ピンクの潮流

Pink tide

☆ ピンクの潮流(スペイン語: marea rosa、ポルトガル語: onda rosa、フランス語: marée rose)、または左傾化(スペイン語: giro a la izquierda、ポルトガル語: virada à esquerda、フランス語: tournant à gauche)は、21世紀を通じてラテンアメリカにおける左翼政権への政治的な波動と転向である。このような政府は「中道左派」、「左寄り」、「急進的 社会民主主義」と呼ばれている。また、アメリカ大陸の左派政党やその他の組織で構成されるサンパウロ・フォーラムのメンバーでもある。このイデオロギー的 傾向の一部とみなされるラテンアメリカ諸国は、ピンク・タイド国家と呼ばれており、ポスト新自由主義や21世紀の社会主義という 言葉もこの運動を表現するのに使われている。 この運動の要素にはワシントン・コンセンサスの拒否が含まれており、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、ベネズエラなどのピンク・タイド政権は、「反米」、ポピュリズムに傾きやすい、権威主義的であると様々な特徴づけがなされてきた。

| The pink tide

(Spanish: marea rosa, Portuguese: onda rosa, French: marée rose), or

the turn to the left (Spanish: giro a la izquierda, Portuguese: virada

à esquerda, French: tournant à gauche), is a political wave and turn

towards left-wing governments in Latin America throughout the 21st

century. As a term, both phrases are used in political analysis in the

news media and elsewhere to refer to a move toward more economic

progressive or social progressive policies in the region.[1][2][3] Such

governments have been referred to as "left-of-centre", "left-leaning",

and "radical social-democratic".[4] They are also members of the São

Paulo Forum, a conference of left-wing political parties and other

organizations from the Americas.[5] The Latin American countries viewed as part of this ideological trend have been referred to as pink tide nations,[6] with the term post-neoliberalism or socialism of the 21st century also being used to describe the movement.[7] Elements of the movement have included a rejection of the Washington Consensus,[8] while some pink tide governments, such as those of Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela,[9] have been varyingly characterized as being "anti-American",[10][11][12] prone to populism,[13][14][15] as well as authoritarian,[14] particularly in the case of Nicaragua and Venezuela by the 2010s, although many others remained democratic.[16] The pink tide was followed by the conservative wave, a political phenomenon that emerged in the early 2010s as a direct reaction to the pink tide. Some authors have proposed that there are multiple distinct pink tides rather than a single one, with the first pink tide happening during the late 1990s and early 2000s,[17][18] and a second pink tide encompassing the elections of the late 2010s to early 2020s.[19][20] A resurgence of the pink tide was kicked off by Mexico in 2018 and Argentina in 2019,[21] and further established by Bolivia in 2020,[22] along with Peru,[23] Honduras,[24] and Chile in 2021,[25] and then Colombia and Brazil in 2022,[26][27][28] with Colombia electing the first left-wing president in their history.[29][30][31] In 2023, centre-left Bernardo Arévalo secured a surprise victory in Guatemala.[32][33] |

ピ

ンクの潮流(スペイン語: marea rosa、ポルトガル語: onda rosa、フランス語: marée

rose)、または左傾化(スペイン語: giro a la izquierda、ポルトガル語: virada à

esquerda、フランス語: tournant à

gauche)は、21世紀を通じてラテンアメリカにおける左翼政権への政治的な波動と転向である。このような政府は「中道左派」、「左寄り」、「急進的

社会民主主義」と呼ばれている[4]。また、アメリカ大陸の左派政党やその他の組織で構成されるサンパウロ・フォーラムのメンバーでもある[5]。 このイデオロギー的傾向の一部とみなされるラテンアメリカ諸国は、ピンク・タイド国家と呼ばれており[6]、ポスト新自由主義や21世紀の社会主義という 言葉もこの運動を表現するのに使われている。 [7]この運動の要素にはワシントン・コンセンサスの拒否が含まれており[8]、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、ベネズエラ[9]などのピンク・タイド政権は、 「反米」[10][11][12]、ポピュリズムに傾きやすい[13][14][15]、権威主義的であると様々な特徴づけがなされてきた。 ピンクの潮流に続いて、2010年代初頭にピンクの潮流への直接的な反動として現れた政治現象である保守の波が起こった。著者の中には、ピンク色の潮流は 1つではなく複数存在し、最初のピンク色の潮流は1990年代後半から2000年代前半にかけて起こり[17][18]、2つ目のピンク色の潮流は 2010年代後半から2020年代前半の選挙を包含していると提唱する者もいる[19][20]。 [19][20]ピンクタイドの復活は、2018年のメキシコと2019年のアルゼンチンによってキックオフされ[21]、2020年のボリビア [22]、2021年のペルー、[23]ホンジュラス、[24]、チリ[25]、そして2022年のコロンビアとブラジルによってさらに確立された [26][27][28]。 [29][30][31]2023年にはグアテマラで中道左派のベルナルド・アレバロがサプライズ勝利を収めた[32][33]。 |

| During

the Cold War, a series of left-leaning governments were elected in

Latin America.[34] These governments faced coups sponsored by the

United States government as part of its geostrategic interest in the

region.[35][36][37] Among these were the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état,

1964 Brazilian coup d'état, 1973 Chilean coup d'état, and 1976

Argentine coup d'état. All of these coups were followed by United

States-backed and sponsored right-wing, military dictatorships as part

of the United States government's Operation Condor.[34][37][36] These authoritarian regimes committed several human rights violations including illegal political prisoners, tortures, political disappearances, and child trafficking.[38] As these regimes started to decline due to international pressure, internal outcry in the United States from the population due to the involvement in the atrocities forced Washington to relinquish its support for them. New democratic processes began during the late 1970s and up to the early 1990s.[39] With the exception of Costa Rica, virtually all Latin American countries had at least one experience with a United States-supported dictator:[40] Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, the Somoza family in Nicaragua, Tiburcio Carias Andino in Honduras, Carlos Castillo Armas and Efraín Ríos Montt in Guatemala, Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez in El Salvador, Manuel Noriega in Panama, Hugo Banzer in Bolivia, Juan María Bordaberry in Uruguay, Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina, Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, François Duvalier in Haiti, Artur da Costa e Silva and his successor Emílio Garrastazu Médici in Brazil, Manuel Odria and Alberto Fujimori in Peru, the Institutional Revolutionary Party in Mexico,[41] Laureano Gomez and Rojas Pinilla in Colombia,[42] and Marcos Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela.[43] This caused a strong anti-American sentiment in wide sectors of the population.[44][45][46] |

