民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッ セー

Essays on

Ethnicity, Ethnic Groups, and Ethnicity

民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッ セー

Essays on

Ethnicity, Ethnic Groups, and Ethnicity

解説:池田 光穂 仮想・医療人類学・辞典

民族ないしは民族集団(ethnic group)とは、文化(言語、習慣、宗教など)で区分される集団のことである。

集団を区分する境界は、歴史的にも社会的にも変化し、また、民族集団が自己の集団から定義される 場合と、国家や他の民族集団と定義される場合にも齟齬があることから、民族集団は固定的で、永続的なものではない。

ただし、近代国家制度の中では、さまざまな政治経済的あるいは法的な要因で、民族集団としての独 自性が一定の権利をもって保証される必要性がある。その際には、民族集団としての文化的尊厳は尊重されなければならない対象になる。

■エスニシティ(ethnicity)は、民族集団から派生した用語で、民族の(ethnic)という形容詞の名詞形から、それ自体で民族=民族集団の意味

をもつ。

■エトニー(ethnie)とはアンソニー・スミス(1982) らの独自的な使い方で、前近代の民族——つまり本源主義な (primordialists)的な意味での——集団を措定しているが、これは自己評価と他者評価においてとりわけ著しい齟齬のない民族集団であると理 解してよい。

***

■部族:民族集団と同義ないしは、その下位集団ともみなされるが部族(ぶぞく, tribe)も、しばしばもちいられる。英語のトライブの翻訳語である部族は、大英帝国の植民地ではしばしばよく用いられてきた。部族集団(tribal group)ともいわれる。エスニック・グループ(=民族集団)とエスニシティの関係のように、トライバル・グループは具体的な民族(=文化や言語を共有 する集団)を、トライブは、その集団という抽象ないしは一般概念という意味で使われるこ とがある[→部族,強い文化概 念としての部族]

日本語の民族(minzoku)に相当する欧米語にはつぎのようなものがある(井 上 1987:749-50)。

★英語:people, ethnic group, ethnicity, nation

★ドイツ語:Volk, Ethnos, Nation

★フランス語:peuple, ethnie, nation

日本語においては、民族という言葉は専門用語というよりは一般的な言葉であり、後者はきわめて多 様である。これが民族を研究対象とすることの多い文化人類学者にとって頭痛のたねである。この説明の下の部分にある[人種概念としての「ミンゾク」]を参照にしてください。

【文化人類学における民族の定義】

文化人類学・民族学者による古典的な民族とは、ある土地に集団を形成する人びとのことであった。 これは、文化人類学の研究対象が、もともと先住民族つまり「土着の人」たちであり、形成期の文化人類学者の出身であった「西洋からきた文明国の人びと」で はなく、土地に張りつき、土着の固有の言語と文化を保持している人びとであったことに由来する。それゆえ、文化人類学者は、非西洋で、なるべく文明に接触 したことのない、固有の文化をもつ(文化人類学者たちが考える)人びと、つまり土着の集団を捜そうとしてきたし、それが民族だと考えていた。

やがて(実際には言語の混交や交流があるにも関わらず)言語の独自性が民族集団を弁別する特徴と みなされるようになった。つまり、独立した言語集団と、ある言語グループにおける方言集団を分ける見方である。にもかかわらず、他方で言語が異なっても、 ある広域的な土地においては、文化的慣習が類似のものがあり、文化による弁別が、別の民族集団を峻別する指標にも採用された。もちろん、集団は婚姻によっ て再生産の基礎をおくので、婚姻のルールもまた民族集団の特徴として採用される。そして、それにより生物学的な集団的特性——つまり人種的特徴——もま た、民族集団との関連性があるとも考えられた。これらの特徴を累積すると、膨大な分類体系ができあがることは想像に難くない。植民地時代後期には、このよ うな民族集団の多様なリストができあがり、一種のバロック的とも言える状態を形成していた(cf. ベネディクト・アンダーソン『想像の共同体』1991年版、第10章「セン サス・地図・博物館」を参照)。

現在の人類学者の多く理解するする民族概念とは、民族集団(ethnic group)のことであると言ってよいだろう。民族集団は現在ではフレデリック・バース『民族諸集団と境界』(1969)が与えた定義であるところの、自 他共に承認された帰属意識が作用する場(容器)のことである【民族境界論の解説へリンク】。人 間のグループの概念範疇であるはずの民族集団が、場や容器といった空間的表象であらわされているのは、民族が特定の空間(物理空間のみならず象徴空間や意 味空間なども包摂する空間)との結びつきがつよいためである。また場や容器への帰属意識と、その境界を維持するということは表裏一体となるので、この民族 集団のモデルは、基本的に他の民族に空間的に排他的であり、常に境界をつくりあげることで帰属意識の安定をはかっていることになる。

ところが、人間の集団一般には、このような民族集団のモデルに完全に合致しないものも少なくな く、また帰属意識や境界も歴史的にみれば動態的に変化している。文化人類学の専門家の中には、このモデルを批判したり、より詳しい修正モデルを提案するも のもおり、またそれについての議論も多い。

このようにみると、文化人類学における民族概念は、ある土地にはりつく集団(=それにより本物の 民族がどうかを識別できる)から、民族意識を共有する人たち(=民族集団であるかどうかは生活を観察するだけでなく、本人たちに「あなたは何人なのか」と いう問いかけをおこなわないとならない)というふうに、長期的に変化してきたことがわかる。つまり、文化人類学者たちによる民族集団の定義は、民族が確固 とした集団だという意識(これを本質主義的理解という)から、民族は帰属アイデンティティにより規定されるダイナミックな過程にあると考えられるように なってきた(エドマンド・リーチ『高地ビルマの政治体系』を読めば、カチンと呼ばれている人たちがこのダイナミズムの中に生 きている集団であること、つま りカチンであることは固有の属性ではなく、カチンという生き方そのものであることが、見事に論述されている——これは実際のカチンがそう意識するかどうか とは別の議論ではあるのだが……)。

【近代日本における「民族」概念の変遷】

近代日本における民族の概念は、柳田國男による雑誌『民族』(1925)の発刊の以前と以後にわ けてみるとわかりやすい。

人種概念としての「ミンゾ ク」、ネーション(国民)としての日本民族

1925年以前には、志賀重昴(1863-1927)、三宅雪嶺(1860-1945)、徳 富蘇峰(1863-1957)などが「我等大和民族」などと使い、ナショナリズム的文脈で、他者と区別する際に使っていた。

つまり、この文脈で使われる「民族」(特にヤマトミンゾクと発話された時にみられるミンゾ ク)は、端的に言うと、人間の集団の特性における固有性が全面に出た概念であり、文化人類学者がいうところの人種(race)の概念として使っていること に注意すべきである。この「人種としての民族」の使い方は、国民=ネーション(nation)概念との混同に起因するものであり、日本人が素朴に使ってき た「我々は単一民族国家であり、一つの家のようなものだ!」という表現 の中に典型的に現れる。そして、現在でもなお「民族(ミンゾク)」という言葉が発せられた時に、じつはネーションという意味をもっていたものが、国民の意 味であったことを忘却して、今日では、さまざまな解釈を生み、議論が混乱する原因となっている。

おまけに、日本では、例えば、かつての「日本の民族責任」という用語は「日本国民の責任」に

ほかならないのだが、戦争責任論などの議論では、「責任の所在は当時の政府にあったのではなく国民ではない」という責任の回避論を平気でおこなう自民党や

民主党(現在の民進党)の国会議員が出てくる始末である。総力戦概念の登場以降——戦費の調達も議会の承認がいる——政府の戦争遂行に対して国民が全く免

責される根拠というものはなく、政府は国民の下僕なのであるから、かつての戦争遂行や他の主権国家に対する侵略行為や領土併合などの権力行為には、当然「日本国民の責任」が生じているのである。だが、こうい

うことを忘却した/健忘した人たちは、靖国神社が、かつては、帝国陸海軍の護持と指揮管理下にあり、霊璽簿に登録する業務と直接関係する、戦死者への恩給

などの登録システムと無関係であったことを再度思いだす/学ぶべきだろう(1945年の敗戦後はそれらの業務が厚生省援護局、厚生労働省援護局に引き継が

れる)(→「国民国家」)。

★エスニックアイデンティティ

旧 大和朝廷に由来する皆さん(日本先住民族と言っても良いと思います)と言われたらハイっていいます? 僕(池)だったら嫌だな.自分のエスニックアイデン ティティはお前に名指しされるようなものではなくて自分で決めるからお前のその勝手なラベル貼りだけはやめてくれと言いたい。

「私たちが、しばしば無思慮に、文献の中で基本的な与件として受け入れている民族的アイデンティティという名前は、し

ばしば恣意的に、あるいはさらに悪いことに不正確に押し付けられているのである」(ロナルド・コーエン 1978)

★エスニシティ(Ethnicity):その定義と概念の歴史(→「エスニシティ・民族性」 より)

| Ethnography begins

in classical antiquity; after early authors like Anaximander and

Hecataeus of Miletus, Herodotus laid the foundation of both

historiography and ethnography of the ancient world c. 480 BC. The

Greeks had developed a concept of their own ethnicity, which they

grouped under the name of Hellenes. Herodotus (8.144.2) gave a famous

account of what defined Greek (Hellenic) ethnic identity in his day,

enumerating |

民族誌学は古典古代に始まる。アナクシマンダーやミレトスのヘカタエウ

スといった初期の著者に続き、紀元前480年頃にはヘロドトスが古代世界の歴史学と民

族学の基礎を築いた。ギリシア人は自分たちの民族概念を確立しており、ヘレネー人という名前でグループ化していた。ヘロドトス(8.144.2)は、当時

のギリシア(ヘレニズム)の民族的アイデンティティを定義するものとして、次のような有名な記述を残している。 |

| shared descent (ὅμαιμον –

homaimon, "of the same blood"),[14] shared language (ὁμόγλωσσον – homoglōsson, "speaking the same language"),[15] shared sanctuaries and sacrifices (Greek: θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι – theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai),[16] shared customs (Greek: ἤθεα ὁμότροπα – ēthea homotropa, "customs of like fashion").[17][18][19] |

共通の血統(ὅμαιμον -

homaimon、「同じ血の」)、[14]。 言語の共有(ὁμόγλωσσον - homoglōsson、「同じ言語を話す」)、[15]。 聖域と犠牲の共有(ギリシャ語:θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι - theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai)、[16]。 共有された風習(ギリシャ語:ἤθεα ὁμότροπα - ēthea homotropa、「同じような風習」)[17][18][19]。 |

| Whether ethnicity qualifies as a

cultural universal is to some extent dependent on the exact definition

used. Many social scientists,[20] such as anthropologists Fredrik Barth

and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They

regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group

interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human

groups.[21][irrelevant citation] |

エスニシティが文化的普遍性を持つかどうかは、使用される正確な定義に

よってある程度左右される。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフのよ

うな多くの社会科学者[20]は、民族的アイデンティティが普遍的であるとは考えていない。彼らはエスニシティを人間集団に固有の本質的な性質ではなく、

特定の種類の集団間相互作用の産物とみなしている[21][無関係な引用]。 |

| According to Thomas Hylland

Eriksen, the study of ethnicity was dominated by two distinct debates

until recently. |

トーマス・ヒランド・エリクセンによれば、エスニシティ研究は最近まで

2つの異なる議論に支配されていた。 |

| One is between "primordialism"

and "instrumentalism". In the primordialist view, the participant

perceives ethnic ties collectively, as an externally given, even

coercive, social bond.[22] The instrumentalist approach, on the other

hand, treats ethnicity primarily as an ad hoc element of a political

strategy, used as a resource for interest groups for achieving

secondary goals such as, for instance, an increase in wealth, power, or

status.[23][24] This debate is still an important point of reference in

Political science, although most scholars' approaches fall between the

two poles.[25] |

ひとつは「原初主義」と「道具主義」である。原初主義的な見解では、参 加者は民族的な結びつきを、外部から与えられた、強制的ですらある社会的な結びつき として集団的に認識する[22]。他方、道具主義的なアプローチでは、エスニシティを主に政治戦略のアドホックな要素として扱い、例えば富や権力、地位の 向上といった二次的な目標を達成するための利益集団の資源として利用する[23][24]。この議論は、ほとんどの学者のアプローチが両極の中間に位置す るものの、政治学において依然として重要な参照点となっている[25]。 |

| The second debate is between

"constructivism" and "essentialism". Constructivists view national and

ethnic identities as the product of historical forces, often recent,

even when the identities are presented as old.[26][27] Essentialists

view such identities as ontological categories defining social

actors.[28][29] |

2つ目の議論は「構成主義」と「本質主義」の間のものである。構成主義

者は国家や民族のアイデンティティを歴史的な力の産物としてとらえ、そのアイデンティティが古いものとして提示されている場合でも、しばしば最近のもので

あるとする[26][27]。本質主義者は、このようなアイデンティティを、社会的な行為者を定義する存在論的なカテゴリーと見なしている。 |

| According to Eriksen, these

debates have been superseded, especially in anthropology, by scholars'

attempts to respond to increasingly politicized forms of

self-representation by members of different ethnic groups and nations.

