人種主義(レイシズム)理論

Theory of Racism

★ この項目は「人種」のページのさらなる詳しい解説である。情報は英語の"Racism"からの翻訳 が中心である。

☆

レイシズム(人種主義)とは、人種や民族に基づく人々に対する差別や偏見である。レイシズムは、差別的慣行における偏見や嫌悪の表現を助長する社会的行

動、慣行、政治制度(例えばアパルトヘイト)に存在しうる。レイシズム的慣行の根底にあるイデオロギーは、しばしば人間を、社会的行動や生得的能力が異な

り、劣等または優等としてランク付けできる明確なグループに細分化できると想定する。レイシズム的イデオロギーは、社会生活の多くの側面で顕在化する可能

性がある。関連する社会的行動には、ネイティビズム、外国人排斥、他者性、隔離、階層的ランク付け、優越主義、および関連する社会現象などが含まれる。人

種差別とは、機会均等(形式的な平等)に基づく、または異なる人種や民族における結果の平等に基づく人種的平等の侵害を指し、実質的平等とも呼ばれる。

人種と民族の概念は現代の社会科学では別個のものと考えられているが、この2つの用語は一般的に長い歴史の中で同等に扱われてきた。「民族性」は、伝統的

に「人種」に帰属するものに近い意味で使用されることが多く、グループの本質的または先天的な特性(例えば、共通の祖先や共通の行動様式)に基づく人間の

グループの区分である。人種差別や人種的差別は、これらの相違が人種的であるかどうかに関わらず、民族や文化に基づく差別を表現するためにしばしば使用さ

れる。国連のレイシズム撤廃条約によると、「人種的」差別と「民族的」差別の区別はない。さらに、人種的差異に基づく優越性は科学的には誤りであり、道徳

的に非難されるべきであり、社会的に不公平であり、危険であると結論づけている。この条約はまた、理論上であれ実際上であれ、いかなる場所においてもレイ

シズムを正当化する理由はないと宣言している。[2]

レイシズムは、紀元前3世紀に記録された反ユダヤレイシズムを含め、比較的近代的な概念であるとされることが多い。[3]

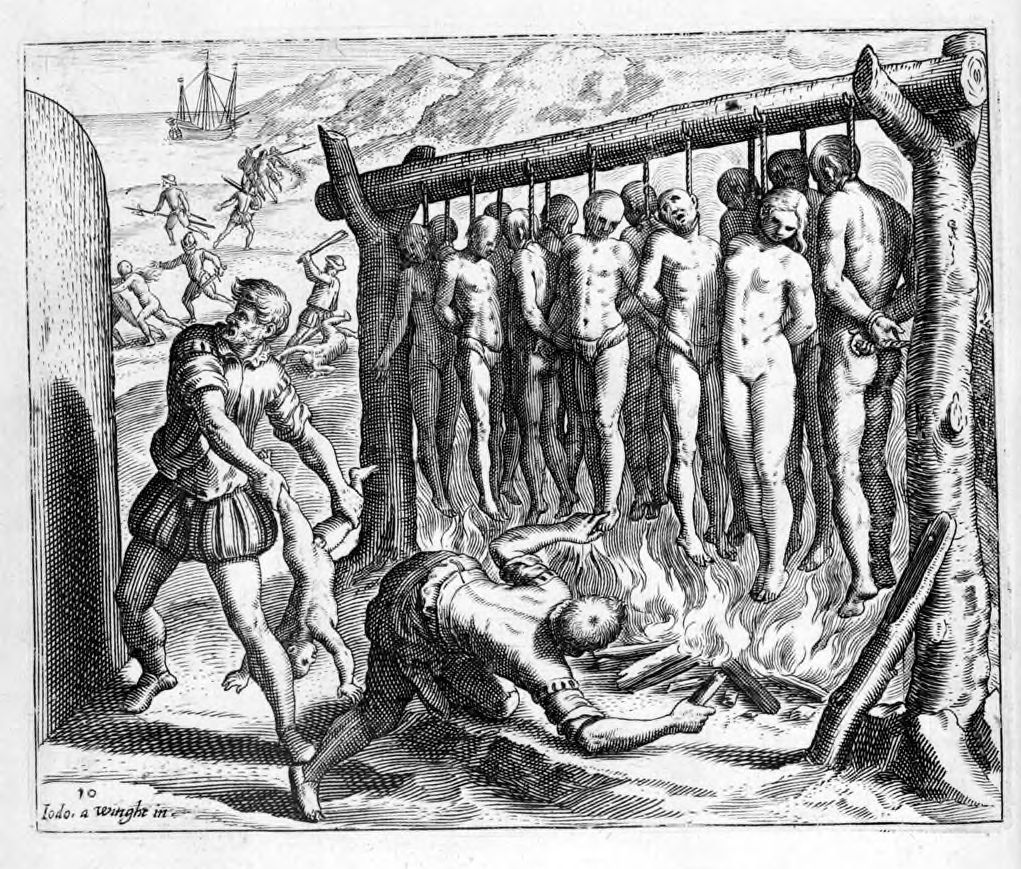

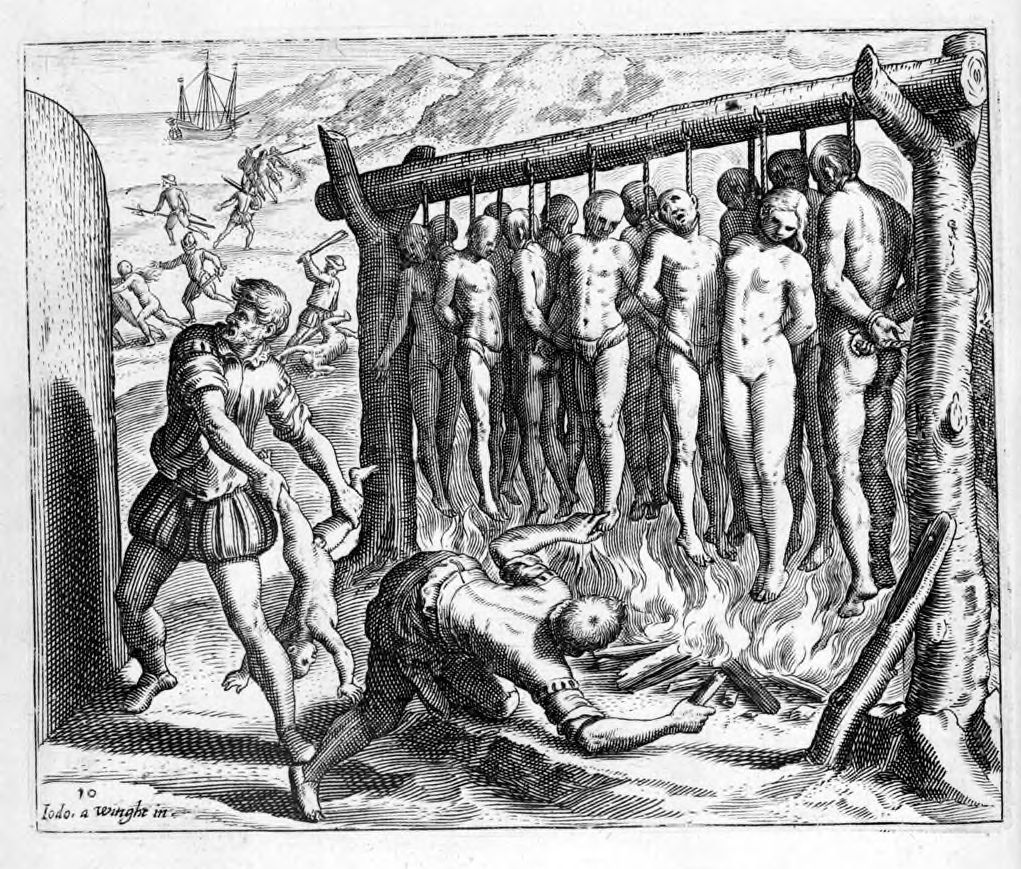

ヨーロッパの帝国主義時代に発展し、資本主義によって変容し、[4] 大西洋奴隷貿易の主要な推進力となった。[5][6] また、

19世紀から20世紀初頭のアメリカ合衆国における人種隔離政策、および南アフリカのアパルトヘイト政策の推進力となった。19世紀から20世紀にかけて

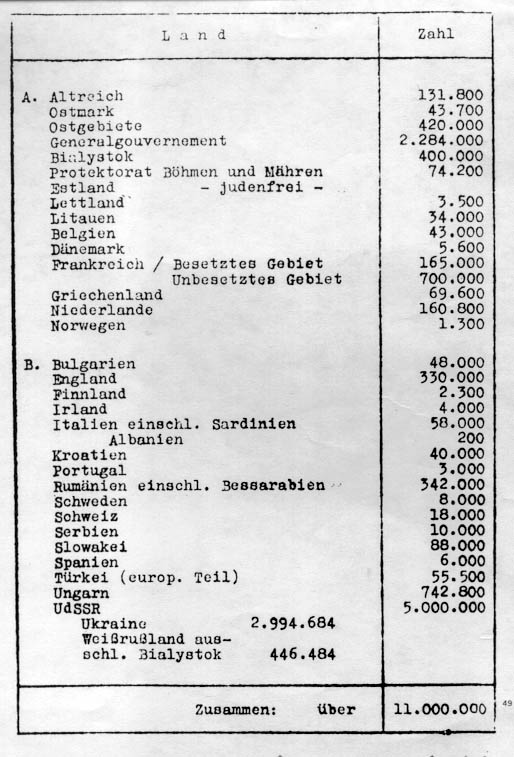

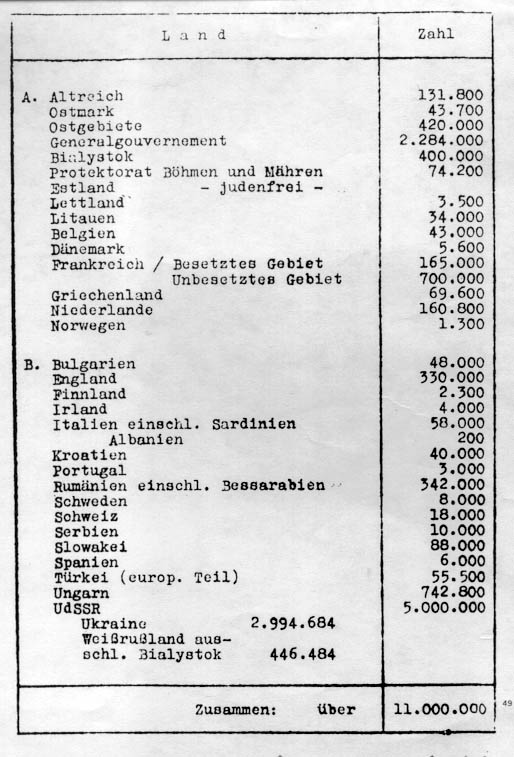

の西洋文化におけるレイシズムは、特に詳細に記録されており、レイシズムに関する研究や言説の参照点となっている。[8] レイシズムは、ホロコースト

、アルメニア人虐殺、ルワンダ大虐殺、クロアチア独立国におけるセルビア人虐殺、さらにはアメリカ大陸、アフリカ、アジアにおけるヨーロッパの植民地化、

ソビエト連邦における先住少数民族の強制移住を含む植民地化計画などにおいて、レイシズムは重要な役割を果たしてきた。[9]

先住民は、過去も現在も、レイシズム的な態度に晒されることが多い。

An

early use of the word racism by Richard Henry Pratt in 1902:

"Association of races and classes is necessary to destroy racism and

classism." 1902年にリチャード・ヘンリー・プラットが「レイシズム(人種主義)」という言葉を使用した初期の例:「レイシズムと階級差別

をなくすためには、人種と階級の関連付けが必要である。」

| Racism is

discrimination and prejudice against people based on their race or

ethnicity. Racism can be present in social actions, practices, or

political systems (e.g. apartheid) that support the expression of

prejudice or aversion in discriminatory practices. The ideology

underlying racist practices often assumes that humans can be subdivided

into distinct groups that are different in their social behavior and

innate capacities and that can be ranked as inferior or superior.

Racist ideology can become manifest in many aspects of social life.

Associated social actions may include nativism, xenophobia, otherness,

segregation, hierarchical ranking, supremacism, and related social

phenomena. Racism refers to violation of racial equality based on equal

opportunities (formal equality) or based on equality of outcomes for

different races or ethnicities, also called substantive equality.[1] While the concepts of race and ethnicity are considered to be separate in contemporary social science, the two terms have a long history of equivalence in popular usage and older social science literature. "Ethnicity" is often used in a sense close to one traditionally attributed to "race", the division of human groups based on qualities assumed to be essential or innate to the group (e.g. shared ancestry or shared behavior). Racism and racial discrimination are often used to describe discrimination on an ethnic or cultural basis, independent of whether these differences are described as racial. According to the United Nations's Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, there is no distinction between the terms "racial" and "ethnic" discrimination. It further concludes that superiority based on racial differentiation is scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially unjust, and dangerous. The convention also declared that there is no justification for racial discrimination, anywhere, in theory or in practice.[2] Racism is frequently described as a relatively modern concept, including anti-jewish racism documented in the 3rd century BCE,[3] evolving in the European age of imperialism, transformed by capitalism,[4] and the Atlantic slave trade,[5][6] of which it was a major driving force.[7] It was also a major force behind racial segregation in the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and of apartheid in South Africa; 19th and 20th-century racism in Western culture is particularly well documented and constitutes a reference point in studies and discourses about racism.[8] Racism has played a role in genocides such as the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide, and the Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia, as well as colonial projects including the European colonization of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and the population transfer in the Soviet Union including deportations of indigenous minorities.[9] Indigenous peoples have been—and are—often subject to racist attitudes. |

