スラヴォイ・ジジェク

シナリオA:「あなたは私にリベラルデモクラットの 言葉と振る舞いを期待しているわけですね,ではお望みなだけ高潔なリベラリストとして振る舞う夢を見て差し上げましょう」

シナリオB:「君は僕に本当に醜いネトウヨであるこ とを期待しているわけだね,もちろん夢の中では僕はキモい差別主義者だよ」

※これは、フロイトの「女性同性愛の一事例の心的成 因 について」藤野寛訳、『フロイト全集17』岩波書店の女性患者の振る舞いのパロディである。ジジェクの人の良心を逆撫でするような、ジョークとも真意とも とれない言辞を受け止めるためには、ジジェクそのものがこの女性ヒステリー患者かも しれないと、疑ってよめば、ストレスなく、ジジェクを自家薬籠中にでき るのではないかと僕(垂水源之介)は思うのであった。

︎● ジジェクポータル

☆

| Slavoj

Žižek (/ˈslɑːvɔɪ ˈʒiːʒɛk/ (listen) SLAH-voy ZHEE-zhek, Slovene:

[ˈslaʋɔj ˈʒiʒɛk];[needs tone marked IPA] born 21 March 1949) is a

Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.[5][6]

He is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the

Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New York

University and a senior researcher at the University of Ljubljana's

Department of Philosophy.[7] He primarily works on continental

philosophy (particularly Hegelianism, psychoanalysis and Marxism) and

political theory, as well as film criticism and theology. Žižek is the most famous associate of the Ljubljana School of Psychoanalysis, a group of Slovenian academics working on German idealism, Lacanian psychoanalysis, ideology critique, and media criticism. His breakthrough work was 1989's The Sublime Object of Ideology, his first book in English, which was decisive in the introduction of the Ljubljana School's thought to English-speaking audiences. He has written over 50 books in multiple languages. The idiosyncratic style of his public appearances, frequent magazine op-eds, and academic works, characterised by the use of obscene jokes and pop cultural examples, as well as politically incorrect provocations, have gained him fame, controversy and criticism both in and outside academia.[8] In 2012, Foreign Policy listed Žižek on its list of Top 100 Global Thinkers, calling him "a celebrity philosopher",[9] while elsewhere he has been dubbed the "Elvis of cultural theory"[10] and "the most dangerous philosopher in the West".[11] Žižek has been called "the leading Hegelian of our time",[12] and "the foremost exponent of Lacanian theory".[13] A journal, the International Journal of Žižek Studies, was founded by professors David J. Gunkel and Paul A. Taylor to engage with his work.[14] |

ス

ラヴォイ・ジジェク(/ˈslɑːvɔɪ ˈʒːʒˈɑː (聞き) SLAH-voy ZHEE-zhek, スロベニア語:

[1949年3月21日生まれ。ロンドン大学バークベック人文科学研究所国際ディレクター、ニューヨーク大学客員教授、リュブリャナ大学哲学科上級研究員

[5][6]。 [主に大陸哲学(特にヘーゲル主義、精神分析、マルクス主義)、政治理論、映画批評、神学を研究。 ジジェクは、ドイツ観念論、ラカン派精神分析、イデオロギー批評、メディア批評に取り組むスロベニアの学者グループ、リュブリャナ精神分析学派の最も有名 な仲間である。リュブリャナ学派の思想を英語圏の聴衆に紹介する上で決定的な役割を果たした。多言語で50冊以上の著作がある。猥雑なジョークやポップカ ルチャーの例を用いたり、政治的に正しくない挑発をしたりするのが特徴で、公の場に登場したり、頻繁に雑誌に寄稿したり、学術的な著作を発表したりする特 異なスタイルは、学界内外で名声を博し、論争や批判を巻き起こしている[8]。 2012年、フォーリン・ポリシーはジジェクを「世界の思想家トップ100」に挙げ、「有名人の哲学者」と呼び[9]、また別の場所では「文化理論のエル ビス」[10]や「西洋で最も危険な哲学者」と呼ばれている[11]。 [11]ジジェクは「現代を代表するヘーゲル主義者」[12]、「ラカン理論の第一人者」[13]と呼ばれている。ジジェクの研究に取り組むために、デイ ヴィッド・J・ガンケル教授とポール・A・テイラー教授によって「ジジェク研究国際ジャーナル」が創刊された[14]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavoj_%C5%BDi%C5%BEek |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Life and career Early life Žižek was born in Ljubljana, PR Slovenia, Yugoslavia, into a middle-class family.[15] His father Jože Žižek was an economist and civil servant from the region of Prekmurje in eastern Slovenia. His mother Vesna, a native of the Gorizia Hills in the Slovenian Littoral, was an accountant in a state enterprise. His parents were atheists.[16] He spent most of his childhood in the coastal town of Portorož, where he was exposed to Western film, theory and popular culture.[3][17] When Žižek was a teenager his family moved back to Ljubljana where he attended Bežigrad High School.[17] Originally wanting to become a filmmaker himself, he abandoned these ambitions and chose to pursue philosophy instead.[18] Education In 1967, during an era of liberalization in Titoist Yugoslavia, Žižek enrolled at the University of Ljubljana and studied philosophy and sociology.[19] Žižek had already begun reading French structuralists prior to entering university, and in 1967 he published the first translation of a text by Jacques Derrida into Slovenian.[20] Žižek frequented the circles of dissident intellectuals, including the Heideggerian philosophers Tine Hribar and Ivo Urbančič,[20] and published articles in alternative magazines, such as Praxis, Tribuna and Problemi, which he also edited.[17] In 1971 he accepted a job as an assistant researcher with the promise of tenure, but was dismissed after his Master's thesis was denounced by the authorities as being "non-Marxist".[21] He graduated from the University of Ljubljana in 1981 with a Doctor of Arts in Philosophy for his dissertation entitled The Theoretical and Practical Relevance of French Structuralism.[19] He spent the next few years in what was described as "professional wilderness", also fulfilling his legal duty of undertaking a year-long national service in the Yugoslav People's Army in Karlovac.[19] Academic career During the 1980s, Žižek edited and translated Jacques Lacan, Sigmund Freud, and Louis Althusser.[22] He used Lacan's work to interpret Hegelian and Marxist philosophy.[citation needed] In 1986, Žižek completed a second doctorate (Doctor of Philosophy in psychoanalysis) at the University of Paris VIII under Jacques-Alain Miller, entitled "La philosophie entre le symptôme et le fantasme".[23] Žižek wrote the introduction to Slovene translations of G. K. Chesterton's and John Le Carré's detective novels.[24] In 1988, he published his first book dedicated entirely to film theory, Pogled s strani.[25] The following year, he achieved international recognition as a social theorist with the 1989 publication of his first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology.[26][3] Žižek has been publishing in journals such as Lacanian Ink and In These Times in the United States, the New Left Review and The London Review of Books in the United Kingdom, and with the Slovenian left-liberal magazine Mladina and newspapers Dnevnik and Delo. He also cooperates with the Polish leftist magazine Krytyka Polityczna, regional southeast European left-wing journal Novi Plamen, and serves on the editorial board of the psychoanalytical journal Problemi.[27] Žižek is a series editor of the Northwestern University Press series Diaeresis that publishes works that "deal not only with philosophy, but also will intervene at the levels of ideology critique, politics, and art theory".[28] Political career In the late 1980s, Žižek came to public attention as a columnist for the alternative youth magazine Mladina, which was critical of Tito's policies, Yugoslav politics, especially the militarization of society. He was a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia until October 1988, when he quit in protest against the JBTZ trial together with 32 other Slovenian intellectuals.[29] Between 1988 and 1990, he was actively involved in several political and civil society movements which fought for the democratization of Slovenia, most notably the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights.[30] In the first free elections in 1990, he ran as the Liberal Democratic Party's candidate for the former four-person collective presidency of Slovenia.[26] Public life Žižek speaking in 2011 In 2003, Žižek wrote text to accompany Bruce Weber's photographs in a catalog for Abercrombie & Fitch. Questioned as to the seemliness of a major intellectual writing ad copy, Žižek told The Boston Globe, "If I were asked to choose between doing things like this to earn money and becoming fully employed as an American academic, kissing ass to get a tenured post, I would with pleasure choose writing for such journals!"[31] Žižek and his thought have been the subject of several documentaries. The 1996 Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! is a German documentary on him. In the 2004 The Reality of the Virtual, Žižek gave a one-hour lecture on his interpretation of Lacan's tripartite thesis of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real.[32] Zizek! is a 2005 documentary by Astra Taylor on his philosophy. The 2006 The Pervert's Guide to Cinema and 2012 The Pervert's Guide to Ideology also portray Žižek's ideas and cultural criticism. Examined Life (2008) features Žižek speaking about his conception of ecology at a garbage dump. He was also featured in the 2011 Marx Reloaded, directed by Jason Barker.[33] Foreign Policy named Žižek one of its 2012 Top 100 Global Thinkers "for giving voice to an era of absurdity".[9] In 2019, Žižek began hosting a mini-series called How to Watch the News with Slavoj Žižek on the RT network.[34] In April, Žižek debated psychology professor Jordan Peterson at the Sony Centre in Toronto, Canada over happiness under capitalism versus Marxism.[35][36] |

生涯とキャリア 生い立ち ジジェクはユーゴスラビア、スロベニアのリュブリャナで中流階級の家庭に生まれる[15]。父ヨジェ・ジジェク(Jože Žižek)はスロベニア東部のPrekmurje地方出身の経済学者で公務員。母ヴェスナはスロヴェニア・リトラル地方のゴリツィア丘陵出身で、国営企 業の会計士だった。両親は無神論者であった[16]。幼少期のほとんどを海岸沿いの町ポルトロジュで過ごし、そこで西洋の映画、理論、大衆文化に触れる。 [3][17]ジジェクが10代の頃、家族はリュブリャナに戻り、ベジグラード高校に通う。 教育 1967年、チトー主義ユーゴスラビアの自由化の時代に、ジジェクはリュブリャナ大学に入学し、哲学と社会学を学んだ[19]。 ジジェクは大学に入学する前にすでにフランスの構造主義者を読み始めており、1967年にはジャック・デリダのテキストをスロヴェニア語に翻訳した最初の 翻訳書を出版した[20]。 [17] 1971年、終身在職権を約束された助手の職を得るが、修士論文が「非マルクス主義的」であるとして当局から糾弾され、解雇された[21]。1981年、 『フランス構造主義の理論的および実践的妥当性』と題する論文でリュブリャナ大学を卒業し、哲学博士号を取得。 [19]その後数年間は、カルロヴァツにあるユーゴスラビア人民軍で1年間の兵役に就くという法的義務も果たしながら、「プロフェッショナルな荒野」と称 される日々を過ごした[19]。 学者としてのキャリア 1980年代、ジジェクはジャック・ラカン、ジークムント・フロイト、ルイ・アルチュセールを編集、翻訳した。 1986年、ジジェクはパリ第8大学でジャック=アラン・ミラーのもとで「La philosophie entre le symptôme et le fantasme」と題する2つ目の博士号(精神分析における哲学博士)を取得した[23]。 1988年、映画理論に特化した初の著書『Pogled s strani』を出版。翌1989年、初の英語著書『The Sublime Object of Ideology』を出版し、社会理論家として国際的に知られるようになる[26][3]。 ジジェクは、アメリカの『ラカニアン・インク』や『イン・ジセズ・タイムズ』、イギリスの『ニュー・レフト・レビュー』や『ロンドン・レビュー・オブ・ ブックス』、スロヴェニアの左派雑誌『ムラディナ』や新聞『ドネヴニク』や『デロ』などの雑誌に発表している。また、ポーランドの左翼雑誌 『Krytyka Polityczna』、南東ヨーロッパの左翼雑誌『Novi Plamen』に協力し、精神分析雑誌『Problemi』の編集委員を務めている[27]。ジジェクは、「哲学だけでなく、イデオロギー批判、政治、芸 術理論のレベルにも介入する」作品を出版するノースウェスタン大学出版局のシリーズ『Diaeresis』の編集者である[28]。 政治的キャリア 1980年代後半、ジジェクはチトーの政策やユーゴスラビア政治、特に社会の軍事化に批判的なオルタナティヴ・ユース誌『ムラディナ』のコラムニストとし て世間の注目を浴びるようになる。1988年10月までスロベニア共産党の党員であったが、JBTZ裁判に抗議して他の32人のスロベニアの知識人と共に 党を離党した[29]。1988年から1990年にかけて、スロベニアの民主化のために戦ったいくつかの政治運動や市民社会運動に積極的に関わり、特に人 権擁護委員会に参加した[30]。1990年の最初の自由選挙では、自由民主党の候補者としてスロベニアの旧4人制大統領選挙に立候補した[26]。 公的生活 2011年、講演するジジェク 2003年、ジジェクはアバクロンビー&フィッチのカタログに掲載されたブルース・ウェーバーの写真に文章を添えた。ジジェクはボストン・グローブ紙に対 し、「もし私が、お金を稼ぐためにこのようなことをするか、アメリカの学者として終身雇用のポストを得るためにケツにキスしながら完全に雇用されるかのど ちらかを選べと言われたら、喜んでこのような雑誌に書くことを選ぶだろう!」と語った[31]。 ジジェクと彼の思想は、いくつかのドキュメンタリー映画の題材となっている。1996年の『Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! 2004年の『The Reality of the Virtual』では、ジジェクはラカンの想像、象徴、現実の三部構成のテーゼの解釈について1時間の講義を行った[32]。2006年の『The Pervert's Guide to Cinema』と2012年の『The Pervert's Guide to Ideology』もジジェクの思想と文化批評を描いている。Examined Life』(2008年)は、ゴミ捨て場でエコロジーの概念について語るジジェクを描いている。ジェイソン・バーカー監督による2011年の『マルクス・ リローデッド』にも登場している[33]。 フォーリン・ポリシー』誌はジジェクを「不条理の時代に声を与えた」として、2012年の「世界の思想家トップ100」に選出した[9]。 2019年、ジジェクはRTネットワークで「How to Watch the News with Slavoj Žižek」というミニシリーズのホストを始めた[34]。 4月、ジジェクはカナダ・トロントのソニーセンターで心理学教授のジョーダン・ピーターソンと資本主義下の幸福とマルクス主義をめぐって討論した[35] [36]。 |

