メランコリア I

Melencolia I

Melencolia I, 1514 /Lucas Cranach the Elder's 1532 painting Melancholia (Colmar version)

☆

「デューラーのメランコリーのまえにひしめいている小道具には、犬が含まれている。メ

ランコリカーの心の状態を描いたアエギーディウス・アルベルティーヌスの記述が狂犬病

に連想を向けさせようとしているのは、なにも偶然ではない。古い伝承によると、「脾臓

が犬の生体を支配している」。犬はこの点で、メランコリカーと共通しているのである。

とりわけデリケートだと記されているこの臓器が悪化すると、犬は元気を失い、狂犬病に

かかるのだという。この点で犬は、メランコリー気質の暗い局面を具現しているのであ

る。その反面、犬の嗅覚と持久力を根拠に、倦むことなく研究にはげみ思索にふける人の

姿を犬に見たてることもあった。「ピエリオ・ヴァレリアーノは、このヒエログリュフ(ヒエログリフ)の

注釈のなかではっきりこういっている。〈メランコリーの相貌をはっきりと示している〉犬

は、ものを嗅ぎつけることと走ることにかけてはもっとも優れている。とくにデューラ

ーの版画では、犬が眠っている姿で描かれているため、このような寓意の二面性が増幅さ

れている。つまり、悪夢が牌臓に由来するのだとすれば、一方、予言の夢もメランコリカー

の特権なのである。予言の夢は、君王や殉教者の共有財として、悲哀劇ではおなじみの ものである」(ベンヤミン 2001:238)[→「犬とメランコリー」]

| Melencolia

I is a large 1514 engraving by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht

Dürer. Its central subject is an enigmatic and gloomy winged female

figure thought to be a personification of melancholia – melancholy.

Holding her head in her hand, she stares past the busy scene in front

of her. The area is strewn with symbols and tools associated with craft

and carpentry, including an hourglass, weighing scales, a hand plane, a

claw hammer, and a saw. Other objects relate to alchemy, geometry or

numerology. Behind the figure is a structure with an embedded magic

square, and a ladder leading beyond the frame. The sky contains a

rainbow, a comet or planet, and a bat-like creature bearing the text

that has become the print's title. Dürer's engraving is one of the most well-known extant old master prints, but, despite a vast art-historical literature, it has resisted any definitive interpretation. Dürer may have associated melancholia with creative activity;[2] the woman may be a representation of a Muse, awaiting inspiration but fearful that it will not return. As such, Dürer may have intended the print as a veiled self-portrait. Other art historians see the figure as pondering the nature of beauty or the value of artistic creativity in light of rationalism,[3] or as a purposely obscure work that highlights the limitations of allegorical or symbolic art. The art historian Erwin Panofsky, whose writing on the print has received the most attention, detailed its possible relation to Renaissance humanists' conception of melancholia. Summarizing its art-historical legacy, he wrote that "the influence of Dürer's Melencolia I—the first representation in which the concept of melancholy was transplanted from the plane of scientific and pseudo-scientific folklore to the level of art—extended all over the European continent and lasted for more than three centuries."[4] |

「メランコリア I」は、ドイツのルネサンス期の画家アルブレヒト・デューラーによる1514年の大作である。その中心的な主題は、メランコリア(憂鬱)の擬

人化と考えられる、謎めいた陰鬱な翼の生えた女性像である。手で頭を抱え、目の前の賑やかな光景を見つめている。このエリアには、砂時計、秤、手鉋、爪ハ

ンマー、のこぎりなど、工芸品や大工仕事に関連するシンボルや道具が散らばっている。その他、錬金術、幾何学、数秘術に関するものもある。人物の背後に

は、魔法の正方形が埋め込まれた構造物があり、枠の向こうへと続く梯子がある。空には虹、彗星や惑星、そしてこの版画のタイトルにもなっている文字が書か

れたコウモリのような生き物がいる。 デューラーの版画は、現存するオールドマスターの版画の中で最もよく知られた作品のひとつだが、膨大な美術史的文献があるにもかかわらず、決定的な解釈に は至っていない。デューラーはメランコリアを創作活動と結びつけていたのかもしれない[2]。この女性は、インスピレーションを待ち望みながらも、それが 戻ってこないことを恐れているミューズの表象なのかもしれない。そのため、デューラーはこの版画をベールに包まれた自画像として意図したのかもしれない。 他の美術史家は、合理主義[3]に照らして美の本質や芸術的創造性の価値について熟考している、あるいは寓意的あるいは象徴的芸術の限界を浮き彫りにする 意図的に不明瞭な作品であると見ている。 この版画に関する著作で最も注目されている美術史家エルヴィン・パノフスキーは、ルネサンス期の人文主義者のメランコリア概念との関係の可能性について詳 述している。その美術史的遺産を要約し、彼は「デューラーのメランコリアIの影響は、憂鬱の概念が科学的および疑似科学的な民間伝承の平面から芸術のレベ ルに移植された最初の表現であり、ヨーロッパ大陸全体に広がり、3世紀以上続いた」と書いている[4]。 |

