 |

「ラカンの主張は、フロイトのいう無意識の《脱中心化された》主体とは、デカルト的コギトにほかならない。つまり、無意識の《脱中心化された》主体とは、デカルトを突き詰めた、カントの超越論的主体にほかならない」(ジジェク 2003)

| 鏡像段階 |  鏡像段階(仏:stade du

miroir)論とは、幼児は自分の身体を統一体と捉えられないが、成長して鏡を見ることによって(もしくは自分の姿を他者の鏡像として見ることによっ

て)、鏡に映った像(signe)が自分であり、統一体であることに気づくという理

論。幼児は、鏡に映る自己の姿を見ることにより、自分の身体を認識

し、自己を同定していく。この鏡とは、まぎれもなく他者のことでもある。つまり、人は、他者を鏡にすることにより、他者の中に自己像を見出す(この自己像

が「自我」となる)。ラカンの鏡像段階論は、フロイトのエディプスコンプレックス理論をラカン流に読み替えたものとも言える。 鏡像段階(仏:stade du

miroir)論とは、幼児は自分の身体を統一体と捉えられないが、成長して鏡を見ることによって(もしくは自分の姿を他者の鏡像として見ることによっ

て)、鏡に映った像(signe)が自分であり、統一体であることに気づくという理

論。幼児は、鏡に映る自己の姿を見ることにより、自分の身体を認識

し、自己を同定していく。この鏡とは、まぎれもなく他者のことでもある。つまり、人は、他者を鏡にすることにより、他者の中に自己像を見出す(この自己像

が「自我」となる)。ラカンの鏡像段階論は、フロイトのエディプスコンプレックス理論をラカン流に読み替えたものとも言える。「鏡像段階(stade du miroir)は、ジャック・ラカンの精神分析理論における概念である。鏡像段階とは、生後6ヶ月頃から、幼児が鏡(文字どおり)や他の象徴的な仕掛けの 中で自分自身を認識することで、アペルセプション(自分自身を自分の外から見ることができる対象に変えること)を誘発するという考えに基づいている。 当初ラカンは、1936年にマリエンバードで開催された第14回国際精神分析会議で概説されたように、鏡像段階は6ヶ月から18ヶ月までの乳児の発達の一 部であると提唱した。1950年代初頭までに、ラカンの鏡像段階の概念は進化していた。彼はもはや鏡像段階を幼児の一生の一瞬とは考えず、主観性の永続的 な構造、あるいは「想像的秩序」のパラダイムを表すものと考えていた。ラカンの思考におけるこの進化は、「主体の転覆と欲望の弁証法」と題された後のエッ セイで明らかになる。」https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mirror_stage ★ ラカン / ポール=ロラン・アスン著 ; 西尾彰泰訳、白水社 , 2013 . - (文庫クセジュ, 978)は、鏡像段階から、ラカンの「思想」の解説をはじめるので。 【書誌解説】「フロイトを読み解く背景から生まれた理論「シェーマ」や「グラフ」。その解説にこだわりすぎることなく、ラカンが立ち向かった問題とそのと きの思考に重点が置かれている。また、彼が取った行動を示すことで「ラカン思想」の変遷がわかる。日本ではまだ紹介されていない後期を含めた網羅的な入門 書」 【目次】第1部 想像界、象徴界、現実界の基礎(鏡像段階から想像界へ;シニフィアンの理論;父の名から象徴界へ;現実界とその機能)→ 第2部 ラカンのマテシス。他者、対象、欲望(他者の姿;対象の力;主体の機能)→ 第3部 分析的行為とマテーム。構造と症状(神経症、精神病、倒錯;分析の終わりと、「分析家の欲望」;メタ心理学からマテームへ:分析の記述;「ラカン 思想」とその争点) |

| 父の名(Noms-du-Père) |

象

徴的父(→当該項目)がもつ部分のひとつ。想像界に安住するのを禁ず

る父の命令を受け入れることであり、このこと

は社会的な法の要求を受け入れること、自分が全能ではないとい

う事実を受け入れることと同義である。この父の命令にあたるものを、ラカンは、フランス語における「non(否)」と「nom(名)」を

ひっかけて父の名

(仏:Noms-du-Père)と呼んだ。 |

| 去勢(castration) |

・ラカンのいう去勢は、外科手術のことではない。ラカンのいう去勢は、ファルスの「機能」を削いでしまうものだ。ファルスは別項

の説明にあるように「享楽を作り出す手段」なので、ファルスの機能を削いでしまう去

勢は、享楽のはたらきを削いでしまうもののことになる。 ・父の名を受け容れる過程は、幼児の全能性である「ファルス」(仏: phallus)を傷つけることという意味で、去勢(仏: castration)と呼ばれるわけだが、この去勢によって、人間は自らの不完全性を認め、不完全であるところの自己を逆に積極的に確立するのである。 ・皆の前での「私は大した人間ではありません」というのは——皆の前で、象徴的な去勢を敢行することで、のちに大衆から本当にファルスの機能を削いでしまう畏れのあることを、自ら去勢することで、予防策を張っておく(=予防注射をしておく)ことである(垂水源之介)。 |

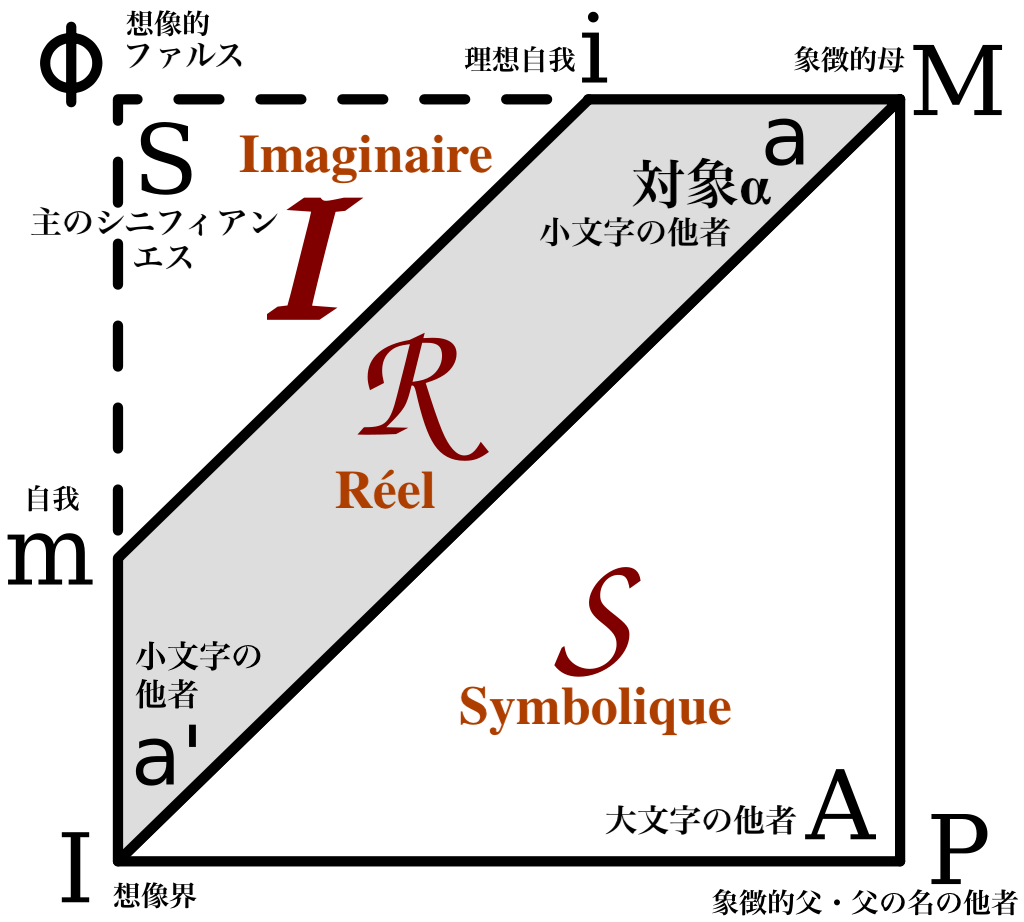

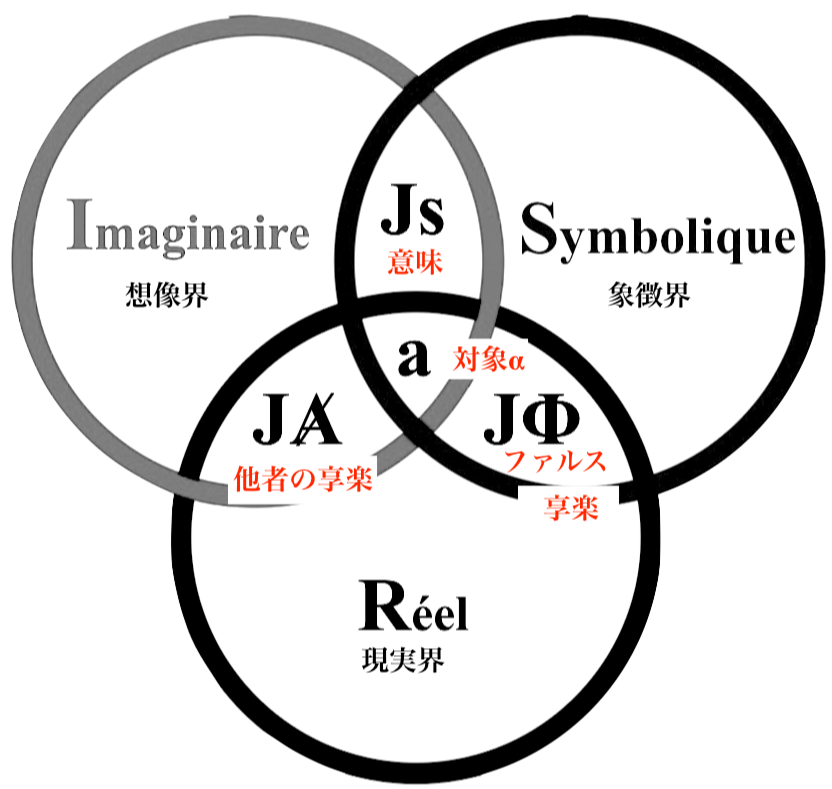

| 象徴界 (l'symbolique)S of RSI |

象

徴界とは言語的次元であり「言葉、文字、数字の領域=次元」である。 ラカンはセミナーIV「オブジェの関係」の中で、「法則」と「構造」と いう概念は言語なしには考えられない、つまり象徴界とは言語的次元であると 論じている。ほかに象徴界とは「言葉、文字、数字の領域=次元」のこととも。 しかし、この秩序は言語と等価ではない。言語には想像界や現実界も 含まれるからだ。象徴における言語にふさわしい次元とは、シニフィエの次元である。つまり、要素は積極的な存在を持たないが、相互の差異によって構成され る次元である。象徴界はまた、根本的な変質の場、すなわち他者であり、無意識はこの他者の言説である。それはエディプス・コンプレックスにおける欲望を規 制する法の領域である。象徴界とは、自然の想像的秩序とは対照的な文化の領域である。シンボリックの重要な要素として、死と欠落(manque)の概念 は、快楽原理を事物からの距離(ドイツ語では「das Ding an sich」)の調整装置とし、「反復によって快楽原理を超える」死の衝動--「死の衝動はシンボリック秩序の仮面にすぎない」--となるように企図してい る。象徴的秩序に働きかけることによって、分析者は精神分析を受けている人の主観的立場に変化をもたらすことができる。想像界は象徴界によって構造化され ているため、こうした変化はイマジナリーな効果を生み出すことになる。 ・RSIと表記するように現実界・象徴界・想 像界は三位一体の概念 |

| 現実界(le Réel)R of RSI | 現実界と、実際の「現実」は異なる。ラカンにとって現実界とは、主体の外側にあり「不可能なもの全体/全部」のことである。ラカン

の現実界の概念は1936年、精神病に関する博士論文にまで遡

る。それは当時流行していた用語であり、特にエミール・メイヤソンはそれを「存在論的な絶対的存在、真なる存在-in-itself」と呼んでいた。ラカ

ンは1953年に現実界のテーマに戻り、亡くなるまでそれを発展させ続けた。ラカンにとっての現実界は現実と同義ではない。想像界と対立するだけでなく、

現実界はシンボリックの外部でもある。シンボリックの「存在/不在」という対立が、シンボリックから何かが欠落している可能性を示唆してい

るのに対して、

「現実界は常にその場所にある」。記号は記号化の過程において「現実における切れ目」を導入する:

