ニコマコス倫理学

Ēthika Nikomacheia

ニコマコス倫理学

Ēthika Nikomacheia

ニコマコ ス倫理学(/ˌnɪkoʊˈmækiən/; 古代ギリシャ語: Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, Ēthika Nikomacheia)は、アリストテレスの倫理学に関する最も有名な著作に通常付けられる名称である。全10巻。こ の著作はアリストテレス倫理学の定義において卓越した役割を果たしており、もともと別々の巻物であった十巻から成り、リュケイオンでの講義のノートに基づ いていると考えられている。題名はしばしば彼の息子ニコマコスに由来すると推測される。この著作は彼に献呈されたか、あるいは彼が編集した可能性がある (ただし彼の若年さからするとこの可能性は低い)。あるいは、この著作は彼の父、同じくニコマコスと呼ばれた人物に捧げられた可能性もある。

The Nicomachean Ethics

(/ˌnɪkoʊˈmækiən/; Ancient Greek: Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, Ēthika Nikomacheia)

is the name normally given to Aristotle's best-known work on ethics.

The work, which plays a pre-eminent role in defining Aristotelian

ethics, consists of ten books, originally separate scrolls, and is

understood to be based on notes from his lectures at the Lyceum. The

title is often assumed to refer to his son Nicomachus, to whom the work

was dedicated or who may have edited it (although his young age makes

this less likely). Alternatively, the work may have been dedicated to

his father, who was also called Nicomachus.

1.第1巻(序説、幸福)

2.第2巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての概説 1)

3.第3巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての概説 2・各論1)

4.第4巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての各論 2)

5.第5巻(正義)

6.第6巻(知性的な卓越性(徳)についての概説・ 各論)

7.第7巻(抑制と無抑制、快楽-A稿)

8.第8巻(愛1)

9.第9巻(愛2)

10.第10巻(快楽-B稿、結び)

★

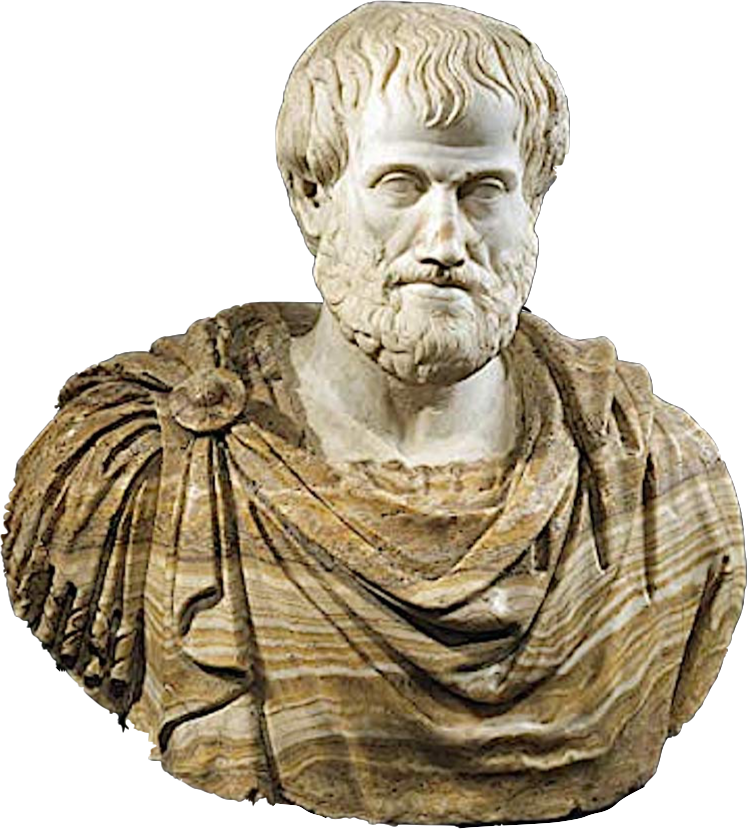

1837年版の最初のページ/ ニコマコス倫理学の第6巻の冒頭部分。南イタリアのアトリ公アンドレア・マッテオ・アクアヴィーヴァのために作成された写本。オーストリア国立図書館(ウィーン)所蔵、Cod. phil. gr. 4、fol. 45v(15世紀後半)。

| Die Nikomachische Ethik

(altgriechisch ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, Ēthiká Nikomácheia) ist die

bedeutendste der drei unter dem Namen des Aristoteles überlieferten

ethischen Schriften. Da sie mit der Eudemischen Ethik einige Bücher

teilt, ist sie möglicherweise nicht von Aristoteles selbst in der

erhaltenen Form zusammengestellt worden. Weshalb die Schrift diesen

Titel trägt, ist unklar. Vielleicht bezieht er sich auf seinen Sohn

oder seinen eigenen Vater, die beide Nikomachos hießen.[1] |

ニコマコス倫理学(古代ギリシャ語:ἠθικὰ

Νικομάχεια、Ēthiká

Nikomácheia)は、アリストテレスの名で伝わる3つの倫理学著作の中で最も重要なものである。この著作は『エウデモス倫理学』と数冊の書籍を共

有しているため、現存する形でアリストテレス自身によって編集されたものではない可能性がある。この著作がなぜこのタイトルが付けられているのかは不明

だ。おそらく、彼の息子、あるいは彼自身の父親、どちらもニコマコスという名前だったことに由来しているのだろう。[1] |

| Ziel der Nikomachischen Ethik Das Werk soll einen Leitfaden dazu geben, wie man ein guter Mensch werden und ein Leben im Sinne der Eudaimonia führen kann. Da hierfür der Begriff des Handelns zentral ist, ist bereits im ersten Satz davon die Rede: „Jedes praktische Können und jede wissenschaftliche Untersuchung, ebenso alles Handeln und Wählen, strebt nach einem Gut, wie allgemein angenommen wird.“[2] Ein Gut kann dabei entweder nur dazu da sein, ein weiteres Gut zu befördern (es wird dann zu den poietischen Handlungen gezählt), oder es kann ein anderes Gut befördern und gleichzeitig „um seiner selbst willen erstrebt werden“ (es hat dann praktischen Charakter), oder aber es kann als höchstes Gut das Endziel allen Handelns darstellen (= absolute praxis). Dadurch wird das Werk durch die Frage bestimmt, wie das höchste Gut, oder auch das höchste Ziel, beschaffen und wie es zu erreichen ist. |

ニコマコス倫理学の目的 この著作は、良い人間になり、ユーダイモニアの精神に基づいた人生を送るための指針を示すことを目的としている。この目的のために「行動」という概念が重 要であるため、最初の文で「あらゆる実践的能力や科学的調査、そしてあらゆる行動や選択は、一般的に認められているように、ある善を追求するものである」 と述べられている[2]。善は、別の善を促進するためだけに存在する(その場合は、ポイエーティックな行動に分類される)、あるいは別の善を促進すると同 時に「それ自体のために追求される」(その場合は実践的な性格を持つ)、あるいは最高の善として、あらゆる行動の最終目標となる(= 絶対的な実践)ことができる。これにより、この著作は、最高の善、あるいは最高の目標とはどのようなものであり、それをどのように達成すべきかという問題 によって決定づけられる。 |

| Glückseligkeit Die erste Antwort des Aristoteles auf die Frage nach dem Wesen des höchsten Gutes ist, dass die Glückseligkeit (eudaimonía) das höchste Gut ist. Sie ist ein seelisches Glück. Das folgt für Aristoteles daraus, dass die Glückseligkeit für sich selbst steht. Sie ist nicht, wie andere Güter, lediglich Mittel zum Zweck. Im Gegensatz zu anderen Gütern erstreben wir Glückseligkeit um ihrer selbst willen. Sie ist, wie Aristoteles sagt, „das vollkommene und selbstgenügsame Gut und das Endziel des Handelns.“ (1097b20) Ergon-Argument Um den eigentlichen Inhalt der Glückseligkeit zu bestimmen, führt Aristoteles das Ergon-Argument ein. Hierbei geht er von einem Essentialismus aus, welcher besagt, dass jedes Wesen durch Eigenschaften gekennzeichnet ist, die es ermöglichen, dieses Wesen von anderen Wesen abzugrenzen. Des Weiteren verfolgt er einen eigenen Perfektionismus, welcher die Erfüllung der Bestimmung des Wesens von der Ausbildung seiner Wesenszüge abhängig macht. Das Wesen des Menschen findet man in der Betrachtung seiner spezifisch eigentümlichen Leistung, welche ihn von anderen Lebewesen unterscheidet. Diese ist das Tätigsein der Seele gemäß dem rationalen Element (dem Nachdenken, der Vernunft) oder jedenfalls nicht ohne dieses. Daneben ist es entscheidend, dass der Mensch seine Vernunft sowohl auf vollendete Weise einsetzt als auch in seinem ganzen Leben und mehr zur Geltung bringt. „Und mehr“ bedeutet in diesem Fall, dass sogar die Hinterlassenschaften des Menschen (etwa Kinder) von der intensiven Nutzung seiner Vernunft zeugen. Diese drei Argumente – Tätigsein der Seele gemäß der Vernunft, Tätigsein auf eine vollendete Weise und in einem vollen Leben – werden allgemeinhin als erste Glücksdefinition des Aristoteles betrachtet. Dreiteilung in äußere, körperliche und seelische Güter Zur Erlangung von Glückseligkeit ist, so gesteht Aristoteles zu, nicht nur vernunftgemäße Betätigung der Seele nötig, sondern auch erstens äußere und zweitens körperliche Güter. Äußere Güter sind etwa Reichtum, Freundschaft, Herkunft, Nachkommen, Ehre und ein günstig gestimmtes persönliches Schicksal. Gesundheit, Schönheit, physische Stärke, Sportlichkeit entsprechen körperlichen bzw. inneren Gütern des Körpers. Aus der vernunftgemäßen Betätigung der Seele ergeben sich die seelischen Güter, die Tugenden. Die äußeren Güter ordnet Aristoteles dem zufälligen Glück zu, der eutychia. Körperliche Güter sind teils ebenfalls von Zufall abhängend (z. B. unter Umständen Schönheit), teils aber auch auf eigenes Handeln (z. B. durch Sport oder Ernährung) zurückzuführen. Seelische Güter dagegen können nur von wirklich guten Menschen erlangt werden. Alles zusammen ergibt eine Glückseligkeit, die Aristoteles in seinem Werk nur kurz erwähnt: Die des „vollkommen glücklichen Menschen vor und nach seinem Leben“. Dieser Mensch ist dann wahrhaft glücklich, oder anders: er ist makarios. Praktische und theoretische Lebensweise Aristoteles definiert die Glückseligkeit als eine Tätigkeit der Seele gemäß der vollkommenen Tugend (arete) in einem vollen Menschenleben. Allerdings können bestimmte dianoetische (verstandesmäßige) Tugenden nicht von jedem in vollkommener Form erreicht werden. Daher gibt es laut Aristoteles zwei grundlegende Weisen, wie ein glückliches Leben möglich ist. Die vollkommene Glückseligkeit besteht im bios theoretikos, im kontemplativen Leben. Dieses schließt wissenschaftliche Betätigung, Gebrauch der Vernunft (Nous) in die für den Erkenntnisgewinn grundlegenden Wahrheiten, und Erlangung von Weisheit ein. Auch die übrigen Tugenden sind bei dieser Lebensweise vollkommen ausgebildet, stehen aber nicht im Mittelpunkt des Handelns. Da einige Menschen sich von Natur aus nicht zu dieser Lebensweise eignen, weil sie laut Aristoteles insbesondere nicht in vollendeter Form über die Vernunft verfügen und dieses auch als einzige Tugend überhaupt nicht angebildet werden kann, gibt es eine zweite Lebensweise. Der bios praktikos, das praktische Leben, beschränkt sich auf den vollkommenen Gebrauch der Vernunft in Bezug auf kontingente Tatsachen, d. h. auf den Gebrauch von Klugheit und Kunstfertigkeit in Verbindung mit den ethischen Tugenden. |

至福 至高の善の本質に関する質問に対するアリストテレスの最初の答えは、至福(eudaimonía)が至高の善である、というものである。それは精神的な幸 福である。アリストテレスにとって、それは至福がそれ自体で存在するということに由来する。それは他の善のように、単なる手段ではない。他の善とは対照的 に、私たちは幸福そのものを求めている。アリストテレスが言うように、幸福は「完全かつ自足的な善であり、行動の最終目標」である(1097b20)。 エルゴン論証 幸福の真の意味を定義するために、アリストテレスはエルゴン論を導入している。ここでは、あらゆる存在は、他の存在と区別できる特徴によって特徴づけられ るという本質主義を前提としている。さらに、彼は独自の完璧主義を追求しており、存在の運命の達成は、その存在の特質の形成に依存すると考えている。 人間の本質は、他の生物と人間を区別する、人間特有の能力の考察に見出すことができる。それは、理性(思考、理知)に基づく、あるいは少なくとも理性を 伴った魂の活動である。さらに、人間は、その理性を完璧に活用すると同時に、人生全体を通じて、そしてそれ以上にその理性を発揮することが重要だ。この場 合の「さらに」とは、人間の遺産(子供など)でさえ、その理性の集中的な活用を証明しているということを意味する。 これらの 3 つの議論、すなわち、理性に基づく魂の活動、完全な形で、そして充実した人生における活動は、一般的にアリストテレスの最初の幸福の定義と見なされている。 外的、身体的、精神的財産の三区分 幸福を得るためには、アリストテレスが認めるように、理性に基づく魂の活動だけでなく、第一に外的財産、第二に身体的財産も必要だ。外的財産とは、富、友 情、出身、子孫、名誉、そして好都合な個人的な運命などだ。健康、美しさ、体力、運動能力は、身体的、あるいは内面の財産に相当する。魂の理性的な活動か ら、精神的な財産、つまり美徳が生まれる。 アリストテレスは、外的な財産を偶然の幸福、つまりユーティキアに分類している。身体的な財産は、一部は偶然にも依存する(例えば、状況によっては美しさ など)が、一部は自分の行動(例えば、スポーツや食事など)にも起因する。一方、精神的な財産は、本当に善良な人間だけが得ることができる。これらすべて が合わさって、アリストテレスが彼の著作で簡単に触れている「人生の前後において完全に幸福な人間」の幸福が生まれる。この人間は、真に幸せ、つまりマカ リオスである。 実践的および理論的な生き方 アリストテレスは、至福を、完全な美徳(アレテ)に従った、充実した人生における魂の活動と定義している。しかし、特定のダイアノエティック(知性的な) 美徳は、誰もが完全な形で達成できるわけではない。したがって、アリストテレスによれば、幸せな人生を送るには、基本的に 2 つの方法がある。 完全な幸福は、bios theoretikos、つまり思索的な生活にある。これには、科学的活動、認識の獲得に基本的な真理に対する理性(Nous)の使用、そして知恵の獲得が含まれる。他の美徳も、この生き方では完全に発達するけど、行動の中心にはならない。 アリストテレスによれば、一部の人々は、特に完全な形で理性を備えておらず、また、この理性は唯一の美徳としてまったく形成することができないため、生ま れつきこの生き方に適していない。そのため、2つ目の生き方がある。bios praktikos、つまり実践的な生活は、偶発的な事実に関する理性の完全な使用、つまり倫理的徳と関連した賢明さと技能の使用に限定される。 |

