文化的ステレオタイプ

cultural stereotype

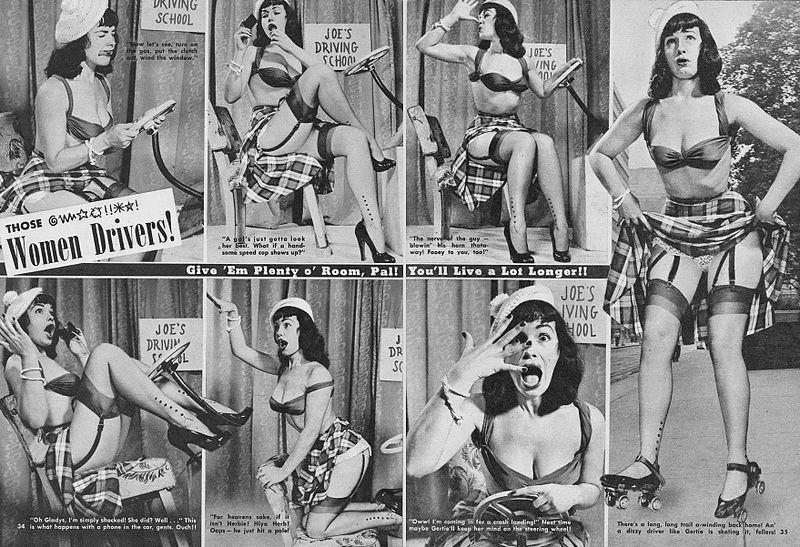

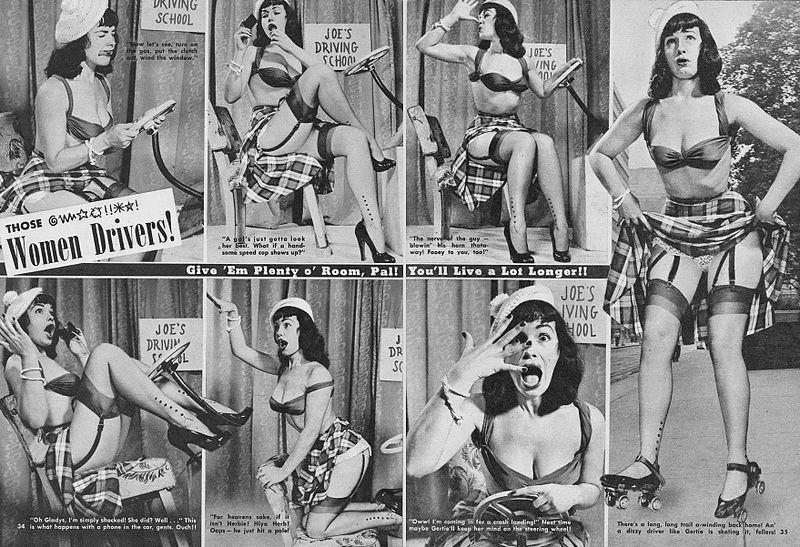

1952

年3月の『Beauty Parade』誌に掲載された、女性ドライバーをステレオタイプ化した特集。モデルにはベティ・ペイジが起用されている。

文化的ステレオタイプ

cultural stereotype

1952

年3月の『Beauty Parade』誌に掲載された、女性ドライバーをステレオタイプ化した特集。モデルにはベティ・ペイジが起用されている。

解説:池田光穂

「文化というのは物事を明らかに

するが、 それ以上に隠蔽もする」――エドワード・ホール(1966:51)

|

文化的一般化のうち、文化の様式を固定

的に決めつけることを「文化的ステレオタイプ」と呼びます。 文化的ステレオタイプは、自文化中心主義から生まれることが多く、また、異文化・異民族への差別の偏見の原因になるものもあります。 ただし、どのような社会や集団においても、自分たち以外の人たちをステレオタイプで観る思考パターンがみられ、また「さまざまな事件」を通して新しく生ま れることがあるために、完全に廃絶することは困難です。 |

文化的一般化のうち、文化の様式を固定的 に決めつけることを「文化的ステレオタイプ」と呼びます。

文化的ステレオタイプは、自文化中心主義から生まれることが多く、また、 異文化・異民族への差別の偏見の原因になるものもあります。

ただし、どのような社会や集団において も、自分たち以外の人たちをステレオタイプで観る思考パターンがみられ、また「さまざまな事件」を通して 新しく生まれることがあるために、完全に廃絶することは困難です。

【事例】

「嘘かホントかしらんけど」といって、真 偽不明なことあげをしてオチに「この國の人の性格(ナショナル・キャラクター)」とありえるかもしれないねと無関係な議論をすること など。

★ウィキペディア(英語版)の「ステレオ

タイプ」の解説から

| In

social psychology, a stereotype

is a generalized belief about a

particular category of people.[2] It is an expectation that people

might have about every person of a particular group. The type of

expectation can vary; it can be, for example, an expectation about the

group's personality, preferences, appearance or ability. Stereotypes

are often overgeneralized, inaccurate, and resistant to new

information.[3] A stereotype does not necessarily need to be a negative

assumption. They may be positive, neutral, or negative. |

社

会心理学において、ステレオタイプとは、ある特定のカテゴ リーに属する人々に関する一般化された信念のことである[2]

。期待の種類は様々で、例えば、集団の性格、嗜好、外見、能力などに関する期待である。ステレオタイプは多くの場合、過度に一般化され、不正確で、新しい

情報に対して抵抗がある。肯定的であっても、中立的であっても、否定的であってもよい。 |

| Explicit stereotypes An explicit stereotype refers to stereotypes that one is aware that one holds, and is aware that one is using to judge people. If person A is making judgments about a particular person B from a group G, and person A has an explicit stereotype for group G, their decision bias can be partially mitigated using conscious control; however, attempts to offset bias due to conscious awareness of a stereotype often fail at being truly impartial, due to either underestimating or overestimating the amount of bias being created by the stereotype |

明白なステレオタイプ 明示的ステレオタイプとは、自分が持っていることを自覚し、人を判断するために使っていることを自覚しているステレオタイプを指す。しかし、ステレオタイ プを意識的に意識することによるバイアスを相殺しようとする試みは、ステレオタイプによって生み出されるバイアスの量を過小評価または過大評価することに より、真に公平であることに失敗することが多い。 |

| Implicit stereotypes Implicit stereotypes are those that lay on individuals' subconsciousness, that they have no control or awareness of.[4] "Implicit stereotypes are built based on two concepts, associative networks in semantic (knowledge) memory and automatic activation".[5] Implicit stereotypes are automatic and involuntary associations that people make between a social group and a domain or attribute. For example, one can have beliefs that women and men are equally capable of becoming successful electricians but at the same time many can associate electricians more with men than women.[5] In social psychology, a stereotype is any thought widely adopted about specific types of individuals or certain ways of behaving intended to represent the entire group of those individuals or behaviors as a whole.[6] These thoughts or beliefs may or may not accurately reflect reality.[7][8] Within psychology and across other disciplines, different conceptualizations and theories of stereotyping exist, at times sharing commonalities, as well as containing contradictory elements. Even in the social sciences and some sub-disciplines of psychology, stereotypes are occasionally reproduced and can be identified in certain theories, for example, in assumptions about other cultures.[9] |

暗黙のステレオタイプ 暗黙のステレオタイプとは、個人の潜在意識に横たわるものであり、本人がコントロールすることも意識することもできないものである[4]。「暗黙のステレ オタイプは、意味(知識)記憶における連想ネットワークと自動的な活性化という2つの概念に基づいて構築されている」[5]。暗黙のステレオタイプとは、 人々が社会的グループとある領域や属性との間に作る自動的で不随意的な連想である。例えば、女性も男性も同じように電気技師として成功する能力があるとい う信念を持つことができるが、同時に多くの人は女性よりも男性に電気技師を連想することができる[5]。 社会心理学においてステレオタイプとは、特定のタイプの個人または特定の行動方法について、それらの個人または行動のグループ全体を全体として代表するこ とを意図して広く採用されている思考のことである[6]。これらの思考や信念は現実を正確に反映している場合もあれば、そうでない場合もある[7] [8]。心理学の中だけでなく他の学問分野においても、ステレオタイプの異なる概念化や理論が存在し、時には共通点を共有することもあれば、矛盾する要素 を含むこともある。社会科学や心理学のいくつかの下位領域においてさえ、ステレオタイプは時折再生産され、例えば他の文化についての仮定など、特定の理論 において特定されることがある[9]。 |

| Etymology The term stereotype comes from the French adjective stéréotype and derives from the Greek words στερεός (stereos), 'firm, solid'[10] and τύπος (typos), 'impression',[11] hence 'solid impression on one or more ideas/theories'. The term was first used in the printing trade in 1798 by Firmin Didot, to describe a printing plate that duplicated any typography. The duplicate printing plate, or the stereotype, is used for printing instead of the original. Outside of printing, the first reference to stereotype in English was in 1850, as a noun that meant 'image perpetuated without change'.[12] However, it was not until 1922 that stereotype was first used in the modern psychological sense by American journalist Walter Lippmann in his work Public Opinion.[13 |

語源 ステレオタイプという用語はフランス語の形容詞stéréotypeに由来し、ギリシャ語のστερεός(stereos)「しっかりした、固い」 [10]とτύπος(typos)「印象」に由来する[11]。 この用語は、1798年にFirmin Didotによって印刷業界で初めて使用された。複製版(ステレオタイプ)は原版の代わりに印刷に使われる。 印刷以外では、英語でステレオタイプが初めて言及されたのは1850年で、「変化することなく永続するイメージ」を意味する名詞としてであった[12]。 しかし、ステレオタイプが現代心理学的な意味で初めて使われたのは、1922年になってからで、アメリカのジャーナリスト、ウォルター・リップマンがその 著作『世論』の中で使用した[13]。 |

| Relationship with other types of

intergroup attitudes Stereotypes, prejudice, racism, and discrimination[14] are understood as related but different concepts.[15][16][17][18] Stereotypes are regarded as the most cognitive component and often occurs without conscious awareness, whereas prejudice is the affective component of stereotyping and discrimination is one of the behavioral components of prejudicial reactions.[15][16][19] In this tripartite view of intergroup attitudes, stereotypes reflect expectations and beliefs about the members of groups perceived as different from one's own, prejudice represents the emotional response, and discrimination refers to actions.[15][16] Although related, the three concepts can exist independently of each other.[16][20] According to Daniel Katz and Kenneth Braly, stereotyping leads to racial prejudice when people emotionally react to the name of a group, ascribe characteristics to members of that group, and then evaluate those characteristics.[17] Possible prejudicial effects of stereotypes[8] are: Justification of ill-founded prejudices or ignorance Unwillingness to rethink one's attitudes and behavior Preventing some people of stereotyped groups from entering or succeeding in activities or fields[21] |

他のタイプの集団間態度との関係 ステレオタイプ、偏見、人種差別、差別[14]は関連するが異なる概念として理解されている。[15][16][17][18]ステレオタイプは最も認知 的な要素とみなされ、しばしば意識せずに生じるのに対し、偏見はステレオタイプの感情的要素であり、差別は偏見反応の行動的要素の1つである。 [15][16][19]集団間態度に関するこの三者構成の見解では、ステレオタイプは自分とは異なると認識される集団のメンバーに対する期待や信念を反 映し、偏見は感情的な反応を表し、差別は行動を指す[15][16]。 ダニエル・カッツとケネス・ブラリーによれば、ステレオタイプは、人々がある集団の名前に感情的に反応し、その集団のメンバーに特徴を当てはめ、そしてそ れらの特徴を評価するときに人種的偏見につながる[17]。 ステレオタイプ[8]の考えられる偏見的影響は以下のとおりである: 根拠のない偏見や無知の正当化 自分の態度や行動を見直そうとしないこと ステレオタイプ化された集団の一部の人々が活動や分野に参入したり成功したりすることを妨げること[21]。 |

