文化的人種主義

Cultural racism, カルチュラル・レイシズム

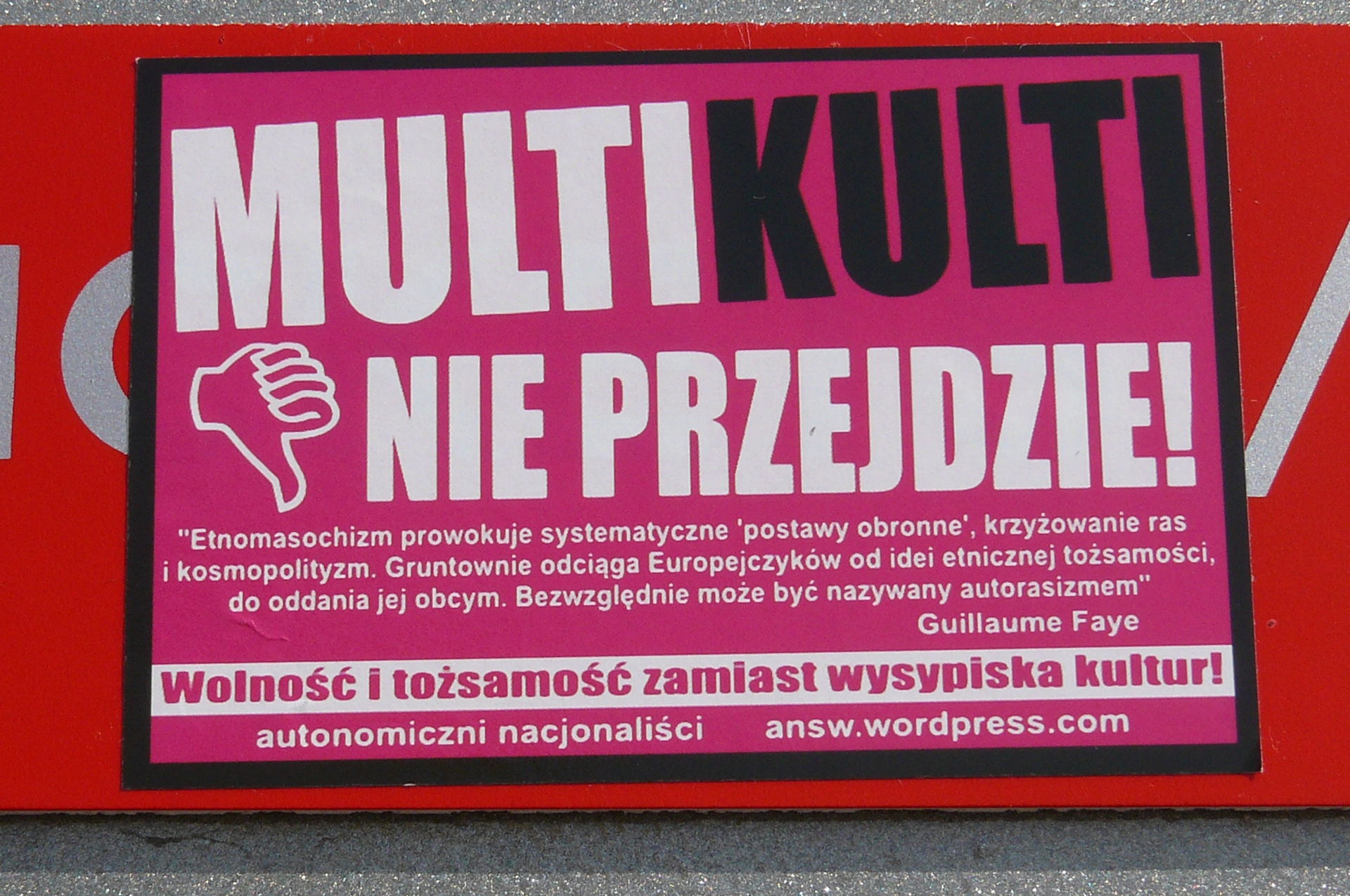

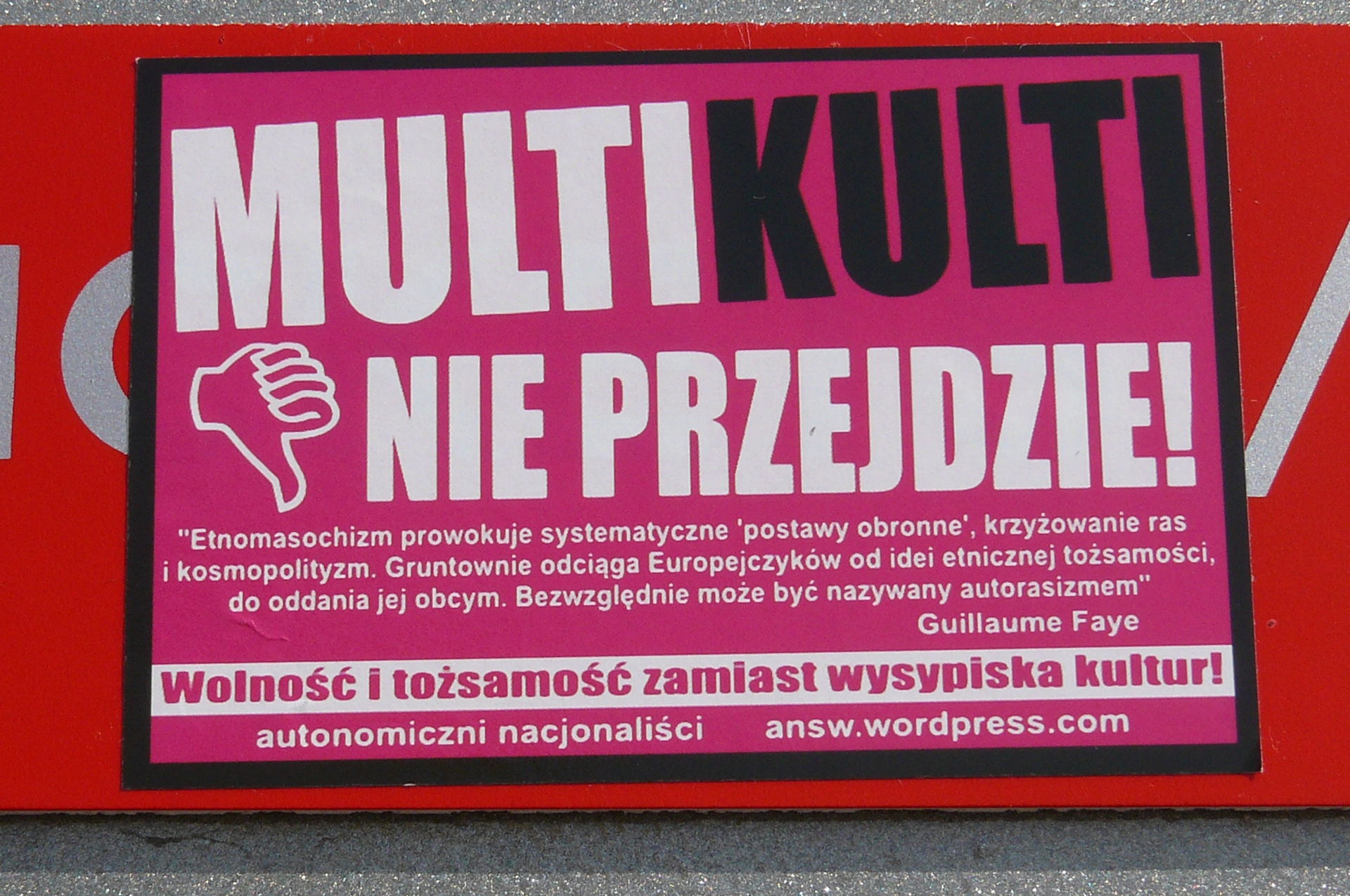

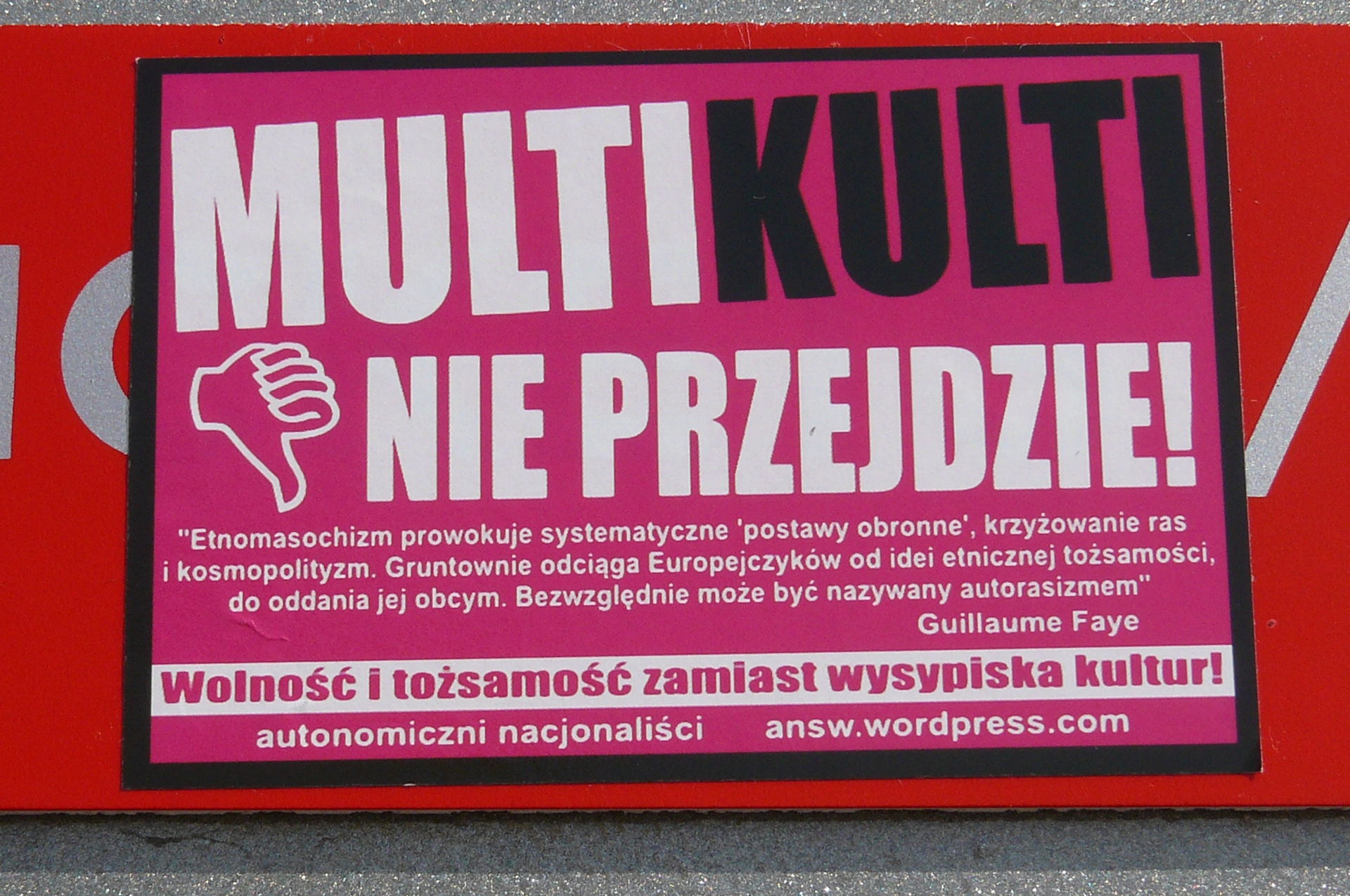

ヴロツワフ(ブレスラウ)でのマルチカルチャリズムに反対するポスター(2011年ごろ)

