文化とパーソナリティ論

Culture and Personality School, 1930s-1940s

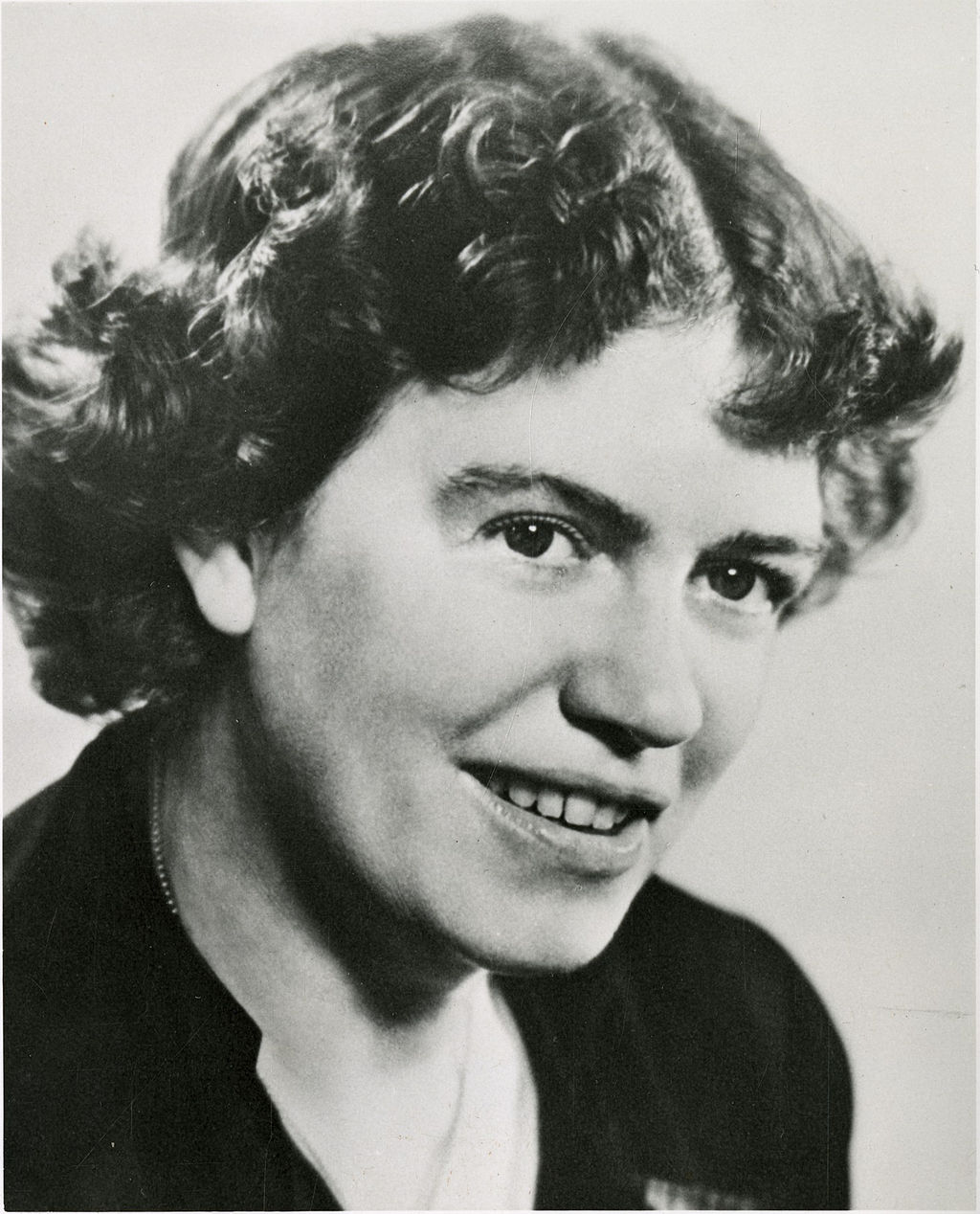

左から、リントン、ベネディクト、

ミード、クラックホーン

解説:池田光穂

文化とパーソナリティ論

Culture and Personality School, 1930s-1940s

左から、リントン、ベネディクト、 ミード、クラックホーン

解説:池田光穂

人間の 発達の概念を軸に、文化が個人のパーソナリ ティにどのような影響を与えるのかについての、比較文化 と発達の理論をあわせもつ理論体系ないしはその研究枠組みを共有する学派を、文化とパーソナリティ学派(Culture and Personality School)という。表題にあるように、1930年代から1940年 代の文化人類学および児童心理学、発達心理学に大きな影響を与えた。