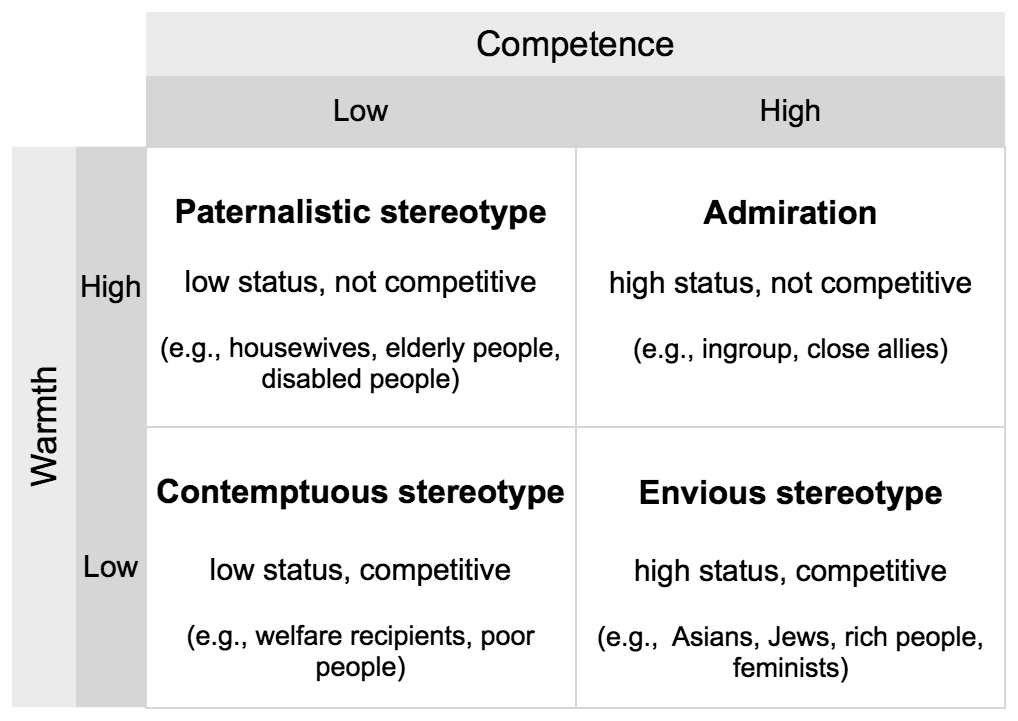

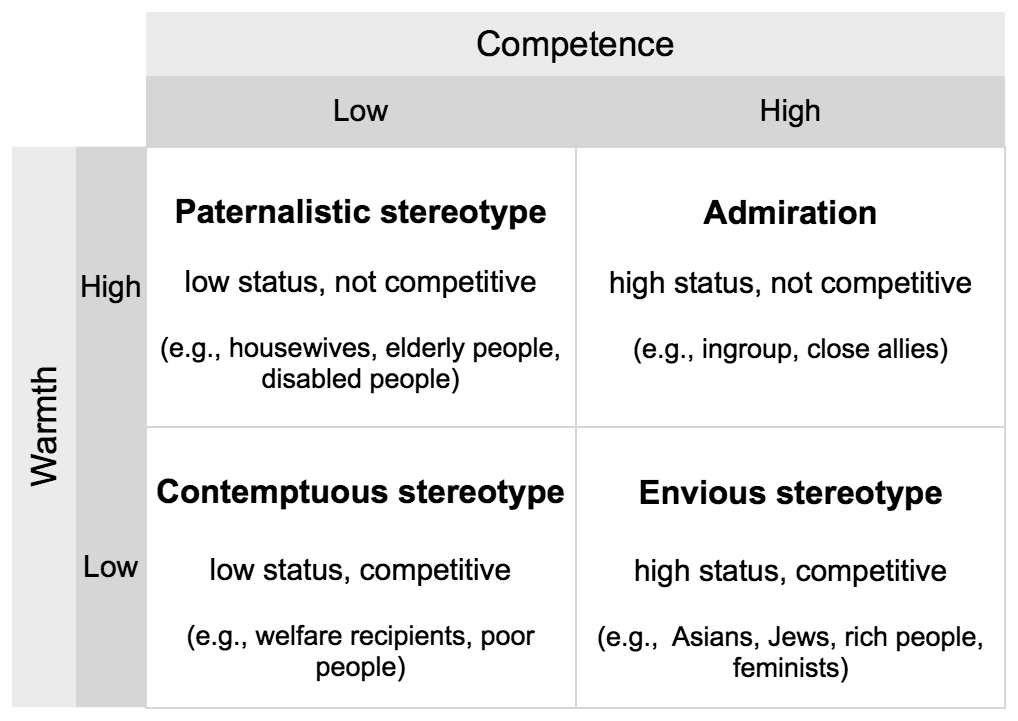

Content Stereotype content model, adapted from Fiske et al. (2002): Four types of stereotypes resulting from combinations of perceived warmth and competence. Stereotype content refers to the attributes that people think characterize a group. Studies of stereotype content examine what people think of others, rather than the reasons and mechanisms involved in stereotyping.[22] Early theories of stereotype content proposed by social psychologists such as Gordon Allport assumed that stereotypes of outgroups reflected uniform antipathy.[23][24] For instance, Katz and Braly argued in their classic 1933 study that ethnic stereotypes were uniformly negative.[22] By contrast, a newer model of stereotype content theorizes that stereotypes are frequently ambivalent and vary along two dimensions: warmth and competence. Warmth and competence are respectively predicted by lack of competition and status. Groups that do not compete with the in-group for the same resources (e.g., college space) are perceived as warm, whereas high-status (e.g., economically or educationally successful) groups are considered competent. The groups within each of the four combinations of high and low levels of warmth and competence elicit distinct emotions.[25] The model explains the phenomenon that some out-groups are admired but disliked, whereas others are liked but disrespected. This model was empirically tested on a variety of national and international samples and was found to reliably predict stereotype content.[23][26] An even more recent model of stereotype content called the agency–beliefs–communion (ABC) model suggested that methods to study warmth and competence in the stereotype content model (SCM) were missing a crucial element, that being, stereotypes of social groups are often spontaneously generated.[27] Experiments on the SCM usually ask participants to rate traits according to warmth and competence but this does not allow participants to use any other stereotype dimensions.[28] The ABC model, proposed by Koch and colleagues in 2016 is an estimate of how people spontaneously stereotype U.S social groups of people using traits. Koch et al. conducted several studies asking participants to list groups and sort them according to their similarity.[27] Using statistical techniques, they revealed three dimensions that explained the similarity ratings. These three dimensions were agency (A), beliefs (B), and communion (C). Agency is associated with reaching goals, standing out and socio-economic status and is related to competence in the SCM, with some examples of traits including poor and wealthy, powerful and powerless, low status and high status. Beliefs is associated with views on the world, morals and conservative-progressive beliefs with some examples of traits including traditional and modern, religious and science-oriented or conventional and alternative. Finally, communion is associated with connecting with others and fitting in and is similar to warmth from the SCM, with some examples of traits including trustworthy and untrustworthy, cold and warm and repellent and likeable.[29] According to research using this model, there is a curvilinear relationship between agency and communion.[30] For example, if a group is high or low in the agency dimension then they may be seen as un-communal, whereas groups that are average in agency are seen as more communal.[31] This model has many implications in predicting behaviour towards stereotyped groups. For example, Koch and colleagues recently proposed that perceived similarity in agency and beliefs increases inter-group cooperation.[32] |

内容 Fiskeら(2002)のステレオタイプ内容モデル: 知覚される暖かさと能力の組み合わせから生じる4種類のステレオタイプ。 ステレオタイプの内容とは、ある集団を特徴づけていると人々が考える属性である。ステレオタイプの内容に関する研究では、ステレオタイプに関与する理由や メカニズムよりもむしろ、人々が他者について何を考えているかを調査している[22]。 ゴードン・オールポートなどの社会心理学者によって提唱されたステレオタイプの内容に関する初期の理論は、アウトグループのステレオタイプは一様な反感を 反映していると仮定していた[23][24]。例えば、カッツとブラリーは1933年の古典的な研究で、民族的ステレオタイプは一様に否定的であると主張 した[22]。 対照的に、ステレオタイプの内容に関する新しいモデルは、ステレオタイプはしばしば両価的であり、温かさと有能さという2つの次元に沿って変化すると理論 化している。温かさと有能さはそれぞれ、競争の欠如と地位によって予測される。同じ資源(例えば、大学のスペース)をめぐって内集団と競合しない集団は温 厚であると認識され、一方、地位の高い(例えば、経済的または教育的に成功した)集団は有能であるとみなされる。このモデルは、ある外集団は賞賛されるが 嫌われ、他 の集団は好かれるが軽蔑されるという現象を説明する。このモデルは国内外の様々なサンプルで経験的にテストされ、ステレオタイプの内容を確実に予測するこ とがわかった[23][26]。 ABC(agency-beliefs-communion)モデルと呼ばれるさらに最近のステレオタイプ内容のモデルは、ステレオタイプ内容モデル (SCM)における暖かさと有能さを研究する方法が重要な要素を見逃していることを示唆した。 [27] SCMに関する実験では通常、温かさと有能さに従って特 徴を評価するよう参加者に求めるが、これでは参加 者が他のステレオタイプの次元を使用することはできな い。コッホらは、参加者にグループをリストアップし、その類似性に従って並べ替えるよう求めるいくつかの研究を実施した[27]。統計的手法を用いて、彼 らは類似性評価を説明する3つの次元を明らかにした。この3つの次元とは、主体性(A)、信念(B)、共同性(C)である。主体性は、目標達成、目立つこ と、社会経済的地位と関連し、SCMにおける能力と関連しており、貧乏と裕福、権力者と無力、低い地位と高い地位などの特性の例がある。信条は、世界観、 道徳観、保守的・進歩的信条と関連しており、伝統的と現代的、宗教的と科学志向、伝統的と代替的などの特徴がある。29]このモデルを用いた研究による と、主体性とコミュニ ケーションの間には曲線的な関係がある。 [31]このモデルは、ステレオタイプ化された集団に対す る行動を予測する上で多くの意味を持つ。例えば、コッホと同僚は最近、エージェンシーと信念の知覚的類似性が集団間の協力を増加させることを提案した [32]。 |

| Functions Early studies suggested that stereotypes were only used by rigid, repressed, and authoritarian people. This idea has been refuted by contemporary studies that suggest the ubiquity of stereotypes and it was suggested to regard stereotypes as collective group beliefs, meaning that people who belong to the same social group share the same set of stereotypes.[20] Modern research asserts that full understanding of stereotypes requires considering them from two complementary perspectives: as shared within a particular culture/subculture and as formed in the mind of an individual person.[33] Relationship between cognitive and social functions Stereotyping can serve cognitive functions on an interpersonal level, and social functions on an intergroup level.[8][20] For stereotyping to function on an intergroup level (see social identity approaches: social identity theory and self-categorization theory), an individual must see themselves as part of a group and being part of that group must also be salient for the individual.[20] Craig McGarty, Russell Spears, and Vincent Y. Yzerbyt (2002) argued that the cognitive functions of stereotyping are best understood in relation to its social functions, and vice versa.[34] Cognitive functions Stereotypes can help make sense of the world. They are a form of categorization that helps to simplify and systematize information. Thus, information is more easily identified, recalled, predicted, and reacted to.[20] Stereotypes are categories of objects or people. Between stereotypes, objects or people are as different from each other as possible.[6] Within stereotypes, objects or people are as similar to each other as possible.[6] Gordon Allport has suggested possible answers to why people find it easier to understand categorized information.[35] First, people can consult a category to identify response patterns. Second, categorized information is more specific than non-categorized information, as categorization accentuates properties that are shared by all members of a group. Third, people can readily describe objects in a category because objects in the same category have distinct characteristics. Finally, people can take for granted the characteristics of a particular category because the category itself may be an arbitrary grouping. A complementary perspective theorizes how stereotypes function as time- and energy-savers that allow people to act more efficiently.[6] Yet another perspective suggests that stereotypes are people's biased perceptions of their social contexts.[6] In this view, people use stereotypes as shortcuts to make sense of their social contexts, and this makes a person's task of understanding his or her world less cognitively demanding.[6] Social functions Social categorization In the following situations, the overarching purpose of stereotyping is for people to put their collective self (their in-group membership) in a positive light:[36] when stereotypes are used for explaining social events when stereotypes are used for justifying activities of one's own group (ingroup) to another group (outgroup) when stereotypes are used for differentiating the ingroup as positively distinct from outgroups Explanation purposes  An antisemitic 1873 caricature depicting the stereotypical physical features of a Jewish male As mentioned previously, stereotypes can be used to explain social events.[20][36] Henri Tajfel[20] described his observations of how some people found that the antisemitic fabricated contents of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion only made sense if Jews have certain characteristics. Therefore, according to Tajfel,[20] Jews were stereotyped as being evil and yearning for world domination to match the antisemitic "facts" as presented in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Justification purposes People create stereotypes of an outgroup to justify the actions that their in-group has committed (or plans to commit) towards that outgroup.[20][35][36] For example, according to Tajfel,[20] Europeans stereotyped African, Indian, and Chinese people as being incapable of achieving financial advances without European help. This stereotype was used to justify European colonialism in Africa, India, and China. Intergroup differentiation An assumption is that people want their ingroup to have a positive image relative to outgroups, and so people want to differentiate their ingroup from relevant outgroups in a desirable way.[20] If an outgroup does not affect the ingroup's image, then from an image preservation point of view, there is no point for the ingroup to be positively distinct from that outgroup.[20] People can actively create certain images for relevant outgroups by stereotyping. People do so when they see that their ingroup is no longer as clearly and/or as positively differentiated from relevant outgroups, and they want to restore the intergroup differentiation to a state that favours the ingroup.[20][36] Self-categorization Stereotypes can emphasize a person's group membership in two steps: Stereotypes emphasize the person's similarities with ingroup members on relevant dimensions, and also the person's differences from outgroup members on relevant dimensions.[24] People change the stereotype of their ingroups and outgroups to suit context.[24] Once an outgroup treats an ingroup member badly, they are more drawn to the members of their own group.[37] This can be seen as members within a group are able to relate to each other though a stereotype because of identical situations. A person can embrace a stereotype to avoid humiliation such as failing a task and blaming it on a stereotype.[38] Social influence and consensus Stereotypes are an indicator of ingroup consensus.[36] When there are intragroup disagreements over stereotypes of the ingroup and/or outgroups, ingroup members take collective action to prevent other ingroup members from diverging from each other.[36] John C. Turner proposed in 1987[36] that if ingroup members disagree on an outgroup stereotype, then one of three possible collective actions follow: First, ingroup members may negotiate with each other and conclude that they have different outgroup stereotypes because they are stereotyping different subgroups of an outgroup (e.g., Russian gymnasts versus Russian boxers). Second, ingroup members may negotiate with each other, but conclude that they are disagreeing because of categorical differences amongst themselves. Accordingly, in this context, it is better to categorise ingroup members under different categories (e.g., Democrats versus Republican) than under a shared category (e.g., American). Finally, ingroup members may influence each other to arrive at a common outgroup stereotype. |

