価値とはなにか?

What is

Value?

☆ 倫理学や社会科学において、価値(value) とは、ある物事や行為の重要性の度合い(degree of importance)を示すものであり、どのような行為を行うのが 最善か、どのような生き方が最善かを決 定したり(倫理学における規範倫理)、異なる行為の意義を説明したりすることを目的とする。価値体系とは、規定的信念と規定的信念であり、人の倫理的行動 に影響を与えたり、人の意図的活動の基礎となるものである。多くの場合、一次的価値は強く、二次的価値は変化に適している。ある行為を価値あるものにする ものは、その行為が増加、減少、変化させる対象の倫理的価値に依存する場合がある。倫理的価値」を持つ対象は「倫理的または哲学的な善」(名詞的な意味) と呼ばれることがある。

★ジンメルによると、価値は、そのモノの本質的に宿るものではなく、主体がそのように判断するものである(『貨幣の哲学』1907年)という。

| In ethics and social

sciences, value

denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim

of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live

(normative ethics in ethics), or to describe the significance of

different actions. Value systems are proscriptive and prescriptive

beliefs; they affect the ethical behavior of a person or are the basis

of their intentional activities. Often primary values are strong and

secondary values are suitable for changes. What makes an action

valuable may in turn depend on the ethical values of the objects it

increases, decreases, or alters. An object with "ethic value" may be

termed an "ethic or philosophic good" (noun sense).[1] Values can be defined as broad preferences concerning appropriate courses of actions or outcomes. As such, values reflect a person's sense of right and wrong or what "ought" to be. "Equal rights for all", "Excellence deserves admiration", and "People should be treated with respect and dignity" are representatives of values. Values tend to influence attitudes and behavior and these types include ethical/moral values, doctrinal/ideological (religious, political) values, social values, and aesthetic values. It is debated whether some values that are not clearly physiologically determined, such as altruism, are intrinsic, and whether some, such as acquisitiveness, should be classified as vices or virtues. |

倫理学や社会科学において、価値(value)

とは、ある物事や行為の重要性の度合いを示すものであり、どのような行為を行うのが最善か、どのような生き方が最善かを決定したり(倫理学における規範倫

理)、異なる行為の意義を説明したりすることを目的とする。価値体系とは、規定的信念と規定的信念であり、人の倫理的行動に影響を与えたり、人の意図的活

動の基礎となるものである。多くの場合、一次的価値は強く、二次的価値は変化に適している。ある行為を価値あるものにするものは、その行為が増加、減少、

変化させる対象の倫理的価値に依存する場合がある。倫理的価値」を持つ対象は「倫理的または哲学的な善」(名詞的な意味)と呼ばれることがある[1]。 価値観は、適切な行動方針や結果に関する幅広い選好として定義することができる。そのため、価値観は人の善悪や「あるべき姿」に対する感覚を反映する。 「すべての人に平等な権利を」、「卓越性は賞賛に値する」、「人は尊敬と尊厳をもって扱われるべきである」などが価値観の代表である。価値観は態度や行動 に影響を与える傾向があり、その種類には倫理的/道徳的価値観、教義的/理念的(宗教的、政治的)価値観、社会的価値観、美的価値観などがある。利他主義 のような生理学的に明確に決定されていない価値観は本質的なものなのか、また、獲得欲のような価値観は悪徳と美徳のどちらに分類されるべきかが議論されて いる。 |

| Fields of study Ethical issues that value may be regarded as a study under ethics, which, in turn, may be grouped as philosophy. Similarly, ethical value may be regarded as a subgroup of a broader field of philosophic value sometimes referred to as axiology. Ethical value denotes something's degree of importance, with the aim of determining what action or life is best to do, or at least attempt to describe the value of different actions. The study of ethical value is also included in value theory. In addition, values have been studied in various disciplines: anthropology, behavioral economics, business ethics, corporate governance, moral philosophy, political sciences, social psychology, sociology and theology. Similar concepts Ethical value is sometimes used synonymously with goodness. However, goodness has many other meanings and may be regarded as more ambiguous. |

研究分野 倫理的価値観は、倫理学に属する学問であり、哲学に属する学問である。同様に、倫理的価値は、より広範な哲学的価値の分野のサブグループとみなされること もある。倫理的価値とは、どのような行為や生活をするのが最善かを決定する目的で、何かの重要度を示すものであり、少なくとも異なる行為の価値を説明しよ うとするものである。 倫理的価値の研究も価値論に含まれる。さらに、価値は人類学、行動経済学、企業倫理、企業統治、道徳哲学、政治科学、社会心理学、社会学、神学など、さま ざまな分野で研究されている。 類似概念 倫理的価値は「善」と同義語として使われることがある。しかし、「善」には他にも様々な意味があり、より曖昧なものとみなされることもある。 |

