エスニシティ

Ethnicity; 民族性

☆ エスニシティ(ethnicity)またはエスニック・グループ(ethnic group)とは、他のグループと区別される共通の属性に基づいて、互いに識別しあう人々のグループである。これらの属性には、共通の出身国、または共通 の祖先、伝統、言語、歴史、社会、宗教、社会的待遇などが含まれる。エスニシティという用語は、特にエスニック・ナショナリズムの場合、しば しば国家という用語と互換的に使用される。エスニシティは受け継がれたもの、または社会的に押し付けられたものとして解釈されることがある。民族の構成員は、共有する文化的遺産、祖先、起源神話、 歴史、祖国、言語、方言、宗教、神話、伝承、儀式、料理、服装、芸術、または身体的外見によって定義される傾向がある。民族集団は、集団の識別によって、 遺伝的祖先の狭い範囲または広い範囲を共有することがあり、多くの集団は遺伝的祖先が混在している(→「民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッセー」も参照のこと)。

★民族ないしは民族集団(ethnic group)とは、文化(言語、習慣、宗教など)で区分される集団のことである。民族には「民族名」 というものがある。

目次

++

| An ethnicity

or ethnic group is a grouping of people who identify with each other on

the basis of perceived shared attributes that distinguish them from

other groups. Those attributes can include a common nation of origin,

or common sets of ancestry, traditions, language, history, society,

religion, or social treatment.[1][2] The term ethnicity is often used

interchangeably with the term nation, particularly in cases of ethnic

nationalism. Ethnicity may be construed as an inherited or societally imposed construct. Ethnic membership tends to be defined by a shared cultural heritage, ancestry, origin myth, history, homeland, language, dialect, religion, mythology, folklore, ritual, cuisine, dressing style, art, or physical appearance. Ethnic groups may share a narrow or broad spectrum of genetic ancestry, depending on group identification, with many groups having mixed genetic ancestry.[3][4][5] By way of language shift, acculturation, adoption, and religious conversion, individuals or groups may over time shift from one ethnic group to another. Ethnic groups may be divided into subgroups or tribes, which over time may become separate ethnic groups themselves due to endogamy or physical isolation from the parent group. Conversely, formerly separate ethnicities can merge to form a pan-ethnicity and may eventually merge into one single ethnicity. Whether through division or amalgamation, the formation of a separate ethnic identity is referred to as ethnogenesis. Although both organic and performative criteria characterise ethnic groups, debate in the past has dichotomised between primordialism and constructivism. Earlier 20th-century "Primordialists" viewed ethnic groups as real phenomena whose distinct characteristics have endured since the distant past.[6] Perspectives that developed after the 1960s increasingly viewed ethnic groups as social constructs, with identity assigned by societal rules.[7] |

エ

スニシティ(ethnicity)またはエスニック・グループ(ethnic

group)とは、他のグループと区別される共通の属性に基づいて、互いに識別しあう人々のグループである。これらの属性には、共通の出身国、または共通

の祖先、伝統、言語、歴史、社会、宗教、社会的待遇などが含まれる[1][2]。エスニシティという用語は、特にエスニック・ナショナリズムの場合、しば

しば国家という用語と互換的に使用される。 エスニシティは受け継がれたもの、または社会的に押し付けられたものとして解釈されることがある。民族の構成員は、共有する文化的遺産、祖先、起源神話、 歴史、祖国、言語、方言、宗教、神話、伝承、儀式、料理、服装、芸術、または身体的外見によって定義される傾向がある。民族集団は、集団の識別によって、 遺伝的祖先の狭い範囲または広い範囲を共有することがあり、多くの集団は遺伝的祖先が混在している[3][4][5]。 言語の変化、文化順応、養子縁組、宗教的改宗などによって、個人または集団は、ある民族集団から別の民族集団へと移行することがある。民族集団は小集団や 部族に分けられることがあり、それらは内縁関係や親集団からの物理的な隔離により、時間の経過とともに別の民族集団となることがある。逆に、以前は別々の 民族であったものが合併して汎民族となり、最終的には一つの単一民族に統合されることもある。分裂であれ合併であれ、別個のエスニック・アイデンティティ の形成は民族形成と呼ばれる。 有機的な基準と実行的な基準の両方がエスニック集団を特徴づけるが、過去の議論では原初主義と構成主義に二分されてきた。20世紀初頭の「原初主義者」 は、民族集団を遠い過去から続く明確な特徴を持つ現実的な現象とみなしていた[6]。1960年代以降に発展した視点は、民族集団を社会的な構築物とみな す傾向が強まり、社会的な規則によってアイデンティティが割り当てられるようになった[7]。 |

| Terminology The term ethnic is derived from the Greek word ἔθνος ethnos (more precisely, from the adjective ἐθνικός ethnikos,[8] which was loaned into Latin as ethnicus). The inherited English language term for this concept is folk, used alongside the latinate people since the late Middle English period. In Early Modern English and until the mid-19th century, ethnic was used to mean heathen or pagan (in the sense of disparate "nations" which did not yet participate in the Christian oikumene), as the Septuagint used ta ethne ("the nations") to translate the Hebrew goyim "the foreign nations, non-Hebrews, non-Jews".[9] The Greek term in early antiquity (Homeric Greek) could refer to any large group, a host of men, a band of comrades as well as a swarm or flock of animals. In Classical Greek, the term took on a meaning comparable to the concept now expressed by "ethnic group", mostly translated as "nation, tribe, a unique people group"; only in Hellenistic Greek did the term tend to become further narrowed to refer to "foreign" or "barbarous" nations in particular (whence the later meaning "heathen, pagan").[10] In the 19th century, the term came to be used in the sense of "peculiar to a tribe, race, people or nation", in a return to the original Greek meaning. The sense of "different cultural groups", and in American English "tribal, racial, cultural or national minority group" arises in the 1930s to 1940s,[11] serving as a replacement of the term race which had earlier taken this sense but was now becoming deprecated due to its association with ideological racism. The abstract ethnicity had been used as a stand-in for "paganism" in the 18th century, but now came to express the meaning of an "ethnic character" (first recorded 1953). The term ethnic group was first recorded in 1935 and entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 1972.[12] Depending on context, the term nationality may be used either synonymously with ethnicity or synonymously with citizenship (in a sovereign state). The process that results in emergence of an ethnicity is called ethnogenesis, a term in use in ethnological literature since about 1950. The term may also be used with the connotation of something unique and unusually exotic (cf. "an ethnic restaurant", etc.), generally related to cultures of more recent immigrants, who arrived after the dominant population of an area was established. Depending on which source of group identity is emphasized to define membership, the following types of (often mutually overlapping) groups can be identified: Ethno-linguistic, emphasizing shared language, dialect (and possibly script) – example: French Canadians Ethno-national, emphasizing a shared polity or sense of national identity – example: Austrians Ethno-racial, emphasizing shared physical appearance based on phenotype – example: African Americans Ethno-regional, emphasizing a distinct local sense of belonging stemming from relative geographic isolation – example: South Islanders of New Zealand Ethno-religious, emphasizing shared affiliation with a particular religion, denomination or sect – example: Sikhs Ethno-cultural, emphasizing shared culture or tradition, often overlapping with other forms of ethnicity – example: Travellers In many cases, more than one aspect determines membership: for instance, Armenian ethnicity can be defined by Armenian citizenship, having Armenian heritage, native use of the Armenian language, or membership of the Armenian Apostolic Church. |

用語法 エスニック(ethnic)という用語は、ギリシア語のἔθνος ethnos(より正確には形容詞ἐθνικός ethnikos、[8])に由来する。この概念を表す英語の継承語はフォーク(folk)で、中英語時代後期からラテン語のピープル(people)と 並んで使われるようになった。 近世英語および19世紀半ばまでは、ethnicは異教徒または異教徒(キリスト教のイクメンにまだ参加していない異質な「諸国民」の意味で)という意味 で使われていた。 [9]古代初期のギリシャ語(ホメロスギリシャ語)では、あらゆる大集団、人の群れ、同志の一団、動物の群れなどを指すことがあった。古典ギリシア語で は、この用語は、現在「民族集団」で表現される概念に匹敵する意味を持ち、主に「国家、部族、固有の民族集団」と訳された。ヘレニズムギリシア語において のみ、この用語は、特に「外国」または「野蛮な」国々を指すようにさらに狭められる傾向があった(これが後に「異教徒、異教徒」という意味になる) [10]。異なる文化集団」、アメリカ英語では「部族的、人種的、文化的、国民的少数集団」という意味は1930年代から1940年代に生まれ[11]、 以前はこのような意味で使われていたが、イデオロギー的な人種差別主義との関連性から今では使われなくなりつつあったraceという用語に取って代わる役 割を果たした。抽象的なエスニシティは、18世紀には「異教」の代名詞として使われていたが、現在では「民族的性格」の意味を表すようになった(最初の記 録は1953年)。エスニック・グループという用語は1935年に初めて記録され、1972年にオックスフォード英語辞典に掲載された[12]。文脈に よっては、国籍という用語はエスニシティと同義に使われることもあれば、(主権国家における)市民権と同義に使われることもある。民族の出現をもたらす過 程は民族発生と呼ばれ、民族学の文献では1950年頃から使用されている用語である。この用語は、独特で異国情緒のあるもの(「エスニック・レストラン」 など)という意味合いで使われることもあり、一般的には、ある地域の支配的な人口が確立した後に到着した、より新しい移民の文化に関連する。 メンバーシップを定義するために、集団アイデンティティのどの源泉を重視するかによって、以下のタイプの(しばしば相互に重複する)集団が識別される: 民族言語的集団:共有する言語、方言(および場合によっては文字)を重視する: フランス系カナダ人 エスノ・ナショナル:共有する政治や国民的アイデンティティを重視する: オーストリア人 表現型に基づく共通の身体的外見を強調する: アフリカ系アメリカ人 エスノ・リージョナル(Ethno-Regional):相対的な地理的孤立に由来する明確な地域的帰属意識を強調する: 例:ニュージーランドの南島人 特定の宗教、宗派、宗派に属していることを強調する: シーク教徒 民族文化的(Ethno-Cultural):共有する文化や伝統を強調するもの: トラベラー 例えば、アルメニア人のエスニシティは、アルメニア市民権、アルメニア人の遺産を持つこと、アルメニア語を母語とすること、アルメニア使徒教会の会員であることなどによって定義される。 |

