Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

Systems

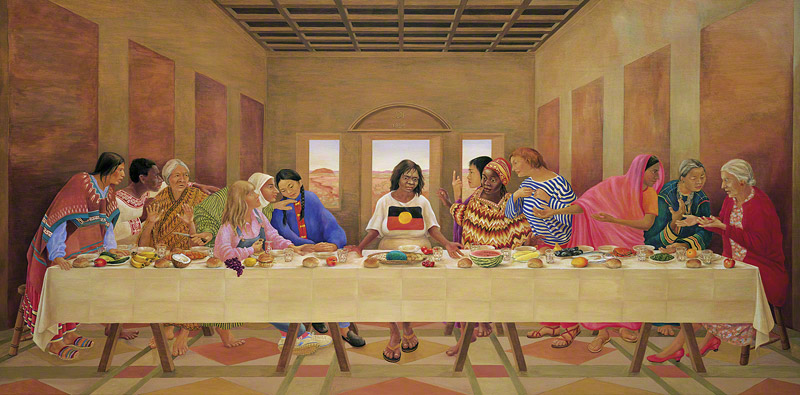

The First Supper 1988 acrylic on panel, 120 x 240 cm by Susan

Dorothea White

セックス+ジェンダー+セクシュアリティ・システム

Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

Systems

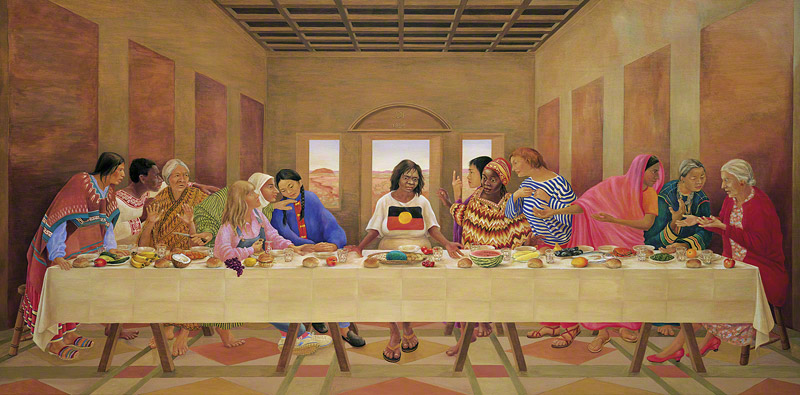

The First Supper 1988 acrylic on panel, 120 x 240 cm by Susan

Dorothea White

■ 「セックス/ジェンダー/セクシュアリティ・システム」の定義とその意味(→ジェンダー▶︎セクシュアリティ▶セックス)

「セックス/ジェンダー・システム」あるいは「セッ クス/ジェンダー/セクシュアリティ・システム」という言葉は、ゲイル・ルービン(1984)によって作られたもので「ある社会が生物学的な性を人間活動 の産物に変換する一連の取り決め」を表している。つまり、ルービンは、生物学的性別、社会的性別、性的魅力の間のつながりは、文化の産物であると提唱し た。この場合、ジェンダーとは、私たちが生物学的な性の概念に付加する「社会的産物」である。私たちの異性愛文化では、誰もが異性愛者(女性であれば男性 に、男性であれば女性に惹かれる)であると仮定される。人々は、生物学的性徴(染色体、ホルモン、第二次性徴、生殖器)を表すとされる外見上の身体的特徴 の認識に基づいて、他者が社会生活の中でどのように行動すべきか、誰に惹かれるべきかを推測するのである。ルービンは、出生時に女性と割り当てられた人は すべて女性として認識し、男性に惹かれるとする生物学的決定論者の議論に疑問を示している。生物学的決定論者によれば、「生物学は運命」であり、これは自 然が意図した方法である。しかし、この考え方は、人間の介入を考慮していない。人間として、私たちは社会の取り決めに影響を及ぼしているのです。社会構築 主義者は、私たちが通常、従来の生活様式として疑問を持たずにいる多くのことは、実は歴史的・文化的に根付いた人々の集団間の力関係を反映しており、それ は、私たちが家族やコミュニティから従来の考え方や行動を学ぶ、社会化の過程を通じて部分的に再生されると考えているのだ。女性であっても、子供を産むと いうことは、必ずしもその子供の世話をするのに適しているわけではなく、また男性にない「本能」を持っているわけでもない(https: //openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/chapter/the-sexgendersexuality-system/)。

