民族

ethnos, ethnic group, ethnicity

民族

ethnos, ethnic group, ethnicity

解説:池田 光穂 仮想・医療人類学・辞典

民族ないしは民族集団(ethnic group)とは、文化(言語、習慣、宗教など)で区分される集団のことである。民族には「民族名」 というものがある。

集団を区分する境界は、歴史的にも社会的にも変化し、また、民族集団が自己の集団から定義される 場合と、国家や他の民族集団と定義される場合にも齟齬があることから、民族集団は固定的で、永続的なものではない。すなわち「民族」は、社会構成的な概念 であるという考え方がそれである。

ただし、近代国家制度の中では、さまざまな政治経済的あるいは法的な要因で、民族集団としての独 自性が一定の権利をもって保証される必要性がある——言い方を変えると、より本質主義的な概念だという理解である。その際には、民族集団としての文化的尊 厳は尊重されなければならない対象になる。他方「人種」 という誤った信念(=つまり、ありもしないのにあると信じるフィクション=仮構を盲信する)は、その本質的主義的な盲信(=錯認)なので、国民国家概念が 「単一民族国家」であるという妄想に取り憑かれると、人種と民族が合致するという不幸が生じる。戦前の日本では、ナショナリスト、民俗学者、そして民族学 者ですら「大和民族」という人種(レイス)概念を信じたことがある(→「民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッセー」を参照)

エスニシティ(ethnicity)は、民族集団から派生した用語で、民族の(ethnic)という形容詞の名詞形から、それ自体で民族=民族集団の意味

をもつ。エスニシティ(ethnicity)は民族とも民族性とも訳される

エトニー(ethnie)とはアンソニー・スミス(1982) らの独自的な使い方で、前近代の民族——つまり本源主義な (primorodalists)的な意味での——集団を措定しているが、これは自己評価と他者評価においてとりわけ著しい齟齬のない民族集団であると理 解してよい。

部族:民族集団と同義ないしは、その下位集団ともみなされるが部族(ぶぞく, tribe)も、しばしばもちいられる。英語のトライブの翻訳語である部族は、大英帝国の植民地ではしばしばよく用いられてきた。部族集団(tribal group)ともいわれる。エスニック・グループ(=民族集団)とエスニシティの関係のように、トライバル・グループは具体的な民族(=文化や言語を共有 する集団)を、トライブは、その集団という抽象ないしは一般概念という意味で使われるこ とがある[→部族,強い文化的概 念としての部族]

★エスニック・アイデンティティと民族 (エスニシティ)

☆ 民 族(ethnicity)とは、他の集 団と区別される共通の属性に基づいて互いに帰属意識を持つ人々の集団である。民族が共有すると考える属性には、言 語、文化、共通の祖先、伝統、社会、宗教、歴史、あるいは社会的扱いなどが含まれる。民族性は長期にわたる民族集団内の内婚制によって維持され、遺伝的祖 先の範囲は[理論的には]狭くも広くもなり得る。しかし実際には「混血」の遺伝的祖先を持つ集団も存在するが、それは生物学的というよりも社会的あるいは 文化的識別マーカーによっておこなわれる。このような民族集団における構成員が共通してもつ集団的仲間意識が民族的アイデンティティ(ethnic identity)である。

Ethnicity

refers to a group of people who share a sense of belonging based on

common attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Attributes

considered shared by an ethnic group include language, culture, common

ancestry, traditions, society, religion, history, or social treatment.

Ethnicity is maintained through long-term endogamy within ethnic

groups, and the scope of genetic ancestry can [theoretically] be narrow

or broad. However, in practice, groups with “mixed” genetic ancestry

also exist, identified more by social or cultural markers than

biological ones. The collective sense of belonging shared by members

within such ethnic groups constitutes ethnic identity.

| An ethnicity or ethnic group is a

group of people who identify with each other on the

basis of perceived shared attributes that distinguish them from other

groups. Attributes that ethnicities believe to share include language,

culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, religion,

history or social treatment.[1][2] Ethnicities are maintained through

long-term endogamy[3] and may have a narrow or broad spectrum of

genetic ancestry, with some groups having mixed genetic

ancestry.[4][5][6] Ethnicity is sometimes used interchangeably with

nation, particularly in cases of ethnic nationalism. It is also used

interchangeably with race although not all ethnicities identify as

racial groups.[7] |

民族(エスニシティ)とは、他の集団と区別される共通の属性に基づいて

互いに帰属意識を持つ人々の集団である。民族が共有すると考える属性には、言語、文化、共通の祖先、伝統、社会、宗教、歴史、あるいは社会的扱いなどが含

まれる。[1][2]

民族性は長期にわたる内婚制[3]によって維持され、遺伝的祖先の範囲は狭くも広くもなり得る。混血の遺伝的祖先を持つ集団も存在する。[4][5]

[6]

民族性は特に民族ナショナリズムの場合、国民と同義に使われることがある。また人種と同義に使われることもあるが、全ての民族性が人種集団として認識され

るわけではない。[7] |

| By way of assimilation,

acculturation, amalgamation, language shift, intermarriage, adoption

and religious conversion, individuals or groups may over time shift

from one ethnic group to another. Ethnic groups may be divided into

subgroups or tribes, which over time may become separate ethnic groups

themselves due to endogamy or physical isolation from the parent group.

Conversely, formerly separate ethnicities can merge to form a

panethnicity and may eventually merge into one single ethnicity.

Whether through division or amalgamation, the formation of a separate

ethnic identity is referred to as ethnogenesis. |

同化、文化適応、融合、言語転換、異民族間結婚、養子縁組、宗教改宗と

いった過程を通じて、個人や集団は時間をかけてある民族集団から別の民族集団へと移行することがある。民族集団は小集団や部族に分かれることがあり、近親

婚や親集団からの物理的隔離によって、やがてそれ自体が別の民族集団となる場合がある。逆に、かつて別々の民族集団が融合して汎民族性を形成し、最終的に

は単一の民族集団に統合されることもある。分裂によるものであれ融合によるものであれ、独立した民族的アイデンティティの形成は民族形成

(ethnogenesis)と呼ばれる。 |

| Two

theories exist in understanding ethnicities, mainly primordialism and

constructivism. Early 20th-century primordialists viewed ethnic groups

as real phenomena whose distinct characteristics have endured since the

distant past.[8] Perspectives that developed after the 1960s

increasingly viewed ethnic groups as social constructs, with identity

assigned by societal rules.[9] |

民

族性を理解する理論には主に二つの流派がある。本源主義と構成主義だ。20世紀初頭の本源主義者は、民族集団を遠い過去からその特徴を保ち続ける実在の現

象と見なした[8]。1960年代以降に発展した見解は、民族集団を社会的構築物と捉える傾向が強まり、アイデンティティは社会の規範によって付与される

ものだとする[9]。 |

| Terminology The term ethnic is ultimately derived from the Greek ethnos, through its adjectival form ethnikos,[10] loaned into Latin as ethnicus. The inherited English language term for this concept is folk, used alongside the latinate people since the late Middle English period. In Early Modern English and until the mid-19th century, ethnic was used to mean heathen or pagan (in the sense of disparate "nations" which did not yet participate in the Christian ecumene), as the Septuagint used ta ethne 'the nations' to translate the Hebrew goyim "the foreign nations, non-Hebrews, non-Jews".[11] The Greek term in early antiquity (Homeric Greek) could refer to any large group, a host of men, a band of comrades as well as a swarm or flock of animals. In Classical Greek, the word took on a meaning comparable to the concept now expressed by "ethnic group", mostly translated as "nation, tribe, a unique people group"; only in Hellenistic Greek did the term tend to become further narrowed to refer to "foreign" or "barbarous" nations in particular (whence the later meaning "heathen, pagan").[12] In the 19th century the term came to be used in the sense of "peculiar to a tribe, race, people or nation", in a return to the original Greek meaning. The sense of "different cultural groups", and in American English "tribal, racial, cultural or national minority group" arises in the 1930s to 1940s,[13] serving as a replacement of the term race which had earlier taken this sense but was now becoming deprecated due to its association with ideological racism. The abstract ethnicity had been used as a stand-in for "paganism" in the 18th century, but now came to express the meaning of an "ethnic character" (first recorded 1953). The term ethnic group was first recorded in 1935 and entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 1972.[14] Depending on context, the term nationality may be used either synonymously with ethnicity or synonymously with citizenship (in a sovereign state). The process that results in emergence of an ethnicity is called ethnogenesis, a term in use in ethnological literature since about 1950. The term may also be used with the connotation of something unique and unusually exotic (cf. "an ethnic restaurant", etc.), generally related to cultures of more recent immigrants, who arrived after the dominant population of an area was established. Depending on which source of group identity is emphasized to define membership, the following types of (often mutually overlapping) groups can be identified: Ethno-linguistic, emphasizing shared language, dialect (and possibly script) – example: French Canadians Ethno-national, emphasizing a shared polity or sense of national identity – example: Austrians Ethno-racial, emphasizing shared physical appearance based on phenotype – example: African Americans Ethno-regional, emphasizing a distinct local sense of belonging stemming from relative geographic isolation – example: South Islanders of New Zealand Ethno-religious, emphasizing shared affiliation with a particular religion, denomination or sect – example: Mormons, Sikhs Ethno-cultural, emphasizing shared culture or tradition, often overlapping with other forms of ethnicity – example: Travellers In many cases, more than one aspect determines membership: for instance, Armenian ethnicity can be defined by Armenian citizenship, having Armenian heritage, native use of the Armenian language, or membership of the Armenian Apostolic Church. |

