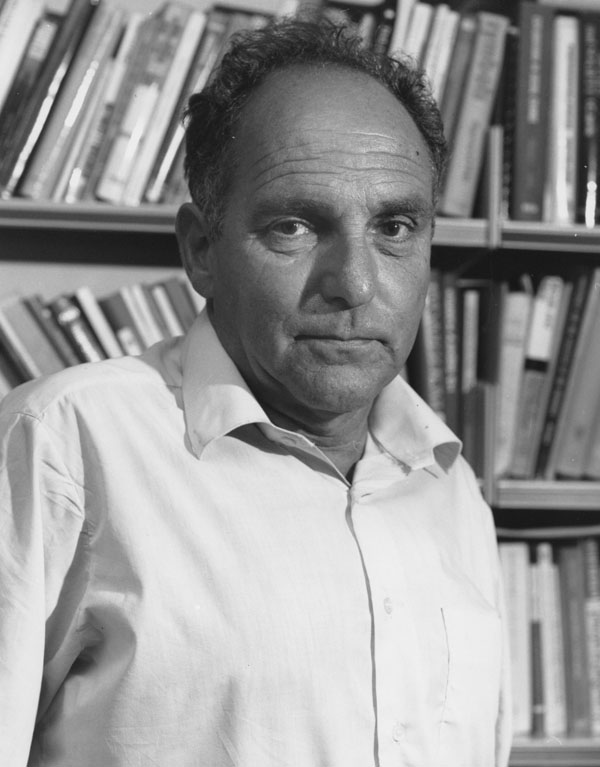

アーネスト・ゲルナー

Ernest Gellner, 1925-1995

☆ アーネスト・ゲルナーあるいは、エルネスト・ゲルナー(Ernest André Gellner FRAI、1925年12月9日 - 1995年11月5日)はイギリス系チェコ人の哲学者、社会人類学者で、死去した当時、デイリー・テレグラフ紙は「世界で最も精力的な知識人の一人」、イ ンディペンデント紙は「批判的合理主義のための孤独な十字軍兵士」と 評した

| Ernest

André Gellner FRAI (9 December 1925 – 5 November 1995) was a

British-Czech philosopher and social anthropologist described by The

Daily Telegraph, when he died, as one of the world's most vigorous

intellectuals, and by The Independent as a "one-man crusader for

critical rationalism".[1] His first book, Words and Things (1959), prompted a leader in The Times and a month-long correspondence on its letters page over his attack on linguistic philosophy. As the Professor of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics for 22 years, the William Wyse Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge for eight years, and head of the new Centre for the Study of Nationalism in Prague, Gellner fought all his life—in his writing, teaching and political activism—against what he saw as closed systems of thought, particularly communism, psychoanalysis, relativism and the dictatorship of the free market.[clarification needed][citation needed] Among other issues in social thought, modernization theory and nationalism were two of his central themes, his multicultural perspective allowing him to work within the subject-matter of three separate civilizations: Western, Islamic, and Russian. He is considered one of the leading theoreticians on the issue of nationalism.[2] |

アー

ネスト・アンドレ・ゲルナー(Ernest André Gellner FRAI、1925年12月9日 -

1995年11月5日)はイギリス系チェコ人の哲学者、社会人類学者で、死去した当時、デイリー・テレグラフ紙は「世界で最も精力的な知識人の一人」、イ

ンディペンデント紙は「批判的合理主義のための孤独な十字軍兵士」と評した[1]。 彼の最初の著書『Words and Things』(1959年)は、『タイムズ』紙のリーダー的存在となり、言語哲学に対する彼の攻撃をめぐって、同紙のレターページで1ヶ月に及ぶやり取 りが行われた。22年間ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの哲学、論理学、科学的方法の教授を務め、8年間ケンブリッジ大学のウィリアム・ワイズ社 会人類学教授を務め、プラハの新しいナショナリズム研究センターの代表を務めたゲルナーは、執筆、教育、政治活動において、生涯、特に共産主義、精神分 析、相対主義、自由市場の独裁など、閉ざされた思想体系と見なされるものと闘った。 [社会思想における他の問題の中でも、近代化論とナショナリズムは彼の中心的テーマの2つであり、彼の多文化的な視点は、3つの別々の文明の主題の中で働 くことを可能にした: 彼の多文化的な視点は、西洋、イスラム、ロシアという3つの文明の主題の中で仕事をすることを可能にした。ナショナリズムの問題については、主要な理論家 の一人とみなされている[2]。 |