レイシズム(人種主義)とは、人種や民族に基づく人々に対する差別や偏

見である。レイシズムは、差別的慣行における偏見や嫌悪の表現を助長する社会的行動、慣行、政治制度(例えばアパルトヘイト)に存在しうる。レイシズム的

慣行の根底にあるイデオロギーは、しばしば人間を、社会的行動や生得的能力が異なり、劣等または優等としてランク付けできる明確なグループに細分化できる

と想定する。レイシズム的イデオロギーは、社会生活の多くの側面で顕在化する可能性がある。関連する社会的行動には、ネイティビズム、外国人排斥、他者

性、隔離、階層的ランク付け、優越主義、および関連する社会現象などが含まれる。人種差別とは、機会均等(形式的な平等)に基づく、または異なる人種や民

族における結果の平等に基づく人種的平等の侵害を指し、実質的平等とも呼ばれる。 人種と民族の概念は現代の社会科学では別個のものと考えられているが、この2つの用語は一般的に長い歴史の中で同等に扱われてきた。「民族性」は、伝統的 に「人種」に帰属するものに近い意味で使用されることが多く、グループの本質的または先天的な特性(例えば、共通の祖先や共通の行動様式)に基づく人間の グループの区分である。人種差別や人種的差別は、これらの相違が人種的であるかどうかに関わらず、民族や文化に基づく差別を表現するためにしばしば使用さ れる。国連のレイシズム撤廃条約によると、「人種的」差別と「民族的」差別の区別はない。さらに、人種的差異に基づく優越性は科学的には誤りであり、道徳 的に非難されるべきであり、社会的に不公平であり、危険であると結論づけている。この条約はまた、理論上であれ実際上であれ、いかなる場所においてもレイ シズムを正当化する理由はないと宣言している。[2] レイシズムは、紀元前3世紀に記録された反ユダヤレイシズムを含め、比較的近代的な概念であるとされることが多い。[3] ヨーロッパの帝国主義時代に発展し、資本主義によって変容し、[4] 大西洋奴隷貿易の主要な推進力となった。[5][6] また、 19世紀から20世紀初頭のアメリカ合衆国における人種隔離政策、および南アフリカのアパルトヘイト政策の推進力となった。19世紀から20世紀にかけて の西洋文化におけるレイシズムは、特に詳細に記録されており、レイシズムに関する研究や言説の参照点となっている。[8] レイシズムは、ホロコースト 、アルメニア人虐殺、ルワンダ大虐殺、クロアチア独立国におけるセルビア人虐殺、さらにはアメリカ大陸、アフリカ、アジアにおけるヨーロッパの植民地化、 ソビエト連邦における先住少数民族の強制移住を含む植民地化計画などにおいて、レイシズムは重要な役割を果たしてきた。[9] 先住民は、過去も現在も、レイシズム的な態度に晒されることが多い。 |

| Etymology, definition, and usage In the 19th century, many scientists subscribed to the belief that the human population can be divided into races. The term racism is a noun describing the state of being racist, i.e., subscribing to the belief that the human population can or should be classified into races with differential abilities and dispositions, which in turn may motivate a political ideology in which rights and privileges are differentially distributed based on racial categories. The term "racist" may be an adjective or a noun, the latter describing a person who holds those beliefs.[10] The origin of the root word "race" is not clear. Linguists generally agree that it came to the English language from Middle French, but there is no such agreement on how it generally came into Latin-based languages. A recent proposal is that it derives from the Arabic ra's, which means "head, beginning, origin" or the Hebrew rosh, which has a similar meaning.[11] Early race theorists generally held the view that some races were inferior to others and they consequently believed that the differential treatment of races was fully justified.[12][13][14] These early theories guided pseudo-scientific research assumptions; the collective endeavors to adequately define and form hypotheses about racial differences are generally termed scientific racism, though this term is a misnomer, due to the lack of any actual science backing the claims. Most biologists, anthropologists, and sociologists reject a taxonomy of races in favor of more specific and/or empirically verifiable criteria, such as geography, ethnicity, or a history of endogamy.[15] Human genome research indicates that race is not a meaningful genetic classification of humans.[16][17][18][19] An entry in the Oxford English Dictionary (2008) defines racialism as "[a]n earlier term than racism, but now largely superseded by it", and cites the term "racialism" in a 1902 quote.[20] The revised Oxford English Dictionary cites the shorter term "racism" in a quote from the year 1903.[21] It was defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edition 1989) as "[t]he theory that distinctive human characteristics and abilities are determined by race"; the same dictionary termed racism a synonym of racialism: "belief in the superiority of a particular race". By the end of World War II, racism had acquired the same supremacist connotations formerly associated with racialism: racism by then implied racial discrimination, racial supremacism, and a harmful intent. The term "race hatred" had also been used by sociologist Frederick Hertz in the late 1920s. As its history indicates, the popular use of the word racism is relatively recent. The word came into widespread usage in the Western world in the 1930s, when it was used to describe the social and political ideology of Nazism, which treated "race" as a naturally given political unit.[22] It is commonly agreed that racism existed before the coinage of the word, but there is not a wide agreement on a single definition of what racism is and what it is not.[12] Today, some scholars of racism prefer to use the concept in the plural racisms, in order to emphasize its many different forms that do not easily fall under a single definition. They also argue that different forms of racism have characterized different historical periods and geographical areas.[23] Garner (2009: p. 11) summarizes different existing definitions of racism and identifies three common elements contained in those definitions of racism. First, a historical, hierarchical power relationship between groups; second, a set of ideas (an ideology) about racial differences; and, third, discriminatory actions (practices).[12] Legal Though many countries around the globe have passed laws related to race and discrimination, the first significant international human rights instrument developed by the United Nations (UN) was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR),[24] which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. The UDHR recognizes that if people are to be treated with dignity, they require economic rights, social rights including education, and the rights to cultural and political participation and civil liberty. It further states that everyone is entitled to these rights "without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status". The UN does not define "racism"; however, it does define "racial discrimination". According to the 1965 UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,[25] The term "racial discrimination" shall mean any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life. In their 1978 United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice (Article 1), the UN states, "All human beings belong to a single species and are descended from a common stock. They are born equal in dignity and rights and all form an integral part of humanity."[26] The UN definition of racial discrimination does not make any distinction between discrimination based on ethnicity and race, in part because the distinction between the two has been a matter of debate among academics, including anthropologists.[27] Similarly, in British law, the phrase racial group means "any group of people who are defined by reference to their race, colour, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origin".[28] In Norway, the word "race" has been removed from national laws concerning discrimination because the use of the phrase is considered problematic and unethical.[29][30] The Norwegian Anti-Discrimination Act bans discrimination based on ethnicity, national origin, descent, and skin color.[31] Social and behavioral sciences Main article: Sociology of race and ethnic relations Sociologists, in general, recognize "race" as a social construct. This means that, although the concepts of race and racism are based on observable biological characteristics, any conclusions drawn about race on the basis of those observations are heavily influenced by cultural ideologies. Racism, as an ideology, exists in a society at both the individual and institutional level. While much of the research and work on racism during the last half-century or so has concentrated on "white racism" in the Western world, historical accounts of race-based social practices can be found across the globe.[32] Thus, racism can be broadly defined to encompass individual and group prejudices and acts of discrimination that result in material and cultural advantages conferred on a majority or a dominant social group.[33] So-called "white racism" focuses on societies in which white populations are the majority or the dominant social group. In studies of these majority white societies, the aggregate of material and cultural advantages is usually termed "white privilege". Race and race relations are prominent areas of study in sociology and economics. Much of the sociological literature focuses on white racism. Some of the earliest sociological works on racism were written by sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, the first African American to earn a doctoral degree from Harvard University. Du Bois wrote, "[t]he problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line."[34] Wellman (1993) defines racism as "culturally sanctioned beliefs, which, regardless of intentions involved, defend the advantages whites have because of the subordinated position of racial minorities".[35] In both sociology and economics, the outcomes of racist actions are often measured by the inequality in income, wealth, net worth, and access to other cultural resources (such as education), between racial groups.[36] In sociology and social psychology, racial identity and the acquisition of that identity, is often used as a variable in racism studies. Racial ideologies and racial identity affect individuals' perception of race and discrimination. Cazenave and Maddern (1999) define racism as "a highly organized system of 'race'-based group privilege that operates at every level of society and is held together by a sophisticated ideology of color/'race' supremacy. Racial centrality (the extent to which a culture recognizes individuals' racial identity) appears to affect the degree of discrimination African-American young adults perceive whereas racial ideology may buffer the detrimental emotional effects of that discrimination."[37] Sellers and Shelton (2003) found that a relationship between racial discrimination and emotional distress was moderated by racial ideology and social beliefs.[38] Some sociologists also argue that, particularly in the West, where racism is often negatively sanctioned in society, racism has changed from being a blatant to a more covert expression of racial prejudice. The "newer" (more hidden and less easily detectable) forms of racism—which can be considered embedded in social processes and structures—are more difficult to explore and challenge. It has been suggested that, while in many countries overt or explicit racism has become increasingly taboo, even among those who display egalitarian explicit attitudes, an implicit or aversive racism is still maintained subconsciously.[39] This process has been studied extensively in social psychology as implicit associations and implicit attitudes, a component of implicit cognition. Implicit attitudes are evaluations that occur without conscious awareness towards an attitude object or the self. These evaluations are generally either favorable or unfavorable. They come about from various influences in the individual experience.[40] Implicit attitudes are not consciously identified (or they are inaccurately identified) traces of past experience that mediate favorable or unfavorable feelings, thoughts, or actions towards social objects.[39] These feelings, thoughts, or actions have an influence on behavior of which the individual may not be aware.[41] Therefore, subconscious racism can influence our visual processing and how our minds work when we are subliminally exposed to faces of different colors. In thinking about crime, for example, social psychologist Jennifer L. Eberhardt (2004) of Stanford University holds that, "blackness is so associated with crime you're ready to pick out these crime objects."[42] Such exposures influence our minds and they can cause subconscious racism in our behavior towards other people or even towards objects. Thus, racist thoughts and actions can arise from stereotypes and fears of which we are not aware.[43] For example, scientists and activists have warned that the use of the stereotype "Nigerian Prince" for referring to advance-fee scammers is racist, i.e. "reducing Nigeria to a nation of scammers and fraudulent princes, as some people still do online, is a stereotype that needs to be called out".[44] Humanities Language, linguistics, and discourse are active areas of study in the humanities, along with literature and the arts. Discourse analysis seeks to reveal the meaning of race and the actions of racists through careful study of the ways in which these factors of human society are described and discussed in various written and oral works. For example, Van Dijk (1992) examines the different ways in which descriptions of racism and racist actions are depicted by the perpetrators of such actions as well as by their victims.[45] He notes that when descriptions of actions have negative implications for the majority, and especially for white elites, they are often seen as controversial and such controversial interpretations are typically marked with quotation marks or they are greeted with expressions of distance or doubt. The previously cited book, The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois, represents early African-American literature that describes the author's experiences with racism when he was traveling in the South as an African American. Much American fictional literature has focused on issues of racism and the black "racial experience" in the US, including works written by whites, such as Uncle Tom's Cabin, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Imitation of Life, or even the non-fiction work Black Like Me. These books, and others like them, feed into what has been called the "white savior narrative in film", in which the heroes and heroines are white even though the story is about things that happen to black characters. Textual analysis of such writings can contrast sharply with black authors' descriptions of African Americans and their experiences in US society. African-American writers have sometimes been portrayed in African-American studies as retreating from racial issues when they write about "whiteness", while others identify this as an African-American literary tradition called "the literature of white estrangement", part of a multi-pronged effort to challenge and dismantle white supremacy in the US.[46] Popular usage According to dictionary definitions, racism is prejudice and discrimination based on race.[47][48] Racism can also be said to describe a condition in society in which a dominant racial group benefits from the oppression of others, whether that group wants such benefits or not.[49] Foucauldian scholar Ladelle McWhorter, in her 2009 book, Racism and Sexual Oppression in Anglo-America: A Genealogy, posits modern racism similarly, focusing on the notion of a dominant group, usually whites, vying for racial purity and progress, rather than an overt or obvious ideology focused on the oppression of nonwhites.[50] In popular usage, as in some academic usage, little distinction is made between "racism" and "ethnocentrism". Often, the two are listed together as "racial and ethnic" in describing some action or outcome that is associated with prejudice within a majority or dominant group in society. Furthermore, the meaning of the term racism is often conflated with the terms prejudice, bigotry, and discrimination. Racism is a complex concept that can involve each of those; but it cannot be equated with, nor is it synonymous, with these other terms.[citation needed] The term is often used in relation to what is seen as prejudice within a minority or subjugated group, as in the concept of reverse racism. "Reverse racism" is a concept often used to describe acts of discrimination or hostility against members of a dominant racial or ethnic group while favoring members of minority groups.[51][52] This concept has been used especially in the United States in debates over color-conscious policies (such as affirmative action) intended to remedy racial inequalities.[53] However, many experts and other commenters view reverse racism as a myth rather than a reality.[54][55][56][57] Academics commonly define racism not only in terms of individual prejudice, but also in terms of a power structure that protects the interests of the dominant culture and actively discriminates against ethnic minorities.[51][52] From this perspective, while members of ethnic minorities may be prejudiced against members of the dominant culture, they lack the political and economic power to actively oppress them, and they are therefore not practicing "racism".[5][51][58] |