用語 「民族的」という語は、ギリシャ語のethnosに由来し、その形容詞形ethnikosを経て、ラテン語にethnicusとして借用されたものであ る。この概念を表す英語の継承語はfolkであり、中英語後期以降、ラテン語由来のpeopleと並行して用いられてきた。 近世英語期から19世紀中頃まで、「ethnic」は異教徒や異邦人を意味した(キリスト教世界に参加していない異質な「諸国民」という意味で)。これは 七十人訳聖書がヘブライ語の「goyim」(異邦人、非ヘブライ人、非ユダヤ人)を「ta ethne」(諸国民)と訳したことに由来する。[11] 古代初期(ホメロス期ギリシャ語)におけるギリシャ語のこの用語は、大規模な集団、大勢の男たち、仲間の一団、さらには動物の群れや群集を指し得た。古典 ギリシャ語では、この語は主に「国民、部族、独自の民集団」と訳される「民族集団」の概念に相当する意味を獲得した。ヘレニズム期のギリシャ語においての み、この用語は特に「異邦人」や「蛮族」を指すようにさらに狭義化される傾向が見られた(これが後の「異教徒、異教」の意味の起源である)。[12] 19世紀には、この用語は「部族、人種、民族、国民に特有の」という意味で用いられるようになり、元のギリシャ語の意味に戻った。「異なる文化集団」とい う意味、そしてアメリカ英語における「部族的、人種的、文化的、あるいは国家的少数派集団」という意味は、1930年代から1940年代にかけて現れた [13]。これは、以前はこの意味を持っていたが、イデオロギー的な人種主義との関連から現在では廃れつつあった「人種」という用語の代わりとして機能し た。抽象的な「民族性」は18世紀に「異教」の代用語として使われていたが、この頃には「民族的特性」の意味を表すようになった(初出1953年)。 民族集団(ethnic group)という用語は1935年に初めて記録され、1972年にオックスフォード英語辞典に収録された[14]。文脈によっては、国籍 (nationality)という用語は、民族性(ethnicity)と同義として、あるいは(主権国家における)市民権と同義として用いられることが ある。民族性が形成される過程は「エスノジェネシス」と呼ばれる。この用語は1950年頃から民族学文献で使用されている。また「エスニック」は独特で異 国的なもの(例:「エスニックレストラン」など)を意味する場合もあり、一般に、地域の支配的集団が確立した後に到着した比較的新しい移民の文化に関連し て用いられる。 集団の帰属を定義する際にどの要素を重視するかによって、以下の(しばしば重複する)グループ類型が識別される: 民族言語的:共通の言語・方言(場合により文字)を重視する例:フランス系カナダ人 民族国家的:共通の政治体制や国民的アイデンティティを重視する例:オーストリア人 民族人種的:表現型に基づく共通の身体的特徴を強調する。例:アフリカ系アメリカ人 民族地域的:地理的隔離から生じる独特の地域帰属意識を強調する。例:ニュージーランドの南島住民 民族宗教的:特定の宗教・宗派・教団への共通の帰属を強調する。例:モルモン教徒、シク教徒 民族文化的:共有された文化や伝統を強調し、他の民族性の形態と重なることが多い。例:トラベラー 多くの場合、複数の側面が所属を決定する。例えば、アルメニア民族性は、アルメニア国籍、アルメニアの血統、アルメニア語の母語使用、あるいはアルメニア 使徒教会の所属によって定義されうる。 |

Definitions and conceptual

history A group of ethnic Bengalis in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Bengalis form the third-largest ethnic group in the world after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[15]  The Javanese people of Indonesia are the largest Austronesian ethnic group. Ethnography begins in classical antiquity; after early authors like Anaximander and Hecataeus of Miletus, Herodotus laid the foundation of both historiography and ethnography of the ancient world c. 480 BC. The Greeks had developed a concept of their own ethnicity, which they grouped under the name of Hellenes. Although there were exceptions, such as Macedonia, which was ruled by nobility in a way that was not typically Greek, and Sparta, which had an unusual ruling class, the ancient Greeks generally enslaved only non-Greeks due to their strong belief in ethnic nationalism.[16][17] The Greeks sometimes believed that even their lowest citizens were superior to any barbarian. In his Politics 1.2–7; 3.14, Aristotle even described barbarians as natural slaves in contrast to the Greeks. Herodotus (8.144.2) gave a famous account of what defined Greek (Hellenic) ethnic identity in his day, enumerating shared descent (Greek: ὅμαιμον – homaimon, "of the same blood"),[18][19][20] shared language (Greek: ὁμόγλωσσον – homoglōsson, "speaking the same language"),[21] shared sanctuaries and sacrifices (Greek: θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι – theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai),[22] shared customs (Greek: ἤθεα ὁμότροπα – ēthea homotropa, "customs of like fashion").[19][20][23][24][25] However, earlier Greek individuals did not define the Greek ethnicity by blood. According to Isocrates in his speech Panegyricus: "And so far has our city distanced the rest of mankind in thought and in speech that her pupils have become the teachers of the rest of the world; and she has brought it about that the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and that the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood".[26] Whether ethnicity qualifies as a cultural universal is to some extent dependent on the exact definition used. Many social scientists,[27] such as anthropologists Fredrik Barth and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human groups.[28] According to Thomas Hylland Eriksen, the study of ethnicity was dominated by two distinct debates until recently. One is between "primordialism" and "instrumentalism". In the primordialist view, the participant perceives ethnic ties collectively, as an externally given, even coercive, social bond.[29] The instrumentalist approach, on the other hand, treats ethnicity primarily as an ad hoc element of a political strategy, used as a resource for interest groups for achieving secondary goals such as, for instance, an increase in wealth, power, or status.[30][31] This debate is still an important point of reference in political science, although most scholars' approaches fall between the two poles.[32] The second debate is between "constructivism" and "essentialism". Constructivists view national and ethnic identities as the product of historical forces, often recent, even when the identities are presented as old.[33][34] Essentialists view such identities as ontological categories defining social actors.[35][36] According to Eriksen, these debates have been superseded, especially in anthropology, by scholars' attempts to respond to increasingly politicized forms of self-representation by members of different ethnic groups and nations. This is in the context of debates over multiculturalism in countries, such as the United States and Canada, which have large immigrant populations from many different cultures, and post-colonialism in the Caribbean and South Asia.[37] Max Weber maintained that ethnic groups were künstlich (artificial, i.e. a social construct) because they were based on a subjective belief in shared Gemeinschaft (community). Secondly, this belief in shared Gemeinschaft did not create the group; the group created the belief. Third, group formation resulted from the drive to monopolize power and status. This was contrary to the prevailing naturalist belief of the time, which held that socio-cultural and behavioral differences between peoples stemmed from inherited traits and tendencies derived from common descent, then called "race".[38] Another influential theoretician of ethnicity was Barth, whose "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries" from 1969 has been described as instrumental in spreading the usage of the term in social studies in the 1980s and 1990s.[39] Barth went further than Weber in stressing the constructed nature of ethnicity. To Barth, ethnicity was perpetually negotiated and renegotiated by both external ascription and internal self-identification. Barth's view is that ethnic groups are not discontinuous cultural isolates or logical a priori to which people naturally belong. He wanted to part with anthropological notions of cultures as bounded entities, and ethnicity as primordialist bonds, replacing it with a focus on the interface between groups. "Ethnic Groups and Boundaries", therefore, is a focus on the interconnectedness of ethnic identities. Barth writes: "... categorical ethnic distinctions do not depend on an absence of mobility, contact, and information, but do entail social processes of exclusion and incorporation whereby discrete categories are maintained despite changing participation and membership in the course of individual life histories."[40] In 1978 the anthropologist Ronald Cohen claimed that the identification of "ethnic groups" in the usage of social scientists often reflected inaccurate labels more than indigenous realities: ... the named ethnic identities we accept, often unthinkingly, as basic givens in the literature are often arbitrarily, or even worse inaccurately, imposed.[39] In this way, he pointed to the fact that identification of an ethnic group by outsiders, e.g. anthropologists, may not coincide with the self-identification of the members of that group. He also described that in the first decades of usage, the term ethnicity had often been used in lieu of older terms such as "cultural" or "tribal" when referring to smaller groups with shared cultural systems and shared heritage, but that "ethnicity" had the added value of being able to describe the commonalities between systems of group identity in both tribal and modern societies. Cohen also suggested that claims concerning "ethnic" identity (like earlier claims concerning "tribal" identity) are often colonialist practices and effects of the relations between colonized peoples and nation-states.[39] According to Paul James, formations of identity were often changed and distorted by colonization, but identities are not made out of nothing: Categorizations about identity, even when codified and hardened into clear typologies by processes of colonization, state formation or general modernizing processes, are always full of tensions and contradictions. Sometimes these contradictions are destructive, but they can also be creative and positive.[41] Social scientists have thus focused on how, when, and why different markers of ethnic identity become salient. Thus, anthropologist Joan Vincent observed that ethnic boundaries often have a mercurial character.[42] Ronald Cohen concluded that ethnicity is "a series of nesting dichotomizations of inclusiveness and exclusiveness".[39] He agrees with Joan Vincent's observation that (in Cohen's paraphrase) "Ethnicity ... can be narrowed or broadened in boundary terms in relation to the specific needs of political mobilization."[39] This may be why descent is sometimes a marker of ethnicity, and sometimes not: which diacritic of ethnicity is salient depends on whether people are scaling ethnic boundaries up or down, and whether they are scaling them up or down depends generally on the political situation. Kanchan Chandra rejects the expansive definitions of ethnic identity (such as those that include common culture, common language, common history and common territory), choosing instead to define ethnic identity narrowly as a subset of identity categories determined by the belief of common descent.[43] Jóhanna Birnir similarly defines ethnicity as "group self-identification around a characteristic that is very difficult or even impossible to change, such as language, race, or location."[44] |