| Background Gellner was born in Paris[3] to Anna, née Fantl, and Rudolf, a lawyer, an urban intellectual German-speaking Austrian Jewish couple from Bohemia (which, since 1918, was part of the newly established Czechoslovakia). Julius Gellner was his uncle. He was brought up in Prague, attending a Czech language primary school before entering the English-language grammar school. This was Franz Kafka's tricultural Prague: antisemitic but "stunningly beautiful", a city he later spent years longing for.[4] In 1939, when Gellner was 13, the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany persuaded his family to leave Czechoslovakia and move to St Albans, just north of London, where Gellner attended St Albans Boys Modern School, now Verulam School (Hertfordshire). At the age of 17, he won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, as a result of what he called "Portuguese colonial policy", which involved keeping "the natives peaceful by getting able ones from below into Balliol."[4]  "Prague is a stunningly beautiful town, and during the first period of my exile, which was during the war, I constantly used to dream about it, in the literal sense: it was a strong longing."[4] At Balliol, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) and specialised in philosophy. He interrupted his studies after one year to serve with the 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade, which took part in the Siege of Dunkirk (1944–45), and then returned to Prague to attend university there for half a term. During this period, Prague lost its strong hold over him: foreseeing the communist takeover, he decided to return to England. One of his recollections of the city in 1945 was a communist poster saying: "Everyone with a clean shield into the Party", ostensibly meaning that those whose records were good during the occupation were welcome. In reality, Gellner said, it meant exactly the opposite: |

生い立ち ゲルナーは、ボヘミア(1918年以降、新設されたチェコスロバキアの一部だった)出身のドイツ語を話すオーストリア系ユダヤ人のアンナ(旧姓ファント ル)と弁護士のルドルフの間にパリで生まれた[3]。ユリウス・ゲルナーは叔父にあたる。彼はプラハで育ち、チェコ語の小学校に通った後、英語の文法学校 に入学した。フランツ・カフカが描いた三文化圏のプラハは、反ユダヤ的でありながら「驚くほど美しく」、後に彼が何年も憧れた街であった[4]。 1939年、ゲルナーが13歳のとき、ドイツでアドルフ・ヒトラーが台頭したため、彼の家族はチェコスロバキアを離れ、ロンドンのすぐ北にあるセント・ オールバンズに移り住んだ。17歳のとき、彼は「ポルトガルの植民地政策」と呼ばれる、「下から有能な者をバリオールに入れることで原住民を平和に保つ」 政策の結果、オックスフォードのバリオール・カレッジへの奨学金を獲得した[4]。  「プラハは驚くほど美しい街で、戦争中だった最初の亡命期間中、私は常にプラハの夢を見ていた。 バリオール大学では、哲学、政治学、経済学(PPE)を学び、哲学を専攻した。ダンケルク包囲戦(1944-45年)に参加した第1チェコスロバキア機甲 旅団に従軍するため、1年で学業を中断。 この間、プラハは彼を強く惹きつけるものを失った。共産党による占領を予見し、彼はイギリスに戻ることを決意した。1945年のプラハの思い出のひとつ に、共産主義者のポスターがある: 「表向きは、占領時代に良い記録を残した者は歓迎されるという意味である。ゲルナーによれば、実際はまったく逆の意味であった: |

