ナショナリズム

Nationalism

ナ ショナリズム(nationalism)とは、人々のあつまりの基本的な単位を国家(→国民国 家)とし、それ の構成員たる国民=ネイション(nation)を維持・発展させていこうとする政治信条のこと。 やさしく言えば、ネーション主義なので、ネイション=国民 のまとまり強調し、それに重きをおく考え方全部をナショナリズムと呼ぶ。ナショナリズムの正しい翻訳語は「国民主義」であり、それは歴 史的には生松敬三をはじめ概念を理解している人たちからそのように翻訳され てきたからである。

ナ ショナリズムを民族主義と訳するのは、ネーションを人種(= レイス, race)と混同してきた戦前から伝統であるが、これは今日的水準からみて完全な誤 訳である。その理由は、我が国(=日本国)では、国民の単位を長いあい だ(1920年代以降今日まで)「大和民族」「日本民族」と言い習わしてきたために、「民族主義(みんぞくしゅぎ)」と言われることがあるが、これはナ ショナリズムのことである。(→日本語の「民族」をチェックする)

ナ ショナリストは、(我が国では)「右翼で、頭の構造が単純な奴」というステレオタイプが あった が、これは我が国の特殊事情に由来するし、史実を必ず反映するわけではない。また、歴史的にも社会的にも左翼のインテリがナショナリストであった国民国家 は数多く存在する。

ひ とつのネイション=国民に重きをおく考え方をナショナリズムと呼ぶのであるから、ナショナリズ ムの反対語あるいは対語は、インターナショナリズム(国際主義)である。インターナショナリズムは、ネーション間の障壁を超えて結びつこう、あるいは、そ れに重きをおく考え方なので、国際連合(国連)などの国際協調主義がその代表である。ただし、国連の前身の国際連盟などは、その枠組みづくりに失敗したと いう歴史的経緯も忘れてはならない。また、国際連盟の時期には、もうすこし別のタイプの国際主義であったインターナショナリズム(第1、第2などと序数が つく)があった。これはプロレタリアート(=革命的労働者)によるネーション=国民概念 を超えた共同体の試み、すなわちソビエト連邦(現在は消滅)が主導 して、世界中にマルクス主義者のネットワークつくりあげようとしたものである。しかし、実際には、モスクワ(ソビエトの首都があった)からの世界マルクス 主義戦略のコントロールを目的としたものであって、その組織化にはさまざまな軋轢が生じて、最終的に瓦解した。

★ さて、 文化ナショナリズム/文化的ナショナリズム(Cultural nationalism) とは、ナショナリズムの研究者たちが、共通の文化を強調することで国民共同体(community of nation)を形成しようとする知識人たちの取り組みを説明する際に用いる用語である。こ れは、「政治的」ナショナリズムと対比される。政治的ナショナリズムとは、国民国家の樹立を通じて「国民の自己決定権」を主張する特定の運動を指す。しか しながら、 化ナショナリズムをめぐる議論のなかで、この概念の必要性を説く人たちが、政治的ナショナリズム(政治ナショナリズム)と、文化ナショナリズムを峻別する ことに対する、賛同と批判である。後者の批判の議論においては「政治ナショナリズム」の派生が「文化ナショナリズムであり」ともに「ナショナリズム」の内 実から意図的に分離することはできないと考える(→「文化ナショナリズム」「ナショナリズムの諸類型」)。

★訳語についての考え方(→「ナショナリズム・民族集団・少数民の研究に関する基礎知識」)

| 英語 |

日本語 |

備考 |

| nation |

国民 |

ネーションを民族と訳してはならない |

| people |

民族・人民・人びと |

|

| folk |

人びと |

folkloreは「人びとの語り」で学問名称は民俗学 |

| ethnic group |

民族集団 |

|

| ethnie |

エトニー・民族 |

|

| ethnicity |

民族性・エスニシティ |

|

| race |

人種 |

|

| assimilation |

同化 |

|

| integration |

統合 |

|

| insertion |

編入 |

|

| transnational |

国家を超えた/トランスナショナル |

|

| nation state |

国民国家 |

| Nationalism

is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent

with the state.[1][2] As a movement, it presupposes the existence[3]

and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,[4]

especially with the aim of gaining and maintaining its sovereignty

(self-governance) over its perceived homeland to create a nation-state.

It holds that each nation should govern itself, free from outside

interference (self-determination), that a nation is a natural and ideal

basis for a polity,[5] and that the nation is the only rightful source

of political power.[4][6] It further aims to build and maintain a

single national identity, based on a combination of shared social

characteristics such as culture, ethnicity, geographic location,

language, politics (or the government), religion, traditions and belief

in a shared singular history,[7][8] and to promote national unity or

solidarity.[4] Nationalism, therefore, seeks to preserve and foster a

nation's traditional culture.[9] There are various definitions of a

"nation", which leads to different types of nationalism.[10] The two

main divergent forms identified by scholars are ethnic nationalism and

civic nationalism. Beginning in the late 18th century, particularly with the French Revolution and the spread of the principle of popular sovereignty or self determination, the idea that "the people" should rule is developed by political theorists.[11] Three main theories have been used to explain the emergence of nationalism: 1.Primordialism (perennialism) developed alongside nationalism during the romantic era and held that there have always been nations. This view has since been rejected by most scholars,[12] and nations are now viewed as socially constructed and historically contingent.[13][10] 2. Modernization theory, currently the most commonly accepted theory of nationalism,[14] adopts a constructivist approach and proposes that nationalism emerged due to processes of modernization, such as industrialization, urbanization, and mass education, which made national consciousness possible.[13][15] Proponents of this theory describe nations as "imagined communities" and nationalism as an "invented tradition" in which shared sentiment provides a form of collective identity and binds individuals together in political solidarity.[13][16][17] 3. A third theory, ethnosymbolism explains nationalism as a product of symbols, myths, and traditions, and is associated with the work of Anthony D. Smith.[11] The moral value of nationalism, the relationship between nationalism and patriotism, and the compatibility of nationalism and cosmopolitanism are all subjects of philosophical debate.[13] Nationalism can be combined with diverse political goals and ideologies such as conservatism (national conservatism and right-wing populism) or socialism (left-wing nationalism).[18][19][20][21] In practice, nationalism is seen as positive or negative depending on its ideology and outcomes. Nationalism has been a feature of movements for freedom and justice,[22] has been associated with cultural revivals,[9] and encourages pride in national achievements.[23] It has also been used to legitimize racial, ethnic, and religious divisions, suppress or attack minorities, undermine human rights and democratic traditions,[13] and start wars, being frequently cited as a cause of both World Wars.[24] |

ナ

ショナリズムとは、国家は国家と一致すべきであるとする思想であり運動である[1][2]。運動としては、特定の国家の存在[3]を前提とし、その利益を

促進する傾向があり[4]、特に国民国家を創設するために、認識された祖国に対する主権(自治権)を獲得し維持することを目的としている。ナショナリズム

はさらに、文化、民族性、地理的位置、言語、政治(または政府)、宗教、伝統、共有された特異な歴史に対する信念などの共有された社会的特徴の組み合わせ

に基づいて、単一の国民的アイデンティティを構築し、維持することを目的としている[7][8]。

[したがって、ナショナリズムは国家の伝統的な文化を維持し、育成することを目的としている[9]。 18世紀後半、特にフランス革命と人民主権または自己決定の原則の普及に始まり、「人民」が支配すべきであるという考え方が政治理論家によって発展した: 1. 原初主義(通年主義)は、ロマン主義時代にナショナリズムとともに発展したもので、国家は常に存在してきたとするものである。この見解はその後ほとんどの 学者によって否定され[12]、現在では国家は社会的に構築されたものであり、歴史的に偶発的なものとみなされている[13][10]。 2. 現在ナショナリズムについて最も一般的に受け入れられている近代化理論[14]は、構成主義的なアプローチを採用しており、工業化、都市化、大衆教育と いった近代化のプロセスによってナショナリズムが出現し、それによって国家意識が可能になったと提唱している[13][15]。この理論の支持者は、国家 を「想像された共同体」、ナショナリズムを「発明された伝統」と表現しており、共有された感情が集団的アイデンティティの一形態を提供し、政治的連帯にお いて個人を結びつけると述べている[13][16][17]。 3. 第三の理論であるエスノシンボリズムは、ナショナリズムを象徴、神話、伝統の産物として説明し、アンソニー・D・スミスの研究に関連している[11]。 ナショナリズムの道徳的価値、ナショナリズムと愛国主義の関係、ナショナリズムとコスモポリタニズムの両立はすべて哲学的議論の対象である[13]。ナ ショナリズムは自由と正義を求める運動の特徴であり[22]、文化的復興と関連しており[9]、国家的達成に対する誇りを促している[23]。また人種 的、民族的、宗教的分裂を正当化し、少数派を抑圧または攻撃し、人権と民主主義の伝統を弱体化させ[13]、戦争を始めるために使用されており、両世界大 戦の原因として頻繁に挙げられている[24]。 |

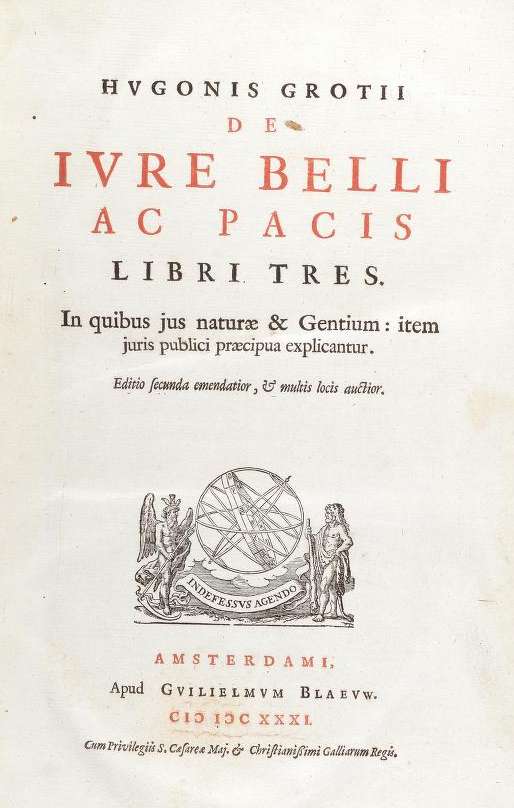

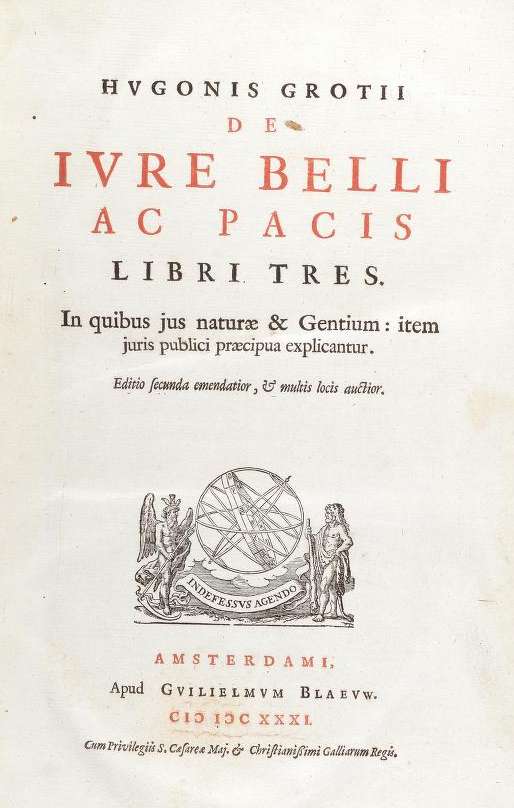

Terminology Title page from the second edition (Amsterdam 1631) of De jure belli ac pacis The terminological use of "nations", "sovereignty" and associated concepts were significantly refined with the writing by Hugo Grotius of De jure belli ac pacis in the early 17th century.[how?] Living in the times of the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands and the Thirty Years' War between Catholic and Protestant European nations, Grotius was deeply concerned with matters of conflicts between nations in the context of oppositions stemming from religious differences. The word nation was also applied before 1800 in Europe in reference to the inhabitants of a country as well as to collective identities that could include shared history, law, language, political rights, religion and traditions, in a sense more akin to the modern conception.[25] Nationalism as derived from the noun designating 'nations' is a newer word; in the English language, dating to around 1798.[26][27][better source needed] The term gained wider prominence in the 19th century.[28] The term increasingly became negative in its connotations after 1914. Glenda Sluga notes that "The twentieth century, a time of profound disillusionment with nationalism, was also the great age of globalism."[29] Academics define nationalism as a political principle that holds that the nation and state should be congruent.[1][2][30] According to Lisa Weeden, nationalist ideology presumes that "the people" and the state are congruent.[31] |

用語解説 『De jure belli ac pacis』第2版(アムステルダム、1631年)のタイトルページ。 「国家」、「主権」、およびそれらに関連する概念の用語的使用は、17世紀初頭にフーゴー・グロティウスが『De jure belli ac pacis』を著したことで大きく洗練された。スペインとオランダの間の80年戦争や、ヨーロッパのカトリックとプロテスタントの間の30年戦争の時代に 生きたグロティウスは、宗教の違いからくる対立という文脈の中で、国家間の対立の問題に深く関心を抱いていた。1800年以前のヨーロッパでは、国家とい う言葉は、国の住民を指すだけでなく、歴史、法律、言語、政治的権利、宗教、伝統などを共有する集団的アイデンティティを指すこともあり、近代的な概念に 近い意味で用いられていた[25]。 「国家」を意味する名詞に由来するナショナリズムは、英語では1798年頃まで遡る新しい言葉である[26][27][要出典]。 この用語は19世紀に広く知られるようになった[28]。1914年以降、この用語はその意味合いにおいて次第に否定的になっていった。グレンダ・スルー ガは「ナショナリズムに対する深い幻滅の時代であった20世紀は、グローバリズムの偉大な時代でもあった」と指摘している[29]。 リサ・ウィーデンによれば、ナショナリズムのイデオロギーは「国民」と国家が一致していることを前提としている[31]。 |