Definitions and conceptual history (see below) A group of ethnic Bengalis in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Bengalis form the third-largest ethnic group in the world after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[13]  The Javanese people of Indonesia are the largest Austronesian ethnic group. Ethnicity theory in the United States Ethnicity theory argues that race is a social category and is only one of several factors in determining ethnicity. Other criteria include "religion, language, 'customs', nationality, and political identification".[56] This theory was put forward by sociologist Robert E. Park in the 1920s. It is based on the notion of "culture". This theory was preceded by more than 100 years during which biological essentialism was the dominant paradigm on race. Biological essentialism is the belief that some races, specifically white Europeans in western versions of the paradigm, are biologically superior and other races, specifically non-white races in western debates, are inherently inferior. This view arose as a way to justify enslavement of African Americans and genocide of Native Americans in a society that was officially founded on freedom for all. This was a notion that developed slowly and came to be a preoccupation with scientists, theologians, and the public. Religious institutions asked questions about whether there had been multiple creations of races (polygenesis) and whether God had created lesser races. Many of the foremost scientists of the time took up the idea of racial difference and found that white Europeans were superior.[57] The ethnicity theory was based on the assimilation model. Park outlined four steps to assimilation: contact, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation. Instead of attributing the marginalized status of people of color in the United States to their inherent biological inferiority, he attributed it to their failure to assimilate into American culture. They could become equal if they abandoned their inferior cultures. Michael Omi and Howard Winant's theory of racial formation directly confronts both the premises and the practices of ethnicity theory. They argue in Racial Formation in the United States that the ethnicity theory was exclusively based on the immigration patterns of the white population and did take into account the unique experiences of non-whites in the United States.[58] While Park's theory identified different stages in the immigration process – contact, conflict, struggle, and as the last and best response, assimilation – it did so only for white communities.[58] The ethnicity paradigm neglected the ways in which race can complicate a community's interactions with social and political structures, especially upon contact. Assimilation – shedding the particular qualities of a native culture for the purpose of blending in with a host culture – did not work for some groups as a response to racism and discrimination, though it did for others.[58] Once the legal barriers to achieving equality had been dismantled, the problem of racism became the sole responsibility of already disadvantaged communities.[59] It was assumed that if a Black or Latino community was not "making it" by the standards that had been set by whites, it was because that community did not hold the right values or beliefs, or were stubbornly resisting dominant norms because they did not want to fit in. Omi and Winant's critique of ethnicity theory explains how looking to cultural defect as the source of inequality ignores the "concrete sociopolitical dynamics within which racial phenomena operate in the U.S."[60] It prevents critical examination of the structural components of racism and encourages a "benign neglect" of social inequality.[60] |

定義と概念の歴史(別枠で説明) バングラデシュのダッカに住むベンガル人の集団。ベンガル人は漢民族、アラブ人に次いで世界第3位の民族集団を形成している[13]。  インドネシアのジャワ人は「オーストロネシア系」最大の民族集団である。 アメリカにおけるエスニシティ論 エスニシティ論は、人種は社会的カテゴリーであり、エスニシティを決定するいくつかの要因の一つに過ぎないと主張する。この理論は1920年代に社会学者ロバート・E・パークによって提唱された。これは「文化」という概念に基づいている。 この理論に先立つこと100年以上、生物学的本質主義が人種に関する支配的なパラダイムであった。生物学的本質主義とは、一部の人種、特に西洋のパラダイ ムでは白人ヨーロッパ人は生物学的に優れており、他の人種、特に西洋の議論では非白人人種は本質的に劣っているという信念である。この考え方は、万人の自 由を建前とする社会の中で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷化やアメリカ先住民の大量虐殺を正当化する方法として生まれた。この考え方は徐々に発展し、科学 者、神学者、そして一般の人々の関心を集めるようになった。宗教団体は、複数の人種の創造(ポリジェネシス)があったのかどうか、神はより劣った人種を創 造したのかどうかという疑問を投げかけた。当時の一流の科学者の多くが人種の違いという考えを取り上げ、ヨーロッパ白人が優れていることを発見した [57]。 エスニシティ理論は同化モデルに基づいていた。パークは同化のための4つの段階、すなわち接触、衝突、融和、同化を概説した。彼は、アメリカにおける有色 人種の疎外された地位を、彼らの先天的な生物学的劣等性に帰するのではなく、彼らがアメリカ文化に同化できなかったことに帰した。劣った文化を捨てれば、 彼らは平等になれるのだ。 マイケル・オミとハワード・ワイナントの人種形成論は、エスニシティ論の前提にも実践にも真っ向から対立している。彼らは『アメリカにおける人種形成』 (Racial Formation in the United States)の中で、エスニシティ理論はもっぱら白人集団の移民パターンに基づいており、アメリカにおける非白人のユニークな経験を考慮していなかった と論じている[58]。 パークの理論は移民プロセスにおけるさまざまな段階(接触、葛藤、闘争、そして最後にして最良の対応としての同化)を特定していたが、それは白人コミュニ ティについてのみそうしていた[58]。エスニシティ・パラダイムは、人種がコミュニティと社会的・政治的構造との相互作用を複雑にする方法を、特に接触 時に軽視していた。 同化、つまり受け入れ側の文化に溶け込むために固有の文化の特質を捨て去ることは、人種差別や差別への対応として、ある集団にとっては機能しなかったが、 他の集団にとっては機能した[58]。平等を達成するための法的障壁が解体されると、人種差別の問題はすでに不利な立場に置かれているコミュニティだけの 責任となった。 [黒人やラテン系のコミュニティが白人によって設定された基準によって「成功」していない場合、それはそのコミュニティが正しい価値観や信念を持っていな いか、あるいは自分たちがなじむことを望んでいないために支配的な規範に頑なに抵抗しているためであると考えられた。エスニシティ理論に対する近江とワイ ナントの批判は、不平等の根源として文化的欠陥に注目することが、いかに「人種現象が米国で作用している具体的な社会政治的力学」を無視しているかを説明 している[60]。それは人種差別の構造的構成要素に対する批判的な検討を妨げ、社会的不平等に対する「良性の無視」を助長している[60]。 |

| Ethnicity and nationality Further information: Nation state and minority group. In some cases, especially those involving transnational migration or colonial expansion, ethnicity is linked to nationality. Anthropologists and historians, following the modernist understanding of ethnicity as proposed by Ernest Gellner[61] and Benedict Anderson[62] see nations and nationalism as developing with the rise of the modern state system in the 17th century. They culminated in the rise of "nation-states" in which the presumptive boundaries of the nation coincided (or ideally coincided) with state boundaries. Thus, in the West, the notion of ethnicity, like race and nation, developed in the context of European colonial expansion, when mercantilism and capitalism were promoting global movements of populations at the same time that state boundaries were being more clearly and rigidly defined. In the 19th century, modern states generally sought legitimacy through their claim to represent "nations". Nation-states, however, invariably include populations who have been excluded from national life for one reason or another. Members of excluded groups, consequently, will either demand inclusion based on equality or seek autonomy, sometimes even to the extent of complete political separation in their nation-state.[63] Under these conditions when people moved from one state to another,[64] or one state conquered or colonized peoples beyond its national boundaries – ethnic groups were formed by people who identified with one nation, but lived in another state. In the 1920s Estonia introduced a flexible system of ethnicity/nationality self-choice for its citizens,[65] which included Estonians Russians, Baltic Germans and Jews. Multi-ethnic states can be the result of two opposite events, either the recent creation of state borders at variance with traditional tribal territories, or the recent immigration of ethnic minorities into a former nation-state. Examples for the first case are found throughout Africa, where countries created during decolonization inherited arbitrary colonial borders, but also in European countries such as Belgium or United Kingdom. Examples for the second case are countries such as Netherlands, which were relatively ethnically homogeneous when they attained statehood but have received significant immigration in the 17th century and even more so in the second half of the 20th century. States such as the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland comprised distinct ethnic groups from their formation and have likewise experienced substantial immigration, resulting in what has been termed "multicultural" societies, especially in large cities. The states of the New World were multi-ethnic from the onset, as they were formed as colonies imposed on existing indigenous populations. In recent decades, feminist scholars (most notably Nira Yuval-Davis)[66] have drawn attention to the fundamental ways in which women participate in the creation and reproduction of ethnic and national categories. Though these categories are usually discussed as belonging to the public, political sphere, they are upheld within the private, family sphere to a great extent.[67] It is here that women act not just as biological reproducers but also as "cultural carriers", transmitting knowledge and enforcing behaviors that belong to a specific collectivity.[68] Women also often play a significant symbolic role in conceptions of nation or ethnicity, for example in the notion that "women and children" constitute the kernel of a nation which must be defended in times of conflict, or in iconic figures such as Britannia or Marianne. |