| If

your shield is absolutely filthy we'll scrub it for you; you are safe

with us; we like you the better because the filthier your record the

more we have a hold on you. So all the bastards, all the distinctive

authoritarian personalities, rapidly went into the Party, and it

rapidly acquired this kind of character. So what was coming was totally

clear to me, and it cured me of the emotional hold which Prague had

previously had over me. I could foresee that a Stalinoid dictatorship

was due: it came in '48. The precise date I couldn't foresee, but that

it was due to come was absolutely obvious for various reasons.... I

wanted no part of it and got out as quickly as I could and forgot about

it.[4] |

あなたの盾が絶対に不

潔であれば、私たちがあなたのために磨いてあげる。だから、ろくでなしの連中、権威主義的な個性的な連中はみんな党に入り込み、党はこのような性格を急速

に獲得していった。プラハが私に抱いていた感情的な支配から解放されたのだ。スターリノイド独裁政権が48年に誕生することは予見できた。正確な日付は予

見できなかったが、さまざまな理由から、その時期が来ることは明らかだった......。私はそれに関わりたくなかったし、できるだけ早く出て行って、そ

のことを忘れた[4]。 |

| He

returned to Balliol College in 1945 to finish his degree, winning the

John Locke prize and taking first class honours in 1947. The same year,

he began his academic career at the University of Edinburgh as an

assistant to Professor John Macmurray in the Department of Moral

Philosophy. He moved to the London School of Economics in 1949, joining

the sociology department under Morris Ginsberg. Ginsberg admired

philosophy and believed that philosophy and sociology were very close

to each other. |

1945

年にバリオール・カレッジに戻って学位を取得し、1947年にはジョン・ロック賞を受賞して最優等を受けた。同年、エジンバラ大学道徳哲学科のジョン・マ

クマレー教授の助手として学問的キャリアをスタート。1949年にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスに移り、モリス・ギンズバーグのもとで社会学部

に入った。ギンズバーグは哲学を敬愛し、哲学と社会学は非常に近い関係にあると考えていた。 |

| He

employed me because I was a philosopher. Even though he was technically

a professor of sociology, he wouldn't employ his own students, so I

benefited from this, and he assumed that anybody in philosophy would be

an evolutionary Hobhousean like himself. It took him some time to

discover that I wasn't.[5] |

彼は、私が哲学者であるという理由で私を雇ったのです。彼は社会学の教

授であるにもかかわらず、自分の学生を雇うことはしなかったので、私はその恩恵を受けた。彼は私がそうでないことに気づくのに時間がかかりました[5]。 |

| Leonard

Trelawny Hobhouse had preceded Ginsberg as Martin White Professor of

Sociology at the LSE. Hobhouse's Mind in Evolution (1901) had proposed

that society should be regarded as an organism, a product of evolution,

with the individual as its basic unit, the subtext being that society

would improve over time as it evolved, a teleological view that Gellner

firmly opposed. |

レナード・トレローニー・ホブハウスは、ギンズバーグに先んじてLSE

のマーティン・ホワイト社会学教授を務めていた。ホブハウスの『進化における心』(1901年)は、社会を、個人を基本単位とする進化の産物である有機体

とみなすべきであると提唱していた。 |

| Ginsberg...

was totally unoriginal and lacked any sharpness. He simply reproduced

the kind of evolutionary rationalistic vision which had already been

formulated by Hobhouse and which incidentally was a kind of

extrapolation of his own personal life: starting in Poland and ending

up as a fairly influential professor at LSE. He evolved, he had an idea

of a great chain of being where the lowest form of life was the drunk,

Polish, anti-Semitic peasant and the next stage was the Polish gentry,

a bit better, or the Staedtl, better still. And then he came to

England, first to University College under Dawes Hicks, who was quite

rational (not all that rational—he still had some anti-Semitic

prejudices, it seems) and finally ended up at LSE with Hobhouse, who

was so rational that rationality came out of his ears. And so Ginsberg

extrapolated this, and on his view the whole of humanity moved to ever

greater rationality, from drunk Polish peasant to T.L. Hobhouse and a

Hampstead garden.[5] |

ギ

ンズバーグは...まったく独創性がなく、鋭さに欠けていた。彼は、ホブハウスによってすでに定式化されていた進化論的合理主義的ヴィジョンを再現しただ

けであり、ちなみにそれは彼自身の個人的な人生の外挿のようなものだった。ポーランドから出発し、LSEでかなり影響力のある教授になった。彼は、飲酒を

し、ポーランド人で反ユダヤ主義者の農民が最低の生活様式で、次の段階はポーランドの貴族で、もう少しましなもの、あるいはシュタットルがもっとましなも

のという、偉大な存在の連鎖という考えを持っていた。そして彼はイギリスに渡り、まずユニヴァーシティ・カレッジでドーズ・ヒックスのもとで学んだが、彼

は非常に合理的であった(それほど合理的ではなかった-反ユダヤ的な偏見もまだ持っていたようだ)。そしてギンズバーグはこれを外挿し、彼の見解によれ

ば、酔っぱらいのポーランドの農民からT.L.ホブハウスやハムステッドの庭に至るまで、人類全体がより大きな合理性へと移行していった[5]。 |

| Gellner's

critique of linguistic philosophy in Words and Things (1959) focused on

J. L. Austin and the later work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, criticizing

them for failing to question their own methods. The book brought

Gellner critical acclaim. He obtained his Ph.D. in 1961 with a thesis

on Organization and the Role of a Berber Zawiya and became Professor of

Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method just one year later. Thought