それは、ものの世界を創造する言葉の世界であり、それは元来、すべてのものが誕生する過程の「今、ここ」で混同されていたものである」。現実界とは、言語の

外側にあり、象徴化に絶対的に抵抗するものである。ラカンは『セミナーXI』において、現実界を「不可能なもの」と定義しているが、それは想像することが

不可能であり、象徴に統合することが不可能であり、到達することが不可能だからである。この象徴化への抵抗こそが、現実界にトラウマ的な質を与えているの

である。最後に、現実界は、それがいかなる可能な媒介をも欠いており、「もはや対象ではない本質的な対象であるが、すべての言葉が停止し、すべてのカテゴ

リーが失敗するこの何かに直面している、卓越した不安の対象」である限りにおいて、不安の対象である。 ・現実界は「非–現実」(=不可能なもの)であり、現実界を精神病そのものと理解するむきもある。 ・RSIと表記するように現実界・象徴界・想 像界は三位一体の概念 |

| 想像界(l'Imaginaire)I of RSI | 想

像界とはイメージと想像力の分野である。この秩序の主な幻想は、統

合、自律性、二元性、類似性である。ラカンは、自我と反射されたイメージの間に鏡の段階で作られる関係は、自我と想像界秩序そのものが根本的な疎外の場で

あることを意味すると考えた:

「疎外は想像界の秩序を構成するものである」『精神分析の4つの基本概念』の中でラカンは、象徴秩序が想像界の視覚的場を構造化していると論じている。シ

ニフィエが象徴の基礎であるならば、シニフィエとシニフィケーションは想像界の秩序の一部である。言語には象徴的な意味合いと想像界的な意味合いがあり、

想像界的な側面では、言語は他者の言説を反転させ、歪曲させる「言語の壁」である。しかし、想像界は、主体が自らの身体(のイメージ)との関係に根ざして

いる。ラカンは『フェティシズム:象徴界、想像界、現実界』の中で、性的な平面において想像界は性的なディスプレイや求愛として現れると論じている。 ・RSIと表記するように現実界・象徴界・想 像界は三位一体の概念 |

| 他者(大文字の他者)A |

・フロイトが「他者」という用語を使い、der Andere(他者)やdas

Andere(他者性)に言及しているのに対して、ラカンは(アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのセミナーの影響を受け)ヘーゲル哲学により近い方法で分身を理

論化している。大文字の他者(l'Autre)はAと命名され、小文字の他者

(l'autre)はaと命名される:

「分析者はAとaの違いに染まらなければならず、そうすれば他者ではなく他者の場所に自らを位置づけることができる」。セクシュアリティにおける他者はファルスを所有しているために、その他者は享楽を所有している

あるいは、享楽を享受していることになる。 ・フロイトが「他者」という用語を使い、der Andere(他者)やdas

Andere(他者性)に言及しているのに対して、ラカンは(アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのセミナーの影響を受け)ヘーゲル哲学により近い方法で分身を理

論化している。大文字の他者(l'Autre)はAと命名され、小文字の他者

(l'autre)はaと命名される:

「分析者はAとaの違いに染まらなければならず、そうすれば他者ではなく他者の場所に自らを位置づけることができる」。セクシュアリティにおける他者はファルスを所有しているために、その他者は享楽を所有している

あるいは、享楽を享受していることになる。+++++++++ ・大文字の他者(l'Autre)すなわちAは、言語活動(→象徴 界)の他者であり、「父の名」(→当該項目)であり、シニフィアン(→当該項目)であり、言語であり、ファルス(→当該項目)である。 ・小文字の他者(l'autre)すなわちaは、欲望の原因であり、 欲望の対象である。 ・他者は対象の別名である。 ・大文字の他者はいつも仮想的だ。 ・Aには、斜線をひかれたものがある。「斜線を引かれたA」と読む。欠如するものとしての、構造的 に不完全なものとしての、その欠知へとやってくる主体によって不完全なものとして経験される〈他者〉」(→「ラカンの用語の解説」)。 ・他者が大文字で書かれるのは、それが「象徴界」の次元にあるからである。 |

| 主体 +++++++++++  |

主体は、ラカンに言わせれば、おおむね人間のこと。主体は他者抜きには

ありえない。なぜなら、対象である他者は、主体性を作ったり支えたりするあらゆるものをさすからである。「欲望」の項目にあるように、主体の生は欲望を中

心に回っている。 ・主体は、欲望の対象(a)と大文字の他者(A)により、つねに分割されている。 +++++++++++ 「斜線を引かれた主体」。主体には二つの側面がある。(1)言語のなかに/によって疎外されたものとしての、去勢(=疎外)されたものとしての、「死ん だ」意味の沈着としての主体。ここでの主体は、〈他者〉によって、すなわち象徴的秩序によって侵食されているので、存在を欠いている。( 2 )他なるものが「自分自身のもの」になる主体化のプロセスにおいて、二つのシニフイアンの問に走る閃光としての主体 ・主体が変容するのは、行為の瞬間ではなく、宣言の瞬間だ。 |

| 無意識、エス |

・無意識というトポロジーには「隠蔽された欲望」が潜んでいる。それゆ

え、この「隠蔽された欲望」は、症状やシニフィアンや言葉として、表出(=表に出てくること)されることを「じっと待っている」という状態なのである。 ・フロイトによると、無意識には、4つの形成物がある。1)症状 Symptoms、2)日常生活での錯誤 Error of everyday life、3)機知 Jokes、4)夢 Dreams 。ラカンもそれを踏襲している。 ・「無意識とは、その存在論的位置が思考のそれではないような思考形態である。つまり、思考そのものの外にある思考形態である」(『イデオロギーの崇高な 対象』文庫版, p.41) ・無意識は外傷的な真理が声を発する場所のことである。 |

| ファルス |

ファルスは「男根・ペニス」のことではない。変化をしめす道具は、ペニスを含めて、全部ファルスだという。ラカンによると、

ブランコや、速度計、妊娠した女も、「変化をしめす道具」なので、ファルスなのである。ファルスは、享楽を作り出す手段である。 |

| 自我 | ・自我は、己の無意識の欲望と、世界とのあいだをとりもつ存在である。

無

意識の欲望(→当該項目)は隠蔽されており、自我はそのことに気づかないので、(意識されない欲望に支配され)偽りの関係を「世界」ととり結ぶことにな

る。自我という概念は、主体が認識し感じるものであるが、自分自身の相——自分の身体——に対して想像的なイメージを抱くものとされている。そのために、

主体がもつ自我の概念は、複雑なものになる。 ・自我は自分の主人すなわち無意識のことを知らない。 |

| 象徴的父 |

象徴的父とは、母ないしは《母》を子どもから引き離す審級(=判断を引

き出す段階)のすべて。例えば、「母親の仕事」は、実質的に、母あるいは《母》的なるものを、子どもから引き離すので、「象徴的父」になる。 |

| 症状 |

症状は、ファルスと同様に、享楽を引き出すものであるが、症状は主体の「無意識の欲望」を象徴的に「話す」ものとされている。「症状は、ファルスと同様に享楽を作り出す」ために、症状のなかにすでに享楽があ

る(症状は享楽をつくりだしている)であり、症状は享楽であり、享楽

は症状が作り出すものだとも言える。 |

| 享楽 | 享楽は、文字通り気持ちいいこと、嬉しいこと、楽しいことである。セッ クスにおけるオーガズムから、セクシュアリティや食べることや、症 状をもつ(→症状はラカン派ではファルスと同様に享楽を作り出す)ことなど、幅広い意味をもつ。症状は、ファルスと同様に享楽を作り出す」ために、症状のなかにすでに享楽があ る(症状は享楽をつくりだしている)であり、症状は享楽であり、享楽 は症状が作り出すものだとも言える。 ラカンは、いつも、享楽をあきらめるな、享楽を追及せよと言っているように覚える——あるいは享楽が帰結するために、症状は終わらないとも言える。しか し、ラカンは他方で、「性関係は存在しない」などのように、セックスやセク シュアリティが享楽にいつも直結するとは考えるな(=なぜならば享楽は症状の帰結だからだ)とラカンは我々に対して釘をさしているとも思える。 |

| ラカンの著作 |

・精神疾患の本以外に、精神分析の本は存命中は出版しなかった。 ・Eは、『エクリ』(1966) ・AEは、『オトール・エクリ』(2001)と表現する(アスン 2013:38) |

| 欲求(need) |

欲求は生理的なものである。欲求とは感覚にむけられ、かつ与えられるものだ。新生児は欲求の段階だ。新生児

の要求に対してコントロールするのが《母》という存在である。 |

| 要求(demand) | 要求は、対象が提示されるかぎり、求められるが、その対象は与えられな い。つまり、要求とは与えられない対象にむけられるもの。《母》に要 求する子ども は、それが満たされると次々と要求の連鎖が続く。子どもは、《母》が与えることができないものを要求している——欲求している——。ここでの要求は、愛の 要求である。愛は、決して具体的な形象をもたないからである。 |

| 欲望(desire) | ・欲望は主体の基盤であり、主体という存在の核になる(→享楽を諦める

な、享楽を追及せよ、は主体本来のあり方を示している)。欲望は言語活動に伴われる属性である(→言語化しないと欲望とは言えない)が、無意識のなかでも

(非言語あるいがプロト言語の形で)欲望は臥在している。つまり、欲望は、手の届く

こともある対象にむけられるものだ。欲望はつねに、他者の欲望への欲

望である。欲望とは差異への欲望である。 ・人間の欲望は、〈他者〉の欲望である ・他者の欲望の謎に答えを与えてくれるのは、幻想である。 |

| ラカン思想の3つの層 |

1)【前期】セミネールがはじまる時期(1951-1953)から、中

断された時期(1963)までの、10-12年間 2)【中期】1964年から,1968年/1969年まで。ラカンはこの時期にすべての人に語りかけるようになる 3)【後期】1970年から1979年まで、ラカンは「理解できる者」あるいは「大文字の他者(A)」に向けて語るようになる。 |

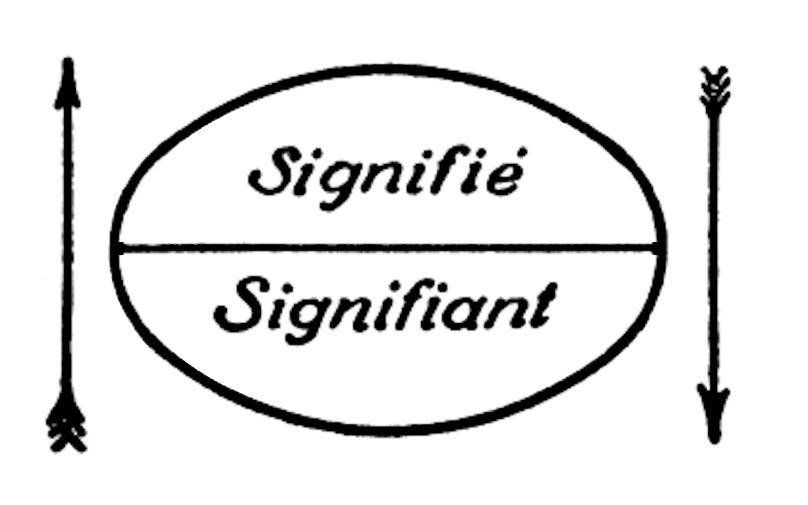

| シニフィアン | ソシュール派では「指示するもの(名辞)」であるが、ラカン派もまた、 言葉のことをさす。 |

| 対象 | 対象は「他者」の別名のことである。対象は、主体性を作ったり支えたり するあらゆるものをさす。 |

| 幻想(fantasy) |

・幻想は欲望を支え、欲望を進ませることにある。 ・他者の欲望の謎に答えを与えてくれるのは、幻想である。 |

| 転移(transference) |

転移は一種の翻訳である。 |

| フロ

イトへの回帰 |

・フロイトの言ったことに帰れという意味ではなく、フロイト自身も気が

つかなかった、フロイトによる革命の核心に回帰せよと言ったのだ。 ・フロイトそのものの理論には、ラカンの重要な概念に相当するものがない。 |

| 精神分析 |

・心の病を治療する理論と技法ではない。個人を人間存在の基本的次元と

対決させる理論と技法のことである。 |

| 読解 |

・読解とは、党派的に読むことだ |

| 沈黙 |

・何も秘密を話さないことと、何も話さないと公言することは、根本的に

異なる |

| 隣人 |

・隣人は怪物であり、隣人は物(das Ding)である |

| 性的快楽 |

・現実の他者との性的快楽は自明のものではなく、本質的に外傷的であ

り、その他者が主体の幻想の枠組みに入ったときに(性的快楽は)はじめて得られる。 ・性関係は存在しない |

| 真理 |

・ラカンにおいて、真理とは主体の原因なのである(アラン・バディウ)

[バディウ 2019:113] |

| 愛 |

・しつこいけれど言っちゃうわよ,

知へと差し向けられるのは愛なのよ,決して欲望じゃないからね,その点ヨ・ロ・シ・ク!!!(ジャッキー・L)[バディウ 2019:195] ・「真理愛が弱さの愛であり、真理が隠しているものの愛であること、すなわち最終的には去勢の愛であることです。……。真理愛は、ある無力さへの愛なので す」[バディウ 2019:197] |

★ジャック・ラカンの

生涯は、こちらが詳しいです!!!

