クライド・クラックホーン

Clyde Kluckhohn, 1905-1960

クライド・クラックホーン

Clyde Kluckhohn, 1905-1960

解説:池田光穂

| Clyde Kluckhohn

(/ˈklʌkhoʊn/; January 11, 1905 in Le Mars, Iowa – July 28, 1960 near

Santa Fe, New Mexico), was an American anthropologist and social

theorist, best known for his long-term ethnographic work among the

Navajo and his contributions to the development of theory of culture

within American anthropology. |

クライド・クラックホーン(/ˈ

Kllʊ、1905年1月11日アイオワ州ル・マーズ -

1960年7月28日ニューメキシコ州サンタフェ付近)は、アメリカの人類学者、社会理論家で、ナバホ族の長期民族誌調査とアメリカ人類学における文化理

論の発展への貢献で最もよく知られている。 |

| Early life and education Kluckhohn matriculated at Princeton University, but was forced by ill health to take a break from study and went to convalesce on a ranch in New Mexico owned by his mother's cousin's husband, Evon Z. Vogt (father of anthropologist Evon Z. Vogt, Jr.). During this period he first came into contact with neighboring Navajo and began a lifelong love of their language and culture. He wrote two popular books based on his experiences in Navajo country, To the Foot of the Rainbow (1927) and Beyond the Rainbow (1933). He resumed study at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and received his AB in Greek 1928. He then studied classics at Corpus Christi College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in 1928–1930[1] For the following two years, he studied anthropology at the University of Vienna and was exposed to psychoanalysis.[1] After teaching at the University of New Mexico from 1932–1934, he continued graduate work in anthropology at Harvard University where he received his Ph.D in 1936. He remained at Harvard as a professor in Social Anthropology and later also Social Relations for the rest of his life.[2][3] |

幼少期と教育 プリンストン大学に入学したが、体調不良で休学を余儀なくされ、母の従兄弟の夫であるエボンZ.フォクトが所有するニューメキシコ州の牧場で療養すること になった。ヴォクト(人類学者エヴァン・Z・ヴォート・ジュニアの父)の所有するニューメキシコの牧場で療養することになった。この頃、近隣のナバホ族と 初めて接触し、彼らの言語と文化を生涯にわたって愛し続けるようになった。虹のふもとへ」(1927年)、「虹の彼方へ」(1933年)というナバホでの 体験に基づく2冊の人気作を著した。 ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校で勉強を再開し、1928年にギリシャ語で学士号を取得した。その後、1928年から1930年にかけてローズ奨学生とし てオックスフォードのコーパス・クリスティ・カレッジで古典を学ぶ[1]。1932年から1934年にかけてニューメキシコ大学で教鞭をとった後、ハー バード大学の大学院で人類学を学び、1936年に博士号を取得した[1]。彼は社会人類学の教授としてハーバード大学に残り、後に社会関係学の教授として も生涯を過ごすことになる[2][3]。 |

| Major works In 1949, Kluckhohn began to work among five adjacent communities in the Southwest: Zuni, Navajo, Mormon (LDS), Spanish-American (Mexican-American), and Texas Homesteaders[4] A key methodological approach that he developed together with his wife Florence Rockwood Kluckhohn and colleagues Evon Z. Vogt and Ethel M. Albert, among others, was the Values Orientation Theory. They believed that cross-cultural understanding and communication could be facilitated by analyzing a given culture's orientation to five key aspects of human life: Human Nature (people seen as intrinsically good, evil, or mixed); Man-Nature Relationship (the view that humans should be subordinate to nature, dominant over nature, or live in harmony with nature); Time (primary value placed on past/tradition, present/enjoyment, or future/posterity/delayed gratification); Activity (being, becoming/inner development, or doing/striving/industriousness); and Social Relations (hierarchical, collateral/collective-egalitarian, or individualistic). The Values Orientation Method was developed furthest by Florence Kluckhohn and her colleagues and students in later years.[5][6] Kluckhohn received many honors throughout his career. In 1947 he served as president of the American Anthropological Association and became first director of the Russian Research Center at Harvard. In the same year his book Mirror for Man won the McGraw Hill award for best popular writing on science. Kluckhohn initially believed in the biological equality of races but later reversed his position. Kluckhohn wrote in 1959 that "in the light of accumulating information as to significantly varying incidence of mapped genes among different peoples, it seems unwise to assume flatly that ‘man’s innate capacity does not vary from one population to another’.... On the premise that specific capacities are influenced by the properties of each gene pool, it seems very likely indeed that populations differ quantitatively in their potentialities for particular kinds of achievement.”[7] Clyde Kluckhohn died of a heart attack in a cabin on the Upper Pecos River near Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was survived by his wife, Dr. Florence Rockwood Kluckhohn, who also taught anthropology at Harvard's Department of Social Relations. Clyde Kluckhohn was also survived by his son, Richard Kluckhohn. Most of his papers are held at Harvard University, but some early manuscripts are kept at the University of Iowa. |