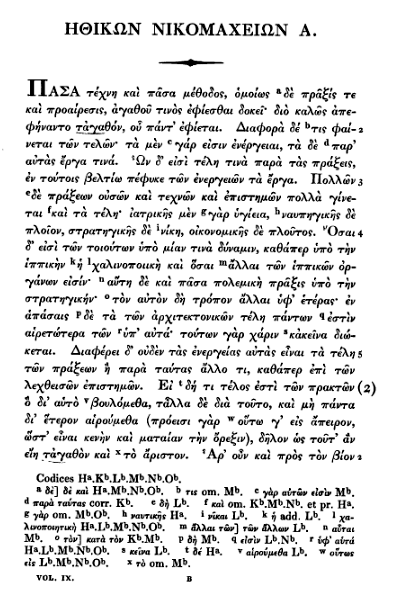

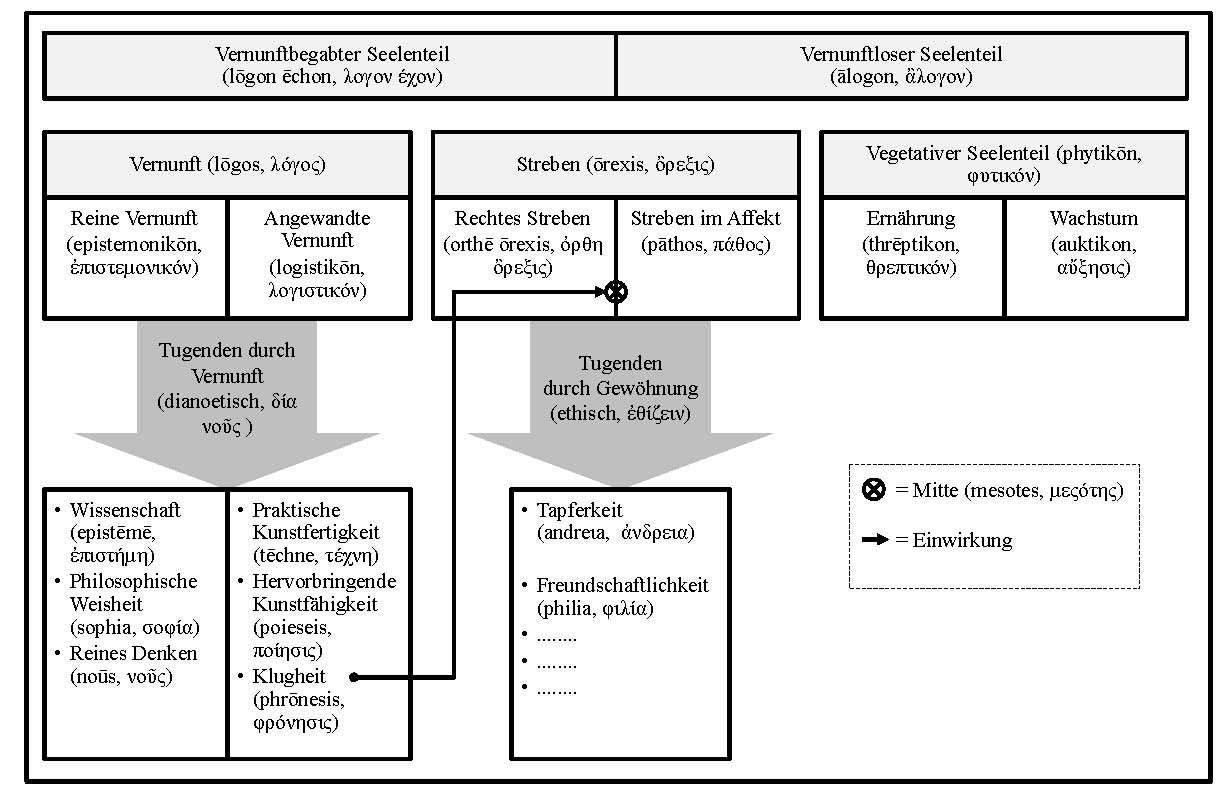

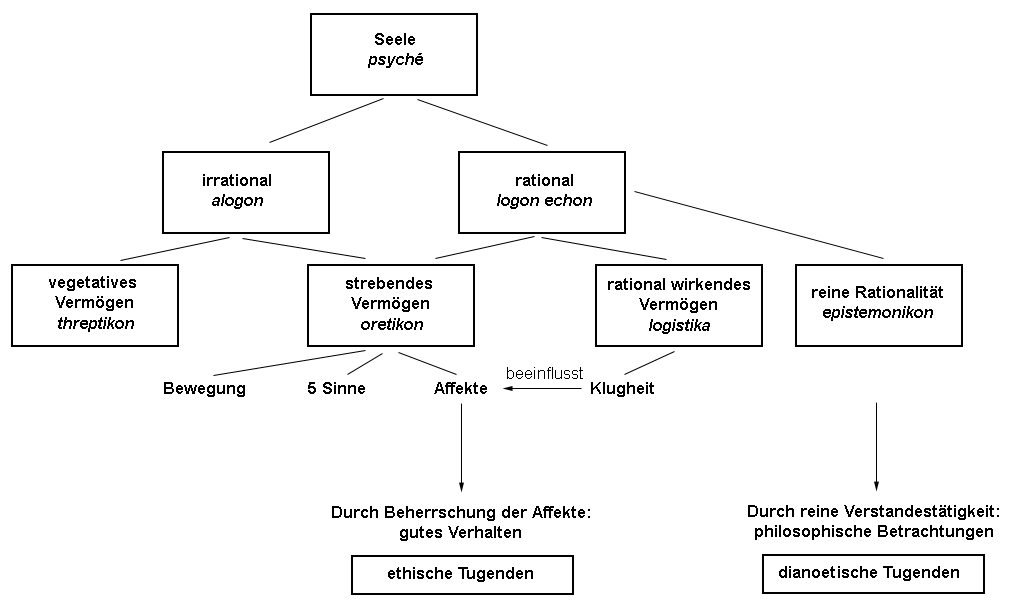

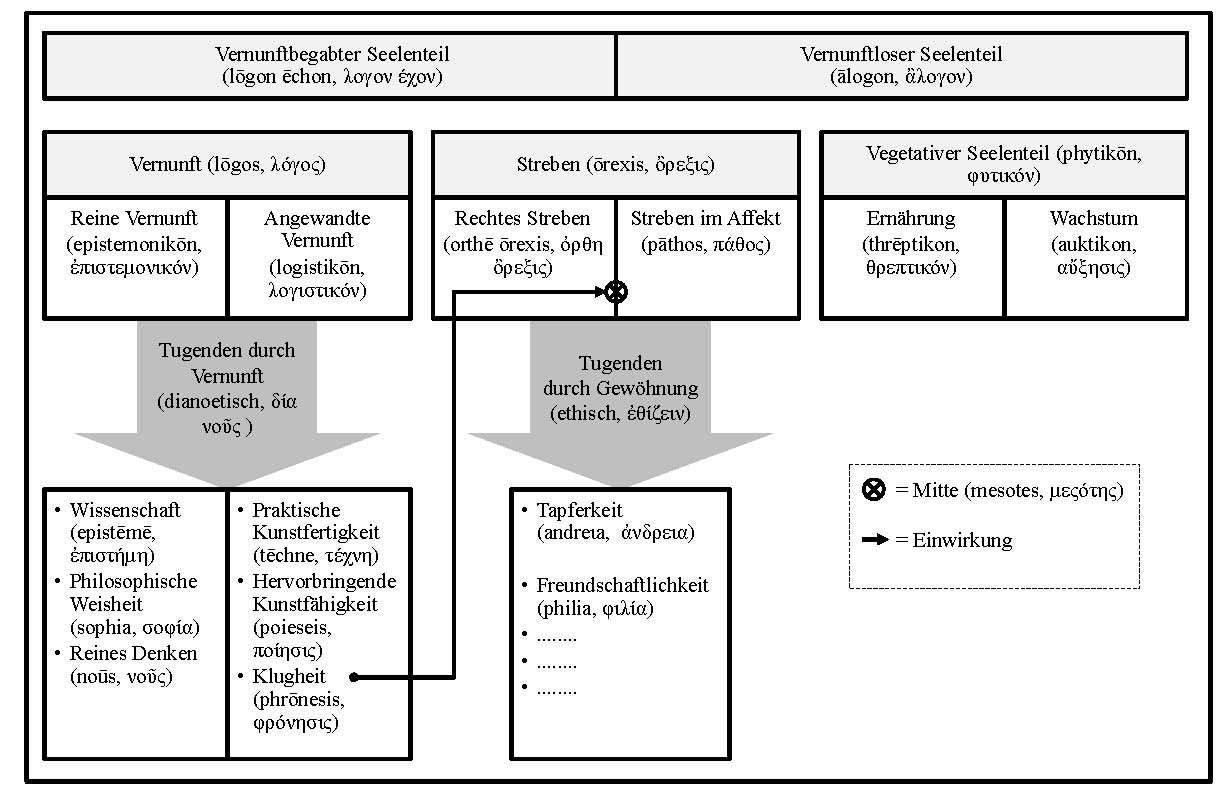

| Tugenden Die Tugenden sind seelische Güter. Aristoteles teilt diese entsprechend der Seele in dianoetische Tugenden, welche aus Belehrung entstehen, und ethische Tugenden, die sich aus der Gewohnheit ergeben. In Analogie zum Beherrschen eines Musikinstruments erwirbt man die Tugenden, indem man sie ausübt. Einteilung der Seele  Schaubild der Seele nach Aristoteles  Schaubild: Seelenlehre des Aristoteles (Nikomachische Ethik) Aristoteles unterteilt die Seele in einen spezifisch menschlichen, vernunftbegabten Teil (λόγον ἔχον) und einen vernunftlosen Teil (ἂλογον). Der vernunftlose Seelenteil (ἄλογον) besteht aus einem vegetativen Teil, der sich aus Wachstum (αὔξησις) und Ernährung (θρεπτικόν) zusammensetzt, aber auch das Strebevermögen der Seele beherbergt (ὂρεξις). Bis hierher ist der Mensch mit den Pflanzen bzw. Tieren auf einer Stufe, es sind nur Herzschlag und Stoffwechsel sowie Wachstum und Fortpflanzung sichergestellt. Der Mensch ist jedoch auch ein vernunft- und sprachbegabtes Wesen (ζῷον λόγον ἔχον), sein Strebevermögen (ὂρεξις) ist mit dem vernünftigen Teil der Seele verbunden. Deswegen kann er die Gemütsbewegungen wie Furcht, Zorn, Mitleid und andere zwar nicht in ihrem Aufkommen kontrollieren, wohl aber in der weiteren „Verarbeitung“. Der vernunftbegabte Teil hat ebenso wie der vernunftlose Anteil am Strebevermögen und ist „Ort“ der menschlichen Vernunft (λόγος). Diese besteht aus zwei Teilen: Der sich selbst genügenden Vernunft (ἐπιστημονικόν) und der angewandten Vernunft, also Überlegung (λογιστικόν) und Beratung (βουλευτικόν). In der selbstgenügsamen Vernunft (ἐπιστημονικόν) geht es um Wissenschaft (ἐπιστήμη), philosophische Weisheit (σοφία) und das reine Denken, das – losgelöst von allem – völlige geistige Selbstreferentialität bedeutet (νοῦς). Sie bezieht sich auf die unveränderlich seienden Dinge, auf die Mathematik, den Kosmos und die Metaphysik. In der angewandten Vernunft geht es um praktische Kunstfertigkeit (τέχνη), herstellende Kunstfertigkeit (ποίησις) und Klugheit (φρόνησις). Sie bezieht sich auf das praktische Leben. Die Klugheit (φρόνησις) spielt eine große Rolle, denn sie wirkt sich wieder auf das Strebevermögen aus. Während alle bisherigen Tugenden dianoetisch waren, sich also direkt aus der Vernunft ergeben haben, entstehen im Zusammenspiel von Klugheit (φρόνησις) und Strebevermögen (ὂρεξις) die ethischen Tugenden, die durch Entschluss (προαίρεσις) und Gewöhnung (ἐθίζειν) zur Haltung (ἕξις) werden können. Die Klugheit (φρόνησις) bringt die affektiven Extreme, die im Strebevermögen (ὂρεξις) aufkommen, in eine tugendhafte Mitte (μεσότης). So bewirkt sie beispielsweise, dass der Mensch weder zu feige noch zu tollkühn in seiner Haltung ist, weder zu gefallsüchtig noch zu streitsüchtig. Tugendhaft sein bedeutet bei Aristoteles nicht, frei von Affekten zu sein, sondern seine eigenen Affekte zu beherrschen. |