エスニシティとナショナリティ 詳しくは、国民国家、および、マイノリティグループ 場合によっては、特に国境を越えた移民や植民地拡大に関わるものでは、エスニシティはナショナリティと結びついている。人類学者や歴史家は、アーネスト・ ゲルナー[61]やベネディクト・アンダーソン[62]によって提唱されたエスニシティの近代主義的理解に従って、国家とナショナリズムは17世紀におけ る近代国家システムの台頭とともに発展したと見ている。それらは「国民国家」の台頭において頂点に達し、そこでは国家の推定上の境界線が国家の境界線と一 致した(あるいは理想的に一致した)。このように西洋では、人種や国家と同様、エスニシティという概念も、ヨーロッパの植民地拡大という背景の中で発展し た。 19世紀、近代国家は一般に「国家」を代表するという主張を通じて正当性を求めた。しかし、国家には必ず、何らかの理由で国民生活から排除された人々が含 まれている。その結果、排除された集団の構成員は、平等性に基づく包摂を要求するか、あるいは自治を求めるようになり、ときには国民国家において完全に政 治的に分離することさえある[63]。このような状況下で、人々がある国家から別の国家へと移動したり[64]、ある国家が国境を越えて民族を征服したり 植民地化したりすると、ある国家に帰属しながら別の国家に住む人々によって民族集団が形成された。 1920年代にエストニアは、エストニア系ロシア人、バルト系ドイツ人、ユダヤ人を含む国民に対して、民族/国籍の柔軟な自己選択制度を導入した[65]。 多民族国家は、伝統的な部族の領土と異なる国家の国境が最近になって設けられた場合と、少数民族が旧民族国家に最近になって移民してきた場合という、2つ の正反対の出来事の結果として生じることがある。第一のケースは、脱植民地化の際につくられた国々が植民地時代の恣意的な国境を受け継いだアフリカ全土に 見られる例であり、ベルギーやイギリスのようなヨーロッパ諸国にも見られる。第二の例としては、オランダのような国が挙げられる。これらの国は、国家とし て成立した時点では比較的同質的な民族であったが、17世紀に大きな移民を受け入れ、20世紀後半にはさらに大きな移民を受け入れた。イギリス、フラン ス、スイスのような国家は、成立当初から異なる民族集団で構成されていたが、同様に多くの移民を受け入れた結果、特に大都市では「多文化社会」と呼ばれる ようになった。 新世界の国家は、既存の先住民に押し付けられた植民地として形成されたため、当初から多民族国家であった。 ここ数十年、フェミニスト研究者(特にニラ・ユヴァル=デイヴィス)[66]は、女性が民族的・国家的カテゴリーの創造と再生産に参加する基本的な方法に 注目してきた。このようなカテゴリーは通常、公的な政治圏に属するものとして議論されるが、私的な家族圏の中でもかなりの程度維持されている[67]。女 性が生物学的な再生産者としてだけでなく、特定の集団に属する知識を伝達し、行動を強制する「文化的な担い手」としても行動するのはここでのことである。 [例えば、「女性と子ども」が紛争時に守らなければならない国家の核を構成するという概念や、ブリタニアやマリアンヌのような象徴的な人物においてであ る。 |

