ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスの宗教学

Religion in Wilfred Cantwell Smiths

ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスの宗教学

Religion in Wilfred Cantwell Smiths

ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスにおける宗教(Religion)の概念を検討する のがこのページの目標である。ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスは『宗教の意味と終焉』において、「宗教」という言葉が「定義不可能」であり、その 理由は詞形(形容詞形の「宗教的(religious)」に対して「宗教(religion)」)が、現実を歪めるからだと主張する。さらに、この言葉は 西洋 文明に特有のものであり、他の文明の言語にはこれに対応する言葉はない、という。スミスはまた、この用語が「偏見を生み」「敬虔さを殺す」ことができると 指摘し ている。彼はつまりこの用語「宗教(religion)」がその目的を終えたとみなしている。

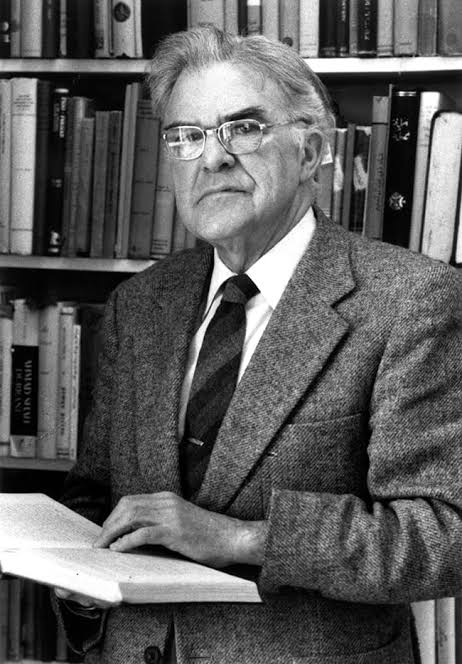

人物評:"Wilfred Cantwell Smith OC FRSC[15] (1916–2000) was a Canadian Islamicist, comparative religion scholar,[16] and Presbyterian minister.[17] He was the founder of the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University in Quebec and later the director of Harvard University's Center for the Study of World Religions. The Harvard University Gazette said he was one of the field's most influential figures of the past century.[18] In his 1962 work The Meaning and End of Religion he notably questioned the modern sectarian concept of religion.[19]"- Wilfred Cantwell Smith.

「ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスOC

FRSC[15](1916-2000)はカナダのイスラーム学者、比較宗教学者[16]、長老派の牧師である[17]。

ケベックのマギル大学イスラーム研究所を創設し、後にハーバード大学世界宗教研究センター長を務めた。ハーバード大学公報は、彼が前世紀のこの分野で最も

影響力のある人物の一人であると述べている[18]。

1962年の著作『宗教の意味と終わり』では、宗教の現代の宗派的概念に顕著な疑問を呈している[19]」。

● The Meaning and End of Religion, by Wilfred Cantwell Smith, 1991.[1963]

| Foreword (pp.

v-xii), by John Hick |

Wilfred Cantwell

Smith’s The Meaning and End of Religion has already become a modern

classic of religious studies. Such a work should be continuously

available, both to students and the general public, and its reissue now

is to be warmly welcomed. Although I can add nothing whatever to the

book itself, I am happy to have the privilege of pointing out its very

great significance for some of our most lively current discussions and

debates. | ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミス著『宗教の意味と終焉』

は、すでに宗教研究の現代的な古典となっている。このような著作は、学生にも一般市民にも継続的に提供されるべきものであり、今回の再発行は温かく歓迎さ

れるべきものである。私はこの本自体には何も付け加えることはできないが、現在最も活発な議論や討論のいくつかに対して、この本の非常に大きな意義を指摘

する特権を得ることができたことを嬉しく思っている。 |

| CHAPTER ONE

Introduction (pp. 1-14) WHAT IS RELIGION? What is religious faith? |

Such questions,

asked either from the outside or from within, must nowadays be set in a

wide context, and a rather exacting one. The modern student may look

upon religion as something that other people do, or he may see and feel

it as something in which also he himself is involved. In either case he

approaches any attempt to understand it conscious not only of many

traditional problems but also of new complications. Sensitive men have

ever known that they are dealing here with a mystery. Some modern

investigators have thought to... | こ

のような問いは、外からであれ内からであれ、今日、広い文脈で、しかもかなり厳密な文脈で設定されなければならないのです。現代の学生は、宗教を他人がす

るものと見なすかもしれませんし、自分自身も関わっているものと見なし、感じるかもしれません。どちらの場合でも、宗教を理解しようとするとき、多くの伝

統的な問題だけでなく、新たな複雑さも意識して取り組むことになります。感受性の強い人は、自分が謎を相手にしていることを常に意識している。現代の研究

者の中には、このようなことを考えた人もいるが…… |

| CHAPTER TWO

‘Religion’ in the West (pp. 15-50) |

IT IS CUSTOMARY

nowadays to hold that there is in human life and society something

distinctive called ‘religion’; and that this phenomenon is found on

earth at present in a variety of minor forms, chiefly among outlying or

eccentric peoples, and in a half-dozen or so major forms. Each of these

major forms is also called ‘a religion’, and each one has a name:

Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and so on.