機能 初期の研究では、ステレオタイプは硬直的で抑圧的で権威主義的な人々だけが使うものだと示唆されていた。この考えは、ステレオタイプの偏在性を示唆する現 代の研究によって否定され、ステレオタイプを集団的な信念、つまり同じ社会集団に属する人々が同じステレオタイプを共有しているとみなすことが提案された [20]。現代の研究では、ステレオタイプを完全に理解するには、特定の文化/サブカルチャー内で共有されるものと、個人の心の中で形成されるものという 2つの相補的な視点からステレオタイプを考慮する必要があると主張している[33]。 認知的機能と社会的機能の関係 ステレオタイプは、対人関係レベルでは認知的機能を、集団間レベルでは社会的機能を果たすことができる[8][20]。ステレオタイプが集団間レベルで機 能するためには(社会的アイデンティティ・アプローチ:社会的アイデンティティ理論と自己カテゴリー化理論を参照)、個人が自分自身を集団の一部と見な し、その集団の一部であることも個人にとって顕著でなければならない[20]。 クレイグ・マクガティ(Craig McGarty)、ラッセル・スピアーズ(Russell Spears)、ヴィンセント・Y・イザービット(Vincent Y. Yzerbyt)(2002年)は、ステレオタイプの認知機能はその社会的機能との関係において最もよく理解され、逆もまた同様であると主張している [34]。 認知機能 ステレオタイプは世界を理解するのに役立つ。ステレオタイプは情報を単純化し体系化するのに役立つ分類の一形態である。したがって、情報はより容易に識別 され、想起され、予 測され、反応される。ステレオタイプの間では、物や人は可能な限り互いに異なっている[6]。ステレオタイプの中では、物や人は可能な限り互いに類似して いる[6]。 ゴードン・オールポートは、なぜ人は分類された情報の方が理解し やすいのかについて考えられる答えを提示している。第2に、カテゴライズされた情報は、カテゴライズされていない 情報よりも具体的である。第三に、同じカテゴリーに含まれる対象には明確な特徴があるため、人はカテゴリーに含まれる対象について容易に説明することがで きる。最後に、カテゴリー自体が恣意的なグループ化である可能性があるため、人々は特定のカテゴリーの特性を当然と考えることができる。 補完的な視点は、ステレオタイプが時間やエネルギーの節約として機能し、人々がより効率的に行動できるようにすることを理論化している[6]。さらに別の 視点は、ステレオタイプは社会的文脈に対する人々の偏った認識であることを示唆している[6]。この見解では、人々はステレオタイプを社会的文脈を理解す るためのショートカットとして使用し、これによって自分の世界を理解する人のタスクが認知的にそれほど要求されなくなる[6]。 社会的機能 社会的分類 以下の状況において、ステレオタイプの包括的な目的は、人々が集団的自己(内集団のメンバー)を肯定的にとらえることである:[36]。 ステレオタイプが社会的出来事を説明するために使用される場合 ステレオタイプが他のグループ(外集団)に対して自分のグループ(内集団)の活動を正当化するために使われるとき ステレオタイプがイングループをアウトグループと積極的に区別するために使われるとき 説明の目的  ユダヤ人男性のステレオタイプな身体的特徴を描いた1873年の反ユダヤ風刺画 前述したように、ステレオタイプは社会的事象を説明するために使用されることがある[20][36]。アンリ・タージフェル[20]は、『シオンの長老の 議定書』の反ユダヤ主義的な捏造内容が、ユダヤ人が特定の特徴を持っている場合にのみ意味をなすことを発見する人々がいることを観察したことを述べてい る。したがって、タジフェルによれば[20]、ユダヤ人は『シオンの長老の議定書』で提示された反ユダヤ主義的な「事実」に合致するように、邪悪であり、 世界征服を熱望しているというステレオタイプ化されたのである。 正当化の目的 例えば、タジフェルによると[20]、ヨーロッパ人はアフリカ人、インド人、中国人に対して、ヨーロッパ人の援助なしには経済的な進歩を達成することがで きないとステレオタイプ化した。このステレオタイプは、アフリカ、インド、中国におけるヨーロッパの植民地主義を正当化するために用いられた。 グループ間の差別化 仮定として、人々は自分のイングループがアウトグループに対して肯定的なイメージを持つことを望んでおり、そのため人々は自分のイングループを関連するア ウトグループから望ましい方法で差別化したいと望んでいる[20]。アウトグループがイングループのイメージに影響を与えない場合、イメージ保持の観点か らは、イングループがそのアウトグループから肯定的に区別される意味はない[20]。 人はステレオタイプ化することで、関連するアウトグループに対して特定のイメージを積極的に作り出すことができる。人々がそうするのは、自分のイングルー プがもはや関連するアウトグループから明確かつ/または積極的 に差別化されておらず、イングループに有利な状態にグループ間 の差別化を回復したいと考えるときである[20][36]。 自己カテゴリー化 ステレオタイプは、2つのステップで人の集団への帰属を強調することができる: ステレオタイプは、関連する次元でその人のイングルー プ・メンバーとの類似性を強調し、また関連する次元でその人の アウトグループ・メンバーとの相違性を強調する[24]。人は仕事を失敗してそれをステレオタイプのせいにするなどの屈辱を避けるためにステレオタイプを 受け入れることができる[38]。 社会的影響とコンセンサス ステレオタイプは集団内コンセンサスの指標である[36]。イングループおよび/またはアウトグループのステレオタイプをめぐって集団内で意見の相違があ る場合、イングループのメンバーは他のイングループのメンバーが互いに乖離するのを防ぐために集団的行動をとる[36]。 ジョン・C・ターナー(John C. Turner)は1987年[36]に、イングループのメンバーがアウトグループのステレオタイプについて意見が一致しない場合、3つの可能な集団行動の うちの1つが続くと提案した: 第1に、イングルー プのメンバーは互いに交渉し、アウトグループの異なるサブグルー プをステレオタイプ化しているため、アウトグループの ステレオタイプが異なると結論づけることができる(例 えば、ロシア人体操選手対ロシア人ボクサー)。第2に、イングループのメンバー同士が交渉することがあるが、自分たちの間にカテゴリー的な違いがあるた め、意見が食い違っていると結論付けることがある。したがって、この文脈では、イングループのメンバーを、共有するカテゴリー(たとえばアメリカ人)より も、異なるカテゴリー(たとえば民主党対共和党)に分類する方がよい。最後に、イングループの成員は、共通のアウトグループ・ステレオタイプに到達するた めに、互いに影響しあうかもしれない。 |

| Formation Different disciplines give different accounts of how stereotypes develop: Psychologists may focus on an individual's experience with groups, patterns of communication about those groups, and intergroup conflict. As for sociologists, they may focus on the relations among different groups in a social structure. They suggest that stereotypes are the result of conflict, poor parenting, and inadequate mental and emotional development. Once stereotypes have formed, there are two main factors that explain their persistence. First, the cognitive effects of schematic processing (see schema) make it so that when a member of a group behaves as we expect, the behavior confirms and even strengthens existing stereotypes. Second, the affective or emotional aspects of prejudice render logical arguments against stereotypes ineffective in countering the power of emotional responses.[39] Correspondence bias Main article: Correspondence bias Correspondence bias refers to the tendency to ascribe a person's behavior to disposition or personality, and to underestimate the extent to which situational factors elicited the behavior. Correspondence bias can play an important role in stereotype formation.[40] For example, in a study by Roguer and Yzerbyt (1999) participants watched a video showing students who were randomly instructed to find arguments either for or against euthanasia. The students that argued in favor of euthanasia came from the same law department or from different departments. Results showed that participants attributed the students' responses to their attitudes although it had been made clear in the video that students had no choice about their position. Participants reported that group membership, i.e., the department that the students belonged to, affected the students' opinions about euthanasia. Law students were perceived to be more in favor of euthanasia than students from different departments despite the fact that a pretest had revealed that subjects had no preexisting expectations about attitudes toward euthanasia and the department that students belong to. The attribution error created the new stereotype that law students are more likely to support euthanasia.[41] Nier et al. (2012) found that people who tend to draw dispositional inferences from behavior and ignore situational constraints are more likely to stereotype low-status groups as incompetent and high-status groups as competent. Participants listened to descriptions of two fictitious groups of Pacific Islanders, one of which was described as being higher in status than the other. In a second study, subjects rated actual groups – the poor and wealthy, women and men – in the United States in terms of their competence. Subjects who scored high on the measure of correspondence bias stereotyped the poor, women, and the fictitious lower-status Pacific Islanders as incompetent whereas they stereotyped the wealthy, men, and the high-status Pacific Islanders as competent. The correspondence bias was a significant predictor of stereotyping even after controlling for other measures that have been linked to beliefs about low status groups, the just-world hypothesis and social dominance orientation.[42] Based on the anti-public sector bias,[43] Döring and Willems (2021)[44] found that employees in the public sector are considered as less professional compared to employees in the private sector. They build on the assumption that the red-tape and bureaucratic nature of the public sector spills over in the perception that citizens have about the employees working in the sector. With an experimental vignette study, they analyze how citizens process information on employees' sector affiliation, and integrate non-work role-referencing to test the stereotype confirmation assumption underlying the representativeness heuristic. The results show that sector as well as non-work role-referencing influences perceived employee professionalism but has little effect on the confirmation of particular public sector stereotypes.[45] Moreover, the results do not confirm a congruity effect of consistent stereotypical information: non-work role-referencing does not aggravate the negative effect of sector affiliation on perceived employee professionalism. Illusory correlation Main article: Illusory correlation Research has shown that stereotypes can develop based on a cognitive mechanism known as illusory correlation – an erroneous inference about the relationship between two events.[6][46][47] If two statistically infrequent events co-occur, observers overestimate the frequency of co-occurrence of these events. The underlying reason is that rare, infrequent events are distinctive and salient and, when paired, become even more so. The heightened salience results in more attention and more effective encoding, which strengthens the belief that the events are correlated.[48][49][50] In the inter-group context, illusory correlations lead people to misattribute rare behaviors or traits at higher rates to minority group members than to majority groups, even when both display the same proportion of the behaviors or traits. Black people, for instance, are a minority group in the United States and interaction with blacks is a relatively infrequent event for an average white American.[51] Similarly, undesirable behavior (e.g. crime) is statistically less frequent than desirable behavior. Since both events "blackness" and "undesirable behavior" are distinctive in the sense that they are infrequent, the combination of the two leads observers to overestimate the rate of co-occurrence.[48] Similarly, in workplaces where women are underrepresented and negative behaviors such as errors occur less frequently than positive behaviors, women become more strongly associated with mistakes than men.[52] In a landmark study, David Hamilton and Richard Gifford (1976) examined the role of illusory correlation in stereotype formation. Subjects were instructed to read descriptions of behaviors performed by members of groups A and B. Negative behaviors outnumbered positive actions and group B was smaller than group A, making negative behaviors and membership in group B relatively infrequent and distinctive. Participants were then asked who had performed a set of actions: a person of group A or group B. Results showed that subjects overestimated the frequency with which both distinctive events, membership in group B and negative behavior, co-occurred, and evaluated group B more negatively. This despite the fact the proportion of positive to negative behaviors was equivalent for both groups and that there was no actual correlation between group membership and behaviors.[48] Although Hamilton and Gifford found a similar effect for positive behaviors as the infrequent events, a meta-analytic review of studies showed that illusory correlation effects are stronger when the infrequent, distinctive information is negative.[46] Hamilton and Gifford's distinctiveness-based explanation of stereotype formation was subsequently extended.[49] A 1994 study by McConnell, Sherman, and Hamilton found that people formed stereotypes based on information that was not distinctive at the time of presentation, but was considered distinctive at the time of judgement.[53] Once a person judges non-distinctive information in memory to be distinctive, that information is re-encoded and re-represented as if it had been distinctive when it was first processed.[53] Common environment One explanation for why stereotypes are shared is that they are the result of a common environment that stimulates people to react in the same way.[6] The problem with the 'common environment' is that explanation in general is that it does not explain how shared stereotypes can occur without direct stimuli.[6] Research since the 1930s suggested that people are highly similar with each other in how they describe different racial and national groups, although those people have no personal experience with the groups they are describing.[54] Socialization and upbringing Another explanation says that people are socialised to adopt the same stereotypes.[6] Some psychologists believe that although stereotypes can be absorbed at any age, stereotypes are usually acquired in early childhood under the influence of parents, teachers, peers, and the media. If stereotypes are defined by social values, then stereotypes only change as per changes in social values.[6] The suggestion that stereotype content depends on social values reflects Walter Lippman's argument in his 1922 publication that stereotypes are rigid because they cannot be changed at will.[17] Studies emerging since the 1940s refuted the suggestion that stereotype contents cannot be changed at will. Those studies suggested that one group's stereotype of another group would become more or less positive depending on whether their intergroup relationship had improved or degraded.[17][55][56] Intergroup events (e.g., World War II, Persian Gulf conflicts) often changed intergroup relationships. For example, after WWII, Black American students held a more negative stereotype of people from countries that were the United States's WWII enemies.[17] If there are no changes to an intergroup relationship, then relevant stereotypes do not change.[18] Intergroup relations According to a third explanation, shared stereotypes are neither caused by the coincidence of common stimuli, nor by socialisation. This explanation posits that stereotypes are shared because group members are motivated to behave in certain ways, and stereotypes reflect those behaviours.[6] It is important to note from this explanation that stereotypes are the consequence, not the cause, of intergroup relations. This explanation assumes that when it is important for people to acknowledge both their ingroup and outgroup, they will emphasise their difference from outgroup members, and their similarity to ingroup members.[6] International migration creates more opportunities for intergroup relations, but the interactions do not always disconfirm stereotypes. They are also known to form and maintain them.[57] |

