エボ・モラーレス

Juan Evo Morales Ayma, b.1959

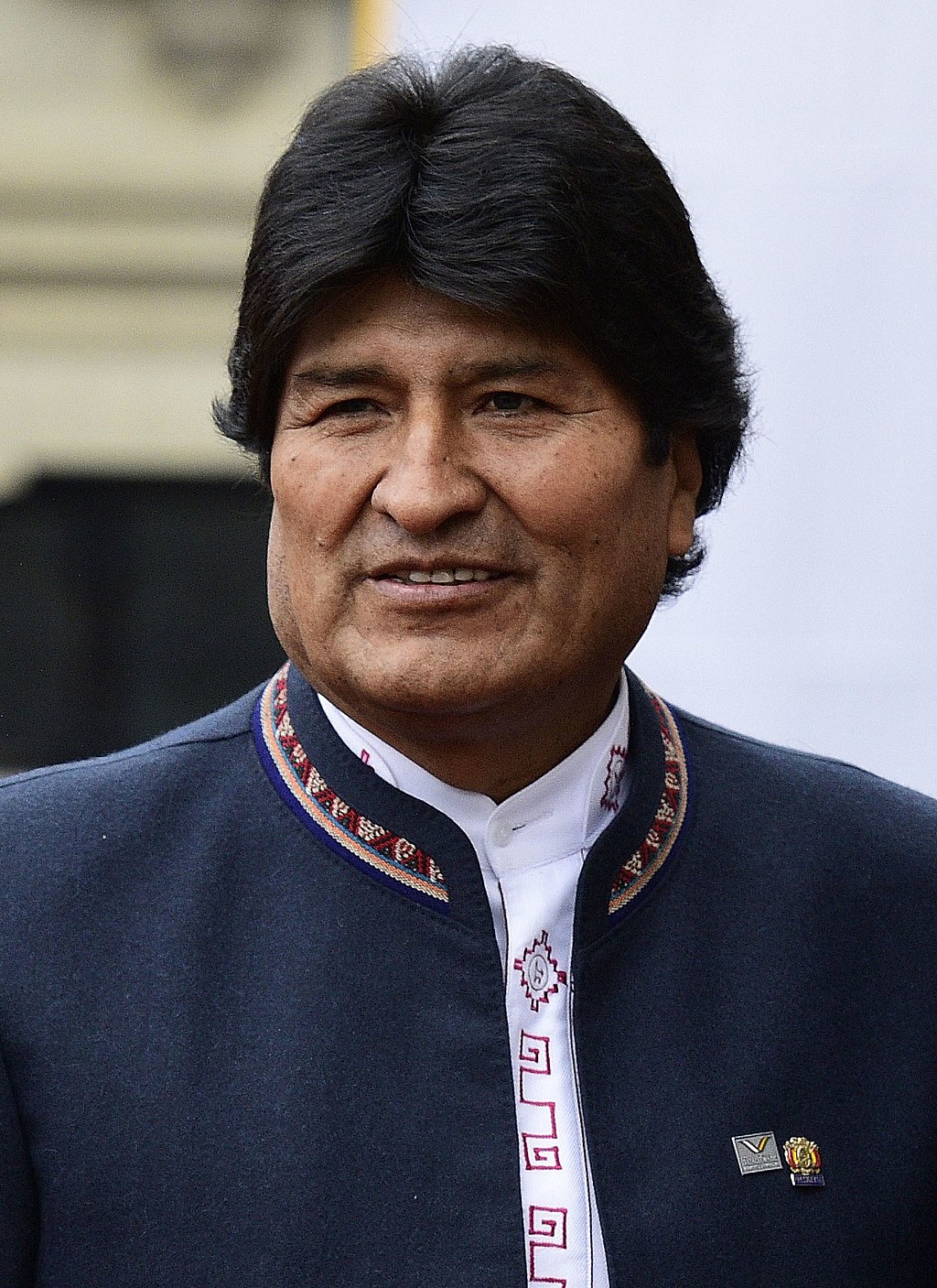

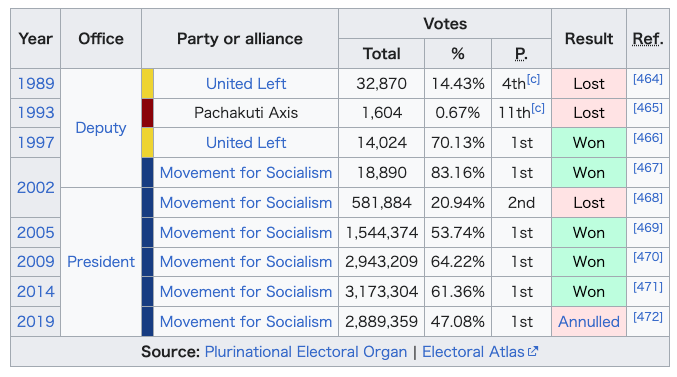

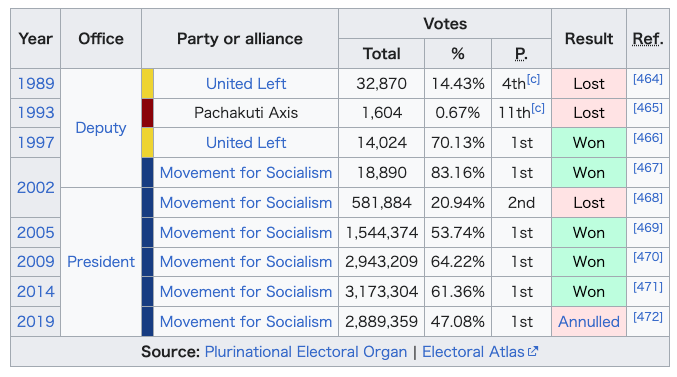

☆ Juan Evo Morales Ayma[a](スペイン語: [xwan ˈ ↪Ll_eβo moˈ↪Lm_2C8]; 1959年10月26日生まれ)は、ボリビアの政治家、労働組合組織者、元コカレロ活動家で、2006年から2019年まで第65代大統領を務めた。ボリ ビア初の先住民出身の大統領として知られ[b]、ボリビアのこれまで境界となっていた先住民の法的保護と社会経済的条件に重点を置き、米国と資源採掘を行 う多国籍企業の政治的影響力に対抗し、左翼的政策の実施に努めた。思想的には社会主義者で、1998年から2024年まで社会主義運動(MAS)党を率い た。 オリノカ州イサラウィで自給自足の農業を営むアイマラ人の家庭に生まれたモラレスは、基礎教育と義務兵役を経て、1978年にチャパレ州に移住した。コカ を栽培しながら労働組合員となり、カンペシーノ(「農村労働者」)組合で頭角を現した。その立場から、麻薬戦争の一環としてコカを撲滅しようとするアメリ カとボリビアの共同の試みに反対する運動を展開し、これをアンデス土着の文化を侵害する帝国主義的行為だと非難した。反政府直接行動に参加した結果、何度 も逮捕された。モラレスは1995年に選挙政治に参入し、1997年に下院議員に当選、1998年にMASの指導者となった。ポピュリスト的なレトリック と相まって、彼は先住民や貧しいコミュニティに影響を与える問題で選挙戦を展開し、土地改革やボリビアのガス採掘から得られる資金のより平等な再分配を提 唱した。コチャバンバ水戦争とガス紛争を通じて知名度を上げた。2002年、反政府デモを奨励したとして議会から追放されたが、同年の大統領選挙では2位 になった。 2005年に大統領に選出されると、モラレスは社会支出を強化するために炭化水素産業への課税を強化し、非識字、貧困、人種・男女差別と闘うプロジェクト を強調した。新自由主義を声高に批判するモラレス政権は、ボリビアを混合経済へと移行させ、世界銀行と国際通貨基金(IMF)への依存を減らし、力強い経 済成長を指揮した。ボリビアにおける米国の影響力を縮小し、ラテンアメリカのピンクタイドの左派政権、特にウゴ・チャベスのベネズエラやフィデル・カスト ロのキューバと関係を築き、ボリビアを米州ボリバル同盟に加盟させた。彼の政権は、ボリビア東部の州の自治主義的要求に反対し、2008年のリコール国民 投票で勝利し、ボリビアを多民族国家として確立する新憲法を制定した。2009年と2014年に再選され、ボリビアの南アジア銀行とラテンアメリカ・カリ ブ海諸国共同体への加盟を監督したが、大統領の任期制限を廃止しようとしたため人気は低迷した。2019年の選挙とそれに続く騒乱を受け、モラレスは辞任 要求に同意した。この一時的な亡命の後、ルイス・アルセ大統領の選出後に復帰した。 モラレスの支持者は、先住民の権利、反帝国主義、環境主義の擁護を指摘し、著しい経済成長と貧困削減、学校、病院、インフラへの投資の増加を監督したと評 価している。批評家は、在任中の民主主義の後退を指摘し、彼の政策が環境保護主義や先住民の権利のレトリックを反映しないことがあり、コカの擁護が違法な コカイン生産を助長したと主張している。

| Juan Evo Morales

Ayma[a] (Spanish: [xwan ˈeβo moˈɾales ˈajma]; born 26 October 1959) is

a Bolivian politician, trade union organizer, and former cocalero

activist who served as the 65th president of Bolivia from 2006 to 2019.

Widely regarded as the country's first president to come from its

indigenous population,[b] his administration worked towards the

implementation of left-wing policies, focusing on the legal protections

and socioeconomic conditions of Bolivia's previously marginalized

indigenous population and combating the political influence of the

United States and resource-extracting multinational corporations.

Ideologically a socialist, he led the Movement for Socialism (MAS)

party from 1998 to 2024. Born to an Aymara family of subsistence farmers in Isallawi, Orinoca Canton, Morales undertook a basic education and mandatory military service before moving to the Chapare Province in 1978. Growing coca and becoming a trade unionist, he rose to prominence in the campesino ("rural laborers") union. In that capacity, he campaigned against joint U.S.–Bolivian attempts to eradicate coca as part of the War on Drugs, denouncing these as an imperialist violation of indigenous Andean culture. His involvement in anti-government direct action protests resulted in multiple arrests. Morales entered electoral politics in 1995, was elected to Congress in 1997 and became leader of MAS in 1998. Coupled with populist rhetoric, he campaigned on issues affecting indigenous and poor communities, advocating land reform and more equal redistribution of money from Bolivian gas extraction. He gained increased visibility through the Cochabamba Water War and gas conflict. In 2002, he was expelled from Congress for encouraging anti-government protesters, although he came second in that year's presidential election. Once elected president in 2005, Morales increased taxation on the hydrocarbon industry to bolster social spending and emphasized projects to combat illiteracy, poverty, and racial and gender discrimination. Vocally criticizing neoliberalism, Morales' government moved Bolivia towards a mixed economy, reduced its dependence on the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), and oversaw strong economic growth. Scaling back United States influence in the country, he built relationships with leftist governments in the Latin American pink tide, especially Hugo Chávez's Venezuela and Fidel Castro's Cuba, and signed Bolivia into the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas. His administration opposed the autonomist demands of Bolivia's eastern provinces, won a 2008 recall referendum, and instituted a new constitution that established Bolivia as a plurinational state. Re-elected in 2009 and 2014, he oversaw Bolivia's admission to the Bank of the South and Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, although his popularity was dented by attempts to abolish presidential term limits. Following the disputed 2019 election and the ensuing unrest, Morales agreed to calls for his resignation. After this temporary exile, he returned following the election of President Luis Arce. Morales' supporters point to his championing of indigenous rights, anti-imperialism, and environmentalism, and credit him with overseeing significant economic growth and poverty reduction as well as increased investment in schools, hospitals, and infrastructure. Critics point to democratic backsliding during his tenure, argue that his policies sometimes failed to reflect his environmentalist and indigenous rights rhetoric, and that his defence of coca contributed to illegal cocaine production. |

Juan Evo Morales Ayma[a](スペイン語:

[xwan ˈ ↪Ll_eβo moˈ↪Lm_2C8];

