多文化主義

Multiculturalism

Sydney's Chinatown

☆ 多文化主義[multiculturalism]という用語は、社会学、政治哲学、口語的な用法など、文脈によってさまざまな意味を持つ。社会学や日常的な用法では、それは民族多元主義と同義 であり、この2つの用語はしばしば互換的に使用され、単一の社会にさまざまな民族や文化集団が存在する文化多元主義を意味する。複数の文化伝統が存在する 混合民族地域(ニューヨーク市、ロンドン、香港、パリなど)や、単一国家内に複数の文化伝統が存在する地域(スイス、ベルギー、シンガポール、ロシアな ど)を指す場合がある。先住民族、土着民族、自生民族、入植者由来の民族グループに関連するグループが、しばしば焦点となる。 社会学の観点では、多文化主義は自然または人為的なプロセス(例えば、合法的に管理された移民)の最終段階であり、国家レベルの大規模なものと、国内のコ ミュニティレベルの小規模なものがある。小規模な多文化主義は、2つ以上の異なる文化を持つ地域(例えば、フランス系カナダと英語系カナダ)を統合して管 轄区域を新設または拡大する際に、人為的に発生することがある。大規模な多文化主義は、世界中の異なる管轄区域間の合法的または非合法的な移住の結果とし て発生することがある。 政治学の観点では、多文化主義とは、主権国家の領域内で文化の多様性を効果的かつ効率的に処理する国家の能力と定義できる。政治哲学としての多文化主義に は、さまざまなイデオロギーや政策が関わっている。それは「サラダボウル」(=サラダのようにさまざまな具材が融合せず個別に存在する)や「文化のモザイ ク」(=モザイクのようにそれぞれのタイルは隣の色とは混じらないが、全体で大きたフィギュアを形成する)と表現されることもあるが、「人種のるつぼ」 (=民族が混血を通して融合してゆくことの例え)とは対照的である(→旧ページは「多文化主義の隆盛と衰退」に移転しました)。

目次

★多文化主義[multiculturalism]

★Cultural pluralism (文化的多元主義)

☆Cultural diversity(文化的多様性)

☆Interculturalism(間文化主義)

| The term

multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of

sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and

in everyday usage, it is a synonym for ethnic pluralism, with the two

terms often used interchangeably, and for cultural pluralism[1] in

which various ethnic and cultural groups exist in a single society. It

can describe a mixed ethnic community area where multiple cultural

traditions exist (such as New York City, London, Hong Kong, or Paris)

or a single country within which they do (such as Switzerland, Belgium,

Singapore or Russia). Groups associated with an indigenous, aboriginal

or autochthonous ethnic group and settler-descended ethnic groups are

often the focus.[2] In reference to sociology, multiculturalism is the end-state of either a natural or artificial process (for example: legally controlled immigration) and occurs on either a large national scale or on a smaller scale within a nation's communities. On a smaller scale this can occur artificially when a jurisdiction is established or expanded by amalgamating areas with two or more different cultures (e.g. French Canada and English Canada). On a large scale, it can occur as a result of either legal or illegal migration to and from different jurisdictions around the world. In reference to political science, multiculturalism can be defined as a state's capacity to effectively and efficiently deal with cultural plurality within its sovereign borders. Multiculturalism as a political philosophy involves ideologies and policies which vary widely.[3] It has been described as a "salad bowl" and as a "cultural mosaic",[4] in contrast to a "melting pot".[5] |

多文化主義[multiculturalism]という用語は、社会学、政治哲学、口語的な用法など、文脈に

よってさまざまな意味を持つ。社会学や日常的な用法では、それは民族多元主義と同義であり、この2つの用語はしばしば互換的に使用され、単一の社会にさま

ざまな民族や文化集団が存在する文化多元主義[1]を意味する。複数の文化伝統が存在する混合民族地域(ニューヨーク市、ロンドン、香港、パリなど)や、

単一国家内に複数の文化伝統が存在する地域(スイス、ベルギー、シンガポール、ロシアなど)を指す場合がある。先住民族、土着民族、自生民族、入植者由来

の民族グループに関連するグループが、しばしば焦点となる。 社会学の観点では、多文化主義は自然または人為的なプロセス(例えば、合法的に管理された移民)の最終段階であり、国家レベルの大規模なものと、国内のコ ミュニティレベルの小規模なものがある。小規模な多文化主義は、2つ以上の異なる文化を持つ地域(例えば、フランス系カナダと英語系カナダ)を統合して管 轄区域を新設または拡大する際に、人為的に発生することがある。大規模な多文化主義は、世界中の異なる管轄区域間の合法的または非合法的な移住の結果とし て発生することがある。 政治学の観点では、多文化主義とは、主権国家の領域内で文化の多様性を効果的かつ効率的に処理する国家の能力と定義できる。政治哲学としての多文化主義に は、さまざまなイデオロギーや政策が関わっている。[3] それは「サラダボウル」や「文化のモザイク」と表現されることもあるが、[4] 「人種のるつぼ」とは対照的である。[5] |

