ミンスキー先生と感情

Minsky's emotion, with on Joke

ミンスキー先生と感情

Minsky's emotion, with on Joke

★『心の社会』のなかで、マーヴィン・ミンスキーが感情について言及するときには、明らか

に、感情を理性的理解(つまり知性?)を妨害するノイズと考えている点は明白である。つまり、ミンスキー先生は、その点で(ソマティック・マーカー仮説には対立し)明らかにデカルト主義者なのであ

る。この項目では、ミンスキーの検閲と笑いやユーモアの関係について論じる。それを取り上げる私の理由は明確である、つまり「ユーモアの気持ち(古代ギリ

シア人なら退役説で説明するかもしれないが)や笑いは感情のレパートリーとして理解できうるのか?」である。

| 16.1 EMOTION Why do so many people think emotion is harder to explain than intellect? They're always saying things like this: "I understand, in principle, how a computer might solve problems by reasoning. But I can't imagine how a computer could have emotions, or comprehend them. That doesn't seem at all the sort of thing machines could ever do." |

16.1 感情 なぜ多くの人が、感情は知性よりも説明しにくいと思っているのだろうか。 彼らはいつも次のようなことを言っている。 「コンピュータが推論によってどのように問題を解決するかは原理的に理解できる。しかし、コンピュータがどうやって感情を持ち、それを理解するのか、想像 がつかない」。それは機械ができることではなさそうだ」。 |

| We often think of anger as

nonrational. But in our Challenger

scenario, the way that Work

employs Anger to subdue Sleep seems no less rational than using a stick

to reach for something

beyond one's grasp. Anger is merely an implement that Work can use to

solve one of its

problems. The only complication is that Work cannot arouse Anger

directly; however, it discovers

a way to do this indirectly, by turning on the fantasy of Professor

Challenger. No matter

that this leads to states of mind that people call emotional. To Work

it's merely one more way

to do what it's assigned to do. We're always using images and fantasies

in ordinary thought. We

use "imagination" to solve a geometry problem, plan a walk to some

familiar place, or choose

what to eat for dinner: in each, we must envision things that aren't

actually there. The use of

fantasies, emotional or not, is indispensable for every complicated

problem-solving process. We

always have to deal with nonexistent scenes, because only when a mind

can change the ways

things appear to be can it really start to think of how to change the

ways things are.

In any case, our culture wrongly teaches us that thoughts and feelings

lie in almost separate

worlds. In fact, they're always intertwined. In the next few sections

we'll propose to regard

emotions not as separate from thoughts in general, but as varieties or

types of thoughts, each

based on a different brain-machine that specializes in some particular

domain of thought. In

infancy, these "protospecialists" have little to do with one another,

but later they grow together

as they learn to exploit one another, albeit without understanding one

another, the way Work

exploits Anger to stop Sleep. |

私たちはしばしば怒りを非合理的なものと考える。しかし、「挑戦者」のシナリオでは、「仕事」が「睡眠」を抑制するために「怒り」を使うのは、手の届か

ないところにあるものに手を伸ばすために棒を使うのと同じくらい合理的であるように見える。怒りは、ワークが問題の一つを解決するために使われる道具に過

ぎない。ただ、複雑なのは、ワークが「怒り」を直接的に呼び起こすことはできないが、チャレンジャー教授の幻想をオンにすることで、間接的

に呼び起こす方法を発見していることである。これが、人が感情的と呼ぶ心の状態につながることは問題ではない。仕事にとっては、与えられた仕事をこなすた

めの手段のひとつに過ぎないのだ。私たちは、普段の思考の中で、常にイメージやファンタジーを使われている。幾何学の問題を解くとき、身近な場所への散歩

を計画するとき、夕食に何を食べるか選ぶとき、私たちは「想像力」を使っている。いずれも、実際にはそこにないものを思い描く必要があります。感情的であ

ろうとなかろうと、空想はあらゆる複雑な問題解決のプロセスに使われているのである。なぜなら、物事の「見え方」を変えることができて初めて、物事の「あ

り方」を変えるための思考が可能になるからだ。いずれにせよ、私たちの文化は、思考と感情はほとんど別の世界にあると誤って教えている。しかし、実際に

は、両者は常に絡み合っている。次のセクションでは、感情を一般的な思考から切り離すのではなく、思考の様々な種類と見なすことを提案する。幼少期には、

これらの「原始人」は互いにほとんど関わりを持たないが、後に、互いを理解せずに、しかし、仕事が怒りを利用して睡眠を止めるように、互いを利用すること

を学ぶにつれて、共に発展していく。 |

| Another reason we consider

emotion to be more mysterious and powerful than reason is that we wrongly credit it with many

things that reason does. We're all so

insensitive to the complexity

of ordinary thinking that we take the marvels of our common sense for

granted. Then, whenever

anyone does something outstanding, instead of trying to understand the

process of thought

that did the real work, we attribute that virtue to whichever

superficial emotional signs we can

easily discern, like motivation, passion, inspiration, or sensibility. |

私たちが感情を理性よりも神秘的で強力なものと考えるもう一つの理由

は、理性が行う多くのことを間違って感情(it)で信用してしまうからである。

私たちは皆、普通の思考の複雑さには鈍感で、自分の常識のすばらしさを当然のことと思っている。そして、誰かが何か優れたことをするたびに、その本当の仕事をした思考のプロセスを理解しようとせず、

