ヨーロッパ人によるアメリカ大陸の植民地化

European colonization of the Americas

★European colonization of the Americas(ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化)

☆

大航海時代、ヨーロッパ諸国を巻き込んだアメリカ大陸の大規模な植民地化は、主に15世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて行われた。北欧人は北大西洋の地域

に定住し、グリーンランドを植民地化し、西暦1000年頃にはニューファンドランドの北端近くに短期間の入植地を作った。しかし、その長い期間と重要性か

ら、クリストファー・コロンブスの航海以降のヨーロッパ人による植民地化の方がよく知られている。[1][2][3][4]この時期、スペイン、ポルトガ

ル、イギリス、フランス、ロシア、オランダ、デンマーク、スウェーデンといったヨーロッパの植民地帝国は、アメリカ大陸とその天然資源、人的資本を探索

し、主張し始めた。[1][2][3][4][5]

オスマン帝国がアジアへの通商路を支配していたため、西ヨーロッパの君主たちはそれに代わるものを探すようになり、その結果、クリストファー・コロンブス

の航海と偶然の新大陸到達がもたらされた。1494年のトルデシリャス条約調印により、ポルトガルとスペインは地球を2分割することに合意し、ポルトガル

は世界の東半分の非キリスト教地域を、スペインは西半分の地域を支配することになった。スペインの領有権は基本的にアメリカ大陸全域に及んでいたが、トル

デシリャス条約によって南アメリカ大陸の東端はポルトガルに与えられ、1500年代初頭にブラジルを建設、東インド諸島はスペインに与えられ、フィリピン

を建設した。現在のドミニカ共和国にあるサント・ドミンゴは、1496年にコロンブスによって建設され、アメリカ大陸で最も古くからヨーロッパ人が住み続

けている入植地として知られている[7]。

1530年代までに、他の西欧列強もアメリカ大陸への航海から利益を得られることに気づき、現在のアメリカを含むアメリカ大陸の北東端にイギリスとフラン

スが植民地を作ることになった。1世紀以内に、スウェーデンがニュー・スウェーデンを、オランダがニュー・ネーデルラントを、デンマーク・ノルウェーがス

ウェーデン、オランダとともにカリブ海の一部を植民地化した。1700年代になると、デンマーク・ノルウェーはグリーンランドにかつての植民地を復活さ

せ、ロシアはアラスカからカリフォルニアまでの太平洋岸を探検し、領有権を主張し始めた。ロシアは18世紀半ば、毛皮貿易用の毛皮を求めて太平洋岸北西部

を植民地化し始めた。宗教、[8][9]政治的境界、共通語など、21世紀の西半球で主流となっている社会構造の多くは、この時期に確立されたものの子孫

である。

この時代の初期には、先住民が増加するヨーロッパ人入植者や、ヨーロッパの技術を身につけた敵対的な隣人から領土の一体性を守るために戦ったため、暴力的

な紛争が起こった。ヨーロッパのさまざまな植民地帝国とアメリカ・インディアン部族との間の紛争は、1800年代までアメリカ大陸の主要なダイナミックな

動きであった。たとえばアメリカは、マニフェスト・デスティニー(運命共同体)とインディアン排除という入植者植民地政策を実践した。カリフォルニア、パ

タゴニア、ノース・ウェスタン・テリトリー、グレート・プレインズ北部など他の地域は、1800年代まで植民地化をほとんど、あるいはまったく経験しな

かった。ヨーロッパ人との接触と植民地化は、アメリカ大陸の先住民やその社会に悲惨な影響を与えた[1][2][3][4]。

| During the Age of

Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving

European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century

and early 19th century. The Norse settled areas of the North Atlantic,

colonizing Greenland and creating a short-term settlement near the

northern tip of Newfoundland circa 1000 AD. However, due to its long

duration and importance, the later colonization by Europeans, after

Christopher Columbus’s voyages, is more well-known.[1][2][3][4] During

this time, the European colonial empires of Spain, Portugal, Great

Britain, France, Russia, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden began to

explore and claim the Americas, its natural resources, and human

capital,[1][2][3][4] leading to the displacement, disestablishment,

enslavement, and genocide of the Indigenous peoples in the

Americas,[1][2][3][4] and the establishment of several settler colonial

states.[1][2][3][4][5] The rapid rate at which some European nations grew in wealth and power was unforeseeable in the early 15th century because it had been preoccupied with internal wars and it was slowly recovering from the loss of population caused by the Black Death.[6] The Ottoman Empire's domination of trade routes to Asia prompted Western European monarchs to search for alternatives, resulting in the voyages of Christopher Columbus and his accidental arrival at the New World. With the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, Portugal and Spain agreed to divide the Earth in two, with Portugal having dominion over non-Christian lands in the world's eastern half, and Spain over those in the western half. Spanish claims essentially included all of the Americas; however, the Treaty of Tordesillas granted the eastern tip of South America to Portugal, where it established Brazil in the early 1500s, and the East Indies to Spain, where It established the Philippines. The city of Santo Domingo, in the current-day Dominican Republic, founded in 1496 by Columbus, is credited as the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in the Americas.[7] By the 1530s, other Western European powers realized they too could benefit from voyages to the Americas, leading to British and French colonization in the northeast tip of the Americas, including in the present-day United States. Within a century, the Swedish established New Sweden; the Dutch established New Netherland; and Denmark–Norway along with the Swedish and Dutch established colonization of parts of the Caribbean. By the 1700s, Denmark–Norway revived its former colonies in Greenland, and Russia began to explore and claim the Pacific Coast from Alaska to California. Russia began colonizing the Pacific Northwest in the mid-18th century, seeking pelts for the fur trade. Many of the social structures—including religions,[8][9] political boundaries, and linguae francae—which predominate in the Western Hemisphere in the 21st century are the descendants of those that were established during this period. Violent conflicts arose during the beginning of this period as indigenous peoples fought to preserve their territorial integrity from increasing European settlers and from hostile indigenous neighbors who were equipped with European technology. Conflict between the various European colonial empires and the American Indian tribes was a leading dynamic in the Americas into the 1800s, although some parts of the continent gained their independence from Europe by then, countries such as the United States continued to fight against Indian tribes and practiced settler colonialism. The United States for example practiced a settler colonial policy of Manifest destiny and Indian removal. Other regions, including California, Patagonia, the North Western Territory, and the northern Great Plains, experienced little to no colonization at all until the 1800s. European contact and colonization had disastrous effects on the indigenous peoples of the Americas and their societies.[1][2][3][4] |

大航海時代、ヨーロッパ諸国を巻き込んだアメリカ大陸の大規模な植民地

化は、主に15世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて行われた。北欧人は北大西洋の地域に定住し、グリーンランドを植民地化し、西暦1000年頃にはニュー

ファンドランドの北端近くに短期間の入植地を作った。しかし、その長い期間と重要性から、クリストファー・コロンブスの航海以降のヨーロッパ人による植民

地化の方がよく知られている。[1][2][3][4]この時期、スペイン、ポルトガル、イギリス、フランス、ロシア、オランダ、デンマーク、スウェーデ

ンといったヨーロッパの植民地帝国は、アメリカ大陸とその天然資源、人的資本を探索し、主張し始めた。[1][2][3][4][5] オスマン帝国がアジアへの通商路を支配していたため、西ヨーロッパの君主たちはそれに代わるものを探すようになり、その結果、クリストファー・コロンブス の航海と偶然の新大陸到達がもたらされた。1494年のトルデシリャス条約調印により、ポルトガルとスペインは地球を2分割することに合意し、ポルトガル は世界の東半分の非キリスト教地域を、スペインは西半分の地域を支配することになった。スペインの領有権は基本的にアメリカ大陸全域に及んでいたが、トル デシリャス条約によって南アメリカ大陸の東端はポルトガルに与えられ、1500年代初頭にブラジルを建設、東インド諸島はスペインに与えられ、フィリピン を建設した。現在のドミニカ共和国にあるサント・ドミンゴは、1496年にコロンブスによって建設され、アメリカ大陸で最も古くからヨーロッパ人が住み続 けている入植地として知られている[7]。 1530年代までに、他の西欧列強もアメリカ大陸への航海から利益を得られることに気づき、現在のアメリカを含むアメリカ大陸の北東端にイギリスとフラン スが植民地を作ることになった。1世紀以内に、スウェーデンがニュー・スウェーデンを、オランダがニュー・ネーデルラントを、デンマーク・ノルウェーがス ウェーデン、オランダとともにカリブ海の一部を植民地化した。1700年代になると、デンマーク・ノルウェーはグリーンランドにかつての植民地を復活さ せ、ロシアはアラスカからカリフォルニアまでの太平洋岸を探検し、領有権を主張し始めた。ロシアは18世紀半ば、毛皮貿易用の毛皮を求めて太平洋岸北西部 を植民地化し始めた。宗教、[8][9]政治的境界、共通語など、21世紀の西半球で主流となっている社会構造の多くは、この時期に確立されたものの子孫 である。 この時代の初期には、先住民が増加するヨーロッパ人入植者や、ヨーロッパの技術を身につけた敵対的な隣人から領土の一体性を守るために戦ったため、暴力的 な紛争が起こった。ヨーロッパのさまざまな植民地帝国とアメリカ・インディアン部族との間の紛争は、1800年代までアメリカ大陸の主要なダイナミックな 動きであった。たとえばアメリカは、マニフェスト・デスティニー(運命共同体)とインディアン排除という入植者植民地政策を実践した。カリフォルニア、パ タゴニア、ノース・ウェスタン・テリトリー、グレート・プレインズ北部など他の地域は、1800年代まで植民地化をほとんど、あるいはまったく経験しな かった。ヨーロッパ人との接触と植民地化は、アメリカ大陸の先住民やその社会に悲惨な影響を与えた[1][2][3][4]。 |

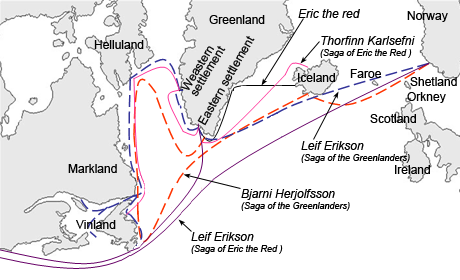

| Western European powers Norsemen Main article: Norse settlement of North America  Various sailing routes to Greenland, Vinland (Newfoundland), Helluland (Baffin Island), and Markland (Labrador) travelled by the Icelandic Sagas, including in the Saga of Erik the Red and Saga of the Greenlanders Norse Viking explorers were the first known Europeans to set foot in North America. Norse journeys to Greenland and Canada are supported by historical and archaeological evidence.[10] The Norsemen established a colony in Greenland in the late tenth century, which lasted until the mid 15th-century, with court and parliament assemblies (þing) taking place at Brattahlíð and a bishop located at Garðar.[11] The remains of a settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, were discovered in 1960 and were dated to around the year 1000 (carbon dating estimate 990–1050).[12] L'Anse aux Meadows is the only site widely accepted as evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1978.[13] It is also notable for its possible connection with the attempted colony of Vinland, established by Leif Erikson around the same period or, more broadly, with the Norse colonization of the Americas.[14] Leif Erikson's brother is said to have had the first contact with the native population of North America which would come to be known as the skrælings. After capturing and killing eight of the natives, they were attacked at their beached ships, which they defended.[15] |

西欧列強 北欧人 主な記事 北欧人の北アメリカ入植  グリーンランド、ヴィンランド(ニューファンドランド島)、ヘルランド(バフィン島)、マークランド(ラブラドール島)への様々な航海ルートは、『赤毛のエリックの物語』や『グリーンランド人の物語』など、アイスランドの『サガ』に描かれている。 北欧のヴァイキング探検家は、北アメリカに初めて足を踏み入れたヨーロッパ人として知られている。グリーンランドとカナダへの北欧人の旅は、歴史的・考古 学的証拠によって裏付けられている[10]。北欧人は10世紀後半にグリーンランドに植民地を築き、15世紀半ばまで続いた。[1960年にカナダの ニューファンドランドにあるランス・オー・メドウズの集落跡が発見され、その年代は1000年頃と推定された(炭素年代測定では990年~1050年) [12]。1978年にユネスコの世界遺産に登録された[13]。また、同時期にレイフ・エリクソンが築こうとしたヴィンランドの植民地、あるいはより広 義には北欧人のアメリカ大陸植民地化との関連が考えられることでも注目されている[14]。レイフ・エリクソンの弟は、後にスケーリング族として知られる ようになる北アメリカの先住民と初めて接触したと言われている。8人の原住民を捕らえ殺害した後、彼らは停泊していた船で攻撃を受け、それを防いだ [15]。 |