★ジャック・ラカンの生涯は、こちらが詳しいで

す!!! ★ジャック・ラカンの生涯は、こちらが詳しいで

す!!!ジャック=マリー=エミール・ラカン(Jacques-Marie-Émile Lacan、1901年4月13日 - 1981年9月9日)は、フランスの哲学者、精神科医、精神分析家。 1901年、カトリックのブルジョワ階級の家に生まれる。初め独学で哲学を学ぶが、転学しパリ大学に移り、25歳の頃にアンリ・クロード教授のもとで精神 神経学を学ぶ。1928年、ラカンはパリ警察庁に入庁し、精神監察医ガエタン・ドゥ・クレランボー(クレランボーは後に鏡の前で拳銃自殺)のもとで学ぶ。 ここで精神病者の犯罪に親しく触れることとなり、犯罪心理学の研究を深めてゆく。師クレランボーの自殺を契機に、徐々に、犯罪心理学のみならず、フロイト の精神分析学に傾倒していった。 1932年、ラカンは、パラノイア女性エメを描いた学位論文『人格との関係から見たパラノイア性精神病』を発表し、博士号を取得。 さらに、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのヘーゲル講義などに参加した。ここにはジョルジュ・バタイユも参加しており、当時友人であった。ちなみに、バタイユ は、当時女優をしていたシルヴィア・バタイユと結婚生活を送っていたが、1933年には別居していた。シルヴィアは、ジャック・ラカンと愛人関係となり、 1938年に2人の間には女児が生まれた。 1940年からナチス・ドイツによるフランス占領が続き、1944年にパリ解放がなされるまでの間、ナチスによる検閲がラカンの論文にもなされたが、これ に対してラカンは精神科医にしか理解できない文体で記述したため、ドイツ兵士たちには全く意味不明だとされ、検閲の手から逃れた。[1][2]この戦時中 の記憶が、その後のラカンの文体に残っている。 1953年1月、パリ精神分析学会会長に選ばれる。 しかし、会長就任後、サシャ・ナシュトとの間に亀裂が生じ、同協会は内紛状態となる。結局、会長就任からたった5カ月で不信任案が可決されてしまい、ラカ ンは会長職を辞任する。この騒動で、パリ精神分析学会は分裂した。ラカンは、ダニエル・ラガーシュらとともに、「フランス精神分析学会」を新しく立ち上げ るに至った。 1964年、自ら「パリ・フロイト派」を立ち上げた。だが、同派も結局1980年に解散することになった。1981年8月に大腸癌の手術を受けたが、縫合 部が破れて腹膜炎と敗血症を併発した。同年9月9日にモルヒネを投与されて亡くなった。ラカンの最後の言葉は、「私は強情だが・・・消えるよ。」だった [3]。ラカンの私生活の、滑稽かつ悲哀を帯びた実像を描いた小説に、フィリップ・ソレルスの『女たち』がある。 ★鏡像段階に ついては、こちらが詳しいです!!! Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (UK: /læˈkɒ̃/,[3] US: /ləˈkɑːn/,[4][5] French: [ʒak maʁi emil lakɑ̃]; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud",[6] Lacan gave yearly seminars in Paris, from 1953 to 1981, and published papers that were later collected in the book Écrits. His work made a significant impact on continental philosophy and cultural theory in areas such as post-structuralism, critical theory, feminist theory and film theory, as well as on the practice of psychoanalysis itself. Lacan took up and discussed the whole range of Freudian concepts, emphasizing the philosophical dimension of Freud's thought and applying concepts derived from structuralism in linguistics and anthropology to its development in his own work, which he would further augment by employing formulae from predicate logic and topology. Taking this new direction, and introducing controversial innovations in clinical practice, led to expulsion for Lacan and his followers from the International Psychoanalytic Association.[7] In consequence, Lacan went on to establish new psychoanalytic institutions to promote and develop his work, which he declared to be a "return to Freud", in opposition to prevalent trends in psychology and institutional psychoanalysis collusive of adaptation to social norms. |

|

鏡像段階論 1937年発表の初期ラカンを代表する、発達論的観点から

の理論。 1937年発表の初期ラカンを代表する、発達論的観点から

の理論。鏡像段階(仏:stade du miroir)論とは、幼児は自分の身体を統一体と捉えられないが、成長して鏡を見ることによって(もしくは自分の姿を他者の鏡像として見ることによっ て)、鏡に映った像(仏:signe)が自分であり、統一体であることに気づくという理論である。一般的に、生後6ヶ月から18ヶ月の間 に、幼児はこの過 程を経るとされる。 幼児は、いまだ神経系が未発達であるため、自己の「身体的統一性」(仏:unité corporelle)を獲得していない。つまり、自分が一個の身体であるという自覚がない。言い換えれば、「寸断された身体」(仏:corps morcelé)のイメージの中に生きているわけである。 そこで、幼児は、鏡に映る自己の姿を見ることにより、自分の身体を認識し、自己を同 定していく。この鏡とは、まぎれもなく他者のことでもある。つまり、人は、他者を鏡にすることにより、他者の中に自己像を見出す(この自己像が「自我」と なる)。 すなわち、人間というものは、それ自体まずは空虚なベース(エス)そのものである一 方で、他方では、自我とは、その上に覆い被さり、その空虚さ・無根拠性を覆い隠す (主として)想像的なものである。自らの無根拠や無能力に目を瞑っていられるこの想像的段階に安住することは、幼児にとって快いことではあ る。この段階 が、鏡像段階に対応する。 父の名(Noms-du-Père) さらに、このことは、想像界に安住するのを禁ずる父の命令を受け入れることであり、 このことは社会的な法の要求を受け入れること、自分が全能ではないとい う事実を受け入れることと同義である。この父の命令にあたるものを、ラカンは、フランス語における「non(否)」と「nom(名)」を ひっかけて父の名 (仏:Noms-du-Père)と呼んだ。 したがって、父の名とは、個別の具体的な父親の姓名を指すのではなく、人である限りすべての子どもに割り当てられ、彼らの行為に一定の限界をもうける、父 性的機能のことである。いわば、象徴的な掟である。 ラカンは、このような掟が、言語活動(仏:langage)によって生じるとする。つまり、象徴的な掟は、具体的に聞こえたり見えたりはしないものの、さ まざまな形をとってわれわれの生活を制禦してくる。そのとき、われわれは「自らの限界を思い知る」。 精神分析学では、このことを去勢(仏:castration)と呼ぶ。そして、去勢なくして言語活動の開始はないというのが、ラカンの立場である。 ・フロイトの格言「エスを追い出したところにしか自我はやってこない(Wo es war soll ich werden)"Where It was, shall I be"」 |

|

現実界・象徴界・想像界(→これらは一種の三

位一体) 人間は、いつまでも鏡像段階に留まることは許されず、成長するにしたがって、

やがて自己同一性(仏:identité)や主体性(仏:sujet)を持ち、それ

を自ら認識しなければならない。その際、言語の媒介・介入は、不可欠である。 人間は、いつまでも鏡像段階に留まることは許されず、成長するにしたがって、

やがて自己同一性(仏:identité)や主体性(仏:sujet)を持ち、それ

を自ら認識しなければならない。その際、言語の媒介・介入は、不可欠である。ラカンによれば、主体性は、構造的に現実界・象徴界・想像界(仏: Réel Symbolique Imaginaire:R.S.I.と略称される)という三つの領界もしくは機能から成るものであり、鏡像段階を経て人が主体性を獲得し、言語に介入され るということは、すなわち象徴界へと参入するということであるとされる。  |

|

| 去勢と自己の確立 上記のことを言い換えれば、父の名を受け容れる過程は、幼児の全能性である「ファル ス」(仏:phallus)を傷つけることという意味で、去勢(仏: castration)と呼ばれるわけだが、この去勢によって、人間 は自らの不完全性を認め、不完全であるところの自己を逆に積極的に確立するのである。 逆に見れば、「これが自分だ」と自己を同定し、自我を確立するためには他者が必要だが、そこで真の自己と出会えるわけでは決してない。人は常に「出会い損ね」ている存在なのだ。ここに人間の根源的な空虚さを見出せ るとも言える。 このように、彼の言う「我、思わぬ故に我あり」は、フロイトの「エスがあったところに自我が生じなければならない」という警句の別言である。ラカンの鏡像段階論は、フロイトのエディプスコンプレックス理論をラカン流に読み替えたも のなのである。 +++++++++++ 母子関係と言語 ゆえに、母子関係からラカン理論を、あくまでも一般的な理解のために、わかりやすくおおまかに言い換えれば、次のようになる。 まず、胎児として子宮の内部に浮遊している状態では、人は「ママ!」という原初の言葉を持つ必要がない。だから、言語活動は発生しない。 さらに、生まれてからも(原初の状態を象徴的にいうならば)乳児の口には母の乳房が詰まっている。これは乳児の必要をすべて満たしているから、言葉を発し て何かを求める必要もないし、そもそも口に乳房が詰まっているから言葉の発しようもない。一方、これは、乳児にとっては全世界を支配しているかのような快 楽の状態である。 だが、やがて口から乳房が去る。そこに欠如(もしくは不在)が生まれる。欠如が生まれて初めて、乳児は母を求めるなり、乳を求めるなり、「マー」などと叫 びをあげる。これは言語 - より正確には言語活動(仏:langage) - の発生である。 こうした象徴的な意味での言語の発生は、人間が人間となるためにどうしても通らなければならない段階である。言語とは、人間が自分の頭に思い描いているも の、すなわち想像的なもの(仏:l'Imaginaire)を他者と共有しようとしたり、他者に伝達しようとしたりするために用いる象徴的なもの(仏: l'symbolique)であるから、言語は象徴界のものであると云える。 一方、社会はさまざまな人間がせめぎあう場であるがゆえに、無数の掟・契約・約束事などでできている。こうした掟は、象徴的な意味では言語で書かれている わけである。たとえば、不文律や「黙契」といった概念ですら、人間が言語を持たなければ存在しえない。また、掟を与えるのは象徴的な父である。 ゆえに、上記の意味においては象徴界とは掟であり、父であり、言語であるといった図式が成り立つ。 |

|

| 言語活動と現実界 たとえば、ある大事件に遭遇した人々は、口々にその事件を語る。これは、その大事件という現実的なこと、もしくは現実界(仏:le Réel)を、言語という象徴界(仏:l'symbolique)を以って描き出そうとしているわけである。証言者Aは事件の決定的瞬間を語り、証言者B は事件の背景に秘められた事情を語るなど、あらゆる角度から証言がなされる。これらを集めて「事件の全容を解明しよう」という動きが起こったりする。しか し、マスコミ用語としては耳に親しい「事件の全容」なるものは、実際には語り尽くされるのは不可能である。 同じように、どうがんばっても言葉では現実そのものを語ることはできない。「言語は現実を語れない」のである。ところが同時に、人は「言語でしか現実を語 れない」。これら二つの命題は、平板に見れば矛盾しているかのように聞こえるが、メビウスの輪のような立体的な論理として考えればそうでないことがわか る。 したがって、人は、より的確な言葉を探したり、より多くの言葉を重ねていくことによって、少しでも現実に近いものを描き出そうと奮闘する。この誠実さは、 評価されるかもしれない。しかし、それでも言語活動=現実となる瞬間はない。これが象徴界と現実界が分かたれる一面である。 すなわち、象徴界の参入という「言語との出会い」は、現実をラカンのいう「不可能なもの」(仏:l'impossible)に変える。われわれは一生、そ れに対する抵抗とあこがれの間で揺れ惑う。しかし、人が事故的に現実を垣間見たり、現実に触れたりすることがある。その一形態こそが、精神病である。 言語活動と想像界 一方、想像界(仏:l'Imaginaire)は、たとえば「日常」「平和」「不幸」といった、人であれば誰しも漠然とイメージできるけれども、その正確 な描写となると大変な労力を要するような、言語(象徴界)に縛られている世界であり、なおかつわれわれが思っているものから成っている。この想像界も、 けっして現実界と一致することはない。 上記のように、現実界・象徴界・想像界が分かたれることから、ラカン流に人間世界を解明していくことが可能となるのである。 |