その美徳を、動機、情熱、インスピレーション、感性など、簡単に見分けられる表面的な感情のサインに帰してしまうのだ。 |

| In any case, no matter how

neutral and rational a goal may seem, it will eventually conflict

with other goals if it persists for long enough. No long-term project

can be carried out without

some defense against competing interests, and this is likely to produce

what we call emotional

reactions to the conflicts that come about among our most insistent

goals. The question is not

whether intelligent machines can have any emotions, but whether

machines can be intelligent

without any emotions. I suspect that once we give machines the ability

to alter their own

abilities we'll have to provide them with all sorts of complex checks

and balances. It is probably

no accident that the term "machinelike" has come to have two opposite

connotations. One

means completely unconcerned, unfeeling, and emotionless, devoid of any

interest. The other

means being implacably committed to some single cause. Thus each

suggests not only inhumanity,

but also some stupidity. Too much commitment leads to doing only one

single thing;

too little concern produces aimless wandering. (p.163) |

いずれにせよ、どんなに中立的で合理的に見える目標でも、それが長く続

けば、やがて他の目標と対立することになる。競合する利害関係に対して何らかの防衛策を講じなければ、長期的なプロジェクトは遂行できない。そのため、最も執拗な目標の間で生じる衝突に対して、我々が感情的反応と呼ぶものが生じる可能性がある。

問題は、知的な機械が感情を持ちうるかどうかではなく、機械が感情を持たずに知的になりうるかどうかである。いったん機械に自らの能力を変

化させる能力を与えたら、あらゆる種類の複雑なチェックとバランスを機械に与えなければならないだろうと私は考えている。「機械のような(machinelike)」という言葉が、二つの正反対の意味合いを持つよう