語源・定義・用法 19世紀には、多くの科学者が、人間の人口は人種に分類できるという信念を信奉していた。人種差別主義という用語は、人種差別主義の状態を指す名詞であ り、すなわち、人間の集団は能力や気質によって異なる人種に分類できる、あるいは分類すべきであるという信念を信奉することを意味する。この信念は、人種 カテゴリーに基づいて権利や特権を差別的に分配する政治的イデオロギーの動機となる可能性がある。「人種差別主義者」という用語は形容詞または名詞であ り、後者はそのような信念を持つ人を指す。[10] 「人種」という語の語源は明らかではない。言語学者は一般的に、それが中世フランス語から英語に入ってきたという点では同意しているが、それがラテン語系 の言語に一般的にどのようにして入ってきたかについては、そのような合意はない。最近の提案では、それがアラビア語のra's(「頭、始まり、起源」を意 味する)またはヘブライ語のrosh(同様の意味を持つ)に由来するというものがある。初期の人種理論家は一般的に、ある人種は他の人種よりも劣っている という見解を持ち、その結果、人種に対する差別的な扱いは 正当化されるという見解を持っていた。[12][13][14] これらの初期の理論は疑似科学的な研究仮説の指針となり、人種間の差異について適切に定義し仮説を立てるための総合的な取り組みは一般的に科学的人種主義 と呼ばれているが、この用語は主張を裏付ける実際の科学が欠如しているため、誤称である。 ほとんどの生物学者、人類学者、社会学者は、地理、民族、同族婚の歴史など、より具体的かつ/または経験的に検証可能な基準を支持し、人種分類を否定して いる。[15] ヒトゲノム研究は、人種はヒトの遺伝子を意味のある形で分類するものではないことを示している。[16][17][18][19] オックスフォード英語辞典(2008年版)の項目では、「人種主義」を「人種差別よりも古い用語だが、現在はほぼ置き換えられている」と定義し、1902 年の引用文に「人種主義」という用語が使用されていることを挙げている。[20] 改訂版オックスフォード英語辞典では、1903年の引用文に「人種差別」というより短い用語が使用されていることを挙げている 1903年の引用文では、より短い「人種主義」という用語が引用されている。[21] オックスフォード英語辞典(第2版、1989年)では、「人種によって人間の特性や能力が決まるという理論」と定義されている。同辞典では、人種主義を 「特定の人種の優越性を信じる」という意味で、人種主義の同義語として人種差別主義を挙げている。第二次世界大戦が終結する頃には、人種差別主義という言 葉はかつての人種至上主義と同じような優越主義的な意味合いを持つようになっていた。人種差別主義は、人種差別、人種至上主義、有害な意図を意味するよう になっていた。「人種憎悪」という言葉も、1920年代後半に社会学者のフレデリック・ハーツによって使用されていた。 その歴史が示すように、「人種差別」という言葉が一般的に使用されるようになったのは比較的最近のことである。この言葉が西洋世界で広く使用されるように なったのは1930年代で、ナチズムの社会的・政治的イデオロギーを表現するために使用された。ナチズムでは、「人種」は自然に与えられた政治単位として 扱われていた。[22] 人種差別という言葉が作られる前から人種差別は存在していたという点では一般的に同意されているが、 が、人種差別とは何か、また人種差別ではないものは何かという点については、単一の定義について広く合意が得られているわけではない。[12] 今日では、人種差別に関する研究者の一部は、単一の定義に容易に当てはまらないその多様な形態を強調するために、racisms(複数形)という概念を用 いることを好む。また、人種差別のさまざまな形態は、異なる歴史的時代や地理的地域を特徴づけてきたとも主張している。[23] Garner (2009: p. 11) は、人種差別に関するさまざまな定義をまとめ、それらの定義に共通する3つの要素を特定している。第1に、集団間の歴史的かつ階層的な権力関係、第2に、 人種間の差異に関する一連の考え(イデオロギー)、第3に、差別的行動(慣行)である。[12] 法的 世界中の多くの国々で人種や差別に関する法律が制定されているが、国連(UN)が策定した最初の重要な国際的人権文書は、1948年に国連総会で採択され た世界人権宣言(UDHR)である。UDHRは、人々が尊厳を持って扱われるためには、経済的権利、教育を含む社会的権利、文化や政治への参加や市民的自 由の権利が必要であると認識している。さらに、これらの権利は「人種、皮膚の色、性、言語、宗教、政治的その他の意見、国民的もしくは社会的出身、財産、 門地その他の地位またはこれに類するいかなる事由による差別をも受けることなく」万人に認められると規定している。 国連は「人種主義」を定義していないが、「人種差別」は定義している。1965年の国連「あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する国際条約」によると、 「人種差別」とは、人種、皮膚の色、世系又は民族的若しくは種族的出身に基づくあらゆる区別、排除、制限又は優先であって、政治的、経済的、社会的、文化 的その他のあらゆる公的生活の分野における平等の立場での人権及び基本的自由を認識し、享有し又は行使することを妨げ又は害する目的又は効果を有するもの をいう。 1978年の国連教育科学文化機関(UNESCO)による人種と人種的偏見に関する宣言(第1条)において、国連は「すべての人間は唯一の種に属し、共通 の祖先を持つ。人間は尊厳と権利において平等に生まれ、すべての人類の不可欠な一部である」と述べている。[26] 国連による人種差別の定義では、民族と人種に基づく差別を区別していないが、その理由の一つとして、両者の区別は人類学者を含む学者の間でも議論の的と なっていることが挙げられる。[27] 同様に、英国法では、「人種集団」という表現は、「人種、肌の色、国籍(市民権を含む)、民族もしくは国民的出身によって定義される人々のグループ」を意 味する。[28] ノルウェーでは、「人種」という言葉は差別に関する国内法から削除されている。なぜなら、この表現の使用は問題があり、非倫理的であると考えられているか らである。[29][30] ノルウェーの反差別法は、民族、国民の出身、家系、肌の色に基づく差別を禁止している。[31] 社会科学および行動科学 詳細は「人種と民族関係の社会学」を参照 社会学者は一般的に、「人種」を社会的構築物として認識している。つまり、「人種」や「人種差別」の概念は観察可能な生物学的特徴に基づいているが、それ らの観察に基づいて「人種」について導き出される結論は、文化的なイデオロギーに強く影響されるということである。イデオロギーとしての人種差別は、個人 レベルおよび制度レベルの両方において社会に存在している。 過去半世紀ほどの間の人種差別に関する研究や活動の多くは、西洋世界の「白人による人種差別」に集中しているが、人種に基づく社会慣習の歴史的記述は世界 中で見られる。[32] したがって、人種差別とは、 個人や集団の偏見、および、多数派や支配的な社会集団に物質的・文化的な利益をもたらす差別行為を包含するものとして広く定義することができる。[33] いわゆる「白人による人種差別」は、白人が多数派または支配的な社会集団である社会に焦点を当てている。こうした白人多数派社会の研究では、物質的・文化 的な利益の集約は通常、「白人特権」と呼ばれる。 人種および人種関係は、社会学および経済学における主要な研究分野である。社会学の文献の多くは、白人による人種差別に焦点を当てている。人種差別に関す る社会学の初期の著作のいくつかは、ハーバード大学で博士号を取得した初の黒人である社会学者W. E. B. デュボイスによって書かれた。デュボイスは「20世紀の問題は人種問題である」と書いた。[34] ウェルマン(1993年)は人種差別を「文化的背景から正当化された信念であり、その背景にはどのような意図があるにせよ、白人が持つ優位性を擁護するも のである。。[35] 社会学および経済学の両分野において、人種差別的行為の結果は、人種集団間の所得、富、純資産、およびその他の文化資源(教育など)へのアクセスにおける 不平等によってしばしば測定される。[36] 社会学や社会心理学では、人種的アイデンティティとその獲得が、人種差別研究における変数としてよく用いられる。人種的イデオロギーや人種的アイデンティ ティは、人種や差別に対する個人の認識に影響を与える。CazenaveとMaddern(1999年)は、人種差別を「社会のあらゆるレベルで機能し、 色や人種至上主義の洗練されたイデオロギーによって維持されている、人種に基づくグループ特権の高度に組織化されたシステム」と定義している。人種中心的 傾向(文化が個人の人種的アイデンティティをどの程度認識しているか)は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の若年成人の認識する差別の程度に影響を及ぼしているよう である。一方、人種的イデオロギーは、その差別による有害な感情的影響を緩和する可能性がある。」[37] SellersとShelton(2003年)は、人種的差別と感情的苦痛の関係は、人種的イデオロギーと社会的信念によって緩和されることを発見した。 [38] また、一部の社会学者は、特に西洋社会では人種差別が社会的に否定的に是認されることが多いため、人種差別はあからさまな人種偏見の表現から、より隠れた 表現へと変化したと主張している。より隠れた、発見されにくい「新しい」形態の人種差別(社会のプロセスや構造に組み込まれているとみなされる)は、調査 や挑戦がより困難である。多くの国々では、あからさまな人種差別はますますタブー視されるようになったが、平等主義的な態度を明確に表明する人々の中に も、潜在的な人種差別や嫌悪的な人種差別は依然として無意識のうちに維持されているという指摘がある。 このプロセスは、潜在連合や潜在意識の認知の要素である潜在意識の態度として、社会心理学で広く研究されている。潜在意識の態度は、態度の対象または自己 に対する意識的な認識なしに生じる評価である。これらの評価は一般的に、好ましいか好ましくないかのいずれかである。これらは個人の経験におけるさまざま な影響から生じる。[40] 潜在意識下の態度は、意識的に特定されない(または不正確に特定される)過去の経験の痕跡であり、社会的対象に対する好ましいまたは好ましくない感情、思 考、または行動を媒介する。[39] これらの感情、思考、または行動は、個人が気づいていない行動に影響を与える。[41] したがって、潜在的な人種差別は、私たちが異なる色の顔をサブリミナル的に目にした場合の視覚処理や心の働きに影響を与える可能性がある。犯罪について考 える場合、例えば、スタンフォード大学の社会心理学者ジェニファー・L・エバハート(2004年)は、「黒人は犯罪と強く結びついているため、犯罪の対象 としてすぐに思い浮かぶ」と主張している。[42] このような暴露は私たちの心に影響を与え、他者に対する行動、さらには物に対する行動に潜在的な人種差別を引き起こす可能性がある。したがって、人種差別 的な思考や行動は、私たちが気づいていない固定観念や恐怖から生じる可能性がある。[43] 例えば、科学者や活動家は、前払詐欺師を指す際に「ナイジェリアの王子」という固定観念を用いることは人種差別的であると警告している。すなわち、「一部 の人が今でもオンラインで行っているように、ナイジェリアを詐欺師や詐欺師の王子の国とみなすことは、糾弾されるべき固定観念である」[44]。 人文科学 言語、言語学、談話は、文学や芸術とともに、人文科学の活発な研究分野である。 談話分析は、人間社会におけるこれらの要素が、さまざまな書面や口頭による作品でどのように描写され、議論されているかを慎重に研究することで、人種や人 種差別主義者の行動の意味を明らかにしようとするものである。例えば、ヴァン・ダイク(1992年)は、人種差別や人種差別的行為の描写が、加害者側と被 害者側でそれぞれどのように表現されているかを検証している。[45] 彼は、行為の描写が大多数の人々、特に白人エリート層にとって否定的な意味合いを持つ場合、その描写はしばしば物議を醸すものとして見なされ、そのような 物議を醸す解釈は通常、引用符で囲まれるか、距離や疑いの表現を伴うと指摘している。先に引用したW.E.B. デュ・ボア著『黒人の魂』は、南部を旅した際の著者の人種差別体験を描写した初期のアフリカ系アメリカ人文学の代表作である。 多くのアメリカのフィクション文学は、人種差別や米国における黒人の「人種的経験」の問題に焦点を当てており、白人作家による作品、例えば『アンクル・ト ムの小屋』、『アラバマ物語』、『イミテーション・オブ・ライフ』、あるいはノンフィクション作品『ブラック・ライク・ミー』なども含まれる。これらの本 や同様の本は、黒人キャラクターに起こる出来事を描いているにもかかわらず、ヒーローやヒロインが白人である「映画における白人による救済物語」と呼ばれ るものに影響を与えている。このような著作のテキスト分析は、黒人作家が描く米国社会におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人や彼らの経験とは大きく異なる。アフリ カ系アメリカ人研究では、アフリカ系アメリカ人作家が「白人」について書く際に人種問題から退却していると描写されることがあるが、一方で、これを「白人 疎外の文学」と呼ばれるアフリカ系アメリカ文学の伝統の一部であり、米国における白人至上主義に異議を唱え、それを解体するための多角的な取り組みの一環 であると位置づける見方もある。 一般的な用法 辞書的な定義によると、人種差別とは人種に基づく偏見や差別である。[47][48] 人種差別とはまた、支配的な人種集団が、その集団がそのような利益を望むかどうかに関わらず、他者の抑圧から利益を得る社会の状態を指すともいえる。 [49] フーコー学者のラデル・マクウォーターは、2009年の著書『英米における人種差別と性的抑圧: 優勢なグループ、通常は白人が人種的純血と進歩を競い合うという概念に焦点を当て、非白人の抑圧に焦点を当てた明白なイデオロギーよりも、同様に現代の差 別を仮定している。[50] 一般的に使用される場合、一部の学術的な用法と同様に、「人種差別」と「自民族中心主義」の間にほとんど区別はない。社会における多数派または支配的なグ ループ内の偏見に関連する行動や結果を説明する際に、この2つは「人種的および民族的」なものとして一緒に挙げられることが多い。さらに、人種差別という 用語の意味は、偏見、偏狭、差別という用語と混同されることが多い。人種差別は、これらのそれぞれを含む可能性がある複雑な概念であるが、これらの他の用 語と同一視することはできず、また同義語でもない。 この用語は、逆人種差別という概念のように、少数派や被支配集団における偏見と見なされるものに関連して使用されることが多い。「逆人種差別」とは、支配 的な人種や民族集団のメンバーを優遇する一方で、少数派集団のメンバーに対して差別的または敵対的な行為を行うことを指す概念である。[51][52] この概念は、特に米国において 人種的不平等を是正することを目的とした、人種を意識した政策(例えば、アファーマティブ・アクション)に関する議論において、この概念が用いられてき た。[53] しかし、多くの専門家やその他の論者は、逆人種差別を現実ではなく神話として捉えている。[54][55][56][57] 学術的には、人種差別は個人の偏見だけでなく、支配的文化の利益を守り、少数民族を積極的に差別する権力構造という観点からも定義されることが多い。 [51][52] この観点では、少数民族のメンバーが支配的文化のメンバーに対して偏見を抱くことはあっても、彼らには積極的に抑圧する政治的・経済的権力が欠けているた め、「人種差別」を行っていることにはならない。[5][51][58] |