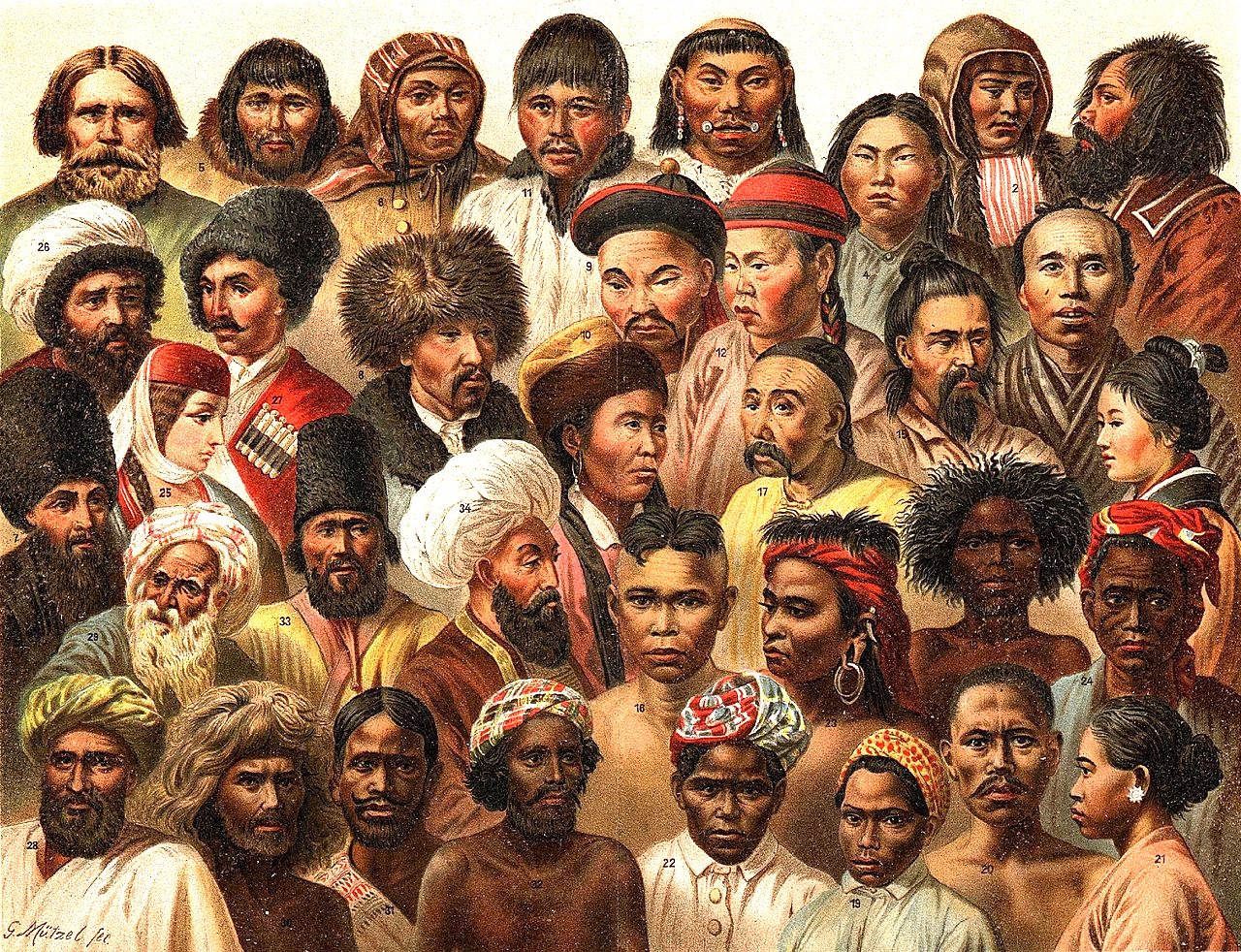

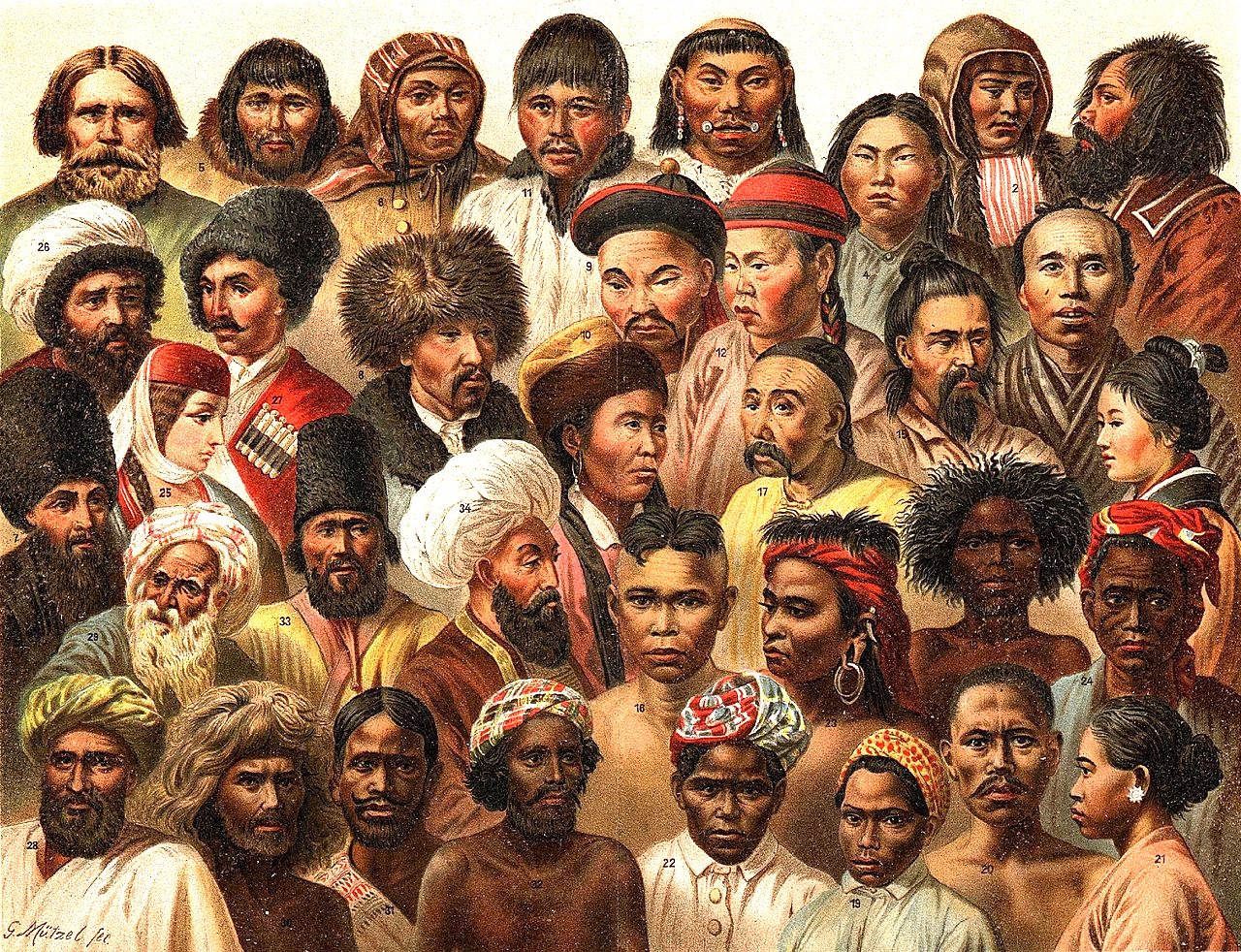

Ethnicity and race The racial diversity of Asia's ethnic groups (original caption: Asiatiska folk), Nordisk familjebok (1904) Ethnicity is used as a matter of cultural identity of a group, often based on shared ancestry, language, and cultural traditions, while race is applied as a taxonomic grouping, based on physical similarities among groups. Race is a more controversial subject than ethnicity, due to common political use of the term.[citation needed] Ramón Grosfoguel (University of California, Berkeley) argues that "racial/ethnic identity" is one concept and concepts of race and ethnicity cannot be used as separate and autonomous categories.[69] Before Weber (1864–1920), race and ethnicity were primarily seen as two aspects of the same thing. Around 1900 and before, the primordialist understanding of ethnicity predominated: cultural differences between peoples were seen as being the result of inherited traits and tendencies.[70] With Weber's introduction of the idea of ethnicity as a social construct, race and ethnicity became more divided from each other. In 1950, the UNESCO statement "The Race Question", signed by some of the internationally renowned scholars of the time (including Ashley Montagu, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Gunnar Myrdal, Julian Huxley, etc.), said: National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups: and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connection with racial traits. Because serious errors of this kind are habitually committed when the term "race" is used in popular parlance, it would be better when speaking of human races to drop the term "race" altogether and speak of "ethnic groups".[71] In 1982, anthropologist David Craig Griffith summed up forty years of ethnographic research, arguing that racial and ethnic categories are symbolic markers for different ways people from different parts of the world have been incorporated into a global economy: The opposing interests that divide the working classes are further reinforced through appeals to "racial" and "ethnic" distinctions. Such appeals serve to allocate different categories of workers to rungs on the scale of labor markets, relegating stigmatized populations to the lower levels and insulating the higher echelons from competition from below. Capitalism did not create all the distinctions of ethnicity and race that function to set off categories of workers from one another. It is, nevertheless, the process of labor mobilization under capitalism that imparts to these distinctions their effective values.[72] According to Wolf, racial categories were constructed and incorporated during the period of European mercantile expansion, and ethnic groupings during the period of capitalist expansion.[73] Writing in 1977 about the usage of the term "ethnic" in the ordinary language of Great Britain and the United States, Wallman noted The term "ethnic" popularly connotes "[race]" in Britain, only less precisely, and with a lighter value load. In North America, by contrast, "[race]" most commonly means color, and "ethnics" are the descendants of relatively recent immigrants from non-English-speaking countries. "[Ethnic]" is not a noun in Britain. In effect there are no "ethnics"; there are only "ethnic relations".[74] In the U.S., the OMB says the definition of race as used for the purposes of the US Census is not "scientific or anthropological" and takes into account "social and cultural characteristics as well as ancestry", using "appropriate scientific methodologies" that are not "primarily biological or genetic in reference".[75] |

エスニシティと人種 アジアの民族集団の人種的多様性(オリジナルキャプション:Asiatiska folk)、Nordisk familjebok (1904) エスニシティは、多くの場合、共通の祖先、言語、文化的伝統に基づく集団の文化的アイデンティティの問題として使われ、人種は、集団間の身体的類似性に基 づく分類学的グループ分けとして適用される。ラモン・グロスフォゲル(カリフォルニア大学バークレー校)は、「人種的/民族的アイデンティティ」は1つの 概念であり、人種と民族の概念は別個の自律的なカテゴリーとして使用することはできないと主張している[69]。 ウェーバー(1864年~1920年)以前は、人種とエスニシティは主に同じものの2つの側面とみなされていた。1900年前後とそれ以前は、民族の原初 主義的な理解が優勢であり、民族間の文化的相違は遺伝的な形質や傾向の結果であると見なされていた[70]。ウェーバーが社会的構築物としての民族性の考 え方を導入することで、人種と民族性はより互いに分けられるようになった。 1950年、当時の国際的に著名な学者たち(アシュレイ・モンタグ、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、グンナー・ミルダル、ジュリアン・ハックスレーなど)が署名したユネスコの声明「人種問題」はこう述べている: 国家的、宗教的、地理的、言語的、文化的集団は、必ずしも人種的集団と一致するわけではない。この種の深刻な誤りは、「人種」という用語が一般的な言い回 しで使用される際に常習的に犯されているため、人間の人種について語る際には、「人種」という用語を完全に捨て去り、「民族集団」について語る方がよいだ ろう[71]。 1982年、人類学者のデイヴィッド・クレイグ・グリフィスは、40年にわたる民族誌的研究を総括し、人種や民族のカテゴリーは、世界のさまざまな地域の人々がグローバル経済に組み込まれたさまざまな方法を象徴する目印であると主張した: 労働者階級を分断する対立的な利害は、「人種」と「民族」の区別に訴えることでさらに強化される。このような訴えは、労働市場の規模に応じて労働者のカテ ゴリーを分け、汚名を着せられた人々を下層に追いやり、上層を下層からの競争から守る役割を果たす。資本主義は、労働者のカテゴリーを互いに引き離すため に機能する民族や人種の区別をすべて生み出したわけではない。それにもかかわらず、資本主義のもとでの労働動員のプロセスが、これらの区別に有効な価値を 与えているのである[72]。 ウルフによれば、人種的カテゴリーが構築され、組み込まれたのはヨーロッパ商業の拡大期であり、民族的グループ分けが行われたのは資本主義の拡大期であった[73]。 1977年にイギリスとアメリカの通常の言語における「エスニック」という用語の用法について書いたウォールマンは次のように指摘している。 「エスニック」という用語は、イギリスでは一般的に「[人種]」を意味する。対照的に北米では、「[人種]」は最も一般的に肌の色を意味し、「エスニッ ク」は非英語圏からの比較的最近の移民の子孫を指す。イギリスでは「[民族]」は名詞ではない。事実上、「エスニック」は存在せず、「エスニック関係」が 存在するだけである[74]。 米国では、OMBは、米国国勢調査の目的で使用される人種の定義は「科学的または人類学的」ではなく、「主に生物学的または遺伝学的な参照」ではない「適切な科学的方法論」を使用して、「社会的および文化的特徴ならびに祖先」を考慮に入れるとしている[75]。 |

| Ethno-national conflict Further information: Ethnic conflict Sometimes ethnic groups are subject to prejudicial attitudes and actions by the state or its constituents. In the 20th century, people began to argue that conflicts among ethnic groups or between members of an ethnic group and the state can and should be resolved in one of two ways. Some, like Jürgen Habermas and Bruce Barry, have argued that the legitimacy of modern states must be based on a notion of political rights of autonomous individual subjects. According to this view, the state should not acknowledge ethnic, national or racial identity but rather instead enforce political and legal equality of all individuals. Others, like Charles Taylor and Will Kymlicka, argue that the notion of the autonomous individual is itself a cultural construct. According to this view, states must recognize ethnic identity and develop processes through which the particular needs of ethnic groups can be accommodated within the boundaries of the nation-state. The 19th century saw the development of the political ideology of ethnic nationalism, when the concept of race was tied to nationalism, first by German theorists including Johann Gottfried von Herder. Instances of societies focusing on ethnic ties, arguably to the exclusion of history or historical context, have resulted in the justification of nationalist goals. Two periods frequently cited as examples of this are the 19th-century consolidation and expansion of the German Empire and the 20th century Nazi Germany. Each promoted the pan-ethnic idea that these governments were acquiring only lands that had always been inhabited by ethnic Germans. The history of late-comers to the nation-state model, such as those arising in the Near East and south-eastern Europe out of the dissolution of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, as well as those arising out of the USSR, is marked by inter-ethnic conflicts. Such conflicts usually occur within multi-ethnic states, as opposed to between them, as in other regions of the world. Thus, the conflicts are often misleadingly labeled and characterized as civil wars when they are inter-ethnic conflicts in a multi-ethnic state. |

民族紛争 さらに詳しい情報 民族紛争 民族が国家やその構成員から偏見に満ちた態度や行動をとられることがある。20世紀には、民族間の紛争、あるいは民族と国家との間の紛争は、2つの方法の いずれかで解決され、また解決されるべきであると主張する人々が現れ始めた。ユルゲン・ハーバーマスやブルース・バリーのように、近代国家の正当性は自律 的な個々の主体の政治的権利という概念に基づかなければならないと主張する者もいる。この考え方によれば、国家は民族的、国家的、人種的アイデンティティ を認めず、むしろすべての個人の政治的、法的平等を強制すべきである。また、チャールズ・テイラーやウィル・キムリッカのように、自律した個人という概念 自体が文化的構築物であると主張する者もいる。この見解によれば、国家は民族のアイデンティティを認め、民族集団の特定のニーズを国民国家の境界の中で受 け入れることができるようなプロセスを開発しなければならない。 19世紀には、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・フォン・ヘルダーをはじめとするドイツの理論家たちによって、民族の概念がナショナリズムと結びつけられ、民族ナ ショナリズムという政治イデオロギーが発展した。社会が民族的な結びつきを重視した結果、歴史や歴史的背景が排除され、ナショナリズムの目標が正当化され た例もある。その例としてよく挙げられるのが、19世紀のドイツ帝国の強化と拡大、そして20世紀のナチス・ドイツである。いずれも、これらの政府はドイ ツ民族が常に居住していた土地のみを取得するという汎民族的な考えを推進した。オスマン帝国やオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の解体によって近東や南東ヨー ロッパに生まれた国家や、ソビエト連邦から生まれた国家など、国民国家モデルの後発国の歴史は、民族間紛争によって特徴づけられる。このような紛争は通 常、世界の他の地域のように多民族国家間で起こるのではなく、多民族国家内で起こる。そのため、紛争は多民族国家内の民族間紛争であるにもかかわらず、内 戦と誤解されることが多い。 |

| Ethnic groups by continent は、問題含みの解説が多いので省略 |

Ethnic groups by continent は、問題含みの解説が多いので省略 |

| Ancestor Clan Diaspora Ethnic cleansing Ethnic interest group Ethnic flag Ethnic nationalism Ethnic penalty Ethnocentrism Ethnocultural empathy Ethnogenesis Ethnocide Ethnographic group Ethnography Genealogy Genetic genealogy Homeland Human Genome Diversity Project Identity politics Ingroups and outgroups Intersectionality Kinship List of contemporary ethnic groups List of countries by ethnic groups List of indigenous peoples Meta-ethnicity Minority group Minzu (anthropology) Multiculturalism Nation National symbol Passing (sociology) Polyethnicity Population genetics Race (human categorization) Race and ethnicity in censuses Race and ethnicity in the United States Census Race and health Segmentary lineage Stateless nation Tribe Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world |