I suggest that we might investigate our custom here, scrutinizing our

practice of giving religious names and indeed of calling them

religions. So firmly fixed in our minds has this... | 今

日、人間の生活と社会には「宗教」と呼ばれる独特のものがあり、この現象は現在地球上に、主に辺境の地や風変わりな民族の間に見られるさまざまな小さな形

態と、半ダースほどの大きな形態とがあるとするのが通例となっている。これらの主要な形態はそれぞれ「宗教」とも呼ばれ、キリスト教、仏教、ヒンズー教な

ど、それぞれ名前がついている。ここで、私たちの習慣を調べてみてはどうだろう。宗教的な名前をつけ、実際に宗教と呼んでいる私たちの習慣を精査してみる

のである。私たちの心の中には、このようにしっかりと固定されている... |

| CHAPTER THREE

Other Cultures. ‘The Religions’ (pp. 51-79) |

THE CONCEPT

‘RELIGION’, then, in the West has evolved. Its evolution has included a

long-range development that we may term a process of reification:

mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive it

as an objective systematic entity. In this development one factor has

been the rise into Western consciousness in relatively recently times

of several so conceived entities, constituting a series: the religions

of the world. This point has in our day become of dominating

importance. Inquiry in this realm no longer concerns itself with only

one tradition; our understanding of man’s religious situation, our

meanings for... | 西

洋では、「宗教」という概念は進化してきた。その進化には、再定義のプロセスとでも呼ぶべき長期的な発展が含まれています。精神的に宗教を物にして、次第

に客観的な体系的実体として意識するようになった。この発展には、比較的最近になって、西洋人の意識の中に、そのように考えられたいくつかの実体が台頭し

てきたことが一つの要因となっている。この点は、現代では圧倒的な重要性を持つようになった。この領域での探求は、もはや一つの伝統だけに関わるものでは

ない。人間の宗教的状況に対する理解、宗教的意味に対する理解、そして、宗教的価値観に対する理解もまた、重要である。 |

| CHAPTER FOUR The

Special Case of Islam (pp. 80-118) |

SO FAR we have

not dealt with the Islamic situation. This particular case has been

reserved for separate treatment because it is both unusual and

intricate. It is in some ways different from the others, and in some

ways similar. On both scores it is illuminating.

We may take the differences first, since they lie closer to the

surface. The first observation is that of all the world’s religious

traditions the Islamic would seem to be the one with a built-in name.

The word ‘Islam’ occurs in the Qur’an itself, and Muslims are

insistent on using this term to designate... | こ

れまで、私たちはイスラムの状況を扱ってこなかった。この特殊なケースを別扱いにしたのは、それが異常であり複雑であるからである。ある意味では他の事例

と異なっており、またある意味では類似している。どちらの点でも、この事件は示唆に富んでいる。まず、表面的な違いから説明しよう。第一に、世界の宗教的

伝統の中で、イスラム教はその名称を内蔵しているように思われることである。イスラム教」という言葉はコーランの中に出てくるが、イスラム教徒はこの言葉

を使うことに固執している... |

| CHAPTER FIVE Is

the Concept Adequate? (pp. 119-153) |

IF WE LOOK at the

development of mankind’s religious life in some sort of total

historical perspective, then, we recognize that an understanding of it

may involve new terms of understanding. As the content of our human

awareness grows in this realm in modern times, so also the forms of our

awareness are undergoing, and should undergo, evolution. In particular,

my argument so far has been devoted to bring into consciousness the

fact that a use of the concept religion, the religions, and the

specific named religions, has been one part of the whole process, and a

particular, limited, and... | 人

類の宗教生活の発展をある種の総合的な歴史的観点から見ると、それを理解することは、新しい理解の用語を含むかもしれないことを認識する。現代において、

人間の意識の内容がこの領域で成長するにつれて、意識の形態も進化しつつあり、また進化させるべきであると思われる。特に、私のこれまでの議論は、宗教と

いう概念の使用、宗教、そして特定の名前のついた宗教が、全体のプロセスの一部であり、特定の、限られた、そして...であるという事実を意識化すること

に専念してきたのである。 |

| CHAPTER SIX The

Cumulative Tradition (pp. 154-169) |

THE MAN of

religious faith lives in this world. He is subject to its pressures,

limited within its imperfections, particularized within one or another

of its always varying contexts of time and place, and he is observable.

