ルース・フルトン・ベネディクト

Ruth Fulton Benedict, 1887-1948

解説:池田光穂

ルース・フルトン・ベネディクト(1887年6月5日 - 1948年9月17日)は、アメリカの人類学者、民俗学者である。 ニューヨークで生まれ、ヴァッサー大学に入学し、1909年に卒業した。ニュースクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチでエルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ に人類学を学んだ後、1921年にコロンビア大学大学院に入学し、フランツ・ボースに師事した。1923年に博士号を取得し、コロンビア大学に入学した。 恋愛関係にあったマーガレット・ミードやマービン・オプラーも彼女の学生や同僚であった。 ベネディクトは、アメリカ人類学会の会長であり、アメリカ民俗学会の有力メンバーでもあった。彼女は、人類学と民俗学の双方を、文化特性の拡散研究という 限られた枠から、文化の解釈に不可欠なパフォーマンスの理論へと方向転換させ、その分野における過渡的な人物と見なすことができる。彼女は、人格、芸術、言語、文化の関係を研究し、どのような特性も単独では存在しない、あるいは自己完 結していないと主張し、この理論を1934年の著書『文化のパターン』で提唱した。

| Ruth Fulton Benedict

(June 5, 1887 – September 17, 1948) was an American anthropologist and

folklorist. She was born in New York City, attended Vassar College, and graduated in 1909. After studying anthropology at the New School of Social Research under Elsie Clews Parsons, she entered graduate studies at Columbia University in 1921, where she studied under Franz Boas. She received her Ph.D. and joined the faculty in 1923. Margaret Mead, with whom she shared a romantic relationship,[1] and Marvin Opler were among her students and colleagues. Benedict was president of the American Anthropological Association and also a prominent member of the American Folklore Society.[2] She became the first woman to be recognized as a prominent leader of a learned profession.[2] She can be viewed as a transitional figure in her field by redirecting both anthropology and folklore away from the limited confines of culture-trait diffusion studies and towards theories of performance as integral to the interpretation of culture. She studied the relationships between personality, art, language, and culture and insisted that no trait existed in isolation or self-sufficiency, a theory that she championed in her 1934 book Patterns of Culture. |

ルース・フルトン・ベネディクト(Ruth Fulton

Benedict、1887年6月5日 - 1948年9月17日)はアメリカの人類学者、民俗学者である。 ニューヨークに生まれ、ヴァッサー・カレッジで学び、1909年に卒業した。ニュー・スクール・オブ・ソーシャル・リサーチでエルジー・クリューズ・パー ソンズのもとで人類学を学んだ後、1921年にコロンビア大学大学院に入学し、フランツ・ボースに師事した。博士号を取得し、1923年にコロンビア大学 の教員となる。恋愛関係にあったマーガレット・ミード[1]やマービン・オプラーも彼女の学生であり同僚であった。 ベネディクトはアメリカ人類学会の会長であり、またアメリカ民俗学会の著名な会員でもあった[2]。 彼女は学識ある専門職の著名な指導者として認められた最初の女性となった[2]。彼女は人格、芸術、言語、文化の関係を研究し、どのような特質も孤立した り自給自足したりすることはないと主張した。 |

| Early life Childhood Benedict was born Ruth Fulton in New York City on June 5, 1887, to Beatrice (Shattuck) and Frederick Fulton.[3][4][5] Her mother worked in the city as a school teacher, and her father was a homeopathic doctor and surgeon.[3] Mr. Fulton loved his work and research, but they eventually led to his premature death, as he acquired an unknown disease during one of his surgeries in 1888.[6] His illness caused the family to move back to Norwich, New York, to the farm of Ruth's maternal grandparents, the Shattucks.[4] A year later, he died ten days after he had returned from a trip to Trinidad to search for a cure.[6] Mrs. Fulton was deeply affected by her husband's passing. Any mention of him caused her to be overwhelmed by grief; every March, she cried at church and in bed.[6] Ruth hated her mother's sorrow and viewed it as a weakness. For Ruth, the greatest taboos in life were crying in front of people and showing expressions of pain.[6] She reminisced, "I did not love my mother; I resented her cult of grief."[6] The psychological effects on her childhood were thus profound since "in one stroke she [Ruth] experienced the loss of the two most nourishing and protective people around her—the loss of her father at death and her mother to grief."[4] As a toddler, she contracted measles, which left her partially deaf; that was not discovered until she began school.[7] Ruth also had a fascination with death as a young child. When she was four years old, her grandmother took her to see an infant that had recently died. Upon seeing the dead child's face, Ruth claimed that it was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen.[6] At seven, Ruth began to write short verses and read any book that she could get her hands on. Her favorite author was Jean Ingelow, and her favorite readings were A Legend of Bregenz and The Judas Tree.[6] Through writing, she gained approval from her family. Writing was her outlet, and she wrote with an insightful perception about the realities of life. For example, in her senior year of high school, she wrote a piece, "Lulu's Wedding (A True Story)," in which she recalled the wedding of a family serving girl. Instead of romanticizing the event, she revealed the true unromantic arranged marriage that Lulu went through because the man would take her even though he was much older.[4] Although her fascination with death started at an early age, she continued to study how death affected people throughout her career. In her book Patterns of Culture, Benedict shows how the Pueblo culture dealt with grieving and death. She describes in the book that individuals may deal with reactions to death, such as frustration and grief, differently from one another. Societies all have social norms that they follow; some allow more expression in dealing with death, such as mourning, but other societies are not allowed to acknowledge it.[3] College and marriage After high school, Ruth and her sister entered St Margaret's School for Girls, a college preparatory school, with the help from a full-time scholarship. The girls were successful in school and entered Vassar College in September 1905, where Ruth thrived in an all-female atmosphere.[4] Stories were then circulating that going to college led girls to become childless and remain unmarried. Nevertheless, Ruth explored her interests in college and found writing as her way of expressing herself as an "intellectual radical" as she was sometimes called by her classmates.[4] The author Walter Pater was a large influence on her life during this time as she strove to be like him and live a well-lived life. She graduated with her sister in 1909 with a major in English Literature.[4] Unsure of what to do after college, she received an invitation to go on an all-expense-paid tour around Europe by a wealthy trustee of the college. Accompanied by two girls from California whom she had never met, Katherine Norton and Elizabeth Atsatt, she traveled through France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, and England for one year with the opportunity of various home stays throughout the trip.[4] Over the next few years, Ruth took up many different jobs. She first tried paid social work for the Charity Organization Society, and later, she accepted a job as a teacher at the Westlake School for Girls in Los Angeles, California. While working there, she gained her interest in Asia that would later affect her choice of fieldwork as a working anthropologist. However, she was unhappy with that job as well and, after one year, left to teach English in Pasadena at the Orton School for Girls.[4] Those years were difficult, and she had depression and severe loneliness.[8] However, through reading authors like Walt Whitman and Richard Jefferies, who stressed a worth, importance, and enthusiasm for life, she held onto hope for a better future.[8] The summer after her first year teaching at the Orton School, she returned home to the Shattucks' farm to spend some time in thought and peace. There, Stanley Rossiter Benedict, an engineer at Cornell Medical College, began to visit her at the farm. She had met him by chance in Buffalo, New York around 1910. That summer, Ruth fell deeply in love with Stanley as he began to visit her more and accepted his proposal for marriage.[4] Invigorated by love, she undertook several writing projects to keep busy besides the everyday housework chores in her new life with Stanley. She began to publish poems under different pseudonyms: Ruth Stanhope, Edgar Stanhope, and Anne Singleton.[9] She also began work on writing a biography about Mary Wollstonecraft and other lesser-known women that she felt deserved more acknowledgement for their work and contributions.[4] By 1918, the couple had begun to drift apart. Stanley suffered an injury that made him want to spend more time away from the city, and Ruth was not happy when the couple moved to Bedford Hills, far away from the city. |