になったのは偶然ではないだろう。一つは、全く無関心、無感動、無感動で、何の興味もないことを意味する。もうひとつは、あるひとつの目的のために断固と

した態度で取り組むという意味である。このように、それぞれは非人間性だけでなく、ある種の愚かさも示唆している。あまりに献身的だと一つのことしかでき

なくなり、あまりに無関心だと目的のない放浪をするようになる。 |

|

|

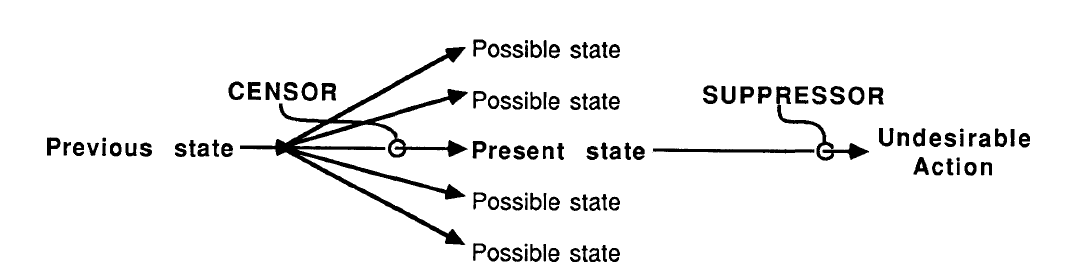

| 27.3 CENSORS To see what suppressors and censors have to do, we must consider not only the mental states that actually occur, but others that might occur under slightly different circumstances. Suppressors work by interceding to prevent actions just before they would be performed. This leads to a certain loss of time, because nothing can be done until acceptable alternatives can be found. Censors avoid this waste of time by interceding earlier. Instead of waiting until an action is about to occur, and then shutting it off, a censor operates earlier, when there still remains time to select alternatives. Then, instead of blocking the course of thought, the censor can merely deflect it into an acceptable direction. Accordingly, no time is lost. Clearly, censors can be more efficient than suppressors, but we have to pay a price for this. The farther back we go in time, the larger the variety of ways to reach each unwanted state of mind. Accordingly, to prevent a particular mental state from occurring, an early-acting censor must learn to recognize all the states of mind that might precede it. Thus, each censor may, in time, require a substantial memory bank. For all we know, each person accumulates millions of censor memories, to avoid the thought-patterns found to be ineffectual or harmful. Why not move farther back in time, to deflect those undesired actions even earlier? Then intercepting agents could have even larger effects with smaller efforts and, by selecting good paths early enough, we could solve complex problems without making any mistakes at all. Unfortunately, this cannot be accomplished only by using censors. This is because as we extend a censor's range back into time, the amount of inhibitory memory that would be needed (in order to prevent turns in every possible wrong direction) would grow exponentially. To solve a complex problem, it is not enough to know what might go wrong. One also needs some positive plan. As I mentioned before, it is easier to notice what your mind does than to notice what it doesn't do, and this means that we can't use introspection to perceive the work of these inhibitory agencies. I suspect that this effect has seriously distorted our conceptions of psychology and that once we recognize the importance of censors and other forms of "negative recognizers," we'll find that they constitute large portions of our minds. Sometimes, though, our censors and suppressors must themselves be suppressed. In order to sketch out long-range plans, for example, we must adopt a style of thought that clears the mind of trivia and sets minor obstacles aside. But that could be very hard to do if too many censors remained on the scene; they'd make us shy away from strategies that aren't guaranteed to work, and tear apart our sketchy plans before we can start to accomplish them.(p.276) |

27.3 検閲者(CENSORS) 抑制者と検閲者が何をしなければならないかを見るために、実際に起こる精神状態だけでなく、わずかに異なる状況下で起こるかもしれない他の精神状態も考慮 しなければならない。 抑制者は、実行される直前の行動を阻止するために介入することで機能する。これは、許容できる代替案を見つけるまで何もできないので、ある種の時間のロス につながる。センサは、この時間の浪費を避けるために、より早い段階で介入する。ある行動が起ころうとするまで待って、それからそれを止めるのではなく、 検閲者は、代替案を選択する時間がまだ残っているときに、より早い段階で操作する。そして、思考のコースをブロックする代わりに、検閲者は単に許容される 方向にそれをそらすことができる。したがって、時間が失われることはない。 明らかに、検閲者は抑制者よりも効率的であることができるが、私たちはこのために代価を支払わなければならない。時間を遡れば遡るほど、それぞれの望まな い精神状態に到達する方法は多岐にわたる。したがって、特定の精神状態が発生するのを防ぐために、早期に行動する検閲者は、それに先行する可能性のあるす べての精神状態を認識することを学ばなければならない。したがって、各検閲者は、時間内に、かなりのメモリバンクを必要とするかもしれない。私たちが知っ ている限りでは、各人が何百万もの検閲の記憶を蓄積し、効果がないか有害であることがわかった思考パターンを回避するためには。 なぜ、もっと過去にさかのぼって、望ましくない行動をもっと早く避けることができないのだろうか?そうすれば、阻止するエージェントはより小さな努力でよ り大きな効果を発揮することができるし、良い道を早期に選択することによって、複雑な問題を全く間違わずに解決することができるだろう。残念ながら、これ は検閲を使うだけでは実現できない。というのも、センサーの範囲を時間方向に広げると、(ありとあらゆる間違った方向に曲がらないようにするために)必要 となる抑制記憶の量が指数関数的に増大してしまうからである。複雑な問題を解決するためには、何が間違っているのかを知るだけでは不十分である。何か積極 的な計画が必要なのだ。 前にも述べたように、自分の心が何をするのかに気づくのは、何をしないのかに気づくより簡単で、このことは、これらの抑制機関の働きを知覚するために内観 を使うことができないことを意味する。私は、この効果が心理学の概念を著しく歪めているのではないかと考えている。いったん検閲官やその他の「否定的認識 者」の重要性を認識すれば、それらが私たちの心の大部分を構成していることを見つけることができるはずである。 しかし、時には、私たちの検閲者や抑制者自身が抑制されなければならないこともある。例えば、長期的な計画を描くためには、雑念を払い、些細な障害を取り 除くような思考スタイルを採用しなければならない。しかし、検閲官が多すぎると、うまくいく保証のない戦略から遠ざかり、大まかな計画を達成する前にバラ バラにしてしまうからである。 |

