Nation State

1916年の絵葉書で、第一次世界大戦の連合国の擬人化された国民が、それぞれ国民を代表する旗を持っている

国民国家

Nation State

1916年の絵葉書で、第一次世界大戦の連合国の擬人化された国民が、それぞれ国民を代表する旗を持っている

解説:池田光穂

至高なる領域としての国土(=国家が空間 的に占有している領域)を政治的に統治している民(people)が国民(nation)としての統一 性やまとまりをもつ[ないしは、もたせようとしている]国家を、国民国家と呼ぶ。あるいは、国家(state)と国民(nation/ ネーション)が、分かち難く結びついている政治と統治の形態、あるいは、その理想形 (ideal type)を国民国家と呼ぶ。

ベネディクト・アンダーソンは、国家 (state)と国民(nation/ ネーション)とは、元来異質なものなので、国民国家が、一 種の結婚状態だと言っている。国民国家は異質なものの結合ゆえに、その紐帯を保つような働きかけが国家からも国民からもあるということになる。

それゆえ、国民国家概念は、国民=国家=

領土の一致(=三位一体)をもとにする法的擬制のことであり、国民国家という形態は、民主主義ととも

に、常に最善で最良のものではない。経済と文化のグローバリゼーションおよび、世界的規模での移民の存在や、個々の国民国家内における統治の破綻から生じ

る難民の発生は、国民国家という統治方法が限界にきていることは明らかである(ハンナ・アーレントによる誕生の時点から破綻しているという/それは難民の

存在によって裏付けられている:「ハンナ・アーレント「国民国家の没落と人権の終

焉」ノート」)。

国家と国民は主権 (sovereignty)をもつことを自ら任じているのみならず、他の国民や国家によって独立性を承認されている国民として の統合性は、民族性(ethnic entity:例、集合的な指標としての「国籍」)や文化性(cultural entity:例、公用語としての言語使用)により境界づけられることもあるが、 国民としての統合性が担保されるかぎり、それらの内実の多様性は権利として認められている。なぜなら国民は市民としての主権=至高性を同時に合わせ持って いるからである。(→「政治的アイデンティティとしての〈地元民〉」)(→「地政学」)

他方で、ネーションは、ステート(国家)

という概念の縛りから外れると、その友愛の共同性を回復し、ポテンシャルをもつ概念となる。政治革命運

動の一形態である国民解放戦線(national liberation

front)とは、しばしば、ネーション概念をよく理解できない過去の社会科学者たちにより「民族解放戦線」と誤訳がなされてきたが、ネーションを解放す

るとは、それまでのネーションが誤った共同性によって定義されてきたことを修正し、あらたなネーションを「再想像」することにほかならないからである(→

「民族境界論」)

ネーションは、共同性をもつメンバーシッ プというイメージももつ。例えば、カナダでは、先住民(先住民族)は、 ファースト・ネーション(first nation)と呼ばれる。それは、カナダの入植に先立つ、カナダの重要な国民であり/あり続けているというカナダ政府の国家的認識を示している。より積 極的には、入植を征服ではなく(=この主張都合のいい入植者の強弁だという批判は常に存在するが)、先住民との交渉や和解し、共存するという多民族・多文 化国家としてのカナダ政府の政治的立場を表していると言えよう。

また、テレサ・ド・ローレティス (Teresa de Lauretis, 1991)は、レズビアンとゲイのための共同体論として、クイア・ネーション(Queer nation)を提唱したが、ここでの、ネーションは、包括的である(Inclusivity)友愛の共同性を模索する未来への言語として開かれるいう可 能性をもつ(→「クイア理論」)

| A

nation-state is a political unit where the state, a centralized

political organization ruling over a population within a territory, and

the nation, a community based on a common identity, are

congruent.[1][2][3][4] It is a more precise concept than "country",

since a country does not need to have a predominant national or ethnic

group. A nation, sometimes used in the sense of a common ethnicity, may include a diaspora or refugees who live outside the nation-state; some nations of this sense do not have a state where that ethnicity predominates. In a more general sense, a nation-state is simply a large, politically sovereign country or administrative territory. A nation-state may be contrasted with: An empire, a political unit made up of several territories and peoples, typically established through conquest and marked by a dominant center and subordinate peripheries. A multinational state, where no one ethnic or cultural group dominates (such a state may also be considered a multicultural state depending on the degree of cultural assimilation of various groups). A city-state, which is both smaller than a "nation" in the sense of a "large sovereign country" and which may or may not be dominated by all or part of a single "nation" in the sense of a common ethnicity or culture.[5][6][7] A confederation, a league of sovereign states, which might or might not include nation-states. A federated state, which may or may not be a nation-state, and which is only partially self-governing within a larger federation (for example, the state boundaries of Bosnia and Herzegovina are drawn along ethnic lines, but those of the United States are not). This article mainly discusses the more specific definition of a nation-state as a typically sovereign country dominated by a particular ethnicity. |

国民国家とは、領土内の人口を統治する中央集権的な政治組織である「国

家」と、共通のアイデンティティに基づく共同体である「国民」が一致する政治単位である[1][2][3][4]。「国」よりも正確な概念である。 国民は、共通の民族という意味で使われることもあるが、国民国家の外に住むディアスポラや難民を含むこともある。この意味で使われる国家の中には、その民 族が優勢な国家を持たないものもある。より一般的な意味では、国民国家とは単に政治的に主権を持つ大きな国や行政区域のことである。国民国家は以下のもの と対比される: 帝国とは、いくつかの領土と民族からなる政治単位であり、一般的には征服によって成立し、支配的な中心と従属的な周辺によって特徴づけられる。 一つの民族や文化的集団が支配することのない多国籍国家(このような国家は、様々な集団の文化的同化の度合いによって多文化国家とみなされることもあ る)。 都市国家。「大きな主権を持つ国」という意味での「国民」よりも小さく、共通の民族や文化という意味での単一の「国民」の全部または一部によって支配され ている場合もあれば、支配されていない場合もある[5][6][7]。 国民国家を含むかもしれないし、含まないかもしれない主権国家の連合体。 連邦国家とは、国民国家である場合もあればそうでない場合もあり、より大きな連邦の中で部分的にしか自治されていない国家である(例えば、ボスニア・ヘル ツェゴビナの州境は民族の境界線に沿って引かれているが、アメリカの州境は引かれていない)。 本稿では主に、国民国家のより具体的な定義として、特定の民族が支配する典型的な主権国家について論じる。 |

| Complexity The relationship between a nation (in the ethnic sense) and a state can be complex. The presence of a state can encourage ethnogenesis, and a group with a pre-existing ethnic identity can influence the drawing of territorial boundaries or argue for political legitimacy. This definition of a "nation-state" is not universally accepted. "All attempts to develop terminological consensus around 'nation' failed", concludes academic Valery Tishkov.[8] Walker Connor discusses the impressions surrounding the characters of "nation", "(sovereign) state", "nation-state", and "nationalism". Connor, who gave the term "ethnonationalism" wide currency, also discusses the tendency to confuse nation and state and the treatment of all states as if nation states.[9] |

複雑さ 民族的な意味での)国民と国家の関係は複雑である。国家の存在は民族の新生を促し、既存の民族的アイデンティティを持つ集団は、領土の境界線設定に影響を 与えたり、政治的正当性を主張したりすることができる。この「国民国家」の定義は、普遍的に受け入れられているわけではない。「ウォーカー・コナーは、 「国民」、「(主権)国家」、「国民国家」、「ナショナリズム」の文字にまつわる印象を論じている[8]。エスノナショナリズム」という言葉を広く普及さ せたコナーは、国民と国家を混同する傾向や、すべての国家をあたかも国民国家のように扱うことについても論じている[9]。 |

