帰結主義

Consequentialism

☆ 帰結主義(consequentialism)とは、帰結から最初の行為を肯定するあらゆる立場のこと。道徳哲学において、帰結主義(結果主義とも言う; consequentialism)は、ある行為の善悪を判断する究極的な基準はその行為の結果であるとする、規範的・目的論的倫理理論の一 種である。したがって、帰結主義の観点では、道徳的に正しい行為(行動をしないことも含む)とは、良い結果をもたらすものである。帰結主義は、幸福論ととも に、目的論的倫理学というより広いカテゴリーに分類される。目的論的倫理学は、あらゆる行為の道徳的価値は、本質的な価値を持つものを生み出す傾向にある という主張の集合体である。一般的に、行為は、その行為(または、その行為が該当するルール)が、利用可能な代替案よりも善悪のバランスをより大きく保 つ、または保つ可能性が高い、あるいはそう意図されている場合にのみ正しいとされる。功利主義の諸理論は、道徳的な善をどのように定義するかによって異な り、主な候補としては、快楽、苦痛の不在、自身の好みの満足、より広義の「一般善」の概念などが挙げられる。

☆ 功利主義は、通常、義務論的倫理(または義務論)と対比される。義務論=デオントロジーは、ある行為の道徳性は、その行為の結果に基づく[→帰結主義]のではなく、[その行為が生む結果がどのようなものであれ]一連の規則や原則の下で、その行為自体が正しいか間違っているかに基づくべきであるという規範的倫理の理論である。

| In

moral philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative,

teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's

conduct are the ultimate basis for judgement about the rightness or

wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, a

morally right act (including omission from acting) is one that will

produce a good outcome. Consequentialism, along with eudaimonism, falls

under the broader category of teleological ethics, a group of views

which claim that the moral value of any act consists in its tendency to

produce things of intrinsic value.[1] Consequentialists hold in general

that an act is right if and only if the act (or in some views, the rule

under which it falls) will produce, will probably produce, or is

intended to produce, a greater balance of good over evil than any

available alternative. Different consequentialist theories differ in

how they define moral goods, with chief candidates including pleasure,

the absence of pain, the satisfaction of one's preferences, and broader

notions of the "general good". Consequentialism is usually contrasted with deontological ethics (or deontology): deontology, in which rules and moral duty are central, derives the rightness or wrongness of one's conduct from the character of the behaviour itself, rather than the outcomes of the conduct. It is also contrasted with both virtue ethics, which focuses on the character of the agent rather than on the nature or consequences of the act (or omission) itself, and pragmatic ethics, which treats morality like science: advancing collectively as a society over the course of many lifetimes, such that any moral criterion is subject to revision. Some argue that consequentialist theories (such as utilitarianism) and deontological theories (such as Kantian ethics) are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For example, T. M. Scanlon advances the idea that human rights, which are commonly considered a "deontological" concept, can only be justified with reference to the consequences of having those rights.[2] Similarly, Robert Nozick argued for a theory that is mostly consequentialist, but incorporates inviolable "side-constraints" which restrict the sort of actions agents are permitted to do.[2] Derek Parfit argued that, in practice, when understood properly, rule consequentialism, Kantian deontology, and contractualism would all end up prescribing the same behavior.[3] |

道徳哲学において、帰結主義(結果主義とも言う)は、ある行為の善悪を判断する究極的な基準はその行為の結果であるとする、規範的・目的論的倫理理論の一

種である。したがって、帰結主義の観点では、道徳的に正しい行為(行動をしないことも含む)とは、良い結果をもたらすものである。帰結主義は、幸福論ととも

に、目的論的倫理学というより広いカテゴリーに分類される。目的論的倫理学は、あらゆる行為の道徳的価値は、本質的な価値を持つものを生み出す傾向にある

という主張の集合体である。一般的に、行為は、その行為(または、その行為が該当するルール)が、利用可能な代替案よりも善悪のバランスをより大きく保

つ、または保つ可能性が高い、あるいはそう意図されている場合にのみ正しいとされる。功利主義の諸理論は、道徳的な善をどのように定義するかによって異な

り、主な候補としては、快楽、苦痛の不在、自身の好みの満足、より広義の「一般善」の概念などが挙げられる。 功利主義は、通常、義務論的倫理(または義務論)と対比される。義務論では、規則と道徳的義務が中心であり、行動の結果ではなく、行動そのものの性質か ら、その行動の善し悪しを導き出す。また、行為(または不作為)そのものの性質や結果よりも行為者の性格に焦点を当てる美徳倫理や、道徳を科学のように扱 う実用主義倫理とも対照的である。実用主義倫理では、道徳的基準は、社会が多くの世代にわたって集合的に進歩するにつれて修正されるべきものである。 功利主義などの結果論的理論とカント主義などの義務論的理論は、必ずしも相容れないものではないという意見もある。例えば、T. M. スキャロンは、一般的に「義務論的」概念と考えられている人権は、その権利を持つことによる結果を参照することでのみ正当化できるという考えを提唱してい る。[2] 同様に、ロバート・ノージックは、ほとんどが結果論的であるが、 行動主体が許される行動の種類を制限する、不可侵の「副次的な制約」を組み込んでいる。[2] デレク・パーフィットは、適切に理解された場合、ルール結果論、カント的義務論、契約主義は、実際にはすべて同じ行動を規定することになると主張した。 [3] |

| The

term consequentialism was coined by G. E. M. Anscombe in her essay

"Modern Moral Philosophy" in 1958.[4][5] However, the meaning of the

word has changed over the time since Anscombe used it: in the sense she

coined it, she had explicitly placed J.S. Mill in the

nonconsequentialist and W.D. Ross in the consequentialist camp,

whereas, in the contemporary sense of the word, they would be

classified the other way round.[4][6] This is due to changes in the

meaning of the word, not due to changes in perceptions of W.D. Ross's

and J.S. Mill's views.[4][6] |

「帰

結主義」という用語は、1958年にG. E. M. アンコムが「現代道徳哲学」という論文で造語したものである。[4][5]

しかし、アンコムが用いて以来、この言葉の意味は時代とともに変化している。彼女の造語の意味では、彼女はJ.S.ミルを非帰結主義者、W.D.ロスを帰

結主義者の陣営に明確に位置づけていたが、現代的な言葉の意味では、この二人は逆に分類されることになる。これは言葉の意味の変化によるものであり、

W.D.ロスやJ.S.ミルの見解に対する認識の変化によるものではない。 |

| Classification One common view is to classify consequentialism, together with virtue ethics, under a broader label of "teleological ethics".[7][1] Proponents of teleological ethics (Greek: telos, 'end, purpose' + logos, 'science') argue that the moral value of any act consists in its tendency to produce things of intrinsic value,[1] meaning that an act is right if and only if it, or the rule under which it falls, produces, will probably produce, or is intended to produce, a greater balance of good over evil than any alternative act. This concept is exemplified by the famous aphorism, "the end justifies the means," variously attributed to Machiavelli or Ovid[8] i.e. if a goal is morally important enough, any method of achieving it is acceptable.[9][10] Teleological ethical theories are contrasted with deontological ethical theories, which hold that acts themselves are inherently good or bad, rather than good or bad because of extrinsic factors (such as the act's consequences or the moral character of the person who acts).[11] |

分類 一般的な見解の一つは、帰結主義を徳倫理学とともに「目的論的倫理学」という広いラベルの下に分類することである。 [7][1]目的論的倫理学(ギリシア語:テロス、「目的、目的」+ロゴス、「科学」)の支持者は、あらゆる行為の道徳的価値は、本質的価値のあるものを 生み出す傾向にあると主張する[1]。つまり、ある行為が正しいのは、その行為、またはその行為が該当するルールが、代替的な行為よりも悪に対する善のバ ランスが大きいものを生み出す場合、おそらく生み出す場合、または生み出すことを意図している場合に限られる。この概念は、マキアヴェッリやオヴィッド [8]のものとされる様々な有名な格言「目的は手段を正当化する(the end justifies the means)」によって例証される。 テレオロジー的な倫理理論は、外在的な要因(行為の結果や行為者の道徳的性格など)によって善悪が決まるのではなく、行為自体が本質的に善悪であるとする非論理的な倫理理論と対比される[11]。 |