☆文化的人種主義[Cultural racism] とは、民族や人種間の文化的差異に基づく偏見や差別に適用されてきた概念である。これには、ある文化が他の文化より優れているという考えや、より極端な場 合には、様々な文化は根本的に相容れないものであり、同じ社会や国家に共存すべきではないという考えも含まれる。この点で、人種主義とは生物学的人種主義 や科学的人種主義とは異なっている。 文化的人種主義という概念は、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、マーティン・バーカー、エティエンヌ・バリバール、ピエール=アンドレ・タギエフと いった西ヨーロッパの学者たちによって提唱された。これらの理論家たちは、当時西欧諸国で顕著だった移民に対する敵意は人種主義と呼ばれるべきであり、 20世紀初頭以来、生物学的人種を理由とする差別を表す言葉として使われてきたと主張した。彼らは、生物学的人種主義が20世紀後半に西欧社会でますます 不人気となった一方で、それに代わって、本質的で克服不可能な文化的差異を信じる文化的人種主義が新たに台頭してきたと主張した。彼らは、この変化がフラ ンスのヌーベル・ドロワットのような極右運動によって推進されていると指摘した。 本質的で克服不可能な文化的差異を信じることがなぜ人種差別的と見なされるべきかについては、主に3つの議論が提唱されている。ひとつは、文化的基盤に基 づく敵意は、本質的な生物学的差異に対する信念と同じ差別的で有害な慣行、たとえば搾取、抑圧、絶滅をもたらしうるというものである。もうひとつは、生物 学的差異と文化的差異に対する信念はしばしば相互に関連しており、生物学的人種主義者は、生物学的人種主義が社会的に容認されないと考えられている文脈に おいて、文化的差異の主張を利用して自分たちの考えを促進するというものである。第三の論点は、文化的人種主義という考え方は、多くの社会で移民やイスラ ム教徒のような集団が人種主義化を受け、その文化的特質に基づいて多数派から切り離された別個の社会集団とみなされるようになったことを認識しているとい うことである。批判的教育学の影響を受け、欧米諸国における文化的人種主義の根絶を求める人々は、学校や大学を通じて多文化教育や反人種主義を推進するこ とでこれを実現すべきだと主張してきた。 この概念の有用性については議論がある。文化に基づく偏見や敵意は生物学的人種主義とは十分に異なるため、人種主義という言葉を両者に用いるのは適切では ないと主張する学者もいる。この見解によれば、人種主義の概念に文化的偏見を取り入れることは、後者を拡大しすぎ、その有用性を弱めてしまうことになる。 人種主義という概念を使ってきた学者の間では、その範囲について議論がなされてきた。イスラム嫌悪を人種主義の一形態とみなすべきだと主張する学者もい る。また、文化的人種主義が衣服や料理、言語といった目に見える違いの象徴に関係するのに対し、イスラム嫌悪は主に宗教的信条に基づく敵意に関係すると主 張し、これに反対する学者もいる。

| Cultural racism[b] is a concept that has been applied to prejudices and discrimination based on cultural differences between ethnic or racial groups. This includes the idea that some cultures are superior to others or in more extreme cases that various cultures are fundamentally incompatible and should not co-exist in the same society or state. In this it differs from biological or scientific racism, which refers to prejudices and discrimination rooted in perceived biological differences between ethnic or racial groups. | 文化的人種主義[Cultural racism]とは、民族や人種間の文化的差異に基づく偏見や差 別に適用されてきた概念である。これには、ある文化が他の文化より優れているという考えや、より極端な場合には、様々な文化は根本的に相容れないものであ り、同じ社会や国家に共存すべきではないという考えも含まれる。この点で、人種主義とは生物学的人種主義や科学的人種主義とは異なっている。 |

| The concept of cultural racism was developed in the 1980s and 1990s by West European scholars such as Martin Barker, Étienne Balibar, and Pierre-André Taguieff. These theorists argued that the hostility to immigrants then evident in Western countries should be labelled racism, a term that had been used to describe discrimination on the grounds of perceived biological race since the early 20th century. They argued that while biological racism had become increasingly unpopular in Western societies during the second half of the 20th century, it had been replaced by a new, cultural racism that relied on a belief in intrinsic and insurmountable cultural differences instead. They noted that this change was being promoted by far-right movements such as the French Nouvelle Droite. | 文化的人種主義という概念は、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、マーティン・バーカー、エティエンヌ・バリバール、ピエール=アンドレ・タギエフと いった西ヨーロッパの学者たちによって提唱された。これらの理論家たちは、当時西欧諸国で顕著だった移民に対する敵意は人種主義と呼ばれるべきであり、 20世紀初頭以来、生物学的人種を理由とする差別を表す言葉として使われてきたと主張した。彼らは、生物学的人種主義が20世紀後半に西欧社会でますます 不人気となった一方で、それに代わって、本質的で克服不可能な文化的差異を信じる文化的人種主義が新たに台頭してきたと主張した。彼らは、この変化がフラ ンスのヌーベル・ドロワットのような極右運動によって推進されていると指摘した。 |

| Three main arguments as to why beliefs in intrinsic and insurmountable cultural differences should be considered racist have been put forward. One is that hostility on a cultural basis can result in the same discriminatory and harmful practices as belief in intrinsic biological differences, such as exploitation, oppression, or extermination. The second is that beliefs in biological and cultural difference are often interlinked and that biological racists use claims of cultural difference to promote their ideas in contexts where biological racism is considered socially unacceptable. The third argument is that the idea of cultural racism recognizes that in many societies, groups like immigrants and Muslims have undergone racialization, coming to be seen as distinct social groups separate from the majority on the basis of their cultural traits. Influenced by critical pedagogy, those calling for the eradication of cultural racism in Western countries have largely argued that this should be done by promoting multicultural education and anti-racism through schools and universities. | 本質的で克服不可能な文化的差異を信じることがなぜ人種差別的と見なされるべきかについては、主に3つの議論が提唱されている。ひとつは、(1)文化的基盤に基 づく敵意は、本質的な生物学的差異に対する信念と同じ差別的で有害な慣行、たとえば搾取、抑圧、絶滅をもたらしうるというものである。もうひとつは、(2)生物 学的差異と文化的差異に対する信念はしばしば相互に関連しており、生物学的人種主義者は、生物学的人種主義が社会的に容認されないと考えられている文脈に おいて、文化的差異の主張を利用して自分たちの考えを促進するというものである。第三の論点は、(3)文化的人種主義という考え方は、多くの社会で移民やイスラ ム教徒のような集団が人種主義化を受け、その文化的特質に基づいて多数派から切り離された別個の社会集団とみなされるようになったことを認識しているとい うことである。批判的教育学の影響を受け、欧米諸国における文化的人種主義の根絶を求める人々は、学校や大学を通じて多文化教育や反人種主義を推進するこ とでこれを実現すべきだと主張してきた。 |

| The utility of the concept has been debated. Some scholars have argued that prejudices and hostility based on culture are sufficiently different from biological racism that it is not appropriate to use the term racism for both. According to this view, incorporating cultural prejudices into the concept of racism expands the latter too much and weakens its utility. Among scholars who have used the concept of cultural racism, there have been debates as to its scope. Some scholars have argued that Islamophobia should be considered a form of cultural racism. Others have disagreed, arguing that while cultural racism pertains to visible symbols of difference like clothing, cuisine, and language, Islamophobia primarily pertains to hostility on the basis of someone's religious beliefs. | この概念の有用性については議論がある。文化に基づく偏見や敵意は生物学的人種主義とは十分に異なるため、人種主義という言葉を両者に用いるのは適切では ないと主張する学者もいる。この見解によれば、人種主義の概念に文化的偏見を取り入れることは、後者を拡大しすぎ、その有用性を弱めてしまうことになる。 人種主義という概念を使ってきた学者の間では、その範囲について議論がなされてきた。イスラム嫌悪を人種主義の一形態とみなすべきだと主張する学者もい る。また、文化的人種主義が衣服や料理、言語といった目に見える違いの象徴に関係するのに対し、イスラム嫌悪は主に宗教的信条に基づく敵意に関係すると主 張し、これに反対する学者もいる。 |

A poster in Wroclaw expressing opposition to multiculturalism, the idea that people of different cultures can reside in the same state ("multiculti will not pass!"), along with a quote from Nouvelle Droite leader Guillaume Faye;[a] this stance is described by some theorists as "cultural racism". |

ヴロツワフ(ブレスラウ)に貼られた多文化主義に反対するポスター(「多文化主義は通らない!」)。ヌーヴェル・ドロワットの指導者ギヨーム・フェイの言葉が添えられている[a]。 |

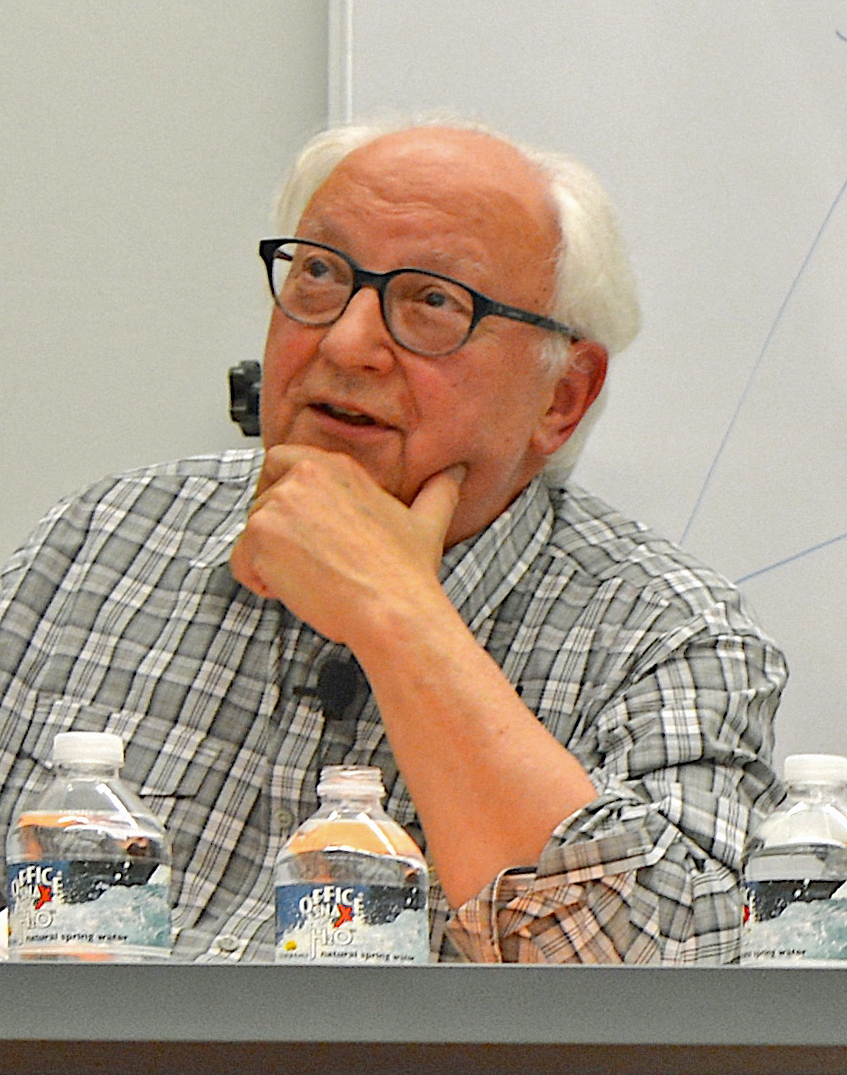

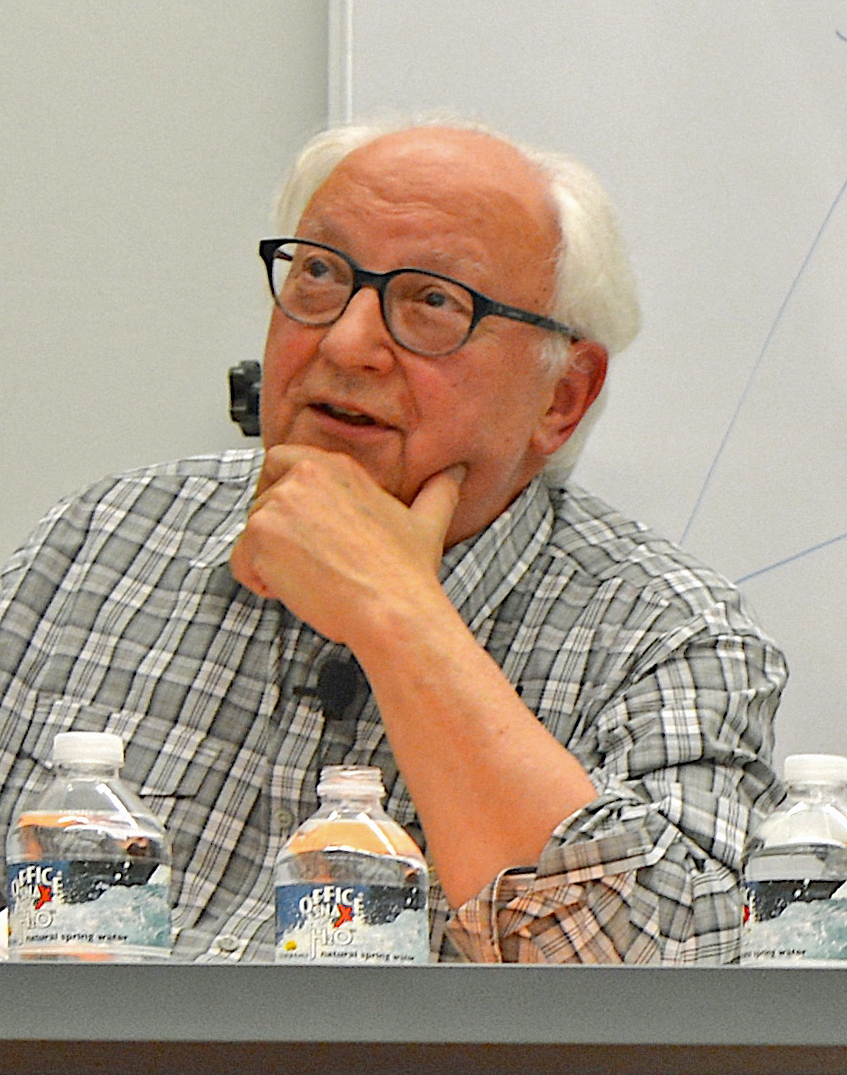

| Concept The concept of "cultural racism" has been given various names, particularly as it was being developed by academic theorists in the 1980s and early 1990s. The British scholar of media studies and cultural studies Martin Barker termed it the "new racism",[1] whereas the French philosopher Étienne Balibar favoured "neo-racism",[2] and later "cultural-differential racism".[3] Another French philosopher, Pierre-André Taguieff, used the term "differentialist racism",[4] while a similar term used in the literature has been "the racism of cultural difference".[5] The Spanish sociologist Ramón Flecha instead used the term "postmodern racism".[6]  Étienne Balibar in a blue pullover sweater, at a desk with a microphone. Étienne Balibar's concept of "neo-racism" was an early formulation of what later became widely termed "cultural racism". |