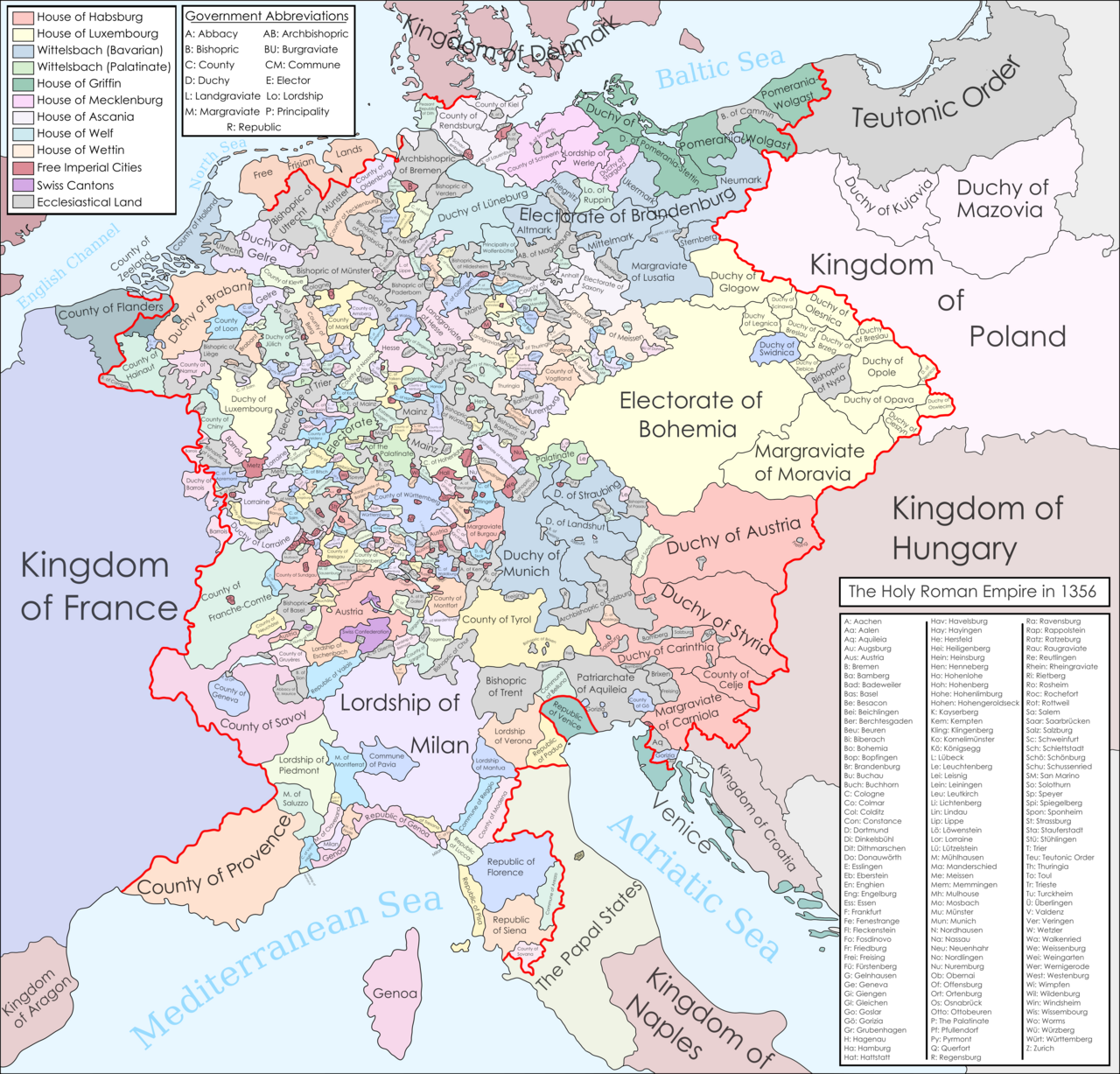

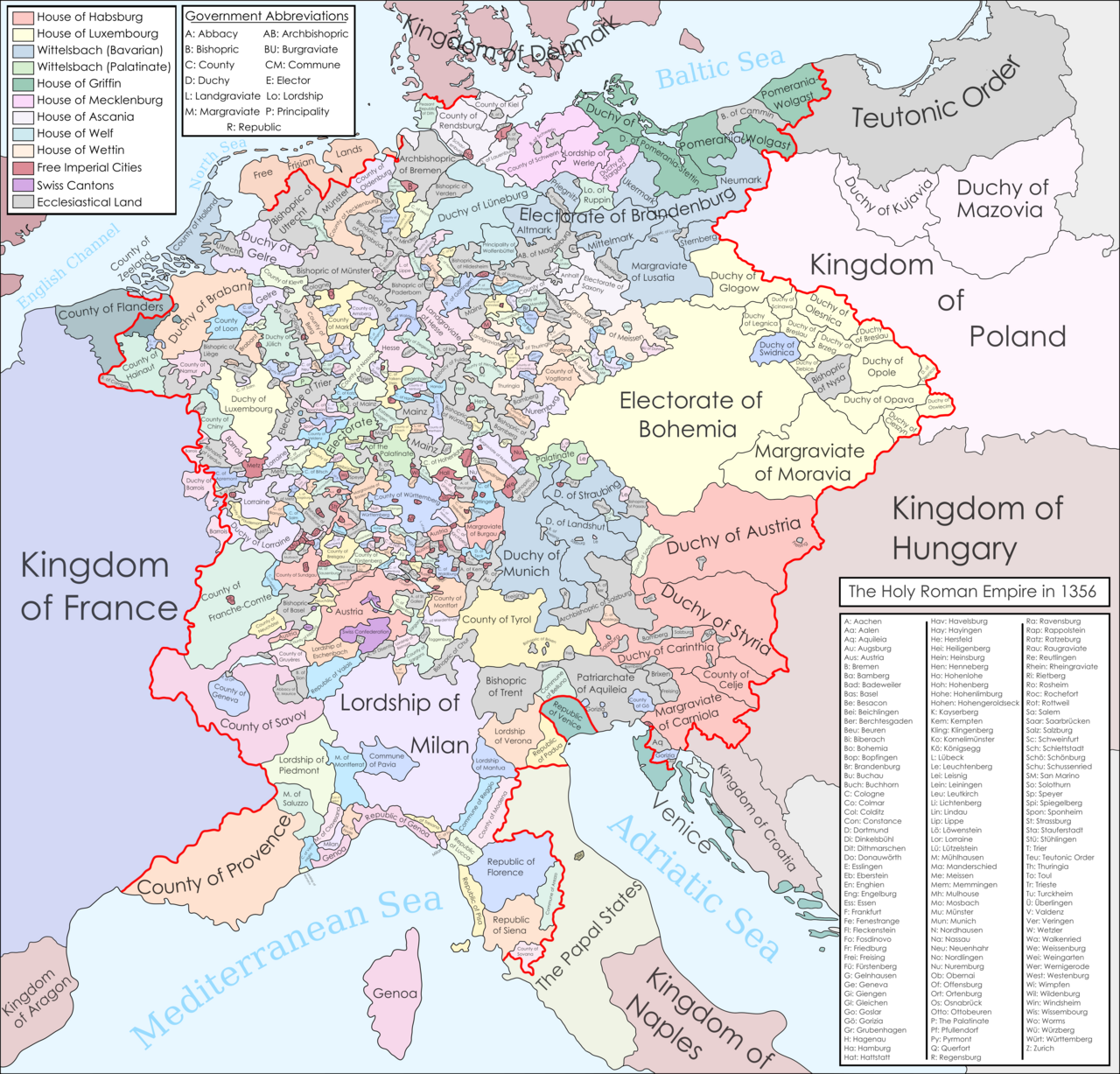

| History Origins Main article: Nation The origins and early history of nation-states are disputed. A major theoretical question is: "Which came first, the nation or the nation-state?" Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, Michel Foucault and Jeremy Black[10][11][12] have advanced the hypothesis that the nation-state did not arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it a political invention; rather, it is an inadvertent by-product of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy, capitalism, mercantilism, political geography, and geography[13][14] combined with cartography[15][16] and advances in map-making technologies.[17][18] It was with these intellectual discoveries and technological advances that the nation-state arose. For others, the nation existed first, then nationalist movements arose for sovereignty, and the nation-state was created to meet that demand. Some "modernization theories" of nationalism see it as a product of government policies to unify and modernize an already existing state. Most theories see the nation-state as a 19th-century European phenomenon facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy and mass media. However, historians[who?] also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal and the Dutch Republic,[19] and some date the emergence of nations even earlier. Adrian Hastings, for instance, argued that Ancient Israel as depicted in the Hebrew Bible "gave the world the model of nationhood, and even nation-statehood"; however, after the fall of Jerusalem, the Jews lost this status for nearly two millennia, while still preserving their national identity until "the more inevitable rise of Zionism", in modern times, which sought to establish a nation-state.[20] Eric Hobsbawm argues that the establishment of a French nation was not the result of French nationalism, which would not emerge until the end of the 19th century, but rather the policies implemented by pre-existing French states. Many of these reforms were implemented since the French Revolution, at which time only half of the French people spoke some French – with only a quarter of those speaking the version of it found in literature and places of learning.[21] As the number of Italian speakers in Italy was even lower at the time of Italian unification, similar arguments have been made regarding the modern Italian nation, with both the French and the Italian states promoting the replacement of various regional dialects and languages with standardized dialects. The introduction of conscription and the Third Republic's 1880s laws on public instruction facilitated the creation of a national identity under this theory.[22] The Revolutions of 1848 were democratic and liberal, intending to remove the old monarchical structures and creating independent nation-states. Some nation-states, such as Germany and Italy, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists during the 19th century. In both cases, the territory was previously divided among other states, some very small. At first, the sense of common identity was a cultural movement, such as in the Völkisch movement in German-speaking states, which rapidly acquired a political significance. In these cases, the nationalist sentiment and the nationalist movement precede the unification of the German and Italian nation-states.[citation needed] Historians Hans Kohn, Liah Greenfeld, Philip White, and others have classified nations such as Germany or Italy, where they believe cultural unification preceded state unification, as ethnic nations or ethnic nationalities. However, "state-driven" national unifications, such as in France, England or China, are more likely to flourish in multiethnic societies, producing a traditional national heritage of civic nations, or territory-based nationalities.[23][24][25] The idea of a nation-state was and is associated with the rise of the modern system of states, often called the "Westphalian system", following the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). The balance of power, which characterized that system, depended for its effectiveness upon clearly defined, centrally controlled, independent entities, whether empires or nation states, which recognize each other's sovereignty and territory. The Westphalian system did not create the nation-state, but the nation-state meets the criteria for its component states (by assuming that there is no disputed territory).[citation needed] Before the Westphalian system, the closest geopolitical system was the "Chanyuan system" established in East Asia in 1005 through the Treaty of Chanyuan, which, like the Westphalian peace treaties, designated national borders between the independent regimes of China's Song dynasty and the semi-nomadic Liao dynasty.[26] This system was copied and developed in East Asia in the following centuries until the establishment of the pan-Eurasian Mongol Empire in the 13th century.[27] The nation-state received a philosophical underpinning in the era of Romanticism, at first as the "natural" expression of the individual peoples (romantic nationalism: see Johann Gottlieb Fichte's conception of the Volk, later opposed by Ernest Renan). The increasing emphasis during the 19th century on the ethnic and racial origins of the nation led to a redefinition of the nation-state in these terms.[25] Racism, which in Boulainvilliers's theories was inherently antipatriotic and antinationalist, joined itself with colonialist imperialism and "continental imperialism", most notably in pan-Germanic and pan-Slavic movements.[28] The relationship between racism and ethnic nationalism reached its height in the 20th century through fascism and Nazism. The specific combination of "nation" ("people") and "state" expressed in such terms as the völkischer Staat and implemented in laws such as the 1935 Nuremberg laws made fascist states such as early Nazi Germany qualitatively different from non-fascist nation-states. Minorities were not considered part of the people (Volk) and were consequently denied to have an authentic or legitimate role in such a state. In Germany, neither Jews nor the Roma were considered part of the people, and both were specifically targeted for persecution. German nationality law defined "German" based on German ancestry, excluding all non-Germans from the people.[29] In recent years, a nation-state's claim to absolute sovereignty within its borders has been criticized.[25] A global political system based on international agreements and supra-national blocs characterized the post-war era. Non-state actors, such as international corporations and non-governmental organizations, are widely seen as eroding the economic and political power of nation-states. According to Andreas Wimmer and Yuval Feinstein, nation-states tended to emerge when power shifts allowed nationalists to overthrow existing regimes or absorb existing administrative units.[30] Xue Li and Alexander Hicks links the frequency of nation-state creation to processes of diffusion that emanate from international organizations.[31] Before the nation-state  Dissolution of the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire (1918) In Europe, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multiethnic empires, the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of France (and its empire), the Kingdom of Hungary,[32] the Russian Empire, the Portuguese Empire, the Spanish Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, the Dutch Empire and smaller nations at what would now be called sub-state level. The multi-ethnic empire was a monarchy, usually absolute, ruled by a king, emperor or sultan.[a] The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty was usually, but not always, from that group. This type of state is not specifically European: such empires existed in Asia, Africa and the Americas. Chinese dynasties, such as the Tang dynasty, the Yuan dynasty, and the Qing dynasty, were all multiethnic regimes governed by a ruling ethnic group. In the three examples, their ruling ethnic groups were the Han-Chinese, Mongols, and the Manchus. In the Muslim world, immediately after Muhammad died in 632, Caliphates were established.[33] Caliphates were Islamic states under the leadership of a political-religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[34] These polities developed into multi-ethnic trans-national empires.[35] The Ottoman sultan, Selim I (1512–1520) reclaimed the title of caliph, which had been in dispute and asserted by a diversity of rulers and "shadow caliphs" in the centuries of the Abbasid-Mamluk Caliphate since the Mongols' sacking of Baghdad and the killing of the last Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Iraq 1258. The Ottoman Caliphate as an office of the Ottoman Empire was abolished under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1924 as part of Atatürk's Reforms.  The Holy Roman Empire was a limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of state-like entities. Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse but were also dynastic states ruled by a royal house. Their territory could expand by royal intermarriage or merge with another state when the dynasty merged. In some parts of Europe, notably Germany, minimal territorial units existed. They were recognized by their neighbours as independent and had their government and laws. Some were ruled by princes or other hereditary rulers; some were governed by bishops or abbots. Because they were so small, however, they had no separate language or culture: the inhabitants shared the language of the surrounding region. In some cases, these states were overthrown by nationalist uprisings in the 19th century. Liberal ideas of free trade played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. However, the Austro-Prussian War and the German alliances in the Franco-Prussian War were decisive in the unification. The Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire broke up after the First World War, but the Russian Empire was replaced by the Soviet Union in most of its multinational territory after the Russian Civil War. A few of the smaller states survived: the independent principalities of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, and the Republic of San Marino. (Vatican City is a special case. All of the larger Papal States save the Vatican itself were occupied and absorbed by Italy by 1870. The resulting Roman Question was resolved with the rise of the modern state under the 1929 Lateran treaties between Italy and the Holy See.) |