This is in the context of debates over multiculturalism in countries,

such as the United States and Canada, which have large immigrant

populations from many different cultures, and post-colonialism in the

Caribbean and South Asia.[30] |

エリクセンによれば、このような議論は、特に人類学においては、異なる

民族集団や国家の構成員による自己表象のますます政治化された形態に対応しようとす

る学者たちの試みによって取って代わられた。これは、多くの異なる文化からの移民人口を抱えるアメリカやカナダなどの国々における多文化主義をめぐる議論

や、カリブ海地域や南アジアにおけるポストコロニアリズムの文脈にある[30]。 |

| Max Weber maintained that ethnic

groups were künstlich (artificial, i.e. a social construct) because

they were based on a subjective belief in shared Gemeinschaft

(community). Secondly, this belief in shared Gemeinschaft did not

create the group; the group created the belief. Third, group formation

resulted from the drive to monopolize power and status. This was

contrary to the prevailing naturalist belief of the time, which held

that socio-cultural and behavioral differences between peoples stemmed

from inherited traits and tendencies derived from common descent, then

called "race".[31] |

マックス・ウェーバーは、民族集団は共有されたゲマインシャフト(共同

体)という主観的な信念に基づいているため、künstlich(人為的、すなわち

社会的構築物)であると主張した。第二に、この共有されたゲマインシャフトに対する信念が集団を作り出したのではなく、集団が信念を作り出したのである。

第三に、集団の形成は、権力と地位を独占しようとする衝動から生じた。これは当時の一般的な自然主義的信念に反するものであり、民族間の社会文化的・行動

的差異は、当時「人種」と呼ばれていた共通の家系に由来する遺伝的形質や傾向から生じているとした[31]。 |

| Another influential theoretician

of ethnicity was Fredrik Barth, whose "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries"

from 1969 has been described as instrumental in spreading the usage of

the term in social studies in the 1980s and 1990s.[32] Barth went

further than Weber in stressing the constructed nature of ethnicity. To

Barth, ethnicity was perpetually negotiated and renegotiated by both

external ascription and internal self-identification. Barth's view is

that ethnic groups are not discontinuous cultural isolates or logical a

priori to which people naturally belong. He wanted to part with

anthropological notions of cultures as bounded entities, and ethnicity

as primordialist bonds, replacing it with a focus on the interface

between groups. "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries", therefore, is a focus

on the interconnectedness of ethnic identities. Barth writes: "...

categorical ethnic distinctions do not depend on an absence of

mobility, contact, and information, but do entail social processes of

exclusion and incorporation whereby discrete categories are maintained

despite changing participation and membership in the course of

individual life histories."[citation needed] |

エスニシティのもう一人の影響力のある理論家はフレドリック・バルトで

あり、彼の1969年の『民族集団と境界』は1980年代と1990年代の社会学に

おけるこの用語の普及に貢献したと評されている。バルトにとって、エスニシティは外的な帰属と内的な自己同一化の両方によって永続的に交渉され、再交渉さ

れるものであった。バルトの見解は、民族集団は非連続的な文化的孤立でもなければ、人々が自然に属する論理的先験的なものでもないというものである。バル

トは、境界を持つ実体としての文化や、原初的な絆としてのエスニシティといった人類学的な概念と決別し、グループ間の接点に焦点を当てることに置き換えた

かったのである。「エスニック・グループと境界」は、エスニック・アイデンティティの相互関連性に焦点を当てたものである。バースは次のように書いてい

る:「......カテゴライズされた民族的区別は、移動、接触、情報の不在に依存するものではなく、個人の生活史の過程で参加やメンバーシップが変化す

るにもかかわらず、個別のカテゴリーが維持される排除と取り込みの社会的プロセスを伴うものである」[要出典]。 |

| In 1978, anthropologist Ronald

Cohen claimed that the identification of "ethnic groups" in the usage

of social scientists often reflected inaccurate labels more than

indigenous realities: |

1978年、人類学者のロナルド・コーエンは、社会科学者が使用する

「民族グループ」の識別は、土着の現実よりも不正確なラベルを反映していることが多いと主張した: |

| ... the named ethnic identities

we accept, often unthinkingly, as basic givens in the literature are

often arbitrarily, or even worse inaccurately, imposed.[32] |

......私たちが、しばしば無思慮に、文献の中で基本的な与件とし

て受け入れている民族的アイデンティティという名前は、しばしば恣意的に、あるいはさらに悪いことに不正確に押し付けられているのである」[32]。 |

| In this way, he pointed to the

fact that identification of an ethnic group by outsiders, e.g.

anthropologists, may not coincide with the self-identification of the

members of that group. He also described that in the first decades of

usage, the term ethnicity had often been used in lieu of older terms

such as "cultural" or "tribal" when referring to smaller groups with

shared cultural systems and shared heritage, but that "ethnicity" had

the added value of being able to describe the commonalities between

systems of group identity in both tribal and modern societies. Cohen

also suggested that claims concerning "ethnic" identity (like earlier

claims concerning "tribal" identity) are often colonialist practices

and effects of the relations between colonized peoples and

nation-states.[32] |

このようにして、彼は、人類学者などの部外者による民族集団の識別が、

その集団の構成員の自認と一致しない場合があるという事実を指摘した。また、エスニ

シティという用語が使われ始めた最初の数十年間は、文化システムを共有し、遺産を共有する小集団を指す場合、「文化的」や「部族的」といった古い用語の代

わりに使われることが多かったが、「エスニシティ」には、部族社会と現代社会の両方における集団アイデンティティのシステム間の共通性を記述できるという

付加価値があると述べた。コーエンはまた、「エスニック」アイデンティティに関する主張は(以前の「部族的」アイデンティティに関する主張と同様に)しば

しば植民地主義的な実践であり、植民地化された民族と国民国家との関係の影響であることを示唆していた[32]。 |

| According to Paul James,

formations of identity were often changed and distorted by

colonization, but identities are not made out of nothing: |

ポール・ジェイムズによれば、アイデンティティの形成はしばしば植民地

化によって変化し歪められたが、アイデンティティは無から作られるものではない: |

| Categorizations about identity,

even when codified and hardened into clear typologies by processes of

colonization, state formation or general modernizing processes, are

always full of tensions and contradictions. Sometimes these

contradictions are destructive, but they can also be creative and

positive.[33] |

アイデンティティに関するカテゴライゼーションは、植民地化、国家形

成、あるいは一般的な近代化のプロセスによって明確な類型に体系化され、固められたと

しても、常に緊張と矛盾に満ちている。こうした矛盾が破壊的であることもあるが、創造的で肯定的であることもある[33]。 |

| Social scientists have thus

focused on how, when, and why different markers of ethnic identity

become salient. Thus, anthropologist Joan Vincent observed that ethnic

boundaries often have a mercurial character.[34] Ronald Cohen concluded

that ethnicity is "a series of nesting dichotomizations of

inclusiveness and exclusiveness".[32] He agrees with Joan Vincent's

observation that (in Cohen's paraphrase) "Ethnicity ... can be narrowed

or broadened in boundary terms in relation to the specific needs of

political mobilization.[32] This may be why descent is sometimes a

marker of ethnicity, and sometimes not: which diacritic of ethnicity is

salient depends on whether people are scaling ethnic boundaries up or

down, and whether they are scaling them up or down depends generally on

the political situation. |

したがって、社会科学者は、民族のアイデンティティを示すさまざまな

マーカーが、いつ、どのように、そしてなぜ顕著になるかに焦点を当ててきた。人類学者のジョアン・ヴィンセントは、民族境界はしばしば流動的な性格を持つ

と指摘している。[34] ロナルド・コーエンは、民族性は「包含性と排他性の二分法の入れ子構造」であると結論付けている。[32]

彼はジョアン・ヴィンセントの観察に同意し(コーエンの要約によると)、「民族性は、政治的動員における特定のニーズに応じて、境界の観点から狭めたり広

げたりすることができる」と述べている。[32]

これが、血統が民族性のマーカーとなる場合とそうでない場合がある理由かもしれない。どの民族性の特徴が顕著になるかは、人々が民族の境界を拡大するか縮

小するかによって決まり、境界を拡大するか縮小するかは、一般的に政治情勢によって決まる。 |

| Kanchan Chandra rejects the

expansive definitions of ethnic identity (such as those that include

common culture, common language, common history and common territory),

choosing instead to define ethnic identity narrowly as a subset of

identity categories determined by the belief of common descent.[35]

Jóhanna Birnir similarly defines ethnicity as "group

self-identification around a characteristic that is very difficult or

even impossible to change, such as language, race, or location."[36] |

カンチャン・チャンドラはエスニック・アイデンティティの拡大的な定義

(共通の文化、共通の言語、共通の歴史、共通の領土を含むものなど)を否定し、代わ

りにエスニック・アイデンティティを共通の血統という信念によって決定されるアイデンティティ・カテゴリーのサブセットとして狭く定義することを選択した

[35]。

ジョーハンナ・ビルニルも同様にエスニシティを「言語、人種、場所など、変えることが非常に困難であるか不可能でさえある特徴をめぐる集団の自己同一化」

と定義している[36]。 |

| Approaches to understanding

ethnicity |

エスニシティを理解するためのアプローチ |

| Different approaches to

understanding ethnicity have been used by different social scientists

when trying to understand the nature of ethnicity as a factor in human

life and society. As Jonathan M. Hall observes, World War II was a

turning point in ethnic studies. The consequences of Nazi racism

discouraged essentialist interpretations of ethnic groups and race.

Ethnic groups came to be defined as social rather than biological

entities. Their coherence was attributed to shared myths, descent,

kinship, a commonplace of origin, language, religion, customs, and

national character. So, ethnic groups are conceived as mutable rather

than stable, constructed in discursive practices rather than written in

the genes.[37] |

エスニシティを理解するためのさまざまなアプローチが、人間の生活や社

会における要因としてのエスニシティの本質を理解しようとする際に、さまざまな社会

科学者によって用いられてきた。ジョナサン・M・ホールが観察するように、第二次世界大戦はエスニシティ研究の転換点であった。ナチスによる人種差別の結

果、民族集団と人種に関する本質主義的な解釈は否定された。民族集団は、生物学的な存在というよりも、むしろ社会的な存在として定義されるようになった。

その首尾一貫性は、神話、家系、親族関係、出身地の共有、言語、宗教、慣習、国民性などに起因する。そのため、民族集団は安定的というよりもむしろ変幻自

在であり、遺伝子に書き込まれるよりもむしろ言説的実践のなかで構築されるものと考えられている[37]。 |

| Examples of various approaches

are primordialism, essentialism, perennialism, constructivism,

modernism, and instrumentalism. |

様々なアプローチの例として、原初主義、本質主義、永続主義、構成主

義、近代主義、道具主義が挙げられる。 |

| "Primordialism", holds that

ethnicity has existed at all times of human history and that modern

ethnic groups have historical continuity into the far past. For them,

the idea of ethnicity is closely linked to the idea of nations and is

rooted in the pre-Weber understanding of humanity as being divided into

primordially existing groups rooted by kinship and biological heritage. |

「原初主義」は、エスニシティは人類史のあらゆる時代に存在しており、

現代のエスニック集団は遥か過去へと歴史的に連続しているとする。彼らにとって、エ

スニシティという考え方は国家という考え方と密接に結びついており、人類は親族関係や生物学的遺産に根ざした原初的に存在する集団に分かれているという

ウェーバー以前の理解に根ざしている。 |

| "Essentialist primordialism"