At the same time and because of his faith or through it, he is or

claims to be in touch with another world transcending this. The duality

of this position some would say is the greatness and some the very

meaning of human life; the heart of its distinctive quality, its

tragedy and its glory. Others would dismiss the claim as false,

though... | 信

仰を持つ人は、この世界に生きている。彼はその圧力にさらされ、その不完全さの中で制限され、時間と場所の常に変化する文脈の一つまたは別の中に特定さ

れ、彼は観察可能である。同時に、その信仰ゆえに、あるいは信仰を通じて、この世を超越したもう一つの世界と接触している、あるいは接触していると主張し

ているのである。この立場の二面性こそ、ある者は人間の生の偉大さであり、ある者はその意味そのものであると言い、その独特の質、悲劇と栄光の核心である

と言うだろう。しかし、そのような主張は誤りであると断じる人もいる…… |

| CHAPTER SEVEN

Faith (pp. 170-192) |

ON

THE ONE HAND, great religious minds have regularly affirmed that faith

cannot be precisely delineated or verbalized; that it is something too

profound, too personal, and too divine for public exposition. And I

myself have been at pains to stress throughout this study that men’s

faith lies beyond that sector of their religious life that can be

imparted to an outsider for his inspection.

On the other hand, different men, at differing times and places,

adherents of differing traditions, have differed conspicuously in

whatever they have had to say on the subject. Again, our own study has

not failed... | 一

方では、偉大な宗教家たちは、信仰は正確に定義したり、言語化したりすることはできない、それは公に説明するにはあまりにも深く、あまりにも個人的で、あ

まりにも神聖なものである、と常々断言している。そして私自身、この研究を通して、人の信仰は、部外者に伝えられるような宗教生活の領域を超えたところに

あることを強調することに苦心してきた。一方、時代や場所、伝統の違いによって、このテーマで語るべきことは異なっている。また、私たち自身の研究も失敗

していない......。 |

| CHAPTER EIGHT

Conclusion (pp. 193-202) |

USUALLY

WE SEE the world through a pattern of concepts that we have inherited.

Sometimes these windows need cleaning: so much so that almost we may be

seeing the windows that we have constructed rather than the world

outside. Sometimes too on thoughtful examination we may come to

recognize that by rearranging the windows as well as by cleaning them

we could get a better view of the real world beyond. Certainly we may

be grateful to our ancestors who have built these windows through which

we see. Without them we should still be walled up within the confines

of... | 通

常、私たちは、自分たちが受け継いできた概念のパターンを通して世界を見ている。そのため、私たちは外の世界ではなく、自分たちが作り上げた窓を見ている

ようなものだ。しかし、よく考えてみると、窓を掃除するだけでなく、窓の配置を変えることで、よりよく外の世界を見ることができることに気づくかもしれな

い。確かに、私たちは、この窓を作った先人たちに感謝しなければならない。この窓がなかったら、私たちはまだ...... |

| Wilfred Cantwell Smithの単純なテーゼ | ・

地上にも天国にも宗教というものがないと考えれば、宗教がないわけであるから、宗教は真理でも、誤りであるという主張も無効である。宗教の真偽の議論は不

毛である。次に、もし、人が宗教という概念を諦めなければ(=固執すれば、とも取れる)、「宗教が真理であると言った場合、どのような言明が可能になるの

か?」「宗教が誤りであると言った場合、それには(そのような前提条件とした場合)どのような言明が可能か?」それらについて探究すべきだろう。 ・キリスト教(仏教でもいい)を可能なものにする条件は、それを自分のものとして我有し、実践している限り「真理」になることができる。 ・宗教的生活は、抽象的なものではなく、具体的なものだ。つまり、宇宙大の宗教(例えばキリスト教)というものなどない。 ・宗教に真理があるとすれば、それは各人の信仰の中にある。 ・キャントウェル・スミスの宗教真理観は、アリストテレスの可能態のような議論であるともいえる——つまり未来に向かって拓いている。アリストテレス命題 の真理を含むとまで言う(スミス 1971: 82)。 ・「神は人間を見ている」という主張は、無謬論として退けられている。 ・宗教を人間生活の外側に外在化して研究するという態度ではなく、宗教を内在化した人間( "personalist" by C. Geertz)が、宗教をどのように考えるのかということが重要(葛西 1971:146-147)。 ・人間は変化を伴侶として生きていかねばならない(=宗教に普遍性を信じない立場をこのように表現できる) |

●クリフォード・ギアーツの、スミスの"On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies"

の書評 On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies, by Wilfred Cantwell