生い立ち 幼少期 ベネディクトは1887年6月5日、ニューヨークでベアトリス(シャタック)とフレデリック・フルトンの間にルース・フルトンとして生まれた[3][4] [5]。母親は学校の教師として市内で働き、父親はホメオパシー医で外科医であった[3]。 [6]彼の病気が原因で、一家はルースの母方の祖父母であるシャタックス家の農場であるニューヨーク州ノーウィッチに戻ることになった[4]。1年後、彼 は治療法を探すためのトリニダードへの旅から戻った10日後に亡くなった[6]。 フルトン夫人は夫の死に深く心を痛めた。毎年3月になると、彼女は教会やベッドで泣いた[6]。ルースは母の悲しみを嫌い、それを弱さとみなしていた。 ルースにとって人生最大のタブーは、人前で泣くことと、苦痛の表情を見せることであった[6]。私は母を愛していたのではなく、母の悲しみのカルトを恨ん でいたのです」[6]。 幼児期に麻疹にかかり、耳の一部が聞こえなくなったが、それは学校に通い始めるまで発見されなかった[7]。彼女が4歳のとき、祖母は彼女を最近死んだ幼 児に会わせた。死んだ子供の顔を見たルースは、今まで見た中で一番美しいと言った[6]。 7歳になると、ルースは短い詩を書き始め、手に入る本は何でも読んだ。彼女の好きな作家はジーン・インゲロウで、愛読書は『ブレゲンツの伝説』と『ユダの 木』だった[6]。書くことは彼女のはけ口であり、彼女は人生の現実について洞察に満ちた認識を持って書いていた。例えば、高校3年生のとき、彼女は「ル ルの結婚式(実話)」という作品を書いた。彼女はその出来事をロマンチックに描くのではなく、ルルが年上であるにもかかわらず、その男性が彼女を娶るため に経験した、ロマンチックではない本当の見合い結婚を明らかにした[4]。 死に対する彼女の魅力は幼い頃から始まったが、彼女はそのキャリアを通じて、死が人々にどのような影響を与えるかを研究し続けた。ベネディクトは著書『文 化のパターン』の中で、プエブロ文化が悲嘆と死にどのように対処していたかを示している。彼女はこの本の中で、苛立ちや悲しみといった死に対する反応は、 個人によって対処の仕方が異なる可能性があると述べている。ある社会では喪に服すなど、死を扱う上でより多くの表現が許されるが、別の社会では死を認める ことは許されない[3]。 大学と結婚 高校卒業後、ルースと姉は奨学金を得て、大学進学準備校であるセント・マーガレット女学校に入学した。ルースは女性だけの雰囲気の中で成長した[4]。当 時、大学に進学すると、女の子は子供を産まなくなり、未婚のままになるという話が広まっていた。それでもルースは大学で自分の興味を探求し、同級生から 「知的急進派」と呼ばれることもあったように、自分を表現する方法として文章を書くことを見つけた[4]。大学卒業後の進路に迷っていた彼女は、大学の裕 福な評議員からヨーロッパ周遊の招待を受ける。キャサリン・ノートンとエリザベス・アツアットという、会ったこともないカリフォルニア出身の2人の少女を 伴って、彼女はフランス、スイス、イタリア、ドイツ、イギリスを1年間旅行し、旅行中さまざまなホームステイを経験した[4]。 その後数年間、ルースはさまざまな仕事に就いた。最初は慈善団体協会でソーシャルワークの仕事に就き、その後、カリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスのウェストレ イク女学校で教師の仕事を引き受けた。そこで働くうちに、彼女はアジアに興味を持つようになり、それが後に人類学者としてのフィールドワークの選択に影響 を与えることになる。しかし、その仕事にも満足できず、1年後にパサディナのオートン・スクール・フォー・ガールズで英語を教えるために退職した[4]。 その数年間は苦しく、彼女はうつ病と深刻な孤独を抱えていた[8]。 オートン・スクールで教えた1年目の夏、彼女はシャタック家の農場に戻り、しばらくの間、考え事と平穏な時間を過ごした。そこに、コーネル医科大学のエン ジニアであったスタンリー・ロシター・ベネディクトが農場を訪ねてくるようになった。彼女は1910年頃、ニューヨーク州バッファローで偶然彼と知り合っ た。その夏、ルースはスタンリーの訪問が増えるにつれて深く愛し合うようになり、彼のプロポーズを受け入れた。彼女はさまざまなペンネームで詩を発表し始 めた: ルース・スタンホープ、エドガー・スタンホープ、アン・シングルトン[9]。また、メアリ・ウルストンクラフトや他のあまり知られていない女性についての 伝記を書く仕事も始めた。 1918年までに、夫妻は疎遠になり始めていた。スタンリーは怪我に苦しみ、都会から離れて過ごすことを望むようになり、ルースは夫婦が都会から遠く離れ たベッドフォード・ヒルズに引っ越しても満足しなかった。 |

| Career in anthropology Education and early career In her search for a career, she decided to attend some lectures at the New School for Social Research while looking into the possibility of becoming an educational philosopher.[4] While at the school, she took a class called "Sex in Ethnology" taught by Elsie Clews Parsons. She enjoyed the class and took another anthropology course with Alexander Goldenweiser, a student of noted anthropologist Franz Boas. With Goldenweiser as her teacher, Ruth's love for anthropology steadily grew.[4] As close friend Margaret Mead explained, "Anthropology made the first 'sense' that any ordered approach to life had ever made to Ruth Benedict."[10] After working with Goldenweiser for a year, he sent her to work as a graduate student with Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1921. She developed a close friendship with Boas, who took on a role as a kind of father figure in her life. Benedict lovingly referred to him as "Papa Franz."[11] Boas gave her graduate credit for the courses that she had completed at the New School for Social Research. Benedict wrote her dissertation, "The Concept of the Guardian Spirit in North America," and received the PhD in anthropology in 1923.[3] Benedict also started a friendship with Edward Sapir, who encouraged her to continue the study of the relations between individual creativity and cultural patterns. Sapir and Benedict shared an interest in poetry and read and critiqued each other's work; both submitted to the same publishers and both were rejected. Both also were interested in psychology and the relation between individual personalities and cultural patterns, and in their correspondences, they frequently psychoanalyzed each other. However, Sapir showed little understanding for Benedict's private thoughts and feelings. In particular, his conservative gender ideology jarred with Benedict's struggle for emancipation. While they were very close friends for a while, the differences in worldview and personality ultimately led their friendship to strain.[12] Benedict taught her first anthropology course at Barnard College in 1922 and among the students was Margaret Mead. Benedict was a significant influence on Mead.[13] Boas regarded Benedict as an asset to the anthropology department, and in 1931, he appointed her as assistant professor in anthropology, something that was impossible until her divorce from Stanley Benedict that same year. One student who felt especially fond of Ruth Benedict was Ruth Landes.[14] Letters that Landes sent to Benedict state that she was enthralled by the way in which Benedict taught her classes and with the way that she forced the students to think in an unconventional way.[14] When Boas retired in 1937, most of his students considered Ruth Benedict to be the obvious choice for the head of the anthropology department. However, the administration of Columbia was not as progressive in its attitude towards female professionals as Boas had been, and the university president, Nicholas Murray Butler, was eager to curb the influence of the Boasians whom he considered to be political radicals. Instead, Ralph Linton, one of Boas's former students, a World War I veteran and a fierce critic of Benedict's "Culture and Personality" approach, was named head of the department.[15] Benedict was understandably insulted by Linton's appointment, and the Columbia department was divided between the two rival figures of Linton and Benedict, both accomplished anthropologists with influential publications, neither of whom ever mentioned the work of the other.[16] Relationship with Margaret Mead Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict were two of the most influential and famous anthropologists of their time. Both got along well with their shared passion for each other's work and the sense of pride that they felt in being successful working women while that was still uncommon.[17] They were frequently known to critique each other's work; they entered into a companionship that began through their work, but during its early period, it also had an erotic character.[18][19][20][21] Both Benedict and Mead wanted to dislodge stereotypes about women that were widely believed during their time and to show people that working women could also be successful even though working society was seen as a man's world.[22] In her memoir about her parents, With a Daughter's Eye, Mead's daughter strongly implies that the relationship between Benedict and Mead was partly sexual. In 1946, Benedict received the Achievement Award from the American Association of University Women. After Benedict died of a heart attack in 1948, Mead kept the legacy of Benedict's work going by supervising projects that Benedict would have looked after and by editing and publishing notes from studies that Benedict had collected throughout her life.[21] Postwar Before World War II began, Benedict had been giving lectures at the Bryn Mawr College for the Anna Howard Shaw Memorial Lectureship. The lectures were focused around the idea of synergy. However, World War II made her focus on other areas of concentration of anthropology, and the lectures were never presented in their entirety.[23] After the war, she focused on finishing her book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword.[24] Her original notes for the synergy lecture were never found after her death.[25] She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1947.[26] She continued her teaching after the war and advanced to the rank of full professor only two months before her death in New York on September 17, 1948. |

