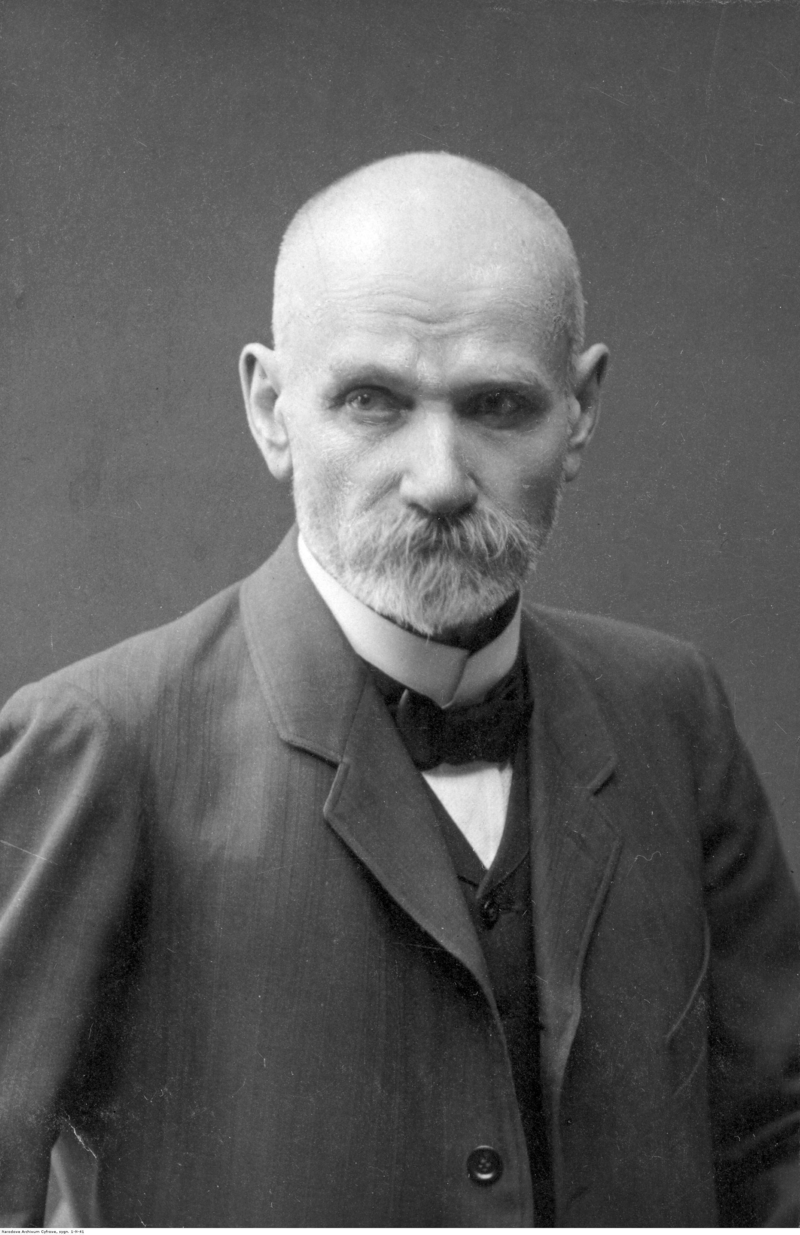

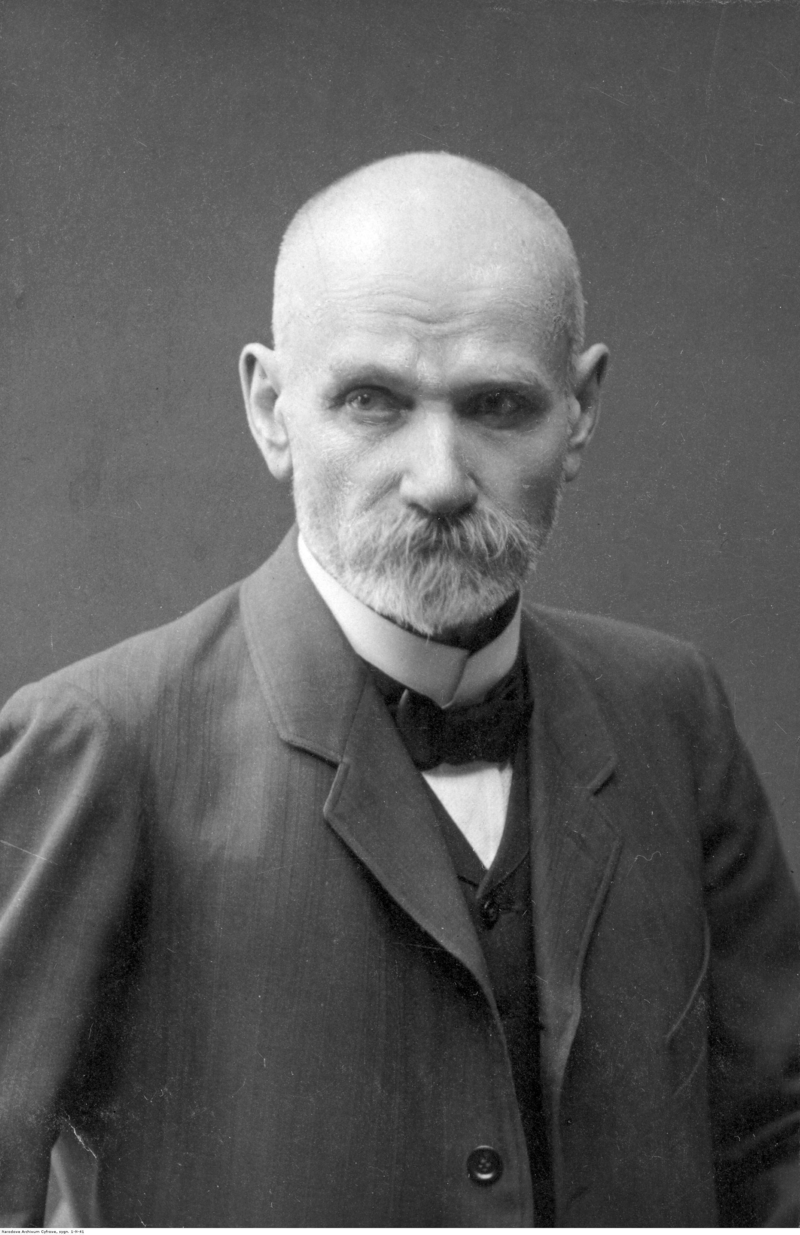

フェルディナン・ド・ソシュール

Ferdinand de Saussure, 1857-1913

☆ フェ ルディナン・ド・ソシュール(Ferdinand de Saussure、1857年11月26日 - 1913年2月22日)はスイスの言語学者、記号学者、哲学者。彼の思想は、20世紀の言語学と記号論における多くの重要な発展の基礎を築いた。彼は20 世紀の言語学の創始者の一人であり、ソシュールが記号学(セミオロジー)と呼んだ記号論の二大創始者(チャールズ・サンダース・パースと共に)の一人であ ると広く考えられている。

★ シニフィアンとシニフィエ(→「レヴィ=ストロースにおける記号概念の無理解」 より)

「シ ニフィアンとシニフィエの関係 ソシュールは1916年の『一般言語学講義』において、記号を2つの異なる構成要素、すなわちシニフィアン(「音像」)とシニフィエ(「概念」)に分けて いる[2]: 2 ソシュールにとって、シニフィエとシニフィエは純粋に心理的なものであり、それらは実体ではなく形式である[5]: 22。 今日、ルイ・ヘルムスレフに倣って、シニフィエは概念的な物質形態、すなわち見たり、聞いたり、触れたり、匂いを嗅いだり、味わったりすることができるも のとして解釈され、シニフィエは概念的な理想形態として解釈されている[6]: 14言い換えれば、「現代の論者たちは、シニフィエを記号がとる形式とし て、シニフィエを記号が参照する概念として記述する傾向がある」[7]: 「このことは、「決して完全に恣意的ではない」[2]: 9記号とは異なる。シニフィアンとシニフィエの両方が不可分であるという考えは、ソシュールの図によって説明される。 シニフィアンとシニフィエがどのように関係し合っているかを理解するためには、記号を解釈できなければならない。「シニフィエがシニフィエを内包する唯一 の理由は、従来の関係が作用しているからである」[8]: 4 つまり、記号を構成する2つの要素の関係が合意されて初めて、記号は理解できるのである。例えば、「木」のような個々の単語を理解するためには、「茂み」 という単語も理解しなければならず、その2つが互いにどのように関連しているのかを理解しなければならない[7]。」

【一 般言語学講義】

一般言語学講義

(フランス語: Cours de linguistique générale)

は、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールが1906年から1911年にかけて行った講義の内容を、シャルル・バイイとアルベール・セシュエが編集し出版された

本である。ソシュールの死後1916年に出版され、20世紀前半にヨーロッパ、アメリカで栄えた構造主義言語学の起こりと一般にみなされている。

ソシュールは特に比較言語学に興味を持っていたが、一般言語学講義ではより一般的に適用できる構造主義理論を発達させている。ソシュール自身の手稿を含ん

だ原稿が1996年に見つかり、Writings in General Linguisticsとして出版されている。

本記事では、ソシュールがジュネーブ大学で行った講義と区別するため、バイイとセシュエが編集した本「一般言語学講義」を『講義』と記す。

| Ferdinand

de Saussure

(/soʊˈsjʊər/;[4] French: [fɛʁdinɑ̃ də sosyʁ]; 26 November 1857 – 22

February 1913) was a Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher. His

ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in both

linguistics and semiotics in the 20th century.[5][6] He is widely

considered one of the founders of 20th-century linguistics[7][8][9][10]

and one of two major founders (together with Charles Sanders Peirce) of

semiotics, or semiology, as Saussure called it.[11] One of his translators, Roy Harris, summarized Saussure's contribution to linguistics and the study of "the whole range of human sciences. It is particularly marked in linguistics, philosophy, psychoanalysis, psychology, sociology and anthropology."[12] Although they have undergone extension and critique over time, the dimensions of organization introduced by Saussure continue to inform contemporary approaches to the phenomenon of language. As Leonard Bloomfield stated after reviewing the Cours: "he has given us the theoretical basis for a science of human speech".[13] |

フェルディナン・ド・ソシュール(Ferdinand

de Saussure、1857

年11月26日 -

1913年2月22日)はスイスの言語学者、記号学者、哲学者。彼の思想は、20世紀の言語学と記号論における多くの重要な発展の基礎を築いた。彼は20

世紀の言語学の創始者の一人であり、ソシュールが記号学(セミオロジー)と呼んだ記号論の二大創始者(チャールズ・サンダース・パースと共に)の一人であ

ると広く考えられている。 彼の翻訳者の一人であるロイ・ハリスは、言語学と「人間科学全般」の研究に対するソシュールの貢献を要約している。それは言語学、哲学、精神分析、心理 学、社会学、人類学において特に顕著である。レオナード・ブルームフィールドが『ツール』を再検討した後、次のように述べている: 「彼は人間の発話を科学するための理論的基礎を我々に与えた」[13]。 |

| Biography Saussure was born in Geneva in 1857. His father, Henri Louis Frédéric de Saussure, was a mineralogist, entomologist, and taxonomist. Saussure showed signs of considerable talent and intellectual ability as early as the age of fourteen.[14] In the autumn of 1870, he began attending the Institution Martine (previously the Institution Lecoultre until 1969), in Geneva. There he lived with the family of a classmate, Elie David.[15] After graduating at the top of class, Saussure expected to continue his studies at the Gymnase de Genève, but his father decided he was not mature enough at fourteen and a half, and sent him to the Collège de Genève instead. Saussure was not pleased, as he complained: "I entered the Collège de Genève, to waste a year there as completely as a year can be wasted."[16] After a year of studying Latin, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit and taking a variety of courses at the University of Geneva, he commenced graduate work at the University of Leipzig in 1876. Two years later, at 21, Saussure published a book entitled Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes (Dissertation on the Primitive Vowel System in Indo-European Languages). After this, he studied for a year at the University of Berlin under the Privatdozent Heinrich Zimmer, with whom he studied Celtic and Hermann Oldenberg with whom he continued his studies of Sanskrit.[17] He returned to Leipzig to defend his doctoral dissertation De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit, and was awarded his doctorate in February 1880. Soon, he relocated to the University of Paris, where he lectured on Sanskrit, Gothic, Old High German, and occasionally other subjects. Ferdinand de Saussure is one of the world's most quoted linguists, which is remarkable as he hardly published anything during his lifetime. Even his few scientific articles are not unproblematic. Thus, for example, his publication on Lithuanian phonetics[18] is mostly taken from studies by the Lithuanian researcher Friedrich Kurschat, with whom Saussure traveled through Lithuania in August 1880 for two weeks and whose (German) books Saussure had read.[19] Saussure, who had studied some basic grammar of Lithuanian in Leipzig for one semester but was unable to speak the language, was thus dependent on Kurschat. Saussure taught at the École pratique des hautes études for eleven years during which he was named Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor).[20] When offered a professorship in Geneva in 1892, he returned to Switzerland. Saussure lectured on Sanskrit and Indo-European at the University of Geneva for the remainder of his life. It was not until 1907 that Saussure began teaching the Course of General Linguistics, which he would offer three times, ending in the summer of 1911. He died in 1913 in Vufflens-le-Château, Vaud, Switzerland. His brothers were the linguist and Esperantist René de Saussure, and scholar of ancient Chinese astronomy, Léopold de Saussure. His son Raymond de Saussure was a psychiatrist and prolific psychoanalytic theorist, who was trained under Sigmund Freud himself.[21] Saussure attempted, at various times in the 1880s and 1890s, to write a book on general linguistic matters. His lectures about important principles of language description in Geneva between 1907 and 1911 were collected and published by his pupils posthumously in the famous Cours de linguistique générale in 1916. Work published in his lifetime includes two monographs and a few dozen papers and notes, all of them collected in a volume of some 600 pages published in 1922.[22] Saussure did not publish anything of his work on ancient poetics even though he had filled more than a hundred notebooks. Jean Starobinski edited and presented material from them in the 1970s[23] and more has been published since then.[24] Some of his manuscripts, including an unfinished essay discovered in 1996, were published in Writings in General Linguistics, but most of the material in it had already been published in Engler's critical edition of the Course, in 1967 and 1974. Today it is clear that Cours owes much to its so-called editors Charles Bally and Albert Sèchehaye and various details are difficult to track to Saussure himself or his manuscripts.[25] |

略歴 ソシュールは1857年ジュネーブ生まれ。父は鉱物学者、昆虫学者、分類学者であったアンリ・ルイ・フレデリック・ド・ソシュール。1870年の秋、ジュ ネーブのマルティーヌ研究所(1969年まではルクルト研究所)に通い始める。首席で卒業したソシュールは、ジュネーヴ・ジムナースで勉強を続けることを 期待したが、父親は14歳半ではまだ未熟だと判断し、代わりにジュネーヴ・コレージュに進学させた。ソシュールは不満だった: 「ジュネーヴのコレージュに入学したのは、そこで1年を無駄にするためだった。 ジュネーヴ大学でラテン語、古代ギリシャ語、サンスクリット語を1年間学び、さまざまな科目を履修した後、1876年にライプツィヒ大学の大学院に入学。 2年後、21歳のときに『Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes』(インド・ヨーロッパ諸語における原始母音体系に関する論文)を出版。その後、ベルリン大学で1年間、ハインリヒ・ ツィンマー(Heinrich Zimmer)に師事し、ケルト語を学び、ヘルマン・オルデンベルク(Hermann Oldenberg)とはサンスクリット語の研究を続けた[17]。すぐにパリ大学に移り、サンスクリット語、ゴート語、古高ドイツ語、時にはその他の テーマで講義を行った。 フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールは、世界で最も引用される言語学者の一人である。彼の数少ない科学論文でさえ、問題がないわけではない。例えば、リトアニ ア語の音声学に関する彼の出版物[18]は、ソシュールが1880年8月に2週間一緒にリトアニアを旅行し、ソシュールがその(ドイツ語の)本を読んだリ トアニア人研究者フリードリッヒ・クルシャット(Friedrich Kurschat)の研究からの引用がほとんどである[19]。 ソシュールはライプツィヒで1学期間リトアニア語の基礎文法を学んだが、その言語を話すことができなかったため、クルシャットに依存していた。 1892年、ジュネーヴで教授職のオファーを受けたソシュールはスイスに戻った。ソシュールはジュネーヴ大学でサンスクリット語と印欧語の講義を行った。 ソシュールが一般言語学の講義を始めたのは1907年のことで、1911年の夏まで3回にわたって講義を行った。1913年、スイスのヴォー州ヴュフラン =ル=シャトーで死去。兄弟に言語学者でエスペランティストのルネ・ド・ソシュール、古代中国天文学者のレオポルド・ド・ソシュールがいた。息子のレイモ ン・ド・ソシュールは精神科医で、ジークムント・フロイトに師事した精神分析理論家であった[21]。 ソシュールは1880年代から1890年代にかけて、一般的な言語学に関する本を書こうと試みた。1907年から1911年にかけてジュネーヴで行われた 言語記述の重要な原理についての講義は、彼の弟子たちによって1916年に有名な『Cours de linguistique générale』として収集・出版された。生前に出版された作品には、2冊の単行本と数十の論文とノートがあり、それらはすべて1922年に出版された 約600ページの本にまとめられている[22]。1996年に発見された未完のエッセイを含むいくつかの原稿は『一般言語学の著作』として出版されたが、 その中のほとんどの内容は1967年と1974年にエングラーが出版した『講座』の批評版ですでに発表されていた。今日、『コース』がいわゆる編集者であ るシャルル・バリーとアルベール・セーシェイに多くを負っていることは明らかであり、様々な詳細はソシュール自身や彼の手稿を追跡することは困難である [25]。 |