| Core Principles of Culture and Personality Theory 1. Cultural Determinism: The belief that the culture in which we are raised largely determines our behaviors and personalities. 2. Personality Types in Culture: Benedict theorized that every culture tends to favor certain personality traits and discourage others. 3. Synergy Between Culture and Personality: The interaction between an individual’s personality and their cultural environment is seen as a dynamic process. |

文化と人格(パーソナリティ)理論の核心原則 1. 文化決定論:私たちが育った文化が、私たちの行動や人格を大きく決定するという考え。 2. 文化における人格タイプ:ベネディクトは、あらゆる文化は特定の性格特性を好む傾向があり、他の特性を抑制する傾向があると理論化した。 3. 文化と人格の相乗効果:個人の人格と文化環境との相互作用は、動的なプロセスとして捉えられている。 |

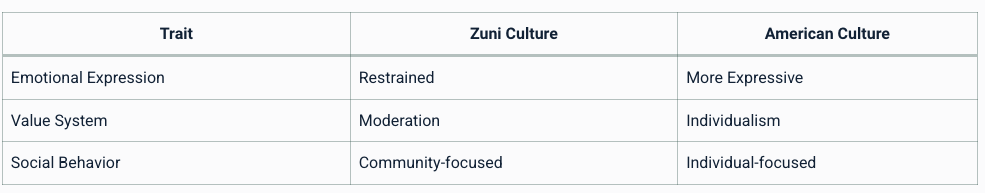

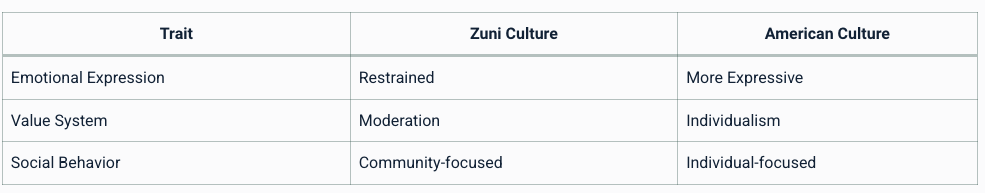

| Case Study: The Zuni People Example: The Zuni, a Native American tribe, were studied by Benedict. She noted their culture emphasized values like moderation, restraint, and a dislike for extreme emotional expressions. Table: Comparison of Zuni and American Personality Traits  |

ケーススタディ:ズニ人民 例:ベネディクトは、ネイティブアメリカンの部族であるズニ人民を研究した。彼女は、彼らの文化は節度、自制心、極端な感情表現を嫌うといった価値観を重視していることに注目した。 表:ズニ人民とアメリカ人の性格特性の比較  |

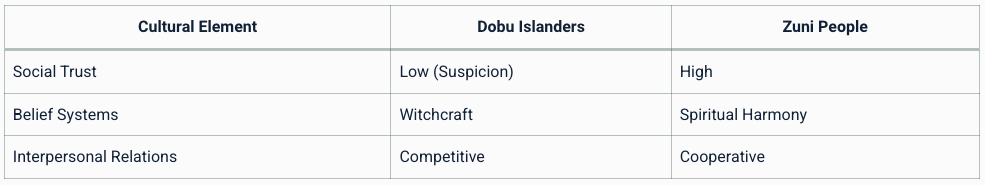

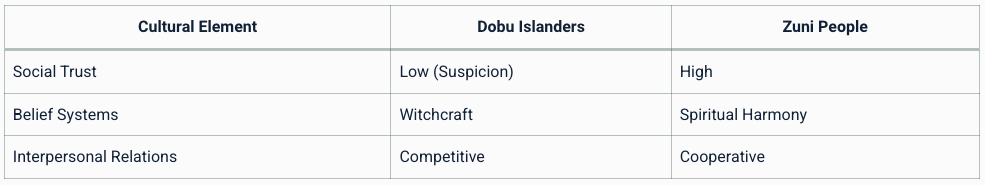

| Case Study: The Dobu Islanders Example: The Dobu Islanders of Papua New Guinea were another focus of Benedict’s research. She observed that their culture was based on suspicion, witchcraft beliefs, and competitiveness. Table: Comparison of Dobu and Zuni Cultural Traits  |