further holds that ethnicity is an a priori fact of human existence,

that ethnicity precedes any human social interaction and that it is

unchanged by it. This theory sees ethnic groups as natural, not just as

historical. It also has problems dealing with the consequences of

intermarriage, migration and colonization for the composition of

modern-day multi-ethnic societies.[38] |

「本質主義的原初主義」はさらに、エスニシティは人間存在の先験的な事

実であり、エスニシティは人間の社会的相互作用に先行し、それによって不変であると

する。この理論は、民族集団を歴史的なものとしてだけでなく、自然なものとして捉える。また、現代の多民族社会の構成における異種婚姻、移住、植民地化の

結果への対処にも問題がある[38]。 |

| "Kinship primordialism" holds

that ethnic communities are extensions of kinship units, basically

being derived by kinship or clan ties where the choices of cultural

signs (language, religion, traditions) are made exactly to show this

biological affinity. In this way, the myths of common biological

ancestry that are a defining feature of ethnic communities are to be

understood as representing actual biological history. A problem with

this view on ethnicity is that it is more often than not the case that

mythic origins of specific ethnic groups directly contradict the known

biological history of an ethnic community.[38] |

「親族原初主義」は、民族共同体は親族単位の延長であり、基本的には親

族や氏族の結びつきによって派生し、文化的標識(言語、宗教、伝統)の選択はまさに

この生物学的親和性を示すためになされるとする。このように、民族共同体の特徴である共通の生物学的祖先の神話は、実際の生物学的歴史を表していると理解

される。エスニシティに関するこの見解の問題点は、特定のエスニック集団の神話的起源が、エスニック共同体の既知の生物学的歴史と真っ向から矛盾している

ことが往々にしてあるということである[38]。 |

| "Geertz's primordialism",

notably espoused by anthropologist Clifford Geertz, argues that humans

in general attribute an overwhelming power to primordial human "givens"

such as blood ties, language, territory, and cultural differences. In

Geertz' opinion, ethnicity is not in itself primordial but humans

perceive it as such because it is embedded in their experience of the

world.[38] |

人類学者クリフォード・ギアーツが提唱した

"ギアーツの原初主義(プリモーディアリズム) "は、一般的に人間は血のつながり、言語、領土、文化の違いといった人間の原初的な "与件

"に圧倒的な力を帰結させると主張している。ギアーツの意見では、民族性それ自体は根源的なものではないが、人間はそれが世界の経験に埋め込まれているた

め、そのように認識している[38]。 |

| "Perennialism", an approach that

is primarily concerned with nationhood but tends to see nations and

ethnic communities as basically the same phenomenon holds that the

nation, as a type of social and political organization, is of an

immemorial or "perennial" character.[39] Smith (1999) distinguishes two

variants: "continuous perennialism", which claims that particular

nations have existed for very long periods, and "recurrent

perennialism", which focuses on the emergence, dissolution and

reappearance of nations as a recurring aspect of human history.[40] |

「多年生主義」は、主に国民性に関わるアプローチであるが、国家と民族

共同体を基本的に同じ現象として捉える傾向があり、社会的・政治的組織の一種である

国家は、太古のもの、あるいは「多年生」の性格を有していると考えている[39]:

特定の国家が非常に長い期間にわたって存在してきたと主張する「継続的通年主義」と、人類史の反復的な側面としての国家の出現、解散、再出現に焦点を当て

る「反復的通年主義」である[40]。 |

| "Perpetual perennialism" holds

that specific ethnic groups have existed continuously throughout

history. |

「永続的通年主義」は、特定の民族集団が歴史を通じて継続的に存在して

きたとするものである。 |

| "Situational perennialism" holds

that nations and ethnic groups emerge, change and vanish through the

course of history. This view holds that the concept of ethnicity is a

tool used by political groups to manipulate resources such as wealth,

power, territory or status in their particular groups' interests.

Accordingly, ethnicity emerges when it is relevant as a means of

furthering emergent collective interests and changes according to

political changes in society. Examples of a perennialist interpretation

of ethnicity are also found in Barth and Seidner who see ethnicity as

ever-changing boundaries between groups of people established through

ongoing social negotiation and interaction. |

「状況的永続主義」は、国家や民族集団は歴史の過程で出現し、変化し、

消滅するとする。この考え方は、エスニシティという概念は、政治集団が富、権力、領

土、地位などの資源を特定の集団の利益のために操作するための道具であるとする。従って、エスニシティは、出現した集団的利益を促進する手段として関連性

があるときに出現し、社会の政治的変化に応じて変化する。エスニシティの通年主義的解釈の例は、エスニシティを継続的な社会的交渉と相互作用を通じて確立

された、絶えず変化する集団間の境界とみなすバースやザイドナーにも見られる。 |

| "Instrumentalist perennialism",

while seeing ethnicity primarily as a versatile tool that identified

different ethnics groups and limits through time, explains ethnicity as

a mechanism of social stratification, meaning that ethnicity is the

basis for a hierarchical arrangement of individuals. According to

Donald Noel, a sociologist who developed a theory on the origin of

ethnic stratification, ethnic stratification is a "system of

stratification wherein some relatively fixed group membership (e.g.,

race, religion, or nationality) is used as a major criterion for

assigning social positions".[41] Ethnic stratification is one of many

different types of social stratification, including stratification

based on socio-economic status, race, or gender. According to Donald

Noel, ethnic stratification will emerge only when specific ethnic

groups are brought into contact with one another, and only when those

groups are characterized by a high degree of ethnocentrism,

competition, and differential power. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to

look at the world primarily from the perspective of one's own culture,

and to downgrade all other groups outside one's own culture. Some

sociologists, such as Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings, say the

origin of ethnic stratification lies in individual dispositions of

ethnic prejudice, which relates to the theory of ethnocentrism.[42]

Continuing with Noel's theory, some degree of differential power must

be present for the emergence of ethnic stratification. In other words,

an inequality of power among ethnic groups means "they are of such

unequal power that one is able to impose its will upon another".[41] In

addition to differential power, a degree of competition structured

along ethnic lines is a prerequisite to ethnic stratification as well.

The different ethnic groups must be competing for some common goal,

such as power or influence, or a material interest, such as wealth or

territory. Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings propose that competition

is driven by self-interest and hostility, and results in inevitable

stratification and conflict.[42] |

「道具主義的永続主義」は、エスニシティを主に、時代を通じて異なる民

族集団と限界を識別する汎用性のある道具とみなす一方で、エスニシティを社会階層化

のメカニズム、つまりエスニシティが個人の階層的配置の基礎となっていると説明している。民族的階層化の起源に関する理論を構築した社会学者ドナルド・ノ

エルによれば、民族的階層化とは「ある比較的固定された集団の構成員(例えば、人種、宗教、国籍)が、社会的地位を割り当てるための主要な基準として使用

される階層化のシステム」である[41]。ドナルド・ノエルによれば、エスニック階層化は、特定のエスニック集団が互いに接触し、それらの集団が高度なエ

スノセントリズム、競争、権力の差を特徴とする場合にのみ出現する。エスノセントリズムとは、主に自文化の視点から世界を見ようとする傾向のことであり、

自文化の外にある他のすべての集団を見下そうとするものである。ローレンス・ボボやヴィンセント・ハッチングスのような一部の社会学者は、民族階層化の起

源は民族的偏見という個人の気質にあると述べており、これはエスノセントリズムの理論に関連している[42]。ノエルの理論を続けると、民族階層化が出現

するためには、ある程度の力の差が存在しなければならない。言い換えれば、民族集団間の力の不平等とは、「一方が他方に対してその意志を押しつけることが

できるような不平等な力をもっている」ことを意味する[41]。力の差に加えて、民族的な線に沿って構造化された競争の程度も民族階層化の前提条件であ

る。異なる民族集団は、権力や影響力といった共通の目標、あるいは富や領土といった物質的利益のために競争しなければならない。ローレンス・ボボとヴィン

セント・ハッチングスは、競争は利己心と敵意によって引き起こされ、必然的に階層化と紛争をもたらすと提唱している[42]。 |

| "Constructivism" sees both

primordialist and perennialist views as basically flawed,[42] and

rejects the notion of ethnicity as a basic human condition. It holds

that ethnic groups are only products of human social interaction,

maintained only in so far as they are maintained as valid social

constructs in societies. |

「構成主義」は、原初主義的な見解と永続主義的な見解の双方に基本的な

欠陥があるとみなしており[42]、人間の基本的条件としての民族性の概念を否定し

ている。民族集団は人間の社会的相互作用の産物にすぎず、社会における有効な社会構成物として維持されている限りにおいてのみ維持されているとする。 |

| "Modernist constructivism"

correlates the emergence of ethnicity with the movement towards nation

states beginning in the early modern period.[43] Proponents of this

theory, such as Eric Hobsbawm, argue that ethnicity and notions of

ethnic pride, such as nationalism, are purely modern inventions,

appearing only in the modern period of world history. They hold that

prior to this ethnic homogeneity was not considered an ideal or

necessary factor in the forging of large-scale societies. Ethnicity is an important means by which people may identify with a larger group. Many social scientists, such as anthropologists Fredrik Barth and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human groups.[21] The process that results in emergence of such identification is called ethnogenesis. Members of an ethnic group, on the whole, claim cultural continuities over time, although historians and cultural anthropologists have documented that many of the values, practices, and norms that imply continuity with the past are of relatively recent invention.[44][45] |

「モダニズム構成主義」は、民族性の出現を、近世初期に始まった国民国

家への動きと関連付けています[43]。エリック・ホブズボームなどのこの理論の支持者は、民族性やナショナリズムなどの民族的誇りの概念は、世界史の近

代にのみ出現した純粋に近代的な発明であると主張しています。彼らは、それ以前は、民族の均質性は、大規模な社会を構築する上で理想的な要素や必要な要素

とは考えられていなかったと主張しています。 民族性は、人々がより大きな集団に帰属意識を持つための重要な手段です。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフなど、多くの社会科学者は、民 族的アイデンティティを普遍的なものとは考えていません。彼らは、民族性を、人間集団に固有の性質ではなく、特定の種類の集団間の相互作用の産物であると 考えています[21]。このようなアイデンティティの形成に至る過程は、民族形成と呼ばれています。民族集団の成員は、全体として時間的な文化的連続性を 主張するが、歴史学者や文化人類学者は、過去との連続性を暗示する多くの価値観、実践、規範が比較的最近に発明されたものであることを記録している。 [44][45] |

| Ethnic groups can form a

cultural mosaic in a society. That could be in a city like New York

City or Trieste, but also the fallen monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire or the United States. Current topics are in particular social

and cultural differentiation, multilingualism, competing identity

offers, multiple cultural identities and the formation of Salad bowl

and melting pot.[46][47][48][49] Ethnic groups differ from other social

groups, such as subcultures, interest groups or social classes, because

they emerge and change over historical periods (centuries) in a process

known as ethnogenesis, a period of several generations of endogamy

resulting in common ancestry (which is then sometimes cast in terms of

a mythological narrative of a founding figure); ethnic identity is

reinforced by reference to "boundary markers" – characteristics said to

be unique to the group which set it apart from other

groups.[50][51][52][53][54][55] |

民族グループは、社会の中で文化のモザイクを形成することがあります。

それは、ニューヨークやトリエステのような都市でも、オーストリア・ハンガリー帝国やアメリカ合衆国のような崩壊した君主制でも起こり得ます。現在の話題

としては、特に社会的・文化的差別化、多言語主義、競合するアイデンティティの提示、複数の文化的アイデンティティ、サラダボウルとメルティングポットの

形成などが挙げられます。[46][47][48][49]

