ピーター・シンガー

Peter Singer, b.1946

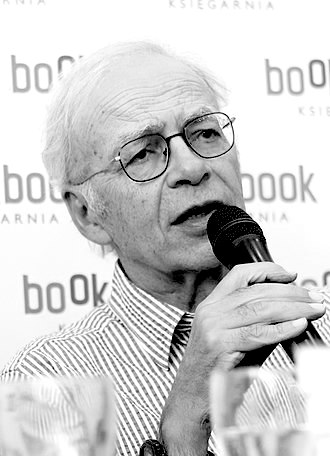

Singer in 2017

☆ ピーター・アルバート・デビッド・シンガーAC(1946年7月6日生まれ)[2]は、オーストラリアの道徳哲学者であり、プリンストン大学のアイラ・ W・デキャンプ教授(生命倫理学)。応用倫理学を専門とし、世俗的、功利主義的観点からアプローチしている。菜食主義を主張する『動物の解放』(1975 年)や、世界の貧困層を救うための寄付を支持するエッセイ『飢饉、豊かさ、そして道徳』を執筆。キャリアの大半は選好的功利主義者だったが、カタジナ・ ド・ラザリ=ラデックとの共著『宇宙の視点』(2014年)では快楽主義的功利主義者(hedonistic utilitarian)になったことを明かしている。

| Peter Albert David Singer AC

(born 6 July 1946)[2] is an Australian moral philosopher and the Ira W.

DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University. He specialises

in applied ethics, approaching the subject from a secular, utilitarian

perspective. He wrote the book Animal Liberation (1975), in which he

argues for vegetarianism, and the essay "Famine, Affluence, and

Morality", which favours donating to help the global poor. For most of

his career, he was a preference utilitarian, but he revealed in The

Point of View of the Universe (2014), coauthored with Katarzyna de

Lazari-Radek, that he had become a hedonistic utilitarian. On two occasions, Singer served as chair of the philosophy department at Monash University, where he founded its Centre for Human Bioethics. In 1996 he stood unsuccessfully as a Greens candidate for the Australian Senate. In 2004 Singer was recognised as the Australian Humanist of the Year by the Council of Australian Humanist Societies. In 2005, The Sydney Morning Herald placed him among Australia's ten most influential public intellectuals.[4] Singer is a cofounder of Animals Australia and the founder of The Life You Can Save.[5] +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Preference utilitarianism Preference utilitarianism (also known as preferentialism) is a form of utilitarianism in contemporary philosophy.[1] Unlike value monist forms of utilitarianism, preferentialism values actions that fulfill the most personal interests for the entire circle of people affected by said action. Description Unlike classical utilitarianism, in which right actions are defined as those that maximize pleasure and minimize pain, preference utilitarianism entails promoting actions that fulfil the interests (i.e., preferences) of those beings involved.[2] Here beings might be rational, that is to say, that their interests have been carefully selected and they have not made some kind of error. However, 'beings' can also be extended to all sentient beings, even those who lack the capacity to contemplate long-term interests and consequences.[3] Since what is good and right depends solely on individual preferences, there can be nothing that is in itself good or bad: for preference utilitarians, the source of both morality and ethics in general is subjective preference.[3] Preference utilitarianism therefore can be distinguished by its acknowledgement that every person's experience of satisfaction is unique. The theory, as outlined by R. M. Hare in 1981,[4] is controversial, insofar as it presupposes some basis by which a conflict between A's preferences and B's preferences can be resolved (for example, by weighting them mathematically).[5] In a similar vein, Peter Singer, for much of his career a major proponent of preference utilitarianism and himself influenced by the views of Hare, has been criticised for giving priority to the views of beings capable of holding preferences (being able actively to contemplate the future and its interaction with the present) over those solely concerned with their immediate situation, a group that includes animals and young children. There are, he writes in regard to killing in general, times when "the preference of the victim could sometimes be outweighed by the preferences of others". Singer does, however, still place a high value on the life of rational beings, since killing them does not infringe upon just one of their preferences, but "a wide range of the most central and significant preferences a being can have".[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preference_utilitarianism |

ピー

ター・アルバート・デビッド・シンガーAC(1946年7月6日生まれ)[2]は、オーストラリアの道徳哲学者であり、プリンストン大学のアイラ・W・デ

キャンプ教授(生命倫理学)。応用倫理学を専門とし、世俗的、功利主義的観点からアプローチしている。菜食主義を主張する『動物の解放』(1975年)

や、世界の貧困層を救うための寄付を支持するエッセイ『飢饉、豊かさ、そして道徳』を執筆。キャリアの大半は選好的功利主義者だったが、カタジナ・ド・ラ

ザリ=ラデックとの共著『宇宙の視点』(2014年)では快楽主義的功利主義者になったことを明かしている。 シンガーはモナシュ大学の哲学科の主任教授を2度務め、人間生命倫理センターを設立した。1996年、オーストラリア上院議員選挙に緑の党から立候補し落 選。2004年、シンガーはオーストラリア・ヒューマニスト協会評議会(Council of Australian Humanist Societies)より「オーストラリア・ヒューマニスト・オブ・ザ・イヤー」を受賞。2005年、シドニー・モーニング・ヘラルド紙は彼をオーストラ リアで最も影響力のある10人の知識人の一人に選んだ[4]。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 選好功利主義 選好功利主義(せんこうこうりしゅぎ、preferentialism)とは、現代哲学における功利主義の一形態である[1]。価値一元論の功利主義とは異なり、選好功利主義は、その行為によって影響を受ける人々の輪全体にとって最も個人的な利益を満たす行為を重視する。 説明 正しい行為が快楽を最大化し苦痛を最小化するものとして定義される古典的功利主義とは異なり、選好功利主義は関係する存在の利益(すなわち選好)を満たす 行為を促進することを伴う[2]。しかし、「存在者」は、長期的な利益と結果を熟考する能力を持たない存在者であっても、すべての感覚を持つ存在者に拡張 することもできる[3]。何が善で何が正しいかは個人の選好にのみ依存するため、それ自体が善であったり悪であったりするものは存在し得ない。選好功利主 義者にとって、道徳と倫理全般の源は主観的選好である[3]。したがって、選好功利主義は、すべての人の満足の経験が唯一無二であることを認めることに よって区別することができる。 この理論は、1981年にR・M・ヘアが 提唱した通り[4]、Aの選好とBの選好の衝突を解決する何らかの基盤(例えば数学的な重み付け)を前提としている点で議論の余地がある。同様に、ピー ター・シンガーも批判を受けている。彼はキャリアの大半で選好功利主義の主要な提唱者であり、ヘアーの思想に影響を受けていたが、選好を持つ能力(未来と 現在との相互作用を積極的に考察できる能力)を持つ存在の意見を、動物や幼い子供を含む、直近の状況のみに関心を持つ存在の意見よりも優先させたからだ。 シンガーは殺害一般について「被害者の選好が他の者の選好によって上回る場合もある」と記している。ただし彼は依然として、理性を持つ存在の生命を高く評 価している。なぜなら彼らを殺すことは、単なる一つの選好を侵害するのではなく、「存在が持つ最も核心的で重要な選好の広範な領域」を侵害するからであ る。[6] |

| Biography Singer's parents were Austrian Jews who immigrated to Australia from Vienna after Austria's annexation by Nazi Germany in 1938.[6] They settled in Melbourne, where Singer was born in 1946.[7] His grandparents were less fortunate: his paternal grandparents were taken by the Nazis to Łódź, and were most likely murdered since they were never heard from again; his maternal grandfather David Ernst Oppenheim (1881–1943), an educator and psychologist who collaborated with Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, was murdered in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.[8] Oppenheim was a member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society and wrote a joint article with Sigmund Freud, before joining the Adlerian Society for Individual Psychology.[9] Singer later wrote a biography of Oppenheim.[10] Singer is an atheist and was raised in a prosperous, nonreligious[11] family. His father had a successful business importing tea and coffee.[6] His family rarely observed Jewish holidays, and Singer declined to have a Bar Mitzvah.[12] Singer attended Preshil[13] and later Scotch College. After leaving school, Singer studied law, history, and philosophy at the University of Melbourne, earning a bachelor's degree in 1967.[14] He has explained that he elected to major in philosophy after his interest was piqued by discussions with his sister's then-boyfriend.[15] He earned a master's degree for a thesis entitled Why Should I Be Moral? at the same university in 1969. He was awarded a scholarship to study at the University of Oxford and obtained from there a Bachelor of Philosophy in 1971 with a thesis on civil disobedience supervised by R. M. Hare and published as a book in 1973.[16] Singer names Hare, Australian philosopher H. J. McCloskey and British philosopher J.L.H. Thomas, who taught him "how to read and understand Hegel",[17] as his most important mentors.[18] In the preface to Hegel: A Very Short Introduction,[19] Singer recalls his time in Thomas' "remarkable" classes at Oxford where students were forced to "probe passages of the Phenomenology sentence by sentence, until they yielded their meaning." One day at Balliol College in Oxford, he had what he refers to as probably the decisive formative experience of his life. He was having a discussion after class with fellow graduate student Richard Keshen, a Canadian, who would later become a professor at Cape Breton University. During their lunch Keshen opted to have a salad after being told that the spaghetti sauce contained meat. Singer had the spaghetti. Singer eventually questioned Keshen about his reason for avoiding meat. Keshen explained his ethical objections. Singer would later state, "I'd never met a vegetarian who gave such a straightforward answer that I could understand and relate to". Keshen later introduced Singer to his vegetarian friends. Singer was able to find one book in which he could read up on the issue (Animal Machines by Ruth Harrison) and within a week or two he approached his wife saying that he thought they needed to make a change to their diet and that he did not think they could justify eating meat.[20][21][22] After spending three years as a Radcliffe lecturer at University College, Oxford, he was a visiting professor at New York University for 16 months. In 1977 he returned to Melbourne where he spent most of his career, aside from appointments as visiting faculty abroad, until his move to Princeton in 1999.[23] In June 2011 it was announced he would join the professoriate of New College of the Humanities, a private college in London, in addition to his work at Princeton.[24] He also has been a regular contributor to Project Syndicate since 2001. According to philosopher Helga Kuhse, Singer is almost certainly the best-known and most widely read of all contemporary philosophers.[25] Michael Specter wrote that Singer is among the most influential of contemporary philosophers.[26] |

