マーガレット・ミード

Margaret Mead,

1901-1978

解説:池田光穂

| General description |

Margaret Mead

(December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural

anthropologist who featured frequently as an author and speaker in the

mass media during the 1960s and 1970s.[1] She earned her bachelor's

degree at Barnard College in New York City and her MA and PhD degrees

from Columbia University. Mead served as President of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science in 1975.[2] Mead was a communicator of anthropology in modern American and Western culture and was often controversial as an academic.[3] Her reports detailing the attitudes towards sex in South Pacific and Southeast Asian traditional cultures influenced the 1960s sexual revolution.[4] She was a proponent of broadening sexual conventions within the context of Western cultural traditions. |

マー

ガレット・ミード(Margaret Mead、1901年12月16日 -

1978年11月15日)は、アメリカの文化人類学者で、1960年代から1970年代にかけてマスメディアで著者や講演者として頻繁に取り上げられた

[1]。ニューヨークのバーナード大学で学士号を取得し、コロンビア大学で修士号と博士号を取得しました。ミードは1975年にアメリカ科学振興協会の会

長を務めた[2]。 南太平洋や東南アジアの伝統的な文化におけるセックスに対する考え方を詳細に説明した彼女の報告は、1960年代の性革命に影響を与えた[4]。 |

| Birth, early

family life, and education |

Margaret Mead,

the first of five children, was born in Philadelphia, but raised in

nearby Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Her father, Edward Sherwood Mead, was

a professor of finance at the Wharton School of the University of

Pennsylvania, and her mother, Emily (née Fogg) Mead,[5] was a

sociologist who studied Italian immigrants.[6] Her sister Katharine

(1906–1907) died at the age of nine months. This was a traumatic event

for Mead, who had named the girl, and thoughts of her lost sister

permeated her daydreams for many years.[7] Her family moved frequently,

so her early education was directed by her grandmother until, at age

11, she was enrolled by her family at Buckingham Friends School in

Lahaska, Pennsylvania.[8] Her family owned the Longland farm from 1912

to 1926.[9] Born into a family of various religious outlooks, she

searched for a form of religion that gave an expression of the faith

that she had been formally acquainted with, Christianity.[10] In doing

so, she found the rituals of the United States Episcopal Church to fit

the expression of religion she was seeking.[10] Mead studied one year,

1919, at DePauw University, then transferred to Barnard College. Mead earned her bachelor's degree from Barnard in 1923, then began studying with professor Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict at Columbia University, earning her master's degree in 1924.[11] Mead set out in 1925 to do fieldwork in Samoa.[12] In 1926, she joined the American Museum of Natural History, New York City, as assistant curator.[13] She received her PhD from Columbia University in 1929.[14] |

マー

ガレット・ミードは5人兄弟の長女で、フィラデルフィアで生まれ、ペンシルベニア州のドイルタウンで育った。父エドワード・シャーウッド・ミードはペンシ

ルベニア大学ウォートン・スクールの金融学の教授であり、母エミリー(旧姓フォッグ)・ミードはイタリア移民を研究する社会学者であった[6]。このこと

は、少女に名前をつけていたミードにとってトラウマとなる出来事であり、失われた妹のことが長年にわたって彼女の白昼夢の中にあった[7]。彼女の家族は

頻繁に引っ越したため、11歳でペンシルバニア州ラハスカのバッキンガム・フレンズスクールに家族によって入学させられるまでの彼女の幼児教育は祖母に

よって指示された。

[1912年から1926年まで、彼女の家族はロングランド農場を所有していた[9]。様々な宗教観を持つ家族に生まれた彼女は、正式に知っていた信仰で

あるキリスト教を表現できるような宗教を探した。 [1919年にデポー大学で1年間学んだ後、バーナード大学に編入した[10]。 1923年にバーナード大学で学士号を取得した後、コロンビア大学でフランツ・ボアズ教授とルース・ベネディクトに師事し、1924年に修士号を取得した [11]。1925年にサモアでのフィールドワークに出発[12]。1926年にはニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館にアシスタントキュレーターとして 参加[13]、1929年にコロンビア大学で博士号を取得[14]。 |

| Personal life |

Before departing

for Samoa, Mead had a short affair with the linguist Edward Sapir, a

close friend of her instructor Ruth Benedict. But Sapir's conservative

stances about marriage and the woman's role were unacceptable to Mead,

and as Mead left to do field work in Samoa the two separated

permanently. Mead received news of Sapir's remarriage while living in

Samoa, where, on a beach, she later burned their correspondence.[15] Before departing

for Samoa, Mead had a short affair with the linguist Edward Sapir, a

close friend of her instructor Ruth Benedict. But Sapir's conservative

stances about marriage and the woman's role were unacceptable to Mead,

and as Mead left to do field work in Samoa the two separated

permanently. Mead received news of Sapir's remarriage while living in

Samoa, where, on a beach, she later burned their correspondence.[15]Mead was married three times. After a six-year engagement,[16] she married her first husband (1923–1928) American Luther Cressman, a theology student at the time who eventually became an anthropologist. Between 1925 and 1926 she was in Samoa returning wherefrom on the boat she met Reo Fortune, a New Zealander headed to Cambridge, England, to study psychology.[17] They were married in 1928, after Mead's divorce from Cressman. Mead dismissively characterized her union with her first husband as "my student marriage" in her 1972 autobiography Blackberry Winter, a sobriquet with which Cressman took vigorous issue. Mead's third and longest-lasting marriage (1936–1950) was to the British anthropologist Gregory Bateson, with whom she had a daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson, who would also become an anthropologist. Mead's pediatrician was Benjamin Spock,[1] whose subsequent writings on child rearing incorporated some of Mead's own practices and beliefs acquired from her ethnological field observations which she shared with him; in particular, breastfeeding on the baby's demand rather than a schedule.[18] She readily acknowledged that Gregory Bateson was the husband she loved the most. She was devastated when he left her, and she remained his loving friend ever after, keeping his photograph by her bedside wherever she traveled, including beside her hospital deathbed.[7] : 428  Margaret Mead (1972) Mead also had an exceptionally close relationship with Ruth Benedict, one of her instructors. In her memoir about her parents, With a Daughter's Eye, Mary Catherine Bateson implies that the relationship between Benedict and Mead was partly sexual.[19]: 117–118 Mead never openly identified herself as lesbian or bisexual. In her writings, she proposed that it is to be expected that an individual's sexual orientation may evolve throughout life.[19] She spent her last years in a close personal and professional collaboration with anthropologist Rhoda Metraux, with whom she lived from 1955 until her death in 1978. Letters between the two published in 2006 with the permission of Mead's daughter[20] clearly express a romantic relationship.[21] Mead had two sisters and a brother, Elizabeth, Priscilla, and Richard. Elizabeth Mead (1909–1983), an artist and teacher, married cartoonist William Steig, and Priscilla Mead (1911–1959) married author Leo Rosten.[22] Mead's brother, Richard, was a professor. Mead was also the aunt of Jeremy Steig.[23] |

