アメリカ合衆国における優生学

Eugenics in the United States

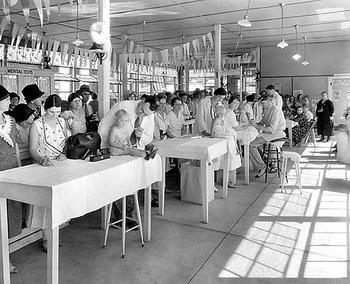

The

main sign reads: "Eugenic and Health Exhibit"; charts concern the

heritability of illiteracy and the relatively higher birth rate of

immigrants

☆ 優生学(人間の遺伝的質を改善することを目的とする信念と実践の体系)は、19世紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけて、米国の歴史と文化において重要な役割を 果たした。 そのアメリカの実践は表向きには遺伝的資質の改善を目的としたものだったが、優生学はむしろ人口における支配的集団の地位を維持することに主眼があったと いう主張もある。学術研究では、優生学運動の標的となったのは、社会に適さないと見なされた人々、つまり貧困層、障害者、精神疾患患者、特定の有色人種コ ミュニティであり、優生学者による不妊手術の犠牲者の多くは、アフリカ系アメリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人、ネイティブアメリカンと特定された女性であった ことが判明している。アジア系アメリカ人、またはネイティブアメリカンであると特定された女性であった。その結果、米国の優生学運動は、現在では一般的に 人種差別主義や自国中心主義の要素と関連付けられている。この運動はある程度、科学的な遺伝学というよりも、人口統計や人口の変化、経済や社会福祉への懸 念への反応であったからだ(Eugenics in the United States)(→「年表・アメリカ合衆国の優生学」)。

| Eugenics, the set of

beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of

the human population,[1][2] played a significant role in the history

and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the

mid-20th century.[3] The cause became increasingly promoted by

intellectuals of the Progressive Era.[4][5] While its American practice was ostensibly about improving genetic quality, it has been argued that eugenics was more about preserving the position of the dominant groups in the population. Scholarly research has determined that people who found themselves targets of the eugenics movement were those who were seen as unfit for society—the poor, the disabled, the mentally ill, and specific communities of color—and a disproportionate number of those who fell victim to eugenicists' sterilization initiatives were women who were identified as African American, Asian American, or Native American.[6][7] As a result, the United States' eugenics movement is now generally associated with racist and nativist elements, as the movement was to some extent a reaction to demographic and population changes, as well as concerns over the economy and social well-being, rather than scientific genetics.[8][7] |

優生学(人間の遺伝的質を改善することを目的とする信念と実践の体系)

は、19世紀後半から20世紀半ばにかけて、米国の歴史と文化において重要な役割を果たした。 そのアメリカの実践は表向きには遺伝的資質の改善を目的としたものだったが、優生学はむしろ人口における支配的集団の地位を維持することに主眼があったと いう主張もある。学術研究では、優生学運動の標的となったのは、社会に適さないと見なされた人々、つまり貧困層、障害者、精神疾患患者、特定の有色人種コ ミュニティであり、優生学者による不妊手術の犠牲者の多くは、アフリカ系アメリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人、ネイティブアメリカンと特定された女性であった ことが判明している。アジア系アメリカ人、またはネイティブアメリカンであると特定された女性であった。[6][7] その結果、米国の優生学運動は、現在では一般的に人種差別主義や自国中心主義の要素と関連付けられている。この運動はある程度、科学的な遺伝学というより も、人口統計や人口の変化、経済や社会福祉への懸念への反応であったからだ。[8][7] |