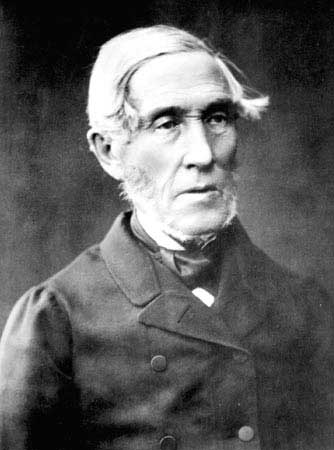

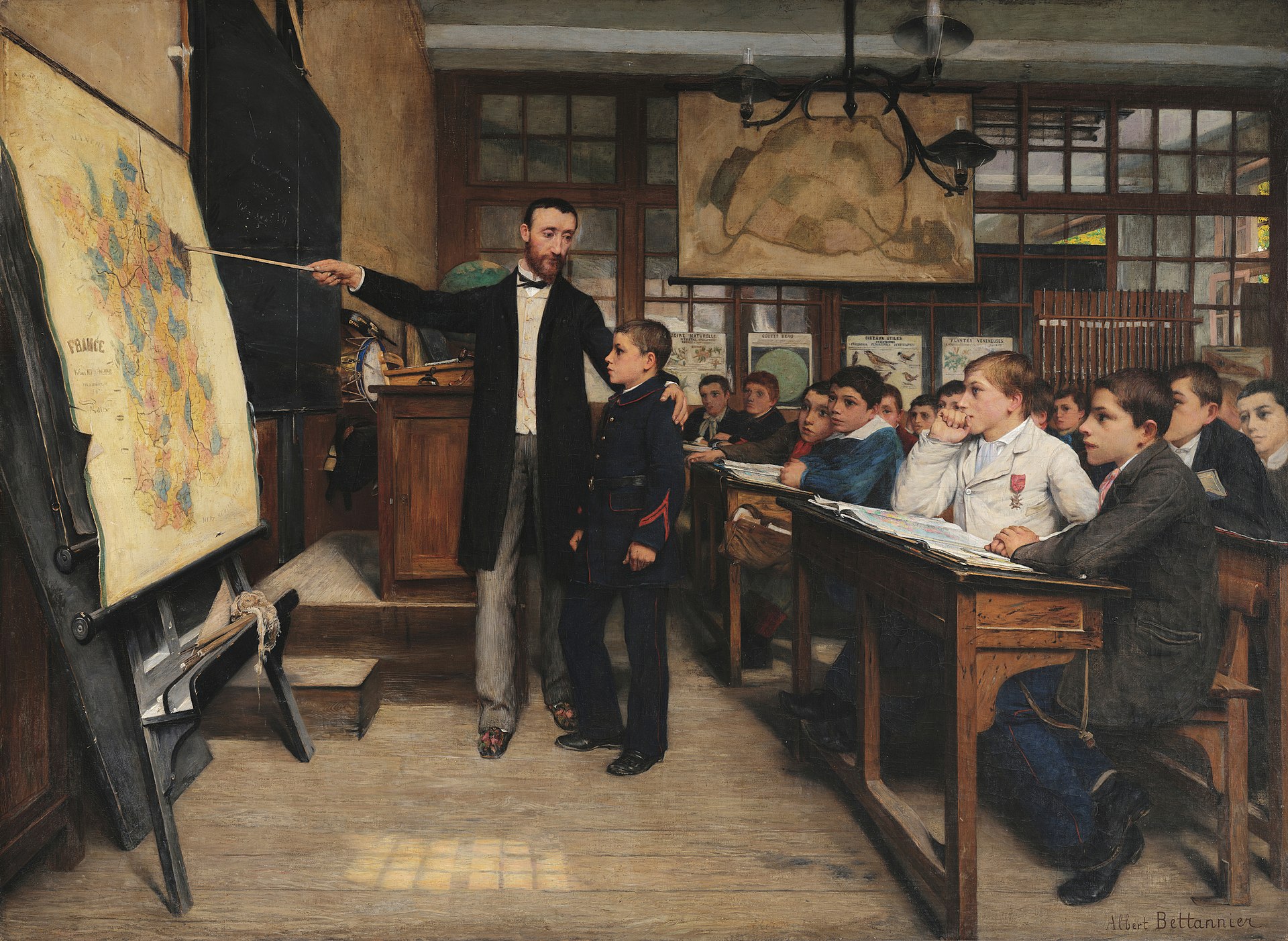

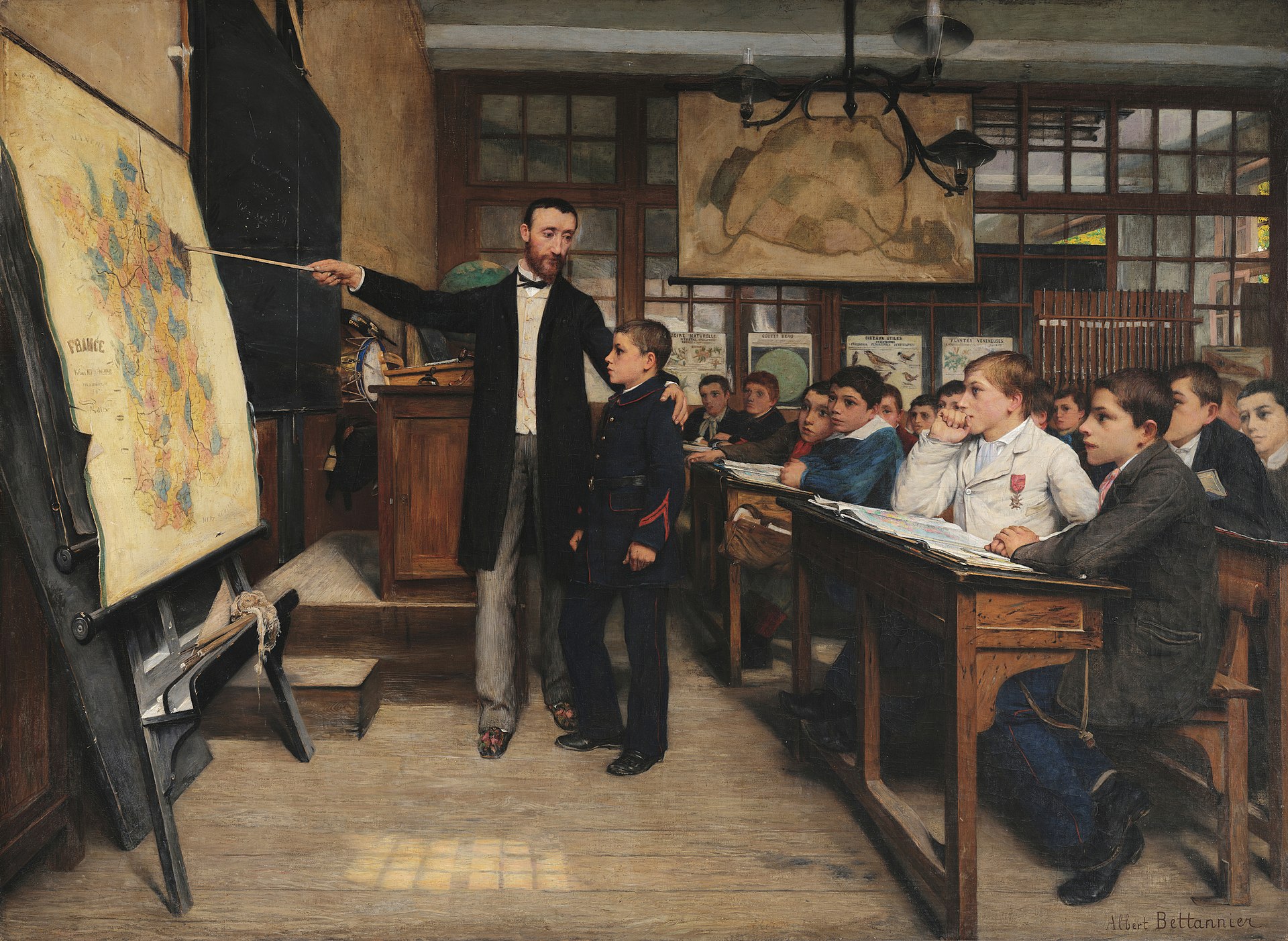

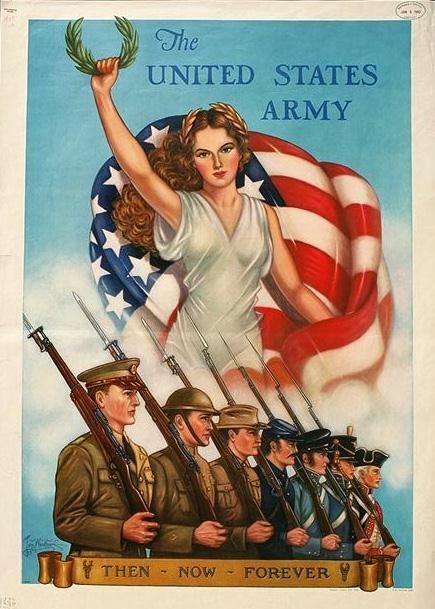

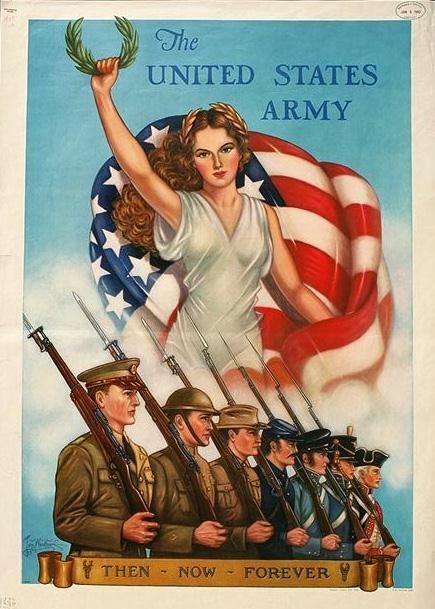

| History Further information: Nationalist historiography Intellectual origins Anthony D. Smith describes how intellectuals played a primary role in generating cultural perceptions of nationalism and providing the ideology of political nationalism: Wherever one turns in Europe, their seminal position in generating and analysing the concepts, myths, symbols and ideology of nationalism is apparent. This applies to the first appearance of the core doctrine and to the antecedent concepts of national character, genius of the nation and national will.[32] Smith posits the challenges posed to traditional religion and society in the Age of Revolution propelled many intellectuals to "discover alternative principles and concepts, and a new mythology and symbolism, to legitimate and ground human thought and action".[33] He discusses the simultaneous concept of 'historicism' to describe an emerging belief in the birth, growth, and decay of specific peoples and cultures, which became "increasingly attractive as a framework for inquiry into the past and present and [...] an explanatory principle in elucidating the meaning of events, past and present".[34] The Prussian scholar Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) originated the term[clarification needed] in 1772 in his "Treatise on the Origin of Language" stressing the role of a common language.[35][36] He attached exceptional importance to the concepts of nationality and of patriotism – "he that has lost his patriotic spirit has lost himself and the whole world about himself", whilst teaching that "in a certain sense every human perfection is national".[37] Erica Benner identifies Herder as the first philosopher to explicitly suggest "that identities based on language should be regarded as the primary source of legitimate political authority or locus of political resistance".[38] Herder also encouraged the creation of a common cultural and language policy amongst the separate German states.[39] Dating the emergence of nationalism Scholars frequently place the beginning of nationalism in the late 18th century or early 19th century with the American Declaration of Independence or with the French Revolution.[40][41][42] The consensus is that nationalism as a concept was firmly established by the 19th century.[43][44][45] In histories of nationalism, the French Revolution (1789) is seen as an important starting point, not only for its impact on French nationalism but even more for its impact on Germans and Italians and on European intellectuals.[46] The template of nationalism, as a method for mobilizing public opinion around a new state based on popular sovereignty, went back further than 1789: philosophers such as Rousseau and Voltaire, whose ideas influenced the French Revolution, had themselves been influenced or encouraged by the example of earlier constitutionalist liberation movements, notably the Corsican Republic (1755–1768) and American Revolution (1775–1783).[47]  A postcard from 1916 showing national personifications of some of the Allies of World War I, each holding a national flag Due to the Industrial Revolution, there was an emergence of an integrated, nation-encompassing economy and a national public sphere, where British people began to mobilize on a state-wide scale, rather than just in the smaller units of their province, town or family.[48] The early emergence of a popular patriotic nationalism took place in the mid-18th century and was actively promoted by the British government and by the writers and intellectuals of the time.[49] National symbols, anthems, myths, flags and narratives were assiduously constructed by nationalists and widely adopted. The Union Jack was adopted in 1801 as the national one.[50] Thomas Arne composed the patriotic song "Rule, Britannia!" in 1740,[51] and the cartoonist John Arbuthnot invented the character of John Bull as the personification of the English national spirit in 1712.[52] The political convulsions of the late 18th century associated with the American and French revolutions massively augmented the widespread appeal of patriotic nationalism.[53][54] Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power further established nationalism when he invaded much of Europe. Napoleon used this opportunity to spread revolutionary ideas, resulting in much of the 19th-century European Nationalism.[55] Some scholars argue that variants of nationalism emerged prior to the 18th century. American philosopher and historian Hans Kohn wrote in 1944 that nationalism emerged in the 17th century.[56] In Britons, Forging the Nation 1707–1837, Linda Colley explores how the role of nationalism emerged about 1700 and developed in Britain reaching full form in the 1830s. Writing shortly after World War I, the popular British author H.G. Wells traced the origin of European nationalism to the aftermath of the Reformation, when it filled the moral void left by the decline of Christian faith: [A]s the idea of Christianity as a world brotherhood of men sank into discredit because of its fatal entanglement with priestcraft and the Papacy on the one hand and with the authority of princes on the other, and the age of faith passed into our present age of doubt and disbelief, men shifted the reference of their lives from the kingdom of God and the brotherhood of mankind to these apparently more living realities, France and England, Holy Russia, Spain, Prussia.... **** In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the general population of Europe was religious and only vaguely patriotic; by the nineteenth it had become wholly patriotic.[57] 19th century Main article: International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)  Senator Johan Vilhelm Snellman (1806–1881), who also possessed the professions of philosopher, journalist and author, was one of the most influential Fennomans and Finnish nationalists in the 19th century.[58][59][60][61][62] The political development of nationalism and the push for popular sovereignty culminated with the ethnic/national revolutions of Europe. During the 19th century nationalism became one of the most significant political and social forces in history; it is typically listed among the top causes of World War I.[63][64] Napoleon's conquests of the German and Italian states around 1800–1806 played a major role in stimulating nationalism and the demands for national unity.[65] English historian J. P. T. Bury argues: Between 1830 and 1870 nationalism had thus made great strides. It inspired great literature, quickened scholarship, and nurtured heroes. It had shown its power both to unify and to divide. It had led to great achievements of political construction and consolidation in Germany and Italy; but it was more clear than ever a threat to the Ottoman and Habsburg empires, which were essentially multi-national. European culture had been enriched by the new vernacular contributions of little-known or forgotten peoples, but at the same time such unity as it had was imperiled by fragmentation. Moreover, the antagonisms fostered by nationalism had made not only for wars, insurrections, and local hatreds—they had accentuated or created new spiritual divisions in a nominally Christian Europe.[66] France Main article: French nationalism Further information: French–German enmity and Revanchism  A painting by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville from 1887 depicting French students being taught about the lost provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, taken by Germany in 1871 Nationalism in France gained early expressions in France's revolutionary government. In 1793, that government declared a mass conscription (levée en masse) with a call to service: Henceforth, until the enemies have been driven from the territory of the Republic, all the French are in permanent requisition for army service. The young men shall go to battle; the married men shall forge arms in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen to lint; the old men shall repair to the public places, to stimulate the courage of the warriors and preach the unity of the Republic and the hatred of kings.[67] This nationalism gained pace after the French Revolution came to a close. Defeat in war, with a loss in territory, was a powerful force in nationalism. In France, revenge and return of Alsace-Lorraine was a powerful motivating force for a quarter century after their defeat by Germany in 1871. After 1895, French nationalists focused on Dreyfus and internal subversion, and the Alsace issue petered out.[68] The French reaction was a famous case of Revanchism ("revenge") which demands the return of lost territory that "belongs" to the national homeland. Revanchism draws its strength from patriotic and retributionist thought and it is often motivated by economic or geo-political factors. Extreme revanchist ideologues often represent a hawkish stance, suggesting that their desired objectives can be achieved through the positive outcome of another war. It is linked with irredentism, the conception that a part of the cultural and ethnic nation remains "unredeemed" outside the borders of its appropriate nation state. Revanchist politics often rely on the identification of a nation with a nation state, often mobilizing deep-rooted sentiments of ethnic nationalism, claiming territories outside the state where members of the ethnic group live, while using heavy-handed nationalism to mobilize support for these aims. Revanchist justifications are often presented as based on ancient or even autochthonous occupation of a territory since "time immemorial", an assertion that is usually inextricably involved in revanchism and irredentism, justifying them in the eyes of their proponents.[69] The Dreyfus Affair in France 1894–1906 made the battle against treason and disloyalty a central theme for conservative Catholic French nationalists. Dreyfus, a Jew, was an outsider, that is in the views of intense nationalists, not a true Frenchman, not one to be trusted, not one to be given the benefit of the doubt. True loyalty to the nation, from the conservative viewpoint, was threatened by liberal and republican principles of liberty and equality that were leading the country to disaster.[70] Russia Main article: Russian nationalism  The Millennium of Russia monument which was built in 1862 in celebration of one thousand years of Russian history Before 1815, the sense of Russian nationalism was weak—what sense there was focused on loyalty and obedience to the tsar. The Russian motto "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality" was coined by Count Sergey Uvarov and it was adopted by Emperor Nicholas I as the official ideology of the Russian Empire.