サ

モアに出発する前、ミードは指導教官ルース・ベネディクトの親友である言語学者エドワード・サピアと短い交際をした。しかし、サピアの結婚や女性の役割に

関する保守的な姿勢はミードには受け入れられず、ミードがサモアでのフィールドワークに出発する際に、二人は永久に別れることになった。サモアでの生活で

サピアの再婚の知らせを受けたミードは、海岸で二人の通信を燃やした[15]。 サ

モアに出発する前、ミードは指導教官ルース・ベネディクトの親友である言語学者エドワード・サピアと短い交際をした。しかし、サピアの結婚や女性の役割に

関する保守的な姿勢はミードには受け入れられず、ミードがサモアでのフィールドワークに出発する際に、二人は永久に別れることになった。サモアでの生活で

サピアの再婚の知らせを受けたミードは、海岸で二人の通信を燃やした[15]。ミードは3度結婚している。6年間の婚約の後、最初の夫(1923-1928)であるアメリカ人のルーサー・クレスマン(当時神学生で、やがて人類学者に なった)と結婚した[16]。1925年から1926年にかけてサモアに滞在していた彼女は、帰路の船上で、心理学を学ぶためにイギリスのケンブリッジに 向かったニュージーランド人のレオ・フォーチュンと出会った[17] 二人は1928年、ミードがクレスマンと離婚した後に結婚した。ミードは1972年の自伝『ブラックベリー・ウィンター』の中で、最初の夫との結婚を「私 の学生時代の結婚」と揶揄しているが、この揶揄にクレスマンは激しく反論している。3度目の結婚(1936-1950年)は、イギリスの人類学者グレゴ リー・ベイトソンとのもので、彼女との間に娘メアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソンが生まれ、彼女もまた人類学者となる。 ミードの小児科医はベンジャミン・スポックであり[1]、その後の育児に関する著作には、ミードが民族学の野外観察から得た独自の実践と信念が盛り込まれ ており、特にスケジュールよりも赤ちゃんの要求に応じて母乳を与えることを共有していた[18]。 ミードはグレゴリー・ベイトソンが最も愛していた夫だとすぐに認めている。彼女は、彼が自分のもとを去ったとき、大きなショックを受けたが、その後も彼の 愛すべき友人であり続け、旅先でもベッドサイドに彼の写真を置き、病院での死の床にも置いていた[7]:428。  ミー

ドはまた、彼女の指導教官の一人であったルース・ベネディクトと特別に親密な関係にあった。メアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソンは、両親についての回想録

『娘の眼で』の中で、ベネディクトとミードの関係が部分的に性的なものであったことを暗示している[19]: 117-118

ミードは自分をレズビアンやバイセクシャルであると公言することはなかった。彼女は著作の中で、個人の性的指向が生涯を通じて進化することが予想されると

提案している[19]。 ミー

ドはまた、彼女の指導教官の一人であったルース・ベネディクトと特別に親密な関係にあった。メアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソンは、両親についての回想録

『娘の眼で』の中で、ベネディクトとミードの関係が部分的に性的なものであったことを暗示している[19]: 117-118

ミードは自分をレズビアンやバイセクシャルであると公言することはなかった。彼女は著作の中で、個人の性的指向が生涯を通じて進化することが予想されると

提案している[19]。晩年は、人類学者のローダ・メトローと個人的にも仕事的にも密接な協力関係を築き、1955年から1978年に亡くなるまで共に暮らした。2006年に ミードの娘の許可を得て出版された2人の書簡[20]は、明らかに恋愛関係を表している[21]。 ミードにはエリザベス、プリシラ、リチャードという2人の姉と弟がいた。エリザベス・ミード(1909-1983)は芸術家で教師、漫画家ウィリアム・ス タイグと結婚し、プリシラ・ミード(1911-1959)は作家レオ・ローステンと結婚した[22] ミードの兄リチャードは教授であった。ミードはジェレミー・スタイグの叔母でもあった[23]。 |

| Career and later

life |

During World War

II, Mead was executive secretary of the National Research Council's

Committee on Food Habits. She was curator of ethnology at the American

Museum of Natural History from 1946 to 1969. She was elected a Fellow

of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1948.[24] She taught at

The New School and Columbia University, where she was an adjunct

professor from 1954 to 1978 and was a professor of anthropology and

chair of the Division of Social Sciences at Fordham University's

Lincoln Center campus from 1968 to 1970, founding their anthropology

department. In 1970, she joined the faculty of the University of Rhode

Island as a Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Anthropology.[25] Following Ruth Benedict's example, Mead focused her research on problems of child rearing, personality, and culture.[26] She served as president of the Society for Applied Anthropology in 1950[27] and of the American Anthropological Association in 1960. In the mid-1960s, Mead joined forces with communications theorist Rudolf Modley, jointly establishing an organization called Glyphs Inc., whose goal was to create a universal graphic symbol language to be understood by any members of culture, no matter how "primitive".[28] In the 1960s, Mead served as the Vice President of the New York Academy of Sciences.[29] She held various positions in the American Association for the Advancement of Science, notably president in 1975 and chair of the executive committee of the board of directors in 1976.[30] She was a recognizable figure in academia, usually wearing a distinctive cape and carrying a walking-stick.[1] Mead was featured on two record albums published by Folkways Records. The first, released in 1959, An Interview With Margaret Mead, explored the topics of morals and anthropology. In 1971, she was included in a compilation of talks by prominent women, But the Women Rose, Vol.2: Voices of Women in American History.[31] She is credited with the term "semiotics", making it a noun.[32] In later life, Mead was a mentor to many young anthropologists and sociologists, including Jean Houston.[7]: 370–371 In 1976, Mead was a key participant at UN Habitat I, the first UN forum on human settlements. Mead died of pancreatic cancer on November 15, 1978, and is buried at Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Buckingham, Pennsylvania.[33] |

