ケンブリッジ大学トレス海峡探検隊

The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits and

Sarawak

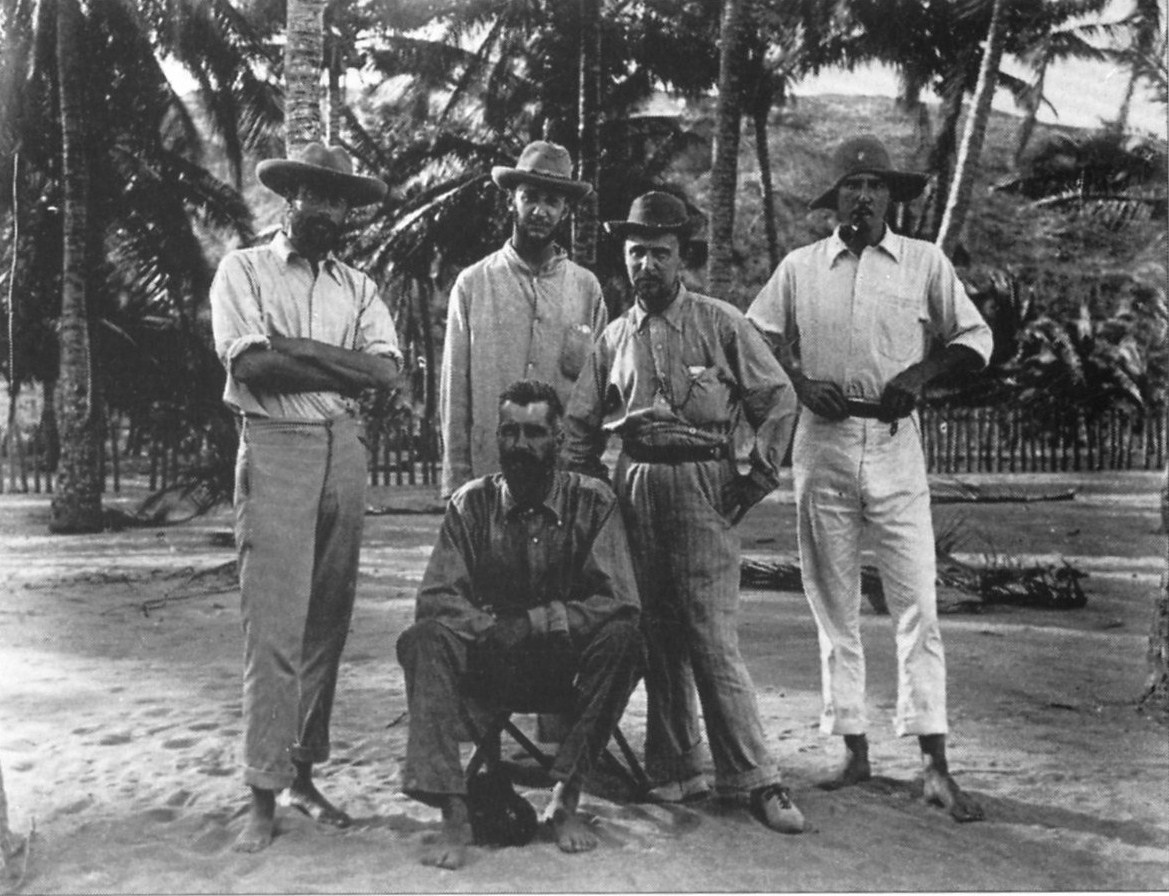

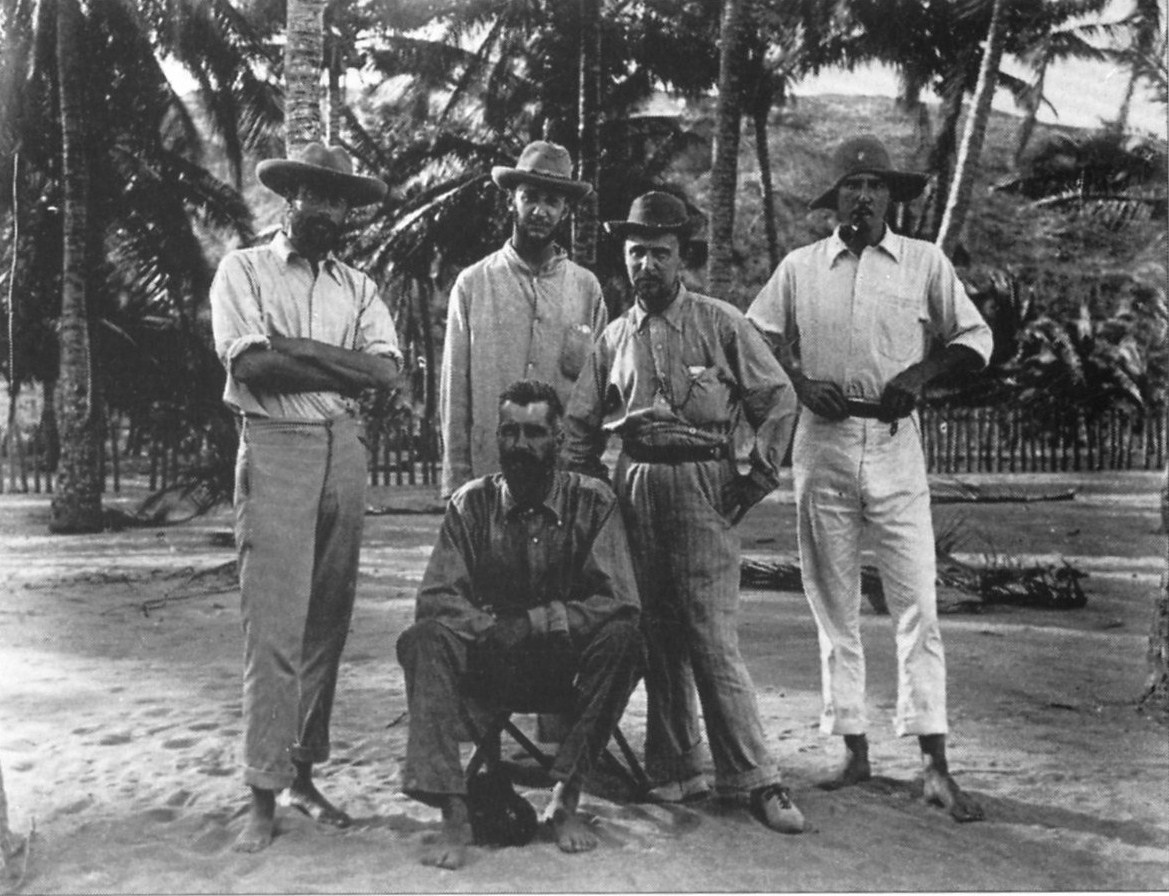

Members of the 1898 Torres Straits Expedition. Standing (from left to right): Rivers, Seligman, Ray, Wilkin. Seated: Haddon

ケンブリッジ大学トレス海峡探検隊

The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits and

Sarawak

Members of the 1898 Torres Straits Expedition. Standing (from left to right): Rivers, Seligman, Ray, Wilkin. Seated: Haddon

" Is 1888, Dr. A. C. Haddon, F.R.S., went to Torres Straits solely with the intention of studying the coral reefs and marine zoology of that district. MiThen engaged in his zoological studies, Dr. Haddon's interest was attracted towards the natives, and he devoted his spare time to recording all he could learn about their past manners and customs, in addition to what he observed of their present mode of life. He was led to devote a good deal of tiIne to the subject, as he found that none of the white residents in Torres Straits knew much about the natives, or cared about them personally, and as the natives were in some cases rapidly either dying out or becoming modified by contact with alien races. Some of the results of these investigations were published in the Journal of the Anthropoloyical Institute, xix. (1890) p. 297; Folk-lore, i. (1890) pp. 47, 172; Internationales Archiv fur Ethnographie, iv. (1891) p. 177; vi. (1893) p. 131; Proceedinys Royal Irish Academy, (2) ii. (1893) p. 463, iv. (1897) p. 119; Cunningham Memoir, x.; Royal Irish Academy, 1894. All of the zoological results have not yet been published, and the geogra- phical and geological observations were published in a joint paper, ' On the Gealogy of Torres Straits,' by Professors A. C. Haddon, W. J. Sollas, and G. A. J. Cole, in the The transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, xxx. (1894) p. 419." - The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits and Sarawak. The Geographical Journal.Vol. 14, No. 3 (Sep., 1899), pp. 302-306.