概念 「文化的人種主義」という概念は、特に1980年代から1990年代初頭にかけて学問的理論家たちによって発展していく中で、さまざまな呼び名がつけられ てきた。イギリスのメディア研究とカルチュラル・スタディーズの研究者であるマーティン・バーカーはこれを「新しい人種主義」と呼び[1]、フランスの哲 学者であるエティエンヌ・バリバールは「ネオ人種主義」[2]、後に「文化的差異による人種主義」と呼んだ。 [スペインの社会学者ラモン・フレチャは代わりに「ポストモダンの人種主義」という言葉を用いていた[6]。  ブルーのプルオーバーセーターに身を包み、マイクを持って机に向かうエティエンヌ・バリバール。 エティエンヌ・バリバールの「ネオ人種主義」という概念は、後に広く「文化的人種主義」と呼ばれるようになるものの初期の定式化であった。 |

|

The term "racism" is one of the most controversial and ambiguous words

used within the social sciences.[7] Balibar characterised it as a

concept plagued by "extreme tension" as well as "extreme confusion".[8]

This academic usage is complicated by the fact that the word is also

common in popular discourse, often as a term of "political abuse";[9]

many of those who term themselves "anti-racists" use the term "racism"

in a highly generalised and indeterminate way.[10] The word "racisme" was used in the French language by the late 19th century, where French nationalists employed it to describe themselves and their belief in the inherent superiority of the French people over other groups.[11] The earliest recorded use of the term "racism" in the English language dates from 1902, and for the first half of the 20th century the word was used interchangeably with the term "racialism".[12] According to Taguieff, up until the 1980s, the term "racism" was typically used to describe "essentially a theory of races, the latter distinct and unequal, defined in biological terms and in eternal conflict for the domination of the earth".[13] The popularisation of the term "racism" in Western countries came later, when "racism" was increasingly used to describe the antisemitic policies enacted in Nazi Germany during the 1930s and 1940s.[14] These policies were rooted in the Nazi government's belief that Jews constituted a biologically distinct race that was separate from what the Nazis believed to be the Nordic race inhabiting Northern Europe.[15] The term was further popularised in the 1950s and 1960s amid the civil rights movement's campaign to end racial inequalities in the United States.[14] Following the Second World War, when Nazi Germany was defeated and biologists developed the science of genetics, the idea that the human species sub-divided into biologically distinct races began to decline.[16] At this, anti-racists declared that the scientific validity behind racism had been discredited.[13] From the 1980s onward, there was considerable debate—particularly in Britain, France, and the United States—about the relationship between biological racism and prejudices rooted in cultural difference.[5] By this point, most scholars of critical race theory rejected the idea that there are biologically distinct races, arguing that "race" is a culturally constructed concept created through racist practices.[17] These academic theorists argued that the hostility to migrants evident in Western Europe during the latter decades of the twentieth century should be regarded as "racism" but recognised that it was different from historical phenomena commonly called "racism", such as racial antisemitism or European colonialism.[18] They therefore argued that while historic forms of racism were rooted in ideas of biological difference, the new "racism" was rooted in beliefs about different groups being culturally incompatible with each other.[19] |

「人種主義」という用語は、社会科学の中で使用される最も論争的で曖昧な言葉の一つである[7]。バリバールはこの言葉を「極度の緊張」と「極度の混乱」

に悩まされる概念であると特徴づけている[8]。この学術的な用法は、この言葉がしばしば「政治的罵倒」の言葉として一般的な言説でもよく使われるという

事実によって複雑になっている[9]。 「racisme(人種主義)」という言葉は19世紀後半までにフランス語で使用され、フランスの民族主義者たちが自分たち自身とフランス人が他の集団よ りも本質的に優れているという信念を表現するために使用していた[11]。英語における「racism(人種主義)」という言葉の最も古い使用記録は 1902年に始まり、20世紀前半は「人種主義」という言葉と互換的に使用されていた。 [12]タギエフによれば、1980年代まで、「人種主義」という用語は「本質的に、後者は別個の不平等な人種であり、生物学的な用語で定義され、地球の 支配をめぐって永遠に対立し続ける」という理論[13]を説明するために一般的に使用されていた。 「人種主義」という言葉が西欧諸国で一般化したのは、1930年代から1940年代にかけてナチス・ドイツで実施された反ユダヤ主義的な政策を説明するた めに「人種主義」が使用されるようになった後のことである。 [第二次世界大戦後、ナチス・ドイツが敗北し、生物学者が遺伝学を発展させると、人間の種が生物学的に異なる人種に分かれるという考えは衰退し始めた。 1980年代以降、生物学的人種主義と文化的差異に根ざした偏見との関係について、特にイギリス、フランス、アメリカにおいてかなりの議論がなされた。 [17] こ れらの学問的理論家たちは、20世紀後半の数十年間に西ヨーロッパで明らかになった移民に対する敵意は「人種主義」とみなされるべきであると主張したが、 それは人種的反ユダヤ主義やヨーロッパの植民地主義といった一般的に「人種主義」と呼ばれる歴史的現象とは異なるものであると認識していた[18]。 したがって彼らは、歴史的な人種主義の形態が生物学的差異に対する考え方に根ざしていたのに対して、新しい「人種主義」は異なる集団が互いに文化的に相容 れないものであるという信念に根ざしていると主張していた[19]。 |

|

Definitions An important characteristic of the so-called 'new racism', 'cultural racism' or 'differential racism' is the fact that it essentialises ethnicity and religion, and traps people in supposedly immutable reference categories, as if they are incapable of adapting to a new reality or changing their identity. By these means cultural racism treats the 'other culture' as a threat that might contaminate the dominant culture and its internal coherence. Such a view is clearly based on the assumption that certain groups are the genuine carriers of the national culture and the exclusive heirs of their history while others are potential slayers of its 'purity'. —Sociologist Uri Ben-Eliezer, 2004[20] Not all scholars that have used the concept of "cultural racism" have done so in the same way.[21] The scholars Carol C. Mukhopadhyay and Peter Chua defined "cultural racism" as "a form of racism (that is, a structurally unequal practice) that relies on cultural differences rather than on biological markers of racial superiority or inferiority. The cultural differences can be real, imagined, or constructed".[21] Elsewhere, in The Wiley‐Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory, Chua defined cultural racism as "the institutional domination and sense of racial‐ethnic superiority of one social group over others, justified by and based on allusively constructed markers, instead of outdated biologically ascribed distinctions".[22] Balibar linked what he called "neo-racism" to the process of decolonization, arguing that while older, biological racisms were employed when European countries were engaged in colonising other parts of the world, the new racism was linked to the rise of non-European migration into Europe in the decades following the Second World War.[23] He argued that "neo-racism" replaced "the notion of race" with "the category of immigration",[24] and in this way produced a "racism without races".[23] Balibar described this racism as having as its dominant theme not biological heredity, "but the insurmountability of cultural differences, a racism which, at first sight, does not postulate the superiority of certain groups or peoples in relation to others but 'only' the harmfulness of abolishing frontiers, the incompatibility of lifestyles and traditions".[23] He nevertheless thought that cultural racism's claims that different cultures are equal was "more apparent than real" and that when put into practice, cultural racist ideas reveal that they inherently rely on a belief that some cultures are superior to others.[25] 23. Balibar 1991, p. 21. 24. Balibar 1991, p. 20 25. Balibar 1991, p. 24 Balibar, Étienne (1991). "Is there a Neo-Racism?". In Étienne Balibar; Immanuel Wallerstein (eds.). Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. London: Verso. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-0860915423. Drawing on developments in French culture during the 1980s, Taguieff drew a distinction between "imperialist/colonialist racism", which he also called the "racism of assimilation", and "differentialist/mixophobic racism", which he also termed "the racism of exclusion".[26] Taguieff suggested that this latter phenomenon differed from its predecessor by talking about "ethnicity/culture" rather than "race", by promoting notions of "difference" in place of "inequality", and by presenting itself as a champion of "heterophilia", the love of difference, rather than "heterophobia", the fear of difference.[27] In this, he argued that it engaged in what he called "mixophobia", the fear of cultural mixing, and linked in closely with nationalism.[28] The geographer Karen Wren defined cultural racism as "a theory of human nature where humans are considered equal, but where cultural differences make it natural for nation states to form closed communities, as relations between different cultures are essentially hostile".[29] She added that cultural racism stereotypes ethnic groups, treats cultures as fixed entities, and rejects ideas of cultural hybridity.[30] Wren argued that nationalism, and the idea that there is a nation-state to which foreigners do not belong, is "essential" to cultural racism. She noted that "cultural racism relies on the closure of culture by territory and the idea that 'foreigners' should not share the 'national' resources, particularly if they are under threat of scarcity."[30] The sociologist Ramón Grosfoguel noted that "cultural racism assumes that the metropolitan culture is different from ethnic minorities' culture" while simultaneously taking on the view that minorities fail to "understand the cultural norms" that are dominant in a given country.[31] Grosfoguel also noted that cultural racism relies on a belief that separate cultural groups are so different that they "cannot get along".[31] In addition, he argued that cultural racist views hold that any widespread poverty or unemployment faced by an ethnic minority arises from that minority's own "cultural values and behavior" rather than from broader systems of discrimination within the society it inhabits. In this way, Grosfoguel argued, cultural racism encompasses attempts by dominant communities to claim that marginalised communities are at fault for their own problems.[32] |

