ポスト新自由主義は可能か?

Is Post-Neoliberalism Possible?

☆ポスト新自由主義?——なんじゃ、それ?ここからはじまるのが、このページの目的である。

★金融危機以降、政治的右派からは新自由主義秩序に対するさまざまな挑戦がみられた。冷戦構造の崩壊により、共産主義や社会主義が「敗北」したと同時に、リベラリズムを「改造強化」した、ある種のサイボーグリベラリズムの旗手であるネオリベラル(新自由主義)に負けはないとみられた。実際、当時、ネオコンの最重要論客と呼ばれたフランシス・フクヤマは「歴史の終わり」をも宣言した。しかしその後、新自由主義は、今度は仲間であったはずの保守主義からは「腑抜け」と呼ばれ、リバタリアニズムとの関係を精査することに迫られた。その後、ペイルオコンサバティヴィズム、ネオリアクション政治、ナショナリズム、リバタリアン・パターナリズム、そしてさまざまな主権形態とエリート権力によって新自由主義秩序に脅威がもたらされていのである。

☆William Davies らの "Post-Neoliberalism? An Introduction,"Theory, Culture & Society, September 15, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211036722 の冒頭から……

| 2008

年以降、新自由主義というカテゴリーに関して、2つの重要な学術的傾向が組み合わさっている。まず、この期間は、新自由主義の歴史的・社会学的分析が著し

く拡大、深化、改善された期間であった。2008年に発表されたフーコーによる新自由主義に関する著名な講義の英訳版(Foucault,

2008)は、フーコーによる新自由主義の系譜学(Dardot and Laval, 2014; Brown,

2015)を基にした多数の有力な著作の出版につながった。同時に、経済と思想の歴史家たちは、新自由主義思想のさまざまな学派の形成と相互作用に関する

画期的な出版物をいくつか発表している(ミロフスキーとプレヴェ、2009年、バーギン、2012年、ステッドマン・ジョーンズ、2012年、ミロフス

キー、2013年)。さらに最近では、新自由主義思想と政治の歴史は、家族(Cooper, 2017)、国際市場(Slobodian,

2018)、人権(Whyte,

2019)など、さまざまな観点からさらに充実したものとなっている。これらの研究に共通しているのは、新自由主義のルーツを「サッチャリズム」の起源や

ケインズ主義の危機をはるかに遡り、1920年代と30年代の知的核まで遡って追跡することに専心していることである。 |

|

| 第

二に、この期間は新自由主義の存在意義が繰り返し問われた時期でもあった。新自由主義とは対極にあると思われる方法で対処された銀行危機は、1970年代

後半にマネタリストやその他の新自由主義的な考え方が台頭するきっかけとなった「政策パラダイムの転換」を予兆するかのように見えた(Hall,

1993)。これはすぐに幻であることが判明した。その理由のひとつは、危機を「緊急事態」、「戦争」、あるいは「例外」と位置づけることで、政策エリー

トたちが金融の現状を維持するために必要なことを何でも行うことが許されたからである(Davies, 2013; Tooze,

2018)。しかし、その後の数年間で、新自由主義が実際に無傷で生き残ったのか、それとも何か別のものに変異したのかという疑問が生じた。ペックを筆頭

に、学者たちは「ポスト新自由主義」(Peck et al., 2010; Springer, 2014)、「ゾンビ新自由主義」(Peck,

2010)、「変異型新自由主義」(Callison and Manfredi,

2020)の可能性を提起し、それが「依然として新自由主義なのか」(Peck and Theodore,

2019)という問いを投げかけ続けている。2010年代に「ポピュリスト」の指導者や政党が選挙で優勢となったことは、多くの人々によって、テクノク

ラート的な新自由主義の政策の拒絶として解釈された(Hopkin and Blyth,

2019など)。新自由主義は、一部の人々には新たに「権威主義的」、「非自由主義的」、あるいは「反民主主義的」な性質を帯びているように見えた

(Bruff, 2014; Rose, 2017; Hendrikse, 2018; Brown, 2019)。 |

