誠実

Sincerity

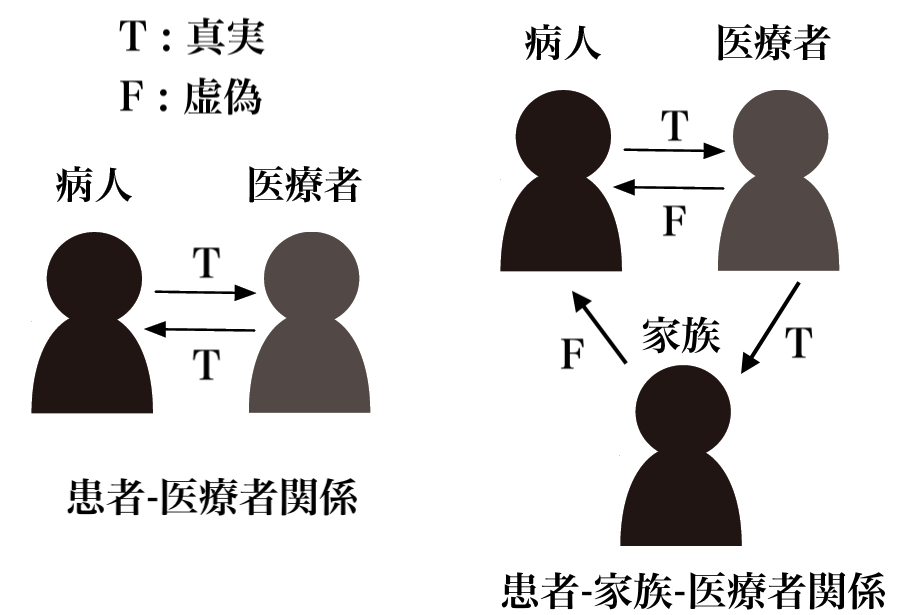

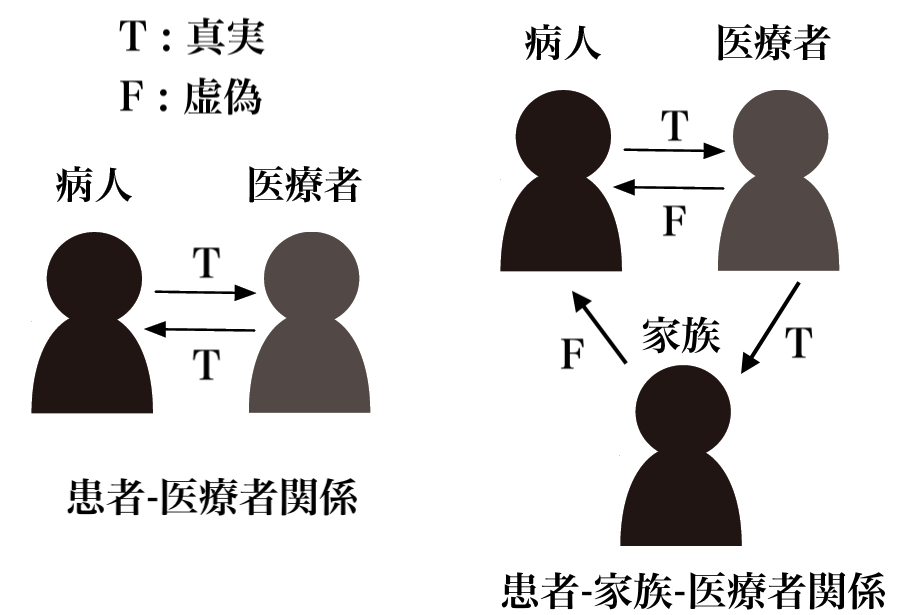

インフォーム・ド・コンセントは患者-医者関係のなかで真実が交換される必要がある/重たい病名を患者に隠しておくことは「不誠実」をなす

☆ 誠実さ(Sincerity)とは、自分の感情、信念、思考、欲求のすべてに従って、正直かつ真正直に伝え、行動する人の美徳である。コミュニケーションとは対照的に)行動における誠実さは、「真摯さ」と呼ばれることもある(→「真面目さと誠実さ」)。

| Sincerity

is the virtue of one who communicates and acts in accordance with the

entirety of their feelings, beliefs, thoughts, and desires in a manner

that is honest and genuine.[1] Sincerity in one's actions (as opposed

to one's communications) may be called "earnestness". |

誠実さとは、自分の感情、信念、思考、欲求のすべてに従って、正直かつ真正直に伝え、行動する人の美徳である。(コミュニケーションとは対照的に)行動における誠実さは、「真摯さ」と呼ばれることもある。 |

| Etymology The Oxford English Dictionary and most scholars state that sincerity from sincere is derived from the Latin sincerus meaning clean, pure, sound. Sincerus may have once meant "one growth" (not mixed), from sin- (one) and crescere (to grow).[2] Crescere is cognate with "Ceres," the goddess of grain, as in "cereal".[3] According to the American Heritage Dictionary,[4] the Latin word sincerus is derived from the Indo-European root *sm̥kēros, itself derived from the zero-grade of *sem (one) and the suffixed, lengthened e-grade of *ker (grow), generating the underlying meaning of one growth, hence pure, clean. |

語源 オックスフォード英語辞典やほとんどの学者は、誠実のsincerityは、清潔、純粋、健全を意味するラテン語のsincerusに由来すると 述べている。sincerusはかつて、sin-(1つ)とcrescere(成長する)から「1つの成長」(混じり気のない)を意味していたのかもしれ ない[2]。crescereは「穀物」のように穀物の女神である「Ceres」と同義語である[3]。 アメリカン・ヘリテージ・ディクショナリーによると[4]、ラテン語のsincerusはインド・ヨーロッパ語源の*sm̥kērosに由来し、*sem (1つ)のゼロ級と*ker(成長する)の接尾辞、長くなったe級から派生し、1つの成長、それ故に純粋、清潔という根本的な意味を生み出す。 |

| Controversy An often repeated folk etymology proposes that sincere is derived from the Latin sine "without" and cera "wax". According to one popular explanation, dishonest sculptors in Rome or Greece would cover flaws in their work with wax to deceive the viewer; therefore, a sculpture "without wax" would be one that was honestly represented. It has been said, "One spoke of sincere wine... simply to mean that it had not been adulterated, or, as was once said, sophisticated."[5]: 12–13 Another explanation is that this etymology "is derived from a Greeks-bearing-gifts story of deceit and betrayal. For the feat of victory, the Romans demanded the handing over of obligatory tributes. Following bad advice, the Greeks resorted to some faux-marble statues made of wax, which they offered as tribute. These promptly melted in the warm Greek sun."[6] The Oxford English Dictionary states, however, that "there is no probability in the old explanation from sine cera 'without wax'".[citation needed] The popularity of the without wax etymology is reflected in its use as a minor subplot in Dan Brown's 1998 thriller novel Digital Fortress, though Brown attributes it to the Spanish language, not Latin. Reference to the same etymology, this time attributed to Latin, later appears in his 2009 novel, The Lost Symbol. |