| 27.5 JOKES Two villagers decided to go bird hunting. They packed their guns and set out with their dog into the fields. Near evening, with no success at all, one said to the other, "We must be doing something wrong." "Yes," agreed the friend, "perhaps we're not throwing the dog high enough." Why do jokes have such peculiar psychological effects? In 1905, Sigmund Freud published a book explaining that we form censors in our minds as barriers against forbidden thoughts. Most jokes, he said, are stories designed to fool the censors. A joke's power comes from a description that fits two different frames at once. The first meaning must be transparent and innocent, while the second meaning is disguised and reprehensible. The censors recognize only the innocent meaning because they are too simple-minded to penetrate the forbidden meaning's disguise. Then, once that first interpretation is firmly planted in the mind, a final tum of word or phrase suddenly replaces it with the other one. The censored thought has been slipped through; a prohibited wish has been enjoyed. Freud suggested that children construct censors in response to prohibitions by their parents or peers. This explains why so many jokes involve taboos concerning cruelty, sexuality, and other subjects that human communities typically link to guilt, disgust, or shame. But it troubled Freud that this theory did not account for the "nonsense jokes" people seem to enjoy so much. The trouble was that these seemed unrelated to social prohibitions. He could not explain why people find humor in the idea of "a knife that has lost both its blade and its handle." Freud considered several explanations to account for pointless nonsense jokes but concluded that none of those theories was good enough. One theory was that people tell nonsense jokes for the pleasure of arousing the expectation of a real joke and then frustrating the listener. Another theory was that senselessness reflects "a wish to return to carefree childhood, when one was permitted to think without any compulsion to be logical, and to put words together without sense, for the simpler pleasures of rhythm or rhyme." Freud put it this way: Little by little the child is forbidden this enjoyment, till there remain only significant combinations of words. But attempts still emerge to disregard restrictions which were learned. In yet a third theory, Freud conjectured that humor is a way to ward off suffering-as when, in desperate situations, we make jokes as though the world were nothing but a game. Freud suggested that this is when the superego tries to comfort the childlike ego by rejecting all reality; but he was uneasy about this idea because such kindliness conflicted with his image of the superego's usual stern, strict character. Despite Freud's complicated doubts, I'll argue that he was right all along. Once we recognize that ordinary thinking, too, requires censors to suppress ineffectual mental processes, then all the different-seeming forms of jokes will seem more similar. Absurd results of reasoning must be tabooed as thoroughly as social mistakes and inanities! And that's why stupid thoughts can seem as humorous as antisocial ones.(p.278) |

27.5 ジョーク 二人の村人が鳥を狩りに行くことにしました。二人は銃を持ち、犬を連れて野原に出かけた。夕方近くになっても全く成果が上がらず、一人がもう一人に言っ た。「何か間違っているに違いない」。「そうだ、犬を高く投げていないのだろう」と友人は同意した。 なぜ、ジョークがこのような特異な心理的効果を持つのだろうか?1905年、ジークムント・フロイトは、人間は禁断の思考を防ぐために、心の中に検閲装置 を作っていると説明する本を出版した。そして、ほとんどのジョークは、検閲を欺くために作られた物語であることを説明した。ジョークの力は、2つの異なる フレームに一度にフィットする描写から生まれる。最初の意味は透明で無邪気でなければならないが、2番目の意味は偽装され非難されるべきものである。検閲 は無邪気な意味しか認めない。なぜなら、彼らは単純すぎて、禁じられた意味の変装を突き通すことができないからだ。そして、その最初の解釈が心にしっかり と植え付けられると、最後の言葉やフレーズの tum が突然それをもう一つの解釈と置き換える。検閲された思考はすり抜けられ、禁止された願いは享受されたのだ。 フロイトは、子供は親や仲間による禁止事項に反応して検閲装置を作ることを示唆した。このことは、なぜ多くのジョークが、残酷さ、性的なもの、その他人間 社会が一般的に罪悪感、嫌悪感、あるいは恥と結びつけるテーマに関するタブーを含んでいるのかを説明するものである。しかし、この理論では、人々がとても 楽しんでいるように見える「ナンセンスなジョーク」を説明できないことがフロイトを悩ませた。問題は、これらが社会的な禁止事項とは無関係に思えることで あった。彼は、なぜ人々が「刃も柄も失ったナイフ」というアイデアにユーモアを見いだすのか、説明できなかった。 フロイトは、無意味なジョークを説明するためにいくつかの説明を考えたが、どの説も十分ではないと結論づけた。一つは、人は本当の冗談を期待させるために 無意味な冗談を言い、聞く人を苛立たせるという快感を得るためだという説である。もう一つは、無意味なことは、「論理的であることを強制されることなく考 えることが許され、リズムや韻の単純な快楽のために意味なく言葉を並べることが許された、気楽な子供時代に戻りたいという願い」を反映しているという説で あった。フロイトは次のように言っている。 子供は少しずつこの楽しみを禁じられ、重要な言葉の組み合わせしか残らなくなる。しかし、学習された制限を無視 しようとする試みはまだ生じている。 さらに第三の説として、フロイトはユーモアが苦しみを回避する方法であると推測している。絶望的な状況において、まるで世界がゲームであるかのように冗談 を言うとき、ユーモアは苦しみを回避することができる。これは、超自我が現実を否定することで、子供っぽい自我を慰めようとしているのだというが、超自我 の持つ厳格なイメージと相反する優しさであるため、フロイトはこの考えに不安を抱いた。 フロイトの複雑な疑問はともかく、私はフロイトが正しかったと主張したい。普通の思 考も、効果のない精神的プロセスを抑制するための検閲を必要とすることをいったん認識すれば、すべての異なるように見えるジョークの形態がより似ているよ うに見えるだろう。不条理な推論の結果は、社会的な間違いや無意味なことと同様に、徹底的にタブー視されなければならない。だからこそ、愚かな思考は反社会的な思考と同じくらいユーモラスに見えるのだ。 |