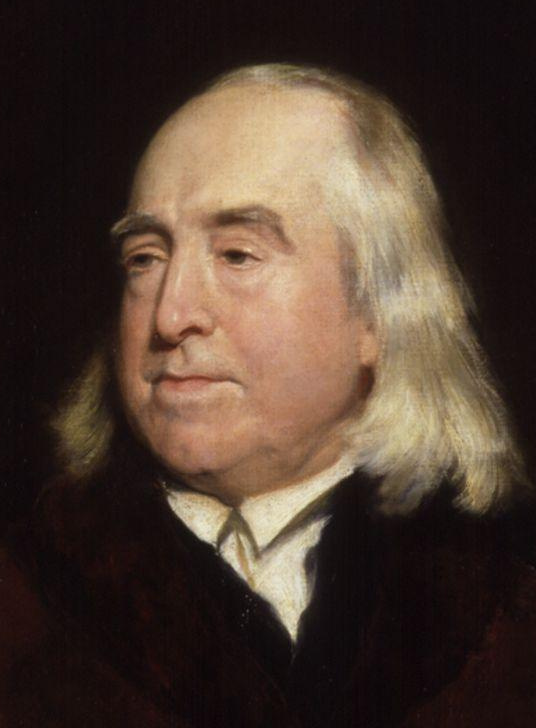

| Forms of consequentialism Utilitarianism Main article: Utilitarianism  Jeremy Bentham, best known for his advocacy of utilitarianism Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think... — Jeremy Bentham, The Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789) Ch I, p 1 In summary, Jeremy Bentham states that people are driven by their interests and their fears, but their interests take precedence over their fears; their interests are carried out in accordance with how people view the consequences that might be involved with their interests. Happiness, in this account, is defined as the maximization of pleasure and the minimization of pain. It can be argued that the existence of phenomenal consciousness and "qualia" is required for the experience of pleasure or pain to have an ethical significance.[12][13] Historically, hedonistic utilitarianism is the paradigmatic example of a consequentialist moral theory. This form of utilitarianism holds that what matters is the aggregate happiness; the happiness of everyone, and not the happiness of any particular person. John Stuart Mill, in his exposition of hedonistic utilitarianism, proposed a hierarchy of pleasures, meaning that the pursuit of certain kinds of pleasure is more highly valued than the pursuit of other pleasures.[14] However, some contemporary utilitarians, such as Peter Singer, are concerned with maximizing the satisfaction of preferences, hence preference utilitarianism. Other contemporary forms of utilitarianism mirror the forms of consequentialism outlined below. Rule consequentialism See also: Rule utilitarianism In general, consequentialist theories focus on actions. However, this need not be the case. Rule consequentialism is a theory that is sometimes seen as an attempt to reconcile consequentialism with deontology, or rules-based ethics[15]—and in some cases, this is stated as a criticism of rule consequentialism.[16] Like deontology, rule consequentialism holds that moral behavior involves following certain rules. However, rule consequentialism chooses rules based on the consequences that the selection of those rules has. Rule consequentialism exists in the forms of rule utilitarianism and rule egoism. Various theorists are split as to whether the rules are the only determinant of moral behavior or not. For example, Robert Nozick held that a certain set of minimal rules, which he calls "side-constraints," are necessary to ensure appropriate actions.[2] There are also differences as to how absolute these moral rules are. Thus, while Nozick's side-constraints are absolute restrictions on behavior, Amartya Sen proposes a theory that recognizes the importance of certain rules, but these rules are not absolute.[2] That is, they may be violated if strict adherence to the rule would lead to much more undesirable consequences. One of the most common objections to rule-consequentialism is that it is incoherent, because it is based on the consequentialist principle that what we should be concerned with is maximizing the good, but then it tells us not to act to maximize the good, but to follow rules (even in cases where we know that breaking the rule could produce better results). In Ideal Code, Real World, Brad Hooker avoids this objection by not basing his form of rule-consequentialism on the ideal of maximizing the good. He writes:[17] [T]he best argument for rule-consequentialism is not that it derives from an overarching commitment to maximise the good. The best argument for rule-consequentialism is that it does a better job than its rivals of matching and tying together our moral convictions, as well as offering us help with our moral disagreements and uncertainties. Derek Parfit described Hooker's book as the "best statement and defence, so far, of one of the most important moral theories."[18] State consequentialism Main article: State consequentialism It is the business of the benevolent man to seek to promote what is beneficial to the world and to eliminate what is harmful, and to provide a model for the world. What benefits he will carry out; what does not benefit men he will leave alone (Chinese: 仁之事者, 必务求于天下之利, 除天下之害, 将以为法乎天下. 利人乎, 即为; 不利人乎, 即止).[19] — Mozi, Mozi (5th century BC) (Chapter 8: Against Music Part I) State consequentialism, also known as Mohist consequentialism,[20] is an ethical theory that evaluates the moral worth of an action based on how much it contributes to the welfare of a state.[20] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Mohist consequentialism, dating back to the 5th century BCE, is the "world's earliest form of consequentialism, a remarkably sophisticated version based on a plurality of intrinsic goods taken as constitutive of human welfare."[21] Unlike utilitarianism, which views utility as the sole moral good, "the basic goods in Mohist consequentialist thinking are...order, material wealth, and increase in population."[22] The word "order" refers to Mozi's stance against warfare and violence, which he viewed as pointless and a threat to social stability; "material wealth" of Mohist consequentialism refers to basic needs, like shelter and clothing; and "increase in population" relates to the time of Mozi, war and famine were common, and population growth was seen as a moral necessity for a harmonious society.[23] In The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Stanford sinologist David Shepherd Nivison writes that the moral goods of Mohism "are interrelated: more basic wealth, then more reproduction; more people, then more production and wealth...if people have plenty, they would be good, filial, kind, and so on unproblematically."[22] The Mohists believed that morality is based on "promoting the benefit of all under heaven and eliminating harm to all under heaven." In contrast to Jeremy Bentham's views, state consequentialism is not utilitarian because it is not hedonistic or individualistic. The importance of outcomes that are good for the community outweigh the importance of individual pleasure and pain.[24] The term state consequentialism has also been applied to the political philosophy of the Confucian philosopher Xunzi.[25] On the other hand, "legalist" Han Fei "is motivated almost totally from the ruler's point of view."[26] Ethical egoism Main article: Ethical egoism Ethical egoism can be understood as a consequentialist theory according to which the consequences for the individual agent are taken to matter more than any other result. Thus, egoism will prescribe actions that may be beneficial, detrimental, or neutral to the welfare of others. Some, like Henry Sidgwick, argue that a certain degree of egoism promotes the general welfare of society for two reasons: because individuals know how to please themselves best, and because if everyone were an austere altruist then general welfare would inevitably decrease.[27] Ethical altruism Main article: Altruism (ethics) Ethical altruism can be seen as a consequentialist theory which prescribes that an individual take actions that have the best consequences for everyone, not necessarily including themselves (similar to selflessness).[28] This was advocated by Auguste Comte, who coined the term altruism, and whose ethics can be summed up in the phrase "Live for others."[29] Two-level consequentialism The two-level approach involves engaging in critical reasoning and considering all the possible ramifications of one's actions before making an ethical decision, but reverting to generally reliable moral rules when one is not in a position to stand back and examine the dilemma as a whole. In practice, this equates to adhering to rule consequentialism when one can only reason on an intuitive level, and to act consequentialism when in a position to stand back and reason on a more critical level.[30] This position can be described as a reconciliation between act consequentialism—in which the morality of an action is determined by that action's effects—and rule consequentialism—in which moral behavior is derived from following rules that lead to positive outcomes.[30] The two-level approach to consequentialism is most often associated with R. M. Hare and Peter Singer.[30] Motive consequentialism Another consequentialist application view is motive consequentialism, which looks at whether the state of affairs that results from the motive to choose an action is better or at least as good as each alternative state of affairs that would have resulted from alternative actions. This version gives relevance to the motive of an act and links it to its consequences. An act can therefore not be wrong if the decision to act was based on a right motive. A possible inference is that one can not be blamed for mistaken judgments if the motivation was to do good.[31] Negative consequentialism See also: Negative consequentialism Most consequentialist theories focus on promoting some sort of good consequences. However, negative utilitarianism lays out a consequentialist theory that focuses solely on minimizing bad consequences. One major difference between these two approaches is the agent's responsibility. Positive consequentialism demands that we bring about good states of affairs, whereas negative consequentialism requires that we avoid bad ones. Stronger versions of negative consequentialism will require active intervention to prevent bad and ameliorate existing harm. In weaker versions, simple forbearance from acts tending to harm others is sufficient. An example of this is the slippery-slope argument, which encourages others to avoid a specified act on the grounds that it may ultimately lead to undesirable consequences.[32] Often "negative" consequentialist theories assert that reducing suffering is more important than increasing pleasure. Karl Popper, for example, claimed that "from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure."[33] (While Popper is not a consequentialist per se, this is taken as a classic statement of negative utilitarianism.) When considering a theory of justice, negative consequentialists may use a statewide or global-reaching principle: the reduction of suffering (for the disadvantaged) is more valuable than increased pleasure (for the affluent or luxurious). Acts and omissions Since pure consequentialism holds that an action is to be judged solely by its result, most consequentialist theories hold that a deliberate action is no different from a deliberate decision not to act. This contrasts with the "acts and omissions doctrine", which is upheld by some medical ethicists and some religions: it asserts there is a significant moral distinction between acts and deliberate non-actions which lead to the same outcome. This contrast is brought out in issues such as voluntary euthanasia. Actualism and possibilism This section is about actualism and possibilism in ethics. For actualism and possibilism in metaphysics, see Actualism. The normative status of an action depends on its consequences according to consequentialism. The consequences of the actions of an agent may include other actions by this agent. Actualism and possibilism disagree on how later possible actions impact the normative status of the current action by the same agent. Actualists assert that it is only relevant what the agent would actually do later for assessing the value of an alternative. Possibilists, on the other hand, hold that we should also take into account what the agent could do, even if she would not do it.[34][35][36][37] For example, assume that Gifre has the choice between two alternatives, eating a cookie or not eating anything. Having eaten the first cookie, Gifre could stop eating cookies, which is the best alternative. But after having tasted one cookie, Gifre would freely decide to continue eating cookies until the whole bag is finished, which would result in a terrible stomach ache and would be the worst alternative. Not eating any cookies at all, on the other hand, would be the second-best alternative. Now the question is: should Gifre eat the first cookie or not? Actualists are only concerned with the actual consequences. According to them, Gifre should not eat any cookies at all since it is better than the alternative leading to a stomach ache. Possibilists, however, contend that the best possible course of action involves eating the first cookie and this is therefore what Gifre should do.[38] One counterintuitive consequence of actualism is that agents can avoid moral obligations simply by having an imperfect moral character.[34][36] For example, a lazy person might justify rejecting a request to help a friend by arguing that, due to her lazy character, she would not have done the work anyway, even if she had accepted the request. By rejecting the offer right away, she managed at least not to waste anyone's time. Actualists might even consider her behavior praiseworthy since she did what, according to actualism, she ought to have done. This seems to be a very easy way to "get off the hook" that is avoided by possibilism. But possibilism has to face the objection that in some cases it sanctions and even recommends what actually leads to the worst outcome.[34][39] Douglas W. Portmore has suggested that these and other problems of actualism and possibilism can be avoided by constraining what counts as a genuine alternative for the agent.[40] On his view, it is a requirement that the agent has rational control over the event in question. For example, eating only one cookie and stopping afterward only is an option for Gifre if she has the rational capacity to repress her temptation to continue eating. If the temptation is irrepressible then this course of action is not considered to be an option and is therefore not relevant when assessing what the best alternative is. Portmore suggests that, given this adjustment, we should prefer a view very closely associated with possibilism called maximalism.[38] |