人類学におけるキャリア 教育と初期のキャリア キャリアを模索していた彼女は、教育哲学者になる可能性を調べながら、ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチの講義に出席することにした。その 授業が楽しかった彼女は、著名な人類学者フランツ・ボースの弟子であるアレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザーの人類学の別の授業を取った。親しい友人である マーガレット・ミードが説明するように、「ルース・ベネディクトにとって人類学は、人生への秩序あるアプローチとして初めて "理にかなった "ものであった」[10]。ゴールデンヴァイザーと1年間働いた後、彼は1921年に彼女をコロンビア大学のフランツ・ボースのもとで大学院生として働か せる。彼女はボアスと親交を深め、ボアスは彼女の人生における父親のような役割を担った。ベネディクトは愛情を込めて彼を「パパ・フランツ」と呼んだ [11]。 ボアスは、彼女がニュースクール社会調査で履修した科目を大学院の単位として認定した。ベネディクトは学位論文「北アメリカにおける守護霊の概念」を執筆 し、1923年に人類学の博士号を取得した[3]。サピアとベネディクトは詩への関心を共有し、お互いの作品を読んで批評し合った。ふたりは心理学や、個 人の人格と文化的パターンとの関係にも関心があり、文通の中でしばしば互いを精神分析した。しかし、サピアはベネディクトの私的な考えや感情にほとんど理 解を示さなかった。特に、彼の保守的なジェンダー・イデオロギーは、解放を求めるベネディクトの闘争と対立していた。しばらくの間、二人は非常に親しい友 人であったが、世界観や性格の違いから、最終的に二人の友情はぎくしゃくすることになった[12]。 ベネディクトは1922年にバーナード大学で初めて人類学の講義を担当し、その受講生の中にマーガレット・ミードがいた。ベネディクトはミードに大きな影 響を与えた[13]。 ボースはベネディクトを人類学部の戦力とみなし、1931年に彼女を人類学の助教授に任命したが、これは同年にスタンリー・ベネディクトと離婚するまで不 可能であったことであった。 ルース・ベネディクトを特に気に入っていた学生のひとりがルース・ランデスであった[14]。ランデスがベネディクトに送った手紙には、ベネディクトの授 業の進め方や、学生に型破りな考え方をさせるやり方に魅了されたと書かれている[14]。 1937年にボースが引退したとき、彼の学生たちの多くは、ルース・ベネディクトが人類学部長として当然の人選であると考えていた。しかし、コロンビア大 学の経営陣は、ボアスがそうであったように、女性の専門家に対して進歩的な態度をとっておらず、学長のニコラス・マーレー・バトラーは、政治的急進派とみ なしたボアス派の影響力を抑えようと躍起になっていた。その代わりに、ボースの元教え子の一人で、第一次世界大戦の退役軍人であり、ベネディクトの「文化 と人格」アプローチを激しく批判していたラルフ・リントンが学部長に任命された[15]。ベネディクトは当然のことながらリントンの任命に侮辱され、コロ ンビア大学学部はリントンとベネディクトという2人のライバルに二分された。2人とも影響力のある出版物を持つ熟練した人類学者であったが、2人とも相手 の研究に言及することはなかった[16]。 マーガレット・ミードとの関係 マーガレット・ミードとルース・ベネディクトは、当時最も影響力のある有名な人類学者であった。二人は互いの仕事への情熱を共有し、まだそれが珍しいこと であった時代に成功した働く女性であることに誇りを感じて意気投合した。 [18][19][20][21]ベネディクトとミードはともに、当時広く信じられていた女性に対する固定観念を取り払い、労働社会が男の世界とみなされ ていたとしても、働く女性も成功しうることを人々に示したかった[22]。ミードの娘は、両親についての回想録『娘の眼で』の中で、ベネディクトとミード の関係が部分的に性的なものであったことを強く示唆している。 1946年、ベネディクトはアメリカ大学女性協会から業績賞を受賞。ベネディクトが1948年に心臓発作で亡くなった後、ミードはベネディクトが世話した であろうプロジェクトを監督したり、ベネディクトが生涯かけて収集した研究のノートを編集して出版したりすることで、ベネディクトの仕事の遺産を守り続け た[21]。 戦後 第二次世界大戦が始まる前、ベネディクトはブリンマー・カレッジでアンナ・ハワード・ショー記念レクチャーシップの講義を行っていた。その講義は、相乗効 果という考えに焦点を当てたものであった。しかし、第二次世界大戦の影響で、彼女は人類学の他の分野に集中するようになり、講義の全容が発表されることは なかった[23]。戦後、彼女は著書『菊と刀』の完成に専念した[24]。シナジー講義のためのオリジナルのノートは、彼女の死後、発見されることはな かった[25]。彼女は1947年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[26]。 |

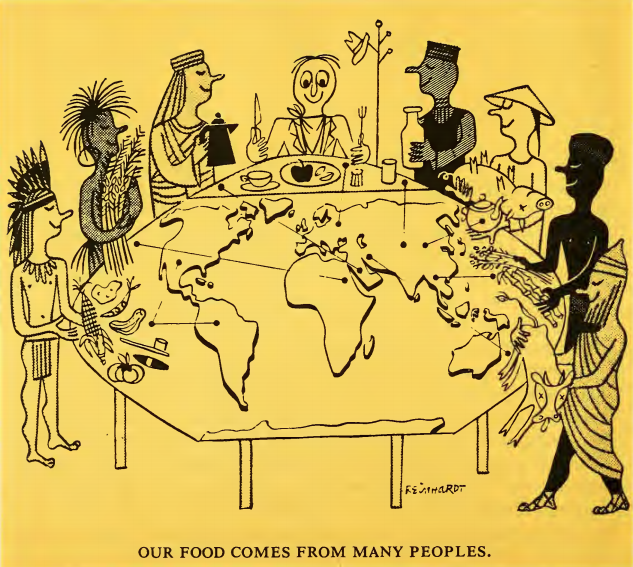

| Work Patterns of Culture Benedict's Patterns of Culture (1934) was translated into fourteen languages and was for years published in many editions and used as standard reading material for anthropology courses in American universities. The essential idea in Patterns of Culture is, according to the foreword by Margaret Mead, "her view that human cultures are 'personality writ large.'" As Benedict wrote in that book, "A culture, like an individual, is a more or less consistent pattern of thought and action" (46). Each culture, she held, chooses from "the great arc of human potentialities" only a few characteristics, which become the leading personality traits of the persons living in that culture. Those traits comprise an interdependent constellation of aesthetics and values in each culture which together add up to a unique gestalt. For example, she described the emphasis on restraint in Pueblo cultures of the American Southwest and the emphasis on abandon in the Native American cultures of the Great Plains. She used the Nietzschean opposites of "Apollonian" and "Dionysian" as the stimulus for her thought about these Native American cultures. She describes how in ancient Greece the worshipers of Apollo emphasized order and calm in their celebrations. In contrast, the worshipers of Dionysus, the god of wine, emphasized wildness, abandon, and letting go, like Native Americans. She described in detail the contrasts between rituals, beliefs, and personal preferences among people of diverse cultures to show how each culture had a "personality," which was encouraged in each individual. Other anthropologists of the culture and personality school also developed those ideas, notably Margaret Mead in her Coming of Age in Samoa (published before "Patterns of Culture") and Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (published just after Benedict's book came out). Benedict was a senior student of Franz Boas when Mead began to study with them, and they had extensive and reciprocal influence on each other's work. Abram Kardiner was also affected by these ideas, and in time, the concept of "modal personality" was born: the cluster of traits most commonly thought to be observed in people of any given culture. Benedict in Patterns of Culture, expresses her belief in cultural relativism. She desired to show that each culture has its own moral imperatives that can be understood only if one studies that culture as a whole. It was wrong, she felt, to disparage the customs or values of a culture different from one's own. Those customs had a meaning to the people who lived them that should not be dismissed or trivialized. Others should not try to evaluate people by their standards alone. Morality, she argued, was relative to the values of the culture in which one operated. As she described the Kwakiutl of the Pacific Northwest (based on the fieldwork of her mentor Boas), the Pueblo of New Mexico (among whom she had direct experience), the nations of the Great Plains, and the Dobu culture of New Guinea (regarding whom she relied upon Mead and Reo Fortune's fieldwork), she gave evidence that their values, even where they may seem strange, are intelligible in terms of their own coherent cultural systems and should be understood and respected. That also formed a central argument in her later work on the Japanese following World War II. Critics have objected to the degree of abstraction and generalization inherent in the "culture and personality" approach. Some have argued that particular patterns that she found may be only a part or a subset of the whole cultures. For example, David Friend Aberle writes that the Pueblo people may be calm, gentle, and much given to ritual in one mood or set of circumstances, but they may be suspicious, retaliatory, and warlike in other circumstances. In 1936, she was appointed an associate professor at Columbia University. However, Benedict had already assisted in the training and guidance of several Columbia students of anthropology including Margaret Mead and Ruth Landes.[27] Benedict was among the leading cultural anthropologists who were recruited by the US government for war-related research and consultation after the US entered World War II. "The Races of Mankind" One of Benedict's lesser-known works was a pamphlet "The Races of Mankind," which she wrote with her colleague at the Columbia University Department of Anthropology, Gene Weltfish. The pamphlet was intended for American troops and set forth in simple language with cartoon illustrations the scientific case against racist beliefs. "The world is shrinking," begin Benedict and Weltfish. "Thirty-four nations are now united in a common cause—victory over Axis aggression, the military destruction of fascism" (p. 1). The nations united against fascism, they continue, include "the most different physical types of men." The writers explicate, in section after section, their best evidence for human equality. They want to encourage all types of people to join and not fight among themselves. "[A]ll the peoples of the earth," they point out, "are a single family and have a common origin." We all have just so many teeth, so many molars, just so many little bones and muscles, and so we can have come from only one set of ancestors, no matter what our color, the shape of our head, the texture of our hair. "The races of mankind are what the Bible says they are—brothers. In their bodies is the record of their brotherhood."[28] The Chrysanthemum and the Sword Main article: The Chrysanthemum and the Sword See also: Guilt-Shame-Fear spectrum of cultures Benedict is known not only for her earlier Patterns of Culture but also for her later book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, the study of the society and culture of Japan that she published in 1946, incorporating results of her wartime research. This book is an instance of anthropology at a distance. The study of a culture through its literature, newspaper clippings, films and recordings, etc. was necessary when anthropologists aided the United States and its allies during World War II. Unable to visit Nazi Germany or Japan under Hirohito, anthropologists used the cultural materials to produce studies at a distance. They attempted to understand the cultural patterns that might be driving their aggression and hoped to find possible weaknesses or means of persuasion that had been missed. Benedict's war work included a major study, largely completed in 1944, aimed at understanding Japanese culture, which had matters that Americans found themselves unable to comprehend. For instance, Americans considered it quite natural for American prisoners-of-war to want their families to know they were alive and to keep quiet when asked for information about troop movements, etc. However, Japanese prisoners-of-war apparently gave information freely and did not try to contact their families. Why was that? Why, too, did Asian peoples neither treat the Japanese as their liberators from Western colonialism nor accept their own supposedly-just place in a hierarchy that had Japanese at the top? Benedict played a major role in grasping the place of the Emperor of Japan in Japanese popular culture, and formulating the recommendation to US President Franklin Roosevelt that permitting continuation of the Emperor's reign had to be part of the eventual surrender offer. Other Japanese who have read this work, according to Margaret Mead, found it on the whole accurate but somewhat "moralistic." Sections of the book were mentioned in Takeo Doi's book, The Anatomy of Dependence, but Doi is highly critical of Benedict's concept that Japan has a "shame" culture, whose emphasis is on how one's moral conduct appears to outsiders in contradistinction to the Christian American "guilt" culture in which the emphasis is on the individual's internal conscience. Doi considered that claim to imply clearly that the former value system is inferior to the latter one. |