| 27.6 HUMOR AND CENSORSHIP People often wonder if a computer could ever have a sense of humor. This question seems natural to those who think of humor as a pleasant but unnecessary luxury. But I'll argue quite the opposite-that humor has a practical and possibly essential function in how we learn. When we learn in a serious context, the result is to change connections among ordinary agents. But when we learn in a humorous context, the principal result is to change the connections that involve our censors and suppressors. In other words, my theory is that humor is involved with how our censors ]earn; it is mainly involved with "negative" thinking, though people rarely realize this. Why use such a distinct and peculiar medium as humor for this purpose? Because we must make a sharp distinction between our positive, action-oriented memories and the negative, inhibitory memories embodied in our censors. Positive memory-agents must learn which mental states are desirable. Negative memory-agents must learn which mental states are undesirable. Because these two types of learning required different processes, it was natural to evolve social signals to communicate that distinction. When people do things that we regard as good, we speak to them in encouraging tones-and this switches on their positive learning machinery. However, when people do things we consider stupid or wrong, we then complain in scornful tones or laugh derisively; this switches on their negative learning machinery. I suspect that scolding and laughing have somewhat different effects: scolding tends to produce suppressors, but laughing tends to produce censors. Accordingly, the effect of derisive humor is somewhat more likely to disrupt our present activity. This is because the process of constructing a censor deprives us of the use of our temporary memories, which must be frozen to maintain the records of our recent states of mind. Suppressors merely need to learn which mental states are undesirable. Censors must remember and learn which mental states were undesirable. To see why humor is so often concerned with prohibition, consider that our most productive forms of thought are just the ones most subject to mistakes. We can make fewer errors by confining ourselves to cautious, "logical" reasoning, but we'll also discover fewer new ideas. More can be gained by using metaphors and analogies, even though they are often defective and misleading. I think this is why so many jokes are based on recognizing inappropriate comparisons. Why, by the way, do we so rarely recognize the negative character of humor itself? Perhaps it has a funny side effect: while shutting off those censored thoughts, our censors also shut off thoughts about themselves-and make themselves invisible. This solves Freud's problem about nonsense jokes. The taboos that grow within social communities can be learned only from other people. But when it comes to intellectual mistakes, a child needs no helpful friend to scold it when a tower falls, when it puts a spoon in its ear, or thinks a thought that sets its mind into a fruitless and confusing loop. In other words, we can detect many of our own intellectual failures all by ourselves. Freud's theory of jokes was based on the idea that censors suppress thoughts that would be considered "naughty" by those to whom we are attached. He must simply have overlooked the fact that ineffectual reasoning is equally "naughty"-and therefore equally "funny"-in the sense that it, too, ought to be suppressed. There is no need for our censors to distinguish between social incompetence and intellectual stupidity.(p.279) |

