Sexism

Sexism

セクシズムとは性別(sexual difference)にもとづく差別のことをいう。したがって長く、性差別主義とも呼ばれてきた。この言い方は、人種主義(レイシズム)が、人種差別主義と同義であることと同じである。

性別には、ジェンダーとセッ クスと いう、社会的性別と生物学的性別の2つの区別があるが、ジュディス・バトラーらの主張によると、我々は社会的存在であり、いくら自然科学の客観・中立な立 場を表向き取ろうとも、研究者ですら、日常の社会的性別(ジェンダー)の認識論的枠組みの影響を受けているため、言語という社会的コミュニケーションを とっている限り、セックス(生物学的性別)は、当該社会におけるジェンダー区分の影響やイデ オロギーから自由になれないだろうという。また、そのような議論の枠組みを踏襲すれば、社会的性別ないしは文化的性別(ともにジェンダー)すら、生物学的性別(セッ クス)の峻別や、それらの差異についてのメタファーを生物学的性別の概念から借りてくるために、ジェンダーとセックスの境界における明確な峻別が可能であると主張することも幻想である。 社会的性別は、生物学的性別の影響を受け形成し、生物学的性別は社会的性別の概念形成に影響を与えているからである。

セクシズムという言葉は、1960年代の

北米大陸のフェミニズム運動のなかで、性に基づく差別構造、とりわけ女性への社会的構造的抑圧への批判

を込めて誕生したことは忘れてはならないだろう。

【設問】

1.セクシズムがしばしば「犠牲者非難」のなかで登場するが、そのことを実例をまじ えながら表現することができるか?

2.セクシズムは性別をとりあげて非難す

ることだけではなく、雇用の現場で、女性やクイアをしらないうちに男性と区別して後者をしらないうちに優遇するような「性差別(性別に基づく差別)」の現場でよくあらわれます。みなさ

んの職場において性差別がないか点検してみましょう。

★セクシズム(Sexism)

| Sexism

is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can

affect anyone, but primarily affects women and girls.[1] It has been

linked to gender roles and stereotypes,[2][3] and may include the

belief that one sex or gender is intrinsically superior to another.[4]

Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of

sexual violence.[5][6] Discrimination in this context is defined as

discrimination toward people based on their gender identity[7] or their

gender or sex differences.[8] An example of this is workplace

inequality.[8] Sexism refers to violation of equal opportunities

(formal equality) based on gender or refers to violation of equality of

outcomes based on gender, also called substantive equality.[9] Sexism

may arise from social or cultural customs and norms.[10] |

性差別とは、性別や性自認に基づく偏見や差別を指す。性差別は誰にでも

影響を及ぼす可能性があるが、主に女性や少女に影響を及ぼす。[1] 性差別はジェンダーの役割や固定観念と関連しており、[2][3]

ある性別や性自認が本質的に他よりも優れているという信念を含む場合がある。[4]

極端な性差別は、セクハラやレイプ、その他の性的暴力を助長する可能性がある。[5][6] この文脈における差別とは、

性自認[7]または性別や性差に基づく人々に対する差別と定義される。[8] その例としては職場における不平等が挙げられる。[8]

セクシズムとは、性別に基づく機会均等(形式的な平等)の侵害を指すか、または性別に基づく結果の平等の侵害を指し、実質的平等とも呼ばれる。[9]

セクシズムは、社会的または文化的慣習や規範から生じる可能性がある。[10] |

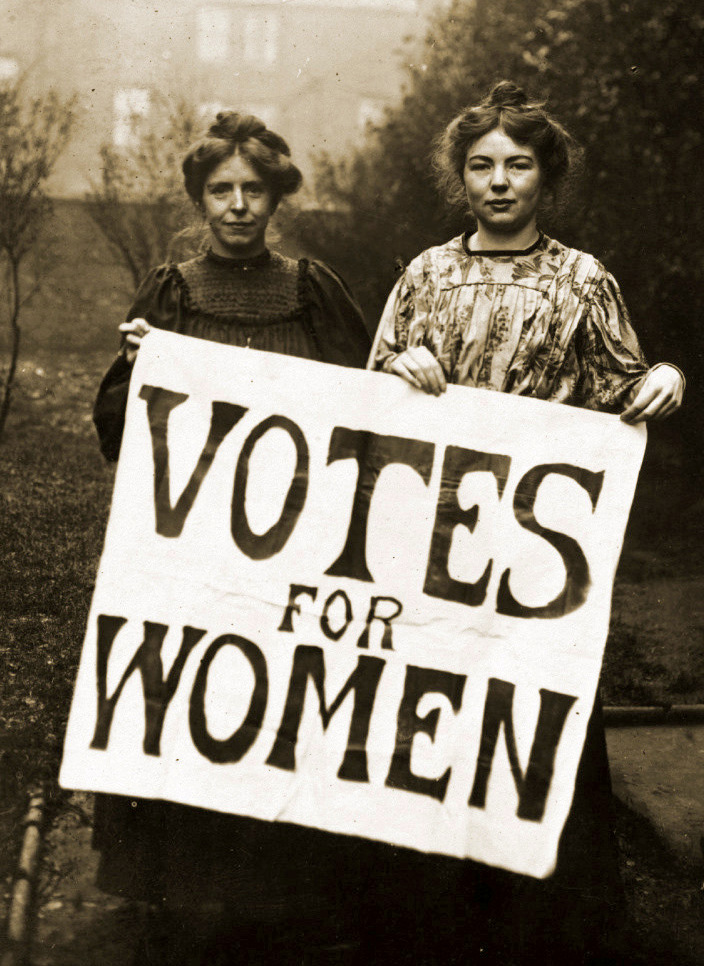

Suffragette organizations campaigned for women's right to vote.1914 |

女性参政権を求める運動が展開された。1914年 |

| Etymology and definitions According to legal scholar Fred R. Shapiro, the term "sexism" was most likely coined on November 18, 1965, by Pauline M. Leet during a "Student-Faculty Forum" at Franklin and Marshall College. Specifically, the word sexism appears in Leet's forum contribution "Women and the Undergraduate", and she defines it by comparing it to racism, stating in part, "When you argue ... that since fewer women write good poetry this justifies their total exclusion, you are taking a position analogous to that of the racist—I might call you, in this case, a 'sexist' ... Both the racist and the sexist are acting as if all that has happened had never happened, and both of them are making decisions and coming to conclusions about someone's value by referring to factors which are in both cases irrelevant."[11] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first time the term sexism appeared in print was in Caroline Bird’s speech "On Being Born Female", which was delivered before the Episcopal Church Executive Council in Greenwich, Connecticut, and subsequently published on November 15, 1968, in Vital Speeches of the Day (p. 6).[12] Sexism may be defined as an ideology based on the belief that one sex is superior to another.[4][13][14] It is discrimination, prejudice, or stereotyping based on gender, and is most often expressed toward women and girls.[1] Sociology has examined sexism as manifesting at both the individual and the institutional level.[14] According to Richard Schaefer, sexism is perpetuated by all major social institutions.[14] Sociologists describe parallels among other ideological systems of oppression such as racism, which also operates at both the individual and institutional level.[15] Early female sociologists Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Ida B. Wells, and Harriet Martineau described systems of gender inequality, but did not use the term sexism, which was coined later. Sociologists who adopted the functionalist paradigm, e.g. Talcott Parsons, understood gender inequality as the natural outcome of a dimorphic model of gender.[16] Psychologists Mary Crawford and Rhoda Unger define sexism as prejudice held by individuals that encompasses "negative attitudes and values about women as a group."[17] Peter Glick and Susan Fiske coined the term ambivalent sexism to describe how stereotypes about women can be both positive and negative, and that individuals compartmentalize the stereotypes they hold into hostile sexism or benevolent sexism.[18] Feminist author bell hooks defines sexism as a system of oppression that results in disadvantages for women.[19] Feminist philosopher Marilyn Frye defines sexism as an "attitudinal-conceptual-cognitive-orientational complex" of male supremacy, male chauvinism, and misogyny.[20] Philosopher Kate Manne defines sexism as one branch of a patriarchal order. In her definition, sexism rationalizes and justifies patriarchal norms, in contrast with misogyny, the branch which polices and enforces patriarchal norms. Manne says that sexism often attempts to make patriarchal social arrangements seem natural, good, or inevitable so that there appears to be no reason to resist them.[21] |

語源と定義 法律学者のフレッド・R・シャピロ氏によると、「性差別」という用語は、1965年11月18日にフランクリン・アンド・マーシャル大学で開催された「学 生と教職員のフォーラム」において、ポーリン・M・リート氏によって初めて使用された可能性が高い。具体的には、リー氏のフォーラムへの投稿「女性と学部 生」に「性差別」という言葉が使われており、彼女は人種主義と比較しながら次のように定義している。「女性が優れた詩を書くことが少ないからといって、彼 女たちを完全に排除することが正当化されると主張するなら、あなたは人種差別主義者と類似した立場を取っていることになる。この場合、私はあなたを『性差 別主義者』と呼ぶかもしれない。人種差別主義者も性差別主義者も、あたかも何も起こらなかったかのように振る舞い、どちらも、どちらの場合も無関係な要因 を参照して、誰かの価値について決定を下し結論を出している」[11] オックスフォード英語辞典によると、性差別という用語が印刷物に初めて登場したのは、コネチカット州グリニッジの聖公会執行協議会で発表されたキャロライ ン・バードの演説「女性として生まれて」であり、その後、1968年11月15日に『Vital Speeches of the Day』(p. 6)に掲載された。[12] 性差別とは、一方の性が他方より優れているという信念に基づくイデオロギーと定義されることがある。[4][13][14] 性差別とは、性別に基づく差別、偏見、または固定観念であり、女性や少女に対して最も頻繁に表れる。[1] 社会学では、性差別は個人レベルと制度レベルの両方で現れるものとして研究されている。[14] リチャード・シェーファーによると、性差別はすべての主要な社会制度によって永続化されている。[14] 社会学者は、人種主義などの他の抑圧的イデオロギー体系との類似点を指摘している 。これもまた個人と制度の両方のレベルで作用している。[15] 初期の女性社会学者であるシャーロット・パーキンス・ギルマン、アイダ・B・ウェルズ、ハリエット・マーティノーは、ジェンダーの不平等なシステムについ て説明したが、後に作られた「性差別」という用語は使用しなかった。機能主義的パラダイムを採用した社会学者、例えばタルコット・パーソンズは、ジェン ダーの不平等をジェンダーの二形モデルの自然な帰結として理解していた。[16] 心理学者のメアリー・クロフォードとローダ・ウンガーは、性差別を「女性という集団に対する否定的な態度や価値観」を含む個人による偏見と定義している。 [17] ピーター・グリックとスーザン・フィスクは、女性に対するステレオタイプが肯定的にも否定的にもなりうることを説明するために「アンビヴァレント・セクシ ズム」という用語を考案した。また、個人が抱くステレオタイプを敵対的性差別と好意的性差別に区分する。[18] フェミニストの著述家ベル・フックスは、性差別を女性にとって不利益をもたらす抑圧の体系と定義している。[19] フェミニストの哲学者マリリン・フライは、性差別を男性至上主義、男性中心主義、女性嫌悪の「態度・概念・認知・志向の複合体」と定義している。[20] 哲学者のケイト・マンは、性差別を家父長制の一形態と定義している。彼女の定義では、性差別は家父長制の規範を合理化し正当化するものであり、家父長制の 規範を監視し強制する役割である女性嫌悪とは対照的である。マンは、性差別はしばしば家父長制の社会的取り決めを自然で良いもの、あるいは不可避なものと して見せかけ、それらに抵抗する理由がないように見せかけると述べている。[21] |