| Personal life Žižek has been married four times and has two adult sons, Tim and Kostja. His second wife was Slovene philosopher and socio-legal theorist Renata Salecl, fellow member of the Ljubljana School of Psychoanalysis.[37] His third wife was Argentinian model and Lacanian scholar Analia Hounie, whom he married in 2005.[38] Currently, he is married to Slovene journalist, author and philosopher, Jela Krečič.[39] In early 2018, Žižek experienced Bell's palsy on the right side of his face. He went on to give several lectures and interviews with this condition; on March 9 of that year, during a lecture on political revolutions in London, he commented on the treatment he had been receiving, and used his paralysis as a metaphor for political idleness.[40][41][42] Aside from his native Slovene, Žižek is a fluent speaker of Serbo-Croatian, French, German and English.[43] Taste In the 2012 Sight & Sound critics' poll, Žižek listed his 10 favourite films: 3:10 to Yuma, Dune, The Fountainhead, Hero, Hitman, Nightmare Alley, On Dangerous Ground, Opfergang, The Sound of Music, and We the Living. On this list, he clarified: "I opted for pure madness: the list contains only ‘guilty pleasures’".[44] In his tour of The Criterion Collection closet, he chose Trouble in Paradise, Sweet Smell of Success, Picnic at Hanging Rock, Murmur of the Heart, The Joke, The Ice Storm, Great Expectations, Roberto Rossellini's History Films, City Lights, a box set of Carl Theodor Dreyer's films, Y tu mamá también and Antichrist.[45] In an article called 'My Favourite Classics', Žižek states that Arnold Schoenberg's Gurre-Lieder is the piece of music he would take to a desert island. He goes on to list other favourites, including Beethoven's Fidelio, Schubert's Winterreise, Mussorgsky's Khovanshchina and Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore. He expresses a particular love for Wagner, particularly Das Rheingold and Parsifal. He ranks Schoenberg over Stravinsky, and insists on Eisler's importance among Schoenberg's followers.[46] Žižek often lists Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett and Andrei Platonov as his "three absolute masters of 20th century literature".[47] He ranks/prefers Varlam Shalamov over Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Marina Tsvetaeva and Osip Mandelstam over Anna Akhmatova,[48] Daphne du Maurier over Virginia Woolf, and Samuel Beckett over James Joyce.[47] |

私生活 ジジェクには4度の結婚歴があり、ティムとコスチャという2人の息子がいる。2人目の妻はスロベニアの哲学者で社会法学者のレナータ・サレクル(リュブ リャナ精神分析学派のメンバー)[37]。3人目の妻はアルゼンチンのモデルでラカンの研究者であるアナリア・ホウニ(2005年に結婚)[38]。 2018年初め、ジジェクは顔の右側にベル麻痺を経験。同年3月9日、ロンドンで行われた政治革命に関する講義の中で、彼は自分が受けていた治療について コメントし、麻痺を政治的怠惰の比喩として用いた[40][41][42]。 母国語であるスロベニア語の他に、ジジェクはセルボ・クロアチア語、フランス語、ドイツ語、英語を流暢に話すことができる[43]。 趣味・嗜好 2012年のSight & Sound誌の批評家投票で、ジジェクはお気に入りの映画10本を挙げている:『3:10 to Yuma』、『Dune』、『The Fountainhead』、『Hero』、『Hitman』、『Nightmare Alley』、『On Dangerous Ground』、『Opfergang』、『The Sound of Music』、『We the Living』。このリストについて、彼はこう明言している: クライテリオン・コレクションのクローゼット巡りでは、『Trouble in Paradise』、『Sweet Smell of Success』、『Picnic at Hanging Rock』、『Murmur of the Heart』、『The Joke』、『The Ice Storm』、『Great Expectations』、『Roberto Rossellini's History Films』、『City Lights』、カール・テオドール・ドレイヤー監督作品のボックスセット、『Y tu mamá también』、『Antichrist』を選んだ[45]。 ジジェクは「マイ・フェイバリット・クラシック」という記事の中で、無人島に持っていく音楽はアーノルド・シェーンベルクの「グール歌曲集」だと述べてい る。さらに、ベートーヴェンの『フィデリオ』、シューベルトの『ヴィンターライゼ』、ムソルグスキーの『ホヴァンシチナ』、ドニゼッティの『エリシール・ ダモーレ』など、お気に入りの曲を挙げている。彼はワーグナー、特に『ラインゴルト』と『パルジファル』への特別な愛を表明している。彼はストラヴィンス キーよりもシェーンベルクを高く評価し、シェーンベルクのフォロワーの中でもアイスラーの重要性を主張している[46]。 ジジェクはしばしばフランツ・カフカ、サミュエル・ベケット、アンドレイ・プラトーノフを「20世紀文学の絶対的な3人の巨匠」として挙げる[47]。 アレクサンドル・ソルジェニーツィンよりもヴァルラム・シャラモフを、アンナ・アフマトワよりもマリーナ・ツヴェターエワとオシップ・マンデルスタムを、 ヴァージニア・ウルフよりもダフネ・デュ・モーリエを、ジェイムズ・ジョイスよりもサミュエル・ベケットを、それぞれランク付け/支持している[48]。 |

| Political theory Ideology Žižek's Lacanian-informed theory of ideology is one of his major contributions to political theory; his first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology, and the documentary The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, in which he stars, are among the well-known places in which it is discussed. Žižek believes that ideology has been frequently misinterpreted as dualistic and, according to him, this misinterpreted dualism posits that there is a real world of material relations and objects outside of oneself, which is accessible to reason.[61] For Žižek, as for Marx, ideology is made up of fictions that structure political life; in Lacan's terms, ideology belongs to the symbolic order. Žižek argues that these fictions are primarily maintained at an unconscious level, rather than a conscious one. Since, according to psychoanalytic theory, the unconscious can determine one's actions directly, bypassing one's conscious awareness (as in parapraxes), ideology can be expressed in one's behaviour, regardless of one's conscious beliefs. Hence, Žižek breaks with orthodox Marxist accounts that view ideology purely as a system of mistaken beliefs (see False consciousness). Drawing on Peter Sloterdijk's Critique of Cynical Reason, Žižek argues that adopting a cynical perspective is not enough to escape ideology, since, according to Žižek, even though postmodern subjects are consciously cynical about the political situation, they continue to reinforce it through their behaviour.[62] Freedom Žižek claims that (a sense of) political freedom is sustained by a deeper unfreedom, at least under liberal capitalism. In a 2002 article, Žižek endorses Lenin's distinction between formal and actual freedom, claiming that liberal society only contains formal freedom, "freedom of choice within the coordinates of the existing power relations", while prohibiting actual freedom, "the site of an intervention that undermines these very coordinates."[63] In an oft-quoted passage from a book published in the same year, he writes that, in these conditions of liberal censorship, "we 'feel free' because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom".[64] In a 2019 article, he writes that Marx "made a valuable point with his claim that the market economy combines in a unique way political and personal freedom with social unfreedom: personal freedom (freely selling myself on the market) is the very form of my unfreedom."[65] However, in 2014, he rejects the "pseudo-Marxist" total derision of 'formal freedom', claiming that it is necessary for critique: "When we are formally free, only then we become aware how limited this freedom actually is."[47] Žižek co-signed a petition condemning the “use of disproportionate force and retaliatory brutality by the Hong Kong Police against students in university campuses in Hong Kong” during the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. The petition concludes with the statement: "We believe the defence of academic freedom, the freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and association, and the responsibility to protect the safety of our students are universal causes common to all."[66] Theology Žižek has asserted that "Atheism is a legacy worth fighting for" in The New York Times.[67] However, he nonetheless finds extensive conceptual value in Christianity, particularly Protestantism: the subtitle of his 2000 book The Fragile Absolute is "Or, Why Is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For?". Hence, he labels his position 'Christian Atheism',[68] and has written about theology at length.[69] In The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, Žižek suggests that "the only way to be an Atheist is through Christianity", since, he claims, atheism often fails to escape the religious paradigm by remaining faithful to an external guarantor of meaning, simply switching God for natural necessity or evolution. Christianity, on the other hand, in the doctrine of the incarnation, brings God down from the 'beyond' and onto earth, into human affairs; for Žižek, this paradigm is more authentically godless, since the external guarantee is abolished.[70] |