Smith, Mouton (Hawthorne, New York), 351 pp., DM 105(approx. $52.50)

| The "personalist" theme appears,

indeed virtually explodes, as part of the analysis of comparative

religion in Wilfred Cantwell Smith's provocative new collection of

Arabist essays, On Understanding Islam. For about twenty years now,

Smith, professor of the comparative history of religion at Harvard and

an ordained minister in the United Church of Canada, the union of

Methodists, Congregationalists, and softer Presbyterians formed there

in the 1920s, has been developing a fideist view of Islam as centered

around the inner commitment of the individual Muslim to God, "the act

of dedication wherein he as a specific and live person in his concrete

situation is deliberately and numinously related to a transcendent

divine reality which he recognizes, and to a cosmic imperative which he

accepts." |

ウィルフレッド・キャントウェル・スミスの刺激的な新しいアラブ系エッ

セイ集"On Understanding

Islam"(イスラームの理解について)では、比較宗教学の分析の一環として「人格主義」のテーマが登場し、事実上、爆発している。ハーバード大学の比

較宗教史の教授であり、1920年代にカナダで結成されたメソジスト、会衆派、ソフト・プレズビテリアンの連合教会の聖職者でもあるスミスは、20年ほど

前から、フィデリスム的な見解を展開してきた。それは、「具体的な状況の中で、具体的で生きた人間としての自分が、自分が認識する超越的な神の現実と、自

分が受け入れる宇宙の命令とを、意図的に、かつ能動的に結びつけるための献身的な行為」である。 |

| Smith, canvassing texts, sorting

out grammar, anatomizing words, traces this conception of what Islam as

a faith amounts to through a series of subjects central to Muslim

thought from the Prophet's time to ours: the foundations of law, the

nature of truth and reality, the significance of the Confession of

Faith, the relative importance of inward attitude and outward behavior,

and the meaning of the term "Islam" itself. Relentlessly, and with a

scholastic intensity that may not entirely serve his cause (a fair

amount of the book's Arabic is left untranslated and precious little

help is given the reader who may not know Ibn Battah from Ibn Babawah),

Smith builds an ingenious case for an ingenious argument: Islam, once a

human response to a divine summons, or supposed to be such, has been

steadily transformed into a reified system of moralized cultural

ideals. Its history is that of the progressive, if yet incomplete,

triumph of religio over pietas. |

スミスは、テキストを吟味し、文法を整理し、言葉を解剖しながら、預言

者の時代から私たちの時代までのムスリムの思想の中心となる一連のテーマを通して、信仰としてのイスラム教がどのようなものであるかという概念をたどって

いる。すなわち、法の基礎、真実と現実の性質、信仰告白の意義、内的態度と外的行動の相対的重要性、そして「イスラム教」という言葉自体の意味である。こ

の本のアラビア語のかなりの部分は翻訳されておらず、Ibn BattahとIbn

Babawahを知らない読者にはほとんど助けにならない)、Smithは執拗に、そして完全に彼の目的のためではないかもしれない学究的な激しさで、独

創的な議論を構築する。かつては神の召喚に対する人間の応答であった、あるいはそうであるとされていたイスラム教は、道徳化された文化的理想の再構成され

たシステムへと着実に変容してきた。その歴史は、まだ不完全ではあるが、religioがpietasに勝利するという進歩的なものである。 |

| Smith is able in this way to

clarify much that is obscure in Islamic history—the crystallization of

religious communalism in Mughal India, the peculiar rigidity of Islamic

modernism, the equivocal nature of the encounter with Christianity. But

the question is whether this deeply Protestant notion of what faith is,

and what history does to it, does not itself impose on Islam something

alien to it and to its development. The replacement of a primitive

vision of the Divine Word and an immediate response to it by a

conceptual prison of abstract beliefs, the dogmas of scribes and

pedants, is too reminiscent of other faiths to be entirely credible.

And when this religious reification of personal faith is discerned as

well in every tradition from the Hindu to the Hebraic, so that the

history of Islam becomes but "one link in a total chain" of something

called "the world history of religion," the sense of Muslim facts

supporting Christian ideas merely grows. |

スミスはこのようにして、ムガル帝国における宗教的コミュナリズムの結晶、イスラム近代主義の特異な硬直性、キリスト教との出会いの曖昧な性質など、イスラム史において不明瞭な点の多くを明らかにすることができる。しかし問題は、信仰とは何か、そして歴史は信仰に何をもたらすのかというプロテスタント的な概念が、それ自体、イスラムとその発展にとって異質なものをイスラムに押し付けていないかということである。

神の言葉の原始的なビジョンとそれに対する即時の反応を、抽象的な信念の概念的な牢獄、つまり律法学者や教育者のドグマに置き換えることは、他の信仰をあ

まりにも彷彿とさせるため、完全に信用することはできない。そして、このような個人的な信仰の宗教的再構成が、ヒンズー教からヘブライ教までのあらゆる伝

統にも見られるようになり、イスラム教の歴史が「宗教の世界史」と呼ばれるものの「全体的な連鎖の中の1つのリンク」に過ぎなくなると、イスラム教の事実

がキリスト教の思想を支えているという感覚が強まるだけである。 |

| Yet, for all that, one does see

something of what Smith means when one turns to what, for the moment

anyway, is the paradigm expression of "Islamic revivalism," the

writings of Imam Khomeini, now given a scholarly and felicitous

translation under the title Islam and Revolution by Hamid Algar, and to

the discreetly apologetic commentary and notes, a sort of Muslim

catechism, which Algar, an English-born convert to Islam, educated at

Cambridge and teaching at Berkeley, appends to them. The ideological

quality of Khomeini's own writings is, of course, intense; even his

most purely religious discourses, the "Lectures on the Surat al-Fatiha"