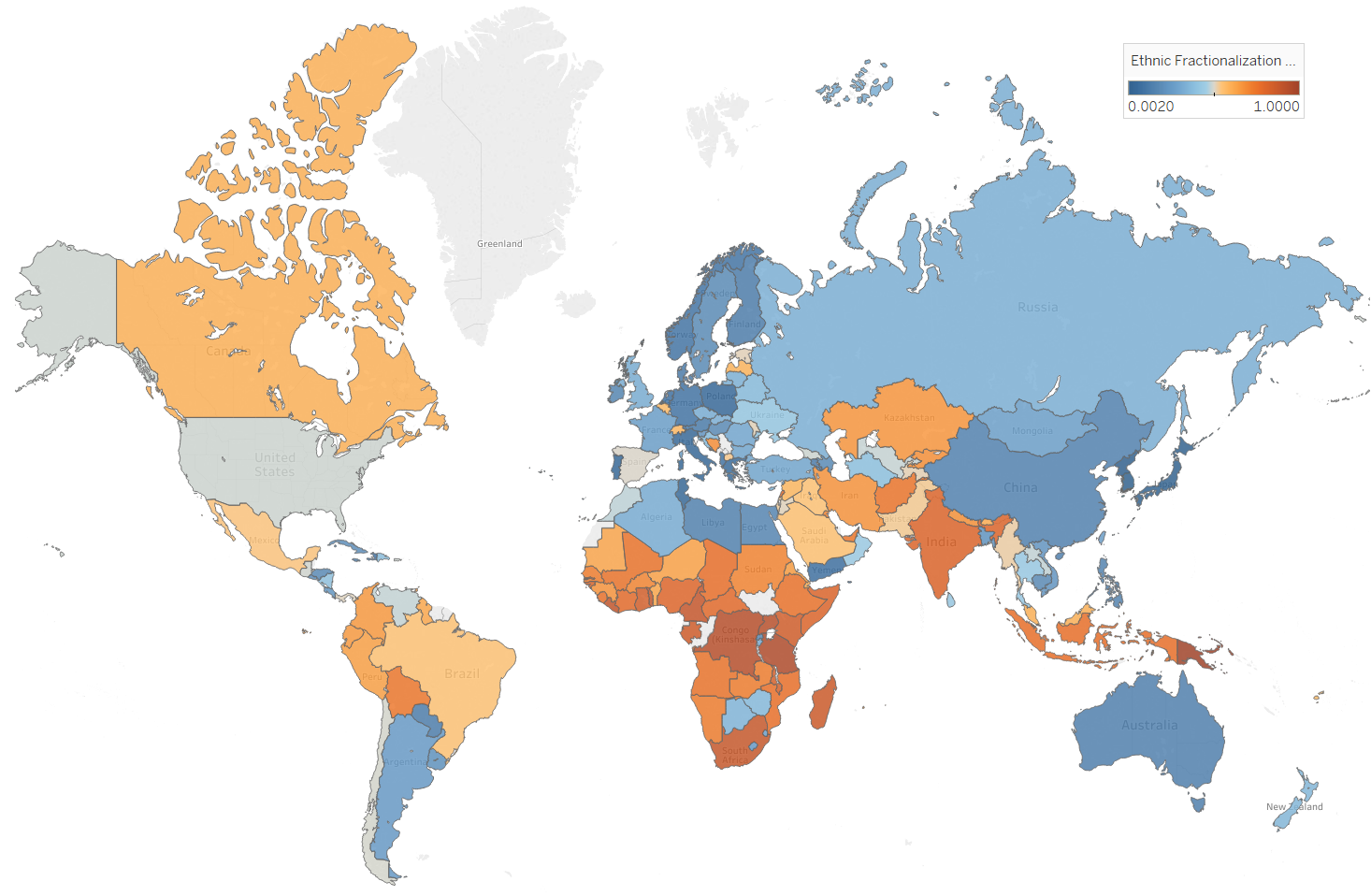

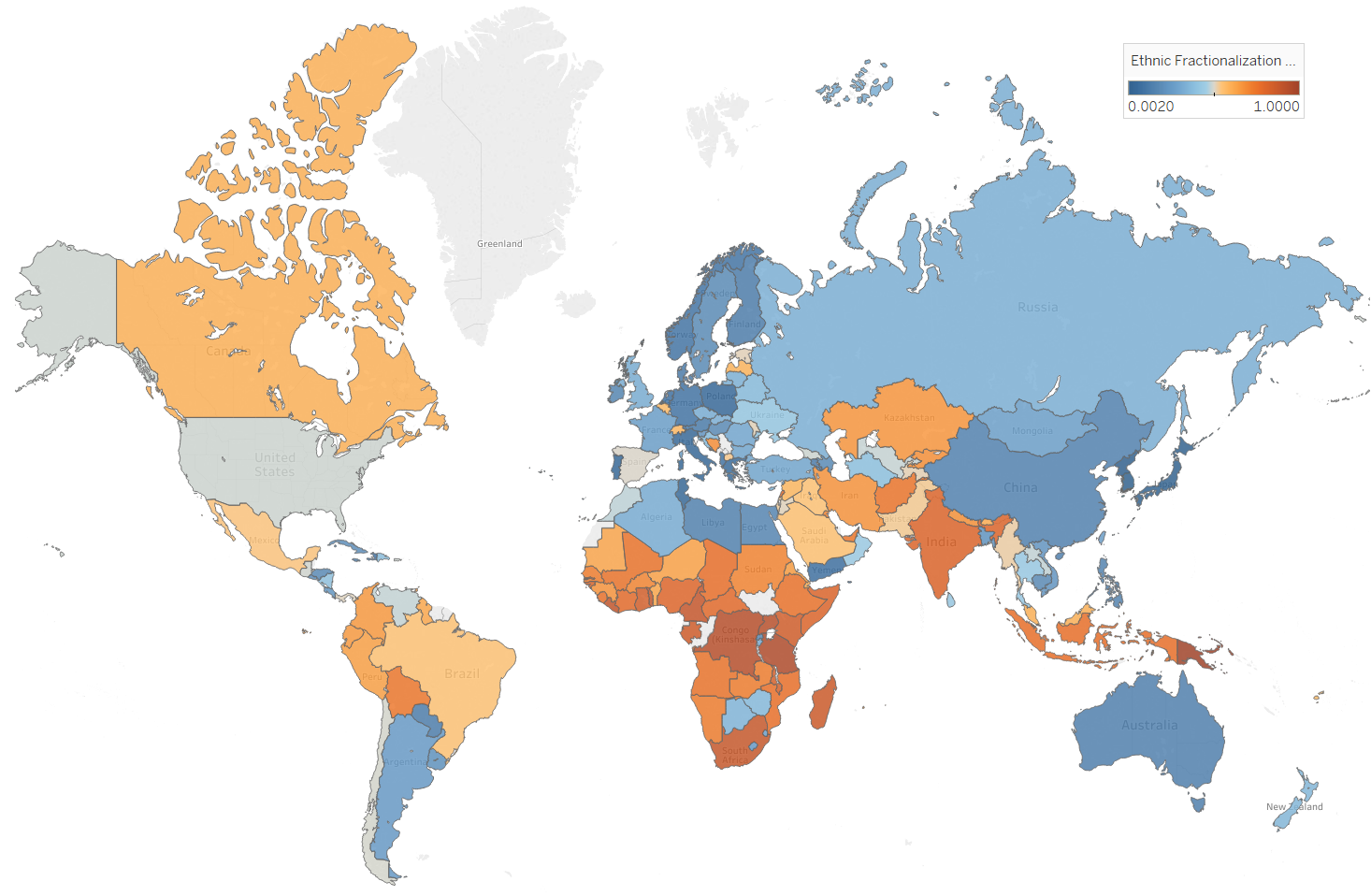

| Prevalence History States that embody multicultural ideals have arguably existed since ancient times. The Achaemenid Empire founded by Cyrus the Great followed a policy of incorporating and tolerating various cultures.[6]  Ethnographic map of Austria-Hungarian Empire A historical example of multiculturalism was the Habsburg monarchy, which had broken up in 1918 and under whose roof many different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups lived together. The Habsburg rule was mired in controversy, including events such as the mass murder committed against Székelys by the Habsburg army in 1764 and the destruction of Romanian Orthodox Churches and Monasteries in Transylvania by Adolf Nikolaus von Buccow. [7] Both events had happened during the rule of Maria Theresa. Today's topical issues such as social and cultural differentiation, multilingualism, competing identity offers or multiple cultural identities have already shaped the scientific theories of many thinkers of this multi-ethnic empire.[8] After the First World War, ethnic minorities were disadvantaged, forced to emigrate or even murdered in most regions in the area of the former Habsburg monarchy due to the prevailing nationalism at the time. In many areas, these ethnic mosaics no longer exist today. The ethnic mix of that time can only be experienced in a few areas, such as in the former Habsburg port city of Trieste.[9] In the political philosophy of multiculturalism, ideas are focused on the ways in which societies are either believed to or should, respond to cultural and Christian differences. It is often associated with "identity politics", "the politics of difference", and "the politics of recognition". It is also a matter of economic interests and political power.[10] In more recent times political multiculturalist ideologies have been expanding in their use to include and define disadvantaged groups such as African Americans and the LGBT community, with arguments often focusing on ethnic and religious minorities, minority nations, indigenous peoples and even people with disabilities. It is within this context in which the term is most commonly understood and the broadness and scope of the definition, as well as its practical use, has been the subject of serious debate. Most debates over multiculturalism center around whether or not multiculturalism is the appropriate way to deal with diversity and immigrant integration. The arguments regarding the perceived rights to a multicultural education include the proposition that it acts as a way to demand recognition of aspects of a group's culture subordination and its entire experience in contrast to a melting pot or non-multicultural societies. The term multiculturalism is most often used in reference to Western nation-states, which had seemingly achieved a de facto single national identity during the 18th and/or 19th centuries.[11] Multiculturalism has been official policy in several Western nations since the 1970s, for reasons that varied from country to country,[12][13][14] including the fact that many of the great cities of the Western world are increasingly made of a mosaic of cultures.[15] The Canadian government has often been described as the instigator of multicultural ideology because of its public emphasis on the social importance of immigration.[16][17] The Canadian Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism is often referred to as the origins of modern political awareness of multiculturalism.[18] Canada has provided provisions to the French speaking majority of Quebec, whereby they function as an autonomous community with special rights to govern the members of their community, as well as establish French as one of the official languages. In the Western English-speaking countries, multiculturalism as an official national policy started in Canada in 1971, followed by Australia in 1973 where it is maintained today.[19][20][21][22] It was quickly adopted as official policy by most member-states of the European Union. Recently, right-of-center governments in several European states – notably the Netherlands and Denmark – have reversed the national policy and returned to an official monoculturalism.[23]A similar reversal is the subject of debate in the United Kingdom, among others, due to evidence of incipient segregation and anxieties over "home-grown" terrorism.[24] Several heads-of-state or heads-of-government have expressed doubts about the success of multicultural policies: The United Kingdom's ex-Prime Minister David Cameron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Australia's ex-prime minister John Howard, Spanish ex-prime minister José María Aznar and French ex-president Nicolas Sarkozy have voiced concerns about the effectiveness of their multicultural policies for integrating immigrants.[25][26] Many nation-states in Africa, Asia, and the Americas are culturally diverse and are 'multicultural' in a descriptive sense. In some, ethnic communalism is a major political issue. The policies adopted by these states often have parallels with multiculturalist policies in the Western world, but the historical background is different, and the goal may be a mono-cultural or mono-ethnic nation-building – for instance in the Malaysian government's attempt to create a 'Malaysian race' by 2020.[27] Support  People of Indian origin have been able to achieve a high demographic profile in India Square, Jersey City, New Jersey, US, known as Little Bombay,[28] home to the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere[29] and one of at least 24 enclaves characterized as a Little India which have emerged within the New York City Metropolitan Area, with the largest metropolitan Indian population outside Asia, as large-scale immigration from India continues into New York City,[30][31] through the support of the surrounding community. Multiculturalism is seen by its supporters as a fairer system that allows people to truly express who they are within a society, that is more tolerant and that adapts better to social issues.[32] They argue that culture is not one definable thing based on one race or religion, but rather the result of multiple factors that change as the world changes. Historically, support for modern multiculturalism stems from the changes in Western societies after World War II, in what Susanne Wessendorf calls the "human rights revolution", in which the horrors of institutionalized racism and ethnic cleansing became almost impossible to ignore in the wake of the Holocaust; with the collapse of the European colonial system, as colonized nations in Africa and Asia successfully fought for their independence and pointed out the discriminatory underpinnings of the colonial system; and, in the United States in particular, with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, which criticized ideals of assimilation that often led to prejudices against those who did not act according to Anglo-American standards and which led to the development of academic ethnic studies programs as a way to counteract the neglect of contributions by racial minorities in classrooms.[33][34] As this history shows, multiculturalism in Western countries was seen to combat racism, to protect minority communities of all types, and to undo policies that had prevented minorities from having full access to the opportunities for freedom and equality promised by the liberalism that has been the hallmark of Western societies since the Age of Enlightenment. The contact hypothesis in sociology is a well-documented phenomenon in which cooperative interactions with those from a different group than one's own reduce prejudice and inter-group hostility. Will Kymlicka argues for "group differentiated rights", that help both religious and cultural minorities operate within the larger state as a whole, without impinging on the rights of the larger society. He bases this on his opinion that human rights fall short in protecting the rights of minorities, as the state has no stake in protecting the minorities.[35] C. James Trotman argues that multiculturalism is valuable because it "uses several disciplines to highlight neglected aspects of our social history, particularly the histories of women and minorities [...and] promotes respect for the dignity of the lives and voices of the forgotten.[36] By closing gaps, by raising consciousness about the past, multiculturalism tries to restore a sense of wholeness in a postmodern era that fragments human life and thought."[36] Tariq Modood argues that in the early years of the 21st century, multiculturalism "is most timely and necessary, and [...] we need more not less", since it is "the form of integration" that (1) best fits the ideal of egalitarianism, (2) has "the best chance of succeeding" in the "post-9/11, post 7/7" world, and (3) has remained "moderate [and] pragmatic".[37] Bhikhu Parekh counters what he sees as the tendencies to equate multiculturalism with racial minorities "demanding special rights" and to see these as promoting a "thinly veiled racis[m]". Instead, he argues that multiculturalism is in fact "not about minorities" but "is about the proper terms of the relationship between different cultural communities", which means that the standards by which the communities resolve their differences, e.g., "the principles of justice" must not come from only one of the cultures but must come "through an open and equal dialogue between them."[38] Balibar characterizes criticisms of multiculturalism as "differentialist racism", which he describes as a covert form of racism that does not purport ethnic superiority as much as it asserts stereotypes of perceived "incompatibility of life-styles and traditions".[39] While there is research that suggests that ethnic diversity increases chances of war, lower public goods provision and decreases democratization, there is also research that shows that ethnic diversity in itself is not detrimental to peace,[40][41] public goods provision[42][43] or democracy.[44] Rather, it was found that promoting diversity actually helps in advancing disadvantaged students.[45] A 2018 study in the American Political Science Review cast doubts on findings that ethnoracial homogeneity led to greater public goods provision.[46] A 2015 study in the American Journal of Sociology challenged past research showing that racial diversity adversely affected trust.[47] Criticism Main article: Criticism of multiculturalism Critics of multiculturalism often debate whether the multicultural ideal of benignly co-existing cultures that interrelate and influence one another, and yet remain distinct, is sustainable, paradoxical, or even desirable.[48][49][50] It is argued that nation states, who would previously have been synonymous with a distinctive cultural identity of their own, lose out to enforced multiculturalism and that this ultimately erodes the host nations' distinct culture.[51] Sarah Song views cultures as historically shaped entities by its members, and that they lack boundaries due to globalization, thereby making them stronger than others might assume.[52] She goes on to argue against the notion of special rights as she feels cultures are mutually constructive, and are shaped by the dominant culture. Brian Barry advocates a difference-blind approach to culture in the political realm and he rejects group-based rights as antithetical to the universalist liberal project, which he views as based on the individual.[53] Susan Moller Okin, a feminist professor of political philosophy, argued in 1999, in "Is multiculturalism bad for women?", that the principle that all cultures are equal means that the equal rights of women in particular are sometimes severely violated.[54] Harvard professor of political science Robert D. Putnam conducted a nearly decade-long study on how multiculturalism affects social trust.[55] He surveyed 26,200 people in 40 American communities, finding that when the data were adjusted for class, income and other factors, the more racially diverse a community is, the greater the loss of trust. People in diverse communities "don't trust the local mayor, they don't trust the local paper, they don't trust other people and they don't trust institutions," writes Putnam.[56] In the presence of such ethnic diversity, Putnam maintains that, "[W]e hunker down. We act like turtles. The effect of diversity is worse than had been imagined. And it's not just that we don't trust people who are not like us. In diverse communities, we don't trust people who do not look like us".[55] Putnam has also stated, however, that "this allergy to diversity tends to diminish and to go away... I think in the long run we'll all be better."[57] Putnam denied allegations he was arguing against diversity in society and contended that his paper had been "twisted" to make a case against race-conscious admissions to universities. He asserted that his "extensive research and experience confirm the substantial benefits of diversity, including racial and ethnic diversity, to our society."[58] Ethnologist Frank Salter writes: Relatively homogeneous societies invest more in public goods, indicating a higher level of public altruism. For example, the degree of ethnic homogeneity correlates with the government's share of gross domestic product as well as the average wealth of citizens. Case studies of the United States, Africa and South-East Asia find that multi-ethnic societies are less charitable and less able to cooperate to develop public infrastructure. Moscow beggars receive more gifts from fellow ethnics than from other ethnies [sic]. A recent multi-city study of municipal spending on public goods in the United States found that ethnically or racially diverse cities spend a smaller portion of their budgets and less per capita on public services than do the more homogeneous cities.[59] Dick Lamm, former three-term Democratic governor of the US state of Colorado, argued that "diverse peoples worldwide are mostly engaged in hating each other—that is, when they are not killing each other. A diverse, peaceful, or stable society is against most historical precedent."[60] The American classicist Victor Davis Hanson used the perceived differences in "rationality" between Moctezuma and Cortés to argue that Western culture was superior to every culture in the entire world, which thus led him to reject multiculturalism as a false doctrine that placed all cultures on an equal footing.[61] In New Zealand (Aotearoa), which is officially bi-cultural, multiculturalism has been seen as a threat to the Māori as an attempt by the New Zealand Government to undermine Māori demands for self-determination and encourage assimilation.[62] Right wing sympathisers have been shown to increasingly take part in a multitude of online discursive efforts directed against global brands' multicultural advertisements.[63] |