| Work and influence Saussure's theoretical reconstructions of the Proto-Indo-European language vocalic system and particularly his theory of laryngeals, otherwise unattested at the time, bore fruit and found confirmation after the decipherment of Hittite in the work of later generations of linguists such as Émile Benveniste and Walter Couvreur, who both drew direct inspiration from their reading of the 1878 Mémoire.[26] Saussure had a major impact on the development of linguistic theory in the first half of the 20th century with his notions becoming incorporated in the central tenets of structural linguistics. His main contribution to structuralism was his theory of a two-tiered reality about language. The first is the langue, the abstract and invisible layer, while the second, the parole, refers to the actual speech that we hear in real life.[27] This framework was later adopted by Claude Levi-Strauss, who used the two-tiered model to determine the reality of myths. His idea was that all myths have an underlying pattern, which forms the structure that makes them myths.[27] In Europe, the most important work after Saussure's death was done by the Prague school. Most notably, Nikolay Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson headed the efforts of the Prague School in setting the course of phonological theory in the decades from 1940. Jakobson's universalizing structural-functional theory of phonology, based on a markedness hierarchy of distinctive features, was the first successful solution of a plane of linguistic analysis according to the Saussurean hypotheses. Elsewhere, Louis Hjelmslev and the Copenhagen School proposed new interpretations of linguistics from structuralist theoretical frameworks.[citation needed] In America, where the term 'structuralism' became highly ambiguous, Saussure's ideas informed the distributionalism of Leonard Bloomfield, but his influence remained limited.[28][29] Systemic functional linguistics is a theory considered to be based firmly on the Saussurean principles of the sign, albeit with some modifications. Ruqaiya Hasan describes systemic functional linguistics as a 'post-Saussurean' linguistic theory. Michael Halliday argues: Saussure took the sign as the organizing concept for linguistic structure, using it to express the conventional nature of language in the phrase "l'arbitraire du signe". This has the effect of highlighting what is, in fact, the one point of arbitrariness in the system, namely the phonological shape of words, and hence allows the non-arbitrariness of the rest to emerge with greater clarity. An example of something that is distinctly non-arbitrary is the way different kinds of meaning in language are expressed by different kinds of grammatical structure, as appears when linguistic structure is interpreted in functional terms[30] Course in General Linguistics Main article: Course in General Linguistics Saussure's most influential work, Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale), was published posthumously in 1916 by former students Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye, based on notes taken from Saussure's lectures in Geneva.[31] The Course became one of the seminal linguistics works of the 20th century not primarily for the content (many of the ideas had been anticipated in the works of other 20th-century linguists) but for the innovative approach that Saussure applied in discussing linguistic phenomena. Its central notion is that language may be analyzed as a formal system of differential elements, apart from the messy dialectics of real-time production and comprehension. Examples of these elements include his notion of the linguistic sign, which is composed of the signifier and the signified. Though the sign may also have a referent, Saussure took that to lie beyond the linguist's purview.[citation needed] Throughout the book, he stated that a linguist can develop a diachronic analysis of a text or theory of language but must learn just as much or more about the language/text as it exists at any moment in time (i.e. "synchronically"): "Language is a system of signs that expresses ideas". A science that studies the life of signs within society and is a part of social and general psychology. Saussure believed that semiotics is concerned with everything that can be taken as a sign, and he called it semiology.[32] Laryngeal theory Main article: Laryngeal theory While a student, Saussure published an important work about Proto-Indo-European, which explained unusual forms of word roots in terms of lost phonemes he called sonant coefficients. The Scandinavian scholar Hermann Möller suggested that they might be laryngeal consonants, leading to what is now known as the laryngeal theory. After Hittite texts were discovered and deciphered, Polish linguist Jerzy Kuryłowicz recognized that a Hittite consonant stood in the positions where Saussure had theorized a lost phoneme some 48 years earlier, confirming the theory. It has been argued[citation needed] that Saussure's work on this problem, systematizing the irregular word forms by hypothesizing then-unknown phonemes, stimulated his development of structuralism. Influence outside linguistics The principles and methods employed by structuralism were later adapted in diverse fields by French intellectuals such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Such scholars took influence from Saussure's ideas in their areas of study (literary studies/philosophy, psychoanalysis, anthropology, etc.).[citation needed] |

業績と影響 ソシュールによる原インド・ヨーロッパ語族の声調システムの理論的再構築、特に喉頭音に関する彼の理論は、当時は未証明であったが、ヒッタイト語の解読後 に実を結び、エミール・ベンヴェニステやウォルター・クヴルールといった後世の言語学者の研究において確認された。 ソシュールは20世紀前半の言語理論の発展に大きな影響を与え、彼の概念は構造言語学の中心的な考え方に組み込まれるようになった。構造主義への彼の主な 貢献は、言語に関する2層の現実についての彼の理論であった。第一は抽象的で目に見えない層であるラングであり、第二のパロールは私たちが現実の生活で耳 にする実際の音声を指す。彼の考えは、すべての神話には根底にあるパターンがあり、それが神話を神話たらしめている構造を形成しているというものであった [27]。 ヨーロッパでは、ソシュールの死後、最も重要な仕事はプラハ学派によって行われた。特に、ニコライ・トルベツコイとロマン・ヤコブソンはプラハ学派の先頭 に立ち、1940年からの数十年間、音韻論の方向性を定めることに尽力した。ヤコブソンの音韻論の普遍化構造機能理論は、特徴的な特徴の顕著性階層に基づ くもので、ソシュールの仮説に従った言語分析の平面の解決に初めて成功した。他にも、ルイス・ヒェルムスレフ(Louis Hjelmslev)とコペンハーゲン学派は、構造主義の理論的枠組みから言語学の新しい解釈を提案した[citation needed]。 構造主義」という用語が非常に曖昧になったアメリカでは、ソシュールの考え方はレナード・ブルームフィールドの分配主義に影響を与えたが、彼の影響は限定 的なものにとどまった[28][29]。体系機能言語学は、いくつかの修正は加えられたものの、ソシュール的な記号の原則にしっかりと基づいていると考え られている理論である。Ruqaiya Hasanは体系機能言語学を「ポスト・ソシュール的」言語理論であると説明している。マイケル・ハリデーはこう主張する: ソシュールは記号を言語構造の組織的概念とし、それを用いて言語の慣習的性質を "l'arbitraire du signe "という言葉で表現した。このことは、実際、システムにおける恣意性の一点、すなわち単語の音韻的形状を強調する効果があり、それゆえ、それ以外の部分の 非恣意性をより明確に浮かび上がらせることができる。明確に非恣意的であるものの例として、言語構造を機能的な用語で解釈したときに現れるように、言語に おける異なる種類の意味が異なる種類の文法構造によって表現される方法が挙げられる[30]。 一般言語学コース 主な記事 一般言語学コース ソシュールの最も影響力のある著作である『一般言語学講座』(Cours de linguistique générale)は、ソシュールのジュネーブでの講義のノートをもとに、かつての教え子であるシャルル・バリー(Charles Bally)とアルベール・セシェイ(Albert Sechehaye)によって1916年に死後出版された[31]。この講座は、その内容(アイデアの多くは他の20世紀の言語学者の著作で先取りされて いた)ではなく、ソシュールが言語現象を論じる際に適用した革新的なアプローチによって、20世紀を代表する言語学の著作となった。 その中心的な考え方は、言語は、リアルタイムの生産と理解という厄介な弁証法とは別に、微分的要素の形式的システムとして分析できるというものである。こ れらの要素の例としては、彼の言語的記号の概念が挙げられる。記号は参照も持つかもしれないが、ソシュールはそれを言語学者の範疇を超えたところにあると 考えた[要出典]。 ソシュールはこの本を通して、言語学者はテキストの通時的分析や言語理論を展開することはできるが、言語/テキストがどの時点においても存在するのと同じ かそれ以上のことを(つまり「同期的に」)学ばなければならないと述べている: 「言語とは、思想を表現する記号の体系である」。社会における記号の一生を研究する科学であり、社会心理学および一般心理学の一部である。ソシュールは記 号論は記号として捉えることができるすべてのものに関係していると考え、それを記号学と呼んだ[32]。 喉頭理論 主な記事 喉頭理論 ソシュールは学生時代、原インド・ヨーロッパ語に関する重要な著作を発表し、ソナント係数と呼ばれる失われた音素の観点から語根の異常な形を説明した。ス カンジナビアの学者ヘルマン・メラーは、これが喉頭子音である可能性を示唆し、現在喉頭子音説として知られているものにつながった。ヒッタイト語のテキス トが発見され、解読された後、ポーランドの言語学者Jerzy Kuryłowiczは、ソシュールが約48年前に失われた音素を理論化した位置にヒッタイト語の子音があることを認識し、この理論を確認した。ソシュー ルがこの問題に取り組み、当時はまだ知られていなかった音素の仮説を立てることで不規則な語形を体系化したことが、構造主義の発展を促したと主張されてい る[citation needed]。 言語学以外への影響 構造主義が採用した原理と方法は、その後、ロラン・バルト、ジャック・ラカン、ジャック・デリダ、ミシェル・フーコー、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースと いったフランスの知識人によって、さまざまな分野で応用された。このような学者たちは、それぞれの研究分野(文学研究/哲学、精神分析、人類学など)にお いてソシュールの思想から影響を受けた[要出典]。 |