「トレス海峡とサラワクへのケンブリッジ人類学探検隊

1888年、A.C.ハッドン博士(F.R.S.)は、もっぱらトレス海峡のサンゴ礁と海洋動物学を研究する目的でトレス海峡に赴いた。その後、動物学の

研究に没頭していたハッドン博士は、原住民に興味を持ち、現在の生活様式を観察したことに加え、彼らの過去の風俗や習慣について知り得る限りのことを記録

することに余暇を費やした。トーレス海峡に住む白人は誰も原住民のことをよく知らず、個人的に気にかけてもいなかったこと、また原住民が急速に滅びたり、

異民族との接触によって変化したりしていることがわかったため、彼はこのテーマに多くの時間を割くようになった。これらの調査結果の一部は、人類学研究所

のジャーナルに掲載された、」

| Alfred Cort Haddon,

Sc.D., FRS,[1] FRGS FRAI (24 May 1855 – 20 April 1940, Cambridge) was

an influential British anthropologist and ethnologist. Initially a

biologist, who achieved his most notable fieldwork, with W.H.R. Rivers,

C.G. Seligman and Sidney Ray on the Torres Strait Islands. He returned

to Christ's College, Cambridge, where he had been an undergraduate, and

effectively founded the School of Anthropology. Haddon was a major

influence on the work of the American ethnologist Caroline Furness

Jayne.[2] In 2011, Haddon's 1898 The Recordings of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits were added to the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia's Sounds of Australia registry.[3] The original recordings are housed at the British Library[4] and many have been made available online.[5] |

アルフレッド・コート・ハッドン(Alfred Cort Haddon, Sc.D.,

FRS,[1] FRGS FRAI (1855/5/24 - 1940/4/20, Cambridge)

は、イギリスの有力な人類学者、民族学者であった。当初は生物学者で、W.H.R.リヴァース、C.G.セリグマン、シドニー・レイとともにトレス海峡諸

島で最も重要なフィールドワークを成し遂げた。彼は学部生だったケンブリッジのクライスト・カレッジに戻り、人類学部の実質的な創設者となった。ハッドン

は、アメリカの民族学者キャロライン・ファーネス・ジェインの研究に大きな影響を与えた[2]。 2011年、ハッドンの1898年の『The Recordings of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits』がオーストラリア国立フィルム・サウンドアーカイブの『Sounds of Australia』に登録された[3]。オリジナルの録音は大英図書館に収蔵され[4]、多くはオンラインで利用できるようになっている[5]。 |

| Alfred Cort Haddon was born on

24 May 1855, near London, the elder son of John Haddon, the head of a

firm of typefounders and printers. He attended lectures at King's

College London and taught zoology and geology at a girls' school in

Dover, before entering Christ's College, Cambridge in 1875.[6] At Cambridge he studied zoology and became the friend of John Holland Rose (afterwards Harmsworth Professor of Naval History), whose sister he married in 1881. Shortly after achieving his Master of Arts degree, he was appointed as Demonstrator in Zoology at Cambridge in 1879. For a time he studied marine biology in Naples.[7] |

1855年5月24日、ロンドン近郊で、活字鋳造・印刷会社の社長ジョン・ハッドンの長男として生まれた。キングス・カレッジ・ロンドンで講義を受け、ドーバーの女子校で動物学と地質学を教え、1875年にケンブリッジのクライスト・カレッジに入学した[6]。 ケンブリッジでは動物学を学び、ジョン・ホランド・ローズ(後のハームズワース海軍史教授)の友人となり、1881年に彼女の妹と結婚する。1879年、 修士号を取得した直後、ケンブリッジ大学の動物学のデモンストレーターに任命される。一時期はナポリで海洋生物学を学んだ[7]。 |

| In 1880 he was appointed

Professor of Zoology at the College of Science in Dublin. While there

he founded the Dublin Field Club in 1885.[8] His first publications

were an Introduction to the Study of Embryology in 1887, and various

papers on marine biology, which led to his expedition to the Torres

Strait Islands to study coral reefs and marine zoology, and while thus

engaged he first became attracted to anthropology.[9] |

1880年、ダブリン理科大学の動物学教授に任命される。最初の出版物は1887年の『発生学研究序説』と海洋生物学に関する様々な論文で、これが珊瑚礁と海洋動物学を研究するためにトレス海峡諸島に遠征し、その間に人類学に初めて魅了されることになった[9]。 |

| Torres Strait Expedition On his return home he published many papers dealing with the indigenous people, urging the importance of securing all possible information about these and kindred peoples before they were overwhelmed by civilisation. He advocated that in Cambridge[1] (encouraged thereto by Thomas Henry Huxley), whither he came to give lectures at the Anatomy School from 1894 to 1898, and at last funds were raised to equip an expedition to the Torres Straits Islands to make a scientific study of the people, and Dr Haddon was asked to assume the leadership.[7] To assist him he succeeded in obtaining the help of Dr W.H.R. Rivers, and in after years he used to say that he counted it his chief claim to fame that he had diverted Dr. Rivers from psychology to anthropology.[10] In April 1898, the expedition arrived at its field of work and spent over a year in the Torres Strait Islands, and Borneo, and brought home a large collection of ethnographical specimens, some of which are now in the British Museum, but the bulk of them form one of the glories of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge. The University of Cambridge later passed the wax cylinder recordings to the British Library. The main results of the expedition are published in The Reports of the Cambridge Expedition to Torres Straits.[7] Haddon was convinced that hundreds of art objects collected had to be saved from almost certain destruction by the zealous Christian missionaries intent on obliterating the religious traditions and ceremonies of the native islanders. Film footage of ceremonial dances was also collected. His findings were published in his 1901 book "Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown[11] Similar anthropological work, the recording of myths and legends from the Torres Strait Islands was coordinated by Margaret Lawrie during 1960–72. Her collection complements Haddon's work and can be found at the State Library of Queensland[12] In 1897, Haddon had obtained his Sc.D. degree in recognition of the work he had already done, some of which he had incorporated in his Decorative art of New Guinea, a large monograph published as one of the Cunningham Memoirs in 1894, and on his return home from his second expedition he was elected a fellow of his college (junior fellow in 1901, senior fellow in 1904).[1] He was appointed lecturer in ethnology in the University of Cambridge in 1900, and reader in 1909, a post from which he retired in 1926. He was appointed advisory curator to the Horniman Museum in London in 1901. Haddon paid a third visit to New Guinea in 1914 returned during the First World War.[1] Accompanied by his daughter Kathleen Haddon (1888–1961), a zoologist, photographer and scholar of string-figures,[13] the Haddons travelled along the Papuan coast from Daru to Aroma. While less discussed then his earlier work in the Torres Straits, this trip was influential in helping shape Haddon's later work on the distribution of material culture across New Guinea.[14][15] The war effort had largely destroyed the study of anthropology at the university, however, and Haddon went to France to work for the Y.M.C.A. After the war, he renewed his constant struggle to establish a sound School of Anthropology in Cambridge.[7] |

トレス海峡探検 帰国後、彼は先住民に関する多くの論文を発表し、先住民が文明に圧倒される前に、先住民や同種の人々に関するあらゆる情報を確保することの重要性を訴え た。1894年から1898年まで解剖学教室で講義をしていたケンブリッジ[1]でそれを提唱し、ついにトレス海峡諸島に遠征して人々を科学的に研究する ための資金を調達し、ハッドン博士がその指導者となるよう依頼された[7]。 彼を支援するために彼はW.H.R.リヴァース博士の助けを得ることに成功し、後年、彼はリヴァース博士を心理学から人類学に転向させたことを自分の名声の最大要因とみなしていた[10]とよく言っていた。 1898年4月、探検隊は現地に到着し、トレス海峡諸島とボルネオ島で1年以上を過ごし、民族学的標本の大規模なコレクションを持ち帰った。その一部は現 在大英博物館に収蔵されているが、その大部分はケンブリッジ大学考古学・人類学博物館の栄光を形成するものである。ケンブリッジ大学はその後、ワックスシ リンダーによる録音を大英図書館に譲り渡した。探検の主な成果は『ケンブリッジ大学トレス海峡探検隊報告書』として出版されている[7]。 ハッドンは、島民の宗教的伝統や儀式を抹殺しようとする熱心なキリスト教宣教師によるほぼ確実な破壊から、収集した何百もの美術品を救わなければならない と確信したのである。また、儀式の踊りを撮影した映像も収集しました。その成果は、1901年に出版された『首狩り族、黒、白、褐色[11]』に収録され ています。 同様の人類学的研究として、トレス海峡諸島の神話と伝説の記録は、1960年から72年にかけてマーガレット・ローリー(Margaret Lawrie)によって行われた。彼女のコレクションはハッドンの仕事を補完するものであり、クイーンズランド州立図書館で見ることができる[12]。 1897年、ハッドンはすでに行っていた研究(その一部は1894年に『カニンガム・メモワール』の一冊として出版された大型モノグラフ『ニューギニアの 装飾美術』に取り入れられている)が認められ、理学博士の学位を取得した。2度目の探検から帰国すると、大学のフェロー(1901年にジュニアフェロー、 1904年にシニアフェロー)に選出された[1]。 1900年にはケンブリッジ大学の民族学講師に、1909年には読書家に任命され、1926年に退官した[1]。1901年、ロンドンのホーニマン博物館の顧問学芸員に任命された。第一次世界大戦中の1914年、ハッドンは3度目のニューギニア訪問を果たした[1]。 動物学者、写真家、糸状菌の研究者である娘のキャサリーン・ハッドン(1888-1961)を伴って、ハッドンはダルからアロマまでパプア海岸沿いを旅し た[13]。トレス海峡での以前の仕事に比べてあまり議論されていないが、この旅は、ニューギニア全体の物質文化の分布に関するハッドンの後の仕事を形作 るのに影響的であった[14][15]。 しかし、戦争努力によって大学での人類学の研究はほとんど破壊され、ハッドンはフランスに行き、YMCAで働くことになった。戦後、彼はケンブリッジに健全な人類学の学校を設立するために絶え間ない努力を続けていた[7]。 |

| Retirement On his retirement Haddon was made honorary keeper of the rich collections from New Guinea which the Cambridge Museum possesses, and also wrote up the remaining parts of the Torres Straits Reports, which his busy teaching and administrative life had forced him to set aside. His help and counsel to younger men was then still more freely at their service, and as always he continually laid aside his own work to help them with theirs.[7] Haddon was president of Section H (Anthropology) in the British Association meetings of 1902 and 1905. He was president of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, of the Folk Lore Society, and of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society;[1] received from the R.A.I. the Huxley Medal in 1920; and was the first recipient of the Rivers Medal in 1924. He was the first to recognise the ethnological importance of string figures and tricks, known in England as "cat's cradles," but found all over the world as a pastime among native peoples. He and Rivers invented a nomenclature and method of describing the process of making the different figures, and one of his daughters, Kathleen Rishbeth, became an expert authority on the subject.[7] His main publications, besides those already mentioned, were: Evolution in Art (1895), The Study of Man (1898), Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown (1901), The Races of Man (1909; second, entirely rewritten, ed. 1924), and The Wanderings of People (1911). He contributed to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary of National Biography, and several articles to Hastings's Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. A bibliography of his writings and papers runs to over 200 entries, even without his book reviews.[7] Though subsequently sidelined by Bronisław Malinowski, and the new paradigm of functionalism within anthropology, Haddon was profoundly influential mentoring and supporting various anthropologists conducted then nascent fieldwork: A.R. Brown in the Andaman Islands (1906–08), Gunnar Landtman on Kiwai in now Papua New Guinea (1910–12),[16] Diamond Jenness (1911–12), R.R. Marrett's student at the University of Oxford,[17] as well as John Layard on Malakula, Vanuatu (1914–15),[18] and to have Bronisław Malinowski stationed in Mailu and later the Trobriand Islands during WWI.[19] Haddon actively gave advice to missionaries, government officers, traders and anthropologists; collecting in return information about New Guinea and elsewhere.[20] Haddon's photographic archive and artefact collections can be found in the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Cambridge University, while his papers are in the Cambridge University's Library's Special Collections.[21] |