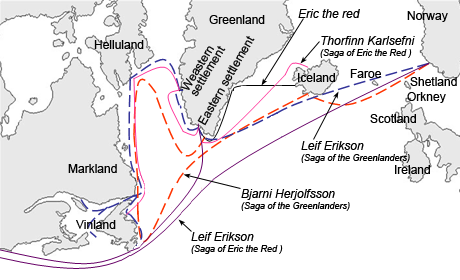

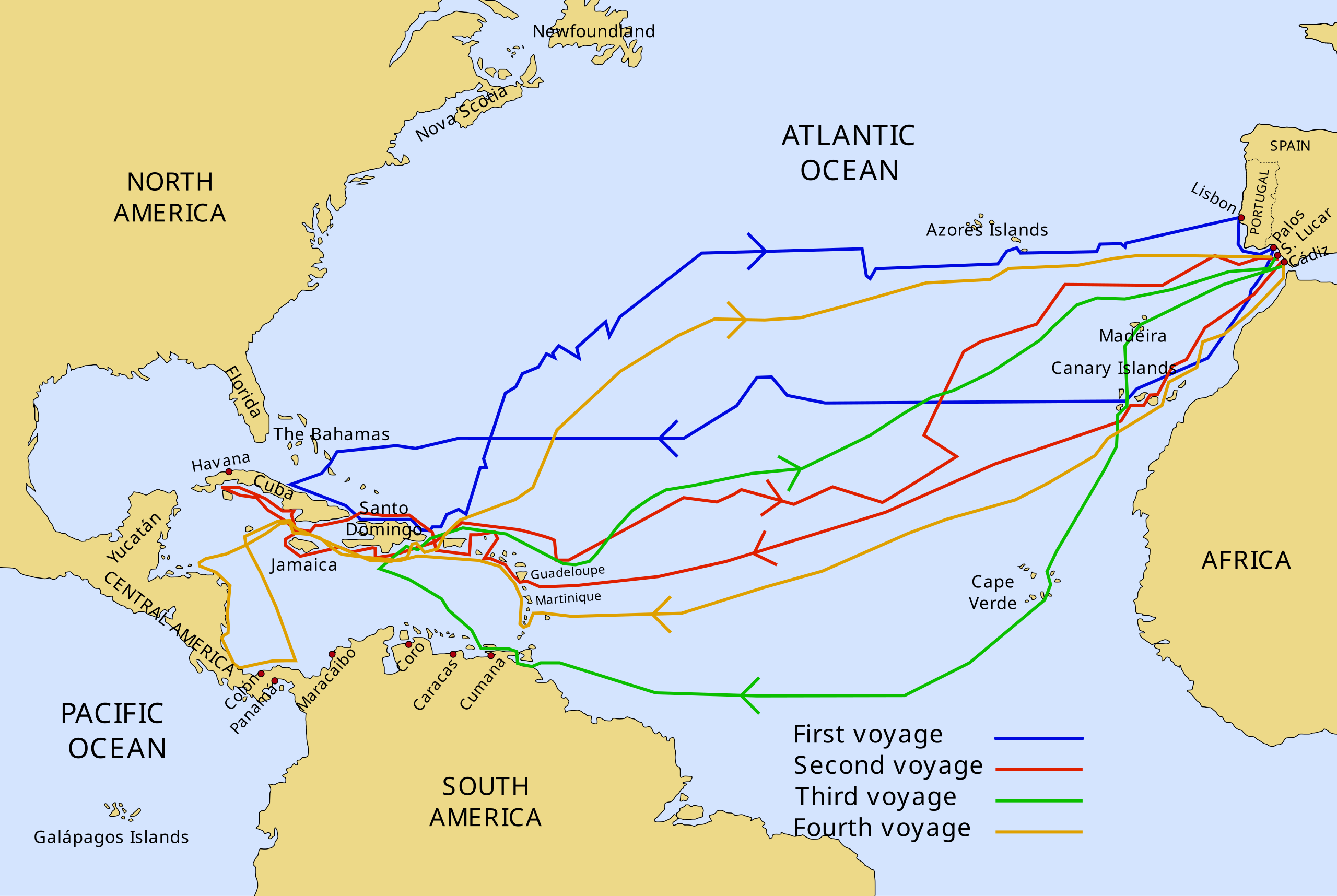

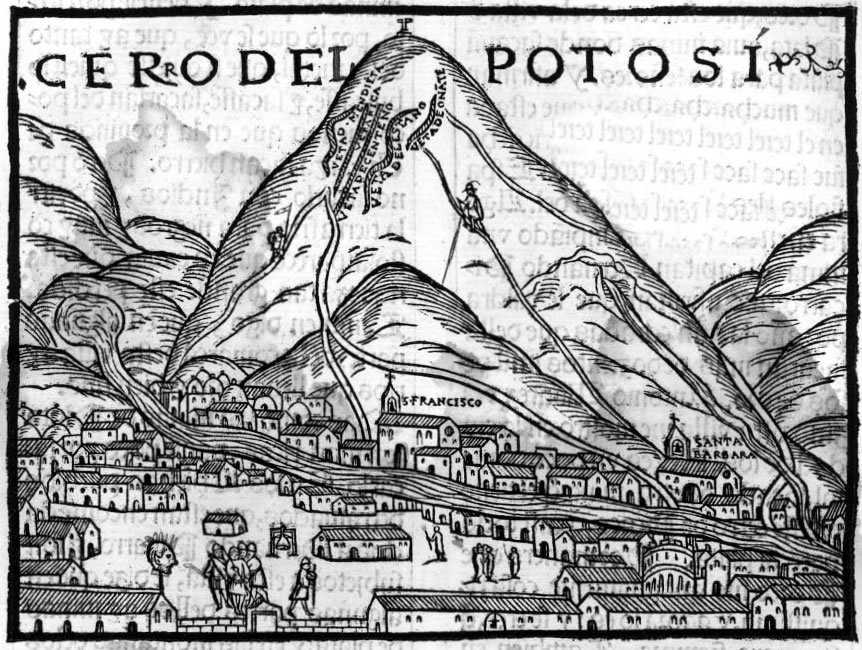

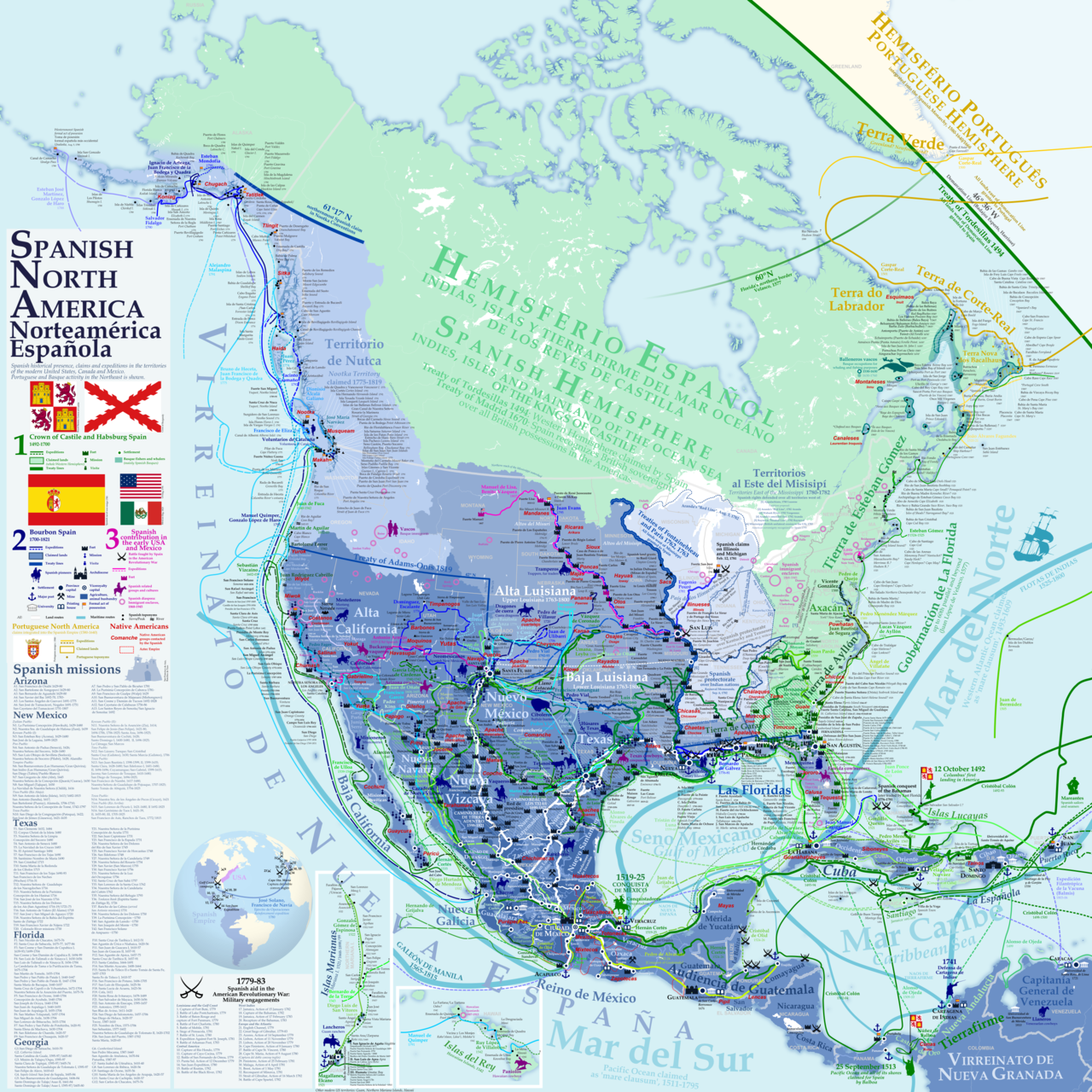

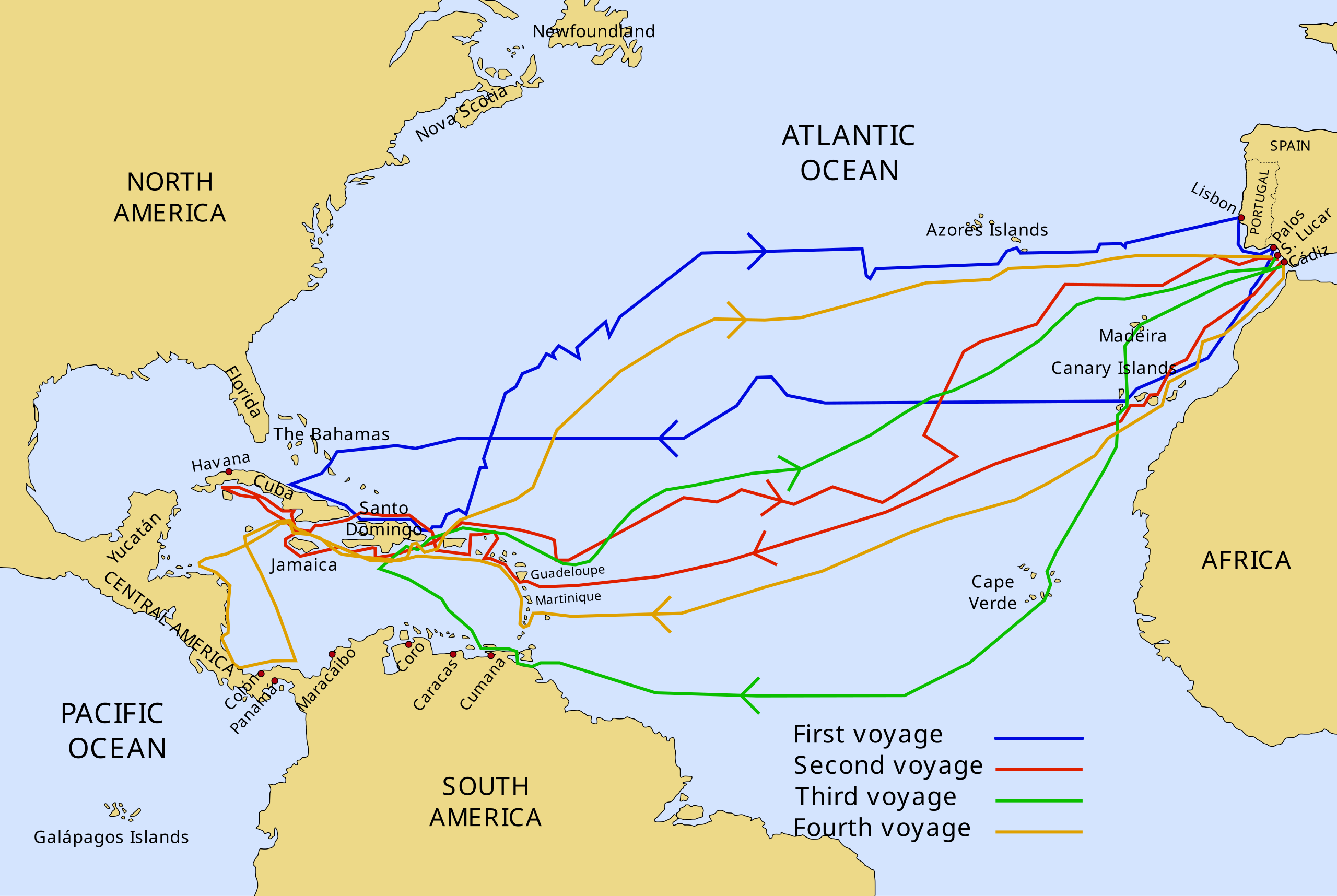

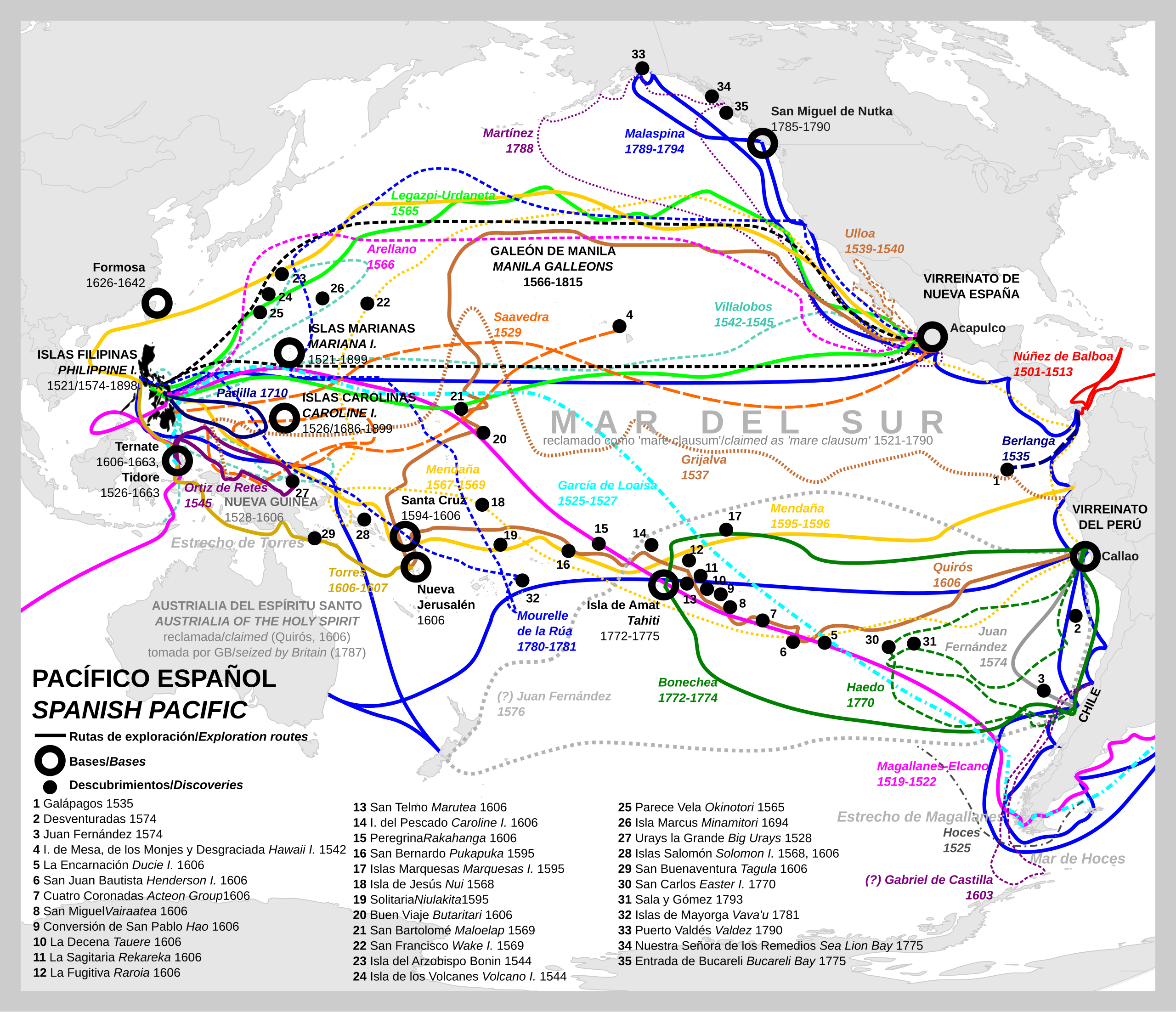

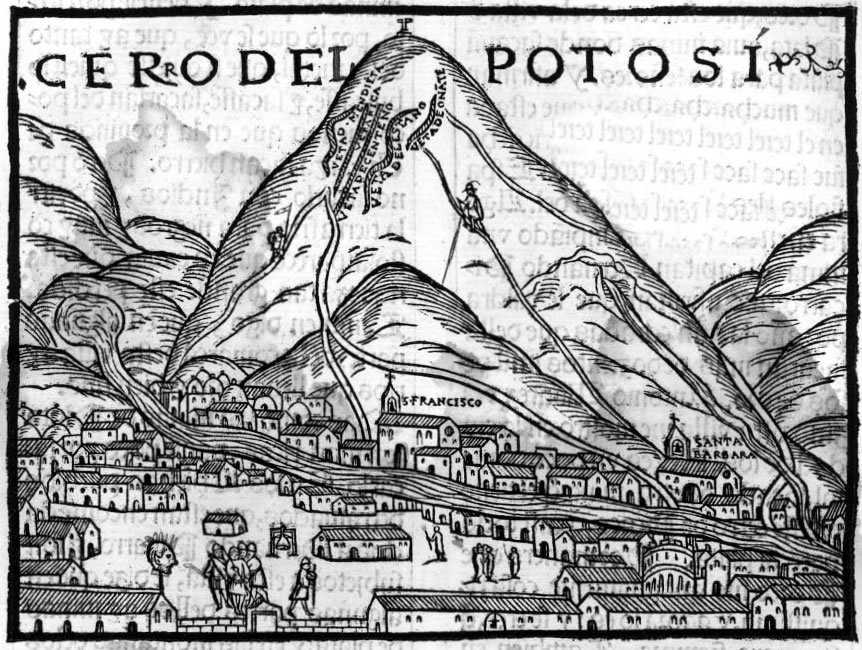

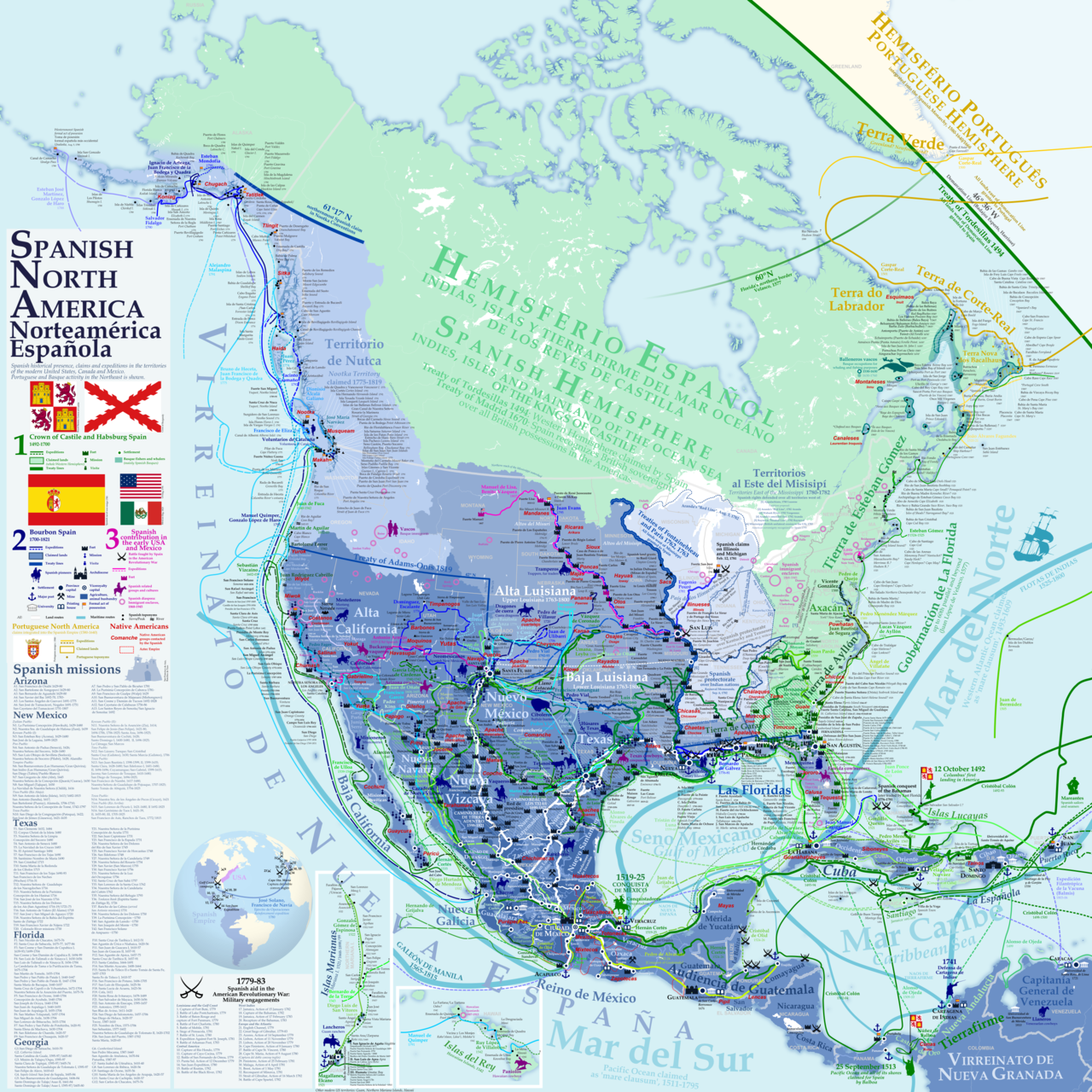

| Spain Main article: Spanish colonization of the Americas Further information: First wave of European colonization, Spanish America, and Spanish Empire  Christopher Columbus voyages  Christopher Columbus and his crew are landing in the West Indies, on an island named San Salvador, on October 12, 1492.  The Discovery of America (Johann Moritz Rugendas)  Amerigo Vespucci wakes up "America" in Americae Retectio, engraving by the Flemish artist Jan Galle (circa 1615). Systematic European colonization began in 1492. A Spanish expedition sailed west to find a new trade route to the Orient, the source of spices, silks, porcelains, and other rich trade goods. Ottoman control of the Silk Road, the traditional route for trade between Europe and Asia, forced European traders to look for alternative routes. The Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus led an expedition to find a route to East Asia, but instead landed in The Bahamas.[16] Columbus encountered the Lucayan people on the island Guanahani (possibly Cat Island), which they had inhabited since the ninth century. In his reports, Columbus exaggerated the quantity of gold in the East Indies, which he called the "New World". These claims, along with the slaves he brought back, convinced the monarchy to fund a second voyage. Word of Columbus's exploits spread quickly, sparking the Western European exploration, conquest, and colonization of the Americas.  Ferdinand Magellan and other explorers of the Pacific Spanish explorers, conquerors, and settlers sought material wealth, prestige, and the spread of Christianity, often summed up in the phrase "gold, glory, and God".[17] The Spanish justified their claims to the New World based on the ideals of the Christian Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims, completed in 1492.[18] In the New World, military conquest to incorporate indigenous peoples into Christendom was considered the "spiritual conquest". In 1493, Pope Alexander VI, the first Spaniard to become Pope, issued a series of Papal Bulls that confirmed Spanish claims to the newly discovered lands.[19] After the final Reconquista of Iberia, the Treaty of Tordesillas was ratified by the Pope, the two kingdoms of Castile (in a personal union with other kingdoms of Spain) and Portugal in 1494. The treaty divided the entire non-European world into two spheres of exploration and colonization. The longitudinal boundary cut through the Atlantic Ocean and the eastern part of present-day Brazil. The countries declared their rights to the land despite the fact that Indigenous populations had settled from pole to pole in the hemisphere and it was their homeland. After European contact, the native population of the Americas plummeted by an estimated 80% (from around 50 million in 1492 to eight million in 1650), due in part to Old World diseases carried to the New World. Smallpox was especially devastating, for it could be passed through touch, allowing native tribes to be wiped out,[20] and the conditions that colonization imposed on Indigenous populations, such as forced labor and removal from homelands and traditional medicines.[21][5][22] Some scholars have argued that this demographic collapse was the result of the first large-scale act of genocide in the modern era.[3][23]  The silver mountain of Potosí, in what is now Bolivia. It was the source of vast amounts of silver that transformed the world economy. For example, the labor and tribute of inhabitants of Hispaniola were granted in encomienda to Spaniards, a practice established in Spain for conquered Muslims. Although not technically slavery, it was coerced labor for the benefit of the Spanish grantees, called encomenderos. Spain had a legal tradition and devised a proclamation known as The Requerimento to be read to indigenous populations in Spanish, often far from the field of battle, stating that the indigenous were now subjects of the Spanish Crown and would be punished if they resisted.[24] When the news of this situation and the abuse of the institution reached Spain, the New Laws were passed to regulate and gradually abolish the system in the Americas, as well as to reiterate the prohibition of enslaving Native Americans. By the time the new laws were passed, in 1542, the Spanish crown had acknowledged their inability to control and properly ensure compliance with traditional laws overseas, so they granted to Native Americans specific protections not even Spaniards had, such as the prohibition of enslaving them even in the case of crime or war. These extra protections were an attempt to avoid the proliferation of irregular claims to slavery.[25] However, as historian Andrés Reséndez has noted, "this categorical prohibition did not stop generations of determined conquistadors and colonists from taking Native slaves on a planetary scale, ... The fact that this other slavery had to be carried out clandestinely made it even more insidious. It is a tale of good intentions gone badly astray."[26] A major event in early Spanish colonization, which had so far yielded paltry returns, was the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521). It was led by Hernán Cortés and made possible by securing indigenous alliances with the Aztecs' enemies, mobilizing thousands of warriors against the Aztecs for their own political reasons. The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, became Mexico City, the chief city of the "New Spain". More than an estimated 240,000 Aztecs died during the siege of Tenochtitlan, 100,000 in combat,[27] while 500–1,000 of the Spaniards engaged in the conquest died. The other great conquest was of the Inca Empire (1531–35), led by Francisco Pizarro.  Spanish historical and territorial presence in North America During the early period of exploration, conquest, and settlement, c. 1492–1550, the overseas possessions claimed by Spain were only loosely controlled by the crown. With the conquests of the Aztecs and the Incas, the New World now commanded the crown's attention. Both Mexico and Peru had dense, hierarchically organized indigenous populations that could be incorporated and ruled. Even more importantly, both Mexico and Peru had large deposits of silver, which became the economic motor of the Spanish empire and transformed the world economy. In Peru, the singular, hugely rich silver mine of Potosí was worked by traditional forced indigenous labor drafts, known as the mit'a. In Mexico, silver was found outside the zone of dense indigenous settlement, so laborers migrated to the mines in Guanajuato and Zacatecas. The crown established the Council of the Indies in 1524, based in Seville, and issued laws of the Indies to assert its power against the early conquerors. The crown created the viceroyalty of New Spain and the viceroyalty of Peru to tighten crown control over these rich prizes of conquest. |