| View of language Saussure approaches the theory of language from two different perspectives. On the one hand, language is a system of signs. That is, a semiotic system; or a semiological system as he calls it. On the other hand, a language is also a social phenomenon: a product of the language community. Language as semiology The bilateral sign One of Saussure's key contributions to semiotics lies in what he called semiology, the concept of the bilateral (two-sided) sign which consists of 'the signifier' (a linguistic form, e.g. a word) and 'the signified' (the meaning of the form). Saussure supported the argument for the arbitrariness of the sign although he did not deny the fact that some words are onomatopoeic, or claim that picture-like symbols are fully arbitrary. Saussure also did not consider the linguistic sign as random, but as historically cemented.[a] All in all, he did not invent the philosophy of arbitrariness but made a very influential contribution to it.[33] The arbitrariness of words of different languages itself is a fundamental concept in Western thinking of language, dating back to Ancient Greek philosophers.[34] The question of whether words are natural or arbitrary (and artificially made by people) returned as a controversial topic during the Age of Enlightenment when the medieval scholastic dogma, that languages were created by God, became opposed by the advocates of humanistic philosophy. There were efforts to construct a 'universal language', based on the lost Adamic language, with various attempts to uncover universal words or characters which would be readily understood by all people regardless of their nationality. John Locke, on the other hand, was among those who believed that languages were a rational human innovation,[35] and argued for the arbitrariness of words.[34] Saussure took it for granted in his time that "No one disputes the principle of the arbitrary nature of the sign."[b] He however disagreed with the common notion that each word corresponds "to the thing that it names" or what is called the referent in modern semiotics. For example, in Saussure's notion, the word 'tree' does not refer to a tree as a physical object, but to the psychological concept of a tree. The linguistic sign thus arises from the psychological association between the signifier (a 'sound-image') and the signified (a 'concept'). There can therefore be no linguistic expression without meaning, but also no meaning without linguistic expression.[c] Saussure's structuralism, as it later became called, therefore includes an implication of linguistic relativity. However, Saussure's view has been described instead as a form of semantic holism that acknowledged that the interconnection between terms in a language was not fully arbitrary and only methodologically bracketed the relationship between linguistic terms and the physical world.[36] The naming of spectral colours exemplifies how meaning and expression arise simultaneously from their interlinkage. Different colour frequencies are per se meaningless, or mere substance or meaning potential. Likewise, phonemic combinations that are not associated with any content are only meaningless expression potential, and therefore not considered as signs. It is only when a region of the spectrum is outlined and given an arbitrary name, for example, 'blue', that the sign emerges. The sign consists of the signifier ('blue') and the signified (the colour region), and of the associative link which connects them. Arising from an arbitrary demarcation of meaning potential, the signified is not a property of the physical world. In Saussure's concept, language is ultimately not a function of reality, but a self-contained system. Thus, Saussure's semiology entails a bilateral (two-sided) perspective of semiotics. The same idea is applied to any concept. For example, natural law does not dictate which plants are 'trees' and which are 'shrubs' or a different type of woody plant; or whether these should be divided into further groups. Like blue, all signs gain semantic value in opposition to other signs of the system (e.g. red, colourless). If more signs emerge (e.g. 'marine blue'), the semantic field of the original word may narrow down. Conversely, words may become antiquated, whereby competition for the semantic field lessens. Or, the meaning of a word may change altogether.[37] After his death, structural and functional linguists applied Saussure's concept to the analysis of the linguistic form as motivated by meaning. The opposite direction of the linguistic expressions as giving rise to the conceptual system, on the other hand, became the foundation of the post-Second World War structuralists who adopted Saussure's concept of structural linguistics as the model for all human sciences as the study of how language shapes our concepts of the world. Thus, Saussure's model became important not only for linguistics but for humanities and social sciences as a whole.[38] Opposition theory See also: Binary opposition and Markedness A second key contribution comes from Saussure's notion of the organisation of language based on the principle of opposition. Saussure made a distinction between meaning (significance) and value. On the semantic side, concepts gain value by being contrasted with related concepts, creating a conceptual system that could in modern terms be described as a semantic network. On the level of the sound-image, phonemes and morphemes gain value by being contrasted with related phonemes and morphemes; and on the level of the grammar, parts of speech gain value by being contrasted with each other.[d] Each element within each system is eventually contrasted with all other elements in different types of relations so that no two elements have the same value: "Within the same language, all words used to express related ideas limit each other reciprocally; synonyms like French redouter 'dread', craindre 'fear,' and avoir peur 'be afraid' have value only through their opposition: if redouter did not exist, all its content would go to its competitors."[e] Saussure defined his theory in terms of binary oppositions: sign—signified, meaning—value, language—speech, synchronic—diachronic, internal linguistics—external linguistics, and so on. The related term markedness denotes the assessment of value between binary oppositions. These were studied extensively by post-war structuralists such as Claude Lévi-Strauss to explain the organisation of social conceptualisation, and later by the post-structuralists to criticise it. Cognitive semantics also diverges from Saussure on this point, emphasizing the importance of similarity in defining categories in the mind as well as opposition.[39] Based on markedness theory, the Prague Linguistic Circle made great advances in the study of phonetics reforming it as the systemic study of phonology. Although the terms opposition and markedness are rightly associated with Saussure's concept of language as a semiological system, he did not invent the terms and concepts that had been discussed by various 19th-century grammarians before him.[40] Language as a social phenomenon In his treatment of language as a 'social fact', Saussure touches on topics that were controversial in his time, and that would continue to split opinions in the post-war structuralist movement.[38] Saussure's relationship with 19th-century theories of language was somewhat ambivalent. These included social Darwinism and Völkerpsychologie or Volksgeist thinking which were regarded by many intellectuals as nationalist and racist pseudoscience.[41][42][43] Saussure, however, considered the ideas useful if treated properly. Instead of discarding August Schleicher's organicism or Heymann Steinthal's "spirit of the nation", he restricted their sphere in ways that were meant to preclude any chauvinistic interpretations.[44][41] Organic analogy Saussure exploited the sociobiological concept of language as a living organism. He criticises August Schleicher and Max Müller's ideas of languages as organisms struggling for living space but settles with promoting the idea of linguistics as a natural science as long as the study of the 'organism' of language excludes its adaptation to its territory.[44] This concept would be modified in post-Saussurean linguistics by the Prague circle linguists Roman Jakobson and Nikolai Trubetzkoy,[45] and eventually diminished.[46] The speech circuit Main article: Langue and parole Perhaps the most famous of Saussure's ideas is the distinction between language and speech (Fr. langue et parole), with 'speech' referring to the individual occurrences of language usage. These constitute two parts of three of Saussure's 'speech circuit' (circuit de parole). The third part is the brain, that is, the mind of the individual member of the language community.[f] This idea is in principle borrowed from Steinthal, so Saussure's concept of a language as a social fact corresponds to "Volksgeist", although he was careful to preclude any nationalistic interpretations. In Saussure's and Durkheim's thinking, social facts and norms do not elevate the individuals but shackle them.[41][42] Saussure's definition of language is statistical rather than idealised. "Among all the individuals that are linked together by speech, some sort of average will be set up : all will reproduce — not exactly of course, but approximately — the same signs united with the same concepts."[g] Saussure argues that language is a 'social fact'; a conventionalised set of rules or norms relating to speech. When at least two people are engaged in conversation, there forms a communicative circuit between the minds of the individual speakers. Saussure explains that language, as a social system, is neither situated in speech nor the mind. It only properly exists between the two within the loop. It is located in – and is the product of – the collective mind of the linguistic group.[h] An individual has to learn the normative rules of language and can never control them.[i] The task of the linguist is to study the language by analysing samples of speech. For practical reasons, this is ordinarily the analysis of written texts.[j] The idea that language is studied through texts is by no means revolutionary as it had been the common practice since the beginning of linguistics. Saussure does not advise against introspection and takes up many linguistic examples without reference to a source in a text corpus.[44] The idea that linguistics is not the study of the mind, however, contradicts Wilhelm Wundt's Völkerpsychologie in Saussure's contemporary context; and in a later context, generative grammar and cognitive linguistics.[47] |