論争 よく繰り返される民間の語源説では、誠実はラテン語のsine「なく」とcera「蝋」に由来するとされている。ローマやギリシャの不正直な彫刻家は、見 る者を欺くために作品の欠点を蝋で覆っていたという説がある。誠実なワインとは......単に、不純物が混ざっていない、あるいはかつて言われたように 洗練されたワインという意味である」とも言われている[5]: 12-13 別の説明では、この語源は「ギリシア人が欺瞞と裏切りの贈り物をする物語に由来する」という。勝利の偉業に対して、ローマ人は義務的な貢ぎ物を渡すよう要 求した。ギリシア人は悪い忠告に従い、蝋で作った偽の大理石の彫像を貢ぎ物として差し出した。しかし、オックスフォード英語辞典は、「sine cera『蝋なし』からの古い説明には信憑性がない」と述べている[要出典]。 蝋なしという語源の人気は、ダン・ブラウンの1998年のスリラー小説『デジタル・フォートレス』で小ネタとして使われていることに反映されているが、ブ ラウンはこれをラテン語ではなくスペイン語に由来するとしている。同じ語源への言及は、今度はラテン語によるものだが、後に2009年の小説『ロスト・シ ンボル』にも登場する。 |

| In Western societies Sincerity was discussed by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. It resurfaced to become an ideal (virtue) in Europe and North America in the 17th century. It gained considerable momentum during the Romantic movement, when sincerity was first celebrated as an artistic and social ideal, exemplified in the writings of Thomas Carlyle and John Henry Newman.[7] In middle to late nineteenth century America, sincerity was reflected in mannerisms, hairstyles, women's dress, and the literature of the time. Literary critic Lionel Trilling dealt with the subject of sincerity, its roots, its evolution, its moral quotient, and its relationship to authenticity in a series of lectures published as Sincerity and Authenticity.[5] Aristotle's views According to Aristotle "truthfulness or sincerity is a desirable mean state between the deficiency of irony or self-deprecation and the excess of boastfulness."[8] |

西洋社会では 誠実さについては、アリストテレスが『ニコマコス倫理学』で論じている。17世紀にヨーロッパと北米で理想(美徳)として再浮上した。19世紀中頃から後半にかけてのアメリカでは、誠実さはマナーや髪型、女性の服装、当時の文学に反映されていた。 文芸批評家のライオネル・トリリングは、『誠意と真正性』として出版された一連の講義の中で、誠意という主題、そのルーツ、進化、道徳的指数、そして真正性との関係を扱っている[5]。 アリストテレスの見解 アリストテレスによれば、「真実性または真摯さは、皮肉や自己卑下の欠乏と自慢の過剰との間の望ましい平均状態(=中庸)である」[8]。 |

| In Islam In the Islamic context, sincerity means: being free from worldly motives and not being a hypocrite.[9] In the Qur'an, all acts of worship and human life should be motivated by the pleasure of God, and the prophets of God have called man to sincere servitude in all aspects of life. Sincerity in Islam is divided into sincerity in belief and sincerity in action. Sincerity in belief means monotheism—in other words not associating partners with God[10]—and sincerity in action means performing sincere worship only for God.[11] |

イスラームにおける誠実とは? イスラームにおける誠意とは、世俗的な動機から自由であること、偽善者でないことを意味する[9]。クルアーンでは、礼拝行為や人間生活はすべて神の喜び に突き動かされているべきであり、神の預言者たちは生活のあらゆる側面において人間に誠実な奉仕を呼びかけている。イスラームにおける誠意とは、信仰にお ける誠意と行動における誠意に分けられる。信仰における誠意とは、一神教、つまり神とパートナーを結びつけないことを意味し[10]、行動における誠意と は、神に対してのみ誠実に礼拝を行うことを意味する[11]。 |

| In East Asian societies See also: The Analects Sincerity is developed as a virtue in East Asian societies (e.g. China, Korea, and Japan). The concept of chéng (誠、诚)—as expounded in two of the Confucian classics, the Da Xue and the Zhong Yong—is generally translated as sincerity. As in the West, the term implies a congruence of avowal and inner feeling, but inner feeling is in turn ideally responsive to ritual propriety and social hierarchy. Specifically, Confucius's Analects contains the following statement in Chapter I: (主忠信。毋友不如己者。過,則勿憚改。) "Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles. Then no friends would not be like yourself (all friends would be as loyal as yourself). If you make a mistake, do not be afraid to correct it." Thus, even today, a powerful leader will praise leaders of other realms as "sincere" to the extent that they know their place in the sense of fulfilling a role in the drama of life. In Japanese the character for chéng may be pronounced makoto, which carries still more strongly the sense of loyal avowal and belief. |

東アジア社会 参照: 論語 東アジア社会(中国、韓国、日本など)では、誠は美徳として発展してきた。誠、诚」という概念は、儒教の古典である『大雪』と『中庸』の中で説かれてお り、一般的に「誠意」と訳されている。西洋と同様、この言葉は公言と内心の一致を意味するが、内心は儀礼的な礼儀や社会的なヒエラルキーに理想的に対応す るものである。具体的には、孔子の『論語』の第一章に次のような記述がある。忠信と誠実を第一の原則としなさい。そうすれば、どんな友もあなた自身と同じ ようにはならない(すべての友はあなた自身と同じように忠実である)。過ちを犯したら、それを正すことを恐れてはならない。" このように、今日でも力のある指導者は、人生のドラマの中で役割を果たすという意味で、自分の立場をわきまえている限りにおいて、他界の指導者を「誠実」 だと称賛する。日本語では「誠」の字を「まこと」と発音することがあるが、これは忠誠を誓い、信じるという意味をさらに強く持っている。 |

| Honesty Insincere charm(Superficial charm) Parrhesia Radical Honesty Sincerely (disambiguation) New Sincerity |

誠実さ=正直 不誠実な魅力(表面的な魅力) パレーシア 過激な正直さ 誠実(曖昧さ回避) 新しい誠意 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sincerity |

|

| Superficial charm

(or insincere charm) refers to the social act of saying or doing things

because they are well received by others, rather than what one actually

believes or wants to do. It is sometimes referred to as "telling people

what they want to hear".[1] Generally, superficial charm is an

effective way to ingratiate or persuade[2] and it is one of the many

elements of impression management/self-presentation.[3] Flattery and charm accompanied by obvious ulterior motives is generally not socially appreciated, and most people consider themselves to be skilled at distinguishing sincere compliments from superficial;[2] however, researchers have demonstrated that even obviously manipulative charm can be effective.[4] While expressed attitudes are negative or dismissive, implicit attitudes are often positively affected.[2][4] The effectiveness of charm and flattery, in general, stems from the recipient’s natural desire to feel good about one's self.[4] On the contrary, superficial charm can be self damaging. However, the ability to be superficially charming often leads to success in areas like the theatre, salesmanship, or politics and diplomacy. In excess, being adept in social intelligence and endlessly taking social cues from other people, can lead to the sacrificing of one's motivations and sense of self.[5] Superficial charm can be exploitative. Individuals with psychopathy, for example, are known to have limited guilt or anxiety when it comes to exploiting others in harmful ways. While intimidation and violence are common means of exploitation, the use of superficial charm is not uncommon.[6] Superficial charm is listed on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist. |

表面的な魅力

(または不誠実な魅力)とは、実際に自分が信じていることややりたいことではなく、他人から受けが良いからという理由で言動する社会的行為を指す。一般的

に、表面的な魅力は恩を着せたり説得したりする効果的な方法であり[2]、印象管理/自己呈示の多くの要素の一つである[3]。 明らかな下心を伴うお世辞や魅力は一般的に社会的に評価されず、ほとんどの人は心からの賛辞と表面的なものを区別することに長けていると考えている[2]が、研究者は明らかに操作的な魅力でさえも効果的であり得ることを実証している[4]。 逆に、表面的な魅力は自己を傷つける可能性がある。しかし、表面的に愛嬌を振りまく能力は、演劇、セールスマン、政治や外交といった分野での成功につなが ることが多い。過剰に、社会的知性に精通し、他者から社会的な手がかりを際限なく得ることは、自分の動機や自己意識を犠牲にすることにつながりかねない [5]。 表面的な魅力は搾取的である。例えば、サイコパスの人は、有害な方法で他者を利用することに関して、罪悪感や不安が乏しいことが知られている。脅迫や暴力 は搾取の一般的な手段であるが、表面的な魅力の使用も珍しくない[6]。表面的な魅力はヘア(による)・サイコパシー・チェックリストに記載されている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superficial_charm |

|

| The Psychopathy Checklist or Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, now the Psychopathy Checklist—revised