|

| そ

れゆえ、私たちは10年以上にわたって、より詳細な「現在の歴史」から恩恵を受けてきたが、同時に、これが本当に私たちの「現在」の状態であるのかどう

か、確信が持てなくなっている。「新自由主義」(1920年代以降に発展した一連の思想と政策)と私たちの現在の時代との関係は、少なくとも疑問の余地が

ある。新自由主義というカテゴリーは、今日における政治経済や社会を理解するための貴重なツールであり続けている。その理由は、新自由主義に関する研究

が、その豊かさと範囲において成長し続けているからである。しかし、年を追うごとに、新自由主義の内部や対抗勢力として、一見相反する傾向も増え続けてい

る。新自由主義とは何かという理解が大幅に深まった今、少なくとも、新自由主義がパラダイムを転換する決定的な危機とともに終焉を迎えることはありそうも

ないという点では同意できる。その意味で、「ポスト新自由主義」とは、新自由主義の後にのみ訪れるものを指すのではなく、「ポスト・フォード主義」という

概念と同様に、新自由主義社会に根付き、新自由主義の理念や政治の主要原則を弱体化させたり変容させたりし始めた、新たな合理性、批判、運動、改革を指す

ものである。 |

|

| ケ

インズ主義の危機は、新自由主義的政策のアイデアが採用され実施されるきっかけとなったが、それは古典的なクーンのパラダイムシフトのリズムに従ったもの

であった。一連のエリート機関に埋め込まれた一貫した理論と予測は、多くの資本主義社会を苦しめていた問題を説明できなくなった。一方、ライバルとなる一

連の理論は、シカゴ学派と強く関連し、シンクタンクやメディアを通じて広められ、特にインフレという危機を緩和することを約束した。戦時体制の知識と技術

的潜在能力を基盤として構築されたケインズ主義は、同様に計画的で、技術的で、マクロ経済的な野望を持つ代替案と対峙することとなった

(Mitchell,

1998)。右派の推進により誕生した体制は、金融政策によるインフレ対策、組織労働力の弱体化、高額所得および資本への減税、公共資産の私有化、独占に

対する規制の緩和、そして労働、家族、そして「個人の責任」を優先させるための福祉国家の着実な再編を優先するものであった(Harvey,

2005)。1990年代には、この体制が政治的な黄金時代を迎え、インフレはほぼ克服され、資本はますます流動的になる中、より中道的な新自由主義モデ

ルが西側民主主義諸国でヘゲモニーを握るようになった。このモデルでは、国家の「競争力」を高め、国内投資を誘致することを目的として、積極的な国家が社

会領域に革新性と柔軟性を浸透させようとした。同時に、増大する民間債務が消費、住宅所有、高等教育の成長を促進した。新自由主義のこの段階は、右派より

も中道左派の政党によって主導されることが多かったが、これは、政治プロジェクトとして、資本への制約を軽減することと同じくらい、起業家的な方向で「社

会」領域を改革し、刷新する努力を意味している(Dardot and Laval, 2014)。 |

|

| し

かし、この新自由主義の同じ局面(国家社会主義の終焉後に発生)は、新自由主義が政策パラダイムや制度の雛形であるだけでなく、主観性の様式であり、国家

内外の毛細血管のような権力のネットワークを通じて機能し、中央銀行、政府機関、外注業者、多国間機関といった技術官僚的な準国家機関に特に根付いている

という、フーコーの洞察を裏付けるものでもある。それは倫理的かつ社会的な生き方であり、政策のコンセンサスが変化しただけで簡単に置き換えられたり、

取って代わられたりするものではない。 |

|

ケインズ主義が、それと形式的な類似点を持つ「パラダイム」に取って代わられたように、新自由主義は、国家への疑念、地方分権の重視、個人の主観性の再構 築といった、その形式的な性質の一部を共有する論理や合理性によって腐食され、取って代わられつつある。スミスとバロウズがこの特集号で「再分散化」と呼 ぶ、自由主義的かつ技術主導の国家への攻撃を、より本質的な自由の名のもとに再開するさまざまな動きを目撃することができる。この点において、ポスト新自 由主義的な傾向は、政府の統治能力を不安定化させ、私有財産と私的統治の権限を再主張しながら、限界領域で活動している。しかし、私たちはまた、テクノク ラート、多国間、金融当局によって奪われた権限を国家と主権者(その解釈はともかく)に回復させる、さまざまな「再中央集権化」の動きを目撃することもで きる。 |