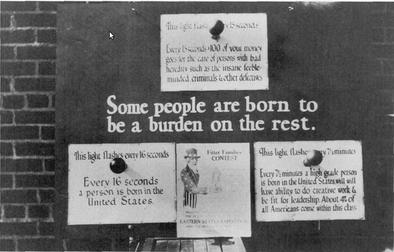

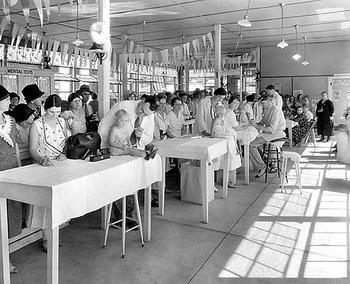

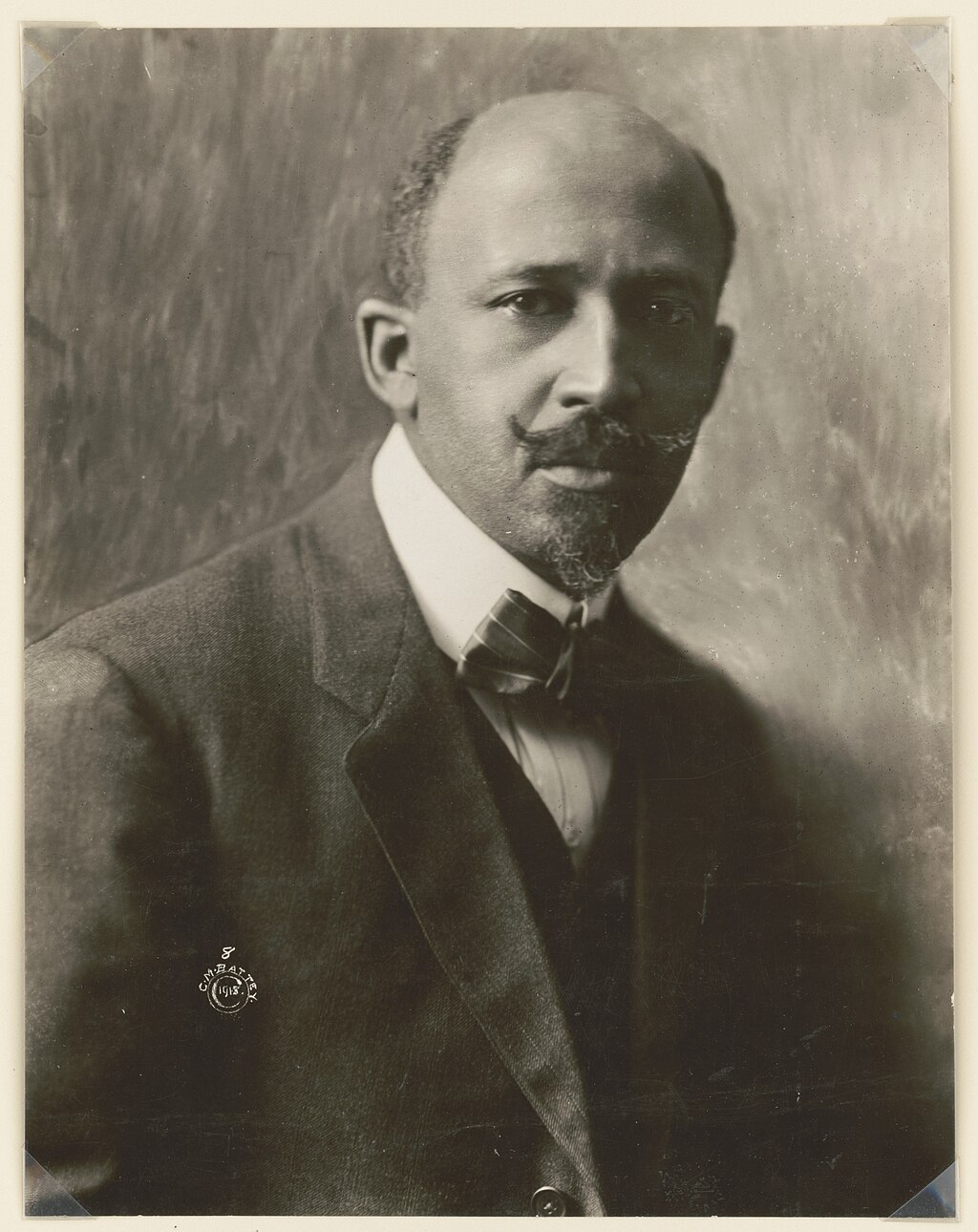

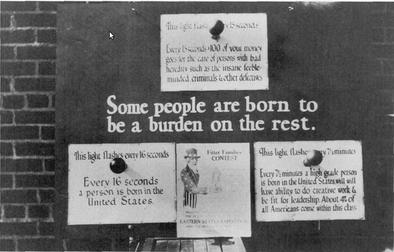

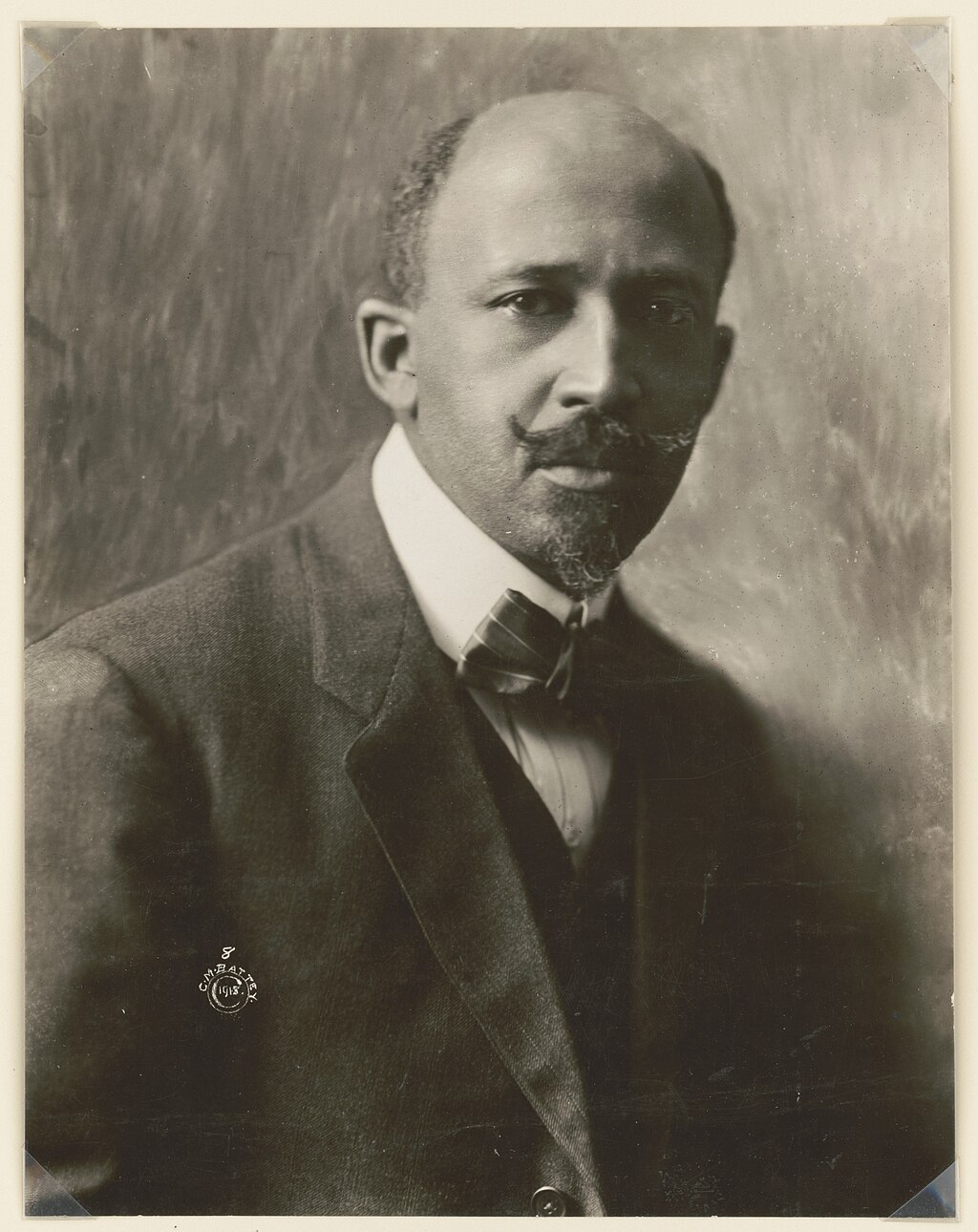

| History Early proponents The American eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of Sir Francis Galton, which originated in the 1880s. In 1883, Galton first used the word eugenics to describe scientifically, the biological improvement of genes in human races and the concept of being "well-born".[9] He believed that differences in a person's ability were acquired primarily through genetics and that eugenics could be implemented through selective breeding in order for the human race to improve in its overall quality, therefore allowing for humans to direct their own evolution.[10] In the US, eugenics was largely supported after the discovery of Mendel's law led to a widespread interest in the idea of breeding for specific traits.[11] Galton studied the upper classes of Britain, and arrived at the conclusion that their social positions could be attributed to a superior genetic makeup.[12] American eugenicists tended to believe in the genetic superiority of Nordic, Germanic, and Anglo-Saxon peoples, supported strict immigration and anti-miscegenation laws, and supported the forcible sterilization of the poor, disabled and "immoral."[13]  Eugenics supporters hold signs criticizing various "genetically inferior" groups. Wall Street, New York, c. 1915. The American eugenics movement received extensive funding from various corporate foundations including the Carnegie Institution, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Harriman railroad fortune.[14] In 1906, J.H. Kellogg provided funding to help found the Race Betterment Foundation in Battle Creek, Michigan.[12] The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) was founded in Cold Spring Harbor, New York in 1911 by the renowned biologist Charles B. Davenport, using money from both the Harriman railroad fortune and the Carnegie Institution.[15] As late as the 1920s, the ERO was one of the leading organizations in the American eugenics movement.[12][16] In years to come, the ERO and the American Eugenics Society collected a mass of family pedigrees and provided training for eugenics field workers who were sent to analyze individuals at various institutions, such as mental hospitals and orphanage institutions, across the United States.[17] Eugenicists such as Davenport, the psychologist Henry H. Goddard, Harry H. Laughlin, and the conservationist Madison Grant (all of whom were well-respected during their time) began to lobby for various solutions to the problem of the "unfit."[15] Davenport favored immigration restriction and sterilization as primary methods; Goddard favored segregation in his The Kallikak Family; Grant favored all of the above and more, even entertaining the idea of extermination.[18] By 1910, there was a large and dynamic network of scientists, reformers, and professionals engaged in national eugenics projects and actively promoting eugenic legislation. The American Breeder's Association, the first eugenic body in the U.S., expanded in 1906 to include a specific eugenics committee under the direction of Charles B. Davenport.[19][20] The ABA was formed specifically to "investigate and report on heredity in the human race, and emphasize the value of superior blood and the menace to society of inferior blood."[21] Membership included Alexander Graham Bell,[22] Stanford president David Starr Jordan and Luther Burbank.[23][24] The American Association for the Study and Prevention of Infant Mortality was one of the first organizations to begin investigating infant mortality rates in terms of eugenics.[25] They promoted government intervention in attempts to promote the health of future citizens.[26][verification needed] Several feminist reformers advocated an agenda of eugenic legal reform. The National Federation of Women's Clubs, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and the National League of Women Voters were among the variety of state and local feminist organizations that at some point lobbied for eugenic reforms.[27] One of the most prominent feminists to champion the eugenic agenda was Margaret Sanger, the leader of the American birth control movement and founder of Planned Parenthood. Sanger saw birth control as a means to prevent unwanted children from being born into a disadvantaged life, and incorporated the language of eugenics to advance the movement.[28][29] Sanger also sought to discourage the reproduction of persons who, it was believed, would pass on mental disease or serious physical defects.[30] In these cases, she approved of the use of sterilization.[28] In Sanger's opinion, it was individual women (if able-bodied) and not the state who should determine whether or not to have a child.[31][32]  U.S. eugenics poster advocating for the removal of genetic "defectives" such as the insane, "feeble-minded" and criminals, and supporting the selective breeding of "high-grade" individuals, c. 1926 In the Deep South, women's associations played an important role in rallying support for eugenic legal reform. Eugenicists recognized the political and social influence of southern clubwomen in their communities, and used them to help implement eugenics across the region.[33] Between 1915 and 1920, federated women's clubs in every state of the Deep South had a critical role in establishing public eugenic institutions that were segregated by sex.[34] For example, the Legislative Committee of the Florida State Federation of Women's Clubs successfully lobbied to institute a eugenic institution for the mentally retarded that was segregated by sex.[35] Their aim was to separate mentally retarded men and women in order to prevent them from breeding more "feebleminded" individuals. Public acceptance in the U.S. led to various state legislatures working to establish eugenic initiatives. Beginning with Connecticut in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded"[36] from marrying.[37] The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was Michigan in 1897 – although the proposed law failed to garner enough votes by legislators to be adopted, it did set the stage for other sterilization bills.[38] Eight years later, Pennsylvania's state legislators passed a sterilization bill that was vetoed by the governor.[39] Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907,[40] followed closely by Washington, California, and Connecticut in 1909.[41][42][43] Sterilization rates across the country were relatively low (California being the sole exception) until the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell, which upheld under the U.S. Constitution the forced sterilization of patients at a Virginia home for those who were seen as mentally retarded.[44] Immigration restrictions In the late 19th century, many scientists, who were concerned about the population leaning too far away from the favored "Anglo-Saxon superiority" due to a rise in immigration from Europe, partnered with other interest groups to implement immigration laws that could be justified on the basis of genetics.[45] After the 1890 U.S. census, people began to believe that immigrants who were of Nordic or Anglo-Saxon ancestry were greatly favored over Southern and Eastern Europeans, specifically Jews (a diasporic, Middle Eastern people), who were seen by some eugenicists, such as Harry Laughlin, to be genetically inferior.[45] During the early 20th century as the United States and Canada began to receive higher numbers of immigrants, influential eugenicists such as Lothrop Stoddard and Laughlin (who was appointed as an expert witness for the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in 1920) presented arguments that these immigrants would pollute the national gene pool if their numbers went unrestricted.