[71] Three components of Uvarov's triad were: Orthodoxy – Orthodox Christianity and protection of the Russian Orthodox Church. Autocracy – unconditional loyalty to the House of Romanov in return for paternalist protection for all social estates. Nationality (Narodnost, has been also translated as national spirit)[72] – recognition of the state-founding role on Russian nationality. By the 1860s, as a result of educational indoctrination, and due to conservative resistance to ideas and ideologies which were transmitted from Western Europe, a pan-Slavic movement had emerged and it produced both a sense of Russian nationalism and a nationalistic mission to support and protect pan-Slavism. This Slavophile movement became popular in 19th-century Russia. Pan-Slavism was fueled by, and it was also the fuel for Russia's numerous wars against the Ottoman Empire which were waged in order to achieve the alleged goal of liberating Orthodox nationalities, such as Bulgarians, Romanians, Serbs and Greeks, from Ottoman rule. Slavophiles opposed the Western European influences which had been transmitted to Russia and they were also determined to protect Russian culture and traditions. Aleksey Khomyakov, Ivan Kireyevsky, and Konstantin Aksakov are credited with co-founding the movement.[73] Latin America  General Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), a leader of independence in Latin America This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) Main article: Latin American Wars of Independence An upsurge in nationalism in Latin America in the 1810s and 1820s sparked revolutions that cost Spain nearly all of its colonies which were located there.[74] Spain was at war with Britain from 1798 to 1808, and the British Royal Navy cut off its contacts with its colonies, so nationalism flourished and trade with Spain was suspended. The colonies set up temporary governments or juntas which were effectively independent from Spain. These juntas were established as a result of Napoleon's resistance failure in Spain. They served to determine new leadership and, in colonies like Caracas, abolished the slave trade as well as the Indian tribute.[75] The division exploded between Spaniards who were born in Spain (called "peninsulares") versus those of Spanish descent born in New Spain (called "criollos" in Spanish or "creoles" in English). The two groups wrestled for power, with the criollos leading the call for independence. Spain tried to use its armies to fight back but had no help from European powers. Indeed, Britain and the United States worked against Spain, enforcing the Monroe Doctrine.[76] Spain lost all of its American colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, in a complex series of revolts from 1808 to 1826.[77] Germany Main article: German nationalism  Revolutionaries in Vienna with German tricolor flags, May 1848 In the German states west of Prussia, Napoleon abolished many of the old or medieval relics, such as dissolving the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[78] He imposed rational legal systems and demonstrated how dramatic changes were possible. His organization of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806 promoted a feeling of nationalism. Nationalists sought to encompass masculinity in their quest for strength and unity.[79] It was Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck who achieved German unification through a series of highly successful short wars against Denmark, Austria and France which thrilled the pan-German nationalists in the smaller German states. They fought in his wars and eagerly joined the new German Empire, which Bismarck ran as a force for balance and peace in Europe after 1871.[80] In the 19th century, German nationalism was promoted by Hegelian-oriented academic historians who saw Prussia as the true carrier of the German spirit, and the power of the state as the ultimate goal of nationalism. The three main historians were Johann Gustav Droysen (1808–1884), Heinrich von Sybel (1817–1895) and Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896). Droysen moved from liberalism to an intense nationalism that celebrated Prussian Protestantism, efficiency, progress, and reform, in striking contrast to Austrian Catholicism, impotency and backwardness. He idealized the Hohenzollern kings of Prussia. His large-scale History of Prussian Politics (14 vol 1855–1886) was foundational for nationalistic students and scholars. Von Sybel founded and edited the leading academic history journal, Historische Zeitschrift and as the director of the Prussian state archives published massive compilations that were devoured by scholars of nationalism.[81] The most influential of the German nationalist historians, was Treitschke who had an enormous influence on elite students at Heidelberg and Berlin universities.[82] Treitschke vehemently attacked parliamentarianism, socialism, pacifism, the English, the French, the Jews, and the internationalists. The core of his message was the need for a strong, unified state—a unified Germany under Prussian supervision. "It is the highest duty of the State to increase its power," he stated. Although he was a descendant of a Czech family, he considered himself not Slavic but German: "I am 1000 times more the patriot than a professor."[83]  Adolf Hitler being welcomed by a crowd in Sudetenland, where the pro-Nazi Sudeten German Party gained 88% of ethnic-German votes in May 1938[84] German nationalism, expressed through the ideology of Nazism, may also be understood as trans-national in nature. This aspect was primarily advocated by Adolf Hitler, who later became the leader of the Nazi Party. This party was devoted to what they identified as an Aryan race, residing in various European countries, but sometime mixed with alien elements such as Jews.[85] Meanwhile, the Nazis rejected many of the well-established citizens within those same countries, such as the Romani (Gypsies) and of course Jews, whom they did not identify as Aryan. A key Nazi doctrine was "Living Space" (for Aryans only) or "Lebensraum," which was a vast undertaking to transplant Aryans throughout Poland, much of Eastern Europe and the Baltic nations, and all of Western Russia and Ukraine. Lebensraum was thus a vast project for advancing the Aryan race far outside of any particular nation or national borders. The Nazi's goals were racist focused on advancing the Aryan race as they perceived it, eugenics modification of the human race, and the eradication of human beings that they deemed inferior. But their goals were trans-national and intended to spread across as much of the world as they could achieve. Although Nazism glorified German history, it also embraced the supposed virtues and achievements of the Aryan race in other countries,[86] including India.[87] The Nazis' Aryanism longed for now-extinct species of superior bulls once used as livestock by Aryans and other features of Aryan history that never resided within the borders of Germany as a nation.[88] Italy Main articles: Italian Fascism, Italian nationalism, and Italian unification  People cheering as Giuseppe Garibaldi enters Naples in 1860 Italian nationalism emerged in the 19th century and was the driving force for Italian unification or the Risorgimento (meaning the "Resurgence" or "Revival"). It was the political and intellectual movement that consolidated the different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861. The memory of the Risorgimento is central to Italian nationalism but it was based in the liberal middle classes and ultimately proved a bit weak.[89] The new government treated the newly annexed South as a kind of underdeveloped province due to its "backward" and poverty-stricken society, its poor grasp of standard Italian (as Italo-Dalmatian dialects of Neapolitan and Sicilian were prevalent in the common use) and its local traditions.[citation needed] The liberals had always been strong opponents of the pope and the very well organized Catholic Church. The liberal government under the Sicilian Francesco Crispi sought to enlarge his political base by emulating Otto von Bismarck and firing up Italian nationalism with an aggressive foreign policy. It partially crashed and his cause was set back. Of his nationalistic foreign policy, historian R. J. B. Bosworth says: [Crispi] pursued policies whose openly aggressive character would not be equaled until the days of the Fascist regime. Crispi increased military expenditure, talked cheerfully of a European conflagration, and alarmed his German or British friends with these suggestions of preventative attacks on his enemies. His policies were ruinous, both for Italy's trade with France, and, more humiliatingly, for colonial ambitions in East Africa. Crispi's lust for territory there was thwarted when on 1 March 1896, the armies of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik routed Italian forces at Adowa [...] in what has been defined as an unparalleled disaster for a modern army. Crispi, whose private life and personal finances [...] were objects of perennial scandal, went into dishonorable retirement.[90] Italy joined the Allies in the First World War after getting promises of territory, but its war effort was not honored after the war and this fact discredited liberalism paving the way for Benito Mussolini and a political doctrine of his own creation, Fascism. Mussolini's 20-year dictatorship involved a highly aggressive nationalism that led to a series of wars with the creation of the Italian Empire, an alliance with Hitler's Germany, and humiliation and hardship in the Second World War. After 1945, the Catholics returned to government and tensions eased somewhat, but the former two Sicilies remained poor and partially underdeveloped (by industrial country standards). In the 1950s and early 1960s, Italy had an economic boom that pushed its economy to the fifth place in the world. The working class in those decades voted mostly for the Communist Party, and it looked to Moscow rather than Rome for inspiration and was kept out of the national government even as it controlled some industrial cities across the North. In the 21st century, the Communists have become marginal but political tensions remained high as shown by Umberto Bossi's Padanism in the 1980s[91] (whose party Lega Nord has come to partially embrace a moderate version of Italian nationalism over the years) and other separatist movements spread across the country.[citation needed] Spain After the War of the Spanish Succession, rooted in the political position of the Count-Duke of Olivares and the absolutism of Philip V, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Decrees of Nova planta was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state. As in other contemporary European states, political union was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state, in this case not on a uniform ethnic basis, but through the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilians, over those of other ethnic groups, who became national minorities to be assimilated.[92][93] In fact, since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards Catalan-speaking territories (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, part of Aragon) and other national minorities, as Basques and Galicians, have been a historical constant.[94][95][96][97][98] The nationalization process accelerated in the 19th century, in parallel to the origin of Spanish nationalism, the social, political and ideological movement that tried to shape a Spanish national identity based on the Castilian model, in conflict with the other historical nations of the State. Politicians of the time were aware that despite the aggressive policies pursued up to that time, the uniform and monocultural "Spanish nation" did not exist, as indicated in 1835 by Antonio Alcalà Galiano, when in the Cortes del Estatuto Real he defended the effort "To make the Spanish nation a nation that neither is nor has been until now."