|

構造論的転回 ラカンは、ローマン・ヤコブソンやエミール・バンヴェニストらを通じて、フェ ルディナン・ド・ソシュールの構造主義言語学の影響を受けている。 ソシュールによれば、記号は、シニフィアン(SA)とシニフィエ(SE)の対からなる。ソシュールはそのことを  と表記した。ラカンはそれを上下逆にし、SA→S、SE→sと記号を変えて  と書く。上下を逆にしたのは、ラカンの「シニフィアンの優位」という 考え方に関係がある。ソシュールにとっても、シニフィアンの差異こそがシニフィエの差 異を生みだすのだから、その考え方においてはソシュールとラカンは共通している。しかし上が下を規定する、というニュアンスからラカンはこの分数表記を上 下逆にしている。 さらに、ラカンは、ヤコブソンの失語症研究より、失語症に見られる2つのタイプが、それぞれ隠喩と換喩という修辞表現の対立と並行関係がある、との示唆を 受ける。 |

|

| https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/ジャッ

ク・ラカン or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan |

|

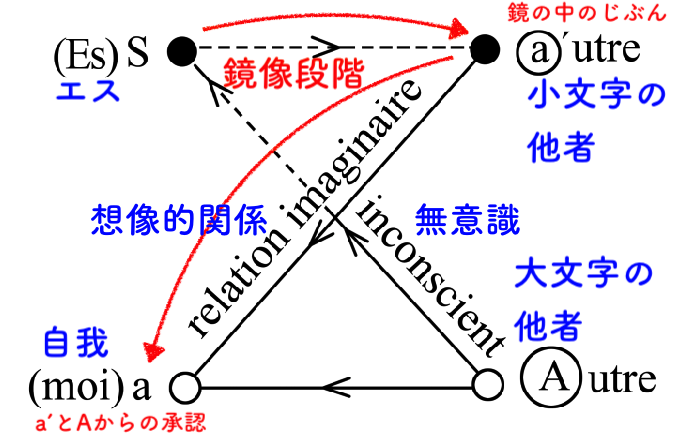

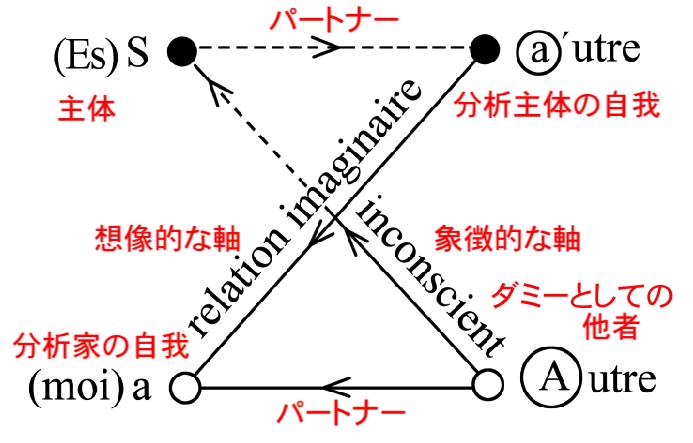

シェーマL(仏:schéma L)は主体S、他者A、他者a'、自我aからなる。 Sは主体(仏:sujet)を表すとともに、エス(独:Es )も表す。Aは他者を表す。 a'は他者を表す。aは自我を表す。Aとa'は異なるものである。 主体Sと他者Aを結ぶ軸を象徴的な軸という。他者a'と自我aを結ぶ軸を想像的な軸という。 |

|

| ラカン / ポール=ロラン・アスン著 ; 西尾彰泰訳, 東京 : 白水社 , 2013.3. - (文庫クセジュ ; 978) フ ロイトを読み解く背景から生まれた理論「シェーマ」や「グラフ」。その解説にこだわりすぎることなく、ラカンが立ち向かった問題とそのときの思考に重点が 置かれている。また、彼が取った行動を示すことで「ラカン思想」の変遷がわかる。日本ではまだ紹介されていない後期を含めた網羅的な入門書。 第1部 想像界、象徴界、現実界の基礎

|

|

| ラカンのセミネールの時期は3期あった 1)1951-1953, 1963年 ラカンは分析家だけに語る 2)1965-1968〜1969年まで ラカンはすべての人に語る 3)1970-1979年 ラカンは理解できる者、あるいは「大文字の他者」に向けて語る |

|

大文字の「〈他者〉。これは多くの形式を持つ。たとえば、あらゆるシ ニフイアンの宝庫あるいは貯蔵庫、〈母=他者〉語、要求としての〈他者〉、欲望としての〈他者〉、享楽としての〈他者〉、無意識、神」。 ・欲望は大文字の他者からやってくる。 |

|

| 【ジャック・ラカン:テーゼ集01】 |

|

| 無意識はランガージュのように構造化されている |

|

| 人間の欲望は他者の欲望である |

|

| 女は存在しない |

|

| 愛とは自分のもっていないものを与えることである |

|

| 私の贈るものを拒絶してくれ、なぜならそれではないのだから |

|

| das

Dingの場は、すべてのものが過ちから洗われるところであり、不在の場に存在を与える |

|

| メタランガージュは存在しない |

|

『エクリ』に登場する欲望のグラフのスキーマは「二階建て」構造をもつ (アスン 2013:145) 一階部分のs(A)とAを結ぶ線は、大文字の他者へのメッセージを示す。 土台にある、「斜線をひかれた主体=分割された主体」とI(A)=理想自我を結ぶ曲線は「ランガージュの主体化」を示す。 グラフの二階部分では、愛の要求との関係で分割された、右の部分と左の部分がつながっていて、左には「根源的幻想」すなわち、ファンタズムが1階の部分を 媒介している(アスン 2013:145-146)。 ●「エクリ」を読む : 文字に添って / ブルース・フィンク著 ; 上尾真道, 小倉拓也, 渋谷亮訳, 人文書院 , 2015年/Lacan to the letter : reading Écrits closely, Bruce Fink, University of Minnesota Press c2004. 第1章 「治療の指針」におけるラカンの精神分析技法 第2章 ラカンによる自我心理学三人衆の批判:ハルトマン、クリス、レーヴェンシュタイン 第3章 「無意識における文字の審級」を読む 第4章 「主体の転覆」を読む 第5章 ラカン的ファルスとルートマイナス1 第6章 テクストの外で—知と享楽:セミネール第20巻の注釈 |

|

【ジャック・ラカン:テーゼ集02】 |

|

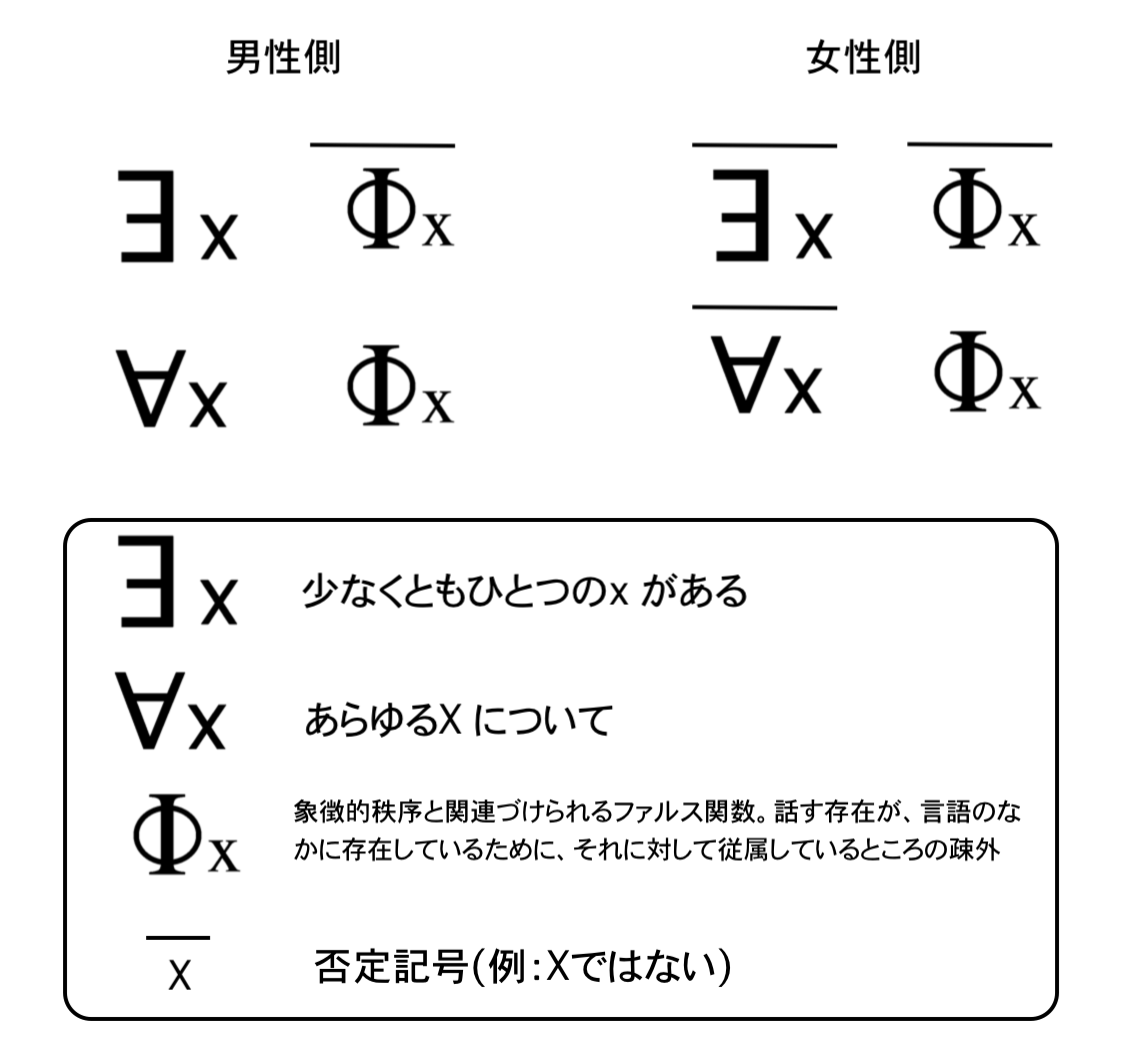

・性関係は不可能である/性関係は存在しない(アスン

2013:152) ・3つのテーゼ(アスン 2013:152-153) 1)性関係は存在しない 2)性関係について可能なエクリチュールは存在しない 3)性関係を補うのは、まさに愛である ・これらの関係において、少なくとも一人は、去勢を免れているものがいる→例外が規則をつくる ・女性は父殺しの罪を免れてるので、ファルスの機能に拘束されない。そのかわり、大文字の他者の享楽という「余分な」享楽に浴している(アスン 2013:154)。 ・ラカンによると「ファルスの優位性」がある ・精神分析において未解決なことは「女性がなにを欲しているのか」だ。 ・享楽の場所は、大文字の他者にある。 |