1959年10月26日生まれ)は、ボリビアの政治家、労働組合組織者、元コカレロ活動家で、2006年から2019年まで第65代大統領を務めた。ボリ

ビア初の先住民出身の大統領として知られ[b]、ボリビアのこれまで境界となっていた先住民の法的保護と社会経済的条件に重点を置き、米国と資源採掘を行

う多国籍企業の政治的影響力に対抗し、左翼的政策の実施に努めた。思想的には社会主義者で、1998年から2024年まで社会主義運動(MAS)党を率い

た。 オリノカ州イサラウィで自給自足の農業を営むアイマラ人の家庭に生まれたモラレスは、基礎教育と義務兵役を経て、1978年にチャパレ州に移住した。コカ を栽培しながら労働組合員となり、カンペシーノ(「農村労働者」)組合で頭角を現した。その立場から、麻薬戦争の一環としてコカを撲滅しようとするアメリ カとボリビアの共同の試みに反対する運動を展開し、これをアンデス土着の文化を侵害する帝国主義的行為だと非難した。反政府直接行動に参加した結果、何度 も逮捕された。モラレスは1995年に選挙政治に参入し、1997年に下院議員に当選、1998年にMASの指導者となった。ポピュリスト的なレトリック と相まって、彼は先住民や貧しいコミュニティに影響を与える問題で選挙戦を展開し、土地改革やボリビアのガス採掘から得られる資金のより平等な再分配を提 唱した。コチャバンバ水戦争とガス紛争を通じて知名度を上げた。2002年、反政府デモを奨励したとして議会から追放されたが、同年の大統領選挙では2位 になった。 2005年に大統領に選出されると、モラレスは社会支出を強化するために炭化水素産業への課税を強化し、非識字、貧困、人種・男女差別と闘うプロジェクト を強調した。新自由主義を声高に批判するモラレス政権は、ボリビアを混合経済へと移行させ、世界銀行と国際通貨基金(IMF)への依存を減らし、力強い経 済成長を指揮した。ボリビアにおける米国の影響力を縮小し、ラテンアメリカのピンクタイドの左派政権、特にウゴ・チャベスのベネズエラやフィデル・カスト ロのキューバと関係を築き、ボリビアを米州ボリバル同盟に加盟させた。彼の政権は、ボリビア東部の州の自治主義的要求に反対し、2008年のリコール国民 投票で勝利し、ボリビアを多民族国家として確立する新憲法を制定した。2009年と2014年に再選され、ボリビアの南アジア銀行とラテンアメリカ・カリ ブ海諸国共同体への加盟を監督したが、大統領の任期制限を廃止しようとしたため人気は低迷した。2019年の選挙とそれに続く騒乱を受け、モラレスは辞任 要求に同意した。この一時的な亡命の後、ルイス・アルセ大統領の選出後に復帰した。 モラレスの支持者は、先住民の権利、反帝国主義、環境主義の擁護を指摘し、著しい経済成長と貧困削減、学校、病院、インフラへの投資の増加を監督したと評 価している。批評家は、在任中の民主主義の後退を指摘し、彼の政策が環境保護主義や先住民の権利のレトリックを反映しないことがあり、コカの擁護が違法な コカイン生産を助長したと主張している。 |

| Early life and activism Childhood, education, and military service: 1959–1978 Morales was born in the small rural village of Isallawi in Orinoca Canton, part of western Bolivia's Oruro Department, on 26 October 1959, to an Aymara family.[9][10] One of seven children born to Dionisio Morales Choque and his wife María Ayma Mamani,[11] only he and two siblings, Esther and Hugo, survived past childhood.[12] His mother almost died from a postpartum haemorrhage following his birth.[13] In keeping with Aymara custom, his father buried the placenta produced after his birth in a place specially chosen for the occasion.[13] His childhood home was a traditional adobe house,[14] and he grew up speaking the Aymara language, although later commentators would remark that by the time he had become president he was no longer an entirely fluent speaker.[15]   Aymara in traditional dress (left); Lake Poopó was the dominant geographical feature around Morales's home village of Isallawi (right).[13] Morales' family were farmers; from an early age, he helped them to plant and harvest crops and guard their herd of llamas and sheep, taking a homemade soccer ball to amuse himself.[16] As a toddler, he briefly attended Orinoca's preparatory school, and at five began schooling at the single-room primary school in Isallawi.[17] Aged 6, he spent six months in northern Argentina with his sister and father. There, Dionisio harvested sugar cane while Evo sold ice cream and briefly attended a Spanish-language school.[18] As a child, he regularly traveled on foot to Arani province in Cochabamba with his father and their llamas, a journey lasting up to two weeks, in order to exchange salt and potatoes for maize and coca.[19] A big fan of soccer, at age 13 he organized a community soccer team with himself as team captain. Within two years, he was elected training coach for the whole region, and thus gained early experience in leadership.[20] After finishing primary education, Morales attended the Agrarian Humanistic Technical Institute of Orinoca (ITAHO), completing all but the final year.[21] His parents then sent him to study for a degree in Oruro; although he did poorly academically, he finished all of his courses and exams by 1977, earning money on the side as a brick-maker, day laborer, baker and a trumpet player for the Royal Imperial Band. The latter position allowed him to travel across Bolivia.[22] At the end of his higher education, he failed to collect his degree certificate.[21] Although interested in studying journalism, he did not pursue it as a profession.[23] Morales served his mandatory military service in the Bolivian Army from 1977 to 1978. Initially signed up at the Centre for Instruction of Special Troops (CITE) in Cochabamba, he was sent into the Fourth Ingavi Cavalry Regiment and stationed at the army headquarters in the Bolivian capital La Paz.[24] These two years were one of Bolivia's politically most unstable periods, with five presidents and two military coups, led by General Juan Pereda and General David Padilla respectively; under the latter's regime, Morales was stationed as a guard at the Palacio Quemado (Presidential Palace).[25] |

生い立ちと活動 幼少期、教育、兵役:1959-1978年 モラレスは1959年10月26日、ボリビア西部オルーロ県のオリノカ県にあるイサラウィという小さな農村でアイマラ人の家庭に生まれた[9][10]。 ディオニシオ・モラレス・チョケとその妻マリア・アイマ・ママニとの間に生まれた7人の子供のうちの1人であり[11]、幼少期を生き延びたのは彼と2人 の兄弟、エステルとウーゴだけであった[12]。[13]。幼少期の家は伝統的なアドベの家であり[14]、彼はアイマラ語を話しながら育ったが、後の評 論家は、彼が大統領になる頃には、彼はもはや完全に流暢に話すことはできなかったと述べている[15]。   伝統的な衣装を着たアイマラ人(左)、ポポー湖はモラレスの故郷であるイサラウィ村(右)周辺の主要な地形である[13]。 モラレスの家族は農民で、幼い頃から作物の植え付けや収穫、ラマや羊の群れの番を手伝い、自家製のサッカーボールを持って遊んでいた[16]。幼児期には オリノカの準備学校に短期間通い、5歳でイサラウィにある1人部屋の小学校に通い始めた[17]。そこでディオニシオはサトウキビを収穫し、エボはアイス クリームを売ったり、スペイン語学校に短期間通ったりした[18]。幼少期には、塩やジャガイモとトウモロコシやコカを交換するために、父親とラマと一緒 にコチャバンバのアラニ県まで徒歩で定期的に通った。2年も経たないうちに地域全体のトレーニングコーチに選ばれ、早くから指導者としての経験を積んだ [20]。 初等教育を終えた後、モラレスはオリノカ農業人文技術専門学校(ITAHO)に通い、最終学年以外のすべてを修了した[21]。その後、両親は彼をオルー ロで学位取得のために勉強させた。学業成績は悪かったが、1977年までにすべてのコースと試験を終え、副業としてレンガ職人、日雇い労働者、パン職人、 王立帝国楽団のトランペット奏者として収入を得た。後者の地位のおかげでボリビア全土を旅行することができた[22]。高等教育の終わりには学位証明書を 受け取ることができなかった[21]。ジャーナリズムを学ぶことに興味を持ったが、職業として追求することはなかった[23]。 モラレスは1977年から1978年までボリビア陸軍で義務兵役を務めた。当初、コチャバンバにある特殊部隊教育センター(CITE)と契約し、第4イン ガビ騎兵連隊に送られ、ボリビアの首都ラパスの陸軍本部に駐屯した。[24]この2年間はボリビアで最も政治的に不安定な時期であり、5人の大統領と、そ れぞれフアン・ペレダ将軍とダヴィド・パディージャ将軍が率いた2度の軍事クーデターがあった。後者の政権下で、モラレスはケマド宮殿(大統領官邸)の衛 兵として駐屯した[25]。 |

| Early cocalero activism: 1978–1983 Following his military service, Morales returned to his family, who had escaped the agricultural devastation of 1980's El Niño storm cycle by relocating to the Tropics of Cochabamba in the eastern lowlands.[26] Setting up home in the town of Villa 14 de Septiembre, El Chapare, using a loan from Morales' maternal uncle, the family cleared a plot of land in the forest to grow rice, oranges, grapefruit, papaya, bananas and later on coca.[27] It was here that Morales learned to speak Quechua, the indigenous local language.[28] The arrival of the Morales family was a part of a much wider migration to the region; in 1981 El Chapare's population was 40,000 but by 1988 it had risen to 215,000. Many Bolivians hoped to set up farms where they could earn a living growing coca, which was experiencing a steady rise in price and which could be cultivated up to four times a year; a traditional medicinal and ritual substance in Andean culture, it was also sold abroad as the key ingredient in cocaine.[29] Morales joined the local soccer team, before founding his own team, New Horizon, which proved victorious at the 2 August Central Tournament.[29] The El Chapare region remained special to Morales for many years to come; during his presidency he often talked of it in speeches and regularly visited.[30]   Morales policy was "Coca Yes, Cocaine No". A Bolivian man holding a coca leaf, (left); Coca tea, a traditional Andean infusion (right). In El Chapare, Morales joined a trade union of cocaleros (coca growers), being appointed local Secretary of Sports. Organizing soccer tournaments, among union members he earned the nickname of "the young ball player" because of his tendency to organize matches during meeting recesses.[29] Influenced in joining the union by wider events, in 1980 the far-right General Luis García Meza had seized power in a military coup, banning other political parties and declaring himself president; for Morales, a "foundational event in his relationship with politics" occurred in 1981, when a campesino (coca grower) was accused of cocaine trafficking by soldiers, beaten up, and burned to death.[31] In 1982 the leftist Hernán Siles Zuazo and the Democratic and Popular Union (Unidad Democrática y Popular – UDP) took power in representative democratic elections, before implementing neoliberal capitalist reforms and privatizing much of the state sector with United States support; hyperinflation came under control, but unemployment rose to 25%.[32] Becoming increasingly active in the union, from 1982 to 1983, Morales served as the general secretary of his local San Francisco syndicate.[33] In 1983, Morales' father Dionisio died, and although he missed the funeral, he temporarily retreated from his union work to organize his father's affairs.[34] As part of the War on Drugs, the United States government hoped to stem the cocaine trade by preventing the production of coca; they pressured the Bolivian government to eradicate it, sending troops to Bolivia to aid the operation.[35] Bolivian troops would burn coca crops and, in many cases, beat up coca growers who challenged them.[36] Angered by this, Morales returned to cocalero campaigning; like many of his comrades, he refused the US$2,500 compensation offered by the government for each acre of coca he eradicated. Deeply embedded in Bolivian culture, the campesinos had an ancestral relationship with coca and did not want to lose their most profitable means of subsistence. For them, it was an issue of national sovereignty, with the United States viewed as imperialists; activists regularly proclaimed "Long live coca! Death to the Yankees!" ("Causachun coca! Wañuchun yanquis!").[33] |

