ウィリアム・ジェームズ

William James, 1842-1910

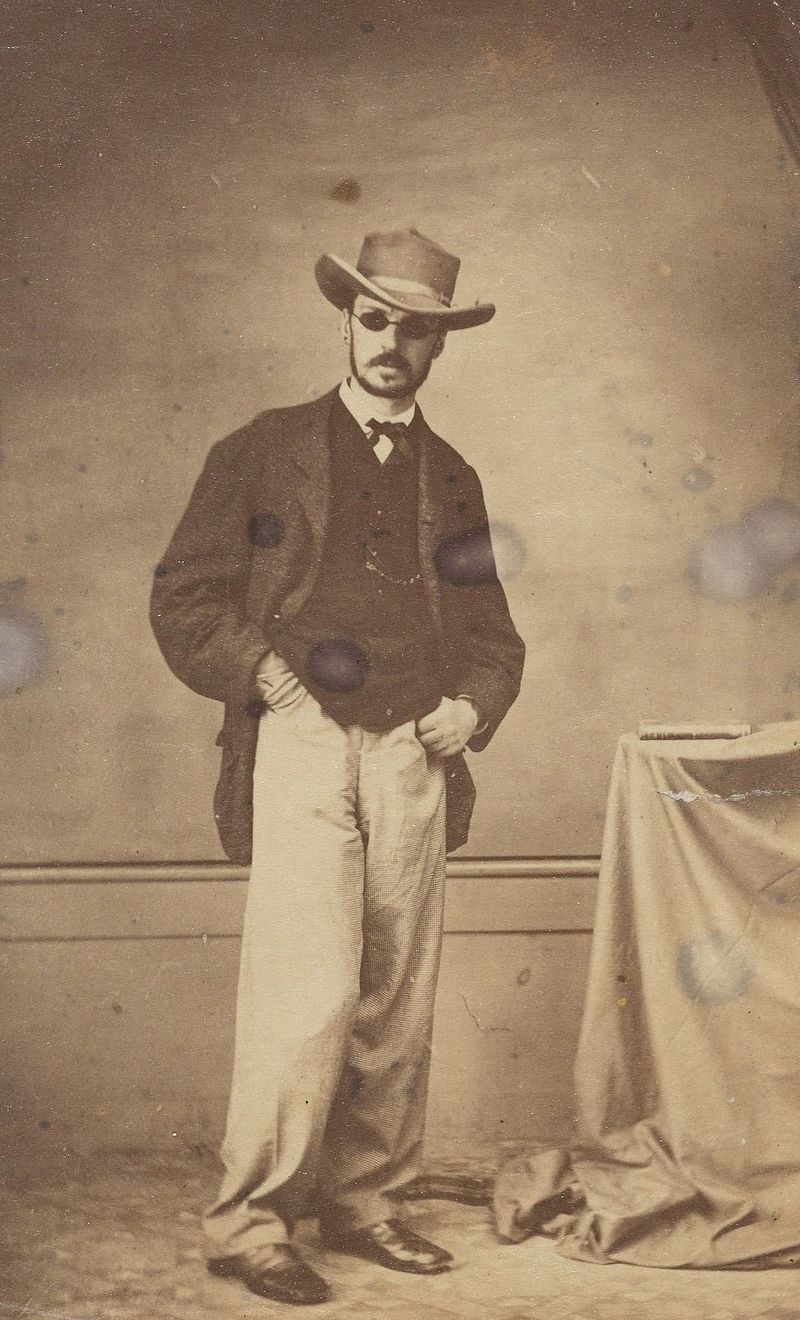

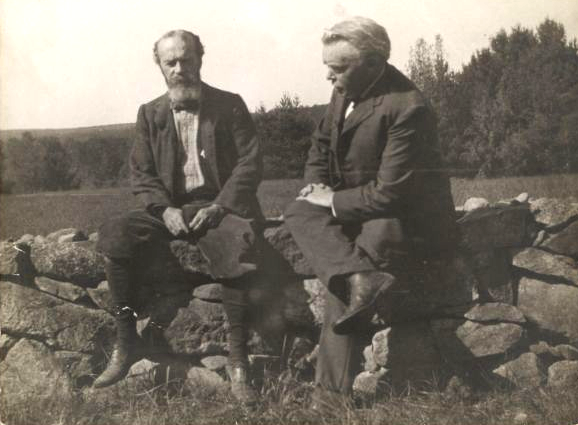

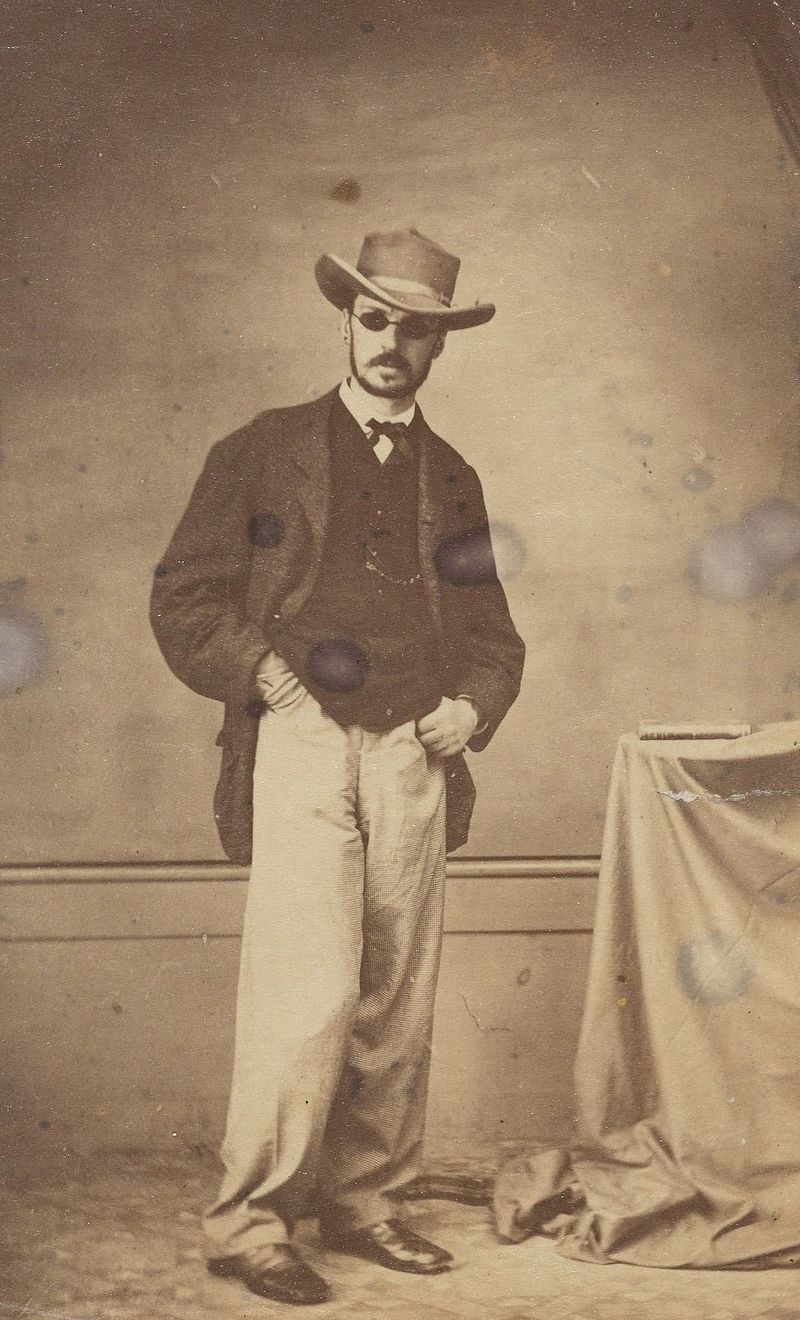

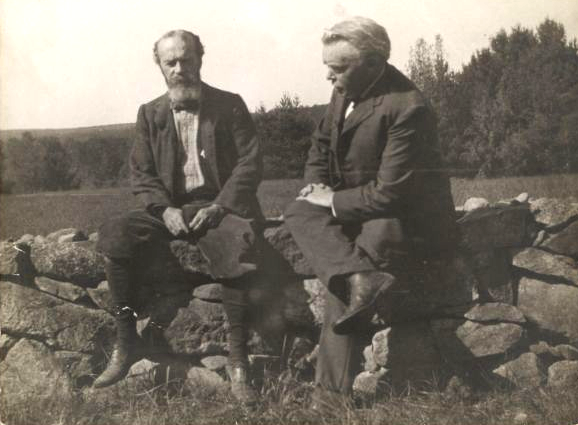

William James in Brazil, 1865/ William James and Josiah Royce.

☆ ウィリアム・ジェイムズ(William James、1842年1月11日 - 1910年8月26日)は、アメリカの哲学者、心理学者であり、アメリカで初めて心理学講座を開設した教育者。チャールズ・サンダース・パイアースとともにプラグマティズムとして知られる哲学学派を確立し、機能心理学の創始者のひとりとしても挙げられている。

William

James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher,

psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in

the United States.[4] James is considered to be a leading thinker of

the late 19th century, one of the most influential philosophers of the

United States, and the "Father of American psychology."[5][6][7] William

James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher,

psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in

the United States.[4] James is considered to be a leading thinker of

the late 19th century, one of the most influential philosophers of the

United States, and the "Father of American psychology."[5][6][7]Along with Charles Sanders Peirce, James established the philosophical school known as pragmatism, and is also cited as one of the founders of functional psychology. A Review of General Psychology analysis, published in 2002, ranked James as the 14th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[8] A survey published in American Psychologist in 1991 ranked James's reputation in second place,[9] after Wilhelm Wundt, who is widely regarded as the founder of experimental psychology.[10][11] James also developed the philosophical perspective known as radical empiricism. James's work has influenced philosophers and academics such as Émile Durkheim, W. E. B. Du Bois, Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Hilary Putnam, Richard Rorty, and Marilynne Robinson.[12] Born into a wealthy family, James was the son of the Swedenborgian theologian Henry James Sr. and the brother of both the prominent novelist Henry James and the diarist Alice James. James trained as a physician and taught anatomy at Harvard, but never practiced medicine. Instead, he pursued his interests in psychology and then philosophy. He wrote widely on many topics, including epistemology, education, metaphysics, psychology, religion, and mysticism. Among his most influential books are The Principles of Psychology, a groundbreaking text in the field of psychology; Essays in Radical Empiricism, an important text in philosophy; and The Varieties of Religious Experience, an investigation of different forms of religious experience, including theories on mind-cure.[13] |

ウィ

リアム・ジェイムズ(William James、1842年1月11日 -

1910年8月26日)は、アメリカの哲学者、心理学者であり、アメリカで初めて心理学講座を開設した教育者である[4]。ジェイムズは19世紀後半を代

表する思想家であり、アメリカで最も影響力のある哲学者の一人であり、「アメリカ心理学の父」であると考えられている[5][6][7]。 ウィ

リアム・ジェイムズ(William James、1842年1月11日 -

1910年8月26日)は、アメリカの哲学者、心理学者であり、アメリカで初めて心理学講座を開設した教育者である[4]。ジェイムズは19世紀後半を代

表する思想家であり、アメリカで最も影響力のある哲学者の一人であり、「アメリカ心理学の父」であると考えられている[5][6][7]。ジェームズはチャールズ・サンダース・パイアースとともにプラグマティズムとして知られる哲学学派を確立し、機能心理学の創始者のひとりとしても挙げられ ている。2002年に発表されたReview of General Psychologyの分析では、ジェームズは20世紀で14番目に著名な心理学者としてランク付けされた[8]。 1991年にAmerican Psychologistに掲載された調査では、ジェームズの評価は、実験心理学の創始者として広く知られているヴィルヘルム・ヴントに次いで2位にラン ク付けされた[9]。ジェームズの研究は、エミール・デュルケーム、W・E・B・デュボア、エドムント・フッサール、バートランド・ラッセル、ルートヴィ ヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、ヒラリー・パットナム、リチャード・ローティ、マリリン・ロビンソンなどの哲学者や学者に影響を与えている[12]。 裕福な家庭に生まれたジェームズは、スウェーデンボルグの神学者ヘンリー・ジェイムズ・シニアの息子であり、著名な小説家ヘンリー・ジェイムズと日記作家 アリス・ジェイムズの兄でもある。ジェームズは医師としての訓練を受け、ハーバード大学で解剖学を教えたが、医学を実践することはなかった。その代わり、 心理学、そして哲学に興味を持った。認識論、教育、形而上学、心理学、宗教、神秘主義など、多くのテーマについて幅広く執筆した。彼の最も影響力のある著 書の中には、心理学の分野で画期的なテキストである『心理学の原理』、哲学の重要なテキストである『急進的経験論』、宗教的経験のさまざまな形態について の調査である『宗教的経験の多様性』(心治療に関する理論を含む)がある[13]。 |