民族グループは、サブカルチャー、利益団体、社会階級などの他の社会集団とは、以下の点で異なる。民族グループは、民族形成と呼ばれる、数世代にわたる同

族結婚によって共通の祖先が生まれる過程を経て、歴史的期間(数世紀)にわたって出現し、変化していく。民族的アイデンティティは、「境界マーカー」と呼

ばれる、その集団に特有で他の集団と区別する特徴への言及によって強化される。[50][51][52][53][54][55] |

| Ethnicity theory in the United

States |

アメリカにおけるエスニシティ論 |

| Ethnicity theory argues that race is a social category and is only one of several factors in determining ethnicity. Other criteria include "religion, language, 'customs', nationality, and political identification".[56] This theory was put forward by sociologist Robert E. Park in the 1920s. It is based on the notion of "culture". | 民族性理論は、人種は社会的カテゴリーであり、民族性を決定するいくつ かの要因のうちの1つにすぎない、と主張している。その他の基準としては、「宗教、 言語、「慣習」、国籍、政治的アイデンティティ」などが挙げられる[56]。この理論は、1920年代に社会学者ロバート・E・パークによって提唱され た。これは「文化」という概念に基づいている。 |

| This theory was preceded by more

than 100 years during which biological essentialism was the dominant

paradigm on race. Biological essentialism is the belief that some

races, specifically white Europeans in western versions of the

paradigm, are biologically superior and other races, specifically

non-white races in western debates, are inherently inferior. This view

arose as a way to justify enslavement of African Americans and genocide

of Native Americans in a society that was officially founded on freedom

for all. This was a notion that developed slowly and came to be a

preoccupation with scientists, theologians, and the public. Religious

institutions asked questions about whether there had been multiple

creations of races (polygenesis) and whether God had created lesser

races. Many of the foremost scientists of the time took up the idea of

racial difference and found that white Europeans were superior.[57] |

この理論に先立つこと100年以上、生物学的本質主義が人種に関する支

配的なパラダイムであった。生物学的本質主義とは、一部の人種、特に西洋のパラダイ

ムでは白人ヨーロッパ人は生物学的に優れており、他の人種、特に西洋の議論では非白人人種は本質的に劣っているという信念である。この考え方は、万人の自

由を建前とする社会の中で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷化やアメリカ先住民の大量虐殺を正当化する方法として生まれた。この考え方は徐々に発展し、科学

者、神学者、そして一般の人々の関心を集めるようになった。宗教団体は、複数の人種の創造(ポリジェネシス)があったのかどうか、神はより劣った人種を創

造したのかどうかという疑問を投げかけた。当時の一流の科学者の多くが人種の違いという考えを取り上げ、ヨーロッパ白人が優れていることを発見した

[57]。 |

| The ethnicity theory was based

on the assimilation model. Park outlined four steps to assimilation:

contact, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation. Instead of

attributing the marginalized status of people of color in the United

States to their inherent biological inferiority, he attributed it to

their failure to assimilate into American culture. They could become

equal if they abandoned their inferior cultures. |

エスニシティ理論は同化モデルに基づいていた。パークは同化のための4

つの段階、すなわち接触、衝突、融和、同化を概説した。彼は、アメリカにおける有色

人種の疎外された地位を、彼らの先天的な生物学的劣等性に帰するのではなく、彼らがアメリカ文化に同化できなかったことに帰した。劣った文化を捨てれば、

彼らは平等になれるのだ。 |

| Michael Omi and Howard Winant's

theory of racial formation directly confronts both the premises and the

practices of ethnicity theory. They argue in Racial Formation in the

United States that the ethnicity theory was exclusively based on the

immigration patterns of the white population and did take into account

the unique experiences of non-whites in the United States.[58] While

Park's theory identified different stages in the immigration process –

contact, conflict, struggle, and as the last and best response,

assimilation – it did so only for white communities.[58] The ethnicity

paradigm neglected the ways in which race can complicate a community's

interactions with social and political structures, especially upon

contact. |

マイケル・オミとハワード・ワイナントの人種形成論は、エスニシティ論

の前提にも実践にも真っ向から対立している。彼らは『アメリカにおける人種形成』 (Racial Formation in the United

States)の中で、エスニシティ理論はもっぱら白人集団の移民パターンに基づいており、アメリカにおける非白人のユニークな経験を考慮していなかった

と論じている[58]。

パークの理論は移民プロセスにおけるさまざまな段階(接触、葛藤、闘争、そして最後にして最良の対応としての同化)を特定していたが、それは白人コミュニ

ティについてのみそうしていた[58]。エスニシティ・パラダイムは、人種がコミュニティと社会的・政治的構造との相互作用を複雑にする方法を、特に接触

時に軽視していた。 |

| Assimilation – shedding the

particular qualities of a native culture for the purpose of blending in

with a host culture – did not work for some groups as a response to

racism and discrimination, though it did for others.[58] Once the legal

barriers to achieving equality had been dismantled, the problem of

racism became the sole responsibility of already disadvantaged

communities.[59] It was assumed that if a Black or Latino community was

not "making it" by the standards that had been set by whites, it was

because that community did not hold the right values or beliefs, or

were stubbornly resisting dominant norms because they did not want to

fit in. Omi and Winant's critique of ethnicity theory explains how

looking to cultural defect as the source of inequality ignores the

"concrete sociopolitical dynamics within which racial phenomena operate

in the U.S."[60] It prevents critical examination of the structural

components of racism and encourages a "benign neglect" of social

inequality.[60] |

同化、つまり受け入れ側の文化に溶け込むために固有の文化の特質を捨て

去ることは、人種差別や差別への対応として、ある集団にとっては機能しなかったが、

他の集団にとっては機能した[58]。平等を達成するための法的障壁が解体されると、人種差別の問題はすでに不利な立場に置かれているコミュニティだけの

責任となった。

[黒人やラテン系のコミュニティが白人によって設定された基準によって「成功」していない場合、それはそのコミュニティが正しい価値観や信念を持っていな

いか、あるいは自分たちがなじむことを望んでいないために支配的な規範に頑なに抵抗しているためであると考えられた。エスニシティ理論に対する近江とワイ

ナントの批判は、不平等の根源として文化的欠陥に注目することが、いかに「人種現象が米国で作用している具体的な社会政治的力学」を無視しているかを説明

している[60]。それは人種差別の構造的構成要素に対する批判的な検討を妨げ、社会的不平等に対する「良性の無視」を助長している[60]。 |

| Ancestor Diaspora Ethnic cleansing Ethnic interest group Ethnic flag Ethnic penalty Ethnocultural empathy Ethnocide Ethnographic group Genealogy Genetic genealogy Human Genome Diversity Project Identity politics Ingroups and outgroups Intersectionality List of contemporary ethnic groups List of countries by ethnic groups List of Indigenous peoples Meta-ethnicity Minzu (anthropology) National symbol Passing (sociology) Polyethnicity Population genetics Race and ethnicity in censuses Race and ethnicity in the United States census Race and health Stateless nation Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world |

祖先 ディアスポラ 民族浄化 民族利益団体 民族旗 民族差別 民族文化の共感 民族虐殺 民族誌的グループ 系図 遺伝的系図 ヒトゲノム多様性プロジェクト アイデンティティ政治 イングループとアウトグループ 交差性 現代民族グループの一覧 民族グループ別国の一覧 先住民の一覧 メタエスニシティ Minzu (人類学) 国家の象徴 パッシング(社会学 多民族性 集団遺伝学 国勢調査における人種と民族 アメリカ合衆国国勢調査における人種と民族 人種と保健 無国籍国民 世界の人口の Y 染色体ハプログループ |

| Sources Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Omi, Michael; Winant, Howard (1986). Racial Formation in the United States from the 1960s to the 1980s. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Inc. Smith, Anthony D. (1999). Myths and memories of the Nation. Oxford University Press. |

出典 Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. オミ、マイケル、ウィナント、ハワード (1986)。1960年代から1980年代にかけてのアメリカ合衆国の人種形成。ニューヨーク:Routledge and Kegan Paul, Inc. スミス、アンソニー D. (1999)。国民の神話と記憶。オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Further reading Barth, Fredrik (ed). Ethnic groups and boundaries. The social organization of culture difference, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1969 Billinger, Michael S. (2007), "Another Look at Ethnicity as a Biological Concept: Moving Anthropology Beyond the Race Concept" Archived 9 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Critique of Anthropology 27, 1:5–35. Craig, Gary, et al., eds. Understanding 'race' and ethnicity: theory, history, policy, practice (Policy Press, 2012) Danver, Steven L. Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues (2012) Eriksen, Thomas Hylland (1993) Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives, London: Pluto Press Eysenck, H.J., Race, Education and Intelligence (London: Temple Smith, 1971) (ISBN 0851170099) Healey, Joseph F., and Eileen O'Brien. Race, ethnicity, gender, and class: The sociology of group conflict and change (Sage Publications, 2014) Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, editors, The Invention of Tradition. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). Kappeler, Andreas. The Russian empire: A multi-ethnic history (Routledge, 2014) Levinson, David, Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group (1998), ISBN 978-1573560191. Magocsi, Paul Robert, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1999) Morales-Díaz, Enrique; Gabriel Aquino; & Michael Sletcher, "Ethnicity", in Michael Sletcher, ed., New England, (Westport, CT, 2004) Seeger, A. 1987. Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Sider, Gerald, Lumbee Indian Histories (Cambridge University Press, 1993). Smith, Anthony D. (1987). The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Blackwell. Smith, Anthony D. (1998). Nationalism and modernism. A Critical Survey of Recent Theories of Nations and Nationalism. Routledge. Steele, Liza G.; Bostic, Amie; Lynch, Scott M.; Abdelaaty, Lamis (2022). "Measuring Ethnic Diversity". Annual Review of Sociology. 48 (1). Thernstrom, Stephan A. ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1981) ^ U.S. Census Bureau State & County QuickFacts: Race. |

さらに詳しく読む Barth, Fredrik (ed). Ethnic groups and boundaries. The social organization of culture difference, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1969 Billinger, Michael S. (2007), 「生物学的概念としての民族性に関する別の見方:人種概念を超えた人類学」 2009年7月9日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、Critique of Anthropology 27、1:5–35。 クレイグ、ゲイリーほか、編。人種と民族性を理解する:理論、歴史、政策、実践(Policy Press、2012年 ダンバー、スティーブン L. 世界の先住民:集団、文化、現代の問題に関する百科事典 (2012) エリクセン、トーマス・ヒランド (1993) 『民族性とナショナリズム:人類学的視点』 ロンドン:Pluto Press アイゼンク、H.J.、『人種、教育、知能』 (ロンドン:テンプル・スミス、1971) (ISBN 0851170099) ヒーリー、ジョセフ F.、およびアイリーン・オブライエン。人種、民族、性別、および階級:集団の対立と変化の社会学(Sage Publications、2014 年) ホブズボーム、エリック、およびテレンス・レンジャー、編集者、伝統の発明。(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1983 年)。 カペラー、アンドレアス。ロシア帝国:多民族の歴史(Routledge、2014年 レヴィンソン、デビッド、世界各国の民族グループ:すぐに使えるハンドブック、グリーンウッド出版グループ(1998年)、ISBN 978-1573560191。 マゴチ、ポール・ロバート、編。カナダの人々の百科事典 (1999) Morales-Díaz, Enrique; Gabriel Aquino; & Michael Sletcher, 「Ethnicity」, in Michael Sletcher, ed., New England, (Westport, CT, 2004) Seeger, A. 1987. Why Suyá Sing: A Musical Anthropology of an Amazonian People, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. サイダー、ジェラルド、ルムビー・インディアン史(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1993年)。 スミス、アンソニー・D.(1987)。『The Ethnic Origins of Nations(国民の民族的起源)』。ブラックウェル。 スミス、アンソニー・D.(1998)。『ナショナリズムとモダニズム。国民とナショナリズムに関する最近の理論の批判的調査』。ラウトレッジ。 スティール、ライザ G.、ボスティック、アミ、リンチ、スコット M.、アブデラティ、ラミス (2022)。「民族の多様性の測定」。社会学年報。48 (1)。 サーンストローム、ステファン A. 編。ハーバード・アメリカ民族グループ事典 (1981) ^ 米国国勢調査局州および郡のクイックファクト:人種。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnicity |

★

★フォークとエトノス:柳田國男の理解

それに対して柳田は1925年前後——つまり岡正雄と共に雑誌『民族』を刊行する時期 (1925-29)——に講演をおこない次のように述べている。Volkは単数形で「我が民族」のことを、Ethnosは、自国以外の多くの民族を研究す るものだと主張した。

柳田には、海外経験をもつ知識人と共通する外国語コンプレックスとそれと無関係ではない西欧 諸国家との「対等」の立場に日本をひきあげるべきだという考えるふしがあった(村井 2004)。柳田の独自性は、これらを西欧の学問の直輸入ではないオリジナルなものをうち立てようとしたところにある。もっともこの独自性は、また日本の 民俗学/民族学の発展にとって功罪あわせもつ効果をうんだ。

功罪のうち功はすでに多くの書物や文献において主張されているのでここでは省略する。

問題は罪のほうである。柳田の枠組は、後世には国粋的で経験主義的な民俗学研究と、異国趣味 で自国の状況に対する省察を欠く民族学研究へと二極分解をもたらした(→「捉え難い真理への探求と、人類学の研究倫理」)。

◎ロドルフォ・スタヴェンハーゲン『エスニック問題と国際社会 : 紛争・開発・人権』(原題:The ethnic question : conflicts, development, and human rights, 1990.)

| 第 1章 今日のエスニック問題 | |

| 第2章 国家と民族—理 論的考察 | |

| 第3章 民族とエトニー —エスニック問題の枠組み | |

| 第4章 ラテンアメリカ の文化と社会 | |

| 第5章 国際システムに おけるエスニック権利 | |

| 第6章 エスニック紛争 | |

| 第7章 エスノサイドと 民族発展 | |

| 第8章 先住民族と部族 民族—特別なケース | |

| 第9章 西ヨーロッパの 移民とレイシズム | |

| 第10章 エスニック権 利と民族政策 | |

| 第11章 教育と文化の 諸問題 |

★韓国に少数民族が「存在しない」という意識は、自民族中心主義か?