初期のコカレロ活動:1978年〜1983年 兵役を終えたモラレスは、1980年のエルニーニョによる暴風雨の農業被害から逃れて、東部低地のコチャバンバ熱帯地方に移住した家族のもとに戻った [26]。モラレスの母方の叔父からの借金を元手に、エル・チャパレのビジャ14・デ・セプティエンブレという町に家を構えた一家は、森の中に土地を切り 開き、米、オレンジ、グレープフルーツ、パパイヤ、バナナ、そして後にコカを栽培した。[1981年のエル・チャパレの人口は40,000人だったが、 1988年には215,000人に増加した。ボリビア人の多くは、コカ栽培で生計を立てられる農場を作ることを望んでいた。コカは、アンデス文化における 伝統的な薬用・儀式用物質であり、コカインの主要成分として海外にも販売されていた。[29]モラレスは地元のサッカーチームに参加した後、自身のチーム 「ニュー・ホライズン」を創設し、8月2日のセントラル・トーナメントで勝利を収めた[29]。モラレスにとってエル・チャパレ地域はその後も長年にわ たって特別な存在であり続け、大統領在任中、彼はしばしば演説でこの地域のことを語り、定期的に訪れていた[30]。   モラレスの政策は「コカはイエス、コカインはノー」だった。コカの葉を持つボリビア人男性(左)、伝統的なアンデスの煎じ薬であるコカ茶(右)。 エル・チャパレで、モラレスはコカレロ(コカ栽培者)の労働組合に加入し、地元のスポーツ長官に任命された。サッカーのトーナメントを組織し、組合員の間 では、会議の休憩時間に試合を組織する傾向があることから、「若い球児」というニックネームで呼ばれるようになった[29]。[1980年、極右のルイ ス・ガルシア・メサ将軍が軍事クーデターで権力を掌握し、他の政党を追放して自らを大統領と宣言した。モラレスにとって「政治との関係の基礎となる出来 事」は1981年、カンペシーノ(コカ栽培農民)が兵士にコカイン密売の嫌疑をかけられ、殴打され、焼き殺されたときに起こった。[1982年、左派エル ナン・シレス・ズアソと民主・人民連合(UDP)が代表的な民主選挙で政権を握ったが、その後、新自由主義的な資本主義改革を実施し、米国の支援を受けて 国家部門の多くを民営化した。[1983年、モラレスの父ディオニシオが死去し、葬儀には出席しなかったが、父のことを整理するために組合の仕事から一時 的に離れた[34]。 対麻薬戦争の一環として、アメリカ政府はコカの生産を阻止することでコカイン取引を食い止めようと考え、ボリビア政府にコカの撲滅を迫り、作戦を支援する ためにボリビアに軍隊を派遣した[35]。[35]ボリビア軍はコカ作物を焼き払い、多くの場合、挑発するコカ栽培者を殴打した[36]。これに怒ったモ ラレスはコカレロ運動に復帰し、多くの同志と同様に、コカ1エーカーを撲滅するごとに政府から提示される2,500米ドルの補償金を拒否した。ボリビアの 文化に深く根ざしたカンペシーノたちは、コカと先祖代々の関係を持ち、最も収益性の高い生計手段を失いたくなかった。彼らにとって、コカは国民主権の問題 であり、アメリカは帝国主義者とみなされていた!コカ万歳!ヤンキーに死を!」(『コサチュン・コカ』)と活動家たちは常々叫んでいた。(コサチュン・コ カ! ワニュチュン・ヤンキス!」)[33]。 |

| General Secretary of the Cocalero Union: 1984–1994 From 1984 to 1985, Morales served as Secretary of Records for the movement,[33] and in 1985 he became General Secretary of the August Second Headquarters.[33] From 1984 to 1991, the sindicatos embarked on a series of protests against the forced eradication of coca by occupying local government offices, setting up roadblocks, going on hunger strike, and organizing mass marches and demonstrations.[37] Morales was personally involved in this direct activism and in 1984 was present at a roadblock where 3 campesinos were killed.[38] In 1988, Morales was elected to the position of Executive Secretary of the Federation of the Tropics.[33] In 1989, he spoke at a one-year commemoratory event of the Villa Tunari massacre in which 11 coca farmers had been killed by agents of the Rural Area Mobile Patrol Unit (Unidad Móvil Policial para Áreas Rurales – UMOPAR).[38] The following day, UMOPAR agents beat Morales up, leaving him in the mountains to die, but he was rescued by other union members.[39] To combat this violence, Morales concluded that an armed cocalero militia could launch a guerrilla war against the government, but he soon chose to pursue an electoral path.[40] In 1992, he made various international trips to champion the cocalero cause, speaking at a conference in Cuba,[41] and also traveling to Canada, during which he learned of his mother's death.[42]  The Wiphala, flag of the Aymara. In his speeches, Morales presented the coca leaf as a symbol of Andean culture that was under threat from the imperialist oppression of the United States. In his view, the United States should deal with their domestic cocaine abuse problems without interfering in Bolivia, arguing that they had no right trying to eliminate coca, a legitimate product with many uses which played a rich role in Andean culture.[43] In a speech, Morales told reporters "I am not a drug trafficker. I am a coca grower. I cultivate coca leaf, which is a natural product. I do not refine (it into) cocaine, and neither cocaine nor drugs have ever been part of the Andean culture".[6] Morales has stated that "We produce our coca, we bring it to the main markets, we sell it and that's where our responsibility ends".[44] Morales presented the coca growers as victims of a wealthy, urban social elite who had bowed to United States pressure by implementing neoliberal economic reforms.[43] He argued that these reforms were to the detriment of Bolivia's majority, and thus the country's representative democratic system of governance failed to reflect the true democratic will of the majority.[43] This situation was exacerbated following the 1993 general election when the centrist Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario – MNR) won the election and Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada became president. He adopted a policy of "shock therapy", implementing economic liberalization and widescale privatization of state-owned assets.[45] Sánchez also agreed with the U.S. DEA to relaunch its offensive against the Bolivian coca growers, committing Bolivia to eradicating 12,500 acres (5,100 ha) of coca by March 1994 in exchange for US$20 million worth of United States aid, something Morales stated would be opposed by the cocalero movement.[46] In August 1994, Morales was arrested; reporters present at the scene witnessed him being beaten and accosted with racial slurs by civil agents. Accused of sedition, in jail he began a dry hunger strike to protest his arrest.[47] The following day, 3000 campesinos began a 360 mi (580 km) march from Villa Tunari to La Paz. Morales would be freed on 7 September 1994, and soon joined the march, which arrived at its destination on 19 September 1994, where they covered the city with political graffiti.[48] He was again arrested in April 1995 during a sting operation that rounded up those at a meeting of the Andean Council of Coca Producers that he was chairing on the shores of Lake Titicaca. Accusing the group of plotting a coup with the aid of Colombia's FARC and Peru's Shining Path, a number of his comrades were tortured, although no evidence of a coup was brought forth and he was freed within a week.[49] He proceeded to Argentina to attend a seminar on liberation struggles.[50] |

コカレロ連合書記長:1984-1994年 1984年から1985年まで、モラレスは運動の記録書記を務め[33]、1985年には8月第2本部の書記長に就任した[33]。1984年から 1991年まで、シンジカートたちは、地方自治体の事務所を占拠し、道路を封鎖し、ハンガーストライキを行い、大規模な行進やデモを組織することによっ て、コカの強制撲滅に反対する一連の抗議活動に着手した[37]。[1988年、モラレスは熱帯連合の事務局長に選出された。[1989年には、11人の コカ農民が農村機動パトロール隊(Unidad Móvil Policial para Áreas Rurales - UMOPAR)の隊員によって殺害されたビジャ・トゥナリの虐殺事件の1周年記念行事で演説した[38]。翌日、UMOPARの隊員はモラレスを殴打し、 山中に放置して死なせたが、他の組合員によって救出された。[39]この暴力に対抗するために、モラレスは武装したコカレロ民兵組織が政府に対してゲリラ 戦を仕掛けることができると結論づけたが、すぐに選挙への道を選んだ[40]。 1992年、彼はコカレロの大義を擁護するために様々な海外旅行を行い、キューバで開催された会議で演説を行い[41]、またカナダにも旅行し、その際に 母親の死を知った[42]。  アイマラ族の旗であるウィファラ。 演説の中でモラレスは、コカの葉を、アメリカの帝国主義的抑圧から脅威にさらされているアンデス文化の象徴として提示した。彼の見解では、アメリカはボリ ビアに干渉することなく、国内のコカイン乱用問題に対処すべきであり、アンデス文化において豊かな役割を果たし、多くの用途を持つ合法的な産物であるコカ を消去しようとする権利はないと主張した[43]。 モラレスは演説の中で、記者団に「私は麻薬密売人ではない。私はコカの栽培者だ。私は自然の産物であるコカの葉を栽培している。私はコカインを精製しない し、コカインも麻薬もアンデスの文化の一部ではなかった」[6]。モラレスは「私たちはコカを生産し、主要な市場に運び、販売し、そこで私たちの責任は終 わる」と述べた[44]。 モラレスはコカ生産者を、新自由主義的な経済改革を実施することで米国の圧力に屈した裕福な都市社会エリートの犠牲者として提示した[43]。 彼は、これらの改革はボリビアの多数派に不利益をもたらすものであり、そのためボリビアの代表制民主主義統治システムは、多数派の真の民主的意思を反映す ることができなかったと主張した[43]。[この状況は、1993年の総選挙で中道派の革命ナショナリスト運動(Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario - MNR)が勝利し、ゴンサロ・サンチェス・デ・ロサダが大統領に就任したことで悪化した。彼は「ショック療法」の政策を採用し、経済の自由化と国有資産の 広範な民営化を実施した[45]。サンチェスはまた、ボリビアのコカ栽培農家に対する攻撃を再開することでアメリカDEAと合意し、2000万米ドル相当 のアメリカからの援助と引き換えに、1994年3月までに12,500エーカー(5,100ヘクタール)のコカを根絶することをボリビアに約束したが、モ ラレスはコカレロ運動が反対するだろうと述べた[46]。 1994年8月、モラレスは逮捕された。現場に居合わせた記者は、彼が市民捜査官によって殴打され、人種差別的な中傷を受けているのを目撃した。その翌 日、3000人のカンペシーノがビジャ・トゥナリからラパスまで360マイル(580キロ)の行進を開始した。モラレスは1994年9月7日に釈放され、 すぐに行進に加わり、1994年9月19日に目的地に到着し、街を政治的な落書きで覆った[48]。1995年4月、チチカカ湖畔で彼が議長を務めていた アンデス・コカ生産者協議会の会合の参加者を一網打尽にするおとり捜査で再び逮捕された。コロンビアのFARCとペルーのシャイニング・パスの援助を受け てクーデターを企てたとグループを告発し、多くの仲間が拷問を受けたが、クーデターの証拠は持ち出されず、彼は1週間以内に釈放された[49]。解放闘争 に関するセミナーに出席するためにアルゼンチンに向かった[50]。 |

| Political rise ASP, IPSP, and MAS: 1995–1999 Members of the sindicato social movement first suggested a move into the political arena in 1986. This was controversial, with many fearing that politicians would co-opt the movement for personal gain.[51] Morales began supporting the formation of a political wing in 1989, although a consensus in favor of its formation only emerged in 1993.[52] On 27 March 1995, at the 7th Congress of the Unique Confederation of Rural Laborers of Bolivia (Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia – CSUTCB), a "political instrument" (a term employed over "political party") was formed, named the Assembly for the Sovereignty of the Peoples (Asamblea por la Sobernía de los Pueblos – ASP).[53] At the ASP's 1st Congress, the CSUTCB participated alongside three other Bolivian unions, representing miners, peasants and indigenous peoples.[52] In 1996, Morales was appointed chairman of the Committee of the Six Federations of the Tropics of Cochabamba, a position that he retained until 2006.[54] Bolivia's National Electoral Court (Corte Nacional Electoral – CNE) refused to recognize the ASP, citing minor procedural infringements.[52] The coca activists circumvented this problem by running under the banner of the United Left (IU), a coalition of leftist parties headed by the Communist Party of Bolivia (Partido Comunista Boliviano – PCB).[55] They won landslide victories in those areas which were local strongholds of the movement, producing 11 mayors and 49 municipal councilors.[52] Morales was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in the National Congress as a representative for El Chapare, having secured 70.1% of the local vote.[54] In the national elections of 1997, the IU/ASP gained four seats in Congress, obtaining 3.7% of the national vote, with this rising to 17.5% in the department of Cochabamba.[56] The election resulted in the establishment of a coalition government led by the right-wing Nationalist Democratic Action (Acción Democrática Nacionalista – ADN), with Hugo Banzer as president; Morales lambasted him as "the worst politician in Bolivian history".[57]  MAS-IPSP partisans celebrate the 16th anniversary of the IPSP party's founding in Sacaba, Cochabamba. Rising electoral success was accompanied by factional in-fighting, with a leadership contest emerging in the ASP between the incumbent Alejo Véliz and Morales, who had the electoral backing of the social movement's bases.[56] The conflict led to a schism, with Morales and his supporters splitting to form their own party, the Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples (Instrumento Político por la Soberanía de los Pueblos – IPSP).[58] The movement's bases defected en masse to the IPSP, leaving the ASP to crumble and Véliz to join the center-right New Republican Force (Nueva Fuerza Republicana – NFR), for which Morales denounced him as a traitor to the cocalero cause.[59] Continuing his activism, in 1998 Morales led another cocalero march from El Chapare to la Paz,[60] and came under increasing criticism from the government, who repeatedly accused him of being involved in the cocaine trade and mocked him for how he spoke and his lack of education.[61] Morales came to an agreement with David Añez Pedraza, the leader of a defunct yet still registered falangist party named the Movement for Socialism (MAS); under this agreement, Morales and the Six Federaciónes could take over the party name, with Pendraza stipulating the condition that they must maintain MAS's own acronym, name and colors. Thus, the MAS and IPSP merged, becoming known as the Movement for Socialism – Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples.[62] The MAS would come to be described as "an indigenous-based political party that calls for the nationalization of industry, legalization of the coca leaf ... and fairer distribution of national resources."[63] The party lacked the finance available to the mainstream parties, and so relied largely on the work of volunteers in order to operate.[64] It was not structured like other political parties, instead operating as the political wing of the social movement, with all tiers in the movement involved in decision making; this form of organisation would continue until 2004.[65] In the December 1999 municipal elections, the MAS secured 79 municipal council seats and 10 mayoral positions, gaining 3.27% of the national vote, although 70% of the vote in Cochabamba.[62] |