普及 歴史 多文化主義の理念を体現する国家は、古代から存在していたと言える。 キュロス大王が建国したアケメネス朝は、さまざまな文化を取り入れ、寛容に受け入れる政策をとっていた。  オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の民族誌地図 多文化主義の歴史的な例としては、1918年に崩壊したハプスブルク君主国が挙げられる。この君主国のもとでは、さまざまな民族、言語、宗教集団が共存し ていた。ハプスブルク家の支配は論争の的となり、1764年にハプスブルク軍がセーケイ人に対して大量殺人を行った事件や、アドルフ・ニコラウス・フォ ン・ブコウがトランシルヴァニアのルーマニア正教会や修道院を破壊した事件などが起こった。[7] いずれの事件もマリア・テレジアの統治下で起こった。社会や文化の分化、多言語主義、アイデンティティの競合、複数の文化的なアイデンティティなど、今日 話題となっている問題は、すでにこの多民族帝国の多くの思想家の科学的理論を形成していた。[8] 第1次世界大戦後、当時の主流であったナショナリズムの影響により、旧ハプスブルク君主国のほとんどの地域で、少数民族は不利な立場に置かれ、移住を余儀 なくされたり、殺害されたりした。多くの地域では、今日ではもはやこうした民族のモザイクは存在していない。当時の民族の混合は、ハプスブルク家の旧港町 トリエステなど、ごく一部の地域でしか体験できない。 多文化主義の政治哲学では、社会が文化的およびキリスト教的な相違にどう反応すべきか、あるいは反応すると考えられているかに焦点が当てられている。それ はしばしば、「アイデンティティ政治」、「差異の政治」、「承認の政治」と関連付けられている。また、経済的利益や政治的権力の問題でもある。[10] 近年では、政治的多文化主義のイデオロギーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人やLGBTコミュニティなどの不利な立場にあるグループを含め、定義する使用法が拡大 している。議論は、しばしば民族や宗教の少数派、少数民族、先住民、さらには障害者にも焦点を当てている。この文脈において、この用語は最も一般的に理解 されており、定義の広さと範囲、およびその実用的な使用法は、深刻な議論の対象となっている。 多文化主義に関する議論のほとんどは、多文化主義が多様性や移民の統合に対処する適切な方法であるかどうかという点に集中している。多文化教育を受ける権 利に関する議論には、多文化教育が、メルティング・ポットや非多文化社会とは対照的に、集団の文化の従属的な側面やその集団の経験全体を認識することを求 める手段として機能するという命題が含まれている。 多文化主義という用語は、18世紀および/または19世紀に事実上の単一の国民的アイデンティティを達成したように見える西欧の国民国家について言及され ることが多い。[11] 多文化主義は、 。その理由は国によって異なるが、[12][13][14] 西洋世界の多くの大都市がますます文化のモザイクとなっているという事実も含まれる。 カナダ政府は、移民の社会的重要性を公に強調していることから、多文化主義の推進者としてしばしば言及されている。[16][17] カナダのバイリンガリズムおよびバイカルチュラリズムに関する王立委員会は、 。カナダはケベック州のフランス語話者多数派に対して、フランス語を公用語の一つとして定めるとともに、そのコミュニティのメンバーを統治する特別な権利 を持つ自治コミュニティとして機能する規定を設けた。英語圏の西側諸国では、多文化主義が国家の公式政策として採用されたのは1971年のカナダが最初で あり、1973年のオーストラリアに続き、現在も継続されている。[19][20][21][22] その後、欧州連合(EU)のほとんどの加盟国で公式政策として急速に採用された。最近では、ヨーロッパのいくつかの国々(特にオランダやデンマーク)の右 派・中道派の政府が、国家政策を転換し、単一文化主義に回帰している。[23] 同様の政策転換は、イギリスでも議論の対象となっている。その理由としては、初期の分離現象の兆候や「自国発」のテロに対する不安が挙げられる。[24] 複数の国家元首や政府首脳が、多文化主義政策の成功に疑問を呈している。英国の元首相デービッド・キャメロン、ドイツのアンゲラ・メルケル首相、オースト ラリアのジョン・ハワード元首相、スペインのホセ・マリア・アスナル元首相、フランスのニコラ・サルコジ元大統領は、移民の統合を目的とした多文化主義政 策の有効性について懸念を表明している。 アフリカ、アジア、アメリカ大陸の多くの国民国家は文化的に多様であり、記述的な意味では「多文化」である。一部の国では、民族共同体主義が主要な政治問 題となっている。これらの国々で採用されている政策は、西洋諸国の多文化主義政策と類似していることが多いが、歴史的背景は異なり、単一文化または単一民 族の国家建設を目指している場合もある。例えば、マレーシア政府は2020年までに「マレーシア人種」を創出しようとしている。 支援  インド系の人々は、リトルボンベイとして知られるアメリカ合衆国ニュージャージー州ジャージーシティのインド・スクエアで高い人口比率を占めるようになっ ている。[28] ここは西半球で最もインド系住民が集中している地域であり[29]、 ニューヨーク都市圏内に現れた24の「リトル・インディア」と呼ばれる飛び地のうちの1つであり、ニューヨーク市へのインドからの大規模な移民が継続して いるため、アジア以外では最大のインド系住民の都市圏となっている。 多文化主義の支持者たちは、多文化主義は社会の中で人々が自分自身をより真に表現できる、より寛容で社会問題によりうまく適応できるより公平なシステムで あると見ている。彼らは、文化は一つの人種や宗教に基づく一つの明確なものではなく、むしろ世界が変化するにつれて変化する複数の要因の結果であると主張 している。 歴史的に見ると、現代の多文化主義の支持は第二次世界大戦後の西洋社会の変化に由来しており、スザンヌ・ウェッセンドルフが「人権革命」と呼ぶこの変化 は、ホロコーストの余波で制度化された人種差別や民族浄化の恐ろしさがほとんど無視できなくなったこと、ヨーロッパの植民地体制が崩壊し、アフリカやアジ アの植民地化されていた国民が独立を勝ち取るために戦い、 独立を勝ち取り、植民地制度の差別的な基盤を指摘した。また、特に米国では、市民権運動の高まりにより、アングロサクソン的な基準に従わない人々に対する 偏見につながる同化の理想が批判され、教室におけるマイノリティの貢献の軽視に対抗する手段として、学術的な民族研究プログラムが開発されるようになった 教室における人種的少数派の貢献を無視する傾向に対抗する手段として、学術的な民族研究プログラムが開発された。[33][34] この歴史が示すように、欧米諸国における多文化主義は、人種差別と戦い、あらゆるタイプの少数派コミュニティを保護し、啓蒙時代以降の欧米社会の特徴であ る自由主義が約束する自由と平等の機会を少数派が十分に利用することを妨げてきた政策を覆すものと見なされていた。社会学における接触仮説は、自らの所属 する集団とは異なる集団に属する人々との協力的な交流が偏見や集団間の敵対感情を減少させるという、よく知られた現象である。 ウィル・キムリッカは、宗教的・文化的マイノリティが、より大きな社会全体の権利を侵害することなく、より大きな国家の中で活動できるようにするための 「グループ別権利」を主張している。彼は、国家にはマイノリティを保護する利害関係がないため、人権はマイノリティの権利保護には不十分であるという意見 に基づいている。 C. ジェームズ・トロットマンは、多文化主義が価値あるものであるのは、「複数の学問分野を活用して、特に女性やマイノリティの歴史など、これまで顧みられる ことのなかった社会史の側面を浮き彫りにし、忘れ去られた人々の生活や声の尊厳に対する敬意を促進するからだ」と主張している。[36] ギャップを埋め、過去に対する意識を高めることで、多文化主義は、ポストモダン時代に断片化された人間の生活や思考に全体性を取り戻そうとしている。 [36] タリク・モドゥードは、21世紀の初期においては、多文化主義は「最も時宜を得たものであり、必要とされている。そして、私たちはより多くを必要としてい る」と主張している。なぜなら、それは(1)平等主義の理想に最も適合する「統合の形態」であり、(2)「9.11以降、7.7以降」の世界において「成 功する最大のチャンス」があり、(3)「穏健かつ現実的」なものであるからだ。平等主義の理想に最も適合し、(2) 「9.11以降、7.7以降」の世界において「成功する最高のチャンス」があり、(3) 「穏健かつ現実的」なものであるからだ。[37] ビク・パレクは、多文化主義を「特別な権利を要求する」人種的少数派と同一視し、それを「隠された人種差別」を助長するものと見なす傾向があると指摘す る。むしろ、多文化主義は実際には「マイノリティの問題ではない」が、「異なる文化コミュニティ間の適切な関係のあり方」に関するものであると彼は主張す る。つまり、コミュニティが相違点を解決するための基準、例えば「正義の原則」は、いずれか一つの文化から来るものであってはならず、「両者の間のオープ ンで対等な対話を通じて」生み出されるものでなければならないということである。[38] バリバールは、多文化主義に対する批判を「差異主義的レイシズム」と特徴づけている。これは、人種差別を隠ぺいする形であり、民族の優越性を主張するのではなく、むしろ「生活様式や伝統の相容れなさ」というステレオタイプを主張するものであると彼は述べている。[39] 民族的多様性は戦争の可能性を高め、公共財の供給を低下させ、民主化を妨げるという研究がある一方で、民族的多様性それ自体は平和[40][41]、公共 財の供給[42][43]、民主化[44]にとって有害ではないという研究もある。むしろ、多様性を推進することは 実際には不利な立場にある学生の進歩に役立つことが分かっている。[45] 2018年の『アメリカ政治科学評論』誌に掲載された研究では、民族・人種的な均質性が公共財の提供を促進するという研究結果に疑問を投げかけている。 [46] 2015年の『アメリカ社会学ジャーナル』誌に掲載された研究では、人種的多様性が信頼に悪影響を与えるという過去の研究結果に異議を唱えている。 [47] 批判(→「多文化主義の隆盛と衰退」) 詳細は「多文化主義への批判」を参照 多文化主義の批判者たちは、互いに影響し合いながらも独自性を保ちつつ共存する文化の多文化主義的理想が持続可能であるか、逆説的であるか、あるいは望ま しいことであるかについて、しばしば議論している。[48][49][50] 国民国家は、以前は独自の文化アイデンティティと同義語であったが、強制的な多文化主義に敗北し、最終的にはホスト国の独自文化を浸食する、と主張されて いる。[51] サラ・ソングは、文化は歴史的にその構成員によって形作られた存在であり、グローバル化によって境界が曖昧になっているため、人々が考える以上に強固なも のになっていると主張している。[52] 彼女は、文化は相互に建設的であり、支配的文化によって形作られるという考えに基づき、特別な権利という概念に反対している。ブライアン・バリーは政治領 域における文化に対して差異を無視するアプローチを提唱しており、個人を基本とする普遍的自由主義プロジェクトとは対極にあるとして、集団に基づく権利を 否定している。 政治哲学のフェミニスト教授であるスーザン・モーラー・オキンは、1999年の論文「多文化主義は女性にとって悪いのか?」で、すべての文化は平等であるという原則は、特に女性の平等な権利が時に深刻に侵害されることを意味すると主張した。 ハーバード大学の政治学教授であるロバート・D・パットナムは、多文化主義が社会の信頼にどのような影響を与えるかについて、10年近くにわたる研究を 行った。[55] 彼は、アメリカの40のコミュニティで26,200人を対象に調査を行い、階級や収入、その他の要因を調整したデータでは、人種的多様性が高いコミュニ ティほど信頼の喪失が大きいことが分かった。多様なコミュニティの人々は、「地元の市長を信頼せず、地元の新聞を信頼せず、他人を信頼せず、制度を信頼し ない」とパットナムは書いている。[56] このような民族的多様性が存在する状況下では、「私たちは身を潜める。カメのように身を隠す。多様性の影響は想像以上に悪い。そして、自分たちと異なる人 々を信頼しないというだけではない。多様性のあるコミュニティでは、自分たちと異なる外見の人々を信用しない」と述べている。[55] しかし、パットナムは「この多様性に対するアレルギーは、次第に弱まり、消えていく傾向にある。長い目で見れば、私たちは皆、より良くなっていくと思う」 とも述べている。[57] パットナムは、社会における多様性に反対する主張をしているという非難を否定し、自身の論文は、人種を考慮した大学入学に反対する主張をするために「ねじ 曲げられた」と主張した。彼は、「広範囲にわたる研究と経験から、人種や民族の多様性を含む多様性が社会にもたらす実質的な利益が確認されている」と主張 している。[58] 人類学者のフランク・ソルターは次のように書いている。 比較的均質な社会は公共財により多く投資しており、公共の利益を優先する度合いが高いことを示している。例えば、民族の均質性の度合いは、政府の国内総生 産(GDP)に占める割合や市民の平均的な資産と相関関係にある。米国、アフリカ、東南アジアの事例研究では、多民族社会は慈善活動が少なく、公共インフ ラの開発に協力する能力も低いことが分かっている。モスクワの物乞いは、他の民族よりも同じ民族からより多くの贈り物を受け取っている。米国における公共 財に対する自治体の支出に関する最近の複数の都市を対象とした研究では、民族や人種が多様な都市は、より均質な都市よりも予算の割合が小さく、公共サービ スへの支出が一人当たり少ないことが分かった。 米国コロラド州の元民主党知事で3期務めたディック・ラムは、「世界中の多様な人々は、お互いを憎み合っている。つまり、殺し合っていないときには、お互いを憎み合っているのだ。多様で平和な、あるいは安定した社会は、ほとんどの歴史的事例に反している」と主張している。 アメリカの古典学者ビクター・デイヴィス・ハンソンは、モクテスマとコルテスの「合理性」における認識された相違を理由に、西洋文化は世界のあらゆる文化よりも優れていると主張し、それゆえ、あらゆる文化を平等に扱う誤った教義であるとして多文化主義を否定した。 公式に二文化主義を掲げるニュージーランド(マオリ語で「アオテアロア」)では、多文化主義はマオリ族に対する脅威であり、マオリ族の自己決定要求を弱体化させ、同化を促すニュージーランド政府の試みであると見られている。 右翼のシンパは、グローバルブランドの多文化主義的な広告に対するオンラインでの議論の場にますます参加するようになっている。 |