主な作品 1949年、クラックホーンは、南西部の隣接する5つの共同体の間で活動を開始した。ズニ族、ナバホ族、モルモン教徒(LDS)、スパニッシュ・アメリカ ン(メキシコ系アメリカ人)、テキサス・ホームステーダー[4]の5つの隣接する共同体において、妻のフローレンス・ロックウッド・クラックホーンと同僚 のエボン Z. ヴォート、エセル M. アルバートらと共に開発した重要な方法論的アプローチであった。ヴォート、エセル・M・アルバートらとともに開発した重要な方法論が「価値観志向理論」で あった。彼らは、ある文化が人間生活の5つの重要な側面に対してどのような志向性を持っているかを分析することによって、異文化理解とコミュニケーション が促進されると考えた。人間性(人間は本質的に善、悪、混血のいずれかと見られる)、人間と自然の関係(人間は自然に従属すべき、自然に支配すべき、自然 と調和して生きるべきという考え方)、時間(過去・伝統、現在・享受、未来・後景・遅延充足に置かれる主要な価値)、活動(存在、なること・内面の発展、 行うこと・努力・産業化)、社会関係(階層性、付随的・集団的平等主義、個人主義)である。価値観志向法はフローレンス・クラックホーンと彼女の同僚や学 生によって後年最も発展した[5][6]。 クラックホーンはそのキャリアを通じて多くの栄誉を受けた。1947年にはアメリカ人類学会の会長を務め、ハーバード大学のロシア研究センターの初代所長 に就任した。同年、彼の著書『Mirror for Man』は、McGraw Hill award for best popular writing on scienceを受賞している。 クラックホーンは、当初は人種間の生物学的平等性を信じていたが、後に その立場を覆した。1959年、クラックホーンは次のように書いている。「異なる民族の間で、マッピングされた遺伝子の発生率が著しく異なるという情報が 蓄積されていることからすると、『人間の生来の能力は集団によって異なるものではない』ときっぱり断定するのは賢明ではないように思われる......」 と。特定の能力がそれぞれの遺伝子プールの特性によって影響されるという前提に立てば、集団が特定の種類の業績に対する潜在能力において定量的に異なると いうことは、実にありそうなことである」[7]。 クライド・クラックホーンは、ニューメキシコ州サンタフェ近郊のペコス川上流の小屋で心臓発作のため死去した。妻のフローレンス・ロックウッド博士は、 ハーバード大学の社会関係学部で人類学を教えていたこともあり、彼の遺族となった。クライド・クラックホーンには、息子のリチャード・クラックホーンもい る。彼の論文の大半はハーバード大学に所蔵されているが、初期の原稿の一部はアイオワ大学に保管されている。 |

| Edward Low Elizabeth Colson Florence Rockwood Kluckhohn Alfred L. Kroeber Dorothea Leighton Talcott Parsons Evon Z. Vogt |

|

| Selected publications Kluckhohn, Clyde (1927) To the Foot of the Rainbow, a 1920s equestrian exploration through the Old Southwest Kluckhohn, Clyde (1933) Beyond the Rainbow, a book about traveling in Hopi and Navaho land Kluckhohn, Clyde (1949) Mirror for Man, New York: Fawcett Kluckhohn, Clyde, Leonard McCombe, and Evon Z. Vogt (1951) Navajo means People. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Kluckhohn, Clyde (1951). "Values and value-orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification." In T. Parsons & E. Shils (Eds.), Toward a general theory of action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Kroeber, Alfred and Kluckhohn, Clyde (1952) Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions Murray, Henry A. and Clyde Kluckhohn, (1953) Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture Kluckhohn, Clyde (1961) Anthropology and the Classics, Brown University Press Kluckhohn, Clyde (1962) Culture and Behavior: Collected Essays, Free Press of Glencoe |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clyde_Kluckhohn |

クラックホーン(1971[1949])は、クローバー(Alfred Louis Kroeber, 1876-1960)とともに、さまざまな著者による文化概念 の収集・渉猟とそれらの総合をおこなった人類学者である(クラックホーン 1971:26-41)。