歴史 起源 主な記事 国民 国民国家の起源と初期の歴史については議論がある。主な理論的疑問は、「国民と国民国家のどちらが先に生まれたのか」というものである。スティーブン・ ウェーバー、デイヴィッド・ウッドワード、ミシェル・フーコー、ジェレミー・ブラック[10][11][12]といった学者たちは、国民国家は政治的な創 意工夫や未知の未確定な源泉から生じたものではなく、政治的な発明でもないという仮説を提唱している; むしろそれは、政治経済学、資本主義、重商主義、政治地理学、地理学[13][14]における15世紀の知的発見と、地図製作[15][16]や地図製作 技術の進歩が組み合わさった不慮の副産物なのである。 [17][18]国民国家が誕生したのは、こうした知的発見と技術の進歩によるものであった。 また、国民がまず存在し、その後に主権を求める民族主義運動が起こり、その要求に応えるために国民国家が誕生したという説もある。ナショナリズムの「近代 化理論」のなかには、ナショナリズムを、すでに存在する国家を統一し近代化するための政府の政策の産物としてとらえるものもある。ほとんどの理論では、国 民国家は19世紀のヨーロッパの現象であり、国家が義務付けた教育、大衆識字率、マスメディアなどの発展によって促進されたと見ている。しかし、歴史家 [who?]は、ポルトガルやオランダ共和国において、比較的早くから統一された国家やアイデンティティが出現していたことを指摘しており[19]、国民 の出現をさらに早い時期とする者もいる。たとえばエイドリアン・ヘイスティングスは、ヘブライ語の聖書に描かれた古代イスラエルは「国民性、さらには国民 国家性のモデルを世界に与えた」と主張している。しかし、エルサレムの陥落後、ユダヤ人はこの地位をほぼ2千年にわたって失ったが、国民国家を樹立しよう とした近代の「より必然的なシオニズムの台頭」までは、依然として国民的アイデンティティを維持していた[20]。 エリック・ホブズボームは、フランスの国民国家の樹立は、19世紀末まで出現することのなかったフランスのナショナリズムの結果ではなく、むしろ既存のフ ランス国家によって実施された政策の結果であったと論じている。これらの改革の多くは、フランス革命以降に実施されたものであり、当時、フランス国民の半 数しかフランス語を話せず、文学や学問の場で見られるようなフランス語を話す者はその4分の1に過ぎなかった[21]。イタリア統一当時、イタリアでイタ リア語を話す者の数はさらに少なかったため、近代イタリア国民に関しても同様の議論がなされており、フランスとイタリアの両国家は、さまざまな地域の方言 や言語を標準化された方言に置き換えることを推進した。徴兵制の導入と1880年代の第三共和政の公教育に関する法律は、この理論に基づく国民アイデン ティティの創造を促進した[22]。 1848年の革命は民主的で自由主義的なものであり、古い君主制の構造を取り除き、独立した国民国家を創設することを意図していた。 ドイツやイタリアなどいくつかの国民国家は、少なくとも部分的には19世紀の民族主義者による政治運動の結果として誕生した。いずれの場合も、領土は以前 から他の国家に分割されており、その中には非常に小さな国家もあった。最初は、ドイツ語圏のヴォルキッシュ運動のように、共通のアイデンティティを意識す ることは文化的な運動であったが、それが急速に政治的な意味を持つようになった。このような場合、ナショナリズム感情やナショナリズム運動は、ドイツやイ タリアの国民国家の統一に先行している[要出典]。 歴史家のハンス・コーン、ライア・グリーンフェルド、フィリップ・ホワイトなどは、文化的統一が国家統一に先行したと考えるドイツやイタリアのような国民 を、民族国家または民族民族として分類している。しかし、フランス、イギリス、中国のような「国家主導型」の国民統合は、多民族社会においてはより繁栄し やすく、市民国家、あるいは領土に基づく国民性という伝統的な国民的遺産を生み出す[23][24][25]。 国民国家という考え方は、ウェストファリア条約(1648年)に続く、しばしば「ウェストファリア体制」と呼ばれる近代国家体制の台頭と関連している。 ウェストファリア体制を特徴づける力の均衡は、帝国であれ国民国家であれ、明確に定義され、中央集権的に統制され、互いに主権と領土を認め合う独立した存 在にその有効性が依存していた。ウェストファリア体制が国民国家を創設したわけではないが、国民国家はその構成国としての基準を満たすものである(紛争地 域が存在しないと仮定することで)。 [この条約はウェストファリア条約と同様に、中国の宋王朝と半遊牧民であった遼王朝の独立政権間の国境を指定したものであった[26]。このシステムは、 13世紀に汎ユーラシアのモンゴル帝国が成立するまで、その後の数世紀に東アジアで模倣され発展した[27]。 国民国家はロマン主義の時代に、最初は個々の民族の「自然な」表現として哲学的な裏付けを得た(ロマン主義的ナショナリズム:後にエルネスト・ルナンに よって反対されたヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテの民族概念を参照)。ブーランヴィリエの理論では人種主義は本質的に反愛国的であり反民族主義的であった が、植民地主義的帝国主義や「大陸帝国主義」、とりわけ汎ゲルマン運動や汎スラヴ運動と結びついた[28]。 人種主義と民族ナショナリズムの関係は、ファシズムとナチズムを通じて20世紀に最高潮に達した。国民」(「国民」)と「国家」の特異な組み合わせは、 フェルキッシャー・シュタートのような用語で表現され、1935年のニュルンベルク法のような法律で実施された。マイノリティは人民(ヴォルク)の一員と はみなされず、その結果、このような国家において真正な、あるいは正当な役割を果たすことは否定された。ドイツでは、ユダヤ人もロマ人も人民の一部とはみ なされず、どちらも特に迫害の対象とされた。ドイツの国籍法は、ドイツ人の祖先に基づいて「ドイツ人」を定義し、すべての非ドイツ人を国民から除外してい た[29]。 近年、国民国家がその国境内で絶対的な主権を主張することは批判されている[25]。国際協定や超国家的ブロックに基づくグローバルな政治システムが戦後 を特徴づけている。国際企業や非政府組織などの非国家主体は、国民国家の経済的・政治的権力を侵食していると広く見られている。 アンドレアス・ヴィマー(Andreas Wimmer)とユヴァル・ファインスタイン(Yuval Feinstein)によれば、国民国家は、権力シフトによってナショナリストが既存の体制を転覆させたり、既存の行政単位を吸収したりすることが可能に なったときに出現する傾向があった[30]。 国民国家以前  多民族国家オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の解体(1918年) 18世紀のヨーロッパにおいて、古典的な非国家国家は多民族帝国、オーストリア帝国、フランス王国(およびその帝国)、ハンガリー王国[32]、ロシア帝 国、ポルトガル帝国、スペイン帝国、オスマン帝国、大英帝国、オランダ帝国、そして現在でいう亜国家レベルの小国家であった。多民族帝国は、通常は絶対君 主制であり、国王、皇帝、スルタンによって統治されていた[a]。帝国は1つの民族によって支配され、その民族の言語が通常行政の言語であった。支配王朝 は通常、その集団の出身者であったが、必ずしもそうではなかった。 このような帝国はアジア、アフリカ、アメリカ大陸にも存在した。唐、元、清といった中国の王朝は、いずれも支配民族によって統治された多民族国家であっ た。この3つの例では、支配民族は漢民族、モンゴル民族、満州族であった。イスラム世界では、ムハンマドが632年に死去した直後、カリフ制が確立された [33]。カリフ制は、イスラムの預言者ムハンマドの政治的・宗教的後継者が指導するイスラム国家であった[34]。 [35]オスマン帝国のスルタン、セリム1世(1512-1520)は、モンゴル軍によるバグダッド略奪と1258年にイラクのバグダッドで最後のアッ バース朝カリフが殺害されて以来、アッバース朝・マムルーク朝カリフの何世紀にもわたって多様な支配者と「影のカリフ」たちによって争われ、主張されてき たカリフの称号を取り戻した。オスマン帝国の役職としてのオスマン・カリフは、アタテュルクの改革の一環として1924年にムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュ ルクの下で廃止された。  神聖ローマ帝国は、何百もの国家のようなものからなる限定的な選帝侯君主制であった。 ヨーロッパのいくつかの小国家は、民族的にはそれほど多様ではなかったが、王家が支配する王朝国家でもあった。その領土は、王家の婚姻によって拡大した り、王朝の合併によって他の国家と合併したりした。ヨーロッパのいくつかの地域、特にドイツでは、最小限の領土単位が存在した。彼らは近隣諸国から独立国 家として認められ、独自の政府と法律を持っていた。あるものは王子やその他の世襲統治者によって統治され、あるものは司教や修道院長によって統治された。 しかし、非常に小規模であったため、独立した言語や文化はなく、住民は周辺地域の言語を共有していた。 これらの国家は、19世紀に民族主義者の反乱によって打倒された例もある。自由貿易のリベラルな考え方がドイツ統一の一翼を担い、それに先立って関税同盟 (ツォルフェライン)が結ばれた。しかし、普墺戦争と普仏戦争におけるドイツの同盟が、統一を決定的なものにした。オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国とオスマ ン帝国は第一次世界大戦後に解体したが、ロシア帝国はロシア内戦後、その多国籍領土のほとんどでソビエト連邦に取って代わられた。 リヒテンシュタイン、アンドラ、モナコ、サンマリノ共和国などの独立公国は生き残った。(バチカン市国は特殊なケースだ。バチカン市国を除く大きな教皇領 国家はすべて、1870年までにイタリアに占領され、吸収された。その結果生じたローマ問題は、1929年のイタリアとローマ教皇庁間のラテラノ条約によ り、近代国家の台頭とともに解決された) |

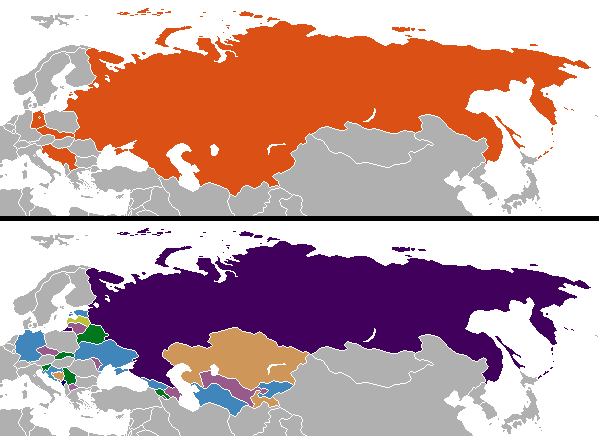

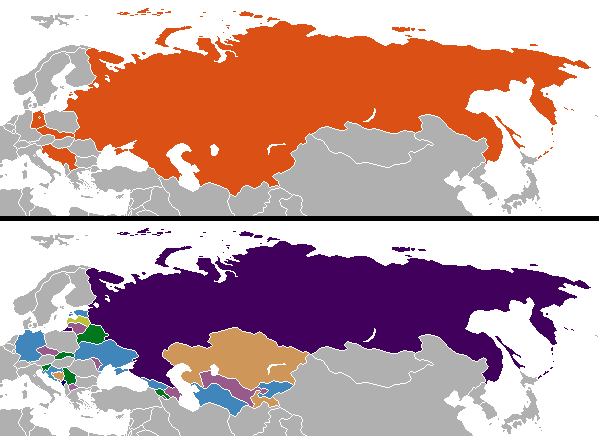

| Characteristics This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Changes in national boundaries after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, breakup of Yugoslavia and reunification of Germany "Legitimate states that govern effectively and dynamic industrial economies are widely regarded today [2004] as the defining characteristics of a modern nation-state."[36] Nation-states have their characteristics differing from pre-national states. For a start, they have a different attitude to their territory compared to dynastic monarchies: it is semisacred and nontransferable. No nation would swap territory with other states simply, for example, because the king's daughter married. They have a different type of border, in principle, defined only by the national group's settlement area. However, many nation-states also sought natural borders (rivers, mountain ranges). They are constantly changing in population size and power because of the limited restrictions of their borders. The most noticeable characteristic is the degree to which nation-states use the state as an instrument of national unity in economic, social and cultural life. The nation-state promoted economic unity by abolishing internal customs and tolls. In Germany, that process, the creation of the Zollverein, preceded formal national unity. Nation states typically have a policy to create and maintain national transportation infrastructure, facilitating trade and travel. In 19th-century Europe, the expansion of the rail transport networks was at first largely a matter for private railway companies but gradually came under the control of the national governments. The French rail network, with its main lines radiating from Paris to all corners of France, is often seen as a reflection of the centralised French nation-state, which directed its construction. Nation states continue to build, for instance, specifically national motorway networks. Specifically, transnational infrastructure programmes, such as the Trans-European Networks, are a recent innovation. The nation-states typically had a more centralised and uniform public administration than their imperial predecessors: they were smaller, and the population was less diverse. (The internal diversity of the Ottoman Empire, for instance, was very great.) After the 19th-century triumph of the nation-state in Europe, regional identity was subordinate to national identity in regions such as Alsace-Lorraine, Catalonia, Brittany and Corsica. In many cases, the regional administration was also subordinated to the central (national) government. This process was partially reversed from the 1970s onward, with the introduction of various forms of regional autonomy, in formerly centralised states such as Spain or Italy. The most apparent impact of the nation-state, as compared to its non-national predecessors, is creating a uniform national culture through state policy. The model of the nation-state implies that its population constitutes a nation, united by a common descent, a common language and many forms of shared culture. When implied unity was absent, the nation-state often tried to create it. It promoted a uniform national language through language policy. The creation of national systems of compulsory primary education and a relatively uniform curriculum in secondary schools was the most effective instrument in the spread of the national languages. The schools also taught national history, often in a propagandistic and mythologised version, and (especially during conflicts) some nation-states still teach this kind of history.[37][38][39][40][41] Language and cultural policy was sometimes hostile, aimed at suppressing non-national elements. Language prohibitions were sometimes used to accelerate the adoption of national languages and the decline of minority languages (see examples: Anglicisation, Bulgarization, Croatization, Czechization, Dutchification, Francisation, Germanisation, Hellenization, Hispanicization, Italianization, Lithuanization, Magyarisation, Polonisation, Russification, Serbization, Slovakisation, Swedification, Turkification). In some cases, these policies triggered bitter conflicts and further ethnic separatism. But where it worked, the cultural uniformity and homogeneity of the population increased. Conversely, the cultural divergence at the border became sharper: in theory, a uniform French identity extends from the Atlantic coast to the Rhine, and on the other bank of the Rhine, a uniform German identity begins. Both sides have divergent language policy and educational systems to enforce that model. |