形成 ステレオタイプがどのように形成されるかについては、分野によって説明が異なる: 心理学者は、個人と集団の経験、集団に関するコミュニケーションのパターン、集団間の対立に注目する。社会学者は、社会構造における異なる集団間の関係に 注目する。社会学者たちは、ステレオタイプは対立や不適切な子育て、不十分な精神的・感情的発達の結果であると指摘する。いったんステレオタイプが形成さ れると、その持続性を説明する主な要因は2つある。第一に、スキーマ処理(スキーマを参照)の認知的効果によって、ある集団の成員が期待通りに行動する と、その行動が既存のステレオタイプを確認し、さらに強化する。第2に、偏見の感情的な側面は、ステレオタイプに対す る論理的な議論を、感情的な反応の力に対抗するのに有効でない ものにしてしまう[39]。 対応バイアス 主な記事 対応関係バイアス コレスポンデンス・バイアスとは、人の行動を気質や性格に帰属させ、状況的要因がその行動を引き出した程度を過小評価する傾向のことである。コレスポンデ ンス・バイアスはステレオタイプの形成において重要な役割を果たすことがある[40]。 例えば、Roguer and Yzerbyt (1999)の研究では、参加者は、安楽死に賛成か反対のどちらかの主張を見つけるように無作為に指示された学生を映したビデオを見た。安楽死に賛成する 学生は、同じ法学部の学生であったり、異なる学部の学生であったりした。その結果、ビデオでは学生の立場について選択の余地がないことが明らかにされてい たにもかかわらず、参加者は学生の反応を彼らの態度に起因するものと考えていた。参加者は、グループメンバー、すなわち学生の所属学部が、安楽死に関する 学生の意見に影響を与えたと報告した。事前のテストでは、安楽死に対する態度や学生が所属する学部について、被験者が事前に予想していなかったにもかかわ らず、法学部の学生は、異なる学部の学生よりも安楽死に賛成であると認識された。この帰属エラーは、法学部の学生は安楽死を支持する傾向が高いという新た なステレオタイプを生み出した[41]。 Nierら(2012)は、行動から気質的推論を行い、状況的制約を無視する傾向のある人は、地位の低いグループを無能とし、地位の高いグループを有能と するステレオタイプを作りやすいことを発見した。参加者は、太平洋諸島民の2つの架空のグループの説明を聞き、一方は他方より地位が高いと説明された。2 つ目の研究では、被験者が米国で実際に存在するグループ(貧困層と富裕層、女性と男性)を能力という観点から評価した。対応バイアスの測定で高得点を得た 被験者は、貧困層、女性、架空の地位の低い太平洋諸島民を無能とステレオタイプ化したのに対し、富裕層、男性、地位の高い太平洋諸島民を有能とステレオタ イプ化した。対応バイアスは、地位の低い集団についての信念と関連づけられた他の尺度、公正世界仮説、社会的優位志向を統制した後でも、ステレオタイプの 有意な予測因子であった[42]。 反公共部門バイアスに基づき、[43]Döring and Willems (2021)[44]は、公共部門の従業員は民間部門の従業員に比べて専門性が低いと考えられていることを発見した。彼らは、公共部門のお役所仕事的な性 質が、市民が公共部門で働く従業員に対して抱く認識にも波及しているという仮説に基づいている。実験的なビネット研究を用いて、市民が従業員の所属部門に 関する情報をどのように処理するかを分析し、代表性ヒューリスティックの基礎となるステレオタイプ確認仮説を検証するために、仕事以外の役割参照を統合し た。その結果、部門および非職業役割参照は、従業員の専門性の認知に影響を与えるが、特定の公共部門のステレオタイプの確認にはほとんど影響を与えないこ とが示された[45]。さらに、結果は一貫したステレオタイプ情報の一致効果を確認しなかった:非職業役割参照は、従業員の専門性の認知に対する部門所属 の負の効果を悪化させなかった。 幻想的相関 主な記事 錯覚的相関 研究により、ステレオタイプは錯覚相関として知られる認知メカニズ ム-2つの事象間の関係についての誤った推論-に基づ いて発達しうることが示されている[6][46][47]。統計的に頻度の低い2つの事象が共起する場 合、観察者はこれらの事象の共起頻度を過大評価する。その根本的な理由は、まれで頻度の低い事象は特徴的で顕著であり、ペアになるとさらに顕著になるから である。顕著性が高まることで、より多くの注意 が払われ、より効果的な符号化が行われ、事象が相関 しているという信念が強化される[48][49][50]。 集団間の文脈では、錯覚的な相関関係によって、たとえ両者 が同じ割合の行動や特徴を示していたとしても、人々は希 少な行動や特徴を多数派集団よりも少数派集団のメンバー に高い割合で誤って帰属させる。例えば、黒人はアメリカでは少数派であり、平均的な白人アメリカ人にとって黒人との交流は比較的まれな出来事である [51]。同様に、望ましくない行動(例えば犯罪)は望ましい行動よりも統計的に頻度が低い。黒人であること」と「望ましくない行動」はどちらも頻度が低 いという意味で特徴的な事象であるため、この2つの組み合わせによって観察者は共起率を過大評価することになる[48]。同様に、女性の割合が低く、ミス のような否定的な行動が肯定的な行動よりも発生頻度が低い職場では、女性は男性よりもミスと強く関連付けられるようになる[52]。 画期的な研究において、デイヴィッド・ハミルトンとリチャード・ギフォード(1976年)は、ステレオタイプ形成における錯覚的相関の役割を検討した。否 定的な行動は肯定的な行動よりも多く、B群はA群よりも小 さかったため、否定的な行動とB群の一員であることは比較的少 なく、特徴的であった。被験者に、ある行動をしたのはA群とB群のどちらであるかを尋ねた。その結果、被験者は、特徴的な出来事であるB群の一員であるこ とと否定的な行動が同時に起こる頻度を過大評価し、B群をより否定的に評価した。これは、肯定的な行動と否定的な行動の割合が両グループで同等であり、グ ループへの所属と行動の間に実際の相関がないにもかかわらず、であった[48]。ハミルトンとギフォードは、肯定的な行動に対して、頻度の低い事象と同様 の効果があることを発見したが、研究のメタ分析レビューでは、頻度の低い特徴的な情報が否定的である場合、錯覚的相関効果が強くなることが示された [46]。 ハミルトンとギフォードのステレオタイプ形成の識別性に基づ く説明はその後拡張された[49]。1994年のMcConnell、Sherman、Hamiltonによる研 究では、人は提示時には識別的でなかったが、判断時には識別 的であると考えられる情報に基づいてステレオタイプを 形成することが発見された[53]。一旦人が記憶の中の識別的でない情報 を識別的であると判断すると、その情報は最初に処理された時 に識別的であったかのように再エンコードされ再表現される[53]。 共通の環境 ステレオタイプが共有される理由の説明の1つは、ステレオタイプが同じように反応するように人々を刺激する共通の環境の結果であるというものである [6]。 1930年代以降の研究では、人々は異なる人種や国民集団をどのように描写するかにおいて、互いに非常に類似していることが示唆されているが、それらの人 々は描写している集団との個人的な経験を持っていない[54]。 社会化と生い立ち 別の説明では、人々は同じステレオタイプを採用するように社 会化されるという。 ステレオタイプはどの年齢でも吸収することができるが、ステ レオタイプは通常幼児期に両親、教師、仲間、メディアの影響 のもとで獲得されると考える心理学者もいる。 ステレオタイプが社会的価値によって定義されるのであれば、ステレオタイプは社会的価値の変化に従ってのみ変化する。ステレオタイプの内容が社会的価値に 依存するという示唆は、ウォルター・リップマンが1922年に発表した「ステレオタイプは自由に変えることができないので硬直的である」という議論を反映 している[17]。 1940年代以降に登場した研究は、ステレオタイプの内容は自由に変えることができないという示唆に反論している。これらの研究は、ある集団の他の集団に 対するステレオタイプは、その集団間の関係が改善されたか悪化したかによって、より肯定的になったり、より否定的になったりすることを示唆した[17] [55][56]。例えば、第二次世界大戦後、アメリカの黒人の学 生は、アメリカの第二次世界大戦の敵であった国の人々に対して より否定的なステレオタイプを抱くようになった[17]。 集団間関係 第3の説明によれば、共有されたステレオタイプは共通の刺激の偶然の一致によっても社会化によっても引き起こされない。この説明では、ステレオタイプが共 有されるのは、集団成員が特定の方法で行動するように動機づけられ、ステレオタイプがそれらの行動を反映するからであると仮定する[6]。この説明から、 ステレオタイプが集団間関係の原因ではなく結果であることに注意することが重要である。この説明では、人々が自分のイングルー プとアウトグループの両方を認めることが重要である場 合、アウトグループのメンバーとの違いを強調し、イングルー プのメンバーとの類似性を強調すると仮定している[6]。またステレオタイプを形成し維持することも知られている[57]。 |