・「文化は人間の本性に源を発し、文化形式は人間の生物学的資質と自然法則によって制約され る」(クラックホーン 1971:26)。

・文化は理論である:「文化は人間と個別に存在する力ではない。人間によって受け継がれる」 (クラックホーン 1971:28)

・「ある考え方、感じ方、それが文化である」(クラックホーン 1971:28)。

・「文化が抽象概念であるだけに、文化と社会とを混同しないように注意することが大切であ る」(クラックホーン 1971:29)。

・「ひとつの文化は、当該集団の知恵をプールした貯蔵庫をなしている」(クラックホーン 1971:30)。

・「どの文化もそれぞれの範疇体系に従って自然界を分析する」(クラックホーン 1971:31)。

・「文化プロセスの本質はその選択性にある」(クラックホーン 1971:31)。「文化が問題を解決するばかりでなく、問題を生むこともまた真実である」(クラックホーン 1971:33)。

・「自分の文化に対して感情的に無関心であり得る人間はいない。/……個人はある特定の集団 に属している結果として、その集団の文化を習得する。習得した行動のうちで他人と共有している部分が文化である。生物学的遺伝に対して、文化はわれわれの 社会的遺産である」(クラックホーン 1971:32)。

・「およそ文化慣行というからには機能的でなければならず、さもなければ遠からず消滅するは ずである。つまり何らかの意味で社会の存続ないし個人の適応に資するところがなくてはならない」(クラックホーン 1971:34)。

・「すべての文化は歴史の沈殿物である」(クラックホーン 1971:34)。

・「文化は地図のようなものである。……文化はある人間集団の言語、行動、人工物にみられる 統 一性w志向する傾向を抽象的に記述したものである」(クラックホーン 1971:35)。

・「現代人も文化を創り保有する」(クラックホーン 1971:35)。

・「一つの文化の中には、成員全員が習得すべきもの、代替範型から選択するもの、特定の社会 的役割を然るべき範型に従って果たす者のみ該当するもの、と三通りある」(クラックホーン 1971:37)。

・「文化の諸相の多くは明示的である。……[他方、暗示的な文化もあり——引用者]暗示的文 化に何か一つ大原理というべきものがある時、しばしばこれを指して「エトス」または「時代精神」と呼ぶ」(クラックホーン 1971:38-40)。

・「すべての文化には内容と並んで組織がある」(クラックホーン 1971:40)。

・「在庫目録の上ではほとんど同じものと見える二つの文化が、実はまったく違っていることも ある。文化体系に含まれている要素のどの一つを考えてみても、その意義を完全に知るためには、その要素と他の要素の関係が織りなしているマトリクス全体の 中に据えて眺めてみなければならない。その際、位置ばかりでなく強調なし強勢も問題とすべきことは当然である」(クラックホーン 1971:41)。[→マーガレット・ミード]

彼の『人間のための鏡(Mirror for Man)』には多様な文化概念の紹介の後に、これらの文化概念を学ぶことに関する以下のような「効用」が説かれている。なお、彼の効用は箇条書きしている わけではないので、その項目数は引用者が恣意的に当て填めたものである(クラックホーン 1971:44-51)。

(i) 自分自身と自分の行動を理解しようとする人間の果てしない探求について助ける

(ii) 人間の行動を予測する上で役にたつ

(iii) あらゆる人々の論理は究極的には同じかもしれないが、思考過程はそれぞれ根本的 に違う前提(もしくは無意識)から出発していることがわかる

(iv) ある文化を知っていれば、その文化を共有している人間の行動をかなり多く予知でき る

(v) 意識されたもの/されないものを含めて、自分の文化の感情的価値観からある程度自由 になれる

(vi) 自分の文化の目録に載っているものはなんでも盲信してしまう忠誠心から人間を解放 してくれる

(vii) 人間が努力し、闘争し、模索している目標は生物学的に全く与えられたものではな いし、(また)環境の力によって全く与えられたものでもないことに気づく。

A.L. Kroeber and C. Kluckhohn, 1952. Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions. with the assistance of Wayne Untereiner and appendices by Alfred G. Meyer, (Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, v. 47, no. 1)Peabody Museum, 1952.