帰結主義の形式 功利主義 主な記事 功利主義  功利主義の提唱で知られるジェレミー・ベンサム 自然は人間を、苦痛と快楽という2人の主権者の支配下に置いた。我々が何をなすべきかを指し示すのも、何をなすべきかを決定するのも、この二人だけのため である。一方では善悪の基準が、他方では原因と結果の連鎖が、彼らの玉座に固定されている。それらは、われわれのすべての行動、すべての発言、すべての思 考において、われわれを支配する...。 - ジェレミー・ベンサム『道徳と立法の原理』(1789年)第一章、p1 要約すると、ジェレミー・ベンサムは、人は自分の利益と恐れによって動かされるが、自分の利益は恐れよりも優先される。この説明では、幸福とは快楽の最大 化と苦痛の最小化と定義される。快楽や苦痛の経験が倫理的意義を持つためには、現象意識と「クオリア」の存在が必要であると主張することができる[12] [13]。 歴史的には、快楽主義的功利主義は帰結主義的道徳理論の典型的な例である。この形態の功利主義は、重要なのは総体的な幸福であり、すべての人の幸福であっ て、特定の人の幸福ではないとする。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは快楽主義的功利主義の説明の中で、快楽の階層を提唱した。つまり、ある種の快楽の追求は 他の快楽の追求よりも高く評価されるということである。その他の現代的な功利主義の形態は、以下に概説する帰結主義の形態を反映している。 ルール帰結主義 以下も参照のこと: ルール功利主義 一般的に、帰結主義理論は行為に焦点を当てる。しかし、そうである必要はない。ルール帰結主義は、帰結主義と脱ontology(ルールに基づく倫理学) を調和させる試みと見られることもある理論であり[15]、ルール帰結主義に対する批判として述べられている場合もある[16]。しかし、ルール帰結主義 は、それらのルールの選択がもたらす結果に基づいてルールを選択する。ルール帰結主義はルール功利主義とルールエゴ主義の形で存在する。 ルールが道徳的行動の唯一の決定要因であるか否かについては、さまざまな理論家に意見が分かれている。例えば、ロバート・ノージックは、適切な行動を保証 するためには、彼が「傍制約」と呼ぶ一定の最小限のルールセットが必要であるとした[2]。また、これらの道徳的ルールがどの程度絶対的なものであるかに ついても違いがある。したがって、ノージックの傍拘束が行動に対する絶対的な制限であるのに対して、アマルティア・センは一定のルールの重要性を認めつつ も、これらのルールは絶対的なものではないという理論を提唱している[2]。つまり、ルールを厳格に遵守することがより望ましくない結果をもたらす場合に は、違反する可能性があるということである。 ルール帰結主義に対する最も一般的な反論の一つは、それが支離滅裂であるというものである。なぜなら、ルール帰結主義は、我々が関心を持つべきは善を最大 化することであるという帰結主義的な原則に基づいているが、その上で、善を最大化するために行動するのではなく、(たとえルールを破った方がより良い結果 を生むと分かっている場合であっても)ルールに従えと説いているからである。 ブラッド・フッカーは『理想のコード、現実の世界』(原題:Ideal Code, Real World)において、善を最大化するという理想をルール帰結主義の基盤としないことで、この反論を回避している。彼は次のように書いている[17]。 [ルール帰結主義の最良の論拠は、それが善を最大化するという包括的なコミットメントに由来するということではない。ルール=帰結主義の最良の論拠は、私 たちの道徳的信念を一致させ、結びつけ、道徳的不一致や不確実性を解決する手助けを提供するという点で、ライバルよりも優れているということである。 デレク・パーフィットはフッカーの著書を「最も重要な道徳理論の1つについて、今のところ最高の声明であり擁護である」と評している[18]。 国家帰結主義 主な記事 国家帰結主義 世界にとって有益なことを促進し、有害なことを排除しようとするのは、善意者の仕事であり、世界に模範を示すことである。利益になることは実行し、人のた めにならないことは放っておく(中国語:仁之事者、必务求于天下之利、除天下之害、将以为法乎天下。 利人乎、即为;不利人乎、即止)[19]。 - 墨子(前5世紀)(第8章 音楽に反対する 第一部) スタンフォード哲学百科事典(Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)によれば、紀元前5世紀まで遡るモヒスト的帰結主義は、「世界最古の帰結主義の形態であり、人間の福利を構成するものとして捉えら れた複数の内在財に基づく著しく洗練されたバージョン」である[21]。 効用を唯一の道徳的善とみなす功利主義とは異なり、「モヒストの帰結主義的思考における基本的な財は、秩序、物質的豊かさ、人口の増加である。 「秩序」とは、茂吉が戦争や暴力を無意味で社会の安定を脅かすものと見なしたことに反対する茂吉の姿勢を指し、「物質的豊かさ」とは、住居や衣服のような 基本的なニーズを指し、「人口の増加」とは、戦争や飢饉が一般的であった茂吉の時代に関連しており、人口増加は調和のとれた社会のために道徳的に必要であ ると見なされていた。 [23]スタンフォード大学の中国研究者デイヴィッド・シェパード・ニヴィソンは『ケンブリッジ古代中国史』の中で、モヒズムの道徳的財は「相互に関連し ている:基本的な富が多ければ、再生産が増え、人が多ければ、生産と富が増える......人々が豊かであれば、善良で、孝行で、親切で......等 々、問題なくなる」と書いている[22]。 モヒスト教徒は、道徳は 「天下万民の利益を促進し、天下万民の害を排除すること 」に基づいていると信じていた。ジェレミー・ベンサムの見解とは対照的に、国家帰結主義は快楽主義でも個人主義でもないため、功利主義ではない。共同体に とって良い結果の重要性は、個人の快楽や苦痛の重要性を凌駕する[24]。国家帰結主義という言葉は、儒教の哲学者である孫子の政治哲学にも適用されてい る[25]。一方、「法治主義者」である韓非子は、「ほとんど完全に支配者の視点から動機づけられている」[26]。 倫理的エゴイズム 主な記事 倫理的エゴイズム 倫理的エゴイズムは、個々の主体にとっての結果が他のどんな結果よりも重要であるとする帰結主義理論として理解することができる。したがって、エゴイズム は、他者の福祉にとって有益、有害、あるいは中立的な行動を規定することになる。ヘンリー・シドウィックのように、ある程度のエゴイズムは社会の一般的な 厚生を促進すると主張する者もいるが、その理由は2つある:個人は自分自身を最も喜ばせる方法を知っているからであり、もし全員が厳格な利他主義者であれ ば一般的な厚生は必然的に減少するからである[27]。 倫理的利他主義 主な記事 利他主義(倫理) 倫理的利他主義は帰結主義的な理論であり、個人が必ずしも自分自身を含めないすべての人にとって最良の結果をもたらす行動をとることを規定する(無私に似 ている)[28]。これは利他主義という言葉を作ったオーギュスト・コントによって提唱され、彼の倫理は「他人のために生きよ」という言葉に要約される [29]。 二段階帰結主義 二段階アプローチでは、倫理的決定を下す前に、批判的推論を行い、自分の行動がもたらす可能性のある影響をすべて考慮するが、ジレンマ全体に立ち戻って検 討する立場にない場合は、一般的に信頼できる道徳的ルールに回帰する。実際には、直感的なレベルでしか推論できないときにはルール帰結主義を堅持し、より 批判的なレベルに立って推論できる立場にあるときには行為帰結主義を堅持することに等しい[30]。 この立場は、行為の道徳性がその行為の結果によって決定されるという行為帰結主義と、道徳的行動が肯定的な結果をもたらすルールに従うことから導かれるというルール帰結主義との間の和解と表現することができる[30]。 帰結主義に対する二段階アプローチはR.M.ヘアーやピーター・シンガーと最もよく関連している[30]。 動機的帰結主義 別の帰結主義的応用の視点は動機帰結主義であり、行動を選択する動機から生じる問題の状態が、代替的な行動から生じたであろう各代替的な問題の状態よりも 良いか、少なくとも同じくらい良いかどうかを見る。このバージョンでは、行為の動機に関連性を与え、それをその結果と結びつける。したがって、行動の決定 が正しい動機に基づくものであれば、その行為が間違っているとは言えない。可能な推論としては、動機が善を行うためであれば、誤った判断に対して非難され ることはないということである[31]。 否定的帰結主義 以下も参照: 否定的帰結主義 ほとんどの帰結主義理論は、ある種の善い結果を促進することに焦点を当てている。しかし、否定的功利主義は、悪い結果を最小化することだけに焦点を当てた結果論的理論を打ち出している。 これら2つのアプローチの大きな違いの一つは、エージェントの責任である。積極的帰結主義は良い状態をもたらすことを要求するが、消極的帰結主義は悪い状 態を避けることを要求する。否定的帰結主義の強いバージョンでは、悪いことを防ぎ、既存の害を改善するために積極的な介入が必要となる。より弱いバージョ ンでは、他者に危害を加えるような行為を避けるだけで十分である。この例として、最終的に望ましくない結果につながる可能性があるという理由で、特定の行 為を避けるように他者に勧めるスリッパ坂の議論がある[32]。 しばしば「否定的な」帰結主義理論は、苦痛を減らすことが快楽を増やすことよりも重要であると主張する。例えば、カール・ポパーは、「道徳的観点からは、 苦痛は快楽に勝ることはできない」と主張している[33](ポパーは帰結主義者ではないが、これは否定的功利主義の古典的な声明とみなされている)。正義 の理論を考えるとき、否定的帰結主義者は、(恵まれない人々にとっての)苦痛の軽減は(裕福な人々や贅沢な人々にとっての)快楽の増大よりも価値がある、 というような全体的あるいは世界的な原理を用いることがある。 行為と不作為 純粋帰結主義は、行為はその結果のみによって判断されるべきであるとするため、ほとんどの帰結主義理論は、意図的な行為は意図的な不作為の決定と変わらな いとする。これは、一部の医療倫理学者や一部の宗教が支持する「行為と不作為の教義」とは対照的で、同じ結果をもたらす行為と意図的な不作為の間には、道 徳的に重要な違いがあると主張する。この対立は、自発的安楽死などの問題で浮き彫りになる。 現実主義と可能性主義 このセクションでは、倫理学におけるアクチュアリズムとポッシビリズムについて述べる。形而上学におけるアクチュアリズムとポッシビリズムについては、アクチュアリズムを参照のこと。 帰結主義によれば、行為の規範的地位はその結果に依存する。ある行為者の行為の結果には、その行為者による他の行為も含まれる。アクチュアリズムとポッシ ビリズムは、同じエージェントによる現在の行為の規範的地位に、後に起こりうる行為がどのような影響を与えるかについて意見が分かれる。アクチュアリスト は、代替案の価値を評価するためには、エージェントが後で実際に何をするかが重要であると主張する。他方、可能性主義者は、たとえエージェントがそれをし ないとしても、エージェントがしうることも考慮に入れるべきだと主張する[34][35][36][37]。 例えば、ジフレがクッキーを食べるか何も食べないかという2つの選択肢から選ぶとする。最初のクッキーを食べた後、ギフ レはクッキーを食べるのをやめることができた。しかし、クッキーを一枚食べた後、ギフレは自由に袋全部を食べ終わるまでクッキーを食べ続けることを決める だろう。一方、クッキーを全く食べないことは、二番目に良い選択肢である。さて、問題はギフレは最初のクッキーを食べるべきか、食べないべきかである。現 実主義者は実際の結果にしか関心がない。彼らによれば、ギフレはクッキーを全く食べるべきではない。しかし、可能性主義者は、可能な限り最善の行動には最 初のクッキーを食べることが含まれ、したがってギフレはそうすべきであると主張する[38]。 実在論の反直観的な帰結の一つは、不完全な道徳的性格を持つだけで、代理人は道徳的義務を回避することができるということである[34][36]。例え ば、怠け者は、自分の怠け者の性格のために、たとえその依頼を受けたとしても、どのみちその仕事をしなかっただろうと主張することによって、友人を助けて ほしいという依頼を断ることを正当化するかもしれない。すぐに申し出を断ることで、少なくとも誰の時間も無駄にせずにすんだのだ。アクチュアリストは、彼 女の行動は賞賛に値すると考えるかもしれない。これは、可能性主義が避けている「罪を免れる」非常に簡単な方法のように思える。しかし、可能性主義は、場 合によっては実際に最悪の結果をもたらすことを是認し、推奨さえしてしまうという反論に直面しなければならない[34][39]。 ダグラス・W・ポートモアは、これらのアクチュアリズムとポッシビリズムの他の問題は、エージェントにとって何が真の代替案としてカウントされるかを制約 することによって回避することができると提案している[40]。彼の見解によれば、それはエージェントが問題の事象に対して合理的なコントロールを持って いるという要件である。例えば、クッキーを一枚だけ食べて、その後に食べるのをやめることは、ジフレにとって、食べ続けたいという誘惑を抑える合理的能力 があれば、選択肢となる。誘惑が抑えられないのであれば、このような行動は選択肢とはみなされず、したがって最良の代替案が何かを評価する際には関係な い。ポートモアは、このような調整を考慮すると、最大主義と呼ばれる可能性主義と非常に密接に関連した見方を好むべきだと提案している[38]。 |

| Issues Action guidance One important characteristic of many normative moral theories such as consequentialism is the ability to produce practical moral judgements. At the very least, any moral theory needs to define the standpoint from which the goodness of the consequences are to be determined. What is primarily at stake here is the responsibility of the agent.[41] The ideal observer One common tactic among consequentialists, particularly those committed to an altruistic (selfless) account of consequentialism, is to employ an ideal, neutral observer from which moral judgements can be made. John Rawls, a critic of utilitarianism, argues that utilitarianism, in common with other forms of consequentialism, relies on the perspective of such an ideal observer.[2] The particular characteristics of this ideal observer can vary from an omniscient observer, who would grasp all the consequences of any action, to an ideally informed observer, who knows as much as could reasonably be expected, but not necessarily all the circumstances or all the possible consequences. Consequentialist theories that adopt this paradigm hold that right action is the action that will bring about the best consequences from this ideal observer's perspective.[citation needed] The real observer In practice, it is very difficult, and at times arguably impossible, to adopt the point of view of an ideal observer. Individual moral agents do not know everything about their particular situations, and thus do not know all the possible consequences of their potential actions. For this reason, some theorists have argued that consequentialist theories can only require agents to choose the best action in line with what they know about the situation.[42] However, if this approach is naïvely adopted, then moral agents who, for example, recklessly fail to reflect on their situation, and act in a way that brings about terrible results, could be said to be acting in a morally justifiable way. Acting in a situation without first informing oneself of the circumstances of the situation can lead to even the most well-intended actions yielding miserable consequences. As a result, it could be argued that there is a moral imperative for agents to inform themselves as much as possible about a situation before judging the appropriate course of action. This imperative, of course, is derived from consequential thinking: a better-informed agent is able to bring about better consequences.[citation needed] Consequences for whom Moral action always has consequences for certain people or things. Varieties of consequentialism can be differentiated by the beneficiary of the good consequences. That is, one might ask "Consequences for whom?" Agent-focused or agent-neutral A fundamental distinction can be drawn between theories which require that agents act for ends perhaps disconnected from their own interests and drives, and theories which permit that agents act for ends in which they have some personal interest or motivation. These are called "agent-neutral" and "agent-focused" theories respectively. Agent-neutral consequentialism ignores the specific value a state of affairs has for any particular agent. Thus, in an agent-neutral theory, an actor's personal goals do not count any more than anyone else's goals in evaluating what action the actor should take. Agent-focused consequentialism, on the other hand, focuses on the particular needs of the moral agent. Thus, in an agent-focused account, such as one that Peter Railton outlines, the agent might be concerned with the general welfare, but the agent is more concerned with the immediate welfare of herself and her friends and family.[2] These two approaches could be reconciled by acknowledging the tension between an agent's interests as an individual and as a member of various groups, and seeking to somehow optimize among all of these interests.[citation needed] For example, it may be meaningful to speak of an action as being good for someone as an individual, but bad for them as a citizen of their town. Human-centered? Many consequentialist theories may seem primarily concerned with human beings and their relationships with other human beings. However, some philosophers argue that we should not limit our ethical consideration to the interests of human beings alone. Jeremy Bentham, who is regarded as the founder of utilitarianism, argues that animals can experience pleasure and pain, thus demanding that 'non-human animals' should be a serious object of moral concern.[43] More recently, Peter Singer has argued that it is unreasonable that we do not give equal consideration to the interests of animals as to those of human beings when we choose the way we are to treat them.[44] Such equal consideration does not necessarily imply identical treatment of humans and non-humans, any more than it necessarily implies identical treatment of all humans. Value of consequences One way to divide various consequentialisms is by the types of consequences that are taken to matter most, that is, which consequences count as good states of affairs. According to utilitarianism, a good action is one that results in an increase in pleasure, and the best action is one that results in the most pleasure for the greatest number. Closely related is eudaimonic consequentialism, according to which a full, flourishing life, which may or may not be the same as enjoying a great deal of pleasure, is the ultimate aim. Similarly, one might adopt an aesthetic consequentialism, in which the ultimate aim is to produce beauty. However, one might fix on non-psychological goods as the relevant effect. Thus, one might pursue an increase in material equality or political liberty instead of something like the more ephemeral "pleasure". Other theories adopt a package of several goods, all to be promoted equally. As the consequentialist approach contains an inherent assumption that the outcomes of a moral decision can be quantified in terms of "goodness" or "badness," or at least put in order of increasing preference, it is an especially suited moral theory for a probabilistic and decision theoretical approach.[45][46] Virtue ethics Consequentialism can also be contrasted with aretaic moral theories such as virtue ethics. Whereas consequentialist theories posit that consequences of action should be the primary focus of our thinking about ethics, virtue ethics insists that it is the character rather than the consequences of actions that should be the focal point. Some virtue ethicists hold that consequentialist theories totally disregard the development and importance of moral character. For example, Philippa Foot argues that consequences in themselves have no ethical content, unless it has been provided by a virtue such as benevolence.[2] However, consequentialism and virtue ethics need not be entirely antagonistic. Iain King has developed an approach that reconciles the two schools.[47][48][49][50] Other consequentialists consider effects on the character of people involved in an action when assessing consequence. Similarly, a consequentialist theory may aim at the maximization of a particular virtue or set of virtues. Finally, following Foot's lead, one might adopt a sort of consequentialism that argues that virtuous activity ultimately produces the best consequences.[clarification needed] Max Weber Ultimate end  The ultimate end is a concept in the moral philosophy of Max Weber, in which individuals act in a faithful, rather than rational, manner.[51] We must be clear about the fact that all ethically oriented conduct may be guided by one of two fundamentally differing and irreconcilably opposed maxims: conduct can be oriented to an ethic of ultimate ends or to an ethic of responsibility. [...] There is an abysmal contrast between conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of ultimate ends — that is in religious terms, "the Christian does rightly and leaves the results with the Lord" — and conduct that follows the maxim of an ethic of responsibility, in which case one has to give an account of the foreseeable results of one's action. — Max Weber, Politics as a Vocation, 1918[52] |