| Activation The dual-process model of cognitive processing of stereotypes asserts that automatic activation of stereotypes is followed by a controlled processing stage, during which an individual may choose to disregard or ignore the stereotyped information that has been brought to mind.[19] A number of studies have found that stereotypes are activated automatically. Patricia Devine (1989), for example, suggested that stereotypes are automatically activated in the presence of a member (or some symbolic equivalent) of a stereotyped group and that the unintentional activation of the stereotype is equally strong for high- and low-prejudice persons. Words related to the cultural stereotype of blacks were presented subliminally. During an ostensibly unrelated impression-formation task, subjects read a paragraph describing a race-unspecified target person's behaviors and rated the target person on several trait scales. Results showed that participants who received a high proportion of racial words rated the target person in the story as significantly more hostile than participants who were presented with a lower proportion of words related to the stereotype. This effect held true for both high- and low-prejudice subjects (as measured by the Modern Racism Scale). Thus, the racial stereotype was activated even for low-prejudice individuals who did not personally endorse it.[19][58][59] Studies using alternative priming methods have shown that the activation of gender and age stereotypes can also be automatic.[60][61] Subsequent research suggested that the relation between category activation and stereotype activation was more complex.[59][62] Lepore and Brown (1997), for instance, noted that the words used in Devine's study were both neutral category labels (e.g., "Blacks") and stereotypic attributes (e.g., "lazy"). They argued that if only the neutral category labels were presented, people high and low in prejudice would respond differently. In a design similar to Devine's, Lepore and Brown primed the category of African-Americans using labels such as "blacks" and "West Indians" and then assessed the differential activation of the associated stereotype in the subsequent impression-formation task. They found that high-prejudice participants increased their ratings of the target person on the negative stereotypic dimensions and decreased them on the positive dimension whereas low-prejudice subjects tended in the opposite direction. The results suggest that the level of prejudice and stereotype endorsement affects people's judgements when the category – and not the stereotype per se – is primed.[63] Research has shown that people can be trained to activate counterstereotypic information and thereby reduce the automatic activation of negative stereotypes. In a study by Kawakami et al. (2000), for example, participants were presented with a category label and taught to respond "No" to stereotypic traits and "Yes" to nonstereotypic traits. After this training period, subjects showed reduced stereotype activation.[64][65] This effect is based on the learning of new and more positive stereotypes rather than the negation of already existing ones.[65] Automatic behavioral outcomes Empirical evidence suggests that stereotype activation can automatically influence social behavior.[66][67][68][69] For example, Bargh, Chen, and Burrows (1996) activated the stereotype of the elderly among half of their participants by administering a scrambled-sentence test where participants saw words related to age stereotypes. Subjects primed with the stereotype walked significantly more slowly than the control group (although the test did not include any words specifically referring to slowness), thus acting in a way that the stereotype suggests that elderly people will act. And the stereotype of the elder will affect the subjective perception of them through depression.[70] In another experiment, Bargh, Chen, and Burrows also found that because the stereotype about blacks includes the notion of aggression, subliminal exposure to black faces increased the likelihood that randomly selected white college students reacted with more aggression and hostility than participants who subconsciously viewed a white face.[71] Similarly, Correll et al. (2002) showed that activated stereotypes about blacks can influence people's behavior. In a series of experiments, black and white participants played a video game, in which a black or white person was shown holding a gun or a harmless object (e.g., a mobile phone). Participants had to decide as quickly as possible whether to shoot the target. When the target person was armed, both black and white participants were faster in deciding to shoot the target when he was black than when he was white. When the target was unarmed, the participants avoided shooting him more quickly when he was white. Time pressure made the shooter bias even more pronounced.[72] |

活性化 ステレオタイプの認知的処理に関する二重過程モデルは、ステレオタイプの自動的な活性化の後に制御された処理段階が続くと主張しており、この段階では、個 人は心に浮かんだステレオタイプ化された情報を無視するか無視することを選択することができる[19]。 多くの研究がステレオタイプが自動的に活性化されることを発見している。例えば、パトリシア・デヴァイン(1989)は、ステレオタイプはステレオタイプ 化された集団のメンバー(または何らかの象徴的等価物)が存在すると自動的に活性化され、ステレオタイプの意図的でない活性化は偏見の高い人も低い人も同 様に強いことを示唆した。黒人の文化的ステレオタイプに関連する言葉がサブリミナル的に提示された。表向きは無関係な印象形成課題において、被験者は人種 不特定の対象人物の行動を記述した段落を読み、いくつかの特性尺度で対象人物を評価した。その結果、人種に関する単語の割合が高い被験者は、ステレオタイ プに関連する単語の割合が低い被験者よりも、物語中の対象人物を有意に敵対的と評価した。この効果は、偏見が高い被験者にも低い被験者にも当てはまった (Modern Racism Scaleで測定)。したがって、人種的ステレオタイプは、個人的にそれを支持していない低偏見者であっても活性化された[19][58][59]。代替 プライミング法を用いた研究は、ジェンダーと年齢のステレオタイプの活性化も自動的でありうることを示している[60][61]。 例えば、LeporeとBrown(1997)は、Devineの研究で使用された単語が中立的なカテゴリー・ラベル(例えば、「黒人」)とステレオタイ プの属性(例えば、「怠け者」)の両方であったことを指摘した。彼らは、中立的なカテゴリー・ラベルだけが提示された場合、偏見の高い人と低い人では反応 が異なるだろうと主張した。LeporeとBrownは、Devineと同様のデザインで、「黒人」や「西インド人」といったラベルを用いてアフリカ系ア メリカ人というカテゴリーをプライミングし、その後の印象形成課題において、関連するステレオタイプの差異的活性化を評価した。その結果、偏見が高い被験 者は、否定的なステレオタイプ次元で対象人物の評価を高め、肯定的な次元で評価を下げたのに対し、偏見が低い被験者は逆の傾向を示した。この結果は、偏見 とステレオタイプ支持のレベルが、ステレオタイプ自体ではなくカテゴリーがプライムされたときの人々の判断に影響することを示唆している[63]。 研究は、人々がカウンターステレオタイプの情報を活性化し、それによって否定的なステレオタイプの自動的な活性化を減少させるように訓練できることを示し ている。例えば、川上ら(2000)の研究では、被験者にカテゴリー・ラベルが提示され、ステレオタイプ的特徴には「いいえ」、非ステレオタイプ的特徴に は「はい」と答えるように教育された。この訓練期間の後、被験者はステ レオタイプの活性化の減少を示した[64][65]。この効果は、既 存のステレオタイプを否定するのではなく、むしろ新し くより肯定的なステレオタイプの学習に基づくものであ る[65]。 自動的な行動の結果 例えば、Bargh、Chen、およびBurrows(1996年) は、参加者が年齢のステレオタイプに関連する単語を見 るスクランブル・センテンス・テストを実施することによって、 参加者の半数において高齢者のステレオタイプを活性 化させた。ステレオタイプでプライムされた被験者は、対照群よりも有意にゆっくり歩き(ただし、このテストには特に遅さを示す単語は含まれていなかっ た)、その結果、ステレオタイプが示唆するように高齢者が行動するようになった。また、高齢者のステレオタイプは、抑うつを通じて、彼らに対する主観的な 認知に影響を与える[70]。別の実験で、Bargh、Chen、Burrowsは、黒人に関するステレオタイプには攻撃性の概念が含まれているため、サ ブリミナル的に黒人の顔にさらされると、無作為に選ばれた白人の大学生が、無意識に白人の顔を見た参加者よりも攻撃性や敵意をもって反応する可能性が高く なることを発見した[71]。同様に、Correllら(2002)は、黒人に関する活性化されたステレオタイプが人々の行動に影響を与える可能性がある ことを示した。一連の実験では、黒人と白人の参加者がビデオゲームを行い、その中で黒人または白人が銃または無害な物体(例えば携帯電話)を持っている様 子が示された。参加者は標的を撃つべきかどうかをできるだけ早く決めなければならなかった。標的が武装している場合、黒人参加者も白人参加者も、標的が白 人の場合よりも黒人の場合の方が、標的を撃つ決断が早かった。標的が非武装の場合、白人の方がより早く射殺を避けた。時間的プレッシャーが射手バイアスを より顕著にした[72]。 |

Accuracy A magazine feature from Beauty Parade from March 1952 stereotyping women drivers. It features Bettie Page as the model. Stereotypes can be efficient shortcuts and sense-making tools. They can, however, keep people from processing new or unexpected information about each individual, thus biasing the impression formation process.[6] Early researchers believed that stereotypes were inaccurate representations of reality.[54] A series of pioneering studies in the 1930s found no empirical support for widely held racial stereotypes.[17] By the mid-1950s, Gordon Allport wrote that, "It is possible for a stereotype to grow in defiance of all evidence."[35] Research on the role of illusory correlations in the formation of stereotypes suggests that stereotypes can develop because of incorrect inferences about the relationship between two events (e.g., membership in a social group and bad or good attributes). This means that at least some stereotypes are inaccurate.[46][48][50][53] A 1995 book by Yueh-Ting Lee et al. argued that stereotypes are sometimes accurate.[73] Similarly, a 2015 study by Jussim et al. reviewed four studies of racial stereotypes, and seven studies of gender stereotypes regarding demographic characteristics, academic achievement, personality and behavior, and argued that some aspects of ethnic and gender stereotypes are accurate while stereotypes concerning political affiliation and nationality are much less accurate.[74] A 2005 study by Terracciano et al. found that stereotypic beliefs about nationality do not reflect the actual personality traits of people from different cultures.[75] In a 1973 paper, Marlene MacKie argued that while stereotypes are inaccurate, this is a definition rather than empirical claim – stereotypes were simply defined as inaccurate, even though the supposed inaccuracy of stereotypes was treated as though it was an empirical discovery.[76] |

正確さ 女性ドライバーをステレオタイプ化した1952年3月の『ビューティー・パレード』誌の特集。ベティ・ペイジがモデル。 ステレオタイプは効率的な近道であり、感覚を働かせる道具である。1930年代の一連の先駆的な研究は、広く信じられている人種的ステレオタイプに経験的 な裏付けがないことを発見した[17] 。 ステレオタイプの形成における錯覚的な相関関係の役割に関する研究は、ステレオタイプが2つの出来事(例えば、社会的集団の一員であることと悪い属性や良 い属性)の関係についての誤った推測のために発展する可能性があることを示唆している。これは少なくともいくつかのステレオタイプが不正確であることを意 味する[46][48][50][53]。 1995年のYueh-Ting Leeらによる著書は、ステレオタイプは時に正確であると論じている[73]。同様に、Jussimらによる2015年の研究は、人口統計学的特徴、学業 成績、性格、行動に関する人種的ステレオタイプに関する4つの研究、性別的ステレオタイプに関する7つの研究をレビューし、民族的ステレオタイプと性別的 ステレオタイプのいくつかの側面は正確であるが、政治的所属や国籍に関するステレオタイプははるかに正確ではないと論じている[74]。 Terraccianoらによる2005年の研究では、国籍に関するステレオタイプ的な信念は異なる文化圏の人々の実際の性格特性を反映していないことが 判明している[75]。 1973年の論文において、マーリーン・マッキーは、ステレオタイプは不正確であるが、これは経験的主張ではなく定義であると主張した。 |