ケーススタディ:ドブ島民 例:パプアニューギニアのドブ島民も、ベネディクトの研究のもう一つの焦点だった。彼女は、彼らの文化は、疑心、妖術信仰、競争心に基づいていることを観察した。 表:ドブとズニの文化特性の比較  |

| Criticisms and Limitations While influential, Benedict’s theory has faced criticism for potentially overgeneralizing cultures and underestimating the variability within cultural groups. Critics argue that the theory might oversimplify the complex interplay between culture and personality. Despite criticisms, Benedict’s “Culture and Personality” theory remains a cornerstone in anthropological studies. It paved the way for understanding how cultural contexts shape individual behaviors and personality traits. |

批判と限界 影響力がある一方で、ベネディクトの理論は、文化を過度に一般化し、文化集団内の多様性を過小評価しているとの批判を受けています。批判者は、この理論が 文化と人格の複雑な相互作用を過度に単純化している可能性があると指摘しています。批判にもかかわらず、ベネディクトの「文化と人格」理論は、人類学の研 究における基礎的な理論として依然として重要な位置を占めています。この理論は、文化的背景が個人の行動や人格特性をどのように形成するかを理解する上 で、道筋を築いたものです。 |

| Application in Modern Anthropology With the evolution of cultural studies, Benedict’s theory continues to influence contemporary anthropology. It serves as a foundation for understanding the relationship between culture and individual behavior in diverse societies. |

現代人類学における応用 文化研究の発展に伴い、ベネディクトの理論は現代人類学にも引き続き影響を与えている。この理論は、多様な社会における文化と個人の行動の関係を理解するための基礎となっている。 |

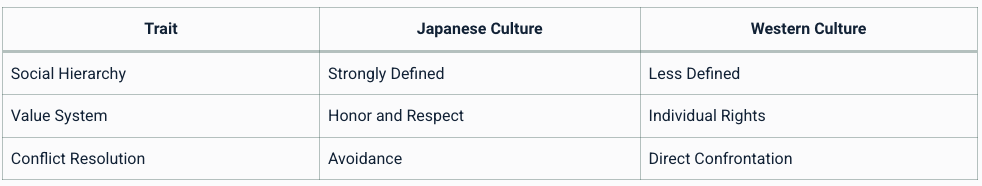

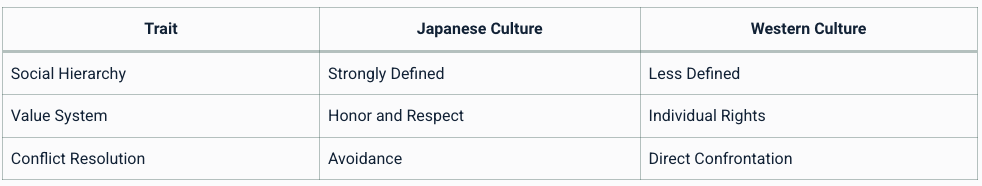

| Case Study: Japanese Society Example: Benedict’s work on Japanese culture, particularly in her book “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword,” is a notable application of her theory. She examined how Japanese culture values honor, respect, and hierarchy, shaping the personalities of its people. Table: Traits in Japanese and Western Cultures  |

ケーススタディ:日本社会 例:ベネディクトの日本文化に関する研究、特に著書『菊と刀』は、彼女の理論の顕著な応用例です。彼女は、日本文化が名誉、尊敬、階層をどのように重視し、それが日本人の人格形成に影響を与えているかを考察しました。 表:日本文化と西洋文化の特徴  |