"Korean historiography has experienced an ethnicisation of its discourse, asserting an ethnically homogeneous Korean ‘national people’ since 4,000 years ago that has supposedly never harboured any minority groups." by Arnaud NANTA, 2008.

Arnaud

NANTA, Physical Anthropology and the Reconstruction of Japanese

Identity in Postcolonial Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, Volume

11, Issue 1, Summer 2008, Pages 29–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyn019

■ 民族と民族表象(→「先住民表象と先住民運動」)

民 族(または民族集団)とは、社会文化的特徴と価値を共有する人たちの集団である。民族表象とはしばしば、言語、衣装、遺跡モニュメン ト、生活習慣のよう な眼に見えて顕示的な徴であるものから詩歌や文学作品さらには思想やアイデンティティと いう見えにくいものまで多種多様にわたる。人類学者の多くは、民族 や民族表象の定義や規定をする際に、本質主義的なものよりも構成主義的なことを採用する傾向が強くなってきた。社会集団の成員は、しばしば超時間的に人々 が維持している共通項よりも、国家や隣接する集団との関係の中でおこった「出来事」の中で取捨選択されてきたものを、その民族の固有の特徴や成員のアイデンティティとして理解することが多いからである。ただし、このような歴史は容易に忘却 されてしまい、一度何らかの理由で廃絶した民族表象が復興される際に は、現実には想像的に復元されたにも関わらず、当事者自身にも本質主義的なものとして普遍的な価値が主張されるという、文化の客体化ないしは文化の再領域 化という現象が広く認められる。民族や文化の定義をめぐって古典的合意が崩壊し、これまでの学術的議論の枠を超えて、現代政治をも巻き込んだ社会的な論争 的なテーマとして、今日浮上している(→「先住民表象と先住民運動」)。

★Polyethnicity(多 民族性)

多

民族性(ポリエスニシティ)とは、一国あるいは特定の地理的領域内で、異なる民族的背景を持つ人々の社会的近接性と相互交流によって特徴づけられる特定の

文化的現象を指す。[1]

同じ用語は、個人が複数の民族性に自己を同一視する能力や意思にも関連する。これは、移民、異民族間の結婚、交易、征服、戦後の領土分割などを通じて、複

数の民族性が特定の地域に居住する際に生じる。[2][3][4] これは国や地域に多くの政治的・社会的影響をもたらしてきた。[5] [6]

多くの国々、おそらく全ての国々には、ある程度の多民族性が存在する。ナイジェリアやカナダのような国々ではそのレベルが高く、日本やポーランドのような

国々では非常に低い(より具体的には、均質性の感覚が強い)。[7][8][9] [10]

一部の西洋諸国で見られる多民族性の広がりは、それに反対する議論を引き起こしている。その中には、多民族性が各社会の強みを弱体化させるという見解や、

多民族人口を抱える国々における政治的・民族的問題は、特定の民族に対する異なる法律によってより適切に扱われるべきだという見解が含まれている。

[11][12]

| Polyethnicity, also

known as pluri-ethnicity or multi-ethnicity, refers to specific

cultural phenomena that are characterized by social proximity and

mutual interaction of people from different ethnic backgrounds, within

a country or other specific geographic region.[1] Same terms may also relate to the ability and willingness of individuals to identify themselves with multiple ethnicities. It occurs when multiple ethnicities inhabit a given area, specifically through means of immigration, intermarriage, trade, conquest and post-war land-divisions.[2][3][4] This has had many political and social implications on countries and regions.[5][6] Many, if not all, countries have some degree of polyethnicity, with countries like Nigeria and Canada having high levels and countries like Japan and Poland having very low levels (and more specifically, a sense of homogeneity).[7][8][9][10] The amount of polyethnicity prevalent in some Western countries has spurred some arguments against it, which include a belief that it leads to the weakening of each society's strengths, and also a belief that political-ethnic issues in countries with polyethnic populations are better handled with different laws for certain ethnicities.[11][12] |

多民族性(ポリエスニシティ)とは、一国あるいは特定の地理的領域内

で、異なる民族的背景を持つ人々の社会的近接性と相互交流によって特徴づけられる特定の文化的現象を指す。[1] 同じ用語は、個人が複数の民族性に自己を同一視する能力や意思にも関連する。これは、移民、異民族間の結婚、交易、征服、戦後の領土分割などを通じて、複 数の民族性が特定の地域に居住する際に生じる。[2][3][4] これは国や地域に多くの政治的・社会的影響をもたらしてきた。[5] [6] 多くの国々、おそらく全ての国々には、ある程度の多民族性が存在する。ナイジェリアやカナダのような国々ではそのレベルが高く、日本やポーランドのような 国々では非常に低い(より具体的には、均質性の感覚が強い)。[7][8][9] [10] 一部の西洋諸国で見られる多民族性の広がりは、それに反対する議論を引き起こしている。その中には、多民族性が各社会の強みを弱体化させるという見解や、 多民族人口を抱える国々における政治的・民族的問題は、特定の民族に対する異なる法律によってより適切に扱われるべきだという見解が含まれている。 [11][12] |

| Conceptual history In 1985, Canadian historian William H. McNeill gave a series of three lectures on polyethnicity in ancient and modern cultures at the University of Toronto.[13] The main thesis throughout his lectures was the argument that it has been the cultural norm for societies to be composed of different ethnic groups. McNeill argued that the ideal of homogeneous societies may have grown between 1750 and 1920 in Western Europe because of the growth in the belief in a single nationalistic base for the political organization of society. McNeill believed that during World War I, the desire for homogeneous nations began to weaken.[14] |

概念史 1985年、カナダ人歴史家ウィリアム・H・マクニールはトロント大学で古代と現代文化における多民族性について三回の講義を行った[13]。彼の講演全 体を通じた主たる主張は、社会が異なる民族集団で構成されることが文化的規範であったという論点であった。マクニールは、1750年から1920年にかけ て西ヨーロッパで均質な社会の理想が台頭したのは、社会の政治組織化における単一のナショナリスト的基盤への信念が高まったためだと論じた。マクニールは 第一次世界大戦中、均質な国家への願望が弱まり始めたと考えた。[14] |

| Impact on politics Polyethnicity divides nations, complicating the politics as local and national governments attempt to satisfy all ethnic groups.[5] Many politicians in countries attempt to find the balance between ethnic identities within their country and the identity of the nation as a whole.[5] Nationalism also plays a large part in these political debates, as cultural pluralism and consociationalism are the democratic alternatives to nationalism for the polyethnic state.[15] The idea of nationalism being social instead of ethnic entails a variety of culture, a shared sense of identity and a community not based on descent.[16] Culturally-plural states vary constitutionally between a decentralized and unitary state (such as the United Kingdom) and a federal state (such as Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada).[17] Ethnic parties in these polyethnic regions are not anti-state but instead seek maximum power within this state.[11][16] Many polyethnic countries face that dilemma with their policy decisions.[18] The following nations and regions are just a few specific examples of this dilemma and its effects: |

政治への影響 多民族性は国家を分断し、地方政府と中央政府が全ての民族集団を満足させようとする中で政治を複雑化する。[5] 多くの政治家は、国内の民族的アイデンティティと国民全体のアイデンティティのバランスを取ろうと試みる。[5] ナショナリズムもまた、こうした政治的議論において大きな役割を果たす。なぜなら、文化的多元主義と協調主義は、多民族国家におけるナショナリズムに代わ る民主的な選択肢だからだ。[15] ナショナリズムが民族的ではなく社会的であるという考え方は、多様な文化、共有されたアイデンティティ、そして血統に基づかない共同体を意味する。 [16] 文化的に多元的な国家は、憲法上、分散型国家(例えばイギリス)と単一国家、あるいは連邦国家(例えばベルギー、スイス、カナダ)の間で異なる形態をと る。[17] こうした多民族地域における民族政党は反国家的ではなく、むしろ国家内での最大権力獲得を目指す。[11][16] 多くの多民族国家は政策決定においてこのジレンマに直面している。[18] 以下に挙げる国や地域は、このジレンマとその影響を示す具体例の一部に過ぎない: |

United States The United States is a nation founded by different ethnicities frequently described as coming together in a "melting pot," a term used to emphasize the degree to which constituent groups influence and are influenced by each other, or a "salad bowl," a term more recently coined in contrast to the "melting pot" metaphor and emphasizing those groups' retention of fundamentally distinct identities despite their proximity to each other and their influence on the overall culture that all of those groups inhabit.[19] A controversial political issue in recent years has been the question of bilingualism.[20] Many immigrants have come from Hispanic America, who are native Spanish speakers, in the past centuries and have become a significant minority and even a majority in many areas of the Southwest.[7][21] In New Mexico the Spanish speaking population exceeds 40%.[7][22] Disputes have emerged over language policy, since a sizeable part of the population, and in many areas the majority of the population, speak Spanish as a native language.[20] The biggest debates are over bilingual education for language minority students, the availability of non-English ballots and election materials and whether or not English is the official language.[20][23][24] It has evolved into an ethnic conflict between the pluralists who support bilingualism and linguistic access and the assimilationists who strongly oppose this and lead the official English movement.[25] The United States does not have an official language, but English is the de facto national language and is spoken by the overwhelming majority of the country's population.[26] |