|

| 本

記事で紹介する「ポスト・ネオリベラリズム?」特集号は、2018年から2020年にかけて構想され、編集され、執筆された。大半の論文は、近年、新自由

主義の現状に対する批判をますます活発化させ、世界中で多くの選挙での躍進を遂げている欧米における右派の政治運動や思想の台頭について考察している。し

かし、そのタイミングの関係で、どの論文も新自由主義の最も最近の危機、すなわち2020年に世界を襲った新型コロナウイルス(COVID-19)のパン

デミックに完全に立ち向かうことも、評価することもできなかった。本稿では、現代の「ポスト新自由主義」を理解することを目的として、2つの観点から論文

を位置づけたい。まず、新自由主義思想の歴史に潜むいくつかの緊張関係について、保守思想やリバタリアン思想の並行する伝統との関連で考察する。今日、新

自由主義的なテクノクラシーやグローバリゼーションに対する強力な挑戦が右派から生じていることを踏まえれば、その対立を形作り、活性化させる長年にわた

る相違や違いを明確にすることが重要である。第二に、より思索的に、私たちは、新型コロナウイルス(COVID-19)を巡る政治の「ポスト新自由主義」

的特徴について考察する。2020年から2021年にかけての出来事は、多くの公共サービスや公共財の新たな民営化形態を促進したが、それらが(特にマク

ロ経済政策の観点において)過去40年間の新自由主義的オーソドックスからの脱却を告げるものであることも否定できない。本号の論文で取り上げられている

現象や考え方と、これらの出来事がどのように交差する可能性があるかを考察し、社会やグローバルな組織の運営原則としての「市場」と「競争」の自律性の低

下について指摘して結論とする。 |

|

| https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/02632764211036722 |

|

| Socialism of the 21st century Socialism of the 21st century (Spanish: Socialismo del siglo XXI; Portuguese: Socialismo do século XXI; German: Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts) is an interpretation of socialist principles first advocated by German sociologist and political analyst Heinz Dieterich and taken up by a number of Latin American leaders. Dieterich argued in 1996 that both free-market industrial capitalism and 20th-century socialism have failed to solve urgent problems of humanity such as poverty, hunger, exploitation of labour, economic oppression, sexism, racism, the destruction of natural resources and the absence of true democracy.[1] Socialism of the 21st century has democratic socialist elements, but it also resembles Marxist revisionism.[2] Leaders who have advocated for this form of socialism include Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Rafael Correa of Ecuador, Evo Morales of Bolivia, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil and Michelle Bachelet of Chile.[3] Because of the local unique historical conditions, socialism of the 21st century is often contrasted with previous applications of socialism in other countries, with a major difference being the effort towards a more effective economic planning process.[2] |

21世紀の社会主義 21世紀の社会主義(スペイン語: Socialismo del siglo XXI、ポルトガル語: Socialismo do século XXI、ドイツ語: Sozialismus des 21. Jahrhunderts)とは、ドイツの社会学者で政治アナリストのハインツ・ディーターリヒが最初に提唱し、ラテンアメリカの指導者たちによって取り 上げられた社会主義の原則の解釈である。ディートリヒは1996年に、自由市場の産業資本主義も20世紀の社会主義も、貧困、飢餓、労働搾取、経済的抑 圧、性差別、人種差別、天然資源の破壊、真の民主主義の不在といった人類の喫緊の課題を解決できなかったと主張した。[1] 21世紀の社会主義には民主的社会主義の要素があるが、マルクス主義の修正主義にも似ている。[2] この社会主義を提唱する指導者には、ベネズエラのウゴ・チャベス、エクアドルのラファエル・コレア、ボリビアのエボ・モラレス、ブラジルのルイス・イナシ オ・ルーラ・ダ・シルヴァ、チリのミシェル・バチェレなどがいる。[3] 21世紀の社会主義は、その地域独自の歴史的条件により、他の国々で過去に試みられた社会主義と対比されることが多い。大きな違いは、より効果的な経済計 画プロセスに向けた取り組みである。[2] |

| Historical foundations After a series of structural adjustment loans and debt restructuring led by the International Monetary Fund in the late 20th century, Latin America experienced a significant increase in inequality. Between 1990 and 1999, the Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality in the income or wealth distribution, rose in almost every Latin American country.[4] Volatile prices and inflation led to dissatisfaction. In 2000, only 37% of Latin Americans were satisfied with their democracies (20 points less than Europeans and 10 points less than sub-Saharan Africans).[5] In this context, a wave of left-leaning socio-political movements, called the Pink tide, on behalf of indigenous rights, cocaleros, labor rights, women's rights, land rights and educational reform emerged to eventually provide momentum for the election of socialist leaders.[2] Socialism of the 21st century draws on indigenous traditions of communal governance and previous Latin America socialist and communist movements, including those of Salvador Allende, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and the Sandinista National Liberation Front.[2] |