第

二次世界大戦中、ミードは全米研究評議会の食習慣に関する委員会の事務局長を務めた。1946年から1969年までアメリカ自然史博物館で民族学の学芸員

を務めた。1948年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された[24]。1954年から1978年までニュースクールとコロンビア大学で非常

勤講師を務め、1968年から1970年までフォーダム大学のリンカーンセンターキャンパスで人類学の教授と社会科学部門の議長を務め、人類学講座を創

設。1970年、ロードアイランド大学の社会学・人類学の特別教授として教壇に立つ[25]。 ルース・ベネディクトに倣って、ミードは子育て、人格、文化の問題に研究を集中させた[26]。1950年には応用人類学会の会長を、1960年にはアメ リカ人類学協会の会長を務めた[27]。1960年代半ば、ミードはコミュニケーション理論家のルドルフ・モドレーと手を組み、共同でグリフ社という組織 を設立した、 1960年代半ば、ミードはコミュニケーション理論家のルドルフ・モドレーと共同でグリフ社という組織を設立し、どんなに「原始的」な文化圏でも理解でき る普遍的な図形記号言語を作ることを目標としていた[28]。 1960年代、ミードはニューヨーク科学アカデミー副会長を務めた[29]。 アメリカ科学振興協会では様々な役職を務め、特に1975年に会長、1976年には理事会の執行委員長になった[30]。 ミードは、フォークウェイズ・レコードから出版された2枚のレコード・アルバムで紹介されました。1959年に発売された最初のアルバム『An Interview With Margaret Mead』は、道徳と人類学というテーマを探求したものである。1971年には、著名な女性による講演をまとめた『But the Women Rose, Vol.2: Voices of Women in American History』に収録されている[31]。 彼女は「記号論」という言葉を名詞化したことで知られている[32]。 後年、ミードはジーン・ヒューストンをはじめとする多くの若い人類学者や社会学者の師匠となった[7]: 370-371 1976年、ミードは人間居住に関する最初の国連フォーラムであるUN Habitat Iに主要な参加者として参加した。 ミードは1978年11月15日に膵臓癌で亡くなり、ペンシルバニア州バッキンガムのトリニティ・エピスコパル教会墓地に埋葬されている[33]。 |

| Coming of Age in

Samoa (1928) |

In the foreword

to Coming of Age in Samoa, Mead's advisor, Franz Boas, wrote of its

significance:[34] Courtesy, modesty, good manners, conformity to definite ethical standards are universal, but what constitutes courtesy, modesty, very good manners, and definite ethical standards is not universal. It is instructive to know that standards differ in the most unexpected ways. Mead's findings suggested that the community ignores both boys and girls until they are about 15 or 16. Before then, children have no social standing within the community. Mead also found that marriage is regarded as a social and economic arrangement where wealth, rank, and job skills of the husband and wife are taken into consideration. In 1970, National Educational Television produced a documentary in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of Dr. Margaret Mead's first expedition to New Guinea. Through the eyes of Dr. Mead on this her final visit to the village of Peri, the film records how the role of the anthropologist has changed in the forty years since 1928.[35] Mead, ca. 1950. In 1983, five years after Mead had died, New Zealand anthropologist Derek Freeman published Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, in which he challenged Mead's major findings about sexuality in Samoan society.[36] Freeman's book was controversial in its turn: later in 1983 a special session of Mead's supporters in the American Anthropological Association (to which Freeman was not invited) declared it to be "poorly written, unscientific, irresponsible and misleading."[37] In 1999, Freeman published another book, The Fateful Hoaxing of Margaret Mead: A Historical Analysis of Her Samoan Research, including previously unavailable material. In his obituary in The New York Times, John Shaw stated that his thesis, though upsetting many, had by the time of his death generally gained widespread acceptance.[38] Recent work has nonetheless challenged his critique.[39] A frequent criticism of Freeman is that he regularly misrepresented Mead's research and views.[40][41] In a 2009 evaluation of the debate, anthropologist Paul Shankman concluded that:[40] There is now a large body of criticism of Freeman's work from a number of perspectives in which Mead, Samoa, and anthropology appear in a very different light than they do in Freeman's work. Indeed, the immense significance that Freeman gave his critique looks like 'much ado about nothing' to many of his critics. While nurture-oriented anthropologists are more inclined to agree with Mead's conclusions, there are other non-anthropologists who take a nature-oriented approach following Freeman's lead, among them Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, biologist Richard Dawkins, evolutionary psychologist David Buss, science writer Matt Ridley and classicist Mary Lefkowitz.[42] The philosopher Peter Singer has also criticized Mead in his book A Darwinian Left, where he states that "Freeman compiles a convincing case that Mead had misunderstood Samoan customs".[43] In 1996, author Martin Orans examined Mead's notes preserved at the Library of Congress, and credits her for leaving all of her recorded data available to the general public. Orans point out that Freeman's basic criticisms, that Mead was duped by ceremonial virgin Fa'apua'a Fa'amu (who later swore to Freeman that she had played a joke on Mead) were equivocal for several reasons: first, Mead was well aware of the forms and frequency of Samoan joking; second, she provided a careful account of the sexual restrictions on ceremonial virgins that corresponds to Fa'apua'a Fa'auma'a's account to Freeman, and third, that Mead's notes make clear that she had reached her conclusions about Samoan sexuality before meeting Fa'apua'a Fa'amu. Orans points out that Mead's data support several different conclusions, and that Mead's conclusions hinge on an interpretive, rather than positivist, approach to culture. Orans goes on to point out, concerning Mead's work elsewhere, that her own notes do not support her published conclusive claims. Evaluating Mead's work in Samoa from a positivist stance, Martin Orans' assessment of the controversy was that Mead did not formulate her research agenda in scientific terms, and that "her work may properly be damned with the harshest scientific criticism of all, that it is 'not even wrong'."[44] The Intercollegiate Review [1], published by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute which promotes conservative thought on college campuses,[45][46] listed the book as No. 1 on its The Fifty Worst Books of the Century list.[47] |