| Types of value Personal versus cultural Personal values exist in relation to cultural values, either in agreement with or divergence from prevailing norms. A culture is a social system that shares a set of common values, in which such values permit social expectations and collective understandings of the good, beautiful and constructive. Without normative personal values, there would be no cultural reference against which to measure the virtue of individual values and so cultural identity would disintegrate. Relative or absolute Relative values differ between people, and on a larger scale, between people of different cultures. On the other hand, there are theories of the existence of absolute values,[2] which can also be termed noumenal values (and not to be confused with mathematical absolute value). An absolute value can be described as philosophically absolute and independent of individual and cultural views, as well as independent of whether it is known or apprehended or not. Ludwig Wittgenstein was pessimistic towards the idea that an elucidation would ever happen regarding the absolute values of actions or objects; "we can speak as much as we want about "life" and "its meaning," and believe that what we say is important. But these are no more than expressions and can never be facts, resulting from a tendency of the mind and not the heart or the will".[3] Intrinsic or extrinsic Philosophic value may be split into instrumental value and intrinsic values. An instrumental value is worth having as a means towards getting something else that is good (e.g., a radio is instrumentally good in order to hear music). An intrinsically valuable thing is worth for itself, not as a means to something else. It is giving value intrinsic and extrinsic properties. An ethic good with instrumental value may be termed an ethic mean, and an ethic good with intrinsic value may be termed an end-in-itself. An object may be both a mean and end-in-itself. Summation Intrinsic and instrumental goods are not mutually exclusive categories.[4] Some objects are both good in themselves, and also good for getting other objects that are good. "Understanding science" may be such a good, being both worthwhile in and of itself, and as a means of achieving other goods. In these cases, the sum of instrumental (specifically the all instrumental value) and intrinsic value of an object may be used when putting that object in value systems, which is a set of consistent values and measures. Universal values Main article: Universal value S. H. Schwartz, along with a number of psychology colleagues, has carried out empirical research investigating whether there are universal values, and what those values are. Schwartz defined 'values' as "conceptions of the desirable that influence the way people select action and evaluate events".[5] He hypothesised that universal values would relate to three different types of human need: biological needs, social co-ordination needs, and needs related to the welfare and survival of groups[6] Intensity The intensity of philosophic value is the degree it is generated or carried out, and may be regarded as the prevalence of the good, the object having the value.[4] It should not be confused with the amount of value per object, although the latter may vary too, e.g. because of instrumental value conditionality. For example, taking a fictional life-stance of accepting waffle-eating as being the end-in-itself, the intensity may be the speed that waffles are eaten, and is zero when no waffles are eaten, e.g. if no waffles are present. Still, each waffle that had been present would still have value, no matter if it was being eaten or not, independent on intensity. Instrumental value conditionality in this case could be exampled by every waffle not present, making them less valued by being far away rather than easily accessible. In many life stances it is the product of value and intensity that is ultimately desirable, i.e. not only to generate value, but to generate it in large degree. Maximizing life-stances have the highest possible intensity as an imperative. Positive and negative value There may be a distinction between positive and negative philosophic or ethic value. While positive ethic value generally correlates with something that is pursued or maximized, negative ethic value correlates with something that is avoided or minimized[citation needed]. Protected value A protected value (also sacred value) is one that an individual is unwilling to trade off no matter what the benefits of doing so may be. For example, some people may be unwilling to kill another person, even if it means saving many other individuals. Protected values tend to be "intrinsically good", and most people can in fact imagine a scenario when trading off their most precious values would be necessary.[7] If such trade-offs happen between two competing protected values such as killing a person and defending your family they are called tragic trade-offs.