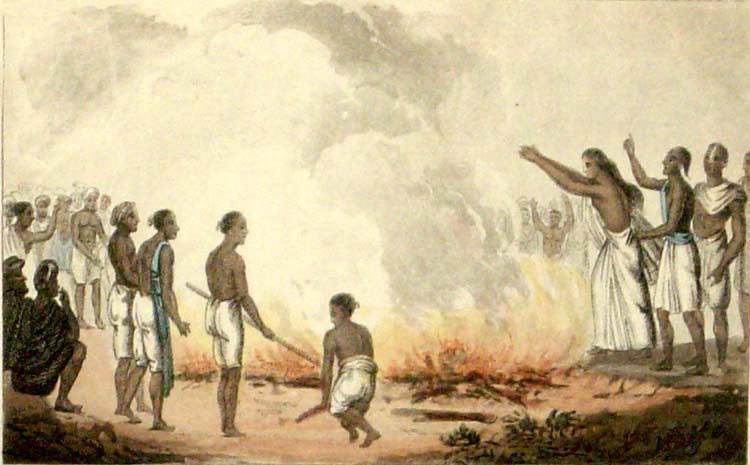

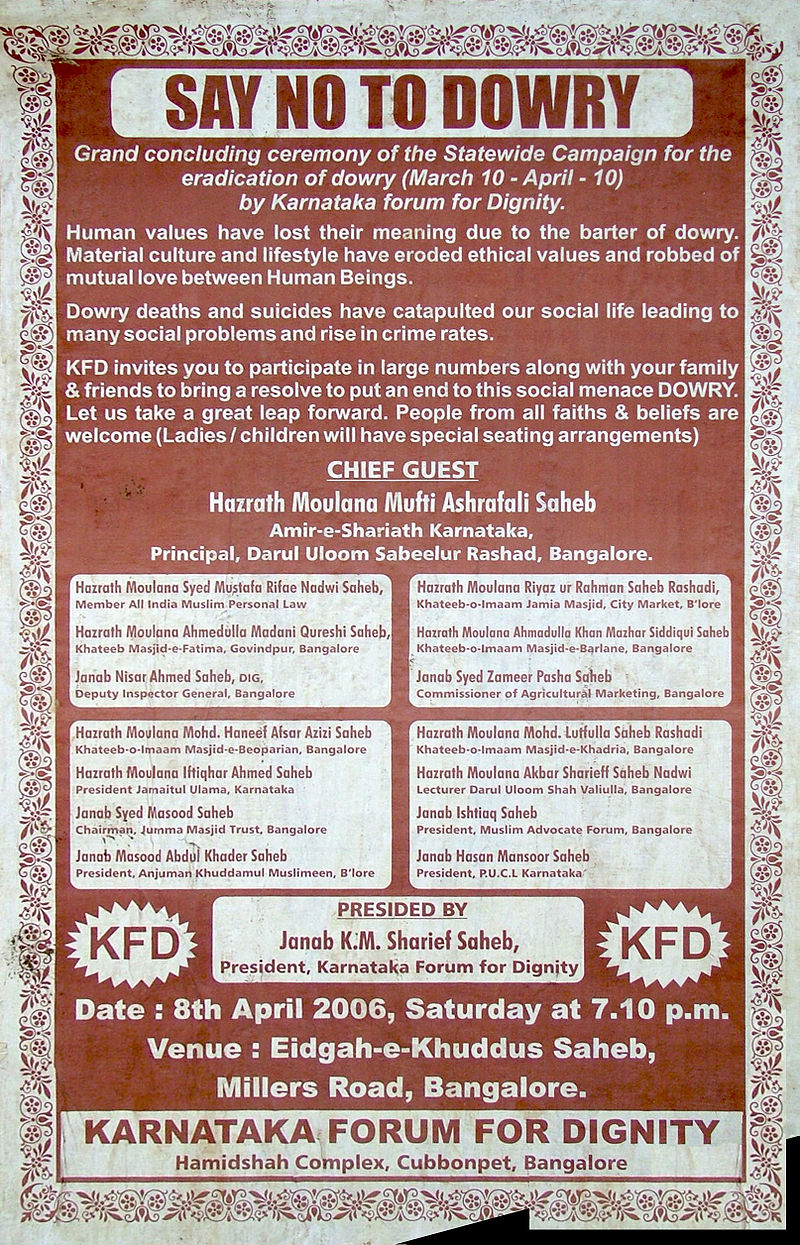

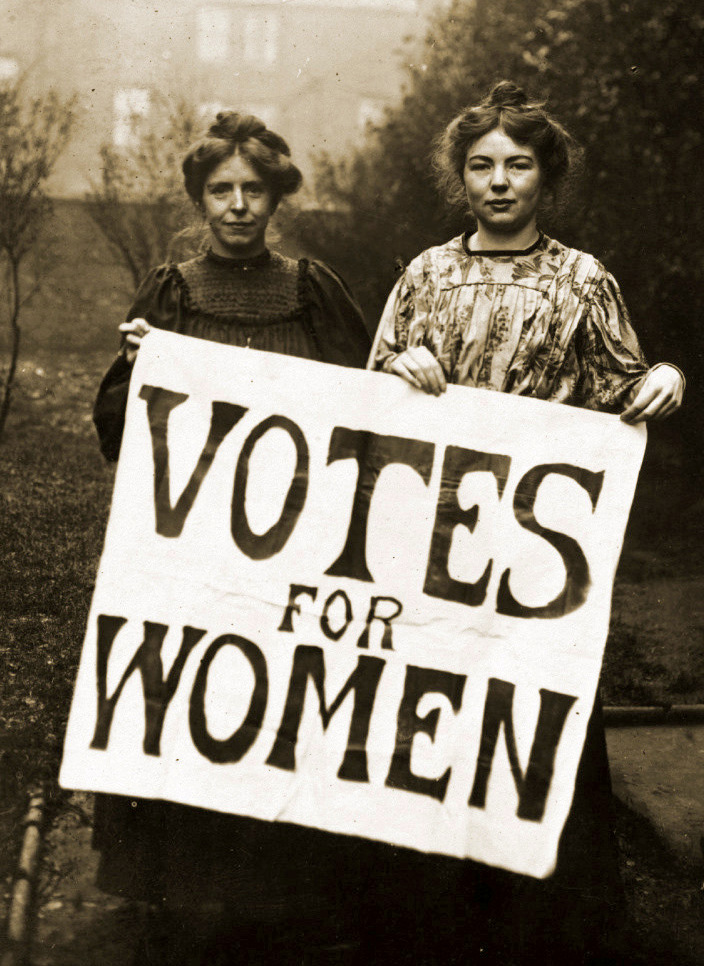

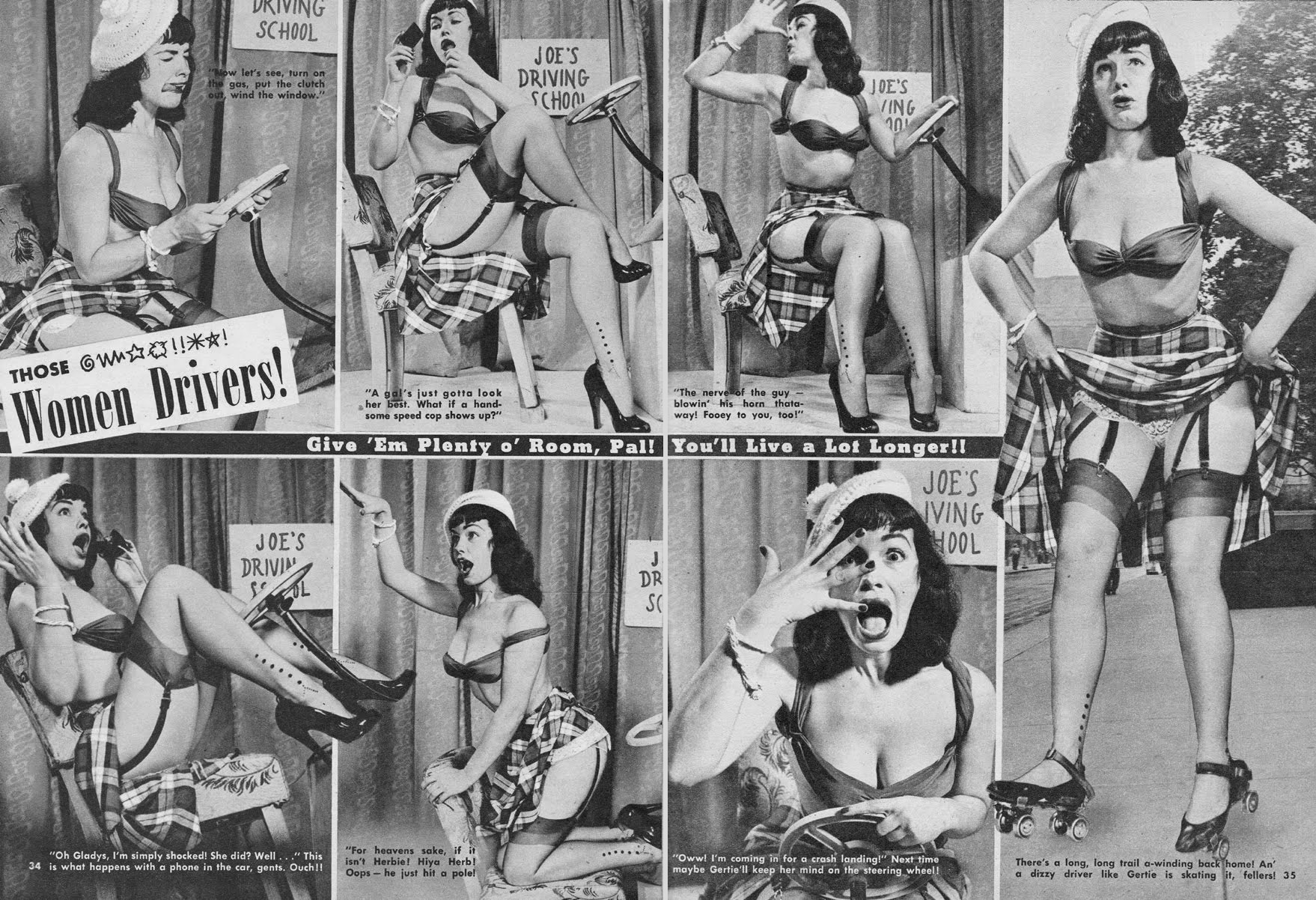

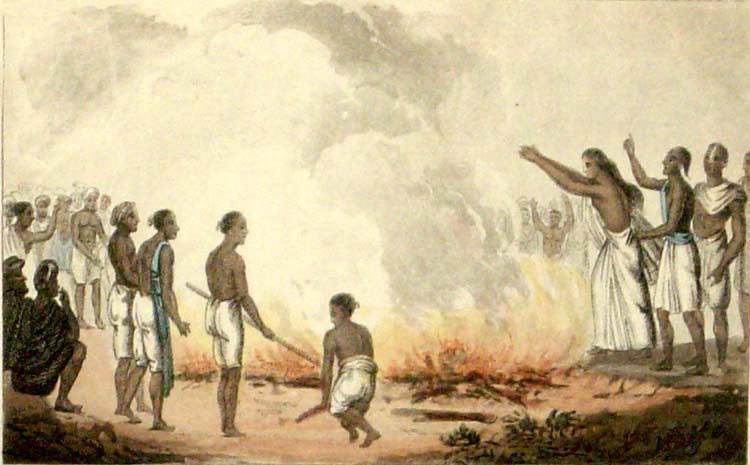

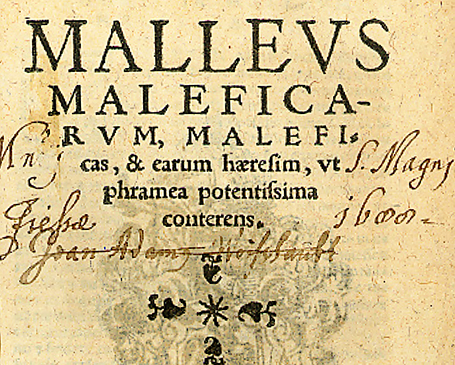

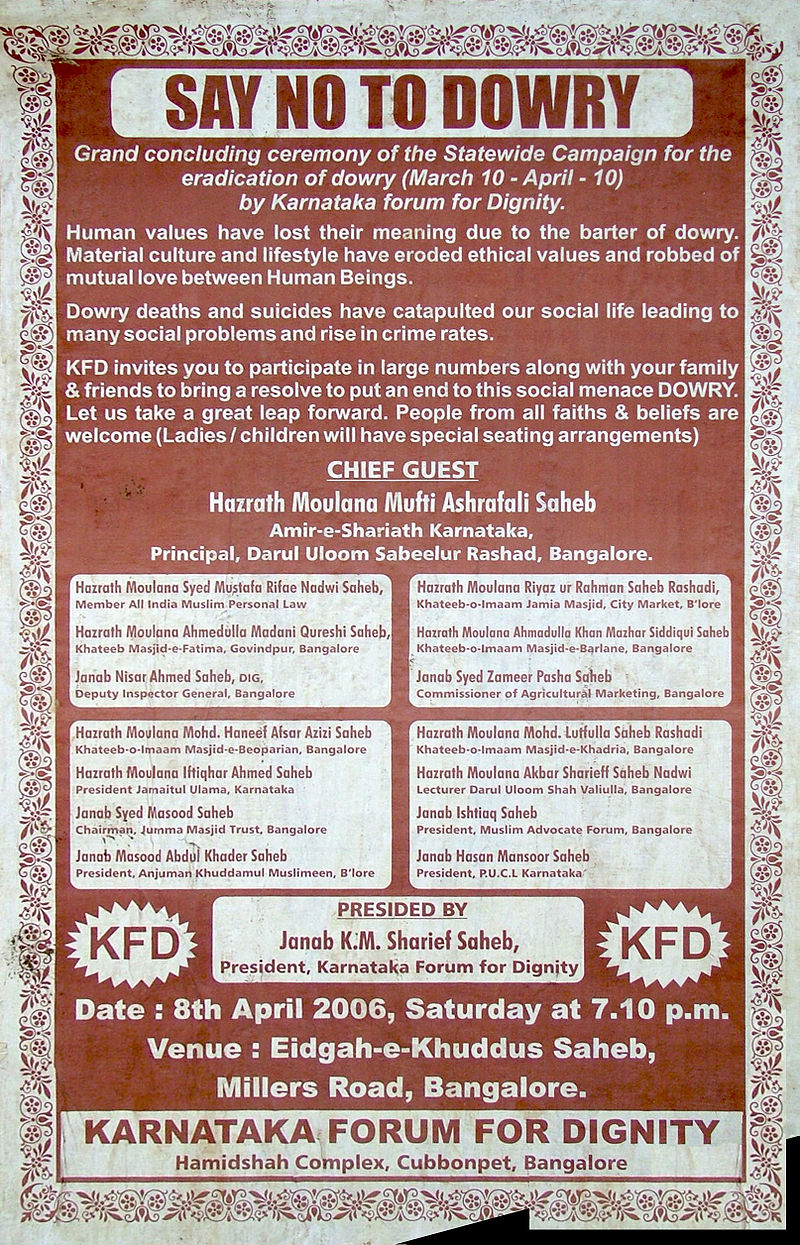

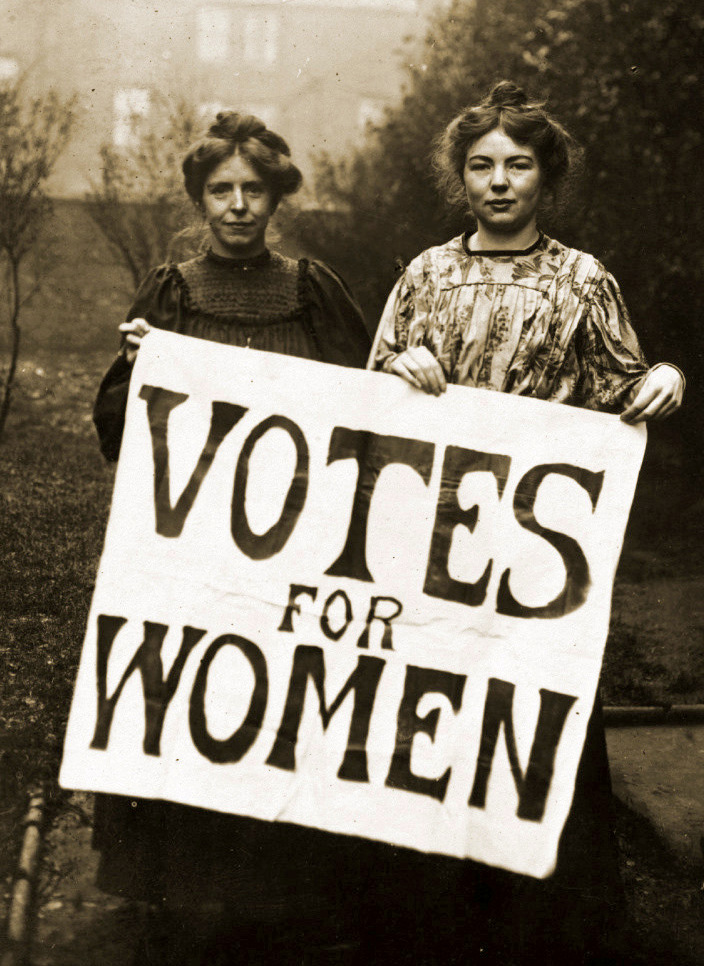

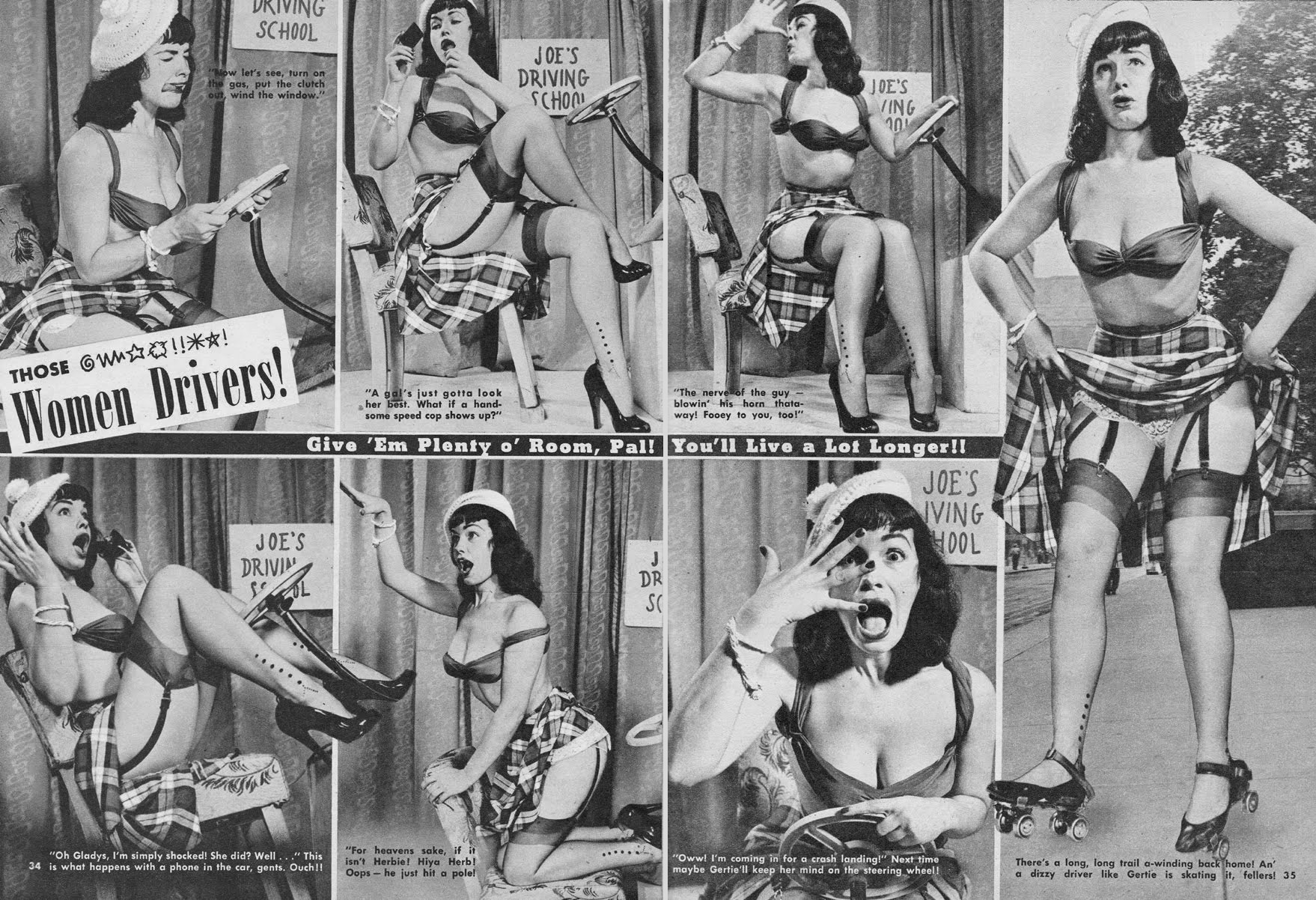

| History Pre-agricultural world Evidence is lacking to support the idea that many pre-agricultural societies afforded women a higher status than women today,[22] however, historians are reasonably sure that women had roughly equal social power to men in many such societies.[23] Ancient civilizations  Engraving of a woman preparing to self-immolate with her husband's corpse Sati, or self-immolation by widows, was prevalent in Hindu society until the early 19th century. After the adoption of agriculture and sedentary cultures, the concept that one gender was inferior to the other was established; most often this was imposed upon women and girls.[24] The status of women in ancient Egypt depended on their fathers or husbands, but they had property rights and could attend court, including as plaintiffs.[25] Examples of unequal treatment of women in the ancient world include written laws preventing women from participating in the political process; for instance, women in ancient Rome could not vote or hold political office.[26] Another example is scholarly texts that indoctrinate children in female inferiority; women in ancient China were taught the Confucian principles that a woman should obey her father in childhood, husband in marriage, and son in widowhood.[27] On the other hand, women of the Anglo-Saxon era were commonly afforded equal status.[28] Witch hunts and trials Main article: Witch hunt  Titlepage from the book Malleus Maleficarum "The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword". Title page of the seventh Cologne edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, 1520, from the University of Sydney Library.[29] Sexism may have been the impetus that fueled the witch trials between the 15th and 18th centuries.[30] In early modern Europe, and in the European colonies in North America, claims were made that witches were a threat to Christendom. The misogyny of that period played a role in the persecution of these women.[31][32] In Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer, the book which played a major role in the witch hunts and trials, the author argues that women are more likely to practice witchcraft than men, and writes that: All wickedness is but little to the wickedness of a woman ... What else is a woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colors![33] Witchcraft remains illegal in several countries, including Saudi Arabia, where it is punishable by death. In 2011, a woman was beheaded in that country for "witchcraft and sorcery".[34] Murders of women after being accused of witchcraft remain common in some parts of the world; for example, in Tanzania, about 500 elderly women are murdered each year following such accusations.[35] When women are targeted with accusations of witchcraft and subsequent violence, it is often the case that several forms of discrimination interact – for example, discrimination based on gender with discrimination based on caste, as is the case in India and Nepal, where such crimes are relatively common.[36][37] Coverture and other marriage regulations Main articles: Coverture, Marital power, Restitution of conjugal rights, Kirchberg v. Feenstra, and Marriage bar  An Indian Anti-dowry poster headed Say No To Dowry Anti-dowry poster in Bangalore, India. According to Amnesty International, "[T]he ongoing reality of dowry-related violence is an example of what can happen when women are treated as property."[38] Until the 20th century, U.S. and English law observed the system of coverture, where "by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage".[39] U.S. women were not legally defined as "persons" until 1875 (Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162).[40] A similar legal doctrine, called marital power, existed under Roman Dutch law (and is still partially in force in present-day Eswatini).[citation needed] Restrictions on married women's rights were common in Western countries until a few decades ago: for instance, French married women obtained the right to work without their husband's permission in 1965,[41][42][43] and in West Germany women obtained this right in 1977.[44][45] During the Franco era, in Spain, a married woman required her husband's consent (called permiso marital) for employment, ownership of property and traveling away from home; the permiso marital was abolished in 1975.[46] In Australia, until 1983, a married woman's passport application had to be authorized by her husband.[47] Women in parts of the world continue to lose their legal rights in marriage. For example, Yemeni marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[48] In Iraq, the law allows husbands to legally "punish" their wives.[49] In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Family Code states that the husband is the head of the household; the wife owes her obedience to her husband; a wife has to live with her husband wherever he chooses to live; and wives must have their husbands' authorization to bring a case in court or initiate other legal proceedings.[50] Abuses and discriminatory practices against women in marriage are often rooted in financial payments such as dowry, bride price, and dower.[51] These transactions often serve as legitimizing coercive control of the wife by her husband and in giving him authority over her; for instance Article 13 of the Code of Personal Status (Tunisia) states that, "The husband shall not, in default of payment of the dower, force the woman to consummate the marriage",[52][53] implying that, if the dower is paid, marital rape is permitted. In this regard, critics have questioned the alleged gains of women in Tunisia, and its image as a progressive country in the region, arguing that discrimination against women remains very strong there.[54][55][56] The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) has recognized the "independence and ability to leave an abusive husband" as crucial in stopping mistreatment of women.[57] However, in some parts of the world, once married, women have very little chance of leaving a violent husband: obtaining a divorce is very difficult in many jurisdictions because of the need to prove fault in court. While attempting a de facto separation (moving away from the marital home) is also impossible because of laws preventing this. For instance, in Afghanistan, a wife who leaves her marital home risks being imprisoned for "running away".[58][59] In addition, many former British colonies, including India, maintain the concept of restitution of conjugal rights,[60] under which a wife may be ordered by court to return to her husband; if she fails to do so, she may be held in contempt of court.[61][62] Other problems have to do with the payment of the bride price: if the wife wants to leave, her husband may demand the return of the bride price that he had paid to the woman's family; and the woman's family often cannot or does not want to pay it back.[63][64][65] Laws, regulations, and traditions related to marriage continue to discriminate against women in many parts of the world, and to contribute to the mistreatment of women, in particular in areas related to sexual violence and to self-determination regarding sexuality, the violation of the latter now being acknowledged as a violation of women's rights. In 2012, Navi Pillay, then High Commissioner for Human Rights, stated that: Women are frequently treated as property, they are sold into marriage, into trafficking, into sexual slavery. Violence against women frequently takes the form of sexual violence. Victims of such violence are often accused of promiscuity and held responsible for their fate, while infertile women are rejected by husbands, families and communities. In many countries, married women may not refuse to have sexual relations with their husbands, and often have no say in whether they use contraception ... Ensuring that women have full autonomy over their bodies is the first crucial step towards achieving substantive equality between women and men. Personal issues—such as when, how and with whom they choose to have sex, and when, how and with whom they choose to have children—are at the heart of living a life in dignity.[66] Suffrage and politics  Two woman carry a sign reading "Votes for Women". Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst Gender has been used as a tool for discrimination against women in the political sphere. Women's suffrage was not achieved until 1893, when New Zealand was the first country to grant women the right to vote. Saudi Arabia is the most recent country, as of August 2015, to extend the right to vote to women in 2011.[67] Some Western countries allowed women the right to vote only relatively recently. Swiss women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971,[68] and Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last canton to grant women the right to vote on local issues in 1991, when it was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[69] French women were granted the right to vote in 1944.[70][71] In Greece, women obtained the right to vote in 1952.[72] In Liechtenstein, women obtained the right to vote in 1984, through the women's suffrage referendum of 1984.