言語観 ソシュールは2つの異なる視点から言語論に取り組んでいる。一方では、言語は記号の体系である。つまり記号論的体系、あるいは意味論的体系である。他方、 言語は社会現象でもあり、言語共同体の産物でもある。 記号論としての言語 二国間記号 ソシュールの記号論への重要な貢献のひとつは、彼が記号学と呼んだもの、すなわち「意味詞」(単語などの言語形式)と「意味詞」(その形式の意味)からな る両側(両面)記号の概念にある。ソシュールは記号の恣意性を主張したが、オノマトペ的な単語があることは否定しなかったし、絵のような記号が完全に恣意 的であるとは主張しなかった。またソシュールは言語記号をランダムなものとしてではなく、歴史的に固められたものとして考えていた[a]。全体として、彼 は恣意性の哲学を発明したわけではないが、非常に影響力のある貢献をした[33]。 言葉は神によって創造されたという中世のスコラ学の教義が人文主義哲学の提唱者たちによって反対されるようになった啓蒙主義の時代に、言葉は自然なものな のか、それとも恣意的なものなのか(そして人為的に作られたものなのか)という疑問が論争的なテーマとして戻ってきた。失われたアダムの言語に基づいて 「普遍的な言語」を構築しようとする努力がなされ、国籍に関係なくすべての人が容易に理解できる普遍的な言葉や文字を発見しようとするさまざまな試みがな された。一方、ジョン・ロックは、言語は人間の合理的な革新であると信じていた人々の一人であり[35]、言葉の恣意性を主張していた[34]。 ソシュールは「記号の恣意性の原則に異論を唱える者はいない」[b]ことを当時は当然のこととしていたが、各単語が「それが名づけるもの」、つまり現代の 記号論において参照語と呼ばれるものに対応するという一般的な概念には反対であった。例えば、ソシュールの概念では、「木」という言葉は物理的な物体とし ての木を指すのではなく、木という心理的概念を指す。このように、言語的記号は、シニフィアン(「音像」)とシニフィエ(「概念」)の間の心理的関連から 生じる。したがって、意味のない言語表現はあり得ないが、言語表現のない意味もまたあり得ないのである[c] 。しかしソシュールの見解は、言語における用語間の相互接続が完全に恣意的なものではなく、言語用語と物理的世界との関係を方法論的に括るだけであること を認めた意味論的全体主義の一形態として代わりに説明されている[36]。 スペクトル色の命名は、意味と表現がそれらの相互連結からいかに同時に生じるかを例証している。異なる色の度数はそれ自体無意味であり、あるいは単なる実 体や意味の可能性にすぎない。同様に、いかなる内容とも関連しない音素の組み合わせは、意味のない表現の可能性にすぎず、したがって記号とはみなされな い。記号が現れるのは、スペクトルのある領域が輪郭を描かれ、例えば「青」のような任意の名前が与えられたときだけである。記号は、シニフィアン (「青」)とシニフィエ(色域)、そしてそれらをつなぐ連想的リンクから構成される。意味の可能性の恣意的な区分から生じる記号化されたものは、物理的世 界の性質ではない。ソシュールの概念では、言語は究極的には現実の機能ではなく、自己完結したシステムである。このように、ソシュールの記号論は、記号論 のバイラテラル(両面的)な視点を伴う。 同じ考え方があらゆる概念に適用される。例えば、自然法則は、どの植物が「木」で、どれが「低木」あるいは別の種類の木本植物であるか、あるいは、これら をさらに別のグループに分けるべきかどうかを指示するものではない。青と同様、すべての標識はシステムの他の標識(例えば赤、無色)と対立して意味的価値 を得る。より多くの記号が出現すれば(例えば「マリンブルー」)、元の単語の意味領域は狭まるかもしれない。逆に、単語が古くなり、意味分野の競争が少な くなることもある。あるいは、単語の意味がまったく変わってしまうこともある[37]。 ソシュールの死後、構造言語学者と機能言語学者はソシュールの概念を意味によって動かされる言語形式の分析に適用した。一方、言語表現が概念体系を生じさ せるという逆の方向性は、第二次世界大戦後の構造主義者の基礎となった。構造主義者は、ソシュールの構造言語学の概念を、言語がどのように世界の概念を形 成するかという研究として、すべての人間科学のモデルとして採用した。こうしてソシュールのモデルは言語学のみならず、人文科学や社会科学全体にとって重 要なものとなった[38]。 対立理論 以下も参照: 二項対立と標識性 2つ目の重要な貢献は、対立の原理に基づく言語の組織化に関するソシュールの概念である。ソシュールは意味(意義)と価値を区別した。意味面では、概念は 関連する概念と対比されることによって価値を獲得し、現代の用語で意味ネットワークと表現される概念体系を作り上げる。音像のレベルでは、音素や形態素は 関連する音素や形態素と対比されることによって価値を獲得し、文法のレベルでは、品詞は互いに対比されることによって価値を獲得する: フランス語のredouter「恐い」、craindre「恐れる」、avoir peur「恐れる」のような同義語は、その対立によってのみ価値を持つ。もしredouterが存在しなければ、その内容はすべてその競争相手に向かうだ ろう」[e]。 ソシュールは、記号-記号化、意味-価値、言語-言語、共時的-通時的、内部言語学-外部言語学といった二項対立の観点から彼の理論を定義した。関連用語 のmarkednessは、二項対立間の価値評価を示す。これらは、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースのような戦後の構造主義者たちによって、社会的概念化の 組織を説明するために幅広く研究され、後にポスト構造主義者たちによって、それを批判するために研究された。認知意味論もこの点ではソシュールから乖離し ており、対立と同様に心の中のカテゴリーを定義する際の類似性の重要性を強調している[39]。 マークネス理論に基づき、プラハ言語学サークルは音声学の研究を大きく前進させ、音声学の体系的な研究として改革した。対立とマーク付けという用語は、意 味論的体系としての言語というソシュールの概念と正しく関連付けられているが、ソシュール以前の様々な19世紀の文法家によって議論されていた用語や概念 を彼が発明したわけではない[40]。 社会現象としての言語 ソシュールの「社会的事実」としての言語の扱いでは、彼の時代において論争を巻き起こし、戦後の構造主義運動においても意見を二分し続けることになったト ピックに触れている[38]。ソシュールと19世紀の言語理論との関係はやや両義的であった。これらの理論には社会ダーウィニズムやフォルカー心理学や フォルクスガイスト思想が含まれており、これらは多くの知識人によって民族主義的で人種差別的な疑似科学とみなされていた[41][42][43]。 しかし、ソシュールは、適切に扱われるのであれば、これらの考え方は有用であると考えていた。アウグスト・シュライヒャーの有機主義やヘイマン・シュタイ ンタールの「民族の精神」を破棄する代わりに、彼は排外主義的な解釈を排除するような方法でそれらの領域を制限した[44][41]。 有機的類推 ソシュールは、言語を生命体として捉える社会生物学的な概念を利用した。彼はアウグスト・シュライヒャーとマックス・ミュラーの言語を生活空間のために奮 闘する有機体としての考え方を批判しているが、言語の「有機体」の研究がその領域への適応を除外する限りにおいて、自然科学としての言語学の考え方を推進 することで決着している[44]。 この概念はプラハ・サークルの言語学者であるロマン・ヤコブソンとニコライ・トルベツコイによってソシュール以降の言語学で修正され[45]、最終的には 減少することになる[46]。 音声回路 主な記事 言語とパロール おそらくソシュールの考えで最も有名なのは言語と音声(Fr. langue et parole)の区別であり、「音声」は言語使用の個々の発生を指す。これらはソシュールの「発話回路」(circuit de parole)の3つのうちの2つの部分を構成している。第三の部分は脳、つまり言語共同体の個々のメンバーの心である[f]。この考え方は原則としてス タインタルから借用したものであり、社会的事実としての言語というソシュールの概念は「フォルクスガイスト」に相当するが、彼は民族主義的な解釈を排除す るように注意した。ソシュールやデュルケムの考え方では、社会的事実や規範は個人を高めるものではなく、個人を束縛するものである[41][42]。 「発話によって結ばれたすべての個人の間で、ある種の平均が設定される:すべての人が-もちろん正確ではないが、おおよそ-同じ概念と結びついた同じ記号 を再現する」[g]。 ソシュールは、言語とは「社会的事実」であり、発話に関する規則や規範の慣例化された集合であると主張する。少なくとも二人の人間が会話をしているとき、 個々の話者の心の間にコミュニケーション回路が形成される。ソシュールは、社会システムとしての言語は、音声の中にも心の中にも存在しないと説明する。 ループの中で、両者の間にのみ適切に存在する。個人は言語の規範的ルールを学ばなければならないが、それをコントロールすることは決してできない。 言語学者の仕事は、音声サンプルを分析することによって言語を研究することである。実用的な理由から、これは通常、書かれたテキストの分析である。[j] テキストを通じて言語を研究するという考えは、言語学が始まって以来、一般的に行われてきたことであり、決して革命的なものではない。しかし、言語学が心 の研究ではないという考えは、ソシュールの同時代の文脈ではヴィルヘルム・ヴントのVölkerpsychologieに、後の文脈では生成文法や認知言 語学に矛盾する[47]。 |

| A legacy of ideological disputes Structuralism versus generative grammar Saussure's influence was restricted to American linguistics which was dominated by the advocates of Wilhelm Wundt's psychological approach to language, especially Leonard Bloomfield (1887–1949).[48] The Bloomfieldian school rejected Saussure's and other structuralists' sociological or even anti-psychological (e.g. Louis Hjelmslev, Lucien Tesnière) approaches to the theory of language. Problematically, the post-Bloomfieldian school was nicknamed 'American structuralism', confusing.[49] Although Bloomfield denounced Wundt's Völkerpsychologie and opted for behavioural psychology in his 1933 textbook Language, he and other American linguists stuck to Wundt's practice of analysing the grammatical object as part of the verb phrase. Since this practice is not semantically motivated, they argued for the disconnectedness of syntax from semantics,[50] thus fully rejecting structuralism. The question remained why the object should be in the verb phrase, vexing American linguists for decades.[50] The post-Bloomfieldian approach was eventually reformed as a sociobiological[51] framework by Noam Chomsky who argued that linguistics is a cognitive science; and claimed that linguistic structures are the manifestation of a random mutation in the human genome.[52] Advocates of the new school, generative grammar, claim that Saussure's structuralism has been reformed and replaced by Chomsky's modern approach to linguistics. Jan Koster asserts: it is certainly the case that Saussure considered the most important linguist of the century in Europe until the 1950s, hardly plays a role in current theoretical thinking about language. As a result of the Chomskyan revolution, linguistics has gone through a number of conceptual transformations which have led to all kinds of technical pre-occupations that are far beyond linguistic practice of the days of Saussure. For the most it seems Saussure has rightly sunk into near oblivion.[53] French historian and philosopher François Dosse however argues that there have been various misunderstandings. He points out that Chomsky's criticism of 'structuralism' is directed at the Bloomfieldian school and not the proper address of the term; and that structural linguistics is not to be reduced to mere sentence analysis.[54] It is also argued that "'Chomsky the Saussurean' is nothing but "an academic fable". This fable is a result of misreading – by Chomsky himself (1964) and also by others – of Saussure's la langue (in the singular form) as generativist concept of 'competence' and, therefore, its grammar as the Universal Grammar (UG)."[55] Saussure versus the social Darwinists Saussure's Course in General Linguistics begins[k] and ends[l] with a criticism of 19th-century linguistics where he is especially critical of Volkgeist thinking and the evolutionary linguistics of August Schleicher and his colleagues. Saussure's ideas replaced social Darwinism in Europe as it was banished from humanities at the end of World War II.[56] The publication of Richard Dawkins's memetics in 1976 brought the Darwinian idea of linguistic units as cultural replicators back to vogue.[57] It became necessary for adherents of this movement to redefine linguistics in a way that would be simultaneously anti-Saussurean and anti-Chomskyan. This led to a redefinition of old humanistic terms such as structuralism, formalism, functionalism, and constructionism along Darwinian lines through debates that were marked by an acrimonious tone. In a functionalism–formalism debate of the decades following The Selfish Gene, the 'functionalism' camp attacking Saussure's legacy includes frameworks such as Cognitive Linguistics, Construction Grammar, Usage-based linguistics, and Emergent Linguistics.[58][59] Arguing for 'functional-typological theory', William Croft criticises Saussure's use of the organic analogy: When comparing functional-typological theory to biological theory, one must take care to avoid a caricature of the latter. In particular, in comparing the structure of language to an ecosystem, one must not assume that in contemporary biological theory, it is believed that an organism possesses a perfect adaptation to a stable niche inside an ecosystem in equilibrium. The analogy of a language as a perfectly adapted 'organic' system where tout se tient is a characteristic of the structuralist approach, and was prominent in early structuralist writing. The static view of adaptation in biology is not tenable in the face of empirical evidence of nonadaptive variation and competing adaptive motivations of organisms.[60] Structural linguist Henning Andersen disagrees with Croft. He criticises memetics and other models of cultural evolution and points out that the concept of 'adaptation' is not to be taken in linguistics in the same meaning as in biology.[46] Humanistic and structuralistic notions are likewise defended by Esa Itkonen[61][62] and Jacques François;[63] the Saussurean standpoint is explained and defended by Tomáš Hoskovec, representing the Prague Linguistic Circle.[64] Conversely, other cognitive linguists claim to continue and expand Saussure's work on the bilateral sign. Dutch philologist Elise Elffers, however, argues that their view of the subject is incompatible with Saussure's ideas.[65] The term 'structuralism' continues to be used in structural–functional inguistics[66][67] which despite the contrary claims defines itself as a humanistic approach to language.[68] |