|

| ・性関係についての可能なエクリチュールは存在しない(セミネール

18, 1971年2月17日) |

|

| ・性関係を補うのはまさに愛である(セミネール20, 1973年1月

16日) |

|

| ・「リビドーは男性的である(フロイト)」 |

|

| ・「女性が何を欲しているのか(それが精神分析に未解決の問題だ)」

——これもフロイトの主張 |

|

| ・「フロイトは理解されていません。フロイト自身も理解していないで

しょう」(アスン 2013:156) |

|

| ・人は常に「出会い損ね」ている存在 | |

| ・モノ(das

Ding)はフロイトの『科学的心理学草稿』に登場する。ラカンによると、モノと母親は同一視することができる。 |

|

| ・自我は、想像以上に強い |

★「ジャック・ラカン」

でも、同じように解説しています。内容は、それぞれ酷似しています。

| Return to Freud Lacan's "return to Freud" emphasizes a renewed attention to the original texts of Freud, and included a radical critique of ego psychology, whereas "Lacan's quarrel with Object Relations psychoanalysis"[34]: 25 was a more muted affair. Here he attempted "to restore to the notion of the Object Relation... the capital of experience that legitimately belongs to it",[35] building upon what he termed "the hesitant, but controlled work of Melanie Klein... Through her we know the function of the imaginary primordial enclosure formed by the imago of the mother's body",[36] as well as upon "the notion of the transitional object, introduced by D. W. Winnicott... a key-point for the explanation of the genesis of fetishism".[37] Nevertheless, "Lacan systematically questioned those psychoanalytic developments from the 1930s to the 1970s, which were increasingly and almost exclusively focused on the child's early relations with the mother... the pre-Oedipal or Kleinian mother";[38] and Lacan's rereading of Freud—"characteristically, Lacan insists that his return to Freud supplies the only valid model"[39]—formed a basic conceptual starting-point in that oppositional strategy. Lacan thought that Freud's ideas of "slips of the tongue", jokes, and the interpretation of dreams all emphasized the agency of language in subjects' own constitution of themselves. In "The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason Since Freud," he proposes that "the psychoanalytic experience discovers in the unconscious the whole structure of language". The unconscious is not a primitive or archetypal part of the mind separate from the conscious, linguistic ego, he explained, but rather a formation as complex and structurally sophisticated as consciousness itself. Lacan is associated with the idea that "the unconscious is structured like a language", but the first time this sentence occurs in his work,[40] he clarifies that he means that both the unconscious and language are structured, not that they share a single structure; and that the structure of language is such that the subject cannot necessarily be equated with the speaker. This results in the self being denied any point of reference to which to be "restored" following trauma or a crisis of identity. André Green objected that "when you read Freud, it is obvious that this proposition doesn't work for a minute. Freud very clearly opposes the unconscious (which he says is constituted by thing-presentations and nothing else) to the pre-conscious. What is related to language can only belong to the pre-conscious".[34]: 5n Freud certainly contrasted "the presentation of the word and the presentation of the thing... the unconscious presentation is the presentation of the thing alone"[41] in his metapsychology. Dylan Evans, however, in his Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, "... takes issue with those who, like André Green, question the linguistic aspect of the unconscious, emphasizing Lacan's distinction between das Ding and die Sache in Freud's account of thing-presentation".[34]: 8n Green's criticism of Lacan also included accusations of intellectual dishonesty, he said, "[He] cheated everybody... the return to Freud was an excuse, it just meant going to Lacan."[42] |

フロイトへの回帰 ラカンの「フロイトへの回帰」は、フロイトの原典への新たな注意を強調し、自我心理学の根本的な批判を含んでいたが、「オブジェクト関係精神分析に対する ラカンの論争」[34] : 25は、 より控えめな出来事であった。ここで彼は、「オブジェクト関係の概念を復元しようとしました...合法的にそれに属する経験の資本」[35]と 彼が呼んだ「躊躇しながらも制御されたメラニー・クラインの作品...彼女を通して」を構築しました。私たちは、母体の成虫に よって形成される想像上の原 始的な囲いの機能を知っています。」 [36]だけでなく、、 DW ウィニコットによって紹介された...フェティシズムの起源を説明するための重要なポイント」。[37]それにもかかわらず、「ラカンは、1930 年代から 1970 年代にかけての精神分析の発展に体系的に疑問を呈しました。子供の初期の母親との関係...エディプス以前またはクライン派の母親」[38]お よびラカン のフロイトの再読 - 「特徴的に、ラカンはフロイトへの回帰が唯一の有効なモデルを提供すると主張している」[39] - 基本的な概念を形成したその反対戦略の概念的な出発点。 ラカンは、フロイトの「失言」、冗談、夢の解釈などの考えはすべて、被験者自身の構成における言語の主体性を強調していると考えた。『無意識における手紙 の事例、あるいはフロイト以来の理性』の中で、彼は「精神分析的経験は無意識の中に言語の構造全体を発見する」と提案している。無意識は、意識的で言語的 な自我から切り離された原始的または原型的な心の部分ではなく、むしろ意識そのものと同じくらい複雑で構造的に洗練された形成物である、と彼は説明した。 ラカンは「無意識は言語のように構造化されている」という考えと関連付けられていますが、この文が彼の作品で初めて出てくるのは、[40]彼は、無意識と 言語の両方が構造化されているということを意味しており、それらが単一の構造を共有しているということではないことを明確にしています。そして、言語の構 造は主語と話者を必ずしも同一視できないものであるということ。その結果、トラウマやアイデンティティの危機の後に「回復」すべき参照点が自己に否定され ることになる。 アンドレ・グリーンは、「フロイトを読めば、この命題が一瞬でも成り立たないことは明らかだ。フロイトは、無意識(彼によれば、無意識は物表現だけで構成 されており、それ以外は何もない)が前意識に対して非常に明確に反対している。」と反論した。言語に関係するものは前意識にのみ属することができる。」 [34] : 5n フロイトは確かに、彼のメタ心理学において「言葉の提示と物の提示…無意識の提示は物だけの提示である」[41]と対比した。しかし、ディラン・エ ヴァンスは、ラカン精神分析辞典の中で次のように述べています。「…アンドレ・グリーンのように、無意識の言語的側面に疑問を呈する人々を問題視し、フロ イトの物提示に関する記述におけるラカンのdas Dingとdie Sacheの区別を強調している。」[34] : 8n グリーンのラカン批判には知的不正の告発も含まれており、彼は「[彼は]皆を騙した…フロイトへの回帰は言い訳であり、それは単にラカンへ行くこと を意味するだけだった。」と述べた。[42] |

| Mirror stage Lacan's first official contribution to psychoanalysis was the mirror stage, which he described as "formative of the function of the 'I' as revealed in psychoanalytic experience." By the early 1950s, he came to regard the mirror stage as more than a moment in the life of the infant; instead, it formed part of the permanent structure of subjectivity. In the "imaginary order", the subject's own image permanently catches and captivates the subject. Lacan explains that "the mirror stage is a phenomenon to which I assign a twofold value. In the first place, it has historical value as it marks a decisive turning-point in the mental development of the child. In the second place, it typifies an essential libidinal relationship with the body-image".[43] As this concept developed further, the stress fell less on its historical value and more on its structural value.[44] In his fourth seminar, "La relation d'objet", Lacan states that "the mirror stage is far from a mere phenomenon which occurs in the development of the child. It illustrates the conflictual nature of the dual relationship. " The mirror stage describes the formation of the ego via the process of objectification, the ego being the result of a conflict between one's perceived visual appearance and one's emotional experience. This identification is what Lacan called "alienation". At six months, the baby still lacks physical co-ordination. The child is able to recognize itself in a mirror prior to the attainment of control over their bodily movements. The child sees its image as a whole and the synthesis of this image produces a sense of contrast with the lack of co-ordination of the body, which is perceived as a fragmented body. The child experiences this contrast initially as a rivalry with its image, because the wholeness of the image threatens the child with fragmentation—thus the mirror stage gives rise to an aggressive tension between the subject and the image. To resolve this aggressive tension, the child identifies with the image: this primary identification with the counterpart forms the ego.[44] Lacan understood this moment of identification as a moment of jubilation, since it leads to an imaginary sense of mastery; yet when the child compares its own precarious sense of mastery with the omnipotence of the mother, a depressive reaction may accompany the jubilation.[45] Lacan calls the specular image "orthopaedic", since it leads the child to anticipate the overcoming of its "real specific prematurity of birth". The vision of the body as integrated and contained, in opposition to the child's actual experience of motor incapacity and the sense of his or her body as fragmented, induces a movement from "insufficiency to anticipation".[46] In other words, the mirror image initiates and then aids, like a crutch, the process of the formation of an integrated sense of self. In the mirror stage a "misunderstanding" (méconnaissance) constitutes the ego—the "me" (moi) becomes alienated from itself through the introduction of an imaginary dimension to the subject. The mirror stage also has a significant symbolic dimension, due to the presence of the figure of the adult who carries the infant. Having jubilantly assumed the image as their own, the child turns their head towards this adult, who represents the big other, as if to call on the adult to ratify this image.[47] |

鏡の段階 ラカンの精神分析への最初の公式な貢献は鏡像段階であり、彼はそれを「精神分析的経験において明らかにされる『私』の機能の形成的なもの」と説明した。 1950年代初頭までに、彼は鏡段階を幼児の一生における一時的なものにとどまらず、主観性の永続的な構造の一部をなすものと考えるようになった。想像の 秩序」においては、主体自身のイメージが主体を永続的にとらえ、魅了する。ラカンは「鏡の段階は、私が二重の価値を与える現象である」と説明する。第一 に、子どもの精神発達における決定的な転換点を示すものとして、歴史的価値がある。第二に、それは身体イメージとの本質的なリビドー的関係を象徴してい る」[43]。 この概念がさらに発展するにつれて、その歴史的価値よりもその構造的価値の方が強調されるようになった[44]。ラカンは彼の第4のセミナーである "La relation d'objet "の中で、「鏡の段階は子どもの発達の中で起こる単なる現象からはかけ離れている。鏡の段階は、二重関係の対立的性質を示している」と述べている。" 鏡の段階は、対象化の過程を経た自我の形成について述べており、自我とは、知覚された視覚的外見と感情的経験との間の葛藤の結果である。この同一化は、ラ カンが「疎外」と呼んだものである。生後6ヶ月の赤ちゃんは、まだ身体的な協調性に欠けている。身体の動きをコントロールできるようになる前に、子供は鏡 の中の自分を認識することができる。子どもは自分のイメージを全体として見ており、このイメージの統合によって、断片的な身体として知覚される身体の協調 性の欠如との対比の感覚が生まれる。なぜなら、イメージの全体性が子どもを断片化で脅かすからである。このように鏡の段階は、主体とイメージの間に攻撃的 な緊張を生じさせる。この攻撃的な緊張を解決するために、子どもはイメージと同一化する。この第一次的な相手との同一化は自我を形成する[44]。ラカン はこの同一化の瞬間を、それが想像上の支配者意識につながるので、歓喜の瞬間として理解した。 ラカンは鏡像のことを「整形外科的」と呼ぶが、それは「誕生という現実的な未熟さ」の克服を予期するように子どもを導くからである。統合され、内包された 身体としての身体像は、運動能力の欠如という子どもの実際の経験や、断片化された身体としての感覚と対立し、「不全から予期へ」の動きを誘発する [46]。言い換えれば、鏡像が、統合された自己の感覚の形成のプロセスを、松葉杖のように開始し、そして援助する。 鏡の段階では「誤解」(méconnaissance)が自我を構成し、「私」(moi)は主体に想像的な次元を導入することによって、それ自体から疎外 される。鏡の段階はまた、幼児を抱く大人の姿の存在によって、重要な象徴的側面を持っている。歓喜してそのイメージを自分のものとして引き受けた子ども は、このイメージを批准するように大人に呼びかけるかのように、大きな他者を象徴するこの大人の方に顔を向ける[47]。 |

| Other While Freud uses the term "other", referring to der Andere (the other person) and das Andere (otherness), Lacan (influenced by the seminar of Alexandre Kojève) theorizes alterity in a manner more closely resembling Hegel's philosophy. Lacan often used an algebraic symbology for his concepts: the big other (l'Autre) is designated A, and the little other (l'autre) is designated a.[48] He asserts that an awareness of this distinction is fundamental to analytic practice: "the analyst must be imbued with the difference between A and a, so he can situate himself in the place of Other, and not the other".[44]: 135 Dylan Evans explains that: The little other is the other who is not really other, but a reflection and projection of the ego. Evans adds that for this reason the symbol a can represent both the little other and the ego in the schema L.[49] It is simultaneously the counterpart and the specular image. The little other is thus entirely inscribed in the imaginary order. The big other designates radical alterity, an other-ness which transcends the illusory otherness of the imaginary because it cannot be assimilated through identification. Lacan equates this radical alterity with language and the law, and hence the big other is inscribed in the order of the symbolic. Indeed, the big other is the symbolic insofar as it is particularized for each subject. The other is thus both another subject, in its radical alterity and unassimilable uniqueness, and also the symbolic order which mediates the relationship with that other subject."[50] For Lacan "the Other must first of all be considered a locus in which speech is constituted," so that the other as another subject is secondary to the other as symbolic order.[51] We can speak of the other as a subject in a secondary sense only when a subject occupies this position and thereby embodies the other for another subject.[52] In arguing that speech originates in neither the ego nor in the subject but rather in the other, Lacan stresses that speech and language are beyond the subject's conscious control. They come from another place, outside of consciousness—"the unconscious is the discourse of the Other".[53] When conceiving the other as a place, Lacan refers to Freud's concept of psychical locality, in which the unconscious is described as "the other scene". "It is the mother who first occupies the position of the big Other for the child", Dylan Evans explains, "it is she who receives the child's primitive cries and retroactively sanctions them as a particular message".[44] The castration complex is formed when the child discovers that this other is not complete because there is a "lack (manque)" in the other. This means that there is always a signifier missing from the trove of signifiers constituted by the other. Lacan illustrates this incomplete other graphically by striking a bar through the symbol A; hence another name for the castrated, incomplete other is the "barred other".[54] |