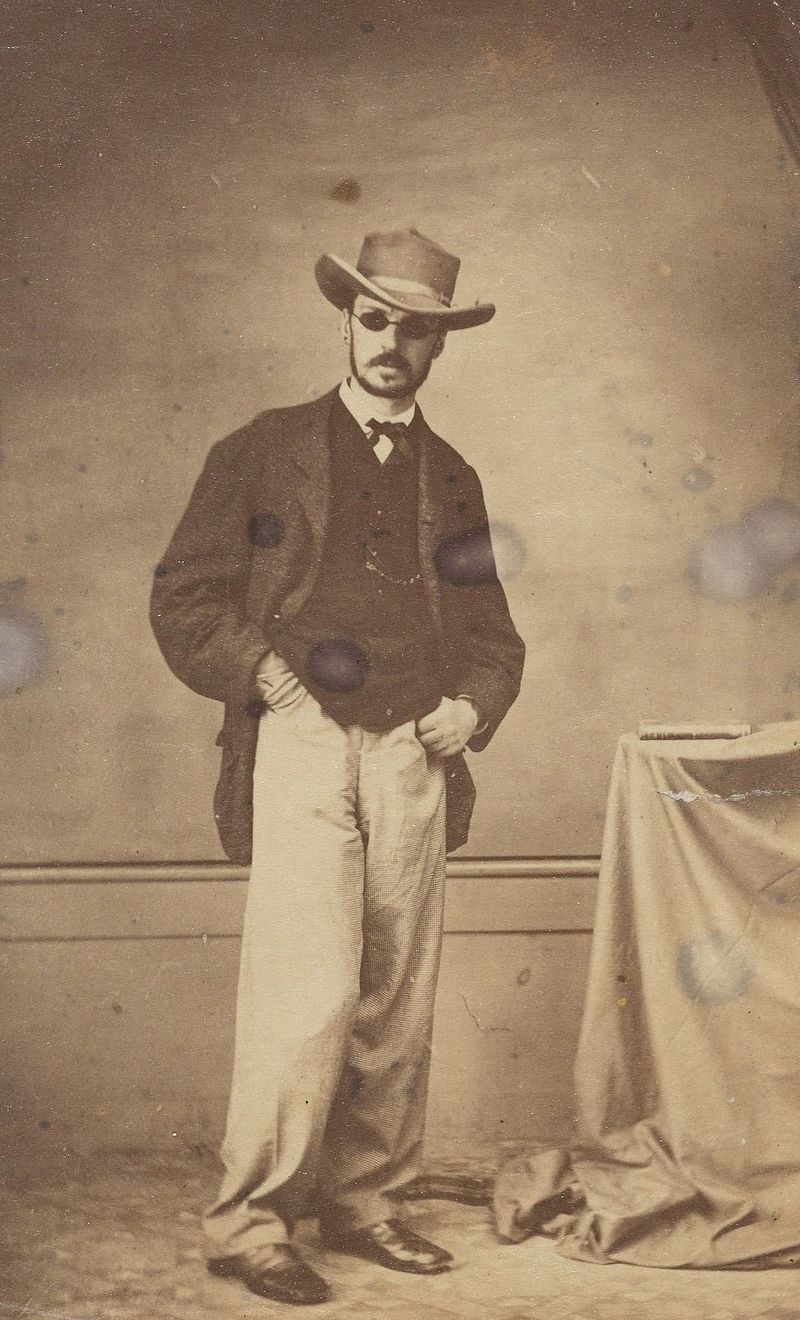

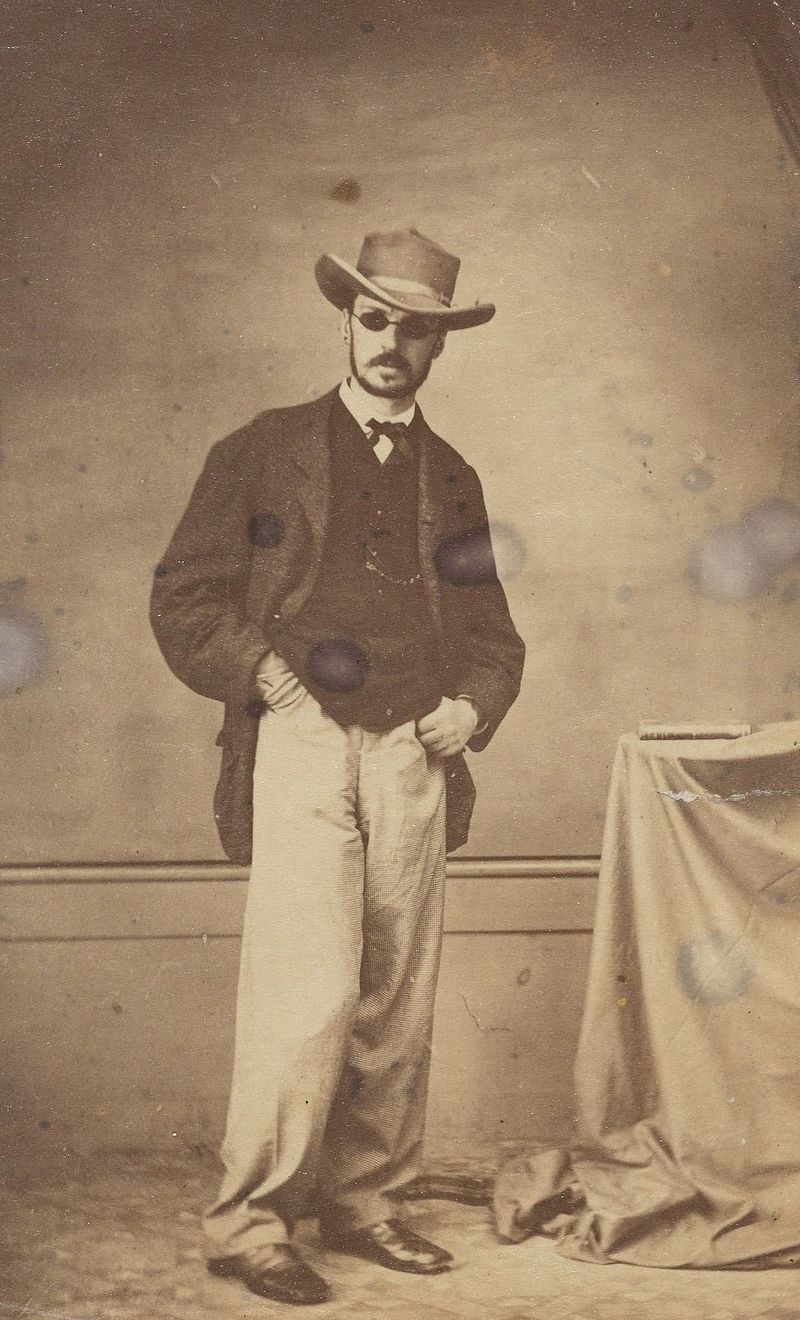

Early life William James in Brazil, 1865 William James was born at the Astor House in New York City on January 11, 1842. He was the son of Henry James Sr., a noted and independently wealthy Swedenborgian theologian well acquainted with the literary and intellectual elites of his day. The intellectual brilliance of the James family milieu and the remarkable epistolary talents of several of its members have made them a subject of continuing interest to historians, biographers, and critics. William James received an eclectic trans-Atlantic education, developing fluency in both German and French. Education in the James household encouraged cosmopolitanism. The family made two trips to Europe while William James was still a child, setting a pattern that resulted in thirteen more European journeys during his life. James wished to pursue painting, his early artistic bent led to an apprenticeship in the studio of William Morris Hunt in Newport, Rhode Island, but his father urged him to become a physician instead. Since this did not align with James's interests, he stated that he wanted to specialize in physiology. Once he figured this was also not what he wanted to do, he then announced he was going to specialize in the nervous system and psychology. James then switched in 1861 to scientific studies at the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard College. In his early adulthood, James suffered from a variety of physical ailments, including those of the eyes, back, stomach, and skin. He was also tone deaf.[14] He was subject to a variety of psychological symptoms which were diagnosed at the time as neurasthenia, and which included periods of depression during which he contemplated suicide for months on end. Two younger brothers, Garth Wilkinson (Wilkie) and Robertson (Bob), fought in the Civil War. James himself was an advocate of peace. He suggested that instead of youth serving in the military that they serve the public in a term of service, "to get the childishness knocked out of them." The other three siblings (William, Henry, and Alice James) all suffered from periods of invalidism.[citation needed] He took up medical studies at Harvard Medical School in 1864 (according to his brother Henry James, the author). He took a break in the spring of 1865 to join naturalist Louis Agassiz on a scientific expedition up the Amazon River, but aborted his trip after eight months, as he suffered bouts of severe seasickness and mild smallpox. His studies were interrupted once again due to illness in April 1867. He traveled to Germany in search of a cure and remained there until November 1868; at that time he was 26 years old. During this period, he began to publish; reviews of his works appeared in literary periodicals such as the North American Review.[citation needed] James finally earned his MD degree in June 1869 but he never practiced medicine. What he called his "soul-sickness" would only be resolved in 1872, after an extended period of philosophical searching. He married Alice Gibbens in 1878. In 1882 he joined the Theosophical Society.[15] James's time in Germany proved intellectually fertile, helping him find that his true interests lay not in medicine but in philosophy and psychology. Later, in 1902 he would write: "I originally studied medicine in order to be a physiologist, but I drifted into psychology and philosophy from a sort of fatality. I never had any philosophic instruction, the first lecture on psychology I ever heard being the first I ever gave".[16] Family William James was the son of Henry James (Senior) of Albany, and Mary Robertson Walsh. He had four siblings: Henry (the novelist), Garth Wilkinson, Robertson, and Alice.[23] William became engaged to Alice Howe Gibbens on May 10, 1878; they were married on July 10. They had 5 children: Henry (May 18, 1879 – 1947), William (June 17, 1882 – 1961), Herman (1884, died in infancy), Margaret (March 1887 – 1950) and Alexander (December 22, 1890 – 1946). Most of William James's ancestors arrived in America from Scotland or Ireland in the 18th century. Many of them settled in eastern New York or New Jersey. All of James's ancestors were Protestant, well educated, and of character. Within their communities, they worked as farmers, merchants, and traders who were all heavily involved with their church. The last ancestor to arrive in America was William James's paternal grandfather also named William James. He came to America from Ballyjamesduff, County Cavan, Ireland in 1789 when he was 18 years old. There is suspicion that he fled to America because his family tried to force him into the ministry. After traveling to America with no money left, he found a job at a store as a clerk. After continuously working, he was able to own the store himself. As he traveled west to find more job opportunities, he was involved in various jobs such as the salt industry and the Erie Canal project. After being a significant worker in the Erie Canal project and helping Albany become a major center of trade, he then became the first Vice-President of the Albany Savings Bank. William James (grandfather) went from being a poor Irish immigrant to one of the richest men in New York. After his death, his son Henry James inherited his fortune and lived in Europe and the United States searching for the meaning of life.[citation needed] Of James' five children, two -- Margaret and Alexander -- are known to have had children. Alexander's descendants are still living. |

生い立ち 1865年、ブラジルでのウィリアム・ジェームズ ウィリアム・ジェームズは1842年1月11日、ニューヨークのアスター・ハウスで生まれた。ヘンリー・ジェームズ・シニアの息子であり、当時の文学的・ 知的エリートたちと親交のあったスウェーデンボルグ派の神学者であった。ジェイムズ一家の知的な輝きと、そのメンバーの何人かの卓越した叙事詩の才能は、 歴史家、伝記作家、批評家たちの関心を惹きつけてやまない。 ウィリアム・ジェームズは、大西洋を横断する折衷的な教育を受け、ドイツ語とフランス語に堪能であった。ジェームズ家の教育は国際主義を奨励した。ウィリ アム・ジェームズは幼少期に一家でヨーロッパへ2度旅行し、生涯に13回ものヨーロッパ旅行を経験する。ジェームズは絵画の道を志し、ロードアイランド州 ニューポートにあるウィリアム・モリス・ハントのアトリエで見習い画家として働くことになったが、父親からは医者になるよう勧められた。これはジェームズ の興味と一致しなかったので、彼は生理学を専門にしたいと述べた。これも自分のやりたいことではないと考えた彼は、神経系と心理学を専門にすると宣言し た。ジェームズはその後、1861年にハーバード大学のローレンス科学学校での科学研究に転向した。 成人初期、ジェームズは目、背中、胃、皮膚など、さまざまな身体の不調に悩まされた。当時は神経衰弱と診断されたさまざまな精神的症状に悩まされ、うつ病 の時期には何ヶ月も自殺を考えることもあった[14]。2人の弟、ガース・ウィルキンソン(ウィルキー)とロバートソン(ボブ)は南北戦争で戦った。 ジェームズ自身は平和の擁護者だった。彼は青少年が兵役に就く代わりに、"子供っぽさを叩き出すために "国民に奉仕する期間を設けることを提案した。他の3人の兄弟(ウィリアム、ヘンリー、アリス・ジェームズ)は皆、病弱な時期があった[要出典]。 1864年、ハーバード大学医学部で医学を学ぶ(著者の兄ヘンリー・ジェイムズによれば)。1865年の春、自然科学者ルイ・アガシとアマゾン川探検に参 加するために休学したが、ひどい船酔いと軽い天然痘にかかり、8ヶ月で旅を中止した。1867年4月、病気により再び研究が中断された。治療法を求めてド イツに渡り、1868年11月まで滞在した。この時期、ジェームズは出版活動を開始し、『ノース・アメリカン・レビュー』誌などの文芸誌に彼の作品の批評 が掲載された[要出典]。 ジェームズは1869年6月にようやく医学博士号を取得したが、医学を実践することはなかった。彼が「魂の病」と呼んだものは、哲学的探求の長期間を経 て、1872年になってようやく解消された。1878年にアリス・ギベンスと結婚。1882年には神智学協会に入会した[15]。 ジェームズのドイツでの時間は、彼の真の関心が医学ではなく、哲学と心理学にあることを発見するのに役立ち、知的に肥沃であることを証明した。後に 1902年に彼はこう書いている: 「私はもともと生理学者になるために医学を学んだが、ある種の宿命から心理学と哲学に流れ込んだ。哲学的な指導を受けたことは一度もなく、心理学の講義を 初めて聞いたのが、私が初めて行った講義だった」[16]。 家族 ウィリアム・ジェームズはオルバニーのヘンリー・ジェイムズ(シニア)とメアリー・ロバートソン・ウォルシュの息子。兄弟は4人: ウィリアムは1878年5月10日にアリス・ハウ・ギベンズと婚約し、7月10日に結婚。7月10日に結婚: ヘンリー(1879年5月18日 - 1947年)、ウィリアム(1882年6月17日 - 1961年)、ハーマン(1884年、幼児期に死亡)、マーガレット(1887年3月 - 1950年)、アレクサンダー(1890年12月22日 - 1946年)。 ウィリアム・ジェームズの先祖のほとんどは、18世紀にスコットランドかアイルランドからアメリカに渡った。その多くはニューヨーク東部かニュージャー ジーに定住した。ジェームズの先祖はみなプロテスタントで、教養があり、人格者であった。彼らのコミュニティでは、農民、商人、貿易商として働き、教会と 深く関わっていた。アメリカに到着した最後の祖先は、ウィリアム・ジェームズの父方の祖父で、ウィリアム・ジェームスという名前であった。彼は1789 年、18歳のときにアイルランドのキャバン州バリージェームズダフからアメリカに渡った。家族に無理やり聖職に就かせようとされたため、アメリカに逃亡し た疑いがある。無一文でアメリカに渡った彼は、ある店で店員として働く。働き続けた結果、その店を自分で持つことができた。より多くの仕事の機会を求めて 西へ旅立った彼は、製塩業やエリー運河プロジェクトなどさまざまな仕事に携わった。エリー運河プロジェクトで重要な働きをし、アルバニーが貿易の中心地と なるのを助けた後、アルバニー貯蓄銀行の初代副頭取となった。ウィリアム・ジェームズ(祖父)は、貧しいアイルランド移民からニューヨークで最も裕福な男 のひとりとなった。彼の死後、息子のヘンリー・ジェームズは彼の財産を相続し、人生の意味を求めてヨーロッパとアメリカに住んだ[要出典]。 ジェームズの5人の子供のうち、マーガレットとアレクサンダーの2人に子供がいたことが知られている。アレクサンダーの子孫はまだ生きている。 |