冷

戦時代、ラテンアメリカでは左派政権が相次いで選出された[34]。これらの政権は、この地域における地政学的利益の一環として、アメリカ政府がスポン

サーとなったクーデターに直面した[35][36][37]。これらのクーデターはすべて、米国政府の「コンドル作戦」の一環として、米国が支援・後援す

る右派の軍事独裁政権によって行われた[34][37][36]。 これらの権威主義政権は、違法な政治犯、拷問、政治的失踪、子どもの人身売買など、いくつかの人権侵害を行った[38]。国際的な圧力によってこれらの政 権が衰退し始めると、残虐行為への関与に起因する国民からの米国内の反発によって、ワシントンは彼らに対する支援を放棄せざるを得なくなった。1970年 代後半から1990年代前半にかけて、新たな民主化プロセスが始まった[39]。 コスタリカを除いて、事実上すべてのラテンアメリカ諸国は、アメリカが支援した独裁者を少なくとも一度は経験している: [キューバのフルヘンシオ・バティスタ、ドミニカ共和国のラファエル・トルヒーヨ、ニカラグアのソモサ一族、ホンジュラスのティブルシオ・カリアス・アン ディーノ、グアテマラのカルロス・カスティージョ・アルマスとエフライン・リオス・モント、エルサルバドルのハイメ・アブドゥル・グティエレス、パナマの マヌエル・ノリエガ、ボリビアのウゴ・バンザー、ウルグアイのフアン・マリア・ボルダベリー、アルゼンチンのホルヘ・ラファエル・ビデラ、 チリのアウグスト・ピノチェト、パラグアイのアルフレド・ストロエスナー、ハイチのフランソワ・デュヴァリエ、ブラジルのアルトゥール・ダ・コスタ・エ・ シルヴァとその後継者エミリオ・ガラスタズ・メディチ、ペルーのマヌエル・オドリアとアルベルト・フジモリ、メキシコの制度的革命党[41]、コロンビア のラウレアノ・ゴメスとロハス・ピニージャ[42]、ベネズエラのマルコス・ペレス・ヒメネス。 [43]これは国民の幅広い層に強い反米感情を引き起こした[44][45][46]。 |

