E・ゲルナーの『ネーションズとナショナリズム』

Nations and nationalism / Ernest Gellner

解 説:池田光穂

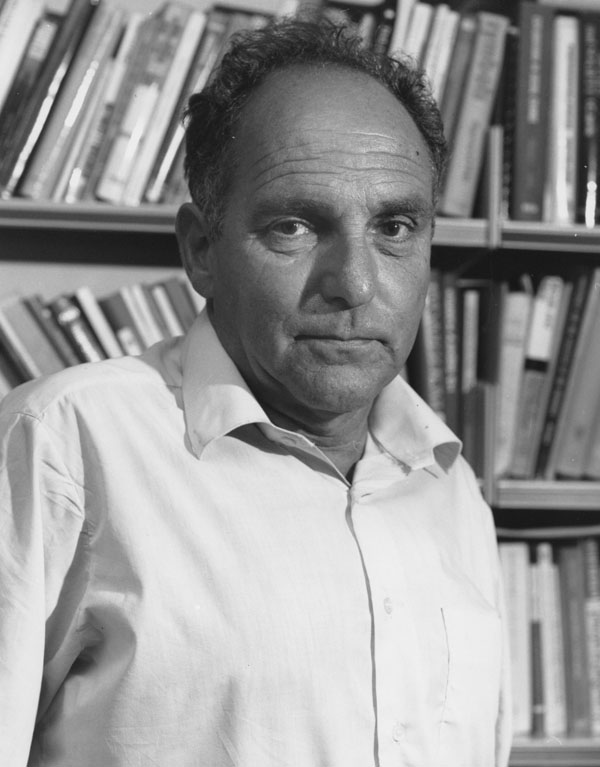

アーネスト・ゲルナー(Ernest Gellner, 1925-1995)「ナショナリズムは国民の自意識の覚醒ではない。ナショナリズムは、もともと存在して いないところに国民を発明することだ。」(ベネディクト・アンダーソン『想像の共同体』p.17)

| Gellner's theory of

nationalism was developed by Ernest Gellner over a number of

publications from around the early 1960s to his 1995 death.[1][2]

Gellner discussed nationalism in a number of works, starting with

Thought and Change (1964), and he most notably developed it in Nations

and Nationalism (1983).[2] His theory is modernist. |

ゲルナーのナショナリズム論は、アーネスト・ゲルナーによって1960

年代初頭頃から1995年に亡くなるまで、多くの出版物を通じて展開された[1][2]。ゲルナーは、『思想と変化』(1964年)に始まる多くの著作で

ナショナリズムについて論じており、最も顕著なのは『国家とナショナリズム』(1983年)でそれを発展させた。 |

| Characteristics Gellner defined nationalism as "primarily a political principle which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent"[3] and as the general imposition of a high culture on society, where previously low cultures had taken up the lives of the majority, and in some cases the totality, of the population. It means the general diffusion of a school-mediated, academy supervised idiom, codified for the requirements of a reasonably precise bureaucratic and technological communication. It is the establishment of an anonymous impersonal society, with mutually sustainable atomised individuals, held together above all by a shared culture of this kind, in place of the previous complex structure of local groups, sustained by folk cultures reproduced locally and idiosyncratically by the micro-groups themselves.[4] Gellner analyzed nationalism by a historical perspective.[5] He saw the history of humanity culminating in the discovery of modernity, nationalism being a key functional element.[5] Modernity, by changes in political and economic system, is tied to the popularization of education, which, in turn, is tied to the unification of language.[5] However, as modernization spread around the world, it did so slowly, and in numerous places, cultural elites were able to resist cultural assimilation and defend their own culture and language successfully.[5] For Gellner, nationalism was a sociological condition[5] and a likely but not guaranteed (he noted exceptions in multilingual states like Switzerland, Belgium and Canada[2]) result of modernisation, the transition from agrarian to industrial society.[1][2] His theory focused on the political and cultural aspects of that transition.[1] In particular, he focused on the unifying and culturally homogenising roles of the educational systems, national labour markets and improved communication and mobility in the context of urbanisation.[1] He thus argued that nationalism was highly compatible with industrialisation and served the purpose of replacing the ideological void left by both the disappearance of the prior agrarian society culture and the political and economical system of feudalism, which it legitimised.[1][2] Thomas Hylland Eriksen lists these as "some of the central features of nationalism" in Gellner's theory:[1] Shared, formal educational system Cultural homogenisation and "social entropy" Central monitoring of polity, with extensive bureaucratic control Linguistic standardisation National identification as abstract community Cultural similarity as a basis for political legitimacy Anonymity, single-stranded social relationships Gellner also provided a typology of "nationalism-inducing and nationalism-thwarting situations".[2] Gellner criticised a number of other theoretical explanations of nationalism, including the "naturality theory", which states that it is "natural, self-evident and self-generating" and a basic quality of human being, and a neutral or a positive quality; its dark version, the "Dark Gods theory", which sees nationalism as an inevitable expression of basic human atavistic, irrational passions; and Elie Kedourie's idealist argument that it was an accidental development, an intellectual error of disseminating unhelpful ideas, and not related to industrialisation and the Marxist theory in which nations appropriated the leading role of social classes.[2] On October 24, 1995, at Warwick University, Gellner debated one of his former students, Anthony D. Smith in what became known as the Warwick Debates. Smith presented an ethnosymbolist view, Gellner a modernist one. The debate has been described as epitomizing their positions.[6][7][8] |