イデオロギー論争の遺産 構造主義対生成文法 ソシュールの影響は、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの言語に対する心理学的アプローチの提唱者、特にレナード・ブルームフィールド(Leonard Bloomfield, 1887-1949)によって支配されていたアメリカの言語学に限定されていた[48]。ブルームフィールド学派は、ソシュールや他の構造主義者の言語理 論に対する社会学的、あるいは反心理学的なアプローチ(ルイス・ヘルムスレフ(Louis Hjelmslev)、ルシアン・テズニエール(Lucien Tesnière)など)を否定していた。問題なのは、ブルームフィールド以後の学派が「アメリカ構造主義」とあだ名され、混乱していたことである [49]。ブルームフィールドは1933年の教科書『言語』において、ヴントのVölkerpsychologieを非難し、行動心理学を選択したが、彼 と他のアメリカの言語学者たちは、動詞句の一部として文法的目的語を分析するというヴントの実践に固執した。この実践は意味論的に動機づけられたものでは ないため、彼らは統語論が意味論から切り離されていることを主張し、構造主義を完全に否定した[50]。 ブルームフィールド以降のアプローチは、やがてノーム・チョムスキーによって社会生物学的[51]な枠組みとして改革され、彼は言語学は認知科学であると 主張し、言語構造は人間のゲノムにおけるランダムな突然変異の現れであると主張した[52]。ヤン・コスターはこう主張する: 1950年代までヨーロッパで今世紀最も重要な言語学者と考えられていたソシュールが、現在の言語に関する理論的思考においてほとんど役割を果たしていな いことは確かである。チョムスキー革命の結果、言語学は多くの概念的な変容を遂げ、ソシュールの時代の言語実践をはるかに超えた、あらゆる種類の技術的な 先入観を持つようになった。ほとんどの場合、ソシュールは正しく忘却の彼方に沈んでしまったようである[53]。 しかし、フランスの歴史家であり哲学者であるフランソワ・ドセは、様々な誤解があったと主張している。彼は、チョムスキーの「構造主義」批判はブルーム フィールド学派に向けられたものであり、この用語の適切な扱いではないこと、そして構造言語学は単なる文章分析に還元されるべきものではないことを指摘し ている[54]。 ソシュール人チョムスキー」は「学問的寓話」に過ぎない。この寓話は、ソシュールのラング(単数形)を「能力」の生成論的概念として、したがってその文法 を普遍文法(UG)として、チョムスキー自身(1964年)や他の人々によって誤読された結果である」[55]。 ソシュール対社会ダーウィン主義者 ソシュールの『一般言語学講座』は19世紀の言語学に対する批判で始まり[k]、終わり[l]、特にヴォルクガイストの考え方とアウグスト・シュライ ヒャーとその同僚たちの進化言語学を批判している。ソシュールの思想は、ヨーロッパにおいて社会ダーウィニズムに取って代わり、第二次世界大戦の終わりに は人文科学から追放された[56]。 1976年にリチャード・ドーキンスのミーム論が発表されると、文化的複製者としての言語単位というダーウィン的な考え方が再び流行するようになった [57]。この運動の支持者たちは、反ソシュールと反チョムスキーを同時に実現するような形で言語学を再定義する必要が生じた。このため、構造主義、形式 主義、機能主義、構築主義といった旧来の人文主義的な用語を、険悪な論調を特徴とする議論を通じてダーウィン的な線に沿って再定義することになった。利己 的な遺伝子』に続く数十年間の機能主義-形式主義論争において、ソシュールの遺産を攻撃する「機能主義」陣営には、認知言語学、構成文法、用法に基づく言 語学、創発言語学などのフレームワークが含まれる[58][59]。機能的類型論」を主張するウィリアム・クロフトはソシュールの有機的アナロジーの使用 を批判している: 機能的類型論と生物学的類型論を比較する際には、後者を戯画化しないように注意しなければならない。特に、言語の構造を生態系に例える場合、現代の生物学 理論において、生物が平衡状態にある生態系内の安定したニッチに完璧に適応していると信じられていることを前提にしてはならない。言語が完全に適応した 「有機的な」システムであり、tout se tientが存在するというアナロジーは、構造主義的アプローチの特徴であり、初期の構造主義的な著作で顕著であった。生物学における適応の静的な見解 は、生物の非適応的変異や競合する適応的動機の経験的証拠の前では通用しない[60]。 構造言語学者のヘニング・アンダーセンはクロフトに同意していない。彼はミメティックスやその他の文化的進化のモデルを批判し、言語学において「適応」と いう概念は生物学と同じ意味で捉えられるべきではないと指摘している[46]。 人文主義的および構造主義的な概念も同様にエサ・イトコネン[61][62]やジャック・フランソワによって擁護されており[63]、ソシュールの立場は プラハ言語学サークルを代表するトマーシュ・ホスコヴェックによって説明され擁護されている[64]。 逆に、他の認知言語学者たちはソシュールの二者間記号に関する研究を継承し、発展させると主張している。しかしオランダの言語学者エリーゼ・エルファース は、彼らの主体観はソシュールの考えとは相容れないと主張している[65]。 構造主義」という用語は構造機能言語学[66][67]で使用され続けており、その構造機能言語学は反対の主張にもかかわらず、言語に対する人文主義的ア プローチとして自らを定義している[68]。 |

| Works (1878) Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes [= Dissertation on the Primitive System of Vowels in Indo-European Languages]. Leipzig: Teubner. (online version in Gallica Program, Bibliothèque nationale de France). (1881) De l'emploi du génitif absolu en Sanscrit: Thèse pour le doctorat présentée à la Faculté de Philosophie de l'Université de Leipzig [= On the Use of the Genitive Absolute in Sanskrit: Doctoral thesis presented to the Philosophy Department of Leipzig University]. Geneva: Jules-Guillamaume Fick. (online version on the Internet Archive). (1916) Cours de linguistique générale, eds. Charles Bally & Albert Sechehaye, with the assistance of Albert Riedlinger. Lausanne – Paris: Payot. 1st trans.: Wade Baskin, trans. Course in General Linguistics. New York: The Philosophical Society, 1959; subsequently edited by Perry Meisel & Haun Saussy, NY: Columbia University Press, 2011. 2nd trans.: Roy Harris, trans. Course in General Linguistics. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, 1983. (1922) Recueil des publications scientifiques de F. de Saussure. Eds. Charles Bally & Léopold Gautier. Lausanne – Geneva: Payot. (1993) Saussure's Third Course of Lectures in General Linguistics (1910–1911) from the Notebooks of Emile Constantin. (Language and Communication series, vol. 12). French text edited by Eisuke Komatsu & trans. by Roy Harris. Oxford: Pergamon Press. (1995) Phonétique: Il manoscritto di Harvard Houghton Library bMS Fr 266 (8). Ed. Maria Pia Marchese. Padova: Unipress, 1995. (2002) Écrits de linguistique générale. Eds. Simon Bouquet & Rudolf Engler. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-076116-6. Trans.: Carol Sanders & Matthew Pires, trans. Writings in General Linguistics. NY: Oxford University Press, 2006. This volume, which consists mostly of material previously published by Rudolf Engler, includes an attempt at reconstructing a text from a set of Saussure's manuscript pages headed "The Double Essence of Language", found in 1996 in Geneva. These pages contain ideas already familiar to Saussure scholars, both from Engler's critical edition of the Course and from another unfinished book manuscript of Saussure's, published in 1995 by Maria Pia Marchese. (2013) Anagrammes homériques. Ed. Pierre-Yves Testenoire. Limoges: Lambert Lucas. (2014) Une vie en lettres 1866 – 1913. Ed. Claudia Mejía Quijano. ed. Nouvelles Cécile Defaut. |

|

| Theory of language Geneva School Jan Baudouin de Courtenay https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_de_Saussure |

言語理論 ジュネーブ学派 ヤン・ボードゥアン・ド・コートネー |

Jan Niecisław Ignacy Baudouin de Courtenay,

also Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay (Russian: Иван

Александрович Бодуэн де Куртенэ; 13 March 1845 – 3 November 1929) was a

Russian and Polish[2] linguist and Slavist, best known for his theory

of the phoneme and phonetic alternations. Jan Niecisław Ignacy Baudouin de Courtenay,

also Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay (Russian: Иван

Александрович Бодуэн де Куртенэ; 13 March 1845 – 3 November 1929) was a

Russian and Polish[2] linguist and Slavist, best known for his theory

of the phoneme and phonetic alternations.For most of his life Baudouin de Courtenay worked at Imperial Russian universities: Kazan (1874–1883), Dorpat (now Estonia) (1883–1893), Kraków (1893–1899) in Austria-Hungary, and St. Petersburg (1900–1918).[3] In 1919–1929 he was a professor at the re-established University of Warsaw in a once again independent Poland. Biography He was born in Radzymin, in the Warsaw Governorate of Congress Poland (a state in personal union with the Russian Empire), to a family of distant French extraction.[1]: 70 One of his ancestors had been a French aristocrat who immigrated to Poland during the reign of Polish King Augustus II the Strong. In 1862 Baudouin de Courtenay entered the "Main School," a predecessor of the University of Warsaw. In 1866 he graduated from its historical and philological faculty and won a scholarship of the Russian Imperial Ministry of Education. After leaving Poland, he studied at various foreign universities, including those of Prague, Jena and Berlin. In 1870 he received a doctorate from the University of Leipzig for his work on analogy and a master's degree from St. Petersburg for his Polish-language dissertation On the Old Polish Language Prior to the 14th Century.[1]: 71 Baudouin de Courtenay established the Kazan School of linguistics in the mid-1870s and served as professor at the local university from 1875. Later he was chosen as the head of linguistics faculty at the University of Dorpat (1883–1893). In 1882 he married historian and journalist Romualda Bagnicka. Between 1894 and 1898 he occupied the same post at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków only to be appointed to St. Petersburg, where he continued to refine his theory of phonetic alternations. After Poland regained independence in 1918, he returned to Warsaw, where he formed the core of the linguistics faculty of the University of Warsaw. From 1887 he held a permanent seat in the Polish Academy of Skills and from 1897 he was a member of the Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Baudouin de Courtenay was the editor of the 3rd (1903–1909) and 4th (1912–1914) editions of the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language compiled by Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dahl (1801–1872). Apart from his scientific work, Baudouin de Courtenay was also a strong supporter of the national revival of various national minority and ethnic groups. In 1915 he was arrested by the Okhrana, the Russian secret service, for publishing a brochure on the autonomy of peoples under Russian rule. He spent three months in prison, but was released. In 1922, without his knowledge, he was proposed by the national minorities of Poland as a presidential candidate, but was defeated in the third round of voting in the Polish parliament and eventually Gabriel Narutowicz was chosen. He was also an active Esperantist and president of the Polish Esperanto Association. In 1925, he was one of the co-founders of the Polish Linguistic Society. In 1927 he formally withdrew from the Roman Catholic Church without joining any other religious denomination. He died in Warsaw. He is buried at the Protestant Reformed Cemetery in Warsaw with the epitaph "He sought truth and justice". Contribution to linguistics His work had a major influence on 20th-century linguistic theory, and it served as a foundation for several schools of phonology. He was an early champion of synchronic linguistics, the study of contemporary spoken languages, which he developed contemporaneously with the structuralist linguistic theory of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. Among the most notable of his achievements is the distinction between statics and dynamics of languages and between a language (an abstract group of elements) and speech (its implementation by individuals) – compare Saussure's concepts of langue and parole. Together with his students, Mikołaj Kruszewski and Lev Shcherba, Baudouin de Courtenay also shaped the modern usage of the term "phoneme" (Baudouin de Courtenay 1876–77 and Baudouin de Courtenay 1894),[4][5] which had been coined in 1873 by the French linguist A. Dufriche-Desgenettes[6] who proposed it as a one-word equivalent for the German Sprachlaut.[7] His work on the theory of phonetic alternations may have had an influence on the work of Ferdinand de Saussure according to E. F. K. Koerner.[8] Three major schools of 20th-century phonology arose directly from his distinction between physiophonetic (phonological) and psychophonetic (morphophonological) alternations: the Leningrad school of phonology, the Moscow school of phonology, and the Prague school of phonology. All three schools developed different positions on the nature of Baudouin's alternational dichotomy. The Prague School was best known outside the field of Slavic linguistics. Throughout his life he published hundreds of scientific works in Polish, Russian, Czech, Slovenian, Italian, French and German. Views According to historian Norman Davies, Baudouin de Courtenay was one of the most extraordinary Polish thinkers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Davies writes: "He was a pacifist, an advocate of the fight for environmental protection, a feminist, a fighter for progress in the field of education, and a free thinker, and he was against most of the social and intellectual conventions of his day."[9] Baudouin de Courtenay was an atheist[10] and did not consider himself a member of the Catholic Church for most of his life. He was Chairman of the Polish Association of Freethinkers. Baudouin de Courtenay was in favor of introducing Polish science to all Jewish schools in the Second Polish Republic, and Yiddish to all Polish schools. In his public appearances, he openly criticized anti-semitism and manifestations of organized xenophobia, for which he was repeatedly attacked.[11] Legacy His daughter, Cezaria Baudouin de Courtenay Ehrenkreutz Jędrzejewiczowa was one of the founders of the Polish school of ethnology and anthropology as well as a professor at the universities of Vilnius and Warsaw. He had four other children: Zofia, a painter and sculptor; Świętosław, a lawyer and diplomat; Ewelina, a historian; and Maria, a lawyer. He appears as a character in Joseph Skibell's 2010 novel, A Curable Romantic. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Baudouin_de_Courtenay |

Jan Niecisław Ignacy Baudouin de Courtenay,

またの名を Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay (Russian: Иван

Александрович Бодуэн де Куртенэ; 1845年3月13日 - 1929年11月3日)

はロシア人およびポーランド人[2]の言語学者、スラヴ学者で、音素と音韻交替の理論で最もよく知られている。 Jan Niecisław Ignacy Baudouin de Courtenay,

またの名を Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay (Russian: Иван

Александрович Бодуэн де Куртенэ; 1845年3月13日 - 1929年11月3日)

はロシア人およびポーランド人[2]の言語学者、スラヴ学者で、音素と音韻交替の理論で最もよく知られている。ボードゥアン・ド・コートネは生涯の大半をロシア帝国の大学で過ごした: カザン(1874-1883)、ドルパト(現在のエストニア)(1883-1893)、オーストリア=ハンガリーのクラクフ(1893-1899)、サン クトペテルブルク(1900-1918)[3]。1919-1929年には、再び独立したポーランドのワルシャワ大学で教授を務めた。 略歴 先祖のひとりはフランス貴族で、ポーランド王アウグスト2世の時代にポーランドに移住した。1862年、ボードゥアン・ド・コートネはワルシャワ大学の前 身である「メイン・スクール」に入学。1866年に同大学の歴史言語学部を卒業し、ロシア帝国教育省の奨学金を獲得した。ポーランドを離れた後、プラハ、 イエナ、ベルリンなど海外のさまざまな大学で学ぶ。1870年、類推に関する研究でライプツィヒ大学から博士号を、ポーランド語の論文『14世紀以前の古 いポーランド語について』でサンクトペテルブルクから修士号を授与された[1]: 71。 ボードゥアン・ド・コートネーは、1870年代半ばにカザン言語学派を設立し、1875年から地元大学の教授を務めた。その後、ドルパト大学の言語学部長 (1883-1893)に抜擢される。1882年、歴史家でジャーナリストのロムアルダ・バグニツカと結婚。1894年から1898年にかけてはクラクフ のヤギェウォ大学で同じポストを務めたが、その後サンクトペテルブルクに赴任し、そこで音韻交替の理論に磨きをかけた。1918年にポーランドが独立を回 復するとワルシャワに戻り、ワルシャワ大学の言語学部の中核を担った。1887年からはポーランド技能アカデミーの常任理事、1897年からはペテルブル ク科学アカデミーの会員となった。 ボードゥアン・ド・コートネーは、ロシアの辞書編纂者ウラジーミル・ダール(1801~1872)が編纂した『生きた大ロシア語解説辞典』の第3版 (1903~1909年)および第4版(1912~1914年)の編集者を務めた。 科学的な業績とは別に、ボードゥアン・ド・コートネーは、さまざまな少数民族や民族の民族復興の強力な支援者でもあった。1915年、彼はロシア統治下の 民族の自治に関するパンフレットを出版したため、ロシアの秘密機関オクラナに逮捕された。彼は3ヵ月間獄中で過ごしたが、釈放された。1922年、本人が 知らないうちに、ポーランドの少数民族から大統領候補として推薦されたが、ポーランド議会の第3回投票で敗れ、最終的にガブリエル・ナルトヴィッチが選ば れた。エスペランティストとしても活躍し、ポーランド・エスペラント協会の会長も務めた。1925年、ポーランド言語学会の共同設立者の一人となる。 1927年、ローマ・カトリック教会から正式に脱退。ワルシャワで死去。ワルシャワのプロテスタント改革派墓地に埋葬され、墓碑銘は「彼は真理と正義を求 めた」。 言語学への貢献 彼の研究は20世紀の言語理論に大きな影響を与え、音韻論のいくつかの学派の基礎となった。彼は、スイスの言語学者フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの構造 主義言語学と同時期に発展させた、現代の話し言葉を研究する共時言語学の初期の支持者であった。ソシュールのラングとパロールの概念と比較し、言語の静態 と動態を区別し、言語(抽象的な要素群)と音声(個人によるその実行)を区別した。 ボードゥアン・ド・コートネは、彼の弟子であるミコワ・クルシェフスキとレフ・シュチェルバとともに、1873年にフランスの言語学者A. 彼の音韻交替理論に関する研究は、E. F. K. Koernerによればフェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの研究に影響を与えた可能性がある[8]。 レニングラード音韻学派、モスクワ音韻学派、プラハ音韻学派である。この3つの学派はすべて、ボードゥアンの交替二分法の性質について異なる立場をとって いた。プラハ学派はスラブ言語学の分野以外では最もよく知られていた。彼は生涯を通じて、ポーランド語、ロシア語、チェコ語、スロベニア語、イタリア語、 フランス語、ドイツ語で何百もの科学的著作を発表した。 見解 歴史家のノーマン・デイヴィスによれば、ボードゥアン・ド・コートネーは19世紀から20世紀にかけてのポーランドで最も傑出した思想家の一人であった。 デイヴィスはこう書いている: 「彼は平和主義者であり、環境保護のための闘いの擁護者であり、フェミニストであり、教育の分野における進歩の闘士であり、自由な思想家であり、当時の社 会的・知的慣習のほとんどに反対していた」[9]。 ボードゥアン・ド・コートネは無神論者であり[10]、生涯のほとんどをカトリック教会の信者とは考えていなかった。ポーランド自由思想家協会の会長を務 めた。 ボードゥアン・ド・クルトネは、第二次ポーランド共和国のすべてのユダヤ人学校にポーランド語の科学を、すべてのポーランド人学校にイディッシュ語を導入 することに賛成していた。公の場では、反ユダヤ主義や組織的な排外主義を公然と批判し、繰り返し攻撃を受けた[11]。 遺産 娘のセザリア・ボードゥアン・ド・コートゥネー・エーレンクロイツ・イェドルツェイェヴィツォワは、ポーランド民族学・人類学の創始者の一人であり、ヴィ リニュスとワルシャワの大学で教授を務めた。彼には他に4人の子供がいた: ゾフィアは画家で彫刻家、シヴィエトスワフは弁護士で外交官、エヴェリナは歴史家、マリアは弁護士である。 ジョセフ・スキベルが2010年に発表した小説『A Curable Romantic』にも登場する。 |