[46][47] In 1921, a temporary measure was passed to slowdown the open door on immigration. The Immigration Restriction League was the first American entity to be closely associated with eugenics and was founded in 1894 by three recent Harvard graduates. The overall goal of the League was to prevent what they perceived as inferior races from diluting "the superior American racial stock" (those who were of the upper-class Anglo-Saxon heritage), and they began working to have stricter anti-immigration laws in the United States.[48] The League lobbied for a literacy test for immigrants as they attempted to enter the United States, based on the belief that literacy rates were low among "inferior races".[45] Eugenicists believed that immigrants were often degenerate, had low IQs, and were afflicted with shiftlessness, alcoholism and insubordination. According to Eugenicists, all of these problems were transmitted through genes. Literacy test bills were vetoed by presidents in 1897, 1913 and 1915; eventually, President Wilson's second veto was overruled by Congress in 1917.[49] With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, eugenicists for the first time played an important role in the Congressional debate as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior stock" from eastern and southern Europe.[50][51] The new act, inspired by the eugenic belief in the racial superiority of "old stock" white Americans as members of the "Nordic race" (a form of white supremacy), strengthened the position of existing laws prohibiting race-mixing.[52] Whereas Anglo-Saxon and Nordic people were seen as the most desirable immigrants, the Chinese and Japanese were seen as the least desirable and were largely banned from entering the U.S as a result of the immigration act.[52][53] In addition to the immigration act, eugenic considerations also lay behind the adoption of incest laws in much of the U.S. and were used to justify many anti-miscegenation laws.[54] Efforts to shape American families Anti-miscegenation laws Further information: Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States Anti-miscegenation laws prohibited interracial marriages.[54] The first anti-miscegenation law was passed in Virginia in 1661.[55] This law not only prohibited marriage between individuals of different races, but it also prohibited ministers from marrying interracial couples.[55] Despite a rising number of interracial relationships, more states passed anti-miscegenation laws, over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries.[56] At the beginning of the twentieth century, at least twenty-eight states had anti-miscegenation legislation.[55] During this time period, the one-drop rule emerged, which stated that anyone with a single drop of African blood was considered “black.”[57] Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States made it a crime for individuals to wed someone categorized as belonging to a different race.[58] These laws were part of a broader policy of racial segregation in the United States to minimize contact between people of different ethnicities. Race laws and practices in the United States were explicitly used as models by the Nazi regime when it developed the Nuremberg Laws, stripping Jewish citizens of their citizenship.[59] This rule is reflected in Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924.[60] This law prohibited miscegenation and defined a white person as having “no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons.”[60] This law and other anti-miscegenation legislature were not overturned until 1967 with the Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia decision.[61] In 1958, Mildred Jeter, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, were residents of Virginia but were married in Washington, DC. Upon returning to Virginia, they were arrested and charged with violating the anti-miscegenation legislature.[55] The case was eventually brought to the United States Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court ruled that this legislature violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[61] Unfit v. fit individuals Both class and race factored into the eugenic definitions of "fit" and "unfit." By using intelligence testing, American eugenicists asserted that social mobility was indicative of one's genetic fitness.[62] This reaffirmed the existing class and racial hierarchies and explained why the upper-to-middle class was predominantly white. Middle-to-upper class status was a marker of "superior strains."[35] In contrast, eugenicists believed poverty to be a characteristic of genetic inferiority, which meant that those deemed "unfit" were predominantly of the lower classes.[35][63] Because class status designated some more fit than others, eugenicists treated upper and lower-class women differently. Positive eugenicists, who promoted procreation among the fittest in society, encouraged middle-class women to bear more children. Between 1900 and 1960, eugenicists appealed to middle class white women to become more "family minded," and to help better the race.[64] To this end, eugenicists often denied middle and upper-class women sterilization and birth control.[65] However, since poverty was associated with prostitution and "mental idiocy," women of the lower classes were the first to be deemed "unfit" and "promiscuous."[35] Concerns over hereditary genes In the 19th century, based on a view of Lamarckism, it was believed that the damage done to people by diseases could be inherited and therefore, through eugenics, these diseases could be eradicated. This belief was carried into the 20th century as public health measures were taken to improve health with the hope that such measures would result in better health of future generations.[citation needed] A 1911 Carnegie Institute report explored eighteen methods for removing defective genetic attributes; the eighth method was euthanasia.[14] Though the most commonly suggested method of euthanasia was to set up local gas chambers,[14] many in the eugenics movement did not believe that Americans were ready to implement a large-scale euthanasia program, so many doctors came up with alternative ways of subtly implementing eugenic euthanasia in various medical institutions.[14] For example, a mental institution in Lincoln, Illinois fed its incoming patients milk infected with tuberculosis (reasoning that genetically fit individuals would be resistant), resulting in 30–40% annual death rates.[14] Other doctors practiced euthanasia through various forms of lethal neglect.[14] In the 1930s, there was a wave of portrayals of eugenic "mercy killings" in American film, newspapers, and magazines. In 1931, the Illinois Homeopathic Medicine Association began lobbying for the right to euthanize "imbeciles" and other defectives.[66] A few years later, in 1938, the Euthanasia Society of America was founded.[67] However, despite this, euthanasia saw marginal support in the U.S., motivating people to turn to forced segregation and sterilization programs as a means for keeping the "unfit" from reproducing.[14] Better Baby Contests Mary deGormo, a former teacher, was the first person to combine ideas about health and intelligence standards with competitions at state fairs, in the form of baby contests.[68] She developed the first such contest, the "Scientific Baby Contest" for the Louisiana State Fair in Shreveport, in 1908.[69] She saw these contests as a contribution to the "social efficiency" movement, which was advocating for the standardization of all aspects of American life as a means of increasing efficiency.[25] DeGarmo was assisted by Doctor Jacob Bodenheimer, a pediatrician who helped her develop grading sheets for contestants, which combined physical measurements with standardized measurements of intelligence.