歴史的基盤 20世紀後半に国際通貨基金(IMF)が主導した一連の構造調整融資と債務再編の後、ラテンアメリカでは格差が大幅に拡大した。1990年から1999年 の間に、所得や富の分配における格差の指標であるジニ係数は、ほぼすべてのラテンアメリカ諸国で上昇した。[4] 価格の変動やインフレは不満につながった。2000年には、ラテンアメリカ人のうち民主主義に満足しているのは37%に過ぎず(ヨーロッパ人より20ポイ ント、サハラ以南のアフリカ人より10ポイント低い)[5]、このような状況下で、 先住民の権利、コカ栽培農家の権利、労働者の権利、女性の権利、土地の権利、教育改革を掲げた左派寄りの社会政治運動の波、いわゆる「ピンクの潮流」が現 れ、最終的には社会主義指導者の当選に弾みをつけた。 21世紀の社会主義は、先住民の伝統的な共同体統治や、サルバドール・アジェンデ、フィデル・カストロ、チェ・ゲバラ、サンディニスタ民族解放戦線などのラテンアメリカにおける過去の社会主義・共産主義運動に由来している。[2] |

| Theoretical tenets According to Dieterich, this form of socialism is revolutionary in that the existing society is altered to be qualitatively different, but the process itself should be gradual and non-violent, instead utilising democracy to secure power, education, scientific knowledge about society and international cooperation. Dieterich suggests the construction of four basic institutions within the new reality of post-capitalist civilisation:[1] Equivalent economy based on the Marxian economic labor theory of value and democratically determined by those who directly create value instead of principles of market economies. Majority democracy which makes use of referendums to decide upon important societal questions. Basic state democracy with a suitable protection of minority rights. Citizens who are responsible, rational and self-determined. |

理論的根拠 ディートリッヒによると、この社会主義の形態は、既存の社会が質的に異なるものへと変化するという点で革命的であるが、そのプロセス自体は段階的かつ非暴 力的であるべきであり、その代わりに民主主義を活用して権力を確保し、教育、社会に関する科学的知識、国際協力を推進すべきである。ディートリッヒは、資 本主義後の文明という新たな現実の中で、4つの基本的な制度の構築を提案している。 マルクス経済学の労働価値説に基づく平等経済であり、市場経済の原則ではなく、価値を直接創造する人々によって民主的に決定される。 国民投票を活用して重要な社会問題を決定する多数決民主主義。 少数派の権利を適切に保護する基本的な国家民主主義。 責任感があり、理性的で、自己決定能力のある市民。 |

