Outline of development of Psychological Anthropology

心理人類学の流れ

Outline of development of Psychological Anthropology

解説 池田光穂

[アウトライン]

・「心 理人類学 Psychological Anthropology」という名称そのものは、Francis L.K. Hue の同名の編著(1960)による。

・1960年代以前には、“文 化 とパーソナリティ”(1940年代に命名された)と呼ばれていた(一連 の学派・方法)ことをさす。

・「文化とパーソナリティ研究は、学習とゲシュタルト心理学*、および若干のフロイト理論を 非西 洋世界*に適用しようとするものであったが、その焦点は文化が個人に与える影響を解明する点にあった」(ガバリーノ,1987:154/*訳語改変)

・1920年代に米国においてフロイトの精神分析学が流行し、人類学にも膾炙する。

(→特異なところでは、ハンガリーの精神分析家・人類学者G・ローハイム(1891-1953)がいる。彼の人類学上 における評価については、ロビンソン『フロイト左派』せりか書房、1972:85-149、およびクラックホーンの『文化人類学リーディングス』 (1968)所収論文、pp.142-3、を参照。後期の代表作はG・ローハイム『精神分析と人類学』上・下、小田・黒田訳、思索社、1980 [1950]がある。)

・20年から30年代は、米国内で少年非行や思春期の情緒障害の問題が社会的にもクローズアップ されていた。

・E.Sapir「社会内の行動における無意識的な型」(1927)/個人が言語を学ぶように、 文化パターンも無意識的に学習されるものである。

・エドワード・サピアは、民族 誌における人びとの個人差や感情について配慮が足りないという不満を抱いていた。そのために心理学の理論と方法を導入すべきだと考えたのだった。ただし、 彼自身はパーソナリティ研究をテーマにしたフィールド調査は行なわなかった。

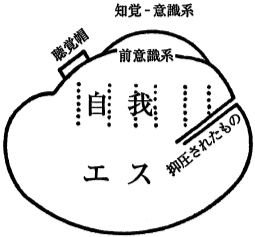

【下図の説明】(→自我とエスの関係、 より)

「このような名称を使うことで、記述と理解の面でど のような効用があるかは、いずれ明

らかになろう。われわれにとっては個人とは、一つの心的なエス、未知で無意識的なもの

である。自我はその表面にのっているのであり、自我からその核として知覚(W) シス テムが形成される。これは図解すると次のようになる。

自我はエスの全体を覆うものではなく、肺が卵の上 にのっているように、知覚(W)システムが自我の

上にのっている範囲に限って、自我はエスを覆ってい るのである。自我とエスの聞に明瞭な境界はなく、自 我は下の方でエスと合流している。/

しかし抑圧されたものもエスと合流するのであり、 その一部を構成するにすぎない。抑圧されたものは、

抑圧抵抗によって自我と明瞭に区別されるのであり、 抑圧されたものはエスを通じて自我と連絡することができる」(フロイト

1996:221)。「自我は「聴覚帽」をかぶっているが、脳の解剖学的な経験から、この帽子は片側だけにあることが示されている」(フロイト

1996:222)。

・The social edges of psychoanalysis / Neil J. Smelser, Berkeley, Calif. : University of California Press , c1998s

| Psychoanalysis[i] is

a set of theories and therapeutic techniques[ii] that deal in part with

the unconscious mind,[iii] and which together form a method of

treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the

early 1890s by Sigmund Freud,[1] whose work stemmed partly from the

clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Freud developed and refined

the theory and practice of psychoanalysis until his death in 1939. In

an encyclopedic article, he identified the cornerstones of

psychoanalysis as "the assumption that there are unconscious mental

processes, the recognition of the theory of repression and resistance,

the appreciation of the importance of sexuality and of the Oedipus

complex."[2] Freud's colleagues Alfred Adler and Carl Gustav Jung

developed offshoots of psychoanalysis which they called individual

psychology (Adler) and analytical psychology (Jung), although Freud

himself wrote a number of criticisms of them and emphatically denied

that they were forms of psychoanalysis.[3] Psychoanalysis was later

developed in different directions by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as

Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.[4] Freud distinguished between the conscious and the unconscious mind, arguing that the unconscious mind largely determines behaviour and cognition owing to unconscious drives. Freud observed that attempts to bring such drives into awareness triggers resistance in the form of defense mechanisms, particularly repression, and that conflicts between conscious and unconscious material can result in mental disturbances. He also postulated that unconscious material can be found in dreams and unintentional acts, including mannerisms and Freudian slips. Psychoanalytic therapy, or simply analytical therapy,[5] developed as a means to improve mental health by bringing unconscious material into consciousness. Psychoanalysts place a large emphasis on early childhood in an individual's development. During therapy, a psychoanalyst aims to induce transference, whereby patients relive their infantile conflicts by projecting onto the analyst feelings of love, dependence and anger.[6][7] During psychoanalytic sessions a patient traditionally lies on a couch, and an analyst sits just behind and out of sight. The patient expresses their thoughts, including free associations, fantasies, and dreams, from which the analyst infers the unconscious conflicts causing the patient's symptoms and character problems. Through the analysis of these conflicts, which includes interpreting the transference and countertransference (the analyst's feelings for the patient), the analyst confronts the patient's pathological defence mechanisms to help patients understand themselves better.[8] Psychoanalysis is a controversial discipline, and its effectiveness as a treatment has been contested, although it retains influence within psychiatry.[iv][v] Psychoanalytic concepts are also widely used outside the therapeutic arena, in areas such as psychoanalytic literary criticism and film criticism, analysis of fairy tales, philosophical perspectives such as Freudo-Marxism, and other cultural phenomena. |

精神分析[i]とは、無意識[iii]の一部を取り扱う理論と治療技術

[ii]の集合体であり、精神障害の治療法として確立されている。この学問は、1890年代初頭にジークムント・フロイト[1]によって確立された。フロ

イトの研究は、ヨーゼフ・ブロイアーらの臨床研究にも一部基づいている。フロイトは、1939年に亡くなるまで精神分析の理論と実践を発展させ、洗練させ

た。百科事典の記事の中で、彼は精神分析の礎石を「無意識の精神過程の存在という仮定、抑圧と抵抗の理論の認識、性欲とエディプスコンプレックスの重要性

の評価」と定義した[2]。フロイトの同僚であるアルフレッド・アドラーとカール・グスタフ・ユングは、それぞれ個人心理学(アドラー)と分析心理学(ユ

ング)と呼ばれる精神分析の派生理論を展開したが、

しかし、フロイト自身は彼らを批判し、彼らが精神分析の一形態であることを強く否定した[3]。精神分析はその後、フロム、ホーニー、サリバンといった新

フロイト派思想家たちによって、さまざまな方向に発展していった[4]。 フロイトは、意識と無意識を区別し、無意識の衝動によって行動や認知が主に決定されると主張した。フロイトは、そのような衝動を自覚させようとすると、防 衛機制、特に抑圧という形で抵抗が生じ、意識と無意識の間の葛藤が精神障害を引き起こす可能性があることを指摘した。また、無意識の材料は夢や無意識的な 行動、癖やフロイト的失言などに見られるという仮説を立てた。精神分析療法、または単に分析療法[5]は、無意識の材料を自覚させることで精神衛生を改善 するための手段として開発された。精神分析医は、個人の発達における幼児期を非常に重視する。治療中、精神分析医は転移を誘発することを目指す。転移と は、患者が愛、依存、怒りの感情を精神分析医に投影することで、幼児期の葛藤を再現することである[6][7]。 精神分析セッションでは、患者は伝統的にソファに横になり、精神分析医はそのすぐ後ろで目に見えない位置に座る。患者は、自由連想、空想、夢など、自分の 考えを口にし、それをもとに分析医は患者の症状や性格上の問題を引き起こしている無意識の葛藤を推測する。転移と逆転移(分析者の患者に対する感情)の解 釈を含むこれらの葛藤の分析を通じて、分析者は患者の病的防衛機制と向き合い、患者が自分自身をよりよく理解できるように手助けする[8]。 精神分析は物議を醸す学問であり、その治療としての有効性は しかし、精神医学界では依然として影響力を保っている[iv][v]。精神分析的概念は、精神分析文学批評や映画批評、童話分析、フロイト=マルクス主義 などの哲学的観点、その他の文化的現象など、治療の場以外でも広く用いられている。 |