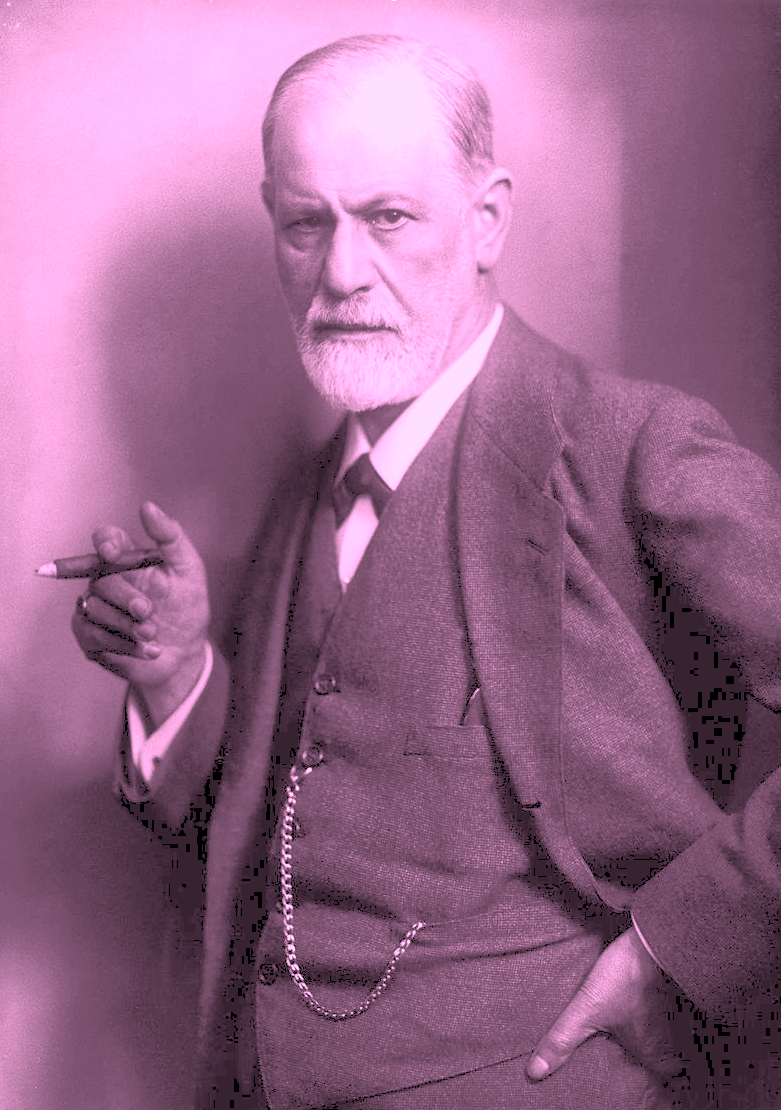

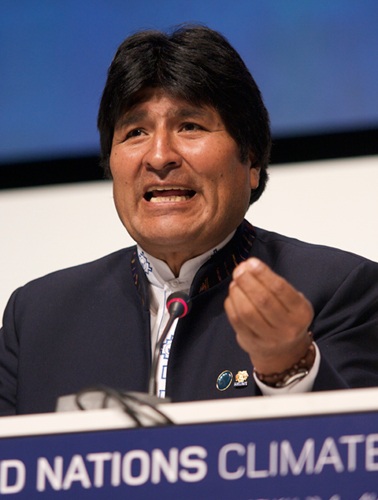

| History Rise of the left: 1990s and 2000s See also: Latin American debt crisis and La Década Perdida Following the third wave of democratization in the 1980s, the institutionalisation of electoral competition in Latin America opened up the possibility for the left to ascend to power. For much of the region's history, formal electoral contestation excluded leftist movements, first through limited suffrage and later through military intervention and repression during the second half of the 20th century.[47] The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War changed the geopolitical environment, as many revolutionary movements vanished, and the left embraced the core tenets of capitalism. In turn, the United States no longer perceived leftist governments as a security threat, creating a political opening for the left.[48] In the 1990s, as the Latin American elite no longer feared a communist takeover of their assets, the left exploited this opportunity to solidify their base, run for local offices, and gain experience governing on the local level. At the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, the region's initial unsuccessful attempts with the neoliberal policies of privatisation, cuts in social spending, and foreign investment left countries with high levels of unemployment, inflation, and rising social inequality.[49] This period saw increasing numbers of people working in the informal economy and suffering material insecurity, and ties between the working classes and the traditional political parties weakening, resulting in a growth of mass protest against the negative social effects of these policies, such as the piqueteros in Argentina, and in Bolivia indigenous and peasant movements rooted among small coca farmers, or cocaleros, whose activism culminated in the Bolivian gas conflict of the early-to-mid 2000s.[50] The left's social platforms, which were centered on economic change and redistributive policies, offered an attractive alternative that mobilized large sectors of the population across the region, who voted leftist leaders into office.[48]  ALBA was founded by left-wing populist leaders such as Nicaraguan revolutionary Daniel Ortega, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, and Bolivian president Evo Morales. The pink tide was led by Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, who was elected into the presidency in 1998.[51] According to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a pink tide president herself, Chávez of Venezuela (inaugurated 1999), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil (inaugurated 2003) and Evo Morales of Bolivia (inaugurated 2006) were "the three musketeers" of the left in South America.[52] National policies among the left in Latin America are divided between the styles of Chávez and Lula as the latter not only focused on those affected by inequality, but also catered to private enterprises and global capital.[53] Commodities boom and growth Further information: 2000s commodities boom With the difficulties facing emerging markets across the world at the time, Latin Americans turned away from liberal economics and elected leftist leaders who had recently turned toward more democratic processes.[54] The popularity of such leftist governments relied upon by their ability to use the 2000s commodities boom to initiate populist policies,[55][56] such as those used by the Bolivarian government in Venezuela.[57] According to Daniel Lansberg, this resulted in "high public expectations in regard to continuing economic growth, subsidies, and social services".[56] With China becoming a more industrialized nation at the same time and requiring resources for its growing economy, it took advantage of the strained relations with the United States and partnered with the leftist governments in Latin America.[55][58] South America in particular initially saw a drop in inequality and a growth in its economy as a result of Chinese commodity trade.[58] As the prices of commodities lowered into the 2010s, coupled with overspending with little savings by pink tide governments, policies became unsustainable and supporters became disenchanted, eventually leading to the rejection of leftist governments.[56][59] Analysts state that such unsustainable policies were more apparent in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela,[58][59] who received Chinese funds without any oversight.[58][60] As a result, some scholars have stated that the pink tide's rise and fall was "a byproduct of the commodity cycle's acceleration and decadence".[55] Some pink tide governments, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, allegedly ignored international sanctions against Iran, allowing the Iranian government access to funds bypassing sanctions as well as resources such as uranium for the Iranian nuclear program.[61] |

歴史 左派の台頭:1990年代と2000年代 以下も参照: ラテンアメリカ債務危機とラ・デカーダ・ペルディダ 1980年代の第三次民主化の波を受けて、ラテンアメリカでは選挙競争が制度化され、左派が権力を握る可能性が出てきた。ソビエト連邦の解体や冷戦の終結 は地政学的環境を変化させ、多くの革命運動は消滅し、左派は資本主義の核心を受け入れた。その結果、アメリカは左派政権を安全保障上の脅威と認識しなくな り、左派に政治的な隙が生まれた。 1990年代、ラテンアメリカのエリートたちはもはや共産主義者による資産の乗っ取りを恐れていなかったため、左派はこの機会を利用して基盤を固め、地方 選挙に出馬し、地方レベルでの統治経験を積んだ。1990年代末から2000年代初頭にかけて、この地域は民営化、社会支出の削減、外国投資といった新自 由主義的な政策で最初の試みは失敗に終わり、各国は高水準の失業率、インフレ、社会的不平等の上昇を余儀なくされた[49]。 この時期、インフォーマル経済で働き、物質的な不安に苦しむ人々の数が増加し、労働者階級と伝統的な政党との結びつきが弱まり、アルゼンチンのピケテロ や、ボリビアの先住民や小規模なコカ農家(コカレロ)に根ざした農民運動など、こうした政策の社会的悪影響に対する大衆的な抗議が増加した。 [経済改革と再分配政策を中心とした左派の社会的プラットフォームは、地域全体の人口の大部分を動員する魅力的な代替案を提供し、彼らは左派指導者に投票 し政権に就いた[48]。  ALBAは、ニカラグアの革命家ダニエル・オルテガ、ベネズエラの大統領ウゴ・チャベス、ボリビアの大統領エボ・モラレスといった左翼ポピュリストの指導者によって設立された。 ピンク・タイドは、1998年に大統領に選出されたベネズエラのウゴ・チャベスに率いられていた[51]。自身もピンク・タイドの大統領であるクリス ティーナ・フェルナンデス・デ・キルチネルによれば、ベネズエラのチャベス(1999年就任)、ブラジルのルイス・イナシオ・ルーラ・ダ・シルヴァ (2003年就任)、ボリビアのエボ・モラレス(2006年就任)は、南米における左翼の「三銃士」であった。 [52]ラテンアメリカの左派の国家政策は、チャベスとルーラのスタイルに分かれており、後者は不平等の影響を受ける人々に焦点を当てるだけでなく、民間 企業やグローバル資本にも配慮している[53]。 商品ブームと成長 詳細情報:2000年代の商品ブーム 当時、世界中の新興市場が直面していた困難に伴い、ラテンアメリカの人々は自由主義経済から離れ、最近になってより民主的なプロセスを志向するようになっ た左派の指導者を選出した[54]。そのような左派政権の人気は、ベネズエラのボリバル政権が用いたような、ポピュリスト的な政策を開始するために 2000年代の商品ブームを利用する能力によって依存していた[55][56]。 [ダニエル・ランスバーグによれば、これは「継続的な経済成長、補助金、社会サービスに対する国民の高い期待」[56]をもたらした。同時に中国がより工 業化された国家となり、成長する経済のための資源を必要とするようになったことで、中国は米国との緊張関係を利用し、ラテンアメリカの左派政権と提携し た。 2010年代に入ってコモディティ価格が下落し、ピンクタイド政権による貯蓄の少ない過剰支出も相まって、政策は持続不可能となり、支持者は幻滅し、最終 的には左派政権の拒否につながった。 [56][59]アナリストは、そのような持続不可能な政策は、中国の資金を何の監視もなしに受け取ったアルゼンチン、ブラジル、エクアドル、ベネズエラ においてより明白であったと述べている[58][59]。 その結果、ピンクタイドの盛衰は「商品サイクルの加速と退廃の副産物」であったと述べる学者もいる[55]。 ボリビア、エクアドル、ベネズエラのような一部のピンク・タイド政府は、イランに対する国際制裁を無視し、イラン政府に制裁を迂回した資金やイランの核計画のためのウランなどの資源へのアクセスを許したとされている[61]。 |