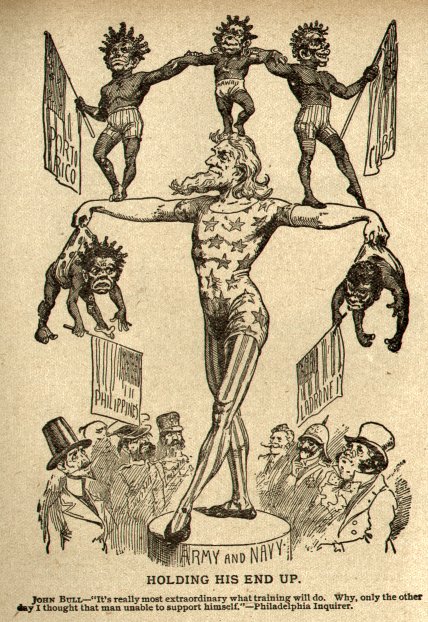

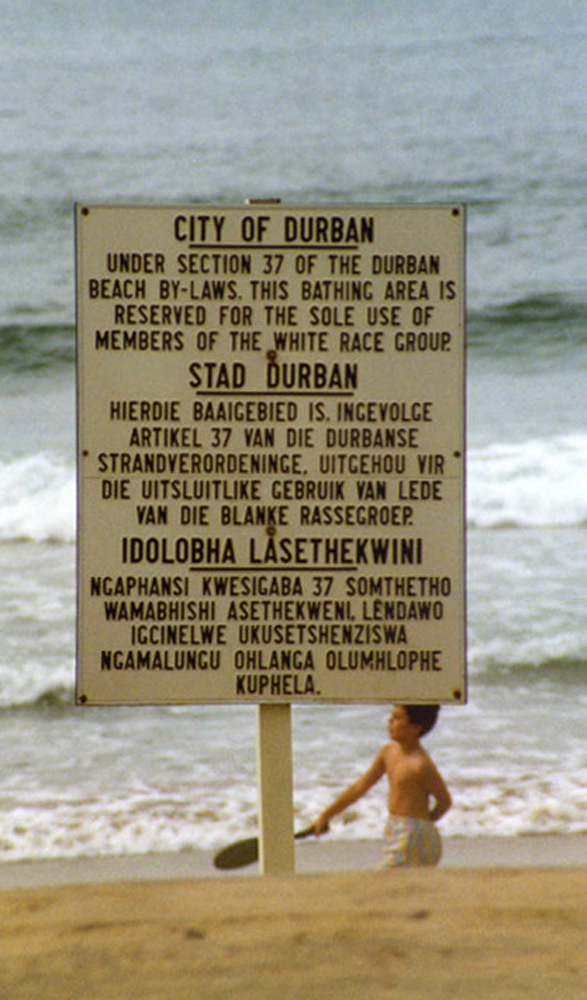

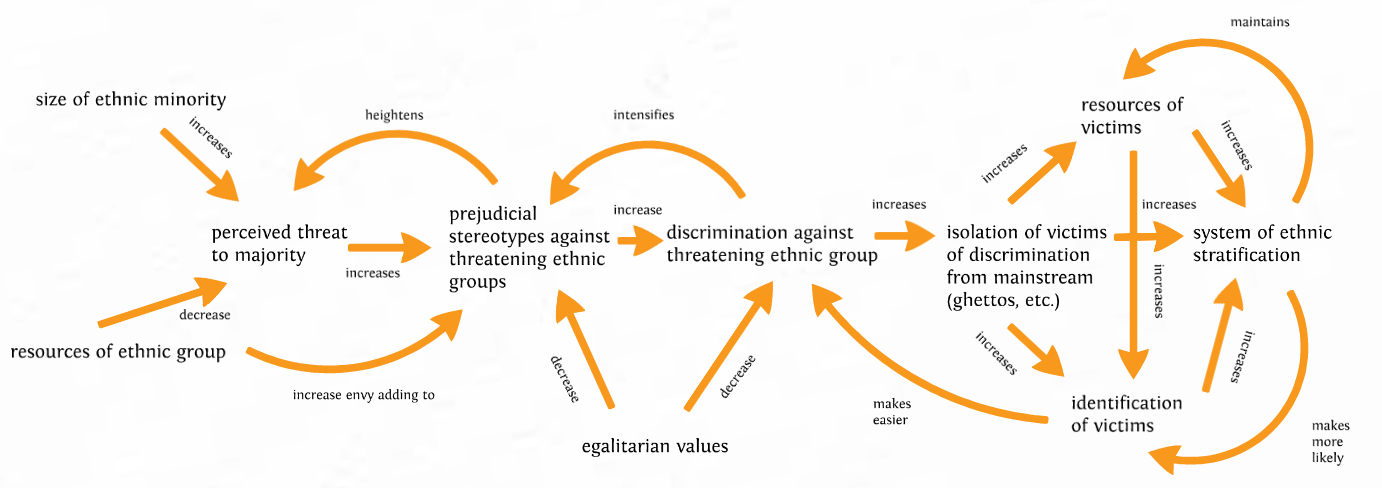

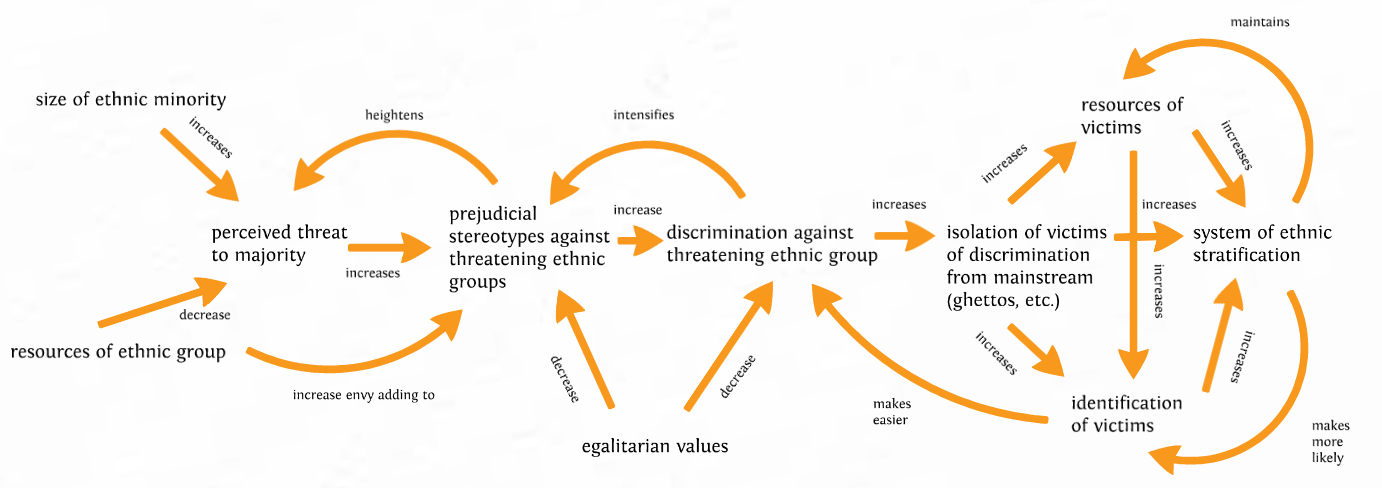

| Aspects Globe icon. The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (May 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The ideology underlying racism can manifest in many aspects of social life. Such aspects are described in this section, although the list is not exhaustive. Aversive racism Main article: Aversive racism Aversive racism is a form of implicit racism, in which a person's unconscious negative evaluations of racial or ethnic minorities are realized by a persistent avoidance of interaction with other racial and ethnic groups. As opposed to traditional, overt racism, which is characterized by overt hatred for and explicit discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities, aversive racism is characterized by more complex, ambivalent expressions and attitudes.[59] Aversive racism is similar in implications to the concept of symbolic or modern racism (described below), which is also a form of implicit, unconscious, or covert attitude which results in unconscious forms of discrimination. The term was coined by Joel Kovel to describe the subtle racial behaviors of any ethnic or racial group who rationalize their aversion to a particular group by appeal to rules or stereotypes.[59] People who behave in an aversively racial way may profess egalitarian beliefs, and will often deny their racially motivated behavior; nevertheless they change their behavior when dealing with a member of another race or ethnic group than the one they belong to. The motivation for the change is thought to be implicit or subconscious. Experiments have provided empirical support for the existence of aversive racism. Aversive racism has been shown to have potentially serious implications for decision making in employment, in legal decisions and in helping behavior.[60][61] Color blindness Main article: Color blindness (race) In relation to racism, color blindness is the disregard of racial characteristics in social interaction, for example in the rejection of affirmative action, as a way to address the results of past patterns of discrimination. Critics of this attitude argue that by refusing to attend to racial disparities, racial color blindness in fact unconsciously perpetuates the patterns that produce racial inequality.[62] Eduardo Bonilla-Silva argues that color blind racism arises from an "abstract liberalism, biologization of culture, naturalization of racial matters, and minimization of racism".[63] Color blind practices are "subtle, institutional, and apparently nonracial"[64] because race is explicitly ignored in decision-making. If race is disregarded in predominantly white populations, for example, whiteness becomes the normative standard, whereas people of color are othered, and the racism these individuals experience may be minimized or erased.[65][66] At an individual level, people with "color blind prejudice" reject racist ideology, but also reject systemic policies intended to fix institutional racism.[66] Cultural See also: Cultural racism and Xenophobia Cultural racism manifests as societal beliefs and customs that promote the assumption that the products of a given culture, including the language and traditions of that culture, are superior to those of other cultures. It shares a great deal with xenophobia, which is often characterized by fear of, or aggression toward, members of an outgroup by members of an ingroup.[67] In that sense it is also similar to communalism as used in South Asia.[68] Cultural racism exists when there is a widespread acceptance of stereotypes concerning diverse ethnic or population groups.[69] Whereas racism can be characterised by the belief that one race is inherently superior to another, cultural racism can be characterised by the belief that one culture is inherently superior to another.[70] Economic Further information: Criticism of capitalism § Racism, Racial pay gap in the United States, and Racial wealth gap in the United States Historical economic or social disparity is alleged to be a form of discrimination caused by past racism and historical reasons, affecting the present generation through deficits in the formal education and kinds of preparation in previous generations, and through primarily unconscious racist attitudes and actions on members of the general population. Some view that capitalism generally transformed racism depending on local circumstances, but racism is not necessary for capitalism.[71] Economic discrimination may lead to choices that perpetuate racism. For example, color photographic film was tuned for white skin[72] as are automatic soap dispensers[73] and facial recognition systems.[74] Institutional Further information: Institutional racism, Structural racism, State racism, Racial profiling, and Racism by country  African-American university student Vivian Malone entering the University of Alabama in the U.S. to register for classes as one of the first African-American students to attend the institution. Until 1963, the university was racially segregated and African-American students were not allowed to attend. Institutional racism (also known as structural racism, state racism or systemic racism) is racial discrimination by governments, corporations, religions, or educational institutions or other large organizations with the power to influence the lives of many individuals. Stokely Carmichael is credited for coining the phrase institutional racism in the late 1960s. He defined the term as "the collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin".[75] Maulana Karenga argued that racism constituted the destruction of culture, language, religion, and human possibility and that the effects of racism were "the morally monstrous destruction of human possibility involved redefining African humanity to the world, poisoning past, present and future relations with others who only know us through this stereotyping and thus damaging the truly human relations among peoples".[76] Othering Main article: Othering Othering is the term used by some to describe a system of discrimination whereby the characteristics of a group are used to distinguish them as separate from the norm.[77] Othering plays a fundamental role in the history and continuation of racism. To objectify a culture as something different, exotic or underdeveloped is to generalize that it is not like 'normal' society. Europe's colonial attitude towards the Orientals exemplifies this as it was thought that the East was the opposite of the West; feminine where the West was masculine, weak where the West was strong and traditional where the West was progressive.[78] By making these generalizations and othering the East, Europe was simultaneously defining herself as the norm, further entrenching the gap.[79] Much of the process of othering relies on imagined difference, or the expectation of difference. Spatial difference can be enough to conclude that "we" are "here" and the "others" are over "there".[78] Imagined differences serve to categorize people into groups and assign them characteristics that suit the imaginer's expectations.[80] Racial discrimination Main article: Racial discrimination Racial discrimination refers to discrimination against someone on the basis of their race. Racial segregation Main article: Racial segregation External videos video icon James A. White Sr.: The little problem I had renting a house, TED Talks, 14:20, February 20, 2015 Racial segregation is the separation of humans into socially constructed racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a bathroom, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home.[81] Segregation is generally outlawed, but may exist through social norms, even when there is no strong individual preference for it, as suggested by Thomas Schelling's models of segregation and subsequent work. Supremacism Main article: Supremacism  In 1899 Uncle Sam (a personification of the United States) balances his new possessions which are depicted as savage children. The figures are Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Cuba, Philippines and "Ladrones" (the Mariana Islands). Centuries of European colonialism in the Americas, Africa and Asia were often justified by white supremacist attitudes.[82] During the early 20th century, the phrase "The White Man's Burden" was widely used to justify an imperialist policy as a noble enterprise.[83][84] A justification for the policy of conquest and subjugation of Native Americans emanated from the stereotyped perceptions of the indigenous people as "merciless Indian savages", as they are described in the United States Declaration of Independence.[85] Sam Wolfson of The Guardian writes that "the declaration's passage has often been cited as an encapsulation of the dehumanizing attitude toward indigenous Americans that the US was founded on."[86] In an 1890 article about colonial expansion onto Native American land, author L. Frank Baum wrote: "The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians."[87] In his Notes on the State of Virginia, published in 1785, Thomas Jefferson wrote: "blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time or circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments of both body and mind."[88] Attitudes of black supremacy, Arab supremacy, and East Asian supremacy also exist. Symbolic/modern Main article: Symbolic racism  A rally against school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1959 Some scholars argue that in the US, earlier violent and aggressive forms of racism have evolved into a more subtle form of prejudice in the late 20th century. This new form of racism is sometimes referred to as "modern racism" and it is characterized by outwardly acting unprejudiced while inwardly maintaining prejudiced attitudes, displaying subtle prejudiced behaviors such as actions informed by attributing qualities to others based on racial stereotypes, and evaluating the same behavior differently based on the race of the person being evaluated.[89] This view is based on studies of prejudice and discriminatory behavior, where some people will act ambivalently towards black people, with positive reactions in certain, more public contexts, but more negative views and expressions in more private contexts. This ambivalence may also be visible for example in hiring decisions where job candidates that are otherwise positively evaluated may be unconsciously disfavored by employers in the final decision because of their race.[90][91][92] Some scholars consider modern racism to be characterized by an explicit rejection of stereotypes, combined with resistance to changing structures of discrimination for reasons that are ostensibly non-racial, an ideology that considers opportunity at a purely individual basis denying the relevance of race in determining individual opportunities and the exhibition of indirect forms of micro-aggression toward and/or avoidance of people of other races.[93] Subconscious biases Main article: Implicit bias § Racial bias Recent research has shown that individuals who consciously claim to reject racism may still exhibit race-based subconscious biases in their decision-making processes. While such "subconscious racial biases" do not fully fit the definition of racism, their impact can be similar, though typically less pronounced, not being explicit, conscious or deliberate.[94] |