[8] Protected values have been found to be play a role in protracted conflicts (e.g., the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) because they can hinder businesslike (''utilitarian'') negotiations.[9][10] A series of experimental studies directed by Scott Atran and Ángel Gómez among combatants on the ISIS front line in Iraq and with ordinary citizens in Western Europe [11] suggest that commitment to sacred values motivate the most "devoted actors" to make the costliest sacrifices, including willingness to fight and die, as well as a readiness to forsake close kin and comrades for those values if necessary.[12] From the perspective of utilitarianism, protected values are biases when they prevent utility from being maximized across individuals.[13] According to Jonathan Baron and Mark Spranca,[14] protected values arise from norms as described in theories of deontological ethics (the latter often being referred to in context with Immanuel Kant). The protectedness implies that people are concerned with their participation in transactions rather than just the consequences of it. Economic versus philosophic value Further information: Value (economics) Philosophical value is distinguished from economic value, since it is independent from some other desired condition or commodity. The economic value of an object may rise when the exchangeable desired condition or commodity, e.g. money, become high in supply, and vice versa when supply of money becomes low. Nevertheless, economic value may be regarded as a result of philosophical value. In the subjective theory of value, the personal philosophic value a person puts in possessing something is reflected in what economic value this person puts on it. The limit where a person considers to purchase something may be regarded as the point where the personal philosophic value of possessing something exceeds the personal philosophic value of what is given up in exchange for it, e.g. money. In this light, everything can be said to have a "personal economic value" in contrast to its "societal economic value." |

価値の種類 個人的価値と文化的価値 個人的価値観は文化的価値観と関連して存在し、一般的な規範と一致する場合もあれば、乖離している場合もある。文化とは、共通の価値観を共有する社会シス テムのことであり、そのような価値観は、善、美、建設的なものに対する社会的期待や集団的理解を可能にする。規範となる個人の価値観がなければ、個人の価 値観の価値を測る文化的基準は存在せず、文化的アイデンティティは崩壊してしまう。 相対的か絶対的か 相対的な価値観は人によって異なり、より大きなスケールでは、異なる文化を持つ人々の間でも異なる。一方、絶対的な価値(数学的な絶対的価値と混同しては ならない)の存在を主張する説もある[2]。絶対的価値とは、哲学的に絶対的であり、個人的・文化的見解に依存せず、またそれが知られているか、理解され ているかどうかにも依存しないものである。ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインは、行為や対象の絶対的価値について解明がなされることはないだろうと悲観 的だった。しかし、これらは単なる表現にすぎず、心や意志ではなく、心の傾向から生じるものであり、決して事実にはなりえない」[3]。 本質的か外在的か 哲学的価値は、道具的価値と内在的価値に分けられる。道具的価値とは、何か他の良いものを得るための手段として持つ価値のことである(例えば、ラジオは音 楽を聴くために道具的に良いものである)。本源的価値とは、それ自体に価値があるものであり、他の何かを得るための手段としては価値がない。本質的価値と 外在的価値を与えるのである。 道具的価値を持つ倫理的善は倫理的平均と呼ばれ、本質的価値を持つ倫理的善はそれ自体が目的であると呼ばれる。ある対象は、平均であると同時に、それ自体 が目的であることもある。 加法、加重、累積 本質的財と手段的財は、相互に排他的なカテゴリーではない[4]。ある対象は、それ自体が善であると同時に、善である他の対象を得るためにも善である。 「科学を理解すること」はそのような財であり、それ自体に価値があると同時に、他の財を達成する手段としても価値がある。このような場合、ある対象を価値 体系(一貫した価値と尺度の集合)に当てはめる際には、その対象の道具的価値(特にすべての道具的価値)と本源的価値の合計を用いることができる。 普遍的価値 主な記事 普遍的価値 S. H.シュワルツは多くの心理学仲間とともに、普遍的価値が存在するかどうか、またその価値とは何かを調査する実証的研究を行ってきた。シュワルツは「価値 観」を「人々が行動を選択し、出来事を評価する方法に影響を与える望ましいものの概念」と定義した[5]。彼は普遍的価値観が3つの異なるタイプの人間の 欲求、すなわち生物学的欲求、社会的調整欲求、集団の福祉と生存に関連する欲求に関係するという仮説を立てた[6]。 強度 哲学的価値の強度とは、それが生み出される度合いや遂行される度合いであり、価値を持つ対象である善の普及度とみなすことができる[4]。 後者も、例えば道具的価値条件性のために変化することがあるが、対象ごとの価値の量と混同すべきではない。例えば、ワッフルを食べることをそれ自体が目的 であるとして受け入れるという架空のライフスタンスを取ると、強度はワッフルが食べられる速度であり、ワッフルが食べられないとき、例えばワッフルが存在 しないときにはゼロであるかもしれない。それでも、存在していたそれぞれのワッフルは、食べられようと食べられまいと、強度とは無関係に価値を持つことに なる。 この場合の道具的価値条件性は、ワッフルが存在しないことで、簡単に手に入るのではなく、遠く離れていることで価値が低くなっていることを示すことができ る。 多くの生活スタンスでは、最終的に望ましいのは価値と強度の積であり、つまり価値を生み出すだけでなく、それを大きく生み出すことである。最大化する生活 スタンスは、可能な限り高い強度を必須条件としている。 正の価値と負の価値 哲学的価値や倫理的価値には、肯定的なものと否定的なものがある。肯定的な倫理的価値は一般的に追求されるもの、最大化されるものと相関するが、否定的な 倫理的価値は回避されるもの、最小化されるものと相関する[要出典]。 保護価値 保護された価値(聖なる価値ともいう)とは、そうすることでどのような利益が得られるとしても、個人が引き換えにしたくないものである。例えば、たとえ多 くの人を救うことになったとしても、他人を殺したくないという人もいるだろう。保護された価値は「本質的に善」である傾向があり、ほとんどの人は実際、最 も大切な価値をトレードオフすることが必要になるシナリオを想像することができる[7]。人を殺すことと家族を守ることなど、競合する2つの保護された価 値の間でこのようなトレードオフが起こる場合、それは悲劇的トレードオフと呼ばれる[8]。 保護された価値は、長期化する紛争(例えば、イスラエルとパレスチナの紛争、 スコット・アトランとアンヘル・ゴメスがイラクのISIS最前線にいる戦闘員や西欧の一般市民を対象に行った一連の実験的研究[11]は、神聖な価値観へ のコミットメントが、最も「献身的な行為者」に、必要であればその価値観のために近親者や仲間を見捨てる覚悟だけでなく、戦いや死を厭わないなど、最も犠 牲を払う犠牲を払う動機を与えることを示唆している。 [12] 功利主義の観点からは、保護された価値観は、それが個人全体の効用を最大化することを妨げる場合、バイアスである[13]。 ジョナサン・バロンとマーク・スプランカによれば[14]、保護された価値観は、脱ontological ethics(後者はしばしばイマニュエル・カントとの文脈で言及される)の理論で説明されるような規範から生じる。保護された価値とは、人々が取引の結 果だけでなく、取引への参加に関心を持つことを意味する。 経済的価値と哲学的価値 さらに詳しい情報 価値(経済学) 哲学的価値は経済的価値とは区別され、他の望ましい条件や商品から独立している。ある物体の経済的価値は、交換可能な望ましい条件や商品、例えば貨幣の供 給が多くなれば上昇し、逆に貨幣の供給が少なくなれば下落する。 とはいえ、経済的価値は哲学的価値の結果とみなすこともできる。主観的価値理論では、人が何かを所有することに置く個人的な哲学的価値は、その人がそれに どのような経済的価値を置くかに反映される。人が何かを購入しようと考える限界は、何かを所有することの個人的哲学的価値が、それと引き換えに手放される もの、例えば金銭の個人的哲学的価値を上回る点であると考えることができる。このように考えると、すべてのものは、「社会的経済価値 」に対して 「個人的経済価値 」を持っていると言える。 |