特徴 ゲルナーはナショナリズムを「主として、政治的な単位と国民的な単位は一致すべきであるとする政治的な原理」[3]であり、次のように定義した。 以前は低俗な文化が人口の大多数、場合によっては全人口の生活を占めていたところに、高度の文化が一般的に社会に押しつけられること。それは、学校が仲介 し、アカデミーが監督するイディオムの一般的な普及を意味し、合理的に正確な官僚的・技術的コミュニケーションの要求のために成文化されたものである。そ れは、微小集団自身によって局所的かつ特異的に再生産される民俗文化によって支えられていた地域集団の複雑な構造に代わって、この種の共有文化によってと りわけ一つに支えられている、相互に持続可能な原子化された個人からなる匿名の非人間的社会の確立である[4]。 ゲルナーは歴史的な観点からナショナリズムを分析した[5]。 彼は人類の歴史が近代の発見において頂点に達すると見ており、ナショナリズムは重要な機能的要素であった[5]。 近代は政治的・経済的システムの変化によって、教育の大衆化と結びついており、それは言語の統一と結びついている[5]。しかし、近代化が世界中に広まる につれて、それはゆっくりと行われ、多くの場所で文化的エリートたちは文化的同化に抵抗し、独自の文化と言語をうまく守ることができた[5]。 ゲルナーにとって、ナショナリズムは社会学的な条件[5]であり、農耕社会から工業社会への移行である近代化の結果である可能性は高いが保証されたもので はない(彼はスイス、ベルギー、カナダなどの多言語国家における例外を指摘している[2])。 [1]特に、彼は教育制度、全国的な労働市場、都市化の文脈におけるコミュニケーションと移動性の向上がもたらす統一的かつ文化的に均質化する役割に焦点 を当てた[1]。したがって、彼はナショナリズムが工業化と非常に適合的であり、それまでの農耕社会文化の消滅と、それが正当化した封建制の政治的・経済 的システムの両方によって残されたイデオロギー的空白を置き換えるという目的を果たすと主張した[1][2]。 トーマス・ヒランド・エリクセンは、ゲルナーの理論における「ナショナリズムの中心的な特徴のいくつか」として以下を挙げている[1]。 共有された正式な教育システム 文化の均質化と「社会的エントロピー 広範な官僚統制を伴う政治の中央監視 言語の標準化 抽象的共同体としての国民識別 政治的正当性の基礎としての文化的類似性 匿名性、一本鎖の社会関係 ゲルナーはまた、「ナショナリズムを誘発する状況とナショナリズムを喪失させる状況」の類型論も提供している[2]。 ゲルナーは、ナショナリズムが「自然であり、自明であり、自己生成的」であり、人間の基本的な資質であり、中立的または肯定的な資質であるとする「自然性 理論」、その暗黒版である「暗黒神理論」、ナショナリズムを人間の基本的な原初的で非合理的な情熱の必然的な表現とみなす理論など、ナショナリズムに関す る他の多くの理論的説明を批判した; そして、エリー・ケドゥーリの理想主義的な議論では、ナショナリズムは偶発的な発展であり、有益でない考えを広めたことによる知的過ちであり、工業化や、 国家が社会階級の主導的役割を担うというマルクス主義理論とは無関係である。 [2] 1995年10月24日、ゲルナーはウォーリック大学で、かつての教え子の一人であるアンソニー・D・スミスと、ウォーリック討論会として知られるように なった討論を行った。スミスはエスノシンボル主義的な見解を示し、ゲルナーは近代主義的な見解を示した。このディベートは両者の立場を象徴するものとして 語られている[6][7][8]。 |

| Influence Gellner is considered one of the leading theoreticians on nationalism. Eriksen notes that "nobody contests Ernest Gellner's central place in the research on nationalism over the last few decades".[1] O'Leary refers to the theory as "the best-known modernist explanatory theory of nationalism".[2] |