祖先 一族 ディアスポラ 民族浄化 民族利益団体 民族旗 民族ナショナリズム 民族処罰 民族中心主義 民族文化的共感 民族発生 民族虐殺 民族誌的集団 民族誌 系譜学 遺伝的系譜学 祖国 ヒトゲノム多様性プロジェクト アイデンティティ政治 イングループとアウトグループ 交差性 親族関係 現代の民族グループのリスト 民族グループ別国名リスト 先住民族のリスト メタ民族 少数民族 民衆(人類学) 多文化主義 国家 ナショナル・シンボル パッシング(社会学) 多民族性 集団遺伝学 人種(人間の分類) 国勢調査における人種と民族 米国国勢調査における人種とエスニシティ 人種と健康 分節的血統 無国籍国家 部族 世界の集団におけるY染色体ハプログループ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnicity |

|

★

★エスニシティ(Ethnicity):その定義と概念の歴史(→「民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッセー」も参照のこと)

| Ethnography begins

in classical antiquity; after early authors like Anaximander and

Hecataeus of Miletus, Herodotus laid the foundation of both

historiography and ethnography of the ancient world c. 480 BC. The

Greeks had developed a concept of their own ethnicity, which they

grouped under the name of Hellenes. Herodotus (8.144.2) gave a famous

account of what defined Greek (Hellenic) ethnic identity in his day,

enumerating |

民族誌学は古典古代に始まる。アナクシマンダーやミレトスのヘカタエウ

スといった初期の著者に続き、紀元前480年頃にはヘロドトスが古代世界の歴史学と民

族学の基礎を築いた。ギリシア人は自分たちの民族概念を確立しており、ヘレネー人という名前でグループ化していた。ヘロドトス(8.144.2)は、当時

のギリシア(ヘレニズム)の民族的アイデンティティを定義するものとして、次のような有名な記述を残している。 |

| shared descent (ὅμαιμον – homaimon, "of the same blood"),[14] shared language (ὁμόγλωσσον – homoglōsson, "speaking the same language"),[15] shared sanctuaries and sacrifices (Greek: θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι – theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai),[16] shared customs (Greek: ἤθεα ὁμότροπα – ēthea homotropa, "customs of like fashion").[17][18][19] |

共通の血統(ὅμαιμον - homaimon、「同じ血の」)、[14]。 言語の共有(ὁμόγλωσσον - homoglōsson、「同じ言語を話す」)、[15]。 聖域と犠牲の共有(ギリシャ語:θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι - theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai)、[16]。 共有された風習(ギリシャ語:ἤθεα ὁμότροπα - ēthea homotropa、「同じような風習」)[17][18][19]。 |

| Whether ethnicity qualifies as a

cultural universal is to some extent dependent on the exact definition

used. Many social scientists,[20] such as anthropologists Fredrik Barth

and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They

regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group

interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human

groups.[21][irrelevant citation] |

エスニシティが文化的普遍性を持つかどうかは、使用される正確な定義に

よってある程度左右される。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフのよ

うな多くの社会科学者[20]は、民族的アイデンティティが普遍的であるとは考えていない。彼らはエスニシティを人間集団に固有の本質的な性質ではなく、

特定の種類の集団間相互作用の産物とみなしている[21][無関係な引用]。 |

| According to Thomas Hylland Eriksen, the study of ethnicity was dominated by two distinct debates until recently. |

トーマス・ヒランド・エリクセンによれば、エスニシティ研究は最近まで2つの異なる議論に支配されていた。 |

| One is between "primordialism"

and "instrumentalism". In the primordialist view, the participant

perceives ethnic ties collectively, as an externally given, even

coercive, social bond.[22] The instrumentalist approach, on the other

hand, treats ethnicity primarily as an ad hoc element of a political

strategy, used as a resource for interest groups for achieving

secondary goals such as, for instance, an increase in wealth, power, or

status.[23][24] This debate is still an important point of reference in

Political science, although most scholars' approaches fall between the

two poles.[25] |

ひとつは「原初主義」と「道具主義」である。原初主義的な見解では、参 加者は民族的な結びつきを、外部から与えられた、強制的ですらある社会的な結びつき として集団的に認識する[22]。他方、道具主義的なアプローチでは、エスニシティを主に政治戦略のアドホックな要素として扱い、例えば富や権力、地位の 向上といった二次的な目標を達成するための利益集団の資源として利用する[23][24]。この議論は、ほとんどの学者のアプローチが両極の中間に位置す るものの、政治学において依然として重要な参照点となっている[25]。 |

| The second debate is between

"constructivism" and "essentialism". Constructivists view national and

ethnic identities as the product of historical forces, often recent,

even when the identities are presented as old.[26][27] Essentialists

view such identities as ontological categories defining social

actors.[28][29] |

2つ目の議論は「構成主義」と「本質主義」の間のものである。構成主義

者は国家や民族のアイデンティティを歴史的な力の産物としてとらえ、そのアイデンティティが古いものとして提示されている場合でも、しばしば最近のもので

あるとする[26][27]。本質主義者は、このようなアイデンティティを、社会的な行為者を定義する存在論的なカテゴリーと見なしている。 |

| According to Eriksen, these

debates have been superseded, especially in anthropology, by scholars'

attempts to respond to increasingly politicized forms of

self-representation by members of different ethnic groups and nations.

This is in the context of debates over multiculturalism in countries,

such as the United States and Canada, which have large immigrant

populations from many different cultures, and post-colonialism in the

Caribbean and South Asia.[30] |

エリクセンによれば、このような議論は、特に人類学においては、異なる

民族集団や国家の構成員による自己表象のますます政治化された形態に対応しようとす

る学者たちの試みによって取って代わられた。これは、多くの異なる文化からの移民人口を抱えるアメリカやカナダなどの国々における多文化主義をめぐる議論

や、カリブ海地域や南アジアにおけるポストコロニアリズムの文脈にある[30]。 |

| Max Weber maintained that ethnic

groups were künstlich (artificial, i.e. a social construct) because

they were based on a subjective belief in shared Gemeinschaft

(community). Secondly, this belief in shared Gemeinschaft did not

create the group; the group created the belief. Third, group formation

resulted from the drive to monopolize power and status. This was

contrary to the prevailing naturalist belief of the time, which held

that socio-cultural and behavioral differences between peoples stemmed

from inherited traits and tendencies derived from common descent, then

called "race".[31] |

マックス・ウェーバーは、民族集団は共有されたゲマインシャフト(共同

体)という主観的な信念に基づいているため、künstlich(人為的、すなわち

社会的構築物)であると主張した。第二に、この共有されたゲマインシャフトに対する信念が集団を作り出したのではなく、集団が信念を作り出したのである。

第三に、集団の形成は、権力と地位を独占しようとする衝動から生じた。これは当時の一般的な自然主義的信念に反するものであり、民族間の社会文化的・行動

的差異は、当時「人種」と呼ばれていた共通の家系に由来する遺伝的形質や傾向から生じているとした[31]。 |

| Another influential theoretician

of ethnicity was Fredrik Barth, whose "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries"

from 1969 has been described as instrumental in spreading the usage of

the term in social studies in the 1980s and 1990s.[32] Barth went

further than Weber in stressing the constructed nature of ethnicity. To

Barth, ethnicity was perpetually negotiated and renegotiated by both

external ascription and internal self-identification. Barth's view is

that ethnic groups are not discontinuous cultural isolates or logical a

priori to which people naturally belong. He wanted to part with

anthropological notions of cultures as bounded entities, and ethnicity

as primordialist bonds, replacing it with a focus on the interface

between groups. "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries", therefore, is a focus

on the interconnectedness of ethnic identities. Barth writes: "...

categorical ethnic distinctions do not depend on an absence of

mobility, contact, and information, but do entail social processes of

exclusion and incorporation whereby discrete categories are maintained

despite changing participation and membership in the course of

individual life histories."[citation needed] |

エスニシティのもう一人の影響力のある理論家はフレドリック・バルトで

あり、彼の1969年の『民族集団と境界』は1980年代と1990年代の社会学に

おけるこの用語の普及に貢献したと評されている。バルトにとって、エスニシティは外的な帰属と内的な自己同一化の両方によって永続的に交渉され、再交渉さ

れるものであった。バルトの見解は、民族集団は非連続的な文化的孤立でもなければ、人々が自然に属する論理的先験的なものでもないというものである。バル

トは、境界を持つ実体としての文化や、原初的な絆としてのエスニシティといった人類学的な概念と決別し、グループ間の接点に焦点を当てることに置き換えた

かったのである。「エスニック・グループと境界」は、エスニック・アイデンティティの相互関連性に焦点を当てたものである。バースは次のように書いてい

る:「......カテゴライズされた民族的区別は、移動、接触、情報の不在に依存するものではなく、個人の生活史の過程で参加やメンバーシップが変化す

るにもかかわらず、個別のカテゴリーが維持される排除と取り込みの社会的プロセスを伴うものである」[要出典]。 |

| In 1978, anthropologist Ronald

Cohen claimed that the identification of "ethnic groups" in the usage

of social scientists often reflected inaccurate labels more than

indigenous realities: |

1978年、人類学者のロナルド・コーエンは、社会科学者が使用する「民族グループ」の識別は、土着の現実よりも不正確なラベルを反映していることが多いと主張した: |

| ... the named ethnic identities

we accept, often unthinkingly, as basic givens in the literature are

often arbitrarily, or even worse inaccurately, imposed.[32] |

......私たちが、しばしば無思慮に、文献の中で基本的な与件として受け入れている民族的アイデンティティという名前は、しばしば恣意的に、あるいはさらに悪いことに不正確に押し付けられているのである」[32]。 |

| In this way, he pointed to the

fact that identification of an ethnic group by outsiders, e.g.