引退後 引退後、ハッドンはケンブリッジ博物館が所蔵するニューギニアの豊富なコレクションの名誉館長となり、また多忙な教育・管理生活の中で脇に追いやられてい た『トレス海峡レポート』の残りの部分を書き上げることになった。若手に対する彼の援助と助言は、当時もなお自由に行われ、いつものように自分の仕事を中 断して若手の仕事を手伝い続けていた[7]。 ハッドンは、1902年と1905年の英国学会のセクションH(人類学)の会長であった。グレートブリテンおよびアイルランド王立人類学研究所、民間伝承協会、ケンブリッジ古物協会の会長を務め、王立協会のフェローに選出された[1]。 彼は、イギリスでは「猫のゆりかご(=あやとり)」として知られているが、先住民の娯楽として世界中に見られる糸を使った図形やトリックの民族学的重要性 を最初に認識した人物であった。彼とリヴァースは、さまざまなフィギュアの製作過程を説明する名称と方法を考案し、彼の娘の一人であるキャサリン・リシュ ベスは、この分野の専門家として権威となった[7]。 既に述べたものの他に、彼の主な出版物は以下の通りである。芸術における進化』(1895)、『人間の研究』(1898)、『首狩り族、黒、白、茶』 (1901)、『人間の種族』(1909、第二版、1924)、『人間の放浪』(1911)である。Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary of National Biographyに寄稿し、Hastings's Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethicsにいくつかの記事を寄稿している。彼の著作や論文の書誌は、書評を除いても200項目以上に及ぶ[7]。 その後、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーや人類学の新しいパラダイムである機能主義に押され気味ではあったが、ハッドンは当時まだ始まったばかりのフィール ドワークを行う様々な人類学者を指導、支援し、大きな影響力を発揮していた。アンダマン諸島のA.R.ブラウン(1906-08)、現在のパプアニューギ ニアのキワイのグンナー・ランドマン(1910-12)[16]、オックスフォード大学でR.R.マレットの学生だったダイヤモンド・ジェネス(1911 -12)、バヌアツのマラクラのジョン・レイヤー(1914-15) [18] そしてブロニスワフ・マリノフスキがマイユと後のトロブリアン諸島に滞在するために第一次大戦中、様々な人類学者を指導し支援しました[19]。 [ハッドンは宣教師や政府高官、商人、人類学者などに積極的に助言を与え、その見返りとしてニューギニアやその他の地域の情報を収集した[20]。 ハッドンの写真アーカイブと遺品コレクションはケンブリッジ大学の人類学・考古学博物館に、彼の論文はケンブリッジ大学図書館の特別コレクションに所蔵されている[21]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Cort_Haddon. |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator. |

● アルフレッド・コート・ハッドン(Alfred Cort Haddon, 1855-1940)

| Alfred

Cort Haddon, Sc.D., FRS,[1] FRGS FRAI (24 May 1855 – 20 April 1940,

Cambridge) was an influential British anthropologist and ethnologist.

Initially a biologist, who achieved his most notable fieldwork, with

W.H.R. Rivers, C.G. Seligman and Sidney Ray on the Torres Strait

Islands. He returned to Christ's College, Cambridge, where he had been

an undergraduate, and effectively founded the School of Anthropology.

Haddon was a major influence on the work of the American ethnologist

Caroline Furness Jayne.[2] In 2011, Haddon's 1898 The Recordings of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits were added to the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia's Sounds of Australia registry.[3] The original recordings are housed at the British Library[4] and many have been made available online.[5] |

Alfred Cort Haddon, Sc.D.,

FRS,[1] FRGS FRAI (1855/5/24 - 1940/4/20, Cambridge)

は、イギリスの有力な人類学者、民族学者であった。当初は生物学者で、W.H.R.リヴァース、C.G.セリグマン、シドニー・レイとともにトレス海峡諸

島で最も重要なフィールドワークを成し遂げた。彼は学部生だったケンブリッジのクライスト・カレッジに戻り、人類学部の実質的な創設者となった。ハッドン

は、アメリカの民族学者キャロライン・ファーネス・ジェインの研究に大きな影響を与えた[2]。 2011年、ハッドンの1898年の『The Recordings of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits』がオーストラリア国立フィルム・サウンドアーカイブの『Sounds of Australia』に登録された[3]。オリジナルの録音は大英図書館に収蔵され[4]、多くはオンラインで利用できるようになっている[5]。 |

| Early life Alfred Cort Haddon was born on 24 May 1855, near London, the elder son of John Haddon, the head of a firm of typefounders and printers. He attended lectures at King's College London and taught zoology and geology at a girls' school in Dover, before entering Christ's College, Cambridge in 1875.[6] At Cambridge he studied zoology and became the friend of John Holland Rose (afterwards Harmsworth Professor of Naval History), whose sister he married in 1881. Shortly after achieving his Master of Arts degree, he was appointed as Demonstrator in Zoology at Cambridge in 1879. For a time he studied marine biology in Naples.[7] |

生い立ち アルフレッド・コルト・ハッドンは、1855年5月24日にロンドン近郊で、活字鋳造・印刷会社の社長であるジョン・ハッドンの長男として生まれた。キン グス・カレッジ・ロンドンで講義を受け、ドーバーの女子校で動物学と地質学を教え、1875年にケンブリッジのクライスト・カレッジに入学した[6]。 ケンブリッジでは動物学を学び、ジョン・ホランド・ローズ(後のハームズワース海軍史教授)の友人となり、1881年に彼女の妹と結婚する。1879年、 修士号を取得した直後、ケンブリッジ大学の動物学のデモンストレーターに任命される。一時期はナポリで海洋生物学を学んだ[7]。 |

| Dublin In 1880 he was appointed Professor of Zoology at the College of Science in Dublin. While there he founded the Dublin Field Club in 1885.[8] His first publications were an Introduction to the Study of Embryology in 1887, and various papers on marine biology, which led to his expedition to the Torres Strait Islands to study coral reefs and marine zoology, and while thus engaged he first became attracted to anthropology.[9] |

ダブリン 1880年、ダブリンにある科学大学の動物学教授に任命される。最初の出版物は1887年の『発生学研究序説』と海洋生物学に関する様々な論文で、これが珊瑚礁と海洋動物学を研究するためにトレス海峡諸島に遠征し、その間に人類学に初めて魅了されることになった[9]。 |

| Torres Strait Expedition On his return home he published many papers dealing with the indigenous people, urging the importance of securing all possible information about these and kindred peoples before they were overwhelmed by civilisation. He advocated that in Cambridge[1] (encouraged thereto by Thomas Henry Huxley), whither he came to give lectures at the Anatomy School from 1894 to 1898, and at last funds were raised to equip an expedition to the Torres Straits Islands to make a scientific study of the people, and Dr Haddon was asked to assume the leadership.[7] To assist him he succeeded in obtaining the help of Dr W.H.R. Rivers, and in after years he used to say that he counted it his chief claim to fame that he had diverted Dr. Rivers from psychology to anthropology.[10] In April 1898, the expedition arrived at its field of work and spent over a year in the Torres Strait Islands, and Borneo, and brought home a large collection of ethnographical specimens, some of which are now in the British Museum, but the bulk of them form one of the glories of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge. The University of Cambridge later passed the wax cylinder recordings to the British Library. The main results of the expedition are published in The Reports of the Cambridge Expedition to Torres Straits.[7] Haddon was convinced that hundreds of art objects collected had to be saved from almost certain destruction by the zealous Christian missionaries intent on obliterating the religious traditions and ceremonies of the native islanders. Film footage of ceremonial dances was also collected. His findings were published in his 1901 book "Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown[11] Similar anthropological work, the recording of myths and legends from the Torres Strait Islands was coordinated by Margaret Lawrie during 1960–72. Her collection complements Haddon's work and can be found at the State Library of Queensland[12] In 1897, Haddon had obtained his Sc.D. degree in recognition of the work he had already done, some of which he had incorporated in his Decorative art of New Guinea, a large monograph published as one of the Cunningham Memoirs in 1894, and on his return home from his second expedition he was elected a fellow of his college (junior fellow in 1901, senior fellow in 1904).[1] He was appointed lecturer in ethnology in the University of Cambridge in 1900, and reader in 1909, a post from which he retired in 1926. He was appointed advisory curator to the Horniman Museum in London in 1901. Haddon paid a third visit to New Guinea in 1914 returned during the First World War.[1] Accompanied by his daughter Kathleen Haddon (1888–1961), a zoologist, photographer and scholar of string-figures,[13] the Haddons travelled along the Papuan coast from Daru to Aroma. While less discussed then his earlier work in the Torres Straits, this trip was influential in helping shape Haddon's later work on the distribution of material culture across New Guinea.[14][15] The war effort had largely destroyed the study of anthropology at the university, however, and Haddon went to France to work for the Y.M.C.A. After the war, he renewed his constant struggle to establish a sound School of Anthropology in Cambridge.[7] |