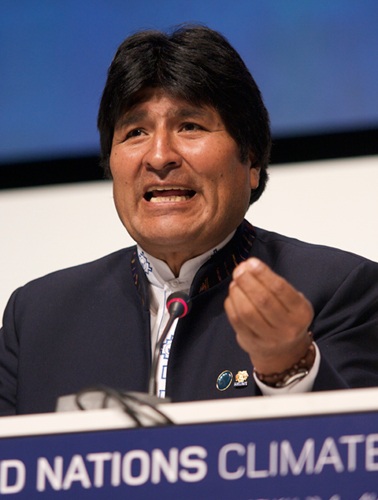

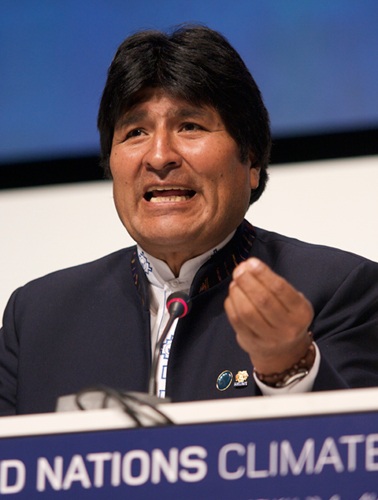

| Post-neoliberalism Post-neoliberalism, also known as anti-neoliberalism, is a set of ideals characterized by its rejection of neoliberalism and the economic policies embodied by the Washington Consensus.[6][7][8] While there is scholarly debate about the defining features of post-neoliberalism, it is often associated with economic progressivism as a response to neoliberalism's perceived excesses or failures, ranging from nationalization and wealth redistribution to embracing protectionism and revival of trade unions; it can also refer to left-wing politics more generally.[8][9] The movement has had particular influence in Latin America, where the pink tide brought about a substantial shift towards left-wing governments in the 2000s.[10] Examples of post-neoliberal governments include the former governments of Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador.[11] It has also been claimed that the Joe Biden administration in the United States exhibits post-neoliberal characteristics.[12][13][14] History  Evo Morales, the former president of Bolivia, is often associated with post-neoliberalism. The idea of post-neoliberalism arose during the pink tide of the 1990s and 2000s, in which left-wing Latin American critics of neoliberalism like Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales were thrust into power. According to researchers, the election of Chávez as the president of Venezuela in 1999 marked a definite start to the pink tide and post-neoliberal movement.[15][16] Following his election, Rafael Correa, Néstor Kirchner, Evo Morales, and numerous other leaders associated with the post-neoliberal movement were elected in Latin America during the 2000s and 2010s.[8] Into the 2020s, the Chilean president-elect Gabriel Boric, who emerged victorious in the 2021 Chilean general election, pledged to end the country's neoliberal economic model, stating: "If Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave."[17] While the ideas of post-neoliberalism are not exclusive to Latin America, they are largely associated with the region.[18][19] Post-neoliberalism has drawn criticism from the right of the political spectrum; right-wing and far-right critics have claimed that the term itself is vague and populistic, while also arguing that "post-neoliberal" policies harm international investment and economic development.[11] Ideology Post-neoliberalism seeks to fundamentally change the role of the state in countries where the Washington Consensus once prevailed.[20] To achieve this, post-neoliberal leaders in Latin America have advocated for the nationalization of several industries, notably the gas, mining, and oil industries.[8] Post-neoliberalism also advocates for the expansion of welfare benefits, greater governmental investment in poverty reduction, and increased state intervention in the economy.[21] |

ポスト新自由主義 ポスト新自由主義は反新自由主義とも呼ばれ、新自由主義とワシントン・コンセンサスに体現される経済政策を拒絶する理想主義の集合体である。[6][7] [8] ポスト新自由主義の特徴を定義する上で学術的な議論がある一方で、 、新自由主義の行き過ぎや失敗に対する反応として、経済的進歩主義と関連付けられることが多い。国有化や富の再分配から保護主義の採用や労働組合の復活ま で、その範囲は多岐にわたる。また、より一般的な左派政治を指す場合もある。 この運動は特にラテンアメリカで大きな影響力を持ち、2000年代には「ピンクの波」が左派政権への大幅な転換をもたらした。[10] ポスト新自由主義政権の例としては、ボリビアのエボ・モラレス前大統領やエクアドルのラファエル・コレア前大統領などが挙げられる。[11] また、アメリカ合衆国のジョー・バイデン政権もポスト新自由主義の特徴を示しているという主張もある。[12][13][14] 歴史  ボリビアの元大統領であるエボ・モラレスは、ポスト新自由主義と関連付けられることが多い。 ポスト新自由主義の概念は、1990年代から2000年代にかけてのピンクの波の間に生まれたもので、ウゴ・チャベスやエボ・モラレスといった新自由主義 に批判的なラテンアメリカの左派指導者が政権の座に就いた。研究者によると、1999年のベネズエラ大統領選挙でチャベスが当選したことが、ピンクの波と ポスト新自由主義運動の明確な始まりとなった。[15][16] チャベスに続き、ラファエル・コレア、ネストル・キルチネル、エボ・モラレスなど、ポスト新自由主義運動に関わる多くの指導者が 2000年代から2010年代にかけて、ラテンアメリカではラファエル・コレア、ネストル・キルチネル、エボ・モラレスなど、ポスト新自由主義運動に関わ る多数の指導者が選出された。[8] 2020年代に入ると、2021年のチリ総選挙で勝利したチリの次期大統領ガブリエル・ボリックは、同国の新自由主義経済モデルを終わらせると公約し、 「チリが新自由主義の発祥地であるならば、それは墓場でもある」と述べた。[17] ポスト新自由主義の考え方はラテンアメリカに限ったものではないが、主にこの地域と関連付けられている。[18][19] ポスト新自由主義は政治的スペクトルの右派から批判を集めている。右派および極右の批評家は、この用語自体が曖昧で大衆迎合的であると主張し、また「ポス ト新自由主義」政策は国際投資と経済発展に悪影響を与えると主張している。[11] イデオロギー ポスト新自由主義は、かつてワシントン・コンセンサスが支配的であった国々において、国家の役割を根本的に変えようとしている。[20] この目的を達成するために、ラテンアメリカにおけるポスト新自由主義の指導者たちは、特にガス、鉱業、石油産業などのいくつかの産業の国有化を提唱してい る。[8] ポスト新自由主義はまた、福祉給付の拡大、貧困削減への政府投資の拡大、経済への国家介入の強化も提唱している。[21] |