and Change was published in 1965, and in State and Society in Soviet

Thought (1988), he examined whether Marxist regimes could be

liberalized. He was elected to the British Academy in 1974. He moved to Cambridge in 1984 to head the Department of Anthropology, holding the William Wyse chair and becoming a fellow of King's College, Cambridge, which provided him with a relaxed atmosphere where he enjoyed drinking beer and playing chess with the students. Described by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as "brilliant, forceful, irreverent, mischievous, sometimes perverse, with a biting wit and love of irony", he was famously popular with his students, was willing to spend many extra hours a day tutoring them, and was regarded as a superb public speaker and gifted teacher.[3] His Plough, Sword and Book (1988) investigated the philosophy of history, and Conditions of Liberty (1994) sought to explain the collapse of socialism with an analogy he called "modular man". In 1993, he returned to Prague, now rid of communism, and to the new Central European University, where he became head of the Center for the Study of Nationalism, a program funded by George Soros, the American billionaire philanthropist, to study the rise of nationalism in the post-communist countries of eastern and central Europe.[6] On 5 November 1995, after returning from a conference in Budapest, he had a heart attack and died at his flat in Prague, one month short of his 70th birthday.[citation needed] Gellner was a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.[7][8] |

ゲ

ルナーは『言葉と物』(1959年)で言語哲学を批判し、J・L・オースティンとその後のルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの研究に焦点を当て、彼らが

自らの方法に疑問を抱かなかったことを批判した。この本はゲルナーに高い評価をもたらした。1961年に「ベルベル人ザウィヤの組織と役割」という論文で

博士号を取得し、わずか1年後に哲学、論理学、科学的方法の教授となった。1965年に『思想と変化』を出版し、『ソ連思想における国家と社会』

(1988年)では、マルクス主義体制が自由化されうるかどうかを検討した。 1974年に英国アカデミー会員に選出。1984年にケンブリッジ大学に移り、人類学部の学部長としてウィリアム・ワイスの講座を受け持ち、ケンブリッジ 大学キングス・カレッジのフェローとなった。Oxford Dictionary of National Biographyによれば、「聡明で、力強く、不遜で、茶目っ気があり、時に倒錯的で、痛烈なウィットと皮肉が好き」と評された彼は、学生たちに人気が あったことで有名で、1日に何時間も個人指導に費やすことを厭わず、優れた演説家であり、才能ある教師であったと評価されている[3]。 彼の『鋤と剣と書』(1988年)は歴史の哲学を研究し、『自由の条件』(1994年)は社会主義の崩壊を彼が「モジュール人間」と呼ぶアナロジーで説明 しようとしたものである。1993年、ゲルナーは共産主義から脱却したプラハに戻り、新設された中欧大学に移って、アメリカの億万長者である慈善家ジョー ジ・ソロスが資金を提供し、東欧・中欧のポスト共産主義諸国におけるナショナリズムの台頭を研究するプログラムであるナショナリズム研究センターのセン ター長に就任した[6]。1995年11月5日、ブダペストでの会議から戻った後、心臓発作に襲われ、70歳の誕生日を1ヵ月後に控えてプラハの自宅ア パートで死去した[要出典]。 ゲルナーはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーとアメリカ哲学協会の会員であった[7][8]。 |

Words and Things Gellner discovered his interest in linguistic philosophy while at Balliol. With the publication in 1959 of Words and Things, his first book, Gellner achieved fame and even notoriety among his fellow philosophers, as well as outside the discipline, for his fierce attack on "linguistic philosophy", as he preferred to call ordinary language philosophy, then the dominant approach at Oxbridge (although the philosophers themselves denied that they were part of any unified school). He first encountered the strong ideological hold of linguistic philosophy while at Balliol: |

言葉と物 ゲルナーはバリオール大学在学中に言語哲学に目覚めた。 ゲルナーは1959年に初の著書『言葉と物』を出版し、当時オクスブリッジで主流であった「言語哲学」(ゲルナーは通常の言語哲学と呼ぶことを好んだが、 哲学者自身は自分たちが統一学派の一員であることを否定していた)を激しく攻撃したことで、哲学者仲間や学外から名声を得、悪名さえも高めた。彼が最初に 言語哲学の強いイデオロギー的影響力を感じたのは、バリオール大学在学中であった: |

| [A]t

that time the orthodoxy best described as linguistic philosophy,

inspired by Wittgenstein, was crystallizing and seemed to me totally

and utterly misguided. Wittgenstein's basic idea was that there is no

general solution to issues other than the custom of the community.