課題 行動指針 帰結主義のような多くの規範的道徳理論の重要な特徴の一つは、実践的な道徳的判断を生み出す能力である。少なくとも、どのような道徳理論であれ、結果の善し悪しを決定する立場を定義する必要がある。ここで主に問題となるのは、行為者の責任である[41]。 理想的観察者 結果論者、特に結果論の利他的(無私)な説明に傾倒する人々の間でよく使われる戦術の一つは、道徳的判断を下すことができる理想的で中立的な観察者を採用 することである。功利主義の批判者であるジョン・ロールズは、功利主義は他の帰結主義の形態と同様に、そのような理想的観察者の視点に依存していると主張 している[2]。この理想的観察者の特定の特徴は、あらゆる行為のすべての結果を把握する全知全能の観察者から、合理的に予想されるだけのことは知ってい るが、必ずしもすべての状況や可能なすべての結果を知っているわけではない理想的情報提供者の観察者まで様々である。このパラダイムを採用する結果論的理 論では、正しい行動とは、この理想的観察者の視点から見て最良の結果をもたらす行動であるとする[要出典]。 現実の観察者 実際には、理想的観察者の視点を採用することは非常に困難であり、時には間違いなく不可能である。個々の道徳的行為者は、特定の状況についてすべてを知っ ているわけではないので、潜在的な行動のすべての可能な結果を知っているわけではない。このため、一部の理論家は、結果論的理論は、状況について知ってい ることに沿って最善の行動を選択することのみを行為者に要求することができると主張している[42]。しかし、このアプローチがナイーブに採用されるなら ば、例えば、無謀にも自分の状況を省みることを怠り、恐ろしい結果をもたらすような行動をとる道徳的行為者は、道徳的に正当な方法で行動していると言うこ とができる。まず状況を把握せずに行動すると、どんなに良かれと思った行動でも悲惨な結果を招くことになる。その結果、適切な行動方針を判断する前に、状 況についてできるだけ多くの情報を得ることが、行為者にとって道徳的に必須であると主張することができる。この要請はもちろん、結果的思考に由来するもの である:より良い情報を得たエージェントは、より良い結果をもたらすことができる。 誰にとっての結果か 道徳的行動は常に特定の人や物事に対して結果をもたらす。帰結主義の種類は、良い結果の受益者によって区別することができる。つまり、「誰のための結果か 」を問うことができる。 代理人重視か代理人中立か 基本的な区別は、エージェントが自分自身の興味や意欲とはおそらく切り離された目的のために行動することを要求する理論と、エージェントが何らかの個人的 な興味や意欲を持つ目的のために行動することを認める理論との間に引くことができる。これらはそれぞれ「エージェント中立」理論、「エージェント重視」理 論と呼ばれる。 エージェント中立的帰結主義は、ある状態が特定のエージェントにとって持つ特定の価値を無視する。したがって、エージェント中立理論では、行為者の個人的 な目標は、その行為者がどのような行動をとるべきかを評価する上で、他の誰の目標よりも重要視されることはない。一方、行為者重視の結果論は、道徳的行為 者の特定のニーズに焦点を当てる。したがって、ピーター・レイルトンが概説しているような行為者重視の説明では、行為者は一般的な福祉に関心を持つかもし れないが、行為者は自分自身と友人や家族の当面の福祉により関心を持つ[2]。 これらの2つのアプローチは、エージェントの個人としての利益と様々な集団の一員としての利益の間に緊張関係があることを認め、これらすべての利益の間で 何とか最適化を図ることによって調和させることができる[要出典]。例えば、ある行為が個人としては誰かにとって良いものであっても、町の市民としては悪 いものであると語ることは意味があるかもしれない。 人間中心主義? 多くの結果論的理論は、主に人間と他の人間との関係に関係しているように見えるかもしれない。しかし、哲学者の中には、倫理的考察を人間の利益だけに限定 すべきではないと主張する者もいる。功利主義の創始者とされるジェレミー・ベンサムは、動物は快楽と苦痛を経験することができるため、「人間以外の動物」 も道徳的配慮の重大な対象であるべきだと主張している[43]。 より最近では、ピーター・シンガーが、動物の扱い方を選択する際に、動物の利益を人間の利益と同等に考慮しないことは不合理であると主張している [44]。このような同等な考慮は、必ずしも人間と非人間との同一の扱いを意味するものではなく、すべての人間に対する同一の扱いを意味するものでもな い。 結果の価値 様々な帰結主義を分ける一つの方法は、最も重要であるとされる結果の種類、つまりどの結果が良い状態としてカウントされるかによって分けられる。功利主義 によれば、良い行為とは快楽の増大をもたらす行為であり、最良の行為とは最大多数の快楽をもたらす行為である。これと密接に関連するのが幸福帰結主義 (eudaimonic consequentialism)であり、これによれば、多くの快楽を享受することと同じかどうかは別として、満ち足りた豊かな生活が究極の目的であ る。同様に、美を生み出すことを究極の目的とする美的帰結主義を採用することもできる。しかし、関連する効果として非心理的な財に焦点を当てるかもしれな い。つまり、より刹那的な「快楽」ではなく、物質的平等や政治的自由の向上を追求するのである。他の理論では、複数の財のパッケージを採用し、すべてを等 しく促進する。結果論的アプローチには、道徳的決定の結果は「善」または「悪」の観点から定量化することができる、あるいは少なくとも選好度の高い順に並 べることができるという固有の前提が含まれているため、確率論的アプローチや決定理論的アプローチに特に適した道徳理論である[45][46]。 徳倫理学 帰結主義はまた、徳倫理学のようなアレテー的道徳理論と対比することができる。帰結主義の理論が、行為の結果が倫理について考える際の主要な焦点であるべ きだとするのに対し、徳倫理学は、焦点となるべきは行為の結果ではなく人格であると主張する。徳倫理学者の中には、帰結主義理論は道徳的人格の発達と重要 性を完全に無視していると主張する者もいる。例えば、フィリッパ・フットは、博愛のような徳によってもたらされたものでない限り、結果それ自体には倫理的 な内容はないと主張している[2]。 しかし、帰結主義と徳倫理は完全に対立する必要はない。アイアン・キングは2つの学派を調和させるアプローチを開発した[47][48][49] [50]。他の帰結主義者は、結果を評価する際に行為に関わる人々の人格への影響を考慮する。同様に、帰結主義者の理論は、特定の徳または徳の集合の最大 化を目指すこともある。最後に、フットの先導に従って、徳のある活動が最終的に最良の結果を生み出すと主張する一種の帰結主義を採用することもある[要解 説]。 マックス・ウェーバー 究極の目的  究極の目的とは、マックス・ウェーバーの道徳哲学における概念であり、個人は合理的というよりもむしろ忠実な方法で行動する[51]。 私たちは、倫理的に指向された行動はすべて、根本的に異なる、相容れないほど対立する2つの極意のうちの1つによって導かれる可能性があるという事実を明 確にしておかなければならない:行動は究極的目的の倫理に指向されることもあれば、責任の倫理に指向されることもある。[中略)究極的な目的の倫理に従う 行動、つまり宗教的な言葉で言えば、「キリスト教徒は正しく行い、その結果を主に委ねる」行動と、責任の倫理に従う行動、つまり自分の行動の予見可能な結 果について説明しなければならない行動との間には、ひどい対照がある。 - マックス・ウェーバー『職業としての政治』1918年[52]。 |

| Criticisms G. E. M. Anscombe objects to the consequentialism of Sidgwick on the grounds that the moral worth of an action is premised on the predictive capabilities of the individual, relieving them of the responsibility for the "badness" of an act should they "make out a case for not having foreseen" negative consequences.[5] Immanuel Kant makes a similar argument against consequentialism in the case of the inquiring murder. The example asks whether or not it would be right to give false statement to an inquiring murderer in order to misdirect the individual away from the intended victim. He argues, in On a Supposed Right to Tell Lies from Benevolent Motives, that lying from "benevolent motives," here the motive to maximize the good consequences by protecting the intended victim, should then make the liar responsible for the consequences of the act. For example, it could be that by misdirecting the inquiring murder away from where one thought the intended victim was actually directed the murder to the intended victim.[53] That such an act is immoral mirrors Anscombe's objection to Sidgwick that his consequentialism would problematically absolve the consequentalist of moral responsibility when the consequentalist fails to foresee the true consequences of an act. The future amplification of the effects of small decisions[54] is an important factor that makes it more difficult to predict the ethical value of consequences,[55] even though most would agree that only predictable consequences are charged with a moral responsibility.[51] Bernard Williams has argued that consequentialism is alienating because it requires moral agents to put too much distance between themselves and their own projects and commitments. Williams argues that consequentialism requires moral agents to take a strictly impersonal view of all actions, since it is only the consequences, and not who produces them, that are said to matter. Williams argues that this demands too much of moral agents—since (he claims) consequentialism demands that they be willing to sacrifice any and all personal projects and commitments in any given circumstance in order to pursue the most beneficent course of action possible. He argues further that consequentialism fails to make sense of intuitions that it can matter whether or not someone is personally the author of a particular consequence. For example, that participating in a crime can matter, even if the crime would have been committed anyway, or would even have been worse, without the agent's participation.[56] Some consequentialists—most notably Peter Railton—have attempted to develop a form of consequentialism that acknowledges and avoids the objections raised by Williams. Railton argues that Williams's criticisms can be avoided by adopting a form of consequentialism in which moral decisions are to be determined by the sort of life that they express. On his account, the agent should choose the sort of life that will, on the whole, produce the best overall effects.[2] |