側面 地球儀アイコン。 この節の例や見解は主にアメリカ合衆国に関するものであり、この主題に 関する世界的な見解を表しているわけではない。必要に応じて、この節を改善したり、トークページで議論したり、新しい節を作成したりすることができる。 (2022年5月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについて学ぶ) 人種差別の根底にあるイデオロギーは、社会生活の多くの側面に現れる可能性がある。そのような側面は、このセクションで説明されているが、リストは網羅的 なものではない。 回避的人種差別 詳細は「回避的人種差別」を参照 回避的人種差別は、人種的または民族的マイノリティに対する無意識の否定的評価が、他の人種や民族集団との交流を継続的に避けることで実現される、潜在的 な人種差別の形態である。人種的・民族的少数派に対するあからさまな憎悪や露骨な差別を特徴とする伝統的なあからさまな人種差別とは対照的に、回避型人種 差別はより複雑で相反する表現や態度を特徴とする。[59] 回避型人種差別は、象徴的または現代型の人種差別(以下に説明)という概念と意味合いが似ており、これもまた無意識の、無自覚の、または隠れた態度の形態 であり、無意識の差別を生み出す。 この用語は、特定のグループに対する嫌悪感を、規則やステレオタイプに訴えることで正当化するあらゆる民族や人種集団の微妙な人種的行動を説明する目的 で、ジョエル・コーベルによって作られたものである。[59] 嫌悪的人種差別的な行動を取る人々は、平等主義的な信念を公言することがあり、人種的動機に基づく行動を否定することが多い。しかし、自分と同じ人種や民 族集団に属さない人種や民族集団のメンバーと接する際には、行動を変える。その変化の動機は潜在的なもの、あるいは無意識的なものであると考えられてい る。実験により、不快な人種差別の存在が実証的に裏付けられている。不快な人種差別は、雇用、法的判断、援助行動における意思決定に深刻な影響を及ぼす可 能性があることが示されている。 カラーブラインドネス 詳細は「人種カラーブラインドネス」を参照 人種差別との関連では、カラーブラインドネスとは、過去の差別的傾向の結果に対処する方法として、例えば積極的差別是正措置を拒否するなど、社会的交流において人種的特徴 を無視することである。この態度に対する批判者たちは、人種的格差に目を向けないことで、人種的色盲は実際には無意識のうちに人種的不平等を生み出す傾向 を永続させていると主張している。 エドゥアルド・ボニーリャ=シルヴァは、人種差別を無視する傾向は、「抽象的なリベラリズム、文化の生物学的解釈、人種問題の自然化、人種差別の最小化」 から生じていると主張している。[63] 人種差別を無視する慣行は、「微妙で、制度的な、一見人種に関係のない」ものである。[64] なぜなら、意思決定において人種が明確に無視されているからである。例えば、白人が大多数を占める集団において人種が無視される場合、白さが規範的な基準 となり、有色人種は「他者化」され、有色人種が経験する人種差別は軽視されたり、無視されたりする可能性がある。[65][66] 個人レベルでは、「カラーブラインドの偏見」を持つ人々は人種差別的なイデオロギーを拒絶するが、制度上の人種差別を是正することを目的とした制度的な政 策も拒絶する。[66] 文化(→文化的人種主義) 関連項目:文化人種主義と外国人排斥 文化的レイシズムは、ある文化の言語や伝統などを含むその文化の産物が他の文化のそれらよりも優れているという想定を助長する社会的な信念や慣習として現 れる。それは外国人嫌悪と多くの共通点があり、外国人嫌悪はしばしば、イングループのメンバーによるアウトグループのメンバーに対する恐怖や攻撃性によっ て特徴づけられる。 文化人種主義は、多様な民族や集団に関する固定観念が広く受け入れられている場合に存在する。[69] 人種主義は、ある人種が他の人種よりも本質的に優れているという信念によって特徴づけることができるが、文化人種主義は、ある文化が他の文化よりも本質的 に優れているという信念によって特徴づけることができる。[70] 経済 詳細情報:資本主義への批判 § 人種差別、米国における人種間賃金格差、米国における人種間資産格差 歴史的な経済的または社会的格差は、過去の差別や歴史的理由による差別の形態であり、前世代における正規の教育や準備の不足、および一般大衆の構成員によ る主に無意識の差別的態度や行動を通じて、現在の世代に影響を与えていると主張されている。資本主義は一般的に、地域事情に応じて人種差別を変容させたと いう見方もあるが、資本主義にとって人種差別は必須ではない。[71] 経済的差別は、人種差別を永続させる選択につながる可能性がある。例えば、カラー写真フィルムは白人の肌に合わせて調整されていた[72]。自動石鹸ディ スペンサー[73]や顔認識システム[74]も同様である。 制度的 詳細は「制度的人種差別」、「構造的差別」、「国家人種差別」、「人種プロファイリング」、および「国別人種差別」を参照  アフリカ系アメリカ人の大学生、ヴィヴィアン・マローンが、アフリカ系アメリカ人学生として初めて同校に通うために、授業の登録のためアラバマ大学に入学 した。1963年まで、同大学は人種隔離政策が敷かれており、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学生は入学を許されていなかった。 制度上の人種差別(構造的人種差別、国家的人種差別、組織的人種差別とも呼ばれる)とは、政府、企業、宗教、教育機関、または多くの個人の生活に影響を与 える力を持つその他の大規模な組織による人種差別である。制度上の人種差別という言葉は、1960年代後半にストークリー・カーマイケルが造語したものと して知られている。彼はこの用語を「人種、文化、民族的な背景を理由に、組織が人々に対して適切かつ専門的なサービスを提供できないこと」と定義した。 [75] マウラーナ・カレンガは、人種差別は文化、言語、宗教、人間の可能性の破壊を構成し、人種差別の影響は「道徳的に恐ろしい人間の可能性の破壊であり、世界 に対するアフリカの人間性の再定義、この固定観念を通してのみ我々を知る他者との過去、現在、未来の関係を毒し、人々間の真の人間関係を損なう」ものであ ると主張した。[76] 他者化 詳細は「他者化」を参照 他者化とは、ある集団の特徴を基準から外れたものとして区別する差別体系を指す用語である。 他者化は、人種差別の歴史と継続において重要な役割を果たしている。文化を異質なもの、エキゾチックなもの、未発達なものとして客観視することは、その文 化が「正常な」社会とは異なると一般化することである。東洋人に対するヨーロッパの植民地主義的な態度は、このことをよく表している。東洋は西洋の対極に あると考えられていた。西洋が男性的であるのに対し、東洋は女性的であり、西洋が強いのに対し、東洋は弱く、西洋が先進的であるのに対し、東洋は伝統的で あった。[78] こうした一般化を行い、東洋を「他者」とすることで、ヨーロッパは同時に自分たちを「標準」と定義し、その差をさらに強固なものとした。[79] 他者化のプロセスは、想像上の相違、あるいは相違の予想に多くを依存している。空間的な相違は、「我々」は「ここ」に、「他者」は「あちら」にいると結論 づけるのに十分である。[78] 想像上の相違は、人々をグループに分類し、想像する者の期待に適う特性を割り当てるのに役立つ。[80] 人種差別 詳細は「人種差別」を参照 人種差別とは、人種を理由とした差別を指す。 人種隔離 詳細は「人種隔離」を参照 外部動画 動画アイコン James A. White Sr.: The little problem I had renting a house, TED Talks, 14:20, February 20, 2015 人種隔離とは、日常生活において人間を社会的に構築された人種グループに分離することである。レストランでの食事、水飲み場の利用、トイレの利用、学校へ の通学、映画鑑賞、あるいは住宅の賃貸や購入といった活動に適用される場合がある。[81] 隔離は一般的に違法とされているが、トーマス・シェリングの隔離モデルとそれ以降の研究が示唆するように、個々人の強い希望がなくても、社会的規範によっ て存在し続ける場合がある。 白人至上主義 詳細は「白人至上主義」を参照  1899年、アンクル・サム(アメリカ合衆国の擬人化)は、野蛮な子供たちとして描かれた新しい領土のバランスを取っている。その図はプエルトリコ、ハワ イ、キューバ、フィリピン、そして「Ladrones」(マリアナ諸島)である。 ヨーロッパによるアメリカ、アフリカ、アジアでの数世紀にわたる植民地主義は、しばしば白人至上主義的な態度によって正当化されていた。[82] 20世紀初頭には、「白人の重荷」という表現が帝国主義政策を崇高な事業として正当化するために広く使用されていた。[83][84] アメリカ先住民の征服と服従政策の正当化は、先住民を「情け容赦のない野蛮なインディアン」とステレオタイプに捉える認識から生じていた。アメリカ独立宣 言にも記されている。[85] ガーディアンのサム・ウォルフソンは、「独立宣言のこの一節は、アメリカが建国された際の先住民に対する非人間的な態度を象徴するものとして、しばしば引 用されてきた」と書いている。[86] 1890年の記事で、作家のL. フランク・バウムは、先住民の土地への植民地拡大について、「白人は征服の法則と文明の正義によって、アメリカ大陸の主人であり、 辺境の入植地の安全を確保するには、残る少数のインディアンを完全に絶滅させることが最善である」と述べている。[87] 1785年に出版された『バージニア州の現状に関する覚書』の中で、トーマス・ジェファーソンは「黒人は、もともと別個の種族であったか、あるいは時代や 環境によって別個の種族となったかに関わらず、肉体と精神の両面において、白人に劣っている」と述べている。[88] 黒人至上主義、アラブ人至上主義、東アジア人至上主義の態度も存在する。 象徴的/現代 詳細は「象徴的レイシズム」を参照  1959年、アーカンソー州リトルロックにおける学校統合反対集会 一部の学者は、米国では、以前の暴力的で攻撃的な人種差別は、20世紀後半にはより微妙な偏見の形態へと変化したと主張している。この新しい人種差別の形 態は「現代型人種差別」と呼ばれることがあり、外見上は偏見を持たないように振る舞いながら、内心では偏見的な態度を維持し、人種的ステレオタイプに基づ いて他者に性質を帰属させるような行動や、同じ行動でも評価される人の人種によって異なる評価を下すといった微妙な偏見的行動を示すという特徴がある 評価される人の人種に基づいて異なる評価を下す。[89] この見解は、偏見や差別的行動に関する研究に基づいている。一部の人々は、黒人に対して相反する態度を取ることがあり、ある種の公の場では肯定的な反応を 示すが、より私的な場ではより否定的な見解や表現を示す。この両価性は、例えば雇用決定の場面でも見られる可能性がある。他の点ではポジティブに評価され ている求職者であっても、人種を理由に雇用者が最終決定において無意識のうちに不利な評価を下す可能性があるのだ。[90][91][92] 現代の差別を特徴づけるものとして、ステレオタイプの明確な拒絶と、 表向きは人種とは関係のない理由による差別構造の変化への抵抗、個人の機会を決定する際に人種の関連性を否定し、純粋に個人的な基盤で機会を考えるイデオ ロギー、および/または他民族の人々に対する間接的なマイクロアグレッションの表明や回避を特徴とするものであると考える学者もいる。 潜在的な偏見 詳細は「潜在的偏見」の項を参照 最近の研究では、人種差別を拒絶していると意識的に主張する人々でも、意思決定のプロセスにおいて人種に基づく潜在的な偏見を示すことがあることが示され ている。このような「潜在的な人種偏見」は人種差別の定義に完全に当てはまるものではないが、その影響は同様であり、通常はより顕著ではないが、明示的で も意識的でも意図的でもないという点で類似している。[94] |

| International law and racial

discrimination In 1919, a proposal to include a racial equality provision in the Covenant of the League of Nations was supported by a majority, but not adopted in the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. In 1943, Japan and its allies declared work for the abolition of racial discrimination to be their aim at the Greater East Asia Conference.[95] Article 1 of the 1945 UN Charter includes "promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race" as UN purpose. In 1950, UNESCO suggested in The Race Question—a statement signed by 21 scholars such as Ashley Montagu, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Gunnar Myrdal, Julian Huxley, etc.—to "drop the term race altogether and instead speak of ethnic groups". The statement condemned scientific racism theories that had played a role in the Holocaust. It aimed both at debunking scientific racist theories, by popularizing modern knowledge concerning "the race question", and morally condemned racism as contrary to the philosophy of the Enlightenment and its assumption of equal rights for all. Along with Myrdal's An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944), The Race Question influenced the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education.[96] Also, in 1950, the European Convention on Human Rights was adopted, which was widely used on racial discrimination issues.[97] The United Nations use the definition of racial discrimination laid out in the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, adopted in 1966:[98] ... any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life. (Part 1 of Article 1 of the U.N. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination) In 2001, the European Union explicitly banned racism, along with many other forms of social discrimination, in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the legal effect of which, if any, would necessarily be limited to Institutions of the European Union: "Article 21 of the charter prohibits discrimination on any ground such as race, color, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, disability, age or sexual orientation and also discrimination on the grounds of nationality."[99] |

国際法と人種差別 1919年、国際連盟規約に人種平等条項を盛り込むという提案は、多数派の支持を得たものの、1919年のパリ講和会議では採択されなかった。1943 年、日本とその同盟国は大東亜会議において人種差別の撤廃を目的とすることを宣言した。[95] 1945年の国連憲章第1条では、国連の目的として「人種によるいかなる差別もなしにすべての人に対する人権及び基本的自由の尊重を促進し、かつ、奨励す ること」が盛り込まれている。 1950年、ユネスコは『人種問題』という声明文を発表した。この声明文には、アシュレイ・モンタギュー、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、グンナー・ミュ ルダール、ジュリアン・ハックスリーなど21人の学者が署名した。声明文は、ホロコーストの一因となった科学的人種理論を非難した。「人種問題」に関する 現代の知識を広めることで科学的人種理論を否定し、啓蒙思想の哲学や万人の平等という前提に反するものとして人種差別を道徳的に非難することを目的として いた。ミルダルの著書『アメリカのジレンマ:黒人問題と近代民主主義』(1944年)とともに、『人種問題』は1954年のブラウン対教育委員会の人種隔 離撤廃に関する米国最高裁判決に影響を与えた。[96] また、1950年には欧州人権条約が採択され、人種差別問題に広く適用された。[97] 国連は、1966年に採択された「あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する国際条約」で定められた人種差別の定義を使用している。 人種、皮膚の色、世系又は民族的若しくは種族的出身に基づくあらゆる区別、排除、制限又は優先であって、政治的、経済的、社会的、文化的その他のあらゆる 公的生活の分野における平等の立場での人権及び基本的自由を認識し、享有し又は行使することを妨げ又は害する目的又は効果を有するもの。(国連のあらゆる 形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する国際条約 第1条1項) 2001年には、欧州連合(EU)は、欧州連合の「基本権憲章」において、人種差別を明確に禁止し、その他多くの社会差別も禁止した。この基本権憲章の法 的効力は、もしあるとしても、必然的に欧州連合の機関に限定される。「憲章第21条は、人種、肌の色、民族的もしくは社会的出身、遺伝的特徴、言語、宗教 もしくは信念、政治的もしくはその他の意見、国民的少数派の所属、財産、障害、年齢もしくは性的指向、および国籍に基づく差別を禁止している。」[99] |