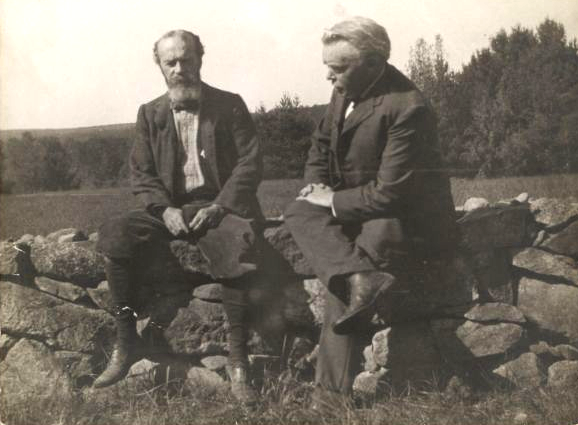

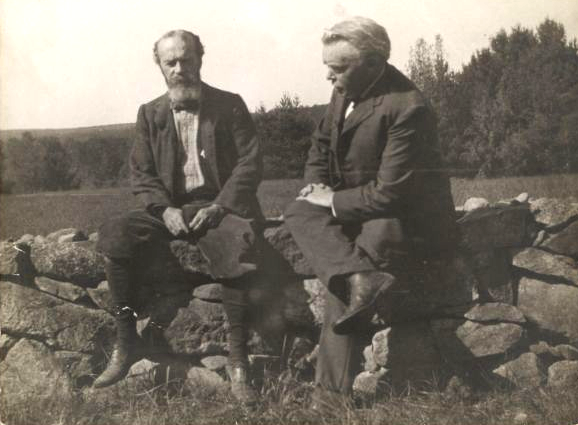

| Career James interacted with a wide array of writers and scholars throughout his life, including his godfather Ralph Waldo Emerson, his godson William James Sidis, as well as Charles Sanders Peirce, Bertrand Russell, Josiah Royce, Ernst Mach, John Dewey, Macedonio Fernández, Walter Lippmann, Mark Twain, Horatio Alger, G. Stanley Hall, Henri Bergson, Carl Jung, Jane Addams and Sigmund Freud. James spent almost all of his academic career at Harvard. He was appointed instructor in physiology for the spring 1873 term, instructor in anatomy and physiology in 1873, assistant professor of psychology in 1876, assistant professor of philosophy in 1881, full professor in 1885, endowed chair in psychology in 1889, return to philosophy in 1897, and emeritus professor of philosophy in 1907. James studied medicine, physiology, and biology, and began to teach in those subjects, but was drawn to the scientific study of the human mind at a time when psychology was constituting itself as a science. James's acquaintance with the work of figures like Hermann Helmholtz in Germany and Pierre Janet in France facilitated his introduction of courses in scientific psychology at Harvard University. He taught his first experimental psychology course at Harvard in the 1875–1876 academic year.[17] During his Harvard years, James joined in philosophical discussions and debates with Charles Peirce, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Chauncey Wright that evolved into a lively group informally known as The Metaphysical Club in 1872. Louis Menand (2001) suggested that this Club provided a foundation for American intellectual thought for decades to come. James joined the Anti-Imperialist League in 1898, in opposition to the United States annexation of the Philippines.  William James and Josiah Royce, near James's country home in Chocorua, New Hampshire in September 1903. James's daughter Peggy took the picture. On hearing the camera click, James cried out: "Royce, you're being photographed! Look out! I say Damn the Absolute!" Among James's students at Harvard University were Boris Sidis, Theodore Roosevelt, George Santayana, W. E. B. Du Bois, G. Stanley Hall, Ralph Barton Perry, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Morris Raphael Cohen, Walter Lippmann, Alain Locke, C. I. Lewis, and Mary Whiton Calkins. Antiquarian bookseller Gabriel Wells tutored under him at Harvard in the late 1890s.[18] His students enjoyed his brilliance and his manner of teaching was free of personal arrogance. They remember him for his kindness and humble attitude. His respectful attitude towards them speaks well of his character.[19] Following his January 1907 retirement from Harvard, James continued to write and lecture, publishing Pragmatism, A Pluralistic Universe, and The Meaning of Truth. James was increasingly afflicted with cardiac pain during his last years. It worsened in 1909 while he worked on a philosophy text (unfinished but posthumously published as Some Problems in Philosophy). He sailed to Europe in the spring of 1910 to take experimental treatments which proved unsuccessful, and returned home on August 18. His heart failed on August 26, 1910, at his home in Chocorua, New Hampshire.[20] He was buried in the family plot in Cambridge Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was one of the strongest proponents of the school of functionalism in psychology and of pragmatism in philosophy. He was a founder of the American Society for Psychical Research, as well as a champion of alternative approaches to healing. In 1884 and 1885 he became president of the British Society for Psychical Research for which he wrote in Mind and in the Psychological Review.[21] He challenged his professional colleagues not to let a narrow mindset prevent an honest appraisal of those beliefs. In an empirical study by Haggbloom et al. using six criteria such as citations and recognition, James was found to be the 14th most eminent psychologist of the 20th century.[22] |

経歴 名付け親のラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン、名付け子のウィリアム・ジェームズ・シディスをはじめ、チャールズ・サンダース・ペアーズ、バートランド・ ラッセル、ジョサイア・ロイス、エルンスト・マッハ、ジョン・デューイ、マセドニオ・フェルナンデス、ウォルター・リップマン、マーク・トウェイン、ホレ イショ・アルジャー、G・スタンレー・ホール、アンリ・ベルクソン、カール・ユング、ジェーン・アダムス、ジークムント・フロイトなど、ジェームズは生涯 を通じてさまざまな作家や学者と交流した。 ジェームズは学問的キャリアのほとんどすべてをハーバード大学で過ごした。1873年春学期に生理学の教官、1873年に解剖学と生理学の教官、1876 年に心理学の助教授、1881年に哲学の助教授、1885年に正教授、1889年に心理学の寄付講座、1897年に哲学に復帰、1907年に哲学の名誉教 授に任命された。 ジェームズは医学、生理学、生物学を学び、それらの科目で教鞭をとるようになったが、心理学が科学として確立しつつあった時期に、人間の心の科学的研究に 惹かれた。ドイツのヘルマン・ヘルムホルツやフランスのピエール・ジャネのような人物の研究を知っていたジェームズは、ハーバード大学で科学的心理学の講 義を始めるきっかけとなった。1875年から1876年にかけて、彼はハーバード大学で初めて実験心理学の講義を行った[17]。 ハーバード大学時代、ジェームズはチャールズ・パース、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ、チャウンシー・ライトらと哲学的な議論や討論に参加し、1872 年には非公式に形而上学クラブとして知られる活発なグループへと発展した。Louis Menand (2001)は、このクラブがその後数十年にわたりアメリカの知的思想の基礎を築いたと指摘している。ジェームズは1898年、アメリカのフィリピン併合 に反対して反帝国主義者同盟に参加した。  ウィリアム・ジェームズとジョサイア・ロイス、1903年9月、ニューハンプシャー州チョコルアにあるジェームズの別荘近く。ジェームズの娘ペギーが撮 影。カメラのクリック音を聞いて、ジェームズは叫んだ: 「ロイス、撮られてるぞ!気をつけろ!絶対的な存在に呪いをかけろ!」。 ハーバード大学でのジェームズの教え子には、ボリス・シディス、セオドア・ルーズベルト、ジョージ・サンタヤーナ、W・E・B・デュボワ、G・スタン レー・ホール、ラルフ・バートン・ペリー、ガートルード・スタイン、ホレス・カレン、モリス・ラファエル・コーエン、ウォルター・リップマン、アラン・ ロック、C・I・ルイス、メアリー・ウィトン・カルキンズらがいた。1890年代後半には、古書商のガブリエル・ウェルズがハーバード大学で彼の家庭教師 を務めた[18]。 彼の教え子たちは、彼の聡明さと、個人的な傲慢さのない教え方を楽しんでいた。彼らは彼の優しさと謙虚な態度を覚えている。彼の尊敬に満ちた態度は、彼の人柄をよく物語っている[19]。 1907年1月にハーバード大学を退職した後も、ジェームズは執筆と講演を続け、『プラグマティズム』(Pragmatism)、『多元的宇宙』(A Pluralistic Universe)、『真理の意味』(The Meaning of Truth)を出版した。ジェイムズは晩年、次第に心臓の痛みに悩まされるようになる。1909年、哲学書(未完成だが、死後に『哲学の諸問題』として出 版)の執筆中に悪化した。1910年春にヨーロッパに渡り、実験的な治療を受けたがうまくいかず、8月18日に帰国した。1910年8月26日、ニューハ ンプシャー州チョコルアの自宅で心不全となり、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジのケンブリッジ墓地の家族の区画に埋葬された[20]。 心理学では機能主義を、哲学ではプラグマティズムを最も強力に支持した一人である。彼はアメリカ心霊研究協会の創設者であり、ヒーリングへの代替的アプ ローチの支持者でもあった。1884年と1885年にはイギリス心霊研究協会の会長となり、『マインド』誌や『サイコロジカル・レビュー』誌に寄稿した。 ハグブルームらによる、引用や知名度など6つの基準を用いた実証的研究において、ジェームズは20世紀で14番目に著名な心理学者であることが判明した[22]。 |