| History 1890s The idea of psychoanalysis (German: Psychoanalyse) first began to receive serious attention under Sigmund Freud, who formulated his own theory of psychoanalysis in Vienna in the 1890s. Freud was a neurologist trying to find an effective treatment for patients with neurotic or hysterical symptoms. Freud realised that there were mental processes that were not conscious whilst he was employed as a neurological consultant at the Children's Hospital, where he noticed that many aphasic children had no apparent organic cause for their symptoms. He then wrote a monograph about this subject.[9] In 1885, Freud obtained a grant to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a famed neurologist, at the Salpêtrière in Paris, where he followed the clinical presentations of Charcot, particularly in the areas of hysteria, paralyses and the anaesthesias. Charcot had introduced hypnotism as an experimental research tool and developed photographic representation of clinical symptoms. Freud's first theory to explain hysterical symptoms was presented in Studies on Hysteria (1895; Studien über Hysterie), co-authored with his mentor the distinguished physician Josef Breuer, which was generally seen as the birth of psychoanalysis.[10] The work was based on Breuer's treatment of Bertha Pappenheim, referred to in case studies by the pseudonym "Anna O.", treatment which Pappenheim herself had dubbed the "talking cure". Breuer wrote that many factors could result in such symptoms, including various types of emotional trauma, and he also credited work by others such as Pierre Janet; while Freud contended that at the root of hysterical symptoms were repressed memories of distressing occurrences, almost always having direct or indirect sexual associations.[10] Around the same time, Freud attempted to develop a neuro-physiological theory of unconscious mental mechanisms, which he soon gave up. It remained unpublished in his lifetime.[11] The term 'psychoanalysis' (psychoanalyse) was first introduced by Freud in his essay titled "Heredity and etiology of neuroses" ("L'hérédité et l'étiologie des névroses"), written and published in French in 1896.[12][13] In 1896, Freud also published his seduction theory, claiming to have uncovered repressed memories of incidents of sexual abuse for all his current patients, from which he proposed that the preconditions for hysterical symptoms are sexual excitations in infancy.[14] Though in 1896 he had reported that his patients "had no feeling of remembering the [infantile sexual] scenes", and assured him "emphatically of their unbelief",[14]: 204 in later accounts he claimed that they had told him that they had been sexually abused in infancy. By 1898 he had privately acknowledged to his friend and colleague Wilhelm Fliess that he no longer believed in his theory, though he did not state this publicly until 1906.[15] Building on his claims that the patients reported infantile sexual abuse experiences, Freud subsequently contended that his clinical findings in the mid-1890s provided evidence of the occurrence of unconscious fantasies, supposedly to cover up memories of infantile masturbation.[15] Only much later did he claim the same findings as evidence for Oedipal desires.[16] In the latter part of the 20th century, several Freud scholars challenged Freud's perception of the patients who informed him of childhood sexual abuse, arguing that he had imposed his preconceived notions on his patients.[17][18][19] By 1899, Freud had theorised that dreams had symbolic significance and generally were specific to the dreamer. Freud formulated his second psychological theory—that the unconscious has or is a "primary process" consisting of symbolic and condensed thoughts, and a "secondary process" of logical, conscious thoughts. This theory was published in his 1899 book, The Interpretation of Dreams, which Freud thought of as his most significant work.[20][21] Freud outlined a new topographic theory, which theorised that unacceptable sexual wishes were repressed into the "System Unconscious". These wishes were made unconscious due to society's condemnation of premarital sexual activity, and this repression created anxiety. This "topographic theory" is still popular in much of Europe, although it has fallen out of favour in much of North America, where it has been largely supplanted by structural theory.