(the first verse of the Koran), for example, are laced with references

to current conflicts and contemporary enemies ("There's many a [Sufi]

cloak that deserves the fire"). But in Algar's commentary, extensive,

learned, carefully instructive, polite, the cast of mind—what I suppose

Smith would call, as he calls that of the rather similar Mughal

reformers such as Aurangzeb, "a rigid, structured, crystallized version

of Islam...not a [spiritual] revival but a revival...of the view of

Islam-as-a-closed-system"—appears in a less headlong and thus in some

ways less idiosyncratic form. |

ホメイニ師の著作は、"Islam and Revolution

(イスラムと革命)"というタイトルでハミド・アルガーによって学術的かつ丁寧に翻訳されている。また、ケンブリッジで教育を受け、バークレーで教鞭を

とるイギリス生まれのイスラム教への改宗者であるアルガーが、イスラム教のカテキズムのような控えめな謝罪の解説と注釈を付けています。ホ

メイニ自身の著作のイデオロギー的な質はもちろん高い。例えば、彼の最も純粋な宗教的言説である「Surat

al-Fatiha(コーランの第一節)に関する講義」でさえ、現在の紛争や現代の敵への言及がふんだんに盛り込まれている(「火に値する多くの(スー

フィーの)マントがある」)。しかし、アルガーの解説では、広範で、学識があり、丁寧に教えてくれる。スミスが、アウラングゼーブのような

似たようなムガル帝国の改革者をそう呼んでいるように、心の動きは、「硬直した、構造化された、結晶化されたイスラムのバージョン......精神的な)

復活ではなく、閉ざされたシステムとしてのイスラムの見方の復活」と呼んでいるのだろうが、そのような姿は、あまり突飛ではなく、ある意味では特異ではな

い形で現れているのである。 |

| The implicit movement of Algar's

commentary is toward portraying the sort of political religionism

Khomeini exemplifies as the recovered consensus of the Muslim

community. Himself a Sunni, Algar not only minimizes Sunni-Shi'i

tensions to the point of barely mentioning them (and then as vanishing

relics), but he conceives of the Ayatollah's doctrinal radicalism as

the essential Islam, constantly obscured by Egyptian traditionalists,

Iraqi Arabizers, Turkish separationists, and, of course, Western

evangelizers. (Khomeini himself is less reticent—"This is the root of

the matter: Sunni-populated countries believe in obeying their rulers,

whereas the Shi'is have always believed in rebellion.") Where Algar,

its exponent, and Smith, its historian, differ is not on what "Islamic

revivalism" is, but on what—authentic faith or flight from it—it is

that is being revived. |

アルガーの解説の暗黙の動きは、ホメイニが例示したような政治的宗教主義を、イスラム社会の回復されたコンセンサスとして描くことである。自身もスンニ派であるアルガーは、スンニ派とシーア派の緊張関係をほとんど言及しない程度に(しかも消えゆく遺物として)最小化するだけでなく、アヤトラの教義上の急進主義を、エジプトの伝統主義者、イラクのアラブ化主義者、トルコの分離主義者、そしてもちろん西洋の伝道者によって常に覆い隠されている本質的なイスラムとして考えているのである。(ホメイニ自身は、「これは問題の根源だ」と控えめに語っている。スンニ派の国々は支配者に従うことを信条としているが、シーア派は常に反逆を信条としている」と。) その提唱者であるアルガーとその歴史家であるスミスが異なるのは、「イスラム復興主義」とは何かということではなく、何が復興されようとしているのか、真の信仰なのか、それとも信仰からの逃避なのか、ということである。 |