定義と概念史 バングラデシュのダッカにおけるベンガル人集団。ベンガル人は漢民族とアラブ人に次いで世界で三番目に大きな民族集団を形成している。[15]  インドネシアのジャワ人は最大のオーストロネシア系民族集団である。 民族誌学は古代に起源を持つ。アナクシマンドロスやミレトスのヘカタイオスといった初期の著述家に続き、ヘロドトスは紀元前480年頃、古代世界の歴史学 と民族誌の基礎を築いた。ギリシャ人は自らの民族性を「ヘレネス」という名称で分類する概念を発展させていた。マケドニアのように貴族による統治形態が典 型的なギリシャとは異なっていたり、スパルタのように特異な支配階級が存在した例もあったが、古代ギリシャ人は民族ナショナリズムへの強い信念から、一般 に非ギリシャ人だけを奴隷化した。[16][17] ギリシャ人は時に、自国の最下層市民でさえあらゆる蛮族より優れていると信じていた。アリストテレスは『政治学』1.2–7; 3.14において、アリストテレスは異邦人をギリシャ人とは対照的な「生まれながらの奴隷」とさえ記述している。ヘロドトス(8.144.2)は、当時の ギリシャ(ヘレネス)民族的アイデンティティを定義する要素として、以下の項目を列挙したことで有名である。 共通の血統(ギリシャ語: ὅμαιμον – homaimon、「同じ血を引く者」)、[18][19] [20] 共通言語(ギリシャ語: ὁμόγλωσσον – homoglōsson、「同じ言語を話す者」)、[21] 共通の神域と犠牲(ギリシャ語: θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι – theōn hidrumata te koina kai thusiai)、 [22] 共通の習俗(ギリシャ語: ἤθεα ὁμότροπα – ēthea homotropa、「同様の様式の習俗」)。[19][20][23][24][25] しかし、初期のギリシャ人たちは、ギリシャ民族性を血によって定義していなかった。イソクラテスの『パネギリコス』演説によれば:「わが都は思考と言葉に おいて他の人類をはるかに凌駕し、その教え子たちが世界の教師となった。そして『ヘレネス』という名称がもはや人種ではなく知性を示し、共通の血を分けた 者よりもむしろ我々の文化を共有する者たちに適用されるようになったのである」。[26] 民族性が文化的普遍性として成立するかは、ある程度その定義次第だ。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフなど多くの社会科学者は、民族的ア イデンティティを普遍的とは見なさない。彼らは民族性を、人間集団に内在する本質的特性ではなく、特定の集団間相互作用の産物と捉えている。[28] トーマス・ヒランド・エリクセンによれば、民族性の研究は最近まで二つの異なる論争に支配されていた。 一つは「本源主義」と「手段主義」の対立である。本源主義の立場では、参加者は民族的絆を、外部から与えられた、時には強制的な社会的絆として集合的に認 識する。[29] 一方、手段主義的アプローチは、民族性を主に政治戦略の臨機応変な要素として扱い、例えば富・権力・地位の向上といった二次的目標達成のための資源とし て、利害集団が利用するものとする。[30][31] この論争は現在も政治学における重要な参照点であるが、大半の研究者のアプローチは両極の中間に位置する。[32] 第二の論争は「構成主義」と「本質主義」の間にある。構成主義者は、たとえ古くから存在するものと提示されていても、国民的・民族的アイデンティティを、 しばしば近年の歴史的力学の産物と見なす。[33][34] 本質主義者は、そうしたアイデンティティを社会的な行為者を定義する存在論的カテゴリーと見なす。[35] [36] エリクセンによれば、特に人類学では、異なる民族や国民による、ますます政治化された自己表現の形式に対応しようとする学者たちの試みによって、これらの 議論は時代遅れになっている。これは、米国やカナダなど、多くの異なる文化からの移民人口が多い国々における多文化主義、およびカリブ海地域や南アジアに おけるポストコロニアリズムに関する議論の文脈にある。[37] マックス・ヴェーバーは、民族集団は、共有されたゲマインシャフト(共同体)に対する主観的な信念に基づくものであるため、クンストリッヒ(人工的、すな わち社会的構築物)であると主張した。第二に、共有されたゲマインシャフトに対するこの信念が集団を生み出したのではなく、集団がこの信念を生み出したの である。第三に、集団の形成は、権力と地位を独占しようとする欲求から生じた。これは、当時主流だった自然主義的信念、すなわち、民族間の社会文化的・行 動的差異は、共通の祖先(当時は「人種」と呼ばれていた)に由来する遺伝的特性や傾向に起因するという信念とは相反するものであった。[38] 民族性に関するもう一人の影響力のある理論家はバースであり、1969年の『民族集団と境界』は、1980年代および1990年代の社会科学におけるこの 用語の使用を広める上で重要な役割を果たしたと評されている。バースは、民族性の構築的性質を強調する点でヴェーバーよりもさらに踏み込んだ。バースに とって、民族性は、外部からの帰属と内部からの自己認識の両方によって絶えず交渉され、再交渉されるものであった。バースの見解では、民族集団は、人民が 自然に属する、不連続な文化的孤立体やア・プリオリな論理的実体ではない。彼は、文化を境界のある実体、民族性を先天的絆とする人類学的概念から離れ、集 団間の接点に焦点を当てることに置き換えたいと考えた。したがって、「民族集団と境界」は、民族的アイデンティティの相互関連性に焦点を当てたものであ る。バースは次のように書いている。「... カテゴリー的な民族的区別は、移動性・接触・情報の欠如に依存するものではない。しかしそれは、個人の生涯における参加や所属関係が変化する中で、分離さ れたカテゴリーを維持するための社会的排除と包摂のプロセスを伴うものである。」[40] 1978年、人類学者ロナルド・コーエンは、社会科学者が用いる「民族集団」の識別は、しばしば現地の実情よりも不正確なラベルを反映していると主張し た: ...文献において我々が、しばしば無思慮に基本的な前提として受け入れる名指された民族的アイデンティティは、往々にして恣意的、あるいはさらに悪いこ とに不正確に押し付けられたものである。[39] このように彼は、人類学者などの外部者による民族集団の識別が、その集団の成員による自己認識と一致しない場合がある事実を指摘した。また彼は、この用語 が使用され始めた最初の数十年において、「民族性」という用語は、共有された文化システムと共有された遺産を持つ小規模な集団を指す際に、「文化的」や 「部族的」といった古い用語の代わりとして頻繁に使われてきたと説明した。しかし「民族性」には、部族的社会と近代社会の双方の集団アイデンティティ体系 における共通点を記述できるという付加価値があった。コーエンはさらに、「民族的」アイデンティティに関する主張(かつての「部族的」アイデンティティに 関する主張と同様に)は、しばしば植民地主義的実践であり、被植民地民衆と国民との関係が生み出す効果であると示唆している。[39] ポール・ジェームズによれば、アイデンティティの形成は植民地化によってしばしば変容・歪められるが、アイデンティティは無から生まれるものではない: アイデンティティに関する分類は、たとえ植民地化や国家形成、あるいは一般的な近代化プロセスによって明確な類型として固定化されても、常に緊張と矛盾に 満ちている。こうした矛盾は時に破壊的だが、創造的で積極的な側面も持つ。[41] したがって社会科学者は、民族的アイデンティティの異なる指標が、いつ、どのように、なぜ顕在化するかに焦点を当ててきた。人類学者ジョアン・ヴィンセン トは、民族境界がしばしば水銀のような流動性を持つと指摘した[42]。ロナルド・コーエンは民族性を「包含性と排他性の入れ子状の二分化」と結論づけた [39]。彼はヴィンセントの観察(コーエンの言い換えによれば)「民族性は…政治動員の具体的必要に応じて境界を狭めたり広げたりできる」という見解に 同意している。[39] これが、血統が時に民族性の指標となり、時にそうならない理由かもしれない。どの民族性の特徴が顕著になるかは、人民が民族境界を拡大するか縮小するかに よって決まり、その拡大縮小は概して政治状況に依存するのだ。 カンチャン・チャンドラは、民族的アイデンティティの拡張的定義(共通文化・共通言語・共通歴史・共通領土を含むような定義)を拒否し、代わりに民族的ア イデンティティを「共通の血統という信念によって決定されるアイデンティティカテゴリーのサブセット」として狭義に定義する。[43] ヨハンナ・ビルニルも同様に、民族性を「言語・人種・居住地など、変更が極めて困難あるいは不可能な特性に基づく集団的自己認識」と定義する。[44] |