スペイン 主な記事 スペインのアメリカ大陸植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 ヨーロッパ植民地化の第一波、スペイン領アメリカ、スペイン帝国  クリストファー・コロンブスの航海  1492年10月12日、クリストファー・コロンブスとその乗組員は西インド諸島のサンサルバドル島に上陸した。  アメリカの発見(ヨハン・モリッツ・ルーゲンダス)  アメリゴ・ヴェスプッチが 「アメリカ 」を目覚めさせる(Americae Retectio、フランドルの画家ヤン・ガレの版画(1615年頃))。 ヨーロッパの組織的な植民地化は1492年に始まった。スペインの探検隊が、香辛料、絹織物、磁器など豊かな交易品の産地であるオリエントへの新しい交易 路を見つけるために西へ航海した。ヨーロッパとアジアを結ぶ伝統的な貿易ルートであったシルクロードがオスマン・トルコに支配されたため、ヨーロッパの貿 易商たちは代替ルートを探さざるを得なくなった。ジェノヴァ人の航海者クリストファー・コロンブスは、東アジアへのルートを見つけるために遠征隊を率いた が、その代わりにバハマに上陸した[16]。コロンブスは、9世紀から彼らが住んでいたグアナハニ島(おそらくキャット島)でルカヤの人々と遭遇した。コ ロンブスは報告書の中で、「新世界」と呼んだ東インド諸島の金の量を誇張した。コロンブスが持ち帰った奴隷とともに、これらの主張は王政を説得し、2度目 の航海に資金を提供させた。コロンブスの功績は瞬く間に広まり、西ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の探検、征服、植民地化の火付け役となった。  フェルディナンド・マゼランと他の太平洋探検家たち スペインの探検家、征服者、入植者たちは、物質的な富、名声、キリスト教の普及を求め、しばしば「黄金、栄光、神」という言葉に集約された[17]。スペ イン人は、1492年に完了したイスラム教徒からのイベリア半島のキリスト教レコンキスタの理想に基づいて、新世界に対する自分たちの主張を正当化した [18]。1493年、スペイン人として初めてローマ教皇となったアレクサンドル6世は、新たに発見された土地に対するスペインの領有権を確認する一連の 教皇勅書を発行した[19]。 イベリア半島の最終的なレコンキスタの後、1494年、トルデシリャス条約がローマ教皇、カスティーリャ2王国(スペインの他の王国と個人的に連合)、ポ ルトガルによって批准された。この条約によって、非ヨーロッパ世界は、探検と植民地化の2つの領域に分割された。縦断境界線は大西洋と現在のブラジルの東 部を貫いた。半球の極から極まで先住民が定住しており、彼らの故郷であったにもかかわらず、各国はその土地に対する権利を宣言した。 ヨーロッパ人との接触後、アメリカ大陸の先住民の人口は推定80%激減した(1492年の約5000万人から1650年には800万人へ)。天然痘は特に 壊滅的であり、接触によって伝染する可能性があったため、先住民族は一掃され[20]、植民地化が先住民族に課した条件、例えば強制労働や故郷や伝統的な 薬からの追放などがあった[21][5][22]。この人口崩壊は近代における最初の大規模なジェノサイド行為の結果であると主張する学者もいる[3] [23]。  現在のボリビアにあるポトシの銀山。世界経済を一変させた莫大な量の銀を産出した。 例えば、イスパニョーラの住民の労働力と貢ぎ物は、スペイン人が征服したイスラム教徒のためにスペインで確立された慣習であるエンコミエンダで与えられ た。厳密には奴隷制ではなかったが、エンコメンデロと呼ばれるスペイン人被支配者の利益のための強制労働だった。スペインには法的伝統があり、レクエリメ ントとして知られる布告を考案し、先住民はスペイン王室の臣民となり、抵抗すれば罰せられるという内容の布告を、しばしば戦場から遠く離れた先住民にスペ イン語で読み聞かせた[24]。この状況と制度の乱用のニュースがスペインに伝わると、アメリカ大陸での制度を規制し、徐々に廃止するための新法が制定さ れ、アメリカ先住民を奴隷にすることの禁止も改めて規定された。1542年に新法が制定されるまでに、スペイン王室は海外における伝統的な法律を管理し、 適切に遵守させることができないことを認めていた。そのため、スペイン人ですら持っていなかった特別な保護、例えば犯罪や戦争の場合であっても彼らを奴隷 にすることを禁止することをアメリカ先住民に認めたのである。このような特別な保護は、非正規の奴隷請求の拡散を避けるための試みであった[25]。しか し、歴史家のアンドレス・レゼンデスが指摘しているように、「この断固とした禁止は、何世代にもわたる決意の固い征服者と植民地主義者が、惑星的規模で先 住民の奴隷を奪うことを止めなかった。このような奴隷制度が密かに行われなければならなかったという事実が、奴隷制度をより狡猾なものにしていた。これ は、善意が悪い方向に迷走した物語である」[26]。 スペインの植民地化初期の大きな出来事は、スペインによるアステカ帝国の征服(1519-1521)であった。エルナン・コルテスが率いたこの征服は、ア ステカの敵である先住民との同盟を確保することで可能となり、彼ら自身の政治的理由から何千人もの戦士をアステカに動員した。アステカの首都テノチティト ランはメキシコシティとなり、「新スペイン」の主要都市となった。テノチティトランの包囲戦でアステカ人は推定24万人以上、戦闘で10万人が死亡し [27]、征服に従事したスペイン人のうち500~1,000人が死亡した。もう一つの大きな征服は、フランシスコ・ピサロが率いたインカ帝国(1531 -35)であった。  北アメリカにおけるスペインの歴史と領土 1492~1550年頃の探検、征服、入植の初期には、スペインが主張する海外領土は王室によってゆるやかに管理されていたに過ぎなかった。アステカとイ ンカの征服により、新大陸はスペイン王室の注目の的となった。メキシコとペルーの両地域には、階層的に組織化された原住民が密集していた。さらに重要なこ とは、メキシコとペルーの両国に大量の銀が埋蔵されていたことである。ペルーでは、ポトシの銀山が非常に豊かで、ミタと呼ばれる伝統的な先住民の強制労働 によって働かされていた。メキシコでは、銀は先住民の密集地帯の外で発見されたため、労働者はグアナファトとサカテカスの鉱山に移住した。王室は1524 年にセビーリャを拠点とするインド評議会を設立し、初期の征服者たちに対して権力を主張するためにインド法を発布した。王室はニュースペイン総督府とペ ルー総督府を創設し、これらの豊かな征服獲物に対する王室の支配を強化した。 |

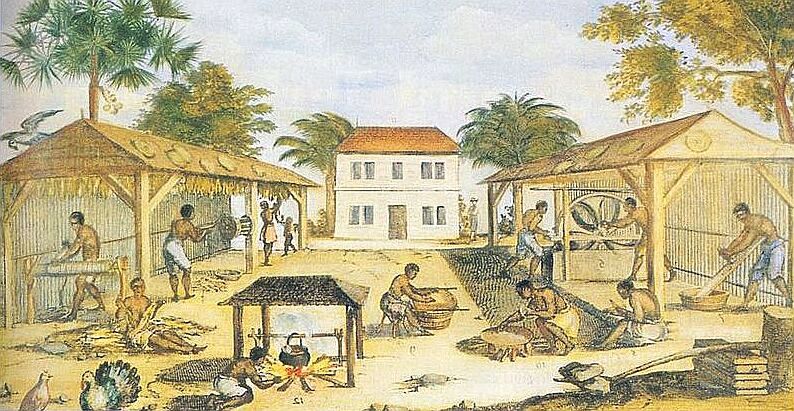

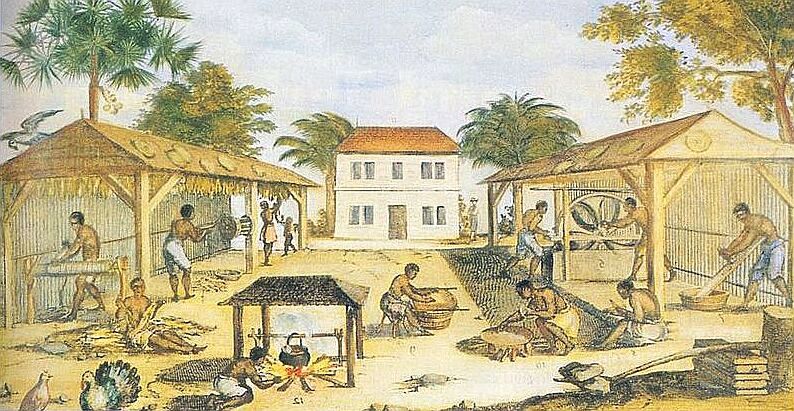

| Portugal Main article: Portuguese colonization of the Americas Further information: First wave of European colonization, Portuguese America, and Portuguese Empire  Discovery of Brazil Over this same time frame as Spain, Portugal claimed lands in North America (Canada) and colonized much of eastern South America naming it Santa Cruz and Brazil. On behalf of both the Portuguese and Spanish crowns, cartographer Amerigo Vespucci explored the South American east coast and published his new book Mundus Novus (New World) in 1502–1503 which disproved the belief that the Americas were the easternmost part of Asia and confirmed that Columbus had reached a set of continents previously unheard of to any Europeans. Cartographers still use a Latinized version of his first name, America, for the two continents. In April 1500, Portuguese noble Pedro Álvares Cabral claimed the region of Brazil to Portugal; the effective colonization of Brazil began three decades later with the founding of São Vicente in 1532 and the establishment of the system of captaincies in 1534, which was later replaced by other systems. Others tried to colonize the eastern coasts of present-day Canada and the River Plate in South America. These explorers include João Vaz Corte-Real in Newfoundland; João Fernandes Lavrador, Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real and João Álvares Fagundes, in Newfoundland, Greenland, Labrador, and Nova Scotia (from 1498 to 1502, and in 1520). During this time, the Portuguese gradually switched from an initial plan of establishing trading posts to extensive colonization of what is now Brazil. They imported millions of slaves to run their plantations. The Portuguese and Spanish royal governments expected to rule these settlements and collect at least 20% of all treasure found (the quinto real collected by the Casa de Contratación), in addition to collecting all the taxes they could. By the late 16th century silver from the Americas accounted for one-fifth of the combined total budget of Portugal and Spain.[28] In the 16th century perhaps 240,000 Europeans entered ports in the Americas.[29][30] |

ポルトガル 主な記事 ポルトガルのアメリカ大陸植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 ヨーロッパ植民地化の第一波、ポルトガル領アメリカ、ポルトガル帝国  ブラジルの発見 スペインと同じ時期に、ポルトガルは北アメリカ(カナダ)の領有権を主張し、南アメリカ東部の大部分をサンタクルスとブラジルと名付けて植民地化した。ポ ルトガルとスペインの両王室を代表して、地図製作者アメリゴ・ヴェスプッチが南米東海岸を探検し、1502年から1503年にかけて新著『新世界』 (Mundus Novus)を出版した。この本は、アメリカ大陸がアジアの最東端であるという信念を覆し、コロンブスがそれまでヨーロッパ人が聞いたことのない大陸に到 達したことを確認するものであった。地図製作者たちは今でも、コロンブスのファーストネームである「アメリカ」をラテン語化したものを2つの大陸に使って いる。1500年4月、ポルトガルの貴族ペドロ・アルヴァレス・カブラルがブラジルの領有権をポルトガルに主張した。ブラジルの効果的な植民地化は、その 30年後の1532年のサン・ヴィセンテの設立と1534年の船長制度の確立によって始まった。また、現在のカナダの東海岸や南米のプレート川を植民地化 しようとした探検家もいた。ニューファンドランドのジョアン・ヴァス・コルテ=リアル、ニューファンドランド、グリーンランド、ラブラドル、ノヴァ・スコ シアのジョアン・フェルナンデス・ラブラドール、ガスパール、ミゲル・コルテ=リアル、ジョアン・アルヴァレス・ファグンデス(1498年から1502 年、1520年)などである。 この間、ポルトガルは貿易拠点の設立という当初の計画から、徐々に現在のブラジルを広範囲に植民地化する計画に切り替えていった。彼らはプランテーション を経営するために何百万人もの奴隷を輸入した。ポルトガル王室とスペイン王室は、これらの入植地を支配し、すべての税金を徴収することに加えて、発見され た財宝の少なくとも20%(カサ・デ・コントラタシオンが徴収したキント・レアル)を徴収することを期待した。16世紀後半には、アメリカ大陸からの銀 は、ポルトガルとスペインの合計予算の5分の1を占めていた[28]。 |

| France Main article: French colonization of the Americas Further information: French America and French colonial empire  Map of territorial claims in North America by 1750, before the French and Indian War, which was part of the greater worldwide conflict known as the Seven Years' War (1756 to 1763). Possessions of Britain (pink), France (blue), and Spain. White border lines mark later Canadian Provinces and US States for reference. France founded colonies in the Americas: in eastern North America (which had not been colonized by Spain north of Florida), a number of Caribbean islands (which had often already been conquered by the Spanish or depopulated by disease), and small coastal parts of South America. Explorers included Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524; Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), and Samuel de Champlain (1567–1635), who explored the region of Canada he reestablished as New France.[31] The first French colonial empire stretched to over 10,000,000 km2 (3,900,000 sq mi) at its peak in 1710, which was the second largest colonial empire in the world, after the Spanish Empire.[32][33] In the French colonial regions, the focus of the economy was on sugar plantations in the French West Indies. In Canada the fur trade with the natives was important. About 16,000 French men and women became colonizers. The great majority became subsistence farmers along the St. Lawrence River. With a favorable disease environment and plenty of land and food, their numbers grew exponentially to 65,000 by 1760. Their colony was taken over by Britain in 1760, but social, religious, legal, cultural, and economic changes were few in a society that clung tightly to its recently formed traditions.[34][35] |