他者 フロイトが「他者」という用語を使い、der Andere(他者)やdas Andere(他者性)に言及しているのに対して、ラカンは(アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのセミナーの影響を受け)ヘーゲル哲学により近い方法で分身を理 論化している。 大きな他者(l'Autre)はAと命名され、小さな他者(l'autre)はaと命名される: 「分析者はAとaの違いに染まらなければならず、そうすれば他者ではなく他者の場所に自らを位置づけることができる」[44]: 135 ディラン・エヴァンスは次のように説明している: 小さな他者とは、本当の他者ではなく、自我の反映であり投影である他者である。このため、記号aはスキーマLにおいて、小さな他者と自我の両方を表すこと ができる[49]。このように、小さな他者は完全に想像上の秩序に刻み込まれている。 大きな他者は急進的な分身を意味し、同一化によって同化することができないために、想像上の幻想的な他者性を超越する他者性である。ラカンはこの急進的な 変質を言語や法と同一視しており、それゆえ大きな他者は象徴の秩序に刻み込まれている。実際、大きな他者は、それがそれぞれの主体にとって特殊化されてい る限りにおいて象徴的である。したがって他者とは、その根本的な変質性と同化不可能な独自性において、別の主体であると同時に、その別の主体との関係を媒 介する象徴的秩序でもある」[50]。 ラカンにとって「他者はまず第一に、発話が構成される場所と見なされなければならない」ので、別の主体としての他者は象徴秩序としての他者にとって二次的 なものである[51]。 ある主体がこの位置を占め、それによって別の主体にとっての他者を体現するときにのみ、二次的な意味での主体としての他者を語ることができる[52]。 発話は自我でも主体でもなく、むしろ他者に由来すると主張する中で、ラカンは発話と言語は主体の意識的な制御を超えたところにあると強調している。無意識 は他者の言説である」[53]。他者を場所として考えるとき、ラカンはフロイトの精神的局所性の概念を参照し、そこでは無意識が「もうひとつの場面」とし て記述されている。 「子どもの原始的な叫びを受け取り、それを特定のメッセージとして遡及的に承認するのは母親である」とディラン・エヴァンスは説明する。つまり、他者に よって構成されるシニフィエの宝庫から常にシニフィエが欠落しているということである。ラカンはこの不完全な他者を、記号Aを貫く棒を打つことによって図 式化している。それゆえ、去勢された不完全な他者を表す別の名前は、" |

| Phallus Feminist thinkers have both utilised and criticised Lacan's concepts of castration and the phallus. Feminists such as Avital Ronell, Jane Gallop,[55] and Elizabeth Grosz,[56] have interpreted Lacan's work as opening up new possibilities for feminist theory. Some feminists have argued that Lacan's phallocentric analysis provides a useful means of understanding gender biases and imposed roles, while others, most notably Luce Irigaray, accuse Lacan of maintaining the sexist tradition in psychoanalysis.[57] For Irigaray, the phallus does not define a single axis of gender by its presence or absence; instead, gender has two positive poles. Like Irigaray, French philosopher Jacques Derrida, in criticizing Lacan's concept of castration, discusses the phallus in a chiasmus with the hymen, as both one and other.[58][59] |

ファルス(もともと男根の意味だがファルスは記号としての意味が強い) フェミニスト思想家は、ラカンの去勢とファルスの概念を利用し、批判してきました。アヴィタル・ロネル、ジェーン・ギャロップ、[55]、エリザベス・グ ロス、[56]などのフェミニストは、ラカンの研究をフェミニスト理論の新たな可能性を開くものとして解釈している。 一部のフェミニストは、ラカンのファルス中心的分析がジェンダーバイアスと押し付けられた役割を理解するのに有用な手段を提供すると主張しているが、他の フェ ミニスト、特にリュス・イリガライは精神分析における性差別の伝統を維持しているとしてラカンを非難している。[57]イリガライにとって、ファルスは その 有無によってジェンダーの単一の軸を定義するものではない。その代わり、ジェンダーには 2 つの正の極があります。イリガライと同様、フランスの哲学者ジャック・デリダは、ラカンの去勢概念を批判する際に、処女膜と交差する状態にあるファルスを 一体のもの として、またもう一方として議論している。[58] [59] |

| Three orders (plus one) Lacan considered psychic functions to occur within a universal matrix. The Real, Imaginary and Symbolic are properties of this matrix, which make up part of every psychic function. This is not analogous to Freud's concept of id, ego and superego since in Freud's model certain functions takes place within components of the psyche while Lacan thought that all three orders were part of every function. Lacan refined the concept of the orders over decades, resulting in inconsistencies in his writings. He eventually added a fourth component, the sinthome.[60]: 77 |

3つの秩序 ラカンは、精神的な機能は普遍的なマトリックス内で発生すると考えました。現実、想像、象徴はこのマトリックスの特性であり、あらゆる精神的機能の一部を 構成します。これは、フロイトのイド、自我、超自我の概念と類似していません。フロイトのモデルでは特定の機能が精神の構成要素内で発生するのに対し、ラ カンは 3 つの秩序すべてがあらゆる機能の一部であると考えていたからです。ラカンは何十年にもわたってオーダーの概念を洗練させましたが、その結果、彼の著作には 矛盾が生じました。彼は最終的に 4 番目のコンポーネントであるシントホームを追加しました。[60] :77 |

| The Imaginary The Imaginary is the field of images and imagination. The main illusions of this order are synthesis, autonomy, duality, and resemblance. Lacan thought that the relationship created within the mirror stage between the ego and the reflected image means that the ego and the Imaginary order itself are places of radical alienation: "alienation is constitutive of the Imaginary order".[61] This relationship is also narcissistic. In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan argues that the Symbolic order structures the visual field of the Imaginary, which means that it involves a linguistic dimension. If the signifier is the foundation of the symbolic, the signified and signification are part of the Imaginary order. Language has symbolic and Imaginary connotations—in its Imaginary aspect, language is the "wall of language" that inverts and distorts the discourse of the Other. The Imaginary, however, is rooted in the subject's relationship with his or her own body (the image of the body). In Fetishism: the Symbolic, the Imaginary and the Real, Lacan argues that in the sexual plane the Imaginary appears as sexual display and courtship love. Insofar as identification with the analyst is the objective of analysis, Lacan accused major psychoanalytic schools of reducing the practice of psychoanalysis to the Imaginary order.[62] Instead, Lacan proposes the use of the symbolic to dislodge the disabling fixations of the Imaginary—the analyst transforms the images into words. "The use of the Symbolic", he argued, "is the only way for the analytic process to cross the plane of identification."[63] |

想

像界 想 像界とはイメージと想像力の分野である。この秩序の主な幻想は、統合、自律性、二元性、類似性である。ラカンは、自我と反射されたイメージの間に鏡の段階 で作られる関係は、自我と想像界秩序そのものが根本的な疎外の場であることを意味すると考えた: 「疎外は想像界の秩序を構成するものである」[61]。 精神分析の4つの基本概念』の中でラカンは、象徴秩序が想像界の視覚的場を構造化していると論じている。シニフィエが象徴の基礎であるならば、シニフィエ とシニフィケーションは想像界の秩序の一部である。言語には象徴的な意味合いと想像界的な意味合いがあり、想像界的な側面では、言語は他者の言説を反転さ せ、歪曲させる「言語の壁」である。しかし、想像界は、主体が自らの身体(のイメージ)との関係に根ざしている。ラカンは『フェティシズム:象徴界、想像 界、現実界』の中で、性的な平面においてイマジナリーは性的なディスプレイや求愛として現れると論じている。 分析者との同一化が分析の目的である限り、ラカンは主要な精神分析学派が精神分析の実践を想像界の秩序に還元していると非難している。「象徴の使用」は 「分析過程が同一化の平面を越える唯一の方法である」と彼は主張した[63]。 |

| The Symbolic In his Seminar IV, "La relation d'objet", Lacan argues that the concepts of "Law" and "Structure" are unthinkable without language—thus the Symbolic is a linguistic dimension. This order is not equivalent to language, however, since language involves the Imaginary and the Real as well. The dimension proper to language in the Symbolic is that of the signifier—that is, a dimension in which elements have no positive existence, but which are constituted by virtue of their mutual differences. The Symbolic is also the field of radical alterity—that is, the Other; the unconscious is the discourse of this Other. It is the realm of the Law that regulates desire in the Oedipus complex. The Symbolic is the domain of culture as opposed to the Imaginary order of nature. As important elements in the Symbolic, the concepts of death and lack (manque) connive to make of the pleasure principle the regulator of the distance from the Thing (in German, "das Ding an sich") and the death drive that goes "beyond the pleasure principle by means of repetition"—"the death drive is only a mask of the Symbolic order".[48] By working in the Symbolic order, the analyst is able to produce changes in the subjective position of the person undergoing psychoanalysis. These changes will produce imaginary effects because the Imaginary is structured by the Symbolic.[44] |

象徴界 ラ カンはセミナーIV「オブジェの関係」の中で、「法則」と「構造」という概念は言語なしには考えられない、つまり象徴界とは言語的次元であると論じてい る。しかし、この秩序は言語と等価ではない。言語には想像界や現実界も含まれるからだ。象徴における言語にふさわしい次元とは、シニフィエの次元である。 つまり、要素は積極的な存在を持たないが、相互の差異によって構成される次元である。 象徴界はまた、根本的な変質の場、すなわち他者であり、無意識はこの他者の言説である。それはエディプス・コンプレックスにおける 欲望を規制する法の領域である。象徴界とは、自然の想像的秩序とは対照的な文化の領域である。シンボリックの重要な要素として、死と欠落(manque) の概念は、快楽原理を事物からの距離(ドイツ語では「das Ding an sich」)の調整装置とし、「反復によって快楽原理を超える」死の衝動--「死の衝動はシンボリック秩序の仮面にすぎない」--となるように企図してい る[48]。 象徴的秩序に働きかけることによって、分析者は精神分析を受けている人の主観的立場に変化をもたらすことができる。想像界は象徴界によって構造化されてい るため、こうした変化はイマジナリーな効果を生み出すことになる[44]。 |

| The Real Lacan's concept of the Real dates back to 1936 and his doctoral thesis on psychosis. It was a term that was popular at the time, particularly with Émile Meyerson, who referred to it as "an ontological absolute, a true being-in-itself".[44]: 162 Lacan returned to the theme of the Real in 1953 and continued to develop it until his death. The Real, for Lacan, is not synonymous with reality. Not only opposed to the Imaginary, the Real is also exterior to the Symbolic. Unlike the latter, which is constituted in terms of oppositions (i.e. presence/absence), "there is no absence in the Real".[48] Whereas the Symbolic opposition "presence/absence" implies the possibility that something may be missing from the Symbolic, "the Real is always in its place".[63] If the Symbolic is a set of differentiated elements (signifiers), the Real in itself is undifferentiated—it bears no fissure. The Symbolic introduces "a cut in the real" in the process of signification: "it is the world of words that creates the world of things—things originally confused in the 'here and now' of the all in the process of coming into being".[64] The Real is that which is outside language and that resists symbolization absolutely. In Seminar XI Lacan defines the Real as "the impossible" because it is impossible to imagine, impossible to integrate into the Symbolic, and impossible to attain. It is this resistance to symbolization that lends the Real its traumatic quality. Finally, the Real is the object of anxiety, insofar as it lacks any possible mediation and is "the essential object which is not an object any longer, but this something faced with which all words cease and all categories fail, the object of anxiety par excellence."[48] |