クレジット:「文化」概念の検討 Clyde Kluckhohn:多様性と文化概念の効用

●Dorothea Cross Leighton , 1908-1989

| Dorothea

Cross Leighton (September 2, 1908 – August 15, 1989) was an American

social psychiatrist and a founder of the field of medical

anthropology.[1] Leighton held faculty positions at Cornell University

and the University of North Carolina and she was the founding president

of the Society for Medical Anthropology. She and her husband, Alexander

Leighton, wrote The Navajo Door, which has been described as the first

written work in applied medical anthropology. |

ドロシア・クロス・レイトン(1908年9月2日 -

1989年8月15日)は、アメリカの社会精神医学者で、医療人類学の分野の創始者です[1]。レイトンはコーネル大学とノースカロライナ大学で教員を務

め、医療人類学会の創立会長を務めています。夫のアレキサンダー・レイトンと共に執筆した『ナバホの扉』は、応用医療人類学の最初の著作と言われている。 |

| Early life and education Born Dorothea Cross in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, on September 2, 1908, she attended Bryn Mawr College, where she studied chemistry and biology. She graduated in 1930, and went to work at the Johns Hopkins Hospital as a technician. After two years, she matriculated at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and graduated with her MD in 1936. She married a classmate, Alexander Leighton, in 1937 (she did not receive an appointment at Johns Hopkins; he did) and had two children, then divorced in 1965.[1] |

幼少期と教育 1908年9月2日、マサチューセッツ州ルネバーグでドロシア・クロスに生まれ、ブリンマー大学で化学と生物学を学んだ。1930年に卒業し、ジョンズ・ ホプキンス病院に技師として就職した。2年後、ジョンズ・ホプキンス医科大学に入学し、1936年に医学博士号を取得した。1937年に同級生のアレクサ ンダー・レイトンと結婚し(彼女はジョンズ・ホプキンス大学での任命を受けず、彼が受けた)、2人の子供をもうけたが、1965年に離婚している[1]。 |

| Career and research After earning a medical degree, Leighton studied anthropology at Creighton University. She was a resident physician in psychiatry at a clinic in Baltimore. In 1940, Leighton did fieldwork with Navajo people in Arizona and New Mexico, affiliated with the University of Chicago. She and her husband also did fieldwork in Alaska; both studies were part of an effort to incorporate anthropological methods into psychiatric interviews. In 1942, Leighton published a book that compared the Navajo philosophy of health with that of whites. She then served as a physician with the Indian Personality Research Project from 1942 to 1945. During this time, she worked with Clyde Kluckhohn and John Adair.[1] Her 1944 book The Navajo Door, with Alexander Leighton, is considered "the earliest example of applied medical anthropology".[2] She was a professor of child development and family relations at Cornell University from 1949 to 1952. While at Cornell, she studied psychiatry in a rural context, via fieldwork in Stirling County, Nova Scotia.[3] Around 1960, she traveled to Nigeria to do similar fieldwork with Yoruba people, and also did similar studies in Sweden. Leighton then became a professor of public health and anthropology at the University of North Carolina, a position she held from 1965 to 1974, when she retired. She moved to Fresno, California, and continued to be somewhat involved in academia. In 1977, she was a lecturer at the University of California, San Francisco, and from 1981 to 1982 she was a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, her last academic position before her death on August 15, 1989.[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothea_Leighton |

経歴と研究内容 医学博士号を取得後、クレイトン大学で人類学を学ぶ。ボルチモアのクリニックで精神科の研修医を務めた。1940年、シカゴ大学に所属し、アリゾナ州と ニューメキシコ州でナバホ族を対象にフィールドワークを行った。また、夫とともにアラスカでもフィールドワークを行いました。どちらの調査も、精神科の面 接に人類学的手法を取り入れようとする試みの一環でした。1942年、レイトンは、ナバホ族の健康哲学を白人のそれと比較した本を出版しました。その後、 1942年から1945年まで、インディアン人格研究プロジェクトで医師として勤務しました。この間、クライド・クラックホーンやジョン・エイダーと仕事 をした[1]。1944年にアレキサンダー・レイトンとの共著『The Navajo Door』は「応用医人類学の最も早い例」とされている[2]。 1949年から1952年まで、コーネル大学の児童発達と家族関係の教授を務めた。コーネル大学在学中、ノバスコシア州スターリング郡でフィールドワーク を行い、農村における精神医学を研究した[3]。 1960年頃、ナイジェリアに渡り、ヨルバの人々を対象に同様のフィールドワークを行い、またスウェーデンでも同様の調査を行った。その後、レイトンは ノースカロライナ大学の公衆衛生学と人類学の教授となり、1965年から1974年までその職を務め、退職した。その後、カリフォルニア州フレズノに移り 住み、学問の世界に身を置くことになる。1977年にはカリフォルニア大学サンフランシスコ校で講師を務め、1981年から1982年まではカリフォルニ ア大学バークレー校の客員教授を務め、1989年8月15日に亡くなるまでこれが彼女の最後の学問的地位となった[1]。 |