| End of commodity boom and decline: 2010s Main article: Conservative wave  The impeachment of Dilma Rousseff gave rise to the conservative wave in the 2010s. Chávez, who was seen as having "dreams of continental domination", was determined to be a threat to his own people according to Michael Reid in American magazine, Foreign Affairs, with his influence reaching a peak in 2007.[62] The interest in Chávez waned after his dependence on oil revenue led Venezuela into an economic crisis and as he grew increasingly authoritarian.[62] The death of Chávez in 2013 left the most radical wing without a clear leader as Nicolás Maduro did not have the international influence of his predecessor. By the mid-2010s, Chinese investment in Latin America had also begun to decline,[58] especially following the 2015–16 Chinese stock market turbulence. In 2015, the shift away from the left became more pronounced in Latin America, with The Economist saying the pink tide had ebbed,[63] and Vice News stating that 2015 was "The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned".[52] In the 2015 Argentine general election, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's favoured candidate for the presidency Daniel Scioli was defeated by his centre-right opponent Mauricio Macri, against a background of rising inflation, reductions in GDP, and declining prices for soybeans, which is a key export for the country, leading to falls in public revenues and social spending.[50] Shortly afterwards, the impeachment of Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff began, culminating in her removal from office. In Ecuador, retiring president Rafael Correa's successor was his vice-president, Lenín Moreno, who took a narrow victory in the 2017 Ecuadorian general election, a win that received a negative reaction from the business community at home and abroad: however, after his election, Moreno shifted his positions rightwards, resulting in Correa branding his former deputy as "a traitor" and "a wolf in sheep's clothing".[50][64] By 2016, the decline of the pink tide saw an emergence of a "new right" in Latin America,[65] with The New York Times stating "Latin America's leftist ramparts appear to be crumbling because of widespread corruption, a slowdown in China's economy and poor economic choices", with the newspaper elaborating that leftist leaders did not diversify economies, had unsustainable welfare policies and disregarded democratic behaviors.[66] In mid-2016, the Harvard International Review stated that "South America, a historical bastion of populism, has always had a penchant for the left, but the continent's predilection for unsustainable welfarism might be approaching a dramatic end."[9] Far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro was elected in Brazil in 2018 Brazilian general election, providing Brazil with its most right-wing government since the military dictatorship.[67] |

商品ブームの終焉と衰退:2010年代 主な記事 保守の波  ディルマ・ルセフの弾劾は、2010年代に保守の波をもたらした。 アメリカの雑誌『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』のマイケル・リードによれば、「大陸支配の夢」を持っていると見られていたチャベスは、自国民にとって脅威で あると判断され、その影響力は2007年にピークに達した[62]。チャベスへの関心は、石油収入への依存によってベネズエラが経済危機に陥り、彼がます ます権威主義的になったことで薄れていった[62]。 2013年にチャベスが死去すると、ニコラス・マドゥロは前任者のような国際的影響力を持たなくなり、最も急進的な勢力は明確な指導者を失った。2010 年代半ばまでに、中国のラテンアメリカへの投資も減少し始めていた[58]。2015年、ラテンアメリカでは左派離れが顕著になり、エコノミストはピンク の潮が引いたと述べ[63]、バイス・ニュースは2015年を「『ピンクの潮』が変わった年」と述べた。 [52] 2015年のアルゼンチン総選挙では、クリスティーナ・フェルナンデス・デ・キルチネルが推す大統領候補ダニエル・シオリが中道右派の対立候補マウリシ オ・マクリに敗れ、インフレ率の上昇、GDPの減少、同国の主要輸出品である大豆の価格下落を背景に、公的収入と社会支出の減少につながった[50]。 その直後、ブラジルのディルマ・ルセフ大統領の弾劾が始まり、罷免に至った。エクアドルでは、引退したラファエル・コレア大統領の後任は副大統領のレニ ン・モレノで、彼は2017年のエクアドル総選挙で僅差の勝利を収めたが、この勝利は国内外の経済界から否定的な反応を受けた。しかし当選後、モレノは自 身の立場を右傾化させ、その結果コレアは元副大統領を「裏切り者」「羊の皮を被った狼」と烙印を押した[50][64]。 2016年までに、ピンクの潮流の衰退はラテンアメリカにおける「新しい右派」の出現を見た[65]。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は「ラテンアメリカの左派 の城壁は、広範な汚職、中国経済の減速、貧しい経済的選択のために崩れているように見える」と述べ、同紙は左派の指導者たちが経済を多様化せず、持続不可 能な福祉政策をとり、民主的な行動を軽視していると詳しく述べている。 [66]2016年半ば、ハーバード・インターナショナル・レビューは、「ポピュリズムの歴史的砦である南米は、常に左派を好んできたが、持続不可能な福 祉主義に対する大陸の嗜好は劇的な終焉に近づいているかもしれない」と述べている[9]。 ブラジルでは2018年のブラジル総選挙で極右候補のジャイル・ボルソナロが当選し、軍事独裁政権以来の右派政権が誕生した[67]。 |