政治理論 イデオロギー ジジェクのラカン主義に基づくイデオロギー論は、政治理論における彼の主要な貢献のひとつである。彼の英語による最初の著書『イデオロギーの崇高な対象』 や、彼が主演したドキュメンタリー映画『The Pervert's Guide to Ideology』などが、イデオロギー論が語られる有名な場である。ジジェクによれば、イデオロギーはしばしば二元論的なものとして誤って解釈されてお り、この誤って解釈された二元論は、理性にアクセス可能な物質的な関係や物体の現実世界が自分の外側に存在すると仮定していると考えている[61]。 ジジェクにとって、マルクスにとってと同様に、イデオロギーは政治生活を構造化する虚構から構成されている。ジジェクによれば、これらの虚構は意識的なレ ベルではなく、主として無意識的なレベルで維持されている。精神分析理論によれば、無意識は(パラプレクスのように)人の意識を迂回して、人の行動を直接 決定することができるため、イデオロギーは意識的な信念とは関係なく、人の行動に表れることがある。それゆえジジェクは、イデオロギーを純粋に誤った信念 の体系とみなすマルクス主義の正統的な説明とは一線を画している(「誤った意識」を参照)。ジジェクはピーター・スローターダイクの『冷笑的理性批判』を 引きながら、冷笑的な視点を採用するだけではイデオロギーから逃れるには不十分であると論じている。ジジェクによれば、ポストモダンの主体は政治的状況に 対して意識的に冷笑的であるにもかかわらず、行動を通じてそれを強化し続けているからである[62]。 自由 ジジェクは、(政治的な)自由という感覚は、少なくとも自由資本主義のもとでは、より深い不自由によって支えられていると主張している。2002年の論文 でジジェクはレーニンの形式的自由と現実的自由の区別を支持し、自由主義社会は形式的自由、「既存の力関係の座標軸の中での選択の自由」しか含まず、現実 的自由、「これらの座標軸そのものを弱体化させる介入の場」を禁止していると主張している[63]。 [64]2019年の記事では、彼はマルクスが「市場経済が政治的・個人的自由と社会的不自由を独特な方法で結合させるという主張で貴重な指摘をしてい る: 「私たちが形式的に自由であるとき、初めて私たちはこの自由が実際にはどれほど制限されたものであるかを自覚する」[47]。 ジジェクは、2019年から2020年にかけての香港抗議行動における「香港警察による香港の大学キャンパスでの学生に対する不釣り合いな武力行使と報復 的な残虐行為」を非難する請願書に共同署名した。嘆願書は次のような声明で結ばれている: 「学問の自由の擁護、言論の自由、報道の自由、集会と結社の自由、そして学生の安全を守る責任は、すべての人に共通する普遍的な大義であると信じていま す」[66]。 神学 ジジェクはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で「無神論は戦うに値する遺産である」と主張している[67]。しかし、それにもかかわらず、彼はキリスト教、特にプ ロテスタント主義に広範な概念的価値を見出している。2000年に出版された彼の著書『The Fragile Absolute』の副題は「あるいは、なぜキリスト教の遺産は戦うに値するのか」である。それゆえ、彼は自身の立場を「キリスト教的無神論」と名付け [68]、神学について長々と書いている[69]。 ジジェクは『変態のイデオロギー入門』の中で、「無神論者になる唯一の方法はキリスト教を通すことだ」と提案している。他方、キリスト教は受肉の教義にお いて、神を「彼方」から地上に降ろし、人間の問題に取り込む。ジジェクにとって、このパラダイムは、外的な保証が廃されているため、より真正に無神的であ る[70]。 |

生物学者に反論し西洋音楽史を解説するジジェク(日本語字幕) |

|

| Communism Although sometimes adopting the title of 'radical leftist',[71] Žižek also controversially insists on identifying as a communist, even though he rejects 20th century communism as a "total failure", and decries "the communism of the 20th century, more specifically all the network of phenomena we refer to as Stalinism as "maybe the worst ideological, political, ethical, social (and so on) catastrophe in the history of humanity."[72] Žižek justifies this choice by claiming that only the term 'communism' signals a genuine step outside of the existing order, in part since the term 'socialism' no longer has radical enough implications, and means nothing more than that one "care[s] for society"[73] See also: Spontaneous order, Self-organization, and Council communism In Marx Reloaded, Žižek rejects both 20th-century totalitarianism and "spontaneous local self-organisation, direct democracy, councils, and so on". There, he endorses a definition of communism as "a society where you, everyone would be allowed to dwell in his or her stupidity", an idea with which he credits Fredric Jameson as the inspiration.[74] Žižek has labelled himself a "communist in a qualified sense".[75] When he spoke at a conference on The Idea of Communism, he applied (in qualified form) the 'communist' label to the Occupy Wall Street protestors: They are not communists, if 'communism' means the system which deservedly collapsed in 1990—and remember that the communists who are still in power today run the most ruthless capitalism (in China). ... The only sense in which the protestors are 'communists' is that they care for the commons—the commons of nature, of knowledge—which are threatened by the system. They are dismissed as dreamers, but the true dreamers are those who think that things can go on indefinitely the way they are now, with just a few cosmetic changes. They are not dreamers; they are awakening from a dream which is turning into a nightmare. They are not destroying anything; they are reacting to how the system is gradually destroying itself.[76] |

共産主義 ジジェクは「急進左翼」という肩書きを採用することもあるが[71]、20世紀の共産主義を「完全な失敗」として否定し、「20世紀の共産主義、より具体 的には、我々がスターリニズムと呼ぶすべての現象のネットワークは、人類史上最悪のイデオロギー的、政治的、倫理的、社会的(など)大惨事かもしれない」 と断罪しているにもかかわらず、共産主義者であることを主張する[72]。 ジジェクは、「共産主義」という用語だけが既存の秩序からの真の一歩を示すものであり、「社会主義」という用語はもはや十分に急進的な意味合いを持たず、 「社会を憂慮する」こと以上の意味を持たないと主張することで、この選択を正当化している[73]。 以下も参照: 自発的秩序、自己組織化、評議会共産主義 ジジェクは『マルクス・リローデッド』の中で、20世紀の全体主義と「自然発生的な地域の自己組織化、直接民主制、評議会など」の両方を否定している。そ こでは、共産主義の定義を「誰もが自分の愚かさに溺れることを許される社会」として支持しており、フレドリック・ジェイムソンがその着想を得たとしている [74]。 ジジェクは自らを「修飾された意味での共産主義者」と名乗っている[75]。共産主義の思想に関する会議で講演した際、彼は(修飾された形で)「共産主義 者」というレッテルをウォール街を占拠せよのデモ参加者に貼った: 共産主義』が1990年に崩壊して当然の体制を意味するのであれば、彼らは共産主義者ではない。... 抗議者たちが「共産主義者」であるという唯一の意味は、体制によって脅かされているコモンズ(自然や知識の共有物)を気にかけているということだ。彼らは 夢想家として排除されるが、真の夢想家とは、物事が今のまま、ほんの少し体裁を変えるだけで、いつまでも続くと考えている人たちのことである。彼らは夢想 家ではなく、悪夢と化しつつある夢から覚めようとしているのだ。彼らは何かを破壊しているのではなく、システムが徐々に自壊していく様子に反応しているの だ[76]。 |

| Electoral politics In May 2013, during Subversive Festival, Žižek commented: "If they don't support SYRIZA, then, in my vision of the democratic future, all these people will get from me [is] a first-class one-way ticket to [a] gulag." In response, the center-right New Democracy party claimed Žižek's comments should be understood literally, not ironically.[77][78] Just before the 2017 French presidential election, Žižek stated that one could not choose between Macron and Le Pen, arguing that the neoliberalism of Macron just gives rise to neofascism anyway. This was in response to many on the left calling for support for Macron to prevent a Le Pen victory.[79] In 2022, Žižek expressed his support for the Slovenian political party Levica (The Left) at its 5th annual conference.[80] Support for Donald Trump's election In a 2016 interview with Channel 4, Žižek said that were he American, he would vote for Donald Trump in the 2016 United States presidential election: I'm horrified at him [Trump]. I'm just thinking that Hillary is the true danger. ... if Trump wins, both big parties, Republicans and Democratics, would have to return to basics, rethink themselves, and maybe some things can happen there. That's my desperate, very desperate hope, that if Trump wins—listen, America is not a dictatorial state, he will not introduce Fascism—but it will be a kind of big awakening. New political processes will be set in motion, will be triggered. But I'm well aware that things are very dangerous here ... I'm just aware that Hillary stands for this absolute inertia, the most dangerous one. Because she is a cold warrior, and so on, connected with banks, pretending to be socially progressive.[81] These views were derisively characterised as accelerationist by Left Voice,[82] and were labelled "regressive" by Noam Chomsky, who claimed that "it was the same point that people like him said about Hitler in the early ['30s]."[83] In 2019 and 2020, Žižek defended his views,[84] saying that Trump's election "created, for the first time in I don't know how many decades, a true American left", citing the boost it gave Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.[49] However, regarding the 2020 United States presidential election, Žižek reported himself "tempted by changing his position", saying "Trump is a little too much".[49] In another interview, he stood by his 2016 "wager" that Trump's election would lead to a socialist reaction ("maybe I was right"), but claimed that "now with coronavirus: no, no—no Trump. ... difficult as it is for me to say this, but now I would say 'Biden better than Trump', although he is far from ideal."[85] In his 2022 book, Heaven in Disorder, Žižek continued to express a preference for Joe Biden over Donald Trump, stating "Trump was corroding the ethical substance of our lives", while Biden lies and represents big capital more politely.[86] |

選挙政治 2013年5月、破壊的フェスティバルの中でジジェクはこうコメントした: 「もし彼らがSYRIZAを支持しないのであれば、私が考える民主主義の未来において、この人たちが私から得られるのは、収容所行きのファーストクラスの 片道切符だけだ」。これに対して中道右派の新民主主義党は、ジジェクの発言は皮肉ではなく文字通りに理解されるべきだと主張した[77][78]。 2017年のフランス大統領選挙の直前、ジジェクはマクロンとルペンのどちらかを選ぶことはできないと述べ、マクロンの新自由主義はいずれにせよネオファ シズムを生み出すだけだと主張した。これは、左派の多くがルペンの勝利を防ぐためにマクロン支持を呼びかけたことに呼応したものだった[79]。 2022年、ジジェクはスロヴェニアの政党レヴィカ(ザ・レフト)の第5回年次大会で支持を表明した[80]。 ドナルド・トランプ当選支持 2016年のチャンネル4とのインタビューで、ジジェクは、もし自分がアメリカ人だったら、2016年のアメリカ大統領選挙でドナルド・トランプに投票す るだろうと語った: 彼(トランプ氏)にはぞっとする。ヒラリーこそ真の危険人物だと思う。...トランプが勝てば、共和党も民主党も大政党は基本に立ち返り、自分たちを見直 さなければならなくなる。トランプが勝てば、アメリカは独裁国家ではないし、ファシズムを導入することもないだろうが、一種の大きな目覚めとなるだろう。 新しい政治的プロセスが動き出し、引き金となるだろう。しかし、私はここが非常に危険な状態であることをよく知っている。ヒラリーはこの絶対的な惰性を象 徴する存在であり、最も危険な存在だ。彼女は冷たい戦士であり、銀行とつながっていて、社会的に進歩的なふりをしているからだ」[81]。 これらの見解は、レフト・ボイスによって加速主義者と揶揄され[82]、ノーム・チョムスキーによって「退行的」とされ、「それは彼のような人々が初期の ['30年代]にヒトラーについて言ったのと同じ点だ」と主張した[83]。 2019年と2020年、ジジェクは自身の見解を擁護し[84]、トランプの当選がバーニー・サンダースとアレクサンドリア・オカシオ=コルテスを後押し したことを引き合いに出し、「何十年ぶりかわからないが、真のアメリカの左翼を生み出した」と述べた[49]。 しかし、2020年のアメリカ大統領選挙について、ジジェクは「トランプは少しやりすぎだ」と述べ、「自分の立場を変えたいと思うようになった」と報告し ている[49]。別のインタビューでは、トランプの当選が社会主義的な反動につながるとした2016年の「賭け」(「たぶん私は正しかった」)を支持して いるが、「今はコロナウイルスで、トランプはダメだ、ダメだ」と主張している。...私がこれを言うのは難しいが、今なら、彼は理想からはほど遠いもの の、『トランプよりバイデンの方がいい』と言うだろう」[85]。2022年の著書『無秩序の天国』において、ジジェクは引き続きドナルド・トランプより ジョー・バイデンの方を好むと表明し、「トランプは私たちの生活の倫理的な実質を腐食していた」と述べ、一方でバイデンは嘘をつき、大資本をより丁寧に表 現している[86]。 |