トレス海峡探検 帰国後、彼は先住民に関する多くの論文を発表し、先住民が文明に圧倒される前に、先住民や同種の人々に関するあらゆる情報を確保することの重要性を訴え た。1894年から1898年まで解剖学教室で講義をしていたケンブリッジ[1]でそれを提唱し、ついにトレス海峡諸島に遠征して人々を科学的に研究する ための資金を調達し、ハッドン博士がその指導者となるよう依頼された[7]。 彼を助けるために彼はW.H.R.Rivers博士の助けを得ることに成功し、後年、彼はRivers博士を心理学から人類学に転向させたことを自分の最大の功績とみなしているとよく言っていた[10]。 1898年4月、探検隊は現地に到着し、トレス海峡諸島とボルネオ島で1年以上を過ごし、民族学的標本の大規模なコレクションを持ち帰った。その一部は現 在大英博物館に収蔵されているが、その大部分はケンブリッジ大学考古学・人類学博物館の栄光を形成するものである。ケンブリッジ大学はその後、ワックスシ リンダーによる録音を大英図書館に譲り渡した。探検の主な成果は『ケンブリッジ大学トレス海峡探検隊報告書』として出版されている[7]。 ハッドンは、島民の宗教的伝統や儀式を抹殺しようとする熱心なキリスト教宣教師によるほぼ確実な破壊から、収集した何百もの美術品を救わなければならない と確信したのである[8]。また、儀式の踊りを撮影した映像も収集した。彼の発見は、1901年の著書『首狩り族、黒、白、褐色[11]』に掲載された。 人類学と同様に、トレス海峡諸島の神話と伝説の記録は、1960年から72年にかけてMargaret Lawrieによってコーディネートされた。彼女のコレクションはハッドンの研究を補完するものであり、クイーンズランド州立図書館で見ることができる[12]。 1897年、ハッドンはすでに行っていた研究(その一部は1894年に『カニンガム・メモワール』の一冊として出版された大型モノグラフ『ニューギニアの 装飾美術』に取り入れられている)が認められ、博士号を取得し、2度目の探検から帰国すると大学のフェローに選出された(1901年にジュニア・フェ ロー、1904年にシニア・フェロー)[1]。 1900年にはケンブリッジ大学の民族学講師に、1909年には読書家に任命され、1926年に退官した[1]。1901年、ロンドンのホーニマン博物館の顧問学芸員に任命された。第一次世界大戦中の1914年、ハッドンは3度目のニューギニア訪問を果たした[1]。 動物学者、写真家、糸状菌の研究者である娘のキャサリーン・ハッドン(1888-1961)を伴って、ハッドンはダルからアロマまでパプア海岸沿いを旅し た[13]。トレス海峡での以前の仕事に比べてあまり議論されていないが、この旅は、ニューギニア全体の物質文化の分布に関するハッドンの後の仕事を形作 るのに影響的であった[14][15]。 しかし、戦争努力によって大学での人類学の研究はほとんど破壊され、ハッドンはフランスに行き、YMCAで働くことになった。戦後、彼はケンブリッジに健全な人類学の学校を設立するために絶え間ない努力を続けていた[7]。 |

| Retirement On his retirement Haddon was made honorary keeper of the rich collections from New Guinea which the Cambridge Museum possesses, and also wrote up the remaining parts of the Torres Straits Reports, which his busy teaching and administrative life had forced him to set aside. His help and counsel to younger men was then still more freely at their service, and as always he continually laid aside his own work to help them with theirs.[7] Haddon was president of Section H (Anthropology) in the British Association meetings of 1902 and 1905. He was president of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, of the Folk Lore Society, and of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society;[1] received from the R.A.I. the Huxley Medal in 1920; and was the first recipient of the Rivers Medal in 1924. He was the first to recognise the ethnological importance of string figures and tricks, known in England as "cats' cradles," but found all over the world as a pastime among native peoples. He and Rivers invented a nomenclature and method of describing the process of making the different figures, and one of his daughters, Kathleen Rishbeth, became an expert authority on the subject.[7] His main publications, besides those already mentioned, were: Evolution in Art (1895), The Study of Man (1898), Head-hunters, Black, White and Brown (1901), The Races of Man (1909; second, entirely rewritten, ed. 1924), and The Wanderings of People (1911). He contributed to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary of National Biography, and several articles to Hastings's Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. A bibliography of his writings and papers runs to over 200 entries, even without his book reviews.[7] Though subsequently sidelined by Bronisław Malinowski, and the new paradigm of functionalism within anthropology, Haddon was profoundly influential mentoring and supporting various anthropologists conducted then nascent fieldwork: A.R. Brown in the Andaman Islands (1906–08), Gunnar Landtman on Kiwai in now Papua New Guinea (1910–12),[16] Diamond Jenness (1911–12), R.R. Marrett's student at the University of Oxford,[17] as well as John Layard on Malakula, Vanuatu (1914–15),[18] and to have Bronisław Malinowski stationed in Mailu and later the Trobriand Islands during WWI.[19] Haddon actively gave advice to missionaries, government officers, traders and anthropologists; collecting in return information about New Guinea and elsewhere.[20] Haddon's photographic archive and artefact collections can be found in the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Cambridge University, while his papers are in the Cambridge University's Library's Special Collections.[21] |

引退 引退後、ハッドンはケンブリッジ博物館が所蔵するニューギニアの豊富なコレクションの名誉館長となり、また多忙な教育・管理生活の中で脇に追いやられてい た『トレス海峡レポート』の残りの部分を書き上げることになった。若手に対する彼の援助と助言は、その後もより自由に彼らのために行われ、いつものように 自分の仕事を中断して彼らの仕事を助けるということもあった[7]。 ハッドンは、1902年と1905年の英国学会のセクションH(人類学)の会長であった。グレートブリテンおよびアイルランド王立人類学研究所、民間伝承協会、ケンブリッジ古物協会の会長を務め、王立協会のフェローに選出された[1]。 彼は、イギリスでは「猫のゆりかご」として知られているが、先住民の娯楽として世界中に見られる糸を使った図形やトリックの民族学的重要性を最初に認識し た人物であった。彼とリヴァースは、さまざまなフィギュアの製作過程を説明するための命名法と方法を考案し、彼の娘の一人であるキャサリン・リシュベス は、この分野の専門家として権威となった[7]。 既に述べたものの他に、彼の主な出版物は以下の通りである。芸術における進化』(1895)、『人間の研究』(1898)、『首狩り族、黒、白、茶』 (1901)、『人間の種族』(1909、第二版、1924)、『人間の放浪』(1911)である。Encyclopædia Britannica, Dictionary of National Biographyに寄稿し、Hastings's Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethicsにいくつかの記事を寄稿している。彼の著作や論文の書誌は、書評を除いても200項目以上に及ぶ[7]。 その後、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーや人類学の新しいパラダイムである機能主義に押され気味になりましたが、ハッドンは当時まだ始まったばかりのフィー ルドワークを行う様々な人類学者を指導、支援し、大きな影響力を持ちました。アンダマン諸島のA.R.ブラウン(1906-08)、現在のパプアニューギ ニアのキワイのグンナー・ランドマン(1910-12)[16]、オックスフォード大学でR.R.マレットの学生だったダイヤモンドジェネス(1911- 12)、バヌアツのマラクラのジョン・レイヤー(1914-15) [18] そしてブロニスワフ・マリノフスキがマイユと後のトロブリアン諸島に滞在するために第一次大戦中、様々な人類学者を指導し支援しました[19]。 [ハッドンは宣教師や政府高官、商人、人類学者などに積極的に助言を与え、その見返りとしてニューギニアやその他の地域の情報を収集した[19]。 ハッドンの写真アーカイブと遺品コレクションはケンブリッジ大学の人類学・考古学博物館に、彼の論文はケンブリッジ大学図書館の特別コレクションに所蔵されている[21]。 |

Haddon's wife, Fanny Elizabeth Haddon (née Rose), died in 1937, leaving a son and two daughters.[7] Haddon's daughter Kathleen (1888–1961) was a zoologist, photographer, and scholar of string-figures. She accompanied her father on a journey along the coast of New Guinea during his Torres Straits Expedition. She married O. H. T. Rishbeth in 1917.[22] |

ハッドンの妻ファニー・エリザベス・ハッドン(旧姓ローズ)は、1937年に息子と娘2人を残して亡くなった[7] ハッドンの娘キャスリーン(1888-1961)は動物学者、写真家、糸目研究家であった。父のトレス海峡探検の際、ニューギニア沿岸の旅に同行した。 1917年にO・H・T・リシュベスと結婚した[22]。 |

| Torres Strait Islander Haddon Dixon Repatriation Project |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Cort_Haddon |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Torres Strait Islanders

(/ˈtɒrɪs-/ TORR-iss-)[3] are the Indigenous Melanesian people of the

Torres Strait Islands, which are part of the state of Queensland,

Australia. Ethnically distinct from the Aboriginal peoples of the rest

of Australia, they are often grouped with them as Indigenous

Australians. Today there are many more Torres Strait Islander people

living in mainland Australia (nearly 28,000) than on the Islands (about

4,500). Torres Strait Islanders

(/ˈtɒrɪs-/ TORR-iss-)[3] are the Indigenous Melanesian people of the

Torres Strait Islands, which are part of the state of Queensland,

Australia. Ethnically distinct from the Aboriginal peoples of the rest

of Australia, they are often grouped with them as Indigenous

Australians. Today there are many more Torres Strait Islander people

living in mainland Australia (nearly 28,000) than on the Islands (about

4,500).There are five distinct peoples within broader designation of Torres Strait Islander people, based partly on geographical and cultural divisions. There are two main Indigenous language groups, Kalaw Lagaw Ya and Meriam Mir. Torres Strait Creole is also widely spoken as a language of trade and commerce. The core of Island culture is Papuo-Austronesian, and the people are traditionally a seafaring nation. There is a strong artistic culture, particularly in sculpture, printmaking and mask-making. |