政治的台頭 ASP、IPSP、MAS:1995-1999年 シンジカート社会運動のメンバーは、1986年に初めて政治分野への進出を提案した。これは政治家が人格的利益のために運動を共用してしまうのではないか と多くの政治家が懸念し、物議を醸した[51]。モラレスは1989年に政治翼の形成を支持し始めたが、その形成に賛成するコンセンサスが生まれたのは 1993年のことだった。[1995年3月27日、ボリビア農村労働者総同盟(CSUTCB)の第7回大会において、「政治的手段」(「政党」に対する用 語)が結成され、人民主権集会(ASP)と命名された。)[ASPの第1回大会では、CSUTCBは鉱山労働者、農民、先住民を代表する他の3つのボリビ アの組合とともに参加した[52]。1996年、モラレスはコチャバンバ熱帯6団体委員会の委員長に任命され、その地位は2006年まで維持された [54]。 ボリビアの国民選挙裁判所(Corte Nacional Electoral - CNE)は、わずかな手続き違反を理由にASPの承認を拒否した[52]。コカ活動家たちは、ボリビア共産党(Partido Comunista Boliviano - PCB)を党首とする左派政党の連合である統一左翼(IU)の旗の下に出馬することでこの問題を回避した[55]。[1997年の国民選挙では、 IU/ASPは4議席を獲得し、国民投票の3.7%を獲得した。この選挙の結果、右派のナショナリスト民主行動(Acción Democrática Nacionalista - ADN)が率いる連立政権が樹立され、ウゴ・バンザーが大統領に就任したが、モラレスはバンザーを「ボリビア史上最悪の政治家」と非難した[57]。  コチャバンバのサカバでIPSP党結成16周年を祝うMAS-IPSP党員たち。 この対立は分裂につながり、モラレスと彼の支持者は分裂して独自の政党「人民の主権のための政治的手段(Instrumento Político por la Soberanía de los Pueblos - IPSP)」を結成した。[58]運動の拠点は一斉にIPSPに離反し、ASPは崩壊し、ベリズは中道右派の新共和勢力(NFR)に参加することになった が、モラレスは彼をコカレロの大義に対する裏切り者として非難した。[モラレスは活動を続け、1998年にはエル・チャパレからラ・パスへのコカレロ行進 を率いたが[60]、政府からの批判が高まり、コカイン取引に関与していると繰り返し非難され、話し方や教育を受けていないことを嘲笑された[61]。 モラレスは、社会主義運動(MAS)という名称の、消滅したがまだ登録されていたファラン主義政党の指導者であるダヴィド・アニェス・ペドラサと合意に 至った。この合意の下、モラレスと6つのフェデラシオネスは党名を引き継ぐことができ、ペンドラサはMAS自身の頭文字、名称、色を維持しなければならな いという条件を規定した。こうしてMASとIPSPは合併し、「社会主義のための運動-人民の主権のための政治的手段」として知られるようになった [62]。MASは「産業の国有化、コカの葉の合法化...そして国民資源のより公平な分配を求める先住民ベースの政党」[63]と評されるようになる。 [この組織形態は2004年まで続いた[65]。1999年12月の地方自治体選挙で、MASは79議席と10市長の地位を獲得し、国民投票の3.27% を獲得したが、コチャバンバでは70%の得票率だった[62]。 |

| Cochabamba protests: 2000–2002 In 2000, the Tunari Waters corporation doubled the price at which they sold water to Bolivian consumers, resulting in a backlash from leftist activist groups, including the cocaleros. Activists clashed with police and armed forces, in what was dubbed "the Water War", resulting in 6 dead and 175 wounded. Responding to the violence, the government removed the contract from Tunari and placed the utility under cooperative control.[66] In ensuing years further violent protests broke out over a range of issues, resulting in more deaths both among activists and law enforcement. Much of this unrest was connected with the widespread opposition to economic liberalization across Bolivian society, with a common perception that it only benefited a small minority.[67] In the Andean High Plateau, a cocalero group launched a guerrilla uprising under the leadership of Felipe Quispe; an ethnic separatist, he and Morales disliked each other, with Quispe considering Morales to be a traitor and an opportunist for his willingness to cooperate with White Bolivians.[68] Morales had not taken a leading role in these protests but did use them to get across his message that the MAS was not a single-issue party, and that rather than simply fighting for the rights of the cocalero it was arguing for structural change to the political system and a redefinition of citizenship in Bolivia.[69]  Evo Morales (right) with French labor union leader José Bové in 2002 In August 2001, Banzer resigned due to terminal illness, and Jorge Quiroga took over as president.[70] Under U.S. pressure, Quiroga sought to have Morales expelled from Congress by saying that Morales' inflammatory language had caused the deaths of two police officers in Sacaba near Cochabamba. He was unable to provide any evidence of Morales' culpability. 140 deputies voted for Morales' expulsion, which came about in 2002. Morales said that it "was a trial against Aymara and Quechas".[71] MAS activists interpreted it as evidence of the pseudo-democratic credentials of the political class.[72] The MAS gained increasing popularity as a protest party, relying largely on widespread dissatisfaction with the existing mainstream political parties among Bolivians living in rural and poor urban areas.[73] Morales recognized this, and much of his discourse focused on differentiating the MAS from the traditional political class.[74] Their campaign was successful, and in the 2002 presidential election the MAS gained 20.94% of the national vote, becoming Bolivia's second largest party, being only 1.5% behind the victorious MNR, whose candidate, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, became president.[75] They won 8 seats in the Senate and 27 in the Chamber of Deputies.[76] Now the leader of the political opposition, Morales focused on criticising government policies rather than outlining alternatives. He had several unconstructive meetings with Sánchez de Lozada but met with Venezuela's Hugo Chávez for the first time.[77] Just prior to the election, the U.S. ambassador to Bolivia Manuel Rocha issued a statement declaring that U.S. aid to Bolivia would be cut if MAS won the election. However, exit polls revealed that Rocha's comments had served to increase support for Morales.[78] (Ambassador Rocha was later arrested by the U.S. Department of Justice on criminal charges of being an agent for the Cuban government.)[79] Following the election, the U.S. embassy characterised Morales as a criminal and encouraged Bolivia's traditional parties to sign a broad agreement to oppose the MAS; Morales himself began alleging that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency was plotting to assassinate him.[80] |

コチャバンバ抗議行動:2000〜2002年 2000年、トゥナリ・ウォーターズ社がボリビアの消費者への水の販売価格を2倍に引き上げたため、コカレロスを含む左派活動家グループの反発を招いた。 活動家たちは警察や武装勢力と衝突し、「水戦争」と呼ばれ、死者6人、負傷者175人を出した。この暴力に対応するため、政府はトゥナリから契約を解除 し、公共事業を協同組合の管理下に置いた[66]。その後数年間、さまざまな問題をめぐってさらに暴力的な抗議活動が発生し、活動家と法執行機関の両方で さらに死者が出た。この騒乱の多くは、ボリビア社会全体に広まった経済自由化への反対と関連しており、経済自由化は少数派にしか利益をもたらさないという 共通の認識があった[67]。 アンデス高地では、コカレロ・グループがフェリペ・キスペの指導のもとゲリラ蜂起を起こした。民族分離主義者である彼とモラレスは互いに嫌っており、キス ペはモラレスを裏切り者であり、白人ボリビア人と協力しようとする日和見主義者であると考えていた。[モラレスはこれらの抗議行動で主導的な役割を担って いなかったが、MASが単一イシューの政党ではなく、単にコカレロの権利のために戦うのではなく、政治システムの構造的な変化とボリビアにおける市民権の 再定義を主張しているというメッセージを伝えるために抗議行動を利用した[69]。  エボ・モラレス(右)とフランスの労働組合指導者ホセ・ボベ(2002年 2001年8月、バンザーは末期の病気のため辞任し、ホルヘ・キロガが大統領に就任した[70]。米国の圧力により、キロガは、モラレスの扇動的な言動が コチャバンバ近郊のサカバで2人の警察官を死亡させた原因であるとして、モラレスを議会から追放しようとした。彼はモラレスが犯人であるという証拠を提示 することはできなかった。モラレスの除名には140人の下院議員が賛成し、2002年に実現した。モラレスは「アイマラ人とケチャ人に対する裁判だった」 と述べた[71]。MASの活動家たちは、これを政治家階級の疑似民主主義的資格の証拠と解釈した[72]。 モラレスはこのことを認識しており、彼の言説の多くはMASを伝統的な政治階級から差別化することに焦点を当てていた[74]。彼らのキャンペーンは成功 し、2002年の大統領選挙でMASは20.彼らは上院で8議席、下院で27議席を獲得した[76]。今や政治的野党のリーダーであるモラレスは、代替案 を示すよりも政府の政策を批判することに重点を置いた。サンチェス・デ・ロサダとは何度か非建設的な会談を行ったが、ベネズエラのウゴ・チャベスとは初め て会談した[77]。 選挙の直前、マヌエル・ロシャ駐ボリビア米国大使は、MASが選挙で勝利した場合、ボリビアに対する米国の援助を削減すると宣言する声明を発表した。しか し、出口調査の結果、ロチャの発言はモラレスへの支持を高めるものであったことが明らかになった[78](ロチャ大使はその後、キューバ政府のエージェン トであったという刑事容疑でアメリカ司法省に逮捕された)[79]。選挙後、アメリカ大使館はモラレスを犯罪者と決めつけ、ボリビアの伝統的な政党に MASに対抗するための幅広い協定に署名するよう促した。モラレス自身、アメリカ中央情報局が彼の暗殺を企てていると主張し始めた[80]。 |