[70]  Contestants preparing for the Better Baby Contest at the 1931 Indiana State Fair. The contest spread to other U.S. states in the early 20th century. In Indiana, for example, Ada Estelle Schweitzer, a eugenics advocate and director of the Indiana State Board of Health's Division of Child and Infant Hygiene, organized and supervised the state's Better Baby contests at the Indiana State Fair from 1920 to 1932. It was among the fair's most popular events. During the contest's first year at the fair, a total of 78 babies were examined; in 1925 the total reached 885. Contestants peaked at 1,301 infants in 1930, and the following year the number of entrants was capped at 1,200. Although the specific consequences of the contests were difficult to assess, statistics helped to support Schweitzer's claims that the contests helped reduce infant mortality.[71][72] The contest intended to educate the public about raising healthy children at a time when approximately 10% of children died in their first year of life.[73] However, its exclusionary practices reinforced social class and racial discrimination. In Indiana, for example, the contestants were limited to white infants; African-American and immigrant children were barred from the competition for ribbons and cash prizes. In addition, the scoring was biased toward white, middle-class babies.[74][75] The contest procedure included recording each child's health history, as well as evaluations of each contestant's physical and mental health and overall development using medical professionals. Using a process similar to the one introduced at the Louisiana State Fair, and contest guidelines that the AMA and U.S. Children's Bureau recommended, scoring for each contestant began with 1,000 points. Deductions were made for defects, including a child's measurements below a designated average. The contestant with the most points was declared the winner.[76][72][77] Standardization through scientific judgment was a topic that was very serious in the eyes of the scientific community, but has often been downplayed as just a popular fad or trend. Nevertheless, a lot of time, effort, and money was put into these contests and their scientific backing, which would influence cultural ideas as well as local and state government practices.[78] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People promoted eugenics by hosting "Better Baby" contests and the proceeds would go to its anti-lynching campaign.[79] Fitter Families  Winning family of a Fitter Family contest stand outside of the Eugenics Building[80] (where contestants register) at the Kansas Free Fair, in Topeka, Kansas. First appearing in 1920 at the Kansas Free Fair, "Fitter Families for Future Firesides" competitions continued all the way up to World War II. Mary T. Watts and Florence Brown Sherbon,[81][82] both initiators of the Better Baby Contests in Iowa, took the idea of positive eugenics for babies and combined it with a determinist concept of biology to come up with fitter family competitions.[83] There were several different categories that families were judged in: size of the family, overall attractiveness, and health of the family, all of which helped to determine the likelihood of having healthy children. These competitions were simply a continuation of the Better Baby contests that promoted certain physical and mental qualities.[84][85] At the time, it was believed that certain behavioral qualities were inherited from one's parents. This led to the addition of several judging categories including: generosity, self-sacrificing, and quality of familial bonds. Additionally, there were negative features that were judged: selfishness, jealousy, suspiciousness, high-temperedness, and cruelty. Feeblemindedness, alcoholism, and paralysis were few among other traits that were included as physical traits to be judged when looking at family lineage.[86] Doctors and specialists from the community would offer their time to judge these competitions, which were originally sponsored by the Red Cross.[86] The winners of these competitions were given a Bronze Medal as well as champion cups called "Capper Medals." The cups were named after then-Governor and Senator, Arthur Capper and he would present them to "Grade A individuals".[87] The perks of entering into the contests were that the competitions provided a way for families to get a free health check-up by a doctor as well as some of the pride and prestige that came from winning the competitions.[86] By 1925, the Eugenics Records Office was distributing standardized forms for judging eugenically fit families, which were used in contests in several U.S. states.[88] Compulsory sterilization See also: Compulsory sterilization § United States  A depiction of "defectives" from the 1915 book Mental defectives in Virginia. A depiction of "defectives" from the 1915 book Mental defectives in Virginia.In 1907, Indiana passed the first eugenics-based compulsory sterilization law in the world. Thirty U.S. states would soon follow their lead.[89][90] Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1921,[91] in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924, allowing for the compulsory sterilization of patients of state mental institutions.[92] The number of sterilizations performed per year increased until another Supreme Court case, Skinner v. Oklahoma, 1942, which ruled that under the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, laws that permitted the compulsory sterilization of criminals were unconstitutional if these laws treated similar crimes differently.[93] Although Skinner determined that the right to procreate was a fundamental right under the constitution, the case did not denounce sterilization laws, because its analysis was based on the equal protection of criminal defendants specifically, therefore leaving those seen as "social undesirables"—the poor, the disabled, and various ethnic groups—as targets of compulsory sterilization.[6] Therefore, though compulsory sterilization is now considered an abuse of human rights, Buck v. Bell has never been overturned, and Virginia specifically did not repeal its sterilization law until 1974.[94] Men and women were compulsorily sterilized for different reasons. Men were sterilized to treat their aggression and to eliminate their criminal behavior, while women were sterilized to control the results of their sexuality.[95] Since women bore children, eugenicists held women more accountable than men for the reproduction of the less "desirable" members of society.[95] Eugenicists therefore predominantly targeted women in their efforts to regulate the birth rate, to "protect" white racial health, and weed out the "defectives" of society.[95] The most significant era of eugenic sterilization was between 1907 and 1963, when over 64,000 individuals were forcibly sterilized under eugenic legislation in the United States.[96] Beginning around 1930, there was a steady increase in the percentage of women sterilized, and in a few states only young women were sterilized. A 1937 Fortune magazine poll found that 2/3 of respondents supported eugenic sterilization of "mental defectives", 63% supported sterilization of criminals, and only 15% opposed both.[97][98] From 1930 to the 1960s, sterilizations were performed on many more institutionalized women than men.[99] By 1961, 61 percent of the 62,162 total eugenic sterilizations in the United States were performed on women.[99] A favorable report on the results of sterilization in California, the state that conducted the most sterilizations (20,000 of the 60,000 that occurred between 1909 and 1960),[23] was published in 1929 in book form by the biologist Paul Popenoe and was widely cited by the Nazi government as evidence that wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.[100][101] After World War II, eugenics and eugenic organizations began to revise their standards of reproductive fitness to reflect contemporary social concerns of the later half of the 20th century, notably concerns over welfare, Mexican immigration, overpopulation, civil rights, and sexual revolution, and gave way to what has been termed neo-eugenics.