(PCL-R), is a psychological assessment tool that is commonly used to

assess the presence and extent of the personality trait psychopathy in

individuals—most often those institutionalized in the criminal justice

system—and to differentiate those high in this trait from those with

antisocial personality disorder, a related diagnosable disorder.[1] It

is a 20-item inventory of perceived personality traits and recorded

behaviors, intended to be completed on the basis of a semi-structured

interview along with a review of "collateral information" such as

official records.[2] The psychopath tends to display a constellation or

combination of high narcissistic, borderline, and antisocial

personality disorder traits, which includes superficial charm,

charisma/attractiveness, sexual seductiveness and promiscuity,

affective instability, suicidality, lack of empathy, feelings of

emptiness, self-harm, and splitting (black and white thinking).[3] In

addition, sadistic and paranoid traits are usually also present.[4] The PCL was originally developed in the 1970s by Canadian psychologist Robert D. Hare[5] for use in psychology experiments, based partly on Hare's work with male offenders and forensic inmates in Vancouver, and partly on an influential clinical profile by American psychiatrist Hervey M. Cleckley first published in 1941. An individual's score may have important consequences for their future, and because the potential for harm if the test is used or administered incorrectly is considerable, Hare argues that the test should be considered valid only if administered by a suitably qualified and experienced clinician under scientifically controlled and licensed, standardized conditions.[6][7] Hare receives royalties on licensed use of the test.[8] In psychometric terms, the current version of the checklist has two factors (sets of related scores) that correlate about 0.5 with each other, with Factor One closer to Cleckley's original personality concept than Factor Two. Hare's checklist does not incorporate the "positive adjustment features" that Cleckley did.[9] |

サイコパシー・チェックリストまたはヘア・サイコパシー・チェックリス

ト改訂版(現在はサイコパシー・チェックリスト改訂版(PCL-R))は、心理学的アセスメント・ツールであり、個人の人格特性であるサイコパシーの存在

と程度を評価するために、また、この特性が高い人を、関連する診断可能な障害である反社会性人格障害と区別するために、一般的に使用されている。

[1]

これは、認識された性格特性と記録された行動に関する20項目の目録であり、半構造化面接と公的記録などの「付随情報」の検討に基づいて記入されることを

意図している。 [2]

サイコパスは、表面的な魅力、カリスマ性/魅力、性的誘惑と乱交、情緒不安定、自殺傾向、共感性の欠如、虚無感、自傷、分裂(白か黒かの思考)を含む、高

い自己愛性、境界性、反社会性人格障害の特徴のコンステレーションまたは組み合わせを示す傾向がある[3]。 PCLはもともと1970年代にカナダの心理学者ロバート・D・ヘア[5]によって心理学実験に使用するために開発されたもので、一部はバンクーバーの男 性犯罪者と法医学受刑者を対象としたヘアの研究に基づいており、一部は1941年に発表されたアメリカの精神科医ハーベイ・M・クレックリーによる影響力 のある臨床プロファイルに基づいている。 個人のスコアは、その人の将来にとって重要な結果をもたらす可能性があり、テストの使用や実施方法を誤ると害を及ぼす可能性がかなりあるため、ヘアは、科 学的に管理され、認可された標準化された条件下で、適切な資格を持ち、経験を積んだ臨床医によって実施された場合にのみ、テストは有効であるとみなされる べきであると主張している[6][7]。 心理測定用語では、現行版のチェックリストには2つの因子(関連する得点の集合)があり、互いに約0.5の相関があり、第1因子は第2因子よりもクレク リーの元のパーソナリティ概念に近い。ヘアのチェックリストは、クレックリーが行った「ポジティブな適応の特徴」を取り入れていない[9]。 |

| PCL-R model of psychopathy The PCL-R is used for indicating a dimensional score, or a categorical diagnosis, of psychopathy for clinical, legal, or research purposes.[6] It is rated by a mental health professional (such as a psychologist or other professional trained in the field of mental health, psychology, or psychiatry), using 20 items. Each of the items in the PCL-R is scored on a three-point scale according to specific criteria through file information and a semi-structured interview. The scores are used to predict risk for criminal re-offense and probability of rehabilitation. The current edition of the PCL-R officially lists three factors (1.a, 1.b, and 2.a), which summarize the 20 assessed areas via factor analysis. The previous edition of the PCL-R[10] listed two factors. Factor 1 is labelled "selfish, callous and remorseless use of others". Factor 2 is labelled as "chronically unstable, antisocial and socially deviant lifestyle". There is a high risk of recidivism and mostly small likelihood of rehabilitation for those who are labelled as having "psychopathy" on the basis of the PCL-R ratings in the manual for the test, although treatment research is ongoing. PCL-R Factors 1a and 1b are correlated with narcissistic personality disorder.[3] They are associated with extraversion and positive affect. Factor 1, the so-called core personality traits of psychopathy, may even be beneficial for the psychopath (in terms of nondeviant social functioning).[11] PCL-R Factors 2a and 2b are particularly strongly correlated to antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder and are associated with reactive anger, criminality, and impulsive violence. The target group for the PCL-R in prisons in some countries is criminals convicted of delict and/or felony. The quality of ratings may depend on how much background information is available and whether the person rated is honest and forthright.[3][11] |

サイコパシーのPCL-Rモデル PCL-Rは、臨床目的、法的目的、または研究目的で、サイコパシーの次元スコア、またはカテゴリー診断を示すために使用される[6]。PCL-Rは、メ ンタルヘルス専門家(心理学者、またはメンタルヘルス、心理学、精神医学の分野で訓練を受けた他の専門家など)によって、20の項目を用いて評価される。 PCL-Rの各項目は、ファイル情報と半構造化面接により、特定の基準に従って3段階で得点化される。 得点は、犯罪の再犯リスクと更生の可能性を予測するために用いられる。 PCL-Rの現行版は、因子分析によって20の評価領域を要約した3つの因子(1.a、1.b、2.a)を公式にリストアップしている。旧版のPCL-R [10]では、2つの因子が挙げられていた。第1因子は「利己的、冷淡、無慈悲な他者利用」とラベル付けされている。第2因子は「慢性的に不安定で、反社 会的で、社会的に逸脱した生活様式」である。PCL-R検査のマニュアルにある評価に基づいて「サイコパス」とされた人には、再犯のリスクが高く、ほとん ど更生の可能性は低いが、治療研究は進行中である。 PCL-Rの第1a因子と第1b因子は、自己愛性パーソナリティ障害と相関している。第1因子、いわゆるサイコパスの中核的性格特性は、サイコパスにとって(反抗的でない社会的機能という点で)有益である可能性さえある[11]。 PCL-Rの第2a因子と第2b因子は、反社会性人格障害と境界性人格障害と特に強く相関しており、反応的怒り、犯罪性、衝動的暴力と関連している。ある 国の刑務所では、PCL-Rの対象集団は、不法行為や重罪で有罪判決を受けた犯罪者である。評価の質は、背景情報がどれだけ利用可能か、また評価された人 が正直で率直であるかどうかに左右されることがある[3][11]。 |