例えば、女性が子どもを世話する仕組みには歴史的な 伝統がある(→ジェンダー労働市場問題)。母親だけでなく、保育士、乳母、小学校の先生、ベビーシッターなど、他の女性も子どもの世話をしていることがわ かる。これらの仕事に共通しているのは、いずれも女性優位の職業であること、そしてこの仕事が経済的に過小評価されていることである。このような人たちの 賃金は一般的に高くはない。ある調査によると、ニューヨーク市では、駐車場係の方が保育士よりも平均して収入が多いという結果が出ている(Clawson and Gerstel, 2002)。「母親業」が仕事としてではなく、女性の「自然な」行動として捉えられているため、その仕事の大変さを反映した形で報酬が支払われないからで ある。もしあなたが丸一日ベビーシッターをしたことがあるなら、それを18年かけて計算し、それが仕事ではないという主張をしてみてみなさい(=理不尽で 不当だと思うはずだ)。男性も女性と同じようにこの仕事をすることができるが、そうすべきであるとする文化的な指示は見当たらない。その上、もし有給の介 護人がほとんど男性だったら、もっとたくさん稼げるはずだという意見もある。 実際、女性が多い職業に就いている男性は、女性よりも収入が多く、昇進も早いのだ。この現象は、「ガラスのエスカレーター」と呼ばれている。この例は、社 会構築主義者のアビー・ファーバー(Abby Ferber, 2009)が主張するように、社会システムが男女間の差異を生み出すのであって、その逆ではないことを示している(→「再生産労働」を参照)(https: //openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/chapter/the-sexgendersexuality-system/)。

★政治的アイデンティティとしてのXジェンダー

Xジェンダーの現在の政治的パワーがどれぐらいなの

か私は不案内だが[その歴史的意義あるいは大義は]Xジェンダーが自己アイデンティティとしての名乗りとしての機能よりも「お前はどちらのジェンダーなの

だ?」という権力の側からの問いかけに応答を拒否する宣言行為だったのだ.

★再生産労働について

| ●再生産労働より |

|

| Another solution proposed by

Marxist feminists is to liberate women from their forced connection to

reproductive labor. In her critique of traditional Marxist feminist

movements such as the Wages for Housework Campaign, Heidi Hartmann

(1981) argues that these efforts "take as their question the

relationship of women to the economic system, rather than that of women

to men, apparently assuming the latter will be explained in their

discussion of the former."[6] Hartmann (1981) believes that traditional

discourse has ignored the importance of women's oppression as women,

and instead focused on women's oppression as members of the capitalist

system. Similarly, Gayle Rubin, who

has written on a range of subjects including sadomasochism,

prostitution, pornography, and lesbian literature as well as

anthropological studies and histories of sexual subcultures, first rose

to prominence through her 1975 essay ''"The Traffic in Women:

Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex"'', in which she coins the

phrase "sex/gender system" and criticizes Marxism for what she claims

is its incomplete analysis of sexism under capitalism, without

dismissing or dismantling Marxist fundamentals in the process. More recently, many Marxist feminists have shifted their focus to the ways in which women are now potentially in worse conditions after gaining access to productive labor. Nancy Folbre (1994) proposes that feminist movements begin to focus on women's subordinate status to men both in the reproductive (private) sphere, as well as in the workplace (public sphere).[16] In an interview in 2013, Silvia Federici urges feminist movements to consider the fact that many women are now forced into productive and reproductive labor, resulting in a "double day".[17] Federici (2013) argues that the emancipation of women still cannot occur until they are free from their burdens of unwaged labor, which she proposes will involve institutional changes such as closing the wage gap and implementing child care programs in the workplace. Federici's (2013) suggestions are echoed in a similar interview with Selma James (2012) and these issues have been touched on in recent presidential elections.[12][18] |