フランス 主な記事 フランスのアメリカ大陸植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 フランス領アメリカ、フランス植民地帝国  七年戦争(1756年~1763年)として知られる世界的な紛争の一部であったフレンチ・インディアン戦争前の1750年までの北アメリカにおける領有権 主張の地図。イギリス(ピンク)、フランス(青)、スペインの領土。白い境界線は、後のカナダの州とアメリカの州を示す。 フランスはアメリカ大陸に植民地を設立した。北アメリカ大陸東部(フロリダ以北はスペインによって植民地化されていなかった)、カリブ海の島々(すでにス ペインによって征服されていたり、病気で人口が減少していたりしていた)、南アメリカ大陸の小さな沿岸部である。探検家としては、1524年のジョヴァン ニ・ダ・ヴェラッツァーノ、ジャック・カルティエ(1491年-1557年)、サミュエル・ド・シャンプラン(1567年-1635年)などがいる。 最初のフランス植民地帝国は1710年のピーク時には10,000,000 km2 (3,900,000平方マイル)を超え、スペイン帝国に次いで世界で2番目に大きな植民地帝国であった[32][33]。 フランス植民地地域では、経済の中心はフランス領西インド諸島の砂糖プランテーションであった。カナダでは原住民との毛皮貿易が重要であった。約 16,000人のフランス人男女が植民者となった。大多数はセントローレンス川沿いの自給自足の農民となった。有利な疾病環境と豊富な土地と食料により、 彼らの数は飛躍的に増加し、1760年までに65,000人に達した。彼らの植民地は1760年にイギリスに占領されたが、最近形成された伝統に固くしが みつく社会では、社会的、宗教的、法的、文化的、経済的な変化はほとんどなかった[34][35]。 |

| British Main article: British colonization of the Americas Further information: British America and British Empire British colonization began in North America almost a century after Spain. The relatively late arrival meant that the British could use the other European colonization powers as models for their endeavors.[36] Inspired by the Spanish riches from colonies founded upon the conquest of the Aztecs, Incas, and other large Native American populations in the 16th century, their first attempt at colonization occurred in Roanoke and Newfoundland, although unsuccessful.[37] In 1606, King James I granted a charter with the purpose of discovering the riches at their first permanent settlement in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. They were sponsored by common stock companies such as the chartered Virginia Company financed by wealthy Englishmen who exaggerated the economic potential of the land.[6]  James II established the Colony of New York and the Dominion of New England. The Reformation of the 16th century broke the unity of Western Christendom and led to the formation of numerous new religious sects, which often faced persecution by governmental authorities. In England, many people came to question the organization of the Church of England by the end of the 16th century. One of the primary manifestations of this was the Puritan movement, which sought to purify the existing Church of England of its residual Catholic rites. The first of these people, known as the Pilgrims, landed on Plymouth Rock in November 1620. Continuous waves of repression led to the migration of about 20,000 Puritans to New England between 1629 and 1642, where they founded multiple colonies. Later in the century, the new Province of Pennsylvania was given to William Penn in settlement of a debt the king owed his father. Its government was established by William Penn in about 1682 to become primarily a refuge for persecuted English Quakers, but others were welcomed. Baptists, German and Swiss Protestants, and Anabaptists also flocked to Pennsylvania. The lure of cheap land, religious freedom and the right to improve themselves with their own hand was very attractive.[38]  Thirteen Colonies of North America: Dark Red = New England colonies. Bright Red = Middle Atlantic colonies. Red-brown = Southern colonies. Mainly due to discrimination, there was often a separation between English colonial communities and indigenous communities. The Europeans viewed the natives as savages who were not worthy of participating in what they considered civilized society. The native people of North America did not die out nearly as rapidly nor as greatly as those in Central and South America due in part to their exclusion from British society. The indigenous people continued to be stripped of their native lands and were pushed further out west.[39] The English eventually went on to control much of Eastern North America, the Caribbean, and parts of South America. They also gained Florida and Quebec in the French and Indian War. John Smith convinced the colonists of Jamestown that searching for gold was not taking care of their immediate needs for food and shelter. The lack of food security leading to an extremely high mortality rate was quite distressing and cause for despair among the colonists. To support the colony, numerous supply missions were organized. Tobacco later became a cash crop, with the work of John Rolfe and others, for export and the sustaining economic driver of Virginia and the neighboring colony of Maryland. Plantation agriculture was a primary aspect of the economies of the Southern Colonies and in the British West Indies. They heavily relied on African slave labor to sustain their economic pursuits. From the beginning of Virginia's settlements in 1587 until the 1680s, the main source of labor and a large portion of the immigrants were indentured servants looking for a new life in the overseas colonies. During the 17th century, indentured servants constituted three-quarters of all European immigrants to the Chesapeake Colonies. Most of the indentured servants were teenagers from England with poor economic prospects at home. Their fathers signed the papers that gave them free passage to America and an unpaid job until they came of age. They were given food, clothing, and housing and taught farming or household skills. American landowners were in need of laborers and were willing to pay for a laborer's passage to America if they served them for several years. By selling passage for five to seven years worth of work, they could then start on their own in America.[40] Many of the migrants from England died in the first few years.[6] Economic advantage also prompted the Darien scheme, an ill-fated venture by the Kingdom of Scotland to settle the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s. The Darien Scheme aimed to control trade through that part of the world and thereby promote Scotland into a world trading power. However, it was doomed by poor planning, short provisions, weak leadership, lack of demand for trade goods, and devastating disease.[41] The failure of the Darien scheme was one of the factors that led the Kingdom of Scotland into the Act of Union 1707 with the Kingdom of England, creating the united Kingdom of Great Britain and giving Scotland commercial access to English, now British, colonies.[42] |

イギリス 主な記事 イギリスのアメリカ大陸植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 イギリス領アメリカ、大英帝国 イギリスの植民地化はスペインのほぼ1世紀後に北アメリカ大陸で始まった。1606年、ジェームズ1世は、1607年にヴァージニア州ジェームズタウンに 定住した最初の入植地で富を発見することを目的に、勅許を与えた。彼らは、土地の経済的可能性を誇張した裕福なイギリス人によって資金提供された、チャー ターされたヴァージニア会社などの株式会社によってスポンサーされた[6]。  ジェームズ2世はニューヨーク植民地とニューイングランド領を設立した。 16世紀の宗教改革は、西方キリスト教の統一を破り、多くの新しい宗教宗派の形成につながったが、それらはしばしば政府当局による迫害に直面した。イング ランドでは、16世紀末までに多くの人々が英国国教会の組織に疑問を抱くようになった。その主要な表れの一つが清教徒運動であり、既存の英国国教会から残 存するカトリックの儀式を浄化しようとした。1620年11月、ピルグリムとして知られるこれらの人々がプリマス・ロックに上陸した。その後も弾圧が続 き、1629年から1642年にかけて約2万人の清教徒がニューイングランドに移住し、複数の植民地を築いた。世紀の後半、新しいペンシルベニア州は、国 王が彼の父に負っていた借金の清算としてウィリアム・ペンに与えられた。ウィリアム・ペンによって1682年頃に設立されたペンシルバニア州政府は、主に 迫害されていたイギリスのクエーカー教徒の避難所となったが、他の人々も歓迎された。バプテスト、ドイツやスイスのプロテスタント、アナバプテストもペン シルベニアに集まった。安い土地、信教の自由、自分たちの手で自分たちを向上させる権利という誘惑は非常に魅力的だった[38]。  北アメリカの13植民地: 濃い赤=ニューイングランド植民地。 明るい赤=大西洋中部の植民地。 赤茶色=南部の植民地。 主に差別のために、イギリス植民地社会と先住民社会との間にはしばしば隔たりがあった。ヨーロッパ人は原住民を、彼らの考える文明社会に参加するに値しな い野蛮人とみなしていた。北アメリカの先住民は、イギリス社会から排除されたこともあって、中南米の先住民ほど急速に、また大きく滅びることはなかった。 先住民は自分たちの土地を奪われ続け、さらに西に押しやられた[39]。イギリス人は最終的に北アメリカ東部の大部分、カリブ海地域、南アメリカの一部を 支配するようになった。また、フレンチ・インディアン戦争でフロリダとケベックを獲得した。 ジョン・スミスはジェームズタウンの入植者たちに、金鉱を探すことは彼らの当面の必要である食料と住居を確保することではないと説得した。食料の確保がで きず、死亡率が非常に高くなったことは、入植者たちを非常に苦しめ、絶望の原因となった。植民地を支援するため、数多くの補給使節団が組織された。後にタ バコは、ジョン・ロルフらの働きによって換金作物として輸出されるようになり、ヴァージニアと隣接するメリーランドの経済を支える原動力となった。プラン テーション農業は、南部植民地とイギリス領西インド諸島の経済の主要な側面であった。南部植民地とイギリス領西インド諸島の経済は、プランテーション農業 に依存していた。 1587年のヴァージニア入植開始から1680年代まで、主な労働力と移民の大部分は、海外植民地での新しい生活を求める年季奉公人であった。17世紀、 年季奉公人はチェサピーク植民地へのヨーロッパ人移民の4分の3を占めていた。年季奉公人の大半は、イギリスから来た10代の若者で、自国での経済的見込 みが乏しかった。彼らの父親は、アメリカへの無料渡航と、成人するまでの無給の仕事を与える書類に署名した。彼らは衣食住を与えられ、農業や家事の技術を 教えられた。アメリカの地主たちは労働者を必要としており、数年間仕えてくれれば、アメリカへの渡航費用を喜んで支払った。イギリスからの移民の多くは、 最初の数年で死亡した[40]。 1690年代後半にスコットランド王国がパナマ地峡を開拓するために行った不運な事業であるダリエン計画も、経済的な利点を背景にしていた。ダリエン計画 は、パナマ地峡の貿易を支配し、スコットランドを世界の貿易大国にすることを目的としていた。ダリエン計画の失敗は、スコットランド王国をイングランド王 国との連合法1707年へと導いた要因のひとつであり、グレートブリテン連合王国が誕生し、スコットランドはイングランド(現在はイギリス)の植民地への 商業的アクセスを得ることになった[42]。 |

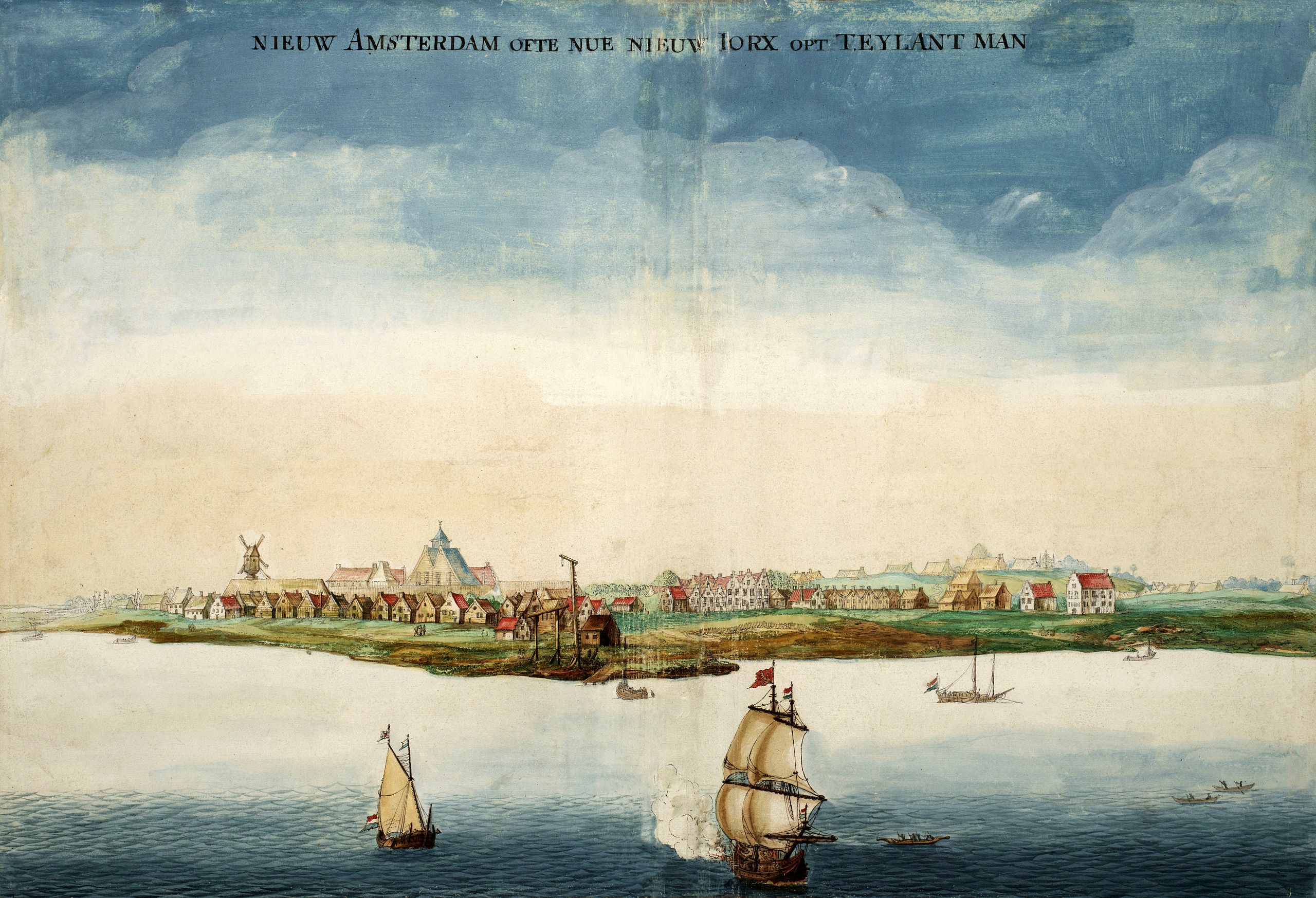

| Dutch Main article: Dutch colonization of the Americas Further information: Dutch America and Dutch Empire  New Amsterdam on lower Manhattan island, was captured by the English in 1665, becoming New York. The Netherlands had been part of the Spanish Empire, due to the inheritance of Charles V of Spain. Many Dutch people converted to Protestantism and sought their political independence from Spain. They were a seafaring nation and built a global empire in regions where the Portuguese had originally explored. In the Dutch Golden Age, it sought colonies. In the Americas, the Dutch conquered the northeast of Brazil in 1630, where the Portuguese had built sugar cane plantations worked by black slave labor from Africa. Prince Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen became the administrator of the colony (1637–43), building a capital city and royal palace, fully expecting the Dutch to retain control of this rich area. As the Dutch had in Europe, it tolerated the presence of Jews and other religious groups in the colony. After Maurits departed in 1643, the Dutch West India Company took over the colony until it was lost to the Portuguese in 1654. The Dutch retained some territory in Dutch Guiana, now Suriname. The Dutch also seized islands in the Caribbean that Spain had originally claimed but had largely abandoned, including Sint Maarten in 1618, Bonaire in 1634, Curaçao in 1634, Sint Eustatius in 1636, Aruba in 1637, some of which remain in Dutch hands and retain Dutch cultural traditions. On the east coast of North America, the Dutch planted the colony of New Netherland on the lower end of the island of Manhattan, at New Amsterdam starting in 1624. The Dutch sought to protect their investments and purchased Manhattan from a band of Canarse from Brooklyn who occupied the bottom quarter of Manhattan, known then as the Manhattoes, for 60 guilders' worth of trade goods. Minuit conducted the transaction with the Canarse chief Seyseys, who accepted valuable merchandise in exchange for an island that was actually mostly controlled by another indigenous group, the Weckquaesgeeks.[43] Dutch fur traders set up a network upstream on the Hudson River. There were Jewish settlers from 1654 onward, and they remained following the English capture of New Amsterdam in 1664. The naval capture was despite both nations being at peace with the other. |

オランダ 主な記事 アメリカ大陸のオランダ植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 オランダ領アメリカ、オランダ帝国  マンハッタン島下部のニューアムステルダムは、1665年にイギリスに占領され、ニューヨークとなった。 オランダは、スペインのシャルル5世が継承したスペイン帝国の一部であった。多くのオランダ人がプロテスタントに改宗し、スペインからの政治的独立を求め た。彼らは海洋国家であり、もともとポルトガルが探検した地域に世界帝国を築いた。オランダ黄金時代には、植民地を求めた。アメリカ大陸では、オランダは 1630年にブラジル北東部を征服し、ポルトガル人がアフリカからの黒人奴隷労働者によってサトウキビ・プランテーションを建設した。ヨハン・マウリッ ツ・ファン・ナッソー・シーゲン王子は植民地の管理者となり(1637-43年)、首都と王宮を建設し、オランダがこの豊かな地域の支配権を保持すること を十分に期待した。オランダはヨーロッパと同様、植民地にユダヤ人やその他の宗教団体が存在することを容認した。1643年にマウリッツが去った後、 1654年にポルトガル軍に奪われるまで、オランダ西インド会社が植民地を支配した。オランダはオランダ領ギアナ(現在のスリナム)の一部領土を保持し た。オランダはまた、1618年にシント・マールテン島、1634年にボネール島、1634年にキュラソー島、1636年にシント・ユースタティウス島、 1637年にアルバ島など、もともとスペインが領有権を主張していたが、ほとんど放棄していたカリブ海の島々を占領した。 北アメリカ東海岸では、オランダは1624年からマンハッタン島の下端、ニューアムステルダムにニューネーデルラントの植民地を築いた。オランダは自分た ちの投資を保護するために、マンハッタン島下部の4分の1を占拠していたブルックリン出身のカナース人の一団(当時はマンハット族として知られていた)か ら、60ギルダー相当の交易品でマンハッタンを購入した。ミニュイはカナースの族長セイセイと取引を行い、セイセイは、実際には別の先住民グループである ウェッククウェスギークがほとんどを支配していた島と引き換えに、貴重な商品を受け取った[43]。オランダの毛皮商人たちは、ハドソン川の上流にネット ワークを築いた。1654年以降、ユダヤ人入植者が存在し、1664年にイギリスがニューアムステルダムを占領した後も彼らは残った。ナショナリズムの占 領は、両国が平和条約を結んでいたにもかかわらず行われた。 |