| Approaches to understanding

ethnicity Different approaches to understanding ethnicity have been used by different social scientists when trying to understand the nature of ethnicity as a factor in human life and society. As Jonathan M. Hall observes, World War II was a turning point in ethnic studies. The consequences of Nazi racism discouraged essentialist interpretations of ethnic groups and race. Ethnic groups came to be defined as social rather than biological entities. Their coherence was attributed to shared myths, descent, kinship, a common place of origin, language, religion, customs and national character. So, ethnic groups are conceived as mutable rather than stable, constructed in discursive practices rather than written in the genes.[45] Examples of various approaches are primordialism, essentialism, perennialism, constructivism, modernism and instrumentalism. "Primordialism", holds that ethnicity has existed at all times of human history and that modern ethnic groups have historical continuity into the far past. For them, the idea of ethnicity is closely linked to the idea of nations and is rooted in the pre-Weber understanding of humanity as being divided into primordially existing groups rooted by kinship and biological heritage. "Essentialist primordialism" further holds that ethnicity is an a priori fact of human existence, that ethnicity precedes any human social interaction and that it is unchanged by it. This theory sees ethnic groups as natural, not just as historical. However, this theory ignores the impact of intermarriage, migration and colonization, which shape the composition of modern-day multi-ethnic societies.[46] "Kinship primordialism" holds that ethnic communities are extensions of kinship units, basically being derived by kinship or clan ties where the choices of cultural signs (language, religion, traditions) are made exactly to show this biological affinity. In this way, the myths of common biological ancestry that are a defining feature of ethnic communities are to be understood as representing actual biological history. A problem with this view on ethnicity is that it is more often than not the case that mythic origins of specific ethnic groups directly contradict the known biological history of an ethnic community.[46] "Geertz's primordialism", notably espoused by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz, argues that humans in general attribute an overwhelming power to primordial human "givens" such as blood ties, language, territory, and cultural differences. In Geertz' opinion, ethnicity is not in itself primordial but humans perceive it as such because it is embedded in their experience of the world.[46] "Perennialism" is an approach that is primarily concerned with nationhood but tends to see nations and ethnic communities as basically the same phenomenon. It holds that the nation, as a type of social and political organization, is of an immemorial or "perennial" character.[47] Smith (1999) distinguishes two variants: "continuous perennialism", which claims that particular nations have existed for very long periods, and "recurrent perennialism", which focuses on the emergence, dissolution and reappearance of nations as a recurring aspect of human history.[48] "Perpetual perennialism" holds that specific ethnic groups have existed continuously throughout history. "Situational perennialism" holds that nations and ethnic groups emerge, change and vanish through the course of history. This view holds that the concept of ethnicity is a tool used by political groups to manipulate resources such as wealth, power, territory or status in their particular groups' interests. Accordingly, ethnicity emerges when it is relevant as a means of furthering emergent collective interests and changes according to political changes in society. Examples of a perennialist interpretation of ethnicity are also found in Barth and Seidner who see ethnicity as ever-changing boundaries between groups of people established through ongoing social negotiation and interaction. "Instrumentalist perennialism", while seeing ethnicity primarily as a versatile tool that identified different ethnics groups and limits through time, explains ethnicity as a mechanism of social stratification, meaning that ethnicity is the basis for a hierarchical arrangement of individuals. According to Donald Noel, a sociologist who developed a theory on the origin of ethnic stratification, ethnic stratification is a "system of stratification wherein some relatively fixed group membership (e.g., race, religion, or nationality) is used as a major criterion for assigning social positions".[49] Ethnic stratification is one of many different types of social stratification, including stratification based on socio-economic status, race, or gender. According to Donald Noel, ethnic stratification will emerge only when specific ethnic groups are brought into contact with one another, and only when those groups are characterized by a high degree of ethnocentrism, competition, and differential power. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one's own culture, and to downgrade all other groups outside one's own culture. Some sociologists, such as Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings, say the origin of ethnic stratification lies in individual dispositions of ethnic prejudice, which relates to the theory of ethnocentrism.[50] Continuing with Noel's theory, some degree of differential power must be present for the emergence of ethnic stratification. In other words, an inequality of power among ethnic groups means "they are of such unequal power that one is able to impose its will upon another".[49] In addition to differential power, a degree of competition structured along ethnic lines is a prerequisite to ethnic stratification as well. The different ethnic groups must be competing for some common goal, such as power or influence, or a material interest, such as wealth or territory. Lawrence Bobo and Vincent Hutchings propose that competition is driven by self-interest and hostility, and results in inevitable stratification and conflict.[50] "Constructivism" sees both primordialist and perennialist views as basically flawed,[50] and rejects the notion of ethnicity as a basic human condition. It holds that ethnic groups are only products of human social interaction, maintained only in so far as they are maintained as valid social constructs in societies. "Modernist constructivism" correlates the emergence of ethnicity with the movement towards nation states beginning in the early modern period.[51] Proponents of this theory, such as Eric Hobsbawm, argue that ethnicity and notions of ethnic pride, such as nationalism, are purely modern inventions, appearing only in the modern period of world history. They hold that prior to this ethnic homogeneity was not considered an ideal or necessary factor in the forging of large-scale societies. Ethnicity is an important means by which people may identify with a larger group. Many social scientists, such as the anthropologists Fredrik Barth and Eric Wolf, do not consider ethnic identity to be universal. They regard ethnicity as a product of specific kinds of inter-group interactions, rather than an essential quality inherent to human groups.[28] The process that results in emergence of such identification is called ethnogenesis. Members of an ethnic group, on the whole, claim cultural continuities over time, although historians and cultural anthropologists have documented that many of the values, practices, and norms that imply continuity with the past are of relatively recent invention.[52][53] Ethnic groups can form a cultural mosaic in a society. That could be in a city like New York City or Trieste, but also the fallen monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or the United States. Current topics are in particular social and cultural differentiation, multilingualism, competing identity offers, multiple cultural identities and the formation of Salad bowl and melting pot.[54][55][56][57] Ethnic groups differ from other social groups, such as subcultures, interest groups or social classes, because they emerge and change over historical periods (centuries) in a process known as ethnogenesis, a period of several generations of endogamy resulting in common ancestry (which is then sometimes cast in terms of a mythological narrative of a founding figure); ethnic identity is reinforced by reference to "boundary markers" – characteristics said to be unique to the group which set it apart from other groups.[58][59][60][61][62][63] |