| The tendency has always been

marked among Western Islamicists, of whom Algar is one as much as

Smith, to try to write Muslim theology from without, to provide the

spiritual self-reflection they see either as somehow missing in it or

as there but clouded over by routine formula-mongering. D.B. Macdonald

made al-Ghazzali into a kind of Muslim St. Thomas. Ignaz Glodziher

centered Islam in traditionalist legal debates, and Louis Massignon

centered it in the Sufi martyrdom of al-Hallaj. Henri Laoust defended

puritan fundamentalism from the charge of heresy. A half-conscious

desire not just to understand Islam but to have a hand in its destiny

has animated most of the major scholars who have written on it as a

form of faith. |

スミスと同様にアルガーもその一人であるが、西欧のイスラム主義者の間

では、イスラム神学を外部から書こうとする傾向が常に顕著であり、イスラム神学に欠けている、あるいは存在していても日常的な公式崇拝によって曇っている

とみなす精神的な自己省察を提供しようとする。D.B.マクドナルドは、アル=ガッツァーリを一種のイスラム教徒の聖トマスに仕立て上げた。イグナス・グ

ロッジハーはイスラム教を伝統的な法律の議論の中に位置づけ、ルイ・マシニョンはイスラム教をスーフィーの殉教者であるアル・ハラージの中に位置づけた。

アンリ・ラウストは、ピューリタン原理主義を異端の罪から守った。イスラム教を理解するだけでなく、その運命に関与したいという半ば意識的な願望が、信仰

の一形態としてのイスラム教について書いた主要な学者のほとんどを動かしている。 |

| Something of the insights thus

gained and of the misunderstandings thus engendered, both of them

profound, can be seen from the excellent collection of French and

German "Orientalist" essays, carefully selected and fluently translated

by Merlin Swartz as Studies on Islam. The essays, which range in time

from 1913 (Goldziher's) to 1975 (one on Hanbali rigorism by Laoust's

student, George Makdisi) and in subject from Western interpretations of

Sufism (R. Caspar) to recent studies on Muhammad (Maxime Rodinson),

make any simple political interpretation of at least modern

"Orientalism" seem difficult to sustain; almost all are unworldly to a

fault. But they raise, as do Smith's and Algar's works, the even more

troubling question: how far can a wish to improve Islam comport with

the wish to understand it? If studies of "Islam" from the sociological

side have trouble getting close enough to their subject to avoid

schematizing it, those from the religious side have trouble maintaining

enough distance to avoid remaking it. |

このようにして得られた洞察と、このようにして生じた誤解(いずれも深

遠なものである)の一部は、フランスとドイツの「オリエンタリズム」エッセイを厳選し、マーリン・スワルツが『Studies on

Islam』として流暢に翻訳した優れたコレクションから見ることができる。時代的には1913年(Goldziherのもの)から1975年

(Laoustの弟子であるGeorge Makdisiによるハンバリの厳格主義に関するもの)まで、テーマ的にはスーフィズムの西洋的解釈(R.

Caspar)からムハンマドに関する最近の研究(Maxime

Rodinson)まで、少なくとも現代の「オリエンタリズム」に対する単純な政治的解釈を維持することは困難であると思わせるエッセイである。しかし、

スミスやアルガーの作品と同様に、これらの作品もまた、より厄介な問題を提起している。それは、イスラムを向上させたいという願いが、それを理解したいと

いう願いとどこまで一致するのかということである。社会学的な側面から「イスラム」を研究することが、対象を図式化することを避けるために十分な距離を取

ることが難しいとすれば、宗教的な側面から研究することは、対象を作り変えることを避けるために十分な距離を取ることが難しい。 |

| www.DeepL.com/Translator |

Wilfred Cantwell Smith's Views on religion

| In

his best known and most controversial work,[citation needed] The

Meaning and End of Religion: A New Approach to the Religious Traditions

of Mankind (1962),[16] Smith examines the concept of "religion" in the

sense of "a systematic religious entity, conceptually identifiable and

characterizing a distinct community".[28] He concludes that it is a

misleading term for both the practitioners and observers and it should

be abandoned in favour of other concepts.[16] The reasons for the

objection are that the word 'religion' is "not definable" and its noun

form ('religion' as opposed to the adjectival form 'religious')

"distorts reality". Moreover, the term is unique to the Western

civilization; there are no terms in the languages of other

civilizations that correspond to it. Smith also notes that it "begets

bigotry" and can "kill piety". He regards the term as having outlived

its purpose.[29] |

彼の最もよく知られ、最も議論を呼んだ著作

[citation needed]『宗教の意味と終焉』(The Meaning and End of Religion)において。A New

Approach to the Religious Traditions of Mankind (1962), [16]

スミスは「概念的に識別可能で、異なるコミュニティを特徴づける体系的な宗教的実体」という意味での「宗教」の概念について検討している。 [28]

彼はそれが実践者と観察者の両方にとって誤解を招く用語であり、他の概念を支持して放棄されるべきであると結論付けている[16]