[22] In addition, The Interpretation of Dreams contained Freud's first conceptualisation of the Oedipal complex, which asserted that young boys are sexually attracted to their mothers and envious of their fathers for being able to have sex with their mothers. Psychologist Frank Sulloway in his book Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend argues that Freud's biological theories like libido were rooted in the biological hypothesis that accompanied the work of Charles Darwin, citing theories of Krafft-Ebing, Molland, Havelock Ellis, Haeckel, Wilhelm Fliess as influencing Freud.[23]: 30 1900–1940s In 1905, Freud published Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in which he laid out his discovery of the psychosexual phases, which categorised early childhood development into five stages depending on what sexual affinity a child possessed at the stage:[24] Oral (ages 0–2); Anal (2–4); Phallic-oedipal or First genital (3–6); Latency (6–puberty); and Mature genital (puberty–onward). His early formulation included the idea that because of societal restrictions, sexual wishes were repressed into an unconscious state, and that the energy of these unconscious wishes could be result in anxiety or physical symptoms. Early treatment techniques, including hypnotism and abreaction, were designed to make the unconscious conscious in order to relieve the pressure and the apparently resulting symptoms. This method would later on be left aside by Freud, giving free association a bigger role. In On Narcissism (1915), Freud turned his attention to the titular subject of narcissism.[25] Freud characterized the difference between energy directed at the self versus energy directed at others using a system known as cathexis. By 1917, in "Mourning and Melancholia", he suggested that certain depressions were caused by turning guilt-ridden anger on the self.[26] In 1919, through "A Child is Being Beaten", he began to address the problems of self-destructive behavior and sexual masochism.[27] Based on his experience with depressed and self-destructive patients, and pondering the carnage of World War I, Freud became dissatisfied with considering only oral and sexual motivations for behavior. By 1920, Freud addressed the power of identification (with the leader and with other members) in groups as a motivation for behavior in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego.[28][29] In that same year, Freud suggested his dual drive theory of sexuality and aggression in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, to try to begin to explain human destructiveness. Also, it was the first appearance of his "structural theory" consisting of three new concepts id, ego, and superego.[30] Three years later, in 1923, he summarised the ideas of id, ego, and superego in The Ego and the Id.[31] In the book, he revised the whole theory of mental functioning, now considering that repression was only one of many defense mechanisms, and that it occurred to reduce anxiety. Hence, Freud characterised repression as both a cause and a result of anxiety. In 1926, in "Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety", Freud characterised how intrapsychic conflict among drive and superego caused anxiety, and how that anxiety could lead to an inhibition of mental functions, such as intellect and speech.[32] In 1924, Otto Rank published The Trauma of Birth, which analysed culture and philosophy in relation to separation anxiety which occurred before the development of an Oedipal complex.[33] Freud's theories, however, characterized no such phase. According to Freud, the Oedipus complex was at the centre of neurosis, and was the foundational source of all art, myth, religion, philosophy, therapy—indeed of all human culture and civilization. It was the first time that anyone in Freud's inner circle had characterised something other than the Oedipus complex as contributing to intrapsychic development, a notion that was rejected by Freud and his followers at the time. By 1936 the "Principle of Multiple Function" was clarified by Robert Waelder.[34] He widened the formulation that psychological symptoms were caused by and relieved conflict simultaneously. Moreover, symptoms (such as phobias and compulsions) each represented elements of some drive wish (sexual and/or aggressive), superego, anxiety, reality, and defenses. Also in 1936, Anna Freud, Sigmund's daughter, published her seminal book, The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense, outlining numerous ways the mind could shut upsetting things out of consciousness.[35] |