マルクス主義フェミニストが提案するもうひとつの解決策は、生殖労働への強制的な結びつきから女性を解放することである。ハイディ・ハート

マン(1981)は、「家事労働のための賃金キャンペーン」のような

伝統的なマルクス主義フェミニズム運動に対する批判において、これらの取り組みが

「女性と男性の関係ではなく、経済システムと女性の関係を問題として取り上げ、明らかに前者についての議論において後者が説明されると想定」していると論

じている[6]。ハルトマン(1981)は、従来の言説が女性の女性としての抑圧の重要性を無視して、資本主義システムの一員としての女性

の抑圧に焦点を当てたと信じている。同様に、サドマゾヒズム、売春、ポルノ、レズビアン文学、人類学的研究、性的サブカルチャーの歴史など、さまざまな

テーマで執筆しているゲイル・ルービンは、1975年のエッセイ『女性の交通』に

よって脚光を浴びることになる。この論文で彼女は「セックス/ジェンダー・システム」という言葉を作り、マルクス主義の基本を否定したり解体したりするこ

となく、資本主義下の性差別の分析が不完全であると主張し、マルクス主義を批判している。 より最近では、多くのマルクス主義的フェミニストが、生産的労働へのアクセスを得た後、女性がより悪い状況に置かれる可能性があることに焦点を移してい る。ナンシー・フォルブレ(1994)は、フェミニスト運動が職場(公的領域)と同様に生殖(私的)領域における女性の男性に対する従属的地位に焦点を当 て始めることを提案している[16]。2013年のインタビューでシルヴィア・フェデリーチは、多くの女性が現在生産と生殖労働に強制されており「ダブル デイ」をもたらしているという事実を考慮するようフェミニスト運動に促している[17]。 [17] フェデリーチ (2013) は、女性が未賃金労働という重荷から解放されない限り、女性の解放はまだ起こらないと主張し、そのためには賃金格差の解消や職場における育児プログラムの 導入といった制度的な変化が必要だと提案している。フェデリーチ(2013)の提案は、セルマ・ジェームス(2012)の同様のインタビューでも繰り返さ れており、これらの問題は最近の大統領選挙でも触れられている[12][18]。 |

| Evelyn Nakano Glenn provided the

insight that reproductive labor was divided based on race and

ethnicity, a pattern she called the "racial division of reproductive

labor." Industrialization in the nineteenth century morphed society’s

roles assigned to men and women, with men being seen as the primary

breadwinners for their family and women as home maker.[19] However,

many middle-class white families in the United States were able to

afford to outsource some of the more unpleasant household chores to

domestic servants.[20] This racial and ethnic background of the women

hired in these roles varied by location.[21] In the Northeast United

States, European immigrants, mainly from Germany or Ireland, made up

the majority of domestic servants until the beginning of the twentieth

century.[22] Throughout time, as the social status of the role declined

and the overall working conditions worsened it started to become more

racially stratified.[22] The role was mainly taken on by African

American women in the South, Mexicans in the Southwest, and Japanese

people in northern California and Hawaii.[23] In addition to workers in

this position making low wages, they were also often treated as

subordinates by their employer, the woman of the house, and the only

women that would take these jobs did so because there were no other

opportunities available to them.[24] There was an ideology produced

that said Black and Latina women were “made” to work and serve for

white families as domestic workers.[25] This changed in the late 20th

century, where the amount of women working as domestic servants first

declined due to modernization, development, and an increase in other

job opportunities for the women previously taking on this role[26]

However, Saskia Sassen-Koob explained that when the economy shifted to

service based, it created a demand for immigrant women because low wage

jobs were made available in developed countries. Mainly these roles

were being taken on largely by immigrants from Mexico, Central America,

and the Caribbean.[26]These jobs drew a female workforce to them

because of the low wage, so that they are viewed as “women’s jobs.”[27]

Drawing on the work of Glenn and Sassen-Koob's work, Parrenas brought

together Glenn's ideas about the racial division of reproductive labor

and Sassen-Koob's ideas about feminization and globalization and used

them to analyze paid reproductive work. The term international division of reproductive labor was coined by Rhacel Parrenas in her book, Servants of Globalization: Migrants and Domestic Work, where she discusses Filipino migrant domestic workers. The international division of reproductive labor involves a transfer of labor among three actors in a developed and developing country. It refers to three tiers: wealthier upper class women who use the migrants to take care of domestic work and the lower class who stay back home to watch the migrant’s children. The wealthier women in developed countries have entered the workforce at greater numbers which has led to them having more responsibilities inside and outside of the home. These women are able to hire help and use this privilege of race and class to transfer their reproductive labor responsibilities over to a less privileged woman.[28] Migrant women maintain a hierarchy over their family members and other women who stay back to watch the migrant’s children. Parrenas’ research explains that the sexual division of labor remains in reproductive labor since women are the ones migrating to work as domestic workers in developed countries.[29] |

イヴリン・ナカノ・グレンは、生殖労働が人種や民族によって分担されて

いることを洞察し、"racial division of reproductive labor

"と呼んだ[19]。19世紀の産業化によって社会の男女の役割分担は変化し、男性は一家の稼ぎ手、女性は家庭の主婦とみなされた[19]。

しかし、アメリカの多くの中流白人家庭は、より不快な家事の一部を家事使用人に委託する余裕があった[20]。

こうした役割で雇われる女性の人種・民族的背景は地域によって異なっていた[21]。 [21]

アメリカ北東部では、20世紀初頭まで、主にドイツやアイルランドからのヨーロッパ系移民が家事使用人の大半を占めていた[22]。

時を経て、この役割の社会的地位が低下し、労働条件全体が悪化すると、より人種的階層化が進み始めた[22]。

この役割は主に南部でアフリカ系アメリカ人女性、南西部でメキシコ系、北カリフォルニアとハワイで日本人が担ってきた。

[このような立場の労働者は低賃金であることに加え、雇用主である家の女性からしばしば部下として扱われ、これらの仕事を引き受ける唯一の女性は、他に機

会がなかったためにそうした。 24]