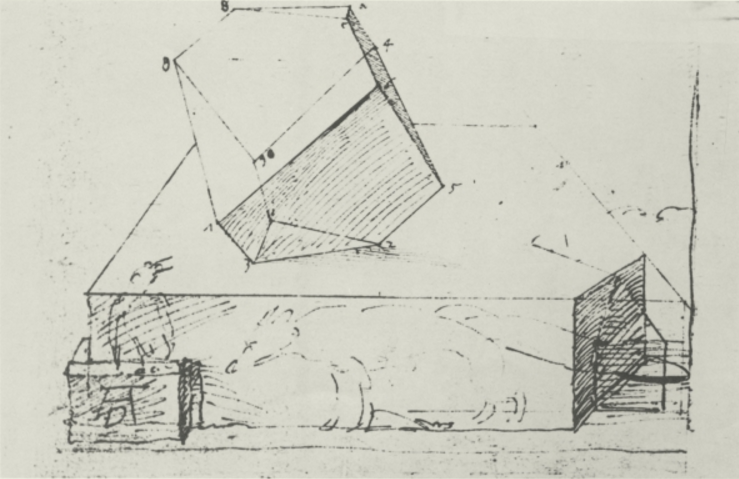

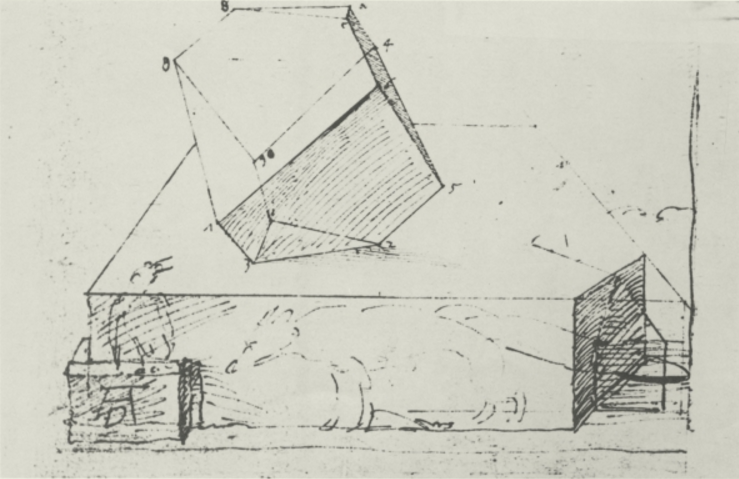

Context A preparatory sketch for the engraving; see also this sketch. Melencolia I has been the subject of more scholarship than probably any other print. As the art historian Campbell Dodgson wrote in 1926, "The literature on Melancholia is more extensive than that on any other engraving by Dürer: that statement would probably remain true if the last two words were omitted."[5] Panofsky's studies in German and English, between 1923 and 1964 and sometimes with coauthors, have been especially influential.[6] Melencolia I is one of Dürer's three Meisterstiche ("master prints"), along with Knight, Death and the Devil (1513) and St. Jerome in His Study (1514).[7][8] The prints are considered thematically related by some art historians, depicting labours that are intellectual (Melencolia I), moral (Knight), or spiritual (St. Jerome) in nature.[9] While Dürer sometimes distributed Melencolia I with St. Jerome in His Study, there is no evidence that he conceived of them as a thematic group.[6] The print has two states; in the first, the number nine in the magic square appears backward,[10] but in the second, more common impressions it is a somewhat odd-looking regular nine. There is little documentation to provide insight into Dürer's intent.[6] He made a few pencil studies for the engraving and some of his notes relate to it. A commonly quoted note refers to the keys and the purse—"Schlüssel—gewalt/pewtell—reichtum beteut" ("keys mean power, purse means wealth")[11]—although this can be read as a simple record of their traditional symbolism.[12] Another note reflects on the nature of beauty. In 1513 and 1514, Dürer experienced the death of a number of friends, followed by his mother (whose portrait he drew in this period), engendering a grief that may be expressed in this engraving.[6][13][14] Dürer mentions melancholy only once in his surviving writings. In an unfinished book for young artists, he cautions that too much exertion may lead one to "fall under the hand of melancholy".[15] Panofsky considered but rejected the suggestion that the "I" in the title might indicate that Dürer had planned three other engravings on the four temperaments.[16] He suggested instead that the "I" referred to the first of three types of melancholy defined by Cornelius Agrippa (see Interpretation). Others see the "I" as a reference to nigredo, the first stage of the alchemical process.[17] |

コンテクスト このスケッチも参照のこと。 メランコリア(I)は、おそらく他のどの版画よりも多くの研究対象になっている。美術史家のキャンベル・ドジソンが1926年に書いたように、「メランコリ アに関する文献は、デューラーの他のどの版画に関する文献よりも広範である。 「メランコリアⅠ》は、《騎士と死と悪魔》(1513年)、《書斎の聖ジェローム》(1514年)とともに、デューラーの3つのマイスター版画のひとつで ある。 [7][8]これらの版画は、一部の美術史家によって、知的(メレンコリア1世)、道徳的(騎士)、または精神的(聖ジェローム)な労働を描いた、テーマ に関連したものと考えられている[9]。この版画には2つの状態があり、1つ目は、マジックスクエアの数字の9が逆向きに描かれている[10]。 デューラーの意図を知るための資料はほとんどない[6]が、彼はこの版画のために鉛筆による習作を数点残しており、それに関連したメモもある。よく引用さ れるメモでは、鍵と財布について言及している-「鍵は権力を、財布は富を意味する」[11]。1513年と1514年、デューラーは多くの友人の死を経験 し、次いで母親(この時期に肖像画を描いている)の死を経験し、このエングレーヴィングに表現されているかもしれない悲しみを生んだ[6][13] [14]。デューラーは残された著作の中で一度だけ憂鬱について言及している。若い芸術家のための未完の本の中で、彼はあまりの努力のしすぎが「憂鬱の手 に落ちる」ことにつながるかもしれないと警告している[15]。 パノフスキーは、タイトルの「I」が、デューラーが4つの気質に関する他の3つの版画を計画していたことを示しているのではないかという提案を検討したが却下した[16]。また、"I "は錬金術の第一段階であるニグレドへの言及であるとする説もある[17]。 |