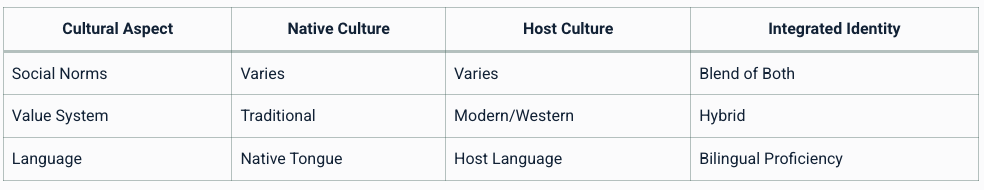

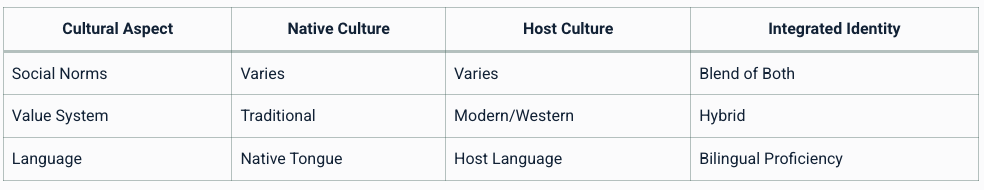

| Case Study: Contemporary Global Cultures In the modern globalized world, the theory helps in understanding cultural assimilation and the development of multicultural identities. For instance, how immigrants integrate and negotiate their native cultural traits with those of the host country. Table: Multicultural Identity Development  |

ケーススタディ:現代のグローバル文化 現代の世界では、この理論は文化の同化や多文化アイデンティティの形成を理解するのに役立ちます。例えば、移民が自国の文化の特徴を、受入国の文化とどのように融合させ、折り合いをつけていくかといったことです。 表:多文化アイデンティティの形成  |

| Impact on Other Disciplines Benedict’s theory transcends anthropology, influencing fields like psychology, sociology, and cultural studies. It provides a framework for understanding how culture impacts mental health, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships. |

他の分野への影響 ベネディクトの理論は人類学を超え、心理学、社会学、文化研究などの分野に影響を与えている。文化がメンタル健康、社会的行動、対人関係にどのように影響するかを理解するための枠組みを提供している。 |

| Conclusion and Future Directions Ruth Benedict’s “Culture and Personality” theory remains a significant contribution to anthropology. Its relevance extends into contemporary studies of cultural identity, globalization, and multiculturalism. Future research may continue to explore the nuances of cultural influences on personality, adapting Benedict’s insights to the complexities of an increasingly interconnected world. Benedict’s theory is particularly relevant in our contemporary, globalized world, where cultural intersections are increasingly common. It offers a framework for understanding how individuals navigate and reconcile the often conflicting demands of multiple cultural identities. For example, in multicultural societies, individuals may blend traits from their heritage culture with those of their adopted culture, leading to unique personality formations that reflect a synthesis of cultural influences. Furthermore, Benedict’s insights have profound implications for areas such as cross-cultural psychology and international relations. Understanding how cultural norms shape personality can aid in developing more effective communication strategies and fostering greater empathy between different cultural groups. It also highlights the importance of cultural sensitivity in global politics, business, and education. |

結論と今後の展望 ルース・ベネディクトの「文化と人格」理論は、人類学に重要な貢献を続けている。その関連性は、現代の文化アイデンティティ、グローバル化、多文化主義の 研究にも及んでいる。今後の研究では、文化が人格に与える影響の微妙な点をさらに探求し、ベネディクトの洞察をますます相互接続が進む世界の複雑さに適応 させる可能性がある。 ベネディクトの理論は、文化の交差がますます一般的になっている現代のグローバル化した世界において、特に重要な意味を持ちます。この理論は、個人が複数 の文化的アイデンティティのしばしば対立する要求をどのようにナビゲートし、調和させるかを理解するための枠組みを提供します。例えば、多文化社会では、 個人が祖先の文化の特性と採用した文化の特性を融合させ、文化的影響の融合を反映した独自の人格形成が生じる可能性があります。 さらに、ベネディクトの洞察は、異文化心理学や国際関係などの分野にも深い影響を与えています。文化規範が人格形成に与える影響を理解することは、より効 果的なコミュニケーション戦略の策定や、異なる文化集団間の共感の促進に役立ちます。また、グローバルな政治、ビジネス、教育における文化的感度の重要性 を浮き彫りにしています。 |

| https://anthroholic.com/culture-and-personality |

★支配的な学者

その支 配的な学者としては、下記に掲げるように、ラルフ・リントン、ルース・ベネディクト、マーガレッ ト・ミード、クライド・クラックホーンなどの数多くの学者がいる。