[73][74] While almost every woman today has the right to vote, there is still progress to be made for women in politics. Studies have shown that in several democracies including Australia, Canada, and the United States, women are still represented using gender stereotypes in the press.[75] Multiple authors have shown that gender differences in the media are less evident today than they used to be in the 1980s, but are still present. Certain issues (e.g., education) are likely to be linked with female candidates, while other issues (e.g., taxes) are likely to be linked with male candidates.[75] In addition, there is more emphasis on female candidates' personal qualities, such as their appearance and their personality, as females are portrayed as emotional and dependent.[75] There is a widespread imbalance of lawmaking power between men and women. The ratio of women to men in legislatures is used as a measure of gender equality in the United Nations' Gender Empowerment Measure and its newer incarnation the Gender Inequality Index. Speaking about China, Lanyan Chen stated that, since men more than women serve as the gatekeepers of policy making, this may lead to women's needs not being properly represented. In this sense, the inequality in lawmaking power also causes gender discrimination.[76] Menus Until the early 1980s, some high-end restaurants had two menus: a regular menu with the prices listed for men and a second menu for women, which did not have the prices listed (it was called the "ladies' menu"), so that the female diner would not know the prices of the items.[77] In 1980, Kathleen Bick took a male business partner out to dinner at L'Orangerie in West Hollywood. After she was given a women's menu without prices and her guest got one with prices, Bick hired lawyer Gloria Allred to file a discrimination lawsuit, on the grounds that the women's menu went against the California Civil Rights Act.[77] Bick stated that getting a women's menu without prices left her feeling "humiliated and incensed". The owners of the restaurant defended the practice, saying it was done as a courtesy, like the way men would stand up when a woman enters the room. Even though the lawsuit was dropped, the restaurant ended its gender-based menu policy.[77] Trends over time Globe icon. The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (March 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) A 2021 study found little evidence that levels of sexism had changed from 2004 to 2018 in the United States.[78] Gender stereotypes See also: Gender role § Gender stereotypes, and Implicit stereotype § Gender stereotypes  Series of photographs lampooning women drivers Bettie Page portrays stereotypes about women drivers in 1952. Gender stereotypes are widely held beliefs about the characteristics and behavior of women and men.[79] Empirical studies have found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women in a number of activities.[80][81] Dustin B. Thoman and others (2008) hypothesize that "[t]he socio-cultural salience of ability versus other components of the gender-math stereotype may impact women pursuing math". Through the experiment comparing the math outcomes of women under two various gender-math stereotype components, which are the ability of math and the effort on math respectively, Thoman and others found that women's math performance is more likely to be affected by the negative ability stereotype, which is influenced by sociocultural beliefs in the United States, rather than the effort component. As a result of this experiment and the sociocultural beliefs in the United States, Thoman and others concluded that individuals' academic outcomes can be affected by the gender-math stereotype component that is influenced by the sociocultural beliefs.[82] |

歴史 農業以前の世界 多くの農業以前の社会において、現代の女性よりも高い地位が女性に与えられていたという考え方を裏付ける証拠は見当たらないが[22]、多くの社会におい て女性は男性とほぼ同等の社会的権力を持っていたことは、歴史家たちもほぼ確信している[23]。 古代文明  夫の遺体とともに焼身自殺する準備をする女性の彫刻 サティ(寡婦の焼身自殺)は、19世紀初頭までヒンドゥー社会で広く見られた。 農業と定住文化が採用された後、一方の性が他方より劣っているという概念が確立された。この概念は、ほとんどの場合、女性や少女に押し付けられた。 古代エジプトにおける女性の地位は父親や夫に依存していたが、財産権は認められており、原告として法廷に立つこともできた。[25] 古代世界における女性への不平等な扱いの例としては、女性が政治プロセスに参加することを禁じる成文法がある。例えば、古代ローマでは女性は投票すること も政治的役職に就くこともできなかった。[26] 。別の例としては、女性は男性より劣っているという考えを子供たちに教え込む学術的な文章がある。古代中国の女性は、幼少期には父親に従い、結婚後は夫に 従い、夫に先立たれた後は息子に従うべきであるという儒教の原則を教えられていた。[27] 一方、アングロ・サクソン時代の女性は、一般的に平等な地位を与えられていた。[28] 魔女狩りと裁判 詳細は「魔女狩り」を参照  『魔女ハンマー』の表紙 「魔女ハンマーは、両刃の剣のごとく、魔女とその異端を滅ぼす」。1520年、ケルンで出版された『魔女ハンマー』の表紙。シドニー大学図書館所蔵。 15世紀から18世紀にかけての魔女裁判の火付け役となったのは性差別であった可能性がある。[30] 近世ヨーロッパ、および北米のヨーロッパ植民地では、魔女はキリスト教社会に対する脅威であると主張された。この時代の女性嫌悪が、これらの女性に対する 迫害の一因となった。[31][32] 魔女狩りと裁判に大きな役割を果たしたハインリヒ・クラマー著『魔女ハンターの鉄槌』では、著者は女性の方が男性よりも魔術を行う可能性が高いと主張し、 次のように書いている。 女性の悪は、あらゆる悪の中でもとりわけ大きい。女性とは、友情の敵であり、避けられない罰であり、必要悪であり、自然な誘惑であり、望ましい災難であ り、家庭内の危険であり、魅力的な害悪であり、自然の悪であり、美しい色で描かれたものなのだ![33] サウジアラビアを含むいくつかの国では、今でも魔術は違法であり、処罰には死刑が科せられる。2011年には、その国で「魔術と妖術」の罪で女性が処刑さ れた。[34] 魔術の罪を着せられた後の女性の殺害は、世界のいくつかの地域では依然として一般的である。例えば、タンザニアでは、毎年約500人の高齢女性がそのよう な罪を着せられて殺害されている。[35] 女性が魔術の嫌疑をかけられ、その後の暴力の標的となる場合、多くの場合、いくつかの形態の差別が相互に作用している。例えば、インドやネパールのよう に、こうした犯罪が比較的よく見られる国々では、性別に基づく差別とカーストに基づく差別が相互に作用している。 覆婚制およびその他の婚姻規定 主な記事:覆婚制、夫婦別財産、夫婦別財産権の回復、Kirchberg v. Feenstra、婚姻禁止  インドの持参金反対ポスター「持参金にノーを」 インド、バンガロールの持参金反対ポスター。アムネスティ・インターナショナルによると、「持参金に関連する暴力が現在も続いていることは、女性が財産と して扱われた場合に起こりうることを示す一例である」[38] 20世紀まで、米国と英国の法律では、結婚によって「夫と妻は法律上は1人の人間となる。つまり、結婚中は女性の存在や法的実在が停止される」という制度 が認められていた。[39] 米国の女性は、 1875年(Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162)まで「人」として法的に定義されていなかった。[40] 類似の法理論である夫婦別権は、ローマ・オランダ法の下で存在していた(そして、現在のエスワティニでは現在でも部分的に有効である)。[要出典] 結婚した女性の権利に対する制限は、数十年前まで西洋諸国では一般的であった。例えば、フランスの結婚した女性は1965年に夫の許可なしに働く権利を得 た[41][42][43]。西ドイツでは1977年に女性がこの権利を得た[44][45]。スペインのフランコ時代には、既婚女性が就労、財産所有、 自宅外への旅行をするには夫の同意(permiso maritalと呼ばれる)が必要であった。permiso maritalは1975年に廃止された。[46] オーストラリアでは1983年まで、既婚女性のパスポート申請には夫の承認が必要であった。[47] 世界のいくつかの地域では、結婚によって法的権利を失う女性が今も存在する。例えば、イエメンの婚姻規定では、妻は夫に従う義務があり、夫の許可なく家を 出てはならないと定めている。[48] イラクでは、法律により夫が妻を合法的に「罰する」ことが認められている。[49] コンゴ民主共和国では、家族法により 夫が世帯主であり、妻は夫に従う義務があり、妻は夫がどこに住もうとも一緒に暮らさねばならず、また、妻が裁判を起こしたりその他の法的措置を取るには夫 の許可が必要である、と定めている。 結婚における女性に対する虐待や差別的慣行は、持参金、花嫁の値段、持参財産といった金銭的支払いによって根付いていることが多い。[51] これらの取引は、夫による妻に対する強制的な支配を正当化し、妻に対する夫の権限を強化する役割を果たしていることが多い。例えば、 「持参金の支払いがなされない場合、夫は女性に婚姻の完遂を強制してはならない」と定めているが、これは「持参金が支払われれば、婚姻中のレイプが許され る」という意味である。この点について、批評家たちは、チュニジアにおける女性の権利向上と、その地域における先進国としてのイメージに疑問を呈し、同国 では依然として女性に対する差別が根強いと主張している。[54][55][56] 拷問禁止団体(OMCT)は、女性に対する虐待を止めるためには、「虐待的な夫と別れるための独立性と能力」が重要であると認識している。[57] しかし、世界のいくつかの地域では、結婚した女性が暴力的な夫と別れるチャンスはほとんどない。離婚は、法廷で過失を証明する必要があるため、多くの管轄 区域で非常に難しい。事実上の別居(結婚生活を送っていた家からの引っ越し)を試みることも、それを禁じる法律があるため不可能である。例えば、アフガニ スタンでは、結婚生活を送っていた家を出た妻は「家出」の罪で投獄される危険性がある。[58][59] さらに、インドを含む多くの旧イギリス植民地では、夫婦間の権利の回復という概念が維持されており、[60] その下では、妻は裁判所によって夫のもとに戻るよう命じられる可能性がある。もし妻がそれに従わない場合、 。[61][62] その他の問題は、花嫁の持参金の支払いに関するものである。妻が離別を望む場合、夫は女性側の家族に支払った持参金の返還を要求できる。そして、女性側の 家族は、持参金を返還できないか、あるいは返還したくない場合が多い。[63][64][65] 結婚に関する法律や規則、伝統は、世界の多くの地域で女性に対する差別を継続し、特に性的暴力や性的自己決定に関連する分野において、女性の虐待を助長し ている。後者の侵害は、現在では女性の権利の侵害として認められている。2012年、当時人権高等弁務官であったナビ・ピレイは次のように述べた。 女性は財産として扱われることが多く、結婚相手として売られたり、人身売買や性的奴隷として売られたりする。女性に対する暴力は、性的暴力という形をとる ことが多い。そのような暴力の被害者は、不貞を疑われたり、自らの運命に責任があると非難されたりすることが多い。また、不妊の女性は夫や家族、地域社会 から拒絶される。多くの国々では、既婚女性は夫との性的関係を拒否することができず、避妊をするかどうかについても発言権がないことが多い。女性が自分の 身体に対して完全な自律性を持つことは、男女間の実質的な平等を達成するための第一歩である。 いつ、どのように、誰と性交渉を持つか、また、いつ、どのように、誰と子どもを持つかといった個人的な問題は、尊厳のある生活を送る上で中心的なものであ る。[66] 参政権と政治  「女性に投票を」と書かれたプラカードを持つ2人の女性。 アニー・ケニーとクリスタベル・パンクハースト ジェンダーは政治分野における女性差別の道具として使われてきた。女性参政権が実現したのは1893年になってからで、ニュージーランドが世界で初めて女 性に選挙権を認めた国となった。2011年に女性に選挙権を認めた国としては、2015年8月現在、サウジアラビアが最も新しい。スイスの女性は1971 年に連邦選挙での投票権を獲得し[68]、アッペンツェル・インナーローデン準州は1991年にスイス連邦最高裁判所の命令により、州の地方問題に関する 投票権を女性に与えた最後の州となった[69]。フランスの女性は 1944年に投票権が認められた。[70][71] ギリシャでは、1952年に女性に投票権が認められた。[72] リヒテンシュタインでは、1984年の女性参政権に関する国民投票により、1984年に女性に投票権が認められた。[73][74] 今日ではほとんどの女性に投票権があるが、政治の世界ではまだ女性の進出が進んでいない。オーストラリア、カナダ、アメリカ合衆国を含むいくつかの民主主 義国家では、報道において女性が性別によるステレオタイプで表現されていることが研究により示されている。[75] 複数の著者が、メディアにおける性差は1980年代に比べると現在では目立たなくなっているが、依然として存在していることを示している。特定の問題(例 えば教育)は女性候補と関連付けられやすく、他の問題(例えば税金)は男性候補と関連付けられやすい。[75] さらに、女性は感情的で依存的であると描写されるため、女性候補の個人的な資質、例えば外見や性格などがより重視される。[75] 男女間の立法権力の不均衡は広範囲にわたっている。立法機関における男女の比率は、国連のジェンダーエンパワーメント指数(GEM)や、その新しい形であ るジェンダー不平等指数(GII)で、男女平等の指標として用いられている。中国について、Lanyan Chenは、政策立案のキーパーソンに就くのは女性よりも男性の方が多いことから、女性のニーズが適切に反映されない可能性があると述べている。この意味 で、立法権における不平等も男女差別を引き起こしている。[76] メニュー 1980年代初頭まで、一部の高級レストランでは、男性向けの価格が記載された通常メニューと、女性向けの価格が記載されていない(「女性用メニュー」と 呼ばれていた)メニューの2種類を用意し、女性客が品物の価格を知ることがないようにしていた。[77] 1980年、キャスリーン・ビックは、ウェストハリウッドの「L'Orangerie」で男性のビジネスパートナーとディナーを楽しんだ。彼女には価格の 記載されていない女性用メニューが渡され、ゲストには価格の記載された男性用メニューが渡されたため、ビックは弁護士のグロリア・オールレッドを雇い、女 性用メニューはカリフォルニア州公民権法に違反しているとして、差別訴訟を起こした。[77] ビックは、価格の記載されていない女性用メニューを受け取ったことで「屈辱的で憤慨した」と述べた。レストランのオーナーは、女性客が入店した際に男性が 立ち上がるような礼儀として行っていることだと弁明した。訴訟は取り下げられたが、レストランは性別に基づくメニューのポリシーを廃止した。 経年変化 地球のアイコン。 このセクションの例や見解は、その主題に関する世界的な見解を表していない場合がある。必要に応じて、このセクションを改善したり、トークページで問題に ついて議論したり、新しいセクションを作成したりすることができる。 (2021年3月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについて学ぶ) 2021年の研究では、2004年から2018年の間にアメリカ合衆国で性差別が変化したという証拠はほとんど見つからなかった。[78] ジェンダー・ステレオタイプ 関連項目:ジェンダー・ロール § ジェンダー・ステレオタイプ、潜在的ステレオタイプ § ジェンダー・ステレオタイプ  女性ドライバーを風刺した写真シリーズ ベティ・ペイジは1952年に女性ドライバーに関するステレオタイプを描いている。 性別によるステレオタイプとは、女性および男性の特徴や行動に関する広く共有された信念である。[79] 実証研究では、男性は女性よりも多くの活動において社会的に高く評価され、有能であるという文化的な信念が広く共有されていることが分かっている。 [80][81] ダスティン・B・トーマン(Dustin B. Thoman)ら(2008年)は、「能力に対する社会文化的な重要度と、性別と数学のステレオタイプにおけるその他の要素が、数学を学ぶ女性に影響を与 える可能性がある」という仮説を立てている。トーマンらは、2つのジェンダー・数学ステレオタイプ要素、すなわち数学能力と数学への努力、それぞれについ て、女性を対象に数学の成果を比較する実験を行った。その結果、女性の数学の成績は、努力よりもむしろ、米国の社会文化的信念に影響される否定的な能力ス テレオタイプに影響されやすいことが分かった。この実験と米国の社会文化的信念の結果、トーマンらは、個人の学業成績は、社会文化的信念に影響されるジェ ンダーと数学のステレオタイプ的要素によって影響を受ける可能性があると結論づけた。[82] |