批判 G.E.M.アンスコムは、ある行為の道徳的価値は個人の予見能力を前提としており、否定的な結果を「予見しなかったことを言い立てる」場合には行為の「悪さ」に対する責任を免除するという理由で、シドウィックの結果論に異議を唱えている[5]。 イマヌエル・カントは、帰結主義に対して、探究的殺人の場合にも同様の議論を行っている。この例では、意図する被害者から被害者を遠ざけるために、問い合 わせ殺人犯に虚偽の供述をすることが正しいかどうかを問うている。彼は、『善意の動機から嘘をつく権利について』の中で、「善意の動機」から嘘をつくこ と、ここでは意図した被害者を守ることによって善い結果を最大化しようとする動機から嘘をつくことは、その行為の結果に対して嘘をつく者に責任を負わせる べきだと主張している。例えば、意図された被害者がいると思っていた場所から離れた場所に、問い合わせた殺人を誤導することによって、実際に意図された被 害者に殺人を向けることができる[53]。このような行為が不道徳であるということは、結果論者が行為の真の結果を予見できなかった場合に、結果論者の道 徳的責任を免除することに問題があるというシドウィックに対するアンスコムの反論を反映している。 小さな決定[54]の影響が将来的に増幅されることは、結果の倫理的価値を予測することをより困難にする重要な要因であり[55]、たとえ予測可能な結果のみが道徳的責任を問われることにほとんどの人が同意するとしてもである[51]。 バーナード・ウィリアムズは、帰結主義は道徳的主体が自分自身と自分自身のプロジェクトやコミットメントとの間に距離を置きすぎることを要求するため、疎 外的であると主張している。ウィリアムズは、帰結主義は道徳的行為者に、すべての行為について厳密に非人間的な見方をすることを求めると主張する。という のも、帰結主義では、可能な限り最も有益な行動指針を追求するために、あらゆる状況においてあらゆる個人的な計画やコミットメントを犠牲にすることを厭わ ないことが求められるからである。彼はさらに、帰結主義は、誰かが個人的に特定の結果をもたらしたかどうかが重要であるという直観を理解できないと主張す る。例えば、犯罪に参加することは、たとえその犯罪がエージェントの参加がなければいずれにせよ犯されていたとしても、あるいはさらに悪化していたとして も、重要でありうるということである[56]。 ピーター・レイルトン(Peter Railton)を筆頭とする一部の結果論者は、ウィリアムズによって提起された異論を認め、それを回避する結果論の形態を発展させようと試みている。レ イルトンは、道徳的決定はそれが表現する人生の種類によって決定されるという帰結主義の形式を採用することによって、ウィリアムズの批判を回避することが できると主張している。彼の説明によれば、エージェントは全体として最良の全体的効果を生み出すような生き方を選ぶべきである[2]。 |

| Notable consequentialists See also: List of utilitarians R. M. Adams (born 1937) Jonathan Baron (born 1944) Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) Richard B. Brandt (1910–1997) John Dewey (1857–1952) Julia Driver (1961- ) Milton Friedman (1912–2006) David Friedman (born 1945) William Godwin (1756–1836) R. M. Hare (1919–2002) John Harsanyi (1920–2000) Brad Hooker (born 1957) Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) Shelly Kagan (born 1963) Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) James Mill (1773–1836) John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) G. E. Moore (1873–1958) Mozi (470–391 BCE) Philip Pettit (born 1945) Peter Railton (born 1950) Henry Sidgwick (1838–1900) Peter Singer (born 1946) J. J. C. Smart (1920–2012) |

著名な帰結主義者 も参照のこと: 功利主義者のリスト R. M.アダムズ(1937年生) ジョナサン・バロン(1944年生) ジェレミー・ベンサム(1748年-1832年) リチャード・B・ブラント(1910~1997年) ジョン・デューイ(1857年~1952年) ジュリア・ドライバー(1961- ) ミルトン・フリードマン(1912-2006) デビッド・フリードマン (1945年生) ウィリアム・ゴドウィン(1756-1836) R. M.ヘアー(1919-2002) ジョン・ハーサニ(1920-2000) ブラッド・フッカー(1957年生) フランシス・ハッチソン(1694~1746年) シェリー・ケーガン(1963年生) ニッコロ・マキャベリ(1469-1527年) ジェームズ・ミル(1773-1836) ジョン・スチュアート・ミル(1806-1873) G・E・ムーア(1873~1958年) 墨子(前470~391年) フィリップ・ペティット(1945年生) ピーター・レイルトン(1950年生) ヘンリー・シジウィック(1838~1900年) ピーター・シンガー(1946年生) J. J.C.スマート(1920~2012年) |

| Charvaka Demandingness objection Dharma-yuddha Effective altruism Instrumental and intrinsic value Lesser of two evils principle Mental reservation Mohism Omission bias Principle of double effect Situational ethics Utilitarianism Welfarism +++++++++++++++ Further reading Darwall, Stephen, ed. (2002). Consequentialism. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631231080. Goodman, Charles (2009). Consequences of Compassion: An interpretation and Defense of Buddhist Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195375190. Honderich, Ted (October 1996). "Consequentialism, Moralities of Concern and Selfishness". Philosophy. 71 (278): 499–520. doi:10.1017/S0031819100053432. S2CID 146267944. Retrieved 2023-09-18. Portmore, Douglas W. (2011). Commonsense Consequentialism: Wherein Morality Meets Rationality. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199794539. Price, Terry (2008). "Consequentialism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 91–93. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n60. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Scheffler, Samuel (1994). The Rejection of Consequentialism: A Philosophical Investigation of the Considerations Underlying Rival Moral Conceptions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198235118. Portmore, Douglas W. (2020). The Oxford handbook of consequentialism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190905323. |

チャールヴァカ 要求性異議 ダルマ・ユッダ 効果的利他主義 道具的価値と本質的価値 二つの悪のうち小さい方の原則 精神的留保 モヒズム 省略バイアス 二重効果の原則 状況倫理 功利主義 ウェルファリズム(福利主義?) ++++++++++++++++++++ さらに読む ダーウォール、スティーブン編(2002)。『帰結主義』オックスフォード:ブラックウェル。ISBN 978-0631231080。 グッドマン、チャールズ(2009)。『思いやりの結果:仏教倫理の解釈と擁護』オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0195375190。 Honderich, Ted (1996年10月). 「帰結主義、関心と利己主義の道徳」. Philosophy. 71 (278): 499–520. doi:10.1017/S0031819100053432. S2CID 146267944. 2023年9月18日取得。 ポートモア、ダグラス・W.(2011年)。『常識的帰結主義:道徳と合理性の出会い』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0199794539。 プライス、テリー(2008)。「帰結主義」。ハモウィ、ロナルド(編)。『リバタリアニズム事典』。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:SAGE;カ トー研究所。91–93頁。doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n60。ISBN 978-1412965804。 LCCN 2008009151。 OCLC 750831024。 シェフラー、サミュエル(1994)。『帰結主義の拒絶:対立する道徳観念の根底にある考察の『哲学探究』』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0198235118。 ポートモア、ダグラス・W.(2020)。『帰結主義のオックスフォード・ハンドブック』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0190905323 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consequentialism |

★アンスコムについては、こちらに詳しい説明があります |

| 現代倫理学基本論文集III: 規範倫理学篇2 (双書現代倫理学) 英米圏の現代倫理学の展開を追う上で、まずおさえておくべき重要文献を精選して収録。本巻では契約論・契約主義と徳倫理学を扱う。 ホッブズ的な契約論を批判的に継承し、自己利益の最大化を目指す個人間の合意形成を描いたゴティエ。自由で平等な個人間の相互尊重を論じたスキャンロン。 徳倫理学の復興に道を拓いたアンスコム。独自の徳倫理学を探るスロート。アリストテレス主義の徳倫理学を牽引するハーストハウス。各論文を紹介する充実し た監訳者解説つき。 【目次】 監訳者まえがき 第I部契約論/契約主義 第一章なぜ契約論か? [デイヴィッド・ゴティエ](池田誠訳) 第二章契約主義の構造[T・M・スキャンロン](池田誠訳) 第II部徳倫理学、またはその先駆 第三章現代道徳哲学[G・E・M・アンスコム](生野剛志訳) 第四章行為者基底的な徳倫理学[マイケル・スロート](相松慎也訳) 第五章規範的な徳倫理学[ロザリンド・ハーストハウス](古田徹也訳) 監訳者解説[古田徹也] 監訳者あとがき 事項索引 人名索引 |

ガートルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム(1919-2001)、オックスフォードの哲学者の中の最大級の変人、ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子,カソリック教徒、「ローマ教皇よりもより篤信なカソリック」と言われた。 |

| Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe

FBA (/ˈænskəm/; 18 March 1919 – 5 January 2001), usually cited as G. E.

M. Anscombe or Elizabeth Anscombe, was a British[1] analytic

philosopher. She wrote on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of action,

philosophical logic, philosophy of language, and ethics. She was a

prominent figure of analytical Thomism, a Fellow of Somerville College,

Oxford, and a professor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Anscombe was a student of Ludwig Wittgenstein and became an authority on his work and edited and translated many books drawn from his writings, above all his Philosophical Investigations. Anscombe's 1958 article "Modern Moral Philosophy" introduced the term consequentialism into the language of analytic philosophy, and had a seminal influence on contemporary virtue ethics.[2] Her monograph Intention (1957) was described by Donald Davidson as "the most important treatment of action since Aristotle".[3][4] It is "widely considered a foundational text in contemporary philosophy of action" and has also had influence in the philosophy of practical reason."[5] |

ガー

トルード・エリザベス・マーガレット・アンスコム(Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe FBA / 発音例:

ˈænskəm /、1919年3月18日 - 2001年1月5日)は、通常G. E. M.

アンスコムまたはエリザベス・アンスコムと表記され、イギリスの分析哲学者である。彼女は心の哲学、行動の哲学、哲学論理学、言語哲学、倫理学について執

筆した。彼女は分析的トミズムの著名な人物であり、オックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジのフェロー、ケンブリッジ大学哲学科の教授であった。 彼女はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子であり、彼の研究の権威となり、彼の著作から多くの書籍を編集・翻訳した。特に『哲学探究』は有名であ る。1958年に発表された論文「現代道徳哲学」では、分析哲学の用語に帰結主義という概念を導入し、現代の徳倫理学に多大な影響を与えた。彼女の単行本 『意図』(1957年)は、 ドナルド・デヴィッドソンによって「アリストテレス以来の行動に関する最も重要な研究」と評された。[3][4] これは「現代の行動哲学の基礎となるテキストとして広く考えられている」ものであり、実践理性の哲学にも影響を与えている。[5] |