仕事 文化のパターン ベネディクトの『文化のパターン』(1934年)は14ヶ国語に翻訳され、何年もの間、多くの版が出版され、アメリカの大学の人類学コースの標準的な読み 物として使われた。 マーガレット・ミードによる序文によれば、『文化のパターン』における本質的な考え方は、「人間の文化は "パーソナリティの拡大版 "であるという彼女の見解」である。ベネディクトがその著書で書いているように、「文化とは、個人のように、多かれ少なかれ一貫した思考と行動のパターン である」(46)。ベネディクトは、それぞれの文化は「人間の可能性の大きな弧」の中から数個の特性だけを選び出し、それがその文化に生きる人々の主要な 性格特性となる、と主張した。それらの特徴は、それぞれの文化における美学と価値観の相互依存的なコンステレーションを構成し、それが一体となって独特の ゲシュタルトを形成する。 例えば、アメリカ南西部のプエブロ文化では自制心が強調され、グレートプレーンズのネイティブアメリカン文化では放縦が強調される。彼女はニーチェの「ア ポロン的」と「ディオニュソス的」という対立概念を、これらのネイティブ・アメリカン文化について考えるための刺激として用いた。彼女は、古代ギリシャで アポロを崇拝する者たちが、その祝祭において秩序と平穏を重視していたことを説明する。 対照的に、ワインの神ディオニュソスを崇拝する人々は、ネイティブ・アメリカンのように荒々しさ、奔放さ、放任を強調した。彼女は、多様な文化圏の人々の 儀式、信仰、個人的嗜好の対比を詳しく説明し、それぞれの文化圏に「個性」があり、それが各個人に奨励されていることを示した。 文化・性格学派の他の人類学者もこうした考えを発展させ、特にマーガレット・ミードの『サモアの青春』(『文化のパターン』以前に出版)や『3つの原始社 会における性と気質』(ベネディクトの本が出版された直後に出版)は有名である。ベネディクトは、ミードがフランツ・ボースに師事し始めたころの上級生で あり、互いの研究に広範かつ相互的な影響を与えた。アブラム・カーディナーもまたこうした考え方に影響を受け、やがて「モードパーソナリティ」という概念 が生まれた。 ベネディクトは『文化のパターン』の中で、文化相対主義の信念を表明している。彼女は、それぞれの文化には独自の道徳的要請があり、それはその文化を全体 として研究しなければ理解できないことを示したかったのである。自国とは異なる文化の習慣や価値観を軽んじるのは間違っていると彼女は感じた。それらの習 慣は、それを生きる人々にとって意味があり、それを否定したり矮小化したりすべきではない。他人は、その人の基準だけで人を評価しようとすべきではない。 道徳とは、その人が活動する文化の価値観に相対するものなのだ、と彼女は主張した。 太平洋岸北西部のクワキウトル族(彼女の師であるボースのフィールドワークに基づく)、ニューメキシコのプエブロ族(彼女が直接体験した人々)、グレート プレーンズの諸民族、ニューギニアのドブ文化(ミードとレオ・フォーチュンのフィールドワークに基づく)について説明しながら、彼らの価値観は奇妙に見え るかもしれないが、彼ら自身の首尾一貫した文化システムの観点から理解可能であり、理解され尊重されるべきであるという証拠を示した。このことは、後に彼 女が第二次世界大戦後の日本人について行った研究においても、中心的な議論となった。 批評家たちは、「文化と個性」というアプローチに内在する抽象化と一般化の度合いに異議を唱えてきた。彼女が発見した特定のパターンは、文化全体の一部ま たは部分集合に過ぎないのではないかという主張もある。たとえば、デビッド・フレンド・アベールは、プエブロの人々はある気分や状況下では穏やかで優し く、儀式をよく行うが、別の状況下では疑い深く、報復的で戦争好きかもしれないと書いている。 1936年、彼女はコロンビア大学の助教授に任命された。しかし、ベネディクトはすでにマーガレット・ミードやルース・ランデスを含むコロンビア大学の人 類学の学生たちの訓練と指導を援助していた[27]。 ベネディクトは、アメリカが第二次世界大戦に参戦した後、戦争関連の調査や相談のためにアメリカ政府によって採用された主要な文化人類学者の一人であっ た。 "人類の諸人種(The Races of Mankind)" ベネディクトのあまり知られていない著作のひとつに、コロンビア大学人類学部の同僚であったジーン・ウェルトフィッシュとともに執筆したパンフレット "The Races of Mankind "がある。このパンフレットはアメリカ軍向けに作られたもので、人種差別的な考えに対する科学的根拠を、漫画のイラストを交えて平易な言葉で述べている。 「世界は縮小している。「枢軸国の侵略に対する勝利、ファシズムの軍事的破壊という共通の目的のために、34カ国が今結束している」(p.1)。 ファシズムに対抗するために団結した国々には、"最も身体的なタイプの異なる人々 "が含まれている。 作家たちは、人間の平等を証明する最良の証拠を次から次へと述べている。彼らは、あらゆるタイプの人々が、自分たちの間で争うことなく、団結することを望 んでいる。「地球上のすべての民族は一つの家族であり、共通の起源を持っている。私たちは皆、たくさんの歯、たくさんの臼歯、たくさんの小さな骨や筋肉を 持っている。だから、肌の色や頭の形、髪の質感がどうであれ、私たちはたった一組の祖先から生まれたのだ。「人類の種族は、聖書が言うところの兄弟であ る。彼らの体には、兄弟であることの記録がある」[28]。 菊と刀 主な記事 菊と刀 こちらも参照: 罪悪感-羞恥心-恐怖の文化スペクトラム ベネディクトは、初期の『文化のパターン』だけでなく、戦時中の研究成果を取り入れて1946年に出版した日本の社会と文化に関する研究書『菊と刀』でも 知られている。 この本は、距離を置いた人類学の一例である。第二次世界大戦中、人類学者がアメリカとその同盟国を支援する際に必要だったのが、文献、新聞の切り抜き、映 画や録音などを通して文化を研究することだった。ナチス・ドイツやヒロヒト政権下の日本を訪問することができなかった人類学者たちは、文化資料を使って遠 隔地での研究を行った。彼らは彼らの侵略の原動力となっている文化的パターンを理解しようと試み、見逃していた可能性のある弱点や説得の手段を見つけるこ とを望んだ。 ベネディクトの戦争中の仕事には、1944年に大部分が完了した、アメリカ人が理解できないような事柄を持つ日本文化を理解することを目的とした主要な研 究が含まれる。例えば、アメリカ人は、アメリカ人捕虜が、自分が生きていることを家族に知らせたがったり、部隊の動きなどについての情報を求められても 黙っていたりするのは、ごく自然なことだと考えていた。しかし、日本人の捕虜は自由に情報を与え、家族に連絡しようとはしなかったようだ。それはなぜか。 なぜアジアの人々は、日本人を欧米の植民地主義からの解放者として扱わず、日本人を頂点とするヒエラルキーの中での自分たちの正当なはずの立場を受け入れ なかったのだろうか? ベネディクトは、日本の大衆文化における天皇の位置づけを把握し、フランクリン・ルーズベルト米大統領に対して、天皇の統治継続を最終的な降伏の申し出の 一部として認めなければならないという提言をまとめる上で、大きな役割を果たした。 マーガレット・ミードによれば、この著作を読んだ他の日本人は、全体的に正確だが、やや「道徳主義的」だと感じたという。この本の一部は土居丈朗の著書 『依存の解剖学』でも触れられているが、土居はベネディクトの「日本には "恥 "の文化がある。土井はこの主張が、前者の価値観が後者の価値観より劣っていることを明確に示唆していると考えた。 |

| Legacy The American Anthropology Association awards an annual prize named after Benedict. The Ruth Benedict Prize has two categories, one for monographs by one writer and one for edited volumes. The prize recognizes "excellence in a scholarly book written from an anthropological perspective about a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender topic."[29][30] A 46¢ Great Americans series postage stamp in her honor was issued on October 20, 1995. Benedict College in Stony Brook University is named after her. In 2005, Benedict was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[31] |