影響力 ゲルナーはナショナリズムに関する主要な理論家の一人とみなされている。エリクセンは、「ここ数十年のナショナリズム研究において、アーネスト・ゲルナー が中心的な位置を占めていることに異議を唱える者はいない」と指摘している[1]。 |

| Criticisms Gellner's theory has been subject to various criticisms:[2] It is too functionalist, as it explains the phenomenon with reference to the eventual historical outcome that industrial society could not 'function' without nationalism.[9] It misreads the relationship between nationalism and industrialisation.[10] It accounts poorly for national movements of Ancient Rome and Greece since it insists that nationalism is tied to modernity and so cannot exist without a clearly defined modern industrialisation.[5][11] It fails to account for either nationalism in non-industrial society and resurgences of nationalism in post-industrial society.[10] It fails to account for nationalism in 16th-century Europe.[12] It cannot explain the passions generated by nationalism and why anyone should fight and die for a country.[13] It fails to take into account either the role of war and the military in fostering both cultural homogenisation and nationalism or the relationship between militarism and compulsory education.[14] It has been compared to technological determinism, as it disregards the views of individuals.[5] Philip Gorski has argued that modernization theorists, such as Gellner, have gotten the timing of nationalism wrong: nationalism existed prior to modernity, and even had medieval roots.[15] |

批判 ゲルナーの理論は様々な批判にさらされてきた。 産業社会はナショナリズムなしには「機能」し得ないという最終的な歴史的帰結を参照して現象を説明しているため、機能主義的すぎる[9]。 ナショナリズムと工業化の関係を見誤っている[10]。 ナショナリズムは近代性と結びついているため、明確に定義された近代の工業化なしには存在し得ないと主張しているため、古代ローマやギリシャの民族運動に ついての説明が不十分である[5][11]。 非工業化社会におけるナショナリズムやポスト工業化社会におけるナショナリズムの復活を説明することができない[10]。 16世紀のヨーロッパにおけるナショナリズムを説明することができない[12]。 ナショナリズムが生み出す情熱や、なぜ誰もが国のために戦い、死ぬべきなのかを説明することができない[13]。 文化的均質化とナショナリズムの育成における戦争と軍隊の役割や、軍国主義と義務教育の関係も考慮に入れていない[14]。 それは個人の意見を無視しているため、技術決定論と比較されている[5]。 フィリップ・ゴルスキーは、ゲルナーのような近代化論者はナショナリズムの時期を誤っていると主張している。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gellner%27s_theory_of_nationalism |

|

Nations and nationalism / Ernest Gellner: pbk.. - Ithaca : Cornell University Press , 1983. - (New perspectives on the past). - (Cornell paperbacks)

Introduction, by John Breuilly

1. Definitions

State and Nation

The Nation

2. Culture in Agrarian Society

Power and Culture in the Agro-literate Polity

Culture

The State in Agrarian Society

The Varieties of Agrarian Rulers

3. Industrial Society

The Society of Perpetual Growth

Social Genetics

The Age of Universal High Culture

4. The Transition to an Age of Nationalism

A Note on the Weakness of Nationalism

Wild and Garden Cultures

5. What is a Nation?

The Course of True Nationalism Never did Run Smooth

6. Social Entropy and Equality in Industrial Society

Obstacles to Entropy

Fissures and Barriers

A Diversity of Focus

7. A Typology of Nationalisms

The Varieties of Nationalist Experience

Diaspora Nationalism

8. The Future of Nationalism

Industrial Culture - One or Many?

9. Nationalism and Ideology

Who is for Nuremberg?

One Nation, One State

10. Conclusion

What is not being Said

Summary

Select Bibliography

Bibliography of Ernest Gellner's Writings on Nationalism, by Ian Jamie Index

リンク先

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