| Life Anscombe was born to Gertrude Elizabeth (née Thomas) and Captain Allen Wells Anscombe, on 18 March 1919, in Limerick, Ireland, where her father had been stationed with the Royal Welch Fusiliers during the Irish War of Independence.[6] Both her mother and father were involved with education. Her mother was a headmistress and her father went on to head the science and engineering side at Dulwich College.[7] Anscombe attended Sydenham High School and then, in 1937, went on to read literae humaniores ('Greats') at St Hugh's College, Oxford. She was awarded a Second Class in her honour moderations in 1939 and (albeit it with reservations on the part of her Ancient History examiners[8]) a First in her degree finals in 1941.[7] While still at Sydenham High School, Anscombe converted to Catholicism. During her first year at St Hugh's, she was received into the church, and was a practising Catholic thereafter.[7] In 1941 she married Peter Geach. Like her, Geach was a Catholic convert who became a student of Wittgenstein and a distinguished academic philosopher. Together they had three sons and four daughters.[7] After graduating from Oxford, Anscombe was awarded a research fellowship for postgraduate study at Newnham College, Cambridge, from 1942 to 1945.[7] Her purpose was to attend Ludwig Wittgenstein's lectures. Her interest in Wittgenstein's philosophy arose from reading the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as an undergraduate. She claimed to have conceived the idea of studying with Wittgenstein as soon as she opened the book in Blackwell's and read section 5.53, "Identity of object I express by identity of sign, and not by using a sign for identity. Difference of objects I express by difference of signs." She became an enthusiastic student, feeling that Wittgenstein's therapeutic method helped to free her from philosophical difficulties in ways that her training in traditional systematic philosophy could not. As she wrote: For years, I would spend time, in cafés, for example, staring at objects saying to myself: 'I see a packet. But what do I really see? How can I say that I see here anything more than a yellow expanse?' ... I always hated phenomenalism and felt trapped by it. I couldn't see my way out of it but I didn't believe it. It was no good pointing to difficulties about it, things which Russell found wrong with it, for example. The strength, the central nerve of it remained alive and raged achingly. It was only in Wittgenstein's classes in 1944 that I saw the nerve being extracted, the central thought "I have got this, and I define 'yellow' (say) as this" being effectively attacked. — Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind: The Collected Philosophical Papers of G.E.M. Anscombe, Volume 2 (1981) pp. vii–x. After her fellowship at Cambridge ended, she was awarded a research fellowship at Somerville College, Oxford,[7] but during the academic year of 1946/47, she continued to travel to Cambridge once a week to attend tutorials with Wittgenstein that were devoted mainly to the philosophy of religion.[9] She became one of Wittgenstein's favourite students and one of his closest friends.[10][11] Wittgenstein affectionately addressed her by the pet name "old man" – she being (according to Ray Monk) "an exception to his general dislike of academic women".[10][11] His confidence in Anscombe's understanding of his perspective is shown by his choice of her as the translator of his Philosophical Investigations (for which purpose he arranged for her to spend some time in Vienna to improve her German[12][6]). Wittgenstein appointed Anscombe as one of his three literary executors and so she played a major role in translating and spreading his works.[13] Anscombe visited Wittgenstein many times after he left Cambridge in 1947, and Wittgenstein stayed at her house in Oxford for a period in 1950. She travelled to Cambridge in April 1951 to visit him on his deathbed. Wittgenstein named her, along with Rush Rhees and Georg Henrik von Wright, as his literary executor.[6][14] After his death in 1951 she was responsible for editing, translating, and publishing many of Wittgenstein's manuscripts and notebooks.[6][11] Anscombe did not avoid controversy. As an undergraduate in 1939 she had publicly criticised Britain's entry into the Second World War.[15] And, in 1956, while a research fellow, she unsuccessfully protested against Oxford granting an honorary degree to Harry S. Truman, whom she denounced as a mass murderer for his use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[16][17][18] She would further publicise her position in a (sometimes erroneously dated[19]) pamphlet privately printed soon after Truman's nomination for the degree was approved. In the same she said she "should fear to go" to the Encaenia (the degree conferral ceremony) "in case God's patience suddenly ends."[20] She would also court controversy with some of her colleagues by defending the Catholic Church's opposition to contraception.[11] Later in life, she would be arrested protesting outside an abortion clinic, after abortion had been legalised in Great Britain.[17][21] Having remained at Somerville College since 1946, Anscombe was elected Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge in 1970, where she served until her retirement in 1986. She was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1967, and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1979.[22] In her later years, Anscombe suffered from heart disease, and was nearly killed in a car crash in 1996. She never fully recovered and she spent her last years in the care of her family in Cambridge.[7] On 5 January 2001, she died from kidney failure at Addenbrooke's Hospital at the age of 81, with her husband and four of their seven children at her bedside, just after praying the Sorrowful Mysteries of the rosary.[7][6][23] Anscombe's "last intentional act was kissing Peter Geach", her husband of sixty years.[24] Anscombe was buried adjacent to Wittgenstein in the St Giles' graveyard, Huntingdon Road, (now the Ascension Parish burial ground). her husband joined her there in 2013.[7][25] Debate with C. S. Lewis As a young philosophy don, Anscombe acquired a reputation as a formidable debater. In 1948, she presented a paper at a meeting of Oxford's Socratic Club in which she disputed C. S. Lewis's argument that naturalism was self-refuting (found in the third chapter of the original publication of his book Miracles). Some associates of Lewis, primarily George Sayer and Derek Brewer, have remarked that Lewis lost the subsequent debate on her paper and that this loss was so humiliating that he abandoned theological argument and turned entirely to devotional writing and children's literature.[26] This is a claim disputed by Walter Hooper[27] and Anscombe's impression of the effect upon Lewis was somewhat different: The fact that Lewis rewrote that chapter, and rewrote it so that it now has those qualities [to address Anscombe's objections], shows his honesty and seriousness. The meeting of the Socratic Club at which I read my paper has been described by several of his friends as a horrible and shocking experience which upset him very much. Neither Dr Havard (who had Lewis and me to dinner a few weeks later) nor Professor Jack Bennet remembered any such feelings on Lewis' part ... My own recollection is that it was an occasion of sober discussion of certain quite definite criticisms, which Lewis' rethinking and rewriting showed he thought was accurate. I am inclined to construe the odd accounts of the matter by some of his friends – who seem not to have been interested in the actual arguments or the subject matter – as an interesting example of the phenomenon called "projection". — Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind: The Collected Philosophical Papers of G.E.M. Anscombe, Volume 2 (1981) p.x. As a result of the debate, Lewis substantially rewrote chapter 3 of Miracles for the 1960 paperback edition.[28] |

生涯 アンスコムは、1919年3月18日にアイルランドのリムリックで、ゲートルード・エリザベス(旧姓トーマス)とアレン・ウェルズ・アンスコム大尉の間に 生まれた。父親はアイルランド独立戦争中にロイヤル・ウェールズ・フュージリアーズに所属していた。[6] 母親も父親も教育関係の仕事に携わっていた。母親は校長を務め、父親はダルウィッチ・カレッジの科学・工学部門の責任者となった。[7] アンスコムはシドナム・ハイスクールに通い、1937年にオックスフォード大学セント・ヒューズ・カレッジの「リテラエ・ヒューニオル(グレート)」課程に進学した。1939年に優等で卒業し、1941年には学位取得のための最終試験で首席の成績を収めた。 シドナム・ハイスクール在学中に、アンスコムはカトリックに改宗した。セント・ヒューズ・カレッジに入学した最初の年に彼女は教会に受け入れられ、それ以降はカトリックの信者となった。 1941年、彼女はピーター・ギーチと結婚した。ギーチも彼女と同じくカトリックに改宗し、ウィトゲンシュタインの弟子となり、著名な学術哲学者となった。二人には3人の息子と4人の娘が生まれた。 オックスフォード大学を卒業後、アンスコムは1942年から1945年まで、ケンブリッジ大学ニューナム・カレッジの大学院研究員として研究奨学金を授与 された。[7] 彼女の目的はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの講義に出席することであった。ウィトゲンシュタインの哲学への関心は、学部生時代に『論理哲学論考』を 読んだことから生じた。ブラックウェルズでその本を開き、第5.53項「対象の同一性は記号の同一性によって表現され、記号の同一性によって表現されるの ではない。対象の差異は記号の差異によって表現される」を読んだ瞬間、ウィトゲンシュタインのもとで学ぶという考えが浮かんだと彼女は主張している。ウィ トゲンシュタインの治療的な方法は、従来の体系的な哲学の訓練では不可能だった方法で、彼女を哲学上の困難から解放してくれたと感じた彼女は、熱心な学生 となった。彼女は次のように書いている。 何年もの間、私はカフェなどで時間を費やし、物を見つめながらこう自問していた。『私は包み紙を見ている。しかし、私は本当に何を見ているのか? ここで黄色い広がり以上の何かを見ていると言えるのか?』...私は現象論を嫌い、それに囚われていると感じていた。そこから抜け出す方法が見つからな かったが、それを信じてはいなかった。例えばラッセルが間違っていると指摘したような、そのことに関する困難を指摘しても意味がなかった。その強さ、その 中心的な神経は生き続け、痛烈に猛威を振るっていた。1944年のウィトゲンシュタインの授業で、その神経が引き抜かれ、中心的な考えである「私はこれを 持っている。そして、『黄色』を(例えば)このように定義する」という考えが効果的に攻撃されているのを目にした。 —『形而上学と心の哲学:G.E.M. アンスコムの哲学論文集 第2巻』(1981年)pp. vii–x. ケンブリッジでの研究員としての任期が終了した後、彼女はオックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジの研究員に任命されたが[7]、1946年から 1947年の学年度の間は、ウィトゲンシュタインの宗教哲学を主題とするチュートリアルに出席するために、週に一度ケンブリッジを訪れ続けた[9]。彼女 はウィトゲンシュタインのお気に入りの学生の一人となり、最も親しい友人の一人となった[10][11]。ウィトゲンシュタインは 彼女を「オールドマン」という愛称で親しみを込めて呼んでいた。彼女は(レイ・モンクによると)「学究肌の女性に対する彼の一般的な嫌悪感の例外」であっ た。[10][11] 彼の視点に対するアンスコムの理解に対する信頼は、彼の著書『哲学探究』の翻訳者に彼女を選んだことからも明らかである(その目的のために、彼は彼女がド イツ語を上達させるためにウィーンでしばらく過ごすよう手配した[12][6])。 ウィトゲンシュタインはアンスコムを3人の遺稿整理人のうちの1人に指名し、彼女は彼の作品の翻訳と普及において重要な役割を果たした。 アンスコムは1947年にウィトゲンシュタインがケンブリッジを去った後も何度も彼を訪問し、1950年にはウィトゲンシュタインがオックスフォードの彼 女の家に滞在した時期もあった。彼女は1951年4月にケンブリッジを訪れ、彼の臨終に立ち会った。ウィトゲンシュタインは、ラッシュ・リースとゲオル ク・ヘンリク・フォン・ライトとともに、彼女を文学上の遺言執行者として指名した。[6][14] 1951年の彼の死後、彼女はウィトゲンシュタインの原稿やノートブックの多くを編集、翻訳、出版する責任を担った。[6][11] アンスコムは論争を避けなかった。1939年、学部生だった彼女はイギリスの第二次世界大戦参戦を公に批判していた。また、1956年には研究員として、 オックスフォード大学がトルーマンに名誉学位を授与することに抗議したが、これは失敗に終わった。トルーマンを 広島と長崎への原爆投下を理由に大量殺人者と非難した。[16][17][18] トルーマンが学位授与候補として承認された直後に、彼女は個人的に印刷したパンフレット(日付が誤っている場合もある[19])で、自らの立場をさらに公 表した。その中で彼女は、「神の忍耐が突然尽きるようなことがあれば、エンケイニア(学位授与式)に出席するのは恐ろしい」と述べた。[20] また、彼女は避妊に対するカトリック教会の反対を擁護することで、一部の同僚と論争を繰り広げることにもなった。[11] その後、英国で中絶が合法化された後、彼女は中絶クリニックの外で抗議活動を行い、逮捕された。[17][21] 1946年よりソマーヴィル・カレッジに在籍していたアンスコムは、1970年にケンブリッジ大学の哲学教授に選出され、1986年に引退するまでその職 に就いた。1967年には英国学士院のフェローに、1979年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選出された。 晩年、アンスコムは心臓病を患い、1996年には交通事故で死にかけた。その後、彼女は完全に回復することはなく、ケンブリッジの家族の世話になりながら 晩年を過ごした。2001年1月5日、彼女は81歳で腎不全によりアデンブルーク病院で死去した。7人の子供のうち4人が枕元に付き添う中、ロザリオの悲 しみの神秘を祈った直後に亡くなった。[7][6][23] アンカムの「最後の意図的な行為は、60年間連れ添った夫のピーター・ギーチにキスをしたこと」だった。[24] アンスコムは、ハンティンドン・ロードの聖ジャイルズ墓地(現アセンション教区墓地)でウィトゲンシュタインの隣に埋葬された。2013年には夫もそこに合葬された。 C. S. ルイスとの論争 若い哲学講師であった頃、アンスコムは優れた論客として評判を得ていた。1948年、彼女はオックスフォードのソクラテス・クラブの会合で、C. S. ルイスの著書『奇蹟』の原著の第3章で展開された自然主義は自己矛盾であるという主張に異議を唱える論文を発表した。ルイスの友人であったジョージ・セイ ヤーやデレク・ブリューワーらは、ルイスは彼女の論文に関するその後の討論で敗北し、その屈辱が原因で神学上の議論を放棄し、信仰に関する執筆や児童文学 に専念するようになったと述べている。[26] しかし、ウォルター・フーパーはこれを否定しており[27]、ルイスに対するアンスコムの印象は多少異なっていた。 ルイスがその章を書き直し、書き直した結果、今ではそれらの性質を備えるようになったという事実は、彼の誠実さと真剣さを示している。私が論文を読んだソ クラテス・クラブの会合は、彼の友人たちの何人かによって、彼をひどく動揺させた恐ろしく衝撃的な経験であったと描写されている。ハーバード博士(数週間 後、博士はルイスと私を夕食に招待した)もジャック・ベネット教授も、ルイスがそのような感情を抱いていたとはまったく覚えていない... 私の記憶では、それはある明確な批判について冷静に議論した機会であり、ルイスの再考と書き直しは、その批判が的を射たものだったことを示していた。私 は、実際の議論や主題には興味がなかったと思われる彼の友人たちの奇妙な証言を、「投影」と呼ばれる現象の興味深い例と解釈したい。 —『形而上学と心の哲学:G.E.M. アンスコムの哲学論文集 第2巻』(1981年)p.x. この論争の結果、ルイスは1960年のペーパーバック版のために『奇跡』の第3章を大幅に書き直した。[28] |