ト

レス海峡諸島人(/ˈtɒ/

TORR-iss-)[3]は、オーストラリアのクイーンズランド州に属するトレス海峡諸島のメラネシア系先住民族である。オーストラリアの他の地域に住

むアボリジニとは民族的に異なるため、オーストラリア先住民として一緒に扱われることが多い。現在、オーストラリア本土には、トレス海峡諸島(約

4,500人)よりも多くのトレス海峡諸島人(約28,000人)が暮らしている。 ト

レス海峡諸島人(/ˈtɒ/

TORR-iss-)[3]は、オーストラリアのクイーンズランド州に属するトレス海峡諸島のメラネシア系先住民族である。オーストラリアの他の地域に住

むアボリジニとは民族的に異なるため、オーストラリア先住民として一緒に扱われることが多い。現在、オーストラリア本土には、トレス海峡諸島(約

4,500人)よりも多くのトレス海峡諸島人(約28,000人)が暮らしている。トレス海峡諸島民という広い呼称の中には、地理的・文化的な区分にもとづいて、5つの異なる民族が存在する。カラウ・ラガウ・ヤ(Kalaw Lagaw Ya)とメリアム・ミル(Meriam Mir)という2つの主要な先住民言語グループがある。トレス海峡クレオール語も貿易や商業の言語として広く話されている。島の文化の中心はパプオ=オー ストロネシア語で、人々は伝統的に海洋民族である。芸術文化も盛んで、特に彫刻、版画、仮面作りが盛んである。 |

| Of the 133 islands, only 38 are

inhabited. The islands are culturally unique, with much to distinguish

them from neighbouring Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and the Pacific

Islands. Today the islands are multicultural, having attracted Asian

and Pacific Island traders to the beche-de-mer, mother-of-pearl and

trochus-shell industries over the years.[5] The 2016 Australian census counted 4,514 people living on the islands, of whom 91.8% were Torres Strait Islander or Aboriginal Australian people. (64% of the population identified as Torres Strait Islander; 8.3% as Aboriginal Australian; 6.5% as Papua New Guinean; 3.6% as other Australian and 2.6% as "Maritime South-East Asian", etc.).[1] In 2006 the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) had reported 6,800 Torres Strait Islanders living in the Torres Strait area.[6] People identifying themselves as of Torres Strait Islander descent in the whole of Australia in the 2016 census numbered 32,345, while those with both Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal ancestry numbered a further 26,767 (compared with 29,515 and 17,811 respectively in 2006).[7] Five communities of Torres Strait Islanders and Aboriginal Australians live on the coast of mainland Queensland, mainly at Bamaga, Seisia, Injinoo, Umagico and New Mapoon in the Northern Peninsula area of Cape York.[8] In June 1875 a measles epidemic killed about 25% of the population, with some islands suffering losses of up to 80% of their people, as the islanders had no natural immunity to European diseases.[9] |

133の島々のうち、人が住んでいるのは38だけである。近隣のパプア

ニューギニア、インドネシア、太平洋諸島とは異なる、文化的にユニークな島々である。今日、島々は多文化であり、アジアや太平洋諸島の貿易商が長年にわた

りベチョメール、真珠母貝、トロッカス貝の産業に従事してきた[5]。 2016年のオーストラリアの国勢調査では、島に4,514人が住んでおり、そのうち91.8%がトレス海峡諸島民またはオーストラリア先住民であった。 (人口の64%はトレス海峡諸島民、8.3%はオーストラリア先住民、6.5%はパプアニューギニア人、3.6%はその他のオーストラリア人、2.6%は 「海洋性東南アジア人」など)[1] 2006年、オーストラリア外務貿易省(DFAT)はトレス海峡地域に住む6,800人のトレス海峡諸島民を報告していた[6]。 2016年の国勢調査では、オーストラリア全体でトレス海峡諸島民の血を引くと自認する人は32,345人であり、トレス海峡諸島民とアボリジニの両方の 祖先を持つ人はさらに26,767人であった(2006年にはそれぞれ29,515人と17,811人であった)[7]。 クイーンズランド州本土の海岸沿いには、主にヨーク岬のノーザン・ペニンシュラ地域のバマガ、セイシア、インジヌー、ウマギコ、ニュー・マプーンに5つのトレス海峡諸島民とオーストラリア先住民のコミュニティがある[8]。 1875年6月、はしかの流行で人口の約25%が死亡し、島民はヨーロッパの病気に対する自然免疫を持たなかったため、最大で80%が死亡した島もあった[9]。 |

| Until the late 20th century,

Torres Strait Islanders had been administered by a system of elected

councils, a system based partly on traditional pre-Christian local

government and partly on the introduced mission management system.[10] Today, the Torres Strait Regional Authority, an Australian government body established in 1994 and consisting of 20 elected representatives, oversees the islands, with its primary function being to strengthen the economic, social and cultural development of the peoples of the Torres Strait area.[11] Further to the TSRA, there are several Queensland LGAs which administer areas occupied by Torres Strait Islander communities: the Torres Strait Island Region, covering a large proportion of the Island; the Northern Peninsula Area Region, administered from Bamaga, on the northern tip of Cape York; and the Shire of Torres, which governs several islands as well as portions of Cape York Peninsula, is effectively colocated with the Northern Peninsula Area Region, which covers a number of Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT) areas on the peninsula, and the Torres Strait Island Region and administers those sections of its area which are not autonomous.[12] |

20世紀後半まで、トレス海峡諸島の人々は、伝統的なキリスト教以前の地方自治と、導入されたミッション・マネジメント・システムに部分的に基づいた、選挙で選ばれた評議会のシステムによって管理されていた[10]。 現在では、1994年に設立されたオーストラリア政府の機関であり、選挙で選ばれた20人の代表で構成されるトレス海峡地域当局が島々を監督しており、その主な機能はトレス海峡地域の人々の経済的、社会的、文化的発展を強化することである[11]。 TSRAのほかにも、クイーンズランド州には、トレス海峡諸島民のコミュニティが居住する地域を管轄するLGAがいくつかある: トレス海峡島地域(Torres Strait Island Region):島の大部分を占める; ヨーク岬北端のバマガ(Bamaga)を管轄するノーザン半島地域(Northern Peninsula Area Region)、そして トーレスシャイアは、ヨーク岬半島の一部といくつかの島々を管轄しているが、事実上、半島の多くのDOGIT(Deed of Grant in Trust)地域を管轄する北部半島地域地域と、トーレス海峡島地域と同居しており、自治権を持たない地域の一部を管轄している[12]。 |

| Torres Strait Islander people

are of predominantly Melanesian descent, distinct from Aboriginal

Australians on the mainland and some other Australian islands,[13][14]

and share some genetic and cultural traits with the people of New

Guinea.[15] The five-pointed star on the national flag represents the five cultural groups;[15] another source says that it originally represented the five groups of islands, but today (as of 2001) it represents the five major political divisions.[16] Pre-colonial Island people were not a homogeneous group and until then did not regard themselves as a single people. They have links with the people of Papua New Guinea, several islands being much closer to PNG than Australia, as well as the northern tip of Cape York on the Australian continent.[16] Sources are generally agreed that there are five distinct geographical and/or cultural divisions, but descriptions and naming of the groups differ widely. Encyclopaedia Britannica: the Eastern (Meriam, or Murray Island), Top Western (Guda Maluilgal), Near Western (Maluilgal), Central (Kulkalgal), and Inner Islands (Kaiwalagal).[15] Multicultural Queensland 2001 (a Queensland Government publication): five groups may be distinguished, based on linguistic and cultural differences, and also related to their places of origin, type of area of settlement, and long-standing relationships with other peoples. these nations are: Saibailgal (Top Western Islanders), Maluilgal (Mid-Western Islanders), Kaurareg (Lower Western Islanders), Kulkalgal (Central Islanders) and Meriam Le (Eastern Islanders).[16] Torres Shire Council official website (Queensland Government): Five major island clusters – the Top Western Group (Boigu, Dauan and Saibai), the Near Western Group (Badu, Mabuiag and Moa), the Central Group (Yam, Warraber, Coconut and Masig), the Eastern Group (Murray, Darnley and Stephen), and the TI Group (Thursday Island, Tabar Island, Horn, Hammond, Prince of Wales and Friday).[5] Ethno-linguistic groups include: Badu people, based on the central-west Badu island Kaurareg people, lower Western Islanders, based on the Muralag (Prince of Wales Island) group. Mabuiag (or Mabuygiwgal) people, across a number of the islands. Meriam people, who living on a number of inner eastern islands, including Murray Island (also known as Mer Island) and Tabar Island. |