[102] Neo-eugenicists like Clarence Gamble, an affluent researcher at Harvard Medical school and a founder of public birth control clinics, revived the eugenics movement in the United States through sterilization. Supporters of this revival of eugenic sterilizations believed that they would bring an end to social issues such as poverty and mental illness while also saving taxpayer money and boost the economy.[103] Whereas eugenic sterilization programs before World War II were mostly conducted on prisoners or patients in mental hospitals, after the war, compulsory sterilizations were targeted at poor people and minorities.[103] As a result of these new sterilization initiatives, though most scholars agree that there were over 64,000 known cases of eugenic sterilization in the U.S. by 1963, no one knows for certain how many compulsory sterilizations occurred between the late 1960s to 1970s, though it is estimated that at least 80,000 may have been conducted.[104] A large number of those who were targets of coerced sterilizations in the later half of the century were African American, Hispanic, and Native American women. Eugenics, sterilization, and the African American community Black support for eugenics (Progressive Era)  Du Bois in 1918 Early proponents of the eugenics movement included not only influential white Americans but also several proponent African-American intellectuals such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Thomas Wyatt Turner, and many academics at Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Hampton University.[79] However, unlike many white eugenicists, these black intellectuals believed the best African Americans were as good as the best White Americans, and "The Talented Tenth" of all races should mix.[79] Indeed, Du Bois believed "only fit blacks should procreate to eradicate the race's heritage of moral iniquity."[105] With the support of leaders like Du Bois, efforts were made in the early 20th century to control the reproduction of the country's black population; one of the most visible initiatives was Margaret Sanger's 1939 proposal, The Negro Project.[15] That year, Sanger, Florence Rose, her assistant, and Mary Woodward Reinhardt, then secretary of the new Birth Control Federation of America (BCFA), drafted a report on "Birth Control and the Negro."[15] In this report, they stated that African Americans were the group with "the greatest economic, health and social problems," were largely illiterate and "still breed carelessly and disastrously," a line taken from W.E.B. DuBois' article in the June 1932 Birth Control Review.[15] The Project often sought after prominent African-American leaders to spread knowledge regarding birth control and the perceived positive effects it would have on the African-American community, such as poverty and the lack of education.[106] Sanger particularly sought out black ministers from the South to serve as leaders in the Project in the hopes of countering any ideas that the project was a strategic attempt to eradicate the black population.[15] However, despite Sanger's best efforts, white medical scientists took control over the initiative, and with the Negro Project receiving praise from white leaders and eugenicists, many of Sanger's opponents, both during the creation of the Project and years after, saw her work as an attempt to terminate African Americans.[15][106] Eugenics during the civil rights era Opposition to initiatives to control reproduction within the African-American community grew in the 1960s, particularly after President Lyndon B. Johnson, in 1965, announced the establishment of federal funding of birth control used on the poor.[45] In the 1960's, many African Americans throughout the country took the government's decision to fund birth-control clinics as an attempt to limit the growth of the black population and along with it, the increased political power that black Americans were fighting to acquire.[45] Scholars have stated that African Americans' fear about their reproductive health and ability was rooted in history as under U.S. slavery, enslaved women were often coerced or forced to have children to increase a plantation owner's wealth.[45][107] Therefore, many African Americans, particularly those in the Black Power Movement, saw birth control, and federal support of the Pill, as equivalent to black genocide, declaring it as such at the 1967 Black Power Conference.[45] Federal funding for birth control went alongside family planning initiatives that were a part of state welfare programs. These initiatives, in addition to advocating the use of the Pill, supported sterilization as a means of curbing the number of people receiving welfare and control the reproduction of 'unfit' women.[102] The 1950s and 1960s were the height of the sterilization abuse that African-American women as a group experienced at the hands of the white medical establishment.[45] During this period, the sterilization of African-American women largely took place in the South and assumed two forms: the sterilization of poor unwed black mothers, and "Mississippi appendectomies."[102] Under these "Mississippi appendectomies," women who went to the hospital to give birth, or for some other medical treatment, often found themselves incapable of having more children upon leaving the hospital due to unnecessary hysterectomies performed on them by southern medical students.[45][108] By the 1970s, the coerced sterilization of women of color spread from the South to the rest of the country through federal family planning and under the guise of voluntary contraceptive surgery as physicians began to require their patients to sign consent forms to surgeries they did not want or understand.[102] Sterilization of African American women Though it is unknown the exact number of African American women who were sterilized throughout the country in the 20th century, records from a few states offer some estimates. In the state of North Carolina, which was seen as having the most aggressive eugenics program out of the 32 states that had one,[109] during the 45-year reign of the North Carolina Eugenics Board, from 1929 to 1974, a disproportionate number of those who were targeted for forced or coerced sterilization were black and female, with almost all being poor.[110] Of the 7,600 women who were sterilized by the state between the years of 1933 and 1973, about 5,000 were African American.[6] In light of this history, North Carolina became the first state to offer compensation to surviving victims of compulsory sterilization.[110] Additionally, whereas African Americans made up just over 1% of California's population, they accounted for at least 4% of the total number of sterilization operations conducted by the state between 1909 and 1979.[111] Overall, according to one 1989 study, 31.6% of African American women without a high school diploma were sterilized while only 14.5% of white women of the same educational status were sterilized.[6] Sterilization abuse brought to media attention In 1972, U.S. Senate committee testimony brought to light that at least 2,000 involuntary sterilizations had been performed on poor black women without their consent or knowledge.[112] An investigation revealed that the surgeries were all performed in the South, and were all performed on black women with multiple children who were receiving welfare.[112] Testimony revealed that many of these women were threatened with an end to their welfare benefits unless they consented to sterilization.[112] These surgeries were instances of sterilization abuse, a term applied to any sterilization performed without the consent or knowledge of the recipient, or in which the recipient is pressured into accepting the surgery. Because the funds used to carry out the surgeries came from the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity, the sterilization abuse raised suspicions, especially among members of the black community, that "federal programs were underwriting eugenicists who wanted to impose their views about population quality on minorities and poor women."