| Resurgence in late 2010s and early 2020s Some countries, however, pushed back against the trend and elected more left-leaning leaders, such as Mexico with the electoral victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the 2018 Mexican general election and Argentina where the incumbent centre-right president Mauricio Macri lost against centre-left challenger Alberto Fernández (Peronist) in the 2019 Argentine general election.[68][69][70] This development was later strengthened by the landslide victory of the left-wing Movement for Socialism and its presidential candidate Luis Arce in Bolivia in the 2020 Bolivian general election.[71][72] A series of violent protests against austerity measures and income inequality scattered throughout Latin America have also occurred within this period in Chile, Colombia (in 2019 and 2021), Haiti and Ecuador.[68][73] This trend continued throughout 2021 and 2022, when multiple left-wing leaders won elections in Latin America. In the 2021 Peruvian general election, Peru elected the maverick peasant union leader Pedro Castillo on a socialist platform, defeating neoliberal rivals.[74] In the 2021 Honduran general election held in November, leftist Xiomara Castro was elected president of Honduras,[20] and weeks later leftist Gabriel Boric won the 2021 Chilean general election to become the new president of Chile.[75] The 2022 Colombian presidential election was won by leftist Gustavo Petro,[76] making him the first left-wing president of Colombia in the country's 212-year history.[77][78] Lula followed suit in October 2022 by returning to power after narrowly beating Bolsonaro.[79] Since mid-2022, some political commentators have suggested that Latin America's second pink tide may be dissipating, citing the unpopularity of Gabriel Boric and the 2022 Chilean national plebiscite,[80][81] the deposition of Pedro Castillo,[80] the shift of many elected leaders towards the political center[81] and the election of conservative Santiago Peña as president of Paraguay.[82] In 2023, Guatemala elected centre-left Bernardo Arévalo as its president.[83][84] Also in 2023, Argentina elected —for the first time in the country's history— a far-right candidate, Javier Milei, as president, after November 19th's ballotage elections.[85] Economy and social development The pink tide governments aimed to improve the welfare of the constituencies that brought them to power, which they attempted through measures intended to increase wages, such as raising minimum wages, and softening the effects of neoliberal economic policies through expanding welfare spending, such as subsidizing basic services and providing cash transfers to vulnerable groups like the unemployed, mothers outside of formal employment, and the precariat.[50] In Venezuela, the first pink tide government of Chávez increased spending on social welfare, housing, and local infrastructures, and established the Bolivarian missions, decentralised programmes that delivered free services in fields, such as healthcare and education, as well as subsidised food distribution.[50] Before Lula's election, Brazil suffered from one of the highest rates of poverty in the Americas, with the infamous favelas known internationally for its levels of extreme poverty, malnutrition, and health problems. Extreme poverty was also a problem in rural areas. During Lula's presidency several social programs like Zero Hunger (Fome Zero) were praised internationally for reducing hunger in Brazil,[86] poverty, and inequality, while also improving the health and education of the population.[86][87] Around 29 million people became middle class during Lula's eight years tenure.[87] During Lula's government, Brazil became an economic power and member of BRICS.[86][87] Lula ended his tenure with 80% approval ratings.[88] In Argentina, the administrations of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner restored sectoral collective bargaining, strengthening trade unions: unionisation increased from 20 percent of the workforce in the 1990s to 30 percent in the 2010s, and wages rose for an increasing proportion of the working class.[50] Universal allocation per child, a conditional cash transfer programme, was introduced in 2009 for families without formal employment and earning less than the minimum wage who ensured their children attended school, received vaccines, and underwent health checks;[89] it covered over two million poor families by 2013,[50] and 29 percent of all Argentinian children by 2015. A 2015 analysis by staff at Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council estimated that the programme had increased school attendance for children between the ages of 15 and 17 by 3.9 percent.[89] The Kirchners also increased social spending significantly: upon Fernández de Kirchner leaving office in 2015, Argentina had the second highest level of social spending as a percentage of GDP in Latin America, behind only Chile. Their administrations also achieved a drop of 20 percentage points in the proportion of the population living on three US dollars a day or less. As a result, Argentina also became one of the most equal countries in the region according to its Gini coefficient.[50] In Bolivia, Morales's government was praised internationally for its reduction of poverty, increases in economic growth,[90] and the improvement of indigenous, women,[91] and LGBTI rights,[92] in the very traditionally minded Bolivian society. During his first five years in office, Bolivia's Gini coefficient saw an unusually sharp reduction from 0.6 to 0.47, indicating a significant drop in income inequality.[50] Rafael Correa, economist from the University of Illinois,[93] won the 2006 Ecuadorian general election following the harsh economic crisis and social turmoil that caused right-wing[citation needed] Lucio Gutiérrez resignation as president. Correa, a practicing Catholic influenced by liberation theology,[93] was pragmatic in his economical approach in a similar manner to Morales in Bolivia.[51] Ecuador soon experienced a non-precedent economic growth that bolstered Correa's popularity to the point that he was the most popular president of the Americas' for several years in a row,[93] with an approval rate between 60 and 85%.[94] In Paraguay, Lugo's government was praised for its social reforms, including investments in low-income housing,[95] the introduction of free treatment in public hospitals,[96][97] the introduction of cash transfers for Paraguay's most impoverished citizens,[98] and indigenous rights.[99] Some of the initial results after the first pink tide governments were elected in Latin America included a reduction in the income gap,[7] unemployment, extreme poverty,[7] malnutrition and hunger,[2][100] and rapid increase in literacy.[2] The decrease in these indicators during the same period of time happened faster than in non-pink tide governments.[101] Several of countries ruled by pink tide governments, such as Bolivia, Costa Rica,[102] Ecuador,[103][104] El Salvador, and Nicaragua,[105] among others, experienced notable economic growth during this period. Both Bolivia and El Salvador also saw a notable reduction in poverty according to the World Bank.[106][107] Economic hardships occurred in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela, as oil and commodity prices declined and because of their unsustainable policies according to analysts.[58][59][108] In regard to the economic situation, the president of Inter-American Dialogue, Michael Shifter, stated: "The United States–Cuban Thaw occurred with Cuba reapproaching the United States when Cuba's main international partner, Venezuela, began experiencing economic hardships."[109][110] |

