現実界

The Real

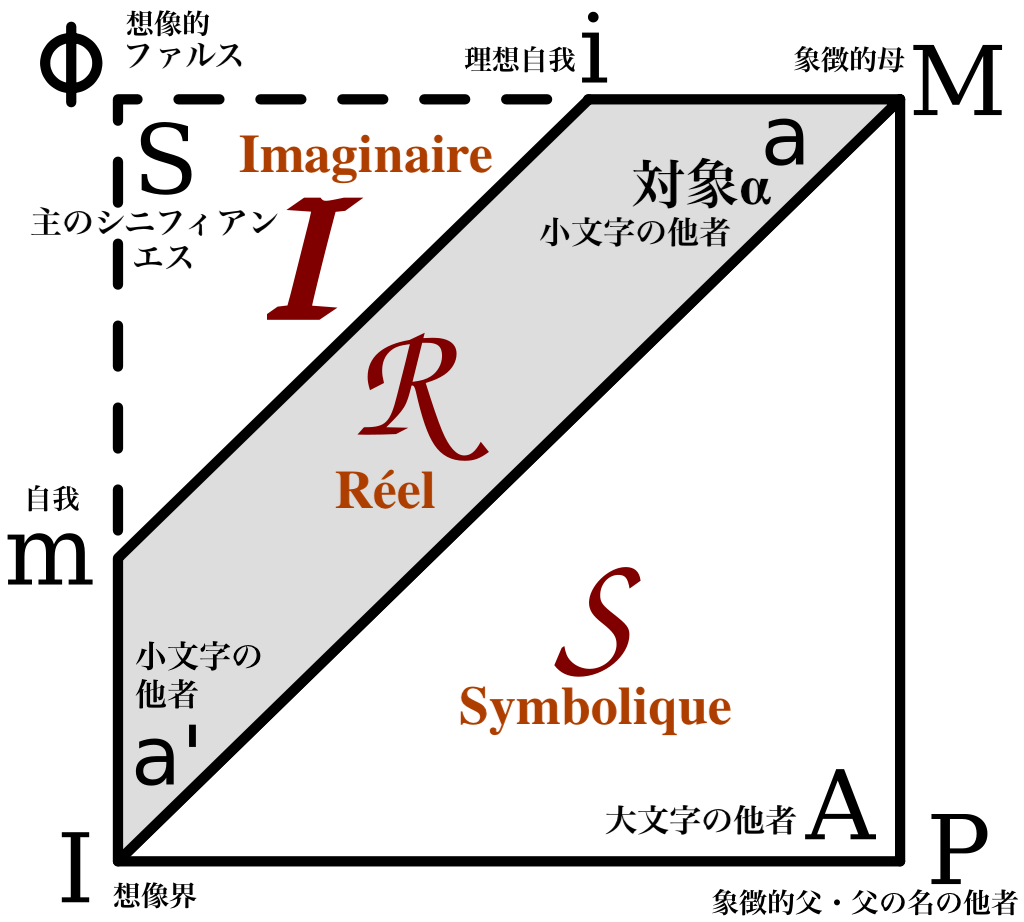

☆現実界は、ラカン派哲学(Lacanianism)では、表現と概念化に反対する「不可能な」カテゴリーのことである。RSIと表記するように現実界・象徴界・想像界は三位一体の概念である。

★現実界はすべての主体形成の限界点とみなしてよいのか?——ジュディス・バトラーの審問(『偶発性・ヘゲモニー・普遍性』)

| In

continental philosophy, the Real refers to the demarcation of reality

that is correlated with subjectivity and intentionality.[1][2] In

Lacanianism, it is an "impossible" category because of its opposition

to expression and inconceivability.[3][4] The Real Order is a

topological ring (lalangue) and ex-ists as an infinite homonym.[5][6] [T]he real in itself is meaningless: it has no truth for human existence. In Lacan's terms, it is speech that "introduces the dimension of truth into the real."[7]— James DiCenso |