| Writings William James wrote voluminously throughout his life. A non-exhaustive bibliography of his writings, compiled by John McDermott, is 47 pages long.[24] He gained widespread recognition with his monumental The Principles of Psychology (1890), totaling twelve hundred pages in two volumes, which took twelve years to complete. Psychology: The Briefer Course, was an 1892 abridgement designed as a less rigorous introduction to the field. These works criticized both the English associationist school and the Hegelianism of his day as competing dogmatisms of little explanatory value, and sought to re-conceive the human mind as inherently purposive and selective. President Jimmy Carter's Moral Equivalent of War Speech, on April 17, 1977, equating the United States' 1970s energy crisis, oil crisis and the changes and sacrifices Carter's proposed plans would require with the "moral equivalent of war," may have borrowed its title, much of its theme and the memorable phrase from James's classic essay "The Moral Equivalent of War" derived from his last speech, delivered at Stanford University in 1906, and published in 1910, in which "James considered one of the classic problems of politics: how to sustain political unity and civic virtue in the absence of war or a credible threat ..." and which "... sounds a rallying cry for service in the interests of the individual and the nation."[25][26][27][28] In simple terms, his philosophy and writings can be understood as an emphasis on "fruits over roots," a reflection of his pragmatist tendency to focus on the practical consequences of ideas rather than become mired in unproductive metaphysical arguments or fruitless attempts to ground truth in abstract ways. Ever the empiricist, James believes we are better off evaluating the fruitfulness of ideas by testing them in the common ground of lived experience.[29] James was remembered as one of America's representative thinkers, psychologist, and philosopher. William James was also one of the most influential writers on religion, psychical research, and self-help. He was told to have a few disciples that followed his writing since they were inspired and enriched by his research. Epistemology James defined true beliefs as those that prove useful to the believer. His pragmatic theory of truth was a synthesis of correspondence theory of truth and coherence theory of truth, with an added dimension. Truth is verifiable to the extent that thoughts and statements correspond with actual things, as well as the extent to which they "hang together," or cohere, as pieces of a puzzle might fit together; these are in turn verified by the observed results of the application of an idea to actual practice.[30][31] The most ancient parts of truth … also once were plastic. They also were called true for human reasons. They also mediated between still earlier truths and what in those days were novel observations. Purely objective truth, truth in whose establishment the function of giving human satisfaction in marrying previous parts of experience with newer parts played no role whatsoever, is nowhere to be found. The reasons why we call things true is the reason why they are true, for 'to be true' means only to perform this marriage-function. — "Pragmatism's Conception of Truth," Pragmatism (1907), p. 83. James held a world view in line with pragmatism, declaring that the value of any truth was utterly dependent upon its use to the person who held it. Additional tenets of James's pragmatism include the view that the world is a mosaic of diverse experiences that can only be properly interpreted and understood through an application of 'radical empiricism.' Radical empiricism, not related to the everyday scientific empiricism, asserts that the world and experience can never be halted for an entirely objective analysis; the mind of the observer and the act of observation affect any empirical approach to truth. The mind, its experiences, and nature are inseparable. James's emphasis on diversity as the default human condition—over and against duality, especially Hegelian dialectical duality—has maintained a strong influence in American culture. James's description of the mind-world connection, which he described in terms of a 'stream of consciousness,' had a direct and significant impact on avant-garde and modernist literature and art, notably in the case of James Joyce. In "What Pragmatism Means" (1906), James writes that the central point of his own doctrine of truth is, in brief:[32] Truths emerge from facts, but they dip forward into facts again and add to them; which facts again create or reveal new truth (the word is indifferent) and so on indefinitely. The 'facts' themselves meanwhile are not true. They simply are. Truth is the function of the beliefs that start and terminate among them. Richard Rorty made the contested claim that James did not mean to give a theory of truth with this statement and that we should not regard it as such. However, other pragmatism scholars such as Susan Haack and Howard Mounce do not share Rorty's instrumentalist interpretation of James.[33] In The Meaning of Truth (1909), James seems to speak of truth in relativistic terms, in reference to critics of pragmatism: "The critic's trouble … seems to come from his taking the word 'true' irrelatively, whereas the pragmatist always means 'true for him who experiences the workings.'"[34] However, James responded to critics accusing him of relativism, skepticism, or agnosticism, and of believing only in relative truths. To the contrary, he supported an epistemological realism position.[i] Pragmatism and "cash value" Pragmatism is a philosophical approach that seeks to both define truth and resolve metaphysical issues. William James demonstrates an application of his method in the form of a simple story:[35][32] A live squirrel supposed to be clinging on one side of a tree-trunk; while over against the tree's opposite side a human being was imagined to stand. This human witness tries to get sight of the squirrel by moving rapidly round the tree, but no matter how fast he goes, the squirrel moves as fast in the opposite direction, and always keeps the tree between himself and the man, so that never a glimpse of him is caught. The resultant metaphysical problem now is this: Does the man go round the squirrel or not? James solves the issue by making a distinction between practical meaning. That is, the distinction between meanings of "round." Round in the sense that the man occupies the space north, east, south, and west of the squirrel; and round in the sense that the man occupies the space facing the squirrel's belly, back and sides. Depending on what the debaters meant by "going round," the answer would be clear. From this example James derives the definition of the pragmatic method: to settle metaphysical disputes, one must simply make a distinction of practical consequences between notions, then, the answer is either clear, or the "dispute is idle."[35] Both James and his colleague, Charles Sanders Peirce, coined the term "cash value":[36] When he said that the whole meaning of a (clear) conception consists in the entire set of its practical consequences, he had in mind that a meaningful conception must have some sort of experiential "cash value," must somehow be capable of being related to some sort of collection of possible empirical observations under specifiable conditions. A statement's truthfulness is verifiable through its correspondence to reality, and its observable effects of putting the idea to practice. For example, James extends his Pragmatism to the hypothesis of God: "On pragmatic principles, if the hypothesis of God works satisfactorily in the widest sense of the word, it is true. … The problem is to build it out and determine it so that it will combine satisfactorily with all the other working truths."[37] From this, we also know that "new" truths must also correspond to already existent truths as well. From the introduction by Bruce Kuklick (1981, p. xiv) to James's Pragmatism: James went on to apply the pragmatic method to the epistemological problem of truth. He would seek the meaning of "true" by examining how the idea functioned in our lives. A belief was true, he said, if it worked for all of us, and guided us expeditiously through our semihospitable world. James was anxious to uncover what true beliefs amounted to in human life, what their "cash value" was, and what consequences they led to. A belief was not a mental entity which somehow mysteriously corresponded to an external reality if the belief were true. Beliefs were ways of acting with reference to a precarious environment, and to say they were true was to say they were efficacious in this environment. In this sense the pragmatic theory of truth applied Darwinian ideas in philosophy; it made survival the test of intellectual as well as biological fitness. James's book of lectures on pragmatism is arguably the most influential book of American philosophy. The lectures inside depict his position on the subject. In his sixth lecture, he begins by defining truth as "agreement with reality."[30] With this, James warns that there will be disagreements between pragmatics and intellectualists over the concepts of "agreement" and "reality", the last reasoning before thoughts settle and become autonomous for us. However, he contrasts this by supporting a more practical interpretation that: a true idea or belief is one that we can blend with our thinking so that it can be justified through experiences.[38] If theological ideas prove to have a value for concrete life, they will be true, for pragmatism, in the sense of being good for so much. For how much more they are true, will depend entirely on their relations to the other truths that also have to be acknowledged. — Pragmatism (1907), p. 29 Whereby the agreement of truths with "reality" results in useful outcomes, "the 'reality' with which truths must agree has three dimensions:"[38][12] "matters of fact;" "relations of ideas;" and "the entire set of other truths to which we are committed." According to James's pragmatic approach to belief, knowledge is commonly viewed as a justified and true belief. James will accept a view if its conception of truth is analyzed and justified through interpretation, pragmatically. As a matter of fact, James's whole philosophy is of productive beliefs. Belief in anything involves conceiving of how it is real, but disbelief is the result when we dismiss something because it contradicts another thing we think of as real. In his "Sentiment of Rationality", saying that crucial beliefs are not known is to doubt their truth, even if it seems possible. James names four "postulates of rationality" as valuable but unknowable: God, immorality, freedom, and moral duty.[38][39] In contrast, the weak side to pragmatism is that the best justification for a claim is whether it works. However, a claim that does not have outcomes cannot be justified, or unjustified, because it will not make a difference. "There can be no difference that doesn't make a difference." — Pragmatism (1907), p. 45 When James moves on to then state that pragmatism's goal is ultimately "to try to interpret each notion by tracing its respective practical consequences," he does not clarify what he means by "practical consequences."[40] On the other hand, his friend, colleague, and another key founder in establishing pragmatist beliefs, Charles S. Peirce, dives deeper in defining these consequences. For Peirce, "the consequences we are concerned with are general and intelligible."[41] He further explains this in his 1878 paper "How to Make Ideas Clear," when he introduces a maxim that allows one to interpret consequences as grades of clarity and conception.[42] Describing how everything is derived from perception, Peirce uses the example of the doctrine of transubstantiation to show exactly how he defines practical consequences. Protestants interpret the bread and wine of the Eucharist is flesh and blood in only a subjective sense, while Catholics would label them as actual, and divinely mystical properties of flesh via the "body, blood, soul, and divinity", even with the physical properties remaining as bread and wine in appearance. But to everyone, there can be no knowledge of the wine and bread of the Eucharist unless it is established that either wine and bread possesses certain properties or that anything that is interpreted as the blood and body of Christ is the blood and body of Christ. With this Peirce declares that "our action has exclusive reference to what affects the senses," and that we can mean nothing by transubstantiation than "what has certain effects, direct or indirect, upon our senses."[43] In this sense, James's pragmatic influencer Peirce establishes that what counts as a practical consequence or effect is what can affect one's senses and what is comprehendible and fathomable in the natural world. Yet James never "[works] out his understanding of 'practical consequences' as fully as Peirce did," nor does he limit these consequences to the senses like Peirce.[41] It then raises the question: what does it mean to be practical? Whether James means the greatest number of positive consequences (in light of utilitarianism), a consequence that considers other perspectives (like his compromise of the tender and tough ways of thinking),[44] or a completely different take altogether, it is unclear to truly tell what consequence truly fits the pragmatic standard, and what doesn't. The closest James is able to get in explaining this idea is by telling his audience to weigh the difference it would "practically make to anyone" if one opinion over the other were true, and although he attempts to clarify it, he never specifies nor establishes the method in which one would weigh the difference between one opinion over the other.[40] Thus, the flaw in his argument appears in that it is difficult to fathom how he would determine these practical consequences, which he continually refers to throughout his work, to be measured or interpreted. Will to believe doctrine Main article: The Will to Believe In William James's 1896 lecture titled "The Will to Believe", James defends the right to violate the principle of evidentialism in order to justify hypothesis venturing. This idea foresaw 20th century objections to evidentialism and sought to ground justified belief in an unwavering principle that would prove more beneficial. Through his philosophy of pragmatism William James justifies religious beliefs by using the results of his hypothetical venturing as evidence to support the hypothesis's truth. Therefore, this doctrine allows one to assume belief in a god and prove its existence by what the belief brings to one's life. This was criticized by advocates of skepticism rationality, like Bertrand Russell in Free Thought and Official Propaganda and Alfred Henry Lloyd with The Will to Doubt. Both argued that one must always adhere to fallibilism, recognizing of all human knowledge that "None of our beliefs are quite true; all have at least a penumbra of vagueness and error," and that the only means of progressing ever-closer to the truth is to never assume certainty, but always examine all sides and try to reach a conclusion objectively. |