Communities are ultimate. He didn't put it this way, but that was what

it amounted to. And this doesn't make sense in a world in which

communities are not stable and are not clearly isolated from each

other. Nevertheless, Wittgenstein managed to sell this idea, and it was

enthusiastically adopted as an unquestionable revelation. It is very

hard nowadays for people to understand what the atmosphere was like

then. This was the Revelation. It wasn't doubted. But it was quite

obvious to me it was wrong. It was obvious to me the moment I came

across it, although initially, if your entire environment, and all the

bright people in it, hold something to be true, you assume you must be

wrong, not understanding it properly, and they must be right. And so I

explored it further and finally came to the conclusion that I did

understand it right, and it was rubbish, which indeed it is.[5] |

そ

の頃、ウィトゲンシュタインに触発された言語哲学とでも言うべき正統性が結晶化しつつあり、私にはまったく見当違いに思えた。ウィトゲンシュタインの基本

的な考え方は、共同体の慣習以外に問題に対する一般的な解決策はないというものだった。共同体は究極のものなのだ。ウィトゲンシュタインはこのような言い

方はしなかったが、つまりはそういうことなのだ。そしてこれは、共同体が安定しておらず、互いに明確に隔離されていない世界では意味をなさない。にもかか

わらず、ウィトゲンシュタインはこの考えを売り込むことに成功し、疑う余地のない啓示として熱狂的に採用された。当時の雰囲気を理解するのは、今ではとて

も難しい。これが啓示だった。疑われることはなかった。しかし、それが間違っていることは明らかだった。当初は、自分の環境全体、そしてそこにいる聡明な

人たち全員が何かを真実だと信じていれば、自分が間違っているに違いない、正しく理解していないに違いない、彼らが正しいに違いないと思い込んでしまう。

そして、私はさらにそれを探求し、最終的に、私はそれを正しく理解しており、それはゴミであるという結論に達した。 |

| Words and Things is fiercely

critical of the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, J. L. Austin, Gilbert

Ryle, Antony Flew, P. F. Strawson and many others. Ryle refused to have

the book reviewed in the philosophical journal Mind (which he edited),

and Bertrand Russell (who had written an approving foreword) protested

in a letter to The Times. A response from Ryle and a lengthy

correspondence ensued.[9] |

『言葉と物』は、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、J・L・オース

ティン、ギルバート・ライル、アントニー・フリュー、P・F・ストローソン、その他多くの人々の仕事を激しく批判している。ライルは(彼が編集していた)

哲学雑誌『マインド』での書評を拒否し、バートランド・ラッセル(序文を執筆していた)は『タイムズ』紙に抗議した。ライルからの返答と長い文通が続いた

[9]。 |

| Social anthropology In the 1950s, Gellner discovered his great love of social anthropology. Chris Hann, director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, writes that following the hard-nosed empiricism of Bronisław Malinowski, Gellner made major contributions to the subject over the next 40 years, ranging from "conceptual critiques in the analysis of kinship to frameworks for understanding political order outside the state in tribal Morocco (Saints of the Atlas, 1969); from sympathetic exposition of the works of Soviet Marxist anthropologists to elegant syntheses of the Durkheimian and Weberian traditions in western social theory; and from grand elaboration of 'the structure of human history' to path-breaking analyses of ethnicity and nationalism (Thought and Change, 1964; Nations and Nationalism, 1983)".[3] He also developed a friendship with the Moroccan-French sociologist Paul Pascon, whose work he admired.[11] |