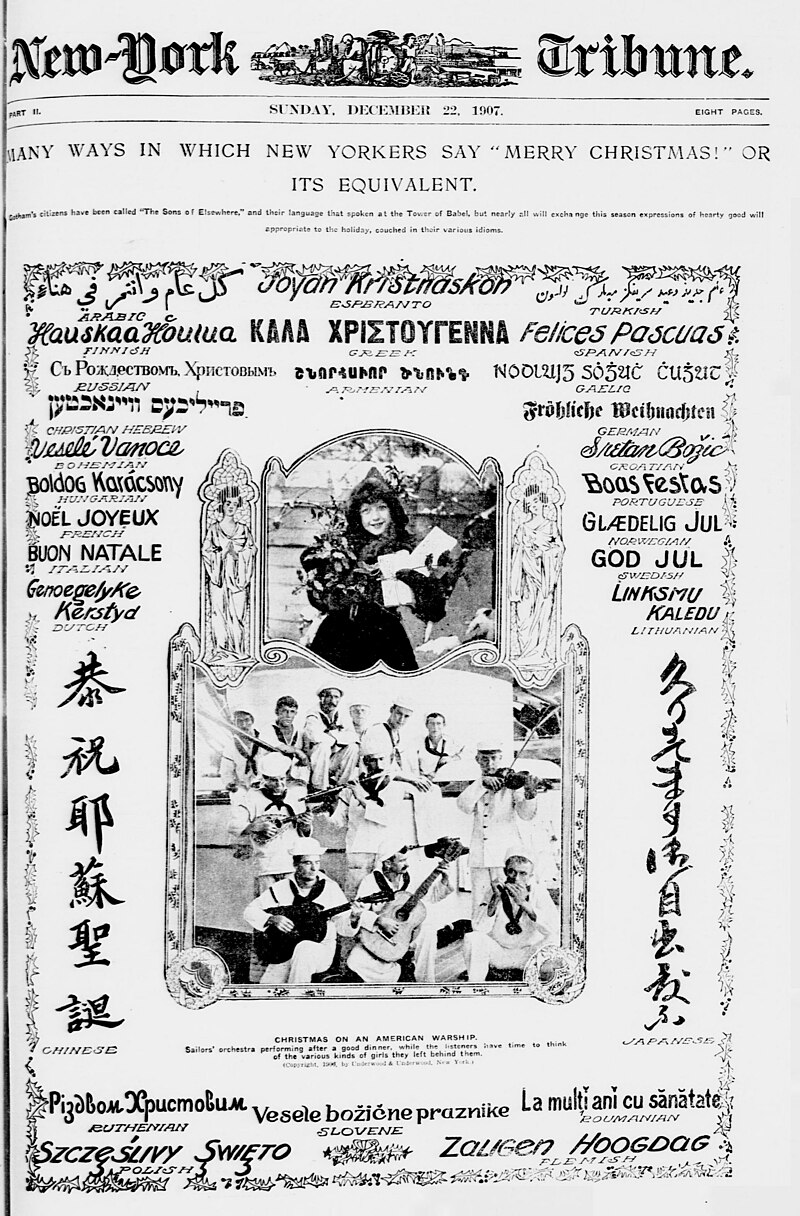

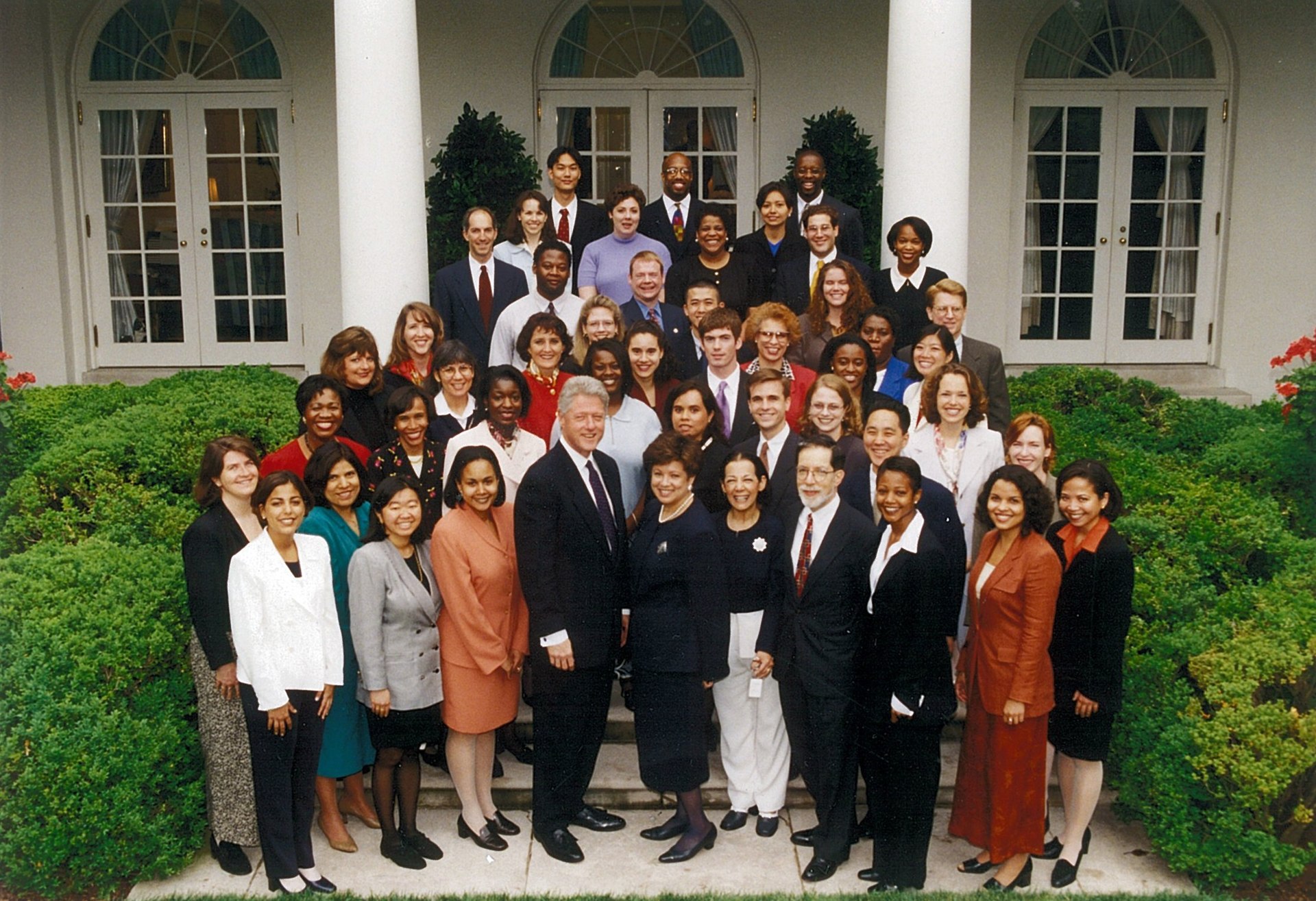

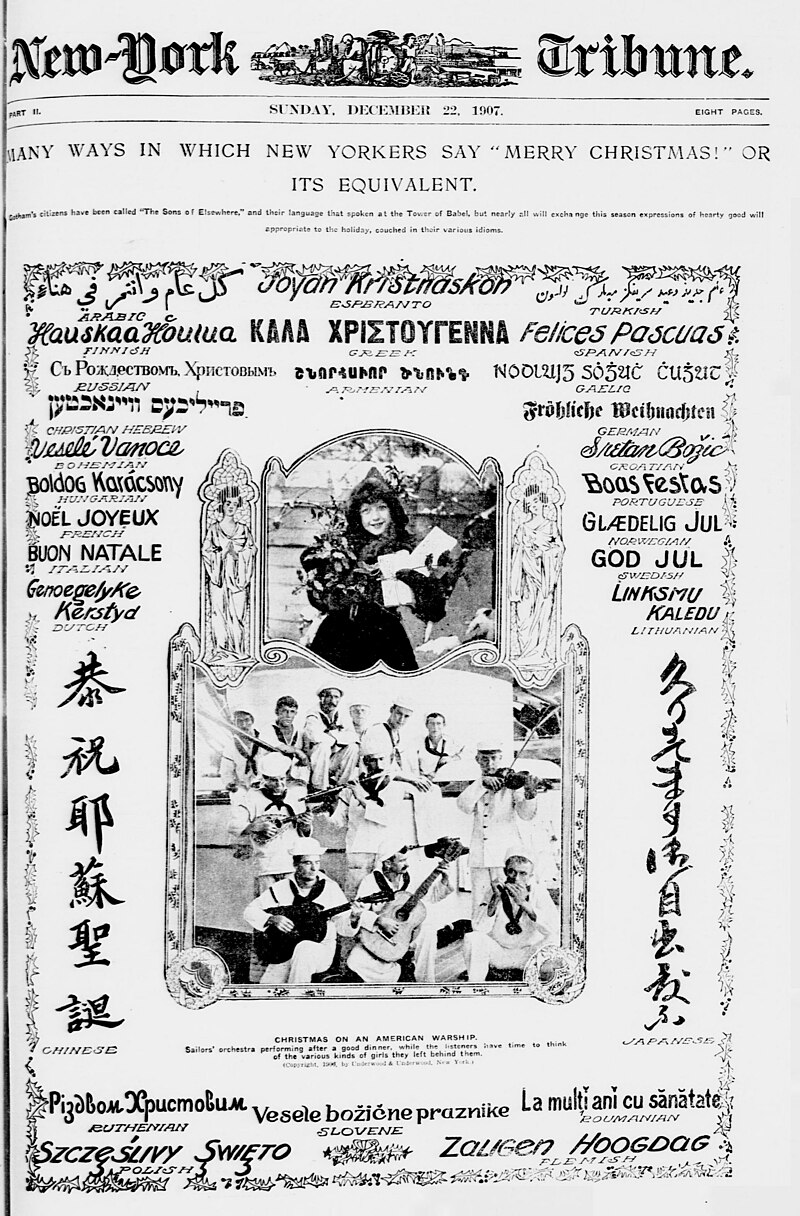

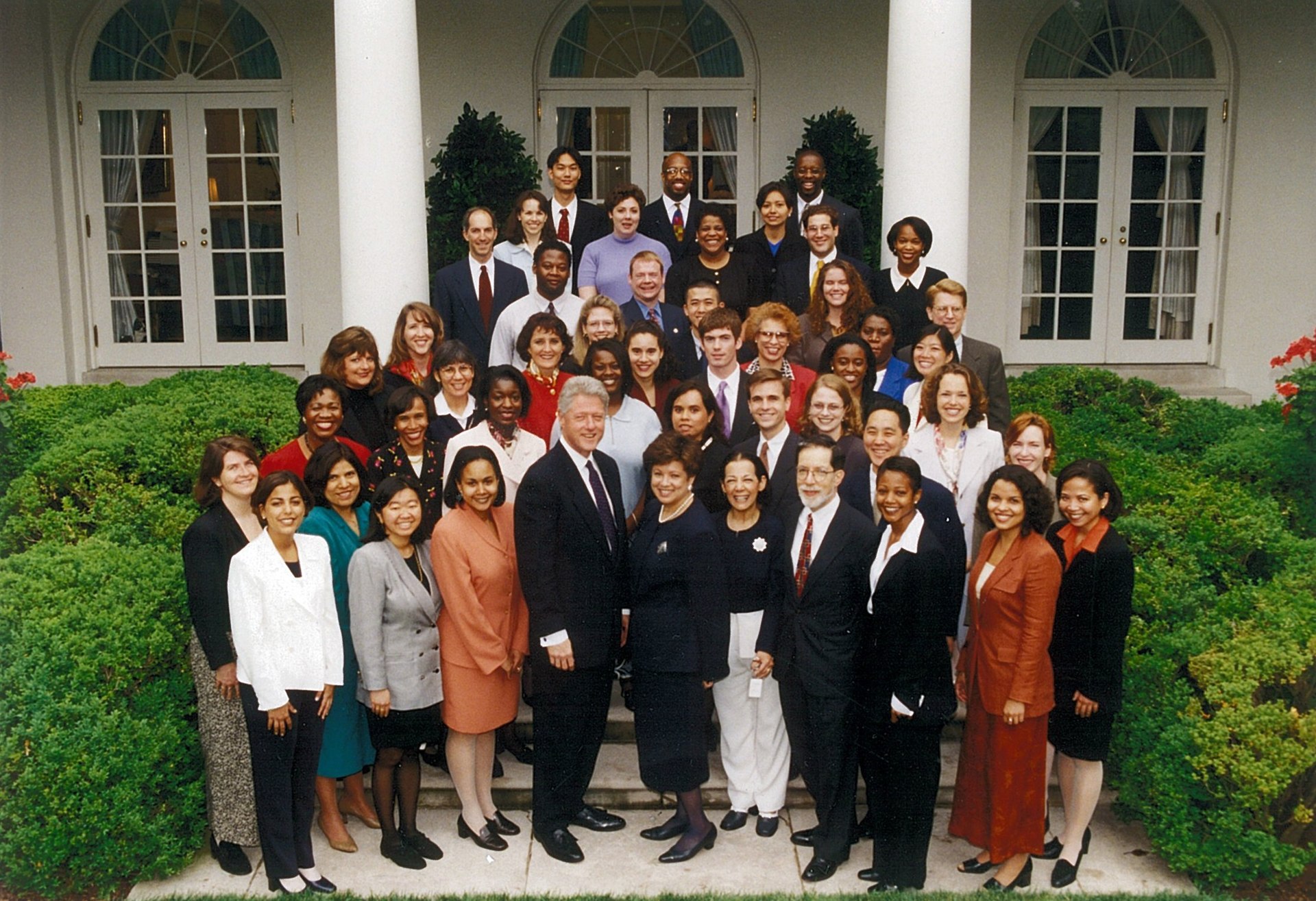

| Americas Argentina Main articles: Demographics of Argentina and Immigration to Argentina  Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity in Buenos Aires Though not called Multiculturalism as such, the preamble of Argentina's constitution explicitly promotes immigration, and recognizes the individual's multiple citizenship from other countries. Though 97% of Argentina's population self-identify as of European descent and mestizo[64] to this day a high level of multiculturalism remains a feature of Argentina's culture,[65][66] allowing foreign festivals and holidays (e.g. Saint Patrick's Day), supporting all kinds of art or cultural expression from ethnic groups, as well as their diffusion through an important multicultural presence in the media. In Argentina there are recognized regional languages Guaraní in Corrientes,[67] Quechua in Santiago del Estero,[68] Qom, Mocoví, and Wichí in Chaco.[69] According to the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs published on its website, there are 1,779 registered indigenous communities in Argentina, belonging to 39 indigenous peoples.[70] [71] Bolivia Bolivia is a diverse country made up of 36 different types of indigenous groups.[72] Over 62% of Bolivia's population falls into these different indigenous groups, making it the most indigenous country in Latin America.[73] Out of the indigenous groups the Aymara and the Quechua are the largest.[72] The latter 30% of the population is a part of the mestizo, which are a people mixed with European and indigenous ancestry.[73] Bolivia's political administrations have endorsed multicultural politics and in 2009 Bolivia's Constitution was inscribed with multicultural principles.[74] The Constitution of Bolivia recognizes 36 official languages besides Spanish, each language has its own culture and indigenous group.[75] Bolivian culture is celebrated across the country and has heavy influences from the Aymara, the Quechua, the Spanish, and other popular cultures from around Latin America. Brazil  House with elements of people from different countries, including Russians and Germans, in Carambeí, south of the country, a city of Dutch majority Brazil has been known to acclaim multiculturalism and has undergone many changes regarding this in the past few decades. Brazil is a controversial country when it comes to defining a multicultural country.[76] There are two views: the Harvard Institute of Economic Research states that Brazil has an intersection of many cultures because of recent migration, while the Pew Research Center states that Brazil is culturally diverse but the majority of the country speaks Portuguese.[77] Cities such as São Paulo are home to migrants from Japan, Italy, Lebanon and Portugal.[78] There is a multicultural presence in this city, and this is prevalent throughout Brazil. Furthermore, Brazil is a country that has made great strides to embrace migrant cultures. There has been increased awareness of anti-blackness and active efforts to combat racism.[79] Canada Main article: Multiculturalism in Canada  Sikhs celebrating the Sikh new year in Toronto, Canada Canadian society is often depicted as being "very progressive, diverse, and multicultural" often acknowledging several different cultures and beliefs.[80] Multiculturalism (a Just Society[81]) was adopted as the official policy of the Canadian government during the premiership of Pierre Elliott Trudeau in the 1970s and 1980s.[82] Multiculturalism is reflected in the law through the Canadian Multiculturalism Act[83] and section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[84] The Broadcasting Act of 1991 asserts the Canadian broadcasting system should reflect the diversity of cultures in the country.[85][86] Canadian multiculturalism is looked upon with admiration outside the country, resulting in the Canadian public dismissing most critics of the concept.[87][88] Multiculturalism in Canada is often looked at as one of Canada's significant accomplishments,[89] and a key distinguishing element of Canadian identity.[90][91] In a 2002 interview with The Globe and Mail, Karīm al-Hussainī, the 49th Aga Khan of the Ismaili Muslims, described Canada as "the most successful pluralist society on the face of our globe", citing it as "a model for the world".[92] He explained that the experience of Canadian governance—its commitment to pluralism and its support for the rich multicultural diversity of its people—is something that must be shared and would be of benefit to all societies in other parts of the world.[92] The Economist ran a cover story in 2016 praising Canada as the most successful multicultural society in the West.[93] The Economist argued that Canada's multiculturalism was a source of strength that united the diverse population and by attracting immigrants from around the world was also an engine of economic growth as well.[93] Many public and private groups in Canada work to support both multiculturalism and recent immigrants to Canada.[94] In an effort to support recent Filipino immigrants to Alberta, for example, one school board partnered with a local university and an immigration agency to support these new families in their school and community.[95] Mexico  Teotihuacan Mexico has historically always been a multicultural country. After the betrayal of Hernán Cortés to the Aztecs, the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire and colonized indigenous people. They influenced the indigenous religion, politics, culture and ethnicity.[citation needed] The Spanish opened schools in which they taught Christianity, and the Spanish language eventually surpassed indigenous languages, making it the most spoken language in Mexico. Mestizo was also born from the conquest, which meant being half-Indigenous and half-Spanish.[96] Mexico City has recently been integrating rapidly, doing much better than many cities in a sample conducted by the Intercultural Cities Index (being the only non-European city, alongside Montreal, on the index).[97] Mexico is an ethnically diverse country with a population composed of approximately 123 million in 2017. There is a wide variety of ethnic groups, the major group being Mestizos followed by White Mexicans and Indigenous Mexicans.[98] There are many other ethnic groups such as Arab Mexicans, Afro-Mexicans and Asian Mexicans. From the year 2000 to 2010, the number of people in Mexico that were born in another country doubled, reaching a total of 961,121 people, mostly coming from Guatemala and the United States.[99] Mexico is quickly becoming a melting pot, with many immigrants coming into the country. It is considered to be a cradle of civilization, which influences their multiculturalism and diversity, by having different civilizations influence them. A distinguishable trait of Mexico's culture is the mestizaje of its people, which caused the combination of Spanish influence, their indigenous roots while also adapting the culture traditions from their immigrants. Peru Peru is an exemplary country of multiculturalism, in 2016 the INEI reported a total population of 31 million people. They share their borders with Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Chile and Bolivia, and have welcomed many immigrants into their country creating a diverse community.  