[99] Building the nation (as in France, it was the state that created the nation, and not the opposite process) is an ideal that the Spanish elites constantly reiterated, and, one hundred years later than Alcalá Galiano, for example, we can also find it in the mouth of the fascist José Pemartín, who admired the German and Italian modeling policies:[100] "There is an intimate and decisive dualism, both in Italian fascism and in German National Socialism. On the one hand, the Hegelian doctrine of the absolutism of the state is felt. The State originates in the Nation, educates and shapes the mentality of the individual; is, in Mussolini's words, the soul of the soul» And will be found again two hundred years later, from the socialist Josep Borrell:[101] The modern history of Spain is an unfortunate history that meant that we did not consolidate a modern State. Independenceists think that the nation makes the State. I think the opposite. The State makes the nation. A strong State, which imposes its language, culture, education. The creation of the tradition of the political community of Spaniards as common destiny over other communities has been argued to trace back to the Cortes of Cádiz.[102] From 1812 on, revisiting the previous history of Spain, Spanish liberalism tended to take for granted the national conscience and the Spanish nation.[103] A by-product of 19th-century Spanish nationalist thinking is the concept of Reconquista, which holds the power of propelling the weaponized notion of Spain being a nation shaped against Islam.[104] The strong interface of nationalism with colonialism is another feature of 19th-century nation building in Spain, with the defence of slavery and colonialism in Cuba being often able to reconcile tensions between mainland elites of Catalonia and Madrid throughout the period.[105] During the first half of 20th century (notably during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the dictatorship of Franco), a new brand of Spanish nationalism with a marked military flavour and an authoritarian stance (as well as promoting policies favouring the Spanish language against the other languages in the country) as a means of modernizing the country was developed by Spanish conservatives, fusing regenerationist principles with traditional Spanish nationalism.[106] The authoritarian national ideal resumed during the Francoist dictatorship, in the form of National-Catholicism,[106] which was in turn complemented by the myth of Hispanidad.[107] A distinct manifestation of Spanish nationalism in modern Spanish politics is the interchange of attacks with competing regional nationalisms.[108] Initially present after the end of Francoism in a rather diffuse and reactive form, the Spanish nationalist discourse has been often self-branded as "constitutional patriotism" since the 1980s.[109] Often ignored as in the case of other State nationalisms,[110] its alleged "non-existence" has been a commonplace espoused by prominent figures in the public sphere as well as the mass-media in the country.[111]  Beginning in 1821, the Greek War of Independence began as a rebellion by Greek revolutionaries against the ruling Ottoman Empire. Greece During the early 19th century, inspired by romanticism, classicism, former movements of Greek nationalism and failed Greek revolts against the Ottoman Empire (such as the Orlofika revolt in southern Greece in 1770, and the Epirus-Macedonian revolt of Northern Greece in 1575), Greek nationalism led to the Greek war of independence.[112] The Greek drive for independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1820s and 1830s inspired supporters across Christian Europe, especially in Britain, which was the result of western idealization of Classical Greece and romanticism. France, Russia and Britain critically intervened to ensure the success of this nationalist endeavor.[113] Serbia Main articles: History of Serbia, History of Serbs, and Serbian nationalism  Breakup of Yugoslavia For centuries the Orthodox Christian Serbs were ruled by the Muslim Ottoman Empire.[114] The success of the Serbian Revolution against Ottoman rule in 1817 marked the birth of the Principality of Serbia. It achieved de facto independence in 1867 and finally gained international recognition in 1878. Serbia had sought to liberate and unite with Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west and Old Serbia (Kosovo and Vardar Macedonia) to the south. Nationalist circles in both Serbia and Croatia (part of Austria-Hungary) began to advocate for a greater South Slavic union in the 1860s, claiming Bosnia as their common land based on shared language and tradition.[115] In 1914, Serb revolutionaries in Bosnia assassinated Archduke Ferdinand. Austria-Hungary, with German backing, tried to crush Serbia in 1914, thus igniting the First World War in which Austria-Hungary dissolved into nation states.[116] In 1918, the region of Banat, Bačka and Baranja came under control of the Serbian army, later the Great National Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs voted to join Serbia; the Kingdom of Serbia joined the union with State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on 1 December 1918, and the country was named Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It was renamed Yugoslavia in 1929, and a Yugoslav identity was promoted, which ultimately failed. After the Second World War, Yugoslav Communists established a new socialist republic of Yugoslavia. That state broke up again in the 1990s.[117] Poland Main articles: History of Poland and Polish nationalism The cause of Polish nationalism was repeatedly frustrated before 1918. In the 1790s, the Habsburg monarchy, Prussia and Russia invaded, annexed, and subsequently partitioned Poland. Napoleon set up the Duchy of Warsaw, a new Polish state that ignited a spirit of nationalism. Russia took it over in 1815 as Congress Poland with the tsar proclaimed as "King of Poland". Large-scale nationalist revolts erupted in 1830 and 1863–64 but were harshly crushed by Russia, which tried to make the Polish language, culture and religion more like Russia's. The collapse of the Russian Empire in the First World War enabled the major powers to re-establish an independent Poland, which survived until 1939. Meanwhile, Poles in areas controlled by Germany moved into heavy industry but their religion came under attack by Bismarck in the Kulturkampf of the 1870s. The Poles joined German Catholics in a well-organized new Centre Party, and defeated Bismarck politically. He responded by stopping the harassment and cooperating with the Centre Party.[118][119] In the late 19th and early 20th century, many Polish nationalist leaders endorsed the Piast Concept. It held there was a Polish utopia during the Piast Dynasty a thousand years before, and modern Polish nationalists should restore its central values of Poland for the Poles. Jan Poplawski had developed the "Piast Concept" in the 1890s, and it formed the centerpiece of Polish nationalist ideology, especially as presented by the National Democracy Party, known as the "Endecja," which was led by Roman Dmowski. In contrast with the Jagiellon concept, there was no concept for a multi-ethnic Poland.[120] The Piast concept stood in opposition to the "Jagiellon Concept," which allowed for multi-ethnicism and Polish rule over numerous minority groups such as those in the Kresy. The Jagiellon Concept was the official policy of the government in the 1920s and 1930s. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin at Tehran in 1943 rejected the Jagiellon Concept because it involved Polish rule over Ukrainians and Belarusians. He instead endorsed the Piast Concept, which justified a massive shift of Poland's frontiers to the west.[121] After 1945 the Soviet-back puppet communist regime wholeheartedly adopted the Piast Concept, making it the centerpiece of their claim to be the "true inheritors of Polish nationalism". After all the killings, including Nazi German occupation, terror in Poland and population transfers during and after the war, the nation was officially declared as 99% ethnically Polish.[122] In current Polish politics, Polish nationalism is most openly represented by parties linked in the Liberty and Independence Confederation coalition.[citation needed] As of 2020 the Confederation, composed of several smaller parties, had 11 deputies (under 7%) in the Sejm. Bulgaria Main articles: National awakening of Bulgaria, Bulgarian National Awakening, Bulgarian National Revival, and April Uprising of 1876 Bulgarian modern nationalism emerged under Ottoman rule in the late 18th and early 19th century, under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French Revolution. The Bulgarian national revival started with the work of Saint Paisius of Hilendar, who opposed Greek domination of Bulgaria's culture and religion. His work Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya ("History of the Slav-Bulgarians"), which appeared in 1762, was the first work of Bulgarian historiography. It is considered Paisius' greatest work and one of the greatest pieces of Bulgarian literature. In it, Paisius interpreted Bulgarian medieval history with the goal of reviving the spirit of his nation. His successor was Saint Sophronius of Vratsa, who started the struggle for an independent Bulgarian church. An autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate was established in 1870/1872 for the Bulgarian diocese wherein at least two-thirds of Orthodox Christians were willing to join it. In 1869 the Internal Revolutionary Organization was initiated. The April Uprising of 1876 indirectly resulted in the re-establishment of Bulgaria in 1878. Jewish Nationalism Jewish nationalism arose in the latter half of the 19th century, largely as a response to the rise of nation-states. Traditionally Jews lived under uncertain and oppressive conditions. In western Europe, Jews not subject to such restrictions since emancipation of early 19th century often assimilated into the dominant culture. Both assimilation and the traditional second-class status of Jews were considered as threats to the Jewish identity by Jewish nationalists. The method of combatting these threats were different among different national movements among Jews. Zionism, ultimately the most successful of Jewish nationalist movements, advocated in the creation of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. Labour Zionism hoped that the new Jewish state would be based on socialist principles. They imagined a new Jew that, in contrast to the Jews of the diaspora, was strong, worked the land, and spoke Hebrew. Religious Zionism instead had various religious reasonings for returning to Israel. Although according to historian David Engel, Zionism was more about fear that Jews would end up dispersed and unprotected, rather than fulfilling old prophecies of historical texts.[123] The efforts of the Zionist movement culminated in the establishment of the State of Israel. Jewish Territorialism split from the Zionist Movement in 1903, arguing for a Jewish state no matter where. As more Jews moved to Palestine, the main territorialist organization lost support, eventually disbanding in the 1925.[124] Smaller territorialist movements lasted until the establishment of the State of Israel. Jewish Autonomism and Bundism instead advocated for Jewish national autonomy within the territory they already lived in. Most manifestations of this movement were left-wing in nature, and actively anti-Zionist. While successful among Eastern European Jews in the early 20th century, it lost most of its support due to the Holocaust, although some support lasted through the 20th century. |