定義 いわゆる「新しい人種主義」、「文化的人種主義」、「差異的人種主義」の重要な特徴は、民族や宗教を本質化し、あたかも人々が新しい現実に適応したり、ア イデンティティを変えたりすることができないかのように、不変の参照カテゴリーに閉じ込めるという事実である。このような意味から、人種主義は「他の文 化」を、支配文化とその内部の一貫性を汚染するかもしれない脅威として扱うのである。このような見方は明らかに、特定の集団が国民文化の真の担い手であ り、その歴史の排他的な継承者である一方で、他の集団はその「純粋性」の潜在的な殺害者であるという仮定に基づいている。 -社会学者ウリ・ベン=エリエゼル、2004年[20])。 キャロル・C・ムコパディヤイとピーター・チュアは、「文化的人種主義」を「人種的優劣を示す生物学的指標ではなく、文化的差異に依拠する人種主義(すな わち構造的不平等行為)の一形態」と定義している。その文化的差異とは、現実のものであったり、想像上のものであったり、構築されたものであったりする」 [21]。また、『The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory』において、チュアは文化的人種主義を「時代遅れの生物学的に付与された区別ではなく、あらゆる意味で構築されたマーカーによって正当化され、それに基づく、ある社会集団の他者に対する制度的支配と人種的・民族的優越感」と定義している[22]。 バリバールは、彼が「ネオ・レイシズム」と呼ぶもの を脱植民地化のプロセスと関連づけ、ヨーロッパ諸国が世界の他の地域の植民地化に従事していたときには古い生物学的な人種主義が採用されていたが、新しい 人種主義は第二次世界大戦後の数十年間におけるヨーロッパへの非ヨーロッパ系移民の増加と関連していると主張していた[23]。 彼は「ネオ・レイシズム」が「人種という概念」を「移民というカテゴリー」に置き換え[24]、このようにして「人種なき人種主義」 を生み出したと主張していた。 [23]バリバールはこの人種主義を、その支配的なテーマとして生物学的な遺伝ではなく、「文化的差異の克服不可能性、一見したところ、特定の集団や民族 の他者に対する優位性ではなく、フロンティアを廃止することの有害性、生活様式や伝統の非互換性『のみ』を前提とする人種主義」であると説明した。 [23]にもかかわらず彼は、異なる文化は平等であるという文化人種主義の主張は「現実よりも見かけ倒し」であり、文化人種主義的な考えが実践されると、 それが本質的にある文化が他の文化よりも優れているという信念に依拠していることが明らかになると考えていた[25]。 23. Balibar 1991, p. 21. 24. Balibar 1991, p. 20 25. Balibar 1991, p. 24 Balibar, Étienne (1991). "Is there a Neo-Racism?". In Étienne Balibar; Immanuel Wallerstein (eds.). Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. London: Verso. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-0860915423. タギエフは1980年代のフランス文化における発展から、「同化の人種主義」とも呼ばれる「帝国主義的/植民地主義的人種主義」と、「排除の人種主義」と も呼ばれる「差異主義的/ミクソフォビア的人種主義」を区別した。 [26]タギエフは、この後者の現象は、「人種」ではなく「民族/文化」について語ること、「不平等」の代わりに「差異」の概念を促進すること、差異を恐 れる「ヘテロフォビア」ではなく差異を愛する「ヘテロフィリア」の擁護者として自らを提示することによって、その前身とは異なっていると示唆した [27]。この点で、彼は、文化的混合を恐れる「ミクソフォビア」と呼ばれるものに関与しており、国民主義と密接に結びついていると主張した[28]。 地理学者であるカレン・レンは文化的人種主義を「人間は平等であると考えられているが、異なる文化間の関係は本質的に敵対的であるため、文化的差異によっ て国民国家が閉鎖的な共同体を形成することが自然であるという人間性の理論」と定義した[29]。 彼女はさらに、文化的人種主義は民族集団をステレオタイプ化し、文化を固定的な存在として扱い、文化的混血の考え方を否定すると付け加えた[30]。彼女 は「人種主義は、領土による文化の閉鎖性と、『外国人』は『国民』の資源を共有すべきではないという考えに依拠しており、特にそれらが欠乏の脅威にさらさ れている場合はそうである」と指摘している[30]。 社会学者のラモン・グロスフォゲルは、「文化人種主義は、大都会の文化は少数民族の文化とは異なると仮定する」と同時に、少数民族はある国で支配的である 「文化規範を理解することができない」という見解をとっていると指摘している。 [31]またグロスフォゲルは、文化的人種主義は、別々の文化集団は「仲良くなれない」ほど異なっているという信念に依拠していると指摘した[31]。さ らに彼は、文化的人種主義者の見解は、少数民族が直面する広範な貧困や失業は、その少数民族が住む社会内の広範な差別制度からではなく、その少数民族自身 の「文化的価値観と行動」から生じていると主張している。このようにグロスフォゲルは、文化的人種主義は、社会から疎外されたコミュニティが自分たちの問 題のために落ち度があると主張する支配的コミュニティによる試みを包含していると主張した[32]。 |

★

|

Alternative definitions of "cultural racism" As a concept developed in Europe, "cultural racism" has had less of an impact in the United States.[21] Referring specifically to the situation in the U.S., the psychologist Janet Helms defined cultural racism as "societal beliefs and customs that promote the assumption that the products of White culture (e.g., language, traditions, appearance) are superior to those of non-White cultures".[33] She identified it as one of three forms of racism, alongside personal racism and institutional racism.[33] Again using a U.S.-centric definition, the psychologist James M. Jones noted that a belief in the "cultural inferiority" both of Native Americans and African Americans had long persisted in U.S. culture, and that this was often connected to beliefs that said groups were biologically inferior to European Americans.[34] In Jones' view, when individuals reject a belief in biological race, notions regarding the relative cultural inferiority and superiority of different groups can remain, and that "cultural racism remains as a residue of expunged biological racism."[35] Offering a very different definition, the scholar of multicultural education Robin DiAngelo used the term "cultural racism" to define "the racism deeply embedded in the culture and thus always in circulation. Cultural racism keeps our racist socialization alive and continually reinforced."[36] |

「人種主義 "の別の定義 文化的人種主義」はヨーロッパで発展した概念であるため、アメリカではあまり影響を及ぼしていない[21]。特にアメリカの状況に言及し、心理学者のジャ ネット・ヘルムズは文化的人種主義を「白人文化の産物(言語、伝統、外見など)が非白人文化の産物よりも優れているという思い込みを助長する社会的信念や 慣習」と定義した[33]。 心理学者のジェームズ・M・ジョーンズは、米国中心の定義を用いて、ネイティブ・アメリカンやアフリカ系アメリカ人の「文化的劣等性」に対する信念が長い 間米国文化に根強く残っており、この信念はしばしばこれらのグループが生物学的にヨーロッパ系アメリカ人より劣っているという信念と結びついていると指摘 した。 [34]ジョーンズの見解では、個人が生物学的人種に対する信念を拒絶したとき、異なる集団の相対的な文化的劣等性や優越性に関する観念が残る可能性があ り、「文化的人種主義は、生物学的人種主義を追い出した残滓として残る」[35]。文化的人種主義は、私たちの人種主義的社会化を生かし続け、絶えず強化 している」[36]。 |

|

Cultural prejudices as racism Theorists have put forward three main arguments as to why they deem the term "racism" appropriate for hostility and prejudice on the basis of cultural differences.[19] The first is the argument that a belief in fundamental cultural differences between human groups can lead to the same harmful acts as a belief in fundamental biological differences, namely exploitation and oppression or exclusion and extermination.[19] As the academics Hans Siebers and Marjolein H. J. Dennissen noted, this claim has yet to be empirically demonstrated.[19] The second argument is that ideas of biological and cultural difference are intimately linked. Various scholars have argued that racist discourses often emphasise both biological and cultural difference at the same time. Others have argued that racist groups have often moved toward publicly emphasising cultural differences because of growing social disapproval of biological racism and that it represents a switch in tactics rather than a fundamental change in underlying racist belief.[19] The third argument is the "racism-without-race" approach. This holds that categories like "migrants" and "Muslims" have—despite not representing biologically united groups—undergone a process of "racialization" in that they have come to be regarded as unitary groups on the basis of shared cultural traits.[19] |

人種主義としての文化的偏見 理論家たちは、文化的差異に基づく敵意や偏見に対して「人種主義」という用語が適切であるとみなす理由として、3つの主要な論拠を提示している[19]。 1つ目は、人間集団間の根本的な文化的差異に対する信念は、根本的な生物学的差異に対する信念と同じ有害な行為、すなわち搾取や抑圧、あるいは排除や絶滅 につながりうるという主張である[19]。学者であるハンス・シーバースとマージョレイン・H・J・デニッセンが指摘しているように、この主張はまだ経験 的に実証されていない[19]。 第二の主張は、生物学的差異と文化的差異の観念は密接に結びついているというものである。様々な学者が、人種差別的言説はしばしば生物学的差異と文化的差 異の両方を同時に強調していると論じている。また、人種主義的集団がしばしば文化的差異を公に強調する方向に向かったのは、生物学的人種主義に対する社会 的不支持が高まったためであり、それは根本的な人種主義的信念の変化というよりはむしろ戦術の転換を意味すると主張する者もいる。これは、「移民」や「イ スラム教徒」のようなカテゴリーは、生物学的に統一された集団を表していないにもかかわらず、共有された文化的特質に基づいて統一された集団とみなされる ようになるという「人種化」のプロセスを経てきたとするものである[19]。 |

| Critiques Several academics have critiqued the use of cultural racism to describe prejudices and discrimination on the basis of cultural difference. Those who reserve the term racism for biological racism for instance do not believe that cultural racism is a useful or appropriate concept.[37] The sociologist Ali Rattansi asked the question whether cultural racism could be seen to stretch the notion of racism "to a point where it becomes too wide to be useful as anything but a rhetorical ploy?"[38] He suggested that beliefs which insist that group identification require the adoption of cultural traits such as specific dress, language, custom, and religion might better be termed ethnicism or ethnocentrism and that when these also incorporate hostility to foreigners they may be described as bordering on xenophobia.[38] He does however acknowledge that "it is possible to talk of ‘cultural racism’ despite the fact that strictly speaking modern ideas of race have always had one or other biological foundation."[39] The critique "misses the point that generalizations, stereotypes, and other forms of cultural essentialism rest and draw upon a wider reservoir of concepts that are in circulation in popular and public culture. Thus, the racist elements of any particular proposition can only be judged by understanding the general context of public and private discourses in which ethnicity, national identifications, and race coexist in blurred and overlapping forms without clear demarcations."[39] [C]an a combination of religious and other cultural antipathy be described as 'racist'? Is this not to rob the idea of racism of any analytical specificity and open the floodgates to a conceptual inflation that simply undermines the legitimacy of the idea? —Sociologist Ali Rattansi, 2007[16] Similarly, Siebers and Dennissen questioned whether bringing "together the exclusion/oppression of groups as different as current migrants in Europe, Afro-Americans and Latinos in the US, Jews in the Holocaust and in the Spanish Reconquista, slaves and indigenous peoples in the Spanish Conquista and so on into the concept of racism, irrespective of justifications, does the concept not run the risk of losing in historical precision and pertinence what it gains in universality?"[40] They suggested that in attempting to develop a concept of "racism" that could be applied universally, exponents of the "cultural racism" idea risked undermining the "historicity and contextuality" of specific prejudices.[41] In analysing the prejudices faced by Moroccan-Dutch people in the Netherlands during the 2010s, Siebers and Dennissen argued that these individuals' experiences were very different both from those encountered by Dutch Jews in the first half of the 20th century and colonial subjects in the Dutch East Indies. Accordingly, they argued that concepts of "cultural essentialism" and "cultural fundamentalism" were far better ways of explaining hostility to migrants than that of "racism".[42] Baker's notion of the "new racism" was critiqued by the sociologists Robert Miles and Malcolm Brown. They thought it problematic because it relied on defining racism not as a system based on the belief in the superiority and inferiority of different groups, but as encompassing any ideas that saw a culturally-defined group as a biological entity. Thus, Miles and Brown argued, Baker's "new racism" relied on a definition of racism which eliminated any distinctions between that concept and others such as nationalism and sexism.[43] The sociologist Floya Anthias critiqued early ideas of the "neo-racism" for failing to provide explanations for prejudices and discrimination towards groups like the Black British, who shared a common culture with the dominant White British population.[44] She also argued that the framework failed to take into account positive images of ethnic and cultural minorities, for instance in the way that British Caribbean culture had often been depicted positively in British youth culture.[45] In addition, she suggested that, despite its emphasis on culture, early work on "neo-racism" still betrayed its focus on biological differences by devoting its attention to black people—however defined—and neglecting the experiences of lighter-skinned ethnic minorities in Britain, such as Jews, Romanis, the Irish, and Cypriots.[46] |