| Sexism in language exists when

language devalues members of a certain gender.[83] Sexist language, in

many instances, promotes male superiority.[84] Sexism in language

affects consciousness, perceptions of reality, encoding and

transmitting cultural meanings and socialization.[83] Researchers have

pointed to the semantic rule in operation in language of the

male-as-norm. This results in sexism as the male becomes the standard

and those who are not male are relegated to the inferior.[85] Sexism in

language is considered a form of indirect sexism because it is not

always overt.[86] Examples include: Using generic masculine terms to reference a group of mixed gender, such as "mankind", "man" (referring to humanity), "guys", or "officers and men" Using the singular masculine pronoun (he, his, him) as the default to refer to a person of unknown gender Terms ending in "-man" that may be performed by those of non-male genders, such as businessman, chairman, or policeman Using unnecessary gender markers, such as "male nurse" implying that simply a "nurse" is by default assumed to be female.[87] Sexist and gender-neutral language See also: Gender-neutral language Various 20th century feminist movements, from liberal feminism and radical feminism to standpoint feminism, postmodern feminism and queer theory, have considered language in their theorizing.[88] Most of these theories have maintained a critical stance on language that calls for a change in the way speakers use their language. One of the most common calls is for gender-neutral language. Many have called attention, however, to the fact that the English language is not inherently sexist in its linguistic system, but the way it is used becomes sexist and gender-neutral language could thus be employed.[89] Sexism in languages other than English Romanic languages such as French[90] and Spanish[91] may be seen as reinforcing sexism, in that the masculine form is the default. The word "mademoiselle", meaning "miss", was declared banished from French administrative forms in 2012 by Prime Minister François Fillon.[90] Current pressure calls for the use of the masculine plural pronoun as the default in a mixed-sex group to change.[92] As for Spanish, Mexico's Ministry of the Interior published a guide on how to reduce the use of sexist language.[91] German speakers have also raised questions about how sexism intersects with grammar.[93] The German language is heavily inflected for gender, number, and case; nearly all nouns denoting the occupations or statuses of human beings are gender-differentiated. For more gender-neutral constructions, gerund nouns are sometimes used instead, as this eliminates the grammatical gender distinction in the plural, and significantly reduces it in the singular. For example, instead of die Studenten ("the men students") or die Studentinnen ("the women students"), one writes die Studierenden ("the [people who are] studying").[94] However, this approach introduces an element of ambiguity, because gerund nouns more precisely denote one currently engaged in the activity, rather than one who routinely engages in it as their primary occupation.[95] In Chinese, some writers have pointed to sexism inherent in the structure of written characters. For example, the character for man is linked to those for positive qualities like courage and effect while the character for wife is composed of a female part and a broom, considered of low worth.[96] Gender-specific pejorative terms See also: Category:Sex- and gender-related slurs Gender-specific pejorative terms intimidate or harm another person because of their gender. Sexism can be expressed in language with negative gender-oriented implications,[97] such as condescension. For example, one may refer to a female as a "girl" rather than a "woman", implying that she is subordinate or not fully mature. Other examples include obscene language. Some words are offensive to transgender people, including "tranny", "she-male", or "he-she". Intentional misgendering (assigning the wrong gender to someone) and the pronoun "it" are also considered pejorative.[98][99] |

言語における性差別は、ある特定の性別の価値を言語が低く見るときに存

在する。[83] 多くの場合、性差別的な表現は男性の優位性を助長する。[84]

言語における性差別は、意識、現実の認識、文化的な意味の符号化と伝達、社会化に影響を与える。[83]

研究者は、男性を標準とする意味の規則が言語で機能していることを指摘している。その結果、男性が標準となり、男性でない人々は劣った存在として扱われる

という性差別が生じるのである。[85] 言語における性差別は、必ずしも露骨ではないため、間接的な性差別の一形態であると考えられている。[86] 例としては以下のようなものがある。 性別が混在する集団を指すのに、一般的な男性用語を使用する。例えば、「人類」、「人間」(人類を指す)、「男たち」、「将校と兵士」など 性別が不明である人物を指す際に、男性単数代名詞(he、his、him)をデフォルトとして使用すること ビジネスマン、会長、警察官など、「-man」で終わる用語は、男性以外の性別の人々によって行われる可能性がある 「男性看護師」のように、単に「看護師」というだけでデフォルトで女性と想定されていることを暗示するような、不必要な性別マーカーを使用すること。 [87] 性差別的およびジェンダーニュートラルな言語 関連項目:ジェンダーニュートラル言語 リベラルフェミニズムやラディカルフェミニズムから、立場フェミニズム、ポストモダンフェミニズム、クィア理論に至るまで、20世紀のさまざまなフェミニ ズム運動は、理論化の過程で言語について考察してきた。[88] これらの理論のほとんどは、話し手が言語を使用する方法の変化を求める言語に対する批判的な立場を維持してきた。 最も一般的な呼びかけのひとつは、ジェンダーニュートラルな言語を求めるものである。しかし、英語は言語体系として本質的に性差別的ではないが、その使用 法が性差別的になるという事実を指摘する声も多い。したがって、ジェンダーニュートラルな言語が採用される可能性もある。 英語以外の言語における性差別 フランス語[90]やスペイン語[91]などのロマンス諸語では、男性形がデフォルトであるという点で、性差別を強化していると見なされる可能性がある。 「ミス」を意味する「マドモアゼル」という単語は、2012年にフランソワ・フィヨン首相によって、フランスの行政書類から追放することが宣言された。 [90] 現在の圧力は、男女混合グループでは男性形の複数代名詞をデフォルトとして使用するように変更することを求めている。[92] スペイン語に関しては、メキシコ内務省が性差別的な表現の使用を減らす方法についてのガイドを発行した。[91] ドイツ語話者も、性差別が文法とどのように交差するのかについて疑問を呈している。[93] ドイツ語は性、数、格によって大きく屈折する。人間の職業や地位を示す名詞のほとんどは性別によって区別される。より性差のない表現にするために、代わり に現在分詞の名詞が使われることもある。現在分詞の名詞は複数形では文法上の性別による区別がなくなり、単数形ではその区別が大幅に軽減される。例えば、 「die Studenten(男性学生)」や「die Studentinnen(女性学生)」ではなく、「die Studierenden(学習中の人々)」と表記する。[94] しかし、このアプローチには曖昧さの要素が含まれる。なぜなら、現在進行形で活動に従事している人々をより正確に表すのが現在分詞であるため、日常的にそ の活動を主な職業として従事している人々を表すよりも、曖昧さが生じるからである。[95] 中国語では、文字の構造に内在する性差別を指摘する作家もいる。例えば、「人」という文字は「勇気」や「影響力」といったポジティブな性質を持つものに関 連付けられている一方で、「妻」という文字は価値が低いとみなされる女性の部位と箒で構成されている。 性別に基づく侮蔑的な用語 関連項目:カテゴリー:性別および性自認に関する侮辱的な表現 性別に基づく侮蔑的な用語は、性別を理由に他者を威嚇したり傷つけたりする。性差別は、見下すような態度など、性別を否定的に意味する言語で表現されるこ とがある。例えば、女性を「女性」ではなく「少女」と呼ぶことは、その女性が従属的であるか、あるいは成熟していないことを暗示している。その他の例とし ては、卑猥な言葉が挙げられる。トランスジェンダーの人々を不快にさせる言葉には、「トランシー」、「シーメール」、「ヘーシー」などがある。意図的な 誤った性別表現(誤った性別を割り当てること)や代名詞「それ」も、侮蔑的であると考えられている。[98][99] |