民族性を理解するアプローチ 人間生活や社会における要因としての民族性の本質を理解しようと試みる際、様々な社会科学者が異なるアプローチを採用してきた。ジョナサン・M・ホールが 指摘するように、第二次世界大戦は民族研究における転換点であった。ナチスの人種主義がもたらした結果は、民族集団や人種に対する本質主義的解釈を阻ん だ。民族集団は生物学的実体ではなく社会的実体として定義されるようになった。その結束性は、共有された神話、血統、親族関係、共通の起源地、言語、宗 教、習慣、国民性などに帰せられた。したがって民族集団は、遺伝的に刻印されたものではなく、言説的実践によって構築される可変的な存在として捉えられる ようになった。[45] 様々なアプローチの例としては、本源主義、本質主義、恒常主義、構成主義、現代主義、機能主義が挙げられる。 「本源主義」は、民族性は人類の歴史のあらゆる時代に存在しており、現代の民族集団は遠い過去まで歴史的に連続していると主張する。彼らにとって、民族性 の概念は国民の概念と密接に関連しており、ヴェーバー以前の、人類は血縁や生物学的遺産によって根ざした、原初的に存在する集団に分かれているという理解 に根ざしている。 「本質主義的本源主義」はさらに、民族性は人間存在におけるア・プリオリに定められた事実であり、民族性はあらゆる人間社会的な相互作用に先行し、それに よって変化することはないと主張する。この理論は、民族集団を歴史的なものだけでなく、自然なものとして捉える。しかし、この理論は、現代の多民族社会の 構成を形作る、異民族間の結婚、移住、植民地化の影響を無視している。[46] 「血縁本源主義」は、民族共同体が血縁単位の延長であり、基本的に血縁や氏族の絆から派生したものであると主張する。そこでは文化的記号(言語、宗教、伝 統)の選択が、まさにこの生物学的親和性を示すためになされる。このように、民族共同体の特徴を定義づける共通の生物学的祖先に関する神話は、実際の生物 学的歴史を表すものと理解されるべきである。この民族観の問題点は、特定の民族集団の神話的起源が、その民族共同体の既知の生物学的歴史と直接矛盾する場 合が少なくないことだ。[46] 人類学者クリフォード・ギアーツが特に提唱した「ギアーツの本源主義」は、人間は一般的に血縁、言語、領土、文化的差異といった原始的な「与えられたも の」に圧倒的な力を帰属させると論じる。ギアーツの見解では、民族性自体は原初的ではないが、人間はそれを自らの世界認識に埋め込まれたものとして原初的 に認識するのだ。[46] 「永続主義」は主に国民性を扱うアプローチだが、国家と民族共同体を基本的に同一の現象と見なす傾向がある。国家という社会的・政治的組織形態は、記憶に ないほど古い、あるいは「永続的」な性格を持つと主張する。[47] スミス(1999)は二つの変種を区別する:「連続的永続主義」は特定の国民が非常に長い期間存在してきたと主張し、「反復的永続主義」は国民の出現、解 体、再出現が人類史の反復的側面であることに焦点を当てる。[48] 「永続的永続主義」は特定の民族集団が歴史を通じて継続的に存在してきたと主張する。 「状況的永続主義」は、国民や民族集団が歴史の過程で出現・変化・消滅すると主張する。この見解によれば、民族性の概念は、富・権力・領土・地位といった 資源を特定の集団の利益のために操作する手段として政治集団が用いる道具である。したがって、民族性は新たな集団的利益を推進する手段として関連性を持つ 時に出現し、社会の政治的変化に応じて変化する。民族性を永続主義的に解釈する例は、バルトやサイドナーにも見られる。彼らは民族性を、継続的な社会的交 渉と相互作用を通じて確立される、人々の集団間の絶えず変化する境界と捉えている。 「手段主義的永続主義」は、民族性を主に異なる民族集団と境界を時間的に識別する多目的ツールと見なす一方で、民族性を社会階層化のメカニズムとして説明 する。つまり民族性は、個人の階層的配置の基盤であるという意味だ。民族階層化の起源に関する理論を展開した社会学者ドナルド・ノエルによれば、民族階層 化とは「比較的固定された集団所属(例:人種、宗教、国籍)を社会的地位の主要な基準として用いる階層化システム」である[49]。民族階層化は、社会経 済的地位、人種、性別に基づく階層化など、様々な社会的階層化の一形態に過ぎない。ドナルド・ノエルによれば、民族階層化は特定の民族集団が互いに接触し た時のみ発生し、かつそれらの集団が高い程度の民族中心主義、競争、力関係の違いによって特徴づけられる場合にのみ現れる。民族中心主義とは、世界を主に 自らの文化の視点から見て、自らの文化以外の全ての集団を軽視する傾向である。ローレンス・ボボやヴィンセント・ハッチングスといった社会学者らは、民族 階層化の起源は個人の民族的偏見の傾向にあり、これは民族中心主義の理論と関連すると述べる[50]。ノエルの理論を継承すれば、民族階層化が出現するに は、ある程度の力関係の違いが存在しなければならない。つまり、民族集団間の力の不均衡とは「一方が他方に自らの意思を押し付けられるほどの力の格差」を 意味する[49]。力の差異に加え、民族線を軸とした競争の存在も民族階層化の前提条件である。異なる民族集団は、権力や影響力といった共通の目標、ある いは富や領土といった物質的利益をめぐって競合していなければならない。ローレンス・ボボとヴィンセント・ハッチングスは、競争は自己利益と敵意によって 駆動され、必然的な階層化と紛争をもたらすと提唱している[50]。 「構成主義」は、原初主義と永続主義の両方の見解を基本的に欠陥があると見なし[50]、民族性が人間の基本的条件であるという概念を拒否する。民族集団 は人間の社会的相互作用の産物に過ぎず、社会において有効な社会的構築物として維持される限りにおいてのみ存続すると主張する。 「近代主義的構成主義」は、民族性の出現を近世初期に始まった国民国家への動きと関連づける[51]。エリック・ホブズボームらこの理論の支持者は、民族 性やナショナリズムのような民族的誇りの概念は純粋に近代的な発明であり、世界史の近代期にのみ出現したと主張する。彼らは、それ以前には民族的同質性が 大規模な社会を形成する上で理想的あるいは必要な要素とは見なされていなかったと考える。 民族性は、人民がより大きな集団と同一視するための重要な手段である。人類学者のフレドリック・バースやエリック・ウルフなど多くの社会科学者は、民族的 アイデンティティを普遍的なものと見なさない。彼らは民族性を、人間集団に内在する本質的性質ではなく、特定の種類の集団間相互作用の産物と見なしている [28]。このような同一視の出現をもたらす過程は、エスノジェネシスと呼ばれる。民族集団の成員は概して、時間を超えた文化的連続性を主張する。しかし 歴史学者や文化人類学者が実証しているように、過去との連続性を示唆する多くの価値観、慣行、規範は比較的最近に発明されたものである。[52] [53] 民族集団は社会において文化的モザイクを形成しうる。それはニューヨーク市やトリエステのような都市でも、崩壊したオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国やアメリ カ合衆国でも見られる。現在の論点は特に社会的・文化的分化、多言語主義、競合するアイデンティティの提示、複数の文化的アイデンティティ、そしてサラダ ボウルとメルティングポットの形成にある。[54] [55][56][57] 民族集団は、サブカルチャーや利益団体、社会階級といった他の社会集団とは異なる。なぜなら、民族集団は「民族形成」と呼ばれる過程で、歴史的期間(数世 紀)をかけて出現し変化するからだ。この過程では、数世代にわたる内婚制が続き、共通の祖先が生まれる(これは時に、創始者に関する神話的物語として語ら れる)。民族的アイデンティティは「境界マーカー」への言及によって強化される。境界マーカーとは、当該集団に固有であり他集団と区別する特徴とされるも のである。[58][59][60][61][62][63] |