批判 何人かの学者が、文化的差異に基づく偏見や差別を表現するために人種主義を用いることを批判している。例えば、人種主義という用語を生物学的人種主義に対 して留保する人々は、文化的人種主義が有用で適切な概念であるとは考えていない[37]。 社会学者アリ・ラッタンシは、文化的人種主義が人種主義という概念を「修辞的な策略以外の何ものでもなく有用であるには広範になりすぎる点まで」拡大解釈 しているのではないかと疑問を投げかけている。 「38]彼は、集団の識別には特定の服装、言語、習慣、宗教などの文化的特徴の採用が必要であると主張する信念は、民族主義または民族中心主義と呼んだ方 がよく、これらが外国人に対する敵意をも含んでいる場合は、外国人嫌いに近いと言えるかもしれないと示唆した。 [しかし彼は「厳密に言えば、近代的な人種に関する考え方は常に何らかの生物学的基盤を持っていたにもかかわらず、『文化的人種主義』について語ることは 可能である」[39]と認めている。したがって、いかなる特定の命題の人種主義的要素も、民族性、国民的アイデンティティ、人種が明確な区分けなしに曖昧 で重なり合った形で共存している公的・私的言説の一般的文脈を理解することによってのみ判断することができる」[39]。 [宗教的反感とその他の文化的反感の組み合わせは「人種差別的」と言えるのだろうか。これは人種主義という考えから分析的な特異性を奪い、単にその考えの正当性を損なう概念的な膨張への門戸を開くことにならないだろうか。 -社会学者アリ・ラッタンシ、2007[16])。 同様に、シーバースとデニッセンは、「ヨーロッパにおける現在の移民、アメリカにおけるアフロ・アメリカンやラテン系、ホロコーストやスペインのレコンキ スタにおけるユダヤ人、スペインのコンキスタにおける奴隷や先住民など、異なる集団の排除/抑圧を、正当化とは無関係に人種主義の概念にまとめることは、 その概念が普遍性において得るものを歴史的な正確さや妥当性において失う危険性がないのか」と疑問を呈している。 「40] 彼らは、普遍的に適用可能な「人種主義」の概念を発展させようとすることで、「文化的人種主義」の考え方の支持者は特定の偏見の「歴史性と文脈性」を損な う危険性があることを示唆した[41]。2010年代にオランダでモロッコ系オランダ人が直面した偏見を分析する中で、シーバースとデニッセンは、これら の人々の経験は20世紀前半にオランダ系ユダヤ人が遭遇したものとも、オランダ領東インドにおける植民地臣民が遭遇したものとも大きく異なっていると主張 した。したがって、彼らは「人種主義」よりも「文化的本質主義」や「文化的原理主義」の概念の方が、移民に対する敵意を説明する方法としてはるかに優れて いると主張した[42]。 ベイカーの「新しい人種主義」という概念は、社会学者のロバート・マイルズとマルコム・ブラウンによって批判された。マイルズとブラウンは、人種主義を異 なる集団の優越性と劣等性への信念に基づくシステムとしてではなく、文化的に定義された集団を生物学的な存在とみなすあらゆる考え方を包含するものとして 定義することに依存しているため、問題があると考えたのである。したがってマイルズとブラウンは、ベイカーの「新しい人種主義」は、人種主義とナショナリ ズムや性差別主義といった他の概念との間の区別を排除した人種主義の定義に依拠していると主張した[43]。社会学者のフローヤ・アンシアスは、「新人種 主義」の初期のアイデアについて、支配的なイギリス白人と共通の文化を共有するイギリス黒人のような集団に対する偏見や差別に対する説明を提供できていな いと批判した[44]。 [44]また彼女は、この枠組みは、例えばイギリスの若者文化の中でイギリスのカリブ海文化がしばしば肯定的に描かれているような、民族的・文化的マイノ リティの肯定的なイメージを考慮に入れていないと主張した[45]。さらに彼女は、文化に重点を置いているにもかかわらず、「ネオレイシズム」に関する初 期の研究は、どのように定義されようとも黒人に注意を向け、ユダヤ人、ルーマニア人、アイルランド人、キプロス人などのイギリスにおける肌の薄い少数民族 の経験を無視することによって、生物学的差異に焦点を当てていることを裏切っていると示唆した[46]。 |