| Latin American application See also: Pink tide Regional integration The model of socialism of the 21st century encourages economic and political integration among nations in Latin America and the Caribbean. This is often accompanied with opposition to North American influence. Regional organizations like ALBA and CELAC promote cooperation with Latin America and exclude North American countries. ALBA is most explicitly related to socialism of the 21st century while other organizations focus on economic integration, ALBA promotes social, political and economic integration among countries that subscribe to democratic socialism. Its creation was announced in direct opposition to George W. Bush's attempts to establish a Free Trade Area of the Americas that included the United States. In 2008, ALBA introduced a monetary union using the SUCRE as its regional currency. Bolivarian process Further information: Bolivarian Revolution Former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez initiated a process of social reforms in Venezuela known as the Bolivarian Revolution. This approach was more heavily influenced by the theories of István Mészáros, Michael Lebowitz and Marta Harnecker (who was Chávez's adviser between 2004 and 2011) than by those of Heinz Dieterich. The process draws its name from Latin American liberator Simón Bolívar and is a contemporary example of Bolivarianism.[citation needed] Buen vivir Further information: Sumak kawsay Often translated to good living or living well, the concept of buen vivir is related to the movement for indigenous rights and rights of nature. It focuses on the living sustainably as the member of a community that includes both human beings and Nature.[22] Buen vivir is enshrined in 2008 Constitution of Ecuador as an alternative to neoliberal development. The constitution outlines a set of rights, one of which is the rights of nature.[23] In line with the assertion of these rights, buen vivir seeks to change the relationship between nature and humans to a more bio-pluralistic view, eliminating the separation between nature and society.[23][24] This approach has been applied to the Yasuní-ITT Initiative. Buen vivir is sometimes conceptualised as collaborative consumption in a sharing economy and the term is used to look at the world in way sharply differentiated from natural, social or human capital.[25] |

ラテンアメリカにおける適用 関連項目:ピンクタイド(→「ピンクの潮流」) 地域統合 21世紀の社会主義モデルは、ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海諸国における経済および政治統合を促している。これはしばしば北米の影響力に対する反対と結び ついている。ALBAやCELACのような地域組織は、ラテンアメリカとの協力を推進し、北米諸国を排除している。ALBAは21世紀の社会主義と最も明 確な関連性があるが、他の組織は経済統合に重点を置いている。ALBAは、民主的社会主義を標榜する諸国間の社会、政治、経済の統合を推進している。 ALBAの創設は、アメリカ合衆国を含む米州自由貿易圏(FTAA)の設立を試みたジョージ・W・ブッシュの試みへの直接的な反対として発表された。 2008年、ALBAは地域通貨としてスクレ(SUCRE)を使用する通貨同盟を導入した。 ボリバル主義のプロセス 詳細情報:ボリバル革命 ベネズエラのウゴ・チャベス前大統領は、ベネズエラにおける社会改革のプロセスを「ボリバル革命」として開始した。このアプローチは、ハインツ・ディート リッヒの理論よりも、イシュトヴァーン・メシュアローシュ、マイケル・レボウィッツ、マルタ・アルネケル(2004年から2011年までチャベスの顧問を 務めた)の理論に強く影響を受けている。このプロセスは、ラテンアメリカの解放者シモン・ボリバルにちなんで名付けられ、ボリバル主義の現代的な例であ る。 善き生き方 詳細は「スーマク・カウサイ」を参照 善き生き方(善き生き方)または善き暮らし(善き暮らし)と訳されることが多いが、善き生き方の概念は、先住民の権利と自然の権利のための運動に関連して いる。それは、人間と自然の両方を含むコミュニティの一員として、持続可能な生活に焦点を当てている。[22] 善き生き方は、新自由主義的な開発に対する代替案として、2008年のエクアドル憲法に盛り込まれている。この憲法は一連の権利を概説しており、その一つ は自然の権利である。[23] これらの権利の主張に沿って、ブエン・ビビールは自然と人間との関係をより生物多様的な見方に変え、自然と社会の分離をなくそうとしている。[23] [24] このアプローチは、ヤスニ・ITTイニシアティブに適用されている。「善き生き方」は、共有経済における共同消費として概念化されることがあり、この用語 は、自然、社会、人的資本から鋭く区別された方法で世界を見るために用いられる。[25] |