特徴 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性がある。(2015年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  ソ連解体、チェコスロバキア、ユーゴスラビア解体、ドイツ再統一後の国民国境の変化 「効果的に統治する合法的な国家とダイナミックな産業経済は、今日[2004年]、近代国民国家の決定的な特徴として広くみなされている」[36]。 国民国家には、前国家国家とは異なる特徴がある。まず、領土は半聖域であり、譲渡不可能であるという点だ。例えば、国王の娘が結婚したからといって、他の 国家と領土を交換する国民はいない。原則的には、国民集団の居住地域によってのみ定義される、異なるタイプの国境がある。しかし、多くの国民国家は自然の 国境(河川、山脈)も求めている。彼らは、国境の制約が限られているため、人口規模や国力が絶えず変化している。 最も顕著な特徴は、国民国家が経済的、社会的、文化的生活において国家を国民統合の道具として用いる度合いである。 国民国家は、国内の関税や通行税を廃止することによって経済的統一を促進した。ドイツでは、その過程であるツォルフェラインの創設が、正式な国民統合に先 行した。国民国家は通常、国家的な交通インフラを整備・維持し、貿易や旅行を促進する政策をとる。19世紀のヨーロッパでは、鉄道輸送網の拡張は当初、主 に民間の鉄道会社の問題であったが、次第に国民政府の管理下に置かれるようになった。パリからフランス全土へと放射状に伸びる主要路線を持つフランスの鉄 道網は、しばしば、その建設を指揮した中央集権的なフランス国民国家の反映と見なされる。国民国家は、たとえば自動車道路網の建設に力を注いでいる。特 に、ヨーロッパ横断ネットワークのような国境を越えたインフラ計画は、最近の技術革新である。 国民国家は通常、帝国時代の前身よりも中央集権的で画一的な行政を行っていた。(19世紀の国民国家の勝利後、アルザス・ロレーヌ、カタルーニャ、ブル ターニュ、コルシカなどの地域では、地域のアイデンティティが国家のアイデンティティに従属するようになった。多くの場合、地域行政も中央(国民)政府に 従属した。このプロセスは、1970年代以降、スペインやイタリアのようなかつて中央集権国家であった地域で、さまざまな形態の地域自治が導入され、部分 的に逆転した。 国民国家の最も明白な影響は、その非国家的な前身と比較して、国家政策を通じて均一な国民文化を作り上げることである。国民国家のモデルは、その国民が共 通の血統、共通の言語、多くの共有文化によって結ばれた国民を構成していることを意味している。暗黙の統一が存在しない場合、国民国家はしばしばそれを作 り出そうとした。国民国家は言語政策を通じて、統一された国民言語を推進した。義務初等教育の国民制度と、中等学校における比較的統一されたカリキュラム の創設は、国語の普及に最も効果的な手段であった。学校はまた、しばしば宣伝的で神話化された形で、国民史を教えた。(特に紛争時には)一部の国民国家 は、いまだにこの種の歴史を教えている[37][38][39][40][41]。 言語・文化政策は時に敵対的であり、非国民的要素を抑圧することを目的としていた。言語の禁止は時として、国民言語の採用と少数言語の衰退を加速させるた めに用いられた(例を参照): 英語化、ブルガリア語化、クロアチア語化、チェコ語化、オランダ語化、フランス語化、ドイツ語化、ヘレン語化、ヒスパニック語化、イタリア語化、リトアニ ア語化、マジャール語化、ポロン語化、ロシア語化、セルビア語化、スロバキア語化、スウェーデン語化、トルコ語化など)。 場合によっては、こうした政策が苛烈な対立を引き起こし、民族分離主義がさらに進んだ。しかし、それが功を奏した地域では、人口の文化的均一性と同質性が 高まった。理論的には、大西洋岸からライン川までは一様なフランスのアイデンティティが広がり、ライン川の対岸では一様なドイツのアイデンティティが始ま る。そのモデルを強制するために、双方とも言語政策と教育制度が乖離している。 |

| In practice This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (May 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Map of territorial changes in Europe after World War I (as of 1923) The notion of a unifying "national identity" also extends to countries that host multiple ethnic or language groups, such as India. For example, Switzerland is constitutionally a confederation of cantons and has four official languages. Still, it also has a "Swiss" national identity, a national history and a classic national hero, Wilhelm Tell.[42] Innumerable conflicts have arisen where political boundaries did not correspond with ethnic or cultural boundaries. After World War II in the Josip Broz Tito era, nationalism was appealed to for uniting South Slav peoples. Later in the 20th century, after the break-up of the Soviet Union, leaders appealed to ancient ethnic feuds or tensions that ignited conflict between the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as well as Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Macedonians, eventually breaking up the long collaboration of peoples. Ethnic cleansing was carried out in the Balkans, destroying the formerly socialist republic and producing the civil wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992–95, resulting in mass population displacements and segregation that radically altered what was once a highly diverse and intermixed ethnic makeup of the region. These conflicts were mainly about creating a new political framework of states, each of which would be ethnically and politically homogeneous. Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks insisted they were ethnically distinct, although many communities had a long history of intermarriage.[citation needed] Belgium is a classic example of a state that is not a nation-state.[citation needed] The state was formed by secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830, whose neutrality and integrity was protected by the Treaty of London 1839; thus, it served as a buffer state after the Napoleonic Wars between the European powers France, Prussia (after 1871 the German Empire) and the United Kingdom until World War I, when the Germans breached its neutrality. Currently, Belgium is divided between the Flemings in the north, the French-speaking population in the south, and the German-speaking population in the east. The Flemish population in the north speaks Dutch, the Walloon population in the south speaks either French or, in the east of Liège Province, German. The Brussels population speaks French or Dutch. The Flemish identity is also cultural, and there is a strong separatist movement espoused by the political parties, the right-wing Vlaams Belang and the New Flemish Alliance. The Francophone Walloon identity of Belgium is linguistically distinct and regionalist. There is also unitary Belgian nationalism, several versions of a Greater Netherlands ideal, and a German-speaking community of Belgium annexed from Germany in 1920 and re-annexed by Germany in 1940–1944. However, these ideologies are all very marginal and politically insignificant during elections.  Ethnolinguistic map of mainland China and Taiwan[43] China covers a large geographic area and uses the concept of "Zhonghua minzu" or Chinese nationality, in the sense of ethnic groups. Still, it also officially recognizes the majority Han ethnic group which accounts for over 90% of the population, and no fewer than 55 ethnic national minorities. According to Philip G. Roeder, Moldova is an example of a Soviet-era "segment-state" (Moldavian SSR), where the "nation-state project of the segment-state trumped the nation-state project of prior statehood. In Moldova, despite strong agitation from university faculty and students for reunification with Romania, the nation-state project forged within the Moldavian SSR trumped the project for a return to the interwar nation-state project of Greater Romania."[44] See Controversy over linguistic and ethnic identity in Moldova for further details. |

現実 このセクションにはオリジナルの研究が含まれている可能性がある。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してほしい。独自研究のみからなる記 述は削除すべきである。(2016年5月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパの領土変遷図(1923年現在) 統一的な「国民アイデンティティ」という概念は、インドのように複数の民族や言語集団を抱える国にも及ぶ。例えば、スイスは憲法上、州の連合体であり、4 つの公用語がある。それでもなお、「スイス」国民としてのアイデンティティ、国民史、そして古典的な国民的英雄であるヴィルヘルム・テルが存在する [42]。 第二次世界大戦後、ヨハネスブルクとスイスの間には、民族的、文化的な境界線が存在しなかった。 第二次世界大戦後のヨシップ・ブロズ・チトー時代には、南スラブ民族を統合するために国民主義が訴えられた。20世紀後半、ソビエト連邦が崩壊した後、指 導者たちは古くからの民族間の確執や緊張に訴え、セルビア人、クロアチア人、スロベニア人、ボスニア人、モンテネグロ人、マケドニア人の間の紛争に火をつ け、最終的には民族の長い協力関係を崩壊させた。バルカン半島では民族浄化が行われ、かつての社会主義共和国が破壊され、1992年から95年にかけてク ロアチアとボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナで内戦が発生し、大量の人口移動と隔離がもたらされ、かつては非常に多様で混在していたこの地域の民族構成が根本的に 変化した。これらの紛争は主に、民族的にも政治的にも同質な国家という新しい政治的枠組みを作ることを目的としていた。セルビア人、クロアチア人、ボスニ ア人は自分たちが民族的に別個の存在であると主張したが、多くのコミュニティは長い間婚姻の歴史を持っていた[要出典]。 ベルギーは、国民国家ではない国家の典型的な例である[要出典]。1830年にオランダ連合王国から分離独立して成立した国家であり、その中立性と完全性 は1839年のロンドン条約によって保護されていた。そのため、ナポレオン戦争後、ヨーロッパ列強のフランス、プロイセン(1871年以降はドイツ帝 国)、イギリスの間で、ドイツ軍が中立を破る第一次世界大戦まで緩衝国としての役割を果たした。現在、ベルギーは北部のフラマン人、南部のフランス語圏、 東部のドイツ語圏に分かれている。北部のフラマン人はオランダ語を話し、南部のワロン人はフランス語か、リエージュ県東部ではドイツ語を話す。ブリュッセ ルの住民はフランス語かオランダ語を話す。 フラマン人のアイデンティティは文化的なものでもあり、政党では右派のVlaams Belangと新フラマン同盟が強力な分離主義運動を展開している。ベルギーのフランス語圏ワロン人のアイデンティティは、言語的に区別され、地域主義的 である。また、ベルギーの単一民族主義、大オランダを理想とするいくつかのバージョン、1920年にドイツから併合され、1940年から1944年にかけ てドイツに再併合されたベルギーのドイツ語圏共同体もある。しかし、これらのイデオロギーはいずれも、選挙の際には非常に少数派であり、政治的には取るに 足らないものである。  中国本土と台湾の民族言語地図[43]。 中国は広大な地理的範囲をカバーし、民族の意味で「中華民國」または中国の国民という概念を使用している。それでもなお、人口の90%以上を占める多数派 の漢民族と、55を下らない少数民族を公式に認めている。 フィリップ・G・ローダーによれば、モルドバはソ連時代の「分断国家」(モルダビアSSR)の一例であり、「分断国家の国民国家プロジェクトが先行国家の 国民国家プロジェクトに取って代わった」のである。モルドバでは、ルーマニアとの再統一を求める大学教員や学生の強い煽動にもかかわらず、モルダビア SSR内で形成された国民国家プロジェクトが、大ルーマニアという戦間期の国民国家プロジェクトへの回帰を求めるプロジェクトに優先した」[44]。 |