トレス海峡諸島民は主にメラネシア系で、オーストラリア本土や他の島々のアボリジニとは区別され[13][14]、ニューギニアの人々といくつかの遺伝的・文化的特徴を共有している[15]。 国旗の五芒星は5つの文化グループを表している[15]。別の資料によれば、もともとは5つの島々のグループを表していたが、現在(2001年現在)では5つの主要な政治部門を表している[16]。 植民地時代以前の島の人々は同質的な集団ではなく、それまでは自分たちをひとつの民族とはみなしていなかった。彼らはパプアニューギニアの人々とつながり があり、いくつかの島はオーストラリアよりもパプアニューギニアに近く、オーストラリア大陸のヨーク岬の北端にもある[16]。 地理的および/または文化的に5つの明確な区分があるという情報源は一般的に一致しているが、グループの記述や命名は大きく異なっている。 ブリタニカ百科事典:東部(メリアム、またはマレー島)、上部西部(グダ・マルイルガル)、近西部(マルイルガル)、中部(クルカルガル)、内島(カイワラガル)[15]。 マルチカルチュラル・クイーンズランド2001(クイーンズランド州政府刊行物):言語的・文化的差異に基づき、また出身地、定住地域の種類、他の民族と の長年の関係に関連して、5つのグループが区別される: サイベイルガル(トップウェスタン島民)、マルイルガル(ミッドウェスタン島民)、カウラレガル(ロワーウェスタン島民)、クルカルガル(セントラル島 民)、メリアム・レ(イースタン島民)である[16]。 トーレスシャイアーカウンシル公式サイト(クイーンズランド州政府): 5つの主要な島群 - トップウェスタングループ(ボイグ、ダウアン、サイバイ)、ニアウェスタングループ(バドゥ、マブイアグ、モア)、セントラルグループ(ヤム、ワラバー、 ココナッツ、マシグ)、イースタングループ(マレー、ダーンリー、スティーブン)、TIグループ(木曜日島、タバル島、ホーン、ハモンド、プリンスオブ ウェールズ、金曜日)[5]。 民族言語グループには以下のものがある: バドゥ人(Badu people):中西部のバドゥ島を拠点とする。 カウラレグ人、ムララグ(プリンス・オブ・ウェールズ島)を中心とする西部の島民。 マブイアグ人(またはマブイギウガル人):多くの島々で暮らす。 Meriam人、Murray島(Mer島とも呼ばれる)やTabar島を含む東部内諸島に住む。 |

| There are two distinct Indigenous languages spoken on the Islands, as well as a creole language.[13] The Western-central Torres Strait Language, or Kalaw Lagaw Ya, is spoken on the southwestern, western, northern and central islands;[17] a further dialect, Kala Kawa Ya (Top Western and Western) may be distinguished.[5] It is a member of the Pama-Nyungan family of languages of Australia. Meriam Mir is spoken on the eastern islands. It is one of the four Eastern Trans-Fly languages, the other three being spoken in Papua New Guinea.[17] Torres Strait Creole, an English-based creole language, is also spoken.[5] |

諸島では2つの異なる先住民言語とクレオール語が話されている[13]。 西・中央トレス海峡語(Kalaw Lagaw Ya)は、南西部、西部、北部、中央部の島々で話されている[17]。カラ・カワ・ヤ(Top Western and Western)という方言もある[5]。 東部の島々で話されている。他の3つはパプアニューギニアで話されている[17]。 英語ベースのクレオール語であるトレス海峡クレオール語も話されている[5]。 |

| Culture Archaeological, linguistic and folk history evidence suggests that the core of Island culture is Papuo-Austronesian. The people have long been agriculturalists (evidenced, for example, by tobacco plantations on Aureed Island[18]) as well as engaging in hunting and gathering. Dugong, turtles, crayfish, crabs, shellfish, reef fish and wild fruits and vegetables were traditionally hunted and collected and remain an important part of their subsistence lifestyle. Traditional foods play an important role in ceremonies and celebrations even when they do not live on the islands. Dugong and turtle hunting as well as fishing are seen as a way of continuing the Islander tradition of being closely associated with the sea.[19] The islands have long history of trade and interactions with explorers from other parts of the globe, both east and west, which has influenced their lifestyle and culture.[20] The Indigenous people of the Torres Strait have a distinct culture which has slight variants on the different islands where they live. Cultural practices share similarities with Australian Aboriginal and Papuan culture. Historically, they have an oral tradition, with stories handed down and communicated through song, dance and ceremonial performance. As a seafaring people, sea, sky and land feature strongly in their stories and art.[21] |

文化 考古学的、言語学的、民俗史的な証拠から、島の文化の中核はパプオ=オーストロネシア系であることが示唆されている。人々は狩猟や採集だけでなく、古くか ら農耕も営んできた(例えばアウリード島のタバコ農園[18])。ジュゴン、カメ、ザリガニ、カニ、貝類、サンゴ礁の魚、野生の果物や野菜は、伝統的に狩 猟や採集が行われており、今でも彼らの自給自足のライフスタイルの重要な部分を占めている。伝統的な食べ物は、島に住んでいなくても、儀式やお祝いの席で 重要な役割を果たしている。ジュゴンやウミガメの捕獲や漁業は、海と密接な関係にある島民の伝統を継承する方法と考えられている[19]。この島々には長 い交易の歴史があり、東西を問わず他の地域からの探検家との交流があり、それが彼らのライフスタイルや文化に影響を与えている[20]。 トレス海峡の先住民は、住んでいる島によって若干の違いがある独特の文化を持っている。文化的慣習はオーストラリアのアボリジニやパプア文化と類似してい る。歴史的に口承の伝統があり、歌や踊り、儀式を通して物語が伝えられ、伝えられてきた。海洋民族である彼らの物語や芸術には、海、空、陸が強く登場する [21]。 |

| Post-colonisation Post-colonisation history has seen new cultural influences on the people, most notably the place of Christianity. After the "Coming of Light" (see below), artefacts previously important to their ceremonies lost their relevance, instead replaced by crucifixes and other symbols of Christianity. In some cases the missionaries prohibited the use of traditional sacred objects, and eventually production ceased. Missionaries, anthropologists and museums "collected" a huge amount of material: all of the pieces collected by missionary Samuel McFarlane, were in London and then split between three European museums and a number of mainland Australian museums.[22] In 1898–1899, British anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon collected about 2000 objects, convinced that hundreds of art objects collected had to be saved from destruction by the zealous Christian missionaries intent on obliterating the religious traditions and ceremonies of the native islanders. Film footage of ceremonial dances was also collected.[23] The collection at Cambridge University is known as the Haddon Collection and is the most comprehensive collection of Torres Strait Islander artefacts in the world.[21] During the first half of the 20th century, Torres Strait Islander culture was largely restricted to dance and song, weaving and producing a few items for particular festive occasions.[22] In the 1960s and 1970s, researchers trying to salvage what was left of traditional knowledge from surviving elders influenced the revival of interest in the old ways of life. An Australian historian, Margaret Lawrie, employed by the Queensland State Library, spent much time travelling the Islands, speaking to local people and recording their stories, which have since influenced visual art on the Islands.[24] |

植民地化後 植民地化後の歴史は、人々に新たな文化的影響を及ぼしたが、特にキリスト教の影響は大きかった。光の到来」(下記参照)の後、それまで儀式に重要だった工 芸品はその関連性を失い、代わりに十字架やキリスト教の他のシンボルに取って代わられた。場合によっては、宣教師が伝統的な聖具の使用を禁止し、最終的に は生産が中止されることもあった。宣教師、人類学者、博物館は膨大な量の資料を「収集」した。宣教師サミュエル・マクファーレンが収集した作品はすべてロ ンドンに置かれ、その後ヨーロッパの3つの博物館とオーストラリア本土のいくつかの博物館に分割された[22]。 1898年から1899年にかけて、英国の人類学者アルフレッド・コート・ハドンは、先住民の宗教的伝統や儀式を抹殺しようとする熱心なキリスト教宣教師 による破壊から、収集された何百もの美術品を救う必要があると確信し、約2000点を収集した。ケンブリッジ大学のコレクションはハドン・コレクションと して知られ、トレス海峡諸島民の工芸品のコレクションとしては世界で最も包括的なものである[21]。 20世紀前半、トレス海峡諸島民の文化は、踊りと歌、織物、特定の祝祭のための少数の品物の生産に大きく制限されていた[22]。1960年代と1970 年代には、生き残った長老たちから伝統的な知識の残されたものを救い出そうとする研究者たちが、古い生活様式への関心の復活に影響を与えた。クイーンズラ ンド州立図書館に雇われたオーストラリアの歴史家マーガレット・ローリーは、島々を旅して地元の人々と話し、彼らの話を記録することに多くの時間を費やし た。 |

| Art See also: Indigenous Australian art  Ritual face mask from a Torres Strait Island (19th century). Mythology and culture, deeply influenced by the ocean and the natural life around the islands, have always informed traditional artforms. Featured strongly are turtles, fish, dugongs, sharks, seabirds and saltwater crocodiles, which are considered totemic beings.[20] Torres Strait Islander people are the only culture in the world to make turtleshell masks, known as krar (turtleshell) in the Western Islands and le-op (human face) in the Eastern Islands.[21] Prominent among the artforms is wame (alt. wameya), many different string figures.[25][26][27] Elaborate headdresses or dhari (also spelt dari[28]), as featured on the Torres Strait Islander Flag, are created for the purposes of ceremonial dances.[29] The Islands have a long tradition of woodcarving, creating masks and drums, and carving decorative features on these and other items for ceremonial use. From the 1970s, young artists were beginning their studies at around the same time that a significant re-connection to traditional myths and legends was happening. Margaret Lawrie's publications, Myths and Legends of the Torres Strait (1970) and Tales from the Torres Strait (1972), reviving stories which had all but been forgotten, influenced the artists greatly.[30][31] While some of these stories had been written down by Haddon after his 1898 expedition to the Torres Strait,[32] many had subsequently fallen out of use or been forgotten.  Torres Islanders dance on Yorke Island, 1931 In the 1990s a group of younger artists, including the award-winning Dennis Nona (b.1973), started translating these skills into the more portable forms of printmaking, linocut and etching, as well as larger scale bronze sculptures. Other outstanding artists include Billy Missi (1970-2012), known for his decorated black and white linocuts of the local vegetation and eco-systems, and Alick Tipoti (b.1975). These and other Torres Strait artists have greatly expanded the forms of Indigenous art within Australia, bringing superb Melanesian carving skills as well as new stories and subject matter.[21] The College of Technical and Further Education on Thursday Island was a starting point for young Islanders to pursue studies in art. Many went on to further art studies, especially in printmaking, initially in Cairns, Queensland and later at the Australian National University in what is now the School of Art and Design. Other artists such as Laurie Nona, Brian Robinson, David Bosun, Glen Mackie, Joemen Nona, Daniel O'Shane and Tommy Pau are known for their printmaking work.[24] An exhibition of Alick Tipoti's work, titled Zugubal, was mounted at the Cairns Regional Gallery in July 2015.[33][34] |