歴史 さらに詳しい情報 ナショナリストの歴史学 知識の起源 アンソニー・D・スミスは、ナショナリズムに対する文化的認識を生み出し、政治的ナショナリズムのイデオロギーを提供する上で、知識人がいかに主要な役割 を果たしたかを述べている: ヨーロッパのどこを向いても、ナショナリズムの概念、神話、シンボル、イデオロギーを生み出し、分析する上で、知識人が重要な役割を果たしたことは明らか である。このことは、核となる教義の最初の登場や、国民性、民族の天才性、国家意志といった先行概念にも当てはまる[32]。 スミスは、革命の時代において伝統的な宗教と社会に突きつけられた挑戦が、多くの知識人を「人間の思考と行動を正当化し、根拠づけるための代替的な原理と 概念、そして新たな神話と象徴主義を発見すること」へと駆り立てたと仮定している[33]。 彼は、特定の民族と文化の誕生、成長、衰退に対する新たな信仰を説明するために「歴史主義」という概念を同時に論じており、それは「過去と現在に対する探 求の枠組みとして、また[中略]過去と現在の出来事の意味を解明するための説明原理として、ますます魅力的なものとなった」と述べている[34]。 プロイセンの学者であるヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー(Johann Gottfried Herder、1744年-1803年)は、1772年に『言語の起源に関する論考』において共通語の役割を強調する中でこの用語を生み出した [clarification needed]。 [エリカ・ベナーは、ヘルダーを「言語に基づくアイデンティティが正当な政治的権威や政治的抵抗の拠り所の第一の源泉とみなされるべき」[38]であるこ とを明確に示唆した最初の哲学者であるとしている。 ナショナリズムの勃興 ナショナリズムの始まりは18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけてのアメリカ独立宣言やフランス革命とされることが多い[40][41][42]。 ナショナリズムの歴史において、フランス革命(1789年)はフランスのナショナリズムへの影響だけでなく、ドイツ人やイタリア人、ヨーロッパの知識人へ の影響から重要な出発点であると考えられている[43][44][45]。 [フランス革命に影響を与えたルソーやヴォルテールのような哲学者たちは、コルシカ共和国(1755年-1768年)やアメリカ革命(1775年- 1783年)のような立憲主義的な解放運動から影響を受けたり、勇気づけられたりしていた。  1916年の絵葉書。第一次世界大戦の連合国の擬人化された国旗を持っている。 産業革命によって、統合された、国家を包括する経済と国家的公共圏が出現し、イギリス国民は、自分の州、町、家族といった小さな単位だけでなく、州全体の 規模で動員され始めた[48]。ユニオンジャックは1801年に国家的なものとして採用され[50]、トーマス・アルンは1740年に愛国的な歌 "Rule, Britannia!"を作曲し[51]、漫画家のジョン・アーバスノットは1712年にイギリスの国民精神の擬人化としてジョン・ブルのキャラクターを 考案した[52]。 18世紀後半のアメリカ革命とフランス革命に関連した政治的混乱は、愛国的ナショナリズムの広範な魅力を大幅に増大させた[53][54]。ナポレオンは この機会を利用して革命思想を広め、19世紀のヨーロッパ・ナショナリズムの多くを生み出した[55]。 ナショナリズムの変種が18世紀以前に出現したと主張する学者もいる。アメリカの哲学者であり歴史家でもあるハンス・コーン(Hans Kohn)は1944年に、ナショナリズムは17世紀に出現したと書いている[56]。 リンダ・コリー(Linda Colley)は『Britons, Forging the Nation 1707-1837』の中で、ナショナリズムの役割が1700年頃にどのように出現し、1830年代に完全な形になるまでイギリスで発展したかを探求して いる。イギリスの人気作家H.G.ウェルズは、第一次世界大戦直後の著作で、ヨーロッパのナショナリズムの起源を、キリスト教信仰の衰退によって残された 道徳的空白を埋めた宗教改革の余波にまでさかのぼった: [キリスト教が、一方では司祭術や教皇庁と、他方では君主の権威と、致命的に絡み合ったために信用を失い、信仰の時代が疑いと不信の時代へと移り変わるに つれ、人々は自分たちの生活の基準を、神の国や人類の兄弟愛から、フランスやイギリス、神聖ロシア、スペイン、プロイセン......といった、より生き ているように見える現実に移していった。**** 13世紀と14世紀には、ヨーロッパの一般市民は宗教的であり、漠然と愛国的であったが、19世紀には完全に愛国的になった[57]。 19世紀 主な記事 列強の国際関係(1814年~1919年)  ヨハン・ヴィルヘルム・スネルマン上院議員(1806年-1881年)は、哲学者、ジャーナリスト、作家の顔も持ち、19世紀に最も影響力を持ったフェノ マ人およびフィンランドのナショナリストの一人であった[58][59][60][61][62]。 ナショナリズムの政治的発展と国民主権の推進は、ヨーロッパの民族/国家革命によって頂点に達した。19世紀にはナショナリズムは歴史上最も重要な政治 的・社会的勢力のひとつとなり、第一次世界大戦の原因の上位に挙げられることが一般的である[63][64]。 1800年から1806年にかけてのナポレオンによるドイツとイタリアの征服は、ナショナリズムと国民統合の要求を刺激する上で大きな役割を果たした [65]。 イギリスの歴史家J・P・T・ビューリーは次のように論じている: 1830年から1870年にかけて、ナショナリズムは大きな発展を遂げた。ナショナリズムは偉大な文学を鼓舞し、学問を活発化させ、英雄を育てた。ナショ ナリズムは統一する力も分裂させる力も示した。ナショナリズムは、ドイツとイタリアにおいて政治的建設と統合という偉大な成果をもたらしたが、本質的に多 国籍であったオスマン帝国とハプスブルク帝国にとっては、かつてないほどの脅威であった。ヨーロッパ文化は、あまり知られていなかったり忘れ去られていた 民族の新たな方言の貢献によって豊かになったが、同時にそのような統一は断片化によって危うくなった。さらに、ナショナリズムによって醸成された対立は、 戦争、反乱、地域的な憎悪を生むだけでなく、名目上はキリスト教徒であったヨーロッパにおいて、精神的な分裂を強調したり、新たな分裂を生み出したりして いた[66]。 フランス 主な記事 フランスのナショナリズム さらに詳しい情報 フランスとドイツの敵対とレヴァンキズム  1887年にアルフォンス=マリー=アドルフ・ド・ヌーヴィルによって描かれた、1871年にドイツに奪われたアルザス=ロレーヌ地方について教わるフラ ンスの学生たち。 フランスにおけるナショナリズムは、フランスの革命政府において早くから表れた。1793年、同政府は兵役招集とともに集団徴兵(levée en masse)を宣言した: 今後、敵が共和国の領土から追い出されるまで、すべてのフランス人は永久に兵役を徴用される。若者は戦いに赴き、既婚者は病院で武器を鍛え、子供は古い麻 布を糸くずとし、老人は公共の場に出て、戦士の勇気を鼓舞し、共和国の統一と王への憎悪を説くのである[67]。 このナショナリズムは、フランス革命が終結した後に勢いを増した。領土を失った戦争での敗北は、ナショナリズムの強力な力となった。フランスでは、 1871年にドイツに敗北した後、四半世紀にわたってアルザス・ロレーヌへの復讐と返還が強力な原動力となった。1895年以降、フランスのナショナリス トたちはドレフュスと内部破壊に焦点を当て、アルザス問題は沈静化した[68]。 フランスの反動は、祖国に「属する」失われた領土の返還を要求するレヴァンキズム(「復讐」)の有名な事例であった。レヴァンヒズムは愛国主義的、報復主 義的な思想から力を得ており、経済的、地政学的な要因によって動機づけられることが多い。極端なレバンチ主義のイデオローグはしばしばタカ派的なスタンス を示し、自分たちの望む目的は別の戦争の肯定的な結果を通じて達成できると示唆する。ナショナリズムとは、文化的・民族的国家の一部が、その適切な国家の 境界の 外に「救済されずに」残っているという考え方である。レバンチ主義の政治は、しばしば民族と国家の同一性に依拠しており、しばしば民族ナショナリズムの根 深い感情を動員し、民族集団の構成員が居住する国家の外側に領土を主張し、強引なナショナリズムを利用してこれらの目的への支持を動員する。レバンチ主義 の正当化は、しばしば「太古の昔」からの領土の古代の、あるいは自国民による占領に基づくものとして提示されるが、この主張は通常レバンチ主義と無宗教主 義に表裏一体となっており、支持者の目にはこれらを正当化するものと映る[69]。 1894年から1906年にかけてフランスで起こったドレフュス事件は、反逆と不誠実さとの戦いを保守的なカトリックのフランスナショナリズム者たちの中 心的な テーマとした。ユダヤ人であったドレフュスは、強烈なナショナリズム者たちから見れば部外者であり、真のフランス人ではなく、信頼されるべきでもなく、疑 われる べきでもなかった。保守的な視点から見れば、国家に対する真の忠誠心は、自由と平等というリベラルで共和主義的な原則によって脅かされ、国を破滅へと導い ていた[70]。 ロシア 主な記事 ロシアのナショナリズム  1862年、ロシア千年の歴史を記念して建てられたロシア千年記念碑 1815年以前は、ロシアのナショナリズムの意識は弱く、皇帝への忠誠と服従に重点が置かれていた。ロシアのモットーである「正教、自治、民族」はセルゲ イ・ウヴァーロフ伯爵によって作られ、皇帝ニコライ1世によってロシア帝国の公式イデオロギーとして採用された[71]: 正教 - 正教とロシア正教会の保護。 独裁 - すべての社会階層に対する父権主義的な保護と引き換えに、ロマノフ家に対する無条件の忠誠。 国民性(ナロドノスト、民族精神とも訳される)[72]-ロシアの国民性に関する国家の創設的役割の認識。 1860年代までには、教育的洗脳の結果として、また西ヨーロッパから伝わった思想やイデオロギーに対する保守的な抵抗のために、汎スラヴ運動が勃興し、 ロシアナショナリズムの感覚と汎スラヴ主義を支持し保護するナショナリズム的使命感の両方が生み出された。このスラブ愛好運動は19世紀のロシアで人気を 博した。汎ス ラブ主義は、ブルガリア人、ルーマニア人、セルビア人、ギリシア人などの正統派民族をオスマン帝国の支配から解放するという目的を達成するために、ロシア がオスマン帝国に対して起こした数々の戦争の燃料ともなった。スラブ愛好家たちは、ロシアに伝わった西欧の影響に反対し、ロシアの文化と伝統を守ろうと決 意した。アレクセイ・ホミャコフ、イワン・キレエフスキー、コンスタンチン・アクサコフがこの運動の共同創設者とされている[73]。 ラテンアメリカ  ラテンアメリカの独立指導者シモン・ボリーバル将軍(1783年-1830年 このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで支援できます。(2019年1月) 主な記事 ラテンアメリカ独立戦争 1810年代から1820年代にかけてラテンアメリカでナショナリズムが高揚し、革命が勃発、スペインはラテンアメリカにあった植民地のほぼすべてを失っ た[74]。植民地はスペインから事実上独立した臨時政府またはジュンタを設立した。これらのジュンタは、ナポレオンがスペインでの抵抗に失敗した結果樹 立された。彼らは新たな指導者を決定する役割を果たし、カラカスなどの植民地では奴隷貿易とインディオ貢納を廃止した[75]。スペインで生まれたスペイ ン人(「ペニンシュラ人」と呼ばれた)とニュー・スペインで生まれたスペイン系の人々(スペイン語では「クリオージョ」、英語では「クレオール」と呼ばれ た)の間で分裂が爆発した。この2つのグループは権力をめぐって争い、クリオージョが独立の呼びかけを主導した。スペインは軍隊を使って反撃しようとした が、ヨーロッパ列強の助けは得られなかった。実際、イギリスとアメリカはモンロー・ドクトリンを施行し、スペインに対抗した[76]。スペインは1808 年から1826年までの複雑な一連の反乱で、キューバとプエルトリコを除くアメリカの植民地をすべて失った[77]。 ドイツ 主な記事 ドイツナショナリズム  1848年5月、ドイツの三色旗を掲げたウィーンの革命家たち プロイセン以西のドイツ諸州では、ナポレオンは1806年に神聖ローマ帝国を解体するなど、古い、あるいは中世の遺物の多くを廃止した[78]。彼が 1806年にライン同盟を組織したことで、ナショナリズムの気運が高まった。 ナショナリストたちは、強さと統一を求める中で男性性を包含しようとした[79]。プロイセンの首相オットー・フォン・ビスマルクは、デンマーク、オース トリア、フランスとの一連の短期戦争で大成功を収め、ドイツの小国の汎ドイツ的ナショナリストたちを興奮させることでドイツ統一を達成した。彼らはビスマ ルクの戦争に参戦し、1871年以降はヨーロッパの均衡と平和のためにビスマルクが運営する新しいドイツ帝国に熱心に参加した[80]。 19世紀、ドイツのナショナリズムは、プロイセンをドイツ精神の真の担い手とみなし、国家権力をナショナリズムの究極の目標とみなすヘーゲル志向の学問的 歴史家によって推進された。ヨハン・グスタフ・ドロイセン(1808-1884)、ハインリヒ・フォン・シーベル(1817-1895)、ハインリヒ・ フォン・トライチケ(1834-1896)の3人がその中心であった。ドロイセンは自由主義から強烈なナショナリズムへと移行し、プロイセンのプロテスタ ンティズム、効率性、進歩、改革を称え、オーストリアのカトリシズム、無力さ、後進性とは著しく対照的であった。彼はプロイセンのホーエンツォレルン王家 を理想化した。彼の大規模な『プロイセン政治史』(1855-1886年、全14巻)は、ナショナリズム的な学生や学者の基礎となった。フォン・シーベル は主要 な歴史学術誌であるHistorische Zeitschriftを創刊・編集し、プロイセン国立公文書館館長としてナショナリズムの研究者たちがむさぼるように読んだ膨大な編纂物を出版した [81]。 ドイツのナショナリストの歴史家の中で最も影響力があったのは、ハイデルベルクとベルリンの大学のエリート学生たちに絶大な影響力を持ったツァイツケで あった[82]。ツァイツケは議会主義、社会主義、平和主義、イギリス人、フランス人、ユダヤ人、国際主義者を激しく攻撃した。彼のメッセージの核心は、 強力な統一国家、すなわちプロイセンの監督下にある統一ドイツの必要性であった。「国力を高めることは国家の最高の義務である」と彼は述べた。彼はチェコ の家系の末裔であったが、自らをスラヴ人ではなくドイツ人であると考えていた。「私は教授よりも1000倍愛国者である」[83]。  1938年5月、親ナチス派のスデーテン独立党がドイツ民族票の88%を獲得したスデーテンラントで群衆に迎えられるアドルフ・ヒトラー[84]。 ナチズムのイデオロギーを通じて表現されたドイツのナショナリズムもまた、本質的には国家を超えたものとして理解されるかもしれない。この側面は、後にナ チ党の指導者となるアドルフ・ヒトラーによって主に提唱された。この党は、ヨーロッパの様々な国に居住し、時にはユダヤ人のような異質な要素も混在する アーリア人種として認識されるものに傾倒していた[85]。 その一方で、ナチスは、ロマニ(ジプシー)やもちろんユダヤ人のような、アーリア人とは認めない、同じ国々に定着している多くの市民を拒絶した。ナチスの 重要な教義は「生活空間」(アーリア人のためだけの空間)あるいは「レーベンスラウム」であり、ポーランド全土、東欧の大部分とバルト諸国、西ロシアとウ クライナ全土にアーリア人を移植するという広大な事業であった。レーベンスラウムはこのように、特定の国家や国境をはるかに越えてアーリア人種を発展させ るための広大な事業だった。ナチスの目標は、彼らが認識するアーリア人種の進化、優生学による人類の改造、劣等とみなす人間の根絶を中心とした人種差別主 義的なものだった。しかし、彼らの目標は国家を超えたものであり、達成できる限り世界中に広がることを意図していた。ナチズムはドイツの歴史を美化してい たが、インドを含む他の国々におけるアーリア人種の美徳とされる功績も受け入れていた[86][87]。