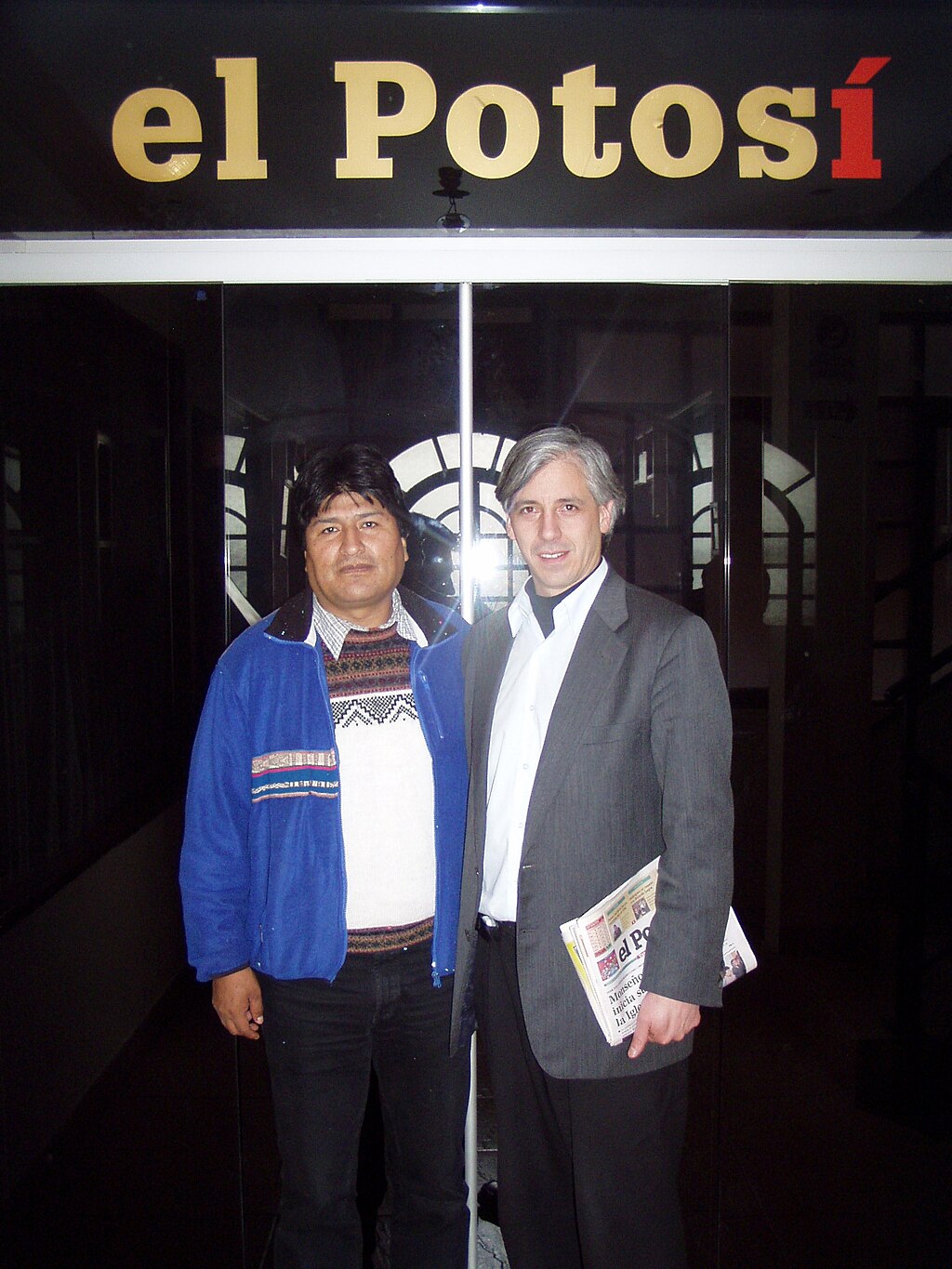

Rise to prominence: 2003–2005 Morales with his vice-presidential running mate, Álvaro García Linera, in 2005 In 2003, the Bolivian gas conflict broke out as activists – including coca growers – protested against the privatization of the country's natural gas supply and its sale to U.S. companies below the market value. Activists blocked off the road into La Paz, resulting in clashes with police. 80 were killed and 411 injured, among them officers, activists, and civilians, including children.[81] Morales did not take an active role in the conflict, instead traveling to Libya and Switzerland, there describing the uprising as a "peaceful revolution in progress".[82] The government accused Morales and the MAS of using the protests to overthrow Bolivia's parliamentary democracy with the aid of organized crime, FARC, and the governments of Venezuela, Cuba, and Libya.[83] Morales led calls for President Sánchez de Lozada to step down over the death toll, gaining widespread support from the MAS, other activist groups, and the middle classes; with pressure building, Sánchez resigned and fled to Miami, Florida.[84] He was replaced by Carlos Mesa, who tried to strike a balance between U.S. and cocalero demands, but whom Morales mistrusted.[85] In November, Morales spent 24 hours with Cuban President Fidel Castro in Havana,[86] and then met Argentinian President Nestor Kirchner.[87] In the 2004 municipal election, the MAS became the country's largest national party, with 28.6% of all councilors in Bolivia. However, they failed to win the mayoralty in any big cities, reflecting their inability to gain widespread support among the urban middle-classes.[88] In Bolivia's wealthy Santa Cruz region, a strong movement for autonomy had developed under the leadership of the Pro Santa Cruz Committee (Comite Pro Santa Cruz). Favorable to neoliberal economics and strongly critical of the cocaleros, they considered armed insurrection to secede from Bolivia should MAS take power.[89] In March 2005, Mesa resigned, citing the pressure of Morales and the cocalero roadblocks and riots.[90] Amid fears of civil war,[91] Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé became president of a transitional government, preparing Bolivia for a general election in December 2005.[92] Hiring the Peruvian Walter Chávez as its campaign manager, the MAS electoral campaign was based on Salvador Allende's successful campaign in the 1970 Chilean presidential election.[93] Measures were implemented to institutionalize the party structure, giving it greater independence from the social movement; this was done to allow Morales and other MAS leaders to respond quickly to new developments without the lengthy process of consulting the bases, and to present a more moderate image away from the bases' radicalism.[94] Although he had initially hoped for a female running mate, Morales eventually chose Marxist intellectual Álvaro García Linera as his vice-presidential candidate,[95] with some Bolivian press speculating as to a romantic relationship between the two.[96] MAS' primary opponent was Jorge Quiroga and his center-right Social and Democratic Power, whose campaign was centered in Santa Cruz and which advocated continued neo-liberal reform; Quiroga accused Morales of promoting the legalization of cocaine and being a puppet for Venezuela.[97] With a turnout of 84.5%, the election saw Morales gain 53.7% of the vote, while Quiroga came second with 28.6%; Morales' was the first victory with an absolute majority in Bolivia for 40 years[98] and the highest national vote percentage of any presidential candidate in Latin American history.[99] Given that he was the sixth self-described leftist president to be elected in Latin America since 1998, his victory was identified as part of the broader regional pink tide.[100] Becoming president-elect, Morales was widely described as Bolivia's first indigenous leader, at a time when around 62% of the population identified as indigenous; political analysts therefore drew comparisons with the election of Nelson Mandela to the South African Presidency in 1994.[101] This resulted in widespread excitement among the indigenous people in the Americas, particularly those of Bolivia.[102] His election caused concern among the country's wealthy and landowning classes, who feared state expropriation and nationalisation of their property, as well as far-right groups, who said it would spark a race war.[102] He traveled to Cuba to spend time with Castro, before going to Venezuela, and then on tour to Europe, China, and South Africa; significantly, he avoided the U.S.[103] In January 2006, Morales attended an indigenous spiritual ceremony at Tiwanaku where he was crowned Apu Mallku (Supreme Leader) of the Aymara, receiving gifts from indigenous peoples across Latin America and thanking the goddess Pachamama for his victory.[104] |

台頭:2003年から2005年 副大統領候補のアルバロ・ガルシア・リネラとモラレス(2005年) 2003年、ボリビアのガス紛争が勃発した。コカ栽培農家を含む活動家たちが、ボリビアの天然ガス供給が民営化され、米国企業に市場価格より安く売却され たことに抗議したのだ。活動家たちはラパスへの道を封鎖し、警察と衝突した。モラレスは紛争に積極的に関与せず、代わりにリビアとスイスに行き、そこで蜂 起を「進行中の平和的革命」と表現した[82]。政府は、モラレスとMASが組織犯罪、FARC、ベネズエラ、キューバ、リビア政府の援助を受けてボリビ アの議会制民主主義を転覆させるために抗議行動を利用したと非難した[83]。 モラレスは、死者数の問題でサンチェス・デ・ロサダ大統領の退陣を求める声を主導し、MAS、他の活動家グループ、中産階級から広範な支持を得た。圧力が 高まる中、サンチェスは辞任し、フロリダのマイアミに逃亡した[84]。11月、モラレスはハバナでキューバのフィデル・カストロ大統領と24時間過ごし [86]、その後アルゼンチンのネストル・キルチネル大統領と会談した[87]。 2004年の市町村選挙で、MASはボリビアの全議員の28.6%を占め、国民最大の政党となった。ボリビアの裕福なサンタクルス地方では、プロ・サンタ クルス委員会(Comite Pro Santa Cruz)の指導の下、自治を求める強力な運動が展開されていた。新自由主義経済学に好意的で、コカレロを強く批判する彼らは、メサが権力を握った場合、 ボリビアから分離独立するための武装蜂起を考えていた[89]。 2005年3月、メサはモラレスの圧力とコカレロの道路封鎖と暴動を理由に辞任した[90]。内戦が懸念されるなか[91]、エドゥアルド・ロドリゲス・ ベルチェが暫定政府の大統領に就任し、2005年12月の総選挙に向けてボリビアを準備した[92]。 ペルーのワルテル・チャベスを選挙キャンペーン・マネージャーに起用したMASの選挙キャンペーンは、1970年のチリ大統領選挙で成功したサルバドー ル・アジェンデのキャンペーンに基づいていた。[これは、モラレスや他のMAS指導者たちが、基地と協議する長いプロセスを経ることなく、新しい展開に迅 速に対応できるようにするためであり、また、基地の急進主義から離れ、より穏健なイメージを提示するためであった。[94]当初は女性の伴走者を希望して いたが、モラレスは最終的にマルクス主義知識人のアルバロ・ガルシア・リネラを副大統領候補に選んだ[95]。[96]MASの第一次対立候補はホルヘ・ キロガと彼の中道右派である社会民主勢力であり、彼の選挙運動はサンタクルスを中心に展開され、新自由主義改革の継続を主張していた。キロガはモラレスが コカインの合法化を推進し、ベネズエラの傀儡であると非難した[97]。 投票率は84.5%で、モラレスが53.7%の票を獲得し、キローガは28.6%で2位となった。モラレスはボリビアで40年ぶりに絶対過半数を獲得し [98]、ラテンアメリカ史上最高の国民得票率となった。[1998年以降、ラテンアメリカで選出された自称左派の大統領としては6人目であったことか ら、彼の勝利はより広範な地域のピンクの潮流の一部であると認識された[100]。次期大統領となったモラレスは、人口の約62%が先住民であると認識さ れていた当時、ボリビア初の先住民の指導者であると広く評された。[101]この結果、アメリカ大陸の先住民、特にボリビアの先住民の間で広範な興奮が起 こった[102]。 彼の当選は、国家による財産収用や国有化を恐れる国内の富裕層や地主層、人種戦争の火種になるとする極右グループの懸念を引き起こした。[モラレスは 2006年1月、ティワナクで開催された先住民の儀式に出席し、アイマラ族のアプ・マルク(最高指導者)の戴冠式を行い、ラテンアメリカ中の先住民から贈 り物を受け取り、女神パチャママに勝利を感謝した[104]。 |

| President (2006–2019) Main article: Presidency of Evo Morales First presidential term: 2006–2009 In the world there are large and small countries, rich countries and poor countries, but we are equal in one thing, which is our right to dignity and sovereignty. — Evo Morales, Inaugural Speech, 22 January 2006.[105] Morales' inauguration took place on 22 January in La Paz. It was attended by various heads of state, including Argentina's Kirchner, Venezuela's Chávez, Brazil's Lula da Silva, and Chile's Ricardo Lagos.[106] Morales wore an Andeanized suit designed by fashion designer Beatriz Canedo Patiño,[107] and gave a speech that included a minute silence in memory of cocaleros and indigenous activists killed in the struggle.[106] He condemned Bolivia's former "colonial" regimes, likening them to South Africa under apartheid and stating that the MAS' election would lead to a "refoundation" of the country, a term that the MAS consistently used over "revolution".[108] Morales repeated these views in his convocation of the Constituent Assembly.[109] In taking office, Morales emphasized nationalism, anti-imperialism, and anti-neoliberalism, although did not initially refer to his administration as socialist.[110] He immediately reduced both his own presidential wage and that of his ministers by 57% to $1,875 a month, also urging members of Congress to do the same.[111][112][113] Morales gathered together a largely inexperienced cabinet made up of indigenous activists and leftist intellectuals,[114] although over the first three years of government there was a rapid turnover in the cabinet as Morales replaced many of the indigenous members with trained middle-class leftist politicians.[115] By 2012 only 3 of the 20 cabinet members identified as indigenous.[116] |

大統領(2006年~2019年) 主な記事 エボ・モラレス大統領 大統領第1期:2006年〜2009年 世界には大国も小国もあり、豊かな国も貧しい国もあるが、尊厳と主権を持つ権利という点では平等である。 - エボ・モラレス、就任演説、2006年1月22日[105]。 モラレスの就任式は1月22日にラパスで行われた。アルゼンチンのキルチネル、ベネズエラのチャベス、ブラジルのルーラ・ダ・シルヴァ、チリのリカルド・ ラゴスなど様々な国家元首が出席した[106]。モラレスはファッションデザイナーのベアトリス・カネド・パティーニョがデザインしたアンデス風のスーツ を着用し[107]、闘争で死亡したコカレロと先住民の活動家を追悼する1分間の黙祷を含む演説を行った。[106]彼はボリビアのかつての「植民地」政 権を非難し、アパルトヘイト下の南アフリカになぞらえ、MASの選挙は国の「再創造」につながると述べた。 大統領に就任したモラレスはナショナリズム、反帝国主義、反新自由主義を強調したが、当初は自身の政権を社会主義とは言わなかった[110]。[111] [112][113]モラレスは、先住民の活動家と左派知識人で構成された経験の浅い内閣を集めたが[114]、政権発足から3年の間に、モラレスが先住 民のメンバーの多くを訓練された中産階級の左派政治家と入れ替えたため、内閣の入れ替わりが急速に進んだ[115]。 2012年までに、20人の閣僚のうち先住民だと認めたのはわずか3人だけだった[116]。 |