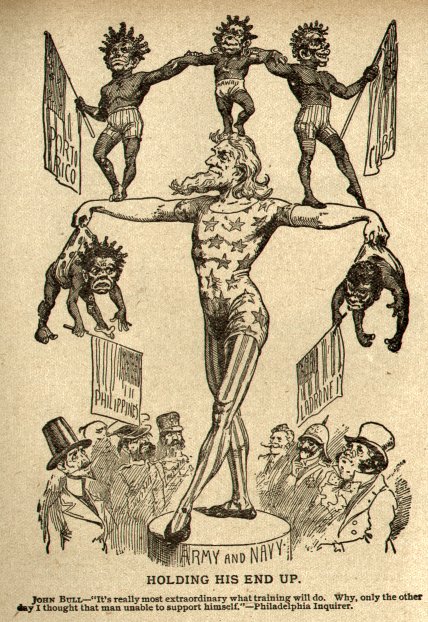

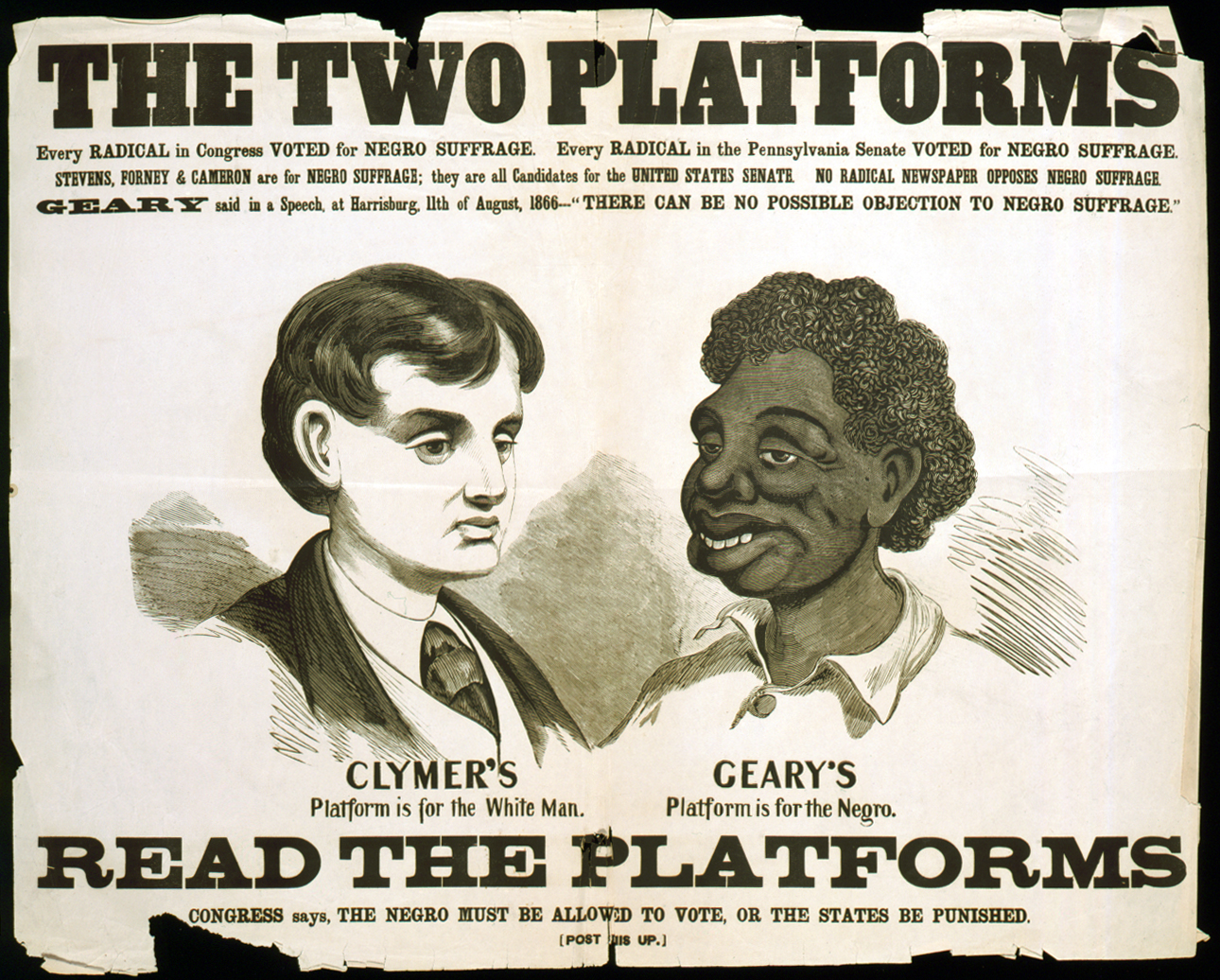

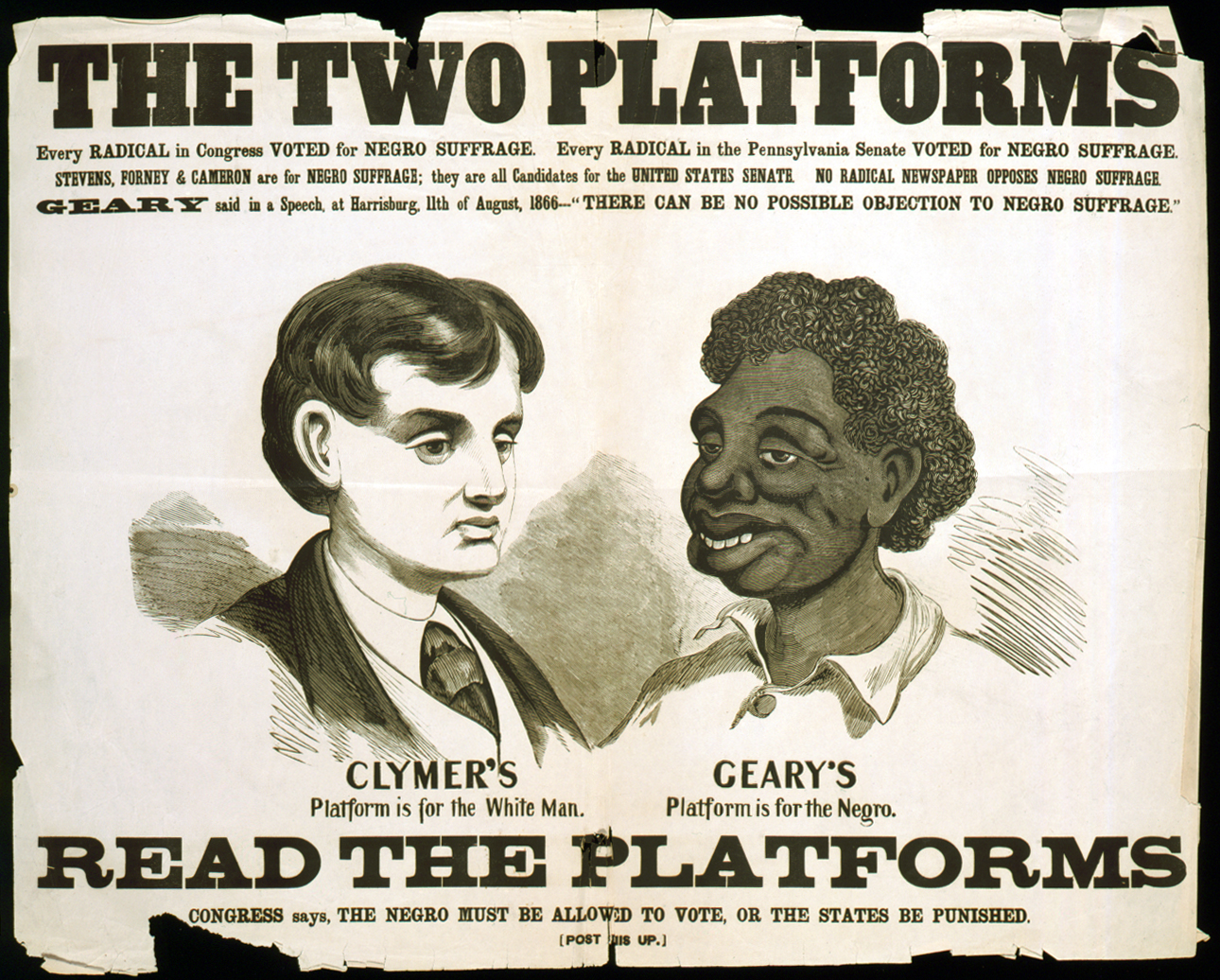

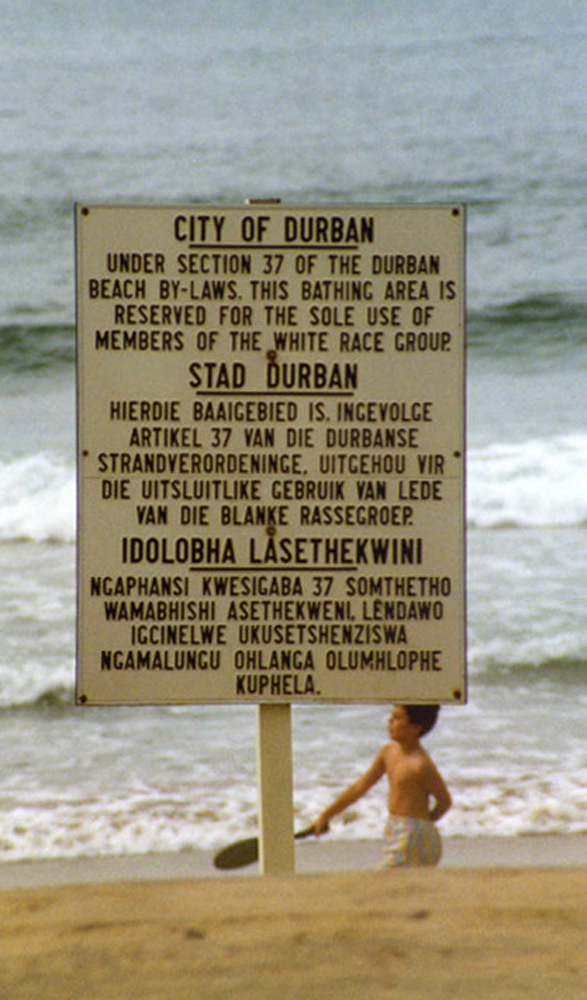

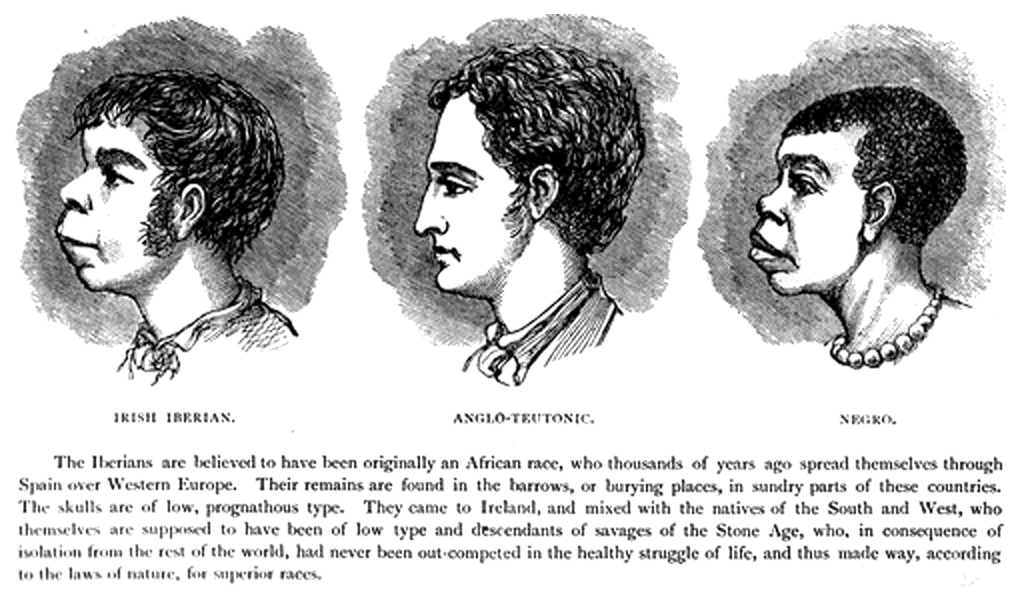

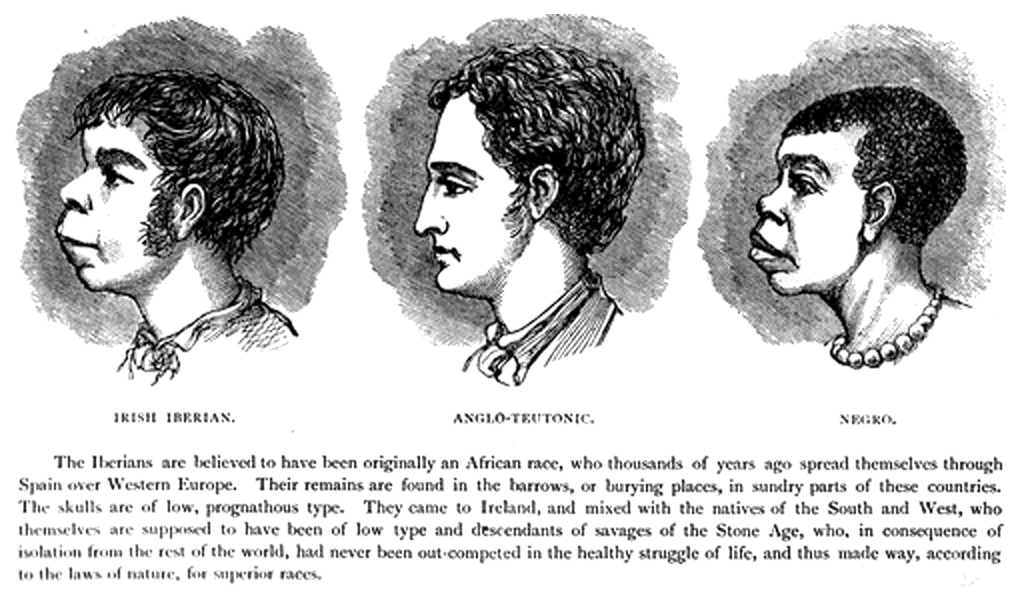

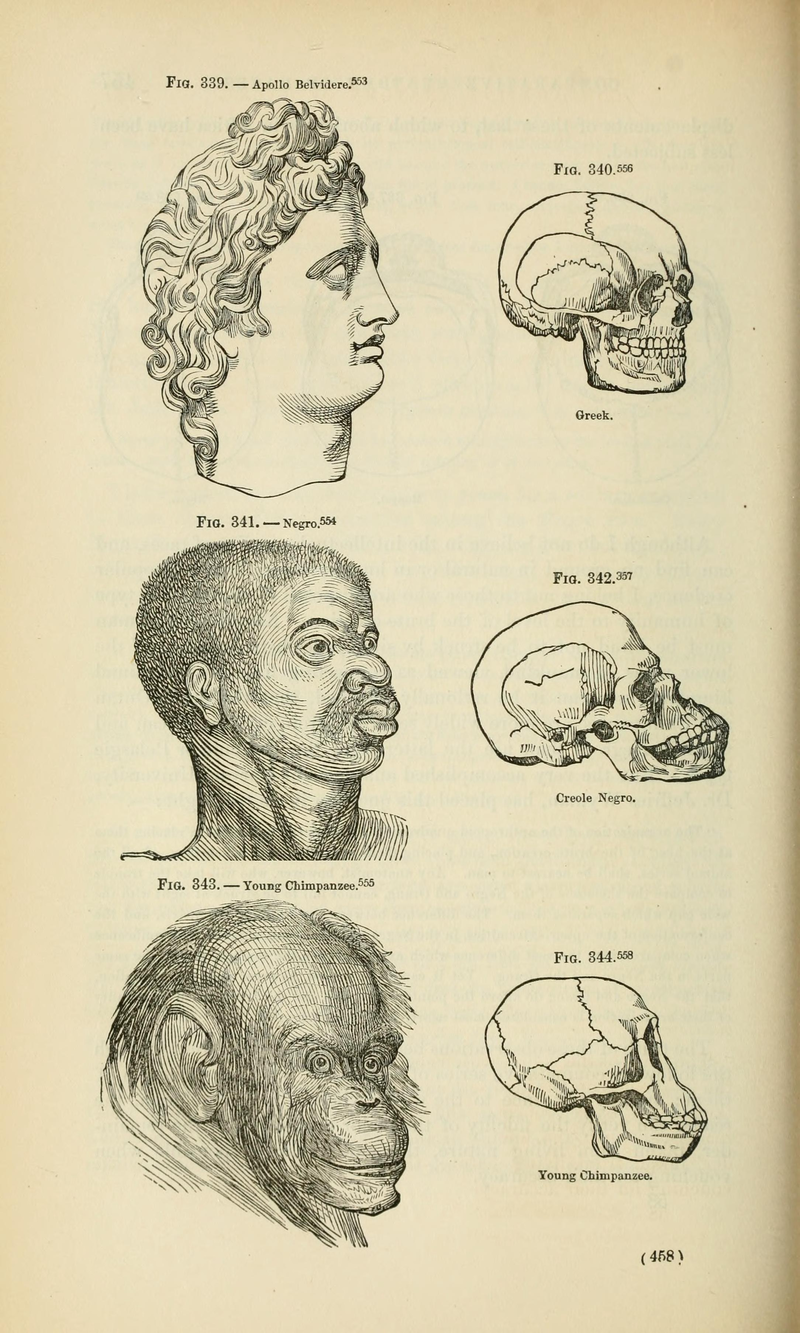

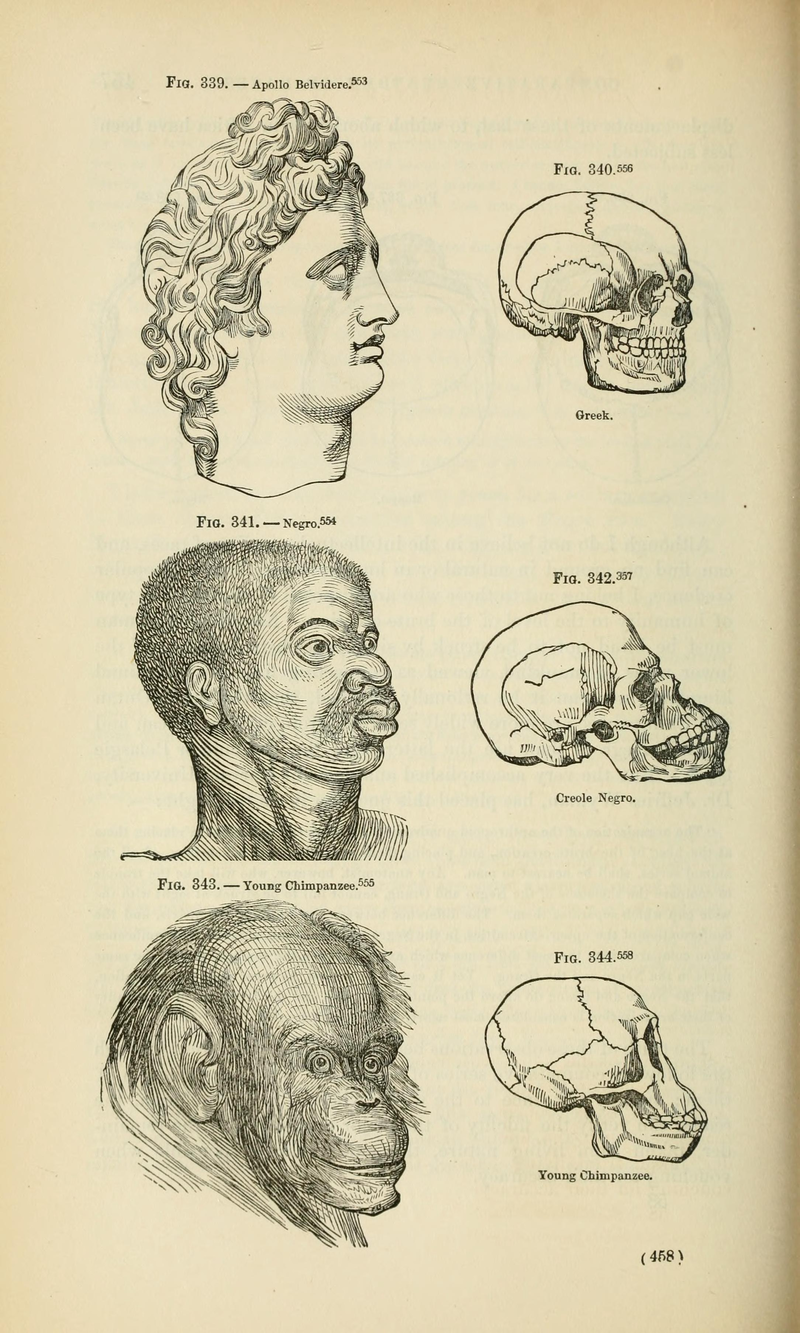

Ideology A pro–Hiester Clymer racist political campaign poster from the 1866 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election Racism existed during the 19th century as scientific racism, which attempted to provide a racial classification of humanity.[100] In 1775 Johann Blumenbach divided the world's population into five groups according to skin color (Caucasians, Mongols, etc.), positing the view that the non-Caucasians had arisen through a process of degeneration. Another early view in scientific racism was the polygenist view, which held that the different races had been separately created. Polygenist Christoph Meiners (1747 – May 1810) for example, split mankind into two divisions which he labeled the "beautiful White race" and the "ugly Black race". In Meiners' book, The Outline of History of Mankind, he claimed that a main characteristic of race is either beauty or ugliness. He viewed only the white race as beautiful. He considered ugly races to be inferior, immoral and animal-like. Anders Retzius (1796— 1860) demonstrated that neither Europeans nor others are one "pure race", but of mixed origins. While discredited, derivations of Blumenbach's taxonomy are still widely used for the classification of the population in the United States. Hans Peder Steensby, while strongly emphasizing that all humans today are of mixed origins, in 1907 claimed that the origins of human differences must be traced extraordinarily far back in time, and conjectured that the "purest race" today would be the Australian Aboriginals.[101]  A sign on a racially segregated beach during Apartheid in South Africa, stating that the area is for the "sole use of members of the white race group" Scientific racism fell strongly out of favor in the early 20th century, but the origins of fundamental human and societal differences are still researched within academia, in fields such as human genetics including paleogenetics, social anthropology, comparative politics, history of religions, history of ideas, prehistory, history, ethics, and psychiatry. There is widespread rejection of any methodology based on anything similar to Blumenbach's races. It is more unclear to which extent and when ethnic and national stereotypes are accepted. Although after World War II and the Holocaust, racist ideologies were discredited on ethical, political and scientific grounds, racism and racial discrimination have remained widespread around the world. Du Bois observed that it is not so much "race" that we think about, but culture: "... a common history, common laws and religion, similar habits of thought and a conscious striving together for certain ideals of life".[102] Late 19th century nationalists were the first to embrace contemporary discourses on "race", ethnicity, and "survival of the fittest" to shape new nationalist doctrines. Ultimately, race came to represent not only the most important traits of the human body, but was also regarded as decisively shaping the character and personality of the nation.