美徳 美徳は精神的な財産だ。アリストテレスは、魂に応じて、教育から生まれる知性的な美徳と、習慣から生まれる倫理的な美徳に分類している。楽器を習得するのと同様に、美徳は実践することによって獲得する。 魂の分類  アリストテレスによる魂の図式  図式:アリストテレスの魂の教義(ニコマコス倫理学) アリストテレスは、魂を、人間特有の、理性を備えた部分(λόγον ἔχον)と、理性を備えていない部分(ἂλογον)に分類している。理性を持たない魂の部分(ἄλογον)は、成長(αὔξησις)と栄養 (θρεπτικόν)で構成される植物的な部分で構成されているが、魂の欲求能力(ὂρεξις)も備えている。ここまで、人間は植物や動物と同じレベ ルにあり、心拍や代謝、成長、生殖だけが確保されている。しかし、人間は理性と言語能力を備えた存在(ζῷον λόγον ἔχον)でもあり、その欲求能力(ὂρεξις)は、魂の理性的な部分と結びついている。そのため、恐怖、怒り、同情などの感情の発生は制御できない が、その後の「処理」は制御できる。 理性を持つ部分は、理性を持たない部分と同様に、欲求能力の一部であり、人間の理性(λόγος)の「場所」でもある。これは 2 つの部分で構成されている。自足的な理性(ἐπιστημονικόν)と、応用的な理性、つまり考察(λογιστικόν)と相談 (βουλευτικόν)だ。自足的な理性(ἐπιστημονικόν)は、科学(ἐπιστήμη)、哲学的知恵(σοφία)、そしてあらゆるも のから切り離された、完全な精神的自己参照性(νοῦς)を意味する純粋な思考に関するものである。これは、不変の存在、数学、宇宙、形而上学に関するも のである。 応用的な理性は、実践的な技術(τέχνη)、創造的な技術(ποίησις)、そして賢明さ(φρόνησις)を扱う。これは実践的な生活に関連して いる。賢明さ(φρόνησις)は、努力能力に影響を与えるため、大きな役割を果たしている。これまでの美徳はすべて、理性から直接派生したダイアノエ ティックなものであったが、賢明さ(φρόνησις)と努力能力(ὂρεξις)の相互作用によって、倫理的な美徳が生まれ、決断 (προαίρεσις)と習慣化(ἐθίζειν)によって態度(ἕξις)となることができる。賢明さ(φρόνησις)は、意欲(ὂρεξις) に生じる感情的な極端さを、徳のある中庸(μεσότης)へと導く。例えば、それは、人間が自分の態度において、臆病にも無謀にもならず、人当たりも良 く、争いも好まないようにさせる。アリストテレスにとって、徳のある人間とは、感情に支配されない人間ではなく、自分の感情をコントロールできる人間であ る。 |

| Ethische Tugenden Die ethischen Tugenden beziehen sich auf die Leidenschaften und die Handlungen, die aus diesen Leidenschaften hervorgehen. Sie bestehen in der Zähmung und Steuerung des irrationalen, triebhaften Teils der Seele. Dabei postuliert Aristoteles eine Ethik des Maßhaltens. Bei den ethischen Tugenden gilt es, die richtige Mitte (mesotes) zwischen Übermaß und Mangel zu treffen. Am besten lässt sich dies am Beispiel der Tapferkeit verdeutlichen. Die Tapferkeit bewegt sich zwischen den Extremen der Feigheit und der Tollkühnheit – weder die Feigheit ist wünschenswert, noch eine übersteigerte, vernunftlose Tapferkeit, die Aristoteles als Tollkühnheit bezeichnet. Der Tapfere hält hingegen das richtige Maß. Ähnlich verhält es sich für andere ethische Tugenden wie Großgesinntheit, Besonnenheit, richtige Ernährungsweise usw. Um die Mitte (mesotes) zu verstehen und nachzuvollziehen, sollte man das irrationale und triebhafte Treiben der menschlichen Seele erlebt haben. So erhalte man ein Verständnis für die mesotes und könne verstehen, dass die Maßlosigkeit des Treibens zu nichts führt. Die Besonnenheit wird sich einstellen, wenn man verstanden hat, dass ein maßloses Treiben sowie ein vollkommener Rückzug des „Ich“ zu nichts führt, und erkennt, dass nur die Mitte zwischen beiden Extremen (mesotes) als richtiges Maß zählt. Die ethischen Tugenden werden von den Menschen bewertet. Sie sind daher sittlich werthaftig. Von Wert kann aber nur etwas sein, das keine spontane Bewegung ist, sondern ein Dauerzustand. Aufgrund dessen definiert Aristoteles die ethische Tugend zu einer festen Grundhaltung (hexis) (siehe auch Habitus). |

倫理的徳 倫理的徳とは、情熱と、その情熱から生じる行動に関するものである。それは、魂の非合理的で衝動的な部分を抑制し、制御することにある。アリストテレス は、節度ある倫理観を提唱している。倫理的徳では、過剰と不足の間の適切な中庸(mesotes)を見出すことが重要だ。これは、勇気を例に挙げるとよく わかる。勇気は、臆病と無謀という両極端の間にある。臆病も、アリストテレスが「無謀」と呼ぶ、過度で理性を欠いた勇気も、望ましいものではない。一方、 勇気ある者は、適切な節度を保っている。寛大さ、慎重さ、正しい食事など、他の倫理的徳についても同様だ。 中庸(mesotes)を理解し、理解するためには、人間の魂の非合理的で衝動的な行動を経験すべきだ。そうすることで、mesotes を理解し、過度な行動は何も生まないことを理解できる。節度ある行動と「自我」の完全な撤退は、どちらも何の結果も生まないことを理解し、両極端の中間 (メソテス)だけが正しいバランスであると認識することで、慎重さが身についていく。 倫理的徳は人間によって評価される。したがって、それらは道徳的価値を持つ。しかし、価値を持つことができるのは、自発的な動きではなく、永続的な状態で あるものだけだ。このことから、アリストテレスは倫理的徳を、確固とした基本姿勢(ヘキシス)と定義している(ハビトゥスも参照)。 |

| Dianoetische Tugenden Die dianoetischen Tugenden lassen sich gemäß Aristoteles in zwei Teile gliedern: Diejenigen Tugenden, die sich auf kontingente Tatsachen beziehen, und diejenigen, die sich auf notwendige Tatsachen beziehen. Erstere sind die Kunstfertigkeit (techne), also ein spezifisches Herstellungswissen (z. B. die Fertigkeit des Tischlerns) und die weit wichtigere Klugheit (phronesis), die sämtliche ethischen Tugenden steuert und die richtige Anwendung dieser erkennen lässt. Auf notwendige Tatsachen beziehen sich die Wissenschaft (episteme), welche die Fähigkeit des richtigen Schließens bedeutet, die Vernunft (Nous) und die Weisheit (sophia). Die Vernunft ist eine Art „intuitiver Verstand“ bzw. ein Wissen von den „obersten Sätzen“ (1141a15 ff.), aus denen die Wissenschaft dann Schlüsse ziehen kann. Weil die Vernunft als einzige Tugend überhaupt nicht erworben werden kann, sondern jedem in unterschiedlich ausgeprägter Weise gegeben ist, bleibt ihre Ausübung den zufällig Begünstigten vorbehalten. Auch die Wissenschaft ist auf eine hervorragend ausgeprägte Vernunft angewiesen und die Weisheit ist das Vorhandensein von Vernunft und Wissenschaft. Daher kann das Leben in der reinen Schau der Wahrheit (theoria), der bios theoretikos, nicht von jedem erreicht werden (siehe Abschnitt zur theoretischen und praktischen Lebensweise). |

ダイアノティックの美徳 アリストテレスによれば、ダイアノティックの美徳は、偶発的な事実に関連する美徳と、必然的な事実に関連する美徳の 2 つに分類される。前者は、技術(テクネー)、つまり特定の製造知識(例えば、大工の技能)と、より重要な賢明さ(フロネシス)であり、これはすべての倫理 的徳を支配し、その正しい適用を認識させるものである。 必然的な事実に関連するものは、正しい結論を導き出す能力である科学(エピステーム)、理性(ヌース)、そして知恵(ソフィア)だ。理性とは、一種の「直 感的な知性」、すなわち「最上位の命題」(1141a15 ff.)に関する知識であり、科学はそこから結論を導き出すことができる。理性は、唯一の徳としてまったく習得できないものであり、各人にさまざまな形で 与えられているものであるため、その行使は偶然に恵まれた者たちにのみ留保されている。科学も、卓越した理性に依存しており、知恵とは、理性と科学の存在 である。したがって、真実の純粋な観照(テオリア)、すなわち、bios theoretikos は、誰もが達成できるものではない(理論的および実践的な生き方に関するセクションを参照)。 |

| Lust und Schmerz Die ethischen Tugenden stehen in engem Zusammenhang mit Lust und Schmerz. Die Hinwendung der Menschen zum Schlechten erklärt Aristoteles damit, dass die Menschen die Lust suchen und den Schmerz fürchten. Diese natürliche Verhaltensweise gilt es, durch Erziehung zum Guten zu beeinflussen und zu steuern. Aus diesem Grund rechtfertigt er auch Züchtigungen: „Sie sind eine Art Heilung, und die Heilungen werden naturgemäß durch das Entgegengesetzte vollzogen.“ Doch auch die Ausübung der Tugend ist mit dem Angenehmen und der Lust verbunden. Aristoteles differenziert aufgrund seiner Theorie der Seele zwischen körperlichen und geistigen Lüsten. Die körperlichen Lüste weisen auf Grundbedürfnisse des Menschen hin, sollten jedoch nicht, wie von den Hedonisten praktiziert, über das in diesem Rahmen sinnvolle Maß bedient werden. Geistige Lüste lassen sich mit Tugenden verbinden, wie etwa die Lust der intellektuellen Betätigung im Sinne der Wissenschaft oder ganz allgemein die Lust, Gutes zu tun. In diesem Sinne wird also ein tugendhafter Mensch ein lustvolles Leben führen. |

快楽と苦痛 倫理的徳は、快楽と苦痛と密接に関連している。アリストテレスは、人間が悪に傾倒するのは、快楽を求め、苦痛を恐れるからだと説明している。この自然な行 動様式は、教育によって善へと導き、制御しなければならない。そのため、彼は体罰も正当化している。「体罰は一種の治療であり、治療は当然、その反対の行 為によって行われる」と。 しかし、美徳の実践も、快楽や喜びと関連している。アリストテレスは、魂に関する理論に基づいて、肉体的快楽と精神的快楽を区別している。肉体的快楽は人 間の基本的欲求を示すものだが、快楽主義者が実践しているように、この枠組みの中で意味のある程度を超えて満たすべきではない。精神的快楽は、科学という 観点からの知的活動への欲求や、より一般的には善を行う欲求など、美徳と結びつけることができる。この意味で、美徳のある人間は快楽に満ちた人生を送ると いうことになる。 |

| Gerechtigkeit Das V. Buch wird in traditionellen Einteilungen als Erörterung des Begriffs der Gerechtigkeit angesehen. Dieser Teilabschnitt ist allerdings "in keinem guten Zustandt"[3], weil sowohl die Überlieferung des Textes problematisch ist, als auch seine Verortung innerhalb des Systems der Ethik. Der zweite Punkt kann darauf zurückgeführt werden, dass Aristoteles als erstes oder wenigstens als einer der ersten versucht hat, eine Systematik der Gerechtigkeit anzufertigen und nicht auf eine schon bestehende Einteilung zurückgreifen konnte.[3] Er versteht auch die Gerechtigkeit als Tugend und sucht hier erneut nach einer Mitte. Hinzu kommt die Beschreibung als "Charakterdisposition"[4] und bezieht sie damit ein in die Notwendigkeit, das ganze Leben darauf auszurichten und dafür zu sorgen, dass der jeweils Handelnde auf Grund seiner grundsätzlichen Gestimmtheit das gerechte in einer Situation tut. Das hat zur Folge, dass auch die Gerechtigkeit kein abstrakter Begriff oder eine Idee des Guten ist, sondern Ergebnis von Erziehung, Tadel und Lob.[5] |

正義 第5巻は、伝統的な分類では、正義の概念に関する考察とみなされている。しかし、この部分は「良好な状態ではない」[3]。なぜなら、このテキストの伝承 が問題であるだけでなく、倫理体系におけるその位置付けも問題であるからだ。2つ目の点は、アリストテレスが、正義の体系を構築しようとした最初の人物、 あるいは少なくとも最初の人物の一人であり、既存の分類を利用できなかったことに起因すると考えられる[3]。 彼はまた、正義を美徳として理解し、ここでも再び中庸を模索している。さらに、それを「性格的傾向」[4] と表現し、人生全体をそれに基づいて生き、その行動者がその基本的な気質に基づいて、その状況において正義を行うよう努める必要性を強調している。その結 果、正義も抽象的な概念や善の観念ではなく、教育、叱責、称賛の結果であるということになる。[5] |

| Staatsformenlehre In der Nikomachischen Ethik entwickelt Aristoteles auch eine Rangordnung ihm bekannter Staatsformen ihrer Tugendhaftigkeit nach. Für die beste Staatsform hält Aristoteles die Monarchie, die er mit der fürsorglichen Obhut des Vaters über seine Söhne vergleicht. Es folgt die Aristokratie als Herrschaft der Tugendhaftesten und Tüchtigsten, die ihre Entsprechung in der – Aristoteles zufolge auf natürlichem Vorzug beruhenden – Herrschaft des Mannes über die Frau finde. Schließlich lobt Aristoteles eine auf Zensus beruhende Verfassung, die er Timokratie nennt, und vergleicht sie mit der Freundschaft zwischen älterem und jüngerem Bruder. Den drei tugendhaften Staatsformen steht in Aristoteles’ Systematik jeweils eine „Entartung“ gegenüber. Die Monarchie verkomme zur Tyrannis, wenn der Alleinherrscher um seines eigenen Vorteils willen eine Gewaltherrschaft errichte – gleich einem Vater, der seine Söhne wie Sklaven behandelt. Die Aristokratie verwandele sich in eine Oligarchie, wenn eine geringe Zahl nicht tugendhafter, sondern habgieriger Machthaber die Herrschaft monopolisiere und die Staatsgüter unter sich aufteile. Aristoteles bemüht als Analogie hier das Bild der reichen Erbtochter, die trotz vermeintlichen Mangels des natürlichen Vorzugs der Männlichkeit Gewalt ausübe aufgrund von Reichtum und Macht. Die Demokratie hält Aristoteles schließlich für die „am wenigsten schlechte“ ausgeartete Staatsform, da sie sich nur graduell (durch niedrigere Zulassungsbeschränkungen zur Bürgerschaft) von der Timokratie unterscheide. In Aristoteles’ Parallelisierung von Staatsformen und Familienbeziehungen erscheint die Demokratie als ein Haus, „wo der Herr fehlt“, alle folglich gleichberechtigt sind „und jeder tut, was ihm gefällt.“[6] |