| Economic program At the time of Morales' election, Bolivia was South America's poorest nation.[117] Morales' government did not initiate fundamental change to Bolivia's economic structure,[118] and their National Development Plan (PDN) for 2006–10 adhered largely to the country's previous liberal economic model.[119] Bolivia's economy was based largely on the extraction of natural resources, with the nation having South America's second largest reserves of natural gas.[120] Keeping to his election pledge, Morales took increasing state control of the hydrocarbon industry with Supreme Decree 2870; previously, corporations paid 18% of their profits to the state, but Morales symbolically reversed this, so that 82% of profits went to the state and 18% to the companies. The oil companies threatened to take the case to the international courts or cease operating in Bolivia, but ultimately relented. As a result, Bolivia's income from hydrocarbon extraction increased from $173 million in 2002 to $1.3 billion by 2006.[121] Although not technically a form of nationalization, Morales and his government referred to it as such, resulting in criticism from sectors of the Bolivian left.[122] In June 2006, Morales announced his plan to nationalize mining, electricity, telephones, and railroads. In February 2007, the government nationalized the Vinto metallurgy plant and refused to compensate Glencore, which the government said had obtained the contract illegally.[123] Although the FSTMB miners' federation called for the government to nationalize the mines, the government did not do so, instead stating that any transnational corporations operating in Bolivia legally would not be expropriated.[124] Under Morales, Bolivia experienced unprecedented economic strength, resulting in an increase in value of its currency, the boliviano.[125] Morales' first year in office ended with no fiscal deficit, which was the first time this had happened in Bolivia for 30 years.[126] During the 2008 financial crisis, Bolivia maintained one of the world's highest levels of economic growth.[127] Such economic strength led to a nationwide boom in construction,[125] and allowed the state to build up strong financial reserves.[125] Although the level of social spending was increased, it remained relatively low, with a priority being the construction of paved roads and community spaces such as soccer fields and union buildings.[128] In particular, the government focused on rural infrastructure improvement, to bring roads, running water, and electricity to areas that lacked them.[129] The government's stated intention was to reduce Bolivia's most acute poverty levels from 35% to 27% of the population, and moderate poverty levels from 58.9% to 49% over five years.[130] The welfare state was expanded, as characterized by the introduction of non-contributory old-age pensions and payments to mothers provided their babies are taken for health checks and that their children attend school. Hundreds of free tractors were also handed out. The prices of gas and many foodstuffs were controlled, and local food producers were made to sell in the local market rather than export. A new state-owned body was also set up to distribute food at subsidized prices. All these measures helped to curb inflation, while the economy grew (partly because of rising public spending), accompanied by stronger public finances which brought economic stability.[131] During Morales' first term, Bolivia broke free of the domination of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) which had characterized previous regimes by refusing their financial aid and connected regulations.[132] In May 2007, it became the world's first country to withdraw from the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes, with Morales stating that the institution had consistently favored multinational corporations in its judgments. Bolivia's lead was followed by other Latin American nations.[133] Despite being encouraged to do so by the U.S., Bolivia refused to join the Free Trade Area of the Americas, deeming it a form of U.S. imperialism.[134] A major dilemma faced by Morales' administration was between the desire to expand extractive industries in order to fund social programs and provide employment, and to protect the country's environment from the pollution caused by those industries.[135] Although his government professed an environmentalist ethos, expanding environmental monitoring and becoming a leader in the voluntary Forest Stewardship Council, Bolivia continued to witness rapid deforestation for agriculture and illegal logging.[136] Economists on both the left and right expressed concern over the government's lack of economic diversification.[127] Many Bolivians opined that Morales' government had failed to bring about sufficient job creation.[118] |

経済プログラム モラレスが当選した当時、ボリビアは南米最貧国であった[117]。モラレス政権はボリビアの経済構造の根本的な変革に着手せず[118]、2006年か ら10年にかけての国家開発計画(PDN)は、ボリビアの以前の自由主義経済モデルをほぼ踏襲していた[119]。[120]選挙公約を守り、モラレスは 最高法令2870号で炭化水素産業の国家統制を強化した。以前は企業は利益の18%を国家に納めていたが、モラレスはこれを象徴的に逆転させ、利益の 82%を国家に、18%を企業に納めるようにした。石油会社は、国際裁判所に提訴するか、ボリビアでの操業を停止すると脅したが、最終的には譲歩した。そ の結果、ボリビアの炭化水素採掘による収入は、2002年の1億7300万ドルから2006年には13億ドルに増加した[121]。技術的にはナショナリ ズムの一形態ではないが、モラレスとその政府はナショナリズムと称し、ボリビアの左派の一部から批判を浴びた[122]。2007年2月、政府はビント冶 金工場を国有化し、政府が違法に契約を得たとするグレンコアへの補償を拒否した[123]。FSTMB鉱山連盟は政府に鉱山の国有化を求めたが、政府は国 有化を行わず、代わりにボリビアで合法的に操業する多国籍企業は収用されないと表明した[124]。 モラレスのもと、ボリビアはかつてない経済力を経験し、その結果、通貨ボリビアーノの価値が上昇した[125]。モラレスの就任初年度は財政赤字ゼロで終 わり、これはボリビアで30年ぶりのことであった[126]。[このような経済力は、全国的な建設ブームをもたらし[125]、国家が強力な財政的蓄えを 築くことを可能にした[125]。社会支出の水準は引き上げられたものの、比較的低い水準にとどまり、舗装道路や、サッカー場や組合の建物のようなコミュ ニティスペースの建設が優先された[128]。個別主義では、政府は農村部のインフラ整備に重点を置き、道路、水道、電気が不足している地域にそれらを提 供した[129]。 政府は、5年間でボリビアの最も深刻な貧困レベルを人口の35%から27%へ、中程度の貧困レベルを58.9%から49%へ削減することを意図していた [130]。無拠出の老齢年金の導入や、乳児を保健検診に連れて行き、子どもが学校に通うことを条件とした母親への支給によって特徴づけられるように、福 祉国家が拡大された。また、何百台ものトラクターが無料で配布された。ガスや多くの食料品の価格が統制され、地元の食料生産者は輸出ではなく地元市場で販 売するようになった。また、補助金付きの価格で食料を流通させるために、国営の新組織が設立された。これらの措置はすべてインフレ抑制に役立ち、一方経済 は(公共支出の増加もあって)成長し、財政の強化も伴って経済の安定をもたらした[131]。 モラレスの最初の任期中、ボリビアは、世界銀行と国際通貨基金(IMF)の金融支援と連結規制を拒否することによって、以前の政権を特徴づけていた世界銀 行とIMFの支配から脱却した[132]。 2007年5月、ボリビアは、投資紛争解決国際センターから脱退した世界初の国となり、モラレスは、この機関はその判断において一貫して多国籍企業を優遇 してきたと述べた。ボリビアのリードは他のラテンアメリカ諸国にも追随された[133]。ボリビアは、アメリカからそうするよう奨励されていたにもかかわ らず、アメリカ大陸自由貿易地域(FTA)への参加を拒否し、これをアメリカ帝国主義の一形態とみなした[134]。 モラレス政権が直面した大きなジレンマは、社会事業に資金を供給し雇用を提供するために採掘産業を拡大したいという願望と、それらの産業によって引き起こ される汚染から国の環境を保護したいという願望の間にあった。[135]モラレス政権は環境保護主義を公言し、環境モニタリングを拡大し、自主的な森林管 理協議会のリーダーとなったが、ボリビアでは農業や違法伐採のための急速な森林伐採が続いていた[136]。左右両派のエコノミストは政府の経済多様化の 欠如に懸念を表明した[127]。 |

ALBA and international appearances Morales with regional allies, at the Fórum Social Mundial for Latin America: President of Paraguay Lugo, President of Brasil Lula, President of Ecuador Correa and President of Venezuela Chávez. Morales' administration sought strong links with the governments of Cuba and Venezuela.[137] In April 2005 Morales traveled to Havana for knee surgery, there meeting with the two nations' presidents, Castro and Chávez.[138] In April 2006, Bolivia agreed to join Cuba and Venezuela in founding the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (ALBA), with Morales attending ALBA's conference in May, at which they initiated with a Peoples' Trade Agreement (PTA).[139] Meanwhile, his administration became "the least US-friendly government in Bolivian history".[140] In September Morales visited the U.S. for the first time to attend the UN General Assembly, where he gave a speech condemning U.S. President George W. Bush as a terrorist for launching the War in Afghanistan and Iraq War and called for the UN Headquarters to be moved out of the country. In the U.S., he met with former presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter and with Native American groups.[141] Relations were further strained between the two nations when in December Morales issued a Supreme Decree requiring all U.S. citizens visiting Bolivia to have a visa.[142] His government also refused to grant legal immunity to U.S. soldiers in Bolivia; hence the U.S. cut back their military support to the country by 96%.[134] In December 2006, he attended the first South-South conference in Abuja, Nigeria, there meeting Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, whose government had recently awarded Morales the Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights.[143] Morales proceeded straight to Havana for a conference celebrating Castro's life, where he gave a speech arguing for stronger links between Latin America and the Middle East to combat U.S. imperialism.[144] Under his administration, diplomatic relations were established with Iran, with Morales praising Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a revolutionary comrade.[145] In April 2007 he attended the first South American Energy Summit in Venezuela, arguing with many allies over the issue of biofuel, which he opposed.[146] He had a particularly fierce argument with Brazilian President Lula over Morales' desire to bring Bolivia's refineries – which were largely owned by Brazil's Petrobrás – under state control. In May, Bolivia purchased the refineries and transferred them to the Bolivian State Petroleum Company (YPFB).[147] |

ALBAと国際的な場 モラレスとラテンアメリカの盟友たち: パラグアイのルーゴ大統領、ブラジルのルーラ大統領、エクアドルのコレア大統領、ベネズエラのチャベス大統領である(2009)。 2005年4月、モラレスは膝の手術のためにハバナを訪れ、そこで両国のカストロ大統領、チャベス大統領と会談した[138]。2006年4月、ボリビア はキューバ、ベネズエラとともに米州ボリバル代替案(ALBA)を設立することに合意し、モラレスは5月に開催されたALBAの会議に出席し、人民貿易協 定(PTA)を締結した。[9月、モラレスは国連総会に出席するため初めて訪米し、アフガニスタン戦争とイラク戦争を開始したブッシュ米大統領をテロリス トとして非難する演説を行い、国連本部を国外に移転するよう求めた。アメリカでは、ビル・クリントン元大統領やジミー・カーター元大統領、ネイティブ・ア メリカン・グループと会談した[141]。12月にモラレスがボリビアを訪問するすべてのアメリカ国民にビザを要求する最高命令を出したことで、両国の関 係はさらに緊張した[142]。 2006年12月、モラレスはナイジェリアのアブジャで開催された第1回南南会議に出席し、そこでリビアの指導者ムアンマル・カダフィと会談した。カダ フィは最近、モラレスにアル・カダフィ国際人権賞を授与した。[144] 彼の政権下でイランとの国交が樹立され、モラレスはイランのマフムード・アフマディネジャド大統領を革命の同志として賞賛した[145] 2007年4月、彼はベネズエラで開催された第1回南米エネルギー・サミットに出席し、彼が反対するバイオ燃料の問題をめぐって多くの同盟国と論争した [146]。 ブラジルのペトロブラスが大部分を所有していたボリビアの製油所を国の管理下に置こうとするモラレスの意向をめぐって、彼はブラジルのルラ大統領と個別主 義的に激しい論争を繰り広げた。5月、ボリビアは製油所を買い取り、ボリビア国営石油会社(YPFB)に譲渡した[147]。 |

Social reform Morales with Brazilian President Lula Morales' government sought to encourage a model of development based upon the premise of vivir bien, or "to live well".[117] This entailed seeking social harmony, consensus, the elimination of discrimination, and wealth redistribution; in doing so, it was rooted in communal rather than individual values and owed more to indigenous Andean forms of social organization than Western ones.[117] Upon Morales' election, Bolivia's illiteracy rate was at 16%, the highest in South America.[148] Attempting to rectify this with the aid of left-wing allies, Bolivia launched a literacy campaign with Cuban assistance, and Venezuela invited 5,000 Bolivian high school graduates to study in Venezuela for free.[148] By 2009, UNESCO declared Bolivia free from illiteracy.[149] The World Bank stated that illiteracy had declined by 5%.[150] Cuba also aided Bolivia in the development of its medical care, opening ophthalmological centers in the country to treat 100,000 Bolivians for free per year, and offering 5,000 free scholarships for Bolivian students to study medicine in Cuba.[151] The government sought to expand state medical facilities, opening twenty hospitals by 2014, and increasing basic medical coverage up to the age of 25.[152] Their approach sought to utilize and harmonize both mainstream Western medicine and Bolivia's traditional medicine.[153] The 2006 Bono Juancito Pinto program provided US$29 per year to parents who kept their children in public school with an attendance rate above 80%.[154][155][156] 2008's Renta Dignidad initiative expanded the previous Bonosol social security for seniors program, increasing payments to $344 per year, and lowering the eligibility age from 65 to 60.[157][158][159] 2009's Bono Juana Azurduy program expanded a previous public maternity insurance, giving cash to low-income mothers who proved that they and their baby had received pre- and post-natal medical care, and gave birth in an authorized medical facility.[160][161] Conservative critics of Morales' government said that these measures were designed to buy off the poor and ensure continued support for the government, particularly the Bono Juancito Pinto which is distributed very close to election day.[162][163] Morales announced that one of the top priorities of his government was to eliminate racism against the country's indigenous population.[164] To do this, he announced that all civil servants were required to learn one of Bolivia's three indigenous languages, Quechua, Aymara, or Guaraní, within two years.[165] His government encouraged the development of indigenous cultural projects,[166] and sought to encourage more indigenous people to attend university; by 2008, it was estimated that half of the students enrolled in Bolivia's 11 public universities were indigenous,[167] while three indigenous-specific universities had been established, offering subsidized education.[168] In 2009, a Vice Ministry for Decolonization was established, which proceeded to pass the 2010 Law against Racism and Discrimination banning the espousal of racist views in private or public institutions.[169] Various commentators noted that there was a renewed sense of pride among the country's indigenous population following Morales' election.[170] Conversely, the opposition accused Morales' administration of aggravating racial tensions between indigenous, white, and mestizo populations,[171] and of using the Racism and Discrimination law to attack freedom of the press.[172][173][174] |