アメリカ合衆国 アメリカ合衆国は、異なる民族によって築かれた国だ。よく「るつぼ」に集まったと表現される。この隠喩は、構成集団が互いに影響を与え合う度合いを強調す るために用いられる。あるいは「サラダボウル」という概念もある。これは近年提唱された概念で、「溶解鍋」の隠喩とは対照的に、集団が互いに近接し全体文 化に影響を与えながらも、根本的に異なるアイデンティティを維持している点を強調するものである。[19] 近年、政治的に議論を呼んでいる問題の一つがバイリンガリズムである。[20] 過去数世紀にわたり、スペイン語を母語とするヒスパニック系アメリカからの移民が多く流入し、南西部では多くの地域で重要な少数派、さらには多数派となっ ている。[7][21] ニューメキシコ州ではスペイン語話者人口が40%を超える。[7][22] 人口の相当部分、多くの地域では過半数がスペイン語を母語とするため、言語政策をめぐる論争が生じている。[20] 最大の論争点は、言語的少数派の生徒に対するバイリンガル教育、非英語の投票用紙や選挙資料の提供の有無、そして英語を公用語とするか否かである。 [20][23][24] これは、バイリンガリズムと言語的アクセスを支持する多元主義者と、これに強く反対し公用語英語運動を主導する同化主義者との民族的対立へと発展した。 [25] 米国には公用語は存在しないが、英語は事実上の国語であり、国民の大多数が使用している。[26] |

| Canada Canada has had many political debates between the French speakers and English speakers, particularly in the province of Quebec.[27] Canada holds both French and English as official languages.[28] The politics in Quebec are largely defined by nationalism as French Québécois wish to gain independence from Canada as a whole, based on ethnic and linguistic boundaries.[29] The main separatist party, Parti Québécois, attempted to gain sovereignty twice (once in 1980 and again in 1995) and failed by a narrow margin of 1.2% in 1995.[30] Since then, in order to remain united, Canada granted Quebec statut particulier, recognizing Quebec as a nation within the united nation of Canada.[31] Belgium The divide between the Dutch-speaking north (Flanders) and the French-speaking South (Wallonia) has caused the parliamentary democracy to become ethnically polarized.[32] Though an equal number of seats in the Chamber of Representatives are prescribed to the Flemish and Walloons, Belgian political parties have all divided into two ideologically identical but linguistically and ethnically different parties.[32] The political crisis has grown so bad in recent years that the partition of Belgium has been feared.[33] Ethiopia Ethiopia is a polyethnic nation consisting of 80 different ethnic groups and 84 indigenous languages.[34][35] The diverse population and the rural areas throughout the nation made it nearly impossible to create a strong centralized state, but it was eventually accomplished through political evolution.[36] Prior to 1974, nationalism was discussed only within radical student groups, but by the late 20th century, the issue had come to the forefront of political debate.[37][38] Ethiopia was forced to modernize their political system to properly handle nationalism debates.[38] The Derg military government took control with a Marxist–Leninist ideology, urging self-determination and rejecting compromise over any nationality issues.[39] In the 1980s, Ethiopia suffered a series of famines and, after the Soviet Union broke apart, lost its aid from the Soviets; the Derg government later collapsed.[39] Eventually, Ethiopia restabilized and adopted a modern political system that models a federal parliamentary republic.[40] It was still impossible to create a central government holding all power and so the central government was torn.[41] It now presides over ethnically-based regional states, and each ethnic state is granted the right to establish its own government with democracy.[42] |

カナダ カナダでは、特にケベック州において、フランス語話者と英語話者の間で多くの政治的議論が交わされてきた。[27] カナダはフランス語と英語を共に公用語としている。[28] ケベック州の政治は、民族的・言語的境界に基づき、フランス系ケベック人がカナダ全体からの独立を望むナショナリズムによって大きく定義されている。 [29] 主な分離独立政党であるケベック党は、二度にわたり主権獲得を試みた(1980年と1995年)。1995年にはわずか1.2%の差で失敗した。[30] その後、カナダは統一を維持するため、ケベックに「特別地位」を認め、カナダという統一国家内の国家としてケベックを承認した。[31] ベルギー オランダ語圏の北部(フランダース)とフランス語圏の南部(ワロン)の分断により、議会制民主主義は民族的に二極化した。[32] 衆議院の議席数はフランダースとワロンに均等に割り当てられているが、ベルギーの政党はすべて、イデオロギー的には同一だが言語的・民族的に異なる二つの 政党に分裂している。[32] 近年、政治危機は深刻化し、ベルギーの分裂が懸念されるほどである。[33] エチオピア エチオピアは80の異なる民族集団と84の固有言語からなる多民族国家である。[34] [35] 多様な人口構成と国土全体の農村地域は、強力な中央集権国家の構築をほぼ不可能にしていたが、政治的進化を通じて最終的に達成された。[36] 1974年以前、ナショナリズムは過激な学生グループ内でのみ議論されていたが、20世紀後半にはこの問題が政治的議論の最前線に浮上した。[37] [38] エチオピアはナショナリズム論争を適切に処理するため、政治体制の近代化を余儀なくされた。[38] デルグ軍事政権はマルクス・レーニン主義イデオロギーで権力を掌握し、民族自決を主張し、いかなる民族問題についても妥協を拒んだ。[39] 1980年代、エチオピアは一連の飢饉に見舞われ、ソビエト連邦崩壊後はソ連からの援助を失った。デルグ政権は後に崩壊した。[39] 結局、エチオピアは再び安定を取り戻し、連邦議会制共和国をモデルとした近代的な政治体制を採用した。[40] 依然として全ての権力を掌握する中央政府を創設することは不可能であり、中央政府は分裂した状態が続いた。[41] 現在では民族を基盤とする地域州を統括しており、各民族州には民主主義に基づく独自の政府を樹立する権利が認められている。[42] |

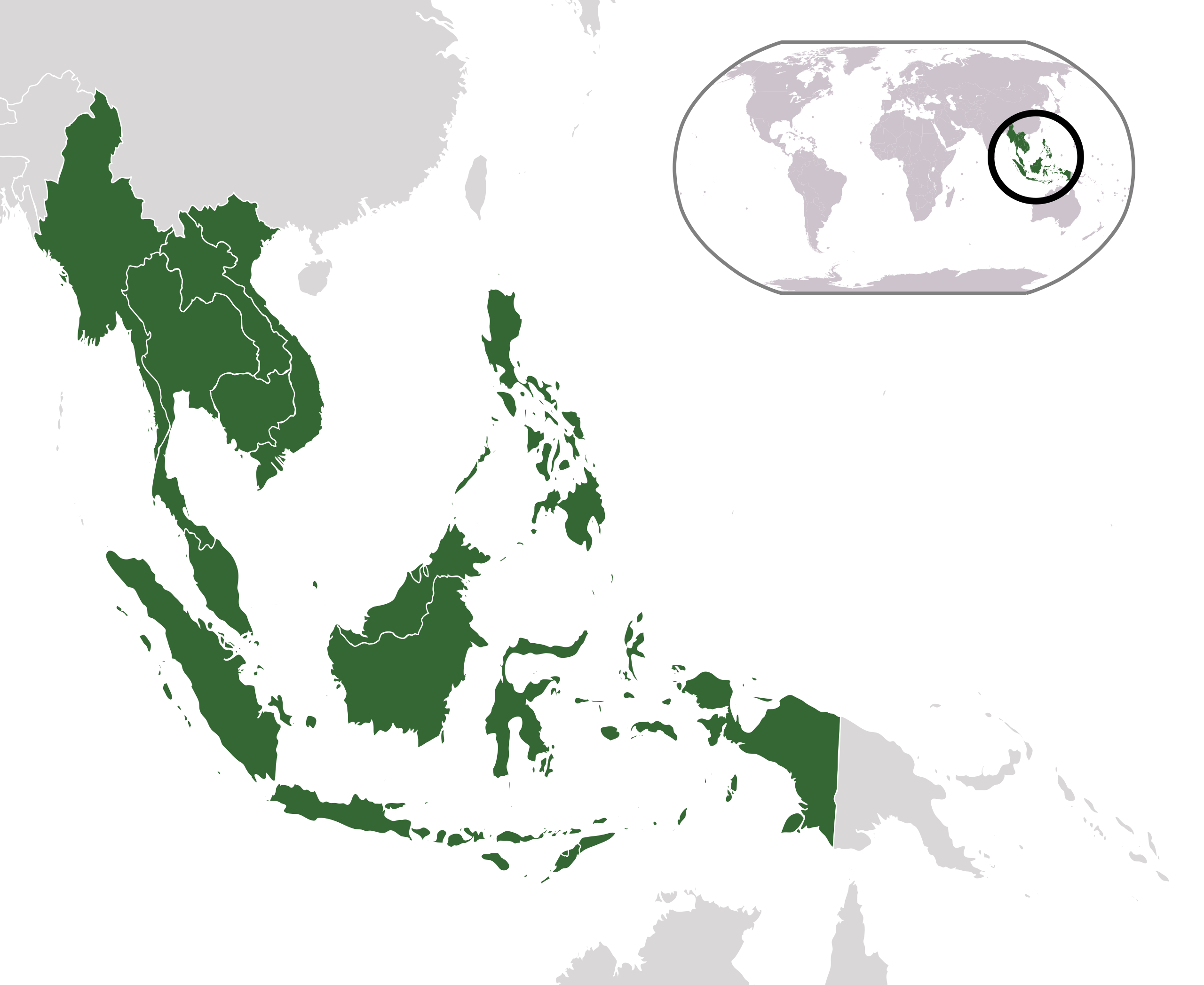

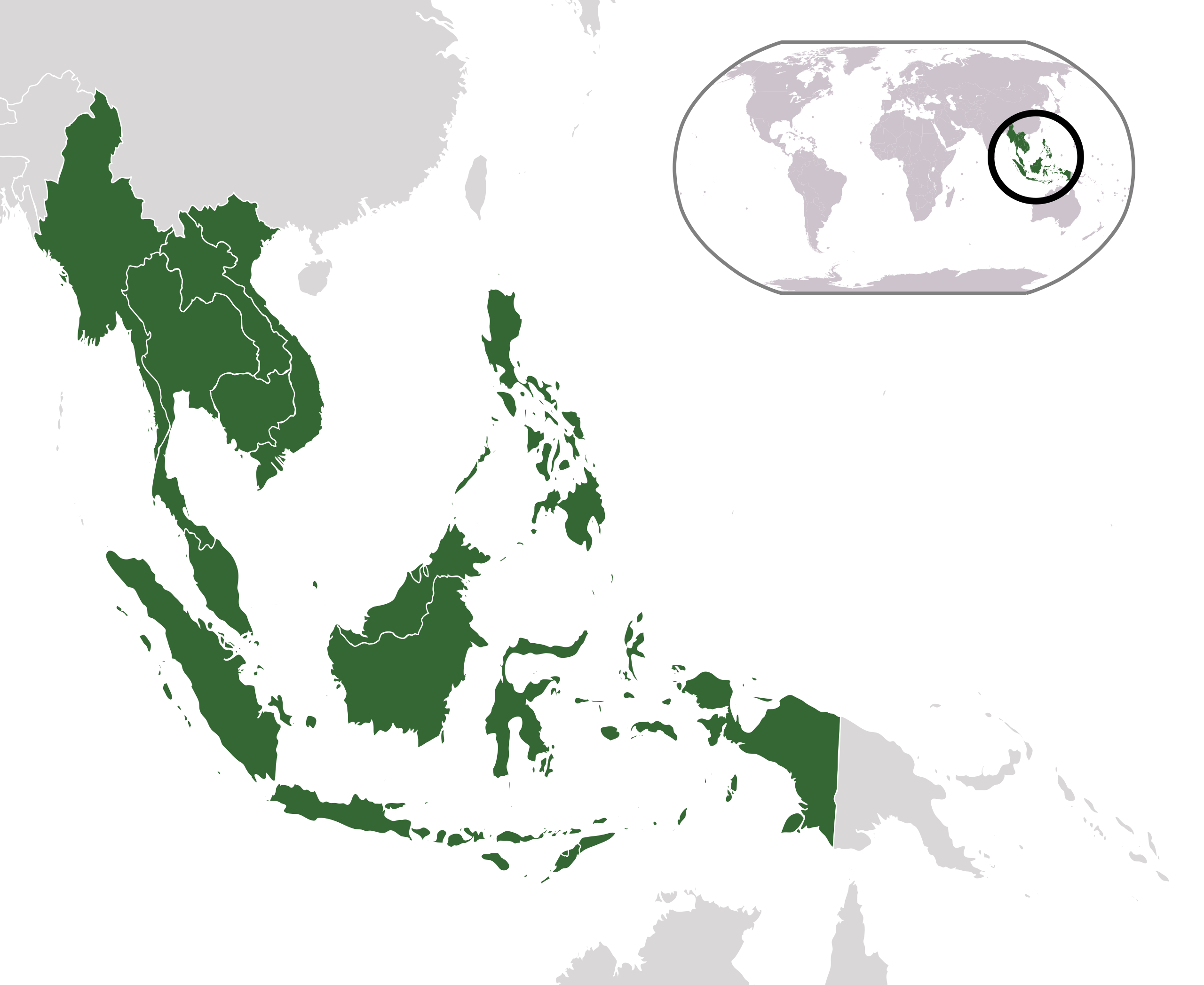

| Spain In Spain from 1808 to 1814, the Spanish War of Independence took place in a multicultural Spain.[43] Spain, at the time, was then under the control of King Joseph Bonaparte, who was Napoleon Bonaparte's brother.[43] Because they were under the control of French rule, the Spanish formed coalitions of ethnic groups to reclaim their own political representation to replace the French political system, which had lost power.[43] Southeast Asia  Southeast Asia countries, 2009-10-10 In Southeast Asia the continental area (Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam) generally practices Theravada or Mahayana Buddhism.[44] Most of insular Southeast Asia (namely Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia) practices mostly Sunni Islam.[45] The rest of the insular region (Philippines and East Timor) practices mostly Roman Catholic Christianity and Singapore practises mostly Mahayana Buddhism.[45] Significant long-distance labor migration that occurred during the late 19th century and the early 20th century provided many different types of ethnic diversity.[46] Relations between the indigenous population of the region arose from regional variations of cultural and linguistic groups.[46] Immigrant minorities, especially the Chinese, then developed as well.[46] Although there were extreme political differences for each minority and religion, they were still legitimate members of political communities, and there has been a significant amount of unity throughout history.[47] This differs from both nearby East and South Asia.[47] |