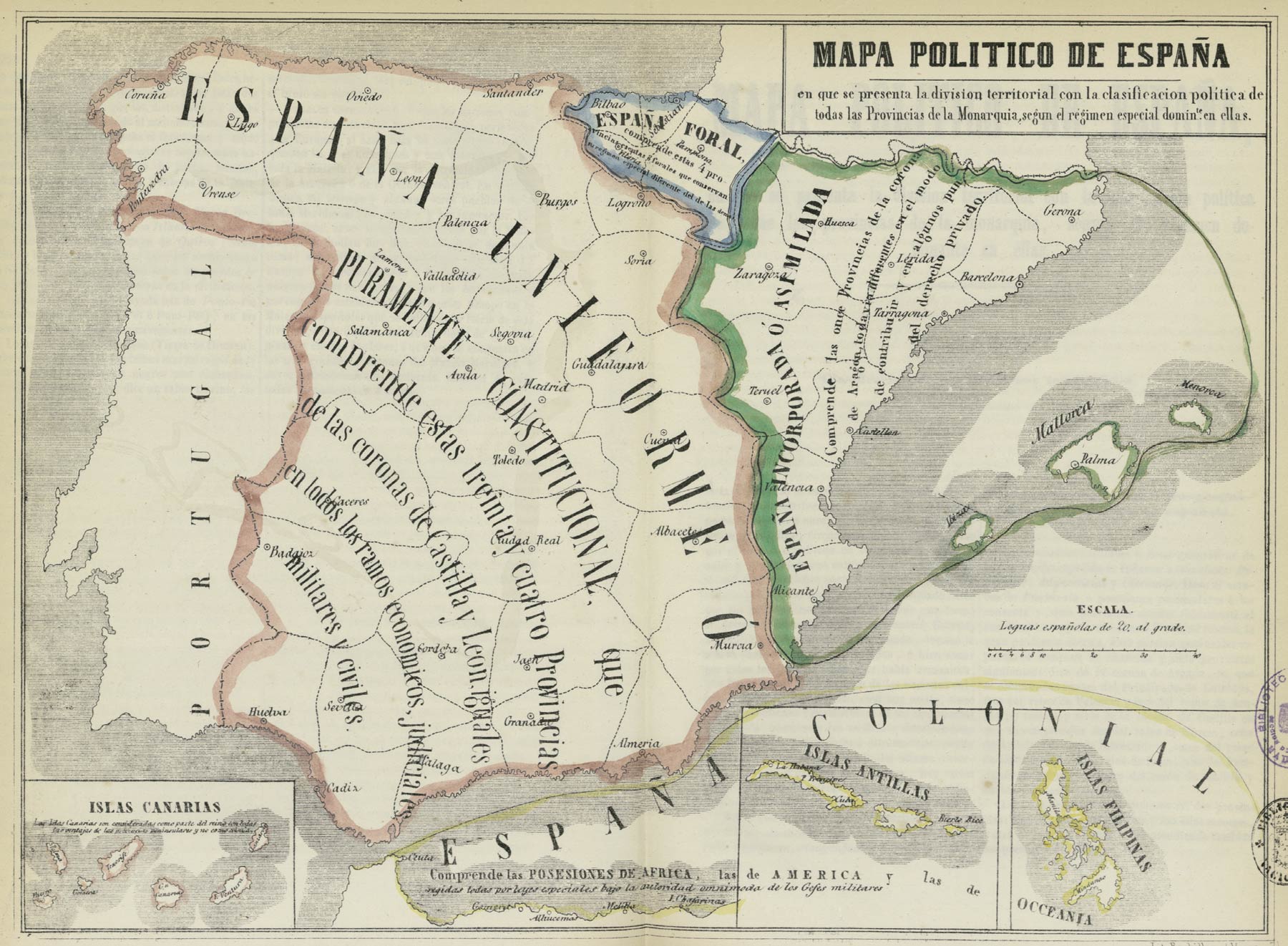

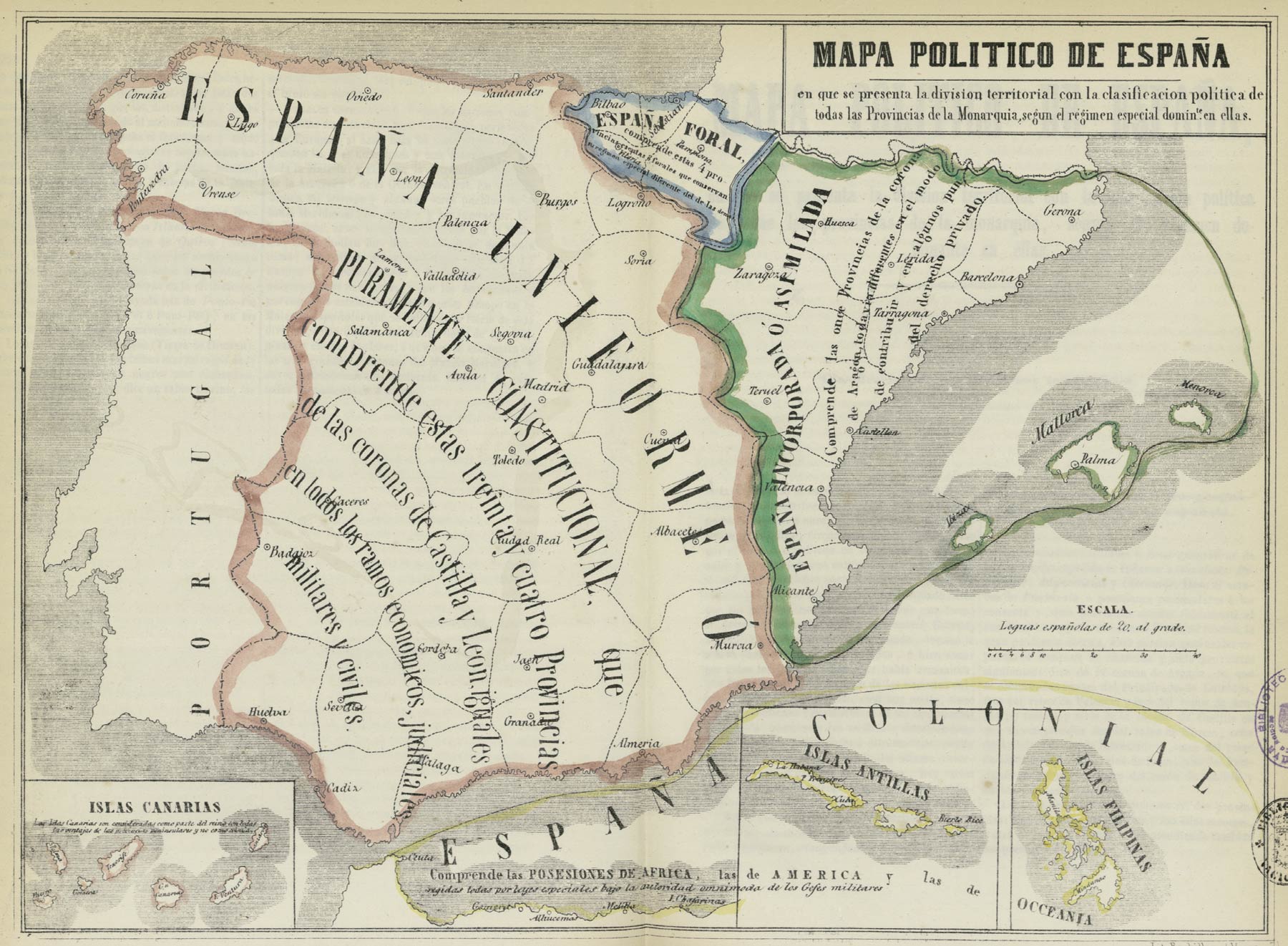

| Specific cases This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. Please help improve this section or discuss this issue on the talk page. (March 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Israel Israel was founded as a Jewish state in 1948. Its "Basic Laws" describe it as both a Jewish and a democratic state. The Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People (2018) explicitly specifies the nature of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people.[45][46] According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 75.7% of Israel's population are Jews.[47] Arabs, who make up 20.4% of the population, are the largest ethnic minority in Israel. Israel also has very small communities of Armenians, Circassians, Assyrians, Samaritans.[48] There are also some non-Jewish spouses of Israeli Jews. However, these communities are very small, and usually number only in the hundreds or thousands.[49] Kingdom of the Netherlands The Kingdom of the Netherlands presents an unusual example in which one kingdom represents four distinct countries. The four countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands are:[50] Netherlands (including the provinces in continental Europe and the special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba) Aruba Curaçao Sint Maarten Each is expressly designated as a land in Dutch law by the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[51] Unlike the German Länder and the Austrian Bundesländer, landen is consistently translated as "countries" by the Dutch government.[52][53][54] Spain See also: Spanish nationalism  Iberian Kingdoms in 1400 While historical monarchies often brought together different kingdoms/territories/ethnic groups under the same crown, in modern nation states political elites seek a uniformity of the population, leading to state nationalism.[55][56] In the case of the Christian territories of the future Spain, neighboring Al-Andalus, there was an early perception of ethnicity, faith and shared territory in the Middle Ages (13th–14th centuries), as documented by the Chronicle of Muntaner in the proposal of the Castilian king to the other Christian kings of the peninsula: "...if these four Kings of Spain whom he named, who are of one flesh and blood, held together, little need they fear all the other powers of the world...".[57][58][59] After the dynastic union of the Catholic Monarchs in the 15th century, the Spanish Monarchy ruled over different kingdoms, each with its own cultural, linguistic and political particularities, and the kings had to swear by the Laws of each territory before the respective Parliaments. Forming the Spanish Empire, at this time the Hispanic Monarchy had its maximum territorial expansion. After the War of the Spanish Succession, rooted in the political position of the Count-Duke of Olivares and the absolutism of Philip V, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Decrees of Nueva Planta was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state. As in other contemporary European states, political union was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation-state, in this case not on a uniform ethnic basis, but through the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilians, over those of other ethnic groups, who became national minorities to be assimilated.[60][61] In fact, since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards Catalan-speaking territories (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, part of Aragon) and other national minorities, as Basques and Galicians, have been a historical constant.[62][63][64][65][66]  School map of Spain from 1850. On it, the State is divided into four parts: – "Fully constitutional Spain", which includes Castile and the Galician-speaking territories. – "Annexed or assimilated Spain": the territories of the Crown of Aragon, the more significant part of which, except Aragon proper, are Catalan-speaking-, "Foral Spain", which includes Basque-speaking territories, – and "Colonial Spain", with the last overseas colonial territories. The process of assimilation began with secret instructions to the corregidores of the Catalan territory: they "will take the utmost care to introduce the Castilian language, for which purpose he will give the most temperate and disguised measures so that the effect is achieved, without the care being noticed."[67] From there, actions in the service of assimilation, discreet or aggressive, were continued, and reached to the last detail, such as, in 1799, the Royal Certificate forbidding anyone to "represent, sing and dance pieces that were not in Spanish."[67] These nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[68][69][70][71] and still in force,[72][73][74][75] have been, and still are, the seed of repeated territorial conflicts within the State. Although official Spanish history describes a "natural" decline of the Catalan language and increasing replacement by Spanish between the 16th and 19th centuries, especially among the upper classes, a survey of language usage in 1807, commissioned by Napoleon, indicates that except in the royal courts, Spanish is absent from everyday life. It is indicated that Catalan "is taught in schools, printed and spoken, not only among the lower class, but also among people of first quality, also in social gatherings, as in visits and congresses", indicating that it is spoken everywhere "except in the royal courts". He also indicates that Catalan is also spoken "in the Kingdom of Valencia, in the islands of Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza, Sardinia, Corsica and much of Sicily, in the Vall of Aran and Cerdaña".[76] The nationalization process accelerated in the 19th century, in parallel to the origin of Spanish nationalism, the social, political and ideological movement that tried to shape a Spanish national identity based on the Castilian model, in conflict with the other historical nations of the State. Politicians of the time were aware that despite the aggressive policies pursued up to that time, the uniform and monocultural "Spanish nation" did not exist, as indicated in 1835 by Antonio Alcalà Galiano, when in the Cortes del Estatuto Real he defended the effort "To make the Spanish nation a nation that neither is nor has been until now."[77] In 1906, the Catalanist party Solidaritat Catalana was founded to try to mitigate the economically and culturally oppressive treatment of Spain towards the Catalans. One of the responses of Spanish nationalism came from the military state with statements such as that of the publication La Correspondencia militar: "The Catalan problem is not solved, well, by freedom, but by restriction; not by palliatives and pacts, but by iron and fire". Another came from important Spanish intellectuals, such Pio Baroja and Blasco Ibañez, calling the Catalans "Jews", considered a serious insult at that time when racism was gaining strength.[71] Building the nation (as in France, it was the state that created the nation, and not the opposite process) is an ideal that the Spanish elites constantly reiterated, and, one hundred years later than Alcalá Galiano, for example, we can also find it in the mouth of the fascist José Pemartín, who admired the German and Italian modeling policies:[71] "There is an intimate and decisive dualism, both in Italian fascism and in German National Socialism. On the one hand, the Hegelian doctrine of the absolutism of the state is felt. The State originates in the Nation, educates and shapes the mentality of the individual; is, in Mussolini's words, the soul of the soul» And will be found again two hundred years later, from the socialist Josep Borrell:[78] The modern history of Spain is an unfortunate history that meant that we did not consolidate a modern State. Independenceists think that the nation makes the State. I think the opposite. The State makes the nation. A strong State, which imposes its language, culture, education. The turn of the 20th century, and the first half of that century, have seen the most ethnic violence, coinciding with a racism that even came to identify states with races; in the case of Spain, with a supposed Spanish race sublimated in Castilian, of which national minorities were degenerate forms, and the first of those that needed to be exterminated.[71] There were even public proposals for the repression of whole Catalonia, and even the extermination of Catalans, such as that of Juan Pujol, Head of Press and Propaganda of the Junta de Defensa Nacional during the Spanish Civil War, in La Voz de España,[79] or that of Queipo de Llano, in a radio address[80][81] in 1936, among others. The influence of Spanish nationalism could be found in a pogrom in Argentina, during the Tragic Week, in 1919.[82] It was called to attack Jews and Catalans indiscriminately, possibly because the influence of Spanish nationalism, which at the time described Catalans as a Semitic ethnicity.[71] Also, one can find discourses on the alienation of Catalan speakers, such as, for example, an article entitled «Cataluña bilingüe», by Menéndez Pidal, in which he defends the Romanones decree against the Catalan language, published in El Imparcial, on 15 December 1902:[71] «… There they will see that the Courts of the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation never had Catalan as their official language; that the kings of Aragon, even those of the Catalan dynasty, used Catalan only in Catalonia, and used Spanish not only in the Cortes of Aragon, but also in foreign relations, the same with Castile or Navarre as with the infidel kings of Granada , from Africa or Asia, because even in the most important days of Catalonia, Spanish prevailed as the language of the Aragonese kingdom and Catalan was reserved for the peculiar affairs of the Catalan county..." or the article "Los Catalanes. A las Cortes Constituyentes », appeared in several newspapers, among others: El Dia de Alicante, June 23, 1931, El Porvenir Castellano and El Noticiero de Soria, July 2, 1931, in the Heraldo de Almeria on June 4, 1931, sent by the "Pro-Justice Committee", with a post office box in Madrid:[71] "The Catalanists have recently declared that they are not Spanish, nor do they want to be, nor can they be. They have also been saying for a long time that they are an oppressed, enslaved, exploited people. It is imperative to do them justice... That they return to Phenicia or that they go wherever they want to admit them. When the Catalan tribes saw Spain and settled in the Spanish territory that is now occupied by the provinces of Barcelona, Gerona, Lérida and Tarragona, how little they imagined that the case of the captivity of the tribes of Israel in Egypt would be repeated there! !... Let us respect his most holy will. They are eternally inadaptable... Their cowardice and selfishness leaves them no room for fraternity... So, we propose to the Constituent Cortes the expulsion of the Catalanists... You are free! The Republic opens wide the doors of Spain, your prison. go away Get out of here. Go back to Phenicia, or go wherever you want, how big is the world." The main scapegoat of Spanish nationalism is the non-Spanish languages, which over the last three hundred years have been tried to be replaced by Spanish with hundreds of laws and regulations,[70] but also with acts of great violence, such as during the civil war. For example, the statements of Queipo de Llano can be found in the article entitled "Against Catalonia, the Israel of the Modern World", published in the Diario Palentino on November 26, 1936, where it is dropped that in America Catalans are considered a race of Jews, because they use the same procedures that the Hebrews perform in all the nations of the Globe. And considering the Catalans as Hebrews and considering his anti-Semitism "Our struggle is not a civil war, but a war for Western civilization against the Jewish world," it is not surprising that Queipo de Llano expressed his anti-Catalan intentions: "When the war is over, Pompeu Fabra and his works will be dragged along the Ramblas"[71] (it was not talk to talk, the house of Pompeu Fabra, the standardizer of Catalan language, was raided and his huge personal library burned in the middle of the street. Pompeu Fabra was able to escape into exile).[83] Another example of fascist aggression towards the Catalan language is pointed out by Paul Preston in "The Spanish Holocaust",[84] given that during the civil war it practically led to an ethnic conflict: "In the days following the occupation of Lleida (…), the republican prisoners identified as Catalans were executed without trial. Anyone who heard them speak Catalan was very likely to be arrested. The arbitrary brutality of the anti-Catalan repression reached such a point that Franco himself had to issue an order ordering that mistakes that could later be regretted be avoided ". "There are examples of the murder of peasants for no other apparent reason than that of speaking Catalan" After a possible attempt at ethnic cleansing,[63][71] the biopolitical imposition of Spanish during the Franco dictatorship, to the point of being considered an attempt at cultural genocide, democracy consolidated an apparent asymmetric regime of bilingualism of sorts, wherein the Spanish government has employed a system of laws that favored Spanish over Catalan,[85][86][87][88][72][73][89][74] which becomes the weaker of the two languages, and therefore, in the absence of other states where it is spoken, is doomed to extinction in the medium or short term. In the same vein, its use in the Spanish Congress is prevented,[90][91] and it is prevented from achieving official status Europe, unlike less spoken languages such as Gaelic.[92] In other institutional areas, such as justice, Plataforma per la Llengua has denounced Catalanophobia. The association Soberania i Justícia have also denounced it in an act in the European Parliament. It also takes the form of linguistic secessionism, originally advocated by the Spanish extreme right and which has finally been adopted by the Spanish government itself and state bodies.[93][94][95] In November 2005, Omnium Cultural organized a meeting of Catalan and Madrid intellectuals in the Círculo de bellas artes in Madrid to show support for ongoing reform of Catalan Statute of Autonomy, which sought to resolve territorial tensions, and among other things better protect the Catalan language. On the Catalan side, a flight was made with one hundred representatives of the cultural, civic, intellectual, artistic and sporting world of Catalonia, but on the Spanish side, except Santiago Carrillo, a politician from the Second Republic, did not attend any more.[96][97] The subsequent failure of the statutory reform with respect to its objectives opened the door to the growth of Catalan sovereignty.[98] Apart from language discrimination by public officials,[99][100] e.g. in the hospitals,[101] the prohibition until September 2023 (47 years after Franco's death) of using the Catalan language in state institutions such as Court,[102] despite being the former Crown of Aragon, with three Catalan-speaking territories, one of the co-founders of the current Spanish state, is nothing more than the continuation of the foreignization of Catalan-speaking people from the first third of the 20th century, in full swing of state racism and fascism. It also can be pointed the linguistic secessionism, originally advocated by the Spanish far right and which has finally been adopted by the Spanish government itself and state bodies.[93][103] By fragmenting Catalan language into as many languages as territories, it becomes inoperative, economically suffocated, and becomes a political toy in the hands of territorial politicians. Susceptible to be classified as an ethnic democracy, the Spanish State currently only recognizes the Romani as a national minority, excluding Catalans (and, of course, Valencians and Balearic), Basques and Galicians. However, it is evident to any external observer that there are social diversities within the Spanish State that qualify as manifestations of national minorities, such as, for example, the existence of the main three linguistic minorities in their ancestral territories.[104] United Kingdom  Nation state is located in the United KingdomEnglandEnglandScotlandScotlandNorthern IrelandNorthern IrelandWalesWales Home Nations of the United Kingdom The United Kingdom is an unusual example of a nation state due to its "countries within a country". The United Kingdom is formed by the union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but it is a unitary state formed initially by the merger of two independent kingdoms, the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland, but the Treaty of Union (1707) that set out the agreed terms has ensured the continuation of distinct features of each state, including separate legal systems and separate national churches.[105][106][107] In 2003, the British Government described the United Kingdom as "countries within a country".[108] While the Office for National Statistics and others describe the United Kingdom as a "nation state",[109][110] others, including a then Prime Minister, describe it as a "multinational state",[111][112][113] and the term Home Nations is used to describe the four national teams that represent the four nations of the United Kingdom (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales).[114] Some refer to it as a "Union State".[115][116] |