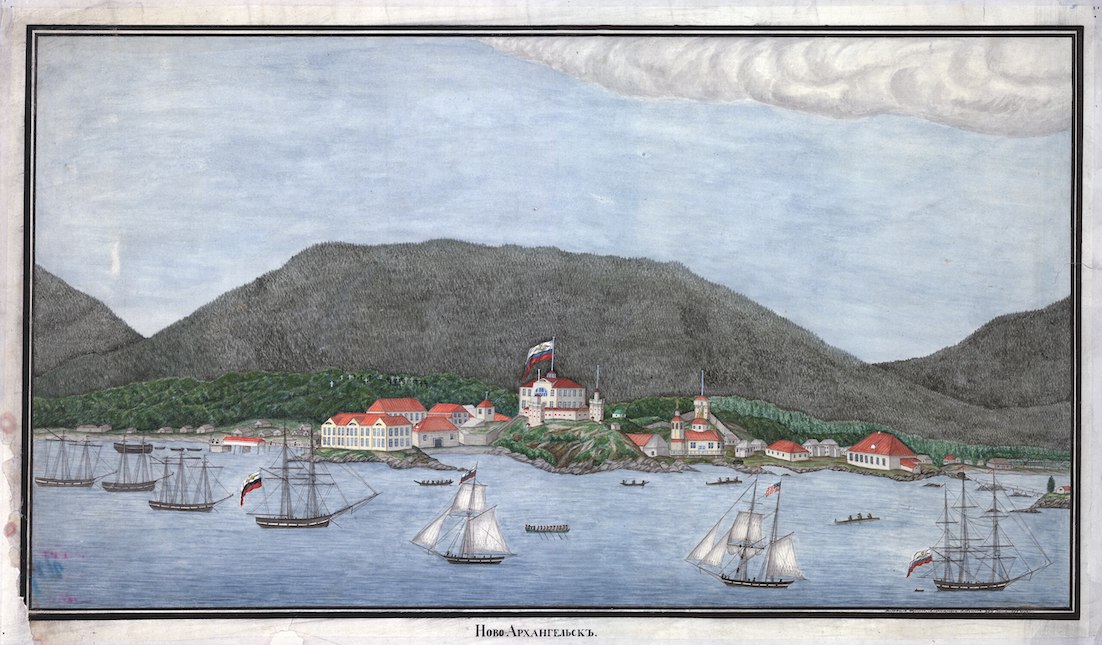

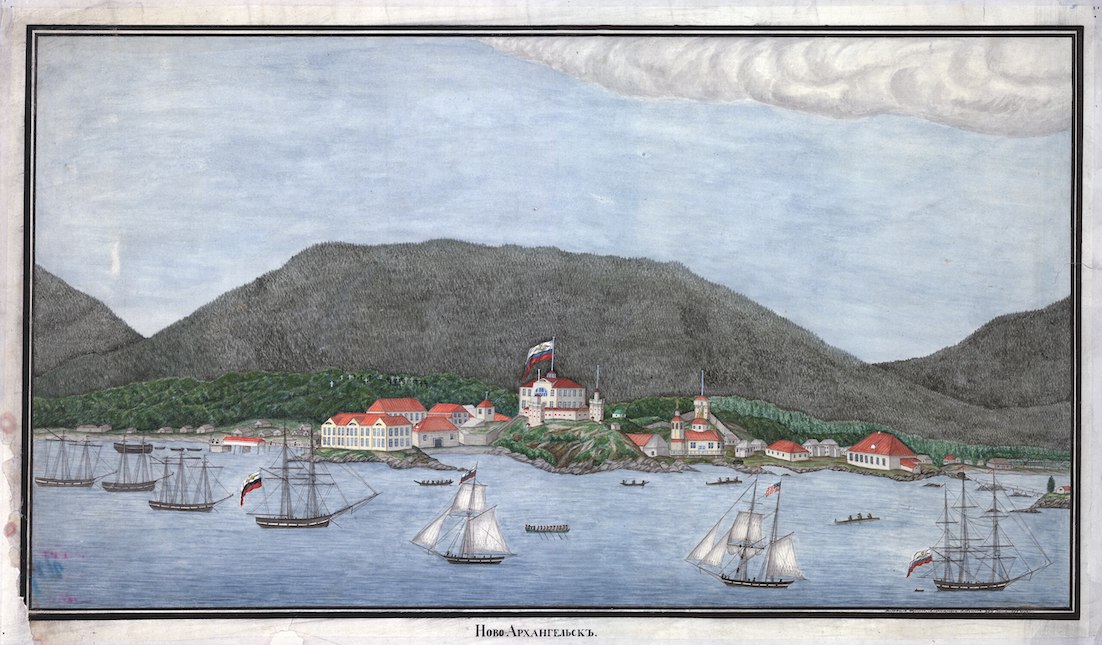

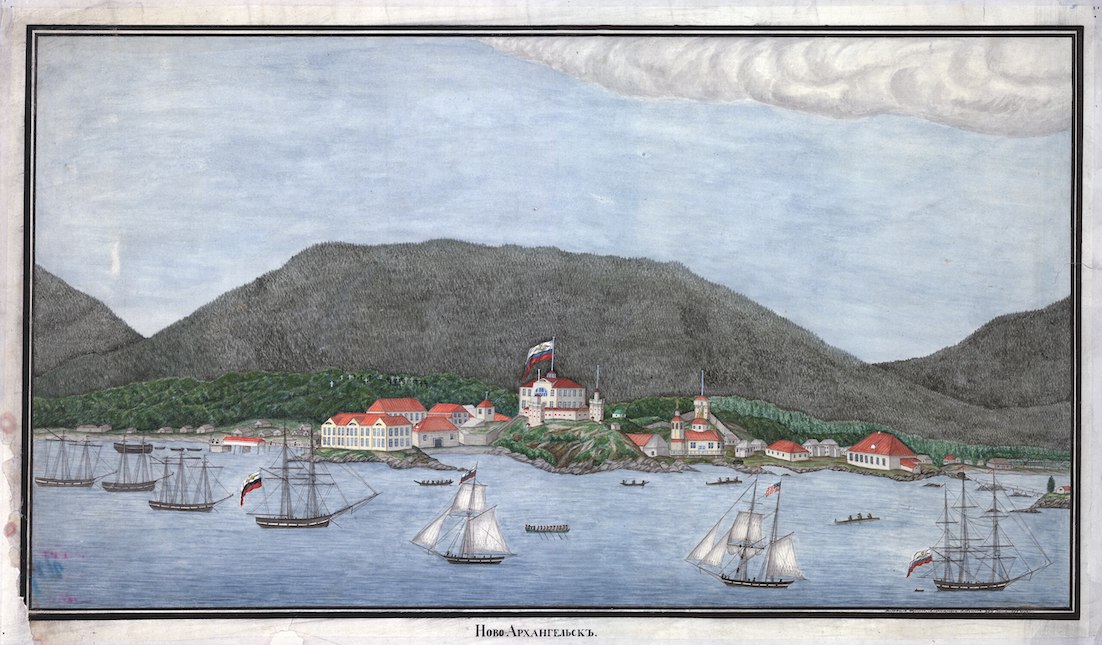

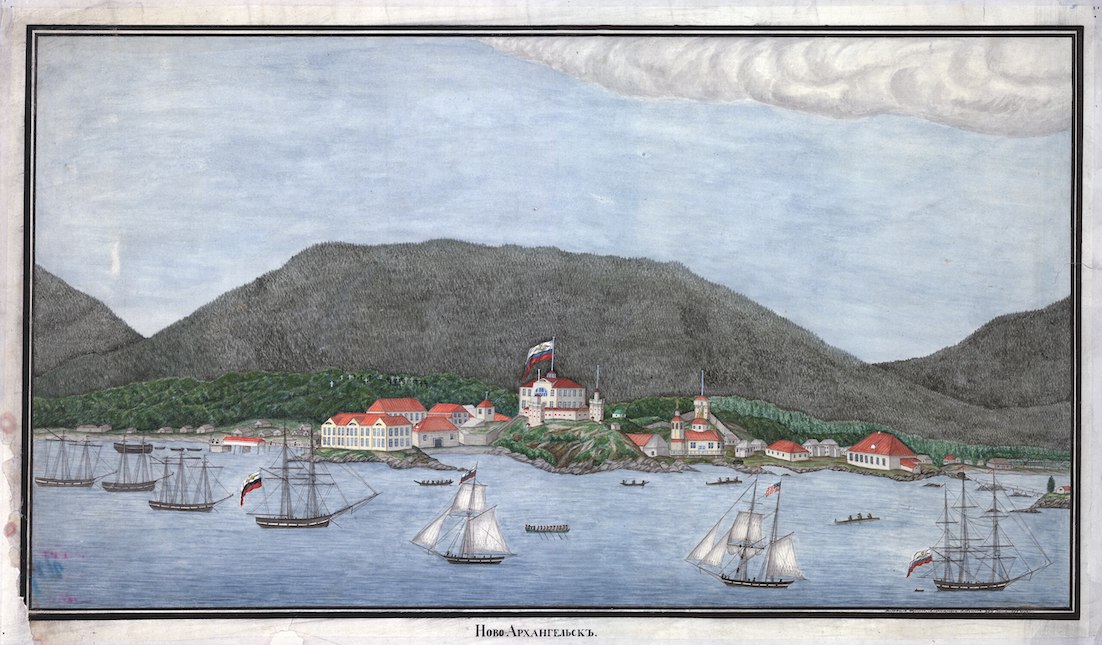

| Russia Main article: Russian colonization of North America Further information: Russian America and Russian Empire  New Archangel (present-day Sitka, Alaska), the capital of Russian America, in 1837 Russia came to colonization late compared to Spain or Portugal, or even England. Siberia was added to the Russian Empire and Cossack explorers along rivers sought valuable furs of ermine, sable, and fox. Cossacks enlisted the aid of indigenous Siberians, who sought protection from nomadic peoples, and those peoples paid tribute in fur to the czar. Thus, prior to the eighteenth-century Russian expansion that pushed beyond the Bering Strait dividing Eurasia from North America, Russia had experience with northern indigenous peoples and accumulated wealth from the hunting of fur-bearing animals. Siberia had already attracted a core group of scientists, who sought to map and catalogue the flora, fauna, and other aspects of the natural world. A major Russian expedition for exploration was mounted in 1742, contemporaneous with other eighteenth-century European state-sponsored ventures. It was not clear at the time whether Eurasia and North America were completely separate continents. The first voyages were made by Vitus Bering and Aleksei Chirikov, with settlement beginning after 1743. By the 1790s the first permanent settlements were established. Explorations continued down the Pacific coast of North America, and Russia established a settlement in the early nineteenth century at what is now called Fort Ross, California.[44][45][46] Russian fur traders forced indigenous Aleut men into seasonal labor.[47] Never very profitable, Russia sold its North American holdings to the United States in 1867, called at the time "Seward's Folly". |

ロシア 主な記事 ロシアの北米植民地化 さらに詳しい情報 ロシア領アメリカ、ロシア帝国  1837年、ロシア領アメリカの首都ニューアーチエンジェル(現在のアラスカ州シトカ)。 ロシアは、スペインやポルトガル、あるいはイギリスと比べて植民地化が遅かった。シベリアはロシア帝国に加えられ、河川沿いのコサック探検家たちはエルミ ン、セーブル、キツネなどの貴重な毛皮を求めた。コサックは遊牧民からの保護を求める先住民シベリアの人々の助けを借り、それらの人々は毛皮を皇帝に貢納 した。このように、ユーラシア大陸と北アメリカ大陸を隔てるベーリング海峡を越えて18世紀にロシアが進出する以前から、ロシアは北方先住民との付き合い を経験し、毛皮を持つ動物の狩猟で富を蓄積していた。シベリアにはすでに中核となる科学者たちが集まっており、彼らは植物相や動物相など、自然界のさまざ まな側面を地図やカタログにまとめようとしていた。 18世紀ヨーロッパの国家主導による探検と同時期の1742年、ロシアによる大規模な探検が行われた。当時は、ユーラシア大陸と北アメリカ大陸が完全に別 の大陸であるかどうかは明らかではなかった。最初の航海はヴィトゥス・ベーリングとアレクセイ・チリコフによって行われ、1743年以降に入植が始まっ た。1790年代には、最初の定住地が築かれた。探検は北アメリカの太平洋岸まで続き、ロシアは19世紀初頭に現在カリフォルニア州のフォート・ロスと呼 ばれる場所に入植地を築いた[44][45][46]。ロシアの毛皮商人たちは、先住民のアリュート族に季節労働を強いるようになった[47]。ロシアは あまり利益を上げることなく、1867年に北アメリカの保有地をアメリカに売却し、当時「スワードの愚行」と呼ばれた。 |

| Tuscany Main article: Thornton expedition Further information: Grand Duchy of Tuscany and The Guianas Duke Ferdinand I de Medici made the only Italian attempt to create colonies in America. For this purpose, the Grand Duke organized in 1608 an expedition to the north of Brazil, under the command of the English captain Robert Thornton. Thornton, on his return from the preparatory trip in 1609 (he had been to the Amazon), found Ferdinand I dead and all projects were cancelled by his successor Cosimo II.[48] |

トスカーナ 主な記事 ソーントン遠征 さらに詳しい情報 トスカーナ大公国とギアナ諸島 フェルディナンド1世デ・メディチ公は、イタリアで唯一、アメリカに植民地を作ろうとした。この目的のため、大公は1608年、イギリス人船長ロバート・ソーントンの指揮の下、ブラジル北部への遠征隊を組織した。 1609年に準備旅行から戻ったソーントンは(彼はアマゾンに行っていた)、フェルディナンド1世が亡くなっているのを発見し、すべての計画は後継者のコジモ2世によって中止された[48]。 |

Religion and colonization The Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue in Mauritsstad (Recife) is the oldest synagogue in the Americas. An estimated number of 700 Jews lived in Dutch Brazil, about 4.7% of the total population.[49] Roman Catholics were the first major religious group to immigrate to the New World, as settlers in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of Portugal and Spain, and later, France in New France. No other religion was tolerated and there was a concerted effort to convert indigenous peoples and black slaves to Catholicism. The Catholic Church established three offices of the Spanish Inquisition, in Mexico City; Lima, Peru; and Cartagena de Indias in Colombia to maintain religious orthodoxy and practice. The Portuguese did not establish a permanent office of the Portuguese Inquisition in Brazil, but did send visitations of inquisitors in the seventeenth century.[50] English and Dutch colonies, on the other hand, tended to be more religiously diverse. Settlers to these colonies included Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, English Puritans and other nonconformists, English Catholics, Scottish Presbyterians, French Protestant Huguenots, German and Swedish Lutherans, as well as Jews, Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, and Moravians.[51] Jews fled to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam when the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions cracked down on their presence.[52] |

宗教と植民地化 マウリッツスタッド(レシフェ)のカハル・ズール・イスラエル・シナゴーグは、アメリカ大陸最古のシナゴーグである。オランダ領ブラジルには、全人口の約4.7%にあたる700人のユダヤ人が住んでいたと推定されている[49]。 ローマ・カトリックは、スペインとポルトガルの植民地、そして後にフランスがニュー・フランスに入植した際に、新大陸に移住した最初の主要な宗教集団で あった。他の宗教は容認されず、先住民や黒人奴隷をカトリックに改宗させるための努力が行われた。カトリック教会は、宗教の正統性と実践を維持するため に、メキシコシティ、ペルーのリマ、コロンビアのカルタヘナ・デ・インディアスに3つのスペイン異端審問所を設置した。ポルトガル人はブラジルに常設の異 端審問所を設置しなかったが、17世紀には異端審問官を派遣していた[50]。 一方、イギリスとオランダの植民地は、より宗教的に多様である傾向があった。これらの植民地への入植者には、英国国教会、オランダのカルヴァン派、イギリ スの清教徒やその他の非改宗者、イギリスのカトリック、スコットランドの長老派、フランスのプロテスタントであるユグノー、ドイツやスウェーデンのルター 派、さらにはユダヤ人、クエーカー教徒、メノナイト、アーミッシュ、モラヴィア人などがいた[51]。スペインとポルトガルの異端審問が取り締まったと き、ユダヤ人はオランダの植民地ニューアムステルダムに逃れた[52]。 |