バイオグラフィー シンガーの両親はオーストリアのユダヤ人で、1938年にオーストリアがナチス・ドイツに併合された後、ウィーンからオーストラリアに移住した[6]。 両親はメルボルンに定住し、シンガーはそこで1946年に生まれた[7]。 [父方の祖父母はナチスによってウッチに連行され、その後消息不明となったため殺害された可能性が高い。母方の祖父デイヴィッド・エルンスト・オッペンハ イム(1881-1943)は、ジークムント・フロイトやアルフレッド・アドラーと協力した教育者であり心理学者であったが、テレジエンシュタット強制収 容所で殺害された。 [8] オッペンハイムはウィーン精神分析学会のメンバーであり、ジークムント・フロイトと共同論文を書いた後、アドラー個人心理学会に参加した[9]。 シンガーは無神論者であり、豊かな無宗教の家庭で育った[11]。父親は紅茶とコーヒーの輸入業で成功を収めていた[6]。家族はユダヤ教の祝日をほとん ど守らず、シンガーはバー・ミツバを拒否した[12]。退学後、シンガーはメルボルン大学で法学、歴史学、哲学を学び、1967年に学士号を取得した [14]。妹のボーイフレンド(当時)との話し合いで興味を持ち、哲学を専攻することにしたと説明している[15]。 1969年、同大学で『なぜ道徳的でなければならないのか』という論文で修士号を取得。彼は奨学金を得てオックスフォード大学に留学し、1971年に R.M.ヘアが監修した市民的不服従に関する論文で哲学の学士号を取得し、1973年に書籍として出版された[16]。シンガーはヘア、オーストラリアの 哲学者H.J.マクロスキー、イギリスの哲学者J.L.H.トーマスを「ヘーゲルの読み方と理解の仕方」を教えてくれた最も重要な恩師として挙げている [17]: シンガーは『A Very Short Introduction』[19]の序文で、オックスフォードでのトーマスの「驚くべき」授業に参加したときのことを回想している。 オックスフォードのバリオール・カレッジでのある日、シンガーは、彼の人生においておそらく決定的な形成的体験をした。同じ大学院生で、後にケープ・ブレ トン大学の教授となるカナダ人のリチャード・ケシェンと授業後に議論をしていたときのことである。昼食の際、ケシェンはスパゲッティのソースに肉が入って いると言われ、サラダを選んだ。シンガーはスパゲティを食べた。シンガーはやがて、肉を避ける理由についてケシェンに質問した。ケシェンは倫理的な反対を 説明した。シンガーは後に、「私が理解し、共感できるような、これほどストレートな答えをするベジタリアンに会ったのは初めてだった」と述べている。ケ シェンは後にシンガーをベジタリアンの友人に紹介した。シンガーは、この問題についての本(ルース・ハリソン著『Animal Machines』)を1冊見つけることができ、1、2週間のうちに、食生活を変える必要があると思う、肉を食べることを正当化できるとは思えない、と妻 に持ちかけた[20][21][22]。 オックスフォード大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジのラドクリフ講師として3年間を過ごした後、ニューヨーク大学の客員教授として16ヶ月間勤務。1977年 にメルボルンに戻り、1999年にプリンストン大学に移るまで、海外での客員教授としての任命を除けば、キャリアのほとんどをメルボルンで過ごした [23]。2011年6月、プリンストン大学での仕事に加えて、ロンドンの私立大学であるニュー・カレッジ・オブ・ヒューマニティーズの教授に就任するこ とが発表された[24]。また、2001年以来、プロジェクト・シンジケートに定期的に寄稿している。 哲学者のヘルガ・クーセによれば、シンガーは現代の哲学者の中で最もよく知られ、最も広く読まれている哲学者である。 |

| Applied Ethics Singer's Practical Ethics (1979) analyzes why and how living beings' interests should be weighed. His principle of equal consideration of interests does not dictate equal treatment of all those with interests, since different interests warrant different treatment. All have an interest in avoiding pain, for instance, but relatively few have an interest in cultivating their abilities. Not only does his principle justify different treatment for different interests, but it allows different treatment for the same interest when diminishing marginal utility is a factor. For example, this approach would privilege a starving person's interest in food over the same interest of someone who is only slightly hungry. Among the more important human interests are those in avoiding pain, in developing one's abilities, in satisfying basic needs for food and shelter, in enjoying warm personal relationships, in being free to pursue one's projects without interference, "and many others". The fundamental interest that entitles a being to equal consideration is the capacity for "suffering and/or enjoyment or happiness". Singer holds that a being's interests should always be weighed according to that being's concrete properties. He favors a "journey" model of life, which measures the wrongness of taking a life by the degree to which doing so frustrates a life journey's goals. So taking a life is less wrong at the beginning, when no goals have been set, and at the end, when the goals have either been met or are unlikely to be accomplished. The journey model is tolerant of some frustrated desire and explains why persons who have embarked on their journeys are not replaceable. Only a personal interest in continuing to live brings the journey model into play. This model also explains the priority that Singer attaches to interests over trivial desires and pleasures. Ethical conduct is justified by reasons that go beyond prudence to "something bigger than the individual", addressing a larger audience. Singer thinks this going-beyond identifies moral reasons as "somehow universal", specifically in the injunction to 'love thy neighbour as thyself', interpreted by him as demanding that one give the same weight to the interests of others as one gives to one's own interests. This universalising step, which Singer traces from Kant to Hare,[27]: 11 is crucial and sets him apart from those moral theorists, from Hobbes to David Gauthier, who tie morality to prudence. Universalisation leads directly to utilitarianism, Singer argues, on the strength of the thought that one's own interests cannot count for more than the interests of others.[28] Taking these into account, one must weigh them up and adopt the course of action that is most likely to maximise the interests of those affected; utilitarianism has been arrived at. Singer's universalising step applies to interests without reference to who has them, whereas the Kantian's applies to the judgments of rational agents (in Kant's kingdom of Ends, or Rawls's original position, etc.). Singer regards Kantian universalisation as unjust to animals.[28] As for the Hobbesians, Singer attempts a response in the final chapter of Practical Ethics, arguing that self-interested reasons support adoption of the moral point of view, such as 'the paradox of hedonism', which counsels that happiness is best found by not looking for it, and the need most people feel to relate to something larger than their own concerns. Singer identifies as a sentientist.[29] Sentientism is an ethical position that grants moral consideration to all sentient beings. Effective altruism and world poverty Main article: Effective altruism Singer's ideas have contributed to the rise of effective altruism.[30] He argues that people should try not only to reduce suffering but to reduce it in the most effective manner possible. While Singer has previously written at length about the moral imperative to reduce poverty and eliminate the suffering of nonhuman animals, particularly in the meat industry, he writes about how the effective altruism movement is doing these things more effectively in his 2015 book The Most Good You Can Do. He is a board member of Animal Charity Evaluators, a charity evaluator used by many members of the effective altruism community which recommends the most cost-effective animal advocacy charities and interventions.[31] His own organisation, The Life You Can Save (TLYCS), also recommends a selection of charities deemed by charity evaluators such as GiveWell to be the most effective when it comes to helping those in extreme poverty. TLYCS was founded after Singer released his 2009 eponymous book, in which he argues more generally in favour of giving to charities that help to end global poverty. In particular, he expands upon some of the arguments made in his 1972 essay "Famine, Affluence, and Morality", in which he posits that citizens of rich nations are morally obligated to give at least some of their disposable income to charities that help the global poor. He supports this using the "drowning child analogy", which states that most people would rescue a drowning child from a pond, even if it meant that their expensive clothes were ruined, so we clearly value a human life more than the value of our material possessions. As a result, we should take a significant portion of the money that we spend on our possessions and instead donate it to charity.[32][33] Since November 2009, Singer is a member of Giving What We Can, an international organisation whose members pledge to give at least 10% of their income to effective charities.[34] Animal liberation and speciesism Published in 1975, Animal Liberation has been cited as a formative influence on leaders of the modern animal liberation movement.[35] The central argument of the book is an expansion of the utilitarian concept that "the greatest good of the greatest number" is the only measure of good or ethical behaviour, and Singer believes that there is no reason not to apply this principle to other animals, arguing that the boundary between human and "animal" is completely arbitrary. There are far more differences between a great ape and an oyster, for example, than between a human and a great ape, and yet the former two are lumped together as "animals", whereas we are considered "human" in a way that supposedly differentiates us from all other "animals". He popularised the term "speciesism", which had been coined by English writer Richard D. Ryder to describe the practice of privileging humans over other animals, and therefore argues in favour of the equal consideration of interests of all sentient beings.[36] In Animal Liberation, Singer argues in favour of vegetarianism and against most animal experimentation. He stated in a 2006 interview that he doesn't eat meat and that he's been a vegetarian since 1971. He also said that he has "gradually become increasingly vegan" and that "I am largely vegan but I'm a flexible vegan. I don't go to the supermarket and buy non-vegan stuff for myself. But when I'm traveling or going to other people's places I will be quite happy to eat vegetarian rather than vegan."[37] More recently, Singer has stated that he isn't fully vegan, because he will occasionally consume oysters, mussels and clams due to their lack of a central nervous system.[38] According to Singer, meat-eating can be ethically permissible if "farms really give the animals good lives, and then humanely kill them, preferably without transporting them to slaughterhouses or disturbing them. In Animal Liberation, I don't really say that it's the killing that makes [meat-eating] wrong, it's the suffering".[39] In an article for the online publication Chinadialogue, Singer called Western-style meat production cruel, unhealthy, and damaging to the ecosystem.[40] He rejected the idea that the method was necessary to meet the population's increasing demand, explaining that animals in factory farms have to eat food grown explicitly for them, and they burn up most of the food's energy just to breathe and keep their bodies warm. In a 2010 Guardian article he titled, "Fish: the forgotten victims on our plate", Singer drew attention to the welfare of fish. He quoted author Alison Mood's startling statistics from a report she wrote, which was released on fishcount.org.uk just a month before the Guardian article. Singer states that she "has put together what may well be the first-ever systematic estimate of the size of the annual global capture of wild fish. It is, she calculates, in the order of one trillion, although it could be as high as 2.7tn."[41][42][a] Some chapters of Animal Liberation are dedicated to criticising testing on animals but, unlike groups such as PETA, Singer is willing to accept testing when there is a clear benefit for medicine. In November 2006, Singer appeared on the BBC programme Monkeys, Rats and Me: Animal Testing and said that he felt that Tipu Aziz's experiments on monkeys for research into treating Parkinson's disease could be justified.[43] Whereas Singer has continued since the publication of Animal Liberation to promote vegetarianism and veganism, he has been much less vocal in recent years on the subject of animal experimentation. Singer has defended some of the actions of the Animal Liberation Front, such as the stealing of footage from Dr. Thomas Gennarelli's laboratory in May 1984 (as shown in the documentary Unnecessary Fuss), but he has condemned other actions such as the use of explosives by some animal-rights activists and sees the freeing of captive animals as largely futile when they are easily replaced.[44][45] Singer features in the 2017 documentary Empathy, directed by Ed Antoja, which aims to promote a more respectful way of life towards all animals. The documentary won the "Public Choice Award" of the Greenpeace Film Festival.[46] |