| Ethnicity theory in the United

States Ethnicity theory argues that race is a social category and is only one of several factors in determining ethnicity. Other criteria include "religion, language, 'customs', nationality, and political identification".[64] This theory was put forward by the sociologist Robert E. Park in the 1920s. It is based on the notion of "culture". This theory was preceded by more than 100 years during which biological essentialism was the dominant paradigm on race. Biological essentialism is the belief that some races, specifically White Europeans in western versions of the paradigm, are biologically superior and other races, specifically non-White races in western debates, are inherently inferior. This view arose as a way to justify enslavement of African Americans and genocide of Native Americans in a society that was officially founded on freedom for all. This was a notion that developed slowly and came to be a preoccupation with scientists, theologians, and the public. Religious institutions asked questions about whether there had been multiple creations of races (polygenesis) and whether God had created lesser races. Many of the foremost scientists of the time took up the idea of racial difference and found that White Europeans were superior.[65] The ethnicity theory was based on the assimilation model. Park outlined four steps to assimilation: contact, conflict, accommodation, and assimilation. Instead of attributing the marginalized status of people of colour in the United States to their inherent biological inferiority, he attributed it to their failure to assimilate into American culture. They could become equal if they abandoned their inferior cultures. Michael Omi's and Howard Winant's theory of racial formation directly confronts both the premises and the practices of ethnicity theory. They argue in Racial Formation in the United States that the ethnicity theory was exclusively based on the immigration patterns of the White population and did take into account the unique experiences of non-Whites in the United States.[66] While Park's theory identified different stages in the immigration process – contact, conflict, struggle, and as the last and best response, assimilation – it did so only for White communities.[66] The ethnicity paradigm neglected the ways in which race can complicate a community's interactions with social and political structures, especially upon contact. Assimilation – shedding the particular qualities of a native culture for the purpose of blending in with a host culture – did not work for some groups as a response to racism and discrimination, though it did for others.[66] Once the legal barriers to achieving equality had been dismantled, the problem of racism became the sole responsibility of already disadvantaged communities.[67] It was assumed that if a Black or Latino community was not "making it" by the standards that had been set by Whites, it was because that community did not hold the right values or beliefs, or were stubbornly resisting dominant norms because they did not want to fit in. Omi and Winant's critique of ethnicity theory explains how looking to cultural defect as the source of inequality ignores the "concrete sociopolitical dynamics within which racial phenomena operate in the U.S."[68] It prevents critical examination of the structural components of racism and encourages a "benign neglect" of social inequality.[68] |

アメリカにおける民族性理論 民族性理論は、人種が社会的カテゴリーであり、民族性を決定する複数の要素の一つに過ぎないと主張する。その他の基準には「宗教、言語、『習慣』、国籍、 政治的帰属意識」が含まれる[64]。この理論は1920年代に社会学者ロバート・E・パークによって提唱された。それは「文化」という概念に基づいてい る。 この理論が提唱される以前、100年以上にわたり人種に関する支配的なパラダイムは生物学的本質主義であった。生物学的本質主義とは、特定の人種(西洋版 パラダイムでは特に白人ヨーロッパ系)が生物学的に優越し、他の人種(西洋の議論では特に非白人種)が本質的に劣っているという信念である。この見解は、 公式には万人の自由を基盤とする社会において、アフリカ系アメリカ人の奴隷化や先住民の大量虐殺を正当化する手段として生まれた。この概念は徐々に発展 し、科学者、神学者、一般市民の関心事となった。宗教機関は人種の複数創造(多源説)や神による劣等人種の創造について問うた。当時の主要な科学者の多く が人種差別の概念を取り上げ、白人ヨーロッパ人が優越していると結論づけた。[65] 民族性理論は同化モデルに基づいていた。パークは同化の四段階を提示した:接触、衝突、適応、同化。米国における有色人民の境界化を、彼らの生来の生物学 的劣性に帰するのではなく、アメリカ文化への同化失敗に帰した。劣った文化を捨てれば平等になれると主張したのである。 マイケル・オミとハワード・ウィナントの人種形成理論は、民族性理論の前提と実践の両方に直接的に異議を唱えるものである。彼らは『アメリカ合衆国におけ る人種形成』において、エスニシティ理論が白人移民のパターンにのみ基づいており、アメリカにおける非白人の独自の経験を考慮に入れていなかったと論じて いる[66]。パークの理論は移民過程における異なる段階——接触、衝突、闘争、そして最終的かつ最善の対応としての同化——を特定したが、それは白人コ ミュニティにのみ当てはまるものだった。[66] エスニシティ・パラダイムは、人種がコミュニティの社会的・政治的構造との相互作用を複雑化する方法、特に接触段階におけるそれを無視した。 同化――すなわち、受け入れ文化に溶け込む目的で母国の文化の特質を捨てること――は、人種主義や差別への対応として、一部の集団には機能しなかった。他 の集団には機能したが。[66] 平等達成への法的障壁が撤廃されると、人種主義の問題は既に不利な立場にあるコミュニティの単独責任となった。[67] 黒人やラテン系コミュニティが白人が設定した基準で「成功」していない場合、そのコミュニティが正しい価値観や信念を持たないか、あるいは同化を拒む頑固 な抵抗ゆえだと想定されたのである。オミとウィナントによるエスニシティ理論への批判は、不平等の根源を文化的欠陥に求める見方が「米国における人種現象 が作用する具体的な社会政治的力学」を無視していることを説明している[68]。それは人種主義の構造的要素に対する批判的検証を妨げ、社会的不平等に対 する「良性の放置」を助長するのだ[68]。 |

| Ethnicity and nationality In some cases, especially those involving transnational migration or colonial expansion, people may link ethnicity to nationality. Anthropologists and historians, following the modernist understanding of ethnicity as proposed by Ernest Gellner[69] and by Benedict Anderson[70] see nations and nationalism as developing with the rise of the modern state-system in the 17th century. This process culminated in the rise of "nation-states" in which the presumptive boundaries of the nation coincided (or ideally coincided) with state boundaries. Thus, in the Western world, the notion of ethnicity, like race and nation, developed in the context of European colonial expansion, when mercantilism and capitalism were promoting global movements of populations at the same time that state boundaries were being more clearly and rigidly defined. In the 19th century modern states generally sought legitimacy through their claim to represent "nations". Nation states, however, invariably include populations who have been excluded from national life for one reason or another. Members of excluded groups, consequently, will either demand inclusion based on equality, or they will seek autonomy, sometimes even to the extent of complete political separation from their existing nation-state.[71] Under these conditions, when people moved from one state to another,[72] or when one state conquered or colonized peoples beyond its national boundaries, ethnic groups were formed by people who identified with one nation but lived in another state. Multi-ethnic states can result from one of two opposite events: either the recent creation of state borders at variance with traditional tribal territories or the recent immigration of ethnic minorities into a formerly homogenous nation-state Examples for the first case occur throughout Africa, where countries formed during decolonization inherited arbitrary colonial borders, but also in European countries such as Belgium or the United Kingdom. Examples for the second case are countries such as Netherlands, which were relatively ethnically homogeneous when they attained statehood but have received significant immigration in the 17th century and even more so in the second half of the 20th century. States such as the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland comprised distinct ethnic groups from their formation and have likewise experienced substantial immigration, resulting in what have been termed "multicultural" societies, especially in large cities. The states of the New World were multi-ethnic from the onset, as they developed as settler colonies imposed on existing indigenous populations. In recent decades, feminist scholars (most notably Nira Yuval-Davis)[73] have drawn attention to the fundamental ways in which women participate in the creation and reproduction of ethnic and national categories. Though these categories are usually discussed as belonging to the public, political sphere, they are upheld within the private, family sphere to a great extent.[74] It is here that women act not just as biological reproducers but also as "cultural carriers", transmitting knowledge and enforcing behaviors that belong to a specific collectivity.[75] Women also often play a significant symbolic role in conceptions of nation or ethnicity, for example in the notion that "women and children" constitute the kernel of a nation which must be defended in times of conflict, or in iconic figures such as Britannia or Marianne. |