27.6 ユーモアと検閲 人々はしばしば、コンピュータがユーモアのセンスを持つことができるのだろうかと考える。この疑問は、ユーモアを楽しいが不必要な贅沢品と考える人々に とっては当然のことだと思われる。しかし、私は全く逆のことを主張しよう。ユーモアは、私たちがどのように学ぶかにおいて、実用的で、おそらく不可欠な機 能を持っている。真面目な文脈で学ぶと、その結果、普通のエージェント同士のつながりが変化する。しかし、ユーモラスな文脈で学ぶと、検閲や抑圧に関わる 人たちのつながりが変化することが主な結果となるのである。 つまり、ユーモアは「検閲」の働きに関わるもので、主に「ネガティブ」な思考に関わるものだというのが私の持論である(ただし、そのことに気づいている人 はほとんどいない)。なぜ、ユーモアという特殊な媒体が使われるのか。それは、私たちのポジティブで行動的な記憶と、検閲官に具現化されたネガティブで抑 制的な記憶とを峻別しなければならないからだ。 ポジティブな記憶エージェントたちは、どのような精神状態が望ましいかを学ばなければならない。ネガティブな記憶エージェントは、どの精神状態が望ましく ないかを学ばなければならない。 この2種類の学習は異なるプロセスを必要とするため、その区別を伝える社会的シグナルを進化させるのは自然なことだった。私たちが良いと思うことをした人 には、励ますような言葉をかけ、ポジティブな学習装置のスイッチを入れます。一方、私たちが愚かだと思うこと、間違っていると思うことをした人には、軽蔑 した調子で文句を言ったり、軽蔑的に笑ったりして、その人のネガティブな学習装置のスイッチを入れるのです。叱ることは抑制者を生み、笑うことは検閲者を 生むというように、叱ることと笑うことの効果はやや異なるのではないかと思る。従って、嘲笑的なユーモアの効果は、我々の現在の活動を混乱させる可能性が やや高い。というのも、検閲を作る過程で、最近の心の状態の記録を維持するために凍結しなければならない一時的な記憶の使用を奪われるからである。 サプレッサー(抑圧)は、どの精神状態が望ましくないかを学ぶだけでよい。検閲は、どのような精神状態が望ましくないかを記憶し、学ばなければならない。 ユーモアがなぜこれほどまでに禁止に関係しているのかを理解するために、私たちの最も生産的な思考形態は、まさに最も間違いが起こりやすいものだと考えて みてほしい。私たちは、慎重で「論理的」な推論に自分自身を限定することによって、より少ない誤りを犯すことができるが、より少ない新しいアイデアも発見 することになる。比喩や類比を使えば、欠陥や誤解を招くことが多いとはいえ、より多くのものを得ることができる。多くのジョークが不適切な比較の認識に基 づいているのは、このためだと思う。ところで、なぜ私たちは、ユーモアそのものの否定的な性格をほとんど認識しないのであろうか。検閲された思考を遮断す る一方で、検閲者は自分自身についての思考も遮断し、自分自身を見えなくしてしまうのだ。 これは、フロイトのナンセンスなジョークに関する問題を解決する。社会的共同体の中で発展しているタブーは、他の人々からだけ学ぶことができる。しかし、 知的な間違いに関しては、子供は塔が倒れたとき、スプーンを耳に入れたとき、実りのない混乱したループに入るような考えをしたときに、それを叱ってくれる 親切な友人を必要としないのである。つまり、私たちは自分自身の知的失敗の多くを自分自身で発見することができるのだ。フロイトのジョーク論は、愛着のあ る相手から「いたずら」と思われるような思考は検閲によって抑制されるという考えに基づいている。彼は、非効率的な理性もまた、同様に「いたずら」であ り、したがって同様に「面白い」のであって、それもまた抑制されるべきであるという事実を見落としていただけに違いない。検閲が社会的無能と知的愚鈍を区 別する必要はない。 |

| 27.7 LAUGHTER What would a Martian visitor think to see a human being laugh? It must look truly horrible: the sight of furious gestures, flailing limbs, and thorax heaving in frenzied contortions. The air is torn with dreadful sounds as though, all at once, that person wheezes, barks, and chokes to death. The face contorts in grimaces that mix smiles and yawns with snarls and frowns. What could cause such a frightful seizure? Our theory suggests a simple answer: The function of laughing is to disrupt another person's reasoning! To see and hear a person laugh creates such chaos in the mind that you can't proceed along your present train of thought. Derision makes you feel ridiculous; it prevents you from "being serious." What happens then? Our theory has a second part: Laughter focuses attention on the present state of mind! Laughter seems to freeze one's present state of mind in its tracks and hold it up to ridicule. All further reasoning is disrupted, and only the joke-thought remains in sharp focus. What is the function of this petrifying effect? By preventing you from "taking seriously" your present thought, and thus proceeding to develop it, laughter gives you time to build a censor against that state of mind. In order to construct or improve a censor, you must retain your records of the recent states of mind that made you think the censored thought. This takes some time, during which your short-term memories are fully occupied-and that will naturally disrupt whichever other processes might try to change those memories. How could all this have evolved? Like smiling, laughter has a curious ambiguity, combining elements of affection and conciliation with elements of rejection and aggression. Perhaps all these ancestral means of social communication became fused to compose a single, absolutely irresistible way to make another person cease an activity regarded as objectionable or ridiculous. If so, it is no accident that so many jokes mix elements of pleasure, cruelty, sexuality, aggression, and absurdity. Humor must have grown along with our abilities to criticize ourselves, starting with simple internal suppressors that evolved into more sophisticated censors. Perhaps they then split off into B-brain layers that became increasingly able to predict and manipulate what the older A-brains were about to do. At this point, our ancestors must have started to experience what humanists call "conscience." For the first time, animals could start to reflect upon their own mental activities and evaluate their purposes, plans, and goals. This endowed us with great new mental powers but, at the same time, exposed us to new and different kinds of conceptual mistakes and inefficiencies. Our humor-agencies become internalized in adult life as we learn to produce the same effects entirely inside our own minds. We no longer need the ridicule of those other people, once we can make ourselves ashamed by laughing silently at our own mistakes.(p.280) |