Tambomachay, Cuzco, Peru Peru is the home to Amerindians but after the Spanish Conquest, the Spanish brought African, and Asian peoples as slaves to Peru creating a mix of ethnic groups. After slavery was no longer permitted in Peru, African-Peruvians and Asian-Peruvians have contributed to Peruvian culture in many ways. Today, Amerindians make up 45% of the population, Mestizos 37%, white 15% and 3% is composed by black, Chinese, and others.[100] In 1821, Peru's president José de San Martín gave foreigners the freedom to start industries in Peru's ground, 2 years after, foreigners that lived in Peru for more than 5 years were considered naturalized citizens, which then decreased to 3 years. United States See also: Multicultural education and Race and ethnicity in the United States   Little Italy (top, c. 1900) in New York City abuts Manhattan's Chinatown.  People waiting to cross Fifth Avenue  Poster from 1907: The many ways in which New Yorkers say "Merry Christmas" or its equivalent; in Arabic, Armenian, Chinese, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Esperanto, Finnish, Flemish, French, Gaelic, German, Greek, Yiddish (labeled as "Christian Hebrew"), Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish and Ukrainian. "Gotham's citizens have been called "The Sons of Elsewhere", and their language that spoken at the Tower of Babel..." Although official multiculturalism policy is not established at the federal level, ethnic and cultural diversity is common in rural, suburban and urban areas.[101] Continuous mass immigration was a feature of the United States economy and society since the first half of the 19th century.[102] The absorption of the stream of immigrants became, in itself, a prominent feature of America's national myth. The idea of the melting pot is a metaphor that implies that all the immigrant cultures are mixed and amalgamated without state intervention.[103] The melting pot theory implied that each individual immigrant, and each group of immigrants, assimilated into American society at their own pace. This is different from multiculturalism as it is defined above, which does not include complete assimilation and integration.[104] The melting pot tradition co-exists with a belief in national unity, dating from the American founding fathers: Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people – a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs... This country and this people seem to have been made for each other, and it appears as if it was the design of Providence, that an inheritance so proper and convenient for a band of brethren, united to each other by the strongest ties, should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties.[105]  Staff of President Clinton's One America Initiative. The President's Initiative on Race was a critical element in President Clinton's effort to prepare the country to embrace diversity. As a philosophy, multiculturalism began as part of the pragmatism movement at the end of the 19th century in Europe and the United States, then as political and cultural pluralism at the turn of the 20th century.[106] It was partly in response to a new wave of European imperialism in sub-Saharan Africa and the massive immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans to the United States and Latin America. Philosophers, psychologists and historians and early sociologists such as Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, George Santayana, Horace Kallen, John Dewey, W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke developed concepts of cultural pluralism, from which emerged what we understand today as multiculturalism. In Pluralistic Universe (1909), William James espoused the idea of a "plural society". James saw pluralism as "crucial to the formation of philosophical and social humanism to help build a better, more egalitarian society.[107] The educational approach to multiculturalism has since spread to the grade school system, as school systems try to rework their curricula to introduce students to diversity earlier – often on the grounds that it is important for minority students to see themselves represented in the classroom.[108][109] Studies estimated 46 million Americans ages 14 to 24 to be the most diverse generation in American society.[110] In 2009 and 2010, controversy erupted in Texas as the state's curriculum committee made several changes to the state's requirements, often at the expense of minorities. They chose to juxtapose Abraham Lincoln's inaugural address with that of Confederate president Jefferson Davis;[111] they debated removing Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and labor-leader Cesar Chavez[112] and rejected calls to include more Hispanic figures, in spite of the high Hispanic population in the state.[113] According to a 2000 analysis of domestic terrorism in the United States, "A distinctive feature of American terrorism is the ideological diversity of perpetrators. White racists are responsible for over a third of the deaths, and black militants have claimed almost as many. Almost all of the remaining deaths are attributable to Puerto Rican nationalists, Islamic extremists, revolutionary leftists and emigre groups."[114] Twenty years later, far-right and white racists were observed as the leading perpetrators of domestic terrorism in the U.S.[115] According to a 2020 study by the Strategic & International Studies, right-wing extremists are responsible for the murder of 329 people since 1994 [116] (over half due to the terrorist bombing of the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah building in Oklahoma City, which killed 168 people).[117] Effect of diversity on civic engagement A 2007 study by Robert Putnam encompassing 30,000 people across the US found that diversity had a negative effect on civic engagement. The greater the diversity, the fewer people voted and the less they volunteered for community projects; also, trust among neighbours was only half that of homogenous communities.[118] Putnam says, however, that "in the long run immigration and diversity are likely to have important cultural, economic, fiscal, and developmental benefits", as long as society successfully overcomes the short-term problems.[55] Putnam adds that his "extensive research and experience confirm the substantial benefits of diversity, including racial and ethnic diversity, to our society."[119]  Bartizan in Venezuela Venezuela Venezuela is home to a variety of ethnic groups, with an estimated population of 32 million.[120] Their population is composed of approximately 68% mestizo, which means of mixed race.[121] Venezuelan culture is mainly composed of a mixture of their indigenous culture, Spanish, and African.[122] There was a heavy influence of Spanish culture due to the Spanish Conquest, which influenced their religion, language and traditions. African influence can be seen in their music.[122] While Spanish is Venezuela's main language, there are more than 40 indigenous languages spoken to this day.[123] Colombia Colombia, with an estimated population of 51 million inhabitants, is populated by a great variety of ethnic groups. Approximately 49% of its population is mestizo, 37% white, 10% Afro-descendant, 3.4% indigenous and 0.6 Gypsy. It is estimated that 18.8 million Colombians are direct descendants of Europeans, either by one of their parents or grandparents. Mainly from Spain, Italy, Germany, Poland and England, they represent 37% of its population. The Arab (Asian) descent also predominates in the country. The Syrians, Lebanese and Palestinians are the largest post-independence immigrants to the country, so much so that Colombia has the second largest Arab colony in Latin America, with a little more than 3.2 million descendants, which represents 6.4% of its population. |