遺産 アメリカ人類学協会は、ベネディクトの名を冠した賞を毎年授与している。ルース・ベネディクト賞には2つの部門があり、1つは1人の作家による単行本、も う1つは編集本である。この賞は「レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーのトピックについて人類学の視点から書かれた学術書の優秀性」 を評価するものである[29][30]。 1995年10月20日には、彼女を記念した46¢のGreat Americansシリーズの切手が発行された。 ストーニー・ブルック大学のベネディクト・カレッジは彼女にちなんで命名された。 2005年、ベネディクトは全米女性殿堂入りを果たした[31]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Benedict |

1887.06.05 ニューヨーク州シナンゴ・ヴァレーで生まれる。はしかにより片耳(どち ら?)の聴力を失う。母はバブティスト派で、ヴァツサー大学(Vassar College) の卒業生。

1889 前年に術中感染症に罹ったホメオパシー医の父フレデリック・フルトンが死亡(3月26日)。

1894 母ベアトリスが高校教員に赴任(ミズーリ州セントジョセフ)

1896 ミネソタ州オトワンナに転居。

1897-1902 フランツ・ボアズ、ジェサップ北太平洋調査

1898 ニューヨーク州バッファローに転居。癇癪の最後の発作がおこる、その後、憂鬱症の傾向 が習慣化。

1902 セントマーガレット女学校入学

1905 ヴァッサー大学入学、英文学専攻。母親は、同大学の図書館職員に就職する。

1909 同大学を首席卒業。10年まで奨学金でヨーロッパ旅行。

1910 ニューヨーク州バッファローの慈善事業協会(CSO)に勤務。

1911 ロサンゼルス、パサデナで英語教師(〜1914年)1913年からスタンレー・ベネ

ディクトと恋愛関係に。

1914

コーネル大学生化学者スタンレー・ベネディクト(〜1936)と結婚。(スタンレーは第一次大戦期 に毒ガスの研究に従事し、後年後遺症に悩まされる)。小説などの創作に打ち込む。不妊症の傾向があることが判明。

1917 伝記『メアリー・ウルストンクラフト』を脱稿(41年後公刊)。当時、米国は第一次大 戦に参戦。

1918-1919 コロンビア大学でジョン・デューイによる哲学の授業を受け、感銘を受ける。デューイはNew School for Social Research の開校に関わる。

"No man ever looks at the world with pristine eyes. He sees it edited by a definite set of customs and institutions and ways of thinking. Even in his philosophical probings he cannot go behind these stereotypes; his very concepts of the true and the false will still have reference to his particular traditional customs. John Dewey has said in all seriousness that the part played by custom in shaping the behaviour of the individual as over against any way in which he can affect traditional custom, is as the proportion of the total vocabulary of his mother tongue over against those words of his own baby 'talk that are taken up into the vernacular' of his family." (Benedict, Patterns of Culture, 1934:2).

人は誰しも、純粋な目で世界を見ることはできない。彼は、特定の習慣や制度、考え方によって編集された世界を見てい

る。哲学的な探求をするときでさえ、こうした固定観念の裏をかくことはできない。真実と偽りに関する彼の概念そのものが、その人固有の伝統的な慣習を参照

していることに変わりはない。ジョン・デューイは、伝統的な慣習に影響を与えることができるあらゆる方法に対して、個人の行動を形成する上で慣習が果たす

役割は、自分の家族の「バナキュラーな言葉に取り込まれる」自分の赤ん坊の「話し言葉」に対して、母語の語彙が占める割合のようなものである、と真面目に

述べている。

ニュースクール・ フォ・ソーシャル・リサーチ(大学院)が開校する。そこでの聴講(〜21):エルシー・ パーソンズ(Elsie Clews Parsons, 1875-1941)の授業「民族学における性」、アレキサンダー・ゴールデンワイザー(Goldenweiser, Alexander A. 1880-1940)の授業「文明の基礎」をうける。

アレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザーならびにエルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズの授業を受け る。

1921 34歳。コロンビア大学博士課程に入学。9か月で博士論文「北米における守護霊の観 念」を審査のために提出(学位取得は23年)。

1922 バーナードカレッジで、フランツ・ ボアズの助手。マーガレット・ミードと知り合う。処女論文「平原文化における幻 視」。夏にセラノ先住民を調査(〜26年)。

1923

学位論文「北アメリカにおける守護霊の概念」。コロンビア大学で1年ごとの講師契約。

The concept of the guardian spirit in

North America / by Ruth Fulton B enedict. -- Kraus Reprint, 1964. --

(Memoirs of the American anthropol ogical association ; no. 29, 1923)

1924 ズニ調査。セリグマン「人類学と精神分析」論文(ca.)

1925 ズニとコチティの調査。Journal of Amrican Folklore の編集(〜1939)。

1926-27 バーナードでも教鞭。

1926年 マリノフスキーと出会う:「彼(マリノフスキー)は鋭い想像力と、七日間喜びを

もたらす、遊びの心をもっている」(カフリー 1993:214)

1927 O'odham creation and related events /

as told to Ruth Benedict in 1927 in prose, oratory, and song by the

Pimas William Blackwater ... [et al.] ; edited by Donald Bahr ; :cloth.

-- University of Arizona Press, 2001. -- (The Southwest Center series)

1926 マリノフスキー、コロンビア大学に現る。ローマでのアメリカニスト国際会議に参加。

1927 ピマ調査(プエブロとプレーンの対照性について気づくといわれる[→文化の諸パターン])

1928 エドワード・サピアと ともに詩(アン・シングルトンのペンネーム)の原稿を出版社に送るが没となる。ニューヨークでアメリカニスト国際会議開催。

Edward Sapir (1884-1939)

1930 論文「南西部諸文化における心理学的タイプ」「北アメリカにおける文化の統合形態」

1931 スタンレーと離婚。メスカレロ・アパッチ調査。コロンビア大学助教授(〜1937):

Benedict, Ruth. 1931. Tales of the Cochiti Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology

1932 アルフレッド・クローバー(Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960)がコロンビアに招聘され教鞭をとる。ベネディクトは「文化の 型」の出版の構想を決意。

Configurations of culture in North America

/ by Ruth Benedict. -- [s.n .], 1932

1933

「呪術」(『社会科学事典』)

このころ、ボアズは、ドイツにおける思想の自由を訴え、ナチス御用学者の採用を抗議する。アメリカに反ユダヤ主義や人

種主義の流入を防ぐように活動する。

『文化の型』 (Patterns of Culture)/Patterns of culture / Ruth Benedict. -- Houghton Mifflin, 1934

Benedict, Ruth "Anthropology and the Abnormal," Journal of General Psychology, 10, 1934.(このタイトルで検索するとpdfダウンロード可能)

文化とパーソナリティ学派と

みなされる。

1935 『ズニの神話』を刊行

Zuni mythology /

by Ruth Benedict ; pt. 1,

pt. 2. -- Columbia Universi ty Press, 1935. -- (Columbia University

contributions to anthropology ; v. 21)

1936 ボアズ、コロンビア大学を退職。

1937

ベネディクト、コロンビア大学准教授。ラルフ・リントン(Ralph Linton, 1893-1953)、ボアズの後任(head of the Anthropology department)としてコロンビアに赴任。ボアズ派の人はベネディクトが主任になると予想していたので、これは予想外であった。

リントンは、ボアズ派の人たちを、FBIに共産主義者と密告していた。ジーン・ウェルト

フィッシュ(Gene

Weltfish, 1902-1980)

[1928-1953年までコロンビアで働いた]は、リントンの密告で、FBIのブラックリストに収載されてしまった一人。リントンは、エール時代の同僚

のシドニー・ミンツに「かつて冗談めかして、タナラの魔法の魅力を使ってベネディクトを殺したと自慢していた」という。リントンは戦後の46年にエールに

転職。-Ralph Linton.