社会人類学 1950年代、ゲルナーは社会人類学という大きな愛に目覚めた。マックス・プランク社会人類学研究所の所長であるクリス・ハンは、ブロニスワフ・マリノフ スキーの硬直した経験主義に続いて、ゲルナーはその後40年にわたって、「親族関係の分析における概念的批判から、モロッコ部族における国家外の政治秩序 を理解するための枠組み(『アトラスの聖者たち』1969年)まで、このテーマに大きな貢献をした」と書いている; ソビエトのマルクス主義人類学者の著作の共感的な解説から、西洋の社会理論におけるデュルケームとウェーバーの伝統のエレガントな統合まで、そして『人類 史の構造』の壮大な精緻化から、民族性とナショナリズムの画期的な分析まで(『思想と変化』1964年、『国家とナショナリズム』1983年)」。 [3]彼はまた、モロッコ系フランス人の社会学者ポール・パスコンとも親交を深め、彼の仕事を賞賛していた[10]。 |

| Nationalism Main article: Gellner's theory of nationalism In 1983, Gellner published Nations and Nationalism. For Gellner, "nationalism is primarily a political principle that holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent".[12] Gellner argues that nationalism appeared and became a sociological necessity only in the modern world. In previous times ("the agro-literate" stage of history), rulers had little incentive to impose cultural homogeneity on the ruled. But in modern society, work becomes technical; one must operate a machine, and to do so, one must learn a standard language. There is a need for impersonal, context-free communication and a high degree of cultural standardisation imposed through a national school system.[citation needed] Furthermore, industrial society is underlined by the fact that there is perpetual growth: employment types vary and new skills must be learned. Thus, generic employment training precedes specialised job training. On a territorial level, there is competition for the overlapping catchment areas (such as Alsace-Lorraine). To maintain its grip on resources and its survival and progress, the state and culture must for these reasons be congruent. Nationalism, therefore, is a necessity.[citation needed] |

ナショナリズム 詳細な記事: ゲルナーのナショナリズム論 1983年、ゲルナーは『国家とナショナリズム』を出版した。ゲルナーにとって「ナショナリズムとは、政治単位と国民単位が一致すべきだという政治原理で ある」[12]。ゲルナーは、ナショナリズムが現れ社会学的必然となったのは近代世界においてのみだと論じる。それ以前の時代(歴史上の「農業・識字段 階」)では、支配者が被支配者に文化的均質性を強いる動機はほとんどなかった。しかし近代社会では、労働は技術的になる。機械を操作しなければならず、そ のためには標準言語を学ぶ必要がある。非個人的で文脈に依存しないコミュニケーションと、国民の学校制度を通じて課される高度な文化的標準化が必要とな る。[出典が必要] さらに、産業社会は永続的な成長を前提としている。雇用形態は多様化し、新たな技能の習得が求められる。したがって、専門的な職業訓練に先立ち、汎用的な 職業訓練が行われる。地域レベルでは、重なり合う影響圏(アルザス=ロレーヌなど)を巡る競争が存在する。資源への支配を維持し、国民の存続と発展を図る ためには、国家と文化が一致していなければならない。ゆえにナショナリズムは必然なのである。[出典が必要] |

| Selected works Words and Things: A Critical Account of Linguistic Philosophy and a Study in Ideology, London: Gollancz; Boston: Beacon (1959). Also see correspondence in The Times, 10 November to 23 November 1959. Thought and Change (1964) Populism: Its Meaning and Characteristics (1969). With Ghiță Ionescu [ro]. New York: Macmillan. Saints of the Atlas (1969) Contemporary Thought and Politics (1974) The Devil in Modern Philosophy (1974) Legitimation of Belief (1974) Spectacles and Predicaments (1979) Soviet and Western Anthropology (1980) (editor) Muslim Society (1981) Nations and Nationalism (1983) Relativism and the Social Sciences (1985) The Psychoanalytic Movement (1985) The Concept of Kinship and Other Essays (1986) Culture, Identity and Politics (1987) State and Society in Soviet Thought (1988) Plough, Sword and Book (1988) Postmodernism, Reason and Religion (1992) Reason and Culture (1992) Conditions of Liberty (1994) Anthropology and Politics: Revolutions in the Sacred Grove (1995) Liberalism in Modern Times: Essays in Honour of José G. Merquior (1996) Nationalism (1997) Language and Solitude: Wittgenstein, Malinowski and the Habsburg Dilemma (1998) Resources on Gellner and his research Hall, John A. Ernest Gellner: An Intellectual Biography. Verso, (2010). ISBN 9781844676026 Hall, John A. (ed.) The State of the Nation: Ernest Gellner and the Theory of Nationalism. Cambridge University Press, 1998. Malešević, Siniša, and Mark Haugaard (eds.), Ernest Gellner and Contemporary Social Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. |