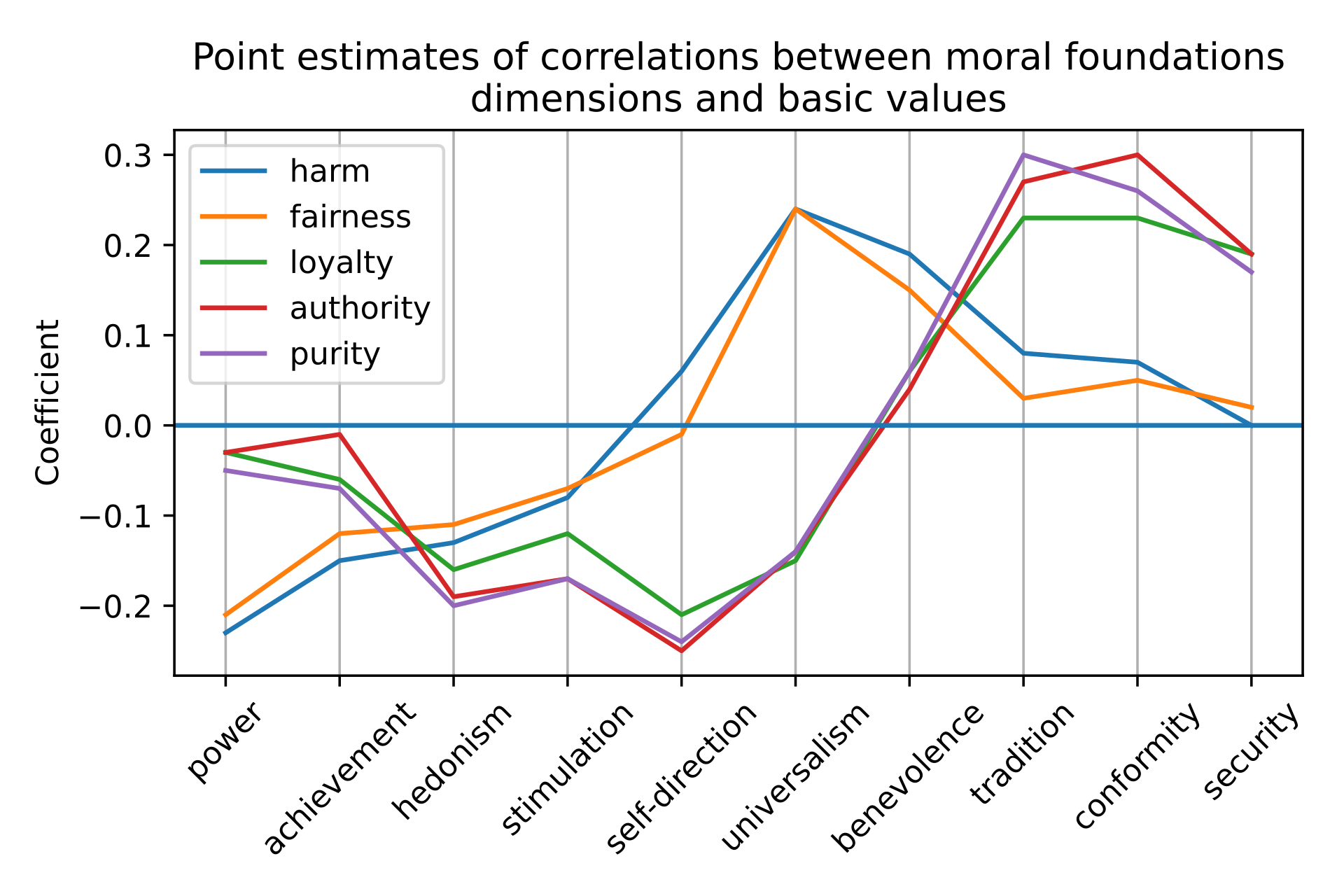

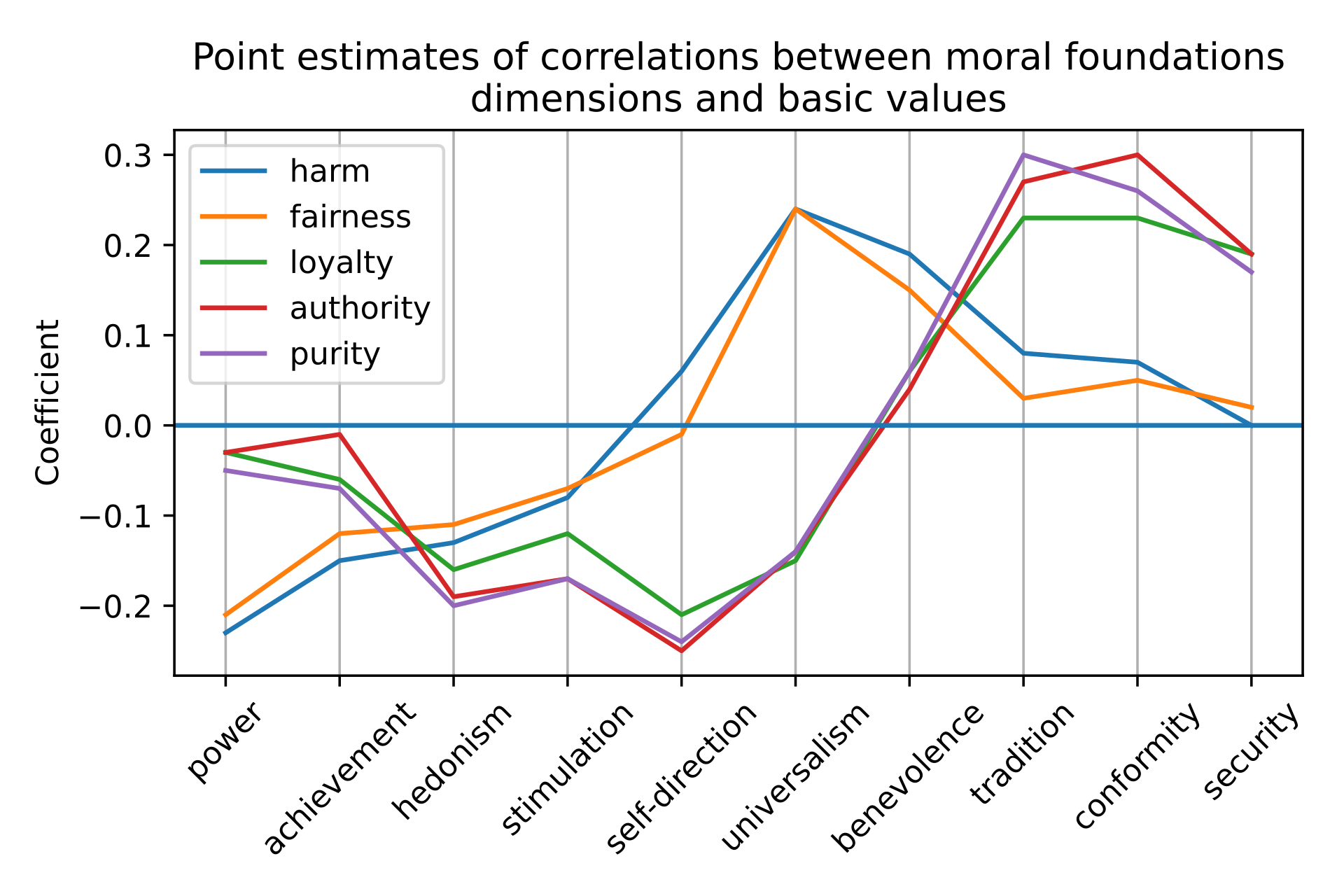

| Personal values Personal values provide an internal reference for what is good, beneficial, important, useful, beautiful, desirable and constructive. Values are one of the factors that generate behavior (besides needs, interests and habits) and influence the choices made by an individual. Values may help common human problems for survival by comparative rankings of value, the results of which provide answers to questions of why people do what they do and in what order they choose to do them.[clarification needed] Moral, religious, and personal values, when held rigidly, may also give rise to conflicts that result from a clash between differing world views.[15] Over time the public expression of personal values that groups of people find important in their day-to-day lives, lay the foundations of law, custom and tradition. Recent research has thereby stressed the implicit nature of value communication.[16] Consumer behavior research proposes there are six internal values and three external values. They are known as List of Values (LOV) in management studies. They are self respect, warm relationships, sense of accomplishment, self-fulfillment, fun and enjoyment, excitement, sense of belonging, being well respected, and security. From a functional aspect these values are categorized into three and they are interpersonal relationship area, personal factors, and non-personal factors.[17] From an ethnocentric perspective, it could be assumed that a same set of values will not reflect equally between two groups of people from two countries. Though the core values are related, the processing of values can differ based on the cultural identity of an individual.[18] Individual differences Main article: Theory of Basic Human Values Schwartz proposed a theory of individual values based on surveys data. His model groups values in terms of growth versus protection, and personal versus social focus. Values are then associated with openness to change (which Schwartz views as related to personal growth), self-enhancement (which Schwartz views as mostly to do with self-protection), conservation (which Schwartz views as mostly related to social-protection), and self-transcendence (which Schwartz views as a form of social growth). Within this Schwartz places 10 universal values: self-direction, stimulation and hedonism (related to openness growth), achievement and power (related to self enhancement), security, conformity and tradition (related to conservation), and humility, benevolence and universalism (relate to self-transcendence).[19]: 523 Personality traits using the big 5 measure correlate with Schwartz's value construct. Openness and extraversion correlates with the values related to openness-to-change (openness especially with self-direction, extraversion especially with stimulation); agreeableness correlates with self-transcendence values (especially benevolence); extraversion is correlated with self-enhancement and negatively with traditional values. Conscientiousness correlates with achievement, conformity and security.[19]: 530 Men are found to value achievement, self-direction, hedonism, and stimulation more than women, while women value benevolence, universality and tradition higher.[20]: 1012 The order of Schwartz's traits are substantially stability amongst adults over time. Migrants values change when they move to a new country, but the order of preferences is still quite stable. Motherhood causes women to shift their values towards stability and away from openness-to-change but not fathers.[19]: 528  Correlations between Moral foundations and Schwartz's basic values with values taken from[21] Feldman, Gilad (2021). "Personal Values and Moral Foundations: Examining Relations and Joint Prediction of Moral Variables". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 12 (5): 676–686. doi:10.1177/1948550620933434. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 225402232 Moral foundations theory Main article: Moral foundations theory Moral foundation theory identifies five forms of moral foundation harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, in-group/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sancity. Harm and fairness are often called individualizing foundations, while the other three factors are termed binding foundations. The moral foundations were found to be correlated with the theory of basic human values. The strong correlations are between conservatives values and binding foundations.[22] |