異議の理由は、「宗教」という言葉が「定義不可能」であり、その名詞形(形容詞形の「宗教的」に対して「宗教」)が「現実を歪める」ためである。さらに、

この言葉は西洋文明に特有のものであり、他の文明の言語にはこれに対応する言葉はない。スミスはまた、この用語が「偏見を生み」、「敬虔さを殺す」ことが

できると指摘している。彼はこの用語がその目的を終えたとみなしている[29]。 |

| Smith

contends that the concept of religion, rather than being a universally

valid category as is generally supposed, is a peculiarly European

construct of recent origin. Religion, he argues, is a static concept

that does not adequately address the complexity and flux of religious

lives. Instead of the concept of religion, Smith proffers a new

conceptual apparatus: the dynamic dialectic between cumulative

tradition (all historically observable rituals, art, music, theologies,

etc.) and personal faith.[30] |

スミスは、宗教という概念は、一般に考えられているような

普遍的に有効なカテゴリーではなく、近年生まれたヨーロッパ特有の概念であると論じている。宗教は静的な概念であり、宗教的生活の複雑さと流動性を適切に

扱うことができない、と彼は主張する。宗教の概念の代わりに、スミスは新しい概念装置を提示している。それは累積的な伝統(歴史的に観察可能なすべての儀

式、芸術、音楽、神学など)と個人の信仰との間の動的な弁証法である[30]。 |

| Smith

sets out chapter by chapter to demonstrate that none of the founders or

followers of the world's major religions had any understanding that

they were engaging in a defined system called religion. The major

exception to this rule, Smith points out, is Islam which he describes

as "the most entity-like."[31] In a chapter titled "The Special Case of

Islam", Smith points out that the term Islam appears in the Qur'an,

making it the only religion not named in opposition to or by another

tradition.[32] Other than the prophet Mani, only the prophet Muhammad

was conscious of the establishment of a religion.[33] Smith points out

that the Arabic language does not have a word for religion, strictly

speaking: he details how the word din, customarily translated as such,

differs in significant important respects from the European concept. |

スミスは、世界の主要な宗教の創始者や信奉者の誰一人とし

て、自分たちが宗教という定義された体系に従事していることを理解していなかったことを、章立てで実証しているのである。このルールの主要な例外は、スミ

スが「最も実体に近い」と表現するイスラム教であると指摘する[31]。「イスラム教の特殊なケース」と題する章で、スミスはイスラムという言葉がコーラ

ンに現れており、他の伝統と対立して、あるいはそれによって名づけられなかった唯一の宗教になっていることを指摘する[32]。 [32]

預言者マニ以外では、預言者ムハンマドのみが宗教の成立を意識していた[33]

スミスは、アラビア語には厳密に言えば宗教を表す言葉がないことを指摘している。彼は、慣習的にそのように訳されているdinという言葉が、ヨーロッパの

概念と重要な点で異なることを詳細に述べている。 |

| The

terms for major world religions today, including Hinduism, Buddhism,

and Shintoism, did not exist until the 19th century. Smith suggests

that practitioners of any given faith do not historically come to

regard what they do as religion until they have developed a degree of

cultural self-regard, causing them to see their collective spiritual

practices and beliefs as in some way significantly different from the

other. Religion in the contemporary sense of the word is for Smith the

product of both identity politics and apologetics: |

ヒンズー教、仏教、神道など、今日の主要な世界宗教の用語

は、19世紀まで存在しなかった。スミスは、ある特定の信仰の実践者たちが、文化的な自尊心をある程度高め、自分たちの集団的な精神的実践や信仰を他とは

何らかの形で著しく異なるものと見なすようになるまで、自分たちの行うことを歴史的に宗教とみなすようになることはない、と指摘している。スミスにとっ

て、現代的な意味での宗教は、アイデンティティ・ポリティクスと弁証論の両方の産物である。 |

| One's

own "religion" may be piety and faith, obedience, worship, and a vision

of God. An alien "religion" is a system of beliefs or rituals, an

abstract and impersonal pattern of observables. A dialectic ensues, however. If one's own "religion" is attacked, by unbelievers who necessarily conceptualize it schematically, or all religion is, by the indifferent, one tends to leap to the defence of what is attacked, so that presently participants of a faith – especially those most involved in argument – are using the term in the same externalist and theoretical sense as their opponents. Religion as a systematic entity, as it emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, is a concept of polemics and apologetics.[34] |

自分の "宗教 "は信心深さや信仰、服従、崇拝、そして神のビジョンかもしれない。異質な「宗教」とは、信念や儀式のシステムであり、観察可能な抽象的で非人格的なパターンである。 しかし、弁証法が生じる。もし自分の「宗教」が、それを必然的に図式的に概念化する不信心者から、あるいは無関心者からすべての宗教が攻撃された場合、人 は攻撃されたものの擁護に躍起になる傾向がある。したがって、現在ある信仰の参加者は、特に議論に最も関与している人々は、その用語を相手と同じ外在主義 的・理論的意味で使っているのである。17世紀と18世紀に登場した体系的な存在としての宗教は、極論と弁証の概念である[34]。 |