主要著作 『ことばと事物:言語哲学の批判的概説およびイデオロギー研究』ロンドン:Gollancz、ボストン:Beacon(1959年)。1959年11月 10日から11月23日までの『タイムズ』紙の書簡欄も参照。 『思想と変化』(1964年) ポピュリズム:その意味と特徴(1969年)。ギタ・イオネスクとの共著。ニューヨーク:マクミラン。 アトラスの聖者たち(1969年) 現代思想と政治(1974年) 近代哲学における悪魔(1974年) 信念の正当化(1974年) 眼鏡と苦境(1979年) ソ連と西欧の民族学(1980年)(編集者) イスラム社会(1981年 国民とナショナリズム(1983年 相対主義と社会科学(1985年 精神分析運動(1985年 親族の概念とその他の論文(1986年 文化、アイデンティティ、政治(1987年 ソビエト思想における国家と社会 (1988) 鋤・剣・書物 (1988) ポストモダニズム、理性と宗教 (1992) 理性と文化 (1992) 自由の条件 (1994) 人類学と政治:聖なる森の革命 (1995) 『近代におけるリベラリズム:ホセ・G・メルキオールへのオマージュ』(1996年) 『国民』(1997年) 『言語と孤独:ウィトゲンシュタイン、マリノフスキー、そしてハプスブルク家のジレンマ』(1998年) ゲルナーと彼の研究に関するリソース ジョン・A・ホール著『アーネスト・ゲルナー:知の伝記』Verso、2010年。ISBN 9781844676026 ジョン・A・ホール編『国民国家の現状:アーネスト・ゲルナーとナショナリズム理論』ケンブリッジ大学出版、1998年。 Malešević, Siniša, and Mark Haugaard (eds.), Ernest Gellner and Contemporary Social Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Gellner |

|

| Notes 1. Eriksen, Thomas Hylland (January 2007). "Nationalism and the Internet". Nations and Nationalism. 13 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00273.x. 2. Stirling, Paul (9 November 1995). "Ernest Gellner Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 3. Chris Hann, Obituary Archived 13 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 8 November 1995 4. "Gellner Interview". Retrieved 5 November 2015. 5. "Interview section 2". Retrieved 5 November 2015. 6. Nationalism Studies Program at the CEU 7. "Ernest Andre Gellner". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 16 March 2022. 8. "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 16 March 2022. 9. T. P. Uschanov, The Strange Death of Ordinary Language Philosophy. The controversy has been described by the writer Ved Mehta in Fly and the Fly Bottle (1963). 10. Tripodi, Paolo (2020). Analytic Philosophy and the Later Wittgensteinian Tradition. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 37. 11. "Obituary: Paul Pascon". Anthropology Today. 1 (6): 21–22. 1985. JSTOR 3033252. 12. Gellner, Nationalism, 1983, p. 1 |

注記 1. エリクセン、トーマス・ヒランド(2007年1月)。「ナショナリズムとインターネット」。『国民とナショナリズム』。13巻1号:1–17頁。doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00273.x。 2. スターリング、ポール(1995年11月9日)。「アーネスト・ゲルナー追悼記事」。デイリー・テレグラフ。 3. クリス・ハン、追悼記事(2006年2月13日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ)、インディペンデント、1995年11月8日 4. 「ゲルナーインタビュー」。2015年11月5日取得。 5. 「インタビュー第2部」。2015年11月5日取得。 6. CEUにおけるナショナリズム研究プログラム 7. 「アーネスト・アンドレ・ゲルナー」。アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー。2022年3月16日取得。 8. 「APS会員履歴」。search.amphilsoc.org。2022年3月16日取得。 9. T. P. ウシャノフ『日常言語哲学の奇妙な死』。この論争は作家ヴェド・メータが『蝿と蝿取り瓶』(1963年)で記述している。 10. トリポディ、パオロ(2020年)。『分析哲学と後期ウィトゲンシュタイン的伝統』。パルグレイブ・マクミランUK。p. 37。 11. 「訃報:ポール・パスコン」『Anthropology Today』1巻6号、21-22頁、1985年。JSTOR 3033252。 12. ゲルナー『ナショナリズム』1983年、p. 1 |