| Items Item 1: Glibness/superficial charm Item 2: Grandiose sense of self-worth Item 3: Need for stimulation/proneness to boredom Item 4: Pathological lying Item 5: Conning/manipulative[12] Item 6: Lack of remorse or guilt Item 7: Shallow affect Item 8: Callous/lack of empathy Item 9: Parasitic lifestyle Item 10: Poor behavioral controls Item 11: Promiscuous sexual behavior Item 12: Early behavior problems Item 13: Lack of realistic long-term goals Item 14: Impulsivity Item 15: Irresponsibility Item 16: Failure to accept responsibility for own actions Item 17: Many short-term marital relationships Item 18: Juvenile delinquency Item 19: Revocation of conditional release Item 20: Criminal versatility Each of the 20 items in the PCL-R is scored on a three-point scale, with a rating of 0 if it does not apply at all, 1 if there is a partial match or mixed information, and 2 if there is a reasonably good match to the offender. This is to be done through a face-to-face interview together with supporting information on lifetime behavior (e.g., from case files). It can take up to three hours to collect and review the information.[13] Out of a maximum score of 40, the cut-off for the label of psychopathy is 30 in the United States and 25 in the United Kingdom.[13][14] A cut-off score of 25 is also sometimes used for research purposes.[13] High PCL-R scores are positively associated with measures of impulsivity and aggression, Machiavellianism, persistent criminal behavior, and negatively associated with measures of empathy and affiliation.[13][15] Early factor analysis of the PCL-R indicated it consisted of two factors. Factor 1 captures traits dealing with the interpersonal and affective deficits of psychopathy (e.g., shallow affect, superficial charm, manipulativeness, lack of empathy) whereas factor 2 deals with symptoms relating to antisocial behavior (e.g., criminal versatility, impulsiveness, irresponsibility, poor behavior controls, juvenile delinquency).[16] The two factors have been found by those following this theory to display different correlates. Factor 1 has been correlated with narcissistic personality disorder, low anxiety,[16] low empathy,[17] low stress reaction[18] and low suicide risk[18] but high scores on scales of achievement and social potency.[18] In addition, the use of item response theory analysis of female offender PCL-R scores indicates factor 1 items are more important in measuring and generalizing the construct of psychopathy in women than factor 2 items.[19] In contrast, Factor 2 was found to be related to antisocial personality disorder, social deviance, sensation seeking, low socioeconomic status[16] and high risk of suicide.[18] The two factors are nonetheless highly correlated[16] and there are strong indications they do result from a single underlying disorder.[20] Research, however, has failed to replicate the two-factor model in female samples.[21] In 2001 researchers Cooke and Michie at Glasgow Caledonian University suggested, using statistical analysis involving confirmatory factor analysis,[22] that a three-factor structure may provide a better model, with those items from factor 2 strictly relating to antisocial behavior (criminal versatility, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional release, early behavioral problems and poor behavioral controls) removed. The remaining items would be divided into three factors: arrogant and deceitful interpersonal style, deficient affective experience, and impulsive and irresponsible behavioral style.[22] Hare and colleagues have criticized the Cooke and Michie three-factor model for statistical and conceptual problems, for example, for resulting in impossible parameter combinations (negative variances).[23] In the 2003 edition of the PCL-R, Hare added a fourth antisocial behavior factor, consisting of those factor 2 items excluded in the previous model.[6] Again, these models are presumed to be hierarchical with a single, unified psychopathy disorder underlying the distinct but correlated factors.[24] In the four-factor model of psychopathy, supported by a range of samples, the factors represent the interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and overt antisocial features of the personality disorder.[25] ******** Criticism In addition to the aforementioned report by Cooke and Michie that a three-factor structure may provide a better model than the two-factor structure, Hare's concept and checklist have faced other criticisms.[22] In 2010, there was controversy after it emerged that Hare had threatened legal action that stopped publication of a peer-reviewed article on the PCL-R. Hare alleged the article quoted or paraphrased him incorrectly. The article eventually appeared, three years later. It alleged that the checklist is wrongly viewed by many as the basic definition of psychopathy, yet it leaves out key factors, while also making criminality too central to the concept. The authors claimed this leads to problems in over-diagnosis and in the use of the checklist to secure convictions. Hare has since stated that he receives less than $35,000 a year from royalties associated with the checklist and its derivatives.[47] Hare's concept has also been criticised as being only weakly applicable to real-world settings and tending towards tautology. It is also said to be vulnerable to "labeling effects", to be over-simplistic, reductionist, to embody fundamental attribution error, and not pay enough attention to context and the dynamic nature of human behavior.[48] It has been pointed out that half the criteria can also be signs of mania, hypomania, or frontal lobe dysfunction (e.g., glibness/superficial charm, grandiosity, poor behavioral controls, promiscuous sexual behavior, and irresponsibility).[49] Some research suggests that ratings made using the PCL system depend on the personality of the person doing the rating, including how empathic they themselves are. One forensic researcher has suggested that future studies need to examine the class background, race and philosophical beliefs of raters because they may not be aware of enacting biased judgments of people whose section of society or individual lives for whom they have no understanding of or empathy.[50][51] Further, a review which pooled various risk assessment instruments including the PCL, found that peer-reviewed studies for which the developer or translator of the instrument was an author (which in no case was disclosed in the journal article) were twice as likely to report positive predictive findings.[52] |