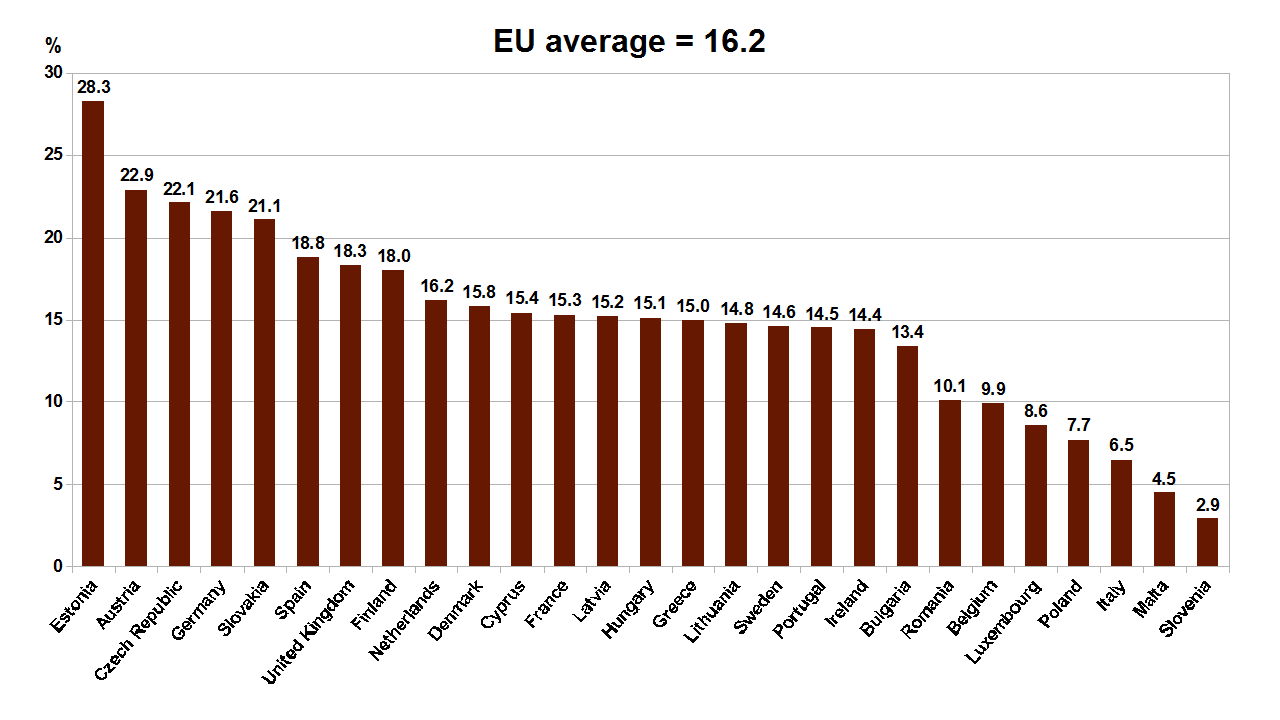

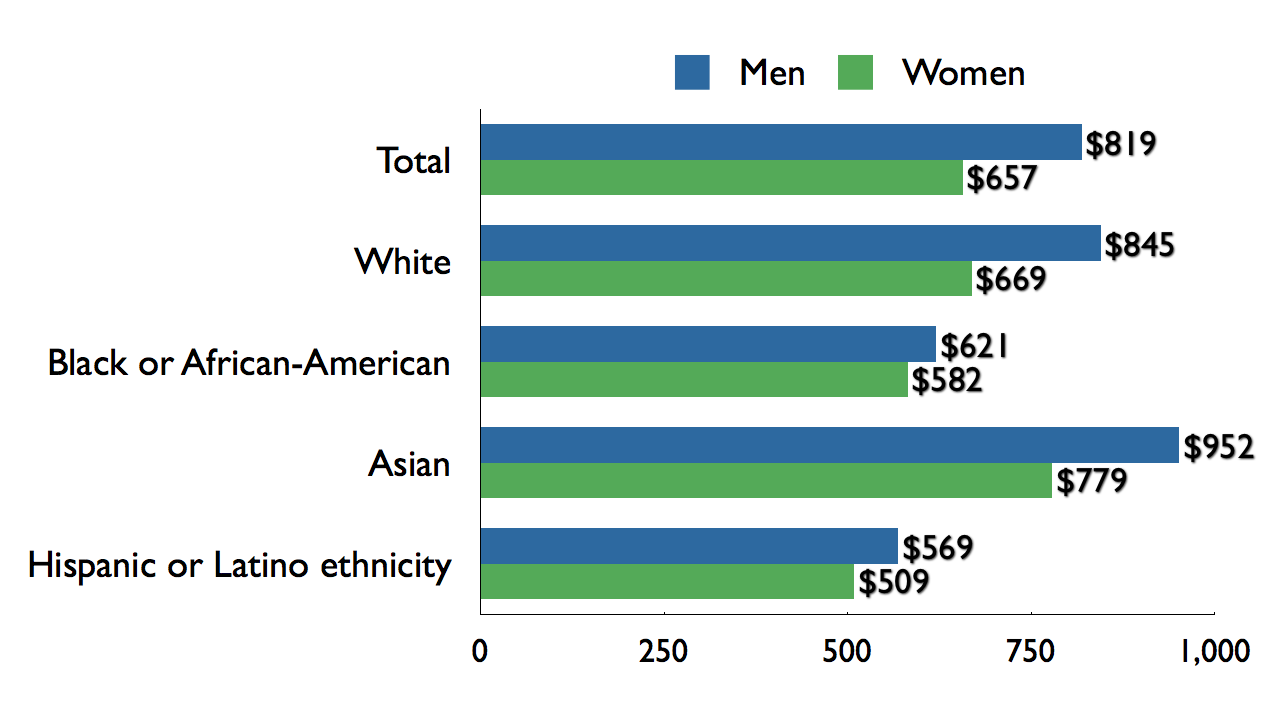

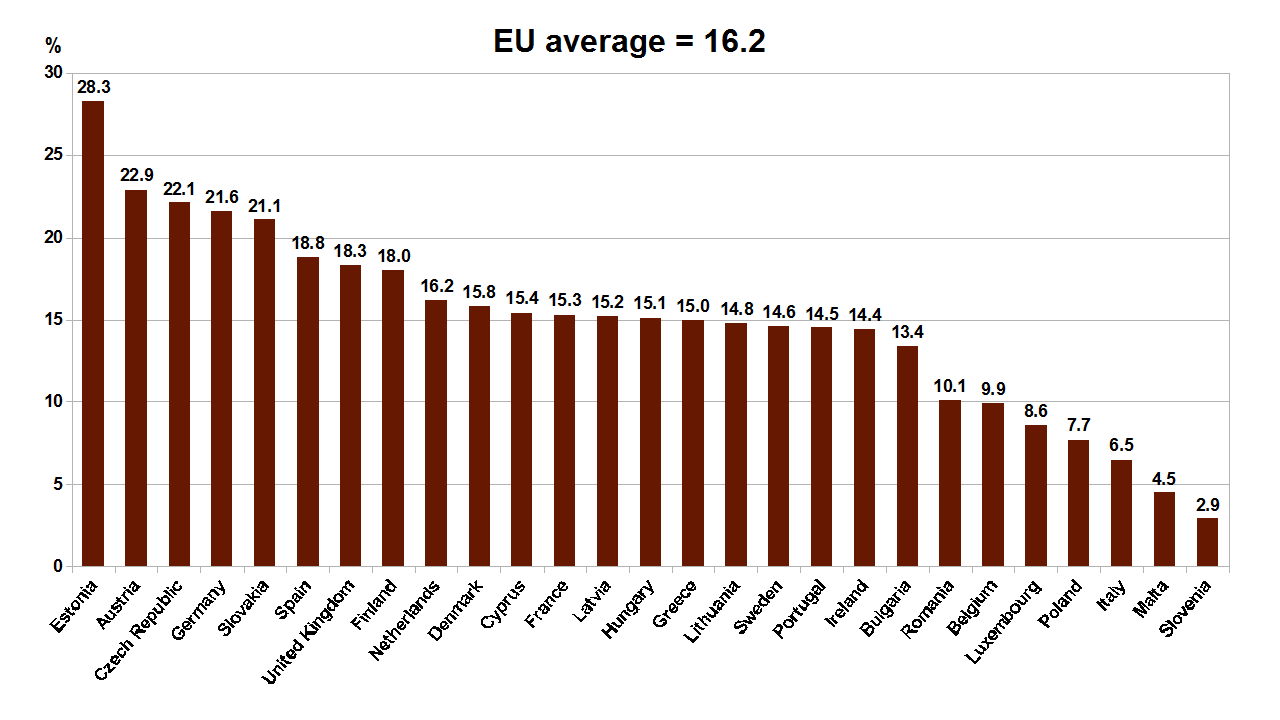

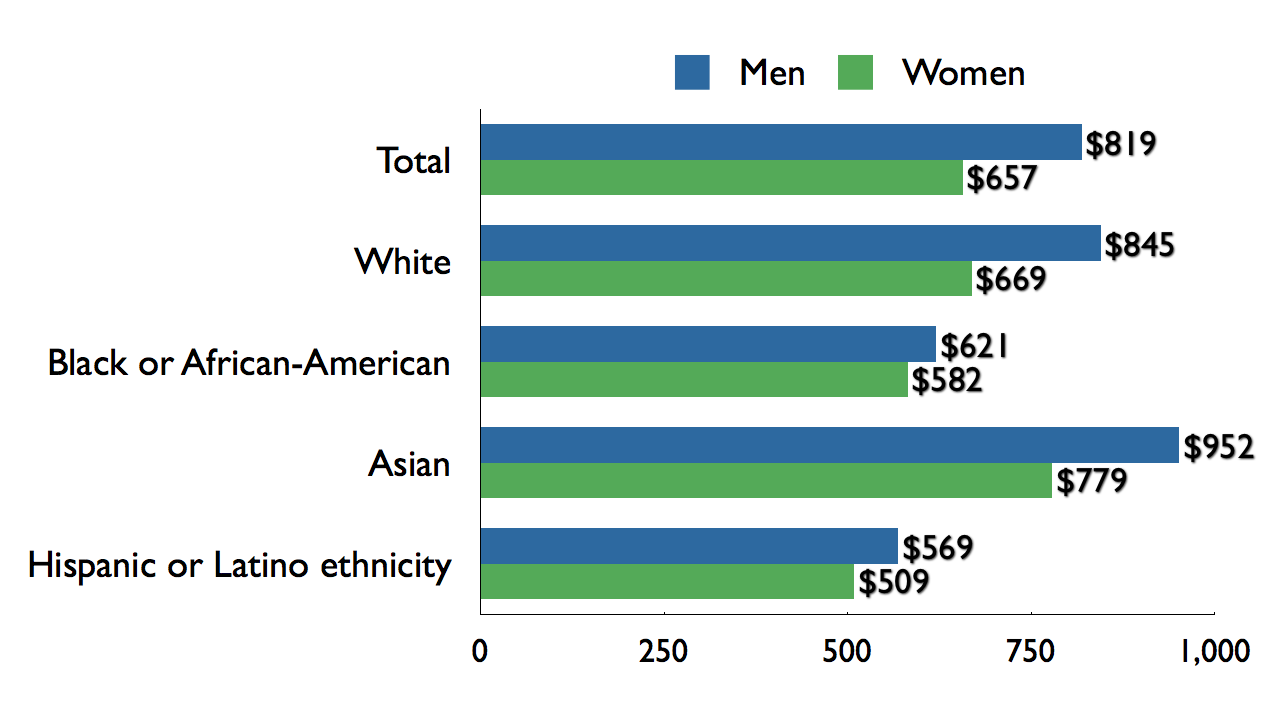

| Occupational sexism Main articles: Occupational sexism and Second-generation gender bias "Calling nurses by their first names" The practice of using first names for individuals from a profession that is predominantly female occurs in health care. Physicians are typically referred to using their last name, but nurses are referred to, even by physicians they do not know, by their first name. According to Suzanne Gordon, a typical conversation between a physician and a nurse is: "Hello Jane. I'm Dr. Smith. Would you hand me the patient's chart?" –Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care[100] Occupational sexism refers to discriminatory practices, statements or actions, based on a person's sex, occurring in the workplace. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination. In 2008, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have 20% less chance to have a job and are paid 17% less than men.[101] The report stated: [In] many countries, labour market discrimination—i.e. the unequal treatment of equally productive individuals only because they belong to a specific group—is still a crucial factor inflating disparities in employment and the quality of job opportunities [...] Evidence presented in this edition of the Employment Outlook suggests that about 8 percent of the variation in gender employment gaps and 30 percent of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labor market.[101][102] It also found that although almost all OECD countries, including the U.S.,[103] have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce.[101] Women who enter predominantly male work groups can experience the negative consequences of tokenism: performance pressures, social isolation, and role encapsulation.[104] Tokenism could be used to camouflage sexism, to preserve male workers' advantage in the workplace.[104] No link exists between the proportion of women working in an organization/company and the improvement of their working conditions. Ignoring sexist issues may exacerbate women's occupational problems.[105] In the World Values Survey of 2005, responders were asked if they thought wage work should be restricted to men only. In Iceland, the percentage that agreed was 3.6%, whereas in Egypt it was 94.9%.[106] Gap in hiring Research has repeatedly shown that mothers in the United States are less likely to be hired than equally qualified fathers and if hired, receive a lower salary than male applicants with children.[107][108][109][110] One study found that female applicants were favored; however, its results have been met with skepticism from other researchers, since it contradicts most other studies on the issue. Joan C. Williams, a distinguished professor at the University of California's Hastings College of Law, raised issues with its methodology, pointing out that the fictional female candidates it used were unusually well-qualified. Studies using more moderately qualified graduate students have found that male students are much more likely to be hired, offered better salaries, and offered mentorship.[111][112] In Europe, studies based on field experiments in the labor market, provide evidence for no severe levels of discrimination based on female gender. However, unequal treatment is still measured in particular situations, for instance, when candidates apply for positions at a higher functional level in Belgium,[113] when they apply at their fertile ages in France,[114] and when they apply for male-dominated occupations in Austria.[115] Earnings gap Main article: Gender pay gap  Bar graph showing the gender pay gap in European countries Gender pay gap in average gross hourly earnings according to Eurostat 2014[116] Studies have concluded that on average women earn lower wages than men worldwide. Some people argue that this results from widespread gender discrimination in the workplace. Others argue that the wage gap results from different choices by men and women, such as women placing more value than men on having children, and men being more likely than women to choose careers in high paying fields such as business, engineering, and technology. Eurostat found a persistent, average gender pay gap of 27.5% in the 27 EU member states in 2008.[116] Similarly, the OECD found that female full-time employees earned 27% less than their male counterparts in OECD countries in 2009.[101][102] In the United States, the female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2009; female full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers earned 77% as much as male FTYR workers. Women's earnings relative to men's fell from 1960 to 1980 (56.7–54.2%), rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (54.2–67.6%), leveled off from 1990 to 2000 (67.6–71.2%) and rose from 2000 to 2009 (71.2–77.0%).[117][118] As of the late 2010s, it has decreased back to around 1990 to 2000 levels (68.6-71.1%).[119][120] When the first Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963, female full-time workers earned 48.9% as much as male full-time workers.[117] Research conducted in Czechia and Slovakia shows that, even after the governments passed anti-discrimination legislation, two thirds of the gender gap in wages remained unexplained and segregation continued to "represent a major source of the gap".[121] The gender gap can also vary across-occupation and within occupation. In Taiwan, for example, studies show how the bulk of gender wage discrepancies occur within-occupation.[122] In Russia, research shows that the gender wage gap is distributed unevenly across income levels, and that it mainly occurs at the lower end of income distribution.[123] The research also found that "wage arrears and payment in-kind attenuated wage discrimination, particularly amongst the lowest paid workers, suggesting that Russian enterprise managers assigned lowest importance to equity considerations when allocating these forms of payment".[123] The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between men and women (such as education, hours worked and occupation), innate behavioral and biological differences between men and women and discrimination in the labor market (such as gender stereotypes and customer and employer bias). Women take significantly more time off to raise children than men.[124] In certain countries such as South Korea, it has also been a long-established practice to lay-off female employees upon marriage.[125] A study by Professor Linda C. Babcock in her book Women Don't Ask shows that men are eight times more likely to ask for a pay raise, suggesting that pay inequality may be partly a result of behavioral differences between the sexes.[126] However, studies generally find that a portion of the gender pay gap remains unexplained after accounting for factors assumed to influence earnings; the unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.[127] Estimates of the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap vary. The OECD estimated that approximately 30% of the gender pay gap across OECD countries is because of discrimination.[101] Australian research shows that discrimination accounts for approximately 60% of the wage differential between men and women.[128][129] Studies examining the gender pay gap in the United States show that a much of the wage differential remains unexplained, after controlling for factors affecting pay. One study of college graduates found that the portion of the pay gap unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is five percent one year after graduating and 12% a decade after graduation.[130][131][132][133] A study by the American Association of University Women found that women graduates in the United States are paid less than men doing the same work and majoring in the same field.[134]  Graph showing weekly earnings by various categories Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers, by sex, race, and ethnicity, U.S., 2009[135] Wage discrimination is theorized as contradicting the economic concept of supply and demand, which states that if a good or service (in this case, labor) is in demand and has value it will find its price in the market. If a worker offered equal value for less pay, supply and demand would indicate a greater demand for lower-paid workers. If a business hired lower-wage workers for the same work, it would lower its costs and enjoy a competitive advantage. According to supply and demand, if women offered equal value demand (and wages) should rise since they offer a better price (lower wages) for their service than men do.[136] Research at Cornell University and elsewhere indicates that mothers in the United States are less likely to be hired than equally qualified fathers and, if hired, receive a lower salary than male applicants with children.[107][108][137][138][109][110] The OECD found that "a significant impact of children on women's pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States".[139] Fathers earn $7,500 more, on average, than men without children do.[140] There is research to suggest that the gender wage gap leads to big losses for the economy.[141] Causes for wage discrimination The non-adjusted gender pay gap (the difference without taking into account differences in working hours, occupations, education, and work experience) is not itself a measure of discrimination. Rather, it combines differences in the average pay of women and men to serve as a barometer of comparison. Differences in pay are caused by: occupational segregation (with more men in higher paid industries and women in lower paid industries), vertical segregation (fewer women in senior, and hence better paying positions), ineffective equal pay legislation, women's overall paid working hours, and barriers to entry into the labor market (such as education level and single parenting rate).[142] Some variables that help explain the non-adjusted gender pay gap include economic activity, working time, and job tenure.[142] Gender-specific factors, including gender differences in qualifications and discrimination, overall wage structure, and the differences in remuneration across industry sectors all influence the gender pay gap.[143] Eurostat estimated in 2016 that after allowing for average characteristics of men and women, women still earn 11.5% less than men. Since this estimate accounts for average differences between men and women, it is an estimation of the unexplained gender pay gap (i.e., that which cannot be accounted for by factors such as differences in profession).[144] Glass ceiling effect Main article: Glass ceiling "The popular notion of glass ceiling effects implies that gender (or other) disadvantages are stronger at the top of the hierarchy than at lower levels and that these disadvantages become worse later in a person's career."[145] In the United States, women account for 52% of the overall labor force, but make up only three percent of corporate CEOs and top executives.[146] Some researchers see the root cause of this situation in the tacit discrimination based on gender, conducted by current top executives and corporate directors (primarily male), and "the historic absence of women in top positions", which "may lead to hysteresis, preventing women from accessing powerful, male-dominated professional networks, or same-sex mentors".[146] The glass ceiling effect is noted as being especially persistent for women of color. According to a report, "women of colour perceive a 'concrete ceiling' and not simply a glass ceiling".[146] In the economics profession, it has been observed that women are more inclined than men to dedicate their time to teaching and service. Since continuous research work is crucial for promotion, "the cumulative effect of small, contemporaneous differences in research orientation could generate the observed significant gender difference in promotion".[147] In the high-tech industry, research shows that, regardless of the intra-firm changes, "extra-organizational pressures will likely contribute to continued gender stratification as firms upgrade, leading to the potential masculinization of skilled high-tech work".[148] The United Nations asserts that "progress in bringing women into leadership and decision making positions around the world remains far too slow".[149] Potential remedies Research by David Matsa and Amalia Miller suggests that a remedy to the glass ceiling could be increasing the number of women on corporate boards, which could lead to increases in the number of women working in top management positions.[146] The same research suggests that this could also result in a "feedback cycle in which the presence of more female managers increases the qualified pool of potential female board members (for the companies they manage, as well as other companies), leading to greater female board membership and then further increases in female executives".[149] Weight-based sexism A 2009 study found that being overweight harms women's career advancement, but presents no barrier for men. Overweight women were significantly underrepresented among company bosses, making up between five and 22% of female CEOs. However, the proportion of overweight male CEOs was between 45% and 61%, over-representing overweight men. On the other hand, approximately five percent of CEOs were obese among both genders. The author of the study stated that the results suggest that "the 'glass ceiling effect' on women's advancement may reflect not only general negative stereotypes about the competencies of women but also weight bias that results in the application of stricter appearance standards to women."[150][151] Transgender discrimination See also: Transgender inequality Transgender people also experience significant workplace discrimination and harassment.[152] Unlike sex-based discrimination, refusing to hire (or firing) a worker for their gender identity or expression is not explicitly illegal in most U.S. states.[153] In June 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that federal civil rights law protects gay, lesbian and transgender workers. Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote: "An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids."[154] The ruling however did not protect LGBT employees from being fired based on their sexual orientation or gender identity in businesses of 15 workers or less.[155] In August 1995, Kimberly Nixon filed a complaint with the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal against Vancouver Rape Relief & Women's Shelter. Nixon, a trans woman, had been interested in volunteering as a counsellor with the shelter. When the shelter learned that she was transsexual, they told Nixon that she would not be allowed to volunteer with the organization. Nixon argued that this constituted illegal discrimination under Section 41 of the British Columbia Human Rights Code. Vancouver Rape Relief countered that individuals are shaped by the socialization and experiences of their formative years, and that Nixon had been socialized as a male growing up, and that, therefore, Nixon would not be able to provide sufficiently effective counselling to the female born women that the shelter served. Nixon took her case to the Supreme Court of Canada, which refused to hear the case.[156] |