国家形態論 『ニコマコス倫理学』の中で、アリストテレスは、彼が知っている国家形態をその徳の高さに基づいて順位付けしている。アリストテレスは、最良の国家形態は 君主制であると考えており、それを父親が息子たちを慈しむように世話をする姿に例えている。次に、最も徳が高く有能な者による支配である貴族制が続き、こ れは、アリストテレスによれば、男性が女性に対して持つ、自然な優位性に基づく支配に相当する。最後に、アリストテレスは、資産に基づく憲法を称賛し、そ れをティモクラシーと呼び、兄と弟の友情に例えている。 アリストテレスの体系では、3つの高潔な政体それぞれに対して「堕落」が対置されている。君主制は、独裁者が自分の利益のために暴政を敷くことで、専制政 治へと堕落する。それは、息子たちを奴隷のように扱う父親のようなものだ。貴族政治は、少数の徳のある者ではなく、貪欲な権力者たちが支配を独占し、国家 の財産を分け合うことで、寡頭政治へと変質する。アリストテレスは、ここでは、男性という自然の優位性を欠いているにもかかわらず、富と権力によって権力 を行使する、裕福な相続人の娘という例えを用いている。アリストテレスは、民主主義は、ティモクラシーと(市民権取得の制限が緩いという点で)わずかに異 なるだけなので、最終的には「最も悪くない」国家形態だと考えている。アリストテレスが国家の形態と家族関係を並行して考察したところ、民主主義は「主人 のいない家」のように、その結果、すべての人が平等であり、「誰もが自分の好きなことをする」[6] ものとして描かれている。 |

| Textausgaben Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Hrsg. von Immanuel Bekker, 3. Auflage, Georg Reimer, Berlin 1861. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Hrsg. und kommentiert von Gottfried Ramsauer, Teubner, Leipzig 1878. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Hrsg. von Ingram Bywater, Oxford Classical Texts, Oxford 1894. (mehrfach nachgedruckt) Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Hrsg. von Franz Susemihl und Otto Apelt, 3. Auflage, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Leipzig 1912. Aristotle: The Nicomachean Ethics. Griechisch–Englisch, übersetzt von Harris Rackham, Loeb Classical Library, New York und London 1934. (mehrfach nachgedruckt) Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Griechisch–Deutsch, übersetzt von Olof Gigon, neu hrsg. von Rainer Nickel, Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-7608-1725-4. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Griechisch–Deutsch, übersetzt und hrsg. von Gernot Krapinger, Reclam, Stuttgart 2020, ISBN 978-3-15-019670-0. |

テキスト版 アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。イマヌエル・ベッカー編、第 3 版、ゲオルク・ライマー、ベルリン、1861 年。 アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。ゴットフリート・ラムサウアー編、解説、テューブナー、ライプツィヒ、1878 年。 アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。イングラム・バイウォーター編、オックスフォード古典テキスト、オックスフォード、1894年。(複数回再版) アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。フランツ・スゼミルとオットー・アペルト編、第3版、ビブリオテカ・テューブナーリアナ、ライプツィヒ、1912年。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ギリシャ語・英語、ハリス・ラックハム訳、ローブ古典文庫、ニューヨークおよびロンドン、1934年。(複数回再版) アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ギリシャ語・ドイツ語、オロフ・ギゴン訳、ライナー・ニッケル新編、アルテミス&ウィンクラー、デュッセルドルフ、2001年、 ISBN 3-7608-1725-4。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ギリシャ語-ドイツ語、ゲルノット・クラピンガー訳、レクラム、シュトゥットガルト、2020年、ISBN 978-3-15-019670-0。 |

| Übersetzungen Die Ethik des Aristoteles. 2 Bände, übersetzt und erläutert von Christian Garve: Band 1: Die zwey ersten Bücher der Ethik nebst einer zur Einleitung dienenden Abhandlung über die verschiednen Principe der Sittenlehre, von Aristoteles an bis auf unsre Zeiten. Korn, Breslau 1798. Band 2: Die acht übrigen Bücher der Ethik. Hrsg. von Johann Kaspar Friedrich Manso, Korn, Breslau 1801. Des Aristoteles Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt und erläutert von Julius Hermann von Kirchmann, Koschny, Leipzig 1876. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt von Adolf Lasson, Diederichs, Jena 1909. Aristoteles: Die Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt und mit einer Einleitung und erklärenden Anmerkungen versehen von Olof Gigon, 2., überarbeitete Auflage, Artemis, Zürich 1967. (mehrfach nachgedruckt) Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt und kommentiert von Franz Dirlmeier, 6., durchgesehene Auflage, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1974. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt von Eugen Rolfes, hrsg. von Günther Bien, 4., durchgesehene Auflage, Meiner, Hamburg 1985, ISBN 978-3-7873-0655-8. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt von Franz Dirlmeier, Anmerkungen von Ernst A. Schmidt, bibliographisch ergänzte Auflage, Reclam, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-008586-1. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt und hrsg. von Ursula Wolf, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-499-55651-0. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. Übersetzt von Gernot Krapinger, Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-019448-5. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. In: Werke in deutscher Übersetzung. Band 6 (in zwei Halbbänden), übersetzt, eingeleitet und kommentiert von Dorothea Frede, De Gruyter, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-534-27209-9. |

翻訳 アリストテレスの倫理学。2巻、クリスチャン・ガルヴェによる翻訳および解説: 第1巻:倫理学の最初の2冊と、アリストテレスから現代までの倫理学のさまざまな原則に関する序論。コーン、ブレスラウ、1798年。 第 2 巻:倫理学の残りの 8 冊。ヨハン・カスパー・フリードリッヒ・マンスオ編、コーン、ブレスラウ、1801 年。 アリストテレスのニコマコス倫理学。ユリウス・ヘルマン・フォン・キルヒマンによる翻訳および解説、コシュニー、ライプツィヒ、1876 年。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。アドルフ・ラッソン訳、ディーデリヒス、イエナ、1909年。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。オロフ・ギゴンによる翻訳、序文および解説付き、第2版、改訂版、アルテミス、チューリッヒ、1967年。(複数回再版) アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。フランツ・ディルマイヤーによる翻訳および注釈、第 6 版、改訂版、アカデミー出版社、ベルリン、1974 年。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。オイゲン・ロルフェスによる翻訳、ギュンター・ビーンによる編集、第 4 版、改訂版、マイナー、ハンブルク、1985 年、 ISBN 978-3-7873-0655-8。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。フランツ・ディルマイヤー訳、エルンスト・A・シュミット注釈、書誌情報追加版、レクラム社、シュトゥットガルト、2003年、ISBN 3-15-008586-1。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ウルスラ・ヴォルフ訳、レクラム社、2006年、ISBN 3-499-55651-0。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ゲルノット・クラピンガー訳、レクラム社、2017年、ISBN 978-3-15-019448-5。 アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。ドイツ語訳作品集。第 6 巻(2 冊)、翻訳、序文、解説:ドロテア・フレデ、デ・グルイター、ベルリン、2020 年、ISBN 978-3-534-27209-9。 |

| Literatur Sarah W. Broadie: Ethics with Aristotle. Oxford University Press, New York und Oxford 1991, ISBN 978-0-19-508560-0. John Dudley: Gott und theōria bei Aristoteles. Die metaphysische Grundlage der Nikomachischen Ethik. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main und Berlin 1982, ISBN 978-3-8204-5738-4. Artur von Fragstein: Studien zur Ethik des Aristoteles. B. R. Grüner, Amsterdam 1974, ISBN 978-90-6032-006-8. Albert Goedeckemeyer (Hrsg.): Aristoteles’ praktische Philosophie. Dieterich, Leipzig 1922. John-Stewart Gordon: Aristoteles über Gerechtigkeit. Das V. Buch der Nikomachischen Ethik. Karl Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau und München 2007, ISBN 978-3-495-48226-1. Andree Hahmann: Aristoteles’ »Nikomachische Ethik«. Ein systematischer Kommentar. Reclam, Ditzingen 2022, ISBN 978-3-15-014301-8. William Francis Ross Hardie: Aristotle’s Ethical Theory. 2. Auflage, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1980, ISBN 978-0-19-824632-9. Magdalena Hoffmann: Der Standard des Guten bei Aristoteles: Regularität im Unbestimmten. Aristoteles’ Nikomachische Ethik als Gegenstand der Partikularismus-Generalismus-Debatte. Karl Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau und München 2010, ISBN 978-3-495-48383-1. Otfried Höffe (Hrsg.): Aristoteles: Die Nikomachische Ethik. 4., neubearbeitete und ergänzte Auflage, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin und Boston 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-057874-4. Otfried Höffe (Hrsg.): Aristoteles-Lexikon. Kröner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-520-45901-9. (= Kröners Taschenausgabe. Band 459) Christoph Horn, Christof Rapp (Hrsg.): Wörterbuch der antiken Philosophie. 2., überarbeitete Auflage, Beck, München 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56846-6. Marta Jimenez: Aristotle on Shame and Learning to Be Good. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2020 Richard Kraut: Aristotle on the Human Good. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ) 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-07349-1. (insbesondere zu NE I, X). Ronald Polansky (Hrsg.): The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Cambridge University Press, New York, New York 2014. Christof Rapp: Aristoteles zur Einführung. 6., erweiterte Auflage, Junius, Hamburg 2020, ISBN 978-3-88506-690-3. Hermann Rassow: Forschungen über die nikomachische Ethik des Aristoteles. Böhlau, Weimar 1874. Nathalie von Siemens: Aristoteles über Freundschaft. Untersuchungen zur Nikomachischen Ethik VIII und IX. Karl Alber, Freiburg im Breisgau und München 2007, ISBN 978-3-495-48241-4. Erwin Sonderegger: Der spekulative Aristoteles. Untersuchungen zur Frage nach dem Sein in den mittleren Büchern der Metaphysik und zur Frage nach dem Sein des Menschen in der Nikomachischen Ethik. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8260-4261-4. Petrus Martyr Vermigli: Kommentar zur Nikomachischen Ethik des Aristoteles. Hrsg. von Luca Baschera und Christian Moser, Brill, Leiden 2011, ISBN 978-90-04-21873-4. Ursula Wolf: Aristoteles’ „Nikomachische Ethik“. 3. Auflage, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-534-26238-0. |

参考文献 サラ・W・ブロディ『アリストテレスの倫理学』オックスフォード大学出版局、ニューヨークおよびオックスフォード、1991年、ISBN 978-0-19-508560-0。 ジョン・ダドリー『アリストテレスにおける神とテオリア』 ニコマコス倫理学の形而上学的な基礎。ピーター・ラング、フランクフルト・アム・マインおよびベルリン、1982年、ISBN 978-3-8204-5738-4。 アルトゥール・フォン・フラグシュタイン:アリストテレスの倫理に関する研究。B. R. グリューナー、アムステルダム、1974年、ISBN 978-90-6032-006-8。 アルベルト・ゲデッケマイヤー(編):アリストテレスの実践哲学。ディーターリッヒ、ライプツィヒ、1922年。 ジョン・スチュワート・ゴードン:正義に関するアリストテレス。ニコマコス倫理学の第5巻。カール・アルバー、フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウおよびミュンヘン、2007年、ISBN 978-3-495-48226-1。 アンドレ・ハーマン:アリストテレスの『ニコマコス倫理学』。体系的な解説。レクラム、ディッツィンゲン、2022年、ISBN 978-3-15-014301-8。 ウィリアム・フランシス・ロス・ハーディ:アリストテレスの倫理理論。第 2 版、オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、1980 年、ISBN 978-0-19-824632-9。 マグダレーナ・ホフマン:アリストテレスにおける善の基準:不確定性における規則性。アリストテレスのニコマコス倫理学を、個別主義と一般主義の議論の対 象として。カール・アルバー、フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウおよびミュンヘン、2010 年、ISBN 978-3-495-48383-1。 オットフリード・ヘッフェ(編):アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学。第 4 版、改訂および補遺版、アカデミー出版社、ベルリンおよびボストン、2019 年、 ISBN 978-3-11-057874-4。 オットフリード・ヘッフェ(編):アリストテレス事典。クローナー、シュトゥットガルト、2005年、ISBN 3-520-45901-9。(= クローナーのポケット版。第 459 巻) クリストフ・ホーン、クリストフ・ラップ(編):古代哲学辞典。第 2 版、改訂版、ベック、ミュンヘン、2008 年、ISBN 978-3-406-56846-6。 マルタ・ヒメネス:恥と善を学ぶことに関するアリストテレス。オックスフォード大学出版局、オックスフォード、2020 年 リチャード・クラウト:Aristotle on the Human Good(人間の善に関するアリストテレス)。プリンストン大学出版、プリンストン(ニュージャージー州)1989年、ISBN 978-0-691-07349-1。(特に NE I、X について)。 ロナルド・ポランスキー(編):The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics(アリストテレスのニコマコス倫理学に関するケンブリッジ・コンパニオン)。ケンブリッジ大学出版、ニューヨーク、ニューヨーク 2014年。 クリストフ・ラップ:Aristoteles zur Einführung(アリストテレス入門)。第 6 版、増補版、Junius、ハンブルク、2020 年、ISBN 978-3-88506-690-3。 ヘルマン・ラッソウ:Forschungen über die nikomachische Ethik des Aristoteles(アリストテレスのニコマコス倫理学に関する研究)。Böhlau、ワイマール、1874 年。 ナタリー・フォン・ジーメンス:友情に関するアリストテレス。ニコマコス倫理学 VIII および IX に関する研究。カール・アルバー、フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウおよびミュンヘン、2007 年、ISBN 978-3-495-48241-4。 エルヴィン・ゾンデレガー:思弁的なアリストテレス。形而上学の中巻における存在の問題と、ニコマコス倫理学における人間の存在の問題に関する研究。ケーニヒスハウゼン&ノイマン、ヴュルツブルク、2010年、ISBN 978-3-8260-4261-4。 ペトルス・マルティル・ヴェルミグリ:アリストテレスのニコマコス倫理学に関する解説。ルカ・バシェラとクリスチャン・モーザー編、ブリル、ライデン、2011年、ISBN 978-90-04-21873-4。 ウルスラ・ヴォルフ:アリストテレスの『ニコマコス倫理学』。第3版、ヴィッセンシャフトリッシェ・ブッフゲゼルシャフト、ダルムシュタット、2013年、ISBN 978-3-534-26238-0。 |

| Weblinks Textausgaben und Übersetzungen Nikomachische Ethik. Griechischer Originaltext bei Wikisource. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Griechischer Originaltext, hrsg. von Immanuel Bekker, tertium edita, Berlin 1861. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Griechischer Originaltext, hrsg. von Ingram Bywater, Oxford 1890. Aristotelis Ethica Nicomachea. Griechischer Originaltext, hrsg. von Franz Susemihl und Otto Apelt, editio altera, Leipzig 1903. Nikomachische Ethik. Deutsche Übersetzung von Adolf Lasson, Jena 1909. Nikomachische Ethik. Deutsche Übersetzung von Eugen Rolfes, Leipzig 1911. Ethica Nicomachea. Englische Übersetzung von William D. Ross, Oxford 1925. Englische Übersetzung von William D. Ross nebst griechischem Text bei mikrosapoplous.gr (Teilausgabe) Englische Übersetzung von William D. Ross mit Abschnittsübersicht bei nothingistic.org Englische Übersetzung von Harris Rackham, New York und London 1934, beim Perseus Project Sekundärliteratur Richard Kraut: Aristotle’s Ethics. In: Edward N. Zalta (Hrsg.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 17. Juli 2007. |