スペイン 1808年から1814年にかけて、多文化国家であったスペインでスペイン独立戦争が起きた。[43] 当時のスペインはナポレオン・ボナパルトの弟であるジョゼフ・ボナパルト王の支配下にあった。[43] フランス支配下に置かれていたため、スペイン人は民族グループの連合を形成し、権力を失ったフランス政治体制に代わる自らの政治的代表権を取り戻そうとし た。[43] 東南アジア  東南アジア諸国、2009-10-10 東南アジアでは、大陸部(ミャンマー、タイ、ラオス、カンボジア、ベトナム)では一般的に上座部仏教または大乗仏教が実践されている。[44] 島嶼部東南アジアの大部分(すなわちマレーシア、ブルネイ、インドネシア)では主にスンニ派イスラム教が実践されている。[45] 島嶼部の残りの地域(フィリピンと東ティモール)では主にローマ・カトリックキリスト教が、シンガポールでは主に大乗仏教が実践されている。[45] 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて発生した大規模な長距離労働移民は、異なる民族的多様性をもたらした。[46] この地域の先住民族間の関係は、文化的・言語的集団の地域的差異から生じた。[46] その後、移民少数民族、特に中国系住民も発展した。[46] 各少数民族や宗教間には極端な政治的差異があったものの、彼らは依然として政治共同体の正当な構成員であり、歴史を通じてかなりの結束が見られた。 [47] これは近隣の東アジア・南アジア双方の状況とは異なる。[47] |

| Impact on society Polyethnicity, over time, can change the way societies practice cultural norms.[6] Marriage An increase in intermarriage in the United States has led to the blurring of ethnic lines.[2] Anti-miscegenation laws (laws banning interracial marriages) were abolished in the United States in 1967 and now it is estimated that one-fifth of the population in the United States by 2050 will be part of the polyethnic population.[48] In 2000, self-identified Multiracial Americans numbered 6.8 million or 2.4% of the population.[7][49] While the number of interethnic marriages is on the rise, there are certain ethnic groups that have been found more likely to become polyethnic and recognize themselves with more than one ethnic background. Bhavani Arabandi states in his article on polyethnicity that: Asians and Latinos have much higher rates of interethnic marriages than do blacks, and they are more likely to report polyethnicity than blacks who more often claim a single ethnicity and racial identity. This is the case, the authors [Lee, J & Bean, F.D] argue, because blacks have a "legacy of slavery," a history of discrimination, and have been victimized by the "one-drop rule" (where having any black blood automatically labeled one as black) in the US.[2] |

社会への影響 多民族性は、時間の経過とともに、社会が文化的規範を実践する方法を変えることがある。[6] 結婚 アメリカ合衆国における異民族間結婚の増加は、民族の境界線を曖昧にする結果をもたらした。[2] 異人種間結婚禁止法(異人種間の結婚を禁じる法律)は1967年にアメリカで廃止され、現在では2050年までにアメリカ人口の5分の1が多民族集団に属 すると推定されている。[48] 2000年には、自らを複数人種系アメリカ人と認識する者は680万人、人口の2.4%を占めた。[7] [49] 異民族間の結婚数は増加傾向にあるが、特定の民族グループは多民族化が進みやすく、複数の民族的背景を持つと自認する傾向が強い。バヴァニ・アラバンディ は多民族性に関する論文で次のように述べている: アジア系とラテン系は黒人よりも異民族間結婚率がはるかに高く、単一の民族・人種的アイデンティティを主張する傾向が強い黒人よりも、多民族性を自認する 可能性が高い。著者ら[Lee, J & Bean, F.D]は、この現象の背景として、黒人が「奴隷制の遺産」という差別史を有し、米国における「一滴の法則」(黒人の血を少しでも持つ者は自動的に黒人と みなされる)の被害者となってきたことを挙げている[2]。 |

Military Maj. Gen. William B. Garrett III, commander of U.S. Army Africa, Gen. Nyakayirima Aronda, Chief of Defense Forces, Ugandan People's Defense Force and Gen. Jeremiah Kianga, Chief of General Staff, Kenya, render honors during the opening ceremony for Natural Fire 10, Kitgum, Uganda, Oct. 16, 2009. Presently, most armed forces are composed of people from different ethnic backgrounds.[14] They are considered to be polyethnic due to the differences in race, ethnicity, language or background.[50] While there are many examples of polyethnic forces, the most prominent are among the largest armed forces in the world, including those of the United States, the former Soviet Union, and China.[14] Polyethnic armed forces are not a new phenomenon since multi-ethnic forces existed during the Roman Empire, the Middle Eastern Empires, and even the Mongol Khans.[50] The US military was one of the first modern militaries to begin ethnic integration, by order of President Harry Truman in 1945.[51] |

軍事 2009年10月16日、ウガンダのキットガムで行われた「ナチュラル・ファイア10」開会式において、米陸軍アフリカ司令官ウィリアム・B・ギャレット 三世少将、ウガンダ人民防衛軍総司令官ニャカイルマ・アロンダ将軍、ケニア参謀総長ジェレマイア・キアンガ将軍が敬礼を捧げた。 現在、ほとんどの軍隊は異なる民族的背景を持つ人々で構成されている[14]。人種、民族、言語、背景の違いから、それらは多民族的と見なされている [50]。多民族的な軍隊の例は数多く存在するが、最も顕著なのは世界最大級の軍隊、すなわちアメリカ合衆国、旧ソビエト連邦、中国の軍隊である。 [14] 多民族軍隊は新しい現象ではない。ローマ帝国、中東帝国、さらにはモンゴル帝国にも多民族軍隊は存在した。[50] 米軍は1945年にハリー・トルーマン大統領の命令により民族統合を開始した最初の近代軍隊の一つである。[51] |

| Criticisms There are also arguments against polyethnicity, as well as the assimilation of ethnicities in polyethnic regions. Wilmot Robertson in The Ethnostate and Dennis L. Thomson in The Political Demands of Isolated Indian Bands in British Columbia, argue for some level of separatism.[11][12] In The Ethnostate, Robertson declares polyethnicity as an ideal that only lessens each culture.[11] He believes that, within a polyethnic culture, the nation or region as a whole is less capable of cultural culmination than each of the individual ethnicities that make it up.[52] Essentially, polyethnicity promotes the dilution of ethnicity and thus hinders each ethnicity in all aspects of culture.[52] In The Political Demands of Isolated Indian Bands in British Columbia, Thomson points out the benefits in some level (albeit small) of separatist policies.[12] He argues the benefits of allowing ethnic groups, like the Amish and the Hutterites in the United States and Canada or the Sami in Norway, to live on the edges of governance.[12] These are ethnic groups that would prefer to retain their ethnic identity and thus prefer separatist policies for themselves, as they do not require them to conform to policies for all ethnicities of the nation.[12] |

批判 多民族性、および多民族地域における民族の同化に対して反対の議論もある。ウィルモット・ロバートソンは『The Ethnostate』で、デニス・L・トムソンは『The Political Demands of Isolated Indian Bands in British Columbia』で、ある程度の分離主義を主張している[11]。[12] 『民族国家(The Ethnostate)』の中で、ロバートソンは多民族主義は各文化を弱体化させるだけの理想であると宣言している。[11] 彼は、多民族文化の中では、国家や地域全体が、それを構成する個々の民族よりも文化の集大成を達成する能力が低いと信じている。[52] 本質的に、多民族主義は民族性の希薄化を促進し、その結果、文化のあらゆる側面において各民族の成長を妨げる。[52] 『ブリティッシュコロンビア州における孤立したインディアン部族の政治的要求』の中で、トムソンは、分離主義政策にある程度(わずかではあるが)の利点が あることを指摘している。[12] 彼は、米国やカナダのアーミッシュやフッター派、ノルウェーのサーミ族のような民族集団が、統治の縁辺で生活することを認めることの利点を主張している。 [12] これらは自らの民族的アイデンティティを維持することを望み、したがって分離主義政策を自らに適用することを好む民族集団である。なぜなら、それらは国家 の全民族に対する政策に順応することを要求されないからである。[12] |

| Diaspora politics Ethnic group Ethnopolitics Supraethnicity Interculturalism Interracial marriage Millet Multiculturalism Multilingualism Multinational state Nationalism Transnationalism |

ディアスポラ政治 民族集団 エスノポリティクス 超民族性 異文化間主義 異人種間結婚 ミレット 多文化主義 多言語主義 多民族国家 ナショナリズム トランスナショナル主義 |

| Notes 1. McNeil 1985, pages 85 Arabandi 2000, Online Smith 1998, page 190 Smith 1998, page 200 Safran 2000, Introduction Benhabib 1996, pages 154–155 U.S. Census Bureau Thomson 2000, pages 213-215 Burgess 2007, Online 10. Safran 2000, pages 1-2 Robertson 1992, pages 1-10 Thomson 2000, pages 214–215 Ritzer 2004, page 141 Dreisziger 1990, pages 1-2 Kellas 1991, page 8 Kellas 1991, page 65 Kellas 1991, pages 180-183 Safran 2000, pages 2-3 Adams 2001 [page needed] 20. Navarrette 2007, online Hakimzadeh 2007, Online Crawford 1992, page 154 Cromwell 1998, Online Roache 1996, Online Young 1993, page 73 McArthur 1998, page 38 Bélanger 2000, online Tuohy 1992, page 325 McNeil 1985, page 86 30. Leyton-Brown 2002, page 5 The Calgary Declaration Lijphart 199, page 39 Bryant, Online Levinson 1998, page 131 Grimes 1996 Young 1993, page 147 Tiruneh 1993, page 150 Young 1993, page 149 Young 1993, page 152 40. Kavalski 2008, page 31 Young 1993, page 159 Young 1993, page 209 Baramendi 2000, pages 80-84 Hirschman 1995 page 19 Hirschman 1995 page 20 Hirschman 1995 page 21 Hirschman 1995 page 22 Lee 2000, pages 221-245 Jones & Smith 2000 Online 50. Dreisziger 1990 page 1 Yang 2000, page 168 Robertson 1992 p. 10 |