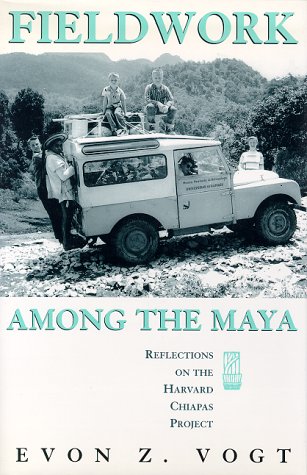

| Evon Zartman Vogt, Jr.

(August 18, 1918 – May 13, 2004) was an American cultural

anthropologist best known for his work among the Tzotzil Mayas of

Chiapas, Mexico.[1] Vogt was the author of numerous articles and 19 books. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1960),[2] a member of the National Academy of Sciences (1979),[3] a member of the American Philosophical Society (1999),[4] and a recipient of the Order of the Aztec Eagle, the highest honor awarded to foreigners by the Mexican government.[5][6] |

エヴォン・ヴォート・ジュニア(Evon Zartman Vogt, Jr.は、メキシコ・チアパスのツォツィル族マヤ族での研究で最もよく知られているアメリカの文化人類学者である[1]。 ヴォーグは多数の論文と19冊の本を執筆している。アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー会員(1960年)[2]、全米科学アカデミー会員(1979年)[3]、 アメリカ哲学協会会員(1999年)[4]、メキシコ政府から外国人に与えられる最高の名誉、アステカ・イーグル勲章を授与された[5][6]。 |

| Biography Vogt Jr., born in Gallup, New Mexico to Evon Z. Vogt Sr. and Shirley Bergman. Vogt attended the University of Chicago on a full scholarship, and earned his B.A. in Geography in 1941. After spending the years of World War II in the Navy, Vogt returned to the University of Chicago to pursue graduate studies. He received his M.A. in 1946 and his Ph.D. in 1948. Vogt initially joined the faculty at Harvard University as an instructor in the Department of Social Relations. He was later promoted to professor, and would spend the entirety of his career at Harvard, serving in time as Chairman of the Department of Anthropology, Co-Master of Kirkland House (with his wife Catherine C. Vogt), and Chairman of the Center for Latin American Studies. He directed the Harvard Chiapas Project, which focused on the indigenous Tzotzil Maya of the central highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. Vogt died on May 13, 2004 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. |

生涯 エヴォン・ヴォート・ジュニア.は、ニューメキシコ州ギャラップにて、エボンZ.とシャーリー・バーグマンの間に生まれた。Vogt S.S.とShirley Bergmanの間に生まれた。奨学金を得てシカゴ大学に入学し、1941年に地理学の学士号を取得した。第二次世界大戦中は海軍に所属し、その後シカゴ 大学に戻り大学院で勉強した。1946年に修士号、1948年に博士号を取得した。 ハーバード大学では、社会関係学部の講師として教壇に立った。その後、人類学部長、カークランド・ハウスの共同館長(キャサリン・C・ボクト夫人ととも に)、ラテンアメリカ研究センターの会長などを歴任し、ハーバード大学でのキャリアを全うすることになる。また、メキシコ・チアパス州中央高地の先住民族 ツォツィル・マヤに焦点を当てた「ハーバード・チアパス計画」を指揮した。 2004年5月13日、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで死去。 |

| 1951 Navaho Means People. Harvard University Press, with Clyde Kluckhohn, photos by Leonard McCombe. 1955 Modern Homesteaders. The Life of a Twentieth-Century Frontier Community. Belknap Press (of Harvard University Press). 1959 Water Witching USA. University of Chicago Press, with Ray Hyman. 1966 People of Rimrock; a study of values in five cultures. Harvard University Press, edited by Evon Z. Vogt and Ethel M. Albert 1969 Zinacantan: A Maya Community in the Highlands of Chiapas. Cambridge: The Belknap Press (of Harvard University Press). 1976 Tortillas for the Gods: A Symbolic Analysis of Zinacanteco Rituals. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1979 Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach. Allyn & Bacon; 4 edition (January 20, 1997) with William A. Lessa. 1994 Fieldwork Among the Maya: Reflections on the Harvard Chiapas Project. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evon_Z._Vogt |

リンク

文献

その他の情報