ウェブリンク テキスト版と翻訳 ニコマコス倫理学。ウィキソースのギリシャ語原文。 アリストテレスのエティカ・ニコマケーア。ギリシャ語原文、イマニュエル・ベッカー編、第三版、ベルリン、1861年。 アリストテレスの『ニコマコス倫理学』。ギリシャ語原文、イングラム・バイウォーター編、オックスフォード、1890年。 アリストテレスの『ニコマコス倫理学』。ギリシャ語原文、フランツ・スゼミルとオットー・アペルト編、editio altera、ライプツィヒ、1903年。 ニコマコス倫理学。アドルフ・ラッソンによるドイツ語訳、イエナ、1909年。 ニコマコス倫理学。オイゲン・ロルフェスによるドイツ語訳、ライプツィヒ、1911年。 ニコマコス倫理学。ウィリアム・D・ロスによる英語訳、オックスフォード、1925年。 ウィリアム・D・ロスによる英語訳とギリシャ語原文 mikrosapoplous.gr (部分版) ウィリアム・D・ロスによる英語訳とセクション概要 nothingistic.org ハリス・ラックハムによる英語訳、ニューヨークおよびロンドン 1934 年、Perseus Project 二次文献 リチャード・クラウト: アリストテレスの倫理学。エドワード・N・ザルタ編: 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』、2007年7月17日。 |

| Einzelbelege 1. Otfried Höffe (Hrsg.): Aristoteles. Die Nikomachische Ethik. Berlin 2010, S. 6. 2. Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik. 1094a1 (übersetzt von Franz Dirlmeier) 3. WOLF, Ursula und ARISTOTELES, 2013. Aristoteles „Nikomachische Ethik“. 3. Auflage = 3., bibliografisch erweiterte Ausgabe. Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft). ISBN 9783534262397, S. 93. 4. WOLF, Ursula und ARISTOTELES, 2013. Aristoteles „Nikomachische Ethik“. 3. Auflage = 3., bibliografisch erweiterte Ausgabe. Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft). ISBN 9783534262397, S. 95. 5. WOLF, Ursula und ARISTOTELES, 2013. Aristoteles „Nikomachische Ethik“. 3. Auflage = 3., bibliografisch erweiterte Ausgabe. Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft). ISBN 9783534262397, S. 115. 6.Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik, Buch VIII, Kapitel 12 (1160a–1161a) |

個別出典 1. Otfried Höffe (編): アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』ベルリン 2010年、6 ページ。 2. アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』1094a1 (フランツ・ディルマイヤー訳) 3. WOLF, Ursula および ARISTOTELES, 2013. アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。第 3 版 = 第 3 版、書誌情報追加版。ダルムシュタット:WBG(Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft)。ISBN 9783534262397、93 ページ。 4. WOLF、ウルスラおよびアリストテレス、2013 年。アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。第 3 版 = 第 3 版、書誌情報追加版。ダルムシュタット:WBG(Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft)。ISBN 9783534262397、95 ページ。 5. WOLF、ウルスラ、および ARISTOTELES、2013 年。アリストテレス『ニコマコス倫理学』。第 3 版 = 第 3 版、参考文献追加版。ダルムシュタット:WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft)。ISBN 9783534262397、115 ページ。 6.アリストテレス:ニコマコス倫理学、第 VIII 巻、第 12 章 (1160a–1161a) |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikomachische_Ethik |

+++++

以下の情報はウィキペディア『ニコマコ ス倫理学』などによる(→「アリストテレスの倫理学入門」)。

序言

書き出しで「いかなる技術や研究、実践や選択も、何

らかの『善』を希求している」と取り上げ、「国(ポリス)においていかなる学問が行われるべきか、各人はいかなる学問をいかなる程度まで学

ぶべきであるか

を規律するのは『政治』であり、最も尊敬される能力、たとえば統帥・家政・弁論などもやはりその下に従属しているのをわれわれは見るのである。」と述べら

れている。「『人間というものの善』こそが政治の究極目的でなくてはならぬ」(第1巻第2章)とするが、「政治学の探求とは、知識ではなく実践が目的であ

り、年少者を含め情念(パトス)のままに追求するひとびとにとっては、無抑制的なひとに同じく知識は無益におわる」とも述べている(第1巻第3章)。

| 巻 |

パラグラフ | Nicomachean

Ethics. |

|||

| 1 |

1 |

第1巻(序説、幸福) |

Concerning

accuracy and whether ethics can be treated in an objective way,

Aristotle points out that the "things that are beautiful and just,

about which politics investigates, involve great disagreement and

inconsistency, so that they are thought to belong only to convention

and not to nature". For this reason Aristotle claims it is important

not to demand too much precision, like the demonstrations we would

demand from a mathematician, but rather to treat the beautiful and the

just as "things that are so for the most part." We can do this because

people are good judges of what they are acquainted with, but this in

turn implies that the young (in age or in character), being

inexperienced, are not suitable for study of this type of political

subject.[19]

Chapter 6 contains a famous digression in which Aristotle appears to

question his "friends" who "introduced the forms". This is understood

to be referring to Plato and his school, famous for what is now known

as the Theory of Forms. Aristotle says that while both "the truth and

one's friends" are loved, "it is a sacred thing to give the highest

honor to the truth". The section is yet another explanation of why the

Ethics will not start from first principles, which would mean starting

out by trying to discuss "The Good" as a universal thing that all

things called good have in common. Aristotle says that while all the

different things called good do not seem to have the same name by

chance, it is perhaps better to "let go for now" because this attempt

at precision "would be more at home in another type of philosophic

inquiry", and would not seem to be helpful for discussing how

particular humans should act, in the same way that doctors do not need

to philosophize over the definition of health in order to treat each

case.[20] In other words, Aristotle is insisting on the importance of

his distinction between theoretical and practical philosophy, and the

Nicomachean Ethics is practical. |

倫

理学が客観的に扱えるかどうか、その正確さについて、アリストテレスは、「政治学が調査する美しいもの、正しいものは、大きな不一致と矛盾を伴うので、自

然にではなく、慣習にのみ属すると考えられている」と指摘している。だからアリストテレスは、数学者に要求するような精密さを求めすぎず、美しいもの、正

しいものを "大体そうである

"として扱うことが重要であると主張する。しかし、これは逆に、(年齢的にも性格的にも)未熟な若者は、この種の政治的主題の研究には適さないことを意味

している[19]。

第6章には有名な脱線があり、アリストテレスは「形を導入」した「友人」に疑問を呈しているようにみえる。これは、現在『形式論』として知られているもの

で有名なプラトンとその学派を指していると理解される。アリストテレスは、「真理も友人も」愛されるが、「真理に最高の栄誉を与えることは神聖なことであ

る」と言うのである。この部分は、『倫理学』がなぜ第一原理から出発しないのか、つまり、善と呼ばれるものが共通して持っている普遍的なものとしての

「善」を論じようとすることから出発することの、また別の説明である。アリストテレスは、善と呼ばれる様々なものが偶然同じ名前を持っているようには見え

ないが、おそらく「今のところ放っておく」方がよいと言う。このような正確さを求める試みは「別の種類の哲学的探究においてより馴染むだろう」し、特定の

人間がどう行動すべきかを議論するのに役立つとは思えない、医師が個々の症例を治療するために健康の定義について哲学する必要がないのと同じである、と。

[つまり、アリストテレスは理論哲学と実践哲学の区別の重要性を主張しているのであり、『ニコマコス倫理学』は実践的なものなのである。 |

|

| 2 |

2 |

第2巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての

概説1) |

Aristotle says

that whereas virtue of thinking needs teaching, experience and time,

virtue of character (moral virtue) comes about as a consequence of

following the right habits. According to Aristotle the potential for

this virtue is by nature in humans, but whether virtues come to be

present or not is not determined by human nature.[36]

Trying to follow the method of starting with approximate things

gentlemen can agree on, and looking at all circumstances, Aristotle

says that we can describe virtues as things that are destroyed by

deficiency or excess. Someone who runs away becomes a coward, while

someone who fears nothing is rash. In this way the virtue "bravery" can

be seen as depending upon a "mean" between two extremes. (For this

reason, Aristotle is sometimes considered a proponent of a doctrine of

a golden mean.[37]) People become habituated well by first performing

actions that are virtuous, possibly because of the guidance of teachers

or experience, and in turn these habitual actions then become real

virtue where we choose good actions deliberately.[38]

According to Aristotle, character properly understood (i.e. one's

virtue or vice), is not just any tendency or habit but something that

affects when we feel pleasure or pain. A virtuous person feels pleasure

when she performs the most beautiful or noble (kalos) actions. A person

who is not virtuous will often find his or her perceptions of what is

most pleasant to be misleading. For this reason, any concern with

virtue or politics requires consideration of pleasure and pain.[39]

When a person does virtuous actions, for example by chance, or under

advice, they are not yet necessarily a virtuous person. It is not like

in the productive arts, where the thing being made is what is judged as

well made or not. To truly be a virtuous person, one's virtuous actions

must meet three conditions: (a) they are done knowingly, (b) they are

chosen for their own sakes, and (c) they are chosen according to a

stable disposition (not at a whim, or in any way that the acting person

might easily change his choice about). And just knowing what would be

virtuous is not enough.[40] According to Aristotle's analysis, three

kinds of things come to be present in the soul that virtue is: a

feeling (pathos), an inborn predisposition or capacity (dunamis), or a

stable disposition that has been acquired (hexis).[41] In fact, it has

already been mentioned that virtue is made up of hexeis, but on this

occasion the contrast with feelings and capacities is made

clearer—neither is chosen, and neither is praiseworthy in the way that

virtue is.[42]

Comparing virtue to productive arts (technai) as with arts, virtue of

character must not only be the making of a good human, but also the way

humans do their own work well. Being skilled in an art can also be

described as a mean between excess and deficiency: when they are well

done we say that we would not want to take away or add anything from

them. But Aristotle points to a simplification in this idea of hitting

a mean. In terms of what is best, we aim at an extreme, not a mean, and

in terms of what is base, the opposite.[43]

Chapter 7 turns from general comments to specifics. Aristotle gives a

list of character virtues and vices that he later discusses in Books II

and III. As Sachs points out, (2002, p. 30) it appears the list is not

especially fixed, because it differs between the Nicomachean and

Eudemian Ethics, and also because Aristotle repeats several times that

this is a rough outline.[44]

Aristotle also mentions some "mean conditions" involving feelings: a

sense of shame is sometimes praised, or said to be in excess or

deficiency. Righteous indignation (Greek: nemesis) is a sort of mean

between joy at the misfortunes of others and envy. Aristotle says that

such cases will need to be discussed later, before the discussion of

Justice in Book V, which will also require special discussion. But the

Nicomachean Ethics only discusses the sense of shame at that point, and

not righteous indignation (which is however discussed in the Eudemian

Ethics Book VIII).

In practice Aristotle explains that people tend more by nature towards

pleasures, and therefore see virtues as being relatively closer to the

less obviously pleasant extremes. While every case can be different,

given the difficulty of getting the mean perfectly right it is indeed

often most important to guard against going the pleasant and easy

way.[45] However this rule of thumb is shown in later parts of the

Ethics to apply mainly to some bodily pleasures, and is shown to be

wrong as an accurate general rule in Book X. |

ア

リストテレスは、思考の徳が教えや経験や時間を必要とするのに対して、人格の徳(徳)は正しい習慣を守ることの結果として生まれると述べている[36]。

アリストテレスによれば、この徳の可能性はもともと人間の中にあるが、徳が存在するようになるかどうかは人間の本性によって決まるものではない[36]。

紳士が同意できるおおよそのことから始めて、あらゆる状況を見るという方法に従おうとして、アリストテレスは徳を不足や過剰によって滅びるものとして説明

できると言う。逃げる者は臆病になり、何も恐れない者は猪突猛進になる。このように、「勇敢さ」という美徳は、二つの極端なものの間の「平均」に依存して

いると見ることができる。(このため、アリストテレスは黄金平均の教義の提唱者と見なされることがある[37])。人は、おそらく教師の指導や経験によっ

て、最初に徳のある行動を行うことによってよく習慣化され、その習慣的な行動が、良い行動を意図的に選択する真の徳となる[38]。アリストテレスによれ

ば、正しく理解された性格(すなわち、人の徳や悪)は、単なる傾向や習慣ではなく、我々が喜びや痛みを感じるときに影響を与えるものであるという。徳の高

い人は、最も美しい、あるいは高貴な(kalos)行為を行うときに喜びを感じる。徳のない人は、何が最も楽しいかについて、しばしば自分の認識を誤らせ

ることになる。このため、美徳や政治に関心を持つには、快楽と苦痛を考慮する必要がある[39]。例えば、偶然に、あるいは助言を受けて、人が徳の高い行

為を行うとき、その人はまだ必ずしも徳の高い人ではない。生産芸術のように、作られるものがよくできたかどうか判断されるのではない。徳のある人であるた

めには、徳のある行動が、(a)わかってやっている、(b)自分のために選んでいる、(c)安定した性質に従って選んでいる(気まぐれでなく、行動する人

が簡単に選択を変えるようなやり方でない)、という三つの条件を満たしていなければならない。そして、何が徳になるかを知っているだけでは十分ではない

[40]。

アリストテレスの分析によれば、徳がある魂には、感情(パトス)、先天的な素質や能力(デュナミス)、獲得された安定した性質(ヘキス)の3種類のものが

存在するようになるとされている。

[41]実際、徳がヘクシスで構成されていることはすでに言及されているが、この機会に感情や能力との対比がより明確になる-どちらも選択されるものでは

なく、徳のあり方において賞賛に値するものではない。

42]芸術と同様に徳を生産芸術(テクナイ)に比較すると、人格の徳は良い人間を作るだけでなく、人間が自身の仕事をうまく行う方法でもあるに違いない。

ある芸術に熟練しているということは、過剰と不足の間の平均値とも表現できる。それらがよくできているとき、私たちはそこから何かを取り去ったり、付け加

えたりしたくないと言うのである。しかし、アリストテレスは、この平均をとるという考え方に単純化を指摘している。何が最善であるかという点では、私たち

は平均ではなく極端を目指し、何が基本であるかという点ではその逆である[43]