詳しく

は、心理人類学の流れ(Outline of

development of Psychological Anthropology)を参考にしてください。

■Ralph Linton (1893-1953)

1939 -43年にAmerican Anthropologistの編集に従事する。

パーソナリティを、社会構成員共通の「基本的パーソ ナリティ」と、その人間が属する分節化した下位集 団の「身分的パーソナリティ」の2つに分ける。

| Ralph Linton (27 February 1893 – 24 December 1953) was a respected American anthropologist of the mid-20th century, particularly remembered for his texts The Study of Man (1936) and The Tree of Culture (1955). One of Linton's major contributions to anthropology was defining a distinction between status and role. | ラルフ・リントン(1893年2月27日-1953年12月24日)

は、20世紀半ばのアメリカの著名な人類学者であり、特に『人間の研究』(1936年)と『文化の木』(1955年)で知られている。リントンの人類学へ

の大きな貢献のひとつは、地位と役割の区別を定義したことである。 |

| Early life and education; Linton was born into a family of Quaker restaurant entrepreneurs in Philadelphia in 1893 and entered Swarthmore College in 1911. He was an indifferent student and resisted his father's pressures to prepare himself for the life of a professional. He grew interested in archaeology after participating in a field school in the southwest and took a year off of his studies to participate in another archaeological excavation at Quiriguá in Guatemala. Having found a strong focus he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1915.[1] Although Linton became a prominent anthropologist, his graduate education took place largely at the periphery of the discipline. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned his master's degree studying with Frank Speck while undertaking additional archaeological field work in New Jersey and New Mexico.[1] He was admitted to a Ph.D. program at Columbia University thereafter, but did not become close to Franz Boas, the doyen of anthropology in that era. When America entered World War I, Linton enlisted and served in France during 1917–1919 with Battery D, 149th Field Artillery, 42nd (Rainbow) Division. Linton served as a corporal and saw battle at the trenches, experiencing first hand a German gas attack. Linton's military experience would be a major influence on his subsequent work. One of his first published articles was "Totemism and the A.E.F." (Published in American Anthropologist vol. 26:294–300)", in which he argued that the way in which military units often identified with their symbols could be considered a kind of totemism.[2] His military fervor probably did not do anything to improve his relationship with the pacifist Franz Boas, who abhorred all displays of nationalism or jingoism. An anecdote has it that Linton was rebuked by Boas when he appeared in class in his military uniform.[3] Whatever the cause, shortly after his return to the United States, he transferred from Columbia to Harvard, where he studied with Earnest Hooton, Alfred Tozzer, and Roland Dixon.[1] After a year of classes at Harvard, Linton proceeded to do more fieldwork, first at Mesa Verde and then as a member of the Bayard Dominick Expedition led by E.S.C. Handy under the auspices of the Bishop Museum to the Marquesas.[4] While in the Pacific, his focus shifted from archaeology to cultural anthropology, although he would retain a keen interest in material culture and 'primitive' art throughout his life. He returned from the Marquesas in 1922 and eventually received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1925.[1] |