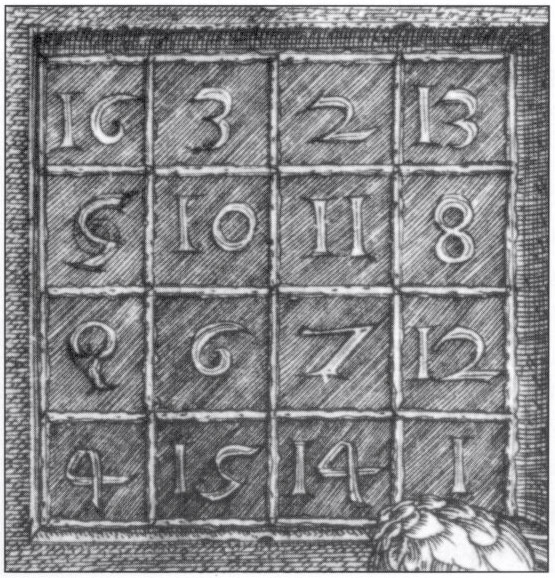

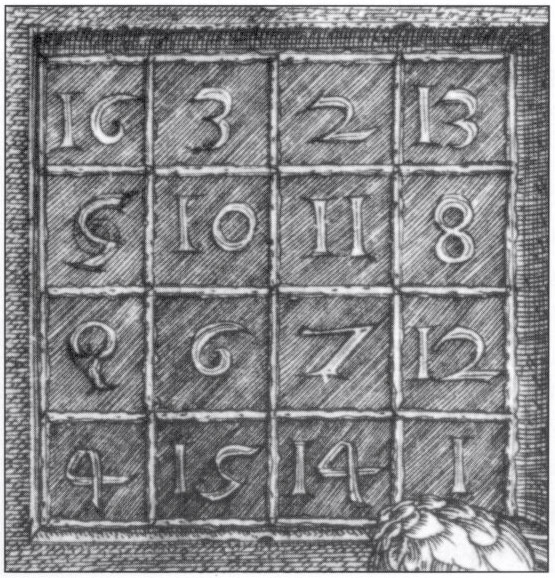

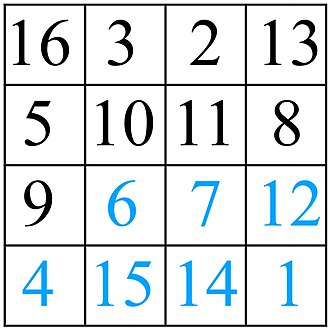

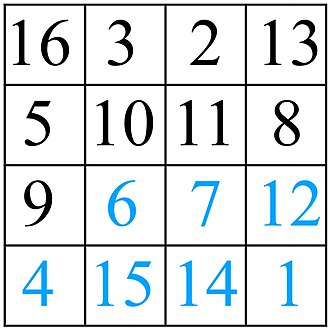

| Description The winged, central figure is thought to be a personification of melancholia or geometry.[19] She sits on a slab with a closed book on her lap, holds a compass loosely, and gazes intensely into the distance. Seemingly immobilized by gloom, she pays no attention to the many objects around her.[11] Reflecting the medieval iconographical depiction of melancholy, she rests her head on a closed fist.[9] Her face is relatively dark, indicating the accumulation of black bile, and she wears a wreath of watery plants (water parsley and watercress[20][21] or lovage). A set of keys and a purse hang from the belt of her long dress. Behind her, a windowless building with no clear architectural function[22][20] rises beyond the top of the frame. A ladder with seven rungs leans against the structure, but neither its beginning nor end is visible. A putto sits atop a millstone (or grindstone) with a chip in it. He scribbles on a tablet, or perhaps a burin used for engraving; he is generally the only active element of the picture.[23] Attached to the structure is a balance scale above the putto, and above Melancholy is a bell and an hourglass with a sundial at the top. Numerous unused tools and mathematical instruments are scattered around, including a hammer and nails, a saw, a plane, pincers, a straightedge, a molder's form, and either the nozzle of a bellows or an enema syringe (clyster). On the low wall behind the large polyhedron is a brazier with a goldsmith's crucible and a pair of tongs.[19] To the left of the emaciated, sleeping dog is a censer, or an inkwell with a strap connecting a pen holder.[24] A bat-like creature spreads its wings across the sky, revealing a banner printed with the words "Melencolia I". Beyond it is a rainbow and an object which is either Saturn or a comet. In the far distance is a landscape with small treed islands, suggesting flooding, and a sea. The rightmost portion of the background may show a large wave crashing over land. Panofsky believes that it is night, citing the "cast-shadow" of the hourglass on the building, with the moon lighting the scene and creating a lunar rainbow.[7]  A 4×4 magic square has columns, rows, and diagonals that sum to 34. In this configuration, many other sets of four squares also sum to 34. Dürer includes the year in the two bottom squares, and the squares adding to 5 and 17 may refer to his mother's death in May of that year. (First number of second row is "5" and third row "9"). The print contains numerous references to mathematics and geometry. In front of the dog lies a perfect sphere, which has a radius equal to the apparent distance marked by the figure's compass.[6] On the face of the building is a 4×4 magic square—the first printed in Europe[25]—with the two middle cells of the bottom row giving the date of the engraving, 1514, which is also seen above Dürer's monogram at bottom right. The square follows the traditional rules of magic squares: each of its rows, columns, and diagonals adds to the same number, 34. It is also associative, meaning that any number added to its symmetric opposite equals 17 (e.g., 15+2, 9+8). Additionally, the corners and each quadrant sum to 34, as do still more combinations.[26][27] Dürer's mother died on May 17, 1514;[28] some interpreters connect the digits of this date with the sets of two squares that sum to 5 and 17. The unusual solid that dominates the left half of the image is a truncated rhombohedron[29][30] with what may be a faint skull[6] or face, possibly even of Dürer.[31] This shape is now known as Dürer's solid, and over the years, there have been numerous analyses of its mathematical properties.[32] In contrast with Saint Jerome in His Study, which has a strong sense of linear perspective and an obvious source of light, Melencolia I is disorderly and lacks a "visual center".[33] It has few perspective lines leading to the vanishing point (below the bat-like creature at the horizon), which divides the diameter of the rainbow in the golden ratio.[34] The work otherwise scarcely has any strong lines. The unusual polyhedron destabilizes the image by blocking some of the view into the distance and sending the eye in different directions.[31] There is little tonal contrast and, despite its stillness, a sense of chaos, a "negation of order",[20] is noted by many art historians. The mysterious light source at right, which illuminates the image, is unusually placed for Dürer and contributes to the "airless, dreamlike space".[33] |

解説 翼のある中央の人物は、メランコリアまたは幾何学の擬人化と考えられている[19]。中世の憂鬱の図像的描写を反映して、彼女は頭を閉じた拳の上に載せて いる[9]。彼女の顔は比較的暗く、黒い胆汁の蓄積を示しており、水のような植物(セリやクレソン[20][21]、あるいはラベッジ)の花輪をつけてい る。ロングドレスのベルトには鍵と財布がぶら下がっている。彼女の背後には、明確な建築的機能を持たない窓のない建物[22][20]がフレームの上部を 越えてそびえている。7段の梯子が建物に寄りかかっているが、その始まりも終わりも見えない。プットが欠けた石臼の上に座っている。彼は石版、あるいは彫 刻用のビュランに落書きをしている。ハンマーと釘、のこぎり、かんな、はさみ、定規、鋳型、ふいごのノズルか浣腸の注射器(クライスター)など、数多くの 未使用の道具や数学的器具が散らばっている。大きな多面体の背後の低い壁には、金細工の坩堝と一対のトングを備えた火鉢がある[19]。やせ細って眠る犬 の左側には、香炉、あるいはペン・ホルダーをつなぐ紐のついたインク壺がある[24]。 蝙蝠のような生き物が空に向かって翼を広げ、「メレンコリア1世」と印刷された旗を見せる。その向こうには虹と、土星か彗星と思われる天体がある。はるか 彼方には、洪水を思わせる小さな木の生えた島々と海が広がる風景がある。背景の右端は、陸地に打ち寄せる大波を示しているのかもしれない。パノフスキー は、建物上の砂時計の「鋳型の影」が月によって照らされ、月の虹を作り出していることから、夜だと考えている[7]。  4×4のマジックスクエアは、列、行、対角線の合計が34になる。この構成では、他の多くの4つの正方形のセットも34になる。デューラーは下の2つの正 方形に西暦を入れており、5と17を足した正方形は、その年の5月に母親が亡くなったことを意味しているのかもしれない。(列目の最初の数字は「5」、3 列目の数字は「9」)。 この版画には、数学と幾何学への言及が数多く含まれている。建物の表面には、ヨーロッパで初めて印刷された[25]4×4のマジック・スクエアが描かれて おり、最下段の中央の2つのマス目には、右下のデューラーのモノグラムの上にも見える、この版画の日付である1514年が記されている。この正方形は、伝 統的なマジック・スクエアのルールに従っている:行、列、対角線のそれぞれが同じ数、34になる。また、この正方形は連想正方形でもあり、対称な反対側の 正方形にどの数字を足しても17になる(例:15+2、9+8)。26][27]デューラーの母は1514年5月17日に亡くなった[28]。この日付の 数字を、5と17になる2つの正方形の集合と結びつける解釈者もいる。画像の左半分を占める珍しい立体は、切り詰められた菱面体[29][30]で、かす かな髑髏[6]あるいはデューラーの顔と思われるものが描かれている[31]。この形は現在ではデューラーの立体と呼ばれ、長年にわたってその数学的性質 について多くの分析がなされてきた[32]。 線遠近法の強い感覚と明らかな光源を持つ『書斎の聖ジェローム』とは対照的に、『メレンコリアⅠ』は無秩序で「視覚的中心」を欠いている[33]。虹の直 径を黄金比で分割する消失点(地平線のコウモリのような生き物の下)につながる遠近法はほとんどない[34]。トーンのコントラストはほとんどなく、静止 しているにもかかわらず、「秩序の否定」[20]ともいうべきカオスの感覚を多くの美術史家が指摘している。画像を照らす右側の謎めいた光源は、デュー ラーにしては珍しく配置されており、「空気のない、夢のような空間」を助長している[33]。 |