27.7 笑い 火星人が人間の笑い声を見たらどう思うだろう?猛烈なジェスチャー、暴れる手足、狂喜乱舞する胸郭の姿は、本当に恐ろしいものに見えるに違いない。喘ぎ 声、吠え声、窒息死するような恐ろしい音で空気は引き裂かれる。顔は、微笑みとあくび、そして唸り声としかめっ面を混ぜたような険しい顔で歪む。何がこの ような恐ろしい発作を引き起こすのだろうか?私たちの理論では、簡単な答えがある。 笑いの機能は、他人の理性を混乱させることである。 人が笑うのを見たり聞いたりすると、心の中に混乱が生じ、今の思考回路を進められなくなるのだ。嘲笑は、あなたを馬鹿馬鹿しいと感じさせ、「真剣になる」 ことを妨げるのである。するとどうだろう?私たちの理論には第二の部分があることになる。 笑いは、現在の心の状態に注意を集中させるのだ。 笑いは、自分の現在の心境を凍りつかせ、嘲笑の対象にするようだ。それ以上の推論は中断され、冗談の思考だけがシャープな焦点で残っている。この石化作用 にはどのような働きがあるのだろうか。 あなたの現在の思考を「真剣に受け止め」、したがってそれを発展させる ことを妨げることによって、笑いはあなたにその心の状態に対する検閲を構築する時間を与える。 検閲を構築または改善するために、あなたは検閲された思考を考えさせた最近の心の状態のあなたの記録を保持する必要がある。これは、いくつかの時間がかか り、その間にあなたの短期記憶は完全に占有され、そしてそれは自然にそれらの記憶を変更しようとするかもしれない他のどのプロセスも混乱させる。 なぜ、このようなことが起こるようになったのだろうか?笑顔と同様、笑いには不思議な曖昧さがあり、愛情や和解の要素と拒絶や攻撃の要素が混在している。 おそらく、社会的コミュニケーションのためのこれらの祖先の手段がすべて融合して、不快またはばかばかしいとみなされる活動を相手にやめさせるための、 たった一つの、絶対に抵抗できない方法を構成するようになったのであろう。そうであれば、多くのジョークが快楽、残酷さ、性欲、攻撃性、不条理などの要素 を兼ね備えているのは偶然ではない。ユーモアは、私たちの自己批判能力とともに発展してきたのであろう。そして、B-brainに分化し、A-brain が行おうとしていることを予測し、操作することができるようになったのだろう。この時点で、私たちの祖先はヒューマニストたちが「良心」と呼ぶものを経験 し始めたに違いない。このとき初めて、動物は自分の精神活動を振り返り、その目的、計画、目標を評価することができるようになったのである。このことは、 私たちに大きな新しい精神力を与えたが、同時に、新しい、さまざまな種類の概念の誤りや非効率性に私たちをさらけ出したのである。 ユーモア能力は、大人になってから、自分の心の中で完全に同じ効果を生み出すことを学び、内面化される。自分の間違いを黙って笑うことで、自分自身を恥じ ることができるようになれば、もはや他人の嘲笑は必要ない。 |

| 27.8 GOOD HUMOR Some readers might object that the censor-learning theory of jokes is too narrow to be an explanation of humor in general. What of all the other roles that humor plays in occasions of enjoyment and companionship? Our answer is the same as usual: we can't expect any single, simple theory to explain adult psychology. To ask how humor works in a grown-up person is to ask how everything works in a grown-up person, since humor gets involved with so many other things. I didn't mean to suggest that every aspect of humor is involved in making censors learn. When humor evolved, as when any other mechanism develops in biology, it must have been built upon other mechanisms that already existed, and embodied mixtures of those other functions. Just as the voice is used for many social purposes, the mechanisms involved in humor are also used for other effects that are less involved with memory. In later life the effect of "functional autonomy" can make it hard to recognize the original function not only of humor, but of many other aspects of adult psychology. To understand how feelings work, we need to understand both their evolutionary and their individual histories. We've seen how important it is for us to learn about mistakes. To keep from making old mistakes ourselves, we learn about them from our families and friends. But a peculiar problem arises when we tell another person that something is wrong, for if this is interpreted as an expression of disapproval and rejection, it can evoke a sense of pain and loss-and lead to withdrawal and avoidance. Accordingly, to point out mistakes to someone whose loyalty and love we want to keep, we must adopt some pleasant or conciliatory form. Thus humor has evolved its graciously disarming ways to do its basically distasteful job! You don't want the recipient to "kill the messenger who brings bad news"-especially when you're the messenger. Many people seem genuinely surprised when shown that humor is so concerned with unpleasant, painful, and disgusting subjects. In a certain sense, there's really nothing humorous about most jokes-except, perhaps, in the skill and subtlety with which their dreadful content is disguised; frequently, the thought itself is little more than "See what happened to somebody else; now, aren't you glad it wasn't you?" In this sense most jokes are not actually frivolous at all but reflect the most serious of concerns. Why, by the way, are jokes usually less funny when heard again? Because the censors learn some more each time and prepare to act more quickly and effectively. Why, then, do certain kinds of jokes, particularly those about forbidden sexual subjects, seem to remain persistently funny to so many people? Why do those censors remain unchanged for so long? Here we can reuse our explanation of the prolonged persistence of attachment, infatuation, sexuality, and mourning-grief; because these areas relate to self-ideals, their memories, once formed, are slow to change. Thus the peculiar robustness of sexual humor may mean only that the censors of human sexuality are among the "slow learners" of the mind, like retarded children. In fact, we could argue that they literally are retarded children-that is, they are among the frozen remnants of our earlier selves.(p.281) |