エスニシティとナショナリティ 場合によっては、特に国境を越えた移住や植民地拡大が関係している場合には、人民は民族性と国籍を結びつけることがある。人類学者や歴史学者は、アーネス ト・ゲルナー[69] やベネディクト・アンダーソン[70] が提唱した、民族性に関するモダニズム的な理解に従って、国民とナショナリズムは 17 世紀の近代国家システムの台頭とともに発展してきたとみなしている。この過程は、国家の推定境界が(理想的には)国家の境界と一致する「国民国家」の台頭 で頂点に達した。したがって、西洋世界では、人種や国家と同様に、民族性の概念も、重商主義と資本主義が世界的な人口移動を促進すると同時に、国家の境界 がより明確かつ厳格に定義された、ヨーロッパの植民地拡大の文脈の中で発展した。 19世紀、近代国家は概して「国民」を代表するとの主張を通じて正当性を求めた。しかし国民国家には、何らかの理由で国民生活から排除された集団が常に含 まれる。排除された集団の成員は、結果として平等に基づく包摂を要求するか、あるいは自治を求めることになる。時には既存の国民国家からの完全な政治的分 離に至る場合さえある[71]。こうした状況下で、人民が国家間を移動した時[72]、あるいはある国民が自国境界を越えて他民族を征服・植民地化した 時、一つの国民に帰属意識を持ちながらも別の国家に居住する人民によって民族集団が形成された。 多民族国家は、二つの相反する事象のいずれかから生じうる: 伝統的な部族領域と矛盾する国家境界の近年の設定 あるいは、従来均質な国民国家への少数民族の近年の移住 前者の事例はアフリカ全域に見られる。脱植民地化期に形成された国々が恣意的な植民地境界を継承したためだ。ベルギーやイギリスといった欧州諸国も同様で ある。後者の事例としてはオランダが挙げられる。国家成立時は比較的民族的に均質だったが、17世紀に大規模な移民を受け入れ、20世紀後半にはさらに増 加した。英国、フランス、スイスなどの国家は、その形成時から異なる民族グループで構成されており、同様に大規模な移民を受け入れてきた結果、特に大都市 では「多文化」社会と呼ばれるものとなっている。 新世界の国家は、既存の先住民に課せられた入植者植民地として発展したため、当初から多民族国家であった。 ここ数十年、フェミニスト学者(特にニラ・ユヴァル=デイヴィス)は、女性が民族や国民のカテゴリーを作り出し、再生産する基本的な方法に注目してきた。 これらのカテゴリーは通常、公共の政治的領域に属するものとして議論されるが、私的な家族領域でも大きく支持されている。[74] ここで女性は、生物学的再生産者としての役割だけでなく、「文化的担い手」としても行動し、特定の集団に属する知識を伝達し、行動を強制する。[75] 女性はまた、国民や民族性の概念において、しばしば重要な象徴的役割を果たす。例えば、「女性と子供」は、紛争時に守らなければならない国民の核を構成す るという概念や、ブリタニアやマリアンヌなどの象徴的な人物像がそれである。 |