1938

ボアズ編『総合人類学(General Anthropology)』に宗教の章を寄稿

11月9〜10日ドイツで「水晶の

夜」ユダヤ人排斥激化。ハンガリーからマックス・ベネディクトというユダヤ人家族からの手紙を受け取り、アメリカでの保証人になるように依頼され

る(ケント 1997:212)。

1939

ブラックフット(モンタナ州、カナダ・アルバータ州)調査。国民道徳委員会(ベイトソ ンやミードがいた)。この時期、コロンビアでは学科主任となっていた同僚(ラルフ・リントン)との関係がさらに悪化する[1943年にOWIからの誘いに すぐに応諾したのは、それが理由と言われている]。

この年に、ジョン・

エンブリー『須恵村』公刊。

1940

『人種:科学と政治』Race : science and politics / by Ruth Benedict. -- Rev. ed., with The races of mankind, by Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish. -- Viking Press, 1945[1940](→「人種」)

ボアズ; Race, Language, and Culture. University of

Chicago Press.

1941 (→「ジェフリー・ ゴーラーの研究」も参照)

食習慣委員会委員に任命。ベイトソン、ミードら、通文化関連協議会(後の通文化研究 所)を組織。後にベネディクトの部下になるロバート・ハシマが日本から帰国。

1942

コロンビア大学で・人種差別対策委員会は、パブリックアフェアーズ(非営利組織)と月刊パンフレットで人種差別を取り

上げることを決定。ベネディクトは、ジーン・ウェルトフィッシュと共著で、Race

of Mankind.の出版を計画、翌年刊行。

Race and racism / Ruth Benedict. -- G.

Routledge, 1942/

12月21日フランツ・ボアズ死去

1943

戦時情報局(United States Office of War Information)に、ロバート・ハリー・ローウィ(1883-1957)と 共に関わる。最初の研究委託は、ヨーロッパ研究。OWIの海外情報部・基礎分析課主任。

"In her capacity as a researcher in the OWl, Benedict was also privileged to restricted and confidential information provided not only by the OWl but also intelligence reports from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), British Intelligence and other related wartime departments. Benedict first started with the OWl in 1943, as a Cultural Analyst of European cultures but soon took up work on Thailand, Burma, Rumania, Norway, The Netherlands, Germany, China and other countries. She collaborated with the OSS to write a report on Japanese films' but did not begin a fully fledged investigation on the Japanese until she joined the FMAD, which was newly formed specifically for the purpose of assessing the morale and will to fight of both front line and home front Japanese, as well as providing information on ways to use propaganda to end the war as early as possible. A list of the members of this Division and their fields of research or speciality has also been provided to give an idea of the environment in which Benedict formed her ideas." (Kent 1995:108)

「OWIの研究者として、ベネディクトはOWIだけでなく、戦略事務局(OSS)、英国情報部、その他の関連戦時 省庁からの機密情報にもアクセスする特権も有していた。ベネディクトは1943年にOWIでヨーロッパ文化の文化アナリストとして働き始め、その後すぐに タイ、ビルマ、ルーマニア、ノルウェー、オランダ、ドイツ、中国などの国々の調査を担当するようになった。OSSと協力して日本映画に関する報告書を執筆したが、日本に関する本格的 な調査を開始したのは、戦地および国内の日本人の士気と戦う意志を評価し、宣伝を駆使して早期に戦争を終結させる方法に関する情報を提供することを目的と して新たに結成されたFMAD(Foreign Morale Analysis Division)に参加してからであった。 この部門のメンバーのリストと、各人の研究分野や専門分野も提供されており、ベネディクトが自身の考えを形成した環境について知ることができる。」

10月25日Race of Mankind.が出版される(最初のヴァージョン)冊子「人類の諸人種」

The

races of mankind / by Ruth Benedict

and Gene Weltfish. -- rev. ed. . -- Public Affairs Committee,

1946[1943]. -- (Public affairs pamphlet ; no. 85)[pdf

in online]

1944

1月USO(連合奉仕組織)の会長チェスター・バーナードがThe

races of mankindを、マイノリティに加担するために、配布の中止を

要請。3月にはケンタッキー下院議員アンドリュー・メイが妨害(ケント 1997:216-217)

6月OWIの海外情報部基礎分析課主任のまま、海外情報部(Bureau of Overseas Information, BOT)・外国戦意識調査課分析官(Foreign Morale Analysis Division, FMAD)を兼務。(その時の辞令が)6 月「わたしは日本研究を委託された。日本人とはどのようなものか、文化人類学者として駆使することのできる手法を総動員して説明せよ、とのことであった」 『菊と刀』(角田訳, p.17)。研究テーマは「日本人の行動パターン(Japanese Behavior Patterns)」

「OSSと協力して日本映画に関する報告書を執筆したが、日本に関する本格的

な調査を開始したのは、戦地および国内の日本人の士気と戦う意志を評価し、宣伝を駆使して早期に戦争を終結させる方法に関する情報を提供することを目的と

して新たに結成されたFMAD(Foreign Morale Analysis Division)に参加してからであった」(再掲)

12月16〜17日太 平洋問題調査会(IPR)がニューヨークで開催される(福井 2011:228)。

1945

1月、ロバート・ハシマが外国 戦意識調査課に赴任した時には、タイピスト他は一人で研究していた(角田「解説」509ページ)

"The FMAD was made up of social scientists, some of whom had Japanese expertise, and staff that were Japanese or of Japanese descent who analysed and translated information within the Division. Robert Hashima, a kibei (a Japanese who had returned to America at the onset of war), worked closely with her, providing information through formal interviews. He also answered a multitude of questions Benedict posed on the meanings of Japanese concepts, words and things she had read or seen but had not fully understood. Tom Sasaki also helped her to understand meanings of certain concepts as no doubt did many other members of the Division. Benedict's notes on Embree's research suggests she took advantage of his knowledge too. Outside the FMAD, Nathan Leites, in OWl, and Andrew Meadow in psychology, in the OSS, also provided her with a number of notes on psychoanalytical aspects of the Japanese character. " (Kent 1995:107-108)

「FMADは、日本専門の社会科学者や、日系人スタッフで構成され、部門内で情報を分析し翻訳し

ていた。 ロバート・ハシマは、帰米日本人(開戦時にアメリカに戻った日本人)で、彼女と緊密に協力し、正式なインタビューを通じて情報を提供した。

また、ベネディクトが読んだり見たりしたが、十分に理解できなかった日本的な概念、言葉、事物の意味について、数多くの質問に答えた。トム・ササキもま

た、おそらくは他の多くの部門のメンバー同様、彼女が特定の概念の意味を理解する手助けをした。ベネディクトがエンブリーの研究について書いたメモから、

彼女が彼の知識も活用していたことがうかがえる。FMADの外部では、OWIのネイサン・レイテスと心理学のOSSのアンドリュー・メドウが、日本人の性

格の精神分析的な側面について多くのメモを提供した。」

"The Division also had a large processing and analysis staff which worked to process incoming information including materials on Japanese Prisoners of War which were all coded and rocorded on cards, complete with cross-referencing. This information was evaluated both quantitatively and qualitatively. It was this information that Benedict used when she wrote on what POW's had said and thought after their capture-as it was not possible for her to directly interview them herself. (It is often incorrectly assumed that Benedict actually interviewed the prisoners.) As mentioned above, she interviewed people like Hashima but throughout her time in the OWl Benedict often made use of "consultants" who were instructed to write about certain subjects, or answer questions on a particular theme such as childhood discipline, sleeping, etc. In the case of Japan, she used both those of Japanese descent and people who had some knowledge of Japan. She also used two intermediate consultants, Sula Benet and Hsien Chin Hu to conduct interviews for her. Moreover, as many of the members of the Division had worked at the War Relocation Camps (although some of the Japanese had been interned there) she had access to the information that had come out of the research that had been carried out there, too. " (Kent 1995:108)

「また、この部門には、膨大な量の処理と分析を行うスタッフがおり、日本軍の捕虜に関する資料を

含む受信情報の処理にあたった。これらの情報はすべてコード化され、相互参照情報とともにカードに記録されていた。この情報は量的にも質的にも評価され

た。ベネディクトが捕虜が捕らえられた後に何を話し、何を考えたかについて書いた際には、この情報を利用した。なぜなら、彼女自身が捕虜に直接インタ

ビューすることは不可能だったからだ。(ベネディクトが実際に捕

虜たちにインタビューを行ったと誤解されることが多いが、実際にはそうではない。)

前述の通り、彼女はハシマのような人々にインタビューを行ったが、OWIに滞在している間、特定のテーマについて執筆するよう指示された「コンサルタン

ト」や、幼少期のしつけや睡眠など特定のテーマに関する質問に答える「コンサルタント」をたびたび活用した。日本については、日系人や日本について何らか

の知識を持つ人々をコンサルタントとして起用した。また、彼女はスラ・ベネットとシェン・チン・フーという2人の中間コンサルタントにインタビューを行わ

せた。さらに、この部門の多くのメンバーが戦時転住

センターで働いていたため(一部の日本人も収容されていた)、彼女はそこで実施された調査から得られた情報にもアクセスすることができた。」

5月初旬から8月初旬に「日本 人の行動パターン(Japanese Behavior Patterns)」(福井七子訳、日本放送出版協会、1997年)を執筆。9月15日付で国務省に提出。

"Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the

Sword (1946) is considered a

classic in Japan Studies and still generates a relatively large amount

of discussion.