| Social issues Žižek's views on social issues such as Eurocentrism, immigration and the LGBT movement have drawn criticism and accusations of bigotry.[87] Europe and multiculturalism In his 1997 article 'Multiculturalism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Multinational Capitalism', Žižek critiqued multiculturalism for privileging a culturally 'neutral' perspective from which all cultures are disaffectedly apprehended in their particularity because this distancing reproduces the racist procedure of Othering. He further argues that a fixation on particular identities and struggles corresponds to an abandonment of the universal struggle against global capitalism.[88] In his 1998 article 'A Leftist Plea for "Eurocentrism"', he argued that Leftists should 'undermine the global empire of capital, not by asserting particular identities, but through the assertion of a new universality',[89] and that in this struggle the European universalist value of egaliberte (Etienne Balibar's term) should be foregrounded, proposing 'a Leftist appropriation of the European legacy'.[90] Elsewhere, he has also argued, defending Marx, that Europe's destruction of non-European tradition (eg through imperialism and slavery) has opened up the space for a 'double liberation', both from tradition and from European domination.[91] In her 2010 article 'The Two Zizeks', Nivedita Menon criticised Žižek for focusing on differentiation as a colonial project, ignoring how assimilation was also such a project; she also critiqued him for privileging the European Enlightenment Christian legacy as neutral, 'free of the cultural markers that fatally afflict all other religions.'[92] David Pavón Cuéllar, closer to Žižek, also criticised him.[93] In the mid-2010s, over the issue of Eurocentrism, there was a dispute between Žižek and Walter Mignolo, in which Mignolo (supporting a previous article by Hamid Dabashi,[94] which argued against the centrality of European philosophers like Žižek, criticised by Michael Marder[95]) argued, against Žižek, that decolonial struggle should forget European philosophy, purportedly following Frantz Fanon;[96] in response, Žižek pointed out Fanon's European intellectual influences, and his resistance to being confined within the black tradition, and claimed to be following Fanon on this point.[97] In his book Can Non-Europeans Think? (foreworded by Mignolo), Dabashi also critiqued Žižek for privileging Europe;[98] Žižek argued that Dabashi slanderously and comically misrepresents him through misattribution,[99] a critique supported by Ilan Kapoor.[87] Transgender issues In his 2016 article "The Sexual Is Political", Žižek argued that all subjects are, like transgender subjects, in discord with the sexual position assigned to them. For Žižek, any attempt to escape this antagonism is false and utopian: thus, he rejects both the reactionary attempt to violently impose sexual fixity and the "postgenderist" attempt to escape sexual fixity entirely; he aligns the latter with 'transgenderism', which he claims does not adequately describe the behaviour of actual transgender subjects, who seek a stable "place where they could recognise themselves" (ie a bathroom that confirms their identity). Žižek argues for a third bathroom: a "GENERAL GENDER" bathroom that would represent the fact that both sexual positions (Žižek insists on the unavoidable "twoness" of the sexual landscape) are missing something and thus fail to adequately represent the subjects that take them on.[100] In his 2019 article "Transgender dogma is naive and incompatible with Freud", Žižek argued that there is "a tension in LGBT+ ideology between social constructivism and (some kind of biological) determinism", between the idea that gender is a social construct, and the idea that gender is essential and pre-social. He concludes the essay with a "Freudian solution" to this deadlock: ...psychic sexual identity is a choice, not a biological fact, but it is not a conscious choice that the subject can playfully repeat and transform. It is an unconscious choice which precedes subjective constitution and which is, as such, formative of subjectivity, which means that the change of this choice entails the radical transformation of the bearer of the choice.[101] Che Gossett criticized Žižek for his use of the "pathologising" term "transgenderism" throughout the 2016 article, and for writing "about trans subjectivity with such assumed authority while ignoring the voices of trans theorists (academics and activists) entirely", as well as for purportedly claiming that a "futuristic" vision underlies so-called "transgenderism", ignoring present-day oppression.[102] Sam Warren Miell and Chris Coffman, both psychoanalytically inclined, have separately criticized Žižek for conflating transgenderism and postgenderism; Miell further criticised the 2014 article for rehearsing homophobic/transphobic clichés (including Žižek's designation of inter-species marriage as a possible "anti-discriminatory demand"), and misusing Lacanian theory; Coffman argued that Žižek should have engaged with contemporary Lacanian trans studies, which would have shown that psychoanalytic and transgender discourses were aligned, not opposed.[103] In response to the title of the 2019 article, McKenzie Wark had t-shirts made with the transgender flag and "Incompatible with Freud" printed on them.[104] Žižek defended his 2016 article in two follow-up pieces. The first addresses purported misreadings of his position,[105] while the second is a more sustained defence (against Miell) of the article's application of Lacanian theory,[106] to which Miell responded in turn.[107] Douglas Lain also defended Žižek, claiming that context makes that it clear that Žižek is "not opposed [to] the struggle of LGBTQ people" but is instead critiquing "a phony liberal ideology that set up the terms of the LGBTQ struggle", "a certain utopian postmodern ideology that seeks to eliminate all limits, to eliminate all binaries, to go beyond norms because the imposition of a limit is patriarchal and oppressive."[108] In a 2023 piece for Compact Magazine, Žižek took a hard stance against access to puberty blockers for trans youth, and against trans adults being sent to prisons matching their gender, citing the case of Isla Bryson, whom he referred to as "a person who identifies itself as a woman using its penis to rape two women". Both of these things, Žižek attributed to wokeness (the wider subject of the article).[109][110] |

社会問題 ヨーロッパ中心主義、移民、LGBT運動などの社会問題に対するジジェクの見解は、批判や偏見による非難を浴びている[87]。 ヨーロッパと多文化主義 1997年に発表した論文「多文化主義、あるいは多国籍資本主義の文化的論理」において、ジジェクは多文化主義が文化的に「中立」な視点を特権化し、そこ からすべての文化がその特殊性において不愉快に理解されることを批判している。彼はさらに、特定のアイデンティティや闘争に固執することは、グローバル資 本主義に対する普遍的な闘いを放棄することにつながると主張している[88]。 彼の1998年の論文「A Leftist Plea for "Eurocentrism"(ヨーロッパ中心主義に対する左派の嘆願)」において、彼は左派は「特定のアイデンティティを主張することによってではな く、新たな普遍性を主張することを通して資本のグローバル帝国を弱体化させる」べきであり[89]、この闘いにおいてヨーロッパの普遍主義的価値であるエ ガリベルテ(Etienne Balibarの用語)が前景化されるべきであり、「ヨーロッパの遺産の左派的充当」を提案すべきであると主張している。 [また別のところでは、彼はマルクスを擁護する形で、ヨーロッパが(帝国主義や奴隷制などを通じて)非ヨーロッパ的伝統を破壊したことによって、伝統から もヨーロッパの支配からも「二重の解放」の空間が開かれたと主張している[91]。 ニヴェディタ・メノン(Nivedita Menon)は2010年の論文「2つのジゼク(The Two Zizeks)」において、ジジェクが植民地プロジェクトとしての差異化に焦点を当て、同化もまたそのようなプロジェクトであったことを無視していると批 判し、またジジェクがヨーロッパの啓蒙主義的なキリスト教の遺産を中立的であり、「他のすべての宗教を致命的に苦しめている文化的な印がない」ものとして 特権化していると批判していた[92]。 2010年代半ば、ヨーロッパ中心主義の問題をめぐって、ジジェクと ウォルター・ミニョーロ(ワルター・ミグノーロ)の間で論争があり、ミニョーロは(ジジェクのようなヨーロッパ の哲学者の中心性に反対するハミド・ダバシによる以前の論文[94]を支持し、マイケル・マーダーによって批判されていた[95])ジジェクに対して、フ ランツ・ファノンに倣うと称して、脱植民地闘争はヨーロッパの哲学を忘れるべきだと主張していた; [96]これに対してジジェクは、ファノンのヨーロッパ的な知的影響と、黒人の伝統 の中に閉じ込められることへの抵抗を指摘し、この点についてファノンに 従っていると主張した。 [彼の著書『非ヨーロッパ人は考えることができるか?(ミニョーロが序文を寄せている)において、ダバシはまたジジェクをヨーロッパを特権化していると批 判している[98]。ジジェクはダバシが中傷的かつ滑稽に、誤った帰属によって彼を誤って表現していると主張しており[99]、この批判はイラン・カプー ルによって支持されている[87]。 トランスジェンダーの問題 2016年の論文「性的なものは政治的である」において、ジジェクはすべての主体はトランスジェンダーの主体同様、彼らに割り当てられた性的な立場と不和 であると主張した。ジジェクにとって、この拮抗関係から逃れようとする試みは偽りであり、ユートピア的である。したがって、彼は、性の固定性を暴力的に押 し付けようとする反動的な試みも、性の固定性から完全に逃れようとする「ポストジェンダー主義」的な試みも拒絶する。彼は後者を「トランスジェンダー主 義」と同列に扱うが、これは、安定した「自分自身を認識できる場所」(つまり、自分のアイデンティティを確認できるトイレ)を求める実際のトランスジェン ダーの主体の行動を適切に表現していないと主張する。ジジェクは第三のトイレ、すなわち「GENERAL GENDER」トイレを主張しており、それは両方の性的立場(ジジェクは性的風景の不可避な「二性」を主張している)が何かを欠いており、したがってそれ らを取る主体を適切に表現できていないという事実を表すものである[100]。 2019年の論文「トランスジェンダーのドグマはナイーブでフロイトとは相容れない」において、ジジェクはLGBT+のイデオロギーには「社会構成主義と (ある種の生物学的な)決定論との間に緊張関係がある」と主張し、ジェンダーは社会的な構築物であるという考え方と、ジェンダーは本質的であり社会的以前 のものであるという考え方との間にあるとしている。彼はこの行き詰まりに対する「フロイト的解決策」でエッセイを締めくくっている: 精神的な性的アイデンティティは選択であり、生物学的な事実ではない。それは主観的な構成に先行する無意識的な選択であり、そのようなものとして主観性の 形成的なものであり、この選択の変化は選択の担い手の根本的な変容を伴うということである[101]。 チェ・ゴセットは、ジジェクが2016年の論文を通して「トランスジェンダー主義」という「病理学的な」用語を使用していること、そして「トランスの理論 家(学者や活動家)の声を完全に無視している一方で、トランスの主観性についてそのような権威を前提にして」書いていること、さらにいわゆる「トランス ジェンダー主義」の根底には「未来的な」ヴィジョンがあると主張し、現在の抑圧を無視していると称していることを批判していた[102]。 [精神分析に傾倒しているサム・ウォーレン・ミエルとクリス・コフマンは、トランスジェンダーとポストジェンダーを混同しているとしてジジェクを批判して いる。ミエルはさらに、2014年の論文が同性愛嫌悪/トランスフォビックな決まり文句(ジジェクが「反差別的要求」の可能性として異種間結婚を指定した ことを含む)を再演しており、ラカン理論を誤用していると批判している; コフマンは、ジジェクは現代のラカンのトランス研究と関わるべきであり、それは精神分析的言説とトランスジェンダーの言説が対立するものではなく、一致し ていることを示すものであったと主張した。 [103]2019年の論文のタイトルに対して、マッケンジー・ワークはトランスジェンダーの旗と「フロイトとは相容れない」とプリントされたTシャツを 作らせた[104]。 ジジェクは2つのフォローアップ記事で2016年の論文を擁護した。1つ目は彼の立場の誤読とされるものに対処するものであり[105]、2つ目は論文の ラカン理論の適用に対する(ミエルに対する)より持続的な擁護であり[106]、これに対してミエルは順次反論している。 [107] ダグラス・レインもまたジジェクを擁護し、文脈からジジェクが「LGBTQの人々の闘いに反対しているわけではない」ことは明らかであるが、その代わりに 「LGBTQの闘いの条件を設定したインチキなリベラル・イデオロギー」、「限界を課すことは家父長制的で抑圧的であるため、すべての限界を排除し、すべ ての二項対立を排除し、規範を超えようとするある種のユートピア的なポストモダン・イデオロギー」を批判していると主張している[108]。 ジジェクは2023年に『コンパクト』誌に寄稿した論文で、トランスの若者が思春期ブロッカーを利用することに反対し、トランスの成人が自分の性別に合っ た刑務所に送られることに反対する厳しい姿勢を示し、アイラ・ブライソンのケースを引き合いに出して、「女性であることを自認する人間が、ペニスを使って 2人の女性をレイプした」と述べた。ジジェクはこれら2つのことを、ヲタクネス(この記事のより広い主題)に起因するとした[109][110]。 |

| Other Žižek wrote that the convention center in which nationalist Slovene writers hold their conventions should be blown up, adding, "Since we live in the time without any sense of irony, I must add I don't mean it literally."[111] In 2013, Žižek corresponded with imprisoned Russian activist and Pussy Riot member Nadezhda Tolokonnikova.[112] All hearts were beating for you as long as you were perceived as just another version of the liberal-democratic protest against the authoritarian state. The moment it became clear that you rejected global capitalism, reporting on Pussy Riot became much more ambiguous. He criticized Western military interventions in developing countries and wrote that it was the 2011 military intervention in Libya "which threw the country in chaos" and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq "which created the conditions for the rise" of the Islamic State.[113] Žižek believes that China is the combination of capitalism and authoritarianism in their extreme forms. And the Chinese Communist Party is the best protector of the interests of capitalists. From the Cultural Revolution to Deng’s reforms, "Mao himself created the ideological condition for rapid capitalist development by tearing apart the fabric of traditional society."[114] It is capitalism, again and again, that emerges as the only alternative, the only way to move forward and the dynamic force for change when social life gets stuck into some fixed form. Today, capitalism is much more revolutionary than the traditional Left obsessed with protecting the old achievements of the welfare state. Just consider how much capitalism has changed the entire texture of our societies in the past decades. In an opinion article for The Guardian, Žižek argued in favour of giving full support to Ukraine after the Russian invasion and for creating a stronger NATO in response to Russian aggression,[115] later arguing that it would also be a tragedy for Ukraine to yoke itself to western neoliberalism.[116] He compared the struggle of Ukraine against the occupiers to the Palestinians' struggle against the Israeli occupation.[117] |