ミー

ドのアドバイザーであったフランツ・ボアズは、『Coming of Age in

Samoa』の序文で、その意義について次のように書いている。[34]礼儀、慎み、良いマナー、明確な倫理基準への適合は普遍的だが、何が礼儀、慎み、

非常に良いマナー、明確な倫理基準を構成するかは普遍的ではない。ミードの調査結果によると、コミュニティは15歳か16歳くらいまでは少年も少女も無視

するそうです。それ以前の子どもは、コミュニティの中で社会的な地位を確立していない。1970年、全米教育テレビは、マーガレット・ミード博士のニュー

ギニア探検40周年を記念して、ドキュメンタリー番組を制作しました。ミード博士が最後に訪れたペリ村の様子を通して、1928年から40年の間に人類学

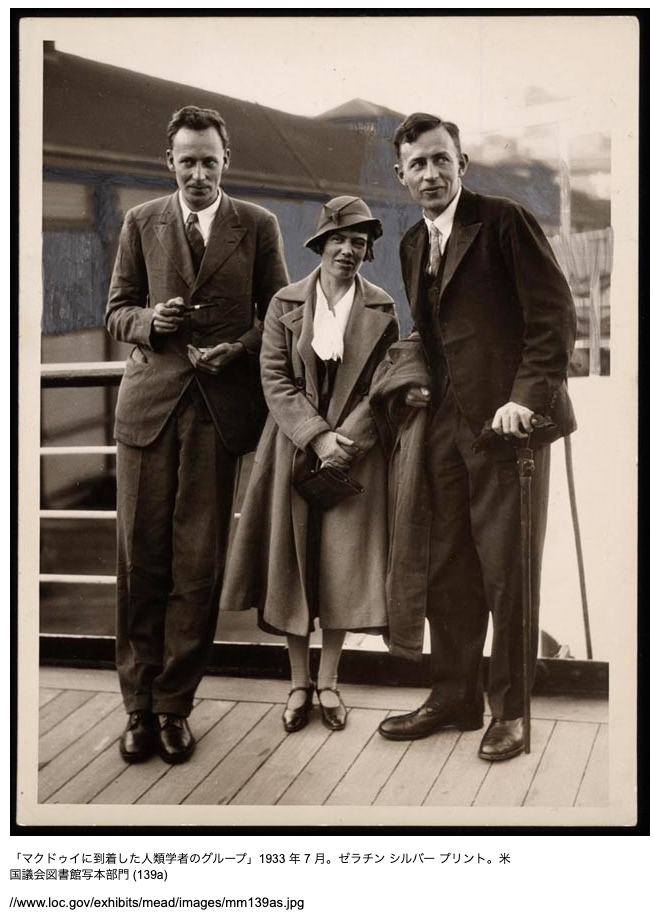

者の役割がどのように変化したかを記録している[35]ミード

1950年頃ミードが亡くなって5年後の1983年に、ニュージーランドの人類学者デレク・フリーマンが『Margaret Mead and

Samoa:

1983年、ニュージーランドの人類学者デレク・フリーマンは『マーガレット・ミードとサモア:人類学的神話の形成と解除』を出版し、サモア社会における

セクシュアリティに関するミードの主要な発見に異議を唱えた。フリーマンの本はその時点で物議を醸した。その後1983年にアメリカ人類学会のミード支持

者による特別セッション(フリーマンは招待されていない)で、「お粗末で科学的ではなく、無責任かつミスリーディング」であると発表した。1999年にフ

リーマンは別の本『運命に惑うマーガレット・ミードの虚偽行為』[37]を出した:

フリーマンは1999年、『マーガレット・ミードの運命的なデマ:彼女のサモア研究の歴史的分析』を出版し、これまで入手できなかった資料も掲載した。

ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の彼の追悼記事において、ジョン・ショーは、彼の論文は多くの人を動揺させたものの、彼の死の時点では一般的に広く受け入れられ

ていたと述べている[38]。 それでも最近の研究は彼の批判に異議を唱えている[39]。

フリーマンに対する頻繁な批判は、彼がミードの研究と見解を定期的に誤って表現しているというものである[40][41]。

人類学者ポール・シャンクマンが2009年に行った論争の評価で、次のように結論付けた[40]。 現在、フリーマンの著作に対して、さまざまな観点から多くの批判がなされており、ミード、サモア、人類学は、フリーマンの著作とはまったく異なる光で描か れている。実際、フリーマンがその批評に与えた大きな意義は、彼の批評家の多くにとっては「たいしたことない」ように見える。育成志向の人類学者がミード の結論に同意する傾向が強い一方で、フリーマンのリードに従って自然志向のアプローチをとる非人類学者もおり、ハーバードの心理学者スティーヴン・ピン カー、生物学者リチャード・ドーキンス、進化心理学者デヴィッド・バス、科学作家マット・リドリーや古典学者メアリー・レフコウィッツなどがいる。 [42]哲学者のピーター・シンガーも、著書『ダーウィニアン・レフト』の中でミードを批判し、「フリーマンはミードがサモアの習慣を誤解していたという 説得力のある事例をまとめた」と述べている[43]。 1996年に、著者のマーティン・オランスは、議会図書館に保存されているミードのメモを調べ、彼女が記録したデータをすべて一般に公開したと評価する。 オランズは、フリーマンの基本的な批判である、ミードは儀式の処女ファアプアア・ファアム(彼女は後にフリーマンに対して、ミードに冗談を言ったと誓って いる)に騙された、というのはいくつかの理由から妥当ではない、と指摘している: 第一に、ミードはサモアの冗談の形式と頻度をよく知っていたこと、第二に、儀式的処女に対する性的制限について、ファアプア・ファアムアのフリーマンへの 説明と対応する慎重な説明を行ったこと、第三に、ミードのメモから、ファアプア・ファアムに会う前にサモアの性に関して結論を出していたことが明らかなこ と。オランズは、ミードのデータがいくつかの異なる結論を支えていること、ミードの結論は、文化に対する実証主義的アプローチではなく、解釈主義的アプ ローチに依存していることを指摘する。さらに、ミードの他の研究についても、彼女自身のメモが、発表された決定的な主張を支持していないことを指摘してい る。サモアでのミードの仕事を実証主義の立場から評価したマーティン・オランズは、この論争について、ミードが自分の研究課題を科学的に定式化しておら ず、「彼女の仕事は、『間違ってさえいない』という、最も厳しい科学的批判で非難されるのが妥当だろう」と評価する。 "[44]大学キャンパスで保守的な思想を推進するIntercollegiate Studies Instituteが発行するIntercollegiate Review [1]は[45][46]、この本をThe Fifty Worst Books of the Centuryの1位として挙げている[47]。 |

| Sex and

Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (1935) |

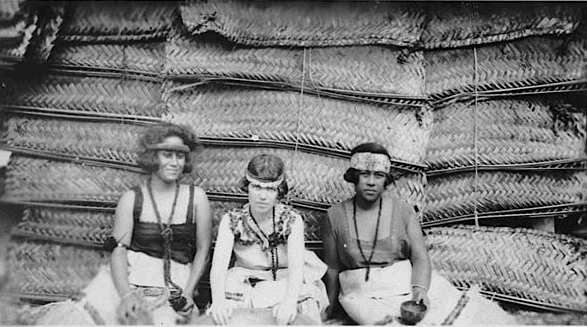

Another

influential book by Mead was Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive

Societies.[48] This became a major cornerstone of the feminist

movement, since it claimed that females are dominant in the Tchambuli

(now spelled Chambri) Lake region of the Sepik basin of Papua New

Guinea (in the western Pacific) without causing any special problems.

The lack of male dominance may have been the result of the Australian

administration's outlawing of warfare. According to contemporary

research, males are dominant throughout Melanesia (although some

believe that female witches have special powers)[citation needed].

Others have argued that there is still much cultural variation

throughout Melanesia, and especially in the large island of New Guinea.

Moreover, anthropologists often overlook the significance of networks

of political influence among females. The formal male-dominated

institutions typical of some areas of high population density were not,

for example, present in the same way in Oksapmin, West Sepik Province,

a more sparsely populated area. Cultural patterns there were different

from, say, Mt. Hagen. They were closer to those described by Mead. Mead stated that the Arapesh people, also in the Sepik, were pacifists, although she noted that they do on occasion engage in warfare. Her observations about the sharing of garden plots among the Arapesh, the egalitarian emphasis in child rearing, and her documentation of predominantly peaceful relations among relatives are very different from the "big man" displays of dominance that were documented in more stratified New Guinea cultures—e.g. by Andrew Strathern. They are a different cultural pattern. In brief, her comparative study revealed a full range of contrasting gender roles: "Among the Arapesh, both men and women were peaceful in temperament and neither men nor women made war. "Among the Mundugumor, the opposite was true: both men and women were warlike in temperament. "And the Tchambuli were different from both. The men 'primped' and spent their time decorating themselves while the women worked and were the practical ones—the opposite of how it seemed in early 20th century America."[49] Deborah Gewertz (1981) studied the Chambri (called Tchambuli by Mead) in 1974–1975 and found no evidence of such gender roles. Gewertz states that as far back in history as there is evidence (1850s) Chambri men dominated the women, controlled their produce and made all important political decisions. In later years there has been a diligent search for societies in which women dominate men, or for signs of such past societies, but none have been found (Bamberger, 1974).[50] Jessie Bernard criticised Mead's interpretations of her findings, arguing that Mead was biased in her descriptions due to use of subjective descriptions. Bernard argues that while Mead claimed the Mundugumor women were temperamentally identical to men, her reports indicate that there were in fact sex differences; Mundugumor women hazed each other less than men hazed each other, they made efforts to make themselves physically desirable to others, married women had fewer affairs than married men, women were not taught to use weapons, women were used less as hostages and Mundugumor men engaged in physical fights more often than women. In contrast, the Arapesh were also described as equal in temperament, yet Bernard states that Mead's own writings indicate that men physically fought over women, yet women did not fight over men. The Arapesh also seemed to have some conception of sex differences in temperament, as they would sometimes describe a woman as acting like a particularly quarrelsome man. Bernard also questioned if the behaviour of men and women in these societies differed as much from Western behaviour as Mead claimed it did, arguing that some of her descriptions could be equally descriptive of a Western context.[51] Despite its feminist roots, Mead's work on women and men was also criticized by Betty Friedan on the basis that it contributes to infantilizing women.[52] |

こ

の本は、パプアニューギニア(西太平洋)のセピック盆地のチャンブリ(現在はチャンブリと表記)湖周辺では、女性が優位であり、特別な問題は起きていない

と主張し、フェミニスト運動の大きな礎となった[48]。男性が優位でないのは、オーストラリア政権が戦争を非合法化した結果かもしれない。現代の研究に

よれば、メラネシア全域で男性が優勢である(ただし、女性の魔女が特別な力を持っているという説もある)[要出典]。また、メラネシア全体、特に大きな島

であるニューギニアには、まだ多くの文化的差異があると主張する者もいる。さらに、人類学者はしばしば女性の間の政治的影響力のネットワークの重要性を見

落としている。例えば、人口密度の高い地域では典型的な男性優位の公式制度が、人口の少ない西セピック州オクサプミンでは同じように存在しない。この地域

の文化パターンは、例えばハーゲン山とは異なっていた。ミードが述べたものに近いのである。 ミードは、同じセピック州のアラペシュ族は平和主義者であるが、時には戦争もすると述べている。アラペシュ族の庭の区画の共有、平等主義的な子育ての強 調、親族間の平和的な関係の記録は、ニューギニアの階層文化で記録されている「大きな男」の支配の誇示(例えばアンドリュー・ストラザーン)とは全く異な るものである。これらは異なる文化パターンである。 つまり、彼女の比較研究は、対照的な性別役割分担の全容を明らかにしたのである: アラペシュ族では、男女とも平和的な気質で、男女とも戦争はしなかった」「ムンドゥグモール族では、その逆で、男女とも戦争好きだった」「チャンブリ族 は、どちらとも違っていた。男性は "身だしなみを整え"、自分を飾ることに時間を費やし、女性は働き、実用的な者であった-20世紀初頭のアメリカでの印象とは正反対だった」[49] Deborah Gewertz(1981)は1974-1975年にチャンブリ族(MeadはTchambuliという)を調査したが、そうした性役割に関する証拠はな かった。Gewertzは、証拠がある限り(1850年代)、チャンブリ族の男性は女性を支配し、農産物を管理し、すべての重要な政治的決定を行ったと述 べる。後年、女性が男性を支配する社会、あるいはそのような過去の社会の兆候を熱心に探したが、どれも見つからなかった(Bamberger, 1974)[50]。ジェシー・バーナードはミードの発見に対する解釈を批判し、ミードが主観的記述を用いているために偏りがあると主張している。バー ナードは、ミードがムンドゥグモールの女性は気質的に男性と同じであると主張する一方で、彼女の報告は、ムンドゥグモールの女性は男性よりもお互いにハズ レを引かない、他者から身体的に好まれるように努力する、既婚女性は既婚男性よりも浮気が少ない、女性は武器を使うことを教えられない、女性は人質として あまり使われなかった、ムンドゥグモールの男性は女性よりも頻繁に肉体戦をする、といった性差がある事実を示したと主張している。これに対して、アラペ シュ族も気質は平等であるとされているが、バーナードは、ミード自身の著作によれば、男性が女性に対して物理的に喧嘩をすることはあっても、女性が男性に 対して喧嘩をすることはなかったと述べている。また、アラペシュ族は、女性が特に喧嘩の強い男性のように振る舞うことを表現することもあり、気質の性差に ついてもある程度の認識を持っていたようである。バーナードはまた、これらの社会における男女の行動が、ミードが主張するほど西洋の行動と異なるかどうか を疑問視し、彼女の記述のいくつかは西洋の文脈を同様に説明することができると主張している[51]。 フェミニストとしてのルーツがあるにもかかわらず、ミードの女性と男性に関する研究は、ベティ・フリーダンによって、女性を幼児化することに寄与している という理由で批判された[52]。 |