Yet despite the influence of this book, up until now very little has

been known about

the background research conducted before publication.' The fact that

Benedict

wrote the book based on research she conducted during the war while

attached to the

Foreign Morale Analysis Division (FMAD), Bureau of Overseas Information

(BOI),

Office of War Information (OWl) has caused speculations concerning her

intentions

behind writing the book. It is often suggested that the book was

written for the

express purpose of guiding MacArthur and the Occupation Forces but this

is far from

the case. Benedict did prepare a report entitled "Report 25: Japanese

Behavior

Patterns" during the early summer of 1945. Once capitulation became

certain it

seems that "Report 25" was retrieved from the files, annotated and

circulated to a

wider audience that included policy makers in the field of Japan."

(Kent 1995:107)

「ルース・ベネディクト著『菊と刀』(1946年)は日本研究の古典とされ、現在でも多くの議論 を呼んでいる。しかし、この本がこれほどまでに影響力を 持っていたにもかかわらず、出版前の背景調査についてはこれまでほとんど知られていなかった。ベネディクトが戦時中に外務省情報局(BOI)海外情報局 (OWI)の戦時情報局(OWI)に所属していた際に実施した調査に基づいてこの本を書いたという事実から、彼女がこの本を書いた意図について推測がなさ れている。マッカーサーおよび占領軍を導くことを明確な目的として書かれたという見解がしばしば示されるが、実際にはそうではない。ベネディクトは 1945年初夏に「レポート25:日本人の行動パターン」と題する報告書を作成していた。降伏が確実になると、「レポート25」はファイルから回収され、 注釈が付けられ、日本の政策立案者を含むより幅広い層に配布されたようだ」。

9月よりサバティカルをとり、『菊と刀』の原稿を書き始める

1946

11月『菊と刀』公刊。コロンビア大学に復帰。全米女性大学人協会の年間功労賞受賞。コロン ビア大学の同僚(=宿敵)リントンの後任としてJ・スチュアード(Julian Steward, 1902–1972)が赴任[→「学際研究を継続させる要因とは何か」]。

1947

1948

長谷川松治訳『菊と刀:日本文化の型』社会思想社

1949

1950

志村義雄訳『民族(Race)』北隆館

1951

尾高京子訳『文化の諸様式』中央公論社

1952

1952年から53年にかけて、ウェルトフィッシュは、

マッカーシー反米委員会で査問をうける。

++

1973

米山俊直訳『文化の型』社会思想社(2007年講談社)

++

| The

Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture is a 1946

study of Japan by American anthropologist Ruth Benedict compiled from

her analyses of Japanese culture during World War II for the U.S.

Office of War Information. Her analyses were requested in order to

understand and predict the behavior of the Japanese during the war by

reference to a series of contradictions in traditional culture. The

book was influential in shaping American ideas about Japanese culture

during the occupation of Japan, and popularized the distinction between

guilt cultures and shame cultures.[1] Although it has received harsh criticism, the book has continued to be influential. Two anthropologists wrote in 1992 that there is "a sense in which all of us have been writing footnotes to [Chrysanthemum] since it appeared in 1946".[2] The Japanese, Benedict wrote, are both aggressive and unaggressive, both militaristic and aesthetic, both insolent and polite, rigid and adaptable, submissive and resentful of being pushed around, loyal and treacherous, brave and timid, conservative and hospitable to new ways...[3] The book also affected Japanese conceptions of themselves.[4] The book was translated into Japanese in 1948 and became a bestseller in the People's Republic of China when relations with Japan soured.[5] |

『菊と刀:日本文化のパターン』は、第二次世界大戦中に米国戦争情報局

のために日本の文化を分析した内容をまとめた、米国の文化人類学者ルース・ベネディクトによる1946年の日本研究である。彼女の分析は、伝統文化におけ

る一連の矛盾を参考に、戦争中の日本人の行動を理解し予測するために求められた。この本は、日本占領中のアメリカ人の日本文化に対する考え方に影響を与

え、罪悪感文化と恥の文化の区別を広めた。 この本は厳しい批判も受けたが、依然として影響力を持っている。1992年には、2人の人類学者が「1946年に『菊』が発表されて以来、我々は皆、この 本に脚注を書き続けているような感覚がある」と述べている。[2] ベネディクトは、日本人は 攻撃的かつ非攻撃的、軍国主義的かつ美的、無礼かつ礼儀正しい、融通が利かないが順応性がある、従順だが振り回されることに憤りを感じる、忠実だが裏切り 的、勇敢だが臆病、保守的だが新しいやり方に対しては寛容である...[3] この本は、日本人の自己概念にも影響を与えた。[4] 1948年に日本語に翻訳され、日本との関係が悪化した中華人民共和国でベストセラーとなった。[5] [2] Plath, David W., and Robert J. Smith, "How 'American' Are Studies of Modern Japan Done in the United States", in Harumi Befu and Joseph Kreiner, eds., Otherness of Japan: Historical and Cultural Influences on Japanese Studies in Ten Countries, Munchen: The German Institute of Japanese Studies, as quoted in Ryang, Sonia, "Chrysanthemum's Strange Life: Ruth Benedict in Postwar Japan", |

| Research circumstances See also: Empire of Japan This book which resulted from Benedict's wartime research, like several other United States Office of War Information wartime studies of Japan and Germany,[6] is an instance of "culture at a distance", the study of a culture through its literature, newspaper clippings, films, and recordings, as well as extensive interviews with German-Americans or Japanese-Americans. The techniques were necessitated by anthropologists' inability to visit Nazi Germany or wartime Japan. One later ethnographer pointed out, however, that although "culture at a distance" had the "elaborate aura of a good academic fad, the method was not so different from what any good historian does: to make the most creative use possible of written documents."[7] Anthropologists were attempting to understand the cultural patterns that might be driving the aggression of once-friendly nations, and they hoped to find possible weaknesses or means of persuasion that had been missed. Americans found themselves unable to comprehend matters in Japanese culture. For instance, Americans considered it quite natural that American prisoners of war would want their families to know that they were alive and that they would keep quiet when they were asked for information about troop movements, etc. However, Japanese prisoners of war apparently gave information freely and did not try to contact their families. |

研究環境 参照:大日本帝国 ベネディクトの戦時中の研究の成果であるこの本は、米国戦争情報局による戦時中の日本およびドイツ研究のいくつかと同様に、[6]「距離のある文化」の例 である。すなわち、文学、新聞の切り抜き、映画、録音物、およびドイツ系アメリカ人や日系アメリカ人との広範なインタビューを通して文化を研究するもので ある。この手法は、人類学者がナチス・ドイツや戦時中の日本を訪問できなかったために必要となった。しかし、後に民族誌学者の一人が指摘したように、「遠 隔地の文化」は「学問上の流行の凝ったオーラをまとっているが、その方法は、優れた歴史家が行うこととそれほど変わらない。つまり、書かれた文書を最大限 に創造的に利用することである」[7]。人類学者たちは、かつて友好的であった国家の侵略を推進しているかもしれない文化パターンを理解しようとしてお り、見逃されていた可能性のある弱点や説得手段を見つけたいと考えていた。 アメリカ人は、自分たちが日本文化を理解できないことに気づいた。例えば、アメリカ人捕虜が、自分が生きていることを家族に知らせたいと思うのはごく自然 なことであり、部隊の移動などに関する情報を求められても口をつぐむだろうとアメリカ人は考えていた。しかし、日本人の捕虜は、進んで情報を提供し、家族 に連絡しようとはしなかったようだ。 |

| Reception in the United States Between 1946 and 1971, the book sold only 28,000 hardback copies, and a paperback edition was not issued until 1967.[8] Benedict played a major role in grasping the place of the Emperor of Japan in Japanese popular culture, and formulating the recommendation to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that permitting continuation of the Emperor's reign had to be part of the eventual surrender offer.[citation needed] As of 1999, 350,000 copies were sold in the US.[4] |