黒人とラテン系の女性は家事労働者として白人家族のために働いて奉仕するように「作られている」という思想が生み出されていた。

[しかし、サスキア・サッセン=クーブは、経済がサービス業に移行したとき、先進国では低賃金の仕事が可能になったため、移民の女性に対する需要が生まれ

たと説明しています。主にこれらの役割はメキシコ、中米、カリブ海からの移民によって主に担われていた[26]。これらの仕事は低賃金のために女性の労働

力を引き寄せ、「女性の仕事」とみなされるようになった[27]。パレナスは、グレンとサッセン・クーブの仕事を引きながら、グレンの生殖労働の人種分業

に関する考えとサッセン・クーブの女性化とグローバル化に関する考えをまとめ、それを用いて有償生殖労働について分析を行っている。 生殖労働の国際分業という言葉は、レイセル・パレナスによって、その著 書『グローバリゼーションのしもべたち』の中で作られたものである。そこで彼女は、フィリピンの移民家事労働者について論じています。生殖的労働の国際分 業には、先進国と発展途上国の3つのアクター間の労働力の移動が含まれる。それは、裕福な上流階級の女性が家事労働の世話をするために移民を利用し、下流 階級の女性が家に残って移民の子供を見るという3つの階層を指す。先進国の裕福な女性たちは、より多くの労働力に参入し、家庭内外でより多くの責任を負う ようになった。このような女性は人手を借りることができ、人種や階級による特権を利用して、生殖労働の責任をより特権的でない女性に転嫁することができる [28]。移住女性は、家族や移住者の子どもを見てくれる他の女性に対するヒエラルキーを維持している。パレナスの研究は、先進国では家事労働者として働 くために移住しているのは女性であるため、生殖労働において性的分業が残っていると説明している[29]。 |

| Parrenas argues that the

international division of reproductive labor arose out of globalization

and capitalism. Components of globalization including privatization and

feminization of labor also contributed to the rise of this division of

labor. She explains that globalization has led to reproductive labor to

be comodified and demanded internationally. Sending countries are stuck

with losing valuable labor while receiving countries take advantage of

this labor to grow their economies.[30] Parrenas highlights the role

United States colonialism and the International Monetary Fund play in

developing countries, such as the Philippines, becoming exporters of

migrant workers. This explanation of the root of the concept is crucial

because it explains that the financial inequalities the women across

the three tiers face are rooted in the economy.[31] The concept has been expanded by others and applied to locations other than the Philippines where Parrenas conducted her research. In a study done in Guatemala and Mexico, instead of a global transfer of labor, a more local transfer was done between the women who work in the labor force and those other women relatives who take care of the children.[3] A “new international division of reproductive labor” is said to have occurred in Singapore because of outsourcing and taking advantage of a low skilled labor force which has led to the international division of reproductive labor. In order to maintain a strong, growing economy in Southeast Asia, this transfer of reproductive labor is needed. In Singapore, hiring migrant help is a necessity to sustain the economy and the Singaporean woman’s status.[32] |

パ

レナスは、国際的な繁殖的労働の分業は、グローバリゼーションと資本

主義から生じたと主張している。民営化や労働の女性化などのグローバリゼーションの要素も、この分業制の台頭に貢献した。彼女は、グローバリゼーションに

よって、生殖労働が国際的に共同化され、要求されるようになったと説明する。派遣国は貴重な労働力を失うことになり、一方、受け入れ国はこの労働力を利用

して経済成長を図る[30]。パレナスは、フィリピンなどの途上国が移民労働者の輸出国となる上で、アメリカの植民地主義や国際通貨基金が果たす役割を強

調する。この概念の根源に関する説明は、3つの階層にまたがる女性たちが直面している経済的不平等が経済に根ざしていることを説明しているため、極めて重

要である[31]。 この概念は他の人々によって拡張され、パレナスが研究を行ったフィリピ ン以外の場所にも適用されている。グアテマラとメキシコで行われた研究では、グローバルな労働力の移動の代わりに、労働力として働く女性と子供の世話をす る他の女性親族の間でよりローカルな移動が行われた[3]。シンガポールでは、アウトソーシングと低スキルの労働力を利用したことにより「新しい国際生殖 労働分業」が起こり、国際生殖労働分業につながったと言われている。東南アジアで強く成長する経済を維持するためには、この生殖労働の移動が必要である。 シンガポールでは、移民の助けを借りることは経済とシンガポール人女性の地位を維持するために必要なことである[32]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reproductive_labor. |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