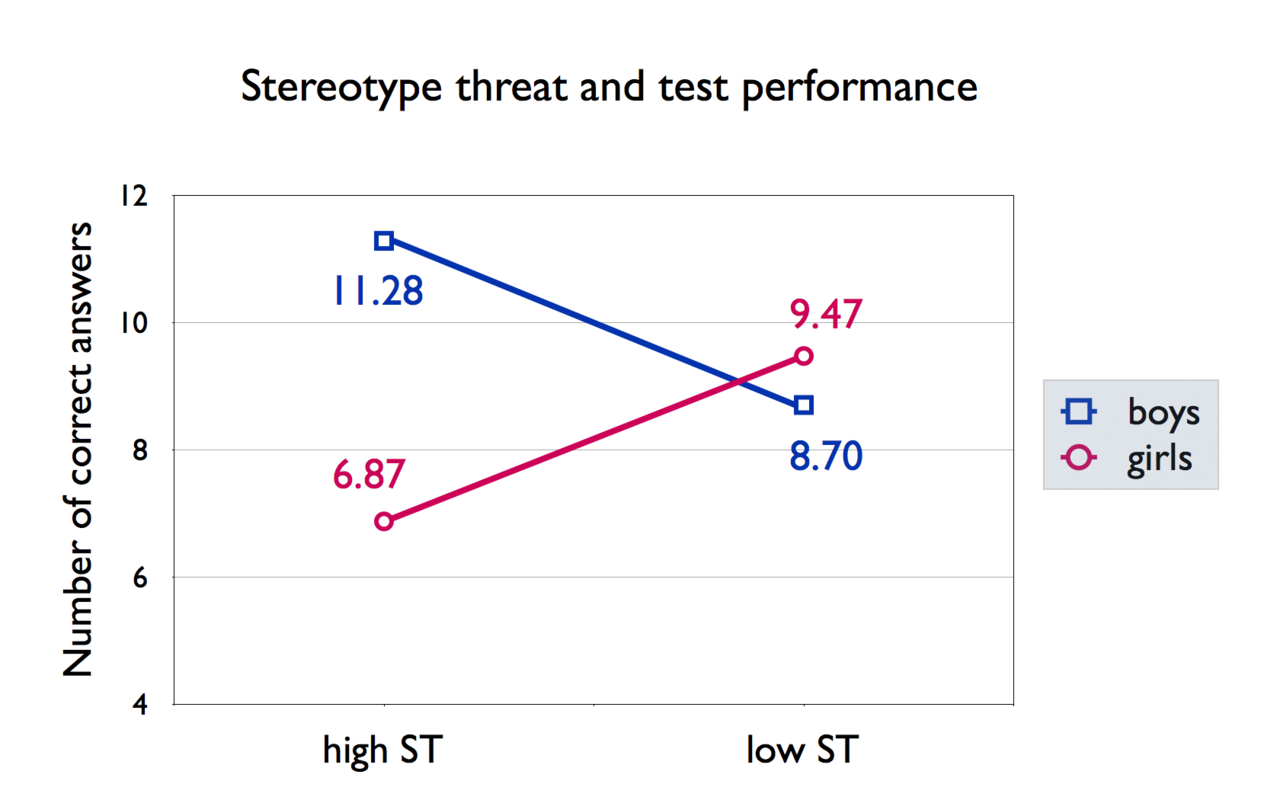

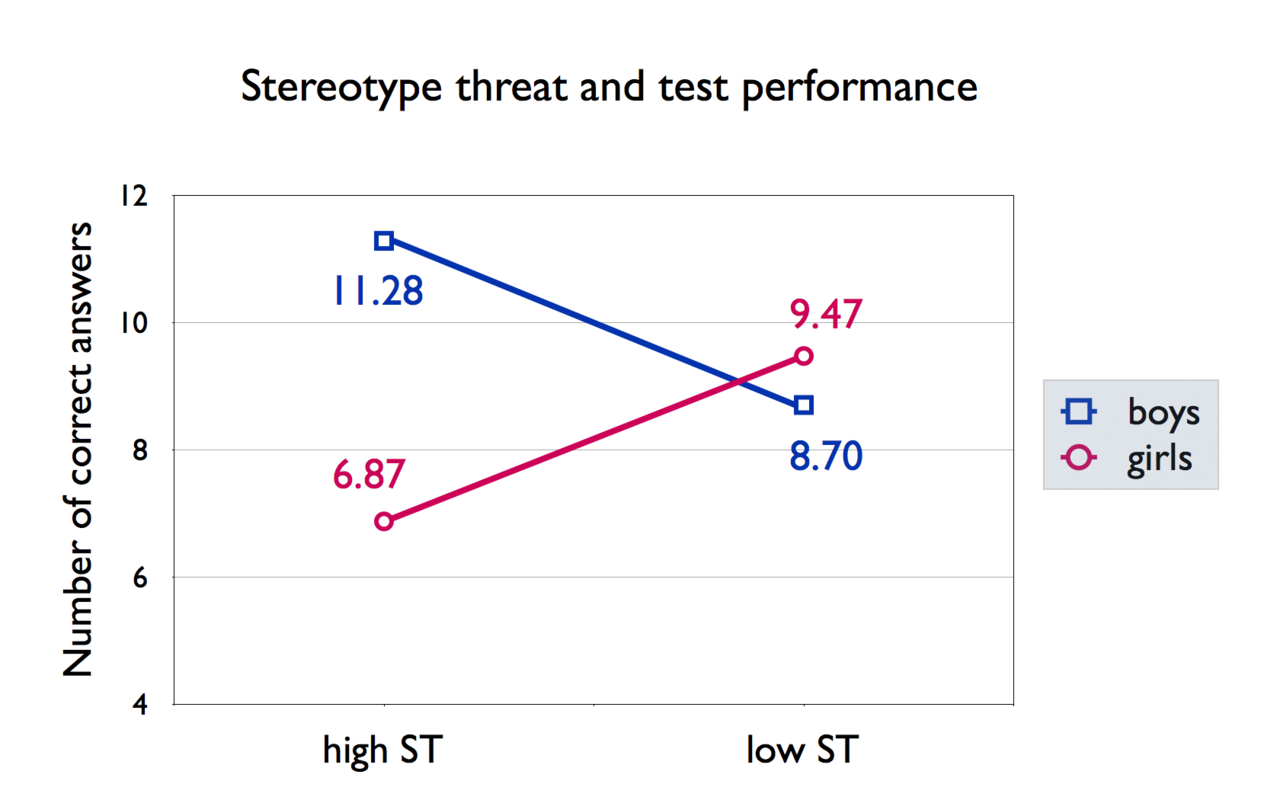

| Effects Attributional ambiguity Main article: Attributional ambiguity Attributive ambiguity refers to the uncertainty that members of stereotyped groups experience in interpreting the causes of others' behavior toward them. Stereotyped individuals who receive negative feedback can attribute it either to personal shortcomings, such as lack of ability or poor effort, or the evaluator's stereotypes and prejudice toward their social group. Alternatively, positive feedback can either be attributed to personal merit or discounted as a form of sympathy or pity.[77][78][79] Crocker et al. (1991) showed that when black participants were evaluated by a white person who was aware of their race, black subjects mistrusted the feedback, attributing negative feedback to the evaluator's stereotypes and positive feedback to the evaluator's desire to appear unbiased. When the black participants' race was unknown to the evaluator, they were more accepting of the feedback.[80] Attributional ambiguity has been shown to affect a person's self-esteem. When they receive positive evaluations, stereotyped individuals are uncertain of whether they really deserved their success and, consequently, they find it difficult to take credit for their achievements. In the case of negative feedback, ambiguity has been shown to have a protective effect on self-esteem as it allows people to assign blame to external causes. Some studies, however, have found that this effect only holds when stereotyped individuals can be absolutely certain that their negative outcomes are due to the evaluators's prejudice. If any room for uncertainty remains, stereotyped individuals tend to blame themselves.[78] Attributional ambiguity can also make it difficult to assess one's skills because performance-related evaluations are mistrusted or discounted. Moreover, it can lead to the belief that one's efforts are not directly linked to the outcomes, thereby depressing one's motivation to succeed.[77] Stereotype threat  The effect of stereotype threat (ST) on math test scores for girls and boys. Data from Osborne (2007).[81] Main article: Stereotype threat Stereotype threat occurs when people are aware of a negative stereotype about their social group and experience anxiety or concern that they might confirm the stereotype.[82] Stereotype threat has been shown to undermine performance in a variety of domains.[83][84] Claude M. Steele and Joshua Aronson conducted the first experiments showing that stereotype threat can depress intellectual performance on standardized tests. In one study, they found that black college students performed worse than white students on a verbal test when the task was framed as a measure of intelligence. When it was not presented in that manner, the performance gap narrowed. Subsequent experiments showed that framing the test as diagnostic of intellectual ability made black students more aware of negative stereotypes about their group, which in turn impaired their performance.[85] Stereotype threat effects have been demonstrated for an array of social groups in many different arenas, including not only academics but also sports,[86] chess[87] and business.[88] Some researchers have suggested that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-life performance gaps, and have raised the possibility of publication bias.[89][90][91] Other critics have focused on correcting what they claim are misconceptions of early studies showing a large effect.[92] However, meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown significant evidence for the effects of stereotype threat, though the phenomenon defies over-simplistic characterization.[93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100] Self-fulfilling prophecy Main article: Self-fulfilling prophecy Stereotypes lead people to expect certain actions from members of social groups. These stereotype-based expectations may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, in which one's inaccurate expectations about a person's behavior, through social interaction, prompt that person to act in stereotype-consistent ways, thus confirming one's erroneous expectations and validating the stereotype.[101][102][103] Word, Zanna, and Cooper (1974) demonstrated the effects of stereotypes in the context of a job interview. White participants interviewed black and white subjects who, prior to the experiments, had been trained to act in a standardized manner. Analysis of the videotaped interviews showed that black job applicants were treated differently: They received shorter amounts of interview time and less eye contact; interviewers made more speech errors (e.g., stutters, sentence incompletions, incoherent sounds) and physically distanced themselves from black applicants. In a second experiment, trained interviewers were instructed to treat applicants, all of whom were white, like the whites or blacks had been treated in the first experiment. As a result, applicants treated like the blacks of the first experiment behaved in a more nervous manner and received more negative performance ratings than interviewees receiving the treatment previously afforded to whites.[104] A 1977 study by Snyder, Tanke, and Berscheid found a similar pattern in social interactions between men and women. Male undergraduate students were asked to talk to female undergraduates, whom they believed to be physically attractive or unattractive, on the phone. The conversations were taped and analysis showed that men who thought that they were talking to an attractive woman communicated in a more positive and friendlier manner than men who believed that they were talking to unattractive women. This altered the women's behavior: Female subjects who, unknowingly to them, were perceived to be physically attractive behaved in a friendly, likeable, and sociable manner in comparison with subjects who were regarded as unattractive.[105] A 2005 study by J. Thomas Kellow and Brett D. Jones looked at the effects of self-fulfilling prophecy on African American and Caucasian high school freshman students. Both white and black students were informed that their test performance would be predictive of their performance on a statewide, high stakes standardized test. They were also told that historically, white students had outperformed black students on the test. This knowledge created a self-fulfilling prophecy in both the white and black students, where the white students scored statistically significantly higher than the African American students on the test. The stereotype threat of underperforming on standardized tests affected the African American students in this study.[106] In accountancy, there is a popular stereotype which represents members of the profession as being humorless, introspective beancounters.[107][108] Discrimination and prejudice Because stereotypes simplify and justify social reality, they have potentially powerful effects on how people perceive and treat one another.[109] As a result, stereotypes can lead to discrimination in labor markets and other domains.[110] For example, Tilcsik (2011) has found that employers who seek job applicants with stereotypically male heterosexual traits are particularly likely to engage in discrimination against gay men, suggesting that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is partly rooted in specific stereotypes and that these stereotypes loom large in many labor markets.[21] Agerström and Rooth (2011) showed that automatic obesity stereotypes captured by the Implicit Association Test can predict real hiring discrimination against the obese.[111] Similarly, experiments suggest that gender stereotypes play an important role in judgments that affect hiring decisions.[112][113] Stereotypes can cause racist prejudice. For example, scientists and activists have warned that the use of the stereotype "Nigerian Prince" for referring to Advance-fee scammers is racist, i.e. "reducing Nigeria to a nation of scammers and fraudulent princes, as some people still do online, is a stereotype that needs to be called out".[114] Self-stereotyping Main article: Self-stereotyping Stereotypes can affect self-evaluations and lead to self-stereotyping.[8][115] For instance, Correll (2001, 2004) found that specific stereotypes (e.g., the stereotype that women have lower mathematical ability) affect women's and men's evaluations of their abilities (e.g., in math and science), such that men assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level.[116][117] Similarly, a study by Sinclair et al. (2006) has shown that Asian American women rated their math ability more favorably when their ethnicity and the relevant stereotype that Asian Americans excel in math was made salient. In contrast, they rated their math ability less favorably when their gender and the corresponding stereotype of women's inferior math skills was made salient. Sinclair et al. found, however, that the effect of stereotypes on self-evaluations is mediated by the degree to which close people in someone's life endorse these stereotypes. People's self-stereotyping can increase or decrease depending on whether close others view them in stereotype-consistent or inconsistent manner.[118] Stereotyping can also play a central role in depression, when people have negative self-stereotypes about themselves. According to Cox, Abramson, Devine, and Hollon (2012).[8] , stereotyping can also play a central role in depression, which is characterized by negative self-schemas. Stereotypes and self-schemas are the same type of cognitive structure, therefore, they suggest that an integrated perspective of prejudice and depression provides useful insight on how stereotypes are acquired. Negative stereotypes are set in motion within the Source, who conveys the prejudice towards the Target, which in turn will lead the Target to suffer from depression. Members of stigmatized groups may internalize the negative evaluation of their group and develop depression. People may also show prejudice internalization through self-stereotyping because of negative childhood experiences such as verbal and physical abuse. This depression that is caused by prejudice (i.e., "deprejudice") can be related to group membership (e.g., Me–Gay–Bad) or not (e.g., Me–Bad). If someone holds prejudicial beliefs about a stigmatized group and then becomes a member of that group, they may internalize their prejudice and develop depression. People may also show prejudice internalization through self-stereotyping because of negative childhood experiences such as verbal and physical abuse.[119] Substitute for observations Stereotypes are traditional and familiar symbol clusters, expressing a more or less complex idea in a convenient way. They are often simplistic pronouncements about gender, racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds and they can become a source of misinformation and delusion. For example, in a school when students are confronted with the task of writing a theme, they think in terms of literary associations, often using stereotypes picked up from books, films, and magazines that they have read or viewed. The danger in stereotyping lies not in its existence, but in the fact that it can become a substitute for observation and a misinterpretation of a cultural identity.[120] Promoting information literacy is a pedagogical approach that can effectively combat the entrenchment of stereotypes. The necessity for using information literacy to separate multicultural "fact from fiction" is well illustrated with examples from literature and media.[121] |