著作 ウィリアム・ジェームズは生涯を通じて膨大な量の著作を残した。ジョン・マクダーモットによって編纂された彼の著作の非網羅的な書誌は47ページにも及ぶ[24]。 彼は『心理学の原理』(The Principles of Psychology、1890年)で広く知られるようになった。心理学: The Brieffer Course』(1892年)は、この分野への厳密な入門書として作られた要約版である。これらの著作は、イギリスの連合主義学派と当時のヘーゲル主義の 両方を、説明価値の乏しい対立する教条主義として批判し、人間の心を本質的に目的的で選択的なものとして捉え直そうとした。 ジミー・カーター大統領が1977年4月17日に行った「戦争の道徳的等価性」演説は、1970年代の米国のエネルギー危機、石油危機、そしてカーター大 統領が提案した計画が必要とする変化と犠牲を「戦争の道徳的等価性」と同一視したものであったが、そのタイトル、テーマの大部分、そして印象的なフレーズ は、1906年にスタンフォード大学で行われ、1910年に出版されたジェームズの最後の演説に由来するジェームズの古典的エッセイ「戦争の道徳的等価 性」から借用したものであろう: 戦争や信頼できる脅威がない場合に、いかにして政治的団結と市民の美徳を維持するか。 そして「......個人と国家の利益のための奉仕の叫びを鳴らしている」[25][26][27][28]。 これは、非生産的な形而上学的議論や、抽象的な方法で真理を基礎づけようとする実りのない試みに没頭するよりも、むしろ思想の実際的な結果に焦点を当てよ うとする彼のプラグマティズムの傾向を反映したものである。経験主義者であるジェームズは、私たちは生きた経験という共通の基盤の中でそれを検証すること によって、アイデアの有用性を評価する方がよいと信じている[29]。 ジェームズはアメリカを代表する思想家、心理学者、哲学者として記憶されている。ウィリアム・ジェームズはまた、宗教、心理学的研究、自己啓発に関する最 も影響力のある作家の一人でもあった。ジェームズは、宗教、心霊研究、自己啓発の分野で最も影響力のある作家の一人であり、彼の研究によってインスピレー ションを受け、豊かになったことから、彼の著作に従う数人の弟子がいたと言われている。 認識論 ジェームズは真の信念とは、信じる者にとって役に立つと証明されるものだと定義した。彼のプラグマティックな真理論は、真理の対応理論 (correspondence theory of truth)と真理の首尾一貫理論(coherence theory of truth)を統合したもので、さらに次のような側面がある。真理は、思考や言明が実際の事柄とどの程度対応しているか、またパズルのピースが組み合わさ るように、どの程度「一緒に吊り下がる」(coherent)かによって検証可能であり、これらは次に、ある考えを実際の実践に適用したときに観察される 結果によって検証される[30][31]。 真理の最も古い部分も、かつては可塑的であった。それらはまた、人間的な理由から真理と呼ばれた。それらはまた、さらに以前の真理と、当時は斬新な観察で あったものとの間を媒介した。純粋に客観的な真理、すなわち、経験の以前の部分と新しい部分とを結びつけることによって人間に満足を与えるという機能が、 その成立においてまったく役割を果たしていない真理は、どこにも見いだせない。私たちが物事を真と呼ぶ理由は、それが真である理由であり、「真である」と いうことは、この結婚機能を果たすことだけを意味するからである。 - プラグマティズムの真理観」『プラグマティズム』(1907年)83頁。 ジェームズはプラグマティズムに沿った世界観を持っており、いかなる真理の価値も、それを持つ人間にとってのその用途にまったく依存していると宣言した。 ジェイムズのプラグマティズムの更なる信条には、世界は多様な経験のモザイクであり、「急進的経験主義」の適用によってのみ適切に解釈され理解されるとい う見解が含まれる。急進的経験主義は、日常的な科学的経験主義とは関係なく、世界と経験を完全に客観的に分析するために停止することは決してできないと主 張する。心、経験、自然は切り離せないものなのだ。二元性、特にヘーゲルの弁証法的二元性に対して、人間のデフォルトの状態としての多様性を強調する ジェームズの姿勢は、アメリカ文化に強い影響力を持ち続けている。ジェイムズが「意識の流れ」という言葉で表現した心と世界のつながりは、特にジェイム ズ・ジョイスの場合、アヴァンギャルドやモダニズムの文学や芸術に直接的で重要な影響を与えた。 ジェイムズは『プラグマティズムの意味するもの』(1906年)の中で、彼自身の真理に関する教義の中心点を簡潔に次のように書いている[32]。 真理は事実の中から生まれるが、それらは再び事実の中に浸み込み、それらに追加され、その事実がまた新たな真理(この言葉は無関心である)を生み出し、あ るいは明らかにし、そうして無限に続く。一方、「事実」そのものは真実ではない。単にそうなのだ。真実とは、事実の中で始まり、事実の中で終わる信念の機 能である。 リチャード・ローティは、ジェイムズはこの声明で真理論を与えるつもりはなかったし、そのように見なすべきではないと主張した。しかしながら、スーザン・ ハークやハワード・マウンスのような他のプラグマティズム研究者はローティのジェイムズに対する道具論的解釈を共有していない[33]。 ジェイムズは『真理の意味』(1909年)において、プラグマティズムの批評家たちに対して相対主義的な言葉で真理について語っているように思われる: 批評家の悩みは......彼が "真 "という言葉を非相対的にとらえていることに起因しているように思われるが、プラグマティストは常に "働きを経験する者にとっての真 "という意味である」[34]。しかしジェイムズは、彼を相対主義、懐疑主義、不可知論であり、相対的な真理しか信じていないと非難する批評家に反論して いた。それどころか、彼は認識論的実在論の立場を支持していた[i]。 プラグマティズムと "換金性" プラグマティズムは真理を定義し、形而上学的な問題を解決しようとする哲学的アプローチである。ウィリアム・ジェームズは単純な物語の形で彼の方法の応用を示している[35][32]。 生きたリスが木の幹の片側にしがみついていると仮定し、木の反対側には人間が立っていると想像した。この証人は木の周りを素早く移動してリスを見ようとす るが、彼がどんなに速く移動しても、リスは同じ速さで反対方向に移動し、常に自分と人間の間に木を保っているため、彼の姿を垣間見ることはできない。その 結果、形而上学的な問題はこうなる: 男はリスを追いかけるのか、それとも追いかけないのか? ジェームズはこの問題を、実際的な意味の区別をすることで解決している。つまり、"round "の意味の区別である。男がリスの北、東、南、西の空間を占めるという意味での丸と、男がリスの腹、背中、側面に面した空間を占めるという意味での丸。丸 い」とは、リスの腹、背中、側面に面した空間を占めるという意味である。この例からジェームズはプラグマティックな方法の定義を導き出した。形而上学的な 論争に決着をつけるには、単に観念の間に実際的な結果の区別をつければよい。 ジェイムズと彼の同僚であったチャールズ・サンダース・ピアースはともに「現金価値」という言葉を生み出した[36]。 彼が「(明確な)概念の意味全体はその実践的帰結の集合全体からなる」と言ったとき、彼が念頭に置いていたのは、意味のある概念はある種の経験的な「現金 価値」を持たなければならず、特定可能な条件下で可能な経験的観察のある種の集合に何らかの形で関連づけることができなければならないということであっ た。 陳述の真実性は、現実との対応や、その考えを実践することによる観察可能な効果を通じて検証可能である。例えば、ジェームズはプラグマティズムを神の仮説 にまで広げている: 「プラグマティズムの原則に基づけば、神の仮説が最も広い意味で満足に機能するならば、それは真実である。......問題は、それを構築し、それが他の すべての働く真理と満足に結合するように決定することである」[37]。 このことから、「新しい」真理はすでに存在する真理にも対応しなければならないこともわかる。 ジェイムズのプラグマティズム』へのブルース・クックリックによる序論(1981年、p.xiv)より: ジェイムズは真理の認識論的問題にプラグマティックな方法を適用していった。ジェームズは「真」の意味を、その考え方が私たちの生活の中でどのように機能 するかを調べることによって追求した。ある信念が私たち全員にとって機能し、私たちの半人前的な世界を迅速に導いてくれるなら、その信念は真実であると彼 は言った。ジェームズは、人間の生活の中で真の信念がどのような意味を持つのか、その「現金価値」 はどのようなものなのか、そしてそれがどのような結果をもたらすのかを明らかにする ことに躍起になっていた。信念とは、もしその信念が真実であれば、不思議なことに外的な現実に対応する心的実体ではない。信念とは、不安定な環境を基準に して行動する方法であり、信念が真実であ ると言うことは、その環境において有効であると言うことなのだ。この意味で、プラグマティックな真理論は哲学におけるダーウィンの考え方を応用した。 ジェイムズのプラグマティズムに関する講義集は、アメリカ哲学において最も影響力のある本であることは間違いない。その中の講義は、このテーマに対する彼 の立場を描き出している。この講義でジェームズは、プラグマティズムと知識主義者の間には、「一致」と「現実」という概念をめぐって意見の相違が生じるだ ろうと警告している。しかし彼はこれとは対照的に、「真の思想や信念とは、経験を通じて正当化できるように、私たちの思考と融合させることができるもので ある」という、より実践的な解釈を支持している[38]。 神学的な考え方が具体的な生活にとって価値があると証明されれば、プラグマティズムにとって、それは多くのことに役立つという意味で真であろう。それ以上にどれほど真理であるかは、同じく認められなければならない他の真理との関係によって決まる。 - プラグマティズム (1907), p. 29 それによって真理が「現実」と一致することが有用な結果をもたらすが、「真理が一致しなければならない『現実』には三つの次元がある」[38][12]。 "事実の問題" 「観念の関係」、そして "私たちがコミットしている他の真理のセット全体" 信念に対するジェイムズのプラグマティックなアプローチによれば、知識は一般的に正当化された真の信念とみなされる。ジェームズは、その真実の観念が解釈 を通じて分析され、プラグマティックに正当化されれば、その見解を受け入れる。実のところ、ジェイムズの哲学全体は生産的な信念の哲学である。 何かを信じるということは、それがどのように実在するかを考えることである。彼の『合理性の感情』では、重要な信念がわからないと言うことは、たとえそれ が可能であるように見えても、その真理を疑うことである。ジェームズは、価値はあるが知ることができないものとして、4つの「合理性の仮定」を挙げてい る: 神、不道徳、自由、道徳的義務である[38][39]。 対照的に、プラグマティズムの弱い側面は、主張に対する最善の正当化はそれが機能するかどうかであるということである。しかし、結果を伴わない主張は正当化されることも正当化されないこともない。 "違いを生み出さない違いはありえない" - プラグマティズム』(1907年)45頁 ジェイムズはプラグマティズムの目標は究極的には「それぞれの実践的帰結をたどることによって、それぞれの概念を解釈しようとすること」であると述べてい るが、「実践的帰結」[40]とは何を意味するのかは明確にしていない。一方、彼の友人であり同僚であり、プラグマティズムの信念を確立したもう一人の重 要な創始者であるチャールズ・S・パースは、これらの帰結の定義に深く踏み込んでいる。ピアースは1878年の論文「How to Make Ideas Clear」において、結果を明瞭さと着想の等級として解釈することを可能にする格言を紹介し、このことをさらに説明している[42]。プロテスタント は、聖体のパンとぶどう酒を主観的な意味においてのみ肉と血であると解釈するが、カトリックは、物理的な性質はパンとぶどう酒のままであっても、外見上は 「体、血、魂、神性」を介して、実際の、そして神の神秘的な肉の性質であるとレッテルを貼るだろう。しかし誰にとっても、葡萄酒とパンが特定の性質を持つ か、あるいはキリストの血と身体と解釈されるものがキリストの血と身体であると立証されない限り、聖体の葡萄酒とパンについての知識は存在し得ない。この 意味において、ジェイムズのプラグマティックな影響者であるピアースは、実際的な結果や効果として数えられるものは、自分の感覚に影響を与えることができ るものであり、自然界において理解可能であり、理解しうるものである。 しかし、ジェイムズは「『実際的な結果』についての理解を、ペイスのように全面的に展開することはない」し、またこれらの結果をペイスのように感覚に限定 することもない[41]。ジェイムズが(功利主義に照らして)最大数の肯定的な帰結を意味するのか、(彼の優柔不断な考え方と強靭な考え方の妥協のよう に)他の観点を考慮した帰結を意味するのか[44]、あるいは全く異なる捉え方を意味するのか、どのような帰結が真にプラグマティックな基準に合致し、何 が合致しないのかを真に語ることは不明瞭である。ジェイムズがこの考えを説明する際に最も近づけたのは、一方の意見が他方の意見よりも真実であった場合に 「誰にとっても実際的に生じる」違いを量るように聴衆に伝えることであり、彼はそれを明確にしようと試みるものの、一方の意見が他方の意見よりも真実で あった場合の違いを量る方法を特定したり確立したりすることはない[40]。したがって、彼の議論の欠陥は、彼が著作全体を通して絶えず言及しているこれ らの実際的な結果を、どのように測定したり解釈したりするかを決定するのかを理解することが難しいという点に現れている。 信じる意志の教義 主な記事 信じる意志 ウィリアム・ジェームズは1896年の「信じる意志」と題する講演で、仮説の発想を正当化するために証拠主義の原則に反する権利を擁護している。この考え 方は、証拠主義に対する20世紀の異論を予見し、正当化された信念を、より有益であることを証明する揺るぎない原則に基づかせようとしたものである。ウィ リアム・ジェームズはプラグマティズムの哲学を通して、仮説の真理を裏付ける証拠として、仮説のベンチャーリングの結果を使うことで、宗教的信念を正当化 する。したがって、この教義では、神を信じることを前提とし、その信念が自分の人生にもたらすものによってその存在を証明することができる。 これを批判したのが、『自由思想と公式宣伝』のバートランド・ラッセルや『疑う意志』のアルフレッド・ヘンリー・ロイドといった懐疑論的合理性の擁護者た ちである。両者とも、人は常に誤謬主義を堅持しなければならないと主張し、あらゆる人間の知識について、「私たちの信念はどれも完全には真実ではなく、す べての信念には少なくとも曖昧さと誤謬のペナンブラがある」と認識し、真実に近づき続ける唯一の手段は、決して確実だと思い込まず、常にあらゆる側面を検 証し、客観的に結論に到達しようとすることだと主張した。 |