具体的事例 このセクションには、記事のトピックとは関係のない内容が含まれている可能性がある。このセクションの改善にご協力いただくか、トークページでこの問題に ついて議論してほしい。(2024年3月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) イスラエル イスラエルは1948年にユダヤ人国家として建国された。その「基本法」には、ユダヤ人国家であると同時に民主主義国家でもあると記されている。基本法 イスラエル中央統計局によると、イスラエルの人口の75.7%はユダヤ人である[47]。人口の20.4%を占めるアラブ人はイスラエル最大の少数民族で ある。イスラエルには、アルメニア人、サーカシア人、アッシリア人、サマリア人のごく小規模なコミュニティもある[48]。しかし、これらのコミュニティ は非常に小さく、通常は数百人から数千人程度である[49]。 オランダ王国 オランダ王国は、1つの王国が4つの異なる国を代表している珍しい例である。オランダ王国の4つの国は以下の通りである[50]。 オランダ(ヨーロッパ大陸の州とボネール、シント・ユースタティウス、サバの特別自治体を含む) アルバ キュラソー シント・マールテン島 ドイツ連邦やオーストリア連邦とは異なり、オランダ政府はlandenを一貫して「国」と訳している[52][53][54]。 スペイン 以下も参照: スペイン国民主義  1400年のイベリア王国 歴史的な君主制では異なる王国・領土・民族を同じ王家の下にまとめることが多かったが、近代国民国家では政治的エリートが国民の統一を求め、国家ナショナ リズムへとつながっていく。 [55][56]アル=アンダルスに隣接する将来のスペインのキリスト教領土の場合、中世(13世紀~14世紀)には民族、信仰、領土の共有という認識が 早くから存在しており、『ムンタネル年代記』がカスティーリャ王から半島の他のキリスト教王への提案として記録している。 ...もし彼が名指ししたスペインの4人の王が、血も肉も同じであり、共に保持するならば、世界の他のすべての勢力を恐れる必要はほとんどない..." [57][58][59] 15世紀のカトリック君主の王朝統合後、スペイン君主制は、それぞれが文化的、言語的、政治的な特殊性を持つ異なる王国を統治し、王はそれぞれの議会でそ れぞれの領土の法律に誓わなくてはならなかった。スペイン帝国を形成したこの時期、ヒスパニック王政は領土を最大限に拡大した。 スペイン継承戦争の後、オリヴァレス伯爵の政治的立場とフィリップ5世の絶対主義に根ざし、ヌエバ・プランタ勅令によるカスティーリャ王家によるアラゴン 王家の同化が、スペイン国民国家の成立の第一歩となった。他のヨーロッパの現代国家と同様、政治的結合がスペイン国民国家創設の第一歩であったが、この場 合、統一された民族的基盤ではなく、支配的な民族集団(この場合はカスティーリャ人)の政治的・文化的特徴を、同化されるべき少数民族となった他の民族集 団に押し付けることによってであった。 [実際、1714年の政治的統一以来、カタルーニャ語圏(カタルーニャ、バレンシア、バレアレス諸島、アラゴンの一部)やバスク人、ガリシア人などの少数 民族に対するスペインの同化政策は歴史的に一貫している[62][63][64][65][66]。  1850年のスペインの学校地図。カスティーリャとガリシア語圏が含まれる。- 併合または同化されたスペイン」:アラゴン王家の領土で、アラゴン本国を除く大部分はカタルーニャ語を話す領土、「フォラル・スペイン」:バスク語を話す 領土、「植民地スペイン」:最後の海外植民地領土。 同化のプロセスは、カタルーニャ領のコレギドールに対する「カスティーリャ語を導入するために最大限の注意を払うこと。 「1799年には、「スペイン語でない曲を表現し、歌い、踊る」ことを禁止する勅令が出された[67]。このような民族主義的な政策は、時に非常に攻撃的 であり[68][69][70][71]、現在も有効である[72][73][74][75]。 スペインの公式な歴史では、16世紀から19世紀にかけて、特に上流階級の間でカタルーニャ語の「自然な」衰退とスペイン語への置き換えが進んだとされて いるが、1807年にナポレオンの依頼で行われた言語使用状況の調査では、王宮を除いて日常生活からスペイン語が消えていることが示されている。カタルー ニャ語は「学校で教えられ、印刷され、下層階級だけでなく、一流の人々の間でも話され、訪問や会議のような社交の場でも話される」ことが示されており、 「王宮を除けば」どこでも話されていることを示している。また、カタルーニャ語は「バレンシア王国、マヨルカ島、メノルカ島、イビサ島、サルデーニャ島、 コルシカ島、シチリア島の大部分、アラン渓谷、セルダーニャ」でも話されている[76]。 国有化プロセスは19世紀に加速し、スペインナショナリズム(スペインの他の歴史的国民と対立しながら、カスティーリャ・モデルに基づくスペインの国民的 アイデンティティを形成しようとした社会的、政治的、イデオロギー的運動)の起源と並行して進行した。1835年、アントニオ・アルカラ・ガリャノは、エ スタトゥート・レアル会議(Cortes del Estatuto Real)において、「スペイン国民を単一民族にすること」を擁護した。 「スペイン国民を、現在も昔もない国民にすること」[77]であった。 1906年、スペインのカタルーニャ人に対する経済的・文化的抑圧を緩和するために、カタルーニャ主義政党「カタルーニャ連帯」が設立された。スペインの 国民主義の反応のひとつは、『La Correspondencia militar』誌のような声明を出した軍事国家からのものであった: 「カタルーニャ問題は、自由によって解決されるのではなく、制限によって解決される。また、ピオ・バロハやブラスコ・イバニェスといったスペインの重要な 知識人が、カタルーニャ人を「ユダヤ人」と呼び、人種差別が強まりつつあった当時、深刻な侮辱とみなされた。 [71]国民を建設すること(フランスと同様、国民を創造したのは国家であり、その逆のプロセスではない)は、スペインのエリートたちが常に繰り返してい た理想であり、例えば、アルカラ・ガリャノから100年後、ドイツやイタリアのモデル化政策を賞賛していたファシスト、ホセ・ペマルティンの口からも見出 すことができる[71]。 「イタリアのファシズムにもドイツの国家社会主義にも、親密で決定的な二元論がある。一方では、国家の絶対主義というヘーゲルの教義が感じられる。国家は 国民に由来し、個人の精神を教育し、形成する。ムッソリーニの言葉を借りれば、魂の魂である」。 そして、200年後、社会主義者ジョセップ・ボレルの言葉[78]から再び発見されるだろう。 スペインの近代史は、近代国家を形成できなかった不幸な歴史である。独立論者は、国民が国家を作ると考えている。私はその反対だ。国家が国民を作るのだ。 強力な国家は、自国の言語、文化、教育を押し付ける。 スペインの場合、カスティーリャ語に昇華されたスペイン民族が想定され、国民的マイノリティは退化した形態であり、絶滅させるべきものの筆頭であった。 [71]カタルーニャ全土の弾圧、さらにはカタルーニャ人の抹殺を公的に提案することさえあった。たとえば、スペイン内戦中に国家防衛委員会の報道宣伝部 長であったフアン・プジョルが『ラ・ボス・デ・エスパーニャ(La Voz de España)』に寄せた言葉[79]や、ケイポ・デ・ラーノが1936年にラジオで行った演説[80][81]などである。 スペインの国民主義の影響は、1919年の悲劇的な一週間の間にアルゼンチンで起こったポグロムに見出すことができる[82]。ユダヤ人とカタロニア人を 無差別に攻撃することが呼びかけられたが、それはおそらく、当時カタロニア人をセム系民族として記述していたスペインの国民主義の影響によるものであった [71]。 また、例えば、1902年12月15日にEl Imparcial誌に掲載されたメネンデス・ピダルによる「カタルーニャのバイリンガル化」と題された記事で、カタルーニャ語に対するロマノネス法令を 擁護しているように、カタルーニャ語話者の疎外に関する言説を見つけることができる[71]。 「... そこには、カタルーニャ・アラゴン同盟の宮廷がカタルーニャ語を公用語としたことは一度もなかったことが書かれている; アラゴンの王たちは、カタルーニャ王朝の王たちでさえも、カタルーニャ地方でのみカタルーニャ語を使用し、アラゴンのコルテスだけでなく、対外関係におい てもスペイン語を使用していた。 ..」 または、"Los Catalanes. A las Cortes Constituyentes "という記事がいくつかの新聞に掲載された: 1931年6月23日付のエル・ディア・デ・アリカンテ紙、1931年7月2日付のエル・ポルヴェニール・カステジャーノ紙、エル・ノティシエロ・デ・ソ リア紙、1931年6月4日付のヘラルド・デ・アルメリア紙に掲載された。 「カタルーニャ人は最近、自分たちはスペイン人ではないし、スペイン人になりたいとも思わないし、スペイン人になることもできないと宣言した。彼らはま た、長い間、自分たちは抑圧され、奴隷となり、搾取されている人々だと言い続けてきた。彼らを正当に評価する必要がある。彼らがフェニキアに戻るか、彼ら が受け入れたいところに行くことだ。カタルーニャの諸部族がスペインを見て、現在バルセロナ、ジェローナ、レリダ、タラゴナの各州が占めているスペイン領 に定住したとき、エジプトでイスラエルの諸部族が捕囚されたケースがそこで繰り返されるとは、どれほど想像もしなかったことだろう!!... 彼の最も神聖な意志を尊重しよう。彼らは永遠に不適格だ... 臆病で利己的な彼らに友愛の余地はない。だから、我々は立憲コルテスにカタルーニャ主義者の追放を提案する... 君たちは自由だ!共和国はスペインという牢獄の扉を大きく開く。フェニキアに帰るか、どこへでも好きなところへ行くがいい。"世界はなんと広いのだろう。 スペインのナショナリズムの主なスケープゴートはスペイン語以外の言語であり、過去300年間、何百もの法律や規制[70]によってスペイン語に置き換え られようとしてきたが、内戦時のような大きな暴力行為もあった。例えば、ケイポ・デ・ラーノの発言は、1936年11月26日付の『ディアリオ・パレン ティーノ』紙に掲載された「現代世界のイスラエル、カタルーニャに対して」と題された記事の中に見ることができる。そこでは、アメリカではカタルーニャ人 はユダヤ人の一種とみなされている。そして、カタルーニャ人をヘブライ人とみなし、彼の反ユダヤ主義を考慮すると、「我々の闘いは内戦ではなく、ユダヤ世 界に対する西洋文明のための戦争である: 「戦争が終われば、ポンペウ・ファブラと彼の作品はランブラス通りに引きずり込まれるだろう」[71](口先だけでなく、カタルーニャ語の標準化者である ポンペウ・ファブラの家は襲撃され、彼の膨大な個人蔵書は通りの真ん中で燃やされた。ポンペウ・ファブラは亡命することができた)[83] カタルーニャ語に対するファシストの侵略のもうひとつの例は、ポール・プレストンが『スペインのホロコースト』の中で指摘している[84]: 「リェイダ占領後の数日間(...)、カタルーニャ人と確認された共和派の囚人は裁判を受けることなく処刑された。彼らがカタルーニャ語を話すのを聞いた 者は、逮捕される可能性が非常に高かった。反カタルーニャ弾圧の恣意的な残忍さは、フランコ自身が「後で後悔するような過ちを犯さないように」と命令を出 さなければならないほどであった。「カタルーニャ語を話すという理由以外に明白な理由はなく、農民が殺害された例もある」 民族浄化の試みの可能性の後[63][71]、フランコ独裁政権下におけるスペイン語の生政治的な押し付けは、文化的ジェノサイドの試みと見なされるほど であったが、民主主義は一種のバイリンガリズムという見かけ上非対称な体制を強化した、 スペイン政府はカタルーニャ語よりもスペイン語を優遇する法制度を採用しており[85][86][87][88][72][73][89][74]、スペ イン語は2つの言語のうち弱いほうの言語となるため、他にスペイン語が話されている州がない場合、中長期的にも短期的にも消滅する運命にある。同じよう に、スペイン議会での使用が妨げられており[90][91]、ゲール語のようなあまり話されていない言語とは異なり、ヨーロッパでの公用語化が妨げられて いる[92]。司法など他の制度分野では、Plataforma per la Llenguaがカタルーニャ恐怖症を糾弾している。また、Soberania i Justícia協会も、欧州議会での行動でこれを非難している。また、もともとはスペインの極右勢力によって提唱され、最終的にはスペイン政府自身や国 家機関によって採用された言語分離主義という形もとっている[93][94][95]。 2005年11月、Omnium CulturalはマドリードのCírculo de bellas artesでカタルーニャとマドリードの知識人による会合を開催し、現在進行中のカタルーニャ自治憲章改革への支持を表明した。カタルーニャ側では、カタ ルーニャの文化、市民、知識人、芸術、スポーツ界の代表者100人が出席したが、スペイン側では、第二共和政の政治家サンティアゴ・カリージョ以外は出席 しなかった[96][97]。 その後、法定改革がその目的に対して失敗したことで、カタルーニャの主権拡大への扉が開かれた[98]。 病院などの公務員による言語差別[99][100]は別として[101]、裁判所などの国家機関においてカタルーニャ語を使用することを2023年9月 (フランコの死後47年)まで禁止すること[102]は、カタルーニャ語を話す3つの領土を持つ旧アラゴン王国で、現在のスペイン国家の共同創設者の一人 であるにもかかわらず、国家による人種差別とファシズムが本格化した20世紀の前半3分の1からのカタルーニャ語を話す人々の外国化の継続以外の何もので もない。また、もともとはスペインの極右勢力によって提唱され、ついにはスペイン政府自身や国家機関によって採用された言語分離主義を指摘することもでき る[93][103]。カタルーニャ語を領土の数だけ言語に分断することによって、カタルーニャ語は機能しなくなり、経済的に窒息させられ、領土政治家の 手中にある政治的おもちゃとなる。 民族民主主義に分類されやすいスペイン国家は現在、ロマニ族のみを国民少数民族として認めており、カタルーニャ人(もちろんバレンシア人、バレアレス人 も)、バスク人、ガリシア人は除外されている。しかし、スペイン国家内には、例えば、先祖伝来の領土に主要な3つの言語的少数派が存在するなど、国民的少 数派の現れとして適格な社会的多様性が存在することは、外部の観察者にとっては明らかである[104]。 イギリス  国民国家はイギリスに位置するイギリスEnglandスコットランドNorthern Ireland北アイルランドNorthern IrelandウェールズWales イギリスの国民国家 イギリスは、「国の中に国がある」という珍しい国民国家の例である。イギリスはイングランド、スコットランド、ウェールズ、北アイルランドの連合によって 形成されているが、当初はイングランド王国(ウェールズをすでに含んでいた)とスコットランド王国という2つの独立した王国の合併によって形成された単一 国家であり、合意された条件を定めた連合条約(1707年)によって、別々の法制度や別々の国民教会など、それぞれの国家の明確な特徴の継続が保証されて いる[105][106][107]。 2003年、イギリス政府はイギリスを「国の中の国」と表現した[108]。国家統計局などはイギリスを「国民国家」と表現しているが[109] [110]、当時の首相を含む他の人たちはイギリスを「多国籍国家」と表現している[111][112][113]。ホーム・ネイションズという言葉は、 イギリスの4つの国家(イングランド、北アイルランド、スコットランド、ウェールズ)を代表する4つのナショナル・チームを表現するのに使われている [114]。「ユニオン国家」と呼ぶ人もいる[115][116]。 |