ナチスのアーリアニズムは、かつてアーリア人が家 畜として使用していた今は絶滅してしまった優秀な雄牛の種や、国家としてのドイツの国境内に存在することのないアーリア人の歴史の他の特徴に憧れていた [88]。 イタリア 主な記事 イタリア・ファシズム、イタリア・ナショナリズム、イタリア統一  1860年、ジュゼッペ・ガリバルディのナポリ入城に歓声を上げる人々。 イタリアのナショナリズムは19世紀に台頭し、イタリア統一やリソルジメント(「復活」や「復興」を意味する)の原動力となった。1861年、イタリア半 島のさまざまな国家をイタリア王国という単一の国家に統合した政治的・知的運動である。リソルジメントの記憶はイタリアのナショナリズムの中心であるが、 それはリベラルな中産階級を基盤としており、最終的には少し弱いものであった。 [新政府は、新たに併合された南部を、その「後進的」で貧困にあえぐ社会、標準イタリア語(ナポリ語やシチリア語のイタロ=ダルマチア方言が一般に普及し ていたため)の理解力の低さ、地元の伝統のために、一種の未開発州として扱った[要出典]。自由主義者たちは常に、ローマ教皇と非常によく組織されたカト リック教会に強く反対していた。シチリア出身のフランチェスコ・クリスピが率いる自由主義政権は、オットー・フォン・ビスマルクを模倣し、積極的な外交政 策でイタリアのナショナリズムを煽ることで、政治基盤を拡大しようとした。それは部分的に破綻し、彼の大義は後退した。彼のナショナリスティックな外交政 策について、歴史家のR・J・B・ボズワースは言う: [クリスピは、公然と攻撃的な性格を持つ政策を追求した。クリスピは軍事費を増大させ、ヨーロッパの大火災について陽気に語り、ドイツやイギリスの友人 を、敵に対する予防的攻撃の提案で警戒させた。彼の政策は、イタリアの対フランス貿易にとっても、さらに屈辱的なことに東アフリカの植民地野心にとっても 破滅的なものだった。1896年3月1日、エチオピア皇帝メネリクの軍隊がアドワでイタリア軍を撃退したとき、クリスピの東アフリカでの領土欲は挫折し た。クリスピはその私生活と個人的な財政がたびたびスキャンダルの対象となり、不名誉な引退を余儀なくされた[90]。 第一次世界大戦において、イタリアは領土の約束を得た後に連合国に参加したが、戦後、その戦果は称えられず、この事実が自由主義の信用を失墜させ、ベニー ト・ムッソリーニと彼自身が生み出した政治教義であるファシズムへの道を開いた。ムッソリーニの20年にわたる独裁は、イタリア帝国の創設、ヒトラーのド イツとの同盟、第二次世界大戦での屈辱と苦難など、一連の戦争につながる非常に攻撃的なナショナリズムを伴うものだった。1945年以降、カトリックが政 権に復帰し、緊張はいくぶん緩和されたが、旧2シチリアは依然として貧しく、(工業国の基準からすれば)部分的に未発達だった。1950年代から1960 年代初頭にかけて、イタリアは好景気に沸き、その経済力は世界第5位にまで押し上げられた。 当時の労働者階級はほとんど共産党に投票し、ローマよりもモスクワにインスピレーションを求め、北部のいくつかの工業都市を支配していたにもかかわらず、 国政から締め出されていた。21世紀に入ると、共産党は周縁的な存在となったが、1980年代のウンベルト・ボッシのパダニズム[91](その政党レガ・ ノルドは、長年にわたってイタリア・ナショナリズムの穏健なバージョンを部分的に受け入れるようになった)や全国に広がるその他の分離主義運動が示すよう に、政治的緊張は依然として高いままであった[要出典]。 スペイン オリヴァレス伯爵の政治的立場とフィリップ5世の絶対主義に根ざしたスペイン継承戦争後、ノヴァプランタ勅令によるカスティーリャ王家によるアラゴン王家 の同化は、スペイン国民国家創設の第一歩となった。他のヨーロッパの現代国家と同様、政治的結合がスペイン国民国家創設の第一歩であったが、この場合、統 一された民族的基盤ではなく、支配的な民族集団(この場合カスティーリャ人)の政治的・文化的特徴を、同化されるべき少数民族となった他の民族集団に押し 付けることによってであった。 [実際、1714年の政治的統一以来、カタルーニャ語圏(カタルーニャ、バレンシア、バレアレス諸島、アラゴンの一部)やバスク人、ガリシア人などの少数 民族に対するスペインの同化政策は歴史的に一貫している[94][95][96][97][98]。 国有化プロセスは19世紀に加速し、スペイン・ナショナリズム(スペインの他の歴史的国家と対立しながら、カスティーリャ・モデルに基づくスペインの国民 的アイデンティティを形成しようとした社会的、政治的、イデオロギー的運動)の起源と並行して進行した。1835年、アントニオ・アルカラ・ガリャノがエ スタトゥート・レアル会議(Cortes del Estatuto Real)で次のように述べたように、当時の政治家たちは、それまでの積極的な政策にもかかわらず、一様で単一文化的な「スペイン民族」が存在しないこと を認識していた。 「スペイン国家を、現在も昔もない国家にすること」[99]。 国家を建設すること(フランスのように、国家を作ったのは国家であり、その逆のプロセスではない)は、スペインのエリートたちが常に繰り返していた理想で あり、例えば、アルカラ・ガリャノから100年後、ドイツとイタリアのモデル化政策を賞賛していたファシストのホセ・ペマルティンの口からも見出すことが できる[100]。 「イタリアのファシズムにもドイツの国家社会主義にも、親密で決定的な二元論がある。一方では、国家の絶対主義というヘーゲルの教義が感じられる。ムッソ リーニの言葉を借りれば、国家は魂の魂である。 そして、200年後、社会主義者ジョセップ・ボレルの言葉[101]から再び発見されるだろう。 スペインの近代史は、近代国家を形成できなかった不幸な歴史である。独立論者は、国民が国家をつくると考えている。私はその反対だ。国家が国家を作るの だ。強い国家は、その言語、文化、教育を押し付ける。 スペイン人の政治的共同体が他の共同体に対する共通の宿命であるという伝統の創出は、カディスのコルテスまでさかのぼると主張されている[102]。 1812年以降、スペインの過去の歴史を再検討することで、スペインの自由主義は国民的良心とスペイン国民を当然視する傾向があった[103]。 19世紀スペインのナショナリズム思想の副産物としてレコンキスタの概念があり、これはスペインがイスラムに対して形成された国家であるという武器化され た概念を推進する力を持っていた[104]。ナショナリズムと植民地主義の強い接点は19世紀スペインの国家建設のもう一つの特徴であり、キューバにおけ る奴隷制と植民地主義の擁護は、この時代を通してしばしばカタルーニャとマドリードの本土エリート間の緊張を和解させることができた[105]。 20世紀前半(特にプリモ・デ・リベラの独裁時代とフランコの独裁時代)には、スペインの保守派によって、国の近代化の手段として、顕著な軍事的風味と権 威主義的なスタンス(国内の他の言語に対してスペイン語を優遇する政策を推進する)を持つ新しいスペインのナショナリズムのブランドが開発され、伝統的な スペインのナショナリズムと再生主義の原則が融合された。 [権威主義的な国家理想は、フランコ主義の独裁政権下で、国家カトリック主義という形で再開され[106]、それはイスパニダードの神話によって補完され た[107]。 現代スペイン政治におけるスペインのナショナリズムの明確な現れは、競合する地域ナショナリズムとの攻撃の応酬である[108]。当初はかなり拡散的かつ 反応的な形でフランコ主義の終焉後に存在したスペインのナショナリズムの言説は、1980年代以降、しばしば「憲法愛国主義」として自称されてきた [109]。 他の国家ナショナリズムの場合と同様にしばしば無視され[110]、その「非存在」という主張は、国内のマスメディアだけでなく公共圏の著名人によって信 奉されてきた常套句であった[111]。  1821年に始まったギリシャ独立戦争は、支配者であるオスマン帝国に対するギリシャの革命家たちによる反乱として始まった。 ギリシャ 19世紀初頭、ロマン主義、古典主義、かつてのギリシャナショナリズムの動き、オスマン帝国に対するギリシャの失敗した反乱(1770年のギリシャ南部の オルロ フィカの反乱、1575年の北ギリシャのエピルス・マケドニアの反乱など)に触発され、ギリシャナショナリズムはギリシャ独立戦争につながった [112]。 1820年代から1830年代にかけてのオスマン帝国からの独立を目指すギリシャの動きは、キリスト教ヨーロッパ全域、特にイギリスにおいて支持者を鼓舞 したが、これは古典ギリシャとロマン主義に対する西洋の理想化の結果であった。フランス、ロシア、イギリスは、このナショナリズム的な努力の成功を確実に するた めに批判的に介入した[113]。 セルビア 主な記事 セルビアの歴史、セルビア人の歴史、セルビアナショナリズム  ユーゴスラビア崩壊 1817年、オスマン帝国による支配に反対するセルビア革命が成功し、セルビア公国が誕生した。1867年に事実上の独立を達成し、1878年にようやく 国際的な承認を得た。セルビアは、西のボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ、南の旧セルビア(コソボとヴァルダール・マケドニア)の解放と統合を目指していた。セル ビアとクロアチア(オーストリア=ハンガリーの一部)のナショナリズム者たちは1860年代から南スラヴの統合を主張し始め、ボスニアを共通の言語と伝統 に基づ く共通の土地と主張した[115]。1914年、ボスニアのセルビア人革命家たちはフェルディナント大公を暗殺した。オーストリア=ハンガリーはドイツの 支援を受け、1914年にセルビアを鎮圧しようとしたため、オーストリア=ハンガリーが国民国家に分裂した第一次世界大戦が勃発した[116]。 1918年、バナト、バチュカ、バラーニャの地域がセルビア軍の支配下に入り、後にセルビア人、ブンジェフチ人、その他のスラヴ人による大国民議会がセル ビアへの加盟を決議した。1918年12月1日、セルビア王国はスロヴェニア人、クロアチア人、セルビア人の国家との連合に参加し、国名はセルビア・クロ アチア・スロヴェニア王国となった。1929年にユーゴスラビアと改名され、ユーゴスラビア人としてのアイデンティティが推進されたが、結局は失敗に終 わった。第二次世界大戦後、ユーゴスラビアの共産主義者たちはユーゴスラビア社会主義共和国を新たに樹立した。この国家は1990年代に再び解体した [117]。 ポーランド 主な記事 ポーランドの歴史、ポーランド・ナショナリズム ポーランドのナショナリズムは1918年以前に何度も挫折した。1790年代、ハプスブルク家、プロイセン、ロシアがポーランドを侵略、併合し、その後分 割した。ナポレオンはワルシャワ公国を設立し、ナショナリズムに火をつけた。1815年、ロシアはこの国を議会ポーランドとして引き継ぎ、皇帝は「ポーラ ンド国王」と宣言した。1830年と1863~64年に大規模なナショナリズム革命が勃発したが、ポーランドの言語、文化、宗教をロシアに近づけようとし たロシ アによって厳しく鎮圧された。第一次世界大戦でロシア帝国が崩壊すると、列強はポーランドを再び独立させ、1939年まで存続させた。一方、ドイツが支配 する地域のポーランド人は重工業に進出したが、1870年代の文化闘争で彼らの宗教はビスマルクの攻撃を受けた。ポーランド人はドイツのカトリック教徒と 一緒になって組織化された新中央党を結成し、ビスマルクを政治的に打ち負かした。ビスマルクはこれに対し、嫌がらせを止め、中央党に協力した[118] [119]。 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、ポーランドのナショナリズム指導者の多くがピアスト構想を支持した。それは、1000年前のピアスト王朝時代にポー ランド のユートピアがあり、現代のポーランドナショナリズム者はポーランド人のためのポーランドという中心的価値を回復すべきだとするものであった。ヤン・ポプ ラフス キは1890年代に「ピアスト概念」を発展させ、特にロマン・ドモフスキが率いた「エンデチャ」として知られる国民民主主義党が提示したポーランド民族主 義イデオロギーの中心を形成した。ヤギェウォンの概念とは対照的に、多民族国家ポーランドの概念は存在しなかった[120]。 ピアスト構想は「ヤギェウォン構想」と対立するもので、多ナショナリズムを認め、クレシーのような多数の少数民族をポーランドが支配するものであった。ヤ ギェロ ン構想は、1920年代から1930年代にかけての政府の公式政策であった。1943年、ソ連の独裁者ヨシフ・スターリンはテヘランで、ポーランドがウク ライナ人やベラルーシ人を支配するという理由でヤギェウォン構想を拒否した。1945年以降、ソ連を後ろ盾とする傀儡共産政権はピアスト構想を全面的に採 用し、「ポーランドナショナリズムの真の継承者」であるという主張の中心に据えた。ナチス・ドイツによる占領、ポーランドでのテロ、戦中・戦後の人口移動 など、 あらゆる殺戮を経て、国家は99%が民族的にポーランド人であると公式に宣言された[122]。 現在のポーランド政治において、ポーランドのナショナリズムを最も公然と代表しているのは、自由と独立連合に連なる政党である[引用者注釈]。2020年 現在、いくつかの小政党から成る同連合は、国民議会で11人の代議員(7%未満)を擁している。 ブルガリア 主な記事 ブルガリアの民族覚醒、ブルガリア民族復興、1876年4月蜂起 ブルガリアの近代ナショナリズムは、18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけてオスマン帝国の支配下で、フランス革命後に流入した自由主義やナショナリズムと いった西洋思想の影響を受けて生まれた。 ブルガリアの民族復興は、ギリシャによるブルガリアの文化と宗教の支配に反対したヒレンダーの聖ペイシウスの活動から始まった。1762年に出版された 『スラブ・ブルガリア人の歴史』は、ブルガリア史の最初の著作となった。パイシウスの最高傑作であり、ブルガリア文学の最高傑作の一つとされている。その 中でパイシウスは、ブルガリアの中世史を解釈し、民族の精神を復活させることを目的とした。 彼の後を継いだヴラツァの聖ソフロニウスは、ブルガリアの独立教会のための闘争を開始した。1870/1872年、ブルガリア教区のために、少なくとも3 分の2の正教徒が参加するブルガリア自治教区が設立された。 1869年、内部革命組織が発足した。 1876年の四月蜂起は、1878年のブルガリア再統一に間接的につながった。 ユダヤナショナリズム ユダヤ人ナショナリズムは19世紀後半、主に国民国家の台頭に対する反応として生まれた。伝統的にユダヤ人は、不確実で抑圧的な条件の下で暮らしていた。 西ヨーロッパでは、19世紀初頭の奴隷解放以降、そのような制限を受けなくなったユダヤ人は、支配的な文化に同化することが多かった。同化もユダヤ人の伝 統的な二流身分も、ユダヤ人ナショナリストにとってはユダヤ人のアイデンティティに対する脅威と見なされた。こうした脅威と闘う方法は、ユダヤ人の民族運 動によって異なっていた。 シオニズムは、ユダヤ人ナショナリズム運動の中で最終的に最も成功した運動であり、イスラエルの地にユダヤ人国家を建設することを主張した。労働シオニズ ムは、 新しいユダヤ国家が社会主義の原則に基づくことを望んだ。彼らは、ディアスポラのユダヤ人とは対照的に、強く、土地を耕し、ヘブライ語を話す新しいユダヤ 人を想像した。宗教的シオニズムはその代わりに、イスラエルに帰還するためのさまざまな宗教的理由を持っていた。歴史家デイヴィッド・エンゲルによれば、 シオニズムは、歴史的文章の古い予言を成就させることよりも、ユダヤ人が分散して無防備な状態に陥ることを恐れたものであった[123]。 ユダヤ領土主義は1903年にシオニスト運動から分裂し、ユダヤ人国家をどこにでも建国することを主張した。より多くのユダヤ人がパレスチナに移住するに つれ、領土主義の主要組織は支持を失い、最終的には1925年に解散した[124]。 ユダヤ人自治主義とブンド主義は、その代わりに、彼らがすでに住んでいた領土内でのユダヤ人の民族自治を主張した。この運動の多くは左翼的で、積極的な反 シオニストであった。20世紀初頭には東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の間で成功を収めたが、ホロコーストによってその支持の大半を失った。 |