アート こちらも参照: オーストラリア先住民アート  トレス海峡諸島の儀式用フェイスマスク(19世紀)。 神話と文化は、海や島々の周りの自然から深い影響を受け、伝統的な芸術様式に常に影響を与えてきた。カメ、魚、ジュゴン、サメ、海鳥、海水ワニなどが強く取り上げられており、これらはトーテム的な存在と考えられている[20]。 トレス海峡諸島の人々は、西部の島々ではクラール(亀の甲羅)、東部の島々ではル・オップ(人間の顔)として知られる亀の甲羅のマスクを作る世界で唯一の文化である[21]。 ワメ(alt.wameya)、様々な弦楽器[25][26][27]は、芸術の中で顕著である。 トレス海峡諸島旗に描かれているような精巧な頭飾りやダリ(dhariとも表記される[28])は、儀式的な踊りのために作られる[29]。 トレス海峡諸島には木彫りの長い伝統があり、仮面や太鼓を作り、儀式用の装飾を彫り込んでいる。1970年代以降、伝統的な神話や伝説との重要な結びつき が復活したのとほぼ同時期に、若い芸術家たちが研究を始めた。マーガレット・ローリーが出版した『トーレス海峡の神話と伝説』(Myths and Legends of the Torres Strait、1970年)と『トーレス海峡の物語』(Tales from the Torres Strait、1972年)は、忘れ去られていた物語を蘇らせ、芸術家たちに大きな影響を与えた[30][31]。これらの物語のいくつかは、ハドンが 1898年にトーレス海峡を探検した後に書き留めたものであったが[32]、多くはその後使われなくなったり、忘れ去られたりしていた。  ヨーク島で踊るトレス諸島の人々、1931年 1990年代には、受賞歴のあるデニス・ノナ(Dennis Nona、1973年生まれ)をはじめとする若手アーティストたちが、これらの技術をより持ち運びやすい版画、リノカット、エッチング、そしてよりスケー ルの大きなブロンズ彫刻に転用し始めた。その他の傑出したアーティストには、地元の植生や生態系をモノクロのリノカットで装飾したことで知られるビリー・ ミッシ(Billy Missi 1970-2012)、アリック・ティポティ(Alick Tipoti 1975年生)などがいる。これらのアーティストや他のトレス海峡出身アーティストは、オーストラリアにおける先住民アートの形態を大きく広げ、優れたメ ラネシア彫刻の技術や新しいストーリーや題材をもたらした[21]。当初はクイーンズランド州ケアンズで、後にオーストラリア国立大学の現在のアート・デ ザイン学部で、版画を中心とした芸術の勉強を続けた。ローリー・ノナ、ブライアン・ロビンソン、デヴィッド・ボサン、グレン・マッキー、ジョエメン・ノ ナ、ダニエル・オシェーン、トミー・パウなどのアーティストも版画作品で知られている[24]。 2015年7月にケアンズ・リージョナル・ギャラリーでZugubalと題されたアリック・ティポティの作品展が開催された[33][34]。 |

| Music and dance Main articles: Indigenous music of Australia and Indigenous dance of Australia For Torres Strait Islander people, singing and dancing is their "literature" – "the most important aspect of Torres Strait lifestyle. The Torres Strait Islanders preserve and present their oral history through songs and dances;...the dances act as illustrative material and, of course, the dancer himself is the storyteller" (Ephraim Bani, 1979). There are many songs about the weather; others about the myths and legends; life in the sea and totemic gods; and about important events. "The dancing and its movements express the songs and acts as the illustrative material".[35] Dance is also major form of creative and competitive expression. "Dance machines" (hand held mechanical moving objects), clappers and headdresses (dhari/dari) enhance the dance performances.[29] Dance artefacts used in the ceremonial performances relate to Islander traditions and clan identity, and each island group has its own performances.[36] Artist Ken Thaiday Snr is renowned for his elaborately sculptured dari, often with moving parts and incorporating the hammerhead shark, a powerful totem.[36][37] Christine Anu is an ARIA Award-winning singer-songwriter of Torres Strait Islander heritage, who first became popular with her cover version of the song "My Island Home" (first performed by the Warumpi Band).[38] Sports A picture of Jesse Williams in American football gear, showing their tattoos. Jesse Williams, who won 2013 Super Bowl with the Seattle Seahawks. Sports are popular among Torres Strait Islanders and the community has many sporting stars in Australian and international sports. Sporting events bring together people from across the different islands and help to connect the Torres Strait with mainland Australia and Papua New Guinea. Rugby league is especially popular, including the annual 'Island of Origin' tournament between teams from different islands. Basketball is also extremely popular.[39] Famous sports-people include Muara (Lifu) Wacando, who was awarded a gold medal by the Royal Humane Society for her sea rescue during the 1899 Cyclone Mahina; 1964 Olympic basketballer Michael Ah Matt; 1976 Paralympian field athlete Harry Mosby; 1980 and 1984 Olympic basketballer Danny Morseu; NBA players Patty Mills and Nathan Jawai; and 2013 Super Bowl winner Jesse Williams. |

音楽とダンス 主な記事 オーストラリアの先住民音楽、オーストラリアの先住民ダンス トレス海峡諸島の人々にとって、歌と踊りは「文学」であり、「トレス海峡のライフスタイルの最も重要な側面」である。トレス海峡諸島民は、歌と踊りを通し て自分たちの口承史を保存し、提示している...踊りは説明の材料として機能し、もちろんダンサー自身が語り部である」(Ephraim Bani, 1979)。天候に関する歌、神話や伝説に関する歌、海での生活やトーテムの神々に関する歌、重要な出来事に関する歌などが多い。「踊りとその動きは歌を 表現し、説明の材料として機能する」[35]。 ダンスはまた、創造的で競争的な表現の主要な形態でもある。「ダンス・マシン」(手に持つ機械的な動く物体)、拍子木、頭飾り(ダリ/ダリ)はダンス・パ フォーマンスを盛り上げる[29]。儀式的なパフォーマンスで使用されるダンス・アーティファクトは、島民の伝統や氏族のアイデンティティに関連してお り、各島のグループは独自のパフォーマンスを持っている[36]。 アーティストのケン・タイデー氏は、精巧な彫刻を施したダリで有名であり、しばしば可動部を持ち、強力なトーテムであるシュモクザメを組み込んでいる[36][37]。 クリスティン・アヌはARIA賞を受賞したトレス海峡諸島民の血を引くシンガーソングライターで、「マイ・アイランド・ホーム」(初演はワルンピ・バンド)のカバーバージョンで人気を博した[38]。 スポーツ アメリカンフットボールウェアに身を包み、タトゥーを見せるジェシー・ウィリアムズの写真。 シアトル・シーホークスで2013年のスーパーボウルを制したジェシー・ウィリアムズ。 スポーツはトレス海峡諸島民の間で人気があり、このコミュニティにはオーストラリアや世界のスポーツ界で活躍する多くのスポーツスターがいる。スポーツ・ イベントは、さまざまな島から人々を集め、トレス海峡とオーストラリア本土やパプアニューギニアをつなぐ役割を果たしている。ラグビー・リーグは特に人気 があり、毎年異なる島のチームによる「アイランド・オブ・オリジン」トーナメントが開催される。バスケットボールも非常に人気がある[39]。 有名なスポーツ選手としては、1899年のサイクロン「マヒナ」での海難救助で王立人道協会から金メダルを授与されたムアラ(リフ)・ワカンド、1964 年オリンピックのバスケットボール選手マイケル・アー・マット、1976年パラリンピックのフィールド選手ハリー・モスビー、1980年と1984年オリ ンピックのバスケットボール選手ダニー・モルセウ、NBA選手のパティ・ミルズとネイサン・ジャワイ、2013年スーパーボウル優勝者のジェシー・ウィリ アムズなどがいる。 |