Dürer's

Virgin and Child Seated by a Wall (1514) is compositionally similar to

Melencolia I in the position of the figures and structures, but is much

more coherent to the eye. This comparison highlights the disturbing

function of the polyhedron in Melencolia I.[18] Albrecht Dürer, The Virgin and Child Seated by the Wall, 1514, NGA 6639 |

デューラーの《壁際に座る聖母子》(1514年)は、人物の位置や構造においてメレンコリアⅠ世と構図的に似ているが、目にははるかに首尾一貫している。この比較は、メレンコリアⅠにおける多面体の不穏な機能を浮き彫りにしている[18]。 Albrecht Dürer, The Virgin and Child Seated by the Wall, 1514, NGA 6639 |

| Interpretations Dürer's friend and first biographer Joachim Camerarius wrote the earliest account of the engraving in 1541. Addressing its apparent symbolism, he said, "to show that such [afflicted] minds commonly grasp everything and how they are frequently carried away into absurdities, [Dürer] reared up in front of her a ladder into the clouds, while the ascent by means of rungs is ... impeded by a square block of stone."[35] Later, the 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari described Melencolia I as a technical achievement that "puts the whole world in awe".[36] Most art historians view the print as an allegory, assuming that a unified theme can be found in the image if its constituent symbols are "unlocked" and brought into conceptual order. This sort of interpretation assumes that the print is a Vexierbild (a "puzzle image") or rebus whose ambiguities are resolvable.[37] Others see the ambiguity as intentional and unresolvable. Merback notes that ambiguities remain even after the interpretation of numerous individual symbols: the viewer does not know if it is daytime or twilight, where the figures are located, or the source of illumination.[22] The ladder leaning against the structure has no obvious beginning or end, and the structure overall has no obvious function. The bat may be flying from the scene, or is perhaps some sort of daemon related to the traditional conception of melancholia. Certain relationships in humorism, astrology, and alchemy are important for understanding the interpretive history of the print. Since the ancient Greeks, the health and temperament of an individual were thought to be determined by the four humors: black bile (melancholic humor), yellow bile (choleric), phlegm (phlegmatic), and blood (sanguine). In astrology, each temperament was under the influence of a planet, Saturn in the case of melancholia. Each temperament was also associated with one of the four elements; melancholia was paired with Earth, and was considered "dry and cold" in alchemy. Melancholia was traditionally the least desirable of the four temperaments, making for a constitution that was, according to Panofsky, "awkward, miserly, spiteful, greedy, malicious, cowardly, faithless, irreverent and drowsy".[38] In 1905, Heinrich Wölfflin called the print an "allegory of deep, speculative thought". A few years earlier, the Viennese art historian Karl Giehlow had published two articles that laid the groundwork for Panofsky's extensive study of the print. Giehlow specialized in the German humanist interest in hieroglyphics and interpreted Melencolia I in terms of astrology, which had been an interest of intellectuals connected to the court of Maximilian in Vienna. Giehlow found the print an "erudite summa of these interests, a comprehensive portrayal of the melancholic temperament, its positive and negative values held in perfect balance, its potential for 'genius' suspended between divine inspiration and dark madness".[39] Iconography  An earlier woodcut with an allegory of geometry from Gregor Reisch's Margarita philosophica. It depicts many objects also seen in Melencolia I.[40] According to Panofsky, who wrote about the print three times between 1923 and 1964,[41] Melencolia I combines the traditional iconographies of melancholy and geometry, both governed by Saturn. Geometry was one of the Seven Liberal Arts and its mastery was considered vital to the creation of high art, which had been revolutionised by new understandings of perspective. In the engraving, symbols of geometry, measurement, and trades are numerous: the compass, the scale, the hammer and nails, the plane and saw, the sphere and the unusual polyhedron. Panofsky examined earlier personifications of geometry and found much similarity between Dürer's engraving and an allegory of geometry from Gregor Reisch's Margarita philosophica (1503), a popular encyclopedia.[40][42] Other aspects of the print reflect the traditional symbolism of melancholy, such as the bat, emaciated dog, purse and keys. The figure wears a wreath of "wet" plants to counteract the dryness of melancholy, and she has the dark face and dishevelled appearance associated with the melancholic. The intensity of her gaze, however, suggests an intent to depart from traditional depictions of this temperament. The magic square is a talisman of Jupiter, an auspicious planet that fends off melancholy—different square sizes were associated with different planets, with the 4×4 square representing Jupiter.[43][44] Even the distant seascape, with small islands of flooded trees, relates to Saturn, the "lord of the sea", and his control of floods and tides.[45] Panofsky believed that Dürer's understanding of melancholy was influenced by the writings of the German humanist Cornelius Agrippa, and before him Marsilio Ficino. Ficino thought that most intellectuals were influenced by Saturn and were thus melancholic. He equated melancholia with elevation of the intellect, since black bile "raises thought to the comprehension of the highest, because it corresponds to the highest of the planets".[46] Before the Renaissance, melancholics were portrayed as embodying the vice of acedia, meaning spiritual sloth.[11] Ficino and Agrippa's writing gave melancholia positive connotations, associating it with flights of genius. As art historian Philip Sohm summarizes, Ficino and Agrippa gave Renaissance intellectuals a "Neoplatonic conception of melancholy as divine inspiration ... Under the influence of Saturn, ... the melancholic imagination could be led to remarkable achievements in the arts".[6] Agrippa defined three types of melancholic genius in his De occulta philosophia.[47] The first, melancholia imaginativa, affected artists, whose imaginative faculty was considered stronger than their reason (compared with, e.g., scientists) or intuitive mind (e.g., theologians). Dürer might have been referring to this first type of melancholia, the artist's, by the "I" in the title. Melancholia was thought to attract daemons that produced bouts of frenzy and ecstasy in the afflicted, lifting the mind toward genius.[6] In Panofsky's summary, the imaginative melancholic, the subject of Dürer's print, "typifies the first, or least exalted, form of human ingenuity. She can invent and build, and she can think ... but she has no access to the metaphysical world ... [She] belongs in fact to those who 'cannot extend their thought beyond the limits of space.' Hers is the inertia of a being which renounces what it could reach because it cannot reach for what it longs."[13] Dürer's personification of melancholia is of "a being to whom her allotted realm seems intolerably restricted—of a being whose thoughts 'have reached the limit'".[48] Melencolia I portrays a state of lost inspiration: the figure is "surrounded by the instruments of creative work, but sadly brooding with a feeling that she is achieving nothing."[49] Autobiography runs through many of the interpretations of Melencolia I, including Panofsky's. Iván Fenyő considered the print a representation of an artist beset by a loss of confidence, saying: "shortly before [Dürer] drew Melancholy, he wrote: 'what is beautiful I do not know' ... Melancholy is a lyric confession, the self-conscious introspection of the Renaissance artist, unprecedented in northern art. Erwin Panofsky is right in considering this admirable plate the spiritual self-portrait of Dürer."[50] Quadrato magico "a Gjove"  Within the magic square of Melencolia § I, the combinations to be recognized are varied and surprising: «each corner group, formed by four squares (16, 3, 5, 10 - 2, 13, 11, 8 - 9, 6, 4, 15 – 7, 12, 14, 1), has the sum of 34. The same number is obtained by adding the digits of the central group (10, 11, 6, 7), but also those of the corner squares (16, 13, 4, 1). The same result is obtained by adding the digits on the horizontal, vertical, diagonal lines. We always get 34. In total, the number occurs sixteen times. Sixteen is the total number of enclosed squares. This is a property that also appears in Henricus Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim's Tabula Jovis, but which has gone unnoticed by many, perhaps because it does not appear in the list of its characteristics, drawn up by the author himself.[51] The characteristic of the sums of each zone is also shared in the analogous schemes of Mescupolo and Paracelsus.[52] Despite the similarity with these, the magic square of Melencolia § I does not seem chosen to follow a hermetic tradition. The unspoken exclusivity of this type of square may be the reason for the dedication to Jupiter (privileged among the gods and the greatest of the planets) and for Dürer's choice. In truth, its most reliable source is found in the description that Luca Pacioli proposes as a pleasant curiosity [«ligiadro solazo» (f. 122r)], attributing its origin to the greatest astronomers, "Ptolomeo al humasar ali, al fragano, Geber and to all the others ". These "have dedicated to Jupiter [planet «Giove»][53] the figure made up of 4 squares on each side, with the numbers arranged in such a way as to obtain 34 for each direction, that is 16, 3, 2, 13 and in the following line 5, 10, 11, 8, therefore in the third line 9 [etc.] as seen in the margin."[54]» [55] Since this indicated scheme does not appear in the manuscript, it has been completed with blue digits (see image). The magic square of Melencolia § I represents a jovial exercise (lat. iovialis, from Iovis) to counter the influences of melancholy. In the lower center, the union of the numbers 15 and 14 indicates a very sad year.[56] Beyond allegory In 1991, Peter-Klaus Schuster published Melencolia I: Dürers Denkbild,[57] an exhaustive history of the print's interpretation in two volumes. His analysis, that Melencolia I is an "elaborately wrought allegory of virtue ... structured through an almost diagrammatic opposition of virtue and fortune", arrived as allegorical readings were coming into question.[58] In the 1980s, scholars began to focus on the inherent contradictions of the print, finding a mismatch between "intention and result" in the interpretive effort it seemingly required.[59] Martin Büchsel, in contrast to Panofsky, found the print a negation of Ficino's humanistic conception of melancholia.[59] The chaos of the print lends itself to modern interpretations that find it a comment on the limitations of reason, the mind and senses, and philosophical optimism.[59] For example, Dürer perhaps made the image impenetrable in order to simulate the experience of melancholia in the viewer. Joseph Leo Koerner abandoned allegorical readings in his 1993 commentary, describing the engraving as purposely obscure, such that the viewer reflects on their own interpretive labour. He wrote, "The vast effort of subsequent interpreters, in all their industry and error, testifies to the efficacy of the print as an occasion for thought. Instead of mediating a meaning, Melencolia seems designed to generate multiple and contradictory readings, to clue its viewers to an endless exegetical labor until, exhausted in the end, they discover their own portrait in Dürer's sleepless, inactive personification of melancholy. Interpreting the engraving itself becomes a detour to self-reflection."[9] In 2004, Patrick Doorly argued that Dürer was more concerned with beauty than melancholy. Doorly found textual support for elements of Melencolia I in Plato's Hippias Major, a dialog about what constitutes the beautiful, and other works that Dürer would have read in conjunction with his belief that beauty and geometry, or measurement, were related. (Dürer wrote a treatise on human proportions, one of his last major accomplishments.) Dürer was exposed to a variety of literature that may have influenced the engraving by his friend and collaborator, the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, who also translated from Greek. In Plato's dialog, Socrates and Hippias consider numerous definitions of the beautiful. They ask if that which is pleasant to sight and hearing is the beautiful, which Dürer symbolizes by the intense gaze of the figure, and the bell, respectively. The dialog then examines the notion that the "useful" is the beautiful, and Dürer wrote in his notes, "Usefulness is a part of beauty. Therefore what is useless in a man, is not beautiful." Doorly interprets the many useful tools in the engraving as symbolizing this idea; even the dog is a "useful" hunting hound. At one point the dialog refers to a millstone, an unusually specific object to appear in both sources by coincidence. Further, Dürer may have seen the perfect dodecahedron as representative of the beautiful (the "quintessence"), based on his understanding of Platonic solids. The "botched" polyhedron in the engraving therefore symbolises a failure to understand beauty, and the figure, standing in for the artist, is in a gloom as a result.[19] In Perfection's Therapy (2017), Merback argues that Dürer intended Melencolia I as a therapeutic image. He reviews the history of images of spiritual consolation in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and highlights how Dürer expressed his ethical and spiritual commitment to friends and community through his art. He writes, the "thematic of a virtue-building inner reflection, understood as an ethical-therapeutic imperative for the new type of pious intellectual envisioned by humanism, certainly underlies the conception of Melencolia".[60] Dürer's friendships with humanists enlivened and advanced his artistic projects, building in him the "self-conception of an artist with the power to heal".[61] Treatments for melancholia in ancient times and in the Renaissance occasionally recognized the value of "reasoned reflection and exhortation"[62] and emphasized the regulation of melancholia rather than its elimination "so that it can better fulfill its God-given role as a material aid for the enhancement of human genius".[63] The ambiguity of Melencolia I in this view "offers a moderate mental workout that calms rather than excites the passions, a stimulation of the soul's higher powers, an evacuative that dispels the vapors beclouding the mind... This, in a word, is a form of katharsis—not in the medical or religious sense of a 'purgation' of negative emotions, but a 'clarification' of the passions with both ethical and spiritual consequences".[64] |