| Work On Wittgenstein Some of Anscombe's most frequently cited works are translations, editions, and expositions of the work of her teacher Ludwig Wittgenstein, including an influential exegesis[29] of Wittgenstein's 1921 book, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. This brought to the fore the importance of Gottlob Frege for Wittgenstein's thought and, partly on that basis, attacked "positivist" interpretations of the work. She co-edited his posthumous second book, Philosophische Untersuchungen/Philosophical Investigations (1953) with Rush Rhees. Her English translation of the book appeared simultaneously and remains standard. She went on to edit or co-edit several volumes of selections from his notebooks, (co-)translating many important works like Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics (1956) and Wittgenstein's "sustained treatment" of G. E. Moore's epistemology, On Certainty (1969).[30] In 1978, Anscombe was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class for her work on Wittgenstein.[31] Intention Her most important work is the monograph Intention (1957). Three volumes of collected papers were published in 1981: From Parmenides to Wittgenstein; Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Mind; and Ethics, Religion and Politics. Another collection, Human Life, Action and Ethics appeared posthumously in 2005.[12] The aim of Intention (1957) was to make plain the character of human action and will. Anscombe approaches the matter through the concept of intention, which, as she notes, has three modes of appearance in the English language:  |

ウィトゲンシュタインに関する研究 アンスコムの最もよく引用される研究のいくつかは、彼女の師であるルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの著作の翻訳、版、解説であり、その中には、ウィト ゲンシュタインの1921年の著書『論理哲学論考』に関する影響力のある注釈[29]も含まれる。これにより、ウィトゲンシュタインの思想におけるゴット ロープ・フレーゲの重要性が浮き彫りになり、そのことを根拠に、この作品の「実証主義的」解釈を攻撃した。彼女は、彼の死後に出版された2冊目の著書『哲 学探究』(1953年)をラッシュ・リースと共同編集した。彼女によるこの本の英訳は同時に出版され、現在でも標準的なものとなっている。彼女はその後 も、彼のノートからの抜粋を編集または共同編集し、また『数学の基礎について』(1956年)や、ウィトゲンシュタインによるG. E. ムーアの認識論に関する「持続的考察」『確実性について』(1969年)など、多くの重要な著作の翻訳を共同で行った。[30] 1978年、ウィトゲンシュタインに関する研究により、アンスコムはオーストリア科学・芸術名誉大十字章を授与された。 意図 彼女の最も重要な著作は、単行本『意図』(1957年)である。論文集3巻は1981年に出版された。『パルメニデスからウィトゲンシュタインへ』、『形 而上学と心の哲学』、『倫理・宗教・政治』である。もう一つの論文集『人間の生活、行動、倫理』は、2005年に死後出版された。 『意図』(1957年)の目的は、人間の行動と意志の性質を明らかにすることだった。 アンスコムは、意図という概念を通じてこの問題に取り組んでいる。彼女が指摘しているように、英語では意図には3つの用法がある。  |

| She

suggests that a true account must somehow connect these three uses of

the concept, though later students of intention have sometimes denied

this, and disputed some of the things she presupposes under the first

and third headings. It is clear though that it is the second that is

crucial to her main purpose, which is to comprehend the way in which

human thought and understanding and conceptualisation relate to the

"events in a man's history", or the goings on to which he is subject. Rather than attempt to define intentions in abstraction from actions, thus taking the third heading first, Anscombe begins with the concept of an intentional action. This soon connected with the second heading. She says that what is up with a human being is an intentional action if the question "Why", taken in a certain sense (and evidently conceived as addressed to him), has application.[32] An agent can answer the "why" question by giving a reason or purpose for her action. "To do Y" or "because I want to do Y" would be typical answers to this sort of "why?"; though they are not the only ones, they are crucial to the constitution of the phenomenon as a typical phenomenon of human life.[33] The agent's answer helps supply the descriptions under which the action is intentional. Anscombe was the first to clearly spell out that actions are intentional under some descriptions and not others. In her famous example, a man's action (which we might observe as consisting of moving an arm up and down while holding a handle) may be intentional under the description "pumping water" but not under other descriptions such as "contracting these muscles", "tapping out this rhythm", and so on. This approach to action influenced Donald Davidson's theory, despite the fact that Davidson went on to argue for a causal theory of action that Anscombe never accepted.[34][35] Intention (1957) is also the classic source for the idea that there is a difference in "direction of fit" between cognitive states like beliefs and conative states like desire. (This theme was later taken up and discussed by John Searle.)[36] Cognitive states describe the world and are causally derived from the facts or objects they depict. Conative states do not describe the world, but aim to bring something about in the world. Anscombe used the example of a shopping list to illustrate the difference.[37] The list can be a straightforward observational report of what is actually bought (thereby acting like a cognitive state), or it can function as a conative state such as a command or desire, dictating what the agent should buy. If the agent fails to buy what is listed, we do not say that the list is untrue or incorrect; we say that the mistake is in the action, not the desire. According to Anscombe, this difference in direction of fit is a major difference between speculative knowledge (theoretical, empirical knowledge) and practical knowledge (knowledge of actions and morals). Whereas "speculative knowledge" is "derived from the objects known", practical knowledge is – in a phrase Anscombe lifts from Aquinas – "the cause of what it understands".[38] Ethics Main article: Modern Moral Philosophy Anscombe made great contributions to ethics as well as metaphysics. Her 1958 essay "Modern Moral Philosophy" is credited with having coined the term "consequentialism",[39] as well as with reviving interest in and study of virtue ethics in Western academic philosophy.[40][41] The Anscombe Bioethics Centre in Oxford is named after her, and conducts bioethical research in the Catholic tradition.[42] Brute and institutional facts Anscombe also introduced the idea of a set of facts being 'brute relative to' some fact. When a set of facts xyz stands in this relation to a fact A, they are a subset out of a range some subset among which holds if A holds. Thus if A is the fact that I have paid for something, the brute facts might be that I have handed him a cheque for a sum which he has named as the price for the goods, saying that this is the payment, or that I gave him some cash at the time that he gave me the goods. There tends, according to Anscombe, to be an institutional context which gives its point to the description 'A', but of which 'A' is not itself a description: that I have given someone a shilling is not a description of the institution of money or of the currency of the country. According to her, no brute facts xyz can generally be said to entail the fact A relative to which they are 'brute' except with the proviso "under normal circumstances", for "one cannot mention all the things that were not the case, which would have made a difference if they had been."[43] A set of facts xyz ... may be brute relative to a fact A which itself is one of a set of facts ABC ... which is brute relative to some further fact W. Thus Anscombe's account is not of a distinct class of facts, to be distinguished from another class, 'institutional facts': the essential relation is that of a set of facts being 'brute relative to' some fact. Following Anscombe, John Searle derived another conception of 'brute facts' as non-mental facts to play the foundational role and generate similar hierarchies in his philosophical account of speech acts and institutional reality.[44] First person Her paper "The First Person"[34] buttressed remarks by Wittgenstein (in his Lectures on "Private Experience"[45]) arguing for the now-notorious conclusion that the first-person pronoun, "I", does not refer to anything (not, e.g., to the speaker) because of its immunity from reference failure. Having shown by counter-example that 'I' does not refer to the body, Anscombe objected to the implied Cartesianism of its referring at all. Few people accept the conclusion – though the position was later adopted in a more radical form by David Lewis – but the paper was an important contribution to work on indexicals and self-consciousness that has been carried on by philosophers as varied as John Perry, Peter Strawson, David Kaplan, Gareth Evans, John McDowell, and Sebastian Rödl.[46] Causality In her article, "Causality and Determination",[47] Anscombe defends two main ideas: that causal relations are perceivable, and that causation does not require a necessary connection and a universal generalization linking cause and effect. Regarding her idea that causal relations are perceivable, she believes that we perceive the causal relations between objects and events. In defending her idea that causal relations are perceivable, Anscombe poses a question "How did we come by our primary knowledge of causality?".[47] She proposes two answers to this question: By "learning to speak, we learned the linguistic representation and application of a host of causal concepts"[47] By observing that some action(s) caused a certain event In proposing her first answer, that by "learning to speak, we learned the linguistic representation and application of a host of causal concepts", Anscombe thinks that by learning to speak we already have a linguistic representation of certain causal concepts and she gives an example of transitive verbs, such as scrape, push, carry, knock over. Example: I knocked over a vase of flowers. In proposing her second answer, that by observing some actions we can see causation, Anscombe thinks that we cannot ignore the fact that certain actions, which produced a certain event are possible to observe. Example: a cat spilled milk. The second idea that Anscombe defends in the article "Causality and Determination"[47] is that causation requires neither a necessary connection nor a universal generalization linking cause and effect. Anscombe states that it is assumed that causality is some kind of necessary connection.[47] |