その他 ジジェクは、ナショナリストのスロヴェニア人作家が大会を開くコンベンションセンターを爆破すべきだと書き、「私たちは皮肉という感覚を持たない時代に生 きているので、私は文字通りの意味で言っているのではないことを付け加えなければならない」と付け加えた[111]。 2013年、ジジェクは収監中のロシアの活動家でプッシー・ライオットのメンバーであるナデジダ・トロコンニコワと文通をしていた[112]。 あなたが権威主義的な国家に対する自由民主主義的な抗議の別のバージョンとして認識されている限り、すべての心はあなたのために鼓動していました。あなた がグローバル資本主義を拒否していることが明らかになった瞬間、プッシー・ライオットに関する報道はより曖昧になった。 彼は発展途上国への西側の軍事介入を批判し、2011年のリビアへの軍事介入は「国を混乱に陥れた」ものであり、アメリカ主導のイラク侵攻は「イスラム国 の台頭の条件を作り出した」ものだと書いている[113]。 ジジェクは、中国は資本主義と権威主義が極端な形で結合したものだと考えている。そして中国共産党は資本家の利益を守る最良の庇護者である。文化大革命か ら鄧小平の改革に至るまで、「毛沢東自身が伝統的な社会の構造を引き裂くことによって、急速な資本主義発展のためのイデオロギー的条件を作り出した」 [114]。 何度も何度も、唯一の選択肢、前進する唯一の方法、そして社会生活がある固定された形にはまり込んだときに変化をもたらすダイナミックな力として登場する のが資本主義である。今日、資本主義は、旧態依然とした福祉国家の成果を守ることに執着する従来の左翼よりも、はるかに革命的である。資本主義が過去数十 年の間に、社会の構造全体をどれほど変えたかを考えてみればいい。 ジジェクは『ガーディアン』紙のオピニオン記事において、ロシアの侵攻後にウクライナを全面的に支援し、ロシアの侵略に対抗してより強力なNATOを創設 することに賛成であると主張し[115]、後にウクライナが西側の新自由主義に自らをゆだねることも悲劇であると論じた[116]。 |

| Criticism and controversy Inconsistency and ambiguity Žižek's philosophical and political positions have been described as ambiguous, and his work has been criticized for a failure to take a consistent stance.[118] While he has claimed to stand by a revolutionary Marxist project, his lack of vision concerning the possible circumstances which could lead to successful revolution makes it unclear what that project consists of. According to John Gray and John Holbo, his theoretical argument often lacks grounding in historical fact, which makes him more provocative than insightful.[119][120][121] In a very negative review of Žižek's book Less than Nothing, the British political philosopher John Gray attacked Žižek for his celebrations of violence, his failure to ground his theories in historical facts, and his 'formless radicalism' which, according to Gray, professes to be communist yet lacks the conviction that communism could ever be successfully realized. Gray concluded that Žižek's work, though entertaining, is intellectually worthless: "Achieving a deceptive substance by endlessly reiterating an essentially empty vision, Žižek's work amounts in the end to less than nothing."[119] Žižek's refusal to present an alternative vision has led critics to accuse him of using unsustainable Marxist categories of analysis and having a 19th-century understanding of class.[122] For example, post-Marxist Ernesto Laclau argued that "Žižek uses class as a sort of deus ex machina to play the role of the good guy against the multicultural devils."[123] In his book Living in the End Times, Žižek suggests that the criticism of his positions is itself ambiguous and multilateral: ... I am attacked for being anti-Semitic and for spreading Zionist lies, for being a covert Slovene nationalist and unpatriotic traitor to my nation, for being a crypto-Stalinist defending terror and for spreading Bourgeois lies about Communism... so maybe, just maybe I am on the right path, the path of fidelity to freedom."[124] Stylistic confusion Žižek has been criticized for his chaotic and non-systematic style: Harpham calls Žižek's style "a stream of nonconsecutive units arranged in arbitrary sequences that solicit a sporadic and discontinuous attention".[125] O'Neill concurs: "a dizzying array of wildly entertaining and often quite maddening rhetorical strategies are deployed in order to beguile, browbeat, dumbfound, dazzle, confuse, mislead, overwhelm, and generally subdue the reader into acceptance."[126] Noam Chomsky deems Žižek guilty of "using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretending you have a theory when you have no theory whatsoever", adding that his views are often too obscure to be communicated usefully to common people.[127] Conservative thinker Roger Scruton claims that: To summarize Žižek's position is not easy: he slips between philosophical and psychoanalytical ways of arguing, and is spell-bound by Lacan's gnomic utterances. He is a lover of paradox, and believes strongly in what Hegel called 'the labour of the negative' though taking the idea, as always, one stage further towards the brick wall of paradox.[128] Careless scholarship Žižek has been accused of approaching phenomena without rigour, reductively forcing them to support pre-given theoretical notions. For example, Tania Modleski alleges that "in trying to make Hitchcock 'fit' Lacan, he [Žižek] frequently ends up simplifying what goes on in the films".[129] Similarly, Yannis Stavrakakis criticises Žižek's reading of Antigone, claiming it proceeds without regard for both the play itself and the interpretation, given by Lacan in his 7th Seminar, which Žižek claims to follow. According to Stavrakakis, Žižek mistakenly characterises Antigone's act (illegally burying her brother) as politically radical/revolutionary, when in reality "Her act is a one-off and she couldn't care less about what will happen in the polis after her suicide."[130] Noah Horwitz alleges that Žižek (and the Ljubljana School to which Žižek belongs) mistakenly conflates the insights of Lacan and Hegel, and registers concern that such a move "risks transforming Lacanian psychoanalysis into a discourse of self-consciousness rather than a discourse on the psychoanalytic, Freudian unconscious."[131] Allegations of plagiarism Žižek's tendency to recycle portions of his own texts in subsequent works resulted in the accusation of self-plagiarism by The New York Times in 2014, after Žižek published an op-ed in the magazine which contained portions of his writing from an earlier book.[132] In response, Žižek expressed perplexity at the harsh tone of the denunciation, emphasizing that the recycled passages in question only acted as references from his theoretical books to supplement otherwise original writing.[132] In July 2014, Newsweek reported that online bloggers led by Steve Sailer had discovered that in an article published in 2006, Žižek plagiarized long passages from an earlier review by Stanley Hornbeck that first appeared in the journal American Renaissance, a publication condemned by the Southern Poverty Law Center as the organ of a "white nationalist hate group".[133] In response to the allegations, Žižek stated: The friend send [sic] it to me, assuring me that I can use it freely since it merely resumes another's line of thought. Consequently, I did just that—and I sincerely apologize for not knowing that my friend's resume was largely borrowed from Stanley Hornbeck's review of Macdonald's book.... In no way can I thus be accused of plagiarizing another's line of thought, of 'stealing ideas'. I nonetheless deeply regret the incident.[134] |

批判と論争 矛盾と曖昧さ ジジェクの哲学的、政治的立場は曖昧であると評され、彼の作品は一貫した立場をとっていないとして批判されてきた[118]。彼は革命的なマルクス主義の プロジェクトに立脚していると主張しているが、革命を成功に導く可能性のある状況に関する彼のビジョンの欠如は、そのプロジェクトが何から構成されている かを不明確にしている。ジョン・グレイとジョン・ホルボによれば、彼の理論的議論はしばしば歴史的事実の根拠を欠いており、それは彼を洞察的というよりも 挑発的なものにしている[119][120][121]。 イギリスの政治哲学者であるジョン・グレイは、ジジェクの著書『Less than Nothing』に対する非常に否定的な批評の中で、ジジェクが暴力を賛美していること、彼の理論が歴史的事実に根ざしていないこと、そしてグレイによれ ば、共産主義者であることを公言しながらも共産主義が成功裏に実現されうるという確信を欠いている彼の「形のない急進主義」を攻撃していた。グレイは、ジ ジェクの作品は娯楽的ではあるが、知的には無価値であると結論づけた: 「ジジェクの作品は、本質的に空虚なヴィジョンを際限なく繰り返すことで、欺瞞的な実質を達成しており、結局は無に等しい」[119]。 ジジェクは代替的なヴィジョンを提示することを拒否しているため、批評家たちは彼が持続不可能なマルクス主義的な分析カテゴリーを使用しており、階級につ いて19世紀的な理解を持っていると非難している[122]。例えば、ポスト・マルクス主義者のエルネスト・ラクラウは「ジジェクは階級を一種のデウス・ エクス・マキナとして使用し、多文化的な悪魔に対して善人の役割を演じている」と論じている[123]。 ジジェクは著書『終末の時代に生きる』の中で、自身の立場に対する批判はそれ自体が曖昧で多国間的なものであることを示唆している: ... 私は反ユダヤ主義者であり、シオニストの嘘を広めたことで攻撃され、スロベニアの隠れナショナリストであり、祖国に対する非国民的な裏切り者であり、テロ を擁護する隠れスターリニストであり、共産主義に関するブルジョワの嘘を広めたことで攻撃される。 文体の混乱 ジジェクはその混沌とした非体系的な文体から批判されてきた: ハーファムはジジェクのスタイルを「散発的で非連続的な注意を促す、恣意的な順序で並べられた非連続的な単位の流れ」と呼んでいる[125]: 「荒唐無稽で愉快な、そしてしばしばかなり狂気じみた修辞戦略が、読者を惑わせ、叱責し、呆れさせ、幻惑し、混乱させ、惑わせ、圧倒し、そして一般的に納 得させるために、めまぐるしく展開される。 「126] ノーム・チョムスキーはジジェクを「多義語のような派手な用語を使い、何の理論も持っていないのに理論を持っているふりをする」罪深い人物とみなし、彼の 見解はしばしば曖昧すぎて一般人には有益に伝わらないと付け加えている[127]。 保守思想家のロジャー・スクルトンは次のように主張する: ジジェクの立場を要約するのは容易ではない。彼は哲学的な主張の仕方と精神分析的な主張の仕方の間をすり抜け、ラカンのニヒルな発言に呪縛されている。彼 はパラドックスの愛好者であり、ヘーゲルが「否定の労働」と呼んだものを強く信じている。 不注意な学問 ジジェクは、厳密さを欠いたまま現象に接近し、あらかじめ与えられた理論的観念を支持するよう還元的に強要していると非難されてきた。例えば、タニア・モ ドレスキーは「ヒッチコックをラカンに "適合 "させようとするあまり、彼[ジジェク]はしばしば映画で起こっていることを単純化してしまう」と主張している[129]。同様に、ヤニス・スタヴラカキ スはジジェクの『アンチゴーヌ』読解を批判し、戯曲そのものと、ジジェクが従うと主張するラカンが『第7セミナー』で与えた解釈の両方を無視して進んでい ると主張している。スタヴラカキスによれば、ジジェクはアンティゴネの行為(弟を不法に埋葬すること)を政治的に急進的/革命的であると誤って特徴づけて いるが、実際には「彼女の行為は一回限りのものであり、彼女は自殺後にポリスで何が起こるかなど気にも留めていない」[130]。 ノア・ホルヴィッツはジジェク(そしてジジェクが属するリュブリャナ学派)がラカンとヘーゲルの洞察を誤って混同していると主張し、そのような動きが「ラ カン的精神分析を精神分析的、フロイト的無意識に関する言説ではなく、自己意識に関する言説に変容させる危険性がある」と懸念している[131]。 自己剽窃疑惑 ジジェクは自身の文章の一部をその後の著作で再利用する傾向があり、2014年にジジェクが以前の著作からの文章の一部を含む論説をニューヨーク・タイム ズ誌に発表した後、ニューヨーク・タイムズ誌によって自己盗作の非難を受けた[132]。 これに対してジジェクは非難の厳しいトーンに当惑を表明し、問題の再利用された文章は、そうでなければオリジナルの文章を補足するために彼の理論書からの 参照として機能しただけであると強調した[132]。 2014年7月、ニューズウィーク誌は、スティーブ・セーラが率いるオンライン・ブロガーたちが、2006年に発表された記事の中で、ジジェクが、「白人 ナショナリストのヘイト・グループ」の機関紙として南部貧困法律センターによって非難されている雑誌「アメリカン・ルネッサンス」に最初に掲載された、ス タンリー・ホーンベックによる以前の批評から長い文章を盗用していることを発見したと報じた[133]。 この疑惑に対してジジェクは次のように述べている: その友人はそれを私に送り[中略]、他の人の思想を再開したに過ぎないのだから自由に使っていいと私に保証した。友人のレジュメがマクドナルドの本に対す るスタンリー・ホーンベックの書評から借用したものであることを知らなかったことを心からお詫びします......。このように、私が他人の思想を盗用 し、『アイデアを盗んだ』と非難される筋合いはない。それにもかかわらず、私はこの事件を深く後悔している[134]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavoj_%C5%BDi%C5%BEek |