職業差別 詳細は「職業差別」および「第二世代のジェンダーバイアス」を参照 「看護師をファーストネームで呼ぶ」 女性が大半を占める職業に就く個人に対して、ファーストネームで呼ぶという慣習は医療現場でも見られる。医師は通常、苗字で呼ばれるが、看護師は、たとえ 面識のない医師であっても、ファーストネームで呼ばれる。スザンヌ・ゴードンによると、医師と看護師の典型的な会話は次の通りである。「やあ、ジェーン。 私はスミス医師だ。患者のカルテを取ってくれないか?」 看護の逆境:医療費削減、メディアのステレオタイプ、医療の傲慢が看護師と患者ケアを蝕む[100] 職業上の性差別とは、職場において、個人の性別を理由とした差別的な慣行、発言、行動を指す。職業上の性差別の1つの形態は賃金差別である。2008年、 経済協力開発機構(OECD)は、女性の就業率が拡大し、男女間の就業および賃金格差がほぼすべての国で縮小している一方で、平均すると女性は依然として 男性よりも20%低い就業率と17%低い賃金しか得られていないことを明らかにした。[101] 報告書には次のように記載されている。 多くの国々では、労働市場における差別、すなわち、特定のグループに属しているという理由だけで、生産性は同等であるにもかかわらず不平等な扱いを受ける ことが、依然として雇用と雇用機会の質における格差を拡大させる重要な要因となっている。...本稿で提示された証拠は、 雇用見通し』の最新版で提示された証拠によると、OECD諸国における男女間の雇用格差の8パーセント、男女間の賃金格差の30パーセントは、労働市場に おける差別的慣行によって説明できるという。[101][102] また、米国を含むほぼすべてのOECD諸国が反差別法を制定しているにもかかわらず、これらの法律の施行は困難であることも判明した。[101] 男性が大半を占める職場グループに入った女性は、形ばかりの政策による悪影響を被る可能性がある。すなわち、パフォーマンスに対するプレッシャー、社会的 孤立、役割の固定化などである。形ばかりの政策は、性差別を隠ぺいし、職場における男性労働者の優位性を維持するために利用される可能性がある。組織や企 業で働く女性の割合と、労働条件の改善との間に関連性は見られない。性差別的な問題を無視することは、女性の職業上の問題を悪化させる可能性がある。 2005年の世界価値観調査では、回答者に賃金労働を男性のみに制限すべきかどうかを尋ねた。アイスランドでは、これに賛成する回答者の割合は3.6%で あったのに対し、エジプトでは94.9%であった。[106] 雇用における格差 米国では、母親は同等資格の父親よりも採用される可能性が低く、採用された場合でも、子供を持つ男性応募者よりも給与が低いという研究結果が繰り返し示さ れている。[107][108][109][110] ある研究では、女性応募者が有利であるという結果が出たが、この結果は、この問題に関する他のほとんどの研究結果と矛盾しているため、他の研究者からは懐 疑的に見られている。カリフォルニア大学ヘイスティングス法科大学院のジョアン・C・ウィリアムズ特別教授は、その方法論に問題があると指摘し、その研究 で用いられた架空の女性候補者は異常に高い資格を有していると指摘した。より現実的な資格を有する大学院生を対象とした研究では、男性学生の方がはるかに 高い確率で採用され、より高い給与が提示され、指導役が提供されることが分かっている。 ヨーロッパでは、労働市場におけるフィールド実験に基づく研究により、女性であることを理由とした深刻なレベルの差別は存在しないという証拠が示されてい る。しかし、特定の状況下では依然として不平等な扱いが測定されており、例えばベルギーではより高い職位の職に就くために応募する場合[113]、フラン スでは出産適齢期に申し込む場合[114]、オーストリアでは男性優位の職業に申し込む場合[115]などである。 収入格差 詳細は「男女間賃金格差」を参照  欧州諸国の男女間賃金格差を示す棒グラフ ユーロスタットによる2014年の平均総時間給における男女間賃金格差[116] 研究では、世界的に見て、平均して女性は男性よりも低い賃金しか得ていないという結論が出ている。この結果は職場における広範な性差別によるものだという 主張もある。また、賃金格差は、女性が男性よりも子供を持つことを重視する傾向にあることや、男性が女性よりもビジネス、エンジニアリング、テクノロジー などの高賃金の分野でのキャリアを選ぶ傾向にあることなど、男女の異なる選択によるものだという主張もある。 欧州統計局(Eurostat)は、2008年のEU加盟27カ国において、根強く残る平均的な男女賃金格差は27.5%であることを発見した。 [116] 同様に、OECDは2009年のOECD諸国において、女性フルタイム従業員の賃金は男性の同僚よりも27%低いことを発見した。[101][102] 米国では、2009年の女性と男性の収入比は0.77であり、フルタイムで年間を通じて働く女性(FTYR)の収入は、男性のFTYR労働者の77%で あった。男性に対する女性の収入比率は、1960年から1980年にかけては減少(56.7–54.2%)したが、1980年から1990年にかけては急 速に上昇(54.2–67.6%)し、1990年から2000年にかけては横ばい(67.6–71.2%)となり、 2000年から2009年にかけて上昇した(71.2–77.0%)。[117][118] 2010年代後半の時点で、1990年から2000年頃の水準(68.6-71.1%)まで減少している 1990年から2000年頃の水準(68.6~71.1%)に戻っている。[119][120] 1963年に初の男女同一賃金法が可決された際、女性のフルタイム労働者の賃金は男性のフルタイム労働者の48.9%であった。[117] チェコとスロバキアで行われた調査によると、政府が反差別法を制定した後でも、賃金における男女格差の3分の2は説明がつかず、分離は「格差の主な原因」 であり続けた。 また、性別による賃金格差は職種によっても異なる。例えば台湾では、賃金格差の大部分が同一職種内で発生していることが研究で示されている。[122] ロシアでは、賃金格差が収入レベルによって不均等に分布しており、主に収入分布の下位で発生していることが研究で示されている。[ 123] また、この調査では、「賃金の延滞や現物支給は賃金差別を弱めるが、特に最低賃金の労働者においてその傾向が強い。これは、ロシアの企業経営者が、これら の形態の支払いを割り当てる際に、公平性の考慮を最も重要視していないことを示唆している」ことも判明した。[123] 男女間の賃金格差は、男女間の個人的および職場における特性(教育、就業時間、職業など)の相違、男女間の生来の行動および生物学的相違、労働市場におけ る差別(性別による固定観念や顧客および雇用主の偏見など)に起因している。女性は男性よりも育児のために休む時間がはるかに長い。[124] 韓国などの特定の国では、結婚を機に女性従業員を解雇するという慣行も長年続いてきた。[125] リンダ・C・バブコック教授の著書『Women Don't Ask』に掲載された研究によると、男性は 昇給を求める傾向が強いことを示しており、賃金格差は男女の行動の違いが原因である可能性があることを示唆している。[126] しかし、一般的に、収入に影響を与えると想定される要因を考慮しても、男女間の賃金格差の一部は説明できないことが研究により判明している。賃金格差の説 明できない部分は、性差別によるものとされている。[127] 男女間賃金格差における差別的要素の推定値は様々である。OECDは、OECD諸国における男女間賃金格差の約30%は差別によるものと推定している。 [101] オーストラリアの研究では、賃金格差の約60%が差別によるものとされている。[128][129] 米国における男女間賃金格差を調査した研究では、賃金に影響を与える要因を考慮した後でも、賃金格差の大部分は説明できないままであることが示されてい る。ある大学卒業生を対象とした研究では、他の要因をすべて考慮しても説明できない賃金格差の割合は、卒業後1年で5%、卒業後10年で12%であること が分かった。[130][131][132][133] アメリカ大学女性協会による研究では、米国では女性卒業生の賃金は、同じ仕事で同じ専攻分野の男性卒業生よりも低いことが分かった。[134]  さまざまなカテゴリー別の週収を示すグラフ 性別、人種、民族別のフルタイム賃金・給与労働者の中央値週収、米国、2009年[135] 賃金差別は、需要と供給の経済理論に反するものとされている。需要があり価値がある商品やサービス(この場合、労働)は市場で価格が決まるという理論であ る。労働者が同等の価値を提供しながら賃金を下げれば、需要と供給の観点では低賃金の労働者に対する需要が高まることになる。企業が同じ仕事に対して低賃 金の労働者を雇えば、コストが削減され、競争優位性も得られる。需要と供給の観点では、女性が同等の価値を提供すれば需要(および賃金)は上昇するはずで ある。なぜなら、女性は男性よりもサービスに対してより低い賃金(低賃金)を提示しているからだ。 コーネル大学やその他の研究機関の調査によると、米国では母親は同等資格の父親よりも採用される可能性が低く、採用されたとしても、子供がいる男性応募者 よりも低い給与しか受け取っていないことが示されている。[107][108][137][138][109][1 10] OECDは、「女性の賃金に対する子供の影響は、一般的に英国と米国で顕著である」と結論づけている。[139] 父親は、子供を持たない男性よりも平均で7,500ドル多く稼いでいる。[140] 賃金格差が経済に大きな損失をもたらすことを示す研究結果がある。[141] 賃金差別の原因 調整されていない男女賃金格差(労働時間、職業、教育、職歴の違いを考慮しない場合の差異)は、それ自体は差別を意味するものではない。むしろ、これは男 女の平均賃金の差異を組み合わせたものであり、比較のバロメーターとして用いられる。賃金の差異は、以下のような要因によって生じる。 職業分離(賃金が高い産業に男性が多く、賃金の低い産業に女性が多い)、 垂直分離(上級職に就く女性が少ないため、賃金も高くない)、 平等な賃金に関する法律の非効率性、 女性の総労働時間、 労働市場参入の障壁(学歴や片親家庭の割合など)[142] 調整されていない男女間賃金格差を説明するのに役立つ変数には、経済活動、労働時間、および勤続年数などがある。[142] 性別による要因、すなわち資格や差別における性差、賃金体系全体、および産業部門間の報酬の違いはすべて、男女間賃金格差に影響を及ぼす。[143] 欧州統計局(ユーロスタット)は2016年に、男女の平均的な特性を考慮した後でも、女性の賃金は男性よりも11.5%低いと推定した。この推定値は男女 間の平均的な差異を考慮したものであるため、説明できない男女間の賃金格差(すなわち、職業の違いなどの要因では説明できないもの)の推定値である。 [144] ガラスの天井効果 詳細は「ガラスの天井」を参照 「一般的に考えられているガラスの天井効果とは、性別(またはその他の)による不利益は、階層の下層部よりも上層部でより強く、また、これらの不利益は、 個人のキャリアの後期になるほど悪化するということを意味している」[145] 米国では、女性は労働力の52%を占めているが、企業のCEOや経営陣では3%に過ぎない。[146] 研究者の中には、この状況の根本的原因は、現在の経営陣や企業役員(主に男性)による性別に基づく暗黙の差別と、 主に男性である)現職の経営陣や企業役員による性別に基づく暗黙の差別、および「歴史的に女性がトップの地位に就いてこなかったこと」が原因であり、これ が「ヒステリシスにつながり、女性が男性優位の強力な職業ネットワークや同性の上司にアクセスできない可能性がある」と指摘する研究者もいる。[146] ガラスの天井効果は、有色人種の女性にとって特に根強いと指摘されている。ある報告書によると、「有色人種の女性は、単なるガラスの天井ではなく、『具体 的な天井』を認識している」という。[146] 経済学の分野では、女性は男性よりも教育や奉仕に時間を割く傾向が強いことが観察されている。昇進には継続的な研究活動が不可欠であるため、「研究志向に おける同時的な小さな差異の累積的効果によって、観察されたような著しい性差が昇進に生じる可能性がある」のである。[147] ハイテク産業では、企業内の変化とは関係なく、「企業がアップグレードするにつれ、組織外からの圧力が継続的な性別による階層化に寄与し、熟練したハイテ ク作業の潜在的な男性化につながる可能性が高い」という調査結果が出ている。[148] 国連は、「世界中で女性を指導的立場や意思決定のポジションに就かせるという点において、進歩は依然としてあまりにも遅々としている」と主張している。 [149] 潜在的な解決策 デビッド・マツァとアマリア・ミラーによる研究では、ガラスの天井を打ち破る解決策として、企業取締役会における女性の数を増やすことが挙げられており、 それにより、最高経営責任者のポジションに就く女性の数も増加する可能性があるとしている。[146] 同じ研究では、このことが 「女性管理職の増加が、女性取締役候補者の母集団を(彼女らが管理する企業だけでなく、他の企業も含めて)増大させ、結果として女性取締役の増加につなが り、さらに女性管理職の増加につながる」というフィードバック・サイクルが生まれる可能性があることを示唆している。[149] 体重に基づく性差別 2009年の研究では、太り過ぎは女性のキャリアアップを妨げるが、男性には何の障害にもならないことが分かった。太り過ぎの女性は、会社の経営陣に著し く過小に代表されており、女性CEOの5~22%を占めるに過ぎない。しかし、太り過ぎの男性CEOの割合は45~61%であり、太り過ぎの男性が過剰に 代表されている。一方、男女ともに約5%のCEOが肥満であった。この研究の著者は、この結果は「女性の昇進に対する『ガラスの天井効果』が、女性の能力 に対する一般的な否定的な固定観念だけでなく、女性に対してより厳しい外見基準が適用される結果となる体重に対する偏見を反映している可能性がある」こと を示唆していると述べた。[150][151] トランスジェンダーに対する差別 関連項目:トランスジェンダーに対する不平等 トランスジェンダーの人々も、職場において重大な差別や嫌がらせを経験している。[152] 性別に基づく差別とは異なり、性自認や性表現を理由に労働者を雇用しない(または解雇する)ことは、ほとんどの米国の州では明確に違法とはされていない。 [153] 2020年6月、米国最高裁判所は、連邦公民権法が同性愛者、レズビアン、トランスジェンダーの労働者を保護しているとの判決を下した。多数派を代表し て、ニール・ゴーサッチ判事は次のように述べた。「同性愛者またはトランスジェンダーであることを理由に解雇する雇用主は、異性愛者に対しては疑問を持た ないであろうその人物の特徴や行動を理由に解雇している。性別は、その決定において必要かつ隠しようのない役割を果たしており、まさに第7条が禁じている ことである」[154] しかし、この判決は、従業員15人以下の企業において、性的指向や性自認を理由に解雇されるLGBT従業員を保護するものではなかった。[155] 1995年8月、キンバリー・ニクソンはブリティッシュコロンビア人権法廷に、バンクーバー・レイプ・リリーフ・アンド・ウィメンズ・シェルターに対する 苦情を申し立てた。トランスジェンダーの女性であるニクソンは、シェルターのカウンセラーとしてボランティア活動に興味を持っていた。シェルター側が彼女 がトランスセクシュアルであることを知ると、ニクソンにボランティア活動は許可できないと告げた。ニクソンは、これはブリティッシュコロンビア人権法第 41条に違反する違法な差別であると主張した。バンクーバー・レイプ・リリーフは、個人はその形成期の社会化や経験によって形作られるものであり、ニクソ ンは男性として成長してきたため、シェルターが支援する女性に対して十分な効果的なカウンセリングを提供できないと反論した。ニクソンはカナダ最高裁判所 に訴えたが、最高裁は審理を拒否した。[156] |