| Criticism Authoritarianism Critics claim that socialism of the 21st century in Latin America acts as a façade for authoritarianism. The charisma of figures like Hugo Chávez and mottoes like "Country, Socialism, or Death!" have drawn comparisons to the Latin American dictators and caudillos of the past.[26] According to Steven Levitsky of Harvard University: "Only under the dictatorships of the past [...] were presidents reelected for life", with Levitsky further stating that while Latin America experienced democracy, citizens opposed "indefinite reelection, because of the dictatorships of the past".[27] Levitsky then noted: "In Nicaragua, Venezuela and Ecuador, reelection is associated with the same problems of 100 years ago".[27] The Washington Post also stated in 2014 that "Bolivia's Evo Morales, Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua and the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez [...] used the ballot box to weaken or eliminate term limits".[28] In 2015, The Economist stated that the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela—now under Nicolás Maduro after Chávez's death in 2013—was devolving from authoritarianism to dictatorship as opposition politicians were jailed for plotting to undermine the government, violence was widespread and opposition media shut down.[29] Western media coverage of Chávez and other Latin American leaders from the 21st-century socialist movement has been criticised as unfair by their supporters and leftist media critics.[30][31] Economics The sustainability and stability of economic reforms associated with governments adhering to socialism of the 21st century have been questioned. Latin American countries have primarily financed their social programs with extractive exports like petroleum, natural gas and minerals, creating a dependency that some economists claim has caused inflation and slowed growth.[32] For the Bolivarian government of Venezuela, their economic policies led to shortages in Venezuela, a high inflation rate and a dysfunctional economy.[33] However, the economic policy of the Hugo Chávez administration and Maduro governments have attributed Venezuela's economic problems to the decline in oil prices, sanctions imposed by the United States and economic sabotage by the opposition.[34] In 2015, Venezuela's economy was performing poorly—the currency had collapsed, it had the world's highest inflation rate and its gross domestic product shrank into an economic collapse in 2016.[35] |

批判 権威主義 批評家たちは、ラテンアメリカにおける21世紀の社会主義は権威主義の仮面を被っていると主張している。ウゴ・チャベスなどの指導者のカリスマ性や、「祖 国か、社会主義か、さもなくば死か!」といった標語は、過去のラテンアメリカの独裁者や軍人指導者たちと比較されている。[26] ハーバード大学のスティーブン・レヴィツキーによると、 「過去に独裁政権下でしか...大統領が終身で再選されることはなかった」と述べ、さらにレヴィツキーは、ラテンアメリカが民主主義を経験する一方で、市 民は「過去の独裁政権を理由に、無期限の再選に反対した」と述べている。[27] レヴィツキーはさらに次のように指摘している。「ニカラグア、ベネズエラ、エクアドルでは、再選は100年前と同じ問題と関連している」と述べた。 [27] ワシントン・ポスト紙も2014年に、「ボリビアのエボ・モラレス、ニカラグアのダニエル・オルテガ、故ウゴ・チャベス・ベネズエラ大統領は[...]投 票箱を利用して任期制限を弱体化させたり、撤廃したりした」と述べた。[28] 2015年、エコノミスト誌は、チャベスが2013年に死去した後、ニコラス・マドゥーロが後を継いだベネズエラのボリバル革命は、政府転覆を企てたとし て野党政治家が投獄され 、暴力が蔓延し、野党系メディアは閉鎖された。[29] チャベスや21世紀の社会主義運動の他のラテンアメリカ指導者に対する欧米メディアの報道は、彼らの支持者や左派系メディアの批評家から不公平であると批 判されている。[30][31] 経済 21世紀の社会主義を支持する政府に関連する経済改革の持続可能性と安定性は疑問視されている。ラテンアメリカ諸国は主に石油、天然ガス、鉱物などの採取 輸出で社会プログラムの財源を賄っており、一部の経済学者は、それがインフレと成長の鈍化の原因となっていると主張している。[32] ベネズエラのボリバル政府にとって、その経済政策はベネズエラ国内での物資不足、 高インフレ率と機能不全に陥った経済をもたらした。[33] しかし、ウゴ・チャベス政権とマドゥーロ政権の経済政策は、ベネズエラの経済問題は原油価格の下落、米国による制裁、野党による経済妨害に起因するものと している。[34] 2015年、ベネズエラの経済は低迷しており、通貨は暴落し、世界で最も高いインフレ率を記録し、国内総生産は2016年の経済崩壊に向けて縮小した。[35] |