現実界 ラ カンの現実界の概念は1936年、精神病に関する博士論文にまで遡る。それは当時流行していた用語であり、特にエミール・メイヤソンはそれを「存在論的な 絶対的存在、真なる存在-in-itself」と呼んでいた[44]: 162 ラカンは1953年に現実界のテーマに戻り、亡くなるまでそれを発展させ続けた。ラカンにとっての現実界は現実と同義ではない。想像界と対立するだけでな く、現実界はシンボリックの外部でもある。シンボリックの「存在/不在」という対立が、シンボリックから何かが欠落している可能性を示唆しているのに対し て、「現実界は常にその場所にある」[63]。記号は記号化の過程において「現実における切れ目」を導入する: それは、ものの世界を創造する言葉の世界であり、それは元来、すべてのものが誕生する過程の「今、ここ」で混同されていたものである」[64]。実在と は、言語の外側にあり、象徴化に絶対的に抵抗するものである。ラカンは『セミナーXI』において、現実界を「不可能なもの」と定義しているが、それは想像 することが不可能であり、象徴に統合することが不可能であり、到達することが不可能だからである。この象徴化への抵抗こそが、現実界にトラウマ的な質を与 えているのである。最後に、現実界は、それがいかなる可能な媒介をも欠いており、「もはや対象ではない本質的な対象であるが、すべての言葉が停止し、すべ てのカテゴリーが失敗するこの何かに直面している、卓越した不安の対象」である限りにおいて、不安の対象である[48]。 |

| Sinthome The term "sinthome" (French: [sɛ̃tom]) was introduced by Jacques Lacan in his seminar Le sinthome (1975–76). According to Lacan, sinthome is the Latin way (1495 Rabelais, IV,63[65]) of spelling the Greek origin of the French word symptôme, meaning symptom. The seminar is a continuing elaboration of his topology, extending the previous seminar's focus (RSI) on the Borromean Knot and an exploration of the writings of James Joyce. Lacan redefines the psychoanalytic symptom in terms of his topology of the subject. In "Psychoanalysis and its Teachings" (Écrits) Lacan views the symptom as inscribed in a writing process, not as ciphered message which was the traditional notion. In his seminar "L'angoisse" (1962–63) he states that the symptom does not call for interpretation: in itself it is not a call to the Other but a pure jouissance addressed to no-one. This is a shift from the linguistic definition of the symptom—as a signifier—to his assertion that "the symptom can only be defined as the way in which each subject enjoys (jouit) the unconscious in so far as the unconscious determines the subject". He goes from conceiving the symptom as a message which can be deciphered by reference to the unconscious structured like a language to seeing it as the trace of the particular modality of the subject's jouissance. |

シントーム 「サントメ」(フランス語: [sɛ̃tom] )という用語は、ジャック・ラカンのセミナーLe sinthome (1975–76)で導入されました。ラカンによれば、sinthome は、症状を意味するフランス語のsymptômeのギリシャ語起源の綴りをラテン語で綴ったもの (1495 Rabelais, IV,63 [65] ) です。このセミナーは彼のトポロジーの継続的な精緻化であり、ボロメアンノットとジェイムズ・ジョイスの著作の探求に関する前回のセミナーの焦点( RSI )を拡張します。ラカンは、精神分析の症状を主題のトポロジーの観点から再定義します。 『精神分析とその教え』 ( Écrits ) の中で、ラカンは症状を伝統的な概念である暗号化されたメッセージとしてではなく、執筆プロセスに刻まれたものとして見ています。彼のセミナー「ランゴ ワース」(1962-63)の中で、彼は、この症状は解釈を必要としない、それ自体が他者への呼びかけではなく、誰にも向けられた純粋な喜びであると述べ ています。これは、症状の言語学的定義(記号表現として)から、「症状は各主体が楽しむ方法としてのみ定義できる」という彼の主張への移行です。)無意識 が主体を決定する限り、無意識は無意識である。」 彼は、言語のように構造化された無意識を参照することによって解読できるメッセージとして症状を考えることから、それを主体の喜びの特定の様式の痕跡とし て見ることに移行した。。 |

| Desire Lacan's concept of desire is related to Hegel's Begierde, a term that implies a continuous force, and therefore somehow differs from Freud's concept of Wunsch.[66] Lacan's desire refers always to unconscious desire because it is unconscious desire that forms the central concern of psychoanalysis. The aim of psychoanalysis is to lead the analysand to recognize his/her desire and by doing so to uncover the truth about his/her desire. However this is possible only if desire is articulated in speech:[67] "It is only once it is formulated, named in the presence of the other, that desire appears in the full sense of the term."[68] And again in The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: "what is important is to teach the subject to name, to articulate, to bring desire into existence. The subject should come to recognize and to name her/his desire. But it isn't a question of recognizing something that could be entirely given. In naming it, the subject creates, brings forth, a new presence in the world."[69] The truth about desire is somehow present in discourse, although discourse is never able to articulate the entire truth about desire; whenever discourse attempts to articulate desire, there is always a leftover or surplus.[70] Lacan distinguishes desire from need and from demand. Need is a biological instinct where the subject depends on the Other to satisfy its own needs: in order to get the Other's help, "need" must be articulated in "demand". But the presence of the Other not only ensures the satisfaction of the "need", it also represents the Other's love. Consequently, "demand" acquires a double function: on the one hand, it articulates "need", and on the other, acts as a "demand for love". Even after the "need" articulated in demand is satisfied, the "demand for love" remains unsatisfied since the Other cannot provide the unconditional love that the subject seeks. "Desire is neither the appetite for satisfaction, nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second."[71] Desire is a surplus, a leftover, produced by the articulation of need in demand: "desire begins to take shape in the margin in which demand becomes separated from need".[71] Unlike need, which can be satisfied, desire can never be satisfied: it is constant in its pressure and eternal. The attainment of desire does not consist in being fulfilled but in its reproduction as such. As Slavoj Žižek puts it, "desire's raison d'être is not to realize its goal, to find full satisfaction, but to reproduce itself as desire".[72] Lacan also distinguishes between desire and the drives: desire is one and drives are many. The drives are the partial manifestations of a single force called desire.[73] Lacan's concept of "objet petit a" is the object of desire, although this object is not that towards which desire tends, but rather the cause of desire. Desire is not a relation to an object but a relation to a lack (manque). In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis Lacan argues that "man's desire is the desire of the Other." This entails the following: 1. Desire is the desire of the Other's desire, meaning that desire is the object of another's desire and that desire is also desire for recognition. Here Lacan follows Alexandre Kojève, who follows Hegel: for Kojève the subject must risk his own life if he wants to achieve the desired prestige.[74] This desire to be the object of another's desire is best exemplified in the Oedipus complex, when the subject desires to be the phallus of the mother. 2. In "The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious",[75] Lacan contends that the subject desires from the point of view of another whereby the object of someone's desire is an object desired by another one: what makes the object desirable is that it is precisely desired by someone else. Again Lacan follows Kojève. who follows Hegel. This aspect of desire is present in hysteria, for the hysteric is someone who converts another's desire into his/her own (see Sigmund Freud's "Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria" in SE VII, where Dora desires Frau K because she identifies with Herr K). What matters then in the analysis of a hysteric is not to find out the object of her desire but to discover the subject with whom she identifies. 3. Désir de l'Autre, which is translated as "desire for the Other" (though it could also be "desire of the Other"). The fundamental desire is the incestuous desire for the mother, the primordial Other.[76] 4. Desire is "the desire for something else", since it is impossible to desire what one already has. The object of desire is continually deferred, which is why desire is a metonymy.[77] 5. Desire appears in the field of the Other—that is, in the unconscious. Last but not least for Lacan, the first person who occupies the place of the Other is the mother and at first the child is at her mercy. Only when the father articulates desire with the Law by castrating the mother is the subject liberated from desire for the mother.[78] |

欲望 ラカンの欲望の概念は、継続的な力を意味するヘーゲルのBegierdeという用語に関連しているため、フロイトのWunschの概念とは何らかの形で異 なります。[66]ラカンの欲望は、精神分析の中心的な関心を形成するのは無意識の欲望であるため、常に無意識の欲望を指します。 精神分析の目的は、分析者が自分の欲望を認識できるように導き、そうすることで自分の欲望についての真実を明らかにすることです。しかし、これは欲望が音 声で明確に表現されている場合にのみ可能です。[67]「欲望が言葉の完全な意味で現れるのは、他者の存在下でそれが定式化され、名前が付けられて初めて です。」[68]そして再びフロイトの理論と精神分析の技術における自我の中でこう述べています:「重要なことは、対象に名前を付け、明確に表現し、欲望 を存在させるように教えることです。対象は自分を認識し、名前を付けるようになるべきです/ 「しかし、それは完全に与えられるものを認識するという問題ではありません。それに名前を付けることで、主題は世界に新しい存在を作成し、生み出しま す。」[69]欲望についての真実は、何らかの形で談話の中に存在しますが、談話は欲望についての真実全体を明確に表現することはできません。言説が欲望 を明確に表現しようとするときは常に、残り物または余剰が存在します。[70] ラカンは欲望と必要性、および需要を区別します。欲求は生物の本能ですここで、主体は自分自身のニーズを満たすために他者に依存します。他者の助けを得る ために、「ニーズ」は「要求」として明確に表現されなければなりません。しかし、他者の存在は「欲求」の充足を確実にするだけでなく、他者の愛も表しま す。その結果、「要求」は二重の機能を獲得します。一方では「必要性」を明確にし、他方では「愛の要求」として機能します。要求で明示された「必要性」が 満たされた後でも、主体が求める無条件の愛を他者は提供できないため、「愛の要求」は満たされないままである。「欲望とは、満足を求める欲求でも、愛を求 める欲求でもなく、二番目から最初のものを引いた結果生じる差異である。」[71]欲望は、需要と需要の明確化によって生み出される余剰、残り物です。 「欲望は、需要が必要から分離される余白で形を作り始めます」。[71]満たされる必要性とは異なり、欲望は決して満たされることがありません。その圧力 は常にあり、永遠です。欲望の達成は、満たされることではなく、欲望そのものが再現されることにあります。スラヴォイ・ジジェクが言うように、「欲望の存 在意義は、その目標を実現することではなく、完全な満足を見つけることではなく、欲望としてそれ自体を再生産することである」。[72] ラカンはまた、欲望と衝動を区別しています。欲望は 1 つであり、衝動は多数です。衝動は欲望と呼ばれる単一の力の部分的な現れです。[73]ラカンの「 objet petit a 」という概念は欲望の対象ですが、この対象は欲望が向かう対象ではなく、むしろ欲望の原因です。欲望は対象との関係ではなく、欠乏(マンク)との関係で す。 ラカンは『精神分析の4つの基本概念』の中で、「人間の欲望は他者の欲望である」と主張している。これには次のことが伴います。 欲望は他者の欲望の欲望であり、欲望は他者の欲望の対象であり、その欲望は承認欲求でもあるということです。ここでラカンは、ヘーゲルに従うアレクサンド ル・コジェーヴに続きます。コジェーヴにとって、望ましい名声を達成したいなら、主体は自らの命を危険にさらさなければなりません。[74]他人の欲望の 対象になりたいという欲望は、主体が母親の男根になりたいというエディプス・コンプレックスで最もよく例証される。 「フロイト的無意識における主体の転覆と欲望の弁証法」[75]の中で、ラカンは、主体は他者の観点から欲望する、つまり誰かの欲望の対象は別の人が望む 対象である、と主張している。望ましい対象とは、それがまさに他の誰かによって望まれているということです。再びラカンはコジェーヴに従います。ヘーゲル に従う人。欲望のこの側面はヒステリーにも存在します。ヒステリーとは、他人の欲望を自分の欲望に変換する人のことです(SE VIIのジークムント・フロイトの「ヒステリー症例の分析の断片」を参照してください。ドーラがフラウKを望んでいるのは、彼女が自分を特定しているため です) K 氏と)。したがって、ヒステリーの分析において重要なことは、彼女の欲望の対象を見つけることではなく、彼女が同一視する対象を発見することである。 Désir de l'Autre、これは「他者への欲望」と訳されます(ただし、「他者の欲望」という場合もあります)。根本的な欲望は、根源的な他者である母親に対する 近親相姦的な欲望です。[76] 欲望とは、すでに持っているものを望むことは不可能であるため、「何か他のものへの欲望」です。欲望の対象は継続的に先送りされ、それが欲望が換喩である 理由です。[77] 欲望は他者の領域、つまり無意識の中に現れます。 最後に重要なことですが、ラカンにとって、他者の位置を占める最初の人物は母親であり、最初は子供は母親の言いなりになります。父親が母親を去勢すること によって律法によって欲望を明確にした場合にのみ、主体は母親に対する欲望から解放されます。[78] |