個人の価値観(→「主体と主観」「主観性と客観性」) 個人の価値観は、何が善であり、有益であり、重要であり、有用であり、美しく、望ましく、建設的であるかについての内的基準を提供する。価値観は(ニー ズ、興味、習慣以外に)行動を生み出す要因の一つであり、個人の選択に影響を与える。 価値観は、価値の比較順位付けによって、生存のための人間の共通の問題を助けることがあり、その結果は、人々がなぜ何をするのか、どのような順序でそれを 選択するのかという疑問に対する答えを提供する[clarification needed]。道徳的価値観、宗教的価値観、個人的価値観は、厳格に保持される場合、異なる世界観の衝突から生じる対立を生むこともある[15]。 人々の集団が日常生活において重要であると考える個人的価値観の公的な表明は、長い時間をかけて法律、慣習、伝統の基礎を築く。消費者行動研究では、6つ の内的価値観と3つの外的価値観があると提唱している。これらは経営学では価値リスト(LOV)として知られている。それらは、自尊心、温かい人間関係、 達成感、自己実現、楽しさ、興奮、帰属意識、尊敬されること、安心感である。機能的な側面から、これらの価値観は3つに分類され、対人関係領域、個人的要 因、非個人的要因である[17]。エスノセントリックな観点からは、同じ価値観のセットが2つの国の2つのグループの人々の間で等しく反映されることはな いと考えられる。核となる価値観は関連しているが、価値観の処理は個人の文化的アイデンティティに基づいて異なる可能性がある[18]。 個人差 主な記事 人間の基本的価値観の理論 シュワルツは調査データに基づいて個人の価値観に関する理論を提唱した。彼のモデルは、成長か保護か、個人的か社会的かという観点から価値観をグループ化 している。そして価値観は、変化に対する開放性(シュワルツはこれを個人の成長に関連すると見ている)、自己強化(シュワルツはこれを主に自己保護に関連 すると見ている)、保全(シュワルツはこれを主に社会的保護に関連すると見ている)、自己超越(シュワルツはこれを社会的成長の一形態と見ている)に関連 する。この中でシュワルツは10の普遍的価値を置いている:自己指示、刺激と快楽主義(開放性の成長に関係)、達成と権力(自己強化に関係)、安全、適合 と伝統(保全に関係)、謙虚、博愛と普遍主義(自己超越に関係)[19]: 523 ビッグ5の尺度を用いた性格特性はシュワルツの価値構成と相関する。開放性と外向性は変化への開放性に関連する価値観と相関する(開放性は特に自己指示性 と、外向性は特に刺激性と);同感性は自己超越性の価値観(特に博愛)と相関する;外向性は自己強化と相関し、伝統的価値観とは負の相関を示す。良心性は 達成、適合、安全性と相関する[19]: 530 男性は女性よりも達成、自己指示、快楽主義、刺激を重視し、女性は博愛、普遍性、伝統を重視することがわかった[20]: 1012 シュワルツの特徴の順序は、時間の経過とともに大人たちの間で実質的に安定する。移住者の価値観は新しい国に移住すると変化するが、それでも選好の順序は かなり安定している。母親であることは、女性の価値観を安定性へとシフトさせ、変化への開放性から遠ざけるが、父親はそうではない: 528  道徳的基礎とシュワルツの基本的価値観の相関は[21]から引用した。 Feldman, Gilad (2021). "Personal Values and Moral Foundations: Examining Relations and Joint Prediction of Moral Variables". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 12 (5): 676–686. doi:10.1177/1948550620933434. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 225402232 道徳的基礎理論 主な記事 道徳的基礎理論 道徳的基礎理論では、道徳的基礎の形態として、危害/配慮、公正/互恵、内集団/忠誠、権威/尊重、純粋/潔白の5つを挙げている。危害と公正はしばしば 個別化的基盤と呼ばれ、他の3つの要素は拘束的基盤と呼ばれる。道徳的基盤は人間の基本的価値観と相関していることがわかった。強い相関関係があるのは、 保守的価値観と拘束的基礎の間である[22]。 |

| Cultural values Individual cultures emphasize values which their members broadly share. Values of a society can often be identified by examining the level of honor and respect received by various groups and ideas. Values clarification differs from cognitive moral education:Respect Value clarification consists of "helping people clarify what their lives are for and what is worth working for. It encourages students to define their own values and to understand others' values."[23] Cognitive moral education builds on the belief that students should learn to value things like democracy and justice as their moral reasoning develops.[23] Values relate to the norms of a culture, but they are more global and intellectual than norms. Norms provide rules for behavior in specific situations, while values identify what should be judged as good or evil. While norms are standards, patterns, rules and guides of expected behavior, values are abstract concepts of what is important and worthwhile. Flying the national flag on a holiday is a norm, but it reflects the value of patriotism. Wearing dark clothing and appearing solemn are normative behaviors to manifest respect at a funeral. Different cultures represent values differently and to different levels of emphasis. "Over the last three decades, traditional-age college students have shown an increased interest in personal well-being and a decreased interest in the welfare of others."[23] Values seemed to have changed, affecting the beliefs, and attitudes of the students. Members take part in a culture even if each member's personal values do not entirely agree with some of the normative values sanctioned in that culture. This reflects an individual's ability to synthesize and extract aspects valuable to them from the multiple subcultures they belong to. If a group member expresses a value that seriously conflicts with the group's norms, the group's authority may carry out various ways of encouraging conformity or stigmatizing the non-conforming behavior of that member. For example, imprisonment can result from conflict with social norms that the state has established as law. Furthermore, cultural values can be expressed at a global level through institutions participating in the global economy. For example, values important to global governance can include leadership, legitimacy, and efficiency. Within our current global governance architecture, leadership is expressed through the G20, legitimacy through the United Nations, and efficiency through member-driven international organizations.[24] The expertise provided by international organizations and civil society depends on the incorporation of flexibility in the rules, to preserve the expression of identity in a globalized world.[25][clarification needed] Nonetheless, in warlike economic competition, differing views may contradict each other, particularly in the field of culture. Thus audiences in Europe may regard a movie as an artistic creation and grant it benefits from special treatment, while audiences in the United States may see it as mere entertainment, whatever its artistic merits. EU policies based on the notion of "cultural exception" can become juxtaposed with the liberal policy of "cultural specificity" in English-speaking countries. Indeed, international law traditionally treats films as property and the content of television programs as a service.[citation needed] Consequently, cultural interventionist policies can find themselves opposed to the Anglo-Saxon liberal position, causing failures in international negotiations.[26] Development and transmission Values are generally received through cultural means, especially diffusion and transmission or socialization from parents to children. Parents in different cultures have different values.[27] For example, parents in a hunter–gatherer society or surviving through subsistence agriculture value practical survival skills from a young age. Many such cultures begin teaching babies to use sharp tools, including knives, before their first birthdays.[28] Italian parents value social and emotional abilities and having an even temperament.[27] Spanish parents want their children to be sociable.[27] Swedish parents value security and happiness.[27] Dutch parents value independence, long attention spans, and predictable schedules.[27] American parents are unusual for strongly valuing intellectual ability, especially in a narrow "book learning" sense.[27] The Kipsigis people of Kenya value children who are not only smart, but who employ that intelligence in a responsible and helpful way, which they call ng'om. Luos of Kenya value education and pride which they call "nyadhi".[27] Factors that influence the development of cultural values are summarized below. The Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world is a two-dimensional cultural map showing the cultural values of the countries of the world along two dimensions: The traditional versus secular-rational values reflect the transition from a religious understanding of the world to a dominance of science and bureaucracy. The second dimension named survival values versus self-expression values represents the transition from industrial society to post-industrial society.[29] Cultures can be distinguished as tight and loose in relation to how much they adhere to social norms and tolerates deviance.[30][31] Tight cultures are more restrictive, with stricter disciplinary measures for norm violations while loose cultures have weaker social norms and a higher tolerance for deviant behavior. A history of threats, such as natural disasters, high population density, or vulnerability to infectious diseases, is associated with greater tightness. It has been suggested that tightness allows cultures to coordinate more effectively to survive threats.[32][33] Studies in evolutionary psychology have led to similar findings. The so-called regality theory finds that war and other perceived collective dangers have a profound influence on both the psychology of individuals and on the social structure and cultural values. A dangerous environment leads to a hierarchical, authoritarian, and warlike culture, while a safe and peaceful environment fosters an egalitarian and tolerant culture.[34] |