| Populism Although democratic socialist intellectuals have welcomed a socialism of the 21st century, they have been skeptical of Latin America's examples. While citing their progressive role, they argue that the appropriate label for these governments is populist rather than socialist.[36][37] Similarly, some of the left-wing pink tide governments were criticised for turning from socialism to authoritarianism and populism.[38][39] |

ポピュリズム 民主的社会主義の知識人は21世紀の社会主義を歓迎しているが、ラテンアメリカの例には懐疑的である。彼らは、これらの政府に適切な呼称は社会主義ではな くポピュリズムであると主張している。[36][37] 同様に、左派のピンクタイド政権の一部は、社会主義から権威主義とポピュリズムに転向したとして批判されている。[38][39] |

| List of anti-neoliberal or post-neoliberal political parties "If Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave."[17] —Gabriel Boric, 20 December 2021[40] South America: Argentina: Union for the Homeland, Frente de Todos,[41][42] Front for Victory,[16] Patria Grande Front[43] Bolivia: Movement for Socialism[11] Chile: Social Convergence[44] Ecuador: Citizen Revolution Movement, PAIS Alliance under Rafael Correa[11] Venezuela: Fifth Republic Movement, Great Patriotic Pole, United Socialist Party of Venezuela under Hugo Chávez[15][16] North America: Canada: Québec Solidaire, Green Party of Quebec Mexico: Morena[45] United States: Democratic Socialists of America,[citation needed] Party for Socialism and Liberation[citation needed] Asia Japan: Social Democratic Party[46] South Korea: Progressive Party[47] Turkey: Communist Party of Turkey,[48] Patriotic Party[citation needed], Labour and Freedom Alliance[49] Oceania Australia: Australian Greens[50] |

反新自由主義またはポスト新自由主義の政党の一覧 「チリが新自由主義の発祥地であるならば、それはまたその墓場でもあるだろう。」[17] —ガブリエル・ボリック、2021年12月20日[40] 南アメリカ: アルゼンチン:祖国のための連合、フロンテ・デ・トドス、勝利のための戦線、パトリア・グランデ戦線 ボリビア:社会主義のための運動 チリ:社会合意 エクアドル:市民革命運動、ラファエル・コレア率いるPAIS同盟 ベネズエラ:第五共和運動、大愛国極、ウゴ・チャベス率いるベネズエラ統一社会党 北アメリカ: カナダ: ケベック・ソリデール、ケベック緑の党 メキシコ: モレナ[45] アメリカ合衆国: アメリカ民主社会党(民主党社会主義者)[要出典]、社会主義と解放のための党[要出典] アジア 日本: 社会民主党[46] 韓国: 進歩党[47] トルコ: トルコ共産党[48]、愛国党[要出典]、労働と自由同盟[49] オセアニア オーストラリア:オーストラリア緑の党[50] |

| Anti-capitalism Kirchnerism Millennial socialism Post-capitalism Post-Marxism Project Cybersyn |

反資本主義 キルケネリズム 千年期社会主義 ポスト資本主義 ポスト・マルクス主義 プロジェクト・サイバースン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialism_of_the_21st_century |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099