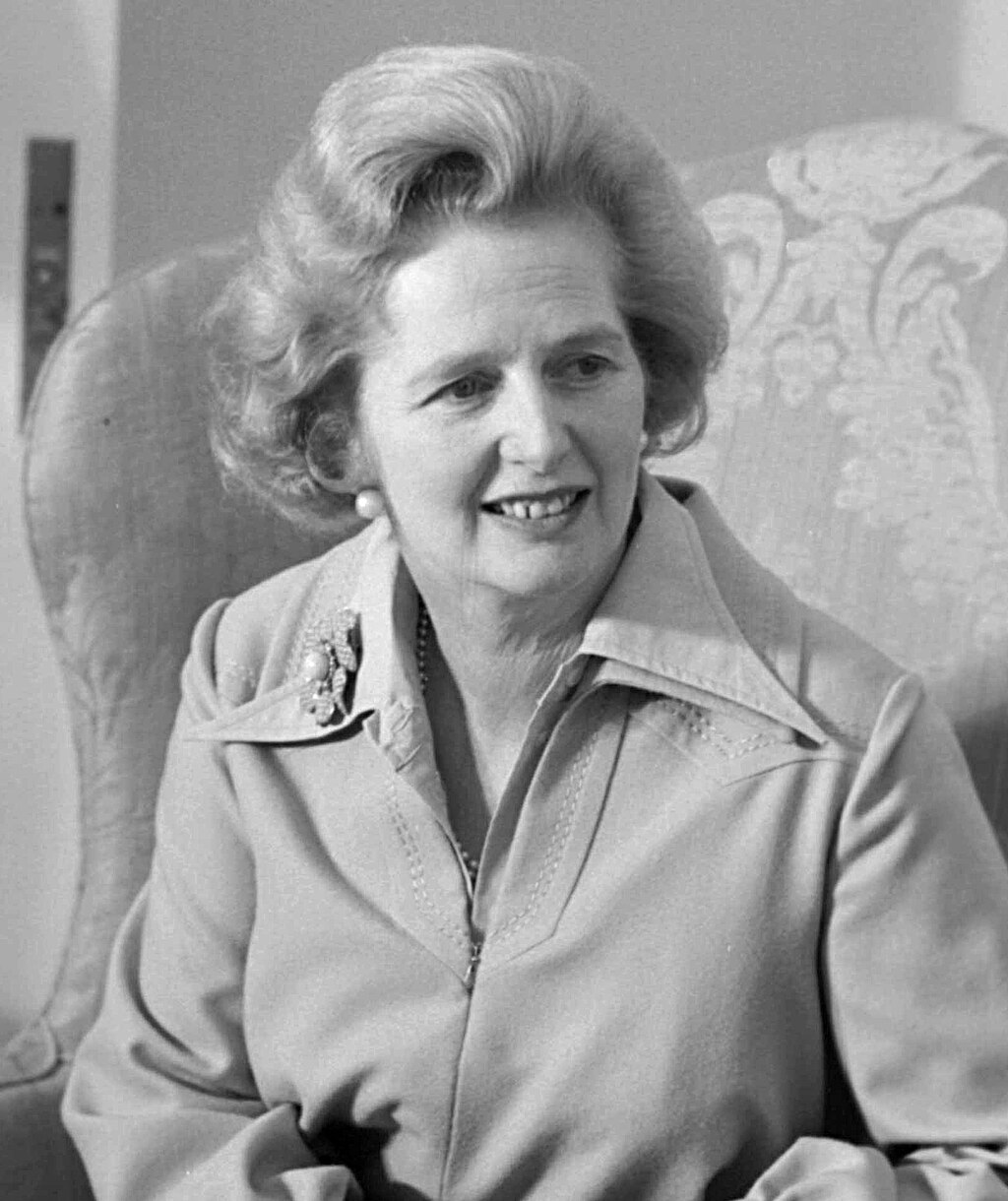

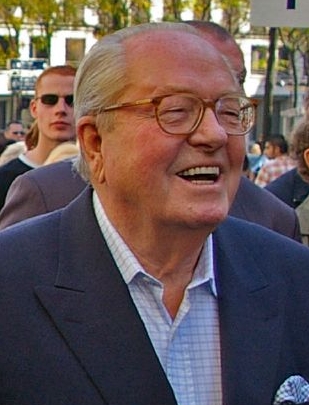

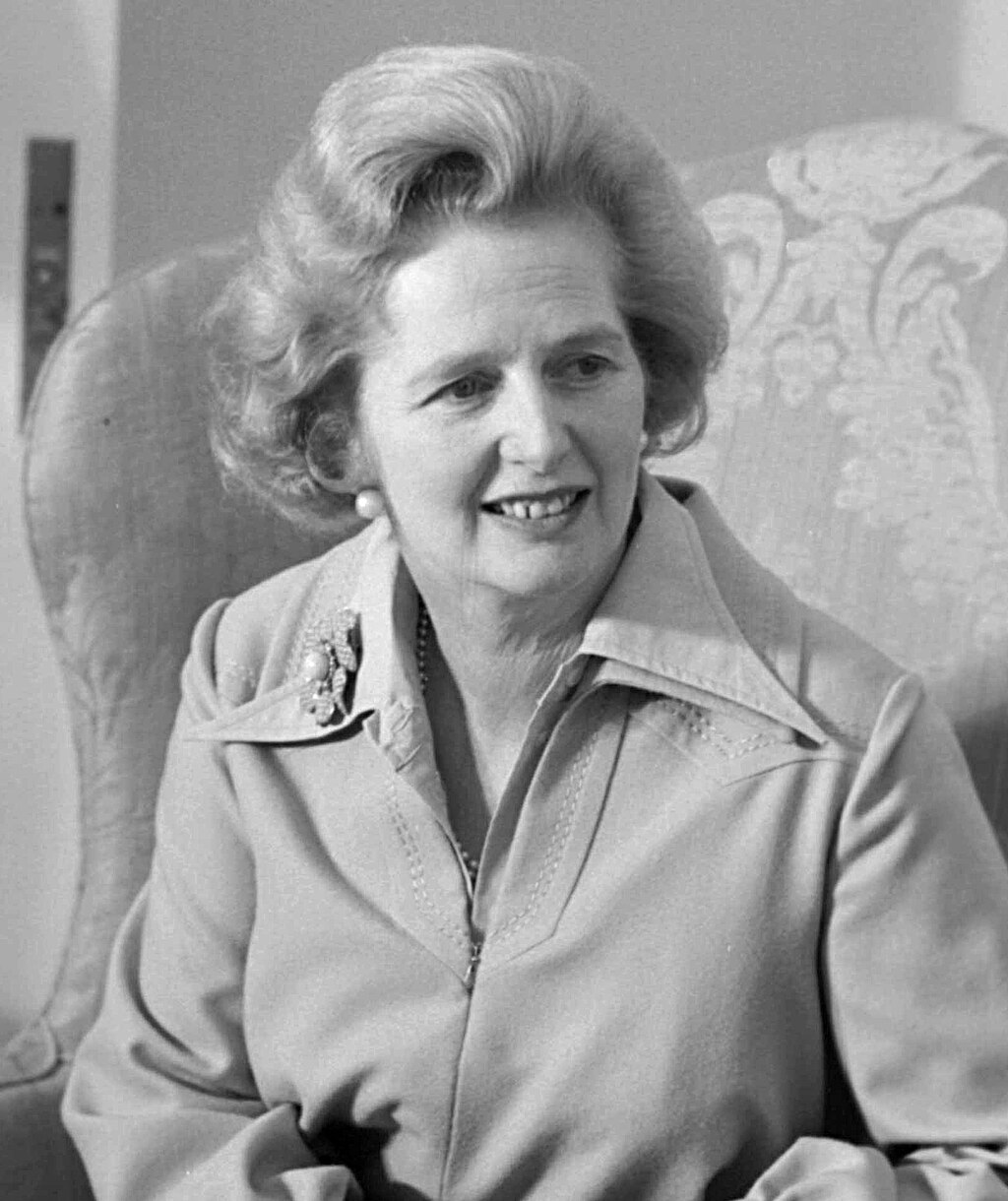

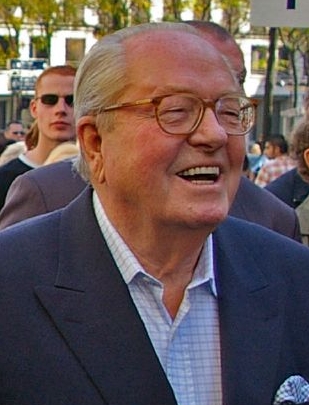

Cultural racism in Western countries Margaret Thatcher in a jacket with a brooch on a lapel, sitting in an armchair. Margaret Thatcher's 1978 claim that Britain was being "swamped by people with a different culture" has been cited as an example of cultural racism.[47] In a 1992 article for Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, the geographer James Morris Blaut argued that in Western contexts, cultural racism replaces the biological concept of the "white race" with that of the "European" as a cultural entity.[48] This argument was subsequently supported by Wren.[29] Blaut argued that cultural racism had encouraged many white Westerners to view themselves not as members of a superior race, but of a superior culture, referred to as "European culture", "Western culture", or "the West".[48] He proposed that culturally racist ideas were developed in the wake of the Second World War by Western academics who were tasked with rationalising the white Western dominance both of communities of colour in Western nations and the Third World.[49] He argued that the sociological concept of modernization was developed to promote the culturally racist idea that the Western powers were wealthier and more economically developed because they were more culturally advanced.[49] Wren argued that cultural racism had manifested in a largely similar way throughout Europe, but with specific variations in different places according to the established ideas of national identity and the form and timing of immigration.[50] She argued that Western societies used the discourse of cultural difference as a form of Othering through which they justify the exclusion of various ethnic or cultural 'others', while at the same time ignoring socio-economic inequalities between different ethnic groups.[30] Using Denmark as an example, she argued that a "culturally racist discourse" had emerged during the 1980s, a time of heightened economic tension and unemployment.[51] Based on fieldwork in the country during 1995, she argued that cultural racism had encouraged anti-immigration sentiment throughout Danish society and generated "various forms of racist practice", including housing quotas that restrict the number of ethnic minorities to around 10%.[52] Furthermore, Dinesh D'Souza spoke about racism being so deeply embedded in "Western consciousness" that it cannot be eradicated, as it is now seen as a 'norm' in western behaviours due to cultural teachings being passed down through generations.[53] However, he mainly based his argument on ethnocentrism being mistaken for racism in Western societies which he believed we often misinterpreted as being racist, his thesis was that early European racists were misunderstood as their views was a way of them trying to "make sense of the diverse world" in other words, they did not understand the culture as it did not match their own, as a result they tried to implement their own.[53] Wren compared anti-immigrant sentiment in 1990s Denmark to the Thatcherite anti-immigrant sentiment expressed in 1980s Britain.[54] The British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher for instance was considered a cultural racist for comments in which she expressed concern about Britain becoming "swamped by people with a different culture".[47] The term has also been used in Turkey. In 2016, Germany's European Commissioner Guenther Oettinger stated that it was unlikely that Turkey would be permitted to join the European Union while Recep Tayyip Erdoğan remained the Turkish President. In response, Turkey's European Union Affairs Minister Omer Celik accused Germany of "cultural racism".[55] The sociologist Xolela Mangcu argued that cultural racism could be seen as a contributing factor in the construction of apartheid, a system of racial segregation that privileged whites, in South Africa during the latter 1940s. He noted that the Dutch-born South African politician Hendrik Verwoerd, a prominent figure in establishing the apartheid system, had argued in favour of separating racial groups on the grounds of cultural difference.[56] The idea of cultural racism has also been used to explain phenomena in the United States. Grosfoguel argued that cultural racism replaced biological racism in the U.S. amid the 1960s civil rights movement.[57] Clare Sheridan stated that cultural racism was an applicable concept to the experiences of Mexican Americans, with various European Americans taking the view that they were not truly American because they spoke Spanish rather than English.[58] The Clash of Civilizations theory, put forward in the 1990s by the American theorist Samuel P. Huntington, has also been cited as a stimulus to cultural racism for its argument that the world is divided up into mutually exclusive cultural blocs.[59]  Samuel P. Huntington in a grey suit with a red tie, seated at a desk at the World Economic Forum. The Clash of Civilizations theory put forward by American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington has been described as a stimulus to cultural racism.[59] In the early 1990s, the scholar of critical pedagogy Henry Giroux argued that cultural racism was evident across the political right in the United States. In his view, conservatives were "reappropriating progressive critiques of race, ethnicity and identity and using them to promote rather than dispel a politics of cultural racism".[60] For Giroux, the conservative administration of President George H. W. Bush acknowledged the presence of racial and ethnic diversity in the U.S., but presented it as a threat to national unity.[61] Drawing on Giroux's work, the scholar of critical pedagogy Rebecca Powell suggested that both the conservative and liberal wings of U.S. politics reflected a culturally racist stance in that both treated European American culture as normative. She argued that while European American liberals acknowledge the existence of institutional racism, their encouragement of cultural assimilationism betrays an underlying belief in the superiority of European American culture over that of non-white groups.[62] The scholar Uri Ben-Eliezer argued that the concept of cultural racism was useful for understanding the experience of Ethiopian Jews living in Israel.[63] After the Ethiopian Jews began migrating to Israel in the 1980s, various young members were sent to boarding school with the intention of assimilating them into mainstream Israeli culture and distancing them from their parental culture.[64] The newcomers found that many Israelis, especially Ashkenazis who adhered to ultra-orthodox interpretations of Judaism, did not regard them as real Jews.[65] When some white Israeli parents removed their children from schools with a high percentage of Ethiopian children, they denied accusations of racism, with one stating: "It's only a matter of cultural differences, we have nothing against blacks".[66] In 1992, Blaut argued that while most academics totally rejected biological racism, cultural racism was widespread within academia.[48] Similarly, in 2000 Powell suggested that cultural racism underpinned many of the policies and decisions made by U.S. educational institutions, although often on an "unconscious level".[67] She argued that the U.S. curriculum was based on the premise that "White cultural knowledge" was superior to that of other ethnic groups, hence why it was taught in Standard English, the literature studied was largely Eurocentric, and history lessons focused on the doings of Europeans and people of European descent.[67] Among the far-right   An elderly white man with receding white hair is wearing glasses. He is outdoors with various people in the background, suggesting a crowd. He is smiling, his mouth open. He is wearing a shirt with a blue jacket. A middle-aged white man with dark brown hair. He is wearing a suit including a black jacket and a striped silver tie. In Western Europe, far-right politicians like Jean-Marie Le Pen (left) and Nick Griffin (right) downplayed their parties' biologically racist positions to argue for the incompatibility of different cultural groups. The scholar of English Daniel Wollenberg stated that in the latter part of the 20th century and early decades of the 21st, many in the European far-right began to distance themselves from the biological racism that characterised neo-Nazi and neo-fascist groups and instead emphasised "culture and heritage" as the "key factors in constructing communal identity".[68] The previous political failures of the domestic terrorist group Organisation Armée Secrète during the Algerian War (1954–62), along with the electoral defeat of far-right candidate Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour in the 1965 French presidential election, led to the adoption of a meta-political strategy of 'cultural hegemony' within the nascent Nouvelle Droite (ND).[69] GRECE, an ethno-nationalist think-thank founded in 1968 to influence established right-wing political parties and diffuse ND ideas within the society at large, advised its members "to abandon an outdated language" by 1969.[70] Nouvelle Droite thinkers progressively shifted from theories of biological racism toward the claim that different ethno-cultural groups should be kept separate in order to preserve their historical and cultural differences, a concept they name ethno-pluralism.[71] During the 1980s, this tactic was adopted by France's National Front (FN) party, which was then growing in support under the leadership of Jean-Marie Le Pen.[72] After observing the electoral gains of Le Pen's party, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a UK fascist group, the British National Party—which had recently come under the leadership of Nick Griffin and his "moderniser" faction—also began downplaying its espousal of biological racism in favour of claims about the cultural incompatibility of different ethnic groups.[73] In Denmark, a far-right group called the Den Danske Forening (The Danish Society) was launched in 1986, presenting arguments about cultural incompatibility aimed largely at refugees entering the country. Its discourse presented Denmark as a culturally homogenous and Christian nation that was threatened by largely Muslim migrants.[74] In Norway, the far-right terrorist Anders Behring Breivik expressed ideas about cultural incompatibility between Muslims and other Europeans, as opposed to biologically racist ideas. In his view, Muslims represented a cultural threat to Europe, but he placed no emphasis on their perceived biological difference.[75] ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Islamophobia and cultural racism ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Some scholars who have studied Islamophobia, or prejudice and discrimination toward Muslims, have labelled it a form of cultural racism.[76] For instance, a range of academics studying the English Defence League, an Islamophobic street protest organisation founded in London in 2009, have labelled it culturally racist.[77] Anthias suggested that it was appropriate to talk of "anti-Muslim racism" because the latter involved attributing the Muslim population "with fixed, unchanging and negative characteristics" and then subjecting them "to relations of inferiorization and exclusion", traits that she associated with the term "racism".[78]  a group of about 60 white, mostly male demonstrators on a road. There about 3 females also. Most are young, probably in their teens, twenties, or thirties. Most are short-haired. Some have their faces covered. One waves the English (as opposed to British) flag; a red cross on a white background. Others have the image of the English flag affixed to their clothing in various forms. Near the back of the image, one demonstrator carries a large white placard written in all caps, "English Defence League: Shut down the Mosque Command & Control Centre". Various scholars who have studied the English Defence League (demonstration pictured) have argued that its Islamophobia can be called "cultural racism". The media studies scholar Arun Kundnani suggested some difference between cultural racism and Islamophobia. He noted that while cultural racism perceived "the body as the essential location of racial identity", specifically through its "forms of dress, rituals, languages and so on", Islamophobia "seems to locate identity not so much in a racialised body but in a set of fixed religious beliefs and practices".[79] The sociologist Ali Rattansi argued that while many forms of Islamophobia did exhibit racism, for instance by conflating Muslims with Arabs and presenting them as being uniformly barbaric, in his view Islamophobia was "not necessarily racist", instead coming in both racist and non-racist forms.[80] In 2018, the UK's all-party parliamentary group on British Muslims, chaired by politicians Anna Soubry and Wes Streeting, proposed that Islamophobia be defined in British law as being "a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness".[81] This generated concerns that such a definition would criminalise criticism of Islam. Writing in The Spectator, David Green referred to it as "a backdoor blasphemy law" that would protect conservative variants of Islam from criticism, including criticism from other Muslims.[82] The British anti-racism campaigner Trevor Phillips also argued that it was inappropriate for the UK government to view Islamophobia as racism.[83][84] Martin Hewitt, the chair of the National Police Chiefs' Council, warned that implementing that definition could exacerbate community tensions and hamper counter-terrorist efforts against Salafi jihadism.[85][86] While the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats adopted the all-party parliamentary group's definition, the Conservative Party government rejected it, stating that the definition required "further careful consideration" and had "not been broadly accepted".[86] Various British Muslims and groups like the Muslim Council of Britain expressed disappointment at the government's decision.[86] |