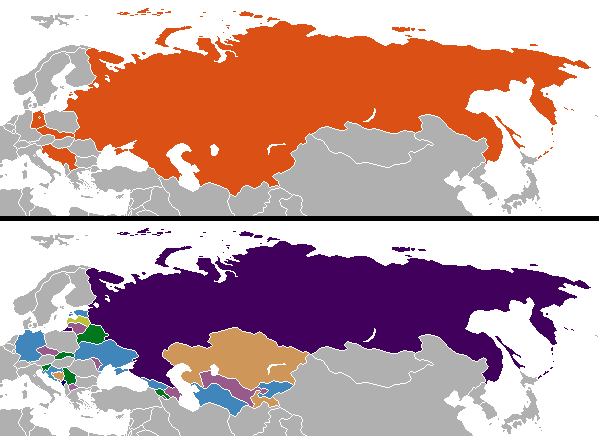

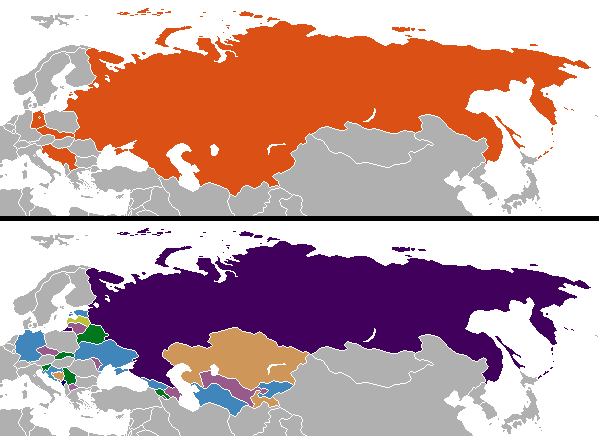

| 20th century China Main article: Chinese nationalism The awakening of nationalism across Asia helped shape the history of the continent. The key episode was the decisive defeat of Russia by Japan in 1905, demonstrating the military advancement of non-Europeans in a modern war. The defeat quickly led to manifestations of a new interest in nationalism in China, as well as Turkey and Persia.[125] In China Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925) launched his new party the Kuomintang (National People's Party) in defiance of the decrepit Empire, which was run by outsiders. The Kuomintang recruits pledged: [F]rom this moment I will destroy the old and build the new, and fight for the self-determination of the people, and will apply all my strength to the support of the Chinese Republic and the realization of democracy through the Three Principles, ... for the progress of good government, the happiness and perpetual peace of the people, and for the strengthening of the foundations of the state in the name of peace throughout the world.[126] The Kuomintang largely ran China until the Communists took over in 1949. But the latter had also been strongly influenced by Sun's nationalism as well as by the May Fourth Movement in 1919. It was a nationwide protest movement about the domestic backwardness of China and has often been depicted as the intellectual foundation for Chinese Communism.[127] The New Culture Movement stimulated by the May Fourth Movement waxed strong throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Historian Patricia Ebrey says: Nationalism, patriotism, progress, science, democracy, and freedom were the goals; imperialism, feudalism, warlordism, autocracy, patriarchy, and blind adherence to tradition were the enemies. Intellectuals struggled with how to be strong and modern and yet Chinese, how to preserve China as a political entity in the world of competing nations.[128] Greece Main article: Greek nationalism Nationalist irredentist movements Greek advocating for Enosis (unity of ethnically Greek states with the Hellenic Republic to create a unified Greek state), used today in the case of Cyprus, as well as the Megali Idea, the Greek movement that advocated for the reconquering of Greek ancestral lands from the Ottoman Empire (such as Crete, Ionia, Pontus, Northern Epirus, Cappadocia, Thrace among others) that were popular in the late 19th and early to 20th centuries, led to many Greek states and regions that were ethnically Greek to eventually unite with Greece and the Greco-Turkish war of 1919. The 4th of August regime was a fascist or fascistic nationalist authoritarian dictatorship inspired by Mussolini's Fascist Italy and Hitler's Germany and led by Greek general Ioannis Metaxas from 1936 to his death in 1941. It advocated for the Third Hellenic Civilization, a culturally superior Greek civilization that would be the successor of the First and Second Greek civilizations, that were Ancient Greece and the Byzantine empire respectively. It promoted Greek traditions, folk music and dances, classicism as well as medievalism. Africa Main articles: African nationalism and History of Africa  Kenneth Kaunda, an anti-colonial political leader from Zambia, pictured at a nationalist rally in colonial Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in 1960 In the 1880s the European powers divided up almost all of Africa (only Ethiopia and Liberia were independent). They ruled until after World War II when forces of nationalism grew much stronger. In the 1950s and the 1960s, colonial holdings became independent states. The process was usually peaceful but there were several long bitter bloody civil wars, as in Algeria,[129] Kenya[130] and elsewhere. Across Africa, nationalism drew upon the organizational skills that natives had learned in the British and French, and other armies during the world wars. It led to organizations that were not controlled by or endorsed by either the colonial powers or the traditional local power structures that had been collaborating with the colonial powers. Nationalistic organizations began to challenge both the traditional and the new colonial structures and finally displaced them. Leaders of nationalist movements took control when the European authorities exited; many ruled for decades or until they died off. These structures included political, educational, religious, and other social organizations. In recent decades, many African countries have undergone the triumph and defeat of nationalistic fervor, changing in the process the loci of the centralizing state power and patrimonial state.[131][132][133] South Africa, a British colony, was exceptional in that it became virtually independent by 1931. From 1948, it was controlled by white Afrikaner nationalists, who focused on racial segregation and white minority rule, known as apartheid. It lasted until 1994, when multiracial elections were held. The international anti-apartheid movement supported black nationalists until success was achieved,[verification needed] and Nelson Mandela was elected president.[134] Middle East  Gamal_Abdel_Nasser_1958 Gamal Abdel Nasser Arab nationalism, a movement toward liberating and empowering the Arab peoples of the Middle East, emerged during the late 19th century, inspired by other independence movements of the 18th and 19th centuries. As the Ottoman Empire declined and the Middle East was carved up by the Great Powers of Europe, Arabs sought to establish their own independent nations ruled by Arabs, rather than foreigners. Syria was established in 1920; Transjordan (later Jordan) gradually gained independence between 1921 and 1946; Saudi Arabia was established in 1932; and Egypt achieved gradually gained independence between 1922 and 1952. The Arab League was established in 1945 to promote Arab interests and cooperation between the new Arab states. The Zionist movement, emerged among European Jews in the 19th century. In 1882, Jews, from Europe, began to emigrate to Ottoman Palestine with the goal of establishing a new Jewish homeland. The majority and local population in Palestine, Palestinian Arabs were demanding independence from the British Mandate. Breakup of Yugoslavia Main article: Breakup of Yugoslavia This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This section possibly contains original research. (March 2023) This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) There was a rise in extreme nationalism after the Revolutions of 1989 had triggered the collapse of communism in the 1990s. That left many people with no identity. The people under communist rule had to integrate, but they now found themselves free to choose. That made long-dormant conflicts rise and create sources of serious conflict.[135] When communism fell in Yugoslavia, serious conflict arose, which led to a rise in extreme nationalism. In his 1992 article Jihad vs. McWorld, Benjamin Barber proposed that the fall of communism would cause large numbers of people to search for unity and that small-scale wars would become common, as groups will attempt to redraw boundaries, identities, cultures and ideologies.[136] The fall of communism also allowed for an "us vs. them" mentality to return.[137] Governments would become vehicles for social interests, and the country would attempt to form national policies based on the majority culture, religion or ethnicity.[135] Some newly sprouted democracies had large differences in policies on matters, which ranged from immigration and human rights to trade and commerce. The academic Steven Berg felt that the root of nationalist conflicts was the demand for autonomy and a separate existence.[135] That nationalism can give rise to strong emotions, which may lead to a group fighting to survive, especially as after the fall of communism, political boundaries did not match ethnic boundaries.[135] Serious conflicts often arose and escalated very easily, as individuals and groups acted upon their beliefs and caused death and destruction.[135] When that happens, states unable to contain the conflict run the risk of slowing their progress at democratization. Yugoslavia was established after the First World War and joined three acknowledged ethnic groups: Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The national census numbers from 1971 to 1981 measured an increase from 1.3% to 5.4% in the population that ethnically identified itself as Yugoslavs.[138] That meant that the country, almost as a whole, was divided by distinctive religious, ethnic and national loyalties after nearly 50 years. Nationalist separatism of Croatia and Slovenia from the rest of Yugoslavia has basis in historical imperialist conquests of the region (Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Empire) and existence within separate spheres of religious, cultural and industrial influence – Catholicism, Protenstantism, Central European cultural orientation in the northwest, versus Orthodoxy, Islam and Orientalism in the southeast. Croatia and Slovenia were subsequently more economically and industrially advanced and remained as such throughout existence of both forms of Yugoslavia.[137] In the 1970s, the leadership of the separate territories in Yugoslavia protected only territorial interests, at the expense of other territories. In Croatia, there was almost a split within the territory between Serbs and Croats so that any political decision would kindle unrest, and tensions could cross adjacent territories: Bosnia and Herzegovina.[138] Bosnia had no group with a majority; Muslim, Serb, Croat, and Yugoslavs stopped leadership from advancing here either. Political organizations were not able to deal successfully with such diverse nationalisms. Within the territories, leaderships would not compromise. To do so would create a winner in one ethnic group and a loser in another and raise the possibility of a serious conflict. That strengthened the political stance promoting ethnic identities and caused intense and divided political leadership within Yugoslavia.  Changes in national boundaries in post-Soviet and post-Yugoslav states after the revolutions of 1989 were followed by a resurgence of nationalism. In the 1980s, Yugoslavia began to break into fragments.[136] Economic conditions within Yugoslavia were deteriorating. Conflict in the disputed territories was stimulated by the rise in mass nationalism and ethnic hostilities.[138] The per capita income of people in the northwestern territory, encompassing Croatia and Slovenia, was several times higher than that of the southern territory. That, combined with escalating violence from ethnic Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo, intensified economic conditions.[138] The violence greatly contributed to the rise of extreme nationalism of Serbs in Serbia and the rest of Yugoslavia. The ongoing conflict in Kosovo was propagandized by a communist Serb, Slobodan Milošević, to increase Serb nationalism further. As mentioned, that nationalism gave rise to powerful emotions which grew the force of Serbian nationalism by highly nationalist demonstrations in Vojvodina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Kosovo. Serbian nationalism was so high that Slobodan Milošević ousted leaders in Vojvodina and Montenegro, repressed Albanians within Kosovo and eventually controlled four of the eight regions/territories.[138] Slovenia, one of the four regions not under communist control, favoured a democratic state. In Slovenia, fear was mounting because Milošević would use the militia to suppress the country, as had occurred in Kosovo.[138] Half of Yugoslavia wanted to be democratic, the other wanted a new nationalist authoritarian regime. In fall of 1989, tensions came to a head, and Slovenia asserted its political and economic independence from Yugoslavia and seceded. In January 1990, there was a total break with Serbia at the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, an institution that had been conceived by Milošević to strengthen unity and later became the backdrop for the fall of communism in Yugoslavia. In August 1990, a warning to the region was issued when ethnically divided groups attempted to alter the government structure. The republic borders established by the Communist regime in the postwar period were extremely vulnerable to challenges from ethnic communities. Ethnic communities arose because they did not share the identity with everyone within the new post-communist borders,[138] which threatened the new governments. The same disputes were erupting that were in place prior to Milošević and were compounded by actions from his regime. Also, within the territory, the Croats and the Serbs were in direct competition for control of government. Elections were held and increased potential conflicts between Serbian and Croat nationalism. Serbia wanted to be separate and to decide its own future based on its own ethnic composition, but that would then give Kosovo encouragement to become independent from Serbia. Albanians in Kosovo were already practically independent from Kosovo, but Serbia did not want to let Kosovo become independent. Albanian nationalists wanted their own territory, but that would require a redrawing of the map and threaten neighboring territories. When communism fell in Yugoslavia, serious conflict arose, which led to the rise in extreme nationalism. Nationalism again gave rise to powerful emotions, which evoked, in some extreme cases, a willingness to die for what one believed, a fight for the survival of the group.[135] The end of communism began a long period of conflict and war for the region. For six years, 200,000–500,000 people died in the Bosnian War.[139] All three major ethnicities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnian Muslims, Croats, Serbs) suffered at the hands of each other.[137][verification needed] The war garnered assistance from groups, Muslim, Orthodox, and Western Christian, and from state actors, which supplied all sides; Saudi Arabia and Iran supported Bosnia; Russia supported Serbia; Central European and the West, including the US, supported Croatia; and the Pope supported Slovenia and Croatia. |