|

| Works https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavoj_%C5%BDi%C5%BEek#Works |

|

| 有馬稲子のパララックスより |

|

| In a philosophic/geometric

sense: an apparent change in the direction of an object, caused by a

change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The

apparent displacement, or difference of position, of an object, as seen

from two different stations, or points of view. In contemporary

writing, parallax can also be the same story, or a similar story from

approximately the same timeline, from one book, told from a different

perspective in another book. The word and concept feature prominently

in James Joyce's 1922 novel, Ulysses. Orson Scott Card also used the

term when referring to Ender's Shadow as compared to Ender's Game. The metaphor is invoked by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek in his 2006 book The Parallax View, borrowing the concept of "parallax view" from the Japanese philosopher and literary critic Kojin Karatani. Žižek notes The philosophical twist to be added (to parallax), of course, is that the observed distance is not simply "subjective", since the same object that exists "out there" is seen from two different stances or points of view. It is rather that, as Hegel would have put it, subject and object are inherently "mediated" so that an "epistemological" shift in the subject's point of view always reflects an "ontological" shift in the object itself. Or—to put it in Lacanese—the subject's gaze is always already inscribed into the perceived object itself, in the guise of its "blind spot," that which is "in the object more than the object itself," the point from which the object itself returns the gaze. "Sure the picture is in my eye, but I am also in the picture"...[25] — Slavoj Žižek, The Parallax View https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallax |

哲学的・幾何学的な意味において:観察位置の変化によって生じる、物体

の方向の見かけ上の変化。2つの異なる場所や視点から見た場合の見かけ上の位置のず

れ、または位置の違い。現代の文章では、視差は同じ話、またはほぼ同じ時間軸の類似した話であり、ある本から別の視点で語られた別の本のことである。この

言葉と概念は、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの1922年の小説『ユリシーズ』でも顕著に用いられている。また、オーソン・スコット・カードは『エンダーの影』を

『エンダーのゲーム』と比較した際に、この用語を使用している。 この比喩は、スロベニアの哲学者スラヴォイ・ジジェクが2006年に出版した著書『パララックス・ビュー』で用いられている。この「パララックス・ ビュー」という概念は、日本の哲学者で文芸評論家の柄谷行人から借用したものである。ジジェクは次のように指摘している。 (視差に)加えられる哲学的ひねりとは、もちろん、観察される距離は単純に「主観的」なものではないということだ。なぜなら、「そこ」に存在する同じ対象 が、2つの異なる立場や視点から見られるからだ。むしろ、ヘーゲルが言うように、主体と対象は本質的に「媒介」されているため、主体の視点における「認識 論的」な変化は、常に対象自体における「存在論的」な変化を反映している。あるいは、ラカネ派の言葉で言えば、主観の視線は常にすでに知覚された対象その ものに刻み込まれている。それは「盲点」という形で、「対象そのものよりも対象の中にある」ものであり、そこから対象そのものが視線を返す。「確かに絵は 私の目の中にあるが、私もまた絵の中にある」...[25] —スラヴォイ・ジジェク、『パララックス・ビュー』 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallax |

| Mr Bloom moved forward, raising

his troubled eyes. Think no more about

that. After one. Timeball on the ballastoffice is down. Dunsink time.

Fascinating little book that is of sir Robert Ball’s. Parallax. I never

exactly understood. There’s a priest. Could ask him. Par it’s Greek:

parallel, parallax. Met him pike hoses she called it till I told her

about the transmigration. O rocks! https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4300/pg4300.txt |

ブルーム氏は前進し、問題を抱えた目を上げた。もうそれについては考え

なくていい。1つ後。ティムボールはバラストオフィスでダウンしている。ダンシンク時間。ロバート・ボール卿の魅力的な小さな本。視差。私は正確には理解

していない。神父がいる。彼に尋ねることができる。ギリシャ語だ:平行、視差。彼女がそれを「平行ホース」と呼んでいた頃、輪廻について私が彼女に話すま

で、彼に会った。岩だらけだ! |

| Now that I come to think of it

that ball falls at Greenwich time. It’s the clock is worked by an

electric wire from Dunsink. Must go out there some first Saturday of

the month. If I could get an introduction to professor Joly or learn up

something about his family. That would do to: man always feels

complimented. Flattery where least expected. Nobleman proud to be

descended from some king’s mistress. His foremother. Lay it on with a

trowel. Cap in hand goes through the land. Not go in and blurt out what

you know you’re not to: what’s parallax? Show this gentleman the door. v |

今考えると、そのボールはグリニッジ標準時で落下している。時計はダン

シンクから伸びる電線で動いている。毎月第一土曜日にそこへ出かけなければならない。もしジョリー教授に紹介してもらえたり、彼の家族について何か学べた

りしたら。それは素晴らしい。人は常に褒められると感じる。思いがけないところで褒められる。貴族は王の愛人から生まれたことを誇りに思う。彼の先祖の女

性。こてで塗りつける。手で帽子を被り、あちこちを回る。入って行って、知っていることを口走らないように:視差とは何か?この紳士をドアまでお見送りす

る。 |

| The voices blend and fuse in

clouded silence: silence that is the

infinite of space: and swiftly, silently the soul is wafted over

regions of cycles of generations that have lived. A region where grey

twilight ever descends, never falls on wide sagegreen pasturefields,

shedding her dusk, scattering a perennial dew of stars. She follows her

mother with ungainly steps, a mare leading her fillyfoal. Twilight

phantoms are they, yet moulded in prophetic grace of structure, slim

shapely haunches, a supple tendonous neck, the meek apprehensive skull.

They fade, sad phantoms: all is gone. Agendath is a waste land, a home

of screechowls and the sandblind upupa. Netaim, the golden, is no more.

And on the highway of the clouds they come, muttering thunder of

rebellion, the ghosts of beasts. Huuh! Hark! Huuh! Parallax stalks

behind and goads them, the lancinating lightnings of whose brow are

scorpions. Elk and yak, the bulls of Bashan and of Babylon, mammoth and

mastodon, they come trooping to the sunken sea, _Lacus Mortis_. Ominous

revengeful zodiacal host! They moan, passing upon the clouds, horned

and capricorned, the trumpeted with the tusked, the lionmaned, the

giantantlered, snouter and crawler, rodent, ruminant and pachyderm, all

their moving moaning multitude, murderers of the sun. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4300/pg4300.txt |

混

ざり合い、融合する声。曇った静寂。それは空間の無限であり、魂は生き抜いてきた世代のサイクルの領域を、静かに、素早く漂う。

灰色の黄昏が降り注ぐ地域。広大な青々とした牧草地に沈むことはなく、夕暮れを落とし、星々の永遠の露を散らす。

彼女はぎこちない足取りで母親の後を追う。雌馬が子馬を導くように。黄昏の幻影であるが、予言的な優雅さで形作られた、スリムで均整のとれた臀部、しなや

かな腱の首、おとなしく不安げな頭蓋骨。 彼らは消え、悲しい幻影:すべてが消え去った。

アゲダスは荒れ地となり、ウズラと砂盲ウズラのすみかとなった。

ネタム、黄金の、もはやない。そして、雲のハイウェイを、反乱の雷鳴を呟きながら、獣の亡霊たちがやって来る。 ヒュー! ヒュー! ヒュー!

視差が後ろから追い立て、彼らを駆り立てる。額に刺すような稲妻を宿したサソリ。

エルクとヤク、バシャンとバビロンの雄牛、マンモスとマストドンが、沈んだ海、死の湖へと群れをなしてやって来る。

恐ろしい復讐心に燃える黄道十二宮の軍勢!彼らはうめき声を上げながら、雲の上を通り過ぎていく。角のあるもの、気まぐれなもの、角笛を吹くもの、牙のあ

るもの、ライオンのような姿のもの、巨大な枝角のあるもの、鼻と這うもの、齧歯類、反芻動物、巨体動物、太陽を殺した者たち。 |

| CHRIS CALLINAN: What is the

parallax of the subsolar ecliptic of Aldebaran? BLOOM: Pleased to hear from you, Chris. K. 11. JOE HYNES: Why aren’t you in uniform? https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4300/pg4300.txt |

クリス・カリーナン:アルデバランの黄道下点の視差はどのくらいか? ブルーム:連絡をくれて嬉しいよ、クリス。K. 11. ジョー・ハインズ:なぜ制服を着ていないんだ? |

| VIRAG: _(Not unpleasantly.)_

Absolutely! Well observed and those pannier pockets of the skirt and

slightly pegtop effect are devised to suggest bunchiness of hip. A new

purchase at some monster sale for which a gull has been mulcted.