| Other research areas |

In 1926, there was much debate

about race and intelligence. Mead felt the methodologies involved in

the experimental psychology research supporting arguments of racial

superiority in intelligence were substantially flawed. In "The

Methodology of Racial Testing: Its Significance for Sociology" Mead

proposes that there are three problems with testing for racial

differences in intelligence. First, there are concerns with the ability

to validly equate one's test score with what Mead refers to as racial

admixture or how much Negro or Indian blood an individual possesses.

She also considers whether this information is relevant when

interpreting IQ scores. Mead remarks that a genealogical method could

be considered valid if it could be "subjected to extensive

verification". In addition, the experiment would need a steady control

group to establish whether racial admixture was actually affecting

intelligence scores. Next, Mead argues that it is difficult to measure

the effect that social status has on the results of a person's

intelligence test. By this she meant that environment (i.e., family

structure, socioeconomic status, exposure to language) has too much

influence on an individual to attribute inferior scores solely to a

physical characteristic such as race. Lastly, Mead adds that language

barriers sometimes create the biggest problem of all. Similarly,

Stephen J. Gould finds three main problems with intelligence testing,

in his 1981 book The Mismeasure of Man, that relate to Mead's view of

the problem of determining whether there are racial differences in

intelligence.[53][54] In 1929 Mead and Fortune visited Manus, now the northernmost province of Papua New Guinea, travelling there by boat from Rabaul. She amply describes her stay there in her autobiography and it is mentioned in her 1984 biography by Jane Howard. On Manus she studied the Manus people of the south coast village of Peri. "Over the next five decades Mead would come back oftener to Peri than to any other field site of her career.[55] Mead has been credited with persuading the American Jewish Committee to sponsor a project to study European Jewish villages, shtetls, in which a team of researchers would conduct mass interviews with Jewish immigrants living in New York City. The resulting book, widely cited for decades, allegedly created the Jewish mother stereotype, a mother intensely loving but controlling to the point of smothering, and engendering guilt in her children through the suffering she professed to undertake for their sakes.[56] Mead worked for the RAND Corporation, a US Air Force military funded private research organization, from 1948 to 1950 to study Russian culture and attitudes toward authority.[57] As an Anglican Christian, Mead played a considerable part in the drafting of the 1979 American Episcopal Book of Common Prayer.[7]: 347–348 |

1926

年当時、人種と知能について多くの議論が交わされていた。ミードは、人種による知能の優劣の議論を支える実験心理学の研究に関わる方法論に、実質的な欠陥

があると感じていました。ミードは、「人種テストの方法論:

ミードは、「人種テストの方法論:社会学にとっての意義」の中で、知能の人種差をテストすることには3つの問題があると提唱しています。まず、ミードが言

うところの人種的混血、つまり黒人やインディアンの血をどれだけ持っているかということと、自分のテストスコアを有効に一致させることができるかどうかが

問題である。また、IQスコアを解釈する際に、この情報が適切かどうかについても考えています。ミードは、系図的な方法が有効であると考えられるのは、

「広範な検証を行う」ことができる場合であると述べている。さらに、人種的混血が実際に知能スコアに影響を及ぼしているかどうかを立証するために、実験に

は安定した対照群が必要であろう。次にミードは、社会的地位が人の知能テストの結果に及ぼす影響を測定することは困難であると主張する。つまり、環境(家

族構成、社会経済的地位、言語への接触など)が個人に与える影響が大きすぎて、劣ったスコアを人種などの身体的特徴だけに帰結させることはできない、とい

うのである。最後に、ミード氏は、言葉の壁が時として最大の問題を引き起こすと付け加えています。同様に、スティーブン・J・グールドは1981年に出版

した『The Mismeasure of

Man』の中で、知能に人種差があるかどうかを判断する問題に対するミードの見解に関連する、知能検査に関する3つの主な問題点を発見した[53]

[54]。 1929年、ミードとフォーチュンは、ラバウルから船で、現在パプアニューギニア最北端の州であるマヌスを訪問している。彼女は自伝の中でそこでの滞在を 十分に記述しており、ジェーン・ハワードによる1984年の伝記でも言及されている。マヌス島では、南海岸のペリという村のマヌス族を研究した。「その後 50年以上にわたって、ミードは彼女のキャリアの中で最も頻繁にペリに戻ることになる。 ミードは、アメリカ・ユダヤ人委員会を説得して、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人の村、シュテットルを研究するプロジェクトのスポンサーとなり、研究者チームが ニューヨーク市に住むユダヤ人移民に大量のインタビューを行ったとされている。その結果、何十年にもわたって広く引用された本書は、ユダヤ人の母親という ステレオタイプを作り出したと言われている。 ミードは1948年から1950年にかけて、アメリカ空軍の軍資金を受けた民間研究機関であるランド・コーポレーションで働き、ロシアの文化と権威に対す る態度を研究していた[57]。 聖公会キリスト教徒であるミードは、1979年の『アメリカン・エピスコパル共通祈祷書』の起草にかなりの役割を果たした[7]: 347-348 |

| Controversy |

After her death, Mead's Samoan

research was criticized by anthropologist Derek Freeman, who published

a book which argued against many of Mead's conclusions in Coming of Age

in Samoa.[58] Freeman argued that Mead had misunderstood Samoan culture

when she argued that Samoan culture did not place many restrictions on

youths' sexual explorations. Freeman argued instead that Samoan culture

prized female chastity and virginity and that Mead had been misled by

her female Samoan informants. Freeman found that the Samoan islanders

whom Mead had depicted in such utopian terms were intensely competitive

and had murder and rape rates higher than those in the United States.