anthropologists, may not coincide with the self-identification of the

members of that group. He also described that in the first decades of

usage, the term ethnicity had often been used in lieu of older terms

such as "cultural" or "tribal" when referring to smaller groups with

shared cultural systems and shared heritage, but that "ethnicity" had

the added value of being able to describe the commonalities between

systems of group identity in both tribal and modern societies. Cohen

also suggested that claims concerning "ethnic" identity (like earlier

claims concerning "tribal" identity) are often colonialist practices

and effects of the relations between colonized peoples and

nation-states.[32] |

このようにして、彼は、人類学者などの部外者による民族集団の識別が、

その集団の構成員の自認と一致しない場合があるという事実を指摘した。また、エスニ

シティという用語が使われ始めた最初の数十年間は、文化システムを共有し、遺産を共有する小集団を指す場合、「文化的」や「部族的」といった古い用語の代

わりに使われることが多かったが、「エスニシティ」には、部族社会と現代社会の両方における集団アイデンティティのシステム間の共通性を記述できるという

付加価値があると述べた。コーエンはまた、「エスニック」アイデンティティに関する主張は(以前の「部族的」アイデンティティに関する主張と同様に)しば

しば植民地主義的な実践であり、植民地化された民族と国民国家との関係の影響であることを示唆していた[32]。 |

| According to Paul James,

formations of identity were often changed and distorted by

colonization, but identities are not made out of nothing: |

ポール・ジェイムズによれば、アイデンティティの形成はしばしば植民地化によって変化し歪められたが、アイデンティティは無から作られるものではない: |

| Categorizations about identity,

even when codified and hardened into clear typologies by processes of

colonization, state formation or general modernizing processes, are

always full of tensions and contradictions. Sometimes these

contradictions are destructive, but they can also be creative and

positive.[33] |

アイデンティティに関するカテゴライゼーションは、植民地化、国家形

成、あるいは一般的な近代化のプロセスによって明確な類型に体系化され、固められたと

しても、常に緊張と矛盾に満ちている。こうした矛盾が破壊的であることもあるが、創造的で肯定的であることもある[33]。 |

| Social scientists have thus

focused on how, when, and why different markers of ethnic identity

become salient. Thus, anthropologist Joan Vincent observed that ethnic

boundaries often have a mercurial character.[34] Ronald Cohen concluded

that ethnicity is "a series of nesting dichotomizations of

inclusiveness and exclusiveness".[32] He agrees with Joan Vincent's

observation that (in Cohen's paraphrase) "Ethnicity ... can be narrowed

or broadened in boundary terms in relation to the specific needs of

political mobilization.[32] This may be why descent is sometimes a

marker of ethnicity, and sometimes not: which diacritic of ethnicity is

salient depends on whether people are scaling ethnic boundaries up or

down, and whether they are scaling them up or down depends generally on

the political situation. |

したがって、社会科学者は、民族のアイデンティティを示すさまざまな

マーカーが、いつ、どのように、そしてなぜ顕著になるかに焦点を当ててきた。人類学者のジョアン・ヴィンセントは、民族境界はしばしば流動的な性格を持つ

と指摘している。[34] ロナルド・コーエンは、民族性は「包含性と排他性の二分法の入れ子構造」であると結論付けている。[32]

彼はジョアン・ヴィンセントの観察に同意し(コーエンの要約によると)、「民族性は、政治的動員における特定のニーズに応じて、境界の観点から狭めたり広

げたりすることができる」と述べている。[32]

これが、血統が民族性のマーカーとなる場合とそうでない場合がある理由かもしれない。どの民族性の特徴が顕著になるかは、人々が民族の境界を拡大するか縮

小するかによって決まり、境界を拡大するか縮小するかは、一般的に政治情勢によって決まる。 |

| Kanchan Chandra rejects the

expansive definitions of ethnic identity (such as those that include

common culture, common language, common history and common territory),

choosing instead to define ethnic identity narrowly as a subset of

identity categories determined by the belief of common descent.[35]

Jóhanna Birnir similarly defines ethnicity as "group

self-identification around a characteristic that is very difficult or

even impossible to change, such as language, race, or location."[36] |

カンチャン・チャンドラはエスニック・アイデンティティの拡大的な定義

(共通の文化、共通の言語、共通の歴史、共通の領土を含むものなど)を否定し、代わ

りにエスニック・アイデンティティを共通の血統という信念によって決定されるアイデンティティ・カテゴリーのサブセットとして狭く定義することを選択した

[35]。

ジョーハンナ・ビルニルも同様にエスニシティを「言語、人種、場所など、変えることが非常に困難であるか不可能でさえある特徴をめぐる集団の自己同一化」

と定義している[36]。 |

| Approaches to understanding ethnicity |

エスニシティを理解するためのアプローチ |

| Different approaches to

understanding ethnicity have been used by different social scientists

when trying to understand the nature of ethnicity as a factor in human

life and society. As Jonathan M. Hall observes, World War II was a

turning point in ethnic studies. The consequences of Nazi racism

discouraged essentialist interpretations of ethnic groups and race.

Ethnic groups came to be defined as social rather than biological

entities. Their coherence was attributed to shared myths, descent,

kinship, a commonplace of origin, language, religion, customs, and

national character. So, ethnic groups are conceived as mutable rather

than stable, constructed in discursive practices rather than written in

the genes.[37] |

エスニシティを理解するためのさまざまなアプローチが、人間の生活や社

会における要因としてのエスニシティの本質を理解しようとする際に、さまざまな社会

科学者によって用いられてきた。ジョナサン・M・ホールが観察するように、第二次世界大戦はエスニシティ研究の転換点であった。ナチスによる人種差別の結

果、民族集団と人種に関する本質主義的な解釈は否定された。民族集団は、生物学的な存在というよりも、むしろ社会的な存在として定義されるようになった。

その首尾一貫性は、神話、家系、親族関係、出身地の共有、言語、宗教、慣習、国民性などに起因する。そのため、民族集団は安定的というよりもむしろ変幻自

在であり、遺伝子に書き込まれるよりもむしろ言説的実践のなかで構築されるものと考えられている[37]。 |

| Examples of various approaches are primordialism, essentialism, perennialism, constructivism, modernism, and instrumentalism. |

様々なアプローチの例として、原初主義、本質主義、永続主義、構成主義、近代主義、道具主義が挙げられる。 |

| "Primordialism", holds that

ethnicity has existed at all times of human history and that modern

ethnic groups have historical continuity into the far past. For them,

the idea of ethnicity is closely linked to the idea of nations and is

rooted in the pre-Weber understanding of humanity as being divided into

primordially existing groups rooted by kinship and biological heritage. |

「原初主義」は、エスニシティは人類史のあらゆる時代に存在しており、

現代のエスニック集団は遥か過去へと歴史的に連続しているとする。彼らにとって、エ

スニシティという考え方は国家という考え方と密接に結びついており、人類は親族関係や生物学的遺産に根ざした原初的に存在する集団に分かれているという

ウェーバー以前の理解に根ざしている。 |

| "Essentialist primordialism"

further holds that ethnicity is an a priori fact of human existence,

that ethnicity precedes any human social interaction and that it is

unchanged by it. This theory sees ethnic groups as natural, not just as

historical. It also has problems dealing with the consequences of

intermarriage, migration and colonization for the composition of

modern-day multi-ethnic societies.[38] |

「本質主義的原初主義」はさらに、エスニシティは人間存在の先験的な事

実であり、エスニシティは人間の社会的相互作用に先行し、それによって不変であると

する。この理論は、民族集団を歴史的なものとしてだけでなく、自然なものとして捉える。また、現代の多民族社会の構成における異種婚姻、移住、植民地化の

結果への対処にも問題がある[38]。 |

| "Kinship primordialism" holds

that ethnic communities are extensions of kinship units, basically

being derived by kinship or clan ties where the choices of cultural

signs (language, religion, traditions) are made exactly to show this

biological affinity. In this way, the myths of common biological

ancestry that are a defining feature of ethnic communities are to be

understood as representing actual biological history. A problem with

this view on ethnicity is that it is more often than not the case that

mythic origins of specific ethnic groups directly contradict the known

biological history of an ethnic community.[38] |

「親族原初主義」は、民族共同体は親族単位の延長であり、基本的には親

族や氏族の結びつきによって派生し、文化的標識(言語、宗教、伝統)の選択はまさに

この生物学的親和性を示すためになされるとする。このように、民族共同体の特徴である共通の生物学的祖先の神話は、実際の生物学的歴史を表していると理解

される。エスニシティに関するこの見解の問題点は、特定のエスニック集団の神話的起源が、エスニック共同体の既知の生物学的歴史と真っ向から矛盾している

ことが往々にしてあるということである[38]。 |

| "Geertz's primordialism",

notably espoused by anthropologist Clifford Geertz, argues that humans

in general attribute an overwhelming power to primordial human "givens"

such as blood ties, language, territory, and cultural differences. In

Geertz' opinion, ethnicity is not in itself primordial but humans

perceive it as such because it is embedded in their experience of the

world.[38] |

人類学者クリフォード・ギアーツが提唱した

"ギアーツの原初主義(プリモーディアリズム) "は、一般的に人間は血のつながり、言語、領土、文化の違いといった人間の原初的な "与件

"に圧倒的な力を帰結させると主張している。ギアーツの意見では、民族性それ自体は根源的なものではないが、人間はそれが世界の経験に埋め込まれているた

め、そのように認識している[38]。 |

| "Perennialism", an approach that

is primarily concerned with nationhood but tends to see nations and

ethnic communities as basically the same phenomenon holds that the

nation, as a type of social and political organization, is of an

immemorial or "perennial" character.[39] Smith (1999) distinguishes two

variants: "continuous perennialism", which claims that particular

nations have existed for very long periods, and "recurrent

perennialism", which focuses on the emergence, dissolution and

reappearance of nations as a recurring aspect of human history.[40] |

「多年生主義」は、主に国民性に関わるアプローチであるが、国家と民族

共同体を基本的に同じ現象として捉える傾向があり、社会的・政治的組織の一種である

国家は、太古のもの、あるいは「多年生」の性格を有していると考えている[39]:

特定の国家が非常に長い期間にわたって存在してきたと主張する「継続的通年主義」と、人類史の反復的な側面としての国家の出現、解散、再出現に焦点を当て

る「反復的通年主義」である[40]。 |

| "Perpetual perennialism" holds that specific ethnic groups have existed continuously throughout history. |

「永続的通年主義」は、特定の民族集団が歴史を通じて継続的に存在してきたとするものである。 |

| "Situational perennialism" holds

that nations and ethnic groups emerge, change and vanish through the

course of history. This view holds that the concept of ethnicity is a

tool used by political groups to manipulate resources such as wealth,

power, territory or status in their particular groups' interests.