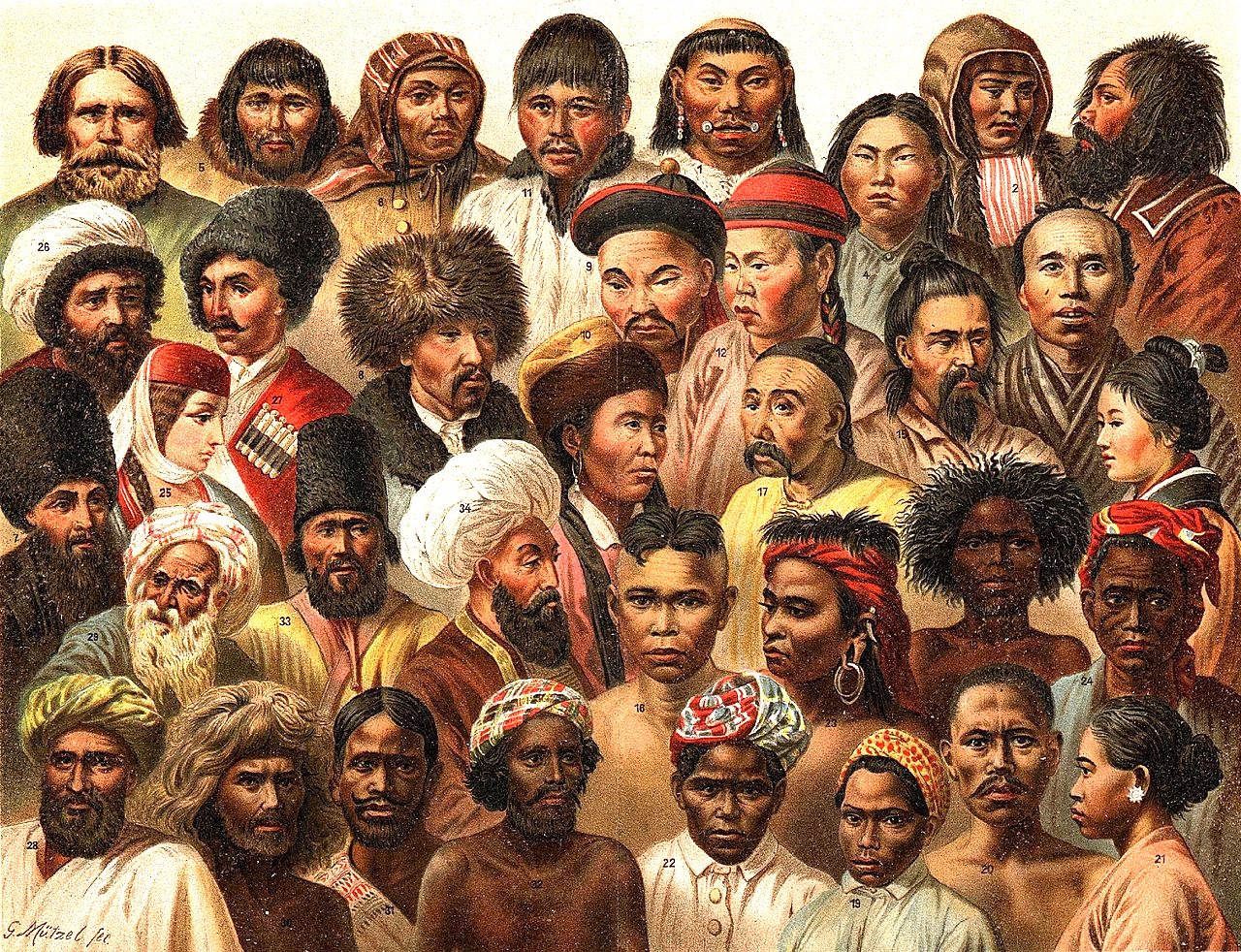

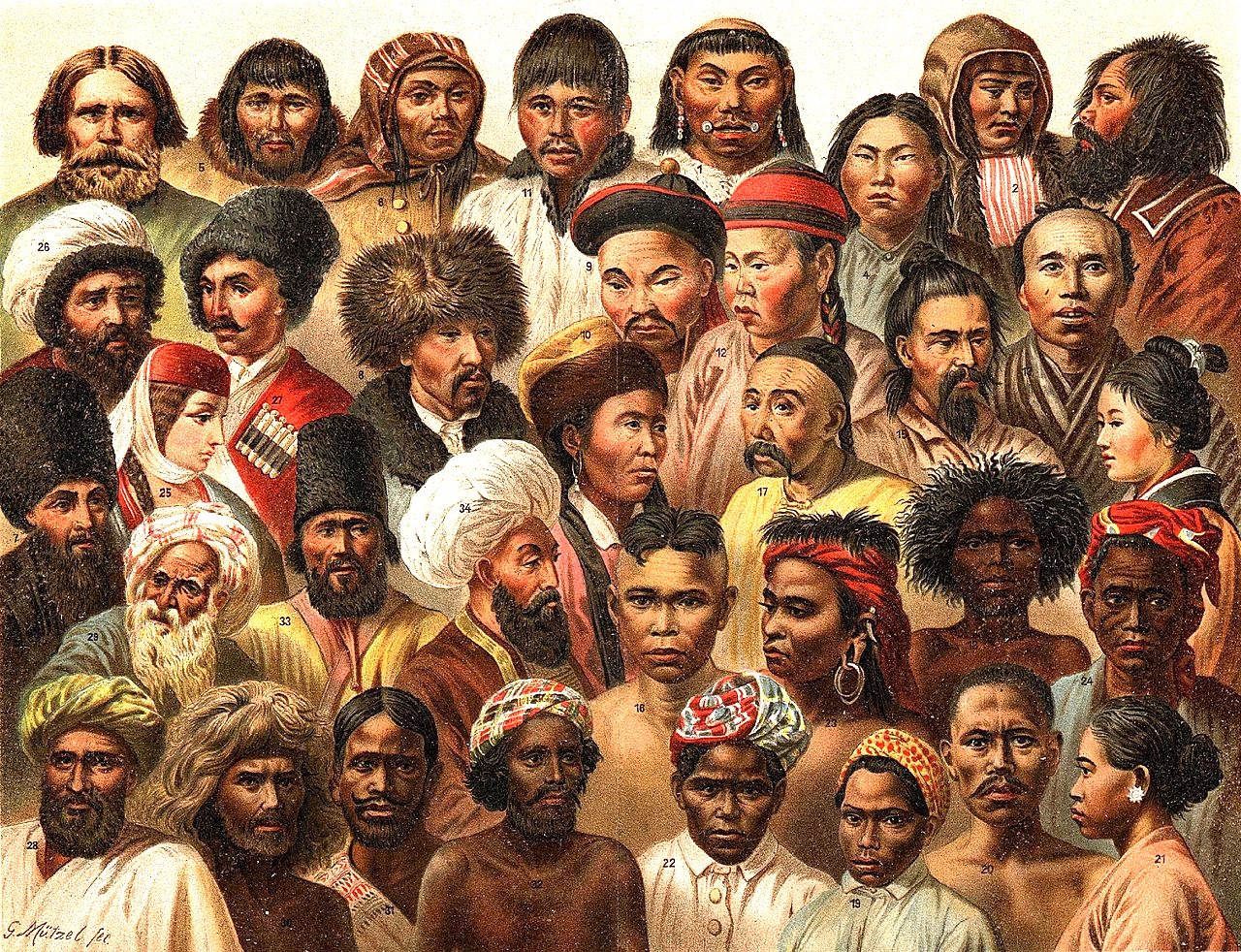

Ethnicity and race The racial diversity of Asia's ethnic groups (original caption: Asiatiska folk), Nordisk familjebok (1904) Before Weber (1864–1920), race and ethnicity were primarily seen as two aspects of the same thing. Around 1900 and before, the primordialist understanding of ethnicity predominated: cultural differences between peoples were seen as being the result of inherited traits and tendencies.[38] With Weber's introduction of the idea of ethnicity as a social construct, race and ethnicity became more divided from each other. In 1950 the UNESCO statement "The Race Question", signed by some of the internationally renowned scholars of the time (including Ashley Montagu, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Gunnar Myrdal, Julian Huxley, etc.), said: National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups: and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connection with racial traits. Because serious errors of this kind are habitually committed when the term "race" is used in popular parlance, it would be better when speaking of human races to drop the term "race" altogether and speak of "ethnic groups".[76] In 1982 the anthropologist David Craig Griffith summarized forty years of ethnographic research, arguing that racial and ethnic categories are symbolic markers for different ways people from different parts of the world have been incorporated into a global economy: The opposing interests that divide the working classes are further reinforced through appeals to "racial" and "ethnic" distinctions. Such appeals serve to allocate different categories of workers to rungs on the scale of labor markets, relegating stigmatized populations to the lower levels and insulating the higher echelons from competition from below. Capitalism did not create all the distinctions of ethnicity and race that function to set off categories of workers from one another. It is, nevertheless, the process of labor mobilization under capitalism that imparts to these distinctions their effective values.[77] According to Wolf, racial categories were constructed and incorporated during the period of European mercantile expansion, and ethnic groupings during the period of capitalist expansion.[78] Writing in 1977 about the usage of the term "ethnic" in the ordinary language of the United Kingdom and the United States, Wallman noted The term "ethnic" popularly connotes "[race]" in Britain, only less precisely, and with a lighter value load. In North America, by contrast, "[race]" most commonly means color, and "ethnics" are the descendants of relatively recent immigrants from non-English-speaking countries. "[Ethnic]" is not a noun in Britain. In effect there are no "ethnics"; there are only "ethnic relations".[79] In the US the Office of Management and Budget says the definition of race as used for the purposes of the US Census is not "scientific or anthropological" and takes into account "social and cultural characteristics as well as ancestry", using "appropriate scientific methodologies" that are not "primarily biological or genetic in reference".[80] Ramón Grosfoguel (University of California, Berkeley) argues that "racial/ethnic identity" is one concept and concepts of race and ethnicity cannot be used as separate and autonomous categories.[81] |

民族と人種 アジアの民族集団の人種的多様性(元のキャプション:Asiatiska folk)、Nordisk familjebok(1904年) ヴェーバー(1864-1920)以前、人種と民族性は主に同じものの二つの側面として見られていた。1900年頃以前、民族性については原初主義的な理 解が主流であった。つまり、民族間の文化的な違いは、受け継がれた特性や傾向の結果であると考えられていた[38]。ヴェーバーが社会構造としての民族性 の概念を導入したことで、人種と民族性はより明確に区別されるようになった。 1950年、当時の国際的に著名な学者たち(アシュリー・モンタギュー、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、グンナー・ミルダル、ジュリアン・ハクスリーな ど)が署名したユネスコの声明「人種問題」は、次のように述べている。 国民、宗教、地理、言語、文化の集団は、必ずしも人種集団と一致するわけではない。また、そのような集団の文化的特徴は、人種的特徴と遺伝的に関連がある ことは証明されていない。「人種」という用語が一般用語として使用される場合、この種の重大な誤りが常習的に行われているため、人種について話す際には 「人種」という用語を完全に廃止し、「民族集団」について話すほうがよいだろう。[76] 1982年、人類学者デビッド・クレイグ・グリフィスは40年にわたる民族誌的研究をまとめ、人種や民族のカテゴリーは、世界各地の異なる人民が世界経済 に組み込まれるさまざまな方法を象徴するマーカーであると主張した。 労働者階級を分断する対立する利害関係は、「人種」や「民族」の区別を訴えることでさらに強化される。こうした訴えは、労働市場の階層において、異なるカ テゴリーの労働者を配置し、汚名を着せられた人々を低いレベルに追いやると同時に、上位層を下位層からの競争から隔離する役割を果たしている。資本主義 は、労働者をカテゴリーごとに区別する、民族や人種に関するあらゆる区別を生み出したわけではない。しかし、資本主義の下での労働動員というプロセスが、 こうした区別に実効的な価値を与えている。[77] ウルフによれば、人種的カテゴリーはヨーロッパの商業的拡張期に構築・組み込まれ、民族的グループ化は資本主義的拡張期に形成されたという。[78] 1977年に英国と米国の日常言語における「ethnic」用語の使用について論じたウォールマンは次のように記している 「エスニック」という用語は、英国では大衆的に「人種」を意味するが、より不正確で、価値的負荷も軽い。対照的に北米では、「人種」は最も一般的に肌の色 を意味し、「エスニック」とは非英語圏からの比較的最近の移民の子孫を指す。「エスニック」は英国では名詞ではない。実質的に「エスニック」という概念は 存在せず、「エスニック関係」のみが存在する。[79] 米国では行政管理予算局が、国勢調査における人種の定義は「科学的または人類学的」なものではなく、「祖先だけでなく社会的・文化的特性」を考慮し、「主 に生物学的・遺伝学的参照ではない適切な科学的メソドロジー」を用いていると述べている。[80] ラモン・グロスフォゲール(カリフォルニア大学バークレー校)は、「人種的/民族的アイデンティティ」は一つの概念であり、人種と民族性の概念を別個かつ 自律的なカテゴリーとして扱うことはできないと論じている。[81] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnicity |

|

| Sources Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Omi, Michael; Winant, Howard (1986). Racial Formation in the United States from the 1960s to the 1980s. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Inc. Smith, Anthony D. (1999). Myths and memories of the Nation. Oxford University Press. |

出典 アナンタ、アリス;アリフィン、エヴィ・ヌルヴィディア;ハスブラ、M・サイリ;ハンダヤニ、ヌル・ブディ;プラモノ、アグス(2015)。『インドネシア民族の人口統計学』。東南アジア研究所。ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8。 オミ、マイケル;ウィナント、ハワード(1986)。『1960年代から1980年代のアメリカにおける人種形成』ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ・アンド・キーガン・ポール社。 スミス、アンソニー・D.(1999)。『国民の神話と記憶』オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

★

リンク

︎仮想医療人類学辞典▶民族・民族集団・エスニシティにまつわるエッセー︎▶︎︎人種▶︎民族的アイデンティティをめぐる覚書▶︎︎ナショナリズム・民族集団・少数民の研究に関する基礎知識▶︎

フレデリック・バース『民族集団と境界』論ノート▶︎︎エスニシティ(ethnicity)▶︎グアテマラ人という民族的アイデンティティ▶︎︎Ethnicity▶︎▶︎

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099