項目 項目1:口達者/表面的な魅力 項目2:誇大な自己価値感 項目3:刺激を求める/退屈になりやすい 項目4:病的な嘘つき 項目5:馴れ馴れしい/人を操る[12]。 項目6:反省や罪悪感の欠如 項目7:浅薄な感情 項目8:無愛想/共感の欠如 項目9:寄生的なライフスタイル 項目10: 行動のコントロールの悪さ 項目11: 乱れた性行動 項目12:早期の行動問題 項目13:現実的な長期目標の欠如 項目14:衝動性 項目15:無責任 項目16: 自分の行動に責任を持てない 項目17:短期的な結婚関係が多い 項目18:少年非行 項目19:条件付釈放の取り消し 項目20:犯罪の汎用性 PCL-Rの20項目はそれぞれ3段階で採点され、まったく当てはまらない場合は0点、部分的に一致するか情報が混在している場合は1点、犯罪者とそれな りに一致する場合は2点と評価される。これは、生涯の行動に関する裏付け情報(例:事件ファイルからの情報)と共に、対面面接によって行われる。情報の収 集と確認には3時間かかることもある[13]。 最高得点40点のうち、サイコパスのラベルを付けるためのカットオフは、米国では30点、英国では25点である[13][14]。 PCL-Rの高得点は、衝動性や攻撃性、マキャベリズム、持続的な犯罪行動の指標と正の関連があり、共感性や親和性の指標と負の関連がある[13][15]。 PCL-Rの初期の因子分析によると、PCL-Rは2つの因子から構成されていた。第1因子は、サイコパシーの対人的および情緒的な欠陥(例えば、浅薄な 情緒、表面的な魅力、操作性、共感の欠如)を扱う特徴をとらえ、第2因子は、反社会的行動(例えば、犯罪多発性、衝動性、無責任、行動制御の乏しさ、少年 非行)に関する症状を扱う[16]。 この理論に従う人々によって、2つの因子は異なる相関を示すことが判明している。第1因子は、自己愛性人格障害、低不安、[16]低共感、[17]低スト レス反応、[18]低自殺リスク[18]と相関しているが、達成度や社会的潜在能力の尺度では高得点である[18]。さらに、女性犯罪者PCL-Rの得点 の項目反応理論分析を用いると、女性のサイコパシーの構成概念を測定し一般化する上で、第1因子の項目が第2因子の項目よりも重要であることが示されてい る[19]。 対照的に、第2因子は、反社会性パーソナリティ障害、社会的逸脱、感覚を求めること、社会経済的地位の低さ[16]、自殺リスクの高さ[18]と関連して いることが判明している。それにもかかわらず、2つの因子は高い相関[16]があり、1つの根本的な障害から生じていることが強く示唆されている [20]。しかし、研究では、女性のサンプルにおいて2因子モデルを再現することはできていない[21]。 2001年にグラスゴー・カレドニアン大学の研究者クックとミッチーは、確証的因子分析を含む統計分析を用いて、3因子構造がより良いモデルを提供するか もしれないことを示唆した[22]。残りの項目は、傲慢で欺瞞的な対人関係スタイル、欠乏した情緒的経験、衝動的で無責任な行動スタイルの3因子に分けら れることになる。 PCL-Rの2003年版で、Hareは、以前のモデルで除外された第2因子の項目からなる第4の反社会的行動因子を追加した[6]。 繰り返すが、これらのモデルは、異なるが相関する因子の根底にある単一の統一された精神病質障害を伴う階層的なものであると推定されている[24]。様々 なサンプルによって支持されている精神病質の4因子モデルでは、因子は、人格障害の対人関係、感情、ライフスタイル、および明白な反社会的特徴を表してい る[25]。 ************ 批判 前述のCookeとMichieによる3因子構造が2因子構造よりも優れたモデルを提供するかもしれないという報告に加え、Hareの概念とチェックリストは他の批判に直面している[22]。 2010年には、ヘアがPCL-Rに関する査読付き論文の出版を差し止める法的措置を脅したことが明らかになり、論争となった。ヘアは、その論文が自分の 言葉を間違って引用したり言い換えたりしていると主張した。結局、その論文は3年後に掲載された。この論文は、チェックリストがサイコパシーの基本的な定 義として多くの人に誤って捉えられているが、重要な要素が抜け落ちており、また犯罪性がサイコパシーの概念の中心的な要素になりすぎていると主張してい る。著者らは、これが過剰診断や、有罪判決を確保するためにチェックリストを使用することの問題につながると主張している。ヘアはその後、チェックリスト とその派生物に関連する印税から年間35,000ドル以下しか受け取っていないと述べている[47]。 また、ヘアのコンセプトは、現実世界の状況には弱くしか適用できず、同語反復の傾向があるとして批判されている。また、「ラベリング効果」に対して脆弱で あり、単純化しすぎ、還元主義的であり、基本的な帰属の誤りを体現しており、文脈や人間の行動の動的な性質に十分な注意を払っていないとも言われている [48]。基準の半分が躁病、軽躁病、前頭葉機能障害(例えば、口達者/表面的な魅力、誇大性、行動制御の乏しさ、乱れた性行動、無責任)の徴候である可 能性も指摘されている[49]。 PCLシステムを用いてなされた評価は、その人自身がどの程度共感的であるかなど、評価を行う人の性格に依存することを示唆する研究もある。ある法医学研 究者は、将来的な研究において、評定者の階級的背景、人種、哲学的信条を調査する必要があることを示唆している。なぜなら、評定者は、社会の一部分や個人 の生活に対して理解も共感もできない人々に対して偏った判断を下していることに気づいていない可能性があるからである。 [50] [51] さらに、PCLを含む様々なリスク評価尺度をプールしたレビューでは、尺度の開発者または翻訳者が著者である査読付き研究(ジャーナル論文では開示されて いない場合)は、予測所見が陽性であると報告する可能性が2倍高いことが明らかにされた[52]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superficial_charm |

|

| New sincerity

(closely related to and sometimes described as synonymous with

post-postmodernism) is a trend in music, aesthetics, literary fiction,

film criticism, poetry, literary criticism and philosophy that

generally describes creative works that expand upon and break away from

concepts of postmodernist irony and cynicism. Its usage dates back to the mid-1980s; however, it was popularized in the 1990s by American author David Foster Wallace.[1][2][3] |

新しい真摯さ(ポスト・ポストモダニズムと密接に関連し、同義語として語られることもある)とは、音楽、美学、文学小説、映画批評、詩、文芸批評、哲学における傾向であり、一般的にはポストモダニズム的な皮肉やシニシズムの概念を拡張し、そこから脱却した創作物を指す。 その用法は1980年代半ばまで遡るが、1990年代にアメリカの作家デヴィッド・フォスター・ウォレスによって広められた[1][2][3]。 |

| In music "New sincerity" was used as a collective name for a loose group of alternative rock bands, centered in Austin, Texas, in the years from about 1985 to 1990, who were perceived as reacting to the ironic and cynical outlook of then-prominent music movements like punk rock and new wave. The use of "new sincerity" in connection with these bands began with an off-handed comment by Austin punk rock artist and author Jesse Sublett to his friend, local music writer Margaret Moser. According to author Barry Shank, Sublett said: "All those new sincerity bands, they're crap."[4] Sublett (at his own website) states that he was misquoted, and actually told Moser, "It's all new sincerity to me ... It's not my cup of tea."[5] In any event, Moser began using the term in print, and it ended up becoming the catch phrase for these bands.[4][6] Nationally, the most successful "new sincerity" band was the Reivers (originally called "Zeitgeist"), who released four well-received albums between 1985 and 1991. True Believers, led by Alejandro Escovedo and Jon Dee Graham, also received extensive critical praise and local acclaim in Austin, but the band had difficulty capturing its live sound on recordings, among other problems.[7] Other important "new sincerity" bands include Doctors Mob,[8][9] Wild Seeds,[10] and Glass Eye.[11] Another significant "new sincerity" figure was the eccentric, critically acclaimed songwriter Daniel Johnston.[4][12] Despite extensive critical attention (including national coverage in Rolling Stone and a 1985 episode of the MTV program The Cutting Edge), none of the "new sincerity" bands met with much commercial success, and the "scene" ended within a few years.[13][14] Other music writers have used "new sincerity" to describe later performers Arcade Fire,[15] Conor Oberst,[16] Cat Power, Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom,[17] Neutral Milk Hotel,[18] Sufjan Stevens,[19] Idlewild,[20] as well as Austin's Okkervil River[21] Leatherbag,[22] and Michael Waller.[23] |

In music "New sincerity" was used as a collective name for a loose group of alternative rock bands, centered in Austin, Texas, in the years from about 1985 to 1990, who were perceived as reacting to the ironic and cynical outlook of then-prominent music movements like punk rock and new wave. The use of "new sincerity" in connection with these bands began with an off-handed comment by Austin punk rock artist and author Jesse Sublett to his friend, local music writer Margaret Moser. According to author Barry Shank, Sublett said: "All those new sincerity bands, they're crap."[4] Sublett (at his own website) states that he was misquoted, and actually told Moser, "It's all new sincerity to me ... It's not my cup of tea."[5] In any event, Moser began using the term in print, and it ended up becoming the catch phrase for these bands.[4][6] Nationally, the most successful "new sincerity" band was the Reivers (originally called "Zeitgeist"), who released four well-received albums between 1985 and 1991. True Believers, led by Alejandro Escovedo and Jon Dee Graham, also received extensive critical praise and local acclaim in Austin, but the band had difficulty capturing its live sound on recordings, among other problems.[7] Other important "new sincerity" bands include Doctors Mob,[8][9] Wild Seeds,[10] and Glass Eye.[11] Another significant "new sincerity" figure was the eccentric, critically acclaimed songwriter Daniel Johnston.[4][12] Despite extensive critical attention (including national coverage in Rolling Stone and a 1985 episode of the MTV program The Cutting Edge), none of the "new sincerity" bands met with much commercial success, and the "scene" ended within a few years.[13][14] Other music writers have used "new sincerity" to describe later performers Arcade Fire,[15] Conor Oberst,[16] Cat Power, Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom,[17] Neutral Milk Hotel,[18] Sufjan Stevens,[19] Idlewild,[20] as well as Austin's Okkervil River[21] Leatherbag,[22] and Michael Waller.[23] |

| In film criticism Critic Jim Collins introduced the concept of "new sincerity" to film criticism in his 1993 essay titled "Genericity in the 90s: Eclectic Irony and the New Sincerity". In this essay he contrasts films that treat genre conventions with "eclectic irony" and those that treat them seriously, with "new sincerity". Collins describes, the "new sincerity" of films like Field of Dreams (1989), Dances With Wolves (1990), and Hook (1991), all of which depend not on hybridization, but on an "ethnographic" rewriting of the classic genre film that serves as their inspiration, all attempting, using one strategy or another, to recover a lost "purity", which apparently pre-dated even the golden age of film genre.[24] |