大陸哲学において、実在とは、主観性と意図性と相関する現実の境界を指す[1][2]。ラカン派哲学では、表現と概念化に反対する「不可能な」カテゴリーである[3][4]。実在秩序は位相幾何学的な環(ラランジュ)であり、無限の同音異義語として実在する[5][6]。 実在それ自体は無意味である。人間の存在にとって真実ではない。ラカンの言葉によれば、それは「現実の中に真実という次元を導入する」[7]言葉である。— ジェームズ・ディセンソ |

| The

Real is the intelligible form of the horizon of truth of the

field-of-objects that has been disclosed.[8][9] As the Real Order of

the Borromean knot in Lacanianism,[10] it is opposed in the unconscious

to the Imaginary, which encompasses fantasy, dreams and

hallucinations.[11][12][13] In depth psychology and human geography,

the Real can be described as a "negative space", analogous to a "black

hole", a philosophical void of sociality and subjectivity, a traumatic

consensus of intersubjectivity, or as an absolute noumenalness between

signifiers.[21] Lewis states that the Real can be a presence or is a

substance and cites Derrida's claim that the real is authenticity.[22] Complete understanding, as in [,on the one hand,] the resolution after the period of mourning, represents [,on the other hand,] clear arrival at the Spinozan “impossible”.[23]— Ian S. Miller Even the word 'trace' is an appropriation of the real. [...] ' Writing is one of the representatives of the trace in general, it is not the trace itself. The trace itself does not exist [Derrida’s italics]. [...] (OG: 167, my italics)'[.][24]— Michael Lewis Jacques Lacan defines the Real as a plenum, a nature beyond culture that is contradistinct from the ontic.[25][26][27] The Lacanian real is a section of the triadic, Borromean knot: the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real; the center of the knot is the sinthome (monad-soul).[28] The Real is reality in its unmediated form. It is what disrupts the subject’s received notions about himself and the world around him. [...] as a shattering enigma, because in order to make sense of it he or she will have to [...] find signifiers that can ensure its control.[30]— Judith Gurewich |

現

実界とは、開示された対象物の場の真理の地平の理解可能な形態である[8][9]。ラカン主義におけるボロミーノの結び目の現実秩序[10]として、それ

は空想、夢、幻覚を含む想像と無意識の中で対立している[11][12][13]。深層心理学や人文地理学では、リアリティは「ブラックホール」に類似し

た「負の空間」、社会性や主観性の哲学的空虚、相互主観性のトラウマ的合意、あるいは記号間の絶対的な本源性として説明できる[21]。ルイスは、リアリ

ティは存在であるか、あるいは実体であり、ダーリ

完全な理解は、一方では、喪の期間を経ての解決を意味し、他方では、スピノザの「不可能」への明確な到達を意味する[23]。 「痕跡」という言葉でさえ、現実の流用である。[...] 「書くことは、痕跡の一般的な表現の一つにすぎない。痕跡そのものではない。痕跡そのものは存在しない[デリダの強調]。[...](OG: 167、強調は筆者による)'[.][24]— マイケル・ルイス ジャック・ラカンは、現実界を「全体」と定義している。実在とは、文化を超越した存在であり、存在論とは区別されるものである[25][26][27]。 ラカン ラカン派の現実界は、三項、ボロメオ結びの1つである。すなわち、想像界、象徴界、そしてリアリティであり、結び目の中心はシンソーム(単子魂)である [28]。 現実界とは、媒介されていない形での現実である。それは、対象が自分自身や周囲の世界について抱いている既成概念を覆すものである。[...] 謎を解く鍵として、それを理解するためには[...]、そのコントロールを保証する記号を見つけなければならないからだ。[30]—ジュディス・グレビッ チ |

| The Real Lacan's concept of the Real dates back to 1936 and his doctoral thesis on psychosis. It was a term that was popular at the time, particularly with Émile Meyerson, who referred to it as "an ontological absolute, a true being-in-itself".[44]: 162 Lacan returned to the theme of the Real in 1953 and continued to develop it until his death. The Real, for Lacan, is not synonymous with reality. Not only opposed to the Imaginary, the Real is also exterior to the Symbolic. Unlike the latter, which is constituted in terms of oppositions (i.e. presence/absence), "there is no absence in the Real".[48] Whereas the Symbolic opposition "presence/absence" implies the possibility that something may be missing from the Symbolic, "the Real is always in its place".[63] If the Symbolic is a set of differentiated elements (signifiers), the Real in itself is undifferentiated—it bears no fissure. The Symbolic introduces "a cut in the real" in the process of signification: "it is the world of words that creates the world of things—things originally confused in the 'here and now' of the all in the process of coming into being".[64] The Real is that which is outside language and that resists symbolization absolutely. In Seminar XI Lacan defines the Real as "the impossible" because it is impossible to imagine, impossible to integrate into the Symbolic, and impossible to attain. It is this resistance to symbolization that lends the Real its traumatic quality. Finally, the Real is the object of anxiety, insofar as it lacks any possible mediation and is "the essential object which is not an object any longer, but this something faced with which all words cease and all categories fail, the object of anxiety par excellence."[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan |

リアル(現実界) ラカンの現実界の概念は1936年、精神病に関する博士論文にまで遡る。それは当時流行していた用語であり、特にエミール・メイヤソンはそれを「存在論的 な絶対的存在、自己のなかの真の存在」と呼んでいた[44]: 162 ラカンは1953年に現実界のテーマに戻り、亡くなるまでそれを発展させ続けた。ラカンにとっての「実在」は現実と同義ではない。想像界と対立するだけで なく、現実界はシンボリックの外部でもある。シンボリックの「存在/不在」という対立が、シンボリックから何かが欠落している可能性を示唆しているのに対 して、「現実界は常にその場所にある」[63]。記号は記号化の過程において「現実における切れ目」を導入する:それは、ものの世界を創造する言葉の世界 であり、それは元来、すべてのものが誕生する過程の「今、ここ」で混同されていたものである」[64]。実在とは、言語の外側にあり、象徴化に絶対的に抵 抗するものである。ラカンは『セミナーXI』において、現実界を「不可能なもの」と定義しているが、それは想像することが不可能であり、象徴に統合するこ とが不可能であり、到達することが不可能だからである。この象徴化への抵抗こそが、現実界にトラウマ的な質を与えているのである。最後に、現実界は、それ がいかなる可能な媒介をも欠いており、「もはや対象ではない本質的な対象であるが、すべての言葉が停止し、すべてのカテゴリーが失敗するこの何かに直面し ている、卓越した不安の対象」である限りにおいて、不安の対象である[48]。 |

Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left is a collaborative book by the political theorists Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, and Slavoj Žižek published in 2000. |

『偶然性、ヘゲモニー、普遍性:現代左派の対話』は、政治理論家のジュディス・バトラー、エルネスト・ラクラウ、スラヴォイ・ジジェクによる共著で、2000年に出版された。 |

| Background, structure and themes Over the course of the 1990s, Butler, Laclau, and Žižek found themselves engaging with each other's work in their own books. In order to focus more closely on their theoretical differences (and similarities), they decided to produce a book in which all three would contribute three essays each, with the authors' respective second and third essays responding to the points of dispute raised by the earlier essays. In this way, the book is structured in three "cycles" of three essays each, with points of dispute and lines of argumentation developed, passed back and forward, and so on. At one point in the exchange, Butler refers to the exercise as an unintentional "comedy of formalisms,"[1]: 137 with each writer accusing the other two of being too abstract and formalist in relation to the declared themes of contingency, hegemony, and universality. At the heart of these themes is a desire to address the question of particularism and political emancipation. For example, while Žižek holds the notion of capitalism as a structure that enables various particular political claims, Butler and Laclau stress that all politics can be conceptualized in terms of a hegemonic struggle, which rejects the notion of any primary structure, such as capitalism or patriarchy. In her review of the book Linda Zirelli writes that the three share the view that "emancipatory" praxis is only possible with a universal dimension, bringing people with a common interest together, but that such a universality cannot efface the conflicting particular concerns which motivate individuals. She ends her review by citing Laclau's claim that universality is better conceived as a project (a horizon) than as a grounds for action.[2] |