応用倫理学 シンガーの『実践倫理学』(1979年)は、生きとし生けるものの利益を、なぜ、どのように衡量すべきかを分析している。シンガーが提唱する利害平等の原 則は、利害を持つすべての人を平等に扱うことを指示するものではない。例えば、すべての人は苦痛を避けることに関心を持つが、自分の能力を高めることに関 心を持つ人は比較的少ない。彼の原則は、異なる利益に対する異なる待遇を正当化するだけでなく、限界効用の逓減が要因である場合には、同じ利益に対しても 異なる待遇を認める。例えば、このアプローチでは、飢餓状態にある人の食物に対する利益を、少ししか空腹でない人の同じ利益よりも優遇することになる。 人間にとってより重要な利益とは、苦痛を避けること、自分の能力を伸ばすこと、衣食住の基本的欲求を満たすこと、温かい人間関係を楽しむこと、干渉される ことなく自由に自分のプロジェクトを追求すること、「その他多くの利益」である。ある存在に平等な配慮を与える基本的利益は、「苦痛および/または享受、 幸福」の能力である。シンガーは、ある存在の利益は、常にその存在の具体的な性質に従って量られるべきであると考える。彼は人生の「旅」モデルを支持し、 それによって人生の旅の目標がどの程度挫折するかによって、命を奪うことの不当性を測る。つまり、目標が設定されていない最初の段階と、目標が達成された か達成されそうにない最後の段階では、命を絶つことの誤りは少なくなる。旅モデルは挫折した願望に寛容であり、旅に出た人が代替不可能である理由を説明す る。生き続けたいという個人的な関心だけが、旅モデルをもたらすのである。このモデルはまた、シンガーが些細な欲望や快楽よりも利益を優先することも説明 する。 倫理的な行動は、思慮深さを超えて「個人よりも大きなもの」、つまりより大きな聴衆に向けた理由によって正当化される。具体的には、「汝の隣人を汝自身の ごとく愛せよ」という戒めである。シンガーは、この「汝の隣人を汝自身のごとく愛せよ」という戒めによって、道徳的理由が「何らかの普遍的なもの」である ことが明らかになると考えている。シンガーがカントからヘアーまで辿ったこの普遍化の一歩[27]: 11 は極めて重要であり、ホッブズからデイヴィッド・ゴーティエに至るまで、道徳を分別に結びつける道徳理論家たちとは一線を画している。普遍化は功利主義に 直接つながるとシンガーは主張するが、それは自分自身の利益を他者の利益よりも高く評価することはできないという考えに基づいている[28]。 これらを考慮に入れて、人はそれらを秤にかけて、影響を受ける人々の利益を最大化する可能性が最も高い行動方針を採用しなければならない。シンガーの普遍 化の段階は、利害を誰が持っているかに関係なく利害に適用されるのに対し、カント派のそれは(カントの「目的の王国」やロールズの本来の立場などにおけ る)合理的な主体の判断に適用される。ホッブズ派に関しては、シンガーは『実践倫理学』の最終章で反論を試みており、幸福はそれを探さないことによって見 出すのが最善であると説く「快楽主義の逆説」や、多くの人が自分の関心事よりも大きなものと関わりたいと感じる必要性など、自己利益的な理由が道徳的視点 の採用を支持していると論じている[28]。 シンガーは感覚主義者であると自認している[29]。感覚主義とは、すべての感覚を持つ存在に道徳的配慮を認める倫理的立場である。 効果的利他主義と世界の貧困 主な記事 効果的利他主義 シンガーの考えは、効果的利他主義の台頭に貢献している[30]。彼は、人々は苦しみを減らすだけでなく、可能な限り効果的な方法で苦しみを減らすよう努 めるべきだと主張している。シンガーは以前にも、貧困を減らし、特に食肉産業における人間以外の動物の苦しみをなくすことが道徳的に必要であることを長々 と書いているが、2015年の著書『The Most Good You Can Do』では、効果的利他主義運動がいかにこれらのことをより効果的に行っているかについて書いている。彼は、最も費用対効果の高い動物擁護チャリティや介 入策を推奨する、効果的利他主義コミュニティの多くのメンバーが利用するチャリティ評価機関であるAnimal Charity Evaluatorsの理事である[31]。 シンガー自身の組織であるThe Life You Can Save (TLYCS)もまた、GiveWellのようなチャリティ評価機関によって、極貧の人々を支援する際に最も効果的であるとみなされたチャリティを推薦し ている。TLYCSは、シンガーが2009年に自身の名を冠した著書を発表した後に設立されたもので、その中でシンガーは、世界の貧困撲滅を支援するチャ リティへの寄付をより一般的に支持することを主張している。特に、1972年に発表したエッセイ『飢饉、豊かさ、そして道徳』での議論を発展させたもの で、豊かな国の市民は、可処分所得の少なくとも一部を、世界の貧困層を支援する慈善団体に寄付する道徳的義務があるとしている。溺れている子供の例え」を 使ってこのことを支持している。たとえ高価な服が台無しになったとしても、ほとんどの人は池で溺れている子供を助けるだろう。その結果、私たちは財産に使 うお金のかなりの部分を、代わりに慈善団体に寄付すべきである[32][33]。 2009年11月より、シンガーはGiving What We Canのメンバーであり、そのメンバーは収入の少なくとも10%を効果的な慈善団体に寄付することを誓約する国際組織である[34]。 動物解放と種差別 1975年に出版された『動物の解放』は、現代の動物解放運動の指導者たちに形成的な影響を与えたとして挙げられている[35]。本書の中心的な主張は、 「最大多数の最大善」が善行や倫理的行動の唯一の尺度であるという功利主義の概念を拡張したものであり、シンガーはこの原則を他の動物に適用しない理由は ないと考え、人間と「動物」の境界は完全に恣意的であると主張している。例えば、類人猿と牡蠣の間には、人間と類人猿の間よりもはるかに多くの違いがある にもかかわらず、前者2つが「動物」としてひとくくりにされるのに対し、人間は他のすべての「動物」から区別されるはずの「人間」とみなされる。 シンガーは『動物の解放』の中で、菜食主義を支持し、ほとんどの動物実験に反対している。彼は2006年のインタビューで、自分は肉を食べず、1971年 以来ベジタリアンであると述べている。また、「徐々にベジタリアンになりつつある」とし、「私は大部分がベジタリアンですが、柔軟なベジタリアンです。 スーパーに行って、自分のためにビーガンでないものを買うことはない。でも、旅行中や他の人のところに行くときは、ヴィーガンではなくベジタリアンの食事 をすることにとても満足している」[37]。 より最近では、シンガーは、中枢神経系がないため、牡蠣、ムール貝、アサリを時折食べることがあるため、完全菜食主義者ではないと述べている[38]。シ ンガーによれば、「農場が本当に動物に良い生活をさせ、人道的に、できれば屠殺場への輸送や動物の邪魔をすることなく殺す」のであれば、肉食は倫理的に許 される。アニマル解放』では、(肉食を)間違っているのは殺すことではなく、苦しむことだと言っている」[39]。 シンガーはオンライン出版物『Chinadialogue』への寄稿で、欧米式の食肉生産を残酷で不健康、生態系にダメージを与えると呼び、その方法が人 口の増加する需要を満たすために必要であるという考えを否定した[40]。シンガーは2010年の『ガーディアン』紙の記事で、「魚:私たちの皿の上の忘 れられた犠牲者」と題し、魚の福祉に注目した。彼は、Guardianの記事のちょうど1ヶ月前にfishcount.org.ukで発表された、作家の アリソン・ムードが書いた報告書の驚くべき統計を引用した。シンガーは、「世界における野生魚の年間捕獲量の規模を、史上初めて体系的に推定した」と述べ ている。その規模は、2兆7000億トンにも上るかもしれないが、1兆のオーダーになると彼女は計算している」[41][42][a]。 アニマル解放』のいくつかの章は、動物実験を批判することに捧げられているが、PETAのようなグループとは異なり、シンガーは、医療に明らかな利益があ る場合には、実験を受け入れることを厭わない。2006年11月、シンガーはBBCの番組『Monkeys, Rats and Me』に出演した: シンガーは『アニマル解放』の出版以来、ベジタリアニズムとヴィーガニズムの推進を続けているが、近年は動物実験についてはあまり積極的でない。 シンガーは、1984年5月にトーマス・ジェンナレリ博士の研究室から映像を盗み出す(ドキュメンタリー『Unnecessary Fuss』で紹介)など、動物解放戦線の行動の一部を擁護しているが、一部の動物権利活動家による爆発物の使用など、他の行動を非難しており、容易に代替 が可能な捕獲動物の解放はほとんど無駄だと考えている[44][45]。 シンガーは、すべての動物に対してより尊重的な生き方を促進することを目的とした、エド・アントージャ監督による2017年のドキュメンタリー映画 『Empathy』に出演している。このドキュメンタリーはグリーンピース映画祭の「パブリック・チョイス賞」を受賞した[46]。 |