西欧諸国における人種主義 襟にブローチのついたジャケットを着用し、肘掛け椅子に座るマーガレット・サッチャー。 マーガレット・サッチャーが1978年に主張した、イギリスは「異なる文化を持つ人々に席巻されている」という主張は、人種主義の一例として挙げられている[47]。 1992年の『Antipode: この議論はその後レンによって支持された[29]。ブラウトは、文化的人種主義が多くの白人西洋人に自分たちを優れた人種の一員としてではなく、「ヨー ロッパ文化」、「西洋文化」、「西洋」と呼ばれる優れた文化のメンバーとして見るように促してきたと主張した。 [48]彼は、文化的人種差別的な考え方は第二次世界大戦の後に、西欧諸国と第三世界の有色人種のコミュニティの両方における白人西欧人の支配を合理化す ることを使命とする西欧の学者たちによって発展させられたと提唱した[49]。彼は、西欧列強がより裕福で経済的に発展しているのは文化的に進んでいるか らであるという文化的人種差別的な考え方を促進するために近代化という社会学的概念が発展させられたと主張した[49]。 レンは、文化的人種主義はヨーロッパ全域でほぼ同様の形で現れていたが、国民的アイデンティティの確立や移民の形態や時期によって場所によって特定の差異 があったと主張していた[50]。 彼女は、西欧社会は様々な民族的あるいは文化的な「他者」を排除することを正当化する他者化の一形態として文化的差異の言説を用いると同時に、異なる民族 集団間の社会経済的不平等を無視していると主張していた。 [30] デンマークを例として、彼女は「文化的人種主義的言説」が、経済的緊張と失業が高まった1980年代に出現したと主張した[51]。1995年のデンマー クでのフィールドワークに基づき、彼女は文化的人種主義がデンマーク社会全体の反移民感情を促し、少数民族の数を10%前後に制限する住宅割当を含む「様 々な形態の人種主義的実践」を生み出したと主張した。 [さらにディネーシュ・ドゥスーザは、人種主義が「西洋人の意識」に深く埋め込まれているため、根絶することができないと語った。 [53]しかし、彼は主に西洋社会で人種差別主義であると誤解されているエスノセントリズムに論拠を置いており、それはしばしば人種差別主義者であると誤 解されていると考えている。彼の論文は、初期のヨーロッパの人種差別主義者は誤解されており、彼らの見解は「多様な世界を理解しようとする」方法であった というものであった。 レンは1990年代のデンマークの反移民感情を、1980年代のイギリスで表明されたサッチャー派の反移民感情と比較していた[54]。 例えばイギリスのマーガレット・サッチャー首相は、イギリスが「異なる文化を持つ人々によって席巻される」ことを懸念する発言をしたことで、文化差別主義 者とみなされていた[47]。 この言葉はトルコでも使われている。2016年、ドイツのグエンテル・オッティンガー欧州委員は、レジェップ・タイイップ・エルドアンがトルコ大統領であ り続ける限り、トルコのEU加盟が認められる可能性は低いと述べた。これに対し、トルコのオメル・チェリク欧州連合担当大臣はドイツを「文化人種主義」と 非難した[55]。 社会学者のXolela Mangcuは、1940年代後半に南アフリカでアパルトヘイト(白人を優遇する人種隔離制度)が構築された一因として、人種主義が見られると主張した。 彼は、アパルトヘイト体制確立の立役者であるオランダ生まれの南アフリカの政治家ヘンドリック・ヴェルウェルドが、文化的差異を理由に人種集団を分離する ことに賛成していたと指摘している[56]。文化的人種主義という考え方は、アメリカにおける現象を説明するためにも用いられてきた。グロスフォゲルは、 1960年代の公民権運動の中で、アメリカでは文化的人種主義が生物学的人種主義に取って代わったと主張した[57]。クレア・シェリダンは、文化的人種 主義はメキシコ系アメリカ人の経験に当てはまる概念であり、様々なヨーロッパ系アメリカ人が、彼らは英語ではなくスペイン語を話すので真のアメリカ人では ないという見解を持っていると述べた[58]。 [58] アメリカの理論家サミュエル・P・ハンティントンが1990年代に提唱した文明の衝突理論も、世界は相互に排他的な文化圏に分割されているという主張のた めに、人種主義を刺激するものとして引用されている[59]。  サミュエル・P・ハンティントンはグレーのスーツに赤いネクタイを締め、世界経済フォーラムのデスクに座っている。 アメリカの政治学者サミュエル・P・ハンティントンが提唱した「文明の衝突」理論は、人種主義を刺激するものだと言われている[59]。 1990年代初頭、批判的教育学の研究者であるヘンリー・ジルーは、文化的人種主義がアメリカの政治的右派全体に顕著であると主張した。彼の見解では、保 守派は「人種、民族、アイデンティティに対する進歩的な批評を再利用し、文化的人種主義の政治を払拭するのではなく、むしろ促進するために利用している」 [60]、 批判的教育学の研究者であるレベッカ・パウエルは、ジルーの研究を参考にしながら、アメリカ政治の保守派とリベラル派の双方が、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の 文化を規範的なものとして扱っているという点で、文化的人種差別的な姿勢を反映していることを示唆した。彼女は、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人のリベラル派は制 度的人種主義の存在を認めながらも、彼らの文化的同化主義の奨励は、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の文化が非白人グループの文化よりも優れているという根底にあ る信念を裏付けていると主張した[62]。 学者ウリ・ベン=エリエゼルは、文化的人種主義の概念はイスラエルに住むエチオピア系ユダヤ人の経験を理解するのに有用であると主張した[63]。 1980年代にエチオピア系ユダヤ人がイスラエルに移住し始めた後、様々な若いメンバーがイスラエルの主流文化に同化させ、彼らの親文化から距離を置くこ とを意図して寄宿学校に送られた。 [64]新入生たちは、多くのイスラエル人、特にユダヤ教の超正統的な解釈を信奉するアシュケナージ人が、自分たちを本当のユダヤ人とはみなしていないこ とに気づいた[65]。エチオピア人の子どもの割合が高い学校から子どもを排除したイスラエルの白人の親たちがいたとき、彼らは人種主義との非難を否定 し、ある親はこう述べた: 「文化の違いに過ぎず、黒人に恨みはない」[66]。 1992年、ブラウトは、ほとんどの学者が生物学的人種主義を完全に否定している一方で、文化的人種主義は学問の世界に広く浸透していると主張した [48]。同様に2000年、パウエルは、文化的人種主義が、しばしば「無意識のレベル」ではあるが、米国の教育機関の政策や決定の多くを支えていると示 唆した[67]。 [彼女は、米国のカリキュラムは「白人の文化的知識」が他の民族のそれよりも優れているという前提に基づいており、それゆえに標準英語で教えられ、研究さ れる文学は大部分がヨーロッパ中心であり、歴史の授業はヨーロッパ人とヨーロッパ系の人々の行いに焦点を当てていると主張した[67]。 極右   髪の後退した白人の老人が眼鏡をかけている。彼は屋外で、背景にいる様々な人々と一緒にいる。口を開けて笑っている。青いジャケットにシャツを着ている。 ダークブラウンの髪をした中年の白人男性。黒いジャケットにストライプのシルバーのネクタイを締めたスーツを着ている。 西ヨーロッパでは、ジャン=マリー・ルペン(左)やニック・グリフィン(右)のような極右政治家が、政党の生物学的人種差別主義的立場を軽視し、異なる文化集団の非互換性を主張している。 ダニエル・ヴォレンベルク(Daniel Wollenberg)という英語学者は、20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、ヨーロッパの極右勢力の多くは、ネオナチやネオファシストの特徴であっ た生物学的人種主義から距離を置くようになり、その代わりに「文化と遺産」を「共同体のアイデンティティを構築する上で重要な要素」として強調するように なったと述べている[68]。 アルジェリア戦争(1954-62年)における国内テロ組織アルメ・セクレートの政治的失敗と、1965年のフランス大統領選挙における極右候補ジャン= ルイ・ティクシエ=ヴィニャンクールの選挙での敗北は、新生ヌーヴェル・ドロワット(ND)において「文化的ヘゲモニー」というメタ政治戦略の採用につな がった。 [1968 年に設立されたエスノナショナリストのシンクタンクであるグレース(GRECE)は、既存の右派政党に影響を与え、NDの思想を社会全体に広めることを目 的としていたが、1969年までにそのメンバーに「時代遅れの言語を捨てるように」と助言した。 [ヌーヴェル・ドロワットの思想家たちは、生物学的人種主義の理論から、異なる民族文化集団はその歴史的・文化的差異を維持するために分離されるべきであ るという主張へと徐々にシフトしていった。 [ルペンの政党が選挙で得た利益を観察した後、1990年代後半から2000年代初頭にかけて、イギリスのファシスト集団であるイギリス国民党(ニック・ グリフィンと彼の「近代化」派閥の指導下にあった)もまた、異なる民族集団の文化的非互換性についての主張を支持して生物学的人種主義の信奉を軽視し始め た[73]。 デンマークでは、1986年にデン・ダンスケ・フォアニング(デンマーク協会)と呼ばれる極右グループが発足し、主に入国してくる難民を対象に文化的不適 合についての主張を展開していた。その言説では、デンマークは文化的に均質なキリスト教国民であり、大部分がイスラム教徒の移民によって脅かされていると していた[74]。ノルウェーでは、極右テロリストのアンダース・ベーリング・ブレイヴィクが、生物学的な人種差別思想とは対照的に、イスラム教徒と他の ヨーロッパ人との文化的非互換性に関する考えを表明していた。彼の見解では、イスラム教徒はヨーロッパにとって文化的脅威であるが、彼らの認識する生物学 的差異には重きを置いていなかった[75]。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ イスラム恐怖症と人種主義 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ イスラム恐怖症、つまりイスラム教徒に対する偏見や差別を研究している学者の中には、それを文化的人種主義の一形態であるとする者もいる[76]。例え ば、2009年にロンドンで設立されたイスラム恐怖症の街頭抗議組織であるイングリッシュ・ディフェンス・リーグを研究している様々な学者は、それを文化 的人種主義であるとする。 [77]アンシアスは、「反イスラム人種主義」について語ることが適切であると示唆した。なぜなら後者は、イスラム教徒に「固定的で不変的かつ否定的な特 性」を帰属させ、「劣等化と排除の関係」に服させるというものであり、彼女が「人種主義」という言葉から連想される特性を持っているからである[78]。  60人ほどの白人(ほとんどが男性)のデモ隊が道路にいた。女性も3人ほどいる。ほとんどが若く、おそらく10代、20代、30代であろう。ほとんどが短 髪である。顔を隠している者もいる。白地に赤の十字架が描かれた英国旗を振っている者もいる。白地に赤い十字架が描かれている。画像の後方近くには、「イ ングリッシュ・ディフェンス・リーグ」と大文字で書かれた大きな白いプラカードを持ったデモ参加者がいる: モスクの指揮統制センターを閉鎖せよ」と書かれた大きな白いプラカードを持っている。 イングリッシュ・ディフェンス・リーグ(写真のデモ)を研究するさまざまな学者は、そのイスラム嫌悪は「文化人種主義」と呼ぶことができると主張している。 メディア研究者のアルン・クンドナニは、文化的人種主義とイスラム恐怖症の違いを指摘している。彼は、文化的人種主義が「人種的アイデンティティの本質的 な場所として身体を」、具体的には「服装、儀式、言語などの形式」を通して認識するのに対して、イスラム恐怖症は「人種化された身体ではなく、一連の固定 した宗教的信念と実践の中にアイデンティティを位置づけるようだ」と指摘した。 [社会学者のアリ・ラッタンシは、イスラム教徒をアラブ人と混同し、一様に野蛮であるかのように見せるなど、イスラム嫌悪の多くの形態が人種主義を示す一 方で、彼の見解ではイスラム嫌悪は「必ずしも人種主義的ではない」のであり、その代わりに人種主義的な形態と非人種主義的な形態の両方があると主張した [80]。 2018年、政治家のAnna SoubryとWes Streetingが議長を務めるイギリスの全政党ムスリムに関する議員連盟は、イスラムフォビアをイギリスの法律で「ムスリムであること、またはムスリ ムであると認識されることの表現を標的とする人種主義の一種」と定義することを提案した[81]。スペクテイター』誌に寄稿したデイヴィッド・グリーン は、これを「裏口の冒とく法」と呼び、イスラム教の保守的な変種を、他のイスラム教徒からの批判を含む批判から守ることになると指摘した[82]。イギリ スの反人種主義運動家トレヴァー・フィリップスも、イギリス政府がイスラム嫌悪を人種主義とみなすのは不適切だと主張した[83]。 [83][84]国民警察長官会議の議長であるマーティン・ヒューイットは、その定義を実施することは地域社会の緊張を悪化させ、サラフィー・ジハード主 義に対するテロ対策の妨げになると警告した。 [85][86]労働党と自由民主党は全政党議員連盟の定義を採用したが、保守党政府はその定義を拒否し、「さらなる慎重な検討」が必要であり、「広く受 け入れられたわけではない」と述べた[86]。様々な英国のイスラム教徒や英国ムスリム評議会のような団体は政府の決定に失望を表明した[86]。 |

| Opposing cultural racism During the 1980 and 1990s, both Balibar and Taguieff expressed the view that established approaches to anti-racist activism were designed to tackle biological racism and thus were destabilized when confronted with cultural racism.[87] In 1999, Flecha argued that the main approach to anti-racist education adopted in Europe had been a "relativistic" one that emphasised diversity and difference between ethnic groups – the same basic message promoted by cultural racism. He thus thought that such programs "exacerbate rather than eliminate racism".[88] Flecha expressed the view that to combat cultural racism, anti-racists should instead utilise a "dialogic" approach which encourages different ethnic groups to live alongside each other according to rules that they have all agreed upon through a "free and egalitarian dialogue".[89] Wollenberg commented that those radical right-wing groups which emphasise cultural difference had converted "multiculturalist anti-racism into a tool of racism".[75] According to Balibar, the cultural racist position argues that when ethnic groups co-exist in the same location it "naturally" results in conflict. Proponents of cultural racism therefore argue that attempts at integrating different ethnic and cultural groups itself leads to prejudice and discrimination. In doing this they seek to portray their own views as the "true anti-racism", as opposed to the views of those activists who call themselves "anti-racists".[90] Through education [S]chools may be one of the few public institutions that have the potential to counteract a culturally racist ideology [in the U.S.] […] [I]t is also imperative that we confront cultural racism in our schools and classrooms so that our society eventually might overcome notions of White supremacy and become more inclusive and accepting of our human diversity. — Scholar of critical pedagogy Rebecca Powell, 2000[91] Arguing from his position as a scholar of critical pedagogy, Giroux proposed using both "a representational pedagogy and a pedagogy of representation" to address cultural racism.[92] This would include encouraging students to read accounts of race relations which challenge those written by liberal commentators, who he thought concealed their underlying ideology and the existence of racial power relations.[93] It would also include teaching students methodologies that would alert them to how different media reinforce existing forms of authority.[94] Specifically, he urged teachers to provide their students with the "analytic tools" through which they could learn to challenge accounts that perpetuated ethnocentric discourses and thus "racism, sexism and colonialism".[95] More broadly, he urged leftist activists not to abandon identity politics in the face of U.S. cultural racism,[60] but instead called on them to "not only construct a new politics of difference but extend and deepen the possibilities of critical cultural work by reasserting the primacy of the pedagogical as a form of cultural politics".[96] Similarly, Powell argued that schools were the best place to counteract "cultural racism", in that it was here that teachers could expose children to the underlying ideas on which cultural assumptions are based.[97] She added that in the U.S., schools should commit themselves to promoting multiculturalism and anti-racism.[98] As practical proposals, she suggested teaching pupils about non-standard vernacular languages other than Standard English and explaining to them how the latter "became (and remains) the language of power". She also suggested getting pupils to discuss how images in popular media reflect prejudicial assumptions about different ethnic groups and to examine historical events and works of literature from a range of different cultural perspectives.[98] |