社会改革 モラレスとブラジルのルーラ大統領 モラレス政権は、「よく生きる(vivir bien)」という前提に基づく発展モデルを奨励しようとした[117]。これは、社会の調和、コンセンサス、差別の消去、富の再分配を求めるものであ り、そうすることで、個人の価値観よりも共同体の価値観に根ざし、西欧の社会組織よりもアンデス先住民の社会組織の形態に負うところが大きかった [117]。 モラレスが選出されたとき、ボリビアの非識字率は16%で、南米で最も高かった[148]。左翼の同盟国の援助によってこれを是正しようとしたボリビア は、キューバの援助を受けて識字率向上キャンペーンを開始し、ベネズエラはボリビアの高校卒業生5,000人をベネズエラに無料で留学させた[148]。 2009年までに、ユネスコはボリビアが非識字から解放されたと宣言した[149]。[キューバはボリビアの医療発展も支援し、国内に眼科センターを開設 して年間10万人のボリビア人を無料で治療し、キューバで医学を学ぶボリビア人学生に5,000人の無償奨学金を提供した[151]。 2006年のBono Juancito Pintoプログラムは、80%以上の出席率で子どもを公立学校に通わせ続けた親に年間29米ドルを支給した[154][155][156]。2008年 のRenta Dignidadイニシアチブは、以前の高齢者向け社会保障プログラムBonosolを拡大し、支給額を年間344ドルに増額し、受給資格を65歳から 60歳に引き下げた[157][158]。[157][158][159]2009年の「ボノ・フアナ・アズルドゥイ」プログラムは、以前の公的出産保険 を拡大したもので、自分と赤ちゃんが出産前後の医療ケアを受け、認可された医療施設で出産したことを証明した低所得の母親に現金を支給するものであった [160][161]。 モラレス政権に対する保守派の批評家たちは、これらの措置は貧困層を買収し、政府への継続的な支持を確保するためのものであり、特に選挙投票日に近い時期 に配布される「ボノ・フアンシト・ピント」はその一環であると述べている[162][163]。 モラレスは、政府の最優先事項のひとつは、ボリビアの先住民に対する人種主義を消去することであると発表した[164]。 これを実現するために、彼はすべての公務員に2年以内にボリビアの3つの先住民言語、ケチュア語、アイマラ語、グアラニー語のいずれかを習得することを義 務付けると発表した。[2008年までに、ボリビアの11の公立大学に在籍する学生の半数が先住民であると推定され[167]、3つの先住民専門大学が設 立され、補助金付きの教育が提供された。[2009年には脱植民地化担当副省が設置され、2010年には人種主義・差別禁止法が制定され、私的機関や公的 機関における人種主義的見解の表明が禁止された[169]。様々なコメンテーターは、モラレスの選挙後、ボリビアの先住民の間に新たな自負心が生まれたと 指摘している。172][173][174]逆に、野党はモラレス政権が先住民、白人、メスティーソの間の人種的緊張を悪化させていると非難し [171]、人種主義・差別禁止法を報道の自由を攻撃するために利用していると非難した[172][173][174]。 |

Morales and Vice President Álvaro García Linera in 2006 shining the shoes of shoeshine boys. On International Workers' Day 2006, Morales issued a presidential decree undoing aspects of the informalization of labor which had been implemented by previous neoliberal governments; this was seen as a highly symbolic act for labor rights in Bolivia.[175] In 2009 his government put forward suggested reforms to the 1939 labor laws, although lengthy discussions with trade unions hampered the reforms' progress.[176] Morales' government increased the legal minimum wage by 50%,[177] and reduced the pension age from 65 to 60, and then in 2010 reduced it again to 58.[178] While policies were brought in to improve the living conditions of the working classes, conversely many middle-class Bolivians felt that they had seen their social standing decline,[179] with Morales personally mistrusting the middle-classes, deeming them fickle.[180] A 2006 law reallocated state-owned lands,[181] with this agrarian reform entailing distributing land to traditional communities rather than individuals.[182] In 2010, a law was introduced permitting the formation of recognized indigenous territories, although the implementation of this was hampered by bureaucracy and contesting claims over ownership.[183] Morales' government also sought to improve women's rights in Bolivia.[184] In 2010, it founded a Unit of Depatriarchalization to oversee this process.[115] Further seeking to provide legal recognition and support to LGBT rights, it declared 28 June to be Sexual Minority Rights Day in the country,[185] and encouraged the establishment of a gay-themed television show on the state channel.[186] Adopting a policy known as "Coca Yes, Cocaine No",[187] Morales' administration ensured the legality of coca growing, and introduced measures to regulate the production and trade of the crop.[188] In 2007, they announced that they would permit the growing of 50,000 acres of coca in the country, primarily for the purposes of domestic consumption,[189] with each family being restricted to the growing of one cato (1600 meters squared) of coca.[190] A social control program was implemented whereby local unions took on responsibility for ensuring that this quota was not exceeded; in doing so, they hoped to remove the need for military and police intervention, and thus stem the violence of previous decades.[191] Measures were implemented to ensure the industrialization of coca production, with Morales inaugurating the first coca industrialization plant in Chulumani, which produced and packaged coca and trimate tea; the project was primarily funded through a $125,000 donation from Venezuela under the PTA scheme.[188] These industrialization measures proved largely unsuccessful given that coca remained illegal in most nations outside Bolivia, thus depriving the growers of an international market.[192] Campaigning against this, in 2012 Bolivia withdrew from the UN 1961 Convention which had called for global criminalisation of coca, and in 2013 successfully convinced the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs to declassify coca as a narcotic.[193] The U.S. State Department criticized Bolivia, saying that it was regressing in its counter-narcotics efforts, and dramatically reduced aid to Bolivia to $34 million to fight the narcotics trade in 2007.[194] Nevertheless, the number of cocaine seizures in Bolivia increased under Morales' government,[195] as they sought to encourage coca growers to report and oppose cocaine producers and traffickers.[196] High levels of police corruption surrounding the illicit trade in cocaine remained a continuing problem for Bolivia.[197] Morales' government also introduced measures to tackle Bolivia's endemic corruption; in 2007, Morales issued a presidential decree to create the Ministry of Institutional Transparency and Fight Against Corruption.[198] Critics said that MAS members were rarely prosecuted for the crime, the main exception being YPFB head Santos Ramírez, who was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment for corruption in 2008. A 2009 law that permitted the retroactive prosecution for corruption led to legal cases being brought against a number of opposition politicians for alleged corruption in the pre-Morales period and many fled abroad to avoid standing trial.[199] |

2006年、モラレスとアルバロ・ガルシア・リネラ副大統領は、靴磨きの少年たちの靴を磨いている。 2006年の国際労働者デーに、モラレスは、以前の新自由主義政権によって実施された労働の非正規化の側面を取り消す大統領令を出した。[モラレス政権 は、法定最低賃金を50%引き上げ[177]、年金受給年齢を65歳から60歳に引き下げ、2010年には再び58歳に引き下げた[178]。 労働者階級の生活条件を改善するための政策が導入された一方で、逆に多くの中産階級のボリビア人は、自分たちの社会的地位が低下していると感じており [179]、モラレスは個人的に中産階級を気まぐれとみなし、不信感を抱いていた[180]。 2006年の法律では国有地が再配分され[181]、この農地改革では個人ではなく伝統的な共同体に土地が分配された。[182]2010年には、公認の 先住民領土の形成を許可する法律が導入されたが、その実施は官僚主義や所有権をめぐる主張の対立によって妨げられた[183]。[184]2010年に は、このプロセスを監督するために脱植民地化ユニットを設立した[115]。さらにLGBTの権利を法的に認め、支援することを求め、6月28日を「性的 少数者の権利の日」と宣言し[185]、国営チャンネルでゲイをテーマにしたテレビ番組の設立を奨励した[186]。 コカ・イエス、コカイン・ノー」として知られる政策を採用し[187]、モラレス政権はコカ栽培の合法性を確保し、コカの生産と取引を規制する措置を導入 した[188]。2007年には、主に国内消費を目的として、国内で50,000エーカーのコカ栽培を許可すると発表し[189]、各家庭は1カト (1600メートル四方)のコカ栽培に制限された[190]。 そうすることで、軍や警察の介入の必要性を排除し、過去数十年間の暴力を食い止めることが期待された[191]。コカ生産の工業化を確実にするための措置 が実施され、モラレスはチュルマニにコカとトリメート茶を生産・包装する最初のコカ工業化工場を発足させた。このプロジェクトは主に、PTAスキームの 下、ベネズエラからの125,000ドルの寄付によって賄われた[188]。 ボリビア以外のほとんどの国民がコカを違法としたままであったため、生産者は国際市場を奪われていた[192]。これに反対するキャンペーンを展開し、ボ リビアは2012年にコカの世界的な犯罪化を求めていた国連1961年条約から脱退し、2013年には国連麻薬単一条約にコカを麻薬として分類しないよう 説得することに成功した[193]。アメリカ国務省は、ボリビアは麻薬撲滅の取り組みが後退していると批判し、2007年には麻薬取引撲滅のためにボリビ アへの援助を3,400万ドルまで大幅に減額した。[196]。コカインの不正取引をめぐる警察の腐敗は、ボリビアにとって継続的な問題であった [197]。 モラレス政権はまた、ボリビアに蔓延する汚職に取り組むための施策を導入した。2007年、モラレスは大統領令を発布し、組織の透明性と汚職との闘い省を 創設した[198]。批評家によれば、MASのメンバーが犯罪で起訴されることはほとんどなく、主な例外は、2008年に汚職で禁固12年の判決を受けた YPFB代表のサントス・ラミレスであった。2009年、汚職の遡及起訴を認める法律が制定され、多くの野党政治家がモラレス以前の汚職の疑いで訴追さ れ、多くの政治家が裁判を避けるために海外に逃亡した[199]。 |

| Domestic unrest and the new constitution During his presidential campaign, Morales had supported calls for regional autonomy for Bolivia's departments. As president, he changed his position, viewing the calls for autonomy – which came from Bolivia's four eastern departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, and Tarija – as an attempt by the wealthy bourgeoisie living in these regions to preserve their economic position.[200] He nevertheless agreed to a referendum on regional autonomy, held in July 2006; the four eastern departments voted in favor of autonomy, but Bolivia as a whole voted against it by 57.6%.[201] In September, autonomy activists launched strikes and blockades across eastern Bolivia, resulting in violent clashes with MAS activists.[202] In January 2007, clashes in Cochabamba between activist groups led to fatalities, with Morales' government sending in troops to maintain the peace. The left-indigenous activists formed a Revolutionary Departmental Government, but Morales denounced it as illegal and continued to recognize the legitimacy of right-wing departmental head Manfred Reyes Villa.[203] In July 2006, an election to form a Constitutional Assembly was held, which saw the highest ever electoral turnout in the nation's history. MAS won 137 of its 255 seats, after which the Assembly was inaugurated in August.[204] The Assembly was the first elected parliamentary body in Bolivia which features strong campesino and indigenous representation.[205] In November, the Assembly approved a new constitution, which converted the Republic of Bolivia into the Plurinational State of Bolivia, describing it as a "plurinational communal and social unified state". The constitution emphasized Bolivian sovereignty of natural resources, separated church and state, forbade foreign military bases in the country, implemented a two-term limit for the presidency, and permitted limited regional autonomy. It also enshrined every Bolivians' right to water, food, free health care, education, and housing.[206] In enshrining the concept of plurinationalism, one commentator noted that it suggested "a profound reconfiguration of the state itself" by recognising the rights to self-determination of various nations within a single state.[207]  Morales in 2008 In May 2008, the eastern departments pushed for greater autonomy, but Morales' government rejected the legitimacy of their position.[208] They called for a referendum on recalling Morales, which saw an 83% turnout and in which Morales was ratified with 67.4% of the vote.[209] Unified as the National Council for Democracy (CONALDE), these groups – financed by the wealthy agro-industrialist, petroleum, and financial elite – embarked on a series of destabilisation campaigns to unseat Morales' government.[210] Unrest then broke out across eastern Bolivia, as radicalized autonomist activists established blockades, occupied airports, clashing with pro-government demonstrations, police, and armed forces. Some formed paramilitaries, bombing state companies, indigenous NGOs, and human rights organisations, also launching armed racist attacks on indigenous communities, culminating in the Pando Massacre of MAS activists.[211] The autonomists gained support from some high-ranking politicians; Santa Cruz Governor Rubén Costas lambasted Morales and his supporters with racist epithets, accusing the president of being an Aymara fundamentalist and a totalitarian dictator responsible for state terrorism.[212] Amid the unrest, foreign commentators began speculating on the possibility of civil war.[213] After it was revealed that USAID's Office of Transition Initiatives had supplied $4.5 million to the pro-autonomist departmental governments of the eastern provinces, in September 2008 Morales accused the U.S. ambassador to Bolivia, Philip Goldberg, of "conspiring against democracy" and encouraging the civil unrest, ordering him to leave the country.[214][215] The U.S. government responded by expelling Bolivian ambassador to the U.S., Gustavo Guzman.[216] Bolivia subsequently expelled the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) from the country, while the U.S. responded by withdrawing their Peace Corps.[217] Chávez stood in solidarity with Bolivia by ordering the U.S. ambassador Patrick Duddy out of his country and withdrawing the Venezuelan ambassador to the U.S.[218] The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) convened a special meeting to discuss the Bolivian situation, expressing full support for Morales' government.[219] |