[113] Despite this investigation, it was not until 1973 that the issue of sterilization abuse was brought to media attention. On June 14, 1973, two black girls, Minnie Lee and Mary Alice Relf, ages fourteen and twelve, respectively, were sterilized without their knowledge in Alabama by the Montgomery Community Action Committee, an OEO-financed organization.[102][111] The summer of that year, the Relf girls sued the government agencies and individuals responsible for their sterilization.[102] As the case was being pursued, it was discovered that the girls' mother, who could not read, unwittingly approved the operations, signing an 'X' on the release forms; Mrs. Relf had believed that she was signing a form authorizing her daughters to receive Depo-Provera injections, a form of birth control.[102] In light of the 1974 case of Relf v. Weinberger, named after Minnie Lee and Mary Alice's older sister, Katie, who had narrowly escaped also being sterilized, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) were ordered to establish new guidelines for its government sterilization policy.[102] By 1979, the new guidelines finally addressed the concern over informed consent, determined that minors under the age of 21 and those with severe mental impairments who could not give consent would not be sterilized, and articulated the provision that doctors could no longer claim that a woman's refusal to be sterilized would result in her being denied welfare benefits.[102] Sterilization of Latina women Main article: Sterilization of Latinas The 20th century demarcated a time in which compulsory sterilization heavily navigated its way into primarily Latino communities, against Latina women. Locations such as Puerto Rico and Los Angeles, California were found to have had large amounts of their female population coerced into sterilization procedures without quality and necessary informed consent nor full awareness of the procedure. Puerto Rico Between the span of the 1930s to the 1970s, nearly one-third of the female population in Puerto Rico was sterilized; at the time, this was the highest rate of sterilization in the world.[114] Some viewed sterilization as a means of rectifying the country's poverty and unemployment rates. Following legalization of the procedure in 1937 a U.S. government endorsed initiative saw health department officials advocating for sterilization in rural parts of the island. Sterilized women were also encouraged to join the workforce, in particular the textile and clothing related industries. The procedure was so common that it was often referred to solely as "la operación", garnering a documentary referenced by the same name.[114] This intentional targeting of Latino communities exemplifies the strategic placement of racial eugenics in modern history. This targeting is also inclusive of those with disabilities and those from marginalized populations, which Puerto Rico is not the only example of this trend. Eugenics did not serve as the only reason for the disproportionate rates of sterilization in the Puerto Rican community. Contraceptive trials were inducted in the 1950s towards Puerto Rican women. John Rock and Gregory Pincus were the two men spearheading the human trials of oral contraceptives. In 1954, the decision was made to conduct the clinical experiment in Puerto Rico, citing the island's large network of birth control clinics and lack of anti-birth control laws, which was in contrast to the United States' thorough cultural and religious opposition to the reproductive service.[115] The decision to conduct the trials in this community was also motivated by the structural implications of supremacy and colonialism. Rock and Pincus monopolized off of the primarily poor and uneducated background of these women, countering that if they "could follow the Pill regimen, then women anywhere in the world could too."[115] These women were purposely ill-informed of the oral contraceptives presence; the researchers only reported that the drug, which was administered at a much higher dosage than what birth control is prescribed at today, was to prevent pregnancy, not that it was tied to a clinical trial in order to jump start oral contraceptive access in America through FDA approval. California In California, by the year 1964, a total of 20,108 people were sterilized, making that the largest amount in all of the United States.[116] It is an important note that during this period in California's population demographic, the total individuals sterilized was disproportionately inclusive of Mexican, Mexican-American, and Chicana women. Andrea Estrada, a UC Santa Barbara affiliate, said: Beginning in 1909 and continuing for 70 years, California led the country in the number of sterilization procedures performed on men and women, often without their full knowledge and consent. Approximately 20,000 sterilizations took place in state institutions, comprising one-third of the total number performed in the 32 states where such action was legal.[117] In 1966, the case of Nancy Hernandez was the first to reach national public attention and resulted in protests on women's rights and reproductive rights across the country. Her story was published in Rebecca Kluchin's book, Fit to be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America, 1950-1980.[118] Cases such as Madrigal v. Quilligan, a class action suit regarding forced or coerced postpartum sterilization of Latina women following cesarean sections, helped bring to light the widespread abuse of sterilization supported by federal funds. The case's plaintiffs were 10 sterilized women of Los Angeles County Hospital who elected to come forward with their stories. Although a grim reality, No más bebés is a documentary that offers an emotional and candid storytelling of the Madrigal v. Quilligan case on behalf of Latina women whom were direct recipients of the coerced sterilization of the Los Angeles' hospital. The judge's ruling sided with the County Hospital, but an aftermath of the case resulted in the accessibility of multiple language informed consent forms. These stories, among many others, serve as backbones for not only the reproductive justice movement that we see today, but a better understanding and recognition of the Chicana feminism movement in contrast to white feminism's perception of reproductive rights. Sterilization of Native American women Main article: Sterilization of Native American women An estimated 40% of Native American women (60,000–70,000 women) and 10% of Native American men in the United States underwent sterilization in the 1970s.[119] A General Accounting Office (GAO) report in 1976 found that 3,406 Native American women, 3,000 of which were of childbearing age,[120] were sterilized by the Indian Health Service (IHS) in Arizona, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and South Dakota from 1973 to 1976.[121][122][123] The GAO report did not conclude any instances of coerced sterilization, but called for the reform of IHS and contract doctors' processes of obtaining informed consent for sterilization procedures.[121] The IHS informed consent processes examined by the GAO did not comply with a 1974 ruling of the U.S. District Court that "any individual contemplating sterilization should be advised orally at the outset that at no time could federal benefits be withdrawn because of failure to agree to sterilization."[122] In examining individual cases and testimonies of Native American women, scholars have found that IHS and contract physicians recommended sterilization to Native American women as the appropriate form of birth control, failing to present potential alternatives and to explain the irreversible nature of sterilization, and threatened that refusal of the procedure would result in the women losing their children and/or federal benefits.[119][121][122] Scholars also identified language barriers in informed consent processes as the absence of interpreters for Native American women hindered them from fully understanding the sterilization procedure and its implications, in some cases.