文化的人種主義への対抗 1980年から1990年代にかけて、バリバールもタギエフも、反人種主義的な活動に対する確立されたアプローチは生物学的人種主義に取り組むためにデザ インされたものであり、したがって文化的人種主義に直面すると不安定になるという見解を表明していた[87]。 1999年、フレチャはヨーロッパで採用されている反人種主義教育への主なアプローチは、民族集団間の多様性と差異を強調する「相対主義的」なものであ り、文化的人種主義が推進するのと同じ基本的なメッセージであると主張していた。したがって彼は、そのようなプログラムは「人種主義を排除するよりもむし ろ悪化させる」と考えていた[88]。フレチャは、文化的人種主義と闘うために、反人種主義者は代わりに「自由で平等主義的な対話」を通じて、異なる民族 集団が全員が合意したルールに従って互いに共存することを奨励する「対話的」アプローチを利用すべきだという見解を表明した[89]。 ウォレンベルクは、文化的差異を強調する急進的な右派グループは「多文化主義的な反人種主義を人種主義の道具に変換した」とコメントしている[75]。 バリバールによれば、文化的人種主義の立場は、民族グループが同じ場所に共存するとき、それは「当然」対立をもたらすと主張している。したがって、人種主 義の支持者は、異なる民族や文化集団を統合しようとする試み自体が偏見や差別につながると主張する。そうすることで、「反人種主義者」を自称する活動家た ちの見解とは対照的に、彼ら自身の見解を「真の反人種主義」として描こうとする[90]。 教育を通じて [学校は、[アメリカにおける]文化的人種主義イデオロギーに対抗する可能性をもつ数少ない公的機関のひとつかもしれない[......]。 - 批判的教育学の研究者レベッカ・パウエル、2000年[91]。 批判的教育学の学者としての立場から、ジルーは文化的人種主義に対処するために「表象の教育学と表象の教育学」の両方を用いることを提案した[92]。 これには、リベラルな論者たちがその根底にあるイデオロギーや人種的力関係の存在を隠していると考え、それらに異議を唱えるような人種関係についての記述 を読むよう生徒に奨励することが含まれる[93]。 [具体的には、彼は教師に対して、民族中心主義的な言説、ひいては「人種主義、性差別主義、植民地主義」を永続させるような説明に挑戦することを学ぶため の「分析ツール」を生徒に提供するよう促した。 米国の文化的人種主義に直面してアイデンティティ・ポリティクスを放棄するのではなく、その代わりに「差異の新しい政治学を構築するだけでなく、文化的政 治学の形式として教育学的なものの優位性を再確認することによって批判的な文化的活動の可能性を拡張し、深める」ことを求めた[60]。 同様にパウエルは、学校は「文化的人種主義」に対抗するための最良の場所であり、教師はここで子どもたちに文化的前提の基礎となる考え方に触れさせること ができると主張した[97]。実践的な提案として、彼女は生徒たちに標準英語以外の非標準的な地方言語について教え、後者がいかに「権力の言語となったか (そして今もそうであるか)」を説明することを提案した。彼女はまた、生徒たちに、ポピュラーメディアのイメージがいかに異なる民族グループに対する偏見 的な思い込みを反映しているかを議論させ、歴史的な出来事や文学作品をさまざまな異なる文化的観点から検討させることを提案した[98]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_racism |

|

Étienne Balibar

(/bælɪˈbɑːr/; French: [etjɛn balibaʁ]; born 23 April 1942) is a French

philosopher. He has taught at the University of Paris X-Nanterre, at

the University of California Irvine and is currently an Anniversary

Chair Professor at the Centre for Research in Modern European

Philosophy (CRMEP) at Kingston University and a visiting professor at

the Department of French and Romance Philology at Columbia University. Étienne Balibar

(/bælɪˈbɑːr/; French: [etjɛn balibaʁ]; born 23 April 1942) is a French

philosopher. He has taught at the University of Paris X-Nanterre, at

the University of California Irvine and is currently an Anniversary

Chair Professor at the Centre for Research in Modern European

Philosophy (CRMEP) at Kingston University and a visiting professor at

the Department of French and Romance Philology at Columbia University.Life Balibar was born in Avallon, Yonne, Burgundy, France in 1942, and first rose to prominence as one of Althusser's pupils at the École normale supérieure. He entered the École normale supérieure in 1960.[1] In 1961, Balibar joined the Parti communiste français. He was expelled in 1981 for critiquing the party's policy on immigration in an article.[2] Balibar participated in Louis Althusser's seminar on Karl Marx's Das Kapital in 1965.[3] This seminar resulted in the book Reading Capital, co-authored by Althusser and his students. Balibar's chapter, "On the Basic Concepts of Historical Materialism," was republished along with those of Althusser in the book's abridged version (trans. 1970),[4] until a complete translation was published in 2016.[5] In 1987, he received his doctorate degree in philosophy from the Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen in the Netherlands.[1] He received his habilitation from the Université Paris I in 1993. Balibar joined the University of Paris X-Nanterre as a professor in 1994, and the University of California, Irvine in 2000. He became professor emeritus of Paris X in 2002.[1] His daughter with the physicist Françoise Balibar is the actress Jeanne Balibar.[6] Work In Masses, Classes, Ideas (1994), Balibar argues that in Das Kapital (or Capital), the theory of historical materialism comes into conflict with the critical theory that Marx begins to develop, particularly in his analysis of the category of labor, which in capitalism becomes a form of property. This conflict involves two distinct uses of the term "labor": labor as the revolutionary class subject (i.e., the "proletariat") and labor as an objective condition for the reproduction of capitalism (the "working class"). In The German Ideology, Marx conflates these two meanings, and treats labor as, in Balibar's words, the "veritable site of truth as well as the place from which the world is changed..."[7]: 92 In Capital, however, the disparity between the two senses of labor becomes apparent. One manifestation of this is the virtual disappearance in the text of the term "proletariat." As Balibar points out, the term appears only twice in the first edition of Capital, published in 1867: in the dedication to Wilhelm Wolff and in the two final sections on the "General Law of Capitalist Accumulation". For Balibar, this implies that "the emergence of a revolutionary form of subjectivity (or identity)... is never a specific property of nature, and therefore brings with it no guarantees, but obliges us to search for the conditions in a conjuncture that can precipitate class struggles into mass movements..." Moreover, "[t]here is no proof… that these forms are always and eternally the same (for example, the party-form, or the trade union)."[7]: 147 In "The Nation Form: History and Ideology," Balibar critiques modern conceptions of the nation-state. He states that he is undertaking a study of the contradiction of the nation-state because "Thinking about racism led us back to nationalism, and nationalism to uncertainty about the historical realities and categorization of the nation".[8]: 329 Balibar contends that it is impossible to pinpoint the beginning of a nation or to argue that the modern people who inhabit a nation-state are the descendants of the nation that preceded it. Balibar argues that, because no nation-state has an ethnic base, every nation-state must create fictive ethnicities in order to project stability on the populace:  Etienne Balibar with Judith Butler in Berkeley, 2014 "the idea of nations without a state, or nations 'before' the state, is thus a contradiction in terms, because a state always is implied in the historic framework of a national formation (even if not necessarily within the limits of its territory). But this contradiction is masked by the fact that national states, whose integrity suffers from internal conflicts that threaten its survival (regional conflicts, and especially class conflicts), project beneath their political existence to a preexisting 'ethnic' or 'popular' unity".[8]: 331 In order to minimize these regional, class, and race conflicts, nation-states fabricate myths of origin that produce the illusion of shared ethnicity among all their inhabitants. In order to create these myths of origins, nation-states scour the historical period during which they were "formed" to find justification for their existence. They also create the illusion of shared ethnicity through linguistic communities: when everyone has access to the same language, they feel as if they share an ethnicity. Balibar argues that "schooling is the principal institution which produces ethnicity as linguistic community."[8]: 351 In addition, this ethnicity is created through the "nationalization of the family," meaning that the state comes to perform certain functions that might traditionally be performed by the family, such as the regulation of marriages and administration of social security. In recent work following the "populist" wave, Balibar has called the incorporation of these different elements "absolute capitalism."[9] |

エ

ティエンヌ・バリバール(/bælɪȨ, French: [etjɛ balibaʁ];

1942年4月23日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者である。パリ第十ナンテール大学、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校で教鞭をとり、現在はキングストン大学

現代ヨーロッパ哲学研究センター(CRMEP)の記念講座教授、コロンビア大学フランス語・ロマンス言語学部の客員教授を務める。 エ

ティエンヌ・バリバール(/bælɪȨ, French: [etjɛ balibaʁ];

1942年4月23日生まれ)はフランスの哲学者である。パリ第十ナンテール大学、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校で教鞭をとり、現在はキングストン大学

現代ヨーロッパ哲学研究センター(CRMEP)の記念講座教授、コロンビア大学フランス語・ロマンス言語学部の客員教授を務める。生涯 バリバールは1942年、フランスのブルゴーニュ地方ヨンヌ県アヴァロンに生まれ、高等師範学校(École normale supérieure)でアルチュセールの教え子のひとりとして脚光を浴びる。1960年に高等師範学校に入学した[1]。 1961年、パリ・コミュニスト・フランセに入党する。1981年、同党の移民政策を批判した論文により除名される[2]。 バリバールは、1965年にルイ・アルチュセールのカール・マルクスの『資本論』に関するセミナーに参加した[3]。このセミナーは、アルチュセールと彼 の学生たちによる共著『資本論を読む』に結実した。バリバールの「史的唯物論の基本概念について」という章は、2016年に全訳が出版されるまで、同書の 要約版(1970年訳)でアルチュセールの章とともに再出版された[4]。 1987年、オランダのナイメーヘン・カトリケ大学で哲学博士号を取得[1]。1993年、パリ第1大学でハビリテーションを取得。1994年にパリ第 10=ナンテール大学教授、2000年にカリフォルニア大学アーバイン校教授となる。2002年にパリ第10大学名誉教授となった[1]。 物理学者フランソワーズ・バリバールとの娘は女優のジャンヌ・バリバールである[6]。 作品 バリバールは『大衆、階級、思想』(1994年)の中で、『資本論』(Das Kapital)において、史的唯物論の理論が、マルクスが展開し始めた批判的理論、特に資本主義において財産の一形態となる労働のカテゴリーの分析にお いて対立していると論じている。この対立は、「労働」という用語の2つの異なる用法、すなわち、革命的階級主体としての労働(すなわち、「プロレタリアー ト」)と、資本主義の再生産のための客観的条件としての労働(「労働者階級」)を含んでいる。『ドイツ・イデオロギー』において、マルクスはこの2つの意 味を混同し、バリバールの言葉を借りれば、労働を「真実の場所であると同時に、世界が変化する場所」[7]:92として扱っている。 しかし、『資本論』においては、労働の2つの意味における乖離が明らかになる。その一つの表れが、本文中で「プロレタリアート」という用語が事実上消滅し ていることである。バリバールが指摘するように、この用語は、1867年に出版された『資本論』の初版では、ヴィルヘルム・ヴォルフへの献辞と、「資本主 義的蓄積の一般法則」に関する2つの最終節に、2回だけ登場する。バリバールにとって、このことは、「主体性(あるいはアイデンティティ)の革命的形態の 出現は......決して自然の特定の性質ではなく、したがって何の保証ももたらさない。さらに、「これらの形態が(例えば、党派形態や労働組合など)常 に永遠に同じであるという...証拠はない」[7]: 147 国民形態: 歴史とイデオロギー」において、バリバールは国民国家についての近代的概念を批判している。彼は、「人種主義について考えることは、私たちをナショナリズ ムへと導き、ナショナリズムは、国民の歴史的現実とカテゴリー化についての不確実性へと導いた」[8]ため、国民国家の矛盾についての研究に取り組んでい ると述べている: 329 バリバールは、国民の始まりを特定することは不可能であり、国民国家に住む現代人がそれ以前の国民の子孫であると主張することも不可能であると主張する。 バリバールは、いかなる国民国家も民族的基盤を持たないため、すべての国民国家は、国民に安定をもたらすために、架空の民族性を作り出さなければならない と主張する:  エティエンヌ・バリバールとジュディス・バトラー(2014年、バークレーにて 国家のない国民、あるいは国家 「以前 」の国民という考え方は、このように矛盾したものである。なぜなら、国家は常に国民形成の歴史的枠組みの中に暗示されているからである(必ずしもその領土 の範囲内でなくても)。しかし、この矛盾は、国民国家が、その存続を脅かす内部紛争(地域紛争、とりわけ階級紛争)に苦しみながら、その政治的存在の下 に、既存の『民族的』あるいは『民衆的』統一を投影しているという事実によって覆い隠されている」[8]: 331 このような地域紛争、階級紛争、人種紛争を最小化するために、国民国家はすべての住民の間で民族性が共有されているかのような幻想を生み出す起源神話を捏 造する。このような起源神話を作り出すために、国民国家は自分たちが「形成」された歴史的時代を徹底的に調べ上げ、自分たちの存在を正当化する理由を見つ ける。国民国家はまた、言語共同体を通じて、民族性を共有しているかのような錯覚も作り出す。バリバールは「学校教育は言語共同体としてのエスニシティを 生み出す主要な制度である」と論じている[8]: 351 さらに、このようなエスニシティは「家族の国民化」によって生み出される。つまり、婚姻の規制や社会保障の管理など、従来は家族が担ってきたかもしれない 特定の機能を国家が担うようになるのである。ポピュリスト」の波に続く最近の研究において、バリバールはこうしたさまざまな要素の取り込みを「絶対資本主 義」と呼んでいる[9]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89tienne_Balibar |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