国内不安と新憲法 大統領選挙期間中、モラレスはボリビアの地方自治を求める声を支持していた。大統領になるとモラレスは立場を変え、ボリビア東部のサンタクルス、ベニ、パ ンド、タリハの4県からの自治を求める声を、これらの地域に住む裕福なブルジョワジーが自分たちの経済的地位を維持しようとする試みとみなした [200]。 それでもモラレスは、2006年7月に実施された地域自治に関する住民投票に同意した。東部の4県は自治に賛成したが、ボリビア全体としては57.6%の 反対票を投じた[201]。9月、自治活動家はボリビア東部全域でストライキと封鎖を開始し、MAS活動家と暴力的な衝突を引き起こした[202]。 2007年1月、コチャバンバで活動家グループ間の衝突が死者を出し、モラレス政府は平和を維持するために軍隊を派遣した。左先住民の活動家たちは革命県 政府を結成したが、モラレスはそれを違法だと非難し、右派の県長マンフレッド・レイエス・ヴィラの正当性を認め続けた[203]。 2006年7月、国民史上最高の投票率を記録した憲法制定議会選挙が実施された。MASは255議席のうち137議席を獲得し、8月に議会が発足した [204]。議会はボリビア初の選挙で選ばれた議会であり、カンペシーノと先住民の代表が強く選出された[205]。11月、議会は新憲法を承認し、ボリ ビア共和国を「ボリビア多民族国」に転換し、「多民族的共同体・社会的統一国家」と表現した。憲法はボリビアの天然資源主権を強調し、政教分離、外国軍基 地の駐留を禁じ、大統領職の2期制を実施し、限定的な地域自治を認めた。また、ボリビア国民一人ひとりが水、食料、無料の保健医療、教育、住居を得る権利 を明記した[206]。ナショナリズムの概念を明記することで、ある論者は、単一国家内のさまざまな国民の自決権を認めることによって、「国家そのものの 深遠な再構成」を示唆していると指摘した[207]。  2008年のモラレス 2008年5月、東部諸州は自治権の拡大を求めたが、モラレス政府はその正当性を否定した[208]。東部諸州はモラレス罷免を問う住民投票を呼びかけ、 投票率は83%に達し、67.4%の得票率でモラレスが罷免された。[209] 国民民主評議会(CONALDE)として統一されたこれらのグループは、裕福な農産業、石油、金融のエリートから資金を得て、モラレス政権を失脚させるた めの一連の不安定化キャンペーンに着手した。 急進化した自治活動家たちが封鎖を確立し、空港を占拠し、親政府デモ、警察、武装勢力と衝突した。一部の活動家は準軍事組織を結成し、国営企業、先住民族 NGO、人権団体を爆撃し、先住民族コミュニティへの人種差別的な武力攻撃を開始し、MAS活動家のパンド虐殺で頂点に達した。[ルベン・コスタスサンタ クルス知事は、モラレスとその支持者たちを人種差別的な言葉で非難し、大統領がアイマラ原理主義者であり、国家テロリズムに責任を負う全体主義的な独裁者 であると非難した[212]。 2008年9月、モラレスはフィリップ・ゴールドバーグ駐ボリビア米国大使を「民主主義に反対し」、内乱を助長していると非難し、国外退去を命じた [214][215]、 ボリビアはその後、アメリカの麻薬取締局(DEA)を追放し、アメリカは平和部隊を撤退させることで対抗した[217]。南米諸国連合(UNASUR)は ボリビア情勢を議論するための特別会議を開催し、モラレス政権への全面的な支持を表明した[219]。 |

Morales meeting with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev in 2009 Although unable to quell the autonomist violence, Morales' government refused to declare a state of emergency, believing that the autonomists were attempting to provoke them into doing so.[220] Instead, they decided to compromise, entering into talks with the parliamentary opposition. As a result, 100 of the 411 elements of the Constitution were changed, with both sides compromising on certain issues.[221] Nevertheless, the governors of the eastern provinces rejected the changes, believing it gave them insufficient autonomy, while various Indianist and leftist members of MAS felt that the amendments conceded too much to the political right.[222] The constitution was put to a referendum in January 2009, in which it was approved by 61.4% of voters.[223] Following the approval of the new Constitution, the 2009 general election was called. The opposition sought to delay the election by demanding a new biometric registry system, hoping that it would give them time to form a united front against MAS.[224] Many MAS activists reacted violently against the demands and attempting to prevent this. Morales went on a five-day hunger strike in April 2009 to push the opposition to rescind their demands. He also agreed to allow for the introduction of a new voter registry but said that it was rushed through so as not to delay the election.[225] Morales and the MAS won with a landslide majority, polling 64.2%, while voter participation had reached an all-time high of 90%.[226] His primary opponent, Reyes Villa, gained 27% of the vote. The MAS won a two-thirds majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.[227] Morales notably increased his support in the east of the country, with MAS gaining a majority in Tarija.[228] In response to his victory, Morales proclaimed that he was "obligated to accelerate the pace of change and deepen socialism" in Bolivia, seeing his re-election as a mandate to further his reforms.[229] |

2009年、ロシアのメドベージェフ大統領と会談するモラレス大統領 自治政府の暴力を鎮めることはできなかったが、モラレス政府は、自治政府がそうするよう挑発しようとしていると考え、非常事態宣言を拒否した[220]。 その代わりに、議会反対派との協議に入り、妥協することを決めた。その結果、憲法の411の要素のうち100が変更され、双方が特定の問題で妥協した [221]。にもかかわらず、東部の州の知事たちは、自分たちに十分な自治権を与えていないと考えて変更を拒否し、MASのさまざまなインド主義者や左派 のメンバーは、改正が政治的右派に譲歩しすぎていると感じた[222]。憲法は2009年1月に国民投票にかけられ、有権者の61.4%が承認した [223]。 新憲法の承認後、2009年の総選挙が招集された。野党は、MASに対抗する統一戦線を形成する時間を与えることを期待して、新しいバイオメトリクス登録 システムを要求することによって選挙を遅らせようとした[224]。モラレスは2009年4月に5日間のハンガーストライキを行い、反対派に要求の撤回を 迫った。モラレスとMASは64.2%の得票率で圧勝し、有権者の投票率は過去最高の90%に達した[226]。MASは下院と上院の両方で3分の2の多 数を獲得した[227]。モラレスは、タリハでMASが多数を獲得したことで、国の東部での支持を顕著に伸ばした[228]。勝利を受け、モラレスはボリ ビアにおいて「変革のペースを加速させ、社会主義を深化させる義務がある」と宣言し、再選を自身の改革をさらに進めるためのマンデートと見なした [229]。 |

Second presidential term: 2009–2014 President Morales with president of Chile Sebastián Piñera at the gold-copper mine San José during the Chilean mining accident and the rescue of 33 miners in 2010, who were trapped for more than two months more than 2,000 feet below the surface.[230] During his second term, Morales began to speak openly of "communitarian socialism" as the ideology that he desired for Bolivia's future.[231] He assembled a new cabinet which was 50% female, a first for Bolivia,[232] although by 2012, that had dropped to a third.[184] One of the main tasks that faced his government during this term was the aim of introducing legislation that would cement the extension of rights featured in the new constitution.[233] In April 2010, the departmental elections saw further gains for MAS.[234] In 2013, the government passed a law to combat domestic violence against women.[235] In December 2009, Morales attended the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark, where he blamed climate change on capitalism and called for a financial transactions tax to fund climate change mitigation. Ultimately deeming the conference to have been a failure, he oversaw the World's People Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth outside of Cochabamba in April 2010.[236] Following the victories of Barack Obama and the Democratic Party in the 2008 U.S. presidential election, relations between Bolivia and the U.S. improved slightly, and in November 2009 the countries entered negotiations to restore diplomatic relations.[237] After the U.S. backed the 2011 military intervention in Libya by NATO forces, Morales condemned Obama, calling for his Nobel Peace Prize to be revoked.[238] The two nations restored diplomatic relations in November 2011,[239] although Morales refused to allow the DEA back into the country.[240] In October 2012, the government passed a Law of Mother Earth that banned genetically modified organisms (GMOs) being grown in Bolivia. This was praised by environmentalists and criticized by the nation's soya growers, who said that it would make them less competitive on the global market.[241] In July 2013, Morales attended a summit in Moscow where he said he was open to offering political asylum to Edward Snowden, who was staying in the Moscow airport at the time. On 2 July 2013, while travelling back to Bolivia from the summit, his presidential plane was forced to land in Austria when Portuguese, French, Spanish and Italian authorities denied it access to their airspace.[242][243] Bolivian Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca said the European states had acted on "unfounded suspicions that Mr. Snowden was on the plane".[243] The Organisation of American States condemned "actions that violate the basic rules and principles of international law such as the inviolability of Heads of State", and demanded that the European governments explain their actions and apologise. An emergency meeting of the Union of South American Nations denounced "the flagrant violation of international treaties" by European powers.[243][244] Latin American leaders describe the incident as a "stunning violation of national sovereignty and disrespect for the region".[245] Morales himself described the incident as a "hostage" situation.[246] France apologised for the incident the next day.[247] Snowden said that the forced grounding of Morales plane may have prompted Russia to allow him to leave the Moscow airport.[248] In 2014, Morales became the oldest active professional soccer player in the world after signing a contract for $200 a month with Sport Boys Warnes.[249]  Morales attending the 6th BRICS summit 2014 On 31 July 2014, Morales condemned the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict and declared Israel a "terrorist state" because of the ongoing offensive in the Gaza Strip. He said: "Israel does not respect the principles or purposes of the United Nations charter nor the Universal Declaration of Human Rights".[250] Domestic protests  Morales addressing Bolivia's Parliament Morales' second term was heavily affected by infighting and dissent from within his support base, as indigenous and leftist activists rejected several government reforms.[251] In May 2010, his government announced a 5% rise in the minimum wage. The Bolivian Workers' Central (COB) felt this insufficient given the rising cost of living, calling a general strike, while protesters clashed with police. The government refused to increase the rise, accusing protesters of being pawns of the right.[252] In August 2010, violent protests broke out in southern Potosí over widespread unemployment and a lack of infrastructure investment.[235] In December 2010, the government cut subsidies for gasoline and diesel fuels, which raised fuel prices and transport costs. Protests led Morales to nullify the decree, responding that he "ruled by obeying".[253] In June 2012, Bolivia's police launched protests against anti-corruption reforms to the police service; they burned disciplinary case records and demanded salary increases. Morales' government relented, canceling many of the proposed reforms and agreeing to the wage rise.[254] In 2011, the government announced it had signed a contract with a Brazilian company to construct a highway connecting Beni to Cochabamba, which would pass through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS). This would better integrate the Beni and Pando departments with the rest of Bolivia and facilitate hydrocarbons exploration. The plan brought condemnation from environmentalists and indigenous communities living in the TIPNIS, who said that it would encourage deforestation and illegal settlement and that it violated the constitution and United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[255] The issue became an international cause célèbre and cast doubt on the government's environmentalist and indigenous rights credentials.[256] In August, 800 protesters embarked on a protest march from Trinidad to La Paz; many were injured in clashes with police and supporters of the road.[257] Two government ministers and other high-ranking officials resigned in protest and Morales' government relented, announcing suspension of the road.[257] In October 2011, he passed Law 180, prohibiting further road construction, although the government proceeded with a consultation, eventually gaining the consent of 55 of the 65 communities in TIPNIS to allow the highway to be built, albeit with a variety of concessions; construction was scheduled to take place after the 2014 general election.[257][258][259] In May 2013, the government announced that it would permit hydrocarbon exploration in Bolivia's 22 national parks, to widespread condemnation from environmentalists.[241] |