第7章は一般論から具体論に転じる。アリストテレスは後に第Ⅱ巻と第Ⅲ巻で論じる性格的な美徳と悪徳のリストを示している。サックスが指摘するように

(2002、p.30)、このリストは『ニコマコス』と『エウデミアン倫理学』の間で異なっており、またアリストテレスがこれが大まかな輪郭であると何度

も繰り返しているので、特に固定されていないようである[44]。アリストテレスはまた感情に関わるいくつかの「平均状態」にも言及している:恥の感覚は

時に賞賛されたり、過剰または不足であると言われている。義憤(ギリシャ語ではネメシス)は他人の不幸に対する喜びと嫉妬の間の一種の平均値である。アリ

ストテレスは、このような場合については、第五巻の「正義」の議論の前に、後で特別な議論をする必要があるとしている。しかし『ニコマコス倫理学』では、

その時点では恥の感覚についてしか論じておらず、義憤については論じていない(ただしこれは『エウデム倫理学』第八巻で論じている)。実際には、アリスト

テレスは、人はもともと快楽に向かう傾向が強いので、美徳は明らかに快楽ではない両極に比較的近いと見ている、と説明している。しかし、この経験則は『倫

理学』の後の部分で、主にいくつかの身体的快楽に適用されることが示され、第十巻では正確な一般規則として間違っていることが示される。 |

|

| 3 |

3 |

第3巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての

概説2・各論1) |

●Chapters 1–5:

Moral virtue as conscious choice Chapter 1 distinguishes actions chosen as relevant to virtue, and whether actions are to be blamed, forgiven, or even pitied.[46] Aristotle divides actions into three categories instead of two:- Voluntary (ekousion) acts. Involuntary or unwilling (akousion) acts, which is the simplest case where people do not praise or blame. In such cases a person does not choose the wrong thing, for example if the wind carries a person off, or if a person has a wrong understanding of the particular facts of a situation. Note that ignorance of what aims are good and bad, such as people of bad character always have, is not something people typically excuse as ignorance in this sense. "Acting on account of ignorance seems different from acting while being ignorant". "Non-voluntary" or "non willing" actions (ouk ekousion) that are bad actions done by choice, or more generally (as in the case of animals and children when desire or spirit causes an action) whenever "the source of the moving of the parts that are instrumental in such actions is in oneself" and anything "up to oneself either to do or not". However, these actions are not taken because they are preferred in their own right, but rather because all options available are worse. It is concerning this third class of actions that there is doubt about whether they should be praised or blamed or condoned in different cases. Several more critical terms are defined and discussed: Deliberate choice (proairesis), "seems to determine one's character more than one's actions do". Things done on the spur of the moment, and things done by animals and children can be willing, but driven by desire and spirit and not what we would normally call true choice. Choice is rational, and according to the understanding of Aristotle, choice can be in opposition to desire. Choice is also not wishing for things one does not believe can be achieved, such as immortality, but rather always concerning realistic aims. Choice is also not simply to do with opinion, because our choices make us the type of person we are, and are not simply true or false. What distinguishes choice is that before a choice is made there is a rational deliberation or thinking things through.[47] Deliberation (bouleusis), at least for sane people, does not include theoretical contemplation about universal and everlasting things, nor about things that might be far away, nor about things we can know precisely, such as letters. "We deliberate about things that are up to us and are matters of action" and concerning things where it is unclear how they will turn out. Deliberation is therefore not how we reason about ends we pursue, health for example, but how we think through the ways we can try to achieve them. Choice then is decided by both desire and deliberation.[48] Wishing (boulēsis) is not deliberation. We cannot say that what people wish for is good by definition, and although we could say that what is wished for is always what appears good, this will still be very variable. Most importantly we could say that a worthy (spoudaios) man will wish for what is "truly" good. Most people are misled by pleasure, "for it seems to them to be a good, though it is not".[49] Chapter 5 considers choice, willingness and deliberation in cases that exemplify not only virtue, but vice. Virtue and vice according to Aristotle are "up to us". This means that although no one is willingly unhappy, vice by definition always involves actions decided on willingly. (As discussed earlier, vice comes from bad habits and aiming at the wrong things, not deliberately aiming to be unhappy.) Lawmakers also work in this way, trying to encourage and discourage the right voluntary actions, but don't concern themselves with involuntary actions. They also tend not to be lenient to people for anything they could have chosen to avoid, such as being drunk, or being ignorant of things easy to know, or even of having allowed themselves to develop bad habits and a bad character. Concerning this point, Aristotle asserts that even though people with a bad character may be ignorant and even seem unable to choose the right things, this condition stems from decisions that were originally voluntary, the same as poor health can develop from past choices—and, "While no one blames those who are ill-formed by nature, people do censure those who are that way through lack of exercise and neglect." The vices then, are voluntary just as the virtues are. He states that people would have to be unconscious not to realize the importance of allowing themselves to live badly, and he dismisses any idea that different people have different innate visions of what is good.[50] +++++++++++ Chapters 6–12, First examples of moral virtues +++++++++++ Aristotle now deals separately with some of the specific character virtues, in a form similar to the listing at the end of Book II, starting with courage and temperance. Courage A virtue theory of courage Concerned with Mean Excess Deficiency fear (phobos) Courage (andreia): mean in fear and confidence First Type. Foolhardy or excessive fearlessness; is one who over indulges in fearful activities. Cowardly (deilos): exceeds in fear and is deficient in confidence confidence (thrasos) Second Type. Rash (thrasus): exceeds in confidence Courage means holding a mean position in one's feelings of confidence and fear. For Aristotle, a courageous person must feel fear.[51] Courage, however, is not thought to relate to fear of evil things it is right to fear, like disgrace—and courage is not the word for a man who does not fear danger to his wife and children, or punishment for breaking the law. Instead, courage usually refers to confidence and fear concerning the most fearful thing, death, and specifically the most potentially beautiful form of death, death in battle.[52] In Book III, Aristotle stated that feeling fear for one's death is particularly pronounced when one has lived a life that is both happy and virtuous, hence, life for this agent is worth living.[51] The courageous man, says Aristotle, sometimes fears even terrors that not everyone feels the need to fear, but he endures fears and feels confident in a rational way, for the sake of what is beautiful (kalos)—because this is what virtue aims at. This is described beautiful because the sophia or wisdom in the courageous person makes the virtue of courage valuable.[53] Beautiful action comes from a beautiful character and aims at beauty. The vices opposed to courage were discussed at the end of Book II. Although there is no special name for it, people who have excessive fearlessness would be mad, which Aristotle remarks that some describe Celts as being in his time. Aristotle also remarks that "rash" people (thrasus), those with excessive confidence, are generally cowards putting on a brave face.[54] Apart from the correct usage above, the word courage is applied to five other types of character according to Aristotle:[55]- An ancient Greek painting on pottery of a woman with her hand outstretched to offer water to a nude man with armor and weapons Hektor, the Trojan hero. Aristotle questions his courage. The courage of citizen soldiers. Aristotle says this is largely a result of penalties imposed by laws for cowardice and honors for bravery,[56] but that it is the closest type of seeming courage to real courage, is very important for making an army fight as if brave, but it is different from true courage because not based on voluntary actions aimed at being beautiful in their own right. Aristotle perhaps surprisingly notes that the Homeric heroes such as Hector had this type of courage. People experienced in some particular danger often seem courageous. This is something that might be seen amongst professional soldiers, who do not panic at false alarms. In another perhaps surprising remark Aristotle specifically notes that such men might be better in a war than even truly courageous people. However, he also notes that when the odds change such soldiers run. Spirit or anger (thumos) often looks like courage. Such people can be blind to the dangers they run into though, meaning even animals can be brave in this way, and unlike truly courageous people they are not aiming at beautiful acts. This type of bravery is the same as that of a mule risking punishment to keep grazing, or an adulterer taking risks. Aristotle however notes that this type of spirit shows an affinity to true courage and combined with deliberate choice and purpose it seems to be true courage. The boldness of someone who feels confident based on many past victories is not true courage. Like a person who is overconfident when drunk, this apparent courage is based on a lack of fear, and will disappear if circumstances change. A truly courageous person is not certain of victory and does endure fear. Similarly, there are people who are overconfident simply due to ignorance. An overconfident person might stand a while when things do not turn out as expected, but a person confident out of ignorance is likely to run at the first signs of such things. Chapter 9. As discussed in Book II already, courage might be described as achieving a mean in confidence and fear, but we must remember that these means are not normally in the middle between the two extremes. Avoiding fear is more important in aiming at courage than avoiding overconfidence. As in the examples above, overconfident people are likely to be called courageous, or considered close to courageous. Aristotle said in Book II that—with the moral virtues such as courage—the extreme one's normal desires tend away from are the most important to aim towards. When it comes to courage, it heads people towards pain in some circumstances, and therefore away from what they would otherwise desire. Men are sometimes even called courageous just for enduring pain. There can be a pleasant end of courageous actions but it is obscured by the circumstances. Death is, by definition, always a possibility—so this is one example of a virtue that does not bring a pleasant result.[57] Aristotle's treatment of the subject is often compared to Plato's. Courage was dealt with by Plato in his Socratic dialogue named the Laches. Temperance (sōphrosunē) A virtue theory of temperance Concerned with Mean Excess Deficiency pleasure (hēdonē) and pain (lupē) Temperance (sōphrosunē) scarcely occurs, but we may call it Insensible (anaisthētos) Profligacy, dissipation, etc. (akolasia) Temperance (sōphrosunē, also translated as soundness of mind, moderation, discretion) is a mean with regards to pleasure. He adds that it is only concerned with pains in a lesser and different way. The vice that occurs most often in the same situations is excess with regards to pleasure (akolasia, translated licentiousness, intemperance, profligacy, dissipation etc.). Pleasures can be divided into those of the soul and of the body. But those who are concerned with pleasures of the soul, honor, learning, for example, or even excessive pleasure in talking, are not usually referred to as the objects of being temperate or dissipate. Also, not all bodily pleasures are relevant, for example delighting in sights or sounds or smells are not things we are temperate or profligate about, unless it is the smell of food or perfume that triggers another yearning. Temperance and dissipation concern the animal-like, Aphrodisiac, pleasures of touch and taste, and indeed especially a certain type of touch, because dissipated people do not delight in refined distinguishing of flavors, and nor indeed do they delight in feelings one gets during a workout or massage in a gymnasium.[58] Chapter 11. Some desires like that of food and drink, and indeed sex, are shared by everyone in a certain way. But not everyone has the same particular manifestations of these desires. In the "natural desires" says Aristotle, few people go wrong, and then normally in one direction, towards too much. What is just to fulfill one's need, whereas people err by either desiring beyond this need, or else desiring what they ought not desire. But regarding pains, temperance is different from courage. A temperate person does not need to endure pains, but rather the intemperate person feels pain even with his pleasures, but also by his excess longing. The opposite is rare, and therefore there is no special name for a person insensitive to pleasures and delight. The temperate person desires the things that are not impediments to health, nor contrary to what is beautiful, nor beyond that person's resources. Such a person judges according to right reason (orthos logos).[59] Chapter 12. Intemperance is a more willingly chosen vice than cowardice, because it positively seeks pleasure, while cowardice avoids pain, and pain can derange a person's choice. So we reproach intemperance more, because it is easier to habituate oneself so as to avoid this problem. The way children act also has some likeness to the vice of akolasia. Just as a child needs to live by instructions, the desiring part of the human soul must be in harmony with the rational part. Desire without understanding can become insatiable, and can even impair reason.[60] Plato's treatment of the same subject is once again frequently compared to Aristotle's, as was apparently Aristotle's intention (see Book I, as explained above): Every virtue, as it comes under examination in the Platonic dialogues, expands far beyond the bounds of its ordinary understanding: but sōphrosunē undergoes, in Plato's Charmides, an especially explosive expansion – from the first definition proposed; a quiet temperament (159b), to "the knowledge of itself and other knowledges" (166e). — Burger (2008) p.80 Aristotle discusses this subject further in Book VII. +++++++++++ +++++++++++ |