文化的(諸)価値 個々の文化は、その構成員が広く共有する価値観を重視する。社会の価値観は、さまざまな集団や考え方が受ける名誉や尊敬の度合いを調べることによって、し ばしば特定することができる。 価値観の明確化は、認知的道徳教育とは異なる。 価値観の明確化とは、「自分の人生は何のためにあるのか、何のために働く価値があるのかを明確にする手助け」をすることである。生徒が自分自身の価値観を 定義し、他者の価値観を理解することを促す」[23]。 認知的道徳教育は、生徒の道徳的推論が発達するにつれて、民主主義や正義といったものの価値を学ぶべきであるという信念に基づいている[23]。 価値観は文化の規範と関連しているが、規範よりもグローバルで知的なものである。規範は特定の状況における行動のルールを示すものであり、価値観は何を善 悪として判断すべきかを明らかにするものである。規範が期待される行動の基準、パターン、ルール、ガイドであるのに対し、価値観は何が重要で価値があるか という抽象的な概念である。祝日に国旗を掲揚するのは規範だが、それは愛国心という価値を反映している。暗い色の服を着て厳粛に振る舞うのは、葬儀で敬意 を表すための規範的な行動である。文化が異なれば、価値観の表し方も、強調するレベルも異なる。「過去30年間で、伝統的な年齢の大学生は、個人の幸福へ の関心が高まり、他人の福祉への関心が低下した」[23]。価値観は変化し、学生の信念や態度に影響を与えたようだ。 各メンバーの個人的価値観が、その文化で承認されている規範的価値観の一部と完全に一致しなくても、メンバーは文化に参加する。これは、所属する複数のサ ブカルチャーから自分にとって価値ある側面を総合し、抽出する個人の能力を反映している。 集団のメンバーが集団の規範と深刻に対立する価値観を表明した場合、集団の権威はそのメンバーの適合を促したり、適合しない行動に汚名を着せたりする様々 な方法を実行することがある。例えば、国家が法律として定めた社会規範に抵触した結果、投獄されることがある。 さらに、文化的価値観は、グローバル経済に参加する機関を通じて、グローバルなレベルで表現されることもある。例えば、グローバル・ガバナンスにとって重 要な価値には、リーダーシップ、正当性、効率性などがある。現在のグローバル・ガバナンス・アーキテクチャーでは、リーダーシップはG20を通じて、正当 性は国連を通じて、効率性はメンバー主導の国際機関を通じて表現されている[24]。国際機関や市民社会が提供する専門知識は、グローバル化した世界にお けるアイデンティティの表現を維持するために、ルールに柔軟性を組み込むことに依存している[25][要解説]。 それにもかかわらず、戦争のような経済競争の中で、特に文化の分野では、異なる見解が互いに矛盾することがある。したがって、欧州の観客は映画を芸術的創 造物とみなし、特別待遇の恩恵を与えるかもしれないが、米国の観客は、その芸術的長所はともかく、単なる娯楽とみなすかもしれない。文化的例外」という概 念に基づくEUの政策は、英語圏における「文化的特異性」というリベラルな政策と並立することになる。実際、国際法は伝統的に映画を財産として扱い、テレ ビ番組のコンテンツをサービスとして扱っている[citation needed]。その結果、文化介入主義的な政策はアングロサクソンのリベラルな立場と対立することになり、国際交渉の失敗を招くことになりかねない [26]。 発展と伝達 価値観は一般的に文化的な手段、特に親から子への拡散や伝達、社会化を通じて受容される。例えば、狩猟採集社会の親や自給自足の農業で生き延びている親 は、幼い頃から実践的な生存技術を重んじる。イタリアの親は、社交的で感情的な能力と平静な気質を重んじる[27]。スペインの親は、子どもが社交的であ ることを望む[27]。 [27]オランダの親は、自立心、注意力の持続時間の長さ、予測可能なスケジュールを重視する[27]。アメリカの親は、特に狭い意味での「本で学ぶ」知 的能力を強く評価する珍しい親である[27]。ケニアのキプシギス族は、頭がよいだけでなく、その知性を責任ある有益な方法で活用する子どもを重視し、こ れをンゴムと呼ぶ。ケニアのルオス人は、彼らが「ニャディ」と呼ぶ教育と誇りを重んじる[27]。 文化的価値の発達に影響を与える要因を以下にまとめる。 イングルハート・ウェルツェルの世界文化地図は、世界各国の文化的価値を2つの次元に沿って示した2次元の文化地図である: 伝統的価値観対世俗的・合理的価値観は、宗教的な世界理解から科学と官僚主義の支配への移行を反映している。生存価値対自己表現価値と名付けられた第二の 次元は、産業社会からポスト産業社会への移行を表している[29]。 文化は、社会規範をどの程度遵守し、逸脱をどの程度許容するかに関連して、タイトとルーズに区別することができる[30][31]。タイトな文化はより制 限的であり、規範違反に対してより厳格な懲罰措置をとる一方、ルーズな文化は社会規範が弱く、逸脱行動に対してより高い許容度を持つ。自然災害、高い人口 密度、感染症に対する脆弱性などの脅威の歴史は、より緊密性と関連している。稠密性は、脅威から生き延びるために文化がより効果的に協調することを可能に することが示唆されている[32][33]。 進化心理学の研究でも同様の結果が得られている。いわゆるレガリティ理論では、戦争やその他の集団的な危険の認知が、個人の心理と社会構造や文化的価値観 の両方に大きな影響を与えることを発見している。危険な環境は階層的、権威主義的、戦争的な文化をもたらし、安全で平和な環境は平等主義的で寛容な文化を 育む[34]。 |

| Value system A value system is a set of consistent values used for the purpose of ethical or ideological integrity. Consistency As a member of a society, group or community, an individual can hold both a personal value system and a communal value system at the same time. In this case, the two value systems (one personal and one communal) are externally consistent provided they bear no contradictions or situational exceptions between them. A value system in its own right is internally consistent when its values do not contradict each other and its exceptions are or could be abstract enough to be used in all situations and consistently applied. Conversely, a value system by itself is internally inconsistent if: its values contradict each other and its exceptions are highly situational and inconsistently applied. Value exceptions Abstract exceptions serve to reinforce the ranking of values. Their definitions are generalized enough to be relevant to any and all situations. Situational exceptions, on the other hand, are ad hoc and pertain only to specific situations. The presence of a type of exception determines one of two more kinds of value systems: An idealized value system is a listing of values that lacks exceptions. It is, therefore, absolute and can be codified as a strict set of proscriptions on behavior. Those who hold to their idealized value system and claim no exceptions (other than the default) are called absolutists. A realized value system contains exceptions to resolve contradictions between values in practical circumstances. This type is what people tend to use in daily life. The difference between these two types of systems can be seen when people state that they hold one value system yet in practice deviate from it, thus holding a different value system. For example, a religion lists an absolute set of values while the practice of that religion may include exceptions. Implicit exceptions bring about a third type of value system called a formal value system. Whether idealized or realized, this type contains an implicit exception associated with each value: "as long as no higher-priority value is violated". For instance, a person might feel that lying is wrong. Since preserving a life is probably more highly valued than adhering to the principle that lying is wrong, lying to save someone's life is acceptable. Perhaps too simplistic in practice, such a hierarchical structure may warrant explicit exceptions. Conflict Although sharing a set of common values, like hockey is better than baseball or ice cream is better than fruit, two different parties might not rank those values equally. Also, two parties might disagree as to certain actions are right or wrong, both in theory and in practice, and find themselves in an ideological or physical conflict. Ethonomics, the discipline of rigorously examining and comparing value systems[citation needed], enables us to understand politics and motivations more fully in order to resolve conflicts. An example conflict would be a value system based on individualism pitted against a value system based on collectivism. A rational value system organized to resolve the conflict between two such value systems might take the form below. Added exceptions can become recursive and often convoluted. Individuals may act freely unless their actions harm others or interfere with others' freedom or with functions of society that individuals need, provided those functions do not themselves interfere with these proscribed individual rights and were agreed to by a majority of the individuals. A society (or more specifically the system of order that enables the workings of a society) exists for the purpose of benefiting the lives of the individuals who are members of that society. The functions of a society in providing such benefits would be those agreed to by the majority of individuals in the society. A society may require contributions from its members in order for them to benefit from the services provided by the society. The failure of individuals to make such required contributions could be considered a reason to deny those benefits to them, although a society could elect to consider hardship situations in determining how much should be contributed. A society may restrict behavior of individuals who are members of the society only for the purpose of performing its designated functions agreed to by the majority of individuals in the society, only insofar as they violate the aforementioned values. This means that a society may abrogate the rights of any of its members who fails to uphold the aforementioned values. |