| Other views Meta-ethical views In the past, Singer did not hold that objective moral values exist, on the basis that reason could favour both egoism and equal consideration of interests. Singer himself adopted utilitarianism on the basis that people's preferences can be universalised, leading to a situation where one takes the "point of view of the universe" and "an impartial standpoint". But in the second edition of Practical Ethics, he concedes that the question of why we should act morally "cannot be given an answer that will provide everyone with overwhelming reasons for acting morally".[27]: 335 However, when co-authoring The Point of View of the Universe (2014), Singer shifted to the position that objective moral values do exist, and defends the 19th century utilitarian philosopher Henry Sidgwick's view that objective morality can be derived from fundamental moral axioms that are knowable by reason. Additionally, he endorses Derek Parfit's view that there are object-given reasons for action.[47]: 126 Furthermore, Singer and Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek (the co-author of the book) argue that evolutionary debunking arguments can be used to demonstrate that it is more rational to take the impartial standpoint of "the point of view of the universe", as opposed to egoism—pursuing one's own self-interest—because the existence of egoism is more likely to be the product of evolution by natural selection, rather than because it is correct, whereas taking an impartial standpoint and equally considering the interests of all sentient beings is in conflict with what we would expect from natural selection, meaning that it is more likely that impartiality in ethics is the correct stance to pursue.[47]: 182–183 Political views Whilst a student in Melbourne, Singer campaigned against the Vietnam War as president of the Melbourne University Campaign Against Conscription.[48] He also spoke publicly for the legalisation of abortion in Australia.[48] Singer joined the Australian Labor Party in 1974, but resigned after disillusionment with the centrist leadership of Bob Hawke.[49] In 1992, he became a founding member of the Victorian Greens.[49] He has run for political office twice for the Greens: in 1994 he received 28% of the vote in the Kooyong by-election, and in 1996 he received 3% of the vote when running for the Senate (elected by proportional representation).[49] Before the 1996 election, he co-authored a book The Greens with Bob Brown.[50] In A Darwinian Left,[51] Singer outlines a plan for the political left to adapt to the lessons of evolutionary biology. He says that evolutionary psychology suggests that humans naturally tend to be self-interested. He further argues that the evidence that selfish tendencies are natural must not be taken as evidence that selfishness is "right". He concludes that game theory (the mathematical study of strategy) and experiments in psychology offer hope that self-interested people will make short-term sacrifices for the good of others, if society provides the right conditions. Essentially, Singer claims that although humans possess selfish, competitive tendencies naturally, they have a substantial capacity for cooperation that also has been selected for during human evolution. Singer's writing in Greater Good magazine, published by the Greater Good Science Center of the University of California, Berkeley, includes the interpretation of scientific research into the roots of compassion, altruism, and peaceful human relationships. Singer has criticised the United States for receiving "oil from countries run by dictators ... who pocket most of the" financial gains, thus "keeping the people in poverty". Singer believes that the wealth of these countries "should belong to the people" within them rather than their "de facto government. In paying dictators for their oil, we are in effect buying stolen goods, and helping to keep people in poverty." Singer holds that America "should be doing more to assist people in extreme poverty". He is disappointed in U.S. foreign aid policy, deeming it "a very small proportion of our GDP, less than a quarter of some other affluent nations." Singer maintains that little "private philanthropy from the U.S." is "directed to helping people in extreme poverty, although there are some exceptions, most notably, of course, the Gates Foundation."[52] Singer describes himself as not anti-capitalist, stating in a 2010 interview with the New Left Project:[53] Capitalism is very far from a perfect system, but so far we have yet to find anything that clearly does a better job of meeting human needs than a regulated capitalist economy coupled with a welfare and health care system that meets the basic needs of those who do not thrive in the capitalist economy. He added that "[i]f we ever do find a better system, I'll be happy to call myself an anti-capitalist".[53] Similarly, in his book Marx, Singer is sympathetic to Marx's criticism of capitalism, but is skeptical about whether a better system is likely to be created, writing: "Marx saw that capitalism is a wasteful, irrational system, a system which controls us when we should be controlling it. That insight is still valid; but we can now see that the construction of a free and equal society is a more difficult task than Marx realised."[54] Singer is opposed to the death penalty, claiming that it does not effectively deter the crimes for which it is the punitive measure,[55] and that he cannot see any other justification for it.[56] In 2010, Singer signed a petition renouncing his right of return to Israel, because it is "a form of racist privilege that abets the colonial oppression of the Palestinians."[57] In 2016, Singer called on Jill Stein to withdraw from the US presidential election in states that were close between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, on the grounds that "The stakes are too high".[58] He argued against the view that there was no significant difference between Clinton and Trump, whilst also saying that he would not advocate such a tactic in Australia's electoral system, which allows for ranking of preferences.[58] When writing in 2017 on Trump's denial of climate change and plans to withdraw from the Paris accords, Singer advocated a boycott of all consumer goods from the United States to pressure the Trump administration to change its environmental policies.[59][60] In 2021, Singer described the war on drugs as an expensive, ineffective and extremely harmful policy.[61] Euthanasia and infanticide Singer holds that the right to life is essentially tied to a being's capacity to hold preferences, which in turn is essentially tied to a being's capacity to feel pain and pleasure. In Practical Ethics, Singer argues in favour of abortion rights on the grounds that fetuses are neither rational nor self-aware, and can therefore hold no preferences. As a result, he argues that the preference of a mother to have an abortion automatically takes precedence. In sum, Singer argues that a fetus lacks personhood. Similar to his argument for abortion rights, Singer argues that newborns lack the essential characteristics of personhood—"rationality, autonomy, and self-consciousness"[62]—and therefore "killing a newborn baby is never equivalent to killing a person, that is, a being who wants to go on living".[63] Singer has clarified that his "view of when life begins isn't very different from that of opponents of abortion." He deems it not "unreasonable to hold that an individual human life begins at conception. If it doesn't, then it begins about 14 days later, when it is no longer possible for the embryo to divide into twins or other multiples." Singer disagrees with abortion rights opponents in that he does not "think that the fact that an embryo is a living human being is sufficient to show that it is wrong to kill it." Singer wishes "to see American jurisprudence, and the national abortion debate, take up the question of which capacities a human being needs to have in order for it to be wrong to kill it" as well as "when, in the development of the early human being, these capacities are present."[64] Singer classifies euthanasia as voluntary, involuntary, or non-voluntary. Voluntary euthanasia is that to which the subject consents. He argues in favour of voluntary euthanasia and some forms of non-voluntary euthanasia, including infanticide in certain instances, but opposes involuntary euthanasia. Bioethicists associated with the disability rights and disability studies communities have argued that his epistemology is based on ableist conceptions of disability.[65] Singer's positions have also been criticised by some advocates for disability rights and right-to-life supporters, concerned with what they see as his attacks upon human dignity. Religious critics have argued that Singer's ethics ignores and undermines the traditional notion of the sanctity of life. Singer agrees and believes the notion of the sanctity of life ought to be discarded as outdated, unscientific, and irrelevant to understanding problems in contemporary bioethics.[66] Disability rights activists have held many protests against Singer at Princeton University and at his lectures over the years. Singer has replied that many people judge him based on secondhand summaries and short quotations taken out of context, not on his books or articles, and that his aim is to elevate the status of animals, not to lower that of humans.[67] American publisher Steve Forbes ceased his donations to Princeton University in 1999 because of Singer's appointment to a prestigious professorship.[68] Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal wrote to organisers of a Swedish book fair to which Singer was invited that "A professor of morals ... who justifies the right to kill handicapped newborns ... is in my opinion unacceptable for representation at your level."[69] Conservative psychiatrist Theodore Dalrymple wrote in 2010 that Singerian moral universalism is "preposterous—psychologically, theoretically, and practically".[70] In 2002, disability rights activist Harriet McBryde Johnson debated Singer, challenging his belief that it is morally permissible to euthanise newborn children with severe disabilities. "Unspeakable Conversations", Johnson's account of her encounters with Singer and the pro-euthanasia movement, was published in the New York Times Magazine in 2003.[71] In 2015, Singer debated Archbishop Anthony Fisher on the legalisation of euthanasia at Sydney Town Hall.[72] Singer rejected arguments that legalising euthanasia would result in a slippery slope where the practice might become widespread as a means to remove undesirable people for financial or other motives.[73] Singer has experienced the complexities of some of these questions in his own life. His mother had Alzheimer's disease. He said, "I think this has made me see how the issues of someone with these kinds of problems are really very difficult".[26] In an interview with Ronald Bailey, published in December 2000, he explained that his sister shares the responsibility of making decisions about his mother. He did say that, if he were solely responsible, his mother might not continue to live.[74] Surrogacy In 1985, Singer wrote a book with the physician Deanne Wells arguing that surrogate motherhood should be allowed and regulated by the state by establishing nonprofit 'State Surrogacy Boards', which would ensure fairness between surrogate mothers and surrogacy-seeking parents. Singer and Wells endorsed both the payment of medical expenses endured by surrogate mothers and an extra "fair fee" to compensate the surrogate mother.[75][76] Religion Singer was a speaker at the 2012 Global Atheist Convention.[77] He has debated with Christians including John Lennox[78] and Dinesh D'Souza.[79] Singer has pointed to the problem of evil as an objection against the Christian conception of God. He stated: "The evidence of our own eyes makes it more plausible to believe that the world was not created by any god at all. If, however, we insist on believing in divine creation, we are forced to admit that the god who made the world cannot be all-powerful and all good. He must be either evil or a bungler."[80] In keeping with his considerations of nonhuman animals, Singer also takes issue with the original sin reply to the problem of evil, saying that, "animals also suffer from floods, fires, and droughts, and, since they are not descended from Adam and Eve, they cannot have inherited original sin."[80] Medical intervention in the aging process Singer supports the view that medical intervention into the aging process would do more to improve human life than research on therapies for specific chronic diseases in the developed world: In developed countries, aging is the ultimate cause of 90 per cent of all human deaths. Thus, treating aging is a form of preventive medicine for all of the diseases of old age. Moreover, even before aging leads to our death, it reduces our capacity to enjoy our lives and to contribute positively to the lives of others. So, instead of targeting specific diseases that are much more likely to occur when people have reached a certain age, wouldn't a better strategy be to try to forestall or repair the damage done to our bodies by the aging process?[81] Singer does worry that "If we discover how to slow aging, we might have a world in which the poor majority must face death at a time when members of the rich minority are only a 10th of the way through their expected lifespans," thus risking "that overcoming aging will increase the stock of injustice in the world."[81] However, Singer cautiously highlights that as with other medical developments, they will reach the more economically disadvantaged over time once developed, whereas they can never do so if they are not.[81] As to the concern that longer lives might contribute to overpopulation, Singer notes that "success in overcoming aging could itself ... delay or eliminate menopause, enabling women to have their first children much later than they can now" and thus slowing the birth rate, and also that technology may reduce the consequences of rising human populations by (for instance) enabling more zero-greenhouse gas energy sources.[81] In 2012, Singer's department sponsored the "Science and Ethics of Eliminating Aging" seminar at Princeton.[82] |