彼

女は、真の説明はこれらの3つの概念の使用法を何らかの形で結びつけなければならないと主張しているが、後の志向性の研究者はこれを否定し、彼女が最初の

見出しと3番目の見出しで前提としているいくつかの事柄を論争することがある。しかし、彼女の主な目的にとって重要なのは2番目の見出しであることは明ら

かである。それは、人間の思考や理解、概念化が「人間の歴史における出来事」、つまり人間が従属する出来事とどのように関係しているかを理解することであ

る。 行動から抽象的に意図を定義しようとするのではなく、つまり第3のテーマを最初に扱うのではなく、アンスコムは意図的な行動の概念から始める。これはすぐ に第2のテーマと関連する。彼女は、ある意味で「なぜ」という問い(明らかに自分自身に向けられたものとして考えられている)が当てはまる場合、人間が意 図的な行動を取る、と述べている。[32] 行為者は、理由や目的を挙げることで「なぜ」という問いに答えることができる。「Yをすること」や「Yをしたいから」は、この種の「なぜ?」に対する典型 的な答えである。ただし、これらが唯一の答えというわけではないが、人間の生活における典型的な現象として、この現象を構成する上で不可欠である。 [33] 行為者の答えは、その行為が意図的なものであることを説明するのに役立つ。アンソムは、ある記述においては行動が意図的であり、別の記述においては意図的 ではないことを明確に説明した最初の人物である。彼女の有名な例では、ある男性の行動(私たちは、その行動を、柄を握りながら腕を上下に動かすものとして 観察するかもしれない)は、「水を汲む」という記述においては意図的であるかもしれないが、「この筋肉を収縮させる」、「このリズムを刻む」など、他の記 述においては意図的ではないかもしれない。この行動に対するアプローチは、ドナルド・デヴィッドソンの理論に影響を与えたが、デヴィッドソンは、アンスコ ムが決して受け入れなかった因果行動理論を主張し続けた。[34][35] また、1957年の著書『意図』は、信念のような認知的状態と欲求のような志向的状態の間には「適合の方向」に違いがあるという考え方の古典的な出典でも ある。(このテーマは後にジョン・サールによって取り上げられ、議論された。)[36] 認知的状態は世界を描写し、描写する事実や対象から因果的に導かれる。志向的状態は世界を描写するのではなく、世界の何らかの事柄を実現することを目的と する。アンスコムは、この違いを説明するために買い物リストの例を挙げている。[37] 買い物リストは、実際に購入したものを単に観察した報告(つまり認識状態)である場合もあれば、購入すべきものを指示する命令や欲求といった志向状態とし て機能する場合もある。もし購入者がリストに書かれたものを購入し損ねたとしても、私たちはそのリストが真実ではないとか間違っているとは言わない。アン スコムによると、この適合の方向性の違いは、思弁的知識(理論的、経験的知識)と実践的知識(行動や道徳に関する知識)の間の大きな違いである。思弁的知 識」が「既知の対象から派生する」ものであるのに対し、実践的知識は、アンスコムがアクィナスから引用した表現を用いれば、「理解するものの原因」であ る。[38] 倫理学 詳細は「近代道徳哲学」を参照 アンスコムは、形而上学だけでなく倫理学にも多大な貢献をした。彼女の1958年の論文「近代道徳哲学」は、「帰結主義」という用語を初めて使用した論文 として知られており[39]、また西洋の学術哲学における徳倫理学への関心と研究を復活させたことでも知られている[40][41]。 オックスフォードにあるアンスコム生命倫理センターは彼女の名にちなんで名付けられ、カトリックの伝統に則った生命倫理の研究を行っている。 事実と制度 アンスコムはまた、ある事実に対して「相対的な事実」という考え方を導入した。ある事実 A に対して、ある事実 xyz が「~に相対する」という関係にある場合、xyz は A が成り立つ場合に成り立つ範囲の一部集合である。 したがって、A が私が何かに対して支払いを済ませたという事実である場合、その「生々しい事実」は、私が彼に商品の代金を指定した金額の小切手を渡し、「これが支払い だ」と言ったことや、彼が私に商品を手渡した際に現金を渡したことであるかもしれない。アンスコムによれば、Aという記述に意味を与える制度的背景がある 傾向にあるが、A自体は記述ではない。つまり、私が誰かに1シリングを渡したことは、貨幣制度やその国の通貨の記述ではない。彼女によれば、「通常の状況 下」という但し書きを付けた場合を除いて、一般的に、xyzという「粗野な事実」が、それらが「粗野」であるという事実Aを必然的に伴うということはでき ない。なぜなら、「そうではなかったすべての事柄を挙げることはできない。それらがそうであったならば違いが生じていただろうから」[43] 事実の集合xyzは、 事実Aに相対するものであり、事実A自体は事実ABCの集合の1つであり、さらに別の事実Wに相対するものである。したがって、アンソムの説明は、別のク ラスである「制度的事実」と区別されるべき、明確なクラスの事実ではない。本質的な関係は、事実の集合が「ある事実の相対する事実」であるという関係であ る。アンスコムに倣い、ジョン・サールは、言語行為と制度上の現実に関する自身の哲学的な説明において、基礎的な役割を果たし、同様の階層を生み出す非精 神的事実としての「生々しい事実」という別の概念を導き出した。 一人称 彼女の論文「一人称」[34]は、ウィトゲンシュタイン(「私的経験」に関する講義[45])の主張を補強し、一人称代名詞「私」は、参照の失敗から免れ ているため、何にも(話し手などには)言及していないという、今では悪名高い結論を論じている。「I」が身体を指し示さないことを反例によって示したアン スコムは、それが指し示しているということが暗黙のうちにデカルト主義的であることに異議を唱えた。この結論を受け入れる人はほとんどいないが、この立場 は後にデイヴィッド・ルイスによってより急進的な形で採用された。しかし、この論文は、ジョン・ペリー、ピーター・ストロースン、デイヴィッド・カプラ ン、ガレス・エヴァンス、ジョン・マクダウェル、セバスチャン・ロドルなど、さまざまな哲学者たちによって引き継がれてきた、指示詞と自己意識に関する研 究への重要な貢献であった。 因果関係 論文「因果関係と決定」において、[47] アンスコムは主に2つの考え方を擁護している。すなわち、因果関係は知覚可能であること、そして因果関係は、原因と結果を結びつける必要不可欠なつながり と普遍的な一般化を必要としないことである。 因果関係は知覚可能であるという考え方について、彼女は、私たちは物事と出来事の因果関係を認識していると信じている。 因果関係が知覚可能であるという考えを擁護するにあたり、アンスコムは「因果関係に関する我々の基本的知識は、どのようにして得られたのか?」という問いを投げかけている。[47] 彼女はこの問いに対する2つの答えを提案している。 「言葉を習得することで、我々は数多くの因果概念の言語表現と応用を学んだ」[47] ある行動が特定の出来事を引き起こしたことを観察すること 最初の答えとして、「話すことを学ぶことで、私たちは言語による因果概念の表現と応用を学んだ」という考えを提示するにあたり、アンスコムは、話すことを 学ぶことで、私たちはすでに特定の因果概念の言語による表現を習得していると考え、その例として、引っかく、押す、運ぶ、倒すなどの他動詞を挙げている。 例:私は花瓶の花を倒してしまった。 彼女の2つ目の回答として、ある行動を観察することで因果関係を理解できるという考えを提示するにあたり、アンスコムは、ある出来事を引き起こした特定の行動が観察可能であるという事実を無視することはできないと考えている。 例:猫がミルクをこぼした。 アンスコムが論文「因果関係と決定」[47]で擁護する2つ目の考え方は、因果関係には、原因と結果を結びつける必要的なつながりも普遍的な一般化も必要ないというものである。 アンスコムは、因果関係は必要的なつながりであると想定されていると述べている。[47] |

| Views of her work The philosopher Candace Vogler says that Anscombe's "strength" is that "'when she is writing for [a] Catholic audience, she presumes they share certain fundamental beliefs,' but she is equally willing to write for people who do not share her assumptions."[48] In 2010, philosopher Roger Scruton wrote that Anscombe was "perhaps the last great philosopher writing in English".[49] Mary Warnock described her as "the undoubted giant among women philosophers"[50] while John Haldane said she "certainly has a good claim to be the greatest woman philosopher of whom we know".[40] |

彼女の研究に対する見解 哲学者のキャンディス・ヴォグラーは、アンスコムの「強み」は、「『カトリックの読者に向けて書いているときは、彼らも特定の基本的な信念を共有している と仮定する』が、彼女の仮定を共有していない人々にも同じように喜んで書く」ことであると述べている。[48] 2010年には、哲学者のロジャー・スクラットンが 「おそらく英語で執筆する最後の偉大な哲学者」と評した。[49] メアリー・ウォーノックは彼女を「女性哲学者の中で疑いようのない巨人」と評し[50]、ジョン・ハルデーンは「我々が知る限り、最も偉大な女性哲学者で あることは間違いない」と述べた。[40] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._E._M._Anscombe |

★ この用語は、1957-1958年ごろ、G.E.M.アンスコムとR. M. ヘアとの間で短い論争(小競り合い)があり、アンスコムが1958年に論文「現代道徳哲 学(Modern Moral Philosophy)」において発表したのが初出だといわれる。アンスコムの議論は、帰結はどうであれ(仮に良い結果が出たとしても)絶対にやってはいけないことがあるという立場(→反帰結主義) である。アンスコムによる帰結主義とは、帰結から最初の行為を肯定するあらゆる立場のことであり、その立場を批判(非難)する。彼女によると義務論も(帰 結主義を肯定する危険性があるために)帰結主義であり、またヘンリー・シジウィックのように「意図と予見の区別は厳密にはなりたたない」という立場も、帰 結主義に道を譲ることを批判してやまない。彼女いうところの、帰結主義者として、問題があるものは、ヒューム、バトラー、カント、ミル、シジウィック、ヘ アなど現代の道徳哲学者のほとんどであり、その代わりにアリストテレスの徳の倫理に回帰を促すものである(児玉 2022:149-150)。

☆

帰結主義は結果を考えて道徳行為を正当化することだ.これを批判するアンスコムは[思慮のなさを直接攻撃するのではなく]熟議以前に絶対的に排除される行

為は存在せずに特定の状況下ではある要素が論証なく優先されることを問題にする.すなわち彼女は暴論の暴走について[経験的に]知っていることになり,そ

れを未然に防ごうとするのだ.

| "Modern Moral

Philosophy" is an article on moral philosophy by G. E. M. Anscombe,

originally published in the journal Philosophy, vol. 33, no. 124

(January 1958).[1] The article has influenced the emergence of contemporary virtue ethics,[2][3][4] especially through the work of Alasdair MacIntyre. Notably, the term "consequentialism" was first coined in this paper,[5] although in a different sense from the one in which it is now used.[5] |

「現代道徳哲学」は、G・E・M・アンスコムによる道徳哲学に関する論文であり、1958年1月発行の学術誌『Philosophy』第33巻第124号に初掲載された。[1] 本論文は、特にアラスデア・マッキンタイアの著作を通じて、現代の徳倫理学の出現に影響を与えた[2][3][4]。特筆すべきは、「結果主義(帰結主 義)」という用語が本論文で初めて造語された点である[5]。ただし、現在使用されている意味とは異なる用法であった[5]。 |

| Theses The beginning of the paper summarizes its main points: I will begin by stating three theses which I present in this paper. The first is that it is not profitable for us at present to do moral philosophy; that should be laid aside at any rate until we have an adequate philosophy of psychology, in which we are conspicuously lacking. The second is that the concepts of obligation, and duty—moral obligation and moral duty, that is to say—and of what is morally right and wrong, and of the moral sense of 'ought', ought to be jettisoned if this is psychologically possible; because they are survivals, or derivatives from survivals, from an earlier conception of ethics which no longer generally survives, and are only harmful without it. My third thesis is that the differences between the well-known English writers on moral philosophy from Sidgwick to the present day are of little importance.[1][4] Onora O'Neill said that "the connections between these three thoughts are not immediately obvious, but their influence is not in doubt", and that "many exponents of virtue ethics take Anscombe's essay as a founding text and have endorsed all three thoughts", whereas "many contemporary consequentialists and theorists of justice, who may reasonably be thought the heirs of the 'modern moral philosophy' that Anscombe criticized, have disputed or disregarded all three".[4] |

論文の冒頭では、その要点をまとめている: まず、本論文で提示する三つの命題を述べる。第一に、現時点で道徳哲学を論じることは我々にとって有益ではない。少なくとも、我々が明らかに欠如している心理学の適切な哲学が確立されるまでは、道徳哲学は脇に置くべきだ。第 二に、義務や義務、つまり道徳的義務や道徳的義務、道徳的に正しいことや間違っていること、そして「あるべき」という道徳的感覚といった概念は、心理的に 可能であれば捨て去るべきだ。なぜなら、それらは、もはや一般的に存続していない、より古い倫理観の残滓、あるいはその派生であり、それがなければ有害で しかないからだ。第三の主張は、シジウィックから現代に至る、道徳哲学に関する有名な英国人作家たちの間の相違は、ほとんど重要ではないということだ。 オノラ・オニールは、「これら三つの考えの関連性はすぐには明らかではないが、その影響力は疑いの余地がない」と述べ、 また、「アンスコムの論文を基礎的なテキストとして、この三つの考え方をすべて支持している徳倫理学の支持者は多い」と述べた。一方、「アンスコムが批判 した『現代道徳哲学』の継承者と合理的に考えられる、多くの現代の結果主義者や正義の理論家は、この三つの考え方をすべて争ったり無視したりしている」と も述べた。[4] |

| Coinage of "consequentialism" In "Modern Moral Philosophy", Anscombe coined the term "consequentialism" to mark a distinction between theories of English moral philosophers from Sidgwick onward ("consequentialists") and theories of earlier philosophers.[5][6] According to Anscombe, the modern "consequentialist" moral philosophers were distinguished from the earlier ones by that their theories allow actions, once they fall under a moral principle or (secondary) rule, to be treated, in practical deliberation, as if they were consequences—objects of maximization and weighing—, such that an unjust act, in spite of being generally prohibited and, prima facie, wrong under one aspect, might, nevertheless, be, all things considered, right, if it produces the greatest balance of happiness, or balance of prima facie rightness over prima facie wrongness.[5] In consequentialism, so construed, there are no actions which are absolutely ruled out in advance of deliberation; everything might, in principle, be outweighed in some circumstances. Anscombe's goal was to advance an objection against all theories with this property.[5] As a result of this conception of consequentialism, Anscombe explicitly classified J.S. Mill as a nonconsequentialist and W.D. Ross as a consequentialist, since she thought that Mill's theories did not allow for this, whereas Ross's did.[5][6] However, from a contemporary perspective, Mill and Ross would be classified the other way round—Mill as a consequentialist, and Ross as a nonconsequentialist.[5][6] This is not because people have come to think that J.S. Mill satisfies the property that Anscombe thought was distinctive of modern consequentialists, and that W.D. Ross does not;[5] rather, it is because the meaning of the word "consequentialism" has changed over time.[5][6] |