第1章~第5章:意識的選択としての道徳

的徳 第1章では、徳に関連するものとして選択された行為を区別し、行為が非難されるべきなのか、許されるべきなのか、あるいは同情されるべきなのかを説明する [46]。アリストテレスは行為を2つではなく3つのカテゴリーに分ける:- 任意(ekousion)行為。不随意的または不本意な行為(akousion)、これは人々が賞賛も非難もしない最も単純なケースである。このような場 合、人は間違ったことを選択しない。例えば、風が人を運んでしまう場合や、人がある状況の特定の事実について間違った理解をしている場合などである。な お、性格の悪い人が常に持っているような、何が良くて何が悪いかという無知は、一般にこの意味での無知として弁解されることはない。「無知を理由に行動す ることと、無知でありながら行動することとは異なるようです。「非自発的」あるいは「非意志的」な行動(ouk ekousion)とは、「そのような行動の道具となる部分の動きの源が自分自身にある」場合、あるいはより一般的に(動物や子供のように欲求や精神が行 動を引き起こす場合)「するかしないかは自分次第」のもので、選択によって行われる悪い行動である。しかし、これらの行為は、それ自体が好ましいから行わ れるのではなく、むしろ、利用可能なすべての選択肢が悪いから行われるのである。この第三の行動については、場合によって賞賛されるべきか非難されるべき か、あるいは容認されるべきかという疑念が存在するのである。さらに重要な用語がいくつか定義され、議論されている。意図的な選択 (proairesis)、「行動よりも人格を決定するようだ」。咄嗟に行ったことや、動物や子供が行ったことは、意志があっても欲望や精神に突き動かさ れており、通常我々が真の選択と呼ぶものではないことがある。選択は合理的であり、アリストテレスの理解では、選択は欲望と対立することができる。選択と は、不老不死のような達成できるとは思えないことを願うことではなく、常に現実的な目標に関わることでもあります。なぜなら、私たちの選択は、私たち自身 をそのような人間にするものであり、単純に真実か偽りかということではないからです。選択を区別するものは、選択がなされる前に合理的な熟慮や考え抜きが あることである[47]。熟慮(bouleusis)は、少なくともまともな人々にとっては、普遍的で永遠に続くもの、遠くにあるものかもしれないもの、 文字のような正確に知ることができるものについての理論的熟考を含んでいない。「私たちが熟考するのは、自分たち次第のこと、行動の問題であり、どうなる かわからないようなことです。したがって、熟慮とは、たとえば健康など、私たちが追求する目的について推論する方法ではなく、それを達成するためにどのよ うな方法があるかを考え抜く方法なのです。そして選択は欲望と熟慮の両方によって決定される[48] 望むこと(boulēsis)は熟慮ではない。人々が望むものが定義上良いものであるとは言えないし、望むものが常に良いと思われるものであると言うこと はできるが、それでも非常に多様であろう。最も重要なことは、立派な(spoudaios)人は「本当に」良いことを願うと言えることです。ほとんどの人 は快楽に惑わされ、「そうではないが、善であるように見えるから」[49]。第5章は徳だけでなく悪の例となるケースでの選択、意志、熟慮について考え る。アリストテレスによれば、美徳と悪徳は「私たち次第」である。つまり、誰も喜んで不幸になることはないが、悪徳は定義上、常に喜んで決めた行動を伴う ということである。(先に述べたように、悪徳は悪い習慣や間違ったものを目指すことから生まれるのであって、意図的に不幸を目指すわけではない)。法律家 もこのように、正しい自発的な行動を奨励したり抑制したりしようとするが、非自発的な行動には関心を示さない。また、酔っぱらうこと、簡単にわかることを 知らないこと、あるいは悪い習慣や悪い性格を身につけることを許してしまったことなど、避けることを選択できたことについては、人に甘くしない傾向があ る。この点についてアリストテレスは、性格の悪い人が無知で、正しいことを選択できないように見えても、その状態はもともと自発的な判断から生じているの であって、健康状態が悪いことが過去の選択から発展するのと同じだと主張し、「誰も生まれつきの不良を責めないが、人々は運動不足や怠慢によってそのよう になった人々を非難する」と述べているのである。悪徳は美徳と同じように自発的なものである。彼は、人は悪い生き方を許容することの重要性に気づかない無 意識でなければならないと述べ、何が良いことなのかについて人によって異なる生得的なビジョンを持っているという考えを否定している[50]。 +++++++++++ 第六章から第十二章、徳の最初の例 +++++++++++ アリストテレスは次に、勇気と節制から始めて、第二巻末のリストと同様の形式で、具体的な性格の徳のいくつかを個別に扱っている。勇気 勇気の徳目論 平均 過剰 欠乏 恐怖(フォボス) 勇気(アンドレア):恐怖と自信における平均 第一型。無鉄砲または過度の恐れを知らない人;恐れのある活動に過度にふける人である。臆病者(deilos):恐怖を超え、自信に欠ける者 (thrasos)第二のタイプ。無謀(thrasus):自信を超える 勇気とは、自信と恐怖の気持ちの中で平均的な位置を保つことを意味する。アリストテレスにとって、勇気のある人は恐怖を感じなければならない[51]。し かし、勇気は不名誉のような恐れることが正しい悪事に対する恐怖に関係すると考えられておらず、妻や子供に対する危険や法を犯したことに対する罰を恐れな い人のことを勇気というのではないのである。その代わりに、勇気は通常、最も恐ろしいもの、死、特に最も潜在的に美しい死の形態である戦死に関する自信と 恐怖を指している[52]。アリストテレスは第III書で、自分の死に対する恐怖を感じることは、幸福で高潔な人生を送ってきたときに特に顕著になり、そ れゆえこの代理人の人生は生きる価値があると述べている[51]。 [アリストテレスは、勇気のある人は、誰もが恐れる必要を感じないような恐怖さえも時には恐れるが、美しいもの(カロス)のために、恐怖に耐えて合理的に 自信を持つ-これが徳の目指すところだからである、と述べている。このように美しいと表現されるのは、勇気のある人の中にあるソフィアや知恵が勇気という 徳に価値を与えているからである[53]。 美しい行動は美しい性格から生まれ、美を目指す。勇気に対立する悪徳については、第II巻の最後で述べた。特別な名称はないが、過度の恐れを知らぬ者は狂 人となり、アリストテレスは彼の時代にはケルト人をそう表現する者もいたと発言している。アリストテレスはまた、「軽率な」人々(thrasus)、過剰 な自信を持つ人々は、一般的に勇敢な顔をした臆病者であると述べている[54]。上記の正しい用法とは別に、勇気という言葉はアリストテレスによれば他の 5種類の性格に適用される[55]-古代ギリシャの陶器の絵には、鎧と武器を持った裸の男性ヘクトルに手を伸ばして水を差し出す女性の姿が描かれている。 アリストテレスは彼の勇気を問う。市民兵の勇気。アリストテレスは、これは臆病な者には法律で罰則が課され、勇敢な者には栄誉が与えられることによるとこ ろが大きいが[56]、本当の勇気に最も近いように見えるタイプのもので、軍隊を勇敢であるかのように戦わせるには非常に重要だが、それ自体が美しくなる ことを目的とした自発的行為に基づいていないため本当の勇気とは異なると述べている。アリストテレスは、ヘクトルなどのホメロスの英雄がこのタイプの勇気 を持っていたことを、意外にも指摘しているのかもしれない。 つまり、動物にも勇気があるわけで、本当に勇気のある人とは違って、美しい行いを目指しているわけではない。ラバが罰を覚悟で放牧したり、姦夫が危険を冒 したりするのと同じである。しかしアリストテレスは、この種の精神は真の勇気に親和性を示し、意図的な選択と目的とが組み合わさって、真の勇気となるよう だと述べている。過去の多くの勝利に基づいて自信を持つ人の大胆さは、真の勇気ではない。酔うと自信過剰になる人のように、この見かけ上の勇気は恐怖心の 欠如に基づくもので、状況が変われば消えてしまう。真の勇気ある人は、勝利を確信せず、恐怖に耐えているのです。同じように、無知が故に自信過剰になる人 もいる。自信過剰の人は、物事が予想通りにならないとき、しばらくは耐えられるかもしれないが、無知から自信を持った人は、そのようなことの最初の兆候で 逃げ出す可能性が高いのである。第九章 すでに第Ⅱ巻で述べたように、勇気とは自信と恐怖の中で平均値を達成することと言えるかもしれないが、この平均値は通常両極端の中間にあるわけではないこ とを忘れてはならない。勇気を目指すには、過信を避けることよりも、恐怖を避けることの方が重要である。上の例のように、自信過剰の人は、勇気があると言 われたり、勇気に近いと思われたりする可能性が高い。アリストテレスは『第二書』で、勇気のような徳は、自分の正常な欲望が遠ざかりがちな極限を目指すこ とが最も重要であると述べている。勇気の場合、状況によっては苦痛に向かい、その結果、他の欲望から遠ざかる。男は痛みに耐えることで、勇気があると言わ れることもある。勇気のある行動には楽しい結末がありうるが、それは状況によって不明瞭になる。死は定義上、常に可能性があるので、これは楽しい結果をも たらさない美徳の一例である[57] アリストテレスのこの主題の扱いはしばしばプラトンのものと比較される。勇気はプラトンが『ラケス』というソクラテスの対話の中で扱ったものである。ま た、このような「潔癖症」は、「潔癖症」とも呼ばれ、「潔癖症」は、「潔癖症」と「潔癖症」を合わせたものである。あくまでも、より少ない、異なる意味で の苦痛に関わるものであると付け加えている。同じ状況で最もよく起こる悪習は、快楽に関する過剰(akolasia、放縦、不摂生、浪費などと訳される) である。 快楽は魂のものと肉体のものとに分けることができる。しかし、魂の快楽、例えば名誉や学問、あるいは話すことに過剰な喜びを感じる人は、通常、節制や放縦 の対象とは呼ばれない。また、身体的な快楽がすべて当てはまるわけではなく、例えば、景色や音や匂いを楽しむことは、食べ物や香水の匂いが別の憧れを引き 起こすのでない限り、節制や放逸の対象にはなりません。節制と放逸は、動物的な、媚薬的な、触覚と味覚の快楽に関係し、実際特にある種の触覚に関係する。 なぜなら放逸者は洗練された味の区別を喜ばないし、ジムでのトレーニングやマッサージ中に得られる感情をも喜ばないからだ[58] 第11章。飲食やセックスのようないくつかの欲望は、ある意味で万人に共有されるものである。しかし、誰もがこれらの欲望の同じ特定の現れ方をしているわ けではない。アリストテレスは言う、「自然な欲望」において、間違った方向に、そして普通には行き過ぎた方向に行く人はほとんどいない。自分の欲求を満た すだけのものであるのに対し、人はその欲求を超えて欲するか、あるいは欲するべきでないものを欲することによって、誤りを犯すのである。しかし、痛みに関 しては、節制は勇気と異なる。温厚な人は苦痛に耐える必要がなく、むしろ不健全な人は、快楽の中にも苦痛を感じ、また、過剰な憧れによって苦痛を感じる。 その逆は稀であるから、快楽や喜びに鈍感な人に特別な名称はない。節制の人は、健康を害することなく、美しいものに反することなく、その人の資力を超える ものでないものを欲している。そのような人は、正しい理性(オルソス・ロゴス)に従って判断する[59]。不摂生は臆病よりも進んで選択される悪である。 なぜなら、不摂生は積極的に快楽を求めるが、臆病は痛みを避け、痛みはその人の選択を狂わせることができるからである。そのため、この問題を回避するため に自分を習慣化することが容易であるため、私たちはより多くの不摂生を非難するのである。子供の行動もまたアコライアの悪習と似ているところがある。子供 が指示されて生きるように、人間の魂の欲望は理性的な部分と調和していなければならない。理解なき欲望は飽くことなく、理性を損なうことさえある [60]。プラトンの同じ主題の扱いは、再びアリストテレスのものと頻繁に比較されるが、それは明らかにアリストテレスの意図であった(上に説明したよう に第一巻を参照)。プラトンの対話で検討されるとき、あらゆる美徳はその通常の理解の範囲をはるかに超えて拡大する。しかし、プラトンの『カルミデス』で は、sōphrosunēは、最初に提案された静かな気質(159b)という定義から、「それ自身と他の知の知識」(166e)へと、特に爆発的に拡大す るのである。- Burger (2008) p.80 アリストテレスはこの主題をさらに第七巻で論じている。 |

|

| 4 |

4 |

第4巻(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての

各論2) |

|||

| 5 |

5 |

第5巻(正義) |

|||

| 6 |

6 |

第6巻(知性的な卓越性(徳)についての

概説・各論) |

Book VI of the

Nicomachean Ethics is identical to Book V of the Eudemian Ethics.

Earlier in both works, both the Nicomachean Ethics Book IV, and the

equivalent book in the Eudemian Ethics (Book III), though different,

ended by stating that the next step was to discuss justice. Indeed, in

Book I Aristotle set out his justification for beginning with

particulars and building up to the highest things. Character virtues

(apart from justice perhaps) were already discussed in an approximate

way, as like achieving a middle point between two extreme options, but

this now raises the question of how we know and recognize the things we

aim at or avoid. Recognizing the mean means recognizing the correct

boundary-marker (horos) which defines the frontier of the mean. And so

practical ethics, having a good character, requires knowledge.

Near the end of Book I Aristotle said that we may follow others in

considering the soul (psuchē) to be divided into a part having reason

and a part without it. Until now, he says, discussion has been about

one type of virtue or excellence (aretē) of the soul — that of the

character (ēthos, the virtue of which is ēthikē aretē, moral virtue).

Now he will discuss the other type: that of thought (dianoia).

The part of the soul with reason is divided into two parts:

One whereby we contemplate or observe the things with invariable causes

One whereby we contemplate the variable things—the part with which we

deliberate concerning actions

Aristotle states that if recognition depends upon likeness and kinship

between the things being recognized and the parts of the soul doing the

recognizing, then the soul grows naturally into two parts, specialised

in these two types of cause.[88]

Aristotle enumerates five types of hexis (stable dispositions) that the

soul can have, and which can disclose truth:[89]

Art (Techne). This is rational, because it involves making things

deliberately, in a way that can be explained. (Making things in a way

that could not be explained would not be techne.) It concerns variable

things, but specifically it concerns intermediate aims. A house is built not for its own sake, but to have a place to live, and so on. Knowledge (Episteme). "We all assume that what we know is not capable of being otherwise." And "it escapes our notice when they are or not". "Also, all knowledge seems to be teachable, and what is known is learnable."[90] Practical Judgement (Phronesis). This is the judgement used in deciding well upon overall actions, not specific acts of making as in techne. While truth in techne would concern making something needed for some higher purpose, phronesis judges things according to the aim of living well overall. This, unlike techne and episteme, is an important virtue, which will require further discussion. Aristotle associates this virtue with the political art. Aristotle distinguishes skilled deliberation from knowledge, because we do not need to deliberate about things we already know. It is also distinct from being good at guessing, or being good at learning, because true consideration is always a type of inquiry and reasoning. Wisdom (Sophia). Because wisdom belongs to the wise, who are unusual, it can not be that which gets hold of the truth. This is left to nous, and Aristotle describes wisdom as a combination of nous and episteme ("knowledge with its head on"). Intellect (Nous). Is the capacity we develop with experience, to grasp the sources of knowledge and truth, our important and fundamental assumptions. Unlike knowledge (episteme), it deals with unarticulated truths.[91] Both phronēsis and nous are directed at limits or extremities, and hence the mean, but nous is not a type of reasoning, rather it is a perception of the universals that can be derived from particular cases, including the aims of practical actions. Nous therefore supplies phronēsis with its aims, without which phronēsis would just be the "natural virtue" (aretē phusikē) called cleverness (deinotēs).[92] In the last chapters of this book (12 and 13) Aristotle compares the importance of practical wisdom (phronesis) and wisdom (sophia). Although Aristotle describes sophia as more serious than practical judgement, because it is concerned with higher things, he mentions the earlier philosophers, Anaxagoras and Thales, as examples proving that one can be wise, having both knowledge and intellect, and yet devoid of practical judgement. The dependency of sophia upon phronesis is described as being like the dependency of health upon medical knowledge. Wisdom is aimed at for its own sake, like health, being a component of that most complete virtue that makes happiness. Aristotle closes by arguing that in any case, when one considers the virtues in their highest form, they would all exist together. |