解釈 デューラーの友人であり、最初の伝記作者であるヨアヒム・カメラリウスは、1541年にこの版画に関する最も古い記述を書いた。その明らかな象徴性につい て、彼は「このような(悩みを抱えた)心が一般的にすべてを把握し、いかに頻繁に不条理に流されるかを示すために、(デューラーは)彼女の前に雲に向かっ て梯子を架け、一方、梯子による昇り口は......四角い石の塊によって妨げられている」と述べている[35]。後に、16世紀の美術史家ジョルジョ・ ヴァザーリは、メレンコリア1世を「全世界を畏怖させる」技術的業績と評した[36]。 ほとんどの美術史家は、この版画を寓意画としてとらえ、その構成要素である象徴を「解きほぐし」、概念的な秩序をもたらすことができれば、統一された主題 を画像の中に見出すことができると仮定している。この種の解釈は、この版画がヴェクシアビルト(「パズル画像」)またはレバスであり、その曖昧さは解決可 能であると仮定している[37]。メルバックは、多数の個々のシンボルを解釈した後でも曖昧さが残っていると指摘する。見る者は、昼なのか薄明かりなの か、人物がどこにいるのか、照明の光源がわからない[22]。蝙蝠はこの場面から飛んできたのかもしれないし、あるいはメランコリアという伝統的な概念に 関連するある種のデーモンなのかもしれない。 ユーモリズム、占星術、錬金術におけるある種の関係は、この版画の解釈の歴史を理解する上で重要である。古代ギリシャの時代から、個人の健康と気質は4つ のユーモアによって決まると考えられていた。黒胆汁(メランコリック・ユーモア)、黄胆汁(コレリック)、痰(ファグマティック)、血(サングイン)であ る。占星術では、それぞれの気質は惑星(メランコリアの場合は土星)の影響下にあった。メランコリアは土と対になり、錬金術では「乾いて冷たい」と考えら れていた。メランコリアは伝統的に4つの気質の中で最も好ましくない気質であり、パノフスキーによれば「不器用、みすぼらしい、唾棄すべき、貪欲、悪意、 臆病、誠実でない、不遜、眠い」体質であった[38]。 1905年、ハインリヒ・ヴェルフリンはこの版画を「深く思索的な思考の寓意」と呼んだ。その数年前、ウィーンの美術史家カール・ギーローは、パノフス キーがこの版画を幅広く研究する下地となる2つの論文を発表していた。ジーロウは、ドイツの人文主義者のヒエログリフへの関心を専門とし、メレンコリア1 世をウィーンのマクシミリアン宮廷に関係する知識人の関心事であった占星術の観点から解釈した。ジーロウは、この版画を「これらの関心を博学にまとめたも のであり、メランコリックな気質、そのポジティブな価値とネガティブな価値が完璧なバランスで保たれていること、神の霊感と暗黒の狂気の間で宙吊りになっ ている『天才』の可能性を包括的に描いたもの」[39]であると評価した。 図像  グレゴール・ライシュの『マルガリータ・フィロソフィカ』(Margarita philosophica)にある幾何学の寓意が描かれた初期の木版画。メレンコリア I』にも見られる多くのものが描かれている[40]。 1923年から1964年にかけて3度この版画について書いたパノフスキーによれば[41]、メレンコリアⅠは、土星に支配されたメランコリーと幾何学の 伝統的な図像を組み合わせたものである。幾何学は「七つの自由芸術」のひとつであり、その習得は、遠近法の新しい理解によって革新された高尚な芸術の創造 に不可欠であると考えられていた。エングレーヴィングには、コンパス、スケール、ハンマーと釘、平面とのこぎり、球体、珍しい多面体など、幾何学、測定、 貿易のシンボルが数多く描かれている。パノフスキーはそれ以前の幾何学の擬人化について調べ、デューラーの版画と、グレゴール・ライシュの『マルガリー タ・フィロソフィカ』(1503年)という大衆的な百科事典に登場する幾何学の寓話との間に多くの類似点を見出した[40][42]。 この版画の他の側面は、コウモリ、衰弱した犬、財布、鍵など、憂鬱の伝統的な象徴を反映している。この人物は、メランコリーの乾きを打ち消すために「濡れ た」植物の花輪を身につけ、メランコリックに関連する暗い顔とだらしない外見をしている。しかし、彼女の視線の強さは、この気質の伝統的な描写から逸脱し ようとする意図を示唆している。魔法の正方形は、憂鬱を退ける吉祥の惑星である木星のお守りであり、異なる正方形の大きさは異なる惑星と関連しており、4 ×4の正方形は木星を表している[43][44]。水浸しの木々の小島がある遠くの海の風景も、「海の支配者」である土星と、洪水や潮の満ち引きを支配す る土星と関連している[45]。 パノフスキーは、デューラーのメランコリーに対する理解は、ドイツの人文主義者コルネリウス・アグリッパ、そしてその前のマルシリオ・フィチーノの著作か ら影響を受けたと考えていた。フィチーノは、ほとんどの知識人は土星の影響を受けており、メランコリックであると考えた。ルネサンス以前は、メランコリッ クは精神的な怠惰を意味するアケディアの悪徳を体現するものとして描かれていた。美術史家のフィリップ・ソームが要約するように、フィチーノとアグリッパ はルネサンスの知識人に「神の霊感としてのメランコリーという新プラトン主義的な概念」を与えた。土星の影響下で、......メランコリックな想像力 は、芸術における目覚ましい業績へと導かれる」[6]。 アグリッパは『De occulta philosophia』[47]の中でメランコリックな天才の3つのタイプを定義している。最初のメランコリア・イマジナティヴァは芸術家に影響を与 え、その想像力は理性(例えば科学者)や直感的な心(例えば神学者)よりも強いと考えられていた。デューラーは、タイトルにある「私」によって、この最初 のタイプのメランコリア、つまり芸術家のメランコリアを指していたのかもしれない。メランコリアはデーモン(悪魔)を引き寄せ、そのデーモンが罹患者に熱 狂と恍惚の発作をもたらし、心を天才に向かって高揚させると考えられていた[6]。パノフスキーの要約によれば、デューラーの版画の主題である想像力豊か なメランコリックは、「人間の創意工夫の最初の、あるいは最も高尚でない形態を代表する。彼女は発明や建設ができ、考えることができる......しか し、形而上学的な世界にはアクセスできない......。[彼女は実際、「思考を空間の限界を超えて拡張できない」人々に属している。メランコリアの擬人 化は、「与えられた領域が耐え難いほど制限されているように見える存在、すなわち思考が『限界に達した』存在」である[48]。 パノフスキーを含め、メレンコリア1世の解釈の多くには自伝が貫かれている。イヴァン・フェニョーは、この版画を自信喪失に悩む芸術家の表象とみなし、次 のように述べている: デューラーは『メランコリー』を描く少し前に、『何が美しいのかわからない』と書いている。メランコリー』は抒情的な告白であり、ルネサンス芸術家の自意 識的内省であり、北方芸術では前例のないものである。エルヴィン・パノフスキーが、この見事な皿をデューラーの精神的自画像と考えたのは正しい」 [50]。 