南北アメリカ アルゼンチン 詳細は「アルゼンチンの人口統計」および「アルゼンチンへの移民」を参照  ブエノスアイレスの至聖三者ロシア正教会 アルゼンチンでは、多文化主義という言葉は使われていないが、憲法の前文では移民の受け入れを明確に推進しており、個人が他の国々から複数の国籍を持つこ とを認めている。アルゼンチンの人口の97%が自らをヨーロッパ系とメスティーソと認識しているが、今日でも高度な多文化主義がアルゼンチンの文化の特徴 であり続けている。外国の祭日(例えばセント・パトリックス・デイ)を認め、メディアにおける重要な多文化主義の存在を通じて、民族集団によるあらゆる芸 術や文化表現を支援している。アルゼンチンでは、コリエンテス州ではグアラニー語、サンティアゴ・デル・エステロ州ではケチュア語、チャコではコム語、モ コヴィ語、ウィチ語が地域言語として認められている。[69] アルゼンチン先住民問題国家研究所のウェブサイトによると、アルゼンチンには39の先住民グループに属する1,779の先住民コミュニティが存在する。 [70][71] ボリビア ボリビアは多様な国であり、36の異なる先住民族グループから構成されている。[72] ボリビアの人口の62%以上がこれらの異なる先住民族グループに属しており、ラテンアメリカで最も先住民族の多い国となっている。[73] 先住民族グループのうち、アイマラ族とケチュア族が最大である。[72] 人口の30%を占める後者はメスティーソであり、ヨーロッパ人と 混血の人々である。[73] ボリビアの政治行政は多文化主義を支持しており、2009年にはボリビア憲法が多文化主義の原則を明記した。[74] ボリビア憲法はスペイン語の他に36の公用語を認めており、それぞれの言語には独自の文化と先住民族グループがある。[75] ボリビア文化は国内で広く祝われており、アイマラ族、ケチュア族、スペイン語、そしてラテンアメリカ各地のポピュラー文化から大きな影響を受けている。 ブラジル  南のカラベイにある、ロシア人やドイツ人など、さまざまな国々の人々の要素が混ざった家屋。オランダ人が多数派の都市 ブラジルは多文化主義を賞賛することで知られており、この点に関して過去数十年で多くの変化を遂げている。ブラジルは多文化国家を定義するにあたっては議 論の多い国である。[76] 2つの見解がある。ハーバード大学経済研究所は、最近の移民によりブラジルには多くの文化が交差していると述べているが、ピュー研究所は、ブラジルは文化 的に多様であるが、国民の大半はポルトガル語を話すとしている。[77] サンパウロなどの都市には、日本、イタリア、レバノン、ポルトガルからの移民が住んでいる。[78] この都市には多文化的な存在があり、それはブラジル全体に広がっている。さらに、ブラジルは移民文化を受け入れるために大きな進歩を遂げた国である。反黒 人意識に対する認識が高まり、人種差別と戦うための積極的な取り組みが行われている。[79] カナダ 詳細は「カナダの多文化主義」を参照  カナダのトロントでシク教の新年を祝うシク教徒 カナダ社会はしばしば「非常に進歩的で多様かつ多文化」であり、しばしば複数の異なる文化や信念を認めていると描写される。[80] 多文化主義(公正な社会[81])は、1970年代と1980年代のピエール・エリオット・トルドー首相の時代にカナダ政府の公式政策として採用された 。多文化主義は、カナダ多文化主義法(Canadian Multiculturalism Act)[83] やカナダ権利の憲章第27条(Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms)[84] を通じて法律に反映されている。1991年の放送法(Broadcasting Act)では、カナダの放送システムは国内の文化の多様性を反映すべきであると主張している。 6] カナダの多文化主義は国外でも賞賛の的となっており、その結果、カナダ国民の多くは、この概念に対する批判のほとんどを退けている。[87][88] カナダの多文化主義は、しばしばカナダの重要な功績のひとつとみなされており[89]、カナダのアイデンティティを特徴づける重要な要素である。[90] [91] 2002年のグローブ・アンド・メール紙とのインタビューで、イスマーイール派イスラム教徒の第49代アガ・カーンであるカリーム・アル・フセインは、カ ナダを「地球上で最も成功した多元的社会」と表現し、「世界のモデル」として挙げた。[92] 彼は、カナダの統治の経験、すなわち多元主義への献身と その多文化主義への献身と、国民の豊かな多文化多様性への支援は、共有されるべきものであり、世界の他の地域のすべての社会にとって有益であると説明し た。[92] エコノミスト誌は2016年に、カナダを西洋で最も成功した多文化社会として称賛する記事を掲載した。[93] エコノミスト誌は、カナダの多文化主義は、多様な人口を団結させる強みの源であり、 また、世界中の移民を惹きつけることで、経済成長の原動力にもなっていると主張している。[93] カナダでは、多くの公的・民間団体が、多文化主義とカナダへの最近の移民の両方を支援する活動を行っている。[94] 例えば、アルバータ州への最近のフィリピン人移民を支援するために、ある教育委員会は地元の大学と移民代理店と提携し、これらの新しい家族を学校や地域社 会で支援している。[95] メキシコ  テオティワカン メキシコは歴史的に常に多文化の国であった。エルナン・コルテスがアステカ族を裏切った後、スペインはアステカ帝国を征服し、先住民を植民地化した。彼ら は先住民の宗教、政治、文化、民族に影響を与えた。スペイン人はキリスト教を教える学校を開校し、スペイン語は最終的に先住民の言語を凌駕し、メキシコで 最も話されている言語となった。征服によりメスティーソも誕生した。メスティーソとは先住民とスペイン人の混血を意味する。[96] メキシコシティは近年急速に統合が進み、インターカルチュラル・シティーズ・インデックスの調査対象となった多くの都市よりもはるかに優れた結果を残して いる(同インデックスではモントリオールと並び、唯一の非ヨーロッパの都市となっている)。[97] メキシコは民族的に多様な国であり、2017年の人口は約1億2300万人である。多種多様な民族集団が存在し、メスティーソが最大の集団で、次いで白人 のメキシコ人、先住民のメキシコ人が続く。[98] アラブ系メキシコ人、アフリカ系メキシコ人、アジア系メキシコ人など、その他にも多くの民族集団が存在する。 2000年から2010年の間に、メキシコで外国で生まれた人の数は倍増し、961,121人に達した。そのほとんどがグアテマラとアメリカ合衆国出身で ある。[99] メキシコは多くの移民を受け入れ、急速に人種のるつぼとなりつつある。 メキシコは文明発祥の地と考えられており、さまざまな文明の影響を受けてきたことが、その多文化主義と多様性に影響を与えている。メキシコ文化の顕著な特 徴は、スペインの影響、先住民のルーツ、そして移民の文化伝統の融合であるメスティソである。 ペルー ペルーは多文化主義の模範的な国であり、2016年のINEIの報告では総人口は3100万人であった。 ペルーは国境をエクアドル、コロンビア、ブラジル、チリ、ボリビアと接しており、多くの移民を受け入れ、多様なコミュニティを形成している。  タンボマチャイ、ペルー、クスコ ペルーはアメリカインディアンの故郷であるが、スペインによる征服後、スペイン人はアフリカやアジアの人々をペルーに奴隷として連れてきたため、さまざま な民族が混在するようになった。ペルーで奴隷制度が廃止された後、アフリカ系ペルー人とアジア系ペルー人はさまざまな形でペルー文化に貢献している。今 日、先住民は人口の45%を占め、メスチゾが37%、白人が15%、そして黒人、中国人、その他が3%を占めている。ペルー大統領ホセ・デ・サン・マル ティンは外国人にペルー国内での産業の自由を認め、2年後にはペルーに5年以上居住する外国人は帰化市民とみなされ、その後3年に短縮された。 アメリカ合衆国 関連項目:多文化教育、アメリカ合衆国の人種と民族   ニューヨーク市のリトル・イタリー(上、1900年頃)はマンハッタンのチャイナタウンに隣接している。  5番街を渡るために待っている人々  1907年のポスター: ニューヨーカーが「メリークリスマス」または同等の挨拶を言う多くの方法; アラビア語、アルメニア語、中国語、クロアチア語、チェコ語、オランダ語、エスペラント語、フィンランド語、フラマン語、フランス語、ゲール語、ドイツ 語、ギリシャ語、イディッシュ語(「キリスト教ヘブライ語」と表記)、ハンガリー語、イタリア語、日本語、リトアニア語、ノルウェー語、ポーランド語、ポ ルトガル語、ルーマニア語、ロシア語、スロベニア語、スペイン語、スウェーデン語、トルコ語、ウクライナ語など。 「ゴッサムの市民は『よそ者の息子たち』と呼ばれており、彼らの言語はバベルの塔で話されていた言語である...」 連邦レベルでは多文化主義政策は確立されていないが、農村部、郊外、都市部では民族や文化の多様性は一般的である。 19世紀前半以来、継続的な大量移民は米国の経済と社会の特徴であった。移民の流入の吸収自体が、アメリカ国民の神話の顕著な特徴となった。「人種のるつ ぼ」という考え方は、国家の介入なしに移民の文化がすべて混ざり合い融合するという意味の隠喩である。[103] 「人種のるつぼ」理論は、各々の移民、および各々の移民グループが、それぞれのペースでアメリカ社会に同化していくことを意味していた。これは、先に定義 したような完全な同化や統合を前提としない多文化主義とは異なるものである。[104] メルティングポットの伝統は、建国の父祖たち以来の国民統合の信念と共存している。 神は、この1つの統一された民族に、この1つのつながった国を与えたことを喜ばしく思っている。同じ祖先から生まれ、同じ言語を話し、同じ宗教を信仰し、 同じ統治の原則に愛着を持ち、その風俗習慣も非常に似ている民族に... この国とこの国民は互いのために作られたかのようで、強い絆で結ばれた兄弟の集団にとってこれほどふさわしく、都合の良い遺産が、非社交的で嫉妬深く、外 国の主権に分裂することのないように、神の思し召しによって設計されたかのようだ。[105]  クリントン大統領の「ワン・アメリカ・イニシアティブ」のスタッフ。大統領の人種に関するイニシアティブは、多様性を受け入れる国づくりを目指すクリントン大統領の取り組みにおける重要な要素であった。 多文化主義は、19世紀末の欧米におけるプラグマティズム運動の一部として始まり、20世紀初頭には政治的・文化的多元主義として発展した。[106] それは、サハラ以南のアフリカにおけるヨーロッパの帝国主義の新たな波と、南欧および東欧から米国およびラテンアメリカへの大規模な移民への対応策でも あった。チャールズ・サンダース・パース、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、ジョージ・サンタヤーナ、ホレス・カレン、ジョン・デューイ、W. E. B. デュボイス、アラン・ロックといった哲学者、心理学者、歴史家、初期の社会学者たちが文化多元主義の概念を展開し、そこから今日私たちが理解するような多 文化主義が生まれた。ウィリアム・ジェームズは著書『多元的社会』(1909年)で「多元的社会」という概念を提唱した。ジェームズは多元主義を「より良 い、より平等な社会を築くための、哲学的・社会的ヒューマニズムの形成に不可欠な要素」と捉えていた。 多文化主義への教育アプローチは、その後小学校のカリキュラムにも取り入れられるようになった。学校システムでは、多様性をより早い段階で生徒に紹介する ためにカリキュラムの再編成が試みられている。その理由として、マイノリティの生徒が教室で自分自身を表現できることが重要であるという理由がしばしば挙 げられる。14歳から24歳までのアメリカ人が、アメリカ社会で最も多様性に富んだ世代であると推定されている。[110] 2009年と2010年には、テキサス州のカリキュラム委員会が州の要件にいくつかの変更を加えたことで論争が巻き起こった。彼らは、リンカーン大統領の 就任演説を南部連合大統領ジェファーソン・デイヴィスの就任演説と並べて比較することを選択した。[111] 彼らは、サーグッド・マーシャル最高裁判事や労働組合指導者シーザー・チャベス[112] を削除するかどうかを議論し、州内のヒスパニック系住民の人口が多いにもかかわらず、ヒスパニック系の人物をより多く取り入れるという要求を却下した。 [113] 2000年のアメリカ合衆国における国内テロリズムの分析によると、「アメリカにおけるテロリズムの特徴は、加害者のイデオロギー的多様性である。白人至 上主義者が死者の3分の1以上を占め、黒人活動家もほぼ同数となっている。残りの死者のほとんどすべては、プエルトリコ民族主義者、イスラム過激派、革命 左派、亡命者グループによるものである」[114] 20年後、米国では極右および白人至上主義者が国内テロの主犯として目撃されている。[115] 2020年の戦略 ストラテジック・アンド・インターナショナル・スタディーズによる2020年の研究によると、1994年以降、右翼過激派が329人の殺害に関与している という[116](その半数以上は、1995年にオクラホマシティのアルフレッド・P・マーラ・ビルで発生した爆破テロによるもので、168人が死亡し た)[117] 多様性が市民参加に及ぼす影響 ロバート・パットナムによる2007年の研究では、全米3万人を対象に、多様性が市民参加に負の影響を及ぼしていることが分かった。多様性が高まれば高ま るほど、投票に行く人は少なくなり、地域プロジェクトにボランティアとして参加する人も少なくなる。また、近隣住民間の信頼関係は、同質的なコミュニティ の半分に過ぎなかった。[118] パットナムは、しかしながら、「長期的に見れば、移民と多様性は、重要な文化的、 経済、財政、発展の面で重要な利益をもたらす可能性が高い」と述べている。ただし、社会が短期的な問題をうまく克服できることが条件である。[55] また、パットナムは「広範な研究と経験から、人種や民族的多様性を含む多様性が我々の社会にもたらす実質的な利益が確認された」とも述べている。 [119]  ベネズエラのバティザン ベネズエラ ベネズエラは多様な民族が暮らす国であり、人口は3,200万人と推定されている。[120] 人口の約68%は混血を意味するメスティーソである。[121] ベネズエラ文化は主に、先住民文化、スペイン文化、アフリカ文化の混合から成り立っている。[122] スペインによる征服によりスペイン文化の影響が強く、宗教、言語、伝統に影響を与えた。アフリカの影響は音楽に見られる。スペイン語がベネズエラの主要言 語であるが、現在でも40以上の先住民の言語が話されている。 コロンビア 推定人口5,100万人のコロンビアには、さまざまな民族が暮らしている。人口の約49%が混血、37%が白人、10%がアフリカ系、3.4%が先住民、0.6%がジプシーである。 コロンビア人の1,880万人は、両親または祖父母のどちらかがヨーロッパ人であるヨーロッパ人の直系の子孫であると推定されている。主にスペイン、イタ リア、ドイツ、ポーランド、イギリスからの移民が人口の37%を占めている。また、アラブ(アジア)系の人々もこの国では多数派である。独立後にコロンビ アへ移住した人々の中で最も多いのはシリア人、レバノン人、パレスチナ人で、コロンビアはラテンアメリカで2番目に大きなアラブ人コミュニティを抱える国 となっている。その数は320万人を超え、人口の6.4%を占めている。 |