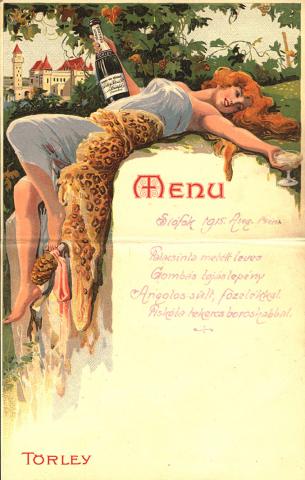

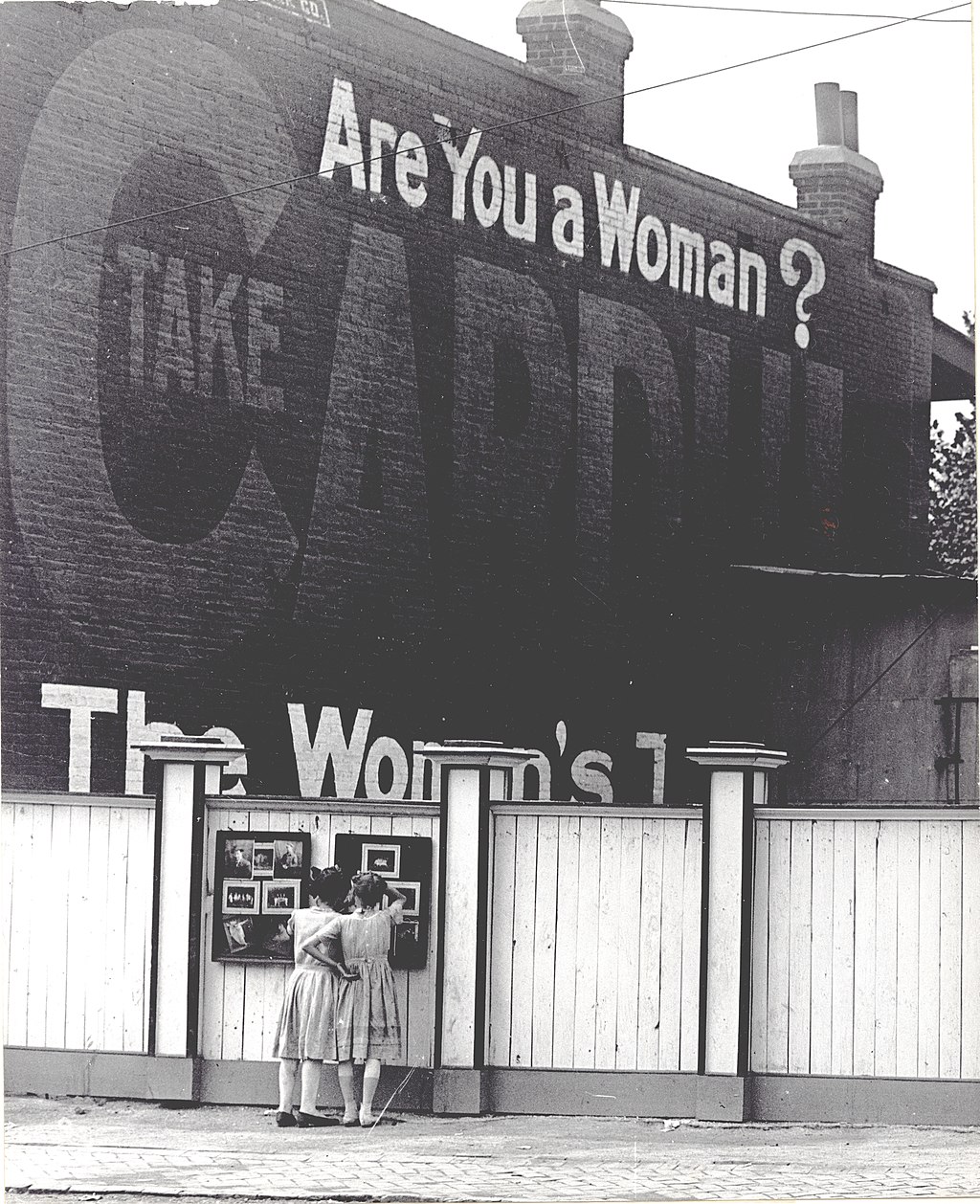

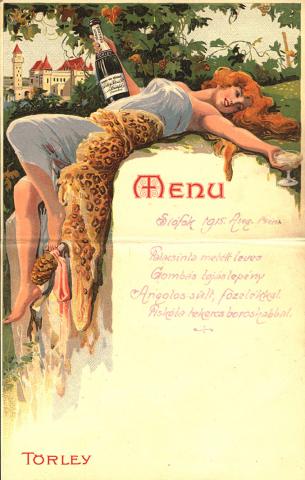

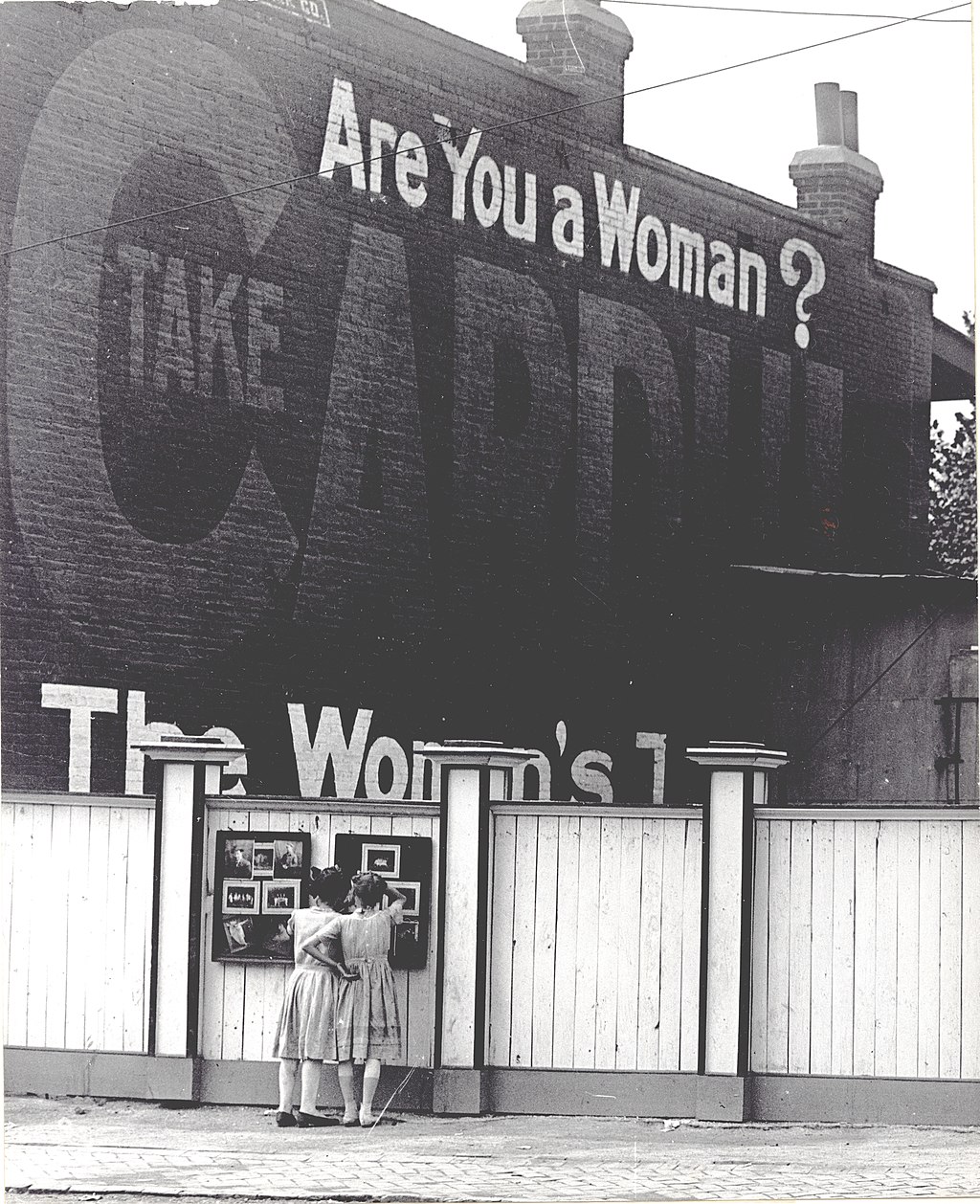

Objectification Illustration of a woman splayed across a wine menu Example of sexual objectification of women on a wine menu In social philosophy, objectification is the act of treating a person as an object or thing. Objectification plays a central role in feminist theory, especially sexual objectification.[157] Feminist writer and gender equality activist Joy Goh-Mah argues that by being objectified, a person is denied agency.[158] According to the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, a person might be objectified if one or more of the following properties are applied to them:[159] Instrumentality: treating the object as a tool for another's purposes: "The objectifier treats the object as a tool of his or her purposes." Denial of autonomy: treating the object as lacking in autonomy or self-determination: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in autonomy and self-determination." Inertness: treating the object as lacking in agency or activity: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in agency, and perhaps also in activity." Fungibility: treating the object as interchangeable with other objects: "The objectifier treats the object as interchangeable (a) with other objects of the same type, and/or (b) with objects of other types." Violability: treating the object as lacking in boundary integrity and violable: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in boundary integrity, as something that it is permissible to break up, smash, break into." Ownership: treating the object as if it can be owned, bought, or sold: "The objectifier treats the object as something that is owned by another, can be bought or sold, etc." Denial of subjectivity: treating the object as if there is no need for concern for its experiences or feelings: "The objectifier treats the object as something whose experience and feelings (if any) need not be taken into account." Rae Helen Langton, in Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification, proposed three more properties to be added to Nussbaum's list:[157][160] Reduction to Body: the treatment of a person as identified with their body, or body parts; Reduction to Appearance: the treatment of a person primarily in terms of how they look, or how they appear to the senses; Silencing: the treatment of a person as if they are silent, lacking the capacity to speak. According to objectification theory, objectification can have important repercussions on women, particularly young women, as it can negatively impact their psychological health and lead to the development of mental disorders, such as unipolar depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders.[161] In advertising  Two girls examining a bulletin board posted on a fence. An advertisement painted above them asks "Are You a Woman?". Women examining a bulletin board posted on a fence. An advertisement painted above them asks "Are You a Woman?" While advertising used to portray women and men in obviously stereotypical roles (e.g., as a housewife, breadwinner), in modern advertisements, they are no longer solely confined to their traditional roles. However, advertising today still stereotypes men and women, albeit in more subtle ways, including by sexually objectifying them.[162] Women are most often targets of sexism in advertising.[citation needed] When in advertisements with men they are often shorter and put in the background of images, shown in more "feminine" poses, and generally present a higher degree of "body display".[163] Today, some countries (for example Norway and Denmark) have laws against sexual objectification in advertising.[164] Nudity is not banned, and nude people can be used to advertise a product if they are relevant to the product advertised. Sol Olving, head of Norway's Kreativt Forum (an association of the country's top advertising agencies) explained, "You could have a naked person advertising shower gel or a cream, but not a woman in a bikini draped across a car".[164] Other countries continue to ban nudity (on traditional obscenity grounds), but also make explicit reference to sexual objectification, such as Israel's ban of billboards that "depicts sexual humiliation or abasement, or presents a human being as an object available for sexual use".[165] Pornography See also: Feminist views on pornography Anti-pornography feminist Catharine MacKinnon argues that pornography contributes to sexism by objectifying women and portraying them in submissive roles.[166] MacKinnon, along with Andrea Dworkin, argues that pornography reduces women to mere tools, and is a form of sex discrimination.[167] The two scholars highlight the link between objectification and pornography by stating: We define pornography as the graphic sexually explicit subordination of women through pictures and words that also includes (i) women are presented dehumanized as sexual objects, things, or commodities; or (ii) women are presented as sexual objects who enjoy humiliation or pain; or (iii) women are presented as sexual objects experiencing sexual pleasure in rape, incest or other sexual assault; or (iv) women are presented as sexual objects tied up, cut up or mutilated or bruised or physically hurt; or (v) women are presented in postures or positions of sexual submission, servility, or display; or (vi) women's body parts—including but not limited to vaginas, breasts, or buttocks—are exhibited such that women are reduced to those parts; or (vii) women are presented being penetrated by objects or animals; or (viii) women are presented in scenarios of degradation, humiliation, injury, torture, shown as filthy or inferior, bleeding, bruised, or hurt in a context that makes these conditions sexual."[168] Robin Morgan and Catharine MacKinnon suggest that certain types of pornography also contribute to violence against women by eroticizing scenes in which women are dominated, coerced, humiliated or sexually assaulted.[169][170] Some people opposed to pornography, including MacKinnon, charge that the production of pornography entails physical, psychological, and economic coercion of the women who perform and model in it.[171][172][173] Opponents of pornography charge that it presents a distorted image of sexual relations and reinforces sexual myths; it shows women as continually available and willing to engage in sex at any time, with any person, on their terms, responding positively to any requests. MacKinnon writes: Pornography affects people's belief in rape myths. So for example if a woman says "I didn't consent" and people have been viewing pornography, they believe rape myths and believe the woman did consent no matter what she said. That when she said no, she meant yes. When she said she didn't want to, that meant more beer. When she said she would prefer to go home, that means she's a lesbian who needs to be given a good corrective experience. Pornography promotes these rape myths and desensitizes people to violence against women so that you need more violence to become sexually aroused if you're a pornography consumer. This is very well documented.[174] Defenders of pornography and anti-censorship activists (including sex-positive feminists) argue that pornography does not seriously impact a mentally healthy individual, since the viewer can distinguish between fantasy and reality.[175] Some also contend that both men and women are objectified in pornography, particularly sadistic or masochistic pornography in which men are objectified and sexually used by women.[176] Prostitution Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual relations for payment.[177][178] Sex workers are often objectified and are seen as existing only to serve clients, thus calling their sense of agency into question. There is a prevailing notion that because they sell sex professionally, prostitutes automatically consent to all sexual contact.[179] As a result, sex workers face higher rates of violence and sexual assault. This is often dismissed, ignored and not taken seriously by authorities.[179] In many countries, prostitution is dominated by brothels or pimps, who often claim ownership over sex workers. This sense of ownership furthers the concept that sex workers are void of agency.[180] This is literally the case in instances of sexual slavery. Various authors have argued that female prostitution is based on male sexism that condones the idea that unwanted sex with a woman is acceptable, that men's desires must be satisfied, and that women are coerced into and exist to serve men sexually.[181][182][183][184] The European Women's Lobby condemned prostitution as "an intolerable form of male violence".[185] Carole Pateman writes that: Prostitution is the use of a woman's body by a man for his own satisfaction. There is no desire or satisfaction on the part of the prostitute. Prostitution is not mutual, pleasurable exchange of the use of bodies, but the unilateral use of a woman's body by a man in exchange for money.[186] Media portrayals See also: Misogyny in rap music and Sexism in heavy metal music Some scholars believe that media portrayals of demographic groups can both maintain and disrupt attitudes and behaviors toward those groups.[187][page needed][188][189][page needed] According to Susan Douglas: "Since the early 1990s, much of the media have come to overrepresent women as having made it-completely-in the professions, as having gained sexual equality with men, and having achieved a level of financial success and comfort enjoyed primarily by Tiffany's-encrusted doyennes of Laguna Beach."[190] These images may be harmful, particularly to women and racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, a study of African American women found they feel that media portrayals of themselves often reinforce stereotypes of this group as overly sexual and idealize images of lighter-skinned, thinner African American women (images African American women describe as objectifying).[191] In a recent analysis of images of Haitian women in the Associated Press photo archive from 1994 to 2009, several themes emerged emphasizing the "otherness" of Haitian women and characterizing them as victims in need of rescue.[192] In an attempt to study the effect of media consumption on males, Samantha and Bridges found an effect on body shame, though not through self-objectification as it was found in comparable studies of women. The authors conclude that the current measures of objectification were designed for women and do not measure men accurately.[193] Another study found a negative effect on eating attitudes and body satisfaction of consumption of beauty and fitness magazines for women and men respectively but again with different mechanisms, namely self-objectification for women and internalization for men.[194] Sexist jokes Frederick Attenborough argues that sexist jokes can be a form of sexual objectification, which reduce the butt of the joke to an object. They not only objectify women, but can also condone violence or prejudice against women.[195] "Sexist humor—the denigration of women through humor—for instance, trivializes sex discrimination under the veil of benign amusement, thus precluding challenges or opposition that nonhumorous sexist communication would likely incur."[196] A study of 73 male undergraduate students by Ford found that "sexist humor can promote the behavioral expression of prejudice against women amongst sexist men".[196] According to the study, when sexism is presented in a humorous manner it is viewed as tolerable and socially acceptable: "Disparagement of women through humor 'freed' sexist participants from having to conform to the more general and more restrictive norms regarding discrimination against women."[196] |