効果 帰属の曖昧さ 主な記事 帰属の曖昧さ 帰属の曖昧さとは、ステレオタイプ化された集団のメンバーが、自分に対する他者の行動の原因を解釈する際に経験する不確実性のことである。否定的なフィー ドバックを受けたステレオタイプ化された人は、それを能力不足や努力不足といった個人的な欠点に帰することもできるし、評価者の社会集団に対するステレオ タイプや偏見に帰することもできる。あるいは、肯定的なフィードバックは、個人的な長所に帰することもできるし、同情や哀れみの一形態として割り引くこと もできる[77][78][79]。 Crockerら(1991)は、黒人の参加者が自分の人種を 知っている白人によって評価されたとき、黒人の被験者は フィードバックを不信に思い、否定的なフィードバックは評 価者のステレオタイプに、肯定的なフィードバックは評価者が偏っ ていないように見せたいという欲求に帰着することを示 した。黒人の被験者が評価者に人種を知らされていない場合、彼らはフィードバックをより受け入れた[80]。 帰属の曖昧さは、人の自尊心に影響することが示されている。肯定的な評価を受けると、固定観念にとらわれた人 は、自分が本当にその成功に値するかどうかがわからなくな り、その結果、自分の功績を認めることが難しくなる。否定的なフィードバックの場合、あいまいさは外的な原因に責任をなすりつけることを可能にするため、 自尊心を保護する効果があることが示されている。しかし、いくつかの研究によると、この効果は、ステレオタイプ化された人が、自分の否定的な結果が評価者 の偏見によるものであると絶対的に確信できる場合にのみ成り立つことが分かっている。不確実性の余地が残っている場合、固定観念に縛られた人 は自分自身を責める傾向がある[78]。 帰属の曖昧さはまた、パフォーマンスに関連した評価が信頼されな かったり、割り引かれたりするため、自分のスキルを評価することを困難に する。さらに、自分の努力は結果に直結していないと考えるようになり、成功への意欲が減退することもある[77]。 ステレオタイプの脅威  ステレオタイプの脅威(ST)が女子と男子の数学テストの得点に及ぼす影響。Osborne(2007)のデータ[81]。 主な記事 ステレオタイプの脅威 ステレオタイプ脅威は、人々が自分の社会的集団に関する否定的なステレオタイプを認識し、そのステレオタイプを確認するかもしれないという不安や懸念を経 験するときに生じる[82]。ステレオタイプ脅威は様々な領域においてパフォーマンスを低下させることが示されている[83][84]。 クロード・M・スティールとジョシュア・アロンソンは、ステレオタイプ脅威が標準化されたテストにおける知的パフォーマンスを低下させる可能性があること を示す最初の実験を行った。ある研究では、黒人の大学生は、課題が知能の測定とし て設定された場合、言語テストで白人の学生よりも成績が悪 くなることがわかった。そうでない場合は、成績の差は縮まった。その後の実験では、テストを知的能力の診断として枠組 むことで、黒人学生が自分たちの集団に対する否定的なステ レオタイプをより意識するようになり、その結果成績が低下するこ とが示された[85]。ステレオタイプ脅威効果は、学問だけでなく、ス ポーツ[86]、チェス[87]、ビジネス[88]など、様々な分野の社会集団に対 して実証されている。 研究者の中には、ステレオタイプ脅威を現実のパフォーマンス格差の要因として解釈すべきではないと指摘する者もおり、出版バイアスの可能性を指摘している [89][90][91]。 [しかし、メタアナリシスやシステマティック・レビューは、ステレオタイプ脅威の効果について有意な証拠を示しているが、その現象は単純化しすぎた特徴付 けを拒んでいる[93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100]。 自己実現的予言 主な記事 自己実現的予言 ステレオタイプは、社会集団のメンバーから特定の行動を期待させる。このようなステレオタイプに基づく期待は自己成就予言につながる可能性があり、社会的 相互作用を通じて、ある人の行動に対する不正確な期待が、その人にステレオタイプに一致した行動をとるように促し、その結果、自分の誤った期待が確認さ れ、ステレオタイプが正当化される[101][102][103]。 ワード、ザナ、クーパー(1974年)は、就職面接の文脈においてステレオタイプの効果を実証した。白人の参加者は、実験前に標準化された方法で行動する よう訓練された黒人と白人の被験者に面接した。ビデオに録画された面接を分析したところ、黒人の求職者は異なる扱いを受けたことがわかった: 面接時間は短く、アイコンタクトも少なかった。面接官は話し間違い(吃音、文の未完成、支離滅裂な音など)が多く、黒人の応募者から物理的に距離をとっ た。2つ目の実験では、訓練を受けた面接官に、応募者全員を白人として、1つ目の実験で白人や黒人がされたような扱いをするよう指示した。その結果、最初 の実験の黒人のように扱われた応募者は、以前白人に与えられた待遇を受けた面接者よりも神経質に振る舞い、より否定的な業績評価を受けた[104]。 Snyder、Tanke、Berscheidによる1977年の研究では、男女間の社会的相互作用にも同様のパターンがあることがわかった。男子学部生 は、肉体的に魅力的または魅力的でないと思われる女子学部生と電話で話すよう求められた。会話は録音され、分析の結果、魅力的な女性と話していると思った 男性は、魅力的でない女性と話していると思った男性よりも、より積極的で友好的なコミュニケーションをとることがわかった。これが女性の行動を変えた: 彼女らにとって知らず知らずのうちに、肉体的に魅力的であると認識されていた女性被験者は、魅力的でないとみなされていた被験者と比較して、友好的で好感 が持て、社交的な振る舞いをしたのである[105]。 J.トーマス・ケローとブレット・D.ジョーンズによる2005年の研究では、アフリカ系アメリカ人と白人の高校1年生に対する自己実現予言の効果を調べ た。白人と黒人の生徒の双方に、自分のテストの成績が、州全体で実施される高得点の標準化テストの成績を予測することになる、と告げた。また、歴史的に白 人の生徒が黒人の生徒よりもテストの成績が良いことも知らされた。この知識は、白人生徒と黒人生徒の双方に自己成就予言を生み出し、白人生徒はテストでア フリカ系アメリカ人生徒より統計的に有意に高い得点を取った。標準化されたテストの成績が悪いというステレオタイプの脅威は、この研究のアフリカ系アメリ カ人の学生に影響を与えた[106]。 会計士という職業には、ユーモアがなく、内省的な会計士というステレオタイプがある[107][108]。 差別と偏見 例えば、Tilcsik (2011)は、ステレオタイプ的な男性異性愛者の特徴を持つ求職者を求める雇用主は、特にゲイ男性に対する差別を行う可能性が高いことを発見しており、 性的指向に基づく差別は部分的に特定のステレオタイプに根ざしており、これらのステレオタイプが多くの労働市場で大きく影響していることを示唆している。 [21] Agerström and Rooth (2011)は、暗黙の関連性テストによって捉 えられる自動的な肥満のステレオタイプが、肥満者に対する実際の雇 用差別を予測できることを示した[111]。同様に、ジェンダー・ステレオタイプが雇 用決定に影響を与える判断において重要な役割を果たすこ とを実験は示唆している[112][113]。 ステレオタイプは人種差別的偏見を引き起こす可能性がある。例えば、科学者や活動家は、「ナイジェリアの王子様」というステレオタイプをアドバンスフィー 詐欺師に使用することは人種差別的である、すなわち「ナイジェリアを詐欺師と詐欺師の王子の国に貶めることは、いまだにネット上で一部の人々が行っている ように、非難されるべきステレオタイプである」と警告している[114]。 自己ステレオタイプ 主な記事 自己ステレオタイプ 例えば、コレル(2001、2004)は、特定のステレオタイプ(例えば、女性は数学的能力が低いというステレオタイプ)が女性や男性の能力(例えば、 同様に、Sinclairら(2006)の研究は、アジア系アメリカ人女性は、民族性とアジア系アメリカ人は数学が得意であるという関連するステレオタイ プが強調された場合、自分の数学能力をより好意的に評価することを示している。対照的に、アジア系アメリカ人女性は、自分の性別と、それに対応する「女性 の数学能力は劣っている」というステレオタイプが強調されると、自分の数学能力をあまり好意的に評価しなかった。しかし、シンクレアらは、ステレオタイプ が自己評価に及ぼす影響は、身近な人がどの程度そのステレオタイプを支持しているかによって媒介されることを発見した。人々の自己ステレオタイプは、親し い他者がステレオタイプに一致した見方をしているか、矛盾した見方をしているかによって増減する可能性がある[118]。 ステレオタイプは、人々が自分自身について否定的な自己ステレオタイプを持っている場合、うつ病においても中心的な役割を果たすことがある。Cox、 Abramson、Devine、Hollon(2012)[8]によると、否定的な自己スキーマによって特徴づけられるうつ病においても、ステレオタイ プは中心的な役割を果たすことがある。ステレオタイプと自己スキーマは同じタイプの認知構造であり、したがって、偏見とうつ病の統合的な視点は、ステレオ タイプがどのように獲得されるかについて有用な洞察を提供することを示唆している。否定的なステレオタイプは、対象者に偏見を伝える情報源の中で動き出 し、その結果、対象者はうつ病に苦しむことになる。汚名を着せられた集団の成員は、その集団に対する否定的な評価を内面化し、うつ病を発症する可能性があ る。また、暴言や身体的虐待などの幼少期の否定的な体験から、自己ステレオタイプ化によって偏見の内面化を示すこともある。このような偏見に起因する抑う つ状態(すなわち「脱偏見」)は、集団の一員であること(例えば、Me-Gay-Bad)に関連することもあれば、そうでないこと(例えば、Me- Bad)に関連することもある。誰かが汚名を着せられた集団に対して偏見に満ちた信念を持ち、その後その集団の一員となった場合、その人は偏見を内面化 し、うつ病を発症する可能性がある。また、暴言や身体的虐待などの幼少期の否定的な体験のために、自己ステレオタイプ化によって偏見の内面化を示すことも ある[119]。 観察の代用 ステレオタイプは伝統的で親しみのあるシンボル・クラスターであり、多かれ少なかれ複雑な考えを便利な方法で表現している。それらはしばしば、性別、人 種、民族、文化的背景に関する単純化された宣告であり、誤った情報や妄想の源となりうる。例えば、学校で生徒がテーマを書くという課題に直面したとき、彼 らは文学的な連想で考え、多くの場合、読んだり見たりした本や映画、雑誌から拾ったステレオタイプを使う。 ステレオタイプの危険性は、その存在にあるのではなく、それが観察の代わりとなり、文化的アイデンティティを誤って解釈してしまうことにある。多文化的な 「事実と虚構」を分離するために情報リテラシーを用いる必要性は、文学やメディアからの例でよく説明されている[121]。 |