その他の見解 メタ倫理観 かつてシンガーは、理性はエゴイズムと利害の平等な考慮の両方を支持しうるとして、客観的な道徳的価値が存在するとは考えていなかった。シンガー自身は、 人々の選好が普遍化され、「宇宙からの視点」と「公平な立場」に立つ状況になりうるという理由で功利主義を採用していた。しかし、『実践倫理学』第2版で は、なぜ道徳的に行動すべきかという問いに対して、「すべての人に道徳的に行動する圧倒的な理由を与えるような答えを与えることはできない」と認めている [27]: 335 しかし、『宇宙の視点』(2014年)の共著者であるシンガーは、客観的な道徳的価値は存在するという立場にシフトし、客観的道徳は理性によって知ること ができる基本的な道徳的公理から導き出すことができるという19世紀の功利主義哲学者ヘンリー・シドウィックの見解を擁護している。さらに、行動には客観 的に与えられた理由があるというデレク・パーフィットの見解も支持している[47]: 126 さらに、シンガーとカタジナ・デ・ラザリ=ラデック(本書の共著者)は、進化論的な論証を用いることで、エゴイズムの存在が自然淘汰による進化の産物であ る可能性が高いため、エゴイズム(自己の利益を追求すること)とは対照的に、「宇宙の視点」という公平な立場に立つことがより合理的であることを証明でき ると主張している、 公平な立場に立ち、すべての衆生の利益を平等に考えることは、自然淘汰から予想されることと相反する。 [47]: 182-183 政治的見解 メルボルンの学生時代、シンガーはメルボルン大学徴兵反対キャンペーンの会長としてベトナム戦争に反対するキャンペーンを行った[48]。 また、オーストラリアにおける中絶の合法化を公に訴えた[48]。1974年にオーストラリア労働党に入党したが、ボブ・ホークの中道的なリーダーシップ に幻滅し、党を辞職した[49]。 [1994年にはクーヨン補欠選挙で28%の得票率を獲得し、1996年には上院議員選挙(比例代表制)に出馬して3%の得票率を獲得した[49]。 1996年の選挙前には、ボブ・ブラウンと共著で『グリーンズ』を出版した[50]。 ダーウィン的左翼』[51]の中で、シンガーは政治的左翼が進化生物学の教訓に適応するための計画を概説している。シンガーによれば、進化心理学は、人間 が自然に利己的になる傾向があることを示唆している。さらに、利己的な傾向が自然であるという証拠を、利己的であることが「正しい」という証拠としてはな らないと主張する。ゲーム理論(戦略に関する数学的研究)や心理学の実験は、社会が適切な条件を提供すれば、利己的な人々が他者の利益のために短期的な犠 牲を払うという希望を与えてくれる、と結論づける。基本的にシンガーは、人間には利己的で競争的な傾向が備わっているが、人類進化の過程で選択された協力 の能力もかなり備わっていると主張している。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校のグレーター・グッド・サイエンス・センターが発行する『グレーター・グッ ド』誌に寄稿したシンガーの文章には、思いやりや利他主義、平和な人間関係の根源に関する科学的研究の解釈が含まれている。 シンガーは、米国が「独裁者が牛耳る国々から石油を供給され......彼らは経済的利益のほとんどを懐に入れている」ため、「国民を貧困に陥れている」 と批判している。シンガーは、これらの国の富は「事実上の政府」ではなく、「国民のもの」であるべきだと考えている。独裁者に石油の対価を支払うことは、 事実上、盗品を買い、人々を貧困に陥れる手助けをしていることになる」。シンガーは、アメリカは「極度の貧困に苦しむ人々を支援するためにもっと努力すべ きだ」と考えている。彼はアメリカの対外援助政策に失望しており、「GDPに占める割合は非常に小さく、他の豊かな国の4分の1にも満たない」と見なして いる。シンガーは、「米国からの民間の慈善事業」が「極度の貧困にあえぐ人々を支援するためのもの」であることはほとんどないと主張している。 シンガーは自らを反資本主義者ではないとし、2010年のニュー・レフト・プロジェクトとのインタビューで次のように述べている[53]。 資本主義は完璧なシステムとは程遠いものだが、今のところ、資本主義経済で成功しない人々の基本的なニーズを満たす福祉や医療制度と結びついた規制された資本主義経済よりも、明らかに人間のニーズを満たす良い仕事をするものはまだ見つかっていない」。 さらに彼は、「もしより良いシステムが見つかったら、私は喜んで反資本主義者を名乗るだろう」と付け加えた[53]。 同様に、シンガーは著書『マルクス』の中で、マルクスの資本主義批判に共感しているが、より良いシステムが生まれるかどうかについては懐疑的であり、次の ように書いている: 「マルクスは、資本主義が浪費的で非合理的なシステムであり、われわれが資本主義を支配すべきときにわれわれを支配するシステムであると考えた。その洞察 は今でも有効だが、自由で平等な社会を構築することは、マルクスが考えていた以上に困難な課題であることがわかる」[54]。 シンガーは死刑制度に反対しており、死刑制度が懲罰手段である犯罪を効果的に抑止することはできず[55]、それ以外の正当な理由が見出せないとしている[56]。 2010年、シンガーはイスラエルへの帰還権を放棄する請願書に署名し、それは「パレスチナ人の植民地的抑圧を教唆する人種差別的特権の一形態」であるとしている[57]。 2016年、シンガーはジル・スタインに対し、ヒラリー・クリントンとドナルド・トランプの間で接戦が繰り広げられている州におけるアメリカ大統領選挙か ら撤退するよう呼びかけ、「出る杭は打たれすぎる」[58]という理由で、クリントンとトランプの間に大きな差はないという見解に反論する一方で、選好順 位を決めることができるオーストラリアの選挙制度ではそのような戦術を提唱しないと述べた[58]。 2017年にトランプが気候変動を否定し、パリ協定からの離脱を計画していることについて執筆した際、シンガーはトランプ政権に環境政策を変更するよう圧力をかけるため、アメリカからのすべての消費財のボイコットを提唱した[59][60]。 2021年、シンガーは麻薬戦争について、高価で効果がなく、極めて有害な政策であると述べた[61]。 安楽死と嬰児殺し シンガーは、生きる権利は本質的に嗜好を保持する能力と結びついており、それは本質的に痛みや喜びを感じる能力と結びついていると考えている。 実践倫理学』の中でシンガーは、胎児は理性も自意識もなく、したがって嗜好を持つことができないという理由で、中絶の権利を支持している。その結果、中絶 したいという母親の希望が自動的に優先されると主張している。要するに、シンガーは胎児には人格がないと主張しているのである。 中絶の権利に関する彼の主張と同様に、シンガーは、新生児には人としての本質的な特徴-「合理性、自律性、自己意識」[62]-が欠けており、したがって 「新生児を殺すことは、人、すなわち生き続けたいと願う存在を殺すことと決して等価ではない」[63]と主張している。シンガーは、「生命がいつ始まるか についての彼の見解は、中絶反対派のそれと大きく異なるものではない」と明言している。彼は「個々の人間の生命は受胎から始まると考えることは不合理では ない」と考えている。もしそうでないなら、受精卵が双子や他の多胎児に分かれることが不可能になる14日後くらいから始まることになる」。シンガーは、 「胚が生きている人間であるという事実は、胚を殺すことが間違っていることを示すのに十分であるとは思わない」という点で、中絶権反対派と意見が合わな い。シンガーは、「アメリカの法学が、そして中絶に関する国内的な議論が、人間を殺すことが誤りであるためには、人間がどのような能力を持っている必要が あるのかという問題を取り上げること」、また「初期の人間の発達において、これらの能力がいつ存在するのか」ということを望んでいる[64]。 シンガーは安楽死を自発的、非自発的、非自発的に分類している。自発的安楽死とは、対象者が同意するものである。シンガーは、自発的安楽死と、ある場合には嬰児殺しを含むいくつかの非自発的安楽死に賛成するが、非自発的安楽死には反対する。 シンガーの立場は、障害者の権利擁護者や生存権支持者の一部からも批判されており、彼らが人間の尊厳を攻撃していると考えることを懸念している。宗教的な 批評家たちは、シンガーの倫理学は生命の尊厳という伝統的な概念を無視し、損なっていると主張している。シンガーもこれに同意しており、生命の尊厳という 概念は時代遅れで非科学的であり、現代の生命倫理の問題を理解するのに無関係であるとして破棄されるべきであると考えている[66]。障害者の権利活動家 たちは、プリンストン大学や彼の講演会において、長年にわたってシンガーに対して多くの抗議活動を行ってきた。シンガーは、多くの人々は彼の著書や論文で はなく、文脈から抜粋された二次的な要約や短い引用に基づいて彼を判断しており、彼の目的は動物の地位を高めることであり、人間の地位を下げることではな いと答えている[67]。 アメリカの出版社スティーブ・フォーブスは、シンガーが権威ある教授に任命されたことを理由に、1999年にプリンストン大学への寄付を中止した [68]。ナチス・ハンターのサイモン・ヴィーゼンタールは、シンガーが招待されたスウェーデンのブックフェアの主催者に対し、「ハンディキャップを持つ 動物を殺す権利を正当化する道徳の教授は......」と書いた。障害のある新生児を殺す権利を正当化する道徳の教授は......私の意見では、あなた 方のようなレベルの代表としては受け入れられない」[69]。保守派の精神科医セオドア・ダリンプルは2010年に、シンガーの道徳万能主義は「とんでも ない-心理学的にも、理論的にも、実際的にも」[70]と書いている。 2002年、障害者権利活動家のハリエット・マクブライド・ジョンソンはシンガーと討論し、重度の障害を持つ新生児を安楽死させることは道徳的に許される という彼の信念に異議を唱えた。シンガーと安楽死推進運動との出会いについてのジョンソンの記録である "Unspeakable Conversations "は、2003年にニューヨーク・タイムズ・マガジンに掲載された[71]。 2015年、シンガーはシドニー・タウンホールでアンソニー・フィッシャー大司教と安楽死の合法化について討論した[72]。シンガーは、安楽死を合法化 すれば、金銭的な理由やその他の動機で好ましくない人々を排除する手段として安楽死が広まるかもしれないという議論を否定した[73]。 シンガーは、このような問題の複雑さを自身の人生で経験している。彼の母親はアルツハイマー病を患っていた。2000年12月に発表されたロナルド・ベイ リーとのインタビューでは、母親のことを決める責任は妹が分担していると説明している。しかし、もし自分だけが責任を負うのであれば、母親は生き続けられ ないかもしれない[74]と語っている。 代理出産 1985年、シンガーは医師のディアン・ウェルズと共著で、代理母出産を許可し、非営利の「州代理出産委員会」を設立することによって、代理母と代理出産 を希望する両親の間の公平性を確保し、国家が規制すべきだと主張した。シンガーとウェルズは、代理母が負担する医療費の支払いと、代理母を補償するための 特別な「公正な料金」の両方を支持した[75][76]。 宗教 ジョン・レノックス[78]やディネシュ・ドゥスーザ[79]を含むキリスト教徒と討論したことがある。彼はこう述べている: 「私たち自身の目から見た証拠は、世界はいかなる神によっても創造されなかったと考える方がもっともらしい。しかし、神の創造を信じようとするならば、世 界を創造した神が万能で善良であるはずがないことを認めざるを得ない。人間以外の動物についての考察と同様に、シンガーは悪の問題に対する原罪の回答にも 異議を唱えており、「動物も洪水、火事、干ばつに苦しんでおり、アダムとイブの子孫ではないので、原罪を受け継ぐことはできない」と述べている[80]。 老化プロセスへの医療介入 シンガーは、先進国における特定の慢性疾患に対する治療法の研究よりも、老化プロセスへの医療介入の方が人間の生活を改善するという見解を支持している: 先進国では、加齢は全人類死亡の90%を占める究極の原因である。したがって、老化を治療することは、老齢に伴うすべての病気に対する予防医学の一形態な のである。さらに、老化は死に至る前に、人生を楽しみ、他人の人生に積極的に貢献する能力を低下させる。つまり、ある年齢に達すると発症しやすくなる特定 の病気をターゲットにするのではなく、老化のプロセスによって私たちの身体にもたらされるダメージを未然に防いだり、修復したりすることを試みる方が、よ り良い戦略ではないだろうか[81]。 シンガーは、「老化を遅らせる方法を発見した場合、貧しい大多数が、豊かな少数派が期待寿命の10分の1しか生きられない時期に死に直面しなければならな い世界になるかもしれない」と懸念している。 [81]長生きが人口過剰の一因になるのではないかという懸念について、シンガーは「老化の克服に成功すれば、それ自体が......閉経を遅らせたりな くしたりすることができ、女性が最初の子どもを産む時期を今よりもずっと遅らせることができるようになる」ため、出生率が低下する可能性があると指摘し、 また、技術が(例えば)温室効果ガスゼロのエネルギー源をより多く可能にすることで、人類の人口増加の影響を軽減する可能性があるとも述べている [81]。 2012年、シンガーの学部はプリンストン大学で「老化をなくす科学と倫理」セミナーを主催した[82]。 |

| Protests In 1989 and 1990, Singer's work was the subject of a number of protests in Germany. A course in ethics led by Hartmut Kliemt at the University of Duisburg where the main text used was Singer's Practical Ethics was, according to Singer, "subjected to organised and repeated disruption by protesters objecting to the use of the book on the grounds that in one of its ten chapters it advocates active euthanasia for severely disabled newborn infants". The protests led to the course being shut down.[83] When Singer tried to speak during a lecture at Saarbrücken, he was interrupted by a group of protesters including advocates for disability rights. One of the protesters expressed that entering serious discussions would be a tactical error.[84] The same year, Singer was invited to speak in Marburg at a European symposium on "Bioengineering, Ethics and Mental Disability". The invitation was fiercely attacked by leading intellectuals and organisations in the German media, with an article in Der Spiegel comparing Singer's positions to Nazism. Eventually, the symposium was cancelled and Singer's invitation withdrawn.[85] A lecture at the Zoological Institute of the University of Zurich was interrupted by two groups of protesters. The first group was a group of disabled people who staged a brief protest at the beginning of the lecture. They objected to inviting an advocate of euthanasia to speak. At the end of this protest, when Singer tried to address their concerns, a second group of protesters rose and began chanting "Singer raus! Singer raus!" ("Singer out!" in German) When Singer attempted to respond, a protester jumped on stage and grabbed his glasses, and the host ended the lecture. Singer explains "my views are not threatening to anyone, even minimally" and says that some groups play on the anxieties of those who hear only keywords that are understandably worrying (given the constant fears of ever repeating the Holocaust) if taken with any less than the full context of his belief system.[27]: 346–359 [86] In 1991, Singer was due to speak along with R. M. Hare and Georg Meggle [de] at the 15th International Wittgenstein Symposium in Kirchberg am Wechsel, Austria. Singer has stated that threats were made to Adolf Hübner, then the president of the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society, that the conference would be disrupted if Singer and Meggle were given a platform. Hübner proposed to the board of the society that Singer's invitation (as well as the invitations of a number of other speakers) be withdrawn. The Society decided to cancel the symposium.[83] In an article originally published in The New York Review of Books, Singer argued that the protests dramatically increased the amount of coverage he received: "instead of a few hundred people hearing views at lectures in Marburg and Dortmund, several millions read about them or listened to them on television". Despite this, Singer argues that it has led to a difficult intellectual climate, with professors in Germany unable to teach courses on applied ethics and campaigns demanding the resignation of professors who invited Singer to speak.[83] Criticism Singer was criticised by Nathan J. Robinson, founder of Current Affairs, for comments in an op-ed defending Anna Stubblefield, a carer and professor who was convicted of aggravated sexual assault against a man with severe physical and intellectual disabilities. The op-ed questioned whether the victim was capable of giving or withholding consent, and stated that "It seems reasonable to assume that the experience was pleasurable to him; for even if he is cognitively impaired, he was capable of struggling to resist." Robinson called the statements "outrageous" and "morally repulsive", and said that they implied that it might be permissible to rape or sexually assault disabled people.[87] Roger Scruton was critical of the consequentialist, utilitarian approach of Singer.[88] Scruton alleged that Singer's works, including Animal Liberation (1975), "contain little or no philosophical argument. They derive their radical moral conclusions from a vacuous utilitarianism that counts the pain and pleasure of all living things as equally significant and that ignores just about everything that has been said in our philosophical tradition about the real distinction between persons and animals."[88] Anthropologists have criticised Singer's foundational essay "Animal Liberation" (1973)[89] for comparing the interests of "slum children" with the interests of the rats that bite them – at a time when poor and predominantly Black American children were indeed regularly attacked and bitten by rats, sometimes fatally.[90] |