27.8 よいユーモア 読者の中には、ジョークの検閲学習理論はユーモア全般を説明するには狭すぎると反論する人もいるかもしれない。ユーモアが楽しみや交友の場で果たす他のす べての役割についてはどうだろうか。私たちの答えはいつもと同じだ。大人の心理を説明するために、単一の単純な理論を期待することはできない。ユーモアが 大人の人間にどのように作用するのかを問うことは、大人の人間のすべてがどのように作用するのかを問うことなのだ。ユーモアは他の多くの事柄と関わってい るのだから。私は、ユーモアのあらゆる側面が検閲官を学習させることに関与していると言いたいわけではない。ユーモアが進化したとき、生物学で他のメカニ ズムが発達するときと同じように、それはすでに存在していた他のメカニズムの上に構築され、それらの他の機能の混合物を具現化したに違いないのだ。音声が 多くの社会的目的に使われるように、ユーモアに関わるメカニズムは、記憶とはあまり関係のない他の効果にも使われるのである。後年、「機能的自律性」の影 響により、ユーモアだけでなく、成人心理の他の多くの側面における本来の機能を認識することが困難になることがある。感情の働きを理解するためには、その 進化的な歴史と個人の歴史の両方を理解する必要がある。 私たちは、失敗から学ぶことがいかに重要であるかを見てきた。自分自身が古い過ちを犯さないようにするために、私たちは家族や友人からその過ちを学ぶ。し かし、他人に「間違っている」と伝えると、それが否定や拒絶の表現として解釈されると、痛みや喪失感を呼び起こし、引きこもりや回避につながるという特殊 な問題が生じる。従って、忠誠心や愛情を保ちたい相手に間違いを指摘するためには、何らかの快い、あるいは和らげる形をとらなければならない。こうして ユーモアは、基本的に不愉快な仕事をするために、優雅に和ませる方法を進化させてきたのだ。特にあなたがメッセンジャーになる場合、「悪い知らせを持って きたメッセンジャーを殺す」ような事態は是非とも避けたいものだ。 ユーモアが不愉快で、苦痛で、嫌悪感を与えるような題材に関係していることを示すと、多くの人が心から驚いているようだ。ある意味で、ほとんどのジョーク にはユーモアがない。恐らく、恐ろしい内容を巧みに隠していることを除けば、その思考自体は「誰かに起こったことを見て、自分でなくてよかったと思わない か?この意味で、ほとんどのジョークは、実は軽薄なものではなく、最も深刻な悩みを反映しているのである。ところで、なぜジョークは聞き直すと面白くなく なるのだろうか。それは、検閲官がその都度もう少し勉強して、より迅速かつ効果的に行動できるように準備しているからである。 ではなぜ、ある種のジョーク、特に禁じられた性的なテーマについてのジョークが、多くの人々にとっていつまでも面白いままであるように見えるのだろうか。 なぜ検閲は長い間変わらないのだろうか?ここで、愛着、恋慕、性愛、喪心-悲嘆が長く続くことの説明を再利用できる。これらの領域は自己理想に関係するた め、一度形成された記憶はゆっくりと変化するのである。したがって、性的ユーモアの独特の強さは、人間のセクシュアリティの検閲が、知恵遅れの子供のよう に、心の「学習速度が遅い」人々の中にいることを意味するに過ぎないかもしれない。実際、彼らは文字通り知恵遅れの子供であり、つまり、以前の自己の凍結 された残骸の一つであると主張することもできる。 |

| https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報