映画批評において 批評家ジム・コリンズは、1993年に「90年代のジェネリシティ」と題したエッセイで、映画批評に「新しい誠実さ」という概念を導入した: Eclectic Irony and the New Sincerity)」と題した1993年のエッセイで、「新しい誠実さ」という概念を映画批評に導入した。このエッセイの中で彼は、ジャンルの定石を 「折衷的皮肉」で扱う映画と、「新しい誠実さ」で真面目に扱う映画を対比している。コリンズはこう語る、 フィールド・オブ・ドリームス』(1989年)、『ダンス・ウィズ・ウルブズ』(1990年)、『フック』(1991年)のような映画の 「新しい真摯さ 」は、ハイブリッド化ではなく、インスピレーション源となる古典的ジャンル映画の 「エスノグラファー 」的書き換えに依存している。 |

| Cinematic examples Bonnie and Clyde (1967) Field of Dreams (1989) Dances With Wolves (1990) Ghost (1990) Hook (1991) Jurassic Park (1993) Forrest Gump (1994) The Lion King (1994) Titanic (1997) Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) Amélie (2001) The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001–2003) The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) Garden State (2004) Moonrise Kingdom (2012) The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013) Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) Creed III (2022) Top Gun: Maverick (2022) Wonka (2023) Sources:[25][26][27][28][29][30] |

映画の例 ボニーとクライド(1967年) フィールド・オブ・ドリームス』(1989年) ダンス・ウィズ・ウルブス(1990年) ゴースト(1990年) フック(1991年) ジュラシック・パーク(1993年) フォレスト・ガンプ(1994年) ライオン・キング(1994年) タイタニック(1997年) スター・ウォーズ エピソード1/ファントム・メナス(1999年) アメリ(2001年) ロード・オブ・ザ・リング』3部作(2001年~2003年) ザ・ロイヤル・テネンバウムズ(2001年) スポットレス・マインドのエターナル・サンシャイン(2004年) ガーデンステート(2004年) ムーンライズ・キングダム(2012年) ウォルター・ミティの秘密の生活(2013年) アバター/ウォーター(2022年) クリードIII (2022) トップガン マーベリック(2022年) ウォンカ』(2023年) Sources:[25][26][27][28][29][30] |

| In literary fiction and criticism In response to the hegemony of metafictional and self-conscious irony in contemporary fiction, writer David Foster Wallace predicted, in his 1993 essay "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction",[1] a new literary movement which would espouse something like the new sincerity ethos: The next real literary "rebels" in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of "anti-rebels," born oglers who dare to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall to actually endorse single-entendre values. Who treat old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that'll be the point, why they'll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk things. Risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. The new rebels might be the ones willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the "How banal." Accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Credulity. Willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows. This was further examined on the blog Fiction Advocate:[31] The theory is this: Infinite Jest is Wallace's attempt to both manifest and dramatize a revolutionary fiction style that he called for in his essay "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction". The style is one in which a new sincerity will overturn the ironic detachment that hollowed out contemporary fiction towards the end of the 20th century. Wallace was trying to write an antidote to the cynicism that had pervaded and saddened so much of American culture in his lifetime. He was trying to create an entertainment that would get us talking again. In his 2010 essay "David Foster Wallace and the New Sincerity in American Fiction", Adam Kelly argues that Wallace's fiction, and that of his generation, is marked by a revival and theoretical reconception of sincerity, challenging the emphasis on authenticity that dominated twentieth-century literature and conceptions of the self.[2] Additionally, numerous authors have been described as contributors to the new sincerity movement, including Jonathan Franzen, Marilynne Robinson,[32] Zadie Smith, Dave Eggers,[33] Stephen Graham Jones,[34] Michael Chabon,[35][36][37] and Victor Pelevin.[38] |

文学小説と批評において 現代小説におけるメタフィクション的で自意識的なアイロニーの覇権に対抗して、作家のデイヴィッド・フォスター・ウォレスは1993年のエッセイ「E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction」[1]で、新しい誠実さのエートスのようなものを信奉する新しい文学運動を予言した: この国における次の真の文学的「反逆者」は、「反反逆者」と呼ばれる奇妙な集団として現れるかもしれない。米国生活における古くからの流行に乗り遅れた人 間の悩みや感情を、畏敬の念と信念をもって扱う。自意識過剰や疲労を避ける。このような反体制派は、もちろん始める前から時代遅れになっている。誠実すぎ る。明らかに抑圧されている。後ろ向きで、古風で、素朴で、時代錯誤だ。もしかしたら、そこがポイントになるかもしれない。私が見る限り、本物の反逆者は 危険を冒す。不評を買うリスクもある。ショック、嫌悪、憤怒、検閲、社会主義、アナーキズム、ニヒリズムへの非難などだ。新たな反逆者たちは、あくびをし たり、目を丸くしたり、冷ややかな笑みを浮かべたり、肋骨をなでたり、アイロニストの才能をパロディにしたり、「How banal」(なんて陳腐なんだ)と言ったりするリスクを厭わないかもしれない。感傷やメロドラマへの非難。信憑性。法のない投獄よりも、視線や嘲笑を恐 れる潜伏者や凝視者の世界に騙されようとする意志。誰が知っているのだろう。 これは、ブログ「Fiction Advocate」でさらに検証された:[31]。 仮説はこうだ: インフィニット・ジェスト』は、ウォレスがエッセイ『E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction』の中で呼びかけた革命的なフィクションのスタイルを、顕在化させ、ドラマ化しようとする試みである。そのスタイルとは、20世紀末の現代 フィクションを空洞化させた皮肉な剥離を、新たな真摯さが覆すというものである。ウォレスは、彼が生きている間にアメリカ文化の多くに蔓延し、悲しませた シニシズムへの解毒剤を書こうとしていた。彼は、私たちが再び語り合えるようなエンターテインメントを作ろうとしていたのだ。 アダム・ケリーは2010年のエッセイ「デイヴィッド・フォスター・ウォレスとアメリカ小説における新しい誠実さ」の中で、ウォレスと彼の世代の小説は誠 実さの復活と理論的な再認識によって特徴付けられ、20世紀の文学と自己の概念を支配していた真正性の強調に挑戦していると論じている。 [さらに、ジョナサン・フランゼン、マリリン・ロビンソン、[32]ザディ・スミス、デイヴ・エガーズ、[33]スティーヴン・グレアム・ジョーンズ、 [34]マイケル・チャボン、[35][36][37]、ヴィクター・ペレヴィンなど、数多くの作家が新たな真摯さの運動の貢献者として語られている [38]。 |

| In philosophy "New sincerity" has also sometimes been used to refer to a philosophical concept deriving from the basic tenets of performatism.[39] It is also seen as one of the key characteristics of metamodernism.[40] Related literature includes Wendy Steiner's The Trouble with Beauty and Elaine Scarry's On Beauty and Being Just. Related movements may include post-postmodernism, New Puritans, Stuckism, the kitsch movement and remodernism, as well as the Dogme 95 film movement led by Lars von Trier.[41] |