[122] Scholars have cited physicians' individual paternalism and beliefs about the population control of poor communities and welfare recipients and the opportunity for financial gain as possible motivations for performing sterilizations on Native American women.[121][122][123] Native American women and activists mobilized in the 1970s across the United States to combat the coerced sterilization of Native American women and advocate for their reproductive rights, alongside tribal sovereignty, in the Red Power movement.[121][122] Some of the most prominent activist organizations established in this decade and active in the Red Power movement and the resistance against coerced sterilization were the American Indian Movement (AIM), United Native Americans, Women of all Red Nations (WARN), the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC), and Indian Women United for Justice, founded by Constance Redbird Pinkerton Uri, a Cherokee-Choctaw physician.[121][122] Some Native American activists have deemed the coerced sterilization of Native American women a "modern form of genocide,"[121] and view these sterilizations as a violation of the rights of tribes as sovereign nations.[121] Others argue that the sterilization of Native American women is interconnected with colonialist and capitalist motives of corporations and the federal government to acquire land and natural resources, including oil, natural gas, and coal, currently located on Native American reservations.[122][120] Scholars and Native American activists have situated the forced sterilizations of Native American women within broader histories of colonialism, violations of Native American tribal sovereignty by the federal government, including a long history of the removal of children from Native American women and families, and population control efforts in the United States.[119][121][122][123] The 1970s brought new federal legislation enacted by the United States government which addressed issues of informed consent, sterilization, and the treatment of Native American children. The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare released new regulations in 1979 on informed consent processes for sterilization procedures, including a longer waiting period of 30 days before the procedure, the presentation of alternative methods of birth control to the patient, and clear verbal affirmation that the patient's access to federal benefits or welfare programs would not be revoked if the procedure were refused.[121] The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 officially recognized the significance and value of the extended family in Native American culture, adopting "minimum federal standards for the removal of Indian children to foster or adoptive homes,"[122] and the central importance of the sovereign tribal governments in decision-making processes surrounding the welfare of Native children.[122] Influence on Nazi Germany See also: Nazi eugenics After the eugenics movement was well established in the United States, it spread to Germany. California eugenicists began producing literature promoting eugenics and sterilization and sending it overseas to German scientists and medical professionals.[14] By 1933, California had subjected more people to forceful sterilization than all other U.S. states combined. The forced sterilization program engineered by the Nazis was partly inspired by California's.[124] The Rockefeller Foundation helped develop and fund various German eugenics programs,[125] including the one that Josef Mengele worked in before he went to Auschwitz.[14] Upon returning from Germany in 1934, where more than 5,000 people per month were being forcibly sterilized, the California eugenics leader C. M. Goethe bragged to a colleague: You will be interested to know that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought ... I want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of your life, that you have really jolted into action a great government of 60 million people.[126] Eugenics researcher Harry H. Laughlin often bragged that his Model Eugenic Sterilization laws had been implemented in the 1935 Nuremberg racial hygiene laws.[127] In 1936, Laughlin was invited to an award ceremony at Heidelberg University in Germany (scheduled on the anniversary of the 1934 purge of Jews from the Heidelberg faculty), to receive an honorary doctorate for his work on the "science of racial cleansing". Due to financial limitations, Laughlin was unable to attend the ceremony and had to pick it up from the Rockefeller Institute. Afterward, he proudly shared the award with his colleagues, remarking that he felt that it symbolized the "common understanding of German and American scientists of the nature of eugenics."[128] Henry Friedlander wrote that although the German and American eugenics movements were similar, the U.S. did not follow the same slippery slope as Nazi eugenics because American "federalism and political heterogeneity encouraged diversity even with a single movement." In contrast, the German eugenics movement was more centralized and had fewer diverse ideas.[129] Unlike the American movement, one publication and one society, the German Society for Racial Hygiene, represented all German eugenicists in the early 20th century.[129][130] After 1945 some historians began to try to portray the U.S. eugenics movement as distinct and distant from Nazi eugenics.[131] Many of the defendants at the Nuremberg trials of 1945 to 1946 attempted to justify their human-rights abuses by claiming similarity between the Nazi eugenics programs and the US eugenics programs.[132] Eugenics after World War II Genetic engineering After the Second World War, the extreme version of eugenics practiced by the Nazis brought the movement into disrepute. However, aspects of the eugenics movement such as forced sterilization were still taking place, just not with as much public visibility as before.[133] As technology developed, the field of genetic engineering emerged. Instead of sterilizing people to remove traits deemed to be "undesirable", genetic engineering "changes or removes genes to prevent disease or improve the body in some significant way."[119] Proponents of genetic engineering cite its ability to cure and prevent life-threatening diseases. Genetic engineering began in the 1970s when scientists began to clone and alter genes. From this, scientists were able to create life-saving health interventions such as human insulin, the first-ever genetically engineered drug.[134] Because of this development, over the years scientists were able to create new drugs to treat devastating diseases. For example, in the early 1990s, a group of scientists were able to use a gene-drug to treat severe combined immunodeficiency in a young girl.[135] However, genetic engineering also further allows for the practice of eliminating "undesirable traits" within humans and other organisms—for example, with current genetic tests, parents are able to test a fetus for any life-threatening diseases that may affect the child's life and then choose to abort the baby.[119] Some fear that this could lead to ethnic cleansing, or alternative form of eugenics.[136] The ethical implications of genetic engineering were heavily considered by scientists at the time, and the Asilomar Conference was held in 1975 to discuss these concerns and set reasonable, voluntary guidelines that researchers would follow while using DNA technologies.[137] Disability-selective abortion Advancements in prenatal testing over the past several decades have contributed to an increase in disability-selective abortions, which refers to the termination of pregnancy after a diagnosis of a genetic anomaly before birth.[138] In 2007, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) began to recommend that all women, regardless of age, should be offered diagnostic genetic testing before 20 weeks gestation.