米国での受け入れ 1946年から1971年の間、この本はハードカバーで2万8千部しか売れず、ペーパーバック版は1967年まで発行されなかった。[8] ベネディクトは、日本の大衆文化における日本の天皇の地位を把握し、天皇の統治の継続を認めることが最終的な降伏条件の一部でなければならないというフラ ンクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領への提言をまとめる上で重要な役割を果たした。[要出典] 1999年時点で、米国では35万部が販売された。[4] |

| Reception in Japan More than 2.3 million copies of the book have been sold in Japan since it first appeared in translation there.[4] John W. Bennett and Michio Nagai, two scholars on Japan, pointed out in 1953 that the translated book "has appeared in Japan during a period of intense national self-examination—a period during which Japanese intellectuals and writers have been studying the sources and meaning of Japanese history and character, in one of their perennial attempts to determine the most desirable course of Japanese development."[9] Japanese social critic and philosopher Tamotsu Aoki said that the translated book "helped invent a new tradition for postwar Japan." It helped to create a growing interest in "ethnic nationalism" in the country, shown in the publication of hundreds of ethnocentric nihonjinron (treatises on 'Japaneseness') published over the next four decades. Although Benedict was criticized for not discriminating among historical developments in the country in her study, "Japanese cultural critics were especially interested in her attempts to portray the whole or total structure ('zentai kōzō') of Japanese Culture," as Helen Hardacre put it.[9] C. Douglas Lummis has said the entire "nihonjinron" genre stems ultimately from Benedict's book.[10] The book began a discussion among Japanese scholars about "shame culture" vs. "guilt culture", which spread beyond academia, and the two terms are now established as ordinary expressions in the country.[10] Soon after the translation was published, Japanese scholars, including Kazuko Tsurumi, Tetsuro Watsuji, and Kunio Yanagita criticized the book as inaccurate and having methodological errors. American scholar C. Douglas Lummis has written that criticisms of Benedict's book that are "now very well known in Japanese scholarly circles" include that it represented the ideology of a class for that of the entire culture, "a state of acute social dislocation for a normal condition, and an extraordinary moment in a nation's history as an unvarying norm of social behavior."[10] Japanese ambassador to Pakistan Sadaaki Numata said the book "has been a must reading for many students of Japanese studies."[11] According to Margaret Mead, the author's former student and a fellow anthropologist, other Japanese who have read it found it on the whole accurate but somewhat "moralistic". Sections of the book were mentioned favorably in Takeo Doi's book, The Anatomy of Dependence, but he is somewhat critical of her analysis of Japan and the West as respectively shame and guilt cultures, noting that while he is "disposed to side with her," she still "allows value judgements to creep into her ideas."[12] In a 2002 symposium at The Library of Congress in the United States, Shinji Yamashita, of the department of anthropology at the University of Tokyo, added that there has been so much change since World War II in Japan that Benedict would not recognize the nation she described in 1946.[13] Lummis wrote, "After some time I realized that I would never be able to live in a decent relationship with the people of that country unless I could drive this book, and its politely arrogant world view, out of my head."[10] Lummis, who went to the Vassar College archives to review Benedict's notes, wrote that he found some of her more important points were developed from interviews with Robert Hashima, a Japanese-American native of the United States who was taken to Japan as a child, educated there, then returned to the US before World War II began. According to Lummis, who interviewed Hashima, the circumstances helped introduce a certain bias into Benedict's research: "For him, coming to Japan for the first time as a teenager smack in the middle of the militaristic period and having no memory of the country before then, what he was taught in school was not 'an ideology', it was Japan itself." Lummis thinks Benedict relied too much on Hashima and says that he was deeply alienated by his experiences in Japan and that "it seems that he became a kind of touchstone, the authority against which she would test information from other sources."[10] |

日本での受容 日本では、翻訳版が出版されて以来、230万部以上が販売されている。[4] 日本研究家であるジョン・W・ベネットと永井道雄は、1953年に、翻訳された本が「日本が国家としてのあり方を厳しく見直していた時期に日本で出版され た」と指摘している。「この時期は、日本の知識人や作家たちが、日本史や国民性の源泉や意味を研究し、日本がとるべき最も望ましい発展の方向性を決定しよ うとする永年の試みの1つであった」[9]。 日本の社会評論家であり哲学者でもある青木保氏は、この翻訳本が「戦後の日本に新たな伝統を生み出すのに役立った」と述べている。この本は、日本国内で 「民族ナショナリズム」への関心が高まるのに一役買い、そのことは、その後40年間に数百もの自民族中心的な「日本人論」が出版されたことにも表れてい る。ベネディクトは自著の中で日本の歴史的展開を区別せずに論じたことで批判されたが、ヘレン・ハーダックは「日本の文化評論家たちは、彼女が日本文化の 全体構造(「全体構造」)を描き出そうとしたことに特に興味を持った」と述べている。[9] C. ダグラス・ルミスは、「日本人論」というジャンル全体が最終的にはベネディクトの著書から派生したものだと述べている。[10] この本は、日本の学者の間で「恥の文化」対「罪悪感の文化」という議論を巻き起こし、それは学術界を超えて広がり、現在ではこの2つの用語は日本で一般的 な表現として定着している。 翻訳が出版されるや否や、鶴見和子、和辻哲郎、柳田国男などの日本の学者たちが、この本は不正確で方法論的な誤りがあると批判した。米国の学者C. Douglas Lummisは、ベネディクトの著書に対する批判は「現在では日本の学術界ではよく知られている」とし、その批判の中には、ある階級のイデオロギーを日本 文化全体のものとして表現していること、また「正常な状態に対する深刻な社会の混乱、そして社会行動の不変の規範としての国家の歴史における異常な瞬間」 と表現しているものもあると述べている。 パキスタン駐在の日本大使、沼田貞昭は、この本は「日本研究の多くの学生にとって必読書となっている」と述べた。[11] 著者の元教え子であり、同じ文化人類学者であるマーガレット・ミードによると、この本を読んだ他の日本人は、全体的には正確であるが、やや「道徳的」であ ると感じたという。この本の一部は、土居健郎『甘えの構造』で好意的に言及されているが、土居は、日本と西洋をそれぞれ恥と罪悪感の文化と分析した彼女の 分析に対しては批判的であり、彼女の意見に賛成する傾向にあるものの、彼女の考えには「価値判断が入り込んでいる」と指摘している。 2002年に米国議会図書館で開催されたシンポジウムで、東京大学人類学部の山下晋司は、ベネディクトが1946年に描いた日本とは、第二次世界大戦後の 日本ではあまりにも多くの変化があったと付け加えた。 ルミスは、「しばらくして、私はこの本を、そしてその丁寧に表現された傲慢な世界観を頭から追い出さなければ、私はその国の人々とまともな関係を築くこと はできないと気づいた」と書いている。[10] ルミスは、 ベネディクトのメモを再調査するためにヴァッサー大学のアーカイブを訪れたルミスは、彼女の重要な指摘のいくつかは、幼少時に日本に連れて行かれ、そこで 教育を受け、第二次世界大戦が始まる前に米国に戻った日系アメリカ人、ロバート・ハシマ氏へのインタビューから発展したものだと書いている。ハシマ氏にイ ンタビューしたルミス氏によると、その経緯がベネディクト氏の研究に一定のバイアスをもたらしたという。「軍国主義の真っ只中の10代で初めて日本を訪 れ、それ以前の日本の記憶を持たない彼にとって、学校で教えられたことは『イデオロギー』ではなく、日本そのものであった。ルミスは、ベネディクトが羽島 に頼りすぎたと考えており、日本での経験に深く傷つき、「他の情報源からの情報を検証する基準となるような存在になったようだ」と述べている。[10] |

| Reception in China The first Chinese translation was made by Taiwanese anthropologist Huang Dao-Ling, and published in Taiwan in April 1974 by Taiwan Kui-Kuang Press. The book became a bestseller in China in 2005, when relations with the Japanese government were strained. In that year alone, 70,000 copies of the book were sold in China.[5] |

中国での反響 最初の中国語訳は台湾人人類学者の黄道琳(ホァン・ダオリン)氏によって行われ、1974年4月に台湾の奎光出版社から出版された。この本は、日本政府と の関係が緊張していた2005年に中国でベストセラーとなった。この年だけで、中国では7万部が売れた。[5] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Chrysanthemum_and_the_Sword |

1946-47 アメリカ人類学会会長

1948

7月コロンビア大学教授に昇進。9月17日に冠状動脈血栓症で死去(61歳)。

Race and cultural relations : America's answer to the myth of a master race / analysis by Ruth Benedict ; teaching aids by Mildred Ellis. -- Rev. [ed.]. -- National Council for the Social Studies, National Asso ciation of Secondary-School Principals, Departments of the National Ed ucation Association, 1949. -- (Problems in American life ; unit no. 5)

12月 社会思想研究会出版部より上下巻で長谷川松治訳『菊と刀』が出版される(諸訳あわせ

て1996年までに累計230万部販売された——角田「解説」による)。

1959 『人類学者の研究生活(An Anthropologist at Work)』公刊:Benedict, Ruth. 1959. An Anthropologist at Work: Writings of Ruth Benedict. Ed. Margaret Mead. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

++++++

関連リンク集

練習問題

1890年当時に撮影されたプレインズ(平原)インディアンの写真

[文献]

欧文については[Ruth Benedict's Bibliography]をご覧ください。

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