価値体系 価値体系とは、倫理的またはイデオロギー的な整合性を保つために用いられる、一貫した価値観の集合である。 一貫性 社会、集団、共同体の一員として、個人は個人的価値体系と共同体的価値体系の両方を同時に持つことができる。この場合、2つの価値体系(個人的価値体系と 共同体的価値体系)は、その間に矛盾や状況的例外がない限り、外形的に一貫している。 それ自体の価値体系が内的に一貫しているのは、次のような場合である。 その価値観が互いに矛盾せず その例外は次のようなものである。 抽象的なものであり、すべての状況において使用され、一貫して適用される 一貫して適用される。 逆に、価値システムそれ自体は、次のような場合、内部的に矛盾している: その価値観が互いに矛盾し その例外が 非常に状況的であり 矛盾して適用される。 価値観の例外 抽象的な例外は、価値のランク付けを強化する役割を果たす。その定義は十分に一般化されており、あらゆる状況に関連する。一方、状況的例外はその場限りの ものであり、特定の状況にのみ関係する。ある種の例外の存在によって、さらに2種類の価値体系のいずれかが決定される: 理想化された価値体系とは、例外のない価値観のリストである。したがって、それは絶対的なものであり、行動に関する厳格な規定として成文化することができ る。理想化された価値体系を堅持し、(デフォルト以外の)例外がないと主張する人々は、絶対主義者と呼ばれる。 実現された価値体系には、現実的な状況における価値観の矛盾を解決するための例外が含まれる。このタイプは、人々が日常生活で使いがちなものである。 この2つのタイプの価値体系の違いは、ある価値体系を保持していると表明しながら、実際にはそこから逸脱し、別の価値体系を保持している場合に見ることが できる。例えば、ある宗教は絶対的な価値観を掲げているが、その宗教の実践には例外が含まれることがある。 暗黙の例外は、形式的価値体系と呼ばれる第三のタイプの価値体系をもたらす。理想化されたものであれ、実現されたものであれ、このタイプは各価値に関連す る暗黙の例外を含んでいる: 「より優先順位の高い価値が侵害されない限り」である。例えば、ある人は嘘をつくことは悪いことだと感じるかもしれない。嘘をつくことは悪いことだという 原則を守ることよりも、命を守ることの方がおそらく高く評価されるので、誰かの命を救うために嘘をつくことは容認される。実際には単純すぎるかもしれない が、このような階層構造は明確な例外を正当化するかもしれない。 対立・紛争 野球よりホッケーがいいとか、果物よりアイスクリームがいいとか、共通の価値観を共有していても、異なる2者がそれらの価値観を同等にランク付けすること はないかもしれない。また、ある行為が正しいのか間違っているのか、理論的にも実際にも二者の意見が一致せず、イデオロギー的あるいは物理的な対立に陥る こともある。価値体系を厳密に検証し比較する学問である倫理学[要出典]は、対立を解決するために政治や動機をより深く理解することを可能にする。 対立の例としては、個人主義に基づく価値体系と集団主義に基づく価値体系との対立が挙げられる。このような2つの価値体系の対立を解決するために組織され た合理的な価値体系は、以下のような形をとるかもしれない。例外を加えると再帰的になり、しばしば複雑になる。 個人は、その行動が他人を傷つけたり、他人の自由を妨げたり、個人が必要とする社会の機能を妨げたりしない限り、自由に行動することができる。ただし、そ れらの機能自体が、これらの規定された個人の権利を妨げず、個人の大多数によって合意されたものであることを条件とする。 社会(より具体的には、社会の働きを可能にする秩序システム)は、その社会の構成員である個人の生活に利益をもたらす目的で存在する。そのような便益を提 供する際の社会の機能は、社会の大多数の個人によって合意されたものである。 結社は、結社が提供するサービスの恩恵を受けるために、結社員からの寄付を要求することができる。社会は、拠出されるべき拠出額を決定する際に、困難な状 況を考慮することを選択することができるが、個人がそのような要求される拠出を行わないことは、そのような利益享受を拒否する理由と考えられる。 社会は、社会の構成員である個人の行動を、それが前述の価値観に反する限りにおいて、社会の構成員である個人の大多数によって合意された社会の機能を果た す目的でのみ制限することができる。つまり、社会は、前述の価値観を守らない構成員の権利を剥奪することができる。 |

| Attitude (psychology) Axiological ethics Axiology Clyde Kluckhohn and his value orientation theory Hofstede's Framework for Assessing Culture Instrumental and intrinsic value Intercultural communication Meaning of life Paideia Rokeach Value Survey Spiral Dynamics The Right and the Good Value judgment World Values Survey Western values |

態度(心理学) 公理論的倫理 公理論 クライド・クラックホーンとその価値志向理論 ホフステードの文化評価の枠組み 道具的価値と本質的価値 異文化間コミュニケーション 人生の意味 パイデイア ロコーチ価値観調査 スパイラル・ダイナミクス 正しさと善 価値判断 世界価値観調査 西洋の価値観 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_(ethics_and_social_sciences) |

|

| A value is a universal value

if it has the same value or worth for all, or almost all, people.