哲学において 「新しい真摯さ」はまた、パフォーマティズムの基本的な信条から派生した哲学的概念を指す言葉として使われることもある[39]。 また、メタモダニズムの重要な特徴のひとつと見なされている[40]。関連する運動としては、ポスト・ポストモダニズム、ニュー・ピューリタン、スタッキ ズム、キッチュ運動、リモダニズム、ラース・フォン・トリアー率いるドグマ95映画運動などが挙げられる[41]。 |

| As a cultural movement "New sincerity" has been espoused since 2002 by radio host Jesse Thorn of PRI's The Sound of Young America (now Bullseye), self-described as "the public radio program about things that are awesome". Thorn characterizes new sincerity as a cultural movement defined by dicta including "maximum fun" and "be more awesome". It celebrates outsized celebration of joy, and rejects irony, and particularly ironic appreciation of cultural products. Thorn has promoted this concept on his program and in interviews.[42][43][44][45] In a September 2009 interview, Thorn commented that "new sincerity" had begun as "a silly, philosophical movement that me and some friends made up in college" and that "everything that we said was a joke, but at the same time it wasn't all a joke in the sense that we weren't being arch or we weren't being campy. While we were talking about ridiculous, funny things we were sincere about them."[46] Thorn's concept of "new sincerity" as a social response has gained popularity since his introduction of the term in 2002. Several point to the September 11, 2001, attacks and the subsequent wake of events that created this movement, in which there was a drastic shift in tone. The 1990s were considered a period of artistic works rife with irony, and the attacks shocked a change in the American culture. Graydon Carter, editor of Vanity Fair, published an editorial a few weeks after the attacks claiming that "this was the end of the age of irony".[47] Jonathan D. Fitzgerald for The Atlantic suggests this new movement could also be attributed to broader periodic shifts that occur in culture.[35] As a result of this movement, several cultural works were considered elements of "new sincerity",[35] but this was also seen to be a mannerism adopted by the general public, to show appreciation for cultural works that they happened to enjoy. Andrew Watercutter of Wired saw this as having been able to enjoy one's guilty pleasures without having to feel guilty about enjoying them, and being able to share that appreciation with others.[48] One such example of a "new sincerity" movement is the brony fandom, generally adult and primarily male fans of the 2010 animated show My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic which is produced by Hasbro to sell its toys to young girls. These fans have been called "internet neo-sincerity at its best", unabashedly enjoying the show and challenging the preconceived gender roles that such a show ordinarily carries.[49][50] A review of a 2016 play by Alena Smith The New Sincerity observes that it "captures the spirit of an age lightly lived and easily forgotten, which strives for a significance and a magnitude that won't be easily achieved".[51] In the early 2020s, the shift toward a more overt embrace of new sincerity was codified in James Poniewozik's New York Times piece titled, "How TV Went From David Brent to Ted Lasso."[52] Poniewozik details the shift, arguing that "In TV's ambitious comedies, as well as dramas, the arc of the last 20 years is not from bold risk-taking to spineless inoffensiveness. But it is, in broad terms, a shift from irony to sincerity. By 'irony' here, I don't mean the popular equation of the term with cynicism or snark. I mean an ironic mode of narrative, in which what a show 'thinks' is different from what its protagonist does. Two decades ago, TV's most distinctive stories were defined by a tone of dark or acerbic detachment. Today, they're more likely to be earnest and direct." Poniewozik goes on to address possible impetus for doing away with the disjoint between writer and character ascribing some cause to what Emily Nussbaum calls "bad fans",[53] but the thrust of his critique centers on the possible shift towards the representation of new and previously unrepresented voices. As Poniewozik puts it, "In some cases, it's also a question of who has gotten to make TV since 2001. Antiheroes like David Brent and Tony Soprano, after all, came along after white guys like them had centuries to be heroes. The voices and faces of the medium have diversified, and if you're telling the stories of people and communities that TV never made room for before, skewering might not be your first choice of tone. I don't want to oversimplify this: Series like Atlanta, Ramy, Master of None and Insecure all have complex stances toward their protagonists. But they also have more sympathy toward them than, say, Arrested Development."[54] With this perspective in mind and considering the shift towards an embrace of diverse views and opinions,[55] the appearance of new sincerity in film and television is understandable if not expected. However, it is important to note that prior to the current shift towards new sincerity, popular culture had embraced a period of "high irony", as Poniewozik deems it.[54] |

文化運動として 「新しい真摯さ」は、PRIの『サウンド・オブ・ヤング・アメリカ』(現ブルズアイ)のラジオ・ホスト、ジェシー・ソーンによって2002年から提唱され ている。ソーンは、新しい真摯さを「最大限の楽しみ」や「より素晴らしくあること」などで定義される文化的なムーブメントと位置づけている。それは、喜び を大げさに祝うことを賞賛し、皮肉、特に文化的生産物に対する皮肉な評価を拒絶する。ソーンは自身の番組やインタビューでこのコンセプトを宣伝している [42][43][44][45]。 2009年9月のインタビューでソーンは、「新しい真摯さ」は「私と何人かの友人たちが大学で作り上げた愚かで哲学的なムーブメント」として始まったとコ メントし、「私たちが言ったことはすべてジョークだったが、同時に、私たちがアーチ的でもキャンピーでもないという意味では、すべてがジョークではなかっ た。ばかばかしくて面白いことを話しながらも、私たちはそれに対して誠実だった」[46]。 社会的反応としての「新しい誠実さ」というソーンのコンセプトは、彼が2002年にこの言葉を発表して以来、人気を博している。このムーブメントを生み出 した2001年9月11日の同時多発テロとそれに続く事件の後、トーンが劇的に変化したことを指摘する人もいる。1990年代はアイロニーに満ちた芸術作 品の時代とされ、同時多発テロはアメリカ文化の変化に衝撃を与えた。Vanity Fair』誌の編集者であるグレイドン・カーターは、同時多発テロの数週間後に社説を発表し、「これはアイロニーの時代の終わりである」と主張した [47]。『The Atlantic』誌のジョナサン・D・フィッツジェラルドは、この新しいムーブメントは、文化において起こる、より広範な周期的なシフトにも起因する可 能性があると示唆している[35]。 この動きの結果、いくつかの文化作品は「新しい真摯さ」の要素とみなされた[35]が、これは一般大衆がたまたま享受した文化作品への感謝を示すために採 用した作法であるともみなされた。ワイアードのアンドリュー・ウォーターカッターはこれを、楽しむことに罪悪感を感じることなく、後ろめたい楽しみを楽し むことができるようになったこと、そしてその感謝を他者と分かち合うことができるようになったことと見ている[48]。これらのファンは、臆することなく この番組を楽しみ、このような番組が通常担っている先入観にとらわれた性別の役割に挑戦し、「最高のインターネット・ネオ真心」と呼ばれている[49] [50]。 アレナ・スミスによる2016年の戯曲『The New Sincerity』の批評は、「軽やかに生き、忘れられやすい時代の精神を捉えており、簡単には達成できない意義と大きさを目指している」と評している[51]。 2020年代初頭、新たな真摯さをよりあからさまに受け入れる方向へのシフトは、ジェームズ・ポニウォジックの「テレビはいかにしてデイヴィッド・ブレン トからテッド・ラッソになったか」と題されたニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事で体系化された[52]。ポニウォジックは、「テレビの野心的なコメディやド ラマにおいて、過去20年の弧は、大胆なリスクテイクから無気力へのものではなかった。しかし、大雑把に言えば、皮肉から誠実さへの転換である。ここで言 う「皮肉」とは、一般的に皮肉や悪口と同一視されるような意味ではない。番組が「考えていること」と「主人公がやっていること」が異なるという、皮肉な物 語の様式という意味である。20年前、テレビの最も特徴的なストーリーは、暗いトーンや辛辣な冷淡さによって定義されていた。今日では、真面目で直接的な ものが多くなっている」。ポニエウォジックは、脚本家と登場人物の間の断絶をなくすきっかけになりうるものについて、エミリー・ヌスバウムが「悪いファ ン」と呼ぶものに何らかの原因があるとして、さらに言及する[53]が、彼の批評の中心は、新しい声や、以前は表現されていなかった声を表現する方向にシ フトする可能性にある。ポニーウォジックが言うように、「場合によっては、2001年以降、誰がテレビを作るようになったかという問題でもある。デヴィッ ド・ブレントやトニー・ソプラノのようなアンチヒーローは、結局のところ、彼らのような白人が何世紀もヒーローであり続けた後に登場したのだ。テレビとい うメディアの声や顔は多様化し、テレビがこれまで扱うことのなかった人々やコミュニティの物語を語る場合、串刺しにするのは最初のトーンの選択ではないか もしれない。このことを単純化しすぎたくはない: アトランタ』、『ラミー』、『マスター・オブ・ノーン』、『インセキュア』のようなシリーズはどれも、主人公に対して複雑なスタンスを持っている。しか し、例えば『アレステッド・ディベロプメント』よりも、彼らに対する共感がある」[54]。このような視点を念頭に置き、多様な意見や見解を受け入れる方 向にシフトしていることを考えれば[55]、映画やテレビに新たな誠実さが現れることは、期待されていないとしても理解できる。しかし、現在のような新た な真摯さへのシフトに先立ち、大衆文化は、ポニエヴォジックが考えるように、「高い皮肉」の時代を受け入れていたことに注意することが重要である [54]。 |