| Minorities This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The most obvious deviation from the ideal of "one nation, one state" is the presence of minorities, especially ethnic minorities, which are clearly not members of the majority nation. An ethnic nationalist definition of a nation is necessarily exclusive: ethnic nations typically do not have open membership. In most cases, there is a clear idea that surrounding nations are different, and that includes members of those nations who live on the "wrong side" of the border. Historical examples of groups who have been specifically singled out as outsiders are the Roma and Jews in Europe. Negative responses to minorities within the nation state have ranged from cultural assimilation enforced by the state, to expulsion, persecution, violence, and extermination. The assimilation policies are usually enforced by the state, but violence against minorities is not always state-initiated: it can occur in the form of mob violence such as lynching or pogroms. Nation states are responsible for some of the worst historical examples of violence against minorities not considered part of the nation. However, many nation states accept specific minorities as being part of the nation, and the term national minority is often used in this sense. The Sorbs in Germany are an example: for centuries they have lived in German-speaking states, surrounded by a much larger ethnic German population, and they have no other historical territory. They are now generally considered to be part of the German nation and are accepted as such by the Federal Republic of Germany, which constitutionally guarantees their cultural rights. Of the thousands of ethnic and cultural minorities in nation states across the world, only a few have this level of acceptance and protection. Multiculturalism is an official policy in some states, establishing the ideal of coexisting existence among multiple and separate ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups. Other states prefer the interculturalism (or "melting pot" approach) alternative to multiculturalism, citing problems with latter as promoting self-segregation tendencies among minority groups, challenging national cohesion, polarizing society in groups that can't relate to one another, generating problems in regard to minorities and immigrants' fluency in the national language of use and integration with the rest of society (generating hate and persecution against them from the "otherness" they would generate in such a case according to its adherents), without minorities having to give up certain parts of their culture before being absorbed into a now changed majority culture by their contribution. Many nations have laws protecting minority rights. When national boundaries that do not match ethnic boundaries are drawn, such as in the Balkans and Central Asia, ethnic tension, massacres and even genocide, sometimes has occurred historically (see Bosnian genocide and 2010 South Kyrgyzstan ethnic clashes). |