| Religion and beliefs The people still have their own traditional belief systems. Stories of the Tagai, their spiritual belief system, represent Torres Strait Islanders as sea people, with a connection to the stars, as well as a system of order in which everything has its place in the world.[40] They follow the instructions of the Tagai. One Tagai story depicts the Tagai as a man standing in a canoe. In his left hand, he holds a fishing spear, representing the Southern Cross. In his right hand, he holds a sorbi (a red fruit). In this story, the Tagai and his crew of 12 were preparing for a journey, but before the journey began, the crew consumed all the food and drink they planned to take. So the Tagai strung the crew together in two groups of six and cast them into the sea, where their images became star patterns in the sky. These patterns can be seen in the star constellations of Pleiades and Orion.[41] Some Torres Strait Islander people share beliefs similar to the Aboriginal peoples' Dreaming and "Everywhen" concepts, passed down in oral history.[42] Oral history One of the stories passed down in oral history tells of four brothers (bala) named Malo, Sagai, Kulka and Siu, who paddled their way up to the central and eastern islands from Cape York (Kay Daol Dai, meaning "big land"), and each established his own tribal following. Sagai landed at Iama Island (known as Yam), and after a time assumed a god-like status. The crocodile was his totem. Kulka settled on Aureed Island, and attained a similar status, as god of hunting. His totem was the fish known as gai gai (Trevally). Siu settled on Masig, becoming god of dancing, with the tiger shark (baidam) as his totem. The eldest brother, Malo, went on to Mer and became responsible for setting out a set of rules for living, a combination of religion and law, which were presented by Eddie Mabo in the famous Mabo native title case in 1992.[43] The cult of Kulka was in evidence on Aureed Island with the finding of a "skull house" by the rescuers of survivors two years after the wreck of Charles Eaton, in 1836.[18] Introduction of Christianity Further information: All Saints Anglican Church, Darnley Island § History A picture of a small white church with spires, nestled next to palm trees and bushes. All Saints Anglican Church on Erub (Darnley Island). From the 1870s, Christianity spread throughout the islands, and it remains strong today among Torres Strait Islander people everywhere. Christianity was first brought to the islands by the London Missionary Society (LMS) mission led by Rev. Samuel Macfarlane[44] and Rev. Archibald Wright Murray,[45][46] who arrived on Erub (Darnley Island) on 1 July 1871 on the schooner Surprise,[47][48][49][50] a schooner[a] chartered by the LMS.[55][56] They sailed to the Torres Strait after the French Government had demanded the removal of the missionaries from the Loyalty Islands and New Caledonia in 1869.[46] Eight teachers and their wives from Loyalty Islands arrived with the missionaries on the boat from Lifu.[45] Clan elder and warrior Dabad greeted them on their arrival. Ready to defend his land and people, Dabad walked to the water's edge when McFarlane dropped to his knees and presented the Bible to Dabad. Dabad accepted the gift, interpreted as the "Light", introducing Christianity to the Torres Strait Islands. The people of the Torres Strait Islands adopted the Christian rituals and ceremonies and continued to uphold their connection to the land, sea and sky, practising their traditional customs, and cultural identity referred to as Ailan Kastom.[44] Religious affiliations of Torres Strait islanders in localities with significant share of Torres Strait islander population.[4] The Islanders refer to this event as "The Coming of the Light", also known as Zulai Wan,[47][57] or Bi Akarida,[48] and all Island communities celebrate the occasion annually on 1 July.[58][47] Coming of the Light, an episode in the 2013 documentary television series Desperate Measures, features the annual event.[59] However the coming of Christianity did not spell the end of the people's traditional beliefs; their culture informed their understanding of the new religion, as the Christian God was welcomed and the new religion was integrated into every aspect of their everyday lives.[57] Religious affiliation, 2016 census In the 2016 Census, a total of 20,658 Torres Strait Islander people (out of a total of 32,345) and 15,586 of both Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal identity (out of 26,767) reported adherence to some form of Christianity. (Across the whole of Australia, the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population were broadly similar with 54% (vs 55%) reporting a Christian affiliation, while less than 2% reported traditional beliefs as their religion, and 36% reported no religion.)[60] |

宗教と信仰 トレス海峡諸島の人々は、今でも独自の伝統的な信仰体系を持っている。彼らの精神的な信仰体系であるタガイ(Tagai)の物語は、トレス海峡諸島民を海 の民として表現しており、星々とのつながりを持ち、すべてのものが世界の中で居場所を持つという秩序体系を持っている[40]。 あるタガイの物語では、タガイはカヌーの中に立っている男として描かれている。左手には南十字星を表す釣りの槍を持っている。右手にはソルビ(赤い果実) を持っている。この物語では、タガイと12人の乗組員が旅の準備をしていたが、旅が始まる前に乗組員が予定していた食べ物や飲み物をすべて消費してしまっ た。そこでタガイは乗組員を6人ずつ2つのグループに分けて海に投げ捨てた。これらの模様は、プレアデス星座とオリオン座に見ることができる[41]。 トレス海峡諸島民の中には、口承史で伝えられてきたアボリジニのドリーミングや「Everywhen」の概念に似た信仰を共有する人々もいる[42]。 オーラルヒストリー オーラルヒストリーに伝わる話のひとつに、マロ、サガイ、クルカ、シウという4人の兄弟(バラ)が、ヨーク岬(Kay Daol Dai、「大きな土地」の意)から中央と東の島々へと漕ぎ登り、それぞれ自分の部族を築いたという話がある。サガイはイアマ島(通称ヤム)に上陸し、やが て神のような地位を築いた。ワニは彼のトーテムだった。クルカはアウリード島に定住し、狩猟の神として同様の地位を得た。彼のトーテムはガイガイと呼ばれ る魚だった。シウはマシグ島に定住し、タイガーシャーク(バイダム)をトーテムとする踊りの神となった。長兄のマロはメルに行き、宗教と法律を組み合わせ た生活規則を定める責任者となり、1992年の有名なマボ先住民権裁判でエディ・マボによって提示された[43]。 クルカのカルトは、1836年にチャールズ・イートンが難破した2年後に生存者の救助隊が「頭蓋骨の家」を発見したことでオーレイド島で証明された[18]。 キリスト教の導入 さらなる情報 オール・セインツ英国国教会、ダーンリー島§歴史 ヤシの木と茂みに囲まれた、尖塔のある小さな白い教会の写真。 エルブ(ダーンリー島)のオール・セインツ英国国教会。 1870年代以降、キリスト教は島全体に広まり、現在もトレス海峡諸島の人々の間で強く信仰されている。キリスト教は、サミュエル・マクファーレン牧師 [44]とアーチボルド・ライト・マレー牧師[45][46]に率いられたロンドン宣教協会(LMS)のミッションによって初めて島々にもたらされ、彼ら は1871年7月1日にLMSがチャーターしたスクーナー船サプライズ号[47][48][49][50]でエルブ(ダーンリー島)に到着した。 [1869年にフランス政府がロイヤリティ諸島とニューカレドニアからの宣教師の撤去を要求した後、彼らはトーレス海峡に航海した[46]。ロイヤリティ 諸島から8人の教師とその妻が宣教師とともにリフーから船で到着した[45]。 氏族の長老であり戦士であったダバドは、彼らの到着を出迎えた。マクファーレンが膝をついて聖書をダバドに贈ると、ダバドは自分の土地と人々を守る覚悟を 決めて水際まで歩いていった。ダバドはその贈り物を「光」と解釈して受け取り、トレス海峡諸島にキリスト教を紹介した。トレス海峡諸島の人々は、キリスト 教の儀式や儀礼を採用し、土地、海、空とのつながりを守り続け、伝統的な習慣を実践し、アイラン・カストムと呼ばれる文化的アイデンティティを確立した [44]。 トレス海峡諸島民の人口比率が高い地方におけるトレス海峡諸島民の宗教的所属[4]。 島民はこの行事を「光の到来」と呼び、ズライ・ワン[47][57]またはビ・アカリダ[48]とも呼ばれ、すべての島のコミュニティが毎年7月1日にこ の行事を祝っている[58][47]。2013年のドキュメンタリーテレビシリーズ『デスパレート・メジャーズ』のエピソード「光の到来」では、毎年この 行事が取り上げられている[59]。 キリスト教の神は歓迎され、新しい宗教は日常生活のあらゆる側面に統合されたため、彼らの文化は新しい宗教に対する彼らの理解に影響を与えた[57]。 2016年国勢調査における宗教構成 2016年の国勢調査では、トレス海峡諸島民の合計20,658人(合計32,345人中)、トレス海峡諸島民とアボリジニの両方のアイデンティティを持 つ15,586人(合計26,767人中)が何らかのキリスト教を信仰していると回答した。(オーストラリア全体では、先住民および非先住民の54%(対 55%)がキリスト教を信仰していると回答し、伝統的な信仰を宗教として回答したのは2%未満、無宗教と回答したのは36%で、ほぼ同様であった) [60]。 |

| Traditional adoptions A traditional cultural practice, known as kupai omasker, allows adoption of a child by a relative or community member for a range of reasons. The reasons differ depending on which of the many Torres Islander cultures the person belongs to, with one example being "where a family requires an heir to carry on the important role of looking after land or being the caretaker of land". Other reasons might relate to "the care and responsibility of relationships between generations".[61] There had been a problem in Queensland law, where such adoptions are not legally recognised by the state's Succession Act 1981,[62] with one issue being that adopted children are not able to take on the surname of their adoptive parents.[61] On 17 July 2020 the Queensland Government introduced a bill in parliament to legally recognise the practice.[63] The bill was passed as the Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa Act 2020 ("For Our Children's Children") on 8 September 2020.[64] |

伝統的養子縁組 クパイ・オマスカー(kupai omasker)と呼ばれる伝統的な文化慣習では、様々な理由で親戚やコミュニティのメンバーによる養子縁組が認められている。その理由は、その人がどの トレス諸島民のどの文化に属しているかによって異なり、一例としては「一族が土地の世話や管理人という重要な役割を継承するために相続人を必要とする場 合」などがある。その他の理由としては、「世代間の関係の世話と責任」に関するものがある[61]。 クイーンズランド州法では、このような養子縁組が1981年の州相続法で法的に認められていないという問題があり[62]、養子が養父母の姓を名乗ること ができないという問題があった[61]。 2020年7月17日、クイーンズランド州政府はこの慣習を法的に認めるための法案を議会に提出した[63]。 この法案は2020年9月8日に「Meriba Omasker Kaziw Kazipa Act 2020」(「For Our Children's Children」)として可決された[64]。 |

| Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts (ACPA) Australian frontier wars Blue Water Empire Indigenous Australians Indigenous health in Australia List of Indigenous Australian firsts Papuan people Pearl hunting § Australia Torres Strait 8, relating to climate change and the Australian Government |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torres_Strait_Islanders |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報