☆ 一般言語学講義

| 一般言語学講義 (フランス語: Cours de linguistique

générale)

は、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールが1906年から1911年にかけて行った講義の内容を、シャルル・バイイとアルベール・セシュエが編集し出版された

本である。ソシュールの死後1916年に出版され、20世紀前半にヨーロッパ、アメリカで栄えた構造主義言語学の起こりと一般にみなされている。 ソシュールは特に比較言語学に興味を持っていたが、一般言語学講義ではより一般的に適用できる構造主義理論を発達させている。ソシュール自身の手稿を含ん だ原稿が1996年に見つかり、Writings in General Linguisticsとして出版されている。 本記事では、ソシュールがジュネーブ大学で行った講義と区別するため、バイイとセシュエが編集した本「一般言語学講義」を『講義』と記す。 |

|

| 講義 ソシュールがジュネーブ大学で教鞭をとっていたのは1891年から1912年までの21年間だが、一般言語学についての講義を行ったのは1907年、 1908-1909年、1910-1911年の僅か3回しかない[1]。この3回の講義も、ジュネーブ大学の言語学教授ヴェルトハイマーの退官のため任命 されたものを、嫌々引き受けたものである[2]。 |

|

| 第1回講義(1907年) 第1回の講義は1907年1月16日から7月3日の間に行われた。ジュネーブ大学が一般言語学の講座にソシュールを任命したのは1906年12月8日であ り、準備に与えられた時間は短かった[3]。出席者は6人であった[4]。講義の内容をうかがえるのは、リードランジュのノートと、カイユの速記録からで ある[5]。 講義は大きく分けて、「序論」と「第一部」の進化言語学から成る。「序論」では、まず旧来の言語学からソシュールが言語学ではないと考えるものを除外す る。その上で言語には「静態的な側面」と「進化的な側面」の2つがあるとする。「進化的な側面」は捉えるのに技術の習得が必要ないため、「進化的な側面」 の研究から言語学の説明を行うのがよいとして、「第一部」の進化言語学に移る。[6] 「第一部」進化言語学は、4つの部分、「音韻変化」「類推的変化」「印欧語族の内的、外的歴史の概観」「再建的方法とその価値」から成る。この内、「類推 的変化」が第一回講義の主題となっている[7]。 |

|

| 第2回講義(1908-1909年) 第二回講義は1908年11月第一週から、1909年6月24日にかけて行われた。出席者は11人で、そのうちの5人の記録が残っている[注釈 1][8]。 |

|

| 第3回講義(1910-1911年) 第三回講義は1910年10月28日[注釈 2]から、1911年7月24日にかけて行われた。出席者は12人で、そのうちの4人の記録が残っている[注釈 3][9]。 |

|

| 成立 ソシュールはメイエに宛てた1894年1月の手紙の中で、一般言語学についての本を計画していることを述べている[10]。だがその困難さのためかこの本 を実際に形にすることはなく[11]、1893年から1894年にかけて僅か6ページを書くにとどまった[10]。1894年より後は一般言語学について はほとんど手を付けなかったと考えられていたが、1996年にソシュール家の倉庫から多くの草稿が発見され、ソシュールが研究を続けていたことがわかった [12]。いずれにせよ、ソシュールの計画した本が、『講義』という本にそのままなったわけではない[10]。 『講義』はソシュールが1907年から1911年にかけて行った3回の講義の内容をバイイとセシュエがまとめたものであるが、この2人は3回のいずれの講 義にも出席していない[13]。2人は授業に出席できなかったことを悔やみ、ソシュールの講義を一つの本にまとめて形に残すことにした[14]。しかし、 ソシュールの講義は整然と言語学を論じるものではなかったため、2人は出席した学生から集めた講義ノートをそのまま本として刊行するのは不適切と考え、ソ シュールが以前に書いた草稿などとまとめて大きな編集を施し、出版することにした[15]。 ソシュールは一般言語学の講義が終わるたびに、準備した走り書きを破り捨てており、これを参考にすることはできなかった。バイイとセシュエが参照したソ シュールの草稿は、1894年前後のものを中心にしており、そのうち主要なものは3つある。「形態論」と題された講義の序論と思われるノート、上述の一般 言語学についての本の草稿、ホイットニーに向けた追悼論文である[16]。2人はこれらを断片的に利用しつつ[17]、比較的バランスの取れていた第3回 講義を元にして、1916年に一般言語学講義を刊行した[18]。 ソシュールの講義ノートをそのままには刊行しないというバイイとセシュエの方針には、同じソシュールの弟子であったルガールが反対していた[19]。『講 義』の刊行から3年経った1919年、一般言語学講義にはソシュールの講義が持っていた魅力が欠けており、講義ノートをそのまま刊行してソシュールの思想 を忠実に伝えたほうがよかったのではないか、と述べている[20]。 |

|

| 影響 スイス・ドイツ語圏 スイスにおけるソシュールの影響は直接的ではあったが、ジュネーブ大学を中心とした「ジュネーブ学派」に限定されていた。スイスのドイツ語圏のほとんどは 批判的であり、例えばヴァルトブルクは、通時的な研究と共時的な研究は両立し得ないというソシュールの主張を幻想だとし、これら2つを統一して扱う必要が あると主張している[21]。 『講義』の編集を行ったバイイとセシュエを始めとし、ソシュールの教えを受けた研究者たちは、単なる教え子にはとどまらず、『講義』の内容形成そのものに 関わっていることが指摘できる。例えば丸山圭三郎は、ソシュールのパロールの概念にバイイの文体論が影響していることは間違いないとしているし、セシュエ の理論がソシュールに影響を与えたことをウンデルリが指摘している[注釈 4][22]。 1931年にロンメルが『講義』をドイツ語訳すると、ドイツからも反応があったが、多くは厳しい批判であった。ドイツのみならず世界から届く批判に対し て、『講義』を文献学的に批判することでこれに答えようとする動きが第二次世界大戦あたりからジュネーブ学派から見られるようになる[23]。その中では 特にゴデルの「F. ド・ソシュール一般言語学講義原資料」(1957)は現在のソシュール研究の出発点となった点で大きな価値がある。エンゲラーの「校訂版」(1967- 1974)も注目される[24]。 フランス フランスでのソシュールの影響は、言語学のみにとどまらず、様々な分野に及んでいる[25]。 ソシュールのパリ時代[注釈 5]の弟子であり、後には友人となったアントワーヌ・メイエは、ソシュールの印欧語学者には心酔していたが、『講義』に関しては消極的な評価をするにとど まった。一方メイエの弟子エミール・バンヴェニストは印欧語学を言語哲学にまで発展させたが、その過程には『講義』が大きな影響を与えている[26]。ア ンドレ・マルティネが『講義』を精密に発展させた点で高く評価される[27]。 東欧 ドイツ 日本 1922年に神保格が『講義』を初めて紹介し、1928年には小林英夫が「言語学原論」というタイトルで翻訳を刊行している[注釈 6]。これは『講義』の翻訳としては世界初であった[28]。1920年代、日本の言語学では研究の指針と成るものを求めており、小林の翻訳した『講義』 はたちまちに普及した。言語学にとどまらない分野においての日本のソシュール理解においても、小林の訳業が大きな影響を与えている[29]。 時枝誠記が著書「国語学原論」内でソシュールの言語認識を批判したのを起こりとして、1940年から60年代にかけて続く時枝論争が発生する。『講義』を 文献学的に検証することはなく、小林の翻訳のみを参照していることもあったため、現在からすると無意味な論点が多くある。しかし、現在においてもソシュー ル研究の手がかりとなる点も多い[30]。 1960年代後半からは、言語学にとどまらない広い分野でソシュールの思想が論じられるようになる。講義ノートやソシュールの残した草稿を直接参照した海 外のソシュール研究が日本にも多く紹介され、日本の学界でもソシュールの原典にあたる研究者が現れ始めている[31]。 |

|

| 参考文献 De Mauro, Tulio 山内貴美夫訳 (1976), 「ソシュール一般言語学講義」校注, 東京: 而立書房 丸山, 圭三郎, ed. (1985), ソシュール小事典, 東京: 大修館書店, ISBN 4-469-04243-9 富盛, 伸夫 (1985a), “ソシュールの生涯”, in 丸山, 圭三郎, ソシュール小事典, pp. 3-60 富盛, 伸夫 (1985b), “『講義』の影響とソシュール学 - スイスおよびドイツ語圏”, in 丸山, 圭三郎, ソシュール小事典, pp. 162-167 前田, 英樹 (1985a), “『一般言語学講義』と原資料の間”, in 丸山, 圭三郎, ソシュール小事典 前田, 英樹 (1985b), “『講義』の影響とソシュール学 - 日本”, in 丸山, 圭三郎, ソシュール小事典, pp. 157-162 前田, 英樹 (1985c), “『講義』の影響とソシュール学 - フランス”, in 丸山, 圭三郎, ソシュール小事典, pp. 167-169 Harris, Roy; Taylor, Talbot 斎藤伸治、滝沢直宏訳 (1997), 言語論のランドマーク: ソクラテスからソシュールまで, 東京: 大修館書店 加賀野井, 秀一 (2004), 知の教科書 ソシュール, 東京: 講談社, ISBN 4-06-258300-3 ブーイサック, ポール 鷲尾翠訳 (2012), ソシュール超入門, 東京: 講談社, ISBN 978-4-06-258542-2 |

|

| https://x.gd/SWdya |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