| By way

of an etymological study of religion (religio, in Latin), Smith further

contends that the term, which at first and for most of the centuries

denoted an attitude towards a relationship between God and man,[35] has

through conceptual slippage come to mean a "system of observances or

beliefs",[36] a historical tradition which has been institutionalized

through a process of reification. Whereas religio denoted personal

piety, religion came to refer to an abstract entity (or transcendental

signifier) which, Smith says, does not exist. |

宗教(ラテン語でreligio)の語源的研究によって、

スミスはさらに、最初、そして何世紀もの間ほとんど神と人間の間の関係に対する態度を示していたこの言葉が、概念的なずれによって「遵守や信念のシステ

ム」[36]、再定義のプロセスを通じて制度化された歴史的伝統を意味するに至ったことを論じている。レリギオが個人的な敬虔さを示していたのに対し、宗

教はスミスによれば、存在しない抽象的な実体(あるいは超越的な意味づけ)を指すようになったのである。 |

| He

argues that the term as found in Lucretius and Cicero was internalized

by the Catholic Church through Lactantius and Augustine of Hippo.

During the Middle Ages it was superseded by the term faith, which Smith

favours by contrast. In the Renaissance, via the Christian Platonist

Marsilio Ficino, religio becomes popular again, retaining its original

emphasis on personal practice, even in John Calvin's Christianae

Religionis Institutio (1536). During 17th-century debates between

Catholics and Protestants, religion begins to refer to an abstract

system of beliefs, especially when describing an oppositional

structure. Through the Enlightenment this concept is further reified,

so that by the nineteenth century G. W. F. Hegel defines religion as

Begriff, "a self-subsisting transcendent idea that unfolds itself in

dynamic expression in the course of ever-changing history ... something

real in itself, a great entity with which man has to reckon, a

something that precedes all its historical manifestation".[37] |

ルクレティウスやキケロに見られるこの言葉は、ラクタン

ティウスやヒッポのアウグスティヌスを通じて、カトリック教会に内面化された、と彼は主張する。中世になると、この言葉は信仰という言葉に取って代わら

れ、スミスは対照的にこの言葉を好んだ。ルネサンス期には、キリスト教プラトン主義者Marsilio Ficinoを経て、John

CalvinのChristianae Religionis

Institutio(1536)においても、個人の実践を重視する本来のレリジョが再び普及する。17世紀のカトリックとプロテスタントの論争では、宗

教は抽象的な信念の体系を指すようになり、特に対立する構造を表現するときに使われる。啓蒙主義を通じてこの概念はさらに再定義され、19世紀までにG.

W. F. ヘーゲルは宗教をベグリフ、「絶えず変化する歴史の過程において動的な表現でそれ自身を展開する自己存続する超越的な思想...

それ自体で実在する何か、人間が計算しなければならない大きな実体、そのすべての歴史的現れに先立つ何か」として定義している[37]。 |

| Smith concludes by arguing that the term religion has now acquired four distinct senses:[38] 1. personal piety (e.g. as meant by the phrase "he is more religious than he was ten years ago"); 2. an overt system of beliefs, practices and values, related to a particular community manifesting itself as the ideal religion that the theologian tries to formulate, but which he knows transcends him (e.g. 'true Christianity'); 3. an overt system of beliefs, practices and values, related to a particular community manifesting itself as the empirical phenomenon, historical and sociological (e.g. the Christianity of history); 4. a generic summation or universal category, i.e. religion in general. The Meaning and End of Religion remains Smith's most influential work. The anthropologist of religion and postcolonial scholar[citation needed] Talal Asad has said that the book is a modern classic and a masterpiece.[39] |

スミスは、宗教という用語が現在では次の4つの異なる意味を獲得していると論じて結論付けている[38]。 1.個人的な信心深さ(例えば、「彼は10年前よりも宗教的だ」というフレーズによって意味されるように)。 2.神学者が定式化しようとするが、自分を超越していると知っている理想的な宗教として現れる特定の共同体に関連する信念、実践、価値の明白なシステム(例えば、「真のキリスト教」)。 特定の共同体に関連し、歴史的、社会学的な経験的現象として現れる信念、実践、 価値観の明白な体系(たとえば、「歴史の中のキリスト教」)。 4.一般的な総括または普遍的なカテゴリー、すなわち宗教一般。 宗教の意味と終焉』は、スミスの最も影響力のある著作である。宗教人類学者でありポストコロニアル研究者[citation needed]のタラル・アサドは、本書が現代の古典であり傑作であると述べている[39]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilfred_Cantwell_Smith. |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

牧師でもあるウィルフレッド・キャントウェ ル・スミスのイスラーム理解は人格主義とも言われていて既視感あるとおもったらメラネシアの人格を議論したこれまた宣教師でのちに本部と仲違いし帰国しフ ランス高等研究院教授のモーリス・レーナルトと酷似しているという気がしてきた。

リンク

リンク

文献(Wilfred Cantwell Smithの著作)

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099