抗議活動 1989年と1990年、シンガーの著作はドイツで多くの抗議の対象となった。シンガーによれば、デュイスブルク大学でハルトムート・クリームトが担当し た倫理学の講座で、シンガーの『実践倫理学』が主なテキストとして使用されたが、「10章のうちの1章で、重度の障害を持つ新生児に対する積極的安楽死を 提唱しているという理由で、この本の使用に反対する抗議者たちによって、組織的かつ度重なる妨害を受けた」。この抗議により、コースは閉鎖された [83]。 シンガーがザールブリュッケンでの講義中に発言しようとしたところ、障害者の権利擁護者を含む抗議者グループによって妨害された。抗議者の一人は、真剣な議論に入ることは戦術的な誤りであると表明した[84]。 同じ年、シンガーはマールブルクで開催された「バイオエンジニアリング、倫理、精神障害」に関するヨーロッパ・シンポジウムに招かれ、講演を行った。この 招待は、ドイツのメディアを代表する知識人や組織から激しい攻撃を受け、『シュピーゲル』誌にはシンガーの立場をナチズムと比較する記事が掲載された。結 局、シンポジウムは中止され、シンガーの招待も撤回された[85]。 チューリヒ大学動物学研究所での講演は、2つの抗議グループによって中断された。最初のグループは障害者のグループで、講演会の冒頭で短い抗議行動を起こ した。彼らは安楽死の擁護者を講演に招くことに反対した。この抗議行動の最後に、シンガーが彼らの懸念に応えようとしたとき、第二の抗議者グループが立ち 上がり、"Singer raus!シンガーは出て行け!" (シンガーがそれに応えようとすると、抗議者がステージに飛び上がって彼の眼鏡をつかみ、司会者は講演を打ち切った。シンガーは、「私の見解は、最小限の ものであっても、誰かを脅かすものではありません」と説明し、一部のグループは、彼の信念体系の完全な文脈に基づかなければ、(ホロコーストが繰り返され るのではないかという絶え間ない恐怖を考えれば)当然心配になるようなキーワードだけを耳にする人々の不安をあおっていると述べている[27]: 346 -359 [86] 1991年、シンガーはオーストリアのキルヒベルク・アム・ヴェヒゼルで開催された第15回国際ウィトゲンシュタイン・シンポジウムでR. M. ヘアー、ゲオルク・メグル[de]とともに講演する予定であった。シンガーは、当時オーストリアのルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタイン協会の会長であった アドルフ・ヒュブナーに対して、シンガーとメグルに演壇を与えたら会議が妨害されるという脅迫があったと述べている。ヒュブナーは学会の理事会に、シン ガーの招待(および他の多くの講演者の招待)を取り下げるよう提案した。学会はシンポジウムの中止を決定した[83]。 ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』誌に掲載された記事の中で、シンガーは、抗議によって彼が受ける報道量が劇的に増加したと主張した: 「マールブルクやドルトムントでの講演で数百人が意見を聞く代わりに、数百万人が講演について読んだり、テレビで聞いたりした」。にもかかわらず、シン ガーは、ドイツの教授が応用倫理の講義を教えることができなくなったり、シンガーを講演に招いた教授の辞任を要求するキャンペーンが行われるなど、困難な 知的風土をもたらしたと主張している[83]。 批判 シンガーは、カレント・アフェアーズの創設者であるネイサン・J・ロビンソンによって、重度の身体的・知的障害を持つ男性に対する加重性的暴行で有罪判決 を受けた介護者で教授のアンナ・スタブルフィールドを擁護する論説のコメントについて批判された。この論説は、被害者に同意を与えたり差し控えたりする能 力があったのかどうか疑問視し、「彼にとってその経験は快楽的であったと考えるのが妥当である。ロビンソンはこの発言を「言語道断」で「道徳的に反吐が出 る」と呼び、障害者をレイプしたり性的暴行を加えたりすることが許されるかもしれないことを暗に示していると述べた[87]。 ロジャー・スクルトンはシンガーの結果主義的、功利主義的アプローチに批判的であった[88]。スクルトンは『動物の解放』(1975年)を含むシンガー の著作が「哲学的議論をほとんど、あるいはまったく含んでいない。それらは、すべての生き物の苦痛と快楽を等しく重要なものとして数え、人と動物の本当の 区別について我々の哲学的伝統で語られてきたことのほとんどすべてを無視する、空虚な功利主義から急進的な道徳的結論を導き出している」[88]。 人類学者たちは、シンガーの基礎となるエッセイ『動物の解放』(1973年)[89]を、「スラムの子供たち」の利益と彼らを噛むネズミの利益を比較することで批判している。 |

| Recognition Singer was inducted into the United States Animal Rights Hall of Fame in 2000.[91] In June 2012, Singer was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) for "eminent service to philosophy and bioethics as a leader of public debate and communicator of ideas in the areas of global poverty, animal welfare and the human condition."[92] Singer received Philosophy Now's 2016 Award for Contributions in the Fight Against Stupidity for his efforts "to disturb the comfortable complacency with which many of us habitually ignore the desperate needs of others ... particularly for this work as it relates to the Effective Altruism movement."[93] In 2018, Singer was noted in the book, Rescuing Ladybugs[94] by author and animal advocate Jennifer Skiff as a "hero among heroes in the world", who, in arguing against speciesism "gave the modern world permission to believe what we innately know – that animals are sentient and that we have a moral obligation not to exploit or mistreat them."[94]: 132 The book states that Singer's "moral philosophy on animal equality was sparked when he asked a fellow student at Oxford University a simple question about his eating habits."[94]: 133 In 2021, Singer was awarded the US$1-million Berggruen Prize,[95] and decided to give it away. He decided, in particular, to give half of the prize money to his foundation The Life You Can Save, because "over the last three years, each dollar spent by it generated an average of $17 in donations for its recommended nonprofits". (He added he has never taken money for personal use from the organisation.) Moreover, he plans to donate more than a third of the money to organisations combating intensive animal farming, and recommended as effective by Animal Charity Evaluators.[96] For 2022 Singer received the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the category of "Humanities and Social Sciences".[97] Personal life Since 1968, he has been married to Renata Singer (née Diamond; b. 1947 Wałbrzych, Poland); they have three children: Ruth, a textile artist; Marion, law student and youth arts specialist; and Esther, linguist and teacher. Renata Singer is a novelist and author and has collaborated on publications with her husband.[98] Until 2021 she was President of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library in Melbourne.[99] |

表彰 シンガーは2000年に米国アニマルライツの殿堂入りを果たした[91]。 2012年6月、シンガーは「世界的貧困、動物福祉、人間の条件の分野における公開討論の指導者、思想の伝達者として、哲学と生命倫理に卓越した貢献をした」[92]として、オーストラリア勲章コンパニオン(AC)に任命された。 シンガーは、「私たちの多くが習慣的に他者の絶望的なニーズを無視する快適な自己満足を乱すために......特に、効果的利他主義運動に関連するこの仕事に対して」、フィロソフィー・ナウの2016年「愚かさとの闘いにおける貢献賞」を受賞した[93]。 2018年、シンガーは作家で動物擁護者のジェニファー・スキフによる著書『てんとう虫を救う』[94]の中で、種差別反対を主張することで「動物には感 覚があり、私たちには動物を搾取したり虐待したりしない道徳的義務があるという、私たちが生来知っていることを信じる許可を現代世界に与えた」「世界の英 雄中の英雄」として注目された[94]: 132 本書によれば、シンガーの「動物の平等に関する道徳哲学は、オックスフォード大学の学生仲間に自分の食習慣について素朴な質問をしたときに閃いた」 [94]: 133 2021年、シンガーは100万米ドルのベルクグリューエン賞を受賞し[95]、それを寄付することを決めた。特に、賞金の半分を自身の財団「The Life You Can Save」に寄付することを決めた。「過去3年間で、財団が支出した1ドルあたり平均17ドルの寄付が、財団が推薦する非営利団体にもたらされた」からで ある。(さらに、彼は賞金の3分の1以上を、Animal Charity Evaluatorsが効果的であると推奨する、集約的畜産と闘う団体に寄付する予定である[96]。 2022年、シンガーはBBVA財団のFrontiers of Knowledge賞を「人文・社会科学」部門で受賞した[97]。 私生活 1968年よりレナータ・シンガー(旧姓ダイアモンド、1947年ポーランド・ヴァウブリッチ生まれ)と結婚: ルースはテキスタイル・アーティスト、マリオンは法学部の学生で青少年芸術の専門家、エステルは言語学者で教師。2021年までメルボルンのカディマ・ユ ダヤ文化センターおよび国立図書館の理事長を務める[99]。 |

| Singly authored books Democracy and Disobedience, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1973; Oxford University Press, New York, 1974; Gregg Revivals, Aldershot, Hampshire, 1994 Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals, New York Review/Random House, New York, 1975; Cape, London, 1976; Avon, New York, 1977; Paladin, London, 1977; Thorsons, London, 1983. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, New York, 2002. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, New York, 2009. Practical Ethics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1980; second edition, 1993; third edition, 2011. ISBN 0-521-22920-0, ISBN 0-521-29720-6, ISBN 978-0-521-70768-8 Marx, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980; Hill & Wang, New York, 1980; reissued as Marx: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000; also included in full in K. Thomas (ed.), Great Political Thinkers: Machiavelli, Hobbes, Mill and Marx, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992 The Expanding Circle: Ethics and Sociobiology, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1981; Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981; New American Library, New York, 1982. ISBN 0-19-283038-4 Hegel, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1982; reissued as Hegel: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2001; also included in full in German Philosophers: Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997 How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-interest, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1993; Mandarin, London, 1995; Prometheus, Buffalo, NY, 1995; Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997 Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of Our Traditional Ethics, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1994; St Martin's Press, New York, 1995; reprint 2008. ISBN 0-312-11880-5 Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1995 Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement, Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland, 1998; Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1999 A Darwinian Left, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1999; Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08323-8 One World: The Ethics of Globalisation, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002; Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2002; 2nd edition, pb, Yale University Press, 2004; Oxford Longman, Hyderabad, 2004. ISBN 0-300-09686-0 Pushing Time Away: My Grandfather and the Tragedy of Jewish Vienna, Ecco Press, New York, 2003; HarperCollins Australia, Melbourne, 2003; Granta, London, 2004 The President of Good and Evil: The Ethics of George W. Bush, Dutton, New York, 2004; Granta, London, 2004; Text, Melbourne, 2004. ISBN 0-525-94813-9 The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty. New York: Random House 2009.[100] The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically. Yale University Press, 2015.[101] Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things That Matter. Princeton University Press, 2016.[101] Why Vegan? Eating Ethically. Liveright, 2020. |