| Drive Lacan maintains Freud's distinction between drive (Trieb) and instinct (Instinkt). Drives differ from biological needs because they can never be satisfied and do not aim at an object but rather circle perpetually around it. He argues that the purpose of the drive (Triebziel) is not to reach a goal but to follow its aim, meaning "the way itself" instead of "the final destination"—that is, to circle around the object. The purpose of the drive is to return to its circular path and the true source of jouissance is the repetitive movement of this closed circuit.[79] Lacan posits drives as both cultural and symbolic constructs: to him, "the drive is not a given, something archaic, primordial".[79] He incorporates the four elements of drives as defined by Freud (pressure, end, object and source) to his theory of the drive's circuit: the drive originates in the erogenous zone, circles round the object, and returns to the erogenous zone. Three grammatical voices structure this circuit: the active voice (to see) the reflexive voice (to see oneself) the passive voice (to be seen) The active and reflexive voices are autoerotic—they lack a subject. It is only when the drive completes its circuit with the passive voice that a new subject appears, implying that, prior to that instance, there was no subject.[79] Despite being the "passive" voice, the drive is essentially active: "to make oneself be seen" rather than "to be seen". The circuit of the drive is the only way for the subject to transgress the pleasure principle. To Freud sexuality is composed of partial drives (i.e. the oral or the anal drives) each specified by a different erotogenic zone. At first these partial drives function independently (i.e. the polymorphous perversity of children), it is only in puberty that they become organized under the aegis of the genital organs.[80] Lacan accepts the partial nature of drives, but (1) he rejects the notion that partial drives can ever attain any complete organization—the primacy of the genital zone, if achieved, is always precarious; and (2) he argues that drives are partial in that they represent sexuality only partially and not in the sense that they are a part of the whole. Drives do not represent the reproductive function of sexuality but only the dimension of jouissance.[79] Lacan identifies four partial drives: the oral drive (the erogenous zones are the lips (the partial object the breast—the verb is "to suck"), the anal drive (the anus and the faeces, "to shit"), the scopic drive (the eyes and the gaze, "to see") and the invocatory drive (the ears and the voice, "to hear"). The first two drives relate to demand and the last two to desire. The notion of dualism is maintained throughout Freud's various reformulations of the drive-theory. From the initial opposition between sexual drives and ego-drives (self-preservation) to the final opposition between the life drives (Lebenstriebe) and the death drives (Todestriebe).[81] Lacan retains Freud's dualism, but in terms of an opposition between the symbolic and the imaginary and not referred to different kinds of drives. For Lacan all drives are sexual drives, and every drive is a death drive (pulsion de mort) since every drive is excessive, repetitive and destructive.[82] The drives are closely related to desire, since both originate in the field of the subject.[79] But they are not to be confused: drives are the partial aspects in which desire is realized—desire is one and undivided, whereas the drives are its partial manifestations. A drive is a demand that is not caught up in the dialectical mediation of desire; drive is a "mechanical" insistence that is not ensnared in demand's dialectical mediation.[83] |

衝動 ラカンは、フロイトの衝動 ( Trieb ) と本能 ( Instinkt ) の区別を維持します。衝動は生物学的欲求とは異なります。なぜなら、衝動は決して満たされることがなく、物体を目指すのではなく、その周りを絶えず回転す るからです。彼は、ドライブ ( Triebziel ) の目的は、目標に到達することではなく、その目的に従うことであり、「最終目的地」ではなく「道そのもの」を意味する、つまり、オブジェクトの周囲を周回 することであると主張します。ドライブの目的は、その円形の経路に戻ることであり、本当の楽しさの源は、この閉回路の反復的な動きです。[79]ラカン は、欲動を文化的かつ象徴的な構築物であると仮定している。彼にとって、「欲動は所与のものではなく、古風で原始的なものである」。彼は、フロイトによっ て定義された衝動の 4 つの要素 (圧力、目的、物体、ソース) を衝動の回路理論に組み込んでいます。つまり、衝動は性感帯から始まり、物体の周囲を一周し、性感帯に戻ります。この回路は 3 つの文法的な音声で構成されています。 能動態(見るために) 反射的な声(自分自身を見るため) 受動態(見られる) 能動的な声と反射的な声は自己エロティックであり、主語がありません。新しい主語が現れるのは、ドライブが受動態でその回路を完了したときのみであり、そ のインスタンスの前には主語が存在しなかったことを意味します。[79]「受動的」な声であるにもかかわらず、その衝動は本質的に能動的であり、「見られ る」というよりも「自分を見てもらいたい」ということである。ドライブの回路は、被験者が快楽原則を超える唯一の方法です。 フロイトによれば、セクシュアリティは、異なる性感帯によってそれぞれ特定される部分的な衝動(つまり、口や肛門の衝動)で構成されています。最初、これ らの部分的衝動は独立して機能しますが(つまり、子供の多形的倒錯)、それらが生殖器官の保護下で組織化されるのは思春期になって初めてです。[80]ラ カンは欲動の部分的な性質を受け入れているが、(1) 彼は、部分的な欲動が完全な組織化を達成することができるという考えを拒否している。(2) 彼は、衝動はセクシュアリティを部分的にのみ表すという点で部分的であり、全体の一部であるという意味ではないと主張します。衝動は性の生殖機能を表すも のではなく、享楽の次元を表すだけです。[79] ラカンは4つの部分的衝動を特定している:口腔的衝動(性感帯は唇(部分的対象物は乳房、動詞は「吸う」))、肛門的衝動(肛門と大便、「クソする」)、 視覚的衝動衝動(目と視線、「見る」)と呼びかけの衝動(耳と声、「聞く」) 最初の 2 つの衝動は要求に関係し、最後の 2 つは欲望に関係します。 二元論の概念は、フロイトによる駆動理論のさまざまな再定式化を通じて維持されています。性的衝動と自我衝動(自己保存)の間の最初の対立から、生の衝動 ( Lebenstriebe)と死の衝動(Todestriebe )の間の最終的な対立まで。[81]ラカンはフロイトの二元論を保持しているが、象徴的なものと想像的なものの対立という観点から、異なる種類の衝動には 言及していない。ラカンにとって、すべての衝動は性的衝動であり、すべての衝動は過剰で、反復的で、破壊的であるため、すべての衝動は死の衝動 (pulsion de mort)です。[82] 両方とも主題の分野に由来するため、これらの衝動は欲望と密接に関連しています。[79]しかし、これらを混同しないでください。欲動は欲望が実現される 部分的な側面です。欲望は一つであり、分割されていませんが、欲動はその部分的な現れです。衝動とは、欲望の弁証法的媒介に囚われない要求です。衝動は、 要求の弁証法的媒介に囚われない「機械的」主張です。[83] |

| Name of the Father |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| The graph of desire |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| Foreclosure (psychoanalysis) |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| Matheme |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| Lack (manque) |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| Objet petit a |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

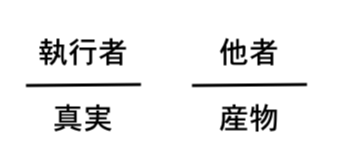

| The Four discourses |

★ジャッ ク・ラカン で説明しています |

| Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan |

|

| セミネール一覧(出典) |

セミネール一覧(出典) |

| Les ecrits techniques de Freud (S I), ,1953-1954, Seuil 1975 Le Moi dans la theorie de Freud et dans la technique de la psychanalyse (S II), 1954-1955, Seuil 1978 Les psychoses (S III), 1955-1956, Seuil 1981 La relation d'objet (S IV), 1956-1957, Seuil 1994 Les formations de l'inconscient (S V), 1957-1958, Seuil 1998 Le desir et son interpretation (S VI), 1958-1959 L'ethique de la psychanalyse (S VII), 1959-1960, Seuil 1986 Le transfert (S VIII), 1960-1961, Seuil 2001 L'identification (S IX), 1961-1962 L'angoisse (S X), 1962-1963, Seuil 2004 Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse (S XI), 1964, Seuil 1973 Problemes cruciaux pour la psychanalyse (S XII), 1964-1965 L'objet de la psychanalyse (S XIII), 1965-1966 La logique du fantasme (S XIV), 1966-1967 L'acte psychanalytique (S XV), 1967-1968 D'un Autre a l'autre (S XVI), 1968-1969 L'envers de la psychanalyse (S XVII), 1969-1970 D'un discours qui ne serait pas du semblant (S XVIII), 1970-1971 Ou pire… (S XIX), 1971-1972 Encore (S XX), 1972-1973 Les non dupes errent (S XXI), 1973-1974 RSI (S XXII), 1974-1975 Le sinthome (S XXIII), 1975-1976 L'insu que sait de l'une bevue s'aile a mourre (S XXIV), 1976-1977 Le moment de conclure (S XXV), 1977-1978 La topologie et le temps (S XXVI), 1978-1979 Dissolution (S XXVII), 1980 |

フロイトの技術的著作(S I)、1953-1954年、Seuil 1975年 フロイトの理論と精神分析の技術における自我(S II)、1954-1955年、Seuil 1978年 精神病(S III)、1955-1956年、Seuil 1981年 対象関係(S IV)、1956-1957、Seuil 1994 無意識の形成(S V)、1957-1958、Seuil 1998 欲望とその解釈(S VI)、1958-1959 精神分析の倫理(S VII)、1959-1960、Seuil 1986 転移(S VIII)、1960-1961、Seuil 2001 同一化(S IX)、1961-1962 不安(S X)、1962-1963、Seuil 2004 精神分析の四つの基本概念(S XI)、1964、Seuil 1973 精神分析にとって重要な問題(S XII)、1964-1965 精神分析の対象(S XIII)、1965-1966 幻想の論理(S XIV)、1966-1967 精神分析的行為(S XV)、1967-1968 ある他者から別の他者へ(S XVI)、1968-1969 精神分析の裏側(S XVII)、1969-1970 見せかけではない言説について(S XVIII)、1970-1971 あるいはさらに悪いことに…(S XIX)、1971-1972 さらに(S XX)、1972-1973 騙されない者たちはさまよう(S XXI)、1973-1974 RSI(S XXII)、1974-1975 シントーム(S XXIII)、1975-1976 誤りを知る無意識は死へと飛び立つ(S XXIV)、1976-1977 結論を出す時(S XXV)、1977-1978 位相と時間(S XXVI)、1978-1979 解体(S XXVII)、1980 |

| 邦訳されているセミネール |

|

| 1991(セミネール第1巻)『フロイトの技法論』(上・下),岩波書店. 1998(セミネール第2巻)『フロイト理論と精神分析技法における自我』(上・下),岩波書店. 1987(セミネール第3巻)『精神病』(上 ・下),岩波書店. 2006(セミネール第4巻)『対象関係』(上・下),岩波書店. 2005-6(セミネール第5巻)『無意識の形成物』(上・下),岩波書店. 2002(セミネール第7巻)『精神分析の倫理』(上 ・下),岩波書店. 2000(セミネール第11巻)『精神分析の四基本概念』,岩波書店. |

|

| 日本では未訳でもフランスで出版されているもの |

|

| Le Seminaire XVI : D'un autre a l'autre Le seminaire de Jacques Lacan : Livre 23, Le sinthome Le seminaire, livre 10 : L'angoisse Le Seminaire. Livre XVIII D'un discours qui ne serait pas du semblant L'envers de la psychanalyse, 1969-1970 Le Seminaire, livre VIII : le transfert Encore : Le seminaire, livre XX |

セミナー XVI:ある他者から別の他者へ ジャック・ラカンのセミナー:第 23 巻、シンターム セミナー、第 10 巻:不安 セミナー。第 18 巻、見せかけではない言説について 精神分析の裏側、1969-1970 セミナー、第8巻:転移 さらに:セミナー、第20巻 |

| 英訳のあるセミネール |

|

| On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX, Encore The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis (Seminar of Jacques Lacan) |

女性の性、愛と知識の限界について:ジャック・ラカン『セメナール』第20巻『アンコール』 ジャック・ラカン『セメナール』第17巻:精神分析のもう一つの側面(ジャック・ラカン『セメナール』) |

| https://kuriggen.hatenablog.com/entry/20070806/p1 |

★涙なしのジャック・ ラカンへ(Jacques Lacan, 1901-1981)の入門を考えてきた。ここで利用される資料は、すべてインターネットから仕入れたもので、このページの制作者のオリジナリティはゼロであ る。そのために、このページの内容保証は一切ない。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