生い立ちと教育 リントンは1893年にフィラデルフィアのクエーカー教徒のレストラン起業家の家に生まれ、1911年にスワースモア大学に入学した。彼は無関心な学生 で、専門家として生きる準備をするようにという父親の圧力に抵抗した。南西部のフィールド・スクールに参加して考古学に興味を持ち、1年間休学してグアテ マラのキリグアでの発掘調査に参加した。リントンは著名な人類学者となったが、彼の大学院教育は主にこの学問の周辺部で行われた。ペンシルベニア大学でフ ランク・スペックに師事し、ニュージャージーとニューメキシコで考古学のフィールドワークを行いながら修士号を取得した[1]。その後、コロンビア大学の 博士課程に入学したが、当時の人類学の大家であったフランツ・ボアズと親しくなることはなかった。アメリカが第一次世界大戦に参戦すると、リントンは入隊 し、1917年から1919年にかけてフランスで第42師団(レインボー)第149野戦砲兵部隊D砲台に所属した。リントンは伍長として従軍し、塹壕で戦 闘を経験し、ドイツ軍のガス攻撃を直接体験した。リントンの軍事体験は、その後の仕事に大きな影響を与えることになる。彼が最初に発表した論文のひとつ が、「Totemism and the A.E.F.」(トーテミズムとA.E.F.)である。(彼の軍事的熱意は、ナショナリズムやジンゴイズムを忌み嫌う平和主義者フランツ・ボアズとの関係 を改善することはなかっただろう。軍服姿で授業に現れたリントンは、ボアズに叱責されたという逸話がある[3]。その原因が何であれ、アメリカに帰国して 間もなく、コロンビア大学からハーバード大学に編入し、そこでアーネスト・フートン、アルフレッド・トッツァー、ローランド・ディクソンに師事した。 [1]ハーバードで1年間授業を受けた後、リントンはさらにフィールドワークを進め、最初はメサ・ヴェルデで、その後ビショップ博物館の後援のもと、 E.S.C.ハンディ率いるバヤルド・ドミニク探検隊の一員としてマルケサス諸島を訪れた[4]。太平洋にいる間、彼の関心は考古学から文化人類学へと 移っていったが、生涯を通じて物質文化と「原始」美術に強い関心を持ち続けた。1922年にマルケサス諸島から戻り、最終的に1925年にハーバード大学 で博士号を取得した[1]。 |

| Academic career: Linton used his Harvard connections to secure a position at the Field Museum of Chicago after his return from the Marquesas. His official position was as Curator of American Indian materials. He continued working on digs in Ohio which he had first begun as a graduate student, but also began working through the museum's archival material on the Pawnee and published data collected by others in a series of articles and museum bulletins. While at the Field Museum he worked with illustrator and future children's book artist and author Holling Clancy Holling. Between 1925 and 1927, Linton undertook an extensive collecting trip to Madagascar for the field museum, exploring the western end of the Austronesian diaspora after having studied the eastern end of this culture in the Marquesas. He did his own fieldwork there as well, and the book that resulted, The Tanala: A Hill Tribe of Madagascar (1933), was the most detailed ethnography he would publish.[1] On his return to the United States, Linton took a position at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where the Department of Sociology had expanded to include an anthropology unit. Linton thus served as the first member of what would later become a separate department. Several of his students went on to become important anthropologists, such as Clyde Kluckhohn, Marvin Opler, Philleo Nash, and Sol Tax. Up to this point, Linton had been primarily a researcher in a rather romantic vein, and his years at Wisconsin were the period in which he developed his ability to teach and publish as a theoretician. This fact, combined with his penchant for popular writing and his intellectual encounter with Radcliffe-Brown (then at the University of Chicago), led to the publication of his textbook The Study of Man (1936).[1] It was also during this period that he married his third wife, Adelin Hohlfeld, who worked as his secretary and editor as well as his collaborator—many of the popular pieces published jointly by them (such as Halloween Through Twenty Centuries) were in fact entirely written by Adelin Hohlfield. In 1937 Linton came to Columbia University, appointed to the post of head of the Anthropology department after the retirement of Franz Boas. The choice was opposed by most of Boas' students, with whom Linton had never been on good terms. The Boasians had expected Ruth Benedict to be the choice for Boas' successor. As head of the department Linton informed against Boas and many of his students to the FBI, accusing them of being communists. This led to some of them being fired and blacklisted, for example Gene Weltfish.[3] Throughout his life Linton maintained an intense personal animosity against the Boasians, particularly against Ruth Benedict, and he was a fierce critic of the Culture and Personality approach. According to Sidney Mintz who was a colleague of Linton at Yale, he even once jokingly boasted that he had killed Benedict using a Tanala magic charm.[5][6] When World War II broke out, Linton became involved in war-planning and his thoughts on the war and the role of the United States (and American Anthropology) could be seen in several works of the post-war period, most notably The Science of Man in the World Crisis (1945) and Most of the World. It was during the war that Linton also undertook a long trip to South America, where he experienced a coronary occlusion that left him in precarious health. After the war Linton moved to Yale University, a center for anthropologists such as G. P. Murdock who had collaborated with the US government. He taught there from 1946 to 1953, where he continued to publish on culture and personality. It was during this period that he also began writing The Tree of Culture, an ambitious global overview of human culture. Linton was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950.[7] He died of complications relating to his trip in South America on Christmas Eve, 1953. His wife, Adelin Hohlfield Linton, completed The Tree of Culture which went on to become a popular textbook. |