Furthermore, the men were intensely sexually jealous, which contrasted

sharply with Mead’s depiction of “free love” among the Samoans.[2] Freeman's critique was met with a considerable backlash and harsh criticism from the anthropology community, whereas it was received enthusiastically by communities of scientists who believed that sexual mores were more or less universal across cultures.[59][60] Some anthropologists who studied Samoan culture argued in favor of Freeman's findings and contradicted those of Mead, whereas others argued that Freeman's work did not invalidate Mead's work because Samoan culture had been changed by the integration of Christianity in the decades between Mead's and Freeman's fieldwork periods.[61] While Mead was careful to shield the identity of all her subjects for confidentiality Freeman was able to find and interview one of her original participants, and Freeman reported that she admitted to having wilfully misled Mead. She said that she and her friends were having fun with Mead and telling her stories.[62] On the whole, anthropologists have rejected the notion that Mead's conclusions rested on the validity of a single interview with a single person, finding instead that Mead based her conclusions on the sum of her observations and interviews during her time in Samoa, and that the status of the single interview did not falsify her work.[63] Some anthropologists have however maintained that even though Freeman's critique was invalid, Mead's study was not sufficiently scientifically rigorous to support the conclusions she drew.[64] In her 2015 book Galileo's Middle Finger, Alice Dreger argues that Freeman's accusations were unfounded and misleading. A detailed review of the controversy by Paul Shankman, published by the University of Wisconsin Press in 2009, supports the contention that Mead's research was essentially correct, and concludes that Freeman cherry-picked his data and misrepresented both Mead and Samoan culture.[65][66][67] |

彼

女の死後、ミードのサモア研究は人類学者のデレク・フリーマンによって批判され、彼は『サモアの思春期』におけるミードの結論の多くに反論する本を出版し

た[58]。フリーマンは、サモア文化が若者の性的探求に多くの制限を加えることはないと主張した時点でミードがサモア文化を誤解していると論じた。フ

リーマンはその代わりに、サモア文化は女性の貞操と処女を重んじ、ミードはサモアの女性情報提供者に惑わされていたと主張した。フリーマンは、ミードが理

想郷のように描いていたサモアの島民は、激しい競争心を持ち、殺人やレイプの発生率は米国よりも高いことを発見した。さらに、男たちは激しく性的に嫉妬し

ており、ミードが描いたサモア人の「自由恋愛」とは対照的であった[2]。 フリーマンの批評は人類学のコミュニティからはかなりの反発と厳しい批判を受けたが、性的モラルは文化圏を越えて多かれ少なかれ普遍的であると信じていた 科学者のコミュニティからは熱狂的に受け入れられた。 サモア文化を研究していた人類学者の中には、フリーマンの発見を支持し、ミードの発見と矛盾すると主張する者もいれば、ミードとフリーマンのフィールド ワーク期間の間の数十年間にサモア文化はキリスト教の統合によって変化していたため、フリーマンの研究はミードの研究を無効にはしないと主張する者もいた [59][60]。 [ミードは守秘義務のためにすべての被験者の身元を隠すように注意していたが、フリーマンは当初の参加者の一人を見つけてインタビューすることができ、フ リーマンは彼女がミードを故意に誤解させたことを認めたと報告している。彼女は、自分と友人たちはミードと一緒に楽しんでいて、彼女に物語を語っていたの だと言った[62]。 全体として、人類学者は、ミードの結論が一人の人間に対する一回のインタビューの有効性に基づいているという考え方を否定し、代わりにミードはサモア滞在 中の観察とインタビューの合計に基づいて結論を出しており、一回のインタビューの状況は彼女の研究を改ざんするものではないと判断した[63]。 しかし一部の人類学者は、フリーマンの批判が無効であっても、ミードの研究は彼女が引き出した結論を支持するほど科学的に厳密ではなかったと主張していた [64]。 アリス・ドレガーは2015年の著書『ガリレオの中指』の中で、フリーマンの非難は根拠がなく、誤解を招くものであったと主張している。2009年にウィ スコンシン大学出版局から出版されたポール・シャンクマンによる論争の詳細なレビューは、ミードの研究が本質的に正しいという主張を支持し、フリーマンが データを選別し、ミードとサモア文化の両方を誤って表現していると結論付けている[65][66][67]。 |

| Legacy |

In 1976, Mead was inducted into

the National Women's Hall of Fame.[68] On January 19, 1979, President Jimmy Carter announced that he was awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously to Mead. UN Ambassador Andrew Young presented the award to Mead's daughter at a special program honoring Mead's contributions, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, where she spent many years of her career. The citation read:[69] Margaret Mead was both a student of civilization and an exemplar of it. To a public of millions, she brought the central insight of cultural anthropology: that varying cultural patterns express an underlying human unity. She mastered her discipline, but she also transcended it. Intrepid, independent, plain spoken, fearless, she remains a model for the young and a teacher from whom all may learn. In 1979, the Supersisters trading card set was produced and distributed; one of the cards featured Mead's name and picture.[70] The 2014 novel Euphoria[71] by Lily King is a fictionalized account of Mead's love/marital relationships with fellow anthropologists Reo Fortune and Gregory Bateson in pre-WWII New Guinea.[72] In addition, there are several schools named after Mead in the United States: a junior high school in Elk Grove Village, Illinois,[73] an elementary school in Sammamish, Washington[74] and another in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, New York.[75] The USPS issued a stamp of face value 32¢ on May 28, 1998, as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series.[76] In the 1967 musical Hair, her name is given to a tranvestite 'tourist' disturbing the show with the song 'My Conviction'.[77] |