背景、構成、テーマ 1990年代、バトラー、ラクラウ、ジジェクは、それぞれの著書の中で、お互いの著作について論評し合うようになった。彼らの理論上の相違点(および共通 点)をより深く考察するため、3人がそれぞれ3つのエッセイを執筆し、2番目と3番目のエッセイでは、前のエッセイで指摘された論点について反論する、と いう形式の書籍を出版することになった。このように、本書は3つの「サイクル」からなる3つのエッセイで構成されており、議論の点と論理展開が展開され、 往復され、繰り返される。 この交換の途中で、バトラーは、この試みを意図しない「形式主義の喜劇」[1]: 137 と表現している。各著者は、偶然性、ヘゲモニー、普遍性という 表明されたテーマに関して、他の 2 人が抽象的かつ形式主義的すぎると非難している。これらのテーマの中心にあるのは、個別主義と政治的解放の問題に取り組むという願望だ。例えば、ジジェク は、資本主義をさまざまな特定の政治的主張を可能にする構造として捉えているのに対し、バトラーとラクラウは、すべての政治は、資本主義や家父長制などの 一次構造という概念を否定するヘゲモニーの闘争という観点から概念化できると主張している。 リンダ・ジレッリは、この本に関する書評で、3人は、「解放」の実践は、共通の利益を持つ人民を結びつける普遍的な次元によってのみ可能であり、しかし、 そのような普遍性は、個人を動機付ける相反する個別的な関心事を消し去ることはできない、という見解を共有していると述べている。彼女は、普遍性は行動の 根拠としてよりも、プロジェクト(地平線)として捉えるほうがよい、というラクラウの主張を引用して、書評を締めくくっている[2]。 |

| Points of dispute between Butler and Laclau The Lacanian Real. In the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, "the Real" is regarded as the limit of representation. Laclau draws upon this concept of the Real to justify his claim that political identities are incomplete. Butler says this approach elevates the Lacanian Real into a transcendental, ahistorical category. Laclau responds by saying that the Lacanian Real introduces a radical disjunction into our idea of history - something which puts the whole idea of a concept being "ahistorical" radically into question.[1]: 66 In other words, for Lacan, there is no continuity to history and, therefore, there can be no stable "ahistorical" concepts. Political Struggles and Identity. Butler disputes Laclau's claim that competing political groups can form a "chain of equivalence" around a common lack (e.g. the incompleteness of their political identity), saying Laclau has no reason to assume that groups on the Left base their struggles on "identity". For this reason, Butler argues for a politics of translation between political groups struggling for liberation, in which groups reformulate their demands in the act of translating these demands into ones which can be placed coherently alongside the demands of other groups.[1]: 168 Citation and Parodic Performance. Butler claims that gender codes such as fashion and physical movements can be self-consciously parodied in such a way as to weaken those codes - a project she believes important to feminist liberation. Laclau says that Butler's use of the word "parody" in this context is overly-playful and restricts feminist politics to less confrontational modes of political resistance. |

バトラーとラクラウの論争点 ラカン的現実。ジャック・ラカンの精神分析理論では、「現実」は表象の限界とみなされている。ラクラウは、この現実の概念を引用して、政治的アイデンティ ティは不完全であるとの主張を正当化している。バトラーは、このアプローチはラカン的現実を超越的で非歴史的なカテゴリーに昇格させるものとしている。ラ クラウは、ラカン的現実が歴史の概念に根本的な断絶を導入し、概念が「非歴史的」であるという考えそのものを根本から疑問視すると反論している。[1]: 66 つまり、ラカンにとって、歴史には連続性はなく、したがって安定した「非歴史的」概念は存在しないのだ。 政治的闘争とアイデンティティ。バトラーは、競合する政治集団が共通の欠如(例えば、政治的アイデンティティの不完全性)を軸に「等価の連鎖」を形成でき るというラクラウの主張に反論し、ラクラウには、左派の集団が「アイデンティティ」を闘争の基盤としていると仮定する理由がないと述べる。このため、バト ラーは解放を闘う政治集団の間で、集団が自らの要求を他の集団の要求と整合的に並置できる形に翻訳する行為を通じて、その要求を再構築する「翻訳の政治」 を主張している。[1]: 168 引用とパロディ的パフォーマンス。バトラーは、ファッションや身体の動きなどのジェンダーの規範は、その規範を弱体化させるような方法で、意識的にパロ ディ化することができると主張している。彼女は、このプロジェクトはフェミニストの解放にとって重要であると信じている。ラクラウは、この文脈でバトラー が「パロディ」という言葉を使用することは、過度に遊び心があり、フェミニストの政治を、対立の少ない政治的抵抗の様式に制限していると述べている。 |

| Points of dispute between Laclau and Žižek Is Capitalism The "Only Game In Town"? Žižek's main argument against Laclau is that capitalism can accommodate all the demands of identity politics, and still continue to economically exploit those who identify with the newly liberated group. For instance, feminists might rejoice at equal pay, yet - from Žižek's point of view - this only serves to encourage women's participation in capitalist economics. Žižek accuses Laclau of accepting the idea that "capitalism is now the only game in town" (95). Is Universality Fleeting Or Impossible? Laclau claims that true political universality is impossible. However, for Laclau, this does not mean that we should abandon any attempt at political universality (as some poststructuralists might urge). Instead, Laclau argues that Leftists have to include this certain failure to achieve universality in their strategies - hence the title of his most successful book (co-written with Chantal Mouffe) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985). However, Žižek claims that universality is possible, although it is fleeting. Žižek believes that once the Left accept the impossibility of universality (as Laclau does), they will have given up all hope of ever over-throwing capitalism. In that sense, Žižek's stand on universality is equally as strategic as Laclau's. |