学者としてのキャリア リントンはマルケサス諸島から帰国後、ハーバード大学のコネを利用してシカゴのフィールド博物館に職を得た。彼の正式な役職はアメリカ・インディアン資料 のキュレーターであった。彼は大学院生として最初に始めたオハイオ州での発掘作業を継続したが、ポーニー族に関する博物館のアーカイブ資料の調査にも着手 し、他の研究者が収集したデータを一連の論文や博物館の紀要として発表した。フィールド博物館在籍中、彼はイラストレーターで後に絵本作家となるホリン グ・クランシー・ホリングと仕事をした。1925年から1927年にかけて、リントンはフィールド博物館のためにマダガスカルへの大規模な収集旅行を行 い、マルケサス諸島でオーストロネシア文化の東端を研究した後、オーストロネシアディアスポラの西端を探検した。彼はマダガスカルでも独自のフィールド ワークを行い、その結果生まれた本が『タナラ』である: 米国に戻ったリントンは、ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校に着任し、社会学部に人類学部門が新設された。こうしてリントンは、後に独立した学部となるもの の最初のメンバーとして活躍した。彼の教え子の中には、クライド・クラックホーン、マービン・オプラー、フィレオ・ナッシュ、ソル・タックスといった重要 な人類学者になった者もいる。この時点まで、リントンは主にロマンチックな傾向の研究者であり、ウィスコンシン大学での数年間は、理論家として教え、発表 する能力を身につけた時期であった。この事実は、ポピュラーな文章を書くことへの彼の嗜好と、ラドクリフ=ブラウン(当時シカゴ大学)との知的な出会いと 相まって、彼の教科書『人間の研究』(1936年)の出版につながった[1]。3番目の妻アデリン・ホールフェルドと結婚したのもこの時期で、彼女は彼の 秘書兼編集者として働き、また彼の共同研究者でもあった。1937年、リントンはコロンビア大学にやってきた。フランツ・ボアズ退任後、人類学部長に任命 されたのである。この人選には、ボアズの学生のほとんどが反対した。ボアズ派は、ルース・ベネディクトがボアズの後継者に選ばれると予想していたのだ。リ ントンは学部長として、ボアズと多くの学生を共産主義者だと非難し、FBIに密告した。リントンは生涯を通じてボアス派、特にルース・ベネディクトに対す る激しい個人的敵意を持ち続け、文化と人格のアプローチを激しく批判した。イェール大学でリントンの同僚であったシドニー・ミンツによれば、彼はタナラの 魔術を使ってベネディクトを殺したと冗談めかして自慢したこともあった[5][6]。第二次世界大戦が勃発すると、リントンは戦争計画に携わるようにな り、戦争とアメリカ(およびアメリカ人類学)の役割に関する彼の考えは、戦後のいくつかの著作、特に『世界の危機における人間の科学』(1945年)や 『世界の大部分』(1945年)に見ることができる。戦時中、リントンは南米への長期旅行にも出かけたが、そこで冠動脈閉塞を経験し、不安定な健康状態を 余儀なくされた。戦後、リントンはG.P.マードックなどアメリカ政府と協力していた人類学者の中心地であったイェール大学に移った。彼はそこで1946 年から1953年まで教鞭をとり、文化とパーソナリティに関する論文を発表し続けた。またこの時期に、人類文化を世界規模で概観した野心的な『文化の木』 の執筆を始めた。リントンは1950年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[7]。1953年のクリスマス・イブに南米旅行中の合併症で 死去。妻のアデリン・ホールフィールド・リントンが『文化の木』を完成させ、人気の高い教科書となった。 |