| Free will In his search for truth and assorted principles of psychology, William James developed his two-stage model of free will. In his model, he tries to explain how it is people come to the making of a decision and what factors are involved in it. He firstly defines our basic ability to choose as free will. Then he specifies our two factors as chance and choice. "James's two-stage model effectively separates chance (the in-deterministic free element) from choice (an arguably determinate decision that follows causally from one's character, values, and especially feelings and desires at the moment of decision)."[45] James argues that the question of free will revolves around "chance." The idea of chance is that some events are possibilities, things that could happen but are not guaranteed. Chance is a neutral term (it is, in this case, neither inherently positive nor "intrinsically irrational and preposterous," connotations it usually has); the only information it gives about the events to which it applies is that they are disconnected from other things – they are "not controlled, secured, or necessitated by other things" before they happen.[46] Chance is made possible regarding our actions because our amount of effort is subject to change. If the amount of effort we put into something is predetermined, our actions are predetermined.[47] Free will in relation to effort also balances "ideals and propensities—the things you see as best versus the things that are easiest to do". Without effort, "the propensity is stronger than the ideal." To act according to your ideals, you must resist the things that are easiest, and this can only be done with effort.[48] James states that the free will question is therefore simple: "it relates solely to the amount of effort of attention or consent which we can at any time put forth."[47] Chance is the 'free element,' that part of the model we have no control over. James says that in the sequence of the model, chance comes before choice. In the moment of decision we are given the chance to make a decision and then the choice is what we do (or do not do) regarding the decision. When it comes to choice, James says we make a choice based on different experiences. It comes from our own past experiences, the observations of others, or:[45] A supply of ideas of the various movements that are … left in the memory by experiences of their involuntary performance is thus the first prerequisite of the voluntary life. What James describes is that once you've made a decision in the past, the experience is stockpiled into your memory where it can be referenced the next time a decision must be made and will be drawn from as a positive solution. However, in his development of the design, James also struggled with being able to prove that free will is actually free or predetermined. People can make judgements of regret, moral approval and moral disapproval, and if those are absent, then that means our will is predetermined. An example of this is "James says the problem is a very 'personal' one and that he cannot personally conceive of the universe as a place where murder must happen."[49] Essentially, if there were no regrets or judgments then all the bad stuff would not be considered bad, only as predetermined because there are no options of 'good' and 'bad'. "The free will option is pragmatically truer because it better accommodates the judgments of regret and morality."[49] Overall, James uses this line of reasoning to prove that our will is indeed free: because of our morality codes, and the conceivable alternate universes where a decision has been regarded different from what we chose. In "The Will to Believe", James simply asserted that his will was free. As his first act of freedom, he said, he chose to believe his will was free. He was encouraged to do this by reading Charles Renouvier, whose work convinced James to convert from monism to pluralism. In his diary entry of April 30, 1870, James wrote:[50] I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier's second Essais and see no reason why his definition of free will—"the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts"—need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present—until next year—that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will. In 1884, James set the terms for all future discussions of determinism and compatibilism in the free will debates with his lecture to Harvard Divinity School students published as "The Dilemma of Determinism".[51] In this talk he defined the common terms hard determinism and soft determinism (now more commonly called compatibilism).[51] Old-fashioned determinism was what we may call hard determinism. It did not shrink from such words as fatality, bondage of the will, necessitation, and the like. Nowadays, we have a soft determinism which abhors harsh words, and, repudiating fatality, necessity, and even predetermination, says that its real name is freedom; for freedom is only necessity understood, and bondage to the highest is identical with true freedom.[52]: 149 James called compatibilism a "quagmire of evasion,"[52]: 149 just as the ideas of Thomas Hobbes and David Hume—that free will was simply freedom from external coercion—were called a "wretched subterfuge" by Immanuel Kant. Indeterminism is "the belief in freedom [which] holds that there is some degree of possibility that is not necessitated by the rest of reality."[53] The word "some" in this definition is crucial in James's argument because it leaves room for a higher power, as it does not require that all events be random. Specifically, indeterminism does not say that no events are guaranteed or connected to previous events; instead, it says that some events are not guaranteed – some events are up to chance.[48] In James's model of free will, choice is deterministic, determined by the person making it, and it "follows casually from one's character, values, and especially feelings and desires at the moment of decision."[54] Chance, on the other hand, is indeterministic, and pertains to possibilities that could happen but are not guaranteed.[46] James described chance as neither hard nor soft determinism, but "indeterminism":[52]: 153 The stronghold of the determinist argument is the antipathy to the idea of chance ... This notion of alternative possibility, this admission that any one of several things may come to pass is, after all, only a roundabout name for chance. James asked the students to consider his choice for walking home from Lowell Lecture Hall after his talk:[52]: 155 What is meant by saying that my choice of which way to walk home after the lecture is ambiguous and matter of chance? ... It means that both Divinity Avenue and Oxford Street are called but only one, and that one either one, shall be chosen. With this simple example, James laid out a two-stage decision process with chance in a present time of random alternatives, leading to a choice of one possibility that transforms an ambiguous future into a simple unalterable past. James's two-stage model separates chance (undetermined alternative possibilities) from choice (the free action of the individual, on which randomness has no effect). Subsequent thinkers using this model include Henri Poincaré, Arthur Holly Compton, and Karl Popper. |

自

由意志真理と心理学の諸原則を探求する中で、ウィリアム・ジェームズは自由意志の二段階モデルを開発した。彼のモデルでは、人がどのようにして意思決定を

するようになるのか、そしてそれにはどのような要素が関係しているのかを説明しようとしている。彼はまず、私たちの基本的な選択能力を自由意志と定義し

た。そして、私たちの2つの要因を偶然と選択とした。「ジェイムズの二段階モデルは、偶然(決定不能な自由要素)と選択(決定の瞬間の人の性格、価値観、

特に感情や欲望から因果的に導かれる議論の余地なく決定可能な決定)を効果的に分離している」[45]。 ジェームズは、自由意志の問題は "偶然性 "を中心に展開すると主張している。偶然性とは、いくつかの出来事は可能性であり、起こりうるが保証されていないものであるという考え方である。偶然は中 立的な用語であり(この場合、偶然は本質的に肯定的なものでも、「本質的に非合理的でばかげたもの」でもない。もし私たちが何かに注ぐ努力の量があらかじ め決まっているならば、私たちの行動はあらかじめ決まっていることになる[47]。努力に関連する自由意志はまた、「理想と傾向-最善と思われることと、 最も簡単にできること-」のバランスをとる。努力がなければ、「性向は理想よりも強い」。理想に従って行動するためには、最も簡単なことに抵抗しなければ ならず、これは努力によってのみ可能である[48]: 自由意志の問題は単純である。「自由意志の問題は、われわれがいつでも行うことのできる注意や同意の努力の量にのみ関係している」[47]。 偶然は「自由な要素」であり、私たちが制御できないモデルの部分である。ジェームズは、このモデルの順序では、偶然が選択の前に来ると言う。決断の瞬間、私たちは決断を下すチャンスを与えられ、その決断に関して私たちが何をするか(あるいは何をしないか)が選択となる。 選択に関して言えば、ジェームズは、私たちはさまざまな経験に基づいて選択をすると言う。それは自分自身の過去の経験、他者の観察、あるいは次のようなものである[45]。 不随意的な動作の経験によって......記憶に残される様々な動作のアイデアの供給は、したがって随意的な生活の最初の前提条件である。 ジェームスが述べているのは、過去に一度決断を下せば、その経験は記憶の中に備蓄され、次に決断を下さなければならないときに参照することができ、積極的 な解決策として引き出されるということである。しかし、ジェームズはデザインを開発する中で、自由意志が実際に自由なのか、それともあらかじめ決められた ものなのかを証明することにも苦心した。 人は後悔、道徳的承認、道徳的不承認の判断を下すことができるが、もしそれがないのであれば、私たちの意志はあらかじめ決められているということになる。 この例として、「ジェームズは、この問題は非常に "個人的 "なものであり、殺人が起こるべき場所としての宇宙を個人的に考えることはできないと言う」[49]。「自由意志の選択肢の方が、後悔や道徳の判断をより うまく受け入れることができるので、実際的には真実である」[49]。全体として、ジェームズはこの推論の筋道を使って、私たちの意志が本当に自由である ことを証明している。信じる意志』の中で、ジェームズは自分の意志が自由であると主張した。自由の最初の行為として、彼は自分の意志が自由であると信じる ことを選んだ。ジェイムズはシャルル・ルヌヴィエの著作を読み、一元論から多元主義への転換を確信した。1870年4月30日の日記の中で、ジェイムズは 次のように書いている[50]。 昨日は私の人生の危機だったと思う。ルヌヴィエの第二エッセの最初の部分を読み終えたが、彼の自由意志の定義、すなわち「他の考えがあるかもしれないとき に、自分がそれを選択するために考えを持続させること」が、幻想の定義でなければならない理由はない。いずれにせよ、私は今のところ(来年までは)、自由 意志が幻想ではないと仮定する。私の自由意志の最初の行為は、自由意志を信じることである。1884年、ジェームズは「決定論のジレンマ(The Dilemma of Determinism)」[51]として出版されたハーバード大学神学部の学生に対する講義によって、自由意志論争における決定論と相同性論に関する将 来のすべての議論の条件を設定した。 この講義の中で、彼は一般的な用語であるハード決定論とソフト決定論(現在では相同性論と呼ばれることが多い)を定義した[51]。 昔ながらの決定論はハード決定論と呼ばれるものであった。それは宿命、意志の束縛、必然性などのような言葉に屈しなかった。今日、われわれは過酷な言葉を 忌み嫌い、宿命性、必然性、そして事前決定さえも否定し、その本当の名前は自由であると言う柔らかい決定論を持っている: 149 ジェイムズは両立主義を「回避の泥沼」と呼んだ[52]: 149 ちょうどトマス・ホッブズとデイヴィッド・ヒュームの考え-自由意志とは単に外的強制からの自由である-がイマニュエル・カントによって「惨めな裏技」と呼ばれたように。 不確定性とは、「現実の他の部分によって必然化されることのない、ある程度の可能性が存在するとする(自由に対する)信念」である[53]。この定義にお ける「ある程度の」という言葉は、ジェイムズの議論において極めて重要である。具体的に言えば、不確定性とは、どのような出来事も保証されていないとか、 以前の出来事と関係があるとは言っていないのであり、その代わりに、いくつかの出来事は保証されていない、つまりいくつかの出来事は偶然次第であると言っ ているのである[48]。ジェイムズの自由意志のモデルでは、選択は決定論的であり、それをする人によって決定され、それは「決定の瞬間の人の性格、価値 観、特に感情や欲望から何気なく導かれる」。 「一方、偶然は決定論的ではなく、起こりうるが保証されていない可能性に関わるものである[46]: 153 決定論者の議論の牙城は、偶然性という考えに対する反感である。この代替可能性という概念、つまり、いくつかの事柄のうちのどれかが実現する可能性があるということを認めるということは、結局のところ、偶然の遠回しの呼び名にすぎない。 ジェイムズは、講演の後、ローウェル講義室から家路につく際の自分の選択について考えるよう、学生たちに求めた[52]: 155 講演の後、どの道を歩いて帰るかという私の選択が曖昧で、偶然の問題であるというのはどういう意味ですか?... ディヴィニティ・アヴェニューとオックスフォード・ストリートの両方が呼び出されるが、どちらか一方しか選ばれないということだ。 この単純な例で、ジェームズは、ランダムな選択肢のある現在において、偶然性を伴う二段階の意思決定プロセスを示した。ジェイムズの2段階モデルは、偶然 性(未決定の代替可能性)と選択(ランダム性が影響しない個人の自由行動)を分離する。このモデルを用いた後の思想家には、アンリ・ポアンカレ、アー サー・ホリー・コンプトン、カール・ポパーなどがいる。 |