ラクラウとジジェクの論争点 資本主義は「唯一のゲーム」なのか?ジジェクがラクラウに対して主張する主な論点は、資本主義はアイデンティティ政治のあらゆる要求に対応しつつ、新たに 解放された集団に属すると自認する人々を経済的に搾取し続けることができる、というものです。例えば、フェミニストは賃金平等を歓迎するかもしれないが、 ジジェクの立場からは、これは女性を資本主義経済への参加を促すだけだとされる。ジジェクは、ラクラウが「資本主義は今や唯一のゲーム」という考えを受け 入れていると非難している(95)。 普遍性は一時的なものか、それとも不可能なのか?ラクラウは、真の政治的普遍性は不可能だと主張している。しかし、ラクラウにとって、それは(一部のポス ト構造主義者が主張するように)政治的普遍性の追求を放棄すべきだという意味ではない。むしろ、ラクラウは、左派は、普遍性を達成できないというこの特定 の失敗を戦略に組み込むべきだと主張している。そのため、彼の最も成功した著書(シャンタル・ムフとの共著)のタイトルは『ヘゲモニーと社会主義戦略』 (1985年)となっている。しかし、ジジェクは、普遍性は可能だが、それは一時的なものだと主張している。ジジェクは、左派が普遍性の不可能さを認める (ラクラウがそうするように)と、資本主義を打倒する希望をすべて失うと信じている。その意味では、ジジェクの普遍性に関する立場は、ラクラウの立場と同 様に戦略的なものだ。 |

| Points of dispute between Butler and Žižek Who Is The True Formalist? Butler accuses Žižek of being a Hegelian formalist on the basis that he appears to simply apply his Hegelian metaphysics to culture, whereas Butler herself is interested in the idea of performativity as a cultural ritual. Thus, Butler thinks that Žižek is uninterested in the specificity of the examples he uses to illustrate his points and that he really only chooses examples which will illustrate and serve his own argument. In turn, Žižek accuses Butler of being a Kantian formalist because, in his view, gender performativity is an empty formalist structure which is filled out by contingent cultural practices. Lacanian Sexual Difference. Following the psychoanalytic theory of Lacan, Žižek claims that sexual difference functions as an "empty" difference onto which all other subsequent differences are projected. Thus, during infancy, a child only enters the semiotic world of language once it has accepted the existence of sexual difference (which remains an "empty" difference because the pre-lingual infant cannot fill it out with any positive content). Against this view (and in defence of their thesis that gender is performatively enacted), Butler argues that, in order to be approached this way, the concept of sexual difference in Lacanian theory must be "emptied out" of positive content, such as the biological difference between males and females. |

バトラーとジジェクの論争点 真の形式主義者は誰なのか? バトラーは、ジジェクがヘーゲル的な形而上学を文化に単純に適用しているように見えることを理由に、彼をヘーゲル的な形式主義者だと非難している。一方、 バトラー自身は、文化的な儀式としてのパフォーマティビティの概念に関心を持っている。したがって、バトラーは、ジジェクは自分の主張を説明するために用 いる例の詳細には関心がなく、実際には自分の主張を説明し、支持する例だけを選んでいると考えている。一方、ジジェクは、ジェンダーのパフォーマティビ ティは、偶発的な文化慣習によって埋め尽くされる空虚な形式主義的構造であるとの見解から、バトラーをカントの形式主義者だと非難している。 ラカン的な性的差異。ラカンの精神分析理論に従って、ジジェクは、性的差異は、その後のすべての差異が投影される「空虚な」差異として機能すると主張して いる。したがって、幼児期には、子供は、性的差異の存在を受け入れた後に初めて、言語の記号世界に入る(言語を習得する前の幼児は、その差異を肯定的な内 容で埋めることができないため、性的差異は「空虚な」差異のままである)。この見解に反して(そして、ジェンダーはパフォーマティビティによって実現され るという彼らの説を擁護して)、バトラーは、このようなアプローチを採用するには、ラカン理論における性的差異の概念から、男性と女性の生物学的差異など のポジティブな内容を「空っぽ」にしなければならないと主張している。 |

| 1.