2010年代後半から2020年代前半にかけての復活 しかし、2018年のメキシコ総選挙でアンドレス・マヌエル・ロペス・オブラドールが勝利したメキシコや、2019年のアルゼンチン総選挙で現職の中道右 派大統領マウリシオ・マクリが中道左派の挑戦者アルベルト・フェルナンデス(ペロニスト)に敗れたアルゼンチンのように、この流れに逆らい、より左寄りの 指導者を選出した国もあった。 [68][69][70]この展開はその後、2020年のボリビア総選挙で左派の社会主義運動とその大統領候補ルイス・アルセが地滑り的勝利を収めたこと で強化された[71][72]。 チリ、コロンビア(2019年と2021年)、ハイチ、エクアドルでも、ラテンアメリカ全域に散らばる緊縮策と所得格差に対する一連の暴力的な抗議行動がこの期間内に発生した[68][73]。 この傾向は、ラテンアメリカで複数の左派指導者が選挙で勝利した2021年から2022年にかけても続いた。2021年のペルー総選挙では、ペルーは新自 由主義のライバルを破り、社会主義を掲げた破天荒な農民組合指導者ペドロ・カスティーヨを選出した[74]。11月に行われた2021年のホンジュラス総 選挙では、左派のシオマラ・カストロがホンジュラス大統領に選出され[20]、その数週間後に行われた2021年のチリ総選挙では、左派のガブリエル・ボ リックが勝利し、チリの新大統領に就任した。 [75]。2022年のコロンビア大統領選挙では左派のグスタボ・ペトロが勝利し[76]、212年のコロンビアの歴史上初の左派大統領となった[77] [78]。2022年10月にはルーラがボルソナロを僅差で下して政権に復帰した[79]。 2022年半ば以降、一部の政治評論家は、ガブリエル・ボリッチの不人気と2022年のチリ国民投票、[80][81]ペドロ・カスティーヨの退陣、 [80]多くの選挙で選ばれた指導者の政治的中心地へのシフト[81]、パラグアイの大統領に保守派のサンティアゴ・ペーニャが選出されたことを挙げ、ラ テンアメリカの第二のピンクの潮流が消滅しつつある可能性を示唆している[82]。 2023年、グアテマラは中道左派のベルナルド・アレバロを大統領に選出した[83][84]。 また2023年、アルゼンチンは11月19日の投票選挙の結果、同国史上初めて極右候補のハビエル・ミレイを大統領に選出した[85]。 経済と社会開発 ピンク・タイド政権は、最低賃金の引き上げなどの賃上げを意図した施策や、基本的なサービスへの補助金や失業者、正規雇用以外の母親、プレカリアートなど の社会的弱者への現金給付などの福祉支出の拡大を通じて、新自由主義経済政策の影響を和らげることによって、政権を獲得した有権者の福祉を改善することを 目指した。 [50]。ベネズエラでは、チャベス政権が社会福祉、住宅、地域インフラへの支出を増やし、医療や教育などの分野で無料サービスを提供する分権プログラム であるボリバル使節団を設立し、食料配給に補助金を出した[50]。 ルーラが当選する以前、ブラジルはアメリカ大陸で最も高い貧困率に苦しんでおり、悪名高い貧民街は極度の貧困、栄養失調、健康問題のレベルで国際的に知ら れていた。極度の貧困は農村部でも問題となっていた。ルーラの在任中、ブラジルは経済大国となり、BRICSの一員となった[86][87]。 アルゼンチンでは、ネストル・キルチネル政権とクリスティーナ・フェルナンデス・デ・キルチネル政権が部門別団体交渉を復活させ、労働組合を強化した。 [50]条件付き現金給付プログラムである子ども一人当たりの普遍的配分は、子どもたちが学校に通い、ワクチンを接種し、健康診断を受けることを保証す る、正規雇用がなく最低賃金以下の収入しか得られない家庭を対象に2009年に導入された[89]。アルゼンチン国立科学技術研究評議会のスタッフによる 2015年の分析では、このプログラムによって15歳から17歳までの子どもの就学率が3.9%上昇したと推定されている[89]。キルチネル家はまた、 社会支出を大幅に増加させた。2015年にフェルナンデス・デ・キルチネルが退任した時点で、アルゼンチンのGDPに占める社会支出の割合は、チリに次い でラテンアメリカで2番目に高い水準となっていた。両政権はまた、1日3米ドル以下で生活する人口の割合を20ポイント低下させた。その結果、アルゼンチ ンは、ジニ係数によれば、この地域で最も平等な国のひとつにもなった[50]。 ボリビアでは、モラレス政権は、貧困の削減、経済成長の増加[90]、そして非常に伝統的な考えを持つボリビア社会における先住民、女性、LGBTIの権 利の改善[92]によって国際的に賞賛された。就任後5年間で、ボリビアのジニ係数は0.6から0.47へと異例の急減を見せ、所得格差の著しい低下を示 した[50]。イリノイ大学出身の経済学者ラファエル・コレア[93]は、右派[要出典]のルシオ・グティエレスが大統領を辞任した厳しい経済危機と社会 的混乱の後、2006年のエクアドル総選挙で勝利した。 コレアは、解放の神学の影響を受けた実践的なカトリック教徒であり[93]、ボリビアのモラレスと同様に現実的な経済的アプローチをとった。 [94]。パラグアイでは、ルーゴ政権は、低所得者向け住宅への投資[95]、公立病院での無料治療の導入[96][97]、パラグアイで最も困窮してい る市民への現金給付の導入[98]、先住民の権利[99]などの社会改革で称賛された。 ラテンアメリカで最初のピンクタイド政権が選出された後の初期の成果としては、所得格差の縮小、[7]失業、極度の貧困、[7]栄養失調と飢餓、[2] [100]識字率の急速な向上などがあった。 [ボリビア、コスタリカ[102]、エクアドル[103][104]、エルサルバドル、ニカラグア[105]など、ピンク・タイド政権が統治する国のいく つかは、この期間に顕著な経済成長を経験した。世界銀行によれば、ボリビアとエルサルバドルの貧困も顕著に減少した[106][107]。 アルゼンチン、ブラジル、ベネズエラのような国々では、石油と商品価格が下落したため、またアナリストによれば持続不可能な政策のため、経済的苦難が発生 した[58][59][108]。 経済状況に関して、米州対話のマイケル・シフター会長は次のように述べている: 「米国とキューバの雪解けは、キューバの主要な国際的パートナーであるベネズエラが経済的苦境に直面し始めたときに、キューバが米国に再接近することで起 こった」[109][110]。 |

| Political outcome Following the initiation of the pink tide's policies, the relationship between both left-leaning and right-leaning governments and the public changed.[111] As leftist governments took power in the region, rising commodity prices funded their welfare policies, which lowered inequality and assisted indigenous rights.[111] These policies of leftist governments in the 2000s eventually declined in popularity, resulting in the election of more conservative governments in the 2010s.[111] Some political analysts consider that enduring legacies from the pink tide changed the location of Latin America's center of the political spectrum,[112] forcing right-wing candidates and succeeding governments to also adopt at least some welfare-oriented policies.[111] Under the Obama administration, which held a less interventionist approach to the region after recognizing that interference would only boost the popularity of populist pink tide leaders like Chávez, Latin American approval of the United States began to improve as well.[113] By the mid-2010s, "negative views of China were widespread" due to the substandard conditions of Chinese goods, professional actions deemed unjust, cultural differences, damage to the Latin American environment and perceptions of Chinese interventionism.[114] |