| Philosophy of religion James did important work in philosophy of religion. In his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh he provided a wide-ranging account of The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and interpreted them according to his pragmatic leanings. Some of the important claims he makes in this regard: Religious genius (experience) should be the primary topic in the study of religion, rather than religious institutions—since institutions are merely the social descendant of genius. The intense, even pathological varieties of experience (religious or otherwise) should be sought by psychologists, because they represent the closest thing to a microscope of the mind—that is, they show us in drastically enlarged form the normal processes of things. In order to usefully interpret the realm of common, shared experience and history, we must each make certain "over-beliefs" in things which, while they cannot be proven on the basis of experience, help us to live fuller and better lives. A variety of characteristics can be seen within a single individual. There are subconscious elements that compose the scattered fragments of a personality. This is the reflection of a greater dissociation which is the separation between science and religion. Religious Mysticism is only one half of mysticism, the other half is composed of the insane and both of these are co-located in the 'great subliminal or transmarginal region'.[55] James investigated mystical experiences throughout his life, leading him to experiment with chloral hydrate (1870), amyl nitrite (1875), nitrous oxide (1882), and peyote (1896).[citation needed] James claimed that it was only when he was under the influence of nitrous oxide that he was able to understand Hegel.[56] He concluded that while the revelations of the mystic hold true, they hold true only for the mystic; for others, they are certainly ideas to be considered, but can hold no claim to truth without personal experience of such. American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia classes him as one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[57] Mysticism William James provided a description of the mystical experience, in his famous collection of lectures published in 1902 as The Varieties of Religious Experience.[58] These criteria are as follows Passivity – a feeling of being grasped and held by a superior power not under your own control. Ineffability – no adequate way to use human language to describe the experience. Noetic – universal truths revealed that are unable to be acquired anywhere else. Transient – the mystical experience is only a temporary experience. James's preference was to focus on human experience, leading to his research of the subconscious. This was the entryway for the awakening transformation of mystical states. Mystical states represent the peak of religious experience. This helped open James's inner process to self-discovery. Instincts See also: Instinct Like Sigmund Freud, James was influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection.[59] At the core of James's theory of psychology, as defined in The Principles of Psychology (1890), was a system of "instincts". James wrote that humans had many instincts, even more than other animals.[59] These instincts, he said, could be overridden by experience and by each other, as many of the instincts were actually in conflict with each other.[59] In the 1920s, however, psychology turned away from evolutionary theory and embraced radical behaviorism.[59] Theory of emotion James is one of the two namesakes of the James–Lange theory of emotion, which he formulated independently of Carl Lange in the 1880s. The theory holds that emotion is the mind's perception of physiological conditions that result from some stimulus. In James's oft-cited example, it is not that we see a bear, fear it, and run; we see a bear and run; consequently, we fear the bear. Our mind's perception of the higher adrenaline level, heartbeat, etc. is the emotion. This way of thinking about emotion has great consequences for the philosophy of aesthetics as well as to the philosophy and practice of education.[60] Here is a passage from his work, The Principles of Psychology, that spells out those consequences: [W]e must immediately insist that aesthetic emotion, pure and simple, the pleasure given us by certain lines and masses, and combinations of colors and sounds, is an absolutely sensational experience, an optical or auricular feeling that is primary, and not due to the repercussion backwards of other sensations elsewhere consecutively aroused. To this simple primary and immediate pleasure in certain pure sensations and harmonious combinations of them, there may, it is true, be added secondary pleasures; and in the practical enjoyment of works of art by the masses of mankind these secondary pleasures play a great part. The more classic one's taste is, however, the less relatively important are the secondary pleasures felt to be, in comparison with those of the primary sensation as it comes in. Classicism and romanticism have their battles over this point. The theory of emotion was also independently developed in Italy by the anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi.[61][62] William James' bear From Joseph LeDoux's description of William James' Emotion:[63] Why do we run away if we notice that we are in danger? Because we are afraid of what will happen if we don't. This obvious answer to a seemingly trivial question has been the central concern of a century-old debate about the nature of our emotions. It all began in 1884 when William James published an article titled "What Is an Emotion?"[64] The article appeared in a philosophy journal called Mind, as there were no psychology journals yet. It was important, not because it definitively answered the question it raised, but because of the way in which James phrased his response. He conceived of an emotion in terms of a sequence of events that starts with the occurrence of an arousing stimulus (the sympathetic nervous system or the parasympathetic nervous system); and ends with a passionate feeling, a conscious emotional experience. A major goal of emotion research is still to elucidate this stimulus-to-feeling sequence—to figure out what processes come between the stimulus and the feeling. James set out to answer his question by asking another: do we run from a bear because we are afraid or are we afraid because we run? He proposed that the obvious answer, that we run because we are afraid, was wrong, and instead argued that we are afraid because we run: Our natural way of thinking about … emotions is that the mental perception of some fact excites the mental affection called emotion, and that this latter state of mind gives rise to the bodily expression. My theory, on the contrary, is that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion (called 'feeling' by Damasio). The essence of James's proposal was simple. It was premised on the fact that emotions are often accompanied by bodily responses (racing heart, tight stomach, sweaty palms, tense muscles, and so on; sympathetic nervous system) and that we can sense what is going on inside our body much the same as we can sense what is going on in the outside world. According to James, emotions feel different from other states of mind because they have these bodily responses that give rise to internal sensations, and different emotions feel different from one another because they are accompanied by different bodily responses and sensations. For example, when we see James's bear, we run away. During this act of escape, the body goes through a physiological upheaval: blood pressure rises, heart rate increases, pupils dilate, palms sweat, muscles contract in certain ways (evolutionary, innate defense mechanisms). Other kinds of emotional situations will result in different bodily upheavals. In each case, the physiological responses return to the brain in the form of bodily sensations, and the unique pattern of sensory feedback gives each emotion its unique quality. Fear feels different from anger or love because it has a different physiological signature (the parasympathetic nervous system for love). The mental aspect of emotion, the feeling, is a slave to its physiology, not vice versa: we do not tremble because we are afraid or cry because we feel sad; we are afraid because we tremble and are sad because we cry. Philosophy of history One of the long-standing schisms in the philosophy of history concerns the role of individuals in social change. One faction sees individuals (as seen in Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities and Thomas Carlyle's The French Revolution, A History) as the motive power of history, and the broader society as the page on which they write their acts. The other sees society as moving according to holistic principles or laws, and sees individuals as its more-or-less willing pawns. In 1880, James waded into this controversy with "Great Men, Great Thoughts, and the Environment", an essay published in the Atlantic Monthly. He took Carlyle's side, but without Carlyle's one-sided emphasis on the political/military sphere, upon heroes as the founders or overthrowers of states and empires. A philosopher, according to James, must accept geniuses as a given entity the same way as a biologist accepts as an entity Darwin's "spontaneous variations". The role of an individual will depend on the degree of its conformity with the social environment, epoch, moment, etc.[65] James introduces a notion of receptivities of the moment. The societal mutations from generation to generation are determined (directly or indirectly) mainly by the acts or examples of individuals whose genius was so adapted to the receptivities of the moment or whose accidental position of authority was so critical that they became ferments, initiators of movements, setters of precedent or fashion, centers of corruption, or destroyers of other persons, whose gifts, had they had free play, would have led society in another direction.[66] View on Social Darwinism While James accepted Darwin's theories of biological evolution, he regarded Social Darwinism as propagated by philosophers such as Herbert Spencer as a sham. He was highly skeptical of applying Darwin's formula of natural selection to human societies in a way that put the Anglo-Saxons on top of the chain. James' rejection of Social Darwinism was a minority opinion at Harvard in the 1870s and 1880s.[67] View on spiritualism and associationism James in a séance with a spiritualist medium James studied closely the schools of thought known as associationism and spiritualism. The view of an associationist is that each experience that one has leads to another, creating a chain of events. The association does not tie together two ideas, but rather physical objects.[68] This association occurs on an atomic level. Small physical changes occur in the brain which eventually form complex ideas or associations. Thoughts are formed as these complex ideas work together and lead to new experiences. Isaac Newton and David Hartley both were precursors to this school of thought, proposing such ideas as "physical vibrations in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves are the basis of all sensations, all ideas, and all motions …"[69] James disagreed with associationism in that he believed it to be too simple. He referred to associationism as "psychology without a soul"[70] because there is nothing from within creating ideas; they just arise by associating objects with one another. On the other hand, a spiritualist believes that mental events are attributed to the soul. Whereas in associationism, ideas and behaviors are separate, in spiritualism, they are connected. Spiritualism encompasses the term innatism, which suggests that ideas cause behavior. Ideas of past behavior influence the way a person will act in the future; these ideas are all tied together by the soul. Therefore, an inner soul causes one to have a thought, which leads them to perform a behavior, and memory of past behaviors determine how one will act in the future.[70] James had a strong opinion about these schools of thought. He was, by nature, a pragmatist and thus took the view that one should use whatever parts of theories make the most sense and can be proven.[69] Therefore, he recommended breaking apart spiritualism and associationism and using the parts of them that make the most sense. James believed that each person has a soul, which exists in a spiritual universe, and leads a person to perform the behaviors they do in the physical world.[69] James was influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg, who first introduced him to this idea. James stated that, although it does appear that humans use associations to move from one event to the next, this cannot be done without this soul tying everything together. For, after an association has been made, it is the person who decides which part of it to focus on, and therefore determines in which direction following associations will lead.[68] Associationism is too simple in that it does not account for decision-making of future behaviors, and memory of what worked well and what did not. Spiritualism, however, does not demonstrate actual physical representations for how associations occur. James combined the views of spiritualism and associationism to create his own way of thinking. James discussed tender-minded thinkers as religious, optimistic, dogmatic, and monistic. Tough-minded thinkers were irreligious, pessimistic, pluralists, and skeptical. Healthy-minded individuals were seen as natural believers by having faith in God and universal order. People who focused on human miseries and suffering were noted as sick souls. James was a founding member and vice president of the American Society for Psychical Research.[71] The lending of his name made Leonora Piper a famous medium. In 1885, the year after the death of his young son, James had his first sitting with Piper at the suggestion of his mother-in-law.[72] He was soon convinced that Piper knew things she could only have discovered by supernatural means. He expressed his belief in Piper by saying, "If you wish to upset the law that all crows are black, it is enough if you prove that one crow is white. My white crow is Mrs. Piper."[73] However, James did not believe that Piper was in contact with spirits. After evaluating sixty-nine reports of Piper's mediumship he considered the hypothesis of telepathy as well as Piper obtaining information about her sitters by natural means such as her memory recalling information. According to James the "spirit-control" hypothesis of her mediumship was incoherent, irrelevant and in cases demonstrably false.[74] James held séances with Piper and was impressed by some of the details he was given; however, according to Massimo Polidoro a maid in the household of James was friendly with a maid in Piper's house and this may have been a source of information that Piper used for private details about James.[75] Bibliographers Frederick Burkhardt and Fredson Bowers who compiled the works of James wrote "It is thus possible that Mrs. Piper's knowledge of the James family was acquired from the gossip of servants and that the whole mystery rests on the failure of the people upstairs to realize that servants [downstairs] also have ears."[76] James was convinced that the "future will corroborate" the existence of telepathy.[77] Psychologists such as James McKeen Cattell and Edward B. Titchener took issue with James's support for psychical research and considered his statements unscientific.[78][79] Cattell in a letter to James wrote that the "Society for Psychical Research is doing much to injure psychology".[80] James' theory of the self James' theory of the self divided a person's mental picture of self into two categories: the "Me" and the "I". The "Me" can be thought of as a separate object or individual a person refers to when describing their personal experiences; while the "I" is the self that knows who they are and what they have done in their life.[38] Both concepts are depicted in the statement; "I know it was me who ate the cookie." He called the "Me" part of self the "empirical me" and the "I" part "the pure Ego".[81] For James, the "I" part of self was the thinking self, which could not be further divided. He linked this part of the self to the soul of a person, or what is now thought of as the mind.[82] Educational theorists have been inspired in various ways by James's theory of self, and have developed various applications to curricular and pedagogical theory and practice.[60] James further divided the "Me" part of self into: a material, a social, and a spiritual self, as below.[81] Material self The material self consists of things that belong to a person or entities that a person belongs to. Thus, things like the body, family, clothes, money, and such make up the material self. For James, the core of the material self was the body.[82] Second to the body, James felt a person's clothes were important to the material self. He believed a person's clothes were one way they expressed who they felt they were; or clothes were a way to show status, thus contributing to forming and maintaining one's self-image.[82] Money and family are critical parts of the material self. James felt that if one lost a family member, a part of who they are was lost also. Money figured in one's material self in a similar way. If a person had significant money then lost it, who they were as a person changed as well.[82] Social self Our social selves are who we are in a given social situation. For James, people change how they act depending on the social situation that they are in. James believed that people had as many social selves as they did social situations they participated in.[82] For example, a person may act in a different way at work when compared to how that same person may act when they are out with a group of friends. James also believed that in a given social group, an individual's social self may be divided even further.[82] An example of this would be, in the social context of an individual's work environment, the difference in behavior when that individual is interacting with their boss versus their behavior when interacting with a co-worker. Spiritual self For James, the spiritual self was who we are at our core. It is more concrete or permanent than the other two selves. The spiritual self is our subjective and most intimate self. Aspects of a spiritual self include things like personality, core values, and conscience that do not typically change throughout an individual's lifetime. The spiritual self involves introspection, or looking inward to deeper spiritual, moral, or intellectual questions without the influence of objective thoughts.[82] For James, achieving a high level of understanding of who we are at our core, or understanding our spiritual selves is more rewarding than satisfying the needs of the social and material selves. Pure ego What James refers to as the "I" self. For James, the pure ego is what provides the thread of continuity between our past, present, and future selves. The pure ego's perception of consistent individual identity arises from a continuous stream of consciousness.[83] James believed that the pure ego was similar to what we think of as the soul, or the mind. The pure ego was not a substance and therefore could not be examined by science.[38] |