| References Obituary A Philosopher on Nationalism Ernest Gellner Died at 69 written by Eric Pace The New York Times 10 November 1995 Davies, John. Obituary in The Guardian, 7 November 1995 Dimonye, Simeon. A Comparative Study of Historicism in Karl Marx and Ernest Gellner (Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012) Hall, John A. Ernest Gellner: An Intellectual Biography (London: Verso, 2010) Hall, John A. and Ian Jarvie (eds). The Social Philosophy of Ernest Gellner (Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V., 1996) Hall, John A. (ed.) The State of the Nation: Ernest Gellner and the Theory of Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998) Lessnoff, Michael. Ernest Gellner and Modernity (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002) Lukes, Steven. "Gellner, Ernest André (1925–1995)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, retrieved 23 September 2005 (requires subscription) Malesevic, Sinisa and Mark Haugaard (eds). Ernest Gellner and Contemporary Social Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007) O'Leary, Brendan. Obituary in The Independent, 8 November 1995 Stirling, Paul. Obituary in The Daily Telegraph, 9 November 1995 "The Social and Political Relevance of Gellner's Thought Today" papers and webcast of conference organised by the Department of Political Science and Sociology in the National University of Ireland, Galway, held on 21–22 May 2005 (10th anniversary of Gellner's death). Kyrchanoff, Maksym. Natsionalizm: politika, mezhdunarodnye otnosheniia, regionalizatsiia (Voronezh, 2007) [1] Detailed review of Gellner's works for students. In Russian language. Further reading Hall, John A. Ernest Gellner: An Intellectual Biography. Verso, (2010). ISBN 9781844676026 Hall, John A. (ed.) The State of the Nation: Ernest Gellner and the Theory of Nationalism. Cambridge University Press, 1998. Malešević, Siniša, and Mark Haugaard (eds.), Ernest Gellner and Contemporary Social Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Ruini, Andrea Ernest Gellner: un profilo intellettuale, Carocci, Roma 2011 |

参考文献 訃報 ナショナリズムに関する哲学者、アーネスト・ゲルナーが69歳で死去 エリック・ペース著 ニューヨーク・タイムズ 1995年11月10日 デービス、ジョン。訃報 ガーディアン紙、1995年11月7日 ディモニエ、シメオン。カール・マルクスとアーネスト・ゲルナーにおける歴史主義の比較研究(ザールブリュッケン:ランバート・アカデミック・パブリッシング、2012年) ホール、ジョン・A. 『アーネスト・ゲルナー:知的な伝記』(ロンドン:Verso、2010年) ホール、ジョン A.、イアン・ジャーヴィ(編)。『アーネスト・ゲルナーの社会哲学』(アムステルダム:ロドピ B.V.、1996年) ホール、ジョン A.(編)。『国家の現状:アーネスト・ゲルナーとナショナリズム論』(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版、1998年) レスノフ、マイケル。『アーネスト・ゲルナーと近代性』(カーディフ:ウェールズ大学出版局、2002年) ルークス、スティーブン。「ゲルナー、アーネスト・アンドレ(1925–1995)」、『オックスフォード国家人物事典』、オックスフォード大学出版局、2004年、2005年9月23日アクセス(購読が必要) マレセヴィッチ、シニサとマーク・ハウガード(編)。『アーネスト・ゲルナーと現代社会思想』(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2007年) オリアリー、ブレンダン。『インディペンデント』紙掲載の訃報、1995年11月8日 スターリング、ポール。訃報『デイリー・テレグラフ』1995年11月9日付 「ゲルナー思想の現代的社会的・政治的意義」アイルランド国立大学ゴールウェイ校政治学・社会学部主催会議論文集及びウェブキャスト(2005年5月21-22日開催、ゲルナー没後10周年) キルチャノフ、マクシム。『ナショナリズム:政治、国際関係、地域化』(ヴォロネジ、2007年)[1] 学生向けゲルナー著作の詳細な解説。ロシア語。 追加文献(さらに読む) ホール、ジョン・A. 『アーネスト・ゲルナー:知的な伝記』。ヴェルソ、(2010年)。ISBN 9781844676026 ホール、ジョン・A(編)『国民の現状:アーネスト・ゲルナーとナショナリズム理論』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1998年。 マレシェヴィッチ、シニシャ、マーク・ハウガード(編)『アーネスト・ゲルナーと現代社会思想』ニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2007年。 ルイーニ、アンドレア『アーネスト・ゲルナー:知的なプロフィール』カロッチ社、ローマ、2011年 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