[103] According to this view, culture is the physical manifestation created by ethnic groupings, as such fully determined by racial characteristics. Culture and race became considered intertwined and dependent upon each other, sometimes even to the extent of including nationality or language to the set of definition. Pureness of race tended to be related to rather superficial characteristics that were easily addressed and advertised, such as blondness. Racial qualities tended to be related to nationality and language rather than the actual geographic distribution of racial characteristics. In the case of Nordicism, the denomination "Germanic" was equivalent to superiority of race. Bolstered by some nationalist and ethnocentric values and achievements of choice, this concept of racial superiority evolved to distinguish from other cultures that were considered inferior or impure. This emphasis on culture corresponds to the modern mainstream definition of racism: "[r]acism does not originate from the existence of 'races'. It creates them through a process of social division into categories: anybody can be racialised, independently of their somatic, cultural, religious differences."[104] This definition explicitly ignores the biological concept of race, which is still subject to scientific debate. In the words of David C. Rowe, "[a] racial concept, although sometimes in the guise of another name, will remain in use in biology and in other fields because scientists, as well as lay persons, are fascinated by human diversity, some of which is captured by race."[105] Racial prejudice became subject to international legislation. For instance, the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on November 20, 1963, addresses racial prejudice explicitly next to discrimination for reasons of race, colour or ethnic origin (Article I).[106] |

イデオロギー 1866年のペンシルベニア州知事選挙における、ヒスター・クライマー支持派の差別主義政治キャンペーンポスター 人種差別は19世紀には科学的根拠に基づく人種差別として存在しており、人類を人種別に分類しようとしていた。[100] 1775年、ヨハン・ブルーメンバッハは世界の人口を肌の色(白人、モンゴル人など)によって5つのグループに分け、非白人は退化の過程を経て生じたとい う見解を提示した。科学人種学における初期の別の見解は、多系説(ポリジェニズム)であり、異なる人種はそれぞれ別個に創造されたという説である。多系説 の支持者であるクリストフ・マイナーズ(1747年 - 1810年5月)は、例えば、人類を「美しい白色人種」と「醜い黒色人種」という2つのグループに分けた。マイナーズの著書『人類史概略』では、人種の主 な特徴は美醜であると主張している。彼は白人のみを美しいと見なした。そして、醜い人種は劣っており、不道徳で動物的なものとみなした。 アンデシュ・レティウス(Anders Retzius、1796年~1860年)は、ヨーロッパ人もその他の人々も、単一の「純粋な人種」ではなく、混血であることを証明した。ブレンナーの分 類学は否定されたが、その派生形は現在でも米国の人口分類に広く使用されている。ハンス・ペデル・スティーンズビーは、現代の人間はすべて混血であると強 く主張しながらも、1907年には、人間の差異の起源は非常に遠い過去まで遡って追跡されなければならないと主張し、現代における「最も純粋な人種」は オーストラリアのアボリジニであろうと推測した。  南アフリカのアパルトヘイト時代に人種隔離政策が敷かれていたビーチに立てられた看板には、「白人種グループのメンバー専用」と書かれていた 科学的人種主義は20世紀初頭に強く嫌われるようになったが、人間と社会の根本的な違いの起源は、古遺伝学を含む人間遺伝学、社会人類学、比較政治学、宗 教史、思想史、先史学、歴史学、倫理学、精神医学などの分野において、今でも学術的に研究されている。ブレンナハの「人種」に類似したものに基づくあらゆ る方法論は広く拒絶されている。民族や国民のステレオタイプがどの程度、いつ頃から受け入れられているのかは、さらに不明瞭である。 第二次世界大戦とホロコーストの後、人種差別的なイデオロギーは倫理的、政治的、科学的根拠から信用を失ったが、人種差別と人種差別は世界中で広く残って いる。 デュ・ボイスは、私たちが考えるのは「人種」というよりもむしろ「文化」であると指摘している。「共通の歴史、共通の法律や宗教、類似した思考習慣、そして 人生のある理想を共に意識的に追求する」[102] 19世紀後半の民族主義者たちは、現代の「人種」、「民族性」、そして「適者生存」に関する議論を初めて受け入れ、新たな民族主義的教義を形作った。最終 的には、人種は人体の最も重要な特徴を表すだけでなく、国民の性格や個性を決定づけるものとして考えられるようになった。[103] この見解によると、文化は民族集団によって生み出された物理的な表現であり、人種的特性によって完全に決定づけられる。文化と人種は互いに絡み合い、依存 し合うものと考えられるようになり、時には定義の枠組みに国籍や言語まで含めることもあった。人種の純粋性は、金髪のように、容易にアピールできる表面的 な特徴と関連付けられる傾向があった。人種的特性は、実際の地理的な分布よりも、むしろ国籍や言語と関連付けられる傾向があった。北欧主義の場合、「ゲル マン」という呼称は人種的優越性を意味した。 一部の民族主義的、自民族中心的な価値観や選択された成果によって後押しされたこの人種的優越性の概念は、劣っている、あるいは不純であると考えられてい た他の文化と区別するために発展した。この文化への重点は、現代の主流派の人種差別主義の定義と一致している。「人種差別は『人種』の存在から生じるもの ではない。それは、社会的区分の過程を通じて人種を作り出す。身体的、文化的、宗教的な相違に関係なく、誰もが人種化される可能性がある」[104] この定義は、現在も科学的な議論の対象となっている生物学的概念としての「人種」を明確に無視している。デビッド・C・ロウの言葉を借りれば、「人種概念 は、別の名称を装っている場合もあるが、科学者だけでなく一般の人々も人間の多様性に魅了されているため、生物学やその他の分野では依然として使用されて いる。その多様性の一部は人種によって捉えられている」[105] 人種的偏見は国際法の対象となった。例えば、1963年11月20日に国連総会で採択された「あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する宣言」では、人種、肌 の色、民族的な出自を理由とする差別(第1条)に次いで、人種的偏見が明確に言及されている。[106] |