[139] Today, prenatal screening for chromosomal abnormalities, including Down syndrome, Edwards syndrome, and Patau syndrome, is offered as routine healthcare. In the United States, it is estimated that anywhere from 61%-93% of infants with Down syndrome are terminated after a definitive prenatal diagnosis each year.[140] Reasons to continue or terminate a pregnancy following a prenatal diagnosis of a genetic abnormality are complex, and often influenced by a combination of social, medical, and ethical considerations. Arguments in favor of disability-selective abortion Defenders of disability-selective abortion suggest that its practice alleviates human suffering and helps parents make informed reproductive decisions.[141] This position considers disability-selective abortion as healthcare, intended to prevent pathology and improve quality of life. Proponents also argue that access to disability-selective abortions is essential to protecting women’s bodily autonomy.[141] In addition, some support disability-selective abortion on the basis of procreative beneficence – the principle of selecting the child with the best-expected life based on available genetic information.[142] Arguments against disability-selective abortion Opponents of disability-selective abortion argue that the normalization of its practice is inherently imbued with a condescending, eugenic attitude toward disability.[143] They suggest that disability-selective abortions are enabled by the normal function view (NFV) of health, which pathologizes disability and assumes that disability is directly correlated with a reduction in health.[144][a] Compulsory sterilization prevention and continuation Banning Sterilization The 1978 Federal Sterilization Regulations, created by the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, or HEW (now the United States Department of Health and Human Services), outline a variety of prohibited sterilization practices that were often used previously to coerce or force women into sterilization.[146] These were intended to prevent such eugenics and neo-eugenics as resulted in the involuntary sterilization of large groups of poor and minority women. Such practices include: not conveying to patients that sterilization is permanent and irreversible, in their own language (including the option to end the process or procedure at any time without conceding any future medical attention or federal benefits, the ability to ask any and all questions about the procedure and its ramifications, the requirement that the consent seeker describes the procedure fully including any and all possible discomforts and/or side-effects and any and all benefits of sterilization); failing to provide alternative information about methods of contraception, family planning, or pregnancy termination that are nonpermanent and/or irreversible (this includes abortion); conditioning receiving welfare and/or Medicaid benefits by the individual or his/her children on the individuals "consenting" to permanent sterilization; tying elected abortion to compulsory sterilization (cannot receive a sought out abortion without "consenting" to sterilization); using hysterectomy as sterilization; and subjecting minors and the mentally incompetent to sterilization.[146][147][79] The regulations also include an extension of the informed consent waiting period from 72 hours to 30 days (with a maximum of 180 days between informed consent and the sterilization procedure).[147][146][79] Lack of Access to Information about Sterilization However, several studies have indicated that the forms are often dense and complex and beyond the literacy aptitude of the average American, and those seeking publicly funded sterilization are more likely to possess below-average literacy skills.[148] High levels of misinformation concerning sterilization still exist among individuals who have already undergone sterilization procedures, with permanence being one of the most common gray factors.[148][149] Additionally, federal enforcement of the requirements of the 1978 Federal Sterilization Regulation is inconsistent and some of the prohibited abuses continue to be pervasive, particularly in underfunded hospitals and lower income patient hospitals and care centers.[147][79] The compulsory sterilization of American men and women continues to this day. In 2013, it was reported that 148 female prisoners in two California prisons were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a supposedly voluntary program, but it was determined that the prisoners did not give consent to the procedures.[150] Sterilization in US Prisons By 1979, California, driven by the eugenic thinking that prisoners were unfit to reproduce, sterilized approximately 20,000 people without their consent.[151] This practice legally ended when eugenics laws were repealed in 1979 for California state hospitals and in 2010 for state prisons.[152] However, the compulsory sterilization of American men and women continues to this day. Between 2005 and 2011, 148 female prisoners were sterilized in California prisons through tubal ligations without required state approvals.[153][154][155] Former inmates claim that medical staff pressured women who had served multiple prison terms or would be likely to return to prison in the future to be sterilized.[156] In September 2014, California enacted Bill SB1135 that bans sterilization in correctional facilities, unless the procedure is required to save an inmate's life.[157] Additionally, in 2021, Gavin Newsom, Governor of California, signed a compensation agreement to pay these 148 victims $25,000 each. Other states have sterilized prisoners in the recent past. In Tennessee, general sessions judge Sam Benningfield signed an order in 2017 allowing inmates to reduce their sentence by 30 days if they undergo voluntary sterilization.[158] His goal was to break a “vicious cycle” of repeat drug offenders who were unemployed or could not pay for child support.[159] While the order was only in place for two months, 38 men signed up to receive vasectomies and 32 women to receive Nexplanon implants, a birth control device.[159] Benningfield claimed this 2017 order was not a eugenics program, writing in a statement that its purpose was to, “protect children and help people in their rehabilitation efforts.”[160] However, criminal justice researchers and news outlets continually compared it to previous prisoner sterilization programs based in eugenics and portrayed it as a continuation of the practice of eugenics. John Raphling, a senior researcher on criminal justice for the U.S. Human Rights Watch, told The Outline that Benningfield was “coercing poor people to have this procedure to prevent them from reproducing.”[160] Sterilization in Immigration Detention Centers In 2020, forced sterilizations at a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in Ocilla, Georgia amassed national attention.[161] Over 50 people detained at the ICE facility, all lower-income immigrant women with minimal understanding of the English language, stated they were pushed to undergo or did undergo medically unnecessary gynecological surgeries including hysterectomies. A Senate briefing on this subject emphasized the “uniform absence of truly informed consent” due in part to language barriers and in part to lack of information provided.[162] Modern eugenics and genetic engineering Human enhancement through genetic alterations is aimed at improving traits considered normal and extinguishing illnesses, defects, and other abnormalities.[163] While genome editing is still being heavily researched and developed, the technology could one day be more developed and used to alter human genetics.[164] Opponents of human enhancement through genetic engineering assert that the technology is founded in eugenic ideals: to develop superior individuals and extinguish those deemed inferior.[163] Supporters claim that this technology is considered reproductive autonomy and will ultimately benefit both individuals and the community. |