注 1. マクニール 1985、85 ページ アラバンディ 2000、オンライン スミス 1998、190 ページ スミス 1998、200 ページ サフラン 2000、序文 ベンハビブ 1996、154-155 ページ 米国国勢調査局 トムソン 2000、213-215 ページ バージェス 2007、オンライン 10. サフラン 2000、1-2 ページ ロバートソン 1992、1-10 ページ トムソン 2000、214-215 ページ リッツァー 2004、141 ページ ドライジガー 1990、1-2 ページ ケラス 1991、8 ページ ケラス 1991、65 ページ ケラス 1991、180-183 ページ サフラン 2000、2-3 ページ アダムス 2001 [ページ番号が必要] 20. ナバレテ 2007, オンライン ハキムザデ 2007, オンライン クロフォード 1992, 154ページ クロムウェル 1998, オンライン ローチ 1996, オンライン ヤング 1993, 73ページ マッカーサー 1998, 38ページ ベランジェ 2000, オンライン トゥーヒー 1992、325 ページ マクニール 1985、86 ページ 30. レイトン=ブラウン 2002、5 ページ カルガリー宣言 リフハート 199、39 ページ ブライアント、オンライン レビンソン 1998、131 ページ グライムズ 1996 ヤング 1993、147 ページ ティルネ 1993、150 ページ ヤング 1993、149 ページ ヤング 1993、152 ページ 40. カバルスキー 2008、31 ページ ヤング 1993、159 ページ ヤング 1993、209 ページ バラメンディ 2000、80-84 ページ ハーシュマン 1995、19 ページ ハーシュマン 1995、20 ページ ハーシュマン 1995、21 ページ ハーシュマン 1995、22 ページ リー 2000、221-245 ページ ジョーンズ&スミス 2000 オンライン 50. ドレイジガー 1990 1 ページ ヤン 2000、168 ページ ロバートソン 1992 10 ページ |

| References Adams, J.Q; Strother-Adams, Pearlie (2001). Dealing with Diversity. Chicago: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN 0-7872-8145-X. Arabandi, Bhavani (2007). George Ritzer (ed.). Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology: Polyethnicity. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1. "B02001. RACE - Universe: TOTAL POPULATION". 2006 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2008-01-30. Bélanger, Claude (August 2000). "The Rise of the Language Issue since the Quiet Revolution". Marianopolis College. Retrieved 2009-11-22. Benhabib, Seyla (1996). Democracy and difference: contesting the boundaries of the political. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04478-3. Beramendi, Justo G (2000). Identity and Territorial Autonomy in Plural Societies: "Identity, Ethnicity, and the State in Spain: 19th and 20th Centuries". Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5027-7. Brittingham, Angela; G. Patricia de la Cruz (June 2004). "Ancestry 2000" (PDF). U.S.Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-09-20. Retrieved 2007-06-13. Bryant, Elizabeth (2007-10-12). "Divisions could lead to a partition in Belgium". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-05-28. Burgess, Chris (March 2007). "Multicultural Japan remains a pipe dream". Japan Times. Retrieved 2009-11-22. "The Calgary Declaration: Premiers' Meeting". Canadian Executive Council. September 14, 1997. Retrieved 2009-11-22. Crawford, James (1992). Language loyalties: a source book on the official English controversy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-12016-3. Cromwell, Sharon (1998). "The Bilingual Education Debate: Part I". Education World. Retrieved 2009-11-22. Dreisziger, Nándor F. (1990). Ethnic armies: polyethnic armed forces from the time of the Habsburgs to the age of the superpowers. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-993-6. Grimes, Joseph Evans; Barbara F. Grimes (1996). Ethnologue: language family index to the thirteenth edition of the Ethnologue. Summer Institute of Linguistics. ISBN 1-55671-028-3. Jones, Nicholas A.; Amy Symens Smith (November 2001). "The Two or More Races Population: 2000. Census 2000 Brief" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-29. Retrieved 2008-05-08. Hakimzadeh, Shirin; D'Vera Cohn (November 2007). "English Usage among Hispanics in the United States". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2009-11-22. Hirschman, Charles (1995). Population, Ethnicity, and Nation-Building. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8953-4. Kavalski, Emilian; Magdalena Żółkoś (2008). Defunct federalisms: critical perspectives on federal failure. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-4984-7. Kellas, James G. (1991). The Politics of Nationalism and Ethnicity. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-06159-5. Lee, J.; Bean, F.D. (2000). American Review of Sociology: America's Changing Color Lines: Immigration, Race/Ethnicity, and Multiracial Identification. Levinson, David (1998). Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 1-57356-019-7. Leyton-Brown, David (2002). Canadian Annual Review of Politics and Public Affairs: 1995. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3673-2. Lijphart, Arend (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University. ISBN 0-300-07893-5. McArthur, Thomas Burns (1998). The English languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48130-9. McNeill, William H. (1985). Polyethnicity and National Unity in World History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6643-7. Navarrette, Ruben (June 2007). "Language debate only divides us further". Oakland Tribune. Retrieved 2009-11-22. [dead link] Rajagopalan, Swarna (2000). Identity and Territorial Autonomy in Plural Societies: "Internal Unit Demarcation and National Identity: India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka". Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5027-7. Ritzer, George (2004). Handbook of social problems: a comparative international perspective. SAGE. ISBN 0-7619-2610-0. Roache, Mario (April 1996). "Panel opens debate on bilingual ballots". The Ledger. Retrieved 2009-11-22. Robertson, Wilmot (1992). The Ethnostate. Cape Canaveral, FL: Howard Allen Enterprises, Inc. ISBN 0-914576-22-4. Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-500-05074-0. Smith, Anthony D. (1998). Nationalism and modernism. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06341-8. "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2007". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2008-10-09. Thomson, Dennis L (2000). Identity and Territorial Autonomy in Plural Societies: "The Political Demands of Isolated Indian Bands in British Columbia". Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5027-7. Tiruneh, Andargachew (1993). The Ethiopian revolution, 1974-1987: a transformation from an aristocratic to a totalitarian autocracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43082-8. Tuohy, Carolyn J. (1992). Policy and politics in Canada: institutionalized ambivalence. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-870-1. Yang, Philip Q. (2000). Ethnic studies: issues and approaches. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-4480-5. Young, Crawford (1993). The Rising Tide of Cultural Pluralism. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-13880-1. United States Census Bureau. "Table 52—Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2006" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States 2009. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2009-10-11. United States Census Bureau. "United States - Data Sets - American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2009-11-22. |

参考文献 Adams, J.Q; Strother-Adams, Pearlie (2001). 『多様性への対応』. シカゴ: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN 0-7872-8145-X. Arabandi, Bhavani (2007). George Ritzer (編). 『ブラックウェル社会学百科事典: 多民族性』. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-2433-1. 「B02001. 人種 - 対象集団: 総人口」. 2006年アメリカコミュニティ調査. アメリカ合衆国国勢調査局. 2020年2月11日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2008年1月30日閲覧. ベランジェ、クロード(2000年8月)。「静かな革命以降の言語問題の台頭」。マリアノポリス大学。2009年11月22日に取得。 ベンハビブ、セイラ(1996)。『民主主義と差異:政治の境界をめぐる争い』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 0-691-04478-3。 ベラメンディ、フスト・G(2000年)。『多元的社会におけるアイデンティティと地域自治:「スペインにおけるアイデンティティ、エスニシティ、国家: 19世紀と20世紀」』。ラウトリッジ。ISBN 0-7146-5027-7。 ブリッティンガム、アンジェラ、G. パトリシア・クルス (2004年6月)。「Ancestry 2000」 (PDF)。米国国勢調査局。2004年9月20日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2007年6月13日に取得。 ブライアント、エリザベス (2007-10-12). 「分裂はベルギーの分割につながる可能性がある」. サンフランシスコ・クロニクル. 2008-05-28 取得. バージェス、クリス (2007年3月). 「多文化主義の日本は夢物語のままである」. ジャパン・タイムズ. 2009-11-22 取得. 「カルガリー宣言:州首相会議」。カナダ行政評議会。1997年9月14日。2009年11月22日取得。 Crawford, James (1992). 言語への忠誠:公用語としての英語をめぐる論争に関する資料集。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-12016-3。 クロムウェル、シャロン (1998). 「二言語教育論争:その I」. Education World. 2009年11月22日取得. ドレイジガー、ナンドール F. (1990). 民族軍:ハプスブルク時代から超大国の時代までの多民族軍隊. ウィルフリッド・ローリエ大学出版. ISBN 0-88920-993-6。 グライムズ、ジョセフ・エヴァンス、バーバラ・F・グライムズ(1996)。『エスノローグ:エスノローグ第 13 版の言語族索引』。サマー・インスティテュート・オブ・リンギスティックス。ISBN 1-55671-028-3。 ジョーンズ、ニコラス A.、エイミー・サイメンズ・スミス (2001年11月)。「2000年の人口:2つ以上の人種」 (PDF)。アメリカ合衆国国勢調査局。2019年7月29日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2008年5月8日に取得。 ハキムザデ、シリン;デベラ・コーン(2007年11月)。「米国におけるヒスパニック系の英語使用状況」。ピュー・リサーチ・センター。2012年12 月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2009年11月22日に取得。 ハーシュマン、チャールズ(1995)。人口、民族、国家建設。コロラド州ボルダー:ウェストビュー・プレス。ISBN 0-8133-8953-4。 カヴァルスキー、エミリアン;マグダレナ・ゾルコス(2008)。消滅した連邦主義:連邦の失敗に関する批判的視点。アッシュゲート出版。ISBN 978-0-7546-4984-7。 ケラス、ジェームズ G. (1991)。ナショナリズムと民族性の政治。ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス。ISBN 0-312-06159-5。 リー、J.、ビーン、F.D. (2000)。アメリカ社会学レビュー:アメリカの変化する人種差別:移民、人種/民族、そして多民族のアイデンティティ。 レヴィンソン、デイヴィッド (1998)。世界各国の民族グループ:即座に参照できるハンドブック。グリーンウッド出版グループ。ISBN 1-57356-019-7。 レイトン・ブラウン、デイヴィッド (2002)。カナダの政治と公共問題に関する年次レビュー:1995年。トロント大学出版局。ISBN 0-8020-3673-2。 ライファート、アレント(1999)。民主主義のパターン:36 カ国の政府形態と実績。イェール大学。ISBN 0-300-07893-5。 マッカーサー、トーマス・バーンズ(1998)。英語。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-48130-9。 マクニール、ウィリアム・H.(1985)。『世界史における多民族性と国民的統一』。トロント:トロント大学出版局。ISBN 0-8020-6643-7。 ナバレッテ、ルーベン(2007年6月)。「言語論争は我々をさらに分断するだけだ」。オークランド・トリビューン。2009年11月22日閲覧。[リン ク切れ] ラジャゴパラン、スワーナ(2000)。『多元的社会におけるアイデンティティと領土的自治:「内部単位の境界設定と国民的アイデンティティ:インド、パ キスタン、スリランカ」』。ラウトリッジ。ISBN 0-7146-5027-7。 リッツァー、ジョージ(2004)。『社会問題ハンドブック:国際比較の視点』。SAGE。ISBN 0-7619-2610-0。 ロアチ、マリオ(1996年4月)。「二か国語投票用紙に関する討論会が開かれる」。The Ledger。2009年11月22日取得。 ロバートソン、ウィルモット (1992). 『エスノステート』. フロリダ州ケープカナベラル: ハワード・アレン・エンタープライズ社. ISBN 0-914576-22-4. ショー、イアン (2003). 『オックスフォード古代エジプト史』. 英国オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 0-500-05074-0. スミス、アンソニー D. (1998). 『ナショナリズムとモダニズム』. ラウトレッジ. ISBN 0-415-06341-8. 「米国の社会特性:2007年」. 米国国勢調査局. 2009年4月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2008年10月9日に取得. トムソン、デニス L (2000). 『多元的社会におけるアイデンティティと領土的自治:「ブリティッシュコロンビア州における孤立した先住民部族の政治的要求」』. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5027-7. ティルネ, アンダルガチェウ (1993). 『エチオピア革命、1974-1987:貴族的専制から全体主義的専制への変容』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-43082-8。 トゥーヒー、キャロリン・J.(1992)。『カナダの政策と政治:制度化された両義性』。テンプル大学出版局。ISBN 0-87722-870-1。 ヤン、フィリップ・Q.(2000)。『エスニック・スタディーズ:課題とアプローチ』。SUNY出版局。ISBN 0-7914-4480-5。 ヤング、クロフォード(1993)。『文化的多元主義の高まり』。ウィスコンシン州マディソン:ウィスコンシン大学出版局。ISBN 0-299-13880-1。 アメリカ合衆国国勢調査局。「表52—言語別家庭内使用言語:2006年」(PDF)。『アメリカ合衆国統計要覧2009年版』米国国勢調査局。2009 年10月11日閲覧。 米国国勢調査局。「アメリカ合衆国 - データセット - American FactFinder」。米国国勢調査局。2020年2月12日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2009年11月22日閲覧。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyethnicity |

【文献】

*この本は私はウェブページを作成した後に出版されましたが、日本学術会議の人類学・民族 学研究連絡委員会の「人種と民族」の概念を検討する委員経験者であるこの本は、人種と民族を考える重要な本です。是非一読してください。

【リンク】

*この本における村井の柳田批判(最初の版は1992年刊)には、論拠が不十分で憶測によ るものが多いという民俗学サイドからの反論があります。しかし、村井の批判を通して、当時の民族学と民俗学の区分の誕生や、それらの両学問と日本の植民地 主義・帝国主義の文化観・人種観・民族観など関係が論じられるようになりました。そういう意味で重要な本です(→「村井紀『南島イデオロギーの発生』ノート」)。

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