宗教哲学 ジェームズは宗教哲学において重要な仕事をした。エジンバラ大学でのギフォード講義において、彼は『宗教的経験の多様性』(1902年)の広範な説明を行い、それを彼のプラグマティックな傾向に従って解釈した。この点に関して彼が主張する重要な点をいくつか挙げてみよう: 宗教制度は天才の社会的子孫にすぎないのだから、宗教制度よりも宗教的天才(経験)を宗教研究の主要なテーマとすべきである。 宗教的であろうとなかろうと)強烈で、病的でさえあるようなさまざまな体験は、心理学者が探し求めるべきものである。 共通の、共有された経験や歴史の領域を有益に解釈するために、私たちはそれぞれ、経験に基づいて証明することはできないが、より充実したより良い人生を送るのに役立つ、ある種の「過剰な信念」を持たなければならない。 一人の人間の中にも、さまざまな特徴が見られる。人格の散らばった断片を構成する潜在意識の要素がある。これは、科学と宗教の分離という、より大きな解離の反映である。 宗教的神秘主義は神秘主義の片割れに過ぎず、もう片割れは狂気によって構成されており、この両者は「大いなるサブリミナルあるいはトランスマージナル領域」に同居している[55]。 ジェームズは生涯を通じて神秘体験を調査し、水和クロラール(1870年)、亜硝酸アミル(1875年)、亜酸化窒素(1882年)、ペヨーテ(1896 年)の実験を行うに至った。 [56]彼は、神秘主義者の啓示は真実であるが、それは神秘主義者にとってのみ真実であり、他の人々にとっては、それらは確かに考慮されるべき考えである が、そのような個人的な経験なしには真実であると主張することはできないと結論づけた。アメリカの哲学: American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia』は、彼を「世界とは別個のものとしての神の見方を否定することで、より汎神論的あるいは汎神論的なアプローチをとった」数人の 人物の一人として分類している[57]。 神秘主義 ウィリアム・ジェームズは、1902年に『宗教的経験の多様性』として出版された有名な講義集の中で、神秘体験についての説明を提供している[58]。 これらの基準は以下の通りである。 受動性 - 自分自身のコントロール下にない優れた力に把握され、保持されているという感覚。 不可触性 - 人間の言葉を用いてその体験を説明する適切な方法がない。 Noetic - 他では得られない普遍的な真理が明らかにされる。 一過性 - 神秘体験は一時的なものに過ぎない。 ジェームズは人間の経験に焦点を当てることを好み、潜在意識の研究につながった。これが神秘的状態の覚醒的変容の入り口となった。神秘的な状態とは、宗教的体験のピークを示すものである。これが、ジェームズの自己発見への内的プロセスを開く助けとなった。 本能 こちらも参照: 本能 ジークムント・フロイトのように、ジェームズはチャールズ・ダーウィンの自然淘汰理論に影響を受けていた。ジェームズは、人間には他の動物よりも多くの本 能があると書いている[59]。これらの本能の多くは、実際には互いに対立しているため、経験や互いによって上書きされる可能性があると述べている [59]。 感情論 ジェームズは、1880年代にカール・ランゲから独立して定式化したジェームス=ランゲ感情理論の2人の名義人のうちの1人である。この理論では、感情と は何らかの刺激から生じる生理的状態を心が知覚することであるとする。ジェームズのよく引き合いに出される例で言えば、熊を見て、それを恐れて走るのでは なく、熊を見て走り、その結果、熊を恐れるのである。アドレナリンのレベルや心臓の鼓動などが高くなったことを私たちの心が認識することが感情なのであ る。 感情についてのこのような考え方は、美学の哲学だけでなく、教育の哲学と実践にも大きな結果をもたらす[60]。以下は彼の著作『心理学の原理』からの一節で、そのような結果を綴っている: [美的感情とは、純粋で単純なものであり、特定の線や塊、色や音の組み合わせによって私たちに与えられる喜びである。ある種の純粋な感覚や、それらの調和 のとれた組み合わせに対する、この単純な一次的かつ直接的な快楽に、二次的な快楽が加わることは事実である。しかし、趣味が古典的であればあるほど、二次 的な快楽は一次的な快楽に比べて相対的に重要でなくなる。古典主義とロマン主義は、この点をめぐって争いを繰り広げる。 感情論はまた人類学者ジュゼッペ・セルジによってイタリアで独自に発展した[61][62]。 ウィリアム・ジェームズの熊 ウィリアム・ジェームズの『感情』に関するジョセフ・ルドゥーの記述より:[63]。 危険にさらされていることに気づいたら、人はなぜ逃げるのか。逃げなければどうなるかを恐れているからだ。一見些細な疑問に対するこの明白な答えは、私たちの感情の本質に関する100年来の議論の中心的な関心事であった。 それは1884年、ウィリアム・ジェイムズが「感情とは何か」と題する論文を発表したことから始まった[64]。 まだ心理学雑誌がなかったため、この論文は「マインド」という哲学雑誌に掲載された。この論文が重要だったのは、それが提起した問いに明確に答えたからで はなく、ジェイムズの回答の言い回しにあった。彼は感情を、興奮刺激(交感神経系または副交感神経系)の発生から始まり、情熱的な感情、つまり意識的な感 情体験で終わる一連の出来事としてとらえたのである。この刺激から感情までの一連の流れを解明し、刺激と感情の間にどのようなプロセスがあるのかを解明す ることが、感情研究の大きな目標である。 熊から逃げるのは怖いからか、それとも逃げるから怖いのか。彼は、「怖いから走る」という明白な答えは間違っているとし、その代わりに「走るから怖いのだ」と主張した: 感情について私たちが考える自然な方法は、ある事実を精神的に認識することによって、感情と呼ばれる精神的情緒が励起され、この後者の精神状態が身体的表 現を生じさせるというものである。それに対して私の理論は、身体の変化は興奮させる事実の知覚に直接的に従うものであり、同じ変化が起こったときに私たち が感じることが感情(ダマシオは「フィーリング」と呼ぶ)であるというものである。 ジェームズの提案の本質は単純だった。それは、感情はしばしば身体的反応(心臓の鼓動、胃の締め付け、手のひらの汗、筋肉の緊張など;交感神経系)を伴う という事実と、私たちは身体の内部で起こっていることを、外界で起こっていることと同じように感じることができるという事実を前提とした。ジェイムズによ れば、感情が他の心の状態と異なって感じられるのは、内的感覚を生じさせるこのような身体的反応があるからであり、異なる感情が互いに異なって感じられる のは、異なる身体的反応や感覚を伴うからである。例えば、ジェームスの熊を見たとき、私たちは逃げる。血圧が上昇し、心拍数が上昇し、瞳孔が開き、手のひ らに汗をかき、筋肉がある特定の方法で収縮する(進化的、生得的な防衛メカニズム)。他の種類の感情的状況でも、異なる身体的動揺が生じる。いずれの場合 も、生理的反応は身体感覚の形で脳に戻り、感覚フィードバックのユニークなパターンが、それぞれの感情にユニークな性質を与える。恐怖は怒りや愛とは異な る生理的特徴(愛の場合は副交感神経系)を持っているため、異なって感じられる。私たちは、怖いから震えるのではなく、悲しいから泣くのでもなく、震える から怖いのであり、泣くから悲しいのである。 歴史哲学 歴史哲学における長年の分裂のひとつは、社会の変化における個人の役割に関するものである。 一方の派閥は、(ディケンズの『二都物語』やトマス・カーライルの『フランス革命史』に見られるように)個人を歴史の原動力とみなし、より広い社会を個人 がその行為を書き記すページとみなす。もう一方は、社会が全体論的な原理や法則に従って動いていると見なし、個人を多かれ少なかれその手先として見てい る。1880年、ジェームズは『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に発表したエッセイ『偉人、偉大な思想、そして環境』でこの論争に割って入った。彼は カーライルの側に立ったが、カーライルが政治的/軍事的領域を一方的に強調し、国家や帝国の創設者や打倒者としての英雄を強調することはなかった。 ジェイムズによれば、哲学者は、生物学者がダーウィンの「自然発生的変異」を実体として受け入れるのと同じように、天才を与えられた実体として受け入れなければならない。個人の役割は、社会環境、時代、瞬間などとの適合の度合いによって決まる[65]。 ジェイムズは瞬間の受容性という概念を導入している。世代から世代への社会の変異は、その天才がその瞬間の受容性に非常に適合していた、あるいはその偶然 の権威の地位が非常に危機的であったために、発酵剤、運動の創始者、先例や流行の設定者、腐敗の中心、あるいは他の人物の破壊者となった個人の行為や事例 によって(直接的または間接的に)決定される。 社会ダーウィニズムに対する見解 ジェームズは、ダーウィンの生物学的進化の理論を受け入れる一方で、ハーバート・スペンサーなどの哲学者によって広められた社会ダーウィニズムはまやかし だと考えていた。彼は、ダーウィンの自然淘汰の公式を、アングロサクソンが連鎖の頂点に立つような形で人間社会に適用することに強い懐疑的であった。社会 ダーウィニズムに対するジェームズの拒絶は、1870年代と1880年代のハーバード大学では少数意見であった[67]。 スピリチュアリズムとアソシエイション主義についての見解 霊媒と交霊するジェームズ ジェームズは、アソシエイション主義やスピリチュアリズムと呼ばれる学派をよく研究していた。連想主義者の見解は、人が経験するひとつひとつが別の経験に つながり、出来事の連鎖を生み出すというものである。連想は2つの観念を結びつけるのではなく、物理的な物体を結びつける[68]。小さな物理的変化が脳 内で起こり、それが最終的に複雑な観念や連想を形成する。思考は、このような複雑な考えが連動し、新しい経験につながることで形成される。アイザック・ ニュートンとデイヴィッド・ハートリーはともにこの学派の先駆者であり、「脳、脊髄、神経における物理的振動が、すべての感覚、すべての観念、すべての運 動の基礎である」といった考えを提唱していた[69]。彼は連想主義を「魂のない心理学」[70]と呼んだ。 一方、スピリチュアリストは、精神的な出来事は魂に帰属すると考える。連想主義では、観念と行動は別個のものであるのに対し、スピリチュアリズムでは、そ れらはつながっている。スピリチュアリズムには、観念が行動を引き起こすとする生得主義という言葉がある。過去の行動に対する考え方が、その人の将来の行 動様式に影響を与えるのであり、これらの考え方はすべて魂によって結びつけられている。したがって、内なる魂が人に思考を起こさせ、それが行動を起こさ せ、過去の行動の記憶が人が将来どのように行動するかを決定するのである[70]。 ジェームズはこれらの学派に対して強い意見を持っていた。したがって、ジェームズはスピリチュアリズムとアソシエイショニズムを分解し、最も理にかなって いる部分を使用することを推奨していた[69]。ジェームズは、各人には魂があり、その魂は霊的な宇宙に存在し、人が物理的な世界で行う行動を行うように 導くと信じていた[69]。ジェームズはこの考えを最初に紹介したエマニュエル・スウェーデンボルグの影響を受けていた。ジェームズは、人間はある出来事 から次の出来事に移るために連想を使っているように見えるが、これは魂がすべてを結びつけていなければできないことだと述べている。連想がなされた後、そ の中のどの部分に焦点を当てるかを決めるのはその人であり、したがって次の連想がどの方向に向かうかを決めるのもその人だからである。しかしスピリチュア リズムは、連想がどのように起こるかについて、実際の物理的な表現を示していない。ジェームズはスピリチュアリズムとアソシエイション論の見解を組み合わ せて、独自の思考法を生み出した。ジェームズは、心の優しい思想家を宗教的、楽観的、独断的、一元論的と論じた。タフマインドな思想家は、無宗教的、悲観 的、多元主義的、懐疑的であった。健全な心の持ち主は、神と普遍的秩序への信仰を持ち、自然な信者と見なされた。人間の不幸や苦しみに焦点を当てる人々 は、病んだ魂として注目された。 ジェームズはアメリカ心霊研究協会の創立メンバーであり、副会長でもあった[71]。1885年、幼い息子を亡くした翌年、ジェームズは義母の勧めで初め てパイパーと対面した[72]。すべてのカラスは黒いという法則を覆したいのなら、一羽のカラスが白いことを証明すれば十分だ。私の白いカラスはパイパー 夫人です」[73] しかし、ジェームズはパイパーが霊と接触しているとは信じていなかった。パイパーの霊媒に関する69の報告を評価した後、彼はテレパシーの仮説だけでな く、パイパーが彼女の記憶を呼び起こすなどの自然な手段によって彼女のシッターに関する情報を得るという仮説も検討した。ジェームズによれば、彼女の霊媒 能力の「スピリット・コントロール」仮説は支離滅裂であり、無関係であり、場合によっては明らかに誤りであった[74]。 しかし、マッシモ・ポリドーロによれば、ジェームズの家のメイドはパイパーの家のメイドと親交があり、このことがパイパーがジェームズのプライベートな情 報を得るための情報源であった可能性がある。 [75]ジェイムズの著作を編纂した書誌学者フレデリック・ブルクハルトとフレドソン・バウワーズは、「したがって、ピペル夫人のジェイムズ家に関する知 識は使用人たちの噂話から得たものであり、すべての謎は、使用人(階下)にも耳があることを階上の人間が気づかなかったことにかかっている可能性がある」 と書いている[76]。 ジェームズはテレパシーの存在を「未来が裏づける」と確信していた[77]。ジェームズ・マッキーン・キャッテルやエドワード・B・ティッチナーのような 心理学者は、ジェームズの心霊研究への支持を問題視し、彼の発言を非科学的であると考えていた[78][79]。 キャッテルはジェームズに宛てた手紙の中で、「心霊研究協会は心理学を傷つけるために多くのことをしている」と書いていた[80]。 ジェイムズの自己論 ジェームズの自己の理論は、人の自己の心的イメージを「私」と「私」の2つのカテゴリーに分けた。私」は、人が自分の個人的な経験を説明するときに言及す る別個の対象や個人と考えることができ、「私」は、自分が誰であり、人生で何をしたかを知っている自己である。ジェイムズは自己の「私」の部分を「経験的 な私」と呼び、「私」の部分を「純粋な自我」と呼んだ[81]。彼は自己のこの部分を人の魂、あるいは現在心として考えられているものと結びつけていた [82]。教育理論家たちはジェームズの自己理論に様々な形で触発され、カリキュラムや教育学の理論や実践への様々な応用を展開してきた[60]。 ジェームズはさらに、自己の「私」の部分を以下のように物質的自己、社会的自己、精神的自己に分けている[81]。 物質的自己 物質的自己は、人に属するもの、あるいは人が属する実体からなる。したがって、身体、家族、衣服、金銭などのようなものが物質的自己を構成する。ジェイム ズにとって、物質的自己の中核は身体であった[82]。身体に次いで、ジェイムズは人の衣服が物質的自己にとって重要であると感じていた。ジェームズは、 人の衣服はその人が自分自身を表現する一つの方法であり、あるいは衣服はステータスを示す方法であり、したがって自己イメージの形成と維持に貢献すると考 えていた[82]。ジェームズは、家族を失えば、自分という人間の一部も失われると感じていた。お金も同様に、物質的な自己の一部である。もしある人が多 額のお金を持っていて、それを失うと、その人の人間性も変わってしまうのである[82]。 社会的自己 社会的自己とは、ある社会的状況において私たちがどのような人間で あるかということである。ジェイムズにとって、人は自分が置かれている社会的状況によって行動様式を変える。ジェームズは、人は自分が参加する社会的状況 の数だけ社会的自我を持っていると考えていた。ジェームズはまた、ある社会的グループにおいて、個人の社会的自己はさらに分割されるかもしれないと考えて いた[82]。この例としては、個人の職場環境という社会的文脈において、その個人が上司と接しているときの行動と同僚と接しているときの行動の違いが挙 げられる。 霊的自己 ジェイムズにとって、スピリチュアルな自己とは、私たちの核となるものである。他の2つの自己に比べ、より具体的で永続的なものである。スピリチュアルな 自己は、主観的で最も親密な自己である。霊的自己の側面には、人格、核となる価値観、良心といったものが含まれ、これらは通常、個人の生涯を通じて変わる ことはない。精神的自己は、客観的思考に影響されることなく、より深い精神的、道徳的、あるいは知的な疑問に対して内観することを含む[82]。ジェイム ズにとって、自分の核心にある自分自身について高いレベルの理解を達成すること、つまり精神的自己を理解することは、社会的自己や物質的自己の欲求を満た すことよりも報われることである。 純粋な自我 ジェームズが「私」と呼ぶ自己。ジェイムズにとって純粋な自我とは、過去、現在、未来の自己の間に連続性の糸をもたらすものである。ジェームズは、純粋な 自我は私たちが魂や心として考えているものに似ていると考えていた。純粋な自我は物質ではなかったので、科学によって調べることはできなかった[38]。 |