20世紀 中国 主な記事 中国のナショナリズム アジア全域でナショナリズムが目覚め、アジア大陸の歴史が形成された。重要なエピソードは、1905年にロシアが日本に決定的な敗北を喫したことである。 この敗戦は、トルコやペルシャだけでなく、中国でもナショナリズムへの新たな関心を急速に高めるきっかけとなった[125]。中国では孫文(1866- 1925)が、部外者によって運営されていた老朽化した帝国に反抗して、国民党という新党を立ち上げた。国民党の新兵はこう誓った: [この瞬間から、私は古いものを破壊し、新しいものを建設し、人民の自決のために戦い、中華民国の支持と三原則による民主主義の実現のため に、......善政の進展、人民の幸福と恒久の平和のために、そして全世界の平和の名において国家の基盤を強化するために、全力を傾ける」[126]。 国民党は、1949年に共産党が政権を奪取するまで、中国をほぼ支配していた。しかし共産党もまた、孫のナショナリズムや1919年の五・四運動から強い 影響を受けていた。五・四運動は中国国内の後進性に対する全国的な抗議運動であり、しばしば中国共産党の知的基盤として描かれてきた。歴史家のパトリシ ア・エブリーは言う: ナショナリズム、愛国主義、進歩、科学、民主主義、自由が目標であり、帝国主義、封建主義、軍閥主義、独裁主義、家父長制、伝統への盲目的な固執が敵で あった。知識人たちは、いかにして強く近代的でありながら中国的であるか、いかにして競合する国家がひしめく世界で政治的実体としての中国を維持するかに 苦闘した[128]。 ギリシャ 主な記事 ギリシャナショナリズム エノーシス(民族的にギリシャの国家とヘレニズム共和国を統合し、統一ギリシャ国家を建設すること)を主張するギリシャのナショナリズム的民族解放運動 は、今 日、キプロスのケースで使用されており、また、オスマン帝国からギリシャの祖先の土地を再征服することを主張したギリシャの運動であるメガリ・イデア(ク レタ島など、 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて盛んに行われた、イオニア、ポントス、北エピルス、カッパドキア、トラキアなどのギリシャの先祖伝来の土地のオスマン 帝国からの奪還を主張するギリシャ運動は、多くのギリシャの国家や民族的にギリシャ的な地域を最終的にギリシャに統合させ、1919年のギリシャ・トルコ 戦争につながった。 8月4日政権は、ムッソリーニのファシスト・イタリアとヒトラーのドイツに影響を受けたファシストまたはファシズムナショナリズムの権威主義独裁政権であ り、 1936年から1941年に死去するまでギリシャの将軍イオアニス・メタクサスに率いられた。第3次ヘレニズム文明を提唱し、それぞれ古代ギリシャとビザ ンチン帝国であった第1次、第2次ギリシャ文明の後継となる文化的に優れたギリシャ文明を提唱した。ギリシャの伝統、民族音楽、舞踊、古典主義、中世主義 を奨励した。 アフリカ 主な記事 アフリカナショナリズム、アフリカ史  ザンビアの反植民地政治指導者ケネス・カウンダ(1960年、植民地時代の北ローデシア(現ザンビア)でのナショナリズム集会にて)。 1880年代、ヨーロッパ列強はアフリカのほぼ全域を分割した(独立したのはエチオピアとリベリアのみ)。第二次世界大戦後、ナショナリズムの勢力が非常 に強くなるまで、彼らはアフリカを支配した。1950年代から1960年代にかけて、植民地は独立国家となった。その過程は通常平和的であったが、アル ジェリア[129]、ケニア[130]などのように、長く苦しい血なまぐさい内戦が何度か起こった。 アフリカ全土において、ナショナリズムは、原住民が世界大戦中にイギリス軍やフランス軍、その他の軍隊で学んだ組織的スキルを活用した。それは、植民地勢 力にも、植民地勢力と協力してきた伝統的な地元の権力機構にも支配されず、支持されない組織を生み出した。ナショナリズム的組織は、伝統的な植民地構造と 新しい 植民地構造の両方に挑戦し始め、ついにはそれらを駆逐した。ナショナリズム運動の指導者たちは、ヨーロッパ当局が撤退すると、その支配権を握った。これら の構造には、政治、教育、宗教、その他の社会組織が含まれる。ここ数十年で、多くのアフリカ諸国はナショナリズム的熱狂の勝利と敗北を経験し、その過程で 中央集 権的な国家権力と愛国的国家の所在が変化した[131][132][133]。 イギリスの植民地であった南アフリカは、1931年までに事実上独立したという点で例外的であった。1948年以降、アパルトヘイトとして知られる人種隔 離と少数派の白人支配に重点を置く白人アフリカーナーナショナリズム者によって支配された。アパルトヘイトは1994年に多民族選挙が実施されるまで続い た。国 際的な反アパルトヘイト運動は、成功を収めるまで黒人ナショナリストを支援し[要検証]、ネルソン・マンデラが大統領に選出された[134]。 中東  Gamal_Abdel_Nasser_1958 ガマル・アブデル・ナセル アラブナショナリズムは、中東のアラブ民族を解放し、力を与えようとする運動であり、18世紀と19世紀の他の独立運動に触発されて、19世紀後半に出現 した。 オスマン帝国が衰退し、中東がヨーロッパの大国によって切り分けられると、アラブ人は外国人ではなくアラブ人が統治する独立国家の樹立を目指した。シリア は1920年に設立され、トランスヨルダン(後のヨルダン)は1921年から1946年にかけて徐々に独立を果たし、サウジアラビアは1932年に設立さ れ、エジプトは1922年から1952年にかけて徐々に独立を果たした。アラブ連盟はアラブの利益と新しいアラブ諸国間の協力を促進するために1945年 に設立された。 シオニズム運動は、19世紀にヨーロッパのユダヤ人の間で生まれた。1882年、ヨーロッパからユダヤ人が新しいユダヤ人の祖国を建設する目的でオスマ ン・パレスチナへの移住を開始した。パレスチナの地元住民であるパレスチナ・アラブ人は、イギリス委任統治からの独立を要求していた。 ユーゴスラビア解体 主な記事 ユーゴスラビア解体 このセクションには複数の問題があります。改善するか、トークページで議論してください。(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学 ぶ) このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性があります。(2023年3月) このセクションは検証のために追加の引用が必要です。(2023年3月) 1989年の革命が1990年代の共産主義崩壊の引き金となった後、極端なナショナリズムが台頭した。その結果、多くの人々がアイデンティティを失った。 共産主義の支配下にあった人々は統合しなければならなかったが、今では自由に選択できるようになった。ユーゴスラビアで共産主義が崩壊すると、深刻な紛争 が発生し、極端なナショナリズムが台頭した。 ベンジャミン・バーバーは1992年の論文『ジハードvs.マクワールド』の中で、共産主義の崩壊によって大勢の人々が結束を求めるようになり、集団が境 界線、アイデンティティ、文化、イデオロギーを引き直そうとするため、小規模な戦争が一般的になると提案している[136]。政府は社会的利害のための手 段となり、国は多数派の文化、宗教、民族性に基づいた国家政策を形成しようとするようになる。 学者であるスティーブン・バーグは、ナショナリズムによる紛争の根源は、自治と独立した存在の要求であると感じていた[135]。ナショナリズムは強い感 情を生む可能性があり、それが集団が生き残るために戦うことにつながる可能性がある。 ユーゴスラビアは第一次世界大戦後に建国され、3つの民族集団が加盟した: セルビア人、クロアチア人、スロベニア人である。1971年から1981年にかけての国勢調査では、民族的にユーゴスラビア人であると自認する人口が 1.3%から5.4%へと増加した[138]。これは、ほぼ全体として、50年近く経った後に、この国が独特の宗教的、民族的、国家的忠誠心によって分断 されたことを意味する。 クロアチアとスロベニアのユーゴスラビアの他の地域からのナショナリズム的分離主義は、この地域の歴史的な帝国主義的征服(オーストリア=ハンガリーとオ スマン 帝国)と、宗教的、文化的、産業的影響力の別々の圏内での存在(北西部ではカトリック、プロテンスタンティズム、中央ヨーロッパ文化志向、南東部では正 教、イスラム教、オリエンタリズム)に基礎を置く。クロアチアとスロヴェニアはその後、より経済的、工業的に発展し、ユーゴスラヴィアの両形態が存在する 間、その状態を維持した[137]。 1970年代、ユーゴスラビアの分離した領土の指導者たちは、他の領土を犠牲にして領土の利益のみを保護した。クロアチアでは、セルビア人とクロアチア人 の間で領土内がほぼ分裂していたため、政治的な決定があれば動揺を呼び起こし、緊張が隣接する領土に及ぶ可能性があった: ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナには多数派を占めるグループはなく、イスラム教徒、セルビア人、クロアチア人、ユーゴスラビア人が、ここでも指導者の進出を阻止 した。政治組織はこのような多様なナショナリズムにうまく対処することができなかった。領土内では、指導者たちは妥協しようとしなかった。妥協すれば、あ る民族に勝者が生まれ、別の民族に敗者が生まれ、深刻な紛争に発展する可能性が高まるからだ。そのため、民族のアイデンティティを推進する政治姿勢が強ま り、ユーゴスラビア国内では政治指導部が激しく分裂することになった。  1989年の革命後、ポスト・ソビエトおよびポスト・ユーゴスラビア諸国における国境線の変化は、ナショナリズムの復活に続いた。 1980年代、ユーゴスラビアは分裂し始めた[136]。クロアチアとスロベニアを含む北西部領土の人々の一人当たりの所得は、南部領土のそれよりも数倍 高かった[138]。この暴力はセルビアとユーゴスラビアの他の地域におけるセルビア人の極端なナショナリズムの台頭に大きく貢献した。コソボで進行中の 紛争は、セルビア人のナショナリズムをさらに高めるために、共産主義者のセルビア人、スロボダン・ミロシェヴィッチによって宣伝された。前述のように、こ のナショナリズムは強力な感情を生み、ヴォイヴォディナ、セルビア、モンテネグロ、コソボでナショナリズム的なデモが行われ、セルビア人ナショナリズムの 勢力を 拡大した。セルビア人のナショナリズムは非常に高まり、スロボダン・ミロシェヴィッチはヴォイヴォディナとモンテネグロの指導者を追放し、コソヴォ内のア ルバニア人を弾圧し、最終的に8つの地域/領土のうち4つを支配した[138]。共産主義の支配下になかった4つの地域の1つであるスロヴェニアは民主主 義国家を支持した。 スロヴェニアでは、ミロシェヴィッチがコソヴォで起きたように民兵を使って国を抑圧するのではないかという恐怖が高まっていた[138]。ユーゴスラヴィ アの半分は民主化を望み、もう半分は新たなナショナリズム的権威主義体制を望んでいた。1989年秋、緊張が頂点に達し、スロベニアはユーゴスラビアから の政治 的・経済的独立を主張し、分離独立した。1990年1月、ミロシェヴィッチが団結強化のために構想し、後にユーゴスラビア共産主義崩壊の背景となったユー ゴスラビア共産主義者同盟で、セルビアとの全面的な断絶が起こった。 1990年8月、民族的に分裂したグループが政府機構を変更しようとしたため、この地域に警告が発せられた。戦後、共産主義政権によって確立された共和国 の国境は、民族共同体からの挑戦に対して極めて脆弱であった。民族共同体は、共産主義後の新しい国境内のすべての人とアイデンティティを共有していなかっ たために発生し[138]、新政府を脅かした。ミロシェヴィッチ以前と同じ紛争が勃発し、ミロシェヴィッチ政権の行動によってさらに悪化した。 また領土内では、クロアチア人とセルビア人が政府の支配権をめぐって直接競争していた。選挙が実施され、セルビア人とクロアチア人のナショナリズムの潜在 的な対立が激化した。セルビアは分離独立を望み、自国の民族構成に基づいて自国の将来を決めたかったが、それではコソボにセルビアからの独立を促すことに なる。コソボのアルバニア人はすでにコソボから実質的に独立していたが、セルビアはコソボを独立させたくなかった。アルバニアのナショナリズム者たちは自 分たち の領土を望んでいたが、そのためには地図を引き直す必要があり、近隣の領土を脅かすことになる。ユーゴスラビアで共産主義が崩壊すると、深刻な対立が生 じ、極端なナショナリズムが台頭した。 ナショナリズムは再び強力な感情を呼び起こし、極端な場合には、自分の信じるもののために死のうとする気持ち、集団の存続のための戦いを呼び起こした [135]。共産主義の終焉は、この地域にとって長い紛争と戦争の時代を始めた。ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナの3つの主要民族(ボスニア・ムスリム、クロア チア人、セルビア人)は互いに苦しめられた[137][要検証]。サウジアラビアとイランはボスニアを支援し、ロシアはセルビアを支援し、中央ヨーロッパ とアメリカを含む西側諸国はクロアチアを支援し、ローマ教皇はスロベニアとクロアチアを支援した。 |