Accordingly, ethnicity emerges when it is relevant as a means of

furthering emergent collective interests and changes according to

political changes in society. Examples of a perennialist interpretation

of ethnicity are also found in Barth and Seidner who see ethnicity as

ever-changing boundaries between groups of people established through

ongoing social negotiation and interaction. |

「状況的永続主義」は、国家や民族集団は歴史の過程で出現し、変化し、

消滅するとする。この考え方は、エスニシティという概念は、政治集団が富、権力、領

土、地位などの資源を特定の集団の利益のために操作するための道具であるとする。従って、エスニシティは、出現した集団的利益を促進する手段として関連性

があるときに出現し、社会の政治的変化に応じて変化する。エスニシティの通年主義的解釈の例は、エスニシティを継続的な社会的交渉と相互作用を通じて確立

された、絶えず変化する集団間の境界とみなすバースやザイドナーにも見られる。 |

| "Instrumentalist perennialism",

while seeing ethnicity primarily as a versatile tool that identified

different ethnics groups and limits through time, explains ethnicity as

a mechanism of social stratification, meaning that ethnicity is the

basis for a hierarchical arrangement of individuals. According to

Donald Noel, a sociologist who developed a theory on the origin of

ethnic stratification, ethnic stratification is a "system of

stratification wherein some relatively fixed group membership (e.g.,

race, religion, or nationality) is used as a major criterion for

assigning social positions".[41] Ethnic stratification is one of many

different types of social stratification, including stratification

based on socio-economic status, race, or gender. According to Donald

Noel, ethnic stratification will emerge only when specific ethnic

groups are brought into contact with one another, and only when those

groups are characterized by a high degree of ethnocentrism,

competition, and differential power. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to

look at the world primarily from the perspective of one's own culture,

and to downgrade all other groups outside one's own culture. Some

sociologists, such as Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings, say the

origin of ethnic stratification lies in individual dispositions of

ethnic prejudice, which relates to the theory of ethnocentrism.[42]

Continuing with Noel's theory, some degree of differential power must

be present for the emergence of ethnic stratification. In other words,

an inequality of power among ethnic groups means "they are of such

unequal power that one is able to impose its will upon another".[41] In

addition to differential power, a degree of competition structured

along ethnic lines is a prerequisite to ethnic stratification as well.

The different ethnic groups must be competing for some common goal,

such as power or influence, or a material interest, such as wealth or

territory. Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings propose that competition

is driven by self-interest and hostility, and results in inevitable

stratification and conflict.[42] |

「道具主義的永続主義」は、エスニシティを主に、時代を通じて異なる民

族集団と限界を識別する汎用性のある道具とみなす一方で、エスニシティを社会階層化

のメカニズム、つまりエスニシティが個人の階層的配置の基礎となっていると説明している。民族的階層化の起源に関する理論を構築した社会学者ドナルド・ノ

エルによれば、民族的階層化とは「ある比較的固定された集団の構成員(例えば、人種、宗教、国籍)が、社会的地位を割り当てるための主要な基準として使用

される階層化のシステム」である[41]。ドナルド・ノエルによれば、エスニック階層化は、特定のエスニック集団が互いに接触し、それらの集団が高度なエ

スノセントリズム、競争、権力の差を特徴とする場合にのみ出現する。エスノセントリズムとは、主に自文化の視点から世界を見ようとする傾向のことであり、

自文化の外にある他のすべての集団を見下そうとするものである。ローレンス・ボボやヴィンセント・ハッチングスのような一部の社会学者は、民族階層化の起

源は民族的偏見という個人の気質にあると述べており、これはエスノセントリズムの理論に関連している[42]。ノエルの理論を続けると、民族階層化が出現

するためには、ある程度の力の差が存在しなければならない。言い換えれば、民族集団間の力の不平等とは、「一方が他方に対してその意志を押しつけることが

できるような不平等な力をもっている」ことを意味する[41]。力の差に加えて、民族的な線に沿って構造化された競争の程度も民族階層化の前提条件であ

る。異なる民族集団は、権力や影響力といった共通の目標、あるいは富や領土といった物質的利益のために競争しなければならない。ローレンス・ボボとヴィン

セント・ハッチングスは、競争は利己心と敵意によって引き起こされ、必然的に階層化と紛争をもたらすと提唱している[42]。 |

| "Constructivism" sees both

primordialist and perennialist views as basically flawed,[42] and

rejects the notion of ethnicity as a basic human condition. It holds

that ethnic groups are only products of human social interaction,

maintained only in so far as they are maintained as valid social

constructs in societies. |

「構成主義」は、原初主義的な見解と永続主義的な見解の双方に基本的な

欠陥があるとみなしており[42]、人間の基本的条件としての民族性の概念を否定し

ている。民族集団は人間の社会的相互作用の産物にすぎず、社会における有効な社会構成物として維持されている限りにおいてのみ維持されているとする。 |

| "Modernist constructivism"

correlates the emergence of ethnicity with the movement towards nation

states beginning in the early modern period.[43] Proponents of this

theory, such as Eric Hobsbawm, argue that ethnicity and notions of

ethnic pride, such as nationalism, are purely modern inventions,

appearing only in the modern period of world history. They hold that

prior to this ethnic homogeneity was not considered an ideal or

necessary factor in the forging of large-scale societies. Ethnicity is an important means by which people may identify with a larger group. Many social scientists, such as anthropologists Fredrik Barth and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human groups.[21] The process that results in emergence of such identification is called ethnogenesis. Members of an ethnic group, on the whole, claim cultural continuities over time, although historians and cultural anthropologists have documented that many of the values, practices, and norms that imply continuity with the past are of relatively recent invention.[44][45] |

「モダニズム構成主義」は、民族性の出現を、近世初期に始まった国民国

家への動きと関連付けています[43]。エリック・ホブズボームなどのこの理論の支持者は、民族性やナショナリズムなどの民族的誇りの概念は、世界史の近

代にのみ出現した純粋に近代的な発明であると主張しています。彼らは、それ以前は、民族の均質性は、大規模な社会を構築する上で理想的な要素や必要な要素

とは考えられていなかったと主張しています。 民族性は、人々がより大きな集団に帰属意識を持つための重要な手段です。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフなど、多くの社会科学者は、民 族的アイデンティティを普遍的なものとは考えていません。彼らは、民族性を、人間集団に固有の性質ではなく、特定の種類の集団間の相互作用の産物であると 考えています[21]。このようなアイデンティティの形成に至る過程は、民族形成と呼ばれています。民族集団の成員は、全体として時間的な文化的連続性を 主張するが、歴史学者や文化人類学者は、過去との連続性を暗示する多くの価値観、実践、規範が比較的最近に発明されたものであることを記録している。 [44][45] |

| Ethnic groups can form a

cultural mosaic in a society. That could be in a city like New York

City or Trieste, but also the fallen monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire or the United States. Current topics are in particular social

and cultural differentiation, multilingualism, competing identity

offers, multiple cultural identities and the formation of Salad bowl

and melting pot.[46][47][48][49] Ethnic groups differ from other social

groups, such as subcultures, interest groups or social classes, because

they emerge and change over historical periods (centuries) in a process

known as ethnogenesis, a period of several generations of endogamy

resulting in common ancestry (which is then sometimes cast in terms of

a mythological narrative of a founding figure); ethnic identity is

reinforced by reference to "boundary markers" – characteristics said to

be unique to the group which set it apart from other

groups.[50][51][52][53][54][55] |

民族グループは、社会の中で文化のモザイクを形成することがあります。

それは、ニューヨークやトリエステのような都市でも、オーストリア・ハンガリー帝国やアメリカ合衆国のような崩壊した君主制でも起こり得ます。現在の話題

としては、特に社会的・文化的差別化、多言語主義、競合するアイデンティティの提示、複数の文化的アイデンティティ、サラダボウルとメルティングポットの

形成などが挙げられます。[46][47][48][49]

民族グループは、サブカルチャー、利益団体、社会階級などの他の社会集団とは、以下の点で異なる。民族グループは、民族形成と呼ばれる、数世代にわたる同

族結婚によって共通の祖先が生まれる過程を経て、歴史的期間(数世紀)にわたって出現し、変化していく。民族的アイデンティティは、「境界マーカー」と呼

ばれる、その集団に特有で他の集団と区別する特徴への言及によって強化される。[50][51][52][53][54][55] |

| Ethnicity theory in the United States |

アメリカにおけるエスニシティ論 |

| Ethnicity theory argues that race is a social category and is only one of several factors in determining ethnicity. Other criteria include "religion, language, 'customs', nationality, and political identification".[56] This theory was put forward by sociologist Robert E. Park in the 1920s. It is based on the notion of "culture". | 民族性理論は、人種は社会的カテゴリーであり、民族性を決定するいくつかの要因のうちの1つにすぎない、と主張している。その他の基準としては、「宗教、 言語、「慣習」、国籍、政治的アイデンティティ」などが挙げられる[56]。この理論は、1920年代に社会学者ロバート・E・パークによって提唱され た。これは「文化」という概念に基づいている。 |

| This theory was preceded by more

than 100 years during which biological essentialism was the dominant

paradigm on race. Biological essentialism is the belief that some

races, specifically white Europeans in western versions of the

paradigm, are biologically superior and other races, specifically

non-white races in western debates, are inherently inferior. This view

arose as a way to justify enslavement of African Americans and genocide

of Native Americans in a society that was officially founded on freedom

for all. This was a notion that developed slowly and came to be a

preoccupation with scientists, theologians, and the public. Religious

institutions asked questions about whether there had been multiple

creations of races (polygenesis) and whether God had created lesser

races. Many of the foremost scientists of the time took up the idea of

racial difference and found that white Europeans were superior.[57] |

この理論に先立つこと100年以上、生物学的本質主義が人種に関する支

配的なパラダイムであった。生物学的本質主義とは、一部の人種、特に西洋のパラダイ

ムでは白人ヨーロッパ人は生物学的に優れており、他の人種、特に西洋の議論では非白人人種は本質的に劣っているという信念である。この考え方は、万人の自

由を建前とする社会の中で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷化やアメリカ先住民の大量虐殺を正当化する方法として生まれた。この考え方は徐々に発展し、科学