政治的結果 ピンク・タイドの政策開始後、左派・右派の両政府と国民との関係は変化した[111]。 左派政権がこの地域で政権を握ると、商品価格の上昇が彼らの福祉政策に資金を供給し、不平等を是正し、先住民の権利を支援した[111]。 [一部の政治アナリストは、ピンクの潮流からの永続的な遺産がラテンアメリカの政治スペクトルの中心の位置を変え[112]、右派の候補者や後継政府も少 なくともいくつかの福祉志向の政策を採用せざるを得なくなったと考える[111]。 干渉はチャベスのようなピンクタイドの指導者の人気を高めるだけであると認識した後、この地域への介入主義的アプローチを抑えたオバマ政権の下で、ラテン アメリカのアメリカに対する支持率も改善し始めた[113]。 2010年代半ばまでに、中国製品の標準以下の状態、不当とみなされる専門家の行動、文化の違い、ラテンアメリカの環境へのダメージ、中国の介入主義に対 する認識などから、「中国に対する否定的な見方が広まった」[114]。 |

| Term As a term, the pink tide had become prominent in contemporary discussion of Latin American politics in the early 21st century. Origins of the term may be linked to a statement by Larry Rohter, a New York Times reporter in Montevideo who characterized the 2004 Uruguayan general election of Tabaré Vázquez as the president of Uruguay as "not so much a red tide ... as a pink one".[15] The term seems to be a play on words based on red tide—a biological phenomenon of an algal bloom rather than a political one—with red, a color long associated with communism, especially as part of the Red Scare and red-baiting in the United States, being replaced with the lighter tone of pink to indicate the more moderate socialist ideas that gained strength.[115] Despite the presence of a number of Latin American governments that professed to embracing left-wing politics, it is difficult to categorize Latin American states "according to dominant political tendencies" like red states and blue states in the United States.[115] While this political shift was difficult to quantify, its effects were widely noticed. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, a left-wing think-tank based in Washington, D.C., 2006 meetings of the South American Summit of Nations and the Social Forum for the Integration of Peoples demonstrated that certain discussions that used to take place on the margins of the dominant discourse of neoliberalism, which moved to the center of public sphere and debate.[115] In the 2011 book The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience, Isbester states: "Ultimately, the term 'the Pink Tide' is not a useful analytical tool as it encompasses too wide a range of governments and policies. It includes those actively overturning neoliberalism (Chávez and Morales), those reforming neoliberalism (Lula), those attempting a confusing mixture of both (the Kirchners and Correa), those having rhetoric but lacking the ability to accomplish much (Toledo), and those using anti-neoliberal rhetoric to consolidate power through non-democratic mechanisms (Ortega)."[112] |

用語 21世紀初頭のラテンアメリカ政治をめぐる現代的な議論において、ピンク・タイドという言葉が目立つようになった。この用語の起源は、モンテビデオ駐在の ニューヨーク・タイムズ記者ラリー・ローターが、2004年のウルグアイ総選挙でタバレ・バスケスが大統領に選出されたことを「赤潮というよ り......ピンクの潮」と評したことにあると思われる[15]。 [15]この言葉は、赤潮(政治的なものというよりは藻の繁殖という生物学的な現象)に基づく言葉遊びのようであり、特にアメリカにおける赤狩りや赤の恐 怖の一環として、共産主義と長い間関連付けられてきた色である赤が、より穏健な社会主義思想が力を得たことを示すために、より明るい色調のピンクに置き換 えられている[115]。 左翼政治の受け入れを公言するラテンアメリカの政府が数多く存在していたにもかかわらず、ラテンアメリカの国家を、アメリカにおける赤の国家と青の国家の ように「支配的な政治的傾向に従って」分類することは困難である[115]。この政治的シフトを定量化することは困難であったが、その影響は広く注目され ていた。ワシントンD.C.を拠点とする左派系シンクタンクである政策研究所によれば、2006年の南米諸国首脳会議と民族統合社会フォーラムは、新自由 主義という支配的な言説の周縁で行われていた特定の議論が、公共圏と議論の中心に移動したことを示した[115]。 2011年に出版された『ラテンアメリカにおける民主主義のパラドックス』(The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: イズベスターは次のように述べている: 結局のところ、"ピンク・タイド "という用語は、あまりにも広範な政府と政策を包含しているため、有用な分析ツールとはならない。そこには、積極的に新自由主義を覆そうとしているもの (チャベスやモラレス)、新自由主義を改革しようとしているもの(ルーラ)、その両方を混同しようとしているもの(キルチネル家やコレア)、美辞麗句を並 べるが、多くのことを成し遂げる能力に欠けているもの(トレド)、非民主的なメカニズムを通じて権力を強化するために反新自由主義のレトリックを使用して いるもの(オルテガ)などが含まれる」[112]。 |

Reception Andrés Manuel López Obrador with Pedro Sánchez in January 2019 In 2006, The Arizona Republic recognized the growing pink tide, stating: "A couple of decades ago, the region, long considered part of the United States' backyard, was basking in a resurgence of democracy, sending military despots back to their barracks", further recognizing the "disfavor" with the United States and the concerns of "a wave of nationalist, leftist leaders washing across Latin America in a 'pink tide'" among United States officials.[116] A 2007 report from the Inter Press Service news agency said how "elections results in Latin America appear to have confirmed a left-wing populist and anti-U.S. trend – the so-called 'pink tide' – which ... poses serious threats to Washington's multibillion-dollar anti-drug effort in the Andes".[117] In 2014, Albrecht Koschützke and Hajo Lanz, directors of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation for Central America, discussed the "hope for greater social justice and a more participatory democracy" following the election of leftist leaders, though the foundation recognized that such elections "still do not mean a shift to the left", but that they are "the result of an ostensible loss of prestige from the right-wing parties that have traditionally ruled".[118] Writing in Americas Quarterly after the election of Pedro Castillo in 2021, Paul J. Angelo and Will Freeman warned of the risk of Latin American left-wing politicians embracing what they dubbed "regressive social values" and "leaning into traditionally conservative positions on gender equality, abortion access, LGBTQ rights, immigration, and the environment". They cited Castillo blaming Peru's femicides on male "idleness" and criticizing what he called "gender ideology" taught in Peruvian schools, as well as Ecuador, governed by left-wing leaders for almost twenty years, having one of the strictest anti-abortion laws worldwide. On immigration, they mentioned Mexico's southern border militarization to stop Central American migrant caravans and Castillo's proposal to give undocumented migrants 72 hours to leave the country after taking office, while on the environment they cited Ecuadorian progressive presidential candidate Andrés Arauz insisting on oil drilling in the Amazon, as well as the Bolivian president Luis Arce allowing agribusinesses unchecked with deforestation.[119] |