1976年、ミードは全米女性殿堂入りを果たした[68]。 1979年1月19日、ジミー・カーター大統領は、ミードに死後、大統領自由勲章を授与することを発表した。ミードが長年過ごしたアメリカ自然史博物館が 主催するミードの貢献を称える特別プログラムで、アンドリュー・ヤング国連大使がミードの娘に賞を授与した。引用文には次のように書かれています [69]。 マーガレット・ミードは文明の研究者であり、文明の模範であった。彼女は何百万人もの人々に、文化人類学の中心的な洞察、すなわち、さまざまな文化的パ ターンが根底にある人間の統一性を表現しているということを伝えたのである。彼女は自分の専門分野を極めたが、それを超越することもできた。勇敢で、独立 心が強く、率直で、恐れを知らない彼女は、今も若者の模範であり、すべての人が学ぶことのできる教師であり続けています。 1979年、スーパーシスターズのトレーディングカードセットが製造・配布され、その中の1枚にミードの名前と写真が掲載されている[70]。 リリー・キングによる2014年の小説『ユーフォリア』[71]は、第二次世界大戦前のニューギニアにおけるミードの人類学者仲間のレオ・フォーチュンや グレゴリー・ベイトソンとの恋愛・結婚関係を描いたフィクションである[72]。 さらに、アメリカにはミードの名を冠した学校がいくつかある。イリノイ州エルク・グローブ・ビレッジの中学校[73]、ワシントン州サマミッシュの小学校 [74]、ニューヨーク州ブルックリンのシープスヘッド・ベイの学校である[75]。 USPSは1998年5月28日にCelebrate the Century切手シートシリーズの一部として額面32¢の切手を発行した[76]。 1967年のミュージカル『Hair』では、「My Conviction」という曲でショーを邪魔する女装の「観光客」に彼女の名前がつけられている[77]。 |

| Publications by Mead(→See also

Margaret Mead: The Complete Bibliography 1925–1975, Joan Gordan, ed.,

The Hague: Mouton.) 【ミード関連書誌】 |

As a sole author Coming of Age in Samoa (1928)[78] Growing Up In New Guinea (1930)[79] The Changing Culture of an Indian Tribe (1932)[80] Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies (1935)[48] And Keep Your Powder Dry: An Anthropologist Looks at America (1942) Male and Female (1949)[81] New Lives for Old: Cultural Transformation in Manus, 1928–1953 (1956) People and Places (1959; a book for young readers) Continuities in Cultural Evolution (1964) Culture and Commitment (1970) The Mountain Arapesh: Stream of events in Alitoa (1971) Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years (1972; autobiography)[82] As editor or coauthor Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis, with Gregory Bateson, 1942, New York Academy of Sciences. Soviet Attitudes Toward Authority (1951) Cultural Patterns and Technical Change, editor (1953) Primitive Heritage: An Anthropological Anthology, edited with Nicholas Calas (1953) An Anthropologist at Work, editor (1959, reprinted 1966; a volume of Ruth Benedict's writings) The Study of Culture at a Distance, edited with Rhoda Metraux, 1953 Themes in French Culture, with Rhoda Metraux, 1954 The Wagon and the Star: A Study of American Community Initiative co-authored with Muriel Whitbeck Brown, 1966 A Rap on Race, with James Baldwin, 1971 A Way of Seeing, with Rhoda Metraux, 1975 |

1901.12.16 ミード、ペンシルバニア州フィラデルフィアに生まれる(→「マーガレット・ミードとその時代」)。︎

マーガレット・ミードとその時代▶︎マーガレット・ミード『サモアの思春期』読書ノート▶デレク・フリーマンによる「検証」︎︎▶︎民族誌という書物と、その責任▶︎︎マーガレット・ミード『男性と女性』▶『サモアの思春期』とその作者マーガレット・ミード︎▶マーガレット・ミード『男性と女性』▶︎サモアにおけるミード▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

SOCIOLOGY - Margaret

Mead/文化人類学に関するマーガレット・ミードのインタビュー(1959)

1919 デ・ポウ大学に入学

1920 秋 デ・ポウ大学からバーナード・カレッジに転学。

1922-23 バーナード・カレッジ最終学年にボアズ(ルース・ベネディクトは助手だった)の人類学の授業を受講する。

1923 ルーサー・クレスマンと結婚

1924 コロンビア大学修士号。アメリカ自然史博物館民族学部門助手

1925 コロンビア大学の博士号試験に合格(学位授与は29年)。サモア調査

サモア・フィールドワークまでの年譜はこちらに詳しく書いています。

1926 二番目の夫となるレオ・フォーチュン(Leo Fortune)とニュージーランドのオークランドで出会う。マヌス調査。

1928 『サモアの思春期』出版(→『サモアの思春期』とその 作者マーガレット・ミード)

1930 『ニューギニアで成育すること』『マヌアの社会組織』出版。オマハ調査(ネブラスカ州)。

1931 アラペシュ調査、ムンドグモ調査

1932-33 チャンブリ調査

1935 『3つの未開社会における性と気質』出版(→『男性と女性』1949年)

男女の気質の違いは、生得的なものではなく、そだてられる文化の違いに起因するという、彼女の生涯の探求のテーゼが生まれる(D・フリーマ

ン説だと、F・ボアズの入れ知恵「説」)。アラペシュでは、男性も女性も穏やかで、反応が良く、協力的な気質がある。ムンドゥグモール族(現在のビワット

族)では、男性も女性も権力と地位を求めて暴力的かつ攻撃的である。チャンブリ(現在のシャンブリ)では、男性と女性の気質は互いに異なっており、女性は

支配的で非人間的で管理的であり、男性は責任感が低く、感情的により依存するという。

1935 レオ・フォーチュンと離婚。グレゴリー・ベイトソンと結婚。

1935-38 バリ調査

1939 メリー・キャサリン・ベイトソン出生

1942 ニューヨークにてフランツ・ボアズ死去。『バリ人の性格』(ベイトソンとの共著)出版。自然史博物館副主事。

1945 ベイトソンと離婚

1949 『男性と女性』出版

1953 マヌス島ペリ村を再訪

1959 『人類学者の研究生活』出版

1964 自然史博物館主事

1969 自然史博物館名誉主事

1971 『怒りと両親——人種問題を語る』(J・ボールドウィンとの共著)出版

1972 『ブラックベリー・ウィンター』出版(→『女として人類学者として』)

1976 ミード、科学振興のためのアメリカ協会(American Association for the Advancement of Science)に選出される。

1978.11.15 ニューヨークにて死去。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