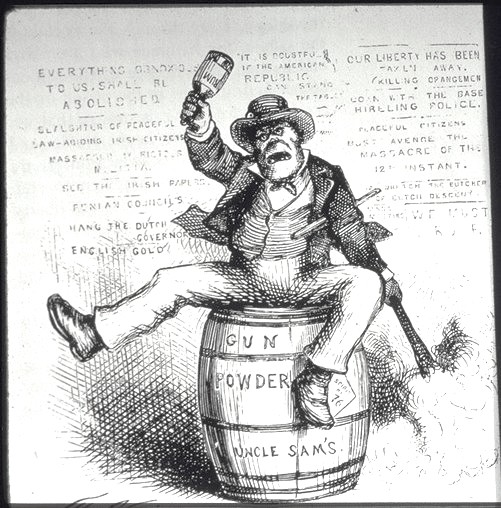

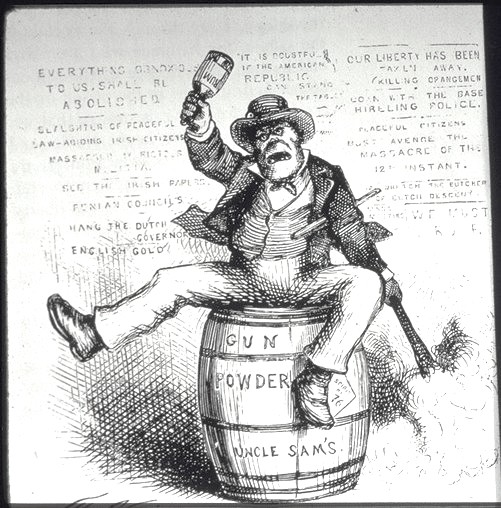

Role in art and culture American political cartoon titled "The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things", depicting a drunken Irishman lighting a powder keg and swinging a bottle. Published in Harper's Weekly, 1871. Stereotypes are common in various cultural media, where they take the form of dramatic stock characters. The instantly recognizable nature of stereotypes mean that they are effective in advertising and situation comedy.[122] Alexander Fedorov (2015) proposed a concept of media stereotypes analysis. This concept refers to identification and analysis of stereotypical images of people, ideas, events, stories, themes, etc. in media context.[123] The characters that do appear in movies greatly affect how people worldwide perceive gender relations, race, and cultural communities. Because approximately 85% of worldwide ticket sales are directed toward Hollywood movies, the American movie industry has been greatly responsible for portraying characters of different cultures and diversity to fit into stereotypical categories.[124] This has led to the spread and persistence of gender, racial, ethnic, and cultural stereotypes seen in the movies.[89] For example, Russians are usually portrayed as ruthless agents, brutal mobsters and villains in Hollywood movies.[125][126][127] According to Russian American professor Nina L. Khrushcheva, "You can't even turn the TV on and go to the movies without reference to Russians as horrible."[128] The portrayals of Latin Americans in film and print media are restricted to a narrow set of characters. Latin Americans are largely depicted as sexualized figures such as the Latino macho or the Latina vixen, gang members, (illegal) immigrants, or entertainers. By comparison, they are rarely portrayed as working professionals, business leaders or politicians.[112] In Hollywood films, there are several Latin American stereotypes that have historically been used. Some examples are El Bandido, the Halfbreed Harlot, The Male Buffoon, The Female Clown, The Latin Lover, The Dark Lady, The Wise Old Man, and The Poor Peon. Many Hispanic characters in Hollywood films consists of one or more of these basic stereotypes, but it has been rare to view Latin American actors representing characters outside of this stereotypical criteria.[129] Media stereotypes of women first emerged in the early 20th century. Various stereotypic depictions or "types" of women appeared in magazines, including Victorian ideals of femininity, the New Woman, the Gibson Girl, the Femme fatale, and the Flapper.[88][130] Stereotypes are also common in video games, with women being portrayed as stereotypes such as the "damsel in distress" or as sexual objects (see Gender representation in video games).[131] Studies show that minorities are portrayed most often in stereotypical roles such as athletes and gangsters[132] (see Race and video games). In literature and art, stereotypes are clichéd or predictable characters or situations. Throughout history, storytellers have drawn from stereotypical characters and situations to immediately connect the audience with new tales.[133] Role in sports Female athletes encounter various pressures and stereotypes, which have significant psychological consequences. These stereotypes give rise to challenges in athletes' lives, including diminished self-esteem, leading to more profound psychological impacts. Female athletes have made considerable strides in overcoming obstacles. They have transitioned from being unable to compete competitively due to biological misconceptions to having equal opportunities as male athletes, thanks to Title IX.[134] Today, there is greater societal acceptance of female athletes. However, the intersection of being a female athlete adds additional pressures. Not only are they expected to excel in competition, but they are also required to conform to societal expectations of femininity. Furthermore, female athletes often face scrutiny and criticism regarding their appearance compared to non-athletic women. Young athletes, in particular, confront an intensified amount of pressure, leading some to quit sports because it is no longer enjoyable and the implications of being a young female athlete become overwhelming. They are unfairly labeled as gay or delicate and subjected to derogatory comments such as "like a girl." Additionally, they grapple with body image concerns that can give rise to severe health issues. Even specific sports contribute to the scrutiny female athletes face, with criticism directed at the uniforms required for competition.[134] The proliferation of stereotypes in women's sports has resulted in a decline in female participation. These social stigmas, including being labeled as gay or delicate, and the expectation to play in a manner deemed "like a girl," have contributed to body image issues, eating disorders, and depression among numerous female athletes. |

芸術と文化における役割 The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things と題されたアメリカの政治漫画。酔っ払ったアイルランド人が火薬樽に火をつけ、瓶を振り回す様子が描かれている。Harper's Weekly (1971)に掲載。 ステレオタイプは、さまざまな文化メディアで一般的であり、そこではドラマチックなストックキャラクターの形をとっている。即座に認識できるステレオタイ プの性質は、広告やシチュエーション・コメディにおいて効果的であることを意味する[122]。アレクサンダー・フェドロフ(2015)は、メディア・ス テレオタイプ分析の概念を提唱した。この概念は、メディアの文脈における人物、アイデア、出来事、物語、テーマなどのステレオタイプ的なイメージの識別と 分析を指す[123]。 映画に登場するキャラクターは、世界中の人々がジェンダー関係、人種、文化的コミュニティをどのように認識するかに大きく影響する。全世界のチケット売上 の約85%がハリウッド映画に向けられるため、アメリカの映画産業は、異なる文化や多様性のある人物をステレオタイプなカテゴリーに当てはめるように描く ことに大きな責任を負っている[124]。このことが、映画で見られるジェンダー、人種、民族、文化的ステレオタイプの広がりと持続につながっている [89]。 例えば、ハリウッド映画においてロシア人は通常、冷酷な諜報員、残忍なマフィア、悪役として描かれている[125][126][127]。 ロシア系アメリカ人のニーナ・L・フルシチョヴァ教授によれば、「ロシア人が恐ろしいという言及なしに、テレビをつけたり映画を観に行ったりすることさえ できない」[128]。映画や印刷メディアにおけるラテンアメリカ人の描写は、狭い範囲の人物に限定されている。ラテンアメリカ人は主に、ラテン系マッ チョやラテン系女狐、ギャングのメンバー、(不法)移民、芸能人など、性的な人物として描かれている。それに比べて、彼らが社会人、ビジネスリーダー、政 治家として描かれることはほとんどない[112]。 ハリウッド映画では、歴史的に使用されてきたラテンアメリカのステレオタイプがいくつかある。例えば、「エル・バンディード」、「混血の娼婦」、「男の道 化師」、「女の道化師」、「ラテンの恋人」、「暗い女」、「賢い老人」、「貧しい小間使い」などである。ハリウッド映画に登場する多くのヒスパニック系の キャラクターは、これらの基本的なステレオタイプの1つまたは複数で構成されているが、ラテンアメリカの俳優がこのステレオタイプ的な基準から外れたキャ ラクターを演じることは稀である[129]。 メディアによる女性のステレオタイプは、20世紀初頭に初めて出現した。ヴィクトリア朝の女性らしさの理想、ニュー・ウーマン、ギブソン・ガール、ファ ム・ファタール、フラッパーなど、様々なステレオタイプな女性の描写や「タイプ」が雑誌に登場した[88][130]。 ステレオタイプはビデオゲームにおいても一般的であり、女性は「苦悩する乙女」のようなステレオタイプとして、あるいは性的対象として描かれる(ビデオ ゲームにおけるジェンダー表現を参照)[131]。研究によれば、マイノリティはスポーツ選手やギャングスターのようなステレオタイプな役割で描かれるこ とが最も多い[132](人種とビデオゲームを参照)。 文学や芸術において、ステレオタイプとは決まりきった、あるいは予測可能なキャラクターや状況のことである。歴史を通して、ストーリーテラーは新しい物語 で観客を即座に結びつけるためにステレオタイプのキャラクターや状況を描いてきた[133]。 スポーツにおける役割 女性アスリートは様々なプレッシャーやステレオタイプに遭遇し、それが心理的に重大な影響を及ぼす。このような固定観念は、自尊心の低下など、アスリート の生活における課題を生じさせ、より深刻な心理的影響につながる。 女性アスリートは障害を克服することで、かなりの進歩を遂げてきた。彼女たちは、生物学的な誤解のために競技に参加することができなかった状態から、タイ トルIXのおかげで、男性アスリートと同等の機会を得られるようになった。しかし、女性アスリートであることが交差することで、さらなるプレッシャーが加 わる。競技において優秀であることが求められるだけでなく、女性らしさに対する社会の期待に沿うことも求められる。さらに、女性アスリートは、非アスリー ト女性と比較して、外見に関する詮索や批判にしばしば直面する。 特に若いアスリートは、より強いプレッシャーに直面し、スポーツが楽しくなくなり、若い女性アスリートであることの意味合いに圧倒されて、スポーツをやめ てしまう人もいる。ゲイやデリケートという不当なレッテルを貼られ、"女の子みたい "などと軽蔑的な言葉を浴びせられる。さらに、深刻な健康問題を引き起こしかねないボディ・イメージの懸念に悩まされる。特定のスポーツでさえ、競技に必 要なユニフォームに批判が向けられるなど、女性アスリートが直面する監視の目を助長している[134]。 女性スポーツにおける固定観念の蔓延は、女性参加者の減少をもたらした。ゲイやデリケートというレッテルを貼られること、「女の子らしく」プレーすること を求められることなど、こうした社会的スティグマは、多くの女性アスリートのボディイメージの問題、摂食障害、うつ病の一因となっている。 |

| Archetype Attribute substitution Attribution bias Base rate fallacy Cognitive bias Conjunction fallacy (Linda problem) Counterstereotype (antonym) Echo chamber (media) Ethnocentrism Face-ism Filter Bubble Habitus (sociology) Implicit stereotype In-group favoritism Labelling Labeling theory Negativity effect Out-group homogeneity Role Role reversal Role suction Scapegoating Similarity (philosophy) Statistical syllogism Stigma management Stigmatization Stock character Trait ascription bias Women-are-wonderful effect Gender Gender stereotypes Femininity Masculinity Psychology portal icon Society portal Examples of stereotypes Cultural and ethnic Ethnic stereotype List of ethnic slurs Stereotypes of African Americans Stereotypes of Africans Stereotypes of Americans Stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in the United States Stereotypes of Argentines Stereotypes of the British Stereotypes of Canadians Stereotypes of French people Stereotypes of Germans Stereotypes of groups within the United States Stereotypes of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States Stereotypes of Indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States Stereotypes of Japanese people Stereotypes of Jews Stereotypes of Russians Stereotypes of South Asians Stereotypes of East and Southeast Asians Sexuality related LGBT stereotypes List of sexuality related phobias Other Blonde stereotypes Nurse stereotypes Physical attractiveness stereotype |

アーキタイプ 属性置換 帰属バイアス 基礎率の誤り 認知バイアス 結合の誤謬(リンダ問題) カウンターステレオタイプ(反意語) エコーチェンバー(メディア) エスノセントリズム 顔イズム フィルター・バブル ハビトゥス(社会学) 暗黙のステレオタイプ 集団内贔屓 ラベリング ラベリング理論 否定効果 外集団の同質性 役割 役割の逆転 役割の吸引 スケープゴーティング 類似性(哲学) 統計的三段論法 スティグマ・マネジメント スティグマ化 ストック・キャラクター 形質帰属バイアス 女性は素晴らしい効果 ジェンダー ジェンダー・ステレオタイプ 女性らしさ 男性性 心理学ポータル アイコン 社会ポータル ステレオタイプの例 文化的・民族的 民族的ステレオタイプ 民族的中傷のリスト アフリカ系アメリカ人のステレオタイプ アフリカ人のステレオタイプ アメリカ人のステレオタイプ アメリカにおけるアラブ人およびイスラム教徒のステレオタイプ アルゼンチン人のステレオタイプ イギリス人のステレオタイプ カナダ人のステレオタイプ フランス人のステレオタイプ ドイツ人のステレオタイプ 米国内のグループのステレオタイプ 米国のヒスパニック系およびラテン系アメリカ人のステレオタイプ カナダと米国の先住民のステレオタイプ 日本人のステレオタイプ ユダヤ人のステレオタイプ ロシア人のステレオタイプ 南アジア人のステレオタイプ 東アジア人および東南アジア人のステレオタイプ セクシュアリティ関連 LGBTのステレオタイプ セクシュアリティ関連恐怖症のリスト その他 金髪のステレオタイプ 看護師のステレオタイプ 身体的魅力のステレオタイプ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotype |

|

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