客体化 ワインメニューに広げられた女性のイラスト ワインメニューにおける女性の性的客体化の例 社会哲学において、客体化とは、ある人物を物や対象として扱う行為である。客体化はフェミニズム理論、特に性的客体化において中心的な役割を果たしてい る。[157] フェミニスト作家であり男女平等活動家のジョイ・ゴー・マーは、客体化されることで、人は主体性を否定されると主張している。[158] 哲学者マーサ・ヌスバウムによると、人は以下の性質のうち一つ以上が当てはまる場合に客体化される可能性がある。[159] 道具化:対象を他者の目的のための道具として扱うこと:「対象化する者は対象を自身の目的のための道具として扱う。 」 不活性:対象を主体性や活動性のないものとして扱うこと:「対象化する者は対象を主体性のないものとして扱い、おそらくは活動性のないものとしても扱う。 代替可能性:対象を他の対象と交換可能であるかのように扱う:「対象化する者は対象を、(a) 同じタイプの他の対象、および/または (b) 他のタイプの対象と交換可能であるかのように扱う。 侵害可能性:対象を境界の完全性を欠き、侵害可能であるかのように扱う:「対象化する者は対象を、境界の完全性を欠き、分割、粉砕、侵入することが許され るものであるかのように扱う。 所有:所有、購入、販売が可能であるかのように対象を扱う:「対象化する者は、対象を他者が所有しているもの、購入または販売が可能であるものなどとして 扱う」 主観性の否定:対象の経験や感情を気にかける必要がないかのように扱う:「対象化する者は、対象を、その経験や感情(もしあれば)を考慮する必要がないも のとして扱う」 レイ・ヘレン・ラングトンは著書『性的自己同一論:ポルノグラフィーと物化に関する哲学的エッセイ』の中で、ヌスバウムのリストにさらに3つの特性を追加 することを提案している。[157][160] 身体への還元:身体または身体の一部と同一視して個人を扱うこと。 外見への還元:主に外見や感覚に映る姿によって個人を扱うこと。 沈黙:あたかもその人が沈黙しているかのように、話す能力がないかのように扱うこと。 物象化理論によると、物象化は特に若い女性にとって重要な影響を及ぼす可能性がある。なぜなら、物象化は彼女たちの心理的健康に悪影響を及ぼし、単極性う つ病、性的機能障害、摂食障害などの精神障害を引き起こす可能性があるからである。[161] 広告では  フェンスに貼られた掲示板を調べる2人の少女。彼女たちの頭上には「あなたは女性ですか?」という広告が描かれている。 フェンスに貼られた掲示板を調べる女性たち。彼女たちの頭上には「あなたは女性ですか?」という広告が描かれている。 かつての広告では、女性と男性は明らかにステレオタイプな役割(例えば、主婦や稼ぎ手など)で描かれていたが、現代の広告では、もはや彼らは伝統的な役割 だけに限定されることはない。しかし、現代の広告は、より微妙な方法ではあるが、男女をステレオタイプ化しており、性的対象として扱うこともある。 [162] 広告における性差別は、女性が最も標的とされることが多い。[要出典] 男性と一緒の広告では、女性は背が低く、画像の背景に置かれることが多く、より「女性的」なポーズで描かれ、一般的に「身体の露出」の度合いが高い。 [163] 今日、一部の国(例えばノルウェーやデンマーク)では、広告における性的対象化を禁止する法律がある。[164] ヌードは禁止されておらず、広告される商品に関連性があれば、裸の人物を商品の広告に使うことができる。ノルウェーの広告代理店協会である Kreativt Forumの代表であるソル・オルビング氏は、「シャワージェルやクリームの広告に裸の人物を使うことは可能だが、ビキニ姿の女性が車に横たわるような広 告は認められない」と説明している。[164] 他の国々では、従来からのわいせつ性という理由でヌードを禁止し続けているが、性的対象化についても明確に言及している。例えば、イスラエルでは「性的屈 辱や蔑視を描写したり、人間を性的利用可能な対象として表現したりする」広告看板を禁止している。[165] ポルノグラフィー 参照:ポルノグラフィーに対するフェミニストの見解 反ポルノグラフィーのフェミニストであるキャサリン・マッキノンは、ポルノグラフィーは女性を客体化し従順な役割として描くことで性差別を助長していると 主張している。[166] マッキノンはアンドレア・ドウォーキンとともに、ポルノグラフィーは女性を単なる道具に貶め、性差別の形態であると主張している。[167] 2人の学者は、客体化とポルノグラフィーの関連性を次のように強調している。 私たちは、ポルノグラフィーを、絵や言葉によって女性の従属を露骨に性的に表現したものと定義する。その表現には、(i) 女性が性的対象物、物、商品として人間性を奪われた形で表現されているもの、(ii) 女性が屈辱や苦痛を享受する性的対象物として表現されているもの、(iii) 女性がレイプ、近親相姦、その他の性的暴行の中で性的快楽を経験する性的対象物として表現されているもの、(iv) 女性が縛られたり、切り刻まれたり、身体を傷つけられたり、あざだらけになったり、肉体的に傷つけられたりする性的対象物として表現されているもの、 (v) 女性が性的服従、卑屈、または服従の姿勢や体勢で表現されているもの、が含まれる。性的暴行、または(iv)女性が性的対象物として縛られ、切り刻まれ、 または身体の一部が損傷を受け、あざができたり、身体的危害を受けているように描写されている、または(v)女性が性的服従、卑屈、または性的な見せ物の ような姿勢や体勢で描写されている、または(vi)女性の身体の一部(膣、乳房、臀部など)が 女性がそれらの部分に還元されるような形で展示されている。または(vii)女性が物体や動物に貫かれている様子が描写されている。または(viii)女 性が、屈辱、侮辱、傷害、拷問などのシナリオの中で、不潔または劣っているものとして、あるいは性的な文脈の中で出血、あざ、負傷などの状態として描かれ ている。」[168] ロビン・モーガンとキャサリン・マッキノンは、特定の種類のポルノグラフィーが、女性が支配されたり、強制されたり、屈辱を受けたり、性的暴行を受けたり する場面をエロティックに描くことで、女性に対する暴力の一因となっていると指摘している。[169][170] マッキノンを含むポルノグラフィーに反対する一部の人々は、ポルノグラフィーの制作は、出演する女性やモデルに対して身体的、心理的、経済的な強制を伴う と主張している。[171][172][173] ポルノグラフィーに反対する人々は、ポルノグラフィーは性的関係の歪んだイメージを提示し、性的な神話を強化していると主張している。ポルノグラフィー は、女性がいつでも、誰とでも、自分の都合に合わせて、あらゆる要求に前向きに応じる用意があるかのように描いている。 マッキノンは次のように書いている。 ポルノはレイプ神話に対する人々の信念に影響を与える。例えば、女性が「私は同意していなかった」と言った場合、人々がポルノを見ていたとしたら、レイプ 神話を信じ、女性が何を言おうと同意していたと信じてしまう。女性が「ノー」と言った場合、それは「イエス」を意味する。彼女が「嫌だ」と言ったのは 「もっとビールが飲みたい」という意味だ。彼女が「帰りたい」と言ったのは「レズビアンだから、良い矯正経験をさせなければならない」という意味だ。ポル ノはこうしたレイプ神話を助長し、女性に対する暴力に対する人々の感覚を鈍らせる。そのため、ポルノの視聴者は、性的興奮を得るためにより多くの暴力を必 要とするようになる。これは十分に立証されている。[174] ポルノ擁護派や反検閲活動家(性肯定派フェミニストを含む)は、ポルノは現実と空想を区別できる精神的に健康な個人には深刻な影響を与えないと主張してい る。[175] また、ポルノでは男女ともに客体化されるが、特にサディストやマゾヒスト向けのポルノでは、男性が客体化され、女性によって性的に利用されると主張する者 もいる。[176] 売春 売春とは、金銭と引き換えに性的関係を持つ商売または行為である。[177][178] セックスワーカーはしばしば客の所有物と見なされ、顧客に奉仕することのみを目的として存在しているとみなされるため、彼女たちの主体性は疑問視される。 セックスを職業として売っているため、売春婦は自動的にあらゆる性的接触に同意しているという考え方が一般的である。[179] その結果、セックスワーカーはより高い割合で暴力や性的暴行に直面している。これは当局によってしばしば無視され、軽視され、真剣に受け止められない。 多くの国々では、売春は売春宿や売春斡旋業者が支配しており、彼らはしばしば性労働者に対して所有権を主張する。この所有権の感覚は、性労働者は主体性が ないという概念をさらに助長する。これは文字通り、性的奴隷の事例に当てはまる。 さまざまな著者が、女性買春は、望まない女性との性行為は許されるという考えを容認する男性の性差別主義に基づいていると主張している。また、男性の欲望 は満たされなければならないし、女性は性的に男性に奉仕するために強制され、存在しているという主張もある。[181][182][183][184] ヨーロッパ女性ロビーは、売春を「耐え難い男性の暴力の形」として非難した。[185] キャロル・パトマンは次のように書いている。 売春とは、男性が自身の満足のために女性の身体を利用することである。売春婦の側には、欲望も満足もない。売春は、身体の相互利用による快楽の交換ではな く、男性が金銭と引き換えに女性の身体を一方的に利用することである。 メディアの描写 関連項目:ラップミュージックにおける女性嫌悪、ヘビーメタル音楽における性差別 一部の学者は、メディアが人口統計的集団を描写することは、その集団に対する態度や行動を維持することにも、破壊することにもなりうると考えている。 [187][要ページ番号][188][189][要ページ番号] スーザン・ダグラスによると、 「1990年代初頭以降、多くのメディアは、女性が完全に職業で成功し、男性と性的に平等になり、主にティファニーの宝石で飾られた『ラグナビーチのオバ さん』たちが享受するような経済的成功と快適さを達成したかのように描きすぎている」[190] このようなイメージは、特に女性や人種的・民族的少数派グループにとって有害である可能性がある。例えば、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性を対象とした研究で は、メディアが自分たちを性的すぎる存在として描き、肌の色が白く、痩せたアフリカ系アメリカ人女性のイメージを理想化していると感じていることが分かっ た(アフリカ系アメリカ人女性は、このイメージを「対象化」と表現している)。[191] 1994年から2009年までのAP通信の写真アーカイブに収められたハイチ人女性のイメージに関する最近の分析では、ハイチ人女性の「他者性」を強調 し、彼女たちを救済を必要とする犠牲者として特徴づけるいくつかのテーマが浮かび上がった。 男性におけるメディア消費の影響を研究しようとしたサマンサとブリッジズは、女性を対象とした同様の研究で発見されたような自己客体化ではないものの、身 体的な恥に対する影響を発見した。著者は、現在の自己客体化の測定方法は女性向けに考案されたものであり、男性を正確に測定するものではないと結論づけて いる。[193] 別の研究では、女性と男性がそれぞれ美容雑誌とフィットネス雑誌を購読することによる、食生活や体型に対する態度への負の影響が発見されたが、そのメカニ ズムは異なっていた。すなわち、女性の場合は自己客体化、男性の場合は内面化である。[194] 性差別的なジョーク フレデリック・アッテンボローは、性差別的なジョークは性的対象化の一形態であり、ジョークの対象を単なる物として扱うものであると主張している。性差別 的なジョークは女性を客体化するだけでなく、女性に対する暴力や偏見を容認する可能性もある。「性差別的なユーモア、つまりユーモアを通じて女性を侮辱す るようなものは、例えば、娯楽という名目で性差別を矮小化し、ユーモアのない性差別的なコミュニケーションが引き起こすであろう挑戦や反対を排除する。 [196] フォードによる男子大学生73人を対象とした研究では、「性差別的なユーモアは、性差別的な男性の間で女性に対する偏見の行動表現を助長する可能性があ る」ことが分かった。[196] この研究によると、性差別がユーモアを交えて表現されると、それは容認可能で社会的に許容されるものとして受け止められる。「ユーモアによる女性蔑視は、 性差別主義者である参加者を、女性差別に関するより一般的で制限的な規範に従う必要から『解放』した」[196]。 |

| Gender identity discrimination Gender discrimination is discrimination based on actual or perceived gender identity.[197][page needed] Gender identity is "the gender-related identity, appearance, or mannerisms or other gender-related characteristics of an individual, with or without regard to the individual's designated sex at birth".[197][page needed] Gender discrimination is theoretically different from sexism.[198][page needed] Whereas sexism is prejudice based on biological sex, gender discrimination specifically addresses discrimination towards gender identities, including third gender, genderqueer, and other non-binary identified people.[7] It is especially attributed to how people are treated in the workplace,[8] and banning discrimination on the basis of gender identity and expression has emerged as a subject of contention in the American legal system.[199] According to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service, "although the majority of federal courts to consider the issue have concluded that discrimination on the basis of gender identity is not sex discrimination, there have been several courts that have reached the opposite conclusion".[197] Hurst states that "[c]ourts often confuse sex, gender and sexual orientation, and confuse them in a way that results in denying the rights not only of gays and lesbians, but also of those who do not present themselves or act in a manner traditionally expected of their sex".[200] Oppositional sexism Oppositional sexism is a term coined by transfeminist author Julia Serano, who defined oppositional sexism as "the belief that male and female are rigid, mutually exclusive categories".[201] Oppositional sexism plays a vital role in a number of social norms, such as cisnormativity and heteronormativity. Oppositional sexism normalizes masculine expression in males and feminine expression in females while simultaneously demonizing femininity in males and masculinity in females. This concept plays a crucial role in supporting cissexism, the social norm that views cisgender people as both natural and privileged as opposed to transgender people.[202] The idea of having two, opposite genders is tied to sexuality through what gender theorist Judith Butler calls a "compulsory practice of heterosexuality".[202] Because oppositional sexism is tied to heteronormativity in this way, non-heterosexuals are seen as breaking gender norms.[202] The concept of opposite genders sets a "dangerous precedent", according to Serano, where "if men are big then women must be small; and if men are strong then women must be weak".[201] The gender binary and oppositional norms work together to support "traditional sexism", the belief that femininity is inferior to and serves masculinity.[202] Serano states that oppositional sexism works in tandem with "traditional sexism". This ensures that "those who are masculine have power over those who are feminine, and that only those that are born male will be seen as authentically masculine."[201] Transgender discrimination See also: Transphobia and Healthcare and the LGBT community Transgender discrimination is discrimination towards peoples whose gender identity differs from the social expectations of the biological sex they were born with.[203] Forms of discrimination include but are not limited to identity documents not reflecting one's gender, sex-segregated public restrooms and other facilities, dress codes according to binary gender codes, and lack of access to and existence of appropriate health care services.[204] In a recent adjudication, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) concluded that discrimination against a transgender person is sex discrimination.[204] The 2008–09 National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS)—a U.S. study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force in collaboration with the National Black Justice Coalition that was, at its time, the most extensive survey of transgender discrimination—showed that Black transgender people in the United States suffer "the combination of anti-transgender bias and persistent, structural and individual racism" and that "black transgender people live in extreme poverty that is more than twice the rate for transgender people of all races (15%), four times the general Black population rate (9%) and over eight times the general US population rate (4%)".[205] Further discrimination is faced by gender nonconforming individuals, whether transitioning or not, because of displacement from societally acceptable gender binaries and visible stigmatization. According to the NTDS, transgender gender nonconforming (TGNC) individuals face between eight percent and 15% higher rates of self and social discrimination and violence than binary transgender individuals. Lisa R. Miller and Eric Anthony Grollman found in their 2015 study that "gender nonconformity may heighten trans people's exposure to discrimination and health-harming behaviors. Gender nonconforming trans adults reported more events of major and everyday transphobic discrimination than their gender conforming counterparts."[206] In another study conducted in collaboration with the League of United Latin American Citizens, Latino/a transgender people who were non-citizens were most vulnerable to harassment, abuse and violence.[207] An updated version of the NTDS survey, called the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, was published in December 2016.[208] |