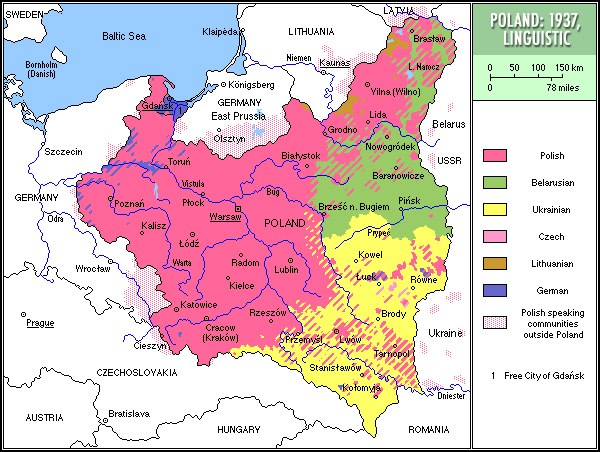

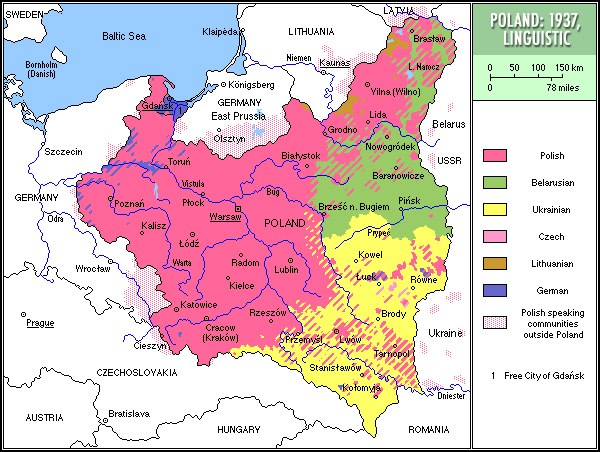

Europe Ethno-linguistic map of Austria-Hungary, 1910  Ethno-linguistic map of the Second Polish Republic, 1937 Historically, Europe has always been a mixture of Latin, Slavic, Germanic, Uralic, Celtic, Hellenic, Illyrian, Thracian and other cultures influenced by the importation of Jewish, Christian, Muslim and other belief systems; although the continent was supposedly unified by the super-position of Imperial Roman Christianity, it is accepted that geographic and cultural differences continued from antiquity into the modern age.[124] In the nineteenth century, the ideology of nationalism transformed the way Europeans thought about the state.[124] Existing states were broken up and new ones created; the new nation-states were founded on the principle that each nation is entitled to its own sovereignty and to engender, protect, and preserve its own unique culture and history. Unity, under this ideology, is seen as an essential feature of the nation and the nation-state; unity of descent, unity of culture, unity of language, and often unity of religion. The nation-state constitutes a culturally homogeneous society, although some national movements recognised regional differences.[125] Where cultural unity was insufficient, it was encouraged and enforced by the state.[126] The nineteenth century nation-states developed an array of policies – the most important was compulsory primary education in the national language.[126] The language itself was often standardised by a linguistic academy, and regional languages were ignored or suppressed. Some nation-states pursued violent policies of cultural assimilation and even ethnic cleansing.[126] Some countries in the European Union have introduced policies for "social cohesion", "integration", and (sometimes) "assimilation". The policies include: Compulsory courses and/or tests on national history, on the constitution and the legal system (e.g., the computer-based test for individuals seeking naturalisation in the UK named Life in the United Kingdom test) Introduction of an official national history, such as the national canon defined for the Netherlands by the van Oostrom Commission,[127] and promotion of that history (e.g., by exhibitions about national heroes) Tests designed to elicit "unacceptable" values. In Baden-Württemberg, immigrants are asked what they would do if their son says he is a homosexual (the desired answer is that they would accept it).[128] Other countries have instituted policies which encourage cultural separation.[129] The concept of "Cultural exception" proposed by France in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations in 1993 was an example of a measure aimed at protecting local cultures.[130] Bulgaria Sofia Synagogue Banya Bashi Mosque in Sofia Since its establishment in the seventh century, Bulgaria has hosted many religions, ethnic groups and nations. The capital city Sofia is the only European city that has peacefully functioning, within walking distance of 300 metres,[131][132] four Places of worship of the major religions: Eastern Orthodox (St Nedelya Church), Islam (Banya Bashi Mosque), Roman Catholicism (St. Joseph Cathedral), and Orthodox Judaism (Sofia Synagogue, the third-largest synagogue in Europe). This unique arrangement has been called by historians a "multicultural cliche".[133] It has also become known as "The Square of Religious Tolerance"[134][135] and has initiated the construction of a 100-square-metre scale model of the site that is to become a symbol of the capital.[136][137][138] Furthermore, unlike some other Nazi Germany allies or German-occupied countries excluding Denmark, Bulgaria managed to save its entire 48,000-strong Jewish population during World War II from deportation to Nazi concentration camps.[139][140] According to Dr Marinova-Christidi, the main reason for the efforts of Bulgarian people to save their Jewish population during WWII is that within the region, they "co-existed for centuries with other religions" – giving it a unique multicultural and multiethnic history.[141] Consequently, within the Balkan region, Bulgaria has become an example for multiculturalism in terms of variety of religions, artistic creativity[142] and ethnicity.[143][144] Its largest ethnic minority groups, Turks and Roma, enjoy wide political representation. In 1984, following a campaign by the Communist regime for a forcible change of the Islamic names of the Turkish minority,[145][146][147][148] an underground organisation called «National Liberation Movement of the Turks in Bulgaria» was formed which headed the Turkish community's opposition movement. On 4 January 1990, the activists of the movement registered an organisation with the legal name Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF) (in Bulgarian: Движение за права и свободи: in Turkish: Hak ve Özgürlükler Hareketi) in the Bulgarian city of Varna. At the moment of registration, it had 33 members, at present, according to the organisation's website, 68,000 members plus 24,000 in the organisation's youth wing [1]. In 2012, Bulgarian Turks were represented at every level of government: local, with MRF having mayors in 35 municipalities, at parliamentary level with MRF having 38 deputies (14% of the votes in Parliamentary elections for 2009–13)[149] and at executive level, where there is one Turkish minister, Vezhdi Rashidov. 21 Roma political organisations were founded between 1997–2003 in Bulgaria.[150] France Further information: Immigration to France After the end of World War II in 1945, immigration significantly increased. During the period of reconstruction, France lacked the labour to do so, and as a result; the French Government was eager to recruit immigrants coming from all over Europe, the Americas, Africa and Asia. Although there was a presence of, Vietnamese in France since the late-nineteenth century (mostly students and workers), a wave of Vietnamese migrated after 1954. These migrants consisted of those who were loyal to the colonial government and those married to French colonists. Following the partition of Vietnam, students and professionals from South Vietnam continued to arrive in France. Although many initially returned to the country after a few years, as the Vietnam War situation worsened, a majority decided to remain in France and brought their families over as well.[151] This period also saw a significant wave of immigrants from Algeria. As the Algerian War started in 1954, there were already 200,000 Algerian immigrants in France.[152] However, because of the tension between the Algerians and the French, these immigrants were no longer welcome. This conflict between the two sides led to the Paris Massacre of 17 October 1961, when the police used force against an Algerian demonstration on the streets of Paris. After the war, after Algeria gained its independence, the free circulation between France and Algeria was once again allowed, and the number of Algerian immigrants started to increase drastically. From 1962–75, the Algerian immigrant population increased from 350,000 to 700,000.[153] Many of these immigrants were known as the "harkis", and the others were known as the "pieds-noirs". The "harkis" were Algerians who supported the French during the Algerian War; once the war was over, they were deeply resented by other Algerians, and thus had to flee to France. The "pieds-noirs" were European settlers who moved to Algeria, but migrated back to France since 1962 when Algeria declared independence. According to Erik Bleich, multiculturalism in France faced stiff resistance in the educational sector, especially regarding recent Muslim arrivals from Algeria. Gatekeepers often warned that multiculturalism was a threat to the historic basis of French culture.[154] Jeremy Jennings finds three positions among elites regarding the question of reconciling traditional French Republican principles with multiculturalism. The traditionalists refuse to make any concessions and instead insist on clinging to the historic republican principles of "laïcité" and the secular state in which religion and ethnicity are always ignored. In the middle are modernising republicans who uphold republicanism but also accept some elements of cultural pluralism. Finally there are multiculturalist republicans who envision a pluralist conception of French identity and seek an appreciation of the positive values brought to France by the minority cultures.[155] A major attack on multiculturalism came in Stasi Report of 2003 which denounces "Islamism" as deeply opposed to the mainstream interpretations of French culture. It is portrayed as a dangerous political agenda that will create a major obstacle for Muslims to comply with French secularism or "laïcité ".[156] Murat Akan, however, argues that the Stasi Report and the new regulations against the hijab and religious symbols in the schools must be set against gestures toward multiculturalism, such as the creation of Muslim schools under contract with the government.[157] Germany Main article: Immigration to Germany In October 2010, Angela Merkel told a meeting of younger members of her Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party at Potsdam, near Berlin, that attempts to build a multicultural society in Germany had "utterly failed",[158] stating: "The concept that we are now living side by side and are happy about it does not work".[158][159] She continued to say that immigrants should integrate and adopt Germany's culture and values. This has added to a growing debate within Germany[160] on the levels of immigration, its effect on Germany and the degree to which middle eastern immigrants have integrated into German society.[161] In 2015, Merkel again criticized multiculturalism on the grounds that it leads to parallel societies.[162] The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community of Germany is the first Muslim group to have been granted "corporation under public law status", putting the community on par with the major Christian churches and Jewish communities of Germany.[163] Luxembourg Luxembourg has one of the highest foreign-born populations in Europe, foreigners account for nearly half of the country's total population.[164] The majority of foreigners are from: Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, and Portugal.[165] In total, 170 different nationalities make up the population of Luxembourg, out of this; 86% are of European descent.[166] The official languages of Luxembourg are German, French, and Luxembourgish all of which are supported in the Luxembourg government and education system.[166][167] In 2005, Luxembourg officially promoted and implemented the objectives of the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. This Convention affirms multicultural policies in Luxembourg and creates political awareness of cultural diversity.[168] Netherlands Main article: Multiculturalism in the Netherlands Süleymanìye Mosque in Tilburg, built in 2001 Multiculturalism in the Netherlands began with major increases in immigration to the Netherlands during the mid-1950s and 1960s.[169] As a consequence, an official national policy of multiculturalism was adopted in the early-1980s.[169] Different groups could themselves determine religious and cultural matters, while state authorities would handle matters of housing and work policy.[170] In the 1990s, the public debate were generally optimistic on immigration and the prevailing view was that a multicultural policy would reduce the social economic disparities over time.[170] This policy subsequently gave way to more assimilationist policies in the 1990s and post-electoral surveys uniformly showed from 1994 onwards that a majority preferred that immigrants assimilated rather than retained the culture of their country of origin.[169][171] Following the September 11 attacks in the United States and the murders of Pim Fortuyn (in 2002) and Theo van Gogh (in 2004), there was increased political debate on the role of multiculturalism in the Netherlands.[170][172] Lord Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, made a distinction between tolerance and multiculturalism, citing the Netherlands as a tolerant, rather than multicultural, society.[173] In June 2011, the First Rutte cabinet said the Netherlands would turn away from multiculturalism: "Dutch culture, norms and values must be dominant" Minister Donner said.[174] Romania Since Antiquity, Romania has hosted many religious and ethnic groups, including Roma people, Hungarians, Germans, Turks, Greeks, Tatars, Slovaks, Serbs, Jews and others. Unfortunately, during the WW2 and the Communism, most of these ethnic groups chose to emigrate to other countries. However, since the 1990s, Romania has received a growing number of immigrants and refugees, most of them from the Arab World, Asia or Africa. Immigration is expected to increase in the future, as large numbers of Romanian workers leave the country and are being replaced by foreigners.[175][176] Scandinavia The Vuosaari district in Helsinki, Finland, is highly multicultural.[177][178] Multiculturalism in Scandinavia has centered on discussions about marriage, dress, religious schools, Muslim funeral rites and gender equality. Forced marriages have been widely debated in Denmark, Sweden and Norway but the countries differ in policy and responses by authorities.[179] Sweden has the most permissive policies while Denmark the most restrictive ones. Denmark Main article: Immigration to Denmark This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This section contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (January 2019) The neutrality of this section is disputed. (January 2019) In 2001, Denmark, a liberal-conservative coalition government with the support of the Danish People's Party which instituted less pluralistic policy, geared more towards assimilation.[179] A 2018 study found that increases in local ethnic diversity in Denmark caused "rightward shifts in election outcomes by shifting electoral support away from traditional "big government" left‐wing parties and towards anti‐immigrant nationalist parties."[180] For decades, Danish immigration policy was built upon the belief that, with support, immigrants and their descendants would eventually reach the same levels of education as Danes. In a 2019 report, the Danish Immigration Service and the Ministry of Education found this to be false. The report found that, while the second-generation immigrants without a Western background do better than their parents, the same is not true for third-generation immigrants. One of the reasons given was that second-generation immigrants may marry someone from their country of origin, which may cause Danish not to be spoken at home, which would put the children at a disadvantage in school. Thereby, the process of integrating has to start from the beginning for each generation.[181][182] Norway Main article: Immigration to Norway Educational attainment of migrants in Norway in 2018[183] Apart from citizens of Nordic countries, all foreigners must apply for permanent residency in order to live and work in Norway.[184] In 2017, the Norwegian immigrant population was made up of: citizens of EU and EEA countries (41.2%); citizens of Asian countries, including Turkey (32.4%); citizens of African countries (13.7%); and citizens of non-EU/EEA European, North American, South American and Oceanian countries (12.7%).[185] In 2015, during the European migrant crisis, a total of 31,145 asylum seekers, most of whom came from Afghanistan and Syria, crossed the Norwegian border.[186] In 2016, the number of asylum seekers dramatically reduced by almost 90%, with 3460 asylum seekers coming to Norway. This was partly due to the stricter border control across Europe, including an agreement between the EU and Turkey.[187][188] As of September 2019, 15 foreign residents who had travelled from Norway to Syria or Iraq to join the Islamic State have had their residence permits revoked.[189] The Progress Party has named the reduction of high levels of immigration from non-European countries one of their goals: "Immigration from countries outside the EEA must be strictly enforced to ensure a successful integration. It can not be accepted that fundamental Western values and human rights are set aside by cultures and attitudes that certain groups of immigrants bring with them to Norway."[190] An extreme form of opposition to immigration in Norway were the 22/7 attacks carried out by the terrorist Anders Behring Breivik on 22 July 2011. He killed 8 people by bombing government buildings in Oslo and massacred 69 young people at a youth summer camp held by the Labour Party, who were in power at the time. He blamed the party for the high level of Muslim immigration and accused it of "promoting multiculturalism".[191] Sweden Main article: Immigration to Sweden Source: Gävle University College[192] Sweden has from the early 1970s experienced a greater share of non-Western immigration than the other Scandinavian countries, which consequently have placed multiculturalism on the political agenda for a longer period of time.[179] Sweden was the first country to adopt an official policy of multiculturalism in Europe. On 14 May 1975, a unanimous Swedish parliament passed an act on a new multiculturalist immigrant and ethnic minority policy put forward by the social democratic government, that explicitly rejected the ideal ethnic homogeneity and the policy of assimilation.[193] The three main principles of the new policy were equality, partnership and freedom of choice. The explicit policy aim of the freedom of choice principle was to create the opportunity for minority groups in Sweden to retain their own languages and cultures. From the mid-1970s, the goal of enabling the preservation of minorities and creating a positive attitude towards the new officially endorsed multicultural society among the majority population became incorporated into the Swedish constitution as well as cultural, educational and media policies. Despite the anti-multiculturalist protestations of the Sweden Democrats, multiculturalism remains official policy in Sweden.[194] A 2008 study which involved questionnaires sent to 5,000 people, showed that less than a quarter of the respondents (23%) wanted to live in areas characterised by cultural, ethnic and social diversity.[195] A 2014 study published by Gävle University College showed that 38% of the population never interacted with anyone from Africa and 20% never interacted with any non-Europeans.[196] The study concluded that while physical distance to the country of origin, also religion and other cultural expressions are significant for the perception of cultural familiarity. In general, peoples with Christianity as the dominant religion were perceived to be culturally closer than peoples from Muslim countries.[192] A 2017 study by Lund University also found that social trust was lower among people in regions with high levels of past non-Nordic immigration than among people in regions with low levels of past immigration.[197] The erosive effect on trust was more pronounced for immigration from culturally distant countries.[198] Serbia Csárdás traditional Hungarian folk dance in Doroslovo In Serbia, there are 19 officially recognised ethnic groups with a status of national minorities.[199] Vojvodina is an autonomous province of Serbia, located in the northern part of the country. It has a multiethnic and multicultural identity;[200] there are more than 26 ethnic groups in the province,[201][202] which has six official languages.[203] Largest ethnic groups in Vojvodina are Serbs (67%), Hungarians (13%), Slovaks, Croats, Romani, Romanians, Montenegrins, Bunjevci, Bosniaks, Rusyns. The Chinese[204][205] and Arabs, are the only two significant immigrant minorities in Serbia. Radio Television of Vojvodina broadcasts program in ten local languages. The project by the Government of AP Vojvodina titled "Promotion of Multiculturalism and Tolerance in Vojvodina", whose primary goal is to foster the cultural diversity and develop the atmosphere of interethnic tolerance among the citizens of Vojvodina, has been successfully implemented since 2005.[206] Serbia is continually working on improving its relationship and inclusion of minorities in its effort to gain full accession to the European Union. Serbia has initiated talks through Stabilisation and Association Agreement on 7 November 2007. United Kingdom Main article: Immigration to the United Kingdom Multicultural policies[207] were adopted by local administrations from the 1970s and 1980s onwards. In 1997, the newly elected Labour government committed to a multiculturalist approach at a national level,[208] but after 2001, there was something of a backlash, led by centre-left commentators such as David Goodhart and Trevor Phillips. The Government then embraced a policy of community cohesion instead. In 2011, Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron said in a speech that "state multiculturalism has failed".[209] Critics argue that analyses which view society as 'too diverse' for social democracy and cohesion have "performative" effects regarding legitimate racism towards those classed as immigrants.[210][211] Russian Federation Main articles: Ethnic groups in Russia and Russian nationality law The idea of multiculturalism in Russia is closely linked to the territory and the Soviet concept of "nationality". The Federation is divided into a series of republics where each ethnic group has preponderance in deciding the laws that affect that republic. A distinction is then made between Rossiyane (Russian citizens) and Russkie (ethnic Russians). Each people within their territories has the right to practice their customs and traditions and even to impose their own laws, as is the case in Chechnya, as long as they do not violate federal and constitutional laws of the Russian Federation. |