魔法の広場 "ア・ジョーヴェ"  メレンコリア§Ⅰの魔法の正方形の中で、認識される組み合わせは多様で驚くべきものである: 「4つの正方形(16, 3, 5, 10 - 2, 13, 11, 8 - 9, 6, 4, 15 - 7, 12, 14, 1)で形成される各コーナー・グループの合計は34である。中央の数字(10, 11, 6, 7)だけでなく、角の数字(16, 13, 4, 1)を足しても同じ数になる。水平、垂直、対角線上の数字を足しても同じ結果が得られる。常に34となる。合計すると、この数字は16回出てくる。16は 囲まれたマスの総数である。これはヘンリクス・コルネリウス・アグリッパ・フォン・ネッテスハイムの『ヨーヴィスの旅』にも登場する性質であるが、著者自 身によって作成されたその特徴のリストには登場しないためか、多くの人に気づかれることはなかった[51]。各ゾーンの和の特徴は、メスクポロとパラケル ススの類似の図式にも共通する[52]。これらとの類似性にもかかわらず、メレンコリア§Ⅰの魔法の正方形は、密儀の伝統に従って選ばれたようには見えな い。この種の正方形の暗黙の排他性が、木星(神々の中で特権的であり、惑星の中で最も偉大なもの)に捧げられた理由であり、デューラーが選んだ理由なのか もしれない。実のところ、最も信頼できる出典は、ルカ・パチョーリが楽しい好奇心として提案した記述["ligiadro solazo" (f. 122r)]にあり、その起源は最も偉大な天文学者たち、「プトロメオ・アル・フマサル・アリ、アル・フラガノ、ゲーバー、そして他のすべての人々」にあ るとされている。これらは「木星(惑星 "Giove")に捧げられた[53]」図であり、一辺が4つの正方形で構成され、各方向に34、すなわち16、3、2、13、次の行に5、10、11、 8、したがって3行目に9(など)が得られるように数字が配置されている[54]。[55] この示された図式は写本にはないので、青数字で補完されている(画像参照)。メレンコリア§Iの魔法の正方形は、憂鬱の影響に対抗するための陽気な運動 (lat. iovialis、Iovisに由来)を表している。中央下部では、15と14の数字の組み合わせが非常に悲しい年を示している[56]。 寓意を超えて 1991年、ペーター=クラウス・シュスターは『メレンコリア I』を出版した: Dürers Denkbild』[57]を2巻に渡って出版した。彼の分析によれば、メレンコリアⅠは「精巧に練られた美徳の寓意であり......美徳と幸運のほと んど図式的な対立によって構成されている」というもので、寓意的な解釈が疑問視されるようになる中で登場した[58]。1980年代に入ると、学者たちは この版画に内在する矛盾に注目し始め、それが一見必要とする解釈の努力に「意図と結果」のミスマッチを見出した。 [59]マルティン・ビュッヒセルは、パノフスキーとは対照的に、この版画がフィチーノのメランコリアに対する人文主義的な概念を否定するものであると考 えた[59]。この版画の混沌は、理性、精神、感覚の限界、哲学的な楽観主義についてのコメントであるとする現代的な解釈に適している[59]。 ジョセフ・レオ・ケルナーは1993年の解説で寓意的な読解を放棄し、この彫像は意図的に不明瞭であり、鑑賞者が自らの解釈の労苦を振り返るようなものだ と述べている。その後の解釈者たちの膨大な努力は、その産業と誤謬のすべてにおいて、思考の機会としての版画の有効性を証明している。メレンコリアは、意 味を媒介する代わりに、複数の矛盾した読解を生み出し、見る者を果てしない釈義的労働へと導き、最後には疲れ果てて、デューラーの眠れない、不活発な憂鬱 の擬人化の中に自分自身の肖像を発見するように設計されているようだ。エングレーヴィングを解釈すること自体が、自己反省への回り道となる」[9]。 2004年、パトリック・ドーリーは、デューラーは憂鬱よりも美に関心があったと主張した。ドーリーは、プラトンの『ヒッピアス大王』(美しいものを構成 するものは何かについての対話)、およびデューラーが美と幾何学、あるいは計測が関連しているという信念と結びつけて読んでいたであろう他の作品に、メレ ンコリアⅠの要素のテキスト的な裏付けを見出した。(デューラーは人間のプロポーションに関する論文を書いているが、これは彼の最後の大きな業績のひとつ である)。デューラーは、友人であり共同研究者でもあった人文主義者ウィリバルト・ピルクハイマー(ギリシャ語からの翻訳も手がけた)によって、彫刻に影 響を与えたと思われる様々な文学に触れている。プラトンの対話の中で、ソクラテスとヒッピアスは美しいものの定義を数多く考えている。彼らは、視覚と聴覚 に心地よいものが美しいかどうかを問う。デューラーはそれぞれ、人物の強いまなざしと鐘によって象徴している。この対話では、「有用なもの」が美であると いう考え方が検討され、デューラーはノートに「有用なものは美の一部である。したがって、人間において役に立たないものは美しくない。" ドアリーは、彫刻に描かれた多くの便利な道具がこの考えを象徴していると解釈している。対話の中で石臼に言及する箇所があるが、これは偶然にも両方の資料 に登場する珍しい具体的なものである。さらに、デューラーはプラトン立体の理解に基づき、完全な正十二面体を美しいもの(「真髄」)の代表と見なしていた のかもしれない。それゆえ、このエングレーヴィングの「不完全な」多面体は、美を理解することの失敗を象徴しており、その結果、画家に成り代わった人物は 憂鬱な気分に陥っている[19]。 パーフェクションの治療』(2017年)の中で、メルバックはデューラーがメレンコリア1世を治療的なイメージとして意図していたと論じている。彼は中世 とルネサンスにおける精神的な慰めのイメージの歴史を振り返り、デューラーが友人や共同体に対する倫理的で精神的なコミットメントを芸術を通してどのよう に表現したかを強調している。人文主義によって構想された新しいタイプの敬虔な知識人のための倫理的・治療的要請として理解される、徳を築く内面的省察と いう主題は、確かにメレンコリアの構想の根底にある」[60]と彼は書いている。デューラーの人文主義者との交友関係は、彼の芸術プロジェクトを活気づ け、前進させ、彼の中に「癒す力を持つ芸術家としての自己概念」を築いた。 [61] 古代やルネサンスにおけるメランコリアの治療は、「理性的な考察と励まし」[62]の価値を認識し、メランコリアが「人間の才能を高めるための物質的な助 力として神から与えられた役割をよりよく果たすことができるように」、メランコリアを排除することよりもむしろ調整することを強調した。 [63] この見解におけるメレンコリアIの両義性は、「情欲を興奮させるよりもむしろ落ち着かせる適度な精神的鍛錬を提供し、魂の高次の力を刺激し、心を曇らせて いる蒸気を払う避難薬を提供する...。これは一言で言えば、カタルシスの一種であり、否定的な感情を『浄化』するという医学的・宗教的な意味ではなく、 倫理的・精神的な結果を伴う情念の『解明』である」[64]。 |