Meretricious finery to deceive the eye. Observe the attention to

details of dustspecks. Never put on you tomorrow what you can wear

today. Parallax! _(With a nervous twitch of his head.)_ Did you hear my

brain go snap? Pollysyllabax! https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4300/pg4300.txt |

VIRAG:

_(不快ではない。)_

もちろん!よく観察しているね。スカートのパニエポケットと、少しペグトップ効果があるのは、ヒップの膨らみを強調するためだ。カモがだまされたような、

モンスターセールでの新しい買い物。目を欺くような見せかけの豪華さ。ほこりやちりの細部へのこだわりに注目。今日着られるものを、明日着ることはない。

視差!(彼は頭を神経質に動かした。)私の頭がパチッと鳴るのを聞いたか? ポリサイラブス! |

| Meditations of evolution

increasingly vaster: of the moon invisible in

incipient lunation, approaching perigee: of the infinite lattiginous

scintillating uncondensed milky way, discernible by daylight by an

observer placed at the lower end of a cylindrical vertical shaft 5000

ft deep sunk from the surface towards the centre of the earth: of

Sirius (alpha in Canis Maior) 10 lightyears (57,000,000,000,000 miles)

distant and in volume 900 times the dimension of our planet: of

Arcturus: of the precession of equinoxes: of Orion with belt and

sextuple sun theta and nebula in which 100 of our solar systems could

be contained: of moribund and of nascent new stars such as Nova in

1901: of our system plunging towards the constellation of Hercules: of

the parallax or parallactic drift of socalled fixed stars, in reality

evermoving wanderers from immeasurably remote eons to infinitely remote

futures in comparison with which the years, threescore and ten, of

allotted human life formed a parenthesis of infinitesimal brevity. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4300/pg4300.txt |

進

化についての思索はますます広大になる:初期の月齢では見えない月が、近地点に近づく:無限に広がるきらめく凝縮していない天の川は、地表から地球の中心

に向かって5000フィートの深さに掘られた円筒形の垂直シャフトの下端に位置する観察者が、昼光によって識別できる:シリウス(大犬座α星)は

10光年(570億マイル)離れたシリウス(おおいぬ座α星)の、地球の900倍の大きさ:アルクトゥルスの:春分点の歳差運動:ベルトと6重太陽シー

タ、そして100個の太陽系が収まる可能性のある星雲を持つオリオン座:

1901年の新星のような、誕生したばかりの新しい星について:私たちの太陽系がヘルクレス座に向かって突き進んでいることについて:いわゆる恒星の視差

または視差ドリフトについて、実際には、それらは計り知れないほど遠い過去から無限に遠い未来へと移動し続けている。それらと比較すると、人間に与えられ

た寿命である70年は、無限に短い期間の括弧で囲まれたものとなる。 |

+このページは「ジ

ジェク大全」からの改造です

| コペンハーゲンの男 |

「量子力学のヒーロ、ニールス・ボーア、コペンハーゲンの男である。彼

が、週末の田舎の別荘かなにかに客と一緒にいった。そこで入り口の横に、馬蹄がかけてある。馬蹄はなにかの魔除けであることを知っている来客は不思議に

思った。ボーアは骨太の科学者で、迷信なんかこれっぽっちも信じない。『ボーアさん、迷信など信じないあなたが、かけてあるこの馬蹄、いったい、あなたは

信じるのでしょうか?』と客はたずねた。ボーアは真顔で言った。『ああ、もちろん、そんなものなど信じていないよ。けど、これは、僕のような不信心者で

も、効き目があるって人が言うんだよね』(会場大爆笑)。みなさん、これこそが、イデオロギーなんですね!!!」スラヴォイ・ジジェクの講演でのジョーク

(梗概) |

| 俺

たちはインディアンだ |

「私(ジジェク)の米国のモンタナ州の(先住民の)友人は、こういう。

『俺たちはインディアンだ、俺たちはネイティブ・アメリカンと呼ばれ

たくない』。どういうことでしょうか?友人の言によれば、こういうことです。なぜ、ネイティブ(と呼ばれること)が嫌なのか?テイディブは自然の領域に属

する(→註:これに は「自然と文化の二分法」

についての知識が必要かもしれません)。だが俺たち(先住民)は、野生で自然ではない、俺たちは『文化的』なのだ。アメリカの白人は、先住民をもちあげ

て、先住民は自然を尊重する、元祖エコロジスト、つまり、先住民はすばらしいと賞賛するが、それは俺たちが『野生で自然』と思い込んでいる。俺たちの側こ

そが『文化』なのだ(→註:これには「自民族中心主義」に関する理解が必要かもしれ

ません)。それゆえにネイティブなどとは呼ばれたくない。むしろ、俺たちをインディアンと呼んでほしい。どうしてか?(南北両大陸の先住民をインド人と間

違えて白人たち呼んだゆえに)インディアンという呼称は、実は『白人たちのバカさ加減』を証明することだからね!!!」 |

| つづきは「ジ

ジェク・ジョーク」へ!! |

続きは「ジジェ ク・ジョーク」へ!! |

簡単な年譜(スラヴォイ・ジジェク, Slavoj Žižek b. March 21, 1949- ならびにトニー・マイヤーズの著作より)【ウェブ用ひな形シー ト:Slavoj_Zizek_works00.html】

1949 (旧ユーゴスラヴィア)のスロベニアのリュブリアナで生まれる

c 1966 哲学者になりたいと思うようになる

1969 最初の本の出版

1971 哲学と社会学の学士号

1975 哲学の修士「フランス構造主義の理論的実 践的重要性」

1977 スロベニア共産党中央委員会に職をえる

1979 リュブリアナ大学社会研究所研究員

1981 リュブリアナ大学大学院で哲学博士号。パ リに旅行。同年、ジャック・ラカン(Jacques Lacan, 1901-1981)が死去。

1985 パリ第八大学のジャック=アラン・ミレー ルで精神分析の博士号(→「ラカンの用語の解説」「ラカン的主体」「ジャック・ラカン理論のスコラ的解釈」「ラカンの欲望グラフ」)

1990 大統領選挙に出馬。5位に終わる。

2020 全世界で大活躍中(International Journal of Zizek

Studies, ISSN 1751-8229)[FB]

| イデオロ

ギーの崇高な対象(原著は1989年) ・《意識形態的崇高客體》(The Sublime Object of Ideology),斯洛維尼亞社會學家與哲學家斯拉沃熱・齊澤克於1989年的首本著作,以英文寫成。主要內容是闡述馬克思的商品概念、路易・皮埃爾・ 阿爾都塞的質詢(Interpellation)概念與雅各・拉岡的分裂主體(divided subjects)的概念。 |

2001,2015 |

The Sublime Object of

Ideology, このコラムは「ジジェク大全」でも続きます。異同があるので、そちらも チェックお忘れなく!! |

| 斜めから見る——大衆文化を通してラカン

理論へ |

1995 |

|

| 為

すところを知らざればなり——政治的要

素として享楽, For they know not what they do : enjoyment as a political

factor. |

||

| 汝の症候を楽しめ——ハリウッド〈対〉ラ

カン |

2001 |

|

| 否定的なもののもとへの滞留——カント、

ヘーゲル、イデオロギー批判 |

1998,2006 |

|

| 快楽の転移 |

1996 |

|

| 仮想化しきれない残余 |

1997 |

|

| 幻想の感染 |

1999 |

『幻想の大疫病』ノート/////////// |

| 厄介なる主体——政治的存在論の空虚な中

心 |

2005,2007 |

厄介な多文化主義批判/「自己植民地化」論/多文化主義/啓

蒙思想としての人種主義/政治神学/リップ・ヴァン・ウィンクル/多文化主義批判について考える///// |

| 脆弱なる絶対——キリスト教の遺産と資本

主義の超克 |

2001 |

|

| いまだ妖怪は徘徊している! |

2000 |

|

| 全体主義——観念の〈誤〉使用について |

2002 |

全体主義の日常的形態/カント倫理学の誤読////////// Welcome to the Desert of the Real, 2002 |

| 信じるということ, On belief |

2003 |

|

| テロルと戦争——現実界の砂漠へようこそ(Welcome to the Desert of the Real, 2002) |

2003 |

|

| 操り人形と小人——キリスト教の倒錯的な

核 |

2004 |

|

| 身

体なき器官, Organs without bodies : on Deleuze and consequences |

||

| イラク——ユートピアへの葬送 |

2004 |

|

| 絶望する勇気 |

2018 |

|

| もっとも崇高なヒステリー者——ラカンと

読むヘーゲル |

2016 |

|

| ラカンはこう読め! |

2008 |

|

| パララックス・ヴュー |

2010 |

|

| 大義を忘れるな——革命・テロ・反資本主

義 |

2010 |

|

| ジジェク、革命を語る——不可能なことを

求めよ |

2014 |

|

| ロベスピエール/毛沢東——革命とテロル |

2008 |

|

| ポストモダンの共産主義——はじめは悲劇

として、二度目は笑劇として |

2010 |

|

| 事件!哲学とは何か |

2015 |

|

| ヒッチコックによるラカン——映画的欲望

の経済 |

1994 |

|

| ヒッチコックXジジェク |

2005 |

|

| 2011 危うく夢見た1年 |

2013 |

|

| ジ

ジェク自身によるジジェク |

2005 |

|

| 人権と国家——世界の本質をめぐる考察 |

2006 |

|

| 迫

り来る革命 レーニンを繰り返す, Revolution at the gates : selected writings of

Lenin from 1917 |

2005 |

|

| 暴力 : 6つの斜めからの省察 |

2010 |

歴史生命倫理学/01.暴君の血まみれのローブ/02.汝の隣人を汝自身のように恐れよ!/03:「血に混濁した潮が解き放たれ」/04:寛容的理性のアンチノミー/05:イデオロギー的カテゴリーとしての寛容/06:神的暴力///// |

| First as Tragedy,

then as Farce, (Verso, 2009). 栗原百代訳『ポストモダンの共産主義──はじめは悲劇として、二度めは笑劇として』(筑摩書房[ちくま新書], 2010年) |

2009 |

|

| The Year of

Dreaming Dangerously, (Verso, 2012). 長原豊訳『2011危うく夢見た一年』(航思社, 2013年) |

2012 |

|

| Demanding the

impossible, (Cambridge : Polity, 2013). パク・ヨンジュン編、中山徹訳『ジジェク、革命を語る――不可能なことを求めよ』(青土社, 2014年) |

2013 |

|

| Event: A

Philosophical Journey Through a Concept, (Penguin Books, 2014). 鈴木晶訳『事件!――哲学とは何か』(河出書房新社[河出ブックス], 2010年) |

2014 |

|

| The

Most Sublime Hysteric: Hegel with Lacan, (Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA:

Polity Press, 2014) [原著は博士号取得論文Le plus sublime des hystériques - Hegel

passe, (Point hors ligne, 1988)] 鈴木國文・古橋忠晃・菅原誠一訳『もっとも崇高なヒステリー者――ラカンと読むヘーゲル』(みすず書房, 2016年) |

2014 |

|

| The Courage of

Hopelessness: Chronicles of a Year of Acting Dangerously, (Penguin

Books, 2017) 中山徹・鈴木英明訳『絶望する勇気――グローバル資本主義・原理主義・ポピュリズム』(青土社, 2018年) |

2017 |

勇気をもらう方法/////////// |

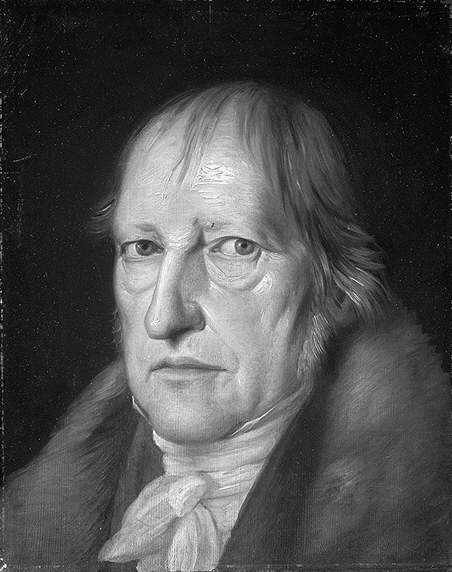

Hegel in A Wired

Brain,  |

2020 |

"In celebration of

the 250th anniversary of the birth of G.W.F. Hegel, Slavoj Žižek gives

us a reading of a philosophical giant that changes our way of thinking

about the post-human era we are entering./ No ordinary study of Hegel,

Hegel in a Wired Brain reveals our time as it appears through Hegel's

eyes. Focusing in on the idea of the wired brain, this is a

philosophical analysis of what happens when a direct link between our

mental processes and a digital machine emerges. Here Žižek explores the

phenomenon of a wired brain affect, and the notion of singularity

subsequently arising when we can share our thoughts and experiences

with others. He hones in on the key question of how it affects our

experience and status as free human individuals, dealing with what

happens with the human spirit, our subjectivity and the very essence of

being-human when a machine can read, action and disperse our thoughts./

With characteristic verve and energy, Žižek connects Hegel to the world

we live in and shows why he is much more fun than anyone gives him

credit for, and why the 21stst century might just be Hegelian." source:

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/hegel-in-a-wired-brain-9781350124417/ *** Introduction: “Un jour, peut-être, le siècle sera hégélien” 1. The Digital Police State: Fichte's Revenge on Hegel 2. The Idea of a Wired Brain and its Limitation 3. The Impasse of Soviet Tech-Gnosis 4. Singularity: the Gnostic Turn 5. The Fall that Makes Us Like God 6. Reflexivity of the Unconscious 7. A Literary Fantasy: the Unnamable Subject of Singularity A Treatise on Digital Apocalypse Index *** YouTube Slavoj Žižek delivers "Hegel in a Wired Brain" Slavoj Žižek - Hegel in a Wired Brain Slavoj Žižek - Hegel with Neuralink (Apr 2019) *** Neuralink, an American neurotechnology company founded by Elon Musk and eight others, is dedicated to developing a mind-machine interface (MMI). Whatever the (dubious, for the time being) scientifc status of this idea, it is clear that its realization will afect the basic features of humans as thinking/speaking beings. But HOW? To indicate an answer, we will turn to a philosopher who had no idea about neuralink: Hegel. The three classes: 1 - The idea of neuralink, its philosophical presuppositions and implications. 2 – The New Age ideological appropriation of MMI: “Singularity” and homo deus. 3 – Hegel with neuralink: are we still human when we are immersed into Singularity? Source; https://egs.edu/seminarPDF/EGS-ZizekSlavoj-2019_June_10-12.pdf |

| 《現実界》と歴史性 (出典:ジュディス・ バトラーら『偶発性・ヘゲモニー・普遍性』青土社、2002年;Pp.17-19) |

1 |

ラカンのいう《現実界》は、究極の基本原

理であり、象徴化の。フロセスを揺る

ぎなく指すことばなのか。それともこれは、まったく実質を欠いた内的限界、挫折の地点であって、これ

によってこそ現実とその象徴化のあいだの裂け目そのものが保たれ、歴史化ー象徴化の偶発的な。フロセス

が作動するのか。 |

| 欠如と反復 |

2 |

反復の動きは、なんらかの原初的欠如に基

づくのか。それとも、根本に原初的欠如が

あるという考えそのもののなかに、反復のプロセスを形而上学の同一性論理へと書きこみ直すことが、か

ならず含まれているのだろうか。 |

| (脱)同一化の社会的論理 |

3 |

脱同一化は、既存の秩序をかならず覆すの

だろうか。それともある種の

様式の脱同一化、自分の象徴的同一性に対して「距離をとる」というかたちの脱同一化は、社会生活に着

実に入りこむことと一体なのだろうか。さまざまに異なる脱同一化の様式とはどんなものなのか。 |

| 主体、主体化、主体の位置 |

4 |

「主体」はたんに主体化の、つまりイデオ

ロギーの呼びかけの、なんら かの「固定した主体の位置」をパフォーマティヴに想定するプロセスの結果にすぎないのか。それともラ カンの「切断線を引かれた主体」の考えは、伝統的な同一性の論理/実体主義の形而上学に対して、それ とは違つありかたをもたらすものなのか。 |

| 性的差異の地位 |

5 |

性的差異はたんに、「男」と「女」という

二つの主体の位置を表しており、個人は

反復というパフォーマンスによってその位置を手に入れ、身に帯びるようになるのか。それとも性的差異

はラカンのいう意味での「現実的なもの」——つまり行き止まり——であり、それを固定した主体の位置

に翻訳しようという試みはけっしてうまくいかないのか。 |

| フアルスのシニフィアン |

6 |

ラカンにおけるファルスは「ファルス=ロ

ゴス中心主義的」なのか—— つまり、ファルスは一種の超越論的な参照点として、セクシュアリティという領域の構造を作り上げてい る中心のシニフィアンなのか。それとも、ラカンにとってファルスというシニフィアンは、主体の欠如を 「補綴する」代補であるという事実によって、なにかが変わるのか。 |

| 《普遍》と歴史主義 |

7 |

現在、「歴史化せよ!」というジェイムソ

ン流のことばにしたがえば、それで

十分なのだろうか。偽りの普遍性に対する歴史主義的批判の限界とはなにか。《普遍》という矛盾にみち

た観念を、不可能でありかつ必然的なものとして保持することのほうが、理論的にも政治的にも、より生

産的なのではないか。 |

| ヘーゲル |

8 |

ヘーゲルとは要するに最高の形而上学者で

あり、つまり時間性-偶発性-有限性という

ポスト形而上学的組み合わせを持ち出そうとすることは、定義上すでに反ヘーゲル的なのか。それともヘ

ーゲルに対するまさにポスト形而上的な敵意は、それ自身の理論的限界をしめしているのか。つまりむし

ろ、「汎論理主義」説にぴったりとは合わない「もう一人のヘーゲル」を明るみに出すことに力を注ぐべ

きなのだろうか。 |

| ラカンと脱構築 |

9 |

ラカンを脱構築の流れに属すと考えるのは

理論的に正しいのだろうか。それとも、

ラカンを脱構築の教義から区別する特徴が山のようにある(コキトとしての主体の観念をなおも保持して

いること、など)という事実は、両者の共約不可能性をしめしているのだろうか。 |

| 政治的問題 |

10 |

自らの認知を求めての(民族、セクシュア

リティ、ライフスタイルなどを主とした)闘 争の複数性という「ポストモダン」な考えを、受け入れるべきだろうか。それとも、最近またも浮上して いる右翼風ポピュリズムを見れば、「ポストモダン」なラディカルな政治の座標軸を考え虹し、「政治経 済学批判」の伝統を蘇らせないわけにいかないのだろうか。これらの問題は、ヘゲモニーと全体性の観念 にどのように影響するだろうか。 |

| ラカンの用語の解説 |

ラカンの欲望グラフ |

|

| トニー・マイヤーズ「ス

ラヴォイ・ジジェク」村山敏勝, [生駒久美, 緒方けいこ] 訳 |

「シニョレリ」という言葉を思い出すこと

ができないことを、オルヴィエトの寺院の黙示録的なフレスコ画に去勢の恐怖をフロイト自身が読み取ったかもしれないことも考えてみましょう(ジャック・ラ

カン) |

|

| Mapping

ideology / edited by Slavoj Žižek, London : Verso , 1994 |

||

| 民主主義は、いま?——不可能な問いへの

8つの思想的介入 |

2011 |

|

| アメリカのユートピア——二重権力と国民

皆兵制 |

2018 |

|

| スラヴォイ・ジジェクの倒錯的映画ガイド 2 倒錯的イデオロギー・ガイド(DVD) | ||

| 神話・狂気・嘲笑(共著) | 2015 | |

| オペラは二度死ぬ(共著) | 2003 |

|

| 偶発性・ヘゲモニー・普遍性——新しい対 抗政治への対話(共著) | 2000 |

|

●トニー・マイヤーズ『スラヴォイ・ジジェク』村山 敏勝ほか訳、青土社、2005年/Slavoj Žižek, by Tony Myers, Routledge , 2003 . - (Routledge critical thinkers : essential guides for literary studies / series editor ; Robert Eaglestone)は、こちらに移転しました→「トニー・マイヤーズのジジェク」。

●ウィキペディア

Slavoj Žižek

"In 1989 Žižek published his first English-language text, The Sublime Object of Ideology, in which he departed from traditional Marxist theory to develop a materialist conception of ideology that drew heavily on Lacanian psychoanalysis and Hegelian idealism.[4][5] His theoretical work became increasingly eclectic and political in the 1990s, dealing frequently in the critical analysis of disparate forms of popular culture and making him a popular figure of the academic left.[4][6] Žižek's idiosyncratic style, popular academic works, frequent magazine op-eds, and critical assimilation of high and low culture have gained him international influence, controversy, criticism and a substantial audience outside academia.[7][8][9][10][11] In 2012, Foreign Policy listed Žižek on its list of Top 100 Global Thinkers, calling him "a celebrity philosopher"[12] while elsewhere he has been dubbed the "Elvis of cultural theory"[13] and "the most dangerous philosopher in the West".[14] A 2005 documentary film entitled Zizek! chronicled Žižek's work. A journal, the International Journal of Žižek Studies, was founded by professors David J. Gunkel and Paul A. Taylor to engage with his work.[15][16]" #Wiki.

1989年、ジジェクは初の英語による著作である

『イデオロギーの崇高な対象』を出版し、伝統的なマルクス主義理論から離れ、ラカンの精神分析とヘーゲルの観念論を多用した唯物論的なイデオロギー概念を

展開した[4][5]。彼の理論的な仕事は1990年代にはますます折衷的で政治的なものとなり、ポピュラーカルチャーの異質な形態の批判的分析を頻繁に

扱い、彼をアカデミックな左派の人気者とした。

[ジジェクの特異なスタイル、ポピュラーな学術的著作、頻繁な雑誌への寄稿、ハイカルチャーとローカルチャーの批評的同化は、国際的な影響力、論争、批

評、学界以外の多くの読者を獲得した。

[7][8][9][10][11]2012年、フォーリン・ポリシー誌はジジェクを「世界の思想家トップ100」に挙げ、「セレブリティの哲学者」

[12]と呼んだ。国際ジジェク研究ジャーナル(International Journal of Žižek

Studies)は、デイヴィッド・ガンケル(David J. Gunkel)教授とポール・A・テイラー(Paul A.

Taylor)教授によって設立され、ジジェクの研究に取り組んでいる。

"Slavoj Žižek en español" #Wiki.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Zizekstudies/

●主体とは、あらゆる信念や関心、示差的特徴をとっ た後に残るものである

●the man who thinks he's a chicken

"“It reminds me of that old joke- you know, a guy walks into a psychiatrist's office and says, hey doc, my brother's crazy! He thinks he's a chicken. Then the doc says, why don't you turn him in? Then the guy says, I would but I need the eggs. I guess that's how I feel about relationships. They're totally crazy, irrational, and absurd, but we keep going through it because we need the eggs.”" - Woody Allen, Annie Hall: Screenplay. source.

精

神科医の診察室に入ってきた男が、「先生、僕の弟は頭がおかしいんです!弟は自分がニワトリだと思ってるんです。すると医者が、なんで警察に突き出さない

んだ?そうしたいけど、卵が必要なんだ。それが私の人間関係に対する感じ方だと思う。完全にクレイジーで、不合理で、不条理で、でも卵が必要だからやり続

ける。

●AI批判—— Ardalan Raghian Matthew Renda「AIが人類を脅 かす可能性とその対策--専門家の見解」2016年7月6日, CNET-Japan.(→AI=人工知能︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎)

「人 工知能と は人間の知性・知能を計算機によって作り出すこと、作り出された〈実体〉、あるいは、このことに関 する学問分野や実践、さらには欲望などを指す複雑な言葉である。ここで言う知性・知能とは、単に計算能力だけでなく、推論や学習などの高度の知的能力(そ れゆえ インテリジェンスの語がつく)のことである。この知的能力の様式をもった[あるいは類似の]活動が計算機=コンピュータにある時[あるいは、あるように思 える時]、技術者は人工知能を使っていると表現する。人間の知性・知能と計算機のそれは、同じ であるのか、そうでないのか。あるいは、将来可能になる のか、ならないのかという学問的議論は、人工知能論争(じんこうちのう・ろんそう, AI論争)と呼ばれており、その決着はついていない(知性・知能の定義次第で、議論は大幅に変わりうるので、永遠に決着が着かないという表現も、もう決着 はついているという表現もともに可能である)」

One

Hundred Year Study on Artificial Intelligence (AI100), by

Stanford University.

リンク

リンク(YouTube画像)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099