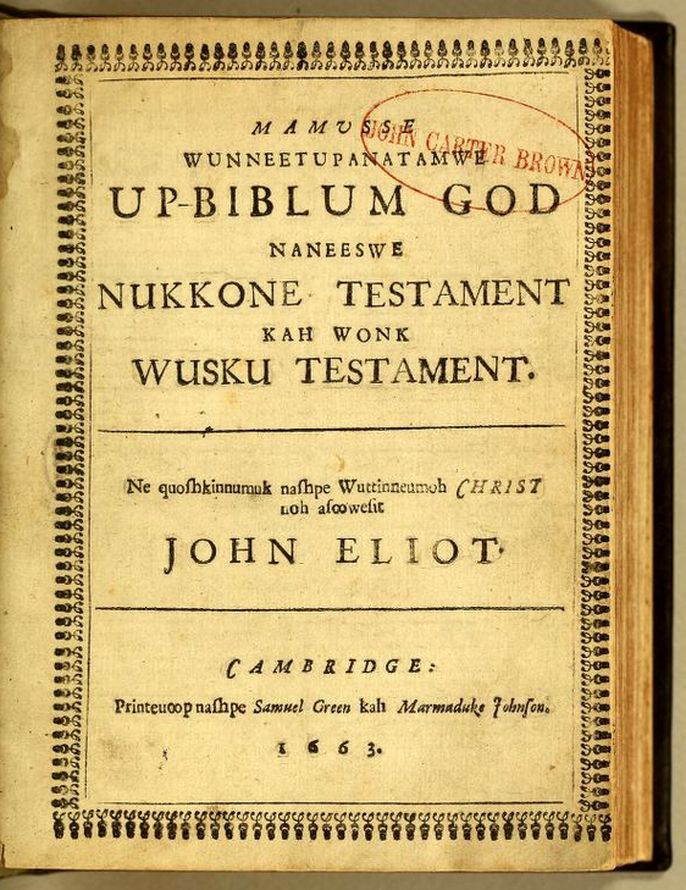

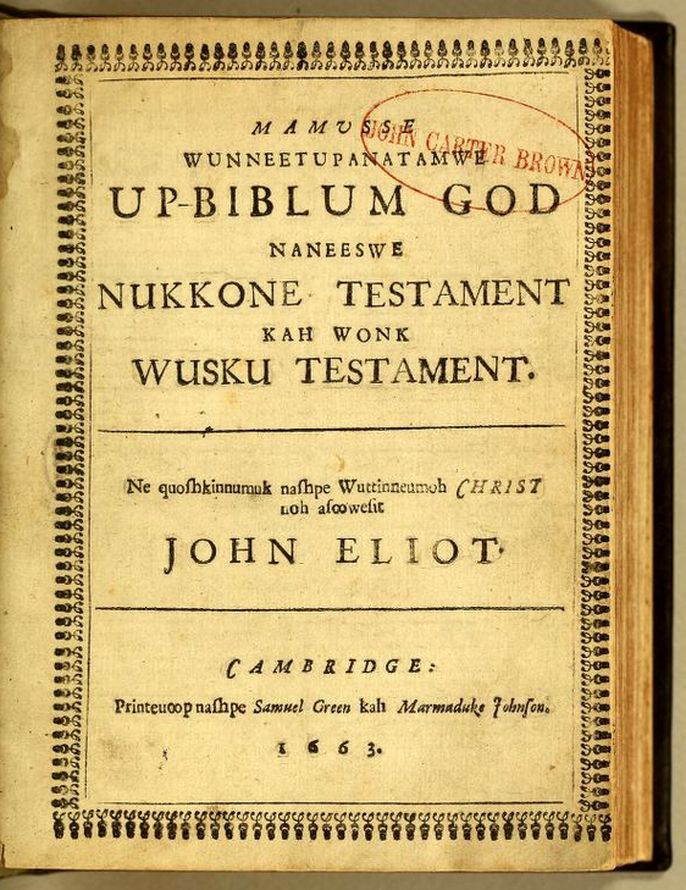

| Christianization Main articles: Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery, Christianization, Forced conversion § Christianity, and Cultural assimilation of Native Americans Further information: Cultural genocide, Ethnocide, Forced assimilation, and Religious persecution  Franciscan Alonso de Molina's 1565 Nahuatl (Aztec) dictionary, conceived for friars to communicate with the indigenous peoples in central Mexico in their own language  Eliot Indian Bible  Catholic cathedral in Mexico City Beginning with the first wave of European colonization, the religious discrimination, persecution, and violence toward the Indigenous peoples' native religions was systematically perpetrated by the European Christian colonists and settlers from the 15th–16th centuries onwards.[2][1][3][4][8][9] During the Age of Discovery and the following centuries, the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires were the most active in attempting to convert the Indigenous peoples of the Americas to the Christian religion.[8][9] Pope Alexander VI issued the Inter caetera bull in May 1493 that confirmed the lands claimed by the Kingdom of Spain, and mandated in exchange that the Indigenous peoples be converted to Catholic Christianity. During Columbus's second voyage, Benedictine friars accompanied him, along with twelve other priests. With the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, evangelization of the dense Indigenous populations was undertaken in what was called the "spiritual conquest".[53] Several mendicant orders were involved in the early campaign to convert the Indigenous peoples. Franciscans and Dominicans learned Indigenous languages of the Americas, such as Nahuatl, Mixtec, and Zapotec.[54] One of the first schools for Indigenous peoples in Mexico was founded by Pedro de Gante in 1523. The friars aimed at converting Indigenous leaders, with the hope and expectation that their communities would follow suit.[55] In densely populated regions, friars mobilized Indigenous communities to build churches, making the religious change visible; these churches and chapels were often in the same places as old temples, often using the same stones. "Native peoples exhibited a range of responses, from outright hostility to active embrace of the new religion."[56] In central and southern Mexico where there was an existing Indigenous tradition of creating written texts, the friars taught Indigenous scribes to write their own languages in Latin letters. There is a significant body of texts in Indigenous languages created by and for Indigenous peoples in their own communities for their own purposes. In frontier areas where there were no settled Indigenous populations, friars and Jesuits often created missions, bringing together dispersed Indigenous populations in communities supervised by the friars in order to more easily preach the gospel and ensure their adherence to the faith. These missions were established throughout Spanish America which extended from the southwestern portions of current-day United States through Mexico and to Argentina and Chile. As slavery was prohibited between Christians and could only be imposed upon non-Christian prisoners of war and/or men already sold as slaves, the debate on Christianization was particularly acute during the early 16th century, when Spanish conquerors and settlers sought to mobilize Indigenous labor. Later, two Dominican friars, Bartolomé de Las Casas and the philosopher Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, held the Valladolid debate, with the former arguing that Native Americans were endowed with souls like all other human beings, while the latter argued to the contrary to justify their enslavement. In 1537, the papal bull Sublimis Deus definitively recognized that Native Americans possessed souls, thus prohibiting their enslavement, without putting an end to the debate. Some claimed that a native who had rebelled and then been captured could be enslaved nonetheless. When the first Franciscans arrived in Mexico in 1524, they burned the sacred places dedicated to the Indigenous peoples' native religions.[57] However, in Pre-Columbian Mexico, burning the temple of a conquered group was standard practice, shown in Indigenous manuscripts, such as Codex Mendoza. Conquered Indigenous groups expected to take on the gods of their new overlords, adding them to the existing pantheon. They likely were unaware that their conversion to Christianity entailed the complete and irrevocable renunciation of their ancestral religious beliefs and practices. In 1539, Mexican bishop Juan de Zumárraga oversaw the trial and execution of the Indigenous nobleman Carlos of Texcoco for apostasy from Christianity.[58] Following that, the Catholic Church removed Indigenous converts from the jurisdiction of the Inquisition, since it had a chilling effect on evangelization. In creating a protected group of Christians, Indigenous men no longer could aspire to be ordained Christian priests.[59] Throughout the Americas, the Jesuits were active in attempting to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity. They had considerable success on the frontiers in New France[60] and Portuguese Brazil, most famously with Antonio de Vieira, S.J;[61] and in Paraguay, almost an autonomous state within a state.[62] The Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, a translation by John Eliot of the gospel into Algonquian, was published in 1663. |

キリスト教化 主な記事 カトリック教会と大航海時代、キリスト教化、強制改宗§キリスト教、アメリカ先住民の文化的同化 さらに詳しい情報 文化的大虐殺、民族虐殺、強制同化、宗教的迫害  フランシスコ会士アロンソ・デ・モリーナが1565年に出版したナワトル語(アステカ語)の辞書。  エリオット・インディアン聖書(1663年)  メキシコシティのカトリック大聖堂 ヨーロッパによる植民地化の第一波に始まり、先住民の土着宗教に対する宗教的差別、迫害、暴力は、15~16世紀以降、ヨーロッパのキリスト教徒による植民者・入植者によって組織的に行われた[2][1][3][4][8][9]。 大航海時代とそれに続く数世紀の間、スペインとポルトガルの植民地帝国はアメリカ大陸の先住民をキリスト教に改宗させようと最も積極的に試みた。 1493年5月、ローマ教皇アレクサンドル6世は、スペイン王国が領有権を主張する土地を確認し、それと引き換えに先住民をカトリックのキリスト教に改宗 させることを義務づけるInter caetera bullを発布した。コロンブスの2度目の航海には、ベネディクト会の修道士が12人の司祭とともに同行した。スペインがアステカ帝国を征服すると、「精 神的征服」と呼ばれるように、密集していた先住民の伝道が行われた。フランシスコ会とドミニコ会は、ナワトル語、ミクステカ語、サポテカ語といったアメリ カ大陸の先住民の言語を学んだ[54]。修道士たちは先住民の指導者たちを改宗させることを目的とし、彼らのコミュニティがそれに従うことを期待した [55]。人口密度の高い地域では、修道士たちは先住民のコミュニティを動員して教会を建てさせ、宗教的変化を目に見えるものにした。これらの教会や礼拝 堂は、しばしば古い寺院と同じ場所であり、しばしば同じ石材を使用していた。「先住民は、明白な敵意から新しい宗教の積極的な受け入れまで、様々な反応を 示した。」[56] 文字のテキストを作成する既存の先住民の伝統があったメキシコ中部と南部では、修道士はラテン文字で自分たちの言語を書くために先住民の書記を教えた。先 住民が自分たちのコミュニティの中で、自分たちのために、自分たちの目的のために作成した先住民の言語によるテキストはかなりの数にのぼる。先住民が定住 していない開拓地では、修道士とイエズス会はしばしば宣教師団を設立し、福音をより容易に宣べ伝え、彼らの信仰への忠誠を保証するために、修道士が監督す る共同体に分散している先住民を集めた。これらの伝道所は、現在のアメリカ南西部からメキシコを経てアルゼンチンやチリに至るまで、スペイン領アメリカ全 土に設立された。 奴隷制度はキリスト教徒同士の間で禁止されており、非キリスト教徒の捕虜やすでに奴隷として売られていた者にしか課すことができなかったため、キリスト教 化に関する議論は、スペインの征服者や入植者が先住民の労働力を動員しようとした16世紀初頭に特に深刻なものとなった。その後、2人のドミニコ会修道 士、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスと哲学者フアン・ジネス・デ・セパルベダがバリャドリッド論争を行い、前者はアメリカ先住民にも他のすべての人間と同じ ように魂が備わっていると主張し、後者は逆に彼らの奴隷化を正当化しようと主張した。1537年、ローマ教皇庁の勅書Sublimis Deusは、アメリカ先住民に魂があることを明確に認め、彼らの奴隷化を禁止したが、この論争に終止符は打たれなかった。反乱を起こし、捕らえられた先住 民も奴隷にできると主張する者もいた。 1524年に最初のフランシスコ会がメキシコに到着したとき、彼らは先住民の固有の宗教に捧げられた聖地を焼いた[57]。しかし、先コロンブス期のメキ シコでは、征服された集団の神殿を焼くことは標準的な慣習であり、メンドーサ写本などの先住民の写本に示されていた。征服された先住民集団は、新しい支配 者の神々を引き受け、既存のパンテオンに加えることを期待していた。彼らはキリスト教への改宗が、先祖伝来の宗教的信仰や慣習を完全に、そして取り消し不 能な形で放棄することを意味することを知らなかったのだろう。1539年、メキシコの司教フアン・デ・ズマラガは、テスココの先住民貴族カルロスをキリス ト教からの背教の罪で裁判にかけ、処刑した[58]。その後、カトリック教会は、異端審問が伝道活動を冷え込ませるという理由から、先住民の改宗者を異端 審問の管轄から外した。保護されたキリスト教徒のグループを作ることで、先住民の男たちはもはやキリスト教の司祭に叙任されることを目指すことができなく なった[59]。 アメリカ大陸全域において、イエズス会は先住民をキリスト教に改宗させようと積極的に活動した。彼らはニュー・フランス[60]とポルトガル領ブラジルの 辺境で大きな成功を収め、最も有名なのはアントニオ・デ・ヴィエイラ聖職者[61]であり、パラグアイではほとんど国家の中の自治州であった[62]。 ジョン・エリオットによる福音書のアルゴン語への翻訳である『Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God』が1663年に出版された。 |

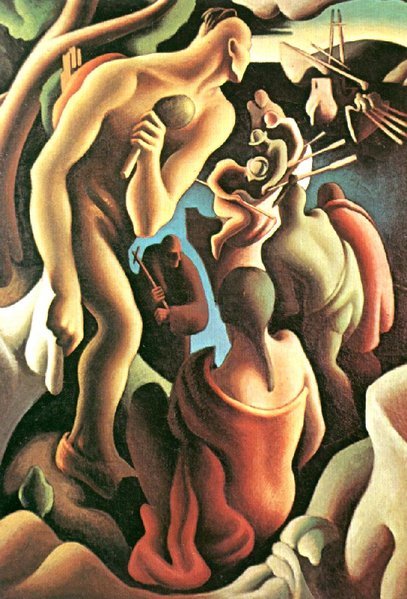

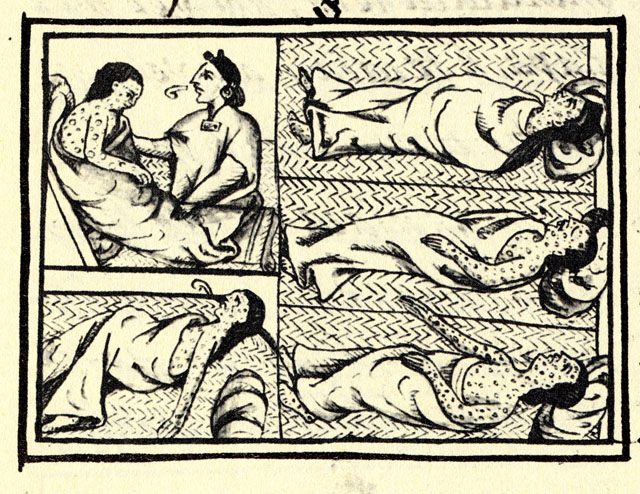

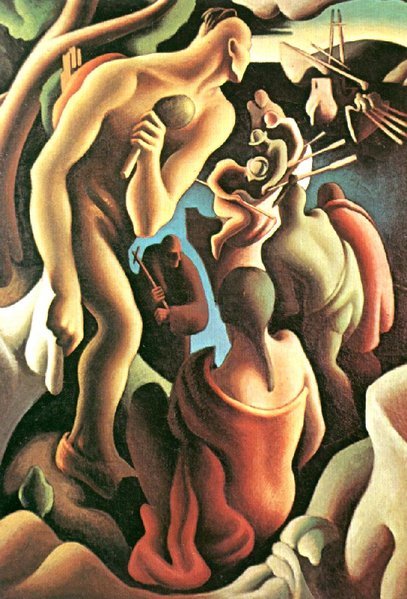

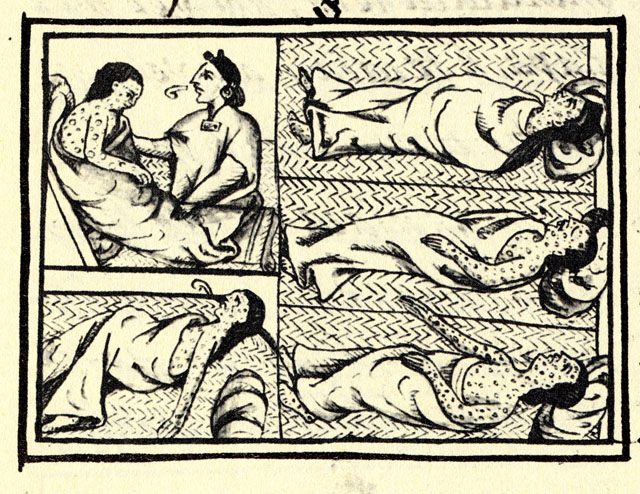

| Disease, genocides, and indigenous population loss See also: Disease in colonial America, Native American disease and epidemics, and Genocide of indigenous peoples § Indigenous peoples of the Americas (pre-1948)  American Discovery Viewed by Native Americans, a 1922 painting by Thomas Hart Benton, now housed in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, United States[63]  Drawing accompanying text in Book XII of the 16th-century Florentine Codex (compiled 1540–1585) Nahua suffering from smallpox The European lifestyle included a long history of sharing close quarters with domesticated animals such as cows, pigs, sheep, goats, horses, dogs and various domesticated fowl, from which many diseases originally stemmed. In contrast to the indigenous people, the Europeans had developed a richer endowment of antibodies.[64] The large-scale contact with Europeans after 1492 introduced Eurasian germs to the indigenous people of the Americas. Epidemics of smallpox (1518, 1521, 1525, 1558, 1589), typhus (1546), influenza (1558), diphtheria (1614) and measles (1618) swept the Americas subsequent to European contact,[65][66] killing between 10 million and 100 million[67] people, up to 95% of the indigenous population of the Americas.[68] The cultural and political instability attending these losses appears to have been of substantial aid in the efforts of various colonists in New England and Massachusetts to acquire control over the great wealth in land and resources of which indigenous societies had customarily made use.[69] Such diseases yielded human mortality of unquestionably enormous gravity and scale – and this has profoundly confused efforts to determine its full extent with any true precision. Estimates of the pre-Columbian population of the Americas vary tremendously. Others have argued that significant variations in population size over pre-Columbian history are reason to view higher-end estimates with caution. Such estimates may reflect historical population maxima, while indigenous populations may have been at a level somewhat below these maxima or in a moment of decline in the period just prior to contact with Europeans. Indigenous populations hit their ultimate lows in most areas of the Americas in the early 20th century; in a number of cases, growth has returned.[70] According to scientists from University College London, the colonization of the Americas by Europeans killed so much of the indigenous population that it resulted in climate change and global cooling.[71][72][73] Some contemporary scholars also attribute significant indigenous population losses in the Caribbean to the widespread practice of slavery and deadly forced labor in gold and silver mines.[74][75][76] Historian Andrés Reséndez, supports this claim and argues that indigenous populations were smaller previous estimations and "a nexus of slavery, overwork and famine killed more Indians in the Caribbean than smallpox, influenza and malaria."[77] According to the Cambridge World History, the Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies, and the Cambridge World History of Genocide, colonial policies in some cases included the deliberate genocide of indigenous peoples in North America.[78][79][80] According to the Cambridge World History of Genocide, Spanish colonization of the Americas also included genocidal massacres.[81] According to Adam Jones, genocidal methods included the following: Genocidal massacres Biological warfare, using pathogens (especially smallpox and plague) to which the indigenous peoples had no resistance Spreading of disease via the 'reduction' of Indians to densely crowded and unhygienic settlements Slavery and forced/indentured labor, especially, though not exclusively, in Latin America, in conditions often rivalling those of Nazi concentration camps Mass population removals to barren 'reservations,' sometimes involving death marches en route, and generally leading to widespread mortality and population collapse upon arrival Deliberate starvation and famine, exacerbated by destruction and occupation of the native land base and food resources Forced education of indigenous children in White-run schools ...[82] |