レセプション アンドレス・マヌエル・ロペス・オブラドールとペドロ・サンチェス(2019年1月 2006年、アリゾナ・リパブリック紙はピンク色の潮流が強まっていることを認識し、こう述べた: 数十年前、長い間アメリカの裏庭の一部とみなされていたこの地域は、民主主義の復活に酔いしれ、軍事専制君主を兵舎に送り返していた」と述べ、さらにアメ リカとの「不仲」を認識し、アメリカ政府関係者の間で「民族主義的、左翼的指導者の波が "ピンクの潮流 "としてラテンアメリカに押し寄せている」という懸念を示した。 [116] インター・プレス・サービス通信社の2007年の報告書は、「ラテンアメリカの選挙結果は、左翼ポピュリストと反米の傾向、いわゆる『ピンクの潮流』を確 認したようだ。 2014年、フリードリヒ・エーベルト中米財団の理事であるAlbrecht KoschützkeとHajo Lanzは、左派指導者の選挙後の「より大きな社会正義と、より参加しやすい民主主義への希望」について論じたが、同財団は、そのような選挙は「依然とし て左派へのシフトを意味するものではない」ものの、「伝統的に支配してきた右派政党からの名声の表向きの喪失の結果」であると認識していた[118]。 ポール・J・アンジェロとウィル・フリーマンは、2021年のペドロ・カスティーヨの選挙後にAmericas Quarterly誌に寄稿し、ラテンアメリカの左派政治家が「退行的な社会的価値観」と彼らが呼ぶものを受け入れ、「男女平等、妊娠中絶の機会、 LGBTQの権利、移民、環境に関して伝統的に保守的な立場に傾く」リスクを警告した。彼らは、ペルーの女性自殺を男性の「怠惰」のせいだと非難し、ペ ルーの学校で教えられている「ジェンダー・イデオロギー」と呼ばれるものを批判するカスティーヨや、20年近く左翼指導者によって統治され、世界で最も厳 しい中絶禁止法のひとつを持つエクアドルを挙げた。移民については、中米からの移民キャラバンを阻止するためにメキシコ南部の国境が軍事化されていること や、非正規移民に就任後72時間の出国猶予を与えるというカスティーヨの提案に言及し、環境については、アマゾンでの石油掘削を主張するエクアドルの進歩 的大統領候補アンドレス・アラウズや、森林伐採を野放しにするアグリビジネスを許すボリビアのルイス・アルセ大統領を挙げた[119]。 |

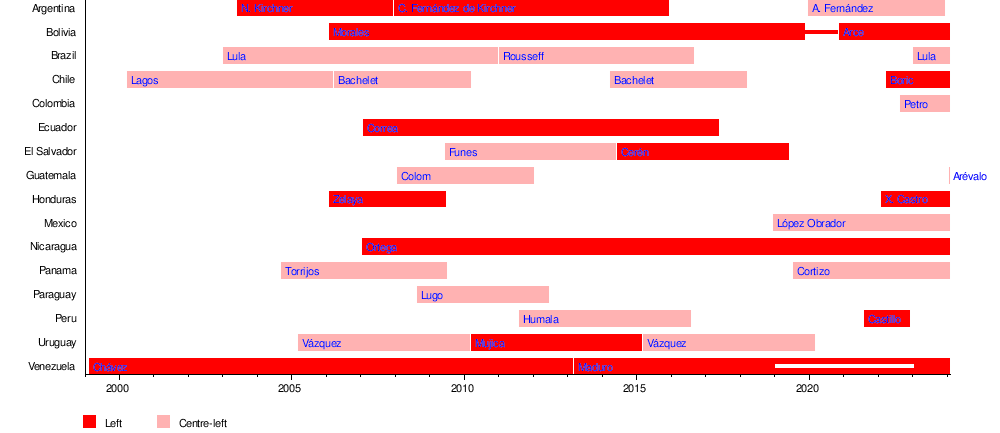

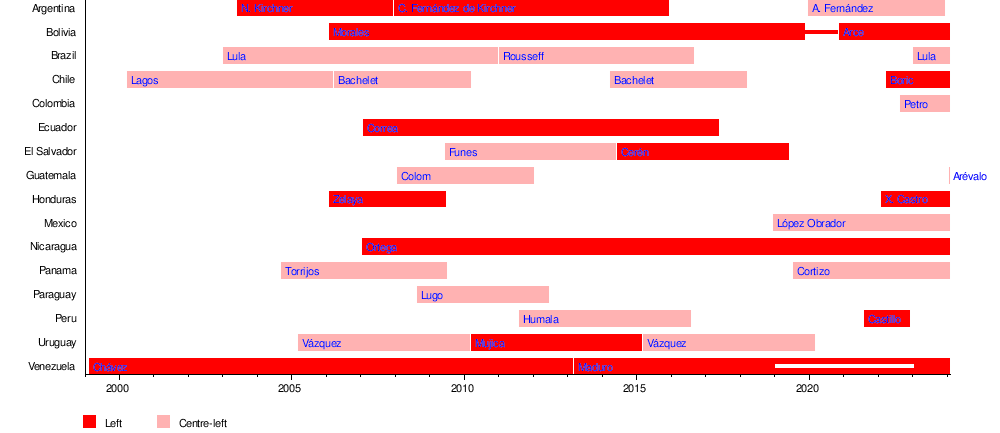

| Timeline The below timeline shows periods where a left-wing or center-left leader governed over a particular country; disputed pink tide leaders are not included.  |

年表 以下の年表は、左翼または中道左派の指導者が特定の国を統治した期間を示している。  |

| Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (→ALBA) Bolivarianism Politics of Fidel Castro Legacy of Che Guevara Conservative wave History of Latin America Indigenismo Kirchnerism Latin American drug legalization Latin American integration Panhispanism Left-wing populism Lulism Pan-Americanism Petrocaribe Populism in Latin America Sandinista ideology Socialism of the 21st century |

米州ボリバル同盟 ボリバル主義 フィデル・カストロの政治 チェ・ゲバラの遺産 保守の波 ラテンアメリカの歴史 インディヘニスモ キルチネリズム ラテンアメリカの麻薬合法化 ラテンアメリカの統合 汎ヒスパニズム 左翼ポピュリズム ルーリズム 汎アメリカ主義 ペトロカリベ ラテンアメリカのポピュリズム サンディニスタ・イデオロギー 21世紀の社会主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pink_tide |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