Legacy The figure in Domenico Fetti's Melancholy or Meditation (c. 1620) personifies Melancholy and Vanity. Artists from the sixteenth century used Melencolia I as a source, either in single images personifying melancholia or in the older type in which all four temperaments appear. Lucas Cranach the Elder used its motifs in numerous paintings between 1528 and 1533.[65][66] They share elements with Melencolia I such as a winged, seated woman, a sleeping or sitting dog, a sphere, and varying numbers of children playing, likely based on Durer's Putto. Cranach's paintings, however, contrast melancholy with childish gaiety, and in the 1528 painting, occult elements appear. Prints by Hans Sebald Beham (1539) and Jost Amman (1589) are clearly related. In the Baroque period, representations of Melancholy and Vanity were combined. Domenico Fetti's Melancholy/Meditation (c. 1620) is an important example; Panofsky et al. wrote that "the meaning of this picture is obvious at first glance; all human activity, practical no less than theoretical, theoretical no less than artistic, is vain, in view of the vanity of all earthly things."[67] The print attracted nineteenth-century Romantic artists; self-portrait drawings by Henry Fuseli and Caspar David Friedrich show their interest in capturing the mood of the Melencolia figure, as does Friedrich's The Woman with the Spider's Web.[68] The Renaissance historian Frances Yates believed George Chapman's 1594 poem The Shadow of Night to be influenced by Dürer's print, and Robert Burton described it in his The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).[66] Dürer's Melencolia is the patroness of the City of Dreadful Night in the final canto of James Thomson's poem of that name. The print was taken up in Romantic poetry of the nineteenth century in English and French.[69] The Passion façade of the Sagrada Família contains a magic square based on[70] the magic square in Melencolia I. The square is rotated and one number in each row and column is reduced by one so the rows and columns add up to 33 instead of the standard 34 for a 4x4 magic square. |