病気、大量虐殺、先住民の人口減少 以下も参照のこと: 植民地時代のアメリカの病気、アメリカ先住民の病気と伝染病、先住民の大量虐殺§アメリカ大陸の先住民(1948年以前)  アメリカ先住民が見たアメリカの発見、トーマス・ハート・ベントンによる1922年の絵画で、現在はアメリカ合衆国マサチューセッツ州セーラムのピーボディ・エセックス博物館に所蔵されている[63]。  16世紀のフィレンツェ写本(1540-1585年編纂)の第XII巻のテキストに添えられた図面。 天然痘で苦悩するナフア族 ヨーロッパ人のライフスタイルには、牛、豚、羊、山羊、馬、犬、さまざまな家禽など、家畜化された動物と密接な距離を共有する長い歴史があり、多くの病気 はもともとそこから派生したものであった。1492年以降のヨーロッパ人との大規模な接触によって、ユーラシアの病原菌がアメリカ大陸の先住民に持ち込ま れた。 天然痘(1518年、1521年、1525年、1558年、1589年)、チフス(1546年)、インフルエンザ(1558年)、ジフテリア(1614 年)、麻疹(1618年)の流行がヨーロッパ人との接触後のアメリカ大陸を席巻し[65][66]、1000万人から1億人[67]、アメリカ大陸の先住 民の最大95%が死亡した。[68]このような損失に伴う文化的・政治的不安定性は、ニューイングランドやマサチューセッツの様々な入植者たちが、先住民 社会が慣習的に利用してきた土地や資源の巨万の富に対する支配権を獲得しようとする努力に大いに役立ったようである[69]。 このような病気は、疑いなく甚大で大規模な人間の死亡率をもたらしたが、このことは、その全容を正確に把握しようとする努力を大きく混乱させた。コロンブ ス以前のアメリカ大陸の人口の推定は、実に様々である。また、コロンブス以前の歴史において、人口規模に大きなばらつきがあることは、高い推定値を慎重に 見るべき理由であると主張する者もいる。このような推計は、歴史的な人口の最大値を反映している可能性があるが、先住民の人口は、ヨーロッパ人と接触する 直前の時期には、これらの最大値よりやや低いレベルにあったか、あるいは減少の一途をたどっていた可能性がある。先住民の人口は、20世紀初頭にアメリカ 大陸のほとんどの地域で最終的な底を打った。 ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの科学者によれば、ヨーロッパ人によるアメリカ大陸の植民地化によって先住民の人口が大幅に減少し、それが気候変動 と地球規模の寒冷化をもたらしたという。[74][75][76]歴史家のアンドレス・レゼンデスはこの主張を支持し、先住民の人口は以前の推定よりも少 なく、「奴隷制度、過労、飢饉の連鎖によってカリブ海では天然痘、インフルエンザ、マラリアよりも多くのインディアンが死亡した」と主張している [77]。 ケンブリッジ世界史』、『ジェノサイド研究のオックスフォード・ハンドブック』、『ジェノサイドのケンブリッジ世界史』によれば、植民地政策には場合に よっては北米先住民の熟議的な大量虐殺も含まれていた[78][79][80]。『ジェノサイドのケンブリッジ世界史』によれば、スペインのアメリカ大陸 植民地化にも大量虐殺が含まれていた[81]。 アダム・ジョーンズによれば、大量虐殺の方法には以下のようなものがあった: 大量虐殺 先住民が抵抗力を持たない病原体(特に天然痘とペスト)を使った生物戦 インディアンを密集した不衛生な居住地に「減少」させることで病気を蔓延させる。 特にラテンアメリカにおいて、ナチスの強制収容所に匹敵するような状況での奴隷労働と強制労働。 不毛の「保留地」への大量人口移動。時には死の行進を伴うこともあり、一般に、到着後すぐに死亡率が広がり、人口が崩壊する。 先住民の土地基盤や食糧資源の破壊と占領によって悪化した、熟議による飢餓と飢饉。 白人が運営する学校での先住民の子供たちの強制教育...[82]。 |

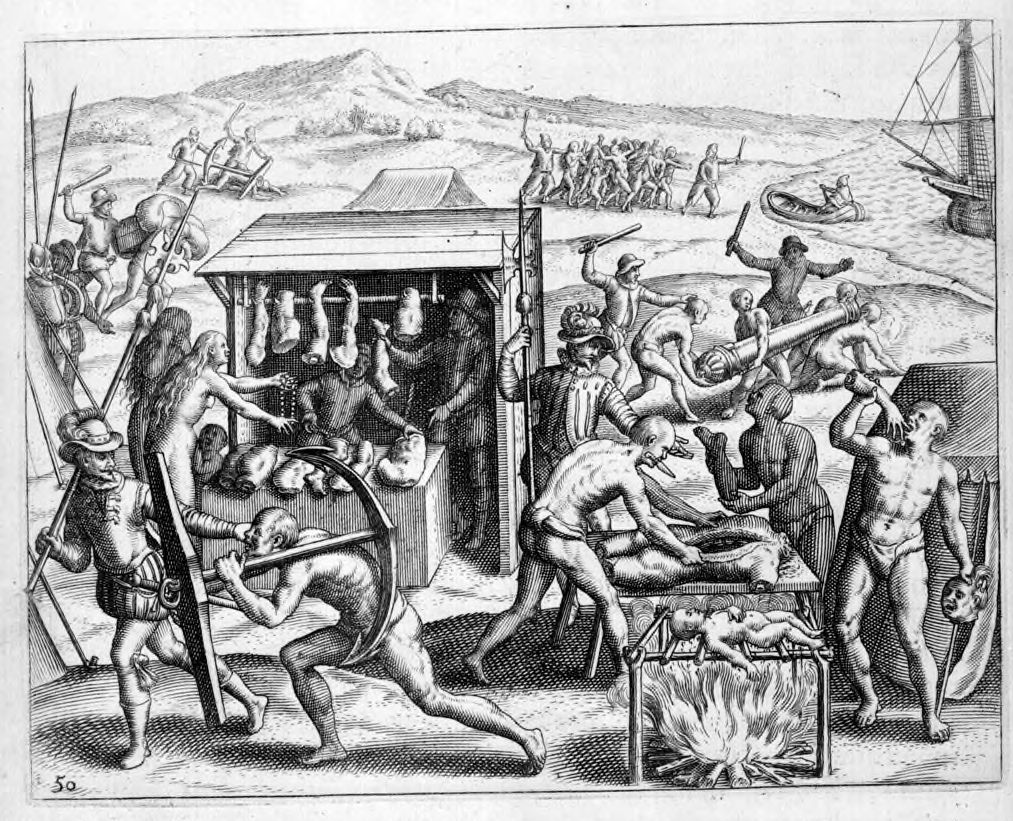

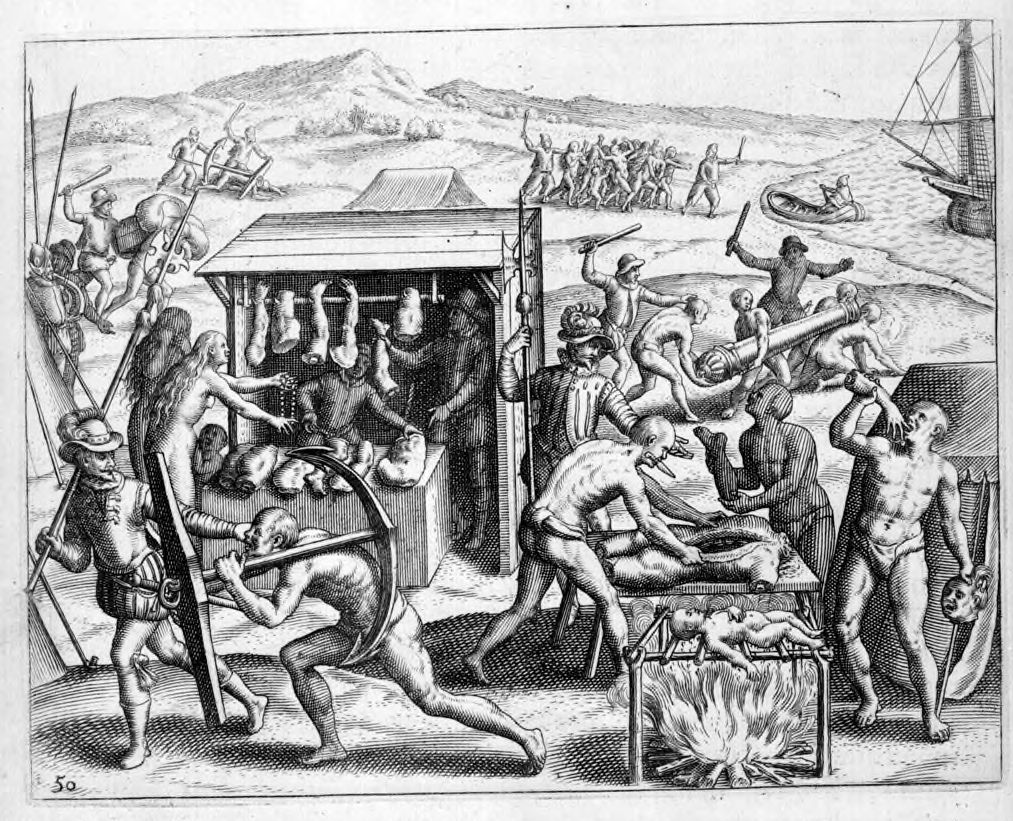

| Slavery Main articles: Atlantic slave trade and European enslavement of Indigenous Americans Further information: Slavery in colonial Spanish America, Slavery in Brazil, Indian slave trade in the American Southeast, Slavery in the British and French Caribbean, Slavery in the colonial history of the United States, and History of slavery § Americas  Depiction of Spanish treatment of the indigenous populations in the Caribbean by Theodore de Bry, illustrating Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas's indictment of early Spanish cruelty, known as the Black legend, and indigenous barbarity, including human cannibalism, in an attempt to justify their enslavement  Triangular trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas  African slaves 17th-century in a tobacco plantation, Virginia, 1670 Indigenous population loss following European contact directly led to Spanish explorations beyond the Caribbean islands they initially claimed and settled in the 1490s, since they required a labor force to both produce food and to mine gold. Slavery was not unknown in Indigenous societies. With the arrival of European colonists, enslavement of Indigenous peoples "became commodified, expanded in unexpected ways, and came to resemble the kinds of human trafficking that are recognizable to us today".[83] While the disease was the main killer of indigenous peoples, the practice of slavery and forced labor was also a significant contributor to the indigenous death toll.[19] With the arrival of Europeans other than the Spanish, enslavement of native populations increased since there were no prohibitions against slavery until decades later. It is estimated that from Columbus's arrival to the end of the 19th century between 2.5 and 5 million Native Americans were forced into slavery. Indigenous men, women, and children were often forced into labor in sparsely populated frontier settings, in the household, or in the toxic gold and silver mines.[84] This practice was known as the encomienda system and granted free native labor to the Spaniards. Based upon the practice of exacting tribute from Muslims and Jews during the Reconquista, the Spanish Crown granted a number of native laborers to an encomendero, who was usually a conquistador or other prominent Spanish male. Under the grant, they were theoretically bound to both protect the natives and convert them to Christianity. In exchange for their forced conversion to Christianity, the natives paid tributes in the form of gold, agricultural products, and labor. The Spanish Crown tried to terminate the system through the Laws of Burgos (1512–13) and the New Laws of the Indies (1542). However, the encomenderos refused to comply with the new measures and the indigenous people continued to be exploited. Eventually, the encomienda system was replaced by the repartimiento system which was not abolished until the late 18th century.[85] In the Caribbean, deposits of gold were quickly exhausted and the precipitous drop in the indigenous population meant a severe labor shortage. Spaniards sought a high-value, low-bulk export product to make their fortunes. Cane sugar was the answer. It had been cultivated on the Iberian Atlantic islands. It was a highly desirable, expensive foodstuff. The problem of a labor force was solved by the importation of African slaves, initiating the creation of sugar plantations worked by chattel slaves. Plantations required a significant workforce to be purchased, housed, and fed; capital investment in building sugar mills on-site, since once cane was cut, the sugar content rapidly declined. Plantation owners were linked to creditors and a network of merchants to sell processed sugar in Europe. The whole system was predicated on a huge, enslaved population. The Portuguese controlled the African slave trade, since the division of spheres with Spain in the Treaty of Tordesillas, they controlled the African coasts. Black slavery dominated the labor force in tropical zones, particularly where sugar was cultivated, in Portuguese Brazil, the English, French, and Dutch Caribbean islands. On the mainland of North America, the English southern colonies imported black slaves, starting in Virginia in 1619, to cultivate other tropical or semi-tropical crops such as tobacco, rice, and cotton. Although black slavery is most associated with agricultural production, in Spanish America enslaved and free blacks and mulattoes were found in numbers in cities, working as artisans. Most newly transported African slaves were not Christians, but their conversion was a priority. For the Catholic Church, black slavery was not incompatible with Christianity. The Jesuits created hugely profitable agricultural enterprises and held a significant black slave labor force. European whites often justified the practice through the belts of latitude theory, supported by Aristotle and Ptolemy. In this perspective, belts of latitude wrapped around the Earth and corresponded with specific human traits. The peoples from the "cold zone" in Northern Europe were "of lesser prudence", while those of the "hot zone" in sub-Sahara Africa were intelligent but "weaker and less spirited".[83] According to the theory, those of the "temperate zone" across the Mediterranean reflected an ideal balance of strength and prudence. Such ideas about latitude and character justified a natural human hierarchy.[83] African slaves were a highly valuable commodity, enriching those involved in the trade. Africans were transported to slave ships to the Americas and were primarily obtained from their African homelands by coastal tribes who captured and sold them. Europeans traded for slaves with the local native African tribes who captured them elsewhere in exchange for rum, guns, gunpowder, and other manufactures. The total slave trade to islands in the Caribbean, Brazil, the Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, and British Empires is estimated to have involved 12 million Africans.[86][87] The vast majority of these slaves went to sugar colonies in the Caribbean and to Brazil, where life expectancy was short and the numbers had to be continually replenished. At most about 600,000 African slaves were imported into the United States, or 5% of the 12 million slaves brought across from Africa.[88] |