単著 『民主主義と不服従』クラレンドン・プレス、オックスフォード、1973年;オックスフォード大学出版局、ニューヨーク、1974年;グレッグ・リバイバルズ、オルダーショット、ハンプシャー、1994年 『動物解放:動物への新たな倫理』ニューヨーク・レビュー/ランダムハウス、ニューヨーク、1975年; ケープ社、ロンドン、1976年;エイボン社、ニューヨーク、1977年;パラディン社、ロンドン、1977年;ソーソンズ社、ロンドン、1983年。 ハーパー・ペレニアル・モダン・クラシックス、ニューヨーク、2002年。ハーパー・ペレニアル・モダン・クラシックス、ニューヨーク、2009年。 『実践倫理学』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、ケンブリッジ、1980年;第2版、1993年;第3版、2011年。ISBN 0-521-22920-0、ISBN 0-521-29720-6、ISBN 978-0-521-70768-8 マルクス、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1980年;ヒル&ワン、ニューヨーク、1980年;改訂版『マルクス:超短編入門』、オック スフォード大学出版局、2000年;また完全版はK.トーマス編『偉大な政治思想家たち:マキャヴェッリ、ホッブズ、ミル、マルクス』、オックスフォード 大学出版局、オックスフォード、1992年に収録 拡大する円環:倫理学と社会生物学、ファラー・ストラウス・アンド・ジルー社、ニューヨーク、1981年;オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1981年;ニュー・アメリカン・ライブラリー、ニューヨーク、1982年。ISBN 0-19-283038-4 ヘーゲル、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード・ニューヨーク、1982年;改訂版『ヘーゲル:超短編入門』、オックスフォード大学出版局、 2001年;また『ドイツ哲学者:カント、ヘーゲル、ショーペンハウアー、ニーチェ』に全文収録、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、 1997年 『我々はどのように生きるべきか? 自己利益の時代における倫理』テキスト出版、メルボルン、1993年、マンダリン、ロンドン、1995年、プロメテウス、ニューヨーク州バッファロー、1995年、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1997年 『生と死の再考:我々の伝統的な倫理の崩壊』テキスト出版、メルボルン、1994年 セント・マーティンズ・プレス、ニューヨーク、1995年、2008年再版。ISBN 0-312-11880-5 オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1995年 倫理を行動へ:ヘンリー・スピラと動物権利運動、ローマン・アンド・リトルフィールド、ラナム、メリーランド、1998年、メルボルン大学出版局、メルボルン、1999年 ダーウィニアン・レフト、ワイデンフェルド・アンド・ニコルソン、ロンドン、1999年、イェール大学出版、ニューヘイブン、2000年。ISBN 0-300-08323-8 ワン・ワールド:グローバリゼーションの倫理、イェール大学出版、ニューヘイブン、2002年、テキスト出版、メルボルン、2002年、第2版、ペーパー バック、イェール大学出版、2004年、 オックスフォード・ロングマン、ハイデラバード、2004年。ISBN 0-300-09686-0 『押し流される時間:祖父とユダヤ人ウィーンの悲劇』、エッコ・プレス、ニューヨーク、2003年、ハーパーコリンズ・オーストラリア、メルボルン、2003年、グランタ、ロンドン、2004年 善と悪の大統領:ジョージ・W・ブッシュの倫理、ダットン、ニューヨーク、2004年、グランタ、ロンドン、2004年、テキスト、メルボルン、2004年。ISBN 0-525-94813-9 救える命:世界の貧困を終わらせるための今できる行動。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス 2009年。[100] 『できる限りの善を:効果的利他主義が倫理的な生き方への考え方を変える』イェール大学出版局、2015年。[101] 『現実世界における倫理:重要な事柄に関する82の短いエッセイ』プリンストン大学出版局、2016年。[101] 『なぜビーガンなのか?倫理的な食生活』リバライト、2020年。 |

| Animal liberationist Argument from marginal cases Demandingness objection Intrinsic value (animal ethics) List of animal rights advocates Utilitarian bioethics Veganism |

動物解放論者 限界事例からの議論 要求性異議 本質的価値(動物倫理) 動物愛護論者のリスト 功利主義的生命倫理 菜食主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Singer |

|

| John Stuart Mill Main article: John Stuart Mill Mill was brought up as a Benthamite with the explicit intention that he would carry on the cause of utilitarianism.[30] Mill's book Utilitarianism first appeared as a series of three articles published in Fraser's Magazine in 1861 and was reprinted as a single book in 1863.[31][32] hedonistic utilitarian Higher and lower pleasures Mill rejects a purely quantitative measurement of utility and says:[31] It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognize the fact, that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone. The word utility is used to mean general well-being or happiness, and Mill's view is that utility is the consequence of a good action. Utility, within the context of utilitarianism, refers to people performing actions for social utility. With social utility, he means the well-being of many people. Mill's explanation of the concept of utility in his work, Utilitarianism, is that people really do desire happiness, and since each individual desires their own happiness, it must follow that all of us desire the happiness of everyone, contributing to a larger social utility. Thus, an action that results in the greatest pleasure for the utility of society is the best action, or as Jeremy Bentham, the founder of early Utilitarianism put it, as the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Mill not only viewed actions as a core part of utility, but as the directive rule of moral human conduct. The rule being that we should only be committing actions that provide pleasure to society. This view of pleasure was hedonistic, as it pursued the thought that pleasure is the highest good in life. This concept was adopted by Bentham and can be seen in his works. According to Mill, good actions result in pleasure, and that there is no higher end than pleasure. Mill says that good actions lead to pleasure and define good character. Better put, the justification of character, and whether an action is good or not, is based on how the person contributes to the concept of social utility. In the long run the best proof of a good character is good actions; and resolutely refuse to consider any mental disposition as good, of which the predominant tendency is to produce bad conduct. In the last chapter of Utilitarianism, Mill concludes that justice, as a classifying factor of our actions (being just or unjust) is one of the certain moral requirements, and when the requirements are all regarded collectively, they are viewed as greater according to this scale of "social utility" as Mill puts it. He also notes that, contrary to what its critics might say, there is "no known Epicurean theory of life which does not assign to the pleasures of the intellect ... a much higher value as pleasures than to those of mere sensation." However, he accepts that this is usually because the intellectual pleasures are thought to have circumstantial advantages, i.e. "greater permanency, safety, uncostliness, &c." Instead, Mill will argue that some pleasures are intrinsically better than others. The accusation that hedonism is a "doctrine worthy only of swine" has a long history. In Nicomachean Ethics (Book 1 Chapter 5), Aristotle says that identifying the good with pleasure is to prefer a life suitable for beasts. The theological utilitarians had the option of grounding their pursuit of happiness in the will of God; the hedonistic utilitarians needed a different defence. Mill's approach is to argue that the pleasures of the intellect are intrinsically superior to physical pleasures. Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for a promise of the fullest allowance of a beast's pleasures; no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs. ... A being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and certainly accessible to it at more points, than one of an inferior type; but in spite of these liabilities, he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence. ... It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question...[32] Mill argues that if people who are "competently acquainted" with two pleasures show a decided preference for one even if it be accompanied by more discontent and "would not resign it for any quantity of the other," then it is legitimate to regard that pleasure as being superior in quality. Mill recognizes that these "competent judges" will not always agree, and states that, in cases of disagreement, the judgment of the majority is to be accepted as final. Mill also acknowledges that "many who are capable of the higher pleasures, occasionally, under the influence of temptation, postpone them to the lower. But this is quite compatible with a full appreciation of the intrinsic superiority of the higher." Mill says that this appeal to those who have experienced the relevant pleasures is no different from what must happen when assessing the quantity of pleasure, for there is no other way of measuring "the acutest of two pains, or the intensest of two pleasurable sensations." "It is indisputable that the being whose capacities of enjoyment are low, has the greatest chance of having them fully satisfied; and a highly-endowed being will always feel that any happiness which he can look for, as the world is constitute, is imperfect."[33] Mill also thinks that "intellectual pursuits have value out of proportion to the amount of contentment or pleasure (the mental state) that they produce."[34] Mill also says that people should pursue these grand ideals, because if they choose to have gratification from petty pleasures, "some displeasure will eventually creep in. We will become bored and depressed."[35] Mill claims that gratification from petty pleasures only gives short-term happiness and, subsequently, worsens the individual who may feel that his life lacks happiness, since the happiness is transient. Whereas, intellectual pursuits give long-term happiness because they provide the individual with constant opportunities throughout the years to improve his life, by benefiting from accruing knowledge. Mill views intellectual pursuits as "capable of incorporating the 'finer things' in life" while petty pursuits do not achieve this goal.[36] Mill is saying that intellectual pursuits give the individual the opportunity to escape the constant depression cycle since these pursuits allow them to achieve their ideals, while petty pleasures do not offer this. Although debate persists about the nature of Mill's view of gratification, this suggests bifurcation in his position. +++++++++++++++++++ 'Proving' the principle of utility In Chapter Four of Utilitarianism, Mill considers what proof can be given for the principle of utility:[37] The only proof capable of being given that an object is visible, is that people actually see it. The only proof that a sound is audible, is that people hear it. ... In like manner, I apprehend, the sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it. ... No reason can be given why the general happiness is desirable, except that each person, so far as he believes it to be attainable, desires his own happiness...we have not only all the proof which the case admits of, but all which it is possible to require, that happiness is a good: that each person's happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons. It is usual to say that Mill is committing a number of fallacies:[38] 1. naturalistic fallacy: Mill is trying to deduce what people ought to do from what they in fact do; 2. equivocation fallacy: Mill moves from the fact that (1) something is desirable, i.e. is capable of being desired, to the claim that (2) it is desirable, i.e. that it ought to be desired; and 3. the fallacy of composition: the fact that people desire their own happiness does not imply that the aggregate of all persons will desire the general happiness. Such allegations began to emerge in Mill's lifetime, shortly after the publication of Utilitarianism, and persisted for well over a century, though the tide has been turning in recent discussions. Nonetheless, a defence of Mill against all three charges, with a chapter devoted to each, can be found in Necip Fikri Alican's Mill's Principle of Utility: A Defense of John Stuart Mill's Notorious Proof (1994). This is the first, and remains[when?] the only, book-length treatment of the subject matter. Yet the alleged fallacies in the proof continue to attract scholarly attention in journal articles and book chapters. Hall (1949) and Popkin (1950) defend Mill against this accusation pointing out that he begins Chapter Four by asserting that "questions of ultimate ends do not admit of proof, in the ordinary acceptation of the term" and that this is "common to all first principles".[39][38] Therefore, according to Hall and Popkin, Mill does not attempt to "establish that what people do desire is desirable but merely attempts to make the principles acceptable."[38] The type of "proof" Mill is offering "consists only of some considerations which, Mill thought, might induce an honest and reasonable man to accept utilitarianism."[38] Having claimed that people do, in fact, desire happiness, Mill now has to show that it is the only thing they desire. Mill anticipates the objection that people desire other things such as virtue. He argues that whilst people might start desiring virtue as a means to happiness, eventually, it becomes part of someone's happiness and is then desired as an end in itself. The principle of utility does not mean that any given pleasure, as music, for instance, or any given exemption from pain, as for example health, are to be looked upon as means to a collective something termed happiness, and to be desired on that account. They are desired and desirable in and for themselves; besides being means, they are a part of the end. Virtue, according to the utilitarian doctrine, is not naturally and originally part of the end, but it is capable of becoming so; and in those who love it disinterestedly it has become so, and is desired and cherished, not as a means to happiness, but as a part of their happiness.[40] We may give what explanation we please of this unwillingness; we may attribute it to pride, a name which is given indiscriminately to some of the most and to some of the least estimable feelings of which is mankind are capable; we may refer it to the love of liberty and personal independence, an appeal to which was with the Stoics one of the most effective means for the inculcation of it; to the love of power, or the love of excitement, both of which do really enter into and contribute to it: but its most appropriate appellation is a sense of dignity, which all humans beings possess in one form or other, and in some, though by no means in exact, proportion to their higher faculties, and which is so essential a part of the happiness of those in whom it is strong, that nothing which conflicts with it could be, otherwise than momentarily, an object of desire to them.[41] |