| Work: The Study of Man established Linton as one of anthropology's premier theorists, particularly amongst sociologists who worked outside of the Boasian mainstream. In this work he developed the concepts of status and role for describing the patterns of behavior in society. According to Linton, ascribed status is assigned to an individual without reference to their innate differences or abilities. Whereas Achieved status is determined by an individual's performance or effort. Linton noted that while the definitions of the two concepts are clear and distinct, it is not always easy to identify whether an individual's status is ascribed or achieved. His perspective offers a deviation from the view that ascribed statuses are always fixed. For Linton a role is the set of behaviors associated with a status, and performing the role by doing the associated behaviors is the way in which a status is inhabited. Throughout this early period Linton became interested in the problem of acculturation, working with Robert Redfield and Melville Herskovits on a prestigious Social Science Research Council subcommittee of the Committee on Personality and Culture. The result was a seminal jointly-authored piece entitled Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation (1936). Linton also obtained money from the Works Progress Administration for students to produce work which studied acculturation. The volume Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes is an example of the work in this period, and Linton's contributions to the volume remain his most influential writings on acculturation. Linton's interest in culture and personality also expressed itself in the form of a seminar he organized with Abram Kardiner at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. |

作品:『人間の研究』 リントンは『人間の研究』によって、人類学の第一級の理論家として、特にボアジアン主流派以外の社会学者たちの間で地位を確立した。この著作の中で彼は、 社会における行動パターンを記述するための地位と役割の概念を開発した。リントンによれば、帰属的地位とは、生まれつきの違いや能力とは無関係に個人に与 えられるものである。一方、達成された地位とは、個人の業績や努力によって決まるものである。リントンは、この2つの概念の定義は明確で区別できるもの の、個人の地位が帰属的なものか達成的なものかを識別することは必ずしも容易ではないと指摘した。彼の視点は、付与された地位は常に固定されたものである という見方から逸脱している。リントンにとって役割とは、ステータスに関連する一連のビヘイビアであり、関連するビヘイビアを行うことによって役割を遂行 することが、ステータスの居住方法なのである。リントンはこの初期の時期を通じて、ロバート・レッドフィールドやメルヴィル・ハースコヴィッツとともに、 権威ある社会科学研究評議会の「人格と文化に関する委員会」の小委員会に参加し、文化化の問題に関心を持つようになった。その結果、『馴化の研究のための 覚書』(1936年)と題する画期的な共著が生まれた。リントンはまた、ワークス・プログレス・アドミニストレーションから資金を獲得し、学生たちに文化 化の研究をさせた。アメリカ・インディアン7部族における馴化』(Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes)は、この時期の研究の一例であり、この巻へのリントンの寄稿は、馴化に関する彼の最も影響力のある著作として残っている。リントンの文化と 人格への関心は、ニューヨーク精神分析研究所でアブラム・カーディナーとともに開催したセミナーの形でも表れた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Linton |

|

■Ruth Benedict (1887-1948) [→ cf. Edward Sapir 1884-1939]——ルース・ベネディクト

"Pattern of culture" 1934

『菊と刀』 1946

■Margaret Mead (1901-1978) [→ cf. Talcott Parsons 1902-1979]——マーガレット・ミード

『サモアの思春期』1928

『ニューギニアの成育』1930

『3つの未開社会における性と気質』1935

ミードの特長は、ボアズのCultural relativism とベネディクトの Patterns of culture が節合されていることである。

『男性と女性』1949

■Clyde Kluckhohn ( 1905-1960)——クライド・クラックホーン

Navaho witchcraft 1944, The Navaho 1946, Children of the people 1947, Mirror for man 1949.

リンク

文

献

(上のもの以外の……)

マンドラー,J.M. とG・マンドラー(1973)「実験心理学におけるディアスポラ:ゲシュタルト主義者を中心に」(近藤邦夫訳)、 Pp.77-141., 『亡命の現代史4:社会科学者・心理学者』ヒューズ、アドルノ等、みすず書房(The intellectual migration : Europe and America, 1930-1960, edited by Donald Fleming and Bernard Bailyn. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1969.)

Anthony F. C. Wallace, Culture and Personality. New York: Random House, 1961, 1970

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099