奴隷制度 主な記事 大西洋奴隷貿易、ヨーロッパ人によるアメリカ先住民の奴隷化 さらなる情報 植民地時代スペイン領アメリカの奴隷制、ブラジルの奴隷制、アメリカ南東部のインディアン奴隷貿易、イギリス・フランス領カリブ海の奴隷制、アメリカ植民地史における奴隷制、奴隷制の歴史§アメリカ大陸  スペイン人ドミニコ会修道士バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが、奴隷化を正当化するために、黒い伝説として知られる初期のスペインの残虐行為と、人肉食を含む先住民の蛮行を告発したことを示す、セオドア・デ・ブライによるカリブ海の先住民に対するスペインの扱いの描写。  ヨーロッパ、アフリカ、アメリカ大陸間の三角貿易  17世紀、バージニア州のタバコ農園にいたアフリカ人奴隷(1670年 ヨーロッパ人との接触による先住民の人口減少は、1490年代にスペインがカリブ海の島々の領有権を主張し、定住を開始したことに直接つながった。先住民 社会では奴隷制度は未知のものではなかった。ヨーロッパ人入植者の到着とともに、先住民の奴隷化は「商品化され、予期せぬ方法で拡大し、今日私たちが認識 できるような人身売買に類似するようになった」[83]。病気が先住民の主な死因であった一方で、奴隷制度や強制労働の慣行も先住民の死者数に大きく寄与 した。コロンブスの到着から19世紀末まで、250万人から500万人のアメリカ先住民が奴隷にされたと推定されている。先住民の男性、女性、子供は、人 口の少ない開拓地、家庭、または有毒な金銀鉱山で強制労働させられることが多かった[84]。この慣習はエンコミエンダ制度として知られ、スペイン人に先 住民の労働力を無償で与えた。レコンキスタ時代にイスラム教徒やユダヤ教徒から年貢を徴収していた慣習に基づき、スペイン王室は通常コンキスタドールやそ の他の著名なスペイン人男性であったエンコメンデロに多数の先住民労働者を与えた。エンコメンデロとは、通常コンキスタドールやその他の著名なスペイン人 男性であった。エンコメンデロには、原住民の保護とキリスト教への改宗が理論上義務付けられていた。キリスト教への改宗を強制される代わりに、原住民は 金、農産物、労働力という形で貢物を支払った。スペイン王室は、ブルゴス法(1512-13年)とインド新法(1542年)によってこの制度を廃止しよう とした。しかし、エンコメンデロは新しい措置に従うことを拒否し、先住民は搾取され続けた。結局、エンコミエンダ制度はレパルティミエント制度に取って代 わられ、18世紀後半まで廃止されることはなかった[85]。 カリブ海では、金の鉱脈はすぐに枯渇し、先住民の人口の急激な減少は深刻な労働力不足を意味した。スペイン人は財産を築くために、高価値で低容量の輸出製 品を求めた。その答えがサトウキビだった。サトウキビはイベリア半島の島々で栽培されていた。サトウキビ砂糖は、イベリア半島の島々で栽培されていた。労 働力の問題は、アフリカ人奴隷の輸入によって解決され、動産奴隷が働く砂糖プランテーションの創設が始まった。プランテーションでは、購入、収容、給食に 多額の労働力が必要であり、サトウキビを刈り取ると糖度が急速に低下するため、現地に製糖工場を建設するための設備投資も必要だった。プランテーションの 所有者は、ヨーロッパで加工砂糖を販売するために、債権者や商人のネットワークとつながっていた。このシステム全体は、膨大な奴隷人口を前提としていた。 トルデシリャス条約でスペインと領域を分割して以来、ポルトガルはアフリカの奴隷貿易を支配し、アフリカ沿岸を支配していた。ポルトガル領ブラジル、イギ リス領、フランス領、オランダ領のカリブ海の島々では、黒人の奴隷制が熱帯地帯、特に砂糖の栽培が盛んな地域の労働力を支配していた。北アメリカ本土で は、1619年にヴァージニアで始まったイギリス南部の植民地が黒人奴隷を輸入し、タバコ、米、綿花などの熱帯または半熱帯の作物を栽培した。 黒人奴隷制度といえば農業生産が連想されるが、スペイン領アメリカでは、奴隷にされた黒人や自由黒人、混血が都市に多く見られ、職人として働いていた。新 しく移送されてきたアフリカ人奴隷のほとんどはキリスト教徒ではなかったが、彼らの改宗が優先された。カトリック教会にとって、黒人奴隷制度はキリスト教 と相容れないものではなかった。イエズス会は莫大な利益を生む農業企業を設立し、かなりの黒人奴隷労働力を保有していた。ヨーロッパの白人はしばしば、ア リストテレスやプトレマイオスによって支持された緯度帯理論によって、この慣習を正当化した。この考え方では、緯度の帯は地球を取り囲み、人間の特定の特 徴と対応していた。この理論によれば、地中海を横切る「温帯」の人々は、強さと慎重さの理想的なバランスを反映していた。このような緯度と性格に関する考 え方は、人間の自然なヒエラルキーを正当化するものであった[83]。 アフリカ人奴隷は非常に価値の高い商品であり、貿易に携わる人々を富ませた。アフリカ人は奴隷船でアメリカ大陸に運ばれ、主に沿岸部族によってアフリカの 故郷から捕らえられ、売られた。ヨーロッパ人は、ラム酒、銃、火薬、その他の製造品と引き換えに、他の場所で奴隷を捕獲した地元のアフリカ原住民部族と奴 隷取引を行った。カリブ海の島々、ブラジル、ポルトガル帝国、スペイン帝国、フランス帝国、オランダ帝国、大英帝国への奴隷貿易の総額は、1200万人の アフリカ人が関与していたと推定されている[86][87]。アメリカに輸入されたアフリカ人奴隷はせいぜい約60万人で、アフリカから渡ってきた 1200万人の奴隷の5%であった[88]。 |

Colonization and race Castas painting depicting Spaniard and mulatta spouse with their morisca daughter by Miguel Cabrera, 1763 Throughout the South American hemisphere, there were three large regional sources of populations: Native Americans, arriving Europeans, and forcibly transported Africans. The mixture of these cultures impacted the ethnic makeup that predominates in the hemisphere's largely independent states today. The term to describe someone of mixed European and indigenous ancestry is mestizo while the term to describe someone of mixed European and African ancestry is mulatto. The mestizo and mulatto population are specific to Iberian-influenced current-day Latin America because the conquistadors had (often forced) sexual relations with the indigenous and African women.[89] The social interaction of these three groups of people inspired the creation of a caste system based on skin tone. The hierarchy centered around those with the lightest skin tone and ordered from highest to lowest was the Peninsulares, Criollos, mestizos, indigenous, mulatto, then African.[19] Unlike the Iberians, the British men came with families with whom they planned to permanently live in what is now North America.[37] They kept the natives on the margins of colonial society. Because the British colonizers' wives were present, the British men rarely had sexual relations with the native women. While the mestizo and mulatto population make up the majority of people in Latin America today, there is only a small mestizo population in present-day North America (excluding Central America).[36] |

植民地化と人種 スペイン人とムラッタの配偶者とモリスカの娘を描いたカスタスの絵(ミゲル・カブレラ作、1763年) 南米半球には、3つの地域的な人口流入源があった: アメリカ先住民、到着したヨーロッパ人、そして強制的に移送されたアフリカ人である。これらの文化が混ざり合い、今日の南米半球の独立国家で主流となって いる民族構成に影響を与えた。ヨーロッパ人と先住民の混血をメスチソ、ヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人の混血をムラートと呼ぶ。メスティーソとムラートは、イベ リア半島の影響を受けた現在のラテンアメリカに特有であり、これは征服者が先住民やアフリカ人女性と(しばしば強制的に)性的関係を持ったからである [89]。肌の色が最も明るい人々を中心とした階層は、ペニンシュラ人、クリオージョ人、メスチーソ人、先住民、混血人、アフリカ人の順であった [19]。 イベリア人とは異なり、イギリス人男性は、現在の北米に永住する予定の家族とともにやってきた[37]。彼らは原住民を植民地社会の境界から遠ざけてい た。イギリス人植民者の妻がいたため、イギリス人男性が先住民の女性と性的関係を持つことはほとんどなかった。今日のラテンアメリカではメスティーソと混 血の人口が大多数を占めるが、現在の北アメリカ(中央アメリカを除く)ではメスティーソの人口はわずかである[36]。 |

| Colonization and gender By the early to mid-16th century, even the Iberian men began to carry their wives and families to the Americas. Some women even carried out the voyage alone.[90] Later, more studies of the role of women and female migration from Europe to the Americas have been made.[91] By the 19th century, the arrival of missionaries in Indigenous territories, along with the imposition of Western educational systems, had introduced colonial concepts of gender to the Americas.[92] |

植民地化とジェンダー 16世紀初頭から半ばになると、イベリア人の男性でさえ、妻や家族をアメリカ大陸に運ぶようになった。その後、女性の役割やヨーロッパからアメリカ大陸へ の女性の移住に関する研究がさらに進んだ[91]。 19世紀になると、先住民の領土に宣教師が到着し、西洋の教育制度が押し付けられるとともに、アメリカ大陸にジェンダーに関する植民地的概念が導入された [92]。 |

| Impact of colonial land ownership on long-term development Eventually, most of the Western Hemisphere came under the control of Western European governments, leading to changes to its landscape, population, and plant and animal life. In the 19th century, over 50 million people left Western Europe for the Americas.[93] The post-1492 era is known as the period of the Columbian exchange, a dramatically widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations (including slaves), ideas, and communicable disease between the American and Afro-Eurasian hemispheres following Columbus's voyages to the Americas. Most scholars writing at the end of the 19th century estimated that the pre-Columbian population was as low as 10 million; by the end of the 20th century most scholars gravitated to a middle estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.[94] A recent estimate is that there were about 60.5 million people living in the Americas immediately before depopulation,[95] of which 90 per cent, mostly in Central and South America, perished from wave after wave of disease, along with war and slavery playing their part.[96][75] Geographic differences between the colonies played a large determinant in the types of political and economic systems that later developed. In their paper on institutions and long-run growth, economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson argue that certain natural endowments gave rise to distinct colonial policies promoting either smallholder or coerced labor production.[97] Densely settled populations, for example, were more easily exploitable and profitable as slave labor. In these regions, landowning elites were economically incentivized to develop forced labor arrangements such as the Peru mit'a system or Argentinian latifundias without regard for democratic norms. French and British colonial leaders, conversely, were incentivized to develop capitalist markets, property rights, and democratic institutions in response to natural environments that supported smallholder production over forced labor. James Mahoney proposes that colonial policy choices made at critical junctures regarding land ownership in coffee-rich Central America fostered enduring path dependent institutions.[98] Coffee economies in Guatemala and El Salvador, for example, were centralized around large plantations that operated under coercive labor systems. By the 19th century, their political structures were largely authoritarian and militarized. In Colombia and Costa Rica, conversely, liberal reforms were enacted at critical junctures to expand commercial agriculture, and they ultimately raised the bargaining power of the middle class. Both nations eventually developed more democratic and egalitarian institutions than their highly concentrated landowning counterparts. |

植民地時代の土地所有が長期的発展に与えた影響 最終的に、西半球の大部分は西ヨーロッパ政府の支配下に入り、その景観、人口、動植物に変化をもたらした。19世紀には、5,000万人以上の人々が西 ヨーロッパからアメリカ大陸に渡った[93]。1492年以降の時代は、コロンブスによるアメリカ大陸への航海の後、アメリカ半球とアフロ・ユーラシア半 球の間で、動物、植物、文化、人間集団(奴隷を含む)、思想、伝染病などが劇的に広まったコロンブス交換の時代として知られている。 19世紀末に書かれたほとんどの学者は、コロンブス以前の人口は1,000万人と低く見積もっていたが、20世紀末には、ほとんどの学者が5,000万人 前後という中間の推定に傾き、1億人以上と主張する歴史家もいた[94]。[94]最近の推定では、過疎化の直前にアメリカ大陸に住んでいた人口は約 6,050万人であり[95]、そのうちの90パーセントは主に中南米に住んでいたが、戦争や奴隷制がその一翼を担っていたのに加えて、相次ぐ疫病によっ て滅亡した[96][75]。 植民地間の地理的な相違は、後に発展した政治・経済システムの種類を大きく左右した。経済学者のダロン・アセモグル(Daron Acemoglu)、サイモン・ジョンソン(Simon Johnson)、ジェームズ・A・ロビンソン(James A. Robinson)は、制度と長期的成長に関する論文の中で、ある種の自然的資質が小作農または強制労働による生産を促進する明確な植民地政策を生み出し たと論じている[97]。このような地域では、土地所有エリートは、ペルーのミタ制度やアルゼンチンのラティフンディアのような強制労働の取り決めを、民 主的規範を無視して発展させる経済的動機付けを受けた。逆に、フランスやイギリスの植民地指導者たちは、強制労働よりも零細農家による生産を支持する自然 環境に対応して、資本主義市場、財産権、民主的制度を発展させるインセンティブを与えられた。 ジェームズ・マホニーは、コーヒーの産地である中米の土地所有に関する植民地政策の選択が、永続的な経路依 存的制度を育んだと指摘している[98]。例えば、グアテマラやエルサルバドルのコーヒー経済は、強制労働制 度の下で運営される大規模なプランテーションを中心に中央集権化されていた。19世紀までに、これらの国の政治構造は権威主義的、ミリタリズム的なものと なった。コロンビアとコスタリカでは逆に、商業農業を拡大するために重要な局面で自由主義改革が実施され、最終的に中産階級の交渉力を高めた。両国とも、 最終的には、土地所有者が集中する国民よりも民主的で平等主義的な制度を発展させた。 |

List of European colonies in the Americas Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Founded in 1496, the city is the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the New World.  Cumaná, Venezuela. Founded in 1510, it is the oldest continuously inhabited European city in the continental Americas. There were at least a dozen European countries involved in the colonization of the Americas. The following list indicates those countries and the Western Hemisphere territories they worked to control.[99]  Mayflower, the ship that carried a colony of English Puritans to North America British and (before 1707) English Main article: British colonization of the Americas See also: § Scottish colonization of the Americas Further information: List of Hudson's Bay Company trading posts British America (1607–1783) Thirteen Colonies (1607–1783) Rupert's Land (1670–1870) British Columbia (1793–1871) British North America (1783–1907) British West Indies Belize Duchy of Courland and Semigallia Main article: Courland colonization of the Americas New Courland (Tobago, Trinidad and Tobago) (1654–1689); Courland is now part of Latvia Danish Main article: Danish colonization of the Americas Dano-Norwegian West Indies (1754–1814) Danish West Indies (1814–1917) Dano-Norwegian North Greenland (1721–1814) Dano-Norwegian South Greenland (1728?–1814) Greenland (1814–1953) Dutch Main article: Dutch colonization of the Americas New Netherland (1614–1667) Essequibo (1616–1815) Dutch Virgin Islands (1625–1680) Berbice (1627–1815) New Walcheren (1628–1677) Dutch Brazil (1630–1654) Pomeroon (1650–1689) Cayenne (1658–1664) Demerara (1745–1815)  Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, the governor of the Dutch colony of Suriname, 1923 Suriname (1667–1954) (Remained within the Kingdom of the Netherlands until 1975 as a constituent country) Curaçao and Dependencies (1634–1954) (Aruba and Curaçao are still in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Bonaire; 1634–present) Sint Eustatius and Dependencies (1636–1954) (Sint Maarten is still in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Sint Eustatius and Saba; 1636–present) French Main article: French colonization of the Americas Further information: List of French forts in North America Present-day Canada New France (1534–1763), and nearby lands: Acadia (1604–1713) Newfoundland Hudson Bay Saint Lawrence River Great Lakes Lake Winnipeg Quebec Present-day United States The Fort Saint Louis (Texas) (1685–1689) Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands (1650–1733) Fort Caroline in French Florida (occupation by Huguenots) (1562–1565) Vincennes and Fort Ouiatenon in Indiana French Louisiana (23.3% of the current U.S. territory) (1801–1804) (sold by Napoleon I) (also see: Louisiana (New Spain)) Lower Louisiana Upper Louisiana Louisiana (New France) (1672–1764) French Guiana (1763–present) French West Indies  Fort Lachine in New France, 1689 Saint-Domingue (1659–1804, now Haiti) Tobago Virgin Islands France Antarctique (1555–1567) Equinoctial France (1612–1615) French Florida (1562–1565) Present-day Dominican Republic (1795–1809) Present-day Suriname Tapanahony (District of Sipaliwini) (Controversial Franco-Dutch in favour of the Netherlands) (25.8% of the current territory) (1814) Present-day Guyana (1782–1784) Present-day Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Christopher Island (1628–1690, 1698–1702, 1706, 1782–1783) Nevis (1782–1784) Present-day Antigua and Barbuda Antigua (briefly in 1666) Present-day Trinidad and Tobago Tobago (1666–1667, 1781–1793, 1802–1803) Dominica (1625–1763, 1778–1783) Grenada (1650–1762, 1779–1783) Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (1719–1763, 1779–1783) Saint Lucia (1650–1723, 1756–1778, 1784–1803) Turks and Caicos Islands (1783) Montserrat (1666, 1712) Falkland Islands (1504, 1701, 1764–1767) Îles des Saintes (1648–present) Marie-Galante (1635–present) la Désirade (1635–present) Guadeloupe (1635–present) Martinique (1635–present) French Guiana (1604–present) Saint Pierre and Miquelon (1604–1713, 1763–present) Collectivity of Saint Martin (1624–present) Saint Barthélemy (1648–1784, 1878–present) Clipperton Island (1858–present) Knights of Malta Main article: Hospitaller colonization of the Americas Saint Barthélemy (1651–1665) Saint Christopher (1651–1665) Saint Croix (1651–1665) Saint Martin (1651–1665) Norwegian Main article: Norwegian colonization of the Americas Further information: List of possessions of Norway Greenland (986–1408[100]) Dano-Norwegian South Greenland (1728?–1814) Dano-Norwegian North Greenland (1721–1814) Dano-Norwegian West Indies (1754–1814) Cooper Island (1844–1905) Sverdrup Islands (1898–1930) Erik the Red's Land (1931–1933) Portuguese Main article: Portuguese colonization of the Americas Colonial Brazil (1500–1815) became a Kingdom, United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Terra do Labrador (1499/1500–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled). Land of the Corte-Real, also known as Terra Nova dos Bacalhaus (Land of Codfish) – Terra Nova (Newfoundland) (1501–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled). Portugal Cove-St. Philip's (1501–1696) Nova Scotia (1519?–1520s?) Claimed region (sporadically settled). Barbados (c.1536–1620) Colonia do Sacramento (1680–1705/1714–1762/1763–1777 (1811–1817)) Cisplatina (1811–1822, now Uruguay) French Guiana (1809–1817) Russian Main article: Russian colonization of the Americas  The Russian-American Company's capital at New Archangel (present-day Sitka, Alaska) in 1837 Russian America (Alaska) (1799–1867) Fort Ross (Sonoma County, California) Russian Fort Elizabeth (Hawaii) Scottish Main article: Scottish colonization of the Americas Nova Scotia (1622–1632) Darien Scheme on the Isthmus of Panama (1698–1700) Stuarts Town, Carolina (1684–1686) Spanish Main article: Spanish colonization of the Americas See also: § Basque colonization of the Americas Hispaniola (1493–1697); the island currently comprising Haiti and the Dominican Republic, under Spanish rule in whole from 1492 to 1697; under the partial rule under the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1697–1821), then again as the Dominican Republic (1861–1865). Puerto Rico (1493–1898); first as the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico Colony of Santiago (1509–1655); conquered by Britain in 1655, currently Jamaica Cuba (1607–1898); first as the Captaincy General of Cuba Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1819) Captaincy General of Venezuela Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) Nueva Extremadura Nueva Galicia Nuevo Reino de León Nuevo Santander Nueva Vizcaya Las Californias Santa Fe de Nuevo México Captaincy General of Guatemala Louisiana (New Spain) (1769–1801) Spanish Florida (1565–1763, 1783–1819) Spanish Texas (1716–1802) Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824) Captaincy General of Chile (1544–1818) Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (1776–1814) Swedish Main article: Swedish colonization of the Americas New Sweden (1638–1655) Saint Barthélemy (1784–1878) Guadeloupe (1813–1814) |