ジョン・スチュワート・ミル 主な記事:ジョン・スチュワート・ミル ミルは、功利主義の理念を継承するという明確な意図のもと、ベンサム主義者として育てられた[30]。ミルの著書『功利主義』は、1861年にフレイザー誌に3回に分けて連載され、1863年に単行本として再版された[31][32]。 快楽主義的功利主義者(hedonistic utilitarian) 高次の快楽と低次の快楽 ミルは効用の純粋に量的な測定を否定し、次のように述べている[31]。 ある種類の快楽が他の種類の快楽よりも望ましく、価値が高いという事実を認識することは、効用の原理とまったく両立する。他のすべての物事を評価する際には、量だけでなく質も考慮されるのに、快楽の評価が量だけに依存すると考えられるのは不合理である。 効用という言葉は、一般的な幸福や幸福という意味で使われ、ミルの見解は、効用は良い行為の結果であるというものである。功利主義の文脈における効用と は、人々が社会的効用のために行為を行うことを指す。社会的効用とは、多くの人々の幸福を意味する。ミルは、彼の作品、功利主義における効用の概念の説明 は、人々は本当に幸福を望んでいるということであり、各個人が自分の幸福を望んでいるので、それは私たちのすべてがより大きな社会的効用に貢献し、皆の幸 福を望んでいることに従わなければならない。したがって、社会の有用性のための最大の喜びをもたらす行動が最良の行動であり、初期の功利主義の創始者ジェ レミー-ベンサムが言うように、最大多数の最大の幸福である。 ミルは、行為を効用の核心部分とみなすだけでなく、道徳的な人間行動の指示規則とみなした。ルールは、我々は唯一の社会に喜びを提供する行動をコミットす べきであるということである。快楽が人生における最高の善であるという考えを追求したため、この快楽観は快楽主義的であった。この概念はベンサムによって 採用され、彼の作品に見ることができる。ミルによれば、善い行為は快楽をもたらし、快楽より上位の目的はないという。ミルは、良い行為は快楽につながり、 良い人格を定義すると言う。よりよく言えば、人格の正当性、ある行為が善であるかどうかは、その人が社会的有用性の概念にどのように貢献するかということ に基づいている。長い目で見れば、善良な人格の最良の証拠は善良な行為であり、悪い行為を生み出す傾向が支配的な精神的気質を善とみなすことは断固として 拒否する。功利主義の最後の章では、ミルは、正義は、私たちの行動の分類要因(正義であるか不正であるか)として、特定の道徳的要件の一つであり、要件が すべて集合的にみなされるとき、それらはミルが言うように、この 「社会的効用 」の尺度に従って大きいとみなされると結論づけている。 彼はまた、その批判者が言うかもしれないことに反して、「知性の快楽に......単なる感覚の快楽よりもはるかに高い価値を与えないエピクロスの人生論 は知られていない 」と指摘する。しかし彼は、知的快楽には状況的な利点、すなわち 「より大きな永続性、安全性、費用のかからなさなど 」があると考えられるからである。代わりに、ミルは、いくつかの快楽は他のものよりも本質的に優れていると主張する。 快楽主義は 「豚にのみ値する教義 」であるという非難は長い歴史を持っている。アリストテレスは『ニコマコス倫理学』(第1巻第5章)の中で、善を快楽と同一視することは、獣にふさわしい 生活を好むことだと述べている。神学的功利主義者は、神の意志に幸福の追求を根拠づけるという選択肢を持っていた;快楽主義的功利主義者は、別の擁護を必 要とした。ミルのアプローチは、知性の快楽は肉体的快楽よりも本質的に優れていると主張することである。 知性のある人間は愚か者になることに同意しないであろうし、賢明な人間は無知であることに同意しないであろうし、感情や良心のある人間は利己的で卑しい人 間であることに同意しないであろう。... 高次の能力を持つ者は、低次の能力を持つ者よりも、自分を幸福にするためにより多くのものを必要とし、より深刻な苦痛を受ける可能性があり、より多くの点 で苦痛を受ける可能性がある。... 満足した豚よりも、不満足な人間であるほうがいい。満足した愚か者よりも、不満足なソクラテスであるほうがいい。そして、愚者や豚が異なる意見を持ってい るとすれば、それは彼らが問題の自分自身の側面しか知らないからである...[32]。 ミルは、2つの快楽を「有能に知っている」人々が、たとえそれがより多くの不満を伴うものであったとしても、一方の快楽を決定的に好み、「他方の快楽のい かなる量のためにもそれを辞さない」のであれば、その快楽が質において優れているとみなすことは正当であると論じている。ミルは、これらの「有能な判断 者」が常に同意するとは限らないことを認め、意見の相違がある場合には、多数派の判断を最終的なものとして受け入れるべきであると述べている。ミルはま た、「より高次の快楽を享受できる多くの者が、誘惑の影響下で、時折、より低次の快楽にそれを先送りする」ことも認めている。しかし、このことは、より高 いものの本質的な優位性を十分に理解することとまったく両立する」。ミルは、このように関連する快楽を経験した者に訴えることは、快楽の量を評価するとき に起こるはずのことと変わらないと言う。「享受の能力が低い存在が、それを完全に満足させる可能性が最も高いことは議論の余地がない。そして、高度に恵ま れた存在は、世界が構成されている以上、自分が求めることのできる幸福は常に不完全であると感じるだろう」[33]。 ミルはまた、「知的な追求は、それが生み出す満足感や快楽(の精神状態)の量に比例しない価値を持つ」と考えている[34]。ミルはまた、人々がこれらの 壮大な理想を追求すべきだと述べている。ミルは、些細な快楽からの満足は短期的な幸福を与えるだけであり、幸福が一過性のものであるため、自分の人生に幸 福が欠けていると感じるかもしれない個人を悪化させると主張している。一方、知的な追求は、知識の獲得から利益を得ることによって、人生を向上させるため の絶え間ない機会を個人に与えるので、長期的な幸福を与える。ミルは、知的な追求は「人生における『より上質なもの』を取り入れることができる」のに対 し、些細な追求はこの目標を達成することができないと見なしている[36]。ミルは、知的な追求は理想を達成することを可能にするため、個人に絶え間ない 憂鬱のサイクルから逃れる機会を与えるが、些細な快楽はこれを提供しないと言っているのである。ミルの満足観の本質については議論が絶えないが、これは彼 の立場の分岐を示唆している。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 功利主義の原理を「証明する」こと 『功利主義』第四章において、ミルは功利主義の原理に対してどのような証明が可能かを考察している: [37] ある物体が視認可能であることの唯一の証明は、人民が実際にそれを見ていることである。ある音が可聴であることの唯一の証明は、人民がそれを聞いているこ とである。…同様に、何かが望ましいものであることの唯一の証拠は、人民が実際にそれを望んでいることだと私は考える。… 一般の幸福が望ましい理由として挙げられるのは、各人が達成可能と信じる限りにおいて、自らの幸福を望むという事実だけである...我々は、幸福が善であ ること、すなわち各人の幸福がその人にとって善であり、したがって一般の幸福は全人の集合にとって善であることについて、この事例が許容するあらゆる証明 だけでなく、要求しうるあらゆる証明を既に得ているのである。 ミルはいくつかの誤謬を犯しているとよく言われる:[38] 1. 自然主義的誤謬:ミルは人々が実際に行うことから、人々がすべきことを導き出そうとしている 2. 曖昧語の誤謬:ミルは(1)何かが望ましい(すなわち、望まれる可能性がある)という事実から、(2)それが望ましい(すなわち、望まれるべきである)という主張へと飛躍している。 3. 構成の誤謬:個人が自身の幸福を望むという事実が、全ての人の集合体が総体としての幸福を望むことを意味しない。 このような主張は、ミルの存命中、『功利主義』の出版直後に現れ始め、1世紀以上にわたって続いたが、最近の議論では流れが変わりつつある。とはいえ、3 つの非難すべてに対するミルの弁護は、それぞれ1章を割いて、ネジップ・フィクリ・アリカンの『ミルの効用原理:ジョン・スチュワート・ミルの悪名高い証 明の弁護』(1994年)に見ることができる。これは、この主題について初めて、そして(いつまで?)唯一の書籍として扱ったものである。しかし、この証 明における誤謬の指摘は、学術誌の記事や書籍の章で、今もなお学者の関心を集め続けている。 ホール(1949)とポプキン(1950)は、ミルをこの非難から擁護し、ミルが第 4 章の冒頭で「究極の目的に関する問題は、その用語の通常の意味において証明を認めない」と主張しており、これは「すべての第一原理に共通」であると指摘し ている。[39][38] したがってホールとポプキンによれば、ミルは「人民が実際に望むものが望ましいと立証しようとしたのではなく、単にその原理を受け入れられるようにしよう とした」のである[38]。ミルが提示する「証明」とは「ミルが誠実で合理的な人間なら功利主義を受け入れるだろうと考えた、いくつかの考察に過ぎない」 [38]。 人民が実際に幸福を欲すると主張したミルは、次にそれが唯一欲するものであることを示さねばならない。人民が徳のような他のものを欲するという反論を予見 している。彼は、人民が幸福への手段として徳を欲し始めるかもしれないが、最終的にはそれが個人の幸福の一部となり、それ自体が目的として欲されるように なると論じる。 効用原理は、例えば音楽のような特定の快楽や、健康のような特定の苦痛からの免除が、幸福という集合的な何かの手段として見なされ、その理由で望まれるべ きだという意味ではない。それらはそれ自体において、それ自体のために望まれ、望ましいものである。手段であることに加え、それらは目的の一部でもあるの だ。功利主義の教義によれば、徳は本来的に目的の一部ではないが、そうなり得る。そして無私無欲に徳を愛する者においては、それはすでに目的の一部とな り、幸福への手段としてではなく、彼らの幸福の一部として求められ、大切にされているのだ。[40] この不本意さについて、我々は好きなように説明できる。誇りという名前に帰することもできる。この言葉は、人類が持つ最も尊い感情から最も卑しい感情ま で、無差別に用いられる。あるいは自由と個人的独立への愛に帰することもできる。ストア派がこれを説く際に用いた最も効果的な手段の一つが、この愛への訴 えであった。権力への愛や興奮への愛に帰することもできる。これら二者は確かにこの感情に内在し、それを助長する。しかし最も適切な呼称は尊厳感である。 これはあらゆる人間が何らかの形で持ち、より高い能力と必ずしも正確ではないが比例して備わるもので、それが強い者にとって幸福の不可欠な要素であるた め、それと矛盾するものは、たとえ一瞬であっても、彼らの欲望の対象となり得ないのだ。[41] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utilitarianism#Higher_and_lower_pleasures |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