ニ

コマコス倫理学』第六巻は、『エウデモス倫理学』第五巻と同一である。両著作のうち、『ニコマコス倫理学』第Ⅳ巻と『エウデモス倫理学』の同等の書(第Ⅲ

巻)は、違いはあるが、その前に、次は正義について論じると言って終わっている。実際、第1巻でアリストテレスは、特殊なものから始めて最高のものへと積

み上げていくことの正当性を示している。人格的な美徳は(おそらく正義は別として)、二つの極端な選択肢の間の中間点を達成するような形ですでに近似的に

論じられていたが、ここで、我々が目指すもの、避けるものをどのように知り、認識するかという問題が提起されることになる。平均を認識するということは、

平均のフロンティアを規定する正しい境界標識(ホロス)を認識することである。そして、実践的な倫理、つまり良い人格を持つためには、知識が必要なのであ

る。アリストテレスは、第1巻の終わりで、魂(プシューケ)を理性を持つ部分と持たない部分に分けて考えることは、他の人たちに倣ってもよい、と述べてい

る。これまで、魂の徳や卓越性(aretē)のうち、人格(ēthos、徳はēthikē

aretē、道徳的徳)の徳について議論されてきた。次に、もう一つのタイプである思考(dianoia)について説明する。理性を持つ魂の部分は二つに

分かれる。アリストテレスは、もし認識が認識されるものと認識する魂の部分との間の類似性と親近性に依存するならば、魂はこれら2種類の原因に特化した2

つの部分に自然に成長すると述べている[88]。アリストテレスは魂が持ちうる、真実を開示しうる5種類のヘキス(安定した性質)を列挙している[89]

芸術(テクネ)。これは合理的であり、なぜならそれは説明できる方法で意図的にものを作ることを含むからである。(説明できない方法で物を作ることはテク

ノではない。)それは可変的なものに関わるが、特に中間的な目的に関わる。 家はそれ自体のためではなく、住む場所を確保するために建てる、など。知識(エピステーメー)。"私たちは皆、自分が知っていることは、そうでないことは あり得ないと思い込んでいる" そして、"そうであるかそうでないかは、私たちの気づかないところで逃げている"。"また、すべての知識は教えることができるようであり、知られているこ とは学ぶことができる"[90]実践的判断(Phronesis)。これは、テクネにおけるような具体的な作る行為ではなく、全体的な行為についてよく判 断するために用いられる判断である。テクネにおける真理は、より高い目的のために必要なものを作ることに関係するが、フロネシスは、全体としてよく生きる という目的に従って物事を判断する。これはテクネやエピステーメーとは異なり、重要な徳目であり、今後さらに議論が必要であろう。アリストテレスはこの徳 目を政治術と結びつけている。アリストテレスは熟練した熟慮を知識と区別しているが、それはすでに知っている事柄について熟慮する必要がないからである。 また、真の熟慮は常に探究と推論の一種であるため、推測が得意であることや、学習が得意であることとも区別される。知恵(ソフィア)。知恵は賢者に属する ものであり、賢者は普通ではないので、真理をつかむものであるはずがない。これはヌースに任されており、アリストテレスは知恵をヌースとエピステーメー (「頭を使った知識」)の組み合わせと表現しています。知性(ヌース)。知識と真理の源、重要かつ基本的な前提を把握するために、経験とともに発達する能 力です。知識(エピステーメー)とは異なり、言語化されていない真理を扱う[91]。フロネシスもヌースも限界や極限、それゆえ平均を指向するが、ヌース は推論の一種ではなく、むしろ実践的行為の目的など特定の事例から導き出される普遍性の認識である。そのため、ヌースはフロネシスにその目的を供給し、そ れがなければフロネシスは利口(deinotēs)と呼ばれる「自然の美徳」(aretē phusikē)に過ぎない[92] 本書の最後の章(12、13)で、アリストテレスは実践智(phronesis)と知恵(sophia)の重要性について比較している。アリストテレスは ソフィアがより高次のものに関係しているため、実践的判断よりも深刻であると述べているが、彼は、知識と知性の両方を持ちながら実践的判断力を欠いた賢者 になりうることを証明する例として、アナクサゴラスとタレスという初期の哲学者たちを挙げている。哲学がフロネシスに依存するのは、健康が医学的知識に依 存するのと同じであると述べている。知恵は、健康のように、幸福をもたらす最も完全な徳の構成要素であり、それ自身のために目指されるのである。アリスト テレスは最後に、いずれにせよ、美徳を最高の形で考えるとき、それらはすべて一緒に存在することになる、と論じている。 |

|

| 7 |

7 |

第7巻(抑制と無抑制、快楽-A稿) |

|||

| 8 |

8 |

第8巻(愛1) |

|||

| 9 |

9 |

第9巻(愛2) |

|||

| 10 |

10 |

第10巻(快楽-B稿、結び) |

|||

| Chapters 6–8:

Happiness |

Turning

to happiness then, the aim of the whole Ethics; according to the

original definition of Book I it is the activity or being-at-work

chosen for its own sake by a morally serious and virtuous person. This

raises the question of why play and bodily pleasures cannot be

happiness, because for example tyrants sometimes choose such

lifestyles. But Aristotle compares tyrants to children, and argues that

play and relaxation are best seen not as ends in themselves, but as

activities for the sake of more serious living. Any random person can

enjoy bodily pleasures, including a slave, and no one would want to be

a slave.[124]

Aristotle says that if perfect

happiness is activity in accordance with the highest virtue, then this

highest virtue must be the virtue of the highest part, and Aristotle

says this must be the intellect (nous) "or whatever else it be that is

thought to rule and lead us by nature, and to have cognizance of what

is noble and divine". This highest activity, Aristotle says, must be

contemplation or speculative thinking (energeia ... theōrētikē). This

is also the most sustainable, pleasant, self-sufficient activity;

something aimed at for its own sake. (In contrast to politics and

warfare it does not involve doing things we'd rather not do, but rather

something we do at our leisure.) However, Aristotle says this

aim is not strictly human, and that to achieve it means to live in

accordance not with our mortal thoughts but with something immortal and

divine which is within humans. According to Aristotle, contemplation is

the only type of happy activity it would not be ridiculous to imagine

the gods having. The intellect is indeed each person's true self, and

this type of happiness would be the happiness most suited to humans,

with both happiness (eudaimonia) and the intellect (nous) being things

other animals do not have. Aristotle also claims that compared to other

virtues, contemplation requires the least in terms of possessions and

allows the most self-reliance, "though it is true that, being a man and

living in the society of others, he chooses to engage in virtuous

action, and so will need external goods to carry on his life as a human

being".[125] |

そ

こで、『ニコマコス倫理学』全体の目的である幸福について考えてみよう。『第一書』の本来の定義によれば、それは、道徳的に真面目で徳の高い人が、それ自

体のために選択する活動、あるいは仕事である。このことは、例えば暴君がそのような生き方を選ぶことがあるから、遊びや肉体的な快楽がなぜ幸福になりえな

いのかという疑問を生じさせる。しかし、アリストテレスは暴君を子供になぞらえて、遊びやくつろぎはそれ自体が目的ではなく、より真剣な生活のための活動

としてとらえるのが最善であると論じている。アリストテレスは、完全な幸福が最高の徳に従った活動であるとすれば、この最高の徳は最高の部分の徳でなけれ

ばならず、アリストテレスはこれが知性(ヌース)「あるいは、生まれつき我々を支配し導くと考えられ、高貴で神々しいものを認識するものである他のもの」

でなければならないと言っている[124] 。アリストテレスは、この最高の活動は、観想または思索的思考(energeia ...

theōrētikē)でなければならないと言う。これはまた、最も持続可能で、楽しく、自己充足的な活動であり、それ自身のために目指されるものであ

る。(政治や戦争とは対照的に、それはやりたくないことをやるのではなく、むしろ気ままにやることである)。しかし、アリストテレスは、この目的は厳密に

は人間的なものではなく、それを達成するためには、人間の死すべき思考ではなく、人間の中にある不滅で神聖なものに従って生きることであるという。アリス

トテレスによれば、神々が持っていると想像してもおかしくない唯一の幸福な活動が観想である。知性はまさに人間の真の自己であり、幸福(エウダイモニア)

も知性(ヌース)も他の動物にはないものであり、この種の幸福は人間に最も適した幸福であろう。アリストテレスはまた、他の美徳と比較して、観照が最も財

産を必要とせず、最も自立を可能にすると主張している。「ただし、人間であり、他者の社会の中で生きている以上、徳のある行動を選択するため、人間として

の生活を営むために外部の財を必要とすることは事実である」。 |

| 巻 |

|||||

| 1 |

1 |

第1章 -

あらゆる人間活動は何らかの「善(アガトン)」を追求している。諸々の「善(アガトン)」の間には従属関係がある。 |

【序説】 |

||

| 2 |

第2章 -

「人間的善」「最高善(ト・アリストン)」を目的とする活動は政治的活動である。我々の研究も政治学的な活動だと言える。 |

||||

| 3 |

第3章 -

素材が許す以上の厳密性を期待すべきではない。聴講者の条件。 |

||||

| 4 |

第4章 -

「最高善(ト・アリストン)」が「幸福(エウダイモニア)」であることは万人の容認せざるを得ないところだが、「幸福」が何であるかについては異論がある

(聴講者の条件としての善き「習慣付け」の重要性)。 |

||||

| 5 |

第5章 -

「善」とか「幸福」とかは「快楽(ヘードネー)」や「名誉(ティメー)」や「富(プルートス)」には存しない。 |

||||

| 6 |

第6章 - 「善のイデア」。 |

||||

| 7 |

第7章 -

「最高善」は究極的な意味における目的であり自足的なものでなくてはならない。「幸福」はこのような性質を持つ。「幸福」とは何か、「人間の機能」から導

く「幸福」の規定。 |

||||

| 8 |

第8章 -

この規定は「幸福」に関する従来の諸々の見解に適合する。 |

||||

| 9 |

第9章 -

「幸福」は「学習」や「習慣付け」によって得られるものか、それとも神与のものか。 |

||||

| 10 |

第10章 -

人は生存中に「幸福」な人と言われ得るか。 |

||||

| 11 |

第11章 -

生きている人々の運・不運が死者の「幸福」に影響を持つか。 |

||||

| 12 |

第12章 -

「幸福」は「賞賛すべきもの」に属するか「尊ぶべきもの」に属するか。 |

||||

| 13 |

第13章 -

「卓越性(徳、アレテー)」論の序説 ---

人間の「機能」の区分。それに基づく人間の「卓越性(徳、アレテー)」の区別。「知性的卓越性」と「倫理的卓越性」。 |

||||

| 2 |

1 |

第1章 -

倫理的な卓越性(徳、アレテー)は本性的に与えられているものではない。それは行為を習慣(エトス)化することによって生まれる。 |

【倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての概説】 |

||

| 2 |

第2章 -

ではいかに行為すべきか、一般に過超と不足とを避けなければならない(中庸(メソテース))。 |

||||

| 3 |

第3章 -

「快楽(ヘードネー)」や「苦痛(リュペー)」が徳に対して有する重要性。 |

||||

| 4 |

第4章 -

徳を生じさせるに至る諸々の行為と、徳に即しての行為とは、同じ意味において「善き行為」であるのではない。 |

||||

| 5 |

第5章 -

徳とは何か。それは「情念(パトス)」でも「能力(デュナミス)」でもなく「状態(ヘクシス)」である。 |

||||

| 6 |

第6章 -

ではいかなる「状態」であるか。それは「中(ト・メソン)」(中庸(メソテース))を選択すべき「状態」に他ならない。 |

||||

| 7 |

第7章 - 前章の定義の例示。 |

||||

| 8 |

第8章 -

両極端は「中(ト・メソン)」に対しても、また相互の間においても反対的である。 |

||||

| 9 |

第9章 -

「中(ト・メソン)」を得るための実際的な助言。 |

||||

| 3 |

1 |

第1章 -

善い悪いと言われるのは「随意的」な行為である。「随意的」とは、1.強要的でなく、2.個々の場合の情況に関する無識に基づくものではない、ことを意味

する。 |

(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての概説

2・各論1) |

||

| 2 |

第2章 -

徳は「善い行為」が更に、3.「選択(プロアイレシス)」に基づくものであることを要求する。「選択(プロアイレシス)」とは「前もって思量した」ことで

ある必要がある。 |

||||

| 3 |

第3章 -

「思量(ブーレウシス)」とは何か --- かくして「選択」とは「我々の自由と責任に属する事柄」に対する「思量的な欲求」である。 |

||||

| 4 |

第4章 -

「選択」が目的への諸々の手立てに関わるのに対して、「願望(ブーレーシス)」は目的それ自身に関わる。 |

||||

| 5 |

第5章 -

かくして徳は我々の「自由(エレウテリア)」に属し、悪徳(カキア)もまた我々の責任に属する。 |

||||

| 6 |

第6章 -

「勇敢」は恐怖と平然(特に戦いにおける死)に関わる。 |

【倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての各論】

【勇敢(アンドレイア)】 |

|||

| 7 |

第7章 -

それに対する悪徳、「怯懦(臆病、デイリア)」「無謀(トラシュテース)」など。 |

||||

| 8 |

第8章 -

「勇敢」に似て非なるもの五つ。 |

||||

| 9 |

第9章 - 「勇敢」の快苦との関係。 |

||||

| 10 |

第10章 -

「節制」は種として触覚的な肉体的快楽に関わる。 |

【節制(ソープロシュネー)】 |

|||

| 11 |

第11章 -

「節制」と「放埒(アコラシア)」「無感覚(アナイステーシア)」。 |

||||

| 12 |

第12章 -

「放埒」は「怯懦(臆病)」より随意的なものであり、それだけにより多くの非難に値する。「放埒」と子供の「わがまま」の比較。 |

||||

| 4 |

1 |

第1章 -

「寛厚(エレウテリオテース)」(※「放漫」と「けち」の中庸。) |

(倫理的な卓越性(徳)についての各論

2)【財貨(クレーマタ)に関する徳 |

||

| 2 |

第2章 -

「豪華(メガロペレペイア)」(※価値あるものへの壮大な出費。「粗大・派手」と「細かさ」の中庸。) |

||||

| 3 |

第3章 -

「矜持(メガロプシュキア)」(※「倨傲・傲慢」と「卑屈」の中庸。) |

【名誉(ティメー)に関する徳】 |

|||

| 4 |

第4章 -

(名誉心の過剰・欠如に対する)「中庸(メソテース)」 |

||||

| 5 |

第5章 -

「温和(プラオテース)」(※「癇癪持ち」と「意気地なし」の中庸。) |

【怒り(オルゲー)に関する徳】 |

|||

| 6 |

第6章 -