| Ethnicity and ethnic conflicts Further information: Ethnicity  A mass grave being dug for frozen bodies from the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, in which the U.S. Army killed 150 Lakota people, marking the end of the American Indian Wars Debates over the origins of racism often suffer from a lack of clarity over the term. Many use the term "racism" to refer to more general phenomena, such as xenophobia and ethnocentrism, although scholars attempt to clearly distinguish those phenomena from racism as an ideology or from scientific racism, which has little to do with ordinary xenophobia. Others conflate recent forms of racism with earlier forms of ethnic and national conflict. In most cases, ethno-national conflict seems to owe itself to conflict over land and strategic resources. In some cases, ethnicity and nationalism were harnessed in order to rally combatants in wars between great religious empires (for example, the Muslim Turks and the Catholic Austro-Hungarians). Notions of race and racism have often played central roles in ethnic conflicts. Throughout history, when an adversary is identified as "other" based on notions of race or ethnicity (in particular when "other" is interpreted to mean "inferior"), the means employed by the self-presumed "superior" party to appropriate territory, human chattel, or material wealth often have been more ruthless, more brutal, and less constrained by moral or ethical considerations. According to historian Daniel Richter, Pontiac's Rebellion saw the emergence on both sides of the conflict of "the novel idea that all Native people were 'Indians,' that all Euro-Americans were 'Whites,' and that all on one side must unite to destroy the other".[107] Basil Davidson states in his documentary, Africa: Different but Equal, that racism, in fact, only just recently surfaced as late as the 19th century, due to the need for a justification for slavery in the Americas. Historically, racism was a major driving force behind the Transatlantic slave trade.[108] It was also a major force behind racial segregation, especially in the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and South Africa under apartheid; 19th and 20th century racism in the Western world is particularly well documented and constitutes a reference point in studies and discourses about racism.[8] Racism has played a role in genocides such as the Armenian genocide, and the Holocaust, and colonial projects like the European colonization of the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Indigenous peoples have been—and are—often subject to racist attitudes. Practices and ideologies of racism are condemned by the United Nations in the Declaration of Human Rights.[109] Ethnic and racial nationalism Further information: Ethnic nationalism, Racial nationalism, and Romantic nationalism  A 1917 anti-conscription propaganda leaflet imploring voters to "keep Australia white". A horde of Asians bearing a dragon flag is shown to the north. After the Napoleonic Wars, Europe was confronted with the new "nationalities question", leading to reconfigurations of the European map, on which the frontiers between the states had been delineated during the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Nationalism had made its first appearance with the invention of the levée en masse by the French Revolutionaries, thus inventing mass conscription in order to be able to defend the newly founded Republic against the Ancien Régime order represented by the European monarchies. This led to the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and then to the conquests of Napoleon, and to the subsequent European-wide debates on the concepts and realities of nations, and in particular of nation-states. The Westphalia Treaty had divided Europe into various empires and kingdoms (such as the Ottoman Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, the Swedish Empire, the Kingdom of France, etc.), and for centuries wars were waged between princes (Kabinettskriege in German). Modern nation-states appeared in the wake of the French Revolution, with the formation of patriotic sentiments for the first time in Spain during the Peninsula War (1808–1813, known in Spain as the Independence War). Despite the restoration of the previous order with the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the "nationalities question" became the main problem of Europe during the Industrial Era, leading in particular to the 1848 Revolutions, the Italian unification completed during the 1871 Franco-Prussian War, which itself culminated in the proclamation of the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, thus achieving the German unification. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire, the "sick man of Europe", was confronted with endless nationalist movements, which, along with the dissolving of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, would lead to the creation, after World War I, of the various nation-states of the Balkans, with "national minorities" in their borders.[110] Ethnic nationalism, which advocated the belief in a hereditary membership of the nation, made its appearance in the historical context surrounding the creation of the modern nation-states. One of its main influences was the Romantic nationalist movement at the turn of the 19th century, represented by figures such as Johann Herder (1744–1803), Johan Fichte (1762–1814) in the Addresses to the German Nation (1808), Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), or also, in France, Jules Michelet (1798–1874). It was opposed to liberal nationalism, represented by authors such as Ernest Renan (1823–1892), who conceived of the nation as a community, which, instead of being based on the Volk ethnic group and on a specific, common language, was founded on the subjective will to live together ("the nation is a daily plebiscite", 1882) or also John Stuart Mill (1806–1873).[111] Ethnic nationalism blended with scientific racist discourses, as well as with "continental imperialist" (Hannah Arendt, 1951[112]) discourses, for example in the pan-Germanism discourses, which postulated the racial superiority of the German Volk (people/folk). The Pan-German League (Alldeutscher Verband), created in 1891, promoted German imperialism and "racial hygiene", and was opposed to intermarriage with Jews. Another popular current, the Völkisch movement, was also an important proponent of the German ethnic nationalist discourse, and it combined Pan-Germanism with modern racial antisemitism. Members of the Völkisch movement, in particular the Thule Society, would participate in the founding of the German Workers' Party (DAP) in Munich in 1918, the predecessor of the Nazi Party. Pan-Germanism played a decisive role in the interwar period of the 1920s–1930s.[112] These currents began to associate the idea of the nation with the biological concept of a "master race" (often the "Aryan race" or the "Nordic race") issued from the scientific racist discourse. They conflated nationalities with ethnic groups, called "races", in a radical distinction from previous racial discourses that posited the existence of a "race struggle" inside the nation and the state itself. Furthermore, they believed that political boundaries should mirror these alleged racial and ethnic groups, thus justifying ethnic cleansing, in order to achieve "racial purity" and also to achieve ethnic homogeneity in the nation-state. Such racist discourses, combined with nationalism, were not, however, limited to pan-Germanism. In France, the transition from Republican liberal nationalism, to ethnic nationalism, which made nationalism a characteristic of far-right movements in France, took place during the Dreyfus Affair at the end of the 19th century. During several years, a nationwide crisis affected French society, concerning the alleged treason of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish military officer. The country polarized itself into two opposite camps, one represented by Émile Zola, who wrote J'Accuse…! in defense of Alfred Dreyfus, and the other represented by the nationalist poet, Maurice Barrès (1862–1923), one of the founders of the ethnic nationalist discourse in France.[113] At the same time, Charles Maurras (1868–1952), founder of the monarchist Action française movement, theorized the "anti-France", composed of the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners" (his actual word for the latter being the pejorative métèques). Indeed, to him the first three were all "internal foreigners", who threatened the ethnic unity of the French people. |

民族と民族紛争 詳細情報:民族(エスニシティ)  1890年の「傷だらけの膝(ウンディド・ニー:地名)の虐殺」で凍死した150人のラコタ族の人々の遺体を埋めるために掘られた集団墓地。この虐殺は、 アメリカ・インディアン戦争の終結を告げるものとなった 人種差別の起源をめぐる議論は、しばしばこの用語の不明瞭さによって混乱する。多くの人々は「人種差別」という用語を、外国人嫌悪や自民族中心主義といっ たより一般的な現象を指すために使用しているが、学者たちは、それらの現象をイデオロギーとしての人種差別や、通常の外国人嫌悪とはほとんど関係のない科 学的人種差別と明確に区別しようとしている。また、最近の形のレイシズムを、以前の形の民族紛争や国民紛争と混同する人もいる。ほとんどの場合、民族紛争 や国民紛争は、土地や戦略的資源をめぐる紛争に起因しているように思われる。一部のケースでは、民族性や国民性が、宗教的大帝国間の戦争(例えば、イスラ ム教徒のトルコ人とカトリックのオーストリア=ハンガリー人)における戦闘員の結集のために利用された。 人種や人種差別に関する概念は、民族紛争においてしばしば中心的な役割を果たしてきた。歴史を通じて、人種や民族に関する概念に基づいて敵対者が「他者」 として認識される場合(特に「他者」が「劣等」を意味すると解釈される場合)、自らが「優等」であると考える側が領土、人間、物質的富を不当に獲得するた めに用いる手段は、より非情で残忍であり、道徳的・倫理的な配慮に縛られることが少なかった。歴史家のダニエル・リクターによると、ポンティアックの反乱 では、紛争の両陣営に「すべてのネイティブアメリカンは『インディアン』であり、すべてのヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は『白人』であり、一方の側はすべて団結 して他方を滅ぼさなければならない」という「斬新な考え」が現れたという。[107] バジル・デビッドソンは、ドキュメンタリー『アフリカ: 実際、人種差別は、アメリカ大陸における奴隷制を正当化する必要性から、19世紀になってようやく表面化したに過ぎない、と述べている。 歴史的に、人種差別は大西洋奴隷貿易の主要な推進力であった。[108] また、特に19世紀から20世紀初頭のアメリカ合衆国やアパルトヘイト体制下の南アフリカ共和国における人種隔離政策の主要な推進力でもあった。19世紀 から20世紀にかけての 西洋における人種差別は特に詳細に記録されており、人種差別に関する研究や言説の基準となっている。[8] 人種差別はアルメニア人虐殺やホロコーストなどの大量虐殺や、ヨーロッパによる南北アメリカ、アフリカ、アジアへの植民地化などの植民地化計画にも関与し てきた。先住民は、過去も現在も人種差別的な態度に晒されることが多い。人種差別の慣行やイデオロギーは、国連の人権宣言で非難されている。[109] 民族・人種ナショナリズム 詳細は、民族ナショナリズム、人種ナショナリズム、ロマン主義的ナショナリズムを参照  1917年の徴兵制反対の宣伝ビラ。有権者に対して「オーストラリアを白人のままに保とう」と呼びかけている。北には龍旗を掲げたアジア人の群れが描かれ ている。 ナポレオン戦争の後、ヨーロッパは新たな「民族問題」に直面し、1648年のウェストファリア条約で国家間の国境が画定されたヨーロッパ地図の再構成につ ながった。ナショナリズムは、フランス革命家たちによる「levée en masse(一斉蜂起)」の発明によって初めて登場した。彼らは、ヨーロッパの君主制によって象徴される旧体制から、新たに建国された共和国を守るため に、大量徴兵制度を考案した。これがフランス革命戦争(1792年~1802年)とナポレオンの征服につながり、国民国家の概念と実態について、特に国民 国家について、ヨーロッパ全体で議論が巻き起こった。ウェストファリア条約によりヨーロッパはさまざまな帝国や王国(オスマン帝国、神聖ローマ帝国、ス ウェーデン帝国、フランス王国など)に分割され、何世紀にもわたって諸侯間の戦争(ドイツ語ではKabinettskriege)が続いた。 近代的な国民国家はフランス革命の後、スペイン半島戦争(1808年~1813年、スペインでは独立戦争として知られる)の際にスペインで初めて愛国心が 芽生えたことにより誕生した。1815年のウィーン会議により以前の秩序が回復されたにもかかわらず、「民族問題」は産業革命期のヨーロッパの主要な問題 となり、特に1848年の革命、1871年の普仏戦争中に完了したイタリア統一、そして最終的にヴェルサイユ宮殿の鏡の回廊でドイツ帝国の成立が宣言さ れ、ドイツ統一が達成された。 一方、「病めるヨーロッパ」と称されたオスマン帝国は、果てしない民族運動に直面し、オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の崩壊と相まって、第一次世界大戦後に バルカン半島にさまざまな民族国家が誕生し、その国境内に「少数民族」が存在することにつながった。 民族国家の永続的な存続を信奉する民族主義は、近代国民国家の形成をめぐる歴史的文脈の中で登場した。 その主な影響のひとつは、19世紀初頭のロマン主義的ナショナリズム運動であり、ヨハン・ヘルダー(1744年-1803年)、ヨハン・フィヒテ (1762年-1814年) 1808年の著書『ドイツ国民への演説』で知られるヨハン・フィヒテ(1762-1814)、フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル(1770-1831)、あるいはフ ランスではジュール・ミシュレ(1798-1874)などが代表的な人物である。それは、国民を民族集団や特定の共通言語に基づくものではなく、共に生き るという主観的な意志に基づいて形成される共同体として捉えた、エルネスト・レナン(1823年-1892年)に代表される自由主義的ナショナリズムに反 対するものであった。また、 ジョン・スチュアート・ミル(1806年 - 1873年)の影響も受けた。[111] 民族ナショナリズムは、科学的人種差別主義の言説と融合し、また「大陸帝国主義」(ハンナ・アレント、1951年[112])の言説とも融合した。例え ば、ドイツ民族(人々/民族)の優越性を主張する汎ゲルマン主義の言説などである。1891年に結成された全ドイツ連盟(Alldeutscher Verband)は、ドイツ帝国主義と「人種衛生学」を推進し、ユダヤ人との混血に反対した。もう一つの有力な潮流である民族主義運動(Völkisch movement)も、ドイツ民族主義的言説の重要な推進者であり、汎ゲルマン主義と近代人種的反ユダヤ主義を結びつけた。民族主義運動のメンバー、特に トゥーレ協会は、1918年にミュンヘンでナチス党の前身であるドイツ労働者党(DAP)の結党に参加した。 1920年代から1930年代の戦間期には、汎ドイツ主義が重要な役割を果たした。[112] こうした潮流は、国民という概念を、科学的人種差別論から生じた「マスター・レース」(しばしば「アーリア人種」または「北欧人種」)という生物学的な概 念と結びつけるようになった。彼らは、国民を「人種」と呼ばれる民族集団と同一視し、国家や国家そのものの中に「人種闘争」が存在するという以前の人種論 とは根本的に異なる見解を示した。さらに、彼らは政治的境界線はこれらの主張される人種や民族集団を反映すべきだと考え、民族浄化を正当化することで、 「人種の純粋性」を達成し、国民国家における民族の均質性を実現しようとした。 このような人種差別的な言説は、ナショナリズムと結びついていたが、しかし、それは汎ゲルマン主義に限られたものではなかった。フランスでは、共和制自由 主義ナショナリズムから民族主義ナショナリズムへの移行が起こり、ナショナリズムはフランスの極右運動の特徴となった。数年にわたって、フランス社会は、 フランス系ユダヤ人の軍人アルフレッド・ドレフュスが反逆罪を犯したとされた事件に揺れた。この事件により、フランスは二つの対立する陣営に分断された。 一方は、アルフレッド・ドレフュスを擁護するために『我弾劾す!』を著したエミール・ゾラが代表する陣営であり、もう一方は、民族主義的な詩人であり、フ ランスにおける民族主義的言説の創始者の一人であるモーリス・バレス(1862-1923)が代表する陣営である。同時に、君主制を標榜するアクション・ フランセーズ運動の創始者シャルル・モラス(1868-1952)は、「プロテスタント、ユダヤ教、フリーメイソン、外国人からなる4つの連合国家」で構 成される「反フランス」を理論化した(後者に対する彼の実際の表現は、軽蔑的な「メテーク」であった)。実際、彼にとって最初の3つはすべて「内なる外国 人」であり、フランス民族の一体性を脅かす存在であった。 |