| Regional variants This conception of "new sincerity" meant the avoidance of cynicism, but not necessarily of irony. In the words of Alexei Yurchak of the University of California, Berkeley,[56] it "is a particular brand of irony, which is sympathetic and warm, and allows its authors to remain committed to the ideals that they discuss, while also being somewhat ironic about this commitment".[56][57] In American poetry Since 2005, poets including Reb Livingston, Joseph Massey, Andrew Mister, and Anthony Robinson have collaborated in a blog-driven poetry movement, described by Massey as "a 'new sincerity' brewing in American poetry – a contrast to the cold, irony-laden poetry dominating the journals and magazines and new books of poetry".[58] Other poets named as associated with this movement, or its tenets, have included David Berman, Catherine Wagner, Dean Young, Matt Hart, Miranda July (who is also a filmmaker herself),[59] Tao Lin,[59] Steve Roggenbuck,[59] D. S. Chapman, Frederick Seidel, Arielle Greenberg,[17] Karyna McGlynn, and Mira Gonzalez.[60] |

地域的変種 この「新しい真摯さ」という概念は、シニシズムの回避を意味するが、必ずしもアイロニーの回避を意味するわけではない。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の アレクセイ・ユルチャック[56]の言葉を借りれば、それは「共感的で温かく、作者が議論する理想にコミットし続けることを可能にする一方で、このコミッ トメントを多少皮肉ることもできる、特殊な皮肉のブランド」である[56][57]。 アメリカの詩において 2005年以降、レブ・リヴィングストン、ジョセフ・マッセイ、アンドリュー・ミスター、アンソニー・ロビンソンといった詩人たちがブログ主導の詩運動に 協力しており、マッセイはこれを「アメリカの詩の中に生まれつつある 「新しい誠実さ」-ジャーナルや雑誌、新刊の詩集を支配している、冷淡で皮肉に満ちた詩とは対照的なもの」と表現している。 [58]この運動、あるいはその信条に関連する詩人としては、他にデヴィッド・バーマン、キャサリン・ワグナー、ディーン・ヤング、マット・ハート、ミラ ンダ・ジュライ(彼女自身も映画監督である)、[59]タオ・リン、[59]スティーヴ・ロッゲンバック、[59]D・S・チャップマン、フレデリック・ サイデル、アリエル・グリーンバーグ、[17]カリナ・マクグリン、ミラ・ゴンザレスなどが挙げられる[60]。 |

| American Eccentric Cinema Metamodernism The Cult of Sincerity Post-irony Reconstructivism |

アメリカン・エキセントリック・シネマ メタモダニズム 真摯さのカルト ポスト・アイロニー 再建主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_sincerity |

|

| Sincerity and Authenticity is a

1972 book by Lionel Trilling, based on a series of lectures he

delivered in 1970 as Charles Eliot Norton Professor at Harvard

University.[1] The lectures examine what Trilling described as "the moral life in process of revising itself", a period of Western history in which (argues Trilling) sincerity became the central aspect of moral life (first observed in pre–Age of Enlightenment literature such as the works of Shakespeare), later to be replaced by authenticity (in the twentieth century). The lectures take great lengths to define and explain the terms "sincerity" and "authenticity", though no clear, concise definition is ever really postulated, and Trilling even considers the possibility that such terms are best not totally defined. However, he does use the short formula "to stay true to oneself" to characterize the modern ideal of authenticity and differentiates it from the older ideal of being a morally sincere person. Trilling draws on a wide range of literature in defense of his thesis, citing many of the key (and some more obscure) Western writers and thinkers of the last 500 years. Trilling's Sincerity and Authenticity has been of influence on literary and cultural critics and philosophers, such as Templeton and Kyoto Prize winner Charles Taylor in his book The Ethics of Authenticity. See also, the more recent work of Kyle Michael James Shuttleworth in The History and Ethics of Authenticity: Freedom, Meaning and Modernity (2020), and Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio in You and Your Profile: Life After Authenticity (2021) |

『誠実と真正』は、ライオネル・トリリングが1972年に発表した著書 である。1970年にハーバード大学のチャールズ・エリオット・ノートン教授として行った一連の講義を基に執筆された[1]。 この講義では、「自己修正の過程にある道徳的生活」と表現した、西洋の歴史における一時期(トリリングの主張によれば)を考察している。この時代、誠実さ が 道徳生活の中心的な側面となった(シェイクスピア作品などの啓蒙時代以前の文学作品に初めて見られる)。その後、20世紀には真正性が取って代わった。講 演では、「誠実」と「真正性」という用語を定義し、説明することに多くの時間を割いているが、明確で簡潔な定義は実際には提示されておらず、トリリング は、これらの用語を完全に定義しないほうが良い可能性もあると考えている。しかし、彼は「自分に忠実であること」という短い公式を使って、現代の真正性の 理想を特徴づけ、道徳的に誠実な人間であることの古い理想と区別している。トリリングは、自身の論文を擁護するために幅広い文献を参照し、過去500年間 の西洋の主要な(そして一部はそれほど知られていない)作家や思想家の多くを引用している。 トリリングの『誠実と真正』は、テンプルトンや京都賞受賞者のチャールズ・テイラー(著 書『真正の倫理』)などの文学・文化評論家や哲学者に影響を与えて いる。また、カイル・マイケル・ジェームズ・シャトルワースの近著『The History and Ethics of Authenticity: Freedom, Meaning and Modernity』(2020年)や、ハンス=ゲオルク・メラーとポール・J・ダンブロシオの『You and Your Profile: Life After Authenticity』(2021年)も参照のこと。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