遺産 ドメニコ・フェッティの『憂鬱または瞑想』(1620年頃)の人物は、憂鬱と虚栄を擬人化している。 16世紀以降の画家たちは、メランコリア1世を、メランコリアを擬人化した単一のイメージや、4つの気質がすべて登場する古いタイプのイメージの資料とし て使用している。1528年から1533年にかけて、長老ルーカス・クラナッハはメレンコリアⅠ世のモチーフを数多く用いている[65][66]。翼のあ る座った女性、眠っているか座っている犬、球体、さまざまな数の遊んでいる子供など、メレンコリアⅠ世と共通する要素があり、おそらくデューラーのプット をもとにしている。しかし、クラナッハの絵は、憂鬱と子供の陽気さを対比させており、1528年の絵ではオカルト的な要素が現れている。ハンス・セバル ト・ベーハム(1539年)とヨスト・アンマン(1589年)の版画は明らかに関連している。バロック時代には、メランコリーと虚栄心の表現が組み合わさ れた。ドメニコ・フェッティの『憂鬱/瞑想』(1620年頃)はその重要な例である。パノフスキーらは、「この絵の意味は一目瞭然である。実用的であれ理 論的であれ、理論的であれ芸術的であれ、地上のあらゆるものの虚栄を考えれば、人間の活動はすべて虚しい」と書いている[67]。 ヘンリー・フューセリとカスパー・ダヴィッド・フリードリヒの自画像デッサンは、フリードリヒの『蜘蛛の巣を持つ女』と同様に、メレンコリア像の雰囲気を捉えることに興味を示している[68]。 ルネサンス史家のフランシス・イェーツは、ジョージ・チャップマンの1594年の詩『夜の影』がデューラーの版画の影響を受けていると考え、ロバート・ バートンは『憂鬱の解剖学』(1621年)の中でそれを描写した[66]。 デューラーのメレンコリアは、ジェームズ・トムソンの同名の詩の最終カントにおける「恐ろしい夜の街」の守護神である。この版画は、19世紀に英語とフラ ンス語で書かれたロマン派の詩で取り上げられた[69]。 サグラダ・ファミリアの受難のファサードには、メレンコリア1世の魔方陣に基づく魔方陣が描かれている[70]。この魔方陣は、正方形を回転させ、各行と各列の数字を1つずつ減らしているため、行と列の合計は、4x4の魔方陣の標準的な34ではなく、33になっている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melencolia_I |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Sigmund Freud and Melancholia In his 1917 essay "Mourning and Melancholia", Freud distinguished mourning, painful but an inevitable part of life, and "melancholia", his term for pathological refusal of a mourner to "decathect" from the lost one. Freud claimed that, in normal mourning, the ego was responsible for narcissistically detaching the libido from the lost one as a means of self-preservation, but that in "melancholia", prior ambivalence towards the lost one prevents this from occurring. Suicide, Freud hypothesized, could result in extreme cases, when unconscious feelings of conflict became directed against the mourner's own ego.[177][178] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund_Freud |

ジークムント・フロイトとメランコリア 1917年に発表された論文「悲嘆とメランコリア」の中で、フロイトは、悲しみは人生において避けられない苦しいものであるが、悲嘆と「メランコリア」は異なるものであると区別した。フロイトは、通常の悲嘆においては自我が自己防衛手段として、喪失した対象からリビドーを自己愛的に切り離す役割を担っているが、「メランコリア」においては、喪失した対象に対する先立つ両価性がそれを妨げる、と主張した。フロイトは、極論すれば、無意識の葛藤感情が喪者の自我に向けられる場合、自殺に至る可能性があると仮説を立てた[177][178]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