Spheres of human value encompass morality, aesthetic preference,

traits, human endeavour, and social order. Whether universal values

exist is an unproven conjecture of moral philosophy and cultural

anthropology, though it is clear that certain values are found across a

great diversity of human cultures, such as primary attributes of

physical attractiveness (e.g. youthfulness, symmetry) whereas other

attributes (e.g. slenderness) are subject to aesthetic relativism as

governed by cultural norms. This objection is not limited to

aesthetics. Relativism concerning morals is known as moral relativism, a

philosophical stance opposed to the existence of universal moral values. The claim for universal values can be understood in two different ways. First, it could be that something has a universal value when everybody finds it valuable. This was Isaiah Berlin's understanding of the term. According to Berlin, "...universal values....are values that a great many human beings in the vast majority of places and situations, at almost all times, do in fact hold in common, whether consciously and explicitly or as expressed in their behaviour..."[1] Second, something could have universal value when all people have reason to believe it has value. Amartya Sen interprets the term in this way, pointing out that when Mahatma Gandhi argued that non-violence is a universal value, he was arguing that all people have reason to value non-violence, not that all people currently value non-violence.[2] Many different things have been claimed to be of universal value, for example, fertility,[3] pleasure,[4] and democracy.[5] The issue of whether anything is of universal value, and, if so, what that thing or those things are, is relevant to psychology, political science, and philosophy, among other fields. |

価値とは、すべての

人々、あるいはほとんどすべての人々にとって同じ価値または価値を持つものである場合、普遍的な価値である。人間の価値観には、道徳、美的な好み、特性、

人間の努力、社会秩序などが含まれる。普遍的価値が存在するかどうかは、道徳哲学や文化人類学における証明されていない推測であるが、ある種の価値観が、

例えば若々しさや対称性といった身体的魅力の主な属性のように、多様な人間の文化に共通して見られる一方で、他の属性(例えば細身)は文化的な規範によっ

て支配される美的相対主義の対象となることは明らかである。この反論は美しさだけに限定されるものではない。道徳に関する相対主義は「道徳的相対主義」と

して知られ、普遍的な道徳的価値の存在に反対する哲学的な立場である。 普遍的価値の主張は、2つの異なる方法で理解することができる。まず、誰もが価値を見出すものには普遍的な価値がある、という考え方である。これはアイザイア・バーリンの 用語に対する理解である。ベルリンによれば、「...普遍的価値とは...広範な場所や状況において、ほとんどの時間、大多数の人間が、意識的かつ明白 に、あるいは行動に表れる形で、実際に共通して抱いている価値である」[1]。第二に、すべての人が価値があると信じる理由がある場合、何かが普遍的価値 を持つ可能性がある。アマルティア・センは、この用語を次のように解釈している。ガンジーが非暴力は普遍的価値であると主張した際、彼は、すべての人が非 暴力を尊重する理由があることを主張したのであって、現在すべての人が非暴力を尊重していることを主張したわけではないと指摘している。[2] これまでにも、 例えば、豊饒[3]、快楽[4]、民主主義[5]など、さまざまなものが普遍的価値であると主張されてきた。何かが普遍的価値であるかどうか、また、そう であるならば、その何かまたはそれらの何かが何であるかという問題は、心理学、政治学、哲学など、他の分野にも関連している。 |

| Perspectives from various

disciplines Philosophy Philosophical study of universal value addresses questions such as the meaningfulness of universal value or whether universal values exist. Sociology Sociological study of universal value addresses how such values are formed in a society. Psychology and the search for universal values See also: Theory of Basic Human Values and Moral foundations theory S. H. Schwartz, along with a number of psychology colleagues, has carried out empirical research investigating whether there are universal values, and what those values are. Schwartz defined 'values' as "conceptions of the desirable that influence the way people select action and evaluate events".[6] He hypothesised that universal values would relate to three different types of human need: biological needs, social co-ordination needs, and needs related to the welfare and survival of groups. Schwartz's results from a series of studies that included surveys of more than 25,000 people in 44 countries with a wide range of different cultural types suggest that there are fifty-six specific universal values and ten types of universal value.[7] Schwartz's ten types of universal value are: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. Below are each of the value types, with the specific related values alongside: Power: authority; leadership; dominance, social power, wealth Achievement: success; capability; ambition; influence; intelligence; self-respect Hedonism: pleasure; enjoying life Stimulation: daring activities; varied life; exciting life Self-direction: creativity; freedom; independence; curiosity; choosing your own goals Universalism: broadmindedness; wisdom; social justice; equality; a world at peace; a world of beauty; unity with nature; protecting the environment; inner harmony Benevolence: helpfulness; honesty; forgiveness; loyalty; responsibility; friendship Tradition: accepting one's portion in life; humility; devoutness; respect for tradition; moderation Conformity: self-discipline; obedience Security: cleanliness; family security; national security; stability of social order; reciprocation of favours; health; sense of belonging Schwartz also tested an eleventh possible universal value, 'spirituality', or 'the goal of finding meaning in life', but found that it does not seem to be recognised in all cultures.[8] |

さまざまな分野からの視点 哲学 普遍的価値の哲学的研究では、普遍的価値の意義や普遍的価値が存在するかどうかといった問題を取り扱う。 社会学 普遍的価値の社会学的研究では、そうした価値が社会でどのように形成されるかを扱う。 心理学と普遍的価値の探究 参照:基本的人間価値の理論、道徳的基盤理論 S. H. シュワルツは、心理学の同僚たちとともに、普遍的価値が存在するのか、またその価値とはどのようなものなのかを調査する実証研究を実施した。シュワルツは 「価値」を「人々が行動を選択し、出来事を評価する方法に影響を与える望ましいものの概念」と定義した。[6] 彼は、普遍的価値は人間の3つの異なるニーズ、すなわち生物学的ニーズ、社会的調整ニーズ、集団の福祉と生存に関連するニーズに関係しているという仮説を 立てた。44カ国、25,000人以上を対象に、さまざまな文化背景を持つ人々を対象に実施した一連の調査の結果、シュワルツは、56の具体的な普遍的価 値と10の普遍的価値のタイプがあることを示唆している。[7] シュワルツの10の普遍的価値のタイプは、権力、達成、快楽主義、刺激、自己実現、普遍主義、博愛、伝統、順応、安全である。以下に、それぞれの価値観と 関連する具体的な価値観を挙げる。 権力:権威、リーダーシップ、支配、社会的権力、富 達成:成功、能力、野心、影響力、知性、自尊心 快楽主義:快楽、人生を楽しむ 刺激:大胆な行動、変化に富んだ生活、刺激的な生活 自己実現:創造性、自由、独立、好奇心、目標を自分で選択する 普遍主義:寛容、知恵、社会正義、平等、平和な世界、美しい世界、自然との調和、環境保護、内面の調和 博愛:親切、誠実、寛容、忠誠、責任、友情 伝統:人生における自分の役割を受け入れる、謙虚、信心深さ、伝統への敬意、節度 順応:自己規律、服従 安全:清潔、家族の安全、国民の安全、社会秩序の安定、恩恵への報い、健康、帰属意識 シュワルツは、11番目の普遍的価値である「精神性」、すなわち「人生の意味を見出すこと」もテストしたが、すべての文化で認識されているわけではないこ とが分かった。[8] |

| Christian universalism Cultural universal Human rights Moral hierarchy Moral universalism Unconditional love Unconditional positive regard Universal basic income Universal basic services Universalism Value system |

キリスト教の普遍主義 文化の普遍性 人権 道徳的階層 道徳的普遍主義 無条件の愛 無条件の積極的評価 普遍的ベーシックインカム 普遍的ベーシックサービス 普遍主義 価値体系 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_value |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