者、神学者、そして一般の人々の関心を集めるようになった。宗教団体は、複数の人種の創造(ポリジェネシス)があったのかどうか、神はより劣った人種を創

造したのかどうかという疑問を投げかけた。当時の一流の科学者の多くが人種の違いという考えを取り上げ、ヨーロッパ白人が優れていることを発見した

[57]。 |

| The ethnicity theory was based

on the assimilation model. Park outlined four steps to assimilation:

contact, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation. Instead of

attributing the marginalized status of people of color in the United

States to their inherent biological inferiority, he attributed it to

their failure to assimilate into American culture. They could become

equal if they abandoned their inferior cultures. |

エスニシティ理論は同化モデルに基づいていた。パークは同化のための4

つの段階、すなわち接触、衝突、融和、同化を概説した。彼は、アメリカにおける有色

人種の疎外された地位を、彼らの先天的な生物学的劣等性に帰するのではなく、彼らがアメリカ文化に同化できなかったことに帰した。劣った文化を捨てれば、

彼らは平等になれるのだ。 |

| Michael Omi and Howard Winant's

theory of racial formation directly confronts both the premises and the

practices of ethnicity theory. They argue in Racial Formation in the

United States that the ethnicity theory was exclusively based on the

immigration patterns of the white population and did take into account

the unique experiences of non-whites in the United States.[58] While

Park's theory identified different stages in the immigration process –

contact, conflict, struggle, and as the last and best response,

assimilation – it did so only for white communities.[58] The ethnicity

paradigm neglected the ways in which race can complicate a community's

interactions with social and political structures, especially upon

contact. |

マイケル・オミとハワード・ワイナントの人種形成論は、エスニシティ論

の前提にも実践にも真っ向から対立している。彼らは『アメリカにおける人種形成』 (Racial Formation in the United

States)の中で、エスニシティ理論はもっぱら白人集団の移民パターンに基づいており、アメリカにおける非白人のユニークな経験を考慮していなかった

と論じている[58]。

パークの理論は移民プロセスにおけるさまざまな段階(接触、葛藤、闘争、そして最後にして最良の対応としての同化)を特定していたが、それは白人コミュニ

ティについてのみそうしていた[58]。エスニシティ・パラダイムは、人種がコミュニティと社会的・政治的構造との相互作用を複雑にする方法を、特に接触

時に軽視していた。 |

| Assimilation – shedding the

particular qualities of a native culture for the purpose of blending in

with a host culture – did not work for some groups as a response to

racism and discrimination, though it did for others.[58] Once the legal

barriers to achieving equality had been dismantled, the problem of

racism became the sole responsibility of already disadvantaged

communities.[59] It was assumed that if a Black or Latino community was

not "making it" by the standards that had been set by whites, it was

because that community did not hold the right values or beliefs, or

were stubbornly resisting dominant norms because they did not want to

fit in. Omi and Winant's critique of ethnicity theory explains how

looking to cultural defect as the source of inequality ignores the

"concrete sociopolitical dynamics within which racial phenomena operate

in the U.S."[60] It prevents critical examination of the structural

components of racism and encourages a "benign neglect" of social

inequality.[60] |

同化、つまり受け入れ側の文化に溶け込むために固有の文化の特質を捨て

去ることは、人種差別や差別への対応として、ある集団にとっては機能しなかったが、

他の集団にとっては機能した[58]。平等を達成するための法的障壁が解体されると、人種差別の問題はすでに不利な立場に置かれているコミュニティだけの

責任となった。

[黒人やラテン系のコミュニティが白人によって設定された基準によって「成功」していない場合、それはそのコミュニティが正しい価値観や信念を持っていな

いか、あるいは自分たちがなじむことを望んでいないために支配的な規範に頑なに抵抗しているためであると考えられた。エスニシティ理論に対する近江とワイ

ナントの批判は、不平等の根源として文化的欠陥に注目することが、いかに「人種現象が米国で作用している具体的な社会政治的力学」を無視しているかを説明

している[60]。それは人種差別の構造的構成要素に対する批判的な検討を妨げ、社会的不平等に対する「良性の無視」を助長している[60]。 |

| Ancestor Diaspora Ethnic cleansing Ethnic interest group Ethnic flag Ethnic penalty Ethnocultural empathy Ethnocide Ethnographic group Genealogy Genetic genealogy Human Genome Diversity Project Identity politics Ingroups and outgroups Intersectionality List of contemporary ethnic groups List of countries by ethnic groups List of Indigenous peoples Meta-ethnicity Minzu (anthropology) National symbol Passing (sociology) Polyethnicity Population genetics Race and ethnicity in censuses Race and ethnicity in the United States census Race and health Stateless nation Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world |

祖先 ディアスポラ 民族浄化 民族利益団体 民族旗 民族差別 民族文化の共感 民族虐殺 民族誌的グループ 系図 遺伝的系図 ヒトゲノム多様性プロジェクト アイデンティティ政治 イングループとアウトグループ 交差性 現代民族グループの一覧 民族グループ別国の一覧 先住民の一覧 メタエスニシティ Minzu (人類学) 国家の象徴 パッシング(社会学 多民族性 集団遺伝学 国勢調査における人種と民族 アメリカ合衆国国勢調査における人種と民族 人種と保健 無国籍国民 世界の人口の Y 染色体ハプログループ |

| Sources Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Omi, Michael; Winant, Howard (1986). Racial Formation in the United States from the 1960s to the 1980s. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Inc. Smith, Anthony D. (1999). Myths and memories of the Nation. Oxford University Press. |

出典 Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. オミ、マイケル、ウィナント、ハワード (1986)。1960年代から1980年代にかけてのアメリカ合衆国の人種形成。ニューヨーク:Routledge and Kegan Paul, Inc. スミス、アンソニー D. (1999)。国民の神話と記憶。オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Further reading Barth, Fredrik (ed). Ethnic groups and boundaries. The social organization of culture difference, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1969 Billinger, Michael S. (2007), "Another Look at Ethnicity as a Biological Concept: Moving Anthropology Beyond the Race Concept" Archived 9 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Critique of Anthropology 27, 1:5–35. Craig, Gary, et al., eds. Understanding 'race' and ethnicity: theory, history, policy, practice (Policy Press, 2012) Danver, Steven L. Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues (2012) Eriksen, Thomas Hylland (1993) Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives, London: Pluto Press Eysenck, H.J., Race, Education and Intelligence (London: Temple Smith, 1971) (ISBN 0851170099) Healey, Joseph F., and Eileen O'Brien. Race, ethnicity, gender, and class: The sociology of group conflict and change (Sage Publications, 2014) Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, editors, The Invention of Tradition. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). Kappeler, Andreas. The Russian empire: A multi-ethnic history (Routledge, 2014) Levinson, David, Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group (1998), ISBN 978-1573560191. Magocsi, Paul Robert, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1999) Morales-Díaz, Enrique; Gabriel Aquino; & Michael Sletcher, "Ethnicity", in Michael Sletcher, ed., New England, (Westport, CT, 2004) Seeger, A. 1987. Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Sider, Gerald, Lumbee Indian Histories (Cambridge University Press, 1993). Smith, Anthony D. (1987). The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Blackwell. Smith, Anthony D. (1998). Nationalism and modernism. A Critical Survey of Recent Theories of Nations and Nationalism. Routledge. Steele, Liza G.; Bostic, Amie; Lynch, Scott M.; Abdelaaty, Lamis (2022). "Measuring Ethnic Diversity". Annual Review of Sociology. 48 (1). Thernstrom, Stephan A. ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1981) ^ U.S. Census Bureau State & County QuickFacts: Race. |

さらに詳しく読む Barth, Fredrik (ed). Ethnic groups and boundaries. The social organization of culture difference, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1969 Billinger, Michael S. (2007), 「生物学的概念としての民族性に関する別の見方:人種概念を超えた人類学」 2009年7月9日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、Critique of Anthropology 27、1:5–35。 クレイグ、ゲイリーほか、編。人種と民族性を理解する:理論、歴史、政策、実践(Policy Press、2012年 ダンバー、スティーブン L. 世界の先住民:集団、文化、現代の問題に関する百科事典 (2012) エリクセン、トーマス・ヒランド (1993) 『民族性とナショナリズム:人類学的視点』 ロンドン:Pluto Press アイゼンク、H.J.、『人種、教育、知能』 (ロンドン:テンプル・スミス、1971) (ISBN 0851170099) ヒーリー、ジョセフ F.、およびアイリーン・オブライエン。人種、民族、性別、および階級:集団の対立と変化の社会学(Sage Publications、2014 年) ホブズボーム、エリック、およびテレンス・レンジャー、編集者、伝統の発明。(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1983 年)。 カペラー、アンドレアス。ロシア帝国:多民族の歴史(Routledge、2014年 レヴィンソン、デビッド、世界各国の民族グループ:すぐに使えるハンドブック、グリーンウッド出版グループ(1998年)、ISBN 978-1573560191。 マゴチ、ポール・ロバート、編。カナダの人々の百科事典 (1999) Morales-Díaz, Enrique; Gabriel Aquino; & Michael Sletcher, 「Ethnicity」, in Michael Sletcher, ed., New England, (Westport, CT, 2004) Seeger, A. 1987. Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. サイダー、ジェラルド、ルムビー・インディアン史(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1993年)。 スミス、アンソニー・D.(1987)。『The Ethnic Origins of Nations(国民の民族的起源)』。ブラックウェル。 スミス、アンソニー・D.(1998)。『ナショナリズムとモダニズム。国民とナショナリズムに関する最近の理論の批判的調査』。ラウトレッジ。 スティール、ライザ G.、ボスティック、アミ、リンチ、スコット M.、アブデラティ、ラミス (2022)。「民族の多様性の測定」。社会学年報。48 (1)。 サーンストローム、ステファン A. 編。ハーバード・アメリカ民族グループ事典 (1981) ^ 米国国勢調査局州および郡のクイックファクト:人種。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnicity |

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