Butler, Judith; Laclau, Ernesto; Žižek, Slavoj (2000). Contingency,

Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues On The Left. London and

New York: Verso. 2. Zerilli, Linda (February 2002). "Review of Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left by Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau, Slavoj Žižek". Political Theory. 30 (1): 167–170. JSTOR 3072492. |

1. バトラー、ジュディス、ラクラウ、エルネスト、ジジェク、スラヴォイ(2000)。『偶然性、ヘゲモニー、普遍性:現代左翼の対話』 ロンドンおよびニューヨーク:Verso。 2. ゼリリ、リンダ (2002年2月)。「ジュディス・バトラー、エルネスト・ラクラウ、スラヴォイ・ジジェク著『偶然性、ヘゲモニー、普遍性:左派の現代的対話』の書評」。政治理論。30 (1): 167–170. JSTOR 3072492。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contingency,_Hegemony,_Universality |

|

| Punti di contesa tra Butler e Žižek Chi è il vero formalista? Butler accusa Žižek di essere un formalista hegeliano, in quanto sembra semplicemente applicare la sua metafisica hegeliana alla cultura, mentre la stessa Butler è interessata all'idea di performatività come rituale culturale. Butler ritiene quindi che Žižek non sia interessato alla specificità degli esempi che usa per illustrare le sue tesi e che in realtà scelga solo esempi che illustrino e supportino la sua argomentazione. A sua volta, Žižek accusa Butler di essere una formalista kantiana perché, a suo avviso, la performatività di genere è una struttura formalista vuota, che viene riempita da pratiche culturali contingenti. Differenza sessuale lacaniana . Seguendo la teoria psicoanalitica di Lacan, Žižek sostiene che la differenza sessuale funziona come una differenza "vuota" su cui vengono proiettate tutte le altre differenze successive. Pertanto, durante l'infanzia, il bambino entra nel mondo semiotico del linguaggio solo dopo aver accettato l'esistenza della differenza sessuale (che rimane una differenza "vuota" perché il bambino prelinguale non può riempirla con alcun contenuto positivo). Contro questa visione (e in difesa della loro tesi secondo cui il genere è messo in atto performativamente), Butler sostiene che, per essere affrontato in questo modo, il concetto di differenza sessuale nella teoria lacaniana deve essere "svuotato" di contenuti positivi, come la differenza biologica tra maschi e femmine. |

バトラーとジジェクの論争点 真の形式主義者は誰なのか?バトラーは、ジジェクがヘーゲル形式主義者であると非難している。ジジェクは、ヘーゲルの形而上学を文化に単純に適用している ように見えるのに対し、バトラーは、文化的な儀式としてのパフォーマンス性という概念に関心を持っているからだ。したがって、バトラーは、ジジェクは自分 の主張を説明するために用いる例の詳細には関心がなく、実際には自分の主張を説明し、支持する例だけを選んでいると主張している。一方、ジジェクは、ジェ ンダーのパフォーマンス性は、その場限りの文化的な実践によって満たされる空虚な形式主義的構造であるとして、バトラーをカントの形式主義者だと非難して いる。 ラカン的な性差。ラカンの精神分析理論に従って、ジジェクは、性差は、その後のすべての他の差異が投影される「空虚な」差異として機能すると主張してい る。したがって、幼児期には、子供は言語の記号的世界に入る前に、性差の存在を受け入れる必要がある(この性差は「空虚な」差のまま残る。なぜなら、言語 を習得していない幼児は、それにポジティブな内容を充填できないから)。この見解に対して(そして、性別はパフォーマンス的に実現されるという彼らの主張 を擁護して)、バトラーは、このような方法で取り上げられる場合、ラカン理論における性差の概念は、男性と女性の生物学的差異のようなポジティブな内容か ら「空っぽ」にされなければならないと主張している。 |

| https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialoghi_sulla_sinistra._Contingenza,_egemonia,_universalit%C3%A0 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