歴史 1890年代 精神分析(ドイツ語:Psychoanalyse)という考え方は、1890年代にウィーンで独自の精神分析理論を提唱したジークムント・フロイトの下で 初めて真剣に注目されるようになった。フロイトは神経科医であり、神経症やヒステリーの症状を持つ患者に効果的な治療法を見つけようとしていた。フロイト は、神経科医として小児病院勤務中に、失語症児たちの症状に明らかな器質的要因が見られないことに気づき、意識下に存在する精神過程の存在に気づいた。そ して、このテーマに関する論文を執筆した[9]。1885年、フロイトはパリのサルペトリエール病院で、著名な神経学者ジャン=マルタン・シャルコーのも とで研究するための助成金を獲得し、特にヒステリー、麻痺、麻酔の分野において、シャルコーの臨床症状を観察した。シャルコーは催眠術を実験研究ツールと して導入し、臨床症状の写真を撮影する方法を開発した。 フロイトがヒステリー症状を説明する最初の理論は、師である著名な医師ヨゼフ・ブロイアーとの共著『ヒステリー研究』(1895年)で発表された。この本 は、一般的に精神分析の [10] この研究は、ブレナーがベルタ・パッペンハイムに対して行った治療に基づいており、パッペンハイムはそれを「トーキング・キュア(会話療法)」と呼んでい た。ブルーワーは、さまざまな種類の精神的外傷など、多くの要因がこのような症状を引き起こす可能性があると記し、ピエール・ジャネなどの他の研究者の業 績も評価した。一方、フロイトは、ヒステリー症状の根底には、苦痛を伴う出来事の記憶が抑圧されていることがあり、ほとんどの場合、直接または間接的に性 的連想がある、と主張した[10]。 ほぼ同時期に、フロイトは無意識の精神メカニズムに関する神経生理学的理論の構築を試みたが、すぐに断念した。この論文は彼の存命中には出版されなかった [11]。「精神分析」(psychoanalyse)という用語は、1896年にフランス語で書かれた「神経症の遺伝と病因」(L'hérédité et l'étiologie des névroses)というタイトルの論文の中で、初めてフロイトによって紹介された[12][13]。1896年[12][13]。 1896年、フロイトは誘惑説も発表し、現在の患者のすべてに性的虐待の記憶が抑圧されていることを発見したと主張し、ヒステリー症状の前提条件として幼 児期の性的興奮があると提唱した[14]。1896年、フロイトは患者たちが「(幼児期の性的)場面を覚えているという感覚はない」と報告し、「彼らの疑 念を明確に否定した」[14]: 204 と述べていたが、その後の説明では、患者たちが幼児期に性的虐待を受けたと彼に話したと主張した。1898年ま でに、彼は友人であり同僚でもあったヴィルヘルム・フリーズに、もはや自分の理論を信じていないと個人的に認めたが、公にそれを表明したのは1906年に なってからだった[15]。 患者たちが幼児期の性的虐待の経験について報告したと主張したことを踏まえ、フロイトはその後、1890年代半ばの臨床所見が、幼児期の自慰行為の記憶を 隠蔽するための無意識の空想の発生の証拠を提供していると主張した[15]。ずっと後になって、彼は同じ発見をエディプス的欲望の証拠であると主張した [16]。20世紀後半、複数のフロイト研究者が、フロイトが幼少期の性的虐待を告げた患者たちに対する認識に異議を唱え、フロイトが患者たちに先入観を 押し付けていたと主張した[17][18][19]。 1899年までに、フロイトは夢には象徴的な意味があり、一般的に夢見る人特有のものであると理論化した。フロイトは、無意識には象徴的で凝縮された思考 からなる「一次過程」と、論理的で意識的な思考からなる「二次過程」があるとする、2つ目の心理学理論を提唱した。この理論は、1899年に出版された著 書『夢判断』で発表された。フロイトはこの本を、自身の最も重要な著作と考えていた[20][21]。フロイトは、新たな「トポグラフィカル理論」を提唱 した。この理論では、受け入れがたい性的願望は「システム無意識」に抑圧されるとされていた。これらの願望は、婚前性行為に対する社会の非難により無意識 化され、この抑圧が不安を生み出していた。この「地形説」は、北米では構造説に取って代わられ、人気が低迷しているものの、ヨーロッパの多くの地域では依 然として広く支持されている[22]。さらに、『夢判断』には、フロイトが最初に提唱したエディプス・コンプレックスの概念が盛り込まれており、それによ ると、幼い男の子は母親に性的魅力を感じ、父親が母親とセックスできることに嫉妬するという。 