ヨーロッパ オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の民族言語地図、1910年  第2ポーランド共和国の民族言語地図、1937年 歴史的に、ヨーロッパは常にラテン、スラブ、ゲルマン、ウラル、ケルト、ヘレニック、イリュリア、トラキア、そしてユダヤ教、キリスト教、イスラム教など の信仰体系の流入の影響を受けた他の文化の混合体であった。大陸はローマ帝国のキリスト教によって統一されたと考えられているが、地理的および文化的な違 いは古代から現代まで続いていると受け止められている。 19世紀には、ナショナリズムの思想がヨーロッパ人の国家観を変化させた。[124] 既存の国家は解体され、新たな国家が誕生した。新しい国民国家は、各国民はそれぞれ独自の主権を有し、独自の文化や歴史を生み出し、保護し、維持する権利 があるという原則に基づいて建国された。この理念の下では、統一性は国民および国民国家の本質的な特徴と見なされ、血統の統一、文化の統一、言語の統一、 そしてしばしば宗教の統一も含まれる。国民国家は文化的に均質な社会を構成するが、一部の民族運動では地域的な差異が認められた。 文化的な統一が不十分な場合には、国家によって奨励され、強制された。[126] 19世紀の国民国家は、さまざまな政策を展開した。最も重要なのは、国民の言語による初等教育の義務化であった。[126] 言語自体は、言語アカデミーによって標準化されることが多く、地域言語は無視されたり、抑圧されたりした。一部の国民国家は、暴力的な文化同化政策や、さ らには民族浄化政策さえも追求した。[126] 欧州連合(EU)の一部の国では、「社会的結束」、「統合」、そして(時には)「同化」のための政策が導入されている。 その政策には以下のようなものがある。 国民の歴史、憲法、法制度に関する必修科目および(または)試験(例えば、英国の帰化希望者向けのコンピューターによる試験「Life in the United Kingdom test」) オランダのヴァン・オストロム委員会が定義したような、国民の正史の導入、およびその歴史の宣伝(例えば、国民的英雄に関する展示会など) 容認できない」価値観を引き出すことを目的としたテスト。バーデン=ヴュルテンベルク州では、移民に対して、もし息子が同性愛者であると告げた場合、どうするかを尋ねている(望ましい回答は、それを受け入れるというものである)。[128] 他の国々では、文化的分離を奨励する政策が導入されている。[129] 1993年の関税貿易一般協定(GATT)交渉でフランスが提案した「文化例外」の概念は、地域文化の保護を目的とした措置の一例である。[130] ブルガリア ソフィアのシナゴーグ ソフィアのバンヤバシ・モスク 7世紀の建国以来、ブルガリアは多くの宗教、民族、国民を受け入れてきた。首都ソフィアは、ヨーロッパで唯一、主要な宗教の4つの礼拝所(東方正教(聖ネ デリャ教会)、イスラム教(バンヤ・バシ・モスク)、ローマ・カトリック(聖ヨセフ大聖堂)、正統派ユダヤ教(ソフィア・シナゴーグ、ヨーロッパで3番目 に大きいシナゴーグ)が、徒歩300メートル圏内に平和的に共存している都市である。 この独特な状況は、歴史家たちによって「多文化の陳腐さ」と呼ばれている。[133] また、「宗教的寛容の広場」としても知られるようになり[134][135]、首都のシンボルとなる予定の敷地の100平方メートルの縮尺模型の建設が開 始された。[136][137][138] さらに、デンマークを除くナチス・ドイツの同盟国やドイツ占領国とは異なり、第二次世界大戦中、ブルガリアは4万8000人いたユダヤ人人口をナチスの強 制収容所への移送から守りきった。マリノヴァ=クリスティディ博士によると、第二次世界大戦中にブルガリア人がユダヤ人住民を救おうとした主な理由は、こ の地域では「何世紀にもわたって他の宗教と共存」してきたこと、つまり、独特な多文化・多民族の歴史があったことである。 その結果、バルカン半島地域において、ブルガリアは宗教の多様性、芸術的創造性[142]、民族性[143][144]の観点から多文化主義の模範となっ ている。最大の少数民族であるトルコ人とロマ人は、幅広い政治的発言力を有している。1984年、共産党政権によるトルコ系少数民族のイスラム名強制変更 キャンペーン[145][146][147][148]の後、「ブルガリア在住トルコ人の民族解放運動」と呼ばれる地下組織が結成され、トルコ系住民の反 対運動を主導した。1990年1月4日、この運動の活動家たちは、ブルガリアのヴァルナ市で「権利と自由のための運動」(MRF)という正式名称の組織を 登録した(ブルガリア語: ブルガリアのヴァルナ市で「権利と自由のための運動」(ブルガリア語:Движение за права и свободи、トルコ語:Hak ve Özgürlükler Hareketi)として登録された。登録時の会員数は33名であったが、現在では、同団体のウェブサイトによると、68,000名の会員と24,000 名の青年部員がいるという[1]。2012年には、ブルガリア・トルコ人は、地方自治体レベルではMRFが35の自治体の市長を輩出し、議会レベルでは MRFが38人の代議士(2009年から2013年の議会選挙での得票率14%)を輩出し、行政レベルではトルコ系大臣ヴェズディ・ラシドフが1人いるな ど、あらゆるレベルで代表者を擁している。1997年から2003年の間に、ブルガリアでは21のロマ人政治組織が設立された。[150] フランス 詳細は「フランスの移民」を参照 1945年の第二次世界大戦終結後、移民は大幅に増加した。復興期には労働力が不足していたため、フランス政府はヨーロッパ、アメリカ、アフリカ、アジアの各地から移民を積極的に受け入れた。 19世紀後半からフランスにはベトナム人が存在していたが(主に学生や労働者)、1954年以降、ベトナム人の移民が急増した。これらの移民は、植民地政 府に忠誠を誓う者や、フランス人入植者と結婚した者たちで構成されていた。ベトナムが南北に分断された後、南ベトナムからの学生や専門職従事者がフランス に到着し続けた。 当初は数年で母国に戻った者も多かったが、ベトナム戦争の情勢が悪化するにつれ、大多数がフランスに留まることを決め、家族も呼び寄せた。[151] この時期には、アルジェリアからの移民の大きな波もあった。1954年にアルジェリア戦争が始まったとき、すでにフランスには20万人のアルジェリア系移 民がいた。[152] しかし、アルジェリア人とフランス人の間の緊張により、これらの移民はもはや歓迎されなくなった。両者の対立は、1961年10月17日にパリで起きたパ リ大虐殺へとつながった。この事件では、パリの路上でアルジェリア人のデモに対して警察が武力を行使した。アルジェリアが独立を勝ち取った戦後、フランス とアルジェリア間の自由な往来が再び認められ、アルジェリアからの移民が急増し始めた。1962年から1975年の間に、アルジェリアからの移民人口は 35万人から70万人に増加した。[153] これらの移民の多くは「アルキ」と呼ばれ、その他の人々は「ピエ・ノワール」と呼ばれた。「ハルキ」とは、アルジェリア戦争中にフランスを支持したアル ジェリア人のことである。戦争が終結すると、彼らは他のアルジェリア人から強い反感を買い、フランスに逃れるしかなかった。「ピエ・ノワール」とは、アル ジェリアに移住したヨーロッパ系入植者のことであるが、1962年にアルジェリアが独立を宣言すると、彼らはフランスへと戻っていった。 エリック・ブレイヒによると、フランスにおける多文化主義は、特にアルジェリアから最近やってきたイスラム教徒に関して、教育分野で強い抵抗に直面した。 門番たちは、多文化主義はフランス文化の歴史的基盤に対する脅威であるとたびたび警告した。 ジェレミー・ジェニングスは、伝統的なフランス共和主義の原則と多文化主義の調和という問題について、エリート層の間には3つの立場があるとしている。伝 統主義者は一切の譲歩を拒否し、宗教や民族が常に無視される世俗国家という歴史的な共和主義の原則に固執することを主張する。中間派は共和制を支持する が、文化多元主義の要素も受け入れる近代共和制派である。そして最後に、フランス人のアイデンティティを多元主義的な概念として捉え、マイノリティ文化が フランスにもたらした肯定的な価値を評価しようとする文化多元主義共和制派がいる。 2003年のシュタージ報告書では、文化多元主義に対する大きな攻撃が行われ、「イスラム主義」はフランス文化の主流解釈に深く対立するものとして非難さ れた。それは、イスラム教徒がフランスの世俗主義、すなわち「ラ・イシェット」に従う上で大きな障害となる危険な政治的アジェンダとして描かれている。 [156] しかし、ムラト・アカンは、シュタージ報告書や、ヒジャブや学校における宗教的シンボルに対する新たな規制は、政府との契約に基づくイスラム系学校の設立 など、多文化主義への歩み寄りと対比して考えなければならないと主張している。[157] ドイツ 詳細は「ドイツへの移民」を参照 2010年10月、アンゲラ・メルケルはベルリン近郊のポツダムで開かれたキリスト教民主同盟(CDU)の若手メンバーの会合で、ドイツにおける多文化社 会の構築の試みは「完全に失敗した」と述べ、「私たちは今、隣り合わせに暮らしていて、それを喜んでいるという考え方はうまくいかない」と語った。 [158][159] メルケルはさらに、移民はドイツの文化や価値観に溶け込むべきだと述べた。この発言は、ドイツ国内で高まりつつあった移民の受け入れの程度、ドイツへの影 響、中東からの移民がドイツ社会にどの程度まで溶け込んでいるか、といった議論に拍車をかけた[161]。2015年、メルケルは再び、多文化主義が平行 社会につながるという理由で批判した[162]。 ドイツのアハマディア・イスラム共同体は、ドイツの主要なキリスト教会やユダヤ人社会と同等の「公法上の地位を有する法人」として認められた最初のイスラム教団体である。 ルクセンブルク ルクセンブルクはヨーロッパで外国生まれの住民が最も多い国のひとつであり、外国人が同国の総人口のほぼ半数を占めている。[164] 外国人の大半はベルギー、フランス、イタリア、ドイツ、ポルトガル出身である。[165] ルクセンブルクの人口は合計170の国籍で構成されており、そのうち8 6%がヨーロッパ系である。[166] ルクセンブルクの公用語はドイツ語、フランス語、ルクセンブルク語であり、いずれもルクセンブルク政府および教育制度でサポートされている。[166] [167] 2005年、ルクセンブルクは正式に「文化表現の多様性の保護と促進に関するユネスコ条約」の目的を推進し、実施した。この条約はルクセンブルクにおける 多文化政策を確立し、文化の多様性に対する政治的意識を生み出した。[168] オランダ 詳細は「オランダの多文化主義」を参照 ティルブルクのスレイマニエ・モスク(2001年建造 オランダにおける多文化主義は、1950年代半ばから1960年代にかけてのオランダへの移民の大幅な増加とともに始まった。[169] その結果、多文化主義という国民の公式政策が1980年代初頭に採択された。[169] 異なるグループは宗教や文化に関する事項を自ら決定することができ、一方で国家当局は住宅や労働政策に関する事項を扱うこととなった。[170] 1990年代には、移民に関する世論は概ね楽観的であり、主流派の見解は、多文化政策が時間をかけて社会経済格差を縮小するというものであった。 しかし、この政策は1990年代に同化政策へと転換し、1994年以降の選挙後の調査では、大多数が移民には出身国の文化を保持するよりも同化することを望んでいるという結果が示された。 アメリカ同時多発テロ事件や、ピム・フォルトゥイン(2002年)とテオ・ファン・ゴッホ(2004年)の殺害事件の後、オランダにおける多文化主義の役割について政治的な議論が活発化した。 英連邦ユダヤ教団の最高ラビであるサックス卿は、オランダを多文化主義社会ではなく寛容な社会であるとして、寛容と多文化主義を区別した。[173] 2011年6月、ルッテ内閣はオランダが多文化主義から離れると発表した。「オランダの文化、規範、価値観が支配的でなければならない」とドナー大臣は述 べた。[174] ルーマニア 古代以来、ルーマニアにはロマ人、ハンガリー人、ドイツ人、トルコ人、ギリシャ人、タタール人、スロバキア人、セルビア人、ユダヤ人など、多くの宗教的・ 民族的集団が居住してきた。残念ながら、第二次世界大戦と共産主義時代には、これらの民族集団のほとんどが他の国々への移住を選んだ。しかし、1990年 代以降、ルーマニアは増加する移民や難民を受け入れており、そのほとんどはアラブ諸国、アジア、アフリカからの人々である。多数のルーマニア人労働者が国 外に移住し、外国人労働者と入れ替わっているため、今後、移民の増加が見込まれている。[175][176] スカンディナヴィア フィンランドのヘルシンキにあるヴオサーリ地区は、多文化的な地域である。 スカンディナヴィアにおける多文化主義は、結婚、服装、宗教系学校、イスラム教徒の葬儀、男女平等に関する議論の中心となっている。 デンマーク、スウェーデン、ノルウェーでは、強制結婚が広く議論されているが、各国の政策や当局の対応は異なっている。 スウェーデンは最も寛容な政策をとり、デンマークは最も制限的な政策をとっている。 デンマーク 詳細は「デンマークへの移民」を参照 この節には複数の問題があります。改善やノートページでの議論にご協力ください。(テンプレートの使い方および削除のタイミングについては、こちらをご覧ください) この節には、あいまいな表現や不確実な情報が含まれています。(2019年1月) この節の中立性は疑問視されています。(2019年1月) 2001年、自由主義と保守主義の連立政権は、デンマーク人民党の支持を受け、より同化政策に重点を置いた、より多元主義的な政策を導入した。[179] 2018年の研究では、デンマークにおける地域的な民族的多様性の増加が、「選挙支援を伝統的な「大きな政府」左派政党から反移民民族主義政党へとシフトさせることで、選挙結果が右傾化する」原因となったことが分かった。[180] 何十年もの間、デンマークの移民政策は、支援があれば移民とその子孫は最終的にデンマーク人と同じレベルの教育を受けられるという信念に基づいていた。 2019年の報告書で、デンマーク移民局と教育省はこれが誤りであることを発見した。報告書では、西洋の背景を持たない移民の2世は親よりも成績が良い が、3世では同じことが当てはまらないことが分かった。その理由の一つとして、移民の第二世代が自国出身者と結婚し、家庭でデンマーク語が話されなくなる 可能性が挙げられ、その結果、子供たちは学校で不利な立場に置かれることになる。そのため、各世代ごとに統合のプロセスを最初からやり直さなければならな い。[181][182] ノルウェー 詳細は「ノルウェーへの移民」を参照 2018年のノルウェーにおける移民の学歴[183] 北欧諸国の国民を除き、ノルウェーで生活し働くためには、すべての外国人は永住権を申請しなければならない。[184] 2017年、ノルウェーの移民人口は、EUおよびEEA諸国の国民(41.2%)、 トルコを含むアジア諸国の市民(32.4%)、アフリカ諸国の市民(13.7%)、EU/EEA非加盟のヨーロッパ、北米、南米、オセアニア諸国の市民 (12.7%)で構成されている。[185] 2015年の欧州移民危機の際には、アフガニスタンとシリアからの難民が大半を占める合計31,145人の庇護希望者がノルウェー国境を越えた。 [186] 2016年には、庇護希望者の数はほぼ90%も劇的に減少し、ノルウェーに来た庇護希望者は3460人であった。これは、EUとトルコの合意を含む、ヨー ロッパ全域で厳格化された国境管理が原因の一部である。[187][188] 2019年9月現在、ノルウェーからシリアまたはイラクに渡航し、イスラム国に参加した外国人居住者15人の在留許可が取り消されている。[189] 進歩党は、非ヨーロッパ諸国からの高度な移民の削減を党の目標の一つに掲げている。 「欧州経済領域(EEA)外からの移民は、統合を成功させるために厳格に管理されなければならない。移民の一部のグループがノルウェーに持ち込む文化や態度によって、西洋の基本的価値観や人権が脇に追いやられることは容認できない」[190] ノルウェーにおける移民反対の極端な形は、2011年7月22日にテロリストのアンネシュ・ブレイヴィクによって実行された22/7テロ事件である。彼は オスロの政府庁舎を爆破して8人を殺害し、当時政権を握っていた労働党が主催する青少年サマーキャンプで69人の若者を虐殺した。彼はイスラム系移民の増 加を労働党の責任とし、労働党を「多文化主義を推進している」と非難した。[191] スウェーデン 詳細は「スウェーデンへの移民」を参照 出典:イェヴレ大学短期大学部[192] スウェーデンは1970年代初頭から、他の北欧諸国よりも非西洋諸国からの移民の割合が高く、その結果、より長い期間にわたって多文化主義を政治課題としてきた。 スウェーデンはヨーロッパで初めて多文化主義の公式政策を採用した国である。1975年5月14日、社会民主党政権が提案した新たな多文化主義的移民・少 数民族政策がスウェーデン議会で満場一致で可決された。この政策は、民族の均質性を理想とする考え方や同化政策を明確に否定するものであった。[193] 新政策の3つの主要原則は、平等、パートナーシップ、選択の自由であった。選択の自由という原則の明確な政策目標は、スウェーデンの少数民族が自分たちの 言語や文化を保持できる機会を創出することだった。1970年代半ば以降、少数民族の保護と、多数派住民の間で新しい公式に承認された多文化社会に対する 前向きな姿勢を醸成するという目標は、文化、教育、メディア政策と同様に、スウェーデンの憲法にも盛り込まれるようになった。スウェーデン民主党による反 多文化主義的な抗議にもかかわらず、多文化主義はスウェーデンにおける公式政策のままである。[194] 2008年の調査では、5,000人にアンケートを送ったところ、回答者の4分の1以下(23%)が文化、民族、社会的に多様性のある地域に住みたいと回答した。[195] イェヴレ・ユニバーシティ・カレッジが2014年に発表した研究では、人口の38%がアフリカ出身者と交流したことがなく、20%が非ヨーロッパ人と交流 したことがないことが示された。[196] この研究では、出身国との物理的な距離、また宗教やその他の文化表現が、文化的な親近感の認識に大きく影響することが結論づけられた。一般的に、キリスト 教が支配的な宗教である人々は、イスラム教国の人々よりも文化的に近いと認識されている。[192] 2017年のルンド大学の研究でも、過去の非北欧移民の割合が高い地域の住民の方が、過去の移民の割合が低い地域の住民よりも社会的な信頼度が低いことが分かった。[197] 信頼を損なう影響は、文化的に遠い国からの移民の方がより顕著であった。[198] セルビア ドロスロボ村のチャールダーシュという伝統的なハンガリーの民族舞踊 セルビアには、国民的少数派として公式に認められている民族が19ある。[199] ヴォイヴォディナはセルビアの自治州であり、同国の北部に位置している。多民族・多文化のアイデンティティを有しており[200]、州内には26以上の民 族集団が存在する[201][202]。6つの公用語がある[203]。ヴォイヴォディナ最大の民族集団はセルビア人(67%)、ハンガリー人 (13%)、スロバキア人、クロアチア人、ロマ人、ルーマニア人、モンテネグロ人、ブンジェフツ人、ボスニア人、ルシン人である。中国系住民[204] [205]とアラブ系住民は、セルビアにおける2つの主要な移民少数民族である。 ヴォイヴォディナラジオテレビは、10の現地語で番組を放送している。APヴォイヴォディナ自治州政府による「ヴォイヴォディナにおける多文化主義と寛容 の促進」と題されたプロジェクトは、ヴォイヴォディナ自治州の市民の間で文化の多様性を促進し、民族間の寛容な雰囲気を醸成することを主な目的としてお り、2005年より成功裏に実施されている。[206] セルビアは、欧州連合(EU)への完全加盟を目指す努力の一環として、少数民族との関係改善と包摂に継続的に取り組んでいる。セルビアは2007年11月 7日に安定化・連合協定に関する協議を開始した。 イギリス 詳細は「イギリスの移民政策」を参照 多文化主義政策[207]は、1970年代から1980年代にかけて地方行政によって採用された。1997年、新たに選出された労働党政権は、多文化主義 的アプローチを国家レベルで採用することを約束したが[208]、2001年以降は、デイヴィッド・グッドハートやトレヴァー・フィリップスといった中道 左派の論客が主導する形で、反動的な動きが見られるようになった。それを受けて、政府は代わりにコミュニティの結束という政策を採用した。2011年、保 守党の首相であるデイヴィッド・キャメロンは演説の中で「国家による多文化主義は失敗した」と述べた。[209] 批判者たちは、社会民主主義や結束にとって社会が「多様すぎる」と見る分析は、移民として分類された人々に対する正当な人種差別に関して「パフォーマティ ビティ」効果を持つと主張している。[210][211] ロシア連邦 詳細は「ロシアの民族」および「ロシア国籍法」を参照 ロシアにおける多文化主義の概念は、領土とソビエト連邦の「国籍」概念と密接に関連している。連邦は一連の共和国に分割されており、各民族集団は、その共 和国に影響を与える法律を決定する際に優勢となる。そして、ロスィヤーネ(ロシア国民)とルースキー(ロシア人)の間に区別が設けられる。 それぞれの民族はその領土内で、慣習や伝統を守る権利があり、場合によっては独自の法律を制定する権利さえある。ただし、ロシア連邦の連邦法や憲法に違反しない限りという条件付きである。チェチェン共和国では、そのような状況が実際に起こっている。 |