マイノリティ このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異 議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性がある。(2015年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 一国民一国家」の理想から最も明白に逸脱しているのは、マイノリティ、特に少数民族の存在であり、これらは明らかに多数民族の一員ではない。民族ナショナ リストによる国民の定義は、必然的に排他的なものである。民族国家は通常、開かれたメンバーシップを持たない。ほとんどの場合、周辺諸国は異なるという明 確な考え方があり、その中には国境の「反対側」に住む国家のメンバーも含まれる。特にアウトサイダーとして特別視されてきた集団の歴史的な例は、ヨーロッ パのロマやユダヤ人である。 国民国家内のマイノリティに対する否定的な反応は、国家によって強制される文化的同化から、追放、迫害、暴力、絶滅にまで及んでいる。同化政策は通常、国 家によって強制されるが、マイノリティに対する暴力は必ずしも国家が主導するとは限らない。国民国家は、国家の一部とみなされていないマイノリティに対す る暴力の歴史的な最悪の例のいくつかに責任がある。 しかし、多くの国民国家は特定のマイノリティを国家の一部として受け入れており、マイノリティという言葉はしばしばこの意味で使われる。ドイツにおけるソ ルブ人はその一例である。彼らは何世紀にもわたり、ドイツ語を話す州に住み、周囲をはるかに多いドイツ系民族に囲まれてきた。ドイツ連邦共和国は憲法で彼 らの文化的権利を保障している。世界の国民国家には何千もの民族的・文化的マイノリティが存在するが、これほどまでに受け入れられ、保護されているのはご く少数である。 多文化主義が公式の政策となっている国家もあり、複数の民族、文化、言語集団の共存という理想を掲げている。他の国家は多文化主義に代わるインターカル チュラリズム(または「メルティング・ポット」アプローチ)を好み、後者の問題点として、マイノリティ集団の自己分離傾向を促進し、国民的結束を困難に し、社会を互いに関係のない集団に二極化させることを挙げている、 マイノリティや移民がその国の言語を流暢に使いこなし、社会の他の部分と統合することに関して問題が生じる(そのような場合、マイノリティはその貢献に よって変化した多数派の文化に吸収される前に、自分たちの文化のある部分をあきらめなければならない。多くの国民は、マイノリティの権利を保護する法律を 持っている。 バルカン半島や中央アジアのように、民族の境界線と一致しない国境が引かれた場合、民族間の緊張、虐殺、さらには大量殺戮が歴史的に起こることもある(ボ スニアの大量虐殺や2010年の南キルギスの民族衝突を参照)。 |

| Irredentism This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Irredentism The Greater German Reich under Nazi Germany in 1943 In principle, the border of a nation state would extend far enough to include all the members of the nation, and all of the national homeland. Again, in practice, some of them always live on the 'wrong side' of the border. Part of the national homeland may be there too, and it may be governed by the 'wrong' nation. The response to the non-inclusion of territory and population may take the form of irredentism: demands to annex unredeemed territory and incorporate it into the nation state. Irredentist claims are usually based on the fact that an identifiable part of the national group lives across the border. However, they can include claims to territory where no members of that nation live at present, because they lived there in the past, the national language is spoken in that region, the national culture has influenced it, geographical unity with the existing territory, or a wide variety of other reasons. Past grievances are usually involved and can cause revanchism. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish irredentism from pan-nationalism, since both claim that all members of an ethnic and cultural nation belong in one specific state. Pan-nationalism is less likely to specify the nation ethnically. For instance, variants of Pan-Germanism have different ideas about what constituted Greater Germany, including the confusing term Grossdeutschland, which, in fact, implied the inclusion of huge Slavic minorities from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Typically, irredentist demands are at first made by members of non-state nationalist movements. When they are adopted by a state, they typically result in tensions, and actual attempts at annexation are always considered a casus belli, a cause for war. In many cases, such claims result in long-term hostile relations between neighbouring states. Irredentist movements typically circulate maps of the claimed national territory, the greater nation state. That territory, which is often much larger than the existing state, plays a central role in their propaganda. Irredentism should not be confused with claims to overseas colonies, which are not generally considered part of the national homeland. Some French overseas colonies would be an exception: French rule in Algeria unsuccessfully treated the colony as a département of France. |

領土回復主義 このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異 議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性がある。(2015年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 主な記事 再統一主義 1943年、ナチス・ドイツ政権下の大ドイツ帝国 原理的には、国民国家の国境は、その国民全員と、その国民の故郷のすべてを包含するのに十分な距離まで広がっている。しかし、実際には、国境線の「反対 側」に住んでいる国民もいる。祖国の一部もそこにあり、「間違った」国民によって統治されているかもしれない。領土と人口の非包摂に対する反応は、贖罪さ れていない領土を併合して国民国家に編入するという要求、すなわちirredentismという形をとることがある。 再定住主義の主張は通常、国民集団の特定可能な一部が国境を越えて居住しているという事実に基づいている。しかし、過去にその地域に住んでいた、民族語が その地域で話されていた、民族文化がその地域に影響を与えた、既存の領土と地理的に一体である、その他さまざまな理由から、現在その国民が住んでいない領 土を主張することもある。通常、過去の不満が関与し、レバンチズムを引き起こすことがある。 民族主義も汎ナショナリズムも、民族的・文化的な国民全員が1つの特定の国家に属すると主張するものであるため、民族主義を汎ナショナリズムと区別するの は難しい場合がある。汎ナショナリズムは国民を民族的に特定することは少ない。たとえば、汎ドイツ主義の諸派は、大ドイツを構成するものについての考え方 が異なっており、グロス・ドイッチュラント(Grossdeutschland)という紛らわしい言葉もあるが、これは実際にはオーストリア=ハンガリー 帝国の膨大なスラブ系少数民族を含めることを意味していた。 通常、民族解放主義的な要求は、最初は非国家的な民族主義運動のメンバーによって出される。それが国家によって採用された場合、一般的には緊張を招き、実 際に併合を試みることは常に詭弁、つまり戦争の原因とみなされる。多くの場合、このような主張は近隣国家間の長期的な敵対関係につながる。領土回復運動は 通常、主張する国家領土、すなわち大国民国家の地図を流通させる。その領土はしばしば既存の国家よりもはるかに大きく、彼らのプロパガンダの中心的役割を 果たす。 領土回復主義を、一般に国民国家の一部とはみなされない海外植民地に対する主張と混同してはならない。フランスの海外植民地は例外である: アルジェリアのフランス統治は、この植民地をフランスのデパートメントとして扱い、失敗した。 |

| Future It has been speculated by both proponents of globalization and various science fiction writers that the concept of a nation state may disappear with the ever-increasing interconnectedness of the world.[25] Such ideas are sometimes expressed around concepts of a world government. Another possibility is a societal collapse and move into communal anarchy or zero world government, in which nation states no longer exist. Clash of civilizations The theory of the clash of civilizations lies in direct contrast to cosmopolitan theories about an ever more connected world that no longer requires nation states. According to political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, people's cultural and religious identities will be the primary source of conflict in the post–Cold War world. The theory was originally formulated in a 1992 lecture[117] at the American Enterprise Institute, which was then developed in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article titled "The Clash of Civilizations?",[118] in response to Francis Fukuyama's 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man. Huntington later expanded his thesis in a 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Huntington began his thinking by surveying the diverse theories about the nature of global politics in the post–Cold War period. Some theorists and writers argued that human rights, liberal democracy and capitalist free market economics had become the only remaining ideological alternative for nations in the post–Cold War world. Specifically, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man, argued that the world had reached a Hegelian "end of history". Huntington believed that while the age of ideology had ended, the world had reverted only to a normal state of affairs characterized by cultural conflict. In his thesis, he argued that the primary axis of conflict in the future will be along cultural and religious lines. As an extension, he posits that the concept of different civilizations, as the highest rank of cultural identity, will become increasingly useful in analyzing the potential for conflict. In the 1993 Foreign Affairs article, Huntington writes: It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.[118] Sandra Joireman suggests that Huntington may be characterised as a neo-primordialist, as, while he sees people as having strong ties to their ethnicity, he does not believe that these ties have always existed.[119] |

未来 グローバリゼーションの推進派やさまざまなSF作家の間では、世界の相互関係がますます深まるにつれて、国民国家という概念が消滅するかもしれないと推測 されている。もうひとつの可能性は、社会が崩壊し、国民国家がもはや存在しない共同体的無政府状態やゼロ世界政府へと移行することである。 文明の衝突 文明の衝突という理論は、もはや国民国家を必要としない、よりつながりの強い世界に関するコスモポリタン理論とは正反対である。政治学者のサミュエル・ P・ハンティントンによれば、人々の文化的・宗教的アイデンティティが、冷戦後の世界における紛争の主な原因となるという。 この理論は1992年にアメリカン・エンタープライズ研究所で行われた講義[117]で提唱されたもので、1992年のフランシス・フクヤマの著書 『The End of History and the Last Man(歴史の終わりと最後の人間)』[118]を受けて、1993年のフォーリン・アフェアーズの記事「文明の衝突?ハンティントンはその後、1996 年に出版した『文明の衝突と世界秩序の再構築』(原題:The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order)において、その論文をさらに発展させた。 ハンチントンは、冷戦後の世界政治のあり方に関する多様な理論を調査することから考えを始めた。一部の理論家や作家は、人権、自由民主主義、資本主義的自 由市場経済が、冷戦後の世界において国民に残された唯一のイデオロギー的選択肢になったと主張した。具体的には、フランシス・フクヤマは『歴史の終わりと 最後の人間』の中で、世界はヘーゲル的な「歴史の終わり」に達したと主張した。 ハンチントンは、イデオロギーの時代は終わったが、世界は文化的対立を特徴とする通常の状態に戻っただけだと考えた。彼は論文の中で、将来における紛争の 主要な軸は文化的・宗教的な線に沿ったものになると主張した。 その延長として、文化的アイデンティティの最高位である異なる文明という概念が、紛争の可能性を分析する上でますます有用になるだろうとした。 1993年のフォーリン・アフェアーズの記事の中で、ハンティントンはこう書いている: この新しい世界における紛争の根本的な原因は、イデオロギー的なものでも経済的なものでもない、というのが私の仮説である。人類間の大きな分断と紛争の主 な原因は文化的なものであろう。国民国家は世界情勢における最も強力なアクターであり続けるだろうが、世界政治の主要な対立は、国家間や異なる文明のグ ループ間で起こるだろう。文明の衝突が世界政治を支配する。文明間の断層線が未来の戦線となる。 サンドラ・ジョイレマンは、ハンティントンがネオ・プリモルディアリストとして特徴づけられるかもしれないと示唆しており、彼は人々が民族と強い絆で結ば れていると見ているが、こうした絆が常に存在していたとは考えていない[119]。 |

| Historiography Further information: Nationalist historiography Historians often look to the past to find the origins of a particular nation state. Indeed, they often put so much emphasis on the importance of the nation state in modern times, that they distort the history of earlier periods in order to emphasize the question of origins. Lansing and English argue that much of the medieval history of Europe was structured to follow the historical winners—especially the nation states that emerged around Paris and London. Important developments that did not directly lead to a nation state get neglected, they argue: one effect of this approach has been to privilege historical winners, aspects of medieval Europe that became important in later centuries, above all the nation state.... Arguably the liveliest cultural innovation in the 13th century was the Mediterranean, centered on Frederick II's polyglot court and administration in Palermo...Sicily and the Italian South in later centuries suffered a long slide into overtaxed poverty and marginality. Textbook narratives, therefore, focus not on medieval Palermo, with its Muslim and Jewish bureaucracies and Arabic-speaking monarch, but on the historical winners, Paris and London.[120] |

歴史学 さらに詳しい情報 ナショナリストの歴史学 歴史家はしばしば、特定の国民国家の起源を見つけるために過去に目を向ける。実際、彼らは近代における国民国家の重要性を強調するあまり、起源という問題 を強調するためにそれ以前の歴史を歪めてしまうことが多い。ランシングとイングリッシュは、中世ヨーロッパ史の多くは、歴史的勝者、とりわけパリとロンド ンを中心に勃興した国民国家に従うように構成されていたと主張する。国民国家に直接結びつかなかった重要な発展が軽視されている、と彼らは主張する: このアプローチの一つの効果は、歴史的勝者、つまり国民国家よりも後の世紀に重要となった中世ヨーロッパの側面を優遇することであった......。13 世紀に最も活気づいた文化的革新は、パレルモにあったフリードリヒ2世の多言語宮廷と行政を中心とする地中海であったことは間違いない......後の世 紀におけるシチリアとイタリア南部は、過重な税金を課された貧困と周縁性への長い転落に苦しんだ。したがって、教科書の物語は、イスラム教徒やユダヤ人の 官僚やアラビア語を話す君主を擁する中世のパレルモではなく、歴史的勝者であるパリやロンドンに焦点を当てている[120]。 |

| Balkanization Caliphate City-state Civilization state Ethnocracy Islamic state Monoethnicity Nation Nationalism National personification State nationalism Titular nation Westphalian sovereignty |

バルカン半島化 カリフ制 都市国家 文明国家 エスノクラシー イスラム国家 単一民族国家 国民 国民主義 国民の擬人化 国家ナショナリズム 称号国民 ウェストファリア主権 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nation_state |

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

☆

☆

☆