心理学者フランク・サローウェイは著書『Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend』の中で、フロイトの性欲などの生物学説はチャールズ・ダーウィンの研究に付随する生物学説に根ざしており、クラフト=エービング、モラン ド、ヘブロック・エリス、ヘッケル、ヴィルヘルム・フリーズの理論がフロイトに影響を与えたと主張している[23]: 30 1900年~1940年代 1905年、フロイトは『性愛理論に関する三つの論文』を発表し、幼児の発育を、その幼児が持つ性的親和性に応じて5つの段階に分類する、心理性的段階の 発見を提示した 段階:[24] 口腔期(0~2歳)、 肛門期(2~4歳)、 ファルス期または第一性器期(3~6歳)、 潜伏期(6~思春期)、 成熟期(思春期以降)。 初期の理論には、社会的な制約のために性的願望が無意識に抑圧され、その無意識のエネルギーが不安や身体症状を引き起こすという考え方があった。初期の治 療法には、催眠療法やabreaction(逆反応)などがあり、無意識を自覚させることでプレッシャーや症状を和らげることを目的としていた。この方法 は後にフロイトによって見捨てられ、自由連想がより大きな役割を担うようになった。 『ナルシシズムについて』(1915年)で、フロイトは表題のテーマであるナルシシズムに注目した[25]。フロイトは、自己に向けられたエネルギーと他 者に向けられたエネルギーの違いを、カセシスと呼ばれるシステムを用いて特徴付けた。1917年、彼は「悲哀とメランコリア」の中で、特定のうつ病は罪悪 感に苛まれた怒りを自分自身に向けることによって引き起こされると示唆した[26]。1919年、「子供が殴られている」を通して、彼は 自己破壊的行動や性的マゾヒズムの問題を取り上げた[27]。うつ病や自己破壊的な患者との経験、そして第一次世界大戦の惨禍について熟考した結果、フロ イトは行動の動機付けを口頭や性的要因のみに求めることに不満を抱くようになった。1920年までに、フロイトは『集団心理学』や『自我の分析』の中で、 集団における同一化(リーダーや他のメンバーとの)が行動の動機となることを指摘した[28][29]。同年、フロイトは『快楽原則の彼方』の中で、人間 の破壊性を説明しようと試みるために、性欲と攻撃性の二重駆動理論を提唱した。また、イド、自我、超自我という3つの新しい概念からなる「構造理論」が初 めて発表されたのもこの年である[30]。 3年後の1923年、フロイトは『自我とイド』の中でイド、自我、超自我の考え方を要約した[31]。この本の中で、フロイトは精神機能の理論全体を修正 し、抑圧は多くの防衛機制の1つに過ぎず、不安を軽減するために生じるものであると主張した。したがって、フロイトは抑圧を不安の原因であり結果でもある と特徴付けた。1926年、フロイトは『抑圧、症状、不安』の中で、衝動と超自我の内的葛藤が不安を引き起こす仕組み、そして、その不安が知性や言語と いった精神機能の抑制につながる仕組みを明らかにした[32]。 1924年、オットー・ランクは『誕生のトラウマ』を出版し、エディプスコンプレックスが形成される前の分離不安と文化や哲学との関連性を分析した [33]。しかし、フロイトの理論ではそのような段階は特徴づけられていなかった。フロイトによれば、エディプスコンプレックスは神経症の核心であり、芸 術、神話、宗教、哲学、療法、そして実際の人間文化と文明のすべての基礎的な源であった。フロイトの親しい関係者がエディプスコンプレックス以外のものを 精神内発達の要因として特徴づけたのはこれが初めてであり、この考えは当時フロイトとその弟子たちによって否定された。 1936年までに、「多重機能原理」がロバート・ウェーラーによって明確化された[34]。彼は、心理的症状は葛藤を引き起こし、同時にそれを和らげると いう理論を拡張した。さらに、症状(恐怖症や強迫観念など)は、それぞれ、ある種の衝動的欲求(性的および/または攻撃的)、超自我、不安、現実、防衛の 要素を表していた。また、1936年には、ジグムントの娘であるアンナ・フロイトが、画期的な著書『自我と防衛機制』を出版し、心が不快なことを意識から 締め出すさまざまな方法を概説した[35]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychoanalysis |

・1930年代アメリカで、文化人類学のなかに心理学、精神医学(とくに精神分析)を取り入れる 風潮がおこる。

・影響を与えた理論は、おもに学習理論、行動主義心理学、ゲシュタルト心理学、当時の児童心理学 などである。フロイト理論の影響は少なかった。(1938年の Freud,"Totem und Tabu" は、人類学者にとっては冷やかに見られた。その代表例は Malinowski である。Malinowski に対しては、Geza Roheim による批判(1943)がある。/フロイト理論がより受け入れられるのは1940年代以降になってからである)

・R.F. Benedict に よるズニ・インディアンをはじめとする一連のインディアン研究、心理的なタイポロジー論("Patterns of Culture", 1934)、無文字社会における精神異常の研究("Anthropology and Abnormal", 1934)。

・ルース・ベネディクトに おいて、社会が個人のパーソナリティを形成する過程は文化化(enculturation)とされた。(※社会が異なれば、そこに帰属する人々の思考の様 式も異なる、という見解はE.デュルケムおよびその学派においてすでに指摘されていた。彼らは思考の型を「集合表象」と呼んでいた)。

・M. Mead によるサモ ア("Coming of Age in Samoa", 1928)、マヌス、ニューギニア("Growing up in New Guinea", 1930)における性格形成の研究、およびその著作が米国の一般の人びとに広く読まれた。その結果、性差と気質("Sex and Temperament", 1935)、育児様式とパーソナリティについての関心が高まった。

■ 関連ページ:文化とパーソナ リティ

・シカゴ大学「インディアン教育調査プロジェクト」(1941〜)における、人類学者、心理学 者、精神分析学者の大規模共同研究。

・(A.I. Hallowell の Ojibwa 研究。ロールシャッハとTATを用いたテスト、歴史研究など多角的な視点から、彼らのパーソナリティが物質的な文化変容を受けながらも保持されていること を描写した。)

・フロイト理論の導入に関して精力的であったのは Abram Kardiner である。精神分析学者である彼は、リントン(Ralf Linton)やデュボア(Cora DuBois)とともに、人びとの「基本的パーソナリティ構造」が、育児様式である「第一次制度」によって形成され、さらに宗教や神話などの「第二次制 度」を作り上げるという図式的な解釈を打ち立てた。

・第二次大戦下における「国民性研究 National Character Study」に、ベネディクト("Chrysanthemum and the Sword", 1946)、ミード、ベイトソンらが関与する。

1945年 "The science of man in the world crisis"(Ralph Linton, ed.)New York : Columbia University Press , 1945より出版される

實業之日本社ならびに新泉社より(1952, 1975)翻訳される:内容一覧

内容:上巻 人類学の範囲と目的(ラルフ・リントン)

社会と生物学的人間(H.L.シャピロ) 人種の概念(W.H.クログマン) 人種心理学(オットー・クラインバーグ)

文化の概念(クライド・クラックホーン,ウィリアム・H.ケリー)

社会諸科学における操作用具としての基礎的パーソナリティ構造の概念(エイブラム・カーディナー) 文化の公分母(ジョージ・ピーター・マードック)

文化変化の過程(メルヴィル・J.ハースコヴィッツ) 文化変容の社会心理学的側面(A.アーヴィング・ハロウェル)

世界現状の文化的展望(ラルフ・リントン) 世界資源の現状(ハワード・A.マイヤホフ)

内容:下巻 人口問題(カール・サックス) 変化するアメリカ・インディアン(ジュリアン・H.スチュアード)

植民地の危機の将来(レイモンド・ケネディ) マイノリティ・グループの問題(ルイス・ワース)

植民地行政における応用人類学(フェリックス・M.キーシング) インディアン主義政策の考察(マニュエル・ガミオ)

現代文明社会に適用されたコミュニティの研究と分析の技法(カール・C.ティラー) 新しい社会的習慣の習得(ジョン・ドラード)

コミュニケーション調査と国際間の協力(ポール・F.ラザースフェルド,ジェネヴィーヴ・ナプファー)

国家主義、国際主義と戦争(グレイソン・カーク) 解説(蒲生正男)

・図式的な解釈への批判が出てくる。

・ホワイティングとチャイルド(John Whiting and Irvin Child)による文献研究が、HRAFを使って行なわれる。

・文化によるパーソナリティ研究そのものは完全に衰退するが、人類学領域への心理学的な関心はよ りひろい文脈のなかで復活する。祖父江孝男によると、そのような研究テーマには「心理的態度や情緒などパーソナリティの部分についての研究、文化変容のな かにおける心理的不適応の問題、精神衛生、文化と精神異常、宗教や俗信その他、種々の文化現象に関する心理学的研究」「認識の構造」などである。これら は、ひろく「心理人類学」とよばれる領域を形成することとなった。(雑誌として Ethos, Journal of Psychoanalystic anthropology)

【関連するリンク】

/医療人類学プロジェクト: Medical Anthropology Project in Japan(MAP-J)/植民地状況における心理学/比較文化精神医学/文化とパーソナ リティ/病気観/アフォーダンス/古典的学習とは?/文化人類学12の知的伝統/医療人類学の四象////////////

【文献】

小さい場合は図をクリックすると単独で拡大します

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